A Comprehensive Guide to Validating CRISPR Edits in Patient-Derived Organoid Models

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to validate CRISPR-Cas9 edits in patient-derived organoids (PDOs).

A Comprehensive Guide to Validating CRISPR Edits in Patient-Derived Organoid Models

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to validate CRISPR-Cas9 edits in patient-derived organoids (PDOs). It covers the foundational principles of why PDOs offer a physiologically relevant platform for functional genomics, details step-by-step methodological protocols for editing and selection, and offers troubleshooting strategies to overcome common challenges like low knockout efficiency. Furthermore, it outlines rigorous validation techniques and discusses how to comparatively analyze edited organoids to predict therapeutic response, ultimately serving as a critical resource for enhancing the precision and clinical translation of CRISPR-based disease models in personalized oncology and beyond.

The Power of Patient-Derived Organoids in CRISPR-Based Disease Modeling

Why Patient-Derived Organoids? Recapitulating Tumor Heterogeneity and the Tumor Microenvironment

Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) have emerged as a transformative preclinical model in cancer research, bridging the gap between traditional two-dimensional cell cultures and in vivo patient responses. These three-dimensional structures faithfully maintain the histological complexity, genetic diversity, and phenotypic heterogeneity of original tumors, enabling more accurate drug screening and personalized treatment prediction. Within the specific context of CRISPR-based research, PDOs provide a physiologically relevant platform for validating gene edits and functional genetic screens. This review objectively examines the capabilities of PDO technology against alternative models, with focused analysis on its unique advantages for studying tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment interactions in genetically engineered systems.

Cancer remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide, with therapeutic efficacy often limited by tumor heterogeneity and the complex interactions within the tumor microenvironment (TME). Traditional cancer models, including two-dimensional (2D) cell lines and patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), have contributed significantly to basic cancer biology but present substantial limitations in clinical translation. Two-dimensional cell cultures undergo genetic drift over time and fail to recapitulate the three-dimensional architecture and cellular diversity of human tumors [1]. Patient-derived xenografts, while maintaining some tumor characteristics, are time-consuming, expensive, and involve species-specific limitations that compromise their predictive accuracy, particularly for immunotherapies [2].

Patient-derived organoids represent a technological advancement that addresses these limitations. PDOs are three-dimensional in vitro cultures derived directly from patient tumor samples that preserve the structural and functional characteristics of the original tissue [3]. When integrated with CRISPR technology, PDOs enable functional genetic screens and validation of gene edits within a pathologically relevant human system, accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic targets and resistance mechanisms [4] [5].

Comparative Analysis of Cancer Models

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of preclinical cancer models

| Feature | 2D Cell Cultures | Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) | Patient-Derived Organoids (PDO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architectural Fidelity | Low - monolayer growth lacks 3D structure | High - maintains in vivo architecture | High - self-organizing 3D structures that mimic microanatomy [1] |

| Tumor Heterogeneity | Limited - clonal selection during adaptation | Moderate - but mouse stromal replacement over time | High - preserves genetic and cellular diversity of original tumor [3] [6] |

| Success Rate & Establishment Time | High (weeks) | Variable, often low (months) | High efficiency across multiple cancers (weeks) [2] |

| Throughput for Drug Screening | Very high | Low | High to very high [3] |

| TME Components | Lacks stromal and immune cells | Human tumor with mouse TME | Initially epithelial; requires co-culture systems for full TME [7] |

| Genetic Stability | Low - genetic drift over time | Moderate - with clonal selection | High - maintains molecular profile of original tumor [1] |

| Cost | Low | Very high | Moderate [8] |

| CRISPR Compatibility | High but physiologically limited | Technically challenging | High and physiologically relevant [4] [5] |

| Personalized Medicine Application | Limited | Limited by throughput and time | High - suitable for clinical decision timelines [3] |

Table 2: Quantitative performance metrics of cancer models

| Parameter | 2D Cell Cultures | Patient-Derived Xenografts | Patient-Derived Organoids |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Accuracy for Clinical Response | ~5% [6] | Variable, ~60-70% | 88-100% (specific to drug classes) [3] |

| Typical Establishment Time | 2-4 weeks | 4-12 months | 2-8 weeks [2] [9] |

| Immune Component Integration | Not applicable | Limited to humanized models | Requires specific co-culture protocols [7] |

| Scalability for High-Throughput Screening | Excellent | Poor | Good to excellent [3] |

| Documented Success Rates Across Cancers | High but irrelevant | Variable (30-80%) | Consistently high (70-90%) [1] |

PDOs in CRISPR-Based Research: Experimental Workflows

CRISPR Screening in Organoid Models

The integration of CRISPR technology with PDOs has created powerful platforms for functional genomics in cancer research. Recent advances enable multiple CRISPR screening modalities in organoids, including knockout (CRISPRko), interference (CRISPRi), activation (CRISPRa), and single-cell approaches [5]. The general workflow involves:

- Organoid Generation: Tumor tissue is dissociated mechanically and/or enzymatically into single cells or small aggregates, then embedded in an extracellular matrix (typically Matrigel) and cultured in specialized media containing tissue-specific growth factors [1] [9].

- CRISPR System Delivery: Lentiviral transduction delivers Cas9 or dCas9 fused to transcriptional regulators (KRAB for repression, VPR for activation) along with guide RNA (gRNA) libraries targeting genes of interest.

- Selection and Expansion: Transduced organoids are selected using antibiotics (e.g., puromycin) and expanded to maintain >1000x coverage of the gRNA library.

- Phenotypic Screening: Organoids are subjected to experimental conditions (e.g., drug treatment), with gRNA abundance monitored by next-generation sequencing to identify genes influencing drug response [5].

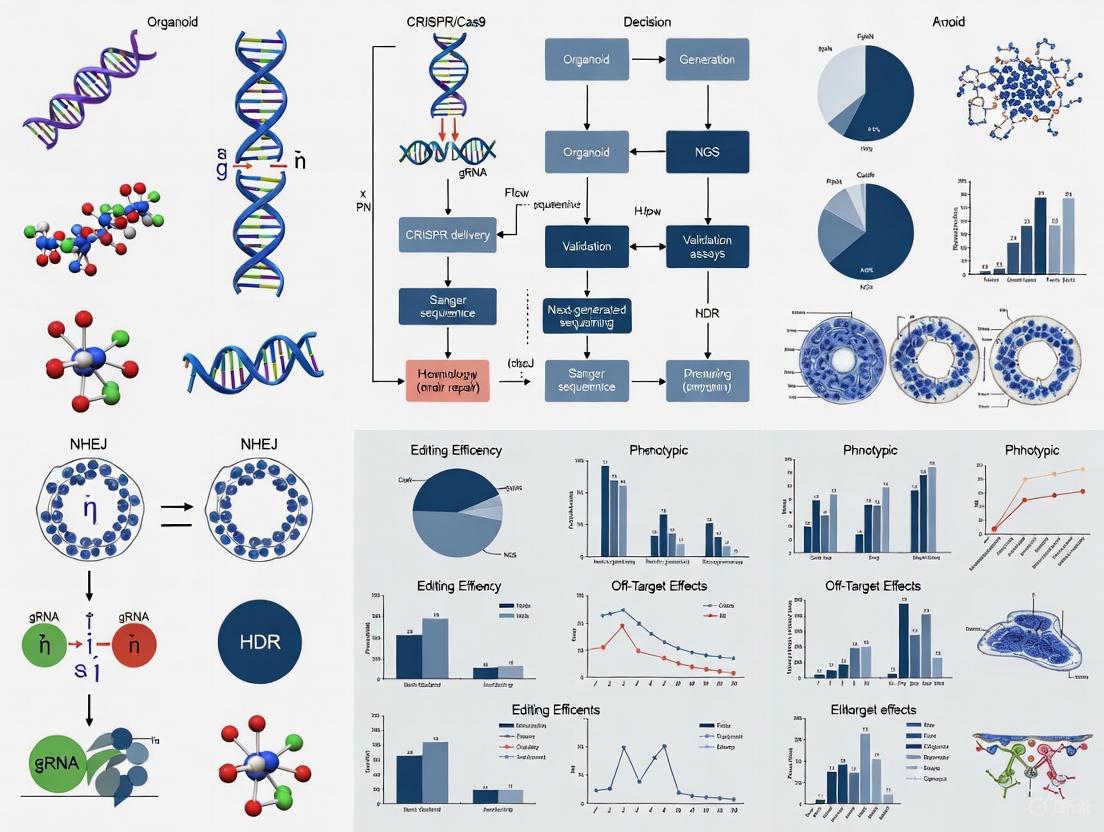

Figure 1: CRISPR screening workflow in patient-derived organoids

Signaling Pathways Critical for Organoid Culture

Successful establishment and maintenance of PDOs require careful optimization of culture conditions that activate specific signaling pathways essential for stem cell maintenance and proliferation. The core pathways include:

- Wnt/β-catenin Pathway: Activation through agonists like R-spondin and Wnt3a is crucial for LGR5+ stem cell expansion, particularly in gastrointestinal cancers [1] [6]. Notably, tumors with Wnt pathway mutations may not require exogenous Wnt activation.

- EGFR Pathway: Stimulated by epidermal growth factor (EGF) supplementation to promote cancer cell proliferation. Tumors with EGFR pathway mutations may have reduced EGF dependency [1].

- Other Pathway Modulations: Additional factors including Noggin (BMP inhibitor), FGF, and prostaglandin E2 are included in specific media formulations to support growth of organoids from different tissue types [6].

Figure 2: Key signaling pathways in organoid culture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential reagents for PDO culture and CRISPR screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrix | Matrigel, BME, synthetic hydrogels (PEG, PLGA) | Provides 3D structural support for organoid growth | Batch variability in natural matrices; synthetic options offer reproducibility [1] |

| Growth Factors | EGF, R-spondin, Wnt3a, Noggin, FGF | Activate signaling pathways for stem cell maintenance | Tissue-specific requirements; mutated pathways may alter factor dependency [1] [6] |

| CRISPR Components | Lentiviral vectors, Cas9/dCas9, gRNA libraries | Enable genetic perturbation screens | Delivery efficiency optimization required; inducible systems offer temporal control [4] [5] |

| Dissociation Reagents | Collagenase, Trypsin-EDTA, Accutase | Tissue dissociation for organoid establishment and passaging | Optimization needed to preserve viability while achieving single cells [9] |

| Culture Media | Advanced DMEM/F12, B27, N2 supplements | Nutritional support with defined components | Formulations must be tailored to cancer type [9] |

| AG 555 | AG 555, CAS:149092-34-2, MF:C19H18N2O3, MW:322.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Camaldulenic acid | Camaldulenic Acid | Camaldulenic acid is a natural oleanane-type triterpenoid for anti-inflammatory research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Recapitulating Tumor Heterogeneity

A defining feature of PDOs is their ability to preserve the genetic and cellular heterogeneity of the original tumor, a critical advantage for both basic research and therapeutic testing.

Molecular and Histological Fidelity

Multiple studies have demonstrated that PDOs maintain the histological architecture, gene expression profiles, and mutation spectrum of their parental tumors [3]. Comprehensive genomic analyses including whole-exome sequencing and RNA sequencing show that PDOs retain driver mutations, copy number alterations, and transcriptional landscapes even after extended culture periods [3] [7]. This genetic stability enables reliable long-term studies not feasible with traditional cell lines that accumulate genetic drift.

Functional Heterogeneity in Drug Responses

The preservation of tumor heterogeneity in PDOs translates to variable drug responses that mirror patient outcomes. In a landmark study of metastatic gastrointestinal cancers, PDOs predicted clinical response with 88% accuracy and non-response with 100% accuracy [3]. This predictive power demonstrates how PDOs capture functional heterogeneity that directly impacts therapeutic efficacy. When combined with CRISPR screening, this platform enables systematic mapping of gene-drug interactions across heterogeneous cellular populations, identifying genetic determinants of drug sensitivity and resistance [5].

Modeling the Tumor Microenvironment

While early PDO cultures primarily contained epithelial components, recent methodological advances have enabled more complete recapitulation of the tumor microenvironment.

Current Limitations and Advanced Co-culture Systems

Standard PDO protocols typically yield cultures dominated by epithelial cancer cells with limited stromal components [3]. This represents a significant limitation for studying therapies that target microenvironmental interactions, particularly immunotherapies. To address this gap, researchers have developed several advanced culture systems:

- Immune Cell Co-culture: Peripheral blood lymphocytes can be co-cultured with PDOs to generate tumor-reactive T cells and assess T-cell-mediated killing [3] [7].

- Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) System: This technique cultures finely sliced tumor tissue with stromal components on collagen-coated filters, preserving native TME elements including fibroblasts and immune cells for up to one month [1].

- Microfluidic and Organ-on-Chip Platforms: These systems enable precise control of microenvironmental conditions and facilitate real-time monitoring of tumor-stromal interactions [8] [10].

TME Modeling in Renal Cell Carcinoma

The importance of TME recapitulation is particularly evident in renal cell carcinoma (RCC), where systemic therapies predominantly target microenvironmental components rather than cancer cells directly. RCC treatments include anti-angiogenic agents targeting VEGF pathway and immune checkpoint inhibitors that reverse T-cell exhaustion [7]. PDO models that incorporate relevant TME elements provide critical platforms for evaluating these therapeutic modalities and identifying novel combination strategies.

Patient-derived organoids represent a significant advancement in cancer modeling that effectively balances physiological relevance with experimental tractability. Their demonstrated ability to recapitulate tumor heterogeneity and, with advanced culture methods, key aspects of the tumor microenvironment positions PDOs as indispensable tools for modern cancer research. When integrated with CRISPR screening technologies, PDOs enable systematic functional genomics studies in biologically relevant contexts, accelerating the identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets. While challenges remain in standardizing protocols and fully recapitulating microenvironment complexity, continued refinement of PDO technology promises to enhance both basic cancer biology and clinical translation in precision oncology.

The field of functional genomics has been revolutionized by the advent of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins, which provide unprecedented capability for targeted genome editing. Since its initial application in mammalian systems, CRISPR-Cas9 technology has transformed our approach to investigating gene function, enabling systematic perturbation of the genome with remarkable precision and efficiency. This technology has become indispensable for mapping complex genotype-phenotype relationships, particularly in cancer research, drug target identification, and understanding disease mechanisms [11].

The original CRISPR-Cas9 system from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) functions as a targeted endonuclease, creating double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA at locations specified by a guide RNA (gRNA). These breaks activate the cell's native DNA repair mechanisms—primarily non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which often results in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, or homology-directed repair (HDR), which allows for precise gene modifications using a DNA template [11] [12]. While this system provides a powerful tool for loss-of-function studies, limitations including off-target effects, dependence on specific protospacer adjacent motifs (PAMs), and delivery challenges have prompted the development of numerous alternatives and enhancements [13].

The integration of these CRISPR tools with patient-derived organoids (PDOs) represents a particularly promising advancement for precision medicine. PDOs are three-dimensional cell culture systems derived from patient tumor tissue that retain the genetic variability and phenotypic diversity characteristic of the primary tumor, providing a physiologically relevant platform for studying tumor biology and treatment response [4] [14]. When combined with CRISPR technologies, PDOs enable functional genomic screens within a model that closely mimics the in vivo environment, accelerating the translation of basic research insights into clinical applications [4] [5].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of current CRISPR-based editing tools, with particular emphasis on their applications in functional genomics research using patient-derived organoid models.

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR Nucleases and Alternatives

Limitations of Standard CRISPR-Cas9

The widespread adoption of SpCas9 has revealed several significant limitations for therapeutic applications and functional genomics research. One primary concern is its tendency to create double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in DNA, which can lead to unintended deletions, chromosomal translocations, and potentially harmful mutations [13]. Additionally, SpCas9 demonstrates a measurable risk of off-target editing, where cleavage occurs at unintended genomic sites with sequence similarity to the target, raising substantial safety concerns for clinical applications [13] [15]. Practical delivery challenges also exist due to the large size of SpCas9 (approximately 4.2 kb), which exceeds the packaging capacity of many viral delivery vectors, particularly adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) that have a cargo capacity of around 4.5kb [13].

Emerging Nuclease Alternatives

To address these limitations, several engineered nucleases and natural alternatives have been developed, each with distinct advantages for specific applications.

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR Nucleases and Their Properties

| Nuclease | Size (aa) | PAM Sequence | Cut Type | Key Advantages | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 (Standard) | 1368 | NGG | Blunt-end DSBs | Well-characterized, reliable | Gene knockouts, basic screening |

| hfCas12Max | 1080 | TN or TTN | Staggered-end DSBs | Compact size, high specificity, broad PAM recognition | CAR-T, gene therapies requiring precision |

| eSpOT-ON (ePsCas9) | ~1100* | NGG | Staggered-end DSBs | High on-target, low off-target, minimizes translocation risk | Safer gene correction, therapeutic knock-ins |

| SaCas9 | ~1053* | NNGRRN | Blunt-end DSBs | Compact size, fits in AAV vectors | in vivo gene therapies |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | ~1300* | T-rich | Staggered-end DSBs | Enhances HDR, targets AT-rich regions | Multiplexed editing, gene knock-in |

| dCas9 | 1368 (inactive) | NGG | No cleavage | Targeted modulation without DSBs | CRISPRi, CRISPRa, base editing |

| Cas3 | Varies | None | Large deletions (>10kb) | Complete functional knockouts | Gene knockout studies |

Note: Exact sizes for some nucleases not provided in search results; approximate sizes based on comparative descriptions. DSBs = Double-Stranded Breaks; PAM = Protospacer Adjacent Motif.

The hfCas12Max nuclease sets a new standard in clinical gene editing with its compact design (1080 amino acids) paired with staggered-end cut outcomes that enhance precision and versatility. Its broad PAM recognition (TN or TTN) significantly expands target accessibility, while demonstrated robust on-target editing with lower off-target effects than SpCas9 or other Cas12 variants in primary human T-cells and mice makes it ideal for applications where precision is critical [13].

The eSpOT-ON (ePsCas9) nuclease, originally identified in Parasutterella secunda, delivers high on-target precision with extremely low off-target editing while recognizing the same NGG PAM as SpCas9. Unlike engineered high-fidelity SpCas9 variants where reduced off-target editing often comes at the cost of on-target activity, eSpOT-ON provides an optimal balance of high on-target activity while maintaining reduced off-target effects. It creates staggered-end DSBs that minimize translocation risks, ensuring safer and more reliable gene editing [13].

For therapeutic applications requiring viral delivery, SaCas9 (from Staphylococcus aureus) offers a significant advantage with its smaller size (approximately 1kb smaller than SpCas9), making it perfectly suited for in vivo gene therapies delivered via adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) [13]. Similarly, Cas12a (Cpf1) creates staggered-end cuts that enhance homology-directed repair efficiency and can target AT-rich regions of the genome inaccessible to SpCas9 [13].

Beyond standard nuclease approaches, dCas9 (catalytically dead Cas9) represents a fundamentally different approach—it lacks cleavage activity but retains DNA-binding capability, enabling targeted modulation without DSBs. This makes it valuable for CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), CRISPR activation (CRISPRa), base editing, and epigenome editing applications where precision is required without DNA cutting [13] [11].

Advanced CRISPR Systems for Specialized Applications

CRISPR Transcriptional Modulation

The development of nuclease-deficient Cas9 (dCas9) has enabled sophisticated transcriptional control systems that modulate gene expression without altering DNA sequence. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) utilizes dCas9 fused to repressive domains like the Krüppel-associated box (KRAB) to block transcription initiation or elongation, effectively knocking down gene expression [11] [16]. Conversely, CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) fuses dCas9 to transcriptional activation domains (e.g., VP64, p65, Rta) to enhance gene expression, enabling gain-of-function studies [11] [16].

These systems are particularly valuable for functional genomics in patient-derived organoids, as demonstrated by recent research showing that inducible CRISPRi and CRISPRa systems can be successfully implemented in human 3D gastric organoids to regulate endogenous gene expression with precise temporal control [5]. The ability to perform both loss-of-function and gain-of-function screens in the same model system provides complementary datasets that increase confidence in target identification and validation [16].

Large-Scale DNA Engineering

For applications requiring insertion of large DNA fragments, traditional HDR-based approaches face efficiency challenges. Recent advances have integrated CRISPR with recombinases and transposases to enable more efficient large-scale DNA engineering. CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems represent a particularly promising development, allowing integration of genetic elements up to 30 kb without introducing double-strand breaks [17].

CAST systems utilize RNA-guided DNA binding to target transposition to specific genomic loci. Type I-F CAST systems have demonstrated efficient insertion of donor sequences up to approximately 15.4 kb in E. coli, while type V-K variants have accommodated inserts as large as 30 kb [17]. Although applications in mammalian cells are still in early development (with current editing efficiencies around 1-3% in HEK293 cells), these systems show tremendous potential for therapeutic applications requiring large gene insertions [17].

Table 2: Advanced CRISPR Systems for Specialized Applications

| System Type | Key Components | Mechanism of Action | Editing Outcomes | Therapeutic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Editors | dCas9 fused to deaminase enzymes | Chemical conversion of base pairs without DSBs | C→T or A→G conversions | Corrects point mutations responsible for genetic diseases |

| Prime Editing | PE2 protein + pegRNA | Reverse transcriptase template integration | Targeted insertions, deletions, all base-to-base conversions | Broad therapeutic potential for diverse mutations |

| CRISPRi/a | dCas9 fused to transcriptional regulators | Modulation of transcription without DNA cleavage | Gene expression knockdown (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) | Disease modeling, target validation |

| CAST Systems | Cas protein + transposase complex | RNA-guided transposition without DSBs | Large DNA insertions (up to 30kb) | Insertion of therapeutic genes |

| Epigenetic Editors | dCas9 fused to chromatin modifiers | Targeted histone or DNA modification | Altered chromatin state and gene expression | Potential for treating epigenetic disorders |

Bioinformatics and Deep Learning Approaches

The growing complexity of CRISPR toolkits has increased the importance of sophisticated bioinformatics tools for experimental design and analysis. Current computational approaches address multiple aspects of CRISPR workflow, including gRNA design, off-target prediction, and analysis of screening data [12]. Tools such as CRISPResso, CHOPCHOP, and Cas-OFFinder are commonly used for these purposes, though most existing tools address narrow tasks, necessitating fragmented workflows [12].

Machine learning and deep learning tools are projected to become leading methods for predicting CRISPR on-target and off-target activity. However, current prediction accuracy is limited by the amount of available training data, and as more sequence features are identified and incorporated into these tools, predictions are expected to better align with experimental results [15]. The increasing focus on ML/DL approaches for predicting off-target sites necessitates large and easily searchable databases to support algorithm training and validation [15].

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR Screening in Patient-Derived Organoids

Workflow for CRISPR Screening in 3D Organoids

The integration of CRISPR screening with patient-derived organoids requires specialized protocols to address the technical challenges of 3D culture systems while maintaining high editing efficiency and library representation. Recent research has established robust methodologies for large-scale genetic screens in primary human gastric organoids [5].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for CRISPR screening in patient-derived 3D organoids, highlighting key steps from model establishment to data analysis.

Detailed Methodological Components

Organoid Line Engineering

Establishing a suitable organoid model is the foundational step for CRISPR screening. For the human gastric tumor organoid model described by [5], TP53/APC double knockout (DKO) organoid lines were established by sequentially disrupting these common oncogenic loci from non-neoplastic human gastric organoids. This engineered model provides a relatively homogeneous genetic background, minimizing variability and enabling precise identification of gene-function relationships. Stable Cas9-expressing organoid lines are generated using lentiviral transduction, with integration confirmed through fluorescence reporters and functional assays [5].

Library Design and Transduction

For genome-wide screens, a pooled lentiviral sgRNA library is designed to target the gene set of interest. A typical approach utilizes approximately 12,461 sgRNAs targeting 1093 genes, with each gene targeted by ~10 sgRNAs alongside 750 negative control non-targeting sgRNAs [5]. Following lentiviral transduction, the number of infected cells should provide cellular coverage of >1000 cells per sgRNA from the outset to maintain library representation. After puromycin selection (typically 2 days post-transduction), a subpopulation is harvested as a reference time point (T0), while the remaining organoids continue culture under the same cellular coverage throughout the screening period [5].

Inducible System Implementation

For temporal control of gene expression, inducible CRISPRi and CRISPRa systems can be engineered using a sequential two-vector lentiviral approach. First, organoid lines expressing rtTA are generated, followed by introduction of a doxycycline-inducible cassette containing a dCas9 fusion protein (dCas9-KRAB for CRISPRi or dCas9-VPR for CRISPRa) along with a fluorescent reporter (e.g., mCherry). Stable lines are established by sorting fluorescent-positive cells after induction, with tight control of the inducible cassettes confirmed through protein degradation upon doxycycline withdrawal and rapid restoration after re-induction [5].

Screening and Data Analysis

During the screening phase, organoids are cultured under experimental conditions (e.g., drug treatment) for a predetermined period, typically 16 population doublings or approximately 28 days [5]. Relative sgRNA abundance is measured by next-generation sequencing at endpoint compared to the T0 reference, with increasing or decreasing sgRNA abundance indicating growth advantages or disadvantages, respectively. Bioinformatic tools such as MAGeCK are commonly employed for statistical analysis of screen results, identifying significantly enriched or depleted sgRNAs and their corresponding genes [12] [16].

Research Reagent Solutions for Organoid-CRISPR Workflows

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Organoid Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations for Organoid Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | hfCas12Max, eSpOT-ON, SaCas9, dCas9-VPR, dCas9-KRAB | Targeted DNA modification or transcriptional control | Size constraints for viral delivery; PAM compatibility with target sites |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lentivirus, AAV, Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Introduction of editing components into cells | AAV capacity limitations; lentiviral tropism for organoid cells |

| Library Resources | Genome-wide sgRNA libraries, Targeted sub-libraries | High-throughput functional screening | Maintain >1000x coverage per sgRNA; include non-targeting controls |

| Selection Markers | Puromycin, Blasticidin, Fluorescent reporters | Selection of successfully transduced cells | Antibiotic sensitivity of organoid lines; FACS compatibility |

| Matrix Scaffolds | Matrigel, Synthetic hydrogels | 3D structural support for organoid growth | Batch-to-batch variability; compatibility with high-throughput screening |

| Culture Supplements | Nodal, BMP4, WNT agonists/antagonists | Maintenance of stemness and differentiation | Tissue-specific requirements; influence on editing efficiency |

The convergence of CRISPR technologies with patient-derived organoid models represents a transformative platform for functional genomics and precision oncology. The expanding toolkit of CRISPR systems—from precision nucleases like hfCas12Max and eSpOT-ON to transcriptional modulators (CRISPRi/a) and large-scale DNA engineering systems (CAST)—provides researchers with an unprecedented capability to dissect gene function in physiologically relevant models.

The successful application of these technologies requires careful consideration of experimental design, including appropriate nuclease selection based on PAM requirements, on/off-target profiles, and delivery constraints. Implementation in patient-derived organoids further necessitates optimization of 3D culture conditions, library complexity management, and specialized analytical approaches. As these methodologies continue to mature, with enhancements in bioinformatics prediction tools and experimental protocols, they promise to accelerate both basic research and translational applications in drug development and personalized cancer therapy.

Future directions will likely focus on improving the efficiency and scalability of these integrated platforms, particularly for large-scale genetic screens in diverse patient-derived models. Additionally, the incorporation of single-cell sequencing technologies with CRISPR screening in organoids offers exciting potential for resolving genetic networks at cellular resolution, further enhancing our understanding of tumor heterogeneity and treatment resistance mechanisms.

The persistently high mortality rates associated with cancer underscore the imperative need for innovative therapeutic agents and a more nuanced understanding of tumor biology [4]. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures and patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) have limitations in accurately recapitulating the complex structural and functional heterogeneity of human tumors, creating a translational gap between preclinical findings and clinical application [4]. In this context, patient-derived organoids (PDOs) have emerged as transformative preclinical models that maintain the genetic, phenotypic, and microenvironmental characteristics of original tumors [4]. When integrated with CRISPR screening technologies, PDOs provide an unprecedented platform for high-throughput functional genomics, enabling systematic identification of cancer driver genes and novel therapeutic targets within physiologically relevant contexts [4] [5].

This combination represents a powerful synergy: PDOs offer a biologically faithful model system that mirrors patient-specific tumor characteristics, while CRISPR screening enables systematic perturbation of gene networks to identify vulnerabilities and resistance mechanisms [4] [18]. The integrated approach is redefining the landscape of drug discovery and therapeutic target identification by providing a precise and scalable platform for functional genomics in models that closely mimic human disease [18]. This guide objectively compares the performance of this combined approach against traditional models, providing experimental data and methodological details to illustrate its transformative potential in precision oncology.

Comparative Analysis of Cancer Models: Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Comparison of key characteristics between traditional cancer models and the integrated PDO-CRISPR platform

| Feature | 2D Cell Cultures | Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDXs) | PDO-CRISPR Integrated Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Microenvironment Recapitulation | Limited to none; lacks stromal and immune components | Preserved in vivo but with murine stroma | Can be co-cultured with human stromal/immune cells [4] |

| Tumor Heterogeneity Maintenance | Low; often lost during adaptation | High; maintains patient tumor heterogeneity | High; retains genetic and phenotypic diversity of primary tumor [4] |

| Throughput Capacity | High | Low; time-consuming and expensive | Moderate to high; adaptable to multi-well formats [5] |

| Genetic Manipulation Efficiency | High with standard methods | Technically challenging | High with optimized protocols [5] |

| Personalized Medicine Application | Limited | Moderate but slow | High; rapid expansion enables patient-specific drug testing [4] |

| Clinical Correlation | Moderate to poor | Good for drug response | Strong correlation with patient drug responses demonstrated [4] |

| Timeline for Experiments | Days to weeks | Months to years | Weeks to months [4] |

| Cost Considerations | Low | Very high | Moderate to high [5] |

Table 2: Quantitative performance metrics of PDO-CRISPR platform in identifying therapeutic targets

| Metric | Traditional CRISPR in 2D Models | PDO-CRISPR Platform | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification of Context-Specific Essential Genes | Limited; misses microenvironment-dependent factors | Enhanced; reveals in-vivo-specific genetic dependencies [19] | CRISPR-StAR screening in mouse melanoma identified in-vivo-specific dependencies missed in 2D culture [19] |

| Predictive Value for Clinical Response | Moderate | High; 80-90% correlation in multiple studies [4] | Gastric cancer PDOs showed high correlation between drug sensitivity in organoids and patient response [5] |

| Success in Identifying Resistance Mechanisms | Limited to cell-autonomous pathways | Comprehensive; includes microenvironment-mediated resistance [20] | 30 genome-scale CRISPR screens identified diverse chemoresistance drivers including microenvironment factors [20] |

| Target Discovery Rate | Standard | Enhanced; identifies novel context-dependent targets [21] | Genome-wide NK cell CRISPR screens identified MED12, ARIH2, CCNC as enhancing antitumor activity [21] |

| Technical Efficiency (Editing Rates) | High (>80%) | Variable (50-95%); optimized protocols achieve >90% [5] | Cas9-expressing gastric organoids showed >95% GFP knockout efficiency [5] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Establishment of Patient-Derived Organoid Biobanks

The generation of PDOs begins with obtaining patient tumor tissue through surgical resection or biopsy. The tissue is processed through mechanical and enzymatic digestion to create single-cell suspensions or small tissue fragments. These cells are then embedded in an extracellular matrix substitute, typically Matrigel, and cultured in specialized medium containing specific growth factors that support the expansion of epithelial cells while inhibiting the growth of normal stromal components [4]. The composition of the medium varies depending on the cancer type but generally includes factors such as Wnt agonists, R-spondin, Noggin, and epidermal growth factor (EGF) [4].

Critical optimization points include: (1) Matrix selection and quality control—Matrigel lots should be pre-screened for optimal organoid formation efficiency; (2) Growth factor titration—determining minimal essential factors to maintain tumor cells while minimizing normal cell overgrowth; (3) Oxygen tension—some systems benefit from physiological oxygen conditions (2-5% O2) rather than standard culture conditions; (4) Passage protocol—enzymatic versus mechanical dissociation methods impact maintenance of cellular heterogeneity [4]. Successfully established PDO biobanks can be cryopreserved while maintaining viability and genetic stability, enabling the creation of renewable resources for high-throughput screening [4].

CRISPR Screening Workflows in PDO Models

The implementation of CRISPR screens in PDOs requires careful optimization due to the technical challenges of 3D culture systems. The following protocol has been successfully demonstrated in gastric cancer organoids [5]:

Stable Cas9 Expression: Generate Cas9-expressing PDO lines using lentiviral transduction. A GFP reporter system can validate editing efficiency, with >95% GFP loss indicating robust Cas9 activity [5].

sgRNA Library Design and Delivery: Select or design pooled sgRNA libraries (e.g., genome-wide, druggable genome, or custom subsets). For a membrane protein screen targeting 1,093 genes with ~10 sgRNAs/gene, transduce at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA [5].

Library Representation Maintenance: Culture transduced organoids with >1000 cells per sgRNA throughout the screening process to maintain library representation. Include puromycin selection 48 hours post-transduction to remove untransduced cells [5].

Selection Pressure Application: For gene-drug interaction studies, apply chemotherapeutic agents like cisplatin at predetermined IC50 values. Harvest reference samples (T0) before application of selection pressure [5].

sgRNA Abundance Quantification: After 2-4 weeks of selection pressure, harvest organoids, extract genomic DNA, and amplify sgRNA regions for next-generation sequencing. Compare sgRNA abundance in final populations versus T0 reference using specialized algorithms (MAGeCK) to calculate gene-level phenotype scores [5].

For more complex in vivo applications, the recently developed CRISPR-StAR method introduces internal controls by activating sgRNAs in only half the progeny of each cell, overcoming limitations of heterogeneity and genetic drift in tumor models [19].

Advanced CRISPR Modalities for Enhanced Screening

Beyond standard CRISPR knockout approaches, several advanced modalities have been adapted for PDO screening:

CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi): Utilizes catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional repressors (KRAB domain) for precise gene knockdown without DNA cleavage. An inducible CRISPRi system in gastric organoids demonstrated efficient gene repression, with CXCR4-positive populations decreasing from 13.1% to 3.3% after induction [5].

CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa): Employs dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators (VP64-p65-Rta) for gene overexpression. The same inducible system enabled increased CXCR4-positive populations to 57.6%, demonstrating robust gene activation [5].

Single-Cell CRISPR Screening: Combines pooled CRISPR screens with single-cell RNA sequencing to simultaneously capture sgRNA identity and transcriptomic profiles. This approach reveals how genetic perturbations affect gene regulatory networks at single-cell resolution, particularly valuable in heterogeneous PDO populations [5].

Key Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms Identified via PDO-CRISPR Platforms

The integration of PDOs with CRISPR screening has enabled the systematic dissection of complex signaling pathways and resistance mechanisms in various cancers. In gastric cancer models, CRISPR screens conducted in TP53/APC double knockout organoids identified LRIG1, a negative regulator of ERBB receptor tyrosine kinases, as a top hit whose depletion conferred growth advantage [5]. Additionally, these screens revealed an unexpected link between fucosylation pathways and cisplatin sensitivity, and identified TAF6L as a key regulator of cell recovery from cisplatin-induced DNA damage [5].

In genome-wide CRISPR screens conducted in primary human natural killer (NK) cells for immunotherapy applications, key regulators of antitumor activity were identified, including MED12, ARIH2, and CCNC [21]. Ablation of these genes significantly improved NK cell antitumor activity against multiple treatment-refractory human cancers both in vitro and in vivo. The enhanced function was associated with improved metabolic fitness, increased proinflammatory cytokine secretion, and expansion of cytotoxic NK cell subsets [21].

For chemoresistance, thirty genome-scale CRISPR knockout screens across multiple cancer cell lines treated with seven chemotherapeutic agents revealed that resistance genes cluster primarily by cell-of-origin rather than drug type, highlighting the importance of genetic background [20]. Functional enrichment analysis demonstrated that "cell cycle" pathways were strongly implicated in oxaliplatin, irinotecan, and doxorubicin resistance, while mitochondria-related terms were specifically associated with irinotecan resistance [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagents and solutions for PDO-CRISPR integration

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Cultrex BME, Collagen | Provides 3D scaffolding for organoid growth | Pre-screen lots for optimal organoid formation efficiency; maintain cold chain [4] |

| Culture Media Components | Wnt-3A, R-spondin, Noggin, EGF, FGF | Supports stem cell maintenance and proliferation | Titrate concentrations to minimize normal cell overgrowth; use fresh aliquots [4] |

| CRISPR Delivery Systems | Lentiviral vectors, Retroviral vectors | Enables sgRNA library delivery | Optimize MOI to ensure single sgRNA incorporation; use packaging plasmids like psPAX2, pMD2.G [21] [5] |

| Cas9 Expression Systems | Lentiviral Cas9, Stable Cas9 lines, Cas9 protein | Provides genome editing capability | For primary NK cells, electroporation of Cas9 protein achieved 90.1% knockout efficiency [21] |

| Selection Agents | Puromycin, Blasticidin, GFP-based sorting | Enriches for successfully transduced cells | Determine minimal effective concentration through kill curves; timing critical for organoid viability [5] |

| sgRNA Libraries | Genome-wide (GeCKO, Brunello), Targeted (druggable genome), Custom libraries | Enables high-throughput genetic screening | For organoid screens, maintain >1000x coverage; include non-targeting controls [5] [20] |

| Single-Cell Analysis Tools | 10x Genomics, Split-pool barcoding | Enables deconvolution of heterogeneous screening results | Optimize organoid dissociation to maintain cell viability while achieving single-cell suspension [5] |

| Pinolenic acid | Pinolenic acid, CAS:16833-54-8, MF:C18H30O2, MW:278.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Pulsatilloside E | Pulsatilloside E, CAS:366814-43-9, MF:C65H106O31, MW:1383.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of PDOs with CRISPR screening represents a transformative approach in cancer research that combines the physiological relevance of patient-derived models with the systematic perturbation capacity of genome editing technologies. As demonstrated across multiple studies, this platform outperforms traditional models in identifying context-specific genetic dependencies, modeling tumor microenvironment interactions, and predicting clinical treatment responses [4] [5] [20]. The experimental protocols and data presented herein provide researchers with a framework for implementing this powerful combination in their own investigations.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on enhancing the complexity of PDO models through incorporation of immune and stromal components, further improving CRISPR efficiency and specificity, and integrating multi-omics readouts [4]. Additionally, the combination of organoid technology with advanced computational approaches, including artificial intelligence and machine learning, promises to extract deeper insights from the rich datasets generated by these screens [18]. As these technologies continue to mature and become more accessible, the PDO-CRISPR platform is poised to accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic targets and advance the implementation of precision oncology approaches in clinical care [4] [18].

In the field of precision medicine, establishing robust experimental models that can accurately delineate the causal effects of genetic variants represents a fundamental challenge. Isogenic cell lines, wherein all genetic background is held constant except for a single engineered variant, provide a powerful solution for unequivocally assessing variant impact. The convergence of adult stem cell-derived organoids with next-generation CRISPR technologies has revolutionized our ability to create such precision models directly from patient tissue [22]. These models faithfully retain the genetic and phenotypic complexity of their tissue of origin, enabling the study of genetic variants within a physiologically relevant human context.

This guide objectively compares the performance of modern genome editing tools—including base editing, prime editing, and conventional CRISPR-Cas9—for generating isogenic lines, with a specific focus on their application in patient-derived organoid (PDO) models [4]. We provide supporting experimental data on key performance metrics including editing efficiency, precision, and functional outcomes, framed within the broader research context of validating CRISPR edits for therapeutic discovery.

Performance Comparison of Genome Editing Technologies

The selection of an appropriate genome editing technology is paramount for the successful generation of isogenic models. The following section provides a comparative analysis of three primary systems based on recent experimental findings in organoid models.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Genome Editing Technologies in Organoids

| Editing Technology | Primary Editing Action | Theoretical Versatility | Reported Efficiency in Organoids | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 HDR [22] [23] | Introduces DSBs, relies on HDR for precise edits | All possible edits | Inefficient, highly variable | Well-established protocol | Low efficiency; high indel byproduct rate; requires DSB |

| Base Editing [22] [23] | Direct chemical conversion of one base pair to another without DSB | Four transition mutations (C>T, T>C, A>G, G>A) | High and reliable (e.g., ~80% for A>G) [22] | High efficiency and precision; no DSB | Restricted to specific single-nucleotide changes |

| Prime Editing [23] | Reverse transcription of edited sequence from a pegRNA template at a nicked site | All 12 possible base substitutions, small insertions, and deletions | Moderate, highly design-dependent (e.g., 20-50% for various edits) [23] | High versatility and precision; no DSB | Requires extensive pegRNA optimization; can be less efficient than base editing |

Quantitative Analysis of Editing Outcomes

Beyond the general characteristics outlined in Table 1, quantitative data on editing outcomes and byproducts are critical for selecting the right tool. The table below summarizes experimental data from direct comparisons in patient-derived organoids.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Editing Outcomes in Patient-Derived Organoids

| Editing Context | Technology Used | Desired Edit Efficiency | Unwanted Indel Rate | Ratio of Correct:Incorrect Edit | Reference/Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repair 3-bp deletion in DGAT1 | Prime Editing (PE3) | Successful functional repair achieved [23] | 1-4% [23] | ~30x higher than HDR [23] | Patient intestinal organoids |

| Repair 3-bp deletion in DGAT1 | Cas9-initiated HDR | Successful functional repair achieved [23] | Not specified | 1x (Baseline for comparison) | Patient intestinal organoids |

| Introduce ABCB11 R1153H mutation | Adenine Base Editor (ABE) | High efficiency [23] | Not specified | Outperformed prime editing for this specific A>G edit [23] | Liver organoids |

| Introduce CTNNB1 in-frame deletions | Prime Editing (PE3) | 30-50% (by amplicon sequencing) [23] | 1-4% [23] | Not specified | Liver and intestinal organoids |

Performance Interpretation and Best Use Cases:

- Base Editors are the tool of choice for specific transition mutations (C>T, A>G, T>C, G>A) due to their superior efficiency and reliability without requiring double-strand breaks [22] [23]. Their performance is more predictable and often requires less optimization.

- Prime Editors offer a vastly larger editing scope, capable of installing all 12 possible point mutations, small insertions, and small deletions with high precision. While their efficiency can be lower and is highly dependent on pegRNA design, they provide a versatile and precise alternative to HDR, generating far fewer unwanted byproducts [23]. They are ideal for mutations that base editors cannot correct.

- Conventional CRISPR-Cas9 HDR is increasingly disadvantaged for most isogenic line generation due to its low efficiency and high propensity for introducing uncontrolled indels at the target site, making the screening process more laborious [23].

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

The following section outlines the core experimental protocols for generating and validating isogenic lines in organoid models, as evidenced by recent studies.

Protocol for Isogenic Line Generation Using Next-Generation CRISPR

This protocol, adapted from Geurts et al., details the steps for creating isogenic models in adult stem cell-derived organoids using DSB-free genome engineering [22].

Strategy Determination and sgRNA Design (Timing: ~1 hour)

- Select Genome Editing Tool: Follow a decision flow diagram to choose the appropriate tool based on the desired mutation (see Section 2). Prime editing is selected for small indels or transversions, while base editing is chosen for specific transition mutations [22].

- Design sgRNAs: For base editors, design sgRNAs to position the target base within the editing window. For prime editors, design pegRNAs with optimized primer binding site (PBS) and reverse transcriptase (RT) template lengths. Testing multiple designs is critical for success [23].

- Cloning: Clone the designed sgRNA or pegRNA sequences into appropriate plasmid vectors expressing the editor protein (e.g., BE4max for C>T, ABE8e for A>G, PE2 for prime editing).

Delivery and Selection (Timing: ~1-2 weeks)

- Electroporation: Dissociate organoids into single cells or small clusters. Electroporate the editor plasmid(s), often co-delivered with a fluorescent reporter plasmid (e.g., GFP) for enrichment [23].

- Selection of Edited Cells: Several days post-electroporation, apply a selective pressure to enrich for successfully edited cells. This can be:

- Functional Selection: Used when the edit confers a growth advantage (e.g., APC KO allows growth without Wnt/Rspo1; TP53 KO allows growth in the presence of Nutlin3a) [22].

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): If co-transfected with a reporter, FACS is used to isolate transfected cells for further clonal expansion [23].

Clonal Expansion and Validation (Timing: ~2-4 weeks)

- Clonal Line Generation: Plate the selected cell population at clonal density in Matrigel. Allow individual organoids to grow from single cells.

- Genotypic Validation: Harvest individual clonal organoid lines. Extract genomic DNA and perform Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing (NGS) of the targeted locus to identify clones with the desired edit and assess zygosity.

- Functional Validation: Confirm that the genetic edit leads to the expected functional consequence (e.g., protein expression restoration/loss via Western blot, assay of pathway activity, or response to a functional stimulus) [23].

Workflow for Functional Repair and Validation in Patient-Derived Organoids

A prime example of functional validation is the correction of a pathogenic 1-bp duplication in ATP7B (c.1288dup, p.S430fs) causing Wilson disease in patient-derived liver organoids [23].

- Prime Editing & Selection: Patient organoids were transfected with PE3 plasmids designed to remove the duplication. Transfected cells were selected and clonally expanded.

- Genetic Confirmation: Sanger sequencing of clones confirmed monoallelic repair of the mutation in a subset of lines.

- Functional Copper Excretion Assay: Edited clonal lines and controls were exposed to a copper challenge. The viability of organoids was measured. Clones with successful genetic repair showed rescued copper excretion capability and significantly higher survival rates compared to uncorrected mutant organoids, thereby demonstrating functional correction at the cellular level [23].

The logical workflow from genetic defect to validated isogenic line is summarized in the following diagram:

Advanced Validation: Single-Cell Sequencing for Editing Fidelity

To ensure the highest safety standards for therapeutic applications, advanced validation methods like single-cell DNA sequencing (scDNA-seq) are employed. The Tapestri platform can be used to comprehensively characterize edited cell products [24].

- Methodology: Single cells from an edited, heterogeneous cell pool are encapsulated. A custom multiplex PCR panel amplifies on-target and putative off-target sites. The amplicons are sequenced, and an automated pipeline analyzes the data.

- Outputs: This method provides a per-cell and per-allele assessment of:

- On-target and off-target editing efficiency.

- Co-occurrence of edits (e.g., ensuring multiple targets are edited in the same cell).

- Zygosity of edits (mono- or biallelic).

- Precise indel spectra and structural variations.

- Performance: This method has demonstrated high sensitivity (99.77%), specificity (99.93%), and accuracy (99.92%) in detecting editing events in isogenic clonal lines, highlighting its power for validating the purity and safety of edited isogenic lines [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Isogenic Line Generation in Organoids

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Adult Stem Cell (ASC) Organoid Culture | 3D in vitro model derived from patient tissue that recapitulates organ structure and function. | Serves as the starting biological material for generating physiologically relevant isogenic models [22] [4]. |

| Base Editor Plasmids | For introducing specific point mutations (C>T, A>G) without double-strand breaks. | AncBE4max (C>T), ABE7.10 (A>G); evolved versions like EvoFERNY lack sequence context restrictions [22]. |

| Prime Editor Plasmids | For introducing point mutations, insertions, and deletions without double-strand breaks. | PE2 and PE3 systems require co-delivery of a pegRNA plasmid [23]. |

| pegRNA | Prime editing guide RNA; specifies the target locus and encodes the desired edit. | Design (PBS and RT template length) is critical for efficiency and requires testing multiple variants [23]. |

| Growth Factor-Refined Media | Supports the growth and maintenance of specific organoid types. | Contains a mix of factors like EGF, Noggin, R-spondin, FGF, HGF, etc., tailored to the organoid lineage [22]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Provides a 3D scaffold for organoid growth and polarization. | Matrigel is commonly used to support the structural integrity of organoids [4]. |

| Selection Agents | Enriches for successfully edited cells based on growth advantage or resistance. | Wnt/Rspo1 withdrawal for APC KO; Nutlin3a for TP53 mutant; fatty acids for corrected DGAT1 [22] [23]. |

| Tapestri scDNA-seq Platform | For high-resolution, single-cell validation of editing outcomes and off-target effects. | Provides co-occurrence, zygosity, and structural variation data across thousands of single cells [24]. |

| Deacylmetaplexigenin | Deacylmetaplexigenin, CAS:3513-04-0, MF:C21H32O6, MW:380.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Perisesaccharide B | Perisesaccharide B | Perisesaccharide B is a high-purity oligosaccharide for life science research. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. |

The strategic integration of patient-derived organoids with next-generation CRISPR tools provides an unparalleled platform for establishing high-fidelity isogenic lines. The choice of editing technology—be it the highly efficient but restricted base editor, the versatile and precise prime editor, or the conventional HDR—must be guided by the nature of the variant and the required level of precision. Quantitative data clearly favors base and prime editing for most applications due to their avoidance of double-strand breaks and superior editing fidelity. The subsequent rigorous validation of these models, employing both functional assays and cutting-edge single-cell sequencing, is non-negotiable to ensure their reliability for modeling disease mechanisms and advancing therapeutic discovery.

A Step-by-Step Protocol for CRISPR Editing and Selection in Organoids

Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) have emerged as transformative preclinical models that accurately recapitulate the structural, functional, and heterogeneous characteristics of primary tumors, providing a powerful platform for identifying cancer driver genes and novel therapeutic targets [4]. When integrated with CRISPR screening technologies, PDOs enable systematic exploration of gene function within physiologically relevant microenvironments [5]. However, the effectiveness of these sophisticated models depends entirely on the precision of the guide RNA (gRNA) molecules that direct CRISPR nucleases to specific genomic targets.

The design and cloning of gRNAs present a critical bottleneck in CRISPR experimental workflows, balancing the competing demands of on-target efficiency and off-target specificity [25]. While computational tools can predict gRNA activity, the complex architecture of primary human organoids and their native tumor microenvironments introduce additional variables that influence editing outcomes [4] [5]. This comparison guide examines current gRNA design strategies and cloning methodologies, providing experimental data and protocols optimized for validating CRISPR edits in patient-derived organoid models—a capability essential for advancing precision oncology and therapeutic development.

gRNA Design Strategies: Computational Tools and Specificity Enhancement

Computational Design Tools and Specificity Considerations

Effective gRNA design begins with computational prediction of on-target activity and off-target potential. Multiple tools have been developed to assist researchers in selecting optimal gRNA sequences, each employing different algorithms and scoring systems [25].

Table 1: Comparison of gRNA Design Considerations and Their Impacts

| Design Factor | Efficient Features | Inefficient Features | Biological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Nucleotide Usage | A count; AG, CA, AC, UA counts [25] | U, G count; GG, GGG counts [25] | Influences gRNA stability and binding affinity |

| Position-Specific Nucleotides | G in position 20; C in positions 16, 18 [25] | C in position 20; U in positions 17-20 [25] | Critical for Cas9 seed region recognition |

| GC Content | 40-60% [25] [26] | <20% or >80% [25] | Affects hybridization energy and specificity |

| PAM Sequence | NGG (esp. CGG) [25] | TGG [25] | Determines Cas9 binding and activation |

| Problematic Motifs | TT, GCC at 3′ end [25] | poly-N (esp. GGGG) [25] | Can cause premature transcription termination |

GuideScan2 represents a significant advancement in gRNA design technology, using a novel search algorithm based on the Burrows-Wheeler transform for memory-efficient, parallelizable construction of high-specificity gRNA databases [27]. This tool enables user-friendly design and analysis of individual gRNAs and gRNA libraries for targeting both coding and non-coding regions in custom genomes. Experimental validation demonstrated that GuideScan2-designed gRNAs with higher predicted specificity reduced confounding effects in CRISPR essentiality screens, where low-specificity gRNAs targeting non-essential genes produced strong negative cell fitness effects due to likely toxicity from non-specific cuts [27].

Other popular tools include the Broad Institute's sgRNA design tool, which reports on-target efficiency as a percentage, and sgRNA Scorer 2.0, which provides a quality score [28]. When designing gRNAs for CRISPR inhibition (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) in organoid models, optimal targeting regions differ: for CRISPRa, gRNAs should target 1-200 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site (TSS), while for CRISPRi, gRNAs should target from 50 bp upstream of the TSS until 300 bp downstream [28].

Innovative Approaches for Enhancing Specificity

Beyond computational design, several molecular strategies have been developed to enhance gRNA specificity:

Chemically Modified gRNAs: Incorporating specific chemical modifications in the gRNA backbone can dramatically reduce off-target cleavage while maintaining high on-target performance. The 2′-O-methyl-3′-phosphonoacetate (MP) modification at strategic positions in the ribose-phosphate backbone of gRNAs has shown particular promise, reducing off-target activities by an order of magnitude or greater in clinically relevant genes [29].

Extended gRNAs (x-gRNAs): Adding short nucleotide extensions (∼6 to ∼16 nts) to the 5′-end of the gRNA spacer can significantly increase targeting specificity. The SECRETS (Selection of Extended CRISPR RNAs with Enhanced Targeting and Specificity) protocol enables high-throughput screening of x-gRNA variants, identifying sequences that maintain robust Cas9 activity on-target while effectively eliminating activity at known off-target sites [30]. In one evaluation, x-gRNAs outperformed other specificity-enhancement methods, including high-fidelity Cas9 variants, for several clinically relevant gRNAs [30].

High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Engineered Cas9 enzymes with enhanced specificity provide an alternative approach to reducing off-target effects. These include eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9, evoCas9, and Sniper-Cas9, each employing different mechanisms to increase fidelity, such as weakening interactions with non-target DNA strands or increasing proofreading capabilities [31].

gRNA Format Comparison: Synthesis Methods and Experimental Performance

Comparison of gRNA Production Methods

gRNAs can be produced using several methodological approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations for organoid research.

Table 2: Comparison of gRNA Synthesis Methods and Performance Characteristics

| Synthesis Method | Production Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Editing Efficiency | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid-Expressed | 1-2 weeks [26] | Cost-effective; stable expression [26] | Prolonged expression increases off-targets; random integration [26] | Variable | Long-term or in vivo studies |

| In Vitro Transcription (IVT) | 1-3 days [26] | No cloning required; flexible sequence design [26] | Labor-intensive; requires purification; 5' end heterogeneity [26] | Moderate | Rapid screening experiments |

| Chemical Synthesis | 1-2 days [26] | High purity; precise sequence control; chemical modifications possible [29] [26] | Higher cost for long RNAs; scale limitations | High (up to 97%) [26] | Therapeutic applications; sensitive cell types |

Experimental Performance Data

Recent studies directly comparing gRNA formats in relevant biological systems provide critical insights for experimental design:

In primary human cell editing, chemically synthesized sgRNAs incorporating terminal modifications demonstrated significantly boosted CRISPR-Cas9 indel rates and homology-directed repair (HDR) editing events, particularly in challenging primary cells [29]. The terminal modifications provide resistance to exonucleases, which is especially valuable in organoid systems where transfection efficiency and editing kinetics can be limiting factors.

When evaluating specificity, MP-modified gRNAs showed dramatic reductions in off-target cleavage activities while maintaining high on-target performance across multiple clinically relevant genes [29]. In one systematic evaluation, MP modifications at specific positions in the guide sequence improved specificity by an order of magnitude or greater in human K562 cells, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) [29].

For organoid research specifically, plasmid-based expression systems have been successfully implemented in large-scale CRISPR screens. In one study utilizing primary human 3D gastric organoids, researchers achieved robust screening outcomes using lentiviral delivery of plasmid-based gRNA libraries, demonstrating the feasibility of this approach in complex 3D model systems [5].

gRNA Cloning Strategies and Protocols for Mammalian Systems

Streamlined Cloning Protocol for gRNA Expression Vectors

The following protocol outlines an efficient method for cloning gRNAs into mammalian expression vectors using the Type IIS restriction enzyme BsmBI, compatible with vectors such as pSB700 [28]:

gRNA Oligonucleotide Design and Ordering:

- Design gRNAs using computational tools (e.g., sgRNA Scorer 2.0, Broad sgRNA design tool) [28].

- Select genomic target sequences and remove the 3′ NGG PAM, leaving only the 20-nt protospacer sequence.

- Append 5′-CACCG- to the protospacer sequence to create the forward oligo.

- Generate the reverse complement of the protospacer and append 5′-AAAC- to the 5′ end and an additional C to the 3′ end to create the reverse oligo.

- Order oligonucleotides without additional modifications and dilute to 100 μM in TE buffer [28].

Annealing and Cloning:

- Mix forward and reverse oligonucleotides in equimolar ratios (typically 10 μL each).

- Incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes without additional heating/cooling steps.

- Digest 1-5 μg of pSB700 vector with BsmBI (0.5 μL per 1 μg) for 1 hour at 55°C.

- Gel-purify the digested vector backbone (~9 kb).

- Ligate annealed oligos into the digested vector using standard ligation protocols.

- Transform into competent E. coli and validate positive clones by Sanger sequencing [28].

For higher efficiency, Golden Gate assembly can be employed as a single-step digestion-ligation reaction, reducing cloning time and increasing efficiency [28].

Multiplexed gRNA Strategies

Many CRISPR experiments in organoids require editing multiple genes simultaneously. Multiplex systems enable researchers to target 2-7 genetic loci by cloning multiple gRNAs into a single plasmid, ensuring all gRNAs are expressed in the same cell [31]. This approach is particularly valuable in organoid research for modeling polygenic diseases or complex genetic interactions. Specific enzymes such as Cas12a can improve multiplexing efficiency due to their inherent ability to process multiple crRNAs from a single transcript [31].

Application in Patient-Derived Organoid Research: Experimental Design and Validation

Implementing CRISPR Screens in 3D Organoid Models

Recent advances have demonstrated the feasibility of large-scale CRISPR screening in primary human 3D organoids. One pioneering study established a full suite of CRISPR-based genetic screens—including knockout, interference (CRISPRi), activation (CRISPRa), and single-cell approaches—in human gastric organoids to systematically identify genes affecting sensitivity to cisplatin [5].

The experimental workflow for successful organoid screening includes:

- Establishing stable Cas9-expressing organoid lines using lentiviral transduction

- Transducing with pooled lentiviral gRNA libraries at sufficient cellular coverage (>1000 cells per sgRNA)

- Maintaining representation throughout the screening period

- Harvesting samples at multiple time points for next-generation sequencing

- Analyzing sgRNA abundance to identify phenotype-associated genes [5]

This approach identified previously unappreciated genes contributing to cell growth and cisplatin sensitivity in gastric cancers, highlighting the power of CRISPR-functional genomics in physiologically relevant models [5].

Diagram 1: CRISPR Screening Workflow in Patient-Derived Organoids. This workflow illustrates the integrated process from organoid establishment through target validation, highlighting critical steps where gRNA design quality impacts final outcomes.

Optimizing Prime Editing in Organoid Systems

Beyond conventional CRISPR-Cas9 editing, prime editing represents a more precise approach that enables all 12 possible base-to-base conversions without double-strand breaks [32]. Optimization of prime editing guide RNAs (pegRNAs) has been shown to dramatically improve editing efficiency in diverse cell types, including pluripotent stem cells [32].

Key optimizations for prime editing in challenging systems like organoids include:

- Stable genomic integration of prime editors via piggyBac transposon system for sustained expression

- Selection of integrated single clones to ensure homogeneous editor expression

- Using enhanced promoters (e.g., CAG) for robust expression

- Lentiviral delivery of pegRNAs ensuring sustained expression [32]

With these optimizations, researchers achieved up to 80% editing efficiency across multiple loci and cell lines, and substantial editing efficiencies of up to 50% in human pluripotent stem cells in both primed and naïve states [32].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for gRNA Experiments

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for gRNA Design and Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations for Organoid Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| gRNA Design Tools | GuideScan2, CHOPCHOP, Broad sgRNA Designer [27] [28] [26] | Computational prediction of efficient, specific gRNAs | GuideScan2 enables design for non-coding regions [27] |

| Cloning Vectors | pSB700, Lentiviral gRNA vectors [28] | gRNA expression and delivery | BsmBI-based cloning enables high-efficiency insertion [28] |

| Cas9 Variants | eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9 [31] | High-fidelity genome editing | Reduce off-target effects in complex genomes |

| Chemical Modifications | 2′-O-methyl-3′-phosphonoacetate (MP) [29] | Enhance gRNA stability and specificity | Particularly valuable for primary cells and organoids |

| Delivery Systems | Lentiviral particles, piggyBac transposon [32] [5] | Efficient nucleic acid delivery | Lentiviral systems enable stable integration in organoids |

| Validation Tools | Next-generation sequencing, T7E1 assay, Sanger sequencing | Confirm editing efficiency and specificity | Essential for quantifying on-target and off-target effects |

The integration of advanced gRNA design strategies with patient-derived organoid models represents a powerful approach for functional genomics and therapeutic target discovery. Based on current evidence and experimental data:

- For high-throughput screening in organoids, plasmid-based gRNA libraries delivered via lentiviral transduction provide practical efficiency and scalability [5].

- For therapeutic applications or precision editing in validated targets, chemically synthesized sgRNAs with strategic modifications offer superior specificity and reduced off-target effects [29] [26].

- Computational design using tools like GuideScan2 significantly improves gRNA specificity and reduces confounding effects in genetic screens [27].

- Advanced gRNA formats including x-gRNAs and MP-modified guides can outperform even high-fidelity Cas9 variants for challenging target/off-target pairs [30].

As CRISPR-based functional genomics continues to evolve in patient-derived organoid systems, refined gRNA design and cloning strategies will be essential for unlocking the full potential of these physiologically relevant models in basic research and therapeutic development.

Selecting the optimal delivery method is a critical step in successfully implementing CRISPR-based workflows, especially in sensitive models like patient-derived organoids. The choice between electroporation, lentiviral transduction, and lipid-based transfection involves balancing efficiency, cell viability, and experimental timeline. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three core techniques to inform your experimental design.

In CRISPR gene editing, the delivery of Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA (gRNA) into cells is a foundational step. These components can be delivered as DNA, RNA, or a pre-complexed ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex [33]. The method of delivery significantly impacts editing efficiency, cellular health, and the potential for off-target effects.

- Physical methods create temporary pores in the cell membrane.

- Chemical methods use reagents to complex with genetic material and facilitate cellular uptake.

- Viral methods employ engineered viruses for highly efficient, stable gene delivery [33].

Understanding the distinct advantages and limitations of each approach is the first step toward robust and reproducible genome editing.

Direct Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of electroporation, lentiviral transduction, and lipid-based transfection to facilitate a direct comparison.

| Feature | Electroporation | Lentiviral Transduction | Lipid-Based Transfection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Electrical pulses create temporary pores in cell membrane [33] | Engineered virus delivers genetic material for stable integration [34] [35] | Cationic lipids form complexes with nucleic acids for membrane fusion [36] |

| Primary Use Case | Delivery of RNPs, DNA, or RNA to hard-to-transfect cells (e.g., primary cells) [33] | Long-term, stable gene expression; difficult-to-transfect cells [33] [34] | Rapid, transient transfection of standard cell lines [33] |

| Typical Efficiency | High (Vero cell study: ~20-40% with optimization) [37] | High (enables stable integration) [37] [35] | Variable; highly cell-type dependent (Vero: up to ~50% with TurboFect) [37] |

| Cell Viability | Lower (requires careful optimization of voltage) [37] [33] | Moderate (cytotoxicity and immune response risks) [37] | Higher (less inherently toxic) [37] |

| Format Delivered | RNP, DNA, RNA [33] | DNA (for Cas9/gRNA expression) [33] | DNA, RNA, RNP (less common) [33] |

| Onset of Expression | Rapid (especially with RNP delivery) [33] | Slow (requires integration and transcription) [34] | Intermediate (requires transcription/translation for DNA) [33] |

| Experimental Timeline | Short (single day for RNP delivery) | Long (weeks for virus production, transduction, and selection) | Short (transfection in days) |

| Throughput | Medium to High [33] | Low to Medium (involves multiple steps) [33] | High [33] |

| Cost & Expertise | Moderate (equipment investment) | High (biosafety, virus production) | Low (commercial reagents) |

| Key Challenge | Optimizing voltage for efficiency vs. viability [37] | Safety, insertional mutagenesis, limited packaging capacity [38] [35] | Serum interference, cytotoxicity, low efficiency in some cells [37] [39] |

Experimental Protocols and Data

Quantitative Efficiency and Viability Data

A study directly comparing these methods in Vero cells provides concrete performance data [37]. Optimal conditions and their outcomes are summarized below.

| Method | Optimal Conditions | Reported GFP+ Efficiency | Key Experimental Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical (TurboFect) | 1 µg DNA, 4 µL reagent, 6x10^4 cells [37] | ~50% [37] | Efficiency assessed via flow cytometry 72h post-transfection [37] |

| Electroporation | 300V, 400V, Ebuffer 2 (OptiMEM + HEPES + sucrose) [37] | ~20-40% [37] | Efficiency highly dependent on voltage and buffer; cell viability decreased at higher voltages [37] |

| Lentiviral Transduction | HIV-1-based lentivectors, polybrene [37] | Lower than chemical method [37] | Achieves stable integration; requires biosafety level 2 containment [37] |

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocols

Lipid-Based Transfection (Using TurboFect)

This protocol is adapted from a study that achieved high efficiency in Vero cells [37].

- Day 1: Seed Cells. Plate Vero cells at a density of 6 × 10^4 cells/well in a 24-well plate and allow them to adhere overnight in complete medium [37].

- Day 2: Prepare Complexes.

- Dilute 1 µg of plasmid DNA (e.g., pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-CopGFP) in 100 µL of Opti-MEM medium.

- Add 4 µL of TurboFect reagent directly to the diluted DNA. Mix by gentle pipetting.

- Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 30 minutes to allow complex formation [37].

- Transfect Cells. Add the DNA-TurboFect complex dropwise to the cells. Gently swirl the plate to ensure even distribution. Incubate the cells at 37°C for 4 hours [37].

- Change Media. After incubation, carefully remove the transfection medium and replace it with fresh complete medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% FBS) [37].

- Assay Results. Analyze transfection efficiency via flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy 48-72 hours post-transfection [37].

Lentiviral Transduction for Stable Expression

This protocol outlines the production of lentiviral particles and transduction of target cells [34].

Part A: Virus Production (in HEK293T cells)

- Seed Producer Cells. Plate HEK293T cells to reach 40-50% confluency on the day of transfection. Handle cells gently as they detach easily [34].

- Prepare Transfection Mix. In two separate tubes with 500 µL Opti-MEM each: