A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Gene Expression Patterns with Multiple In Situ Hybridization Probes

This article provides a detailed framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on validating gene expression patterns using multiple in situ hybridization (ISH) probes.

A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Gene Expression Patterns with Multiple In Situ Hybridization Probes

Abstract

This article provides a detailed framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on validating gene expression patterns using multiple in situ hybridization (ISH) probes. It covers the foundational principles of ISH, explores advanced methodological approaches like the OneSABER platform and multiplex FISH, and addresses key troubleshooting challenges in tissue preparation and signal optimization. Furthermore, the guide outlines rigorous validation strategies and comparative analyses with other molecular techniques, offering a complete roadmap for ensuring specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility in spatial gene expression analysis for both research and diagnostic applications.

Understanding ISH: Core Principles and Probe Design for Effective Validation

The Fundamental Principle of In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a foundational laboratory technique that enables the detection and precise localization of specific DNA or RNA sequences within cells, tissues, or entire biological specimens, preserving their spatial context [1] [2]. By using a labeled complementary nucleic acid strand (a probe), ISH provides invaluable information on the organization, regulation, and function of genes, making it indispensable for research in development, disease, and gene function, as well as for clinical diagnostics [3] [1]. The core principle rests on the ability of single-stranded DNA or RNA to complementary bind to a target nucleic acid sequence in situ [4]. Since its invention by Mary-Lou Pardue and Joseph G. Gall [1], the technique has evolved to include various probe types and signal detection methods, but this fundamental mechanism of hybridization remains constant.

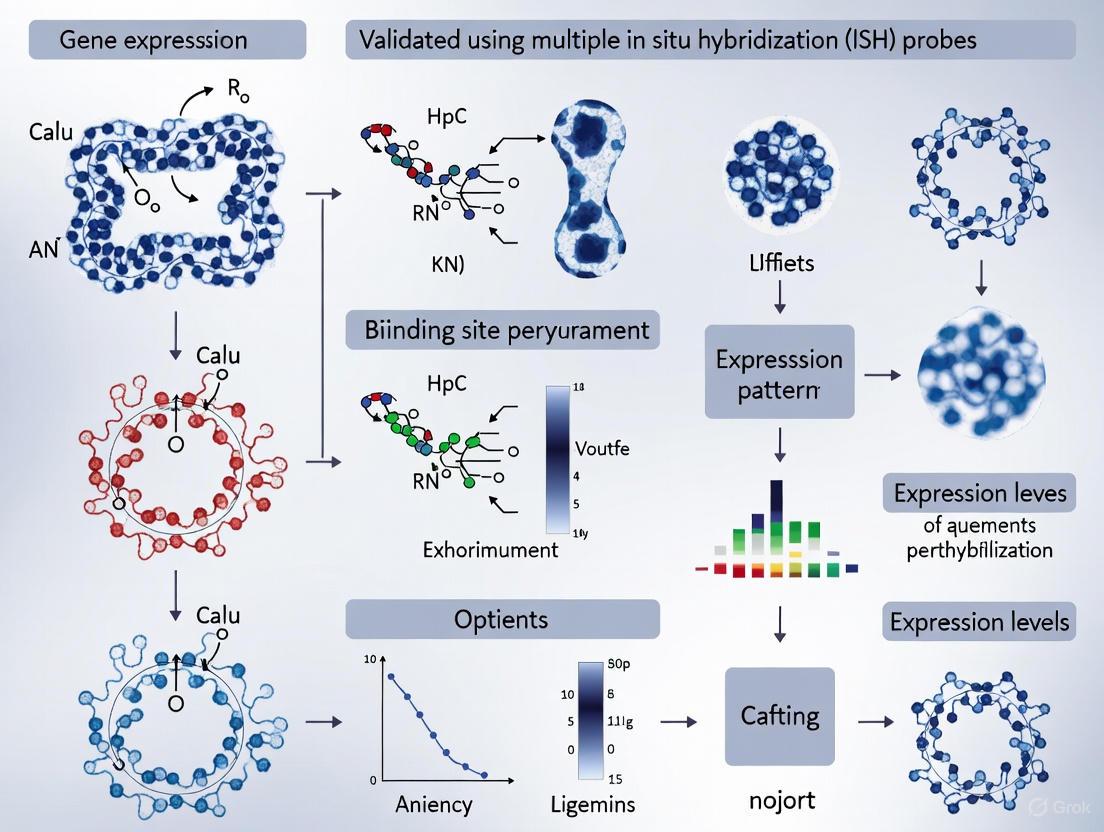

The following diagram illustrates the foundational workflow and key decision points in a typical ISH experiment.

Core Principles and Technical Challenges

The procedural steps of ISH involve fixing the biological sample to preserve tissue architecture and make the target sequences accessible to probes [1] [4]. The probe is then applied and allowed to hybridize under stringent conditions that favor only exact sequence matches. Following this, non-specifically bound probe is washed away, and the bound, labeled probe is detected [1].

Despite its conceptual simplicity, the technique requires precise optimization and faces several key challenges:

- Preservation of Target Nucleic Acids: Crosslinking fixatives like formaldehyde are often essential to retain the target mRNA within tissues [1].

- Probe Specificity and Background: A critical difficulty is not merely obtaining a signal, but performing controlled experiments to ensure that the signal is real and not due to artifactual binding of the probe to the tissue [5]. Regions rich in nuclei, for example, can cause spurious probe binding and high background that can be mistaken for a positive signal [5].

- Sensitivity for Low-Abundance Targets: Detecting low-copy number transcripts often requires sophisticated signal amplification strategies [3] [4].

- Quantification: Traditional ISH protocols are not inherently quantitative, making it difficult to compare mRNA levels across different experiments [6]. Semi-quantitative approaches require careful normalization, for example through the use of an internal standard or "co-stain" [6].

Comparative Analysis of ISH Probe Technologies

The selection of an appropriate probe is the most critical factor in ISH experimental design. Probes are distinguished by their nucleic acid type (DNA or RNA), size, labeling method, and application [4]. The table below compares the key probe types used in modern ISH workflows.

Table 1: Comparison of Key In Situ Hybridization Probe Technologies

| Probe Type | Typical Composition & Label | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations / Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Probes | Oligonucleotides or cloned DNA; labeled with fluorophores (e.g., Cy3) or haptens (e.g., DIG, DNP) [6] [4]. | Detection of specific DNA sequences (genes, chromosomal regions), RNA targets [4]. | High specificity and stability; versatile design [7]. | Signal may be weaker than RNA probes without amplification. |

| RNA Probes (Riboprobes) | Single-stranded RNA; often labeled with radioisotopes or haptens [5] [1]. | High-sensitivity mRNA localization [5]. | High affinity and low background; very sensitive [5]. | Susceptible to RNase degradation; requires careful handling. |

| Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Probes | Modified RNA nucleotides with a bridged sugar-phosphate backbone [4]. | Detection of short or highly similar sequences, especially microRNAs (miRNAs) [4]. | Extremely high thermal stability and binding affinity [4]. | Specialized design and cost. |

| SABER / OneSABER Probes | DNA probes with primer-based concatemerization for signal amplification [3]. | Multiplexed RNA FISH in whole-mount samples and tissue sections [3]. | Open platform; highly customizable; signal amplification without complex chemistry [3]. | Requires careful design of primer sequences. |

Advanced Multiplexed ISH Platforms: An Objective Comparison

Recent innovations have led to highly multiplexed imaging-based technologies that allow for the simultaneous visualization of dozens to hundreds of genes. These platforms often integrate proprietary signal amplification chemistries to achieve single-molecule sensitivity. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of several prominent technologies based on independent benchmarking studies [8].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Multiplexed In Situ Gene Expression Profiling Technologies

| Technology / Platform | Probe Design & Signal Amplification | Key Performance Characteristics | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNAscope | Patented "Z"-probes & branched DNA (bDNA) amplification; uses ~20 oligo pairs per target and pre-amplifiers/amplifiers for ~8000x signal boost [1] [9]. | High sensitivity and single-molecule resolution; high specificity with low background [9]. | Validating single or multiplexed gene signatures in FFPE tissues; clinical biomarker research [9]. |

| OneSABER | Modular DNA probes adapted from SABER method; uses primer exchange reaction to create long concatemers for signal amplification [3]. | Highly customizable open platform; works with colorimetric and fluorescent ISH; efficient signal amplification [3]. | Research in non-model organisms; whole-mount multiplexed imaging; labs seeking a unified, customizable protocol [3]. |

| MERFISH | Combinatorial barcoding with sequential hybridization and imaging; uses single-molecule FISH (smFISH) principles [8]. | High multiplexing capacity (100s to 1000s of genes); transcriptome-wide profiling [8]. | Creating spatially-resolved cell atlases; identifying novel cell types; studying cellular heterogeneity [8]. |

| Xenium | Oligonucleotide probes with cyclic barcode hybridization and fluorescence imaging [8]. | High molecular counts per cell and subcellular resolution [8]. | Detailed analysis of tissue architecture and tumor microenvironments at high resolution [8]. |

A critical consideration when selecting a platform is specificity, as off-target molecular artifacts can confound data interpretation. Independent benchmarking has introduced metrics like the Mutually Exclusive Co-expression Rate (MECR) to quantify non-specific signals. For example, one study found that technologies with the highest raw molecular counts per cell can also exhibit higher MECR, indicating that a component of their sensitivity may be attributable to background artifacts [8]. This underscores the necessity of platform-specific validation controls.

Experimental Protocols for Validation and Quantification

Semi-Quantitative ISH with an Internal Co-Stain

To move beyond qualitative localization and enable comparison of mRNA levels across samples, a semi-quantitative method using a co-stain as an internal standard can be employed [6]. This controls for experimental variability like tissue permeability and hybridization efficiency.

Protocol Overview [6]:

- Sample Preparation: Fix and permeabilize multiple samples (e.g., Drosophila embryos, tissue sections) identically.

- Dual-Probe Hybridization: Co-hybridize with two probes:

- A DNP-labeled probe for your target gene of interest.

- A DIG-labeled probe for a ubiquitously and consistently expressed reference gene (the co-stain, e.g., huckebein (hkb) in Drosophila).

- Sequential Signal Detection: Detect probes successively using HRP-conjugated anti-DNP and anti-DIG antibodies, followed by development with different fluorogenic tyramide substrates (e.g., Cy3 and coumarin).

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Acquire 3D image stacks and convert them into data files containing location and expression levels for each nucleus. Normalize the expression level of the target gene against the co-stain signal in each cell or region of interest to control for embryo-to-embryo variation.

Validating a Multi-Gene Signature with Multiplex FISH

Multiplex FISH (mFISH) is powerful for validating gene expression patterns of a pre-defined set of genes, such as an arsenic-responsive risk model (NKIRAS2, AKTIP, HLA-DQA1) in bladder cancer [9].

Protocol Overview [9]:

- Tissue Processing: Use Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissue sections.

- Multiplexed FISH: Apply a multiplexed FISH panel (e.g., using the RNAscope technology) targeting the signature genes.

- AI-Powered Digital Pathology: Acquire whole-slide mFISH images and perform nuclear segmentation using AI-based tools (e.g., HoverNet).

- Spatial Analysis: Quantify gene expression at single-cell resolution. Calculate a composite model equation score for the gene signature and correlate it with pathological features (e.g., tumor grade). Spatially map gene-enriched regions and analyze their clustering relative to tumor boundaries.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for In Situ Hybridization

| Item | Function in ISH Protocol |

|---|---|

| Fixatives (e.g., Formaldehyde) | Preserves tissue morphology and cross-links nucleic acids in situ to prevent degradation [1]. |

| Permeabilization Agents (e.g., Proteinase K) | Opens cell membranes and tissues to allow penetration of probes into the sample [1] [4]. |

| Hybridization Buffer | Provides optimal salt, pH, and detergent conditions to promote specific binding of the probe to its target sequence while minimizing non-specific binding [4]. |

| Labeled Nucleic Acid Probes | The core reagent; a complementary DNA or RNA strand that binds the target sequence, carrying a label (fluorophore, hapten) for detection [4] [2]. |

| Hapten-Conjugated Antibodies & Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) | For signal amplification. A primary antibody binds the hapten on the probe (e.g., anti-DIG-HRP). HRP then catalyzes the deposition of numerous fluorescent or chromogenic tyramide molecules, dramatically amplifying the signal [6] [9]. |

| Branched DNA (bDNA) Amplification System | Proprietary signal amplification system (e.g., in RNAscope) that uses pre-amplifier and amplifier molecules to build a tree-like structure for high-sensitivity detection without the need for tyramide [1]. |

| 5-Acetamidonaphthalene-1-sulfonamide | 5-Acetamidonaphthalene-1-sulfonamide|High-Purity |

| 2,4-dimethyl-9H-pyrido[2,3-b]indole | 2,4-Dimethyl-9H-pyrido[2,3-b]indole|High-Quality Research Chemical |

The fundamental principle of in situ hybridization—specific complementary base pairing—has remained unchanged for decades. However, as the comparisons and protocols detailed here show, the execution of this principle has evolved into a sophisticated family of technologies. The choice of probe and platform is not one-size-fits-all; it depends heavily on the experimental goals, whether they are the sensitive validation of a few key biomarkers or the unbiased discovery of spatial transcriptomic patterns. For researchers validating gene expression patterns, a careful consideration of specificity controls, quantification strategies, and the growing power of multiplexed, AI-enabled spatial analysis is paramount.

Why Use Multiple Probes? Establishing Specificity and Reliability

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a cornerstone technique for visualizing spatiotemporal gene expression patterns directly within cells and tissues, providing indispensable insights for developmental biology, disease research, and validation of novel cell types. A critical factor influencing the success of any ISH experiment is the probe design strategy. This guide objectively compares the performance of single-probe versus multiple-probe approaches, providing experimental data and methodologies that underscore why using multiple probes is essential for establishing specificity and reliability in research and drug development.

The Fundamental Rationale: How Multiple Probes Enhance Assay Performance

Using multiple probes in an ISH experiment involves designing several short, single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that are complementary to different regions of the same target RNA transcript. This strategy fundamentally improves assay performance through two primary mechanisms:

- Signal Amplification: Each probe contributes to the final signal. When these probes are labeled and detected collectively, they act as multiple reporters binding to a single target, thereby amplifying the output signal. This is particularly crucial for detecting low-abundance transcripts where a single probe might not provide a detectable signal above background noise [10].

- Specificity Verification: True specificity is achieved when a signal is generated from the coordinated binding of several independent probes to their respective unique sequences on the same target molecule. The probability of non-specific binding or off-target hybridization occurring simultaneously for all multiple probes is exponentially lower than for a single probe, dramatically reducing false-positive results [11].

The following table summarizes the core comparative advantages of using multiple probes over a single-probe approach.

| Feature | Single-Probe Approach | Multiple-Probe Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Limited, often insufficient for low-abundance targets [10] | High, due to signal amplification from multiple binding events [10] |

| Specificity | Lower, prone to false positives from off-target binding [11] | High, as it requires simultaneous binding of several independent probes [11] |

| Reliability & Robustness | Variable; highly dependent on the performance of one probe sequence | Consistent; performance is averaged across several probes, mitigating poor performance of any single probe |

| Optimal Probe Length | Long (e.g., 250-1500 bases for RNA probes) [12] | Short (e.g., 35-45 bases for DNA oligonucleotides) [10] |

| Experimental Flexibility | Low; often locked into a single detection method | High; platforms like OneSABER allow the same probe set to be used with diverse signal development techniques [10] |

Experimental Validation: Data Supporting the Multi-Probe Advantage

Case Study 1: The OneSABER Platform in Flatworm Models

The OneSABER framework provides a compelling experimental demonstration of the "one probe fits all" concept, where a single set of multiple DNA probes is used with various detection methods.

- Experimental Protocol: Researchers designed a pool of 15-30 short (~35-45 nt) ssDNA oligonucleotides, each complementary to a different region of the target RNA. Each probe was synthesized with a common "landing-pad" sequence. Through a Primer Exchange Reaction (PER), these initiator sequences were extended to create long concatemers, significantly amplifying the number of sites for secondary, labeled probes to bind. This pool of concatemeric probes was then hybridized to whole-mount samples of the flatworm Macrostomum lignano and could be detected using colorimetric (AP-based), fluorescent (TSA), or enzyme-free (HCR) methods without needing to redesign the core probes [10].

- Supporting Data: This multi-probe system demonstrated high versatility and efficiency in complex whole-mount samples, which are often challenging due to autofluorescence and probe penetration issues. The ability to use the same probe set across different detection platforms validates the robustness of the multiple-probe design and eliminates the resource investment needed to create different probes for different techniques [10].

Case Study 2: QuantISH Analysis in Ovarian Cancer

Research on high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSC) highlights the importance of precise, multi-probe-based quantification for biomarker discovery.

- Experimental Protocol: Researchers used chromogenic RNA-ISH (RNA-CISH) with multiple probes to target genes like CCNE1 and DDIT3 in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) patient samples. The QuantISH image analysis framework was then employed to automatically quantify RNA expression levels from the ISH images. This pipeline involved separating the color channels, segmenting individual nuclei based on morphology, classifying cell types (carcinoma, immune, stromal), and finally quantifying the specific RNA signal on a per-cell basis [13] [14].

- Supporting Data: The multi-probe ISH assay, combined with QuantISH analysis, enabled the quantification of gene expression variability within tumor samples. This approach identified that the average expression of CCNE1 and the expression variability of DDIT3 acted as candidate biomarkers, a finding that would be difficult to reliably establish with a less specific single-probe method [13].

Essential Protocols for Multiple-Probe ISH

Probe Design and Synthesis for OneSABER

This protocol enables the creation of a universal, multi-probe set adaptable for various signal detection methods [10].

- Design: Select 15-30 target-specific sequences (~35-45 nt) from the mRNA of interest. Append an identical 9-nucleotide initiator sequence to the 3' end of each oligonucleotide.

- Synthesis (Primer Exchange Reaction): Incubate the pooled oligonucleotides with a catalytic DNA hairpin and a strand-displacing polymerase (e.g., Bst DNA polymerase). The reaction extends each probe by repeatedly adding a complementary sequence to the initiator, creating a long, concatemeric ssDNA probe. The length (and thus signal amplification strength) is controlled by reaction time.

- Labeling: The concatemers are not directly labeled. Instead, they serve as universal landing pads for short secondary probes, which are conjugated to haptens (e.g., DIG, Fluorescein) or fluorophores depending on the chosen detection method (antibody-based AP/HRP or direct fluorescence).

Chromogenic RNA-ISH with DIG-Labeled Probes

This is a standard, robust protocol for colorimetric detection using multiple RNA probes [15] [12].

- Tissue Preparation: Fix tissues in paraformaldehyde and embed in paraffin (FFPE). Section tissues (4-8 µm) and mount on slides. Deparaffinize and rehydrate sections through xylene and ethanol series.

- Antigen Retrieval & Permeabilization: Treat slides with proteinase K (e.g., 20 µg/mL for 10-20 min at 37°C) to expose target RNAs. Conditions must be optimized for each tissue type to balance signal and morphology.

- Hybridization: Apply a hybridization solution containing the denatured DIG-labeled RNA probes (typically 250-1500 bases long) to the sections. Cover with a coverslip and incubate overnight in a humidified chamber at a optimized temperature (e.g., 55-65°C).

- Stringency Washes: Wash slides post-hybridization with solutions like 50% formamide in 2x SSC at 37-45°C, followed by 0.1-2x SSC at higher temperatures. This removes unbound and non-specifically bound probe.

- Immunodetection: Block sections, then incubate with an anti-DIG antibody conjugated to Alkaline Phosphatase (AP). After washing, apply the colorimetric substrate NBT/BCIP, which produces an insoluble purple precipitate where the probe has hybridized.

Research Reagent Solutions for Multiple-Probe ISH

The following table details key reagents and their functions in a typical multiple-probe ISH workflow.

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| ssDNA Oligonucleotide Pool | A set of short, user-defined DNA sequences that are complementary to different regions of the target RNA; the foundation for platforms like OneSABER [10]. |

| Concatemeric Probes (e.g., SABER) | Long, repetitive DNA strands synthesized from short oligonucleotides; provide multiple binding sites for secondary probes, thereby amplifying the signal [10]. |

| Hapten-Labeled Nucleotides (e.g., DIG-dUTP) | Incorporated into probes during synthesis; serve as antigens for antibody-based detection, enabling high-sensitivity colorimetric or fluorescent signal amplification [15] [12]. |

| Anti-Hapten Antibody (e.g., anti-DIG-AP) | Binds specifically to the hapten label on the probe; the enzyme conjugate (AP or HRP) catalyzes the reaction that produces the detectable signal [15] [12]. |

| Proteinase K | A proteolytic enzyme; digests proteins in the fixed tissue to increase permeability and allow probe access to the target RNA, while preserving tissue morphology [12]. |

| Hybridization Buffer (with Formamide) | A solution that creates optimal conditions for specific probe-target binding; formamide lowers the melting temperature, allowing hybridization to be performed at a lower, less destructive temperature [12]. |

| Stringency Wash Buffer (e.g., SSC) | A saline-sodium citrate buffer; used after hybridization with carefully controlled temperature and salt concentration to wash away imperfectly matched or unbound probes, ensuring high specificity [12]. |

Visualizing the Workflow and Key Concepts

Multi-Probe ISH Logical Framework

OneSABER Probe Assembly and Detection

The experimental evidence and protocols presented clearly demonstrate that employing multiple probes is not merely an alternative but a superior strategy for establishing the specificity and reliability required in modern gene expression validation. This approach directly addresses the critical challenges of sensitivity and false positives, making it an essential methodology for rigorous research and biomarker discovery in drug development.

The visualization of genetic sequences within their native cellular context has been a cornerstone of biological research and clinical diagnostics for decades. This capability, central to validating gene expression patterns, hinges on the use of nucleic acid probes. The journey of probe technology began in the late 1960s with methods using radioisotope-labeled probes and autoradiography [16]. While foundational, these radioactive methods presented significant challenges, including safety hazards, limited resolution, and short probe shelf-life. The critical shift in the field occurred with the introduction of non-radioactive labeling in the early 1980s, which enabled the development of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [16] [17]. This evolution from radioactive to non-radioactive options has expanded the toolkit available to researchers, providing a spectrum of probes that balance specificity, sensitivity, stability, and safety for precise spatial gene expression analysis.

A Comparative Guide to Probe Types

Modern molecular biology utilizes a diverse array of probe types, each with distinct characteristics tailored for specific applications. The table below provides a structured comparison of the most common probes used in research and diagnostics.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Molecular Probe Types

| Probe Type | Specificity | Stability | Immunogenicity | Cost | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Very High | Moderate (can degrade in vivo) | Moderate to High | High | Protein detection, immunohistochemistry [18] |

| Peptides | High | Moderate to High | Low | Moderate | Targeted imaging, drug delivery [18] |

| Aptamers | High | High (especially DNA aptamers) | Very Low | Low to Moderate | Molecular diagnostics, synthetic biology [18] |

| Small Molecules | Moderate to High | High | Very Low | Low | Metabolic imaging, drug discovery [18] |

| Oligonucleotides | High | High in vitro | Very Low | Low to Moderate | FISH, gene expression validation [19] [16] |

Non-Radioactive Labeling and Detection Systems

The advent of non-radioactive haptens revolutionized probe technology by coupling them with sensitive immunofluorescence detection. These haptens provide the critical link that allows a universal detection system to visualize diverse probes.

Table 2: Common Haptens and Fluorochromes in Non-Radioactive Detection

| Label Type | Detection Method | Key Characteristics | Long-Term Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxigenin (DIG) | Anti-DIG antibody conjugated to a reporter (e.g., fluorochrome, enzyme) | High specificity, low background, versatile [20] [21] | Stable for decades when stored at -20°C [17] |

| Biotin | Streptavidin or Avidin conjugated to a reporter | Very strong binding, widely used [17] | Stable for decades when stored at -20°C [17] |

| SpectrumOrange | Direct fluorescence | Bright, sharp signals [17] | Maintains performance for at least 20 years [17] |

| SpectrumGreen | Direct fluorescence | Bright, sharp signals [17] | Maintains performance for at least 20 years [17] |

| SpectrumAqua | Direct fluorescence | Bright signals, useful for multiplexing [17] | Fades after approximately 3 years [17] |

Experimental Protocols: From Probe Design to Application

Computational Probe Design with TrueProbes

Accurate quantification of RNA at the single-cell level using methods like single-molecule RNA FISH (smRNA-FISH) depends heavily on high probe specificity to minimize off-target binding and false positives. The TrueProbes software platform addresses this by integrating genome-wide BLAST-based binding analysis with thermodynamic modeling to generate high-specificity probe sets [19].

Protocol Overview:

- Input: TrueProbes requires the target RNA sequence and can incorporate user-provided gene expression datasets to weight off-target interactions.

- Filtering: The software tiles the RNA with all possible oligonucleotides, then removes probes that bind to ribosomal RNA (rRNA).

- Ranking: Unlike older tools that select probes sequentially, TrueProbes ranks all candidate probes globally based on a combined score of predicted binding affinity, target specificity, and structural constraints.

- Output: The final output is a set of non-overlapping probes optimized for maximum signal-to-noise ratio under user-defined hybridization conditions [19].

Experimental benchmarks demonstrate that probes designed with TrueProbes consistently outperform those from other design tools in both computational metrics and experimental validation, showing enhanced target selectivity [19].

The OneSABER Unified ISH Platform

Navigating different in situ hybridization (ISH) protocols can be challenging, as they often require custom probe types and proprietary chemistry. The OneSABER platform offers a unified, open framework that uses a single type of DNA probe, adapted from the Signal Amplification by Exchange Reaction (SABER) method, for multiple signal development techniques [10].

Protocol Overview:

- Probe Design: A pool of short (~35-45 nt) single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides is designed, each complementary to the target RNA and containing a universal 9-nucleotide initiator sequence.

- Signal Amplification: Using a Primer Exchange Reaction (PER), the initiator is extended in vitro to generate long concatemeric repeats. The length of this extension, which controls signal strength, is customizable by adjusting reaction time.

- Versatile Detection: These concatemers serve as landing pads for short secondary probes labeled with haptens like DIG or fluorescein. This design allows the same primary probe set to be used with various detection methods, including colorimetric (AP-based), fluorescent (TSA), or enzyme-free (HCR) assays [10].

This "one probe fits all" approach increases flexibility, reduces costs, and simplifies experimental design for validating gene expression in complex samples [10].

DNA Probe Longevity and Storage Protocol

A 2025 study demonstrated that hapten-labeled DNA probes, when stored correctly, remain viable for decades, far exceeding typical official shelf-life guidelines of 2-3 years [17].

Experimental Findings:

- Researchers tested 581 FISH probes, aged 1 to 30 years, including both self-labeled and commercial probes.

- All probes, stored consistently at -20°C in the dark, produced brilliant and analyzable FISH signals upon reuse.

- Probes labeled with DIG, biotin, SpectrumOrange, and SpectrumGreen showed no significant loss in performance over time.

- The study concludes that a properly stored FISH probe can be used until the tube is empty, without regard to its official expiration date [17].

Storage Protocol:

- Temperature: Store at -20°C or below.

- Condition: Keep probes in the dark to prevent photobleaching.

- Handling: Aliquot probes to minimize freeze-thaw cycles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful experimentation relies on a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table details essential components for probe-based gene expression validation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Probe-Based Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Digoxigenin (DIG) DNA Labeling Kit | Enzymatically incorporates DIG-hapten into DNA probes for subsequent immuno-detection [20]. | Labeling cDNA probes for ISH in plant-parasitic nematodes [20]. |

| Anti-Digoxigenin-AP-Fab fragments | Antibody fragment conjugated to Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) for detecting DIG-labeled probes. | Colorimetric signal development in ISH (BCIP/NBT substrate) [20]. |

| Pfu DNA Polymerase | High-fidelity DNA polymerase for proof-reading PCR during probe synthesis. | Amplifying specific gene fragments for DIG-labeled probe synthesis [20]. |

| Boehringer Blocking Reagent | Blocks nonspecific binding sites on membranes or tissues to reduce background noise. | Blocking in chemiluminescent immunoassay detection for EMSA [21]. |

| Hybridization Buffer (with Formamide) | Creates a controlled chemical environment to promote specific hybridization and suppress non-specific binding. | Standard component of ISH and FISH protocols [20]. |

| Locked Nucleic Acids (LNAs) | Synthetically modified nucleotides with a bridged sugar backbone, increasing probe affinity and thermal stability. | Component of Invader probes for enhanced double-stranded DNA recognition [21]. |

| TrueProbes Software | Computational pipeline for designing high-specificity smRNA-FISH probe sets with minimal off-target binding. | Quantifying single-molecule RNA in cells and tissues [19]. |

| 4,5,5-trifluoropent-4-enoic Acid | 4,5,5-trifluoropent-4-enoic Acid, CAS:110003-22-0, MF:C5H5F3O2, MW:154.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Aminotetrahydro-1,3-oxazin-2-one | 3-Aminotetrahydro-1,3-oxazin-2-one|CAS 54924-47-9 | 3-Aminotetrahydro-1,3-oxazin-2-one (CAS 54924-47-9), a promising quorum sensing inhibitor for antibacterial research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for detecting a target using a hapten-labeled probe and immuno-detection, a fundamental pathway in modern non-radioactive methods.

The transition from radiolabeled to modern non-radioactive probes has profoundly enhanced our ability to validate gene expression with precision, safety, and versatility. Today's researchers have access to a sophisticated toolkit comprising highly specific probe designs like those from TrueProbes, unified platforms such as OneSABER, and robust labeling systems including DIG and biotin. Supported by experimental data demonstrating exceptional long-term stability, these tools enable highly reliable spatial gene expression analysis. This technological evolution ensures that scientists and drug development professionals can continue to push the boundaries of molecular research and diagnostics with greater confidence and clarity.

The validation of gene expression patterns using multiple in situ hybridization (ISH) probes is a cornerstone of modern spatial biology research. The fidelity of these experiments is fundamentally dependent on the meticulous design of the probes themselves. Key parameters—probe length, GC content, and labeling strategy—directly govern hybridization efficiency, signal-to-noise ratio, and the accuracy of downstream conclusions. This guide provides an objective comparison of probe design methodologies and their performance, equipping researchers with the data needed to select optimal reagents for their experimental context.

Core Design Parameters and Comparative Performance

The thermodynamic behavior and binding specificity of ISH probes are primarily dictated by three interdependent design parameters. The following table summarizes their optimal ranges and impact on experimental outcomes.

Table 1: Key Parameters for ISH Probe Design

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Impact on Performance | Comparative Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Length | 15–30 nucleotides (DNA) [22]; 250–1500 bases (RNA, optimal ~800) [12] | Shorter probes offer better specificity but may reduce binding energy; longer probes increase sensitivity but risk higher background and intramolecular structures [22]. | RNA probes (~800 bases) show highest sensitivity and specificity [12]. DNA oligos (15-30 nt) are preferred for multiplexed FISH [23]. |

| GC Content | Dependent on desired Tm [22] | Directly influences melting temperature (Tm) and hybridization strength. Low GC may require longer probes for stability [22]. | Must be optimized in conjunction with Tm. Extreme GC-rich or AT-rich sequences pose design challenges and require sophisticated thermodynamic modeling [22]. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | Specific to protocol | Temperature at which 50% of probes are hybridized. Higher Tm generally provides better results [22]. | Must be optimized for each tissue type and protocol. TrueProbes simulates performance under user-defined conditions [19]. |

Computational Probe Design Software: A Performance Comparison

Computational tools are essential for designing high-specificity probes, especially for complex or repetitive targets. The table below compares several available platforms based on their design strategies and outputs.

Table 2: Comparison of Oligonucleotide FISH Probe Design Software

| Software Tool | Primary Design Strategy | Specificity Screening Method | Key Features / Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| TrueProbes | Genome-wide BLAST, thermodynamic modeling, and kinetic simulation [19] | Ranks candidates by minimal expressed off-target binding; incorporates gene expression data [19] | Optimizes for specificity under user-defined conditions; models probe performance [19]. |

| Stellaris | Heuristic filtering (GC content), 5' to 3' tiling with repetitive sequence masking [19] | Applies five masking levels to discard repetitive or non-species-specific sequences [19] | A "first-pass" design method; common in commercial applications [19]. |

| Tigerfish | De novo discovery and design for repetitive DNA intervals [23] | Genome-scale profiling to design interval-specific repeat probes [23] | Specialized for targeting highly repetitive regions (e.g., pericentromeric DNA) [23]. |

| PaintSHOP | Conventional filters plus Bowtie2 alignment and machine learning classifier [19] | Machine learning assigns probability of deleterious off-target duplexes [19] | Integrates alignment and ML triage to select top-ranked, non-overlapping probes [19]. |

Experimental data from benchmarking studies indicate that the design algorithm significantly impacts performance. Probes designed with TrueProbes, which employs a global ranking system based on expressed off-target binding, consistently outperformed alternatives by demonstrating enhanced target selectivity and superior experimental performance [19]. In contrast, tools that rely on sequential 5' to 3' tiling and simpler filtering heuristics may yield probes prone to false positives from off-target binding [19].

Experimental Protocols for Probe Validation

Protocol 1: DIG-Labeled RNA ISH for Paraffin-Embedded Sections

This classic protocol is fundamental for validating gene expression patterns in tissue context [12].

- Sample Preparation and Deparaffinization: Rehydrate formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections through a graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, 70%, 50%) and xylene [12].

- Antigen Retrieval and Permeabilization: Digest sections with 20 µg/mL Proteinase K in 50 mM Tris at 37°C for 10-20 minutes. Titrate Proteinase K concentration and time for optimal signal and morphology. Immerse slides in ice-cold 20% acetic acid for 20 seconds, then dehydrate [12].

- Hybridization: Apply DIG-labeled RNA probe (diluted in hybridization solution containing 50% formamide, 5x salts, 10% dextran sulfate) to the section. Denature probe at 95°C for 2 minutes before use. Hybridize overnight at 65°C in a humidified chamber [12].

- Stringency Washes: Remove non-specific binding with sequential washes: first with 50% formamide in 2x SSC at 37-45°C, then with 0.1-2x SSC at 25-75°C. Temperature and SSC concentration should be adjusted based on probe length and complexity [12].

- Immunodetection: Block sections with MABT (Maleic Acid Buffer with Tween-20) containing 2% blocking reagent. Incubate with anti-DIG antibody conjugated to Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) for 1-2 hours. After washing, develop signal with NBT/BCIP chromogenic substrate in pre-staining buffer [12].

Protocol 2: OneSABER - A Unified Platform for Multiplexed FISH

The OneSABER protocol enables a "one probe fits all" approach, allowing a single set of DNA probes to be used with multiple signal amplification methods [10].

- Probe Design and Concatemerization: Design a pool of 15-30 short ssDNA oligonucleotides (35-45 nt) complementary to the target RNA, each with a specific 3' initiator sequence. Extend these primers in vitro via Primer Exchange Reaction (PER) to generate long concatemers. The reaction time controls concatemer length, which directly correlates with signal amplification strength [10].

- Signal Development: The concatemers serve as universal landing pads. For fluorescence, hybridize short secondary probes labeled with haptens (e.g., DIG, Fluorescein) to the concatemers. Detect these haptens with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies or use the concatemers to prime a Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) for further amplification. For colorimetric detection, use anti-hapten antibodies conjugated to AP or Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) [10].

- Multiplexing: The platform's modularity allows for sequential probing and detection of multiple targets in the same whole-mount sample or tissue section [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful ISH experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for ISH/FISH Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| DIG-labeled RNA Probes | Sensitive, strand-specific detection of RNA targets; incorporated via in vitro transcription [12]. | Chromogenic RNA ISH in FFPE tissues; high-sensitivity single-molecule detection [12]. |

| Oligonucleotide Pools (OneSABER) | A set of short ssDNA oligos that are extended to form universal, modular probes for multiple detection methods [10]. | Multiplexed FISH in whole-mount samples (e.g., flatworms); unified protocol for TSA, HCR, and colorimetric ISH [10]. |

| Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) | A highly sensitive enzymatic amplification method that deposits numerous fluorophore-labeled tyramide molecules at the probe site [10] [24]. | Detecting low-abundance targets; enhancing signal in thick, autofluorescent samples (pSABER) [10] [24]. |

| Peroxidase-fused Nanobodies (POD-nAbs) | Small, recombinant immunoreagents that offer superior tissue penetration and are fused with HRP for direct coupling to TSA [24]. | Deep immunolabeling in 3D tissues; highly sensitive detection when combined with FT-GO [24]. |

| Blocking Agents (BSA, Normal Serum) | Reduce non-specific binding of detection antibodies to the sample, lowering background signal [25]. | Essential step in all indirect detection protocols; normal serum from the secondary antibody host species is often recommended [25]. |

Logical Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The diagram below outlines the logical sequence and key decision points in selecting and implementing a probe design and detection strategy for ISH.

Diagram: ISH Probe Design and Detection Workflow. This chart guides the selection of probe type, design tool, and detection method based on the experimental target and goals.

The Critical Role of Tissue Preparation and Fixation in RNA Integrity

In the validation of gene expression patterns using multiple in situ hybridization (ISH) probes, the reliability of results is fundamentally rooted in the pre-analytical phase. Tissue preparation and fixation are not merely preliminary steps but are critical determinants of RNA integrity, directly influencing the sensitivity and accuracy of spatial transcriptomics. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues represent an invaluable repository for biomedical research, accompanied by extensive clinical data. However, the chemical modifications imposed by fixation can severely compromise RNA quality, leading to degraded templates that obscure true gene expression signals. This guide objectively compares the performance of different fixation and RNA extraction methods, providing researchers with the experimental data necessary to inform their protocols and ensure the fidelity of their ISH findings.

Fixation Methods: A Comparative Analysis of Histology and RNA Preservation

The choice of fixative represents a significant trade-off between the imperative for excellent tissue morphology and the need for high-quality biomolecules. The following table synthesizes findings from controlled studies comparing common fixation methods.

Table 1: Impact of Fixation Method on Tissue Morphology and RNA Integrity

| Fixation Method | Tissue Morphology | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | Performance in RT-qPCR | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formalin (FFPE) | Adequate to Excellent [26] | Significantly low [27]; 4.0–7.2 [28] | Inhibited, especially with longer amplicons [28] | RNA quality is significantly lower than fresh frozen tissues; RT-qPCR values can remain comparable for short targets [27]. |

| Methacarn (MFPE) | Excellent [26] | High (Comparable to UFT/RNAlater) [29] | Comparable to unfixed frozen tissue (UFT) [29] | Yields high RNA concentration and purity; suitable for combined histological and biomolecular analysis [29]. |

| PAXgene (Non-formalin) | Comparable to Formalin [28] | High (6.4–7.7) [28] | Performs as well as fresh frozen tissue [28] | Preserves histology similarly to formalin but does not chemically modify RNA [28]. |

| Fresh Frozen (UFT) | N/A (Baseline for RNA) | High (8.0–9.2) [28] | Optimal (Baseline) [29] | Considered the gold standard for RNA quality but lacks the morphological preservation and logistical ease of FFPE [30]. |

Experimental Workflow: From Tissue to Quantifiable RNA

The process of extracting and analyzing RNA from fixed tissues involves a series of critical, interdependent steps. The diagram below outlines a generalized workflow for FFPE tissues, highlighting key stages where protocol optimization is essential.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Tissue Processing and Fixation for FFPE

- Fixation: Immerse tissue bits in formalin for a standardized duration (e.g., 24 hours or 72 hours) [27].

- Washing: Transfer tissues to processing cassettes and wash in running tap water for 30 minutes [27].

- Dehydration: Process tissues through a graded series of isopropyl alcohol (50%, 70%, 90%, and 100%) for 45 minutes each [27].

- Clearing: Submerge tissues in graded xylene (50%, 90%, and 100%) for 30 minutes each [27].

- Embedding: Immerse tissues in a paraffin wax bath and incubate overnight at 65°C. Embed the next day using an embedding machine [27].

RNA Extraction from FFPE Tissues

Multiple methods exist, with commercial kits offering standardized workflows.

- Deparaffinization: Cut 10-μm thick sections and place in a tube. Incubate at 65°C for 5 minutes, then add 1 ml of xylene. Repeat xylene treatment 2-3 times for complete wax removal [27].

- Rehydration: Rehydrate tissue sections using a graded ethanol series (100%, 90%, 70%, 50%, 30%) for 2 minutes per step. Briefly wash with 1x PBS [27].

- Homogenization & Isolation: Add TRIzol reagent and homogenize the sample. Add chloroform, vortex vigorously, and centrifuge to separate layers. Transfer the aqueous RNA-containing layer to a new tube [27].

- Precipitation & Washing: Precipitate RNA with isopropanol and glycogen. Centrifuge, remove supernatant, and wash the pellet with 80% ethanol. Air-dry and resuspend in DEPC water [27].

RNA Integrity and Quantity Assessment

- Spectrophotometry (Purity/Quantity): Use a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. A 260/280 ratio of ~2.0 is generally considered pure for RNA. The use of a slightly alkaline buffer like TE (pH 8.0) is recommended for accurate ratios [31].

- Microcapillary Electrophoresis (Integrity): Use the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. The software generates an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) on a scale of 1 (degraded) to 10 (intact). This metric evaluates the entire electrophoretic trace, providing a robust assessment of RNA quality [31].

Optimizing RNA Yield: Extraction Kits and Fixation Duration

The recovery of usable RNA is influenced by both the extraction chemistry and pre-analytical variables like fixation time.

Performance of Commercial RNA Extraction Kits

A systematic comparison of seven commercial FFPE RNA extraction kits using tonsil, appendix, and lymphoma tissues revealed significant disparities. The Promega ReliaPrep FFPE Total RNA Miniprep System and a Roche kit demonstrated superior performance [30].

Table 2: Comparison of Commercial FFPE RNA Extraction Kits

| Extraction Kit | Relative RNA Quantity | RNA Quality (RQS/DV200) | Key Experimental Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promega ReliaPrep | Highest yield for tonsils and lymph nodes [30] | Among the best quality [30] | Provided the best ratio of both quantity and quality on tested tissues [30]. |

| Roche Kit | Not specified as highest yield | Better-quality recovery than most kits [30] | Delivered systematically better-quality recovery [30]. |

| Thermo Fisher Kit | Highest yield for 2 of 3 appendix samples [30] | Not specified | Performance can vary by tissue type [30]. |

| Other Kits Tested | Variable and generally lower [30] | Lower than top performers [30] | Although kits use similar processes, outcomes vary greatly [30]. |

Impact of Fixation Duration on RNA

Prolonged fixation in formalin exacerbates RNA degradation. A study comparing 24-hour and 72-hour formalin fixation found that while mRNA could be isolated with satisfactory quantity in both groups, the RNA quality was significantly low for formalin-fixed tissues. Despite this, RT-qPCR values for both formalin groups were comparable to those from fresh frozen tissues, indicating that the degraded RNA can still be amplifiable for shorter targets [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

- RNase-free Water (DEPC-treated): Used to resuspend and store extracted RNA to prevent degradation by ubiquitous RNases [27].

- TRIzol/Column-based Lysis Buffers: TRIzol is a mono-phasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate that effectively denatures proteins and maintains RNA integrity during homogenization. Commercial kits use proprietary lysis buffers for this purpose [27] [30].

- Proteinase K: An enzyme that digests proteins and helps break down crosslinks formed by formalin fixation, a key step in extracting RNA from FFPE samples [30].

- DNase I (RNase-free): An enzyme that degrades contaminating genomic DNA, which can otherwise interfere with downstream RNA analysis and lead to inaccurate quantification [27] [31].

- Xylene: An organic solvent used to efficiently dissolve and remove paraffin wax from tissue sections prior to RNA extraction (deparaffinization) [27] [12].

- Graded Ethanol Series (100%, 95%, 70%): Used for rehydrating deparaffinized tissue sections and for washing RNA pellets to remove salts and other contaminants [27] [12].

- RNA Integrity Dyes (e.g., for Bioanalyzer): Fluorescent dyes that intercalate into nucleic acids, allowing for quantification and integrity assessment via instruments like the Agilent Bioanalyzer [31].

A Framework for Method Selection in ISH Research

Choosing the optimal protocol depends on the primary goal of the study. The following decision framework aids in selecting a path that balances morphological and biomolecular needs.

The path to validating gene expression patterns with multiple ISH probes is paved during tissue preparation. While formalin fixation remains the gold standard for morphology, it introduces a significant challenge for RNA integrity. Alternative fixatives like methacarn and PAXgene offer a compelling balance, preserving both histological detail and biomolecular quality. Furthermore, the choice of RNA extraction kit significantly influences the outcome and must be matched to the tissue type. By making informed, evidence-based choices at these critical pre-analytical stages, researchers can ensure that the gene expression patterns they observe are a true reflection of biology, rather than an artifact of their preparation method.

Advanced ISH Protocols: From Multiplexing to Automated Platforms

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a cornerstone technique for visualizing gene expression patterns within their native tissue context, playing a crucial role in developmental biology, disease research, and the validation of novel cell types identified via single-cell RNA sequencing [10]. However, the field has long been hampered by a significant challenge: the proliferation of proprietary and incompatible methods, each requiring its own custom probe design and detection chemistry. This fragmentation forces researchers to lock into a single technique or bear substantial costs when multiple methods are needed in a single project [10]. The "One Probe Fits All" OneSABER platform emerges as a unified, open framework designed to overcome this limitation. This guide provides an objective comparison of the OneSABER approach against other established and emerging ISH alternatives, detailing its performance, experimental protocols, and practical implementation for researchers and drug development professionals.

Platform Comparison: OneSABER Versus Alternatives

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of the OneSABER platform alongside other prominent ISH technologies.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Major ISH Platforms

| Feature | OneSABER | RNAscope | TrueProbes | Tigerfish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Modular DNA probes with primer exchange reaction (PER) amplification [10] | Patented double-Z probe design with branched DNA signal amplification [32] | Computational probe design optimized for specificity via thermodynamic modeling [19] | Computational design of probes targeting repetitive DNA intervals [23] |

| Probe Univerality | High: A single probe set is adaptable to multiple detection methods [10] | Low: Probes are tailored to a proprietary signal amplification system [33] [32] | Varies: Design is method-agnostic, but probes are typically for specific applications [19] | Low: Specialized for repetitive DNA targets, not general use [23] |

| Key Advantage | Unification of canonical and modern ISH methods; cost-effectiveness; open platform [10] | High sensitivity and single-molecule detection; robust clinical validation [32] | Enhanced specificity and reduced off-target binding predicted by genome-wide analysis [19] | Enables FISH for highly repetitive genomic regions, a previously difficult target [23] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Demonstrated for multiplex TSA and HCR FISH [10] | Up to 4-plex with fluorescent labels [32] | High-plex potential, dependent on final assay configuration [19] | High-plex potential for DNA targets [23] |

| Primary Application Shown | Whole-mount samples (flatworms), FFPE tissue sections [10] | FFPE clinical tissues, single-cell analysis [32] [34] | Single-molecule RNA FISH (smFISH) in cells [19] | Metaphase and interphase chromosome imaging in human cells [23] |

| 5-Methyl-3-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole | 5-Methyl-3-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole|High-Purity Research Chemical | Explore 5-Methyl-3-(trifluoromethyl)isoxazole for advanced drug discovery and medicinal chemistry research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for personal use. | Bench Chemicals | |

| Methyl 2-(6-methylnicotinyl)acetate | Methyl 2-(6-methylnicotinyl)acetate, CAS:108522-49-2, MF:C10H11NO3, MW:193.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Performance and Supporting Data

Independent studies and the platform's foundational publication provide data on the performance of these ISH methods.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics Across Model Systems

| Platform | Reported Sensitivity / Signal Amplification | Demonstrated Specificity & Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| OneSABER | Customizable amplification strength via concatemer length (PER reaction time) [10] | Effective in complex, autofluorescent whole-mount flatworm samples (Macrostomum lignano, Schmidtea mediterranea) and FFPE mouse intestine; enables multiplexing in challenging specimens [10] |

| RNAscope | Single-molecule visualization; ~8000 labels per target RNA with 20 probe pairs [32] | High specificity in clinical FFPE samples; validated for diagnostic use and NGS validation; distinguishes highly homologous viral strains [32] [34] |

| TrueProbes | N/A (Computational design tool) | Probes show enhanced target selectivity and superior signal-to-noise in knockout cell models compared to other design tools [19] |

| Tigerfish | High signal from few probes due to repetitive target nature [23] | Specific labeling of individual human chromosomes on metaphase spreads; accurate interphase chromosomal enumeration [23] |

| Multiplex FISH (mFISH) | Single-cell resolution of multi-gene signatures [9] | Spatially resolved a 3-gene arsenic-responsive model in bladder cancer, revealing correlation between expression and tumor grade (r ≈ +0.83) [9] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

OneSABER Workflow

The core protocol for OneSABER, as demonstrated in whole-mount Macrostomum lignano, involves the following key steps [10]:

- Probe Design and Synthesis: A pool of 15-30 short (35-45 nt) ssDNA oligonucleotides is designed to be complementary to the target RNA. Each oligonucleotide contains a unique 9 nt 3' initiator sequence.

- Probe Amplification (Primer Exchange Reaction): The oligonucleotide pool is extended in vitro using a catalytic DNA hairpin and a strand-displacing polymerase. This reaction generates long, concatemerized probes, with the length (and thus signal amplification strength) controlled by the reaction time.

- Sample Preparation and Hybridization: Samples are fixed and permeabilized. The elongated SABER probes are hybridized to the target RNA within the tissue.

- Modular Signal Development: The concatemerized probes serve as a universal "landing pad." Detection is achieved by hybridizing short secondary probes modified according to the chosen method:

- Canonical Colorimetric ISH: Secondary probes labeled with haptens (e.g., DIG, FITC) are detected using anti-hapten antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (AP) or horseradish peroxidase (HRP), followed by chromogenic development.

- Fluorescent TSA: Hapten-labeled secondary probes are detected with HRP-conjugated antibodies, followed by tyramide signal amplification.

- Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR): Secondary probes initiate a hybridization chain reaction with fluorescently labeled DNA hairpins, providing enzyme-free signal amplification.

- Imaging and Analysis: Samples are imaged using brightfield (colorimetric) or fluorescence microscopy. The use of liquid-exchange mini-columns is recommended to minimize sample loss and reduce protocol time [10].

For comparison, the established RNAscope protocol for FFPE tissues includes [32]:

- Sample Pretreatment: Tissue sections are deparaffinized, subjected to heat-induced epitope retrieval in citrate buffer, and treated with protease to expose target RNA.

- Target Probe Hybridization: A set of ~20 "ZZ" probe pairs, designed to bind contiguously to a ~1 kb region of the target RNA, are hybridized to the sample.

- Signal Amplification: Sequential hybridizations with a preamplifier, an amplifier, and enzyme-conjugated (HRP or AP) label probes create a large branching complex on each ZZ pair.

- Signal Detection: A chromogenic (DAB or Fast Red) or fluorescent substrate is added. The double-Z design ensures that signal amplification only occurs if two probes bind adjacent sites, conferring high specificity and single-RNA sensitivity [32].

Visualizing the Core Technologies

The diagrams below illustrate the fundamental mechanisms of the OneSABER and RNAscope platforms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of these ISH platforms requires a set of core reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ISH

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Platform Context |

|---|---|---|

| SABER DNA Oligonucleotides | Short ssDNA probes serving as the universal foundation for assembly into long concatemers. | OneSABER [10] |

| Primer Exchange Reaction (PER) Enzymes | Catalytic DNA hairpin and strand-displacing polymerase used to generate long concatemerized probes from the oligonucleotide pool. | OneSABER [10] |

| Hapten-Labeled Secondary Probes | Short adapter oligonucleotides labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) or fluorescein (FITC) that bind concatemer landing pads for antibody-based detection. | OneSABER, Canonical ISH [10] |

| ZZ Probe Pairs | Proprietary probe pairs that hybridize contiguously to the target RNA; the double-Z structure is essential for initiating the proprietary signal amplification. | RNAscope [32] |

| Branched DNA (bDNA) Amplification System | A series of preamplifier, amplifier, and label probes that build a branching complex on the ZZ probes for significant signal amplification. | RNAscope [32] |

| Computational Probe Design Software | Tools like TrueProbes and Tigerfish that identify optimal probe sequences based on specificity, thermodynamic properties, and genome-wide off-target analysis. | TrueProbes, Tigerfish [19] [23] |

| Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) Reagents | HRP-catalyzed deposition of fluorescent tyramide dyes, providing high-intensity signal amplification for low-abundance targets. | OneSABER (as a detection option), Multiplex FISH [10] [9] |

| 2-Hexynyl-NECA | 2-Hexynyl-NECA | Potent Adenosine Receptor Agonist | 2-Hexynyl-NECA is a potent, selective adenosine receptor agonist for neurological and cardiovascular research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| 2,4-Bis[(trimethylsilyl)oxy]pyridine | 2,4-Bis[(trimethylsilyl)oxy]pyridine, CAS:40982-58-9, MF:C11H21NO2Si2, MW:255.46 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The "One Probe Fits All" OneSABER paradigm represents a significant shift towards flexibility and accessibility in gene expression validation. By decoupling probe design from signal detection, it provides researchers with an open, unified platform that reduces costs and simplifies experimental logistics. While established commercial systems like RNAscope offer exceptional sensitivity and robustness for clinical applications, and specialized computational tools like TrueProbes and Tigerfish solve distinct probe design challenges, OneSABER's strength lies in its modularity. It empowers researchers to adapt a single probe set to answer diverse biological questions—from initial colorimetric screening in development to high-resolution multiplex fluorescence in complex tissues—all within a single, coherent framework.

Validating gene expression patterns with multiple in situ hybridization (ISH) probes requires highly sensitive and specific detection methods. Signal amplification techniques are pivotal for visualizing low-abundance nucleic acid targets within their native cellular and tissue contexts. This guide objectively compares three prominent methods—SABER, HCR, and Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA)—framed within the research goal of accurate gene expression validation. Understanding the mechanisms, performance characteristics, and experimental requirements of each technique enables researchers to select the optimal strategy for their specific ISH projects.

SABER (Signal Amplification By Exchange Reaction)

SABER utilizes a Primer Exchange Reaction (PER) to grow long, single-stranded DNA concatemers from oligonucleotide probes hybridized to their RNA or DNA targets. These concatemers, which can be tuned to achieve different lengths, serve as scaffolds for hybridizing multiple fluorescently labeled "imager" strands, resulting in significant signal amplification. The method is notable for its high programmability and orthogonality [35]. A key advantage is that probes are concatemerized in vitro prior to hybridization, allowing for bulk production and quality control [35]. For highly multiplexed experiments, SABER can be combined with sequential imaging and imager strand displacement (Exchange-SABER) to visualize numerous targets with a limited number of fluorophores [35].

HCR (Hybridization Chain Reaction)

HCR is an enzyme-free, isothermal amplification method. It employs two kinetically trapped DNA hairpins that remain metastable until exposed to an initiator strand attached to an ISH probe. Upon binding to the target, the initiator triggers a cascade of hybridization events between the two hairpin species, leading to the self-assembly of a long nicked duplex polymer. Fluorophores pre-attached to the hairpins accumulate at the site of amplification, enabling visualization [36] [37]. The third-generation HCR (v3.0) introduces split-initiator probes for automatic background suppression. In this system, two probes must bind adjacent sites on the target to colocalize the two halves of the initiator and trigger the amplification cascade, dramatically reducing non-specific amplified background [37].

Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA)

TSA, also known as Catalyzed Reporter Deposition (CARD), is an enzymatic amplification method. It leverages horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated to a detector antibody or probe. In the presence of a low concentration of hydrogen peroxide, the HRP catalyzes the conversion of tyramide substrates into highly reactive radicals that covalently bind to electron-rich tyrosine residues on proteins in the immediate vicinity of the enzyme. When the tyramide is labeled with a fluorophore or a hapten, this results in the deposition of a large number of signal molecules at the target site [38] [39]. This method can be used to amplify signals in ISH as well as in immunoassays (IHC/ICC) [39].

Technical Comparison and Experimental Data

The following tables summarize the key performance characteristics and experimental data for the three amplification techniques.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of SABER, HCR, and TSA

| Feature | SABER | HCR (v3.0) | TSA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification Mechanism | Enzymatic (polymerase), PER-based concatemerization | Enzyme-free, triggered self-assembly of DNA hairpins | Enzymatic (HRP), catalyzed deposition of tyramide |

| Reported Signal Amplification | 5 to 450-fold [35]; 68-fold for proteins with SABERx3 [40] | Not explicitly quantified; enables single-molecule RNA detection [37] | 10 to 200-fold versus conventional methods [38] [39] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High; 17 orthogonal DNA targets demonstrated simultaneously [35] | Moderate; up to 5 targets demonstrated simultaneously [37] | Low with direct fluorescence; multiplexing possible with serial staining and peroxidase quenching [39] |

| Key Advantage | Programmable amplification level; high orthogonality; presynthesized probes | Enzyme-free; isothermal; automatic background suppression (v3.0) | Extreme sensitivity; commercially established; wide reagent availability |

| Key Limitation | Workflow complexity | Limited number of orthogonal amplifiers | Limited inherent multiplexing; enzyme-dependent |

Table 2: Experimental Protocol and Practical Considerations

| Aspect | SABER | HCR | TSA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Workflow Steps | 1. In vitro PER concatemer synthesis2. Sample hybridization with extended probes3. Signal detection with imager strands [35] | 1. Sample hybridization with initiator-bearing probes2. Amplification via HCR hairpin assembly [37] | 1. Hybridization with HRP-conjugated probes2. Incubation with tyramide reagent and Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ [39] |

| Typical Duration | ~1-3 hours for PER reaction [35] | Several hours for hairpin assembly [37] | Rapid enzymatic reaction (minutes) [39] |

| Critical Reagents | PER catalysts (hairpin, polymerase), dNTPs, fluorescent imager strands [35] | DNA hairpins (H1 & H2), initiator-coupled probes [37] | HRP-conjugated reagents, tyramide substrates (fluorophore- or hapten-labeled) [38] [39] |

| Tissue Penetration | Concatemers designed for low secondary structure, effective in thick tissues [35] | Effective in whole-mount vertebrate embryos and thick tissues [37] | Can be limited by antibody/HRP penetration, especially in thicker tissues [41] |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The diagrams below illustrate the core mechanistic workflows for each signal amplification technique.

SABER Workflow

HCR Mechanism

TSA Mechanism

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of these techniques relies on specific reagent kits and core components.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| PER Catalysts & dNTPs | Enzymatic synthesis of DNA concatemers in SABER | In vitro probe extension for SABER-FISH [35] |

| Orthogonal DNA Concatemers | Provide scaffold for imager binding in multiplexed SABER | Simultaneous imaging of multiple DNA/RNA targets [35] [40] |

| HCR Hairpin Sets (H1 & H2) | Amplification monomers for HCR; fluorophore-labeled | Enzyme-free RNA detection in whole-mount samples [37] |

| Split-Initiator Probe Pairs | Enable automatic background suppression in HCR v3.0 | Robust RNA imaging with unoptimized probe sets in complex tissues [37] |

| Fluorophore-Labeled Tyramides | HRP-activated substrates for covalent signal deposition | Ultra-sensitive detection of low-abundance targets in IHC/ISH [38] [39] |

| HRP-Conjugated Antibodies/Probes | Target recognition and enzyme delivery for TSA | Converting any probe system for high-sensitivity TSA detection [39] |

Guidance for Technique Selection

Choosing the right technique depends on the specific requirements of the gene expression validation project.

- For Maximum Multiplexing: SABER is the leading choice due to its high orthogonality and compatibility with sequential imaging, allowing for the simultaneous visualization of dozens of targets [35].

- For Sensitivity with Simplicity: TSA offers exceptional signal gain and is well-suited for detecting very low-abundance transcripts. Its main drawback for validation with multiple probes is limited inherent multiplexing, though serial staining can overcome this [39] [41].

- For Robustness and Ease of Use: HCR v3.0, with its split-initiator probes, provides excellent automatic background suppression. This makes it highly robust for validating new targets in new sample types, as it minimizes the need for extensive probe optimization [37].

- For Enzyme-Free Amplification: HCR is the definitive option, operating under isothermal conditions without enzymatic components, which can simplify protocol design and reduce costs [36] [37].

In the context of validating gene expression patterns, the choice often involves a trade-off between multiplexing capacity, sensitivity, and workflow complexity. SABER excels in highly complex, multiplexed assays. TSA provides unparalleled sensitivity for challenging, low-copy targets. HCR offers a balanced and robust solution, particularly with v3.0, for quantitative and multiplexed RNA imaging in anatomically complex samples like whole-mount embryos [37] [41].

Multiplex In Situ Hybridization (Multiplex ISH) represents a significant advancement in molecular biology, enabling the simultaneous detection and spatial localization of multiple nucleic acid targets within intact cells and tissue samples. This powerful technique preserves crucial architectural context that is lost in bulk extraction methods, allowing researchers to visualize the precise cellular and subcellular distribution of multiple DNA or RNA sequences in a single experiment. Moving beyond the limitations of single or dual ISH, which detect only one or two targets respectively, multiplex ISH dramatically increases the information yield from precious biological samples by exposing them to multiple differentially labeled probes simultaneously [42]. For researchers and drug development professionals focused on validating complex gene expression patterns, this spatial context is indispensable for understanding cellular heterogeneity, tissue organization, and the intricate interplay between different molecular species in health and disease.

The evolution from single to multiplex ISH has been driven by both technical innovations and growing scientific need. In single ISH, researchers examine the presence of a single nucleic acid fragment using radioactive, fluorescent, or enzyme-linked probes, providing high specificity and accurate localization for gene expression studies and viral detection [42]. Dual ISH extends this capability by employing two differentially labeled probes—using methods such as radionuclide with non-radioactive labels, dual non-radioisotope labels, or two radioisotopes—to simultaneously detect two target sequences, enabling gene co-expression studies and cell subgroup analysis [42]. Modern multiplex ISH technologies, including RNAscope and multicolor FISH, now allow researchers to dramatically expand their investigative reach by detecting numerous targets within the same sample, providing comprehensive data for genomics research and complex disease studies [42].

Key Multiplex ISH Technologies and Methodologies

Core Technology Platforms

The landscape of multiplex ISH technologies encompasses both commercially available systems and academically developed methods, each with distinct advantages for specific research applications. Among commercial platforms, Xenium (10x Genomics), MERSCOPE (Vizgen), and Molecular Cartography (Resolve Biosciences) represent prominent solutions that have been systematically benchmarked using publicly available mouse brain datasets [8]. These platforms vary substantially in their target panel sizes, sensitivity, and specificity characteristics. For instance, in a comparative analysis, panel sizes ranged from 99 genes with Molecular Cartography to 1,147 genes with MERFISH, with only seven genes uniformly targeted across all evaluated datasets, highlighting the importance of platform selection based on specific gene panels of interest [8].

Academic laboratories have also developed significant multiplex ISH methodologies, including MERFISH, STARmap PLUS, and EEL FISH [8]. These methods often employ innovative approaches for signal amplification, detection, and error correction. A critical distinction among these technologies lies in their fundamental approach: while some are sequence-based methods returning transcriptome-wide profiles for individual voxels, others are imaging-based technologies performing highly multiplexed hybridization-based profiling with targeted probes [8]. Imaging-based technologies offer clear advantages for high-resolution molecular profiling, as they use uniquely barcoded fluorescent probes to enable multiplexed identification of single molecules, allowing researchers to study both cellular and sub-cellular localization patterns with unambiguous assignment of molecules to single cells [8].

RNAscope Technology

RNAscope technology has emerged as a particularly powerful approach for multiplex ISH, especially in the context of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, which represent the vast majority of clinically archived samples [9]. This method employs a novel double-Z probe design, divided into complementary sections that must simultaneously bind to the target RNA for signal amplification to occur [42]. This proprietary design ensures high sensitivity and specificity, enabling detection of single RNA molecules while minimizing background noise from non-specific hybridization. The technology forms the foundation for advanced multiplex fluorescence RNA in situ hybridization (RNA mFISH) methods that enable simultaneous detection of multiple RNA targets within intact tissue sections while providing precise spatial information at single-cell resolution [9].

The practical application of RNAscope in biomarker validation was demonstrated in a recent bladder cancer study that utilized multiplex FISH with AI-assisted digital pathology to characterize the spatial distribution of a three-gene arsenic-responsive risk model (NKIRAS2, AKTIP, HLA-DQA1) [9]. This approach successfully mapped individual and combinatorial gene expression across five bladder tumor specimens, revealing distinct inter-sample heterogeneity and spatial clustering of tumor cells with elevated expression scores [9]. The study highlighted how multiplex ISH can validate previously identified genomic signatures while adding crucial spatial dimension to the analysis, particularly showing elevated expression in tumor-adjacent regions with a strong positive correlation to tumor grade (Pearson's r = 0.83) [9].

Sequential Hybridization Approaches

For researchers requiring extremely high multiplexing capabilities, sequential FISH (seqFISH) approaches provide an innovative solution that dramatically expands the number of detectable targets. This methodology employs multiple rounds of hybridization, imaging, and probe stripping to build cumulative color barcodes for numerous targets [43]. The fundamental principle involves using a limited number of distinct fluorophores across multiple hybridization rounds, where the number of distinguishable loci scales as F^N, with F representing the number of distinct fluorophores and N representing the number of hybridization rounds [43]. This exponential scaling enables researchers to distinguish dozens to potentially hundreds of individual molecular targets within the same sample.

A particularly innovative application combining CRISPR imaging with DNA seqFISH demonstrates the "track first and identify later" approach for multiplexed visualization of genomic loci [43]. In this methodology, multiple genomic loci are first labeled and tracked in live cells using a single-color CRISPR-Cas9 system, then subsequently identified through highly multiplexed DNA seqFISH after fixation [43]. This separation of dynamic tracking and identification circumvents the multiplexing limitations of live-cell imaging while providing both temporal and spatial information. As demonstrated in telomere tracking experiments in mouse embryonic stem cells, this approach successfully identified 12 unique subtelomeric regions with variable detection efficiencies, enabling researchers to trace back the dynamics of respective chromosomes [43].

Performance Comparison of Multiplex ISH Platforms

Benchmarking Metrics and Methodologies

Systematic benchmarking of multiplex ISH technologies requires careful consideration of multiple performance parameters beyond simple sensitivity metrics. In a comprehensive comparative analysis of six in situ gene expression profiling technologies using mouse brain datasets, researchers found that standard sensitivity metrics such as the number of unique molecules detected per cell are not directly comparable across platforms due to substantial differences in panel composition and incidence of off-target molecular artifacts [8]. This highlights the critical importance of specificity in evaluating platform performance, as false-positive signals can seriously confound downstream analysis including spatially-aware differential expression.