Achieving High Signal-to-Noise Ratio in FISH: A Comprehensive Guide from Probe Design to Automated Analysis

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH) experiments.

Achieving High Signal-to-Noise Ratio in FISH: A Comprehensive Guide from Probe Design to Automated Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH) experiments. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, we detail how computational probe design with tools like TrueProbes enhances specificity, how signal amplification methods such as SABER and HCR boost sensitivity, and how optimized protocols and clearing techniques improve sample integrity. Furthermore, we explore the critical role of AI-powered spot detection with U-FISH and RS-FISH in accurate validation and quantification. This guide synthesizes the latest methodological advances and troubleshooting strategies to ensure precise, reliable, and quantifiable FISH data for spatial genomics and transcriptomics.

The Core Principles of FISH Signal and Noise

Defining Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in FISH Imaging

In fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) imaging, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is a fundamental quantitative metric that defines the ability to distinguish specific probe-derived fluorescence (signal) from non-specific background interference (noise). Achieving a high SNR is paramount for the accuracy and reliability of FISH-based analyses, as it directly impacts sensitivity, resolution, and the validity of quantitative measurements [1]. Within the broader thesis on principles of high SNR in FISH research, this guide explores the core components of SNR, the methodologies for its quantification, and the comprehensive experimental strategies employed to enhance it. The pursuit of superior SNR is not merely a technical exercise; it is the cornerstone for generating biologically definitive data, particularly in advanced applications like spatial transcriptomics and single-molecule detection [2] [3].

The challenge of SNR is multifaceted. The "signal" originates from fluorophores bound to oligonucleotide probes that have hybridized to their target nucleic acid sequences. In contrast, "noise" is a composite of various sources, including autofluorescence from endogenous tissue components, non-specific binding of probes to off-target sites, and optical limitations of the imaging system itself [4] [3]. In plant tissues, for instance, high autofluorescence has historically prevented the detection of single mRNA molecules in intact tissues, a hurdle only recently overcome through optimized clearing protocols [3]. Similarly, in thick animal tissues, light scattering significantly degrades SNR, necessitating the use of optical clearing techniques [5]. This guide details the core principles and practical protocols essential for navigating these challenges and achieving the high SNR required for cutting-edge research and diagnostics.

Core Components and Quantification of SNR in FISH

The following table breaks down the primary contributors to signal and noise in a FISH experiment, which are critical for understanding where to focus optimization efforts.

Table 1: Core Components of Signal and Noise in FISH Imaging

| Component | Source | Impact on SNR |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Signal | Fluorescent probes bound to the target mRNA/DNA sequence. | The primary source of usable data. Amplification strategies (e.g., HCR, SABER) directly increase this component [4]. |

| Background Noise | Autofluorescence from lipids, proteins, and other endogenous molecules in the tissue [5] [3]. | A major source of noise, particularly in plant and brain tissues. Can obscure true signal, especially for low-abundance targets. |

| Technical Noise | Non-specific binding of probes to off-target sequences [1] [6]. | Creates false-positive spots and elevates background, directly reducing quantitative accuracy. |

| Optical Noise | Light scattering within the tissue and detector read noise [5]. | Reduces contrast and sharpness, limiting imaging depth and resolution. |

Quantitative Measures of SNR

Quantifying SNR is essential for objective protocol evaluation and validation. While specific calculations can vary, the underlying principle involves comparing the intensity of the specific signal against the variability of the background.

- Spot Intensity vs. Local Background: For single-molecule RNA-FISH (smFISH), where transcripts appear as distinct diffraction-limited spots, a common metric involves measuring the mean intensity of individual spots and dividing it by the standard deviation of the background intensity in a nearby region devoid of spots [1] [2]. This measure is crucial for the accurate detection and counting of individual RNA molecules.

- Algorithmic and Software-Based Quantification: Advanced analysis pipelines like FISH-quant and U-FISH incorporate robust algorithms to calculate SNR during automated spot detection [2] [3]. These tools often use a pixel-wise intensity comparison or a signal-to-background ratio to distinguish true transcripts from noise. The performance of these tools is frequently benchmarked using metrics like the F1 score (the harmonic mean of precision and recall), which indirectly reflects the effective SNR of the image, as a higher SNR allows for more precise and accurate spot detection [2].

Experimental Strategies for SNR Enhancement

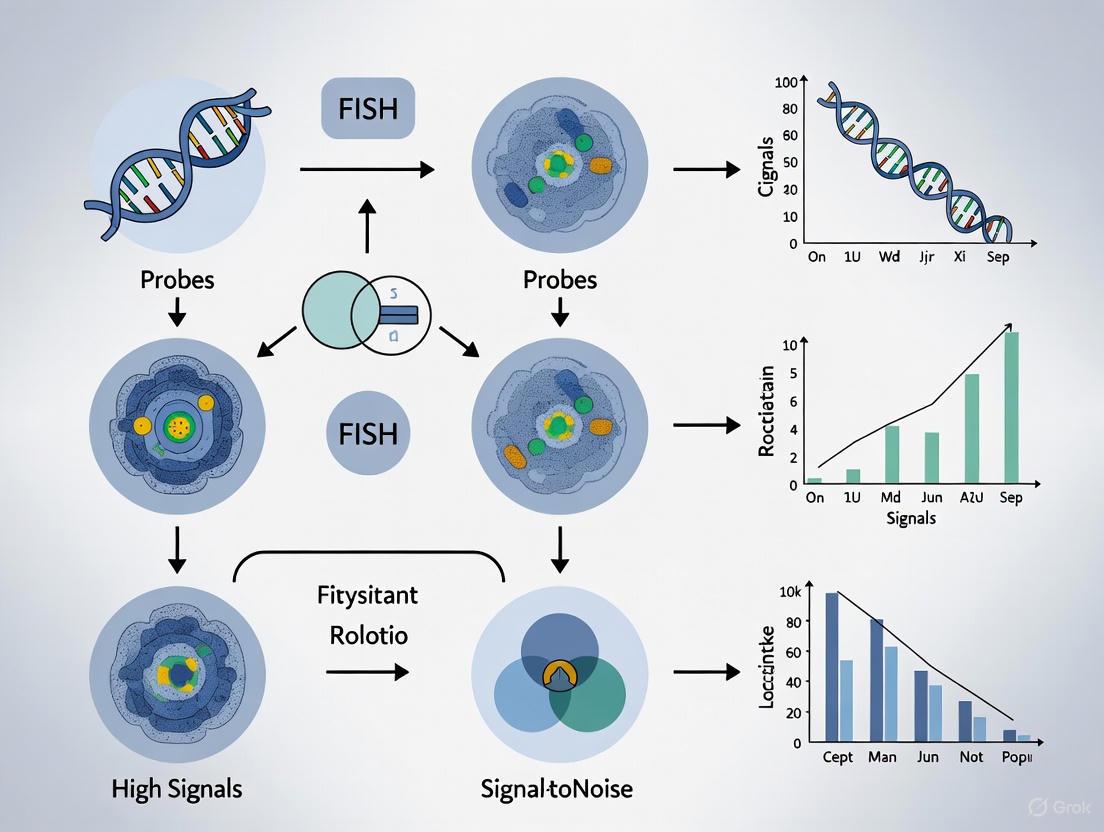

Achieving a high SNR requires a holistic approach, integrating optimized probe design, sophisticated tissue processing, and advanced imaging and computational techniques. The following diagram illustrates the interconnected strategies explored in this section.

Figure 1: A strategic framework for enhancing the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in FISH imaging, spanning biochemical, optical, and computational methods.

Probe Design for Optimal Specificity

The foundation of a high SNR is laid at the probe design stage. Optimal probes exhibit maximal binding to the intended target and minimal interaction with off-target sequences.

- Computational Design and Off-Target Assessment: Modern tools like TrueProbes go beyond traditional filters for GC content and melting temperature. They perform a genome-wide BLAST-based analysis to quantify and minimize potential off-target binding, a major source of background noise. By ranking probes based on predicted binding affinity and specificity, these platforms generate probe sets with superior experimental performance [1].

- Incorporation of Expression Data: Advanced design pipelines can incorporate tissue- or cell-type-specific gene expression data. This allows the algorithm to penalize probes that have complementarity to off-target transcripts known to be expressed in the sample, further reducing the risk of non-specific background [1].

Tissue Processing and Optical Clearing

Tissue preparation is critical for probe accessibility and light penetration, directly influencing SNR.

- Fixation and Permeabilization: 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) is the standard fixative for optimal RNA preservation in FFPE tissues. Fixation time must be carefully controlled; under-fixation leads to RNA degradation, while over-fixation requires harsher permeabilization that can damage morphology. Permeabilization with detergents like Triton X-100 or proteases like proteinase K is essential to allow probe entry [6].

- Optical Clearing with LIMPID: The LIMPID (Lipid-preserving refractive index matching for prolonged imaging depth) method is a single-step aqueous clearing protocol. It uses a solution of saline-sodium citrate, urea, and iohexol to match the refractive index of the tissue to that of the objective lens (e.g., 1.515). This dramatically reduces light scattering, minimizes spherical aberrations, and enables high-resolution imaging deep within thick tissues without damaging the tissue structure or fluorescent signals [5].

- Bleaching and Preservation: A hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) bleaching step can be incorporated to reduce autofluorescence, a significant noise component. Furthermore, omitting delipidation steps helps preserve tissue structure and the integrity of lipophilic dyes, providing a more native biological context [5].

Signal Amplification and Multiplexing

For low-abundance targets, simply increasing the number of fluorophores is a direct method to boost signal above the background noise level.

- Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR): HCR is a powerful linear amplification scheme that builds long chains of fluorescently labeled probes upon initiation by a target-specific probe. This method is noted for its high specificity, low background, and, crucially, its quantitative nature, as the fluorescence intensity scales linearly with the target RNA quantity [5] [4]. This makes it ideal for quantifying gene expression levels.

- Barcoding for Multiplexing: Techniques like MERFISH (Multiplexed Error-robust FISH) use combinatorial barcoding to detect thousands of RNA species simultaneously. Each RNA is assigned a unique binary barcode, which is read out over multiple rounds of hybridization with fluorescent readout probes. The error-robust encoding schemes in MERFISH require multiple bits to be misread for a misidentification, thereby enhancing the effective SNR for accurate transcript identification in highly complex multiplexed experiments [7].

Computational and Deep Learning Enhancement

Post-acquisition computational methods have emerged as a powerful tool for enhancing SNR without altering wet-lab protocols.

- U-FISH: A Universal Deep Learning Model: U-FISH is a deep learning method (U-Net based) trained on a massive dataset of over 4000 images and 1.6 million signal spots. It acts as a universal image enhancer, transforming raw FISH images with variable characteristics into images with uniform spot properties and a drastically improved SNR. This allows for consistent and precise spot detection across diverse datasets without manual parameter tuning, outperforming many rule-based and other deep learning methods in accuracy and generalizability [2].

- Integrated Analysis Pipelines: For whole-mount samples, combining confocal imaging with analysis software is key. A typical workflow involves cell segmentation using Cellpose (based on cell wall staining), followed by mRNA dot counting with FISH-quant, and finally protein intensity measurement with CellProfiler. This integrated pipeline allows for the precise correlation of mRNA and protein levels at single-cell resolution, a process entirely dependent on a high initial SNR [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: 3D-LIMPID-FISH

The following protocol, adapted from a published whole-mount 3D FISH methodology, encapsulates multiple SNR enhancement strategies into a coherent workflow [5].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-LIMPID-FISH

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative for tissue preservation and RNA integrity. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | Chemical bleaching agent to reduce tissue autofluorescence. |

| HCR FISH Probes | Target-specific initiator probes for hybridization chain reaction, enabling sensitive, amplified signal. |

| Proteinase K | Protease for tissue permeabilization, enabling probe access to intracellular targets. |

| LIMPID Solution | Aqueous clearing solution (SSC, Urea, Iohexol) for refractive index matching and tissue transparency. |

| Iohexol | Key component of LIMPID; adjusts the refractive index of the solution to match that of the tissue and objective lens. |

Workflow Timetable:

- Sample Extraction & Fixation: Dissect tissue and fix immediately in 4% PFA for 24 hours at 4°C to preserve morphology and RNA.

- Bleaching (Optional): Incubate tissue in 3% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ for several hours to reduce autofluorescence.

- Permeabilization: Treat tissue with Proteinase K (e.g., 10 μg/mL for 30 minutes) to digest proteins and allow probe penetration. Conditions must be optimized for each tissue type.

- Hybridization and Amplification:

- Hybridize with HCR initiator probes specific to the target mRNA(s) in a humidified chamber (overnight, 37°C).

- Wash stringently to remove unbound probes.

- Add HCR amplification hairpins (fluorescently labeled) for 2-6 hours to build the amplification polymer.

- Optical Clearing: Mount the tissue in the LIMPID solution. The clearing occurs in a single step through passive diffusion, typically within a few hours.

- Imaging: Image using a confocal microscope with a high-NA objective lens. The refractive index of the LIMPID solution should be calibrated to match that of the immersion oil (e.g., 1.515) for minimal aberration [5].

Defining and optimizing the signal-to-noise ratio is a multidimensional challenge at the heart of rigorous and quantitative FISH research. As this guide outlines, there is no single solution; instead, high SNR is achieved through a synergistic combination of intelligent probe design, gentle yet effective tissue processing, robust signal amplification, and powerful computational cleanup. The integration of these strategies, as exemplified by the 3D-LIMPID-FISH protocol, empowers researchers to push the boundaries of spatial biology. By systematically applying these principles, scientists can reliably extract single-molecule quantitative data from complex tissues, thereby unlocking deeper insights into gene expression and regulation with unparalleled spatial context.

In fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) research, achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is paramount for accurate biological interpretation. This ratio determines the confidence with which researchers can detect and quantify molecular targets, such as RNA transcripts or DNA sequences, within their native cellular context. Two fundamental pillars govern this critical parameter: probe binding affinity, which ensures specific localization to the intended target, and fluorophore efficiency, which dictates the brightness and detectability of the resulting signal. This technical guide delves into the core principles and advanced methodologies for optimizing these two sources of signal, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for designing robust and reliable FISH-based assays.

Probe Binding Affinity: The Foundation of Specificity

Probe binding affinity refers to the strength and specificity with which an oligonucleotide probe hybridizes to its complementary nucleic acid target. High affinity is essential for maximizing the on-target signal while minimizing off-target binding, which contributes to background noise.

Key Factors Influencing Probe Binding Affinity

- Sequence Specificity: The degree of complementarity between the probe and its target is the primary determinant of binding affinity and specificity. Even minor mismatches can significantly reduce hybridization stability.

- Melting Temperature (Tm): This is the temperature at which half of the probe-target duplexes dissociate. Optimal FISH conditions require a Tm that allows for stable hybridization under stringent conditions that discourage off-target binding [1].

- Probe Length: The length of the targeting region modulates both affinity and specificity. While longer probes (e.g., 40-50 nt) can form more stable duplexes, they also have a higher probability of non-specific binding to related sequences. Shorter probes (e.g., 20 nt) offer higher specificity but may suffer from reduced brightness [8].

- GC Content: The proportion of guanine and cytosine bases in the probe sequence affects Tm, as GC base pairs form three hydrogen bonds compared to the two in AT pairs. Most design tools enforce a narrow GC content window (e.g., 40-60%) to ensure uniform Tm across a probe set [1].

- Secondary Structure: Intramolecular folding of either the probe or the target RNA can occlude binding sites, dramatically reducing effective binding affinity. Computational tools must account for these structures during design [1] [9].

Computational Design for Optimal Affinity

Advanced probe design software platforms, such as TrueProbes, have moved beyond simple filtering heuristics to integrated thermodynamic and kinetic modeling [1] [9]. These tools perform genome-wide BLAST analyses to comprehensively assess off-target binding potential and rank candidate probes based on a holistic score that incorporates:

- Predicted on-target binding energy

- Number and affinity of off-target binding sites

- Potential for self-hybridization or cross-dimerization with other probes in the set

- User-provided gene expression data to weight the impact of expressed off-targets [1]

This integrated approach consistently outperforms earlier methods like Stellaris and Oligostan-HT, generating probe sets with enhanced target selectivity and superior experimental performance [1] [9].

Table 1: Comparison of smFISH Probe Design Software

| Software | Design Approach | Key Features | Specificity Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| TrueProbes | Genome-wide BLAST + thermodynamic modeling | Ranks all candidates globally by specificity; incorporates expression data | Genome-wide off-target binding analysis |

| Stellaris | Sequential 5' to 3' tiling with filtering | Applies GC content filters and repetitive sequence masking | Limited off-target assessment with five masking levels [1] |

| MERFISH | Hash-based transcriptome screening | Filters oligos based on off-target index and rRNA binding | Computes off-target index using 15/17-mer hashing [1] |

| Oligostan-HT | Energy-based ranking | Ranks probes by Gibbs free energy (ΔG°) proximity to optimum | Applies GC and low-complexity screens [1] |

| PaintSHOP | Machine learning classification | Uses Bowtie2 alignment and ML classifier for deleterious duplexes | Eliminates oligos with many genomic matches [1] |

Experimental Optimization of Binding Conditions

Even optimally designed probes require careful experimental calibration. Key parameters to optimize include:

- Formamide Concentration: Acts as a denaturant to enable precise stringency control. Optimal concentrations must be determined empirically for different target region lengths [8].

- Hybridization Temperature: Typically performed 10-20°C below the average probe Tm to ensure specific binding while allowing access to structured regions.

- Hybridization Duration: Must balance complete target access with practical experimental timelines. For complex samples, hybridization may require 24-48 hours [8].

- Salt Concentration: Ionic strength affects duplex stability by shielding the negative charges on the phosphate backbones of hybridized nucleic acids.

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for Optimizing Probe Binding

| Parameter | Impact on Binding Affinity | Typical Optimization Range | Effect on SNR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formamide Concentration | Reduces Tm; increases stringency | 0-40% in 5% increments [8] | Reduces background from off-target binding at optimal concentration |

| Hybridization Temperature | Must be below Tm for binding to occur | Tm -20°C to Tm -10°C | Higher temperature increases specificity but may reduce on-target signal |

| Hybridization Duration | Allows probes to reach and bind targets | 1-48 hours depending on sample and probe accessibility [8] | Longer duration increases signal until equilibrium is reached |

| Salt Concentration | Higher concentration stabilizes duplex | 100-900 mM monovalent cations | Insufficient salt reduces on-target signal; excess may increase background |

Fluorophore Efficiency: Maximizing Signal Output

Fluorophore efficiency encompasses the physical properties that determine how effectively a fluorophore converts excitation light into detectable emission. This directly impacts the signal intensity in FISH experiments.

Photophysical Properties Governing Efficiency

- Extinction Coefficient: A measure of how strongly a fluorophore absorbs light at a specific wavelength. Higher values indicate greater photon absorption capacity [10].

- Quantum Yield: The ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed, representing the efficiency of the fluorescence process. Fluorophores with quantum yields closer to 1.0 are intrinsically brighter [10].

- Photostability: The resistance of a fluorophore to photobleaching, the irreversible destruction of the fluorophore under intense illumination. This is critical for time-lapse experiments or those requiring extended imaging sessions.

- Stokes Shift: The difference between the excitation and emission maxima. A larger Stokes shift facilitates spectral separation, reducing background from scattered excitation light [10].

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) Applications

FRET is a distance-dependent phenomenon where an excited donor fluorophore non-radiatively transfers energy to a nearby acceptor fluorophore [11] [12]. The efficiency of FRET decreases with the sixth power of the distance between the fluorophores, making it exquisitely sensitive to molecular-scale distances (1-10 nm) [11] [12] [13]. In FISH, FRET can be utilized in:

- Molecular Beacons: Hairpin probes where target binding separates a fluorophore-quencher pair, generating a signal increase.

- Biosensors: Probes designed to change FRET efficiency upon target binding or enzymatic activity.

- Protease Assays: FRET-based substrates where cleavage separates donor and acceptor fluorophores, altering the emission ratio [12] [13].

Advanced Signal Amplification Strategies

To overcome the inherent limitation of labeling individual transcripts with few fluorophores, several amplification strategies have been developed:

- SABER (Signal Amplification By Exchange Reaction): A method that uses primer exchange reaction to generate long concatemeric probes containing multiple binding sites for fluorescently labeled imager probes. This significantly increases the number of fluorophores per target molecule [14].

- HCR (Hybridization Chain Reaction): An enzyme-free method where metastable DNA hairpins self-assemble into long amplification polymers upon initiation by a specific probe [14].

- Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA): An enzyme-based method where horseradish peroxidase (HRP) catalyzes the deposition of multiple fluorescent tyramide molecules near the probe binding site [14].

Table 3: Characteristics of Common Fluorophores and Applications

| Fluorophore | Excitation/Emission Max (nm) | Extinction Coefficient (Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹) | Quantum Yield | Common FISH Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FITC | 495/519 | ~68,000 | 0.79 | Direct labeling; immuno-detection of haptens [15] |

| Cy3 | 550/570 | ~150,000 | 0.15 | Bright, photostable; common for smFISH |

| Alexa Fluor 488 | 495/519 | ~73,000 | 0.92 | High quantum yield; superior to FITC |

| Texas Red | 589/615 | ~85,000 | 0.90 | Red-emitting dye for multiplexing |

| Cy5 | 649/670 | ~250,000 | 0.28 | Far-red emission; low background in tissues |

Integrated Approaches for Maximizing Signal-to-Noise Ratio

The ultimate SNR in a FISH experiment emerges from the interplay between probe binding affinity and fluorophore efficiency. Strategic integration of both aspects is essential.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for FISH Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Encoding Probes (e.g., MERFISH) | Unlabeled DNA probes with targeting and barcode regions | Enable massive multiplexing via two-step hybridization [8] |

| Readout Probes | Fluorescently labeled probes complementary to barcode regions | Allow rapid signal readout in sequential rounds [8] |

| Formamide | Chemical denaturant for stringency control | Concentration must be optimized for each probe set [8] |

| Dextran Sulfate | Crowding agent that increases effective probe concentration | Accelerates hybridization kinetics |

| Blocking DNA (e.g., salmon sperm DNA) | Competes with non-specific probe binding | Reduces background in complex samples |

| Antifade Reagents (e.g., ProLong Diamond) | Reduces photobleaching during imaging | Essential for preserving signal in 3D or time-lapse experiments |

| PER Catalytic Hairpin | Enables primer exchange reaction for SABER | Generates long concatemers for signal amplification [14] |

| Stachyose tetrahydrate | Stachyose tetrahydrate, CAS:10094-58-3, MF:C24H44O22, MW:684.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Neocaesalpin L | Neocaesalpin L|For Research | Neocaesalpin L, a cassane diterpenoid from Caesalpinia minax. For research use only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Protocol: Multiplexed Error-Robust FISH (MERFISH) with Enhanced SNR

This protocol incorporates recent optimizations from systematic performance evaluations [8]:

Probe Design

- Design encoding probes with 30-50 nt target-specific regions for optimal binding affinity and signal brightness [8].

- Incorporate readout sequences for subsequent fluorescent detection.

- Use computational tools (e.g., TrueProbes) to filter probes with potential off-target binding.

Sample Preparation

- Fix cells or tissues with appropriate cross-linking agents (e.g., 4% PFA).

- Permeabilize with 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes.

- Include an RNase inhibitor in all solutions.

Hybridization Optimization

- Prepare hybridization buffer with 10-30% formamide, optimized for your specific probe set [8].

- Add encoding probes at 1-10 nM concentration.

- Hybridize for 24-48 hours at 37°C in a humidified chamber.

Signal Readout and Imaging

- Hybridize fluorescent readout probes at 5-20 nM concentration for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Use optimized imaging buffers with photostabilizing components (e.g., Trolox, PCA/PCD) to enhance fluorophore efficiency.

- Image sequentially with appropriate excitation/emission filter sets, ensuring sufficient spectral separation to minimize bleed-through.

In the pursuit of high signal-to-noise ratio in FISH research, probe binding affinity and fluorophore efficiency represent two complementary frontiers for optimization. Advances in computational probe design, particularly those incorporating genome-wide specificity analysis and thermodynamic modeling, have dramatically improved our ability to generate probes with minimal off-target binding. Concurrently, innovations in fluorophore chemistry and signal amplification strategies have pushed the boundaries of detection sensitivity. By systematically addressing both domains—through careful probe design, experimental condition optimization, and strategic fluorophore selection—researchers can achieve the precise, quantitative measurements required for cutting-edge research and drug development. The integrated approaches outlined in this guide provide a pathway to maximizing SNR, ultimately enabling more confident biological discoveries through FISH-based spatial transcriptomics and genomics.

In Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) research, the signal-to-noise ratio is the cornerstone of assay sensitivity, reliability, and quantitative capability. Achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio is paramount for the accurate detection of nucleic acid targets, whether for basic research, clinical diagnostics, or drug development. The three predominant sources of noise that compromise this ratio are off-target binding, autofluorescence, and general background fluorescence. Off-target binding introduces false-positive signals through non-specific probe hybridization, while autofluorescence arises from the innate fluorescent properties of biological samples and fixatives. Background fluorescence often stems from suboptimal assay conditions. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these noise sources, detailing their mechanisms and presenting validated experimental strategies for their mitigation, thereby providing a framework for optimizing FISH assays.

Off-Target Binding: Mechanisms and Mitigation

Off-target binding occurs when FISH probes hybridize to non-intended genomic sequences, producing false-positive signals that can lead to erroneous biological interpretations. Understanding and controlling this phenomenon is critical for quantitative accuracy.

Fundamental Mechanisms

The primary mechanism of off-target binding is the presence of short, perfectly repeated sequences, or k-mers, within longer probe sequences. Counterintuitively, very short perfect repeats of only 20–25 base pairs within probes that are several hundred nucleotides long can generate significant off-target signals [16]. The surprising extent of this noise is attributable to the signal amplification conferred by haptenylated probes and subsequent immunological detection, which can magnify even a single non-specific hybridization event into a detectable fluorescent signal [16]. Traditional control methods, such as using sense-strand probes, are inadequate for detecting this type of noise because they do not share the same sequence and thus the same repertoire of repetitive k-mers as the antisense probe [16].

Experimental Protocol for k-mer Uniqueness Analysis

A critical step in probe design is the computational assessment of sequence uniqueness to eliminate repetitive k-mers.

- Sequence Input: Input the candidate probe sequence(s) in FASTA format.

- k-mer Enumeration: The algorithm enumerates all possible sub-sequences of a defined length (k-mer, e.g., 20 nt) from the entire reference genome and the probe sequence.

- Sorting and Counting: All k-mers are sorted alphabetically. The algorithm then counts the frequency of each unique k-mer across the genome.

- Probe Interrogation: The probe sequence is scanned, and each of its constituent k-mers is queried against the generated database. K-mers with a frequency greater than one (i.e., present in more than one genomic location) are flagged as repetitive.

- Probe Optimization: Probe sequences are redesigned to eliminate or minimize the presence of flagged repetitive k-mers. This can be achieved by selecting alternative probe templates from different regions of the target gene (e.g., the 3'UTR) that are devoid of such repeats [16].

This process is facilitated by publicly available algorithms, such as the one provided at http://cbio.mskcc.org/∼aarvey/repeatmap, which generates genome-wide annotations of k-mer uniqueness [16].

Quantitative Impact of Probe Optimization

Table 1: Impact of Removing Repeated k-mers on FISH Signal-to-Noise Ratio

| Probe Target | Probe Type | Probe Length (bp) | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drosophila melanogaster Scr | Non-unique Probe | 357 | Produced significant off-target noise, obscuring true expression patterns | [16] |

| Drosophila melanogaster Scr | Unique Probe (repeat-free) | 359 | Increased signal-to-noise ratio by orders of magnitude; enabled quantitative RNA counting | [16] |

| Drosophila melanogaster abd-A | Non-unique Probe | ~1,600 | Generated off-target signals, reducing assay specificity | [16] |

| Drosophila melanogaster abd-A | Unique Probe (repeat-free) | ~1,470 | Drastically reduced background, allowing for high-confidence, quantitative detection | [16] |

Diagram 1: Workflow for optimizing probe specificity through k-mer analysis.

Autofluorescence: Characterization and Correction

Autofluorescence is the background fluorescence inherent to biological samples, which can mask specific FISH signals, particularly those from small or dim probes.

Autofluorescence originates from various intracellular components, including lipofuscin bodies, flavins, and cross-linked proteins induced by aldehyde-based fixation [17]. Its spectral signature is typically broader than that of synthetic fluorophores, often spanning a wide range of the visible spectrum. For example, lipofuscin can be detected from 360 nm to 650 nm [17]. Formaldehyde fixation tends to exacerbate autofluorescence by cross-linking fluorescent enzyme co-factors, whereas fixation with methanol/acetic acid can reduce it by washing these components away [17].

Strategic and Computational Mitigation

Several strategies can be employed to minimize or correct for autofluorescence:

- Fluorophore Selection: Using longer-wavelength fluorophores (e.g., Quasar 570/670, CAL Fluor Red 610) is highly recommended, as autofluorescence is more pronounced and intense in the green region of the spectrum (near 520 nm) [17].

- Enzymatic Reduction: A novel pretreatment protocol using elastase has been demonstrated to significantly reduce autofluorescence in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tissues. In a study of 120 samples, elastase pretreatment reduced the assay retest rate from 86.7% to 0% and enabled the detection of two additional ALK translocation cases that were indeterminable with standard pepsin pretreatment [18]. Elastase was identified as the most effective enzyme for this purpose while preserving nuclear morphology [18].

- Computational Image Correction: A pixel-by-pixel digital subtraction method can be applied. This technique leverages the fact that autofluorescence has broader excitation and emission spectra than FISH probes. The ratio of autofluorescence between multiple color channels is calculated and used to subtract the autofluorescence component from each image [19]. This method has been shown to enhance previously indistinguishable cosmid signals [19].

Protocol: Elastase Pretreatment for Autofluorescence Reduction

This protocol is adapted for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections [18].

- Dewaxing and Rehydration: Process FFPE sections through standard dewaxing and rehydration steps.

- Protease Digestion: Treat the tissue sections with a solution of elastase at an optimized concentration (determined empirically for each tissue type and fixation condition).

- Incubation: Incubate the slides at 37°C for a defined period, typically between 10-30 minutes.

- Washing: Rinse the slides thoroughly to stop the enzymatic reaction.

- Dehydration: Dehydrate the slides through an ethanol series and air-dry.

- FISH Assay: Proceed with the standard FISH denaturation, hybridization, and washing steps.

Background Fluorescence and Assay Optimization

Background fluorescence encompasses non-specific signals arising from suboptimal assay conditions, excluding autofluorescence and specific off-target binding. A systematic approach to the entire FISH workflow is essential for its reduction.

Integrated Workflow for Background Minimization

A robust FISH assay requires optimization at every stage, from sample preparation to final imaging. The following workflow integrates key mitigation strategies:

Diagram 2: Key stages in the FISH workflow and critical parameters for background control.

Detailed Mitigation Strategies

- Sample Preparation and Fixation: Fixation is a critical balance. Under-fixation leads to poor cellular preservation and increased non-specific probe binding, while over-fixation (particularly with formalin) causes excessive cross-linking, masking target sequences and increasing background [20]. For FFPE tissues, sections of 3-4 μm thickness are ideal for probe penetration and interpretation [20]. Always use freshly prepared fixative solutions.

- Pre-treatment and Digestion: The goal of pre-treatment is to unmask target nucleic acids. Insufficient pre-treatment leaves autofluorescent debris and non-specific binding sites, while over-digestion damages the sample and target DNA, reducing specific signal [20]. Use controlled heating (98–100°C) of a pre-treatment solution followed by enzymatic digestion (e.g., pepsin, or elastase for lung tissues) [20] [18].

- Hybridization and Denaturation: For FFPE tissues, denaturation conditions must be precisely controlled. A denaturation temperature that is too low prevents proper probe binding, whereas a temperature that is too high can promote non-specific binding [20]. Similarly, denaturation time must be optimized; short times reduce specific binding, and prolonged times increase background by unmasking non-target sites [20]. Probe volume should also be optimized to ensure sufficient coverage without excess.

- Post-Hybridization Washes: Stringency washes are crucial for removing unbound and weakly bound probes. Stringency is controlled by the pH, temperature, and salt concentration of the wash buffers [20]. Use freshly prepared wash buffers to prevent contamination or degradation that can contribute to background [20].

- Imaging and Filter Maintenance: The optical system itself can be a source of noise. Worn or damaged optical filters on fluorescence microscopes degrade over time (typically 2-4 years), producing a mottled appearance that weakens signal and increases background noise [20]. Regularly inspect and replace filters according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Noise Reduction

Table 2: Key Reagents and Their Functions in Optimizing FISH Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Consideration for Noise Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Elastase | Enzymatic pre-treatment to reduce autofluorescence | Particularly effective in lung tissues; preserves nuclear morphology better than pepsin [18]. |

| Methanol/Acetic Acid Fixative | Alternative to aldehyde-based fixation | Reduces autofluorescence by washing out fluorescent enzyme co-factors, unlike formaldehyde [17]. |

| Carnoy's Solution | Fixative for cytological preparations | Must be freshly prepared and stored at -20°C to maintain effectiveness and prevent moisture absorption [20]. |

| IntelliFISH Hybridization Buffer | Commercial hybridization buffer | Enables rapid hybridization (4 hours vs. 18 hours), improving workflow and maintaining good signal-to-noise [21]. |

| VECTASHIELD HardSet with DAPI | Antifade mounting medium with nuclear stain | Provides a hard-set mounting medium that reduces fading and is fast-setting for efficient workflow [21]. |

| CytoCell LPS 100 Tissue Pretreatment Kit | Standardized kit for tissue pre-treatment | Ensures consistent and optimized pre-treatment conditions for FFPE tissues, minimizing background [20]. |

| Long-wavelength Fluorophores(e.g., Quasar 670) | Label for FISH probes | Their emission spectra are in a region with lower inherent cellular autofluorescence, improving signal discernment [17]. |

| Mullilam diol | Mullilam diol, CAS:36150-04-6, MF:C10H20O3, MW:188.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Eichlerianic acid | Eichlerianic acid, CAS:56421-13-7, MF:C30H50O4, MW:474.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The pursuit of a high signal-to-noise ratio is a fundamental principle in FISH research, directly determining the accuracy, sensitivity, and quantitative potential of the assay. As demonstrated, the major sources of noise—off-target binding, autofluorescence, and general background—can be systematically addressed through rigorous probe design, strategic use of reagents, and meticulous optimization of the entire experimental workflow. Employing computational tools to ensure probe uniqueness, integrating novel enzymatic treatments like elastase, and adhering to best practices in sample handling and imaging are not merely incremental improvements but essential steps for generating reliable, publication-quality data. By embracing this comprehensive approach to noise reduction, researchers and drug developers can fully leverage the power of FISH technology to uncover precise spatial gene expression patterns in complex biological systems.

The Critical Link Between High SNR and Accurate Single-Molecule Quantification

In the realm of molecular biology, single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) has emerged as a transformative technology that enables researchers to visualize, localize, and quantify individual RNA molecules within their native cellular environment with exceptional spatial resolution [22]. This technique provides unparalleled insights into gene expression regulation, transcriptional dynamics, and RNA localization patterns at the single-cell level, revealing cell-to-cell heterogeneity that bulk measurement techniques inevitably obscure [22] [23]. At the heart of this powerful methodology lies a critical technical parameter that fundamentally determines its accuracy and reliability: the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

The SNR in smFISH represents the quantitative relationship between the specific fluorescence signal emanating from target RNA molecules and the non-specific background noise originating from various sources, including autofluorescence, imperfect probe binding, and optical limitations of the imaging system [1]. A high SNR is not merely desirable but essential for accurate single-molecule quantification because it enables the unambiguous discrimination of individual transcripts from background fluorescence, ensuring that each counted spot genuinely represents a single RNA molecule [22] [24]. When SNR is compromised, the consequences for data integrity are severe: low signal intensity increases false negatives (missed transcripts), while elevated background noise introduces false positives (non-specific signals misclassified as transcripts), ultimately distorting quantitative conclusions about gene expression levels [1] [24].

This technical guide explores the fundamental principles governing SNR in smFISH experiments, detailing the experimental factors that influence this critical parameter and providing evidence-based strategies for its optimization. By examining the intricate relationship between SNR and quantification accuracy across diverse biological contexts—from model organisms to clinical samples—we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge necessary to design robust smFISH assays that yield biologically meaningful, reproducible results.

Theoretical Foundation: How SNR Directly Impacts Quantification Accuracy

The imperative for high SNR in smFISH stems from the fundamental physics of single-molecule detection and the statistical principles underlying transcript quantification. In a properly optimized smFISH experiment, each individual RNA molecule is tagged with multiple fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes, creating a diffraction-limited spot whose intensity is proportional to the number of bound probes [22]. The detection and enumeration of these spots through computational algorithms depend critically on the ability to distinguish true signals from background fluorescence with high confidence [25].

The quantitative relationship between SNR and detection accuracy can be expressed through statistical detection theory. When SNR is high, the intensity distribution of true RNA signals separates clearly from the intensity distribution of background noise, allowing detection algorithms to establish a threshold that captures nearly all true signals while excluding most noise [1] [25]. As SNR decreases, these distributions increasingly overlap, forcing a compromise between sensitivity (detection of true transcripts) and specificity (rejection of background), ultimately increasing both false negative and false positive rates [24].

This principle finds practical validation in the development of RollFISH, an advanced smFISH variant that incorporates rolling circle amplification to enhance signal intensity. In a direct comparison with conventional smFISH, RollFISH demonstrated that increased signal intensity directly translated to more accurate transcript counting, particularly in challenging samples like formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections where background fluorescence is typically elevated [24]. The method's signal amplification approach yielded a greater than two-fold improvement in SNR, which correspondingly enhanced the reliability of single-molecule detection and quantification across diverse tissue types [24].

Beyond mere transcript counting, high SNR is equally crucial for analyzing RNA subcellular localization patterns—a key application of smFISH. Low SNR can obscure the precise position of transcripts within cellular compartments, potentially leading to misinterpretation of localization patterns and their biological significance [25]. This is particularly critical when distinguishing between mature cytoplasmic mRNAs and nascent transcripts at transcription sites, or when identifying isoform-specific localization patterns that require multiple probe sets with different fluorophores [26] [23].

Table 1: Impact of SNR on Key smFISH Quantification Metrics

| Quantification Metric | High SNR Impact | Low SNR Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Transcript Detection Efficiency | >90% detection of true transcripts [24] | Increased false negatives (>10% transcript loss) [1] |

| Detection Specificity | Minimal false positives (<5% background misclassification) [1] | Elevated false positive rates (>20% misclassification) [24] |

| Localization Accuracy | Precise subcellular positioning (<200nm resolution) [25] | Ambiguous localization patterns |

| Multi-Color Experiments | Clear signal separation for different targets [26] | Spectral bleed-through and cross-talk |

| Dynamic Range | Accurate counting across broad expression range (1-1000+ transcripts/cell) [22] | Limited to highly expressed genes |

Methodological Framework: Optimizing SNR in smFISH Workflows

Achieving high SNR in smFISH requires a systematic approach that addresses each stage of the experimental workflow, from probe design to image acquisition. The following diagram illustrates the integrated framework for SNR optimization, highlighting the interconnected factors that researchers must control throughout the smFISH procedure:

Probe Design Strategies for Enhanced Specificity and Signal

Probe design represents the foundational element in the pursuit of high SNR, as it directly determines both the intensity of the specific signal and the degree of non-specific background binding. Traditional smFISH employs multiple short DNA oligonucleotides (typically 20-mers) that tile the entire length of the target RNA, with each probe conjugated to a fluorescent dye [22]. The collective binding of these probes—typically 25-48 per target—generates a sufficiently bright signal to detect individual RNA molecules against the cellular background [26].

Modern computational approaches have significantly advanced probe design by systematically addressing the challenge of off-target binding. TrueProbes, a recently developed probe design platform, exemplifies this evolution by integrating genome-wide BLAST-based binding analysis with thermodynamic modeling to generate probe sets with enhanced specificity [1]. Unlike earlier tools that applied relatively simplistic heuristics, TrueProbes ranks and selects probes based on predicted binding affinity, target specificity, and structural constraints, effectively minimizing background fluorescence from cross-hybridization [1]. Experimental validations demonstrate that such sophisticated design approaches consistently outperform alternatives, with TrueProbes-designed probes showing up to 50% improvement in signal discrimination compared to other methods [1] [27].

Key parameters in probe design for optimal SNR include:

- Probe Length and GC Content: 20-mer probes with 45-55% GC content generally provide optimal hybridization kinetics and specificity [26]

- Probe Density: A minimum of 25-30 probes per transcript ensures sufficient signal amplification while minimizing self-quenching [26] [24]

- Sequence Specificity: Comprehensive off-target screening against the entire transcriptome prevents cross-hybridization [1]

- Fluorophore Selection: Bright, photostable dyes with minimal spectral overlap enable clear signal discrimination [26]

Sample Preparation and Hybridization Conditions

The integrity of sample preparation directly influences the ultimate SNR achievable in smFISH experiments. Proper fixation preserves cellular architecture and RNA localization while enabling sufficient probe accessibility. For yeast cells, an optimized protocol specifies fixation with 3% formaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature, followed by overnight fixation at 4°C for meiotic samples to enhance reproducibility [23]. Subsequent digestion with lyticase or zymolyase (15-30 minutes at 30°C) must be carefully calibrated to permeabilize cell walls without compromising structural integrity [26] [23].

Hybridization conditions represent another critical control point for SNR optimization. The standard smFISH hybridization buffer contains 10% formamide, which provides appropriate stringency to minimize non-specific probe binding while maintaining efficient on-target hybridization [22] [23]. Inclusion of ribonucleoside vanadyl complex (VRC) during digestion and hybridization inhibits RNase activity, preserving RNA integrity and consequently enhancing signal intensity [23]. Hybridization is typically performed overnight at 37°C with probe concentrations optimized through empirical testing—often employing serial dilutions (1:250 to 1:2000 from stock solutions) to identify the concentration yielding optimal SNR [26].

Table 2: Optimized smFISH Protocol Parameters for High SNR

| Protocol Step | Optimal Conditions | Impact on SNR |

|---|---|---|

| Fixation | 3% formaldehyde, 20min RT + 4°C overnight [23] | Preserves RNA integrity and cellular structure |

| Digestion | 15-30min at 30°C with zymolyase [26] | Balances permeability and structural preservation |

| Hybridization Buffer | 10% formamide, dextran sulfate [22] | Maximizes specific binding while minimizing background |

| Hybridization Time | Overnight (12-16 hours) at 37°C [26] | Ensures complete target accessibility |

| Probe Concentration | 1:250 dilution from 25μM stock (empirically determined) [26] | Optimizes binding saturation without increasing background |

| Wash Stringency | 10% formamide in 2× SSC [23] | Removes non-specifically bound probes |

Advanced Signal Amplification Strategies

For particularly challenging applications involving low-abundance transcripts or samples with high background fluorescence, advanced signal amplification methods can dramatically enhance SNR. RollFISH represents one such approach that combines the specificity of smFISH with the signal amplification power of rolling circle amplification [24]. In this method, specially designed smFISH probes contain docking sequences for padlock probes, which are subsequently circularized and amplified using Phi29 polymerase [24]. The resulting rolling circle products contain hundreds to thousands of copies of the complementary sequence, enabling detection with brightly fluorescent secondary probes.

The implementation of RollFISH has demonstrated remarkable improvements in SNR, particularly in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples where conventional smFISH signals are often compromised by high background [24]. By enabling robust detection of individual transcripts at low magnification (20×), RollFISH facilitates the analysis of spatial heterogeneity across entire tissue sections—a capability that conventional smFISH struggles to provide due to SNR limitations [24]. Quantitative comparisons show that RollFISH maintains detection efficiency (~70%) comparable to conventional smFISH while significantly enhancing signal intensity, thereby improving the accuracy of transcript quantification in complex tissue environments [24].

Comparative Analysis of smFISH Methodologies and Their SNR Performance

The critical importance of SNR becomes evident when comparing the performance characteristics of different smFISH methodologies across various sample types and experimental contexts. The following table summarizes quantitative performance metrics for three established smFISH approaches, highlighting the direct relationship between methodological choices and SNR outcomes:

Table 3: SNR and Performance Comparison Across smFISH Methods

| Method | Probe Design Strategy | Optimal Probe Count | Detection Efficiency | Applications | SNR Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional smFISH | 20-mer oligos tiling transcript [26] | 25-48 probes [26] | ~67.5% [24] | Cultured cells, yeast [26] [23] | Dim signals in FFPE tissues [24] |

| TrueProbes-Enhanced smFISH | Genome-wide specificity screening [1] | 25-48 probes [1] | >70% [1] | Low-abundance targets, complex transcripts [1] | Computational complexity |

| RollFISH | smFISH probes with docking sequences [24] | 12-48 oligos [24] | ~70% [24] | FFPE tissues, spatial heterogeneity [24] | Additional amplification steps |

The data reveal that while all three methods achieve comparable detection efficiencies, they differ significantly in their SNR characteristics and associated applications. Conventional smFISH provides robust performance in standard laboratory models like cultured cells and yeast but struggles with the autofluorescence and preservation artifacts common in clinical FFPE samples [24]. TrueProbes-enhanced smFISH addresses the limitation of off-target binding through sophisticated computational design, thereby improving SNR by reducing background rather than increasing signal intensity [1]. RollFISH takes the complementary approach of dramatically boosting signal strength through enzymatic amplification, making it particularly suitable for high-background samples where conventional signals would be overwhelmed [24].

The choice between these methodologies should be guided by specific experimental needs. For high-throughput applications in well-characterized model systems, conventional smFISH offers simplicity and established protocols. When studying transcripts with extensive sequence homology or designing large probe panels, TrueProbes provides enhanced specificity. For clinical samples or when analyzing spatial heterogeneity across large tissue areas, RollFISH delivers the necessary SNR for reliable quantification [24].

Computational Analysis: Translating High SNR into Accurate Quantification

The benefits of high SNR can only be fully realized through sophisticated computational analysis pipelines that accurately detect, decompose, and quantify individual RNA molecules from fluorescence images. FISH-quant v2 represents a state-of-the-art solution that addresses the entire analysis workflow, from cell segmentation to RNA localization analysis [25]. This scalable, modular tool integrates machine learning approaches for robust cell segmentation with specialized algorithms for spot detection that effectively leverage high SNR data to maximize quantification accuracy [25].

A key challenge in smFISH quantification is the accurate detection of clustered transcripts—situations where multiple RNA molecules are positioned closer than the diffraction limit of light. Under conditions of high SNR, advanced decomposition algorithms can resolve these clusters into individual molecules by fitting multiple point spread functions, significantly improving counting accuracy in regions of high transcript density [25]. When SNR is compromised, this decomposition becomes increasingly error-prone, leading to undercounting of clustered transcripts and consequently biased expression measurements [25].

The analysis workflow in FISH-quant v2 exemplifies how computational methods exploit high SNR data:

- Cell and Nucleus Segmentation: Deep-learning-based segmentation identifies cellular boundaries, enabling single-cell resolution [25]

- Spot Detection: Radial symmetry or machine learning algorithms detect potential RNA signals [25]

- Cluster Decomposition: Dense RNA clusters are resolved into individual molecules through point spread function fitting [25]

- Subcellular Localization Analysis: Transcript positions are quantified relative to cellular compartments [25]

- Quality Control: Automated metrics assess detection reliability and potential artifacts [25]

This comprehensive approach demonstrates how computational analysis and experimental optimization form a virtuous cycle: high SNR data enables more accurate computational quantification, while sophisticated algorithms provide feedback for further experimental refinements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for High-SNR smFISH

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for High-SNR smFISH Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in SNR Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Design Tools | TrueProbes [1], Stellaris Probe Designer [26] | Maximize specificity and minimize off-target binding |

| Fluorophores | Quasar570, Quasar670 [26] | Provide bright, photostable signals with minimal spectral overlap |

| Fixation Reagents | 3% formaldehyde [23], 32% paraformaldehyde [26] | Preserve cellular structure and RNA integrity |

| Permeabilization Enzymes | Lyticase [26], zymolyase [23] | Enable probe access while maintaining morphology |

| RNase Inhibitors | Vanadyl Ribonucleoside Complex (VRC) [23] | Protect RNA degradation during processing |

| Hybridization Buffer Components | Formamide [22], dextran sulfate [26] | Optimize stringency and hybridization efficiency |

| Signal Amplification Systems | RollFISH amplification system [24] | Enhance signal intensity for challenging samples |

| Mounting Media | ProLong Gold with DAPI [26] | Preserve signals and provide nuclear counterstain |

| Image Analysis Software | FISH-quant v2 [25] | Accurately detect and quantify single molecules |

| Dihydrosesamin | Dihydrosesamin|Synthetic Lignan for Research | Dihydrosesamin is a synthetic lignan for research. It serves as a key intermediate in organic synthesis. This product is for Research Use Only. |

| 1-O-Deacetylkhayanolide E | 1-O-Deacetylkhayanolide E, MF:C27H32O10, MW:516.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The critical link between high SNR and accurate single-molecule quantification establishes SNR optimization as a fundamental consideration throughout smFISH experimental design rather than merely a technical refinement. As this guide has demonstrated, achieving superior SNR requires an integrated approach that addresses probe design, sample preparation, hybridization conditions, and computational analysis in a coordinated manner. The quantitative evidence from methodological comparisons clearly indicates that investments in SNR optimization yield substantial returns in data quality, reliability, and biological insight.

Future developments in smFISH technology will likely continue to focus on SNR enhancement through both improved probe design algorithms and novel signal amplification strategies. The emergence of highly multiplexed smFISH applications—which simultaneously detect dozens or hundreds of RNA species—will place even greater demands on SNR, as spectral overlap and background accumulation become increasingly challenging limitations. By establishing a robust foundation in SNR principles and optimization strategies, researchers will be well-positioned to leverage these advancing technologies for increasingly sophisticated investigations of gene expression at the single-molecule level.

Ultimately, the pursuit of high SNR in smFISH represents more than technical excellence—it embodies the commitment to quantitative rigor and biological accuracy that underpins meaningful scientific discovery. By meticulously optimizing the signal-to-noise ratio, researchers ensure that each counted transcript reflects genuine biology rather than methodological artifact, enabling confident conclusions about the fundamental processes of gene expression that govern cellular function.

Advanced Strategies for SNR Enhancement: From Probe Design to Sample Preparation

Computational Probe Design with TrueProbes for Optimal Specificity and Affinity

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has established itself as an indispensable technique for visualizing and quantifying nucleic acid molecules within their native cellular and tissue contexts. The core principle underpinning any successful FISH experiment is the attainment of a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), where the specific fluorescence from target binding unequivocally exceeds non-specific background. Achieving this hinges almost entirely on the performance of the oligonucleotide probes used. Probe specificity ensures that fluorescent signals originate from true target hybridization rather than off-target interactions, while probe affinity determines the efficiency and strength of the correct target binding. The design of these probes is, therefore, not merely a preliminary step but a decisive factor determining the success and quantitative accuracy of the entire assay [1] [28].

Computational probe design has emerged as a powerful approach to systematically address the multifaceted challenges of FISH. Traditional design tools often rely on simplified heuristics, such as narrow windows for melting temperature (Tm) and GC content, and may employ incomplete assessments of off-target binding potential. These limitations can result in probe sets prone to false positives, inadequate for short or low-abundance transcripts, or ineffective for genes with tissue-specific expression or shared sequence motifs [1]. This paper explores how TrueProbes, a sophisticated computational pipeline, overcomes these hurdles by integrating genome-wide binding analysis with thermodynamic modeling. Framed within the overarching principle of maximizing SNR in FISH research, this guide provides an in-depth technical examination of TrueProbes' methodology, benchmarks its performance against alternative tools, and details protocols for its application in developing probes with optimal specificity and affinity.

Core Computational Methodology of TrueProbes

TrueProbes distinguishes itself through a rigorous, ranking-based architecture that prioritizes predicted experimental utility over sequential, position-ordered selection. Its workflow is engineered to maximize the differential between on-target and off-target binding, the fundamental determinant of SNR.

Workflow Architecture and Specificity Ranking

The software operates via a multi-stage filtering and selection process, as illustrated below.

The cornerstone of TrueProbes is its specificity-first ranking system. Unlike tools that select the first oligo meeting basic criteria from the 5' to 3' end, TrueProbes evaluates all potential oligos tiling the transcript and ranks them globally based on a composite score that integrates [1]:

- Minimal expressed off-target binding, optionally weighted by user-provided gene expression data to contextualize off-target impact.

- Strong on-target binding affinity, derived from thermodynamic calculations.

- Weak off-target binding affinity, ensuring that any incidental off-target binding is unstable.

- Low self-hybridization and minimal cross-dimerization within the probe set to prevent signal loss.

This ranking allows for the assembly of a probe set from the best possible candidates across the entire transcript, rather than being constrained by their positional order.

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Modeling

TrueProbes incorporates advanced thermodynamic modeling to predict probe behavior under specific experimental conditions. For each candidate oligo, it calculates key parameters [1] [29]:

- Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG°): A negative ΔG° value indicates a thermodynamically favorable hybridization reaction. TrueProbes leverages this to ensure strong, stable on-target binding.

- Melting Temperature (Tm): The temperature at which 50% of the probe-target duplexes dissociate. Accurate Tm prediction is vital for determining the optimal hybridization temperature.

Beyond static calculations, TrueProbes features a thermodynamic-kinetic simulation model. This allows users to simulate expected smRNA-FISH outcomes under various user-defined conditions, including probe concentration, salt concentration, and hybridization temperature. This predictive capability is instrumental in optimizing wet-lab protocols computationally before costly and time-consuming experimental validation [1].

Comparative Analysis of Probe Design Tools

The landscape of computational probe design features several established tools, each with distinct strategies and limitations. A comparative analysis highlights TrueProbes' unique positioning.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of smRNA-FISH Probe Design Software

| Software | Core Design Strategy | Specificity Assessment | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TrueProbes | Genome-wide BLAST, thermodynamic modeling, and global ranking by specificity. | Genome-wide BLAST; expressed off-target binding weighted by expression data. | Requires MATLAB runtime; more computationally intensive. |

| Stellaris | Sequential 5' to 3' tiling with GC/content filters and repeat masking. | Five-level masking for repetitive/non-species-specific sequences. | "First-pass" design; narrow heuristic filters; incomplete off-target assessment [1]. |

| MERFISH | GC/Tm filtering, hashing into k-mers for off-target indexing. | Off-target index based on 15/17-mer hashing against transcriptome and rRNA. | Greedy 5' to 3' selection; may not select globally optimal probes [1]. |

| Oligostan-HT | GC/low-complexity screens, ranks by Gibbs free energy (ΔG°). | Specificity filtering based on sequence alignment. | Energy-based ranking may not fully capture complex off-target binding [1]. |

| PaintSHOP | Thermodynamic filters, Bowtie2 alignment, and machine learning classifier. | Machine learning classifier predicts deleterious off-target duplexes. | Design process may be less integrated with expression-level data [1] [30]. |

TrueProbes consistently outperformed these alternatives across multiple computational metrics and experimental validation assays. Benchmarks revealed that probes designed with TrueProbes demonstrated enhanced target selectivity and superior experimental performance, directly contributing to a higher SNR by minimizing off-target mediated background fluorescence [1].

Quantitative Metrics for Probe Performance Evaluation

The performance of computationally designed probes can be quantified using several key metrics, which directly correlate with the observed SNR in experimental settings.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating FISH Probe Performance

| Metric | Description | Impact on Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Optimal Range/Guideline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Length | Number of nucleotides in the oligonucleotide. | Balances specificity (longer) with synthesis yield and accessibility (shorter). | 15-30 nucleotides for DNA probes [29]. 30-37 nt in TrueProbes 'newBalance' sets [30]. |

| GC Content | Percentage of guanine and cytosine bases. | Affects hybridization strength (GC bonds are stronger) and Tm. | Must be within a defined window; extremes can cause non-specific binding or low Tm [1] [29]. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | Temperature for 50% probe-target dissociation. | Critical for determining hybridization temperature; consistent Tm across a set ensures uniform performance. | TrueProbes uses a wide Tm window (41-72°C for newBalance) for flexibility [1] [30]. |

| Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG°) | Thermodynamic parameter indicating reaction favorability. | A more negative ΔG° indicates stronger, more stable on-target binding. | -13 to -20 kcal/mol for DNA probes to maximize efficiency without compromising specificity [29]. |

| Specificity Score | Composite score from genome-wide off-target analysis. | Directly minimizes false-positive signals from off-target binding. | TrueProbes ranks probes to minimize off-targets, ideally zero [1]. |

Experimental Protocol for Probe Validation

Computational design must be followed by rigorous experimental validation to confirm probe performance. The following protocol outlines a standard approach for validating TrueProbes-designed smRNA-FISH probe sets.

Knockout Cell Line Validation

A gold-standard method for assessing probe specificity involves the use of knockout (KO) cell lines where the target gene is deleted.

- Purpose: To directly quantify background intensity attributable to off-target binding. A significant reduction in signal in the KO cells compared to wild-type indicates high specificity [1].

- Procedure:

- Culture wild-type and target KO cells in parallel.

- Perform smRNA-FISH using the same hybridization protocol for both cell types.

- Image both samples under identical microscopy settings.

- Quantify the fluorescence intensity per cell or the number of detectable RNA spots.

- Data Interpretation: The signal in KO cells represents the noise floor. A high SNR is confirmed when the signal in wild-type cells vastly exceeds this noise floor. Note that compensatory shifts in off-target gene expression in KO cells can complicate interpretation [1].

Hybridization Condition Optimization

TrueProbes' simulations provide a starting point, but fine-tuning hybridization conditions is often necessary.

- Purpose: To empirically determine the salt and formamide concentrations, as well as temperature, that maximize SNR.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a series of hybridization buffers with varying stringencies (e.g., different formamide concentrations).

- Hybridize probes to wild-type cells using these different buffers.

- Image and quantify the signal intensity and background for each condition.

- Data Interpretation: The optimal condition is the one that yields the highest signal from the target while minimizing non-specific background. The thermodynamic parameters calculated by TrueProbes, such as Tm, guide this empirical optimization [1] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing a computational and experimental pipeline for FISH requires a suite of key reagents and software tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Computational Probe Design and Validation

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| TrueProbes Software | Command-line probe design platform for generating high-specificity probe sets. | Operates in MATLAB or as a standalone using MATLAB Runtime on macOS, Windows, Linux [1]. |

| Genome Sequence Files | Reference genome (FASTA format) and annotation files (GTF/GFF). | Required for genome-wide BLAST and accurate target sequence identification (e.g., from Ensembl or UCSC). |

| Gene Expression Data | Transcriptome data (e.g., from RNA-seq) for the specific cell or tissue type. | Optional input for TrueProbes to weight off-targets by their expression level, improving specificity prediction [1]. |

| Fluorophore-Labeled Nucleotides | Fluorescent dyes for probe labeling and signal detection. | Choice depends on instrument capabilities, absorption-emission spectra, and Stokes shift [28]. |

| Knockout Cell Line | Genetically engineered cell line with the target gene deleted. | Critical experimental control for definitively assessing probe specificity and off-target background [1]. |

| Hybridization Buffers | Solutions containing salts, formamide, and detergents for FISH assay. | Stringency must be optimized empirically based on the thermodynamic properties of the probe set [29]. |

| 3-O-Methyltirotundin | 3-O-Methyltirotundin, MF:C20H30O6, MW:366.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Olean-12-ene-3,11-dione | Olean-12-ene-3,11-dione, CAS:2935-32-2, MF:C30H46O2, MW:438.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The principles of optimal specificity and affinity embodied by TrueProbes enable its application in sophisticated FISH-based methodologies. Its design flexibility allows for tailored probe sets for diverse applications, including mature RNA detection, intronic nascent RNA detection, isoform-specific or agnostic designs, and multi-fluorophore labeling [1].

The integration of tools like TrueProbes with other emerging computational platforms, such as PaintSHOP for creating ready-to-order probe libraries, is streamlining the path from genomic sequence to functional FISH assay [30]. Furthermore, the ability to incorporate cell-type-specific expression data positions TrueProbes at the forefront of developing precise diagnostic and research tools for complex tissues and disease states, ultimately advancing a fundamental thesis in molecular biology: that achieving clarity in observation—through a high SNR—is paramount to accurate discovery.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has evolved from a method for visualizing single RNA species to a cornerstone of spatial biology, enabling the multiplexed imaging of thousands of different transcripts within their native tissue context. A central challenge in this evolution has been achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio—the reliable detection of true positive signals against background noise—which is fundamental for accurate RNA quantification and localization. Signal amplification platforms directly address this challenge by enhancing specific hybridization events to generate detectable signals. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three pivotal signal amplification technologies: Signal Amplification By Exchange Reaction (SABER), Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR), and Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA). Each offers distinct mechanisms, advantages, and considerations for achieving high-fidelity RNA detection in FISH applications, forming a critical toolkit for advancing research in development, disease, and drug discovery.

Platform Fundamentals and Operational Mechanisms

SABER (Signal Amplification By Exchange Reaction)

The SABER platform utilizes a primer exchange reaction (PER) to synthesize long, single-stranded DNA concatemers in vitro that serve as modular scaffolds for signal amplification [14] [31]. The core innovation lies in its programmable amplification factor, which is controlled by the length of the concatemer.

Key Operational Steps:

- Probe Design: A pool of short ssDNA oligonucleotides (∼35-45 nt) is designed to be complementary to the target RNA. Each probe contains a 3' initiator sequence [14].

- In Vitro Concatemer Synthesis: The initiator sequences are extended using PER, a catalytic DNA hairpin system combined with a strand-displacing polymerase. This reaction repeatedly adds identical sequence units to the 3' end, generating long concatemeric probes. The length (and thus the amplification strength) is tunable by varying reaction time and conditions [14] [31].

- In Situ Hybridization: The extended concatemeric probes are hybridized to the fixed sample.

- Signal Readout: Short, fluorescently labeled "imager" strands complementary to the concatemer sequence are hybridized, resulting in a dense localization of fluorophores at the target site [31]. For multiplexing, orthogonal concatemer sequences can be read out by spectrally separated imagers, and DNA-Exchange Imaging (DEI) allows sequential imaging of multiple targets by stripping and re-hybridizing imager strands [31]. A branching strategy can further enhance signals by allowing multiple rounds of concatemer binding [32].

HCR (Hybridization Chain Reaction)

HCR is an enzyme-free, triggered amplification method that relies on the metastable configuration of DNA hairpins [33]. Upon initiation by a specific probe, it undergoes a controlled, cascading self-assembly to form a long DNA polymer.

Key Operational Steps:

- Probe Design and Hybridization: A primary "initiator" probe binds to the target RNA.

- Triggered Amplification: The initiator probe triggers the opening of the first fluorescently labeled DNA hairpin. This event exposes a sequence that opens the second hairpin, leading to a chain reaction of self-assembly that builds a long, branched nanowire [33].

- Signal Generation: The assembled polymer incorporates numerous fluorophores, creating a bright spot at the location of the target RNA. The latest version of HCR (v3.0) uses split probes to effectively suppress background signal [33].

TSA (Tyramide Signal Amplification)

TSA is an enzyme-catalyzed deposition method renowned for its high sensitivity [14]. It leverages the activity of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to generate a localized, dense signal.

Key Operational Steps:

- Probe Hybridization: A probe labeled with a hapten (e.g., digoxigenin or fluorescein) is hybridized to the target.

- Enzyme Conjugation: An anti-hapten antibody conjugated to HRP is applied.

- Catalytic Deposition: Upon addition of fluorescently labeled tyramide substrates, HRP catalyzes the conversion of tyramide into a highly reactive radical that covalently binds to electron-rich residues of proteins (primarily tyrosine) in the immediate vicinity of the enzyme. This deposits numerous fluorophores at the target site, providing massive signal amplification [14].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Signal Amplification Platforms

| Feature | SABER | HCR | TSA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification Mechanism | Enzymatic synthesis of DNA concatemers in vitro [14] [31] | Triggered, enzyme-free self-assembly of DNA hairpins in situ [33] | Enzyme-catalyzed (HRP) covalent deposition of tyramide [14] |

| Programmability | High (concatemer length and branching) [14] [32] | High (hairpin design) | Low (limited by antibody and tyramide chemistry) |

| Multiplexing Potential | High with orthogonal concatemers and DEI [31] | High with orthogonal hairpin systems | Low, typically one target per round due to enzyme inactivation needs [14] |

| Sensitivity | High and tunable [14] | High [33] | Exceptionally high [14] |

| Resolution Impact | Preserves resolution; concatemers are linear and penetrative [32] | Good resolution with v3.0 split probes [33] | Can reduce resolution due to tyramide diffusion [14] |