Advanced Signal Amplification Methods for Low-Abundance Targets: From Molecular Tools to Clinical Diagnostics

This comprehensive review explores cutting-edge signal amplification technologies that enable sensitive detection of low-abundance molecular targets, addressing a critical challenge in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics.

Advanced Signal Amplification Methods for Low-Abundance Targets: From Molecular Tools to Clinical Diagnostics

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores cutting-edge signal amplification technologies that enable sensitive detection of low-abundance molecular targets, addressing a critical challenge in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, we examine innovative methods including CRISPR-based systems, in situ hybridization techniques like RNAscope and SABER, electrochemical biosensors, and novel approaches such as Amplification by Cyclic Extension (ACE). The article provides practical guidance for researchers on method selection, optimization strategies, and validation protocols, with specific applications in single-cell analysis, spatial transcriptomics, cancer research, and point-of-care diagnostics. This resource equips scientists and drug development professionals with the knowledge to implement these powerful technologies in their work, ultimately advancing capabilities in precision medicine and biomarker discovery.

Understanding Signal Amplification: Core Principles and Technological Evolution

The Critical Need for Signal Amplification in Low-Abundance Target Detection

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

General Principles and Method Selection

Q1: What are the primary reasons I might fail to detect a low-abundance target? Failure typically stems from two categories: signal insufficiency or excessive background noise.

- Low Signal: The target concentration is below the detection limit of your instrument. The target may be genuinely low-abundance or lost during sample preparation (e.g., inefficient protein extraction or RNA recovery) [1] [2].

- High Background: Contaminants or non-specific binding can mask the specific signal. In mass spectrometry, for example, matrix effects can suppress analyte ionization [3]. In western blotting, non-specific antibody binding can create a high background [1].

Q2: How do I choose the right signal amplification strategy for my experiment? The choice depends on your target (DNA, RNA, protein, small molecule) and detection platform. The table below compares common strategies.

| Strategy | Principle | Best For | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Amplification [4] [5] | Uses enzymes (e.g., HRP, Exonuclease III) to generate many reporter molecules per binding event. | Western blotting, ELISA, electrochemical biosensors. | Potential for high background if not optimized. |

| Nanomaterial-Enhanced [6] [5] | Uses nanoparticles (e.g., gold, carbon) with high surface area to load many signal reporters. | Colorimetric assays (LFA), electrochemical sensors, SERS. | Requires careful synthesis and functionalization of nanomaterials. |

| Nucleic Acid-Based [7] [4] | Employs DNA/RNA circuits (e.g., HCR, G-quadruplex) to create a massive signal-generating structure upon target recognition. | Detection of nucleic acids, proteins via aptamers. | Can be complex to design; requires high-purity reagents. |

| Target Pre-Amplification [7] | A preliminary step to selectively amplify the target before detection (e.g., STALARD for RNA). | RT-qPCR for low-abundance transcripts. | Risk of amplifying non-specific targets if not highly selective. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q3: My western blot shows no bands for my low-abundance protein. What should I do? Follow this systematic approach to enhance sensitivity [1]:

- Verify Sample Preparation: Ensure efficient protein extraction using optimized, sample-specific buffers and broad-spectrum protease inhibitors to prevent degradation [1].

- Optimize Electrophoresis and Transfer:

- Use a gel chemistry appropriate for your protein's size (e.g., Bis-Tris for 6-250 kDa, Tris-Acetate for high molecular weight) for optimal resolution [1].

- Ensure complete transfer to the membrane. Neutral-pH gels (Bis-Tris, Tris-Acetate) offer better transfer efficiency than traditional Tris-glycine gels [1].

- Amplify the Signal:

Q4: My Sanger sequencing results for a low-copy plasmid are noisy or unreadable. What are the likely causes? This is a common issue often related to sample quality and quantity [8].

- Primary Cause: Low template concentration or poor-quality DNA is the most frequent reason. Contaminants like salts or residual PCR primers can interfere with the sequencing reaction [8].

- Solution:

- Accurate Quantification: Use a fluorometer or NanoDrop rather than a standard spectrophotometer for accurate concentration measurement of low-yield samples [8].

- Thorough Cleanup: Always clean up your PCR product or plasmid preparation to remove enzymes, salts, and primers. Use a reliable purification kit [8].

- Check Primer: Ensure the primer is of high quality, not degraded, and binds efficiently to your template [8].

Q5: In LC-MS analysis, my target analyte has a weak signal. How can I improve sensitivity? Optimize the entire workflow, from sample preparation to the MS interface [3].

- Sample Cleanup: Use pretreatment (e.g., SPE, precipitation) to remove matrix components that cause ion suppression [3].

- LC Optimization: Consider using a column with smaller particle size or a narrower internal diameter to improve peak concentration.

- MS Source Tuning: Key parameters dramatically impact ionization efficiency [3].

- Capillary Voltage: Optimize for stable and reproducible spray.

- Desolvation Temperature/Gas Flow: Adjust for efficient solvent evaporation. Be cautious with thermally labile compounds [3].

Experimental Workflows for Signal Amplification

Protocol 1: STALARD for Low-Abundance RNA Isoform Quantification

This protocol describes Selective Target Amplification for Low-Abundance RNA Detection (STALARD), a two-step RT-PCR method to pre-amplify specific polyadenylated transcripts for more reliable quantification [7].

1. Principle: A gene-specific primer (GSP) tailed with an oligo(dT) sequence is used for reverse transcription. This incorporates the GSP sequence into the cDNA. A subsequent limited-cycle PCR using only the same GSP then selectively amplifies the target transcript from both ends [7].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Total RNA sample

- GSP-tailed oligo(dT) primer (

GSoligo(dT)) - Gene-specific primer (GSP)

- Reverse Transcriptase Kit (e.g., HiScript IV 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit)

- PCR Kit (e.g., SeqAmp DNA Polymerase)

- Thermal Cycler

- Purification Beads (e.g., AMPure XP)

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Reverse Transcription

- Mix 1 µg of total RNA with 1 µL of 50 µM

GSoligo(dT)primer. - Synthesize first-strand cDNA using a standard reverse transcription protocol [7].

- Mix 1 µg of total RNA with 1 µL of 50 µM

- Step 2: Selective Target Pre-amplification

- Perform a PCR reaction using 1 µL of the resulting cDNA and 1 µL of 10 µM GSP.

- Use a thermocycling program: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 1 min; 9–18 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 1 min/kb; final extension at 72°C for 10 min [7].

- Step 3: Product Purification

- Purify the PCR products using AMPure XP beads at a 1.0:0.7 product-to-bead ratio to remove excess primers and enzymes [7].

- Step 4: Quantification

- Use the purified product for downstream quantification by qPCR or sequencing.

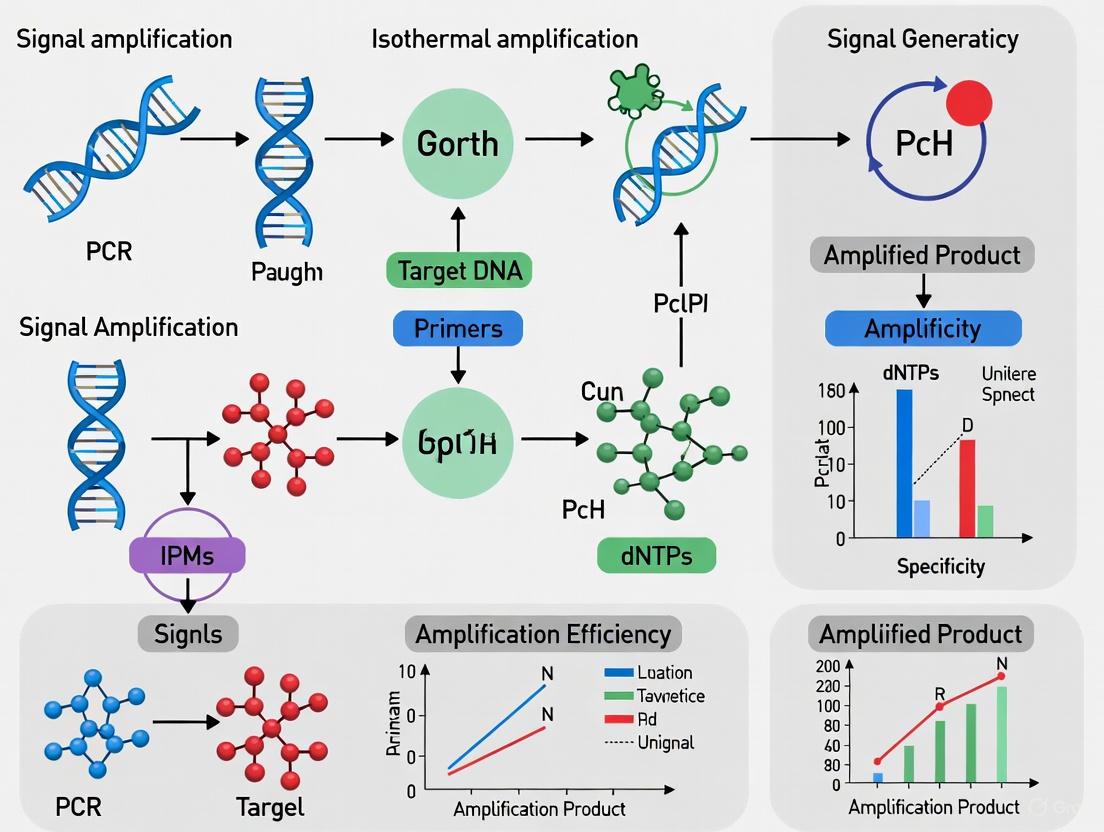

The following diagram illustrates the STALARD workflow and its core principle of selective amplification.

Protocol 2: Constructing a G-Quadruplex Electrochemical Biosensor

This protocol outlines the construction of an ultrasensitive biosensor for protein detection (e.g., Mucin 1) using a G-quadruplex-enriched DNA nanonetwork (GDN) for signal amplification [4].

1. Principle: The target protein is captured by an aptamer, triggering an Exonuclease III-assisted cyclic amplification that produces a large amount of secondary DNA (S1). The S1 strand hybridizes with other strands to form Y-shaped DNA modules, which self-assemble into a GDN. This network loads numerous G-quadruplex structures that, upon binding hemin, produce a strong electrochemical signal [4].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Target protein (e.g., Mucin 1)

- Specific aptamer and complementary DNA (cDNA)

- Hairpin DNA (H1), ssDNA S2, S3, S4

- Exonuclease III (Exo III)

- Hemin

- Gold electrode or screen-printed electrode

- Electrochemical workstation

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Target Recycling Amplification

- Hybridize the aptamer and cDNA to form a double-stranded complex (D1).

- Incubate the target with D1. The target binds the aptamer, releasing cDNA.

- Add hairpin H1 and Exo III. The cDNA opens H1, and Exo III digests the cDNA, releasing the target and a new DNA strand (S1), while H1 is cleaved. This cycle repeats, producing many S1 strands [4].

- Step 2: GDN Formation

- Mix the ssDNA S1 with strands S2 and S3 (which carry split G-quadruplex fragments). They hybridize to form stable Y-modules.

- These Y-modules self-assemble into a large, ordered DNA nanonetwork (GDN) via sticky-end cohesion [4].

- Step 3: Sensor Assembly and Detection

- Immobilize ssDNA S4 on a gold electrode via Au-S bonds.

- Hybridize the pre-formed GDN with the electrode-anchored S4.

- Incubate the electrode with hemin. The numerous G-quadruplex structures in the GDN bind hemin, creating an efficient electrocatalytic unit.

- Measure the electrochemical current (e.g., by DPV). The signal is directly proportional to the target concentration, achieving ultra-sensitive detection down to the femtogram/mL level [4].

The workflow below visualizes this complex DNA-based signal amplification strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions in developing assays for low-abundance targets, as featured in the cited experiments.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Feature / Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| GSP-tailed oligo(dT) Primer [7] | Reverse transcription primer for STALARD. | Enables selective pre-amplification by adding a gene-specific sequence to cDNA. |

| SeqAmp DNA Polymerase [7] | PCR enzyme for target pre-amplification. | High fidelity and processivity for efficient long-range amplification. |

| Exonuclease III (Exo III) [4] | Enzyme for enzymatic signal amplification. | Catalyzes target recycling, generating numerous DNA strands from a single target. |

| Hemin [4] | Electroactive molecule for signal generation. | Binds to G-quadruplex DNA to form a DNAzyme with peroxidase-like activity. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [5] | Nanomaterial for signal enhancement. | High surface area, excellent conductivity, easy functionalization with biomolecules. |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) [5] | Nanomaterial for electrode modification. | Enhances electron transfer rate and provides large surface area for probe immobilization. |

| SuperSignal West Atto Substrate [1] | Chemiluminescent substrate for western blot. | Provides ultra-high sensitivity for detecting low-abundance proteins. |

| Protein G Column [2] | For immunodepletion of abundant proteins. | Removes IgG from serum samples to unmask low-abundance proteins for proteomics. |

| AKOS-22 | AKOS-22, MF:C22H21ClF3N3O3, MW:467.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PF-04880594 | PF-04880594, CAS:1111636-35-1, MF:C19H16F2N8, MW:394.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of modern non-radioactive probes over traditional radioactive probes?

Modern non-radioactive probes offer several critical advantages. Radioactive probes, which use isotopes like 32P and 35S, pose significant safety risks due to radiation exposure, have short half-lives, require costly disposal, and are subject to strict regulatory oversight [9]. In contrast, non-radioactive probes (e.g., fluorescent, biotinylated, or digoxigenin-labeled) eliminate radiation hazards, are more convenient to handle, have longer shelf lives, and reduce safety and compliance requirements [9]. Furthermore, techniques like Amplification by Cyclic Extension (ACE) and G-quadruplex-enriched DNA nanonetworks (GDN) provide exceptionally high sensitivity for detecting low-abundance targets without the drawbacks of radioactivity [10] [4].

Q2: My signal amplification experiment has a high background signal. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

A high background signal is a common issue, often stemming from non-specific probe binding or suboptimal reaction conditions.

- For assays like Immuno-SABER or RCA: High background can be caused by nonspecific concatemer binding or nonspecific background antibody binding [10].

- For G-quadruplex-based electrochemical biosensors: Using split G-quadruplex fragments that only form a complete structure upon successful target recognition can effectively reduce background, as the fragments themselves are poor at capturing signal molecules [4].

- General Troubleshooting Steps:

- Optimize washing stringency: Increase the number or rigor of wash steps after probe hybridization to remove loosely bound materials [10].

- Verify component quality: Use high-quality, purified antibodies and oligonucleotides to minimize non-specific interactions.

- Titrate reagents: Systematically adjust the concentration of probes and detection elements to find the optimal signal-to-noise ratio.

Q3: How can I improve the sensitivity of my mass cytometry for low-abundance proteins?

Conventional mass cytometry requires hundreds of metal-tagged antibodies per epitope to reach detection thresholds, limiting its use for low-abundance proteins [10]. The Amplification by Cyclic Extension (ACE) method directly addresses this. ACE uses thermal-cycling-based DNA concatenation on antibodies, creating hundreds of sites for metal-conjugated detector oligonucleotides to bind, achieving over 500-fold signal amplification [10]. A critical step is incorporating a CNVK photocrosslinker into the detector oligonucleotide. A brief UV exposure after hybridization creates a covalent bond, stabilizing the amplification complex against denaturation during the high-temperature vaporization step in mass cytometry, which would otherwise cause signal loss [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low or No Signal | Instability of DNA complexes during high-temperature processing (e.g., in mass cytometry). | Implement a photocrosslinking step using CNVK-modified detectors and UV exposure to stabilize hybrids [10]. |

| Excessive Non-Specific Background | Non-specific binding of amplifiers or antibodies. | Increase washing stringency; use split-probe systems (e.g., split G-quadruplex) that only assemble upon target binding [10] [4]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Replicates | Unstable reagents; improper thermal cycling. | Check reagent integrity and ensure accurate temperature control during cyclic amplification steps [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Amplification Techniques

Protocol 1: Amplification by Cyclic Extension (ACE) for Mass Cytometry

This protocol enables highly sensitive, multiplexed detection of low-abundance proteins in single-cell samples [10].

- Antibody Staining: Incubate cell suspensions (surface or intracellular) with antibodies conjugated to short DNA oligonucleotide initiators (e.g., TT-a, 11-mer) [10].

- Thermal Cyclic Extension:

- Introduce an extender oligonucleotide (a-T-a, 19-mer) to the stained cells.

- Perform thermal cycling (e.g., 1-500 cycles) between 22°C and 58°C in the presence of Bst polymerase. Each cycle extends the initiator, concatenating hundreds of repeats [10].

- Detector Hybridization & Crosslinking:

- Hybridize metal-conjugated detectors (containing a-T-a sequence) to the extended initiator strands.

- Expose the sample to ultraviolet (UV) light for 1 second to activate the CNVK photocrosslinker, forming a covalent bond and stabilizing the complex [10].

- Acquisition: Analyze the samples using standard mass cytometry procedures. The amplified metal signal allows for detection of low-abundance targets [10].

Protocol 2: G-Quadruplex-Enriched DNA Nanonetwork (GDN) for Ultrasensitive Electrochemical Detection

This protocol details the construction of a biosensor for detecting protein biomarkers like mucin 1 with an ultralow detection limit [4].

- Target Recycling Amplification:

- Hybridize the target-specific aptamer with its complementary DNA (cDNA) to form a double-stranded complex (D1).

- Incubate the target protein (e.g., mucin 1) with D1. The target binds the aptamer, releasing cDNA.

- Add hairpin H1 and Exonuclease III (Exo III). The released cDNA triggers Exo III-assisted cyclic cleavage of H1, producing a large amount of secondary target single-stranded DNA (S1) [4].

- Self-assembly of GDN:

- Mix the resulting ssDNA S1 with ssDNA S2 and ssDNA S3, both carrying split G-quadruplex fragments. They self-assemble into Y-modules, which further interconnect to form the G-quadruplex-enriched DNA nanonetwork (GDN) [4].

- Electrode Immobilization & Detection:

- Immobilize a capture probe (ssDNA S4) on a gold electrode via Au-S bonds.

- Hybridize the pre-formed GDN with the surface-bound S4.

- Add hemin, which is captured by the G-quadruplexes to form an electroactive complex. Measure the electrochemical signal (e.g., via square wave voltammetry) for quantitative detection [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Short DNA Oligonucleotide Initiators (e.g., TT-a) [10] | Short DNA strands conjugated to antibodies; serve as primers for the cyclic extension reaction in ACE. |

| Bst DNA Polymerase | Enzyme used in ACE to perform the strand extension at constant, elevated temperatures [10]. |

| CNVK (3-cyanovinylcarbazole) Photocrosslinker [10] | A modified nucleic acid incorporated into detector oligonucleotides; upon UV exposure, forms covalent bonds to stabilize DNA hybrids against heat denaturation. |

| Exonuclease III (Exo III) [4] | Enzyme used in enzymatic target recycling; cleaves one strand of dsDNA to amplify the target signal. |

| Split G-quadruplex Forming Sequences [4] | Short, guanine-rich DNA fragments that only assemble into a complete G-quadruplex structure upon successful target detection, minimizing background signal. |

| Hemin | An electroactive molecule that binds specifically to G-quadruplex DNA structures, enabling label-free electrochemical detection [4]. |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways & Workflows

ACE Amplification Workflow

GDN Biosensor Mechanism

For researchers in drug development and biomedical science, detecting low-abundance targets represents a significant challenge. The success of these efforts hinges on three fundamental principles: sensitivity (the ability to detect low amounts of a target), specificity (the ability to distinguish the target from similar molecules), and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) (the clarity of the target signal against background interference). A high SNR is particularly crucial, as it directly impacts data integrity, reduces errors, and enables the detection of faint biological signals that would otherwise be lost. This guide provides practical troubleshooting and methodologies to optimize these parameters in your experiments.

Understanding Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

What is SNR and Why is it Critical?

Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is a measure that compares the level of a desired signal to the level of background noise. [11] [12] It is defined as the ratio of signal power to noise power, often expressed in decibels (dB). [11] A ratio higher than 1:1 (greater than 0 dB) indicates more signal than noise. [11] [13]

In practical terms, SNR quantifies how easily you can detect and interpret your target. A high SNR means the signal is clear and easy to detect or interpret, while a low SNR means the signal is corrupted or obscured by noise and may be difficult to distinguish or recover. [11] In digital communications, a high SNR means bits are transmitted clearly, whereas a low SNR increases error rates. [12] This concept directly translates to biomedical detection, where a low SNR can lead to false positives or failure to detect true signals.

How to Calculate SNR

SNR can be calculated using different formulas depending on how the signal and noise are measured. [11] The most common methods are:

- Power Ratio:

SNR (dB) = 10 * logâ‚â‚€(Psignal / Pnoise)where P is average power. [11] [12] - Amplitude Ratio:

SNR (dB) = 20 * logâ‚â‚€(Asignal / Anoise)where A is root mean square (RMS) amplitude. [11] [12] This is common when measuring voltages, such as in audio applications.

For analytical techniques like spectroscopy or chromatography, a common method is to select a region of the data with no signals and calculate either the root mean square or the standard deviation of the data in this region as the noise level. The height of a signal is then divided by this noise level. [14] A peak is generally considered real if its SNR exceeds 3, as there is a greater than 99.9% chance it is not a random noise artifact. [14]

Table 1: Interpretation of SNR Values in Decibels (dB)

| SNR Range (dB) | Interpretation | Practical Implication in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| < 0 dB | Very Poor | Noise dominates; signal is unusable. |

| 0 dB to 10 dB | Poor | Signal is barely detectable; high error rates. |

| 10 dB to 20 dB | Marginal / Low Quality | Signal is understandable but with significant noise. |

| 20 dB to 30 dB | Acceptable / Moderate Quality | Adequate for many applications; some noise noticeable. |

| 30 dB to 40 dB | Good Quality | Good for most data analysis; noise is faint. |

| 40 dB to 60 dB | Very Good / High Quality | Excellent clarity; noise is negligible for most purposes. |

| > 60 dB | Excellent / Professional Quality | Near-perfect signal fidelity. [12] |

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

No Signal or Weak Signal

Problem: You cannot see any signal from your target, or the signal is too faint to be conclusive.

Solutions:

- Increase Target Concentration: Load more protein per well (titrations might be helpful). Use a positive control lysate known to express the target protein. [1] [15]

- Optimize Sample Preparation: Ensure efficient protein extraction using buffers optimized for your sample source and target protein location. Always use broad-spectrum protease inhibitors to prevent protein degradation and loss. [1]

- Check Antibody Specificity and Concentration: Use specificity-verified antibodies designed for your application (e.g., western blotting). Increase the concentration of the primary antibody or extend the incubation time. [1] [15]

- Improve Transfer Efficiency: For western blotting, confirm proteins were successfully transferred to the membrane. Use neutral-pH gels (e.g., Bis-Tris) for cleaner protein release and better transfer efficiency, especially for low-abundance proteins. [1]

- Use Sensitive Detection Reagents: For western blotting, use high-sensitivity chemiluminescent substrates. HRP-based systems can provide detection down to the attogram level when optimized with advanced substrates. [1]

- Increase Exposure Time: For imaging, ensure the exposure time is sufficient to capture the signal. [15]

High Uniform Background

Problem: The entire membrane or image has a high, uniform background that obscures specific signals.

Solutions:

- Optimize Blocking: Increase blocking time, temperature, or the concentration of the blocking reagent (e.g., up to 10%). Consider changing the blocking agent (e.g., BSA vs. milk). Note that milk is not recommended for detecting phosphorylated proteins. [15]

- Reduce Antibody Concentration: High concentrations of primary or secondary antibody can cause non-specific binding. Titrate your antibodies to find the optimal concentration. Include a blocking agent in your antibody buffers. [15]

- Increase Washing: Increase the number, duration, and/or volume of washes to remove unbound antibodies more effectively. [15]

- Perform a Secondary Antibody Control: Omit the primary antibody and incubate the blot with only the secondary antibody to check for non-specific binding of the secondary antibody. [15]

Non-specific Bands or Multiple Bands

Problem: You see bands at unexpected molecular weights or multiple bands where you expect one.

Solutions:

- Verify Antibody Specificity: Non-specific bands often indicate antibody cross-reactivity. Use antibodies with validated specificity for your target via knockout or knockdown controls. [15]

- Prevent Sample Degradation: Use fresh lysates, keep samples on ice, and always include protease and phosphatase inhibitors. [15]

- Consider Protein Modifications: The predicted molecular weight can be influenced by post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation, phosphorylation) or protein processing (cleavage). Use positive controls like recombinant protein to confirm the identity of the band. [15]

- Enrich Your Target: If the target is of low abundance, load more protein or use immunoprecipitation to enrich the target before analysis. [15]

Diagram 1: Troubleshooting Logic for Common Detection Issues

Advanced Signal Amplification: The ACE Method

For targets with extremely low abundance, conventional detection methods may be insufficient. The Amplification by Cyclic Extension (ACE) method is a cutting-edge signal amplification technology that enables high-sensitivity detection in mass cytometry, allowing quantification of low-abundance proteomic substrates in single cells. [16]

ACE Workflow Protocol

- Antibody Staining: Antibodies targeting the protein of interest are conjugated to short DNA oligonucleotide initiators (11-mer). These conjugated antibodies are applied to cell suspensions for staining. [16]

- Thermal Cycling Extension: An extender oligonucleotide is introduced. Through repeated thermal cycles (1 min per cycle), a polymerase successively elongates the initiator, creating hundreds of DNA repeats on each antibody conjugation site. [16]

- Detector Hybridization: Detectors conjugated to metal isotopes (for mass cytometry) are hybridized to the extended initiator strand. Each extended initiator can bind hundreds of metal-conjugated detectors. [16]

- Photocrosslinking (Critical for Mass Cytometry): A brief UV exposure activates a photocrosslinker (CNVK), forming a covalent bond between the detector and the extended DNA strand. This stabilizes the complex against denaturation during the high-temperature vaporization step in mass cytometry. [16]

- Analysis: The sample is analyzed by mass cytometry, where the amplified metal signal enables detection of low-abundance targets. [16]

Diagram 2: ACE Signal Amplification Workflow

Key Advantages of ACE

- High Amplification Power: ACE enables over 500-fold signal amplification with uncompromised signal-to-noise ratios. [16]

- High Multiplexing: It allows simultaneous signal amplification on more than 30 protein epitopes. [16]

- Specificity: The use of short DNA initiators (9-mer) reduces nonspecific binding compared to methods using longer oligonucleotides. [16]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Sensitive Detection of Low-Abundance Targets

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Sensitivity Substrates | Ultrasensitive chemiluminescent detection for western blotting. Ideal for low-abundance targets or precious samples. | SuperSignal West Atto Ultimate Sensitivity Substrate enables protein detection down to the high-attogram level. [1] |

| Optimized Gel Chemistries | For effective separation of target proteins, which is critical for accessibility during antibody binding. | Bis-Tris Gels (6-250 kDa): General use, neutral pH, preserves protein integrity.Tris-Acetate (40-500 kDa): Best for high molecular weight proteins.Tricine (2.5-40 kDa): Optimal for low molecular weight proteins. [1] |

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Ensure specific binding to the target of interest. Critical for both sensitivity and specificity. | Use antibodies that are specificity-verified and application-validated (e.g., for western blotting). Always check validation data provided by the supplier. [1] |

| Low-Noise Secondary Antibodies | Detect the primary antibody with high sensitivity and minimal background. | Use antibodies conjugated to HRP for high sensitivity. Filter antibodies through a 0.2 μm filter to remove aggregates that cause speckled backgrounds. [1] [15] |

| ACE Reagents | For extreme signal amplification in mass cytometry applications for low-abundance proteins. | Includes DNA initiator-conjugated antibodies, extender oligonucleotides, Bst polymerase, and CNVK-modified metal-conjugated detectors. [16] |

| Protease & Phosphatase Inhibitors | Prevent sample degradation during and after preparation, preserving the target protein. | Use broad-spectrum inhibitors in lysis buffers. Essential for obtaining high yields from your sample. [1] [15] |

| VBIT-12 | VBIT-12, MF:C25H27N3O3, MW:417.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| HJC0149 | HJC0149, MF:C15H10ClNO4S, MW:335.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is a good signal-to-noise ratio for my experiment? A: The required SNR depends on the application. For qualitative detection of a peak in chromatography or spectroscopy, an SNR of 3:1 is often the minimum threshold to confirm a signal is real. [14] For reliable quantitative analysis, especially with low-abundance targets, aim for an SNR of 10:1 or higher. [14] [12]

Q2: How can I improve SNR without changing my core detection antibody? A: Several strategies can help:

- Averaging: If your instrument allows, averaging multiple scans or frames can improve SNR, as the improvement is proportional to the square root of the number of frames averaged (e.g., 4 frames improve SNR by 2x). [13]

- Filtering: Use electronic or digital filters to block noise frequencies outside the desired signal band. [12]

- Optimize Blocking and Washing: In immunoassays, these are critical steps for reducing background noise. [15]

- Increase Signal Strength: Amplify the source signal within system limits to avoid distortion. [12]

Q3: My negative control has a band in the same place as my target. Is this a signal-to-noise problem? A: This is more likely a specificity problem than a pure SNR issue. A band in the negative control suggests non-specific antibody binding or a cross-reactive antibody. To troubleshoot, verify your antibody's specificity using a knockout cell line or confirm the band identity with a recombinant protein control. [15] Optimizing blocking conditions and titrating your antibody can also help.

Q4: Can software improve a poor SNR after I've collected my data? A: Yes, denoising algorithms can enhance SNR post-capture, but they cannot recover information that is completely lost in the noise. The best results always come from optimizing SNR during the acquisition phase itself. [13]

Q5: What is the Rose Criterion? A: The Rose Criterion is a rule of thumb from imaging science which states that an SNR of at least 5 is needed to distinguish image features with certainty. An SNR less than 5 means there is less than 100% certainty in identifying details. [11] This principle can be broadly applied to other detection methods.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide: Background Noise in Electrophysiology and Biosensing

Problem: Excessive background noise is obscuring weak target signals. Question: "Why is my signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) so poor in my electrophysiology recordings or electrochemical biosensor?"

1. Investigate Electrical and Environmental Interference

- Action: Check for 50/60 Hz "mains hum" and high-frequency hash.

- Protocol: Use an oscilloscope or spectral analysis software to identify the noise frequency.

- Solution:

- For 50/60 Hz Hum: Verify a single-point grounding scheme for all equipment (amplifier, Faraday cage, table). Inspect for ground loops, which are a major source of this noise [17].

- For High-Frequency Hash: Ensure the Faraday cage is fully sealed and all connections are secure. Move cell phones, wireless routers, and unshielded power supplies away from the experimental setup [17].

- Cable Management: Use shielded, twisted-pair cables and avoid running power cords parallel to signal cables [17].

2. Optimize Your Signal Acquisition Hardware

- Action: Verify the configuration of your instrumentation amplifier.

- Protocol: Ensure the amplifier is using a differential input configuration, which subtracts noise common to both the signal and reference electrodes [17].

- Solution:

- Use an amplifier with a high Common-Mode Rejection Ratio (CMRR) (>100 dB) to effectively reject environmental interference [17].

- Place the headstage (the first amplification stage) as close as possible to the signal source (e.g., the cell or tissue) to minimize the length of the high-impedance signal path, which is highly susceptible to noise [17].

3. Apply Appropriate Digital Signal Processing (DSP)

- Action: Apply post-acquisition digital filters judiciously.

- Protocol: After maximizing hardware solutions, use software filters.

- Solution:

- Low-Pass Filter: Attenuate high-frequency noise. Set the cutoff frequency just above the fastest biologically relevant component of your signal (e.g., action potential spikes) [17].

- High-Pass Filter: Remove slow baseline drift caused by electrode instability or temperature fluctuations [17].

- Notch Filter: Use as a last resort to remove persistent 50/60 Hz line noise, as it can introduce signal artifacts [17].

- AI-Powered Denoising: For complex noises, modern AI algorithms can distinguish between speech and noise, and can be adapted to separate signal from background in various data types [18].

Table: Common Noise Signatures and Corrective Actions

| Noise Signature | Potential Source | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Sharp 60/50 Hz Peaks [17] | Ground loops, poor shielding [17] | Verify single-point grounding; check Faraday cage integrity [17] |

| High-Frequency Hash [17] | Radiofrequency interference (RFI) from cell phones, routers [17] | Seal Faraday cage; use a low-pass filter [17] |

| Slow, Baseline Drift [17] | Thermal noise, electrode drift, temperature variations [17] | Allow equipment warm-up time; use a high-pass filter [17] |

| Excessively Large Noise [17] | Broken ground connection or amplifier saturation (clipping) [17] | Check all electrode connections; reduce amplifier gain [17] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Non-Specific Binding in Biomolecular Assays

Problem: High background signal due to non-specific interactions of detection reagents. Question: "How can I reduce the high background in my ELISA or antibody-oligo conjugate imaging?"

1. Optimize Your Incubation and Buffer Conditions

- Action: Modify the chemical environment to discourage non-specific interactions.

- Protocol: Incorporate blocking agents and competitors into your incubation buffers.

- Solution:

- General Blocking: Use 1-3% BSA, normal IgG (e.g., 0.1 mg/mL), or serum proteins from an unrelated species to block unused binding sites on surfaces [19].

- Electrostatic Shielding: Add 150 mM NaCl to your buffer to shield electrostatic forces between negatively charged reagents (like DNA) and positively charged cellular components [19].

- Polyanion Competitors: Include dextran sulfate (0.02-0.1%) as a polyanion to outcompete conjugated DNA or other charged reagents for non-specific binding sites [19].

2. Employ Specific Blocking Strategies for Oligo Conjugates

- Action: Prevent single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) on antibodies from binding non-specifically.

- Protocol: Pre-hybridize the conjugated ssDNA with a short complementary DNA strand before applying the conjugate to the sample.

- Solution: This converts the ssDNA into double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), which dramatically reduces its ability to hybridize to intracellular nucleic acids or bind DNA-binding proteins, a common cause of nuclear background staining [19].

3. Select the Right Materials and Reagents

- Action: Minimize adsorption to consumables.

- Protocol: Use low-adsorption tubes and plates specifically designed for proteins or nucleic acids.

- Solution: For problematic molecules like peptides, proteins, and nucleic acids, low-adsorption consumables have surface passivation that reduces losses due to adsorption, improving recovery and signal [20].

Table: Strategies to Mitigate Non-Specific Binding Based on Analyte Type

| Analyte Type | Main Challenge | Desorption Strategy | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptides, Proteins, PDCs [20] | Poor solubility; electrostatic/hydrophobic effects [20] | Adjust solvent pH; use organic reagents or BSA as a competitor [20] | Improves solubility; competes for binding sites [20] |

| Nucleic Acids [20] | Electrostatic binding to metal surfaces [20] | Add chelators (EDTA); use low-adsorption liquid phase systems [20] | Reduces metal ion chelation; passivates metal surfaces [20] |

| Cationic Lipids [20] | Strong electrostatic and hydrophobic effects [20] | Add surfactants (e.g., Tween, CHAPS) [20] | Improves dissolution state; disrupts hydrophobic interactions [20] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming Detection Limits in Low-Abundance Targets

Problem: The target signal is too weak to detect reliably, even with low background. Question: "The native abundance of my target is below my assay's detection limit. How can I amplify the signal?"

1. Implement Enzymatic Signal Amplification

- Action: Use enzymes to generate a detectable product cascade.

- Protocol: In ELISA or immunohistochemistry, use an enzyme-linked antibody (e.g., HRP or Alkaline Phosphatase) with a chromogenic, fluorogenic, or chemiluminescent substrate.

- Solution: A single enzyme molecule can turn over many thousands of substrate molecules, resulting in significant signal amplification at the target location [21]. For even greater amplification, use the Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) system, where HRP generates highly reactive tyramide radicals that deposit labeled tyramide nearby, greatly enhancing sensitivity [21].

2. Utilize Nucleic Acid Amplification Strategies

- Action: Increase the number of detectable targets isothermally.

- Protocol: For nucleic acid targets, use isothermal amplification methods like Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) or Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA) coupled with electrochemical or optical detection [22].

- Solution: These methods can amplify target DNA or RNA at a constant temperature, making them suitable for point-of-care settings. The amplified products can be detected with intercalating dyes (e.g., methylene blue) or sequence-specific probes [22].

3. Leverage Affinity-Based Amplification Systems

- Action: Increase the number of detection labels per binding event.

- Protocol: Use the Labeled Streptavidin-Biotin (LSAB) system.

- Solution:

- Use a biotinylated primary or secondary antibody.

- Then, add enzyme- or fluorophore-conjugated streptavidin. Since each biotinylated antibody carries multiple biotins and streptavidin has four biotin-binding sites, this creates a large complex with many reporter molecules, significantly amplifying the signal [23].

4. Convert Interference into Signal

- Action: Use novel strategies that turn background components into an advantage.

- Protocol: In a biosensing nanoassembly, target recognition can be designed to induce cross-linking between the target and non-specific proteins in the sample.

- Solution: This approach uses the abundant non-specific proteins as part of the detection scaffold, forming a large nanoassembly on the sensor surface that generates a strong signal and allows for vigorous washing to remove unbound interference [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical first step to improve my signal-to-noise ratio? The most critical step is to minimize noise at the source through hardware and physical preparation before any electronic or digital processing. This includes ensuring proper grounding, using a Faraday cage, stabilizing your electrodes, and placing the headstage close to your preparation. A low noise floor is the foundation for a high-quality signal [17].

Q2: I'm seeing nuclear staining in my antibody-oligo conjugate experiment. What is the cause and solution? This is a classic sign of non-specific binding caused by the electrostatic interaction between the negatively charged ssDNA on your antibody and positively charged cellular proteins like histones. The solution is to pre-hybridize the conjugated oligo with its complementary DNA to form dsDNA and include dextran sulfate (0.02-0.1%) and 150 mM NaCl in your antibody incubation buffer to block these interactions [19].

Q3: What are the main advantages of signal-based amplification over target-based amplification? Target-based amplification (e.g., PCR, LAMP) increases the number of target molecules and is highly sensitive. However, it often requires enzymes and controlled conditions. Signal-based amplification (e.g., enzymatic detection, LSAB) increases the signal per target and can be simpler, faster, and more suitable for point-of-care diagnostics, as it doesn't alter the native target abundance [22].

Q4: How can I prevent the adsorption of my peptide drug during sample storage and analysis? Peptides are prone to adsorption to container walls. Strategies include:

- Using low-adsorption consumables made from specially treated polymer.

- Adjusting the solution pH to improve solubility.

- Adding a carrier protein like BSA to compete for binding sites.

- Using surfactants to improve dispersion and reduce hydrophobic interactions [20].

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Workflow: Signal Amplification for Low-Abundance Protein Detection

This diagram illustrates a combined strategy using antibody-oligo conjugates and hybridization chain reaction (HCR) for highly sensitive protein detection [19].

Pathway: Differential Amplification for Noise Reduction

This diagram shows how a differential amplifier rejects environmental noise to achieve a clean signal, which is fundamental in electrophysiology and sensor technology [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Managing Background and Amplifying Signal

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dextran Sulfate [19] | Polyanionic competitor that blocks electrostatic non-specific binding. | Reducing nuclear background in antibody-oligo conjugate imaging [19]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [23] [19] | Blocking agent used to saturate non-specific binding sites on surfaces. | Standard component of blocking and incubation buffers in ELISA and immunohistochemistry [23]. |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) [21] [23] | Enzyme for signal amplification; catalyzes substrate turnover. | Conjugated to secondary antibodies for colorimetric, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent detection in ELISA [23]. |

| Streptavidin-Conjugates [23] | High-affinity binding to biotin; used to build large detection complexes. | Labeled Streptavidin-Biotin (LSAB) amplification in immunoassays [23]. |

| Low-Adsorption Tubes/Plates [20] | Surface-passivated consumables that minimize analyte loss. | Storing and processing sensitive samples like peptides, proteins, and nucleic acids [20]. |

| Complementary DNA (for pre-hybridization) [19] | Converts ssDNA on conjugates to dsDNA, preventing non-specific hybridization. | Essential step for clean imaging with antibody-DNA conjugates in techniques like SABER and immuno-HCR [19]. |

| Tyramide Reagents [21] | Substrates for HRP used in Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA); deposit numerous labels at the target site. | Extreme signal amplification for detecting low-abundance proteins in cells and tissues [21]. |

| Deoxynojirimycin | Deoxynojirimycin, CAS:19130-96-2; 73285-50-4, MF:C6H13NO4, MW:163.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ketoconazole-d4 | Ketoconazole-d4, MF:C26H28Cl2N4O4, MW:535.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Signal Amplification for Low-Abundance Targets

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My single-cell RNA-seq experiment shows low cDNA yield. What are the primary causes and solutions?

Low cDNA yield is common when working with the ultra-low RNA masses found in single cells. The table below summarizes common causes and verified solutions based on established protocols [25].

| Cause | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor Carryover | Low yield in both experimental and positive control samples. | Wash and resuspend cells in EDTA-, Mg2+- and Ca2+-free 1X PBS or a specialized FACS Pre-Sort Buffer before sorting [25]. |

| RNA Degradation | Low yield and poor RNA integrity number. | Work quickly; snap-freeze samples after collection and store at -80°C; minimize handling time [25]. |

| Sample Loss | Low yield and high background in negative controls. | Use low RNA/DNA-binding plasticware; ensure complete bead separation during cleanups with a strong magnetic device [25]. |

Q2: For my spatial transcriptomics experiment, what are the key sample preparation considerations for FFPE versus frozen tissues?

The choice between FFPE and frozen tissues significantly impacts which molecules you can detect and the required protocol optimization. The comparison below will guide your decision [26].

| Parameter | FFPE Tissues | Frozen Tissues |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Histopathology; most common archival sample [26]. | Immunology, electron microscopy, mass spectrometry [26]. |

| Pros | Stable at room temperature; excellent for tissue structure and morphology [26]. | Ideal for lipidomics, protein complexes; no fixation-induced crosslinks [26]. |

| Cons | Removes lipid modalities; formaldehyde crosslinking can mask epitopes/nucleotides, requiring antigen retrieval [26]. | Less common in clinical archives; different storage requirements [26]. |

| Key Consideration | Tissue quality can vary greatly over long storage; requires careful sample-by-sample optimization and checks [26]. | Flash-freezing preserves molecules in a near-native state [26]. |

Q3: I am detecting high background or non-specific signal in my multiplexed FISH experiments. How can I improve specificity?

High background is a common challenge in fluorescence in situ hybridization. Newer signal amplification methods are specifically designed to address this.

- Employ Advanced Signal Amplification Methods: Newer techniques like RNA Scope, PLISH, and SABER have been developed with great improvements in accuracy and sensitivity compared to conventional FISH [27]. These methods use proprietary probe designs and amplification chemistries that minimize off-target binding.

- Utilize Open-Source Platforms: For flexible method development, open-source pipelines like PRISMS (Python-based robotic imaging and staining for modular spatial omics) allow for custom optimization of staining and imaging parameters, which can help identify and reduce sources of background [28].

Q4: When comparing imaging-based spatial transcriptomics platforms, why might a key gene (e.g., CD3D) show low or no expression even when expected?

Discrepancies for specific genes can occur due to platform-specific probe design and performance. A 2025 benchmark study using FFPE tumor samples found that:

- Platform Performance Varies: The study showed that some platforms exhibited target gene probes (including CD3D, FOXP3, and MS4A1) with expression levels as low as negative control probes [29]. This indicates the probe itself may not be functioning optimally in that specific assay.

- Consult Platform Performance Data: Before finalizing a panel, check if the platform provider has data on the sensitivity and specificity of the probes for your genes of interest. This objective assessment can prevent relying on a "broken" probe for a critical target [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and reagents used in advanced signal amplification and single-cell analysis workflows.

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Act as carriers for aptamer probes or to enhance electrode conductivity in electrochemical biosensors, amplifying the detection signal [5]. | Aptamer-based electrochemical biosensors for detecting small molecules or pathogens [5]. |

| Carbon Nanomaterials (e.g., Graphene, CNTs) | Provide a large surface area for immobilizing biorecognition elements and improve electrical conductivity in sensor platforms [5]. | Used as a matrix in electrochemical aptasensors to increase sensitivity for targets like Salmonella or exosomes [5]. |

| ACE (Amplification by Cyclic Extension) Reagents | Enable high-sensitivity protein detection via thermal-cycling-based DNA concatenation on antibodies, boosting metal ion tags for mass cytometry [16]. | Detecting low-abundance transcription factors or phosphorylation sites in single-cell mass cytometry [16]. |

| DNA Barcodes / Concatemers | Used in methods like SABER and ACE to create repetitive sequences for hybridizing multiple detection probes, physically amplifying the signal per binding event [27] [16]. | Multiplexed protein or RNA detection in imaging and mass cytometry [27] [16]. |

| Metal-Tagged Antibodies | Antibodies conjugated to heavy metal isotopes instead of fluorophores, enabling high-plex detection without spectral overlap via mass cytometry [30] [16]. | Imaging Mass Cytometry (IMC) for highly multiplexed tissue imaging [30]. |

| Nlrp3-IN-41 | Nlrp3-IN-41, MF:C22H22N2O4S2, MW:442.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SF2312 | SF2312, MF:C4H8NO6P, MW:197.08 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: ACE (Amplification by Cyclic Extension) for Mass Cytometry [16]

This protocol enables high-sensitivity detection of low-abundance proteins in single cells by amplifying the metal signal on antibodies.

- Antibody Staining: Conjugate antibodies targeting your proteins of interest to short DNA oligonucleotide initiators (e.g., 11-mer). Apply the mixture of conjugated antibodies to cell suspensions for surface or intracellular staining.

- Cyclic Extension: Introduce an extender oligonucleotide complementary to the initiator. Using Bst polymerase, perform repeated thermal cycles (e.g., 1 min at 22°C for extension, 1 min at 58°C for denaturation). Each cycle elongates the initiator, creating hundreds of repeats of the detector sequence.

- Photocrosslinking: Hybridize metal-conjugated detectors (containing a CNVK photocrosslinker) to the extended initiator strands. Expose the sample to UV light (1 sec) to form a covalent bond between the detector and the extended strand, stabilizing the complex against heat denaturation.

- Acquisition and Analysis: Proceed with standard mass cytometry acquisition. The amplified metal signal allows for the quantification of low-abundance epitopes.

Protocol 2: Optimized Single-Cell Sorting for RNA-seq [25]

Proper cell handling is critical for success in low-input RNA workflows.

- Cell Preparation: Wash and resuspend your bulk cell suspension in EDTA-, Mg2+- and Ca2+-free 1X PBS, especially if enzymatic dissociation was used.

- Collection Buffer: For FACS sorting, deposit single cells into a lysis buffer containing an RNase inhibitor. The exact volume and buffer composition should be followed as per your specific RNA-seq kit's manual (see Table II in search results [25]).

- Immediate Processing: Once sorted, gently centrifuge the plate or strips (100g) and either process immediately for cDNA synthesis or snap-freeze on dry ice for storage at -80°C.

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Cutting-Edge Amplification Technologies and Their Research Applications

Troubleshooting Guides

CRISPR/Cas Systems Troubleshooting

Problem: Low Editing Efficiency Editing efficiency is low, with few cells showing the desired genetic modification.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal guide RNA (gRNA) | Design gRNAs to target a unique genomic sequence and ensure they are of optimal length. Use online prediction tools to assess specificity [31]. |

| Inefficient delivery | Optimize delivery method (e.g., electroporation, lipofection, viral vectors) for your specific cell type [31]. |

| Low expression of Cas9/gRNA | Use a promoter that is active in your cell type. Verify the quality and concentration of plasmid DNA or mRNA. Consider codon-optimizing Cas9 for your host organism [31]. |

Problem: High Off-Target Activity The Cas enzyme cleaves DNA at unintended sites that resemble the target sequence.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Low gRNA specificity | Design highly specific gRNAs using algorithms that predict potential off-target sites. For Cas12a, note that it discriminates strongly against mismatches across most of the target sequence, not just a "seed" region [32]. |

| Cas9 variant | Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants engineered to reduce off-target cleavage [31]. |

| Cell toxicity | Mitigate toxicity by optimizing the concentration of delivered components, using lower doses, and utilizing Cas9 protein with a nuclear localization signal [31]. |

Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA) Troubleshooting

Problem: Nonspecific Amplification Products The reaction generates unwanted, non-specific DNA products, even in no-template controls.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| False priming | Include a mutant single-stranded DNA binding protein (SSB) from Thermus thermophilus (TthSSB). This protein binds ssDNA, prevents secondary structures, and essentially eliminates nonspecific RCA products by reducing primer-dimer formation [33]. |

| Suboptimal reaction conditions | Use modified random oligonucleotides to improve specificity. The addition of TthSSB mutant protein also increases the overall efficiency and accuracy of phi29 DNA polymerase [33]. |

Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) Troubleshooting

Problem: Low or No Signal in RNA Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) The fluorescent signal is weak or absent, making it difficult to detect the target RNA.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal probe binding | For HCR v3.0, increase the probe concentration from 4 nM to 20 nM in the probe hybridization buffer [34]. |

| Short incubation times | Extend both the probe hybridization and amplifier incubation times to overnight [34]. |

| Low-abundance target | For HCR Gold, consider using a "boosted" probe design with more binding sites. If signal remains low, switch to the more sensitive HCR Pro system [34]. |

Problem: High Background Signal The sample has a high fluorescent background, which obscures the specific signal.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Autofluorescence | For samples with significant autofluorescence, use longer-wavelength fluorophores (e.g., 647 nm, 750 nm) for detection, as autofluorescence is typically higher in shorter-wavelength channels [35]. |

| Non-specific probe binding | Ensure the use of split-initiator probes (as in HCR v3.0), which only trigger amplification when both halves are bound correctly to the target RNA, suppressing background [36]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

CRISPR/Cas Systems FAQ

Q: How does Cas12a achieve higher target specificity compared to Cas9? A: The high specificity of Cas12a arises from its kinetic mechanism. While Cas9 discriminates strongly against mismatches only in a short "seed" region near the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), Cas12a discriminates against mismatches across almost the entire target sequence. This is due to a more reversible R-loop formation process, meaning the complex with a mismatched target is more likely to fall apart before cleavage occurs [32].

Q: What controls are essential for a CRISPR-Cas9 experiment? A: Always include a negative control (e.g., cells transfected with a non-targeting gRNA) to account for background noise and off-target effects. A positive control using a well-validated, effective gRNA is also crucial to confirm your system is working correctly [31].

Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA) FAQ

Q: How does TthSSB mutant protein improve RCA? A: The TthSSB mutant protein binds specifically to single-stranded DNA. This binding prevents the formation of secondary structures and reduces primer-dimer formation, which is a common source of nonspecific amplification. Its addition halves the elongation time required by phi29 DNA polymerase and essentially eliminates nonspecific DNA products [33].

Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) FAQ

Q: How many probes are needed for a successful HCR RNA-FISH experiment? A: The number of probes can be significantly reduced compared to other FISH methods. An optimized HCR v3.0 protocol can achieve high specificity and sensitivity with only five pairs of split-initiator probes per target RNA, which greatly lowers the cost and time of the experiment [36].

Q: Can I multiplex HCR for detecting multiple RNA targets? A: Yes, HCR is highly suitable for multiplexing. You can image multiple targets in the same sample by using a different, orthogonally designed HCR amplifier system (e.g., B1, B2, B3, etc.) with a distinct fluorophore for each target RNA [35] [36].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Optimized HCR v3.0 for RNA-FISH in Drosophila Larvae

This protocol is optimized for bright, specific imaging of RNA in whole-mount Drosophila melanogaster larval nervous tissue, suitable for low-magnification imaging [36].

Fixation and Permeabilization:

- Dissect larvae in Schneider's media and fix for 30 minutes at room temperature in 4% PFA in PBSTx (0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS).

- Rinse three times in PBSTx.

- Permeabilize tissue with two 20-minute incubations in PBSTx at room temperature.

Pre-hybridization and Hybridization:

- Equilibrate samples in 5X SSCT (5X SSC, 0.1% Tween) for 5 minutes.

- Replace with wash solution (5X SSC, 30% formamide, 0.1% Tween) and incubate for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Perform two 20-minute pre-hybridization steps in hybridization solution (5X SSC, 30% formamide, 10% Dextran sulphate, 0.1% Tween) at 37°C.

- Hybridize overnight at 37°C in hybridization solution containing the pooled probes (five pairs, at 10 nM final concentration each).

Post-Hybridization Washes:

- Remove unbound probes with four 15-minute washes in wash solution at 37°C.

- Perform two 5-minute washes with 5X SSCT at room temperature.

Amplification:

- Pre-amplify samples by incubating in amplification solution (5X SSC, 10% Dextran sulphate, 0.1% Tween) for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Prepare hairpins: heat individual hairpin stocks (60 nM final) to 95°C for 90 seconds, then cool at room temperature for 30 minutes in the dark. Pool hairpins in amplification solution.

- Replace the pre-amplification solution with the solution containing the hairpins. Incubate overnight at 37°C in the dark.

Final Washes and Mounting:

- Rinse three times in 5X SSCT, then perform two 30-minute washes in 5X SSCT.

- Counterstain with DAPI and/or other markers as needed.

- Mount samples in an appropriate antifade mounting medium for microscopy.

Protocol: Enhancing RCA Specificity with TthSSB

This protocol modification significantly reduces nonspecific amplification in RCA reactions [33].

- Standard RCA Setup: Perform RCA according to the manufacturer's instructions using phi29 DNA polymerase and random hexamers.

- Addition of TthSSB: Include the purified mutant TthSSB protein (F255P) in the RCA reaction mixture.

- Amplification: Carry out the isothermal amplification. The presence of the TthSSB mutant protein will increase the efficiency of DNA synthesis and eliminate nonspecific DNA products, potentially allowing for a shorter elongation time.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Reagent / Component | Function in Amplification |

|---|---|

| High-fidelity Cas9/Cas12a variants | Engineered nucleases that maintain on-target cleavage activity while significantly reducing off-target effects, crucial for specific editing [31]. |

| TthSSB Mutant Protein (F255P) | A thermostable single-stranded DNA binding protein that prevents secondary structure and primer-dimer formation, thereby eliminating nonspecific products in RCA [33]. |

| HCR Split-Initiator Probes | Pairs of DNA probes that each contain half of the target sequence and half of an initiator sequence. They provide high specificity by only triggering amplification when both bind correctly to the target RNA [36]. |

| HCR Hairpin Amplifiers | Fluorescently labeled DNA hairpins that self-assemble into a tethered polymerization chain upon initiation. This provides signal amplification, enabling detection of low-abundance targets [34] [36]. |

| Phi29 DNA Polymerase | A highly processive DNA polymerase with strong strand-displacement activity, making it the enzyme of choice for isothermal DNA amplification methods like RCA [33]. |

| MTX-211 | MTX-211, MF:C20H14Cl2FN5O2S, MW:478.3 g/mol |

| Nampt-IN-10 TFA | Nampt-IN-10 TFA, MF:C29H29F4N5O4, MW:587.6 g/mol |

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a foundational technique in molecular biology that enables the detection of specific DNA or RNA sequences within intact cells, tissue slices, and even entire organs, preserving crucial spatial and morphological context [27] [37]. While invaluable for basic research and clinical diagnostics, the low sensitivity of conventional ISH has historically limited its application for low-abundance targets [27].

Recent innovations in signal amplification have successfully addressed this limitation. Techniques such as RNAscope, PLISH, and SABER represent a significant advancement over traditional methods, offering major improvements in accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity [27]. These methods are revolutionizing spatial genomics and the study of gene expression by enabling researchers to visualize and quantify even rare transcripts with single-molecule resolution directly in their native tissue environment [27] [38] [37]. This guide provides a technical deep-dive into these methods, with a focus on troubleshooting and optimized protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

Technology Comparison and Quantitative Data

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of the three featured signal amplification techniques, providing a clear comparison of their capabilities and typical applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced In Situ Hybridization Signal Amplification Methods

| Feature | RNAscope | PLISH | SABER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Name | RNAscope In Situ Hybridization [38] | Probe-based Laser-induced Saturable Hybridization [27] | Signal Amplification by Exchange Reaction [37] |

| Key Principle | Proprietary double Z (ZZ) probe design and branched DNA (bDNA) signal amplification [38] [39] | Not specified in detail | DNA primer exchange reaction and concatemerization [37] |

| Primary Application | Detection of mRNA and long non-coding RNA (>300 bp) [39] | Detection of low-abundance RNA targets [27] | Enhanced multiplexed imaging of RNA and DNA in cells and tissues [37] |

| Sensitivity | Single-molecule sensitivity [38] [40] | High sensitivity for low-abundance targets [27] | High signal amplification for sensitive detection [37] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Single-plex up to 12-plex [39] | Information not specified in results | Designed for highly multiplexed imaging [37] |

| Advantages | High specificity and sensitivity, standardized protocol, adaptable to automation [38] [41] | High accuracy and sensitivity [27] | Enhanced multiplexing, ability to use unmodified DNA [37] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of advanced ISH assays, particularly RNAscope, requires specific reagents and materials. The following table lists essential items and their critical functions in the experimental workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for RNAscope Assays

| Item | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Superfrost Plus Microslides [41] [42] | Tissue adhesion and integrity | Required to prevent tissue detachment during the assay [41]. |

| ImmEdge Hydrophobic Barrier Pen [41] [43] | Creates a well for reagents | Maintains a hydrophobic barrier throughout the procedure; other pens are not recommended [41]. |

| RNAscope Target Retrieval Reagents [43] | Antigen retrieval | Critical for accessing target RNA; conditions may require optimization [41]. |

| RNAscope Protease Plus Reagents [43] | Tissue permeabilization | Allows probe access; temperature must be maintained at 40°C [41]. |

| Positive & Negative Control Probes (e.g., PPIB, UBC, dapB) [41] [42] | Assay qualification and troubleshooting | Essential for verifying sample RNA quality, optimal permeabilization, and assay performance [41]. |

| HybEZ Oven [41] [43] | Controlled hybridization environment | Maintains optimum humidity and temperature during key hybridization steps [41]. |

| Assay-Specific Mounting Media (e.g., EcoMount, VectaMount, CytoSeal) [41] [42] | Preserves and coverslips the sample | Using the correct mounting medium is critical; it varies by assay type (e.g., Brown, Red, Fluorescent) [41] [42]. |

The workflow for a manual RNAscope assay can be completed in 7-8 hours and is broadly divided into sample preparation and detection phases [41]. The following diagram illustrates the core steps and the logical sequence of the proprietary RNAscope signal amplification mechanism.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common RNAscope Issues and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common RNAscope Assay Problems

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Signal | Incorrect sample preparation; degraded RNA; omitted amplification steps [41] | Follow sample prep guidelines (16-32h fixation in fresh 10% NBF) [41]. Always run positive control probes (PPIB/UBC) to verify RNA integrity and assay performance [41] [42]. Perform all amplification steps in the correct order [41]. |

| High Background (Non-specific staining) | Incomplete washing; over-digestion with protease; non-optimal pretreatment [41] | Ensure hydrophobic barrier is intact to prevent tissue drying and uneven reagent coverage [41]. Always run a negative control probe (dapB); a score of <1 is acceptable [41] [42]. Use fresh reagents (ethanol, xylene) and ensure adequate washing [41]. |

| Weak or Faint Signal | Under-fixed tissue; under-digestion with protease; sub-optimal pretreatment [41] | Optimize protease incubation time. For over- or under-fixed tissues, adjust Pretreat 2 (boiling) and/or protease treatment times incrementally [41] [42]. |

| Tissue Detachment from Slide | Use of incorrect slide type; drying of tissue sections [41] | Use only Superfrost Plus slides. Ensure the hydrophobic barrier remains intact throughout the assay to prevent tissue from drying out [41]. |

| Patchy or Uneven Staining | Tissue dried out during procedure; incomplete coverage by reagents [41] | Use an ImmEdge Hydrophobic Barrier Pen and ensure the barrier remains intact. Flick slides to remove residual reagent, but do not let slides dry out at any time [41]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How does RNAscope achieve its high specificity and sensitivity for low-abundance targets?

- A: RNAscope uses a proprietary double Z (ZZ) probe design. Each probe is short and requires two ZZ sequences to bind adjacent to each other on the target RNA for the pre-amplifier to attach. This design prevents the binding of incomplete or misfolded probes, providing high specificity. The subsequent branched DNA (bDNA) amplification tree then allows for significant signal amplification, enabling single-molecule detection [38] [39] [40].

Q: What are the key differences between running RNAscope on an automated platform versus manually?

- A: The core chemistry is the same. For automated platforms like the Leica BOND RX or Roche DISCOVERY ULTRA, it is critical not to alter the pre-loaded staining protocol. Key steps include checking instrument maintenance (e.g., decontaminating lines every 3 months), using the correct bulk buffers as specified, and ensuring the "Slide Cleaning" option is unchecked on Ventana/Roche systems [41] [42].

Q: How should I score and interpret my RNAscope results?

- A: RNAscope uses a semi-quantitative scoring system based on the number of dots per cell, not signal intensity. Each dot represents an individual RNA molecule. The standard scoring guideline is: Score 0: <1 dot/10 cells; Score 1: 1-3 dots/cell; Score 2: 4-9 dots/cell; Score 3: 10-15 dots/cell; Score 4: >15 dots/cell with >10% in clusters. Always compare your target gene staining to the positive and negative controls [41] [42].

Q: My tissue is over-fixed. How can I adjust the RNAscope protocol?

- A: For over-fixed tissues, you can extend the pretreatment conditions. On the Leica BOND RX system, for example, this involves increasing the Epitope Retrieval 2 (ER2) time in 5-minute increments and the Protease time in 10-minute increments while keeping temperatures constant (e.g., 20 min ER2 at 95°C and 25 min Protease at 40°C) [41] [42].

Q: What is the fundamental difference between SABER and RNAscope?

- A: While both are signal amplification methods, SABER (Signal Amplification by Exchange Reaction) relies on a DNA primer exchange reaction to create long concatemers that can be labeled with multiple imaging probes. This method is particularly powerful for highly multiplexed imaging applications. RNAscope, in contrast, uses a defined hierarchy of branched DNA amplifiers that hybridize to the ZZ probes [37].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

This guide addresses frequent issues encountered when working with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and carbon nanomaterials for signal amplification in biosensing.

Gold Nanoparticle (AuNP) Conjugation and Stability

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticle Aggregation [44] [45] | High nanoparticle concentration; incorrect pH or ionic strength during conjugation. | Follow recommended concentration guidelines. For conjugation with antibodies, use a pH around 7-8. Sonicate to re-disperse particles before use [44]. |

| Low Binding Efficiency [44] | Suboptimal antibody-to-nanoparticle ratio; improper pH of conjugation buffer. | Optimize the antibody-to-nanoparticle ratio to maximize binding and prevent unbound particles. Use dedicated conjugation buffers with stable pH [44]. |

| Non-specific Binding [44] | Lack of proper surface blocking. | Use blocking agents like BSA or PEG after conjugation to prevent nanoparticles from attaching to unintended molecules [44]. |

| Settling of Nanoparticles [46] [45] | Normal for larger nanoparticles over time; can be reversible settling or irreversible aggregation. | Gentle shaking for 10-30 seconds can re-disperse particles. If aggregation is irreversible, the particles may need to be replaced [46] [45]. |

| Inconsistent Results [47] | Endotoxin contamination or use of commercial materials without in-house verification. | Work under sterile conditions using endotoxin-free reagents. Characterize key nanoparticle parameters (size, charge) in-house under biologically relevant conditions, rather than relying solely on manufacturer specifications [47]. |

Carbon Nanomaterial Performance

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Variability in Sensor Performance [48] | Difficulties in controlling the chirality, diameter, and aggregation of carbon nanotubes; impurities in graphene. | Source materials from reputable suppliers and employ rigorous characterization (e.g., TEM, Raman spectroscopy) for each new batch of material [48]. |

| Poor Biocompatibility or Reproducibility [48] | Incomplete understanding of the interactions between aptamers and carbon nanomaterials. | Further investigate and optimize the immobilization methods (covalent vs. non-covalent) for the specific biorecognition element and carbon nanomaterial used [48]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Nanomaterial Questions

Q: My nanoparticles have settled at the bottom of the vial. Have they gone bad? A: Not necessarily. It is normal for larger gold and silver nanoparticles to settle over time. This is often reversible. Gently shake the container for 10-30 seconds to re-disperse the nanoparticles. If the particles do not re-disperse or the color has changed dramatically, they may have aggregated irreversibly [46] [45].

Q: Why is proper characterization of nanomaterials so critical? A: Unlike small molecules, nanomaterials require complex characterization because their properties (size, charge) can vary with the dispersing medium. Without proper and adequate physicochemical characterization, biological results can be misleading. For example, a nanoparticle's size in a simple buffer may differ significantly from its size in human plasma, which directly impacts its biological behavior [47].

Q: How can I prevent endotoxin contamination in my nano-formulations? A: Endotoxin contamination can be avoided by working under sterile conditions in a biological safety cabinet, using depyrogenated glassware, and ensuring all reagents and water are endotoxin-free. Do not assume commercial reagents are sterile; screen them if possible [47].

Gold Nanoparticle-Specific Questions

Q: What does "OD-mL" mean, and why is it a better measure than gold weight? A: OD-mL (Optical Density per milliliter) measures the concentration (number) of gold nanoparticles in a solution. It is more accurate than selling by gold weight because the production process can be inefficient, and the amount of gold used does not always correlate with the number of nanoparticles produced. OD-mL ensures you know the exact number of particles you are purchasing [46].

Q: Are "bare" or "uncapped" gold nanoparticles available? A: No. All nanoparticles require a capping agent or stabilizer on their surface to remain stable. Without a capping agent like citrate or tannic acid, nanoparticles would aggregate irreversibly within seconds due to van der Waals forces. These standard capping agents can often be displaced by other molecules for functionalization [45].

Carbon Nanomaterial-Specific Questions

Q: What are the main advantages of using carbon nanomaterials in electrochemical aptasensors? A: Carbon nanomaterials, such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO), offer a large surface area, excellent mechanical and electrical properties, and low cost. They improve electrode conductivity, are easy to functionalize with nucleic acids, and increase the loading capacity for biorecognition elements, leading to significant signal amplification [48].

Quantitative Data: Performance of Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensors

The table below summarizes the detection performance of selected biosensors that utilize gold and carbon nanomaterials for signal amplification, demonstrating their effectiveness for low-abundance targets.

| Target Analyte | Nanomaterial Used | Sensor Type | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella | rGO-TiOâ‚‚ Nanocomposite | Electrochemical Aptasensor | 10 cfu·mLâ»Â¹ | [48] |

| Oxytetracycline (OTC) | MWCNTs-AuNPs/rGO-AuNPs Nanocomposite | Electrochemical Aptasensor | 30.0 pM | [48] |

| E. coli O157:H7 | AuNPs/rGO–PVA Composite | Electrochemical Aptasensor | 9.34 CFU mLâ»Â¹ | [48] |

| Protein G on paper arrays | Gold Nanoparticles (with signal enhancement) | Optical Biosensor | Visual detection of <10 nanoparticles | [49] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Signal Enhancement for Gold Nanoprobe-Based Detection

This protocol describes a rapid, enzyme-free method to enhance the signal of gold nanoprobes, enabling visual detection of even low nanoprobe densities [49].

- Detection: First, complete your standard assay procedure (e.g., a microarray or lateral flow assay) using antibody- or aptamer-conjugated gold nanoparticles as the detection nanoprobes.

- Preparation of Enhancement Solution: Prepare a fresh enhancement solution containing:

- 5 mM HAuCl₄·3H₂O

- 50 mM MES buffer (pH 5.0)

- 1.027 M Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚

- Alternative for faster enhancement: 10 mM MES buffer (pH 6.0) with 1.027 M Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ can reduce the enhancement time from 300 to 120 seconds [49].

- Enhancement Reaction: Apply the enhancement solution to the assay substrate (e.g., the paper array or strip). Incubate at room temperature.