Cas9 Protein vs. mRNA Delivery: A Strategic Guide to Optimizing Editing Efficiency for Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical choice between delivering the CRISPR-Cas9 system as a pre-complexed protein (RNP) or as mRNA.

Cas9 Protein vs. mRNA Delivery: A Strategic Guide to Optimizing Editing Efficiency for Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical choice between delivering the CRISPR-Cas9 system as a pre-complexed protein (RNP) or as mRNA. We explore the foundational principles of each cargo type, detailing advanced delivery methodologies like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and virus-like particles (VLPs). The content delves into troubleshooting key challenges such as off-target effects, immunogenicity, and editing kinetics, while presenting the latest optimization strategies from AI-guided LNP design to novel nanostructures. Finally, we offer a comparative validation of therapeutic applications, synthesizing data from recent clinical trials and preclinical studies to guide the selection and refinement of CRISPR-based therapies for enhanced efficacy and safety.

Cas9 Cargo Fundamentals: Understanding Protein RNP and mRNA Delivery Mechanisms

For researchers optimizing the efficiency of Cas9 protein versus mRNA delivery, the choice of cargo form is a fundamental experimental design decision. The CRISPR-Cas9 system can be delivered as plasmid DNA (pDNA), messenger RNA (mRNA), or a pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. Each form has distinct implications for editing kinetics, specificity, biosafety, and delivery requirements [1]. This guide provides a technical breakdown of these cargo types, supported by experimental data and protocols, to help you troubleshoot common issues and select the optimal strategy for your application.

Cargo Comparison and Selection Guide

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three primary CRISPR cargo forms to inform your experimental design.

| Cargo Form | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA (pDNA) | Cost-effective for production; stable and easy to handle [2]. | Requires nuclear entry; prolonged Cas9 expression increases off-target effects and immune responses [2] [1]. | Large-scale, low-cost screening where high specificity is not the primary concern. |

| mRNA | Faster editing onset than pDNA; transient expression reduces off-target risks [2]. | Requires in-cell translation; can trigger innate immune responses [2]. | Applications requiring faster results than pDNA but where RNP delivery is inefficient. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Fastest editing kinetics (immediately active); highest specificity; minimal off-target effects; low immunogenicity; transient activity [3] [2] [1]. | More complex production; limited shelf-life; challenging delivery in some systems [4]. | Therapeutic applications [3], sensitive cells (e.g., stem cells [4]), and experiments demanding the highest fidelity. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Why is RNP often considered the gold standard for therapeutic development?

RNP complexes are favored for therapeutics due to their superior safety and specificity profile. Because the complex is active immediately upon delivery and degrades rapidly inside the cell, the window for off-target editing is significantly reduced compared to pDNA and mRNA, which require transcription and/or translation and lead to prolonged Cas9 expression [3] [2] [1]. Furthermore, RNP delivery avoids the risk of unintended integration of foreign DNA into the host genome, and it elicits a lower immune response than nucleic acid-based delivery methods [3].

FAQ 2: My gene editing efficiency is low with RNPs. What could be the cause?

Low efficiency with RNPs is often a delivery issue. Consider the following troubleshooting steps:

- Verify Delivery Method: RNPs are large, charged complexes. Ensure your delivery method (e.g., electroporation, lipofection with specialized reagents) is optimized for large macromolecules [4]. Standard plasmid transfection reagents may not be effective.

- Check RNP Quality and Stability: Use fresh, properly assembled RNPs. The complex can be unstable, and improper assembly or storage can lead to dissociation and loss of activity.

- Optimize N/P Ratio: When using polymeric or lipid-based nanoparticles, the charge ratio between cationic polymers (N) and anionic phosphates of the nucleic acid/protein (P) is critical. An optimal N/P ratio ensures efficient complex formation, cellular uptake, and endosomal escape [3] [2].

FAQ 3: Can I improve HDR efficiency when using RNP complexes?

Yes. Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is generally less efficient than error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ). To enhance HDR with RNPs:

- Use the TILD-CRISPR Method: Co-deliver your RNP with a linearized double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) donor template featuring long homology arms (e.g., 1000 bp). One study demonstrated that this approach achieved 50% integration efficiency in CHO-K1 cells, significantly outperforming standard methods [3].

- Synergize with Small Molecules: Adding small molecules that modulate DNA repair pathways can boost specific editing outcomes. For instance, Repsox, an inhibitor of the TGF-β pathway, has been shown to enhance NHEJ efficiency [5].

Experimental Protocols for Enhancing Editing Efficiency

Protocol 1: Enhancing NHEJ Efficiency with Small Molecules

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully increased CRISPR/Cas9-mediated NHEJ gene editing efficiency in porcine PK15 cells [5].

- Cell Preparation: Culture PK15 cells in DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS. Trypsinize and count the cells.

- Electroporation: For RNP delivery, pre-incubate 10 µg of Cas9 protein with 100 pmol of sgRNA at room temperature for 10 minutes to form the RNP complex. Electroporate 1 x 10^6 cells with the RNP complex using a square-wave electroporator (e.g., CUY21EDIT II) with parameters set to 150 V, 10 ms, and 3 pulses [5].

- Small Molecule Treatment: Immediately after electroporation, add the optimal concentration of a small molecule to the culture medium. Based on the study:

- Repsox: Showed the greatest effect, increasing NHEJ efficiency by 3.16-fold.

- Zidovudine, GSK-J4, IOX1: Also showed significant improvements (1.17-fold, 1.16-fold, and 1.12-fold, respectively) [5].

- Analysis: Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-electroporation. Analyze editing efficiency via T7E1 assay, TIDE analysis, or next-generation sequencing.

Protocol 2: In Vivo Transfection via Electroporation

This protocol outlines a method for in vivo gene editing in mouse seminiferous tubules, which can be adapted for other tissues [6].

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize the mouse (e.g., 3-5 weeks old) via intraperitoneal injection of lidocaine. Ensure no response to external stimuli and stable vital signs.

- Surgical Exposure: Make a 1 cm incision to access the abdominal cavity. Gently extract the testes and place them on sterile, saline-moistened filter paper.

- Microinjection: Clamp the efferent ductules. Using a glass needle, inject your cargo (e.g., EGFP-N1 plasmid at 1 µg/µL) directly into the seminiferous tubules [6].

- Electroporation: Apply electrode forceps on both sides of the testis. Deliver electrical stimulation using a square-wave electroporation device (e.g., ECM 830) with parameters of 8 pulses at 50 ms per pulse [6].

- Post-operative Care: Return the testes to the abdominal cavity and suture the incision. Monitor the animal until it recovers from anesthesia.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and their functions as cited in the research.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Cationic Hyper-Branched Cyclodextrin-based Polymer (Ppoly) | A nanocarrier for encapsulating and delivering RNP complexes, demonstrating high efficiency and low cytotoxicity. | [3] |

| Repsox | A small molecule TGF-β signaling pathway inhibitor used to enhance the efficiency of NHEJ-mediated gene editing. | [5] |

| PAMAM Dendrimer (G6-OH) | A hyper-branched polymeric nanoparticle used for covalent conjugation and delivery of Cas9 RNP. | [4] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Synthetic nanoparticles used for the in vivo encapsulation and delivery of CRISPR cargo (pDNA, mRNA, or RNP). | [2] [7] |

| CRISPRMAX | A commercial lipid-based transfection reagent used as a benchmark for comparing the performance of novel delivery systems. | [3] |

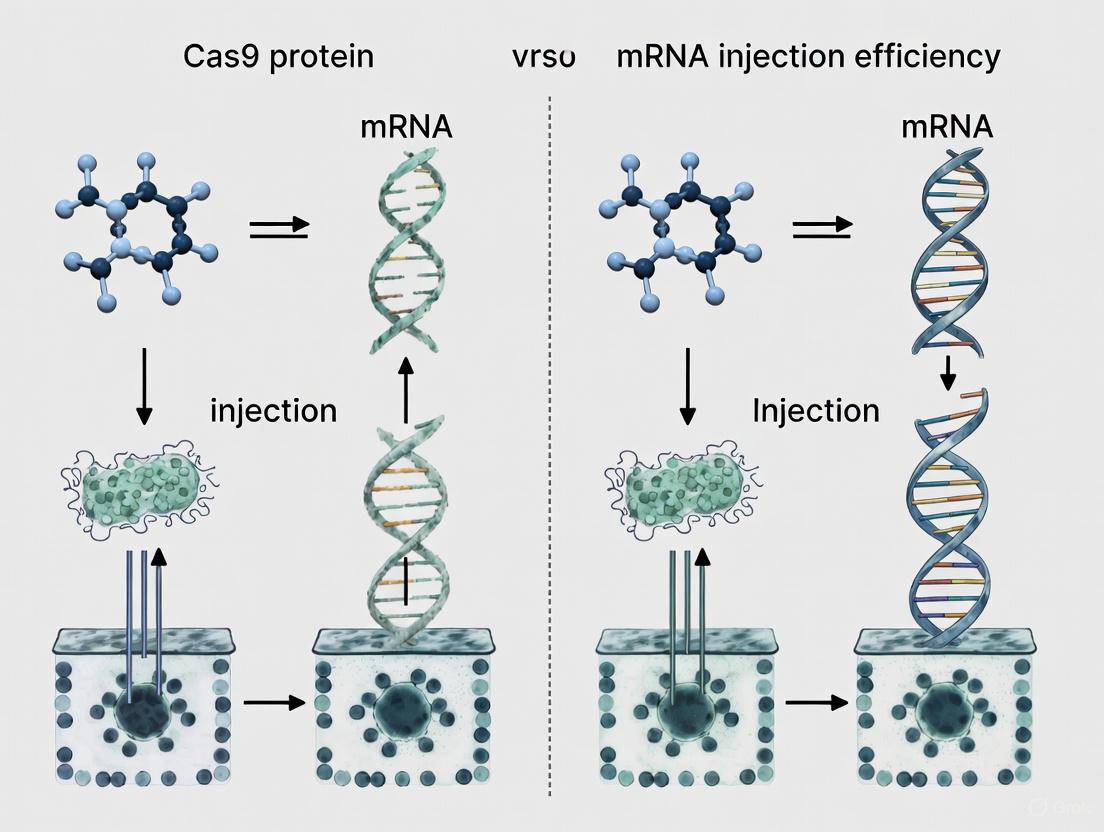

Cargo Selection and Cellular Processing Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in how each cargo form is processed within the cell to achieve genome editing, which directly impacts editing kinetics and specificity.

Experimental Workflow for Cargo Delivery and Analysis

This workflow provides a generalized overview of the key steps involved in a CRISPR-Cas9 experiment, from cargo preparation to analysis.

The decision to use plasmid DNA, mRNA, or RNP complexes hinges on the specific requirements of your experiment regarding efficiency, specificity, timing, and safety. For the highest editing precision and lowest off-target effects, particularly in therapeutic contexts, the evidence strongly supports the use of RNP complexes. By leveraging the troubleshooting guides, protocols, and reagent information provided, researchers can systematically optimize their CRISPR-Cas9 workflows to achieve robust and reliable genomic editing.

For researchers and drug development professionals focused on optimizing CRISPR-Cas9 delivery, the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex method offers distinct advantages over DNA or mRNA-based approaches. RNP delivery involves the direct introduction of preassembled Cas9 protein and single-guide RNA (sgRNA) complexes into cells, enabling immediate genome editing activity. This method addresses critical challenges in therapeutic development, including off-target effects, immunogenicity, and timing control. This technical support center provides comprehensive guidance on leveraging RNP delivery's inherent strengths for your research, complete with troubleshooting advice and experimental protocols.

Core Advantages: The RNP Value Proposition

Rapid Editing Activity

Direct delivery of preassembled Cas9 RNP complexes enables immediate genome editing activity upon reaching the cell nucleus, eliminating the transcription and translation steps required for DNA or mRNA approaches [1] [8]. This rapid activity is particularly valuable for working with cells having low transcription and translation activity, including embryonic stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, and tissue stem cells [8].

Enhanced Specificity & Reduced Off-Target Effects

The transient nature of RNP activity—typically remaining in cells for only 6-24 hours—significantly reduces off-target effects by limiting the time window during which unintended genomic edits can occur [1] [8] [9]. Studies demonstrate that RNP delivery decreases off-target mutations relative to plasmid transfection methods [9]. The minimal duration of RNP activity also lowers risks of insertional mutagenesis and immune responses [8].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of RNP Delivery Advantages

| Performance Metric | RNP Delivery | DNA Plasmid Delivery | mRNA Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Activity | Immediate (hours) [8] | Delayed (24-72 hours) [8] | Moderate (12-48 hours) [8] |

| Duration of Activity | Short (transient, 6-24 hours) [8] | Prolonged (days) [8] | Moderate (hours to days) [8] |

| Off-Target Editing | Significantly reduced [8] [9] | Higher risk [1] [8] | Moderate risk [8] |

| Immune Response | Lower immunogenicity [8] | Higher immunogenicity [8] | Moderate immunogenicity [10] |

| Editing Efficiency in Hard-to-Transfect Cells | High [8] [9] | Variable [1] | Variable [1] |

Experimental Workflow for RNP Delivery

RNP Delivery Methods: Technical Comparison

Physical Delivery Approaches

Physical methods directly introduce RNPs into cells by temporarily disrupting cell membranes:

- Electroporation: Application of electrical pulses creates temporary pores in cell membranes. This method shows high efficiency in hematopoietic stem cells and immune cells [11] [8].

- Microinjection: Direct mechanical injection using glass micropipettes allows quantitative control of delivered RNP complexes, though it requires specialized equipment and expertise [8].

Synthetic Carrier Systems

Chemical and biological carriers facilitate RNP delivery through cellular uptake mechanisms:

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): Synthetic nanoparticles that encapsulate RNPs and facilitate cellular delivery through endocytosis. Recent advancements enable tissue-specific targeting through surface modifications [12] [1].

- Cell-Derived Nanovesicles (Gesicles): Naturally derived membrane vesicles that can package RNP complexes and achieve genome editing in broad cell types with reduced off-target effects [11].

Table 2: RNP Delivery Method Comparison for Experimental Planning

| Delivery Method | Mechanism | Best Applications | Efficiency | Technical Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electroporation [11] [8] | Electrical field-induced membrane pores | Suspension cells (HSCs, lymphocytes) [11] | High | Moderate |

| Microinjection [8] | Direct mechanical injection | Embryos, oocytes, single cells [8] | Very High | High |

| Lipid Nanoparticles [12] [1] | Endocytosis of encapsulated RNPs | In vivo delivery, therapeutic applications [12] | Moderate-High | Moderate |

| Gesicles/Nanovesicles [11] | Membrane fusion-mediated delivery | Broad cell types, reduced off-target editing [11] | Moderate | Low-Moderate |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the recommended molar ratio for forming Cas9 RNP complexes? A: Research indicates optimal gene editing occurs at Cas9:sgRNA molar ratios of 1:3 to 1:5. Studies using HeLa reporter cells demonstrated higher editing efficiency at these ratios compared to 1:1 ratio [12]. The increased sgRNA concentration promotes complete complex formation and enhances target recognition.

Q: How does RNP delivery reduce immune responses compared to other methods? A: RNP delivery minimizes immune activation because the Cas9 protein and modified sgRNAs are less immunogenic than viral vectors or bacterial DNA sequences present in plasmids [8]. Additionally, the transient presence of RNPs (versus sustained expression from DNA vectors) further reduces immune recognition [8].

Q: What storage conditions maintain RNP complex stability? A: RNP-loaded nanoparticles maintain size uniformity (PDI < 0.2) and constant gene editing activity when stored at 4°C for up to 60 days [12]. For long-term storage, consider freezing individual RNP components at -80°C and forming complexes immediately before use.

Q: Can RNP delivery be used for in vivo therapeutic applications? A: Yes, recent advances in LNP technology enable systemic RNP delivery to multiple tissues. Intravenous injection of RNP-loaded LNPs has achieved tissue-specific, multiplexed editing in mouse lungs, liver, and brain [12]. This approach has been used to restore dystrophin expression in DMD mouse models and significantly decrease serum PCSK9 levels [12].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low editing efficiency | Suboptimal RNP complex formation [9] | Verify guide RNA concentration and maintain recommended Cas9:sgRNA ratios (1:3-1:5) [12] [9] |

| Inadequate nuclear localization | Include nuclear localization signals on Cas9 protein [12] | |

| High cell toxicity | Excessive RNP concentration [9] | Titrate RNP dose; use modified sgRNAs to reduce required concentration [9] |

| Delivery method toxicity | Optimize electroporation parameters or try alternative delivery methods [8] | |

| Inconsistent editing between replicates | Variable RNP delivery | Standardize delivery protocol; use internal controls; consider gesicles for more consistent delivery [11] |

| Poor delivery in hard-to-transfect cells | Inefficient cellular uptake | Utilize selective organ targeting (SORT) nanoparticles or cell-penetrating peptide conjugates [1] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for RNP Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Proteins | Electroporation-grade Cas9 [11] | Optimized for stem cells and primary cells; higher purity reduces toxicity |

| Guide RNAs | Chemically synthesized sgRNAs with 2'-O-methyl modifications [9] | Enhanced stability against nucleases; improved editing efficiency; reduced immune stimulation |

| Delivery Materials | Cationic lipids (DOTAP) [12], Gesicles [11] | DOTAP enables RNP encapsulation in LNPs; Gesicles provide natural delivery mechanism |

| Validation Tools | T7 Endonuclease I assay [12], NGS sequencing [9] | T7EI for quick efficiency estimate; NGS for comprehensive sequence analysis |

Advanced RNP Delivery Workflow

The inherent strengths of Cas9 RNP delivery—particularly its high specificity and rapid activity—make it an indispensable approach for researchers optimizing CRISPR-based therapies. By implementing the protocols, troubleshooting guides, and experimental strategies outlined in this technical support center, research teams can effectively leverage RNP delivery to advance their therapeutic development pipelines while minimizing off-target effects and immune responses. As delivery technologies continue evolving, particularly in nanoparticle design and modification strategies, RNP delivery is poised to remain at the forefront of precision genome editing for both research and clinical applications.

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guide

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary safety advantages of using Cas9 mRNA over DNA-based delivery systems?

The primary safety advantages stem from the transient nature of mRNA and its cytoplasmic activity. Unlike plasmid DNA, mRNA does not need to enter the nucleus to be active and lacks the genetic elements required for integration into the host genome. This fundamentally eliminates the risk of unintended insertional mutagenesis. Furthermore, its short half-life limits the window of Cas9 protein expression, thereby reducing the probability of off-target editing events, which are more common with persistent Cas9 expression from DNA vectors [13].

2. Why is Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) delivery often paired with Cas9 mRNA for in vivo applications?

LNPs are the leading non-viral delivery vehicle for Cas9 mRNA due to their proven clinical success, ease of assembly, and ability to protect the fragile mRNA cargo from degradation by nucleases in the blood [13] [1]. They form stable complexes with nucleic acids, exhibit low immunogenicity compared to viral vectors, and can be engineered for specific tissue targeting (e.g., to the liver or lungs) [13] [14]. Their use was validated in mRNA COVID-19 vaccines and is now being applied to CRISPR therapies [1] [7].

3. What are the common causes of low editing efficiency when using Cas9 mRNA and how can they be addressed?

Low editing efficiency can arise from several factors:

- mRNA Instability: Use engineered mRNA with optimized codons and modified nucleotides (e.g., pseudouridine) to enhance stability and translation efficiency while reducing immunogenicity [13].

- Inefficient Delivery: Ensure your LNP formulation or transfection reagent is optimized for your target cell type. Consider using selective organ targeting (SORT) LNPs for specific tissues [1].

- Suboptimal sgRNA Design: Utilize bioinformatics tools to design highly specific sgRNAs with high on-target activity. It is often necessary to test multiple sgRNAs for each target to identify the most effective one [15].

4. Can Cas9 mRNA therapies be re-dosed, and what are the considerations?

Yes, a significant advantage of LNP-delivered mRNA over viral vector delivery is the potential for re-dosing. Viral vectors often elicit strong immune responses against the vector itself, making repeated administration ineffective or dangerous. In contrast, LNPs do not trigger the same level of immune memory against the delivery vehicle. There are already clinical precedents: an infant with CPS1 deficiency safely received three LNP doses, and participants in an Intellia Therapeutics trial for hATTR received a second, higher dose, with each subsequent dose increasing therapeutic efficacy [7].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Cell Viability | Cytotoxicity from transfection reagents or immune response to exogenous mRNA. | Titrate LNP/nanoparticle doses to find optimal balance; use modified nucleotides in mRNA synthesis to dampen immune activation [13] [1]. |

| High Immunogenicity | Recognition of in vitro transcribed mRNA by cellular pattern recognition receptors (e.g., TLRs, RIG-I). | Incorporate purified, base-modified mRNAs (e.g., N1-methylpseudouridine) to avoid dsRNA contaminants and reduce TLR activation [13]. |

| Inconsistent Editing | Batch-to-batch variability in mRNA quality or LNP formulation; variable transfection efficiency. | Use high-quality, HPLC-purified mRNA; standardize LNP formulation protocols; include a reporter to monitor transfection efficiency [2] [15]. |

| Poor In Vivo Performance | Rapid degradation of mRNA in serum; accumulation in non-target organs. | Optimize LNP lipid composition for enhanced stability and organ selectivity (e.g., SORT molecules); utilize organ-specific promoters [1] [14]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Assessing Cas9 mRNA Delivery and Editing Efficiency

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for evaluating the performance of a Cas9 mRNA-based editing system in vitro.

1. mRNA Preparation:

- Template Design: Use a plasmid DNA template containing Cas9 codon-optimized for your target organism, flanked by 5' and 3' UTRs known to enhance stability (e.g., β-globin UTRs). Include a poly(A) tail.

- In Vitro Transcription (IVT): Synthesize the mRNA using an IVT kit. To reduce immunogenicity, include modified nucleotides such as pseudouridine in the reaction [13].

- Purification: Purify the transcribed mRNA using HPLC or affinity chromatography to remove aberrant double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) contaminants, which are potent inducers of interferon responses [13].

2. Delivery:

- Complexation: Formulate the purified Cas9 mRNA and synthetic sgRNA at an optimal mass ratio with your chosen delivery vehicle (e.g., LNPs, commercial transfection reagents).

- Transfection: Deliver the complexes to your target cells. For hard-to-transfect cells like primary T-cells or stem cells, electroporation may yield higher efficiency than lipid-based methods [2] [16].

3. Validation:

- Efficiency Analysis: 72 hours post-transfection, harvest genomic DNA. Assess editing efficiency at the target locus using T7 Endonuclease I assay, TIDE analysis, or next-generation sequencing.

- Off-Target Assessment: Use GUIDE-seq or in silico prediction tools followed by deep sequencing of top potential off-target sites to profile specificity [17] [2].

- Functional Confirmation: Confirm successful gene knockout via western blot (for protein loss) or a functional assay relevant to the target gene.

Protocol 2: In Vivo Gene Editing via LNP-mRNA

This protocol summarizes the key steps for achieving gene editing in living animal models, as demonstrated in recent high-impact studies [14] [7].

1. LNP Formulation Optimization:

- Component Selection: Prepare an LNP mixture containing ionizable cationic lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, and PEG-lipids. The exact composition can be tuned for organ tropism (e.g., adding SORT molecules for lung targeting).

- Encapsulation: Use microfluidics to mix the lipid solution with an aqueous buffer containing the Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA, forming stable, monodisperse LNPs encapsulating the cargo.

- Quality Control: Characterize LNPs for size (e.g., 80-100 nm via DLS), polydispersity index, and mRNA encapsulation efficiency [1] [14].

2. Administration and Analysis:

- Dosing: Administer the LNP-mRNA formulation intravenously via tail-vein injection in mice. Dose is typically measured as mg of mRNA per kg of animal weight.

- Tissue Harvesting: After an appropriate period (e.g., 7-14 days), harvest the target organs (e.g., liver, lungs).

- Editing Quantification: Extract genomic DNA from the tissue and quantify editing efficiency at the target locus using next-generation sequencing. Editing percentages are calculated as the proportion of indel-containing reads.

The table below summarizes quantitative data from a key study using this approach:

Table: In Vivo Editing Efficiency of LNP-Delivered CRISPR Systems [14]

| Cas9 Editor Formulation | Target Organ | Target Gene | Average Editing Efficiency | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iGeoCas9 RNP-LNPs (Biodegradable) | Liver | Reporter (Ai9 mice) | 37% | Efficient editing in a majority of liver tissue. |

| iGeoCas9 RNP-LNPs (Biodegradable) | Liver | PCSK9 | 31% | Therapeutically relevant level of gene disruption. |

| iGeoCas9 RNP-LNPs (Cationic) | Lung | Reporter (Ai9 mice) | 16% | Significant editing across entire lung tissue. |

| iGeoCas9 RNP-LNPs (Cationic) | Lung | Disease-causing SFTPC | 19% | Major improvement over previous viral/nonviral methods. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Cas9 mRNA Delivery Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Codon-Optimized Cas9 mRNA | Template for in vivo translation of the Cas9 nuclease. | Select mRNA with base modifications (e.g., pseudouridine) for enhanced stability and reduced immunogenicity [13]. |

| Synthetic sgRNA | Guides the Cas9 protein to the specific genomic target sequence. | High-purity, chemically modified sgRNA can improve stability and reduce off-target effects [13] [15]. |

| Ionizable Lipids | Key component of LNPs; enables self-assembly, encapsulation, and endosomal escape. | Critical for in vivo efficacy. New biodegradable ionizable lipids are improving safety profiles [1] [14]. |

| Selective Organ Targeting (SORT) Molecules | Lipids engineered to direct LNPs to specific tissues beyond the liver (e.g., lungs, spleen). | Essential for expanding therapeutic applications to other organs [1]. |

| Electroporation Systems | Physical delivery method using electrical pulses to create pores in cell membranes. | Preferred method for hard-to-transfect cells like primary immune cells and stem cells (e.g., in CASGEVY) [2] [16]. |

| CD73-IN-13 | CD73-IN-13, MF:C13H11F3N4O2, MW:312.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sonnerphenolic B | Sonnerphenolic B, MF:C18H18O3, MW:282.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key differences between delivering Cas9 as mRNA versus as a pre-assembled protein (RNP)?

The choice of cargo significantly impacts editing efficiency, specificity, and immunogenicity [2] [1].

- Cas9 mRNA: Once delivered into the cell, mRNA must be translated by ribosomes to produce the Cas9 protein, which then complexes with the gRNA to form the active RNP [2]. This process leads to a slower onset of editing activity and more prolonged Cas9 expression, which can increase the risk of off-target effects [1]. Furthermore, exogenous mRNA can be highly immunogenic, potentially triggering strong innate immune responses [16].

- Cas9 RNP (Ribonucleoprotein): This method involves delivering the pre-assembled complex of the Cas9 protein and guide RNA directly into the cell [2] [1]. RNPs are immediately active and have a shorter intracellular lifetime, leading to faster editing kinetics and a significant reduction in off-target effects due to transient activity [1] [17]. RNP delivery generally results in lower cytotoxicity and reduced immunogenicity compared to mRNA or DNA delivery methods [2].

Q2: Why is nuclear delivery a major barrier for CRISPR-Cas9 editing, especially in non-dividing cells?

The CRISPR-Cas9 complex must ultimately localize to the nucleus to access the genomic DNA. The nuclear envelope, which is intact in non-dividing cells, presents a formidable physical barrier [16]. The Cas9 protein and its RNP complex have a large molecular weight and lack the intrinsic ability to efficiently traverse the nuclear pore complex [16]. While many strategies fuse the Cas9 protein with Nuclear Localization Signals (NLSs) to facilitate nuclear import, this is not always fully efficient, and a significant portion of the editing machinery may fail to reach its target [18] [19]. Overcoming this barrier is a primary focus of delivery system optimization.

Q3: How can I mitigate immunogenic responses to CRISPR components?

Immunogenicity can be directed against both the delivery vehicle and the CRISPR cargo itself.

- Pre-existing Immunity: Pre-existing immunity to Cas9 proteins from common bacterial exposures has been documented in human serum, which could potentially neutralize the therapy [2].

- Delivery Vehicle Choice: Viral vectors, particularly adenoviruses, can provoke strong immune reactions [1] [16]. Non-viral methods, such as Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), are generally associated with milder immune responses [2] [1].

- Cargo Selection: Using RNP complexes can reduce immunogenicity compared to prolonged expression from DNA or mRNA [1]. Researchers are also exploring the use of engineered, humanized, or high-fidelity Cas9 variants to minimize immune recognition [2] [16].

Q4: What strategies can improve the stability and delivery efficiency of Cas9 RNPs?

Stability is crucial for ensuring that a sufficient amount of intact RNP reaches the nucleus.

- Advanced Nanocarriers: Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) and other nanocages (e.g., apoferritin) are highly effective at protecting RNPs from degradation during delivery [2] [19].

- Protein Engineering: Addressing Cas9 protein aggregation is critical, as aggregates can compromise encapsulation efficiency and cellular uptake [2]. Optimizing buffer conditions and protein formulations can help maintain Cas9 in a monodisperse state.

- Enhanced Nuclear Import: As mentioned, NLS tags are standard. Novel approaches are also being developed, such as using small molecule "nuclear triggers" (e.g., doxorubicin) to actively facilitate the nuclear translocation of RNP complexes, even in the absence of a traditional NLS [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Gene Editing Efficiency

A lack of efficient editing can stem from failures at multiple points in the delivery and action pathway.

| Possible Cause | Verification Method | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient cellular uptake | Measure transfection/transduction efficiency using a fluorescent reporter. | Optimize delivery vehicle parameters (e.g., N:P ratio for LNPs) [2]; try alternative delivery methods (e.g., electroporation for hard-to-transfect cells) [16]. |

| Poor endosomal escape | Use confocal microscopy with endosomal/lysosomal markers. | Switch to or formulate delivery vehicles known for enhanced endosomal escape, such as ionizable LNPs or polymers [1]. |

| Inefficient nuclear import | Use fluorescently labeled Cas9 to visualize localization. | Ensure Cas9 is fused with a strong Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) [18]; consider novel nuclear delivery strategies [19]. |

| Low cargo activity/ stability | Perform gel electrophoresis or other assays to check cargo integrity pre-delivery. | Use fresh, high-quality RNPs; optimize RNP formation conditions; use codon-optimized mRNA if using mRNA cargo [17]. |

| Low expression in target cell type | Check Cas9 and gRNA expression levels via qPCR/Western blot. | Use a cell-type-specific promoter to drive expression if using nucleic acid cargo [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Nuclear Localization of Cas9 RNP

- Labeling: Fluorescently label the Cas9 protein (e.g., with a green dye like FITC) and the gRNA (e.g., with a red dye like Cy5).

- Transfection: Deliver the labeled RNP complex into your target cells using your standard method.

- Staining: At a predetermined timepoint (e.g., 6-24 hours post-transfection), fix the cells and stain the nucleus with a blue fluorescent DNA dye (e.g., DAPI).

- Imaging: Analyze the cells using confocal microscopy.

- Analysis: Colocalization of the green (Cas9) and red (gRNA) signals with the blue (nucleus) signal indicates successful nuclear delivery. The absence of signal in the nucleus suggests a failure at the uptake or nuclear import stage.

This workflow helps diagnose whether the bottleneck is nuclear delivery or an earlier step:

Problem 2: High Off-Target Effects or Cell Toxicity

Unwanted editing and cell death are often linked to the persistence and quantity of active Cas9.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High off-target editing | Prolonged Cas9 activity from DNA/mRNA expression; low-specificity gRNA. | Switch to RNP delivery for transient activity [1]; use high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) [2] [17]; improve gRNA design using prediction tools [17]. |

| High cell toxicity/death | Excessive cargo load; immunogenic response; delivery method toxicity. | Titrate down the concentration of CRISPR components [17]; use RNP instead of plasmid DNA to reduce cytotoxicity [2]; optimize delivery vehicle (e.g., use LNPs instead of some viral vectors) [1]. |

| Inflammatory response | Recognition of CRISPR cargo (e.g., bacterial Cas9) or vehicle by the immune system. | Use purified RNP complexes; select non-viral delivery systems like LNPs [2] [7]; consider immunosuppressive agents if applicable to the model. |

Experimental Protocol: Titering RNP Complexes to Minimize Toxicity

- Preparation: Prepare a dilution series of your Cas9 RNP complex (e.g., 0.1 µM, 0.5 µM, 1 µM, 2 µM).

- Delivery: Transfect cells with each concentration using a consistent protocol.

- Assessment: 24-48 hours post-transfection, assess cell viability using a standard assay (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo).

- Analysis: Calculate the percentage of viable cells for each concentration. Choose the lowest RNP concentration that yields acceptable editing efficiency (as measured by a separate assay) while maintaining high cell viability (>80%).

The table below summarizes quantitative data on editing efficiencies from various delivery methods and cargos as reported in the literature. This provides a benchmark for expected outcomes.

| Delivery Method / Cargo Type | Target / Model | Editing Efficiency | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electroporation of RNP (Ex vivo, CASGEVY) | BCL11A in HSPCs | Up to 90% indels | First FDA-approved ex vivo CRISPR therapy; demonstrates high efficiency in human hematopoietic stem cells. | [2] |

| LNP delivering mRNA | Various in vivo targets | Highly efficient (data varies) | Platform demonstrated during COVID-19; high translational potential for liver/lung targets. | [2] [7] |

| Apoferritin delivering RNP (no NLS) | Lcn2 in MDA-MB-231 cells (in vitro) | ~33% | Novel delivery system achieving significant editing without traditional NLS tags. | [19] |

| Apoferritin delivering RNP (no NLS) | copGFP in HeLa model (in vivo) | 16% | Proof-of-concept for in vivo therapeutic application of NLS-independent nuclear delivery. | [19] |

| Microinjection | Various embryos | ~40% (e.g., GFP in HepG2) | Direct physical method allowing precise control over delivered dose. | [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key reagents and their functions for troubleshooting core challenges in Cas9 delivery.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variant | Engineered nuclease with reduced off-target effects. | Essential for therapeutic applications where specificity is critical [2] [17]. |

| Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Synthetic nanoparticles for encapsulating and delivering nucleic acids or RNPs. | Excellent for in vivo delivery; naturally target liver; can be engineered for other tissues (SORT-LNPs) [2] [1]. |

| Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) Peptides | Short amino acid sequences fused to Cas9 to promote its import into the nucleus. | A critical component for efficient editing, especially in non-dividing cells [18] [16]. |

| Apoferritin Nanocages | A biological nanocage used as an alternative delivery vector for RNP complexes. | Can facilitate nuclear delivery via alternative pathways, potentially bypassing NLS requirements [19]. |

| Electroporation System | Physical method using electrical pulses to create transient pores in cell membranes for cargo delivery. | Highly effective for hard-to-transfect cells like primary cells and stem cells (ex vivo) [2] [16]. |

| Aristolan-1(10)-en-9-ol | Aristolan-1(10)-en-9-ol|Natural Sesquiterpene|RUO | Aristolan-1(10)-en-9-ol is a sesquiterpene with researched sedative effects via the GABAergic system. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Ara-F-NAD+ sodium | Ara-F-NAD+ sodium, MF:C21H25FN7NaO13P2, MW:687.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking Pathways for Different Cargoes

Fundamental Concepts: Cargo Types and Their Intracellular Journeys

FAQ: What are the primary forms of CRISPR-Cas9 cargo, and how do their intracellular trafficking pathways differ?

Answer: CRISPR-Cas9 systems can be delivered into cells in three primary forms, each with distinct pathways for cellular uptake, intracellular trafficking, and nuclear entry. The choice of cargo significantly impacts editing efficiency, kinetics, and off-target effects.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each cargo type:

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 Cargo Types and Their Properties

| Cargo Type | Composition | Primary Uptake Mechanism | Intracellular Trafficking & Processing | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA (Plasmid) | DNA plasmid encoding Cas9 and sgRNA [1] | Endocytosis (varies by delivery vector) [20] | Endosomal escape → Nuclear import → Transcription → Translation → Nuclear import of Cas9 protein [20] | Sustained, long-term expression [13] | Risk of host genome integration; prolonged expression increases off-target effects [13] |

| mRNA | mRNA encoding Cas9 + separate sgRNA [1] | Endocytosis (varies by delivery vector) [20] | Endosomal escape → Cytoplasmic translation → Nuclear import of Cas9 protein [13] | No genomic integration risk; shorter half-life reduces off-target effects [13] | mRNA instability and susceptibility to nucleases; can trigger immune responses [13] |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and sgRNA [1] | Endocytosis [21] or membrane fusion (specialized systems) [21] | Endosomal escape → Direct nuclear import (no translation needed) [21] | Immediate activity; highest precision and lowest off-target effects; transient existence [13] [21] [14] | Difficulties in large-scale production and in vivo delivery [13] |

The following diagram illustrates the general intracellular trafficking pathways for these cargo types, from cellular uptake to nuclear entry and editing.

Diagram 1: Intracellular trafficking pathways for DNA, mRNA, and RNP cargo. A critical bottleneck for all cargo types is endosomal escape; failure results in degradation.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Our CRISPR editing efficiency is low. Is this a cargo problem or a delivery problem?

Answer: Low editing efficiency can stem from issues with either the cargo or the delivery vector, and often both. A systematic approach is needed to diagnose the problem. The following troubleshooting guide outlines common issues and solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Low CRISPR Editing Efficiency

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions & Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Low Protein Expression (mRNA cargo) | mRNA instability or poor translation efficiency [13] [22]. | 1. Optimize mRNA sequence: Use codon optimization tools (e.g., RiboDecode) to enhance stability and translation [22]. 2. Incorporate modified nucleotides (e.g., m1Ψ) to reduce immunogenicity [22]. 3. Engineer UTRs: Introduce AU-rich elements (e.g., "AUUUA" repeats) in the 3' UTR to enhance stability and translation [23]. |

| High Cytotoxicity or Immune Response | Delivery vector toxicity; innate immune recognition of foreign nucleic acids [13]. | 1. Switch cargo type: Use RNP complexes to minimize TLR activation compared to mRNA [14]. 2. Purify RNP preparations to remove contaminants. 3. Use LNP vectors with low immunogenicity profiles [13]. |

| Inefficient Nuclear Delivery | Cargo fails to be imported into the nucleus [20]. | 1. Fuse Nuclear Localization Signals (NLS): Attach NLS to the C-terminus, N-terminus, or both termini of the Cas9 protein. Research shows different NLS configurations can yield similar high efficiency [24]. 2. Use peptide-based transduction domains to facilitate nuclear entry. |

| Poor Endosomal Escape | Cargo is trapped and degraded in endo-lysosomal compartments [20] [1]. This is a major bottleneck. | 1. Select vectors that promote endosomal escape: Use ionizable LNPs (iLNPs) that become positively charged in the acidic endosomal environment, disrupting the endosomal membrane [20] [14]. 2. Codelivery with endosomolytic agents (e.g., chloroquine) in vitro. |

| Rapid Clearance & Low Biodistribution (in vivo) | The delivery system is recognized and cleared by the host before reaching target cells [25]. | 1. PEGylate nanoparticles to prolong circulation time [20] [25]. 2. Use tissue-selective LNP formulations: Engineer LNPs with selective organ targeting (SORT) molecules to direct them to specific tissues like lung, spleen, or liver [1] [14]. |

FAQ: We are considering switching from Cas9 mRNA to RNP delivery. What are the critical experimental parameters for successful RNP delivery?

Answer: Transitioning to RNP delivery requires optimization of RNP complex formation, delivery vector selection, and experimental timing. Key parameters to consider are listed below.

Table 3: Critical Parameters for RNP Delivery

| Parameter | Considerations & Recommendations |

|---|---|

| RNP Complex Formation | Pre-complex Cas9 protein and sgRNA at an optimal molar ratio (e.g., 1:1.2 to 1:3) in a suitable buffer. Incubate for 10-30 minutes at room temperature before use to ensure proper complex formation [21]. |

| Delivery Vector | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): Optimal for in vivo use. Ensure the LNP formulation is compatible with protein cargo to avoid denaturation. Thermostable Cas9 variants (e.e., iGeoCas9) are more resistant to formulation stress [14].Electroporation: Highly efficient for ex vivo applications. |

| Cellular Uptake Validation | Use flow cytometry to quantify the uptake of fluorescently labeled RNPs. Employ correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM) to visualize intracellular trafficking and confirm endosomal escape [26]. |

| Timeline for Analysis | RNP action is rapid. Analyze editing efficiency 24-72 hours post-delivery, as the effects are transient due to protein turnover [21] [14]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Quantifying mRNA Cargo Internalization and Uptake Pathways

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to assess mRNA internalization and trafficking in human primary cells [26].

Objective: To quantify the cellular uptake of mRNA complexes and identify the primary endocytic pathways involved.

Reagents Needed:

- Fluorescently labeled mRNA (e.g., Cy5-labeled)

- Transfection reagent (e.g., Lipofectamine 3000, 3DFect)

- Appropriate cell culture medium and plates

- Endocytic inhibitors: Chlorpromazine (clathrin-mediated inhibitor), Wortmannin (macropinocytosis inhibitor), Genistein (caveolae-mediated inhibitor)

- Flow cytometry buffer (e.g., PBS with 1% BSA)

- Fixative (e.g., 4% PFA) - if required for analysis

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells at an appropriate density (e.g., 5 x 10^4 cells per well in a 24-well plate) and culture until 60-80% confluent.

- Inhibitor Pre-treatment (Optional - for pathway identification): Pre-treat cells with endocytic inhibitors for 1 hour.

- Chlorpromazine: 10 μg/mL

- Wortmannin: 100 nM

- Genistein: 200 μM

- Include a vehicle control (e.g., DMSO).

- Transfection Complex Formation:

- Dilute fluorescently labeled mRNA in a serum-free medium.

- Mix the transfection reagent gently and add it to the diluted mRNA. Use the manufacturer's recommended ratio.

- Incubate the mixture for 15-20 minutes at room temperature to form complexes.

- Transfection:

- Wash cells once with PBS.

- Add the mRNA-transfection reagent complexes to the cells.

- Incubate for the desired time (e.g., 1-4 hours) at 37°C.

- Analysis:

- Flow Cytometry: After incubation, wash cells thoroughly with PBS to remove non-internalized complexes. Trypsinize cells, resuspend in flow cytometry buffer, and analyze immediately using a flow cytometer. Measure the fluorescence intensity of the labeled mRNA in at least 10,000 cells per sample. A significant reduction in fluorescence in inhibitor-treated samples indicates the involvement of that pathway.

- Microscopy (CLEM): For spatial resolution, cells can be fixed after uptake and processed for Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (CLEM) to visualize the mRNA in endosomes, lysosomes, or the cytosol [26].

Protocol: Assessing RNP Delivery and Editing in Vitro using LNPs

This protocol is based on successful RNP delivery using the MITO-Porter system and other LNP formulations [21] [14].

Objective: To deliver functional Cas9 RNP complexes into cells using lipid nanoparticles and assess genome editing efficiency.

Reagents Needed:

- Purified Cas9 protein (with NLS, e.g., C-NLS-Cas9)

- Target-specific sgRNA

- LNP formulation components (e.g., ionizable lipid, phospholipid, cholesterol, PEG-lipid) or a commercial RNP transfection reagent

- Microfluidic device (e.g., iLiNP device) or standard LNP preparation equipment

- HEPES buffer

- Target cells

Procedure:

- RNP Complex Formation:

- Combine Cas9 protein and sgRNA at a molar ratio of 1:1.2 to 1:3 in a buffer containing HEPES.

- Incubate for 10-30 minutes at room temperature to form the RNP complex [21].

- LNP Encapsulation (using a microfluidic device):

- Prepare the organic phase: Dissolve lipid components (e.g., DOPE, Sphingomyelin, cationic lipid, PEG-lipid) in ethanol.

- Prepare the aqueous phase: The RNP complex in HEPES buffer.

- Use a microfluidic device to mix the organic and aqueous phases at a defined total flow rate and flow rate ratio (e.g., 3:1 aqueous-to-organic ratio) to form LNPs [21].

- Dialyze the resulting LNP formulation against a buffer (e.g., PBS or HEPES) to remove residual ethanol.

- Characterization of RNP-LNPs:

- Measure particle size, polydispersity index (PdI), and zeta potential using dynamic light scattering.

- Determine encapsulation efficiency using a Ribogreen assay or similar.

- Cell Treatment and Analysis:

- Apply the RNP-LNPs to target cells. Optimize the dose based on particle number or RNP concentration.

- Incubate for 24-72 hours.

- Assess Editing Efficiency:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells and extract genomic DNA.

- T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay: PCR-amplify the target region, denature and reanneal the amplicons, and treat with T7E1 enzyme, which cleaves mismatched heteroduplex DNA. Analyze cleavage products by gel electrophoresis to calculate indel percentage [24].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): For the most accurate quantification of indels and mutation spectra.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for Studying Cargo Uptake and Trafficking

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticles (iLNPs) | Non-viral delivery vector that enables endosomal escape via protonation in acidic endosomes [20] [14]. | In vivo delivery of mRNA or RNP to liver and lung tissue [14]. |

| MITO-Porter System | A specialized LNP designed for mitochondrial targeting, delivering cargo via membrane fusion [21]. | Direct delivery of RNPs to mitochondria for mtDNA editing [21]. |

| Endocytic Inhibitors (Chlorpromazine, Wortmannin, Genistein) | Pharmacological tools to block specific endocytic pathways (clathrin-mediated, macropinocytosis, caveolae-mediated) [26]. | Identifying the primary route of cellular entry for a delivery vector [26]. |

| RiboDecode | A deep learning framework for mRNA codon optimization, enhancing translation efficiency and protein expression [22]. | Designing highly expressive mRNA cargo for therapeutic applications. |

| Nuclear Localization Signals (NLS) | Short amino acid sequences that facilitate active nuclear import when fused to proteins [24]. | Enhancing nuclear delivery of Cas9 protein in DNA, mRNA, and RNP formats. Research shows C-terminal, N-terminal, or dual NLS fusion can be similarly effective [24]. |

| Thermostable Cas9 Variants (e.g., iGeoCas9) | Engineered Cas9 proteins with high stability, making them more resistant to stress during LNP formulation and extending functional half-life [14]. | Achieving high-efficiency editing in vivo with RNP-LNPs, particularly in non-liver tissues like the lung [14]. |

| MTR-106 | MTR-106, MF:C28H27N7O2S, MW:525.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ajugamarin F4 | Ajugamarin F4, MF:C29H42O9, MW:534.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Delivery Systems and Workflows for Protein and mRNA Cargoes

Viral Vector Selection Guide

The choice between Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAV) and Lentiviruses (LV) is fundamental and depends on your experimental goals, cargo, and target cells. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each vector to guide your selection.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of AAV vs. Lentiviral Vectors

| Characteristic | Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Lentivirus (LV) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cargo | DNA (ssDNA) [27] | RNA (which is reverse-transcribed to DNA) [27] |

| Packaging Capacity | ~4.7 kb [28] [29] | ~8-12 kb [29] |

| Genomic Integration | Largely non-integrating (episomal) [29] [27] | Integrates into host genome [29] [27] |

| Ideal Application | In vivo delivery; transient expression; gene editing with small Cas orthologs [27] | Ex vivo delivery; stable, long-term expression; delivery of large genetic payloads [27] |

| Typical Expression Kinetics | Onset within days to weeks; can be long-term in non-dividing cells [29] | Onset within days; stable, long-term expression in dividing cells [29] |

| Immune Response | Generally low immunogenicity [28] [27] | Can elicit immune responses; higher safety profile than early retroviruses [27] |

| Tropism (Targeting) | Determined by capsid serotype (e.g., AAV8 for liver, AAV9 for CNS) [28] [29] | Determined by envelope pseudotype (e.g., VSV-G for broad tropism) [27] |

Viral Vector FAQs and Troubleshooting

AAV (Adeno-Associated Virus)

Q: My gene of interest, including Cas9 and gRNA, exceeds the 4.7 kb packaging limit of AAV. What are my options?

A: The AAV size limitation is a common challenge. You can consider these strategies:

- Use Smaller Cas9 Orthologs: Package your entire system in a single AAV by using compact Cas proteins. Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SaCas9, 1053 aa) and Campylobacter jejuni Cas9 (CjCas9, 984 aa) have been successfully used in vivo [28].

- Utilize a Dual AAV System: Split the Cas9 and gRNA expression cassettes across two separate AAVs. This requires co-infection and relies on intracellular reassembly, which can reduce overall efficiency [28] [1].

- Explore Split Intein Systems: Engineer SpCas9 to be split and packaged into two AAVs, with full-length protein reconstitution post-transduction via protein trans-splicing [28].

Q: I am not seeing the expected editing efficiency in my in vivo model. What could be wrong?

A: Low in vivo efficiency can stem from several factors:

- Serotype Selection: Ensure you are using an AAV serotype that efficiently transduces your target tissue (e.g., AAV8 for liver, AAV9 for heart and CNS) [28] [29].

- Promoter Compatibility: The promoter must be functional in your target cell type. Use tissue-specific promoters to ensure expression is restricted to the desired cells.

- Pre-existing Immunity: Pre-existing antibodies against the AAV serotype in your animal model can neutralize the virus. Screening for antibodies or using less common serotypes can mitigate this [29].

- Titer and Potency: Verify the functional titer of your viral prep and ensure the delivered dose is sufficient for your target organ.

Lentivirus (LV)

Q: My lentiviral production yields are low. How can I improve the titer?

A: Low titer is often related to upstream production factors [30] [31]:

- Plasmid DNA Quality: Do not use mini-prep DNA for transfection. Use high-quality, endotoxin-free midi- or maxi-prep DNA purified using a kit designed for lentiviral work [30] [31].

- Cell Health: Use healthy Lenti-X 293T cells at low passage number (< passage 16). Ensure cells are >90% confluent at the time of transfection [30] [31].

- Toxic Gene Products: If your gene of interest is large or toxic, it can inhibit viral production. Consider using an inducible system or testing a control vector to isolate the issue [30].

- Vector Integrity: Lentiviral vectors can recombine in standard E. coli. Use low-recombination bacterial strains like Stbl3 for plasmid propagation and validate plasmid integrity by restriction digest before use [30] [31].

Q: The transduction efficiency in my target cells is poor, even with a high-titer stock. What can I do?

A: Transduction efficiency depends on the target cell type. Consider these enhancements [30] [31]:

- Use a Transduction Enhancer: Add Polybrene (typically 4-8 µg/mL) to the transduction medium to neutralize charge repulsion between the viral particle and cell membrane. Note that some cell types are sensitive to Polybrene [30].

- Employ Spinoculation (Spinfection): Centrifuging the plate after adding the virus (e.g., 2000 x g for 30-60 minutes at 32°C) can significantly increase infection efficiency by forcing virus-cell contact [31].

- Concentrate Your Virus: Use a concentration reagent like Lenti-X Concentrator or ultracentrifugation to increase the effective viral titer [31].

- Use a Binding Matrix: For sensitive or hard-to-transduce cells like primary T cells, use RetroNectin to pre-coat plates. This binds the virus and co-localizes it with cells, improving transduction while removing inhibitors [31].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their functions for successful viral vector production and transduction.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Viral Vector Research

| Reagent / Kit Name | Primary Function | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Stbl3 E. coli [30] | Cloning of Lentiviral Constructs | Bacterial strain with a recA13 mutation that minimizes unwanted recombination between the LTRs of lentiviral plasmids. |

| Lenti-X 293T Cell Line [31] | Lentivirus Packaging | A specially optimized HEK-293T-based cell line for high-titer lentivirus production when used with compatible packaging systems. |

| Lenti-X Concentrator [31] | Virus Concentration | A chemical precipitation method to concentrate lentiviral supernators, increasing viral titer up to 100-fold without ultracentrifugation. |

| RetroNectin Reagent [31] | Transduction Enhancement | A recombinant fibronectin fragment used to pre-coat plates, enhancing transduction of hard-to-transduce cells (e.g., primary T cells) by co-localizing virus and cells. |

| Polybrene [30] | Transduction Enhancement | A cationic polymer that reduces electrostatic repulsion between viral particles and the cell membrane, thereby increasing infection efficiency for many cell types. |

| Lenti-X GoStix [31] | Rapid Titer Estimation | A dipstick test for p24 capsid protein, providing a quick (10-minute) qualitative assessment of lentivirus production in supernatant. |

| Lenti-X qRT-PCR Titration Kit [31] | Viral Titer Determination | Quantifies the number of viral RNA genome copies per mL via qRT-PCR. Note: this measures physical particles, not all of which are infectious. |

| NucleoBond Xtra Maxi Kit [31] | Plasmid DNA Preparation | A gravity-flow column for purifying high-quality, "transfection-grade" plasmid DNA suitable for lentiviral packaging transfections. |

Experimental Workflow and Protocols

Workflow for AAV-Mediated In Vivo CRISPR Delivery

The diagram below outlines a standard workflow for producing and using AAV to deliver CRISPR components in vivo.

Detailed Protocol: AAV Production via Triple Transfection This protocol describes the production of recombinant AAV using the widely adopted three-plasmid transfection method in HEK293 cells [29].

Plasmid Co-transfection:

- Culture HEK293 cells (adherent or suspension) to an appropriate density.

- Co-transfect the cells with three plasmids:

- Transfer Plasmid (GOI): Contains your gene of interest (e.g., SaCas9 and gRNA) flanked by AAV Inverted Terminal Repeats (ITRs).

- Packaging Plasmid (Rep/Cap): Provides the AAV replication (Rep) and capsid (Cap) proteins. The Cap plasmid determines the serotype (e.g., AAV8, AAV9).

- Adenoviral Helper Plasmid: Supplies essential adenoviral genes (E4, E2a, VA) required for AAV replication.

- Use a transfection reagent optimized for high efficiency, such as polyethylenimine (PEI).

Harvest and Clarification:

- 48-72 hours post-transfection, harvest the cells and supernatant.

- Perform freeze-thaw cycles to lyse the cells and release the virus.

- Clarify the lysate by centrifugation to remove cell debris.

Purification and Concentration:

- Purify the AAV from the crude lysate. Common methods include iodixanol gradient ultracentrifugation or affinity chromatography columns.

- Concentrate the virus if necessary. The final product should be dialyzed into a suitable buffer like PBS.

Titration:

- Determine the viral genome titer (vg/mL) using quantitative PCR (qPCR). This is critical for dosing in animal experiments.

Workflow for Lentiviral-Mediated Ex Vivo CRISPR Delivery

The diagram below outlines a standard workflow for using lentivirus for ex vivo gene editing, such as in primary T cells for CAR-T therapy.

Detailed Protocol: Lentiviral Transduction of Adherent Cells This protocol is for transducing standard adherent cell lines. For primary or hard-to-transduce cells, additional optimization with reagents like RetroNectin is recommended [30] [31].

Day 0: Plate Cells:

- Plate your target cells so they will be 50-80% confluent at the time of transduction (typically the next day). Ensure the culture medium does not contain antibiotics.

Day 1: Transduction:

- Prepare the viral transduction mixture. Replace the cell culture medium with fresh medium containing the lentivirus at the desired Multiplicity of Infection (MOI). For initial experiments, a range of MOIs should be tested.

- Add a transduction enhancer, such as Polybrene, to a final concentration of 4-8 µg/mL.

- Optional but Recommended: Perform spinoculation by centrifuging the culture plate at 2000 x g for 30-90 minutes at 32°C.

- Incubate the cells with the virus-polybrane mixture for 4-24 hours.

Day 2: Refresh Medium:

- Remove the medium containing the virus and replace it with fresh, complete growth medium.

Day 3 Onwards: Analysis and Selection:

- If your vector contains a fluorescent marker, analyze transduction efficiency by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy 48-72 hours post-transduction.

- If your vector contains an antibiotic resistance gene, begin selection with the appropriate antibiotic 48-72 hours post-transduction. Maintain selection pressure for several days to kill non-transduced cells.

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) as a Versatile Platform for mRNA and RNP Delivery

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) have emerged as a leading non-viral delivery platform for genetic medicines, playing a pivotal role in the advancement of CRISPR-Cas9-based genome editing. For researchers optimizing the delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 components, a critical decision lies in choosing the appropriate cargo form: Cas9 mRNA or Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes [13]. While DNA forms of CRISPR-Cas9 offer sustained expression, they carry risks of host genome integration and higher off-target effects [13]. In contrast, mRNA and RNP forms provide transient activity, which minimizes off-target risks and eliminates genome integration concerns [13] [1]. This technical support article provides a comprehensive guide to troubleshooting LNP-based delivery for both Cas9 mRNA and RNPs, addressing key challenges in encapsulation, cellular uptake, and editing efficiency to support your research in developing precise and efficient gene therapies.

Core Concepts: Cargo Selection for CRISPR-LNP Systems

The choice between mRNA and RNP cargo significantly influences experimental design, editing kinetics, and safety profiles. The table below compares these two primary approaches for delivering CRISPR-Cas9 via LNPs.

Table 1: Comparison of Cas9 mRNA vs. RNP Delivery via LNPs

| Characteristic | Cas9 mRNA LNPs | Cas9 RNP LNPs |

|---|---|---|

| Cargo Form | mRNA encoding Cas9 protein + sgRNA | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and sgRNA |

| Onset of Action | Requires translation (hours) | Immediate (minutes to hours) |

| Editing Duration | Moderate (days) | Short (hours to days) |

| Off-Target Risk | Moderate (prolonged expression) | Lower (transient activity) |

| Manufacturing Complexity | Moderate (stable mRNA) | Higher (protein stability) |

| Immune Recognition | Higher (can activate TLRs, RIG-I) [13] | Lower |

| Packaging Capacity | Suitable for larger cargo [13] | Limited by protein size |

| Ideal Applications | In vivo editing requiring sustained Cas9 expression | High-precision editing with minimized off-target effects |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common LNP Delivery Challenges

Poor Encapsulation Efficiency

Problem: Low encapsulation of mRNA or RNP cargo into LNPs results in reduced delivery efficiency and therapeutic payload.

Solutions:

- Optimize Lipid Ratios: Systematically adjust the ionizable lipid to phospholipid ratio. A typical starting point is a molar ratio of 50:10:38.5:1.5 for ionizable lipid:DSPC:cholesterol:DMG-PEG2000 [32].

- Modify N/P Ratio: The nitrogen (from cationic lipids) to phosphate (from RNA) ratio critically influences encapsulation. Test ratios between 6:1 and 8:1 for mRNA encapsulation [32].

- Refine Manufacturing Parameters: In microfluidic mixing, ensure proper total flow rates and a 3:1 aqueous-to-solvent flow rate ratio [32]. Adjust mixing parameters to achieve a turbulent flow regime without compromising mRNA integrity.

Inefficient Cellular Uptake and Endosomal Escape

Problem: LNPs are internalized but fail to release their cargo into the cytoplasm, leading to lysosomal degradation.

Solutions:

- Ionizable Lipid Selection: The ionizable lipid is critical for endosomal escape. Screen different ionizable lipids (e.g., SM-102, ALC-0315, MC3, C12-200) for your specific cell type [32]. Note that in vitro performance does not always predict in vivo efficacy [32].

- Modulate Cholesterol Content: Recent studies show that reducing cholesterol density in LNPs can significantly enhance mRNA uptake and endosomal escape in dendritic cells [33]. Test cholesterol percentages from 20% to 40% molar ratio.

- Surface Functionalization: Conjugate cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) onto the LNP surface to improve cellular uptake [34]. For targeted delivery, incorporate SORT (Selective Organ Targeting) molecules into the formulation to direct LNPs to specific tissues beyond the liver [1] [35].

Limited In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC)

Problem: LNP formulations that perform well in cell culture models show poor efficacy in animal models.

Solutions:

- Use Physiologically Relevant Models: Immortalized cell lines may not accurately predict in vivo performance. Incorporate primary cells or immune cells (e.g., dendritic cells, macrophages) in your screening pipeline [32].

- Characterize Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): Rigorously analyze particle size, PDI, zeta potential, and encapsulation efficiency. All LNP formulations should have comparable physicochemical properties (size 70-100 nm, low PDI, high mRNA encapsulation) before in vivo testing [32].

- Employ Computational Modeling: Utilize molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to predict LNP behavior and stability in biological environments. Coarse-grained MD can model LNP-membrane interactions and endosomal escape mechanisms [36].

Low Gene Editing Efficiency

Problem: Despite successful delivery, the resulting gene editing rates are insufficient for therapeutic applications.

Solutions:

- Optimize sgRNA Co-encapsulation: For RNP delivery, ensure proper stoichiometry between Cas9 protein and sgRNA during pre-complexing. Purify RNPs before encapsulation to remove unbound components.

- Validate mRNA Integrity and Purity: For mRNA delivery, use HPLC-purified mRNA with modified nucleosides (e.g., N1-methylpseudouridine) to reduce immunogenicity and enhance translation [13] [37]. Ensure the mRNA has a optimized 5' cap and 3' poly(A) tail.

- Cell-Type Specific Formulations: Tailor LNP composition to target cells. For example, BLANs with low cholesterol density showed exceptional mRNA uptake and PD-L1 knockout efficiency in dendritic cells [33].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Formulating CRISPR mRNA-LNPs via Microfluidics

This protocol describes the preparation of LNPs encapsulating Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA for genome editing applications.

Materials:

- Lipids: Ionizable lipid (e.g., SM-102, ALC-0315), DSPC, cholesterol, DMG-PEG2000 [32]

- Aqueous Phase: Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA in citrate buffer (pH 4) [32]

- Equipment: Microfluidic mixer (e.g., NanoAssemblr Ignite), Amicon spin filters

Procedure:

- Prepare Lipid Stock: Dissolve lipids in ethanol at a molar ratio of 50:10:38.5:1.5 (ionizable lipid:DSPC:cholesterol:DMG-PEG2000) to a total lipid concentration of 10-12.5 mg/mL.

- Prepare Aqueous Phase: Dissolve Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA in 50 mM citrate buffer (pH 4) to a final mRNA concentration of 70 μg/mL [32].

- Mixing: Use a microfluidic device with a 3:1 aqueous-to-organic flow rate ratio and a total flow rate of 12 mL/min [32].

- Buffer Exchange: Dialyze or use tangential flow filtration against PBS (pH 7.4) to remove ethanol and adjust pH.

- Concentration: Concentrate LNPs using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (100 kDa MWCO).

- Characterization: Measure particle size (target 70-100 nm), PDI (<0.2), zeta potential, and encapsulation efficiency (>90%) [32].

Protocol 2: Assessing Gene Editing Efficiency In Vitro

Materials:

- Target cell line (e.g., HEK293, HeLa, THP-1) [32]

- mRNA-LNPs or RNP-LPs

- Lysis buffer and genomic DNA extraction kit

- T7 Endonuclease I or TIDE analysis reagents

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in 24-well plates at 70-80% confluence.

- Transfection: Treat cells with LNPs at various concentrations (e.g., 50-200 ng/mL mRNA). Include untreated controls.

- Incubation: Incubate for 48-72 hours to allow for editing and protein turnover.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells and extract genomic DNA.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target genomic region using specific primers.

- Editing Analysis:

- T7E1 Assay: Denature and reanneal PCR products, digest with T7 Endonuclease I, and analyze fragments by gel electrophoresis.

- TIDE Analysis: Sequence PCR products and use decomposition software to quantify insertion/deletion mutations.

- Cell Viability: Perform MTT or CellTiter-Glo assays in parallel to assess cytotoxicity.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for LNP Development and Characterization

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | SM-102, ALC-0315, DLin-MC3-DMA (MC3), C12-200 [32] | Form core structure; enable endosomal escape via protonation | pKa should be ~6.5 for optimal endosomal escape; significantly affects efficacy [32] |

| Structural Lipids | DSPC, DOPE [32] [37] | Enhance structural integrity and stability | DSPC provides bilayer stability; DOPE promotes hexagonal phase for endosomal escape |

| Stabilizing Agents | Cholesterol, DMG-PEG2000, ALC-0159 [32] [37] | Modulate membrane fluidity, reduce particle aggregation, prolong circulation | Cholesterol density affects cellular uptake and endosomal escape [33] |

| mRNA Modifications | N1-methylpseudouridine, 5-methoxyuridine [13] [37] | Reduce immunogenicity, enhance stability and translation efficiency | Critical for minimizing TLR7/8 activation and RIG-I signaling [13] |

| Characterization Tools | Dynamic Light Scattering, RiboGreen assay, TEM [38] | Measure size, PDI, encapsulation efficiency, and morphology | Essential Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) for reproducible manufacturing [38] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my LNP formulations show good in vitro transfection but poor in vivo editing efficiency? This is a common challenge due to the complex in vivo environment. The formation of a "protein corona" on LNPs in blood can alter their cellular tropism, typically directing them to the liver via ApoE-mediated uptake [35]. Furthermore, in vitro cell lines may not accurately mimic target cells in vivo [32]. To address this, incorporate immune cells or primary cells in your screening and consider implementing SORT molecules to achieve extra-hepatic targeting [1].

Q2: What is the best method to improve endosomal escape of LNPs? The selection of the ionizable lipid is the most critical factor. Screen different ionizable lipids (e.g., SM-102, ALC-0315) as their chemical structure determines protonation behavior and membrane fusion capacity [32]. Additionally, recent research shows that modulating cholesterol density in LNPs can significantly enhance endosomal escape in specific cell types like dendritic cells [33].

Q3: How can I scale up LNP production without compromising quality? Maintaining consistent particle size and low polydispersity during scale-up requires careful control of mixing parameters. Implement quality-by-design (QbD) principles and use scalable technologies like controlled microfluidics or tangential flow filtration [38]. Rigorous in-process controls for critical quality attributes (size, PDI, encapsulation) are essential throughout scale-up.

Q4: Can I use the same LNP formulation for both Cas9 mRNA and RNPs? While possible, optimization is often required. RNP encapsulation may benefit from adjusted lipid ratios and different stabilization strategies due to the larger size and different charge characteristics of the protein-RNA complex. Some studies suggest incorporating additional helper lipids or peptides to stabilize protein cargo during encapsulation and release.

Q5: How can I reduce the immunogenicity of CRISPR-LNPs? For mRNA LNPs, use nucleoside-modified mRNA (e.g., N1-methylpseudouridine) and HPLC purification to remove double-stranded RNA impurities [13]. For both mRNA and RNP delivery, ensure high encapsulation efficiency to minimize exposure of nucleic acids to extracellular immune sensors. PEGylated lipids can also reduce immune recognition, though anti-PEG immunity is a potential concern with repeated dosing.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using VLPs for RNP delivery in neuronal cells compared to AAVs or LNPs?

VLPs offer a unique combination of benefits for neuronal RNP delivery:

- Transient Activity & Reduced Immunogenicity: As VLPs deliver pre-assembled Cas9 RNP, the editing machinery is active for a short duration, minimizing off-target effects and reducing the risk of an immune response against persistently expressed Cas9. This is a significant advantage over AAVs, which lead to long-term Cas9 expression [39] [13].

- High Editing Efficiency: The RIDE (Ribonucleoprotein delivery) VLP platform demonstrated editing efficiency comparable to lentiviral vectors and higher than lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) in various cell types [39].

- Programmable Tropism: The surface of VLPs can be engineered to display specific ligands or antibodies, enabling targeted delivery to neurons and other hard-to-transfect cells, thereby improving specificity and reducing off-target effects [39] [40].

Q2: My VLP preps show low gene editing efficiency in primary neuronal cultures. What could be going wrong?

Low efficiency can stem from multiple points in the workflow. Consider the following troubleshooting steps:

- Verify RNP Packaging: Confirm that the Cas9 protein and gRNA are efficiently encapsulated within the VLPs. This can be checked using techniques like Western blot for Cas9 and RT-qPCR for gRNA on purified VLP lysates. The packaging is often dependent on specific molecular interactions, such as between the MS2 coat protein and MS2 stem loops incorporated into the gRNA [39].

- Check Viral Titer and Purity: Low particle titer will directly lead to low transduction rates. Use methods like p24 ELISA for lentiviral-based VLPs or other appropriate assays to quantify physical and functional titers. Ensure your preps are free of excessive cellular debris.

- Optimize Transduction Parameters: For neuronal cultures, factors like the age of the culture, the presence of neurotrophic factors during transduction, and the multiplicity of infection (MOI) need optimization. Pilot experiments with a GFP-reporting VLP can help establish optimal conditions.

- Assess Gating Strategy: The use of a constitutively expressed fluorescent marker (e.g., GFP) packaged alongside the RNP cargo is crucial for accurately identifying and sorting successfully transduced neurons for downstream analysis [39].

Q3: I am concerned about off-target effects. How do VLP-delivered RNPs compare to other delivery methods in this regard?

VLP-delivered RNPs are among the best strategies for minimizing off-target effects. Because the RNP complex is active immediately upon delivery but has a short half-life, the window for editing is limited. This transient activity significantly reduces the chance of Cas9 making cuts at unintended, off-target sites with similar sequences. Studies have shown that the RIDE VLP system induced fewer off-target effects than lentiviral vectors, which lead to long-term nuclease expression [39]. Furthermore, the RNP form of CRISPR-Cas9 itself has been reported to have the lowest rate of off-target effects compared to DNA and mRNA forms [13].

Q4: Can VLPs deliver other CRISPR-based editors besides standard Cas9 nuclease?

Yes, the VLP technology is adaptable. Research has demonstrated that the RIDE system can also deliver base editor proteins, achieving editing efficiencies of up to 69% in some cases [39]. Furthermore, streamlined SFV-based VLP platforms have been engineered to deliver not only RNPs but also mRNA and protein cargos, showcasing their versatility as a delivery platform [40].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing VLP-mediated Gene Editing in Neuronal Cultures

This protocol outlines the steps to transduce primary neurons with CRISPR-Cas9 RNPs delivered via VLPs and to quantify the editing outcome.

Materials:

- Primary neuronal cultures (e.g., cortical or hippocampal neurons from rodent E18 brains or human iPSC-derived neurons).

- Purified VLP prep (e.g., RIDE system pseudotyped with VSV-G or neuron-targeting envelopes).

- Neurobasal medium with B27 supplement and GlutaMAX.

- Poly-D-lysine coated culture plates.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Fixative (e.g., 4% PFA) and Permeabilization buffer (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100).

- Antibodies for immunostaining (e.g., against target protein or Cas9).

- Lysis buffer for genomic DNA extraction.

- PCR purification kit.

- T7 Endonuclease I or next-generation sequencing (NGS) library prep reagents.

Procedure:

- Culture Preparation: Plate primary neurons on poly-D-lysine coated plates in complete Neurobasal medium. Allow neurons to mature in vitro for at least 7-10 days before transduction.

- VLP Transduction:

- Thaw VLP stock on ice.

- Replace the neuronal culture medium with a minimal volume of fresh, pre-warmed medium.

- Add the calculated volume of VLPs to achieve the desired MOI. Include a control with non-targeting gRNA VLPs.

- Return the cells to the incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) for 6-24 hours.

- After the incubation, carefully remove the medium containing VLPs and replace it with fresh, complete Neurobasal medium.

- Incubation: Allow the gene editing to proceed for 3-7 days, with half-medium changes every 3-4 days.

- Efficiency Analysis (72 hours post-transduction):