Cell Fate Specification in Gastrulation: Mechanisms, Models, and Biomedical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of cell fate specification during gastrulation, the critical developmental period when the three primary germ layers are established.

Cell Fate Specification in Gastrulation: Mechanisms, Models, and Biomedical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of cell fate specification during gastrulation, the critical developmental period when the three primary germ layers are established. We explore the foundational principles of autonomous, conditional, and syncytial specification, alongside the core signaling pathways and emerging metabolic regulators that guide this process. The review details cutting-edge methodological advances, including human stem cell-based embryo models and high-resolution lineage tracing, that are revolutionizing the study of human development. We also address key technical challenges in the field and comparative analyses across model systems. This synthesis is essential for developmental biologists, stem cell researchers, and professionals seeking to understand the fundamental processes that could inform regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

The Core Principles of Cell Fate Specification: From Classical Concepts to Modern Signaling Pathways

In the field of developmental biology, precisely defining the stages of cell fate commitment is crucial for understanding how a single fertilized egg gives rise to a complex organism. The terms specification and determination represent distinct, sequential phases in this commitment process, with specification representing a reversible, preliminary commitment, and determination constituting an irreversible, final commitment to a particular cellular identity [1]. Within the context of gastrulation research—the stage during embryonic development where the three primary germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) are established—distinguishing between these phases provides critical insights into developmental plasticity, regulatory networks, and the fundamental mechanisms guiding embryonic patterning [2].

The classical view of cell fate commitment has been categorized into three general modes of specification: autonomous, conditional, and syncytial [1]. However, recent advances in stem cell models, single-cell multi-omics technologies, and biomechanical analyses have dramatically refined our understanding of how specification transitions to determination during mammalian gastrulation [3] [4] [5]. This technical guide examines the current molecular and cellular criteria distinguishing these states, with a specific focus on their implications for gastrulation research and therapeutic applications.

Molecular and Cellular Definitions

A cell is considered specified when it will differentiate autonomously into a particular cell type when placed in a neutral environment, but its fate can still be altered when exposed to specific signals from other cells. In contrast, a cell is determined when it will differentiate according to its specified fate even when transplanted into a non-neutral environment or different embryonic region [1]. This distinction is not merely semantic but reflects profound differences in underlying molecular circuitry, epigenetic landscapes, and cellular potentiality.

During mouse gastrulation, a spatiotemporally controlled sequence of events results in the generation of organ progenitors from a mass of pluripotent epiblast tissue [2]. The transition from specification to determination involves the establishment of hierarchical gene regulatory networks (GRNs) and progressive restriction of developmental potential through epigenetic reprogramming [6] [5]. Single-cell multi-omics technologies have revealed that this transition is marked by specific molecular events, including the stabilization of enhancer landscapes, commitment to transcriptional programs, and the loss of plasticity markers [5].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Specification vs. Determination

| Feature | Specification | Determination |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Potential | Multipotent or bipotent | Unipotent |

| Fate Reversibility | Reversible by extrinsic signals | Irreversible |

| Experimental Test | Neutral environment culture | Transplantation to ectopic location |

| Transcriptional State | Poised/primed | Committed/active |

| Epigenetic Landscape | Plastic, bivalent chromatin | Stable, univalent chromatin |

| Signaling Response | Responsive to inductive cues | Unresponsive to reprogramming signals |

Signaling Pathways and Gene Regulatory Networks in Gastrulation

Key Signaling Pathways

At the onset of mammalian gastrulation, secreted signaling molecules belonging to the Bmp, Wnt, Nodal, and Fgf signaling pathways induce and pattern the primitive streak, marking the start of the cellular rearrangements that generate the body plan [3]. These pathways establish a complex signaling network that guides the specification of the three germ layers:

- Nodal Signaling: Creates a proximal-distal gradient that specifies the distal visceral endoderm (DVE) and patterns the anterior-posterior axis. Nodal inhibitors CER1 and LEFTY1 are expressed in the DVE and anterior visceral endoderm (AVE), restricting Nodal signaling to the posterior region where the primitive streak forms [2].

- Wnt Signaling: WNT3a originates from the posterior epiblast and visceral endoderm, with its signaling domain restricted anteriorly by the Wnt inhibitor DKK1 expressed in the AVE [2].

- BMP Signaling: BMP4 secreted from the extra-embryonic ectoderm (ExE) inhibits DVE formation, helping restrict it to the distal pole [2].

These signaling pathways do not operate in isolation but rather form an integrated network that progressively restricts cell fates. Research using mouse gastruloids—3D aggregates of embryonic stem cells that mimic key aspects of gastrulation—has been particularly powerful in deconvoluting these signaling interactions and their temporal dynamics [3] [7].

Gene Regulatory Networks

GRNs represent formal representations of the route from genomic information to biological processes, typically visualized with 'nodes' representing genes and 'edges' representing molecular interactions [6]. During the transition from blastocyst to gastrula, GRNs become increasingly hierarchical and stabilized:

- Pluripotency Network: In the pre-gastrula epiblast, a core network including OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2 maintains pluripotency through tightly auto-regulated and cooperative interactions [6].

- Lineage Specification Networks: As gastrulation proceeds, competing lineage-specifying factors (e.g., Brachyury, Hes1, Eomes) begin to be expressed, positioning cells at the cusp of multiple lineage decisions [6].

- Determination Networks: Irreversible commitment is associated with the activation of terminal selector transcription factors and the silencing of alternative lineage programs.

Table 2: Key Molecular Regulators in Mouse Gastrulation

| Regulator | Expression/Site | Functional Role | Associated Germ Layer |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | Epiblast | Maintains pluripotency | Pre-gastrulation |

| NANOG | Epiblast | Maintains pluripotency | Pre-gastrulation |

| Brachyury (T) | Primitive streak | Mesoderm specification | Mesoderm |

| SOX17 | Anterior primitive streak | Endoderm specification | Definitive endoderm |

| TBX6 | Nascent mesoderm | Mesoderm patterning | Mesoderm |

| MESP1 | Early mesoderm | Cardiovascular progenitors | Mesoderm |

| OTX2 | Anterior epiblast | Anterior neuroectoderm | Ectoderm |

| ZEB2 | Somitic mesoderm | Somitogenesis | Mesoderm |

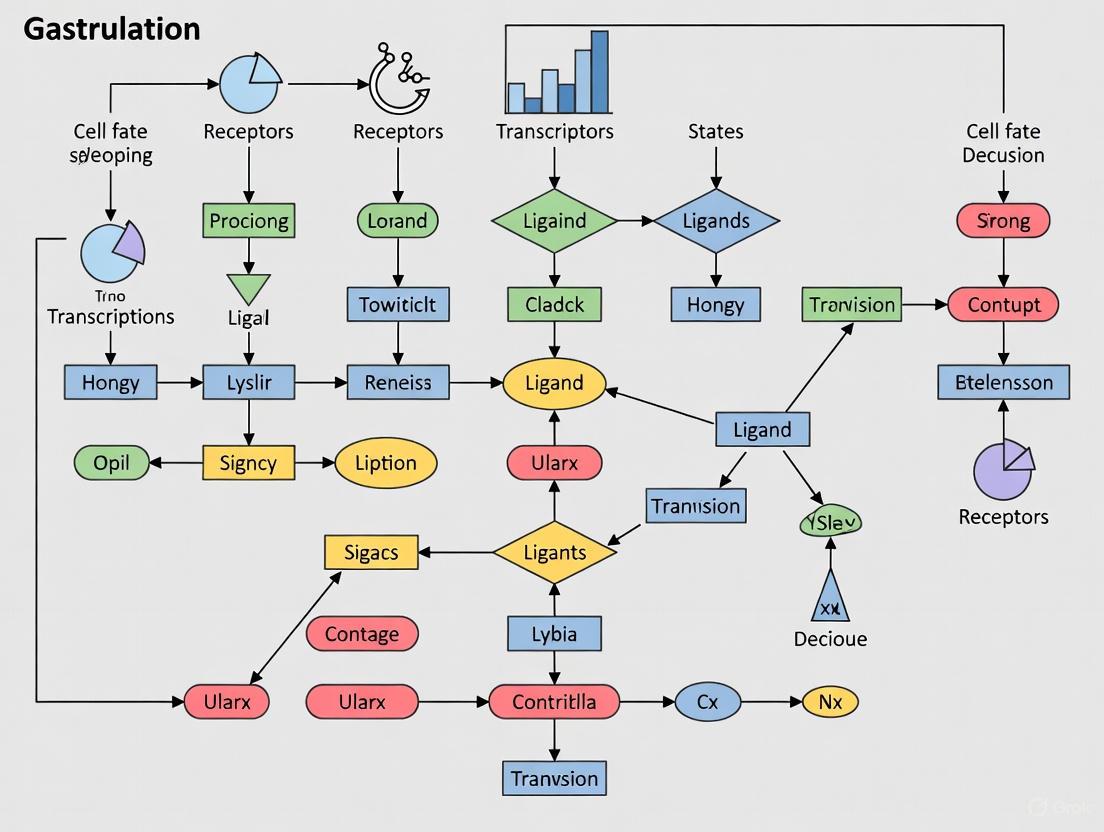

Diagram 1: Integrated molecular and cellular inputs driving the transition from specification to determination during gastrulation. Signaling pathways and GRNs primarily establish specification, while epigenetic and biomechanical inputs reinforce determination.

Experimental Paradigms and Methodologies

Classical Lineage Tracing and Perturbation Studies

The foundation of our knowledge regarding cell fate transitions during gastrulation was established through classical lineage tracing and perturbation experiments:

- Ablation Studies: Specific cells are removed or destroyed to test if neighboring cells can alter their fate to compensate, indicating conditional specification [1].

- Transplantation Studies: Cells are moved to ectopic locations to test if they maintain their original fate (determined) or adopt a new fate based on their environment (specified) [1].

- Lineage Tracing: Using inducible Cre-lox systems with colorful reporters like brainbow to map the differentiation path of individual cells and their descendants [1].

These approaches revealed the fate map of the pluripotent epiblast and demonstrated that the developmental potential of embryonic cells becomes progressively restricted as gastrulation proceeds [2].

Modern Single-Cell and Multi-Omics Technologies

Recent technological advances have enabled unprecedented resolution in studying cell fate decisions:

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): Resolves transcriptional heterogeneity and identifies putative transitional states during lineage commitment [4] [5].

- Single-Cell Epigenomic Profiling: Methods like single-cell ChIP-seq (e.g., CoBATCH) profile histone modifications (H3K27ac, H3K4me1) to map enhancer dynamics and epigenetic priming during fate commitment [5].

- Multi-omics Integration: Combined scRNA-seq with single-cell ChIP-seq reveals "time lag" transition patterns between enhancer activation and gene expression during germ-layer specification [5].

These approaches have demonstrated that epigenetic priming, as reflected by H3K27ac signals, is evident before overt morphological changes, with germ layer-specific epigenetic patterns detectable as early as the Pre-Primitive Streak stage [5].

Gastruloid and Stem Cell Models

Mouse gastruloids have emerged as a powerful model system to study signaling dynamics during primitive streak formation and the transition from specification to determination [3] [7]. These in vitro models allow for real-time visualization of signaling and differentiation, overcoming the molecular and cellular complexity of early developmental events in utero [3]. Key applications include:

- Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics: Global dynamics of (phospho)protein expression during gastruloid differentiation reveal unique expression profiles for each germ layer [4].

- Enhancer Interaction Mapping: P300 proximity labeling reveals global enhancer interactomes and lineage-specific transcription factors [4].

- High-Throughput Perturbation Screening: Degron-based perturbations combined with scRNA-seq identify critical regulators like ZEB2 in mouse and human somitogenesis [4].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflows for delineating cell fate specification and determination, integrating classical and modern approaches across multiple model systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Fate Studies

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq Platforms | Transcriptome profiling at single-cell resolution | Identifying transitional states during germ layer specification [5] |

| Single-cell ChIP-seq (CoBATCH) | Histone modification profiling (H3K27ac, H3K4me1) at single-cell level | Mapping enhancer dynamics during epigenetic priming [5] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Screening | High-throughput gene perturbation | Functional validation of candidate regulators in gastruloids [4] |

| Auxin-Inducible Degron System | Rapid protein degradation | Acute perturbation of transcription factors like ZEB2 [4] |

| P300 Proximity Labeling | Mapping enhancer-promoter interactions | Defining global enhancer interactomes [4] |

| Mass Spectrometry Proteomics | Global (phospho)protein quantification | Tracking proteome rewiring during gastruloid differentiation [4] |

| Lineage Tracing Reporters (Brainbow) | Multicolor cell lineage tracing | Visualizing clonal relationships and fate restrictions [1] |

| Live-Cell Imaging Platforms | Real-time visualization of development | Tracking cell behaviors in gastruloids [3] |

| CPTH2 | CPTH2|HAT Inhibitor|CAS 357649-93-5 | |

| Cpypp | Cpypp, MF:C18H13ClN2O2, MW:324.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Concepts: Biomechanical and Epigenetic Regulation

Biomechanical Influences on Cell Fate

Beyond biochemical signals, physical forces and mechanical cues have emerged as critical regulators of cell fate decisions [8]. The field of mechanobiology has revealed that:

- Extracellular Matrix Stiffness: Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) differentiation is guided by substrate stiffness—soft matrices promote neurogenic fate, while stiff matrices induce osteogenic differentiation [8].

- Cell Shape and Geometry: Controlling the spreading of MSCs is sufficient to direct their fate, with different tissue geometries applying variable strains that influence epithelial fate [8].

- Traction Forces: Mouse pluripotent stem cell differentiation into endoderm depends on traction forces mediated by integrins α5β1 and α3β1, which regulate TGFβ signaling [8].

- Fluid Shear Stress: Promotes MSC osteogenic differentiation via Ca²⺠and MAPK/ERK signaling, and relocalizes β-catenin to the nucleus in mouse ESCs to regulate stemness [8].

These biomechanical inputs are integrated with chemical signals through mechanotransduction pathways involving yes-associated protein (YAP), Piezo1 channels, and the actin cytoskeleton, creating a feedback loop between physical forces and transcriptional responses [8].

Epigenetic Control Mechanisms

Epigenetic regulation provides a crucial layer of control over the specification-determination transition:

- Histone Modifications: H3K27ac (active enhancers) and H3K4me1 (poised enhancers) enable precise identification of enhancers and prediction of promoter-enhancer interactions, reflecting current and prospective developmental potential [5].

- Asynchronous Commitment: Different germ layers exhibit distinct epigenetic dynamics during commitment, with ectoderm cells establishing stable epigenetic states earlier than mesoderm and endoderm cells, which undergo more extensive epigenetic reprogramming [5].

- Chromatin State Transitions: The shift from bivalent chromatin (co-marked by H3K4me3 and H3K27me3) at promoters of developmental genes to univalent states correlates with lineage commitment [5].

Multi-omics integration has revealed a "time lag" between enhancer activation (marked by H3K27ac) and gene expression during germ-layer specification, suggesting that epigenetic priming precedes transcriptional commitment [5].

The distinction between cell fate specification and determination remains a fundamental conceptual framework in developmental biology, but our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying this transition has dramatically evolved. Current research emphasizes:

- Multi-modal Integration: Cell fate decisions integrate transcriptional, epigenetic, biomechanical, and signaling inputs in a spatially and temporally coordinated manner.

- Dynamic Resolution: Single-cell technologies have revealed extensive heterogeneity and asynchronous commitment patterns even within presumed homogeneous cell populations.

- Context-Dependent Plasticity: The boundaries between specification and determination may be more fluid than previously recognized, with certain contexts permitting dedifferentiation or transdifferentiation.

- Conserved Principles: Despite species-specific variations, the core principles of fate restriction appear conserved across model organisms, with mechanical and geometric boundary conditions playing previously underappreciated roles [7].

Future research directions will likely focus on achieving even higher spatiotemporal resolution of fate decisions, engineering more physiological model systems, and leveraging quantitative modeling to predict fate outcomes from integrated multi-omics datasets. These advances will not only deepen our understanding of embryonic development but also enhance our ability to manipulate cell fate for regenerative medicine and disease modeling applications.

Cell fate determination describes the process during embryonic development where a cell becomes committed to developing into a specific cell type [1]. This process involves multiple molecular mechanisms that guide cells through proliferation, differentiation, movement, and even programmed cell death to create a complex multicellular organism [1]. The commitment process occurs through stages: beginning with specification (a labile phase where commitment can be reversed under certain conditions) and progressing to determination (an irreversible commitment to a particular fate) [9]. Understanding these mechanisms is fundamental to gastrulation research, as they establish the foundational cell identities and tissue organizations that emerge during this critical developmental period. This whitepaper examines the three primary modes of cell specification—autonomous, conditional, and syncytial—detailing their mechanisms, experimental evidence, and implications for biomedical research.

Autonomous Specification

Core Principles and Mechanisms

Autonomous specification is a cell-intrinsic process where a cell's developmental fate is determined by inherited cytoplasmic determinants—asymmetric distributions of specific proteins, mRNAs, or regulatory RNAs—that are partitioned into the cell during division [1] [9]. This mode of specification gives rise to mosaic development, where the embryo develops as an assembly of independently self-differentiating parts [9]. The fate of each cell is predetermined by its internal composition rather than signals from its cellular environment, meaning that if a specific blastomere is removed from an early embryo, the embryo will lack precisely those structures that the removed blastomere would have produced [9]. Conversely, when isolated and placed in a neutral environment, the removed blastomere will autonomously differentiate into those same structures it would have formed in the intact embryo [9].

Key Molecular Players

The molecular basis of autonomous specification lies in morphogenetic determinants localized to specific regions of the egg cytoplasm. A classic example is the Macho protein in tunicates, a muscle-specific transcription factor found in yellow-pigmented cytoplasm [10]. Any blastomere that inherits this cytoplasm will form tail muscle cells, and if this Macho-containing cytoplasm is experimentally introduced into other cells, they too will form muscle tissue [10]. Similarly, in the tunicate embryo, only the posterior vegetal blastomeres (B4.1 pair) at the 8-cell stage contain the specific cytoplasmic determinants (including the yellow crescent cytoplasm) necessary to produce tail muscle tissue, as demonstrated by the presence of the muscle-specific enzyme acetylcholinesterase [9].

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

The foundational experiments demonstrating autonomous specification were performed by Laurent Chabry in 1887 using tunicate embryos [1] [9]. Chabry's defect experiments involved removing or destroying specific blastomeres and observing that the resulting larvae lacked exactly those structures normally produced by the missing cells [9]. Modern validation comes from transplantation and isolation experiments:

- Isolation Experiments: When particular blastomeres of the 8-cell tunicate embryo are removed and cultured in isolation, they autonomously form their characteristic structures [9].

- Cytoplasmic Transfer Studies: J.R. Whittaker demonstrated that transferring yellow crescent cytoplasm from a muscle-forming blastomere (B4.1) into an ectoderm-forming blastomere (b4.2) caused the recipient cell to generate muscle cells in addition to its normal ectodermal progeny [9].

Table 1: Key Experiments in Autonomous Specification

| Experiment | Organism | Method | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chabry (1887) [9] | Tunicate | Ablation of specific blastomeres | Embryo lacked structures specific to removed blastomeres |

| Whittaker (1973, 1982) [9] | Tunicate | Cytoplasmic transplantation | Ectoderm-forming blastomeres produced muscle when receiving muscle-forming cytoplasm |

| Autonomous specification test [9] | Various | Blastomere isolation in neutral medium | Isolated cells form their destined structures independently |

Figure 1: Autonomous Specification Pathway. Cells inherit specific cytoplasmic determinants during asymmetric division, leading to predetermined cell fates even when isolated.

Conditional Specification

Core Principles and Mechanisms

Conditional specification represents a cell-extrinsic process where a cell's fate is determined by its interactions with neighboring cells or exposure to concentration gradients of signaling molecules called morphogens [1]. This mechanism underlies regulative development, wherein the embryo can adjust to alterations such as the removal or addition of cells [9]. In this model, cells initially possess broad developmental potential, and their ultimate fates become restricted through signals from their cellular environment [9]. If a blastomere is removed from an early embryo utilizing conditional specification, the remaining cells can alter their fates to compensate for the missing parts, a phenomenon known as regulation [9]. The fate of a cell depends largely on its positional context within the embryo and its exposure to specific paracrine factors secreted by adjacent cells [10].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Conditional specification primarily operates through inductive signaling between cells. Key signaling pathways include:

- Notch Signaling: Critical for lateral inhibition, where neighboring cells influence each other's fates through inhibitory signals [1]. In C. elegans, GLP-1/Notch signaling is essential for distinguishing between ABa and ABp cell fates [11].

- FGF Receptor Pathway: In spiralian embryos with conditional specification, the FGF receptor pathway and ERK1/2 transduction cascade regulate the inductive specification of the embryonic organizer [12].

- Morphogen Gradients: Diffusible signals that provide positional information to cells, influencing their fate based on concentration thresholds [13].

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

The discovery of conditional specification emerged from experiments contradicting the autonomous specification model:

- Hans Driesch's Sea Urchin Experiments (1892): Driesch separated blastomeres of 2-, 4-, and 8-cell sea urchin embryos and found that each isolated blastomere could develop into a complete, though smaller, larva [9] [10]. This demonstrated that early blastomeres retained the ability to regulate their development according to their new circumstances.

- Cell Ablation Studies: In C. elegans embryos, removal of the P2 cell at the 4-cell stage prevents the EMS cell from producing endoderm, causing it to generate only MS cells instead [11]. This indicates that the P2 cell provides an essential inductive signal for endoderm specification.

- Blastomere Repositioning Experiments: When ABa and ABp blastomeres in C. elegans are experimentally reversed, their fates are similarly reversed, confirming that their developmental pathways are determined by positional cues rather than intrinsic factors [11].

Table 2: Key Experiments in Conditional Specification

| Experiment | Organism | Method | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Driesch (1892) [9] [10] | Sea urchin | Blastomere separation | Isolated blastomeres formed complete larvae |

| C. elegans P2 ablation [11] | C. elegans | Single cell removal | EMS cell failed to produce endoderm without P2 signal |

| Blastomere repositioning [11] | C. elegans | Altering cell positions | Cell fates changed according to new positions |

| Compression experiment [10] | Sea urchin | Altered cleavage planes | Normal development despite disrupted cell lineages |

Figure 2: Conditional Specification Pathway. Cell fates are determined by signaling from neighboring cells or morphogen gradients, demonstrating regulatory capacity after experimental perturbation.

Syncytial Specification

Core Principles and Mechanisms

Syncytial specification represents a hybrid mechanism predominantly observed in insects, combining elements of both autonomous and conditional specification within a multinucleate syncytium [1]. In this system, the early embryo exists as a single cell containing multiple nuclei without complete cell membranes separating them [1] [11]. Morphogen gradients diffuse freely throughout this syncytial space, influencing nuclei in a concentration-dependent manner [1]. Cellularization of the blastoderm occurs either during or after the specification of body regions [1]. This mechanism allows for coordinated patterning across a broad field without the need for transmembrane signaling in the earliest developmental stages.

Molecular Mechanisms and Morphogen Gradients

The molecular basis of syncytial specification involves:

- Morphogen Gradient Formation: Transcription factors and signaling molecules form concentration gradients along the anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral axes within the syncytium.

- Nuclear Competence: Individual nuclei respond to these gradients based on their positional information within the syncytium.

- Cellularization Timing: The process of membrane formation between nuclei occurs after initial patterning events, fixing the established patterns into discrete cellular domains.

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Research on syncytial specification primarily utilizes Drosophila melanogaster as a model system. Key experimental approaches include:

- Morphogen Gradient Visualization: Using fluorescent tags and live imaging to track the distribution and concentration of morphogens like Bicoid and Nanos within the syncytial blastoderm.

- Genetic Mutagenesis: Studying patterning defects in mutants with disrupted morphogen gradients or nuclear response mechanisms.

- Transplantation Studies: Investigating how nuclei respond when repositioned within the syncytium, demonstrating the concentration-dependent nature of fate specification.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Specification Modes

| Characteristic | Autonomous | Conditional | Syncytial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependency | Cell-intrinsic | Cell-extrinsic | Combined |

| Developmental Type | Mosaic | Regulative | Hybrid |

| Key Mechanisms | Cytoplasmic determinants | Cell-cell signaling, morphogen gradients | Morphogen gradients in syncytium |

| Compensatory Ability | None | High | Limited |

| Experimental Evidence | Isolation forms same structures | Isolation regulates to form whole structures | Nuclear response to gradient position |

| Model Organisms | Tunicates, molluscs | Vertebrates, sea urchins | Insects |

| Role in Gastrulation | Establces fixed lineages | Permits plasticity & adaptation | Coordinates rapid patterning |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Cell Specification

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Cre-lox Transgenic Systems [1] | Inducible cell lineage tracing | Mapping differentiation paths using reporters like Brainbow |

| Morpholinos | Gene knock-down | Investigating gene function in specification |

| GFP and Fluorescent Reporters [1] | Live cell imaging and fate mapping | Visualizing molecular changes in experimentally manipulated cells |

| Calcium-Free Seawater [9] [10] | Blastomere separation | Isolation experiments in sea urchins |

| Specific Antibodies | Protein localization | Detecting asymmetric distribution of morphogenetic determinants |

| In situ Hybridization Probes | mRNA localization | Identifying spatial distribution of maternal mRNAs |

| Microinjection Systems | Cytoplasmic transfer | Introducing determinants into naive cells |

| Dapt | Dapt, CAS:208255-80-5, MF:C23H26F2N2O4, MW:432.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DDAO | DDAO (Lauryl Dimethylamine Oxide) |

Integration in Gastrulation Research

Convergence of Specification Modes in Gastrulation

While the three specification modes represent distinct mechanisms, most embryos employ combinations of these strategies during development [10]. Even in tunicates, which predominantly use autonomous specification for certain lineages like muscle cells, the nervous system arises through conditional specification via cell interactions [10]. Recent transcriptomic studies in spiralian annelids reveal that despite different specification modes early in development, embryos converge transcriptionally by the gastrula stage, suggesting that gastrulation represents a critical transition point where initially divergent developmental pathways integrate to establish the basic body plan [12]. This convergence occurs even between species with autonomous versus conditional specification, indicating that gastrulation may act as a "mid-developmental transition" or phylotypic stage in annelid embryogenesis [12].

Epigenetic Regulation of Cell Fate

Cell fate determination is significantly influenced by epigenetic mechanisms that regulate gene expression without altering DNA sequence [1]. Key epigenetic processes include:

- DNA Methylation: Typically represses gene activity and helps maintain cellular identity [1].

- Histone Modifications: Acetylation generally enhances transcription by loosening chromatin structure, while other modifications can create repressive states [1].

- Chromatin Remodeling: Dynamic alteration of nucleosome positioning makes specific genomic regions accessible or inaccessible to transcription factors [1].

These epigenetic modifications are orchestrated by networks of enzymes that respond to both intrinsic signals and extrinsic cues from the cellular microenvironment, providing a mechanism for cells to adapt to developmental signals during specification and gastrulation [1].

Technological Advances and Future Directions

Modern research in cell specification increasingly utilizes sophisticated technologies:

- High-Resolution Transcriptomics: Bulk RNA-seq time courses reveal transcriptional dynamics during specification [12].

- Live Confocal and Super-Resolution Microscopy: Enable visualization of molecular changes in real-time at unprecedented resolution [1].

- Lineage Tracing with Inducible Systems: Tools like Brainbow provide colorful reporters to follow differentiation paths of cells in complex tissues [1].

- Dynamical Systems Modeling: Mathematical frameworks help understand the diverging fates and emerging forms of developing embryos by identifying geometric structures that organize cell trajectories [14].

These approaches are revealing the remarkable plasticity of developmental systems and providing new insights into how conserved gene regulatory networks can produce diverse developmental outcomes through evolutionary modifications of specification mechanisms.

Gastrulation represents a pivotal phase in embryonic development, during which a pluripotent cell mass is transformed into the three primary germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—that form the blueprint for all adult tissues. This process is orchestrated by a highly conserved and interactive network of key signaling pathways, namely Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), Nodal, Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF), and Wnt. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the mechanisms by which these pathways direct cell fate specification. We detail the core signal transduction mechanisms, explore the critical crosstalk that ensures robust patterning, and summarize quantitative findings on signaling thresholds. Furthermore, we present structured experimental protocols for manipulating these pathways in vitro, a curated toolkit of essential research reagents, and computational diagrams to visualize complex signaling networks. The insights herein are framed within the context of advancing fundamental gastrulation research and its applications in regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug development.

The formation of the germ layers during gastrulation is a cornerstone of embryonic development. In mammals, this process begins with the formation of the primitive streak, a structure that establishes the cranial-caudal axis and serves as a conduit for the massive cellular rearrangements required to form the trilaminar embryo [15]. The epiblast, a sheet of pluripotent cells, gives rise to all three germ layers: the ectoderm (precursor to the nervous system and epidermis), the mesoderm (precursor to muscle, bone, and the cardiovascular system), and the endoderm (precursor to the gut and associated organs) [16] [17]. The specification of these lineages is not directed by a single signal but is instead the result of a tightly regulated interplay of multiple signaling pathways. The combinatorial action and precise spatiotemporal dynamics of BMP, Nodal, FGF, and Wnt signaling are critical for inducing the primitive streak, guiding ingressing cells to their appropriate fates, and establishing the overall body plan [15] [3]. Dysregulation of these pathways leads to severe developmental defects, underscoring their importance. Moreover, recapitulating these signals in vitro is essential for directing the differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) into specific lineages for research and therapeutic applications [18] [19].

Core Signaling Pathways in Germ Layer Specification

Each signaling pathway utilizes a distinct molecular machinery to convey signals from the extracellular environment to the nucleus, resulting in changes in gene expression that determine cell fate.

Wnt/β-catenin Pathway

The Wnt pathway is a central regulator of cell fate, particularly in mesoderm and endoderm specification. It is categorized into canonical (β-catenin-dependent) and non-canonical branches [20]. In the absence of a Wnt signal, cytoplasmic β-catenin is constantly targeted for proteasomal degradation by a destruction complex that includes Axin, Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC), and Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β (GSK3β) [20]. Upon binding of Wnt ligands to Frizzled (Fzd) receptors and LRP5/6 co-receptors, the destruction complex is disrupted. This stabilization allows β-catenin to accumulate and translocate to the nucleus, where it partners with TCF/LEF transcription factors to activate target genes such as TBXT (Brachyury), a key marker of mesoderm [20] [19]. Wnt signaling is indispensable for the initiation and maintenance of the primitive streak and the subsequent specification of mesodermal progenitors [15] [19].

Nodal/Smad2/3 Pathway

A member of the Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily, Nodal acts as a potent morphogen. It signals through a receptor complex that phosphorylates intracellular SMAD2/3 proteins. Phosphorylated SMAD2/3 forms a complex with SMAD4 and translocates to the nucleus to regulate transcription [21] [19]. Nodal signaling is fundamental for establishing the primitive streak and specifying mesendodermal fates. Its activity is graded, with higher levels of Nodal signaling promoting endoderm formation, while lower levels are sufficient for mesoderm induction [19]. The precise spatial localization of Nodal signaling is critical, and its activity is often confined by antagonists secreted from adjacent tissues, such as the hypoblast [15].

BMP Signaling Pathway

Also a member of the TGF-β superfamily, BMP signaling is crucial for patterning the embryo along the dorsal-ventral axis. BMP ligands signal through receptor serine/threonine kinases, leading to the phosphorylation and activation of SMAD1/5/8. These activated SMads complex with SMAD4 and move to the nucleus to direct the expression of target genes [21] [18]. BMP signaling exhibits a concentration-dependent effect on cell fate. While it is known for its role in promoting epidermal differentiation from ectoderm, within the mesoderm, a low level of BMP activity favors intermediate mesoderm (e.g., kidney, gonads), whereas higher levels drive lateral plate mesoderm formation [19]. BMP signaling has also been identified as an inducer of the totipotent state in mouse embryonic stem cells, a role that is constrained by cross-activation from other pathways [22] [21].

FGF Signaling Pathway

The FGF pathway is a key regulator of multiple processes, including cell proliferation, survival, and migration. FGF ligands bind to FGF receptors (FGFRs), which are receptor tyrosine kinases. This binding triggers a cascade of intracellular events, primarily the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways [18]. During gastrulation, FGF signaling is critical for the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process essential for cells to delaminate from the epiblast and ingress through the primitive streak [15]. By driving EMT, FGF signaling facilitates the formation of the mesoderm layer and helps maintain mesodermal progenitors in an undifferentiated state.

Pathway Crosstalk and Integrated Control of Patterning

The individual pathways do not operate in isolation; they form a complex, interconnected network that ensures precise and robust germ layer patterning. Cross-activation and mutual inhibition between these pathways create a self-regulating system.

- Synergistic Induction: The formation of the primitive streak is initiated by the synergistic action of Wnt and Nodal signaling. Wnt signaling can upregulate the expression of Nodal, creating a positive feedback loop that stabilizes the primitive streak [15] [3].

- Constraining Signals: Research in mouse embryonic stem cells revealed that BMP4's ability to induce a totipotent state is limited by the simultaneous cross-activation of FGF, Nodal, and Wnt pathways. This indicates that the output of one pathway is often modulated by the concurrent activity of others, creating a balanced signaling environment [22] [21].

- Patterning through Antagonism: The establishment of signaling gradients is often achieved through antagonists. For instance, the hypoblast tissue secretes antagonists of Nodal to restrict its activity to the posterior region of the embryo, thereby ensuring the primitive streak forms in the correct location [15]. Similarly, BMP signaling is antagonized in the anterior region to permit neural induction from the ectoderm.

Table 1: Key Pathway Interactions in Early Germ Layer Patterning

| Interaction | Biological Effect | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Wnt & Nodal Synergy | Co-operatively induce primitive streak formation and mesendodermal genes [15] [3]. | Mouse embryo and gastruloid models. |

| BMP & FGF/Nodal/Wnt | Cross-activation of FGF, Nodal, and Wnt constrains BMP-mediated totipotency induction [22] [21]. | Mouse embryonic stem cell culture. |

| Nodal Antagonism | Confines Nodal activity and primitive streak to the posterior embryo [15]. | Chick and mouse embryo studies. |

| Wnt & BMP Coordination | Low BMP with WNT promotes intermediate mesoderm; high BMP with WNT promotes lateral plate mesoderm [19]. | hPSC differentiation to intermediate mesoderm. |

Quantitative Dynamics and Signaling Thresholds

The fate of a cell is often determined by the specific concentration and duration of signal exposure. Quantitative data from in vitro differentiation protocols provide critical insights into these thresholds.

Table 2: Signaling Thresholds for Guiding hPSC Differentiation

| Target Germ Layer / Cell Type | Signaling Inputs | Key Markers Induced | Protocol Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesoderm Progenitors (MP) | 3 μM CHIR99021 (Wnt agonist) for 48 h [19]. | TBXT+/MIXL1+ [19] | [19] |

| Intermediate Mesoderm (IM) | 3 μM CHIR99021 + 4 ng/mL BMP4 for 48 h [19]. | OSR1+/GATA3+/PAX2+ [19] | [19] |

| Primitive Streak / Mesendoderm | 100 ng/mL Activin A (Nodal agonist) + 3 μM CHIR99021 for 48 h [19]. | TBXT+/MIXL1+ [19] | [19] |

| Lateral Plate Mesoderm | High BMP4 concentration (e.g., 100 ng/mL) [19]. | (Inferred from text) | [19] |

The data in Table 2 highlight how precise modulation of pathway activity is essential for specific outcomes. For example, a consistent concentration of the Wnt agonist CHIR99021 (3 μM) is used to derive mesoderm progenitors, but the subsequent fate of those progenitors is determined by the presence and concentration of BMP4.

Experimental Protocols: Modeling Germ Layer FormationIn Vitro

The following protocol, adapted from recent literature, demonstrates a robust method for differentiating human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) into intermediate mesoderm (IM) cells, showcasing the practical application of signaling pathway modulation.

Protocol: Directed Differentiation of hiPSCs to Intermediate Mesoderm

Objective: To generate OSR1+/GATA3+/PAX2+ intermediate mesoderm cells from a feeder-free hiPSC culture [19].

Key Reagents:

- hiPSC Line: UCSD167i-99-1 (or any well-characterized line)

- Basal Medium: mTeSR1 or mTeSR Plus

- Matrigel: hPSC-qualified, for coating plates

- CHIR99021: 3 μM (Wnt pathway agonist)

- BMP4: 4 ng/mL (BMP pathway ligand)

Methodology:

- Maintenance: Culture hiPSCs as colonies in feeder-free conditions on Matrigel-coated plates in mTeSR Plus medium. Passage cells regularly to maintain them in an undifferentiated state.

- Mesoderm Progenitor Induction (Day 0-2): Initiate differentiation by replacing the maintenance medium with a medium containing 3 μM CHIR99021. Culture the cells for 48 hours. This step will induce the formation of TBXT+/MIXL1+ mesoderm progenitor cells.

- Intermediate Mesoderm Induction (Day 2-4): At the 48-hour mark, switch the medium to one containing a combination of 3 μM CHIR99021 and 4 ng/mL BMP4. Culture the cells for a further 48 hours.

- Validation (Day 4): Harvest cells and perform molecular characterization to confirm IM identity. This can include:

- Immunofluorescence Staining: for OSR1, GATA3, and PAX2 proteins.

- RT-qPCR: to quantify the upregulation of OSR1, GATA3, and PAX2 mRNA.

- Flow Cytometry: to determine the percentage of OSR1+/GATA3+/PAX2+ cells in the population.

Critical Considerations: This protocol emphasizes the suppression of high Nodal signaling during the mesoderm step and the use of a low, defined concentration of BMP4 for IM specification, which enhances efficiency and reproducibility compared to earlier methods [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents used in the featured protocol and broader research into these signaling pathways.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Pathway Modulation

| Reagent / Tool | Signaling Pathway Target | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | Wnt/β-catenin | Small molecule agonist that inhibits GSK-3, stabilizing β-catenin and activating canonical Wnt signaling. Used to direct mesoderm differentiation [19]. |

| BMP4 | BMP | Recombinant protein ligand that activates BMP/SMAD1/5/8 signaling. Concentration dictates mesoderm sub-type (e.g., IM vs. LPM) [19]. |

| Activin A | Nodal/TGF-β | Recombinant protein that activates Nodal/SMAD2/3 signaling. Used at high concentrations to specify definitive endoderm [19]. |

| FGF2 (bFGF) | FGF | Recombinant protein ligand that activates the MAPK/ERK pathway. Supports pluripotency and is involved in mesoderm maintenance and patterning [18] [19]. |

| DKK1 | Wnt/β-catenin | Recombinant protein antagonist of Wnt signaling by binding to LRP5/6 co-receptors. Used to inhibit Wnt pathway activity [15]. |

| SB431542 | Nodal/TGF-β | Small molecule inhibitor of the TGF-β type I receptor ALK5, which also inhibits Nodal signaling. Used to block SMAD2/3 phosphorylation [21]. |

| N-pentanoyl-2-benzyltryptamine | N-pentanoyl-2-benzyltryptamine, CAS:343263-95-6, MF:C22H26N2O, MW:334.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DIBA | DIBA, CAS:171744-39-1, MF:C26H22N4O6S4, MW:614.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Signaling Networks and Workflows

Computational diagrams are invaluable for understanding the complex relationships and experimental workflows in germ layer patterning.

Signaling Network in Germ Layer Specification

This diagram illustrates the core interactions between the BMP, Nodal, FGF, and Wnt pathways during the early stages of germ layer patterning.

Experimental Workflow for IM Differentiation

This diagram outlines the sequential two-step protocol for differentiating hiPSCs into intermediate mesoderm cells.

The coordinated actions of the BMP, Nodal, FGF, and Wnt signaling pathways form the fundamental language of germ layer patterning during gastrulation. A quantitative understanding of their individual mechanisms, intricate crosstalk, and concentration-dependent effects is no longer a fundamental biological quest but a prerequisite for advancing applied biomedical science. The development of robust in vitro differentiation protocols, as detailed in this whitepaper, provides a tractable platform for deconstructing this complexity and for generating specific cell types for regenerative medicine and disease modeling. Future research will increasingly focus on the dynamic, real-time visualization of these signaling activities in advanced models like gastruloids [3], coupled with computational modeling to predict cellular outcomes. Furthermore, integrating genetic and epigenetic data will provide a more holistic view of how these extrinsic signals are interpreted to lock in cell fate. Mastering this signaling code is the key to unlocking the full potential of stem cell-based therapies and building more accurate models of human development and disease.

Transcription Factor (TF) networks form the core regulatory system that executes the developmental blueprint for cell identity, particularly during the pivotal embryonic stage of gastrulation. This process transforms a simple ball of cells into a structured embryo with multiple germ layers, establishing the foundational body plan. The molecular basis of this transformation lies in a complex gene regulatory code comprising the DNA-binding specificities of TFs and their combinatorial interactions [23]. While all cells in an organism share the same genetic material, it is the precise spatiotemporal activity of these TF networks that dictates cellular diversity, determining whether a cell becomes part of the nervous system, muscle, or other tissues.

Gastrulation represents a critical period in development where these networks are most active, directing the formation of ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. Research on reef-building corals of the genus Acropora, phylogenetically ancient cnidarians, has revealed that even morphologically conserved gastrulation processes can involve strikingly divergent transcriptional programs between species that diverged approximately 50 million years ago [24]. This phenomenon, known as developmental system drift, demonstrates that different genetic pathways can achieve similar morphological outcomes, highlighting the flexibility and evolvability of TF networks while maintaining core functional outputs essential for embryonic viability.

Theoretical Framework: Architecture of TF Networks

Core Network Components and Their Functions

TF networks operate through sophisticated architectural principles that enable precise control of gene expression. The network comprises several interconnected components:

- Network Kernels: Highly conserved, inflexible subcircuits that define the essential identity of a developmental process. In Acropora gastrulation, a subset of 370 differentially expressed genes was identified as up-regulated at the gastrula stage in both species, forming a conserved regulatory kernel with roles in axis specification, endoderm formation, and neurogenesis [24].

- Pioneer Transcription Factors: Specialized factors with the unique ability to bind condensed chromatin and initiate chromatin remodeling, thereby making genomic regions accessible to other TFs. These factors act as epigenomic pioneers, programming the epigenome during successive steps of cell specification [25].

- Composite Regulatory Elements: Genomic sequences where multiple TFs bind cooperatively in a DNA-dependent manner, creating unique binding specificities not present in individual TFs.

Hierarchy of Transcriptional Control

A multi-layered hierarchical control system governs cell fate determination during gastrulation:

- Pioneer Layer: Pioneer TFs, such as FoxA family members, initially access compacted chromatin and initiate localized decondensation, enabling subsequent TF binding in previously inaccessible genomic regions [25].

- Specification Layer: Tissue-restricted TFs establish broad developmental domains through combinatorial control mechanisms.

- Differentiation Layer: Terminal selector TFs activate genes that define specific cellular phenotypes and functional characteristics.

This hierarchical organization creates a progressive restriction of developmental potential, guiding cells from pluripotent states to committed fates through a series of irreversible decisions executed at the transcriptional level.

Figure 1: Hierarchical organization of transcription factor networks showing progressive fate restriction.

Experimental Methodologies for Mapping TF Networks

Protein-DNA Interaction Mapping Techniques

Advanced methodologies enable comprehensive mapping of TF networks, providing insights into their structure and function during gastrulation:

- CAP-SELEX (Consecutive-Affinity-Purification Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment): A high-throughput in vitro method that simultaneously identifies individual TF binding preferences, TF-TF interactions, and the DNA sequences bound by interacting complexes. Recently scaled to a 384-well microplate format, this approach has screened over 58,000 TF-TF pairs, identifying 2,198 interacting pairs with distinct binding preferences [23].

- ChIP-Seq (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by Sequencing): Maps genome-wide binding sites for specific TFs in vivo by crosslinking proteins to DNA, immunoprecipitating with TF-specific antibodies, and sequencing bound DNA fragments.

- HT-SELEX (High-Throughput Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment): Determines binding specificities of individual TFs using iterative selection and amplification of bound DNA sequences.

Computational Network Inference Approaches

Computational methods leverage gene expression data to reconstruct functional TF networks:

- NetProphet: An algorithm that integrates coexpression and differential expression analyses following TF perturbation to predict thousands of direct, functional regulatory interactions. This approach has demonstrated superior identification of functional TF-promoter interactions compared to binding data alone [26].

- WGCNA (Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis): Identifies modules of co-expressed genes and correlates these modules with developmental stages or experimental treatments. This method has successfully mapped 277 TF networks during striatal neuron development, revealing crucial factors like Meis2 and Six3 for neuronal survival [27].

- ChEA3 (Transcription Factor Enrichment Analysis): A web-based tool that predicts TFs associated with user-input gene sets by comparing them to TF target gene sets assembled from multiple orthogonal omics datasets, including ChIP-seq, co-expression, and TF perturbation data [28].

Figure 2: Experimental workflows for mapping transcription factor networks.

Quantitative Data from TF Network Studies

Table 1: Key quantitative findings from recent TF network studies

| Study Type | Experimental System | Key Quantitative Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAP-SELEX Screening | 58,754 human TF-TF pairs | 2,198 interacting TF pairs identified (1,329 with spacing/orientation preferences; 1,131 with novel composite motifs) | [23] |

| Comparative Transcriptomics | Acropora digitifera vs A. tenuis gastrulation | 370 conserved differentially expressed genes identified despite overall GRN divergence | [24] |

| Network Mapping Algorithm | S. cerevisiae TF network | NetProphet predicted 4,000 regulatory links with functional validation; outperformed ChIP-chip data | [26] |

| Developmental TF Mapping | Striatal neuron development | 277 TF networks mapped; 740 differentially expressed TFs identified across six co-expression modules | [27] |

Table 2: TF-TF interaction patterns identified through CAP-SELEX screening

| Interaction Type | Number Identified | Characteristics | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spacing/Orientation Preferences | 1,329 pairs | TFs bind with preferred distances (typically <5bp) and orientations | Enables fine-tuning of regulatory specificity without changing motif recognition |

| Novel Composite Motifs | 1,131 pairs | Binding specificity markedly different from individual TFs | Creates new regulatory lexicon; explains how similar TFs achieve distinct functions |

| Family-Promiscuous Interactions | TEA (TEAD) family | Interact broadly across TF family boundaries | Facilitates integration of diverse signaling pathways |

| Family-Restricted Interactions | C2H2 zinc fingers | Fewer interactions than other families (P < 1.51 × 10â»â¹Â³) | Specialized regulatory functions with limited partnership capacity |

TF Networks in Gastrulation: Insights from Model Systems

Developmental System Drift in Coral Gastrulation

Studies on Acropora species gastrulation provide compelling evidence for developmental system drift, where conserved morphological outcomes are achieved through divergent molecular mechanisms. Despite approximately 50 million years of evolutionary divergence, A. digitifera and A. tenuis exhibit remarkably similar gastrulation morphology while employing significantly divergent gene regulatory networks [24]. Orthologous genes show substantial temporal and modular expression divergence, indicating GRN diversification rather than strict conservation. This divergence manifests through several mechanisms:

- Paralog Divergence: A. digitifera exhibits greater paralog divergence consistent with neofunctionalization, while A. tenuis shows more redundant expression patterns, suggesting different evolutionary paths to regulatory robustness.

- Alternative Splicing: Species-specific differences in alternative splicing patterns indicate independent peripheral rewiring of conserved regulatory modules.

- Conserved Kernels: Despite overall network divergence, a core set of 370 genes shows conserved up-regulation during gastrulation, representing the essential regulatory kernel for this process.

Resolving the Hox Specificity Paradox

The "hox specificity paradox" presents a fundamental challenge in developmental biology: how do Hox transcription factors with nearly identical TAATTA core binding motifs specify distinct developmental fates along the anterior-posterior axis? Recent research has revealed that the solution lies in DNA-guided TF interactions [23]. Rather than functioning in isolation, Hox proteins achieve specificity through cooperative binding with different TF partners, forming unique composite motifs that direct distinct transcriptional programs. This mechanism expands the regulatory lexicon far beyond what could be accomplished by simple protein-protein interactions or individual binding specificities.

Research Reagent Solutions for Gastrulation Studies

Table 3: Essential research reagents for investigating TF networks in gastrulation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| TF-TF Interaction Screening | CAP-SELEX platform (384-well format) | High-throughput identification of cooperative TF-DNA binding | Screening 58,000+ TF pairs for interactions [23] |

| Computational Prediction Tools | NetProphet algorithm | Infer direct functional TF networks from gene expression data | Mapping yeast TF network; outperformed ChIP data [26] |

| Enrichment Analysis Platforms | ChEA3 web tool | Predict TFs associated with gene sets via multi-omics integration | Identifying regulators of differentially expressed genes [28] |

| Model Organisms | Acropora corals (†A. digitifera, *A. tenuis) | Study developmental system drift and GRN evolution | Comparative transcriptomics during gastrulation [24] |

| Network Visualization | Cytoscape, Gephi, GraphViz | Create, analyze, and explore biological networks | Visualizing protein-protein and TF-gene interactions [29] |

Protocol: CAP-SELEX for Mapping TF-TF-DNA Interactions

Experimental Workflow

The CAP-SELEX protocol enables systematic identification of DNA-mediated TF-TF interactions through the following steps:

Protein Expression and Purification:

- Express human TFs (enriched for evolutionarily conserved factors) in E. coli expression systems.

- Purify TF proteins using affinity tags (e.g., His-tag, GST-tag).

- Confirm protein purity and concentration through SDS-PAGE and spectrophotometry.

TF Pair Combination:

- Combine purified TFs into pairs in 384-well microplate format (total of 58,754 pairs in recent screen).

- Include positive control pairs on each plate (e.g., CEBPD–ETV5, FOXO1–ETV5, TEAD4–CLOCK).

CAP-SELEX Cycling:

- Incubate TF pairs with random oligonucleotide library.

- Perform three consecutive affinity purification cycles to enrich for DNA sequences bound cooperatively by TF pairs.

- Use tandem affinity tags for sequential purification of cooperative complexes.

Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Sequence selected DNA ligands using high-throughput sequencing platforms.

- Apply mutual information-based algorithm to identify TF pairs with preferred spacing and orientation.

- Use k-mer enrichment comparison to detect novel composite motifs different from individual TF specificities.

Data Analysis Methods

- Mutual Information Analysis: Identifies TF pairs that show preferential binding to particular spacings and orientations relative to each other by measuring the mutual information between TF pair presence and DNA sequence features.

- Composite Motif Detection: Compares k-mer enrichment in CAP-SELEX data with enrichment observed in HT-SELEX experiments for individual TFs to identify binding specificities that emerge only when TFs bind cooperatively.

- In Vivo Validation: Cross-references identified composite motifs with ENCODE ChIP-seq data to confirm enrichment in overlapping binding peaks compared to separate peaks for individual TFs.

Discussion: Implications for Disease and Development

Network Dysregulation in Disease

Dysregulation of TF networks underlying gastrulation and cell fate specification has profound implications for human disease. Research on striatal development has demonstrated that TF networks active during embryonic development show strong correlation with pathways involved in Huntington's disease [27]. Specifically, transcriptional programs governing striatal neuron survival during development re-emerge in degenerative contexts, suggesting that understanding developmental TF networks could reveal therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative conditions. The identification of Meis2 and Six3 as crucial regulators of striatal neuron survival through global TF network mapping illustrates how systematic approaches can reveal previously unknown key players in both development and disease [27].

Evolutionary Implications

The modular architecture of TF networks facilitates evolutionary innovation while maintaining essential developmental functions. Developmental system drift observed in Acropora gastrulation demonstrates how species-specific rewiring of network peripheries can occur while conserving core regulatory kernels [24]. This evolutionary flexibility enables adaptation to diverse ecological niches while preserving essential developmental processes. The expansion of regulatory complexity through DNA-guided TF interactions [23] provides a mechanistic basis for increasing biological complexity without corresponding increases in gene number, explaining how relatively limited TF repertoires can generate immense developmental diversity.

Future Directions in TF Network Research

Several emerging frontiers promise to advance understanding of TF networks in cell fate specification:

- Single-Cell Multi-Omics Approaches: Combining single-cell RNA-seq with ATAC-seq will enable mapping TF networks at unprecedented resolution across heterogeneous cell populations during gastrulation.

- Live Imaging of TF Dynamics: Advanced microscopy techniques coupled with fluorescent tagging of TFs will reveal real-time dynamics of network interactions in living embryos.

- Synthetic Biology Applications: Engineering synthetic TF networks based on natural design principles could enable precise control of cell fate for regenerative medicine applications.

- Cross-Species Network Analysis: Comparative studies of TF networks across diverse organisms will reveal core design principles versus species-specific adaptations in developmental programming.

The continued refinement of methods like CAP-SELEX, NetProphet, and integrated analysis platforms will further illuminate how transcription factor networks execute the intricate blueprint for cell identity during gastrulation and beyond, with profound implications for understanding both developmental biology and disease pathogenesis.

Gastrulation is a fundamental process in embryogenesis during which a simple multicellular structure is reorganized into a complex body plan with multiple cell layers. The prevailing dogma has historically attributed this morphological patterning to the combined inputs of transcription factor networks and signaling morphogens. However, emerging research has revealed that cellular metabolism serves as a critical developmental regulator independent of its canonical functions in energy production and biomass accumulation [30]. This whitepaper examines the mechanistic role of glucose metabolism in instructing cell fate and morphogenetic processes during mammalian gastrulation, challenging the traditional view of metabolism as a generic housekeeping function and reframing it as an active instructor of developmental programs.

Recent research has uncovered that the mammalian embryo exhibits precisely regulated, spatiotemporally distinct metabolic waves during gastrulation that directly influence cell fate decisions and morphogenetic movements [31]. This paradigm shift establishes compartmentalized cellular metabolism as integral to guiding cell fate and specialized functions in synergy with established genetic mechanisms and morphogenic gradients. Within the broader context of cell fate specification research, these findings provide a new dimension to our understanding of how metabolic gradients contribute to embryonic patterning, reminiscent of early gradient theories first experimentally introduced over a century ago but only now being fully incorporated into a mechanistic framework [31].

Spatiotemporal Waves of Glucose Metabolism During Gastrulation

Two Distinct Metabolic Waves

Single-cell-resolution quantitative imaging of developing mouse embryos has revealed two spatially resolved, cell-type- and stage-specific waves of glucose metabolism during mammalian gastrulation [31]. These waves demonstrate exquisitely precise temporal and spatial regulation, suggesting distinct functional roles in guiding embryogenesis.

Table 1: Characteristics of Metabolic Waves During Gastrulation

| Wave Type | Developmental Stage | Spatial Localization | Primary Metabolic Pathway | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epiblast Wave | Early-to-mid gastrulation (E6.25-E6.75) | Posteriorly positioned transitionary epiblast cells anterior to primitive streak | Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway (HBP) | Fate acquisition in epiblast; preparation for primitive streak entry |

| Mesodermal Wave | Mid-to-late gastrulation (E6.75-E7.25) | Lateral mesodermal wings; mesenchymal cells after primitive streak exit | Glycolysis | Mesoderm migration and lateral expansion |

The first spatiotemporal wave of glucose metabolism occurs through the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP) to drive fate acquisition in the epiblast, while the second wave utilizes glycolysis to guide mesoderm migration and lateral expansion [31]. Notably, cells within the primitive streak itself exhibit minimal glucose uptake, concomitant with a gradual reduction in GLUT1 expression as cells enter the streak, suggesting a metabolic transition during this critical developmental transition.

Visualization of Metabolic Waves and Fate Transitions

Metabolic Gradients and Gene Expression Patterns

Analysis of spatial transcriptome datasets of mouse gastrula reveals distinct patterns of gene expression corresponding to these metabolic waves. Transcripts such as Slc2a1 (encoding GLUT1), Gpi1, Pfkb, and Ldhb from the glycolysis pathway, as well as Ogt and Gnpnat1 from the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, show graded distribution within epiblast and mesodermal wings during progressive stages of gastrulation [31]. This transcriptional regulation establishes metabolic compartmentalization that aligns with specific developmental functions.

Label-free live imaging of NAD(P)H, an endogenous auto-fluorescent readout of glycolytic activity, via multiphoton microscopy in TCF/LEF:H2B-GFP-reporter developing gastrulas demonstrates that NAD(P)H intensity is intrinsically graded over gastrulation and localized to epiblast cells anterior to the expanding primitive streak population of mesoderm progenitors [31]. This NAD(P)H intensity gradient overlaps with regions of glucose uptake, confirming the specificity of this metabolic imaging approach.

Experimental Evidence: Metabolic Perturbation Studies

Inhibitor Studies Reveal Pathway-Specific Requirements

To delineate the specific metabolic pathways responsible for gastrulation phenotypes, researchers have employed a series of targeted inhibitors that block distinct enzymatic steps of glucose metabolism [31]. These perturbation experiments provide compelling evidence for the functional importance of specific metabolic routes during development.

Table 2: Metabolic Inhibitors and Their Effects on Gastrulation

| Inhibitor | Target | Pathway Affected | Effect on Primitive Streak Development | Rescue Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-DG | Hexokinase | All glucose metabolism | Significant impairment; developmental delay | Not rescuable with standard nutrients |

| BrPA | Glucose phosphate isomerase | All glucose metabolism | Significant impairment; developmental delay | Not rescuable with standard nutrients |

| Azaserine | Fructose-6-phosphate to glucosamine-6-phosphate | Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway (HBP) | Significant impairment; distal elongation failure | Demonstrates HBP specificity |

| YZ9 | PFKFB3 | Late-stage glycolysis | No effect | Not applicable |

| Shikonin | Pyruvate kinase M2 | Late-stage glycolysis | No effect | Not applicable |

| Galloflavin | Lactate dehydrogenase | Lactate production | No effect | Not applicable |

| 6-AN | Pentose phosphate pathway | PPP | No effect | Not applicable |

| Oligomycin | ATP synthase | Oxidative phosphorylation | No effect | Not applicable |

These inhibitor studies reveal a remarkable specificity in metabolic requirements during gastrulation. Blocking the entirety of glucose metabolism with 2-DG and BrPA significantly impaired distal elongation and development of the primitive streak, indicating that epiblast cells require glucose metabolism for mesodermal transition [31]. Crucially, this effect was specifically recapitulated with azaserine, which blocks the HBP pathway, while inhibitors of late-stage glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, lactate dehydrogenase, and ATP synthase had no effect on primitive streak progression.

Quantitative Methodologies for Metabolic Analysis

Glucose Uptake Imaging

The fluorescent glucose analogue 2-NBDG enables ratiometric quantification of glucose uptake in live embryos. This technique, combined with immunofluorescence analysis of glucose transporters (GLUT1 and GLUT3), has revealed compartmentalized glucose uptake in two distinct regions: first within transitionary epiblast cells destined to form the primitive streak, and second within the lateral mesodermal wings [31]. This approach provides spatial and temporal resolution of metabolic activity at single-cell resolution within developing tissues.

NAD(P)H Autofluorescence Imaging

Multiphoton microscopy of endogenous NAD(P)H autofluorescence serves as a label-free method to image glycolytic activity in live gastrulating embryos [31]. This technique leverages the inherent fluorescence of these metabolic cofactors, avoiding potential artifacts from chemical probes or labels and enabling direct observation of metabolic states in undisturbed developing systems.

Metabolic Flux Analysis

Advanced metabolic flux analysis (MFA) techniques using isotope-labeling in vivo provide quantitative assessment of nutrient preferences in central carbon metabolism [32]. These approaches have demonstrated that glucose serves as the major nutritional source for the TCA cycle in physiological conditions, contributing more than lactate as a substrate across multiple tissue types and experimental conditions.

Molecular Mechanisms: Connecting Metabolism to Signaling

Metabolic Regulation of ERK Signaling

A critical finding in understanding how glucose metabolism instructs developmental processes is the connection between glucose metabolic waves and ERK activity. Research has demonstrated that glucose exerts its influence on gastrulation through cellular signaling pathways, with distinct mechanisms connecting glucose with ERK activity in each metabolic wave [31].

In the epiblast wave, glucose metabolism through the HBP pathway modulates ERK signaling to prepare cells for primitive streak entry, while in the mesodermal wave, glycolytic metabolism guides mesenchymal cell migration through ERK-dependent mechanisms. This coupling between metabolic activity and fundamental signaling pathways provides a mechanistic bridge between nutrient utilization and developmental patterning.

Visualization of Metabolic Signaling Integration

Metabolic Regulation of Epigenetic Modifications

Beyond direct signaling pathway modulation, metabolism influences developmental processes through epigenetic regulation. Metabolic pathways provide essential substrates for epigenetic modifications that control gene expression patterns during cell fate specification [30]. Key mechanisms include:

- Acetyl-CoA availability for histone acetylation, which alters chromatin structure and transcription factor accessibility

- S-adenosylmethionine levels for histone methylation, which can either activate or repress gene expression depending on specific residues

- NAD+ levels regulating sirtuin activity, which remove acetyl groups from histones

- α-ketoglutarate availability as a co-factor for histone and DNA demethylases, including the TET family of DNA hydroxylases

These connections establish metabolism as a central regulator of the epigenetic landscape during development, providing a direct mechanism through which nutrient availability can influence cell fate decisions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Metabolism in Gastrulation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Inhibitors | 2-DG, BrPA, Azaserine, YZ9, Shikonin, Galloflavin, 6-AN, Oligomycin | Target specific enzymatic steps to dissect functional contributions of metabolic pathways | Ex vivo embryo culture; stem cell models |

| Fluorescent Metabolic Probes | 2-NBDG (fluorescent glucose analog) | Quantitative imaging of glucose uptake at single-cell resolution | Live imaging of developing embryos |

| Endogenous Metabolic Imaging | NAD(P)H autofluorescence | Label-free imaging of glycolytic activity via multiphoton microscopy | Live metabolic imaging without perturbation |

| Isotopic Tracers | 13C-glucose, 13C-glutamine | Metabolic flux analysis (MFA) to quantify pathway utilization | Stable isotope tracing in vivo and in vitro |

| Glucose Transporter Analysis | GLUT1, GLUT3 antibodies | Immunofluorescence localization of glucose transporters | Spatial mapping of glucose uptake capacity |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Key genes: Slc2a1, Gpi1, Pfkb, Ldhb, Ogt, Gnpnat1 | Mapping metabolic gene expression patterns | Correlation of transcriptional and metabolic patterns |

| Live-Reporter Systems | TCF/LEF:H2B-GFP reporter | Simultaneous monitoring of cell fate and metabolic status | Live imaging of developing gastrulas |

| DIDS sodium salt | DIDS Chloride Channel Blocker|For Research Use | DIDS is a chloride channel blocker and RAD51 inhibitor for research. This product is For Research Use Only, not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| DMNQ | DMNQ, CAS:6956-96-3, MF:C12H10O4, MW:218.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Discussion: Implications for Developmental Biology and Disease

The findings that glucose metabolism actively instructs cell fate and morphogenesis during gastrulation have profound implications for both basic developmental biology and clinical medicine. The compartmentalization of specific metabolic pathways to distinct developmental functions reveals an additional layer of regulation in embryogenesis that operates in synergy with established transcriptional networks and morphogen gradients.

From a clinical perspective, these insights may shed light on the mechanisms underlying certain inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs) that manifest with congenital malformations despite ubiquitous expression of metabolic enzymes [30]. The tissue-specific pathologies observed in many IEMs may reflect the particular importance of specific metabolic pathways in the development of affected structures, with limited capacity for metabolic flexibility in certain cell types during critical developmental windows.

Furthermore, the emerging understanding of metabolic checkpoints - consisting of a metabolic cue, sensor molecule, and downstream effector mechanism - provides a framework for how developing tissues integrate nutrient availability with developmental progression [30]. Key metabolic sensors including mTOR (sensing amino acids and ATP) and AMPK (sensing AMP/ATP ratios) likely play crucial roles in translating metabolic status into developmental decisions, potentially including the entry and exit from diapause under conditions of nutrient stress.

The research summarized in this whitepaper establishes that glucose metabolism plays an instructive role in mammalian gastrulation that extends far beyond its traditional functions in energy production and biomass accumulation. Through two spatiotemporally distinct waves - first utilizing the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway in the epiblast and then glycolysis in the mesoderm - glucose metabolism actively guides cell fate acquisition and morphogenetic movements. These metabolic processes are mechanistically connected to key developmental signaling pathways, particularly ERK signaling, and operate in concert with established transcriptional networks to ensure robust embryonic patterning.

This paradigm shift in understanding metabolic function during development opens new avenues for research into both normal embryogenesis and developmental disorders. The tools and methodologies described herein provide a roadmap for further dissection of metabolic regulation in development, with potential applications in regenerative medicine, stem cell biology, and understanding the developmental origins of disease. As we continue to unravel the complex interplay between metabolism and development, it becomes increasingly clear that metabolic regulation represents a fundamental layer of control in building complex organisms.

In the nascent stages of mammalian development, the pluripotent epiblast undergoes a dramatic transformation, giving rise to the three primary germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—during a process known as gastrulation. This fundamental phase of embryogenesis is not solely directed by the genetic code but is orchestrated by a sophisticated layer of epigenetic regulation. Epigenetic control mechanisms, including chromatin remodeling and DNA methylation, act as critical interpreters of cellular potency, progressively restricting cell fate in response to developmental cues [33] [34]. These mechanisms establish a regulatory landscape that primes lineage-specific genes for activation or ensures the silent state of alternative lineage programs, thereby guiding cells toward their ultimate identities with remarkable precision [33] [35]. Understanding how this epigenetic landscape is written, read, and remodeled is paramount for developmental biology and holds immense promise for regenerative medicine and disease modeling. This whitepaper delves into the core mechanisms of chromatin remodeling and DNA methylation, framing their function within the context of cell fate specification during gastrulation, and provides a technical guide for researchers investigating these pivotal processes.

Core Mechanisms of Epigenetic Control

DNA Methylation and Hydroxymethylation Dynamics