Cellular Heterogeneity in Human Embryo Development: Single-Cell Insights into Fate, Function, and Clinical Translation

This article synthesizes the latest advances in understanding cellular heterogeneity during human embryogenesis, driven by single-cell omics technologies.

Cellular Heterogeneity in Human Embryo Development: Single-Cell Insights into Fate, Function, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest advances in understanding cellular heterogeneity during human embryogenesis, driven by single-cell omics technologies. It explores the foundational role of heterogeneity in lineage specification and embryonic self-organization, details cutting-edge methodological approaches for its analysis, and addresses key challenges in cell fate programming. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content provides a critical comparison of in vivo and in vitro models, highlighting implications for regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and therapeutic discovery.

The Blueprint of Life: How Cellular Heterogeneity Drives Early Human Embryogenesis

The journey from a single fertilized egg to a complex multicellular organism is a masterclass in cellular decision-making. Within a population of seemingly identical cells, molecular heterogeneity arises from a combination of transcriptional noise, stochastic gene expression, and biased regulatory networks, ultimately guiding cells toward specific fates. In the context of human embryo development, understanding this heterogeneity is not merely an academic pursuit; it is fundamental to advancing regenerative medicine, improving assisted reproductive technologies (ART), and deciphering the origins of developmental disorders. This technical guide explores the mechanisms that define cellular heterogeneity, bridging the gap between single-cell observations and the emergence of robust developmental patterns. We frame this discussion within a broader thesis that heterogeneity is not biological "noise" to be filtered out, but a critical, functional property of developing systems that enables plasticity and fate determination.

Mechanisms of Cell Fate Determination: From Speculation to Specification

Cell fate determination is the process by which a cell becomes committed to a specific developmental pathway. Historically, two primary modes of specification have been characterized: autonomous and conditional [1] [2].

Autonomous Specification

This cell-intrinsic mechanism relies on asymmetrically distributed maternal cytoplasmic determinants (proteins, mRNAs, and small regulatory RNAs) within the egg cytoplasm [2]. As the embryo cleaves, these determinants are partitioned unevenly into daughter cells, autonomously directing their fate. This process, first demonstrated by Laurent Chabry in 1887 using tunicate embryos, gives rise to mosaic development [1] [2]. A key experiment by Whittaker (1973) confirmed that isolating the posterior vegetal blastomeres (B4.1) of an 8-cell tunicate embryo, which contain the yellow crescent cytoplasm, resulted in the isolated cells producing acetylcholinesterase-positive muscle tissue, independent of any external signals [2].

Conditional Specification

In contrast, conditional specification is a cell-extrinsic process where a cell's fate is determined by its interactions with neighboring cells or concentration gradients of morphogens [1] [2]. This mechanism underpins regulative development, famously demonstrated by Hans Driesch's 1892 experiment where separated blastomeres of a 2-cell sea urchin embryo each developed into a complete, albeit smaller, larva [2]. The ability of the remaining embryonic cells to alter their fates to compensate for missing parts—a phenomenon known as regulation—highlights the plasticity and interdependence of cells in conditionally specified systems [2]. Most vertebrate embryos, including humans, exhibit a high degree of conditional specification.

Epigenetic Regulation of Fate

Cell fate determination is profoundly influenced by epigenetic mechanisms that regulate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself. These include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling [1]. These modifications, orchestrated by enzymes like DNA methyltransferases and histone acetyltransferases, respond to both intrinsic signals and extrinsic cues from the cellular microenvironment, dynamically restricting or enabling access to genetic information and thereby guiding differentiation [1].

Table 1: Modes of Cell Fate Specification

| Specification Mode | Key Driver | Developmental Pattern | Key Experimental Evidence | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous | Intrinsic, asymmetrically localized morphogenetic determinants (proteins, mRNAs) | Mosaic development | Blastomere isolation/ablation in tunicates (Chabry, 1887; Whittaker, 1973) [2] | Molluscs, annelids, tunicates |

| Conditional | Extrinsic signals from cell-cell interactions & morphogen gradients | Regulative development | Blastomere separation in sea urchins (Driesch, 1892); transplantation experiments [2] | Most vertebrates, including mammals |

Analytical Frameworks: Dissecting Heterogeneity with Single-Cell Technologies

Modern developmental biology relies on high-resolution technologies to capture and quantify cellular heterogeneity.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq)

scRNA-seq has revolutionized our ability to profile gene expression profiles at the individual cell level, revealing previously obscured cell subpopulations and continuous developmental trajectories [3]. A 2025 study leveraging Smart-seq2-based scRNA-seq compared feeder-free extended pluripotent stem cells (ffEPSCs) and their parental human embryonic stem cells (ESCs), uncovering distinct subpopulations and mapping the transition process from a primed to an extended pluripotent state [4].

Key scRNA-seq Protocols: Multiple scRNA-seq protocols have been developed, each with distinct advantages and limitations [3].

- Full-length transcript protocols (e.g., Smart-Seq2, MATQ-Seq) excel at detecting more genes and are ideal for isoform usage analysis and identifying RNA editing.

- 3' or 5' end counting protocols (e.g., Drop-Seq, inDrop, 10x Genomics Chromium) enable higher throughput at a lower cost per cell, making them suitable for analyzing complex tissues and identifying rare cell types [3].

The incorporation of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) is a critical advancement, labeling each mRNA molecule during reverse transcription to control for amplification biases and improve quantitative accuracy [3].

Table 2: Key scRNA-seq Protocols for Studying Heterogeneity

| Protocol | Transcript Coverage | Amplification Method | UMIs | Primary Advantage | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart-Seq2 | Full-length | PCR (Template-switching) | No | High sensitivity, detects more genes [3] | Low |

| MATQ-Seq | Full-length | PCR | Yes | Superior for low-abundance genes [3] | Low |

| Drop-Seq | 3' end | PCR | Yes | Low cost per cell, high throughput [3] | High (Thousands of cells) |

| 10x Genomics Chromium | 3' end | PCR | Yes | High cell throughput, standardized | High (Thousands to millions of cells) |

Volumetric Trans-Scale Imaging

While scRNA-seq reveals molecular states, understanding the spatial context of heterogeneity is equally critical. The AMATERAS-2 volumetric imaging system addresses this by enabling simultaneous observation of millions of cellular dynamics in centimeter-wide three-dimensional tissues and embryos [5]. This system uses a custom giant lens system (×2 magnification, NA 0.25) and a high-megapixel CMOS camera to achieve a ultra-large field-of-view (FOV) of approximately 1.5 × 1.0 cm² with a transverse spatial resolution of about 1.1 µm [5]. Its application in time-lapse imaging of quail embryo development allowed for tracking the movement of over 400,000 vascular endothelial cells across more than 24 hours, providing a powerful tool for linking cell behavior to fate outcomes in a native spatial context [5].

Experimental Protocols: From Data Acquisition to Fate Mapping

Protocol: Smart-seq2 for High-Resolution scRNA-seq

The following methodology is adapted from protocols used in recent studies of human pluripotency [4] [3].

- Single-Cell Isolation: Viable individual cells are extracted from the tissue of interest (e.g., human ESCs or embryo-derived cells). For fragile cells or frozen samples, single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) can be used as an alternative.

- Cell Lysis and Reverse Transcription: Individual cells are lysed, and mRNA is captured using poly(T) primers. Reverse transcription is performed using Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase with template-switching activity. This adds a universal adapter sequence to the 5' end of the cDNA.

- cDNA Amplification: The full-length cDNA is amplified via PCR using primers binding to the universal adapters. This non-linear amplification generates sufficient material for library construction.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The amplified cDNA is fragmented and ligated to sequencing adapters. Libraries are then sequenced on a high-throughput platform, generating full-length or near-full-length transcript data.

Protocol: Pseudotime Analysis for Mapping Fate Transitions

Pseudotime analysis is a computational method that orders single cells along a hypothetical timeline of a dynamic process, such as differentiation, based on their transcriptomic similarity [4].

- Data Preprocessing: scRNA-seq data is filtered for quality, normalized, and log-transformed. Highly variable genes are selected for downstream analysis.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Data is projected into a lower-dimensional space using techniques like PCA (Principal Component Analysis) or UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection).

- Trajectory Inference: A trajectory graph is constructed by connecting cells in the reduced space. The algorithm identifies a starting cell (e.g., a pluripotent stem cell) and then orders all other cells based on their transcriptomic progression along the branches of the graph. This ordering represents the "pseudotime."

- Validation and Interpretation: The resulting trajectory is validated against known markers. Branch points in the trajectory represent fate decisions, and genes whose expression changes along the pseudotime are identified as drivers of the transition, as was done to map the ESC to ffEPSC transition [4].

Protocol: Metabolic Profiling of Spent Culture Media (SCM)

In the context of IVF and human embryo research, a non-invasive method to assess embryo viability involves analyzing the spent culture media (SCM) [6].

- Sample Collection: Culture media in which a single preimplantation embryo has been grown is carefully collected, avoiding contamination.

- Metabolite Analysis: The composition of low-molecular-weight metabolites (e.g., amino acids, energy substrates like pyruvate, lactate, and glucose) is profiled using techniques like mass spectrometry or NMR.

- Data Integration and Outcome Correlation: Absolute metabolite concentrations are quantified. Consumption (depletion from the medium) or secretion (accumulation in the medium) profiles are then correlated with clinical outcomes such as blastocyst formation or implantation success through meta-analysis [6].

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

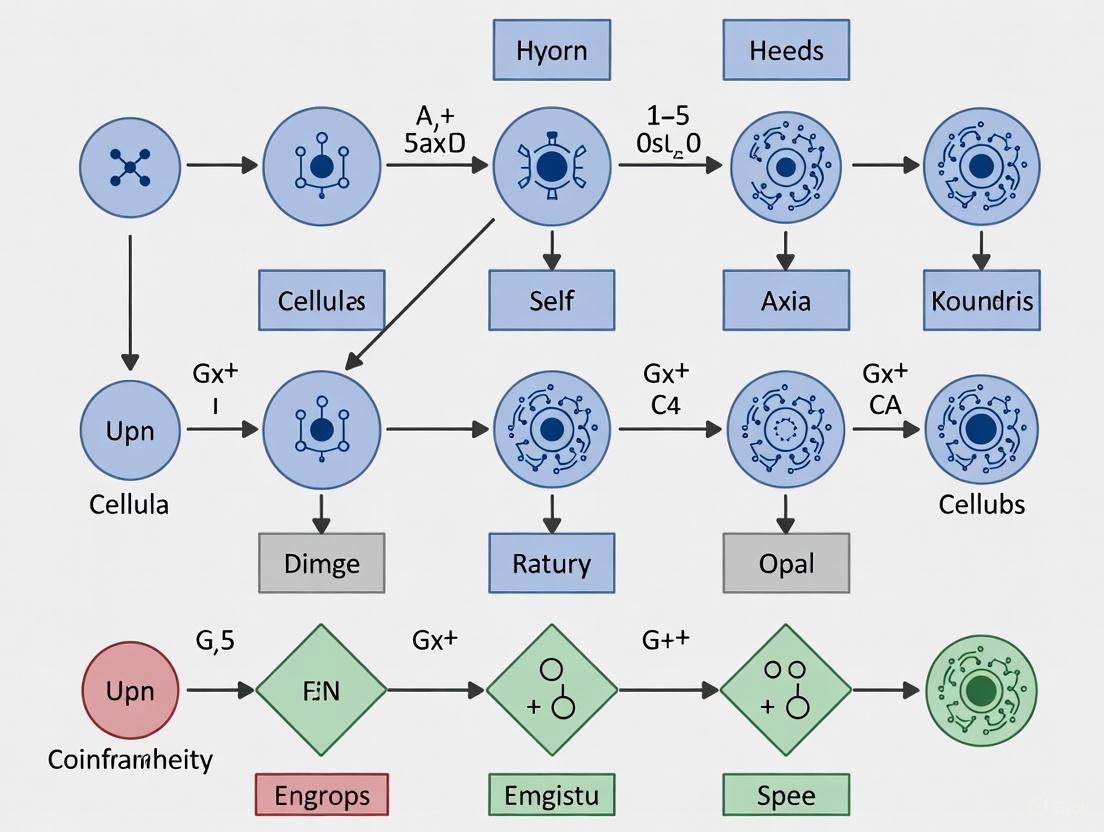

Signaling and Specification Pathways

The following diagram summarizes the key mechanisms of cell fate specification and their interactions.

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow

The standard workflow for a single-cell RNA sequencing experiment, from sample to insight, is outlined below.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Cellular Heterogeneity

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq Protocols | Profiling transcriptomes of individual cells. | Smart-seq2 (high gene detection) [4] [3]; Drop-seq/10x Genomics (high throughput) [3]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Labeling individual mRNA molecules to correct for PCR amplification bias, enabling accurate transcript counting. | Used in CEL-Seq, MARS-Seq, Drop-Seq, 10x Genomics, and other protocols [3]. |

| T2T Genome Database | Complete, telomere-to-telomere human genome reference for accurate sequencing read alignment and repeat element analysis. | Used to identify stage-specific repeat elements in pluripotency studies [4]. |

| Volumetric Imaging Systems | Long-term, large-field-of-view 3D imaging of massive cell populations in tissues and embryos. | AMATERAS-2 system: 1.5x1.0 cm² FOV, ~1.1 µm resolution [5]. |

| Cre-lox Lineage Tracing | Mapping the differentiation path and progeny of specific cell populations in vivo. | Use of colorful reporters like "brainbow" in transgenic mice [1]. |

| Spent Culture Media (SCM) | Non-invasively assessing embryo viability and metabolic activity in IVF. | Metabolites like amino acids and glucose are profiled [6]. |

The journey from a single fertilized oocyte to a complex, multi-lineage blastocyst represents one of the most critical yet least understood periods in human development. Pre-implantation embryogenesis encompasses a meticulously orchestrated sequence of molecular events, including zygotic genome activation (ZGA), maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT), and the first cell fate decisions that establish the foundational lineages of the embryo proper and its supporting tissues [7] [8]. For decades, technical limitations and ethical restrictions on human embryo research have rendered this phase a "black box," with fundamental mechanisms inferred from model organisms. The advent of single-cell omics technologies has fundamentally transformed this landscape, enabling unprecedented resolution of the transcriptional, epigenomic, and proteomic changes that govern cellular heterogeneity and lineage specification during this pivotal window [9] [7].

These advancements are not merely academic; they hold profound implications for addressing human infertility, understanding the causes of early miscarriage, and improving assisted reproductive technologies [10] [7]. Furthermore, the rise of stem cell-based embryo models, such as blastoids and gastruloids, necessitates rigorous benchmarking against authentic in vivo reference data to validate their fidelity [10] [11]. This technical guide synthesizes the most current methodologies, foundational discoveries, and analytical frameworks in single-cell omics that are charting the complex landscape of human pre-implantation development, providing researchers with the tools to decipher the molecular logic of life's earliest stages.

Methodological Foundations: Single-Cell Omics Technologies

The resolution of single-cell analysis has progressed dramatically, moving from broad transcriptional profiling to multi-layered, multimodal integration.

Core Sequencing and Proteomic Technologies

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): This remains the workhorse for profiling transcriptional heterogeneity. Modern platforms can sequence millions of cells simultaneously, capturing dynamic gene expression from the zygote to the blastocyst stage. Standardized processing pipelines, using a common genome reference (e.g., GRCh38), are critical for minimizing batch effects when integrating multiple datasets [10] [7].

- Single-Cell Proteomics (SCP): Mass spectrometry-based technologies like single-cell proteomics by MS (SCoPE-MS) and nanodroplet processing in one pot for trace samples (NanoPOTS) now enable the quantification of thousands of proteins from a single oocyte or embryo [8]. Data-independent acquisition (DIA) modes, such as diaPASEF, have been particularly effective, identifying over 3,600 protein groups from a single 8-cell embryo and providing a direct view of the effector molecules driving development [8].

- Multi-Omic Integration: The field is increasingly moving toward simultaneous measurement of multiple modalities. Foundation models like scGPT (pretrained on over 33 million cells) are now capable of integrating transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data, enabling zero-shot cell type annotation and in silico perturbation modeling [12].

Analytical and Computational Frameworks

The complexity of single-cell data demands sophisticated computational tools.

- Data Integration: Methods like fast mutual nearest neighbor (fastMNN) are employed to correct for technical variation and integrate multiple datasets into a unified reference, allowing cells from different studies to be embedded in a common landscape [10].

- Trajectory Inference: Tools like Slingshot use reduced-dimension embeddings (e.g., UMAP) to reconstruct developmental trajectories and calculate pseudotime, ordering cells along their inferred developmental continuum [10].

- Regulatory Network Analysis: Single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering (SCENIC) infers gene regulatory networks and transcription factor activity from scRNA-seq data, revealing the master regulators controlling lineage decisions [10].

Table 1: Core Single-Cell Omics Technologies in Pre-implantation Research

| Technology | Key Function | Representative Tools/Methods | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq | Transcriptome profiling | fastMNN, Standardized Pipelines | Cell identities, lineage trajectories |

| Single-Cell Proteomics | Protein quantification | SCoPE-MS, NanoPOTS, diaPASEF | Protein abundance, post-translational states |

| Multi-Omic Integration | Combined data analysis | scGPT, scPlantFormer | Unified cell state models |

| Trajectory Inference | Lineage modeling | Slingshot | Pseudotime, developmental paths |

| Network Inference | Regulatory dynamics | SCENIC | Transcription factor networks |

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for single-cell multi-omics analysis of pre-implantation development, from sample collection to biological interpretation.

The Transcriptomic Roadmap from Zygote to Blastocyst

Large-scale integration of scRNA-seq datasets has yielded a high-resolution transcriptomic roadmap of human pre-implantation development, serving as an essential universal reference.

Embryonic Genome Activation and Lineage Segregation

A pivotal finding from recent studies is the timing of embryonic genome activation (EGA). While a major wave of EGA occurs around the 8-cell stage, a significant immediate EGA (iEGA) initiates as early as the one-cell stage in both mice and humans [13]. This iEGA begins within hours of fertilization, initially from the maternal genome, with paternal genomic transcription following around 10 hours post-fertilization [13]. This low-magnitude transcriptional wave is continuous with the previously described "minor EGA" and is critical for the emergence of totipotency.

The first lineage branch point becomes evident around day 5 (E5), as the inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm (TE) cells diverge [10]. This is followed by the bifurcation of the ICM into the epiblast (EPI), which will form the embryo proper, and the hypoblast, which gives rise to the yolk sac [10] [7]. Trajectory inference analysis based on UMAP embeddings has delineated three main trajectories originating from the zygote, corresponding to the epiblast, hypoblast, and TE lineages, each associated with hundreds of transcription factors showing modulated expression over pseudotime [10].

Key Molecular Regulators of Cell Fate

SCENIC analysis and differential expression studies have identified critical transcription factors and markers associated with each lineage and developmental transition.

- Totipotency and Early EGA: Transcription factors such as DUXA and FOXR1 are highly expressed during morula stages but decline as lineages specify [10].

- Epiblast Trajectory: Pluripotency markers NANOG and POU5F1 (OCT4) are highly expressed in the pre-implantation epiblast, decreasing after implantation, while HMGN3 expression increases in post-implantation stages [10].

- Hypoblast Trajectory: GATA4 and SOX17 are early markers, with FOXA2 and HMGN3 becoming prominent in later stages [10].

- TE/Trophectoderm Trajectory: CDX2 and NR2F2 are expressed early, while GATA2, GATA3, and PPARG expression increases during cytotrophoblast (CTB) differentiation [10].

Table 2: Key Lineage Markers and Regulatory Factors in Human Pre-implantation Development

| Developmental Stage/Cell Lineage | Key Molecular Markers & Regulators | Function/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Morula | DUXA, FOXR1 | Associated with totipotency; decrease during lineage specification [10] |

| Inner Cell Mass (ICM) | PRSS3, POU5F1, NANOG | Distinguishes ICM from TE [10] |

| Epiblast (EPI) | POU5F1, NANOG, SOX2, HMGN3 (late) | Pluripotent lineage for embryo proper [10] [7] |

| Hypoblast | GATA4, SOX17, FOXA2, HMGN3 (late) | Gives rise to primitive endoderm and yolk sac [10] |

| Trophectoderm (TE) | CDX2, NR2F2, GATA2, GATA3 | Forms extra-embryonic tissues, including placenta [10] [7] |

| Cytotrophoblast (CTB) | GATA3, PPARG | Differentiated from TE [10] |

Figure 2: Simplified transcriptional roadmap of human pre-implantation development, showing key lineage decisions and associated molecular markers.

Beyond Transcription: The Emergence of Multi-Omic Profiles

While transcriptomics reveals cellular potential, proteomics and other modalities reveal the functional state, and their integration is yielding a more complete picture.

Proteomic Landscapes of Pre-implantation Development

Recent advances in ultrasensitive proteomics, such as the comprehensive solution for ultrasensitive proteomic technology (CS-UPT), have enabled deep coverage of the proteomic landscape. Applying the diaPASEF mode to single human oocytes and embryos has allowed for the identification of over 3,600 protein groups from a single 8-cell embryo [8]. This has revealed critical insights:

- Correlation with Transcriptomics: While generally correlated, the timing of protein abundance for many key regulators does not perfectly mirror their mRNA levels, highlighting the importance of post-transcriptional regulation during EGA and the MZT [8].

- Functional Pathways: Proteomic data has been instrumental in confirming the activity of specific metabolic and signaling pathways that are not apparent from transcriptomics alone, providing a more direct view of the biochemical processes executing the developmental program.

Benchmarking Stem Cell-Derived Embryo Models

A primary application of these integrated in vivo references is the authentication of stem cell-based embryo models (e.g., blastoids). The comprehensive human embryo reference tool allows researchers to project their query datasets (e.g., from a blastoid experiment) onto the in vivo UMAP reference to annotate cell identities and assess transcriptional fidelity [10]. This approach has revealed risks of misannotation when such relevant references are not used. For instance, cells in a model might express a handful of expected markers but occupy an entirely wrong location in the transcriptional landscape compared to real embryos, indicating a lack of true fidelity [10].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Embryo Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated scRNA-seq Reference | Benchmarking and annotation of query datasets | A universal reference integrating 3,304 cells from zygote to gastrula [10] |

| Standardized Genome Reference | Data processing and alignment | GRCh38 (v.3.0.0) to minimize batch effects [10] |

| Ultra-Sensitive Proteomics Kits | Protein extraction and preparation for MS | CS-UPT2 workflow using diaPASEF mode for deep coverage [8] |

| Tandem Mass Tags (TMTs) | Multiplexed protein quantification | Used in isobaric label-based SCP methods like SCoPE2 [8] |

| Microfluidic Platforms | Low-input sample processing | NanoPOTS or OAD chips for handling trace samples [8] |

| Computational Platforms | Data integration and analysis | scGPT, BioLLM for foundation model-based analysis [12] |

Single-cell omics has irrevocably transformed our understanding of human pre-implantation development, moving from a coarse, morphology-based view to a detailed molecular narrative of genome activation, lineage specification, and the emergence of cellular heterogeneity. The creation of integrated reference atlases and the ability to profile the proteome of single embryos provide an unprecedented resource for both basic science and clinical applications.

The future of the field lies in deeper multi-omic integration, including spatial transcriptomics and epigenomics, to capture the full regulatory context. Furthermore, the development of more sophisticated computational foundation models like scGPT promises to unify these disparate data types into predictive models of development [12]. Finally, translating these discoveries to the clinic, for example by identifying proteomic signatures of poor-quality (PQ) embryos to improve IVF outcomes, represents a critical and achievable goal [8]. As these technologies continue to mature, they will undoubtedly illuminate the remaining mysteries of life's first days.

The emergence of the first mammalian cell lineages—the trophectoderm (TE), epiblast (EPI), and primitive endoderm (PrE)—represents a fundamental process in embryonic development, establishing the foundational cellular heterogeneity required for forming the embryo proper and its supporting tissues [14]. In humans, this lineage specification occurs during the pre-implantation period, culminating in the formation of a blastocyst ready for implantation into the uterus approximately 7 days after fertilization [15]. The inner cell mass (ICM) of this blastocyst subsequently differentiates into the pluripotent EPI, which gives rise to all three germ layers of the embryo, and the PrE, which forms the extra-embryonic yolk sac [14]. The TE, an extra-embryonic lineage, forms the outer layer of the blastocyst and develops into the placenta, facilitating implantation and maternal-fetal exchange [16] [15].

Studying these processes in humans presents significant challenges due to the scarcity of human embryo samples, ethical regulations, and the limited translatability of findings from animal models like mice, despite their invaluable contributions to our foundational knowledge [15] [10]. Key differences exist between species; for instance, the activation of the zygote genome and lineage-specific gene expression is delayed in humans, and the formation of the amnion occurs ahead of primitive streak development, unlike in mice [15]. Recent breakthroughs in generating three-dimensional (3D) stem cell-based embryo models (SCBEMs), such as blastoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells, now offer unprecedented tools to explore the molecular mechanisms and cellular interactions underlying this critical phase of human development [16] [15]. These models are pivotal for advancing our understanding of implantation failure, early pregnancy loss, and the causes of infertility [16].

Molecular Mechanisms of the First Lineage Decisions

The journey from a single totipotent zygote to a multilayered blastocyst is governed by a complex interplay of transcription factors, signaling pathways, and biophysical factors like cell position and polarity.

Transcription Factor Networks and Key Signaling Pathways

The first lineage decision involves the separation of the ICM from the TE. Critical transcription factors display lineage-specific expression patterns early in this process [14]:

- CDX2 and GATA3: These are pivotal for TE specification. CDX2 expression, beginning at the eight-cell stage, represses ICM-specific genes like OCT4 and Nanog in outer cells and promotes a TE-specific gene regulatory network [14].

- OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2: These form the core pluripotency network. SOX2 initiates at the four-cell stage and becomes restricted to the inner cells by the 16-cell stage, where it is required to maintain EPI cells in an undifferentiated state [14]. While OCT4 expression is not initially restricted to the ICM, its loss leads to ICM cells expressing TE markers, highlighting its role in maintaining pluripotency [14].

The Hippo signaling pathway integrates cues from cell position and polarity to consolidate these initial transcriptional differences [14]. In outer cells, which have a contact-free apical membrane, the Hippo pathway is inactive. This allows the unphosphorylated transcriptional coactivator YAP1 to translocate to the nucleus. There, it interacts with TEAD4 to drive the expression of TE-specific genes like Cdx2 and Gata3 while repressing pluripotency genes like Sox2 [14]. Conversely, in the apolar inner cells, which are completely enclosed by cell-cell contacts, the Hippo pathway is active. This leads to the phosphorylation and cytoplasmic sequestration of YAP1, preventing the induction of the TE program and thereby permitting ICM fate [14].

The second lineage decision occurs within the ICM, resulting in the formation of the EPI and PrE. Key markers for this separation include NANOG for the EPI and GATA4 and SOX17 for the PrE [10]. Single-cell RNA-sequencing analyses have revealed that genes such as TDGF1 and POU5F1 are associated with the epiblast trajectory, while GATA4 is specifically associated with the hypoblast (PrE) trajectory [10].

Table 1: Key Transcription Factors in Early Lineage Specification

| Lineage | Key Transcription Factors | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Trophectoderm (TE) | CDX2, GATA3, TEAD4 | Represses pluripotency genes; promotes TE maturation and placental development [14]. |

| Epiblast (EPI) | OCT4 (POU5F1), NANOG, SOX2, TDGF1 | Maintains pluripotent state; forms the embryo proper [14] [10]. |

| Primitive Endoderm (PrE) | GATA4, SOX17, GATA6 | Specifies hypoblast lineage; forms the yolk sac [10]. |

Models of Cell Fate Specification

Historically, two primary models have been proposed to explain the initial segregation of the TE and ICM:

- The Inside-Outside Model: This model posits that a cell's fate is determined by its position within the embryo. Inner cells, exposed to a different microenvironment, become ICM, while outer cells become TE [14]. Experimental support comes from studies showing that repositioning cells forces them to adopt the fate of their new location [14].

- The Polarity Model: This model suggests that the inheritance of the apical membrane domain during cell division dictates fate. A cell inheriting the apical domain becomes polar and biased toward TE, while a cell that does not becomes apolar and forms the ICM [14].

Recent research, particularly the elucidation of the Hippo pathway's role, has largely reconciled these two models. Cell position influences cell polarity and the extent of cell-cell contact, which are sensed by molecular machinery like angiomotin (AMOT), ultimately regulating the Hippo pathway and its control over YAP1/TAZ localization to direct cell fate [14].

Quantitative Data in Lineage Specification

Advanced transcriptomic technologies have enabled the quantitative profiling of lineage specification, providing a high-resolution roadmap of early human development.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Markers Identified via Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing

| Cell Type / Stage | Genetic Marker | Function / Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Morula | DUXA | Associated with zygotic genome activation [10]. |

| Inner Cell Mass (ICM) | PRSS3 | A unique marker for ICM cells [10]. |

| Epiblast (EPI) | POU5F1 (OCT4), TDGF1 | Core pluripotency factors [10]. |

| Primitive Endoderm (PrE) / Hypoblast | GATA4, SOX17 | Master regulators of hypoblast specification [10]. |

| Trophectoderm (TE) | CDX2, NR2F2 | Early markers of TE lineage [10]. |

| Cytotrophoblast (CTB) | GATA2, GATA3, PPARG | Markers of mature TE derivatives [10]. |

| Primitive Streak (PriS) | TBXT (Brachyury) | Key regulator of mesoderm formation and gastrulation [10]. |

| Amnion | ISL1, GABRP | Identifies extra-embryonic amniotic ectoderm [10]. |

| Extra-Embryonic Mesoderm (ExE_Mes) | LUM, POSTN | Characteristic markers for this supportive lineage [10]. |

The integration of multiple single-cell RNA-sequencing datasets has created a universal reference map of human development from the zygote to the gastrula stage [10]. This resource allows for the unbiased benchmarking of stem cell-based embryo models. Trajectory inference analyses using this reference have delineated distinct transcriptional paths for the epiblast, hypoblast, and TE lineages, identifying hundreds of transcription factor genes with modulated expression across pseudotime [10]. For instance, pluripotency markers like NANOG and POU5F1 are highly expressed in the pre-implantation epiblast but decrease after implantation, while HMGN3 shows upregulated expression in the post-implantation stages across all three lineages [10].

Experimental Protocols for Studying Lineage Specification

Research in this field relies on both direct embryo culture and the rapidly advancing technology of stem cell-based embryo models.

Generation and Use of Blastoids

Blastoids are 3D models that mimic the cellular composition and architecture of the human blastocyst. The typical protocol for their generation and subsequent use in implantation studies involves several key steps [16]:

- Starting Cells: Use naïve human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), either embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). iBlastoids can also be generated from reprogrammed human somatic cells like fibroblasts [16] [16].

- Aggregation and Differentiation: Cells are aggregated and cultured in defined conditions that promote self-organization. Through protocol optimization, this process can now generate blastoids with high efficiency (>70%) in as little as 4-6 days [16] [14].

- Validation: The resulting blastoids are validated based on their morphology, cellular composition (presence of EPI-, PrE-, and TE-like cells), and transcriptional profile, often by comparing them to the integrated human embryo scRNA-seq reference [16] [10].

- Implantation Modeling: To study implantation, blastoids are placed on various substrates:

- 2D Co-culture: Co-cultured with a layer of human endometrial epithelial or stromal cells [16] [17] [18].

- 3D Extracellular Matrices: Cultured on 3D matrices like Matrigel to study invasion [16] [16] [19].

- 3D Endometrial Organoids: Combined with more complex 3D models of the human endometrium to create a more physiologically relevant environment [16] [15] [10].

These models have demonstrated the capacity to recapitulate key events, such as attachment, multi-nucleation of outer trophoblast-like cells, and secretion of pregnancy markers like human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) [16].

Diagram 1: Blastoid generation and implantation modeling workflow.

Non-Integrated Stem Cell-Based Embryo Models

For studying post-implantation events like gastrulation, non-integrated models that focus on embryonic development are widely used. A key example is the 2D Micropatterned (MP) Colony [15]:

- Micropatterning: hESCs are plated on slides with arrays of circular disks coated with extracellular matrix (ECM) to drive adhesion.

- BMP4 Treatment: The colonies are treated with BMP4, which induces self-organization into radial patterns.

- Lineage Specification: This process results in a structure with an ectodermal center, surrounded by a mesodermal ring where cells undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and an outermost ring of extra-embryonic-like cells of unclear origin [15] [16]. This model is highly reproducible and excellent for studying germ layer specification, though it lacks the 3D morphology of the natural embryo [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Embryo Model Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Naïve Human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs) | The foundational starting material for generating integrated embryo models like blastoids; can be ESCs or iPSCs [16] [18]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) / Matrigel | Provides a 3D biological scaffold for cell adhesion, invasion, and morphogenesis; used in blastoid implantation assays and 3D model cultures [16] [15] [16]. |

| Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4 (BMP4) | A key morphogen used to induce self-organization and pattern formation in 2D micropatterned colony models, leading to germ layer specification [15] [16]. |

| Endometrial Epithelial/Stromal Cells | Used in co-culture systems to create a more physiologically relevant environment for modeling human embryo implantation with blastoids [16] [17]. |

| Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | An essential analytical tool for unbiased transcriptional profiling and validating the fidelity of embryo models against in vivo human embryo references [10]. |

| Defined Culture Media | Specialized media formulations are critical for the efficient and reproducible derivation and maintenance of blastoids and other embryo models [16] [10] [14]. |

| Tinosporol A | Tinosporol A, MF:C21H26O8, MW:406.4 g/mol |

| Rauvovertine C | Rauvovertine C, MF:C20H23N3O, MW:321.4 g/mol |

Signaling Pathways Governing Lineage Specification

The Hippo signaling pathway serves as a central integrator of mechanical and positional cues to determine cell fate. The following diagram summarizes the key mechanisms in the first lineage decision, reconciling the inside-outside and polarity models.

Diagram 2: Hippo pathway integration of position and polarity cues for cell fate.

The specification of the trophectoderm, epiblast, and primitive endoderm is a precisely orchestrated process fundamental to the establishment of pregnancy and embryonic development. The integration of findings from classic mouse embryology with new data from human stem cell-based embryo models and high-resolution transcriptomic atlases is rapidly refining our understanding of this critical period. These technological advances provide a powerful, ethically navigable platform to dissect the molecular circuitry of lineage determination, model the causes of implantation failure and early pregnancy loss, and ultimately develop improved strategies in assisted reproductive technology. The continued benchmarking of these models against in vivo references will be crucial to ensure their fidelity and maximize their potential to illuminate the "black box" of early human development.

This whitepaper explores the fundamental principles of self-organization within the specific context of human early embryo development. Self-organization, defined as the process by which systems achieve reduced internal entropy and develop structured patterns through local interactions, is a critical driver of morphogenesis and cellular specialization [20]. The integration of geometric constraints, mechanical forces, and biochemical signaling feedback loops enables the emergence of complex structures from initially homogeneous cell populations. Recent advances in single-cell omics technologies have revolutionized our understanding of these processes by providing unprecedented resolution of cellular heterogeneity and lineage specification during peri-implantation stages [9]. This technical guide examines the interplay between physical drivers and molecular mechanisms that govern self-organization, with particular emphasis on their implications for regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

Self-organization represents a fundamental paradigm in developmental biology, describing how complex patterns and structures arise in embryonic systems without explicit external instruction. In human embryogenesis, this process is characterized by reduced internal entropy and the emergence of hierarchical organization that enables more robust and efficient system functionality [20]. The principles of self-organization operate across multiple spatiotemporal scales, from subcellular molecular networks to tissue-level structural arrangements, ultimately enabling the transition from a single zygote to a multicellular organism with specialized tissues and organs.

The study of self-organization in human embryos has been transformed by the recent development of single-cell omics technologies, which allow researchers to investigate cellular heterogeneity, lineage relationships, and molecular regulation at unprecedented resolution [9]. These approaches have revealed how mechanical and geometric constraints interact with genetic programs to guide developmental processes. Within this framework, mechanics serves as a primary driver of morphogenesis, influencing cell packing organization, population sorting, and the compartmentalization of distinct cell lineages [21].

Understanding these self-organization principles has significant implications for both basic developmental biology and applied clinical research. For drug development professionals, elucidating these mechanisms offers opportunities for designing targeted interventions that can modulate developmental pathways or recreate specific tissue architectures in vitro. Similarly, the ability to predict and guide self-organizing systems has profound implications for regenerative medicine approaches aimed at generating functional tissues for transplantation and disease modeling.

Theoretical Foundations of Self-Organization

Thermodynamic and Dynamic Principles

Self-organizing systems in embryonic development operate as dissipative structures that maintain their organization through continuous energy exchange with their environment. This process is associated with a reduction in internal entropy as the system becomes more structured, while overall entropy production increases in accordance with the second law of thermodynamics [20]. The emergence of specialized cellular populations during embryogenesis follows these thermodynamic principles, with energy gradients facilitating the necessary transfers that enable structure formation.

From a dynamic perspective, self-organization in developing embryos appears to follow variational principles that optimize certain physical parameters. Recent research has proposed the Least Action Principle (LAP) as a potential driver for these processes, where the developmental path between two states minimizes the action required for transition [20]. This framework suggests that:

- Average Action Efficiency (AAE) increases during self-organization, reflecting improved system performance

- Positive feedback loops connect AAE to other system characteristics

- The principle manifests differently across organizational scales

These dynamic principles provide a theoretical foundation for understanding why embryonic systems tend toward specific organizational states and how mechanical constraints influence developmental trajectories.

Mechanical Drivers of Morphogenesis

Mechanical forces play a fundamental role as organizers of embryonic structure, working in concert with molecular signaling to shape developing tissues. The packing organization of cells represents one of the most basic manifestations of mechanical self-organization, where physical constraints and intercellular adhesions determine spatial arrangements that subsequently influence cell fate decisions [21]. This mechanical environment creates geometric constraints that feed back onto biochemical signaling networks, creating integrated systems that coordinate growth and pattern formation.

At the tissue level, the sorting and compartmentalization of cell populations represents another mechanically-driven self-organization phenomenon. Differential adhesion properties between cell types generate surface tensions that promote tissue separation and boundary formation, essential processes in early embryonic development [21]. These mechanical interactions are complemented by traveling waves of chemical and mechanical signals that propagate organizing cues across developing tissues, enabling long-range coordination of developmental programs.

Table 1: Fundamental Principles of Self-Organization in Embryonic Systems

| Principle | Mechanistic Basis | Developmental Manifestation |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Dissipation | Maintenance of structure through continuous energy exchange | Metabolic gradients enabling pattern formation |

| Least Action Principle | Developmental paths minimize action between states | Optimized morphogenetic trajectories |

| Mechanical Constraint | Physical forces shaping tissue organization | Cell packing and sorting based on adhesion |

| Feedback Integration | Reciprocal interactions between scales | Coupling of mechanical and biochemical signaling |

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Self-Organization

Single-Cell Omics Technologies

The application of single-cell omics technologies has revolutionized the investigation of self-organization principles in human embryo development by enabling detailed characterization of cellular heterogeneity and lineage relationships. These approaches include:

- Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) for transcriptomic profiling of individual cells, enabling identification of distinct cellular states and trajectories during differentiation

- Single-cell ATAC-seq for mapping chromatin accessibility at the single-cell level, revealing epigenetic regulation of development

- Single-cell proteomics for quantifying protein expression and post-translational modifications that drive functional specialization

These technologies have been particularly transformative for understanding peri-implantation development stages that were previously inaccessible due to technical and ethical limitations [9]. The experimental workflow typically involves careful dissociation of embryonic tissues, capture of individual cells using microfluidic or droplet-based platforms, library preparation for the omics modality of interest, and computational analysis to reconstruct developmental trajectories.

Quantitative Analysis of Cell Behavior and Lineage Specification

Rigorous quantitative approaches are essential for characterizing self-organization phenomena in developing embryos. The comparison of quantitative data between different cell populations enables researchers to identify statistically significant differences in gene expression, morphological properties, and functional behaviors that emerge during development [22]. Appropriate statistical summaries and visualization methods are critical for interpreting these complex datasets.

For comparing quantitative variables across different cellular populations, several graphical approaches are particularly valuable:

- Back-to-back stemplots for visualizing distribution differences between two cell populations

- 2-D dot charts with jittering to avoid overplotting when displaying individual observations

- Parallel boxplots for comparing distributions across multiple cell types or developmental stages

These visualization techniques enable researchers to identify emergent patterns in cellular behavior and molecular expression that reflect underlying self-organization principles [22]. When preparing quantitative summaries, it is essential to include appropriate measures of central tendency and dispersion for each population, along with statistical tests evaluating differences between groups.

Table 2: Quantitative Methodologies for Analyzing Self-Organization

| Methodology | Application | Key Output Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq | Lineage tracing and cellular heterogeneity | Differential gene expression, trajectory inference |

| Morphometric Analysis | Quantifying cellular geometry | Cell size, shape descriptors, packing parameters |

| Force Measurement | Characterizing mechanical environment | Traction forces, tissue tension, stiffness |

| Live Imaging | Tracking dynamic behaviors | Cell migration, division orientation, signaling dynamics |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Profiling of Lineage Specification

Single-cell omics approaches have generated comprehensive quantitative datasets characterizing the molecular changes associated with lineage specification during early human embryo development. These data reveal the sequential emergence of trophectoderm, epiblast, and hypoblast lineages from initially totipotent cells, with distinct transcriptional and epigenetic signatures defining each population.

Analysis of transcriptional dynamics during embryonic genome activation has identified precise timing of key developmental transitions and revealed the limited contribution of individual blastomeres to specific lineages [9]. The quantitative comparison of gene expression patterns between these lineages has further elucidated the regulatory networks controlling fate decisions, with mechanical cues influencing these molecular programs through poorly understood mechanisms.

Table 3: Quantitative Characterization of Early Human Embryo Development

| Developmental Stage | Cellular Process | Key Quantitative Findings | Technical Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cleavage Stages | Embryonic Genome Activation | Precise timing of transcriptional initiation; limited blastomere contribution | scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq |

| Blastocyst Formation | Lineage Specification | Sequential specification of TE, EPI, and HYPO; distinct transcriptional signatures | Multimodal single-cell omics |

| Implantation | Trophectoderm Maturation | Mural-polar TE maturation; revised X-chromosome regulation | scRNA-seq, spatial transcriptomics |

| Post-implantation | Rare Population Identification | Identification of PGCs and amnion precursors; spatial organization | Integrated omics approaches |

Effects of Aneuploidy on Self-Organization

Single-cell omics technologies have enabled detailed investigation of how chromosomal abnormalities disrupt self-organization processes in early human embryos. The analysis of aneuploid embryos has revealed:

- Specific patterns of gene expression dysregulation associated with different chromosomal abnormalities

- Compensatory mechanisms that partially maintain developmental progression despite aneuploidy

- Distinct effects on different cell lineages, with varying tolerance for chromosomal imbalances

These findings have important implications for understanding the relatively high frequency of aneuploidy in human embryos and its consequences for developmental success. From a clinical perspective, this knowledge contributes to improving outcomes in medically assisted reproduction by identifying chromosomal configurations compatible with normal development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Self-Organization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| Dissociation Reagents | Trypsin-EDTA, Accutase, collagenase | Gentle dissociation of embryonic tissues into single-cell suspensions |

| Cell Capture Platforms | 10X Genomics Chromium, Fluidigm C1 | High-throughput single-cell isolation for omics profiling |

| Library Preparation Kits | SMART-seq2, Chromium Next GEM | Amplification and barcoding of single-cell nucleic acids |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Seurat, Scanpy, Monocle | Computational analysis of single-cell omics data |

| Live Cell Dyes | CellTracker, Membrane stains | Lineage tracing and live imaging of cell behaviors |

| Inhibitors/Activators | ROCK inhibitors, BMP4, FGF2 | Perturbation of specific signaling pathways |

| Gnetin D | Gnetin D, MF:C28H22O7, MW:470.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tataramide B | Tataramide B, MF:C36H36N2O8, MW:624.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of Self-Organization Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways and experimental workflows relevant to self-organization in embryonic development, created using Graphviz DOT language with the specified color palette.

Signaling Feedback in Lineage Specification

Single-Cell Omics Workflow

Self-Organization Principles Integration

Embryonic plasticity describes the remarkable ability of early embryonic cells to adapt their fate and behavior in response to genetic, epigenetic, or mechanical perturbations. This phenomenon operates within the context of cellular heterogeneity—the inherent diversity of cell states within a developing embryo—which provides a foundational reservoir of potential that can be harnessed when development is challenged. During normal embryogenesis, a single-celled zygote progressively relinquishes its totipotency through a hierarchy of lineage-specific stem cells and progenitors toward tissue-specific cells with specialized functions [23]. This differentiation process involves limited lineage potential and ultimately results in terminal differentiation and a loss of cellular plasticity [23]. However, when embryonic development faces perturbations—whether from genetic abnormalities, environmental stressors, or experimental manipulation—compensatory mechanisms can be activated to maintain developmental trajectory and tissue architecture.

The study of embryonic plasticity has been revolutionized by recent technological advances, particularly single-cell omics technologies that enable unprecedented resolution of cellular heterogeneity, lineage specification, and spatial organization during early development [9]. These approaches have revealed that the gain and loss of plasticity during development and evolution follows distinct patterns across different species and life stages [24]. Understanding these mechanisms provides not only fundamental insights into embryogenesis but also potential therapeutic avenues for regenerative medicine and cancer treatment, where cancer cells often retain elevated levels of plasticity that include switches between epithelial and mesenchymal phenotypes [23].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Embryonic Plasticity

Molecular Regulators of Cell Plasticity

At the molecular level, embryonic plasticity is governed by a complex interplay of transcription factors, epigenetic regulators, and signaling pathways. The core pluripotency factors Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog form a central network that maintains developmental potential in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [23]. These factors co-occupy promoters of numerous target genes, self-regulate their transcription levels, and build protein complexes with each other to activate and repress expression of target genes [23]. Recent insights suggest that rather than cooperatively blocking differentiation, these individual pluripotency factors function as classical lineage factors in constant competition, directing differentiation toward specific lineages [23].

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and its reverse (MET) represent crucial plasticity switches with important roles in embryogenic development, tissue regeneration, and cancer progression [23]. These transitions are controlled on multiple levels including transcriptional repression, post-translational modifications, cell signaling, and epigenetic regulation. A crucial step in EMT is the transcriptional repression of the major epithelial adhesion molecule E-cadherin encoded by the CDH1 gene, mediated by direct repressors including Snail1, Snail2, Zeb1, Zeb2, E47, and Klf8, as well as indirect repressors such as Twist, E2-2, and FoxC2 [23].

Metabolic and Epigenetic Control of Plasticity

Emerging evidence indicates that cellular metabolism and epigenetic regulation are intimately connected in controlling developmental plasticity. Quiescent naive mouse ESCs exhibit a distinct metabolic landscape characterized by decreased mitochondrial membrane potential and reduced levels of the one-carbon metabolite S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) [25]. These metabolic changes are accompanied by a global reduction of H3K27me3, increased chromatin accessibility, and derepression of endogenous retrovirus MERVL and trophoblast master regulators [25]. This metabolic-epigenetic axis enables quiescent ESCs to acquire an unrestricted cell fate, capable of generating both embryonic and extraembryonic cell types.

Human-specific regulatory elements, particularly endogenous retroviruses, have recently been implicated in primate embryonic development. The hominoid-specific HERVK LTR5Hs elements contribute to the diversification of the epiblast transcriptome, with at least one human-specific LTR5Hs element being essential for blastoid-forming potential by enhancing expression of the primate-specific ZNF729 gene [26]. This illustrates how recently evolved regulatory mechanisms can influence fundamental developmental processes.

Compensatory Mechanisms for Developmental Perturbations

Tissue-Specific Compensation for Cell Size Alterations

In polyploid zebrafish, tissue-specific compensatory mechanisms maintain normal tissue architecture and body size independent of cell size [27]. This compensation involves adjustments to the nucleocytoplasmic (N:C) ratio, which is crucial for proper cell function and developmental patterning. Different tissues employ distinct strategies to accommodate larger polyploid cells while preserving overall morphology and function, particularly in vascular and muscle development [27].

Table 1: Compensatory Mechanisms Across Developmental Contexts

| Developmental Context | Perturbation | Compensatory Mechanism | Key Molecular Players |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyploid zebrafish tissues [27] | Increased cell size due to whole genome duplication | Tissue-specific adjustments to maintain architecture | Factors regulating N:C ratio |

| Fly gastrulation [28] | Mechanical stress from concurrent tissue movements | Out-of-plane deformation via cephalic furrow | Buttonhead, Even-skipped, non-muscle Myosin-II |

| Alternative fly strategy [28] | Mechanical stress from concurrent tissue movements | Widespread out-of-plane cell division | Mitotic reorientation machinery |

| Quiescent embryonic stem cells [25] | Cell cycle arrest and metabolic changes | Epigenetic reprogramming for fate expansion | MERVL, 2C-specific genes, reduced H3K27me3 |

| Human blastoid formation [26] | Repression of HERVK LTR5Hs | Apoptosis when compensation fails | ZNF729, caspase activation |

Mechanical Stress Management During Morphogenesis

During gastrulation across insect species, embryos face mechanical conflicts from concurrent tissue movements. In Cyclorrhaphan flies including Drosophila melanogaster, an active out-of-plane deformation of a transient epithelial fold called the cephalic furrow acts as a mechanical sink to pre-empt head-trunk collision [28]. This evolutionary innovation requires overlapping expression of the transcription factors Buttonhead and Even-skipped, which combinatorially specify cephalic furrow initiating cells [28]. Genetic or optogenetic ablation of the cephalic furrow leads to accumulation of compressive stress, tissue buckling at the head-trunk boundary, and late-stage embryonic defects in the head and nervous system [28].

Non-cyclorrhaphan flies such as Chironomus riparius lack cephalic furrow formation and instead undergo widespread out-of-plane cell division that reduces the duration and spatial extent of head expansion [28]. This alternative strategy similarly mitigates mechanical conflict but through a different cellular mechanism. Experimentally re-orienting head mitosis from in-plane to out-of-plane in Drosophila partially suppresses tissue buckling, confirming that this mechanism can function as an alternative mechanical sink [28]. These findings demonstrate that divergent evolutionary strategies can achieve similar mechanical outcomes through different cellular processes.

Diagram Title: Evolutionary Divergence in Mechanical Stress Compensation

Plasticity in Stem Cell Populations and Fate Restriction

Quiescent naive embryonic stem cells (qESCs) demonstrate a unique form of plasticity through their expanded developmental potential. Unlike cycling ESCs, which are restricted to embryonic lineages, qESCs can generate both embryonic and extraembryonic cell types, including trophoblast stem cells [25]. This transition to an unrestricted cell fate is associated with a distinct metabolic state characterized by reduced mitochondrial membrane potential and decreased one-carbon metabolite S-adenosylmethionine, leading to global reduction of H3K27me3 and derepression of endogenous retrovirus MERVL and trophoblast master regulators [25].

The molecular characteristics of qESCs closely resemble those of 2-cell embryos, with increased expression of MERVL, 2C-specific genes such as Zscan4 and Dux, and trophoblast regulators [25]. This expanded potential demonstrates how changes in cellular state can alter developmental constraints and provide alternative routes for cell fate specification when normal development is challenged.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Stem Cell-Derived Embryo Models

Recent advances in stem cell-derived embryo models have revolutionized our ability to study human embryonic development and species-specific regulatory mechanisms. Hematoids—3D multi-lineage structures derived from human pluripotent stem cells—contain tissues comparable to Carnegie stage 12-16 human embryos, including cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, endothelial cells, and hematopoietic cells [11]. These models notably feature SOX17+RUNX1+ hemogenic buds where endothelial-to-hematopoietic transition occurs, containing instructive (DLL4, SCF) and restrictive (FGF23) factors for hematopoietic stem cell maturation [11].

Human blastoids—3D embryo models of the blastocyst—have enabled functional studies of human-specific features of development [26]. These models recapitulate the morphology and lineage specification of human blastocysts, containing analogues to the epiblast, trophectoderm, and hypoblast lineages [26]. This system has been used to investigate the functional contribution of hominoid-specific HERVK LTR5Hs elements to pre-implantation development, revealing their pervasive cis-regulatory contribution to the hominoid-specific diversification of the epiblast transcriptome [26].

Table 2: Experimental Models for Studying Embryonic Plasticity

| Experimental Model | Application | Key Readouts | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human blastoids [26] | Studying human-specific regulatory elements in pre-implantation development | Blastoid formation efficiency, lineage marker expression, scRNA-seq | Nature (2025) |

| Hematoids [11] | Investigating multi-lineage organogenesis and hematopoietic development | Presence of multiple lineages, SOX17+RUNX1+ hemogenic buds | Cell Reports (2025) |

| Zebrafish polyploid models [27] | Understanding tissue-specific compensation for cell size alterations | Tissue architecture, body size measurements, patterning | Developmental Biology (2024) |

| Drosophila gastrulation [28] | Analyzing mechanical stress management during morphogenesis | Tissue buckling, cephalic furrow formation, mitotic orientation | Nature (2025) |

| Quiescent ESC system [25] | probing expanded developmental potential in G0-arrested stem cells | Trophoblast differentiation efficiency, MERVL expression, H3K27me3 levels | Nature Communications (2024) |

Perturbation Approaches and Functional Assessment

CRISPR-based interference technologies have enabled targeted perturbation of specific regulatory elements to assess their functional contribution to developmental processes. The CARGO-CRISPRi system allows for efficient and selective perturbation of HERVK LTR5Hs function across the genome using a 12-mer guide RNA array designed to target the majority of LTR5Hs instances [26]. This approach demonstrated that high repression of LTR5Hs activity is incompatible with blastoid formation, instead resulting in structures resembling dark spheres with increased apoptosis [26].

Optogenetic systems provide precise spatiotemporal control for probing mechanical aspects of development. The Opto-DNRho1 system enables local inhibition of actomyosin contractility, allowing researchers to mechanically block specific morphogenetic events such as cephalic furrow formation without perturbing contractility elsewhere [28]. This approach confirmed that cephalic furrow ablation leads to passive buckling resulting from accumulated compressive stress rather than increased actomyosin contractility or local genetic perturbation [28].

Diagram Title: Experimental Framework for Plasticity Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Embryonic Plasticity Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pluripotency Reporter Systems | MERVL-2C::EGFP, Oct4-GiP, iCdx2 Elf5-2A-mCherry | Tracking pluripotency states and early lineage commitment | [25] |

| Metabolic Probes | TMRM (Tetramethylrhodamine Methyl Ester), Grx1-roGFP2, CCCP | Measuring mitochondrial membrane potential and redox state | [25] |

| CRISPR Perturbation Systems | CARGO-CRISPRi (dCas9-KRAB), LTR5Hs-specific gRNA arrays | Targeted repression of specific regulatory elements | [26] |

| Optogenetic Tools | Opto-DNRho1 | Local inhibition of actomyosin contractility | [28] |

| Lineage Markers | KLF17, NANOG, SUSD2, IFI16 (epiblast); GATA3 (trophectoderm); SOX17, GATA4 (hypoblast) | Identifying and quantifying lineage specification | [26] |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | Phenformin (complex I inhibitor), MAT2a inhibitors | Perturbing mitochondrial function and one-carbon metabolism | [25] |

| Apoptosis Assays | Cleaved CASP3 staining, caspase activity assays | Quantifying cell death in response to perturbations | [26] |

| borapetoside B | Borapetoside B | Borapetoside B is a natural diterpenoid fromTinospora crispawith research applications in diabetes and insulin resistance studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 11-Oxomogroside IV | 11-Oxomogroside IV | 11-Oxomogroside IV is a mogroside derivative for research. Study its metabolism and bioactivity. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Implications and Future Directions

The study of embryonic plasticity and compensatory mechanisms has far-reaching implications for both fundamental biology and clinical applications. In regenerative medicine, understanding how embryonic cells maintain developmental trajectory despite perturbations could inform strategies for tissue engineering and cell replacement therapies. The expanded potential of quiescent ESCs [25] suggests possible avenues for generating difficult-to-obtain cell types for transplantation.

In cancer biology, the parallels between embryonic plasticity and cancer cell plasticity—particularly the reacquisition of stem cell features during cellular reprogramming and transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal phenotypes [23]—provide insights into tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance. Mechanisms that normally constrain plasticity in embryonic development may be dysregulated in cancer, suggesting potential therapeutic targets.

Future research directions include developing more sophisticated in vitro models of human development that better recapitulate the spatial and temporal context of embryogenesis, while leveraging single-cell multi-omics technologies [9] to decode the molecular networks underlying plasticity and compensation across different species and developmental stages. Integrating quantitative live imaging with molecular profiling will be essential for connecting cellular behaviors with their genetic and epigenetic regulation.

The exploration of human-specific regulatory mechanisms [26] highlights the importance of evolutionary comparisons for understanding both conserved and species-specific aspects of developmental plasticity. As research in this field advances, it will continue to reveal the remarkable capacity of embryonic systems to maintain robustness in the face of perturbation, providing fundamental insights into the principles of life itself.

Decoding the Embryo: Single-Cell Multi-Omics and Microfluidic Technologies

The journey of human life begins with a single cell, culminating in a complex organism composed of trillions of specialized cells. Understanding this remarkable transformation is one of biology's greatest challenges, requiring tools that can capture the immense cellular heterogeneity that arises during embryonic development. The emergence of sophisticated single-cell technologies has revolutionized our ability to observe this process at unprecedented resolution, moving beyond population averages to examine the unique molecular signatures of individual cells. These tools have collectively formed an powerful toolkit that enables researchers to dissect the intricate cellular conversations, lineage decisions, and molecular reprogramming events that orchestrate human embryogenesis.

Within the context of human embryo development research, this toolkit is particularly transformative. Traditional bulk analysis methods obscured the dynamic heterogeneity of embryonic cells, but single-cell technologies now allow scientists to map developmental trajectories, identify rare transitional cell states, and unravel the complex regulatory networks that guide a fertilized egg through gastrulation and organogenesis [9]. This technical guide explores the core technologies constituting the single-cell toolkit—single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), epigenomics, and proteomics—detailing their methodologies, applications, and integration strategies specifically for illuminating cellular heterogeneity in human embryonic development.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): Profiling Transcriptional Heterogeneity

Single-cell RNA sequencing has fundamentally transformed transcriptomic analysis by enabling gene expression measurement in individual cells rather than population averages. This capability is crucial for studying embryonic development, where cellular heterogeneity emerges rapidly and cell fate decisions occur asynchronously. The core principle of scRNA-seq involves isolating single cells, capturing their mRNA, converting RNA to cDNA, and preparing sequencing libraries with cell-specific barcodes to trace expression profiles back to individual cells [29] [3].

The standard workflow encompasses several critical stages, as visualized in Figure 1. It begins with single-cell isolation through methods like fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), microfluidics (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium), or microwell technologies. Following isolation, cells are lysed to release RNA, which is then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using primers containing cell barcodes and Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs). These UMIs are random barcode sequences that label individual mRNA molecules, enabling correction for amplification bias and providing accurate transcript quantification [30] [3]. The barcoded cDNA undergoes amplification and library preparation before high-throughput sequencing. Subsequent bioinformatic analysis processes the raw data through quality control, normalization, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and cell type annotation.

Figure 1. scRNA-seq Workflow for Embryonic Cell Analysis. The process begins with tissue dissociation and single-cell isolation, followed by cell lysis and RNA capture. During reverse transcription, cell barcodes (CB) and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) are incorporated to track transcripts to individual cells. After cDNA amplification and library preparation, sequencing data undergoes computational analysis to reveal cellular heterogeneity. Key steps involving barcoding are highlighted in yellow.

Key scRNA-seq Platforms and Methodologies

scRNA-seq technologies have evolved into two primary categories based on transcript coverage: full-length transcript sequencing and 3'/5'-end counting methods. Each approach offers distinct advantages depending on research goals, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Major scRNA-seq Platform Types

| Platform Type | Examples | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ideal Applications in Embryo Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-length Transcript | Smart-seq2, MATQ-seq, SUPeR-seq | Higher sensitivity for gene detection; Identifies isoforms and sequence variants | Lower throughput; Higher cost per cell | Studying alternative splicing during embryogenesis; Allele-specific expression |

| 3'/5'-end Counting | Drop-seq, 10x Genomics Chromium, Seq-Well | High cell throughput; Cost-effective; Better for large cell numbers | Lower sensitivity; Limited to 3'/5' ends | Creating comprehensive atlases of embryonic development; Identifying rare cell populations |

Full-length transcript platforms like Smart-seq2 provide complete transcript coverage, enabling researchers to study alternative splicing, sequence variants, and allele-specific expression—features particularly valuable for understanding regulatory complexity during embryonic genome activation [29]. In contrast, 3'-end counting methods like Drop-seq and 10x Genomics offer significantly higher throughput at lower cost per cell, making them ideal for comprehensive profiling of thousands to millions of embryonic cells to construct detailed developmental atlases [3].

Application to Human Embryo Development

scRNA-seq has dramatically advanced our understanding of human embryogenesis by enabling direct observation of lineage specification events. A landmark 2025 study integrated six published human embryo datasets to create a unified reference atlas covering developmental stages from zygote to gastrula. This resource, comprising 3,304 individual cells, revealed continuous developmental progression with the first lineage branch point occurring as inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm (TE) cells diverge during E5, followed by ICM bifurcation into epiblast and hypoblast lineages [10].

Trajectory inference analysis using tools like Slingshot has identified key transcription factors driving lineage specification. In the epiblast trajectory, pluripotency markers like NANOG and POU5F1 are highly expressed in preimplantation stages but decrease after implantation, while HMGN3 shows upregulated expression at postimplantation stages. Along the hypoblast trajectory, GATA4 and SOX17 appear early, while FOXA2 and HMGN3 increase in later stages. Within the TE trajectory, CDX2 and NR2F2 show early expression, while GATA2, GATA3 and PPARG increase during TE development to cytotrophoblast [10].

For later developmental stages, scRNA-seq of human embryos from 7-9 weeks post-fertilization identified eighteen distinct cell clusters and revealed two primary differentiation pathways: mesenchymal progenitor cells differentiating into either osteoblast progenitor cells or neural stem cells (which further differentiate into neurons), and multipotential stem cells differentiating into adipocytes, hematopoietic stem cells, and neutrophils [31]. This detailed mapping of embryonic cell fate decisions demonstrates scRNA-seq's unparalleled utility for decoding developmental hierarchies.

Single-Cell Epigenomics: Mapping Regulatory Landscapes

Technologies for Profiling Chromatin States

While scRNA-seq reveals transcriptional outputs, single-cell epigenomics uncovers the regulatory mechanisms controlling gene expression—a critical dimension for understanding cell fate commitment during embryogenesis. Epigenomic features including DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin accessibility, and chromatin organization create a complex regulatory landscape that guides embryonic development by defining cellular identity without altering DNA sequence [32].

The single-cell epigenomics toolkit has expanded rapidly, with key technologies summarized in Table 2. These methods employ diverse strategies to map different epigenetic features at single-cell resolution, collectively enabling comprehensive profiling of the regulatory landscape in heterogeneous embryonic cell populations.

Table 2: Single-Cell Epigenomic Technologies for Embryonic Development Studies

| Epigenetic Feature | Key Technologies | Methodological Principle | Biological Insight in Embryos |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation | scBS-seq, scRRBS | Bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines | Regulation of gene expression during lineage specification; X-chromosome inactivation |

| Histone Modifications | scChIP-seq, scCUT&Tag | Antibody-based enrichment of modified histones | Bivalent promoters marking developmental genes; Poised enhancers |

| Chromatin Accessibility | scATAC-seq, scDNase-seq | Enzyme-based tagging or cleavage of open chromatin | Identification of active regulatory elements; Transcription factor binding sites |

| Chromatin Organization | scHi-C, scSPRITE | Proximity ligation of interacting genomic regions | Nuclear compartmentalization; Enhancer-promoter interactions |

Unique Epigenomic Features of Pluripotent Cells

Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and early embryonic cells possess distinctive epigenomic characteristics that reflect their pluripotent state. A particularly notable feature is the prevalence of bivalent promoters—chromatin domains marked by both activating (H3K4me3) and repressing (H3K27me3) histone modifications. These bivalent domains silence developmental genes while keeping them poised for rapid activation upon differentiation, enabling the precise temporal control of gene expression required for proper lineage commitment [32].

Another key feature is the presence of poised enhancers in hESCs, marked by H3K4me1/2 and H3K27me3 but lacking H3K27ac activation marks. These enhancers become activated in specific lineages during differentiation, directing cell fate decisions. Additionally, pluripotent cells exhibit unique DNA methylation patterns characterized by global hypomethylation with hypermethylation at specific CpG-poor promoters, creating a permissive chromatin state that supports developmental plasticity [32].