Conquering Background Noise: A Researcher's Guide to Optimizing Embryo In Situ Hybridization

Background noise and autofluorescence present significant challenges for achieving clear, reliable results in embryo in situ hybridization (ISH), impacting data accuracy in developmental biology, drug research, and diagnostics.

Conquering Background Noise: A Researcher's Guide to Optimizing Embryo In Situ Hybridization

Abstract

Background noise and autofluorescence present significant challenges for achieving clear, reliable results in embryo in situ hybridization (ISH), impacting data accuracy in developmental biology, drug research, and diagnostics. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the sources of ISH background noise—from technical artifacts and tissue autofluorescence to probe non-specificity. We explore foundational principles of noise generation, detail optimized protocols and novel methods like π-FISH rainbow and OMAR bleaching for noise reduction, and offer practical troubleshooting strategies. Furthermore, the article covers validation techniques and comparative analyses of emerging ISH technologies, empowering professionals to enhance the sensitivity and specificity of their spatial transcriptomics data.

What is Background Noise? Exploring the Sources and Impact on Embryo ISH

In embryo in situ hybridization (ISH) research, the accurate interpretation of gene expression data is fundamentally constrained by background noise. This noise can obscure genuine signals, leading to potential misinterpretations of spatial and temporal expression patterns critical for understanding development. Background noise in this context originates from two primary, distinct sources: technical artifacts, introduced during the experimental procedure, and biological autofluorescence, an inherent property of the tissue itself [1] [2] [3]. Technical artifacts arise from suboptimal probe hybridization, inadequate washing stringency, non-specific antibody binding, or tissue preparation issues [4] [5] [3]. In contrast, biological autofluorescence is the natural emission of light from endogenous fluorophores within biological tissues, such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), and lipofuscin, following light absorption [1] [2] [6]. The distinction is critical; while technical noise can often be minimized through protocol optimization, biological autofluorescence is an inherent variable that must be quantified and accounted for [2]. Within the specific context of embryo research, where sample integrity is paramount and the signal from crucial regulatory genes can be weak, understanding and controlling for both noise types is not merely a technical exercise but a prerequisite for reliable scientific discovery [5].

Technical artifacts in ISH are predominantly controllable factors introduced during the experimental workflow. A primary source is the probe hybridization process, where factors such as probe concentration, hybridization temperature, and stringency conditions dictate specificity. As noted in zebrafish embryo protocols, high stringency conditions, often achieved through elevated temperatures and specific formamide concentrations, are necessary to ensure the probe binds only to fully complementary target sequences [5] [7] [3]. Lower stringency can lead to non-specific binding and increased background noise. Furthermore, the design and labeling of the probe are crucial; longer probes can generate more thermally stable hybrids but may also increase the risk of non-specific binding [5] [3].

Another significant source of technical artifact is inadequate tissue preparation and permeabilization. The fixation process must strike a delicate balance: under-fixation compromises tissue morphology and RNA integrity, while over-fixation, particularly with formalin, can create cross-links that mask target sequences, requiring more aggressive and potentially damaging retrieval methods [3]. Permeabilization using detergents or proteases like proteinase K is essential to allow probe access, but the intensity and duration of these treatments must be carefully optimized. Excessive permeabilization can degrade tissue morphology and increase non-specific signal, whereas insufficient treatment will block probe access to the target, resulting in a false-negative signal [3].

Detection system issues also contribute substantially to technical noise. In chromogenic ISH (CISH), the enzymatic precipitation reaction can produce non-specific staining if the development time is too long or if endogenous enzymes are not adequately blocked [5] [8]. In fluorescent ISH (FISH), non-specific binding of fluorescently labeled antibodies or readout probes is a common culprit [7]. For instance, in multiplexed error-robust FISH (MERFISH), certain readout probes can bind non-specifically in a tissue-dependent manner, introducing false-positive counts that can be misidentified as specific RNA signals [7].

Table 1: Common Technical Artifacts and Their Characteristics in ISH

| Artifact Source | Manifestation | Underlying Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Stringency Hybridization | Diffuse, high background across tissue | Probe binding to partially complementary sequences | Optimize temperature and formamide concentration [5] [3] |

| Over-Permeabilization | Poor tissue morphology, speckled background | Tissue over-digestion, release of cellular debris | Titrate protease concentration and incubation time [3] |

| Non-Specific Probe Binding | Off-target signal in unexpected cell types | Electrostatic interactions or sequence similarity | Prescreen readout probes; include competitor DNA (e.g., dextran sulfate) [5] [7] |

| Endogenous Enzyme Activity | Precipitate formation in negative controls | Incomplete blocking of alkaline phosphatase | Use levamisole or other specific enzyme inhibitors [5] |

Biological Autofluorescence: Nature and Impact

Biological autofluorescence is the emission of light by endogenous molecules within cells and tissues upon excitation, constituting a significant source of background noise in fluorescence-based ISH, particularly in embryo imaging [1] [2]. Unlike technical artifacts, autofluorescence is an intrinsic property of biological samples and cannot be eliminated through protocol refinement alone. Its presence is a major confounding factor because it can be mistaken for a specific signal, especially when the expression of the target gene is low [2].

The key endogenous fluorophores in biological tissues include nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and its phosphorylated form (NADPH), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), flavins, and lipofuscin [2]. These molecules are integral to core metabolic processes. NADH and FAD, for instance, are central to cellular respiration, and their fluorescence provides a readout of the metabolic state of the cell. However, their broad and overlapping emission spectra can significantly obscure the signals from exogenous fluorophores used in FISH experiments [2]. The challenge is compounded by the typically low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in autofluorescence images. For example, one study noted that autofluorescent images of retina cells were characterized by an SNR of approximately 5 dB, which is considerably lower than the 20–40 dB typical of conventional fluorescently labelled microscopy images [2].

Critically, the presence of autofluorescence can compromise the perceived advantage of fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM). While FLIM is prized for its insensitivity to fluorophore concentration, this advantage breaks down in biological tissue because autofluorescence, background light, and detector noise contribute to the measured signal. As sensor expression varies, the relative contribution of the specific sensor fluorescence versus these background sources also changes, leading to an apparent and misleading change in the measured fluorescence lifetime [1] [6]. Therefore, autofluorescence is not merely a static background to subtract; it is a dynamic variable that must be quantitatively understood for correct data interpretation.

Table 2: Major Endogenous Fluorophores Contributing to Autofluorescence

| Fluorophore | Excitation/Emission Maxima (approx.) | Localization | Biological Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAD(P)H | ~350 nm / ~450 nm | Cytoplasm, Mitochondria | Coenzyme in redox reactions |

| FAD/FMN | ~450 nm / ~525 nm | Mitochondria | Electron transport in metabolic pathways |

| Lipofuscin | Broad (350-550 nm) / Broad (~450-650 nm) | Lysosomes | Age-related pigment, product of oxidative stress |

| Collagens & Elastins | ~350 nm / ~400-450 nm | Extracellular Matrix | Structural proteins |

Quantitative Characterization of Noise

A rigorous, quantitative approach is essential to distinguish signal from noise reliably. For fluorescence-based techniques, Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a fundamental metric. In multiplexed imaging, the SNR dictates classification accuracy, with shot noise often being the dominant noise source [9]. The relationship between the number of detected photons and the uncertainty in fluorescence lifetime measurements is critical. Simulations using frameworks like FLiSimBA have determined the photon requirements for detecting minimal differences in fluorescence lifetime, providing realistic SNR estimates and necessary error bars for biological tissue [1] [6].

For hyperspectral or multispectral imaging, unsupervised unmixing algorithms like Robust Dependent Component Analysis (RoDECA) provide a powerful method to disentangle multiple fluorescent signals, including autofluorescence [2]. These methods operate on the linear mixing model (LMM), which posits that the observed spectrum at each pixel is a linear combination of the spectra of the individual components (endmembers), weighted by their abundance [2]. The mathematical formulation is:

[ \overrightarrow{yi} = \overrightarrow{M1}s{1i} + \ldots + \overrightarrow{Mp}s_{pi} + \overrightarrow{n} ]

Where (\overrightarrow{yi}) is the observed pixel spectrum, (\overrightarrow{Mj}) are the endmember spectra (e.g., for specific fluorophores and autofluorescence), (s_{ji}) are the abundance fractions, and (\overrightarrow{n}) represents noise [2]. By applying robust statistical minimization, these algorithms can identify the identity and spatial distribution of key endogenous fluorophores and specific probes, even in the presence of high noise (SNR ~5 dB) [2].

Furthermore, computational frameworks are now challenging long-held assumptions. The FLiSimBA tool, for instance, has established that the widely held belief that fluorescence lifetime is independent of sensor expression level has quantitative limits in biological applications. It demonstrates that as sensor expression varies, the relative contribution of autofluorescence and other noise sources changes, leading to an apparent dependence of lifetime on expression level [1] [6]. This finding underscores the necessity of quantifying and incorporating these background factors into any quantitative analysis.

Experimental Protocols for Noise Mitigation

Protocol for High-Stringency Chromogenic ISH in Embryos

This protocol, adapted for whole-mount zebrafish embryos, emphasizes steps critical for minimizing technical background while preserving compatibility with downstream genotyping [5].

Tissue Fixation and Permeabilization:

- Fix embryos in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for optimal morphology and RNA preservation. Avoid over-fixation to prevent masking target sequences.

- Permeabilize using proteinase K. The concentration and incubation time must be empirically determined for each embryo stage and batch to avoid under- or over-digestion [3].

Probe Hybridization:

- Probe Design: Use riboprobes of 300-3,200 base pairs for high thermal stability and hybridization rate. Label with digoxigenin (DIG) for detection.

- Hybridization Buffer: Omit dextran sulfate if post-hybridization genotyping via PCR is required, as it inhibits polymerase activity [5].

- Hybridization Temperature: For highly specific riboprobes, a hybridization temperature of 55-60°C can be used instead of 70°C. This lower temperature accelerates stain development and enhances contrast without compromising specificity for unique targets [5].

Post-Hybridization Washes and Detection:

- Perform low-salt washes to reduce background by preferentially destabilizing non-specific hybrids [5].

- Detect DIG-labeled probes with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibody.

- Develop with NBT/BCIP chromogenic substrate, which yields a purple-blue precipitate. Monitor development closely to prevent high background.

Protocol for Reducing Autofluorescence in Fluorescence ISH

Signal Brightness Optimization:

- Probe Assembly: For methods like MERFISH, ensure high assembly efficiency of encoding probes onto target RNAs. This is a key determinant of single-molecule signal brightness and can be optimized by adjusting formamide concentration in the hybridization buffer [7].

- Imaging Buffers: Utilize imaging buffers that enhance fluorophore photostability and effective brightness. The composition of these buffers can significantly impact signal longevity over multiple imaging rounds [7].

Background Reduction:

- Reagent Prescreening: Pre-screen readout probes against the sample of interest to identify and eliminate probes that bind non-specifically in a tissue-dependent manner, thereby reducing false-positive counts [7].

- Treatment with Reducing Agents: Treat samples with sodium borohydride (e.g., 1 mg/mL for 30 minutes) to reduce the fluorescence of some endogenous fluorophores by quenching their excited states.

- Spectral Unmixing: Acquire hyperspectral image data and employ computational unmixing algorithms (e.g., RoDECA) to mathematically separate the spectral signature of the specific FISH probe from the broad-spectrum autofluorescence [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Frameworks

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Noise Mitigation

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Role in Noise Management |

|---|---|---|

| Formamide | Chemical denaturant in hybridization buffer. | Lowers melting temperature of nucleic acid duplexes, allowing for high-stringency hybridization at lower, morphology-preserving temperatures to reduce non-specific binding [5] [3]. |

| Dextran Sulfate | Macromolecular crowding agent. | Increases the effective concentration of the riboprobe, accelerating hybridization kinetics and improving the contrast of the chromogenic stain. Omit if post-hybridization PCR is planned [5]. |

| Proteinase K | Proteolytic enzyme. | Digests proteins to permeabilize the tissue, allowing probe access. Concentration and time must be tightly optimized to avoid tissue damage and increased background [3]. |

| Sodium Borohydride | Reducing agent. | Chemically quenches certain classes of endogenous fluorophores, directly reducing the intensity of biological autofluorescence in fluorescence-based assays. |

| RNAScope/RNAscope Probes | Commercial tandem oligonucleotide probes. | Provide a standardized, highly sensitive ISH system with built-in signal amplification and background suppression, reducing the need for extensive in-house protocol optimization [8] [3]. |

| FLiSimBA | Computational framework (Python/MATLAB). | Simulates fluorescence lifetime data in the presence of autofluorescence and instrument noise, enabling researchers to quantify measurement uncertainty and design robust FLIM experiments [1] [6]. |

| QuantISH / RoDECA | Image analysis pipelines. | QuantISH is a modular pipeline for quantifying RNA expression in individual cells from CISH or FISH images [8]. RoDECA performs unsupervised hyperspectral unmixing to separate autofluorescence from specific signals, providing quantitative abundance maps of endogenous fluorophores [2]. |

| (E/Z)-BIX02188 | (E/Z)-BIX02188, CAS:1094614-84-2, MF:C25H24N4O2, MW:412.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Maoyerabdosin | Maoyerabdosin, MF:C24H36O9, MW:468.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The path to definitive conclusions in embryo ISH research requires a meticulous, two-pronged approach to background noise. Researchers must systematically control for technical artifacts through rigorous protocol optimization, including precise management of hybridization stringency, tissue permeabilization, and detection chemistry. Concurrently, biological autofluorescence must be acknowledged not as a mere nuisance but as a quantifiable variable, addressed through a combination of chemical treatment, advanced imaging modalities like hyperspectral imaging and FLIM, and robust computational unmixing. By integrating these experimental and analytical strategies as outlined in this guide, scientists can significantly enhance the reliability and quantitative power of their spatial gene expression data, thereby refining the core thesis that a deep understanding of noise is fundamental to illuminating true biological signal in developmental research.

In embryo in situ hybridization (ISH) research, technical noise presents a formidable barrier to data accuracy and reproducibility. This guide systematically analyzes primary noise sources—signal variability, non-specific staining, and large-image artifacts—within the context of whole-mount embryo studies. As imaging advances toward three-dimensional, high-resolution analyses of complex tissues, distinguishing authentic biological signals from technical artifacts becomes increasingly critical. This technical whitepaper provides researchers with a structured framework for identifying, troubleshooting, and mitigating these pervasive noise sources, enabling more robust and interpretable experimental outcomes in developmental biology and drug discovery applications.

Core Noise Categories and Their Impact on Data Integrity

Technical noise in ISH experiments manifests across multiple dimensions, each with distinct characteristics and impacts on data interpretation. The table below summarizes the primary noise categories, their visual manifestations, and consequent effects on experimental data.

Table 1: Core Noise Categories in Embryo In Situ Hybridization

| Noise Category | Primary Manifestations | Impact on Data Interpretation | Common Tissue Contexts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Variability | Inconsistent signal intensity between samples; fading signals over prolonged staining; subcellular signal heterogeneity [10] | Compromised quantification; inaccurate expression pattern comparison; reduced statistical power | Older embryos (E4.5+); thick tissue regions; densely pigmented areas |

| Non-specific Staining | Uniform background fluorescence; signal in negative controls (sense probes); staining in morphologically distinct regions [11] | False positive identification; obscured genuine expression patterns; reduced signal-to-noise ratio | Tissues undergoing cell death [11]; pigment-rich areas [12]; loose mesenchymal tissues [12] |

| Large Image Artifacts | Bubbles within mounted samples; tissue folding/tearing; uneven clearing; pigment interference [13] [12] | Obstructed visualization; reconstruction failures; imaging depth limitations | Whole-mount embryos; cleared tissues; high-magnification imaging |

Developmental and Technical Origins of Variability

Signal variability in embryo ISH arises from both biological and procedural factors. As embryos develop, tissue complexity increases, creating diffusion barriers for probes and reagents. In chicken embryos, for instance, researchers observed significantly reduced hybridization efficiency beyond E4.5 when using standard E3.5 protocols, necessitating protocol modifications to maintain consistent signal detection [10]. This age-dependent variability stems from increasing tissue thickness, extracellular matrix density, and endogenous enzyme activities that differentially affect probe penetration and stability across developmental stages.

Technical handling introduces additional variability sources. Fixation duration significantly impacts signal integrity, with over-fixation leading to reduced FISH signals due to excessive cross-linking that limits probe accessibility [13]. Similarly, proteinase K treatment requires precise optimization—extended incubation damages tissue morphology, while insufficient treatment fails to expose target epitopes [12].

Quantitative Assessment and Normalization Approaches

Signal variability can be quantified and systematically addressed through controlled experimental design and normalization strategies. The following table summarizes key optimization parameters that significantly influence signal consistency.

Table 2: Optimization Parameters for Reducing Signal Variability

| Parameter | Standard Protocol | Optimized Approach | Impact on Signal Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K Treatment | Fixed duration (e.g., 30 min) [12] | Titrated based on embryo age and size | Prevents both over-digestion and insufficient permeabilization |

| Hybridization Time | Standardized duration | Extended for older embryos [10] | Compensates for reduced probe diffusion in dense tissues |

| Fixation Duration | Fixed time (e.g., 24h) | Optimized per tissue type and size [13] | Balances tissue preservation with epitope accessibility |

| Embedding Medium | Conventional mounting media | Refractive index-matched media (e.g., LIMPID) [13] | Reduces optical aberrations and signal attenuation |

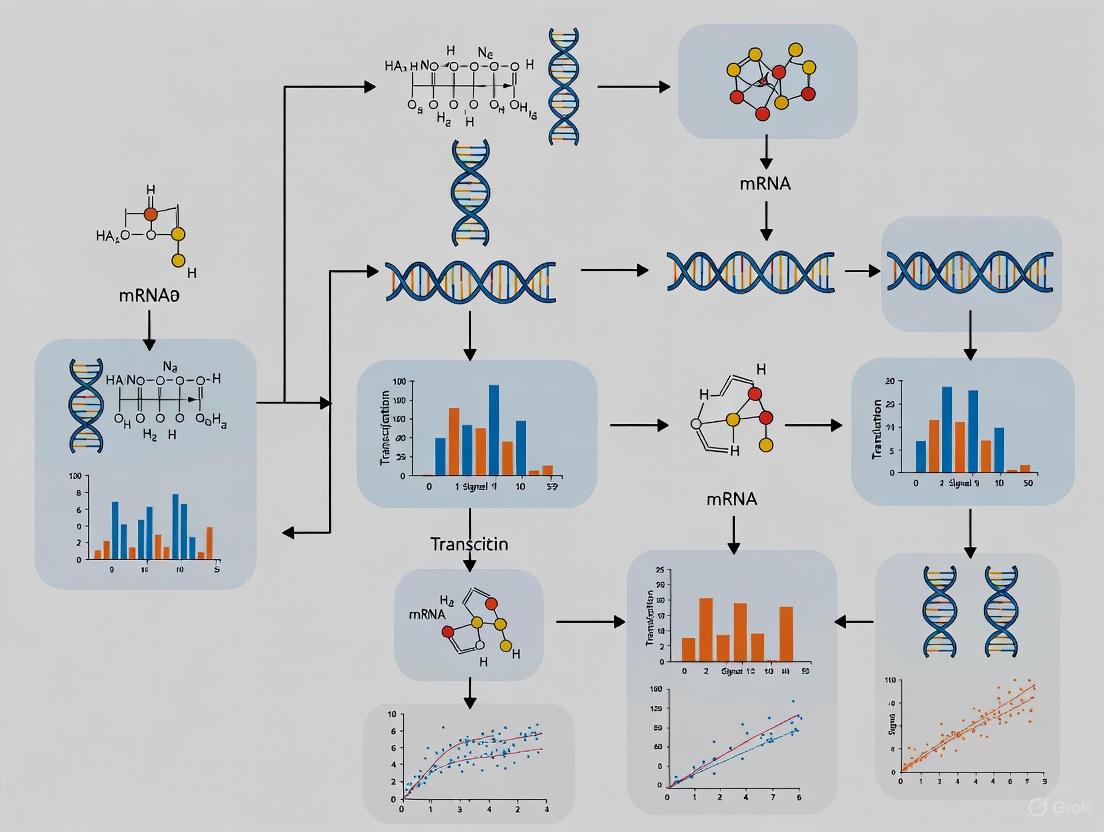

Figure 1: Signal Variability Factors and Mitigation Pathways

Non-specific Staining: Identification and Resolution

Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Non-specific Hybridization

Non-specific staining presents a multifaceted challenge with distinct biological underpinnings. A primary mechanism involves nonspecific hybridization of probes to fragmented nucleic acids in tissues undergoing programmed cell death (PCD). Research in Scots pine embryos demonstrated that sense and antisense probes alike hybridized to degenerating suspensor tissues and the embryo surrounding region, areas characterized by extensive DNA fragmentation [11]. This phenomenon was confirmed through TUNEL assays and acridine orange staining that visualized nucleic acid fragmentation in these regions, explaining the consistent background signal despite appropriate controls [11].

Endogenous pigments constitute another significant source of non-specific signal interference. Melanosomes and melanophores in Xenopus tadpole tails create substantial background noise by overlapping with specific staining patterns and autofluorescence [12]. This interference becomes particularly problematic when targeting low-abundance transcripts that require extended staining incubation, during which pigment interference intensifies.

Systematic Approaches to Background Reduction

Effective reduction of non-specific staining requires combinatorial approaches targeting both probe design and tissue preprocessing. The hybridization chain reaction (HCR) system utilizing split initiator probes demonstrates markedly improved specificity by reducing false-positive signals through its mechanism that requires simultaneous binding of multiple probe pairs for amplification initiation [13] [10].

Strategic tissue preprocessing methods provide powerful background suppression:

- Early Photo-bleaching: Performing bleaching after fixation but before hybridization effectively eliminates melanin interference in pigmented embryos [12].

- Tail Fin Notching: Creating precise incisions in loose fin tissues of Xenopus tadpoles significantly improves reagent washing efficiency, preventing trapping of detection reagents that causes nonspecific chromogenic reactions [12].

- Controlled Permeabilization: Optimizing proteinase K concentration and exposure time enhances probe accessibility while minimizing tissue damage that exacerbates background staining [12].

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Non-specific Staining

| Problem | Probable Cause | Solution | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffuse background throughout tissue | Fragmented nucleic acids in dying cells [11] | Identify and avoid PCD zones; increase hybridization stringency | TUNEL assay; sense probe controls |

| Pigment-associated background | Melanin/ melanosome autofluorescence [12] | Implement pre-hybridization bleaching with H2O2 [12] | Compare bleached vs. non-bleached controls |

| High background in loose tissues | Trapped detection reagents [12] | Create strategic tissue incisions for improved fluid exchange [12] | Visualize background reduction in notched regions |

| Persistent background in cleared samples | Insufficient clearing or refractive index mismatch [13] | Optimize clearing duration; adjust iohexol concentration in LIMPID [13] | Assess transparency; measure signal-to-noise ratio |

Large Image Artifacts: Detection and Compensation

Whole-Mount Specific Artifacts and Their Origins

Large-scale imaging artifacts present unique challenges in three-dimensional embryo analysis, particularly as tissue clearing techniques enable comprehensive visualization. Bubble formation represents a frequent artifact in optical clearing methods, especially in techniques requiring thermal cycling that nucleates bubbles at tissue-hydrogel interfaces [14]. These inclusions disrupt light path continuity and create shadow artifacts in volumetric imaging.

Tissue deformation artifacts manifest as folding, tearing, or shrinkage, particularly in delicate embryonic structures. The choice of clearing method significantly influences these artifacts; hydrophobic organic solvents often induce tissue shrinkage, while aqueous methods like LIMPID better preserve native tissue architecture through lipid preservation and minimal swelling [13]. Refractive index mismatches create another pervasive artifact category, manifesting as spherical aberrations, signal attenuation, and resolution loss at increasing imaging depths, particularly problematic with high-numerical-aperture objectives [13].

Integrated Workflow for Artifact Prevention and Correction

A proactive approach to artifact management incorporates preventive strategies throughout the experimental workflow:

- Clearing Method Selection: Choose clearing methods based on tissue compatibility—aqueous methods like LIMPID for lipid-preservation needs [13], ECi clearing for chicken embryos [10], and fructose-based methods for delicate specimens.

- Refractive Index Calibration: Systematically adjust the concentration of iohexol in LIMPID solution to match the numerical aperture of the objective lens, using calibration curves to achieve optimal index matching [13].

- Handling Protocols: Implement careful sample manipulation using wide-bore tips and viscous solutions to prevent mechanical damage to embryos during fluid exchanges [15].

Figure 2: Large Image Artifact Classification and Prevention

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Successful noise reduction in embryo ISH requires strategic selection and application of specialized reagents. The following table catalogues essential solutions documented in recent literature for addressing technical noise challenges.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Noise Reduction in Embryo ISH

| Reagent/Method | Primary Function | Noise Target | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIMPID Clearing [13] | Aqueous tissue clearing via refractive index matching | Image artifacts, signal attenuation | Compatible with FISH/IHC; preserves lipids; tunable RI with iohexol |

| HCR v3.0 Probes [13] [10] | Multiplexed RNA detection with split initiators | Non-specific staining, background | Requires 20+ probe pairs; enables single-molecule detection |

| Ethyl Cinnamate (ECi) Clearing [10] | Organic solvent-based clearing | Tissue opacity, imaging depth | Effective for E3.5-E5.5 chick embryos; requires post-fixation |

| Proteinase K Titration [12] | Controlled tissue permeabilization | Signal variability, access bias | Over-digestion causes morphology loss; requires optimization |

| Pre-hybridization Bleaching [12] | Melanin pigment removal | Autofluorescence, background | Early protocol placement (post-fixation) most effective |

| Tail Fin Notching [12] | Enhanced reagent penetration/washing | Background in loose tissues | Specific to fin structures; improves fluid exchange |

| Tn5 Transposase + RCA [14] | In situ amplification for DNA microscopy | Signal detection limits | Enables volumetric molecular mapping; avoids thermal cycling |

| 12-Oxograndiflorenic acid | 12-Oxograndiflorenic acid, MF:C20H26O3, MW:314.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Erinacin B | Erinacin B, CAS:156101-10-9, MF:C25H36O6, MW:432.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Technical noise in embryo ISH represents a multidimensional challenge requiring integrated solutions across experimental design, sample processing, and imaging parameters. Through systematic characterization of signal variability, non-specific staining, and large-image artifacts, this guide provides a structured framework for noise identification and mitigation. The reagent toolkit and methodologies detailed herein enable researchers to select appropriate strategies based on their specific embryo model, developmental stage, and imaging requirements. As spatial transcriptomics advances toward whole-embryo volumetric analysis, robust noise management will remain fundamental to extracting biologically meaningful patterns from complex embryonic contexts. Implementation of these proactive noise reduction strategies will enhance data quality, reproducibility, and biological insight in developmental studies.

In embryo in situ hybridization (ISH) research, achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio is paramount for the accurate localization and quantification of gene expression. Biological noise, originating from the intrinsic properties of the specimen itself, presents a significant challenge that can obscure specific staining and lead to data misinterpretation. This technical guide delves into three major sources of biological noise—tissue heterogeneity, pigmentation, and blood vessel autofluorescence—within the context of embryonic studies. Understanding and mitigating these sources is a critical component of a broader thesis on mastering background noise to enhance the reliability and reproducibility of ISH data.

The following table summarizes the primary biological noise sources, their characteristics, and the specific challenges they pose for ISH analysis in embryonic tissues.

Table 1: Characteristics of Core Biological Noise Sources in Embryonic Tissues

| Noise Source | Biological Origin | Spectral Profile | Impact on ISH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Heterogeneity | Complex mix of cell types, extracellular matrix (e.g., collagen), and tissue architectures [16]. | Variable; collagen emits in the blue/green spectrum (~300-450 nm) [17]. | Inconsistent probe accessibility and non-uniform background, complicating segmentation and signal quantification [16]. |

| Pigmentation | Melanin in pigment cells and lipofuscin, an age-associated pigment that accumulates in lysosomes [18] [19]. | Broad emission spectrum; lipofuscin is highly fluorescent across 500-695 nm [17]. | Granular autofluorescence can be mistaken for specific signal; high background masks low-abundance transcripts [18] [19]. |

| Blood Vessel Autofluorescence | Primarily from hemoglobin within red blood cells (RBCs) [20]. | Broad excitation and emission, particularly problematic below 600 nm [20]. | Obscures signals in and around vasculature; a major issue in non-perfused embryonic tissues where RBCs are nucleated and abundant [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Noise Reduction

Whole-Mount Fluorescent ISH (FISH) with Autofluorescence Reduction

This protocol is optimized for whole-mount embryonic samples and incorporates steps to mitigate pigmentation and general autofluorescence [18] [21].

- Fixation and Bleaching:

- Pre-hybridization:

- Permeabilize tissues using a detergent such as Triton X-100.

- Include an acetylation step using Triethanolamine (TEA) buffer with acetic anhydride to neutralize charge from free amines and reduce background [19].

- Hybridization:

- Post-Hybridization Washes and Signal Development:

- Perform stringent washes to remove unbound probe.

- For detection, use the Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) system to generate strong, specific signals with minimal background [18].

- Autofluorescence Quenching (Post-Staining):

- After signal development, incubate samples in a working solution of TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher (e.g., 1X in PBS) to suppress residual autofluorescence from lipofuscin and RBCs [20].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol for Suppressing Red Blood Cell Autofluorescence

This protocol details the use of TrueBlack, an effective alternative to Sudan Black B, for quenching RBC autofluorescence in fixed embryonic tissue sections [20].

- Tissue Preparation:

- Fix embryonic tissue (e.g., E12.5 mouse embryos) in 4% formaldehyde.

- Cryoprotect by incubating in 30% sucrose solution, then embed in O.C.T. compound and section using a cryostat.

- Immunostaining/ISH:

- Perform standard RNA-FISH or immunofluorescence staining protocols on tissue sections.

- TrueBlack Quenching:

- Prepare a 1X dilution of 20X TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher in PBS.

- Incubate the stained sections in TrueBlack solution for the optimized duration (e.g., 30 seconds to 2 minutes).

- Rinse sections briefly in PBS.

- Mounting and Imaging:

- Mount sections with an antifade mounting medium (e.g., Vectashield with DAPI).

- Image using an epifluorescent or confocal microscope.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs essential reagents for managing biological noise in ISH experiments.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Noise Reduction

| Reagent | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| TrueBlack Lipofuscin Autofluorescence Quencher | Suppresses autofluorescence from lipofuscin and red blood cells across red and green wavelengths [20]. | Does not introduce background fluorescence, unlike Sudan Black B, which fluoresces in the far-red channel [20]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | Bleaching agent that oxidizes and reduces pigment-based autofluorescence in fixed samples [18]. | Efficacy is pigment-dependent; works well on blue-black specimens, less on orange-brown ones [18]. |

| Sodium Borohydride (NaBHâ‚„) | Reduces aldehyde-induced autofluorescence from formalin/PAF fixation by breaking Schiff bases [17]. | Can be caustic, may damage tissue integrity, and reduce specific antibody signal; variable results [20] [17]. |

| Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) | Enzyme-mediated system that deposits numerous fluorophores at the target site, amplifying a specific signal above background [18]. | Enables detection of low-abundance transcripts; requires optimization to prevent non-specific deposition [18]. |

| Denhardt's Solution | Macromolecular crowding agent included in hybridization buffers to increase effective probe concentration and signal intensity [18]. | Provides a roughly two-fold increase in signal strength, improving the signal-to-noise ratio [18]. |

| 6-Epidemethylesquirolin D | 6-Epidemethylesquirolin D, MF:C20H28O5, MW:348.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Malonyl CoA | Malonyl-CoA Research Grade|Fatty Acid Synthesis Substrate | High-purity Malonyl-CoA for research into fatty acid synthesis, polyketide production, and metabolic signaling. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Strategic Visualization and Dye Selection

The relationship between noise sources, mitigation strategies, and the final image output is a critical pathway to understand. The following diagram illustrates this workflow and the key decision points.

A strategic choice of fluorophore is a critical and simple method to avoid inherent autofluorescence. Biological molecules like collagen and NADH naturally fluoresce in the blue/green spectrum (300-450 nm) [17]. Therefore, selecting dyes that emit in the far-red (e.g., Cy5, Quasar 670, or CoraLite 647) can automatically separate the specific signal from a significant portion of the background noise [17] [19]. Conversely, the green channel (used for Alexa 488 or FITC) should be avoided, especially in tissues with high background like the brain or embryo, as shorter wavelengths scatter more in tissue, increasing autofluorescence [19].

The Critical Impact of Noise on Sensitivity, Specificity, and Quantitative Accuracy

In the context of embryo in situ hybridization (ISH), "noise" represents a complex interplay of technical and biological variables that obscure specific detection of target nucleic acid sequences. Background noise directly compromises the three pillars of reliable ISH data: sensitivity (the ability to detect low-abundance transcripts), specificity (the ability to distinguish target from non-target sequences), and quantitative accuracy (the precise measurement of expression levels). For researchers investigating spatial gene expression patterns in embryo models such as zebrafish, chicken, and mouse, managing noise is particularly challenging due to autofluorescence from embryonic tissues, non-specific probe binding, and endogenous enzymatic activities [22] [23] [10].

The fundamental challenge in ISH resides in achieving an optimal signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) while preserving morphological integrity. This technical hurdle becomes increasingly pronounced when moving from qualitative assessment to quantitative analysis and single-molecule detection, where noise sources must be systematically characterized and controlled. The following sections examine the biological and technical sources of noise, present quantitative data on their impacts, and provide detailed protocols for noise reduction to enhance experimental rigor in developmental biology research.

Biological noise in embryo ISH originates from the intrinsic properties of embryonic tissues and their interaction with detection methodologies. Autofluorescence represents a significant challenge, particularly in older embryos where pigment deposition and tissue density increase. This autofluorescence arises from endogenous fluorophores such as lipofuscin, NADPH, and collagen, which emit across a broad spectrum when excited [10]. The problem is especially pronounced in zebrafish embryos beyond 7 days post-fertilization (dpf), where pigment formation creates substantial background interference unless inhibited chemically with phenyl-thio-urea (PTU) or through the use of genetically pigment-free lines such as casper [24].

Tissue opacity presents another substantial barrier to high-quality ISH, particularly for whole-mount preparations. As embryonic development progresses, tissue density and complexity increase, resulting in light scattering that diminishes signal resolution and increases background noise. This effect is notably observed in chicken embryos beyond E3.5, where traditional ISH protocols fail to provide adequate penetration and signal clarity [10]. Additionally, endogenous enzymatic activities, particularly phosphatases and peroxidases, can generate non-specific chromogenic or fluorescent signals that mimic true positive results, leading to false positives and compromised specificity [5].

Technical noise arises from methodological limitations and reagent-related factors throughout the ISH workflow. Probe design and hybridization efficiency fundamentally influence noise levels; longer riboprobes, while offering higher thermal stability, exhibit poorer tissue penetration and increased potential for non-specific binding [5]. Conversely, shorter probes like those used in RNAscope (ZZ probe design) provide better penetration but require sophisticated amplification systems to achieve detectable signals [22].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Technical Modifications on Signal-to-Noise Ratio

| Technical Factor | Experimental Condition | Impact on SNR | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hybridization Temperature | 70°C (standard) vs 55-60°C (modified) | Increased contrast, faster development | Zebrafish embryo [5] |

| Dextran Sulfate in Hybridization Buffer | Presence vs Absence | Improved contrast but inhibits PCR genotyping | Zebrafish embryo [5] |

| Tissue Clearing | Non-cleared vs ECi-cleared | Improved depth resolution, reduced scattering | Chicken embryo (E3.5-E5.5) [10] |

| Probe Size | Long riboprobes (>500bp) vs smFISH probes (20-25bp) | Better penetration, reduced non-specific binding | Mouse oocytes/embryos [23] |

| Signal Amplification System | Traditional vs TSA system | >5x sensitivity increase | Mouse oocytes/embryos [23] |

Stringency conditions during hybridization and washing represent another critical variable. Suboptimal stringency allows partial hybridization to non-target sequences, while excessive stringency may diminish specific signals. The concentration of monovalent cations, pH, temperature, and presence of organic solvents like formamide collectively determine stringency, requiring empirical optimization for each probe-embryo system [5]. Detection system limitations, including non-specific antibody binding, fluorophore aggregation, and enzymatic precipitation heterogeneity, further contribute to technical noise. The popular tyramide signal amplification (TSA) system, while dramatically enhancing sensitivity, can exacerbate background through diffusion of activated tyramide radicals and non-specific deposition if not carefully controlled [23].

Quantitative Impacts of Noise on ISH Parameters

Effects on Sensitivity and Detection Threshold

The sensitivity of ISH assays determines the threshold for transcript detection, with noise directly influencing the minimum number of molecules that can be reliably visualized. In single-molecule FISH (smFISH) applications, the theoretical detection limit is one transcript, but practical sensitivity is constrained by background noise. The implementation of hybridization chain reaction (HCR) RNA-FISH has demonstrated significant improvements, enabling detection of mRNAs in whole-mount chicken embryos at stages up to E5.5, where traditional methods fail due to elevated background [10].

Quantitative assessments reveal that optimized probe design can improve sensitivity by orders of magnitude. The RNAscope technology, employing a unique ZZ probe design that requires dual probe binding for signal initiation, achieves a 7-fold increase in signal-to-noise ratio compared to conventional single-probe systems [22]. This approach significantly reduces false-positive signals from non-specific binding while maintaining high detection efficiency for low-abundance transcripts in complex embryonic tissues like the zebrafish pronephros region [22].

Effects on Specificity and Spatial Resolution

Specificity—the accurate discrimination of target versus non-target sequences—is profoundly affected by noise through several mechanisms. Spectral bleed-through occurs when emission from one fluorophore is detected in another channel, creating false co-localization patterns. This problem intensifies in multiplexed ISH, where simultaneous detection of multiple transcripts is essential for understanding gene regulatory networks. The problem is particularly acute in embryo ISH due to high probe concentrations needed for adequate penetration and the inherent autofluorescence of embryonic tissues [10].

Spatial resolution degradation manifests as imprecise transcript localization, especially problematic when studying subcellular RNA distribution patterns. Super-resolution microscopy of mouse oocytes has revealed that RNA granules previously observed by conventional microscopy actually comprise multiple smaller granules, highlighting how noise and resolution limitations can lead to misinterpretation of mRNA organization [23]. Tissue clearing techniques like ethyl cinnamate (ECi) have demonstrated remarkable improvements in spatial resolution by reducing light scattering, enabling precise mapping of transcript distribution in three dimensions within intact chicken embryos [10].

Table 2: Physiological Noise Impacts in Embryo Models

| Stress Indicator | Experimental Condition | Quantitative Change | Developmental Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Rate | 150 dB continuous noise vs control | 191±60 bpm vs 173±30 bpm (3 dpf); 224±50 bpm vs 203±40 bpm (5 dpf) | Zebrafish larva [25] |

| Yolk Sac Consumption | 150 dB continuous noise vs control | Significant increase (p<0.001) | Zebrafish larva (3 & 5 dpf) [25] |

| Cortisol Levels | 150 dB continuous noise vs control | Significant increase (p=0.010) | Zebrafish larva (3 & 5 dpf) [25] |

| Mortality Rate | 150 dB continuous noise vs 130 dB | Significant increase (p=0.036) | Zebrafish larva [25] |

Implications for Quantitative Accuracy

Quantitative ISH methods aim to extract meaningful information about transcript abundance from signal intensity measurements. However, multiple noise sources introduce systematic errors that compromise accuracy. Non-linear amplification in signal detection systems, particularly enzymatic methods like TSA and alkaline phosphatase-based detection, can distort the relationship between transcript number and signal intensity. The TSA system exhibits a steep amplification curve where slight variations in enzyme concentration or substrate incubation time dramatically affect output, creating challenges for between-sample comparisons [23].

Probe accessibility variations across different tissue types represent another significant confounder for quantitative analysis. Dense tissues like notochord and sensory epithelium in zebrafish embryos show reduced probe penetration compared to looser mesenchymal tissues, creating apparent expression differences that reflect technical limitations rather than biological reality [22]. This effect intensifies in older embryos, where extracellular matrix deposition and tissue compaction further impede uniform probe distribution. Computational approaches for normalization must account for these region-specific noise profiles to achieve accurate quantification.

Experimental Protocols for Noise Reduction

Optimized Whole-Mount smFISH with Autofluorescence Reduction

The following protocol, adapted from mouse embryo studies with applications to other model organisms, systematically addresses key noise sources while preserving morphological integrity [23] [21]:

Fixation and Permeabilization

- Fix embryos in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 24 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation. Extended fixation improves structural preservation but may reduce probe accessibility; therefore, avoid over-fixation.

- Permeabilize with Proteinase K (10-20 μg/mL in PBS) for 15-30 minutes based on embryo age and size. Optimization is critical as insufficient permeabilization limits probe penetration, while excessive treatment damages morphology.

- Refix in 4% PFA for 20 minutes to maintain structural integrity during subsequent hybridization steps.

- Treat with sodium borohydride (1 mg/mL in PBS) for 30-60 minutes to reduce autofluorescence by neutralizing aldehydes generated during fixation.

Hybridization and Stringency Control

- Pre-hybridize for 2-4 hours at the hybridization temperature (55-65°C) in hybridization buffer containing 50% formamide, 5× SSC, 0.1% Tween-20, and 50 μg/mL heparin. Include 1% blocking reagent (Roche) to minimize non-specific probe binding.

- Hybridize with target-specific probes (50-100 nM) for 12-16 hours at the optimized temperature. For double-stranded DNA probes, denature at 85°C for 10 minutes before application.

- Perform post-hybridization washes with increasing stringency: 2× SSC at hybridization temperature (30 minutes), 1× SSC (30 minutes), and 0.2× SSC (30 minutes). Incorporate 0.1% SDS in the first wash to reduce non-specific adhesion.

Signal Amplification and Detection

- For TSA-based detection, incubate with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibodies (1:500-1:1000 dilution) for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Develop signal with fluorophore-conjugated tyramide (1:50 dilution in amplification buffer) for 5-15 minutes. Monitor development microscopically to prevent over-amplification, which increases background noise.

- Quench HRP activity with 1% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ in PBS for 30 minutes between sequential TSA reactions when performing multiplex detection.

HCR RNA-FISH Combined with Tissue Clearing

This protocol, optimized for chicken embryos but applicable to other model systems, enhances signal-to-noise ratio through probe design innovation and optical clearing [10]:

Probe Design and Hybridization

- Utilize split-initiator probes (20-25 bp each) designed against target mRNA sequences. The split-initiator system dramatically reduces non-specific amplification by requiring coincidental binding of two proximal probes.

- Hybridize with 1-2 nM probe sets in 30% formamide, 5× SSC, 9 mM citric acid (pH 6.0), 0.1% Tween-20, 50 μg/mL heparin, 1× Denhardt's solution at 37°C for 12-16 hours.

- Wash with 30% formamide in 5× SSCT (5× SSC with 0.1% Tween-20) at 37°C for 30 minutes, followed by three 15-minute washes with 5× SSCT at room temperature.

Amplification and Clearing

- Amplify signals with hairpin amplifiers (60-90 nM) in 5× SSCT for 12-16 hours at room temperature. Hairpin concentrations should be optimized for each target to balance signal intensity and background.

- Post-fix with 4% PFA for 20 minutes after amplification to stabilize signals during clearing.

- Dehydrate through ethanol series (50%, 80%, 100%; 30 minutes each) before clearing in ethyl cinnamate (ECi) for at least 4 hours or until transparent. ECi provides superior clearing efficiency for embryos between E3.5 and E5.5 with minimal signal quenching.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for low-noise embryo in situ hybridization integrating key noise-reduction steps.

Research Reagent Solutions for Noise Mitigation

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Noise Reduction in Embryo ISH

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Noise Control | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permeabilization Agents | Proteinase K, Triton X-100, Tween-20 | Enhances probe penetration while maintaining morphology | Titrate concentration based on embryo age; monitor morphological integrity microscopically |

| Blocking Reagents | Torula RNA, heparin, denatured salmon sperm DNA, BSA | Reduces non-specific probe binding | Use combination approach; include in pre-hybridization and antibody incubation steps |

| Hybridization Enhancers | Dextran sulfate, formamide | Increases effective probe concentration and stringency | Omit dextran sulfate if post-ISH genotyping is required [5] |

| Signal Amplification Systems | TSA, HCR, RNAscope | Enhances signal without proportional background increase | Optimize incubation time to prevent over-amplification; use sequential application for multiplexing |

| Tissue Clearing Reagents | Ethyl cinnamate (ECi), fructose, ScaleS | Reduces light scattering for improved depth resolution | ECi shows best compatibility with HCR FISH in older embryos [10] |

| Autofluorescence Quenchers | Sodium borohydride, Sudan Black B, copper sulfate | Reduces endogenous fluorescence | NaBH4 most effective for aldehyde-induced fluorescence; test efficacy on specific embryo models |

The critical impact of noise on sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative accuracy in embryo ISH necessitates a systematic approach to experimental design and validation. As the field moves toward increasingly quantitative applications, including single-cell transcript counting and spatial transcriptomics in intact embryos, noise characterization and control become paramount. The integration of computational methods for background subtraction and signal normalization will further enhance the quantitative potential of ISH techniques.

Future innovations will likely focus on probe chemistry refinements, such as the development of quantum dots with narrower emission spectra to reduce spectral bleed-through in multiplex applications, and CRISPR-based in situ labeling techniques that offer exceptional specificity [26]. Additionally, machine learning approaches for automated signal segmentation and noise classification hold promise for extracting meaningful biological information from noisy image data. By adopting the rigorous noise mitigation strategies outlined in this technical guide, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and interpretability of their embryo ISH data, advancing our understanding of gene expression dynamics in embryonic development.

Diagram 2: Conceptual framework illustrating the relationship between noise sources, their impacts on ISH quality, mitigation strategies, and resulting experimental outcomes.

Proven Strategies and Novel Methods to Suppress Background Noise

In the field of developmental biology, background noise in embryo in situ hybridization research presents a significant obstacle to obtaining high-quality data. Tissue autofluorescence, emanating from various intracellular molecules like lipofuscin, flavins, and collagen crosslinks, poses a particularly complex challenge for high-sensitivity detection of fluorescently labelled RNA probes and antibody staining [27]. Although these problems can in some cases be ameliorated by digital post-processing of raw images, this approach often introduces computational artifacts and fails to address the fundamental signal-to-noise limitation. Therefore, the ideal solution involves eliminating tissue autofluorescence at its source, prior to fluorescent labelling. Various pre-treatments using irradiation-by-light or chemicals have been attempted on tissue sections, but achieving consistent results for whole-mount specimens such as embryos, tissues, and organs has remained particularly challenging [27]. The Oxidation-Mediated Autofluorescence Reduction (OMAR) protocol represents a significant advancement by combining photochemical bleaching with optimized tissue permeabilization, thereby providing a robust framework for understanding and mitigating background noise in embryo in situ hybridization research.

The OMAR Protocol: A Detailed Technical Guide

Principles and Mechanism of OMAR

The OMAR protocol operates on the principle of photochemical oxidation to reduce or eliminate endogenous fluorophores within tissues. The technique requires a high-intensity cold white light source to drive a chemical reaction in an oxidizing solution, effectively bleaching autofluorescent compounds without compromising cellular architecture or the integrity of target biomolecules. During the successful oxidation reaction, researchers can observe an increasing number and size of bubbles forming in the solution and around the sample [27]. This protocol is particularly valuable for whole-mount Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (RNA-FISH) and can be similarly applied to whole-mount immunofluorescence analyses. The method significantly improves the signal-to-noise ratio by addressing autofluorescence at its source, thus alleviating the need for digital image post-processing which can sometimes introduce artifacts or fail to fully resolve the underlying problem [27].

Equipment and Reagent Specifications

The successful implementation of OMAR requires specific equipment and reagents optimized for photochemical bleaching. The table below summarizes the core components of the "Scientist's Toolkit" for implementing OMAR:

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for OMAR Implementation

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Light Source | High-power LED spotlights (gooseneck) or LED daylight panels (20000 lumen) [27] | Provides high-intensity cold white light to drive the photochemical oxidation reaction |

| Key Chemicals | Hydrogen peroxide (33% w/v), Paraformaldehyde, Methanol, Tween 20 [27] | Forms the oxidizing environment for bleaching and provides fixation and permeabilization |

| HCR Reagents | Probe hybridization buffer, Probe wash buffer, Amplification buffer [27] | Enables specific RNA target detection through the Hybridization Chain Reaction v3.0 |

| Imaging Equipment | Zeiss Axioskop microscope, VisiView Premier Software [27] | Facilitates high-resolution imaging and data capture of processed samples |

Step-by-Step Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for the OMAR protocol, from embryo collection to final image analysis:

OMAR Experimental Workflow

The protocol implementation follows a precise sequence:

Embryo Collection and Fixation: Collect mouse embryos of the relevant developmental stages while adhering to institutional animal care guidelines and 3R principles (Replace, Reduce, Refine). Fix embryos immediately using paraformaldehyde to preserve tissue architecture and RNA integrity [27].

OMAR Photochemical Bleaching: Transfer fixed samples to an OMAR staining solution containing hydrogen peroxide. Illuminate with a high-intensity LED light source (e.g., 20,000 lumen daylight panels) for a predetermined duration. Monitor for bubble formation as an indicator of successful oxidation reaction. The required duration should be determined empirically for different tissue types [27].

Detergent-Based Permeabilization: Treat the bleached samples with a permeabilization buffer containing detergents such as Tween 20 or Triton X-100. This critical step enables subsequent probe penetration throughout the whole-mount specimen without compromising tissue integrity [27].

RNA-FISH with HCR v3.0: Perform whole-mount RNA-fluorescence in situ hybridization using the Hybridization Chain Reaction v3.0 system from Molecular Instruments. This involves hybridizing with specific probe sets, followed by washing and signal amplification with fluorescently labelled hairpins [27].

Optical Clearing: Subject the samples to an optical clearing protocol to reduce light scattering within the tissue. This step significantly improves image quality and penetration depth for both 2D and 3D imaging applications [27].

Image Acquisition and Analysis: Image the processed samples using appropriate fluorescence microscopy systems. Analyze data using software such as ImageJ/Fiji or Imaris, leveraging the improved signal-to-noise ratio achieved through OMAR treatment for more accurate quantification [27].

Validation and Quality Control Metrics

Rigorous validation is essential for confirming OMAR efficacy. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics for assessing protocol performance:

Table 2: Quantitative Assessment of OMAR Efficacy

| Parameter | Pre-OMAR Condition | Post-OMAR Result | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autofluorescence Intensity | High across multiple channels [27] | Low or absent in channels of interest [27] | Fluorescence microscopy |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Compromised by background noise [27] | Significantly improved [27] | Image analysis (e.g., ImageJ) |

| Protocol Duration | Varies with traditional methods | Approximately 1 week (collection to analysis) [27] | Time tracking |

| Bubble Formation | Not applicable | Present during oxidation (quality indicator) [27] | Visual inspection |

Advanced Analysis Frameworks for RNA-FISH Data

Automated Image Analysis Approaches

Following successful OMAR treatment and RNA-FISH, advanced computational methods are required for accurate signal quantification. The QuantISH framework provides an open-source, modular pipeline specifically designed for RNA-ISH image analysis, capable of quantifying marker expressions in individual carcinoma, immune, and stromal cells from chromogenic or fluorescent in situ hybridization images [8]. This approach is particularly valuable for analyzing tumor heterogeneity and expression localization that are not readily obtainable through bulk transcriptomic analysis. For complex environmental samples where intensity thresholds are inconsistent, fuzzy c-means clustering (FCM) provides an effective alternative for classifying cells into target (positive) and nontarget (negative) populations without requiring manually set thresholds that vary between experiments [28].

Analytical Pathways for RNA-FISH Data Interpretation

The diagram below outlines the logical pathway for analyzing RNA-FISH data following OMAR processing:

RNA-FISH Data Analysis Pathway

Discussion and Research Implications

The implementation of OMAR for whole-mount autofluorescence reduction represents a significant methodological advancement in embryo in situ hybridization research. By addressing the fundamental challenge of background noise at its source, this protocol enables researchers to obtain cleaner signals and more reliable data from fluorescent imaging experiments. The technical framework outlined in this guide provides researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for implementing this approach in their investigations of gene expression patterns in embryonic development.

When combined with automated image analysis frameworks like QuantISH [8] and advanced classification algorithms like fuzzy c-means clustering [28], the OMAR protocol establishes a robust pipeline for quantifying RNA expression levels and spatial distribution patterns with minimal interference from autofluorescence. This integrated approach is particularly valuable for drug development professionals seeking to understand precise gene expression patterns in embryonic models and for basic researchers investigating the complex dynamics of developmental biology.

In embryo in situ hybridization (ISH) research, background noise is a significant confounding variable that can compromise data interpretation. Effective tissue permeabilization and pre-treatment are critical first steps to mitigate this noise, as they control the accessibility of the target nucleic acids while preserving morphological integrity. This technical guide examines current methodologies for achieving this balance, with a focus on applications in embryonic research. The optimization of these parameters is foundational to reducing non-specific hybridization and improving the signal-to-noise ratio in spatial transcriptomic studies.

Core Principles of Tissue Preparation

The primary goal of tissue pre-treatment for ISH is to allow probe access to intracellular targets while maintaining RNA integrity and tissue architecture. This process involves a series of critical steps that must be finely tuned to the specific tissue type, fixation method, and probe chemistry.

Fixation: The Foundation of Sample Integrity

Fixation is the most critical pre-analytical factor, as it preserves tissue morphology and nucleic acids by inactivating RNases and cross-linking biomolecules. Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) is the standard fixative in pathology and has been demonstrated as suitable for ISH [3]. The recommended protocol involves preserving tissues (maximum thickness of 5 mm) in a 10:1 ratio of fixative to tissue for approximately 24 hours at room temperature [3]. Under-fixation risks insufficient tissue preservation and RNA degradation during subsequent steps, while over-fixation can lead to excessive cross-linking that hinders probe penetration, requiring more aggressive permeabilization that may damage tissue integrity [3].

For embryonic tissues, specific optimizations exist. A whole-mount RNA-FISH protocol for mouse embryos utilizes fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) [21], while a study on avian embryos compared PFA with Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA), finding TCA improved signal detection for certain targets [29]. The compatibility of the fixative with subsequent optical clearing methods must also be considered for 3D imaging applications [13].

Permeabilization Strategies

Following fixation, permeabilization is necessary to render the tissue accessible to probes and detection reagents. This step involves creating pores in the cellular and tissue matrices without destroying the structural context of the target molecules.

- Detergent-Based Permeabilization: Mild detergents like Tween-20, Triton X-100, or CHAPS at concentrations of 0.1% are commonly used to dissolve lipid membranes and facilitate reagent penetration [3].

- Enzymatic Permeabilization: Proteinase K is frequently employed to digest proteins and loosen the tissue matrix. The intensity and duration of proteinase K treatment must be carefully optimized based on fixation duration and tissue type [3]. Insufficient treatment limits probe access, while excessive digestion damages morphology and releases RNAs.

- Heat-Mediated Antigen Retrieval: This technique uses heat to break protein cross-links formed during fixation, thereby exposing target sequences. The conditions (time, temperature, pH) must be determined empirically [3].

A streamlined protocol for Drosophila embryos and ovaries in a rapid isHCR method successfully eliminated proteinase K treatment and a post-fixation step altogether while still detecting strong RNA signals, demonstrating that less invasive permeabilization can be sufficient for certain applications [30].

Quantitative Comparison of Pre-Treatment Parameters

The table below summarizes key parameters and their optimization based on current literature.

Table 1: Optimization Guidelines for Tissue Pre-Treatment Parameters

| Parameter | Standard Optimization Range | Effect on Signal | Effect on Integrity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation (10% NBF) | 24 ± 12 hours; 10:1 fixative:tissue ratio | Under-fixation → RNA degradation; Over-fixation → reduced probe access | Under-fixation → poor morphology; Standard fixation → optimal | [3] |

| Proteinase K Treatment | Concentration & time tissue-dependent | Insufficient → low signal; Excessive → false positives/background | Excessive → tissue digestion & morphology loss | [3] |

| Detergent Concentration(Tween-20/Triton X-100) | ~0.1% | Optimized → enhanced probe penetration; High → increased background | High concentrations can disrupt ultrastructure | [3] [30] |

| Alternative Permeabilization(Xylene treatment) | 1 hour (Drosophila embryos) | Improves penetration in chitinous structures | Harsh, can damage tissues; Can be omitted in optimized protocols | [30] |

Advanced permeabilization techniques have been developed for specific applications. The 3D-LIMPID-FISH protocol enables single-molecule RNA detection in thick tissue slices (e.g., 250 µm of adult mouse brain) by using a hydrophilic clearing solution that performs refractive index matching while preserving lipids [13]. This method allows for high-resolution confocal imaging deep within tissues with minimal aberrations.

Experimental Protocols for Embryonic Tissues

Optimized Whole-Mount RNA-FISH Protocol for Mouse Embryos

This protocol, adapted from a detailed STAR Protocol, focuses on oxidation-mediated autofluorescence reduction, a key strategy for minimizing background noise [21].

- Sample Extraction and Fixation: Dissect embryos and fix immediately in 4% PFA for 30 minutes.

- Bleaching (Autofluorescence Reduction): Incubate embryos in a hydrogen peroxide-based solution to reduce innate tissue autofluorescence, a major source of background noise.

- Permeabilization: Treat embryos with a permeabilization solution. The exact composition can vary but often includes detergents. Note: Some streamlined protocols omit Proteinase K for certain embryonic tissues [30].

- Hybridization: Hybridize with gene-specific FISH probes.

- Washing and Clearing: Perform stringent washes to remove non-specifically bound probes. For 3D imaging, clear the embryos using an appropriate optical clearing method (e.g., LIMPID) [13].

- Imaging: Image using confocal or light-sheet microscopy.

Rapid isHCR Protocol for Drosophila Embryos

This protocol reduces staining time from 3 days to 1 day, demonstrating how protocol streamlining can impact efficiency [30].

- Fixation: Fix dechorionated embryos in 1:1 heptane: 4% PFA for 30 minutes. Remove vitelline membranes and store in methanol.

- Rehydration: Sequentially rinse embryos from methanol to PBSTr (PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100).

- Pre-hybridization: Incubate in a pre-warmed hybridization buffer containing 15% ethylene carbonate (EC) for 30 minutes at 45°C. EC is a non-toxic solvent that facilitates hybridization, replacing toxic formamide.

- Hybridization: Hybridize with probe solution for 2 hours at 45°C.

- Amplification: Incubate with short hairpin DNA (shHCR) amplifiers for 1.5–2 hours at 25°C.

- Washing and Mounting: Wash and mount for imaging.

Diagram: Workflow Comparison for Embryo FISH Pre-treatment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential reagents for optimizing permeabilization and pre-treatment in embryo ISH.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Permeabilization and Pre-Treatment Optimization

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative | Preserves morphology and nucleic acids; concentration (e.g., 4%) and time must be optimized [21] [30]. |

| Proteinase K | Enzymatic permeabilization | Digests proteins for probe access; concentration and time are critical to balance signal and integrity [3]. |

| Tween-20 / Triton X-100 | Detergent-based permeabilization | Dissolves lipid membranes; typically used at ~0.1% concentration [3] [30]. |

| Ethylene Carbonate (EC) | Hybridization buffer component | Non-toxic formamide substitute; enhances hybridization efficiency and reduces protocol time [30]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | Autofluorescence reduction | Oxidizes endogenous fluorophores in tissue (e.g., lipofuscin), significantly reducing background noise [21]. |

| LIMPID Solution | Aqueous optical clearing | Enables deep-tissue imaging via refractive index matching; compatible with FISH and preserves lipids [13]. |

| Glucoputranjivin | Glucoputranjivin | High-purity Glucoputranjivin, a natural glucosinolate and selective T2R16 agonist. For research use only (RUO). Not for human consumption. |

| Isofistularin-3 | Isofistularin-3, MF:C31H30Br6N4O11, MW:1114.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Techniques: Multiplexed and 3D Imaging

Recent advances in ISH technologies demand increasingly sophisticated pre-treatment regimens. Highly multiplexed techniques like MERFISH (Multiplexed Error-Robust FISH) and seqFISH rely on sequential hybridization and imaging cycles, requiring robust tissue preservation that can withstand multiple rounds of probing and washing [31]. For these applications, fixation must be thorough to prevent sample degradation or dissociation over the extended protocol duration.

For three-dimensional gene expression mapping in whole embryos or thick tissue sections, optical clearing is essential. The 3D-LIMPID-FISH protocol uses a hydrophilic clearing solution containing saline-sodium citrate, urea, and iohexol [13]. This method is notable for its simplicity and speed, working in a single step through passive diffusion. It preserves most lipids and minimizes tissue swelling or shrinking, making it compatible with simultaneous mRNA and protein detection and allowing high-resolution imaging without the absolute need for advanced sectioning instruments like confocal or light-sheet microscopes [13].

Diagram: Relationship Between Pre-treatment and ISH Background

Mastering tissue permeabilization and pre-treatment is a prerequisite for generating reliable, high-quality data in embryo ISH research. The optimal protocol is not universal but must be empirically determined based on the embryo model, fixation method, probe technology, and imaging requirements. A deep understanding of how each parameter—from fixation time to permeabilization stringency—affects the delicate balance between signal intensity and morphological integrity is fundamental to minimizing background noise. As ISH techniques evolve toward higher multiplexing and greater resolution in three dimensions, the principles of rigorous pre-treatment optimization will remain the bedrock upon which successful spatial transcriptomics is built.

In situ hybridization (ISH) is an indispensable tool for visualizing spatial gene expression patterns, a capability that is particularly crucial in embryonic research where the precise localization of mRNA governs development. However, a significant impediment to obtaining clear results is background noise, which can obscure specific signals and lead to inaccurate data interpretation. This challenge is especially pronounced in delicate embryonic tissues, which are often autofluorescent and susceptible to degradation. Traditional probe designs and detection methods often struggle with insufficient signal amplification and off-target binding, limiting their effectiveness. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to three advanced probe design and signal amplification technologies—π-FISH, RNAscope, and branched DNA (bDNA)—that are engineered to overcome these limitations. By focusing on their underlying mechanisms, experimental protocols, and quantitative performance, we equip researchers with the knowledge to select and implement the optimal strategy for achieving high-specificity, low-noise detection in embryo ISH.

The evolution of ISH has been driven by the need for higher sensitivity and specificity. The technologies discussed below represent significant leaps in probe design and signal amplification.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Advanced ISH Technologies

| Technology | Core Mechanism | Best Reported Sensitivity (Signal Spots per Cell) | Best Reported Specificity/False-Positive Rate | Optimal for Short Targets? | Suitability for Embryonic Tissues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| π-FISH Rainbow | π-shaped target probes with U-shaped bilateral amplification [32] | ACTB in HeLa cells: ~18 (significantly higher than smFISH & HCR) [32] | < 0.51% false-positive rate [32] | Yes, especially when combined with HCR (π-FISH+) [32] | Validated in whole-mount samples; high signal ideal for autofluorescent tissue [32] |

| RNAscope | Double-Z probe design with branched DNA amplification [33] | Single-molecule detection (1 dot = 1 mRNA molecule) [34] [33] | Near 100% specificity; requires dual Z-probe binding [33] | Yes, can detect partially degraded and short molecules [33] | Successfully optimized for individual murine oocytes and embryos [34] |

| bDNA (e.g., smFISH) | Multiple singly-labeled oligonucleotide probes [35] | Varies with transcript abundance; enables single-molecule resolution [35] | High, but can be lower than π-FISH or RNAscope in direct comparisons [32] | Requires longer sequences for multiple probe binding [35] | Applied in whole-mount preparations; may require more optimization [35] |

Technology Deep Dive: Mechanisms and Protocols

Ï€-FISH Rainbow

1. Core Principle and Workflow: π-FISH rainbow is distinguished by its unique π-shaped target probes. Unlike traditional linear probes, these contain 2-4 complementary base pairs in their middle region. This design allows pairs of probes to form a stable, π-shaped bond upon hybridization to the target RNA, dramatically increasing thermodynamic stability and specificity during stringent washes [32]. The subsequent signal amplification employs a series of U-shaped bilateral amplification probes, which generate a stronger signal than traditional L-shaped unilateral probes [32].

2. Experimental Protocol for π-FISH:

- Probe Design: Design 10-15 primary π-target probes per mRNA, each with a central 2-4 nucleotide complementary region [32].

- Sample Preparation: Fix tissues according to standard protocols (e.g., 4% PFA). Permeabilization conditions must be optimized for embryonic tissue thickness.

- Hybridization: Hybridize π-target probes in a proprietary or optimized hybridization buffer. This is followed by sequential hybridization of secondary and tertiary U-shaped amplification probes [32].

- Signal Detection: Hybridize fluorescently-labeled signal probes to the amplification scaffold. For multiplexing, use a combinatorial coding approach with 4 fluorophores to detect up to 15 targets in a single round [32].

- Imaging and Analysis: Image using a confocal microscope. Quantify discrete signal spots (representing individual transcripts) using image analysis software like FIJI/ImageJ [36].

The following diagram illustrates the probe structure and hybridization cascade:

RNAscope

1. Core Principle and Workflow: RNAscope leverages a proprietary double-Z probe design. Each probe pair consists of two separate "Z" probes that must bind adjacent to each other on the target RNA before a pre-amplifier molecule can attach. This requirement for dual recognition virtually eliminates false-positive signals from non-specific, single-probe binding [33]. Once bound, a multi-step branched DNA (bDNA) amplification cascade ensues, generating an ~8000-fold amplification for each target mRNA molecule [34].

2. Experimental Protocol for Embryonic Samples (adapted from):

- Sample Preparation: Fix individual oocytes or embryos in 4% paraformaldehyde. Avoid using proprietary permeabilization buffers that may cause lysis; instead, use PBS-based permeabilization and wash buffers established for embryo immunofluorescence [34].

- Hybridization: Perform hybridizations in a specialized 6-well plate to prevent loss of fragile embryos. Use the manufacturer's proprietary buffers for the probe, pre-amplifier, and amplifier hybridization steps, as PBS-based buffers can cause probe aggregation [34].

- Probe Hybridization: Apply the ZZ probe pairs targeting the gene of interest. This is followed by sequential hybridization of pre-amplifier and amplifier molecules [33].