Crispants vs Morphants vs Mutants: A Comprehensive Guide to Phenotypic Comparison in Genetic Research

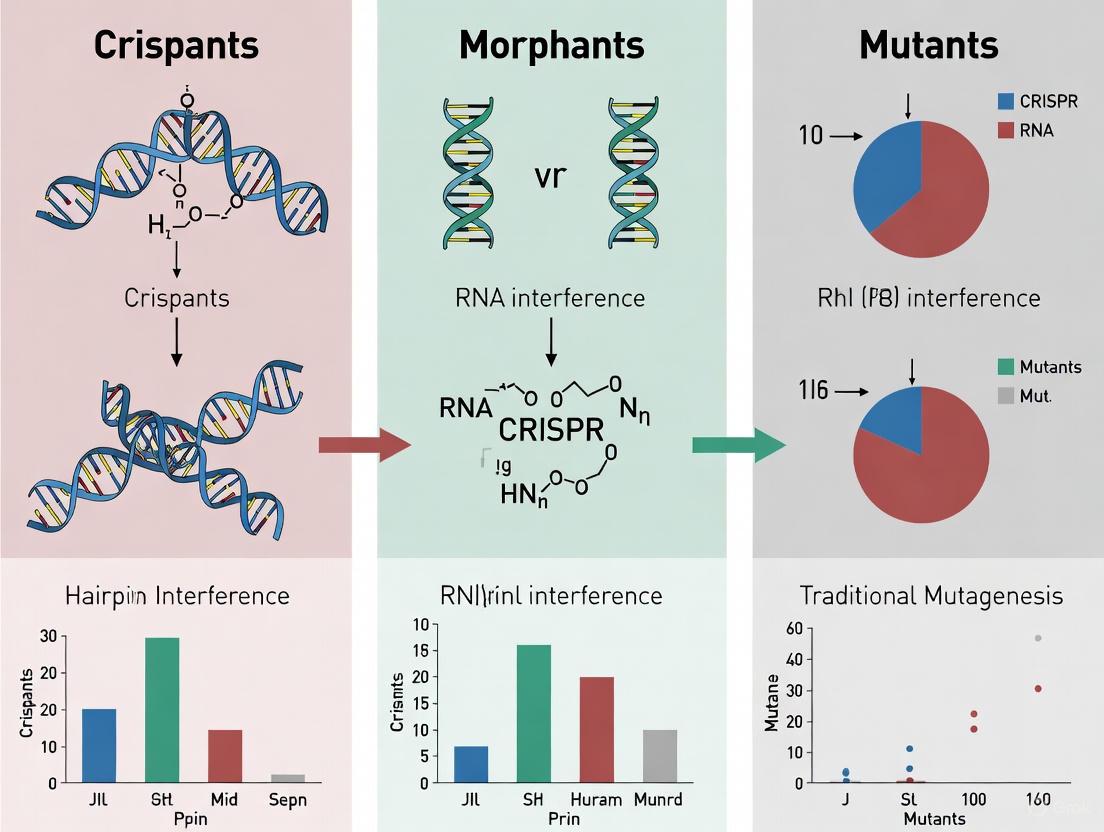

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical phenotypic differences between crispants (F0 CRISPR/Cas9 mutants), morphants (morpholino knockdowns), and stable genetic mutants.

Crispants vs Morphants vs Mutants: A Comprehensive Guide to Phenotypic Comparison in Genetic Research

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical phenotypic differences between crispants (F0 CRISPR/Cas9 mutants), morphants (morpholino knockdowns), and stable genetic mutants. We explore the foundational concepts behind these discrepancies, including the pivotal role of genetic compensation. The content details methodological best practices for creating and analyzing each model, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes a rigorous framework for the validation and comparative analysis of genetic models. By synthesizing recent advances, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to select the appropriate model, accurately interpret phenotypic data, and design robust, efficient genetic screens for functional genomics and therapeutic target validation.

Genetic Compensation: Unraveling the Discrepancy Between Knockdown and Knockout Phenotypes

In functional genomics, establishing a causal link between a gene and a phenotype is fundamental. Researchers primarily use three key models for loss-of-function studies in zebrafish: stable mutants, morphants, and crispants. Each model operates on distinct principles and timelines for gene inactivation, leading to significant implications for phenotypic outcomes. Stable mutants are engineered to carry heritable, permanent mutations across all cells. Morphants achieve transient gene knockdown using morpholino oligonucleotides, while crispants utilize CRISPR/Cas9 to create mosaic, non-inherited mutations in the first generation (F0). Understanding the mechanisms, strengths, and limitations of each approach is crucial for designing robust experiments and accurately interpreting gene function, especially in the context of pervasive challenges like genetic compensation.

Model Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each model to facilitate comparison.

| Feature | Stable Mutant | Morphant | Crispant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Change | Permanent, heritable mutation [1] | Transient; blocks mRNA splicing or translation [2] [3] | Transient, non-heritable; mosaic indels in F0 [4] [5] |

| Molecular Mechanism | CRISPR/TALEN-induced indels creating frameshifts/early stop codons [6] | Antisense morpholino oligonucleotides binding target mRNA [2] | CRISPR/Cas9-induced mosaic indels in somatic cells [4] [7] |

| Development Time | 6-9 months [4] [5] | 1-2 days [3] | 1-7 days (larval phenotyping); ~3 months (adult phenotyping) [4] [5] |

| Key Advantage | Gold standard for stable, reproducible phenotypes; study of adult/long-term effects | Rapid assessment of gene function; targets maternal mRNA [3] | Rapid, cost-effective; circumvents genetic compensation [1] [7] |

| Primary Limitation | Time, cost, resource-intensive; prone to genetic compensation [1] [2] | High off-target effects (e.g., p53 pathway activation); toxicity [2] [3] | Mosaicism can lead to variable expressivity [4] [8] |

Experimental Workflows and Key Protocols

The experimental pathways for creating and validating these models involve distinct steps and timelines.

Key Experimental Steps and Methodologies

1. Crispant Generation and Validation

- gRNA Design and Selection: For each target gene, multiple single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) are designed, typically using bioinformatic platforms like Benchling. The gRNA with the highest predicted out-of-frame efficiency is selected [4] [5].

- Microinjection: A mixture of Cas9 protein (or mRNA) and the selected sgRNA(s) is microinjected into the yolk of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos [4] [7].

- Validation of Editing Efficiency: At 1 day post-fertilization (dpf), DNA is extracted from a pool of injected larvae. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is performed, and tools like Crispresso2 are used to determine the fraction of reads with insertions/deletions (indels) and the out-of-frame rate. Efficiencies of >70% are common and considered sufficient for phenotyping [4] [5].

2. Phenotypic Assessment of Crispants

- Larval Staging (7-14 dpf): Phenotyping can include microscopy for specific cell types (e.g., osteoblasts), whole-mount in situ hybridization for gene expression patterns, or Alizarin Red S staining for bone mineralization [4] [7].

- Adult Staging (~90 dpf): For late-onset or structural phenotypes, crispants are raised to adulthood. Analysis can include micro-computed tomography (microCT) for detailed 3D skeletal architecture, revealing fractures, fusions, and changes in bone volume and density [4] [5].

- Molecular Analysis: Quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) on larval or adult tissue is used to assess the expression of downstream marker genes (e.g.,

bglap,col1a1afor bone studies) to confirm functional molecular consequences [4] [5].

3. Stable Mutant Generation

- Founder (F0) Generation and Raising: The initial step is identical to crispant generation. However, instead of being phenotyped directly, these mosaic F0 fish are raised to sexual maturity.

- Germline Transmission Screening: The outcrossed F0 fish are outcrossed to wild-type fish. Their progeny (F1 generation) are genotyped to identify individuals carrying the mutation in their germline.

- Homozygous Mutant Production: Identified heterozygous F1 fish are incrossed to generate an F2 generation, which will include a Mendelian ratio of wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mutant offspring. These stable homozygous mutants are then subjected to phenotypic analysis [1] [3].

Critical Analysis of Phenotypic Concordance

A central challenge in functional genomics is the frequent discrepancy in phenotypes observed between different models targeting the same gene.

The Genetic Compensation Phenomenon

A key explanation for the differences between crispants/morphants and stable mutants is genetic compensation. This is a phenomenon where stable mutant organisms activate compensatory mechanisms that buffer against the loss of the gene, often resulting in a less severe or absent phenotype than expected [1] [2].

- Mechanism: In stable mutants, nonsense mutations can trigger the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) pathway of the mutant mRNA. This degradation can, in some cases, initiate a feedback loop that leads to the transcriptional upregulation of related genes (paralogs) or other genes within the same network, thereby compensating for the lost function [1] [2].

- Evidence: A compelling example is the

slc25a46gene.slc25a46crispants showed a specific and rescuable phenotype, whereas stable homozygous mutants for the same gene displayed no phenotype. RNA sequencing revealed significant changes in the gene expression profile of the stable mutants, including upregulation of theanxa6gene, which was largely absent in crispants, suggesting a compensatory mechanism had been established in the stable line [1]. - Crispants as a Solution: Because crispants are analyzed acutely in the F0 generation, there is insufficient time for the organism to develop these complex compensatory networks. This makes them particularly valuable for identifying the primary, direct function of a gene [1] [7].

Comparative Case Studies

The table below illustrates specific examples of phenotypic discrepancies and their attributed causes.

| Target Gene | Morphant/Crispant Phenotype | Stable Mutant Phenotype | Attributed Cause/Compensatory Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| slc25a46 | Penetrant disease phenotype [1] | No phenotype observed [1] | Genetic compensation; upregulation of anxa6 and other genes [1] |

| bmp7b | Holoprosencephaly and cyclopia [7] | No obvious developmental defects [7] | Genetic compensation, circumvented by crispant analysis [7] |

| podxl | Reduced hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) [8] | Normal or increased HSCs [8] | Genetic compensation; complex, multi-genic changes in mutants [8] |

| egfl7 | Severe vascular development defects [2] | No obvious defects [2] | Upregulation of paralog emilin3a (Transcriptional Adaptation) [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A successful functional genomics screen relies on a suite of carefully selected reagents and tools.

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 gRNA (IDT) | Synthetic, high-fidelity guide RNA for specific gene targeting; improves efficiency and reduces off-target effects [4] [5]. |

| Cas9 Nuclease | The "molecular scissors" that creates a double-strand break in the DNA at the location specified by the gRNA [4] [6]. |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Synthetic antisense molecules that block translation or splicing of target mRNA; used for transient knockdown [2] [3]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Used to quantitatively assess the efficiency and spectrum of indel mutations in crispant pools (e.g., via Crispresso2 analysis) [4] [5]. |

| Micro-Computed Tomography (microCT) | Provides high-resolution, quantitative 3D imaging of mineralized tissues in adult zebrafish, enabling analysis of bone volume, density, and morphology [4] [5]. |

| (R)-WM-586 | (R)-WM-586, MF:C20H20F3N5O3S, MW:467.5 g/mol |

| Wallichoside | Wallichoside, MF:C20H28O8, MW:396.4 g/mol |

The choice between crispants, morphants, and stable mutants is not a matter of identifying a single "best" model but of selecting the right tool for the specific biological question and stage of research. Morphants offer speed for initial, transient knockdowns. Stable mutants remain the gold standard for studying heritable effects, late-onset phenotypes, and despite the risk of genetic compensation, for providing a stable platform for further research. Crispants have emerged as a powerful intermediate, balancing the speed of morphants with the genetic precision of CRISPR, while effectively circumventing the confounding issue of genetic compensation. A modern, rigorous functional genomics strategy often involves using crispants for rapid initial gene validation and screening, followed by the generation of stable mutant lines for confirmed hits to study long-term and organism-wide effects.

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has cemented its role as a premier model organism for studying vertebrate development and disease, owing to its rapid external development, optical transparency, and genetic tractability [9] [4]. However, a persistent and historical puzzle has challenged researchers: widespread phenotypic discrepancies are observed when the same gene is targeted using different genetic perturbation techniques. A classic manifestation of this puzzle is the frequent lack of a severe phenotype in stable knockout mutants, even when robust, often severe, defects are present in morpholino-induced knockdown embryos (morphants) for the identical gene [9] [4]. This discrepancy initially raised concerns about the specificity of morpholinos but has since been partially explained by a fascinating biological phenomenon known as Genetic Compensation Response (GCR) [9]. This guide objectively compares the performance and outcomes of the primary reverse-genetic approaches—morphants, stable mutants, and the more recent crispants—providing researchers with a framework to select and interpret the appropriate model for their investigative goals.

Comparative Analysis of Genetic Perturbation Platforms

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three primary techniques used in zebrafish functional genomics.

Table 1: Platform Comparison of Zebrafish Genetic Perturbation Techniques

| Feature | Morpholino (MO) Knockdown (Morphants) | Stable Mutant (Knockout) | Crispant (F0 Mosaic Mutant) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanism | Antisense oligonucleotides block translation or splicing [9]. | Heritable, CRISPR/Cas9-induced loss-of-function alleles [9]. | Transient, mosaic CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutations in F0 generation [4]. |

| Technical Timeline | Days (injection at 1-cell stage) [9]. | 6-9 months (to generate F2 homozygous mutants) [9] [4]. | ~3 months (to phenotype adult F0 founders) [4]. |

| Phenotypic Penetrance | High, but can have off-target effects [9]. | Can be absent or mild due to Genetic Compensation [9]. | High; recapitulates stable mutant phenotypes [4]. |

| Key Artifact Sources | Off-target effects, p53-mediated apoptosis [9]. | Genetic Compensation Response (GCR) [9]. | Mosaicism (requires high mutagenesis efficiency) [4]. |

| Ideal Application | Rapid, preliminary assessment of gene function; target validation. | Studying long-term, heritable genetic effects. | High-throughput functional screening and validation [4]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Phenotypic Validation for Selected Genes

| Gene Target | Mutant Phenotype (Stable Line) | Morphant Phenotype | Crispant Phenotype (F0) | Validated Role/Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lrp5 | Not specified in sources | Not specified in sources | Recapitulated stable mutant phenotype [4]. | Bone fragility, Wnt signaling [4]. |

| bmp1a | Not specified in sources | Not specified in sources | Phenotypic convergence with germline mutants [4]. | Osteogenesis Imperfecta, collagen processing [4]. |

| plod2 | Not specified in sources | Not specified in sources | Phenotypic convergence with germline mutants [4]. | Osteogenesis Imperfecta, collagen cross-linking [4]. |

| slc26a5 | Weak expression, no electromotility [10] [11] | Not specified in sources | Not specified in sources | Hair cell function (prestin) [10] [11]. |

| Microexons (e.g., vav2, itsn1) | Mild or no effect [12] | Not specified in sources | Not specified in sources | Neuritogenesis, neural development [12]. |

Decoding the Discrepancy: The Genetic Compensation Response

The divergence between morphant and mutant phenotypes is often attributed to the Genetic Compensation Response (GCR), an adaptive biological mechanism that provides genetic robustness. GCR is triggered by deleterious mutations in stable knockout lines but not by transient protein depletion from morpholinos [9].

This compensatory mechanism involves the upregulation of genetically related genes (homologs or genes within the same pathway) that can functionally substitute for the inactivated gene, thereby masking the expected phenotypic outcome [9]. Recent research indicates that GCR collaborates with the epigenetic machinery and is regulated through processes like Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD) of the PTC-bearing mRNA (the mRNA containing a Premature Termination Codon from the mutation) [9]. The following diagram illustrates this complex mechanism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful functional genetics research in zebrafish relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions in Zebrafish Genomics

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides (MOs) | Antisense oligonucleotides designed to block translation initiation or pre-mRNA splicing, enabling transient gene knockdown [9]. |

| Cas9 Protein & gRNA Complex | Pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex used for CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis. Direct injection into one-cell embryos generates mutants or crispants [9] [4]. |

| p53 Morpholino | Co-injected with gene-targeting MOs to suppress p53-dependent apoptosis, a common off-target effect, thereby improving specificity [9]. |

| Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 gRNAs (IDT) | Commercially available, high-quality guide RNAs used for efficient and specific CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis, as validated in crispant studies [4]. |

| Crispresso2 | A computational tool for the analysis of next-generation sequencing data from CRISPR experiments. It quantifies indel efficiency and out-of-frame rates in crispants [4]. |

| Galectin-4-IN-2 | Galectin-4-IN-2, MF:C17H22O8, MW:354.4 g/mol |

| SDX-7539 | SDX-7539, MF:C23H38N2O5, MW:422.6 g/mol |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Generation and Validation of Stable Mutant Lines

The creation of stable knockout lines via CRISPR/Cas9 is a multi-step process. The workflow begins with microinjection of Cas9/gRNA complexes into one-cell stage embryos. The surviving injected F0 generation are raised to adulthood; these are mosaic founders. These are outcrossed with wild-type fish to generate F1 progeny, which are genotyped to identify heterozygous carriers. Intercrossing of F1 heterozygotes produces F2 embryos, of which 25% are expected to be homozygous mutants [9]. Phenotypic analysis is performed on these F2 homozygotes and compared to their wild-type and heterozygous siblings.

Crispant Screening Protocol for Rapid Validation

Crispant analysis offers a faster alternative for gene function validation. The protocol below is adapted from bone fragility disorder research [4].

- gRNA Design and Selection: Design gRNAs using platforms like Benchling. Select the gRNA with the highest predicted out-of-frame efficiency using a tool like InDelphi-mESC.

- Microinjection: Co-inject Alt-R gRNAs (IDT) with Cas9 protein into the yolk of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Efficiency Validation (at 1 dpf): Pool genomic DNA from ~10 larvae. Amplify the target region and perform Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). Analyze sequencing data with Crispresso2 to determine indel efficiency (aim for >70%) and out-of-frame rates [4].

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Larval Stage (7-14 dpf): Use microscopy and Alizarin Red S staining for skeletal phenotyping.

- Adult Stage (90 dpf): Perform high-resolution microCT imaging to quantify bone volume, density, and architecture.

- Molecular Validation: Conduct RT-qPCR on crispant lysates to analyze expression changes in relevant pathway markers (e.g., bglap and col1a1a for bone studies) [4].

The workflow for generating and applying stable mutants versus crispants is summarized below.

The historical puzzle of phenotypic discrepancies in zebrafish has evolved from a confounding artifact to a rich field of study that underscores the complexity of genetic networks. The choice of model—morphant, stable mutant, or crispant—is not merely a technical decision but a strategic one that directly influences the biological question being addressed.

Morphants remain useful for rapid, preliminary functional screening but require rigorous controls. Stable mutants are essential for studying long-term, heritable effects and the phenomenon of Genetic Compensation itself. Crispants have emerged as a powerful, cost-effective tool for high-throughput functional validation, faithfully recapitulating stable mutant phenotypes for many genes and enabling rapid prioritization of candidate disease genes [4].

Future research will focus on further elucidating the molecular triggers and mechanisms of GCR. Furthermore, the integration of crispant-based screening with advanced transcriptomic and proteomic analyses promises to accelerate the functional annotation of the vertebrate genome and the modeling of human genetic disorders in zebrafish.

Genetic Compensation as a Key Mechanism for Phenotypic Robustness

Phenotypic robustness is the ability of an organism to maintain stable developmental outcomes and fitness despite genetic perturbations or environmental fluctuations [13]. This fundamental biological property ensures consistent phenotypes in the face of mutations that would otherwise be expected to cause dramatic morphological or functional consequences. Genetic compensation has emerged as a crucial molecular mechanism underlying this robustness, wherein the deleterious effects of a gene mutation are buffered by the compensatory expression of related genes [13] [14]. This phenomenon provides a compelling explanation for the frequent discrepancies observed between different genetic perturbation methods, particularly the pronounced phenotypic differences often reported between stable mutants and transient knockdown approaches.

The concept of genetic robustness was first hinted at through observations of dosage compensation in Drosophila in 1932, but has since been documented across model organisms from yeast to mammals [13]. Recent advances in genetic technologies, especially CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, have accelerated our understanding of how organisms actively compensate for genetic lesions through multiple molecular pathways. This review will systematically compare phenotypic outcomes across crispants, morphants, and stable mutants, examining the experimental evidence for genetic compensation as a key mechanism maintaining phenotypic stability in vertebrate models.

Comparative Analysis of Genetic Perturbation Methods

Each major genetic perturbation technique offers distinct advantages and limitations for functional genomics research, with significant implications for observing genetic compensation effects.

Stable Mutants are generated through permanent germline modifications, typically introducing frameshifts or premature termination codons (PTCs) that disrupt gene function. These established mutant lines provide a permanent resource with uniform genotypes but require extended generation times—6-9 months in zebrafish compared to 3 months for crispants [4]. The persistent nature of the genetic lesion in stable mutants allows organisms to activate long-term compensatory mechanisms, often resulting in milder-than-expected phenotypes.

Crispants (F0 mosaic mutants) are generated through CRISPR-Cas9 injections in single-cell embryos, creating somatic mosaics with varying mutation efficiencies across cells. This approach produces high indel rates (71-88% efficiency documented in zebrafish screens) with significantly reduced generation time compared to stable lines [4]. The mosaic nature and rapid analysis of crispants may precede the full activation of compensatory networks, potentially revealing intermediate phenotypes between morphants and stable mutants.

Morphants are created through antisense morpholino oligonucleotides that transiently block mRNA translation or splicing. This method provides rapid protein knockdown within days but involves no genomic DNA alteration. The transient, protein-level perturbation typically does not trigger the same compensatory responses as DNA-level mutations, often resulting in more severe phenotypic consequences [15] [14].

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Genetic Perturbation Methods

| Parameter | Stable Mutants | Crispants | Morphants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic alteration | Permanent germline mutation | Somatic mosaic mutations | No DNA alteration; translational blockade |

| Time to phenotype | Months (6-9 for zebrafish) | Weeks (3 months for adult zebrafish) | Days (early development) |

| Persistence | Permanent, heritable | Somatic, non-heritable | Transient (2-4 days) |

| Mutation efficiency | 100% homozygous | 71-88% indel efficiency [4] | Variable protein knockdown |

| Compensation trigger | Activates transcriptional adaptation & genetic compensation | Partial compensation possible | Minimal compensation activation |

| Key advantages | Uniform genotype, permanent resource | Rapid screening, cost-effective | Extremely fast results, dose-titratable |

Phenotypic Discrepancies Across Methods

Multiple studies across vertebrate models have documented striking phenotypic differences when comparing these perturbation methods, with genetic compensation as the proposed explanatory mechanism.

In salamander limb regeneration studies, Yap knockout mutants regenerated limbs normally, while Yap morpholino knockdown and pharmacological inhibition severely disrupted regeneration, causing delayed blastema formation and failed patterning [15]. This discrepancy was attributed to compensatory upregulation of the homologous gene Taz in knockout animals (2.5-fold increase), which was absent in morphants. Critically, when researchers blocked this compensation by knocking down Taz in the Yap mutant background, the regeneration defects reappeared, confirming the functional significance of this compensatory mechanism [15].

Similar patterns emerge in zebrafish studies, where egfl7 mutants show minimal vascular defects despite severe phenotypes in morphants [13]. This was correlated with upregulated expression of extracellular matrix proteins Emilins in mutants but not morphants. The phenomenon appears widespread—a meta-analysis suggested that approximately 80% of zebrafish genes show discrepancies between mutant and morphant phenotypes during development [15].

Table 2: Documented Cases of Phenotypic Discrepancies Attributed to Genetic Compensation

| Organism | Gene | Mutant Phenotype | Knockdown Phenotype | Compensating Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salamander | Yap | Normal limb regeneration | Severely disrupted regeneration | Taz [15] |

| Zebrafish | egfl7 | Minor or no vascular defects | Severe vascular defects | emilin3a [13] |

| Mouse | Tet1 | Normal stem cell morphology | Loss of undifferentiated morphology | Tet2 [13] |

| Mouse | Dystrophin | Mild muscular dystrophy (mdx) | Severe muscular dystrophy (knockdown) | Utrophin [14] |

| Mouse | Kindlin-2 | Normal focal adhesions | Decreased integrin activation | Kindlin-1 [13] |

Molecular Mechanisms of Genetic Compensation

Transcriptional Adaptation Pathways

Transcriptional adaptation represents a specific genetic compensation mechanism triggered by the presence of mutant mRNA rather than protein loss. This pathway requires the generation of premature termination codons (PTCs) in the mutated gene, which are recognized by nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) factors, particularly UPF3A [15]. In salamander Yap mutants, the two-base pair deletion causing a frameshift and PTC led to UPF3A upregulation, which subsequently activated expression of the compensatory gene Taz during limb regeneration [15].

The dependence on mutant mRNA rather than protein loss explains why transcriptional adaptation occurs in stable mutants but not morphants. Supporting this model, when researchers used antisense oligonucleotides to eliminate the PTC-containing Yap mRNA in mutants, the compensatory Taz upregulation was abolished and regeneration defects emerged [15]. This mechanism appears to operate independently of the classic Upf1/Upf2/Upf3b-mediated NMD pathway, suggesting specialized functions for UPF3A in genetic compensation.

Protein Feedback Loops and Redundancy

Beyond transcriptional adaptation, genetic compensation can occur through protein-level feedback mechanisms. In these cases, the loss of a specific protein disrupts cellular complexes or pathways, triggering signaling cascades that upregulate homologous proteins with overlapping functions.

The classic example involves dystrophin deficiency in muscular dystrophy. Mdx mice lacking dystrophin show milder symptoms than human patients due to compensatory upregulation of the dystrophin-related protein utrophin [14]. This compensation occurs through a protein feedback loop where dystrophin complex instability activates Akt signaling, ultimately increasing utrophin expression and partially restoring sarcolemma stability [14].

Similarly, in mouse models, knockout of one cyclin D family member leads to upregulation of the remaining cyclin D genes, maintaining normal cell cycle progression in most tissues [13]. This form of compensation leverages inherent genetic redundancies from gene duplication events throughout evolution, where related genes retain partial functional overlap that can be co-opted when primary pathways are disrupted.

Experimental Evidence from Key Studies

Salamander Limb Regeneration Model

The recent salamander study provides particularly compelling evidence for genetic compensation in a regenerative context [15]. Researchers established Yap mutant lines using CRISPR-Cas9, introducing a two-base pair deletion in exon 4 that caused a frameshift and premature termination codon. Surprisingly, these mutants displayed normal limb regeneration despite Yap's established role in tissue regeneration.

The experimental workflow involved multiple complementary approaches:

- Mutant analysis: Comparing regeneration in wild-type versus Yap knockout animals

- Morpholino knockdown: Translational inhibition of Yap in wild-type animals

- Pharmacological inhibition: Verteporfin treatment to disrupt YAP protein function

- Rescue experiments: Blocking compensatory Taz in mutant background

Quantitative measurements showed that cell proliferation rates (via EdU assay) and regeneration efficiency (regenerating/uninjured limb ratio) were nearly identical between KO and WT animals, while both morpholino and verteporfin treatments significantly reduced these parameters [15]. Molecular analysis revealed that TAZ-specific target genes were significantly upregulated during early regeneration (1-7 dpa) in Yap KO animals, coinciding with the critical period when YAP protein would normally be required.

Zebrafish Crispant Screening Platform

Zebrafish crispant screens have emerged as valuable tools for high-throughput functional validation while potentially capturing intermediate states of genetic compensation. A recent study targeting ten fragile bone disorder genes demonstrated the efficiency of this approach, achieving mean indel efficiencies of 88% and out-of-frame rates between 49-73% in F0 mosaic founders [4].

The methodology involved:

- gRNA design: Selection of guides with highest predicted out-of-frame efficiency using InDelphi-mESC tool

- Embryo injection: Co-injection of Cas9 protein and gRNAs into one-cell stage embryos

- Validation: Next-generation sequencing of pooled larvae to quantify indel spectra

- Phenotyping: Skeletal analysis at 7, 14, and 90 days post-fertilization

Notably, different genes showed variable phenotypic penetrance in crispants, with aldh7a1 and mbtps2 crispants exhibiting severe skeletal deformities and increased mortality, while others showed more moderate effects [4]. This screening approach captures phenotypes that may represent partial compensation states, as the mosaic nature and rapid assessment may precede full compensatory network activation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Genetic Compensation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, base editors, prime editors | Creating stable mutants and crispants; precise nucleotide changes | Prime editors allow precise edits without double-strand breaks [6] |

| Knockdown Reagents | Morpholino oligonucleotides, siRNA | Transient protein-level knockdown | Useful for distinguishing transcriptional adaptation from protein feedback [13] |

| NMD Pathway Modulators | UPF3A inhibitors/activators, ASOs targeting PTC-containing mRNAs | Investigating transcriptional adaptation mechanisms | ASOs can eliminate mutant mRNA to test compensation dependence [15] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | CTX310 delivery system, other CRISPR-LNP formulations | In vivo delivery of editing components | Liver-tropic LNPs enable efficient hepatic editing [16] [17] |

| Lineage Tracing Systems | Cre-lox, barcoding approaches | Tracking cell fate in compensation contexts | Reveals how compensation affects cellular dynamics |

| Multi-omics Platforms | Single-cell RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, proteomics | Comprehensive molecular profiling | Identifies compensatory networks beyond immediate homologs |

| Drpitor1a | Drpitor1a, MF:C15H8N2O2, MW:248.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| FD1024 | FD1024, MF:C21H20F2N4O2S, MW:430.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Strategies

Understanding genetic compensation has profound implications for therapeutic development, particularly for monogenic disorders. The phenomenon offers both challenges and opportunities for precision medicine.

Compensation mechanisms may explain why some genetic disorders show variable penetrance and expressivity. In Duchenne muscular dystrophy, patients with higher utrophin expression typically experience milder symptoms, suggesting natural compensation moderates disease severity [14]. Therapeutic strategies could potentially enhance these endogenous compensatory pathways—for instance, approaches to increase utrophin expression are being explored as treatments for DMD.

Conversely, genetic compensation can pose challenges for therapeutic gene editing. If compensation already ameliorates the effects of a mutation, simply correcting the causal mutation might not fully restore normal function. Additionally, in conditions where compensation involves multiple genes, single-gene therapies may prove insufficient.

The successful application of CRISPR-based therapies like CASGEVY for sickle cell disease demonstrates that despite potential compensation complexities, effective interventions are achievable [16] [17]. As in vivo editing approaches advance, exemplified by CTX310 for ANGPTL3 reduction showing 82% triglyceride reduction and 81% LDL reduction in clinical trials [17], understanding tissue-specific compensation networks will become increasingly important for predicting therapeutic efficacy and potential resistance mechanisms.

Genetic compensation represents a fundamental biological mechanism maintaining phenotypic robustness in the face of genetic perturbations. The systematic comparison of crispants, morphants, and stable mutants reveals that permanent genetic lesions often trigger compensatory networks that buffer against phenotypic consequences, explaining frequent discrepancies between perturbation methods. Molecular mechanisms include both transcriptional adaptation pathways, triggered by mutant mRNA and mediated through factors like UPF3A, and protein feedback loops that upregulate homologous genes with overlapping functions.

For researchers investigating gene function, these findings emphasize the importance of employing multiple perturbation approaches and considering potential compensation effects when interpreting phenotypes. The expanding toolkit of CRISPR-based technologies, including base editing, prime editing, and epigenetic modifiers, provides powerful approaches to dissect these complex regulatory networks. As therapeutic genome editing advances, understanding genetic compensation will be crucial for predicting treatment efficacy and developing strategies that either exploit or circumvent these endogenous buffering systems to achieve desired clinical outcomes.

The Role of Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD) and Epigenetic Machinery

In the field of functional genomics, researchers employ distinct technologies to interrogate gene function, each with unique mechanistic bases and phenotypic outcomes. The comparative analysis of crispants (CRISPR-generated F0 mosaics), morphants (morpholino-induced knockdowns), and mutants (stable germline knockouts) provides critical insights for experimental design, particularly when studying biological processes involving nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) and epigenetic regulation. These approaches differ fundamentally in their implementation: crispants utilize CRISPR-Cas9 to create mosaic individuals with biallelic mutations in target cells; morphants employ antisense morpholino oligonucleotides to block translation or splicing; and mutants involve established lines with heritable genetic modifications [18] [19]. Understanding how these models interact with cellular quality control mechanisms like NMD and epigenetic machinery is essential for accurate interpretation of gene function studies and drug development pipelines.

Fundamental Mechanisms: Technological Underpinnings and Cellular Interactions

Core Definitions and Methodological Bases

The three primary approaches for gene perturbation in model organisms differ fundamentally in their mechanisms and implementation:

Crispants: Generated through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated editing in F0 embryos, creating mosaic individuals with varying proportions of mutant cells. This approach produces biallelic mutations in target tissues without establishing stable lines, with recent studies reporting indel efficiencies averaging 88% across multiple targets [19].

Morphants: Created using morpholino oligonucleotides that block translation initiation or pre-mRNA splicing through steric hindrance. This method transiently reduces functional protein levels without altering genomic DNA [18].

Mutants: Established through germline transmission of mutations, resulting in stable, heritable genetic modifications. This traditional approach requires crossing to generate homozygous individuals [18] [20].

Interaction with NMD and Epigenetic Machinery

The cellular response to gene perturbations varies significantly across these models, particularly regarding NMD activation and epigenetic adaptations:

Nonsense-Mediated Decay Pathways: NMD serves as a crucial quality control mechanism that degrades mRNAs containing premature termination codons (PTCs), preventing the production of truncated proteins [21] [22]. This pathway relies on core factors including UPF1, UPF2, and UPF3, with UPF1 serving as the central effector that recruits decay machinery when PTCs are detected [23] [22]. The key distinction between approaches lies in their interaction with NMD: mutants and crispants frequently generate PTC-containing transcripts that potentially activate NMD, while morphants typically do not produce PTCs and thus avoid this pathway [18].

Epigenetic Regulation: Epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs, dynamically regulate gene expression in response to genetic perturbations [24]. Stable mutant lines may exhibit compensatory epigenetic reprogramming that alters phenotypic outcomes, while the acute nature of crispant and morphant approaches may limit such adaptation. For instance, HDAC inhibitors have been shown to reverse repressive histone marks at disease-relevant loci in neuromuscular disorders, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of epigenetic modulation [24].

Table 1: Molecular and Cellular Characteristics of Gene Perturbation Approaches

| Characteristic | Crispants | Morphants | Mutants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Basis | Somatic mutations (mosaic) | No genomic alteration | Germline mutations (uniform) |

| NMD Activation | Possible with PTC-generating indels | Unlikely | Yes, with PTC-generating mutations |

| Epigenetic Compensation | Limited due to acute nature | Limited due to acute nature | Established in stable lines |

| Temporal Resolution | Acute (days-weeks) | Rapid (hours-days) | Chronic (generations) |

| Genetic Compensation | Minimal evidence | Minimal evidence | Documented in multiple studies |

Direct Phenotypic Comparisons: Experimental Evidence and Discordance

Systematic Analysis of Phenotypic Concordance

Comparative studies have revealed significant phenotypic discordance between these approaches, with important implications for data interpretation:

A landmark investigation examining 24 genes involved in vascular development found dramatically different outcomes between approaches: only 3 genes (12.5%) showed congruent phenotypes between mutants and morphants, while morphants exhibited previously reported phenotypic defects for most genes that showed no observable phenotypes in corresponding mutant lines [20]. This discrepancy highlights the potential for false positives in morphant-based studies and underscores the importance of validation through genetic mutations.

Case Studies in Phenotypic Discordance

Specific examples illustrate the molecular basis for these phenotypic differences:

egfl7 Gene: Morphants displayed severe vascular defects, while genetic mutants showed normal vascular development. Further investigation revealed that mutants upregulated compensatory genes including emilin3a, which was not observed in morphants [18].

Islet2a Transcription Factor: Morphants exhibited truncated motor neuron axons, while mutants developed normal axons. Transcriptomic analysis revealed 174 differentially expressed genes in morphants compared to 201 in mutants, suggesting distinct compensatory mechanisms [18].

epoa Gene: Morphants showed altered pronephros development, while mutants developed normal renal structures. Genetic compensation was identified in mutants through upregulation of epob as a compensating gene, which did not occur in morphants [18].

Table 2: Documented Cases of Phenotypic Discordance Between Morphants and Mutants

| Gene | Morphant Phenotype | Mutant Phenotype | Compensatory Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| egfl7 | Severe vascular defects | Normal development | Upregulation of emilin3a |

| Islet2a | Truncated axons | Normal axons | Differential expression of 174 vs 201 genes |

| epoa | Altered pronephros development | Normal pronephros | Upregulation of epob gene |

| Reference | [18] | [18] | [18] |

Experimental Design and Workflow Considerations

Methodological Protocols

Crispant Generation Protocol: The cardiodeleter zebrafish line exemplifies a tissue-specific crispant approach. This system utilizes a cardiomyocyte-specific promoter (cmlc2) to drive expression of nuclear GFP and a zebrafish codon-optimized Cas9 [25]. Guide shuttles deliver gene-specific gRNAs while permanently labeling mutant cardiomyocytes with mKate fluorescence. The workflow involves: (1) designing gRNAs with high predicted out-of-frame efficiency using tools like CRISPRScan; (2) co-injecting Cas9 protein and gRNAs into one-cell stage embryos; (3) screening for mosaic mutant cells via fluorescence; and (4) phenotypic analysis at appropriate developmental stages [25] [19].

Mutant Validation Pipeline: Establishing stable mutant lines requires: (1) generating F0 founders through CRISPR injection; (2) outcrossing to identify germline transmission; (3) establishing heterozygous lines; (4) intercrossing heterozygotes to generate homozygous mutants; and (5) comprehensive phenotypic characterization across developmental stages [19].

NMD Inhibition Experiments: To assess NMD involvement in phenotypic outcomes: (1) inhibit NMD pathway chemically (e.g., cycloheximide) or genetically (e.g., UPF1 knockdown); (2) quantify target mRNA levels via RT-qPCR; (3) assess protein truncation via western blot; (4) monitor rescue of physiological phenotypes [21] [22].

NMD Pathway Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the central mechanism of Nonsense-Mediated Decay, which is particularly relevant for interpreting mutant and crispant phenotypes:

NMD Mechanism

Experimental Workflow Comparison

The integrated workflow for comparing crispants, morphants, and mutants involves parallel experimental tracks:

Experimental Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions and Technical Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Gene Perturbation Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Induces targeted DNA double-strand breaks | Codon-optimized versions available for zebrafish; tissue-specific promoters enable spatial control [25] |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Blocks translation or splicing via steric hindrance | Requires careful dose optimization to minimize off-target effects; rescue experiments recommended [18] |

| Guide Shuttle Vectors | Delivers gRNAs and labels mutant cells | Enables tracking of mutant cells; Tol1/Tol2 transposon-based systems improve integration [25] |

| NMD Inhibitors | Blocks nonsense-mediated decay pathway | Chemicals (cycloheximide) or genetic (UPF1 knockdown) tools to assess NMD contribution [21] |

| Epigenetic Modulators | Modifies DNA methylation or histone marks | HDAC inhibitors (e.g., givinostat) test epigenetic compensation [24] |

| Tissue-Specific Cas9 Lines | Restricts mutagenesis to specific cell types | Example: Cardiodeleter zebrafish with cmlc2 promoter [25] |

Interpretation Guidelines and Best Practices

Strategic Application of Technologies

Each gene perturbation technology offers distinct advantages for specific research applications:

Crispants are optimal for: Rapid functional screening of multiple gene targets; bypassing early lethality through mosaicism; adult-stage phenotypic analysis without establishing stable lines; and disease modeling where somatic mutation reflects human pathology [19].

Morphants are appropriate for: Acute protein depletion studies; splicing inhibition analysis; and preliminary gene function assessment when complemented with genetic validation.

Mutants are essential for: Studying chronic adaptation and compensation mechanisms; analyzing complex phenotypes requiring uniform genetics; and establishing faithful animal models of human genetic disorders.

Accounting for NMD and Epigenetic Effects

Accurate interpretation of phenotypic data requires careful consideration of cellular response mechanisms:

NMD Activation Assessment: When PTCs are introduced in mutants or crispants, verify NMD sensitivity through UPF1 dependence tests and mRNA quantification. Consider that PTCs near the start codon may evade NMD, and long exons can reduce NMD efficiency [26] [22].

Epigenetic Compensation Evaluation: Monitor expression changes in related gene family members and pathway components. Employ epigenetic modifiers to test for chromatin-mediated compensation, particularly in stable mutant lines [24].

Genetic Compensation Investigation: In mutants, analyze upregulation of homologous genes or parallel pathways that may mask expected phenotypes. This compensation frequently explains discrepancies with morphant phenotypes [18].

The integration of crispant, morphant, and mutant approaches—with careful attention to NMD and epigenetic contexts—provides a powerful framework for advancing functional genomics and drug development. This comparative understanding enables more accurate interpretation of gene function data and more predictive modeling of human disease mechanisms.

A central challenge in reverse genetics is the frequent discrepancy between the severe phenotypes observed in gene knockdown experiments and the surprisingly mild or absent phenotypes in corresponding gene knockouts. The case of the egfl7 gene in zebrafish provides a foundational example of this phenomenon, revealing how genetic compensation can allow mutants to escape anticipated phenotypic consequences. This guide compares the experimental outcomes and underlying mechanisms across three key reverse genetics approaches—morpholinos, mutants, and crispants—within the broader context of phenotypic comparison research.

Phenotypic Discrepancy: Mutants vs. Morphants

Initial investigations into the function of egfl7, an endothelial extracellular matrix gene, yielded starkly different results depending on the technique used. The table below summarizes the core experimental observations.

| Perturbation Method | Observed Vascular Phenotype | Activation of Compensatory Genes | Key Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphants (Knockdown) | Severe vascular defects [27] [28] | Not observed [27] | Morphants exhibit defective tube formation; defects not rescued in egfl7 mutant background, arguing against off-target effects [27] [29]. |

| Mutants (Knockout) | No obvious vascular defects [27] [29] | Upregulation of related ECM genes (e.g., Emilins) and vegfab [27] [28] | Proteomic and transcriptomic analysis revealed upregulated genes; injecting egfl7 morpholino into mutants did not recreate severe morphant phenotype [27]. |

| CRISPRi (Transcriptional Knockdown) | Severe vascular defects [27] | Not observed [27] | Obstructing transcript elongation did not trigger the compensatory response seen in true mutants, leading to a phenotype [27]. |

The Genetic Compensation Mechanism

The divergent phenotypes in egfl7 mutants and morphants are attributed to a phenomenon known as genetic compensation, where the organism activates a compensatory network to buffer against the loss of a gene. Research indicates this response is triggered specifically by the presence of a mutant mRNA and the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) pathway, not merely the absence of the protein [28] [30].

In egfl7 mutants, the deleterious mutation creates a premature termination codon (PTC), leading to the degradation of the mutant mRNA via NMD. This degradation process appears to collaborate with the epigenetic machinery to initiate a transcriptional response that upregulates genes with related functions, such as other extracellular matrix components, thereby compensating for the loss of Egfl7 [30]. This mechanism is not activated in morphants, where the mRNA is often blocked from translation but not degraded, nor in CRISPRi experiments where transcript elongation is obstructed [27].

Experimental Protocols for Dissecting Compensation

To rigorously establish genetic compensation, a multi-step experimental approach is required, moving from phenotypic observation to mechanistic insight.

Foundational Phenotype Comparison

- Gene Knockdown: Inject a moderate dose of egfl7-targeting morpholino into wild-type zebrafish embryos at the one-cell stage. Analyze vascular development at 2-5 days post-fertilization (dpf) for defects [27].

- Gene Knockout: Generate a stable egfl7 mutant line using CRISPR-Cas9, typically introducing a small indel in an early exon to ensure a frameshift and PTC. Analyze the same phenotypic endpoints as in morphants [27] [29]. The egfl7 cq180 mutant, for example, has a 13-bp deletion in exon 3 [29].

Testing for Off-Target Effects and Compensation

- Rescue Experiment: Inject the egfl7 morpholino into the egfl7 mutant background. The persistence of a wild-type phenotype in these mutants, despite morpholino treatment, provides strong evidence that the morphant phenotype is not due to off-target effects but rather a failure to compensate [27] [28].

- Transcriptomic Analysis: Perform RNA sequencing on both egfl7 mutants and morphants. This unbiased approach identifies genes that are specifically upregulated in the mutant condition, pinpointing potential compensators [27].

Validating Compensatory Genes

- Functional Rescue: Co-inject mRNA of an upregulated compensatory gene (e.g., an Emilin family member) with the egfl7 morpholino into wild-type embryos. If the compensatory gene can rescue the morphant phenotype, it confirms its role in genetic compensation [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table details essential reagents and models used in the cited egfl7 studies and related genetic compensation research.

| Reagent / Model | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| egfl7 Mutant (e.g., cq180, s981) | A stable knockout line with a frameshift mutation; used to study long-term adaptation and genetic compensation in the absence of the gene [27] [29]. |

| egfl7 Morpholino | An antisense oligonucleotide that blocks translation or splicing of egfl7 mRNA; used for transient knockdown to reveal the acute effect of gene loss before compensation sets in [27] [28]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | A genome editing system used to generate knockout mutant lines. It involves co-injecting Cas9 nuclease and a gene-specific guide RNA (gRNA) into one-cell stage embryos [6] [4]. |

| CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) | A modified CRISPR system that uses a catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) to block transcription without cutting DNA; used to demonstrate that transcriptional blockade does not trigger compensation [27]. |

| Tg(egfl7:YFP) Transgenic Line | A reporter line that visualizes the expression pattern of egfl7 in vivo, confirming its expression in endothelial and lymphatic cells [29]. |

| STM2120 | STM2120, MF:C18H15N5O2, MW:333.3 g/mol |

| HTH-01-091 TFA | HTH-01-091 TFA, MF:C28H29Cl2F3N4O4, MW:613.5 g/mol |

Research Implications and Strategic Insights

The egfl7 case study demonstrates that the choice of genetic perturbation method can dictate experimental outcomes and biological interpretations. The following diagram illustrates the divergent molecular pathways activated by each method, leading to distinct phenotypic results.

For researchers, this has several critical implications. When a mutant lacks an expected phenotype, genetic compensation should be investigated as a potential cause, rather than defaulting to assumptions of gene redundancy. The "gold standard" for functional validation now often requires a multi-pronged approach, combining mutant analysis with crispant or morphant studies in the mutant background to dissect acute versus compensated phenotypes. Furthermore, the discovery of genetic compensation opens a novel therapeutic avenue: rather than targeting a defective gene, therapies could aim to manipulate the endogenous compensatory networks to ameliorate disease.

Best Practices in Model Generation: From CRISPR Design to Phenotypic Analysis

The advent of CRISPR/Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic research, enabling precise genome manipulation across diverse model organisms. Within this landscape, two primary approaches have emerged for functional gene analysis: the generation of crispants (F0 generation animals with direct somatic editing) and the establishment of stable mutant lines. This guide objectively compares these methodologies, examining their relative performance in efficiency, timeline, and applicability for phenotypic comparison in preclinical research.

Experimental Protocols and Workflow Comparison

Crispant Generation Protocol

The crispant method enables rapid phenotypic assessment in the F0 generation through direct somatic editing. The following protocol, optimized for zebrafish, can be adapted for other model organisms.

1. Guide RNA Design and Preparation

- Design 4-5 sgRNAs targeting the first conserved domain or early exons of the target gene to maximize functional knockout probability [31].

- Select sgRNAs with high on-target efficiency scores, using predictive algorithms from tools like those cataloged in CRISPR-GATE [32].

- For the injection mix, combine a cocktail of multiple sgRNAs (typically 3-4) with Cas9 protein or mRNA [31].

2. Microinjection

- Prepare injection solution containing multiplexed sgRNAs (typically 50-100 pg of each) and Cas9 protein (typically 300-600 pg) [31].

- Inject into one-cell stage embryos.

- Maintain injected embryos under standard conditions and monitor for development.

3. Phenotypic Analysis

- Assess somatic mutation efficiency through phenotypic screening (for visible traits) or molecular validation (for non-visible traits).

- For genes affecting pigmentation (e.g., yellow-y), screen for mosaic phenotypic changes in G0 animals [33].

- For non-visible traits, use targeted sequencing to confirm editing efficiency in somatic tissues.

Stable Line Generation Protocol

Stable germline mutant lines provide heritable, consistent genetic models suitable for comprehensive phenotypic analysis across generations.

1. Vector Design and Assembly

- Select appropriate CRISPR system (e.g., SpCas9, SaCas9, or Cas12a) based on PAM requirements and efficiency [34].

- For CRISPRa/i applications, utilize self-selecting systems like CRISPRa-sel that employ piggyBac transposon technology for stable integration [35].

- Clone sgRNA expression cassettes into appropriate delivery vectors.

2. Delivery and Selection

- Deliver CRISPR components via microinjection, transfection, or viral transduction.

- For transgenic CRISPRa systems, apply selection pressure (e.g., puromycin) 48-72 hours post-transduction to enrich for successfully modified cells [35].

- Expand surviving cells for 1-2 weeks to establish stable populations.

3. Germline Transmission Analysis

- Outcross F0 injected animals to wild-type partners.

- Screen F1 progeny for germline transmission via PCR, sequencing, or phenotypic analysis.

- Intercross heterozygous F1 animals to generate homozygous F2 mutants for phenotypic characterization.

Table 1: Key Workflow Comparison Between Crispant and Stable Line Approaches

| Parameter | Crispant Method | Stable Line Method |

|---|---|---|

| Timeline to Phenotype | 1-7 days (somatic); ~1 month (germline) [36] | 6-12 months (zebrafish) [31] |

| Mosaic Mutation Efficiency | Up to 80% in G0 [33] | N/A (clonal populations) |

| Germline Transmission Rate | ~30% with 100% LOF phenotypes [33] | Variable (typically 5-80%) |

| Animal Usage | Reduced (single generation) | Extensive (multiple generations) |

| Phenotypic Consistency | Variable (mosaic) | High (uniform genotype) |

CRISPR Workflow Comparison: This diagram illustrates the key procedural differences between generating crispants and stable mutant lines, highlighting the significant timeline advantage of the crispant approach.

Performance and Efficiency Metrics

Editing Efficiency Comparison

Both crispant and stable line approaches demonstrate high editing efficiency, though through different mechanisms and with distinct optimization requirements.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of CRISPR Approaches

| Performance Metric | Crispant Approach | Stable Line Approach | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic Mutation Rate | 78-80% (mosaic phenotypes) [33] | N/A (clonal) | Zebrafish yellow-y targeting [33] |

| Complete LOF Phenotypes | ~30% of G0 animals [33] | >90% in homozygotes | Zebrafish maternal-effect genes [31] |

| Germline Transmission | Achievable in F1 progeny [33] | Required for line establishment | Zebrafish crispant studies [31] |

| Population-wide Activation | N/A | Up to 100% with CRISPRa-sel [35] | Human cell lines (K562) [35] |

| Off-Target Effects | Similar to stable approaches | Reducible with high-fidelity Cas variants [34] | Specificity comparisons [34] |

Applications in Phenotypic Research

The choice between crispant and stable line approaches depends heavily on research goals, timeline, and required phenotypic depth.

Crispant Advantages:

- Speed: Phenotypic analysis possible within days to weeks versus months required for stable line generation [31] [36].

- Efficiency: High rates of biallelic editing in somatic tissues enable rapid functional assessment [31].

- Cost-Effectiveness: Reduced animal housing and maintenance costs compared to multi-generation stable line development [36].

- Lethal Gene Analysis: Enables study of genes causing embryonic lethality when mutated [31].

Stable Line Advantages:

- Phenotypic Consistency: Uniform genotypes eliminate mosaic variability [31].

- Reproducibility: Clonal populations enable standardized assays across experiments and laboratories.

- Long-term Studies: Suitable for chronic disease modeling and aging research.

- CRISPRa Applications: Stable CRISPRa-sel systems enable sustained gene activation in >90% of cell populations [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of CRISPR workflows requires carefully selected reagents and tools optimized for each approach.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Workflows

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Crispant Applications | Stable Line Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Protein/mRNA | CRISPR nuclease component | Direct embryo injection [31] | Vector-based expression |

| Multiplexed sgRNAs | Target sequence guidance | Cocktails of 3-5 sgRNAs for enhanced biallelic editing [31] | Single or minimal sgRNAs |

| CRISPRa-sel System | Gene activation with selection | Limited use | Stable gene activation in >90% of cells [35] |

| piggyBac Transposon | Stable genomic integration | Not typically used | CRISPRa component delivery [35] |

| High-Fidelity Cas Variants | Reduced off-target editing | Available but less critical | eSpCas9, eSpOT-ON for specific editing [37] [34] |

| CRISPR-GATE Database | gRNA design and tool selection | sgRNA design optimization [32] | Comprehensive workflow planning [32] |

| (-)-Bornyl ferulate | (-)-Bornyl ferulate, MF:C20H26O4, MW:330.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Andrastin C | Andrastin C, MF:C25H33Cl2N5O6, MW:570.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The choice between crispant and stable line generation strategies represents a fundamental methodological decision in modern genetic research. Crispants offer unparalleled speed, enabling functional gene assessment in days to weeks with impressive efficiency (80% mosaic phenotypes). This approach is particularly valuable for rapid gene function screening, lethal mutation analysis, and proof-of-concept studies. Conversely, stable lines provide phenotypic consistency and reproducibility essential for detailed mechanistic studies, chronic disease modeling, and standardized drug screening. Recent advances like the CRISPRa-sel system further enhance stable line utility by enabling population-wide gene activation in over 90% of cells. The decision framework should consider research timeline, required phenotypic depth, and specific application needs, with both approaches offering complementary strengths for comprehensive phenotypic comparison in the era of precision genome engineering.

Morpholino oligonucleotides represent a cornerstone technique in molecular biology for transient gene knockdown, enabling researchers to investigate gene function by blocking translation or modulating pre-mRNA splicing. These synthetic molecules feature a morpholine ring backbone with phosphorodiamidate linkages, granting them nuclease resistance and neutral charge that minimize non-specific protein interactions and reduce immune responses compared to other oligonucleotide chemistries [38]. Within contemporary genetic research, particularly in the context of phenotypic comparisons involving crispants (F0 CRISPR/Cas9 mutants), morphants (Morpholino-induced phenotypes), and stable mutants, understanding Morpholino limitations and proper implementation is paramount for generating reliable, interpretable data.

The central challenge in Morpholino use stems from frequent discrepancies observed between morphant phenotypes and those generated by genetic mutations. As Rossi et al. noted, genetic compensation appears induced by deleterious mutations but not by gene knockdowns, potentially explaining why mutants sometimes display less severe phenotypes than morphants [2] [39]. This technical landscape necessitates rigorous guidelines for Morpholino experimental design, dosing, and validation to ensure that observed phenotypes accurately reflect specific gene function rather than off-target effects.

Morpholino Dosing Guidelines and Toxicity

Determining Optimal Dose

Establishing the correct Morpholino concentration is critical for achieving specific target knockdown while minimizing toxicity. Dosing varies significantly by delivery method, target tissue, and experimental organism.

Table 1: Recommended Morpholino Dosing by Application and Organism

| Application/Organism | Recommended Concentration | Delivery Method | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish embryos [40] | 0.2-8.0 ng per embryo | Microinjection | Dose-dependent toxicity above 8 ng; requires titration |

| Mosquito larvae [41] | 0.03-0.06 μg/μl | Bath immersion | 3-hour exposure time; effective for Vivo-Morpholinos |

| Cell culture [40] | 1-10 μM | Transfection or electroporation | Varies with transfection efficiency |

| DMD exon-skipping therapies [38] | High, multiple doses (clinical) | Systemic administration | PMO chemistry allows high doses with minimal toxicity |

Effective Morpholino experiments require oligos that are fully dissolved and at a precisely known concentration to ensure reproducibility. Lyophilized Morpholinos should be resuspended in sterile, nucleus-free water, and concentrations verified using spectrophotometry, taking advantage of the hypochromic effect where single-stranded oligonucleotides exhibit increased absorbance when denatured [40]. Aliquotting and proper storage at -20°C in a humidor prevent degradation and maintain activity.

Toxicity Mitigation Strategies

Morpholino toxicity typically manifests through two primary mechanisms: sequence-independent toxicity and sequence-dependent off-target effects. The former often involves activation of cellular stress pathways, while the latter frequently results from unintended interactions with non-target RNAs.

p53 Pathway Activation: A well-documented concern is the nonspecific induction of p53-dependent apoptosis pathways, which can confound phenotypic interpretation [2]. This can be mitigated by co-injecting a p53-targeting Morpholino, though this approach requires caution as p53 mutants themselves may display developmental abnormalities [2].

Interferon Response: Morpholinos can activate interferon-stimulated genes including

isg15andisg20, along with cellular stress pathway genes such asphlda3,mdm2, andgadd45aain zebrafish [2]. These responses are concentration-dependent and highlight the importance of using the lowest effective dose.Control Strategies: Including mismatch controls with 4-5 base mismatches helps distinguish specific from non-specific effects. Rescue experiments with mRNA resistant to Morpholino binding provide the strongest evidence of specificity [40] [39].

Specificity Controls and Experimental Validation

Essential Control Experiments

Rigorous control experiments are fundamental to confirming that a Morpholino-induced phenotype results from specific target knockdown rather than off-target effects.

Table 2: Required Controls for Morpholino Experiments

| Control Type | Purpose | Implementation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Control [40] | Baseline for comparison | Uninjected or mismatch control embryos | Identifies background developmental variability |

| Mismatch Control [40] | Detect sequence-specificity | Morpholino with 4-5 base mismatches | Phenotype should be absent in mismatch controls |

| p53 Morpholino [2] | Assess p53-dependent apoptosis | Co-injection with target Morpholino | Reduces non-specific cell death; use with caution |

| Rescue Experiment [40] [39] | Confirm specificity | Co-inject target Morpholino with resistant mRNA | Phenotype rescue demonstrates specificity |

| Second, Non-overlapping Morpholino [40] | Verify on-target effect | Target different sequence in same gene | Similar phenotypes strengthen on-target claim |

Phenotypic Validation Against Mutants

The gold standard for validating Morpholino specificity is comparison with genetic mutants. Multiple studies have revealed significant discrepancies between morphant and mutant phenotypes:

Comparative Analysis of Morpholino vs. Mutant Phenotypes

In a comprehensive reverse genetic screening, mutants for ten different genes failed to recapitulate published Morpholino-induced phenotypes [42]. Parallel informatics analysis suggested high false-positive rates for Morpholinos, with approximately 80% of morphant phenotypes not observed in mutant embryos [42]. Specific examples from zebrafish research illustrate this concerning discrepancy:

- pak4 Gene: Morpholino knockdown caused defects in primitive myelopoiesis, vasculature, and somite development with lethality by 6-7 days post-fertilization (dpf), while null mutants displayed normal primitive myelopoiesis [2].

- islet2a Gene: Morphants showed presumptive motor neurons failing to extend axons, while mutants exhibited normal axon formation and morphology [2].

- egfl7 Gene: Severe vascular development defects in morphants contrasted with no obvious defects in TALEN-induced mutants, with research suggesting genetic compensation via

emilin3aupregulation in mutants [2].

These discrepancies may arise from several mechanisms. Genetic compensation in mutants can occur through transcriptional adaptation where related genes are upregulated, potentially masking phenotypes [2]. Additionally, off-target effects of Morpholinos can activate unintended pathways, while maternal contribution of mRNA or protein in mutants (but not morphants) may rescue early developmental phenotypes.

Morpholino Applications and Protocols

Research and Therapeutic Applications

Morpholinos find diverse applications across basic research and clinical development:

- Gene Function Analysis: Used to transiently knock down gene expression and assess resulting phenotypes, particularly valuable for rapid screening [41].

- Exon Skipping Therapies: PMOs form the basis of four FDA-approved therapies for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (eteplirsen, golodirsen, viltolarsen, casimersen) that restore dystrophin reading frames [38].

- Vector Control: Vivo-Morpholinos effectively inhibit insecticide detoxification genes like

ABCG4in mosquito larvae, increasing permethrin susceptibility [41]. - Exosome-Based Delivery: Emerging platforms engineer exosomes loaded with PMOs for targeted therapeutic delivery, demonstrating scalable manufacturing potential [43].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Morpholino Knockdown in Zebrafish

The following workflow outlines a standardized approach for Morpholino-mediated gene knockdown with appropriate controls and validation:

Morpholino Experimental Workflow

Step-by-Step Implementation:

Morpholino Design: Design oligos to minimize off-target RNA binding using BLAST analysis against the appropriate transcriptome. Target sequences near the translation start site for translational blocking or splice junctions for splice-modifying Morpholinos [40] [39].

Solution Preparation: Resuspend lyophilized Morpholino in nucleus-free water. Quantify concentration using spectrophotometry with hypochromicity correction by heating an aliquot to 65°C for 5 minutes then immediately measuring absorbance [40].

Microinjection: Prepare injection solutions with tracer dyes for verification. For zebrafish embryos, inject 1-2 nL into the yolk or cell cytoplasm at the 1-4 cell stage. Include vehicle-only controls and mismatch controls in each experiment [40].

Dose Optimization: Perform initial dose-response experiments with at least three concentrations spanning the typical effective range (0.2-8.0 ng per embryo for zebrafish). Select the lowest dose that produces a consistent, specific phenotype [40].

Specificity Controls: Implement minimum two control strategies:

Phenotypic Validation: Compare Morpholino phenotypes with CRISPR/Cas9-generated crispants or stable mutants. The high indel efficiency of crispants (averaging 88% in recent studies) makes them particularly valuable for rapid validation [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Morpholino Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphorodiamidate Morpholino (PMO) [38] | Gene knockdown via translation blocking or splice modification | Neutral charge; nuclease-resistant; minimal immune activation |

| Vivo-Morpholino [41] | Cell-penetrating Morpholino for whole organism or tissue delivery | Conjugated with delivery moiety; enables bath immersion administration |

| p53-Targeting Morpholino [2] | Control for nonspecific p53 activation | Reduces apoptosis; may confound phenotypes due to p53 role in development |

| Fluorescent Tagged Morpholino [41] | Tracking delivery and distribution | Enables visualization of uptake and tissue distribution |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Components [19] | Generating mutant controls for validation | gRNA + Cas9 protein for crispant production |

| Capillary Electrophoresis System [39] | Quantifying intracellular Morpholino concentration | Verifies delivery and correlates with phenotypic strength |

| LUNA18 | LUNA18, CAS:2676177-63-0, MF:C73H105F5N12O12, MW:1437.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Grandivine A | Grandivine A|RUO | Grandivine A is a steroid alkaloid fromVeratrum grandiflorumwith cited cytotoxic activity. For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

Morpholinos remain valuable tools for gene function analysis when applied with appropriate rigor and validation. The key to successful Morpholino experiments lies in careful oligo design, precise dosing, implementation of multiple control strategies, and crucially, validation against genetic mutants. The discrepancies between morphant and mutant phenotypes observed across numerous studies underscore that Morpholino results should be interpreted cautiously until confirmed by genetic approaches.

Emerging technologies offer promising avenues for enhancing Morpholino specificity and utility. Peptide-conjugated PMOs (PPMOs) demonstrate improved pharmacokinetic profiles and cellular uptake, though they introduce potential toxicity concerns related to their arginine and 6-aminohexanoic acid residues [38]. Exosome-based delivery systems provide a scalable framework for loading Morpholinos into natural nanocarriers, potentially enhancing tissue-specific delivery [43]. Additionally, novel phosphorothioate morpholino analogs synthesized via oxathiaphospholane chemistry show enhanced stability and potential for therapeutic applications [44].

Within the framework of phenotypic comparison research involving crispants, morphants, and mutants, Morpholinos can provide valuable preliminary data when genetic mutant generation is time-consuming or costly. However, the research community increasingly recognizes that mutant phenotypes should become the standard metric for defining gene function, after which Morpholinos that recapitulate these phenotypes can be reliably applied for ancillary analyses [42]. This approach ensures scientific rigor while leveraging the unique advantages of each technological platform.

The emergence of advanced genome engineering technologies has fundamentally transformed the creation of animal models for biomedical research. Within this landscape, a critical comparison of three predominant model systems—CRISPR-generated crispants, antisense oligonucleotide-generated morphants, and classical mutants—is essential for guiding experimental design. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these models, focusing on their performance in phenotypic analysis, with a particular emphasis on quantitative skeletal analysis, advanced imaging modalities, and molecular marker profiling. Understanding the key readouts and inherent characteristics of each model is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to study skeletal development, genetic disorders, and therapeutic efficacy. The choice between these models involves careful consideration of factors such as penetrance, expressivity, temporal control, and technical practicality, all of which directly impact the reliability and translational potential of research findings.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows and logical relationships involved in generating and analyzing the three primary model systems discussed in this guide. It highlights the key technological foundations and the primary analytical pathways for phenotypic comparison.

Comparative Analysis of Key Model Systems

The table below provides a quantitative and objective comparison of the core characteristics of crispants, morphants, and classical mutant models, synthesizing data from current literature and experimental observations.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Genetic Model Systems

| Feature | Crispants (CRISPR/Cas9) | Morphants (Morpholino) | Classical Mutants (ZFNs/TALENs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanism | RNA-guided Cas nuclease creates double-strand breaks; repaired via NHEJ/HDR [45]. | Antisense oligonucleotides block translation or splicing [46]. | Protein-guided (Zinc Finger/TALE) nuclease creates double-strand breaks [46]. |

| Mutational Nature | Somatic, non-heritable indels; potential for mosaicism [45]. | Transient, non-heritable knockdown; no genetic alteration. | Stable, heritable genomic modifications. |

| Development Speed | Very rapid (days to weeks) [46]. | Rapid (effects seen within hours of injection). | Slow (requires breeding to establish stable lines). |

| Penetrance & Expressivity | Variable; can be high but often mosaic, leading to a spectrum of phenotypes within one animal [45]. | High and consistent at optimal doses; phenotype strength is dosage-dependent. | Stable and uniform in established, isogenic lines. |

| Temporal Control | Low; edits occur early in development. | High; timing can be controlled by injection timepoint. | None; mutation is constitutive. |

| Scalability & Cost | High scalability, low cost for initial screening [46]. | High scalability, moderate cost. | Low scalability, very high cost and time investment [46]. |

| Key Risk: Off-Target Effects | Documented risk of off-target mutagenesis and large structural variations [47]. | Risk of non-specific binding and p53-mediated neurotoxicity. | Lower risk due to high-specificity protein DNA-binding [46]. |

| Key Advantage | Rapid functional screening of multiple genes; models complex genetics. | Excellent for assessing acute gene function during development. | Gold standard for reproducible, in-depth phenotypic studies. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Readouts

This section outlines the core methodologies employed for the quantitative phenotypic comparison of crispants, morphants, and mutants.

Protocol for Quantitative Skeletal Analysis

Skeletal analysis provides a primary, quantitative readout of developmental phenotypes, particularly in studies of skeletogenesis and craniofacial disorders.

Sample Preparation and Staining: