CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis of Hox Clusters: Decoding the Genetic Blueprint of Vertebrate Limb Development

This article synthesizes recent advances in CRISPR-Cas9 applications for functional analysis of Hox gene clusters in vertebrate limb development.

CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis of Hox Clusters: Decoding the Genetic Blueprint of Vertebrate Limb Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes recent advances in CRISPR-Cas9 applications for functional analysis of Hox gene clusters in vertebrate limb development. We explore foundational discoveries establishing Hox clusters as essential regulators of anteroposterior limb positioning and patterning, with specific focus on genetic evidence from zebrafish and mouse models. The content details innovative methodological approaches including synthetic regulatory reconstitution and genome-wide screening, while addressing key challenges in troubleshooting functional redundancy and optimization of editing strategies. Furthermore, we examine validation through cross-species comparative analyses and discuss emerging therapeutic implications for human musculoskeletal disorders and regenerative medicine, providing a comprehensive resource for developmental biologists and translational researchers.

Hox Cluster Foundations: Establishing the Genetic Blueprint for Limb Positioning and Pattern

Hox genes are a family of homeodomain-containing transcription factors that are master regulators of embryonic development, specifying positional identity along the anterior-posterior axis in bilaterian animals [1] [2]. These genes are notable for their unique genomic organization into clustered arrays and the phenomenon of colinearity, where the order of genes on the chromosome corresponds to their spatial and temporal expression domains during development [1] [3]. The high degree of evolutionary conservation in Hox genes, maintained over 550 million years, makes them a fascinating subject for comparative genomics and functional studies [4] [2]. This application note examines the architectural and functional conservation of Hox clusters from Drosophila to vertebrate models, with specific protocols for their investigation using CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis in the context of limb development studies.

Evolutionary Conservation of Hox Cluster Architecture

Vertebrate Hox clusters exhibit a significantly higher level of genomic organization compared to their invertebrate counterparts. While cephalochordate or echinoderm clusters span approximately 500 kb, most vertebrate Hox clusters are compacted to barely over 100 kb in size (with the exception of axolotl) [3]. This compacted structure is characterized by a lack of repetitive elements and interspersed genes, with all genes being transcribed from the same DNA strand [3].

Table 1: Comparative Genomic Architecture of HoxA Clusters Across Species

| Species | Genome Size (C-value, pg) | HoxA Cluster Length (kb) | Gene Content Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horn Shark (Heterodontus francisci) | 7.25 | ~110 | Ortholog of HoxA (previously HoxM) |

| Human (Homo sapiens) | 3.50 | 110 | Standard mammalian complement |

| Mouse (Mus musculus) | 3.25 | 105 | Standard mammalian complement |

| Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | 0.99 | 100 (HoxAα) | Retained duplicate cluster |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | 1.75 | 62 (HoxAα), 33 (HoxAβ) | Secondary gene losses in Aβ cluster |

| Pufferfish (Fugu rubripes) | 0.40 | 64 (HoxAα) | Initially thought to lack HoxA7α |

Following two rounds of whole genome duplication in the vertebrate lineage, most jawed vertebrates possess four Hox clusters (A-D), while ray-finned fishes exhibit up to eight clusters due to an additional fish-specific genome duplication [4] [1]. Different presumed regulatory sequences are retained in either the Aα or Aβ duplicated Hox clusters in fish lineages, supporting the duplication-deletion-complementation model of functional divergence [4].

Hox Gene Functions in Limb Development and Specification

Hox genes play crucial roles in specifying limb identity and morphology across animal species. In crustaceans like the amphipod Parhyale hawaiensis, CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis has revealed that Hox genes including Ubx, Antp, Scr, and Dfd confer segmental identity in the developing appendages [5].

Table 2: Hox Gene Functions in Limb and Appendage Specification

| Hox Gene | Species | Function in Limb/Appendage Development |

|---|---|---|

| Ubx | Parhyale | Necessary for gill development and repression of gnathal fate |

| Antp | Parhyale | Dictates claw morphology |

| Scr, Antp | Parhyale | Confer the part-gnathal, part-thoracic hybrid identity of the maxilliped |

| Scr, Dfd | Parhyale | Prevent antennal identity in posterior head segments |

| Antp | Drosophila | Specifies second thoracic segment identity (legs and wings) |

| Ubx | Drosophila | Patterns third thoracic segment (legs and halteres) by repressing wing genes |

| Hoxa13, Hoxd13 | Mouse | Critical for patterning the autopod (distal limb) |

In Drosophila, the famous Antennapedia (Antp) mutation causes the transformation of antenna into legs, demonstrating the profound impact of Hox genes on appendage identity [2]. Similarly, loss of Ultrabithorax (Ubx) function results in the transformation of halteres (balancing organs) into a second pair of wings, creating four-winged flies [2]. In vertebrates, the posterior Hox genes (particularly those in the HoxA and HoxD clusters) are critical for patterning the limb buds, with different combinations specifying proximal-distal identities.

Application Notes: CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis of Hox Clusters

Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Somatic Mutagenesis in Emerging Model Organisms

Application: Functional analysis of Hox genes in limb development without generating stable mutant lines.

Materials:

- CRISPR-Cas9 reagents (sgRNAs, Cas9 protein/mRNA)

- Microinjection apparatus

- Embryos of target species (Parhyale hawaiensis, mouse, zebrafish)

- PCR reagents for genotyping

- Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) reagents

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design: Design sgRNAs targeting exonic regions of the Hox gene of interest. For functional domains like the homeodomain, target sequences encoding critical amino acid residues.

- Reagent Preparation: Synthesize sgRNAs and Cas9 mRNA or prepare Cas9 protein-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes.

- Microinjection: Inject CRISPR-Cas9 reagents into early-stage embryos. For Parhyale, target the egg within 2-4 hours post-laying.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Allow embryos to develop until limb bud stages (species-dependent) and analyze morphology.

- Genotype Confirmation: Extract genomic DNA from a portion of injected embryos and perform PCR/sequencing to verify mutagenesis efficiency.

- Expression Analysis: Fix remaining embryos for WISH to examine changes in gene expression patterns.

Troubleshooting:

- Low mutagenesis efficiency: Optimize sgRNA design and concentration

- High mortality: Titrate Cas9 concentration and optimize injection parameters

- Mosaic phenotypes: Analyze multiple embryos from different clutches

Protocol: Targeted Genomic Inversions in Mouse Hox Clusters

Application: Investigating the functional significance of Hox cluster architecture and transcriptional polarity.

Materials:

- CRISPR-Cas9 reagents (multiple sgRNAs)

- Mouse embryonic stem cells or zygotes

- Homology-directed repair (HDR) templates

- CTCF binding site modifications (optional)

- RNA-seq and chromatin conformation capture (3C/Hi-C) reagents

Procedure:

- Inversion Design: Design sgRNAs flanking the target region (e.g., Hoxd11-Hoxd12). Include appropriate CTCF sites based on experimental design.

- HDR Template Construction: Generate a repair template containing the inverted genomic region with necessary modifications.

- Genome Editing: Co-electroporate/inject CRISPR reagents and HDR templates into mouse embryonic stem cells or zygotes.

- Screening: Identify correctly targeted clones or founders using PCR and Southern blotting.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Examine embryos at E12.5 for alterations in axial patterning and limb development using WISH.

- Molecular Characterization: Perform RNA-seq on developing digits and metanephros to quantify gene expression changes. Use 3C/Hi-C to assess chromatin architecture alterations.

Key Findings: Inversions within the HoxD cluster can cause dramatic up-regulation of neighboring Hox genes (e.g., Hoxd13) due to reorganization of chromatin microdomains rather than transcriptional leakage [3].

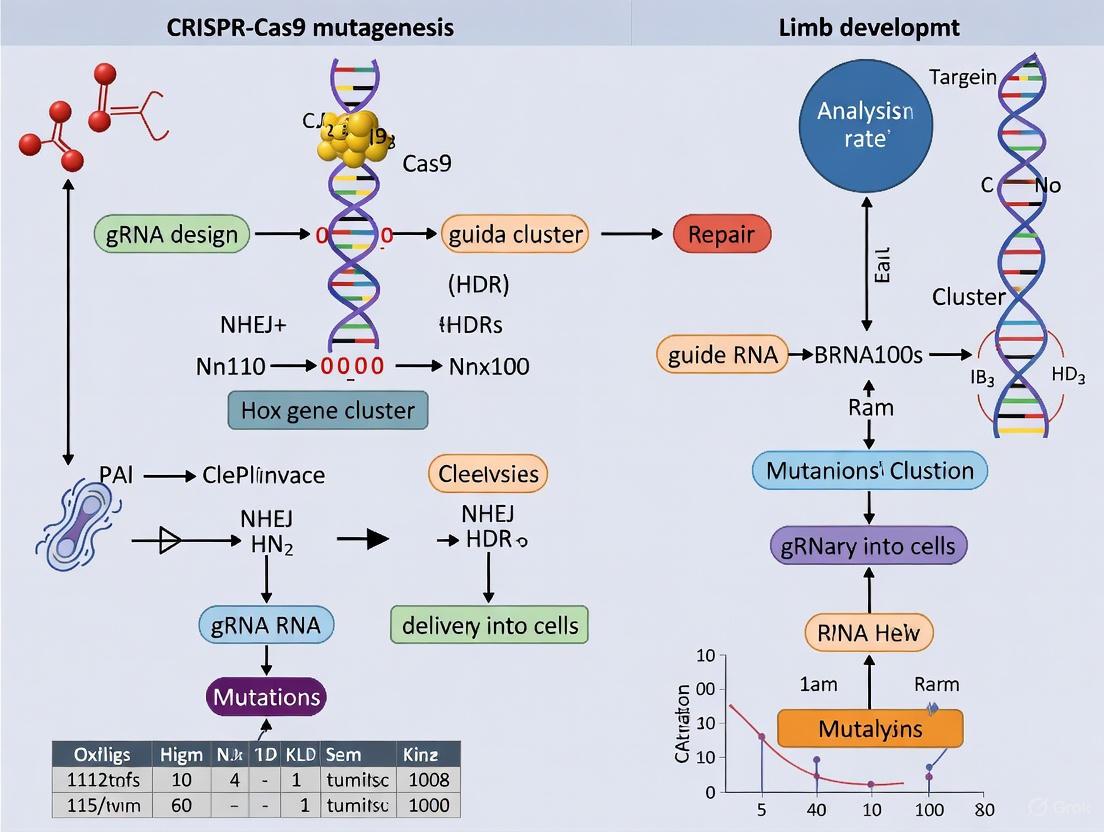

Visualization of Hox Gene Regulation and CRISPR Workflow

Hox Cluster CRISPR Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hox Cluster Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | sgRNAs targeting Hox exons, Cas9 mRNA/protein | Targeted mutagenesis of Hox genes |

| Model Organisms | Parhyale hawaiensis, Mouse (Mus musculus), Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Functional studies in diverse developmental contexts |

| Molecular Analysis | Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH), RNA-seq, 3C/Hi-C | Gene expression and chromatin architecture analysis |

| Hox Antibodies | Anti-Hox protein antibodies, Anti-homeodomain antibodies | Protein localization and expression studies |

| Lineage Tracing | Cre-loxP systems, Fluorescent reporters | Cell fate mapping in Hox mutant backgrounds |

| Bioinformatics Tools | PipMaker, Phylogenetic footprinting, Synteny analysis | Comparative genomics and conserved element identification |

| BC8-15 | BC8-15, MF:C18H15N5O2, MW:333.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ketoconazole-d4 | Ketoconazole-d4, MF:C26H28Cl2N4O4, MW:535.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The remarkable evolutionary conservation of Hox gene clusters provides a powerful framework for understanding the fundamental principles of developmental gene regulation. The compact architecture of vertebrate Hox clusters, with uniform transcriptional polarity and precise regulatory element organization, reflects evolutionary constraints that maintain the intricate spatiotemporal expression patterns necessary for proper body planning [3]. CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis approaches have revolutionized our ability to functionally dissect these gene clusters across diverse model organisms, revealing both conserved and species-specific functions in limb development and evolution [5]. These experimental protocols provide researchers with robust methodologies to investigate Hox gene function in the context of both basic developmental biology and evolutionary studies, with potential applications in understanding the molecular basis of congenital limb disorders and evolutionary diversification of body plans.

Hox gene collinearity is a fundamental principle in developmental biology wherein the genomic order of Hox genes within clusters corresponds systematically with their expression patterns along the embryonic anteroposterior (A-P) axis. First observed by E.B. Lewis in Drosophila, this remarkable property demonstrates that genes located at the 3' end of Hox clusters are expressed in anterior embryonic regions, while genes at the 5' end are expressed in progressively more posterior regions [6] [7]. This review examines the principles of Hox collinearity and its role in A-P axis specification, with particular emphasis on applications in CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis studies of limb development.

Three primary forms of collinearity have been characterized:

- Spatial collinearity: The order of Hox genes along the chromosome corresponds to their expression domains along the A-P axis [6]

- Temporal collinearity: Hox genes are activated sequentially in time, following their genomic order [8]

- Quantitative collinearity: At given A-P positions, more posterior Hox genes exhibit stronger expression levels than anterior genes [6]

Molecular Mechanisms of Hox Collinearity

Chromatin Dynamics and Sequential Activation

The molecular basis for collinear Hox gene activation involves precisely regulated chromatin dynamics. Before activation, Hox clusters are compacted within chromatin territories (CT). During activation, physical forces progressively pull genes toward transcription factories (TF) in the interchromosome domain (ICD) [6] [9]. This sequential extrusion model functions like an irreversibly expanding spring, with Hox genes being progressively pulled out of compact chromatin configurations for transcription [9].

Vertebrates employ a two-tier mechanism for Hox collinearity regulation:

- Nanocollinearity: Chromatin modification within individual Hox clusters

- Macrocollinearity: Coordination and synchronization between different Hox clusters and cells across the embryonic field [8]

Table 1: Forms of Hox Collinearity and Their Characteristics

| Collinearity Type | Definition | Experimental Evidence | Proposed Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Collinearity | Correspondence between genomic order and spatial expression domains along A-P axis | Demonstrated in Drosophila, vertebrates, and many bilaterians [6] | Progressive chromatin opening; Biophysical pulling forces [9] |

| Temporal Collinearity | Sequential activation of Hox genes following genomic order | Observed in vertebrates, cephalochordates, some annelids and arthropods [7] | Time-space translation; Wnt-dependent Hox clock [8] [10] |

| Quantitative Collinearity | Stronger expression of posterior Hox genes at given A-P positions | Documented in vertebrate embryos [6] | Posterior prevalence; protein dominance hierarchies |

Signaling Pathways Regulating the Hox Clock

The sequential activation of Hox genes is coordinated by specific signaling pathways that operate during development:

Hox temporal collinearity is initiated by Wnt signaling, which activates 3' Hox genes first. This is followed by a feed-forward mechanism involving Cdx transcription factors (themselves Wnt-dependent) that activate central Hox genes. Finally, Gdf11 (a TGFβ family signal) activates the most 5' posterior Hox genes [10]. This timed signaling sequence converts temporal information into spatial patterning through the coordinated differentiation of axial progenitors.

CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis Protocols for Hox Gene Functional Analysis

Experimental Workflow for Hox Gene Mutagenesis

The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for functional analysis of Hox genes using CRISPR-Cas9, integrating methodologies from multiple published studies [5] [11] [12].

Detailed Mutagenesis Methodology

Step 1: Target Selection and gRNA Design

- Identify target Hox genes based on expression patterns and paralog group

- Design guide RNAs (gRNAs) with high specificity and efficiency

- For functional domain targeting: Focus on homeodomain regions critical for DNA binding

- For regulatory studies: Target cluster-wide regulatory elements and enhancers

Step 2: Delivery Methods

- Somatic mutagenesis: Direct injection of Cas9/gRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes into developing embryos or tissues

- Germline integration: Generation of stable mutant lines through pronuclear injection

- Electroporation: For targeted delivery to specific embryonic regions

- Viral delivery: Lentiviral or retroviral vectors for efficient infection

Step 3: Screening and Validation

- Genomic DNA extraction from target tissues

- PCR amplification of targeted loci

- T7E1 assay or sequencing for mutation detection

- Western blot or immunohistochemistry for protein expression analysis

Step 4: Phenotypic Analysis

- Morphological assessment of embryonic structures

- Whole-mount in situ hybridization for gene expression patterns

- Immunofluorescence for protein distribution

- Transcriptomic analysis for global expression changes

Table 2: CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis Outcomes in Hox Gene Studies

| Target Gene | Biological System | Mutagenesis Approach | Key Phenotypic Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abd-A, Ubx | Ostrinia furnacalis (corn borer) | CRISPR-Cas9 germline mutagenesis | Larval segment fusion, embryonic lethality, pleiotropic upregulation of other Hox genes [12] | [12] |

| hoxc12/hoxc13 | Xenopus limb regeneration | Somatic CRISPR mutagenesis | Inhibition of cell proliferation, failure of autopod regeneration, disrupted gene regulatory networks [11] | [11] |

| Multiple Hox genes | Parhyale hawaiensis (crustacean) | CRISPR-Cas9 + RNAi combinatorial approach | Homeotic transformations, specialized limb specification defects [5] | [5] |

| HoxA6, HoxB6 | Human embryonic stem cell-derived neurons | Genome-wide loss-of-function screening | Non-redundant functions in caudal neurogenesis, synergistic regulation [13] | [13] |

Applications in Limb Development and Regeneration Studies

Hox Genes in Limb Specification and Evolution

CRISPR-Cas9 studies have revealed versatile roles for Hox genes in crustacean limb specification and evolution. In Parhyale hawaiensis, systematic mutagenesis of six Hox genes expressed in developing mouth and trunk regions demonstrated that:

- Abdominal-A (abd-A) and Abdominal-B (Abd-B) are required for proper posterior patterning

- Ubx is necessary for gill development and repression of gnathal fate

- Antp dictates claw morphology in the thorax

- Scr and Antp confer the hybrid identity of maxillipeds [5]

These findings establish Hox genes as key regulators of limb type specification, with changes in Hox expression domains driving evolutionary diversification of appendage morphology.

Hox Genes in Vertebrate Limb Regeneration

Recent research in Xenopus has identified hoxc12 and hoxc13 as critical regulators for rebooting the developmental program during limb regeneration. These genes exhibit the highest regeneration-specificity in expression and function specifically during the morphogenesis phase after initial blastema formation [11].

Key findings include:

- hoxc12/c13 knockout inhibits cell proliferation and expression of developmentally essential genes

- hoxc12/c13 induction partially restores regenerative capacity in froglets

- These genes function in a regeneration-specific manner without affecting normal development

- They reactivate tissue growth and reestablish axial patterning networks

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Gene Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Cas9 protein, gRNA constructs, CRISPR plasmids | Targeted gene knockout, mutagenesis | Optimize delivery method; validate specificity |

| Model Organisms | Drosophila, Xenopus, mouse, Parhyale hawaiensis | Functional studies in developmental context | Choose based on experimental accessibility and evolutionary position |

| Detection Reagents | Hox gene antibodies, in situ hybridization probes, RNA-seq libraries | Expression pattern analysis, protein localization | Validate cross-reactivity; optimize signal-to-noise |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Single-cell RNA-seq analysis, spatial transcriptomics, ATAC-seq | Genomic profiling, chromatin accessibility | Computational expertise required for data interpretation |

| Lineage Tracing Systems | Cre-loxP, fluorescent reporters, barcoding approaches | Cell fate mapping, progenitor analysis | Temporal control of recombination critical |

Advanced Methodologies and Future Directions

Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics in Hox Research

Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics have revolutionized Hox gene expression analysis. A comprehensive developmental atlas of the human fetal spine revealed that:

- Neural crest derivatives retain the anatomical HOX code of their origin while adopting the code of their destination

- Distinct HOX expression patterns exist in ventral and dorsal spinal cord domains

- 18 HOX genes exhibit the most position-specific expression patterns across stationary cell types [14]

These technologies enable unprecedented resolution in mapping Hox codes across cell types and developmental stages, providing new insights into the modular organization of positional information.

Emerging Concepts: From Collinearity to Chromatin Dynamics

The biophysical model of Hox cluster activation proposes that physical forces pull Hox genes sequentially from compact chromatin territories toward transcription factories [9]. This model is supported by super-resolution imaging data showing gradual elongation of Hox clusters during activation, consistent with an expanding elastic spring mechanism.

The Hox clock in vertebrate axial progenitors represents a sophisticated temporal mechanism that:

- Is initiated by Wnt signaling in the posterior embryonic growth zone

- Progresses through feed-forward Cdx enhancement

- Terminates with Gdf11-mediated activation of posterior Hox genes

- Synchronizes with the production of axial tissues from stem cell-like progenitors [10]

This temporal coordination ensures precise spatial patterning along the extending body axis, with implications for understanding both normal development and evolutionary diversification of body plans.

Hox gene collinearity represents a fundamental developmental principle that connects genomic organization with embryonic patterning. The integration of CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis with advanced genomic technologies has provided unprecedented insights into the mechanisms governing Hox-mediated A-P axis specification. These approaches have revealed both conserved principles and species-specific adaptations in Hox gene function, particularly in the context of limb development and regeneration. Future research will continue to elucidate how temporal and spatial information is encoded within Hox clusters and translated into the complex three-dimensional architecture of animal body plans.

In the field of developmental biology, a fundamental question revolves around how paired appendages, such as limbs in tetrapods and fins in fish, are positioned at specific locations along the anterior-posterior axis of the body. For decades, Hox genes have been prime candidates for determining this positioning, yet clear genetic evidence has remained elusive, particularly in mammalian models [15]. While studies in mice and chicks have suggested Hox involvement in limb positioning, even compound Hox knockout mice have failed to exhibit substantial defects in the initial positioning of limb buds [16] [17]. This gap in our understanding has persisted due to the remarkable functional redundancy among Hox genes across the four Hox clusters in mammals.

Recent breakthrough research utilizing CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis in zebrafish has provided the first definitive genetic evidence that Hox genes indeed specify the positions of paired appendages in vertebrates [15] [16] [17]. This application note details the critical findings that zebrafish mutants with simultaneous deletion of both hoxba and hoxbb clusters—derived from the ancestral HoxB cluster—exhibit a complete absence of pectoral fins. These findings are particularly significant because they reveal a specialized role for HoxB-derived genes in appendage positioning that appears to have been maintained in zebrafish but may be more functionally redundant in mammalian systems.

The implications of this research extend beyond developmental biology to evolutionary studies, providing insights into the evolutionary origin of paired appendages in vertebrates. By understanding the genetic circuitry governing fin and limb positioning, researchers can better comprehend how body plans diversified throughout vertebrate evolution and how mutations in these conserved genetic pathways may contribute to congenital disorders in humans.

Key Experimental Findings

Phenotypic Effects of hox Cluster Deletions

The deletion of specific hox clusters in zebrafish produces distinct and dramatic effects on pectoral fin development, revealing both functional specialization and redundancy within the Hox gene family:

- Single hoxba cluster deletion resulted in morphological abnormalities in pectoral fins at 3 days post-fertilization (dpf), accompanied by reduced but not absent tbx5a expression in pectoral fin buds [15] [17].

- Double hoxba/hoxbb cluster deletion caused a complete absence of pectoral fins in double homozygous mutants, with all embryos lacking pectoral fins (n=15/252; 5.9%) showing perfect concordance with Mendelian expectations for double homozygous mutants (1/16=6.3%) [15] [16] [17].

- Complementary experiments demonstrated that pectoral fins developed normally in hoxba−/−;hoxbb+/− and hoxba+/−;hoxbb−/− mutants, indicating that a single allele from either cluster is sufficient for pectoral fin formation [15].

- Specificity of phenotype was confirmed through the observation that deletions of other hox clusters (hoxaa, hoxab, hoxda) did not recapitulate the complete fin loss seen in hoxba;hoxbb double mutants, though they did produce fin shortening and patterning defects [18].

Table 1: Phenotypic Consequences of hox Cluster Mutations in Zebrafish

| Genetic Manipulation | Pectoral Fin Phenotype | tbx5a Expression | Genetic Penetrance |

|---|---|---|---|

| hoxba cluster deletion | Abnormal morphology | Reduced | Complete |

| hoxbb cluster deletion | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| hoxba;hoxbb double deletion | Complete absence | Nearly undetectable | 100% in double homozygotes |

| hoxaa;hoxab;hoxda triple deletion | Severe shortening | Normal | Complete |

Molecular Mechanisms: The Hox-Tbx5a Pathway

At the molecular level, the pectoral fin loss in hoxba;hoxbb double mutants results from a failure to initiate the genetic program for fin bud formation:

- tbx5a expression failure: In double mutants, tbx5a expression in the pectoral fin field of the lateral plate mesoderm failed to be induced at early stages (30 hpf), suggesting a loss of pectoral fin precursor cells [15] [16].

- Retinoic acid competence: The competence to respond to retinoic acid, a key signaling molecule in limb development, was lost in hoxba;hoxbb cluster mutants, indicating that tbx5a expression cannot be induced in the pectoral fin buds through this pathway [16].

- Key regulatory genes: Subsequent experiments identified hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b as pivotal genes within the hoxba and hoxbb clusters that cooperatively determine pectoral fin positioning through induction of tbx5a expression [15] [16].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental genetic pathway discovered in this research, connecting Hox gene function to the initiation of pectoral fin development:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis of hox Clusters

The groundbreaking findings on hox cluster function were enabled by sophisticated CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing approaches. Below is a detailed protocol for generating hox cluster mutants in zebrafish, adapted from the methodologies used in the cited studies [15] [19]:

Guide RNA Design and Synthesis

- Target Selection: Identify conserved regions spanning entire hox clusters or specific genes of interest (hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b). For cluster-wide deletions, design gRNAs targeting regions flanking the cluster.

- gRNA Design: Design 3-5 gRNAs per target region using established algorithms (CRISPOR, CHOPCHOP) to maximize efficiency and minimize off-target effects.

- Synthesis: Synthesize gRNAs using in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase, followed by purification via phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation.

Microinjection into Zebrafish Embryos

- Preparation of Injection Mix:

- Cas9 protein (1-2 µg/µL)

- Pool of gRNAs (20-50 pg each)

- Phenol red tracer (0.1%)

- Injection Procedure:

- Inject 1-2 nL of the mixture into the yolk of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Raise injected embryos to adulthood (F0 generation).

Screening and Establishment of Mutant Lines

- Genotyping F0 Adults: Cross F0 fish to wild-type partners and screen F1 offspring for germline transmission using PCR and sequencing.

- Establish Stable Lines: Outcross F1 mutants and intercross to generate homozygous mutants.

- Validate Deletions: Use PCR with flanking primers and sequencing to confirm the extent of genomic deletions.

Table 2: Key Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis of hox Clusters

| Reagent/Equipment | Specifications | Function | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 protein | Recombinant, high purity | DNA endonuclease | Commercial suppliers |

| gRNA templates | Target-specific, T7 promoter | Targets Cas9 to genomic loci | Custom synthesis |

| Microinjector | Pneumatic or mechanical | Precise delivery to embryos | Standard lab equipment |

| Zebrafish strains | Wild-type (AB/TU) | Model organism | Zebrafish international resource center |

Phenotypic Analysis Methods

Comprehensive phenotypic analysis is essential for characterizing the effects of hox cluster mutations:

Morphological Assessment

- Live Imaging: Document pectoral fin development daily from 1-5 dpf using brightfield microscopy.

- Cartilage Staining: Use Alcian blue staining (0.1% in 80% ethanol/20% acetic acid) to visualize cartilaginous elements in 5 dpf larvae.

Molecular Analysis of Gene Expression

- Whole-mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH):

- Generate antisense RNA probes for tbx5a, shha, and other marker genes.

- Fix embryos at desired stages (24-48 hpf) in 4% PFA.

- Hybridize with DIG-labeled probes, visualize with NBT/BCIP staining.

- Quantitative RT-PCR:

- Isolate RNA from embryo trunks (20-30 somite stage).

- Reverse transcribe and perform qPCR with gene-specific primers.

The experimental workflow below outlines the key steps from mutant generation to phenotypic analysis:

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table compiles essential research reagents and resources for conducting similar studies on Hox gene function in zebrafish:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Zebrafish Hox Gene Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish Lines | hoxba cluster mutants | Functional studies | Available from authors or zebrafish stock centers |

| hoxbb cluster mutants | Functional studies | Available from authors or zebrafish stock centers | |

| Compound mutants | Redundancy studies | Generate through crossing | |

| Molecular Probes | tbx5a antisense RNA probe | WISH analysis | Marker for pectoral fin bud formation |

| shha antisense RNA probe | WISH analysis | Marker for fin bud patterning | |

| hox gene-specific probes | WISH analysis | Validate cluster deletions | |

| CRISPR Tools | Cas9 protein | Genome editing | Commercially available |

| gRNA synthesis kits | Genome editing | In vitro transcription kits | |

| Genotyping primers | Mutation screening | Design to flank target regions | |

| Visualization Reagents | Alcian blue | Cartilage staining | 0.1% in acid ethanol |

| NBT/BCIP | WISH detection | Alkaline phosphatase substrates | |

| Anti-DIG-AP antibody | WISH detection | Probe detection |

Discussion and Research Applications

The definitive genetic evidence that hoxba and hoxbb clusters are essential for pectoral fin positioning in zebrafish represents a significant advancement in our understanding of limb development. This finding has several important implications for ongoing research:

Evolutionary Developmental Biology

The specialized role of HoxB-derived genes in zebrafish pectoral fin positioning, contrasted with the more subtle phenotypes in mammalian HoxB mutants, provides a fascinating model for studying the evolution of gene regulatory networks after whole-genome duplication events. Zebrafish experienced teleost-specific whole-genome duplication, resulting in seven hox clusters compared to four in mammals [16]. This duplication may have allowed subfunctionalization of the hoxba and hoxbb clusters in appendage positioning—a function that remains more distributed across multiple Hox clusters in mammals.

Applications for Limb Regeneration and Repair

Understanding the genetic pathways that initiate and position appendages has profound implications for regenerative medicine. The core genetic pathway—Hox genes inducing Tbx5 expression—represents a potential target for therapeutic manipulation in cases of congenital limb abnormalities or trauma. Researchers in drug development can utilize this knowledge to screen for small molecules that modulate this pathway, potentially activating regenerative programs in cases where appendage regeneration does not normally occur.

Future Research Directions

Several promising research directions emerge from these findings:

- Mechanistic studies to identify direct versus indirect targets of Hoxb4a/b5a/b5b regulation in the lateral plate mesoderm.

- Comparative studies in other vertebrate models to determine how conserved this HoxB-specific function is across species.

- Single-cell transcriptomics of the lateral plate mesoderm in wild-type and mutant embryos to identify additional components of the genetic network controlling appendage positioning.

- CRISPR-based screens to identify modifiers and cooperating factors in the Hox-Tbx5 pathway.

The robust protocols and reagents described in this application note provide researchers with the necessary tools to pursue these exciting research directions, advancing our fundamental understanding of limb development and its applications to human health.

Application Notes

Recent genetic research in zebrafish has established that the HoxB-derived hoxba and hoxbb gene clusters are fundamental for anterior-posterior patterning and the initiation of pectoral fin development [20]. Within these clusters, the pivotal genes hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b have been identified as core regulators that cooperatively determine the positioning of the pectoral fin field by inducing the expression of the key fin-field specifier tbx5a [20]. The application of CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis to interrogate these Hox clusters provides a powerful model for understanding the evolutionary origin and genetic regulation of paired appendages in vertebrates.

Key Quantitative Findings from hoxba;hoxbb Cluster Mutagenesis

Table 1: Phenotypic Outcomes of Hox Cluster Mutagenesis in Zebrafish

| Genetic Manipulation | Pectoral Fin Phenotype | tbx5a Expression | Key Molecular Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| hoxba;hoxbb cluster deletion | Complete absence | Failed induction in lateral plate mesoderm | Loss of pectoral fin precursor cells [20] |

| Frameshift mutations in hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b | No severe phenotype (not recapitulated) | Not specified | Functional redundancy or compensation suspected [20] |

| Genomic locus deletion of hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b | Absence (low penetrance) | Not specified | Confirms cooperative role in fin positioning [20] |

Table 2: Functional Profile of Essential Hox Genes in Zebrafish Fin Development

| Hox Gene | Role in Pectoral Fin Development | Response to Retinoic Acid |

|---|---|---|

| hoxb4a | Anterior-Posterior positioning of fin field | Competence lost in cluster mutants [20] |

| hoxb5a | Anterior-Posterior positioning of fin field; induction of tbx5a | Competence lost in cluster mutants [20] |

| hoxb5b | Anterior-Posterior positioning of fin field; induction of tbx5a | Competence lost in cluster mutants [20] |

The failure of frameshift mutations in individual genes to recapitulate the full cluster deletion phenotype underscores the cooperative function and potential redundancy among these Hox genes [20]. The low-penetrance phenotype observed from genomic deletions further suggests that the establishment of the fin field is a robust process governed by a network of genetic interactions.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Generation of hox Cluster Mutants in Zebrafish

This protocol details the methodology for creating Hox cluster-deficient mutants, enabling functional analysis of Hox genes in limb development [20] [21] [12].

Materials and Reagents

- Wild-type zebrafish (TU or AB strains)

- CRISPR-Cas9 system: Recombinant Cas9 protein and in vitro transcribed sgRNAs.

- Target-specific sgRNAs: Designed to flank the entire hoxba and hoxbb genomic loci or specific genes (hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b).

- Microinjection apparatus: Micropipette puller, microinjector.

- Embryo handling tools: Agarose injection molds, fine forceps.

- Genomic DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents and gel electrophoresis equipment

- In situ hybridization reagents (for tbx5a expression analysis)

Procedure

sgRNA Design and Synthesis

- Identify ~20 nucleotide target sequences adjacent to 5'-NGG PAM sites at the 5' and 3' boundaries of the target hox cluster or specific gene.

- Synthesize sgRNAs by in vitro transcription from a DNA template.

Preparation of CRISPR-Cas9 Injection Mix

- Combine the following in a microcentrifuge tube:

- 300 ng/µL recombinant Cas9 protein

- 30-50 ng/µL of each locus-flanking sgRNA

- Phenol red dye (0.1%) for visualization

- Centrifuge briefly and keep on ice.

- Combine the following in a microcentrifuge tube:

Zebrafish Embryo Microinjection

- Collect single-cell stage zebrafish embryos and align them in grooves on an injection agarose plate.

- Using a microinjector, deliver approximately 1 nL of the injection mix into the cell cytoplasm or yolk.

- Transfer injected embryos to embryo medium and incubate at 28.5°C.

Founder (F0) Screening and Raising

- At 24-48 hours post-fertilization (hpf), collect 10-20 embryos for genomic DNA extraction to confirm mutagenesis efficiency via PCR and gel electrophoresis.

- Raise the remaining injected embryos to adulthood. These are the mosaic founder (F0) fish.

Establishment of Stable Mutant Lines

- Outcross F0 adult fish to wild-type partners.

- Extract genomic DNA from a clip of the tail fin of the F1 offspring and perform PCR and sequencing to identify individuals carrying the desired deletion.

- Outcross F1 carriers to establish stable mutant lines.

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of Hox Mutants

This protocol outlines the key phenotypic and molecular analyses for characterizing the Hox cluster mutants [20].

Procedure

Phenotypic Screening

- Observe and image live embryos and larvae under a stereomicroscope at 48, 72, and 96 hpf for the presence or absence of pectoral fin buds.

Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH) for tbx5a

- Fix wild-type and mutant embryos at the 18-22 somite stage (prior to fin bud morphogenesis) in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA).

- Generate an antisense RNA probe for tbx5a, labeled with digoxigenin.

- Follow standard WISH protocols to visualize tbx5a expression domains in the lateral plate mesoderm.

- Clear and mount the embryos for imaging under a compound microscope. The absence of tbx5a signal in mutants indicates a failure of fin field specification [20].

Retinoic Acid (RA) Response Assay

- Treat wild-type and hoxba;hoxbb cluster-deleted embryos with a known concentration of all-trans retinoic acid (e.g., 1x10^(-6) M) during early segmentation stages.

- Perform WISH for tbx5a on treated and control embryos.

- A failure to induce or alter tbx5a expression in mutant embryos indicates a loss of competence to respond to RA signaling [20].

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationship between Hox gene function and pectoral fin specification, and the key experimental workflow for their analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Hox Gene Functional Studies in Zebrafish

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function / Application in Hox Studies |

|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted mutagenesis of Hox clusters and specific Hox genes to study loss-of-function phenotypes [20] [21]. |

| In Vitro Transcription Kit | Synthesis of sgRNAs and labeled RNA probes for in situ hybridization [20]. |

| tbx5a RNA Probe | Molecular marker for visualizing and assessing the establishment of the pectoral fin field via in situ hybridization [20]. |

| All-trans Retinoic Acid (RA) | Treatment to assess the competence of the fin field to respond to key patterning signals, revealing upstream genetic control [20]. |

| Hox Gene-specific Antibodies | Immunohistochemical validation of Hox protein expression and localization (though not explicitly mentioned in the cited studies, this is a standard tool in the field). |

| Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization Reagents | Detailed visualization of gene expression patterns in entire embryos, crucial for analyzing patterning defects [20]. |

| NPAS3-IN-1 | NPAS3-IN-1, CAS:2207-44-5, MF:C10H5N3O2S3, MW:295.4 g/mol |

| B32B3 | B32B3, MF:C19H17N5S, MW:347.4 g/mol |

In the field of developmental biology, the precise positioning and patterning of limb buds remain a fundamental area of investigation. This protocol article examines the concept of retinoic acid (RA) competence, defined as the specific molecular preparedness of progenitor cells within the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) to interpret and respond to RA signaling, an essential step for limb bud initiation. We situate this discussion within a modern research framework that utilizes CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis of Hox clusters to dissect the genetic hierarchy governing this process. The synergistic interaction between Hox genes and RA signaling establishes the initial limb-forming territories, ultimately activating the expression of key limb initiator genes such as Tbx5 [22] [15]. The protocols and data presented herein are designed to equip researchers with the methodologies to unravel these complex interactions, with direct implications for understanding congenital limb defects and regenerative medicine strategies.

Key Findings and Quantitative Data

Recent genetic studies, particularly in zebrafish and mice, have clarified the essential roles of specific Hox genes and RA signaling components in limb bud initiation. The following tables summarize the core quantitative findings and the resultant phenotypic outcomes.

Table 1: Key Genetic Findings on Limb Bud Initiation

| Gene/Cluster | Model Organism | Method | Primary Phenotype | Molecular Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoxba & Hoxbb clusters [15] | Zebrafish | CRISPR-Cas9 cluster deletion | Complete absence of pectoral fins (100% penetrance in double homozygotes) | Failure to induce tbx5a expression; loss of RA competence. |

| hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b [15] | Zebrafish | Frameshift mutations & locus deletion | Absence of pectoral fins (low penetrance) | Cooperative role in establishing tbx5a expression domain. |

| Raldh2 [22] | Zebrafish & Mouse | Genetic ablation / Mutation | Failure of forelimb development | Disrupted RA synthesis; reduced Tbx5 expression. |

| CYP26B1 [23] | Mouse | Gene knockout | Severe limb malformation (meromelia) | Expanded RA signaling distally; proximalization of limb elements. |

Table 2: Phenotypic Penetrance of Hox Mutations in Zebrafish

| Genotype | Pectoral Fin Phenotype | Penetrance (Observed) | Penetrance (Mendelian Expectation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| hoxba-/-; hoxbb-/- [15] | Complete absence | 5.9% (15/252) | 6.3% (1/16) |

| hoxba-/-; hoxbb+/- or hoxba+/-; hoxbb-/- [15] | Present | N/A | N/A |

| Mutations in hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b [15] | Absence (low penetrance) | Not Specified | N/A |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Interrogating Hox Gene Function via CRISPR-Cas9 Somatic Mutagenesis in Zebrafish

This protocol describes the generation of hox cluster-deficient mutants to assess their role in pectoral fin development and RA competence [21] [15].

I. Materials

- Wild-type zebrafish embryos (1-4 cell stage)

- CRISPR-Cas9 reagents: Cas9 protein or mRNA; single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) designed against target Hox clusters (e.g., hoxba, hoxbb)

- Microinjection system: Micropipette puller, microinjector, micromanipulator

- Embryo culture reagents: E3 embryo medium, Petri dishes

- Genotyping reagents: PCR primers flanking target sites, gel electrophoresis equipment, DNA sequencing services

- In situ hybridization (ISH) reagents: Digoxigenin-labeled tbx5a RNA probe, anti-digoxigenin antibody, NBT/BCIP staining solution

II. Procedure

- sgRNA Design and Synthesis: Design multiple sgRNAs targeting exonic or critical regulatory regions of the Hox clusters of interest (e.g., hoxba and hoxbb). Synthesize sgRNAs using in vitro transcription.

- Microinjection: Co-inject a mixture of Cas9 protein (or mRNA) and sgRNAs into the cytoplasm of 1-4 cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Embryo Rearing: Maintain injected embryos and uninjected controls in E3 medium at 28.5°C.

- Phenotypic Screening: At 3-5 days post-fertilization (dpf), score embryos under a dissecting microscope for the presence or absence of pectoral fins.

- Genotype Confirmation:

- At 1-2 dpf, pool a subset of embryos for genomic DNA extraction.

- Perform PCR amplification of the targeted genomic regions and analyze products by gel electrophoresis for size shifts. Confirm mutations by Sanger sequencing of cloned PCR products.

- Molecular Phenotyping by In Situ Hybridization (ISH):

- Fix phenotypically screened embryos at the 15-20 somite stage.

- Perform whole-mount ISH using a tbx5a riboprobe to visualize the limb field in the LPM.

- Compare tbx5a expression patterns between mutant and wild-type siblings.

III. Analysis

- Correlate genotypic data (confirmed Hox cluster deletions) with the morphological fin phenotype and the molecular phenotype (loss of tbx5a expression).

- Calculate the penetrance of the finless phenotype among double homozygous mutants.

Protocol B: Functional Rescue of Limb Bud Initiation via Retinoic Acid Administration

This protocol tests whether exogenous RA can restore limb bud gene expression in Hox-deficient embryos, thereby assessing RA competence [22] [15].

I. Materials

- Hox cluster mutant embryos (from Protocol A) and wild-type siblings

- Retinoic Acid Stock Solution: 1mM all-trans RA in DMSO (light-sensitive, store at -20°C)

- Control Solution: 0.1% DMSO in embryo medium

- Embryo culture reagents

- In situ hybridization reagents for tbx5a and Fgf10

II. Procedure

- Embryo Preparation: After genotyping/phenotypic screening, dechorionate wild-type and Hox mutant embryos at the 10-12 somite stage.

- RA Exposure:

- Prepare working solutions of RA (e.g., 1-100 nM) by diluting the stock in embryo medium. Prepare a 0.1% DMSO control solution.

- Incubate separate groups of wild-type and mutant embryos in RA solutions and control solution. Perform all steps under minimal light conditions.

- Incubate for a defined period (e.g., 6-12 hours).

- Fixation and Analysis:

- Wash embryos thoroughly in embryo medium to remove residual RA.

- Fix embryos and process for ISH to detect tbx5a and Fgf10 expression.

III. Analysis

- In wild-type embryos, expect a potential upregulation or anterior expansion of tbx5a and Fgf10 with RA treatment.

- In Hox cluster mutants, the failure of RA to induce tbx5a expression demonstrates a loss of RA competence, indicating that Hox genes function upstream to establish the competent state.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating RA-Hox Gene Interactions in Limb Development

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System (sgRNAs, Cas9 protein) [21] [15] | Somatic or germline mutagenesis of Hox genes and other patterning genes (e.g., Raldh2, Cyp26b1). | Target multiple sites within a cluster for complete deletion. Confirm mutations via sequencing. |

| all-trans Retinoic Acid (RA) [22] [23] | To manipulate RA signaling pathways; used in rescue and overexpression experiments. | Light-sensitive and teratogenic. Use a range of concentrations (low nM to µM) and precise timing. |

| Disulphiram [22] | Chemical inhibitor of RA synthesis. Used to phenocopy Raldh2 mutations. | Apply locally via soaked beads to achieve targeted inhibition. |

| Digoxigenin-labeled RNA Probes (for tbx5a/tbx5, Fgf10, Shh, Hox genes) [22] [15] | In situ hybridization to visualize spatial gene expression patterns. | Critical for assessing molecular phenotypes in mutant embryos. |

| Antibodies (for Tbx5, Hox proteins, RA signaling reporters) | Immunohistochemistry to detect protein localization and abundance. | Can provide post-transcriptional validation. |

| Yohimbine-13C,d3 | Yohimbine-13C,d3, MF:C21H26N2O3, MW:358.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| D-Mannitol-13C6 | D-Mannitol-13C6, MF:C6H14O6, MW:188.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Genetic Hierarchy in Forelimb Initiation. Retinoic acid (RA) from somites induces Hox gene expression. Hox proteins, in turn, confer RA competence to lateral plate mesoderm cells, enabling them to activate Tbx5 expression in response to RA. Tbx5 then directly activates Fgf10, initiating limb bud outgrowth [22] [15].

Diagram 2: Workflow for CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis of Hox Clusters. Key experimental steps include the design and synthesis of CRISPR components, microinjection into zebrafish embryos, and subsequent phenotypic screening combined with molecular genotyping and in situ hybridization (ISH) analysis [21] [15].

Diagram 3: Proxiodistal Patterning by RA and CYP26B1. In the developing limb bud, a gradient of RA is established where high proximal and low distal levels help specify proximal-distal fates. The enzyme CYP26B1, expressed in the distal limb bud and maintained by FGF signaling, degrades RA to protect the distal region from its proximalizing influence, allowing for outgrowth and distal structure formation [23].

Advanced CRISPR Methodologies: From Cluster Deletion to Synthetic Regulatory Reconstitution

CRISPR-Cas9 Strategies for Complete Hox Cluster Deletion in Zebrafish and Mouse Models

The Hox gene family, encoding evolutionarily conserved homeodomain-containing transcription factors, serves as the master regulator of embryonic patterning along the anterior-posterior axis in bilaterian animals [15] [16]. These genes are structurally organized into Hox clusters, with their genomic arrangement exhibiting a distinctive phenomenon known as collinearity, where the order of genes correlates with specific developmental regions along the body axes [16]. In vertebrates, the primordial Hox cluster underwent multiple rounds of whole-genome duplication, resulting in four distinct clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD) in tetrapods, while teleost fishes, including zebrafish, possess seven hox clusters due to an additional teleost-specific duplication event [15] [16].

A compelling area of developmental biology research focuses on the crucial role of Hox genes in paired appendage development, including pectoral fins in fish and forelimbs in tetrapods [15] [18]. These appendages arise at precise locations along the anterior-posterior axis from progenitor cells in the lateral plate mesoderm. While genetic evidence from mouse models has established the essential function of HoxA and HoxD clusters in limb patterning, particularly for proximal-distal axis specification, the precise mechanisms governing the initial anteroposterior positioning of limbs have remained less understood [15] [18]. Recent advances in CRISPR-Cas9 technology have enabled researchers to generate comprehensive hox cluster deletion models, providing unprecedented insights into the functional redundancy and specificity of these genes during limb development [15] [18].

This Application Note details robust CRISPR-Cas9 methodologies for the complete deletion of Hox gene clusters in zebrafish and mouse models, framed within the context of limb development studies. We provide step-by-step protocols, reagent specifications, and data analysis workflows to facilitate the implementation of these approaches in investigating Hox gene function.

Strategic Approaches to Hox Cluster Deletion

Functional Organization of Hox Clusters

The strategic design of Hox cluster deletions requires understanding their genomic organization and functional domains. Vertebrate Hox clusters are characterized by two major regulatory landscapes flanking the gene cluster: a 3' domain (3DOM) controlling anterior gene expression and a 5' domain (5DOM) regulating posterior gene expression [24]. These domains correspond to topologically associating domains (TADs) with conserved positions of CTCF binding sites, forming the structural basis for bimodal Hox gene regulation during appendage development [24].

In zebrafish, the hoxba and hoxbb clusters (derived from the ancestral HoxB cluster) have been identified as essential for anterior-posterior positioning of pectoral fins through induction of tbx5a expression in the lateral plate mesoderm [15] [16]. Simultaneous deletion of both clusters results in complete absence of pectoral fins, demonstrating their cooperative function in specifying appendage position [15]. Conversely, the hoxaa, hoxab, and hoxda clusters (orthologs of mammalian HoxA and HoxD) play complementary roles in pectoral fin growth and patterning after fin bud establishment, with triple mutants showing severe truncation of both the endoskeletal disc and fin-fold without affecting the initial tbx5a expression [18].

Comparative Deletion Strategies

Table: Comparative Hox Cluster Deletion Strategies in Zebrafish and Mice

| Aspect | Zebrafish Model | Mouse Model |

|---|---|---|

| Target Clusters | hoxba, hoxbb, hoxaa, hoxab, hoxda [15] [18] | HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, HoxD [25] |

| Deletion Size | ~100-200 kb for entire clusters [15] [24] | ~100-300 kb for entire clusters [25] [24] |

| Guide RNA Design | 2-4 gRNAs targeting flanking regions of each cluster [15] | 2-4 gRNAs targeting flanking regions of each cluster [26] |

| Delivery Method | Single-cell embryo microinjection of Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes [15] | Embryonic stem cell electroporation or zygote microinjection [26] |

| Efficiency | 5.9-100% for complete cluster deletion [15] [18] | 10-95% depending on strategy [26] |

| Phenotypic Analysis | Pectoral fin formation at 3-5 dpf, tbx5a expression at 30 hpf [15] [18] | Limb bud formation at E9.5-E12.5 [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Complete Hox Cluster Deletion in Zebrafish

Reagent Preparation

- Guide RNA Design: Design 2-4 gRNAs targeting conserved non-coding sequences flanking the target hox cluster. For hoxba cluster deletion, gRNAs should target regions approximately 50-100 kb apart to facilitate complete excision [15].

- CRISPR-Cas9 Complex Formation: Prepare ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes by mixing 300 ng/μL purified Cas9 protein with 50 ng/μL each gRNA in nuclease-free injection buffer (0.25% phenol red, 5 mM KCl). Incubate at 37°C for 10 minutes to allow RNP complex formation [15].

Microinjection Procedure

- Collect single-cell stage zebrafish embryos following standard breeding protocols.

- Using a microinjection system, deliver approximately 1 nL of RNP complex mixture into the cell cytoplasm.

- Maintain injected embryos at 28.5°C in E3 embryo medium.

- At 24 hours post-fertilization (hpf), screen for successfully injected embryos using phenol red tracking.

Genotyping and Validation

- At 48 hpf, extract genomic DNA from individual embryos using alkaline lysis buffer (25 mM NaOH, 0.2 mM EDTA) at 95°C for 20 minutes, followed by neutralization with 40 mM Tris-HCl.

- Perform PCR with primers flanking the deletion sites using a three-primer system: two external primers amplifying the wild-type allele and one internal primer for the deleted allele.

- Confirm deletion size by long-range PCR and Sanger sequencing of junction fragments.

- For quantitative assessment of deletion efficiency, use digital PCR with probes targeting the pre- and post-deletion junctions [15].

Protocol 2: Regulatory Landscape Deletion in Mouse Models

Targeting Vector Construction

- For deletion of regulatory domains such as the 5DOM region controlling Hoxd gene expression in digits [24]:

- Design gRNAs targeting the boundaries of the TAD domain, considering CTCF binding sites.

- Generate a targeting vector containing 5' and 3' homology arms (1-2 kb each) flanking a positive selection marker (e.g., puromycin resistance).

- Incorporate restriction sites for subsequent Southern blot analysis.

Embryonic Stem Cell Electroporation and Screening

- Culture mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) in standard conditions.

- Electroporate 10ⷠmESCs with 5 μg of each gRNA plasmid and 10 μg of Cas9 expression vector.

- At 48 hours post-electroporation, begin selection with appropriate antibiotics.

- After 7-10 days, pick individual colonies and expand for genotyping.

- Screen clones by PCR and confirm correct targeting by Southern blot analysis.

- Use correctly targeted mESC clones to generate chimeric mice through blastocyst injection [25] [26].

Phenotypic Validation

- For limb development studies, analyze embryos at stages E9.5-E12.5.

- Assess Hox gene expression patterns by whole-mount in situ hybridization using digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes.

- Evaluate limb patterning defects by skeletal staining with Alcian Blue and Alizarin Red at E16.5 [25].

Quantitative Phenotypic Analysis

Table: Phenotypic Outcomes of Hox Cluster Deletions in Zebrafish

| Genotype | Pectoral Fin Phenotype | tbx5a Expression | shha Expression | Penetrance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hoxbaâ»/â» | Morphological abnormalities | Reduced | Normal | 100% [15] |

| hoxbaâ»/â»; hoxbbâ»/â» | Complete absence | Nearly undetectable | Not detectable | 100% [15] |

| hoxaaâ»/â»; hoxabâ»/â»; hoxdaâ»/â» | Severe shortening | Normal | Markedly down-regulated | 100% [18] |

| hoxabâ»/â»; hoxdaâ»/â» | Shortened endoskeletal disc and fin-fold | Normal | Reduced | 100% [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagent Solutions for Hox Cluster Deletion Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Components | Purified Cas9 protein, synthetic gRNAs | Efficient genome editing with minimal off-target effects | [15] |

| Detection Probes | tbx5a, shha riboprobes for in situ hybridization | Analysis of gene expression changes in mutant embryos | [15] [18] |

| Cartilage Stains | Alcian Blue | Visualization of cartilaginous structures in zebrafish pectoral fins | [18] |

| Selection Markers | Puromycin, neomycin | Selection of successfully targeted embryonic stem cell clones | [25] [26] |

| Transgenic Reporters | Hoxa5-P2A-mCherry, Hoxa7-P2A-eGFP | Monitoring Hox gene expression dynamics in living cells | [25] |

| Pyrimethanil-d5 | Pyrimethanil-d5, MF:C12H13N3, MW:204.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Erythromycin-13C,d3 | Erythromycin-13C,d3, MF:C37H67NO13, MW:737.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Workflow Visualization

Experimental Workflow for Hox Cluster Deletion

Signaling Pathways in Hox-Mediated Limb Development

Hox Gene Regulation of Limb Development

The CRISPR-Cas9 strategies outlined in this Application Note provide robust methodologies for complete Hox cluster deletion in both zebrafish and mouse models. These approaches have revealed the functional specialization of different Hox clusters during limb development, with HoxB-derived clusters being essential for initial appendage positioning through induction of tbx5a expression, while HoxA and HoxD-derived clusters primarily regulate subsequent patterning and growth phases [15] [18]. The protocols for regulatory landscape deletion further enable dissection of evolutionarily conserved mechanisms governing Hox gene regulation, with demonstrated conservation of topological domain organization between fish and mice despite extensive genomic reorganization [24].

These technical approaches support diverse research applications, including: (1) investigation of gene regulatory networks controlling limb positioning and patterning; (2) analysis of functional redundancy and specificity among Hox clusters; and (3) modeling of human congenital disorders affecting limb development. The reagent specifications and workflow visualizations provided will assist researchers in implementing these powerful genetic tools to advance our understanding of Hox gene function in development and evolution.

Application Notes

Synthetic regulatory reconstitution represents a paradigm shift in functional genomics, providing a bottom-up framework to dissect the regulatory architecture of complex genetic loci. This approach is powerfully complemented by CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis studies in model organisms, which have established that Hox genes play versatile roles in crustacean limb specification and evolution [5]. In Parhyale hawaiensis, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated disruption of Hox genes including Ubx, Antp, Scr, and Dfd results in specific homeotic transformations affecting gnathal, thoracic, and abdominal appendages [5]. These findings establish the functional significance of Hox genes in patterning diverse limb types across species.

The integration of synthetic biology with classical reverse genetics enables researchers to move beyond correlation to causation in understanding gene regulation. By fabricating HoxA cluster variants and testing their function in an ectopic genomic context, this methodology isolates the relative contributions of distal enhancers, intracluster transcription factor binding sites, and topological organization [27]. This is particularly valuable for understanding how Hox expression boundaries are established during development—a process crucial for proper limb patterning as revealed by CRISPR-Cas9 studies [5].

Synthetic reconstitution addresses a fundamental challenge in regulatory genomics: how multiple regulatory elements integrate their inputs across large genomic neighborhoods. At the HoxA cluster, which spans 100-200 kb, this integration converts morphogenetic signals like retinoic acid into stable transcriptional, epigenetic, and topological states that define positional identity along the anterior-posterior axis [27]. The ability to reconstitute this process from minimal components provides unprecedented insight into the modular design principles of developmental gene regulation.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bottom-Up Assembly of Synthetic HoxA Variants

Principle

Harness yeast homologous recombination machinery to assemble synthetic HoxA cluster variants (130-170 kb) from modular DNA components, enabling introduction of arbitrary combinations of regulatory modifications [27].

Reagents

- Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs) containing rat HoxA cluster sequence

- Synthetic DNA pieces with desired regulatory modifications

- Yeast Assembly Vectors (YAVs)

- Yeast strain with efficient homologous recombination capability

- PCR reagents for amplification of DNA segments

Procedure

- Design HoxA Variants: Plan regulatory element modifications (RARE mutations, enhancer deletions, etc.)

- Generate DNA Modules: Amplify HoxA segments from BAC templates or synthesize DNA pieces with overlaps

- Yeast Assembly: Co-transform DNA modules into yeast for homologous recombination

- Assemblon Verification: Isemble assemblons and verify by next-generation sequencing

- Quality Control: Confirm assemblon integrity and correct assembly [27]

Critical Parameters

- Maintain sufficient overlapping sequences (≥40 bp) between DNA modules

- Ensure yeast transformation efficiency supports large construct assembly

- Verify single-copy integration in mammalian cells

Protocol 2: Ectopic Integration of Synthetic HoxA Clusters in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

Principle

Precise, single-copy integration of synthetic HoxA variants into defined genomic landing pads to eliminate position effects and enable direct comparison across constructs [27].

Reagents

- Mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs)

- Landing pad constructs for Hprt1 or Sox2 loci

- Cre recombinase expression system

- Selection media (HAT supplementation for Hprt1 selection)

- Capture-seq reagents for targeted sequencing

Procedure

- Cell Line Preparation: Establish mESCs with landing pads at Hprt1 or Sox2 loci

- Cre-Mediated Integration: Deliver assemblons via Big-FN delivery system

- Selection and Screening: Isolate clones with successful integration using HAT selection

- Copy Number Verification: Confirm single-copy integration by Capture-seq

- Functional Validation: Assess HoxA expression complementation in Hprt1-deficient cells [27]

Critical Parameters

- Use isogenic mESC lines to minimize genetic background effects

- Verify single-copy integration by comparing sequencing coverage to flanking regions

- Include both HoxA+/+ and HoxA-/- genetic backgrounds for comparative studies

Protocol 3: Functional Characterization of Synthetic HoxA Clusters

Principle

Quantify the transcriptional and epigenetic response of synthetic HoxA variants to patterning signals to determine sufficiency of regulatory modules [27].

Reagents

- Retinoic acid (RA) for differentiation induction

- RNA-seq reagents for transcriptome analysis

- ATAC-seq reagents for chromatin accessibility profiling

- CUT&RUN reagents for H3K4me3 and other histone modifications

- Antibodies for specific chromatin marks

Procedure

- RA Induction: Differentiate mESCs with synthetic HoxA clusters using RA treatment

- Transcriptional Analysis: Perform RNA-seq at multiple time points to assess HoxA activation

- Epigenetic Profiling: Conduct ATAC-seq to map chromatin accessibility changes

- Chromatin State Analysis: Use CUT&RUN for H3K4me3 and repressive marks

- Topological Assessment: Analyze domain formation by chromatin conformation capture [27]

Critical Parameters

- Include multiple time points to capture dynamics of gene activation

- Compare synthetic clusters to endogenous HoxA as internal control

- Analyze both gene expression levels and spatial patterning of transcription

Data Presentation

Table 1: Synthetic HoxA Cluster Variants and Their Regulatory Components

| Variant Name | Size (kb) | Distal Enhancers | Intracluster RAREs | Key Features | Functional Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynHoxA | 134 | Absent | Present (wild-type) | Minimal cluster without distal enhancers | Recapitulates correct chromatin boundary and gene activation patterns |

| Enhancers+SynHoxA | 150-170 | Present | Present (wild-type) | Minimal cluster with distal enhancers added | Increases transcriptional output, especially at early time points |

| RAREΔ | 134 | Absent | Mutated (4 RAREs) | Lacking functional retinoic acid response elements | Eliminates RA response at gene expression and chromatin organization levels |

| Enhancers+RAREΔ | 150-170 | Present | Mutated (4 RAREs) | Distal enhancers with RARE mutations | Fails to fully rescue RARE mutation phenotype |

Table 2: Functional Outcomes of HoxA Cluster Variants in Response to Retinoic Acid

| Functional Measure | SynHoxA | Enhancers+SynHoxA | RAREΔ | Endogenous HoxA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Activation | + + | + + + | - | + + + |

| Chromatin Boundary Formation | + + | + + | - | + + |

| Transcript Levels | Moderate | High | Minimal | High |

| Topological Domain Organization | Recapitulated | Recapitulated | Absent | Established |

| Dependence on Distal Enhancers | Independent | Dependent | Independent | Partial dependence |

Table 3: CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis of Hox Genes in Parhyale hawaiensis and Limb Phenotypes

| Hox Gene | CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis Approach | Functional Role in Limb Development | Observed Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abd-B | CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis | Posterior patterning specification | Transformation of abdominal limbs to thoracic type |

| abd-A | CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis | Abdominal and thoracic specialization | Loss of appendage specialization, simplified body plan |

| Ubx | CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis and RNAi | Gill development and gnathal fate repression | Defects in gill development, misexpression of gnathal identity |

| Antp | CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis and RNAi | Claw morphology specification | Altered claw morphology in thoracic appendages |

| Scr | CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis and RNAi | Maxilliped identity specification | Loss of hybrid gnathal-thoracic identity in maxilliped |

| Dfd | CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis and RNAi | Prevention of antennal identity in head segments | Misexpression of antennal identity |

Experimental Visualization

Diagram 1: Synthetic Regulatory Reconstitution Workflow

Diagram 2: HoxA Regulatory Module Integration

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Synthetic Regulatory Reconstitution

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Assembly Systems | Yeast Assembly Vectors (YAVs), Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs) | Large DNA construct assembly and maintenance |

| DNA Components | Synthetic DNA pieces with homologous overlaps, PCR amplicons from BAC templates | Modular building blocks for variant construction |

| Integration Tools | Cre recombinase system, Landing pad constructs (Hprt1, Sox2 loci) | Precise single-copy integration into defined genomic sites |

| Cell Lines | Mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs), HoxA-/- knockout lines | Functional testing in controlled genetic backgrounds |

| Differentiation Inducers | Retinoic acid (RA), Wnt signaling agonists | Patterning signal application to activate Hox expression |

| Genomic Analysis | RNA-seq reagents, ATAC-seq kits, CUT&RUN reagents | Transcriptional, chromatin accessibility, and epigenetic profiling |

| Sequence Verification | Next-generation sequencing platforms, Capture-seq reagents | Quality control of assembled constructs and integration sites |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Tools | Cas9 nucleases, sgRNAs for Hox genes | Functional validation in model organisms [5] |

| Ethambutol-d10 | Ethambutol-d10, MF:C10H24N2O2, MW:214.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fidaxomicin-d7 | Fidaxomicin-d7, MF:C52H74Cl2O18, MW:1065.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This application note details the utilization of genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 loss-of-function screens to identify essential Hox genes and their cofactors in neuronal development and limb regeneration models. We provide validated experimental protocols for conducting such screens in both mammalian stem cell-derived neuronal cultures and Xenopus limb blastema, summarizing key quantitative findings and essential reagent solutions. The data underscore the critical, non-redundant roles of specific Hox paralogs and establish a framework for investigating Hox gene function in developmental and regenerative contexts.

HOX genes, which encode a family of evolutionarily conserved homeodomain transcription factors, are master regulators of anterior-posterior patterning during embryogenesis [28]. In humans, 39 HOX genes are arranged in four clusters (A, B, C, and D) and exhibit remarkable temporal and spatial collinearity—their order on chromosomes corresponds to their expression patterns along the body axis [28] [14]. Beyond embryonic patterning, Hox genes continue to play crucial roles in neuronal circuit formation and have recently been implicated in the regenerative processes of model organisms [29] [11]. The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has enabled systematic, genome-wide screening to identify essential genetic regulators of these complex processes. This note details protocols and key findings from recent studies employing CRISPR screens to investigate Hox gene function in neuronal and limb development.

Key Findings from Genome-Wide CRISPR Screens

Recent genome-wide loss-of-function screens have identified essential Hox genes and their regulatory partners in specific developmental contexts. The table below summarizes core findings from pivotal studies.

Table 1: Essential Hox Genes and Cofactors Identified via CRISPR Screening

| Developmental Context | Essential Hox Genes / Cofactors Identified | Key Phenotypic Outcomes | Experimental Model | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caudal Neurogenesis | HOXA6, HOXB6 | Essential for neuronal differentiation; exhibit synergistic but non-redundant functions; regulate distinct gene sets. | Human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived neuronal cells [13] [30] | |

| Spinal Cord / Motor Neuron Patterning | CTCF, MAZ (Hox cluster regulators) | Disruption causes derepression of posterior Hox genes (e.g., Hoxa7); leads to homeotic transformations. | Mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) differentiated into cervical motor neurons [31] | |

| Limb Regeneration | Hoxc12, Hoxc13 | Critical for rebooting developmental program; knockout inhibits cell proliferation and autopod regeneration without affecting development. | Xenopus laevis limb blastema [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide CRISPR Screen in hESC-Derived Neuronal Cells

This protocol identifies genes essential for caudal neuronal differentiation [13] [30].

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Cell Line Preparation: Utilize a haploid hESC line harboring a genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 knockout library with >180,000 sgRNAs targeting 18,166 protein-coding genes [30].

- Neuronal Differentiation: Differentiate the mutant hESC pool into caudal neuronal cells using a established protocol with retinoic acid over 28 days.

- Critical Step: Validate successful differentiation via immunostaining for neuronal markers (TUJ1, NEFM) and transcriptome analysis. Expect >85% of cells to express neuronal markers [30].

- Cell Sorting and Analysis: After differentiation, harvest cells.

- For reporter-based screens (e.g., Hoxa5:a7 ESCs), use FACS to isolate populations based on reporter expression (e.g., mCherry+/eGFP- for wild-type vs. mCherry+/eGFP+ for boundary-defective cells) [31].

- For non-reporter screens, extract genomic DNA from the final neuronal population and the original hESC library as a reference.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Amplify and sequence the integrated sgRNAs from the harvested cell populations.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process NGS data to quantify sgRNA abundance.

- Use analytical tools like MAGeCK to identify sgRNAs that are significantly depleted or enriched in the differentiated neuronal population compared to the starting hESC library [31].

- Key Analysis: Genes with multiple significantly depleted sgRNAs are classified as essential for caudal neurogenesis.

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of Hox Genes in Limb Regeneration

This protocol validates the role of candidate Hox genes in Xenopus limb regeneration using CRISPR-Cas9 [11].

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Target Selection and sgRNA Design: Select target Hox genes (e.g., hoxc12, hoxc13) based on transcriptomic data showing regeneration-specific expression. Design and synthesize gene-specific sgRNAs.

- CRISPR-Cas9 Microinjection:

- Prepare a mixture of Cas9 protein and sgRNA(s).

- Microinject this mixture into the limb bud of Xenopus larvae or into the newly formed blastema immediately following limb amputation.

- Limb Amputation and Phenotypic Monitoring: Amputate limbs at the desired stage post-injection. Monitor and document regeneration progress over subsequent days compared to control limbs.

- Expected Phenotype (Knockout): Inhibition of autopod (distal limb) regeneration, reduced cell proliferation, and failure to re-express developmental genes, while early blastema formation remains intact [11].

- Molecular and Histological Analysis:

- Genotyping: Extract genomic DNA from tissue. Use PCR and sequencing to confirm the presence of indel mutations at the target site.

- In Situ Hybridization (ISH): Analyze the expression patterns of key patterning genes (e.g., shh) in regenerating limbs.

- Histology: Process and stain limb tissues (e.g., with Alcian Blue) to visualize cartilage patterning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogues essential reagents and tools derived from the cited studies for implementing these protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Gene CRISPR Screens

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Haploid hESC Mutant Library | Enables robust, genome-wide loss-of-function screening in a human developmental context. | Library of >180,000 sgRNAs in haploid hESCs [30]. |

| Hoxa5:a7 Dual-Reporter ESC Line | Fluorescent reporter system for monitoring CTCF boundary function at the HoxA cluster. | Reports Hoxa5 (mCherry) and Hoxa7 (eGFP) expression; used to screen for insulation defects [31]. |