Cross-Species Embryo scRNA-seq: A New Frontier for Developmental Biology and Drug Discovery

Cross-species comparison of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) datasets from embryos is revolutionizing our understanding of developmental biology, disease origins, and evolutionary processes. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of creating and interpreting these atlases. It delves into the methodological pipelines for data generation and integration, explores common analytical challenges and their solutions, and establishes best practices for validating embryo models and translating findings across species. By synthesizing these four core intents, this resource aims to empower robust, reproducible research that bridges the gap between model organisms and human biology, ultimately accelerating therapeutic discovery.

Cross-Species Embryo scRNA-seq: A New Frontier for Developmental Biology and Drug Discovery

Abstract

Cross-species comparison of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) datasets from embryos is revolutionizing our understanding of developmental biology, disease origins, and evolutionary processes. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of creating and interpreting these atlases. It delves into the methodological pipelines for data generation and integration, explores common analytical challenges and their solutions, and establishes best practices for validating embryo models and translating findings across species. By synthesizing these four core intents, this resource aims to empower robust, reproducible research that bridges the gap between model organisms and human biology, ultimately accelerating therapeutic discovery.

Building the Blueprint: Principles of Cross-Species Embryonic Atlases

Cross-species analysis of embryonic development using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a transformative approach in evolutionary and developmental biology. By comparing scRNA-seq datasets from embryos of different species, researchers can explore the fundamental question of how evolutionary forces act at the cellular level to generate diversity while conserving core developmental programs. This comparative approach provides unprecedented resolution for identifying both conserved and divergent mechanisms that shape embryonic development across the tree of life, offering insights with significant implications for understanding human development, congenital disorders, and evolutionary relationships.

Core Objectives of Cross-Species Embryo Comparison

The primary goals of comparing embryonic scRNA-seq data across species center on deciphering evolutionary relationships and developmental mechanisms at cellular resolution.

Identifying Evolutionarily Conserved Cell Types and Lineages: Cross-species comparisons enable researchers to identify cell types with shared transcriptional profiles, suggesting a common evolutionary origin. This helps in constructing cell type phylogenies that describe evolutionary relationships between cell types, much like species phylogenies [1].

Uncovering Divergent Developmental Programs: These analyses reveal species-specific adaptations in development, including the emergence of novel cell types, changes in developmental timing (heterochrony), and divergent gene expression patterns that underlie morphological differences [1] [2].

Understanding Transcriptome Evolution: Comparing gene expression patterns across species sheds light on how evolutionary forces shape transcriptional regulation, including the roles of gene duplication (paralogs), sequence evolution, and regulatory network rewiring [1] [3].

Translating Knowledge from Model to Non-Model Organisms: Cross-species cell-type assignment allows the transfer of well-established cell type annotations from model organisms (e.g., mouse) to non-model species, which often lack prior knowledge of cell-type biomarkers [3].

Providing Insights into Human Development and Disease: Studies of mammalian embryogenesis, for instance, help identify conserved genetic programs and regulatory networks whose disruption may lead to infertility, early miscarriages, or congenital diseases in humans [4] [2].

Methodological Framework and Benchmarking

Robust cross-species integration of scRNA-seq data requires sophisticated computational methods to overcome technical and biological challenges, including batch effects, transcriptome evolutionary divergence, and complex gene homology relationships.

Key Computational Challenges

- Species Effect: Cells from the same species often exhibit higher transcriptional similarity to each other than to their cross-species counterparts, creating a "species effect" that must be corrected to identify homologous cell types [5].

- Gene Homology Mapping: Accurately mapping orthologous and paralogous genes between species is complicated by gene duplications and losses, with non-one-to-one homologous genes often containing important biological information [5] [3].

- Balancing Mixing and Biological Conservation: Overly aggressive integration can obscure species-specific cell types, while insufficient correction fails to reveal true homologies [5].

Performance Comparison of Integration Strategies

A comprehensive benchmarking study (BENGAL pipeline) evaluated 28 integration strategies combining different homology mapping methods and algorithms across 16 biological tasks [5]. The table below summarizes the performance of top-performing methods based on their integrated score (weighted average of species mixing and biology conservation).

Table 1: Performance of Cross-Species Integration Algorithms

| Algorithm | Overall Integrated Score | Species Mixing | Biology Conservation | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scANVI | High | Excellent | Excellent | Semi-supervised learning; balanced performance |

| scVI | High | Excellent | Excellent | Probabilistic modeling; handles large datasets |

| SeuratV4 (CCA/RPCA) | High | Excellent | Good | Anchor-based integration; robust performance |

| SAMap | N/A* | High Alignment | Good | Specialized for distant species; handles complex homology |

| LIGER UINMF | Good | Good | Good | Incorporates unshared features; multiple species |

| Harmony | Good | Good | Good | Iterative clustering; efficient integration |

| fastMNN | Good | Good | Fair | Mutual nearest neighbors; fast computation |

Note: SAMap uses a different workflow and assessment metric (alignment score) [5].

The benchmarking revealed that the choice of integration algorithm has a greater impact on performance than the specific method for homology mapping. However, for evolutionarily distant species (e.g., zebrafish versus mammals), including non-one-to-one orthologs (one-to-many or many-to-many) becomes crucial for accurate cell-type assignment, improving accuracy by an average of 6.26% [5] [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Successful cross-species embryo comparison requires standardized workflows from sample preparation through data integration and analysis.

Sample Preparation and scRNA-seq Workflow

- Sample Origin and Selection: Experiments can utilize fresh or fixed cells/nuclei from embryos at comparable developmental stages. Fixed samples offer advantages for long-term studies and complex logistical arrangements [6].

- Tissue Dissociation: Embryonic tissues require optimized dissociation protocols using specific enzymes (e.g., from the Worthington Tissue Dissociation Guide) or semi-automated systems (e.g., Miltenyi gentleMACS) to generate high-quality single-cell suspensions while preserving RNA integrity [6].

- Single-Cell Sequencing: Platforms such as 10x Genomics Chromium, Singleron, or combinatorial barcoding technologies (e.g., Parse Biosciences) are employed, with choice depending on required throughput, cell size constraints, and sample availability [7] [6].

- Quality Control: Critical steps include assessment of cell viability, RNA integrity, and sequencing metrics. Detection of multiplets (multiple cells with the same barcode) and cell clumping is essential to prevent data skewing [7] [6].

Computational Analysis Pipeline

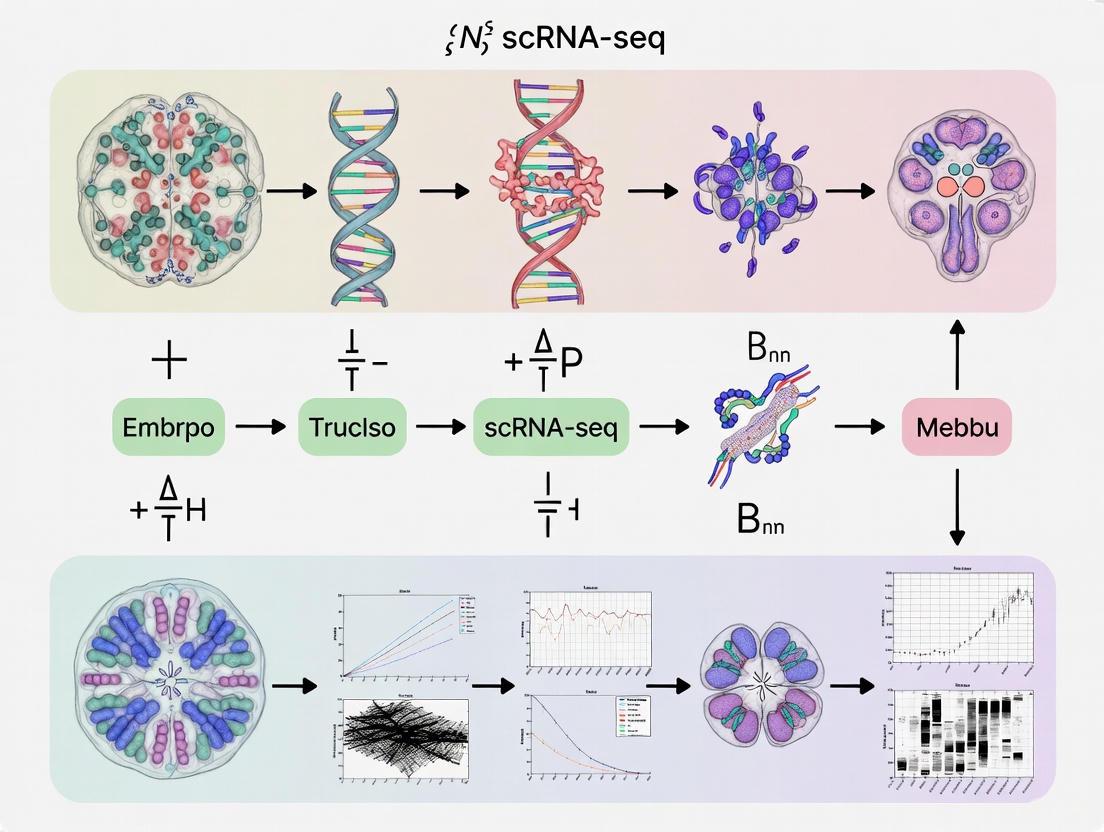

The following diagram illustrates a standard analytical workflow for cross-species embryo scRNA-seq data:

Standard Workflow for Cross-Species Embryo scRNA-seq Analysis

Advanced Integration and Analysis Methods

- Gene Homology Mapping: Utilize ENSEMBL comparative genomics resources to identify one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many orthologs between species. For distant species with challenging annotations, tools like SAMap perform de-novo BLAST analysis to construct gene-gene homology graphs [5].

- Cell-Type Assignment: Machine learning approaches like CAME (a heterogeneous graph neural network) leverage both one-to-one and non-one-to-one homologous mappings to transfer cell-type labels from reference to query species, significantly improving accuracy for non-model organisms [3].

- Trajectory Analysis: Tools like Slingshot can infer developmental trajectories from integrated embeddings, enabling comparison of differentiation pathways and pseudotime dynamics between species [4].

- Regulatory Network Inference: SCENIC analysis identifies conserved and divergent transcription factor regulons, revealing evolutionary changes in gene regulatory networks driving embryonic development [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

This section details key resources required for successful cross-species embryonic scRNA-seq studies.

Table 2: Essential Resources for Cross-Species Embryo scRNA-seq Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents & Kits | 10x Genomics Chromium | Microfluidic platform for high-throughput scRNA-seq library preparation |

| Worthington Tissue Dissociation Enzymes | Optimized enzyme blends for embryonic tissue dissociation | |

| gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi) | Instrument for standardized mechanical tissue dissociation | |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Seurat | Comprehensive R toolkit for scRNA-seq analysis, including integration functions |

| Scanpy | Python-based scRNA-seq analysis suite for large-scale data | |

| Cell Ranger (10x Genomics) | Pipeline for processing raw sequencing data into count matrices | |

| Cross-Species Specialized Tools | CAME | Graph neural network for cross-species cell-type assignment using complex homology [3] |

| SAMap | Specialized method for whole-body atlas integration between distant species [5] | |

| BENGAL Pipeline | Benchmarking framework for evaluating cross-species integration strategies [5] | |

| Reference Databases | ENSEMBL Compara | Database of gene homologies across multiple species |

| Human Embryo Reference Tool | Integrated scRNA-seq dataset from zygote to gastrula stages [4] | |

| Murrayamine O | Murrayamine O | Murrayamine O, a novel carbazole alkaloid for research. Explore its potential in anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Heteroclitin G | Heteroclitin G, MF:C22H24O7, MW:400.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Cross-species comparison of embryonic scRNA-seq datasets represents a powerful approach for deciphering the evolutionary principles governing cellular diversity and developmental programs. The core objectives—identifying conserved and divergent cell types, understanding transcriptome evolution, and translating knowledge across species—are now achievable through advanced computational methods that robustly integrate data across evolutionary distances. As benchmarking studies demonstrate, careful selection of integration strategies that balance species mixing with biological conservation is crucial for generating meaningful insights. This comparative framework not only deepens our fundamental understanding of evolutionary developmental biology but also provides critical insights into human developmental disorders and the fundamental mechanisms of life's earliest stages.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) of embryonic development across species has revolutionized our understanding of evolutionary biology. This guide provides a structured framework for comparing scRNA-seq datasets to uncover patterns of evolutionary conservation and divergence, enabling researchers to identify critical regulatory mechanisms preserved throughout evolution and those that drive species-specific adaptations. The comparative analysis of embryo scRNA-seq datasets allows scientists to trace the evolutionary history of cell types, identify key transcriptional regulators, and understand the molecular basis of morphological evolution. This approach is particularly valuable for drug development professionals seeking to identify conserved therapeutic targets and understand the translatability of model system findings to human biology.

Key Biological Questions and Analytical Approaches

Table 1: Core Biological Questions in Evolutionary scRNA-seq Analysis

| Question Category | Specific Biological Questions | Recommended Analytical Approach | Expected Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Conservation | Which genes show conserved expression patterns across species? | Orthologous gene alignment, cross-species correlation analysis | List of evolutionarily constrained genes with high functional importance |

| Cell Type Evolution | Are homologous cell types present across species? | Cluster alignment, marker gene comparison, phylogenetic analysis | Cell type homology map, novel cell type identification |

| Developmental Timing | How are developmental trajectories conserved or diverged? | Pseudotime alignment, RNA velocity comparison | Aligned developmental trajectories with conserved/divergent transition points |

| Regulatory Network | Are gene regulatory networks conserved across species? | Co-expression network analysis, regulatory inference | Conserved regulatory modules, divergent network connections |

| Pathway Activity | How are signaling pathway activities evolutionarily maintained? | Pathway enrichment analysis, module scoring | Quantified pathway conservation scores across species |

Experimental Design for Cross-Species Comparisons

Species Selection Criteria

Choosing appropriate species for comparison is fundamental to evolutionary studies. Ideal species pairs should represent meaningful evolutionary distances while maintaining practical experimental feasibility. Recommended considerations include phylogenetic distance (divergence time), morphological similarities/differences, availability of reference genomes, and practical aspects of embryonic material accessibility. For mammalian studies, common comparisons include human-mouse (~90 million years divergence), human-marmoset (~43 million years), or mouse-rat (~20 million years). Each distance provides different insights: closer species reveal fine-scale regulatory changes, while more distant comparisons highlight fundamental conserved mechanisms.

Sample Collection and Timing

Proper embryonic staging and tissue collection are critical for meaningful cross-species comparisons. Use Carnegie stages for human embryos and Theiler stages for mouse embryos, with careful alignment based on morphological landmarks rather than purely temporal age. Collect equivalent anatomical structures across species, verified by expert embryological examination. Preserve samples immediately using appropriate methods (e.g., snap-freezing or immediate fixation) to maintain RNA integrity. Document all collection parameters meticulously, including maternal age, environmental conditions, and exact developmental timing.

Computational Tools for Cross-Species Analysis

Table 2: Computational Tools for Evolutionary scRNA-seq Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Species Compatibility | Input Requirements | Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat v5 | Cross-species integration | Multiple species with orthology data | Gene count matrices, ortholog mappings | Integrated UMAP, conserved cluster markers |

| SCENIC+ | Regulatory network inference | Mammalian, with motif databases | scRNA-seq matrix, species motif database | Regulatory networks, transcription factor activity |

| CellRank 2 | Developmental trajectory comparison | Any species with time-series data | RNA velocity, pseudotime estimates | Aligned trajectories, conserved transition points |

| OrthoFinder | Orthologous gene identification | Any eukaryotic species | Protein sequences, genome annotations | Orthogroups, phylogenetic relationships |

| Conos | Multiple dataset integration | Broad species compatibility | Processed scRNA-seq objects | Joint graph, cross-species neighbors |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Cross-Species Cell Type Alignment Protocol

Purpose: To identify homologous cell types across species and detect species-specific cell populations.

Materials:

- Processed scRNA-seq data from multiple species (count matrices)

- Ortholog mapping table (from OrthoFinder or comparable tool)

- High-performance computing environment with R/Python

Methodology:

- Ortholog Mapping: Map genes between species using one-to-one orthologs, excluding paralogs and species-specific genes.

- Integration: Use Seurat's integration workflow (SelectIntegrationAnchors followed by IntegrateData) with 5,000 integration features and k.anchor=5.

- Clustering: Apply graph-based clustering on the integrated space (resolution=0.5-1.0).

- Marker Identification: Find conserved markers using FindConservedMarkers function with min.pct=0.25 and logfc.threshold=0.25.

- Annotation: Annotate clusters using known marker genes from both species.

- Validation: Validate homologous cell types using orthogonal methods (ISH, IHC) when possible.

Expected Results: A unified UMAP visualization showing integrated cell types, with metrics for cluster conservation and identification of species-specific populations.

Developmental Trajectory Alignment Protocol

Purpose: To compare developmental progression across species and identify conserved and divergent differentiation paths.

Materials:

- scRNA-seq data with developmental time series

- Species-specific gene lengths for RNA velocity

- Pre-computed cell type annotations

Methodology:

- Pseudotime Analysis: Calculate pseudotime using Slingshot or Monocle3 for each species independently.

- RNA Velocity: Compute RNA velocity using scVelo for each species.

- Trajectory Alignment: Use CellRank 2 to align trajectories based on terminal states and driver genes.

- Gene Expression Dynamics: Identify genes with conserved versus divergent expression dynamics along aligned trajectories.

- Transition Conservation: Calculate conservation scores for developmental transitions based on gene expression changes.

Expected Results: Aligned developmental trajectories with quantitative measures of conservation for each branch point and transition.

Visualization of Analytical Workflows

Cross-Species scRNA-seq Analysis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Embryonic scRNA-seq Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Product Examples | Manufacturer | Primary Function | Species Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Isolation | Chromium Next GEM Kit | 10x Genomics | Single-cell partitioning | Human, Mouse, Primate, Avian |

| Library Preparation | SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input | Takara Bio | cDNA amplification | Broad eukaryotic compatibility |

| Cell Viability | LIVE/DEAD Cell Staining | Thermo Fisher | Viable cell identification | Mammalian, Avian, Fish |

| Cell Hashing | CellPlex Cell Multiplexing | 10x Genomics | Sample multiplexing | Human, Mouse, commonly studied species |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Visium Spatial Gene Expression | 10x Genomics | Tissue context preservation | Human, Mouse, Zebrafish |

| In Situ Hybridization | RNAscope Multiplex Assay | ACD Bio | Spatial validation | Species-specific probes available |

Signaling Pathway Conservation Analysis

Signaling Pathway Conservation Patterns

Data Interpretation Framework

Quantifying Conservation and Divergence

Develop rigorous metrics for evaluating evolutionary patterns in scRNA-seq data. Conservation scores should integrate multiple aspects: gene expression level preservation, co-expression network maintenance, developmental timing conservation, and cell type homology. Calculate conservation indices for each gene, cell type, and developmental transition to enable systematic comparison across evolutionary distances. Use permutation testing to establish statistical significance for observed conservation patterns, comparing against null distributions generated by randomizing species labels or gene identities.

Biological Validation Strategies

Corroborate computational findings with experimental validation using species-appropriate techniques. Employ cross-species in situ hybridization to validate spatial expression patterns of conserved and divergent genes. Utilize CRISPR-based approaches in model systems to test functional conservation of regulatory elements. Implement organoid culture systems from multiple species to assay conserved developmental processes in controlled environments. Apply spatial transcriptomics to verify conserved tissue organization patterns across species.

Applications in Drug Development

The identification of evolutionarily conserved molecular mechanisms provides particularly valuable insights for pharmaceutical research. Conserved pathways and regulatory networks often represent fundamental biological processes with high translational potential. Drug development professionals can prioritize targets with strong conservation evidence, as these typically demonstrate higher clinical success rates. Additionally, understanding species-specific differences helps optimize preclinical models and predict potential adverse effects resulting from divergent biology. Embryonic scRNA-seq comparisons can reveal conserved therapeutic targets for regenerative medicine applications while identifying potential species-specific toxicities early in drug development pipelines.

Understanding human embryonic development from the pre-implantation stages through organogenesis is fundamental for developmental biology, regenerative medicine, and uncovering the causes of congenital disorders and early pregnancy loss [8]. While mouse models have served as valuable proxies for mammalian development for decades, significant morphological, molecular, and genetic differences exist between mouse and human embryogenesis [9] [10]. The emergence of sophisticated single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies has revolutionized this field, enabling the construction of high-resolution transcriptional atlases of early human development and facilitating cross-species comparative analyses [4] [1]. This guide synthesizes landmark studies that have provided integrated references spanning pre-implantation to organogenesis, objectively comparing their methodologies, findings, and applications within the context of cross-species embryo scRNA-seq research.

Comparative Morphological and Molecular Landscapes

Significant morphological and molecular differences exist between human and mouse embryogenesis, which genetically determine species-specific developmental pathways [9].

Table 1: Key Morphological Differences Between Mouse and Human Embryogenesis

| Developmental Feature | Mouse Embryo | Human Embryo |

|---|---|---|

| Zygotic Genome Activation (ZGA) | Occurs at the 2-cell stage [9] | Occurs between the 4- and 8-cell stages [9] |

| Facial Organ Development | Optic pit appears first [9] | All facial organs appear around the same time [9] |

| Limb Rotation | Little rotation; less flexible joints [9] | Rotates to proper position ventrally; flexible joints [9] |

| Tail Development | Elongates and thins from Theiler Stage (TS) 17 [9] | Regresses during Carnegie Stage (CS) 23 (~9th week) [9] |

| Post-Organogenesis Birth | Born almost immediately after organogenesis (~19-20 days) [9] | Remains in uterus for several more months of fetal growth [9] |

At the molecular level, cross-species comparative transcriptomics reveals that the most significant differences lie not in gene number, but in the spatiotemporal expression patterns and activities of gene products [9]. For instance, while core signaling pathways like Notch, TGFβ/BMP, and Wnt are conserved, significant differences exist for specific genes such as Wnt7a and CAPN3, particularly in neural crest, midbrain, lens, heart, and smooth muscle formation [9].

Landmark scRNA-seq Reference Datasets and Tools

Several landmark studies have created essential scRNA-seq resources to map human embryonic development, addressing the critical scarcity of in vivo samples.

Comprehensive Integrated Reference from Zygote to Gastrula

A landmark 2025 study created a universal integrated scRNA-seq reference by harmonizing six published human datasets, covering development from the zygote to the gastrula stage (Carnegie Stage 7) [4].

Table 2: Key Integrated scRNA-seq Reference Tools and Databases

| Resource Name | Scope/Species | Key Features and Application | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Embryo Reference Tool [4] | Human (Zygote to Gastrula) | Integrated data from 3,304 cells; UMAP projection; cell identity prediction; lineage trajectory inference. | Online prediction tool |

| DRscDB [11] | Drosophila, Zebrafish, Mouse, Human | Repository for published scRNA-seq data; finds orthologous genes and cell type-specific expression across species. | Web database (flyrnai.org) |

This integrated atlas delineates the continuous progression of lineage specification, beginning with the divergence of the inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm (TE), followed by ICM bifurcation into epiblast and hypoblast [4]. The tool utilizes Single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering (SCENIC) analysis to identify key transcription factors driving lineage development, such as DUXA in the 8-cell lineage, VENTX in the epiblast, and OVOL2 in the TE [4]. This resource serves as a critical benchmark for authenticating stem cell-based embryo models.

Gene Expression Profiling During Organogenesis

Earlier microarray studies provided the first genome-wide gene expression profiles of human organogenesis, a period from the 4th to the 9th week (CS10-23) [9]. These studies revealed two major patterns of gene regulation: a down-regulation of "stemness," cell cycle, and metabolic genes, and an up-regulation of genes involved in multi-cellular organismal development, cell adhesion, and cell-cell signaling [9]. Furthermore, many genes exhibited an arch-shaped expression pattern, with peak levels corresponding to the development of specific organs, such as eye development genes peaking during the 5th-7th weeks [9].

Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

Studying human development relies on a combination of direct embryo analysis and innovative stem cell-based models, each with specific protocols.

Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing of Human Embryos

The workflow for creating a comprehensive reference atlas involves several standardized steps [4]:

- Sample Sourcing and Preparation: The process utilizes donated preimplantation embryos, in vitro cultured postimplantation blastocysts, and scarce in vivo gastrula-stage specimens [4] [8].

- Data Generation and Processing: scRNA-seq data from multiple studies are reprocessed using a standardized pipeline, with mapping and feature counting against the same genome reference (GRCh38) to minimize batch effects [4].

- Data Integration and Visualization: Datasets are integrated using computational methods like fast mutual nearest neighbor (fastMNN) to create a unified transcriptional landscape. Cells are visualized in two-dimensional space using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) [4].

- Cell Annotation and Trajectory Inference: Manifold learning and clustering algorithms identify distinct cell populations. Lineage developmental trajectories are inferred using tools like Slingshot, which calculates pseudotime to order cells along a differentiation path [4].

Stem Cell-Derived Embryo Models

To overcome the scarcity of post-implantation embryos, researchers have developed stem cell-derived embryo-like structures (embryoids) that recapitulate aspects of early development [12] [8]. One such model is the microfluidic post-implantation amniotic sac embryoid (μPASE) [12]. The protocol involves:

- Stem Cell Culture: Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) are aggregated and loaded into a microfluidic device [12].

- Controlled Differentiation: The system allows for highly controllable and reproducible development. hPSC clusters undergo lumenogenesis and epithelization to form a central lumen [12].

- Lineage Specification: Exposure to exogenous BMP4 initiates amniotic ectoderm-like cell (AMLC) differentiation. Inductive effects from these cells cause other hPSCs to undergo an epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), forming primitive streak-like and mesoderm-like cells (MeLCs) [12].

- Validation: The resulting cell populations are validated via scRNA-seq and benchmarked against available in vivo primate data to assess fidelity [12].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Embryo scRNA-seq Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| KSOM Media [10] | Advanced in vitro culture medium for pre-implantation mouse embryos. | Supporting embryo development from zygote to blastocyst stage ex vivo. |

| Matrigel [10] | A 3D extracellular matrix hydrogel. | Providing a physiologically relevant substrate for in vitro culture of embryos and embryoids. |

| Microfluidic Devices [12] | Miniaturized systems for cell culture and manipulation. | Enabling highly controlled and scalable culture of embryoid models (e.g., μPASE). |

| BMP4 [12] | A morphogen of the TGF-β superfamily. | Directing differentiation of pluripotent stem cells towards amniotic ectoderm lineage in embryoids. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Gene editing tool for functional genomic studies. | Investigating gene function through targeted knockout in embryos or stem cells [2] [8]. |

| Human U133 Array [9] | Affymetrix microarray platform for gene expression profiling. | Conducting genome-wide expression analysis of human embryos during organogenesis. |

| 10x Genomics [12] | A high-throughput scRNA-seq platform. | Profiling transcriptomes of thousands of individual cells from embryoids or dissociated embryos. |

Critical Challenges and Technical Roadblocks

Research on human embryogenesis faces several significant challenges:

- Sample Scarcity and Access: There is a critical scarcity of human embryonic material, particularly for the post-implantation period between weeks 2 and 4 due to technical and ethical constraints, notably the widespread 14-day culture rule [4] [8]. Access relies on donations from IVF procedures, which can be limited by regulatory hurdles and variable embryo quality [8].

- In Vitro Culture Limitations: Current protocols for culturing human embryos beyond the blastocyst stage often lack proper morphogenesis and maternal tissue interactions, raising concerns about their physiological equivalence to in vivo embryos [8].

- Genetic Manipulation Difficulties: Efficient genetic manipulation in human embryos remains technically challenging, hampered by limited knowledge of DNA repair mechanisms and regulations prohibiting genetic modification in many jurisdictions [8].

- Cross-Species Comparison Complexities: Comparing scRNA-seq data across species is complicated by biological differences, technical batch effects, and challenges in assigning functional conservation to orthologous genes [1].

The construction of integrated scRNA-seq references from pre-implantation to organogenesis represents a transformative advance in developmental biology. These atlases, complemented by cross-species comparative analyses and validated embryoid models, provide unprecedented insights into the molecular underpinnings of human embryogenesis. While significant challenges in sample access, model fidelity, and computational integration remain, the continued refinement of these resources and tools is paving the way for a deeper understanding of human development, with profound implications for regenerative medicine and the treatment of congenital disorders.

Identifying Lineage-Specific Markers and Transcription Factors

The accurate identification of lineage-specific markers and transcription factors is a cornerstone of developmental biology, enabling researchers to decipher the complex processes of cell fate decisions, differentiation, and tissue formation. With the advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), we can now profile gene expression at unprecedented resolution across different stages of embryonic development and in various model systems. However, the utility of this data hinges on robust analytical frameworks and reference tools for correct cell type annotation and lineage validation. This guide provides a comparative analysis of experimental and computational approaches for identifying these crucial molecular signatures, with a specific focus on leveraging cross-species comparative scRNA-seq datasets to enhance the accuracy and biological relevance of the findings. We objectively evaluate the performance of different methodologies, supported by experimental data, to serve as a resource for researchers authenticating stem cell-derived models and studying evolutionary biology.

Core Experimental & Computational Approaches

Integrated Reference Atlases for Authentication

The creation of comprehensive, integrated scRNA-seq reference datasets represents a significant advancement for benchmarking cellular identities.

- Reference Tool Construction: A universal reference for human embryogenesis was developed by integrating six public scRNA-seq datasets, covering developmental stages from zygote to gastrula. The dataset includes 3,304 cells and utilizes the fast Mutual Nearest Neighbor (fastMNN) method for integration to minimize batch effects. This is visualized as a UMAP that displays continuous developmental progression [4].

- Lineage Resolution: The reference captures key lineage bifurcations: the first separates the inner cell mass (ICM) from the trophectoderm (TE), followed by the ICM's division into epiblast and hypoblast. Later stages further resolve the epiblast into primitive streak, mesoderm, definitive endoderm, and amnion, among other lineages [4].

- Performance in Authentication: When used to authenticate stem cell-based embryo models, this integrated reference revealed risks of cell lineage misannotation that occurred when models were benchmarked against less relevant or incomplete references. Its use provides an unbiased method for evaluating the fidelity of in vitro models to their in vivo counterparts [4].

Kinetic Modeling of mRNA Regulation

Understanding the dynamics of gene expression requires dissecting the contributions of mRNA transcription and degradation, which can be achieved by combining scRNA-seq with metabolic labeling.

- Experimental Workflow: Zebrafish embryos at the one-cell stage are injected with 4-thiouridine triphosphate (4sUTP), which is incorporated into newly transcribed (zygotic) RNA. This allows distinction from pre-existing maternal mRNA. Single-cell transcriptomes are then captured, and a chemical conversion step creates T-to-C changes in sequencing reads from labeled RNAs, enabling quantification [13].

- Data Analysis with Kinetic Models: Tools like GRAND-SLAM are used to statistically infer the fraction of newly transcribed mRNA for each gene in each cell. This data feeds into kinetic models that quantify cell-type-specific mRNA transcription and degradation rates during specification [13].

- Key Findings: This approach revealed highly coordinated transcription and degradation rates for many transcripts and identified selective retention of maternal mRNAs in specific early lineages like the primordial germ cells and enveloping layer, highlighting how degradation shapes cell-type-specific expression patterns [13].

Cross-Species Comparative Transcriptomics

Comparing scRNA-seq data across species identifies conserved and species-specific features of lineage specification, providing evolutionary context and validating core regulatory programs.

- Conserved Neutrophil Maturation: A cross-species analysis of neutrophil maturation in zebrafish, mouse, and human identified a high molecular similarity in immature stages. This allowed researchers to define a pan-species neutrophil maturation signature and distinguish it from zebrafish-specific gene signatures. This conserved signature was subsequently applied to human patient data, linking metastatic tumor cell infiltration in the bone marrow to an increase in mature neutrophils [14].

- Conserved Genetic Basis of Spermatogenesis: A comparison of scRNA-seq datasets from the testes of humans, mice, and fruit flies identified 1,277 conserved genes involved in spermatogenesis. Key conserved molecular programs included post-transcriptional regulation, meiosis, and energy metabolism. Systematic gene knockout of 20 candidates in Drosophila confirmed that three genes related to sperm centriole and steroid lipid processes were essential for male fertility, underscoring deep evolutionary conservation [2].

Table 1: Key Outcomes from Cross-Species Comparative Studies

| Study System | Conserved Biological Process | Number of Conserved Genes Identified | Functionally Validated Key Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil Maturation [14] | Innate immune cell differentiation | A pan-species gene signature defined | Granule development, phagocytic capacity |

| Spermatogenesis [2] | Male germ cell development | 1,277 | Sperm centriole function, steroid metabolism, meiosis |

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

Protocol: Building an Integrated Embryo Reference Atlas

This protocol is adapted from the creation of a human embryo reference tool [4].

- Data Collection: Gather publicly available scRNA-seq datasets that cover the desired developmental window and lineages. For the human embryo reference, this included six datasets from pre-implantation embryos, post-implantation blastocysts, and a gastrula.

- Reprocessing: Reprocess all raw data using a standardized pipeline with the same genome reference and annotation (e.g., GRCh38) to minimize technical batch effects from the start. This includes mapping and feature counting.

- Data Integration: Employ a batch-correction algorithm such as fastMNN to integrate the expression profiles of all cells into a unified space.

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Generate a UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) from the integrated data to visualize cellular relationships. Perform clustering to identify distinct cell populations.

- Lineage Annotation: Annotate cell clusters based on known marker genes from original studies and validated against human and non-human primate data. Key markers include:

- Trajectory Inference: Use tools like Slingshot on the UMAP embeddings to infer developmental trajectories (pseudotime) for major lineages (e.g., epiblast, hypoblast, TE) and identify genes with modulated expression.

- Regulatory Network Analysis: Perform SCENIC (Single-Cell Regulatory Network Inference and Clustering) analysis to identify cell-type-specific transcription factor activities and regulons.

- Tool Deployment: Create a user-friendly prediction tool (e.g., a Shiny app) where query datasets can be projected onto the reference to annotate cell identities.

Protocol: Cross-Species scRNA-Seq Comparison

This protocol is synthesized from studies on neutrophils and spermatogenesis [14] [2].

- Dataset Curation: Collect high-quality scRNA-seq datasets from homologous tissues or developmental processes across multiple species (e.g., human, mouse, zebrafish/fly).

- Cell Type Annotation: Independently annotate cell types/states within each species' dataset using established lineage-specific markers.

- Ortholog Mapping: Map genes between species using one-to-one orthology information from databases like Ensembl.

- Identification of Conserved Markers: Perform differential expression analysis between cell types within each species. Identify overlapping differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across species as a conserved marker set. Alternatively, use label-transfer or canonical correlation analysis to align datasets and find shared expression patterns.

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Subject the conserved gene sets to gene ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis to identify biological processes and regulatory networks preserved through evolution.

- Experimental Validation: Design in vivo or in vitro functional experiments to test the role of identified conserved genes. This can include:

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

scRNA-seq Cross-Species Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow for a standard cross-species comparative transcriptomics study.

Figure 1: Cross-species scRNA-seq analysis workflow for identifying conserved lineage factors.

mRNA Kinetic Analysis with Metabolic Labeling

This diagram details the experimental and computational workflow for quantifying mRNA transcription and degradation rates in single cells.

Figure 2: Workflow for cell-type-specific mRNA kinetic analysis in embryos.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Lineage Marker Identification

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated Embryo Reference | A curated, batch-corrected scRNA-seq atlas serving as a universal standard for cell identity annotation. | Authenticating stem cell-derived embryo models by projecting query data onto the reference [4]. |

| Metabolic Labels (e.g., 4sUTP) | Nucleotide analogs incorporated into newly synthesized RNA, allowing it to be distinguished from pre-existing RNA. | Measuring zygotic vs. maternal mRNA contributions and inferring transcription/degradation rates in single cells [13]. |

| Transgenic Reporter Strains | Organisms with fluorescent proteins under control of cell-type-specific promoters, enabling visualization and sorting. | Isolating specific maturation stages of neutrophils (Tg(BACmmp9:Citrine-CAAX)) for transcriptional profiling [14]. |

| CRISPR Knockout Systems | Precision gene-editing tools for functional validation of candidate genes in vivo. | Testing the role of evolutionarily conserved genes in processes like spermatogenesis in model organisms [2]. |

| Trajectory Analysis Software (Slingshot) | Computational tool that infers developmental pathways and pseudotime from scRNA-seq data. | Reconstructing lineage bifurcations (e.g., ICM to epiblast/hypoblast) and identifying associated genes [4]. |

| Regulatory Network Tools (SCENIC) | Infers gene regulatory networks and identifies active transcription factors from scRNA-seq data. | Discovering key transcription factors (e.g., C/ebp-β in neutrophils) driving lineage specification [4] [14]. |

| Cross-Species Alignment Algorithms | Bioinformatics methods for integrating scRNA-seq data from different species based on orthologous genes. | Identifying a core set of conserved lineage markers and regulators across humans, mice, and fish/flies [14] [2]. |

From Cells to Data: scRNA-seq Workflows and Translational Applications

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the characterization of gene expression profiles at the single-cell level, revealing cellular heterogeneity that bulk sequencing approaches inevitably mask. This capability is particularly valuable in cross-species comparative studies, which aim to uncover conserved and divergent biological processes across evolution. For instance, scRNA-seq has been instrumental in comparing inflammatory responses to heart injury in zebrafish and mice, revealing both analogous macrophage subtypes and disparate reaction pathways that may underlie differences in regenerative capacity [15]. The successful execution of an scRNA-seq experiment requires careful consideration of multiple steps, from cell isolation to sequencing. This guide provides a systematic overview of the core workflow, compares leading technological platforms, and outlines specific methodological considerations for cross-species research, with a special focus on embryonic datasets.

Step 1: Cell and Nuclei Isolation

The first critical step is obtaining high-quality single-cell or single-nuclei suspensions.

Single-Cell Isolation: This typically involves fresh tissues. The process includes finely mincing the tissue, followed by enzymatic digestion (e.g., using collagenase, trypsin, or Accutase) and mechanical dissociation to break down the extracellular matrix. The resulting suspension is then filtered through a strainer (e.g., 40 µm) to remove clumps, and dead cells can be removed using techniques like density centrifugation or magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) with dead cell removal kits [16]. A critical consideration is that the dissociation process itself can induce cellular stress and alter transcriptional profiles [16].

Single-Nuclei Isolation: As an alternative, snRNA-seq uses isolated nuclei. Frozen tissue is homogenized in a lysis buffer that breaks down cell membranes but leaves nuclei intact. The suspension is then filtered and centrifuged to purify the nuclei [16]. A key advantage is compatibility with frozen, biobanked samples, which are often the primary resource for rare specimens like human embryos. It also avoids dissociation-induced stress artifacts. However, it primarily captures nascent, nuclear transcripts and may under-represent cytoplasmic mRNAs, leading to a bias in the detected transcriptome [16].

Choosing Between scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq: The decision hinges on the research question and sample availability. scRNA-seq provides a more complete picture of the cytoplasmic transcriptome but requires fresh, viable cells and is susceptible to dissociation artifacts. snRNA-seq is preferable for archived frozen samples, sensitive tissues (like neurons or pancreatic islets), and when aiming to minimize technical stress responses [16]. A comparative study on human pancreatic islets from the same donors confirmed that while both methods identify the same major cell types, they can yield different cell type proportions, underscoring the need to choose the method aligned with the study's goals [16].

Step 2: Single-Cell Library Preparation

Once a high-quality suspension is obtained, the next step is to prepare sequencing libraries. This process involves capturing individual cells, reverse-transcribing their mRNA into cDNA, and adding platform-specific barcodes and sequencing adapters.

Different scRNA-seq technologies have been developed, each with unique strengths and weaknesses. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for several established and emerging platforms based on recent comparative studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of High-Throughput scRNA-seq Platforms

| Platform / Technology | Capture Method | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Suitability for Sensitive Cells (e.g., Neutrophils/Embryos) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium [17] [18] | Droplet-based | High throughput, strong gene sensitivity, widely established | Lower gene sensitivity in granulocytes, requires fresh cells (standard protocol) | Standard protocol challenging for neutrophils; Fixed RNA Profiling Flex kit allows cell fixation |

| BD Rhapsody [17] [18] | Microwell-based | High capture sensitivity for low-RNA cells, suitable for neutrophils | Lower proportion of some cell types (e.g., endothelial cells) | Effective, comparable to flow cytometry for neutrophil capture |

| Parse Biosciences (Evercode) [17] | Combinatorial barcoding (fixed cells) | Low mitochondrial gene expression, high multiplexing (up to 96 samples), no specialized equipment needed | Does not require specialized equipment | Fixed-cell workflow minimizes ex vivo artifacts |

| HIVE scRNA-seq [17] | Nano-wells | Cells can be stabilized and stored at -80°C pre-library prep | Higher levels of mitochondrial genes detected | Successfully used with RBC-depleted blood samples |

| Fluidigm C1 [19] | Microfluidics (plate-based) | High sequencing depth and sensitivity | Lower throughput, higher cost per cell | Not specifically evaluated in provided studies |

Detailed Protocol: 10x Genomics Chromium Workflow

The 10x Genomics Chromium platform is one of the most widely used droplet-based methods. The following is a generalized protocol for library preparation using a system like the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3' Reagent Kit [16].

- Cell Preparation and Loading: The single-cell suspension is diluted to a target concentration (e.g., 700-1,200 cells/µl). It is critical to ensure high cell viability (>80-90%) and to confirm the absence of clumps. A volume of this suspension containing the desired number of cells is added to a master mix containing enzymes, barcoded gel beads, and partitioning oil.

- Gel Bead-in-Emulsion (GEM) Generation: The mixture is loaded onto a Chromium chip and placed in the Chromium Controller. Within the chip, each cell is co-encapsulated with a single barcoded gel bead in a nanoliter-scale oil droplet, forming a GEM.

- Reverse Transcription (RT) Inside GEMs: Within each GEM, the cell is lysed, and the mRNA transcripts hybridize to the gel bead's oligonucleotides. These oligos contain a PCR handle, a cell-specific barcode (the same for all transcripts from that cell), a unique molecular identifier (UMI), and a poly(dT) sequence for mRNA capture. Reverse transcription occurs, creating cDNA strands tagged with the cell barcode and UMI.

- GEM Breakage and cDNA Cleanup: The oil emulsion is broken, and the barcoded cDNA from all GEMs is pooled. The cDNA is then purified using DynaMyneads MyOne SILANE beads.

- cDNA Amplification: The purified cDNA is PCR-amplified to generate sufficient mass for library construction.

- Library Construction: The amplified cDNA is fragmented, and a suite of adapters is ligated. This step adds sample indexes (for multiplexing) and sequences required for cluster generation and sequencing on platforms like Illumina.

- Library QC and Sequencing: The final libraries are quantified (e.g., using qPCR) and assessed for quality (e.g., using a Bioanalyzer). They are then sequenced on an appropriate Illumina platform.

Visual Guide to scRNA-seq Workflow

Step 3: Sequencing and Data Analysis

After library preparation, the next steps are sequencing and computational analysis.

Sequencing: scRNA-seq libraries are typically sequenced on Illumina platforms. The required sequencing depth depends on the project's goals and the complexity of the tissue. A common configuration is paired-end sequencing, where Read 1 contains the cell barcode and UMI, and Read 2 contains the cDNA insert.

Core Bioinformatic Analysis: The raw sequencing data (FASTQ files) undergoes a multi-step computational pipeline:

- Demultiplexing & Alignment: Sequences are assigned to their sample of origin, and reads are aligned to a reference genome.

- Gene-Cell Matrix Generation: Using tools like Cell Ranger (10x Genomics), reads are counted based on their cell barcode and UMI, generating a digital count matrix where rows represent genes and columns represent cells.

- Quality Control (QC): Cells are filtered based on metrics like the number of detected genes, total UMI counts, and the percentage of mitochondrial reads. High mitochondrial percentage can indicate stressed or dying cells [17] [20].

- Normalization & Scaling: Counts are normalized to account for technical variability (e.g., sequencing depth).

- Dimensionality Reduction & Clustering: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is performed, followed by graph-based clustering on the results. Cells are visualized in 2D using UMAP or t-SNE.

- Cell Type Annotation: Clusters are annotated into cell types using manual annotation (checking known marker genes) or reference-based annotation with tools like SingleR or Seurat's label transfer [15] [20] [16].

Special Considerations for Cross-Species Embryonic Research

Applying scRNA-seq to cross-species embryo comparisons introduces specific challenges that require tailored approaches.

Ortholog Mapping: A fundamental step is converting gene symbols from different species (e.g., mouse, zebrafish) to a common set of orthologous genes, typically human symbols. This is done using databases like Ensembl or tools like OrthoFinder, retaining only one-to-one orthologs for a robust comparative analysis [20].

Integration and Batch Effect Correction: Data from different species, technologies, or even batches must be integrated. Batch effect correction tools like Harmony have been shown to achieve high performance in integrating PBMC data from multiple species, allowing for a joint analysis that preserves biological variation while removing technical artifacts [20].

CNV Analysis for Ploidy and Subclone Detection: In cancer and developmental biology, copy number variations (CNVs) can be inferred from scRNA-seq data to identify subpopulations of cells. A 2025 benchmarking study evaluated six CNV callers (InferCNV, copyKat, SCEVAN, CONICSmat, CaSpER, and Numbat), finding that methods incorporating allelic information (e.g., Numbat, CaSpER) performed more robustly for large datasets, though with higher computational demands [21]. This is crucial for identifying chromosomal abnormalities in embryonic cells.

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Cross-Species scRNA-seq Analysis

| Analysis Step | Tool Example | Application in Cross-Species Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Integration | Harmony [20] | Corrects batch effects across samples from different species for unified analysis. |

| Cell Annotation | SingleR [15], Seurat [20] | Automates cell type labeling by referencing annotated datasets. |

| Ortholog Mapping | OrthoFinder [20] | Predicts orthologous gene pairs between species for gene list conversion. |

| CNV Calling | InferCNV, Numbat [21] | Infers copy number variations to identify genetic subclones within a population. |

| Differential Expression | Seurat (Wilcoxon test) [20] | Identifies genes differentially expressed between cell clusters or conditions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Accutase [16] | Enzyme for gentle dissociation of tissue into single cells. | Preparing single-cell suspensions from delicate embryonic tissues. |

| Chromium Nuclei Isolation Kit [16] | Isulates nuclei from frozen tissue for snRNA-seq. | Processing frozen, biobanked embryo samples that are not viable for scRNA-seq. |

| Chromium Next GEM Kits (10x Genomics) [16] | Comprehensive reagent kit for GEM generation, RT, and library prep. | Standardized, high-throughput single-cell library construction. |

| Dead Cell Removal Kit [16] | Magnetic beads for removing dead cells from suspension. | Improving viability of single-cell suspensions to reduce ambient RNA. |

| RNase Inhibitors [17] | Protects RNA from degradation during sample processing. | Critical for preserving RNA in sensitive cells like neutrophils or embryonic cells. |

| Datiscin | Datiscin, MF:C27H30O15, MW:594.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| lespedezaflavanone H | lespedezaflavanone H, MF:C30H36O6, MW:492.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

A successful scRNA-seq experiment, particularly in the complex context of cross-species embryology, relies on a meticulously planned and executed workflow. From the critical first decision of cell versus nuclei isolation to the selection of a platform that balances throughput, sensitivity, and suitability for delicate cells, each step influences the final data quality. The growing suite of bioinformatic tools for integration, annotation, and CNV analysis empowers researchers to draw meaningful biological insights, such as identifying evolutionarily conserved cell types and transcriptional programs. As methods continue to advance, with a clear trend towards fixed-cell protocols and multi-omics integrations, the resolution at which we can compare embryonic development across species will only increase, deepening our understanding of evolutionary biology and the fundamental principles of life.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the characterization of gene expression at the ultimate level of resolution—the individual cell. This is particularly powerful in embryology and cross-species comparative studies, where understanding cellular heterogeneity and lineage specification is paramount. The choice of scRNA-seq platform is critical and involves balancing throughput, sensitivity, cost, and experimental flexibility. This guide provides an objective comparison of the three principal methodological approaches—plate-based, droplet-based microfluidics, and combinatorial indexing—with a specific focus on their application in cross-species embryo research.

The development of scRNA-seq technologies has progressed from low-throughput, manual methods to highly parallelized, automated platforms. The core principle involves isolating single cells, barcoding their transcripts to preserve cellular origin, and preparing sequencing libraries. The methods differ fundamentally in how they achieve this physical separation and molecular barcoding [22].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three main platform types.

Table 1: Core Platform Comparison for scRNA-seq

| Feature | Plate-Based Methods | Droplet-Based Microfluidics | Combinatorial Indexing Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Lowest (improved with combinatorial indexing) [23] | Highest [23] | Intermediate to Very High [23] [24] |

| Cost per Cell | Highest [23] | Lowest [23] | Intermediate [23] |

| Sensitivity | Highest [23] | Lower than plate-based [23] | Lower than plate-based; variable [24] |

| Workflow | Flexible but labor-intensive; involves manual cell sorting and pipetting [23] | Highly automated, but requires expensive dedicated microfluidics equipment [23] | Labor-intensive; involves multiple rounds of splitting and pooling [24] |

| Best For | Smaller-scale, in-depth studies; precious samples [23] | Large-scale atlasing projects; profiling hundreds of thousands of cells [23] [24] | Large-scale studies when cost of microfluidics equipment is prohibitive; custom assay design [23] [25] |

Technical Performance and Experimental Data

To move beyond theoretical specifications, it is essential to consider quantitative performance data from real-world experiments, including direct benchmarking studies.

Throughput and Multiplet Rates

Throughput refers to the number of cells that can be reliably profiled in a single experiment, and it is intrinsically linked to the multiplet rate (the percentage of libraries derived from two or more cells).

- Droplet-Based Microfluidics: Standard protocols for platforms like 10x Genomics are designed to recover up to 10,000 cells per channel, with a significant proportion of droplets remaining empty to control for multiplets [24]. Novel methods like OAK (Overloading And unpacKing) push these boundaries by overloading the microfluidic chip. One study loaded 150,000 fixed cells, achieving a projected recovery of ~88,000 cells with a 6.6% overall multiplet rate. Loading 450,000 cells projected a recovery of ~224,000 cells, albeit with a higher multiplet rate of 10.6% and a mild reduction in genes detected per cell [24].

- Combinatorial Indexing: The UDA-seq protocol, which combines droplet barcoding with a second round of well-based indexing, demonstrated high cell recovery. From a load of 10,000 cells, it recovered 6,245 high-quality single-cell transcriptomes (62% recovery) with a low collision rate of only 1.23% [26].

Sensitivity and Data Quality

Sensitivity is often measured by the number of genes detected per cell, a critical factor for identifying rare cell types or subtle transcriptional states.

- Plate-based methods like SMART-seq3 are renowned for their high sensitivity and full-length transcript coverage, making them ideal for detecting isoform-level information [23] [22].

- Droplet-based methods show strong performance. In a benchmark, the standard 10x Genomics Chromium protocol detected a mean of 3,905 genes per cell in a K562 cell line. The high-throughput OAK method, under matched sequencing depth, detected a mean of 3,014 genes for the same cell line, indicating a mild but notable reduction in sensitivity, primarily for lowly expressed genes [24].

- Combinatorial Indexing methods have historically had lower sensitivity, but newer workflows like OAK show a strong correlation (Spearman correlation = 0.92) with standard droplet-based methods in terms of gene counts across cells, confirming the robustness of the quantitative data [24].

Table 2: Experimental Benchmarking Data from Key Studies

| Study (Method) | Cells Loaded | Cells Recovered | Multiplet/Collision Rate | Key Metric (e.g., Genes/Cell) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAK (Droplet + CI) [24] | 150,000 | 87,864 (projected) | 6.6% (overall) | 3,014 mean genes (K562) |

| OAK (Droplet + CI) [24] | 450,000 | 223,680 (projected) | 10.6% (overall) | Fewer genes vs. lower load |

| Standard Chromium (Droplet) [24] | N/A | Up to 10,000 | Standard | 3,905 mean genes (K562) |

| UDA-seq (Droplet + CI) [26] | 10,000 | 6,245 (62%) | 1.23% | Data quality comparable to standard 10x |

| sci-RNA-seq (CI) [24] | N/A | N/A | N/A | Lower sensitivity vs. OAK & 10x |

Application in Cross-Species Embryo Research

The selection of a scRNA-seq platform is profoundly influenced by the specific research application. In the burgeoning field of cross-species embryology, each method offers distinct advantages.

A primary application is constructing high-resolution transcriptional atlases of embryonic development. A landmark study integrated scRNA-seq data from six published human datasets, covering development from the zygote to the gastrula stage, to create a comprehensive reference of 3,304 cells. This atlas successfully captured the bifurcation of the inner cell mass into epiblast and hypoblast, and the subsequent maturation of trophectoderm and emergence of gastrula lineages [4]. Such detailed, high-sensitivity mapping benefits from methods that prioritize transcriptional depth, making plate-based or standard droplet-based platforms well-suited for the initial atlas creation, especially when starting material is limited but of high value.

Benchmarking Embryo Models

Stem cell-derived embryo models (embryoids) are crucial tools for studying early human development. Their utility depends on faithful recapitulation of in vivo development, which is validated by comparing their scRNA-seq profiles to a ground-truth in vivo reference. The integrated human embryo reference has been used to authenticate embryoid models, revealing the risk of misannotation when relevant references are not used [4]. For these comparative studies, which often require profiling multiple models and conditions, the high throughput and robustness of droplet-based systems are advantageous.

Identifying Conserved Genetic Programs

Cross-species comparative studies aim to identify evolutionarily conserved genetic programs. One such study compared scRNA-seq datasets from the testes of humans, mice, and fruit flies to uncover a core set of 1,277 conserved genes involved in spermatogenesis. Functional validation in Drosophila confirmed that three of these genes were critical for male fertility [2]. The scale of such projects—profiling multiple individuals across species—demands very high throughput and cost-effectiveness, making droplet-based or advanced combinatorial indexing methods like OAK and UDA-seq ideal choices.

Integrated Workflows and Protocol Details

A key trend is the fusion of different methodological strengths to create optimized, next-generation workflows.

UDA-seq Experimental Protocol

UDA-seq is a universal workflow that integrates droplet microfluidics with combinatorial indexing to enhance throughput for multimodal single-cell analyses [26].

- Cell/Nuclei Preparation: Hundreds of thousands of cells or nuclei are fixed and permeabilized. For multiome (ATAC + RNA) analysis, nuclei are subjected to in situ Tn5 tagmentation.

- Droplet Barcoding (Round 1): Cells/nuclei are encapsulated using a standard droplet microfluidics device (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium). Inside the droplets, targeted nucleic acids (RNA or accessible DNA) are labeled with a droplet-specific barcode.

- Emulsion Breaking: The droplet emulsion is broken to release the still-intact cells or nuclei.

- Well Plate Indexing (Round 2): The cells/nuclei are randomly aliquoted into a 96- or 384-well PCR plate. A second, well-specific barcode is added to all molecules via index PCR.

- Library Construction: The PCR products from all wells are pooled, purified, and used for standard library construction. Sequencing reads are demultiplexed using the unique combination of the two barcodes to assign them to individual cells [26].

Workflow for Combinatorial Indexing with Droplets

OAK-seq Experimental Protocol

The OAK protocol shares a similar two-round indexing philosophy but provides detailed performance metrics [24].

- Overloaded Droplet Barcoding: Fixed cells or nuclei are loaded at high concentration ("overloaded") into a microfluidics system (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium) for the first round of barcoding via in situ reverse transcription.

- Unpacking and Aliquoting: The emulsion is broken, and the fixed cells are recovered, mixed, and randomly distributed into multiple aliquots (e.g., 12-96).

- Secondary Indexing: Each aliquot receives a unique secondary index via PCR.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: A subset or all aliquots are processed into libraries. The combination of the initial droplet barcode and the secondary aliquot-specific barcode defines a unique cell identity [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Success in single-cell genomics relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for scRNA-seq Experiments

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Chip | Generates nanoliter-sized droplets for high-throughput cell barcoding. | 10x Genomics Chromium chip [23] [24]. |

| Barcoded Beads | Deliver cell-specific barcodes and primers during droplet encapsulation. | Beads from Drop-seq or 10x Genomics [23]. |

| Combinatorial Indexing Primers | Series of barcoded oligonucleotides for labeling cells over multiple rounds of indexing. | Used in Parse Biosciences Evercode, sci-RNA-seq [23] [25]. |

| Fixation Reagents | (e.g., Methanol, Formaldehyde) preserve cells for delayed analysis or complex workflows. | Methanol fixation is used in OAK and UDA-seq [26] [24]. |

| Cell Hashing Antibodies | Sample multiplexing; barcoded antibodies allow pooling of samples pre-processing. | Compatible with OAK workflow for large-scale studies [24]. |

| Tn5 Transposase | Tags accessible chromatin regions in multimodal single-cell assays (e.g., Multiome). | Used in UDA-seq for single-cell ATAC-seq [26]. |

| Isooxoflaccidin | Isooxoflaccidin, MF:C16H12O5, MW:284.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Safflospermidine A | Safflospermidine A, MF:C34H37N3O6, MW:583.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The landscape of scRNA-seq technologies offers multiple paths for researchers engaged in cross-species embryonic studies. Plate-based methods remain the gold standard for sensitivity in focused studies. Droplet-based microfluidics provides an unparalleled combination of throughput and data quality for large-scale atlas building. Combinatorial indexing offers remarkable scalability and flexibility, particularly for labs without access to costly microfluidics hardware.

The emerging trend of hybrid techniques like UDA-seq and OAK, which merge droplet microfluidics with combinatorial indexing, represents a powerful synthesis of strengths. These methods dramatically increase throughput while maintaining data quality comparable to standard protocols, making them exceptionally well-suited for the massive scale required by cross-species comparisons, clinical studies involving numerous samples, and large-scale perturbation screens. The choice of platform is not static but should be strategically aligned with the specific biological question, scale, and resources of the embryology research project at hand.

The emergence of stem cell-based embryo models represents a transformative development in the study of early human development. These models provide unprecedented experimental tools for investigating embryogenesis while overcoming the ethical limitations and tissue scarcity associated with direct human embryo research [27]. The utility of these models, however, hinges entirely on their fidelity in recapitulating the molecular, cellular, and structural aspects of their in vivo counterparts. Without rigorous benchmarking against genuine embryonic references, the scientific value of these models remains uncertain [28] [4].

Benchmarking exercises face significant challenges due to species-specific differences in developmental pathways between commonly studied model organisms like mice and humans. Mouse models, while valuable, exhibit substantial variations from human embryogenesis in key areas such as signaling sources for gastrulation, embryonic structure formation, and the timing of lineage specification [27]. These differences necessitate the development of human-specific reference tools to properly validate embryo models intended to study human development. The establishment of comprehensive benchmarking frameworks has been accelerated by advances in single-cell technologies, which enable unprecedented resolution in comparing in vitro models to native tissues [28].

This guide systematically outlines the current approaches, technologies, and reference standards for benchmarking stem cell-based embryo models, providing researchers with practical methodologies for validating their experimental systems.

Key Aspects for Evaluating Embryo Model Fidelity

Cell-Type Composition Analysis

The most fundamental aspect of embryo model validation involves demonstrating that the model contains all appropriate cell types in physiologically relevant proportions. Ideal human organoid systems should possess the specific cell types found in the target organ or embryonic structure, including not only the primary functional cells but also supporting components such as nerves, blood vessels, and immune cells [28].

Advanced single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables unbiased transcriptome analysis at cellular resolution, moving beyond the limitations of traditional marker-based characterization. This approach allows researchers to identify whether embryo models contain the expected lineages and whether any aberrant cell populations are present [28] [4]. The detection of rare or transitional cell states provides particularly important information about the model's ability to recapitulate developmental dynamics.

Table: Essential Cell Lineages in Early Human Embryo Models

| Developmental Stage | Essential Lineages | Key Markers | Functional Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-implantation | Trophectoderm (TE) | CDX2, NR2F2 | Contributes to placental structures |

| Pre-implantation | Inner Cell Mass (ICM) | PRSS3, POU5F1 | Forms embryonic proper |

| Pre-implantation | Epiblast | TDGF1, POU5F1 | Pluripotent lineage |

| Pre-implantation | Hypoblast | GATA4, SOX17 | Contributes to yolk sac |

| Post-implantation | Cytotrophoblast (CTB) | GATA2, GATA3 | Placental progenitor |

| Post-implantation | Syncytiotrophoblast (STB) | TEAD3 | Hormone-producing layer |

| Gastrulation | Primitive Streak | TBXT | Site of gastrulation |

| Gastrulation | Amnion | ISL1, GABRP | Forms amniotic cavity |

| Gastrulation | Definitive Endoderm | SOX17, FOXA2 | Forms gut tube |

| Gastrulation | Mesoderm | MESP2 | Forms connective tissues |

Spatial Organization and Morphological Assessment

Beyond cellular composition, embryo models must recapitulate the spatial organization and three-dimensional architecture of natural embryos. This includes the proper arrangement of cell types relative to one another and the formation of higher-order structures characteristic of the developing embryo [28]. For example, sophisticated intestinal organoids should contain epithelial cells organized into villi with crypts containing stem cells, with stroma, muscle, vasculature, neurons, and immune cells in a highly organized structure.

Advanced imaging technologies now enable detailed spatial assessment through methods such as:

- Iterative immunofluorescence (4i): Allows staining of up to 40 proteins on a single tissue section, enabling high-content imaging of spatial relationships [28].

- Spatial transcriptomics: Combines RNA sequencing with imaging to map transcriptomic data to specific locations within tissue structures, though current resolutions typically exceed single-cell level [28].

- High-content image analysis: Computational approaches that quantify spatial patterns and organizational features within embryo models.

Functional Validation

While molecular and spatial characterization provides essential data, functional assessment remains the ultimate test of embryo model fidelity. Functional validation should demonstrate that the model performs specialized activities characteristic of its in vivo counterpart [28]. For example, intestinal organoids should ideally absorb nutrients, undergo peristaltic contractions, secrete mucus, and maintain a healthy microbiome.

In practice, comprehensive functional assessment presents challenges, as most in vitro organoid models lack the full complement of organ-level functions. Therefore, functional analysis often occurs at the cellular level through assays such as nutrient absorption/uptake, electrical activity measurements, contractility assessments, or secretory function quantification. The development of more sophisticated embryo models that include vascular and neuronal networks will enable more comprehensive functional testing in the future.

Established Benchmarking Technologies and Protocols

Single-Cell Genomic Approaches

Single-cell technologies have revolutionized embryo model benchmarking by enabling detailed characterization at unprecedented resolution. The table below summarizes the key methodological approaches:

Table: Single-Cell Technologies for Embryo Model Characterization

| Technology | Primary Application | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq | Transcriptome profiling | Holistic, unbiased analysis of gene expression | Requires cell dissociation |

| snRNA-seq | Nuclear transcriptomics | Enables use of frozen tissue; detects rare cells | May miss cytoplasmic transcripts |

| scATAC-seq | Epigenome mapping | Profiles chromatin accessibility | More complex data interpretation |

| Multiomics | Combined analysis | Simultaneous transcriptome and epigenome profiling | Higher cost and computational demand |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Spatial gene expression | Maintains spatial context | Limited single-cell resolution |

| 4i (Iterative IF) | Protein localization | High-plex protein imaging in situ | Antibody quality dependency |

Each technology offers distinct advantages for specific benchmarking applications. A multimodal approach combining several technologies typically provides the most comprehensive assessment of embryo model fidelity [28].

Performance Comparison of scRNA-seq Protocols

The choice of scRNA-seq protocol significantly impacts benchmarking quality due to substantial differences in performance characteristics. A comprehensive multicenter study comparing 13 commonly used scRNA-seq and single-nucleus RNA-seq protocols revealed marked differences in their capabilities to detect cell-type markers and resolve tissue heterogeneity [29].

Key findings from this benchmarking study include:

- Protocols differed substantially in library complexity and their efficiency at converting RNA molecules into sequencing libraries.

- These technical differences directly affected the predictive value of datasets and their suitability for integration into reference cell atlases.

- Droplet-based methods (e.g., Chromium) generally provided good detection of low-frequency cell types when proper quality controls were implemented.

- Single-nucleus RNA-seq protocols detected a higher proportion of intronic sequences, which could be advantageous for certain applications but might not fully represent cytoplasmic transcripts.

These findings highlight the importance of protocol selection based on the specific benchmarking goals and the need for consistency when comparing multiple embryo models or conducting longitudinal studies.

Integrated Human Embryo Reference Tools

Development of Comprehensive Reference Atlases