Cross-Species Gastrulation Transcriptome Conservation: From Evolutionary Insights to Biomedical Applications

This comprehensive review synthesizes current research on cross-species transcriptome conservation during gastrulation, a pivotal developmental period.

Cross-Species Gastrulation Transcriptome Conservation: From Evolutionary Insights to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current research on cross-species transcriptome conservation during gastrulation, a pivotal developmental period. We explore evolutionary conserved and divergent gene regulatory networks across mammalian models including human, pig, mouse, and non-traditional models like Acropora corals. The article examines methodological advances in single-cell multi-omics and computational tools enabling cross-species prediction, while addressing challenges in developmental tempo synchronization and xenogeneic barriers. Through validation across multiple species and biological contexts, we highlight implications for developmental biology, stem cell research, and organ generation technologies, providing researchers and drug development professionals with critical insights into conserved developmental principles and their translational potential.

Evolutionary Patterns and Conserved Kernels in Gastrulation Transcriptomes

The Phylotypic Stage and Hourglass Model in Mammalian Development

A central question in evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) concerns how embryonic development evolves and which developmental stages are most conserved across species. Two competing models have emerged to explain the relationship between embryogenesis and evolution [1]. The funnel model (or early conservation model) posits that the earliest embryonic stages are most conserved, with divergence increasing as development progresses. In contrast, the hourglass model proposes that early and late stages are more divergent, with a constrained, conserved "phylotypic period" during mid-embryogenesis [1] [2]. This period represents the fundamental body plan for a phylum and exhibits the highest degree of morphological and molecular resemblance among related species [1].

Recent advances in transcriptomic technologies have transformed this debate from morphological comparisons to quantitative molecular analyses. This guide compares the experimental evidence supporting these models, with particular focus on mammalian systems, and provides researchers with methodological frameworks for investigating developmental conservation.

Defining the Phylotypic Stage and Hourglass Model

Historical Foundations and Modern Reformulations

The conceptual origins of the phylotypic stage trace back to Karl Ernst von Baer's 1828 laws of embryology, which noted that general characteristics of animal groups appear earlier in development than specialized features [1]. Ernst Haeckel later proposed that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny (1866), though this hypothesis is now considered outdated [1]. The modern formulation emerged in 1960 with Friedrich Seidel's "Körpergrundgestalt" (basic body shape), followed by Klaus Sander's 1983 naming of the "phylotypic stage" as the period of maximum similarity between species within a phylum [1].

The Hourglass Model Explained

The hourglass model describes a developmental constraint pattern where:

- Early stages (cleavage, blastula) show higher divergence due to varying reproductive strategies and embryonic environments

- Mid-embryonic stages (the phylotypic period) exhibit maximum conservation across species

- Later stages (organ specialization) again diverge as species-specific adaptations emerge [1] [2]

In vertebrates, this phylotypic period typically corresponds to the pharyngula stage, characterized by the presence of a notochord, dorsal hollow nerve cord, post-anal tail, and a series of paired branchial slits [1] [3].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the Vertebrate Phylotypic Stage (Pharyngula)

| Feature | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Pharyngeal arches | Series of paired structures in the pharyngeal region | Foundation for gills/jaw structures across vertebrates |

| Somites | Segmented mesodermal structures | Precursors to vertebrae and skeletal muscle |

| Neural tube | Dorsal hollow nerve cord | Precursor to central nervous system |

| Notochord | Rod-shaped supporting structure | Defining chordate feature |

| Post-anal tail | Extension beyond anal opening | Transient structure in many vertebrates |

Quantitative Evidence Supporting the Hourglass Model

Transcriptomic Conservation in Vertebrates

Seminal transcriptome studies across multiple vertebrate species provide compelling molecular evidence for the hourglass model. A comprehensive 2011 analysis compared gene expression profiles of mice (Mus musculus), chickens (Gallus gallus), African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis), and zebrafish (Danio rerio) throughout development [3]. This research revealed that:

- The highest transcriptome similarity occurs during mid-embryonic stages (neurula to late pharyngula)

- Earlier stages (cleavage to blastula) and later stages show greater transcriptomic divergence

- The most conserved combination of stages across all four species was: mouse E9.5, chicken HH stage 16, Xenopus stage 28, and zebrafish 24 hpf [3]

These stages correspond to Ballard's definition of the pharyngula stage, characterized by the presence of pharyngeal arches, somites, neural tube, and other vertebrate-defining structures [3].

Table 2: Transcriptome Conservation Across Vertebrate Development

| Developmental Period | Transcriptome Similarity | Key Features | Evolutionary Age of Expressed Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early stages (cleavage to blastula) | Lower conservation | Species-specific cleavage patterns, implantation mechanisms | Mixed age genes |

| Phylotypic period (pharyngula stage) | Highest conservation | Pharyngeal arches, somites, neural tube, notochord | Evolutionarily oldest genes |

| Late stages (organogenesis to differentiation) | Lower conservation | Species-specific organ formation, morphological specialization | Younger, specialized genes |

Evolutionary Age of Genes Supports Hourglass Pattern

Genomic phylostratigraphy—tracking the evolutionary age of genes—provides additional support for the hourglass model. Analysis of zebrafish transcriptomes throughout development revealed that genes expressed during mid-embryogenesis are evolutionarily older than those expressed at the beginning and end of development [1]. Similar patterns were observed in Drosophila, mosquitoes (Anopheles), and nematodes (Caenorhabditis elegans) [1].

This pattern suggests stronger evolutionary constraints on mid-embryonic development, with older, more conserved gene networks directing the establishment of the basic body plan, while younger genes contribute to species-specific adaptations in early and late development.

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Developmental Conservation

Transcriptomic Comparison Protocols

The key experiments supporting the hourglass model employ sophisticated transcriptomic analyses:

Multi-Species Developmental Time-Course Analysis

- Sample collection: Embryos collected across developmental stages from multiple species

- RNA sequencing: Whole-embryo transcriptome profiling using RNA-seq

- Orthology mapping: Identification of orthologous genes across species

- Similarity quantification: Calculation of transcriptome similarity between species pairs at each developmental stage

- Conservation identification: Detection of stages with maximal cross-species similarity [3]

Ancestor Index Calculation

- Gene age estimation: Classification of genes by evolutionary origin using phylostratigraphy

- Expression profiling: Determination when evolutionarily ancient genes are expressed

- Index calculation: Computation of the ratio of ancient genes to total genes expressed at each stage

- Peak identification: Recognition of developmental stages with highest expression of ancient genes [4]

Single-Cell Resolution in Gastrulation Studies

Recent advances in single-cell transcriptomics have enabled unprecedented resolution in analyzing conserved developmental processes:

Human Gastrulation Characterization (2021)

- Sample: Complete Carnegie Stage 7 human embryo (16-19 days post-fertilization)

- Technique: Single-cell RNA sequencing of 1,195 individually dissected cells

- Spatial mapping: Correlation of transcriptomes with anatomical location (rostral/caudal embryonic disk, yolk sac)

- Cross-species comparison: Comparison with mouse and non-human primate gastrulation data [5]

Mouse Spatiotemporal Atlas (2025)

- Scope: Integrated analysis from E6.5 to E9.5, covering gastrulation to early organogenesis

- Resolution: 82 refined cell-type annotations across 150,000+ cells

- Spatial transcriptomics: Mapping gene expression to anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral axes

- Application: Framework for projecting in vitro models (e.g., gastruloids) onto in vivo development [6]

Research Reagent Solutions for Developmental Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Developmental Conservation

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomic Profiling | Single-cell RNA sequencing (Smart-Seq2) | Cell-type specific expression analysis | High sensitivity, full-length transcript coverage |

| Spatial Mapping | Spatial transcriptomics platforms | Correlating gene expression with anatomical position | Preservation of spatial information in transcriptomes |

| Metabolic Imaging | 2-NBDG (fluorescent glucose analog) | Visualizing glucose uptake in live embryos | Real-time metabolic activity monitoring |

| Lineage Tracing | TCF/LEF:H2B-GFP reporter mice | Tracking cell fate decisions in gastrulation | Nuclear GFP for precise cell identification |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | 2-DG, Azaserine, BrPA, YZ9, Shikonin | Perturbing specific metabolic pathways | Pathway-specific inhibition for functional studies |

| Cross-Species Alignment | Orthology mapping algorithms | Identifying conserved genes across species | Enables comparative transcriptomics |

Metabolic Regulation of Gastrulation: Emerging Evidence

Recent research has revealed that metabolic pathways play instructive roles in guiding gastrulation beyond their energy-producing functions:

Compartmentalized Glucose Metabolism in Mouse Gastrulation

- Two distinct waves of glucose utilization guide mammalian gastrulation

- First wave: Hexosamine biosynthetic pathway activity in transitionary epiblast cells preceding primitive streak entry

- Second wave: Glycolytic activity in mesodermal cells migrating laterally from the primitive streak

- Metabolic inhibition experiments demonstrate that blocking HBP (with azaserine) impairs primitive streak progression, while inhibiting late glycolysis has minimal effect [7]

This metabolic regulation operates in synergy with transcription factor networks and morphogen gradients, adding another layer to the complex regulation of this conserved developmental period.

Visualizing the Hourglass Model and Experimental Approaches

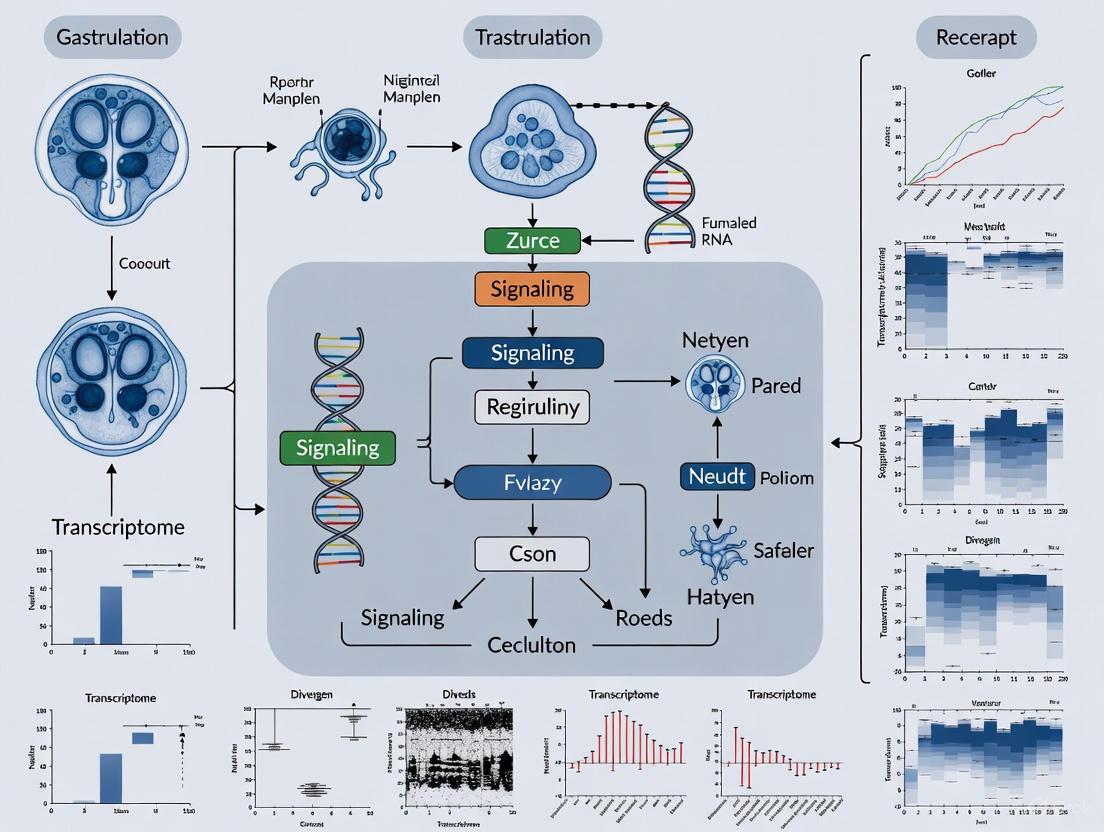

Diagram 1: TheDevelopmental Hourglass Model. Mid-embryonic phylotypic period shows highest conservation, while early and late stages are more divergent across species.

Diagram 2: Transcriptomic Analysis of Developmental Conservation. Two complementary approaches for identifying conserved developmental stages.

The hourglass model, with its constrained phylotypic period, provides a framework for understanding how the basic vertebrate body plan is established and conserved. The phylotypic stage represents a developmental "bottleneck" where evolutionary constraints are strongest, likely due to complex interacting gene networks that establish the fundamental body architecture [1] [2]. This concept extends beyond animals, with similar patterns observed in plants and fungi, suggesting possible universal principles in the evolution of developmental programs [8].

For researchers in drug development and regenerative medicine, understanding these conserved developmental windows provides insights into:

- Developmental vulnerabilities that may contribute to congenital disorders

- Evolutionary constraints on key signaling pathways that may be therapeutic targets

- Conserved mechanisms that can be studied in model organisms with relevance to human development

The integration of transcriptomic, metabolic, and single-cell spatial data continues to refine our understanding of this fundamental biological principle, offering new approaches for investigating the deep conservation of developmental programs across mammalian species.

The process of gastrulation represents a pivotal phase in embryonic development, where a complex cascade of gene expression transforms a simple embryo into a multilayered structure with distinct cellular identities. Underpinning this transformation are gene regulatory networks (GRNs)—complex circuits of transcription factors and their target genes—that orchestrate cell fate decisions with remarkable precision. Research into cross-species gastrulation transcriptome conservation seeks to identify the core regulatory kernels, the evolutionarily conserved subcircuits of these GRNs, which are indispensable for establishing the fundamental body plan across the animal kingdom. Understanding these kernels is not merely an academic pursuit; it provides critical insights into the evolutionary constraints on development and the molecular etiology of congenital disorders. This guide objectively compares the current methodologies, findings, and experimental data shaping this field, providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Conserved Transcriptional Components

Cross-species analyses have revealed that while the sequences of cis-regulatory elements (CREs) can diverge significantly, the core transcription factors and the logic of their interactions often remain conserved. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies on the conservation of regulatory elements and the tempo of developmental processes.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Regulatory Element Conservation and Developmental Tempo

| Comparative Aspect | Species Compared | Key Metric | Quantitative Finding | Identified Core Regulatory Component |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhancer Sequence Conservation [9] | Mouse vs. Chicken | Percentage of heart enhancers with sequence conservation | ~10% of enhancers were sequence-conserved | N/A |

| Positional Enhancer Conservation [9] | Mouse vs. Chicken | Percentage of heart enhancers identified as orthologs via synteny | 42% of enhancers were positionally conserved (orthologs) | Enhancers flanking developmental genes |

| Tempo of Somitogenesis [10] | Human vs. Mouse | Oscillation period of the segmentation clock (Hes7) | Human: 5-6 hours; Mouse: 2-3 hours | Hes7 transcription factor |

| Tempo of Motor Neuron Differentiation [10] | Human vs. Mouse | Temporal scaling factor for differentiation | Human development is ~2.5x slower than mouse | Transcription factors governing motor neuron GRN |

| Pluripotency Progression [11] | Human, Monkey, Pig | Transcriptomic coordination of pluripotency spectrum | Identified divergent metabolic and epigenetic regulation | Transcription factors (e.g., POU5F1, KLF4) |

Table 2: Key Transcription Factors in Conserved GRNs and Their Documented Roles

| Transcription Factor / Regulator | Species Documented | Biological Process / GRN | Conserved Role and Functional Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hes7 [10] | Human, Mouse, Zebrafish | Segmentation Clock / Somitogenesis | Core delayed negative-feedback oscillator; kinetics determine species-specific tempo. |

| RpaA & RpaB [12] | Synechococcus elongatus | Circadian Metabolism | Global regulators of day-night metabolic transitions; functional analogues to developmental clocks. |

| POU5F1 (OCT4) [11] | Human, Monkey, Pig | Early Pluripotency / Blastocyst Development | Highly expressed in inner cell mass and epiblast across species; marker of pluripotent state. |

| KLF4 [11] | Human, Monkey, Pig | Early Lineage Specification | Highly expressed in ICM; downregulated as epiblast develops; expressed in mural trophectoderm in pig. |

| achintya & vismay [13] | Drosophila | Regulation of De Novo Genes | Key regulators for integrating evolutionarily young genes into existing regulatory frameworks. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols in Cross-Species Analysis

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) of Pre-gastrulation Embryos

This protocol is used to construct a complete transcriptomic atlas of early embryonic development, enabling the comparison of pluripotency states and lineage specification across species [11].

- Single-Cell Dissociation: Embryos are isolated at specific developmental stages. A critical optimization often involves a brief centrifugation of blastocysts prior to enzymatic treatment (e.g., with Trypsin, Collagenase IV) to efficiently dissociate resilient structures like the pig inner cell mass into a single-cell suspension.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Single cells are captured, and their mRNA is reverse-transcribed into cDNA. Libraries are prepared with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to account for amplification bias and sequenced using high-throughput platforms (e.g., Illumina).

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequencing reads are aligned to the respective reference genome. Quality control filters out cells with low gene counts. Unsupervised clustering groups cells based on transcriptional similarity, and cell lineages (e.g., epiblast, primitive endoderm, trophectoderm) are annotated using known stage- and lineage-specific marker genes. Pseudotime analysis can be used to reconstruct the temporal progression of each lineage.

- Cross-Species Comparison: Orthologous genes are mapped between species. The transcriptome landscapes are compared to identify conserved and species-specific patterns in pluripotency progression, metabolic states, and epigenetic regulators [11].

Synteny-Based Identification of Conserved Regulatory Elements

This methodology overcomes the limitation of low sequence conservation to identify functional cis-regulatory elements (CREs) across distantly related species [9].

- Chromatin Profiling: Putative CREs (enhancers, promoters) are identified in Species A (e.g., mouse) and Species B (e.g., chicken) using functional genomic assays like ATAC-seq (for chromatin accessibility) and ChIPmentation for histone modifications (e.g., H3K27ac) at equivalent developmental stages.

- Anchor Point Definition: The genomes of the two species are aligned to identify blocks of sequence conservation ("anchor points"). Bridging species can be used to increase the density of these anchor points.

- Interspecies Point Projection (IPP): For a non-alignable CRE in Species A, its position relative to the two closest flanking anchor points is calculated. This relative position is then "projected" into the genome of Species B to predict the location of its orthologous CRE.

- Validation: Predicted orthologous CREs are validated using in vivo reporter assays (e.g., introducing a chicken enhancer coupled to a LacZ reporter gene into a mouse embryo) to confirm conserved function despite sequence divergence [9].

Analysis of Developmental Tempo inIn VitroModels

This approach uses directed differentiation of pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) to study species-specific differences in the pace of development in a controlled environment [10].

- Stem Cell Culture: Pluripotent stem cells from different species (e.g., human, mouse) are maintained under conditions that support their undifferentiated state.

- Directed Differentiation: PSCs are guided toward a specific lineage, such as presomitic mesoderm (for segmentation clock studies) or motor neurons, using well-defined combinations of growth factors and small molecules.

- Temporal Profiling: The differentiation process is monitored over time using high-temporal-resolution RNA-seq, quantitative PCR, or live-cell imaging of fluorescent reporters. Key markers are tracked to define the stages of differentiation.

- Kinetic Measurement: To probe the mechanism of tempo differences, the stability of key proteins and mRNAs is measured, for example, through metabolic labeling (e.g., pulse-chase experiments) for endogenous proteins or luciferase-reporter assays for degradation kinetics. The data is used to parametrize mathematical models of the underlying GRN [10].

Visualizing Core Concepts and Workflows

Research Workflows for Identifying Conserved Kernels

Hes7 Segmentation Clock Negative Feedback

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Cross-Species GRN Research

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq Kits (e.g., 10x Genomics) | High-throughput transcriptomic profiling of individual cells from dissociated embryos. | Cataloging lineage specification in pig, human, and monkey embryos [11]. |

| Chromatin Profiling Kits (e.g., ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq) | Mapping open chromatin and histone modifications to identify putative CREs. | Defining enhancers and promoters in mouse and chicken embryonic hearts [9]. |

| Cross-Species Aligners & IPP Algorithm | Bioinformatics tools for mapping orthologous genomic regions beyond sequence alignment. | Identifying "indirectly conserved" enhancers between mouse and chicken [9]. |

| Pluripotent Stem Cell (PSC) Lines | In vitro models for studying differentiation and developmental tempo. | Comparing motor neuron differentiation speed between human and mouse PSCs [10]. |

| Live-Cell Imaging Reporters | Real-time tracking of gene expression and oscillatory dynamics in living cells/tissues. | Monitoring the oscillation period of the segmentation clock in human and mouse PSCs [10]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational modeling of metabolism integrated with gene regulation. | Studying circadian control of metabolism in cyanobacteria as a model for temporal regulation [12]. |

| Tenofovir hydrate | Tenofovir hydrate, CAS:206184-49-8, MF:C9H16N5O5P, MW:305.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| LTB4-IN-1 | Anti-inflammatory Agent 2|Research Grade|RUO | Anti-inflammatory Agent 2 is a novel research compound for in vitro study. It targets key inflammatory pathways. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

A fundamental paradox in evolutionary developmental biology is how highly conserved morphological structures can arise from divergent molecular processes. This phenomenon, known as Developmental System Drift (DSD), describes how different genetic and regulatory pathways can evolve to produce the same morphological outcomes in divergent lineages. While embryonic gastrulation represents a deeply conserved morphogenetic process across animal phyla, the underlying gene regulatory networks (GRNs) controlling this process exhibit remarkable divergence. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of transcriptional conservation and divergence during gastrulation across multiple model systems, synthesizing recent transcriptomic evidence to explore how conserved morphology is maintained despite molecular rewiring. Understanding these principles provides crucial insights for evolutionary biology and has practical implications for drug development, particularly in predicting how conserved pathways might respond to pharmacological intervention across species.

Comparative Analysis of Gastrulation Transcriptomes Across Species

Quantitative Comparison of Transcriptional Conservation Patterns

Table 1: Transcriptome Conservation Patterns Across Model Organisms

| Organism Pair | Evolutionary Distance | Morphological Similarity | Transcriptional Conservation | Key Divergent Processes | Conserved Regulatory Elements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acropora digitifera & A. tenuis [14] | ~50 million years | High (conserved gastrulation) | Low (divergent GRNs) | Paralog usage, alternative splicing | 370-gene regulatory "kernel" |

| Dictyostelium discoideum & D. purpureum [15] | ~400 million years | High (similar fruiting bodies) | High (75% orthologs conserved) | Timing of developmental progression | Cell-type specific expression programs |

| Paracentrotus lividus & Strongylocentrotus purpuratus [16] | ~40 million years | High (similar morphology) | High (developmental genes) | Homeostasis and response genes | Housekeeping gene expression |

| Mouse, Marmoset, Macaque & Human [17] | ~75 million years (mouse-primate) | Moderate (conserved neocortex) | Mixed (20% mammal-conserved genes) | Cell type composition, non-coding elements | Ubiquitous developmental regulators |

Experimental Methodologies for Cross-Species Transcriptome Comparison

Table 2: Key Methodological Approaches for Comparative Transcriptomics

| Methodology | Key Features | Resolution | Applications in DSD Research | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) [14] | Quantitative transcript profiling | Whole transcriptome | Identifying ortholog expression divergence | Requires high-quality reference genomes |

| Single-cell RNA sequencing [6] [18] | Cell-type specific expression patterns | Single cell | Mapping lineage diversification | Cell dissociation challenges for early embryos |

| Spatial Transcriptomics [6] | Gene expression with spatial context | Tissue region | Analyzing axial patterning during gastrulation | Limited spatial resolution compared to single-cell |

| Single-cell Multiomics [17] | Combined gene expression, chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation | Single cell | Linking regulatory element evolution to expression | Computational integration challenges |

Case Studies in Developmental System Drift

Cnidarian Gastrulation: Divergent Programs Under Morphological Constancy

Recent research on reef-building corals of the genus Acropora reveals a striking example of DSD. Although gastrulation is morphologically conserved between Acropora digitifera and Acropora tenuis (species that diverged approximately 50 million years ago), their transcriptional programs show significant divergence [14]. Orthologous genes exhibited substantial temporal and modular expression differences, indicating extensive GRN diversification rather than conservation. Despite this divergence, researchers identified a conserved regulatory "kernel" of 370 differentially expressed genes that were upregulated at the gastrula stage in both species, with conserved roles in axis specification, endoderm formation, and neurogenesis [14].

The study revealed species-specific differences in paralog usage and alternative splicing patterns, indicating independent peripheral rewiring of this conserved module. Interestingly, A. digitifera exhibited greater paralog divergence consistent with neofunctionalization, while A. tenuis showed more redundant expression, suggesting differences in regulatory robustness between these closely related species [14]. This case demonstrates how conserved morphological processes can be maintained through stabilizing selection on phenotype while allowing for substantial rewiring of underlying genetic networks.

Sea Urchin Development: Conserved Morphogenesis with Divergent Homeostasis

A comparative transcriptomic study of two sea urchin species (Paracentrotus lividus and Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) that shared a common ancestor about 40 million years ago revealed another fascinating dimension of DSD [16]. These geographically distant species show remarkably similar morphology despite evolutionary divergence. The research found that both developmental and housekeeping genes showed highly dynamic and strongly conserved temporal expression patterns, while homeostasis and response genes showed divergent expression [16].

This case illustrates the concept of various transcriptional programs coexisting in the developing embryo and evolving under different constraints. Morphological constraints appear to underlie the conservation of developmental gene expression, while embryonic fitness requires the conservation of housekeeping gene expression, with species-specific adjustments of homeostasis gene expression potentially enabling adaptation to local environmental conditions [16]. The position of the phylotypic stage varied between these gene groups: developmental gene expression showed highest conservation at mid-developmental stage (following the hourglass model), while conservation of housekeeping genes kept increasing with developmental time [16].

Social Amoebae: Exceptional Transcriptional Conservation

In contrast to the patterns observed in cnidarians and sea urchins, studies of social amoebae (Dictyostelium discoideum and Dictyostelium purpureum) reveal a surprising degree of transcriptional conservation despite extensive genome divergence [15]. These species diverged approximately 400 million years ago (making their genomes as different as those of humans and jawed fish) yet exhibit very similar developmental programs and inhabit the same ecological niche [15].

RNA sequencing analysis revealed that the developmental regulation of transcription is highly conserved between orthologs in the two species, with over 75% of orthologs participating in evolutionarily conserved developmental processes [15]. This conservation extends to cell-type specific expression patterns, suggesting that similar developmental anatomies are maintained through deeply conserved transcriptome-level regulation in this system [15]. This case demonstrates that DSD is not universal and that some systems maintain remarkable transcriptional conservation over deep evolutionary time.

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks in DSD

Conceptual Framework of Developmental System Drift

The following diagram illustrates the core principles of Developmental System Drift, showing how conserved morphology can emerge from divergent molecular pathways:

Conserved morphological structures can be maintained through two primary mechanisms despite molecular divergence: (1) stabilizing selection on the phenotype, which allows for molecular changes that do not affect the final morphological outcome, and (2) compensatory evolution, where changes in one part of the network are offset by changes in other components [14] [16]. The regulatory "kernels" identified in Acropora species represent deeply conserved modules that are buffered against evolutionary change, while peripheral network components experience greater evolutionary flexibility [14].

The Hourglass Model and Temporal Patterning of Conservation

A key framework for understanding DSD is the hourglass model, which predicts that mid-embryonic development is more conserved than early or late stages [14] [19]. This model suggests that the phylotypic stage (representing the conserved body plan) experiences the strongest evolutionary constraints, while earlier and later stages can diverge more freely. However, recent transcriptomic analyses reveal that this pattern varies depending on the gene set examined. In sea urchins, developmental genes follow the hourglass pattern with maximum conservation at mid-development, while housekeeping genes show progressively increasing conservation throughout development [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for DSD Investigation

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Considerations for DSD Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, ZFNs | Functional validation of regulatory elements | Requires species-specific optimization |

| Single-Cell Platforms | 10x Genomics, sci-RNA-seq, snm3C-seq | Cell lineage tracing, regulatory network mapping | Computational integration across species |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | 10x Visium, Slide-seq, MERFISH | Spatial mapping of gene expression patterns | Preservation of embryonic spatial organization |

| Cross-Species Alignment | PhyloCSF, MULTIZ, PhastCons | Evolutionary conservation scoring | Reference genome quality dependence |

| Gene Regulatory Analysis | SCENIC, Pando, CellOracle | Inference of regulatory networks from scRNA-seq | Validation required for predicted interactions |

| (R)-(+)-Bay-K-8644 | (R)-(+)-Bay-K-8644, CAS:98791-67-4, MF:C16H15F3N2O4, MW:356.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| MK-8245 | MK-8245, CAS:1030612-90-8, MF:C17H16BrFN6O4, MW:467.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implications for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

The principles of Developmental System Drift have significant implications for drug development and translational research. Understanding which elements of developmental pathways are conserved and which are divergent helps in selecting appropriate model systems for studying human developmental disorders and designing targeted therapies. For example, the finding that cis-regulatory elements diverge more rapidly than trans-regulatory factors [17] suggests that pharmacological targeting of transcription factors might have more conserved effects across species than interventions targeting upstream regulatory elements.

Furthermore, the identification of conserved regulatory "kernels" amidst overall network divergence [14] highlights potential strategic targets for therapeutic intervention that are more likely to be conserved across human populations. Conversely, species-specific differences in paralog usage and alternative splicing [14] underscore the importance of considering individual genetic variation in drug response.

The research tools and comparative frameworks presented in this guide provide a foundation for designing studies that effectively translate findings from model organisms to human biology, while accounting for the expected patterns of conservation and divergence dictated by Developmental System Drift.

Temporal Scaling (Allochrony) and Species-Specific Developmental Tempo

Embryonic development follows a stereotypic sequence of events conserved across vertebrates, yet the speed at which this genetic program executes varies substantially between species, a phenomenon termed developmental allochrony [20]. These differences in developmental tempo are not merely observational curiosities; they represent a fundamental biological scaling principle that can influence organ size, complexity, and function. While the core gene regulatory networks (GRNs) governing differentiation are often identical, the tempo at which they operate can differ by multiples, with profound implications for evolutionary outcomes [20] [21]. Research has moved beyond descriptive studies to uncover the underlying molecular pacemakers, revealing that global cellular processes—including protein stability, metabolic rates, and biochemical kinetics—orchestrate species-specific developmental timing [22] [23]. Understanding these mechanisms is critical for the field of cross-species transcriptome conservation, as it provides context for interpreting the timing and outcome of gene expression data across different organisms. This guide objectively compares key experimental models and findings that have defined our current understanding of developmental tempo.

Comparative Data on Developmental Tempo Across Species

Quantitative studies across diverse species and developmental processes have revealed consistent patterns of temporal scaling. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Developmental Tempo Across Species and Systems

| Developmental System | Species Compared | Observed Tempo Difference (Ratio) | Key Correlated Parameter | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor Neuron Differentiation [20] | Mouse vs. Human | ~2.5x slower in human | Protein half-life, Cell cycle duration | In vitro ESC differentiation |

| Segmentation Clock [20] [24] | Mouse vs. Human | ~2x slower in human (5-6h vs. 2-3h period) | Biochemical reaction speeds, Embryogenesis length | In vitro PSC differentiation (Stem cell zoo) |

| Segmentation Clock [24] | Six Mammals (Marmoset to Rhinoceros) | No correlation with body mass | Scaling with embryogenesis length | In vitro PSC differentiation (Stem cell zoo) |

| Biochemical Kinetics [20] | Mouse vs. Human Neural Progenitors | ~2x higher protein stability in human | Global proteome half-life | Protein stability assays |

Key Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vitro Directed Differentiation of Motor Neurons

The directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) to motor neurons has served as a powerful model to isolate species-intrinsic timing mechanisms from extrinsic in vivo variables [20].

Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Mouse and human ESCs are first directed toward a posterior epiblast identity (neuromesodermal progenitors) using a species-specific pulse of WNT signaling (20h for mouse, 72h for human).

- Neural Induction and Patterning: Cells are subsequently exposed to two key morphogens:

- Retinoic Acid (RA): 100 nM RA is used as a neuralizing signal.

- Smoothened Agonist (SAG): 500 nM SAG is used to ventralize neural progenitors by activating the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signaling pathway.

- Monitoring Differentiation: The progression of the gene regulatory network is tracked over time using:

- Immunostaining: For key transcription factors like PAX6 (early progenitors), OLIG2 (motor neuron progenitors), and ISLET1/HLX1 (post-mitotic motor neurons).

- RT-qPCR: To quantitatively measure gene expression dynamics.

- Bulk Transcriptomics: To assess global changes in the transcriptome and calculate a scaling factor for developmental tempo.

This model recapitulated the in vivo tempo difference, with mouse cells expressing the post-mitotic marker ISLET1 within 2-3 days and human cells taking approximately 6 days, revealing a global transcriptomic scaling factor of 2.5 [20].

The Stem Cell Zoo and the Segmentation Clock

The segmentation clock, an oscillatory genetic network that controls the rhythmic formation of body segments, provides a quantifiable readout of developmental pace [24].

Experimental Protocol:

- Stem Cell Lines: Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) are derived from diverse mammalian species, including marmoset, rabbit, cattle, rhinoceros, mouse, and human.

- In Vitro Oscillation: PSCs are differentiated in vitro toward the presomitic mesoderm lineage to establish oscillating cultures.

- Period Measurement: The period of the core clock gene (e.g., HES7) oscillations is measured using live-cell imaging of reporter gene expression or periodic sampling for transcriptomic analysis.

- Correlation Analysis: The measured oscillation periods are correlated with species parameters such as adult body weight and total gestation/embryogenesis length.

This "stem cell zoo" approach demonstrated that the segmentation clock period scales with the length of embryogenesis, not with adult body size, and that the biochemical kinetics of clock gene products scale with the species-specific period [24].

Mechanisms Governing Developmental Tempo

The search for the cellular "pacemaker" has converged on several fundamental mechanisms.

Protein Turnover and Stability

A seminal study comparing mouse and human motor neuron differentiation found that differences in signaling or genomic sequence were not responsible for the 2.5-fold tempo difference [20]. Instead, global measurements revealed an approximately two-fold increase in protein stability in human cells compared to mouse cells. Mathematical modeling of the motor neuron GRN demonstrated that increasing the stability of its transcription factors was sufficient to slow the pace of the differentiation sequence, matching experimental observations [20] [21]. This suggests that the kinetics of protein degradation act as a master regulator for the speed of developmental transitions.

Metabolic Rate and Mitochondrial Function

Recent evidence points to a crucial role for mitochondrial metabolism as a modifier of developmental tempo. Studies have highlighted the role of mitochondrial metabolism in setting the developmental pace through its control over cellular bioenergetics and redox homeostasis [22] [23]. While the segmentation clock study found no evident correlation with gross cellular metabolic rates [24], more targeted investigations suggest that species-specific differences in mitochondrial function can influence the speed of biochemical networks central to developmental transitions [22].

Diagram: Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Mechanisms in Developmental Tempo

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the featured experiments, providing a resource for researchers seeking to implement these protocols.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Developmental Tempo

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) | In vitro model for developmental processes; source for directed differentiation. | Mouse and human ESCs for motor neuron differentiation [20]. |

| Pluripotent Stem Cells (PSCs) | Basis for "stem cell zoo" approach; allows cross-species comparison. | Marmoset, rabbit, cattle, rhinoceros PSCs for segmentation clock studies [24]. |

| Smoothened Agonist (SAG) | Small molecule agonist of the Shh pathway; used for ventral patterning of neural tissue. | Generation of motor neuron progenitors (pMN domain) [20]. |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | Signaling molecule for posteriorization and neural patterning. | Specification of spinal cord identity in motor neuron differentiation [20]. |

| HES7 Reporter Cell Line | Live-cell imaging of oscillatory gene expression in the segmentation clock. | Quantifying the period of somite formation across species [24]. |

| Antibodies for Key TFs | Immunostaining and tracking of differentiation progression. | Antibodies against PAX6, OLIG2, NKX2.2, ISLET1, HB9/MNX1 [20]. |

| (3S,4R)-Tofacitinib | (3S,4R)-Tofacitinib|Tofacitinib Impurity B | (3S,4R)-Tofacitinib (Tofacitinib Impurity B) is a less active isomer for JAK pathway research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| AZD 2066 | AZD 2066, CAS:934282-55-0, MF:C19H16ClN5O2, MW:381.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The objective comparison of experimental models reveals that developmental tempo is controlled by a combination of global cellular mechanisms, including protein turnover, metabolic rate, and biochemical kinetics. The consistent observation of a ~2-2.5 fold slower pace in human development compared to mouse across multiple systems provides a critical scaling factor for cross-species transcriptome analysis. For researchers in gastrulation and transcriptome conservation, these findings underscore that timing is not just an output but an integral, regulated component of the developmental program. Future work will likely focus on how these cellular pacemakers are themselves encoded in the genome and how their manipulation could impact disease modeling and regenerative medicine strategies where timing is crucial.

Lineage-Specific Adaptations and Ecological Influences on Gastrulation Programs

Gastrulation, the morphogenetic process that establishes the basic body plan, represents a fundamental and evolutionarily conserved phase in animal development. Despite its deep conservation, the molecular programs and cellular mechanisms governing gastrulation exhibit remarkable diversity across species, shaped by lineage-specific adaptations and ecological pressures. Recent comparative studies reveal that even morphologically similar gastrulation processes can be controlled by divergent gene regulatory networks (GRNs), a phenomenon known as developmental system drift [14]. This evolutionary dynamic demonstrates how conserved developmental outcomes can be achieved through different molecular means, highlighting the remarkable plasticity of embryonic development. Understanding the tension between morphological conservation and molecular divergence provides crucial insights into how embryonic development evolves in response to ecological constraints and contributes to species diversification.

The emergence of sophisticated transcriptomic technologies has enabled researchers to probe the molecular underpinnings of gastrulation across diverse species, from corals to mammals. These investigations reveal that while a conserved regulatory "kernel" of genes may underlie gastrulation across metazoans, the peripheral components of GRNs show substantial evolutionary flexibility [14]. This article synthesizes recent findings from comparative embryology and transcriptomics to examine how lineage-specific adaptations and ecological factors have shaped gastrulation programs across the animal kingdom, with implications for understanding evolutionary developmental biology and the origins of morphological diversity.

Comparative Gastrulation Strategies Across Species

Mechanisms of Germ Layer Internalization

The mode of mesendoderm internalization represents a major determinant of gastrulation morphology across species. Comparative analyses reveal a spectrum of strategies ranging from coherent epithelial movement to individual cell ingression:

Table 1: Modes of Mesendoderm Internalization During Gastrulation

| Internalization Mode | Description | Representative Organisms | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invagination | Bending of epithelial sheet inward | Sea urchins, Drosophila | Apical contraction, tissue buckling |

| Involution | Rolling inward through a slit-shaped opening | Xenopus | Telescoping cells, wave-like movement |

| Ingression | Individual cells undergoing EMT | Chick, mouse, human | Mesenchymal phenotype, single-cell motility |

| Multipolar Ingression | Ingression from multiple sites | Nematostella (perturbed) | Dispersed internalization sites |

The distinction between these modes often hinges on the extent to which cells undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Rather than representing a binary switch, EMT encompasses a spectrum of states with varying combinations of adhesion, polarity, and cytoskeletal components [25]. In organisms utilizing invagination or involution, cells maintain epithelial characteristics while coordinating shape changes, whereas in ingression-based gastrulation, cells transition to a mesenchymal state with individual motility.

Experimental evidence demonstrates the remarkable plasticity of these internalization mechanisms. In the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis, which normally employs invagination, disruption of the PAR polarity complex leads to disassembly of adherens junctions, causing cells to acquire a mesenchymal phenotype and internalize via ingression rather than invagination [25]. Similarly, when Nematostella embryos are dissociated and reaggregated, altering the embryonic geometry from a hollow sphere to a compact ball, the embryos utilize multipolar ingression from distinct sites rather than coherent invagination [25]. These findings suggest that transitions between gastrulation modes may not present insurmountable evolutionary constraints.

The Impact of Yolk Content on Gastrulation Morphology

Yolk volume represents a key ecological and developmental constraint influencing gastrulation morphology. Comparative studies across vertebrates reveal that increases in yolk content correlate with significant modifications to gastrulation:

- Anamniotes (e.g., fish, amphibians): Typically exhibit a ring-shaped mesoderm domain that surrounds the embryonic disc

- Amniotes (e.g., reptiles, birds, mammals): Develop a crescent-shaped mesoderm domain that concentrates at the posterior end [25]

This topological shift in mesoderm patterning, driven by differential yolk distribution, has profound implications for gastrulation mechanics. In yolk-rich embryos, the epiblast remains relatively flat during gastrulation, with mesoderm precursors ingressing as individual cells. In contrast, yolk-poor embryos often undergo dramatic morphogenetic movements that fold the entire blastoderm inward during involution-based gastrulation [25].

The transition from a reptilian blastoporal plate/canal to the avian primitive streak represents another key innovation in amniote gastrulation linked to yolk content [25]. This evolutionary modification enables the efficient internalization of mesoderm and endoderm precursors in the context of a large yolk mass, demonstrating how changes in developmental ecology drive modifications to gastrulation programs.

Molecular Programs Underlying Gastrulation Diversity

Conserved Kernels and Divergent Gene Regulatory Networks

Comparative transcriptomic analyses reveal that despite morphological conservation, gastrulation can be controlled by divergent GRNs. A study comparing two coral species of the genus Acropora (A. digitifera and A. tenuis) that diverged approximately 50 million years ago found that each species utilizes divergent transcriptional programs during gastrulation, despite the morphological similarity of the process [14]. This developmental system drift demonstrates how natural selection can shape distinct molecular pathways to achieve similar developmental outcomes.

Despite these divergences, researchers identified a subset of 370 differentially expressed genes that were up-regulated at the gastrula stage in both species, representing a potential conserved regulatory "kernel" with roles in axis specification, endoderm formation, and neurogenesis [14]. This core set of genes appears to be embedded within more flexible peripheral regulatory networks that exhibit species-specific modifications, including differences in paralog usage and alternative splicing patterns.

Table 2: Examples of Gene Family Evolution in Lineage-Specific Gastrulation Adaptations

| Gene Family/Pathway | Evolutionary Pattern | Functional Implications | Lineage Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GATA transcription factors | Conserved inner layer expression | Potential homology with eumetazoan endomesoderm | Sponges to mammals [26] |

| Montipora-specific gene families | Lineage-specific expansion, positive selection | Maternal symbiont transmission | Reef-building corals [27] |

| MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways | Upregulated in pig/monkey vs. mouse epiblast | Signaling pathway divergence | Mammalian comparative gastrulation [28] |

| Paralog pairs | Differential expression and neofunctionalization | GRN rewiring | Acropora coral species [14] |

The molecular toolkit for gastrulation appears to have deep evolutionary roots. Sponges, which lack definitive germ layers, nonetheless utilize gastrulation-like morphogenetic movements and express transcription factors such as GATA in their inner cell layer—a marker highly conserved in eumetazoan endomesoderm [26]. This suggests that the ancestral role of these regulatory genes in specifying internalized cells may predate the origin of true germ layers, with eumetazoan gastrulation evolving from pre-existing developmental programs used for simple patterning in the first multicellular animals.

Lineage-Specific Gene Family Evolution

Genomic comparisons highlight the importance of lineage-specific gene families in evolutionary divergence. In reef-building corals of the genus Montipora, which possess unusual biological traits including vertical transmission of algal symbionts, researchers found that lineage-specific gene families were significantly more numerous than in related Acropora species [27]. Evolutionary rates of these Montipora-specific gene families were significantly higher than other gene families, with 30 of 40 gene families under positive selection specifically detected in Montipora-specific gene families [27].

Notably, among these 30 Montipora-specific gene families under positive selection, 27 are expressed in early life stages [27]. This suggests that lineage-specific genes, particularly those expressed throughout early development, were important in establishing the genus Montipora and its unique symbiotic relationship. Similar lineage-specific genetic innovations likely underlie gastrulation modifications across diverse taxa, reflecting adaptations to specific ecological contexts and developmental strategies.

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Studying Gastrulation

Key Experimental Systems and Protocols

Understanding the diversity of gastrulation programs requires investigations across multiple model systems. Recent research has employed several key approaches:

Micropatterned Human Gastruloids: Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) cultured on confined micro-discs (500µm diameter) of extracellular matrix and stimulated with BMP4 for 44 hours reproducibly differentiate into radially organized cellular rings expressing markers of ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm, and trophectoderm, arranged from center to edge [29]. This 2D micropatterned system generates gastruloids containing cells transcriptionally similar to epiblast, ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm, primordial germ cells, trophectoderm, and amnion, as revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing [29].

Cross-Species Single-Cell Transcriptomics: Comparative single-cell RNA sequencing of gastrulating embryos from multiple species (e.g., pig, mouse, cynomolgus monkey) enables identification of conserved and divergent transcriptional programs [28]. Typical protocols involve:

- Embryo collection at precise developmental stages

- Tissue dissociation and single-cell suspension preparation

- Library preparation using platforms such as 10X Chromium

- Sequencing and bioinformatic analysis using tools like Seurat for integration and clustering

- Cross-species comparisons using high-confidence one-to-one orthologues

Cell Sorting Assays: To test conservation of cell sorting behaviors, gastruloids are dissociated and single cells are reseeded onto ECM micro-discs [29]. The resulting aggregation and segregation patterns (e.g., ectodermal cells segregating from endodermal and extraembryonic but mixing with mesodermal cells) reveal evolutionarily conserved sorting behaviors that may contribute to germ layer separation during gastrulation.

Theoretical and Computational Modeling: A theoretical framework incorporating two key parameters—one related to initial cell distribution and another related to cell behavior—can reproduce and predict gastrulation patterns in chicken embryos [30]. By modifying these parameters, researchers can generate patterns observed naturally in other species, revealing general biophysical principles underlying self-organized flows and forces during embryogenesis.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Gastrulation Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Function in Research | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMP4 | 2D micropatterned gastruloids | Induces radial differentiation pattern | Human gastruloid models [29] |

| Extracellular matrix micro-discs | Micropatterned cultures | Provides confined geometric patterning | Controlling colony size and organization [29] |

| CM-DiI | Cell lineage tracing | Plasma membrane dye for fate mapping | Sponge cell layer studies [26] |

| EdU (5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine) | Proliferation tracking | Thymidine analog for DNA labeling | Identifying proliferating cell populations [26] |

| scRNA-seq platforms (10X Chromium) | Transcriptomic profiling | High-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing | Cellular atlas generation across species [28] |

| TUNEL assay | Apoptosis detection | Labels DNA fragmentation | Studying programmed cell death during metamorphosis [26] |

Signaling Pathways and Cellular Behaviors in Gastrulation

The diversity of gastrulation strategies emerges from variations in conserved signaling pathways and cellular behaviors. Cross-species comparisons reveal both deeply conserved and lineage-specific elements of these programs.

Diagram 1: Signaling pathways and cellular behaviors in gastrulation. Conserved pathways (BMP4, WNT, NODAL) regulate cellular processes (EMT, cell sorting, apoptosis) to establish the three germ layers.

The balance between WNT and hypoblast-derived NODAL signaling appears particularly critical for fate determination during mammalian gastrulation. In pig embryos, soon after the first mesodermal cells appear in the posterior epiblast, a group of embryonic disc cells expressing FOXA2+ delaminate to give rise to definitive endoderm, differing from later FOXA2/TBXT+ cells that give rise to the node/notochord [28]. Both cell types form via a mechanism independent of mesoderm and do not undergo full EMT, highlighting lineage-specific variations in the cellular mechanisms of germ layer formation.

Cell sorting behaviors represent another conserved morphogenetic process during gastrulation. When cells from dissociated human gastruloids are re-aggregated in vitro, they segregate into their distinct germ layers, with ectodermal cells segregating from endodermal and extraembryonic cells but mixing with mesodermal cells [29]. This recapitulates behaviors first described in amphibian gastrulae by Holtfreter and colleagues, suggesting deep evolutionary conservation of differential adhesion and recognition mechanisms that ensure proper tissue boundary formation.

Implications for Evolutionary Developmental Biology and Biomedical Research

The diversity of gastrulation programs has significant implications for understanding evolutionary developmental biology and has practical applications in biomedical research:

Evolutionary Developmental Biology Insights:

- Developmental system drift allows for evolutionary change without disrupting essential developmental processes [14]

- The "hourglass model" of development, with conserved phylotypic stages and divergent early/late development, is supported by transcriptomic comparisons [14]

- Heterochrony (evolutionary changes in developmental timing) contributes to gastrulation diversity, as seen in marsupials where anterior structures initiate earlier and progress faster relative to eutherians [31]

Biomedical Applications:

- Understanding conserved cell sorting behaviors informs stem cell-based tissue engineering approaches

- Cross-species comparisons identify core regulatory programs relevant to human development and congenital disorders

- Gastruloid models provide ethical alternatives for studying early human development beyond technical and ethical limitations of human embryo research [29] [32]

The integration of stem cell technology and engineering tools has created unprecedented opportunities for studying human gastrulation. Pre-gastrulation models (e.g., blastoids), gastrulation models (2D micropatterned systems and 3D gastruloids), and post-gastrulation models (e.g., somitoids) together enable investigation into the peri-gastrulation stage of mammalian development [32]. These systems, enhanced by engineering technologies including micropatterned substrates, microfluidic systems, and synthetic biology tools, allow for precise manipulation and observation of developmental processes that are otherwise inaccessible in human embryos due to ethical constraints.

The study of lineage-specific adaptations and ecological influences on gastrulation programs reveals both remarkable conservation and striking diversity in the molecular and cellular mechanisms that establish the basic body plan across metazoans. While a conserved kernel of regulatory genes and cellular behaviors underlies gastrulation, peripheral components of gene regulatory networks show substantial evolutionary flexibility, enabling adaptations to diverse ecological contexts and developmental strategies.

Recent advances in single-cell transcriptomics, theoretical modeling, and in vitro gastruloid systems have provided unprecedented insights into the evolutionary dynamics of gastrulation. These approaches demonstrate how changes in gene expression, cell behavior, and embryonic geometry can shift gastrulation modes, revealing the principles by which self-organization emerges during embryogenesis. As research continues to integrate comparative embryology with molecular biology and biophysics, we move closer to a comprehensive understanding of how developmental processes evolve and how ecological pressures shape embryonic development across the animal kingdom.

Advanced Computational and Single-Cell Technologies for Cross-Species Analysis

Single-cell multi-omics technologies have revolutionized comparative biology by enabling the simultaneous measurement of multiple molecular layers within individual cells. This approach is particularly transformative for cross-species investigations, where it can disentangle conserved developmental programs from species-specific adaptations. In gastrulation research—the process wherein the three primary germ layers form—these technologies reveal how epigenetic landscapes, transcriptional networks, and cellular differentiation pathways are evolutionarily conserved or diverged. By integrating single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), single-cell ATAC-seq (scATAC-seq), and other modalities, researchers can now construct detailed cellular atlases across species, comparing the fundamental processes of early development at unprecedented resolution. This guide examines the performance of leading single-cell multi-omics platforms and integration methods, providing experimental data and protocols essential for cross-species gastrulation and organogenesis research.

Experimental Approaches for Cross-Species Multi-omics

Core Methodologies and Workflows

Cross-species single-cell multi-omics relies on sophisticated wet-lab and computational approaches. The typical workflow begins with single-cell isolation using microfluidics (e.g., 10X Genomics Chromium) or combinatorial indexing, followed by library preparation where molecules are tagged with cell-specific barcodes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to track cell origin and quantify original molecule abundance [33]. For simultaneous transcriptome and epigenome profiling, single-cell multiome protocols (e.g., 10X Multiome) sequence both RNA and accessible chromatin from the same cell.

Critical to cross-species applications is experimental design that accounts for developmental tempo differences. As demonstrated in a multimodal cross-species comparison of pancreas development, aligning developmental milestones across gestation periods is essential—for example, pancreatic morphogenesis occupies 42% of gestation in mice versus 82% in humans and 65% in pigs [34]. This temporal alignment ensures comparable biological stages are being compared.

Cross-Species Integration Computational Strategies

Computational integration of cross-species data presents distinct challenges. Methods include:

- Unpaired integration (e.g., LIGER, Seurat v3) for data from the same tissue but different cells/species

- Paired integration (e.g., scMVP, MOFA+) for multi-omics data profiling the same cell

- Paired-guided integration (e.g., MultiVI, Cobolt) using paired multi-omics data to assist unpaired data integration [35]

These methods employ various mathematical approaches, including integrative non-negative matrix factorization (iNMF), canonical correlation analysis (CCA), variational autoencoders, and manifold alignment to align cells across species and modalities in a unified latent space.

Platform and Method Comparison

Experimental Platform Capabilities

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Cell Multi-omics Platforms

| Platform/Assay | Measured Modalities | Throughput (Cells/Run) | Key Applications | Species Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10X Genomics Chromium Multiome | RNA + ATAC from same cell | Up to 80,000 nuclei | Gene expression + chromatin accessibility mapping | Species-agnostic [36] |

| 10X Genomics Chromium Flex | Gene expression + protein | Up to 8M cells (1-3,072 samples) | Low-quality and FFPE samples | Species-agnostic [36] |

| scNMT-seq | RNA + DNA methylation + chromatin accessibility | Hundreds to ~1,000 cells | Triple-omics developmental studies | Demonstrated in mouse [37] |

| Single-cell CoBATCH | H3K27ac + H3K4me1 histone marks | 3,000+ cells | Enhancer dynamics during development | Demonstrated in mouse [38] |

Integration Algorithm Performance

Table 2: Benchmarking of Multi-omics Integration Methods for Cross-Species Applications

| Method | Category | Basic Principle | Accuracy (AUROC) | Scalability | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scMKL | Multimodal classification | Multiple kernel learning with biological priors | 0.89-0.95 (superior to benchmarks) | High (O(N) complexity) | High (direct pathway weights) [39] |

| LIGER | Unpaired integration | Integrative non-negative matrix factorization (iNMF) | High cell type conservation | Moderate | Moderate [35] |

| MOFA+ | Paired integration | Variational inference | Good for trajectory conservation | Moderate | Moderate [35] |

| scDART | Unpaired integration | Non-linear gene activity function | Good omics mixing | Moderate | Moderate [35] |

| GLUE | Unpaired integration | Knowledge-based graph + adversarial alignment | High cell type conservation | Moderate | High (incorporates prior knowledge) [35] |

A comprehensive benchmark of 12 integration methods across multiple datasets revealed that no single method excels in all aspects, but performance can be selected based on specific research goals [35]. Methods were evaluated based on omics mixing, cell type conservation, trajectory preservation, and scalability.

Key Experimental Protocols

Cross-Species Pancreas Development Analysis

Sample Preparation: Collect pancreatic tissue from mice, pigs, and humans across equivalent developmental stages based on gestational timing percentages [34]. Dissociate tissues to single-cell suspensions using optimized enzymatic protocols.

Multiome Library Preparation: Use 10X Genomics Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression kit following manufacturer's protocol. For cross-species applications, ensure reference genomes are available for all species. Load approximately 80,000 nuclei per lane.

Sequencing: Sequence libraries on Illumina platforms with recommended coverage: ≥20,000 read pairs per nucleus for ATAC and ≥10,000 read pairs per cell for gene expression.

Data Integration: Process species separately through cellranger-arc pipeline, then integrate using LIGER or Harmony to align homologous cell types. Identify conserved and species-specific gene regulatory networks.

Gastrulation Epigenomic Mapping

Embryo Collection: Collect mouse embryos at precise stages from E6.0 to E7.5 (Pre-Primitive Streak to Early Headfold stages) [38]. Microdissect to isolate embryonic regions.

Single-cell ChIP-seq: Perform CoBATCH for H3K27ac and H3K4me1 using ~500-1,000 cells per stage. Use barcoded Tn5 transposase preloaded with protein A-Tn5 fusion and antibodies.

Multimodal Analysis: Integrate with matched scRNA-seq data using MOFA+ to identify factors corresponding to germ layer specification. Validate enhancer-gene associations through motif enrichment and correlation analysis.

Research Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Cross-Species Multi-omics

| Category | Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platform | 10X Genomics Chromium | Single-cell partitioning and barcoding | High-throughput cell atlas generation [36] |

| Computational Tool | Single-cell Analyst | Web-based multi-omics analysis platform | Accessible analysis for non-computational researchers [40] |

| Integration Method | scMKL | Interpretable multimodal classification | Identifying key pathways in cross-species comparisons [39] |

| Reference Database | JASPAR/Cistrome | TF binding site annotations | Linking chromatin accessibility to regulatory networks [39] |

| Gene Set Resource | MSigDB Hallmark | Curated biological pathways | Biologically informed kernel construction in scMKL [39] |

| PAR 4 (1-6) (human) | PAR 4 (1-6) (human), MF:C28H41N7O9, MW:619.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| ZD 2138 | Potent AKT Inhibitor|RUO|6-[[3-Fluoro-5-(4-methoxyoxan-4-yl)phenoxy]methyl]-1-methylquinolin-2-one | This compound is a potent, selective AKT inhibitor for cancer research. 6-[[3-Fluoro-5-(4-methoxyoxan-4-yl)phenoxy]methyl]-1-methylquinolin-2-one is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathways and Biological Insights

Conserved Regulatory Networks in Gastrulation

Figure 1: Germ Layer Specification Epigenetic Dynamics. Research shows ectoderm enhancers are epigenetically primed in the epiblast (remaining hypomethylated and accessible), while mesoderm and endoderm enhancers undergo active remodeling (demethylation and accessibility increase) during gastrulation [38] [37]. This hierarchical emergence explains the molecular logic of germ layer specification.

Cross-Species Endocrine Development

Figure 2: Cross-Species Endocrine Differentiation Pathway. Studies reveal pigs resemble humans more closely than mice in developmental tempo, with over 50% conservation of transcription factors regulated by NEUROG3 (endocrine master regulator) between pig and human [34]. Emerging beta-cell heterogeneity coincides with a species-conserved primed endocrine cell population alongside NEUROG3-expressing cells.

Single-cell multi-omics technologies have fundamentally enhanced our ability to resolve cellular heterogeneity across species, providing unprecedented insights into evolutionary developmental biology. The integration of transcriptomic, epigenomic, and other molecular data at single-cell resolution has revealed both deeply conserved and species-specific aspects of gastrulation and organogenesis. As the field advances, improvements in scalability, multimodal integration, and computational interpretability will further empower cross-species investigations. The methods and comparisons presented here provide a foundation for selecting appropriate technologies and analytical approaches for specific research questions in comparative developmental biology.

Cross-species comparison of single-cell transcriptomic profiles represents a powerful approach for understanding the evolutionary conservation and diversification of developmental programs. This is particularly crucial for studying early developmental processes like gastrulation, where direct experimental access to human embryos is limited. Computational imputation tools have emerged as essential resources for transferring knowledge from model organisms to humans, enabling scientists to predict cellular behaviors and molecular pathways across species boundaries. These methods must overcome significant challenges including data sparsity, batch effects, and the inherent difficulty of matching individual cells across evolutionary distances.

Within this field, Icebear stands out as a specialized neural network framework designed explicitly for cross-species prediction at single-cell resolution. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of Icebear against other computational approaches, with a specific focus on applications in gastrulation research. We present experimental data, methodological details, and practical resources to help researchers select appropriate tools for their cross-species investigations of developmental biology.

Icebear employs a sophisticated neural network framework that decomposes single-cell RNA sequencing measurements into disentangled factors representing cell identity, species-specific effects, and batch variations [41]. This factorization enables two primary functionalities: accurate prediction of single-cell gene expression profiles across species, and direct comparison of expression patterns for evolutionarily conserved genes [42].

The model's architecture is specifically designed to address the challenge of cross-species cell matching by learning species-invariant representations of cell states while simultaneously capturing species-specific expression patterns [41]. This approach allows researchers to "translate" cellular profiles from well-characterized model organisms (e.g., mouse) to less-accessible species (e.g., human), particularly valuable for studying early developmental processes like gastrulation. Icebear has demonstrated practical utility in predicting transcriptomic alterations in human Alzheimer's disease from mouse models, highlighting its potential for transferring insights across species [41].

Table: Icebear Technical Specifications and Applications

| Feature | Specification | Application in Gastrulation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Core Methodology | Neural network with factor decomposition | Disentangles developmental stage from species effects |

| Species Compatibility | Mammals (human, mouse, opossum) and birds (chicken) | Comparative analysis of gastrulation across evolutionary distances |

| Input Data | Single-cell RNA sequencing profiles | Characterization of emergent cell states during early development |

| Primary Output | Imputed expression profiles for missing species/cell types | Prediction of human gastrulation pathways from model organisms |

| Unique Advantage | Single-cell resolution comparisons without requiring cell type annotations | Identification of novel transitional states in early development |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Benchmarking Against Alternative Approaches

When evaluated against traditional methods for cross-species analysis, Icebear demonstrates distinct advantages, particularly in scenarios requiring single-cell resolution prediction. Conventional approaches typically perform cross-species comparison at the cell type level after clustering and annotation, which introduces dependencies on accurate cell type calling and matching across species [41]. This limitation becomes particularly problematic when studying dynamic processes like gastrulation, where cells exist in transitional states that defy discrete classification.

Icebear's performance has been validated through several experimental applications. In one study focusing on X-chromosome evolution, Icebear successfully predicted and compared gene expression changes across eutherian mammals (mouse), metatherian mammals (opossum), and birds (chicken) [41]. The model managed to integrate single-cell expression profiles across species, batch, and tissue types, demonstrating its robustness to technical variations while capturing biologically meaningful signals.

Another significant advantage is Icebear's ability to make predictions for missing biological contexts. For example, the tool can impute expression profiles for cell types or developmental stages that are not experimentally accessible in certain species, making it particularly valuable for studying early human development where sample availability is limited [41].

Comparison with CytoTRACE 2 for Developmental Potential Assessment

While Icebear specializes in cross-species imputation, CytoTRACE 2 represents another neural network approach with complementary applications in developmental biology. CytoTRACE 2 is an interpretable deep learning framework designed to predict cellular developmental potential from single-cell RNA sequencing data [43]. Rather than focusing on cross-species translation, it specializes in reconstructing developmental hierarchies within a single organism.

The tool employs a novel architecture called gene set binary networks (GSBNs) that assign binary weights (0 or 1) to genes, identifying highly discriminative gene sets that define each potency category [43]. This design provides inherent interpretability, allowing researchers to extract biologically meaningful gene signatures associated with different potency states—from totipotent cells capable of generating entire organisms to fully differentiated cells with restricted potential.

In benchmark evaluations across 33 datasets spanning nine tissue systems and seven platforms, CytoTRACE 2 outperformed eight state-of-the-art machine learning methods for cell potency classification, achieving higher median multiclass F1 scores and lower mean absolute error [43]. It also surpassed eight developmental hierarchy inference methods, demonstrating over 60% higher correlation on average for reconstructing relative orderings in 57 developmental systems [43].

Table: Performance Comparison of Icebear and Alternative Methods

| Method | Primary Function | Cross-Species Capability | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Icebear | Cross-species imputation and comparison | Direct capability | Single-cell resolution, no need for cell type annotations | Limited validation in non-mammalian systems |

| CytoTRACE 2 | Developmental potential assessment | Indirect (via conserved signatures) | Interpretable architecture, continuous potency scores | Not designed for cross-species prediction |

| Traditional Alignment Methods | Cell type matching | Requires 1:1 cell type correspondence | Simple implementation, intuitive results | Loses single-cell resolution, dependent on annotation quality |

| Bulk Tissue Comparisons | Tissue-level expression comparison | Limited by cellular heterogeneity | Established methods, comprehensive gene coverage | Obscures cell-type-specific differences |

Experimental Data and Validation

Key Experimental Protocols