Decoding Hox-Mediated Skeletal Transformations: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Insights

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with the complexities of interpreting Hox gene function in skeletal patterning.

Decoding Hox-Mediated Skeletal Transformations: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Insights

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with the complexities of interpreting Hox gene function in skeletal patterning. It synthesizes foundational principles of Hox-mediated positional identity with cutting-edge methodological approaches, including single-cell transcriptomics, epigenomic profiling, and functional genomics. We address key interpretation challenges such as functional redundancy, paralog specificity, and trans-regulatory effects, while offering troubleshooting strategies for common experimental pitfalls. The content integrates validation frameworks from comparative models and highlights emerging therapeutic implications for HOX-related skeletal disorders and regenerative medicine applications, providing a roadmap for future research and clinical translation.

The Hox Skeletal Code: Unraveling Molecular Principles of Axial Patterning

Hox Gene Organization and Spatiotemporal Collinearity in Vertebrate Development

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: My data on Hox gene temporal expression appears inconsistent or does not show a clear collinear pattern. What could be the issue?

- Problem: Inconsistent detection of temporal collinearity.

- Solution: Ensure you are analyzing the initial phase of Hox gene expression during gastrula-neurula-tailbud stages. Later expression phases, which involve different tissues and functions, can obscure the collinear sequence [1]. Use in situ hybridization to detect expression in specific tissues like the non-organizer mesoderm or presomitic mesoderm, as RNA-seq methods can mask weak initial expression phases if subsequent phases are stronger [1].

- Prevention: Design time-course experiments with a focus on very early development. Normalized measures like half-maximal expression on total RNA-seq time courses may not be ideal for assessing temporal collinearity [1].

Q2: Why do my Hox gene knockout experiments in vertebrates not yield the expected homeotic transformations?

- Problem: Subtle or absent phenotypes in single Hox gene knockouts.

- Solution: Consider functional redundancy from paralogous genes. In vertebrates, due to cluster duplication, paralogous genes (e.g., Hoxa11 and Hoxd11) often have overlapping functions [2]. You may need to generate double or triple mutants for paralogous groups to observe dramatic phenotypes [2].

- Prevention: Review the paralogous group of your target Hox gene and design experiments to target multiple paralogs simultaneously, for example, using CRISPR-Cas9 to target conserved regions.

Q3: I have identified an evolved change in a Hox gene's expression, but introducing the ancestral allele does not produce the predicted phenotypic effect. Why?

- Problem: Epistatic interactions within the Hox-regulated network mask the effect of the individual allele [3].

- Solution: The phenotypic output of a Hox gene is determined by its position within a larger genetic network. Map the expression and function of key downstream targets in your system. In Drosophila santomea, for example, changes in other pigmentation genes (e.g., yellow, tan, ebony) made them insensitive to the Hox protein Abd-B, masking the effect of an introgressed ancestral Abd-B allele [3].

- Prevention: When studying Hox gene evolution, conduct reciprocal hemizygosity tests in hybrid backgrounds to reveal cryptic allelic effects before concluding that a Hox gene change is non-functional [3].

Q4: How can I effectively study the function of a specific Hox gene given its clustered nature and shared regulatory elements?

- Problem: Complexity of regulatory elements and potential for shared enhancers.

- Solution: Be aware that enhancer sharing between adjacent Hox genes is common. For instance, in Drosophila, the iab-5 regulatory region regulates both abd-A and Abd-B, and in mice, the CR3 enhancer regulates both Hoxb4 and Hoxb3 [4]. Use high-resolution techniques like chromosome conformation capture (3C) to map the specific 3D architecture and long-range contacts governing your gene of interest [5].

- Prevention: When interpreting knockout or mutation data, consider the potential impact on neighboring genes within the cluster due to disrupted shared regulatory elements.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is Hox spatiotemporal collinearity, and why is it important?

A: Spatiotemporal collinearity is a fundamental property of Hox genes in many bilaterians. It describes two ordered patterns: Spatial collinearity means the order of Hox genes on the chromosome corresponds to their expression domains along the embryo's anterior-posterior (A-P) axis [4] [6]. Temporal collinearity means the same gene order also corresponds to their sequential activation in time, with anterior genes expressed before posterior ones [4] [7]. This process is crucial for properly patterning the A-P body plan, as the temporal sequence is thought to lay the basis for the spatial pattern [1].

Q: Does temporal collinearity definitively exist in all vertebrates?

A: While some studies have questioned its existence, a substantial body of evidence supports that temporal collinearity is a general rule in vertebrates [1]. Comprehensive studies examining up to 34 Hox genes in chicken, catshark, lamprey, and hagfish, as well as 9 genes in Xenopus, have demonstrated whole-cluster temporal collinearity [1]. Apparent conflicts in the data can often be resolved by focusing on the initial phase of Hox expression in specific embryonic tissues during early development [1].

Q: How do Hox genes specify different regional identities along the axis?

A: Hox genes confer regional identity through a combinatorial code [6]. The specific set or "blend" of Hox genes expressed in a segment or region defines its identity, directing it to develop as a head, thorax, or abdomen segment, or in vertebrates, to form specific types of vertebrae [2]. This is achieved because Hox proteins are transcription factors that regulate distinct sets of downstream target genes, activating or repressing genetic programs for building specific structures [2].

Q: What is the evidence that Hox gene regulation is key to evolutionary changes in body plans?

A: Correlations between shifts in Hox expression domains and morphological changes in serially homologous structures (like vertebrae or insect segments) are widespread [3]. Experimental evidence includes the fact that in snakes, Hox10 genes have lost their rib-blocking ability, which may contribute to their elongated, multi-ribbed body plan [2]. However, evolution often involves polygenic changes, where modifications in a Hox gene are accompanied by changes in its downstream network, which can epistatically mask the Hox gene's individual effect [3].

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

Quantitative Evidence for Temporal Collinearity

The table below summarizes key evidence from studies that support the existence of temporal collinearity in various vertebrate and chordate models.

Table 1: Experimental Evidence for Hox Temporal Collinearity Across Species

| Species | Number of Hox Genes Examined | Key Tissues for Initial Expression | Experimental Method | Primary Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken | 34 | Primitive streak, ingressing mesoderm, presomitic mesoderm | In situ hybridization | [1] |

| Xenopus | 9 | Gastrula non-organizer mesoderm (NOM), presomitic mesoderm | In situ hybridization | [1] |

| Mouse | 12 | Presomitic mesoderm, nascent somites | In situ hybridization, RT-PCR | [1] |

| Catshark | 34 | Presomitic mesoderm | In situ hybridization | [1] |

| Lamprey | 34 | Presomitic mesoderm | In situ hybridization | [1] |

| Branchiostoma (Cephalochordate) | 12 | Presomitic mesoderm | In situ hybridization | [1] |

Core Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Hox Expression via In Situ Hybridization

This protocol is critical for detecting the precise spatial and temporal expression of Hox genes during early development [1].

Probe Synthesis:

- Cloning: Clone a unique, gene-specific fragment (typically 500-1500 bp) of the target Hox gene from genomic DNA or cDNA into a plasmid vector with RNA polymerase promoters (e.g., T7, T3, SP6).

- Transcription: Linearize the plasmid and use the appropriate RNA polymerase to synthesize a digoxigenin (DIG)- or fluorescein-labeled antisense RNA probe in vitro. Purify the probe.

Embryo Collection and Fixation:

- Collect embryos at precise developmental stages (gastrula, neurula, early tailbud) when temporal collinearity is expected to occur.

- Fix embryos immediately in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for several hours at 4°C to preserve RNA and morphology.

Pre-hybridization and Hybridization:

- Rehydrate fixed embryos through a methanol series and permeabilize with proteinase K.

- Pre-hybridize embryos in a hybridization buffer containing formamide, salts, and carrier DNA/RNA to reduce non-specific binding.

- Incubate embryos with the labeled antisense probe in hybridization buffer at 55-65°C for 12-48 hours.

Washing and Antibody Binding:

- Perform a series of stringent washes with saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer containing formamide to remove unbound probe.

- Block non-specific sites with a blocking reagent (e.g., sheep serum, BSA).

- Incubate with an anti-DIG or anti-fluorescein antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (AP).

Colorimetric Detection:

- Wash embryos thoroughly to remove unbound antibody.

- Incubate in an AP substrate solution (e.g., NBT/BCIP) which produces an insoluble colored precipitate where the probe is bound.

- Monitor the reaction and stop it by washing with PBS when the signal is clear and background is low.

Imaging and Analysis:

- Image embryos using a stereomicroscope. Document the temporal sequence of Hox gene activation and the spatial boundaries of expression in tissues like the presomitic mesoderm.

Core Experimental Protocol: Reciprocal Hemizygosity Test

This genetic test is used to determine if an evolutionary difference in a phenotype is caused by cis-regulatory changes in a specific gene, such as a Hox gene [3].

Generate Mutant Alleles:

- Use CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homology-directed repair to delete or disrupt a specific candidate cis-regulatory element (e.g., the IAB5 initiator for Abd-B) in the genomes of two different species (or populations), Species A and Species B. Replace the element with a neutral marker like RFP.

Create Hybrid Crosses:

- Cross a female from Species A (carrying the mutant allele, A-/-) with a male from Species B (wild-type, B/B). The progeny will be hemizygous for the functional B allele (A-/- / B).

- Perform the reciprocal cross: a female from Species B (mutant, B-/-) with a male from Species A (wild-type, A/A). The progeny will be hemizygous for the functional A allele (B-/- / A).

Phenotypic Analysis:

- Compare the phenotype (e.g., pigmentation intensity, gene expression via in situ) between the two groups of hybrid progeny.

- Interpretation: A phenotypic difference between the two hemizygote groups is attributed to a functional difference between the wild-type alleles of the gene from Species A and Species B, demonstrating that evolution has occurred in that gene's cis-regulation.

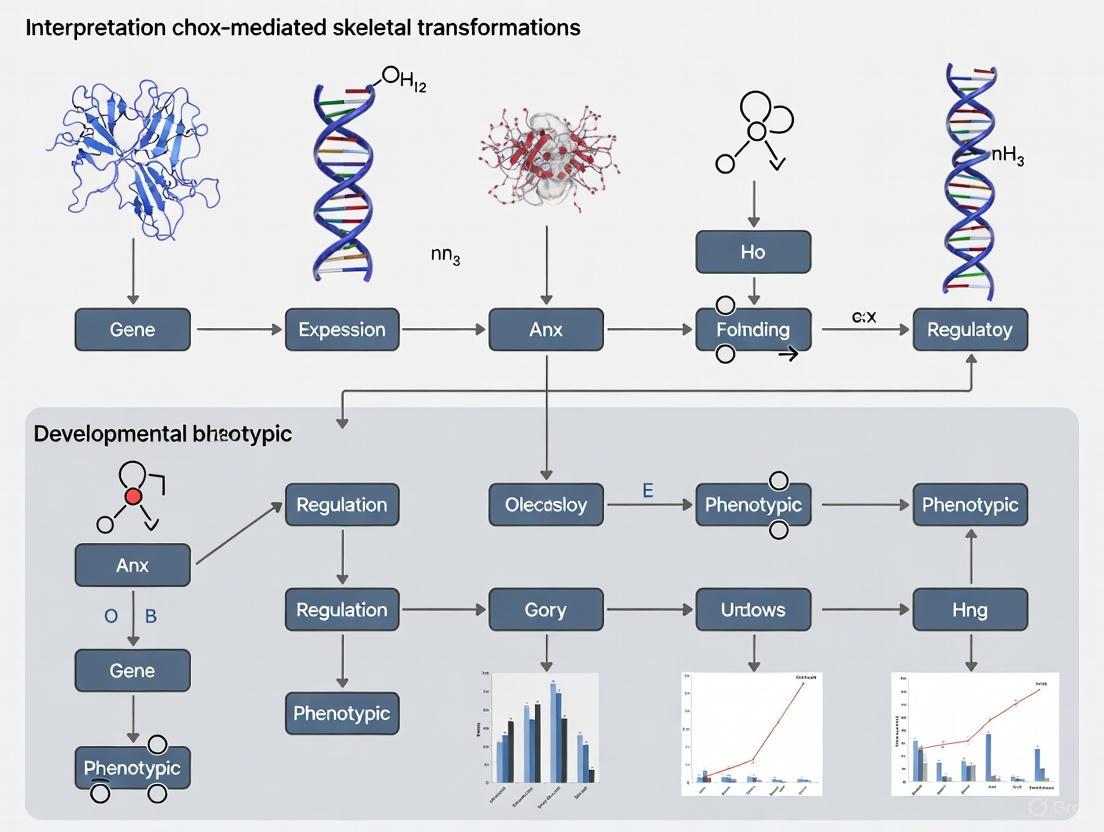

Diagram 1: Hox Time-Space Translation (TST) Hypothesis. This model illustrates how the temporal sequence of Hox gene expression is converted into a spatial pattern along the anterior-posterior axis, a process influenced by signals from the Spemann organizer [1].

Diagram 2: Chromatin-Based Regulation of Hox Genes. A Hox gene's expressibility is governed by its chromatin state, maintained by Polycomb (repressive) and Trithorax (activating) complexes, which is heritable during cell division [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Studying Hox Gene Function and Expression

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 with HDR | Precise genome editing for gene knockout or allele replacement. | Generating deletions in specific Hox cis-regulatory elements (e.g., IAB5) to test their function in vivo [3]. |

| In Situ Hybridization Probes | Detect and visualize the spatial and temporal localization of Hox mRNA transcripts. | Mapping the expression domains of multiple Hox genes during early embryogenesis to establish collinearity [1]. |

| Antibodies against Hox Proteins | Detect and visualize Hox protein localization and abundance. | Confirming the presence and nuclear localization of Hox transcription factors in specific embryonic regions. |

| Chromatin Conformation Capture (3C) | Map the 3D architecture of the genome and identify long-range DNA interactions. | Identifying physical loops and enhancer-promoter contacts within the silent or active Hox cluster [5]. |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | A potent morphogen that can anteriorize or posteriorize Hox expression patterns. | Experimentally shifting Hox expression domains in cell culture (e.g., NT2/D1 cells) or whole embryos to study gene function [5]. |

| Transgenic Reporter Constructs | Assess the regulatory potential of DNA sequences in vivo. | Testing the activity of conserved non-coding sequences (e.g., from iab-5 region) to identify enhancers [3]. |

| GBR 12783 | GBR 12783, MF:C28H34Cl2N2O, MW:485.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PS121912 | PS121912, MF:C24H21F3N2O, MW:410.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Positional Identity and the Combinatorial Hox Code in Skeletal Patterning

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support resource addresses common experimental challenges in interpreting Hox-mediated skeletal transformations, providing practical solutions for researchers and drug development professionals.

FAQ 1: Why don't my single Hox gene knockouts show expected skeletal transformations?

Issue: Researchers often observe minimal or no phenotype in single Hox gene knockout experiments, contrary to expected homeotic transformations based on expression patterns.

Explanation: Hox genes exhibit significant functional redundancy due to their paralogous organization. In vertebrates, the 39 Hox genes are organized into four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, HoxD) with 13 paralogous groups. Members within a paralogous group share similar expression domains and often compensatory functions [8] [9].

Solution: Implement paralogous group knockout strategies targeting all members of a specific paralogous group.

Table: Functional Redundancy in Hox Paralogous Groups

| Paralogous Group | Cluster Members | Single Knockout Phenotype | Complete Paralog Knockout Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox5 | Hoxa5, Hoxb5, Hoxc5 | Mild or partial transformations [9] | Complete anterior transformation of T1 to C7 [9] |

| Hox6 | Hoxa6, Hoxb6, Hoxc6 | Variable effects [9] | Complete transformation of T1 to C7 [9] |

| Hox10 | Hoxa10, Hoxc10, Hoxd10 | Partial transformations [8] | Severe stylopod mis-patterning [8] |

| Hox11 | Hoxa11, Hoxc11, Hoxd11 | Zeugopod defects [8] | Severe zeugopod mis-patterning [8] |

Experimental Protocol: For comprehensive Hox10 paralog analysis:

- Generate Hoxa10 / -; Hoxc10 / -; Hoxd10 / - triple mutant mice

- Analyze E18.5 embryos for skeletal patterning using Alcian Blue and Alizarin Red staining

- Focus on stylopod elements (humerus/femur) where Hox10 function is predominant [8]

- Compare vertebral morphology across anterior-posterior axis for homeotic transformations

FAQ 2: How do I properly interpret and validate homeotic transformations?

Issue: Inconsistent interpretation of vertebral identity changes in Hox mutant models.

Explanation: Homeotic transformations in vertebrates typically manifest as anterior transformations where vertebrae assume the morphology of a more anterior segment, unlike Drosophila where transformations can be bidirectional [8] [10]. This occurs because loss of Hox function results in patterning by the remaining anterior Hox genes in the region.

Solution: Establish precise morphological criteria for vertebral identification.

Table: Vertebral Identity Markers for Homeotic Transformation Analysis

| Vertebral Region | Key Morphological Distinctions | Hox Code Responsible |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical (C1-C7) | Absence of ribs, transverse foramen | Hox4, Hox5 [11] |

| Thoracic (T1-T13) | Presence of articular facets for ribs | Hox6, Hox9 [9] |

| Lumbar | Large body, short thick processes | Hox10 [9] |

| Sacral | Fusion points for pelvic articulation | Hox10, Hox11 [9] |

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Ambiguous vertebral identity in cervicothoracic transition

- Solution: Use rib development as primary marker; in mice, T1-T7 connect to sternum while cervical vertebrae lack ribs [9]

- Problem: Incomplete penetrance of transformation

- Solution: Quantify transformation percentage across multiple litter replicates (n≥5 embryos)

- Validation: Combine skeletal preparation with Hox expression analysis via RNA in situ hybridization [12]

FAQ 3: What techniques can resolve Hox expression patterns at high resolution?

Issue: Traditional methods lack cellular resolution for analyzing the combinatorial Hox code across multiple cell types.

Explanation: The Hox code operates in a cell-type-specific manner, with recent single-cell technologies revealing unexpected complexity in Hox expression patterns [12].

Solution: Implement single-cell RNA sequencing with spatial validation.

Experimental Protocol: Single-cell RNA-seq for Hox Code Mapping

- Tissue Preparation: Dissect spine from E12.5-E15.5 mouse embryos into precise anatomical segments

- Single-cell Suspension: Generate single-cell suspensions using gentle enzymatic digestion (Collagenase II, 1mg/mL, 37°C, 20 min)

- Library Preparation: Use droplet-based scRNA-seq (10X Genomics Chromium)

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Cluster cells by type and quantify Hox expression per cluster

- Spatial Validation: Validate with Visium spatial transcriptomics or in situ sequencing [12]

Key Finding: Recent human fetal spine atlas revealed that neural crest derivatives retain the anatomical Hox code of their origin while adopting the code of their destination [12].

Hox Expression Analysis Workflow

FAQ 4: How do I address limb patterning defects in Hox mutants?

Issue: Limb defects in Hox mutants often reflect patterning errors rather than simple tissue loss.

Explanation: Posterior Hox paralogs (Hox9-13) pattern the limb skeleton along the proximodistal axis in discrete, non-overlapping domains, unlike the overlapping function in axial patterning [8].

Solution: Focus on segment-specific analyses and utilize the unique limb Hox code.

Table: Limb Segment Patterning by Hox Genes

| Limb Segment | Skeletal Elements | Required Hox Genes | Loss-of-Function Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stylopod | Humerus/Femur | Hox10 | Severe stylopod mis-patterning [8] |

| Zeugopod | Radius/Ulna, Tibia/Fibula | Hox11 | Severe zeugopod mis-patterning [8] |

| Autopod | Hand/Foot bones | Hox13 | Complete loss of autopod elements [8] |

Experimental Insight: For forelimb positioning, Hox4/5 genes provide permissive signals throughout the neck region, while Hox6/7 provide instructive cues determining final forelimb position [11].

Hox-Mediated Limb Segment Patterning

FAQ 5: Why do I see different Hox phenotypes across tissue types?

Issue: The same Hox mutation produces different phenotypes in various tissues.

Explanation: Hox genes regulate context-specific genetic networks rather than a conserved set of targets across all tissues [13].

Solution: Perform tissue-specific transcriptomic analyses.

Experimental Approach:

- Collect multiple tissues from Hox mutants (e.g., lung, trachea, somites, BAT)

- Perform bulk RNA-seq on each tissue

- Identify differentially expressed genes

- Validate tissue-specific targets

Key Finding: Bulk RNA-seq in Hoxa5 mutants revealed few common transcriptional changes across tissues, suggesting HOXA5 regulates context-specific effectors rather than a conserved gene set [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Skeletal Patterning Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Models | Paralogous group mutants (e.g., Hoxa5 / -;Hoxb5 / -;Hoxc5 / -) | Addressing functional redundancy [9] | Requires complex breeding strategies; analyze at E18.5 |

| Skeletal Stains | Alcian Blue (cartilage), Alizarin Red (bone) | Visualization of skeletal elements | Optimal at E16.5-E18.5 for embryonic patterning |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | 10X Visium, Cartana ISS | Mapping Hox expression in tissue context [12] | 50μm resolution; validate with ISS for single-cell resolution |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | 10X Chromium | Resolving Hox code across cell types [12] | Process fresh tissue; sequence depth >50,000 reads/cell |

| Lineage Tracing | Cre-lox systems with Hox-specific promoters | Fate mapping of Hox-expressing populations | Use Hox-CreER[T2] for inducible tracing |

| Inhibition/Activation | Dominant-negative Hox constructs [11] | Perturbing Hox function in specific domains | Electroporate into dorsal LPM at HH12 for limb studies |

Advanced Technical Considerations

Integrating Positional Information Concepts

The concept of positional information is fundamental to understanding Hox function. Cells acquire positional identities through morphogen gradients, and Hox genes translate this information into region-specific morphology [14] [10]. Modern tools like MorphoGraphX 2.0 enable quantification of gene expression and growth in the context of these positional coordinate systems [15].

Regulatory Mechanisms in Hox Clusters

Hox gene regulation involves complex mechanisms:

- Collinearity: 3' to 5' gene order correlates with anterior to posterior expression [16]

- RAREs: Retinoic acid response elements embedded within Hox clusters coordinate responses to signaling gradients [16]

- Enhancer Sharing: Cis-regulatory elements can regulate multiple Hox genes within a cluster [16]

Understanding these mechanisms is essential for designing experiments that accurately perturb Hox function without disrupting core regulatory architecture.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental paradox of Hox protein specificity? Hox transcription factors bind to highly similar, AT-rich DNA sequences in vitro (e.g., core motifs like TAAT), yet they perform exquisitely specific functions in vivo, directing the formation of different structures along the anterior-posterior axis. This discrepancy between degenerate DNA-binding specificity in biochemical assays and highly specific functional outcomes in the organism constitutes the "Hox specificity paradox" [17] [18].

FAQ 2: How can paralogous Hox genes have both redundant and specific functions? Paralogs often share expression domains and can regulate a common set of target genes, leading to functional redundancy, where the loss of one gene can be partially compensated by its paralog. However, each paralog also has unique functions, regulating a specific subset of targets that cannot be compensated by others. This specificity arises from differences in their protein sequences outside the homeodomain, which influence interactions with cofactors and collaborators, leading to distinct transcriptional outputs [19] [20] [18].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between a Hox cofactor and a collaborator?

- Cofactors: Proteins like Extradenticle (Exd/Pbx) and Homothorax (Hth/Meis) that bind DNA cooperatively with Hox proteins. They form direct complexes with Hox proteins, dramatically increasing DNA-binding specificity and affinity by recognizing composite DNA sequences [17] [18].

- Collaborators: Other transcription factors that bind in parallel to the same cis-regulatory element as Hox proteins but do not necessarily form a direct complex on DNA. They help dictate whether the Hox protein will activate or repress transcription and contribute to cell-type-specific outcomes [17].

FAQ 4: What molecular mechanisms underlie the specific functions of different Hox paralogs? Key mechanisms include:

- Latent Specificity: Cooperative binding with PBC cofactors (Exd/Pbx) exposes subtle differences in the DNA-binding preferences of Hox paralogs [18].

- Selective Collaborations: Interactions with different sets of transcription factors at cis-regulatory modules can confer paralog-specific regulatory outcomes [21] [18].

- Variable N-terminal Regions: Sequences outside the conserved homeodomain and hexapeptide motif are divergent and can mediate unique protein-protein interactions or post-translational modifications [17] [18].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Issue 1: Interpreting Axial Skeleton Phenotypes in Hox Mutant Mice

| Observation | Possible Interpretation | Recommended Validation Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Homeotic transformation (e.g., a vertebra acquires the identity of a more anterior one) | Loss-of-function of a specific Hox gene. The transformed vertebra is likely within the expression domain of the mutated Hox gene. | - Confirm the expression domain of the mutated Hox gene via in situ hybridization or LacZ reporter in the mutant background [19].- Analyze the expression of molecular markers specific to the acquired identity. |

| No observable phenotype in a single paralog mutant. | Functional redundancy: Compensated by other Hox genes (often paralogs) with overlapping expression and function. | - Generate and analyze double or compound mutants with suspected redundant paralogs (e.g., Hoxa-9 and Hoxd-9) [19].- Perform transcriptomic analysis (RNA-seq) to identify subtle gene expression changes missed by morphological inspection. |

| Synergistic or enhanced phenotype in a double mutant compared to single mutants. | The two genes have redundant functions for that particular trait. The phenotype reveals the full functional requirement shared by both paralogs [19]. | - Conduct a detailed skeletal analysis with Alcian Blue/Alizarin Red staining to quantify all vertebral transformations.- Compare the gene expression changes in single vs. double mutants using RNA-seq. |

| Novel phenotype in a double mutant not seen in either single mutant. | The paralogs may have distinct primary functions, but their combined loss disrupts a larger part of the Hox combinatorial code required for a specific structure [19]. | - Broader phenotypic analysis of other systems (e.g., limb, organs).- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP-seq) to map the genomic binding sites for both paralogs and identify co-regulated targets. |

Issue 2: Investigating Hox Target Genes and Specificity

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Solution / Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|

| A Hox protein binds thousands of sites (ChIP-seq) but regulates very few genes. | Much of the binding may be non-functional, low-affinity, or require specific collaborative partners to become functional. | - Integrate ChIP-seq data with ATAC-seq (chromatin accessibility) and RNA-seq data from the same tissue to focus on bound, accessible regions near differentially expressed genes [21].- Validate candidate cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) with reporter assays in vivo (e.g., in Drosophila or mouse transgenic models) [17] [18]. |

| A cis-regulatory element is activated by one Hox paralog but repressed by another in the same cellular context. | The regulatory outcome is determined by the specific combination of transcription factors (Hox collaborators) bound to the element. | - Map the transcription factor binding motifs within the CRM [18].- Use CRISPR/Cas9 to mutate candidate collaborator binding sites and test the effect on Hox-mediated regulation in a reporter assay. |

| Difficulty recapitulating Hox-specific regulation in cell culture. | The required collaborative factors or chromatin context may be missing in the cell line. | - Use primary cells or stem-cell-derived cultures that more closely mimic the in vivo environment.- Perform co-transfection experiments with expression vectors for the Hox protein and suspected collaborators. |

Quantitative Data on Hox-Mediated Axial Transformations

Table: Axial Skeleton Transformations in Hoxa-9 and Hoxd-9 Single and Double Mutant Mice [19]

| Genotype | Vertebral Transformations (Anteriorizations) | Limb Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| Hoxa-9-/- | Vertebrae #21 - #25 (L1 - L5) | No forelimb defects observed. |

| Hoxd-9-/- | Vertebrae #23 - #25 (L3 - L5), #28, #30, #31 (S2, S4, Ca1) | Reduced humerus length; malformed deltoid crest. |

| Hoxa-9-/-; Hoxd-9-/- (Double Mutant) | - Increased penetrance/expressivity of single mutant transformations.- Novel transformations in the axial skeleton. | - Increased severity of humerus defects.- Novel alterations at the forelimb stylopod. |

Key Insight: The overlapping transformations of vertebrae L3-L5 in single mutants demonstrate redundancy, while the unique transformations and limb phenotypes reveal paralog-specific functions. The synergistic phenotypes in the double mutant confirm their shared essential role in patterning these structures [19].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Genetic Interaction Analysis Using Compound Mutants

Objective: To dissect functional redundancy and specificity between Hox paralogs in vivo.

Methodology:

- Generate Single and Compound Mutants: Use gene targeting in embryonic stem cells to create null alleles for individual Hox genes (e.g., Hoxa-9 and Hoxd-9). Cross single mutant mice to generate double homozygous mutants [19].

- Skeletal Preparation and Staining: Euthanize newborn or adult mice, eviscerate, and skin the carcasses. Fix in 95% ethanol.

- Cartilage Staining: Use Alcian Blue to stain cartilage.

- Bone Staining: Use Alizarin Red to stain mineralized bone.

- Clearing: Treat with potassium hydroxide to clear soft tissue, making the skeleton visible [19].

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Systematically examine each vertebra under a dissecting microscope.

- Identify homeotic transformations by comparing morphological features (e.g., shape of transverse processes, neural spines) to wild-type controls. Anteriorization is indicated by a vertebra acquiring features of a more anterior one.

- Measure long bones for defects in growth and morphology.

Protocol 2: Identifying Direct Hox Targets via Integrated Genomics

Objective: To identify genomic regions directly bound by a Hox factor and distinguish functional binding events.

Methodology:

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation and Sequencing (ChIP-seq):

- Crosslink proteins to DNA in dissected embryonic tissues or relevant cell models.

- Lyse cells and shear chromatin by sonication.

- Immunoprecipitate DNA-protein complexes using a specific antibody against the Hox protein of interest.

- Reverse crosslinks, purify DNA, and prepare libraries for high-throughput sequencing [21] [18].

- Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing (ATAC-seq):

- RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq):

- Extract total RNA from wild-type and Hox-mutant tissues.

- Prepare cDNA libraries and sequence to profile global gene expression changes.

- Data Integration:

- Overlap Hox ChIP-seq peaks with ATAC-seq peaks to identify binding events in accessible chromatin.

- Correlate these high-confidence binding sites with nearby genes that are differentially expressed in the RNA-seq data from mutants to pinpoint direct, functional target genes.

Key Signaling and Regulatory Pathways

Diagram: Hox Specificity Complex on DNA. Hox proteins achieve precise DNA binding and regulatory specificity by forming complexes with PBC and HMP cofactors on composite DNA sites. Collaborator TFs binding nearby determine the ultimate transcriptional outcome (activation or repression) [17] [18].

Diagram: Genetic Workflow for Analyzing Redundancy. This logic flow outlines the experimental steps for determining whether two Hox paralogs have specific or redundant functions through the generation and analysis of single and compound mutants [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Investigating Hox-Mediated Transformations

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application in Hox Research |

|---|---|

| Hox Mutant Mouse Models (Single & Compound Null Alleles) | In vivo analysis of gene function, redundancy, and axial patterning phenotypes. Essential for linking genotype to morphology [19]. |

| Specific Antibodies for Hox Proteins (e.g., for ChIP-seq) | To map the genomic binding sites of endogenous Hox proteins and identify direct target genes [21] [18]. |

| Alcian Blue & Alizarin Red Staining Kit | Standard histological technique for visualizing cartilage and bone in cleared skeletal preparations, allowing detailed analysis of vertebral identities [19]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing System | For creating targeted mutations in Hox genes or their cis-regulatory elements in cell lines or model organisms. Enables functional validation of specific protein domains or DNA binding sites [20]. |

| PBC/HMP Expression Vectors (e.g., Pbx, Meis) | For co-transfection experiments in cell culture to study the cooperative binding and transcriptional outcomes of Hox-cofactor complexes on reporter constructs [18]. |

| Transgenic Reporter Constructs | To test the in vivo activity of candidate Hox cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) and define the roles of specific transcription factor binding sites within them [17] [18]. |

| ATAC-seq Kit | To profile the landscape of open chromatin in a given tissue, helping to distinguish functional from non-functional Hox binding events [22] [21]. |

| (S)-GSK-3685032 | (S)-GSK-3685032, MF:C22H24N6OS, MW:420.5 g/mol |

| FPI-1523 sodium | FPI-1523 sodium, MF:C9H13N4NaO7S, MW:344.28 g/mol |

Hoxa5 functions as a key trans-regulatory transcription factor that orchestrates broader Hox gene expression patterns across multiple tissue contexts, rather than acting through local cis-effects on the HoxA cluster. While Hoxa5 mutant phenotypes manifest in tissue-specific ways, recent multi-tissue transcriptomic analyses reveal a conserved trans-regulatory function wherein Hoxa5 regulates the expression of other Hox genes, particularly those within the HoxA cluster. This trans-regulatory capacity enables Hoxa5 to coordinate the complex genetic addresses required for proper patterning of developing tissues, including the respiratory system, axial skeleton, and musculoskeletal structures. The mechanistic insights into Hoxa5's trans-regulatory network resolve previous interpretation challenges in Hox-mediated skeletal transformations by demonstrating that mutant phenotypes result from genuine trans-acting functions rather than cis-acting disruption of neighboring Hox genes.

Hox genes encode an evolutionarily conserved family of transcription factors that play central regulatory roles in body patterning and development, with 39 Hox genes organized into four clusters (HoxA to HoxD) in mammals [13]. These genes are expressed sequentially along the anterior-posterior axis according to their position within the clusters, a phenomenon known as collinearity [2]. The specific combination of HOX proteins at particular anterior-posterior levels provides a unique "genetic address" that determines segment identity and morphology [23].

Hoxa5 occupies a critical position within this hierarchical system, functioning as a predominant regulator in specific axial domains. Unlike many single Hox mutations that cause relatively mild phenotypes, Hoxa5 loss-of-function leads to severe developmental defects and neonatal lethality in most mutants due to respiratory failure [23]. This unusual severity initially raised questions about whether Hoxa5 mutant phenotypes might result from cis-acting effects on neighboring Hox genes rather than genuine trans-regulatory functions. However, recent comparative studies utilizing two different Hoxa5 mutant mouse lines have demonstrated that both alleles share identical phenotypic consequences and Hox gene misregulation patterns, while epigenetic analyses revealed limited effects on the chromatin landscape of the surrounding HoxA cluster [13]. These findings provide compelling evidence that HOXA5 protein acts predominantly in trans to regulate broader Hox gene expression networks.

Key Experimental Evidence for Hoxa5 Trans-Regulation

Multi-Tissue Transcriptomic Analysis

A comprehensive RNA-seq study examining seven different biological contexts in Hoxa5 null mutants revealed that conserved transcriptional changes across tissues were rare, indicating that HOXA5 primarily regulates context-specific effector genes [13]. However, one consistent pattern emerged across all tissues: misregulation of other Hox genes, particularly a trend toward reduced expression of HoxA genes. This finding suggests that Hox genes themselves represent conserved targets of HOXA5 across diverse tissue contexts.

Table 1: Hox Gene Misregulation in Hoxa5 Null Mutants Across Tissues

| Tissue Context | Developmental Stage | Primary Hox Gene Expression Changes | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | E12.5-E15.5 | Reduced expression of HoxA genes | Impaired branching morphogenesis, lung hypoplasia |

| Trachea | E15.5 | Reduced expression of Hoxa1-Hoxa5 | Tracheal cartilage ring patterning defects |

| Somites | E10.5-E12.5 | Broader Hox misregulation across all four clusters | Homeotic transformations in cervical/thoracic region |

| Diaphragm | E15.5 | Altered Hox expression | Impaired phrenic innervation, respiratory defects |

| Interscapular BAT | E18.5 | Hox gene misregulation | Altered brown adipose tissue depot size |

Genome-Wide Binding Profiles

Recent ChIP-seq experiments using a novel Hoxa5FLAG epitope-tagged mouse line have uncovered the genome-wide occupancy of HOXA5 protein in developing lung tissue [24]. This approach identified an in vivo HOXA5 binding motif and revealed widespread distribution of HOXA5 binding sites throughout the genome, with targets including:

- Other Hox genes known to show expression changes in Hoxa5 null mutants

- Key signaling pathway components (FGF10, SHH, BMP4, WNT2)

- Transcriptional regulators of lung morphogenesis

When combined with ATAC-seq assays and epigenetic analyses, these data demonstrate that HOXA5 directly binds regulatory elements of other Hox genes, providing a mechanistic basis for its trans-regulatory function.

Epigenetic Landscape Analysis

Comparative analysis of epigenetic marks along the HoxA cluster in two different Hoxa5 mutant mouse lines revealed limited effects of either mutation on the chromatin landscape of the surrounding HoxA cluster [13]. This finding argues against the contribution of local cis effects to Hoxa5 mutant phenotypes and supports the model that HOXA5 protein acts in trans in the control of Hox gene expression.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Hoxa5 Trans-Regulatory Networks

| Reagent / Method | Primary Function | Key Application in Hoxa5 Research |

|---|---|---|

| Hoxa5FLAG epitope-tagged mouse line | In vivo protein-DNA interaction mapping | ChIP-seq to identify direct HOXA5 targets [24] |

| Hoxa5 null mutant alleles (multiple strains) | Loss-of-function studies | Comparative phenotyping and transcriptomics [13] |

| ChIP-seq protocol | Genome-wide binding site identification | Defining HOXA5 binding motif and distribution [24] |

| ATAC-seq assay | Chromatin accessibility profiling | Mapping open chromatin regions in Hoxa5 mutants [24] |

| Bulk RNA-seq | Transcriptome quantification | Multi-tissue analysis of Hox gene misregulation [13] |

| In situ hybridization | Spatial expression validation | Confirming Hox target expression patterns [24] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Technical Challenges in Hoxa5 Research

Experimental Design Challenges

Q: How can researchers distinguish between direct and indirect targets of Hoxa5 trans-regulation?

A: The combination of ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq provides the most robust approach for identifying direct targets. The recently developed Hoxa5FLAG mouse line enables precise mapping of HOXA5 binding sites [24]. For confirmation, consider these methodological considerations:

- Perform ChIP-seq at multiple developmental timepoints corresponding to peak Hoxa5 expression

- Combine with RNA-seq from Hoxa5 null tissue to correlate binding with expression changes

- Validate candidate targets through in situ hybridization to confirm spatial expression patterns

- Utilize ATAC-seq to assess chromatin accessibility changes in mutant tissues

Q: What controls are essential when interpreting Hoxa5 mutant phenotypes?

A: Given the potential for cis-acting effects in targeted mutations, employ these rigorous controls:

- Utilize multiple independent mutant alleles to confirm phenotype specificity [13]

- Perform epigenetic profiling of the HoxA cluster to exclude neighborhood effects

- Analyze expression of adjacent Hox genes (particularly Hoxa4 and Hoxa6) to rule out cis disruption

- Consider complementation assays with BAC transgenes containing only Hoxa5

Technical Optimization Issues

Q: How can researchers overcome the challenge of functional redundancy among Hox paralogs?

A: Hox paralogs often exhibit functional redundancy, which can mask phenotypic consequences in single mutants. Address this through:

- Focus on tissues where Hoxa5 shows predominant function (lung, trachea, cervical skeleton) [23]

- Generate compound mutants with other co-expressed Hox genes

- Utilize sensitive transcriptomic approaches to detect subtle gene expression changes

- Employ single-cell RNA-seq to identify cell-type specific requirements

Q: What methods best capture the dynamic nature of Hoxa5 expression and function?

A: Hoxa5 exhibits dynamic spatiotemporal expression patterns during development. To address this:

- Conduct time-course analyses at multiple developmental stages

- Utilize inducible genetic systems for temporal control of Hoxa5 function

- Combine lineage tracing with Hoxa5 perturbation to assess cell-autonomous effects

- Implement live imaging approaches to monitor morphological consequences in real-time

Signaling Pathways in Hoxa5 Trans-Regulatory Networks

Hoxa5 Trans-Regulatory Network Architecture

Molecular Mechanisms of Hoxa5-Mediated Transcription

Hoxa5 achieves transcriptional specificity through several interconnected mechanisms despite the challenge that HOX proteins typically bind similar AT-rich DNA sequences in vitro [21]. The emerging paradigm involves:

DNA Binding Specificity: HOXA5 gains target specificity through interactions with cofactors, primarily members of the PBC (Extradenticle/Pbx) and MEIS (Homothorax/Meis) families [21]. These interactions enhance DNA binding specificity through mechanisms including latent specificity and sensitivity to DNA shape rather than just nucleotide identity.

Chromatin Modification Capacity: Comparative genomic accessibility studies suggest that Hox factors like HOXA5 can differentially modify chromatin accessibility at target loci, potentially exhibiting pioneer-like activities that promote opening of closed chromatin regions [21].

Context-Dependent Cofactor Interactions: HOXA5 interacts with numerous tissue-specific transcription factors and coregulators that determine its transcriptional output in different cellular environments. This explains how the same transcription factor can regulate distinct target genes in various tissue contexts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Does Hoxa5 regulate Hox genes through direct promoter binding or through intermediate factors?

A: Current evidence supports both mechanisms. ChIP-seq data demonstrate direct binding to regulatory elements of other Hox genes [24], while transcriptomic analyses also reveal regulation of signaling pathways that indirectly influence Hox expression [24] [13]. The relative contribution of direct versus indirect regulation likely varies by target gene and cellular context.

Q: How does Hoxa5 trans-regulation differ between tissue contexts?

A: While the trans-regulatory function is conserved across tissues, the specific Hox targets and functional outcomes show considerable context-dependence. For example, in lung development, Hoxa5 predominantly regulates Hoxa1-Hoxa7 and signaling pathways critical for branching morphogenesis [24], while in somites, it influences a broader set of Hox genes across all four clusters [13].

Q: What technical approaches best capture the full scope of Hoxa5 trans-regulatory networks?

A: A multi-assay approach is essential:

- ChIP-seq for direct target identification

- Multi-tissue RNA-seq to assess transcriptional outcomes

- ATAC-seq to evaluate chromatin accessibility changes

- Epigenetic profiling to exclude cis-acting effects

- Spatial transcriptomics to resolve expression patterns at cellular resolution

Q: Are Hoxa5 trans-regulatory functions conserved in human development and disease?

A: Yes, emerging evidence indicates conservation of HOXA5 functions in human development, and its dysregulation is implicated in various pathologies. Notably, altered HOXA5 expression occurs in lung adenocarcinoma and other cancers [25] [26], and recent work has identified roles for HOXA5 in metabolic diseases and adipose tissue dysfunction [25].

The established paradigm of Hoxa5 as a trans-regulatory orchestrator of broader Hox expression provides a framework for resolving long-standing interpretation challenges in Hox-mediated skeletal transformations. Rather than acting through local cis-effects, Hoxa5 functions as a genuine trans-acting factor that coordinates the genetic addresses defining segment identity across multiple tissue contexts.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms by which Hoxa5 achieves transcriptional specificity

- Defining the cofactor interactions that determine context-dependent target gene selection

- Exploring the potential therapeutic applications of modulating Hoxa5 networks in disease contexts

- Investigating the conservation of Hoxa5 trans-regulatory functions across vertebrate evolution

The methodological framework and troubleshooting guidelines presented here provide researchers with essential tools for advancing our understanding of Hoxa5 trans-regulatory networks and their roles in development and disease.

Chromatin Landscape and 3D Genomic Architecture of Hox Clusters

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is the 3D architecture of Hox clusters so important for their function? The linear order of Hox genes is directly mirrored by their spatial and temporal expression during development, a phenomenon known as collinearity. The 3D architecture is crucial for implementing this precise regulatory pattern. Initially, the entire cluster is organized as a single, inactive chromatin compartment. During development, as genes are sequentially activated, they physically switch from an inactive compartment (marked by repressive H3K27me3) to an active compartment (marked by active H3K4me3). This bimodal organization helps to reinforce and maintain correct gene expression states, ensuring that posterior genes do not get activated in anterior regions [27] [28].

2. What are the main epigenetic regulators controlling Hox cluster chromatin? The epigenetic state of Hox clusters is primarily regulated by the opposing actions of Polycomb group (PcG) and Trithorax group (TrxG) protein complexes.

- Polycomb (PcG) complexes, such as PRC2 and PRC1, are responsible for maintaining the repressed state. PRC2 deposits the H3K27me3 repressive mark, which helps recruit PRC1. This leads to chromatin compaction and gene silencing [29] [28].

- Trithorax (TrxG) complexes counteract PcG-mediated silencing. They are associated with the deposition of active marks like H3K4me3, which keeps Hox genes in an "open" and expressible state [29] [30]. In embryonic stem cells, Hox clusters often exist in a "bivalent" state, possessing both active and repressive marks, which keeps them poised for activation upon lineage commitment [29].

3. My Hi-C data on Hox clusters is inconsistent. What could be causing this? Inconsistencies can arise from several technical and biological factors:

- Cell Type and Developmental Stage: Hox cluster architecture is highly dynamic. Data can vary significantly between cell types, anatomical origins, and precise developmental time points [28]. Ensure you are comparing equivalent samples.

- Technology Choice and Limitations: Standard Hi-C relies on formaldehyde cross-linking and restriction enzymes, which can introduce sequence bias and protein-related artifacts [31]. Consider using advanced, ligation-free methods like Micro-C or CAP-C for higher resolution and reduced background noise [31].

- Data Resolution: Low-resolution sequencing may fail to capture critical fine-scale interactions, such as the boundaries between active and inactive compartments. Opt for higher-resolution methods where possible [31].

4. How does the disruption of topological associating domains (TADs) near Hox clusters lead to disease? TADs are fundamental units of chromatin organization that constrain interactions between genes and their regulatory elements. Disruption of TAD boundaries near Hox clusters can allow enhancers to contact and activate incorrect Hox genes, leading to misexpression. This misexpression disrupts the precise Hox code necessary for skeletal patterning, which can result in homeotic transformations (where one body part develops the identity of another) and congenital malformations. For example, such disruptions have been linked to human syndromes like F-syndrome, polydactyly, and brachydactyly [31] [32].

5. We see persistent Hox expression in adult-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Is this normal? Yes, this is a normal and functionally important phenomenon. Fibroblasts and progenitor-enriched MSCs cultured from adult tissues maintain regionally restricted Hox gene expression profiles that reflect their anatomical origin. This "Hox code" is not just a developmental relic; it functions in adult tissue maintenance, regeneration, and fracture healing. Genetic studies confirm that Hox genes are required for the fracture repair process in the adult skeleton [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge: Interpreting Complex Chromatin Interaction Data

Problem: It is difficult to determine whether observed chromatin interactions are causative of gene regulation or merely a consequence of transcription.

Solution Strategy:

- Employ Multi-Modal Integration: Correlate your 3D interaction data (e.g., from Hi-C) with complementary datasets. Map histone modifications (ChIP-seq), transcription factor binding (ChIP-seq or CUT&Tag), and transcriptional output (RNA-seq) from the same biological sample. An interaction is more likely to be functional if it correlates with active chromatin marks and gene activation [31] [28].

- Utilize Ligation-Free Technologies: To overcome biases inherent in cross-linking and restriction enzymes, use methods like Micro-C or CAP-C. These provide a more native view of chromatin structure and can reveal finer details, such as nucleosome-level interactions [31].

- Implement Functional Perturbation: Genetically disrupt specific regulatory elements (e.g., enhancers or CTCF sites) or architectural proteins and observe the concurrent effects on 3D structure and gene expression. A concomitant change in structure and function strongly suggests a causal link [34].

Table 1: Advanced Methods for 3D Genomics Analysis

| Method | Key Principle | Advantage | Best for Analyzing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-C [31] | Uses micrococcal nuclease (MNase) for fragmentation. | Nucleosome-resolution mapping; no restriction enzyme bias. | Fine-scale architecture within Hox clusters. |

| CAP-C [31] | Uses dendrimers and UV for protein removal and DNA fragmentation. | Reduces protein-crosslinking artifacts; high signal-to-noise. | Transcription-dependent changes in chromatin conformation. |

| ChIA-Drop [31] | Identifies multi-way interactions in droplets using DNA barcodes. | Captures complex, multi-loci interactions simultaneously. | Enhancer hubs interacting with multiple promoters. |

| SPRITE [31] | Uses split-pool barcoding to identify interacting DNA and RNA. | Maps multi-way interactions and inter-chromosomal contacts genome-wide. | Hox genes belonging to larger nuclear bodies. |

| Chromatin Tracing [35] | Uses multiplexed FISH to visualize genomic loci in single cells. | Provides single-cell, single-molecule 3D folding paths in situ. | Cell-to-cell heterogeneity in Hox cluster organization. |

Challenge: Investigating Hox Function in Adult Skeletal Regeneration

Problem: The specific molecular mechanisms by which Hox genes function in adult mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) during bone repair are unclear.

Solution Strategy:

- Lineage Tracing and Cell Sorting: Use mice expressing Cre recombinase under Hox gene promoters (e.g., Hoxa11-eGFP) to label and track Hox-expressing cell lineages during fracture healing. Isolate these cells via FACS for downstream transcriptomic and epigenomic analysis [33].

- In Vivo Loss-of-Function Studies: Employ conditional knockout mouse models to delete specific Hox paralogous groups in adult MSCs or osteoprogenitors. Analyze the resulting fracture healing phenotypes, focusing on callus formation, bone remodeling, and integration of musculoskeletal tissues [33] [8].

- Define Expression in Stromal Compartments: Precisely characterize Hox expression in the various connective tissues (perichondrium, tendon, muscle connective tissue) of the adult skeleton, as Hox genes are often highly expressed in stromal cells rather than differentiated skeletal cells [33] [8].

Challenge: Engineering Hox Clusters to Study Gene Regulation

Problem: Targeted inversions or modifications of the Hox cluster often lead to unexpected and severe gene misexpression, complicating data interpretation.

Solution Strategy:

- Respect Transcriptional Polarity: Vertebrate Hox clusters are highly optimized, with all genes transcribed from the same DNA strand. When engineering alleles, avoid inverting transcription units, as this can disrupt the coordinated regulatory landscape and cause aberrant gene activation (e.g., ectopic Hoxd13 expression) [34].

- Preserve CTCF-Binding Sites: CTCF sites often reside between Hox genes and act as critical insulators. Their deletion or inversion can collapse the micro-domain architecture, leading to regulatory leakage. Always map and consider the function of these sites in your genetic designs [34].

- Analyze in Multiple Developmental Contexts: Test your engineered alleles in various tissues (e.g., axial skeleton, limb buds, metanephros), as Hox clusters are regulated by distinct global enhancers in different contexts. A mutation may have a phenotype in one context but not another [34].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: High-Resolution 3D Architecture Analysis Using Micro-C

Objective: To map the 3D chromatin architecture of the Hox cluster at nucleosome resolution.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Crosslinking Buffer (1% Formaldehyde)

- Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase)

- Biotinylated Nucleotides

- DNA Ligase

- Streptavidin Beads

- Proteinase K

- Library Preparation Kit

- High-Throughput Sequencer

Method:

- Crosslinking: Harvest and crosslink ~1 million cells with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. Quench with glycine.

- Chromatin Fragmentation: Lyse cells and digest chromatin with MNase to saturation. MNase cleaves preferentially in linker DNA, creating a population of mononucleosomes.

- End Repair and A-Tailing: Repair the MNase-digested ends and use a Klenow fragment to add an 'A' overhang.

- Proximity Ligation: Add a biotinylated bridge adapter with a 'T' overhang for ligation. Under dilute conditions, perform intra-molecular ligation to join crosslinked DNA fragments.

- Reversal of Crosslinking and Purification: Reverse crosslinks with Proteinase K and purify DNA.

- Biotin Pull-Down: Capture biotinylated ligation products using Streptavidin beads.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: On-bead, prepare the library for paired-end high-throughput sequencing.

- Data Analysis: Process paired-end sequences using a dedicated Micro-C pipeline (e.g., distiller) to generate high-resolution contact matrices and identify TADs and chromatin loops.

Detailed Protocol: Visualizing Hox Cluster Conformation via Multiplexed FISH

Objective: To visualize the 3D folding path of a Hox cluster in single cells within intact tissue.

*Reagents and Equipment:

- Custom Oligopaint FISH Probes targeting the Hox locus

- Formamide

- Fluorescently Labeled Readout Probes

- DAPI Staining Solution

- Super-Resolution Microscope

- Automated Fluidics System

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Fix cells or tissue sections and permeabilize.

- Hybridization: Apply a pool of hundreds to thousands of uniquely barcoded Oligopaint FISH probes that tile the Hox cluster region. Hybridize overnight.

- Sequential Imaging and Stripping:

- Apply a set of fluorescent readout probes that bind to a subset of the barcodes.

- Image the fluorescence signals using a super-resolution microscope.

- Chemically strip the fluorescent readouts without damaging the sample or the primary probes.

- Repeat the process with a new set of readouts for multiple rounds until all barcodes have been imaged.

- Image Analysis and Tracing: Computational algorithms decode the sequential imaging data to identify the precise spatial positions of all targeted loci in 3D. The folding trajectory of the chromatin fiber is then reconstructed by connecting the positions of the imaged loci along the same DNA molecule [35].

Data Presentation

Table 2: Key Chromatin Marks and Their Functional Associations in Hox Regulation

| Chromatin Mark / Protein Complex | Associated Function | Effect on Hox Gene Expression | Experimental Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K27me3 | Repression; Polycomb (PcG) mediated silencing | Repression | ChIP-seq, CUT&Tag |

| H3K4me3 | Activation; Trithorax (TrxG) mediated activation | Activation / Poising | ChIP-seq, CUT&Tag |

| Bivalent Domains (H3K4me3 + H3K27me3) | Poised state in ESCs | Genes are silent but primed for activation | ChIP-seq |

| CTCF | Chromatin looping / Insulation | Defines regulatory boundaries; prevents ectopic activation | ChIP-seq, CTCF Cut&Run |

| Cohesin Complex | Loop extrusion | Facilitates enhancer-promoter communication | ChIP-seq |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Hox Cluster Activation During Development

This diagram illustrates the dynamic transition of Hox clusters from a single inactive state to a bimodal active/inactive structure during embryonic development.

Multimodal 3D Genomics Technology Workflow

This diagram compares the general workflows of sequencing-based and imaging-based technologies for analyzing 3D chromatin architecture.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox Cluster Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Hoxa11-eGFP Reporter Mouse [33] | Fate mapping and isolation of Hox-expressing stromal cells. | Labels zeugopod-specific mesenchymal cells; useful for studying limb development and regeneration. |

| Conditional Hox Alleles (floxed) [33] [8] | Tissue-specific and temporal knockout of Hox paralog groups. | Essential for bypassing embryonic lethality and studying function in adult tissues like MSCs. |

| Oligopaint FISH Probes [35] | High-resolution imaging of Hox cluster conformation. | Allows multiplexed labeling of specific genomic loci for chromatin tracing in single cells. |

| Anti-H3K27me3 Antibody | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to map repressive domains. | High-quality antibody is critical for defining Polycomb-silenced regions within the cluster. |

| Anti-H3K4me3 Antibody | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to map active domains. | High-quality antibody is critical for defining Trithorax-active regions within the cluster. |

| Anti-CTCF Antibody | Mapping chromatin insulator and loop boundaries. | Identifies potential regulatory boundaries that partition the Hox cluster. |

| FTX-6746 | FTX-6746, MF:C16H7ClF2N2O, MW:316.69 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SSI-4 | SSI-4, MF:C19H21ClN4O3, MW:388.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Neural Crest Derivatives and Their Retention of Positional Hox Memory

Core Concepts: Hox Codes and Neural Crest Cell Memory

What is the fundamental principle of positional memory in neural crest derivatives?

Neural crest cells (NCCs) retain a transcriptional memory of their origin along the anterior-posterior axis through maintained Hox gene expression patterns. This "Hox code" is established in the neural tube before migration and persists in derived tissues, providing positional information that influences their developmental potential and differentiation fate [12] [36] [37].

Key Mechanism: This memory operates through a positive-feedback loop that maintains regional identity. For example, in axolotl limb regeneration, posterior identity is safeguarded by sustained Hand2 expression, which primes cells to form a Shh signaling center after injury, creating a stable memory state [38].

How does Hox expression plasticity impact neural crest patterning?

While NCCs carry Hox codes from their origin, their final positional identity results from a complex integration of pre-patterned information and environmental cues received during migration and at destination sites [37].

Critical Consideration: The size of the cell community influences plasticity. Smaller grafts or individual NCCs show greater sensitivity to environmental cues compared to larger cell populations, which tend to maintain their original Hox expression [37].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Mapping Hox Expression in Developing Human Neural Crest Derivatives

This protocol is adapted from single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses of the human fetal spine [12].

| Step | Procedure | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Tissue Collection | Obtain 5-13 week post-conception human fetal spines; from 9 weeks onwards, dissect into precise anatomical segments using anatomical landmarks | Capture inherent rostrocaudal maturation gradient (~6 hours difference between vertebral levels) |

| 2. Single-Cell Suspension | Process fresh tissues to generate single-cell suspensions, enrich for viable cells | Prepare for single-cell RNA sequencing |

| 3. Library Preparation | Generate single-cell mRNA libraries using droplet-based method (Chromium 10X) | Capture transcriptomic profiles of individual cells |

| 4. Spatial Validation | Apply Visium spatial transcriptomics (50μm resolution) and Cartana in-situ sequencing (single-cell resolution, 123-gene panel) on axial sections | Spatially resolve cell types and validate Hox expression patterns |

| 5. Data Integration | Use cell2location algorithm to obtain estimated cell type abundancy values for each voxel | Reconstruct spatial organization of cell types with Hox expression patterns |

Protocol: Testing Hox Plasticity in Avian Neural Crest

This approach, based on classical grafting experiments, examines the stability of Hox positional memory [36] [37].

- Donor Tissue Selection: Isolate midbrain neural crest (Hox-negative) from donor embryo

- Transplantation: Graft to more posterior hindbrain (Hox-positive) regions in host embryo

- Fate Analysis: Track morphological outcomes and Hox gene expression in graft-derived structures

- Control Experiment: Perform orthotopic grafts to verify normal developmental potential

Expected Outcome: Grafted cells often retain identity appropriate for their original position and form ectopic mandibular structures, demonstrating persistence of positional memory [36] [37].

Quantitative Data Analysis

Rostrocaudal HOX Code in Human Fetal Development

Analysis of stationary cell types in human fetal spine revealed 18 genes with strongest position-specific expression patterns [12]:

| Anatomical Region | Key HOX Genes | Specific Markers | Expression Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical | HOXB-AS3, HOXA5 | HOXB6 (osteochondral), HOXC4 (meningeal) | HOXB-AS3 shows strong sensitivity for cervical region (p < 10â»Â³â°â°) |

| Thoracic | HOXC5 (meningeal) | Multiple HOX genes with segment-specific expression | Gradual transition in expression patterns along axis |

| Sacral | HOXC11 (meningeal) | Group 13 genes (very low levels) | Expressed exclusively in sacral samples, including coccyx |

Hox Combinatorial Codes in Zebrafish Neural Crest Lineages

Single-cell transcriptomics of sox10:GFP+ cells in zebrafish reveals distinct Hox signatures across neural crest derivatives [39]:

| Cell Type | Hox Signature | Developmental Timing | Additional Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesenchyme Subtypes | Multiple distinct Hox combinations across subpopulations | 48-70 hpf | Prrx1, Twist1 for mesenchymal fate |

| Enteric Neurons | Specific Hox code combinations | Progressive differentiation from 48-70 hpf | Neuronal differentiation markers |

| Neural Crest Cells | Axial-level specific Hox patterns | Maintained through migration and differentiation | Sox10, FoxD3, Tfap2a |

| Pigment Progenitors | Distinct anterior-posterior Hox codes | Emerging during embryonic-larval transition | Melanocyte differentiation genes |

Signaling Pathways & Molecular Mechanisms

Hand2-Shh Positive Feedback Loop in Positional Memory

This diagram illustrates the core regulatory circuit maintaining posterior identity in limb cells, relevant to understanding how positional memory is sustained in neural crest derivatives [38].

Experimental Workflow for Hox Code Mapping

This workflow diagram outlines the integrated approach for creating a developmental atlas of Hox expression using multiple complementary technologies [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Reagents for Neural Crest Hox Research

| Reagent/Cell Line | Application | Key Features | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hoxa11-CreERT2; ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice | Lineage tracing of Hox-expressing cells | Enables temporal deletion of Hox11 function at adult stages; labels Hox11 lineage cells | Studying continued Hox function in adult skeletal homeostasis [40] |

| ZRS>TFP; loxP-mCherry axolotl | Fate mapping of embryonic Shh cells | Labels Shh-expressing cells during development and regeneration with inducible Cre | Investigating origin of posterior cells during regeneration [38] |

| Tg(−4.9sox10:EGFP) zebrafish | Identifying NCCs and derivatives | GFP expression under sox10 promoter marks neural crest lineage | Single-cell transcriptomics of posterior NCC fates [39] |

| Hand2:EGFP knock-in axolotl | Tracking Hand2 expression | EGFP co-expressed with endogenous Hand2 via T2A sequence | Monitoring posterior identity factor in uninjured and regenerating limbs [38] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

How should researchers interpret conflicting data on neural crest pre-patterning versus plasticity?

Problem: Experimental results show apparent contradictions between fixed Hox codes and plastic Hox expression in neural crest cells.

Solution: Consider these factors when interpreting results:

- Community Size Effect: Smaller cell grafts show greater plasticity than larger populations [37]

- Axial Level Differences: Cranial neural crest may exhibit different regulatory mechanisms than trunk neural crest

- Temporal Factors: Early migratory NCCs may show different plasticity than later differentiated derivatives

- Technical Considerations: Orthotopic vs. heterotopic grafting produces different outcomes

Resolution Framework: The current model integrates both concepts - NCCs carry intrinsic positional information but remain responsive to local environmental cues during migration [37].

What controls should be included when studying Hox gene function in adult skeletal maintenance?

Problem: Distinguishing between developmental patterning defects and ongoing adult functions of Hox genes.

Solution: Implement these experimental controls:

- Temporal Deletion: Use inducible Cre systems (e.g., Hoxd11 conditional allele) to delete Hox function specifically in adulthood after normal development [40]

- Lineage Tracing: Combine with lineage labeling (e.g., Hoxa11-CreERT2; ROSA-LSL-tdTomato) to track mutant cell behavior

- Regional Specificity Controls: Compare effects in Hox-expressing regions versus non-expressing regions

- Differentiation Markers: Assess multiple stages of osteolineage differentiation (Runx2, osteopontin, osteocalcin, SOST) [40]

Frequently Asked Questions

Do all neural crest derivatives maintain their original Hox code?

No. Research shows neural crest derivatives can unexpectedly retain the anatomical Hox code of their origin while also adopting the code of their destination. This trend has been confirmed across multiple organs, suggesting a more complex integration of positional information than previously thought [12].

How stable is Hox positional memory in adult tissues?

Hox positional memory demonstrates remarkable stability in adult tissues. Studies show that:

- Fibroblasts maintain distinct Hox expression patterns for >35 cell generations ex vivo [41]

- Anatomic site-specific Hox patterns are not perturbed by soluble factors or heterotypic cell contact [41]

- Fibroblasts from young vs. old human donors show little difference in position-specific Hox expression [41]

Can positional memory be reprogrammed experimentally?

Yes, but with directional constraints. Research in axolotl limb regeneration demonstrates that:

- Positional memory can be reprogrammed more easily from anterior to posterior than the reverse direction [38]

- Transient exposure of anterior cells to Shh during regeneration can kick-start an ectopic Hand2-Shh loop [38]

- This leads to stable Hand2 expression and lasting competence to express Shh in subsequent amputations [38]

Advanced Profiling and Functional Genomics for Hox Phenotype Deconvolution

Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics for Resolving Hox Expression Atlases

A fundamental challenge in developmental biology research is accurately interpreting the complex, spatially restricted expression of HOX genes—key transcription factors that orchestrate anteroposterior patterning in the embryonic skeleton and other tissues. Traditional bulk sequencing methods obscure critical cellular heterogeneity and spatial context, limiting our understanding of Hox-mediated skeletal transformations. The integration of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics now provides unprecedented resolution to map these expression patterns within their native tissue architecture. However, these advanced technologies introduce new technical and interpretive hurdles that can compromise data reliability and biological insights. This technical support center addresses these specific challenges through targeted troubleshooting guides and detailed experimental protocols, enabling researchers to confidently generate and interpret high-quality Hox expression atlases.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is integrating scRNA-seq with spatial transcriptomics particularly important for studying Hox genes?

Hox genes exhibit precise collinear expression patterns along the anteroposterior axis, where their 3' to 5' genomic arrangement correlates with anterior to posterior body position. ScRNA-seq identifies cellular heterogeneity and transcriptional profiles but loses native spatial context. Spatial transcriptomics preserves anatomical localization but may lack single-cell resolution. Integration is crucial because it links specific Hox codes to their exact anatomical positions and cell types. For example, a recent human embryonic spine atlas combining both techniques revealed that neural crest derivatives retain the anatomical HOX code of their origin while also adopting the code of their destination, a finding impossible with either method alone [42].

Q2: What are the primary sources of technical noise in scRNA-seq data when analyzing transcription factors like Hox genes?

Hox genes and other transcription factors are often expressed at lower levels than structural genes, making them susceptible to several technical artifacts:

- Dropout events: Low-abundance transcripts may fail to be captured or amplified, creating false negatives [43].

- Amplification bias: Stochastic variation during cDNA amplification can skew representation of specific genes [43].

- Low RNA input: The limited starting material from single cells can lead to incomplete reverse transcription and reduced coverage [43].

- Cell doublets: Multiple cells captured in a single droplet can confound analysis, leading to misidentification of co-expressed Hox genes [43].

Q3: How can I validate the spatial expression patterns of Hox genes identified in my transcriptomic data?

Spatial validation requires orthogonal techniques. Beyond spatial transcriptomics (like 10x Visium or Stereo-seq), robust methods include:

- In situ sequencing (ISS): Provides single-cell resolution for a targeted gene panel. This was used to validate HOX gene expression in the developing human spine with high anatomical precision [42].

- RNA in situ hybridization (RNA-ISH): A classic method to visually confirm the expression and localization of specific Hox transcripts [44].

- Spatial imputation tools: New computational methods like ISS-Patcher can impute cell labels from high-plex ISS data onto spatial datasets, strengthening spatial annotation [45].

Q4: What are the key considerations when choosing a spatial transcriptomics platform for Hox atlas projects?

The choice depends on the biological question and required resolution [46]:

- Required Resolution: Are you studying broad tissue zones or fine subcellular structures?

- Tissue Type and Preservation: Ensure platform compatibility with your sample type (FFPE, fresh frozen, fixed frozen) and that RNA quality (RIN, DV200) meets vendor specifications [46].

- Throughput and Coverage: Consider the trade-off between high-resolution and the physical area that can be captured, especially for large embryonic structures.

Troubleshooting Guides

Addressing Low or Inconsistent Hox Gene Detection in scRNA-seq

Problem: Hox genes, often lowly expressed, are missing or show inconsistent expression across expected cell populations.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High dropout rate for Hox genes | Low sequencing depth | Increase sequencing depth to capture low-abundance transcripts. Use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification bias [43]. |

| Inconsistent detection between replicates | Poor cell viability or RNA quality | Implement rigorous quality control (QC). Assess cell viability, library complexity, and RNA Integrity Number (RIN) before sequencing. Use fresh, snap-frozen samples or high-quality FFPE samples with DV200 > 50% [43] [46]. |

| Putative "novel" Hox-expressing populations | Cell doublets | Use computational methods (e.g., DoubletFinder) or cell hashing to identify and exclude doublets from analysis [43]. |

| General low cDNA yield | Suboptimal reverse transcription | Always include positive and negative controls. Optimize cell lysis and RNA extraction. For FACS-sorted cells, ensure they are sorted into an appropriate, EDTA-/Mg2+-/Ca2+-free buffer like PBS to avoid inhibiting RT reactions [47]. |

Resolving Spatial Data Integration and Interpretation Challenges

Problem: Difficulty in aligning scRNA-seq clusters with spatial transcriptomics spots or interpreting spatial Hox patterns.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor alignment between scRNA-seq clusters and spatial data | Batch effects or biological variability | Use batch correction algorithms (e.g., Harmony, Combat) to integrate datasets from different technical runs [43]. Plan experiments to process samples for both modalities in parallel. |

| Ambiguous spatial localization of Hox codes | Low resolution of spatial platform | For fine-scale mapping, choose a higher-resolution platform (e.g., Visium HD, Stereo-seq). Supplement with targeted in-situ sequencing (ISS) for validation [42] [46]. |