Decoding Subtle Limb Patterning: Advanced Methods for Analyzing Hox Mutant Phenotypes

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the current methodologies for identifying and characterizing subtle limb patterning phenotypes in Hox gene mutants.

Decoding Subtle Limb Patterning: Advanced Methods for Analyzing Hox Mutant Phenotypes

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the current methodologies for identifying and characterizing subtle limb patterning phenotypes in Hox gene mutants. Covering both foundational principles and cutting-edge techniques, it explores the transition from traditional genetic and morphological analyses to modern high-resolution tools like single-cell and spatial transcriptomics. The content addresses the critical challenges of genetic redundancy and phenotypic subtlety, offers frameworks for methodological troubleshooting and validation, and highlights the translational implications of this research for understanding congenital limb malformations and regenerative medicine.

Understanding Hox Gene Function and Classic Limb Phenotypes

The Foundational Role of Hox Clusters in Vertebrate Limb Patterning

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Which Hox clusters are most critical for limb development, and what are their primary functions? The HoxA and HoxD clusters are the major players in vertebrate limb development [1]. They orchestrate patterning along the proximodistal axis (from shoulder to fingertip) in two distinct transcriptional waves. The HoxB and HoxC clusters, however, are largely dispensable, as their deletion does not result in limb phenotypes [1]. The primary function of HoxA and HoxD genes is to specify the identity of the three main limb segments: the stylopod (e.g., humerus), zeugopod (e.g., radius/ulna), and autopod (hand/foot) [2] [3].

2. Why might my Hox single-gene knockout show no or a very mild phenotype? This is typically due to extensive functional redundancy between Hox genes, particularly among members of the same paralog group [4] [3]. For example, in mice, all three genes of the Hox10 paralog group (Hoxa10, Hoxc10, Hoxd10) must be knocked out to see a clear homeotic transformation of the lumbar and sacral vertebrae into a rib-bearing, thoracic-like identity [3]. Always consider the potential for redundant functions from other genes within the same paralog group.

3. What molecular readouts can I use to confirm successful Hox cluster mutagenesis?

A key downstream target is Tbx5, a critical transcription factor for forelimb initiation. In zebrafish, deletion of both the hoxba and hoxbb clusters leads to a complete failure to induce tbx5a expression in the pectoral fin field, resulting in a total absence of fins [5]. For later stages of limb patterning, examining the expression of Sonic hedgehog (Shh), which is regulated by Hox genes in the Zone of Polarizing Activity (ZPA), is crucial [2] [1]. The failure to establish or maintain Shh expression is a common phenotype in Hox mutants.

4. Are Hox genes involved in the development of both forelimbs and hindlimbs? Yes, but the specific clusters involved differ. The development of both sets of limbs relies on the HoxA and HoxD clusters [2]. The HoxC cluster is expressed specifically in the hindlimb [2], indicating a specialized role in patterning the posterior appendages.

5. Do Hox genes have functions in the adult skeleton beyond embryonic patterning? Emerging evidence indicates yes. Hox genes are expressed in adult tissues, including mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) in bone [3]. They continue to play a role in skeletal maintenance and fracture repair, suggesting that their function is not limited to embryonic development [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: No Pectoral Fin/Limb Bud Formation

This problem indicates a failure in the very early stages of limb initiation.

Potential Cause 1: Loss of limb field specification.

- Investigation: Analyze the expression of early limb bud markers. In zebrafish, check for the expression of

tbx5ain the lateral plate mesoderm. Its absence suggests a failure in specifying the limb field itself [5]. - Solution: Focus on the genes involved in the earliest positioning of the limb. In zebrafish, the

hoxbaandhoxbbclusters (derived from the HoxB cluster) are essential for this process. Double homozygous mutants for these clusters show a complete absence oftbx5aexpression and pectoral fins [5]. Key genes involved arehoxb4a,hoxb5a, andhoxb5b.

- Investigation: Analyze the expression of early limb bud markers. In zebrafish, check for the expression of

Potential Cause 2: Critical redundancy in HoxA/HoxD early function.

- Investigation: The early phase of Hox gene expression is required for the initial outgrowth of the limb bud and the formation of the Apical Ectodermal Ridge (AER) [1].

- Solution: Consider that a compound mutation affecting multiple genes in the HoxA and HoxD clusters may be necessary to see a phenotype this severe. In mice, the combined loss of HoxA and HoxD cluster function leads to early developmental arrest of limbs [1].

Problem: Homeotic Transformations along the Axial Skeleton

This is a classic Hox phenotype, where the identity of one segment is transformed into that of another.

- Potential Cause: Loss of positional information.

- Investigation: Carefully characterize the skeletal morphology, comparing the identities of specific vertebrae (e.g., cervical, thoracic, lumbar) between mutant and wild-type specimens. Look for anterior transformations, such as the appearance of ribs on lumbar vertebrae [4] [3].

- Solution: This phenotype is best explained by the loss of a specific Hox paralogous group's function. For example, the transformation of lumbar vertebrae to a thoracic fate is the result of losing the entire Hox10 paralogous group (Hoxa10, Hoxc10, Hoxd10) [3]. Ensure your genetic targeting strategy accounts for this high degree of redundancy by generating compound mutants for all members of the relevant paralog group.

Problem: Specific Limb Segment Malformations (e.g., missing digits, shortened zeugopod)

This points to a defect in the second wave of Hox expression, which patterns the distal parts of the limb.

- Potential Cause: Loss of function of posterior Hox genes.

- Investigation: Determine which segment is affected, as this points to specific paralog groups.

- Solution: Target the specific paralog group responsible for patterning the affected segment. Note that the phenotype here is often a severe malformation or loss of structures rather than a homeotic transformation [3].

Problem: Altered Digit Number or Identity

This concerns the patterning of the most distal limb element, the autopod.

Potential Cause 1: Disrupted Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling from the ZPA.

- Investigation: Analyze the expression of

Shhin the posterior limb bud. Hox genes, particularly from the HoxD cluster, are directly involved in its regulation [1]. - Solution: Misexpression of posterior Hoxd genes (e.g., Hoxd11-Hoxd13) in the anterior limb bud can induce mirror-image

Shhexpression, leading to double-posterior limbs and polydactyly [1]. Check that your mutation has not disrupted the precise spatial regulation of these genes.

- Investigation: Analyze the expression of

Potential Cause 2: Direct disruption of autopod-patterning genes.

- Investigation: Examine the expression of genes involved in the final steps of digit formation, which can be direct targets of Hox13 proteins.

- Solution: The deletion of the

5DOMregulatory landscape, which controls the second phase of Hoxd gene expression in the autopod, leads to a complete loss of digits in mice [6]. Ensure your genetic manipulation has not impacted these critical distal enhancers.

Quantitative Data on Hox Mutant Phenotypes

Table 1: Zebrafish Hox Cluster Mutations and Pectoral Fin Phenotypes

This table summarizes key quantitative findings from studies on zebrafish Hox cluster mutants [5].

| Genotype | Phenotype | Penetrance | Key Molecular Readout (tbx5a) |

|---|---|---|---|

| hoxba-/- | Morphological abnormalities | Not Specified | Reduced expression in fin buds |

| hoxba-/-; hoxbb-/- | Complete absence of pectoral fins | 100% (15/15 double homozygous mutants) | Failed induction in lateral plate mesoderm |

| hoxba-/-; hoxbb+/- | Pectoral fins present | Not Applicable | Presumed normal |

| hoxba+/-; hoxbb-/- | Pectoral fins present | Not Applicable | Presumed normal |

Table 2: Mammalian Hox Paralog Mutations and Axial Skeleton Transformations

This table summarizes the characteristic homeotic transformations observed in mouse paralogous group mutants [4] [3].

| Paralog Group Mutated | Vertebral Identity | Wild-Type Morphology | Mutant Phenotype (Transformation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox10 (a10, c10, d10) | Lumbar & Sacral | No ribs | Transformation to rib-bearing thoracic identity |

| Hox11 (a11, c11, d11) | Sacral | Articulates with pelvis | Transformation to lumbar identity |

| Hox5 (a5, b5, c5) | Thoracic (T1, etc.) | Ribs present | Partial transformation to cervical (loss of ribs) |

| Hox6 (a6, b6, c6) | Thoracic (T1) | Ribs present | Complete transformation to C7 (no ribs) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Genetic Deletion of a Hox Cluster in Zebrafish using CRISPR-Cas9

This protocol is adapted from methods used to generate seven distinct hox cluster-deficient mutants in zebrafish [5].

- gRNA Design: Design multiple single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting sequences flanking the entire genomic locus of the target hox cluster (e.g., hoxba or hoxbb). This strategy aims to produce a large chromosomal deletion.

- Microinjection: Co-inject in vitro transcribed sgRNAs and Cas9 mRNA into the yolk of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Founder (F0) Identification: Raise injected embryos to adulthood. These are potential mosaic founders.

- Outcrossing and Screening: Outcross F0 fish to wild-type partners. Screen the resulting F1 offspring for the large deletion by PCR using primers that bind outside the targeted region. A successful deletion will yield a smaller PCR product.

- Establish Stable Lines: Raise PCR-positive F1 fish and confirm germline transmission. Intercross heterozygous (F1) fish to generate homozygous F2 mutants for phenotypic analysis.

- Phenotypic Validation:

- Key Check: At 3 days post-fertilization (dpf), visually inspect for the presence or absence of pectoral fins.

- Molecular Confirmation: Use whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) on earlier stage embryos (e.g., 24-48 hpf) to probe for

tbx5aexpression in the lateral plate mesoderm, a key indicator of successful limb field specification [5].

Protocol 2: Analyzing Skeletal Patterning Phenotypes in Mouse Hox Mutants

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for analyzing the axial skeleton, a common readout for Hox function [4] [3].

- Sample Collection: Euthanize newborn or adult mice. Carefully remove the skin, viscera, and as much muscle tissue as possible from the torso and tail.

- Cartilage Staining (Alcian Blue): Fix eviscerated carcasses in 95% ethanol. Stain for cartilage using Alcian Blue, which binds to glycosaminoglycans in the cartilage matrix.

- Bone Staining (Alizarin Red): After cartilage staining, clear the tissue in a potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution and stain for bone using Alizarin Red, which binds to calcium deposits.

- Clearing and Storage: Transfer the stained skeletons through a series of glycerol/KOH solutions for final clearing. Store in 100% glycerol for long-term preservation.

- Phenotypic Scoring:

- Examine the cleared skeletons under a dissection microscope.

- Identify vertebral elements based on established morphological criteria (e.g., shape of vertebral bodies, presence/absence and size of ribs, articulation points).

- Compare the mutant skeleton to a wild-type littermate control. Look for homeotic transformations, such as the appearance of ribs on normally rib-free lumbar vertebrae (indicative of a Hox10 mutation) or changes in the identity of thoracic vertebrae [4].

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Logic

Hox Gene Regulation of Early Limb Positioning

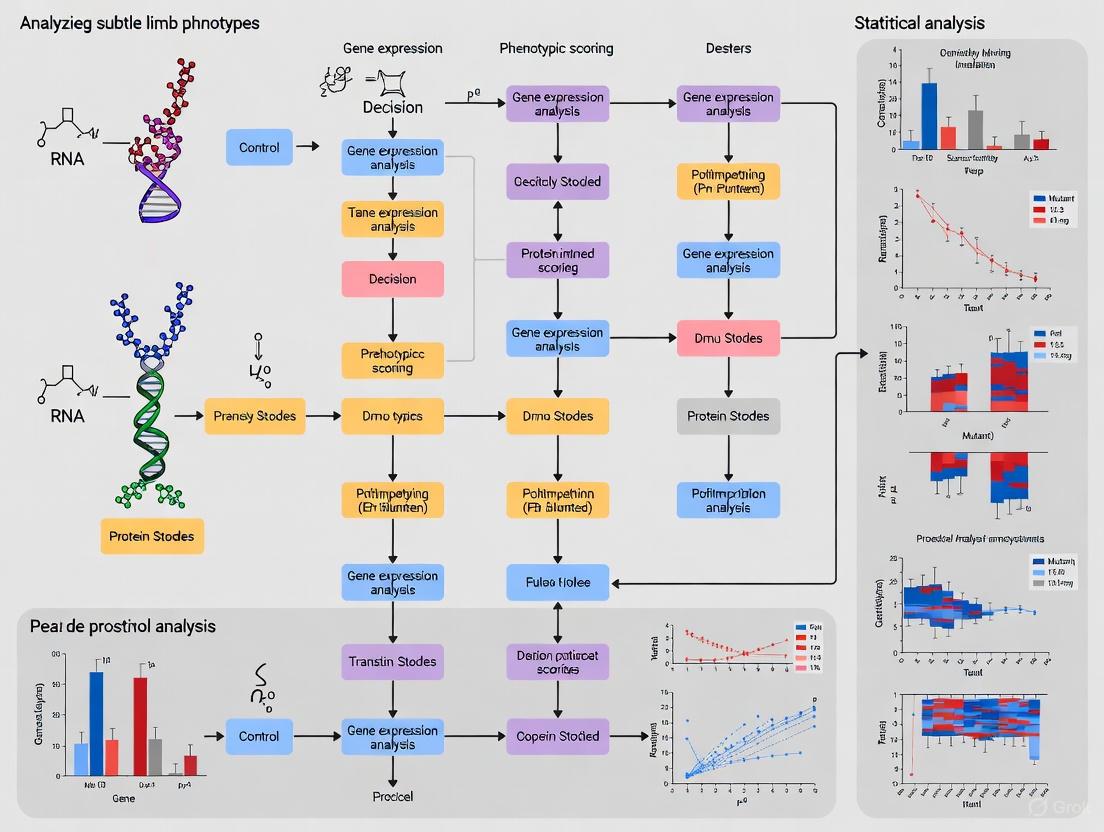

This diagram illustrates the genetic pathway by which Hox genes specify the position of limb initiation, as demonstrated in zebrafish [5].

Hox Gene Logic in Limb Segment Patterning

This diagram summarizes the functional domains of Hox genes along the proximodistal axis of the vertebrate limb, highlighting the two-phase expression strategy of the HoxA and HoxD clusters [2] [1] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Hox Limb Patterning Research

| Reagent / Model | Function / Application | Key Feature / Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish hoxba;hoxbb double mutants | Model for studying limb positioning | Complete loss of pectoral fins due to failed tbx5a induction [5] |

| Mouse Hox Paralogous Mutants (e.g., Hox10) | Model for studying axial identity | Clear homeotic transformations (e.g., ribs on lumbar vertebrae) reveal functional redundancy [3] |

| Hoxd13-/-; Hoxa13-/- double mutants | Model for severe autopod defects | Combined inactivation leads to agenesis of the autopod (hand/foot) [6] |

| Tbx5a In Situ Probe | Molecular marker for limb initiation | Readout for successful specification of the forelimb/pectoral fin field [5] |

| Shh (Sonic Hedgehog) In Situ Probe | Marker for ZPA function and A-P patterning | Essential for assessing the establishment of posterior signaling centers [2] [1] |

| Hoxd Regulatory Landscape Deletions (3DOM, 5DOM) | Tools to dissect gene regulation | Deletion of 5DOM in mouse abolishes digit development by silencing Hoxd13 [6] |

| Alcian Blue & Alizarin Red Stain | Visualization of skeletal morphology | Standard technique for clear assessment of cartilage and bone patterns in cleared specimens [4] |

| NSC 288387 | 10-(2-Methoxyethyl)-3-phenylbenzo[g]pteridine-2,4-dione | 10-(2-Methoxyethyl)-3-phenylbenzo[g]pteridine-2,4-dione (CAS 61369-43-5) is a pan-flavivirus MTase inhibitor and iGluA2 modulator. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| BMS-986339 | BMS-986339, MF:C35H41F4N3O4, MW:643.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The harmonious development of vertebrate limbs is a complex process orchestrated by a set of key regulatory genes, foremost among them the Hox gene family. These genes encode transcription factors that provide cells with positional information, determining the identity of structures along the anterior-posterior (AP), proximal-distal (PD), and other body axes [2]. In the limb, different combinations and concentrations of Hox proteins create a "molecular address" that instructs cells to form a specific bone, joint, or soft tissue. Disruptions to this precise genetic code, through either hereditary mutations or somatic changes, result in a wide spectrum of congenital limb anomalies. This technical support guide is framed within a broader thesis on advanced methods for analyzing subtle limb patterning phenotypes. It aims to equip researchers with the knowledge to troubleshoot experimental challenges in Hox mutant research, from gross morphological defects to nuanced cellular mis-patterning.

Fundamental Concepts: Hox Genes and Limb Patterning

The Genomic Organization and Function of Hox Genes

The 39 Hox genes in mammals are arranged in four clusters (A, B, C, and D) on different chromosomes. Within each cluster, the genes are organized in a spatially and temporally collinear manner: genes at the 3' end are expressed earlier and more anteriorly, while genes at the 5' end are expressed later and more posteriorly [2] [7]. This systematic expression pattern allows Hox genes to orchestrate the formation of complex structures.

- Paralogous Groups: Hox genes across the four clusters that share the most sequence similarity and a similar position within their cluster are grouped into 13 paralogous groups (1-13). Members of the same paralog group often, though not always, exhibit functional redundancy [8].

- Combinatorial Code: The final morphology of a segment is not determined by a single Hox gene but by the specific combination, or code, of Hox genes expressed in that region. This allows for a vast regulatory capacity from a limited set of genes [8].

Hox Control of Limb Segments

In the developing limb, the posterior HoxA and HoxD clusters (paralogs 9-13) play the most prominent roles. Their functions are largely segregated along the PD limb axis in a segmental fashion, a concept often referred to as "phenotypic suppression" where more posterior 5' genes suppress the action of more anterior 3' genes [8] [9].

The following table summarizes the primary Hox paralog groups governing the formation of each major limb segment in the mouse model:

Table 1: Functional Roles of Hox Paralogs in Limb Patterning

| Limb Segment | Skeletal Elements | Primary Hox Paralogs | Phenotype of Combined Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stylopod | Humerus, Femur | Hox9, Hox10 | Severe truncation or mis-patterning [2] [8] |

| Zeugopod | Radius/Ulna, Tibia/Fibula | Hox11 | Severe reduction of ulna/radius; mis-shapen zeugopod [2] [8] [9] |

| Autopod | Wrist, Hand, Foot | Hox12, Hox13 | Complete loss of digit elements; fused or misshapen carpals/tarsals [8] [10] |

This model is supported by genetic loss-of-function studies. For instance, the combined mutation of Hoxa11 and Hoxd11 leads to a dramatically reduced zeugopod (ulna and radius), whereas single mutants show only minor defects, highlighting the significant functional redundancy among paralogs [8].

Signaling Centers and Downstream Pathways

Hox genes exert their patterning effects by regulating key signaling centers within the limb bud, namely the Apical Ectodermal Ridge (AER) and the Zone of Polarizing Activity (ZPA).

- Interaction with Shh: The ZPA, which produces Sonic hedgehog (Shh), is critical for AP patterning. Hox genes are upstream regulators of Shh expression. Specifically, Hox9 genes promote posterior Hand2 expression, which inhibits the hedgehog pathway inhibitor Gli3, thereby allowing for the induction of Shh [2]. Loss of Hox9 function leads to a failure to initiate Shh expression [2].

- Regulation of Fgf signaling: The AER secretes Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGFs) that drive PD outgrowth. The expression of Fgf8 in the AER is dependent on signals from the underlying mesenchyme, which are regulated by Hox genes. Mutants for Hoxa9,10,11/Hoxd9,10,11 show severely reduced Shh expression in the ZPA and decreased Fgf8 expression in the AER [8].

The diagram below illustrates the regulatory network between Hox genes and the key signaling centers during early limb patterning.

Troubleshooting Guide: Phenotypic Analysis in Hox Mutants

This section addresses common experimental challenges and questions that arise when characterizing limb phenotypes in Hox mutant models.

FAQ 1: My Hox mutant model shows no skeletal phenotype at birth. Does this mean the gene is not involved in limb development?

Answer: Not necessarily. The absence of a overt skeletal phenotype is a common frustration often attributable to genetic redundancy.

- Primary Cause (Redundancy): A single Hox gene mutation frequently yields subtle or no phenotypes because paralogous genes (e.g., Hoxa11 and Hoxd11) or flanking genes within the same cluster (e.g., Hoxa9, a10, a11) can compensate for its loss [8] [10]. The model of "phenotypic suppression" suggests that the removal of a single gene may not be sufficient to disrupt the underlying regulatory code [8].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm Targeting and Expression: Verify that your genetic mutation is indeed causing a loss of function and that protein levels are ablated.

- Analyze Earlier Time Points: Phenotypes may be evident during embryonic development but resolve by birth. Examine limb buds at E11.5-E15.5 for changes in size, shape, or the patterning of cartilage condensations (e.g., via Alcian Blue staining) [8].

- Check for Synergistic Effects: Generate trans-heterozygotes (e.g., Hoxa11+/-; Hoxd11+/-). The presence of a phenotype in these animals, absent in single heterozygotes, indicates genetic interaction and functional redundancy [10].

- Create Higher-Order Mutants: As a definitive test, generate combined mutants targeting all major paralogs (e.g., Hoxa11-/-; Hoxd11-/-) [8] or use recombineering approaches to target multiple flanking genes simultaneously (e.g., Hoxa9,10,11) [8].

FAQ 2: The limb phenotype in my model is highly variable and incompletely penetrant. How can I account for this in my analysis?

Answer: Variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance are hallmarks of Hox mutations and can stem from several sources.

- Primary Causes:

- Somatic Mosaicism: In disorders like isolated macrodactyly, the causative mutations (e.g., in PIK3CA or AKT1) are often mosaic, meaning only a subset of cells carry the mutation. The Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) in affected tissue can be as low as 10-33%, leading to dramatic variation in phenotypic severity [11].

- Genetic Background: The strain of mice used can have significant modifiers that alter the expressivity of a Hox mutation.

- Compensatory Mechanisms: Other Hox genes or developmental pathways may be upregulated to varying degrees in different individuals, buffering the mutational effect.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Genotype the Affected Tissue: If working with an overgrowth phenotype, sequence the affected limb tissue directly to confirm and quantify the mosaic mutation, rather than relying on blood or tail DNA [11].

- Increase Sample Size: Account for variability by significantly increasing the number of mutant embryos/animals analyzed.

- Backcrossing: Maintain the mutant allele on a consistent, inbred genetic background for several generations to reduce modifier effects.

- Molecular Phenotyping: Move beyond gross morphology. Use molecular markers (e.g., in situ hybridization for Shh, Fgf8, Alx4) to detect consistent, subtle changes in patterning that precede morphological variation [8].

FAQ 3: How can I determine if a patterning defect is primary to the skeleton or secondary to defects in other tissues?

Answer: This is a critical question, as Hox genes are expressed in multiple limb tissues. The skeleton, tendons, and muscle connective tissues arise from the lateral plate mesoderm, while muscle precursors migrate in from the somites [2].

- Primary Cause (Non-Autonomous Patterning): Classical experiments and muscle-less limb models show that early skeletal and tendon patterning occurs normally in the absence of muscle [2]. However, later integration and maintenance of tendons require muscle interaction [2]. Therefore, a skeletal defect could be secondary to a primary defect in the stromal connective tissues.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Analyze Tissue-Specific Gene Expression: Examine the expression of early cartilage (e.g., Sox9), tendon (e.g., Scleraxis), and muscle markers in your mutant at the onset of patterning (E11.5-E12.5). A primary skeletal defect will show aberrant Sox9 expression patterns.

- Create Tissue-Specific Knockouts: Use Cre-lox technology to delete the Hox gene specifically in the skeletal lineage (e.g., using Prx1-Cre or Col2a1-Cre) versus the connective tissue lineage. This can pinpoint the cell-autonomous requirement for the gene [2].

- Cell Transplantation Studies: In chick models, perform quail-chick grafts to test the autonomy of cell populations.

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Laser Capture Microdissection and RNA-Seq for Molecular Phenotyping

To move beyond gross morphology and understand the downstream pathways affected in Hox mutants, high-resolution transcriptomic analysis is powerful.

- Application: Identifying key pathways regulated by Hox genes during limb development [8].

- Procedure:

- Tissue Preparation: Harvest wild-type and mutant forelimb zeugopods at E15.5. Embed in OCT compound and cryosection.

- Staining: Briefly stain sections with Histogene or another compatible stain to visualize tissue architecture.

- Microdissection: Use a laser capture microdissection system to separately collect cells from the resting, proliferative, and hypertrophic chondrocyte compartments of the developing ulna/radius.

- RNA Extraction and Sequencing: Extract high-quality RNA from each compartment and prepare RNA-Seq libraries. Sequence to a sufficient depth.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map reads, quantify gene expression, and perform differential expression analysis. Pathway analysis (e.g., GO, KEGG) will reveal perturbed biological processes.

- Expected Outcome: This protocol in Hoxa9,10,11/Hoxd9,10,11 mutants revealed altered expression of key genes like Gdf5, Bmpr1b, Igf1, Hand2, and Runx3, defining the pathways downstream of these Hox genes in endochondral ossification [8].

Protocol: Competency Accessory Limb Model (CALM) in Axolotl

This assay tests whether limb cells have achieved the competency to respond to patterning signals, a key question in regeneration and development.

- Application: Assessing patterning competency in regenerative models [12].

- Procedure:

- Nerve Deviation: In a 7-10 cm axolotl, anesthetize and deviate the brachial nerve bundle into a skin wound created on either the anterior or posterior side of the limb.

- Recovery and Competency Induction: Allow the animal to recover. The innervated wound site, over ~6 days, generates a blastema where cells acquire patterning competency.

- Retinoic Acid (RA) Treatment: After 6 days, administer a systemic injection of RA (150 mg/kg) or a vehicle control. RA reprograms positional identity.

- Analysis:

- CALM-P (Molecular): Harvest tissue from the wound site 24 hours post-RA injection. Analyze shifts in A/P gene expression (e.g., Shh, Hand2, Alx4, Fgf8) via qRT-PCR [12].

- CALM-A (Morphological): For the anterior CALM, observe the wound site over 9+ weeks. The induction of ectopic limb structures indicates that cells were competent and responded to the RA-mediated posteriorizing signal [12].

- Troubleshooting: The nerve deviation surgery is technically challenging and requires extensive practice. Using "virgin" limbs that have not undergone prior amputation is recommended for more consistent results [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Hox and Limb Patterning Research

| Reagent / Model | Type | Primary Function in Research | Key Example / Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox Cluster Mutants | Genetic Model | Reveals functional redundancy and segment-specific requirements | Hoxa9,10,11-/-/Hoxd9,10,11-/- mice [8] |

| Ulnaless (Ul) Mutant | Regulatory Mutation Model | Demonstrates the role of long-range enhancers; ectopic Hoxd13 expression transforms zeugopod identity [9] | Inversion of the HoxD cluster [9] |

| PIK3CA/AKT1 Mosaic Models | Disease Model | Models isolated overgrowth disorders like macrodactyly; mimics somatic mutation spectrum [11] | PIK3CA p.His1047Arg; AKT1 p.Glu17Lys [11] |

| Hand-Foot-Genital Syndrome (HFGS) Models | Human Disorder Model | Studies the effect of HOXA13 mutation on distal limb and genitourinary development | HOXA13 p.Gln50Leu, p.Tyr290Ser [7] |

| Accessory Limb Model (ALM/CALM) | Experimental Assay | Tests the A/P identity of grafted tissue or the patterning competency of cells in urodele amphibians [12] | Nerve deviation + skin graft/RA injection [12] |

| Laser Capture Microdissection | Technical Tool | Enables compartment-specific transcriptomic analysis from heterogeneous tissues [8] | Isolation of specific chondrocyte zones from growth plate [8] |

| SHP504 | SHP504, MF:C23H15ClN4O4, MW:446.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Antiflammin 2 | Antiflammin 2, MF:C46H77N13O15S, MW:1084.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Data Presentation: From Genotype to Phenotype

The following table synthesizes quantitative data from a study on isolated macrodactyly, illustrating the relationship between specific genetic mutations and clinical presentation.

Table 3: Genotype-Phenotype Correlation in a Cohort of Isolated Macrodactyly Patients (n=24)

| Genetic Alteration | Number of Patients | Common Affected Digits | Frequent Limb Involvement | Notes / Associated Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIK3CA p.His1047Arg | 7 | Digit 2, Digit 3 | Upper and Lower Limbs | Most common PIK3CA variant in this cohort [11] |

| PIK3CA p.Glu542Lys | 6 | Digit 2, Digit 3 | Lower Limbs | Associated with helical domain; significant correlation with lower limb involvement [11] |

| AKT1 p.Glu17Lys | 4 | Digit 2, Digit 3 | Upper and Lower Limbs | All four patients met diagnostic criteria for Proteus syndrome [11] |

| Other PIK3CA variants* | 7 | Digit 2 | Varies | Includes p.Glu453Lys, p.Glu545Lys, p.Gln546Lys, p.His1047Tyr, p.His1047Leu [11] |

Other variants were each found in 1-2 patients. The second digit was the most frequently affected digit across the entire cohort (22/24 patients) [11].

Core Regulatory Pathways: FAQs

FAQ 1: What is the direct molecular mechanism by which Hox genes position the forelimbs along the body axis?

Hox genes directly control the position of forelimb formation by regulating the expression of the key limb initiation gene Tbx5. This is achieved through a specific 361 base-pair enhancer element located within the second intron of the Tbx5 gene. This enhancer contains several Hox binding sites (Hbs). Studies show that different Hox proteins have opposing functions on this enhancer:

- Activation: Hox proteins expressed in the rostral (anterior) lateral plate mesoderm, such as Hoxc6, can bind to the enhancer and activate

Tbx5transcription [13]. - Repression: Hox proteins expressed in the caudal (posterior) lateral plate mesoderm, such as Hoxc9, bind to the same enhancer and act as potent repressors, preventing

Tbx5expression outside the forelimb territory [13]. - Mechanism: The forelimb-specific expression of

Tbx5is therefore achieved through a combination of broad activation and localized repression, a mechanism known as a "Hox code" [14] [13]. Mutation of specific binding sites (e.g., Hbs2) in theTbx5enhancer leads to a loss of repression and caudal expansion ofTbx5expression into the hindlimb region [13].

FAQ 2: How do Hox genes functionally interact with the Sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway during limb patterning?

The interaction is primarily indirect and is mediated through the Hox-dependent establishment of the limb field and subsequent signaling centers.

- ZPA Induction:

Tbx5, whose expression is initiated by Hox genes, is essential for setting up the signaling environment of the early limb bud. It activatesFgf10in the mesenchyme, which in turn helps establish the Apical Ectodermal Ridge (AER) [15] [13]. The Zone of Polarizing Activity (ZPA), which produces Shh, is established at the posterior limb bud adjacent to this AER. - Regulation of Shh Signaling:

Tbx5also plays a later role in modulating the Shh pathway. It acts as a transcriptional repressor ofPtch1, a receptor and negative regulator of the Shh pathway. By repressingPtch1,Tbx5can potentiate Hedgehog signaling activity, which is critical for proper digit patterning [15]. - Direct Hox Regulation: In some contexts, particularly in the hindlimb, certain Hox genes can directly regulate

Shhexpression. For example, misexpression of posterior Hox genes (e.g.,Hoxd11-d13) in the anterior limb bud can induce a mirror-imageShhexpression pattern, leading to double-posterior limbs [1].

FAQ 3: What are the expected limb phenotypes when Hox gene function is disrupted, and how do they differ from Tbx5 or Shh mutations?

The phenotypes vary significantly based on which gene or gene cluster is affected, revealing their positions in the regulatory hierarchy.

- Hox Gene Mutations: Mutations in

Hoxgenes, particularly theHoxAandHoxDclusters, often result in homeotic transformations (one body part transforming into the identity of another) and changes in the size and number of skeletal elements. For example: - Tbx5 Mutations: Complete loss of

Tbx5prevents forelimb bud initiation entirely, demonstrating its fundamental role at the top of the limb genetic hierarchy [14] [15]. Conditional knockdowns can lead to both polydactyly (extra digits) and oligodactyly (missing digits) due to disrupted Shh signaling [15]. - Shh Mutations: Loss of

Shhresults in a severe truncation of the limb, typically with a single digit forming, highlighting its crucial role in controlling limb outgrowth and anterior-posterior patterning [15].

Table 1: Characteristic Limb Phenotypes from Gene Disruption

| Gene/Gene Group | Primary Role in Limb Development | Characteristic Loss-of-Function Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| Hox Genes (A/D clusters) | Specify positional identity & pattern skeletal elements | Homeotic transformations; changes in digit number, size, and identity (e.g., microdactyly) [16] [1] |

| Tbx5 | Initiate forelimb outgrowth; modulate Shh pathway | Failure of forelimb initiation; or polydactyly/oligodactyly in conditional mutants [14] [15] |

| Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) | Control digit identity and number; promote limb outgrowth | Severe limb truncation; formation of a single, stylized digit [15] |

Troubleshooting Experimental Analysis

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for analyzing subtle limb patterning phenotypes in Hox mutants?

Given the redundancy and complexity of the Hox system, a multi-faceted approach is required.

- 1. Use Skeletal Staining as a First Pass: Clear visualization of the entire skeletal pattern is essential. Alcian Blue (for cartilage) and Alizarin Red (for bone) double staining of whole-mount E14.5-E18.5 mouse embryos is the gold standard. This allows for assessment of homeotic transformations, fusions, and size reductions [16].

- 2. Employ Molecular Domain Markers: Skeletal patterns can be normal despite molecular alterations. Use whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) to examine the expression domains of key genes:

- 3. Target Multiple Paralogs: Due to genetic redundancy, knocking out a single Hox gene may yield no or mild phenotypes. Generate paralogous group knockouts (e.g., delete all Hox5 genes:

Hoxa5,Hoxb5,Hoxc5) to uncover their full function [4]. - 4. Quantitative Morphometrics: For subtle changes in digit or bone length, use precise measurements from stained skeletons or micro-CT scans for statistical comparison between mutant and wild-type littermates [16].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Hox-Limb Pathways

| Research Reagent | Specific Example / Assay | Primary Function in Investigation |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter Constructs | Tbx5 int2(361)-lacZ transgenic mouse line [14] [13] |

Identifies and characterizes enhancer activity and Hox responsiveness in vivo. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Mutagenesis of Hox binding sites (Hbs) in the Tbx5 enhancer [13] |

Determines the functional necessity of specific transcription factor binding sites. |

| In vivo Electroporation | Chick neural tube/limb bud electroporation with Hox expression vectors (e.g., pCIG) [14] | Tests the ability of Hox genes to regulate targets like the Tbx5 enhancer in a developing system. |

| Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) | In vitro binding of Hox proteins to radiolabeled oligonucleotides from the Tbx5 enhancer [14] |

Confirms direct physical binding of a transcription factor to a specific DNA sequence. |

| Genetic Inducible Fate Mapping | Gli1-CreERT2; R26R-lacZ mice with tamoxifen induction [15] |

Marks and tracks the lineage of Hedgehog-receiving cells during limb development. |

FAQ 5: My Hox mutant shows no obvious skeletal defects. Does this mean the gene is not involved in limb development?

Not necessarily. The absence of a phenotype can be due to several factors:

- Genetic Redundancy: This is the most common reason. Other Hox genes or paralogs with similar expression patterns may compensate for the loss of a single gene. The solution is to create compound mutants [4].

- Subtle Molecular Phenotypes: The mutation may affect the expression of downstream target genes without altering the final skeletal morphology. Always analyze the expression of key markers like

Tbx5,Shh, andFgf8in your mutant. - Temporal Specificity: The gene's function might be critical only during a very narrow time window. Consider using inducible/conditional knockout systems (e.g., Cre-ERT2) to target the gene at specific developmental stages [15].

Visualization of Key Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams summarize the core regulatory relationships and a recommended experimental workflow.

Diagram 1: Hox-Tbx5-Shh Gene Regulatory Network. Rostral Hox proteins activate the Tbx5 enhancer, while caudal Hox proteins repress it, restricting Tbx5 expression to the forelimb territory. Tbx5 then drives limb initiation and modulates the Shh pathway for digit patterning, with feedback loops ensuring coordinated growth.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Analyzing Limb Patterning in Mutants. A systematic approach begins with gross phenotypic screening, proceeds to molecular analysis of gene expression, and then uses genetic and biochemical methods to uncover mechanism, especially important when facing subtle or absent phenotypes.

A Technical Support Guide for Hox Researchers

Troubleshooting Guide: Absent or Subtle Phenotypes in Hox Mutants

Problem: You have generated a loss-of-function mutant for a Hox gene but observe no morphological phenotype or a much weaker one than expected.

Explanation: In vertebrates, the presence of genetic redundancy and the phenomenon of genetic compensation frequently mask the phenotypic consequences of inactivating a single Hox gene [4] [17]. Due to genome duplication events, vertebrate Hox genes are organized into four paralog groups (HoxA, B, C, and D). Genes within the same paralog group (e.g., HoxA5, HoxB5, HoxC5) often have overlapping expression domains and similar biochemical functions, allowing one paralog to compensate for the loss of another [4] [17]. A "phenotypic paradox" exists where a gene is clearly important, but its mutation does not produce the expected phenotype [17].

Solution: Systematically target all genes within a paralog group.

- Investigation Workflow: Follow this logical path to diagnose and resolve the issue.

- Recommended Actions:

- Confirm Redundancy: Generate combinatorial mutant embryos lacking the function of all genes in a specific paralog group (e.g., HoxA5, HoxB5, HoxC5). For example, while single HoxA3 or HoxD3 mutants show mild defects, the double knockout results in a severe, specific phenotype where the first cervical vertebra fails to form [4].

- Rule Out Technical Issues: Ensure your mutant allele is a true null. Some hypomorphic alleles (e.g., small in-frame deletions) can trigger stronger compensatory responses than null alleles, potentially masking phenotypes [17].

- Test for Active Compensation: Use transcriptomic methods (RNA-seq) to check if the expression of homologous genes is upregulated in your mutant. This active compensation relies on molecular mechanisms involving nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) pathways and the COMPASS complex [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between genetic redundancy and genetic compensation?

- Genetic Redundancy: A passive state where two or more homologous genes can perform the same biochemical function because of their similar sequences and roles. If one gene is lost, the other(s) can still perform the function, resulting in no phenotype [17].

- Genetic Compensation: An active process triggered by a deleterious mutation. The organism detects the mutation (often via the nonsense-mediated decay pathway for PTC-bearing mRNAs) and responds by upregulating the expression of specific homologous genes to compensate for the lost function [17].

Q2: Why might a CRISPR-generated null mutant show a less severe phenotype than a morpholino knockdown?

This discrepancy is often due to genetic compensation. Morpholinos (transient knockdown) typically do not trigger this robust compensatory response. In contrast, a heritable CRISPR mutation can activate a feedback mechanism that upregulates related genes, thereby rescuing the phenotype. This highlights the importance of using stable genetic mutants for functional studies [17].

Q3: Our transcriptomic data shows only a few differentially expressed genes in our Hox mutant. Is this normal?

Yes. Global transcriptomic analyses of Hoxa5 null mutants across multiple tissues revealed very few common differentially expressed genes, underscoring that HOX proteins often regulate context-specific effectors. However, one consistent trend was the mis-regulation of other Hox genes, suggesting that a key function may be fine-tuning the expression of other members of the Hox network in trans [18].

Q4: Are there specific molecular tools to detect genetic compensation?

Yes. The following table outlines key reagents and their applications for studying Hox gene function and compensation [18] [19] [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application in Hox Research |

|---|---|

| Paralogous Mutant Mice | Mouse models with combined deletions of all Hox genes in a single paralog group (e.g., Hox5: A5, B5, C5) to overcome redundancy and reveal full phenotypic impact [4]. |

| Bulk RNA-seq | Profiling transcriptome-wide changes in Hox mutant tissues to identify mis-regulated genes, including potential upregulation of compensating homologs [18]. |

| Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization | Spatial visualization of gene expression patterns for Hox genes and their putative targets within the developing embryo [19]. |

| Geometric Morphometrics | Quantitative image analysis of shapes, allowing precise measurement of subtle morphological changes in mutant structures (e.g., limb buds, vertebrae) that may be missed by simple observation [19]. |

| COMPASS Complex Inhibitors | Chemical or genetic tools to disrupt the COMPASS complex (e.g., components like KMT2D), which is required for the transcriptional activation seen in genetic compensation [17]. |

Q5: How can we accurately analyze subtle morphological phenotypes in Hox mutants?

Traditional observation may not be sensitive enough. Employ Geometric Morphometrics, a powerful quantitative method that combines whole-mount in situ hybridization with shape analysis [19].

- Workflow:

- Image Acquisition: Capture standardized images of developing structures (e.g., E10.5-12.5 mouse limb buds).

- Domain Segmentation: Use software to segment the expression domain of your gene of interest (e.g., Hoxa11, Hoxa13) at different threshold levels.

- Shape Analysis: Apply Procrustes-based semilandmark or Elliptical Fourier analyses to quantify the shape and size of both the entire structure and the gene expression domain.

- Statistical Comparison: Statistically compare the shape variables between wild-type and mutant samples to reveal subtle, yet significant, patterning changes [19].

Phenotypic Data in Hox Paralog Mutants

The table below summarizes classic homeotic transformations observed in complete paralogous Hox mouse mutants, illustrating the clear phenotypes uncovered once redundancy is overcome [4].

| Hox Paralog Group Mutated | Observed Vertebral Transformation | Morphological Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Hox5 (A5, B5, C5) | Partial transformation of T1 vertebra | Incomplete ribs form, shifting towards a cervical morphology [4]. |

| Hox6 (A6, B6, C6) | Complete transformation of T1 vertebra | T1 resembles the C7 vertebra (no ribs) [4]. |

| Hox10 (A10, B10, C10) | Transformation of lumbar and sacral vertebrae | Ribs form on lumbar vertebrae; sacral vertebrae adopt a lumbar identity [4]. |

| Hox11 (A11, B11, C11) | Transformation of sacral vertebrae | Sacral vertebrae adopt a lumbar identity [4]. |

Hox genes are a family of transcription factors, characterized by a conserved 180-base-pair DNA sequence known as the homeobox, that play a fundamental role in patterning the anterior-posterior (head-to-tail) body axis in all bilaterian animals [20] [21]. These genes are master regulators of embryonic development, specifying regional identity and determining what structures form in different body segments [20] [22]. Their function is deeply conserved; for instance, a mouse Hox gene can substitute for its fruit fly counterpart and prevent the formation of antennae on the fly's head [20]. Despite this deep conservation, changes in Hox gene expression, regulation, and protein function are key drivers of evolutionary innovation and body plan diversification [23] [24].

A central challenge in modern Hox biology is the "Hox Specificity Paradox"—the question of how different Hox proteins, which possess highly similar DNA-binding domains, achieve specificity in regulating distinct sets of target genes to specify different anatomical outcomes [25]. This technical guide is framed within a thesis focused on analyzing subtle limb patterning phenotypes in Hox mutants. We provide targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to help researchers dissect the complex and often nuanced roles of Hox genes across model organisms, with a particular emphasis on limb development.

Hox Gene Fundamentals: Conservation, Colinearity, and Clusters

Core Principles and Evolutionary History

Hox genes are notable not only for their sequence conservation but also for their genomic organization and expression principles. Understanding these core concepts is essential for designing and interpreting functional experiments.

- Genomic Organization and Colinearity: Hox genes are typically arranged in clusters in the genome. A key feature is colinearity—the order of genes on the chromosome corresponds to their spatial and temporal expression domains along the embryo's anterior-posterior axis [22]. Genes at the 3' end of the cluster are expressed earlier and in more anterior regions, while genes at the 5' end are expressed later and in more posterior regions [23].

- Cluster Duplication in Vertebrates: Invertebrates like Drosophila typically have a single Hox cluster. In vertebrates, the entire Hox cluster has been duplicated multiple times. Mammals possess four Hox clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and Hoxd), while teleost fish can have up to eight [20] [23]. These duplicated genes (paralogs) are often retained because they undergo functional divergence, partitioning ancestral roles or acquiring new functions [24].

Table 1: Hox Cluster Composition in Key Model Organisms

| Organism | Number of Hox Clusters | Example Genes and Their Primary Roles |

|---|---|---|

| Fruit Fly (D. melanogaster) | 2 Complexes (ANT-C, BX-C) | Ultrabithorax (Ubx): Specifies third thoracic segment (halteres). Antennapedia (Antp): Promotes leg formation in second thoracic segment [21]. |

| Mouse (M. musculus) | 4 (HoxA, B, C, D) | Hoxa13/Hoxd13: Patterning of digits (autopod) in the limb [26]. Hox10 paralogs (e.g., Hoxa10): Suppress rib formation in the lumbar vertebrae [20] [23]. |

| Zebrafish (D. rerio) | 7-8 | HoxAα and HoxAβ: Result of teleost-specific duplication; subfunctionalization of roles in patterning [27]. |

The following diagram illustrates the conserved organization of Hox clusters and the principle of colinearity in a vertebrate model.

This section details key reagents and methodologies critical for experimental research on Hox gene function, particularly in the context of limb patterning.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Hox Gene Analysis

| Reagent / Resource | Function and Application | Key Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Hox-Specific Antibodies (e.g., α-HOXA13, α-HOXD13) [26] | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to map genome-wide binding sites of Hox transcription factors. | Validate antibody specificity using knockout tissue as a control [26]. High redundancy between paralogs (e.g., HOXA13/HOXD13) may require simultaneous targeting. |

| Histone Modification Antibodies (e.g., α-H3K27ac) [26] | Mark active chromatin states (enhancers, promoters) via ChIP-seq. Identifies cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) impacted by Hox loss. | Allows comparison of chromatin state dynamics between wild-type and mutant limbs to assess Hox impact on the regulatory landscape. |

| RNA-seq Libraries | Profiling transcriptome-wide changes in gene expression in mutant versus wild-type tissue (e.g., microdissected limb buds) [26]. | Use precise morphological landmarks for tissue dissection to ensure consistency. Identify both downstream targets and mis-regulated proximal genes. |

| Phylogenetic Footprinting (via PipMaker) [27] | Bioinformatics alignment of Hox cluster sequences from evolutionarily distant species to identify conserved non-coding elements (CNEs). | CNEs are strong candidates for conserved cis-regulatory elements. Useful for prioritizing regions for functional testing. |

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Key Experimental Challenges

Challenge: Interpreting Subtle or Paradoxical Limb Patterning Phenotypes

Problem: Inactivation of Hox genes, particularly the 5' members like Hoxa13 and Hoxd13 (Hox13), does not always result in clear homeotic transformations in the limb. Instead, phenotypes can include digit agenesis, changes in the molecular identity of cells without immediate morphological changes, or the failure to terminate early developmental programs [26].

Investigation and Solution:

- Hypothesis: Hox13 inactivation disrupts the transition from the early limb bud program to the late, distal limb (autopod) program.

- Experimental Approach: Perform RNA-seq on microdissected late-distal limb buds from wild-type and Hox13-/- mutants at E11.5, using a consistent morphological landmark (e.g., the indentation at the proximal border of the handplate) [26].

- Expected Results: In the mutant, you will observe (Table 3):

- Downregulation of genes normally specific to the late-distal WT program.

- Upregulation of genes normally expressed in the early limb bud or proximal regions, which should be excluded from the autopod [26].

- Follow-up: Use Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to statistically confirm that genes upregulated in the mutant are preferentially expressed in early WT limbs, and downregulated genes are specific to late-distal WT limbs [26].

Table 3: Example Transcriptional Changes in Hox13-/- Limb Buds

| Gene Expression Change in Mutant | Example Genes | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | Hoxa11, Hoxc11, Hoxd4-9 [26] | Failure to repress the early/proximal limb program; a breakdown in "posterior prevalence". |

| Downregulated | Late-distal specific genes (e.g., digit patterning genes) [26] | Failure to activate the terminal differentiation program required for digit formation. |

Challenge: The Hox Specificity Paradox – Identifying Functional Target Genes

Problem: Hox proteins bind highly similar DNA sequences in vitro, making it difficult to predict and validate their genuine, functional in vivo targets. Many high-affinity binding sites identified in vitro may not be biologically relevant [25].

Investigation and Solution:

- Hypothesis: Hox proteins achieve specificity in vivo by binding to clusters of low-affinity sites within enhancers, rather than single high-affinity sites.

- Experimental Approach:

- ChIP-seq: Map in vivo binding sites for Hox proteins (e.g., HOXA13/HOXD13) in developing limb tissue. Co-binding with cofactors like PBC and Meis is common [21] [25].

- Motif Analysis: Perform de novo motif discovery on the bound regions. Do not rely solely on known, high-affinity Hox binding motifs [26] [25].

- Functional Validation: Mutate candidate low-affinity binding sites within an enhancer (e.g., for a gene like shavenbaby) in an animal model and use quantitative measures (e.g., trichome counts in flies) to assess the impact on enhancer activity. Robust function typically requires the entire cluster of sites, not just one [25].

- Key Insight: The regulatory output is sensitive to the number of low-affinity sites. Mutating individual sites may have subtle effects, but disrupting the entire cluster severely compromises enhancer function, especially under suboptimal conditions (e.g., temperature shifts, reduced Hox dosage) [25].

- Experimental Approach:

The following workflow summarizes the integrated multi-omics approach to dissect Hox gene function in limb patterning.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our genetic mutant for a single Hox gene shows no obvious phenotype. How is this possible, given their important roles? A1: This is often due to functional redundancy between paralogous Hox genes. In mammals, the four Hox clusters contain genes of the same paralog group (e.g., Hoxa11, Hoxc11, Hoxd11) that have overlapping functions. Inactivating a single gene may have a subtle effect, while inactivating the entire paralog group is required to reveal dramatic phenotypes [20]. Always consider the genetic background and potential for compensation by other Hox genes.

Q2: How can I determine if a conserved non-coding element (CNE) near my Hox gene of interest is a functional enhancer? A2: Use phylogenetic footprinting [27]. Align the genomic region from multiple, evolutionarily distant species (e.g., human, mouse, zebrafish). CNEs that stand out are strong candidates for functional cis-regulatory elements. These can then be tested in vivo using reporter gene assays (e.g., LacZ in mouse embryos) to confirm enhancer activity and spatiotemporal specificity.

Q3: Why do Hox genes sometimes seem to act as activators in one context and repressors in another? A3: The function of a Hox protein is highly context-dependent. A single Hox protein can act as an activator for one gene and a repressor for another [21]. This is determined by the specific set of co-factors it recruits to an enhancer and the local chromatin environment. The outcome depends on the protein-protein interactions facilitated by the homeodomain and other protein regions [24].

Q4: What is the evidence that Hox gene evolution contributed to morphological diversity? A4: There are numerous examples. In snakes, the expansion of the rib-bearing thoracic region is associated with changes in the expression and regulation of Hox10 and HoxC genes, which have lost the ability to suppress rib formation in specific vertebral regions [23]. Furthermore, after Hox cluster duplications, the homeodomains themselves underwent positive selection, allowing for functional diversification that likely facilitated the evolution of novel vertebrate body plans [24].

High-Resolution Tools for Phenotype Detection and Characterization

Advanced Imaging and 3D Morphometry for Quantitative Skeletal Analysis

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common sources of error in 3D landmark data collection, and how can I minimize them? Intra-observer error is a primary concern in 3D morphometry. Evidence shows that the measurement technique itself can account for a significant portion of total shape variation: 1.7% for a 3D digitizer, 1.8% for a CT scanner, and 4.5% for a surface scanner [28]. To minimize these errors, researchers should:

- Conduct intra-observer error pilot studies as a standard part of their methodology.

- Be aware that surface scanners may yield a higher percentage of missing landmarks compared to CT scanners and 3D digitizers [28].

- Avoid combining landmark data collected using different techniques, as the variation between techniques can account for approximately 18% of total shape variation [28].

Q2: My 3D model shows unexpected surface textures or seems to obscure details. What could be the cause? This is a known challenge when working with archaeological or taphonomically altered material. Studies indicate that 3D model-based techniques, including both CT and surface scanners, can sometimes obscure pre-existing taphonomic damage on crania, making it difficult to distinguish from the original bone morphology [28]. It is critical to perform a thorough macroscopic examination of the specimen prior to scanning and to document any damage meticulously. This ensures that taphonomic changes are not misinterpreted as morphological or pathological traits.

Q3: What is the recommended imaging workflow for documenting suspected skeletal trauma, especially in non-skeletonized remains? A multi-stage imaging protocol is essential for robust documentation. For cases such as suspected child abuse, it is recommended to perform radiographs at three key stages [29]:

- Upon receipt: To document the condition of the remains and any trauma present before any processing.

- After removal of major soft tissue: To visualize trauma more clearly before maceration.

- After full processing: To document the clean, defleshed bone. This sequence empirically demonstrates that observed trauma was present prior to laboratory processing and is not an artifact of the cleaning procedure [29].

Q4: How can I ensure my analysis is sensitive enough to detect subtle phenotypes, like minor shifts in limb positioning? Detecting subtle biological signals requires highly precise data collection methods. Research into fluctuating asymmetry—a small biomarker of developmental instability—confirms that techniques like 3D digitizers, CT scanners, and surface scanners are precise enough to distinguish between individuals in a principal component analysis [28]. This level of precision is necessary for quantifying subtle morphological changes. Furthermore, genetic evidence in zebrafish shows that incomplete penetrance can occur in limb positioning phenotypes; for example, deletion mutants for specific hox genes (hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b) showed an absence of pectoral fins only with low penetrance [5]. This highlights the need for adequate sample sizes and robust quantitative methods like geometric morphometrics.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low precision and high intra-observer error in geometric morphometric analyses.

- Potential Cause: The data collection technique may not be optimized for the required precision, or the observer is not sufficiently trained.

- Solution:

- Select a 3D digitizer or CT scanner for data collection, as these have demonstrated lower intra-observer error (1.7-1.8%) compared to surface scanners (4.5%) [28].

- Implement a rigorous training and calibration protocol where the same observer collects the same set of landmarks multiple times. Analyze this data using Procrustes ANOVA to quantify and monitor your measurement error [28].

Problem: Inability to visualize and quantify internal skeletal structures.

- Potential Cause: Use of surface scanning or photogrammetry, which only captures external morphology.

- Solution: Transition to computed tomography (CT). CT is a non-destructive modality that allows for the documentation of both external and internal structures of skeletal remains, including trabecular bone patterns, healing trauma, and sinus morphology [29]. Micro-CT is particularly valuable for high-resolution 3D assessment of bone architecture, enabling quantification of parameters like trabecular thickness and cortical bone density [30].

Problem: Failure to induce a limb patterning phenotype in a Hox cluster mutant model.

- Potential Cause: Functional redundancy between Hox gene clusters can mask phenotypes in single mutants.

- Solution: Consider generating compound mutants. Research in zebrafish has shown that while single hoxba cluster mutants only exhibit morphological abnormalities, double-deletion mutants of both hoxba and hoxbb clusters result in a complete absence of pectoral fins [31]. Investigate the expression of key downstream markers like tbx5a, as the phenotype in double mutants is linked to a failure to induce this critical gene in the pectoral fin field [5].

Table 1: Comparison of 3D Data Collection Techniques for Cranial Morphometry [28]

| Technique | Intra-observer Error (% of total shape variation) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Digitizer | 1.7% | High precision for landmark placement; tactile feedback. | Cannot capture surface texture; collects landmarks only, not full surface. |

| CT Scanner | 1.8% | Visualizes internal structures; high precision; good for fragile specimens. | Higher cost and limited access; may obscure taphonomic damage. |

| Surface Scanner | 4.5% | Captures surface texture and color. | Higher rate of missing landmarks; can obscure taphonomic damage. |

Table 2: Key Skeletal Phenotypes in Hox Mutant Models

| Model Organism | Genetic Modification | Observed Skeletal Phenotype | Key Molecular Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish [5] [31] | Double deletion of hoxba & hoxbb clusters | Complete absence of pectoral fins. | Near-complete loss of tbx5a expression in the pectoral fin field. |

| Zebrafish [31] | Deletion of hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b loci | Absence of pectoral fins (with low penetrance). | Failure to establish positional cues for fin bud formation. |

| Mouse [31] | Hoxb5 knockout | Rostral shift of forelimb buds (incomplete penetrance). | Suggests a role in anteroposterior positioning. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Fluctuating Asymmetry

This protocol is adapted from methods used to quantify small-scale shape variation in human crania [28].

- Sample Selection: Select specimens that are as complete and well-preserved as possible. Exclude specimens with visible warping, significant surface damage, or signs of pathology.

- 3D Data Acquisition:

- Option A (CT Scanning): Scan specimens using a micro-CT scanner. Recommended settings for mouse bone include a voltage of 50-70 kV and a current of 115-150 μA, with a voxel size of 10 μm or less to accurately capture trabecular microstructure [30].

- Option B (Surface Scanning): Create 3D models using a high-resolution surface scanner.

- Option C (3D Digitizer): Collect 3D landmark coordinates directly from the specimen using a contact digitizer.

- Landmarking:

- Define a landmark protocol consisting of Type I (e.g., suture intersections) and Type II (e.g., maximum curvature) landmarks. Avoid Type III landmarks, which are defined as geometric extremes relative to other landmarks [28].

- Using software (e.g., Viewbox 4), place the defined landmarks on all 3D models.

- Statistical Shape Analysis:

- Import landmark coordinates into geometric morphometrics software (e.g., MorphoJ).

- Perform a Generalized Procrustes Analysis (GPA) to superimpose landmarks, removing the effects of size, position, and orientation.

- Conduct a Procrustes ANOVA to partition total shape variance into components: Individual Variation, Directional Asymmetry, Fluctuating Asymmetry (FA), and Measurement Error.

- Fluctuating Asymmetry, the small, random deviations from perfect symmetry, can account for 15-16% of total shape variation and serves as a biomarker for developmental instability [28].

Protocol 2: Micro-CT Analysis of Mouse Long Bones

This standard protocol is used for the quantitative 3D assessment of bone architecture in preclinical models [30].

- Sample Preparation:

- Isolate femora and tibiae. Fix in formalin for 24 hours.

- Wash in PBS and store in 70% ethanol for scanning. Ensure surrounding soft tissue is removed as much as possible.

- Place samples in a radiolucent holder (e.g., a 1ml syringe) filled with ethanol to prevent desiccation.

- Scanning:

- Use a micro-CT scanner. Standard settings for mouse bone are 55 kV voltage, 145 μA current, and a 0.5 mm aluminium filter to reduce beam hardening.

- For trabecular bone: Scan the proximal tibial metaphysis, starting just distal to the growth plate, and acquire a 1-2 mm volume.

- For cortical bone: Scan the femoral midshaft, defined as 50% of the bone's length, acquiring a 10-15% sub-volume.

- Use an isotropic voxel size of 10 μm or less.

- Reconstruction and Analysis:

- Reconstruct 3D images from projection data using manufacturer software (e.g., NRecon for Bruker scanners). Apply beam-hardening correction (10-25%) and ring artefact reduction.

- Use analysis software (e.g., CTAn for Bruker) to segment the bone from the background.

- Key 3D Parameters:

- Trabecular Bone: Bone Volume/Tissue Volume (BV/TV), Trabecular Thickness (Tb.Th), Trabecular Separation (Tb.Sp).

- Cortical Bone: Cortical Thickness (Ct.Th), Total Cross-Sectional Area (Tt.Ar), Cortical Area (Ct.Ar).

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing Hox mutant skeletal phenotypes.

Diagram 2: Genetic pathway of Hox-mediated limb positioning based on zebrafish studies [5] [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Solutions for Skeletal Phenotyping

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Protocol / Context |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Generation of hox cluster-deficient mutant models. | Used to create seven distinct hox cluster mutants in zebrafish to study gene function [5]. |

| Micro-CT Scanner | High-resolution 3D imaging of mineralized tissues and some soft tissues. | Used for quantitative 3D assessment of bone architecture (trabecular & cortical) in mice [30] and muscle dystrophy in mdx mice [32]. |

| 3D Digitizer | Precise collection of 3D landmark coordinates for geometric morphometrics. | Used for collecting landmarks on crania to measure fluctuating asymmetry with low intra-observer error [28]. |

| Surface Scanner | Creating 3D models with surface texture and color data. | Used in morphometric studies to capture the external form of skeletal elements [28]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Washing and storage medium for skeletal tissue post-fixation. | Used after formalin fixation of bone specimens prior to micro-CT scanning [30]. |

| Ethanol | Storage medium for skeletal specimens; prevents desiccation during micro-CT scanning. | Recommended medium for scanning bone specimens ex vivo [30]. |

| Formalin (10% Neutral Buffered) | Fixation of skeletal and soft tissues for preservation of morphology. | Standard fixative for 24 hours prior to bone processing for micro-CT or histological analysis [30]. |

| SPR741 | SPR741, MF:C44H73N13O13, MW:992.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Milbemycin A3 Oxime | Milbemycin A3 Oxime, MF:C31H43NO7, MW:541.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for Decoding Cellular Heterogeneity in Mutant Limb Buds

FAQs: Addressing Common scRNA-seq Challenges in Limb Bud Research

Q1: Our single-cell data from Hox mutant limb buds shows high background noise in negative controls. What could be the cause and solution? A high background in negative controls often indicates contamination during sample processing. To address this:

- Practice strict RNAse-free techniques: Wear a clean lab coat, sleeve covers, and gloves throughout the procedure, changing gloves between steps [33].

- Maintain separate workspaces: Establish distinct pre- and post-PCR workstations, ideally in a clean room with positive air flow to minimize amplicon or environmental contamination [33].

- Include proper controls: Always run positive controls with RNA input mass similar to your experimental samples (e.g., 10 pg of RNA for single cells) and negative controls treated the same as actual samples (e.g., mock FACS sample buffer) [33].

Q2: We observe unexpected heterogeneity in Hox gene expression in control limb buds. Is this biologically relevant or technical artifact? Recent evidence confirms this is likely biologically relevant. Single-cell transcriptome analysis of wild-type limb buds reveals a high degree of heterogeneity in the expression of Hoxd11 and Hoxd13 genes [34]. In presumptive digit cells, only a minority of cells co-express both Hoxd11 and Hoxd13, with the largest fraction (53%) expressing Hoxd13 alone [34]. This heterogeneous combinatorial expression matches particular cell types and follows a pseudo-time sequence of differentiation [34].

Q3: What quality control thresholds should we implement for limb bud scRNA-seq data? Cell QC should be performed jointly using three key covariates [35]:

- Count depth: Number of counts per barcode

- Gene detection: Number of genes per barcode

- Mitochondrial fraction: Fraction of counts from mitochondrial genes per barcode

Set thresholds as permissive as possible to avoid filtering out viable cell populations unintentionally, as cells with different biological states may exhibit different QC distributions [35].

Q4: How can we properly handle limb bud tissue dissociation for scRNA-seq? Ensure cells are suspended in an appropriate buffer free of components that interfere with reverse transcription:

- Wash and resuspend bulk cell suspension in EDTA-, Mg²âº- and Ca²âº-free 1× PBS [33].

- For FACS sorting, use recommended buffers like BD FACS Pre-Sort Buffer or sort directly into lysis buffer containing RNase inhibitor [33].

- Process samples immediately after collection or snap-freeze in dry ice and store at -80°C to minimize RNA degradation and transcriptome changes [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

RNA Extraction and Quality Issues

Table: Troubleshooting RNA Extraction Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| RNA degradation | RNase contamination; improper sample storage; repeated freeze-thaw cycles [36] | Use RNase-free tubes and reagents; store samples at -85°C to -65°C; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles; wear gloves and use separate clean area [36] |

| Low RNA yield | Too much sample leading to incomplete homogenization; insufficient TRIzol volume [36] | Adjust sample amounts; ensure sufficient TRIzol volume; increase sample lysis time to >5 minutes [36] |

| Genomic DNA contamination | High sample input; incomplete digestion [36] | Reduce starting sample volume; use reverse transcription reagents with genome removal modules; design trans-intron primers [36] |

| Downstream inhibition or low purity | Protein, polysaccharide, or fat contamination; salt residue [36] | Decrease sample starting volume; increase rinses with 75% ethanol; reduce supernatant aspiration [36] |

Single-Cell Library Preparation and Sequencing Issues

Table: Troubleshooting Single-Cell Library Preparation

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low cDNA yield | Carryover of media components that interfere with RT reaction; insufficient PCR cycles [33] | Wash cells in appropriate buffers; adjust number of PCR cycles based on RNA content of specific cell types [33] |

| Poor cell viability after dissociation | Over-digestion with enzymatic dissociation; harsh mechanical disruption | Optimize dissociation protocol; assess viability with trypan blue staining (aim for >85% viability) [37] |

| High doublet rates | Overloading cells in droplet-based systems; incomplete dissociation [35] | Use appropriate cell concentration; employ doublet detection tools (DoubletFinder, Scrublet) [35] |

| Batch effects between experiments | Technical variations between sequencing runs; different processing times [38] | Use batch correction methods (Harmony, Seurat CCA); process samples quickly and consistently [38] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol: Single-Cell RNA-seq of Mouse Limb Buds

Based on: A single-cell census of mouse limb development [39]

1. Tissue Collection and Dissociation:

- Collect limb buds from E10.5-E12.5 mouse embryos in cold PBS.

- Digest tissue with collagenase (0.5-1 mg/mL) in PBS for 15-20 minutes at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Triturate every 5 minutes to aid dissociation.

- Stop digestion with FBS-containing medium.

- Filter through 40μm cell strainer and centrifuge at 300-400g for 5 minutes.

- Resuspend in appropriate buffer for scRNA-seq.

2. Single-Cell Processing:

- Process using 10× Genomics Single Cell 3' v3 Reagent Kit per manufacturer's instructions [37].

- Aim for 5,000-10,000 cells per sample to ensure adequate representation.

- Sort cells using FACS with collection into lysis buffer containing RNase inhibitor.

3. Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Perform reverse transcription and cDNA amplification with adjusted cycles based on RNA content.

- Construct libraries following platform-specific protocols.

- Sequence on Illumina platform (HiSeq X Ten or equivalent) with minimum 50,000 reads per cell.

4. Quality Control:

- Remove cells with <500 detected genes or >7% mitochondrial genes [37].

- Exclude potential doublets with high counts and gene numbers [35].

Protocol: Analyzing Hox Gene Heterogeneity in Mutant Limb Buds

Based on: Heterogeneous combinatorial expression of Hoxd genes [34]

1. Experimental Design:

- Include appropriate controls (wild-type and heterozygous mutants).

- Process mutant and control samples simultaneously to minimize batch effects.

- Sequence to sufficient depth to detect combinatorial Hox gene expression.

2. Data Analysis:

- Pre-process data using Cell Ranger or equivalent pipeline.

- Perform dimensionality reduction (PCA, t-SNE, UMAP).

- Identify cell clusters using Seurat or Scanpy.

- Examine Hox gene expression patterns across clusters.

- Validate findings with RNA-FISH on tissue sections.

3. Heterogeneity Assessment:

- Calculate the percentage of cells expressing specific Hox gene combinations.

- Compare expression distributions between mutant and control.

- Perform trajectory analysis to investigate differentiation patterns.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for scRNA-seq in Limb Development Research

| Reagent/Catalog | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Collagenase Type IV | Tissue dissociation | Concentration and duration must be optimized for embryonic limb buds to preserve cell viability |

| 10× Genomics Single Cell 3' Kit | Library preparation | Provides robust profiling for heterogeneous limb bud populations; v3 or newer recommended |

| SMART-Seq HT/V4 | Full-length RNA-seq | Alternative for plate-based methods; better for detecting non-poly(A) RNAs [33] |

| BD FACS Pre-Sort Buffer | Cell sorting | Maintains cells in suspension without interfering with RT reaction [33] |

| RNase inhibitor | RNA protection | Essential for all steps from tissue collection to cDNA synthesis |

| Takara Bio scRNA-seq kits | Library preparation | Offer oligo-dT and random priming solutions for different applications [33] |

Analytical Framework and Visualization Methods

scRNA-seq Data Analysis Workflow

scRNA-seq Analysis Workflow: From raw data to biological interpretation.

Hox Gene Heterogeneity Analysis in Limb Buds

Hox Gene Heterogeneity: Distribution of Hox gene expression patterns in wild-type limb buds and their biological significance [34].

Advanced Methodologies for Complex Phenotypes

Full-Length Total RNA Sequencing Approach

For comprehensive analysis beyond poly(A) RNAs, consider RamDA-seq (Random Displacement Amplification Sequencing), which provides:

- Detection of non-poly(A) transcripts: Including histone mRNAs, lncRNAs, and enhancer RNAs [40]

- Full-length coverage: Essential for detecting RNA-processing events and recursive splicing [40]

- High sensitivity: ~17,000 transcripts detected from single cells, superior to many oligo-dT-based methods [40]

Structure-Preserving Visualization

For complex limb bud datasets with multiple cell types and states, consider Deep Visualization (DV) methods that:

- Preserve inherent data structure using deep manifold transformation [38]

- Handle batch effects in an end-to-end manner [38]

- Employ hyperbolic embedding (Poincaré or Lorentz models) for better representation of developmental trajectories [38]

Table: Comparison of scRNA-seq Analysis Platforms

| Platform | Programming Language | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat | R | Comprehensive toolkit; good for clustering | Researchers familiar with R; standard analyses |

| Scanpy | Python | Scalable to large datasets; Python integration | Python users; large-scale studies |

| Scater | R | Quality control and visualization | Data QC and preliminary analysis |

| Deep Visualization (DV) | Python | Structure preservation; batch correction | Complex trajectories; batch-effect prone data |

Core Concepts and Relevance to Limb Patterning

What is Spatial Transcriptomics and why is it crucial for studying limb development phenotypes?

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) is a cutting-edge scientific method that merges the study of gene expression with precise spatial location within a tissue. This revolutionary approach allows researchers to visualize the spatial distribution of RNA transcripts, essentially mapping where each gene is expressed in the context of the tissue's anatomy [41].