Decoding Toxicity in Mouse Embryo Cryopreservation: Mechanisms, Mitigation, and Model Validation

Mouse embryo cryopreservation is a cornerstone of biomedical research, enabling the preservation of valuable genetically engineered models.

Decoding Toxicity in Mouse Embryo Cryopreservation: Mechanisms, Mitigation, and Model Validation

Abstract

Mouse embryo cryopreservation is a cornerstone of biomedical research, enabling the preservation of valuable genetically engineered models. However, the toxicity of cryoprotectant agents (CPAs) remains a significant challenge, potentially compromising embryo viability and developmental potential. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientists, covering the foundational mechanisms of CPA toxicity, current methodological approaches for its mitigation, practical strategies for protocol optimization, and essential validation techniques. By synthesizing the latest research, we aim to equip professionals with the knowledge to improve cryopreservation outcomes, ensuring the integrity and reproducibility of mouse models in drug development and basic science.

The Cellular Battlefield: Unraveling the Mechanisms of Cryoprotectant Toxicity

Cryoprotectant toxicity represents the foremost obstacle in cryopreservation, particularly for sensitive biological systems like mouse embryos where viability must be meticulously preserved for research and reproductive applications [1]. As cryoprotective agents (CPAs) are employed to eliminate lethal ice formation during cooling to cryogenic temperatures, their inherent toxicity limits the concentrations that can be safely used, creating a significant barrier to effective vitrification [1] [2]. This technical guide examines CPA toxicity through the critical dichotomy of specific versus non-specific damage pathways, with specific focus on implications for mouse embryo cryopreservation research.

Specific toxicity refers to damage mechanisms unique to particular CPA chemical structures and their direct interactions with cellular components [1]. In contrast, non-specific toxicity encompasses damage resulting from the fundamental properties of CPAs as solutes, primarily through their disruption of water's hydrogen bonding network and the consequent effects on cellular structures and functions [1] [2]. Understanding this distinction is paramount for developing strategies to neutralize CPA toxicity and advance cryopreservation protocols for mouse embryos and other complex biological systems.

Cryoprotectant-Specific Toxicities

Penetrating CPAs exhibit distinct toxicity profiles stemming from their unique chemical properties and biological interactions. These specific toxic mechanisms must be carefully considered when selecting CPAs for mouse embryo cryopreservation.

Table 1: Specific Toxicities of Common Penetrating Cryoprotectants

| Cryoprotectant | Specific Toxicities | Relevance to Mouse Embryos |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) | • Alters membrane channel protein function [1]• Causes myocardial cell shrinkage and action potential duration increase [1]• Induces DNA methylation and histone modification at concentrations >5% [3] | • Reduces developmental competence in mouse oocytes and embryos• Epigenetic modifications may affect gene expression |

| Ethylene glycol (EG) | • Metabolized to glycolic and oxalic acids causing metabolic acidosis [1]• Forms calcium oxalate crystals in tissues [1] | • Lower molecular weight may reduce osmotic stress• Often preferred for mouse oocyte/embryo vitrification |

| Propylene glycol (PG) | • Decreases intracellular pH at high concentrations (>2.5 M) [1]• Impairs developmental potential of mouse zygotes [1] | • pH disruption particularly detrimental to preimplantation embryos• Requires careful concentration control |

| Glycerol (GLY) | • Depletes reduced glutathione leading to oxidative stress [1]• Polymerizes actin cytoskeleton in spermatozoa [1] | • Cytoskeletal disruptions may impact embryonic cell divisions• Oxidative stress can compromise embryo development |

| Formamide (FMD) | • Denatures DNA through displacement of hydrating water [1]• Strong self-association with hydrogen bonding strength exceeding water [1] | • DNA structural damage poses risk to genetic integrity• Limited use in embryo preservation due to high toxicity |

| Methanol (METH) | • Metabolized to formaldehyde and formic acid [1]• Dose-dependent reduction in mitochondrial function measures [1] | • Mitochondrial dysfunction impairs embryonic energy production• Metabolite accumulation detrimental to development |

The specific toxicities outlined in Table 1 demonstrate that CPA selection for mouse embryo cryopreservation requires careful consideration of multiple factors beyond cryoprotective efficacy. For instance, while DMSO offers excellent membrane penetration, its potential for epigenetic modifications warrants caution in research applications where maintaining unaltered gene expression patterns is critical [3]. Similarly, the pH-altering effects of propylene glycol may be particularly detrimental to preimplantation stage mouse embryos, which exhibit sensitivity to intracellular pH fluctuations [1].

Non-Specific Toxicity Pathways

Non-specific CPA toxicity arises from fundamental physicochemical properties shared across cryoprotectant compounds, primarily mediated through their effects on water structure and solute concentration.

Mechanisms of Non-Specific Damage

The hydrogen-bonding characteristics of CPAs with water molecules represent a primary non-specific toxicity pathway. CPAs prevent ice formation by interfering with hydrogen bonding between water molecules, and this disruption of water's normal structure has been proposed as a fundamental mechanism of non-specific toxicity [1]. All CPAs function by displacing water molecules, creating concentrated solutions that dramatically reduce freezing points, but simultaneously generate substantial osmotic stress and potentially disrupt the hydration shells essential for macromolecular function [1] [2].

During freezing procedures, extracellular ice formation excludes solutes, progressively increasing extracellular solute concentration. This establishes osmotic gradients that drive water efflux from cells, resulting in cellular dehydration and elevated intracellular solute concentrations—a phenomenon known as "solution effects" [2]. The consequent macromolecular crowding can denature proteins, disrupt membrane integrity, and alter critical biochemical pathways [2]. This non-specific damage pathway affects all cell types, though sensitivity varies between biological systems.

Intracellular Ice Formation

When cooling rates exceed cellular dehydration capacity, intracellular ice formation (IIF) occurs, representing a particularly lethal non-specific damage pathway [2]. IIF directly damages intracellular structures including organelles, cytoskeletal elements, and membranes. Mouse embryos are especially vulnerable to IIF due to their large volume and surface area-to-volume ratio, which limits water efflux efficiency [2]. The presence of CPAs moderates but does not eliminate IIF risk, particularly during the thawing process where devitrification (ice crystallization during warming) can cause significant damage [4].

Quantitative Toxicity Assessment in Mouse Embryos

Evaluating CPA toxicity requires standardized assays and quantitative measures. For mouse embryo research, specific endpoints include developmental competence, membrane integrity, metabolic activity, and genetic integrity.

Table 2: Quantitative Toxicity Measures for CPAs in Mouse Embryos

| Toxicity Measure | Experimental Method | Typical Values for Mouse Embryos | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental Competence | Blastocyst formation rate post-thaw | • >70% for low-toxicity CPAs [1]• <30% for high-toxicity CPAs | Primary endpoint for embryo viability |

| Membrane Integrity | Fluorescent dye exclusion (propidium iodide) | • >80% intact for viable embryos [3] | Indicator of structural damage |

| Mitochondrial Function | ATP levels, ADP/ATP ratios, membrane potential [1] | • Dose-dependent reduction with methanol [1] | Metabolic competence indicator |

| Oxidative Stress | ROS detection assays, glutathione depletion [1] | • Glycerol depletes reduced glutathione [1] | Oxidative damage marker |

| Cytoskeletal Integrity | Immunofluorescence for actin, tubulin [1] | • Glycerol polymerizes actin at >1.5% [1] | Structural integrity assessment |

The quantitative measures in Table 2 provide researchers with standardized approaches for comparing CPA toxicity in mouse embryo models. Developmental competence remains the most biologically relevant endpoint, as it integrates multiple aspects of embryo health and function [1]. However, mechanistic insights gained from membrane integrity, mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, and cytoskeletal assessments are invaluable for understanding specific toxicity pathways and developing targeted mitigation strategies.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing CPA Toxicity

Concentration-Dependent Toxicity Screening

Objective: To determine the maximum tolerated concentration of individual CPAs for mouse zygotes and early embryos.

Methodology:

- Collect mouse zygotes or 2-cell embryos following standard superovulation protocols.

- Prepare CPA solutions in modified PBS with 0.5% BSA at concentrations ranging from 0.5 M to 8 M in 0.5 M increments.

- Expose embryos to each CPA concentration using a two-step addition method (0.5 M/min) at room temperature (25°C).

- Maintain exposure for 10 minutes, then remove CPAs using reverse two-step dilution.

- Culture embryos in KSOM medium at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 96 hours.

- Assess development to morula and blastocyst stages at 72 and 96 hours, respectively [1] [5].

Critical Parameters:

- Maintain consistent temperature during CPA addition/removal to minimize osmotic shock

- Include carrier solution controls (0 M CPA) to establish baseline development rates

- Use ≥30 embryos per experimental group for statistical power

- Record morphological abnormalities during culture period

Time-Dependent Toxicity at Low Temperatures

Objective: To evaluate the effect of prolonged CPA exposure at low temperatures on mouse embryo viability.

Methodology:

- Prepare mouse morulae-stage embryos in control medium.

- Equilibrate with 60% M22 vitrification solution using stepwise addition (10%, 20%, 40%, 60%) at 10-minute intervals at 2°C.

- Maintain embryos in 60% M22 at 2°C for 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 8 hours (n=15-20 per time point).

- Remove CPAs using sequential 10-minute intervals to 30%, 15%, 7.5%, and 3.75% M22 using 300-600 mM mannitol in LM5 carrier solution at 2°C.

- Culture embryos in fresh KSOM medium at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

- Quantify blastocyst formation rates at 48 hours post-treatment [5].

Applications: This protocol determines safe exposure windows for vitrification procedures and identifies time-dependent toxicity thresholds critical for protocol optimization.

Time-Dependent Toxicity Workflow

Molecular Toxicity Pathway Analysis

Objective: To identify activation of specific stress response pathways in mouse embryos following CPA exposure.

Methodology:

- Expose mouse blastocysts to sublethal CPA concentrations (EC₇₀) for 10 minutes at 25°C.

- Fix immediately for immunocytochemistry or extract RNA/protein for molecular analysis.

- For oxidative stress assessment: Measure ROS production using Hâ‚‚DCFDA fluorescence, glutathione levels via monochlorobimane assay, and antioxidant gene expression (Sod1, Sod2, Gpx1, Cat) by RT-qPCR.

- For apoptosis pathway analysis: Assess caspase-3/7 activation using fluorescent substrates, TUNEL staining for DNA fragmentation, and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio by Western blot.

- For epigenetic effects: Examine DNA methylation patterns via bisulfite sequencing and histone modifications (H3K4me3, H3K27me3) by immunostaining after DMSO exposure [3].

- For cytoskeletal evaluation: Fix and stain for F-actin (phalloidin) and tubulin (anti-α-tubulin) to assess structural integrity.

Data Interpretation: Compare pathway activation across CPA types and concentrations to establish specific toxicity signatures and identify particularly detrimental compounds for mouse embryos.

Protective Strategies and Toxicity Mitigation

Hormesis and Preconditioning

Strategic preconditioning with sublethal stress can activate endogenous cellular defense mechanisms, significantly improving resistance to subsequent CPA exposure. In yeast, heat shock pretreatment increased survival by 18-fold after formamide exposure and over 9-fold after M22 exposure at 30°C [6]. Similar protection was observed in C. elegans, where hydrogen peroxide pretreatment conferred nearly complete protection from M22-induced damage [6]. This approach capitalizes on evolutionarily conserved stress response pathways that can be mobilized prior to cryopreservation procedures.

For mouse embryo applications, mild oxidative preconditioning with low-dose hydrogen peroxide or metabolic preconditioning with mild nutrient restriction may enhance endogenous antioxidant capacity and stress resistance pathways without inducing collateral damage [6]. The timing and intensity of preconditioning require empirical optimization for each embryo stage and CPA combination.

Genetic Modulation of Toxicity Resistance

Forward genetic screening in mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) has identified specific mutations conferring cryoprotectant toxicity resistance (CTR). Transposon-mediated mutagenesis revealed six independent biochemical pathways not previously linked to CPA toxicity, including genes Gm14005, Myh9, Pura, Fgd2, and Opa1 [5]. These CTR mutants demonstrated significantly improved survival after freezing and thawing in 10% DMSO, providing direct evidence that CT can be reduced in mammalian cells by specific molecular interventions [5].

While genetic manipulation of mouse embryos is not practical for routine cryopreservation, identification of protective genetic variants informs the development of small molecule interventions that can mimic these protective effects. Pharmacological activation of the MYC signaling pathway, identified in multiple CTR mutants, represents a promising approach for reducing CPA toxicity in mouse embryos [5].

Biomaterial-Based Protection

Hydrogel microencapsulation technology presents a promising strategy for reducing CPA toxicity by creating a physical barrier that moderates solute exchange and provides structural support. Alginate-based microencapsulation enables effective cryopreservation of mesenchymal stem cells with as low as 2.5% DMSO while maintaining cell viability above the 70% clinical threshold [7]. The hydrogel matrix moderates ice crystal formation and growth during thawing, reducing mechanical damage to delicate cellular structures [7].

For mouse embryos, which are substantially larger than single cells, complete encapsulation may not be feasible. However, modified approaches using alginate matrices to support embryos during CPA exposure and freezing may mitigate specific toxicity pathways by moderating osmotic shock and providing physical protection against ice crystal penetration.

CPA Toxicity Pathways and Protective Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for CPA Toxicity Studies in Mouse Embryos

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use in Mouse Embryo Research |

|---|---|---|

| M22 Vitrification Solution | Multi-component vitrification solution for organs | Toxicity studies at reduced concentrations (e.g., 9-60%) [5] |

| LM5 Carrier Solution | Isotonic carrier for M22 containing electrolytes, sugars, and glutathione | Control solution and CPA diluent [5] |

| CELLBANKER Series | Commercial cryopreservation media with reduced toxicity | Serum-free formulations for standardized freezing [3] |

| Alginate Hydrogels | Biomaterial for cell encapsulation and toxicity reduction | Microencapsulation to reduce CPA concentration requirements [7] |

| MTT Assay Kit | Cell viability and metabolic activity assessment | Quantitative toxicity screening after CPA exposure [5] |

| Caspase-3/7 Apoptosis Assay | Detection of programmed cell death | Assessment of apoptosis pathway activation [3] |

| ROS Detection Probes (Hâ‚‚DCFDA, DHE) | Reactive oxygen species measurement | Oxidative stress evaluation after CPA exposure [1] |

| Anti-Stress Response Antibodies (HSP70, HSP90, Nrf2) | Stress pathway activation analysis | Molecular mechanism studies via immunocytochemistry/Western blot [6] |

| Lanuginosine | Lanuginosine, CAS:23740-25-2, MF:C18H11NO4, MW:305.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Levophacetoperane | Levophacetoperane, CAS:24558-01-8, MF:C14H19NO2, MW:233.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The reagents and materials outlined in Table 3 represent essential tools for comprehensive CPA toxicity assessment in mouse embryo models. Commercial solutions like CELLBANKER provide standardized platforms for comparative studies, while specialized assays enable mechanistic investigations into specific toxicity pathways [3]. Emerging materials such as alginate hydrogels offer innovative approaches to physical protection and toxicity reduction [7].

The distinction between specific and non-specific cryoprotectant toxicity pathways provides a crucial framework for understanding and addressing the primary limitation in mouse embryo cryopreservation. Specific toxicities, arising from unique molecular interactions of individual CPAs, demand careful agent selection and exposure control. Non-specific toxicities, stemming from fundamental solute effects on cellular water and structures, require broader strategic interventions including optimized freezing protocols, biomaterial support, and activation of endogenous cellular defense mechanisms.

Future research directions should focus on the discovery of novel CPA compounds with reduced specific toxicity profiles, such as the heterocyclic amines 1-methylimidazole and pyridazine identified through computer-aided molecular design approaches [8]. Additionally, pharmacological manipulation of identified toxicity resistance pathways, particularly those involving MYC signaling and stress response elements, holds promise for clinical application [5]. Integration of advanced biomaterials that provide physical protection while moderating solute exchange may further reduce CPA requirements and associated toxicity [7].

For mouse embryo research specifically, standardized toxicity assessment protocols that account for stage-specific vulnerabilities will enhance cross-study comparisons and accelerate protocol optimization. By systematically addressing both specific and non-specific toxicity pathways through combined chemical, biological, and materials science approaches, researchers can overcome the critical barriers to efficient mouse embryo cryopreservation, thereby supporting advancements in reproductive science, genetic conservation, and biomedical research.

Cryoprotective agents (CPAs) are indispensable tools in assisted reproductive technologies, enabling the long-term preservation of gametes and embryos by mitigating the damaging effects of ice crystallization. However, the same chemicals that confer protection also introduce risks of specific and non-specific toxicity, which can compromise embryo viability, developmental potential, and even the long-term health of resulting offspring [9]. For researchers working with mouse models, understanding these toxicological profiles is paramount for designing ethical and effective cryopreservation protocols. Specific toxicity refers to direct chemical damage caused by the CPA's inherent properties, such as inducing oxidative stress, disrupting cellular structures, or altering epigenetic patterns [10]. In contrast, non-specific toxicity arises from physical changes in the solution, such as osmotic stress or alterations in the hydrogen bonding network surrounding biomolecules, which can lead to protein denaturation or membrane destabilization [10]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of three predominant penetrating CPAs—dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), glycerol, and ethylene glycol (EG)—within the context of mouse embryo research, integrating quantitative toxicity data, molecular mechanisms, and practical protocol considerations to inform experimental design.

Physicochemical and Toxicological Profiles

The molecular characteristics of CPAs directly influence their permeability, distribution, and toxicological impact on embryonic cells. The table below summarizes key physicochemical and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) parameters for DMSO, glycerol, and ethylene glycol, which are critical for predicting their behavior in cryopreservation solutions.

Table 1: Physicochemical and ADMET Properties of Common CPAs

| Property | DMSO | Glycerol | Ethylene Glycol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight (g/mol) | 78.13 | 92.09 | 62.07 |

| Melting Point (°C) | 18.5 | 18.2 | -12.9 |

| XLogP3 | -1.35 | -2.32 | -1.36 |

| Topological Polar Surface Area (Ų) | 36.8 | 60.7 | 40.5 |

| Caco2 Permeability (log Papp in 10â»â¶ cm/s) | 0.84 | -0.62 (Low) | Data Not Available |

| Volume of Distribution (log L/kg) | -0.04 | -1.04 | Data Not Available |

| Unbound Fraction in Plasma | 0.895 | 0.198 | Data Not Available |

| Tetrahymena pyriformis Toxicity (log µg/L) | -0.303 | -2.230 | Data Not Available |

Data adapted from a comprehensive overview of small-molecule CPA toxicities [9].

The physicochemical data reveals distinct differences. Glycerol's lower Caco2 permeability and higher polar surface area suggest slower cellular uptake compared to DMSO and EG [9]. This can influence the equilibration time required in cryopreservation protocols to prevent osmotic shock. DMSO exhibits a high unbound fraction in plasma, indicating minimal protein binding and potentially greater bioavailability within cells, which may contribute to its specific toxicity profile [9].

Mechanisms of Specific Toxicity

Each CPA exhibits unique mechanisms of specific toxicity that can impact embryonic development at the cellular and molecular level.

DMSO: This CPA poses significant epigenetic risks. Recent studies on vitrified bovine embryos demonstrate that DMSO induces active DNA demethylation by significantly increasing levels of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) while decreasing 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [11]. This effect is linked to the upregulation of the demethylase TET3. Furthermore, DMSO can induce major morphological and physiological alterations in developing vertebrate embryos, including heart edema, altered heart beating frequency, and somite size defects, as observed in zebrafish models [12]. Its mechanism of action also includes interaction with phospholipid membranes, causing membrane fluidization and, at higher concentrations, pore formation and bilayer disintegration [12].

Ethylene Glycol (EG): EG is generally considered less toxic than DMSO, but its potency is concentration-dependent. Research on mouse oocyte vitrification shows that high concentrations (≥20%) can cause cytotoxic and osmotic damage, reducing survival rates [13]. However, the minimal concentration required for effective vitrification can be optimized. A study found that combining 15% EG with 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) significantly improved mouse oocyte survival rates post-warming without compromising embryonic development, highlighting the importance of concentration balancing [13].

Glycerol: As one of the oldest CPAs, glycerol has a long history of use. However, it exhibits lower cellular permeability, which can lead to delayed efflux during thawing and consequent osmotic swelling and damage if not carefully managed [9]. Its low volume of distribution indicates high water solubility or protein binding, meaning it predominantly remains in the seminal plasma or extracellular space, which can alter the physiological properties of the cellular environment [9].

Experimental Data and Protocols in Mouse Research

Quantitative Toxicity and Efficacy Endpoints

Data from mouse models provides critical thresholds for CPA toxicity. The following table summarizes key experimental findings on the effects of these CPAs on mouse embryos and oocytes.

Table 2: Experimental Toxicity and Efficacy Data from Mouse Studies

| CPA | Experimental Model | Concentration | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | Mouse embryos (long-term) | Standard vitrification | Significant differences in morphophysiological and behavioral features in elderly subjects; delayed effects observed. | [14] |

| Ethylene Glycol (EG) | Mouse MII oocytes | 15-20% EG ± 2% PVP | 15% EG + 2% PVP significantly increased survival. Higher EG concentrations (20%+) showed no benefit and increased abnormality. | [13] |

| DMSO | Zebrafish embryos (as a model vertebrate) | 1-5% | Concentrations >5% were lethal. 1-4% induced tail curvature, heart edema, and reduced somite size. | [12] |

| Glycerol | General carnivore semen | Varies by extender | Lower permeability requires longer equilibration times; can alter seminal plasma physiology. | [9] |

Detailed Mouse Oocyte Vitrification Protocol

The following is a standard protocol for mouse oocyte vitrification, adapted from a study optimizing ethylene glycol concentrations [13]. This protocol exemplifies the practical application of CPAs and the critical steps for minimizing toxicity.

Source of Oocytes:

- Female mice (e.g., CD-1 strain, 8-10 weeks old) are superovulated with an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 5 IU PMSG, followed by 5 IU hCG 48 hours later.

- Oocytes are collected from the oviducts 14 hours post-hCG injection. Cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) are released and denuded of cumulus cells using 75 U/mL hyaluronidase and mechanical pipetting.

- Only morphologically normal metaphase II (MII) oocytes, identified by the presence of a first polar body, are selected for vitrification.

Vitrification Procedure using JY Straw and EG-based Solutions:

- Equilibration: Denuded MII oocytes are suspended in an equilibration solution (ES) based on Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS) for 3 minutes at room temperature. The ES contains a lower concentration of permeating CPAs.

- Vitrification Solution: Oocytes are transferred to a DPBS-based vitrification solution (VS) for 1 minute at room temperature. The VS contains the final, high concentration of CPAs. The specific optimized formulation from the study is 15% Ethylene Glycol combined with 2% Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) [13].

- Loading and Cooling: Oocytes are immediately loaded onto a JY Straw and plunged directly into liquid nitrogen. The cooling rate with this system is approximately 442–500 °C/min.

Warning Procedure:

- Thawing: The loading part of the JY Straw is inserted directly into a DPBS-based thawing solution (TS) containing 1.0 M sucrose (a non-permeating CPA for osmotic control) at room temperature for 3 minutes. The warming rate is very high, approximately 2,210–2,652 °C/min.

- Sucrose Dilution: Oocytes are step-wise transferred to solutions containing 0.5 M and 0.25 M sucrose, for 3 minutes each, to gradually remove the permeating CPAs while minimizing osmotic shock.

- Washing: Oocytes are washed twice in a washing medium before transfer to a culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂) for further assessment.

Assessment of Survival and Development:

- Survival Rate: Assessed morphologically based on plasma membrane integrity and the appearance of the ooplasm shortly after warming.

- Embryonic Development: Survived oocytes can be parthenogenetically activated (e.g., with 8.5 mM strontium chloride) and cultured to the blastocyst stage to evaluate developmental competence.

- Cytoskeletal Integrity: Meiotic spindle and chromosome alignment are assessed using immunofluorescence staining after warming to ensure cytoskeletal preservation [13].

Advanced Concepts: Toxicity Modeling and Novel Strategies

Mathematical Modeling of CPA Toxicity

Given the vast landscape of possible CPA mixtures and protocol variables, mathematical models are invaluable for in silico optimization. A recent multi-CPA toxicity model accounts for both specific and non-specific toxicity, as well as intermolecular interactions between CPAs in solution [10]. The model is based on a toxicity cost function, k_tox, which represents the exponential decay rate of cell viability during CPA exposure. The general form of the model is:

k_tox = k_ns + k_s

Where:

k_nsrepresents the non-specific toxicity, a function of the overall solution properties.k_srepresents the specific toxicity, which is a sum of the contributions from individual CPAs and their synergistic or antagonistic interactions [10].

This model, trained on high-throughput toxicity data for five common CPAs (including DMSO, glycerol, EG, and propylene glycol), allows researchers to predict the toxicity of custom CPA mixtures without exhaustive experimental trial and error, facilitating the design of less toxic vitrification solutions [10].

Strategies for Toxicity Mitigation

Research has identified several effective strategies to counter CPA-specific toxicity:

Replacement and Combination: Using less toxic CPAs like propylene glycol (PG) instead of DMSO has been shown to prevent DNA demethylation in vitrified bovine embryos [11]. Furthermore, combining CPAs in balanced mixtures can exploit their individual advantages while minimizing the concentration—and thus the toxicity—of any single agent [10].

Antioxidant Supplementation: Adding antioxidants like N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC, 5 mM) to the vitrification medium containing DMSO has been demonstrated to ameliorate DMSO-induced DNA demethylation, bringing methylation levels in embryos closer to those of fresh controls [11].

Macromolecular Additives: Polymers such as polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) can replace a portion of the penetrating CPAs, thereby reducing the total osmotic and toxic load [15]. PVP increases the viscosity of the solution, which decreases the propensity for ice crystal formation and can have a stabilizing effect on the cell membrane [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for CPA Toxicity Research in Mouse Embryos

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | A penetrating CPA; effective but requires caution due to epigenetic toxicity and morphological alteration risks. |

| Ethylene Glycol (EG) | A penetrating CPA with lower toxicity at optimized concentrations; often used in combination with other agents. |

| Glycerol | A penetrating CPA with lower permeability; requires careful management of equilibration and dilution times. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | A non-permeating polymer; increases solution viscosity, reduces ice crystallization, and can lower required CPA concentrations. |

| Sucrose | A non-penetrating cryoprotectant; used in thawing and dilution solutions to create an osmotic gradient that controls CPA efflux and minimizes swelling. |

| N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC) | An antioxidant supplement; shown to counteract DMSO-induced oxidative stress and DNA demethylation. |

| JY Straw / Cryotop | Device for vitrification; enables high cooling and warming rates critical for survival. |

| Hyaluronidase | Enzyme for digesting cumulus cells to obtain denuded oocytes for consistent cryopreservation. |

| Indatraline | Indatraline, CAS:97229-15-7, MF:C16H15Cl2N, MW:292.2 g/mol |

| Ligustroflavone | Ligustroflavone, CAS:260413-62-5, MF:C33H40O18, MW:724.7 g/mol |

Visualizing Toxicity Pathways and Experimental Workflows

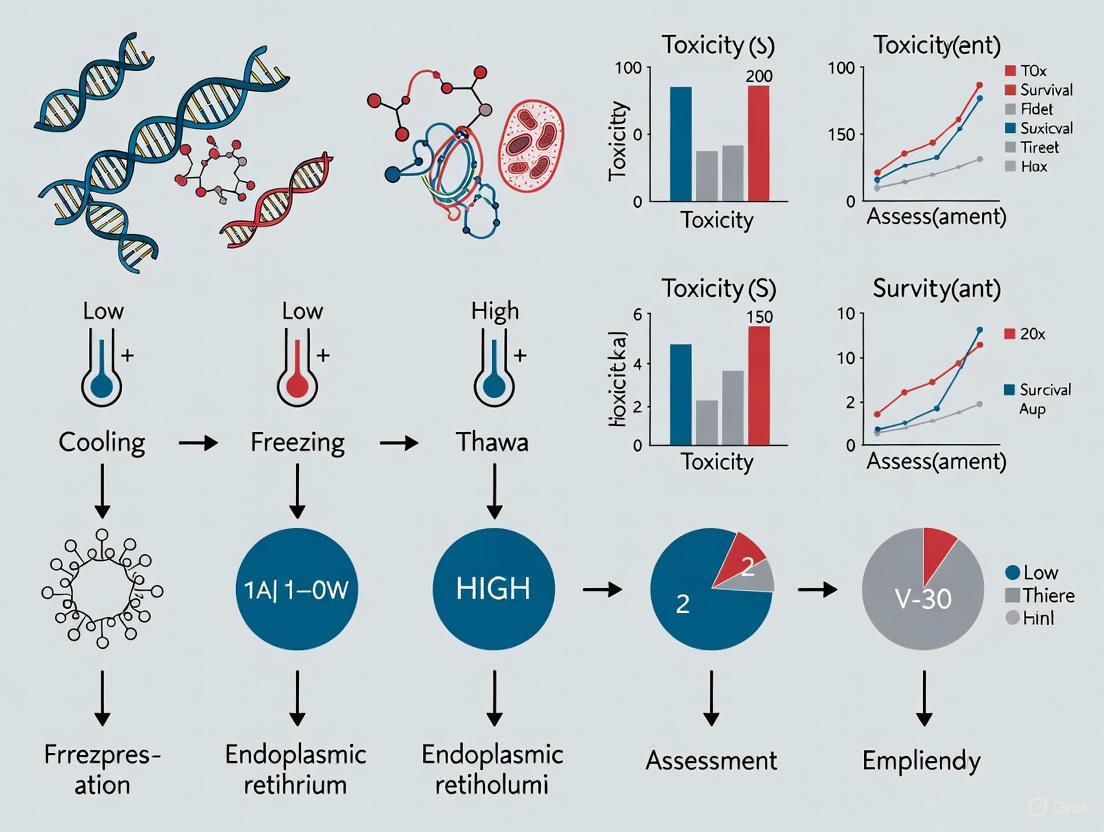

CPA Toxicity Pathways: This diagram outlines the primary mechanisms through which penetrating cryoprotectant agents (CPAs) exert specific and non-specific toxic effects on embryos, ultimately impacting their viability and developmental potential.

Mouse Oocyte Vitrification Workflow: This diagram illustrates the key steps in a standard mouse oocyte vitrification protocol, highlighting the stages of CPA exposure, rapid cooling/warming, and the crucial step-wise dilution process to remove CPAs post-warming.

Cryopreservation is an indispensable tool in biomedical research, particularly for the preservation of genetically engineered mouse lines, which represent significant scientific investments [16]. While this technology enables long-term storage of embryos at ultralow temperatures (typically -196°C), the freezing and thawing processes inevitably induce a spectrum of cellular and molecular injuries that can compromise embryo viability and developmental potential [14] [17]. These injuries extend beyond immediate cell death to include more subtle dysfunctions that may manifest at later developmental stages or even during senescence [14].

Understanding the precise nature of these injuries is crucial for developing safer, more effective cryopreservation protocols. This review synthesizes current knowledge on cryopreservation-induced damage in mouse embryos, with particular focus on membrane integrity, metabolic pathways, and mitochondrial function. We examine both immediate and delayed consequences of cryopreservation through the lens of molecular toxicology, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for assessing and mitigating these injuries in experimental contexts.

Physical and Chemical Injuries During Cryopreservation

Membrane Damage and Permeability Alterations

The cell membrane constitutes the primary barrier against extracellular insults and serves as the initial site of cryoinjury. During freezing, membranes experience multiple stresses including osmotic shock, lipid phase transitions, and mechanical strain from ice crystals [17]. The fundamental mechanism of damage follows the "two-factor hypothesis" of freezing injury, which posits that cell survival depends critically on cooling rate [17].

At slow cooling rates, extracellular ice formation progressively concentrates solutes in the unfrozen fraction, creating osmotic gradients that draw water out of cells. This causes excessive cell shrinkage, potentially damaging the cytoskeleton and protein structures—a phenomenon termed "solution effect injury" [17]. Conversely, overly rapid cooling prevents adequate cellular dehydration, resulting in intracellular ice formation that mechanically disrupts membranes and organelles [17].

Table 1: Types of Membrane Damage During Cryopreservation

| Damage Type | Mechanism | Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Effect Injury | Extracellular ice formation increases solute concentration, causing osmotic water efflux | Cell shrinkage, cytoskeletal damage, protein denaturation |

| Intracellular Ice Formation | Rapid cooling prevents water efflux, leading to intracellular ice | Mechanical membrane rupture, organelle damage |

| Lipid Phase Transition | Temperature-dependent changes in membrane fluidity | Increased permeability, loss of compartmentalization |

| Osmotic Shock | Rapid water movement during CPA addition/removal | Membrane stretching or compression, transient pore formation |

Cryoprotectant Toxicity

Cryoprotectants (CPAs), while essential for mitigating ice formation, introduce their own toxicities. Traditional CPAs like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) exhibit concentration-dependent and time-dependent toxicity [17] [18]. DMSO can induce cell apoptosis even at low concentrations and cause inappropriate differentiation in stem cells [17]. The molecular mechanisms of CPA toxicity include disruption of protein structure, alteration of membrane properties, and induction of oxidative stress [18].

Recent advances in CPA development focus on identifying less toxic alternatives. Natural osmolytes like betaine show promise as nontoxic CPAs that enable high post-thaw survival even with ultrarapid freezing protocols [19]. Similarly, synthetic polymers such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polyampholytes have demonstrated cryoprotective efficacy while minimizing toxicity [17].

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress

Mitochondrial Structural and Functional Impairments

Mitochondria play a pivotal role in cryopreservation injury as both targets and amplifiers of damage. These organelles are particularly vulnerable to cryoinjury due to their complex membrane systems and central role in cellular metabolism [20]. Studies across multiple cell types consistently demonstrate mitochondrial ultrastructural damage following cryopreservation, including vacuolization, reduced matrix density, and disruption of cristae architecture [21].

Functionally, these structural alterations manifest as decreased mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), impaired electron transport chain (ETC) activity, and reduced adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production [20] [21]. In goat sperm, cryopreservation significantly decreased levels of high-membrane potential mitochondria and ATP content, accompanied by substantial increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [21]. Similar impairments likely occur in cryopreserved mouse embryos, compromising their developmental competence.

Oxidative Stress and Redox Imbalance

The intimate relationship between mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress creates a self-perpetuating cycle of damage during cryopreservation [20]. Mitochondria are the primary intracellular source of ROS, with complexes I and III of the ETC being major production sites [20]. When mitochondrial ETC function is impaired, electron leakage increases, generating excessive superoxide ions (O₂•â») that are dismutated to hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) and other reactive species [20].

This ROS overproduction overwhelms cellular antioxidant defenses, creating a state of oxidative distress that damages proteins, lipids, and DNA [20]. Lipid peroxidation of mitochondrial membranes further compromises ETC function, establishing a vicious cycle of escalating damage. The mitochondrial genome is especially vulnerable due to its proximity to ROS generation sites and lack of histone protection [20].

Diagram 1: Oxidative Stress Pathway in Cryopreservation. This diagram illustrates the self-perpetuating cycle of mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress during freezing and thawing processes.

Metabolic Consequences and Energy Deficits

Disruption of Energy Metabolism

Cryopreservation induces profound disturbances in cellular energy metabolism that extend beyond immediate mitochondrial dysfunction. Metabolomic analyses of cryopreserved sperm reveal significant alterations in energy-related metabolites, including decreased levels of capric acid, creatine, and D-glucosamine-6-phosphate [21]. These changes reflect broad dysregulation of metabolic pathways essential for cellular function.

Key enzymatic activities in energy metabolism are particularly vulnerable to cryoinjury. Studies demonstrate considerable reduction in the activity of rate-limiting enzymes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis and β-oxidation, including acetyl-CoA carboxylase, fatty acid synthase, and carnitine palmitoyltransferase I [21]. This enzymatic impairment disrupts the coordinated metabolic processes required for normal embryo development.

Transcriptomic Alterations and Molecular Damage

Recent transcriptomic analyses provide comprehensive views of molecular damage induced by cryopreservation. In oyster D-larvae, cryopreservation significantly altered the expression of 611 genes compared to only 3 genes affected by cryoprotectant exposure alone [22]. The most significantly enriched gene ontology terms included "carbohydrate metabolic process," "integral component of membrane," and "chitin binding" [22].

These transcriptomic changes indicate that the freezing process itself, rather than CPA exposure, causes the most substantial molecular damage. Pathway analysis identified "neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction," "endocytosis," and "spliceosome" as the most enriched pathways, suggesting broad disruption of signaling, trafficking, and RNA processing mechanisms [22].

Table 2: Metabolic and Molecular Alterations Following Cryopreservation

| Affected System | Specific Alterations | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Metabolism | ↓ ATP content, ↓ metabolites (capric acid, creatine), ↓ β-oxidation enzymes | Energy deficit, reduced motility and developmental competence |

| Lipid Metabolism | Disrupted fatty acid biosynthesis and β-oxidation | Membrane synthesis impairment, alternative energy source depletion |

| Carbohydrate Metabolism | Altered carbohydrate metabolic processes | Glycolytic flux disruption, pentose phosphate pathway impairment |

| Gene Expression | 611 differentially expressed genes, spliceosome pathway alteration | Aberrant protein expression, disrupted cellular signaling |

| Antioxidant Systems | Downregulation of antioxidant metabolites (saikosaponin A, probucol) | Increased oxidative stress vulnerability |

Experimental Assessment Methodologies

Protocol for Evaluating Cryopreservation Injury in Mouse Embryos

Assessment of cryopreservation injuries requires integrated methodologies spanning structural, functional, and molecular analyses. The following protocol outlines key procedures for comprehensive evaluation:

Embryo Collection and Cryopreservation

- Superovulate 4-6 week old female mice using pregnant mare's serum gonadotropin (PMSG) followed by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) 48 hours later [16]

- Mate with proven male mice and collect embryos at appropriate developmental stage (typically 8-cell for mice) [16]

- Employ revised two-step freezing method: Equilibrate embryos in freezing medium (1.5 M glycerol in M2 medium, 1960-1980 mOsm) for 10 minutes [16]

- Cool from 0°C to -7°C at 1°C/minute, seed at -7°C, hold for 10 minutes, then cool to -30°C at 0.3°C/minute before plunging into liquid nitrogen [16]

- Thaw rapidly in 37°C water bath and remove CPAs in stepwise dilution [16]

Viability and Functional Assessment

- Evaluate membrane integrity using dye exclusion tests (trypan blue) or fluorescent markers (propidium iodide) [20]

- Assess developmental competence by in vitro culture to blastocyst stage with evaluation of blastocyst formation rates [16]

- Determine implantation potential by embryo transfer to pseudopregnant recipients [16]

Mitochondrial and Metabolic Analyses

- Measure mitochondrial membrane potential using JC-1 or TMRE fluorescent probes [20] [21]

- Quantify ATP content via luciferase-based assays [21]

- Assess ROS production with Hâ‚‚DCFDA or MitoSOX Red probes [20] [21]

- Conduct metabolomic profiling using LC-MS/MS to identify altered metabolic pathways [21]

Molecular and Transcriptomic Evaluation

- Perform RNA sequencing to identify differentially expressed genes [22]

- Validate key gene expression changes by quantitative RT-PCR [22]

- Analyze pathway enrichment using Gene Ontology and KEGG databases [22]

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Assessing Cryoinjury. This workflow outlines the comprehensive evaluation of cryopreservation injuries from embryo collection through multi-parameter assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Cryopreservation Injury

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cryoprotectants | DMSO, glycerol, ethylene glycol, betaine [17] [19] | Ice formation inhibition, membrane stabilization |

| Membrane Integrity Probes | Propidium iodide, trypan blue, SYTOX Green | Viability assessment, membrane damage quantification |

| Mitochondrial Probes | JC-1, TMRE, MitoTracker, MitoSOX Red [20] [21] | Membrane potential measurement, ROS detection |

| Metabolic Assays | ATP luminescence kits, Seahorse XF Analyzer reagents | Energy status assessment, metabolic flux analysis |

| Antioxidants | N-acetylcysteine, glutathione, α-tocopherol | Oxidative stress mitigation, pathway analysis |

| Molecular Biology Kits | RNA extraction kits, cDNA synthesis kits, qPCR reagents [22] | Transcriptomic analysis, biomarker validation |

| Luffariellolide | Luffariellolide, CAS:111149-87-2, MF:C25H38O3, MW:386.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Linetastine | Linetastine, CAS:159776-68-8, MF:C35H40N2O6, MW:584.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Mitigation Strategies and Future Directions

Advanced Cryoprotectant Formulations

Innovative CPA strategies focus on reducing toxicity while maintaining efficacy. Natural zwitterionic molecules like betaine show exceptional promise, enabling post-thaw survival efficiencies exceeding 90% with ultrarapid freezing protocols [19]. Betaine's mechanism involves strong water-binding capacity that depresses freezing point and regulates osmotic stress [19].

Macromolecular cryoprotectants represent another advancement. Polyampholytes—polymers containing both positive and negative charges—demonstrate remarkable ice inhibition properties while exhibiting minimal toxicity [17]. When combined with traditional CPAs, polyampholytes significantly enhance post-thaw recovery and minimize membrane damage [17].

Antioxidant and Metabolic Interventions

Given the central role of oxidative stress in cryoinjury, antioxidant supplementation presents a logical mitigation strategy. Supplementing freezing extenders with metabolites like capric acid (500 μM) significantly enhances motility of frozen-thawed sperm, indicating potential for similar applications in embryo preservation [21]. The targeted restoration of specific downregulated metabolites represents a precision medicine approach to cryopreservation injury.

Novel engineering strategies also show promise for mitigating cryoinjury. Photothermal and electromagnetic rewarming techniques enable more uniform heating rates, reducing devitrification and ice recrystallization [17]. Microencapsulation approaches provide physical protection during freezing and thawing, while synergistic ice inhibition strategies combine multiple protection mechanisms for enhanced efficacy [17].

Cryopreservation induces a complex cascade of cellular and molecular injuries in mouse embryos, spanning from initial membrane breaches to profound metabolic and mitochondrial dysfunction. These injuries are not random but follow specific pathophysiological pathways centered on osmotic stress, ice formation, and oxidative damage. The delayed consequences observed in senescent mice cryopreserved as embryos underscore that these injuries may have long-lasting implications beyond immediate survival [14].

Comprehensive assessment requires integrated methodologies evaluating structural integrity, functional competence, and molecular fidelity. Advanced transcriptomic and metabolomic approaches reveal that the freezing process itself, rather than CPA exposure, induces the most significant molecular damage [22]. Future directions should focus on targeted interventions that address specific injury mechanisms, particularly mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, while developing novel CPA formulations that balance ice inhibition with biological compatibility.

Understanding these injuries at fundamental levels enables more rational design of cryopreservation protocols, ultimately supporting the preservation of valuable genetic resources while minimizing unintended consequences that could confound experimental outcomes in mouse research.

Cryopreservation is an indispensable tool in biomedical research and assisted reproductive technologies, yet it imposes significant stress on living cells. A primary source of this stress is osmotic shock, the physical and chemical damage resulting from solute concentration imbalances and the resulting water flux across cell membranes during the freezing and thawing processes [23]. In the specific context of mouse embryo research, controlling osmotic shock is not merely a technical concern but a fundamental determinant of experimental success, influencing everything from immediate cell survival to long-term developmental potential [24] [25].

When an aqueous solution freezes, pure water crystallizes first, concentrating the dissolved solutes—salts, cryoprotectants (CPAs), and other molecules—in the remaining liquid phase. Cells suspended in this environment experience a sudden, dramatic increase in extracellular osmolality. This imbalance creates an osmotic gradient that drives water out of the cell, leading to potentially lethal cell shrinkage and solute toxicity [23]. The reverse process occurs during thawing; as extracellular ice melts and the environment becomes hypotonic relative to the dehydrated, CPA-loaded cell, water rushes in, causing uncontrolled swelling and risking cell lysis [26]. Understanding and mitigating these forces is critical for designing cryopreservation protocols that maximize the viability and fidelity of mouse embryos for research.

Core Principles and Quantifying Osmotic Stress

The Physical-Chemical Basis of Osmotic Shock

The journey of a cell through cryopreservation is a series of osmotic perturbations. The central challenge is summarized by Mazur's two-factor hypothesis, which posits that cell survival depends on finding a cooling rate that balances two competing injury mechanisms [23]. Excessively slow cooling permits extensive cellular dehydration, exposing the cell to high solute concentrations ("solution effects") and potential osmotic shock for prolonged periods. Excessively rapid cooling does not allow sufficient time for water to exit, resulting in intracellular ice formation (IIF), which is almost universally fatal [23].

The process of warming is equally critical. During the thawing of vitrified samples, there is a risk of devitrification, where ice crystals form as the temperature rises if warming is not sufficiently rapid [23]. Furthermore, ice recrystallization—the growth of larger ice crystals at the expense of smaller ones—can cause mechanical damage during the thawing phase [23]. The following diagram illustrates the damage pathways triggered by these imbalances.

Quantifying Osmotic Pressure in Embryonic Systems

Quantifying osmotic forces is essential for rational protocol design. Recent technological advances have enabled direct measurement of these parameters within living embryonic tissues. A 2023 study employed double emulsion droplet sensors to perform in situ quantification of osmotic pressure within early zebrafish embryos, a model system relevant to mammalian embryonic development [27].

These sensors consist of a biocompatible fluorocarbon oil shell surrounding an inner aqueous droplet containing a calibrated concentration of polyethylenglycol (PEG) osmolyte. The oil shell is permeable to water but not to solutes. When inserted into a cell or interstitial space, water moves across the shell until the osmotic pressure of the inner droplet matches that of its surroundings. By monitoring the resulting volume change of the inner droplet ((VI^E)), the local osmotic pressure ((Î E)) can be calculated using the equilibrium relationship [27]:

[ Î E = \frac{A}{VI^E - V_I^*} ]

Where (A) is a constant related to the inner droplet's osmolyte concentration and (V_I^*) is the osmotically inactive volume.

Using this technique, researchers measured an intracellular osmotic pressure of approximately 0.7 MPa in blastomeres of early zebrafish embryos, a value balanced by a similar interstitial pressure but creating a large pressure imbalance with the outside of the embryo [27]. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings and principles from osmotic stress research.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Osmotic Stress in Biological Systems

| Parameter | Measured Value / Range | Biological Context | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intracellular Osmotic Pressure | ~0.7 MPa [27] | Blastomeres of early zebrafish embryos | Establishes baseline for physiological osmotic state; target for cryoprotectant solution design. |

| Physiological Osmolality Range | 255–295 mOsm/kg [28] | Human embryo culture media | Target osmolality for in vitro culture systems to minimize osmotic stress during non-frozen handling. |

| Osmolality Change in Dry Incubators | Significant increase from Day 1 to Day 7 (D7>D5>D3) [28] | Culture media in IVF lab conditions | Highlights importance of humidified incubators to prevent media evaporation and hyperosmotic stress. |

| Optimal Cooling Rate | Balance between slow (<1 °C/min) and fast (>100 °C/min) [23] | General cell cryopreservation (cell-type specific) | Governed by Mazur's two-factor hypothesis; must balance dehydration injury vs. intracellular ice formation. |

Experimental Methodologies for Analysis and Mitigation

Optimized Protocol: Two-Step CPA Loading for Mouse Oocytes

Directly addressing osmotic shock, a pivotal study developed and validated a mathematically optimized two-step method for loading dimethyl sulfoxide (Meâ‚‚SO) into mouse metaphase II (MII) oocytes [24]. This protocol was designed to minimize the combined damage from osmotic stress and CPA toxicity, outperforming conventional one-step loading.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Osmotic Stress Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Double Emulsion Droplet Sensors [27] | Micro-osmometers for in situ quantification of osmotic pressure within individual cells and interstitial spaces of living embryonic tissues. |

| Hypotonic Diluents (e.g., hypo-PBS) [24] | Aqueous buffers with reduced salt concentration (~55 mOsmol/L); used to prepare CPA solutions to reduce osmotic shock during initial CPA exposure. |

| Non-Permeating CPAs (e.g., Sucrose, Trehalose) [23] [29] | High molecular weight solutes that remain extracellular; draw water out of cells osmotically, promoting protective dehydration and reducing required concentrations of toxic permeating CPAs. |

| Permeating CPAs (e.g., DMSO, EG, PROH) [23] [24] | Small molecules that cross the cell membrane; displace water to inhibit intracellular ice formation but introduce risks of chemical toxicity and osmotic shock. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) / Paraffin Oil [27] [28] | Used in droplet microfluidics and as an overlay for culture media; paraffin oil is superior to mineral oil in reducing media evaporation and osmolality shifts in dry incubators. |

Materials

- Mouse MII oocytes

- Isotonic Ca²âº/Mg²âº-free PBS supplemented with 4 mg/mL BSA

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (Meâ‚‚SO)

- Hypotonic diluent ("hypo-PBS"): Ca²âº/Mg²âº-free PBS diluted to ~55 mOsmol/L, with 10% (v/v) FBS

- Culture medium (e.g., Hypermedium with BSA and gentamycin)

Procedure

- Preparation: Prepare the two loading solutions using the hypotonic diluent.

- Solution A: 0.75 M Meâ‚‚SO in hypo-PBS.

- Solution B: 1.50 M Meâ‚‚SO in hypo-PBS.

- Step 1 - Equilibration: Transfer oocytes to Solution A (0.75 M Me₂SO) for a calculated, optimized duration (e.g., 2-3 minutes) at 23°C or 30°C. This step introduces CPA gradually, minimizing initial water efflux and cell shrinkage.

- Step 2 - Final Loading: After the optimized time, directly transfer oocytes to Solution B (1.50 M Meâ‚‚SO) for a second defined period. The cells are now partially equilibrated, reducing the osmotic differential and the associated stress of the final concentration jump.

- Vitrification: After completing the loading steps, proceed with standard vitrification protocols (ultra-rapid cooling in liquid nitrogen).

- Warming and Removal: For warming, use a multi-step dilution process in decreasing concentrations of Meâ‚‚SO (e.g., 1.0 M, 0.5 M) supplemented with 0.25 M sucrose. The non-permeating sucrose in these solutions acts as an osmotic buffer, preventing a massive, rapid influx of water and controlling rehydration to avoid swelling and lysis [24].

Validation In the foundational study, this optimized two-step protocol resulted in significantly higher rates of fertilization (85% vs. 34%) and embryonic development (87% vs. 60%) compared to conventional one-step loading of 1.5 M Meâ‚‚SO [24]. Subsequent experiments decoupled the factors of shrinkage and Meâ‚‚SO exposure, concluding that the damage from one-step loading results from a synergistic interaction between osmotic stress and CPA toxicity, both of which are mitigated by the optimized protocol.

Workflow for Osmotic Pressure Measurement in Embryos

The following diagram outlines the experimental workflow for using double emulsion droplets to measure osmotic pressure within living embryonic tissues, providing a direct method to quantify the central factor of this review.

Advanced Concepts and Future Directions

Novel Warming Techniques and Osmotic Considerations

The principle of minimizing osmotic shock is also being applied to the warming phase. Recent clinical research has investigated one-step warming protocols for vitrified blastocysts. This approach involves rehydrating embryos in a single solution of 1M sucrose for one minute, a significant simplification over traditional multi-step methods that use decreasing sucrose concentrations [29]. This protocol, which reduces procedure time by over 90%, leverages a high, sustained osmotic buffer (sucrose) to control water influx while rapidly removing CPAs. Studies report comparable survival, clinical pregnancy, and ongoing pregnancy rates to multi-step warming, suggesting it is a viable, efficient protocol that adequately manages osmotic stress during thawing [29].

Induced Cellular Tolerance and the Role of Apoptosis

Beyond physical protocol optimization, research is exploring biological interventions to enhance cellular resilience. One promising avenue is hormesis, where a mild, sublethal stress preconditions cells, making them more resistant to a subsequent, more severe stress. For example, pretreating yeast or nematodes with heat shock or hydrogen peroxide conferred significant protection against the toxicity of high concentrations of vitrification solutions [6]. This concept suggests that mobilizing endogenous cellular defense pathways could be a powerful strategy to mitigate the combined osmotic and chemical stress of cryopreservation.

Furthermore, the freezing process is known to trigger apoptotic pathways in oocytes and embryos [25]. Comparisons between frozen and non-frozen samples show alterations in the expression of key apoptotic regulators like Bcl-2 and Bax. This indicates that osmotic and other cryo-stresses are perceived by the cell at a fundamental level, activating programmed cell death. Therefore, the integration of apoptotic inhibitors into cryopreservation protocols represents a forward-looking strategy to improve survival rates by addressing the downstream cellular response to osmotic shock [25].

In mouse embryo research, cryopreservation is a pivotal technique for preserving genetic resources and managing reproductive cohorts in preclinical studies. While traditional focus has centered on preventing ice crystal formation, contemporary research reveals that cryodamage extends far beyond physical ice effects. Chilling injury and oxidative stress constitute two interconnected mechanistic pathways that significantly compromise embryo viability during freezing and thawing processes. This technical guide examines the sophisticated cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying these damage pathways, providing researchers with current experimental data and methodologies relevant to mouse model systems. Understanding these intricate processes is fundamental for developing targeted strategies to mitigate cryopreservation toxicity and enhance experimental reproducibility in pharmaceutical and basic research applications.

The Dual Assault: Chilling Injury and Oxidative Stress

Chilling Injury: A Cold-Activated Signaling Cascade

Chilling injury occurs at temperatures above the freezing point (typically 0-15°C) and represents a biologically active process rather than passive physical damage. Recent research on zebrafish oocytes, a valuable model for understanding cold sensitivity, has illuminated a mechanosensitive pathway where TRPA1 (Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1) channels act as primary cold sensors [30].

The diagram below illustrates this cold-induced signaling cascade that leads to cell death:

This signaling cascade culminates in significant membrane damage and cell death. Experimental data demonstrates that TRPA1 inhibition with AP-18 dramatically improves oocyte survival from 9% to 70% after chilling at 0°C for 15 minutes, strongly implicating this specific pathway in cold-induced damage [30].

Oxidative Stress: The Free Radical Cascade

Concurrently with chilling injury, cryopreservation induces substantial oxidative stress through massive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The freezing and thawing processes disrupt mitochondrial electron transport, leading to electron leakage and superoxide formation [31] [32]. Multiple factors exacerbate ROS production during cryopreservation, including cryoprotectant toxicity, temperature fluctuations, and exposure to ambient oxygen [31].

Table 1: Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Their Cellular Impacts

| ROS Type | Chemical Formula | Half-Life | Primary Cellular Targets | Neutralizing Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide Radical | O₂•⻠| Short (milliseconds) | Mitochondrial complexes, Iron-sulfur proteins | Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Longer (minutes) | Thiol groups, Transcription factors | Catalase, Glutathione Peroxidase |

| Hydroxyl Radical | •OH | Extremely short (microseconds) | DNA, Proteins, Membrane lipids | None known (most damaging) |

The hydroxyl radical is particularly destructive due to the absence of known enzymatic neutralizing systems, enabling it to cause widespread damage to DNA, proteins, and lipid membranes [31] [32]. This oxidative assault activates several downstream damage pathways in mouse embryos.

Quantifiable Damage and Functional Consequences

Structural and Functional Compromises

The combined effects of chilling injury and oxidative stress manifest through multiple quantifiable damage parameters in mouse embryos and oocytes:

Table 2: Experimentally Measured Cryodamage in Mouse Models

| Damage Parameter | Experimental Measurement | Impact on Development | Reference Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blastocyst Formation Rate | Decrease from 27.8% to 20% | Reduced implantation potential | Mouse GV oocytes [32] |

| Mitochondrial Membrane Potential | Significant decrease post-thaw | Compromised ATP production | Vitrified mouse oocytes [33] |

| DNA Damage | Increased γH2AX foci, strand breaks | Genomic instability, apoptosis | Vitrified mouse blastocysts [34] |

| Reactive Oxygen Species | 2-3 fold increase in ROS levels | Oxidative damage to cellular components | Vitrified mouse oocytes/embryos [33] [34] |

| Cell Number in Blastocysts | Significant reduction | Altered fetal programming | Vitrified mouse embryos [34] |

Epigenetic and Transcriptional Alterations

Beyond immediate structural damage, vitrification induces long-term developmental consequences through epigenetic modifications. Recent research demonstrates that vitrified mouse blastocysts exhibit altered histone modifications, including elevated H3K4me2/3, H4K12ac, and H4K16ac levels, alongside reduced m6A RNA methylation [34]. These changes correlate with significant transcriptome alterations in E18.5 placentas and fetal brains, potentially explaining the reduced live pup rates observed following transfer of vitrified-warmed embryos [34].

The Interplay: How Chilling Injury Amplifies Oxidative Stress

The relationship between chilling injury and oxidative stress is not merely additive but synergistically destructive. The diagram below illustrates how these pathways interconnect to amplify damage:

This interconnected network creates feed-forward loops where calcium dysregulation disrupts mitochondrial function, generating additional ROS that further activate TRP channels and cPLA2α, perpetuating the damage cycle [31] [30] [32].

Experimental Models and Assessment Methodologies

Standardized Viability Assessment Protocols

Researchers have established rigorous experimental approaches for quantifying cryodamage in mouse models:

Oocyte Viability Staining Protocol (from zebrafish oocyte studies applicable to mammalian systems):

- Post-thaw incubation at 25°C for 2 hours

- Staining with propidium iodide (20 µg/mL) for 10 minutes

- Fluorescence examination using U-MWIG2 filter (520-550 nm excitation/580 nm emission)

- Viability determination: dead oocytes emit reddish-white fluorescence; live oocytes exclude dye [30]

Comprehensive Embryo Assessment (mouse model):

- ROS measurement: 10µM DCFH-DA incubation at 37°C for 30 minutes

- Mitochondrial membrane potential: JC-1 staining following manufacturer protocols

- Mitochondrial activity: 500nM MitoTracker Red CMXRos incubation at 37°C for 30 minutes

- DNA damage assessment: γH2AX immunofluorescence and COMET assays [34]

Antioxidant Intervention Studies

Multiple studies have systematically evaluated antioxidant strategies for mitigating oxidative damage:

Table 3: Experimentally Validated Antioxidant Interventions

| Antioxidant | Concentration | Protective Mechanism | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imperatorin | 40 µM | Reduces ROS, increases GSH, improves mitochondrial function | Enhanced fertilization rate, reduced apoptosis in mouse oocytes [33] |

| Melatonin | 10â»Â¹â° M | Scavenges ROS, preserves mitochondrial function, reduces Ca²⺠| Increased inner cell mass, trophectoderm, and total cell count in blastocysts [35] |

| Astaxanthin | Varies by system | Membrane-associated antioxidant, upregulates SOD and catalase | Improved post-thaw sperm motility, oocyte quality across species [36] |

| N-acetylcysteine | 1 µM | Precursor to glutathione, direct ROS scavenging | Reduced ROS accumulation in vitrified mouse embryos [34] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Investigating Cryopreservation Damage Mechanisms

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Mechanistic Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRP Channel Inhibitors | AP-18 (300 µM), Ruthenium Red | Chilling injury pathway dissection | TRPA1 cold-sensing channels [30] |

| Lipid Signaling Inhibitors | Pyrrophenone (cPLA2α), Indomethacin (COX), Zileuton (ALOX5) | Lipid mediator pathway analysis | Eicosanoid synthesis pathways [30] |

| Mitochondrial Probes | MitoTracker Red CMXRos, JC-1, TMRE | Mitochondrial function assessment | Membrane potential, distribution [33] [34] |

| ROS Detection Reagents | DCFH-DA, MitoSOX Red | Oxidative stress quantification | General ROS, mitochondrial superoxide [33] [34] |

| Exogenous Antioxidants | Melatonin, Imperatorin, Astaxanthin, N-acetylcysteine | Intervention studies | Direct ROS scavenging, endogenous antioxidant upregulation [33] [35] [36] |

| DNA Damage Markers | γH2AX antibodies, COMET assay kits | Genotoxicity assessment | DNA strand breaks, repair activation [34] |

| Apoptosis Detectors | Annexin V, TUNEL assay, Caspase inhibitors | Cell death pathway analysis | Phosphatidylserine exposure, DNA fragmentation [34] |

| Lysine hydroxamate | Lysine hydroxamate, CAS:25125-92-2, MF:C6H15N3O2, MW:161.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (+)-Magnoflorine | Magnoflorine | Research-grade Magnoflorine, a natural aporphine alkaloid. Explore its applications in neuroinflammation, metabolism, and OA studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

Chilling injury and oxidative stress represent sophisticated biological response pathways that extend far beyond the physical damage of ice crystal formation in mouse embryo cryopreservation. The mechanistic understanding of TRPA1-initiated signaling cascades and mitochondrial ROS generation provides researchers with specific molecular targets for intervention. The experimental methodologies and reagent toolkit presented here offer practical approaches for investigating and mitigating these damage pathways. As cryopreservation continues to be essential for managing mouse research colonies and preserving valuable genetic resources, addressing these interconnected toxicity mechanisms will be crucial for enhancing experimental reproducibility and supporting rigorous scientific discovery in pharmaceutical development and basic research.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Low-Toxicity Cryopreservation Protocols

For researchers investigating embryo cryopreservation toxicity in mouse models, selecting the optimal cryopreservation method is paramount to experimental validity and translational relevance. The debate between conventional slow freezing and newer vitrification techniques encompasses critical considerations of cellular survival, functional integrity, and potential cryoinjury—each method presenting distinct advantages and challenges for reproductive biology research. This technical analysis synthesizes current evidence to guide scientists in selecting the most appropriate methodology based on specific research endpoints, from basic morphological preservation to complex physiological functionality and long-term developmental outcomes.

Core Principles and Mechanisms of Action

Slow Freezing: Controlled-Rate Cryopreservation

Slow freezing operates on the principle of equilibrium freezing, characterized by a gradual, controlled cooling process that typically ranges from -0.3°C/min to -0.5°C/min [37] [38]. This method employs relatively low concentrations of cryoprotective agents (CPAs)—usually between 1.0-1.5 mol/L—such as propanediol, glycerol, or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) [38]. The gradual cooling process allows for controlled dehydration of cells, as water migrates out of the cell before freezing extracellularly. This minimizes the formation of intracellular ice crystals, which are mechanically destructive to cellular structures [37]. However, the unavoidable extracellular ice formation can potentially cause structural damage to the stromal matrix and disrupt cell-to-cell connections [39]. The process requires specialized, expensive programmable freezing equipment and is more time-consuming than vitrification, but benefits from using lower, potentially less toxic concentrations of CPAs [37] [38].

Vitrification: Ultra-Rapid Glass Transition

Vitrification represents a non-equilibrium approach that completely avoids ice crystal formation through ultra-rapid cooling rates (as high as -20,000°C/min) and high CPA concentrations (ranging from 4-8 mol/L) [37] [38]. This technique converts the liquid cell solution directly into a glass-like amorphous solid without undergoing crystalline formation [40]. The process typically employs a combination of permeating CPAs like ethylene glycol (EG) and DMSO, often supplemented with non-permeating agents such as sucrose and macromolecules like Ficoll [41] [42]. The extremely rapid cooling prevents water molecules from organizing into ice crystals, instead immobilizing them in a vitreous state [37]. While vitrification eliminates mechanical damage from ice formation, it introduces potential chemical toxicity and osmotic stress due to high CPA concentrations [41]. The technique requires minimal equipment but demands significant technical skill for proper execution [37].

Table 1: Fundamental Principles of Cryopreservation Methods

| Parameter | Slow Freezing | Vitrification |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Principle | Equilibrium freezing | Non-equilibrium solidification |

| Cooling Rate | Slow (≈ -0.3°C/min) | Ultra-rapid (up to -20,000°C/min) |

| CPA Concentration | Low (1.0-1.5 mol/L) | High (4-8 mol/L) |

| Ice Formation | Extracellular only | None |

| Primary Equipment | Programmable freezer | Cryocarriers (loops, straws) |

| Technical Skill Required | Moderate | High |

| Process Duration | Several hours | Minutes |

Comparative Performance Analysis in Research Models

Cellular Survival and Morphological Integrity

Multiple studies across different biological systems demonstrate consistently higher immediate post-thaw survival rates with vitrification compared to slow freezing. In human cleavage-stage embryos, vitrification achieved a remarkable 96.9% survival rate versus 82.8% with slow freezing [38]. Morphological integrity followed a similar pattern, with 91.8% of vitrified embryos showing excellent morphology with all blastomeres intact compared to only 56.2% in the slow-frozen group [38].

Research on mouse embryo-derived inner cell mass (ICM) cells revealed that vitrification protocols yielded 100% survival rates (78/78) with 95% attachment capability to feeder layers post-warming, comparable to non-vitrified controls [42]. These vitrified ICM cells maintained expression of critical stem cell markers including SSEA-1, Sox-2, and Oct-4, confirming preservation of pluripotent characteristics [42].

In ovarian tissue cryopreservation, a meta-analysis of 19 studies found significantly better preservation of stromal cell integrity with vitrification, though primordial follicle preservation showed no significant difference between methods [37]. This suggests that vitrification may offer particular advantages for complex tissue architectures where stromal support is crucial for subsequent function.

Functional Recovery and Angiogenic Potential

Functional recovery after transplantation represents a critical endpoint for evaluating cryopreservation efficacy. In heterotopic transplantation of human ovarian tissue to nude mice, vitrification demonstrated superior recovery of endocrine function, with significantly higher estradiol levels at 6 weeks post-transplantation compared to slow-frozen tissue [39]. The proportion of normal follicles was also higher in vitrified tissue at both 4 and 6 weeks post-transplantation [39].

Angiogenic potential—a crucial factor for graft survival—showed no significant differences between vitrification and slow freezing in human ovarian tissue cultured under hypoxic conditions [40]. Analysis of ten angiogenic factors including VEGF, angiogenin, and hepatocyte growth factor revealed comparable expression profiles between the two methods, suggesting both adequately preserve this critical functional aspect [40].

In Vivo Development and Offspring Outcomes

Mouse model research provides valuable insights into the long-term developmental consequences of different cryopreservation methods. One comprehensive study comparing vitrification and slow freezing found no significant differences in postnatal physiology, spatial learning capabilities, or cerebral development parameters in resulting offspring [41]. Expression and distribution of brain development-related proteins GFAP and MBP showed comparable patterns across all groups [41].

However, researchers noted that offspring from both cryopreservation groups demonstrated higher body weights at 8 weeks compared to fresh controls, accompanied by increased expression of fat-associated genes FTO and PGC-1α [41]. This suggests that both cryopreservation methods may induce similar epigenetic or metabolic alterations unrelated to the specific freezing technology.

Experimental Protocols for Mouse Embryo Research

Mouse Embryo Vitrification Protocol

The following protocol has been successfully applied for vitrification of mouse cleavage-stage embryos and ICM cells [41] [42]:

Reagents and Equipment:

- Base medium: HTF medium supplemented with 10% human serum albumin (HSA)

- Equilibration Solution (ES): 7.5% (v/v) ethylene glycol + 7.5% (v/v) DMSO in base medium

- Vitrification Solution (VS): 15% (v/v) EG + 15% (v/v) DMSO + 0.5M sucrose + 10μg/ml Ficoll in base medium

- Warming solutions: Sucrose gradients (0.25M, 0.125M) in base medium

- Cryocarriers: Cryoloops or HSV straws

- Liquid nitrogen storage system

Procedure:

- Equilibration: Transfer embryos to ES at room temperature for 15 minutes

- Vitrification solution exposure: Move embryos to VS for <45 seconds

- Loading: Rapidly load 1-2 embryos in minimal volume onto cryocarrier

- Plunging: Immediately immerse cryocarrier into liquid nitrogen

- Storage: Transfer to long-term LNâ‚‚ storage tanks

Warming process:

- Rapid warming: Immerse cryocarrier directly in 37°C base medium with 0.25M sucrose for 2 minutes

- Sucrose dilution: Transfer embryos to 0.125M sucrose solution for 3 minutes

- Rehydration: Rinse in base medium for 5 minutes

- Culture: Transfer to pre-equilibrated culture medium for further development

Mouse Embryo Slow Freezing Protocol

This protocol adapts traditional slow freezing methods for mouse embryo research [41]:

Reagents and Equipment:

- Freezing medium: DMEM/F12 with 10% glycerol, 10% DPBS, and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS)

- Thawing solutions: Gradients of glycerol (6%, 3%) with 0.3M sucrose, followed by sucrose-only (0.3M) solution

- Programmable freezer (e.g., Cryologic CL3300)

- Seeding forceps

- 0.25ml plastic straws

Procedure:

- Equilibration: Incubate embryos in freezing medium for 15 minutes

- Loading: Pipette embryos into labeled straws

- Programmed freezing:

- Cool from room temperature to -7°C at -0.7°C/min

- Hold at -7°C for 10 minutes, perform manual seeding

- Cool to -33°C at -0.3°C/min

- Plunge into liquid nitrogen for storage

- Thawing:

- Hold straws at room temperature for 60 seconds

- Immerse in 25°C water bath for 30 seconds

- Expel contents into glycerol/sucrose solutions

- Stepwise dilution through decreasing CPA concentrations (6% glycerol/0.3M sucrose → 3% glycerol/0.3M sucrose → 0.3M sucrose → PBS+20% FCS), 5 minutes each

- Transfer to culture medium