DNA vs RNA Probes for ISH: A 2025 Guide to Selection, Optimization, and Application

This article provides a comprehensive and up-to-date analysis of DNA and RNA probes for In Situ Hybridization (ISH), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

DNA vs RNA Probes for ISH: A 2025 Guide to Selection, Optimization, and Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive and up-to-date analysis of DNA and RNA probes for In Situ Hybridization (ISH), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, including probe chemistry and design, and explores advanced methodological applications across techniques like FISH, MERFISH, and RNAscope. A significant focus is placed on practical troubleshooting and protocol optimization based on the latest 2025 research, alongside a rigorous comparative validation of probe performance in key metrics such as sensitivity, specificity, and artifact reduction. The goal is to equip practitioners with the evidence needed to make informed, strategic choices for precise nucleic acid detection in both research and clinical diagnostics.

DNA and RNA Probes Demystified: Core Principles and Design

Core Definitions and Fundamental Principles

Molecular probes are short, labeled sequences of nucleic acids—either DNA or RNA—engineered to bind to complementary DNA or RNA targets within cells or tissues, a process known as in situ hybridization (ISH) [1]. When these probes are labeled with fluorophores, the technique is called fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [2] [3]. The fundamental principle relies on the predictable base-pairing rules of nucleic acids: adenine (A) pairs with thymine (T) or uracil (U), and guanine (G) pairs with cytosine (C) [1]. This complementary binding allows researchers to visually detect and localize specific genetic sequences with high spatial resolution, preserving the architectural context of the sample [2] [4].

- DNA Probes are typically single- or double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides. A key application is in chromatin tracing, where they hybridize to specific DNA sequences to visualize the spatial organization of genomic loci [5].

- RNA Probes (Riboprobes), often single-stranded, are synthesized via in vitro transcription from a DNA template [6]. They are primarily used to detect mRNA transcripts, providing insights into gene expression patterns and cellular heterogeneity [2].

Comparative Analysis: DNA vs. RNA Probes

The choice between DNA and RNA probes significantly impacts the sensitivity, specificity, and application of an ISH experiment. The table below summarizes their core characteristics and optimal use cases.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of DNA and RNA Probes

| Feature | DNA Probes | RNA Probes (Riboprobes) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Structure | Single- or double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides [1] | Single-stranded RNA, synthesized by in vitro transcription [6] |

| Typical Length | ~30 nucleotides for highly multiplexed FISH [5]; 0.5–3 kb for other ISH [6] | 50–150 bp for high penetration; up to 1500 bases, with ~800 bases considered optimal for sensitivity [6] [7] |

| Hybridization Strength | Weaker hybridization to target mRNA; formaldehyde should be avoided in post-hybridization washes [6] | Strong, stable hybridization to target RNA due to RNA-RNA duplex formation [6] |

| Primary Application | Detecting DNA sequences (e.g., chromosomal loci, viral DNA) and some RNA targets [2] [5] | Detecting RNA sequences (mRNA, ncRNA), prized for high sensitivity and specificity in gene expression studies [6] [2] |

| Key Advantage | High sensitivity for DNA detection; useful for multiplexed techniques like chromatin tracing [3] [5] | Superior sensitivity and specificity for RNA targets, leading to lower background noise [6] |

Technical Protocols and Methodologies

Successful ISH requires a meticulous, multi-stage protocol to preserve nucleic acid integrity, ensure specific probe binding, and minimize background noise.

Sample Preparation and Fixation

Proper tissue handling is paramount, especially for RNA detection, due to the ubiquity of RNases. Tissues should be transferred to ice-cold RNase-free PBS immediately after collection and fixed promptly [7].

- Fixation: The most common fixatives are 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) or 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) [7] [8]. For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples, fixation in fresh 10% NBF for 16–32 hours at room temperature is recommended [8]. Inadequate fixation leads to RNA degradation and poor signal [7].

- Permeabilization: Treatment with proteinase K (e.g., 1-20 µg/mL for 5-30 minutes) is required after fixation to digest proteins and allow probe access to the target nucleic acids. The concentration and time must be optimized, as over-digestion damages tissue morphology [6] [7].

Probe Design and Labeling

Probe design is a critical determinant of experimental success, influencing both specificity and signal strength.

- Design Strategy: For mRNA detection, probes should target the coding region (CDS) or the 3' untranslated region (3' UTR) for better sequence specificity [7]. Repetitive elements like poly-A tails must be avoided [7]. Advanced computational tools like TrueProbes and ProbeDealer are now used to design probes by assessing genome-wide binding affinities, minimizing off-target interactions, and optimizing thermodynamic properties [9] [10] [5].

- Labeling: Isotopic labels (e.g., ³²P, ³âµS) offer high sensitivity but are hazardous and less common [1]. Non-isotopic labels are preferred for safety and convenience:

- Biotin and Digoxigenin (DIG) are common haptens detected via enzyme-conjugated antibodies (e.g., streptavidin-HRP or anti-DIG-alkaline phosphatase) in chromogenic assays [1] [7].

- Fluorescent dyes (e.g., Cy3, Alexa Fluor) allow for direct detection in FISH and are widely used in multiplexed assays [2] [3]. Quantum dots are gaining traction for their superior brightness and photostability [3].

Hybridization and Post-Hybridization Washes

This core step involves the annealing of the probe to its target sequence.

- Hybridization Conditions: The probe is diluted in a specialized hybridization buffer containing formamide, salts, and blocking agents, denatured, and applied to the sample [6] [4]. Hybridization occurs overnight in a humidified chamber at a carefully controlled temperature.

- Stringency Washes: After hybridization, a series of washes with solutions of defined salt concentration (SSC) and temperature are performed to remove unbound and weakly bound probes, thereby reducing background signal [6] [4]. Higher temperature and lower salt concentration increase stringency.

Signal Detection and Visualization

The method of detection depends on the probe label.

- Chromogenic Detection: For DIG-labeled probes, an enzyme-conjugated antibody (e.g., anti-DIG-alkaline phosphatase) is applied. The enzyme then catalyzes a reaction with a substrate like NBT/BCIP, producing a colored precipitate visible under a bright-field microscope [7].

- Fluorescent Detection: For directly labeled probes, the sample is mounted with an anti-fade medium and imaged using a fluorescence or confocal microscope. In techniques like smFISH or RNAscope, each punctate dot represents a single mRNA molecule [2] [8].

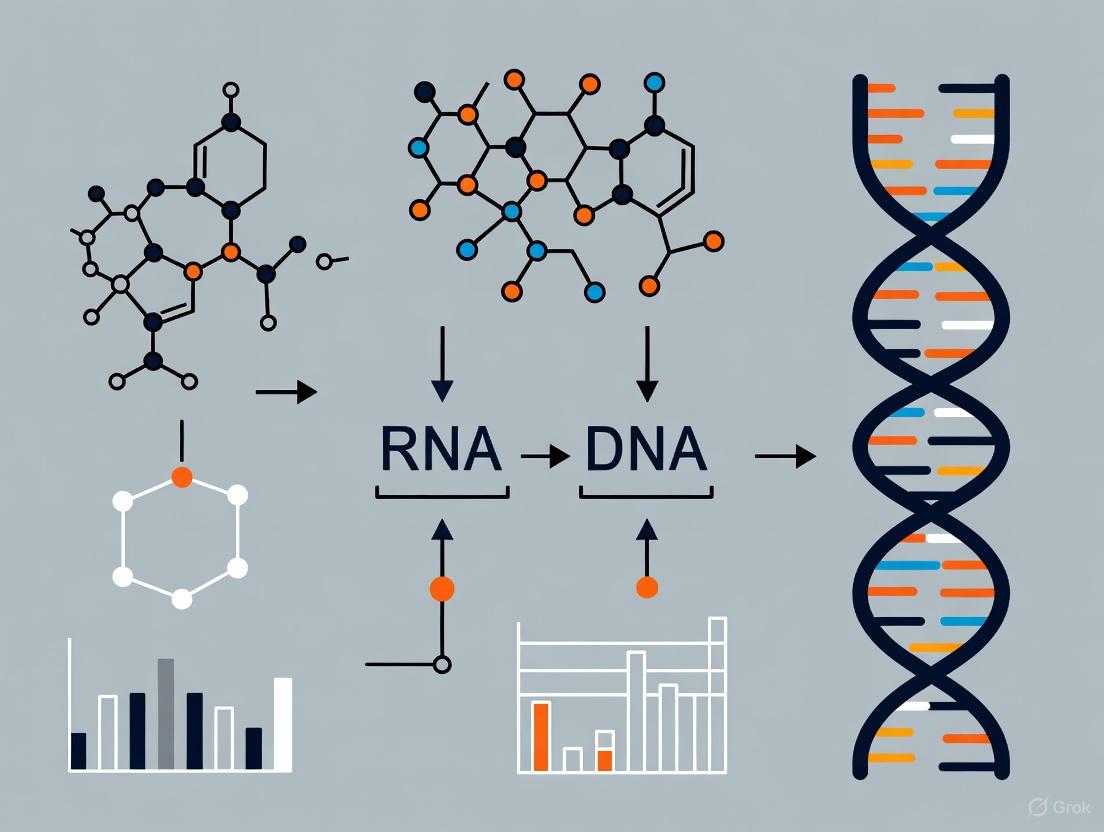

ISH Workflow: A generalized ISH procedure showing key steps from sample preparation to analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for ISH Experiments

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | Preserves cellular structure and nucleic acid integrity. | 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA), 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) [7] [4] |

| Permeabilization Agents | Creates holes in the cell membrane/tissue for probe entry. | Proteinase K, Triton X-100 [6] [4] |

| Hybridization Buffer | Creates optimal chemical conditions for specific probe-target binding. | Contains formamide, salts (SSC), blocking agents (Denhardt's solution) [6] [4] |

| Blocking Reagents | Reduces non-specific binding of probes or antibodies to minimize background. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), casein, heparin, salmon sperm DNA [6] [4] |

| Stringency Wash Buffers | Removes unbound and weakly bound probes after hybridization. | Saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer; stringency is controlled by temperature and salt concentration [6] [7] |

| Detection System | Visualizes the bound probe. | Fluorescent dyes (Cy3, Alexa Fluor), enzymatic substrates (NBT/BCIP, DAB), haptens (DIG, Biotin) [3] [1] [7] |

| Specialized Equipment | Maintains precise conditions for hybridization and imaging. | Humidified hybridization oven (e.g., HybEZ), fluorescence microscope [4] [8] |

| Acoltremon | WS-12 TRPM8 Agonist|High-Purity Research Chemical | |

| Wwl70 | Wwl70, CAS:947669-91-2, MF:C27H23N3O3, MW:437.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Probe Design and Market Landscape

Modern probe design has evolved from simple sequence tiling to sophisticated computational pipelines that integrate genomic and thermodynamic data [9] [10] [5]. Tools like TrueProbes address limitations of earlier software by using genome-wide BLAST analysis and thermodynamic modeling to rank probes based on predicted binding affinity, target specificity, and structural constraints, thereby minimizing off-target binding [9] [10]. Similarly, ProbeDealer offers an all-in-one platform for designing probes for complex, multiplexed FISH techniques like chromatin tracing and MERFISH [5].

The global FISH probe market reflects this technological advancement. Valued at approximately USD 1.14 billion in 2025, it is projected to grow to about USD 2.27 billion by 2034, driven by the rising prevalence of genetic disorders and cancer, and the adoption of precision diagnostics [3]. While DNA probes currently hold the largest market share, the RNA probes segment is growing at the fastest rate, fueled by increasing interest in gene expression analysis and spatial biology [3].

In Situ Hybridization (ISH) stands as a fundamental technique in molecular biology and diagnostic pathology, enabling the precise localization of specific nucleic acid sequences within histologic sections, cells, or entire tissues [11]. The core principle of ISH relies on the hybridization of a complementary, labeled nucleic acid probe to a target DNA or RNA sequence within a biologically preserved sample, allowing researchers to visualize the spatial distribution of genetic elements [11]. The efficacy, sensitivity, and specificity of any ISH experiment are profoundly influenced by the choice of probe and the method used for its synthesis and labeling. Within the broader context of RNA versus DNA probes for ISH research, understanding these techniques is paramount for designing optimal experiments. RNA probes (riboprobes) and DNA probes each possess distinct characteristics that make them suitable for different applications, with the former generally offering higher sensitivity for mRNA detection and the latter providing greater stability [11] [6]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the primary methods for probe synthesis—nick translation and in vitro transcription—along with advanced labeling strategies, protocol details, and a comparative analysis to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their experimental design.

Core Probe Synthesis Methodologies

Nick Translation for DNA Probe Synthesis

Nick translation is a robust, enzymatic method primarily used for labeling double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) probes. The technique employs two key enzymes: DNase I and DNA Polymerase I [12]. DNase I introduces single-strand breaks ("nicks") into the phosphate backbone of the DNA template. DNA Polymerase I then recognizes these nicks and, utilizing its 5'→3' exonuclease activity, sequentially removes nucleotides ahead of the nick while simultaneously replacing them with new nucleotides from the 5'→3' direction. When the reaction mixture includes labeled nucleotides (e.g., biotin-dUTP, digoxigenin-dUTP, or fluorescently tagged dNTPs), they are incorporated into the newly synthesized DNA strand, resulting in a uniformly labeled probe [12].

This method is ideal for both radioactive and non-radioactive labeling and is particularly valued for producing highly labeled probes suitable for techniques like Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) [12] [13]. Commercial systems, such as the Invitrogen Nick Translation System, are optimized to yield high incorporation rates, for example, >10⸠cpm/μg of control DNA when using [α-³²P]-dCTP, and can label 1 μg of DNA in a single reaction [12]. A key advantage of nick translation is its ability to label DNA without requiring prior knowledge of the sequence or a specialized cloning vector, making it a versatile and widely accessible technique.

In Vitro Transcription for RNA Probe (Riboprobe) Synthesis

In vitro transcription is the dominant method for generating single-stranded RNA probes (riboprobes), which are renowned for their high sensitivity and specificity in detecting mRNA targets [6]. This technique requires a DNA template that contains the target sequence of interest downstream of a bacteriophage RNA polymerase promoter, such as T7, T3, or SP6 [14] [6]. The traditional approach involves cloning the target sequence into a plasmid vector containing these opposed promoters, which allows for the generation of both sense (control) and antisense (probe) RNA strands [6].

The linearized plasmid is then incubated with the appropriate RNA polymerase in the presence of nucleotide triphosphates (NTPs), which include a labeled NTP (commonly DIG-UTP, biotin-UTP, or fluorescent UTP). The polymerase synthesizes a complementary RNA strand, efficiently incorporating the labeled nucleotide. The resulting RNA probes are typically between 250 and 1,500 bases in length, with probes of approximately 800 bases considered to exhibit the highest sensitivity and specificity [6].

A significant innovation in this field is the development of a PCR-based method for generating RNA probes, which bypasses the need for time-consuming plasmid cloning [14]. This method uses a two-step PCR amplification. The first PCR amplifies the specific cDNA sequence of interest from a sample. The second PCR incorporates the T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence into the amplified product. This PCR product then serves as the direct template for in vitro transcription, dramatically speeding up the probe generation process and making it suitable for the rapid assessment of gene expression [14].

Alternative Labeling Techniques and Signal Amplification

Beyond the core synthesis methods, several other techniques and amplification strategies are critical for successful ISH.

- Oligonucleotide Probes: Synthetic, single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides (typically 20-50 bases) can be chemically synthesized with labeled nucleotides directly incorporated during synthesis. While easier to produce, they may exhibit lower hybridization strength compared to longer RNA or DNA probes [6].

- Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA): This powerful method can enhance signal intensity by 10 to 200 times compared to standard detection methods [13]. TSA utilizes horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibodies that catalyze the deposition of multiple fluorescent or chromogenic tyramide molecules at the site of the probe-target hybridization. Kits like the Invitrogen SuperBoost kits leverage this technology to achieve superior signal definition and clarity for imaging low-abundance targets [13].

- Enzymatic Detection: For chromogenic ISH (CISH), probes labeled with haptens like digoxigenin (DIG) are typically detected using an enzyme-conjugated antibody (e.g., alkaline phosphatase-anti-DIG). Following antibody binding, an insoluble, colored precipitate is formed upon the addition of a substrate such as nitroblue tetrazolium chloride/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (NBT/BCIP) or Fast Red [15] [6].

Comparative Analysis: RNA vs. DNA Probes

The choice between RNA and DNA probes is a fundamental decision in ISH experimental design, with each type offering distinct advantages and limitations. The table below provides a structured comparison to guide researchers.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of DNA and RNA Probes for ISH

| Characteristic | DNA Probes | RNA Probes (Riboprobes) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Synthesis Method | Nick Translation, PCR | In Vitro Transcription (from plasmid or PCR template) |

| Molecular Structure | Double-stranded or single-stranded | Single-stranded |

| Typical Probe Length | Variable, can be very long | 250 - 1,500 bases (optimal ~800 bases) |

| Hybridization Strength | High, but generally lower than RNA:RNA hybrids [6] | Very high (RNA:RNA hybrids are stable) |

| Sensitivity | High | Very High [15] |

| Stability & RNase Concerns | Stable; minimal RNase concerns | Sensitive to RNase degradation; requires careful handling [6] |

| Key Applications | Detection of DNA sequences (e.g., gene amplification, translocation), FISH [16] [13] | Detection of mRNA (gene expression), high-resolution mapping, viral RNA [15] |

| Relative Cost & Ease of Use | Generally cost-effective and straightforward protocols | Can be more costly and require more stringent conditions |

Market analysis reinforces the practical application of these technical differences. In the in-situ hybridization market, DNA probes currently hold the largest market share (58.7% as of 2025), attributed to their wide utility, stability, and cost-efficiency for detecting gene sequences and chromosomal rearrangements [16]. However, the RNA probe segment is the fastest-growing, driven by the development of novel nucleic acid-based diagnostic assays and an increasing focus on gene expression analysis and transcriptomics in personalized medicine [16] [17].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: PCR-Based RNA Probe Synthesis and ISH

This optimized protocol, adapted from Hua et al. (2018), details a method for generating DIG-labeled RNA probes from a PCR template for use on free-floating mouse brain sections, a common application in neuroscience [14].

1. Probe Template Preparation via Two-Step PCR:

- Primer Design: Design primers using NCBI's Primer-BLAST. The final primer pair must include the T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence (5'-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3') attached to the gene-specific sequence.

- First PCR (Amplify cDNA):

- Reaction Mix: 1-5 ng cDNA, 25 μL of 2x ES-Taq MasterMix, 2 μL each of 10 μM upstream and downstream gene-specific primers, nuclease-free water to 50 μL.

- Cycling Conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 55-60°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 1 min/kb; final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

- Second PCR (Incorporate T7 Promoter): Use the first PCR product as a template with a primer pair that includes the T7 promoter sequence.

2. In Vitro Transcription and Labeling:

- Use the purified second PCR product as a template for in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of a DIG-labeled NTP mix (e.g., DIG-11-UTP).

- Incubate at 37°C for 2 hours.

- Treat with DNase I to remove the DNA template.

- Purify the labeled RNA probe using ethanol precipitation or a purification column.

3. In Situ Hybridization on Tissue Sections:

- Deparaffinization & Rehydration: If using FFPE sections, treat with xylene and a graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, 70%, 50%) [6].

- Permeabilization: Digest with 20 μg/mL proteinase K in pre-warmed 50 mM Tris buffer for 10-20 min at 37°C. The concentration and time require optimization for each tissue type [6].

- Acetylation & Dehydration: Immerse slides in ice-cold 20% acetic acid for 20 seconds, then dehydrate through ethanol series (70%, 95%, 100%) and air dry.

- Pre-hybridization & Hybridization: Apply pre-heated hybridization solution to the section and incubate for 1 hour at the desired temperature (55-62°C). Dilute the denatured RNA probe in hybridization solution, apply to the tissue (50-100 μL per section), cover with a coverslip, and hybridize overnight at 65°C in a humidified chamber [6].

- Stringency Washes:

- Wash 3x5 min with 50% formamide in 2x SSC at 37-45°C.

- Wash 3x5 min with 0.1-2x SSC at 25-75°C (temperature and stringency depend on probe type) [6].

- Immunological Detection:

- Block sections with 2% blocking reagent (BSA, milk, or serum) in MABT (Maleic Acid Buffer with Tween 20) for 1-2 hours.

- Incubate with anti-DIG antibody conjugated to Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

- Wash slides 5x10 min with MABT.

- Develop color by incubating with NBT/BCIP or Fast Red substrate solution in the dark. Monitor development under a microscope.

- Counterstain (if desired), dehydrate, clear, and mount with an aqueous or permanent mounting medium.

Workflow Diagram: RNA Probe Synthesis and ISH

The following diagram visualizes the multi-stage workflow for PCR-based RNA probe synthesis and in situ hybridization, showing how the core techniques integrate into a complete experimental process.

Advanced Applications and Integrated Techniques

The utility of ISH has been greatly expanded by its integration with other powerful biological techniques, creating sophisticated tools for multi-omics investigation.

- Combination with Immunohistochemistry (IHC): ISH and IHC can be performed on the same tissue section to simultaneously detect mRNA and protein. This co-localization is invaluable for linking gene expression with protein production and cellular phenotype, such as identifying neurons that express both somatostatin (SST) mRNA and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) protein [14].

- ISH-Proximity Ligation Assay (ISH-PLA): This advanced technique allows for the visualization of physical interactions between nucleic acids and proteins directly within cells. For example, ISH-PLA has been used to characterize the interaction between HIV-1 genomic RNA and host cell proteins involved in nuclear export and translation, providing spatial and functional insights into viral replication cycles [18].

- Multiplex Fluorescence ISH (FISH): Using spectrally distinct fluorophore labels, multiple DNA or RNA targets can be visualized simultaneously in a single specimen. Probes are labeled via nick translation or in vitro transcription with different haptens or fluorophores (e.g., biotin, DIG, DNP) and detected with corresponding antibodies or streptavidin conjugated to different Alexa Fluor dyes. This approach is powerful for analyzing complex gene expression patterns, chromosomal rearrangements, and the spatial organization of the transcriptome [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Kits

Successful probe synthesis and detection rely on a suite of specialized reagents and commercial systems. The following table lists key solutions and their applications.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Probe Synthesis and Detection

| Product / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Nick Translation System (e.g., Invitrogen) [12] | Enzymatic labeling of dsDNA probes for FISH/CISH. | Labeling control or genomic DNA for karyotyping and phylogenetic analysis. |

| FISH Tag DNA/RNA Kits (e.g., Invitrogen) [13] | Efficient incorporation of amine-modified nucleotides for subsequent dye labeling. | Generating bright, multiplex FISH probes for simultaneous detection of multiple gene targets. |

| Digoxigenin (DIG) Labeling Mix | Provides DIG-labeled nucleotides for incorporation during in vitro transcription or nick translation. | Preparing sensitive, non-radioactive RNA or DNA probes for chromogenic detection. |

| Anti-DIG Antibody Conjugates (e.g., AP- or HRP-linked) | Immunological detection of DIG-labeled probes in tissue. | Visualizing hybridization sites after ISH with NBT/BCIP (AP) or tyramide (HRP). |

| Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) Kits (e.g., SuperBoost) [13] | Signal amplification for low-abundance targets; can boost sensitivity 10-200x. | Detecting rare viral RNA transcripts or weakly expressed mRNAs in FFPE tissues. |

| Proteinase K | Tissue permeabilization by digesting proteins, thereby enabling probe access to nucleic acids. | Standard step in ISH protocols for FFPE tissues; concentration and time are critical. |

| Gnf-2 | Gnf-2, CAS:778270-11-4, MF:C18H13F3N4O2, MW:374.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Xl-999 | Xl-999, CAS:705946-27-6, MF:C26H28FN5O, MW:445.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The selection of an appropriate probe synthesis and labeling technique is a critical determinant of success in ISH research. Nick translation remains a workhorse for generating robust DNA probes, ideal for applications like FISH in genetic diagnostics. In vitro transcription, particularly with modern PCR-based template preparation, is the gold standard for producing highly sensitive RNA probes, which are indispensable for gene expression mapping and transcriptomic studies. The ongoing development of more efficient probe synthesis methods, coupled with powerful signal amplification technologies and the ability to integrate ISH with other anatomical and protein detection techniques, continues to expand the frontiers of molecular pathology, neuroscience, and drug development. As the market trends indicate a growing demand for both DNA and RNA probes, a deep understanding of these core techniques will empower researchers to leverage the full potential of in situ hybridization.

The strategic choice between DNA and RNA probes for in situ hybridization (ISH) is fundamentally rooted in the distinct chemical and physical properties of the nucleic acid duplexes they form. The hybridization event—the specific annealing of a probe to its complementary cellular target—is the cornerstone of ISH technology. Its success hinges on the thermodynamic stability and kinetic behavior of the resulting duplex. Therefore, a deep understanding of the relative stabilities of DNA-DNA, RNA-RNA, and RNA-DNA hybrid duplexes is not merely academic; it is critical for designing sensitive, specific, and robust assays for research and diagnostic applications. This guide provides an in-depth technical analysis of these duplexes, framing their properties within the context of optimizing ISH experiments.

Fundamental Thermodynamic Stability

The stability of a nucleic acid duplex is quantitatively governed by its free energy of formation (ΔG°). A more negative ΔG° indicates a more stable duplex. This stability is influenced by base composition, sequence, and the type of duplex formed.

Relative Stability of Duplex Types

A foundational study systematically compared the thermodynamic stabilities of DNA-DNA, RNA-RNA, and DNA-RNA hybrid duplexes for a set of oligonucleotide sequences. The research demonstrated that stability is not absolute but depends critically on the base composition and the proportion of pyrimidines in the DNA strand (dPy content) for hybrids [19].

Table 1: Relative Thermodynamic Stability of Nucleic Acid Duplexes

| Duplex Type | Relative Stability | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-RNA | Highest | A-form helix structure; strong base stacking. |

| RNA-DNA | Intermediate | Conformation varies between A- and B-forms; stability is highly dependent on sequence. |

| DNA-DNA | Lowest | B-form helix structure. |

A key finding was that hybrids with 70–80% deoxypyrimidine (dC, dT) in the DNA strand and a high or moderate A.T/U fraction displayed the highest relative stability compared to their RNA counterparts [19]. This indicates that for a given application, an optimal probe sequence can be designed to maximize hybrid stability.

Structural Basis for Stability Differences

The differences in thermodynamic stability are a direct consequence of the structural properties of the duplexes.

- RNA-RNA Duplexes: These adopt an A-form helix. The A-form geometry results in stronger base-stacking interactions compared to the B-form, which is a primary reason for their enhanced thermal stability [19].

- DNA-DNA Duplexes: These typically form the B-form helix, characterized by a wider, more open structure with less efficient base stacking.

- RNA-DNA Hybrid Duplexes: These adopt an intermediate conformation between A- and B-forms, though they more closely resemble the A-form [20]. This hybrid conformation is not fixed; it varies continuously based on sequence, and this conformational flexibility is a decisive factor in its relative stability [19].

Mechanical and Kinetic Properties

Beyond thermodynamic stability, the physical and kinetic behaviors of duplexes are crucial for their function in complex biological contexts like ISH.

Flexibility and Bendability

Recent single-molecule studies have revealed that RNA-DNA hybrid (RDH) duplexes exhibit higher bendability than DNA duplexes on short length scales [20]. This intrinsic flexibility is critical for processes like R-loop formation, where the hybrid duplex is bent. The bendability was also found to be sequence-dependent; for instance, a duplex composed of a C-rich DNA strand and a G-rich RNA strand showed significantly higher bendability than the reverse configuration [20].

Hybridization Kinetics

The rate at which a probe finds and binds to its target is governed by hybridization kinetics. The kinetics are sequence-dependent and influenced by:

- Nucleation States: Hybridization proceeds via a slow, rate-limiting bimolecular nucleation step (formation of a short stretch of complementary base pairs), followed by fast "zippering" into the full duplex [21].

- Sequence Repetition: Repetitive sequences, which offer a greater number of possible nucleation sites (including off-register interactions), hybridize more rapidly than non-repetitive sequences [21].

- Probe Charge: Studies on peptide nucleic acids (PNA) show that positive charges (cationic groups) on the probe can moderately enhance the stability of PNA-DNA duplexes at physiological salt concentrations, an effect derived predominantly from faster association kinetics [22].

Implications for In Situ Hybridization (ISH) Probe Design

The biochemical properties of nucleic acid duplexes directly inform the selection and optimization of probes for ISH.

Table 2: Probe Selection Guide for In Situ Hybridization

| Probe Type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Probes | Easy to prepare, label, and handle; cost-effective [23]. | Form less stable duplexes (DNA-DNA); can be less specific; washing steps require optimization to prevent dissociation [23]. | Standard detection of DNA targets. |

| RNA Probes (Riboprobes) | Form highly stable RNA-RNA hybrids; high specificity due to strong mismatch discrimination; uniform size and high labeling efficiency [23]. | RNA is labile and requires careful handling to avoid RNase degradation [23]. | High-sensitivity detection of RNA targets; when maximal specificity is required. |

| Modified Probes (LNA, PNA) | Enhanced hybridization efficiency and stability; improved resistance to nucleases; can be designed for superior specificity [23]. | Higher cost; may require specialized protocols. | Challenging targets; multiplexing; short probe sequences (e.g., miRNAs). |

Maximizing Specificity: The Impact of Point Defects

The ability to discriminate a perfectly matched target from one with a single-base mutation is paramount in genotyping and specific target detection. The position and type of a single base mismatch (MM) or bulge significantly impact duplex binding affinity on surfaces.

- Defect Position: The dominant parameter is the position of the defect within the duplex. The influence is greatest when the mismatch is in the middle of the sequence and least at the ends [24].

- Defect Type: The type of mismatch also matters. In DNA-DNA duplexes, mismatches that disrupt a C•G base pair typically cause a greater reduction in binding affinity than those disrupting an A•T pair [24].

- RNA-DNA Superiority: RNA-DNA purine-purine mismatches are more discriminating than corresponding DNA-DNA mismatches, contributing to the higher specificity of RNA probes [24].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow used to determine the factors affecting mismatch discrimination, a key principle for ensuring probe specificity in ISH.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Determining Thermodynamic Stability

The gold standard for measuring duplex stability is through ultraviolet (UV) melting curve analysis [25] [26].

- Sample Preparation: The oligonucleotide probe and its complement are mixed in an equimolar ratio in a suitable buffer (e.g., 100 mM Na+, 10 mM phosphate, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.1) [19].

- Melting Experiment: The solution is slowly heated while the absorbance at 260 nm is continuously monitored. As the temperature increases, the duplex melts (denatures) into single strands, resulting in a hyperchromic shift (increase in UV absorbance).

- Data Analysis: The melting curve (Absorbance vs. Temperature) is plotted. The melting temperature (Tm), at which 50% of the duplexes are denatured, is determined. Thermodynamic parameters (ΔH°, ΔS°, and ΔG°37) are calculated from the shape of the melt curve, often assuming a two-state model [25] [26].

- High-Throughput Methods: Recent advances, such as the "Array Melt" technique, repurpose Illumina sequencing flow cells to measure the equilibrium stability of hundreds of thousands of DNA hairpins simultaneously, enabling the derivation of improved thermodynamic models [26].

Measuring Flexibility via Single-Molecule Cyclization

The bendability of short duplexes can be quantified using single-molecule Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (smFRET) cyclization experiments [20].

- Construct Design: Short DNA or RNA-DNA hybrid duplexes are prepared with single-stranded overhangs that are complementary to each other. The ends are labeled with a fluorophore (Cy3, donor) and a quencher (BHQ, acceptor).

- Immobilization and Imaging: The molecules are immobilized on a passivated surface at low density. An imaging buffer with high cation concentration (e.g., 1 M NaCl) is introduced to promote bending and cyclization by reducing electrostatic repulsion [20].

- FRET Detection: When the duplex is linear, the FRET efficiency is low. When it bends to form a circle, bringing the fluorophore and quencher close, FRET efficiency increases. The proportion of molecules in the looped state over time provides a measure of the intrinsic bendability of the duplex [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Hybridization Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biotin-dUTP / Digoxigenin-dUTP | Non-radioactive labels for probe synthesis; detected via affinity systems (avidin, anti-digoxigenin antibodies) [23]. | Labeling probes for ISH. |

| Fluorescent-dUTP (e.g., Cy-dyes) | Direct fluorescent labels for probes; enable direct detection by fluorescence microscopy [23]. | Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH). |

| Proteinase K | Protease that digests proteins surrounding nucleic acids; critical for sample permeabilization to allow probe access [23]. | Pre-hybridization treatment of tissue samples for ISH. |

| Formamide | Denaturing agent; reduces the melting temperature of duplexes, allowing hybridization to be performed at lower, biologically gentler temperatures [23]. | Component of hybridization buffer in ISH. |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protect labile RNA probes from degradation by ribonucleases. | Essential for working with RNA riboprobes. |

| Surface-Passivated Coverslips | Coated with a mixture of PEG and biotin-PEG to minimize non-specific binding of molecules in single-molecule studies [20]. | smFRET and cyclization experiments. |

| JW74 | JW74, CAS:863405-60-1, MF:C24H20N6O2S, MW:456.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| IU1 | IU1, CAS:314245-33-5, MF:C18H21FN2O, MW:300.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between DNA and RNA probes for in situ hybridization is guided by a clear hierarchy of duplex stability—RNA-RNA > RNA-DNA > DNA-DNA—but must be fine-tuned by considering sequence-specific factors and the required assay specificity. RNA probes (riboprobes), forming the most stable and specific duplexes, are ideal for high-sensitivity applications but demand careful handling. DNA probes offer practicality and are sufficient for many applications, especially when optimized for pyrimidine content in hybrid formation. Emerging high-throughput thermodynamic methods and a deeper understanding of mechanical properties like bendability are paving the way for the more rational design of probes and assays. Ultimately, the most effective ISH strategy is one that leverages the fundamental chemistry of hybridization to achieve the perfect balance between sensitivity, specificity, and practicality for the biological question at hand.

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, enabling the visualization of specific nucleic acid sequences within cells and tissues. The efficacy of this method hinges entirely on the careful design of the molecular probes used. Within the broader context of selecting between RNA and DNA probes for ISH research, understanding the core parameters of probe design is paramount for experimental success. These parameters—probe length, GC content, and specificity—directly influence hybridization efficiency, signal strength, and the accuracy of gene expression localization [27].

The choice between RNA and DNA probes introduces distinct thermodynamic and biochemical considerations. RNA probes (riboprobes) form RNA:RNA hybrids with target mRNAs, which are more stable than the DNA:RNA hybrids formed by DNA probes [28] [2]. This inherent stability often translates to higher sensitivity for RNA probes, a critical factor in detecting low-abundance transcripts [6]. However, RNA probes are also more susceptible to degradation by ubiquitous RNases, necessitating meticulous handling [28] [6]. DNA probes, conversely, are more chemically stable and are available in diverse formats, from synthetic oligonucleotides to complex bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones, which can span hundreds of kilobases and are ideal for detecting large genomic rearrangements [28] [29]. This guide delves into the key design parameters that researchers must optimize to leverage the unique advantages of each probe type.

Foundational Probe Parameters and Their Optimization

Probe Length

Probe length is a primary determinant of hybridization kinetics, specificity, and accessibility. The optimal length varies significantly depending on the probe type and application.

RNA Probes: For in vitro transcribed RNA probes, a length of 250–1,500 bases is recommended, with probes of approximately 800 bases often providing the highest sensitivity and specificity [6]. These long probes allow for the incorporation of multiple labeled nucleotides, amplifying the signal. However, their large size can hinder tissue penetration.

DNA Probes:

- Oligonucleotide DNA Probes: Used in techniques like single-molecule FISH (smFISH), these are typically short, between 18-22 nucleotides [30]. A set of at least 25-48 such probes, each targeting different regions of the same mRNA, is required to build a detectable signal from a single transcript [30].

- BAC DNA Probes: These are much larger, often averaging several hundred kilobases, and provide unparalleled coverage for detecting large-scale genetic alterations [29].

Table 1: Optimal Probe Length Ranges by Type and Application

| Probe Type | Typical Length Range | Primary Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro transcribed RNA | 250 - 1,500 bases [6] | mRNA localization in tissue sections | High sensitivity; poor penetration if too long |

| Synthetic DNA Oligo | 18 - 22 nucleotides [30] | smFISH for single transcript counting | Requires a set of ~25-48 probes per target |

| BAC DNA | Up to hundreds of kilobases [29] | Detecting gene duplications/deletions | Covers large genomic regions |

GC Content

The guanine-cytosine (GC) content of a probe directly affects its melting temperature ((T_m)), the temperature at which half of the probe-target duplexes dissociate. Probes with skewed GC content can lead to unreliable hybridization.

- Optimal GC Content: Probes should be designed to avoid extremes of GC content. Both high and low GC regions can be problematic for probe design, as they fall outside the optimal melting temperature range for uniform hybridization within a probe set [30].

- Troubleshooting Skewed GC Content: For sequences with non-uniform GC content, several strategies can be employed:

- Vary Probe Length: AT-rich sequences are better targeted by longer probes (21-22 nucleotides), while GC-rich sequences are better targeted by shorter probes (18-19 nucleotides) [30].

- Create Mixed-Mer Probe Sets: Combining non-overlapping probes of different lengths (18-22 nt) from multiple design runs can effectively target sequences with distinct GC-rich and AT-rich regions [30].

- Reduce Probe Spacing: Changing the minimum nucleotide spacing between probe binding sites from the default of 2 down to 1 can increase the number of potential probe binding sites in challenging sequences [30].

Specificity

Specificity ensures that a probe hybridizes exclusively to its intended target sequence, minimizing background noise and false-positive signals. This is controlled by sequence uniqueness and hybridization stringency.

- Sequence Uniqueness: The probe sequence must be unique to the target to avoid cross-hybridization with similar sequences, such as pseudogenes or other members of a gene family. Bioinformatics tools are used to mask repetitive elements during the design process [30].

- Masking Levels: Probe design software often includes adjustable masking levels (e.g., 1-5) to exclude repetitive or non-unique sequences. While lowering the masking level (e.g., from 5 to 3) can make more sequence available for designing probes, it requires post-design validation via BLAST analysis against the relevant transcriptome to ensure specificity [30].

- Hybridization Stringency: Specificity is experimentally controlled during the post-hybridization wash steps by manipulating temperature and salt concentration. Higher wash temperatures and lower salt concentrations (e.g., 0.1-2x SSC) increase stringency, removing imperfectly matched or loosely bound probes [6].

Performance Comparison: RNA vs. DNA Probes

Understanding the theoretical design parameters is crucial, but selecting between RNA and DNA probes requires a practical understanding of their performance characteristics. A systematic comparison reveals trade-offs that must be balanced against experimental needs.

Table 2: Performance and Application Comparison of DNA and RNA Probes in ISH

| Characteristic | DNA Probes | RNA Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Stability | More stable; resistant to hydrolysis [28] | Less stable due to reactive 2' hydroxyl group [28] |

| Hybrid Stability | DNA:RNA hybrids less stable [6] | RNA:RNA hybrids more stable; higher sensitivity [6] |

| Enrichment Efficiency | Lower mapping rates in NGS capture [31] | Superior enrichment efficiency; higher mapping rates [31] |

| Specificity & Background | More effective at reducing artifacts (e.g., NUMTs) [31] | High specificity, but prone to endogenous RNase background |

| Primary ISH Applications | Locus-specific FISH, chromosome counting, BAC-FISH for large rearrangements [28] [29] | RNA-FISH, high-sensitivity mRNA localization in tissues [28] [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Probe Design and Validation

Protocol: Designing and Validating a Custom smFISH Oligo Probe Set

This protocol is adapted from best practices for Stellaris RNA FISH probe design, which involves creating a pool of short, singly-labeled DNA oligonucleotides to target a single mRNA species [30].

- Sequence Input: Obtain the full-length cDNA or mRNA sequence of your target, including untranslated regions (UTRs). Expanding the target sequence can provide more design options.

- Initial Design Run: Submit the sequence to a dedicated probe designer (e.g., Stellaris Probe Designer). Use default settings: probe length of 20 nt, masking level 5, and a minimum probe spacing of 2 nt.

- Troubleshoot Low Probe Count: If the output is below the recommended minimum of 25 probes:

- Reduce Probe Spacing: Change the spacing from 2 to 1.

- Adjust Probe Length: Iteratively run the designer with probe lengths set to 18, 19, 21, and 22 nt to find the optimal setting for your sequence's GC content.

- Combine Designs: Create a mixed-mer set by combining non-overlapping probes from the different design runs of varying lengths.

- Lower Masking Level: If the count is still low, reduce the masking level to 4 or 3. This increases the risk of including less specific probes, making the next step critical.

- Specificity Validation (BLAST): For any design, but especially those with lowered masking levels, perform a BLAST search of each individual probe sequence against the transcriptome of your organism. Remove any probe with 16 or more nucleotides of complementarity to an off-target RNA.

- Ordering: Order the final set of validated oligonucleotides.

Protocol: Optimizing Hybridization and Washes for RNA Probes

This protocol outlines key steps for using in vitro transcribed, digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA probes on paraffin-embedded tissue sections [6].

- Sample Preparation and Permeabilization:

- Deparaffinize and rehydrate tissue sections.

- Perform antigen retrieval by digesting with 20 µg/mL proteinase K in pre-warmed 50 mM Tris for 10–20 min at 37°C. Optimization Note: Conduct a proteinase K titration experiment, as over-digestion damages morphology and under-digestion reduces signal.

- Immerse slides in ice-cold 20% acetic acid for 20 seconds to further permeabilize cells.

- Pre-hybridization and Hybridization:

- Apply hybridization solution (containing 50% formamide, salts, and blocking agents) and pre-hybridize for 1 hour at the hybridization temperature (typically 55-62°C).

- Denature the RNA probe at 95°C for 2 minutes and chill on ice.

- Apply the diluted probe to the section, cover with a coverslip, and incubate in a humidified chamber at 65°C overnight.

- Stringency Washes:

- Wash 1: Wash with 50% formamide in 2x SSC, 3 times for 5 minutes each at 37-45°C. This removes excess probe.

- Wash 2: Wash with 0.1-2x SSC, 3 times for 5 minutes each at 25-75°C. Stringency Adjustment: Use higher temperature (up to 65°C) and lower salt concentration (e.g., 0.1x SSC) for highly specific applications, and lower temperature (up to 45°C) and higher salt (1-2x SSC) for short or complex probes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for ISH

Table 3: Key Reagents for In Situ Hybridization

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Formamide | Denaturant in hybridization buffer; lowers the hybridization temperature to preserve morphology [6] | Used at 50% concentration; enables lower Temp. |

| Saline Sodium Citrate (SSC) | Provides ionic strength for hybridization and washing; critical for controlling stringency [6] | Lower concentration (e.g., 0.1x SSC) increases stringency. |

| Dextran Sulfate | A crowding agent in hybridization buffer that increases the effective probe concentration, enhancing hybridization efficiency [6] | Improves signal intensity. |

| Proteinase K | Proteolytic enzyme for antigen retrieval; digests proteins surrounding nucleic acids, enabling probe access [6] [27] | Concentration and time must be optimized for each tissue type. |

| Formalin / Paraformaldehyde | Cross-linking fixative; preserves tissue morphology and immobilizes nucleic acids [27] | Over-fixation can mask targets, reducing signal. |

| Digoxigenin (DIG) | Non-radioactive hapten label for probes; detected by anti-DIG antibodies conjugated to enzymes or fluorophores [6] | Safe and stable alternative to radioactive labels. |

| C 87 | C 87, CAS:1609281-56-2, MF:C24H15ClN6O3S, MW:502.93 | Chemical Reagent |

| FPTQ | FPTQ||Research Compound | FPTQ is a high-purity research compound for scientific investigation. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Workflow and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing and troubleshooting an ISH probe, integrating the key parameters discussed in this guide.

The strategic design of probes based on length, GC content, and specificity is not merely a technical prelude but the very foundation of a robust and interpretable ISH experiment. The choice between RNA and DNA probes presents a trade-off between the superior sensitivity and hybrid stability of RNA probes and the greater chemical stability and versatility of DNA probes. There is no universal solution; the optimal design must be tailored to the specific biological question, target characteristics, and experimental system. By applying the systematic design and validation protocols outlined in this guide, researchers can make informed decisions, troubleshoot effectively, and harness the full power of in situ hybridization to illuminate the spatial tapestry of gene expression.

Strategic Implementation: Selecting Probes for FISH, smFISH, and Spatial Transcriptomics

The selection of an appropriate probe type is a foundational decision in the design of any in situ hybridization (ISH) experiment, directly determining the success and interpretability of the results. This choice dictates the technique's specificity, sensitivity, and ultimate application, effectively dividing the ISH landscape into two major domains: the analysis of genomic DNA for chromosomal architecture and the detection of RNA for gene expression profiling. Within the context of a broader thesis on RNA versus DNA probes for ISH research, this guide provides a detailed technical framework for matching the probe chemistry and design to the intended biological question. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this decision is not merely technical but strategic, influencing everything from experimental workflow to the validity of conclusions in basic research, diagnostic development, and therapeutic assessment.

The market data underscores the significance of both probe types. The global FISH probe market, valued at over $1.12 billion in 2024, is propelled by the critical applications discussed herein, with DNA probes currently holding a dominant share and RNA probes representing the largest segment by type, driven by their essential role in single-cell gene expression analysis [32] [33]. This guide will dissect the core principles, applications, and methodologies for both DNA and RNA probes, providing a comprehensive toolkit for their effective deployment.

DNA Probes: The Tool for Chromosomal Analysis

DNA probes are designed to hybridize to specific genomic DNA sequences within the nucleus, allowing for the visualization of chromosomal structures and the detection of genetic abnormalities at the molecular level.

Core Applications and Design Principles

DNA FISH is indispensable in clinical diagnostics and basic cytogenetics for detecting chromosomal abnormalities that are beyond the resolution of traditional karyotyping. Its primary applications include the diagnosis of genetic diseases, cancer prognostics, and prenatal testing by identifying characteristic aneuploidies, microdeletions, and translocations [32] [33]. For instance, locus-specific probes (LSPs) are pivotal for detecting specific genetic loci associated with syndromes like DiGeorge syndrome (22q11.2 deletion) and for identifying oncogenic rearrangements such as BCR-ABL1 in chronic myeloid leukemia and ALK in non-small cell lung cancer [34] [35].

The design of DNA probes often leverages large genomic clones, with Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs) being the gold standard. BAC clones contain large inserts of human DNA, averaging several hundred kilobases, which provides two key advantages: unparalleled genomic coverage and the generation of intense, bright fluorescent signals due to the high density of fluorophore labels that can be incorporated [35]. This makes them ideal for detecting large-scale genomic rearrangements and copy number variations. Before designing custom probes, it is highly recommended to check for commercially available, validated options from suppliers like OGT or Abbott/Vysis, which can save significant time and validation effort [35].

Key Technical Considerations

- Fluorophore Selection: The choice of fluorophore is critical and depends on the microscope's filter sets and the need for multiplexing. Key factors include the fluorophore's absorption-emission spectra, Stokes shift (where a larger shift is favorable for distinguishing signals), and sensitivity to pH. Common haptens and fluorochromes used include SpectrumOrange, SpectrumGreen, Texas Red, and cyanine 5 (Cy5) [34] [35].

- Probe Longevity and Storage: A recent comprehensive study has demonstrated that properly stored FISH probes have an exceptionally long functional lifespan. Both self-labeled and commercial DNA probes stored at -20°C in the dark have been shown to perform perfectly for over 30 years, far exceeding official shelf-life guidelines of 2-3 years. This has significant implications for cost management and the use of legacy probes in diagnostics [34].

RNA Probes: The Tool for RNA Localization and Expression Analysis

RNA probes, particularly in single-molecule RNA FISH (smRNA-FISH), are engineered to bind to specific RNA transcripts within cells, enabling the precise quantification and subcellular localization of gene expression.

Core Applications and Design Principles

The primary application of RNA probes is to study spatial gene expression patterns at a single-cell resolution. This provides invaluable insights into cellular heterogeneity, developmental biology, disease mechanisms, and the response to pharmacological treatments [9] [36]. A key emerging application is in drug development, where RNAscope ISH technology is used to visualize and quantify the spatial biodistribution and efficacy of oligonucleotide therapeutics, such as ASOs and siRNAs, within intact tissues [37].

Unlike DNA probes, the effectiveness of RNA probes is intensely dependent on sophisticated computational design to ensure sensitivity and specificity. The fundamental challenge is to minimize off-target binding, which creates background noise and false-positive signals [9]. Advanced software platforms like TrueProbes address this by moving beyond simple heuristic filters. TrueProbes employs a genome-wide BLAST-based analysis combined with thermodynamic modeling to rank all potential probe candidates by their predicted specificity. It selects probes that exhibit strong on-target binding affinity, minimal off-target interactions (optionally weighted by gene expression data), low self-hybridization, and minimal cross-dimerization within the probe set [9] [38]. For detecting short RNAs (e.g., miRNAs) or for live-cell imaging, alternative chemistries are required. Fluorescent small molecules like the near-infrared (NIR) probe O-698 can selectively bind to RNA in live cells, enabling real-time, wash-free imaging of RNA dynamics in nucleoli and cytoplasm, though this approach lacks transcript-specificity [36].

Table: Comparison of DNA and RNA FISH Probes

| Feature | DNA Probes | RNA Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Target Molecule | Genomic DNA | RNA (mRNA, lncRNA, miRNA) |

| Primary Application | Chromosomal structure, copy number variation, translocations | Gene expression analysis, RNA spatial localization, trafficking |

| Typical Probe Type | BAC clones, oligonucleotides | Antisense RNA probes, synthetic oligonucleotides |

| Key Design Consideration | Genomic coverage, signal brightness (probe size) | Specificity, minimization of off-target binding, secondary structure |

| Common Use Context | Fixed cells, clinical diagnostics (cancer, genetic disorders) | Fixed cells & tissues (smFISH), live cells (with specific dyes) |

| Example Commercial Tools | CytoCell probes (OGT), Vysis probes (Abbott) | RNAscope assays (ACD), TrueProbes design software, SYTO RNAselect |

Key Technical Considerations

- Probe Length and Labeling: For in vitro transcribed RNA probes (e.g., DIG-labeled), an optimal length of 250–1500 bases is recommended, with probes of approximately 800 bases offering the highest sensitivity and specificity. These are typically generated from linearized plasmid or PCR product templates [6].

- Hybridization and Stringency Washes: The hybridization temperature must be optimized for each probe and tissue type, typically ranging from 55°C to 65°C. Post-hybridization, stringent washes are critical to remove loosely bound, off-target probes. The temperature and salt concentration (SSC) of these washes are adjusted based on probe complexity, with higher temperatures and lower salt concentrations increasing stringency [6].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

DNA FISH for Chromosomal Analysis

This protocol is adapted from established methods for using locus-specific DNA FISH probes on metaphase chromosomes or interphase nuclei [34] [35].

- Sample Preparation: Cells are treated with a mitotic inhibitor and harvested. Metaphase chromosome spreads are prepared on glass slides using standard cytogenetic techniques, including hypotonic treatment and fixation with methanol:acetic acid.

- Probe Denaturation: The DNA probe mixture, containing the labeled probe, blocking DNA (e.g., Cot-1 DNA to suppress repetitive sequences), and hybridization buffer, is denatured at 75–80°C for 5–10 minutes and then briefly incubated on ice.

- Target Denaturation and Hybridization: The slide with chromosomal DNA is denatured in a solution of 70% formamide/2x SSC at 72–75°C for 5–10 minutes, then dehydrated in an ethanol series. The denatured probe is applied to the denatured slide, covered with a coverslip, and sealed. Hybridization proceeds in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 12–48 hours.

- Post-Hybridization Washes: After hybridization, the coverslip is removed, and slides undergo a series of washes to remove unbound probe. A typical high-stringency wash involves a solution of 0.1–0.3x SSC at 60–72°C for 5–10 minutes.

- Detection and Counterstaining: If a hapten-labeled probe (e.g., biotin or digoxigenin) was used, fluorescently conjugated detection molecules (e.g., avidin or anti-digoxigenin antibodies) are applied. The chromosomes are counterstained with DAPI, and the slide is mounted for imaging.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in a DNA FISH experiment:

RNA FISH for Transcript Localization

This protocol details the use of digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA probes on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections, a common and powerful approach [6].

- Sample Fixation and Storage: Tissue is fixed in formalin or paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin (FFPE). For long-term storage of sectioned slides, store in 100% ethanol at -20°C or in a sealed box at -80°C to prevent RNA degradation. RNase contamination must be scrupulously avoided throughout the procedure.

- Deparaffinization and Rehydration: FFPE sections are deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, 70%, 50%) to water.

- Permeabilization and Protein Digestion: Slides are treated with proteinase K (e.g., 20 µg/mL) at 37°C for 10–20 minutes. The concentration and time must be optimized; insufficient digestion masks the target, while over-digestion damages tissue morphology. Slides are then rinsed and treated with ice-cold 20% acetic acid for 20 seconds to further permeabilize cells.

- Pre-hybridization and Hybridization: A pre-hybridization step with hybridization buffer alone for 1 hour at the hybridization temperature (55–62°C) reduces non-specific binding. The DIG-labeled RNA probe is denatured at 95°C for 2 minutes, chilled on ice, applied to the tissue section, and hybridized overnight at 65°C under a coverslip.

- Stringency Washes: Non-specifically bound probe is removed with sequential washes. A typical regimen includes: a) 50% formamide in 2x SSC at 37–45°C, and b) 0.1–2x SSC at 25–75°C. The temperature and SSC concentration are adjusted based on the probe's characteristics.

- Immunological Detection: Slides are blocked with a solution containing BSA, milk, or serum. An anti-DIG antibody conjugated to a fluorophore (e.g., FITC) is applied and incubated for 1–2 hours at room temperature. After thorough washing, the sample is counterstained with DAPI and mounted for imaging.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in an RNA FISH experiment on FFPE tissue:

Table: Essential Reagents and Resources for FISH Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| BAC Clones | Source of large-insert DNA probes for chromosomal FISH. Provide high signal intensity. | Can be sourced from repositories like BACPAC Resources; identity must be confirmed by sequencing [35]. |

| Oligonucleotide Libraries | Pools of short, synthetic DNA probes for smRNA-FISH. | Require advanced computational design (e.g., with TrueProbes) to ensure specificity and minimize off-target binding [9]. |

| Fluorophores (SpectrumOrange, Cy5, etc.) | Fluorescent molecules conjugated to probes or antibodies for detection. | Selection depends on microscope filters, Stokes shift, and pH sensitivity. SpectrumOrange is noted for bright, stable signals over years [34] [35]. |

| Haptens (Biotin, Digoxigenin) | Non-fluorescent labels incorporated into probes, detected post-hybridization with conjugated antibodies. | Allow for signal amplification. Probes labeled with these haptens remain stable for decades when stored properly [34] [6]. |

| Formamide | Component of hybridization buffer and wash solutions. | Reduces the melting temperature of nucleic acid duplexes, allowing for specific hybridization at manageable temperatures [6]. |

| Saline Sodium Citrate (SSC) | A buffer used in hybridization and stringency washes. | The concentration (e.g., 2x SSC vs. 0.1x SSC) and temperature are the primary determinants of wash stringency [6]. |

| Proteinase K | Proteolytic enzyme used to digest proteins in fixed tissues. | Unmasks target nucleic acids; concentration and time are critical and must be optimized for each tissue type [6]. |

| RNAscope Assays | A commercially available, multiplexed RNA ISH platform. | Provides pre-validated probe sets and optimized kits for highly specific RNA detection, often used in therapeutic development [37]. |

Market Trends and Future Directions

The FISH probe market is dynamic, shaped by technological innovation and clinical demand. A key trend is the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and digital pathology. AI-enabled platforms are now being deployed to automate FISH signal quantification, particularly for HER2 scoring in breast cancer, which reduces inter-observer variability and accelerates turnaround times [33]. Technologically, the field is expanding beyond single-color detection. Multiplex FISH and spectral karyotyping allow for the simultaneous visualization of dozens of genetic loci, while emerging methods like CRISPR-based FISH (CRISPR-Hyb) promise higher signal-to-noise ratios and greater design flexibility [33].

From a clinical perspective, the market is being driven by the expansion of targeted therapies and companion diagnostics. The approval of new antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) for "HER2-low" and "HER2-ultralow" cancers is creating a new, nuanced demand for highly quantitative FISH and ISH tests to identify eligible patient populations [33]. In this evolving landscape, DNA FISH remains a gold standard for confirming specific genetic rearrangements in cancer, while RNA FISH is indispensable for spatial biology and therapeutic monitoring, ensuring both probe types will remain critical tools in the researcher's and diagnostician's arsenal.

In situ hybridization (ISH) has undergone a revolutionary transformation from a qualitative morphological tool to a precise, quantitative technology capable of single-molecule detection. This evolution is largely driven by innovations in probe design and signal amplification strategies. The fundamental challenge in ISH has always been balancing sensitivity (detecting low-abundance targets) with specificity (minimizing false positives), all while preserving tissue morphology and cellular integrity. While traditional ISH methods relied on simple DNA or RNA probes with direct labeling, advanced platforms now employ sophisticated probe systems that decouple target recognition from signal detection, enabling unprecedented analytical capabilities.

The distinction between RNA probes and DNA probes represents a critical foundation for understanding modern ISH platforms. RNA probes, typically produced via in vitro transcription*, offer higher binding affinity and improved signal strength due to the stability of RNA-RNA hybrids compared to DNA-DNA hybrids [39]. However, they are more susceptible to RNase degradation and require careful handling. DNA probes, while more stable chemically, traditionally offered lower sensitivity [28] [39]. Modern platforms like RNAscope and MERFISH have transcended these limitations through innovative probe architectures that maximize both sensitivity and specificity, enabling researchers to move from single-gene detection to highly multiplexed spatial transcriptomics.

RNAscope: Signal Amplification Through Double-Z Probe Design

Core Technology and Working Principle

RNAscope, developed by Advanced Cell Diagnostics (ACD), represents a paradigm shift in chromogenic and fluorescent ISH through its proprietary double-Z probe design. This technology addresses the fundamental limitations of traditional ISH by implementing a novel probe architecture that simultaneously amplifies target-specific signals while suppressing background noise from non-specific hybridization [40] [41].

The core innovation lies in the "Z probe" pairs that function as molecular verification systems. Each Z probe consists of three elements: a lower region that hybridizes to the target RNA, a spacer/linker sequence, and a tail that binds to pre-amplifier sequences [42]. The critical design feature requires two adjacent Z probes to bind correctly to the target RNA before any signal amplification can occur—functioning like a dual-key security system where both "keys" must be present simultaneously to activate detection [40].

The signal amplification cascade begins only when both Z probes form a dimer on the target RNA sequence, creating a complete binding site for the pre-amplifier molecule. Each pre-amplifier then recruits multiple amplifier molecules, which in turn bind numerous enzyme-labeled probes. This hierarchical assembly generates up to 8,000-fold signal amplification per RNA molecule, transforming single transcript detection into readily visible signals without compromising specificity [42].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The RNAscope workflow integrates this probe technology with optimized laboratory procedures:

Sample Preparation: RNAscope is compatible with various sample types including formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, fresh frozen tissues, and tissue microarrays [42]. Proper fixation is critical—24 hours in 10% neutral buffered formalin is recommended for optimal RNA preservation [43]. For FFPE blocks stored long-term, sectioning within 3 months or storage at -20°C to -80°C is advised to maintain RNA integrity [43].

Pretreatment and Hybridization: Samples undergo permeabilization to allow probe access. The proprietary double-Z probes (approximately 20 different probe pairs per target RNA) are hybridized to the target sequence [40] [42]. The manufacturer provides optimized positive control probes (PPIB for moderate expression, Polr2A for low expression, UBC for high expression) and negative controls (bacterial dapB gene) to validate assay performance [42].

Signal Amplification and Detection: The sequential building process occurs through pre-amplifier binding, amplifier attachment, and finally label probe hybridization. Detection utilizes either chromogenic (enzyme-mediated color precipitation) or fluorescent readouts, with the latter enabling multiplexing through different fluorophores [42].

Visualization and Analysis: Results are visualized via brightfield or fluorescence microscopy. Each discrete dot represents an individual RNA molecule, enabling direct quantification manually or using specialized software like Halo, QuPath, or Aperio [42].

MERFISH: Multiplexing Through Combinatorial Barcoding

Core Technology and Working Principle

Multiplexed Error-Robust Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (MERFISH) employs a fundamentally different approach centered on combinatorial barcoding and sequential imaging to achieve massive multiplexing capabilities. Whereas RNAscope amplifies signals from individual transcripts, MERFISH assigns unique identity codes to each RNA species and reads these codes through multiple rounds of hybridization and imaging [44].

The MERFISH system utilizes a two-probe strategy consisting of encoding probes and readout probes. Encoding probes are unlabeled DNA oligonucleotides containing two key regions: a target-binding region complementary to the RNA of interest, and a barcode region with multiple readout sequences that collectively define the RNA's identity [45] [44]. Each RNA species is assigned a unique binary barcode where each bit corresponds to a specific hybridization round.

The readout process involves sequential rounds of hybridization with fluorescent readout probes, imaging, and probe stripping. In each round, readout probes complementary to specific readout sequences are introduced, revealing which RNAs contain that particular sequence. After imaging, fluorophores are photobleached or probes are stripped, and the next round commences with a different set of readout probes. Through multiple cycles (typically 14-16 rounds), each RNA molecule is identified by its unique on-off fluorescence pattern across imaging rounds [44].

A critical innovation in MERFISH is the incorporation of error-robust encoding schemes with Hamming distances of 2 or 4, meaning multiple errors must occur before a barcode is misidentified [44]. This encoding strategy significantly reduces false identification rates while maintaining high multiplexing capabilities—theoretically allowing detection of up to 65,000 different RNA species with 16 rounds of imaging [44].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

Probe Design and Hybridization: MERFISH requires careful design of encoding probes targeting each RNA of interest. Recent optimization studies show that probe performance depends weakly on target region length (20-50 nucleotides tested) within optimal formamide concentrations [45]. Encoding probe hybridization is relatively slow (hours to days), while readout probe hybridization is rapid (minutes) [45] [44].

Sample Preparation: Cells or tissues are fixed and permeabilized similarly to other FISH methods. MERFISH has been successfully applied to various tissues including brain, liver, gut, and heart, with protocol adjustments needed for different tissue types [44]. Sample autofluorescence can be particularly challenging in human tissues due to lipofuscin granules, collagen, and mitochondria [46].

Multiplexed Imaging and Decoding: The sequential imaging process utilizes 4-6 color channels across multiple rounds. Between rounds, fluorophores are photobleached or chemically inactivated. Commercial implementations like the Merscope platform have automated this process, completing measurements in 1-2 days [47]. Buffer composition and reagent stability throughout this extended process significantly impact signal quality, with optimized buffers improving fluorophore performance and reducing background [45].

Data Analysis and Transcript Mapping: Computational algorithms decode the fluorescence patterns into binary barcodes, identifying each RNA species. Cell segmentation assigns transcripts to individual cells, often using nuclear stains (DAPI) and cytoplasmic markers. Advanced analysis pipelines then generate spatial gene expression maps at single-cell resolution.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of RNAscope and MERFISH based on recent comparative studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RNAscope and MERFISH Technologies

| Parameter | RNAscope | MERFISH (Merscope Platform) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Sensitivity | Can detect single RNA molecules [42] | High detection efficiency; 62±14 transcripts per cell in MBEN tumor samples [47] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Moderate (typically 1-12 targets with fluorescence) [42] | High (hundreds to thousands of targets); 138 genes in MBEN study [47] |

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) | Not reported in studies | 5.23%±0.9% in MBEN tumor samples [47] |

| Target Requirements | RNA sequences >300 nucleotides; BaseScope for shorter targets (50-300 nt) [40] | Works better with longer transcripts (>1.5kb); shorter transcripts like neuropeptides challenging [46] |

| Hands-on Time | Varies by application | 5-7 days slide preparation [47] |

| Total Experiment Time | 1-2 days typically | 1-2 days on instrument after preparation [47] |

| Cell Segmentation | Standard nuclear and cytoplasmic stains | Can be challenging; RiboSoma stain in DART-FISH improves segmentation [46] |

| Tissue Compatibility | FFPE, fresh frozen, fixed cells [42] | Fresh frozen, FFPE; human tissues challenging due to autofluorescence [46] |

Experimental Design Considerations

Choosing between RNAscope and MERFISH involves balancing multiple factors depending on research goals:

For Targeted Studies: RNAscope excels when investigating a limited number of pre-defined targets, particularly in clinical samples or when analyzing formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues [42]. Its robust protocol and compatibility with standard microscopy make it accessible for most laboratories.

For Discovery Research: MERFISH is ideal for hypothesis-free exploration of cellular heterogeneity and tissue organization, capable of profiling hundreds to thousands of genes simultaneously [47] [44]. The technology requires specialized instrumentation and computational resources but provides comprehensive spatial transcriptomic data.

Sensitivity vs. Multiplexing Trade-offs: RNAscope typically achieves higher detection efficiency per gene due to its signal amplification approach, while MERFISH provides greater multiplexing capacity through combinatorial barcoding [47]. Recent advancements in both technologies continue to push these boundaries.

Sample Compatibility: Both platforms work with various sample types, but protocol optimization is essential, particularly for challenging tissues like human brain and kidney which exhibit high autofluorescence [46]. Sample preparation and fixation protocols significantly impact performance in both technologies [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced ISH Platforms

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Types | Target recognition and signal generation | RNAscope: Z-probe pairs [42]; MERFISH: Encoding probes with barcode regions [44] |

| Signal Amplification Systems | Enhancing detection sensitivity | RNAscope: Pre-amplifier/amplifier hierarchy [42]; Padlock probes: Rolling circle amplification [46] |

| Tissue Preservation Reagents | Maintaining RNA integrity and morphology | 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (24±12 hours fixation) [43]; Paraformaldehyde (PFA) for fresh frozen samples [46] |

| Permeabilization Agents | Enabling probe access to targets | Detergents: Tween-20, Triton X-100, CHAPS; Proteases: Proteinase K [43] |

| Hybridization Buffers | Controlling stringency of probe binding | Formamide-containing buffers; Optimization of concentration critical for signal-to-noise [45] |

| Fluorophores and Detection Chemistry | Signal generation and visualization | Enzyme-mediated chromogenic precipitation; Fluorescent dyes for multiplexing [39] |

| Cell Segmentation Markers | Defining cellular boundaries for transcript assignment | DAPI (nuclear stain); RiboSoma (cytoplasmic stain in DART-FISH) [46] |

| Controls | Validating assay performance | Positive: Housekeeping genes (PPIB, Polr2A, UBC) [42]; Negative: Bacterial dapB gene [42] |

| YADA | YADA, CAS:1471982-33-8, MF:C15H13N3O10S2, MW:459.4 | Chemical Reagent |

| BNTA | BNTA (N-[2-bromo-4-(phenylsulfonyl)-3-thienyl]-2-chlorobenzamide) | BNTA is a synthetic organic molecule for research on osteoarthritis and oxidative stress. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

RNAscope and MERFISH represent complementary technological philosophies in advanced ISH—one maximizing signal amplification for precision detection of limited targets, the other employing combinatorial strategies for massive multiplexing. Both platforms have dramatically expanded our ability to study gene expression in its native spatial context, revealing new insights into tissue organization, cellular heterogeneity, and disease mechanisms.