Epigenetic Regulation of Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the epigenetic mechanisms governing embryonic stem cell (ESC) differentiation, a fundamental process in developmental biology and regenerative medicine.

Epigenetic Regulation of Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the epigenetic mechanisms governing embryonic stem cell (ESC) differentiation, a fundamental process in developmental biology and regenerative medicine. We explore the dynamic roles of DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin remodeling, and long non-coding RNAs in maintaining pluripotency and directing lineage commitment. The content delves into advanced methodological approaches for studying these processes, including cell-cycle-synchronized models and multi-omics databases. Furthermore, we examine the translation of this knowledge into therapeutic strategies, such as epigenetics-targeted drugs, and discuss current challenges in the field, including specificity and delivery issues. Finally, we highlight the critical validation of these mechanisms in disease models, particularly cancer stem cells, offering insights for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to harness epigenetic regulation for clinical applications.

Core Epigenetic Mechanisms Governing Pluripotency and Lineage Commitment

Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) derived from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst are defined by their dual capacity for long-term self-renewal and pluripotency—the ability to differentiate into every somatic cell type [1]. This pluripotent state is not solely governed by transcription factors but is critically underpinned by a sophisticated epigenetic framework. The ESC epigenome exists in a unique, dynamic configuration that maintains a transcriptionally permissive state, allowing for the rapid activation of diverse genetic programs upon receipt of differentiation signals [2] [3]. This whitepaper delineates the defining features of the DNA methylation and histone modification landscapes in ESCs, framing this knowledge within the broader context of regenerative medicine and therapeutic development. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for harnessing the full potential of ESCs and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for drug screening, disease modeling, and cell-based therapies [1] [4].

DNA Methylation and Hydroxymethylation in ESCs

DNA methylation, the addition of a methyl group to the carbon-5 position of cytosine (5-methylcytosine, 5mC), is a primary epigenetic mechanism involved in gene regulation, genomic imprinting, and repression of transposable elements [1] [5]. In ESCs, the DNA methylation landscape is distinctive and highly dynamic, facilitating the balance between self-renewal and differentiation.

Global Hypomethylation and Promoter-Specific Regulation: ESCs exhibit a relative global DNA hypomethylation compared to differentiated cells, which contributes to an open chromatin structure and transcriptional permissiveness [5]. However, this is not uniform. The promoters of genes can be categorized by their CpG content. High CpG promoters (HCPs), which include many pluripotency genes like OCT4 and NANOG, are typically hypomethylated and associated with active or bivalent histone marks in ESCs. In contrast, low CpG promoters (LCPs) are often hypermethylated and silenced [5]. During differentiation, promoter hypermethylation serves as a stable lock to silence pluripotency genes, ensuring exit from the self-renewal program [5].

The Role of TET Enzymes and Hydroxymethylation: A pivotal discovery in stem cell epigenetics was the rediscovery of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), which is abundant in ESCs and serves as a key intermediate in active DNA demethylation pathways [1]. 5hmC is generated by the Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) family of enzymes (TET1, TET2, TET3), which can further oxidize 5mC to 5hmC, and then to 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), leading to DNA demethylation [1]. This pathway introduces a dynamic and reversible component to DNA methylation, crucial for the plasticity of the ESC state. The levels of 5hmC are significant in ESCs, constituting approximately 5–10% of total methylcytosine in mouse ESCs [1].

Functional Consequences of DNA Methylation Manipulation: The functional importance of DNA methylation is evident from genetic studies. While mouse ESCs deficient in all three DNA methyltransferases (Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b) can maintain self-renewal, they are severely compromised in their ability to differentiate, highlighting that DNA methylation is dispensable for the pluripotent state but essential for lineage commitment [1]. Conversely, in somatic cell reprogramming to iPSCs, DNA demethylation is a critical, rate-limiting step for the reactivation of pluripotency genes, and the use of demethylating agents like 5-azacytidine can enhance reprogramming efficiency [1] [6].

Table 1: Key Enzymes Regulating DNA Methylation in ESCs and Their Roles

| Enzyme | Function | Phenotype in ESC/Reprogramming |

|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance DNA methyltransferase | Downregulation facilitates iPSC reprogramming; knockout ESCs are hypomethylated and fail to differentiate [1]. |

| DNMT3A/B | De novo DNA methyltransferases | Largely dispensable for iPSC reprogramming; knockout ESCs fail to form teratomas and differentiate [1] [5]. |

| TET1/2/3 | Dioxygenases converting 5mC to 5hmC | Depletion reduces iPSC reprogramming efficiency; Triple-knockout ESCs contribute poorly to embryonic development [1]. |

Histone Modification Landscapes in ESCs

Histone modifications provide a complex and combinatorial layer of epigenetic control that regulates chromatin accessibility. ESCs possess a unique histone modification signature characterized by globally high levels of activating marks and the presence of specialized chromatin states that poise genes for future expression [2].

The Bivalent Domain: A hallmark of the pluripotent epigenome is the prevalence of "bivalent" chromatin domains. These are specific promoter regions, often governing key developmental genes, that are simultaneously marked by both the activating histone modification H3K4me3 and the repressive modification H3K27me3 [2] [7]. This configuration, mediated by the competing activities of the COMPASS/SETD1A complex (for H3K4me3) and the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) (for H3K27me3), maintains these genes in a transcriptionally poised, low-expression state. Upon differentiation cues, bivalent domains resolve to a monovalent state—either H3K4me3 for activation or H3K27me3 for stable silencing—thereby directing lineage-specific differentiation [2] [7]. In ground-state naive ESCs, PRC2 and H3K27me3 are particularly abundant and distributed genome-wide in a CpG-dependent fashion to protect against premature lineage priming [8].

Other Key Histone Modifications:

- H3K27ac: This mark identifies active enhancers and is crucial for the expression of genes that define cell identity, including pluripotency factors [4].

- H3K9me3: A hallmark of constitutive heterochromatin, this mark is generally associated with stable gene repression. Its levels increase during ESC differentiation, helping to silence pluripotency genes and stabilize the differentiated state [7] [4]. The removal of H3K9me3 by demethylases like KDM4B is a critical step in somatic cell reprogramming [4].

- Histone Acetylation (e.g., H3K9ac, H3K27ac): ESCs exhibit high global levels of histone acetylation, contributing to a generally open chromatin architecture. The balance between histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) is vital for directing differentiation, with HDAC inhibitors like valproic acid (VPA) shown to improve reprogramming efficiency by maintaining an open chromatin state [4].

Table 2: Defining Histone Modifications in the Pluripotent Epigenome

| Histone Mark | Associated State | Function in ESCs |

|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Active Transcription | Marks promoters of actively transcribed genes (e.g., OCT4, SOX2) [4]. |

| H3K27me3 | Repressed / Poised | Deposited by PRC2; silences developmental genes; part of the bivalent domain [8] [2]. |

| Bivalent (H3K4me3 + H3K27me3) | Poised for Activation | Keeps developmental regulators in a "primed" but inactive state, enabling multilineage potential [2] [7]. |

| H3K27ac | Active Enhancer | Identifies active enhancers and promoters; critical for pluripotency network [4]. |

| H3K9me3 | Heterochromatin / Repressed | Associated with stable gene silencing; a barrier to reprogramming [4]. |

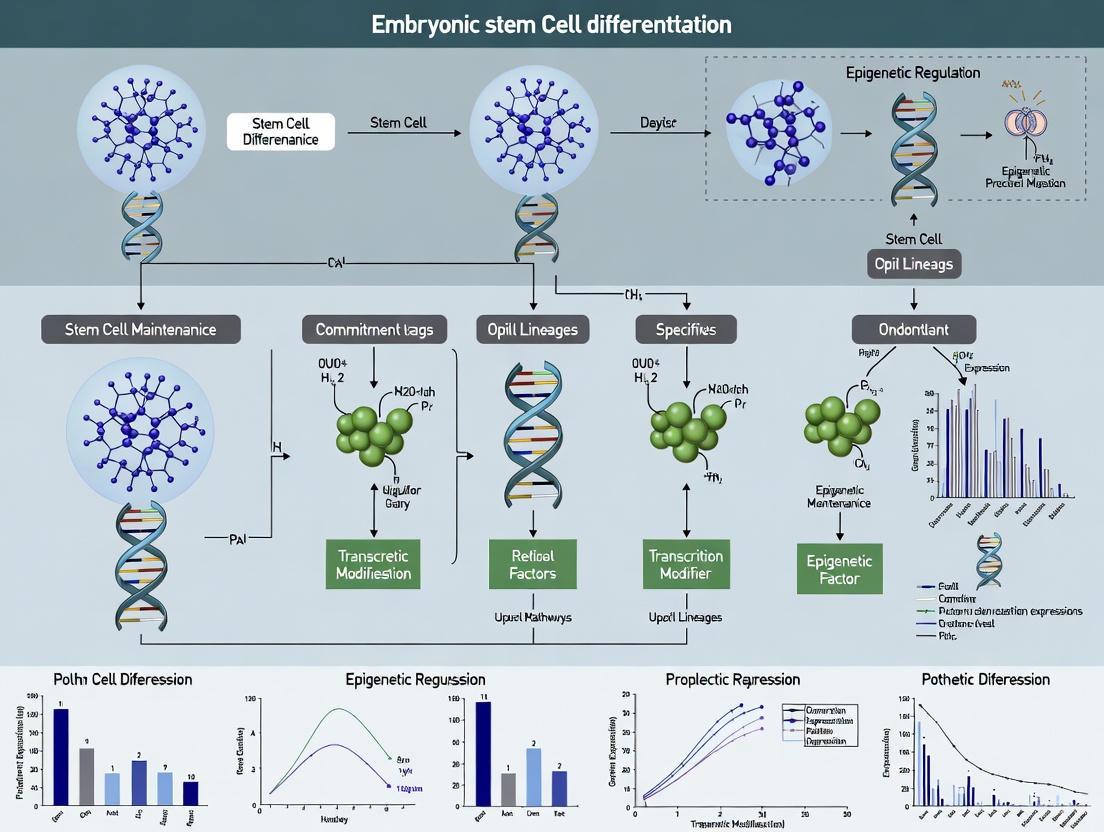

The following diagram illustrates the structure and function of a canonical bivalent promoter in an ESC:

Interplay and Dynamics During Differentiation

The transition from a pluripotent to a differentiated state is orchestrated by a coordinated shift in both DNA methylation and histone modifications. This dynamic interplay is not a simple one-way process but involves active crosstalk between epigenetic layers.

Epigenetic Crosstalk: PRC2-dependent H3K27me3 and DNA methylation engage in a reciprocal relationship. In PRC2-deficient ESCs, a loss of H3K27me3 at target loci leads to a concomitant increase in DNA methylation at those sites, demonstrating that H3K27me3 can protect certain genomic regions from de novo methylation [8]. This crosstalk ensures that developmental genes are silenced by a redundant and robust epigenetic system during differentiation.

Metabolic and Cell Cycle Influences: The epigenetic landscape of ESCs is also shaped by global cellular processes. Histone-modifying enzymes rely on key metabolites as co-factors. For instance, S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) is the methyl donor for methyltransferases, and acetyl-CoA is used by HATs. ESCs, which rely heavily on glycolysis, are sensitive to fluctuations in these metabolites, linking cellular metabolism directly to the epigenetic state [2]. Furthermore, the rapid cell cycle of ESCs influences histone modification kinetics. With each division, newly synthesized, unmodified histones are incorporated, diluting existing marks. The short cell cycle in ESCs, combined with efficient modifying enzymes, helps maintain a hyperdynamic and plastic chromatin state, whereas slower-dividing differentiated cells tend to accumulate more stable methylation marks [2].

The dynamic interplay between key epigenetic regulators during cell fate transition is summarized below:

Key Experimental Methodologies and Reagents

Investigating the pluripotent epigenome requires specialized techniques to map epigenetic marks and manipulate the epigenetic state. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) is the cornerstone method for analyzing histone modifications and transcription factor binding.

Detailed Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Protocol: The following protocol, adapted from studies on cardiac differentiation, provides a robust framework for epigenetic analysis in ESCs and their derivatives [9].

- DNA-Protein Cross-linking: Fix approximately 2 x 10^6 ESCs or embryoid bodies (EBs) using 1% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature with gentle shaking. Quench the reaction with 125 mM glycine for 5 minutes.

- Cell Lysis and Chromatin Fragmentation: Wash cross-linked cells twice with cold PBS. Resuspend the pellet in 1 ml of SDS Lysis Buffer (SB1: 1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8) supplemented with protease inhibitors. Incubate on ice for 15-30 minutes.

- Sonication: Sonicate the samples at 4°C to shear chromatin to an average size of 200-500 bp. For ESCs, a typical program might be 15 cycles of 30 seconds on/30 seconds off. Centrifuge at high speed to remove insoluble debris and collect the chromatin supernatant.

- Immunoprecipitation: Pre-clear chromatin with Protein A/G beads. Incubate 150 µg of chromatin with a specific, validated antibody against the histone mark of interest (e.g., anti-H3K4me3, anti-H3K27me3) overnight at 4°C with rotation. Use beads alone as a negative control.

- Washes and Elution: Capture antibody-chromatin complexes with Protein A/G beads. Wash beads sequentially with Low Salt, High Salt, LiCl, and TE buffers to remove non-specifically bound chromatin. Elute the immunoprecipitated chromatin complexes from the beads using a freshly prepared elution buffer (e.g., 1% SDS, 100 mM NaHCO3).

- Reverse Cross-linking and DNA Purification: Reverse cross-links by adding NaCl to a final concentration of 200 mM and incubating at 65°C for several hours (or overnight). Digest proteins with Proteinase K, and purify the DNA using a commercial PCR purification kit. The resulting DNA can be analyzed by quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) for specific loci or sequenced (ChIP-seq) for genome-wide mapping [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents Table 3: Key Reagents for Epigenetic Research in ESCs

| Reagent / Tool | Function/Target | Application in ESC Research |

|---|---|---|

| 5-Azacytidine | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor | Promotes DNA demethylation; used to improve iPSC reprogramming efficiency [1] [5]. |

| Valproic Acid (VPA) | Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor | Increases histone acetylation; enhances reprogramming efficiency and can influence differentiation [4]. |

| Anti-H3K4me3 Antibody | Histone mark for active promoters | ChIP to identify actively transcribed pluripotency genes and resolve bivalent domains [2] [9]. |

| Anti-H3K27me3 Antibody | Histone mark for repressed/poised promoters | ChIP to map Polycomb targets and bivalent domains in ESCs [8] [9]. |

| Dnmt3a/b shRNA | Knockdown of de novo methyltransferases | Tool to study the role of DNA methylation in stem cell maintenance and differentiation [6]. |

| EZH2 Inhibitor (e.g., GSK126) | Inhibits PRC2 catalytic activity | Used to dissect the role of H3K27me3 in maintaining pluripotency and blocking differentiation [4]. |

Implications for Disease Modeling and Therapeutic Development

The principles governing the pluripotent epigenome have profound implications beyond basic biology, particularly in regenerative medicine and oncology.

Enhancing Reprogramming and Directed Differentiation: Insights into epigenetic barriers have directly improved cellular reprogramming technologies. The demonstration that HDAC and DNMT inhibitors can significantly enhance the efficiency of iPSC generation is a prime example of applied epigenetics [1] [4]. Furthermore, understanding the epigenetic roadblocks that lock cells in a differentiated state is crucial for developing strategies to direct the differentiation of ESCs and iPSCs into pure, functional populations of target cells (e.g., cardiomyocytes, neurons) for transplantation [7] [9].

Cancer Stem Cells and Epigenetic Therapy: Cancer stem cells (CSCs), which drive tumor initiation and therapy resistance, hijack the epigenetic machinery of normal stem cells to maintain their self-renewing, undifferentiated state [4]. For instance, the PRC2 component EZH2, which deposits H3K27me3, is frequently overexpressed in cancers, silencing tumor suppressor genes. Similarly, repressive marks like H3K9me3 help maintain the stemness of CSCs in glioblastoma [4]. Consequently, enzymes like EZH2 and HDACs are prime targets for epigenetic therapy. Inhibitors against these targets are being developed to force CSCs to differentiate or sensitize them to conventional chemotherapy, representing a promising avenue for cancer treatment [4].

The pluripotent state of ESCs is demarcated and maintained by a unique epigenetic signature characterized by dynamic DNA methylation/hydroxymethylation and a specialized histone modification landscape featuring bivalent domains. This epigenome is not static but is highly responsive to intrinsic signals like metabolism and the cell cycle, as well as extrinsic differentiation cues. The meticulous characterization of this landscape has provided not only fundamental insights into developmental biology but also practical tools for improving stem cell-based technologies. As epigenetic profiling and editing tools continue to advance, the ability to precisely manipulate the epigenome will unlock new frontiers in regenerative medicine, drug discovery, and oncology, solidifying the central role of epigenetics in the past, present, and future of stem cell research.

Bivalent chromatin domains represent a fascinating epigenetic phenomenon where functionally opposing histone modifications, specifically the active mark H3K4me3 and the repressive mark H3K27me3, co-exist on the same nucleosomes or genomic regions. First discovered in embryonic stem cells (ESCs), these domains are predominantly found at promoters of key developmental regulator genes and are thought to maintain them in a poised state—transcriptionally repressed yet primed for activation upon receipt of differentiation signals [10] [11]. This unique chromatin configuration effectively resolves the epigenetic paradox of how cells can simultaneously silence developmental genes while keeping them ready for rapid deployment during lineage specification, thereby serving as a critical mechanism maintaining the delicate balance between pluripotency and differentiation in stem cells [12] [11].

The prevailing model suggests that bivalency allows precise temporal control of gene expression during embryonic development, with H3K27me3 preventing premature expression of developmental regulators while H3K4me3 keeps these genes accessible for future activation [10]. Beyond mammalian development, recent evidence indicates that bivalent chromatin represents a fundamental regulatory mechanism that has been conserved across diverse biological systems, including plants and fungi, where it facilitates adaptive responses to environmental stresses and host-pathogen interactions [13] [14].

Molecular Architecture of Bivalent Domains

Histone-Modifying Complexes and Their Interactions

The establishment and maintenance of bivalent chromatin involve a delicate balance between the activities of two major classes of histone-modifying complexes: the Trithorax group (TrxG) proteins, which catalyze H3K4me3 through COMPASS-family complexes, and the Polycomb group (PcG) proteins, which mediate H3K27me3 through Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) [12] [11]. Specifically, KMT2B (MLL2) has been identified as the major H3K4 methyltransferase responsible for establishing bivalency in embryonic stem cells, while EZH1/2 serve as the catalytic subunits of PRC2 that mediate H3K27 trimethylation [11].

These complexes exhibit antagonistic biochemical relationships—H3K4me3 allosterically inhibits PRC2 activity, while H3K27me3 inhibits KMT2 complexes—creating a theoretical barrier to bivalency establishment [12] [15]. However, several mechanisms have evolved to overcome this limitation:

- Spatial segregation: H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 may occupy distinct nucleosomes within the same genomic region [12]

- Asymmetric modification: The modifications may occur on different histone H3 molecules within the same nucleosome [10]

- Sequential deposition: The modifications may be established in a temporally coordinated manner [14]

The underlying DNA sequence, particularly hypomethylated CpG islands, plays a crucial role in recruiting these complexes and establishing bivalent domains, with evidence suggesting that CpG density predisposes genomic regions to bivalency [12] [16] [15].

Structural Organization and Chromatin Environment

Bivalent domains exhibit a distinct chromatin architecture characterized by a more open configuration compared to constitutively repressed regions. This intermediate state of chromatin compaction facilitates dynamic responses to developmental cues while maintaining transcriptional repression in the absence of activation signals [11]. Recent studies utilizing reChIP-seq methodology have confirmed that H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 can indeed co-exist on the same nucleosome, validating the molecular reality of bivalent chromatin [15].

Table 1: Key Molecular Components of Bivalent Chromatin Domains

| Molecular Component | Function | Role in Bivalency |

|---|---|---|

| KMT2B (MLL2) | H3K4 methyltransferase | Primary writer of H3K4me3 mark in bivalent domains |

| PRC2 (EZH1/2) | H3K27 methyltransferase | Primary writer of H3K27me3 mark |

| CpG Islands | Genomic sequence feature | Recruitment platform for chromatin modifiers |

| COMPASS Complex | H3K4 methylation | Establishment of active mark component |

| Polycomb Proteins | Transcriptional repression | Maintenance of repressive mark component |

Functional Roles in Embryonic Development and Cell Differentiation

Pluripotency Maintenance and Lineage Commitment

In embryonic stem cells, bivalent domains function as epigenetic gatekeepers of cellular identity, silencing developmental genes that would otherwise promote differentiation while preventing their permanent inactivation [10] [11]. During ESC differentiation, bivalent domains undergo resolution into either active (H3K4me3-only) or repressive (H3K27me3-only) states depending on the specific lineage commitment, allowing precise control of gene expression programs that guide morphogenesis and tissue specification [10].

This model has been substantiated by genome-wide studies showing that developmental regulator genes critical for patterning and organogenesis—including transcription factors for various lineages—are frequently marked by bivalent domains in ESCs [11]. The resolution process is facilitated by ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers such as SWI/SNF, which help evict Polycomb-group proteins from bivalent chromatin during lineage commitment [10].

Beyond Embryonic Stem Cells: Bivalency in Differentiated Cells

While initially characterized as an ESC-specific feature, bivalent chromatin has been identified in various differentiated cell types, including pyramidal neurons, memory T cells, and tissue-resident stem cells, suggesting broader functional relevance [15] [11]. In human CD4+ memory T cells, for instance, widespread bivalency at hypomethylated CpG islands coincides with inactive promoters of developmental regulators, potentially enabling cellular plasticity in response to immune challenges [15].

Recent research has challenged the original hypothesis that bivalency primarily poises genes for rapid activation. Instead, evidence suggests that H3K4me3 at bivalent promoters may function as a protective mechanism against DNA methylation, maintaining genes in a reversibly repressed state and preventing irreversible silencing [12]. This protective function may be particularly important for lineage-specific genes that must be kept transcriptionally flexible throughout development.

Table 2: Developmental Functions of Bivalent Chromatin Across Biological Systems

| Biological Context | Primary Function | Key Regulatory Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse ESCs | Pluripotency maintenance | Developmental transcription factors |

| Xenopus Embryos | Maternal epigenetic control | Early patterning genes |

| Human T Cells | Immune cell plasticity | Differentiation regulators |

| Plant Development | Environmental stress response | Cold-responsive genes |

| Fungal Pathogenesis | Host immune evasion | Virulence factors |

Experimental Approaches for Bivalent Chromatin Analysis

Genome-Wide Mapping Techniques

The identification and characterization of bivalent domains have been revolutionized by advanced genomic technologies. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has been the cornerstone method for mapping histone modifications genome-wide [12] [13] [16]. However, conventional ChIP-seq has limitations in demonstrating true bivalency, as overlapping H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 signals from separate experiments may reflect heterogeneity within cell populations rather than genuine co-occurrence on the same nucleosomes [15].

To address this limitation, researchers have developed reChIP-seq (sequential ChIP-seq), which enables direct identification of nucleosomes bearing both modifications [15]. This method involves:

- Primary ChIP with antibody against first histone modification (e.g., H3K4me3)

- Mild elution using specific peptides rather than denaturing conditions

- Secondary ChIP with antibody against second modification (e.g., H3K27me3)

- Library preparation and high-throughput sequencing

- Bioinformatic analysis using specialized tools like normR to identify co-enrichment

The reChIP-seq approach, combined with tailored computational methods, has confirmed the existence of genuine bivalent nucleosomes and revealed that conventional ChIP-seq intersection approaches may both overestimate (due to population heterogeneity) and underestimate (due to technical limitations) the true extent of bivalency [15].

Integrative Epigenomic Analysis

Comprehensive characterization of bivalent chromatin requires multi-omics integration, combining histone modification data with other epigenetic features and transcriptional outputs:

- DNA methylation analysis via whole-genome bisulfite sequencing reveals inverse relationships between H3K4me3 and DNA methylation [12] [16]

- Chromatin accessibility assays (DNase-seq, ATAC-seq) identify open chromatin regions associated with bivalent domains [13]

- Transcriptomic profiling (RNA-seq) correlates bivalent status with gene expression levels [12] [13]

- 3D chromatin architecture methods examine spatial organization of bivalent domains

In potato tubers, for example, integrative analysis revealed that cold stress induces both enhanced chromatin accessibility and bivalent histone modifications at active genes, suggesting that bivalency represents a distinct chromatin environment with greater accessibility that may facilitate regulatory protein access [13].

Research Reagent Solutions for Bivalent Chromatin Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Bivalent Chromatin Investigation

| Research Tool | Specific Example | Application in Bivalency Research |

|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 Antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3 (ChIP-grade) | Mapping active mark distribution |

| H3K27me3 Antibodies | Anti-H3K27me3 (ChIP-grade) | Mapping repressive mark distribution |

| ChIP-seq Kits | Commercial ChIP kits | Genome-wide histone modification profiling |

| reChIP Reagents | Peptide elution systems | Direct detection of bivalent nucleosomes |

| Methyltransferase Inhibitors | EZH2 inhibitors | Functional perturbation of PRC2 activity |

| Bioinformatic Tools | normR, DiffBind | Specialized analysis of co-occurring modifications |

| Cell Lines | Embryonic stem cells | Model systems for developmental bivalency |

Evolutionary Conservation and Diverse Biological Contexts

The fundamental principles of bivalent chromatin regulation extend beyond mammalian systems, demonstrating evolutionary conservation across diverse eukaryotes:

In plants, bivalent H3K4me3-H3K27me3 modifications have been identified in Arabidopsis and potato, where they function in environmental stress responses [13]. During cold stress in potato tubers, active genes show enhanced chromatin accessibility and bivalent modifications, with upregulated bivalent genes involved in stress response while downregulated bivalent genes participate in developmental processes [13].

Remarkably, fungal pathogens like Fusarium graminearum employ bivalent modifications to precisely control virulence gene expression during host invasion [14]. The BCG1 gene, encoding a secreted xylanase, displays temporally coordinated bivalent modifications—initial H3K4me3-mediated activation facilitates host cell wall degradation, followed by H3K27me3 incorporation to establish bivalency and enable immune evasion by suppressing this immunogenic factor [14].

These evolutionary parallels highlight bivalent chromatin as a widely deployed epigenetic mechanism for fine-tuning gene expression in response to developmental and environmental cues across biological kingdoms.

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Dynamics

The following diagram illustrates the molecular regulation and functional outcomes of bivalent chromatin domains:

Bivalent Chromatin Regulation and Functional Outcomes

The diagram above illustrates how bivalent domains are established through the coordinated actions of KMT2B/COMPASS and PRC2 complexes at hypomethylated CpG islands, how they maintain genes in a poised state, and how they resolve toward activation or repression during lineage commitment.

Bivalent chromatin domains represent a sophisticated epigenetic mechanism that enables precise spatiotemporal control of gene expression during development. Rather than simply poising genes for rapid activation, emerging evidence suggests these domains function as dynamic regulatory hubs that integrate developmental, environmental, and cellular signals to fine-tune transcriptional outputs [12] [11].

Future research directions will likely focus on:

- Understanding the structural basis of bivalent nucleosome organization

- Elucidating the temporal dynamics of bivalency establishment and resolution at single-cell resolution

- Investigating the dysregulation of bivalent domains in disease states, particularly cancer

- Developing epigenetic editing tools to manipulate bivalency for therapeutic applications

The conservation of bivalent chromatin mechanisms across diverse biological systems underscores their fundamental importance in gene regulation and highlights their potential as targets for therapeutic intervention in developmental disorders and diseases characterized by epigenetic dysregulation.

Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in Orchestrating Multilayered Gene Regulation

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), once considered mere transcriptional "noise," are now recognized as master regulators of gene expression with critical functions in embryonic stem cell (ESC) biology. These molecules, defined as transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with little or no protein-coding potential, orchestrate multilayered genetic and epigenetic control over cell fate decisions. Operating at epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional levels, lncRNAs fine-tune the delicate balance between pluripotency and differentiation in ESCs. This review synthesizes current understanding of lncRNA mechanisms, presents quantitative expression profiles during differentiation, details experimental methodologies for their study, and visualizes their integrated regulatory networks. The comprehensive analysis provided herein establishes a framework for understanding how lncRNAs guide embryonic stem cell differentiation through sophisticated gene regulatory networks, offering new insights for regenerative medicine and therapeutic development.

The human transcriptome is remarkably complex, with a substantial proportion transcribed into non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) that lack protein-coding potential. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) constitute a heterogeneous group with key roles in regulating transcriptional and post-transcriptional processes, including X-chromosome inactivation, epigenetic modulation, genomic imprinting, and mRNA splicing [17]. LncRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II and exhibit features such as 5′ capping, splicing, and polyadenylation, akin to mRNAs [17]. Functionally, lncRNAs participate in chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, and post-transcriptional processing, acting as essential regulators in embryonic stem cell pluripotency, development, differentiation, and tumorigenesis.

LncRNAs can be classified in several ways, with one common method based on their genomic organization relative to protein-coding genes. This classification divides lncRNAs into four main categories [17]:

- Intergenic lncRNAs (lincRNAs): Transcribed from regions of DNA located between two protein-coding genes

- Intronic lncRNAs: Derived from the introns of protein-coding genes

- Overlapping lncRNAs: Transcripts that partially or entirely overlap with known protein-coding genes

- Antisense lncRNAs: Transcribed in the opposite direction of a protein-coding gene

Despite their functional diversity, lncRNAs are generally expressed at low levels, exhibit high cell-type specificity, and are often dysregulated in diseases, including cancer. Their unique ability to modulate gene expression at multiple levels makes lncRNAs powerful tools for controlling cell fate, particularly in the context of embryonic stem cell differentiation and regenerative medicine [18] [17].

Multilayered Regulatory Mechanisms of lncRNAs

Epigenetic Regulation and Chromatin Remodeling

LncRNAs play a crucial role in chromatin remodeling and histone modification, influencing gene expression and cellular differentiation. They achieve this primarily by serving as molecular scaffolds that recruit chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic locations [19] [17]. For example, the well-studied lncRNA HOTAIR interacts with the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) to silence gene expression by depositing repressive histone marks such as H3K27me3 [20] [19]. Similarly, the lncRNA HOTTIP interacts with the Mixed Lineage Leukemia (MLL) complex to activate gene expression by depositing activating histone marks [19]. This precise guidance of chromatin modifiers enables lncRNAs to establish heritable epigenetic states that maintain stem cell identity or drive differentiation.

The lncRNA Xist represents a paradigm of lncRNA-mediated epigenetic regulation, controlling X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) during female ESC differentiation [17]. XCI is regulated by non-coding RNAs like Xist, Tsix, and RepA, which are themselves targets of pluripotency transcription factors. For example, Oct4 and Nanog repress Xist expression in mouse ESCs (mESCs), maintaining two active X chromosomes—a hallmark of pluripotency [17]. Upon differentiation, Xist expression increases, leading to XCI [17]. This dynamic regulation illustrates how lncRNAs respond to developmental cues to execute long-lasting epigenetic programs.

Transcriptional Regulation

LncRNAs regulate transcription through diverse mechanisms, including interactions with transcription factors and modulation of transcriptional complexes. Some lncRNAs function as enhancer RNAs that activate transcription by facilitating enhancer-promoter interactions. Others, like the lncRNA PANDA, regulate transcription by interacting with the transcription factor NF-YA, sequestering it away from its target gene-associated chromatin [17]. LncRNAs can also directly influence transcription by forming RNA-DNA triplex structures that either recruit transcriptional activators or block transcription factor binding.

In embryonic stem cells, specific lncRNAs integrate into the core transcriptional circuitry. For instance, genome-wide studies in mouse ESCs identified lncRNAs such as AK028326 and AK141205, which are transcriptionally regulated by key pluripotency factors Oct4 and Nanog [17]. AK028326 functions as a coactivator of Oct4, creating a positive feedback loop that reinforces the pluripotent state. Similarly, the lncRNA RMST in human ESCs (hESCs) interacts with SOX2 as a transcriptional co-regulator, while SOX2OT modulates SOX2 expression [17]. These examples demonstrate how lncRNAs are embedded in the core transcriptional networks that govern stem cell identity.

Post-transcriptional and Translational Regulation

Beyond nuclear functions, lncRNAs exert significant influence in the cytoplasm through post-transcriptional mechanisms. Cytoplasmic lncRNAs, such as linc-RoR, act as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) or "microRNA sponges," shielding mRNAs of key transcription factors from degradation and supporting ESC maintenance [17]. Linc-RoR protects core pluripotency factors including OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG by sequestering miRNAs that would otherwise target these mRNAs for degradation.

LncRNAs also regulate RNA stability and alternative splicing. For instance, Linc-RoR stabilizes c-Myc by interacting with AUF1 and hnRNP I [17]. The lncRNA MALAT1 influences serine-arginine proteins and regulates alternative splicing by cooperating with hnRNPs [17]. At the translational level, lncRNAs like Linc-RoR can suppress p53 translation by blocking hnRNP I interactions with the p53 5′ UTR, while others, such as Uchl1, enhance translation through UTR-mediated interactions [17]. This multilayered post-transcriptional regulation allows lncRNAs to fine-tune gene expression rapidly in response to differentiation signals.

Quantitative Profiling of lncRNAs in Stem Cell Differentiation

Advanced sequencing technologies have enabled comprehensive quantification of lncRNA expression dynamics during stem cell differentiation. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies profiling lncRNAs in various differentiation contexts.

Table 1: Differential Expression of lncRNAs During hESC Differentiation to Pancreatic Progenitors [21]

| Analysis Type | Number of Cells | lncRNAs Detected | Pseudotime-Associated lncRNAs | Functionally Annotated lncRNAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq of hESC differentiation | 77,382 | 7,382 | 52 (grouped into 3 patterns) | 464 (including 49 pseudotime-associated) |

Table 2: Expression Patterns of Specific Regulatory lncRNAs in Stem Cell Differentiation

| lncRNA | Stem Cell Context | Expression Pattern | Functional Role | Regulatory Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lncR492 | Mouse ESCs | Downregulated during neural differentiation | Inhibitor of neuroectodermal differentiation | Activates Wnt signaling via interaction with HuR [22] |

| HOTAIRM1 | hESC to pancreatic progenitors | Associated with differentiation | Pancreatic progenitor generation | Regulates exocytosis and retinoic acid receptor signaling [21] |

| linc-RoR | Human ESCs | Maintained in pluripotency | Maintains pluripotency | miRNA sponge for core pluripotency factors [17] |

| TUNA | Mouse ESCs | Context-dependent | Pluripotency and neural differentiation | Interacts with RNA-binding proteins [22] |

| Xist | Mouse ESCs | Upregulated upon differentiation | X-chromosome inactivation | Recruits chromatin silencing complexes [17] |

Table 3: Metabolic Regulation by lncRNAs in Yak Liver Development [23]

| Developmental Stage | Total lncRNAs Detected | Differentially Expressed lncRNAs | Metabolism-Related lncRNAs | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn (1 day) | 10,073 | 288 | 88 | Lipid metabolism, collagen remodeling, protein transport |

| Juvenile (15 months) | 10,073 | 288 | 88 | Lipid metabolism, collagen remodeling, protein transport |

| Adult (5 years) | 10,073 | 288 | 88 | Lipid metabolism, collagen remodeling, protein transport |

These quantitative profiles demonstrate that specific lncRNAs exhibit dynamic, stage-specific expression patterns during differentiation, suggesting precise roles in lineage commitment and maturation.

Experimental Protocols for lncRNA Functional Characterization

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for lncRNA Profiling

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful method for characterizing lncRNA expression dynamics during stem cell differentiation. A representative protocol for profiling lncRNAs during hESC differentiation into pancreatic progenitors includes the following key steps [21]:

Cell Culture and Differentiation: Maintain hESCs in feeder-free culture medium (e.g., mTeSR1). For pancreatic differentiation, dissociate hESCs into single cells using TrypLE and initiate differentiation through a staged protocol with specific induction media containing growth factors (Activin A, WNT3a), signaling molecules (retinoic acid), and inhibitors (Noggin).

Single-Cell Library Preparation: Prepare single-cell suspension from each time point. Use a droplet-based platform (10X Genomics) to partition cells into Gel Beads-in-Emulsion (GEMs). Capture polyadenylated RNAs using poly-dT oligos, followed by reverse transcription, amplification, and barcoding.

Quality Control and Pre-processing: Assess library quality using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Sequence libraries on the Illumina HiSeq platform. Filter raw reads using Trimmomatic software with parameters: SLIDINGWINDOW:4:10; TRAILING:3; ILLUMINACLIP:adapter.fa:2:0:7.

Data Analysis: Map clean reads to the reference genome (GRCh38) using Cell Ranger. Filter low-quality cells based on UMI counts, expressed gene numbers (minimum 2000), and mitochondrial gene percentage (maximum 5%). Perform dimension reduction and clustering using Seurat R package. Construct pseudotime trajectories using Monocle 2 to order cells along differentiation paths.

Functional Annotation: Identify co-expression networks using WGCNA. Predict lncRNA functions through module- and hub-based methods, correlating lncRNA expression with potential target genes and pathways.

This approach successfully identified 7,382 lncRNAs during hESC differentiation toward pancreatic progenitors, with 52 showing significant pseudotime-associated expression patterns [21].

Loss-of-Function Screening for lncRNA Functional Analysis

RNA interference (RNAi) screens provide a robust method for high-throughput functional characterization of lncRNAs in stem cell differentiation. A representative protocol for identifying neural differentiation regulators includes [22]:

Cell Line Selection: Utilize reporter ESC lines (e.g., Sox1-GFP for neuroectodermal differentiation, Oct4-GFP for pluripotency, Foxa2-GFP for endoderm, T-GFP for mesoderm).

Library Transfection: Synthesize endoribonuclease-prepared siRNAs (esiRNAs) targeting >640 lncRNAs. Transfect ESCs with esiRNAs using Lipofectamine 2000.

Differentiation and Screening: Induce differentiation 24 hours post-transfection. For ectodermal differentiation, culture cells in N2B27 medium without inhibitors and LIF. For endoderm and mesoderm, add specific inducers (ActivinA or BMP4).

Phenotypic Analysis: Measure GFP fluorescence and cell numbers after 96 hours of differentiation using FACS Calibur equipped with HTS loader. Identify hits based on significant changes in reporter expression compared to controls.

Mechanistic Validation: For candidate lncRNAs (e.g., lncR492), perform transient overexpression and knockdown experiments. Use co-immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry (SILAC-labeling) to identify interacting proteins. Validate interactions through RT-PCR and Northern blot.

This screening approach identified lncR492 as a lineage-specific inhibitor of neuroectodermal differentiation that interacts with the mRNA binding protein HuR and activates Wnt signaling [22].

Visualization of lncRNA Regulatory Networks

The following diagrams illustrate key lncRNA regulatory pathways and experimental workflows using Graphviz DOT language.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for lncRNA Studies in Stem Cell Biology

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Examples | Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Lines | H9 hESCs, Sox1-GFP mESCs, Oct4-GFP ESCs | Differentiation studies | Provide reproducible models for lineage specification [21] [22] |

| Differentiation Media | N2B27, RPMI1640 with inductors | Directed differentiation | Create defined conditions for specific lineage commitment [21] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina HiSeq X, 10X Genomics | scRNA-seq library prep | Enable high-resolution transcriptome profiling [21] |

| Analysis Tools | Seurat, Monocle 2, WGCNA | scRNA-seq data analysis | Identify expression patterns and co-expression networks [21] |

| RNAi Libraries | esiRNAs targeting lncRNAs | Loss-of-function screening | Enable high-throughput functional genomics [22] |

| Transfection Reagents | Lipofectamine 2000 | Nucleic acid delivery | Introduce genetic constructs into stem cells [22] |

LncRNAs represent crucial components of the multilayered regulatory machinery that orchestrates embryonic stem cell differentiation. Through their ability to regulate gene expression at epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional levels, lncRNAs provide precision and specificity to the complex process of lineage commitment. Quantitative expression profiling reveals dynamic patterns of lncRNA expression during differentiation, while functional studies demonstrate their critical roles in fate determination. Advanced methodologies including single-cell RNA sequencing and RNAi screening enable comprehensive characterization of lncRNA functions in stem cell biology. As research continues to unravel the intricate networks through which lncRNAs operate, these molecules are poised to become valuable targets for regenerative medicine applications and therapeutic development for differentiation-related disorders.

Epigenetic Reprogramming During Early Embryonic Development and Gastrulation

Epigenetic reprogramming orchestrates the transformation from a totipotent zygote to a complex multicellular organism during early embryonic development. This process involves genome-wide dynamic changes in DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin architecture, and non-coding RNA expression that collectively regulate cellular potency and lineage specification. From zygotic genome activation through gastrulation, epigenetic mechanisms establish stable yet flexible transcriptional programs that guide the first cell fate decisions. This technical review synthesizes current understanding of these sophisticated regulatory networks, providing methodologies for their investigation and highlighting their implications for stem cell biology and regenerative medicine. The comprehensive analysis presented herein offers researchers a detailed framework for studying epigenetic dynamics during embryogenesis and their therapeutic applications.

The transition from fertilized egg to blastocyst represents the most profound epigenetic reprogramming event in mammalian development. During preimplantation development, the parental epigenomes are extensively reset to establish totipotency, followed by progressive restriction of developmental potential leading to the first lineage specifications. This reprogramming involves coordinated changes across multiple epigenetic layers: DNA methylation patterns are erased and reestablished, histone modifications are dynamically altered, chromatin accessibility is remodeled, and transposable elements are temporarily activated [24] [25]. These changes occur within a specific temporal sequence, beginning with paternal demethylation shortly after fertilization and continuing through zygotic genome activation (ZGA) and implantation.

The epigenetic reprogramming during this period is not merely a reset mechanism but serves as a crucial developmental timer and positioning system that guides spatial organization of the embryo. Recent single-cell epigenomic studies have revealed that the establishment of the embryonic epigenome occurs in a stepwise fashion, with distinct chromatin states emerging prior to morphological signs of differentiation [25]. This prepatterning of epigenetic landscapes creates a molecular framework upon which signaling pathways subsequently act to reinforce cell fate decisions. The period of gastrulation then represents a critical transition when these prepatterned epigenetic states are stabilized into committed lineages through the action of lineage-specific transcription factors and chromatin modifiers.

Epigenetic Dynamics from Zygote to Blastocyst

DNA Methylation Reprogramming

DNA methylation undergoes dramatic global changes during preimplantation development, with distinct patterns of erasure and reestablishment characterizing this period. The following table summarizes the quantitative dynamics of DNA methylation during early embryogenesis:

Table 1: DNA Methylation Dynamics During Preimplantation Development

| Developmental Stage | Global DNA Methylation Level | Key Enzymes Involved | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zygote | Paternal: ~10-20%; Maternal: ~70-80% | TET3, DNMT1 | Active demethylation of paternal genome; Passive demethylation of maternal genome |

| 2-cell to 4-cell | ~30-40% | TET enzymes, UHRF1 | Correlation with ZGA; ERV activation [25] |

| 8-cell to Morula | ~20-30% | DNMT3A, DNMT3B | Lineage-specific patterns begin to emerge |

| Blastocyst | ~60-70% | DNMT1, DNMT3A/B | Differential methylation in ICM vs. TE established |

The asymmetric demethylation between parental genomes represents one of the most striking features of early epigenetic reprogramming. The paternal genome undergoes rapid active demethylation mediated by TET enzymes shortly after fertilization, while the maternal genome is gradually demethylated through passive replication-dependent mechanisms [24]. This differential timing creates a transient epigenetic asymmetry that may contribute to the distinct transcriptional activities of parental genomes during early development.

Histone Modification Transitions

Histone modifications create a complex regulatory landscape that controls chromatin accessibility and gene expression during preimplantation development. The core histones undergo extensive replacement with variants, while specific post-translational modifications are added or removed in a stage-specific manner:

Table 2: Key Histone Modifications During Early Embryonic Development

| Modification | Developmental Pattern | Catalytic Writers/Erasers | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Broad domains at promoters in zygote; becomes focused after ZGA | SET1/MLL complexes, KDM5 family | Promotes open chromatin; Bivalent with H3K27me3 at developmental genes |

| H3K27me3 | Establishes after ZGA; patterns become lineage-specific by blastocyst | PRC2 (EED, EZH2), KDM6 family | Represses developmental regulators; Maintains pluripotency [26] |

| H3K9me3 | Low in early stages; increases during differentiation | SETDB1, KDM4 family | Suppresses transposable elements; Heterochromatin formation |

| H3K27ac | Dynamic at enhancers; marks active regulatory elements | p300/CBP, HDAC1-3 | Defines active enhancers; Correlates with gene activation |

| H3K36me3 | Associated with transcribed regions after ZGA | SETD2, KDM2/4 | Transcription elongation; Prevents spurious transcription |

The Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) and its core scaffold subunit Embryonic Ectoderm Development (EED) play particularly important roles in stabilizing the pluripotent state in the inner cell mass (ICM) by depositing H3K27me3 marks at developmental regulator genes [26]. This creates a "poised" state that allows rapid activation upon receipt of differentiation signals. Simultaneously, activating marks such as H3K4me3 and H3K27ac define the transcriptional identity of different cell lineages as they emerge.

Figure 1: Histone Modification Dynamics During Preimplantation Development. The transitions of key histone modifications across developmental stages from zygote to blastocyst, highlighting their establishment during critical transitions like ZGA and lineage specification.

Chromatin Architecture Remodeling

The higher-order chromatin structure undergoes profound reorganization during preimplantation development. In the zygote and early cleavage stages, chromatin is generally more open and accessible, with gradual establishment of repressive domains as development progresses. Chromatin remodeling complexes such as SWI/SNF utilize ATP to slide nucleosomes or evict histones, creating accessible regions for transcription factor binding [27]. These changes in chromatin accessibility precede and predict cell fate decisions, with distinct patterns emerging in the trophectoderm (TE) and inner cell mass (ICM) lineages prior to their morphological distinction.

Recent techniques such as ATAC-seq and Hi-C have revealed that the establishment of topologically associating domains (TADs) and chromatin compartments occurs progressively during preimplantation development. In early embryos, TADs are weakly defined but become increasingly structured following ZGA, with clear A/B compartments emerging by the blastocyst stage. This architectural reorganization facilitates appropriate enhancer-promoter interactions and contributes to the stabilization of cell-type-specific gene expression programs.

Methodological Approaches for Studying Embryonic Epigenetics

Low-Input Epigenomic Profiling

Studying the epigenome in early embryos presents unique technical challenges due to limited cell numbers. The following experimental protocols enable comprehensive epigenomic profiling from small cell numbers:

Low-Input DNA Methylation Sequencing Protocol

- Cell Lysis: Collect individual embryos or pools of 10-20 cells in lysis buffer containing proteinase K

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat DNA with sodium bisulfite using optimized kits (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit) with extended incubation times

- Library Preparation: Amplify converted DNA using post-bisulfite adapter tagging (PBAT) with pre-amplification steps

- Sequencing: Perform shallow whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (~1-3x coverage) or deep targeted sequencing for specific loci

- Data Analysis: Map reads using Bismark or similar tools; calculate methylation levels for CpG sites with ≥5x coverage

This approach has revealed the global demethylation and remethylation dynamics shown in Table 1, with particular insights into imprinted loci that escape genome-wide demethylation [25].

scNucleosome-ATAC-seq for Chromatin Accessibility

- Nuclei Isolation: Gently lyse single embryos or cells in hypotonic buffer with 0.1% NP-40

- Tagmentation: Treat with Tn5 transposase (Illumina) for 30 minutes at 37°C with optimized enzyme concentration

- Library Amplification: Use barcoded primers for multiplexing with limited cycle PCR

- Sequencing: Run on Illumina platforms with 50-100bp paired-end reads

- Analysis: Process with CellRanger-ATAC or SnapATAC; call peaks with MACS2

This method has uncovered the progressive establishment of lineage-specific accessible chromatin regions during preimplantation development and their correlation with transcription factor binding.

Functional Validation in Embryos

CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Epigenome Editing in Mouse Embryos

- gRNA Design: Design guide RNAs targeting specific genomic regions with minimal off-target effects

- Protein Complex Formation: Complex Cas9-D10A nickase with gRNA and fuse to epigenetic effector domains (e.g., DNMT3A, TET1, p300)

- Microinjection: Inject ribonucleoprotein complexes into pronuclear stage zygotes

- Culture & Assessment: Culture embryos to desired stages; analyze phenotype and molecular changes

- Validation: Assess targeted epigenetic changes using bisulfite sequencing (DNA methylation) or CUT&RUN (histone modifications)

This approach has been instrumental in establishing causal relationships between specific epigenetic marks and developmental outcomes, such as the role of H3K27me3 in repressing pluripotency genes during differentiation [26].

Embryonic Stem Cell to Embryo Model Systems

- 2D Differentiation: Induce differentiation in ES cells toward specific lineages using small molecules or growth factors

- 3D Embryoid Bodies: Form aggregates in low-attachment plates with patterned media for multilineage differentiation

- Gastruloids: Use defined starting cell numbers with timed WNT activation to generate polarized models with germ layer organization

- Blastoid Formation: Combine ES cells with trophoblast stem cells or induce specific transcription factors to form blastocyst-like structures

- Analysis: Apply live imaging, single-cell RNA-seq, and immunostaining to compare with in vivo embryos

These model systems enable higher-throughput screening of epigenetic perturbations while maintaining relevance to embryonic development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Embryonic Epigenetics Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT Inhibitors | 5-Azacytidine, RG108, Decitabine | DNA demethylation studies | Toxicity concerns; Partial inhibition often preferable to complete knockout |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Trichostatin A, Valproic Acid, Sodium Butyrate | Histone acetylation enhancement | Pan-inhibitors vs. class-specific; Concentration-dependent effects |

| BET Inhibitors | JQ1, I-BET151 | Bromodomain inhibition | Disrupts reading of acetylated marks; Affects super-enhancers |

| EZH2 Inhibitors | GSK126, EPZ-6438, UNC1999 | H3K27me3 reduction | Specificity for EZH2 vs. EZH1; Compensation mechanisms |

| TET Activators | Vitamin C, 2-HG analogs | DNA demethylation induction | Vitamin C stabilizes TET activity; Multiple mechanisms of action |

| PRC2 Complex Disruptors | EED binders (A-395, MAK683) | Allosteric PRC2 inhibition [26] | More specific than catalytic inhibitors; Different effects on complex stability |

| Pluripotency Factors | OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) | Cellular reprogramming | Partial vs. complete reprogramming; Tumor risk with c-MYC [28] |

| CCMQ | CCMQ (Constitution in Chinese Medicine Questionnaire) | The CCMQ is a 60-item tool for research on TCM body constitution types. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 3'OMe-m7GpppAmpG | 3'OMe-m7GpppAmpG, CAS:113190-92-4, MF:C9H18NO5P, MW:251.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

These reagents enable targeted manipulation of specific epigenetic pathways to establish causal relationships between epigenetic states and functional outcomes. Appropriate controls, including vehicle treatments and multiple inhibitor classes, are essential to confirm specificity of observed effects.

Epigenetic Control of Gastrulation and Lineage Specification

Gastrulation represents a pivotal period when the relatively homogeneous pluripotent epiblast gives rise to the three primary germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. Epigenetic mechanisms play crucial roles in this process by stabilizing lineage commitments and reinforcing cell fate decisions initiated by signaling pathways.

Germ Layer-Specific Epigenetic Landscapes

Each germ layer acquires distinct epigenetic characteristics during gastrulation that define its transcriptional identity and developmental potential:

Ectoderm specification involves establishment of repressive marks on mesendodermal genes while maintaining accessibility for neural and epidermal regulators. The PRC2 complex and its core subunit EED are particularly important for stabilizing the ectodermal fate by depositing H3K27me3 marks at alternative lineage specifiers [26]. Neural induction involves further demethylation of neural gene promoters and activation of specific enhancer regions marked by H3K27ac.

Mesoderm formation is characterized by dynamic DNA methylation changes at key transcription factor genes such as T/Brachyury and TWIST1. Enhancers for mesodermal genes become selectively accessible in response to WNT and NODAL signaling, with pioneer factors like FOXA2 and EOMES facilitating chromatin opening at these regulatory elements.

Endoderm commitment involves widespread DNA hypomethylation at digestive and metabolic genes, coupled with establishment of repressive marks at alternative lineage determinants. Histone variant H2A.Z becomes incorporated at endodermal enhancers, facilitating responsive gene expression to developmental signals.

Figure 2: Epigenetic Mechanisms Stabilizing Germ Layer Identity. Signaling pathways induce transcription factors that recruit chromatin modifiers to establish stable epigenetic states during germ layer specification.

Enhancer Dynamics During Lineage Specification

Enhancer activation and decommissioning represent critical epigenetic processes during gastrulation. Primed enhancers in the epiblast, marked by H3K4me1 alone, become activated through acquisition of H3K27ac or decommissioned through loss of H3K4me1 as cells commit to specific lineages. Lineage-specific transcription factors bind to these regulatory elements and recruit co-activators such as p300/CBP that facilitate histone acetylation and chromatin opening. Simultaneously, Polycomb complexes are recruited to silence enhancers associated with alternative fates, creating a stable commitment to the chosen lineage.

Recent single-cell studies have revealed considerable heterogeneity in enhancer states during gastrulation, suggesting that cells transition through intermediate epigenetic states before stabilizing their identity. This heterogeneity may provide developmental plasticity, allowing cells to alter their fate in response to environmental cues or experimental perturbations until a critical threshold of epigenetic regulation is reached.

Technical Challenges and Future Perspectives

The study of epigenetic reprogramming during early embryogenesis faces several significant technical challenges. The limited biological material available from early embryos necessitates specialized low-input methods that may introduce biases or noise. Dynamic nature of epigenetic marks requires high temporal resolution analyses to capture transient states. Functional validation of epigenetic mechanisms in embryo models may not fully recapitulate the in vivo context, while direct manipulation of embryos is technically demanding and low-throughput.

Future advances will likely come from improved single-cell multi-omics technologies that simultaneously capture multiple epigenetic layers from the same cell, providing more integrated views of epigenetic regulation. CRISPR-based epigenome editing tools with enhanced specificity will enable more precise functional studies. Better in vitro models that recapitulate the spatial organization and signaling environment of the embryo will facilitate higher-throughput experimentation. Finally, computational methods that integrate epigenetic data with transcriptional outputs and signaling states will generate more predictive models of cell fate decisions.

The therapeutic implications of understanding embryonic epigenetic reprogramming are substantial. Insights from natural reprogramming during development have already inspired approaches to generate induced pluripotent stem cells and directly reprogram somatic cells to alternative lineages [28] [27]. A more complete understanding of these processes may enable improved regenerative medicine strategies, better in vitro differentiation protocols for cell-based therapies, and novel approaches to reverse pathological epigenetic states in disease.

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) possess a unique epigenetic landscape that encodes the potential for pluripotency and enables differentiation into all embryonic germ layers. Critical to this potential are distal regulatory elements, enhancers, which adopt preactive states—"primed" and "poised"—to facilitate rapid transcriptional responses to developmental cues. This whitepaper delineates the molecular signatures, functional roles, and mechanisms of these enhancer states in maintaining permissive chromatin, thereby orchestrating lineage choices during mammalian development. We integrate recent multi-omic findings and provide a detailed guide for researchers investigating the epigenetic regulation of cell fate, including standardized experimental protocols and essential reagent solutions.

The precise spatiotemporal control of gene expression during embryonic development is governed by cis-regulatory elements, with enhancers playing a pivotal role in establishing cell identity [29]. In pluripotent stem cells, developmental enhancers are not uniformly active but are often maintained in preparatory epigenetic states that poise them for future activation upon receipt of lineage-specific signals [30] [31]. These preactive states—"primed" and "poised"—enable the rapid and coordinated gene expression changes required for efficient lineage specification without premature differentiation. The establishment and maintenance of these states represent a fundamental mechanism of transcriptional anticipation, allowing the epigenome to encode future developmental potential [31]. This review examines the chromatin features defining these enhancer states, their dynamics during early embryogenesis, and the experimental frameworks for their study, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers in stem cell biology and regenerative medicine.

Molecular Signatures of Primed and Poised Enhancers

Enhancer states are defined by specific combinations of histone modifications, chromatin accessibility, and DNA methylation patterns. These epigenetic signatures serve as molecular barcodes that can be read through genomic assays to infer functional potential.

Histone Modification Profiles

The core signature distinguishing enhancer states revolves around the combinatorial patterns of histone H3 modifications at lysine residues 4, 27, and 9 [29] [30] [32].

- Primed Enhancers are characterized by monomethylation of H3K4 (H3K4me1) in the absence of both the active mark H3K27ac and the repressive mark H3K27me3 [30] [31]. This neutral state is associated with open chromatin (euchromatin) and is thought to represent a basal permissive configuration.

- Poised Enhancers retain H3K4me1 but are additionally marked by the repressive H3K27me3 modification, deposited by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) [29] [30]. They lack H3K27ac. This combination creates a conflicted chromatin state that is accessible but transcriptionally inactive, often bookmarked for activation later in development.

- Active Enhancers are defined by the coexistence of H3K4me1 and H3K27ac, the latter of which is catalyzed by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) like p300/CBP [32]. This state is correlated with active transcription of target genes.

Table 1: Histone Modification Signatures Defining Enhancer States

| Enhancer State | H3K4me1 | H3K27ac | H3K27me3 | Functional Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inactive | - | - | - / + | Silenced; no regulatory activity |

| Primed | + | - | - | Permissive; prepared for activation |

| Poised | + | - | + | Repressed but activatable; bookmarked |

| Active | + | + | - | Transcriptionally enhancing target genes |

Associated Chromatin Features

Beyond core histone modifications, other epigenetic features reinforce these states. Primed and poised enhancers display increased chromatin accessibility, as measured by ATAC-seq or DNase I hypersensitivity, and DNA hypomethylation compared to inactive regions [31]. A distinct class of enhancers, termed "super-enhancers" or "stretch enhancers," are large clusters of active enhancers with robust enrichment for transcriptional coactivators. These often regulate genes that define cell identity, including master regulators of pluripotency like OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG [29].

Biological Functions in Lineage Determination

Preactive enhancer states are not merely static markers but play dynamic, functional roles in guiding embryonic development.

Establishing Developmental Competence

The priming of lineage-specific enhancers occurs surprisingly early in development. Multi-omic analyses of human and mouse ESCs have revealed that enhancers destined to be active in post-gastrulation lineages (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) are frequently pre-marked with H3K4me1 within the epiblast [31]. In some cases, this priming is established as early as the zygote, weeks before the enhancer's activation during lineage specification [31]. This early establishment creates a "blueprint" for future gene regulatory networks.

Facilitating Rapid Fate Transitions

The presence of a pre-established primed enhancer landscape allows for rapid transcriptional responses to differentiation signals. For example, the pioneer factor FOXA2 is required for enhancer priming during the differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) into pancreatic lineages [29]. Similarly, the master regulator Scl binds to pre-established primed enhancers in the mesoderm to regulate the divergence of hematopoietic and cardiac fates [29]. The poised state, with its repressive H3K27me3 layer, ensures that developmental genes are kept inactive in ESCs but can be rapidly activated upon differentiation once the PRC2 complex is displaced and H3K27ac is deposited [30].

Experimental Profiling and Methodologies

Accurate identification and characterization of primed and poised enhancers require integrated multi-omics approaches. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments.

Genome-Wide Mapping with Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP-seq)

ChIP-seq is the cornerstone method for mapping histone modifications genome-wide.

Detailed Protocol:

- Cross-linking: Fix cells with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to covalently link proteins to DNA. Quench with 125mM glycine.

- Cell Lysis and Chromatin Shearing: Lyse cells and isolate nuclei. Shear chromatin to 200-500 bp fragments using a focused ultrasonicator (e.g., Covaris S220). Optimize shearing conditions for each cell type.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate sheared chromatin with 2-5 µg of target-specific antibody (e.g., anti-H3K4me1, anti-H3K27ac, anti-H3K27me3) overnight at 4°C with rotation. Use magnetic protein A/G beads for capture.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads sequentially with low-salt, high-salt, and LiCl buffers, followed by TE buffer. Elute complexes in freshly prepared elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1M NaHCO3).

- Reverse Cross-linking and Purification: Incubate eluates at 65°C overnight with 200mM NaCl to reverse crosslinks. Treat with RNase A and Proteinase K. Purify DNA using a spin column-based kit.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from the immunoprecipitated DNA using a commercial library prep kit (e.g., Illumina). Sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) to a depth of 20-50 million reads per sample.

Data Analysis Workflow:

- Alignment: Map sequenced reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38/hg38) using tools like Bowtie2 or BWA.

- Peak Calling: Identify significant regions of enrichment (peaks) for each histone mark using callers such as MACS2.

- Enhancer Annotation: Annotate peaks relative to genes using tools like ChIPseeker. Distal H3K4me1 peaks (e.g., >2kb from a TSS) are candidate enhancers.

- State Classification: Integrate calls from H3K4me1, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3 ChIP-seq to classify enhancers as primed, poised, or active based on the logic in Table 1.

An Integrated Multi-Omic Analysis Workflow

To definitively characterize the functional state of a primed or poised enhancer, a multi-tiered experimental approach is required, integrating data on histone modifications, chromatin accessibility, and 3D genome architecture.

Functional Validation

Candidate enhancers identified computationally must be validated functionally.

- Reporter Assays: Clone the candidate enhancer sequence (200-500 bp) into a luciferase reporter vector (e.g., pGL4.23) upstream of a minimal promoter. Transfect into ESCs and differentiated cells. Measure activity; primed/poised enhancers will show higher activity in differentiated cells.

- CRISPR-Based Perturbation: Use CRISPR/Cas9 to delete the enhancer in ESCs. Differentiate the knockout cells and assess expression of putative target genes via qRT-PCR or RNA-seq. Impaired upregulation indicates a functional role for the enhancer in lineage specification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful investigation of enhancer biology relies on a suite of validated reagents and tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enhancer Biology

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-H3K4me1 Antibody | Mapping primed and poised enhancer loci via ChIP-seq. | Differentiating primed (H3K4me1+/H3K27ac-) from active (H3K4me1+/H3K27ac+) enhancers. |

| Anti-H3K27me3 Antibody | Identifying Polycomb-poised enhancers via ChIP-seq. | Mapping the repressive layer on poised enhancers (H3K4me1+/H3K27me3+). |

| Anti-H3K27ac Antibody | Defining actively engaged enhancers via ChIP-seq. | Benchmarking enhancer activity states against primed/poised signatures. |

| p300/CBP Antibody | An alternative method to map active enhancer regions. | Independent validation of active enhancer calls from histone mark ChIP-seq. |

| Tn5 Transposase (for ATAC-seq) | Profiling genome-wide chromatin accessibility. | Confirming that primed/poised enhancers reside in nucleosome-depleted, open chromatin. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Functional validation through targeted enhancer deletion. | Establishing causal links between enhancer elements and gene expression programs. |

| pGL4.23[luc2/minP] Vector | Testing enhancer activity in vitro via reporter assays. | Measuring the transcriptional potential of a cloned enhancer sequence. |

| PEPA | PEPA, CAS:141286-78-4, MF:C16H16F2N2O4S2, MW:402.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MTEP | MTEP Hydrochloride|Selective mGluR5 Antagonist | MTEP hydrochloride is a potent, selective mGluR5 antagonist for neuroscience research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Recent Advances and Future Perspectives

Recent studies have further illuminated the dynamics and mechanisms of enhancer priming. A 2025 study using comparative multi-omic analyses of human and mouse early embryonic development confirmed that priming at lineage-specific enhancers for all three germ layers occurs within the epiblast [31]. This epigenetic priming was shown to confer lineage-specific regulation of key developmental gene networks. Notably, this work also outlined a strategy to use natural human genetic variation to delineate sequence determinants of primed enhancer function, opening new avenues for connecting non-coding genetic variation to developmental outcomes [31].

Furthermore, the role of specific enzymes in modulating these states is becoming clearer. For instance, the histone demethylase Jmjd2c (KDM4C) is recruited to active and poised enhancers in ESCs, where it forms a complex with the Mediator complex and the methyltransferase G9a. This complex is essential for the stable assembly of enhancer complexes and for proper multi-lineage differentiation [33].

Therapeutically, the understanding of enhancer biology is informing new approaches in disease modeling and cancer treatment, particularly regarding cancer stem cells (CSCs) where aberrant enhancer states maintain stemness and drive therapy resistance [4]. Epigenetic drugs targeting the writers and erasers of histone marks, such as EZH2 (PRC2) inhibitors, are being explored to disrupt these pathogenic enhancer programs [34] [4].

Primed and poised enhancers represent a fundamental layer of epigenetic regulation that equips embryonic stem cells with the plasticity needed for guided development. Their distinct chromatin signatures, established by a balance of permissive and repressive histone modifications, create a molecular memory of developmental potential. The continued refinement of multi-omic profiling technologies and functional genetic tools will enable an even deeper understanding of how these elements orchestrate the complex dance of lineage specification, with profound implications for regenerative medicine and disease therapeutics.

Advanced Research Models and Epigenetic-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

Cell-Cycle Synchronized hPSC Systems for Studying Epigenetic Dynamics During Differentiation

The interplay between the cell cycle and epigenetic regulation is a fundamental aspect of cell fate determination in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). Research has established that specification of germ layers is regulated by cell cycle regulators, yet molecular studies of these interplays remain challenging due to difficulties in synchronizing large quantities of stem cells [35]. The emergence of sophisticated cell cycle synchronization techniques coupled with high-resolution epigenetic mapping technologies has enabled unprecedented investigation into these dynamic processes. This technical guide examines established methodologies for synchronizing hPSCs and their application in studying epigenetic dynamics during differentiation, providing researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these approaches in developmental biology and regenerative medicine research.

Core Synchronization Methodologies for hPSCs

FUCCI-Based Live Cell Sorting

The Fluorescent Ubiquitination-based Cell Cycle Indicator (FUCCI) system enables live imaging and sorting of cells in different cell cycle phases without chemical inhibitors [36] [37]. This approach uses a two-color (red and green) indicator to track cell cycle progression in live cells:

- Early G1 phase cells display red fluorescence and demonstrate particular readiness for endoderm differentiation, with SMAD2/3 pre-bound to endoderm loci like MIXL1 and SOX17 in undifferentiated hPSCs [37].

- Technical implementation: Cells sorted in early G1 phase (EG1-hPSCs) using FUCCI can be replated in differentiation conditions, maintaining synchronization for approximately 24 hours (the duration of the first cell cycle post-differentiation induction) [36].

This method provides high temporal resolution but presents limitations for large-scale biochemical analyses due to potential viability compromise during sorting and inability to separate S and G2/M phases [35].

Chemical Synchronization with Nocodazole

Small molecule inhibitors offer a complementary approach to cell cycle synchronization. Systematic screening identified nocodazole as the most efficient synchronizing agent for hPSCs [35]:

- Mechanism: Inhibits microtubule polymerization, arresting cells in G2/M phase

- Optimal treatment: 16-hour exposure with doses approximately 10 times lower than conventional somatic cell concentrations

- Synchronization efficiency: >90% of cells in G2/M phase, with synchronous progression through subsequent cycles post-release