Epitope Preservation in Whole Mount Staining: A Complete Guide for 3D Tissue Imaging

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on mastering epitope preservation for successful whole-mount immunohistochemistry.

Epitope Preservation in Whole Mount Staining: A Complete Guide for 3D Tissue Imaging

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on mastering epitope preservation for successful whole-mount immunohistochemistry. It covers the foundational principles of antigen-antibody interactions and the unique challenges of 3D tissue staining, including the critical role of fixation chemistry. The content delivers optimized methodologies and protocols for achieving uniform antibody penetration, practical troubleshooting strategies for common issues like background staining and poor signal, and advanced validation techniques using precision engineering and tissue clearing. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging technologies, this resource enables robust, reproducible whole-organ and whole-body imaging for advanced biomedical research.

The Science of Epitopes and the Whole Mount Challenge

Epitopes, the specific regions on antigens recognized by antibodies, are fundamental to the specificity and function of the immune response. These binding sites are broadly categorized into two distinct types: linear epitopes and conformational epitopes. A linear epitope, also known as a sequential epitope, is defined by a continuous stretch of amino acids within a protein's primary sequence. In contrast, a conformational epitope (also called a discontinuous epitope) is formed by amino acids that are brought into close proximity by the protein's three-dimensional folding but are dispersed in the linear sequence [1]. The distinction is critical; approximately 90% of B-cell epitopes are conformational, while only about 10% are linear [2].

Understanding the nature of the epitope targeted by an antibody is not merely an academic exercise—it is a practical necessity for predicting an antibody's performance in various immunoassays. This knowledge becomes particularly crucial in the context of whole mount staining, a technique used to visualize protein expression in intact tissue samples while preserving their three-dimensional architecture [3]. The choice of fixative, permeabilization method, and antibody in these protocols can dramatically impact the success of the experiment, as these factors are directly influenced by whether the target epitope is linear or conformational.

Characteristics and Experimental Implications

Linear Epitopes

Linear epitopes are composed of a contiguous sequence of amino acids, typically involving 5-20 residues. Their defining characteristic is that the primary structure alone is sufficient for antibody binding; the protein's folded conformation is not required [1]. This makes antibodies targeting linear epitopes particularly robust to conditions that denature proteins.

- Immunogen Design: They are often generated using short synthetic peptides (10-20 amino acids) coupled to carrier proteins [1].

- Assay Compatibility: These antibodies excel in techniques where the target protein is denatured, such as Western blotting (WB) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues that undergo antigen retrieval [1]. In Western blot assays, antibodies targeting linear epitopes frequently produce bands of the correct molecular weight, as their binding is unaffected by SDS-induced denaturation [1].

Conformational Epitopes

Conformational epitopes are formed by amino acids from different parts of the linear sequence that cluster together on the protein's surface due to folding. Their existence is dependent on the native, three-dimensional structure of the protein.

- Immunogen Design: Generating these antibodies typically requires immunizing with full-length proteins or large protein fragments that preserve the native structure [1] [2].

- Assay Compatibility: They are ideal for detecting proteins in their native state, as in flow cytometry, live-cell imaging, and therapeutic applications [1]. However, they often fail in Western blot and other denaturing assays because the process of denaturation destroys the epitope's structure. One study noted that many antibodies targeting conformational epitopes did not bind their target proteins in Western blot assays [1].

Comparative Analysis: Linear vs. Conformational Epitopes

The table below summarizes the core differences between linear and conformational epitopes, providing a guide for experimental planning.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Linear and Conformational Epitopes

| Feature | Linear Epitopes | Conformational Epitopes |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Basis | Continuous amino acid sequence [1] | Discontinuous amino acids brought together by folding [1] |

| Dependency | Protein's primary structure | Protein's native 3D conformation |

| Prevalence | ~10% of B-cell epitopes [2] | ~90% of B-cell epitopes [2] |

| Common Immunogen | Short synthetic peptides [1] | Full-length proteins or large folded fragments [1] [2] |

| Stability to Denaturation | High (resistant to SDS, heat) [1] | Low (destroyed by denaturation) [1] |

| Ideal Applications | Western Blot, IHC-P (after AR) [1] | Flow cytometry, native IP, therapeutics [1] |

The Critical Challenge of Epitope Preservation in Whole Mount Staining

Whole mount immunohistochemistry (IHC) allows for the visualization of protein localization within intact tissue samples, such as embryos, without sectioning, thereby preserving valuable three-dimensional spatial relationships [3]. The core challenge in this technique is achieving adequate penetration of staining reagents throughout the thick tissue while simultaneously preserving the native epitope structure for antibody recognition. This challenge is profoundly influenced by whether the target is a linear or conformational epitope.

The process begins with fixation, which is critical for preserving tissue architecture and antigenicity. However, the very fixatives that preserve structure can mask or destroy epitopes. Paraformaldehyde (PFA), a common cross-linking fixative, stabilizes proteins but can block antibody access to conformational epitopes by creating cross-links [3]. For conformational epitopes sensitive to PFA, methanol fixation, which precipitates proteins without cross-linking, can be a preferable alternative [3]. A significant limitation of whole-mount techniques is that heat-induced antigen retrieval—a standard method to unmask epitopes in sectioned IHC—is typically not feasible for whole embryos or other delicate whole-mount samples, as the heating process would destroy the tissue [3]. Therefore, the initial choice of fixative is often irreversible and dictates the success of detecting conformational epitopes.

Following fixation, permeabilization is necessary to allow antibodies to access the interior of the tissue. For thick samples, this requires extended incubation times with detergents like Triton X-100 [3] [4]. Despite these measures, conventional whole mount staining often yields unsatisfactory results for antibodies, particularly against intracellular antigens or in dense tissues like the cornea, because large IgG molecules cannot readily penetrate deep tissue layers [4]. This problem is especially acute for antibodies targeting conformational epitopes, which require the protein to remain in its native state deep within the tissue—a condition that is difficult to guarantee after fixation.

Table 2: Impact of Whole Mount Staining Steps on Linear vs. Conformational Epitopes

| Protocol Step | Impact on Linear Epitopes | Impact on Conformational Epitopes |

|---|---|---|

| Fixation (4% PFA) | Minimal impact; sequence remains intact [1] | High risk of masking via protein cross-linking [3] |

| Permeabilization | Required for antibody access to interior sequences | Required, but may not fully preserve native lipid environment |

| Antigen Retrieval | Not feasible in whole mounts [3] | Not feasible in whole mounts [3] |

| Antibody Incubation | Long incubation needed for deep penetration [3] | Long incubation needed; native folding must be maintained throughout tissue |

| Primary Challenge | Physical penetration through dense tissue | Preserving native structure during fixation and penetration |

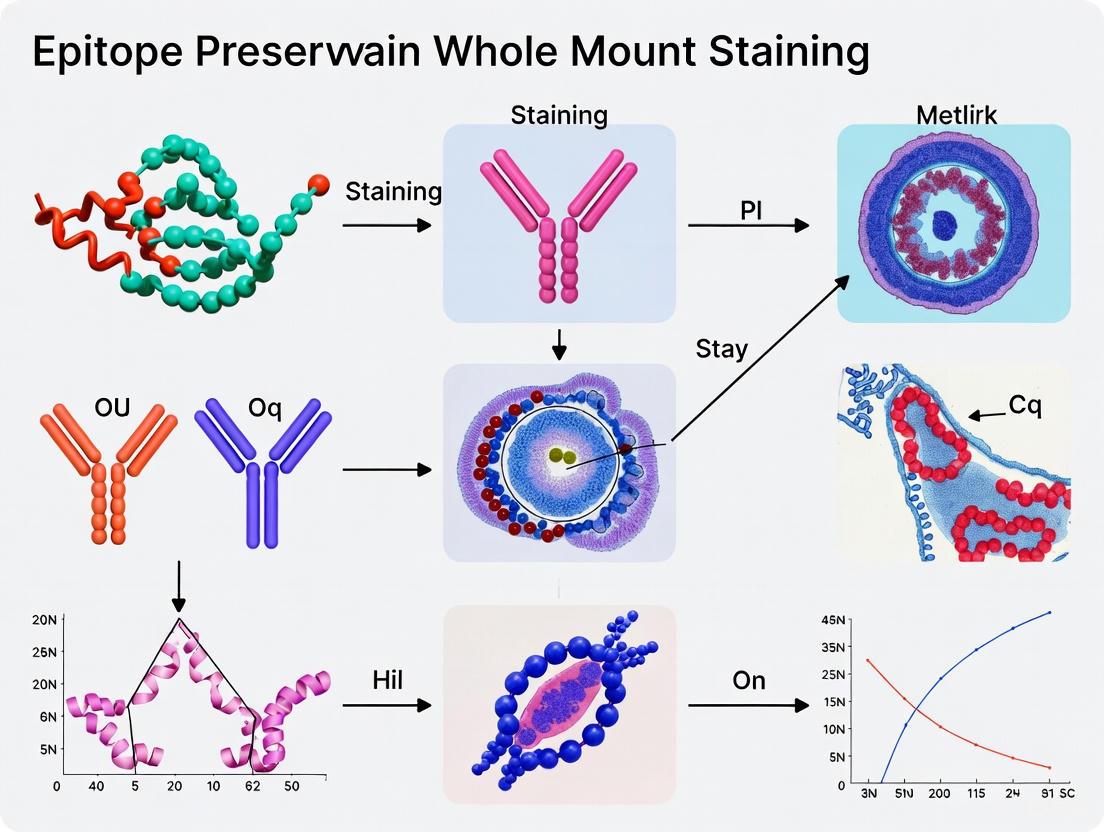

Figure 1: Epitope Integrity in Whole Mount Staining. The diagram contrasts the fates of linear and conformational epitopes during the critical fixation step of whole mount staining. While linear epitopes remain accessible, conformational epitopes are highly susceptible to masking by cross-linking fixatives like PFA, often requiring alternative fixation strategies.

Advanced Protocol: Whole Mount Electro-Immunofluorescence

To overcome the pervasive challenge of antibody penetration in dense whole mount tissues, an advanced technique known as whole mount electro-immunofluorescence has been developed. This method uses a mild electric current to actively drive IgG conjugates and other staining reagents deep into the tissue, significantly improving the distribution and quality of staining for both linear and conformational epitopes [4].

The following workflow details the key steps of this protocol, adapted for corneal tissue but applicable in principle to other whole mount samples [4]:

- Tissue Preparation: Fix the whole mount tissue (e.g., mouse cornea) overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde. For better preservation of soluble proteins and antigenicity, a mixture of 4% PFA and 0.2% glutaraldehyde can be used.

- Permeabilization: Wash the fixed tissue in a buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for one hour.

- Embedding: Embed the tissue in a plastic column filled with 1% solidified agarose. The tissue should be oriented appropriately (e.g., corneal endothelium face up).

- Reagent Application: Overlay the embedded specimen with the primary antibody conjugate (e.g., Alexa Fluor 555-IgG) prepared in 0.5% liquid agarose and allow it to solidify.

- Electrophoresis: Seal the column with 2% agarose and directionally immerse it in a submarine gel electrophoresis apparatus filled with Tris-glycine buffer (pH 7.4). The direction of immersion is critical and depends on the net charge of the staining reagent in the buffer.

- Run Electrophoresis: Electrophorese the staining reagents into the tissue at a constant current of 4-10 mA for 10-24 hours.

- Imaging: After electrophoresis, carefully remove the tissue from the agarose and image using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM).

This method has proven highly effective, allowing for the detection of antigens in all layers of the cornea, including epithelium, stroma, and endothelium, with a uniform distribution pattern that matches section-staining results [4]. It is particularly useful for detecting extracellular matrix components, integral membrane proteins, and intracellular structural proteins that are otherwise inaccessible via conventional whole mount staining.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful experimentation in this field relies on a suite of specialized reagents. The table below catalogs key materials used in the experiments and protocols cited within this guide.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Epitope and Whole Mount Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Overlapping 15-mer Peptides | Synthetic peptides used for linear epitope mapping via PEPscreen [1] | Epitope mapping and specificity characterization |

| Recombinant Protein Fragments (PrESTs) | 50-150 aa unique fragments used as immunogens to generate specific antibodies [1] | Antibody production with defined epitope targets |

| Hitrap Streptavidin HP Columns | Affinity chromatography columns for purifying epitope-specific antibody fractions [1] | Fractionation of polyclonal sera |

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) 4% | Cross-linking fixative that preserves structure but may mask conformational epitopes [3] [4] | Primary fixation for whole mount tissues |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent used to permeabilize cell membranes for antibody access [3] [4] | Permeabilization step in whole mount staining |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer (TGB) | Electrophoresis buffer (pH 7.4) used as a medium for driving reagents into tissue [4] | Running buffer in electro-immunofluorescence |

| Agarose (0.5% - 2%) | Polysaccharide used to create a matrix for embedding tissue and holding staining reagents [4] | Tissue embedding and reagent matrix in electro-immunofluorescence |

| Phalloidin-Rhodamine | Small molecule probe derived from mushrooms that selectively binds to F-actin [4] | Staining of cytoskeletal structures in whole mounts |

| Guvacoline hydrochloride | Guvacoline hydrochloride, CAS:6197-39-3, MF:C7H12ClNO2, MW:177.63 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Aminomethyltrioxsalen hydrochloride | Aminomethyltrioxsalen hydrochloride, CAS:62442-61-9, MF:C15H16ClNO3, MW:293.74 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Technologies and Computational Prediction

The field of epitope-antibody interaction research is being rapidly transformed by advancements in computational prediction and artificial intelligence. Tools like AlphaFold2, a deep learning-based protein structure prediction system, are now being adapted to predict linear antibody epitopes. A pipeline known as PAbFold uses the localColabFold implementation of AlphaFold2 to predict the structure of complexes formed between single-chain antibody fragments (scFvs) and peptide sequences derived from antigens [5].

This approach offers a significant reduction in the time and cost associated with traditional epitope mapping methods, such as peptide competition ELISA. PAbFold operates by breaking the target antigen sequence into small, overlapping linear peptides and then predicting the structure of each peptide in complex with the antibody's complementarity-determining regions (CDRs). Accurate predictions can flag known epitope sequences and provide a structural model for the interaction, which is invaluable for reagent design [5]. This emergent capability is highly sensitive to methodological details like peptide length and the version of the AlphaFold2 neural network.

Concurrently, there are significant efforts focused on conserving conformational epitopes, especially for challenging targets like membrane proteins (MPs). Novel strategies using nanoformulations—such as nanodiscs, Saposin lipid nanoparticles (SapNPs), and Styrene-maleic acid lipid particles (SMALPs)—are being employed to solubilize and present MPs in an artificial bilayer that closely mimics the native membrane environment [2]. This preservation of the native lipid-protein interaction is essential for maintaining the conformational epitopes necessary to generate antibodies that recognize the functional, native state of the protein, which is critical for therapeutic, diagnostic, and vaccine development.

Why Whole Mount Staining Poses Unique Epitope Preservation Challenges

Whole mount staining enables unparalleled three-dimensional analysis of biological structures, preserving spatial context critical for developmental biology and neurobiology research. However, this technique presents significant epitope preservation challenges that distinguish it from traditional section-based immunohistochemistry. The fundamental conflict between maintaining structural integrity and ensuring antibody accessibility creates unique obstacles throughout the fixation, permeabilization, and staining processes. This technical guide examines the multifaceted challenges of epitope preservation in whole mount specimens and provides structured experimental methodologies to overcome these limitations, framed within the broader context of optimizing tissue preparation for three-dimensional analysis.

Whole mount immunohistochemistry represents a specialized approach that preserves the complete three-dimensional architecture of tissue samples, typically embryos or intact organs, without sectioning. Unlike traditional section-based methods that expose internal epitopes through physical cutting, whole mount techniques require reagents to penetrate entire tissue structures while maintaining epitope integrity. This fundamental difference introduces a complex set of challenges centered on the competing demands of tissue preservation and analyte accessibility.

The core dilemma in whole mount staining stems from the need to balance fixation strength against epitope availability. Strong fixation preserves tissue architecture but can mask epitopes through excessive cross-linking, while weak fixation maintains epitope accessibility but risks tissue degradation. This challenge is compounded by the thickness of specimens, which imposes diffusion limitations on antibodies and detection reagents. Researchers must navigate these competing priorities through careful protocol optimization to achieve successful staining while preserving the three-dimensional context that makes whole mount techniques valuable.

Fundamental Technical Challenges

Fixation-Induced Epitope Masking

Fixation represents the most critical stage where epitope preservation challenges first emerge in whole mount staining. The primary fixative used for whole mount samples is 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), which preserves tissue architecture through protein cross-linking [3]. However, this cross-linking creates a dense matrix that can physically block antibody access to target epitopes. The extended fixation times required for adequate penetration in thick specimens—often overnight at 4°C—exacerbate this masking effect through more extensive cross-linking compared to the brief fixation used for thin sections [3].

The irreversible nature of epitope masking in whole mount specimens presents a particular challenge. While sectioned specimens routinely undergo antigen retrieval techniques using heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) to reverse fixation-induced masking, these methods are generally not feasible for whole mount samples due to their fragility and susceptibility to structural damage from heat exposure [3]. This limitation eliminates the most effective tool for recovering masked epitopes, making prevention through optimized fixation the only viable strategy.

Penetration Barriers in Three-Dimensional Tissues

The three-dimensional nature of whole mount specimens creates substantial penetration barriers that directly impact epitope preservation and detection. Antibodies and detection reagents must diffuse through the entire tissue thickness, encountering multiple obstacles including dense extracellular matrices, intact plasma membranes, and cellular organelles. The time required for complete penetration increases exponentially with tissue thickness, creating extended exposure to potentially degradative conditions that can compromise epitope integrity.

The limited penetration capacity of standard antibodies necessitates extended incubation times—often 24-72 hours for larger specimens—during which epitopes remain exposed to proteolytic degradation and conformational changes [3]. This problem is particularly acute for internal epitopes, which may become degraded before antibodies can reach them, creating false-negative results that misinterpret inadequate penetration as epitope absence. Additionally, the size of antibody complexes (approximately 150-900 kDa for IgG antibodies with secondary detection systems) creates physical limitations to diffusion that smaller molecules like fixatives do not encounter.

Structural Preservation Versus Epitope Accessibility Trade-offs

Whole mount staining necessitates navigating fundamental trade-offs between structural preservation and epitope accessibility. Strong fixation with cross-linking agents like PFA optimally preserves tissue architecture but creates the epitope masking challenges described previously. Alternative fixatives such as methanol better preserve some epitopes by precipitating proteins rather than cross-linking them, but provide inferior structural preservation, particularly for delicate cellular structures [3].

This compromise extends to permeabilization strategies, where insufficient permeabilization limits antibody access while excessive treatment damages ultrastructure. Detergents like Triton X-100 must be carefully titrated to balance the creation of diffusion pathways against the preservation of membrane integrity and subcellular organization. The optimal balance point varies significantly between tissue types and target epitopes, requiring extensive empirical optimization for each new application.

Table 1: Primary Challenges in Whole Mount Epitope Preservation

| Challenge Category | Specific Technical Issues | Impact on Epitope Preservation |

|---|---|---|

| Fixation Limitations | Extended cross-linking time, No antigen retrieval option, Epitope masking | Irreversible epitope occlusion, Conformational alterations |

| Penetration Barriers | Limited antibody diffusion, Extended incubation times, Size exclusion effects | Epitope degradation during staining, Incomplete target access |

| Structural Trade-offs | Fixative selection constraints, Permeabilization optimization, Tissue size limitations | Compromised epitope recognition, Variable preservation quality |

Quantitative Analysis of Preservation Challenges

Tissue Size and Antibody Penetration Limitations

The relationship between tissue dimensions and antibody penetration represents a quantifiable limitation in whole mount staining. As tissue size increases, the time required for antibody penetration grows exponentially due to the physics of diffusion through porous media. For mammalian embryos, practical size limitations exist—mouse embryos beyond 12 days gestation and chick embryos beyond 6 days become increasingly challenging for complete antibody penetration [3]. Beyond these developmental stages, tissues must be dissected into smaller segments to enable effective staining, compromising the three-dimensional context that whole mount techniques aim to preserve.

The penetration challenge extends beyond simple size considerations to include tissue density and composition. Different tissue types present varying resistance to antibody diffusion, with epithelial barriers and extracellular matrix density creating particular challenges. The renal glomerulus, intestinal villi, and neural ganglia exemplify structures where high cellular density and specialized matrices significantly impede antibody penetration, requiring extended permeabilization and staining times that further jeopardize epitope stability.

Temporal Factors in Epitope Degradation

The extended protocol durations inherent to whole mount staining create temporal challenges for epitope preservation. Whereas standard IHC on sections may be completed within 1-2 days, whole mount protocols routinely require 5-7 days for adequate fixation, permeabilization, antibody incubation, and washing [3]. During this extended timeline, epitopes remain vulnerable to gradual degradation despite fixation, particularly through residual enzymatic activity and oxidative damage.

The relationship between time and epitope preservation is nonlinear, with significant degradation occurring during the extended antibody incubation phases required for adequate penetration. This creates a fundamental optimization challenge where increasing incubation time improves penetration but risks epitope degradation, while decreasing incubation preserves epitopes but produces incomplete staining. This balance must be empirically determined for each epitope-tissue combination, with limited predictive value from section-based protocols.

Table 2: Quantitative Challenges in Whole Mount Staining Protocols

| Parameter | Standard IHC (Sections) | Whole Mount IHC | Challenge Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation Time | 30 minutes - 2 hours | 2 hours - overnight (4°C) | 2-8x longer |

| Antibody Incubation | 1-2 hours | 24-72 hours | 12-36x longer |

| Total Protocol Duration | 1-2 days | 5-7 days | 3-5x longer |

| Maximum Effective Thickness | 5-20 μm | 100-1000 μm | 20-200x thicker |

| Permeabilization Requirement | 5-30 minutes | 2-12 hours | 10-40x longer |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Optimized Whole Mount Staining Protocol

Successful whole mount staining requires meticulous protocol optimization to balance epitope preservation with adequate penetration. The following methodology represents a generalized approach that can be adapted for specific tissue types and epitopes:

Fixation and Preparation: Fix tissues immediately after dissection in freshly prepared 4% PFA for time periods optimized to tissue size (30 minutes to overnight at 4°C) [6] [3]. For larger specimens, consider vascular perfusion fixation when possible to ensure uniform preservation. Following fixation, wash tissues thoroughly with PBS to remove residual fixative that could continue cross-linking during subsequent steps.

Permeabilization and Blocking: Permeabilize tissues with 0.3-1.0% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2-12 hours depending on tissue density [6]. Follow with extensive blocking using protein-based blockers (3-10% serum) supplemented with 0.1-0.3% Triton X-100 for 4-24 hours to prevent non-specific antibody binding while maintaining permeability.

Antibody Incubation and Detection: Incubate with primary antibodies for 24-72 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation, using concentrations typically 2-5 times higher than those used for section IHC [3]. Follow with extended washes (6-24 hours total with multiple buffer changes) before secondary antibody incubation under similar conditions. For fluorescence detection, use photostable fluorophores and include antifade reagents in mounting media.

Imaging and Analysis: Clear tissues using appropriate optical clearing techniques if needed for deep imaging [7]. Mount specimens in configurations that minimize compression while providing optical access, using specialized chambers or supports with appropriate mounting media [6]. Image using confocal or light sheet microscopy to obtain three-dimensional data while minimizing photobleaching.

Alternative Fixation Strategies

When standard PFA fixation results in epitope masking despite optimization, alternative fixation strategies may preserve vulnerable epitopes:

Methanol Fixation: For epitopes sensitive to PFA-induced cross-linking, methanol fixation at -20°C for 15-30 minutes may preserve antigenicity through protein precipitation rather than cross-linking [3]. This approach particularly benefits cytoplasmic and membrane epitopes vulnerable to conformational changes from aldehyde fixation.

Combination Fixatives: Sequential or mixed fixatives can sometimes balance structural preservation with epitope accessibility. Approaches including low concentrations of glutaraldehyde (0.05-0.25%) with PFA may provide superior ultrastructural preservation while maintaining some epitopes, though this requires extensive optimization and is incompatible with many epitopes.

Heat-Sensitive Epitope Recovery: While standard HIER is not feasible for whole mount specimens, moderate heating (37-45°C) during antibody incubation or using proteinase K at very low concentrations (0.1-1 μg/mL) for limited durations (5-15 minutes) may partially recover some masked epitopes without causing significant tissue damage.

Visualization of Whole Mount Staining Challenges

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental challenges and decision points in whole mount staining that impact epitope preservation:

Diagram 1: Whole Mount Staining Challenges and Solutions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Whole Mount Epitope Preservation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Epitope Preservation | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 4% Paraformaldehyde, Methanol, Trichloroacetic acid | Preserve tissue architecture while maintaining epitope accessibility | Test multiple fixatives; PFA concentration (2-4%); duration (30 min-overnight) |

| Permeabilization Agents | Triton X-100, Tween-20, Saponin, Digitonin | Enable antibody access to internal epitopes | Concentration (0.1-1.0%); combine with blocking; duration (2-12 hours) |

| Blocking Solutions | Normal serum (3-10%), BSA (1-5%), Commercial blocking reagents | Reduce nonspecific background while maintaining permeability | Include 0.1-0.3% permeabilization agent; extend duration (4-24 hours) |

| Antibody Diluents | PBS with carrier proteins, Commercial antibody stabilizers | Maintain antibody and epitope stability during extended incubations | Include protease inhibitors; sodium azide for microbial prevention |

| Mounting Media | Glycerol-based, Commercial antifade media, Optical clearing solutions | Preserve fluorescence signals and tissue integrity for imaging | Match refractive index; include antifade compounds; optimize for imaging modality |

| 2-Hydroxy-4-(methylthio)butyric acid | 2-Hydroxy-4-(methylthio)butyric acid, CAS:583-91-5, MF:C5H10O3S, MW:150.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Diisopropyl phthalate | Diisopropyl Phthalate|CAS 605-45-8|For Research | Diisopropyl phthalate for research. Used in analytical standards and phthalate studies. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

Whole mount staining presents unique epitope preservation challenges that stem from the fundamental conflict between maintaining three-dimensional tissue integrity and providing adequate antibody accessibility. The extended protocols required for thorough tissue penetration, combined with the irreversible nature of fixation-induced epitope masking and the impossibility of standard antigen retrieval techniques, create a complex optimization landscape for researchers. Success in whole mount staining requires meticulous attention to fixation conditions, permeabilization strategies, and temporal factors throughout the multi-day protocol. By understanding these challenges and implementing the systematic approaches outlined in this technical guide, researchers can better navigate the competing priorities of structural preservation and epitope accessibility, ultimately expanding the utility of whole mount techniques for three-dimensional spatial analysis in biological research.

In whole mount staining research, the fixation process establishes a fundamental trade-off: the chemical cross-linking that optimally preserves tissue architecture simultaneously masks epitopes, thereby compromising antigen accessibility for immunohistochemical and molecular analyses. This technical guide explores the biochemical foundations of this dilemma, evaluating fixation methodologies from conventional cross-linking to emerging physical stabilization techniques. We present quantitative data on epitope stability across conditions, detailed protocols for maximizing antigen recovery, and visualization of critical workflows. Within the broader context of epitope preservation research, understanding these dynamics is paramount for advancing volumetric tissue imaging, multiplexed proteomic analysis, and nanoscopic investigation of biological systems in drug development and basic research.

Fixation serves as the cornerstone of histological and cytological analysis, fundamentally aimed at preserving biological structures in a state that closely resembles their living condition. In the field of whole mount staining and three-dimensional tissue analysis, the "fixation dilemma" represents a critical balancing act: achieving optimal tissue integrity through chemical stabilization while maintaining maximum antigen accessibility for molecular probes. This challenge intensifies as researchers pursue increasingly sophisticated multiplexed staining and super-resolution imaging techniques, where epitope preservation directly determines experimental success and data quality [8] [9].

The core issue stems from the very mechanism of the most common fixatives. Aldehyde-based fixatives like formaldehyde work by forming methylene bridges between amino acid residues, creating stable cross-links that preserve tissue morphology but simultaneously alter the three-dimensional structure of proteins. This chemical modification can physically block antibody-binding sites, a phenomenon known as epitope masking [8] [10]. As one review notes, "Fixation alone does not characteristically cause a loss of immunorecognition of tissue antigens. Immunorecognition for some antigens is lost after specific combinations of fixation, tissue processing and paraffin embedding" [10]. The irreversible nature of fixation means that initial processing decisions fundamentally constrain all subsequent analytical possibilities, making the choice of fixation protocol one of the most critical steps in experimental design for whole mount studies.

Fixation Methodologies: Chemical Principles and Practical Implications

Fixation methods broadly fall into two categories based on their mechanism of action: cross-linking fixatives that create covalent bonds between molecules, and precipitating fixatives that denature and insolubilize biomolecules through dehydration and structural disruption.

Cross-Linking Fixatives

Formaldehyde and its derivatives represent the most widely used cross-linking fixatives in histology. The biochemistry involves a two-step process: formaldehyde initially reacts with amino groups to form carbonyl compounds, followed by the formation of stable methylene bridges between amino groups [8]. This cross-linking network effectively preserves cellular architecture but presents significant challenges for epitope accessibility. As one PMC article explains, "Formaldehyde principally reacts with amino groups on proteins to form carbonyl compounds, initiating fixation through insolubilization. Subsequently, the reaction progresses to the formation of methylene bridges through methylol, creating stable cross-links" [8].

Glutaraldehyde provides more extensive cross-linking due to its two aldehyde groups, resulting in superior ultrastructural preservation for electron microscopy but exacerbating epitope masking for immunohistochemical applications. Specialized formulations like periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde (PLP) target specific macromolecules; PLP is particularly effective for glycoprotein preservation through oxidation of carbohydrate moieties and cross-linking via lysine residues [8].

Precipitating Fixatives

Alcohol-based fixatives (methanol, ethanol) and acetone operate through a different mechanism, displacing water and disrupting hydrophobic interactions to precipitate proteins. While these fixatives generally preserve epitope accessibility better than cross-linking alternatives, they often compromise morphological detail through tissue shrinkage and extraction of lipid components [11]. As one technical resource notes, "Alcohol fixation better preserves antigen and antigenicity" but "can distort nuclear and cytoplasmic detail" compared to formalin [11].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Fixative Types

| Fixative Type | Mechanism | Tissue Morphology | Antigen Preservation | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde (4%) | Cross-linking | Excellent | Variable (often requires retrieval) | General histology, diagnostic pathology |

| Glutaraldehyde | Extensive cross-linking | Superior ultrastructure | Poor (severe masking) | Electron microscopy |

| PLP Fixative | Targeted cross-linking | Good | Good for carbohydrates | Glycoprotein studies, lectin histochemistry |

| Ethanol/Methanol | Precipitation/dehydration | Moderate (shrinkage) | Good (minimal masking) | Immunocytochemistry, phosphorylated epitopes |

| Acetone | Precipitation | Fair (extracts lipids) | Excellent | Frozen sections, cell smears |

Quantitative Evidence: Documenting Epitope Vulnerability

The impact of fixation on epitope integrity extends beyond qualitative observations, with multiple studies providing quantitative evidence of antigen degradation under various conditions.

A systematic investigation into epitope stability on tissue microarrays revealed significant time-dependent loss of immunoreactivity. When precut slides were stored under different conditions for one year, the overall median percentage immunoreactivity dropped to 51% compared to time zero. The study further demonstrated that storage conditions significantly influenced degradation rates, with temperatures of -20°C proving most protective [12].

Table 2: Epitope Preservation Across Storage Conditions (1 Year)

| Storage Condition | Median Immunoreactivity | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Room Temperature (air) | 51% | - | Rapid degradation |

| 4°C (air) | 66% | Short-term storage | Moderate degradation |

| -20°C (air) | 87% | Long-term storage | Optimal balance |

| Paraffin Coating | 55% | - | Limited protection |

| Vacuum Sealing | Variable | Specific antibodies | Inconsistent results |

Advanced techniques like epitope-preserving magnified analysis of proteome (eMAP) demonstrate how fixation methodology dramatically impacts antibody compatibility. In one study, conventional chemical hydrogel-tissue fusion (MAP) was compatible with only 35 of 51 synaptic antibodies tested (68.6%), while the physical hybridization approach (eMAP) successfully preserved epitopes for 49 of the same 51 antibodies (96.1%) [13]. This represents a 40% increase in usable targets through optimized fixation alone, highlighting the profound impact of fixation choice on experimental capabilities in multiplexed proteomic studies.

The same study provided quantitative measures of signal quality improvement, with eMAP-processed tissues exhibiting up to 8.3-fold brighter signals and higher correlation coefficients in colabeling experiments compared to conventional methods [13]. These metrics underscore the tangible benefits of epitope-preserving approaches for quantitative imaging and analysis.

Experimental Protocols for Optimal Epitope Preservation

eMAP Protocol for Expansion Microscopy

The eMAP (epitope-preserving magnified analysis of proteome) protocol represents a significant advancement for super-resolution imaging while maintaining epitope integrity. The key modification involves physical hydrogel-tissue hybridization instead of chemical conjugation:

- Tissue Preparation: Begin with formaldehyde-fixed tissue (perfused with 4% formaldehyde). Hemisect and wash thoroughly to remove excess formaldehyde [13].

- Monomer Infusion: Incubate tissue in hydrogel monomer solution (30% acrylamide, 10% sodium acrylate, 0.1% bis-acrylamide, 0.03% VA-044) WITHOUT formaldehyde [13].

- Gelation: Polymerize at 37°C for 2-3 hours. The absence of formaldehyde during this step prevents covalent anchoring of biomolecules to the hydrogel matrix.

- Protein Dissociation: Incubate tissue-hydrogel hybrid in SDS buffer at 95°C for 10 minutes to dissociate protein complexes.

- Expansion: Transfer to deionized water for isotropic expansion (4-10x linear expansion possible).

- Immunostaining: Proceed with standard antibody labeling protocols.

This approach minimizes epitope damage by avoiding chemical modification while enabling nanoscopic resolution imaging with diffraction-limited microscopes [13].

CUBIC-HistoVIsion for Whole-Mount Staining

The CUBIC (Clear, Unobstructed Brain/Body Imaging Cocktails) protocol optimizes whole-organ/body staining by treating tissue as an electrolyte gel:

- Fixation: Perfuse with 4% PFA followed by immersion fixation for 24-48 hours.

- Delipidation: Immerse in CUBIC-L solution (25 wt% urea, 25 wt% N-butyldiethanolamine, 15 wt% Triton X-100) for 2-7 days at 37°C.

- Refractive Index Matching: Transfer to CUBIC-R solution (45 wt% sucrose, 25 wt% urea, 10 wt% 2,2',2''-nitrilotriethanol, 0.1% Triton X-100) for 1-2 days.

- Staining: Incubate with primary antibodies (1-7 days) followed by secondary antibodies (1-3 days) in appropriate blocking buffer.

- Clearing: Return to CUBIC-R solution for final clearing before imaging [9].

This protocol capitalizes on the characterization of fixed, delipidated tissue as an electrolyte gel with fractal nature, enabling uniform antibody penetration throughout entire adult mouse brains and similar large specimens [9].

Visualization of the Fixation and Antigen Recovery Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points in fixation and antigen recovery, highlighting how protocol choices impact tissue integrity and antigen accessibility:

Fixation and Antigen Recovery Workflow: This diagram maps the decision pathway in tissue fixation, illustrating how initial method selection creates divergent trajectories with distinct trade-offs between morphology preservation and epitope accessibility, and the potential restoration pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Epitope Preservation

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RNAlater | RNA stabilization without tissue destruction | Molecular studies requiring histo-molecular correlation |

| Periodate-Lysine-Paraformaldehyde (PLP) | Targeted glycoprotein fixation | Carbohydrate antigen preservation |

| CUBIC-L/CUBIC-R | Tissue delipidation and clearing | Whole-organ 3D staining and imaging |

| eMAP Hydrogel Monomers | Physical tissue hybridization | Expansion microscopy with epitope preservation |

| Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval (HIER) | Reversal of formaldehyde cross-links | Antigen recovery in formalin-fixed tissues |

| Proteolytic Induced Epitope Retrieval (PIER) | Enzymatic unmasking of epitopes | Limited antigen retrieval in sensitive tissues |

| MILAN Buffer | Antibody removal for multiplexing | Cyclic immunofluorescence staining |

| Hydroxythiohomosildenafil | Hydroxythiohomosildenafil, CAS:479073-82-0, MF:C23H32N6O4S2, MW:520.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pipequaline hydrochloride | Pipequaline hydrochloride, CAS:80221-58-5, MF:C22H25ClN2, MW:352.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Discussion: Integrated Strategies for the Fixation Dilemma

The fixation dilemma remains a fundamental consideration in experimental design for whole mount staining research. Rather than seeking a universal solution, researchers must adopt context-dependent strategies that align fixation protocols with specific analytical goals. The emerging paradigm recognizes that optimal outcomes often require either: (1) balanced compromise between structural preservation and antigen accessibility through standardized protocols with appropriate antigen retrieval, or (2) specialized approaches that prioritize one aspect while implementing compensatory measures.

For studies requiring both ultrastructural detail and comprehensive molecular profiling, sequential or multimodal approaches show increasing promise. Techniques like eMAP demonstrate that physical stabilization methods can circumvent the limitations of chemical fixation while enabling advanced imaging modalities [13]. Similarly, the characterization of fixed tissues as electrolyte gels with responsive swelling-shrinkage behaviors opens new possibilities for manipulating tissue properties to enhance reagent penetration without compromising structural integrity [9].

The critical importance of post-fixation handling must be emphasized, as even optimal fixation can be undermined by improper storage. Evidence indicates that storage temperature significantly impacts epitope stability, with -20°C proving most effective for maintaining immunoreactivity over time [12]. Standardization across laboratories remains challenging, as "the formulation of the fixative used i.e. NBF, formal saline, or the use of other solutions of formalin such as formal calcium, has traditionally been left to each individual laboratory" [10].

The fixation dilemma represents both a persistent challenge and a catalyst for innovation in whole mount staining research. As molecular profiling advances toward increasingly multiplexed and nanoscopic analysis, the demand for fixation methods that simultaneously preserve architectural and molecular integrity will intensify. Current research directions—including physical stabilization techniques, computational correction of fixation artifacts, and novel chemistry that reversibly cross-links biomolecules—suggest a future where the compromise between tissue integrity and antigen accessibility becomes less constraining.

For the contemporary researcher, navigating the fixation dilemma requires understanding the biochemical principles of fixation, implementing validated protocols with appropriate controls, and remaining adaptable to emerging methodologies. By viewing fixation not as a standalone procedure but as an integrated component of the analytical pipeline, scientists can better balance the competing demands of structural preservation and molecular accessibility, thereby maximizing the biological insights gained from precious research specimens.

This technical guide explores the characterization of biological tissue as an electrolyte gel, a perspective that revolutionizes the approach to whole mount staining and epitope preservation. By examining fixed and delipidated tissue through a material science lens, researchers can overcome significant bottlenecks in antibody penetration for large-volume samples. The electrolyte-gel model provides a physicochemical framework for understanding staining heterogeneity and enables bottom-up design of superior staining protocols. This paradigm offers advanced opportunities for organ- and organism-scale histological analysis while maintaining epitope integrity, directly supporting the broader thesis that understanding fundamental material properties is essential for advancing whole mount staining research.

The characterization of biological tissue as an electrolyte gel represents a significant shift from purely biological to physicochemical thinking in histology. This perspective emerged from precise material characterization of fixed and delipidated tissue, revealing that biological tissues share fundamental properties with synthetic electrolyte gels [9]. When biological samples undergo standard histological processing including paraformaldehyde (PFA) fixation and delipidation for optical clearing, they transform into a material system primarily composed of cross-linked proteins with distinctive electrolyte properties [9].

This electrolyte-gel model has profound implications for epitope preservation in whole mount staining, as it provides a theoretical foundation for understanding how staining reagents interact with tissue components at molecular scales. The model explains why traditional staining protocols often fail in large tissue volumes and enables researchers to systematically address these limitations through controlled manipulation of the tissue's physicochemical environment [9]. The recognition that fixed tissue constitutes an ionized polypeptide gel dominated by anionic carboxyl groups creates opportunities for precisely engineering staining conditions that maintain epitope accessibility while enabling uniform reagent penetration throughout large tissue volumes [9].

Physicochemical Foundation of Tissue as an Electrolyte Gel

Experimental Evidence for the Electrolyte-Gel Characterization

The electrolyte-gel characterization of biological tissue rests on multiple lines of experimental evidence obtained through material science techniques:

- Swelling-shrinkage behavior: Processed tissue exhibits repeated and reversible swelling and shrinkage under various chemical conditions, fulfilling a key criterion for gel classification in materials science [9]

- Compositional analysis: During clearing procedures, tissue demonstrates coordinated reduction in phospholipids and cholesterol with complementary increase in water content, while protein amount remains largely conserved, resulting in a gel primarily composed of cross-linked proteins [9]

- Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS): Analysis reveals salt-dependent peaks in the scattering intensity profile (q ≈ 0.02–0.04 Ã…â»Â¹, corresponding to ~15–30 nm structures) that disappear at high NaCl concentrations, indicating ionic interaction-dependent long-range spatial correlations characteristic of electrolyte gels [9]

- Fractal nature: The power-law behavior of SAXS profiles (I ∠qâ»á´°) with mass fractal dimension D ≈ 2 indicates a highly heterogeneous gel structure [9]

- Ionization properties: The isoelectric point of CUBIC-delipidated brain tissue is approximately pH 5, confirming that dominant ionized residues in the polymer network are anionic carboxyl groups [9]

Comparative Analysis with Artificial Gel Systems

Table 1: Swelling-shrinkage behavior comparison between biological tissue and artificial gels

| Gel Type | Response to Ionic Strength | Response to pH Changes | Response to Acetone Fraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delipidated Brain Tissue | Sharp shrinkage with increased ionic strength | Multistate swelling/shrinkage dependent on carboxyl group ionization | >4× area shrinkage (8× volume decrease) |

| PFA-fixed Gelatin Gel | Similar to tissue | More dynamic volume change than tissue | Higher sensitivity than tissue |

| PFA-fixed Agarose Gel | No response | No response | No response |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | No response | No response | Limited response |

Comparative studies with artificial gel systems demonstrate that the swelling-shrinkage behaviors of gelatin gel under various ionic strengths, pH values, and acetone fractions closely mimic those of delipidated tissue, while non-ionized agarose and polyacrylamide gels show markedly different responses [9]. This similarity to ionized polypeptide gels further validates the electrolyte-gel model and establishes gelatin as a suitable mimic for method development.

Implications for Whole Mount Staining and Epitope Preservation

Fundamental Staining Challenges in Large Tissues

The insufficient penetration of stains and antibodies remains a crucial bottleneck in three-dimensional staining of large tissue samples [9]. Traditional approaches have included:

- Intensive permeabilization procedures to increase tissue pore size through delipidation, dehydration, weaker fixation, or partial digestion with proteases [9]

- Chemical modifiers such as urea or SDS to control binding affinity of stains and antibodies during penetration [9]

- Physical methods including electrophoresis and pressure application on acrylamide-embedded samples [9]

Despite these approaches, researchers frequently encounter situations where even small dyes fail to penetrate three-dimensional samples, highlighting the complex physicochemical environment of the staining system [9]. The electrolyte-gel model provides a fundamental explanation for these challenges and enables systematic solutions.

Electrolyte-Gel Guided Staining Optimization

Viewing tissue as an electrolyte gel enables rational design of staining conditions based on governing physicochemical principles:

- Ionic strength manipulation: Controlled adjustment of buffer ionic strength manages tissue swelling and shrinkage, directly impacting reagent penetration pathways [9]

- pH optimization: Precise pH control manages the ionization state of carboxyl groups in the tissue matrix, influencing both electrostatic interactions with charged staining reagents and tissue porosity [9]

- Solvent composition: Adjustment of hydrophobic solvent fractions modulates tissue shrinkage and solubility parameters that affect reagent partitioning [9]

The CUBIC-HistoVIsion pipeline exemplifies this approach by using precise characterization of biological tissues as electrolyte gels to experimentally evaluate broad 3D staining conditions using artificial tissue-mimicking material, enabling bottom-up design of superior staining protocols [9].

Quantitative Experimental Data and Methodologies

Key Experimental Findings

Table 2: Quantitative characterization of delipidated tissue as an electrolyte gel

| Parameter | Measurement Technique | Key Findings | Implications for Staining |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesh Size | Small-angle X-ray scattering | Broad peak at q ≈ 0.02–0.04 Ã…â»Â¹ (~15–30 nm) | Determines size exclusion limits for reagent penetration |

| Swelling Ratio | Dimensional analysis | >4× area shrinkage with acetone fraction increase | Enables controlled tissue compaction/expansion |

| Ionic Response | Swelling-shrinkage curves | Sharp shrinkage with increased ionic strength | Permits ionic control of tissue porosity |

| Fractal Dimension | SAXS power-law analysis | D ≈ 2, indicating highly heterogeneous structure | Explains heterogeneous staining patterns |

| Composition | Biochemical analysis | Protein conservation with lipid removal | Confirms cross-linked protein matrix dominates |

CUBIC-HistoVIsion Staining Protocol

The CUBIC-HistoVIsion pipeline represents a comprehensive implementation of the electrolyte-gel perspective, enabling uniform labeling of:

- Whole adult mouse brains

- Adult marmoset brain hemispheres

- ~1 cm³ tissue blocks of postmortem adult human cerebellum

- Entire infant marmoset bodies

with dozens of antibodies and cell-impermeant nuclear stains [9]. The protocol leverages the electrolyte-gel properties through:

- Tissue preconditioning using optimized ionic environments

- Stain application under precisely controlled physicochemical conditions

- Controlled washing to maintain epitope integrity while removing non-specific binding

- Clearing and imaging compatible with light-sheet microscopy

This pipeline has demonstrated success with various cell-impermeant nuclear stains and antibodies, providing high signal-to-background ratios sufficient for computational detection of labeled cells [9].

Research Reagent Solutions for Electrolyte-Gel Based Staining

Table 3: Essential research reagents for electrolyte-gel informed staining protocols

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol | Considerations for Electrolyte Gels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS | Preserves tissue morphology and antigenicity | Creates cross-linked polypeptide network base |

| Permeabilization Agents | Triton X-100, Tween-20 | Solubilizes membranes for antibody access | Concentration critical for mesh size control |

| Blocking Agents | BSA, normal serum, glycine | Reduces non-specific antibody binding | Must account for ionic interactions with gel matrix |

| Buffering Systems | PBS with varied ionic strength | Maintains pH and ionic environment | Directly controls tissue swelling/shrinkage |

| Organic Solvents | Ethanol, methanol, acetone | Dehydration and lipid extraction | Induces controlled shrinkage through reduced solubility |

Visualization of Key Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Logic of electrolyte-gel informed staining. The diagram illustrates how controlling physicochemical parameters (ionic strength, pH, solvent composition) enables optimized staining through managed tissue swelling and mesh size.

Advanced Methodologies and Validation Approaches

Protocol Optimization Through Quantitative Assessment

Advanced staining methodologies incorporate quantitative assessment of staining quality using three key criteria [14]:

- Antibody stain specificity - verification of target-specific binding

- Signal intensity - quantitative measurement of achieved staining strength

- Staining homogeneity - correlation of signal intensity with homogeneously dispersed fluorescent dye distribution

These criteria enable objective evaluation of immunostaining efficiency for large three-dimensional specimens, moving beyond subjective visual assessment [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for studying protein expression distribution and cell types within complex tissue structures without physical sectioning.

Sequential Immunofluorescence for Spatial Proteomics

Sequential Immunofluorescence (seqIF) represents an advanced implementation of electrolyte-gel principles through fully automated iterative staining and elution cycles [15]. This methodology enables:

- Hyperplex spatial proteomics with detection of up to 40 protein biomarkers in a single FFPE tissue section

- Preserved tissue antigenicity and morphology through gentle elution conditions

- Microfluidics-enhanced kinetics reducing incubation times from >1 hour to <5 minutes through optimized surface-to-volume ratios [15]

The seqIF approach demonstrates how precise control of the staining physicochemical environment enables unprecedented multiplexing capability while maintaining epitope integrity across multiple cycles.

The characterization of biological tissue as an electrolyte gel provides a powerful framework for advancing whole mount staining methodologies. This material science perspective enables researchers to overcome fundamental limitations in reagent penetration and epitope preservation through controlled manipulation of ionic strength, pH, and solvent composition. The CUBIC-HistoVIsion pipeline and related methodologies demonstrate how this understanding translates to practical protocols for uniform staining of large tissue volumes. As tissue clearing and 3D imaging technologies continue to evolve, the electrolyte-gel model will remain essential for optimizing staining conditions and extracting maximum biological information from intact tissue systems, directly supporting the broader thesis that epitope preservation in whole mount staining requires fundamental understanding of tissue material properties.

Optimized Protocols for Maximum Epitope Accessibility in 3D Tissues

In whole mount immunohistochemistry (IHC), the three-dimensional architecture of tissues and embryos remains intact, providing a comprehensive view of protein localization and expression patterns within their native spatial context. This technique is particularly valuable in developmental biology, neurobiology, and embryology, where preserving structural relationships is paramount [3]. The foundation of successful whole mount staining lies in effective fixation, a process that halts degradation and preserves cellular morphology. The choice of fixative is arguably the most critical factor, as it directly impacts epitope preservation, antibody penetration, and the overall reliability of experimental outcomes. Among the available options, paraformaldehyde (PFA), methanol, and trichloroacetic acid (TCA) represent fixatives with distinct mechanisms of action and applications. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these fixatives, framing the discussion within the broader context of epitope preservation for research and drug development.

Mechanisms of Action and Epitope Compatibility

Fixatives preserve tissue through different biochemical mechanisms, which directly influence their ability to maintain various epitopes in a recognizable state for antibody binding.

Paraformaldehyde (PFA): As a crosslinking fixative, PFA creates covalent bonds between proteins, primarily by reacting with amine groups. This excellently preserves tissue architecture and the spatial relationships of proteins within the cell [16]. However, this same crosslinking activity can physically obscure or alter epitopes, a phenomenon known as "epitope masking," making them inaccessible to antibodies [3]. While antigen retrieval techniques can sometimes reverse this in sectioned samples, they are generally not feasible for fragile whole mount specimens like embryos, as the heating process would destroy the sample [3].

Methanol: This alcohol-based fixative acts as a coagulant, precipitating proteins by dehydrating the tissue and disrupting hydrophobic interactions. It is less likely to cause epitope masking compared to PFA, making it a valuable alternative when crosslinking-sensitive antibodies are used [3]. A significant advantage is its role in permeabilizing tissues, often reducing the need for additional detergents. However, a potential drawback is that methanol can cause tissue shrinkage and may not preserve fine cellular structures as well as crosslinking fixatives [17].

Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA): TCA is a strong acid that fixes tissues by precipitating proteins through acid-induced denaturation and aggregation [16]. Recent research indicates that this process involves the formation of a reversible, "molten globule-like" partially structured intermediate state in proteins [18]. This unique mechanism can expose epitopes that are otherwise hidden in PFA-fixed tissues, as the denaturation process unfolds protein structures, potentially revealing internal antigenic sites [16]. The precipitation profile of TCA is U-shaped, with maximum efficiency between 5% and 45% (w/v) [18].

Comparative Performance Across Tissue and Target Types

The efficacy of a fixative is highly dependent on the specific tissue being processed and the subcellular localization of the target protein. The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of PFA, Methanol, and TCA for whole mount staining.

Table 1: Fixative Comparison for Whole Mount Staining

| Feature | Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Methanol | Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Protein cross-linking [16] | Protein coagulation & dehydration [3] | Acid-induced protein precipitation [16] [18] |

| Tissue Morphology | Excellent structural preservation [16] | Good, but can cause shrinkage [17] | Alters morphology; results in larger, more circular nuclei [16] |

| Epitope Preservation | Can mask crosslinking-sensitive epitopes [3] | Good for many crosslinking-sensitive epitopes [3] | Can reveal epitopes inaccessible to PFA [16] |

| Ideal for Protein Localization | Nuclear, cytoplasmic, and membrane proteins [16] | Varies; useful for retinal ganglion cells [17] | Cytoskeletal (e.g., Tubulin) and membrane-bound (e.g., Cadherin) proteins [16] |

| Permeabilization | Requires separate detergent treatment | Intrinsic permeabilization ability [3] | Requires separate detergent treatment |

| Typical Concentration | 4% [3] [16] | 100% (cold) [17] | 2% (in PBS) [16] |

| Incubation Time | 20 min - Overnight [3] [16] | Minutes to long-term storage [17] | 1 - 3 hours [16] |

Performance by Subcellular Localization

Research directly comparing PFA and TCA fixation in chicken embryos highlights the profound impact of fixative choice on results, which is tightly linked to the target protein's localization [16] [19].

- Nuclear Proteins (Transcription Factors): PFA fixation is generally optimal for nuclear-localized proteins like transcription factors (e.g., SOX, PAX), providing strong and specific signal intensity [16] [19].

- Cytoskeletal and Membrane Proteins: TCA fixation may be superior for certain targets in these compartments. Studies show it can provide a clearer visualization of cytosolic microtubule subunits (TUBA4A) and membrane-bound cadherin proteins (ECAD, NCAD) compared to PFA [16] [19].

- Retinal Tissues: For whole mount retinas, methanol has been used successfully as an auxiliary fixative. A protocol involves pipetting cold methanol onto the retina during dissection, which helps fix the tissue, facilitate permeability, and allows for long-term storage at -20°C before immunostaining for targets like retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) [17].

Experimental Protocols for Whole Mount Staining

Protocol: PFA Fixation for Embryos

This is a common starting point for many whole mount IHC procedures [3] [16].

- Fixative Preparation: Prepare a 4% (w/v) solution of PFA in phosphate buffer (e.g., 0.2M PBS), pH 7.4.

- Fixation: Immerse the freshly dissected tissue or embryo in the 4% PFA solution. Incubation times must be optimized for tissue size but can range from 20 minutes at room temperature to overnight at 4°C [16].

- Washing: Remove the fixative by washing the sample thoroughly with a buffer containing a detergent, such as PBS with 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 (PBST), to ensure complete PFA removal before proceeding.

Protocol: Methanol Fixation for Retinal Whole Mounts

This protocol is adapted from a method designed for the investigation of retinal ganglion cells [17].

- Initial Fixation: First, fix the enucleated eyeball in 4% PFA for 45 minutes at room temperature. Wash in PBS to remove excess PFA.

- Retina Isolation and Methanol Treatment: Isolate the retina from the eyecup and flatten it. Using a pipette, slowly add cold methanol (pre-cooled to -20°C) drop by drop onto the inner surface of the retina until it is fully covered. The tissue will turn white and become more pliable.

- Storage: Transfer the methanol-treated retina to a storage vial and keep it soaked in methanol. It can be stored at -20°C for immediate use or for long-term preservation.

Protocol: TCA Fixation for Zebrafish Larvae and Chick Embryos

This protocol is effective for zebrafish larvae and has been applied to chick embryos [16] [20].

- Fixative Preparation: Prepare a 2% (w/v) solution of TCA in PBS. A 20% stock solution can be made and stored at -20°C, then diluted fresh before use [16].

- Fixation: Immerse the samples in the 2% TCA solution and fix for 1 to 3 hours at room temperature [16]. For zebrafish larvae, fixation times around 1 hour are common [20].

- Washing: After fixation, wash the samples extensively with PBST or TBST (Tris-buffered saline with Triton X-100) to remove the acid before beginning immunostaining [16].

Decision Workflow and The Scientist's Toolkit

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting the appropriate fixative based on your experimental goals and target antigen.

Diagram 1: Fixative selection workflow for epitope preservation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Whole Mount IHC

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Crosslinking fixative for general structural and antigen preservation. | Primary fixative for chick and mouse embryos; standard for many nuclear targets [3] [16]. |

| Methanol | Coagulant fixative and permeabilization agent. | Auxiliary fixation and long-term storage of retinal whole mounts; alternative for PFA-sensitive antibodies [3] [17]. |

| Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) | Precipitating fixative for revealing hidden epitopes. | Enhancing signal for cytoskeletal (Tubulin) and membrane-bound (Cadherin) proteins [16] [20]. |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent for permeabilizing lipid membranes. | Added to wash buffers (PBST/TBST) after fixation to allow antibody penetration into the tissue [16] [17]. |

| Donkey Serum | Protein source for blocking non-specific antibody binding sites. | Used in blocking buffer (e.g., 10% in PBST) to reduce background staining [16]. |

| Sodium Bicarbonate | Neutralizing agent. | Can be used to help resolubilize and recover native conformation of proteins from TCA precipitates [18]. |

| small cardioactive peptide A | small cardioactive peptide A, CAS:98035-79-1, MF:C59H92N18O12S, MW:1277.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3,5-Dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid | 3,5-Dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid, CAS:89-35-0, MF:C11H8O4, MW:204.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The selection of a fixative is a fundamental decision that balances the preservation of tissue morphology with the optimal exposure of the target epitope. There is no universal fixative that is ideal for all situations. PFA remains the gold standard for general use, particularly for nuclear targets, but its tendency for epitope masking is a significant limitation. Methanol serves as an excellent alternative for crosslinking-sensitive antibodies and offers convenient permeabilization and storage capabilities. TCA has emerged as a powerful tool for visualizing specific classes of proteins, particularly those in the cytoskeleton and membrane, by employing a unique precipitation mechanism that can expose otherwise cryptic epitopes.

Given the profound impact of fixation on experimental outcomes, empirical validation is essential. Researchers should compare multiple fixatives during antibody validation, especially when working with new targets or model systems. This systematic approach to fixative selection ensures that the resulting data most accurately reflect the true biological context, thereby strengthening the conclusions drawn from whole mount immunohistochemistry in both basic research and drug development.

Advanced Permeabilization Strategies for Whole Organs and Embryos

The pursuit of a comprehensive, three-dimensional understanding of biological structures at cellular and sub-cellular resolution has become a central goal in modern life sciences. A significant bottleneck in this endeavor is the need for effective permeabilization strategies that allow large-molecule probes, such as antibodies and RNA in situ hybridization reagents, to penetrate deep into whole organs and embryos while preserving the structural integrity and biomolecular information of the sample. Permeabilization is no longer merely about creating physical pores in tissue; it has evolved into a sophisticated balancing act between achieving sufficient probe penetration and maintaining optimal epitope preservation for accurate biological interpretation. Within the context of a broader thesis on understanding epitope preservation in whole mount staining research, this technical guide examines the latest advanced permeabilization strategies, their physicochemical principles, and their application across diverse tissue types from rodent brains to human organoids.

The fundamental challenge lies in the complex nature of biological tissue. As revealed by material chemistry analyses, fixed and delipidated tissue behaves as an electrolyte gel composed primarily of cross-linked proteins [9]. This gel-like structure responds dynamically to its chemical environment, swelling and shrinking in response to changes in ionic strength, pH, and solvent composition. These physicochemical properties directly impact how permeabilization agents interact with tissue components, ultimately determining both staining efficiency and epitope preservation. The advanced strategies discussed herein are designed with these material properties in mind, enabling researchers to navigate the critical trade-offs between tissue transparency, macromolecular probe penetration, and structural preservation.

Physicochemical Principles of Tissue Permeabilization

Biological Tissue as an Electrolyte Gel

Fixed biological tissue, after delipidation for clearing, undergoes a fundamental transformation in its material properties. Comprehensive characterization using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and swelling-shrinkage analysis reveals that delipidated tissue exhibits properties consistent with an ionized electrolyte gel [9]. This gel state primarily consists of cross-linked proteins, with most cationic amino residues masked by paraformaldehyde (PFA) fixation, leaving anionic carboxyl groups as the dominant ionized residues. This electrolyte gel responds dramatically to its chemical environment, shrinking significantly with increased ionic strength and exhibiting pH-dependent swelling behavior characteristic of ionized polypeptide gels [9].

The practical implication of this gel characterization is profound for permeabilization strategy design. The tissue's mesh network structure, with spatial correlations on the order of 15-30 nm as detected by SAXS, creates a natural barrier for macromolecular probes [9]. Effective permeabilization must therefore modulate this mesh size through controlled chemical interactions while maintaining the gel's overall integrity. This understanding moves permeabilization from a simple detergent-based process to a sophisticated manipulation of polyelectrolyte gel properties.

Detergent Mechanisms and Epitope Preservation

The choice of detergent represents a critical decision point in permeabilization protocol design, with direct consequences for epitope preservation. Traditional methods often rely on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), a strong ionic detergent with high aggregation numbers (80-90) and large micelle formation [7]. While effective for delipidation, SDS's potent detergent properties carry significant risk of protein disruption and epitope denaturation, potentially compromising antibody recognition in subsequent staining steps [7].

Advanced permeabilization strategies have increasingly turned to alternative detergents such as sodium cholate (SC), a bile salt detergent with facial amphiphilicity [7]. SC exhibits superior properties for epitope preservation, including:

- Lower aggregation number (4-16) and smaller micelle size

- Higher critical micelle concentration (14 mM versus 8 mM for SDS)

- Non-denaturing characteristics that better preserve native protein structure

- Easier wash-out due to smaller micelle size, reducing background

These properties make SC-based permeabilization particularly valuable for applications requiring preservation of delicate epitopes or multiphoton imaging where fluorescent protein integrity is essential [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Detergents for Tissue Permeabilization

| Property | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Sodium Cholate (SC) |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure | Linear alkyl sulfate | Steroidal bile salt |

| Micelle Size | Large | Small |

| Aggregation Number | 80-90 | 4-16 |

| Critical Micelle Concentration | 8 mM | 14 mM |

| Protein Preservation | Poor (denaturing) | Good (non-denaturing) |

| Tissue Penetration Efficiency | Moderate | High |

| Epitope Preservation | Low | High |

Advanced Permeabilization Methodologies

Passive Tissue Clearing with Enhanced Permeabilization

The OptiMuS-prime method represents a significant advancement in passive permeabilization techniques, combining sodium cholate with urea in an optimized formulation [7]. This approach leverages urea's ability to disrupt hydrogen bonds and induce tissue hyperhydration, thereby enhancing probe penetration while SC provides gentle yet effective delipidation. The balanced chemical environment preserves tissue architecture and protein integrity while achieving robust permeabilization for whole-organ immunostaining.

The protocol involves immersion of fixed samples in OptiMuS-prime solution (10% SC, 10% D-sorbitol, 4M urea in Tris-EDTA buffer, pH 7.5) at 37°C with gentle shaking [7]. Permeabilization time varies with tissue type and thickness:

- 150-μm-thick mouse brain: 2 minutes

- 1-mm-thick mouse brain: 18 hours

- Whole mouse brain: 4-5 days

- Whole rat brain: 7 days

This method has demonstrated particular efficacy for immunostaining densely packed organs including kidney, spleen, and heart, as well as challenging samples like post-mortem human tissues and human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived brain organoids [7].

Whole-Mount Permeabilization for Specialized Tissues

Specialized tissues demand customized permeabilization approaches. For ocular lens imaging, researchers have developed optimized whole-mount permeabilization using a solution containing 0.3% Triton X-100, 0.3% bovine serum albumin, and 3% goat serum in phosphate-buffered saline [6]. This combination provides sufficient permeabilization while maintaining the delicate structure of lens epithelial and fiber cells, enabling visualization of capsule thickness, epithelial cell area, and nuclear morphology.

For zebrafish spinal cords, an optimized whole-mount immunofluorescence protocol incorporates permeabilization as part of a comprehensive clearing and staining pipeline [21]. The method emphasizes the importance of balancing permeabilization intensity with tissue preservation, particularly for delicate neural structures.

Enzyme-Based Permeabilization for Subcellular Structures

Beyond detergent-based approaches, enzymatic permeabilization offers unique advantages for specific applications. A recently developed protocol for analyzing ribonucleoprotein granules uses mild Tween-20 permeabilization followed by targeted enzymatic treatment with nucleases or proteases [22]. This approach allows researchers to selectively degrade specific cellular components to determine their structural contributions to organelles.

For RNA visualization, the protocol incorporates a sophisticated permeabilization strategy that maintains granule architecture while allowing access for single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) probes [22]. This precision permeabilization enables investigation of protein-RNA, protein-protein, and RNA-RNA interactions within intact cellular contexts.

Experimental Protocols for Advanced Permeabilization

OptiMuS-Prime Protocol for Whole Organs

Materials:

- Sodium cholate (C2154, Sigma)

- Urea (29700, Thermo Scientific)

- D-sorbitol (S7547, Sigma)

- Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (252859, Sigma)

- Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (17385-0401, Junsei Chemical)

Protocol Steps:

Solution Preparation: Dissolve 100 mM Tris and 0.34 mM EDTA in distilled water, adjusting pH to 7.5. Add 10% (w/v) sodium cholate, 10% (w/v) D-sorbitol, and 4M urea to the Tris-EDTA solution. Dissolve completely at 60°C, then cool to room temperature [7].

Tissue Preparation: Fix tissues by perfusion or immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). For optimal permeabilization, post-fix in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight, then rinse with PBS before clearing [7].

Permeabilization Process: Immerse fixed samples in 10-20 mL of OptiMuS-prime solution at 37°C with gentle shaking. Adjust timing based on tissue type and thickness as detailed in Section 3.1 [7].

Immunostaining: Following permeabilization, proceed directly to immunostaining in the same solution or transfer to antibody solution diluted in permeabilization buffer.