Evo-Devo in Biomedicine: How Evolutionary Developmental Biology is Revolutionizing Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative impact of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) concepts on biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Evo-Devo in Biomedicine: How Evolutionary Developmental Biology is Revolutionizing Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) concepts on biomedical research and therapeutic development. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, we examine foundational principles like developmental bias and deep homology, methodological approaches including comparative genomics and ancestral protein reconstruction, common conceptual challenges in applying evolutionary frameworks, and validation through case studies like kinase inhibitor development. The synthesis provides a comprehensive framework for leveraging developmental evolution to address complex disease mechanisms and overcome therapeutic design limitations.

Core Evo-Devo Concepts: From Developmental Bias to Deep Homology

The Modern Synthesis (MS) of the early 20th century successfully integrated Darwin's theory of natural selection with Mendelian genetics, establishing a dominant paradigm that viewed evolution primarily as a process of change in gene frequencies within populations through mechanisms such as random mutation and natural selection [1]. This framework, often termed Neo-Darwinism, provided a robust foundation for biological research for decades. However, the latter part of the 20th century witnessed an accumulation of research findings that severely challenged the MS's core assumptions [1]. Discoveries in molecular biology, genomics, and developmental biology revealed a biological reality far more complex than the MS had envisaged—including super-abundant genetic variation not solely shaped by selection, cells that incorporate genes and organelles of diverse historical origins, and the realization that DNA sequences often evolve in ways that reduce organismal fitness [1].

These challenges have catalyzed a broader, more integrative conceptual framework often referred to as the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES). A cornerstone of this extension is Evolutionary Developmental Biology (Evo-Devo), which posits that evolution cannot be fully understood without considering the processes of organismal development [2] [3]. This paper argues that development is not merely a passive outcome of genetic programs shaped by selection but an active and central player in evolutionary change. By focusing on the role of development in generating phenotypic variation, structuring genetic variation, and facilitating the origin of evolutionary novelties, Evo-Devo provides critical mechanistic explanations for evolutionary patterns that the Modern Synthesis struggled to explain.

The Limitations of the Modern Synthesis

The Modern Synthesis was shaped, in part, by ignorance of important biological features, particularly the complex molecular biology of the cell [1]. Its foundational assumptions, while useful for a time, have been systematically dismantled by subsequent research. A partial list of these now-discarded assumptions includes [1]:

- The genome is a well-organized library of genes: It was imagined as a stable repository of hereditary information.

- Genes have single, honed functions: Each gene was thought to have a specific function finely tuned by powerful natural selection.

- Species are finely adjusted to their environments: Efficient adaptive adjustment of all biochemical functions was assumed.

- Species are the durable units of evolution: The genes, cells, and organs characteristic of a species were thought to evolve in parallel with the species itself.

A key limitation was the MS's "gene-centric" and "externalist" view, where the environment poses challenges, random mutations provide raw material, and natural selection alone acts as a creative force to shape the species. This view rendered development a mere executor of genetic instructions, a black box between genotype and phenotype. The MS assumed a one-way flow of information from DNA to phenotype, with no meaningful feedback. Furthermore, it largely ignored the question of how novel, complex traits originate, focusing instead on the gradual modification of existing structures.

Evolutionary Developmental Biology: Core Conceptual Principles

Evo-Devo shifts the focus from mere gene frequency change to the evolution of the developmental systems that generate the organism. Its principles provide a more dynamic and interactive view of evolutionary change.

Developmental Bias and Facilitated Variation

Organisms are not infinitely malleable; their developmental systems make some phenotypic variants more likely to arise than others. This non-random generation of phenotypic variation is known as developmental bias or facilitated variation [4]. The developmental pathways and mechanisms inherited from an organism's ancestors channel or constrain the phenotypic outcomes of genetic variation. For instance, the repeated, independent evolution of limb loss in reptiles consistently follows a reduction sequence from the digits toward more proximal elements, a pattern dictated by the underlying developmental program for limb patterning [4].

Plasticity-Led Evolution and Genetic Assimilation

Phenotypic plasticity—the ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in response to environmental conditions—is not just a source of temporary adaptation but can be a catalyst for permanent evolutionary change. The "plasticity-first" hypothesis proposes that a new environmental stimulus can first induce a novel phenotype via plasticity. If this phenotype is adaptive, genetic changes that stabilize or refine it—a process known as genetic assimilation—can subsequently follow [4]. The blind Mexican cavefish (Astyanax mexicanus), which evolved eyelessness and enhanced non-visual senses in cave environments, is a key model for studying how developmental plasticity in response to darkness can lead to permanent, genetically encoded traits [4].

The Re-Conceptualized Role of Natural Selection

Within the Evo-Devo framework, natural selection remains a crucial evolutionary force but its role is refined. It is no longer the sole creative agent but acts more as a stochastic sieve [5], filtering the variation that is generated by developmental and mutational processes. The raw materials for selection are not random mutations in an abstract sense, but rather developmental variations with specific biases and structured properties. As one analysis notes, "when variation supplies form (not just substance), it is no longer properly a raw material, and selection is no longer the creator that shapes raw materials into products" [5]. This perspective helps explain the rapid emergence of complex traits and the non-uniform distribution of phenotypic diversity in nature.

Key Evo-Devo Molecular Mechanisms and Experimental Methodologies

The conceptual shift of Evo-Devo is grounded in specific molecular mechanisms that were unknown or underappreciated during the formulation of the Modern Synthesis.

The Read-Write Genome and Natural Genetic Engineering

Contrary to the MS view of the genome as a stable, read-only memory (ROM), it is now understood to be a dynamic, read-write (RW) system [3]. Cells possess a toolkit of enzymes capable of actively restructuring DNA, a process termed natural genetic engineering [3]. This includes mobile genetic elements, genome rearrangements, and gene duplication. A classic example is the Duplication-Degeneration-Complementation (DDC) model, a neutral process where gene duplication allows copies to stochastically accumulate mutations that sub-divide ancestral gene functions, leading to irreversible complexity and dependency [5].

Table 1: Key Molecular Mechanisms Beyond the Modern Synthesis

| Mechanism | Description | Evo-Devo Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) | Networks of genes (e.g., transcription factors) that control the timing and spatial expression of other genes during development. | Explains how small genetic changes can lead to large, coordinated phenotypic shifts through alterations in developmental pathways. |

| Epigenetic Inheritance | Stable, somatically heritable changes in gene expression potential that do not involve changes in DNA sequence (e.g., DNA methylation, histone modifications). | Provides a mechanism for the inheritance of acquired characteristics and for developmental plasticity to influence evolution. |

| Non-Coding RNAs | RNA molecules (e.g., lncRNAs) that regulate gene expression at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. | A vast source of regulatory complexity, often involving repetitive sequences, that controls multicellular development [2]. |

| Cell-Cell Signaling | Communication between cells via signaling pathways (e.g., BMP, Wnt, Hedgehog) to pattern tissues and organs. | Understanding how intercellular communication coordinates development is key to understanding the evolution of form [2]. |

A Key Experimental Workflow: From Phenotype to Genotype

Traditional evolutionary biology often started with genetic variation and sought its phenotypic effect. Evo-Devo frequently inverts this approach, starting with a phenotypic difference and working backward to uncover its developmental and genetic bases.

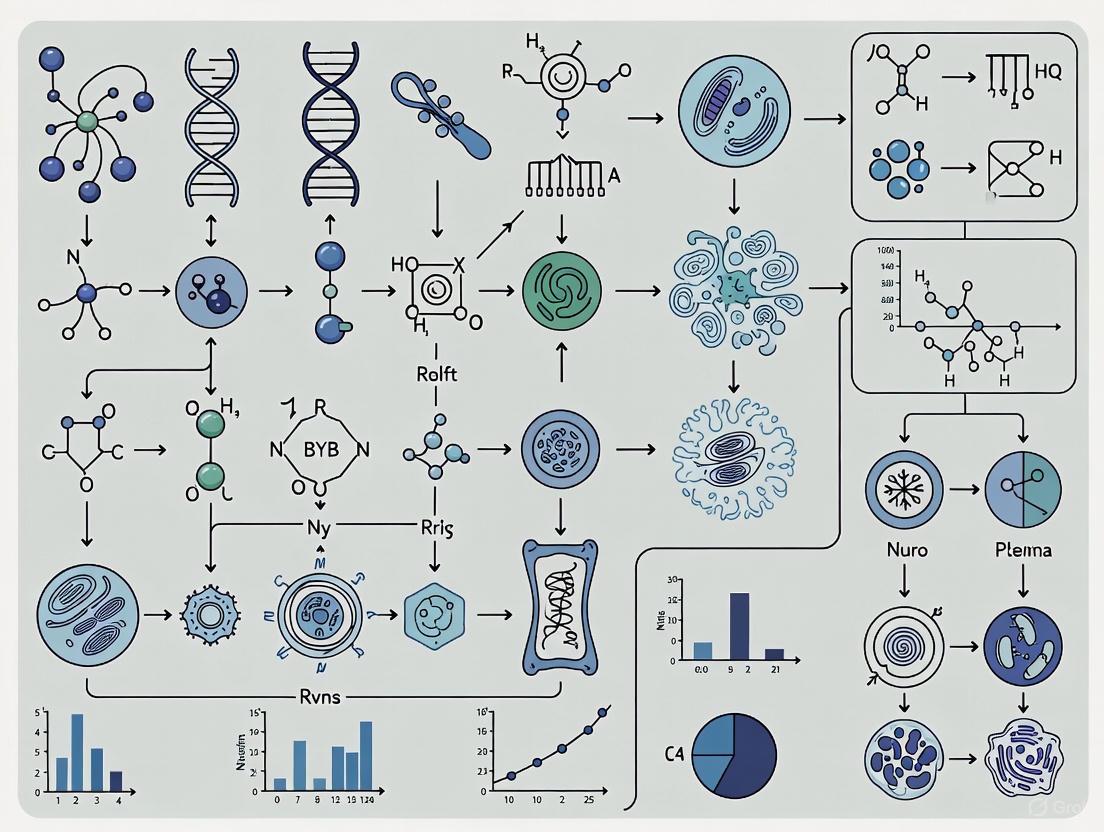

Diagram 1: Evo-Devo Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Evo-Devo

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Evo-Devo Research |

|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing | Enables targeted knockout or modification of candidate genes in non-model organisms to test their functional role in developmental evolution. |

| RNA-seq Reagents | Kits for transcriptome sequencing allow comprehensive profiling of gene expression differences between species or morphs at various developmental stages. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Detect activated signaling pathway components (e.g., pSMAD for BMP pathway) to map where and when key patterning pathways are active. |

| Lineage Tracing Dyes (e.g., DiI) | Fluorescent dyes used to track the fate and movement of specific cell populations during embryogenesis in evolving lineages. |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Kits | Used to map epigenetic marks (e.g., H3K27ac) or transcription factor binding sites to understand the evolution of gene regulation. |

| 2E-3-F16 | F16|Mitochondria-Targeting Agent|RUO |

| LOC14 | LOC14, MF:C16H19N3O2S, MW:317.4 g/mol |

Implications for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

The Evo-Devo perspective has profound implications for human health and disease, moving beyond a purely genetic view of pathology to a developmental and evolutionary one.

Disease as a Result of Developmental and Evolutionary Mismatch

Many modern human diseases, such as obesity, autoimmune disorders, and myopia, can be understood as evolutionary mismatches—conditions where our Paleolithic-developmental adaptations are maladaptive in modern environments. Evo-Devo provides the framework to understand how our developmental programs were shaped by evolution and why they are now prone to failure. Furthermore, some diseases may be viewed as evolutionary legacies, where constraints or compromises from our evolutionary history make us vulnerable (e.g., the narrow human birth canal).

The Role of Epigenetics and the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD)

The Evo-Devo recognition of non-genetic inheritance is transforming disease models. The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis posits that environmental factors during critical developmental windows (e.g., in utero nutrition, stress) can induce epigenetic changes that predispose an individual to disease in adulthood. This provides a mechanistic link between early life experience and late-life pathology, offering new avenues for preventative medicine and early intervention strategies.

Diagram 2: Developmental Origins of Disease

Cancer as a Reversion to an Evolutionary Primitive State

Cancer can be interpreted through an Evo-Devo lens as a breakdown of the multicellular state and a reversion to a more primitive, unicellular-like phenotype characterized by uncontrolled proliferation and motility. The processes of invasion and metastasis reactivate ancient cellular programs related to wound healing and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) that are deeply embedded in our evolutionary history. Understanding cancer as a disease of deregulated development opens the door to novel therapies that aim to re-impose multicellular control rather than simply kill rapidly dividing cells.

The integration of developmental biology into the evolutionary synthesis is not a minor adjustment but a fundamental paradigm shift. The evidence is clear: development is a causative force in evolution, not just its outcome. Principles like developmental bias, plasticity-led evolution, and the dynamics of gene regulatory networks provide a more complete and mechanistic explanation for life's diversity than the gene-centric Modern Synthesis alone could offer.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this expanded perspective is more than academic. It provides a deeper, more nuanced framework for understanding human biology, the origins of disease, and the complex interplay between our evolutionary past, our individual development, and our health. By embracing the Evo-Devo perspective, we can move beyond a view of the body as a static collection of parts optimized by selection, and instead see it as a dynamic system shaped by its deep evolutionary and developmental history, opening up new frontiers for biomedical innovation.

The foundational principle of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) is that the structure of developmental systems non-randomly directs phenotypic variation, thereby influencing evolutionary outcomes. This in-depth technical guide examines the mechanisms of developmental bias and constraint, exploring how gene regulatory networks and physiological processes make some evolutionary trajectories more accessible than others. We synthesize current research demonstrating that developmental bias is not merely a constraint on adaptation but can actively facilitate evolution by aligning the generation of variation with the selective landscape. This analysis is framed within the integrative framework of eco-evo-devo, which connects developmental mechanisms with ecological and evolutionary processes. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these principles provides critical insights into the deep regulatory logic governing morphological evolution and phenotypic diversity.

The neo-Darwinian evolutionary synthesis traditionally posited that random genetic mutations produce isotropic phenotypic variation—equally likely in all directions—upon which natural selection acts deterministically [6]. However, decades of empirical research have revealed this assumption as fundamentally flawed. Phenotypic variation arises through developmental processes, and these processes are inherently structured, producing certain variants more readily than others—a phenomenon termed developmental bias [7] [8].

This technical guide examines developmental bias and constraint as central, evolving properties of biological systems that actively direct evolutionary trajectories. We define these concepts as follows:

- Developmental Bias: The tendency for developmental systems to produce some phenotypic variants more readily than others in response to genetic or environmental perturbation [7] [8]. This encompasses both constraints (limitations) and drives (preferred directions).

- Developmental Constraint: Limitations on phenotypic variability caused by the inherent structure, dynamics, and historical origins of developmental systems [8]. These constraints render certain theoretically possible phenotypes inaccessible or highly improbable.

- Developmental Drive: The inherent tendency of developmental systems to change in particular directions, potentially facilitating adaptation by aligning variation with selective pressures [8].

The emerging eco-evo-devo framework integrates these developmental perspectives with ecological and evolutionary theory, recognizing multidirectional causality across biological scales [9] [10]. This synthesis provides a more complete mechanistic understanding of how biodiversity is generated and maintained.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

The Morphospace Concept and Anisotropic Variation

The morphospace provides a quantitative framework for conceptualizing phenotypic variation—a multidimensional mathematical space where each dimension represents a trait axis, and each organism occupies a point corresponding to its phenotype [8]. Under the isotropic assumption of the modern synthesis, we would expect phenotypes to be evenly distributed throughout this space, limited only by selection. Empirical evidence, however, reveals a starkly different pattern: phenotypes cluster in discrete regions, with large areas of the morphospace remaining empty [7] [8].

This anisotropic distribution demonstrates that developmental architecture makes certain phenotypes more accessible. For example, only a small subset of theoretically possible snail shell shapes exists in nature, with actual species confined to discrete morphospace regions rather than being continuously distributed [8]. Similarly, soil-dwelling centipedes exhibit tremendous variation in leg pair numbers (27-191), yet no species possesses an even number, suggesting either a developmental constraint against even numbers or a drive toward odd numbers [8].

The Genotype-Phenotype Map and Evolvability

The genotype-phenotype map represents the complex relationship between genetic information and expressed phenotypes, mediated by developmental processes [8]. This mapping is highly non-uniform—some genetic changes yield substantial phenotypic effects, while others produce minimal change. This structure determines a population's evolvability: its capacity to generate heritable, adaptive phenotypic variation [6].

Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) are crucial architects of this mapping. Their structure—characterized by hierarchy, modularity, and specific connectivity patterns—determines how perturbations propagate through the system, creating biases in phenotypic output [7]. Theoretical models demonstrate that GRN architectures can evolve to increase the probability of generating adaptive variation, effectively aligning developmental bias with the selective landscape [7] [6].

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence of Developmental Bias Across Biological Systems

| Organism/System | Type of Bias | Experimental Approach | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caenorhabditis nematodes | Vulval development bias | Mutation accumulation lines | Spontaneous mutations produced nonrandom phenotypic variants; features most affected by mutations showed greater variation in stock populations | [7] |

| Drosophila wing | Shape covariation | Mutation accumulation lines + geometric morphometrics | Mutations disproportionately caused covariation among wing parts, producing some shapes more readily than others | [7] |

| Mammalian teeth | Tooth morphology bias | Computational modeling of development | Integration of gene network details with biomechanical properties accurately predicted morphological variation within and across species | [7] |

| Hemingway cat mutants | Digit number bias | Phenotypic analysis of polydactyl cats (n=375) | 20 toes occurred most frequently; 22, 24, or 26 toes with decreasing frequency; odd numbers less common than even | [8] |

| Threespine stickleback | Adaptive divergence along genetic lines of least resistance | Quantitative genetics + comparative analysis | Phenotypic evolution aligned with gmax (direction of greatest genetic variance) more than expected by chance | [6] |

Mechanisms Generating Developmental Bias

Gene Regulatory Networks as Bias Generators

Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) represent the fundamental architecture directing development. Their structure inherently produces bias through several mechanisms:

Network Hierarchy and Modularity: Highly connected core components in GRNs often exhibit evolutionary conservation, while peripheral elements demonstrate greater flexibility. This hierarchical organization creates differential sensitivity to perturbation [7]. For example, mutations affecting early developmental processes typically produce more dramatic and often deleterious effects, while later-acting modifications generate more limited, potentially adaptive variation.

Pleiotropic Relationships: Genes functioning within GRNs frequently influence multiple phenotypic traits (pleiotropy). When selective pressures on these traits conflict, the resulting evolutionary trade-offs can constrain certain evolutionary trajectories while facilitating others [8].

Canalization and Decanalization: Developmental systems exhibit canalization—robustness to genetic and environmental perturbation. However, under specific conditions, this buffering can break down (decanalization), releasing previously hidden variation in biased patterns [7].

Physiological and Biomechanical Factors

Beyond genetic regulation, physical and physiological processes actively constrain and bias development:

Tissue Mechanics and Physical Constraints: Mechanical interactions between tissues during morphogenesis create biases. For instance, the development of the tetrapod limb produces biased patterns in digit number and distribution, with certain skeletal proportions occurring more readily than others [7] [8].

Allometric Growth Relationships: Differential growth rates of body parts (allometry) generate coordinated changes across structures. These allometric relationships often follow predictable trajectories, constraining the range of possible morphologies and creating evolutionary channels [8].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between developmental processes and evolutionary outcomes:

The G-Matrix and P-Matrix as Quantitative Descriptors of Bias

In quantitative genetics, the G-matrix (additive genetic variance-covariance matrix) and P-matrix (phenotypic variance-covariance matrix) statistically represent developmental bias. These matrices describe how traits co-vary, defining the "lines of least resistance" along which populations most readily evolve [8].

When the major axis of genetic variation (gmax) aligns with the direction of selection, evolution proceeds rapidly. When misaligned, response to selection is constrained and may follow a curved trajectory through morphospace [8] [6]. The stability of G-matrices over evolutionary time remains an active research area, with evidence suggesting that the G-matrix itself can evolve in response to selection, potentially reinforcing adaptive biases [6].

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Detecting and Quantifying Developmental Bias

| Methodology | Key Techniques | Applications | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation Accumulation Lines | Propagate lineages with minimal selection; quantify phenotypic effects of spontaneous mutations | Documented bias in vulval development in Caenorhabditis and wing shape in Drosophila [7] | Direct measurement of mutational effects without selection bias | Time-consuming; limited to laboratory model systems |

| Comparative Morphometrics | Geometric morphometrics; morphospace analysis | Snail shell shapes; mammalian dentition; centipede leg patterning [7] [8] | Natural evolutionary patterns; broad phylogenetic scope | Correlative; cannot distinguish bias from selection without developmental data |

| Gene Network Modeling | Computational modeling of developmental processes; in silico evolution | Tooth development models predicting variation across species [7] | Mechanistic understanding; predictive power | Model simplification may miss biological complexity |

| Quantitative Genetics | Estimation of G-matrices and P-matrices; selection experiments | Stickleback adaptive radiation along lines of least resistance [6] | Statistical rigor; predictive framework for short-term evolution | May not capture non-additive genetic effects or epigenetics |

| Environmental Perturbation | Exposure to novel environments or stressors; quantification of plastic responses | Stress-induced variation in house finches; diet-induced jaw morphology changes [7] | Reveals cryptic genetic variation; ecological relevance | Difficult to distinguish genetic from environmental effects |

Experimental Evidence and Case Studies

Mammalian Dentition: A Model of Predictable Evolution

Mammalian tooth morphology provides a compelling case study of developmental bias directing evolutionary trajectories. Salazar-Ciudad and Jernvall developed a computational model integrating molecular details of the gene network underlying molar development with cellular biomechanical properties [7]. This model successfully:

- Reproduced morphological variation observed within species

- Predicted morphological patterns across diverse mammalian species

- Accurately simulated teeth cultivated in vitro

- Retrieved ancestral character states [7]

The predictive power of this model demonstrates that the developmental system for tooth patterning contains inherent biases that explain both microevolutionary variation and macroevolutionary diversification. Similar mechanistic models are being developed for other systems, offering promising approaches for quantifying developmental bias.

Adaptive Radiations: Natural Laboratories for Developmental Bias

Adaptive radiations—rapid diversification of lineages into various ecological niches—provide natural laboratories for studying developmental bias. Several iconic radiations exhibit characteristics suggesting bias as both cause and consequence of diversification [6]:

Cichlid Fishes: African rift lake cichlids demonstrate spectacular diversification in jaw morphology, body shape, and coloration. Their rapid diversification (500+ species in Lake Victoria in ~10,000 years) suggests evolution along "lines of least resistance" provided by shared developmental systems [6].

Caribbean Anoles: These lizards independently evolved similar ecomorphs on different islands. The repeated evolution of these forms suggests underlying developmental biases that channel adaptation toward particular morphological solutions [6].

Threespine Stickleback: Marine stickleback populations repeatedly adapted to freshwater environments, consistently evolving reduced armor plating and specific skeletal changes. Quantitative genetics approaches demonstrate this evolution followed the major axis of genetic variation (gmax) in ancestral populations [6].

The following experimental workflow illustrates approaches for studying developmental bias in adaptive radiations:

Experimental Evolution Approaches

Experimental evolution studies directly demonstrate how developmental bias influences adaptation. For example:

Drosophila melanogaster: Selection for cold tolerance reduced plasticity of life-history traits under thermal stress, demonstrating how developmental associations between environment and phenotype can evolve under sustained selection [9] [10].

Arabidopsis thaliana: Chemical mutagenesis produced phenotypic variants with biased covariance structures between growth, flowering, and seed set, revealing inherent developmental integration [7].

These controlled experiments provide critical evidence that development actively channels rather than passively follows evolutionary change.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Reagents for Developmental Bias Research

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9; TALENs; Zinc Finger Nucleases | Targeted mutagenesis to test developmental hypotheses [7] | Precise modification of regulatory elements; creation of specific mutations to assess phenotypic effects |

| Mutation Accumulation Lines | C. elegans MA lines; Drosophila MA lines | Quantifying distribution of mutational effects [7] | Generation of spontaneous mutations with minimal selection to reveal inherent developmental biases |

| Computational Modeling Platforms | Custom GRN models; finite element analysis; morphospace modeling | In silico simulation of developmental processes and evolution [7] | Prediction of phenotypic variation; testing evolutionary scenarios; identifying developmental constraints |

| Quantitative Morphometrics Software | Geometric morphometrics packages; image analysis algorithms | Quantifying morphological variation and integration [8] | Statistical analysis of shape covariation; morphospace construction and analysis |

| Environmental Manipulation Systems | Controlled environmental chambers; diet manipulation; stress induction | Studying plasticity-induced bias [7] [9] | Revealing cryptic genetic variation; assessing genotype-environment interactions |

| High-Throughput Sequencing | RNA-seq; ATAC-seq; single-cell sequencing | Characterizing gene expression networks and regulatory landscapes [7] | Identifying regulatory elements; mapping gene expression patterns; connecting genotype to phenotype |

| LT175 | LT175, MF:C21H18O3, MW:318.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| LY 165163 | PAPP (4'-Aminopropiophenone) | High-purity 4'-Aminopropiophenone (PAPP) for research use only. Study its role in methemoglobin formation and its application in wildlife management. RUO. | Bench Chemicals |

Implications for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Development

Understanding developmental bias has profound implications for biomedical research and drug development:

Disease Vulnerability and Evolutionary History: Many human diseases represent evolutionary trade-offs or constraints. For example, the human spine's limited safety factors (approximately 1.35 for weightlifters) reflect evolutionary compromises between bipedal locomotion and load-bearing capacity [11]. Understanding these deep constraints informs preventative approaches and therapeutic targets.

Developmental Pathways as Therapeutic Targets: Conserved developmental pathways often represent "obvious" solutions repeatedly employed in evolution. Targeting these pathways (e.g., Hedgehog, Wnt, BMP signaling) in regenerative medicine or cancer therapy aligns with their inherent importance across biological contexts.

Anticipating Evolutionary Responses: In antimicrobial and anticancer drug development, understanding the biased mutational landscape of pathogens and tumors can help predict resistance mechanisms and design combination therapies that block evolutionary escape routes.

Stem Cell Differentiation and Tissue Engineering: Guiding stem cells toward desired fates benefits from understanding inherent developmental biases—the default pathways cells follow with minimal instruction. This knowledge enables more efficient tissue engineering protocols.

Future Directions and Research Agenda

The study of developmental bias requires increasingly integrative approaches:

Integrating Eco-Evo-Devo Perspectives: Future research must connect developmental mechanisms with ecological contexts and evolutionary dynamics across timescales [9] [10]. This includes studying how environmental cues actively shape developmental outcomes and how these interactions evolve.

Multi-Level Modeling Approaches: Developing models that connect genetic variation through cellular and tissue-level processes to organismal phenotypes remains a grand challenge. Such models would dramatically improve predictions of evolutionary trajectories.

Expanding Taxonomic Diversity: Most developmental bias research focuses on traditional model organisms. Expanding to non-model systems, particularly those with exceptional phenotypic diversity or different body plans, will reveal general principles versus lineage-specific phenomena.

Clinical and Translational Applications: Applying developmental bias concepts to medicine may yield insights into congenital disorders, cancer progression, and regenerative processes, where developmental programs are often re-activated or disrupted.

Developmental bias and constraint represent fundamental properties of biological systems that actively direct evolutionary trajectories rather than passively constraining them. Through gene regulatory network architecture, physical constraints, and historical contingencies, developmental systems non-randomly generate phenotypic variation, creating evolutionary channels that influence both the rate and direction of evolutionary change.

The emerging eco-evo-devo synthesis provides a robust framework for understanding how development, ecology, and evolution interact reciprocally across timescales. For researchers and drug development professionals, recognizing these deep developmental patterns offers powerful insights for predicting evolutionary trajectories, understanding disease pathogenesis, and designing novel therapeutic approaches. As research progresses, the principles of developmental bias will increasingly inform our fundamental understanding of life's diversity and our practical approaches to manipulating biological systems.

Deep homology represents a foundational concept in evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), revealing how distantly related organisms share conserved genetic circuitry for building anatomical structures that do not appear homologous by traditional morphological standards. This paradigm shift demonstrates that seemingly novel structures often arise from modification of deeply conserved developmental genetic toolkits inherited from a common bilaterian ancestor. Research in this field has been revolutionized by next-generation sequencing technologies, enabling transcriptome-wide comparisons across diverse species and elevating traditional gene-by-gene analysis to systems-level investigations. This whitepaper examines the core principles of deep homology, presents key experimental methodologies, and explores implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development, providing researchers with both theoretical framework and practical experimental approaches.

Historical and Conceptual Foundations

The principle of homology is central to evolutionary biology, traditionally referring to structures sharing common ancestry despite potential differences in form and function. Sir Richard Owen originally defined homology as "the same organ in different animals under every variety of form and function" [12]. With Darwin's theory of evolution, this concept became linked to historical continuity through descent with modification. However, the emergence of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) revealed limitations in strict historical definitions of homology when applied to molecular mechanisms governing development [12] [13].

Deep homology extends this concept, describing how distantly related species utilize remarkably conserved genetic circuitry during embryogenesis for structures that would not be considered homologous by traditional standards [12]. This represents a paradigm shift in understanding evolutionary innovation, demonstrating that novel features typically result from modifications of pre-existing developmental modules rather than arising de novo. The term was coined to recognize exceptionally conserved gene expression during development of anatomical features lacking clear phylogenetic continuity [12].

Theoretical Framework

At its core, deep homology operates through conserved gene regulatory networks (GRNs) that underlie development across bilaterian animals. These networks exhibit hierarchical organization with different evolutionary dynamics:

- Kernels: These sub-units of GRNs represent the top regulatory hierarchy, central to body plan patterning, exhibiting deep evolutionary conservation, and resisting regulatory rewiring. Their stability underlies the remarkable conservation of animal body plans since the Cambrian explosion [12].

- Character Identity Networks (ChINs): These flexible components define specific morphological characters and can evolve at varying rates from phylum to species level. Unlike kernels, ChINs do not need to be evolutionarily ancient but provide historical continuity through repetitive re-deployment during embryogenesis [12].

- Differentiation Batteries: These assemblies of effector genes direct terminal cell or organ differentiation but lack regulatory information themselves [12].

This framework explains how conservation at the molecular level can produce diversity at the morphological level through regulatory rewiring at intermediate network levels.

Core Mechanisms and Genetic Toolkit

The Evolutionary Developmental Toolkit

All complex animals share a common genetic toolkit of regulatory genes that govern body formation and patterning. This toolkit includes Hox genes, bodybuilder genes, and various regulatory pathways that are conserved across diverse phyla [14]. The discovery of this toolkit overturned previous assumptions that homologous genes could only be found in close relatives, instead revealing deep conservation across evolutionarily distant organisms [14].

Table 1: Key Genetic Toolkit Components in Deep Homology

| Gene/Pathway | Function | Organisms Where Conserved | Phenotypic Effects When Disrupted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pax-6 | Master regulator of eye development | Fruit flies, mice, humans, virtually all bilaterians | Failure of eye development across phyla [14] [15] |

| Distal-Less (DLL) | Appendage development | Chickens, fish, sea squirts, sea urchins | Disrupted limb/fin/appendage formation [14] |

| Tinman (NK2) | Heart/circulatory system development | Insects, vertebrates | Defects in heart development [14] |

| Brachyury | Axial development, notochord formation | Chordates, hemichordates, echinoderms | Disrupted notochord and axial development [16] |

| Hox genes | Anterior-posterior body patterning | All bilaterian animals | Homeotic transformations (e.g., legs where antennae should be) [14] |

| M1001 | M1001, MF:C17H17N3O2S, MW:327.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| CCCP | CCCP, CAS:555-60-2, MF:C9H5ClN4, MW:204.61 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Hierarchical Organization of Developmental Gene Regulatory Networks

The genetic toolkit operates within sophisticated gene regulatory networks (GRNs) that exhibit hierarchical organization. At the top are kernel components that establish the basic body plan, while intermediate plug-ins and I/O switches translate this positional information into specific morphological outcomes [12]. This hierarchical organization explains how small genetic changes can produce substantial morphological evolution while maintaining core body plans.

GRN Hierarchy in Evolutionary Development

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Key Model Systems and Comparative Approaches

Research in deep homology employs comparative approaches across diverse model systems. Key examples include:

- Eye Development: Despite the morphological diversity of eyes across animal phyla, Pax-6 functions as a master control gene in animals ranging from insects to vertebrates [14] [15]. When mouse Pax-6 is expressed in Drosophila, it activates formation of a normal compound fly eye rather than a mouse eye, demonstrating its conserved regulatory function [15].

- Appendage Formation: The Distal-Less (DLL) gene governs appendage development across diverse phyla, forming legs in chickens, fins in fish, siphons in sea squirts, and tube feet in sea urchins [14].

- Heart Development: The Tinman (NK2) gene contributes to circulatory system development across phyla, with conserved function in heart specification in organisms as distant as arthropods and chordates [12].

Experimental Protocols for Deep Homology Research

Protocol 1: Cross-Species Gene Rescue Experiments

Objective: Determine if a gene from one species can functionally replace its ortholog in a distantly related species.

Methodology:

- Identify candidate genes through comparative genomics or transcriptomics

- Clone the orthologous gene (e.g., mouse Pax-6) into appropriate expression vector

- Introduce transgene into mutant host organism (e.g., eyeless Drosophila)

- Assess phenotypic rescue through morphological and molecular analysis

Key Applications:

- Demonstration that mouse Pax-6 can rescue eye development in eyeless flies [14] [15]

- Testing functional equivalence of brachyury genes across chordates and non-chordates [16]

Protocol 2: Gene Expression Network Mapping

Objective: Map conserved gene regulatory networks across species boundaries using high-throughput sequencing.

Methodology:

- Perform RNA-sequencing across multiple developmental timepoints

- Identify co-expression modules using weighted gene co-expression network analysis

- Compare network topology and conserved regulatory relationships across species

- Validate key interactions through functional experiments (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis)

Key Applications:

- Identification of Character Identity Networks (ChINs) for digit identity in avian wings [12]

- Comparative analysis of heart development networks across bilaterians [12]

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Evolutionary Conservation in Genetic Toolkit

| Gene Category | Sequence Identity Range | Structural Conservation | Functional Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox genes | 60-90% across bilaterians | High structural conservation | Conserved anterior-posterior patterning [14] |

| Pax genes | 50-80% in DNA-binding domains | Conservation of DNA-binding domains | Master control of organogenesis [15] |

| Signaling pathways | 40-70% in core components | Conservation of protein interaction domains | Conserved tissue patterning roles [12] |

| Proteasome chaperones | <20% sequence identity | High structural conservation despite divergence | Conserved assembly function [17] |

Structural Biology Approaches to Deep Homology

Recent advances in protein structure prediction have enabled new approaches to identifying deep homology through structural conservation even when sequence similarity is minimal. As demonstrated in studies of proteasome assembly chaperones, proteins can maintain conserved structure and function despite extensive sequence divergence, representing cases of rapid neutral evolution [17].

Experimental Approach:

- Use Foldseek or similar structure-based homology search algorithms

- Compare against traditional sequence-based methods (BLASTP)

- Identify proteins with significant structural homology but minimal sequence similarity

- Validate functional conservation through biochemical and cellular assays

Key Finding: Approximately 204 genes in Candida auris showed significant structural homology with known proteins despite insignificant sequence similarity, enabling functional prediction where sequence-based methods failed [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Deep Homology Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Species Expression Vectors | Pfbra:gfp BAC, Spbra:gfp BAC | Cis-regulatory element analysis [16] | Testing enhancer activity across species |

| Lineage Tracing Systems | Cre-lox, FLP-FRT | Fate mapping of homologous cell populations | Tracking developmental origins of homologous structures |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9, TALENs | Functional validation of conserved elements | Testing necessity/sufficiency of genetic elements |

| Transcriptomic Profiling | RNA-sequencing, single-cell RNA-seq | Comparative gene expression analysis | Identifying conserved expression modules |

| Structural Prediction Software | AlphaFold2, FoldSeek | Detecting structural homology | Identifying homology when sequence similarity is low |

| In Situ Hybridization Probes | Antisense RNA probes for conserved genes | Spatial localization of gene expression | Comparing expression patterns across species |

Research Workflow and Experimental Design

A robust experimental workflow for investigating deep homology integrates comparative genomics, functional validation, and structural analysis as shown in the research pipeline below:

Deep Homology Research Pipeline

Implications for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Development

Disease Modeling and Comparative Genomics

Deep homology provides powerful insights for human disease modeling by revealing conserved genetic pathways across model organisms. For example:

- Studies of Pax-6 in Drosophila have illuminated fundamental mechanisms of eye development relevant to human congenital blindness [15].

- Research on proteasome assembly chaperones in Candida auris demonstrates how structural conservation enables functional prediction even with rapid sequence evolution, with implications for antifungal drug development [17].

- Analysis of brachyury regulation provides insights into notochord development with relevance to chordoma and other axial skeleton disorders [16].

Evolutionary Principles in Drug Discovery

Understanding deep homology enables more informed selection of model systems for drug discovery. Conservation of genetic pathways validates the relevance of particular organisms for studying specific disease mechanisms. Furthermore, identification of structurally conserved proteins with minimal sequence similarity (as demonstrated in fungal proteasome chaperones) may reveal new drug targets that were previously overlooked due to the limitations of sequence-based homology searches [17].

Future Directions and Technological Advances

The field of deep homology continues to evolve with emerging technologies. Single-cell multi-omics enables unprecedented resolution for comparing developmental trajectories across species. Computational protein design leverages insights from deep homology to create artificial proteins that fulfill biological functions, as demonstrated by the design of de novo proteasome chaperones that rescue mutant phenotypes despite being disconnected from evolutionary history [17].

Advanced gene editing technologies now permit experimental testing of deep homology hypotheses in non-model organisms, expanding beyond traditional genetic systems. Meanwhile, integration of paleontology with developmental genetics continues to resolve long-standing mysteries of morphological evolution, such as the debate over digit identity in avian wings [12].

The ongoing synthesis of evolutionary developmental biology with molecular genetics promises to further illuminate how conserved genetic toolkits generate both the astonishing diversity and profound similarities observed throughout the animal kingdom.

Ecological Evolutionary Developmental Biology (Eco-Evo-Devo) has emerged as a definitive integrative discipline dedicated to understanding the causal relationships among environmental cues, developmental mechanisms, and evolutionary processes. Rather than constituting a loose aggregation of research topics, it provides a coherent conceptual framework for exploring how these levels interact to shape phenotypes, morphogenetic patterns, life histories, and biodiversity across multiple scales [18]. This framework aspires to be more than the sum of its parts, contributing to the development of a simpler, more elegant, and heuristically powerful biological theory [18]. The core insight of Eco-Evo-Devo is that the environment is not merely a selective arena but plays an instructive role in development, influencing the generation of phenotypic variation upon which selection acts [18] [19].

This integrative approach challenges the classic view that privileges genetics as the unique central factor in phenotypic evolution [18]. Instead, it recognizes that developmental processes themselves are shaped by ecological interactions, including symbiosis and inter-kingdom communication [18]. Furthermore, it acknowledges that developmental biases and constraints actively direct evolutionary diversification, meaning phenotypic variation is not always random but is influenced by the specific architecture of developmental programs [18]. The expansion of this field signifies a broader transformation in biological thought, one that is increasingly vital for understanding how organisms respond and evolve in relation to rapid ecological change [18] [20].

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

The theoretical foundation of Eco-Evo-Devo rests on several key principles that distinguish it from its parent disciplines. These principles emphasize multi-level causation, the active role of organisms in their development and evolution, and the importance of mechanistic understanding.

Multi-Level Causation and Bidirectional Flows: Eco-Evo-Devo explores a multilevel continuum, from genetic and cellular networks to phenotypic and ecological interactions. This exploration reveals bidirectional causal flows across levels, where, for example, ecological factors can induce developmental changes that subsequently alter evolutionary trajectories [18]. This is metaphorically represented in Figure 1, which shows nested networks generating emergent phenomena.

Developmental Plasticity as a Progenitor of Variation: A central theme is that development itself is a source of phenotypic variation, as it responds to environmental cues. This moves beyond classic reaction-norm approaches that merely describe correlations, toward a causal, mechanistic understanding of how these norms arise and evolve [18] [19]. Plasticity-driven adaptation operates through phenotypic accommodation, genetic accommodation, and genetic assimilation [20].

Niche Construction and Eco-Eco-Devo Feedback: Organisms are not passive recipients of environmental pressure. Through niche construction, they modify their own and other species' environments, thereby altering selective pressures [19] [20]. This creates feedback loops (

eco-evoandeco-devofeedbacks) where ecological changes influence development and evolution, and these changes in turn affect the ecology [19].The Holobiont and Symbiotic Development: The concept of the organism is expanded to the holobiont—a unit of host plus its microbiota. Development is reframed as a symbiotic process, where organismal identity and morphogenesis are produced through interactions with microbial and environmental partners [18] [20].

Extended Inheritance: Inheritance is not solely genetic. Eco-Evo-Devo recognizes other mechanisms, including epigenetic inheritance, cultural inheritance, and ecological inheritance (the legacy of niche-constructing activities), which can transmit developmental resources across generations [19] [20].

The table below defines key terms essential for understanding the Eco-Evo-Devo literature.

Table 1: Glossary of Key Eco-Evo-Devo Terminology

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Eco-Evo-Devo | An integrative discipline aiming to understand how ecological, evolutionary, and developmental processes interact to shape phenotypes and biodiversity [18] [20]. |

| Developmental Plasticity | The ability of an individual to produce different phenotypes under different environmental conditions during development [19]. |

| Niche Construction | The process whereby organisms modify their own and each other's environments, thereby altering selection pressures [19] [20]. |

| Holobiont | The entity composed of a host organism and all of its symbiotic microorganisms, which together function as a unit of selection [18] [20]. |

| Epigenetic Inheritance | The transgenerational transmission of phenotypic variations through non-genetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation or histone modifications, that are induced by environmental factors [19] [20]. |

| Genetic Accommodation | A genetic change, or changes, in the regulation of a trait's expression that occurs after the trait's appearance in response of a novel, often environmental, stimulus [20]. |

| Reaction Norm | The set of phenotypes that a single genotype can express across a range of environments [19]. |

| Eco-Evo Dynamics | The study of how ecological factors (e.g., population dynamics) interact with evolutionary change, often on contemporary timescales [19]. |

Experimental Paradigms and Model Systems

Eco-Evo-Devo leverages diverse model systems and experimental approaches to test its theoretical predictions. The following case studies and methodologies illustrate how this integration is achieved in practice.

Case Study 1: Thermal Adaptation inDrosophila melanogaster

An experimental evolution study in fruit flies demonstrated that selection for cold tolerance directly reduces the plasticity of life-history traits under thermal stress [18]. This highlights that development generates complex associations between environmental cues and phenotypic traits, and that these associations themselves can evolve under sustained environmental selective pressure [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Selection Regime: Establish multiple replicated fly populations.

- Selective Pressure: Maintain experimental populations under a sustained cold stress environment over multiple generations. Control populations are maintained under optimal temperatures.

- Phenotyping: Periodically assay both selected and control populations for key life-history traits (e.g., developmental rate, fecundity, longevity) across a gradient of temperatures.

- Data Analysis: Compare the reaction norms of the selected and control populations. A reduction in plasticity in the selected populations is evidenced by a flattening of the reaction norm curve for the traits under selection.

Case Study 2: Ontogenetic Plasticity in Neotropical Fish

Research on the fish Astyanax lacustris shows how the environment influences phenotypic responses through the dynamics of development itself. The study demonstrated that water temperature modulates developmental responses to different water flow regimes [18]. This indicates that the influence of the environment on phenotypic outcomes is not static but interacts with ontogenetic stage.

Experimental Protocol:

- Factorial Design: Raise fish from fertilization under different environmental treatments in a fully crossed design (e.g., multiple temperature regimes × multiple flow regimes).

- Ontogenetic Tracking: Measure morphological traits (e.g., body shape, fin size) at regular developmental intervals, rather than only at adulthood.

- Analysis of Modulation: Use statistical models (e.g., ANCOVA) to test for significant interaction effects between temperature and flow regime on the measured morphological traits across time. A significant interaction confirms that temperature modulates the developmental response to flow.

Case Study 3: Hominin Brain Expansion

A mathematical model of evolutionary-developmental (evo-devo) dynamics has been used to study the expansion of hominin brain size. The model shows that this expansion can be recovered not by direct selection for larger brains, but through selection on a genetically correlated trait: the number of preovulatory ovarian follicles, which is linked to fertility [21]. This correlation is generated over development when individuals experience a challenging ecology and seemingly cumulative culture [21].

Computational Modeling Protocol:

- Model Formulation: Develop a mechanistic model based on energy conservation principles, describing the developmental dynamics of brain, body, and reproductive tissue sizes as functions of genotypic traits controlling energy allocation [21].

- Parameterization: Estimate key parameters from empirical data, such as brain metabolic costs, which are a major constraint on brain size evolution [21].

- Simulation: Implement the model within an evo-devo dynamics framework to simulate the evolutionary trajectories of brain and body size over millions of years, under different ecological and social scenarios (e.g., challenging vs. benign ecology; presence or absence of culture) [21].

- Causal Analysis: Use the framework to separate the effects of direct selection from developmental constraints by analyzing the evolving genetic covariations between traits [21].

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual framework and causal interactions central to Eco-Evo-Devo, as revealed by the theoretical and empirical studies.

Methodological Considerations and Visualization

Conducting rigorous Eco-Evo-Devo research requires careful experimental design and an awareness of potential methodological biases. A key insight from microbial models is that standard laboratory conditions (e.g., using single strains, constant temperatures, and simplified substrates) can neglect ecologically meaningful contexts, thereby limiting the generalizability of findings [22]. For instance, the developmental phenotypes in the bacterium Myxococcus xanthus were shown to depend on the joint variation of temperature and substrate stiffness, a interaction that would be missed in a simpler design [22].

The experimental workflow for a robust Eco-Evo-Devo investigation, designed to overcome these biases, is visualized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Eco-Evo-Devo Investigations

| Item / Reagent | Function in Eco-Evo-Devo Research |

|---|---|

| Common-Garden & Environmental Chambers | To disentangle genetic and environmental effects on development by raising different genotypes or populations under standardized controlled conditions, while allowing for manipulation of specific factors (e.g., temperature, diet) [19]. |

| RNA-seq / Single-Cell Transcriptomics Kits | To profile gene expression changes across different ecological contexts and developmental stages, identifying the molecular mechanisms underlying plasticity and evolutionary change [18]. |

| Epigenetic Analysis Kits (e.g., Bisulfite Sequencing) | To detect DNA methylation and other epigenetic marks that may mediate the response to environmental cues and be transmitted across generations [19] [20]. |

| Gnotobiotic & Axenic Culture Systems | To rear organisms in the absence of microbes or with a defined microbiota, enabling the study of symbiotic interactions and their role in development (holobiont function) [18] [20]. |

| Geometric Morphometrics Software | To quantitatively analyze and visualize complex morphological changes in response to environmental gradients, providing high-dimensional phenotypic data [18] [19]. |

| Mathematical Modeling Software (e.g., R, Julia) | To develop and simulate mechanistic models of evo-devo dynamics, integrating energy allocation, developmental trajectories, and evolutionary parameters to test causal hypotheses [21]. |

| MCPA (Standard) | MCPA Herbicide|Research-Grade Phenoxy Herbicide |

| Maneb | Maneb |

Quantitative Data Synthesis in Eco-Evo-Devo

The field of Eco-Evo-Devo generates quantitative data across scales, from gene expression to phenotypic traits. The following table synthesizes key types of quantitative data and their interpretations as discussed in the research.

Table 3: Synthesis of Key Quantitative Data in Eco-Evo-Devo Research

| Data Type | Example from Research | Biological Interpretation & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Norm Parameters | "Selection for cold tolerance reduces the plasticity of life-history traits in D. melanogaster" [18]. | Quantifies the change in a phenotype across an environmental gradient. A change in the slope or shape of the reaction norm indicates evolution of plasticity itself. |

| Genetic Covariation / Correlation | Hominin brain expansion driven by genetic correlation with ovarian follicle count [21]. | Measures how two traits co-vary due to genetic influences. A strong correlation can cause a trait to evolve even without direct selection on it (a constraint or facilitator). |

| Metabolic Cost Parameters | Brain metabolic costs used in models to constrain evolution of brain size [21]. | Represents the energetic trade-offs inherent in building and maintaining traits. High costs can limit evolutionary potential unless offset by fitness benefits. |

| Selection Gradient | Inferred selection on follicle count rather than brain size in hominin model [21]. | Measures the direct force of selection on a trait, independent of its correlations with other traits. Crucial for identifying the primary target of selection. |

| Heritability (Broad & Narrow Sense) | Partitioning phenotypic variance (VP = VG + VE) in quantitative genetics [20]. | Estimates the proportion of phenotypic variance due to genetic variance (VG). Essential for predicting evolutionary response, but complicated by non-genetic inheritance in Eco-Evo-Devo. |

The Eco-Evo-Devo expansion represents a foundational shift in biological thinking, providing a more complete framework for understanding the generation of biodiversity. By rigorously integrating environmental context into the heart of developmental and evolutionary analysis, it challenges gene-centric views and emphasizes multi-level causation [18] [19]. The evidence from diverse systems—from fruit flies and fish to hominins and microbes—converges on the conclusion that the environment is an instructive agent in evolution, not merely a selective filter [18] [21] [22].

Future research directions highlighted in the literature include a deeper focus on the mechanistic basis of developmental-environmental interactions, particularly the role of epigenetics and symbiosis [18] [20]. There is also a push for more integrative modeling across biological scales and taxa, and a broader incorporation of niche construction and ecological inheritance into evolutionary models [18] [19]. Furthermore, overcoming laboratory biases by designing experiments with more ecologically relevant contexts will be crucial for the field's progress [22]. As the planet faces unprecedented ecological change, the comprehensive approach offered by Eco-Evo-Devo will be indispensable for predicting biological responses and understanding the dynamics of life in a rapidly altering world [18] [20].

Phenotypic plasticity, defined as the ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in response to environmental conditions, represents a fundamental interface between evolutionary and developmental biology (evo-devo) [23]. This phenomenon is now recognized as a crucial component in understanding how organisms adapt to changing environments, both in natural evolutionary contexts and in disease processes such as cancer progression and drug resistance [24]. The reaction norm—the set of phenotypes a genotype expresses across different environments—provides the most complete and universal description of environment-dependent phenotypic expression and serves as the proper quantitative platform for studying plasticity [23]. Unlike simplified plasticity metrics, reaction norms capture the full biological complexity of environment-phenotype relationships, whether environments are discrete or continuous, simple or multicomponent [23].

Within the evo-devo framework, phenotypic plasticity is understood not merely as a statistical pattern but as a developmental process with mechanistic underpinnings. Recent advances have enabled the mathematical integration of evolutionary and developmental (evo-devo) dynamics, allowing researchers to model how phenotypes are constructed over life and how this construction affects long-term evolution [21]. This perspective reveals that the evolution of exceptionally adaptive traits, including the massive expansion of hominin brain size, may not be caused primarily by direct selection for those traits but by developmental constraints that divert selection through genetic correlations generated over development [21]. This mechanistic, systems approach to phenotypic plasticity provides a powerful framework for understanding both organismal evolution and pathological processes.

Theoretical Foundation: Reaction Norms as the Central Framework

The Reaction Norm Concept and Its Mathematical Representation

The reaction norm framework conceptualizes all forms of learning, memory, and analogous biological processes as special cases of phenotypic plasticity [25]. Formally, this involves expanding the concept of reaction norms to include additional environmental dimensions that quantify sequences of cumulative experience (learning) and time delays between events (forgetting) [25]. Memory, from this perspective, represents just one of several different internal neurological, physiological, hormonal, and anatomical 'states' that mediate the carry-over effects of cumulative environmental experiences on phenotypes across different time periods [25].

Mathematically, reaction norms can be described as either multivariate traits (ordered lists or vectors) over discrete environments or as function-valued traits (curves or surfaces) over continuous environments [23]. This mathematical formalization enables researchers to address questions about phenotypic plasticity with far more depth and realism than simplified, two-environment approaches. The framework easily accommodates various ecological scenarios and closely links statistical estimates with biological processes, providing a conceptual and mathematical structure for investigating the evolution of plasticity across wider ecological contexts [25].

Key Parameters in Reaction Norm Evolution

Table 1: Critical parameters in reaction norm evolution and their biological significance

| Parameter | Biological Significance | Evolutionary Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction norm elevation | Mean phenotype across environments | Can be modified by cumulative prior experience [25] |

| Reaction norm slope | Responsiveness to environmental change | Can be modified by cumulative prior experience [25] |

| Environmental estimate error | Informational memory accuracy | Reflects precision of environmental assessment [25] |

| Phenotypic precision | Skill acquisition capability | Determines fidelity of expressed phenotype [25] |

| Mechanistic socio-genetic covariation | Developmentally generated correlation between traits | Arises from mechanistic description of development rather than regression-based description [21] |

Learning and non-learning plasticity interact whenever cumulative prior experience causes modifications in one or more of these reaction norm parameters [25]. The mathematical and graphical conceptualization of learning as plasticity within a reaction norm framework enables productive cross-fertilization between traditional studies of learning and phenotypic plasticity, encouraging interdisciplinary connections regarding learning mechanisms [25].

Evo-Devo Dynamics: Integrating Development and Evolution

Mathematical Integration of Evolutionary and Developmental Dynamics

A recent mathematical breakthrough—the evo-devo dynamics framework—has enabled the integration of evolutionary and developmental dynamics, allowing researchers to model the evo-devo dynamics for a broad class of models while assuming clonal reproduction and rare, weak, and unbiased mutation [21]. This framework provides equations that separate the effects of selection and constraint for long-term evolution under non-negligible genetic evolution and evolving genetic covariation [21]. Crucially, it offers equations to analyze evolutionary aspects in developmentally explicit models, including what is under selection, how metabolic costs translate into fitness costs, and how phenotypic development translates into genetic covariation [21].

The application of this framework to hominin brain evolution has yielded profound insights. When implemented in a brain model that mechanistically replicates the evolution of adult brain and body sizes of hominin species, the framework shows that brain expansion can occur not through direct selection for brain size but through its genetic correlation with developmentally late preovulatory ovarian follicles [21]. This correlation is generated over development if individuals experience a challenging ecology and seemingly cumulative culture, among other conditions [21]. This demonstrates that the evolution of exceptionally adaptive traits may not be primarily caused by selection for them but by developmental constraints that divert selection.

Visualizing Evo-Devo Dynamics in Phenotypic Plasticity

Evo-Devo Dynamics Framework: This diagram illustrates the integrated relationships between ecological factors, developmental processes, genetic architecture, reaction norm expression, and selective pressures in shaping phenotypic plasticity.

Experimental Approaches: From Framework to Mechanism

Quantitative Methods for Reaction Norm Characterization

Moving beyond simplified two-environment studies is crucial for meaningful insights into phenotypic plasticity. Research confined to two environments or linear reaction norms represents special cases that may not extend to more realistic biological scenarios [23]. Comprehensive experimental designs should incorporate multiple environmental gradients that reflect the actual distribution of conditions organisms encounter in nature.

Essential methodological considerations include:

- Environmental Granularity: Implementing fine and coarse-grained scales of environmental variation across both temporal and spatial dimensions to reflect natural environmental distributions [23]

- Reaction Norm Estimation: Using function-valued methods that require no information about genetics or relatedness to estimate reaction norms across continuous environmental gradients [23]

- Environmental Encounter Documentation: Measuring the actual frequencies of environmental encounters using data loggers, remote sensors, and traditional ecological field work to establish biologically relevant experimental distributions [23]

The distribution of environmental encounters is as crucial to the evolutionary and ecological consequences of plasticity as the reaction norm itself [23]. Yet, studies rarely consider or attempt to measure environmental distributions that species encounter in nature, potentially leading to distorted conclusions when balanced experimental designs overweigh environments that are rare in natural settings.

Research Reagent Solutions for Plasticity Studies

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for experimental studies of phenotypic plasticity

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Data loggers/iButtons | Remote measurement of environmental variables (temperature, COâ‚‚, humidity) | Quantification of environmental encounter distributions in natural settings [23] |

| Two cell-type cancer system model | In vitro model with drug-sensitive and resistant cells | Study of plasticity in cancer cell state transitions and drug resistance [26] |

| Growth rate parameters (râ‚›, ráµ£) | Quantify cell type-specific proliferation rates | Measurement of fitness consequences in different environments [26] |

| Interaction strength parameters (αᵣₛ, αₛᵣ) | Measure competitive inhibition between cell types | Quantification of ecological competition in population dynamics [26] |

| Cell-state transition rates (tâ‚›, táµ£) | Quantify phenotypic switching between states | Measurement of plasticity rates in response to environmental cues [26] |

These research reagents enable the quantification of both environmental parameters and biological responses necessary for comprehensive reaction norm characterization. The two cell-type cancer system provides a particularly valuable model for studying how competition and phenotypic transitions interact in population dynamics, with direct relevance to therapeutic applications [26].

Case Study: Plasticity in Cancer Adaptation and Therapy Resistance

Modeling Competition and Plasticity in Cancer Systems

Cancer adaptation provides a compelling case study for applying reaction norm concepts to understand phenotypic plasticity in pathological contexts. A modified logistic framework modeling a two cell-type cancer system—with drug-sensitive (s) and resistant (r) cells—illustrates the complex interplay between competition and phenotypic transitions [26]. The system dynamics can be described by:

This framework incorporates both density-dependent competition (with interaction strengths αᵣₛ and αₛᵣ) and phenotypic plasticity in the form of cell-state transitions between drug-sensitive and resistant cells (with transition rates tₛ and tᵣ) [26]. The model can be categorized into four types based on parameter values: symmetric competition (SC), symmetric competition with transitions (SC+Tr), asymmetric competition (AC), and asymmetric competition with transitions (AC+Tr) [26].

Experimental Workflow for Therapy Response Modeling

Cancer Therapy Plasticity Workflow: This experimental protocol outlines the key steps in modeling cancer phenotypic plasticity and its implications for therapeutic strategies, particularly adaptive therapy approaches.

This workflow enables researchers to identify distinct balances of competition and phenotypic transitions that determine therapeutic outcomes. The approach reveals that under adaptive therapy, models with cell-state transitions show a higher frequency of fluctuations than those without, suggesting that the balance between ecological competition and phenotypic transitions could determine population-level dynamical properties [26]. The workflow also highlights limitations of phenomenological models in clinical practice, particularly when cell-state transitions are involved, emphasizing the importance of mechanistic modeling even as a population dynamics perspective gains importance in cancer therapy [26].

The reaction norm framework provides an essential conceptual and mathematical structure for advancing the causal understanding of phenotypic plasticity within evo-devo biology. By expanding reaction norms to include dimensions of cumulative experience and temporal dynamics, researchers can bridge traditional divides between studies of learning, development, and evolution [25]. The recent integration of evolutionary and developmental dynamics through mathematical modeling enables deeper insight into how developmental constraints and genetic correlations shape evolutionary trajectories, sometimes diverting selection from what appears to be the primary target [21].

This mechanistic approach has profound implications for both basic evolutionary biology and applied fields such as cancer therapeutics. In cancer, understanding the interplay between ecological competition and phenotypic transitions is essential for designing effective adaptive therapies that manage drug resistance [26]. The recognition that phenotypic plasticity operates alongside genetic mechanisms in cancer progression and drug resistance underscores the importance of this framework for developing novel treatment strategies [24].

Future research should prioritize moving beyond simplified environmental scenarios toward more biologically realistic representations of environmental distributions that organisms actually encounter [23]. This path, while methodologically challenging, promises a more comprehensive understanding of how phenotypic plasticity contributes to adaptation, evolution, and disease processes across biological scales.

Evo-Devo Methodologies: From Comparative Genomics to Therapeutic Discovery

Comparative developmental genetics represents a cornerstone of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), leveraging cross-species analyses to identify conserved genetic regulatory networks that underlie fundamental biological processes. This technical guide examines the integrated experimental and computational methodologies required to decipher these networks, focusing on the interplay between conserved developmental genes and divergent cis-regulatory elements that drive species-specific traits. By synthesizing recent advances in single-cell multiomics, cross-species transcriptomics, and computational modeling, this whitepaper provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for investigating how evolutionary changes in gene regulation contribute to both phenotypic conservation and diversification across mammalian species, with significant implications for understanding the genetic basis of neurological disease and traits.

The central paradox of developmental biology lies in how fundamentally different organisms can arise from a remarkably similar set of developmental genes, a phenomenon now understood to be primarily driven by regulatory changes to similar gene-sets rather than through the evolution of entirely new genes [27]. This paradigm forms the foundational principle of comparative developmental genetics, which seeks to identify conserved regulatory networks by systematically comparing developmental transcriptomes and epigenomes across species. The field operates within the broader conceptual framework of ecological evolutionary developmental biology (eco-evo-devo), which explores the causal relationships among environmental cues, developmental mechanisms, and evolutionary processes across multiple biological scales [9].