Formamide in Hybridization Buffer: A Comprehensive Guide to Mechanism, Optimization, and Safer Alternatives

This article provides a complete resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of formamide in hybridization buffers.

Formamide in Hybridization Buffer: A Comprehensive Guide to Mechanism, Optimization, and Safer Alternatives

Abstract

This article provides a complete resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of formamide in hybridization buffers. It covers the foundational chemistry of how formamide denatures nucleic acids to control stringency, details its application in protocols like FISH and MERFISH for sensitive detection, and offers practical troubleshooting for common issues like high background. The content also evaluates formamide against emerging alternatives such as urea, empowering scientists to optimize hybridization assays for both performance and safety in biomedical and clinical research.

The Biochemical Role of Formamide: How It Controls Hybridization Stringency

This whitepaper elucidates the core function of formamide in hybridization buffers: its role in lowering the melting temperature (Tm) of nucleic acid duplexes. Formamide, a key denaturant, disrupts hydrogen bonding and base stacking interactions, thereby destabilizing double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and RNA structures. This action allows for stringent hybridization to be achieved at lower, biologically favorable temperatures, preserving morphological integrity in techniques such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and Northern blotting. We delve into the quantitative thermodynamics of this process, present experimental data and protocols, and discuss its critical implications for diagnostic and research applications. Understanding this mechanism is foundational for optimizing hybridization conditions and developing next-generation, non-toxic denaturants.

Nucleic acid hybridization—the specific base-pairing of complementary DNA or RNA strands—is a cornerstone technique in molecular biology, central to procedures ranging from diagnostic FISH to microarray analysis [1]. A fundamental challenge in these techniques is that the dissociation of double-stranded nucleic acids into single strands (denaturation) and their subsequent reannealing with complementary probes typically require high temperatures that can damage biological samples or the nucleic acids themselves [2].

Formamide (HCONH₂) addresses this challenge through its core function: effectively lowering the melting temperature (Tm) of nucleic acid duplexes. By adding formamide to hybridization buffers, researchers can significantly lower the energy required for denaturation, enabling high-stringency hybridization to occur at temperatures 20-30°C lower than in aqueous solutions [3]. This temperature reduction is crucial for maintaining tissue architecture in in situ applications and for ensuring the specificity of probe binding in microarray diagnostics [2] [4]. This whitepaper frames this core function within broader research efforts to refine hybridization protocols, enhance assay sensitivity, and develop safer laboratory reagents.

The Mechanistic Basis of Tm Reduction by Formamide

Formamide lowers the Tm of nucleic acids through a multi-faceted mechanism that targets the non-covalent forces stabilizing the double helix.

Disruption of Hydrogen Bonding and Base Stacking

The double helix is stabilized by hydrogen bonds between complementary base pairs and by hydrophobic base-stacking interactions along the helix core. Formamide, a highly polar and water-miscible organic solvent, competes for and disrupts these hydrogen bonds. Its amide group can act as both a hydrogen bond donor and acceptor, effectively interfering with the specific pairing of adenine-thymine and guanine-cytosine bases [5]. Furthermore, formamide penetrates the hydrophobic core of the double helix, destabilizing the cohesive base-stacking interactions that are a major contributor to helical stability [4]. By weakening these two primary stabilizing forces, formamide reduces the thermal energy required to separate the two strands.

Thermodynamic Modeling

The effect of formamide on hybridization thermodynamics can be quantitatively described using a Linear Free Energy Model (LFEM). This model simulates formamide melting by treating the denaturant's effect as an increase in the hybridization free energy (ΔG°). Research has established that formamide increases ΔG° by 0.173 kcal/mol per percent of formamide added (v/v) [4]. This linear relationship allows for the accurate prediction of probe-target duplex stability under various formamide concentrations, which is invaluable for probe design in applications like microbial diagnostic microarrays. The denaturation profile of a probe-target hybrid follows a sigmoidal curve, with the midpoint representing the Tm in a given formamide concentration.

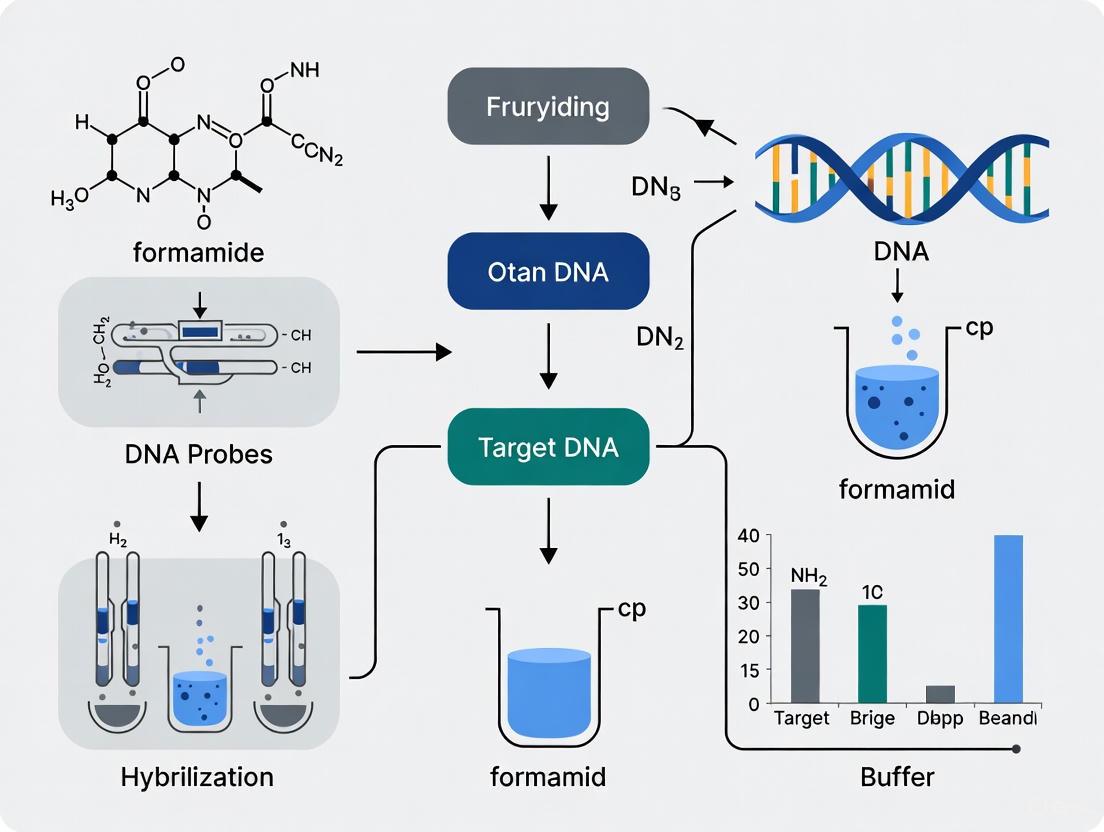

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual mechanism of how formamide disrupts the double helix and the resulting thermodynamic effect.

Quantitative Data and Experimental Evidence

The Tm-lowering effect of formamide is well-characterized and can be precisely quantified, enabling its predictable application in experimental design.

Quantifying the Tm Reduction Effect

The effect of formamide on Tm is concentration-dependent. A general rule of thumb is that for DNA-DNA hybrids, the Tm decreases by approximately 0.6 to 0.7°C for every 1% (v/v) increase in formamide concentration in the hybridization buffer [3]. The relationship can be integrated into Tm calculation formulas. For instance, the formula for the Tm of an RNA:RNA duplex, which is more stable than a DNA:DNA duplex, is:

Tm(RNA:RNA) = 78°C + 16.6 log10([Na+] / (1.0 + 0.7[Na+])) + 0.7(%GC) - 0.35(% Formamide) - 500 / (duplex length) [3].

Table 1: Empirical Data on Formamide Denaturation Efficiency

| Formamide Concentration (% v/v) | Experimental Context | Observed Effect | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30% | SPR-based DNA hybridization with a 22-mer DNA probe | Optimal condition for single base mismatch discrimination; mismatch DNA showed 1.7x less hybridization signal than perfect match DNA. | [6] |

| 50% | SPR-based DNA hybridization with a 22-mer PNA probe | Effective stringency condition; mismatch DNA showed 2.8x less hybridization signal than perfect match DNA. | [6] |

| 45% | Traditional FISH buffer composition | Standard formulation for overnight hybridization protocols. | [2] |

| 15% | Novel "Fast FISH" buffer with alternative solvents (e.g., ethylene carbonate) | Enabled hybridization times as short as 1 hour without the need for denaturation or blocking of repetitive sequences. | [2] |

Application in Stringency Control for Mismatch Discrimination

The primary application of controlled Tm reduction is to enhance hybridization stringency—the ability to discriminate between perfectly matched and mismatched sequences. Since mismatched duplexes are inherently less stable, they denature at a lower formamide concentration than perfect matches. As shown in Table 1, by performing hybridization in 30% formamide, researchers achieved a 1.7-fold discrimination against a single-base mismatch using a DNA probe [6]. This allows for the precise optimization of conditions to maximize signal from true targets while minimizing false positives from closely related sequences, a critical requirement in genetic diagnostics and microbial community analysis [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The following section provides detailed methodologies that leverage the Tm-lowering function of formamide in different technical contexts.

Microarray Hybridization with Formamide Stringency Control

This protocol, adapted from Yilmaz et al. (2012), is used for optimizing probe sensitivity and specificity in microbial diagnostics [4].

Objective: To establish formamide denaturation profiles for microarray probes and determine the optimal formamide concentration for discriminating between perfect match and mismatch sequences.

Materials:

- Labeled Target Nucleic Acid: e.g., Cy3-labeled 16S rRNA gene amplicon.

- Microarray Slide containing the designed oligonucleotide probes.

- Hybridization Buffer Stock: Contains salts (e.g., SSC), detergents (e.g., SDS), and blocking agents (e.g., BSA).

- Formamide (Molecular Biology Grade).

- Hybridization Chamber and wash buffers.

Method:

- Prepare Formamide Gradient Buffers: Prepare a series of hybridization buffers with increasing formamide concentrations (e.g., 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50% v/v). Keep the concentration of all other components constant.

- Hybridization:

- Apply the labeled target to the microarray.

- Hybridize at a constant temperature (e.g., 45°C) for a fixed duration (e.g., 16 hours) using the different formamide buffers.

- Post-Hybridization Washes: Perform stringent washes according to standard microarray protocols to remove non-specifically bound target.

- Signal Detection: Scan the microarray and quantify the fluorescence signal for each probe spot.

- Data Analysis:

- For each probe, plot the normalized signal intensity against the formamide concentration. This will generate a sigmoidal denaturation curve.

- The formamide concentration at the curve's midpoint (C(_{1/2})) is the point at which 50% of the duplexes are denatured.

- The optimal formamide concentration for a specific probe is one that maintains a high signal for the perfect match while abolishing the signal for known mismatches.

Northern Blot Analysis with RNA Probes

This protocol, based on recommendations from Thermo Fisher, utilizes formamide to facilitate high-stringency hybridization at manageable temperatures for sensitive RNA detection [3].

Objective: To detect specific RNA molecules, especially rare mRNAs, with high sensitivity and low background using single-stranded RNA probes.

Materials:

- Membrane: Positively charged nylon membrane with immobilized RNA.

- RNA Probe: In vitro transcribed, labeled RNA probe (antisense to the target mRNA).

- Pre-hybridization/Hybridization Buffer: e.g., ULTRAhyb or a standard 50% formamide-based buffer (5x SSC, 0.1% SDS, 100 µg/mL total yeast RNA, etc.).

- Water Bath or Hybridization Oven.

Method:

- Pre-hybridization: Incubate the membrane in pre-warmed hybridization buffer for 1-2 hours at 68°C. This blocks non-specific binding sites.

- Probe Denaturation: Denature the double-stranded DNA probe or, if using an RNA probe, simply heat it briefly to disrupt secondary structures.

- Hybridization: Add the denatured probe directly to the hybridization buffer. Incubate the membrane at 60-65°C for 16 hours (or as optimized). The 50% formamide allows for this high stringency at a temperature that prevents excessive RNA degradation.

- Stringency Washes:

- Wash the membrane twice for 5 minutes in 2x SSC / 0.1% SDS at room temperature.

- Perform two final washes for 15 minutes in 0.1x SSC / 0.1% SDS at 60-65°C.

- Detection: Proceed with appropriate detection methods (e.g., phosphorimaging for radioactive probes or chemiluminescence for digoxigenin-labeled probes).

The following workflow summarizes the key steps in a formamide-based Northern blot procedure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

A successful hybridization experiment relies on a suite of reagents, each serving a specific function. The table below details essential components of a formamide-containing hybridization buffer.

Table 2: Essential Components of a Formamide-Based Hybridization Buffer

| Reagent | Typical Concentration | Core Function |

|---|---|---|

| Formamide | 15-50% (v/v) | Core Function: Lowers nucleic acid Tm by disrupting hydrogen bonds and base stacking, enabling lower temperature hybridization. |

| Dextran Sulfate | 10-20% (v/v) | A volume-excluding agent that increases the effective probe concentration, thereby accelerating hybridization kinetics. |

| Salts (NaCl, SSC) | 300-600 mM | Neutralizes the negative charge on the sugar-phosphate backbone, stabilizing the duplex by shielding electrostatic repulsion. |

| Citrate or Phosphate Buffer | 5-10 mM | Maintains a stable pH (typically between 6.2 and 7.5) to ensure optimal hybridization efficiency. |

| Blocking Agents (Cot-1 DNA, yeast tRNA, salmon sperm DNA) | 0.1 µg/µL (Cot-1) | Binds to and blocks non-specific binding sites on the membrane or tissue sample, reducing background noise. |

| Detergents (SDS) | 0.1-1% (w/v) | Reduces surface tension and prevents non-specific hydrophobic interactions, further minimizing background. |

| Vista-IN-3 | Vista-IN-3|VISTA Inhibitor|For Research Use | Vista-IN-3 is a potent VISTA checkpoint inhibitor for cancer immunology research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

| Antitumor agent-111 | Antitumor agent-111, MF:C34H29ClF2N6O5, MW:675.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The core function of formamide—lowering the Tm of nucleic acid duplexes—is a foundational principle that has enabled decades of advancement in molecular hybridization techniques. Its ability to facilitate high-stringency binding at physiologically gentle temperatures is indispensable for modern genomics, transcriptomics, and diagnostic pathology.

Current research is building upon this foundation in two key areas. First, there is a drive to develop formamide-free hybridization buffers using less toxic, alternative solvents like ethylene carbonate. These novel buffers have demonstrated the potential to radically reduce hybridization times from over 16 hours to under 1 hour for FISH assays, without requiring heat denaturation or blocking steps [2]. Second, efforts are focused on the precise thermodynamic modeling of formamide's effect, as exemplified by the Linear Free Energy Model. This allows for in-silico prediction of probe behavior, which is crucial for designing high-density microarrays for complex microbial community analysis and genetic screening [4] [6].

In conclusion, a deep understanding of how formamide lowers Tm is not merely a technical detail but a critical factor in designing robust, sensitive, and specific hybridization assays. As the field moves towards faster, safer, and more predictive molecular diagnostics, the principles governing this core function will continue to guide innovation.

In molecular biology, nucleic acid hybridization is a foundational process, and its efficiency critically depends on controlled denaturation. Formamide-containing hybridization buffers are indispensable reagents that facilitate this process by systematically destabilizing the native double-stranded structure of DNA and RNA. Formamide (HCONH2) acts as a chemical denaturant that linearly decreases the melting temperature (Tm) of nucleic acids by 2.4-2.9°C per mole of formamide, depending on the (G+C) composition and helix conformation [7]. This whitepaper details the mechanism by which formamide disrupts the hydrogen bonding and base stacking interactions that maintain nucleic acid structure, framed within the context of its application in hybridization buffer research for diagnostic and therapeutic development. The global market for these specialized buffers, currently valued at approximately $500 million and projected to reach $950 million by 2033, reflects their critical importance in genomics, transcriptomics, and molecular diagnostics [8].

The Molecular Mechanism of Formamide Denaturation

Competitive Hydrogen Bond Displacement

The primary mechanism of formamide denaturation involves the competitive displacement of native hydrogen bonds within the DNA double helix. Formamide molecules, which are both strong proton donors and acceptors, form hydrogen bonds with the nitrogenous bases of DNA (adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine), effectively replacing the inter-strand Watson-Crick hydrogen bonds that hold the duplex together [9]. Recent research quantifying the intermolecular forces involved in DNA denaturation has demonstrated that the proton-donor effect is the dominant mechanism for disrupting hydrogen bonds, with an influence approximately two times greater than that of the proton-acceptor effect [9]. This competitive binding disrupts the cooperative network of hydrogen bonds, leading to strand separation under conditions far milder than those required for thermal denaturation alone.

Destabilization of Base Stacking Interactions

Beyond hydrogen bond disruption, formamide significantly impacts the hydrophobic and stacking interactions between adjacent base pairs. The planar aromatic rings of nucleic acid bases normally stack in a helical arrangement stabilized by van der Waals forces and hydrophobic effects in an aqueous environment. Formamide, with a high dielectric constant, disrupts these stabilizing interactions by altering the solvation shell around the DNA molecule. This disruption decreases the free energy penalty for exposing hydrophobic bases to the solvent, thereby reducing the stability gained from base stacking [7] [9]. Single-molecule studies using optical tweezers have directly visualized this denaturation process, showing a measurable increase in DNA contour length as formamide concentration increases, corresponding to the transition from double-stranded to single-stranded form [10].

Thermodynamic Framework

The denaturation process can be described thermodynamically using a linear free energy model (LFEM). Research has established that formamide increases hybridization free energy (ΔG°) by approximately 0.173 kcal/mol per percent of formamide added (v/v) [4]. This relationship allows researchers to precisely predict hybridization efficiency and optimize stringency conditions for specific experimental applications. The overall effect is a destabilization of the helical state, with the inherent cooperativity of melting remaining unaffected by the denaturant [7].

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Formamide on DNA Stability

| Parameter | Effect | Measurement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Temperature (Tm) Depression | Linear decrease | 2.4-2.9°C per mole formamide | [7] |

| Free Energy Change | Linear increase | 0.173 kcal/mol per % formamide (v/v) | [4] |

| Denaturation Enthalpy | Significant reduction | Lower than thermal denaturation (positive values) | [9] |

| Dominant Mechanism | Hydrogen bond disruption | Proton-donor effect twice as influential as acceptor | [9] |

Quantitative Analysis of Denaturation Efficiency

Concentration-Dependent Effects

Formamide denaturation follows a concentration-dependent sigmoidal profile, with efficiency varying based on application-specific conditions. Systematic characterization of denaturation methods has revealed that 60% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) represents an effective chemical denaturation alternative, fully denaturing DNA in 2-5 minutes [11]. However, formamide remains the dominant choice for most hybridization applications due to its well-characterized properties and effectiveness. In microarray applications, sigmoidal denaturation profiles are obtained with increasing formamide concentrations, enabling precise optimization of probe sensitivity and specificity [4].

Table 2: Comparative Denaturation Efficiency of Chemical Agents

| Denaturation Method | Time to Full Denaturation | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formamide (50%) | 2-5 minutes | Well-characterized, predictable Tm reduction | Toxicity concerns, handling precautions |

| DMSO (60%) | 2-5 minutes | Effective denaturation | May cause different renaturation kinetics |

| NaOH (1 mol/L) | 2-5 minutes | Rapid action | Highly alkaline, may damage nucleic acids |

| Direct Probe Sonication | 5 minutes | Physical method, no chemicals | Specialized equipment required |

Sequence-Dependent Variations

The efficiency of formamide denaturation exhibits sequence-dependent variations due to differences in hydrogen bonding patterns and hydration stability. Notably, poly(dA.dT) tracts exhibit much lower sensitivity to formamide compared to random sequences, attributed to specific patterns of tightly bound, immobilized water bridges that buttress the helix from within the narrow minor groove [7]. This structural particularity makes A-T rich regions more resistant to chemical denaturation, an important consideration for probe design and hybridization optimization. Tracts of three (A-T) pairs behave normally, but tracts of six exhibit the same level of reduced sensitivity as the polymer, suggesting a conformational shift as tracts elongate beyond a critical length [7].

Experimental Protocols for Denaturation Studies

Protocol: DNA Denaturation Using Chemical Denaturants

This protocol is adapted from systematic characterization studies of DNA denaturation and renaturation [11].

Materials:

- DNA sample (e.g., 86-bp dsDNA fragment)

- Molecular biology grade formamide (>99.5%)

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, >99.9%)

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) pellets

- Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) or Saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer

- Spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop) for A260 measurements

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Transfer 40 μL of DNA to a microcentrifuge tube.

- Denaturant Addition: Add the appropriate volume of denaturant to achieve desired concentration:

- For formamide: Add 40 μL of 100% formamide to achieve 50% concentration

- For DMSO: Add 60 μL of 100% DMSO to achieve 60% concentration

- For alkaline denaturation: Add 40 μL of 1 mol/L NaOH

- Incubation: Homogenize the mixture by gentle pipetting and incubate at ambient temperature (20-25°C) for time intervals (1, 2, 5, 10, 20, and 30 minutes).

- Measurement: Immediately measure absorbance at 260 nm using a spectrophotometer after each time interval.

- Analysis: Calculate denaturation percentage based on hyperchromic effect at A260.

Notes: For hybridization applications, the denatured DNA is typically used immediately in the hybridization reaction to prevent significant renaturation.

Protocol: Formamide Denaturation in Microarray Hybridization

This protocol outlines the use of formamide in microarray experiments for microbial diagnostics [4].

Materials:

- High-density microarray slides

- Fluorescently labeled and fragmented target DNA (e.g., 16S rRNA gene amplicon)

- Formamide-containing hybridization buffer

- Hybridization chamber

- Water bath or thermal cycler

Method:

- Target Preparation: Fragment labeled PCR product to lengths between 25-150 bases (average 65 bases) using random prime amplification.

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare hybridization buffer with varying formamide concentrations (0-50%) in appropriate saline buffer (e.g., SSC or SSPE).

- Hybridization: Apply target-buffer mixture to microarray and incubate at appropriate temperature (typically 45-65°C) for 4-16 hours.

- Washing: Perform stringency washes with buffer containing equivalent formamide concentration to hybridization step.

- Scanning: Image microarray using appropriate fluorescence scanner.

- Analysis: Generate sigmoidal denaturation profiles by plotting signal intensity versus formamide concentration for each probe.

Applications: This approach enables probe optimization and cross-hybridization assessment for diagnostic microarray design.

Visualization of Formamide Denaturation Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Formamide-Based Denaturation Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Composition | Function in Denaturation | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formamide Hybridization Buffer | 20-50% formamide, SSC or SSPE buffer, detergents, blocking agents | Lowers nucleic acid melting temperature, reduces background | Northern blotting, microarray hybridization, in situ hybridization [8] [1] |

| Denaturation Control Reagents | DMSO (60%), NaOH (1 mol/L) | Alternative denaturation methods for comparison | Experimental controls, protocol optimization [11] |

| Stringency Wash Buffers | SSC or SSPE with controlled formamide concentration | Removes non-specifically bound probes while maintaining specific hybrids | Post-hybridization washing in microarray and FISH [4] |

| Stabilization Additives | BSA, salmon sperm DNA, calf thymus DNA, yeast tRNA | Blocking agents that minimize non-specific binding | Reduction of background noise in hybridization assays [1] |

| Fluorescence Detection System | Fluorophore-labeled probes, quencher sequences | Signal generation upon successful hybridization | Real-time monitoring of hybridization efficiency [12] |

| Apoptosis inducer 13 | Apoptosis inducer 13, MF:C60H59ClF6N8O4PRu, MW:1237.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Bcl-2-IN-12 | Bcl-2-IN-12, MF:C47H41ClN4O6S, MW:825.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Formamide achieves its denaturing effect through a multi-mechanistic process dominated by competitive hydrogen bond displacement, with the proton-donor effect being twice as influential as the proton-acceptor effect, coupled with significant disruption of base stacking interactions [9]. This dual mechanism efficiently destabilizes the DNA double helix while maintaining the cooperativity of the melting transition, enabling precise control over hybridization stringency in molecular biology applications. The well-characterized quantitative relationship between formamide concentration and melting temperature depression—2.4-2.9°C per mole of formamide—provides researchers with a predictable framework for assay design [7]. As the field advances, current research trends focus on developing safer formamide-free alternatives while maintaining hybridization efficiency, driven by both environmental concerns and the expanding applications of nucleic acid hybridization in clinical diagnostics and therapeutic development [8] [13]. Understanding these fundamental mechanisms provides the foundation for innovation in hybridization-based technologies that continue to advance research and diagnostic capabilities.

Formamide serves as a fundamental chemical denaturant in molecular hybridization techniques, with its concentration acting as a critical determinant for assay stringency and specificity. This technical guide delineates the quantitative relationship between the percentage of formamide in hybridization buffers and the resultant specificity in probing nucleic acid sequences. By systematically reducing the melting temperature (Tm) of duplexes, formamide concentration provides a powerful lever for optimizing the discrimination between perfectly matched and mismatched sequences, a principle foundational to techniques ranging from microarray analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to Northern blotting. Framed within broader research on formamide function, this whitepaper synthesizes current thermodynamic models, empirical data, and experimental protocols to equip researchers and drug development professionals with a predictive framework for assay design.

Hybridization techniques form the cornerstone of modern molecular biology, enabling the detection and characterization of specific DNA and RNA sequences in complex mixtures. The specificity of this process—the ability to distinguish target sequences from non-target sequences with high fidelity—is paramount. Chemical denaturants are employed to fine-tune this specificity, and among them, formamide is preeminent.

Formamide (HCONHâ‚‚) is a water-miscible organic solvent that disrupts the hydrogen bonding between complementary nucleic acid bases. When incorporated into a hybridization buffer, it effectively lowers the thermal stability of the double-stranded helix. This property allows researchers to perform stringent hybridizations at lower, more manageable temperatures, thereby preserving the integrity of biological samples while maintaining high specificity. The core principle is that the denaturing effect of formamide is concentration-dependent; higher percentages of formamide more aggressively destabilize nucleic acid duplexes. This effect is not uniform, however, as mismatched duplexes are destabilized to a greater extent than perfectly matched ones. Consequently, controlling the percent formamide provides a precise mechanism to create a window of stringency where ideal probe-target hybrids remain stable while imperfect hybrids dissociate. The global market for formamide-containing RNA hybridization buffers, a testament to its ubiquity, is projected to grow significantly, driven by advances in genomics and clinical diagnostics [8].

The Mechanistic Basis: Formamide and Duplex Stability

The efficacy of formamide is rooted in its direct impact on the thermodynamics of nucleic acid hybridization. The fundamental parameter governing this interaction is the melting temperature (Tₘ), the temperature at which half of the duplex molecules dissociate into single strands.

Thermodynamic Modeling of Denaturation

The relationship between formamide concentration and duplex stability has been successfully modeled using a Linear Free Energy Model (LFEM). Research on microarray hybridizations has demonstrated that formamide linearly increases the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°) of the duplex formation. Specifically, the denaturant m-value—the rate at which formamide increases the ΔG°—was found to be 0.173 kcal/mol per percent (v/v) formamide [14]. This quantitative relationship allows for the prediction of probe behavior under different stringency conditions, transforming probe design from an empirical art into a predictable science.

Mathematically, this can be represented as: ΔG°ₕᵧbᵣᵢd(formamide) = ΔG°ₕᵧbᵣᵢd + m * [Formamide]

Where:

- ΔG°ₕᵧbᵣᵢd(formamide) is the adjusted free energy change in the presence of formamide.

- ΔG°ₕᵧbᵣᵢd is the free energy change in the absence of formamide.

- m is the denaturant m-value (0.173 kcal/mol/%).

- [Formamide] is the concentration of formamide (v/v).

This model enables the simulation of formamide melting profiles, generating sigmoidal curves where signal intensity decreases as formamide concentration increases. The absolute error in predicting the position of these experimental denaturation profiles was less than 5% formamide for more than 90% of probes, confirming the model's practical utility [14].

The Impact on Mismatch Discrimination

The differential destabilization caused by formamide is the key to its power in enhancing specificity. A perfectly matched duplex has a higher initial stability (more negative ΔG°) than a duplex containing one or more mismatches. The addition of formamide adds a positive increment to the ΔG° of all duplexes, but the fractional increase in instability is greater for the mismatched duplex. As a result, at a given formamide concentration and temperature, a perfectly matched duplex may remain hybridized while a mismatched duplex of similar length and composition will denature. Systematic studies have established free energy rules to predict the stability of various mismatch types, including bulged and tandem mismatches, providing a comprehensive database for specificity optimization [14].

Quantitative Guidance: Formamide Concentration and Applications

The optimal formamide concentration is application-specific and must be determined empirically for each probe-target system. However, established ranges provide a critical starting point for experimental design.

Table 1: Formamide Concentration Guidelines for Hybridization Stringency

| Stringency Level | Typical Formamide Concentration (% v/v) | Primary Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Low Stringency | 20-30% | Initial screening of libraries; hybridization with probes of low homology |

| Medium Stringency | 30-40% | Standard Northern blotting; microarray analysis with well-characterized probes [8] |

| High Stringency | 40-50% | Discrimination of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs); FISH with repetitive sequences [8] |

The choice of concentration within these ranges directly controls the balance between sensitivity (detecting true positives) and specificity (avoiding false positives). For instance, in diagnostic applications aimed at identifying infectious diseases, high specificity is paramount to prevent misidentification, necessitating the use of higher formamide concentrations or other stringency-enhancing conditions [8] [14].

Table 2: Impact of Formamide on Experimental Parameters in Microarray Hybridization

| Parameter | Effect of Low [Formamide] | Effect of High [Formamide] |

|---|---|---|

| Effective Tₘ | Higher | Lower |

| Hybridization Rate | Faster | Slower |

| Probe Specificity | Lower (risk of false positives) | Higher (risk of false negatives) |

| Signal Intensity | Generally higher, but with higher background | Generally lower, with lower background |

Experimental Protocol: Determining Optimal Formamide Concentration

The following detailed protocol, adapted from empirical studies, outlines a method for determining the optimal formamide concentration for a specific oligonucleotide probe using a microarray setup [14].

Materials and Reagents

- High-density Microarray Slides containing the probe(s) of interest.

- Fluorescently Labeled Target (e.g., Cy3-dCTP labeled fragmented PCR product).

- Formamide (Molecular Biology Grade).

- 20X Saline-Sodium Citrate (SSC) Buffer.

- Blocking Agents (e.g., salmon sperm DNA, yeast tRNA).

- Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS).

- Hybridization Chamber and Water Bath or Oven.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Preparation of Hybridization Buffers: Prepare a series of hybridization buffers with identical components except for the formamide concentration. A typical series might range from 0% to 50% formamide in 10% increments. A standard buffer composition is:

- 25% (v/v) Formamide (for the 25% condition; adjust accordingly)

- 5X SSC

- 0.1% (w/v) SDS

- 100 µg/mL sheared salmon sperm DNA The buffer may also include other components like Denhardt's solution or dextran sulfate, depending on the application [15].

Target Denaturation and Hybridization:

- Mix the fluorescently labeled target with each of the formamide-containing hybridization buffers.

- Denature the mixture at 95°C for 5 minutes, then immediately place on ice.

- Apply the denatured mixture to the microarray slide and incubate in a sealed hybridization chamber at a constant, predetermined temperature (e.g., 37°C or 42°C) for 4-16 hours.

Post-Hybridization Washes: Perform a series of washes to remove non-specifically bound target. The stringency of these washes can also be adjusted with formamide and salt concentration, but for this experiment, they should be kept constant across all slides to isolate the effect of the hybridization formamide concentration.

- Wash 1: 2X SSC, 0.1% SDS at room temperature for 5 minutes.

- Wash 2: 1X SSC at room temperature for 5 minutes.

- Wash 3: 0.5X SSC at room temperature for 5 minutes.

Signal Detection and Data Analysis:

- Dry the slides and scan them using a microarray scanner appropriate for the fluorescent label.

- Quantify the signal intensity for each probe feature.

- Plot the normalized signal intensity against the formamide concentration for each probe. The resulting plot should produce a sigmoidal denaturation curve.

- The optimal formamide concentration for specific hybridization is typically chosen at a point on the high-signal plateau of the perfect-match probe, just before the signal from any mismatch controls begins to rise.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key reagents used in formamide-based hybridization experiments, explaining their critical functions in the protocol.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Formamide-Based Hybridization

| Reagent | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Formamide (High Purity) | Primary denaturant; linearly reduces duplex Tₘ by disrupting hydrogen bonding, enabling high-stringency incubations at lower temperatures. |

| Saline-Sodium Citrate (SSC) | Provides ionic strength (Naâº) which shields the negative charges on the phosphate backbones of nucleic acids, promoting duplex stability. |

| Blocking DNA (e.g., Salmon Sperm DNA) | A non-specific, sheared DNA used to pre-absorb and block non-specific probe binding sites on the membrane or slide surface. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Anionic detergent that reduces surface tension and minimizes non-specific hydrophobic interactions, thereby lowering background noise. |

| Dextran Sulfate | A polyanion that acts as a volume excluder, increasing the effective probe concentration and accelerating hybridization kinetics. |

| Denhardt's Solution | A mixture (often of Ficoll, polyvinylpyrrolidone, and BSA) used to block non-specific binding sites, particularly in filter-based hybridizations. |

| Tmv-IN-7 | Tmv-IN-7, MF:C17H15ClN6OS, MW:386.9 g/mol |

| Nardosinonediol | Nardosinonediol, MF:C15H24O3, MW:252.35 g/mol |

Technical Considerations and Emerging Alternatives

While formamide is highly effective, researchers must be aware of its limitations. Formamide can degrade over time, especially if not stored properly, forming formic acid and ammonium ions which can affect pH and hybridization efficiency. Furthermore, a significant finding from 2024 indicates that formamide denaturation in DNA FISH protocols can cause significant alterations to the sub-200 nm chromatin structure, potentially distorting the native architecture that the experiment aims to study [16] [17].

This has spurred the development and adoption of alternative labeling methods that do not rely on formamide denaturation. Techniques such as:

- RASER-FISH (Resolution After Single-strand Exonuclease Resection): Uses exonuclease digestion to generate single-stranded regions for probe access [17].

- CRISPR-Sirius: Utilizes a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) complexed with guide RNAs to fluorescently label specific genomic loci without requiring DNA denaturation [17].

Studies using Partial Wave Spectroscopic (PWS) microscopy have demonstrated that these formamide-free methods have a minimal impact on nanoscale chromatin organization, making them superior for studies where preserving native chromatin structure is critical [17].

The concentration of formamide in a hybridization buffer is a powerful and indispensable parameter for controlling the specificity of molecular assays. The quantitative relationship between formamide percentage and duplex stability, elegantly described by thermodynamic models, provides researchers with a predictive framework for probe design and assay optimization. While formamide remains a staple in laboratories worldwide, evidenced by its significant and growing market, a nuanced understanding of its effects—including potential sample distortion—is crucial. As the field advances, the principles of stringency control mastered with formamide will continue to inform the development and application of next-generation, formamide-free hybridization technologies, further empowering research and diagnostic innovation.

The Formamide-Stringency Relationship in DNA-DNA and DNA-RNA Hybrids

Formamide is a crucial denaturant employed in nucleic acid hybridization techniques to precisely control stringency, thereby optimizing the sensitivity and specificity of molecular assays. This technical guide explores the fundamental relationship between formamide concentration and hybridization stringency within the context of DNA-DNA and DNA-RNA hybrids. It elaborates on the thermodynamic principles governing formamide's denaturing action, presents quantitative models predicting its effects, and provides detailed experimental protocols for its application. Furthermore, the guide examines recent evidence on formamide-induced structural perturbations in chromatin and introduces emerging alternative solvents. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this document aims to serve as a comprehensive resource for leveraging formamide to enhance the accuracy and reliability of hybridization-based analyses in both basic research and diagnostic applications.

Within hybridization buffer research, formamide has long been established as a critical component for adjusting the stringency of nucleic acid hybridization assays. Stringency refers to the specificity required for two nucleic acid strands to form a stable duplex, and it is paramount for distinguishing perfectly complementary target sequences from those containing mismatches. Formamide, by lowering the melting temperature ((T_m)) of double-stranded DNA, allows for high-stringency hybridization to occur at lower, more physiologically compatible temperatures, which is essential for techniques like Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) where sample morphology preservation is critical [18] [15]. Its function extends beyond mere temperature reduction; formamide actively disrupts the hydrogen bonding between complementary bases, thereby modulating the thermodynamic stability of the resulting hybrids [19]. This guide delves into the core relationship between formamide concentration and hybridization stringency, exploring its quantitative effects, practical applications, and recent findings on its impact on biological structures, thereby providing a foundational resource for its use in modern molecular techniques.

Thermodynamic Principles of Formamide Action

Formamide exerts its denaturing effect primarily by disrupting the hydrogen-bonding network of water and, consequently, the hydrogen bonds that stabilize the double helix of DNA or DNA-RNA hybrids. From a thermodynamic perspective, the addition of formamide linearly destabilizes the nucleic acid duplex. Research has quantified this relationship through a Linear Free Energy Model (LFEM), which establishes that formamide increases the standard Gibbs free energy change of hybridization (( \Delta G^\circ )) by approximately 0.173 kcal/mol for every percent (v/v) of formamide added to the hybridization buffer [14]. This linear increase in ( \Delta G^\circ ) translates directly to a decrease in the melting temperature ((T_m)) of the duplex.

The relationship between formamide concentration and (T_m) can be harnessed to predict hybridization efficiency. At a molecular level, higher formamide concentrations decrease stringency by promoting the denaturation of weaker, mismatched duplexes while still allowing perfectly matched, stable hybrids to form [19]. This property is critical for optimizing probe specificity in assays like microarray hybridization and FISH. Computational tools, such as mathFISH, leverage these thermodynamic principles and established nearest-neighbor parameters to predict the formamide dissociation profile of any given probe-target pair, providing researchers with a powerful means to optimize probe design and hybridization conditions in silico [20].

Table 1: Thermodynamic Parameters of Formamide Denaturation

| Parameter | Value | Experimental Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| m-value (Free Energy Increase) | +0.173 kcal/mol per %FA | Microarray hybridization of 16S rRNA amplicons | [14] |

| Typical Working Concentration Range | 0 - 50% (v/v) | Common in FISH and microarray protocols | [14] [15] |

| Prediction Error (LFEM) | < 5% FA for >90% of probes | Enables practical accuracy in probe design | [14] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Microarray Hybridization with Formamide Stringency Adjustment

The application of formamide in microarray hybridization allows for the systematic optimization of probe sensitivity and specificity. The following protocol, adapted from studies on microbial community analysis, details the process [14].

Protocol:

- Probe Design and Microarray Setup: Design oligonucleotide probes (e.g., 18-26 nucleotides in length) targeting the gene of interest (e.g., 16S rRNA). A poly-T linker can be added to the 3' end of the probe to elevate it from the slide surface and minimize steric hindrance.

- Target Preparation and Labeling: Amplify the target gene (e.g., via PCR from a clone library) and fragment it. Label the fragmented target using a random prime amplification method with fluorescently labeled dCTP (e.g., Cy3-dCTP). Purify the labeled target and quantify the yield and incorporated dye concentration.

- Formamide Hybridization Buffer Preparation: Prepare a series of hybridization buffers with formamide concentrations ranging from 0% to 50% (v/v). A standard buffer may contain SSC (e.g., 2x to 6x), SDS, and blocking agents (e.g., dextran sulfate, salmon sperm DNA, or Cot-1 DNA for blocking repetitive sequences) [15].

- Hybridization: Apply the fluorescently labeled target to the microarray in the prepared formamide-containing buffers. Hybridize at a constant temperature (e.g., 46°C) for a defined period.

- Washing and Scanning: Following hybridization, wash the slides with a buffer of appropriate stringency (e.g., based on SSC concentration) to remove non-specifically bound target. Scan the microarray to quantify fluorescence signal intensity for each probe feature.

- Data Analysis: Plot the signal intensity against the formamide concentration for each probe to generate a sigmoidal denaturation profile. The concentration at which 50% of the signal is lost ([FA]m) is a key parameter for comparing duplex stability.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) with Formamide

Formamide is a cornerstone of FISH protocols to denature double-stranded DNA within chromosomes or cells and permit probe access. However, recent studies indicate this step can distort nanoscale chromatin structure [17].

Protocol (Standard 3D FISH):

- Sample Fixation: Fix cells or tissue sections with paraformaldehyde (e.g., 4% PFA for 10 minutes) to preserve morphology.

- Permeabilization: Treat samples with a permeabilization agent (e.g., detergent) to allow probe entry.

- Denaturation with Formamide: Incubate the sample in a high concentration formamide solution (commonly 50-70% in 2x SSC) at an elevated temperature (e.g., 80-85°C) to denature the double-stranded DNA target. Alternatively, a lower temperature (e.g., 73°C) can be used with 70% formamide for specific applications like R-loop formation [21].

- Hybridization: Apply the fluorescent DNA or Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) probe in a hybridization buffer containing formamide (concentration optimized for the specific probe, typically 10-50%). Hybridization is often performed overnight at 37-45°C [18].

- Post-Hybridization Washes: Wash the samples to remove excess and non-specifically bound probe. Washes often include SSC buffers, sometimes with formamide, to maintain stringency.

- Imaging and Analysis: Mount the samples and image using a fluorescence or confocal microscope.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Hybridization Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Formulation / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Formamide | Denaturant that lowers Tm and controls stringency. | Molecular biology grade, deionized. Used at 0-70% (v/v). |

| SSC Buffer (Saline-Sodium Citrate) | Provides ionic strength for hybridization; salt concentration affects stringency. | Commonly used at 0.1x to 6x concentration in washes and buffers. |

| Dextran Sulfate | Volume excluder that increases effective probe concentration. | Accelerates hybridization kinetics. |

| Blocking Agents | Reduce non-specific binding of probes. | Salmon sperm DNA, Cot-1 DNA, or tRNA. |

| PFA (Paraformaldehyde) | Cross-linking fixative for tissue and cell morphology preservation. | Typically used at 4% in buffer. |

| PNA (Peptide Nucleic Acid) Probes | Synthetic probes with neutral backbone; higher affinity and specificity. | Used in FISH with lower formamide requirements [18]. |

Recent Advances and Considerations

Impact of Formamide on Chromatin Structure

Emerging evidence indicates that while formamide is effective for denaturation, it can have unintended consequences on the native structure of the target. A 2024 study demonstrated that the formamide denaturation step in standard 3D FISH protocols significantly alters sub-200 nm chromatin structure [17]. Using Partial Wave Spectroscopic (PWS) microscopy, researchers found that formamide exposure changes the polymer scaling parameter (D) of chromatin packing domains, indicating a shift from a more compact to a more expanded state. This structural distortion poses a challenge for techniques aiming to measure nanoscale genome organization, as the act of labeling perturbs the very structure under investigation.

Alternative Solvents and Methods

In response to the limitations of formamide, researchers are exploring alternative solvents and denaturation-free methods. One study developed a formamide-free hybridization buffer that reduces hybridization time from overnight to one hour for DNA FISH on tissue sections [18]. This "IQFISH" method reportedly eliminates the need for denaturation and blocking of repetitive sequences and is less hazardous. Furthermore, labeling techniques that circumvent formamide denaturation entirely, such as RASER-FISH and CRISPR-Sirius, have shown minimal impact on chromatin structure compared to conventional 3D FISH, providing more reliable tools for studying nanoscale genome architecture [17].

Formamide remains a fundamentally important reagent for controlling stringency in nucleic acid hybridization, with well-characterized thermodynamic properties that enable predictive modeling for probe design. Its ability to lower melting temperatures and destabilize mismatched duplexes is indispensable for techniques ranging from microarrays to FISH. However, a comprehensive understanding of its function must now incorporate recent findings on its potential to distort higher-order chromatin structure. The ongoing development of formamide-free alternatives and denaturation-independent labeling methods heralds a new era in hybridization technology, promising faster, safer, and structurally faithful analyses. As research continues, the optimal choice between traditional formamide-based protocols and emerging alternatives will depend on the specific application, weighing the requirements for stringency and specificity against the need to preserve native molecular architectures.

Protocol Integration: Applying Formamide Buffers in FISH, MERFISH, and Diagnostic Assays

Standard Formamide Buffer Formulations for DNA and RNA FISH

Formamide is a fundamental component of standard hybridization buffers used in fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) techniques, playing an indispensable role in both DNA and RNA detection assays. As a potent chaotropic agent, formamide effectively disrupts hydrogen bonding between nucleic acid strands, thereby lowering the melting temperature (T~m~) of DNA-DNA and DNA-RNA hybrids. This property enables researchers to perform specific hybridizations at lower, more practical temperatures that preserve cellular or tissue integrity while maintaining high stringency conditions to minimize non-specific probe binding [22] [23]. The strategic inclusion of formamide in hybridization buffers represents a cornerstone of FISH methodology, balancing the competing demands of assay sensitivity, hybridization specificity, and sample preservation.

The functional utility of formamide extends across the entire spectrum of FISH applications, from single-molecule RNA FISH (smFISH) to highly multiplexed techniques such as Multiplexed Error-Robust FISH (MERFISH) and spatial transcriptomics [22] [24]. In MERFISH, for instance, formamide concentration is carefully optimized to ensure efficient binding of encoding probes to their target RNAs while suppressing off-target binding in complex sample types, including cultured cells and tissue sections [24]. Similarly, in DNA-FISH applications, formamide concentration directly influences the efficiency and specificity of probe binding to genomic targets, with lower concentrations typically enabling hybridization at lower temperatures [25]. Understanding the standard formulations and functional principles of formamide-containing buffers is therefore essential for researchers aiming to optimize FISH protocols for diverse experimental contexts, from basic research to drug development applications.

Standard Formamide Buffer Compositions and Formulations

Core Components of Standard FISH Hybridization Buffers

Standard formamide-containing hybridization buffers share several key components that collectively create optimal conditions for specific nucleic acid hybridization. The typical composition includes a denaturing agent, salts for ionic strength, blocking agents to reduce non-specific binding, stabilizers, and nuclease inhibitors to protect RNA integrity in sample preparations [26].

The primary component, formamide, typically constitutes 40% (vol/vol) of the final hybridization buffer in MERFISH and many RNA FISH protocols [26]. This concentration has been empirically determined to provide an effective balance between sufficient stringency and acceptable hybridization kinetics. The chaotropic action of formamide denatures secondary structures in target RNAs and facilitates probe access while enabling hybridization to proceed at physiologically compatible temperatures (typically 37°C). The salt component, generally 2× SSC buffer, provides the appropriate ionic strength to promote nucleic acid hybridization by shielding the negative charges on phosphate backbones, while dextran sulfate (typically 10% wt/vol) acts as a volume exclusion agent that effectively increases probe concentration and enhances hybridization kinetics [26].

To minimize non-specific binding, hybridization buffers commonly include blocking agents such as yeast tRNA (0.1% wt/vol) which competes for non-specific binding sites, particularly in cellular and tissue samples with high protein content. Additionally, detergents like Tween 20 (1% vol/vol) help reduce surface adhesion and improve sample permeability. For RNA-targeting applications, murine RNase inhibitor (1% vol/vol) is frequently included to preserve RNA integrity during often lengthy hybridization procedures [26]. This combination of components creates a controlled environment that maximizes the probability of specific probe-target interactions while minimizing degradation and non-specific background.

Standardized Buffer Formulations for FISH Applications

Table 1: Standard Formamide-Containing Hybridization Buffer Formulation for FISH

| Component | Final Concentration | Function | Storage Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formamide | 40% (vol/vol) | Denaturing agent, lowers T~m~ | Added fresh |

| SSC Buffer | 2× | Ionic strength for hybridization | Stable at RT |

| Dextran Sulfate | 10% (wt/vol) | Volume exclusion, enhances kinetics | -20°C in master mix |

| Yeast tRNA | 0.1% (wt/vol) | Blocking agent for non-specific binding | -20°C |

| Tween 20 | 1% (vol/vol) | Surfactant, reduces adhesion | RT |

| Murine RNase Inhibitor | 1% (vol/vol) | Protects RNA integrity | -20°C |

| Encoding Probes | 5-200 μM (pool-dependent) | Target-specific hybridization | -20°C |

This standardized formulation serves as the foundation for both DNA and RNA FISH applications, though specific concentrations may be adjusted based on experimental requirements. For example, in the iterative RNA FISH experimental protocol (SOP002.v.4.6), the "Saber Encoding Hybridization Buffer" follows this formulation precisely, with encoding probes added at concentrations ranging from 5-200μM depending on the size of the probe pool [26]. Similarly, wash buffers used in FISH protocols typically contain 40% formamide in 2× SSC buffer to maintain stringency during post-hybridization rinses [26].

Alternative formulations have been explored to address specific experimental challenges. For instance, some protocols utilize ethylene carbonate (10% vol/vol) in readout hybridization buffers as a stabilizing agent [26]. Additionally, researchers have developed formamide-free FISH protocols for specific applications, such as a DNA-FISH probe for Candida albicans identification that functions with 0% formamide while maintaining high specificity [25]. However, these alternatives typically require extensive optimization and validation, whereas formamide-containing buffers remain the established standard for most FISH applications due to their predictable performance and well-characterized properties.

Quantitative Optimization of Formamide Concentrations

Systematic Analysis of Formamide and Probe Length Effects

Formamide concentration must be precisely optimized in relation to probe characteristics, particularly target region length, to achieve maximum hybridization efficiency. Recent systematic investigations have examined how formamide concentration and probe length interact to influence single-molecule signal brightness in RNA FISH applications [24]. Researchers created encoding probe sets with target regions of 20, 30, 40, or 50 nucleotides in length and performed smFISH on U-2 OS cells while screening a range of formamide concentrations (with fixed hybridization temperature of 37°C and duration of 1 day) [24]. The results demonstrated that signal brightness, used as a proxy for probe assembly efficiency, depends relatively weakly on formamide concentration within the optimal range for each target region length [24].

This systematic optimization revealed that the relationship between probe length and formamide concentration follows predictable thermodynamic principles, with longer probes generally tolerating higher formamide concentrations while maintaining efficient hybridization. The data further indicated that for each probe length, there exists a plateau of optimal performance across a range of formamide concentrations rather than a single precise optimum, providing researchers with flexibility in protocol design. These findings have significant practical implications for FISH experimental design, particularly in multiplexed applications where probe sets may contain heterogeneous target region lengths.

Table 2: Optimal Formamide Concentrations for Different Probe Lengths

| Target Region Length (nt) | Optimal Formamide Concentration Range | Relative Signal Brightness | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 nt | 10-20% | ++ | Shorter probes require lower formamide |

| 30 nt | 20-40% | +++ | Balanced efficiency and specificity |

| 40 nt | 30-50% | ++++ | Optimal for many smFISH applications |

| 50 nt | 40-60% | ++++ | Higher specificity, potentially slower kinetics |

Impact on Detection Efficiency and False Positive Rates

The optimization of formamide concentration directly influences two critical performance metrics in FISH assays: detection efficiency (the fraction of true target molecules correctly identified) and false positive rates (non-target molecules incorrectly identified as targets). In MERFISH measurements, appropriately balanced formamide concentrations enable high detection efficiency while maintaining low false positive rates through several mechanisms [24]. First, optimal formamide concentration ensures sufficient disruption of RNA secondary structure to permit efficient probe binding while providing enough stringency to prevent non-specific binding of probes to off-target sequences with partial complementarity.

Experimental evidence indicates that suboptimal formamide concentrations can significantly impact MERFISH performance. Excessive formamide can reduce detection efficiency by preventing stable hybridization of even perfectly matched probes, particularly those with shorter target regions or lower GC content. Conversely, insufficient formamide can increase false positive rates through non-specific probe retention, especially in complex tissue samples with high autofluorescence or background signal [24]. This balance is particularly crucial when imaging shorter RNAs, where fewer probes can be deployed per molecule and thus each hybridization event carries greater weight in determining overall detection efficiency [22].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Workflow for Formamide-Based FISH Assays

The experimental workflow for formamide-based FISH assays follows a systematic sequence of steps designed to maximize hybridization efficiency while preserving sample integrity. The process begins with sample preparation and fixation, typically using paraformaldehyde to cross-link and preserve cellular structures while maintaining nucleic acid accessibility [27] [26]. For tissue samples, this is often followed by permeabilization using detergents such as Triton X-100 or proteinase treatments to ensure probe access to intracellular targets [26]. For challenging samples like yeast, an optimized lyticase digestion step may be incorporated for more homogeneous results [27].

Following permeabilization, samples undergo pre-hybridization to prepare the cellular environment for probe binding, followed by hybridization with encoding probes in formamide-containing buffer typically for 12-48 hours at 37°C [24] [26]. The extended hybridization duration compensates for the slowed kinetics resulting from formamide-induced stringency while maintaining specific binding conditions. After encoding probe hybridization, samples are washed with formamide-containing wash buffer (typically 40% formamide in 2× SSC) to remove unbound probes while maintaining stringency conditions that preserve specifically bound probes [26]. For multiplexed FISH techniques like MERFISH, this is followed by multiple rounds of readout probe hybridization, imaging, and fluorescence removal using chemical cleavage or other methods [22] [26].

Diagram 1: Standard workflow for formamide-based FISH assays showing key steps from sample preparation through imaging. The loop between fluorescence removal and readout hybridization represents iterative cycles in multiplexed FISH methods.

Protocol Modifications for Enhanced Performance

Recent optimization studies have identified several protocol modifications that can significantly enhance FISH performance. Hybridization acceleration through probe annealing or increased probe concentration can substantially enhance the rate of probe assembly, potentially reducing required hybridization times [24]. For encoding probes, empirical testing has demonstrated that hybridization with a complex 130-RNA species library at 40 nM concentration for 1 day provides efficient labeling, while higher concentrations (4 μM) can achieve similar results in shorter timeframes [24] [28].

Buffer stabilization approaches address the gradual degradation of FISH reagents during extended measurements. Readout hybridization buffers and associated probes can be stabilized for up to 7 days when stored under specific conditions, such as under a layer of mineral oil, without significant performance loss [24] [28]. Additionally, imaging buffer optimization has led to the development of enhanced formulations containing oxygen-scavenging systems like Trolox with PCA (3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid) that improve fluorophore photostability and extend imaging duration [26]. These protocol refinements collectively address key limitations in formamide-based FISH methods, particularly for long-duration or highly multiplexed experiments where reagent stability and signal persistence are critical for success.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Formamide-Based FISH

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Denaturing Agents | Formamide (40% v/v) | Lowers hybridization temperature, maintains stringency |

| Stringency Wash Buffers | 40% Formamide in 2× SSC | Removes non-specifically bound probes |

| Blocking Agents | Yeast tRNA (0.1% w/v), BSA | Reduce non-specific background binding |

| Volume Exclusion Agents | Dextran Sulfate (10% w/v) | Increases effective probe concentration |

| Permeabilization Agents | Triton X-100 (0.5% v/v), Proteinase K | Enable probe access to intracellular targets |

| Nuclease Inhibitors | Murine RNase Inhibitor, RVC | Preserve RNA integrity during hybridization |

| Stabilizing Additives | Ethylene Carbonate (10% v/v) | Enhances reagent stability in readout steps |

| Fluorophore Protection Systems | Trolox Quinone, PCA | Oxygen scavenging for enhanced photostability |

| Cleaving Agents | TCEP (50 mM in 2× SSC) | Chemically cleaves fluorescent reporters between rounds |

| HDAC ligand-1 | HDAC ligand-1, MF:C7H8N2O, MW:136.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| G|Aq/11 protein-IN-1 | G|Aq/11 protein-IN-1, MF:C19H27N5, MW:325.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Molecular Mechanism of Formamide in Hybridization Stringency

Formamide functions as a key modulator of nucleic acid hybridization thermodynamics through its action as a chaotropic agent that disrupts the hydrogen-bonding network of water molecules, thereby reducing the stability of double-stranded nucleic acids [22] [23]. This destabilization effect directly lowers the melting temperature (T~m~) of DNA-DNA and DNA-RNA hybrids in a concentration-dependent manner, enabling highly specific hybridization to occur at experimentally convenient temperatures (typically 37°C) that preserve cellular and tissue architecture [23]. The molecular mechanism involves formamide molecules competing with nucleotide bases for hydrogen bonding sites, effectively weakening the thermodynamic stability of perfectly matched duplexes to a lesser extent than mismatched hybrids, thus enhancing discrimination between specific and non-specific binding events.

The strategic application of formamide's destabilizing properties enables precise control over hybridization stringency at multiple stages of FISH protocols. During the hybridization phase, formamide (typically at 40% vol/vol) creates conditions where only probes with perfect or near-perfect complementarity to their targets form stable duplexes, while those with significant mismatch remain unbound [22] [26]. During post-hybridization washes, formamide-containing wash buffers (again typically 40% formamide in 2× SSC) remove partially bound probes that may have transiently associated with off-target sequences, further enhancing the specificity of the final signal [26]. This dual application—during both hybridization and washing—makes formamide an exceptionally versatile reagent for controlling the stringency of FISH assays across diverse experimental conditions and sample types.

Diagram 2: Molecular mechanism of formamide function in FISH assays showing how formamide-mediated hydrogen bond disruption enables specific hybridization at lower temperatures while removing non-specific binding.

Technical Considerations and Alternative Approaches

Practical Handling and Safety Considerations

While formamide is an essential component of standard FISH hybridization buffers, its use requires careful attention to safety protocols due to its classification as a teratogen with potential developmental effects [26] [25]. Appropriate personal protective equipment, including gloves and lab coats, should always be worn when handling formamide, and all procedures should be conducted in a fume hood to prevent inhalation exposure [26]. Additionally, buffer stability represents a practical consideration, as formamide can degrade over time, generating formic acid and ammonia that may interfere with hybridization efficiency. Aliquoting formamide stocks under inert gas and storing at -20°C can extend useful shelf life, while regular pH monitoring of buffer solutions can help identify degradation before experimental use.

The concentration precision of formamide in hybridization buffers is critical for reproducible results, as relatively small variations (5-10%) can significantly alter stringency conditions and impact detection efficiency. Commercial preparations of formamide vary in purity, with higher grades recommended for sensitive FISH applications. For particularly demanding applications, deionization of formamide immediately before use may be necessary to ensure optimal performance. These practical considerations underscore the importance of careful reagent management in FISH workflows, particularly for extended multiplexed measurements where buffer consistency across multiple rounds of hybridization is essential for quantitative accuracy.

Formamide-Free Alternative Approaches

Despite the established utility of formamide in FISH protocols, research continues into alternative approaches that eliminate or reduce formamide content while maintaining hybridization specificity. One recent innovation developed a DNA-FISH probe for identification of Candida albicans that functions effectively with 0% formamide while maintaining high specificity (98.9% hybridization efficiency with target versus 4.7% or less with non-target yeasts) [25]. This approach leverages carefully designed probe sequences with optimized thermodynamic properties that provide sufficient discrimination between target and non-target sequences without requiring the destabilizing effects of formamide.

Other emerging strategies include the use of alternative denaturants such as urea or ethylene carbonate, though these typically require extensive protocol re-optimization and may not provide equivalent stringency control across diverse probe sequences. Additionally, enhanced probe design strategies utilizing modified nucleotides (such as locked nucleic acids [LNAs]) or computational optimization of binding characteristics can increase binding specificity independently of buffer composition [26]. While these formamide-free approaches offer potential advantages in terms of safety and reagent stability, they have not yet achieved the widespread adoption and validation of standard formamide-containing buffers, particularly for highly multiplexed applications like MERFISH where consistent performance across dozens to hundreds of parallel hybridization events is essential.

Achieving Single-Base Mismatch Discrimination with Stringent Washes

The ability to discriminate between perfectly matched DNA duplexes and those containing a single-base mismatch is a cornerstone of modern genetic analysis, enabling the identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), pathogen strains, and genetic mutations. This technical guide explores the critical role of stringent wash conditions, with a particular focus on formamide-based buffers, in achieving this high level of discrimination. Formamide functions as a denaturant in hybridization buffers, systematically destabilizing nucleic acid duplexes and allowing for fine control over hybridization stringency. Within the context of broader formamide function research, we detail how parameters such as formamide concentration, wash temperature, and probe design can be optimized to distinguish between target and non-target sequences that differ by just a single nucleotide. The protocols and data presented herein provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a framework for developing highly specific diagnostic and research assays.

The stability of a nucleic acid duplex is highly dependent on the perfect complementarity of its base pairs. A single-base mismatch can significantly destabilize the duplex, a property that can be exploited to differentiate between sequences. Stringent washes are a critical step in hybridization-based assays (e.g., microarrays, Southern blots, genosensors) whereby conditions are adjusted to dissociate imperfectly matched duplexes while retaining perfectly matched ones [29] [30].

Formamide is a key component used to control stringency. It acts by denaturing double-stranded nucleic acids, effectively lowering the melting temperature ((T_m)) of the duplex. This allows for high stringency conditions to be achieved at lower, more experimentally manageable temperatures, which helps preserve the integrity of biological samples and array surfaces [31] [32]. Research into formamide function has demonstrated that its effect on hybridization free energy is quantifiable and predictable. A linear free energy model (LFEM) has shown that each percent of formamide added increases the hybridization free energy (ΔG°) by approximately 0.173 kcal/mol, providing a mathematical foundation for precise probe design and stringency optimization [32].

Core Principles of Mismatch Discrimination

The degree of destabilization caused by a mismatch is not uniform; it depends on several factors that must be considered when designing an assay.

Position of the Mismatch

The location of the mismatch within the probe-target duplex has a profound effect on stability. Research on short DNA duplexes (18-25 bases) has consistently shown that mismatches at or near the terminus are less destabilizing than internal mismatches.

- Terminal Mismatches (Positions 1-2): Mismatches located at the very end (particularly the 5' terminus of the probe) cause a minimal reduction in dissociation temperature ((T_d)), making them difficult to discriminate from perfect matches under some conditions [31].

- Near-Terminal Mismatches (Positions 3-5): These mismatches produce a more significant decrease in duplex stability.

- Internal Mismatches: Mismatches located in the central region of the duplex have the most dramatic destabilizing effect. For instance, a central mismatch can reduce the (Td) by over 9°C compared to the perfect match [29]. Sensitivity analysis reveals that the position of the mismatch accounts for approximately 19% of the variability in (Td), second only to formamide concentration [31].

Type of Mismatch

The chemical nature of the mismatched bases also influences stability. The loss of hydrogen bonding and the introduction of structural distortions vary depending on the specific base pair combination (e.g., G-T versus G-G). While position is generally a greater determinant, the type of mismatch still explains about 6% of the variability in (T_d) and can be the overriding factor in some instances [31].

Probe Length and Composition

The length of the oligonucleotide probe is critical for specificity. While longer probes yield higher signal intensities, they can suffer from reduced specificity due to a higher propensity for cross-hybridization. Experimental data suggests that the optimal probe length for single-base specificity is 19–21 nucleotides [33]. Shorter probes in this range provide a better balance between sufficient hybridization energy and the ability to discern the disruptive effect of a single mismatch.

Experimental Optimization and Protocols

Establishing Denaturation Profiles with Formamide

A robust method for optimizing mismatch discrimination involves determining the nonequilibrium dissociation rate, or melting profile, of probe-target duplexes across a gradient of formamide concentrations.

Protocol: Generating Formamide Denaturation Profiles using Microarrays

- Probe Immobilization: Immobilize perfect-match (PM) and single-base mismatch (MM) probes on a microarray surface. The use of a 3D polyacrylamide gel pad format can enhance the stability of the probe-target duplex and improve data quality [31] [29].

- Hybridization: Hybridize the fluorescently labeled target to the array under permissive conditions.

- Stringent Washes: Perform a series of washes with buffers containing increasing concentrations of formamide (e.g., 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%) [31]. Alternatively, a temperature gradient can be used at a fixed formamide concentration.

- Signal Detection: After each wash step, measure the fluorescence signal intensity for each probe.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the dissociation temperature ((T_d))—the temperature or formamide concentration at which 50% of the probe-target duplexes remain hybridized during the wash. Plot the signal intensity against formamide concentration to generate a sigmoidal denaturation profile for each probe [32].

Table 1: Sample Dissociation Temperature ((T_d)) Data for a 19-mer Probe with Varied Mismatch Positions and Formamide Concentrations [31]

| Probe Type | Mismatch Position | Sequence (5' to 3') | Td at 0% Formamide (°C) | Td at 20% Formamide (°C) | ΔTd (vs PM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect Match (PM) | - | TCGCACATCAGCGTCAGTT | 45.4 | 34.8 | 0.0 |

| MM | 1 | ACGCACATCAGCGTCAGTT | 43.1 | 34.0 | -1.8 |

| MM | 2 | TAGCACATCAGCGTCAGTT | 43.1 | 33.9 | -2.0 |

| MM | 3 | TCCCACATCAGCGTCAGTT | 37.8 | ~29.0* | -7.3 |

| MM | 4 | TCGGACATCAGCGTCAGTT | 41.6 | ~30.5* | -3.5 |

Note: Values for 20% formamide are estimated from the original data trend. ΔTd is calculated at 0% formamide. Slight variations may occur based on mismatch type.

Calculating the Discrimination Index

To objectively determine the optimal wash condition for discriminating between PM and MM duplexes, a Discrimination Index (DI) can be calculated at each temperature or formamide concentration of the dissociation curve [29].

Formula: ( DI = \frac{(Signal{PM} - Signal{MM})}{Signal_{PM}} )

The wash condition that yields the maximum DI is the point of optimal discrimination, where the signal from the perfect match remains high while the mismatch signal is minimized.

Practical Wash Optimization for Various Platforms

The principles of formamide denaturation can be applied across different experimental platforms.

- Microarrays: The denaturation profile method is ideal for microarrays, as it allows parallel optimization for hundreds to thousands of probes simultaneously [29].

- Electrochemical Genosensors: Studies have shown that incorporating 25-45% formamide in the hybridization buffer enables discrimination of single-base mismatches. The concentrated formamide environment preferentially denatures the less stable mismatched duplexes [30].