Heterochrony in Extraembryonic Development: Evolutionary Mechanisms and Biomedical Applications

This article synthesizes contemporary research on heterochrony—evolutionary changes in developmental timing—focusing on its critical role in extraembryonic development across species.

Heterochrony in Extraembryonic Development: Evolutionary Mechanisms and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

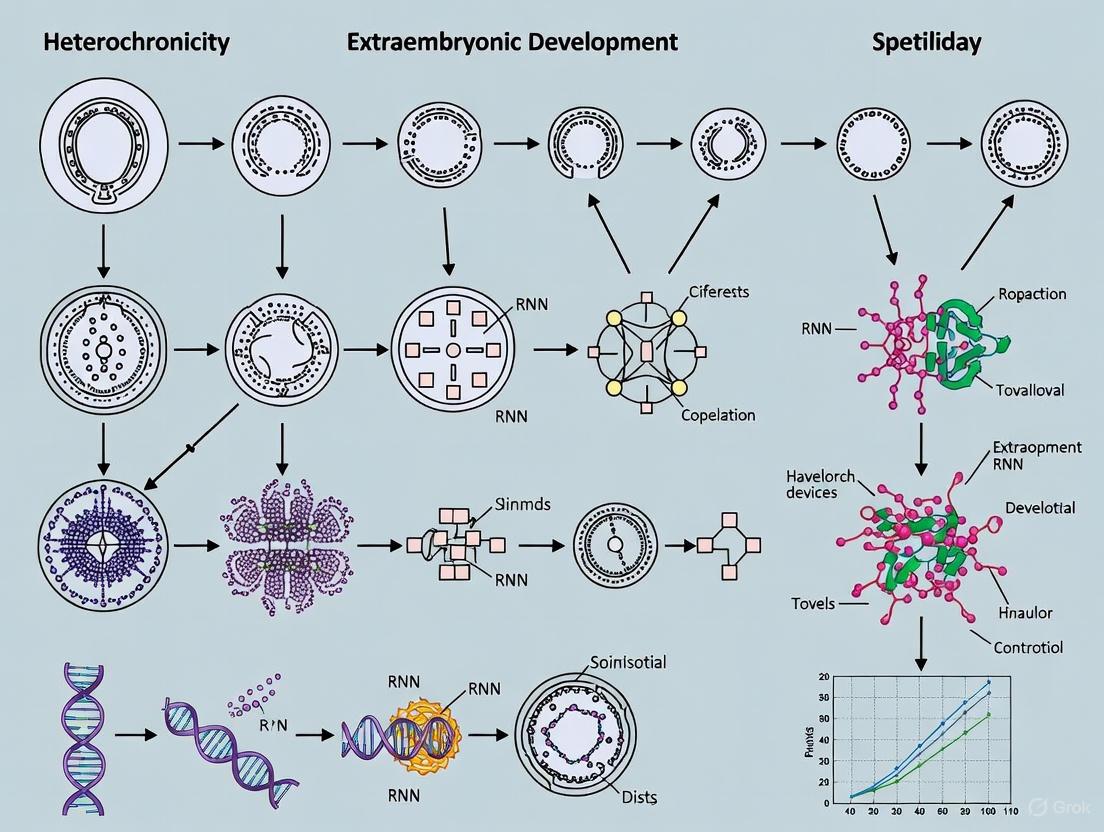

This article synthesizes contemporary research on heterochrony—evolutionary changes in developmental timing—focusing on its critical role in extraembryonic development across species. We explore foundational concepts, from historical theories to modern molecular understanding of developmental timing mechanisms like the somite clock. Methodologically, we detail how advanced tools like comparative RNAseq through ontogeny quantify heterochronic gene expression and identify regulatory architecture. The review addresses key challenges in distinguishing heterochronic shifts from other expression changes and optimizing in vitro models. Through comparative case studies spanning snakes, marsupials, and annelids, we validate heterochrony as a principal driver of evolutionary innovation. Finally, we discuss the translational potential of these insights for modeling developmental disorders and informing regenerative medicine strategies, providing a critical resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this evolving field.

The Clockwork of Life: Unraveling Heterochrony's Role in Evolutionary Development

Heterochrony, defined as a change in the timing or rate of developmental events relative to an ancestral condition, represents a fundamental mechanism linking developmental processes to evolutionary change [1] [2]. The term was originally coined by German biologist Ernst Haeckel in 1875 within the framework of his now-discredited Biogenetic Law, which postulated that "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny" [3] [4] [1]. Haeckel believed embryonic development repeated the adult forms of ancestral species, and he used "heterochrony" to describe deviations from this recapitulatory pattern [1]. His theory allowed only for acceleration of development and terminal addition of new characters, rigidly constraining how evolutionary change could occur [5]. Although Haeckel's recapitulation theory was ultimately abandoned due to arguments from Karl Ernst von Baer and findings from experimental embryology [5], the core concept of heterochrony underwent significant conceptual transformation throughout the 20th century and emerged as a central principle in modern evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) [3] [2].

The modern definition of heterochrony diverges substantially from Haeckel's original conception. Gavin de Beer played a pivotal role in this conceptual shift in the 1930s, redefining heterochrony as comparative changes in developmental timing between related taxa without the recapitulatory baggage [3] [1]. Later, Stephen Jay Gould's influential 1977 work "Ontogeny and Phylogeny" sparked renewed interest in heterochrony as a primary mechanism of evolutionary change [2]. Throughout the late 20th century, the focus of heterochrony studies shifted from Haeckel's descriptive embryology and Gould's emphasis on size-shape relationships toward investigating specific molecular and genetic mechanisms governing developmental timing [3]. This evolution in thinking transformed heterochrony from a descriptive pattern to a causal mechanism explainable through developmental genetics, securing its position as a fundamental concept in modern evolutionary developmental biology [3] [6] [2].

Molecular Mechanisms: The Genetic and Cellular Basis of Timing Changes

The Somite Clock and Vertebrate Segmentation

One of the best-characterized molecular timing mechanisms in vertebrate development is the somite clock, which controls the rhythmic formation of body segments that later develop into vertebrae, skeletal muscle, and dermis [3]. This clock operates through the "Clock and Wavefront" model, where cells in the presomitic mesoderm possess synchronized molecular oscillators that cyclically transition between permissive and non-permissive states for boundary formation [3]. The core molecular components of this segmentation clock include oscillating genes from the Notch, FGF, and Wnt signaling pathways, which create traveling waves of gene expression that coordinate the precise temporal spacing of somite formation [3]. The periodicity of this clock varies significantly between species, with dramatic consequences for morphological evolution.

Research on snake embryogenesis provides a compelling case study of how heterochronic changes in the somite clock can produce major evolutionary innovations. Snakes exhibit a remarkable increase in vertebral number compared to other vertebrates, with between 150-400 vertebrae compared to approximately 60 in mice [3] [1]. This expansion results primarily from acceleration of the segmentation clock, which runs approximately four times faster in snake embryos than in mouse embryos [3] [1]. This accelerated ticking rate produces more numerous, smaller somites within a similar developmental timeframe, ultimately creating the elongated body plan characteristic of snakes [3]. The molecular regulation of this heterochronic change involves modifications to the expression patterns and oscillation frequencies of core clock components, though the precise genetic alterations remain an active area of investigation [3].

Heterochronic Gene Expression and Regulatory Architecture

Beyond morphological timing mechanisms, heterochrony operates at the gene expression level through heterochronic shifts in transcriptional timing and heteromorphic changes in expression levels [6]. A recent study on the marine annelid Streblospio benedicti, which exhibits a developmental dimorphism with both planktotrophic (feeding) and lecithotrophic (non-feeding) larval forms, quantified the relative contributions of these molecular mechanisms to developmental divergence [6]. The research revealed that only 36.2% of expressed genes showed differential expression between morphs at any developmental stage, with early developmental stages exhibiting the greatest number of differentially expressed genes [6]. Through clustering analysis of gene expression profiles, researchers categorized genes as heterochronic (changed timing), heteromorphic (changed expression level), or morph-specific (expressed in only one morph) [6].

Table 1: Types of Gene Expression Differences in Developmental Divergence

| Category | Definition | Contribution to Divergence |

|---|---|---|

| Heterochronic Genes | Genes with shifted expression timing between morphs | Primary driver of morphological timing differences |

| Heteromorphic Genes | Genes with different expression levels but conserved timing | Modifies morphological intensity or size |

| Morph-Specific Genes | Genes expressed exclusively in one morph | Creates novel morphological features |

The regulatory architecture underlying these expression differences was elucidated through reciprocal crosses between morphs, which enabled researchers to distinguish maternal effects from zygotic inheritance patterns [6]. This approach revealed that heterochronic shifts often involve changes in trans-acting regulatory factors, while heteromorphic changes frequently result from cis-regulatory modifications [6]. The study demonstrated that despite major differences in larval morphology and life history, the two developmental morphs share most of their transcriptome, with heterochronic shifts in a relatively small subset of genes responsible for the dramatic phenotypic differences [6].

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies for Investigating Heterochrony

Comparative Embryology and Developmental Staging

Traditional approaches to detecting heterochrony rely on detailed comparative embryology across species, focusing on changes in developmental sequence and timing [5] [7]. The establishment of the Carnegie Stages for human embryonic development created a standardized framework for comparing developmental progression across species [5]. Historically, researchers like Adolf Schultz systematically collected anthropometric measurements from human and non-human primate embryos housed in collections like the Carnegie Institution of Washington's Department of Embryology to document variations in prenatal development [5]. These comparative approaches require careful staging of embryos based on morphological criteria and precise documentation of the timing of key developmental events.

Modern implementations of these comparative approaches often employ event pairing methodology, which compares the relative timing of two developmental events across taxa [1]. This method focuses on sequence heterochrony rather than allometric changes, though it becomes computationally intensive when analyzing multiple events across many taxa [1]. Recent advances have automated this process using tools like the PARSIMOV script, enabling larger-scale analyses of developmental sequences across deep phylogenetic distances [1]. Additionally, continuous analysis methods have been developed that standardize ontogenetic time across species, applying squared-change parsimony and phylogenetic independent contrasts to identify significant heterochronies in developmental datasets [1].

Energy Proxy Traits (EPTs) and High-Dimensional Phenotyping

A innovative methodological approach called Energy Proxy Traits (EPTs) has recently been developed to overcome limitations of traditional event-based heterochrony analyses [7]. Rather than measuring discrete developmental events, EPTs quantify phenotypic change continuously by measuring fluctuations in pixel intensities from video recordings of developing embryos, representing these changes as spectra of energies across different temporal frequencies [7]. This method captures integrated information about morphology, physiology, and behavior without requiring a priori selection of specific characters, thus providing a more objective and comprehensive assessment of developmental timing [7].

Application of EPTs to embryonic development in three freshwater pulmonate snails (Lymnaea stagnalis, Radix balthica, and Physella acuta) revealed that evolutionary differences in the timing of major developmental events (including the onset of ciliary rotation, cardiac function, muscular crawling, and radula function) were associated with detectable shifts in high-dimensional phenotypic space [7]. The EPT methodology involved collecting time-lapse video of embryonic development from the 4-cell stage to hatching using an Open Video Microscope (OpenVIM), which enables long-term repeated imaging of aquatic embryos under controlled environmental conditions [7]. Images were acquired at 200× magnification with dark-field illumination, and EPTs were calculated from these image sequences to construct continuous functional time series of phenotypic change throughout development [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Methodological Approaches to Heterochrony Research

| Methodology | Key Features | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Event Pairing | Compares timing of discrete developmental events | Phylogenetic analyses of developmental sequences | Requires a priori event selection; limited scalability |

| Continuous Analysis | Standardizes ontogenetic time across species | Quantitative comparisons of growth trajectories | Requires precise developmental staging |

| Energy Proxy Traits (EPTs) | Measures phenotypic change continuously from video | High-dimensional phenotypic landscapes; no a priori character selection | Computational intensity; requires specialized equipment |

| Comparative Transcriptomics | Analyzes gene expression timing across species | Molecular mechanisms of heterochrony | Expensive; requires genomic resources |

Experimental Protocols for Key Heterochrony Studies

Protocol 1: Investigating Segmentation Clock Heterochrony in Snake Embryos [3]

- Embryo Collection: Obtain fertilized eggs from snake species with high vertebral counts (e.g., corn snakes) and control species (e.g., mice).

- In Situ Hybridization: Process embryos for whole-mount in situ hybridization using probes for oscillatory genes (e.g., Lfng, Hes7) to visualize segmentation clock dynamics.

- Real-Time Imaging: Culture embryos ex vivo and use time-lapse microscopy to document somite formation rates.

- Quantitative Analysis: Measure oscillation periods of clock genes using quantitative PCR or reporter constructs, comparing cycling frequencies between species.

- Functional Validation: Use pharmacological inhibitors or CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis to perturb clock components and test their role in segment number determination.

Protocol 2: EPT Analysis of Molluscan Embryonic Development [7]

- Embryo Preparation: Collect egg masses from multiple freshwater pulmonate species (Lymnaea stagnalis, Radix balthica, Physella acuta) and isolate individual embryos at the 4-cell stage.

- Video Acquisition: Transfer embryos to 96-well microtiter plates and image using an Open Video Microscope (OpenVIM) with dark-field illumination at 20°C.

- Data Processing: Convert video sequences to spectral data using Welch's method, calculating energy distributions across temporal frequencies.

- Developmental Staging: Document timing of key developmental events (ciliary rotation, heart function, crawling, radula activity) for correlation with EPT spectra.

- Multivariate Analysis: Use principal component analysis and other dimensionality reduction techniques to visualize developmental trajectories in high-dimensional phenotypic space.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Networks

The Vertebrate Segmentation Clock

The molecular machinery underlying the vertebrate somite clock involves an intricate network of interacting signaling pathways that generate oscillatory gene expression. The core circuit comprises cyclic components from the Notch, Wnt, and FGF pathways, which together create a precise timing mechanism that controls the rhythmic formation of body segments.

Diagram 1: Molecular network of vertebrate segmentation clock showing oscillatory components from Notch (yellow), Wnt (green), and FGF (red) signaling pathways. Arrows indicate activation, dashed lines with flat ends indicate inhibition. Each pathway contains negative feedback loops that generate oscillatory expression.

Limb Positioning and Hox Gene Regulation

The development of limb positioning along the anterior-posterior axis provides another excellent example of heterochronic regulation, controlled by the timed expression of Hox genes in response to retinoic acid signaling. Variations in the timing of Hox gene activation and repression between species result in evolutionary changes to limb position.

Diagram 2: Hox gene regulation of vertebrate limb positioning. Retinoic acid (RA) activates anterior (Hox4-5) and posterior (Hox8-9) paralogs. Cyp26a1 degrades RA, controlling its temporal availability. Anterior Hox genes activate Tbx5 (forelimb determinant), while posterior Hox genes activate Pitx1 and Tbx4 (hindlimb determinants) while repressing Tbx5.

Research Reagent Solutions for Heterochrony Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Heterochrony

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Organisms | Snakes (Python, Elaphe), axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum), annelids (Streblospio benedicti), freshwater snails (Lymnaea, Radix, Physella) | Comparative developmental studies | Provide natural variation in developmental timing for evolutionary comparisons |

| Molecular Biology Tools | RNAscope probes, in situ hybridization kits, CRISPR/Cas9 systems, RNAi reagents | Gene expression and functional analysis | Visualize spatial and temporal gene expression; test gene function through perturbation |

| Live Imaging Systems | Open Video Microscope (OpenVIM), temperature-controlled incubation chambers, dark-field illumination | Continuous developmental monitoring | Enable long-term, high-resolution imaging of embryonic development for EPT analysis |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Mfuzz (expression clustering), PARSIMOV (event pairing), custom EPT analysis pipelines | Data analysis and heterochrony detection | Identify heterochronic shifts in gene expression and developmental sequences |

| Signaling Modulators | FGF inhibitors, Notch pathway modulators, Wnt agonists/antagonists, retinoic acid pathway compounds | Experimental manipulation of timing | Test role of specific pathways in controlling developmental timing processes |

Discussion: Implications for Evolutionary Biology and Biomedical Research

The study of heterochrony has profound implications for understanding both evolutionary patterns and human disease mechanisms. In evolutionary biology, heterochrony provides explanations for major transitions, such as the evolution of vertebrates from tunicate larvae through paedomorphosis, where sexual maturity is reached in what was ancestrally a juvenile stage [2]. Similarly, human evolution exhibits a mosaic of heterochronic changes, with peramorphic (hyperdeveloped) traits like increased brain size coexisting with paedomorphic (juvenilized) features such as reduced jaw size [2]. These evolutionary patterns demonstrate how changes in developmental timing can produce coordinated changes across multiple structures, potentially facilitating rapid morphological evolution.

In biomedical research, understanding heterochronic mechanisms has important applications. Many congenital disorders involve disruptions to developmental timing programs, and the same signaling pathways subject to evolutionary heterochrony (Notch, Wnt, FGF) are frequently dysregulated in cancers [3] [8]. The molecular components of timing mechanisms represent potential therapeutic targets for conditions involving abnormal development or tissue regeneration. Furthermore, comparative studies of heterochrony may inform strategies for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine by revealing how different species regulate the timing of developmental processes. As research methodologies continue to advance, particularly in live imaging and single-cell transcriptomics, our understanding of heterochronic mechanisms will likely yield additional insights with both basic and applied significance.

The Clock and Wavefront Model, first proposed by Cooke and Zeeman in 1976, represents a foundational framework for understanding the sequential segmentation of the vertebrate body axis into somites—blocks of tissue that give rise to vertebrae, ribs, and associated muscles [9]. This process, known as somitogenesis, exhibits remarkable evolutionary conservation across vertebrates while displaying species-specific variations in somite number and segmentation timing. Recent research has refined our understanding of this mechanism, revealing complex interactions between molecular oscillators, signaling gradients, and self-organizing cellular behaviors that operate within a heterochrony framework—where evolutionary changes in developmental timing create morphological diversity [6] [10].

The segmentation clock functions as a multicellular genetic oscillator within the presomitic mesoderm (PSM), generating traveling waves of gene expression that sweep anteriorly along the embryonic axis. Concurrently, a wavefront of differentiation, often associated with morphogen gradients, moves posteriorly. Where these two systems interact, somites bud off periodically from the anterior PSM [9]. This review examines current models, experimental evidence, and emerging concepts that position somitogenesis within the broader context of heterochronicity in embryonic development, particularly relevant for researchers investigating evolutionary developmental biology and species-specific patterning.

Comparative Analysis of Somitogenesis Models

The original Clock and Wavefront model has evolved substantially, with several competing and complementary frameworks now explaining different aspects of segmentation.

Table 1: Key Theoretical Models of Somitogenesis

| Model Name | Core Mechanism | Key Supporting Evidence | Limitations/Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original Clock & Wavefront (CWO) [9] | Independent clock and slowly moving wavefront; cells segment when wavefront arrives during specific clock phase | Conceptual framework explaining periodic segmentation | Fails to account for phase waves; posits synchronous oscillations throughout PSM |

| Clock & Gradient (CG) [11] [9] | Posterior-to-anterior gradient of oscillation frequency creates phase shift | Mathematical modeling; explains traveling waves of clock gene expression | Requires precise global frequency gradient; may not fully explain self-organization |

| Progressive Oscillatory Reaction-Diffusion (PORD) [11] | Somite formation triggered by last formed somite via local cell communication | Explains segmentation in tissue explants | Still relies on global frequency profile gradient |

| Clock & Wavefront Self-Organizing (CWS) [11] | Excitable self-organizing region where phase waves form independent of global gradients | Recapitulates mouse PSM excitability in vitro; explains relative phase changes of Wnt/Notch | Complex regulatory network; recently proposed model |

| Phase Shift (PS) [9] | Two clocks propagating at different speeds from posterior; positional information from phase difference | Explains kinematic waves observed in chicken c-hairy1 expression | Less attention in somitogenesis field until recently |

Table 2: Molecular Signatures Across Species and Models

| Signaling Pathway | Role in Segmentation | Species Variations | Experimental Manipulations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Notch Signaling [9] | Core oscillator component; cell-cell synchronization | Oscillations observed in chicken, mouse, zebrafish; required in some but not all species | Mouse Notch mutants show severe segmentation defects |

| Wnt Signaling [11] [12] | Oscillator component; posterior signaling gradient | Relative phase with Notch changes in mouse tailbud | Ectopic Wnt activation affects wave patterns |

| FGF Signaling [13] [12] | Wavefront component; posterior-anterior gradient | Gradient dynamics vary between species | FGF application lengthens cell-intrinsic timer duration in zebrafish |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) [11] | Anterior differentiation signal; counter-gradient to FGF | Conserved anterior localization across vertebrates | RA inhibition disrupts somite boundary formation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Single-Cell Isolation and Culture for Autonomous Timing Studies

Objective: To determine whether segmentation clock dynamics are cell-intrinsic or require tissue-level signals [12].

Protocol:

- Tissue Dissection: Isolate posterior-most quarter of zebrafish PSM (PSM4 region) from Tg(her1-YFP;mesp-ba-mKate2) transgenic embryos

- Dissociation: Manually dissociate PSM4 explants in DPBS (-CaCl2, -MgCl2)

- Culture Conditions: Plate at low density on protein A-coated glass in L15 medium without added signaling molecules, small molecule inhibitors, serum, or BSA

- Imaging: Track Her1-YFP (clock component) and Mesp-ba-mKate2 (differentiation marker) intensity in single cells over ≥5 hours post-dissociation

- Inclusion Criteria: Cells must survive entire imaging period, remain alone in field of view, not divide, and show transient Her1-YFP dynamics

Key Findings: Single PSM4 cells autonomously produced 1-8 Her1-YFP oscillation peaks that slowed before arresting, with arrest coinciding with Mesp-ba-mKate2 onset—mirroring in vivo differentiation timing [12].

Ex Vivo Explant Cultures for Self-Organization Studies

Objective: To test the self-organizing potential of PSM tissue independent of global embryonic signals [11].

Protocol:

- Explant Preparation: Isolate mouse PSM tissue from tailbud region

- Culture Conditions: Maintain in defined medium permissive for oscillation persistence

- Perturbation Conditions:

- Test explants with significant cellular rearrangement

- Mix cells from different tailbud explants to create heterogeneous cultures

- Ectopically activate posterior signaling pathways throughout entire PSM

- Imaging: Monitor oscillation dynamics and wave patterns using live reporters for Notch and Wnt signaling

- Analysis: Track circular wave formation and synchronization patterns

Key Findings: Mouse PSM explants can generate circular phase waves and self-organize upon cellular rearrangement and perturbation of embryonic signals, supporting self-organizing models [11].

Cross-Species Single-Cell Transcriptomics

Objective: To identify heterochronicity in cell differentiation timing across mammalian species [14].

Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Obtain pig, mouse, and monkey embryos at gastrulation and early organogenesis stages

- Tissue Processing: Dissect to remove extra-embryonic tissues before dissociation

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing:

- Construct single-cell libraries using standard protocols (10X Genomics)

- Sequence to appropriate depth for cell type identification

- Cross-Species Analysis:

- Map orthologous genes across species

- Perform reference mapping of human embryo data to pig dataset

- Calculate pseudotime and differentiation trajectories

- Validation: Spatial mapping of mesodermal and endodermal progenitors via immunohistochemistry

Key Findings: Cross-species comparison revealed heterochronicity in extraembryonic cell-types despite broad conservation of cell-type-specific transcriptional programs [14].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The segmentation clock integrates multiple signaling pathways that coordinate temporal and spatial patterning. The core oscillator relies on delayed negative feedback loops in the Hes/Her family of transcription factors, which are synchronized across cells through Delta-Notch signaling [13]. This oscillator is modulated by Wnt and FGF signaling gradients along the anteroposterior axis, with recent evidence showing that cells also possess a cell-autonomous timing mechanism that runs down as they flow anteriorly through the PSM [12]. The retinoic acid (RA) gradient from anterior tissues provides a counter-signal that promotes differentiation and somite boundary formation.

Self-Organizing Principles in Somitogenesis

Recent models emphasize self-organizing principles in somite patterning. The Clock and Wavefront Self-Organizing (CWS) model proposes an excitable region where phase waves form independent of global frequency gradients [11]. This framework, implemented in the "Sevilletor" reaction-diffusion system, demonstrates how delayed negative feedback between two self-enhancing reactants (u and v) can generate periodic phase waves through diffusion-driven excitation of a bistable state. The system exhibits a bifurcation from oscillatory to bistable states as relative self-enhancement strengths vary, creating diverse patterning behaviors including rotating waves and periodic wave patterns that resemble somitogenesis both in vivo and in vitro.

The balance between cell-autonomous programs and tissue-level coordination creates a robust yet evolvable system. Single zebrafish PSM cells exhibit autonomous timing programs that mirror in vivo slowing and arrest dynamics, suggesting intrinsic timing mechanisms [12]. However, cell-cell communication through Delta-Notch signaling enhances precision and robustness, particularly in mouse where isolated PSM cells stop oscillating without density-dependent signals [11] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Cases | Species Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tg(her1:her1-YFP) [12] | Live imaging of core clock component dynamics | Real-time oscillation tracking in single cells and tissue | Zebrafish |

| Tg(mesp-ba:mesp-ba-mKate2) [12] | Differentiation marker for somite formation | Identifying clock arrest and segmental differentiation | Zebrafish |

| Sevilletor Framework [11] | Reaction-diffusion system for modeling patterning | Comparing somitogenesis models; testing self-organization | Theoretical (mouse application) |

| scRNA-seq Atlas [14] | Cross-species transcriptomic comparison | Identifying heterochronic gene expression patterns | Pig, mouse, monkey |

| Protein A-coated substrate [12] | Permissive surface for PSM cell culture | Maintaining oscillations in low-density cultures | Zebrafish, mouse |

| FGF8 Supplementation [12] | Supporting oscillation persistence | Sustaining clock dynamics in dissociated cells | Zebrafish |

| YAP Signaling Inhibitors [12] | Enabling autonomous oscillations | Maintaining clock function in mammalian PSM cells | Mouse, human |

| Open Video Microscope (OpenVIM) [10] | Long-term imaging of embryonic development | Tracking phenotypic changes via Energy Proxy Traits | Molluscs (transferable) |

| EO 1428 | EO 1428, CAS:321351-00-2, MF:C20H16BrClN2O, MW:415.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| AA29504 | AA29504 | AA29504 is a positive allosteric modulator of extrasynaptic GABA-A receptors for neuroscience research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

The somite segmentation clock exemplifies how developmental timing mechanisms evolve through alterations in gene expression timing (heterochrony) and amount (heteromorphy) [6]. Recent evidence supports a modified Clock and Wavefront framework that incorporates self-organizing principles and cell-autonomous timing activities, working in concert with tissue-level gradients and cell-cell communication. This integrated mechanism provides both robustness against perturbation and evolvability through modularity—where the clock and PSM morphogenesis can evolve independently to generate species-specific segment numbers [13].

The emerging paradigm suggests developmental modularity between the segmentation clock and PSM morphogenesis, enabling independent evolution of these processes to produce diversity in vertebrate body plans [13]. Cross-species analyses reveal both conserved core programs and heterochronic shifts in developmental timing, particularly in extra-embryonic tissues [14]. Future research will continue to elucidate how local cell interactions and global tissue patterning integrate to translate temporal oscillations into spatial patterns—a fundamental question in evolutionary developmental biology with implications for understanding congenital vertebral defects and evolutionary morphology.

The concept of heterochrony, which describes evolutionary alterations in the timing of developmental events, has served as a crucial bridge connecting embryology and evolutionary biology since its initial formulation. Gavin de Beer and Stephen Jay Gould represent pivotal figures in the refinement of this concept, transitioning it from a descriptive embryological observation to a sophisticated evolutionary mechanism. De Beer's work fundamentally challenged the germ layer theory and established that homologous structures can arise from different developmental processes, while Gould's theoretical contributions expanded heterochrony's explanatory power to encompass patterns of human evolution and the relationship between ontogeny and phylogeny. Their collective work established heterochrony not merely as a biological curiosity but as a significant mechanism underlying morphological innovation and diversification across taxa.

This intellectual foundation has been progressively transformed through the integration of molecular biology, genomics, and computational approaches. Contemporary research has quantified heterochrony at the transcriptomic level, identified specific genetic regulators, and developed novel phenomic approaches to capture developmental timing without gross simplification of organismal development. The historical perspectives established by de Beer and Gould now provide the conceptual framework for investigating how subtle changes in developmental timing can generate substantial morphological diversity, both in interspecific comparisons and within species exhibiting developmental dimorphisms. This review examines the experimental evidence and methodological advances that have built upon this foundation, focusing specifically on heterochrony in the context of extraembryonic development and its implications for evolutionary developmental biology.

Theoretical Foundations: From de Beer to Gould

Gavin de Beer's contributions to heterochrony research were foundational in establishing a developmental approach to evolutionary questions. As a forerunner of modern evolutionary developmental biology, de Beer emphasized that the homology of morphological structures is not dependent on the sameness of underlying developmental processes or genetic pathways [15]. This conceptual breakthrough liberated the study of homology from strict embryological correspondence and allowed for the exploration of how developmental timing alterations could produce evolutionary innovations. De Beer's work particularly highlighted paedomorphosis (the retention of juvenile characteristics in adults) as a key heterochronic process that increases morphological evolvability and accounts for the origin of numerous taxa, including higher taxonomic groups [15].

Stephen Jay Gould further refined heterochrony theory in his seminal work "Ontogeny and Phylogeny" (1977), systematically categorizing heterochronic processes and exploring their macroevolutionary implications. Gould's theoretical framework differentiated between paedomorphosis and peramorphosis (the extension of development beyond the ancestral state) and connected these processes to changes in the timing of onset, offset, or rate of developmental events. This categorization provided researchers with a precise vocabulary for describing heterochronic patterns and stimulated empirical investigations across diverse taxonomic groups. Gould's work also emphasized the role of developmental modularity, suggesting that heterochronic changes in one system could occur independently of others, thus enabling mosaic evolution and increasing evolutionary flexibility.

The integration of de Beer's embryological perspective with Gould's evolutionary framework established heterochrony as a primary mechanism for evolutionary change, suggesting that relatively simple alterations in developmental timing could produce dramatic morphological innovations. This theoretical foundation continues to guide contemporary research, which has shifted toward identifying the molecular genetic basis of heterochronic shifts and quantifying their effects on phenotype.

Modern Methodological Approaches in Heterochrony Research

Comparative Transcriptomics and Developmental Timing

The advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies has enabled researchers to investigate heterochrony at unprecedented molecular resolution. Comparative RNAseq through ontogeny provides a powerful approach for identifying heterochronic gene expression patterns between taxa with divergent developmental trajectories. In marine annelids (Streblospio benedicti) with developmental dimorphism, this approach has revealed that only a modest proportion of genes (36.2%) are differentially expressed between morphs at any developmental stage, despite major differences in larval morphology and life history [6]. This methodology involves:

- Dense temporal sampling across multiple developmental stages

- Multiple biological replicates per stage and morph (≥4)

- Principal component analysis to visualize variance components attributable to developmental stage and morph

- Differential expression analysis to identify genes with significant expression differences

- Clustering algorithms (e.g., Mfuzz) to categorize expression profiles

This experimental protocol allows researchers to distinguish between heterochronic genes (shifting expression timing between morphs) and heteromorphic genes (differing in expression level but not timing), quantifying their respective contributions to developmental divergence [6].

Energy Proxy Traits (EPTs): A Phenomic Approach

A novel "comparative phenomics" approach using Energy Proxy Traits (EPTs) has been developed to overcome limitations associated with measuring discrete developmental events. EPTs measure organismal development as spectra of energy in pixel values of video, creating high-dimensional landscapes that integrate development of all visible form and function [10]. This method involves:

- Long-term time-lapse video of embryonic development using an Open Video Microscope (OpenVIM)

- Dark field illumination and automated image acquisition at high temporal resolution

- Calculation of EPTs from fluctuations in pixel intensities quantified as a spectrum of energies across different temporal frequencies

- Continuous functional time series construction from EPT spectra

This approach enables continuous quantification of developmental changes in high-dimensional phenotypic space without reducing complex developmental processes to single discrete events, thus providing a more comprehensive assessment of heterochronic changes [10].

Molecular Heterochrony Studies

Molecular developmental approaches incorporate candidate gene expression analysis to identify genetic regulators of heterochronic growth. Studies in belonoid fishes have examined expression of skeletogenic genes (sox9, runx2) and proliferation regulators (bmp4, calmodulin, bmp2) during jaw development [16]. The experimental protocol includes:

- Skeletal staining with alcian blue and alizarin red for cartilage and bone visualization

- Morphometric measurements of developing structures from laterally-oriented specimens

- Gene expression analysis via in situ hybridization or qRT-PCR across developmental stages

- Heterochrony and allometry analysis using shape variables (e.g., jaw ratios) and scaling of developmental time

This approach identifies specific genetic candidates underlying heterochronic shifts, such as calmodulin's role in jaw elongation in belonoid fishes [16].

Key Experimental Models and Findings

Developmental Dimorphism in Marine Annelids

Streblospio benedicti provides a unique intraspecific model for investigating the earliest genetic changes during developmental divergence. This marine annelid exhibits two distinct developmental morphs: planktotrophic (PP) larvae (obligately feeding) and lecithotrophic (LL) larvae (non-feeding), which differ in egg size, embryological development time, larval ecology, and morphology [6]. Despite these differences, adults are morphologically indistinguishable outside reproductive traits. Reciprocal crosses between morphs produce viable F1 offspring with intermediate larval traits, enabling investigation of regulatory architecture.

Research has revealed that:

- LL embryos transcriptionally lag behind PP offspring at equivalent developmental stages

- Only 36.2% of expressed genes show differential expression between morphs

- Early development shows more differentially expressed genes, though with smaller magnitude differences

- Gastrulation exhibits fewer but larger magnitude expression differences

- Gene expression differences shift profiles across morphs via:

- Complete shutdown of expression in one morph

- Changes in expression timing (heterochrony)

- Changes in expression amount (heteromorphy) [6]

Table 1: Transcriptomic Differences Between Developmental Morphs of Streblospio benedicti

| Feature | Planktotrophic (PP) Morph | Lecithotrophic (LL) Morph | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egg size | Smaller | 8× larger volume | Differential maternal provisioning |

| Development time | Faster early development | Slower early development | Absolute timing differences |

| Larval ecology | Obligate feeding | Non-feeding | Trophic specialization |

| Differentially expressed genes | 36.2% of total | 36.2% of total | Modest transcriptomic difference |

| Expression differences | Larger magnitude at gastrulation | Larger magnitude at gastrulation | Stage-specific effects |

| Regulatory architecture | Trans-acting factors | Trans-acting factors | Identified via F1 crosses |

Jaw Elongation in Belonoid Fishes

Belonoid fishes exhibit dramatic heterochronic shifts in jaw development, providing a textbook example of heterochrony. Comparative studies of halfbeak (Dermogenys pusilla), needlefish (Belone belone), and medaka (Oryzias latipes) reveal:

- Halfbeaks show accelerated lower jaw growth early in development

- Needlefish display accelerated lower jaw growth early, followed by secondary acceleration of upper jaw growth later

- Toothless extensions of dentaries represent evolutionary innovations enabling heterochronic growth

- Calmodulin expression patterns match jaw outgrowth, suggesting its role as a heterochrony regulator [16]

Table 2: Heterochronic Jaw Development in Belonoid Fishes

| Species | Jaw Morphology | Heterochronic Pattern | Genetic Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medaka (Oryzias latipes) | Short upper and lower jaws | Ancestral condition | Equal calm1 expression in both jaws |

| Halfbeak (Dermogenys pusilla) | Elongated lower jaw, short upper jaw | Early acceleration of lower jaw growth | Gradually increasing calm1 in lower jaw only |

| Needlefish (Belone belone) | Elongated upper and lower jaws | Mosaic heterochrony: early lower jaw acceleration, followed by upper jaw acceleration | Sequential calm1 expression matching growth patterns |

These heterochronic shifts in jaw development have ecological significance, enabling trophic specialization and contributing to the remarkable species richness of Belonoidei (240 species) compared to their sister group Adrianichthyoidei (33 species) [16].

Freshwater Pulmonate Molluscs

Studies of embryonic development in three freshwater pulmonate snails (Lymnaea stagnalis, Radix balthica, and Physella acuta) have revealed sequence heterochronies in functional developmental events:

- Onset of ciliary-driven rotation

- Onset of cardiac function

- Attachment to egg capsule and transition to muscular crawling

- Onset of radula function [10]

Application of Energy Proxy Traits (EPTs) to these species demonstrates that evolutionary differences in event timings associate with changes in high-dimensional phenotypic space, providing a more comprehensive assessment of heterochronic changes than discrete event analysis alone [10].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The molecular basis of heterochrony involves alterations in the expression patterns or regulation of key developmental genes and pathways. Research across model systems has identified several conserved molecular players:

Calmodulin Signaling in Jaw Elongation

In belonoid fishes, the calcium-binding protein calmodulin (specifically the calm1 paralogue) has been identified as a potential regulator of heterochronic jaw growth. The signaling pathway involves:

Figure 1: Calmodulin-Mediated Heterochronic Jaw Growth

This pathway illustrates how spatial and temporal shifts in calmodulin expression can produce heterochronic growth patterns in developing jaw structures, ultimately leading to the diverse jaw morphologies observed in belonoid fishes [16].

Transcriptional Regulation in Developmental Divergence

In Streblospio benedicti, transcriptomic analyses reveal that heterochronic gene expression differences between developmental morphs are regulated primarily by trans-acting factors, as demonstrated through reciprocal crosses that produce F1 offspring with intermediate expression patterns [6]. The regulatory architecture involves:

Figure 2: Regulatory Architecture of Developmental Divergence

This regulatory model emphasizes the importance of trans-acting factors and maternal mRNA inheritance in initiating developmental divergence through heterochronic shifts in gene expression [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Heterochrony Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNAseq library prep kits | Transcriptomic analysis | Profile gene expression across developmental stages | Identify differentially expressed genes in Streblospio morphs [6] |

| Spatial transcriptomics platforms | Mapping gene expression in tissue context | Localize gene expression to specific embryonic regions | Characterize gastrulating human embryo [17] |

| Alcian blue & alizarin red | Skeletal staining | Differentiate cartilage (blue) and bone (red) | Visualize jaw development in belonoid fishes [16] |

| Open Video Microscope (OpenVIM) | Long-term bioimaging | Capture embryonic development continuously | Measure Energy Proxy Traits in mollusc embryos [10] |

| Anti-calmodulin antibodies | Immunohistochemistry | Localize calmodulin protein expression | Validate expression patterns in fish jaw development [16] |

| Single-cell RNAseq reagents | High-resolution transcriptomics | Profile gene expression in individual cells | Characterize human gastrulation [17] |

| Artificial pond water | Aquatic embryo maintenance | Physiological medium for embryonic development | Culture pulmonate snail embryos [10] |

| Org-24598 | Org-24598, MF:C19H20F3NO3, MW:367.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Fluoflavine | Fluoflavine, MF:C14H10N4, MW:234.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The refinement of heterochrony from de Beer's embryological observations to a molecularly-defined evolutionary mechanism represents a significant achievement in evolutionary developmental biology. Contemporary research has built upon de Beer and Gould's theoretical foundations by:

- Quantifying heterochrony at the transcriptomic level, revealing that relatively modest gene expression differences underlie major developmental divergences [6]

- Identifying specific genetic regulators of heterochronic growth, such as calmodulin in belonoid jaw elongation [16]

- Developing novel methodologies like Energy Proxy Traits that capture developmental timing without reducing complexity [10]

- Establishing experimental models with intraspecific developmental dimorphisms that enable genetic crosses and regulatory analysis [6]

These advances have transformed heterochrony from a descriptive pattern to a mechanistic process with identifiable genetic and developmental components. Future research directions will likely focus on integrating single-cell transcriptomics [17] with high-dimensional phenomics [10] to create comprehensive maps of developmental timing across taxa, further illuminating how alterations to the embryonic clock drive evolutionary innovation.

The historical perspectives established by de Beer and Gould continue to provide a conceptual framework for investigating how temporal reorganizations of development generate biological diversity, affirming heterochrony's enduring importance as a mechanism linking ontogeny and phylogeny.

In the field of evolutionary developmental biology, heterochrony represents a fundamental concept describing evolutionary change arising from alterations in the timing or rate of developmental processes. Formally defined as "change to the timing or rate of developmental events, relative to the same events in the ancestor" [2], heterochrony provides a mechanistic bridge between evolutionary change and developmental processes. The term was originally coined by Ernst Haeckel in 1875 but has undergone significant conceptual refinement over decades of research [18] [1]. This framework has shifted from Haeckel's initial association with recapitulation theory to its modern interpretation, largely shaped by Gavin de Beer and later Stephen Jay Gould, who emphasized heterochrony's role in generating morphological diversity through changes in developmental timing [2] [1].

Heterochrony operates through genetically controlled perturbations to developmental programs that affect the onset, offset, or rate of growth processes [18] [1]. These temporal shifts can produce profound morphological consequences, resulting in two major categories of heterochronic change: paedomorphosis (the retention of juvenile characteristics in adult descendants) and peramorphosis (the development of features beyond the ancestral adult state) [18] [2]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of these heterochronic processes, focusing on their mechanistic bases, experimental investigation, and implications for evolutionary developmental research.

Theoretical Foundations and Classification

The classification of heterochronic changes follows a systematic framework based on modifications to three fundamental developmental parameters: onset, offset, and rate of development. This structure generates six distinct types of heterochrony, categorized under either paedomorphosis or peramorphosis [18] [19].

Table 1: Classification of Heterochronic Types

| Category | Type | Developmental Perturbation | Morphological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paedomorphosis | Neoteny | Slower developmental rate | Juvenile traits in adult |

| Progenesis | Earlier cessation of development | Sexually mature juvenile form | |

| Postdisplacement | Later initiation of development | Truncated development | |

| Peramorphosis | Acceleration | Faster developmental rate | Enhanced traits beyond ancestor |

| Hypermorphosis | Later cessation of development | Extended development beyond ancestor | |

| Predisplacement | Earlier initiation of development | Additional developmental stages |

The following diagram illustrates the relationships between these heterochronic types and their effects on developmental trajectories:

Paedomorphosis describes the retention of ancestral juvenile characteristics in descendant adults, representing a truncated developmental trajectory compared to the ancestor [18] [2]. This can occur through three distinct mechanisms: (1) neoteny, where development proceeds at a slower rate but for the same duration; (2) progenesis, where development begins at the same time but ends earlier; and (3) postdisplacement, where development starts later but proceeds at the normal rate and ends at the normal time [18] [19]. Notable examples include the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum), which reaches sexual maturity while retaining larval gills and aquatic habitat [1], and humans, who exhibit neotenous traits compared to ancestral primates, such as larger brains relative to body size and reduced jaw size [2] [19].

Peramorphosis represents the opposite phenomenon, where descendants develop morphological features that exceed the complexity or extent of their ancestors [18] [19]. This extended developmental trajectory also occurs through three mechanisms: (1) acceleration, where development proceeds at a faster rate; (2) hypermorphosis, where development continues for a longer period; and (3) predisplacement, where development begins earlier [18] [19]. Exemplary cases include the extinct Irish elk, which developed antlers up to 12 feet wide through extended growth periods [1], and insular rodents, which exhibit gigantism, wider cheek teeth, and longer lifespans due to resource abundance on islands [1].

Comparative Analysis: Morphological Outcomes and Evolutionary Significance

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Paedomorphosis and Peramorphosis

| Aspect | Paedomorphosis | Peramorphosis |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Outcome | Truncated development | Extended development |

| Evolutionary Novelty | Retention of ancestral juvenile traits | Elaboration beyond ancestral adult form |

| Primary Mechanisms | Neoteny, Progenesis, Postdisplacement | Acceleration, Hypermorphosis, Predisplacement |

| Evolutionary Implications | Developmental simplification, potential for new evolutionary trajectories | Increased complexity, adaptive elaboration |

| Classic Examples | Axolotl (neoteny), Human cranial features (neoteny), Tunicate-vertebrate transition | Irish elk antlers (hypermorphosis), Snake vertebrae (acceleration), Insular gigantism |

The evolutionary implications of these heterochronic processes are profound. Paedomorphosis can facilitate major evolutionary transitions by retaining flexible juvenile traits in reproductive adults, potentially allowing colonization of new niches [2]. The proposed evolution of vertebrates from tunicate larvae via paedomorphosis represents one such significant macroevolutionary event [2] [1]. Conversely, peramorphosis enables the elaboration of structures that may provide adaptive advantages, such as the extensive antlers of the Irish elk for sexual display or the elongated bodies of snakes for serpentine locomotion [1].

These heterochronic processes are not mutually exclusive and may operate differently on various structures within the same organism. Human evolution exemplifies this mosaic pattern, with some traits (such as enlarged brains) demonstrating peramorphosis while others (such as reduced jaw size) exhibit paedomorphosis [2]. This modularity highlights the precision of heterochronic changes in evolutionary development, where specific structures can be targeted without globally affecting the entire organism.

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

At the molecular level, heterochrony operates through genetic alterations that affect the timing of developmental gene expression and the activity of signaling pathways. Research has identified several key molecular players and mechanisms that drive heterochronic changes:

The microRNA miR156 has been identified as a critical heterochronic regulator in plants. In Eucalyptus globulus, expression variation of EglMIR156.5 is responsible for natural heterochronic variation in vegetative phase change, with higher expression maintaining the juvenile vegetative state [18]. Similarly, in Cardamine hirsuta, cis-regulatory variation in the floral repressor ChFLC causes heterochronic shifts, with low-expressing alleles leading to both early flowering and accelerated acquisition of adult leaf traits [18].

In animal systems, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling and WNT pathways have been implicated in heterochronic changes. Studies of avian cranial evolution reveal that FGF8 and WNT signaling members facilitated paedomorphosis in birds, resulting in skulls that retain the juvenile morphology of their dinosaur ancestors [1]. This retention of juvenile cranial characteristics has enabled the evolution of cranial kinesis in birds, contributing significantly to their ecological success [1].

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular pathways involved in heterochronic regulation:

Additional molecular mechanisms include TCP transcription factors, particularly the CYC2 clade in plants, where heterochronic shifts in expression timing have driven the evolution of corolla monosymmetry from polysymmetrical ancestral flowers [18]. In grasses, delayed transition from shoot meristem to floral meristem results in more complex inflorescence architectures, demonstrating how timing alterations in meristem identity transitions can generate morphological diversity [18].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) Analysis

Protocol Summary: QTL analysis identifies genomic regions associated with heterochronic variation by crossing individuals with divergent developmental timing and analyzing the co-segregation of morphological traits and genetic markers [18].

- Cross Design: Cross parental lines with contrasting heterochronic traits (e.g., early vs. late flowering, different leaf morphologies)

- Population Development: Generate recombinant inbred lines or F2 populations

- Phenotypic Scoring: Quantify developmental timing traits (e.g., phase transition timing, organ initiation rates) throughout ontogeny

- Genotyping: Construct genetic linkage maps using molecular markers

- Statistical Analysis: Identify associations between marker genotypes and phenotypic values

- Candidate Gene Identification: Fine-map QTL regions and test candidate genes

Application Example: In Eucalyptus globulus, QTL analysis identified EglMIR156.5 expression as responsible for heterochronic variation in vegetative phase change [18]. Similarly, in Cardamine hirsuta, QTL mapping revealed that cis-regulatory variation in ChFLC underlies heterochronic variation in both flowering time and leaf development [18].

Morphometric Analysis of Ontogenetic Trajectories

Protocol Summary: This approach quantifies shape changes throughout development to identify heterochronic shifts by comparing allometric relationships and developmental trajectories between species [18] [19].

- Landmark Selection: Identify homologous anatomical landmarks across developmental stages

- Specimen Imaging: Capture digital images of specimens across ontogenetic series

- Data Collection: Record coordinate data for landmarks and linear measurements

- Trajectory Analysis: Compare ontogenetic trajectories using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or similar multivariate methods

- Statistical Comparison: Test for differences in trajectory shape, direction, or length between taxa

Application Example: A PCA of ontogenetic trajectories in marsileaceous ferns (Marsilea, Regnellidium, and Pilularia) revealed paedomorphic phenotypes resulting from accelerated growth rate and early termination at simplified leaf forms compared to more complex ancestral development [18].

Comparative Transcriptomics

Protocol Summary: This method identifies heterochronic shifts in gene expression by comparing transcriptomes across developmental stages and between species [18].

- Sample Collection: Harvest tissues at equivalent developmental stages across species

- RNA Sequencing: Generate transcriptome profiles using RNA-seq

- Developmental Staging: Normalize stages using morphological markers or conserved molecular signatures

- Expression Analysis: Identify differentially expressed genes and co-expression modules

- Divergence Assessment: Compare expression peaks and timing of key regulatory genes

Application Example: Comparison of meristem maturation transcriptomes across five domesticated and wild Solanaceae species revealed a peak of expression divergence resembling the "inverse hourglass" model, where mid-development divergence drives morphological variation [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Heterochrony Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| microRNA Inhibitors | Block specific microRNA function to assess developmental timing roles | miR156 inhibition to study vegetative phase change [18] |

| Transcriptome Profiling Kits | Comprehensive gene expression analysis across development | RNA-seq for comparative developmental transcriptomics [18] |

| In Situ Hybridization Reagents | Spatial localization of gene expression in developing tissues | Detecting heterochronic shifts in CYC2 gene expression [18] |

| Genomic Editing Systems | Targeted manipulation of candidate heterochronic genes | CRISPR/Cas9 for modifying regulatory elements of timing genes |

| Morphometric Software | Quantitative analysis of shape change throughout ontogeny | Landmark-based analysis of ontogenetic trajectories [18] |

| Hormonal Manipulation Compounds | Experimental alteration of developmental timing pathways | Thyroid hormone treatments in amphibian metamorphosis studies [1] |

| Obatoclax | Obatoclax, CAS:803712-67-6, MF:C20H19N3O, MW:317.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (2E)-OBAA | (2E)-OBAA, CAS:134531-42-3, MF:C28H44O3, MW:428.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis of paedomorphosis and peramorphosis provides a robust framework for understanding how temporal changes in development generate evolutionary diversity. From applied perspectives, heterochrony research offers valuable insights for evolutionary developmental biology, agricultural science (through manipulation of growth timing and phase transitions), and biomedical research (by illuminating the evolutionary context of developmental timing disorders).

Future research directions will likely focus on integrating comparative genomics with functional studies to identify causal genetic changes underlying heterochronic shifts, exploring the role of epigenetics in developmental timing regulation, and employing single-cell technologies to resolve heterochrony at cellular resolution. The continued development of sophisticated mathematical frameworks for quantifying heterochrony will further enhance our ability to detect and interpret these evolutionary changes across diverse taxonomic groups [19].

Understanding heterochrony ultimately provides a powerful explanatory framework for evolutionary innovation, demonstrating how the subtle rewiring of developmental schedules can produce the remarkable diversity of forms observed throughout the natural world.

Changes in the timing of developmental events, a phenomenon known as heterochrony, represent a fundamental mechanism driving evolutionary diversification. At the molecular level, heterochronic shifts in gene expression patterns can produce vast morphological differences between organisms despite conserved genetic toolkits. The annelid Streblospio benedicti, with its intraspecific developmental dimorphism, provides a unique model system for investigating the earliest genetic changes underlying developmental divergence. This marine worm exhibits two distinct developmental morphs that differ in egg size, embryological development time, larval ecology, and morphology, yet remain morphologically indistinguishable as adults. One morph develops through obligately feeding planktotrophic (PP) larvae, while the other develops through non-feeding lecithotrophic (LL) larvae, with these larval traits being genetically determined rather than plastic responses to environmental conditions [6] [20].

The molecular foundations of heterochronic development extend beyond simple changes in gene expression timing to encompass complex regulatory architectures. Gene regulatory networks (GRNs)—complex, directed networks composed of transcription factors, target genes, and their regulatory relationships—control essential biological processes including cell differentiation, apoptosis, and organismal development. Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) have enabled the reconstruction of cell type-specific GRNs with unprecedented resolution, offering new opportunities to decipher the regulatory mechanisms underlying heterochronic development in both normal and pathological states [21].

Experimental Approaches for Analyzing Heterochronic Gene Expression

Study System and Embryological Analysis

The comparative analysis of heterochronic gene expression requires a model system with clearly divergent developmental trajectories and the possibility of genetic crosses. The two morphs of Streblospio benedicti proceed through the same conserved spiralian embryological cleavage stages despite starting from eggs with an 8-fold volume difference. Researchers conducted detailed time-course analyses of embryogenesis from the one-cell embryo through the larval phase for both morphs, with morphological staging confirming that although the developmental sequence is conserved, the absolute time between each stage is shifted in the LL embryos, which take longer to reach equivalent larval stages—an expected consequence of larger, more yolky cells requiring longer division times [6] [20].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Streblospio benedicti Developmental Morphs

| Trait | Planktotrophic (PP) Morph | Lecithotrophic (LL) Morph |

|---|---|---|

| Egg size | Smaller | 8x larger volume |

| Development time to larval stage | Faster | Slower |

| Larval ecology | Obligate feeding | Non-feeding |

| Larval morphology | Possess feeding structures | Lack feeding structures |

| Larval period | Extended in water column | Shorter |

| Adult morphology | Indistinguishable from LL | Indistinguishable from PP |

Transcriptomic Time-Course Experimentation

To quantify gene expression differences throughout development, researchers performed comparative RNAseq across six developmental stages with at least four biological replicates per morph at each stage. This dense temporal sampling strategy allowed for the comprehensive identification of genes with divergent expression patterns between the morphs. The experimental workflow encompassed total RNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis using principal component analysis (PCA) to visualize variance components and differential expression testing to identify statistically significant changes in gene expression between morphs across developmental time [6] [20].

The computational pipeline employed Mfuzz (v2.60.0) for clustering gene expression patterns into representative expression profiles, enabling the differentiation between heterochronic shifts (changes in expression timing) and heteromorphic differences (changes in expression amount without timing alterations). Genes were classified as heterochronic when their expression profiles assigned them to different clusters in PP versus LL datasets, while heteromorphic genes showed significant expression differences at specific time points but maintained the same overall expression profile across development [20].

Regulatory Architecture Analysis Through Genetic Crosses

A critical component of understanding the regulatory architecture underlying heterochronic gene expression involves the generation and analysis of reciprocal F1 crosses (PL and LP) between the developmental morphs. These crosses allowed researchers to determine patterns of maternal mRNA inheritance and dissect the cis- and trans-acting regulatory factors governing expression differences. The F1 offspring typically exhibit intermediate larval traits compared to the parental morphs, providing a powerful system for identifying the dominant or additive effects of genetic variants controlling developmental timing [6].

Key Findings: Heterochronic Versus Heteromorphic Gene Expression Patterns

Analysis of the transcriptomic time-course data revealed that only 36.2% of all expressed genes were significantly differentially expressed (DE) between PP and LL morphs at any developmental stage, despite their major differences in larval development and life history. This surprisingly modest proportion highlights the extensive conservation of developmental gene expression programs even between dramatically different developmental strategies within a species [6] [20].

Early in development, over a third of DE genes showed significant differences between morphs, though these differences tended to be relatively small in magnitude. In contrast, during gastrulation, the number of significantly DE genes decreased to less than 5% of the total DE genes, but these remaining expression differences were much larger in magnitude. This pattern suggests that the two morphs are more functionally distinct during early development, likely reflecting different metabolic requirements imposed by their divergent maternal egg provisioning strategies [20].

Table 2: Classification and Distribution of Differentially Expressed Genes

| Gene Category | Definition | Proportion of DE Genes | Representative Expression Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterochronic | Genes with shifted expression timing between morphs | ~54% | Cluster transitions between morphs |

| Heteromorphic | Genes with expression amount differences but conserved timing | ~46% | Maintain same cluster assignment with significant expression level differences |

| Morph-specific | Genes expressed in only one morph | Small subset | Complete absence in one morph |

Further classification of DE genes revealed that approximately 45.9% (354 genes) were heteromorphic, maintaining the same expression profile cluster in both morphs while showing significant expression level differences at specific developmental stages. The remaining DE genes exhibited heterochronic shifts, assigned to different expression profile clusters in PP versus LL morphs. Cluster 2, which showed a pattern of maternal transcript degradation with no subsequent zygotic expression, was enriched for genes associated with embryogenesis shared by both morphs [20].

Advanced Computational Methods for GRN Inference

The reconstruction of gene regulatory networks from transcriptomic data has evolved significantly with the advent of single-cell RNA sequencing technologies. Traditional bulk RNA-seq approaches generated averaged transcriptional profiles that masked cellular heterogeneity, while scRNA-seq enables the reconstruction of cell type-specific GRNs with much greater resolution. Several computational approaches have been developed to infer GRNs from scRNA-seq data, ranging from unsupervised methods to supervised deep learning models [21] [22].

AttentionGRN: A Graph Transformer Approach

AttentionGRN represents a novel graph transformer-based model that addresses limitations of traditional graph neural networks (GNNs), including over-smoothing and over-squashing, which hinder the preservation of essential network structure. The model employs soft encoding to enhance model expressiveness and incorporates GRN-oriented message aggregation strategies designed to capture both directed network structure information and functional information inherent in GRNs [21].

Key innovations of AttentionGRN include:

- Directed structure encoding: Facilitates learning of directed network topologies

- Functional gene sampling: Captures key functional modules and global network structure

- Dual-stream feature extraction: Separately processes gene expression features and directed network structure features related to TF-target gene interactions

The model has been validated on 88 benchmark datasets and successfully applied to reconstruct cell type-specific GRNs for human mature hepatocytes, revealing novel hub genes and previously unidentified transcription factor-target gene regulatory associations [21].

GRLGRN: Graph Representation Learning for GRN Inference

GRLGRN (graph representational learning GRN) is another deep learning model designed to infer latent regulatory dependencies between genes based on prior GRN knowledge and single-cell gene expression profiles. This approach uses a graph transformer network to extract implicit links from prior GRN data and encodes gene features using both an adjacency matrix of implicit links and a matrix of gene expression profiles. The model incorporates attention mechanisms to improve feature extraction and feeds refined gene embeddings into an output module to infer gene regulatory relationships [22].

GRLGRN addresses challenges such as cellular heterogeneity, measurement noise, and data dropout in scRNA-seq data through several technical innovations:

- Implicit link extraction: Leverages graph transformer networks to identify non-obvious regulatory relationships

- Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM): Enhances feature extraction capabilities

- Graph contrastive learning: Regularization approach to prevent over-smoothing of gene features

Evaluation across seven cell-line datasets with three different ground-truth networks demonstrated that GRLGRN achieved superior performance in AUROC and AUPRC metrics compared to existing methods, with an average improvement of 7.3% in AUROC and 30.7% in AUPRC [22].

Visualizing Experimental and Computational Workflows

Figure 1: Heterochronic Gene Expression Analysis Workflow

Figure 2: GRN Inference Computational Pipeline

Research Reagent Solutions for Heterochronicity Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Streblospio benedicti cultures | Developmental model system with intraspecific dimorphism | Heterochronic gene expression analysis |

| RNA extraction kits | High-quality RNA isolation from limited biological material | Transcriptomic time-course experiments |

| scRNA-seq platforms | Single-cell resolution gene expression profiling | Cell type-specific GRN reconstruction |

| BEELINE benchmark datasets | Standardized evaluation datasets | GRN method validation and comparison |

| Mfuzz software | Fuzzy clustering of time-series gene expression data | Heterochronic gene identification |

| AttentionGRN algorithm | Graph transformer-based GRN inference | Regulatory network reconstruction from scRNA-seq |

| GRLGRN platform | Graph representation learning for GRN inference | Implicit regulatory relationship identification |

The molecular foundations of heterochronic development involve complex interactions between shifts in gene expression timing and the regulatory architectures that control these patterns. Research in model systems like Streblospio benedicti has demonstrated that heterochronic gene expression changes—not simply the complete absence or presence of genes—underlie major developmental and life history differences. Meanwhile, advances in computational methods for GRN inference, particularly graph transformer-based approaches like AttentionGRN and GRLGRN, are providing unprecedented capabilities to reconstruct the regulatory networks that control developmental timing.

The integration of experimental developmental biology with cutting-edge computational network analysis offers promising avenues for future research. These integrated approaches will further elucidate how modifications to gene regulatory networks produce heterochronic shifts that drive evolutionary diversification, with potential applications in understanding developmental disorders and designing therapeutic interventions that target specific aspects of gene regulation. As single-cell technologies continue to advance and computational methods become increasingly sophisticated, our ability to decipher the complex relationship between regulatory network architecture and developmental timing will continue to improve, offering new insights into one of the most fundamental mechanisms of evolutionary change.

Extraembryonic Tissues as Evolutionary Platforms for Timing Shifts

Emerging research reveals that extraembryonic tissues are not merely supportive structures, but active evolutionary platforms facilitating developmental timing shifts, or heterochrony. These tissues provide a source of inductive signals and a permissive microenvironment that influences the timing and trajectory of embryonic development. This review compares experimental models demonstrating how extraembryonic mesoderm (ExM) and other extraembryonic derivatives serve as crucial mediators of evolutionary change through heterochronic modifications. We synthesize data from stem cell-derived embryoids, interspecies placental comparisons, and molecular analyses of signaling pathways to provide a comprehensive resource for developmental biologists and translational researchers.

Heterochrony, defined as a change in the timing or rate of developmental events, has re-emerged as a central concept in evolutionary developmental biology [3]. While historical perspectives focused on changes in size and shape, modern analyses investigate molecular timing mechanisms and their modifications [3]. The concept has evolved from Haeckel's association with recapitulation theory to de Beer's comparative framework and Gould's emphasis on allometry, finally arriving at today's focus on specific genetic, cellular, and tissue-level events [3].

Contemporary research has identified that a key location where heterochronic changes can be initiated and accommodated is in the extraembryonic tissues. These tissues—including the placenta, amnion, yolk sac, and chorion—possess several characteristics that make them ideal "evolutionary platforms":

- They establish signaling centers that guide embryonic patterning

- They exhibit evolutionary diversity across species, suggesting adaptability

- They create protected microenvironments where timing shifts can occur without immediate detriment to the embryo proper

This review examines the experimental evidence demonstrating how extraembryonic tissues facilitate heterochrony, compares model systems for studying these phenomena, and provides practical resources for researchers investigating developmental timing.

Experimental Models for Studying Extraembryonic Heterochrony

Stem Cell-Derived Embryo Models

Human embryo models derived from pluripotent stem cells have revolutionized the study of early developmental timing, overcoming limitations associated with human embryo research [23] [24]. These models capture critical developmental windows and allow experimental manipulation of timing mechanisms.

Table 1: Stem Cell-Based Models for Studying Extraembryonic Development

| Model Type | Key Components | Developmental Stage Modeled | Applications in Heterochrony Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naive hESCs | Pre-implantation epiblast-like cells | Pre-implantation blastocyst | Studying origins of pre-gastrulation ExM [25] |

| Primed hESCs | Post-implantation late epiblast-like cells | Post-implantation embryo | Analyzing gastrulation-associated ExM specification [25] |

| Blastoids | Trophoblast stem cells (TSCs), embryonic stem cells (ESCs), extraembryonic endoderm cells (XEN) | Blastocyst formation | Investigating implantation timing [23] |

| Gastruloids | Embryonic and extraembryonic mesoderm derivatives | Gastrulation and early organogenesis | Examining axial patterning and segmentation clocks [23] |

Interspecies Placental Comparisons