Homology-Independent Knock-In in Zebrafish: A Robust Strategy for Precision Genome Editing

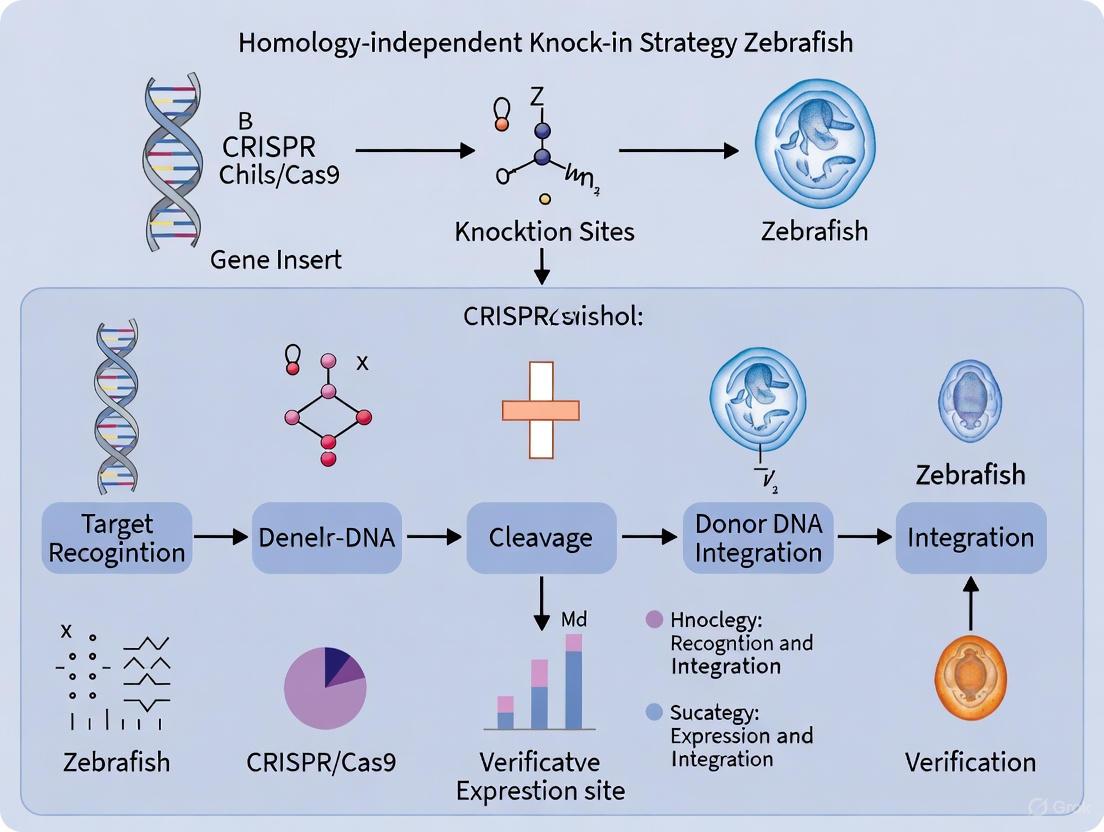

This article provides a comprehensive overview of homology-independent knock-in strategies for precise genome editing in zebrafish, a pivotal model in biomedical and drug discovery research.

Homology-Independent Knock-In in Zebrafish: A Robust Strategy for Precision Genome Editing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of homology-independent knock-in strategies for precise genome editing in zebrafish, a pivotal model in biomedical and drug discovery research. We explore the foundational principles that distinguish homology-independent repair from homology-directed repair (HDR), detailing the core mechanisms like non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) that enable efficient integration of large DNA cassettes. The article offers a practical guide on methodology, from vector design to germline transmission, and presents crucial troubleshooting and optimization protocols, including the use of chemical modulators to enhance efficiency. Finally, we validate the approach through comparative analyses with other editing techniques and showcase its successful application in creating specific reporter lines and disease models, underscoring its transformative potential for functional genomics and the study of human diseases.

Beyond HDR: Understanding the Foundations of Homology-Independent Knock-In

Defining Homology-Independent vs. Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Pathways

The development of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic research, enabling precise modifications in the genomes of model organisms like zebrafish. When CRISPR-Cas9 introduces a double-strand break (DSB) in DNA, the cell activates endogenous repair mechanisms to resolve the break. The two primary competing pathways for this repair are homology-directed repair (HDR) and homology-independent repair, which includes non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ). Understanding the distinct mechanisms, applications, and limitations of these pathways is essential for designing effective genome editing experiments, particularly for knock-in strategies in zebrafish research.

Homology-directed repair is a precise DNA repair mechanism that utilizes homologous sequences—such as a sister chromatid or an exogenously supplied donor template—to accurately repair DSBs. In contrast, homology-independent pathways like NHEJ directly rejoin broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels). The choice between these pathways significantly impacts the outcome of genome editing experiments, making pathway selection a critical consideration in experimental design.

Molecular Mechanisms of DNA Repair Pathways

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Mechanism

HDR is a high-fidelity repair pathway that uses a homologous DNA template to accurately repair double-strand breaks. This pathway is active primarily in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle when sister chromatids are available. The process begins with resection of the 5' ends at the break site, creating 3' single-stranded DNA overhangs. The recombinase RAD51 then coats these overhangs and facilitates strand invasion into a homologous template sequence. DNA polymerase extends the invading strand using the template, and the repair is completed through synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) or double-strand break repair (DSBR) pathways [1].

In CRISPR-mediated HDR applications, researchers supply an exogenous donor template containing the desired modification flanked by homology arms that match sequences surrounding the target site. The cell's repair machinery uses this template to incorporate precise genetic changes, including point mutations, insertions, or gene replacements. The efficiency of HDR is influenced by multiple factors, including template design, cell cycle stage, and the relative activity of competing repair pathways [2].

Homology-Independent Repair Mechanisms

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

NHEJ is the dominant DSB repair pathway in most cells, functioning throughout the cell cycle. This pathway begins with the recognition of broken DNA ends by the Ku heterodimer (Ku70/Ku80), which recruits DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) to form an active complex. The Artemis nuclease processes the DNA ends, and the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex ligates them back together. Unlike HDR, NHEJ does not require a homologous template and is therefore error-prone, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function [2].

NHEJ is particularly useful for generating gene knockouts, as the introduced indels can create frameshift mutations that prematurely truncate the encoded protein. While traditionally considered random, NHEJ can also be harnessed for precise knock-in strategies using carefully designed templates that leverage the pathway's end-joining capabilities [3].

Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ)

MMEJ represents an alternative homology-independent pathway that utilizes short homologous sequences (5-25 bp) flanking the break site for repair. The key regulator of MMEJ is polymerase theta (Polθ), which aligns microhomologous regions before initiating DNA synthesis. MMEJ typically results in deletions flanked by microhomology regions and can be a backup pathway when NHEJ is compromised [4]. While MMEJ can be harnessed for specific editing applications, it often competes with HDR and can reduce precise editing efficiency.

Comparative Analysis of Repair Pathways

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of HDR and homology-independent repair pathways:

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Repair Pathways in Genome Editing

| Feature | HDR | NHEJ | MMEJ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template Requirement | Requires homologous template (endogenous or exogenous) | No template required | No template required; uses microhomology regions |

| Fidelity | High precision, error-free | Error-prone, creates indels | Error-prone, creates deletions |

| Cell Cycle Phase | S and G2 phases | Active throughout cell cycle | Active throughout cell cycle |

| Key Proteins | RAD51, BRCA2, PALB2 | Ku70/Ku80, DNA-PKcs, XRCC4-LigIV | Polθ, PARP1, DNA Ligase I/III |

| Primary Applications | Precise knock-ins, point mutations, gene corrections | Gene knockouts, random mutagenesis | Gene knockouts, deletion studies |

| Efficiency in Zebrafish | Low (typically <10% without enhancement) | High (often >50%) | Variable |

| Advantages | High precision, versatile for various edits | Highly efficient, works in non-dividing cells | Can create specific deletion patterns |

| Disadvantages | Low efficiency, competes with NHEJ/MMEJ, requires donor design | Introduces random mutations, less precise | Limited control over outcomes, less characterized |

Experimental Protocols for HDR in Zebrafish

Optimized HDR Workflow for Zebrafish Embryos

The following protocol has been optimized for precise genome editing in zebrafish using HDR, incorporating recent advancements to enhance efficiency:

Reagent Preparation:

- CRISPR Components: Prepare high-efficiency sgRNA (≥60% cutting efficiency) and Cas9 protein (200-800 pg optimal amount) as ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes [1] [5].

- Donor Template: Design single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) with 30-50 nt homology arms for point mutations or short insertions (<50 nt). For larger insertions, use long single-stranded DNA with 350-700 nt homology arms [6]. Position the desired edit within 10 nt of the Cas9 cut site.

- Template Enhancement: Incorporate silent mutations in the PAM sequence or seed region to prevent re-cutting of successfully edited alleles [6]. Chemically modified Alt-R HDR templates can improve integration efficiency [5].

- Small Molecule Inhibitors: Prepare 50 μM NU7441 (NHEJ inhibitor) dissolved in DMSO for microinjection [7].

Microinjection Procedure:

- Set up zebrafish mating pairs and collect embryos within 15 minutes post-fertilization.

- Prepare injection mixture containing:

- Cas9 RNP complex (final amount 200-800 pg)

- HDR donor template (50-100 pg)

- 50 μM NU7441 (or DMSO vehicle for controls)

- Microinject 1-2 nL of the mixture directly into the cell cytoplasm or yolk of 1-2 cell stage embryos.

- Maintain injected embryos at 28-32°C and monitor development.

Validation and Screening:

- At 24-48 hours post-fertilization, screen for somatic editing using appropriate methods (e.g., fluorescence if using a reporter system, PCR-based assays).

- For germline transmission, raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood and outcross to wild-type fish.

- Screen F1 progeny for the desired edit using PCR, restriction fragment length analysis, or sequencing.

Table 2: Troubleshooting HDR in Zebrafish

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low HDR efficiency | High NHEJ/MMEJ competition | Add NHEJ inhibitors (NU7441); optimize Cas9 amount |

| Mosaic editing in F0 | Late editing after cell division | Inject at earliest embryonic stage; optimize injection site |

| Random integration | dsDNA template toxicity | Switch to single-stranded DNA templates |

| Cell death/toxicity | Excessive Cas9, inhibitor toxicity | Titrate Cas9 concentration; reduce inhibitor amount |

| No germline transmission | Edit not incorporated in germ cells | Increase sample size; use HDR-enhancing chemicals |

HDR Enhancement Using Small Molecule Inhibitors

Chemical inhibition of competing pathways significantly enhances HDR efficiency. The most effective inhibitor identified for zebrafish is NU7441, a DNA-PKcs inhibitor that blocks NHEJ. In quantitative studies, 50 μM NU7441 enhanced HDR-mediated repair up to 13.4-fold compared to DMSO controls [7]. This treatment increased the average number of successfully edited cells per embryo from 4.0 ± 3.0 to 53.7 ± 22.1 in a fluorescent reporter assay.

The HDRobust approach, which combines inhibition of both NHEJ and MMEJ, has demonstrated remarkable efficiency in human cells, achieving HDR rates of up to 93% (median 60%) [4]. While optimized for cell culture, this dual inhibition strategy presents a promising avenue for further optimization in zebrafish embryos.

Pathway Visualization and Experimental Design

DNA Repair Pathway Decision and HDR Enhancement Strategies

Emerging Alternatives and Complementary Technologies

Prime Editing

Prime editing represents a significant advancement beyond traditional HDR, enabling precise edits without requiring double-strand breaks or donor templates. This system uses a catalytically impaired Cas9 (nickase) fused to a reverse transcriptase, programmed with a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that contains both the targeting sequence and the desired edit. In zebrafish, prime editing has demonstrated superior performance for certain applications, with one study reporting up to a fourfold increase in editing efficiency compared to HDR for base substitutions [5].

Two primary prime editing systems have been optimized for zebrafish:

- PE2: A nickase-based system most effective for nucleotide substitutions, achieving precision scores of 40.8% compared to 11.4% for nuclease-based systems [8].

- PEn: A nuclease-based system more effective for inserting short DNA fragments (3-30 bp) with higher efficiency than PE2 for these applications [8].

Base Editing

Base editors enable direct conversion of one nucleotide to another without inducing DSBs, making them valuable for specific point mutations. These include:

- Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs): Convert C:G to T:A base pairs

- Adenine Base Editors (ABEs): Convert A:T to G:C base pairs

Recent developments like the "near PAM-less" cytidine base editor (CBE4max-SpRY) have expanded the targeting scope in zebrafish, achieving editing efficiencies up to 87% at some loci [9]. Base editors are particularly valuable for modeling human genetic diseases caused by point mutations.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Repair Studies in Zebrafish

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Components | Induces targeted double-strand breaks | High-efficiency sgRNA (>60%), Cas9 protein (200-800 pg optimal) [1] [5] |

| HDR Donor Templates | Provides homologous template for precise repair | ssODN (<200 nt), long ssDNA (>500 nt), homology arms (30-50 nt for ssODN; 350-700 nt for long ssDNA) [6] |

| NHEJ Inhibitors | Enhances HDR efficiency by blocking competing pathway | NU7441 (50 μM optimal), DNA-PKcs inhibitors [7] |

| HDR Enhancers | Stimulates homology-directed repair | RS-1 (RAD51 agonist), 15-30 μM [7] |

| Prime Editing Systems | Enables precise edits without DSBs or donors | PE2 (nickase-based), PEn (nuclease-based) [8] |

| Base Editors | Creates point mutations without DSBs | CBEs (C:G to T:A), ABEs (A:T to G:C) [9] |

| Validation Tools | Confirms editing efficiency and specificity | T7E1 assay, amplicon sequencing, fluorescence reporters [7] |

The strategic selection between homology-directed and homology-independent repair pathways is fundamental to successful genome engineering in zebrafish. While HDR enables precise modifications, its efficiency remains limited by competition with endogenous repair pathways. Recent advancements, including small molecule inhibition of NHEJ, optimized donor designs, and the development of novel editors like prime editors and base editors, have significantly improved the toolkit for precise genome modification.

For researchers designing knock-in experiments in zebrafish, we recommend a stratified approach: using HDR with NHEJ inhibition for medium-to-large insertions, prime editing for point mutations and small insertions, and base editing for specific nucleotide conversions. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will further enhance our ability to model human diseases and perform functional genomic studies in zebrafish.

In the context of zebrafish research, the pursuit of precise genomic integration is fundamental to creating accurate models for studying gene function and human diseases. The error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, once considered merely a source of stochastic indel mutations for gene knockouts, has been strategically repurposed as a powerful tool for targeted DNA integration. This application note details how homology-independent knock-in strategies exploit this competing DNA repair mechanism to achieve efficient transgene integration in zebrafish, bypassing the efficiency limitations of homology-directed repair (HDR) that have traditionally constrained precise genome editing in this model organism [10] [11].

The competitive balance between NHEJ and HDR pathways presents both a challenge and an opportunity for genome editors. While HDR is restricted to specific cell cycle phases (primarily S and G2), NHEJ operates throughout the cell cycle, making it the dominant repair pathway in most contexts [12] [13]. In normal human fibroblasts, NHEJ demonstrates higher activity than HR at all cell cycle stages, with its efficiency increasing as cells progress from G1 to G2/M phases [12]. This fundamental biological principle underpins the development of NHEJ-mediated knock-in approaches, which leverage the constant availability of this repair pathway in early zebrafish embryos to achieve high integration rates unattainable through HDR-based methods alone.

Molecular Mechanisms: NHEJ Versus HDR Pathways

Competitive Pathway Dynamics

Double-strand breaks (DSBs) induced by CRISPR/Cas9 activate competing DNA repair pathways, with the balance between these pathways determining editing outcomes. The NHEJ pathway operates throughout the cell cycle by directly ligating broken DNA ends, while HDR is restricted primarily to S and G2 phases where sister chromatids are available as templates [12] [13]. This temporal restriction significantly limits HDR efficiency in many experimental contexts.

In zebrafish embryos, the rapid cell cycles and developmental timing further constrain HDR efficacy, making NHEJ the predominant repair mechanism during early development [14]. Studies in normal human fibroblasts demonstrate that NHEJ activity increases progressively from G1 through S to G2/M phases, whereas HDR peaks during S phase and declines in G2/M [12]. This cell cycle dependency creates a narrow window for HDR efficiency while NHEJ remains constitutively active.

Strategic Exploitation of NHEJ for Integration

Homology-independent knock-in strategies deliberately leverage the NHEJ pathway's error-prone nature by designing donor constructs that are cleaved simultaneously with the genomic target. When both the chromosomal locus and donor plasmid experience DSBs, the cellular repair machinery frequently joins these fragments through NHEJ-mediated ligation [14]. This approach capitalizes on the natural efficiency of NHEJ while bypassing the complex machinery and cell cycle limitations of HDR.

The strategic innovation lies in designing donor vectors with CRISPR target sequences ("bait" sequences) that ensure co-cleavage of the donor and genomic target. This simultaneous cleavage creates compatible ends that NHEJ factors efficiently ligate, resulting in targeted integration without requiring homologous templates [14] [15]. By incorporating short homology arms (10-40 bp) flanking the genomic target in the donor vector, researchers can further enhance precise integration through microhomology-mediated mechanisms [15].

Quantitative Assessment of Editing Efficiencies

Comparative Performance of Knock-in Methods

Table 1: Efficiency Comparison of Genome Editing Methods in Zebrafish

| Method | Mechanism | Typical Efficiency | Key Advantages | Reported Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ-mediated Knock-in | Homology-independent ligation of co-cleaved donor | 22-85% (somatic) [14] [15] | Works throughout cell cycle; suitable for large inserts | eGFP to Gal4 line conversion [14] |

| HDR with ssODN | Homology-directed repair with single-stranded oligos | Variable (typically low) [10] | Precise edits; suitable for small changes | SNP introductions; small tag insertions [10] |

| HDR with Plasmid Donor | Homology-directed repair with double-stranded donor | Often <1.5% (germline) [10] | Can incorporate large inserts with high precision | Endogenous gene tagging [1] |

| NHEJ with Short Homology Arms | Enhanced microhomology-mediated integration | 77% with 40bp arms [15] | Improved precision over standard NHEJ | krtt1c19e-eGFP tagging [15] |

Critical Success Factors

Table 2: Parameters Influencing NHEJ-mediated Knock-in Efficiency

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Impact on Efficiency | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Efficiency | >60% indel rate [1] | Foundational for successful integration | High-efficiency sgRNAs resulted in 75% of injected embryos showing targeted integration [14] |

| Homology Arm Length | 10-40 bp [15] | 77% precise integration with 40bp arms vs 60% with 10bp | Precise integration rates increased with longer homology arms [15] |

| Donor Design | Bait sequences for co-cleavage [14] | Essential for NHEJ-mediated integration | No integration observed without donor cleavage [15] |

| Injection Timing | 1-2 cell stage [1] | Maximizes access to genome before rapid divisions | Standard practice for zebrafish genome editing [1] [15] |

| NHEJ Inhibition | Scr7 (DNA Ligase IV inhibitor) [13] | Up to 19-fold HDR increase in mammalian cells | Demonstrated in cell lines; potential application in zebrafish [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Zebrafish Knock-in

NHEJ-Mediated Knock-in Workflow

Detailed Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Component Design and Preparation

sgRNA Selection: Identify genomic target sites using specialized tools (CHOP-CHOP or CRISPRscan) [10]. Select sgRNAs with demonstrated high efficiency (>60% indel rates) based on prior validation or prediction algorithms. For the bait sequence in the donor plasmid, choose an sgRNA with proven high cleavage efficiency (e.g., eGFP-gRNA with 66% efficiency) [14] [15].

Donor Vector Construction: Clone the desired insert (e.g., fluorescent protein, Gal4) into a suitable backbone. Incorporate the "bait" target sequence for co-cleavage on both sides of the insert. For enhanced precision, include short homology arms (10-40 bp) corresponding to sequences flanking the genomic cut site. Introduce silent mutations in the donor to prevent re-cleavage after integration [15].

Example: Auer et al. designed a donor plasmid containing eGFP bait sequences followed by E2A-KalTA4. This design enabled conversion of eGFP lines to Gal4 drivers with integration rates sufficient to observe RFP-positive cells in >75% of injected embryos when crossed with UAS:RFP reporters [14].

Step 2: Injection Mix Preparation

Formulate the injection mixture containing:

- Cas9 mRNA (100-300 ng/μL) or Cas9 protein (300-600 ng/μL)

- Genomic-targeting sgRNA (25-50 ng/μL)

- Bait-targeting sgRNA (25-50 ng/μL)

- Donor plasmid (25-100 ng/μL)

Optional: Include NHEJ inhibitors such as Scr7 (DNA Ligase IV inhibitor) to potentially shift balance toward HDR, though optimal concentrations for zebrafish require empirical determination [13].

Step 3: Microinjection Procedure

Inject 1-2 nL of the prepared mixture into the cytoplasm or cell body of 1-2 cell stage zebrafish embryos. The rapid cell divisions at this developmental stage necessitate early introduction of editing components to maximize distribution throughout the embryo [1] [15].

Step 4: Screening and Validation

Somatic Screening: For reporter integrations, screen injected embryos (F0) for expression patterns around 24-48 hours post-fertilization. The mosaic nature of F0 animals means expression will likely be restricted to a subset of cells.

Molecular Validation: For precise integration assessment, randomly select injected embryos for PCR analysis using primers flanking the target site and internal to the inserted sequence. Sequence PCR products to verify precise junction formation. Hisano et al. achieved 77% precise integration with 40bp homology arms, with sequence verification confirming accurate junctions [15].

Step 5: Germline Transmission

Raise injected embryos (F0 founders) to adulthood. Outcross to wild-type fish and screen F1 progeny for the integrated sequence. The germline transmission rate typically correlates with the somatic integration efficiency observed in F0 animals. Hisano et al. found that founders exhibiting broad eGFP expression as larvae were more likely to produce positive F1 progeny [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for NHEJ-Mediated Knock-in in Zebrafish

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleases | Cas9 mRNA, Cas9 protein | CRISPR/Cas9 system component; protein form may reduce off-target effects [10] |

| Targeting RNAs | sgRNAs (genomic & bait targets) | Guide Cas9 to specific genomic loci and donor bait sequences [14] |

| Donor Templates | Plasmid donors with bait sequences | Template for integration; include bait sites and optional homology arms [14] [15] |

| NHEJ Modulators | Scr7 (DNA Ligase IV inhibitor) | Shifts repair balance toward HDR; use requires concentration optimization [13] |

| Validation Tools | Junction PCR primers, sequencing primers | Essential for confirming precise integration events and germline transmission [15] |

| Reporter Systems | Fluorescent proteins (eGFP, mCherry), Gal4 | Enable visual screening of successful integration events [14] [16] |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Addressing Common Challenges

Low Integration Efficiency: When encountering insufficient integration rates, first verify sgRNA cutting efficiency using T7E1 assay or sequencing of the target locus in injected embryos. Ensure donor plasmid concentration is optimized (typically 25-100 ng/μL) and consider incorporating short homology arms (20-40 bp) to enhance precise integration through microhomology-mediated mechanisms [15].

Vector Backbone Integration: A common issue with NHEJ-mediated approaches is random integration of entire plasmid backbone. To prevent this, design donors with Cas9 cleavage sites flanking only the insert of interest, enabling precise excision from the backbone. Hisano et al. implemented this strategy by placing eGFP-gRNA target sequences on both sides of the eGFP and polyA signal sequence, successfully generating backbone-free integrations [15].

Mosaicism in Founders: The mosaic nature of F0 founders necessitates screening multiple offspring from each founder to identify germline transmission events. Focus breeding efforts on founders that showed widespread somatic integration as larvae, as these demonstrate higher likelihood of germline transmission [15].

Advanced Optimization Strategies

For difficult-to-edit loci, consider employing dual sgRNA approaches to create defined deletions followed by NHEJ-mediated integration into the deletion site. Additionally, testing Cas9 protein versus mRNA delivery may improve efficiency for some targets, as protein delivery accelerates nuclear activity in early embryos [10]. When targeting essential genes, validate that integration events do not disrupt critical gene functions through functional assays where possible.

Precise genome editing in zebrafish has been fundamentally limited by the inefficiency of Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) and the high prevalence of somatic mosaicism in F0 embryos. This application note details robust experimental protocols that leverage homology-independent knock-in strategies to overcome these challenges. By utilizing non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) pathways, researchers can achieve high-efficiency integration of large DNA cassettes, significantly accelerating the generation of knock-in zebrafish models for drug discovery and functional genomics.

In zebrafish, precise genome editing using conventional HDR-based approaches faces two significant hurdles. First, HDR competes inefficiently with the dominant non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, which introduces random indels at the target site [7]. Second, the extremely rapid early cell divisions in zebrafish embryos create a narrow window for DNA repair before the first cell division, resulting in somatic mosaicism where F0 embryos contain multiple, different editing events [17]. This mosaicism complicates phenotypic analysis and requires extensive outcrossing to obtain stable germline transmissions.

Homology-independent knock-in strategies bypass these limitations by utilizing alternative DNA repair pathways—NHEJ and MMEJ—that are more active during early embryonic stages. These methods facilitate direct ligation of double-strand breaks in donor vectors with breaks at the genomic target site, enabling highly efficient integration without requiring homologous templates [14] [18].

Quantitative Analysis of Editing Efficiency

The tables below summarize key performance metrics for various knock-in strategies, providing researchers with comparative data for experimental planning.

Table 1: Efficiency Comparison of Knock-in Strategies in Zebrafish

| Strategy | Repair Mechanism | Typical Efficiency Range | Key Advantages | Reported Cassette Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional HDR | Homology-Directed Repair | 1-5% | Precise integration; seamless junctions | Limited by homology arm design |

| Chemical-Enhanced HDR | HDR with NHEJ inhibition | Up to 13.4-fold improvement over HDR [7] | Enhanced precision; uses standard donor design | Similar to conventional HDR |

| NHEJ-Mediated Knock-in | Non-Homologous End Joining | >75% of embryos show integration [14] | Very high efficiency; simple vector design | Up to 5.7 kb demonstrated [14] |

| MMEJ-Mediated Knock-in | Microhomology-Mediated End Joining | High efficiency with precise deletion | Predictable deletions; reduced collateral damage | Varies with microhomology arms |

Table 2: Chemical and Physical Enhancement of Genome Editing Efficiency

| Treatment | Concentration/ Condition | Effect on Efficiency | Key Findings | Potential Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NU7441 (NHEJ inhibitor) | 50 µM | 13.4-fold HDR increase [7] | Shifts repair equilibrium toward HDR | Requires optimization of delivery |

| RS-1 (RAD51 agonist) | 15-30 µM | Modest HDR increase (1.5-fold) [7] | Stimulates HDR pathway | Limited effect as standalone treatment |

| Temperature Reduction | 12°C for 30-60 min | Increased mutagenesis rate [17] | Extends single-cell stage by 30-60 min | Prolonged development time |

Homology-Independent Knock-in Protocols

NHEJ-Mediated Knock-in Workflow

This protocol enables highly efficient integration of DNA cassettes through direct ligation of cleaved ends, achieving reporter integration in >75% of injected embryos [14].

Experimental Workflow:

Donor Vector Design:

- Incorporate sgRNA target sequences ("bait" sites) flanking the insert cassette

- Include desired promoter and reporter gene (e.g., KalTA4, eGFP)

- Ensure reading frame maintenance with E2A peptide linkers if needed [14]

Zebrafish Embryo Preparation:

- Collect freshly fertilized zebrafish eggs (within 15 minutes post-fertilization)

- Prepare injection setup with standard microinjection equipment

Injection Mix Preparation:

- 150 ng/µL donor plasmid DNA

- 150 ng/µL Cas9 mRNA or protein

- 50 ng/µL sgRNA targeting genomic locus

- 1 µL phenol red indicator (optional)

- Nuclease-free water to 10 µL total volume

Microinjection:

- Inject 1-2 nL into the cell cytoplasm or yolk of 1-cell stage embryos

- Incubate injected embryos at 28°C in E3 embryo medium

Post-injection Processing:

- For temperature-modulated editing: Transfer embryos to 12°C for 30-60 minutes post-injection, then return to 28°C [17]

- Screen for successful integration via fluorescence (48-72 hpf)

- Raise positive founders to adulthood for germline transmission analysis

MMEJ-Mediated Knock-in Protocol

MMEJ utilizes short microhomology sequences (20-40 bp) flanking the insert to direct integration, resulting in predictable deletions at the target site [18].

Key Protocol Modifications:

Donor Vector Design for MMEJ:

- Incorporate 20-40 bp microhomology arms homologous to sequences flanking the target site

- Position microhomology arms to generate precise deletions upon integration

- Include reporter cassette with appropriate regulatory elements

Injection Mix:

- 100-200 ng/μL MMEJ donor vector

- 50 ng/μL Cas9 protein

- 30 ng/μL sgRNA targeting genomic region between microhomology arms

- Optional: 50 μM NU7441 for NHEJ inhibition [7]

Validation:

- Confirm precise junction sequences by PCR and sequencing

- Assess phenotypic consequences of predictable deletions

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The diagram below illustrates the DNA repair pathways exploited for homology-independent knock-in in zebrafish embryos, highlighting how targeted double-strand breaks lead to successful gene integration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Homology-Independent Knock-in in Zebrafish

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | CRISPR/Cas9 (sgRNA + Cas9 protein/mRNA) | Induces targeted double-strand breaks at genomic locus and donor vector | Cas9 protein provides immediate activity; mRNA allows sustained expression |

| Donor Vectors | NHEJ: Bait-containing plasmids; MMEJ: Microhomology-flanked cassettes | Template for integration; design determines pathway utilization | For NHEJ: Include sgRNA target sites flanking insert; for MMEJ: 20-40 bp homology arms |

| Chemical Enhancers | NU7441 (50 µM), RS-1 (15-30 µM) | Modulate DNA repair pathways; inhibit NHEJ or stimulate HDR | Co-injection with editing components; optimal concentrations vary [7] |

| Physical Modulators | Temperature reduction (12°C) | Extends single-cell stage window for editing | Apply for 30-60 minutes post-injection [17] |

| Visual Reporters | eGFP, tdTomato, KalTA4-UAS systems | Enable rapid screening of successful integration | Tissue-specific promoters allow domain-restricted expression validation |

| (R)-ZG197 | (R)-ZG197, MF:C28H35F3N4O3, MW:532.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Phidianidine B | Phidianidine B|1301638-42-5|CAS Number | Phidianidine B is a marine alkaloid for neuroscience and pharmacology research. It is a potent DAT inhibitor and μ-opioid receptor ligand. For Research Use Only. | Bench Chemicals |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guide

- Low Integration Efficiency: Verify sgRNA activity using T7E1 assay or sequencing; increase donor plasmid concentration; optimize Cas9:sgRNA ratio; implement temperature reduction to 12°C post-injection [17].

- High Embryo Mortality: Reduce injection volume to 1 nL; titrate Cas9 concentration; include phenol red for visualization; use smaller needle apertures.

- Mosaicism Persistence: Inject at earliest possible developmental stage (within 15 minutes post-fertilization); use Cas9 protein instead of mRNA for immediate activity; consider oocyte injection with rainbow trout ovarian fluid preservation [17].

- Off-target Integration: Include multiple sgRNAs for donor linearization; validate integration site with junction PCR and sequencing; use bioinformatics tools to predict and avoid off-target sites.

Homology-independent knock-in methods represent a paradigm shift in zebrafish genome engineering, effectively addressing the long-standing challenges of low HDR efficiency and somatic mosaicism. By leveraging the innate efficiency of NHEJ and MMEJ repair pathways, researchers can achieve integration rates exceeding 75% in F0 embryos, dramatically accelerating the generation of precise genetic models. These protocols provide robust frameworks for implementing these advanced techniques, empowering drug development professionals and researchers to more effectively link genetic modifications to phenotypic outcomes in zebrafish systems.

The emergence of homology-independent knock-in strategies represents a pivotal advancement in zebrafish genome engineering, fundamentally shifting the paradigm from traditional homologous recombination-based methods. Prior to these developments, targeted insertion of foreign DNA cassettes into the zebrafish genome remained challenging due to the characteristically low efficiency of homology-directed repair (HDR) in this model organism [19] [14]. The zebrafish model itself offers unique advantages for developmental studies, including external fertilization, optical transparency during embryogenesis, and high fecundity—with single mating pairs producing 70-300 embryos—making it particularly suitable for large-scale genetic studies [20]. The breakthrough came with the adaptation of CRISPR/Cas9 technology, which leveraged the more active non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway in early zebrafish embryos to enable efficient integration of large DNA fragments without requiring extensive homologous arms [14] [21]. This historical progression from HDR-dependent to homology-independent mechanisms has dramatically expanded the zebrafish genetic toolbox, permitting researchers to create sophisticated reporter lines, lineage tracing tools, and disease models with unprecedented efficiency and precision.

The Evolution of Knock-In Strategies: From Concept to Mainstream Application

Foundational Studies and Key Technological Breakthroughs

The historical development of homology-independent knock-in strategies in zebrafish unfolded through a series of methodological innovations that progressively addressed the limitations of previous approaches. The initial proof-of-concept study in 2014 demonstrated that concurrent cleavage of both the genome and a donor plasmid by CRISPR/Cas9 could facilitate targeted integration via NHEJ repair pathways, achieving integration of DNA cassettes up to 5.7 kb [14]. This foundational work established the core principle that would underpin subsequent refinements: the use of "bait" sequences in donor plasmids that could be cleaved by sgRNAs complementary to the genomic target site, thus creating compatible ends for ligation [14] [22].

Subsequent innovations focused on optimizing multiple aspects of the methodology. Researchers explored various template designs, including the use of chemically modified double-stranded DNA donors with 5' AmC6 modifications that significantly enhanced integration efficiency by reducing degradation and multimerization [23]. The field also witnessed the development of versatile targeting strategies, including 5' knock-in upstream of the start codon, 3' knock-in preceding the stop codon, and intronic insertions, each offering distinct advantages for preserving endogenous gene function or enabling specific genetic manipulations [16] [23]. As the methodology matured, applications expanded from simple reporter lines to more sophisticated genetic tools, including inducible Cre systems for lineage tracing and conditional mutagenesis [23]. The progression of these techniques is summarized in Table 1, which highlights key milestones in the evolution of homology-independent knock-in methods.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key Methodological Developments

| Year | Development | Key Innovation | Significance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Initial homology-independent knock-in | Concurrent genome & plasmid cleavage | Demonstrated NHEJ-mediated integration of large cassettes (>5.7 kb) | [14] |

| 2014 | Expanded application to endogenous loci | Modified donor with hsp70 promoter | Achieved germline transmission at multiple endogenous loci (>25% efficiency) | [22] |

| 2016 | Systematic comparison in human cells | Direct HDR vs NHEJ efficiency comparison | Quantitatively demonstrated superiority of NHEJ for large insertions | [21] |

| 2017 | Endogenous promoter-driven reporters | Knock-in upstream of ATG without gene disruption | Faithful recapitulation of endogenous expression patterns | [16] |

| 2023 | Chemical modification of dsDNA donors | 5' AmC6 modified PCR fragments | Enhanced integration efficiency; cloning-free approach | [23] |

| 2025 | Quantitative parameter optimization | Long-read sequencing analysis | Identified optimal conditions for precise insertion | [19] |

Quantitative Advancements in Efficiency and Precision

The progression of homology-independent knock-in methods has been characterized by significant improvements in both efficiency and precision, with recent studies achieving remarkable success rates. Early efforts demonstrated the feasibility of the approach but with variable efficiency—the seminal 2014 study reported successful conversion of eGFP to Gal4 in approximately 22% of injected embryos exhibiting recapitulated expression patterns [14]. Subsequent optimization studies achieved germline transmission rates exceeding 20% for precise insertions across multiple loci, representing a substantial improvement over traditional HDR-based approaches that typically yielded efficiencies below 5% [19] [23].

Parameter optimization has been instrumental in these efficiency gains. Comparative studies identified that chemically modified templates significantly outperformed those released in vivo from plasmids, while both Cas9 and Cas12a nucleases demonstrated similar efficacy for targeted insertion [19]. The distance between the double-strand break and the insertion site emerged as a critical factor, with closer proximities favoring precise editing rates [19]. Furthermore, the elimination of non-homologous base pairs in homology templates consistently improved outcomes, highlighting the importance of molecular precision in template design [19]. The quantitative progression of these efficiency improvements across key studies is detailed in Table 2, illustrating the collective impact of methodological refinements.

Table 2: Evolution of Knock-In Efficiency Across Methodological Generations

| Study Focus | Template Type | Nuclease | Maximum Efficiency Achieved | Key Determinants of Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial proof-of-concept [14] | Plasmid with bait sequence | Cas9 | 22% (transient) | sgRNA efficiency; concurrent cleavage |

| Endogenous locus targeting [22] | Plasmid with bait sequence & hsp70 promoter | Cas9 | 25% (germline) | sgRNA activity; promoter selection |

| 3' knock-in lineage tracing [23] | AmC6-modified dsDNA PCR fragments | Cas9 RNP | 20% (germline) | Chemical modifications; RNP delivery |

| Multi-locus optimization [19] | Chemically modified ssODNs | Cas9/Cas12a | >20% (germline across 4 loci) | Template design; break-to-insert distance |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Guidelines

Core Protocol: Homology-Independent Knock-In via NHEJ

The following protocol represents a synthesis of the most effective methodologies developed across the historical progression of homology-independent knock-in techniques, incorporating key refinements that maximize efficiency and reproducibility.

Reagent Preparation

sgRNA Design and Synthesis:

- Design sgRNAs targeting the genomic region of interest using tools like CHOP-CHOP [16].

- Select target sites approximately 200-600 bp upstream of the gene start codon for 5' integrations or immediately upstream of the stop codon for 3' integrations [23] [22].

- Critical: Verify target specificity and minimize off-target effects by screening against the zebrafish genome.

- Synthesize sgRNAs using in vitro transcription with T7 or U6 promoters [16].

Donor Template Construction:

- For plasmid-based donors: Clone a "bait" sequence (e.g., Gbait, Tbait, Mbait) upstream of the insertion cassette, followed by your promoter-reporter/payload and polyA signal [14] [22].

- For dsDNA donors: Amplify insertion cassettes using PCR primers with 5' AmC6 modifications and 35-50 bp homology arms [23].

- Optional: Incorporate the hsp70 minimal promoter to enhance expression levels and enable enhancer trapping [22].

Cas9 Preparation:

- Prepare Cas9 as mRNA or recombinant protein. Recent evidence supports superior performance of preassembled Cas9/gRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) for early integration [23].

Microinjection Procedure

Injection Mixture Preparation:

- Combine the following components in nuclease-free water:

- 100-200 ng/μL donor template (plasmid or dsDNA)

- 25-50 ng/μL sgRNA (genomic target)

- 25-50 ng/μL sgRNA (donor bait target, if using plasmid donor)

- 300-500 ng/μL Cas9 mRNA or 100-200 ng/μL Cas9 protein

- Phenol red tracer (0.1%)

- Combine the following components in nuclease-free water:

Zebrafish Embryo Injection:

- Inject 1-2 nL of the mixture into the cell cytoplasm or yolk of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Maintain injected embryos at 28.5°C in E3 embryo medium [16].

Post-Injection Screening:

- For fluorescent reporters: Screen live embryos at 24-48 hpf for mosaic expression patterns.

- Raise approximately 50-100 injected embryos to adulthood to establish founder lines.

Founder Identification and Line Establishment

- Outcrossing and Germline Transmission:

- Outcross potential founder (F0) fish to wild-type partners.

- Screen F1 embryos for transgene expression or use PCR genotyping to identify germline transmission.

- Establish stable lines from positive founders.

Diagram Title: Homology-Independent Knock-In Workflow

Advanced Applications: Lineage Tracing and Conditional Systems

The historical development of knock-in methodologies has enabled increasingly sophisticated genetic applications, particularly in the realm of lineage tracing and conditional systems. The 3' knock-in approach has proven exceptionally valuable for these applications, as it permits the insertion of genetic cassettes immediately upstream of the stop codon, thereby preserving endogenous gene function while adding reporter or recombinase capabilities [23].

Protocol: 3' Knock-In for Lineage Tracing

Donor Design for Lineage Tracing:

- Design a donor cassette containing (in frame): self-cleavable peptide (P2A), fluorescent protein, second self-cleavable peptide (T2A), and Cre recombinase (iCre or CreERT2) [23].

- Flank the cassette with 35-50 bp homology arms targeting the region immediately upstream of the stop codon.

- Incorporate synonymous mutations in the homology arm to prevent re-cleavage of the knock-in allele [23].

Template Generation:

- Amplify the donor cassette using PCR with 5' AmC6-modified primers to enhance stability and integration efficiency.

- Purify PCR products using gel extraction or column purification.

Embryo Injection and Screening:

- Co-inject 100-200 ng/μL of the AmC6-modified dsDNA donor with preassembled Cas9 RNP complexes.

- Screen F0 embryos for fluorescence patterns matching expected endogenous expression.

- Raise mosaic founders with high integration efficiency (>30% mosaic fluorescence) for germline transmission [23].

Lineage Tracing Experiments:

- For CreERT2 lines: Treat adult fish or embryos with 4-hydroxytamoxifen to induce recombination.

- Analyze labeled lineages using fluorescence microscopy at desired timepoints.

The historical optimization of homology-independent knock-in techniques has identified critical reagents that consistently contribute to experimental success. Table 3 summarizes these essential research solutions, their specific functions, and optimization notes derived from the methodological evolution detailed in the literature.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Homology-Independent Knock-In

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Mechanism | Optimization Notes | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | Cas9 mRNA, Cas9 RNP, Cas12a | Creates targeted DSBs for donor integration | RNP complexes enable earlier integration; Cas9 & Cas12a show similar efficacy | [19] [23] |

| Template Types | Plasmids with bait sequences, AmC6-modified dsDNA, ssODNs | Provides donor DNA for integration | Chemically modified templates outperform unmodified; AmC6 modifications reduce degradation | [19] [23] |

| Bait Sequences | Gbait (eGFP-derived), Tbait (Tet1-derived), Mbait (Mc4r-derived) | Enables concurrent donor cleavage for NHEJ | Efficiency varies by sequence; test multiple baits if initial failure | [14] [22] |

| Promoter Systems | hsp70 minimal promoter, endogenous promoters | Drives transgene expression; hsp70 enables enhancer trapping | hsp70 increases expression level; endogenous promoters ensure faithful expression | [16] [22] |

| Genetic Elements | 2A self-cleaving peptides, loxP sites, fluorescent reporters | Enables multicistronic expression, conditional systems, and visualization | 2A peptides maintain endogenous gene function while adding reporters | [23] [22] |

The zebrafish research community has developed extensive curated databases that are invaluable for knock-in experimental design:

- ZFIN (Zebrafish Information Network): Provides comprehensive information on genetic sequences, mutations, and validated reagents [20].

- ZIRC (Zebrafish International Resource Center): Maintains and distributes zebrafish lines, including wild-type strains and genetic mutants [20].

- CHOP-CHOP: Web tool for sgRNA design and off-target prediction [16].

Current State and Future Perspectives

The historical trajectory of homology-independent knock-in strategies in zebrafish research has transformed this model organism into a premier system for precise genetic manipulation. The current state of the field is characterized by remarkably high efficiencies, with germline transmission rates consistently exceeding 20% across multiple loci when optimized parameters are employed [19] [23]. The methodology has evolved from a novel approach to a standardized technique capable of generating a diverse array of genetic tools, including fluorescent reporters, Cre drivers, and conditional alleles with high fidelity to endogenous expression patterns [16] [23].

Recent advances in long-read sequencing technologies have further accelerated methodological refinements by enabling comprehensive quantification of editing outcomes, revealing previously unappreciated factors influencing knock-in efficiency [19]. The integration of chemical modifications in donor templates represents another significant advancement, addressing long-standing challenges related to template stability and concatemerization in vivo [19] [23]. As these methodologies continue to mature, their application is expanding to include increasingly sophisticated genetic manipulations, such as dual-recombinase systems for intersectional labeling and complex disease modeling.

The historical progression from initial discovery to widespread application demonstrates how homology-independent knock-in strategies have effectively addressed the unique challenges of zebrafish genome engineering. By leveraging the naturally active NHEJ pathway in early embryos and systematically optimizing critical parameters, researchers have established a robust and efficient platform for reverse genetic approaches that continues to drive innovation in developmental biology, disease modeling, and functional genomics.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Implementing Homology-Independent Knock-In

This application note provides a detailed protocol for the design and implementation of donor plasmids incorporating 'bait' sequences for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homology-independent knock-in in zebrafish. The homology-independent approach leverages the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway to enable efficient integration of large DNA cassettes (>5.7 kb) into the zebrafish genome [14]. By incorporating specific bait sequences into donor plasmids that are cleaved concurrently with the genomic target site, researchers can achieve knock-in efficiencies exceeding 25% for stable transgenic founder generation [22]. This guide outlines the molecular design principles, provides quantitative performance data, and details step-by-step protocols for implementing this powerful genome engineering strategy.

The concurrent cleavage strategy for knock-in in zebrafish represents a significant advancement over homology-directed repair (HDR) methods, which typically exhibit low efficiency in this model organism [10]. This approach utilizes the cell's endogenous NHEJ pathway to integrate linearized donor DNA fragments into targeted genomic double-strand breaks (DSBs) [14]. The core innovation involves designing donor plasmids with specific 'bait' sequences that are cleaved by CRISPR/Cas9 simultaneously with the chromosomal target, creating compatible ends that facilitate ligation via NHEJ repair mechanisms [24] [22].

This method offers several advantages for zebrafish research: it circumvents the need for extensive homology arms, simplifies donor construction, enables insertion of large DNA cassettes, and demonstrates high efficiency across multiple genomic loci [23] [22]. The technique has been successfully applied to generate reporter lines, convert existing transgenic lines, and create targeted mutations at endogenous loci [14] [16] [24].

Bait Sequence Design and Selection

Characteristics of Effective Bait Sequences

Effective bait sequences share several key characteristics that optimize CRISPR/Cas9 cleavage efficiency and minimize off-target effects:

- Length: Typically 20-23 nucleotides [24] [22]

- PAM Sequence: Must include an appropriate protospacer adjacent motif (NGG for S. pyogenes Cas9) [14]

- Uniqueness: Should not appear elsewhere in the donor plasmid or zebrafish genome to prevent unintended cleavage [24]

- Efficiency: Should be highly amenable to Cas9 cleavage based on established sgRNA design principles [10]

Validated Bait Sequences

The table below summarizes bait sequences successfully implemented in zebrafish studies:

Table 1: Validated Bait Sequences for Zebrafish Knock-In

| Bait Name | Sequence (5' to 3') | PAM | Reported Efficiency | Application | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tbait | GGCTGCTGTCAGGGAGCTCATGG | CGG | >50% founder generation | Medaka and zebrafish transgenesis | [24] |

| Gbait | eGFP-derived sequence | NGG | Successful line conversion | GFP to Gal4 conversion | [22] |

| Mbait | Rat Mc4r-derived sequence | NGG | High efficiency | Reporter integration | [22] |

| eGFP 1 | eGFP-targeting sequence | NGG | 66% indel mutation rate | KalTA4 integration | [14] |

Bait Sequence Incorporation into Donor Plasmids

Bait sequences should be positioned immediately upstream of the insertion cassette in the donor plasmid [24] [22]. The cassette typically includes a minimal promoter (e.g., hsp70) followed by the gene of interest (reporter, Cre recombinase, etc.) [22]. Strategic placement ensures clean cleavage and release of the linear insert while preventing damage to the functional elements of the cassette.

Quantitative Performance Data

Knock-in Efficiency Across Loci

The concurrent cleavage method has demonstrated robust performance across multiple genomic loci in zebrafish:

Table 2: Knock-in Efficiency Across Zebrafish Genomic Loci

| Target Locus | Insert Size | Knock-in Efficiency | Expression Pattern | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| neurod:eGFP | E2A-KalTA4 | >75% injected embryos showed targeted integration | Recapitulated endogenous neurod pattern | [14] |

| evx2 | Gal4 | 12% founder efficiency (2/17 fish) | Broad CNS expression matching Evx2 | [22] |

| eng1b | Gal4 | 3% founder efficiency (1/40 fish) | MHB and muscle pioneers | [22] |

| krt92 | p2A-EGFP-t2A-CreERT2 | 5.1% mosaic embryos; 50% of mosaics produced founders | Skin epithelium | [23] |

| otx2 | Venus | Successful reporter line generation | Midbrain-hindbrain boundary | [16] |

| pax2a | turboRFP | Successful reporter line generation | Midbrain-hindbrain boundary | [16] |

Factors Influencing Efficiency

Several critical factors significantly impact knock-in efficiency:

- sgRNA efficiency: Designs with higher indel formation rates (>70%) substantially improve knock-in success [10]

- Donor format: 5' modified double-stranded DNA donors with AmC6 modifications increase integration efficiency 5-fold compared to unmodified donors [23]

- Developmental timing: Early integration events produce higher mosaicism, improving germline transmission rates [23]

- Component delivery: RNP complex injection yields higher efficiency than DNA/mRNA formats [23] [25]

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Donor Plasmid Construction

Materials:

- Base plasmid with minimal promoter (e.g., hsp70) and reporter/driver gene

- Oligonucleotides containing bait sequence

- Standard molecular cloning reagents

Procedure:

- Insert selected bait sequence immediately upstream of the promoter element using standard molecular cloning techniques

- Verify bait sequence incorporation and orientation by Sanger sequencing

- For 3' knock-in approaches, include 2A peptide sequences (p2A, t2A) to enable multicistronic expression [23]

- For epitope tagging or precise mutations, design donors with in-frame integrations

CRISPR Component Preparation

Materials:

- Cas9 expression vector (e.g., pCS2-hSpCas9) [24]

- sgRNA cloning vector (e.g., pDR274) [24]

- In vitro transcription kits

Procedure:

- Design sgRNAs targeting both the genomic locus and bait sequence

- Synthesize sgRNAs using T7 or SP6 in vitro transcription systems [24]

- Transcribe Cas9 mRNA from linearized template DNA

- Complex sgRNAs with Cas9 protein to form RNPs for improved efficiency [23]

Zebrafish Embryo Injection

Materials:

- One-cell stage zebrafish embryos

- Microinjection apparatus

- Phenol red injection marker

Injection Solution Formulation:

- 9 ng/μl sgRNA for bait sequence digestion [24]

- 18 ng/μl sgRNA for genomic target digestion [24]

- 200 ng/μl Cas9 mRNA or 300-500 ng/μl Cas9 protein for RNP formation [23]

- 9 ng/μl donor plasmid or 25-50 ng/μl PCR-amplified donor fragment [23] [24]

- Optional: 5' AmC6-modified primers for PCR-amplified donors to prevent degradation [23]

Procedure:

- Prepare injection solution and centrifuge briefly to remove particulates

- Load injection needles with prepared solution

- Inject approximately 1-2 nL into the cell cytoplasm or yolk of one-cell stage embryos

- Culture injected embryos at 28.5°C and monitor for development

Screening and Validation

Initial Screening:

- Assess mosaic expression in injected F0 embryos at 24-48 hpf

- Raise embryos showing correct expression patterns to adulthood

Founder Identification:

- Outcross potential F0 founders to wild-type fish

- Screen F1 progeny for transgene expression or using PCR genotyping

- For PCR screening, use one primer outside the targeted integration site and one within the transgene

Molecular Validation:

- Confirm precise integration junctions by Sanger sequencing

- Verify expression pattern recapitulates endogenous gene expression

- Assess potential off-target integrations through systematic PCR screening

Experimental Workflow for Bait Sequence-Mediated Knock-In

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low mosaic rate in F0 | Inefficient sgRNAs | Test multiple sgRNAs; select those with >70% indel efficiency [10] |

| No germline transmission | Late integration events | Use RNP complexes and 5' modified donors for earlier integration [23] |

| Random integration | Off-target cleavage | Verify bait sequence uniqueness; use BLAST against zebrafish genome |

| Incomplete expression pattern | Epigenetic silencing | Include insulator elements; test multiple integration events |

| High embryo mortality | Injection toxicity | Titrate component concentrations; use phenol red as injection marker |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Concurrent Cleavage Knock-In

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bait Sequences | Tbait, Gbait, Mbait | Donor plasmid linearization | [24] [22] |

| Cas9 Source | Cas9 mRNA, recombinant Cas9 protein | Targeted DNA cleavage | [24] [25] |

| Donor Vectors | Tbait-hs-lRl-GFP, Mbait-hs-lRl-GFPTx | Template for integration | [22] |

| sgRNA Templates | pDR274 vector, PCR templates | Guide RNA synthesis | [24] |

| Modification Reagents | AmC6-modified primers | Donor protection and efficiency enhancement | [23] |

| Reporter Cassettes | GFP, RFP, Gal4, CreERT2 | Visualizing and manipulating targeted cells | [14] [23] [22] |

Applications in Zebrafish Research

The concurrent cleavage knock-in strategy has enabled numerous advanced applications in zebrafish research:

- Lineage tracing: Knock-in of CreERT2 cassettes enables temporal control of recombination for fate mapping studies [23]

- Endogenous reporting: Precisely tagged genes report native expression patterns without disruptive random integration [16]

- Driver line generation: Tissue-specific Gal4 lines allow targeted manipulation of specific cell populations [14] [22]

- Disease modeling: Precise insertion of human disease-associated mutations creates accurate models [10]

- Multiplexed editing: Simultaneous targeting of multiple loci enables complex genetic engineering [24]

Molecular Mechanism of Bait Sequence-Mediated Knock-In

The incorporation of bait sequences into donor plasmids for concurrent cleavage with genomic targets represents a highly efficient and robust method for achieving homology-independent knock-in in zebrafish. This approach consistently yields high rates of targeted integration across diverse genomic loci, simplifies donor construction by eliminating the need for extensive homology arms, and supports the insertion of large genetic cassettes. As CRISPR/Cas9 technology continues to evolve, further refinements to bait sequence design and delivery methods promise to enhance the precision and efficiency of this already powerful genome engineering strategy, solidifying its position as a fundamental technique in zebrafish genetic research.

The homology-independent knock-in strategy has emerged as a powerful and efficient alternative to homology-directed repair (HDR) for generating targeted insertions in the zebrafish genome. Unlike HDR, which remains challenging due to its low efficiency, homology-independent insertion leverages the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, enabling highly efficient integration of DNA cassettes. The success of this approach critically depends on the precise formulation of the co-injection mix, comprising sgRNA, Cas9 nuclease, and donor DNA. This protocol details the optimization of these components based on recent quantitative studies, providing researchers with a robust framework for achieving high rates of precise germline transmission.

Key Reagent Solutions for Homology-Independent Knock-In

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Homology-Independent Knock-In in Zebrafish

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples & Key Features | Primary Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nuclease | SpCas9: Creates blunt-end DSBs. [19] | Generates a targeted double-strand break (DSB) in the genome to initiate repair. |

| LbCas12a: Creates 5-nt 5' overhangs; may improve HDR at some loci. [19] | ||

| Donor Template | Plasmid DNA with "bait" sequences: Linearized in vivo by co-injected nuclease (e.g., I-SceI or Cas9). [19] [14] | Serves as the template for integration into the genomic DSB via NHEJ. |

| Chemically modified double-stranded DNA templates: Features modifications that reduce degradation, outperforming plasmid templates. [19] | ||

| Chemical Enhancers | NU7441 (DNA-PK inhibitor): Shifts DNA repair equilibrium toward HDR; can enhance HDR-mediated repair up to 13.4-fold. [7] | Increases the frequency of precise, HDR-based editing events. |

| Screening Tools | Fluorescent PCR and Capillary Electrophoresis (CRISPR-STAT): Detects precise knock-in by analyzing PCR product size changes. [26] | Enables efficient, PCR-based screening for successful knock-in events without cloning. |

| Long-read sequencing (Pacific Biosciences): Accurately quantifies all repair events, including large inserts, overcoming short-read sequencing bias. [19] |

Optimized Co-Injection Ratios and Formulations

The composition of the co-injection mix is a primary determinant of knock-in efficiency. The table below summarizes optimal concentrations and ratios derived from empirical data.

Table 2: Quantitative Optimization of Co-Injection Components

| Component | Recommended Concentration/Ratio | Impact on Efficiency & Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA | Highly active sgRNA (e.g., >70% indel rate in pre-testing). [10] | Foundational prerequisite. Efficiency of the initial DSB is the most critical factor for successful knock-in. [10] |

| Cas9 Protein (RNP) | Pre-complexed with sgRNA as a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. | Direct RNP delivery increases mutagenesis efficiency and can reduce off-target effects. [27] |

| Donor DNA Template | Chemically modified double-stranded DNA templates. | Quantitative side-by-side comparison showed chemically modified templates outperform those released from a plasmid in vivo. [19] |

| NHEJ Inhibitor (NU7441) | 50 µM. | In an HDR reporter assay, this concentration enhanced HDR-mediated repair up to 13.4-fold compared to DMSO control. [7] |

| Targeting Strategy | Donor plasmid contains the same sgRNA target ("bait") sequence as the genomic locus. | Enables concurrent cleavage of the genome and donor plasmid, facilitating efficient homology-independent integration via NHEJ. [14] |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Protocol Workflow

The following diagram outlines the complete experimental workflow for homology-independent knock-in in zebrafish, from sgRNA design to founder identification:

Detailed Protocol Instructions

Step 1: Design and Validation of sgRNA

- Design: Select a target site near the desired integration point using reliable design tools (e.g., CCTop, CRISPRscan). The spacer sequence should directly precede a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence. [10]

- Validation: Synthesize the sgRNA and validate its cutting efficiency before knock-in attempts. Inject the sgRNA and Cas9 mRNA/protein into wild-type embryos, extract genomic DNA from a pool of embryos at 24-48 hpf, and assess the indel mutation rate via T7 endonuclease I (T7EI) assay or deep sequencing. Proceed only with sgRNAs that show high activity (>70% indels in a pool of embryos). [10]

Step 2: Preparation of the Donor Template

- Vector Construction: For homology-independent knock-in, clone your cargo (e.g., reporter gene, epitope tag) into a plasmid backbone. Crucially, flank this cargo with the identical sgRNA target sequence ("bait" sequence) that is being used to target the genomic locus. [14]

- Template Format: While early studies used plasmids linearized by a co-injected nuclease, recent quantitative comparisons show that chemically modified double-stranded DNA templates significantly outperform unmodified plasmid-based templates. Use templates with stability-enhancing modifications (e.g., 5' and 3' end modifications) to reduce degradation in the embryo. [19]

Step 3: Formulation of the Co-Injection Mix

- RNP Complex Formation: Pre-complex the purified Cas9 protein with the validated sgRNA at a molar ratio of 1:2 to 1:3 (Cas9:sgRNA) by incubating at 37°C for 10-15 minutes. This forms the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. [27]

- Final Mix Composition: Combine the following components in nuclease-free water to a final volume suitable for injection:

- RNP complex (final Cas9 concentration: 100-200 µg/mL)

- Donor DNA template (final concentration: 25-50 ng/µL)

- NHEJ inhibitor, NU7441 (final concentration: 50 µM) [7]

- Critical Note: The use of an NHEJ inhibitor like NU7441 is a key optimization. It chemically reprograms the embryo's DNA repair machinery, shifting the balance away from error-prone NHEJ and favoring precise HDR, even in a homology-independent knock-in context. [7]

Step 4: Microinjection and Embryo Handling

- Microinjection: Load the co-injection mix into a needle and inject 1-2 nL directly into the cytoplasm of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Embryo Care: After injection, incubate embryos in egg water at 28.5°C. Remove unfertilized or dead embryos after a few hours. Raise the injected embryos (F0 founders) to adulthood under standard laboratory conditions.

Step 5: Somatic and Germline Screening

- Somatic Screening (CRISPR-STAT): At 1-3 days post-fertilization (dpf), pool a subset of injected embryos and extract genomic DNA. Perform fluorescent PCR with primers flanking the target site. Analyze the PCR products using capillary electrophoresis. Successful precise integration will produce a distinct peak corresponding to the expected size increase, allowing for rapid assessment of knock-in efficiency before raising founders to adulthood. [26]

- Germline Transmission Screening: When F0 founders reach adulthood, perform a fin clip biopsy to screen for the presence of the knock-in allele in somatic tissue. For founders that test positive, outcross them to wild-type fish. Collect and pool embryos from these crosses, and screen the F1 progeny using the same PCR-based methods to confirm germline transmission and establish stable lines. [26]

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- Low Integration Efficiency: If efficiency is low, first re-confirm the activity of your sgRNA. Ensure the donor plasmid is being effectively linearized in vivo by verifying the "bait" target site is identical to the genomic target. Switching to a chemically modified donor template can also yield significant improvements. [19]

- High Embryo Mortality: High mortality can result from injecting too much volume or concentration of the RNP complex. Titrate the Cas9 concentration downward. Toxicity can also occasionally come from in vitro-transcribed gRNAs; using chemically synthesized gRNAs can mitigate this. [28]

- Imprecise Integration: The nature of the NHEJ pathway means that a fraction of integration events will be imprecise. This makes careful screening of the final integrated sequence in F1 animals essential. Long-read sequencing is the most reliable method for characterizing these complex editing outcomes. [19] [26]

Within the broader thesis on advancing homology-independent knock-in strategies in zebrafish, mastering the critical parameters of single guide RNA (sgRNA) efficiency and the precise timing of embryonic injection is paramount. Unlike knock-outs, which rely on the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, homology-independent knock-in requires the precise integration of a DNA cassette into a targeted genomic double-strand break (DSB) [14]. This method leverages the cell's endogenous repair machinery to insert large DNA fragments, such as fluorescent reporters or transcriptional activators, without the need for a homologous template [14] [16]. The success of this sophisticated editing approach is exquisitely sensitive to the quality of the sgRNA and the developmental stage of the embryo at the moment of injection, which collectively determine the rate of mosaicism and the likelihood of germline transmission [29] [30]. This application note details the protocols and parameters essential for optimizing these factors, providing a reliable framework for researchers in drug development and genetic research.

The efficiency of CRISPR-mediated knock-in is influenced by a quantifiable set of factors. The data below summarize critical parameters from key studies.

Table 1: Key Parameters Affecting Knock-in Efficiency

| Parameter | Impact on Efficiency | Optimal Condition / Value | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Efficiency | Directly correlates with knock-in rate [14] [30] | High-efficiency sgRNA (e.g., >66% indel rate) [14] | An sgRNA with 66% indel frequency achieved knock-in in >75% of injected embryos [14]. |

| Cas9 Format | Affects speed and potency of DSB creation [30] | Cas9 protein [30] | Cas9 protein significantly outperformed mRNA, yielding ~5.1% vs. ~0.9% HDR efficiency at one locus [30]. |

| Donor DNA Conformation | Influences HDR pathway engagement [31] [30] | Circular plasmid with flanking CRISPR sites [31] or PAM-distal ssODN [30] | A circular "bait" plasmid increased phenotypic rescue to 46% of larvae [31]. PAM-distal ssODNs outperformed PAM-proximal conformations [30]. |

| Injection Timing | Reduces mosaicism by targeting the one-cell stage [29] | Injection into the zygote shortly after fertilization [29] | Injection into porcine zygotes after IVF resulted in the highest rate of mutant blastocysts, reducing mosaicism [29]. |

| Concentration of Components | High concentration increases biallelic editing but can be toxic [29] | Cas9 protein: 20-100 ng/µL; sgRNA: 20-100 ng/µL [29] | Increasing Cas9/gRNA from 20 ng/µL to 100 ng/µL significantly increased biallelic mutations in porcine blastocysts (0% to 16.7%) [29]. |

Table 2: Homology-Independent vs. Homology-Directed Knock-in Strategies

| Feature | Homology-Independent Knock-in [14] | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [31] |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | NHEJ-mediated ligation of DSBs in genome and donor plasmid. | Homology-directed repair using a template with homologous arms. |

| Donor Template | Circular plasmid flanked by sgRNA target sites ("bait" plasmid). | Long linear DNA fragments or ssODNs with silent mutations in the PAM site. |

| Typical Efficiency | Very high (>75% of embryos with targeted integration) [14]. | Low to moderate (initially ~1%, up to 46% with optimized circular donor) [31]. |

| Primary Advantage | High efficiency for integrating large cassettes; simple design. | High precision for introducing single nucleotide changes. |

| Key Application | Converting existing transgenes (e.g., eGFP to Gal4); creating reporter lines. | Precise single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) exchanges; phenotypic rescue of mutations. |

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

The following diagram and detailed protocol outline the key steps for performing a homology-independent knock-in in zebrafish, highlighting the critical points of intervention for optimizing sgRNA efficiency and injection timing.

Diagram 1: Homology-Independent Knock-in Workflow. The process highlights critical steps for sgRNA validation and zygote injection.

Detailed Protocol for Homology-Independent Knock-in

sgRNA Design, Synthesis, and Validation

The first critical parameter is the generation of a highly efficient sgRNA.

- Design: Identify a 20-nucleotide target sequence immediately upstream of the NGG Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) within the 5' genomic region upstream of the ATG start codon of your gene of interest [16]. Use web tools like CHOP-CHOP or ZiFiT Targeter for design and to check for potential off-target sites with ≤2 bp mismatches [31] [16].

- Synthesis: Clone the target-specific oligonucleotide into an sgRNA expression vector (e.g., pDR274). Perform in vitro transcription using a kit such as the Ambion MEGAshortscript T7 Kit, followed by purification [31] [16].

- Validation of Efficiency: This is a crucial and often overlooked step.

- Co-inject the sgRNA with Cas9 mRNA or protein into wild-type embryos at the one-cell stage.

- At 24-48 hours post-fertilization (hpf), pool 10 embryos and extract genomic DNA.

- Perform PCR amplification of the target genomic locus.

- Quantify the indel mutation efficiency using the Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) tool or next-generation sequencing (NGS). An effective sgRNA should induce indels in >66% of sequenced alleles [14] [30]. Do not proceed with knock-in experiments with a poorly performing sgRNA.

Donor Plasmid Construction for Homology-Independent Integration

- Clone an 853 bp - 1 kb genomic fragment (the "bait") from your target locus into a standard vector (e.g., pGEM-T, pCS2+) [31] [16].

- Insert your desired cargo (e.g., the coding sequence for the fast-maturing fluorescent protein Venus) upstream of the bait sequence's ATG start codon.

- Critical Step: Ensure the bait sequence is flanked by the same sgRNA target sites used for the genomic target. This allows the Cas9 complex to linearize the donor plasmid in vivo, providing the necessary ends for NHEJ-mediated integration [31] [14].

Microinjection into Zebrafish Zygotes

The timing of this step is the second critical parameter for minimizing mosaicism.

- Prepare the Injection Mix:

- Perform Microinjection:

- Collect zebrafish zygotes within 15-30 minutes post-fertilization.

- Using a microinjector and a fine needle, immobilize the zygotes and inject ~1 nL of the injection mix directly into the cell cytoplasm [29] [16].

- The injection must be performed at the one-cell stage to ensure the edited allele is present in as many cells as possible, including the germline, thereby reducing mosaicism [29].

Screening and Germline Transmission

- Somatic Screening: At 1-3 dpf, screen injected embryos (F0) for successful integration using fluorescence microscopy (e.g., for Venus expression) [16].

- Early Genotyping (Highly Recommended): Use the Zebrafish Embryo Genotyper (ZEG) device to extract a tiny amount of genomic DNA from 72 hpf embryos with minimal lethality. Use NGS to quantify the somatic editing efficiency in individual embryos [30].

- Raising Founders: Select and raise only the embryos with the highest somatic editing efficiency to adulthood (F0 founders).

- Germline Screening: Outcross F0 founder fish to wild-types. Screen the resulting F1 progeny at 3 dpf for the presence of the knock-in allele via fluorescence or PCR. A founder with germline transmission will produce a percentage of positive F1 offspring [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Successful execution of this protocol relies on key reagents and tools, summarized below.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA in vitro Transcription Kit | Synthesizes high-quality, functional sgRNA. | Ambion MEGAshortscript T7 Kit [31]. |

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | Provides immediate nuclease activity, leading to higher editing efficiency and reduced mosaicism compared to mRNA [30]. | Guide-it Recombinant Cas9 (Takara Bio) [29]. |

| Homology-Independent Donor Plasmid | Serves as the template for knock-in. The "bait" sequence is flanked by sgRNA sites for in vivo linearization. | Can be cloned into pGEM-T Easy or pCS2+ [31] [16]. |

| Microinjection System | For precise delivery of CRISPR components into the cytoplasm of single-cell zygotes. | FemtoJet 4i microinjector and Femtotips II needles (Eppendorf) [29]. |

| Zebrafish Embryo Genotyper (ZEG) | Enables minimally invasive early genotyping to select embryos with high editing efficiency for raising [30]. | A microdevice for extracting genomic DNA from 72 hpf embryos. |