Hox Gene Expression in Zebrafish Pectoral Fin Development: Mechanisms, Models, and Evolutionary Insights

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Hox gene expression and its critical function in zebrafish pectoral fin development, a key model for understanding vertebrate paired appendage formation.

Hox Gene Expression in Zebrafish Pectoral Fin Development: Mechanisms, Models, and Evolutionary Insights

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Hox gene expression and its critical function in zebrafish pectoral fin development, a key model for understanding vertebrate paired appendage formation. We synthesize recent genetic evidence establishing the essential role of HoxB-derived clusters (hoxba/hoxbb) in anterior-posterior fin positioning through induction of tbx5a expression. The content explores methodological approaches for analyzing Hox function, addresses challenges in functional redundancy and phenotypic penetrance, and validates findings through cross-species and cross-cluster comparisons. For researchers and drug development professionals, this review integrates foundational concepts with cutting-edge discoveries to illustrate how zebrafish studies illuminate conserved developmental mechanisms with potential biomedical applications.

Hox Gene Clusters and Their Foundational Role in Pectoral Fin Positioning

Hox genes, which encode a family of evolutionarily conserved transcription factors, are master regulators of embryonic development along the anterior-posterior axis in bilaterally symmetrical animals [1] [2]. These genes are distinguished by their characteristic homeodomain—a 60-amino-acid DNA-binding motif—and their unique genomic organization into tightly linked clusters [1]. A defining feature of Hox genes is collinearity, where the order of genes within the cluster corresponds to their spatial and temporal expression patterns during embryogenesis [2].

The organization and number of Hox clusters vary significantly across vertebrates, primarily due to genome duplication events (Figure 1) [3]. Mammals possess four Hox clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD) located on different chromosomes, resulting from two rounds of whole-genome duplication (2R-WGD) early in vertebrate evolution [3]. In contrast, teleost fishes, including the zebrafish (Danio rerio), experienced an additional, third round of teleost-specific whole-genome duplication (3R-WGD) [4] [3]. Although this initially produced eight Hox clusters, subsequent gene losses resulted in the retention of seven hox clusters in zebrafish: hoxaa, hoxab, hoxba, hoxbb, hoxca, hoxcb, and hoxda [5] [4] [6]. The hoxdb cluster was lost except for a single microRNA [6].

This application note examines the organizational divergence of Hox genes between mammals and zebrafish, with a specific focus on its implications for pectoral fin development research. We provide standardized protocols and analytical frameworks to support researchers in investigating Hox gene function in this established model organism.

Comparative Hox Cluster Organization

Table 1: Comparative Hox Cluster Organization in Mammals and Zebrafish

| Feature | Mammals (e.g., Mouse, Human) | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Clusters | 4 (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, HoxD) [6] | 7 (hoxaa, hoxab, hoxba, hoxbb, hoxca, hoxcb, hoxda) [4] [6] |

| Origin of Clusters | Two rounds of whole-genome duplication (2R-WGD) [3] | 2R-WGD + additional teleost-specific duplication (3R-WGD) [4] [3] |

| Average Genes per Cluster | Relatively high and stable (e.g., ~11 in Chondrichthyes) [3] | Lower average (~5.1 in Teleostei) due to gene loss after duplication [3] |

| Cluster Fate | Generally stable organization [3] | Significant modification by gene loss and co-option [3] |

| Key Pectoral Fin/Limb Clusters | HoxA and HoxD (paralogs 9-13) [6] | hoxaa, hoxab, hoxda (paralogs 9-13); hoxba, hoxbb (positioning) [4] [6] |

The duplication and diversification of Hox clusters in zebrafish have profound functional implications. While the "posterior" genes (paralogue groups 9-13) in the hoxaa, hoxab, and hoxda clusters are homologous to those in tetrapod HoxA and HoxD clusters and are critical for the outgrowth and patterning of paired appendages [6], the hoxba and hoxbb clusters, derived from the ancestral HoxB cluster, have acquired a novel, essential role in determining the anterior-posterior position of pectoral fin initiation [4] [7].

Application in Zebrafish Pectoral Fin Development

The zebrafish pectoral fin, homologous to tetrapod forelimbs, serves as a powerful model for understanding the genetic basis of paired appendage development. Research has delineated distinct roles for the duplicated zebrafish hox clusters in this process, offering a refined model for functional analysis.

Genetic Control of Pectoral Fin Positioning and Development

Table 2: Key Hox Clusters and Their Roles in Zebrafish Pectoral Fin Development

| Hox Cluster | Homology | Function in Pectoral Fin Development | Phenotype of Cluster Deletion |

|---|---|---|---|

| hoxba & hoxbb | HoxB-derived [4] | Anterior-Posterior positioning; induction of tbx5a expression [4] [7] |

Complete absence of pectoral fins; loss of tbx5a expression [4] [7] |

| hoxaa, hoxab, hoxda | HoxA- and HoxD-derived [6] | Pectoral fin outgrowth and patterning (similar to tetrapod HoxA/D) [6] | Severe shortening of endoskeletal disc and fin-fold; defective posterior fin structures [6] |

| hoxab | HoxA-derived [6] | Major contributor to fin growth and patterning [6] | Shortening of pectoral fin [6] |

| hoxca, hoxcb | HoxC-derived | Less defined role in pectoral fins; primarily involved in axial patterning |

The critical role of hoxba and hoxbb is demonstrated by mutant studies: double homozygous mutants display a complete absence of pectoral fins, accompanied by a failure to induce tbx5a—a master regulator of forelimb initiation—in the lateral plate mesoderm [4] [7]. Within these clusters, hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b have been identified as pivotal genes for this positioning function [7]. Meanwhile, the simultaneous deletion of hoxaa, hoxab, and hoxda clusters results in significantly shortened pectoral fins due to defects in growth and patterning after the fin bud has already formed, confirming a conserved role for these clusters in appendage outgrowth [6].

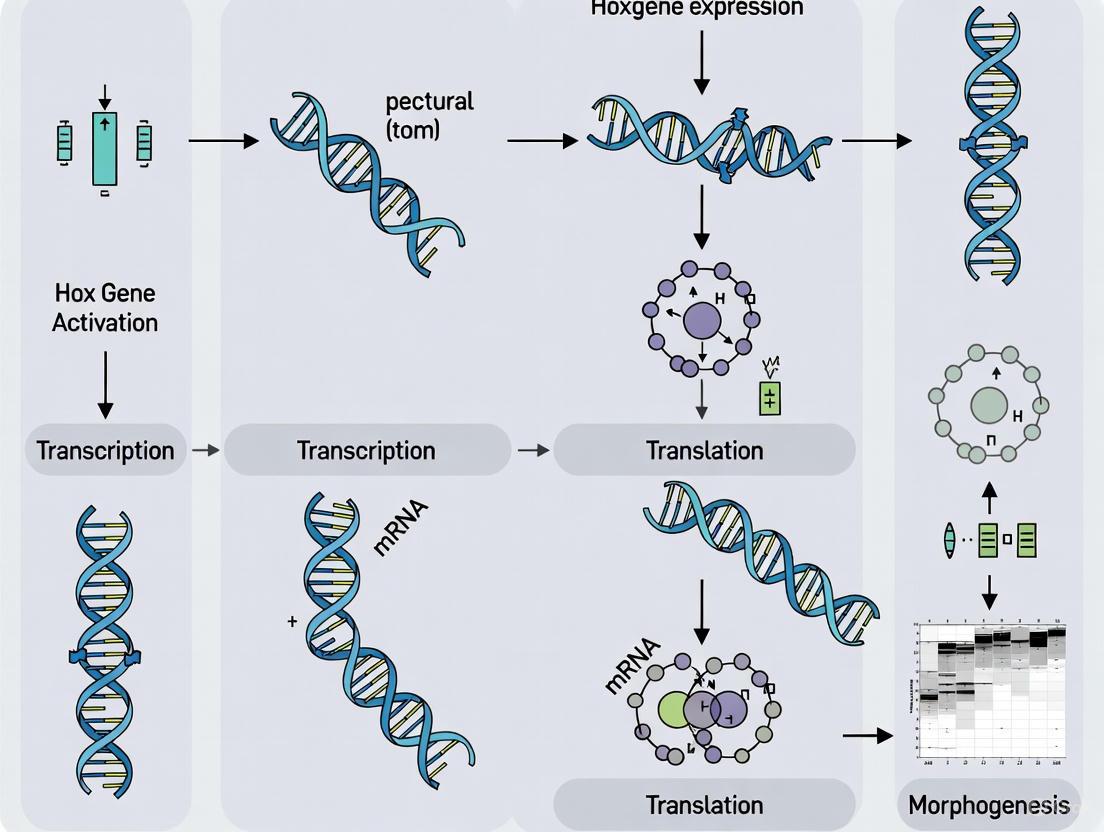

Figure 1: Hox Gene Genetic Pathway in Zebrafish Pectoral Fin Development. The hoxba/hoxbb clusters are essential for initial positioning and induction of the fin field via tbx5a, while the hoxaa/hoxab/hoxda clusters are required for subsequent outgrowth and patterning.

Protocol: Analyzing Hox Gene Function in Zebrafish Pectoral Fins

Objective: To characterize the functional role of specific hox clusters during zebrafish pectoral fin development using CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis and phenotypic analysis.

Materials and Reagents:

- Zebrafish Strains: Wild-type (e.g., TU or AB), and existing hox cluster mutant lines.

- CRISPR-Cas9 Components: Cas9 protein or mRNA; single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) designed to target critical exons of multiple genes within a cluster.

- Microinjection Equipment: Micropipette puller, microinjector.

- Fixation and Staging Reagents: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS, phenylthiourea (PTU) to inhibit pigment formation.

- In Situ Hybridization (ISH) Reagents: Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA probes for

tbx5a,shha, and posterior hox genes (e.g.,hoxa13a,hoxd13a); anti-DIG-AP antibody, NBT/BCIP staining solution. - Cartilage Stain: Alcian Blue solution.

Methodology:

Generation of Cluster Mutants:

- Design 3-5 sgRNAs targeting conserved regions or functional domains of key genes within the desired hox cluster (e.g.,

hoxb4a,hoxb5ainhoxba/bb; orhoxa13a,hoxd13ainhoxaa/da) [4] [6]. - Co-inject sgRNAs and Cas9 into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Raise injected embryos (F0 founders) to adulthood and outcross to identify germline-transmitting fish.

- Intercross F1 heterozygotes to generate F2 homozygous mutants for phenotypic analysis. For functional redundancy studies, generate double or triple cluster mutants via crossing [4] [6].

- Design 3-5 sgRNAs targeting conserved regions or functional domains of key genes within the desired hox cluster (e.g.,

Phenotypic Analysis of Mutant Larvae:

- Fixation: Anesthetize and fix larvae at critical stages (e.g., 30, 48, 60, 72 hours post-fertilization (hpf)) in 4% PFA.

- Morphology: Document fin bud morphology under a dissecting microscope at 3-5 days post-fertilization (dpf).

- Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH):

- Cartilage Staining: Stain 5 dpf larvae with Alcian Blue to visualize the cartilaginous endoskeletal disc of the pectoral fin. Measure the length of the endoskeletal disc and fin-fold under a microscope [6].

Phenotypic Analysis of Adult Fins:

- Raise viable mutant larvae to adulthood.

- Fix and skin the pectoral fins of adult fish.

- Perform micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scanning to analyze the fin skeletal structure in three dimensions, focusing on defects in the endoskeletal elements, particularly the posterior rays [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Zebrafish Hox Gene and Fin Development Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted mutagenesis of hox cluster genes. | Generating stable mutant lines for single or multiple hox clusters [4] [6]. |

| Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA Probes | Detection of specific mRNA transcripts via in situ hybridization. | Visualizing expression domains of tbx5a, shha, and hox genes (e.g., hoxa13b) [4] [6]. |

| Anti-DIG-AP Antibody | Colorimetric detection of hybridized DIG probes. | Used in conjunction with NBT/BCIP for staining in WISH protocols. |

| Alcian Blue | Staining of sulfated glycosaminoglycans in cartilage. | Visualifying the cartilaginous endoskeletal disc in larval pectoral fins [6]. |

| Micro-CT Imaging | High-resolution, non-destructive 3D imaging of mineralized tissues. | Quantitative analysis of skeletal defects in adult pectoral fins [6]. |

| tbx5a Mutant/Reporter Lines | Controls for finless phenotype and tools for tracking fin precursors. | Validating the specificity of tbx5a expression loss in hoxba;hoxbb mutants [4]. |

| HS94 | HS94, MF:C15H15N5O2S, MW:329.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| JBJ-02-112-05 | JBJ-02-112-05, MF:C27H20N4O2S, MW:464.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The evolutionary history of Hox gene clusters, from the four clusters in mammals to the seven in zebrafish, is not merely a genomic curiosity. It has endowed zebrafish with a sophisticated and genetically tractable system for dissecting the distinct phases of appendage development: initial positioning governed by hoxba/bb and subsequent outgrowth controlled by hoxaa/ab/da. The protocols and resources outlined here provide a foundation for researchers to leverage this model system, enabling precise investigations into the genetic circuitry of vertebrate limb development with direct relevance to evolutionary and developmental biology.

This application note details the experimental approaches for analyzing Hox gene function in zebrafish pectoral fin development, a key model for understanding anteroposterior patterning and the evolutionary origin of paired appendages. We provide structured protocols and data from recent studies that establish the essential role of HoxB-derived clusters in determining limb position through regulation of tbx5a expression.

Quantitative Analysis of Hox Cluster Mutants in Zebrafish

Recent genetic studies utilizing CRISPR-Cas9 have systematically dissected the roles of various Hox clusters in zebrafish pectoral fin development. The following tables summarize key phenotypic and molecular data.

Table 1: Pectoral Fin Phenotypes in Zebrafish Hox Cluster Mutants

| Genotype | Pectoral Fin Phenotype | Penetrance | Key Molecular Marker |

|---|---|---|---|

hoxbaâ»/â» |

Abnormal morphology, shortening | Complete | Reduced tbx5a expression [4] |

hoxbbâ»/â» |

Not specified in results | - | - |

hoxbaâ»/â»; hoxbbâ»/â» |

Complete absence | 100% (15/15 homozygous mutants) | Near-complete loss of tbx5a induction [4] [8] |

hoxaaâ»/â»; hoxabâ»/â»; hoxdaâ»/â» |

Severe shortening | Complete | Normal tbx5a bud initiation; downregulated shha [6] |

Table 2: Functional Contribution of Key Hox Genes within hoxba/hoxbb Clusters

| Gene | Functional Role in Pectoral Fin Positioning | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| hoxb4a | Pivotal in establishing positional cues | Deletion mutants show fin absence with low penetrance [4] |

| hoxb5a | Cooperatively induces tbx5a expression |

Deletion mutants show fin absence with low penetrance [4] |

| hoxb5b | Critical for anteroposterior positioning | Deletion mutants show fin absence with low penetrance [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Functional Analysis

Protocol 1: Generating Hox Cluster-Deletion Mutants via CRISPR-Cas9

This protocol is adapted from Yamada et al. (2021) and subsequent studies [4] [6] [8].

Application: Create stable zebrafish lines with single or compound deletions of entire Hox clusters to study functional redundancy and specific roles in pectoral fin development.

Reagents and Equipment:

- CRISPR-Cas9 protein or mRNA

- Multiple single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting the flanking regions of the Hox cluster to be deleted

- Wild-type zebrafish embryos at one-cell stage

- Microinjection apparatus

- Standard equipment and reagents for zebrafish husbandry and genomic DNA extraction

- PCR primers for genotyping, designed to amplify across the deletion junctions

Procedure:

- Design sgRNAs: Select two sgRNAs that target genomic sequences immediately upstream and downstream of the Hox cluster to be deleted (e.g., the entire

hoxbacluster). - Microinjection: Co-inject CRISPR-Cas9 complex (Cas9 protein + pooled sgRNAs) into the cytoplasm of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Raise Founders (F0): Raise injected embryos to adulthood. These mosaic founders are outcrossed to wild-type fish.

- Identify Germline Transmission: Screen the resulting offspring (F1) by PCR genotyping for large deletions at the target locus. Fish carrying the deletion are raised to establish heterozygous mutant lines.

- Generate Compound Mutants: Intercross heterozygous mutants for different clusters (e.g.,

hoxbaâº/â» andhoxbbâº/â») to obtain double homozygous mutants (hoxbaâ»/â»;hoxbbâ»/â») in the F2 generation.

Key Analysis: Genotype all experimental embryos and score for pectoral fin presence/absence and morphology at 3-5 days post-fertilization (dpf).

Protocol 2: Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH) for Gene Expression Analysis

This protocol is used to characterize molecular phenotypes in Hox cluster mutants [4] [6].

Application: Visualize the spatial expression patterns of key genes like tbx5a and shha in wild-type and mutant zebrafish embryos.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Zebrafish embryos (wild-type and mutant) at desired stages (e.g., 30 hpf for

tbx5a, 48 hpf forshha) - Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA antisense probes for

tbx5a,shha - Proteinase K

- Pre-hybridization and hybridization buffers

- Anti-DIG alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody

- NBT/BCIP colorimetric substrate

- PBS, PBT, and other standard buffers

Procedure:

- Fixation: Fix embryos in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C.

- Re-hydration and Permeabilization: Dehydrate embryos through a methanol series and re-hydrate. Treat with Proteinase K to permeabilize tissues.

- Pre-hybridization and Hybridization: Pre-incubate embryos in hybridization buffer, then incubate with the DIG-labeled RNA probe overnight at 65-70°C.

- Immunodetection: Wash embryos stringently to remove unbound probe. Incubate with anti-DIG-AP antibody.

- Color Reaction: Develop color reaction using NBT/BCIP substrate.

- Documentation: Image stained embryos using a stereomicroscope.

Key Analysis: Compare expression domains and intensity of the target gene between wild-type and mutant siblings. For example, a near-complete loss of tbx5a signal in the lateral plate mesoderm of hoxba;hoxbb double mutants indicates a failure in fin bud initiation [4].

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: HoxB-dependent pathway for pectoral fin positioning. The model shows that hoxba and hoxbb clusters, through genes hoxb4a/b5a/b5b, provide positional information that is essential for inducing tbx5a expression and subsequent fin bud formation. Mutation of these clusters prevents tbx5a induction [4] [8].

Diagram 2: Workflow for analyzing Hox gene function in fin development. The experimental pipeline outlines the key steps from mutant generation using CRISPR-Cas9 to phenotypic and molecular analysis [4] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating Hox Code in Zebrafish

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use in Context |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted deletion of Hox gene clusters. | Generation of hoxba;hoxbb double-deletion mutants [4] [8]. |

| DIG-labeled RNA Probes | Detection of specific mRNA transcripts via WISH. | Visualizing tbx5a and shha expression domains in mutant embryos [4] [6]. |

| Anti-DIG Antibody (AP-conj.) | Immunological detection of hybridized probes in WISH. | Colorimetric development for gene expression analysis [6]. |

| Zebrafish Hox Mutant Lines | Models for studying functional redundancy and specificity. | Comparing phenotypes of single vs. compound cluster mutants [4] [6]. |

| Alcian Blue | Staining of cartilaginous structures. | Analyzing endoskeletal disc morphology in larval pectoral fins [6]. |

| TXA6101 | TXA6101, MF:C18H10BrF5N2O3, MW:477.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| RTS-V5 | RTS-V5, MF:C27H35N5O6, MW:525.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This application note details recent breakthroughs in understanding the essential role of HoxB-derived hoxba and hoxbb gene clusters in initiating zebrafish pectoral fin development. The findings provide the first conclusive genetic evidence that these clusters determine anterior-posterior positioning of paired appendages through direct regulation of tbx5a expression, offering new experimental frameworks for evolutionary developmental biology research.

In jawed vertebrates, Hox genes—encoding conserved homeodomain transcription factors—provide positional information along the anterior-posterior axis during embryonic development. A long-standing hypothesis in evolutionary developmental biology proposes that Hox genes determine the precise locations where paired appendages (pectoral fins in fish, forelimbs in tetrapods) emerge from the lateral plate mesoderm [4] [8]. Despite supportive evidence from chick and mouse models, clear genetic demonstration of substantial limb positioning defects in Hox-deficient mutants remained elusive until recent zebrafish studies [4] [7] [8].

Zebrafish possess seven hox clusters resulting from teleost-specific whole-genome duplication, including hoxba and hoxbb clusters derived from the ancestral HoxB cluster [4] [8]. This note synthesizes cutting-edge research establishing their indispensable, cooperative role in pectoral fin bud initiation through precise regulation of the key limb identity gene tbx5a [4] [7].

Key Experimental Findings

Genetic Evidence from Cluster Deletion Mutants

Comprehensive genetic analysis using CRISPR-Cas9-generated mutants reveals that simultaneous deletion of both hoxba and hoxbb clusters produces a complete absence of pectoral fins, whereas single cluster deletions cause only mild abnormalities [4] [8]. This functional redundancy indicates that these duplicated clusters cooperatively control fin bud initiation.

Table 1: Phenotypic Consequences of Hox Cluster Deletions in Zebrafish

| Genotype | Pectoral Fin Phenotype | tbx5a Expression | Penetrance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Normal pectoral fins | Strong, localized expression | 100% |

| hoxba−/− or hoxbb−/− | Mild fin abnormalities | Reduced expression | 100% |

| hoxba−/−;hoxbb+/− or hoxba+/−;hoxbb−/− | Present pectoral fins | Moderate reduction | 100% |

| hoxba−/−;hoxbb−/− | Complete fin absence | Nearly undetectable | 100% (15/15 embryos) |

The complete fin absence in double homozygous mutants demonstrates that these HoxB-derived clusters are essential for the initial establishment of the pectoral fin field, not merely subsequent patterning [4].

Molecular Mechanism: hoxba/hoxbb Regulation of tbx5a

The molecular pathway connecting HoxB-derived clusters to fin initiation centers on their essential role in activating and maintaining tbx5a expression:

- tbx5a induction failure: In hoxba;hoxbb double mutants, tbx5a expression in the lateral plate mesoderm fails to initiate at early stages, indicating loss of pectoral fin precursor cells [4] [8]

- Retinoic acid response loss: Mutants lose competence to respond to retinoic acid signaling, a known regulator of tbx5a expression [4]

- Key regulatory genes: Functional analyses identify hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b as pivotal genes within these clusters responsible for positional specification [4] [7]

Figure 1: Genetic hierarchy of pectoral fin initiation. hoxba/hoxbb clusters enable retinoic acid (RA) competence and directly induce tbx5a expression for fin bud formation.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Hox Cluster Deletion

This protocol enables generation of zebrafish mutants lacking specific hox clusters.

Materials:

- Wild-type zebrafish (AB strain)

- CRISPR-Cas9 reagents: Cas9 protein and guide RNAs targeting hoxba/hoxbb cluster boundaries

- Microinjection apparatus

- Embryo rearing system

Procedure:

- Design guide RNAs targeting conserved regulatory regions flanking hoxba (chr: coordinates) and hoxbb (chr: coordinates) clusters

- Prepare injection mixture: 300 ng/μL Cas9 protein + 50 ng/μL each guide RNA

- Microinject 1 nL mixture into 1-cell stage zebrafish embryos

- Raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood and outcross to identify germline transmission

- Intercross F1 heterozygotes to generate F2 homozygous mutants

- Verify complete cluster deletions via PCR and sequencing [4] [8]

Validation:

- Genotype cluster mutants using junction PCR with primers outside deleted regions

- Confirm absence of cluster genes via whole-mount in situ hybridization

- Assess potential off-target effects by examining similar sequences in other hox clusters

Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization for Gene Expression

This method visualizes spatial expression patterns of key genes in wild-type and mutant embryos.

Materials:

- Wild-type and hoxba;hoxbb mutant embryos (24-48 hpf)

- Digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes for tbx5a, hoxb5a, hoxb4a

- Anti-digoxigenin antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase

- NBT/BCIP color substrate

- PBS, methanol, proteinase K

Procedure:

- Fix embryos in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C

- Permeabilize embryos with proteinase K (10 μg/mL) for 30 minutes

- Hybridize with digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes (65°C overnight)

- Wash stringently and incubate with anti-digoxigenin antibody (1:5000)

- Develop color reaction with NBT/BCIP substrate

- Image expression patterns using brightfield microscopy [4]

Key Application: This protocol confirmed absent tbx5a expression in hoxba;hoxbb double mutants at 30 hpf, demonstrating failure of fin field specification [4].

Retinoic Acid Competence Assay

This functional assay tests whether hoxba/hoxbb clusters enable response to retinoic acid signaling.

Materials:

- Wild-type and hoxba;hoxbb mutant embryos (24 hpf)

- All-trans retinoic acid (RA) stock solution (10 mM in DMSO)

- DMSO vehicle control

- E3 embryo medium

Procedure:

- Dechorionate 24 hpf embryos manually

- Treat experimental group with 1 μM RA in E3 medium

- Treat control group with 0.01% DMSO in E3 medium

- Incubate 6 hours at 28.5°C

- Fix embryos and process for tbx5a in situ hybridization

- Compare tbx5a expression levels between conditions [4]

Expected Results: Wild-type embryos show upregulated tbx5a after RA treatment, while hoxba;hoxbb mutants fail to respond, demonstrating lost signaling competence [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Hox Gene Function Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish Lines | hoxba cluster mutant; hoxbb cluster mutant; hoxba;hoxbb double mutant | Functional genetic analysis | Establish requirement for hoxba/hoxbb in fin initiation |

| Molecular Probes | tbx5a RNA probe; hoxb4a RNA probe; hoxb5a RNA probe | Spatial expression analysis | Visualize gene expression domains in wild-type vs mutants |

| CRISPR Reagents | Cas9 protein; hoxba-flanking gRNAs; hoxbb-flanking gRNAs | Targeted genome editing | Generate precise cluster deletions to assess function |

| Signaling Molecules | All-trans retinoic acid | Competence assays | Test regulatory relationships in fin positioning |

| Antibodies | Anti-digoxigenin-AP | In situ hybridization detection | Amplify signal for RNA probe detection |

| YXL-13 | 4-(4-Bromophenoxy)-N-(2-oxo-1,3-oxazolidin-3-yl)butanamide | Explore 4-(4-Bromophenoxy)-N-(2-oxo-1,3-oxazolidin-3-yl)butanamide for research. This compound is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| CHF-6366 | CHF-6366, MF:C42H48N6O8, MW:764.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Workflow Integration

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for analyzing hoxba/hoxbb function, from mutant generation to mechanistic insight.

Discussion and Research Implications

Evolutionary Developmental Biology Significance

These findings fundamentally advance understanding of vertebrate limb evolution by demonstrating that HoxB-derived clusters provide essential positional cues for appendage emergence along the anterior-posterior axis [4] [7]. The conserved function despite teleost-specific genome duplication highlights the evolutionary constraint on this mechanism.

The specific requirement for hoxba/hoxbb clusters in zebrafish contrasts with mouse models where HoxB cluster deletion causes minimal limb defects, suggesting lineage-specific compensation mechanisms [4] [8]. This comparative perspective illuminates how different vertebrate groups achieve similar developmental outcomes through modified genetic networks.

Future Research Applications

The experimental frameworks established in these studies enable several research directions:

- Gene regulatory networks: Identify direct transcriptional targets of hoxb4a/hoxb5a/hoxb5b using ChIP-seq in fin bud cells

- Human medical relevance: Explore potential HOXB gene roles in congenital limb abnormalities (e.g., Holt-Oram syndrome linked to TBX5)

- Evolutionary diversification: Investigate how Hox-directed positioning mechanisms vary across fish species with different fin morphologies

The protocols and reagents detailed herein provide a foundation for these investigations, particularly leveraging zebrafish advantages for live imaging, genetic manipulation, and high-throughput screening.

Application Notes

This application note details the critical role of the hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b genes in establishing the anterior-posterior position of zebrafish pectoral fins. Framed within a broader thesis on Hox gene expression, it provides consolidated experimental data and validated protocols to support research into the genetic mechanisms of vertebrate paired appendage development [4] [8].

Recent genetic evidence has established that the simultaneous deletion of the hoxba and hoxbb clusters leads to a complete absence of pectoral fins in zebrafish, a phenotype not observed with the deletion of any other single or combination of Hox clusters [4]. Within these clusters, the genes hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b function cooperatively to provide positional cues along the anterior-posterior axis, ultimately specifying the fin field through the induction of the key limb initiation gene tbx5a [8] [7]. The failure of tbx5a expression in the lateral plate mesoderm of hoxba;hoxbb cluster-deleted mutants confirms their upstream regulatory role [4] [9].

Table 1: Quantitative Phenotypic Data of hox Cluster Mutants in Zebrafish

| Genotype | Pectoral Fin Phenotype | Penetrance of Absent Fins | tbx5a Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

hoxba-/-; hoxbb-/- (Double homozygous) |

Complete absence | 5.9% (15/252) [4] | Nearly undetectable in fin buds [4] |

hoxba-/-; hoxbb+/- or hoxba+/-; hoxbb-/- |

Present | Not observed | Reduced [4] |

hoxba cluster mutant only |

Morphological abnormalities | Not observed | Reduced [4] |

hoxaa-/-; hoxab-/-; hoxda-/- |

Severely shortened, but present | Not observed | Indistinguishable from wild-type [6] |

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Pivotal Hox Genes

| Gene | Paralog Group | Primary Role in Pectoral Fin Development | Phenotype of Specific Deletion Mutants |

|---|---|---|---|

| hoxb4a | Anterior (PG 4) | Anterior-Posterior Positioning | Absence of pectoral fins (low penetrance) [8] |

| hoxb5a | Anterior (PG 5) | Anterior-Posterior Positioning | Absence of pectoral fins (low penetrance) [8] |

| hoxb5b | Anterior (PG 5) | Anterior-Posterior Positioning | Absence of pectoral fins (low penetrance) [8] |

| tbx5a | N/A | Initial bud induction (downstream target) | Complete absence of pectoral fins [4] [6] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating hox Cluster-Deletion Mutants via CRISPR-Cas9

This protocol describes the generation of zebrafish mutants with deletions in the hoxba and hoxbb clusters, a prerequisite for studying the functional redundancy of these clusters [4] [9].

Workflow Overview:

Materials & Reagents:

- CRISPR-Cas9 System: Cas9 protein and synthetic guide RNAs (gRNAs) designed to target genomic loci flanking the

hoxbaandhoxbbclusters [4]. - Zebrafish: Wild-type AB strain or similar.

- Microinjection Apparatus: For delivering CRISPR components into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Genotyping Primers: Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) primers designed to span the targeted deletion sites for cluster verification [4] [9].

Procedure:

- Design and Synthesis: Design two gRNAs for each target cluster (

hoxba,hoxbb) to create a large chromosomal deletion. Synthesize gRNAs and purify. - Embryo Injection: Co-inject Cas9 protein and the pool of gRNAs into the cytoplasm of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Founder Generation: Raise the injected embryos (F0 generation) to adulthood. These are potential mosaic founders.

- Screening F1 Carriers: Outcross F0 fish to wild-type partners. Screen the resulting F1 offspring by PCR genotyping to identify individuals carrying the desired deletion. The expected Mendelian ratio for double homozygous mutants in the F2 generation is 1/16 (6.25%) [4].

- Establishing Mutant Lines: Incross identified F1 heterozygous carriers to generate F2 progeny. Genotype the F2 larvae to identify and select

hoxba;hoxbbdouble homozygous mutants for phenotypic analysis.

Protocol 2: Phenotypic Analysis of Pectoral Fin Development

This protocol outlines the methods for confirming the loss of pectoral fins and the underlying molecular deficits in the generated mutants.

Workflow Overview:

Materials & Reagents:

- Fixative: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS).

- RNA Probe for

tbx5a: Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled antisense RNA probe for in situ hybridization [4] [6]. - Antibodies: Anti-DIG antibody conjugated to Alkaline Phosphatase (AP).

- Staining Reagent: NBT/BCIP substrate for AP, which produces a blue-purple precipitate.

- Mounting Medium.

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Anesthetize and fix wild-type and

hoxba;hoxbbdouble homozygous mutant larvae at key developmental stages (e.g., 30 hours post-fertilization fortbx5aexpression) with 4% PFA [4]. - Whole-mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH):

- Permeabilize the fixed larvae.

- Hybridize with the DIG-labeled

tbx5aRNA probe. - Wash to remove unbound probe.

- Incubate with Anti-DIG-AP antibody.

- Develop color using NBT/BCIP substrate.

- Imaging and Analysis: Clear and mount the stained larvae. Image using a stereomicroscope. Compare the

tbx5aexpression signal in the lateral plate mesoderm between wild-type and mutant larvae. The mutant larvae should show a significant reduction or complete absence oftbx5aexpression [4].

Protocol 3: Functional Validation via Retinoic Acid Response Assay

This protocol tests the competence of the fin field to respond to retinoic acid (RA), a key signaling molecule known to interact with Hox gene expression [4].

Materials & Reagents:

- Retinoic Acid (RA): Prepare a stock solution in DMSO.

- Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO): For vehicle control treatments.

- Embryo Water.

Procedure:

- Treatment Groups: Dechorionate wild-type and

hoxba;hoxbbmutant embryos at an early stage (e.g., bud stage). Divide them into two groups: one treated with RA and another with DMSO (vehicle control) [4]. - Exposure: Incubate the embryos in the appropriate solution for a defined period.

- Analysis: After treatment, fix the embryos and perform WISH for

tbx5aas described in Protocol 2. In wild-type embryos, RA treatment is expected to induce or altertbx5aexpression. Thehoxba;hoxbbcluster mutants are expected to lose this competence, demonstrating that the Hox genes are essential for mediating the RA signal upstream oftbx5a[4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Hox Gene Function in Zebrafish

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted genome editing to create knockout mutants. | Generating hoxba;hoxbb double deletion mutants [4] [9]. |

| hoxba/hoxbb Deletion Mutants | Model organism to study functional redundancy of HoxB-derived clusters. | Analyzing the essential role of these clusters in fin positioning [4]. |

| DIG-labeled RNA Probes (e.g., tbx5a) | Detection of specific mRNA transcripts via in situ hybridization. | Visualizing the failure of fin bud induction in mutants [4] [6]. |

| Retinoic Acid (RA) | Signaling molecule that regulates Hox gene expression. | Testing the competence of the fin field to respond to key morphogenetic signals [4]. |

| Anti-DIG-AP Antibody | Immunological detection of hybridized RNA probes in WISH. | Colorimetric detection of gene expression patterns. |

| TALE Proteins (Pbx/Meis) | Key co-factors that form complexes with Hox proteins, enhancing DNA-binding specificity [10] [11]. | Studying the molecular mechanisms of Hox target gene selection. |

| NH2-UAMC1110 | NH2-UAMC1110, MF:C21H23F2N5O3, MW:431.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| GSK3494245 | GSK3494245, CAS:2080410-41-7, MF:C21H23FN6O2, MW:410.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This application note delineates the critical genetic pathway through which Hox signaling governs pectoral fin development in zebrafish, identifying the transcription factor tbx5a as a principal downstream effector. We consolidate recent genetic evidence demonstrating that specific Hox clusters are indispensable for the initiation, patterning, and outgrowth of pectoral fins, homologous to tetrapod forelimbs, via the direct regulation of tbx5a expression. The document provides a synthesized analysis of quantitative phenotypic data from cluster-deletion mutants, detailed protocols for key functional experiments, and visualizations of the core genetic circuitry, serving as a resource for researchers investigating Hox gene function, limb development, and evolutionary biology.

In vertebrate development, Hox genes encode an evolutionarily conserved family of transcription factors that provide positional information along the anterior-posterior body axis. A quintessential function of this positional information is to specify the locations where paired appendages, such as pectoral fins and forelimbs, will form. While the role of Hox genes (particularly HoxA and HoxD clusters) in patterning the proximal-distal axis of formed limbs is well-established, their function in the initial positioning and induction of appendage buds is an area of intense research. Recent work in zebrafish has elucidated a definitive genetic pathway, wherein Hox genes from the B cluster act upstream to directly induce the expression of tbx5a, a T-box transcription factor without which pectoral fin development cannot initiate.

Key Findings: Genetic Evidence Linking Hox Clusters to tbx5a and Fin Phenotypes

Genetic deletion studies of various zebrafish Hox clusters have revealed distinct and cooperative functions in pectoral fin development. The table below summarizes the quantitative data and phenotypic consequences associated with the loss of specific Hox clusters.

Table 1: Phenotypic Consequences of Hox Cluster Deletions in Zebrafish

| Hox Cluster(s) Deleted | Effect on tbx5a Expression | Pectoral Fin Phenotype in Larvae (3-5 dpf) | Key Adult Fin Phenotype (Micro-CT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| hoxba & hoxbb (HoxB-derived) | Complete loss of induction in fin field [12] | Complete absence of pectoral fins [12] | Not applicable (lethal) |

| hoxaa, hoxab, & hoxda (HoxA/D-derived) | Normal initiation; reduced shha in posterior fin bud [6] |

Severely shortened endoskeletal disc and fin-fold [6] | Defects in the posterior portion of the fin [6] |

| hoxab & hoxda (Double mutant) | Reduced shha expression [6] |

Shortened endoskeletal disc and fin-fold [6] | Data not specified |

| hoxab (Single mutant) | Data not specified | Shortening of the pectoral fin [6] | Data not specified |

The HoxB-tbx5a Axis in Fin Positioning

The most profound phenotype arises from the simultaneous deletion of the hoxba and hoxbb clusters. Double-homozygous mutants exhibit a complete absence of pectoral fins, tracing back to a failure to induce tbx5a expression in the lateral plate mesoderm, the source of fin precursor cells [12]. This establishes a linear pathway where HoxB-derived genes provide the positional cue for fin formation by activating tbx5a, a master regulator of forelimb/fin initiation. Further genetic mapping identified hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b as the pivotal genes within these clusters responsible for this inductive event [12].

The HoxA/D-tbx5a Axis in Fin Outgrowth

In contrast, deletion of clusters homologous to the tetrapod HoxA and HoxD clusters (hoxaa, hoxab, hoxda) does not prevent fin bud formation. The initial expression of tbx5a and fin bud establishment occurs normally [6]. However, subsequent development is impaired, leading to significantly shortened fins. This anomaly is linked to defective fin growth after bud formation, accompanied by marked down-regulation of sonic hedgehog a (shha) expression in the posterior fin bud, a key signaling center for limb patterning and outgrowth [6]. This demonstrates that these Hox clusters function downstream of or in parallel to the initial tbx5a-dependent induction to promote fin outgrowth.

Experimental Protocols

The following protocols are adapted from the key studies cited herein [6] [12].

Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Generation of Hox Cluster Deletion Mutants

This protocol describes the creation of heritable deletions of entire Hox clusters in zebrafish.

I. Research Reagent Solutions

- Reagent Setup:

- gRNA Synthesis Kit: e.g., GeneArt Precision gRNA Synthesis Kit.

- Cas9 Nuclease: Recombinant S. pyogenes Cas9 protein.

- Injection Buffer: 0.5x Tango buffer or 150 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5.

- Genomic DNA Lysis Buffer: 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.3% Tween-20, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 100 µg/mL Proteinase K.

II. Procedure

- gRNA Design: Design two single-guide RNAs (gRNAs) flanking the genomic region of the target Hox cluster. gRNAs should be checked for off-target potential.

- gRNA Synthesis: Synthesize gRNAs using a commercial kit following the manufacturer's instructions. Purify and resuspend in nuclease-free water.

- Injection Mix Preparation: Prepare a mixture containing 300 ng/µL of Cas9 protein and 30-50 pg of each gRNA in injection buffer. Centrifuge briefly to remove bubbles.

- Zebrafish Microinjection: Inject 1-2 nL of the mixture into the cell of one-cell stage wild-type zebrafish embryos.

- Founder Screening: Raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood. Outcross individual F0 fish to wild-types and screen their F1 progeny for the desired large deletion by PCR. Use primers that bind outside the gRNA target sites; a larger PCR product indicates a successful deletion.

- Mutant Line Establishment: Identify F0 founders carrying the deletion. Raise multiple F1 offspring from these founders and screen to identify heterozygous carriers. Intercross these heterozygotes to establish a stable mutant line.

Protocol: Functional Analysis of Pectoral Fin Development

This protocol outlines the methods for phenotyping Hox cluster mutant larvae.

I. Research Reagent Solutions

- Reagent Setup:

- Tricaine Stock: 400 mg/mL Tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222) in RO water, adjusted to pH 7.0. Use at 160 mg/mL in egg water for anesthesia.

- Fixative: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS.

- Alcian Blue Staining Solution: 0.1% Alcian Blue 8GX in 80% Ethanol / 20% Glacial Acetic Acid.

- In Situ Hybridization (ISH) Hybridization Buffer: 50% Formamide, 5x SSC, 500 µg/mL Yeast tRNA, 50 µg/mL Heparin, 0.1% Tween-20.

II. Procedure: Morphological and Molecular Analysis

- Larval Imaging (3 dpf):

- Anesthetize 3 days post-fertilization (dpf) larvae in tricaine solution.

- Mount larvae laterally in 3% methylcellulose on a microscope slide.

- Capture bright-field images of the pectoral fin under a dissecting microscope. Measure fin length using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

- Cartilage Staining (5 dpf):

- Fix larvae in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C.

- Wash with PBS and transfer to Alcian Blue staining solution for 4-6 hours with gentle agitation.

- Destain in several changes of 80% Ethanol/20% Glacial Acetic Acid.

- Re-hydrate through a graded ethanol series and clear in glycerol. Image the cartilaginous endoskeletal disc.

- Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH):

- Fix embryos/larvae at desired stages (e.g., 30 hpf for

tbx5a, 48 hpf forshha) in 4% PFA. - After rehydration, permeabilize embryos with Proteinase K.

- Pre-hybridize embryos in ISH hybridization buffer for 2-4 hours at 65-70°C.

- Replace with fresh hybridization buffer containing digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA antisense probe for your gene of interest (

tbx5a,shha). Hybridize overnight at the appropriate temperature. - Wash stringently and incubate with anti-DIG-AP antibody. Develop color reaction using NBT/BCIP.

- Image stained embryos and compare expression patterns between wild-type and mutant siblings.

- Fix embryos/larvae at desired stages (e.g., 30 hpf for

Signaling Pathways and Genetic Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core genetic pathway and experimental workflow.

Diagram Title: Hox Genetic Hierarchy in Zebrafish Fin Development

Diagram Title: Workflow for Generating Hox Cluster Mutants

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Hox-tbx5a Signaling

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Key Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Hox Cluster Deletion Mutants | Models for studying functional redundancy and specific roles of Hox clusters in fin development. | hoxba^(-/-);hoxbb^(-/-) mutants show no tbx5a expression or fin buds [12]. |

| tbx5a:GFP Reporter Line | Visualizing tbx5a expression dynamics in real-time during development and in adults. |

Used to map tbx5a expression to the trabecular myocardium and fin buds [13]. |

| tbx5a:mCherry-p2A-CreERT2; ubb:loxP-lacZ-STOP-loxP-GFP | Inducible genetic fate mapping of tbx5a-lineage cells. |

Traced embryonic tbx5a+ cells contributing to adult cardiac cortical layer [13]. |

| Alcian Blue Cartilage Stain | Visualizing the cartilaginous endoskeletal disc in larval pectoral fins for morphological analysis. | Revealed shortened endoskeletal discs in hoxaa;hoxab;hoxda triple mutants [6]. |

| shha & tbx5a RNA probes | Key molecular tools for Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH) to assess gene expression patterns. | Showed shha downregulation in fin buds of hoxaa;hoxab;hoxda mutants [6]. |

| SV5 | SV5, MF:C21H30N2O4S2, MW:438.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AZD 2066 hydrate | AZD 2066 hydrate, MF:C19H18ClN5O3, MW:399.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Methodologies for Analyzing Hox Gene Function in Zebrafish Models

CRISPR-Cas9 cluster deletion represents a transformative approach in functional genomics, enabling researchers to move beyond single-gene knockout studies to investigate the coordinated function of linked genes. This methodology is particularly valuable for studying gene families organized in clusters, such as the Hox genes, which encode evolutionarily conserved transcription factors that provide positional information along the anterior-posterior axis during embryonic development. In zebrafish, Hox genes are organized into seven clusters due to teleost-specific whole-genome duplication, offering a complex but informative system for understanding the genetic regulation of vertebrate development.

The application of cluster deletion techniques to Hox gene research has resolved long-standing questions in developmental biology. While evidence from various model organisms has supported a role for Hox genes in limb positioning, clear genetic evidence for substantial defects in limb positioning remained limited until the advent of comprehensive cluster deletion approaches. Recent studies employing CRISPR-Cas9 cluster deletion in zebrafish have provided definitive genetic evidence that Hox genes specify the positions of paired appendages, demonstrating the power of this methodology to address previously intractable biological questions.

Application Note: Hox Cluster Deletion in Zebrafish Pectoral Fin Development

A recent groundbreaking study employed CRISPR-Cas9-mediated cluster deletion to investigate the role of HoxB-derived genes in zebrafish pectoral fin development, revealing essential functions that had remained elusive in previous mammalian studies. Researchers generated seven distinct hox cluster-deficient mutants in zebrafish, discovering that double-deletion mutants of the hoxba and hoxbb clusters exhibited a complete absence of pectoral fins, accompanied by the absence of tbx5a expression in pectoral fin buds. This finding provided the first definitive genetic evidence that Hox genes specify the positions of paired appendages in vertebrates.

In these mutants, tbx5a expression in the pectoral fin field of the lateral plate mesoderm failed to be induced at an early stage, suggesting a loss of pectoral fin precursor cells. Furthermore, the competence to respond to retinoic acid was lost in hoxba;hoxbb cluster mutants, indicating that tbx5a expression could not be induced in the pectoral fin buds. The researchers further identified hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b as pivotal genes underlying this process, demonstrating that these genes within hoxba and hoxbb clusters cooperatively determine the positioning of zebrafish pectoral fins through the induction of tbx5a expression in the restricted pectoral fin field.

Table 1: Phenotypic Analysis of Zebrafish Hox Cluster Mutants

| Genotype | Pectoral Fin Phenotype | tbx5a Expression | Penetrance | Genetic Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Normal pectoral fins | Normal expression | 100% | Baseline reference |

| hoxba−/− | Morphological abnormalities | Reduced signal | 100% | Partial function loss |

| hoxbb−/− | Unreported | Unreported | Unreported | Potential redundancy |

| hoxba−/−;hoxbb+/− | Pectoral fins present | Not reported | 100% | Single allele sufficiency |

| hoxba+/−;hoxbb−/− | Pectoral fins present | Not reported | 100% | Single allele sufficiency |

| hoxba−/−;hoxbb−/− | Complete absence | Nearly undetectable | 100% (15/252 embryos) | Essential cooperative function |

Experimental Workflow and Logical Relationships

The experimental approach for Hox cluster deletion in zebrafish follows a systematic workflow that integrates target design, validation, phenotypic analysis, and mechanistic investigation. The diagram below illustrates the key steps and logical relationships in this process:

Experimental Workflow for Hox Cluster Analysis

Detailed Protocols

CRISPR-Cas9 Cluster Deletion Protocol

Principle: This protocol describes the systematic deletion of entire Hox gene clusters using the CRISPR-Cas9 system with multiple guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting flanking regions of the cluster. The method enables complete removal of gene clusters to study functional redundancy and cooperative gene action.

Materials and Reagents:

- Zebrafish strain of choice (e.g., AB wild-type strain)

- Cas9 protein or Cas9 mRNA

- Chemically synthesized sgRNAs targeting cluster boundaries

- Microinjection apparatus

- Embryo rearing equipment

- Genotyping reagents (PCR primers, electrophoresis equipment)

- qEva-CRISPR quantification reagents [14]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Target Selection and sgRNA Design:

- Identify conserved sequences flanking the target Hox cluster (e.g., hoxba or hoxbb cluster)

- Design 4-6 sgRNAs targeting each flanking region (total 8-12 sgRNAs per cluster deletion)

- Select targets with high on-target efficiency and minimal off-target potential using bioinformatic tools

- Synthesize sgRNAs using standard in vitro transcription protocols

CRISPR-Cas9 Complex Preparation:

- Prepare a mixture containing 300 ng/μL Cas9 protein and 25-50 ng/μL of each sgRNA

- Incubate at 37°C for 10 minutes to form ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes

- Add phenol red tracer (0.1%) for visualization during injection

Zebrafish Embryo Microinjection:

- Collect one-cell stage zebrafish embryos

- Inject 1-2 nL of RNP mixture into the cell cytoplasm

- Maintain injected embryos at 28.5°C in E3 embryo medium

- Assess survival rates at 24 hours post-fertilization (hpf)

Mutant Validation and Genotyping:

- At 24-48 hpf, extract genomic DNA from individual embryos

- Perform PCR amplification of the target region using flanking primers

- Analyze deletion efficiency by gel electrophoresis (large deletions visible as band shifts)

- Confirm precise deletion boundaries by Sanger sequencing of PCR products

- Utilize qEva-CRISPR for quantitative evaluation of editing efficiency [14]

Establishment of Stable Lines:

- Raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood

- Outcross F0 fish to wild-type partners

- Screen F1 offspring for germline transmission of cluster deletions

- Intercross heterozygous F1 fish to generate homozygous mutants

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low deletion efficiency: Optimize sgRNA combinations and concentrations

- High embryo mortality: Reduce injection volume or Cas9 concentration

- Mosaic founders: Increase screening of F1 offspring for germline transmission

- Complex rearrangements: Use additional sgRNAs to minimize incorrect repair

Phenotypic Analysis Protocol

Principle: This protocol describes the comprehensive phenotypic characterization of Hox cluster mutants, focusing on pectoral fin development and associated molecular markers.

Materials and Reagents:

- Fixed mutant and control embryos

- tbx5a riboprobe for in situ hybridization

- Retinoic acid solutions for rescue experiments

- Histology equipment (microtome, staining solutions)

- Confocal microscope for high-resolution imaging

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Morphological Assessment:

- Document pectoral fin development daily from 24-72 hpf

- Capture brightfield images of lateral views

- Measure fin bud size and position relative to anatomical landmarks

- Compare mutant phenotypes to wild-type and heterozygous siblings

Gene Expression Analysis by In Situ Hybridization:

- Fix embryos at critical stages (24, 30, 36, 48 hpf) in 4% PFA

- Generate digoxigenin-labeled tbx5a antisense riboprobe

- Perform whole-mount in situ hybridization following standard protocols

- Image and score expression patterns across genotypes

- Quantify expression levels by image intensity analysis

Retinoic Acid Competence Assay:

- Treat mutant and control embryos with retinoic acid (10-100 nM) from 10-24 hpf

- Assess tbx5a expression response at 30 hpf

- Evaluate pectoral fin development at 48-72 hpf

- Compare response amplitudes between genotypes

Molecular Pathway Analysis:

- Analyze expression of additional fin development markers (shh, fgf10)

- Perform immunofluorescence for protein localization

- Conduct RNA sequencing for comprehensive transcriptome analysis

Quality Control Measures:

- Include wild-type and heterozygous controls in all experiments

- Blind scoring of phenotypes to prevent bias

- Biological and technical replicates for statistical power

- Multiple independent mutant lines to confirm genotype-phenotype relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Cluster Deletion Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Components | Cas9 protein, sgRNAs, PX458 plasmid | Induction of double-strand breaks | Multiple sgRNAs (8-12) needed for large deletions |

| Detection & Validation | qEva-CRISPR assay, PCR primers, T7E1 | Quantitative evaluation of editing efficiency | qEva-CRISPR detects all mutation types including large deletions [14] |

| Phenotypic Analysis | tbx5a riboprobe, anti-Tbx5 antibody, retinoic acid | Molecular and functional characterization | tbx5a is key marker for pectoral fin development [4] [8] |

| Control Reagents | Standard control sgRNAs, wild-type embryos | Experimental normalization | Critical for establishing baseline phenotypes |

| Bioinformatics Tools | sgRNA design algorithms, off-target prediction | In silico experiment planning | Essential for minimizing off-target effects |

| PAWI-2 | PAWI-2, MF:C19H21N3O3S, MW:371.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| CHK-336 | CHK-336, CAS:2743436-86-2, MF:C24H20F2N4O4S2, MW:530.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathways and Genetic Interactions

The molecular pathway through which Hox genes regulate pectoral fin development involves a precise genetic hierarchy that positions fin formation along the anterior-posterior axis. The diagram below illustrates the key signaling pathway and genetic interactions identified through cluster deletion studies:

Genetic Pathway of Pectoral Fin Positioning

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The application of CRISPR-Cas9 cluster deletion to Hox gene research in zebrafish has fundamentally advanced our understanding of vertebrate limb development. The technology has enabled researchers to overcome the challenges of functional redundancy that have long complicated the study of gene families, providing clear genetic evidence for the essential role of HoxB-derived genes in pectoral fin positioning. This methodological approach demonstrates the power of moving beyond single-gene analyses to investigate gene families as functional units.

Future applications of cluster deletion technology could expand to investigate other aspects of Hox gene biology, including their roles in axial patterning, organogenesis, and evolutionary adaptations. The integration of cluster deletion with emerging technologies such as spatial transcriptomics—as demonstrated in recent studies of HOX gene expression in the developing human spine—offers promising avenues for multi-dimensional analysis of gene function [15]. Additionally, the combination of cluster deletion with single-cell sequencing technologies could provide unprecedented resolution in understanding cell-type-specific functions of gene families.

The principles and protocols established in zebrafish Hox cluster studies provide a framework that can be adapted to other model organisms and gene families, accelerating functional genomics research across biological systems. As CRISPR technology continues to evolve, refinements in precision editing, delivery methods, and phenotypic analysis will further enhance the power of cluster deletion approaches to resolve complex biological questions.

In vertebrate development, Hox genes are master regulators of positional identity along the anterior-posterior body axis. A key function of these genes is to determine the precise locations where paired appendages, such as the pectoral fins in fish or forelimbs in tetrapods, are established. While their role in patterning the proximal-distal axis of formed limbs is well-characterized, direct genetic evidence for their function in the initial anteroposterior positioning of appendages has been limited. Recent studies in zebrafish, which possess seven hox clusters due to teleost-specific whole-genome duplication, have broken new ground. This application note synthesizes the pivotal genetic evidence from phenotypic analyses of zebrafish hox cluster-deletion mutants, providing protocols and resources to advance research in this field.

Key Genetic Findings from hox Cluster Mutants

The generation of zebrafish mutants deficient for various combinations of hox clusters has revealed distinct and essential roles for the HoxB-derived and HoxA/HoxD-related clusters in pectoral fin development.

HoxB-Derived Clusters are Essential for Fin Bud Positioning

A landmark 2025 study demonstrated that the hoxba and hoxbb clusters, derived from the ancestral HoxB cluster, are indispensable for the initial specification of the pectoral fin field [7] [4] [8].

- Phenotype of Double Mutants: Zebrafish with double homozygous deletions for both the

hoxbaandhoxbbclusters exhibit a complete absence of pectoral fins [4] [8]. This phenotype is fully penetrant, with all double homozygous mutants (15/252, 5.9%, matching Mendelian expectation) lacking fins entirely [4]. - Molecular Mechanism: The finless phenotype results from a failure to induce expression of the critical limb initiation gene

tbx5ain the lateral plate mesoderm at 30 hours post-fertilization (hpf) [7] [4]. The competence to respond to retinoic acid, a key signal fortbx5ainduction, is also lost in these mutants [7]. - Key Genes: The genes

hoxb4a,hoxb5a, andhoxb5bwithin these clusters were identified as pivotal for this positioning function, though individual frameshift mutations did not fully recapitulate the cluster-deletion phenotype, suggesting cooperative action [7] [8].

HoxA- and HoxD-Related Clusters Regulate Fin Growth and Patterning

In contrast, mutants for the hoxaa, hoxab, and hoxda clusters (orthologous to tetrapod HoxA and HoxD) form fin buds but display severe defects in subsequent development [6].

- Phenotype of Triple Mutants: Larvae with the triple homozygous deletion (

hoxaa-/-;hoxab-/-;hoxda-/-) exhibit significantly shortened pectoral fins at 3 days post-fertilization (dpf) due to impaired growth after bud formation [6]. - Affected Structures: The cartilaginous endoskeletal disc and the non-cartilaginous fin-fold are both shortened. The

hoxabcluster was found to have the highest contribution to fin formation, followed byhoxdaand thenhoxaa[6]. - Molecular Mechanism: While

tbx5aexpression is normal, indicating proper bud initiation, the expression ofshha(sonic hedgehog a) in the posterior fin bud is markedly down-regulated. This explains the observed growth defects, as Shh signaling is critical for cell proliferation and patterning in the developing limb [6].

Table 1: Summary of Pectoral Fin Phenotypes in Zebrafish hox Cluster Mutants

| Genotype | Pectoral Fin Phenotype | Key Molecular Deficits | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

hoxba-/-;hoxbb-/- |

Complete absence [4] [8] | Loss of tbx5a induction; no response to retinoic acid [7] |

Anteroposterior positioning; fin field specification |

hoxaa-/-;hoxab-/-;hoxda-/- |

Severe shortening of endoskeletal disc and fin-fold [6] | Down-regulation of shha expression; normal tbx5a [6] |

Post-bud growth and patterning |

hoxab-/-;hoxda-/- |

Shortening of endoskeletal disc and fin-fold [6] | Down-regulation of shha expression [6] |

Post-bud growth and patterning |

hoxaa-/-;hoxab-/- |

Shortening of fin-fold only [6] | Not specified in results | Fin-fold outgrowth |

The following diagram illustrates the distinct roles of Hox clusters in zebrafish pectoral fin development, from initial specification to later growth and patterning.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Generating hox Cluster-Deletion Mutants via CRISPR-Cas9

This protocol is adapted from methods used in recent studies to create single and compound hox cluster mutants [7] [6] [4].

Principle: The CRISPR-Cas9 system is used to induce double-strand breaks at two or more genomic sites flanking a target hox cluster, resulting in a large deletion upon repair.

Materials:

- Wild-type zebrafish (e.g., TU or AB strains)

- CRISPR-Cas9 components:

- Guide RNAs (gRNAs): Design two gRNAs targeting sequences at the 5' and 3' boundaries of the cluster. Example: For the

hoxbacluster, design gRNAs with minimal off-target potential. - Cas9 protein or mRNA: High-purity, recombinant Cas9.

- Guide RNAs (gRNAs): Design two gRNAs targeting sequences at the 5' and 3' boundaries of the cluster. Example: For the

- Microinjection apparatus: Micropipette puller, microinjector, and fine needles.

- Genomic DNA Extraction Kit: For PCR genotyping.

- PCR Reagents: Primers designed to flank the deletion breakpoints and to amplify the internal region of the cluster for genotyping.

Procedure:

- gRNA Design and Synthesis:

- Identify target sites at the 5' and 3' ends of the desired hox cluster using genome databases (e.g., Ensembl).

- Synthesize gRNAs in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase or purchase from a commercial supplier.

- Zebrafish Embryo Injection:

- Prepare an injection mix containing 300 ng/μL of Cas9 protein and 50 ng/μL of each gRNA.

- Inject 1-2 nL of the mix into the cell of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Raise the injected embryos (F0 generation) to adulthood.

- Founder Identification and Outcrossing:

- Outcross the adult F0 fish to wild-type fish to screen for germline transmission.

- Collect fin clips from the F0 adults or screen their F1 progeny.

- Extract genomic DNA and perform PCR with a primer pair that spans the intended deletion. A successful deletion will yield a smaller PCR product than wild-type.

- Outcross identified founders to establish stable mutant lines.

- Generating Compound Mutants:

- Cross individual single-cluster mutant lines to generate double or triple heterozygous fish.

- Intercross these fish to obtain compound homozygous mutants. Note: The expected Mendelian ratio for double homozygous mutants is 1/16 [4].

Protocol: Phenotypic Analysis via Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH)

WISH is used to analyze the spatial expression patterns of key genes like tbx5a and shha in mutant embryos [6] [4].

Principle: Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled antisense RNA probes hybridize to target mRNAs in fixed embryos, and are detected via an enzyme-linked immunoassay that produces a colored precipitate.

Materials:

- Embryos: Wild-type and mutant zebrafish embryos at desired stages (e.g., 30 hpf for

tbx5a, 48 hpf forshha). - Fixative: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS.

- DIG-Labeled RNA Probe: Designed against the target gene (

tbx5a,shha). - Hybridization buffer, SSC buffers, Blocking reagent, Anti-DIG-AP Fab fragments, NBT/BCIP staining solution.

- Microscopy equipment for imaging stained embryos.

Procedure:

- Fixation: Fix embryos in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C. Dechorionate manually if necessary.

- Hybridization:

- Rehydrate fixed embryos through a methanol series into PBS-Tween (PBT).

- Pre-hybridize embryos in hybridization buffer for 2-4 hours at the hybridization temperature (e.g., 65-70°C).

- Replace buffer with fresh hybridization buffer containing the DIG-labeled probe and incubate overnight.

- Washing and Detection:

- Perform stringent washes with SSC buffers to remove unbound probe.

- Block non-specific binding sites with blocking reagent.

- Incubate with Anti-DIG-Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) antibody diluted in blocking solution for several hours or overnight at 4°C.

- Color Reaction:

- Wash embryos thoroughly to remove unbound antibody.

- Incubate in NBT/BCIP staining solution in the dark. Monitor the development of the purple-blue precipitate.

- Stop the reaction by washing with PBT.

- Analysis and Genotyping:

- Image the stained embryos using a stereomicroscope.

- For critical comparisons, post-fix stained embryos and perform PCR genotyping individually to correlate genotype with expression phenotype [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Zebrafish hox Cluster and Pectoral Fin Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Generation of cluster-deletion mutants [7] [6] | gRNAs targeting cluster boundaries; Cas9 protein/mRNA |

| Genotyping Primers | Identification of mutant alleles | Primer pairs flanking deletion sites; internal control primers |

| RNA Probes for WISH | Spatial analysis of gene expression | tbx5a: Fin bud specification [4]. shha: Fin bud growth/patterning [6] |

| Antibodies | Immunohistochemistry / Protein detection | Anti-Tbx5, Anti-Hox (specific paralogs) |

| Retinoic Acid | Signaling pathway studies [7] | Used to test competence of fin field to induction signals |

| Alcian Blue | Cartilage staining in larvae [6] | Visualizes endoskeletal disc morphology at 5 dpf |

| Micro-CT Scanner | High-resolution skeletal analysis of adult fins [6] | Reveals defects in posterior fin elements |

| BTX-A51 | BTX-A51, MF:C18H25ClN6, MW:360.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PK-10 | PK-10, MF:C35H36F3N5O, MW:599.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines the integrated workflow from mutant generation to phenotypic analysis, as described in the protocols.

In vertebrate developmental biology, understanding the molecular cues that instruct the formation of paired appendages remains a fundamental pursuit. The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a powerful model system for these investigations, owing to its external fertilization, optical clarity of embryos, and genetic tractability. Central to the process of pectoral fin development—the evolutionary precursor to tetrapod forelimbs—are the Hox genes and the key regulatory gene tbx5a. These genes provide positional information along the anterior-posterior axis and initiate the genetic programs necessary for appendage formation [4] [8]. This application note provides a detailed protocol for profiling the expression patterns of Hox genes and tbx5a using in situ hybridization, enabling researchers to visualize the critical genetic interactions that define the pectoral fin field. The methodologies outlined here have been refined through recent genetic studies that demonstrate the essential role of HoxB-derived clusters in positioning zebrafish pectoral fins through precise regulation of tbx5a expression [4] [8] [7].

Key Findings: Hox Genes and tbx5a in Zebrafish Pectoral Fin Development

Recent genetic evidence has reshaped our understanding of Hox gene function in appendage positioning. While earlier studies in tetrapod models highlighted the role of HoxA and HoxD clusters in limb patterning, new research in zebrafish reveals that HoxB-derived clusters are specifically required for the initial anteroposterior positioning of pectoral fins [4] [8]. The following table summarizes the core genetic relationships and phenotypes established by recent studies:

Table 1: Key Genetic Interactions in Zebrafish Pectoral Fin Development

| Gene/Cluster | Expression Domain | Functional Role | Phenotype in Mutants |

|---|---|---|---|

| hoxba & hoxbb clusters | Lateral plate mesoderm along anterior-posterior axis | Anteroposterior positioning of pectoral fin field | Complete absence of pectoral fins in double mutants [4] |

| hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b | Presumptive pectoral fin field | Determination of fin position via tbx5a induction | Absence of pectoral fins with low penetrance [4] [8] |

| tbx5a | Pectoral fin bud mesenchyme | Initiation of pectoral fin bud outgrowth | Complete absence of pectoral fins [4] [16] |

| hoxaa, hoxab, hoxda clusters | Developing pectoral fin bud | Patterning and growth of fin bud elements | Shortened pectoral fins with reduced shha expression [6] |

The functional relationships between these genetic components can be visualized as a pathway governing the initiation and positioning of the pectoral fin:

Figure 1: Genetic pathway of zebrafish pectoral fin development. HoxB-derived genes initiate fin positioning via tbx5a induction, while HoxA/D-related genes maintain subsequent patterning.

Experimental Protocols

In Situ Hybridization for Hox and tbx5a Expression Profiling

This protocol enables researchers to visualize the spatial and temporal expression patterns of Hox genes and tbx5a in zebrafish embryos, with specific adaptations based on recently published methodologies [4] [6].

Probe Synthesis

- Template Preparation: Clone specific fragments of target genes (hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b, tbx5a) into appropriate transcription vectors. For hox genes, focus on conserved homeodomain regions; for tbx5a, target the T-domain encoding regions [16].

- Digoxigenin-Labeled RNA Probe Synthesis:

- Linearize plasmid DNA (1 µg) with appropriate restriction enzymes.

- Perform in vitro transcription using T7, T3, or SP6 RNA polymerase with DIG RNA labeling mix.

- Precipitate probes with lithium chloride and ethanol, then resuspend in RNase-free water.

- Quantify probe concentration and quality by spectrophotometry and gel electrophoresis.

Embryo Collection and Fixation

- Collect zebrafish embryos at critical developmental stages (10-somite to 36 hpf) for pectoral fin field analysis.

- Fix embryos in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS overnight at 4°C.

- Dehydrate through methanol series (25%, 50%, 75%, 100%) and store at -20°C for long-term preservation.

Hybridization and Detection

- Rehydrate embryos through methanol series to PBS-Tween (PBT).

- Treat with proteinase K (10 µg/mL) for permeabilization (optimize concentration and duration based on embryo stage).

- Refix with 4% PFA and 0.2% glutaraldehyde for 20 minutes.

- Prehybridize in hybridization buffer for 2-4 hours at 65-70°C.

- Hybridize with DIG-labeled RNA probes (0.5-1.0 ng/µL) overnight at 65-70°C.

- Perform stringency washes with SSC solutions, gradually reducing salt concentration.

- Block with blocking solution (10% fetal bovine serum, 1% BSA in PBT) for 2-4 hours.

- Incubate with anti-DIG alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody (1:5000 dilution) overnight at 4°C.

- Develop color reaction using NBT/BCIP substrate in staining buffer until signal is visible (30 minutes to 48 hours).

- Stop reaction with PBT washes and post-fix with 4% PFA.

Table 2: Critical Developmental Time Points for Expression Analysis

| Developmental Stage | hoxba/hoxbb Expression | tbx5a Expression | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10-somite | Establishing anterior boundary | Not yet detectable | Initial positioning of fin field [4] |

| 24 hpf | Strong in lateral plate mesoderm | Initiation in fin field | Specification of fin precursor cells [4] |

| 30 hpf | Maintained in fin field | Robust in fin buds | Critical for fin bud outgrowth [4] [6] |

| 36-48 hpf | Refining expression domains | Maintaining fin bud growth | Subsequent patterning with shha expression [6] |

Genetic Validation Using Cluster Deletion Mutants

The following workflow illustrates the comprehensive genetic approach required to dissect the functional relationships between Hox clusters and tbx5a:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for validating Hox-tbx5a genetic interactions using cluster deletion mutants.

Generation of hox cluster mutants: Use CRISPR-Cas9 to create deletion mutants for hoxba and hoxbb clusters, as previously described [4] [8]. Design guide RNAs targeting flanking regions of each cluster to facilitate large deletions.

Genotype analysis:

- Extract genomic DNA from individual embryos.

- Perform PCR with primers spanning deletion junctions.

- Confirm deletion size by gel electrophoresis and sequencing.

Phenotypic assessment:

- Document pectoral fin morphology at 24, 48, and 72 hpf.

- Score embryos for complete fin absence, fin reduction, or positional shifts.

- Compare phenotypic penetrance across genotypic classes.

Functional response assays:

- Treat embryos with retinoic acid (RA) to assess competence to induce tbx5a expression.

- Utilize RA concentrations of 1-10 nM administered during early somite stages.

- Assess rescue of tbx5a expression in hoxba;hoxbb double mutants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hox and tbx5a Expression Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Tools | Guide RNAs targeting hox clusters | Generation of deletion mutants | Design pairs for 500bp-2kb deletions [4] |

| In Situ Probes | DIG-labeled hoxb4a, hoxb5a, hoxb5b, tbx5a RNA probes | Spatial localization of gene expression | Validate specificity with cluster mutants [4] |

| Antibodies | Anti-DIG-AP conjugate | Detection of hybridized probes | Optimize dilution (1:2000-1:5000) [6] |

| Visualization Substrates | NBT/BCIP | Colorimetric detection of gene expression | Develop in dark; monitor frequently [6] |

| Chemical Modulators | Retinoic acid | Test competence of fin field | Use 1-10 nM for rescue experiments [4] |

| Zebrafish Lines | hoxbaâ»/â»;hoxbbâ»/â» double mutants | Functional analysis of gene loss | Maintain as separate heterozygotes [4] [8] |

| BAY-390 | BAY-390, MF:C13H15F4NO, MW:277.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Discussion and Technical Considerations

The expression profiling protocols outlined here enable researchers to capture the dynamic regulatory relationships between Hox genes and tbx5a during pectoral fin development. Recent studies demonstrate that hoxba and hoxbb clusters are specifically required for the initial induction of tbx5a expression in the pectoral fin field, while HoxA- and HoxD-related clusters function predominantly in subsequent patterning phases [4] [6]. This temporal distinction is critical for experimental design and interpretation.

A key technical consideration is the stage-specific nature of these genetic interactions. Researchers should note that tbx5a expression is typically initiated around 24 hpf in wild-type embryos, but is completely absent in hoxba;hoxbb double mutants as early as the 10-somite stage [4]. This suggests that Hox gene function precedes visible tbx5a expression by several hours, highlighting the importance of analyzing early developmental time points.

The redundancy between hox clusters presents both challenges and opportunities for experimental design. While single hox cluster mutations may produce mild phenotypes, the combination of hoxba and hoxbb deletions results in complete fin loss [4]. Similarly, the analysis of hoxaa, hoxab, and hoxda triple mutants reveals their cooperative function in fin patterning through regulation of shha expression [6]. These genetic interactions necessitate comprehensive mutant analysis across multiple cluster combinations.

The retinoic acid response assay provides a functional test of the Hox-tbx5a pathway, as hoxba;hoxbb double mutants lose competence to respond to RA induction of tbx5a [4]. This assay serves as a valuable validation step when characterizing new genetic perturbations of this pathway.