Hox Genes as Master Regulators of Limb Musculoskeletal Patterning and Regeneration

This article synthesizes current research on Hox genes, evolutionarily conserved transcription factors that establish positional identity along the limb axes during embryonic development.

Hox Genes as Master Regulators of Limb Musculoskeletal Patterning and Regeneration

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on Hox genes, evolutionarily conserved transcription factors that establish positional identity along the limb axes during embryonic development. We explore their continued expression in adult mesenchymal stem cells and their critical role in regulating tissue integration, fracture repair, and regeneration. The content covers foundational mechanisms of Hox-driven patterning, methodological advances in studying Hox function, troubleshooting of Hox-related repair deficiencies, and comparative analyses of Hox codes across skeletal regions. For researchers and drug development professionals, this review highlights the therapeutic potential of modulating Hox pathways to enhance musculoskeletal regeneration and address healing complications.

The Hox Code: Establishing Positional Identity in Limb Development

Hox Gene Organization and Temporal-Spatial Collinearity in Limb Buds

The development of the vertebrate limb is a fundamental process in organogenesis, serving as a premier model for understanding how genetic information is translated into complex three-dimensional morphology. Central to this process are the Hox genes, a family of transcription factors that function as master regulators of positional identity along the anterior-posterior (AP) body axis. In the developing limb, Hox genes exhibit remarkable temporal-spatial collinearity—their order of activation in time and space directly reflects their physical organization within genomic clusters. This precise spatiotemporal expression pattern is essential for proper limb bud outgrowth, skeletal patterning, and musculoskeletal integration [1] [2]. The mechanistic basis of this collinear regulation involves dynamic changes in chromatin architecture and engagement with distinct enhancer landscapes, forming a sophisticated bimodal regulatory system that orchestrates the formation of proximal versus distal limb structures [3] [4] [5]. Understanding this system is crucial not only for fundamental developmental biology but also for interpreting the molecular etiology of congenital limb defects and evolutionary adaptations in limb morphology across species.

The Molecular Basis of Collinearity in Limb Development

Genomic Organization and Expression Dynamics

The Hox gene family in mammals comprises 39 genes organized into four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD) located on different chromosomes [1]. These genes are further classified into 13 paralogous groups based on sequence similarity and position within each cluster. The collinear principle manifests in limb development through several interrelated dimensions:

- Temporal collinearity: Hox genes are activated sequentially during development, with 3' genes transcribed earlier than 5' genes [2] [5]. In the limb bud, this temporal sequence corresponds to the proximal-to-distal outgrowth of the limb, with different paralog groups dominating distinct phases.

- Spatial collinearity: The spatial expression domains along the proximal-distal limb axis reflect gene order within the clusters, with 3' genes patterning proximal structures and 5' genes controlling distal elements [1] [2].

- Quantitative collinearity: During the late phase of limb development, the expression levels of 5' Hoxd genes follow a quantitative gradient, with Hoxd13 being most strongly expressed and Hoxd10 most weakly in the digit-forming region [3].

The vertebrate limb is patterned into three main segments along the proximal-distal axis: the stylopod (humerus/femur), zeugopod (radius/ulna or tibia/fibula), and autopod (hand/foot) [1] [4]. Different Hox paralog groups play dominant roles in patterning each segment, with functional studies revealing that loss of specific paralog groups leads to severe segment-specific patterning defects [1].

Table 1: Hox Paralog Groups and Their Roles in Limb Patterning

| Paralog Group | Chromosomal Location | Limb Segment | Loss-of-Function Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox9 | All clusters | Proximal limb/Initiation | Failure to initiate Shh expression, disrupted AP patterning [1] |

| Hox10 | HoxA, HoxC, HoxD | Stylopod | Severe stylopod mis-patterning [1] |

| Hox11 | HoxA, HoxC, HoxD | Zeugopod | Severe zeugopod mis-patterning [1] |

| Hox12/Hox13 | HoxA, HoxD | Autopod | Complete loss of autopod skeletal elements [1] |

The Bimodal Regulatory Switch Model

Research over the past decade has revealed that Hox gene regulation during limb development operates through a bimodal switch mechanism that transitions between two large regulatory landscapes [4] [2] [5]. This elegant system enables the same genomic locus to control the development of both proximal and distal limb structures through distinct regulatory modules:

Early Phase - Telomeric Domain (T-DOM) Control: During initial limb bud formation (embryonic day ~9.5-10.5 in mice), the early limb bud mesenchyme exhibits interactions between the HoxD cluster and enhancers located in the telomeric regulatory domain (T-DOM). This phase primarily drives expression of Hoxd1-Hoxd11 genes in the presumptive zeugopod (forearm/shank) and is essential for proximal limb patterning and outgrowth [4] [2].

Late Phase - Centromeric Domain (C-DOM) Control: As development proceeds (E10.5 onward), a regulatory switch occurs in the distal limb bud, whereby the HoxD cluster disengages from T-DOM and establishes new interactions with the centromeric regulatory domain (C-DOM). This late phase drives strong expression of 5' Hoxd genes (Hoxd10-Hoxd13) in the autopod (hand/foot) and is crucial for digit morphogenesis [3] [4].

The transition between these two regulatory states creates a region of low Hox gene expression between the zeugopod and autopod, which subsequently forms the wrist and ankle joints [4]. This bimodal system is largely conserved across tetrapods, though modifications in its implementation contribute to species-specific limb morphologies [4].

Chromatin Topology and 3D Genome Architecture

Dynamic Chromatin Organization

The bimodal regulatory switch described above is implemented through dynamic changes in the three-dimensional organization of chromatin at the Hox loci. Key advancements in understanding this process have come from chromosome conformation capture technologies, which have revealed that Hox gene regulation operates within the framework of topologically associating domains (TADs) [4] [5].

In the early limb bud, the HoxD cluster resides within a TAD that includes the T-DOM enhancers. During the transition to the late phase, the cluster physically repositions itself to interact with the C-DOM enhancers located within a separate TAD [4]. This structural reorganization is facilitated by the presence of a TAD boundary between these two regulatory landscapes, which ensures proper segregation of the early and late regulatory programs [4].

Studies comparing chromatin architecture between anterior and posterior limb bud regions have revealed striking differences in chromatin compaction and modification. In the posterior limb bud, where 5' Hoxd genes are strongly expressed, the HoxD locus shows:

- Loss of H3K27me3 repressive marks catalyzed by Polycomb repressive complexes [3]

- Chromatin decompaction over the HoxD genomic region [3]

- Spatial colocalization between the Global Control Region (GCR) enhancer and 5' HoxD genes, consistent with chromatin looping [3]

In contrast, the anterior limb bud maintains a compact, H3K27me3-marked chromatin state over HoxD with minimal enhancer-promoter interactions [3]. These findings demonstrate that anterior-posterior patterning in the limb is associated with differential implementation of higher-order chromatin architecture.

Table 2: Chromatin States in Anterior vs. Posterior Limb Bud

| Chromatin Feature | Anterior Limb Bud | Posterior Limb Bud |

|---|---|---|

| H3K27me3 Marks | High levels maintained [3] | Loss of repressive marks [3] |

| Chromatin Compaction | Compact state [3] | Decompacted [3] |

| GCR-5'HoxD Colocalization | Minimal interaction [3] | Strong spatial association [3] |

| Hoxd13 Expression | Low or absent [3] | High expression [3] |

| Polycomb Complexes | Active repression [3] | Reduced repression [3] |

Evolutionary Conservation and Variation

Comparative studies between mouse and chicken embryos reveal that the fundamental bimodal regulatory system is evolutionarily conserved, despite major differences in limb morphology between these species [4]. However, important modifications in its implementation have evolved:

- TAD boundary width: The genomic interval separating the T-DOM and C-DOM regulatory landscapes differs between mouse and chick, potentially affecting the precision of the regulatory switch [4].

- Enhancer activity: Specific enhancer elements within the T-DOM show differential activity between forelimbs and hindlimbs in chicken, correlated with morphological specialization of avian wings versus legs [4].

- Regulatory timing: In chicken hindlimb buds, the duration of T-DOM regulation is significantly shortened compared to forelimbs, accounting for reduced Hoxd gene expression and distinct hindlimb morphology [4].

These comparative analyses demonstrate that species-specific and limb-type-specific modifications of the conserved bimodal regulatory system contribute to the remarkable diversity of limb morphologies across tetrapods.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Techniques for Investigating Hox Regulation

Dissecting the complex regulation of Hox genes during limb development requires a multidisciplinary approach combining genetic, molecular, and genomic techniques. The following methodologies have been particularly instrumental in advancing our understanding of Hox collinearity in limb buds:

Gene Expression Analysis

- Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH): Enables spatial visualization of Hox gene expression patterns in developing limb buds [4]. Protocol: Limb buds are fixed, permeabilized, and hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes complementary to specific Hox transcripts. Signal is detected via alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibodies and colorimetric substrates.

- Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq): Provides high-resolution quantification of Hox expression at cellular resolution [6]. Protocol: Single-cell suspensions from microdissected limb buds are processed using droplet-based systems (e.g., 10X Genomics), followed by library preparation and sequencing. Bioinformatic analysis reconstructs Hox expression patterns across cell types and spatial regions.

Chromatin Architecture Analysis

- Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C/4C/Hi-C): Maps physical interactions between genomic loci [5]. Protocol: Limb bud tissue is crosslinked with formaldehyde, chromatin is digested with restriction enzymes, and ligated fragments are quantified by PCR or sequencing. Circular Chromosome Conformation Capture (4C) provides high-resolution interaction profiles for specific bait regions [5].

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): Identifies genomic regions associated with specific histone modifications or transcription factors [3]. Protocol: Chromatin is crosslinked, fragmented, and immunoprecipitated with antibodies against targets like H3K27me3 or Ring1B. Precipitated DNA is sequenced (ChIP-seq) or quantified by qPCR [3].

Functional Genetic Approaches

- Mouse genetic models: Systematic deletion of Hox paralog groups reveals requirements in specific limb segments [1]. Conditional knockout strategies using limb-specific cre drivers (e.g., Prx1-Cre) enable tissue-specific deletion while avoiding embryonic lethality.

- Dominant-negative constructs: Used in chick electroporation studies to dissect functions of specific Hox paralogs [7]. Protocol: Plasmids expressing truncated Hox proteins that dimerize with wild-type counterparts but lack DNA-binding capacity are electroporated into limb bud mesenchyme, effectively inhibiting endogenous Hox function [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Hox Collinearity

| Reagent/Tool | Category | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox Paralog Mutant Mice | Genetic model | Functional analysis | Targeted deletions of specific paralog groups; reveal segment-specific requirements [1] |

| Dominant-negative Hox Constructs | Molecular tool | Functional perturbation | Truncated Hox proteins that inhibit endogenous function; used in chick electroporation [7] |

| H3K27me3 Antibodies | Epigenetic reagent | Chromatin state analysis | Detect repressive Polycomb marks; used in ChIP experiments [3] |

| Hox-specific RNA Probes | Detection reagent | Spatial expression mapping | Digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNAs for whole-mount in situ hybridization [4] |

| T-DOM/C-DOM Reporter Mice | Regulatory sensor | Enhancer activity mapping | Transgenic lines with lacZ or GFP under control of specific regulatory domains [4] |

| Immortomouse Cell Lines | Cell culture model | Mechanistic studies | Conditionally immortalized limb bud mesenchymal cells; maintain anterior-posterior identity [3] |

| Ramiprilat-d5 | Ramiprilat-d5, MF:C21H28N2O5, MW:388.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| AM-8735 | AM-8735, MF:C27H31Cl2NO6S, MW:568.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Limb Positioning and Musculoskeletal Integration

Determining Limb Position Along the Axis

The positioning of limbs at specific locations along the anterior-posterior body axis represents one of the earliest patterning events in limb development. Recent research has elucidated that Hox genes establish the limb fields through a combinatorial code involving both permissive and instructive signals [7]:

- Permissive Hox code: Hox4 and Hox5 paralog groups create a permissive territory in the lateral plate mesoderm where forelimbs can form, spanning the neck region [7].

- Instructive Hox code: Within this permissive domain, Hox6 and Hox7 genes provide specific instructive signals that determine the precise anterior-posterior position of forelimb initiation [7].

This mechanism operates during gastrulation, establishing limb position long before visible limb buds emerge [8] [7]. The collinear activation of Hox genes during gastrulation thus not only patterns the main body axis but also prefigures the location where limbs will form [8].

Integration of Musculoskeletal Tissues

A remarkable aspect of Hox function in limb development is their role in coordinating the patterning of multiple tissue types—bone, muscle, and tendon—into a functional integrated musculoskeletal system [1]. Surprisingly, Hox genes are not expressed in differentiated cartilage or skeletal cells, but rather in the associated stromal connective tissues, where they regulate the patterning of all musculoskeletal components [1].

The developing limb musculoskeletal system derives from two distinct embryonic origins: the lateral plate mesoderm gives rise to skeletal and tendon precursors, while the somitic mesoderm provides muscle precursors that migrate into the limb bud [1]. Hox genes coordinate the integration of these tissues through their expression in the muscle connective tissue and stromal compartments, ensuring proper attachment sites and functional relationships between muscles and bones [1].

The study of Hox gene organization and temporal-spatial collinearity in limb buds has revealed fundamental principles of developmental biology, including how genomic architecture influences gene expression patterns, how evolutionary changes in regulatory mechanisms generate morphological diversity, and how complex three-dimensional structures are assembled through coordinated genetic programs. The bimodal regulatory switch model, with its dynamic chromatin topology and phase-specific enhancer engagement, provides a sophisticated framework for understanding how a limited set of genes can orchestrate the development of complex structures.

Future research directions will likely focus on elucidating the precise mechanisms that control the switching between regulatory domains, the role of non-coding RNAs in modulating Hox expression, and how disease-associated mutations in Hox regulatory elements disrupt normal limb development. Additionally, single-cell multi-omics approaches promise to reveal how Hox collinearity is implemented at unprecedented resolution, potentially uncovering new layers of regulation in this paradigmatic developmental system. As our understanding of Hox gene regulation deepens, so too does our capacity to interpret the genetic basis of congenital limb disorders and evolutionary adaptations in vertebrate limb morphology.

Combinatorial Hox Codes for Proximal-Distal Patterning of Limb Segments

The vertebrate limb serves as a paradigmatic model for understanding the intricate processes of embryonic patterning and organogenesis. A fundamental aspect of limb development is the specification of segments along the proximal-distal (PD) axis—the stylopod (upper limb), zeugopod (lower limb), and autopod (hand/foot). Combinatorial Hox codes, referring to the specific sets of Hox genes expressed in particular domains, are now established as the primary genetic mechanism governing this PD patterning [1] [9]. This review synthesizes current evidence detailing how non-overlapping paralogous groups of posterior HoxA and HoxD genes provide a molecular framework that instructs the identity of each limb segment. We further elaborate on the experimental paradigms, from paralogous gene knockouts in mice to emerging research in limb regeneration, that have decoded this Hox-dependent patterning system, with significant implications for musculoskeletal research and regenerative medicine.

The development of a functionally integrated limb musculoskeletal system requires the spatially and temporally coordinated patterning of bone, tendon, and muscle tissues into a cohesive unit [1]. A central question in developmental biology is how cells along the PD axis acquire positional identity to form structurally distinct segments. The Hox genes, a family of evolutionarily conserved transcription factors, provide a critical part of the answer.

In vertebrates, the 39 Hox genes are organized into four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD) on different chromosomes [1] [10]. A key feature of these genes is collinearity—their order on the chromosome correlates with both their temporal sequence of activation and their spatial domains of expression along the anterior-posterior axis of the body [10] [9]. In the limb, this principle is adapted to pattern the PD axis, with specific paralogous groups (genes of high sequence similarity across the four clusters) acting in a combinatorial fashion to define segment morphology [1] [9]. Unlike the axial skeleton, where Hox genes exhibit functional redundancy and overlapping expression, their roles in the limb are largely non-overlapping and segment-specific [1]. The resulting "Hox code" operates as a digital regulatory mechanism, where the combination of expressed Hox genes determines the morphological output of a given limb segment [9].

Decoding the Proximal-Distal Hox Code

Genetic loss-of-function studies in mice have been instrumental in delineating the specific roles of Hox paralogous groups in limb patterning. The table below summarizes the essential functions and phenotypic outcomes resulting from the loss of key Hox paralogs.

Table 1: Functional Roles of Hox Paralogous Groups in Limb Proximal-Distal Patterning

| Paralogous Group | Limb Segment Specified | Phenotype of Combined Mutant | Key Genetic Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox9 (Posterior) | Initiates Patterning & AP Axis | Failure to initiate Shh expression; loss of AP patterning [1]. | Acts upstream of Hand2 to inhibit Gli3, allowing Shh induction in the posterior limb bud [1]. |

| Hox10 | Stylopod (e.g., Humerus/Femur) | Severe mis-patterning of the stylopod [1]. | Loss-of-function mutations in mice result in a failure to form proper proximal skeletal elements [1]. |

| Hox11 | Zeugopod (e.g., Radius/Ulna) | Severe mis-patterning of the zeugopod [1]. | Mice lacking Hoxa11 and Hoxd11 show absence of the radius and ulna [1] [9]. |

| Hox13 | Autopod (e.g., Hand/Foot) | Complete loss of autopod skeletal elements [1]. | Mutants display a failure to form the bones of the hand and foot [1]. |

This genetic hierarchy reveals a fundamental logic: the sequential activation of 3' to 5' Hox genes along the chromosome corresponds to the specification of proximal to distal fates in the limb [10]. The absence of a paralogous group does not transform one segment into another (a homeotic transformation), as can occur in the axial skeleton, but rather leads to a complete failure to form the corresponding segment [1]. This indicates that each group provides unique, essential patterning information for its respective domain.

Signaling Networks and Transcriptional Regulation of Hox Codes

The establishment of the Hox code is not autonomous but is instead governed by a network of extrinsic signaling gradients. The nested domains of Hox expression arise from the integration of opposing signaling gradients, such as Retinoic Acid (RA) from the proximal trunk and Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGFs) from the distal Apical Ectodermal Ridge (AER) [10] [11].

- Retinoic Acid (RA): RA is a key morphogen that directly regulates Hox gene transcription. This occurs through Retinoic Acid Response Elements (RAREs) embedded within and flanking the Hox clusters [10]. RA signaling is critical for establishing proximal identity, in part by activating genes like Meis1 and Meis2 that specify the stylopod [11].

- FGF Signaling: FGFs (e.g., FGF4, FGF8) secreted by the AER maintain a distal zone of proliferative, undifferentiated cells. The interaction between WNT signaling from the ectoderm and AER-FGFs keeps distal cells in a progenitor state, allowing them to acquire more distal fates (zeugopod, autopod) as they leave this influence [11].

- Sonic Hedgehog (Shh): While primarily involved in anterior-posterior patterning, Shh signaling from the Zone of Polarizing Activity (ZPA) also interacts with the PD patterning system. For instance, posterior Hox9 genes promote Hand2 expression, which in turn inhibits the hedgehog pathway inhibitor Gli3, thereby permitting Shh expression [1].

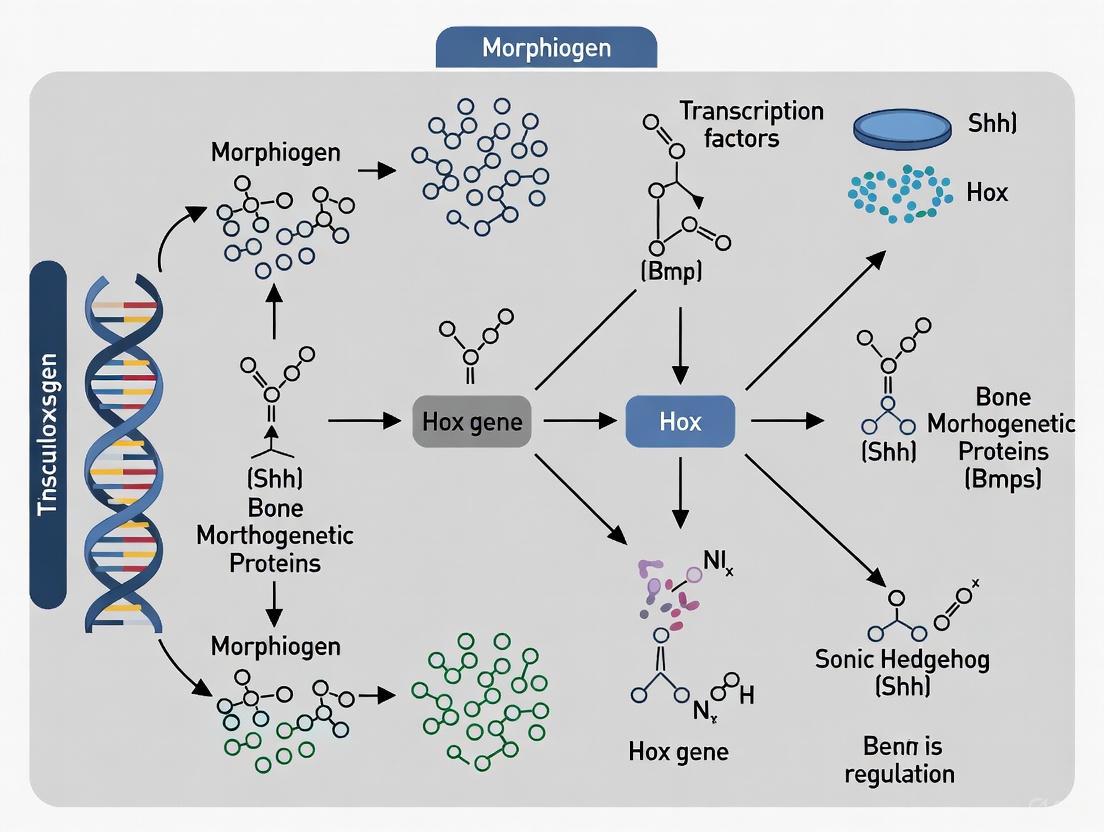

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling logic that regulates Hox gene expression and proximal-distal patterning in the early limb bud.

Figure 1: Signaling inputs that regulate Hox gene expression. Opposing gradients of Retinoic Acid (RA, proximal) and FGFs from the AER (distal) provide positional information that is integrated by Hox genes. Shh signaling from the ZPA also contributes to this regulatory network.

Experimental Paradigms: From Development to Regeneration

Paralogous Gene Knockout Studies in Mice

The definitive evidence for the Hox code model comes from studies where all genes within a paralogous group are inactivated in mice [1] [9].

- Protocol: The standard methodology involves generating mutant mouse lines where individual Hox genes (e.g., Hoxa11, Hoxd11) are knocked out using homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Due to functional redundancy, conclusive results often require the creation of compound mutants lacking multiple genes from the same paralogous group (e.g., Hoxa11-/-; Hoxd11-/-) [1] [9].

- Key Findings: As summarized in Table 1, these experiments revealed the segment-specific requirements for Hox function. For example, loss of Hoxa11 and Hoxd11 leads to a complete absence of the zeugopod (radius and ulna), demonstrating that Hox11 genes are indispensable for the formation of this segment [1].

Insights from Limb Regeneration Models

The axolotl (a salamander) provides a powerful model for studying positional memory, wherein cells retain information about their original location and use it to perfectly regenerate amputated limbs.

- Protocol: Researchers amputate the limb and use transgenic reporters (e.g., ZRS>TFP for Shh, Hand2:EGFP knock-in) to track the expression of key patterning genes during blastema formation and regeneration [12]. Functional studies involve pharmacological inhibition or genetic perturbation (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9) of candidate genes.

- Key Findings: Recent work has identified a positive-feedback loop between Hand2 and Shh that underlies posterior positional memory [12]. Hand2 expression, maintained in posterior connective tissue cells from development, primes them to activate Shh after amputation. During regeneration, Shh signaling, in turn, reinforces Hand2 expression. This loop ensures that posterior identity is preserved and reactivated during regeneration, highlighting the stability of Hox-regulated positional codes [12].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Hox Patterning

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|

| Paralogous Mutant Mice (e.g., Hoxa11-/-; Hoxd11-/-) | In vivo functional analysis of gene requirements. | Established the segment-specific essential roles of Hox paralogs in PD patterning [1] [9]. |

| Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs (e.g., DN-Hoxa4/5/6/7) | Suppresses specific Hox gene signaling in specific tissues (e.g., LPM). | Revealed that Hox4/5 provide permissive, and Hox6/7 provide instructive signals for forelimb positioning in chick embryos [7]. |

| Transgenic Reporter Axolotls (e.g., ZRS>TFP, Hand2:EGFP) | Fate-mapping and live imaging of cells expressing patterning genes. | Identified the Hand2-Shh feedback loop that maintains posterior positional memory during limb regeneration [12]. |

| RARE (Retinoic Acid Response Element) Reporter Assays | Identifies and characterizes RA-dependent enhancers within Hox clusters. | Demonstrated that Hox genes are direct transcriptional targets of retinoids, linking a morphogen gradient to Hox activation [10]. |

Implications for Musculoskeletal Integration and Future Research

The role of Hox genes extends beyond skeletal patterning to the integration of the entire musculoskeletal unit. Surprisingly, Hox genes are not expressed in differentiated cartilage or skeletal cells. Instead, they are highly expressed in the surrounding stromal connective tissues, as well as in tendons and muscle connective tissue [1]. This suggests a model whereby the Hox code established in the connective tissue stroma provides a positional framework that orchestrates the patterning and integration of all musculoskeletal tissues—muscle, tendon, and bone—within a given limb segment [1].

Future research directions include:

- Elucidating Epigenetic Control: Understanding how chromatin architecture and epigenetic modifications lock in the stable expression of Hox codes and positional memory [10] [12].

- Leveraging Regeneration Circuits: Exploring whether the positive-feedback loops identified in salamanders, like the Hand2-Shh circuit, can be harnessed to modify positional memory in mammalian systems for regenerative purposes [12].

- Translating Hox Codes: Investigating the dysregulation of Hox genes in musculoskeletal pathologies and cancers, given their crucial role in development and cell identity [13].

In conclusion, the combinatorial Hox code is a fundamental regulatory module that translates genomic information into the three-dimensional architecture of the vertebrate limb. Its study continues to provide profound insights into the principles of developmental biology, tissue integration, and the potential for regenerative medicine.

Hox-Driven Integration of Bone, Tendon, and Muscle Progenitors

Hox genes, an evolutionarily conserved family of transcription factors, are master regulators of positional identity along the anterior-posterior body axis during embryonic development. Recent research has fundamentally expanded their understood role from solely patterning the skeletal system to orchestrating the precise integration of all musculoskeletal tissues—bone, tendon, and muscle—into functional units within the limb. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence demonstrating that Hox genes provide a regional "zip code" within stromal connective tissue progenitors, directing the coordinated patterning and connectivity of the limb musculoskeletal system. Furthermore, we explore the continued requirement of Hox genes in adult skeletal stem cells for tissue homeostasis and repair, revealing novel therapeutic avenues for regenerative medicine aimed at musculoskeletal regeneration and fracture healing.

Hox Gene Organization and Expression

Hox genes are characterized by several defining features: they are organized in genomic clusters, exhibit spatial and temporal colinearity in their expression, and demonstrate significant functional redundancy among paralogous group members. In mammals, 39 Hox genes are arranged in four clusters (HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD) on separate chromosomes [1]. Genes within each cluster are further classified into 13 paralogous groups (1-13) based on sequence similarity and chromosomal position [1] [14]. During limb development, specific posterior Hox paralogous groups govern patterning along the proximodistal axis: Hox9 and Hox10 genes pattern the proximal stylopod (humerus/femur), Hox11 genes pattern the middle zeugopod (radius/ulna; tibia/fibula), and Hox13 genes pattern the distal autopod (hands/feet) [1] [14]. This segmental specificity is crucial for establishing the initial blueprint of the limb.

Musculoskeletal System Composition and Embryonic Origins

The vertebrate limb musculoskeletal system is a complex integrative structure composed of tissues from distinct embryonic origins that must develop in precise spatial and temporal coordination. The skeletal elements and tendons originate from the lateral plate mesoderm, while the muscle precursors are derived from the somites, migrating into the limb bud after its initial formation [1]. The integration of these diverse tissues into a cohesive functional unit—where specific muscles connect to appropriate tendons which in turn anchor to specific bone locations—represents a fundamental challenge in developmental biology. Emerging evidence indicates that Hox genes provide a central regulatory mechanism for this integration process.

Mechanisms of Hox-Driven Musculoskeletal Integration

Connective Tissue Stroma as a Central Organizer

A paradigm-shifting discovery in Hox biology revealed that these genes are not expressed in differentiated cartilage, bone, or muscle cells during limb development. Instead, Hox expression is restricted to the connective tissue fibroblasts of the perichondrium, tendons, and muscle connective tissue [15] [1]. Utilizing a Hoxa11eGFP knock-in allele, researchers demonstrated that Hox11 genes are specifically expressed in these stromal connective tissues throughout zeugopod development [15]. This expression pattern positions Hox genes within the tissue microenvironment that orchestrates interactions between the different musculoskeletal components, suggesting they provide positional information that guides tissue integration.

Table 1: Hox Gene Expression Domains in the Developing Limb

| Hox Paralogous Group | Limb Segment | Specific Expression Domains in Connective Tissues |

|---|---|---|

| Hox9/Hox10 | Stylopod (humerus/femur) | Perichondrium, muscle connective tissue, tendons |

| Hox11 | Zeugopod (radius/ulna, tibia/fibula) | Outer perichondrium, tendons, muscle connective tissue |

| Hox13 | Autopod (hands/feet) | Perichondrium, tendons, muscle connective tissue |

Autonomous Patterning Roles in Muscle and Tendon

Genetic evidence confirms that Hox genes play direct, autonomous roles in patterning non-skeletal musculoskeletal tissues. In Hox11 compound mutants, both tendon and muscle patterning are disrupted independently of skeletal defects [15]. Some mutant combinations exhibit normal skeletal patterning while displaying profound abnormalities in muscle and tendon organization, demonstrating that Hox function in connective tissue directly coordinates the patterning of all three tissue types [15]. This establishes that Hox genes are not merely regulators of skeletal morphology but are key factors ensuring the functional integration of the entire musculoskeletal system appropriate for each body position.

Figure 1: Hox genes are expressed in connective tissue fibroblasts where they coordinate the integration of muscle, tendon, and bone patterning into a functional musculoskeletal unit.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Hox genes encode transcription factors that regulate downstream target genes by binding to specific AT-rich DNA sequences, often in cooperation with cofactors such as PBC (Extradenticle/Exd) and MEIS (Homothorax/Hth) proteins [16] [17]. In the skeleton, Hox11 genes have been shown to regulate the Ihh (Indian hedgehog) pathway within the growth plate, which is essential for proper endochondral ossification [14]. The molecular pathways through which Hox genes coordinate tendon and muscle patterning are an active area of investigation, but likely involve the regulation of signaling molecules and extracellular matrix components that mediate tissue-tissue interactions.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Genetic Loss-of-Function Strategies

Due to the significant functional redundancy among Hox paralogs, elucidating their roles requires compound mutant analyses. For example, assessing Hox11 function in the forelimb zeugopod requires simultaneous mutation of both Hoxa11 and Hoxd11, as single mutants display minimal phenotypes [18] [14]. The following table summarizes key genetic tools employed in this research:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Hox Function in Musculoskeletal Integration

| Research Reagent | Type/Model | Key Utility and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Hoxa11eGFP | Knock-in allele | Reports Hoxa11 expression; allows tracking of Hox-expressing cells and their lineages |

| Hoxa11-CreERT2 | Inducible Cre line | Enables temporal-specific lineage tracing and gene deletion in Hox11-expressing cells |

| Hoxd11 conditional | Floxed allele (exon 2) | Permits temporal deletion of Hoxd11 function at any developmental stage |

| ROSACreERT2 | Inducible Cre driver | Allows tamoxifen-induced recombination in combination with floxed alleles |

| ROSA-LSL-tdTomato | Cre reporter line | Labels Cre-recombined cells with tdTomato for lineage tracing |

Lineage Tracing and Fate Mapping

The Hoxa11-CreERT2 allele enables inducible genetic labeling of Hox11-expressing cells and their progeny at specific timepoints. When combined with a reporter allele (e.g., ROSA-LSL-tdTomato), this system allows researchers to trace the fate of Hox11-expressing cells throughout development and into adulthood [18]. This approach has demonstrated that Hox11-expressing cells in the perichondrium give rise to all mesenchymal lineages in the zeugopod skeleton—osteoblasts, osteocytes, chondrocytes, and bone marrow adipocytes—and are maintained as self-renewing skeletal stem cells throughout life [18].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for lineage tracing of Hox11-expressing cells using the Hoxa11-CreERT2; ROSA-LSL-tdTomato system to define their contributions to musculoskeletal tissues.

Temporal Control of Gene Function

To distinguish embryonic patterning functions from later roles in tissue homeostasis, researchers have developed conditional alleles that enable temporal deletion of Hox gene function. The Hoxd11 conditional allele, in which exon 2 (encoding the DNA-binding homeodomain) is flanked by loxP sites, allows for Cre-mediated deletion at any developmental stage [18]. This approach has been instrumental in demonstrating that Hox11 genes continue to function in the adult skeleton, regulating osteolineage differentiation and bone matrix organization independently of their embryonic patterning roles [18].

Hox Genes in Adult Skeletal Homeostasis and Repair

Maintenance of Skeletal Stem Cell Populations

Hox expression continues from embryonic stages through postnatal and adult life, exclusively within a skeletal stem cell (SSC) population [18] [19]. These Hox-expressing SSCs are regionally restricted and continuously contribute to skeletal maintenance throughout life. In the adult zeugopod, Hox11-expressing cells are found in the periosteum, on endosteal bone surfaces, trabecular bone surfaces, and within the bone marrow stroma, maintaining their capacity for self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation [18]. This persistent regional Hox expression represents a maintenance of positional identity in adult stem cells.

Functional Requirements in Adult Bone

Conditional deletion of Hox11 function specifically in adult mice results in a progressive replacement of normal lamellar bone with a disorganized woven bone-like matrix [18]. This abnormal matrix lacks the characteristic lacuno-canalicular network of normal bone, and embedded osteocyte-like cells completely lack dendrites and do not express SOST/sclerostin [18]. Molecular analyses reveal that while osteoblast lineage commitment initiates normally with Runx2 expression in Hox11 mutants, the cells fail to mature properly, never progressing to osteopontin or osteocalcin expression [18]. This demonstrates that Hox genes continuously function in the adult skeleton to regulate proper osteolineage differentiation.

Role in Fracture Healing

Hox genes play critical roles in bone repair following injury. Periosteal stem and progenitor cells (PSPCs) that reside in the outer bone layer maintain Hox expression and are the primary contributors to bone regeneration [19] [20]. With aging, both Hox expression and fracture healing capacity decline. Remarkably, short-term local increases in Hoxa10 expression in the tibia of aging mice restored up to 32.5% of fracture repair capacity, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of modulating Hox pathways to enhance bone healing [19]. This suggests that Hox genes maintain PSPCs in a primitive, undifferentiated state ready to activate upon injury, and that enhancing Hox expression can reprogram more mature progenitor cells back to a more primitive, regenerative state.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The discovery that Hox genes continue to function in adult skeletal stem cells and regulate injury responses opens promising therapeutic avenues for regenerative medicine. Strategies aimed at modulating Hox expression or function could potentially enhance bone healing in aging or healing-compromised patients. The location-specific nature of Hox gene expression presents both a challenge and opportunity for developing targeted therapies that respect regional skeletal identity while promoting repair. Future research should focus on identifying small molecules or biologics that can temporarily modulate Hox expression in specific anatomical locations, and developing delivery systems that can target these modulators to precise skeletal sites requiring enhanced regeneration.

Hox genes function as master regulators of musculoskeletal integration, operating through connective tissue fibroblasts to coordinate the patterning of bone, tendon, and muscle into functional units during limb development. Beyond their embryonic roles, Hox genes continue to be expressed in regional skeletal stem cells throughout life, where they maintain stem cell populations and regulate tissue homeostasis and repair. The continued study of Hox gene function in musculoskeletal integration provides not only fundamental insights into developmental biology but also promising therapeutic approaches for regenerating complex musculoskeletal structures following injury or degenerative disease.

Stromal Connective Tissue as the Primary Site of Hox Patterning Activity

The classical view of Hox genes as master regulators of embryonic patterning has been fundamentally revised by recent research. While historically studied for their dramatic homeotic transformations in skeletal structures, a growing body of evidence now identifies stromal connective tissue as the primary site of Hox patterning activity within the developing limb musculoskeletal system. This whitepaper synthesizes current findings demonstrating that Hox genes are not expressed in differentiated cartilage or bone cells, but rather in the connective tissue fibroblasts of the perichondrium, tendons, and muscle connective tissue. Through their regional expression in these stromal compartments, Hox genes coordinate the integration of muscle, tendon, and bone into functional musculoskeletal units. This paradigm shift has profound implications for understanding congenital limb defects and developing regenerative medicine approaches.

Hox genes, a family of highly conserved homeodomain-containing transcription factors, have long been recognized as fundamental regulators of anterior-posterior patterning in bilaterian animals [1]. In the vertebrate limb, posterior Hox genes (paralogous groups 9-13) pattern the skeleton along the proximodistal axis, with different paralogous groups required for the development of specific limb segments: Hox10 for the stylopod (humerus/femur), Hox11 for the zeugopod (radius/ulna, tibia/fibula), and Hox13 for the autopod (hand/foot) [1]. Traditional loss-of-function studies revealed dramatic skeletal phenotypes, leading to the prevailing view that Hox genes primarily function in chondrogenesis and osteogenesis.

However, recent molecular and genetic lineage-tracing experiments have overturned this conventional wisdom. Surprisingly, Hox genes are not expressed in differentiated cartilage or bone cells [15]. Instead, they exhibit highly specific expression patterns in the stromal connective tissues surrounding skeletal elements, forming a sophisticated "Hox code" that specifies positional identity [21]. This whitpaper examines the evidence establishing stromal connective tissue as the primary site of Hox patterning activity and explores the mechanisms through which this stromal Hox code coordinates limb musculoskeletal assembly.

The Stromal Hox Code: Molecular and Anatomical Foundations

Spatial Organization of Hox Expression in Limb Stroma

Detailed analysis of Hox expression patterns using knock-in alleles has revealed a precise spatial organization within limb connective tissues. In the developing zeugopod, Hox11 genes are expressed in connective tissue fibroblasts of the outer perichondrium, tendons, and muscle connective tissue, but are absent from differentiated cartilage, bone, vascular, or muscle cells [15]. This expression pattern persists throughout all stages of limb development, suggesting an ongoing role in patterning beyond initial specification.

The stromal Hox code exhibits regional specificity that corresponds to anatomical boundaries. Examination of Hoxa11eGFP knock-in alleles demonstrates that Hox11 expression is restricted to the zeugopod region, creating a molecular boundary that defines this limb segment [15]. Similarly, different paralogous groups show compartmentalized expression: Hox10 in stylopod connective tissues and Hox13 in autopod connective tissues [1]. This spatially restricted expression in stromal compartments forms a combinatorial code that specifies positional identity along the proximodistal axis.

Embryonic Origin and Maintenance of the Stromal Hox Code

The positional identity encoded by Hox genes in stromal cells is established during early embryogenesis and maintained into adulthood. Lineage tracing data shows that Hox-positive mesenchymal stromal cells in the postnatal period originate from pre-existing embryonic progenitors rather than arising de novo from Hox-negative populations [21]. This maintenance of positional memory enables adult stromal cells to retain information about their embryonic origins and appropriate anatomical context.

Table 1: Hox Gene Expression Patterns in Limb Stromal Compartments

| Hox Paralogue Group | Limb Segment | Skeletal Elements | Stromal Compartments with Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox9-10 | Stylopod | Humerus/Femur | Muscle connective tissue, tendons, perichondrium |

| Hox11 | Zeugopod | Radius/Ulna, Tibia/Fibula | Muscle connective tissue, tendons, perichondrium |

| Hox12-13 | Autopod | Hand/Foot bones | Muscle connective tissue, tendons, perichondrium |

Epigenetic mechanisms play a crucial role in maintaining the stable Hox code in stromal cells. The established expression patterns are precisely and clonally maintained throughout development through repressive Polycomb and Trithorax group complexes that regulate histone methylation [22]. This epigenetic maintenance ensures the fidelity of positional information despite tissue turnover and regeneration.

Mechanisms of Stromal-Mediated Patterning

Autonomous Patterning of Stromal Compartments

The initial patterning of connective tissue compartments occurs autonomously, independent of other musculoskeletal tissues. Several lines of evidence support this conclusion:

- In muscle-less limb models, the early patterning of tendon and muscle connective tissue occurs normally, with proper expression of stromal Hox genes [1]

- Tendon primordia arise directly from lateral plate mesoderm and express Hox genes appropriate to their axial position [1]

- Muscle precursors from any somite level can form normal limb musculature when grafted into the limb field, indicating that patterning information resides in the limb stroma rather than in the muscle precursors themselves [1]

This autonomous patterning establishes a stromal template that subsequently guides the organization of other musculoskeletal components.

Tissue Integration Through Stromal Signaling

After initial autonomous patterning, the Hox-expressing stromal compartments coordinate the integration of muscle, tendon, and bone through complex signaling interactions. Loss-of-function experiments demonstrate that Hox genes in stromal tissue regulate the patterning of all musculoskeletal tissues within their expression domain.

Table 2: Phenotypic Consequences of Hox Gene Deletion in Mouse Models

| Gene Deletion | Skeletal Phenotype | Muscle Patterning Defects | Tendon Patterning Defects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox11 paralogues | Malformation of zeugopod elements; radius/ulna and tibia/fibula defects | Disrupted regional muscle patterning in zeugopod | Disrupted tendon patterning independent of skeletal defects |

| Hox10 paralogues | Severe stylopod mis-patterning | Not reported | Not reported |

| Hox13 paralogues | Complete loss of autopod skeletal elements | Not reported | Not reported |

In Hox11 mutants, the disruption of tendon and muscle patterning occurs even in genetic combinations that do not produce skeletal phenotypes, demonstrating that these patterning functions are independent of skeletal morphogenesis [15]. This indicates that Hox genes in stromal tissue directly regulate the integration of musculoskeletal tissues rather than indirectly through skeletal patterning.

The molecular mechanisms underlying this integration involve Hox-dependent regulation of signaling pathways that coordinate tissue assembly. For example, Hox genes in posterior limb stroma regulate Shh expression through control of Hand2, establishing a positive-feedback loop that maintains posterior identity [12]. Additionally, Hox genes modulate extracellular matrix composition and cell adhesion molecules that create distinct signaling environments [12].

Experimental Approaches and Key Findings

Genetic Fate Mapping of Stromal Lineages

Modern understanding of stromal Hox function has been revolutionized by genetic fate-mapping approaches. These techniques allow precise lineage tracing of Hox-expressing cells throughout development and regeneration:

Methodology:

- Generation of knock-in alleles with inducible Cre recombinase under control of Hox regulatory elements

- Crossing with fluorescent reporter strains (e.g., loxP-mCherry)

- Temporal control of lineage labeling through tamoxifen administration at specific developmental stages

- Analysis of labeled cell contributions to different tissue compartments during limb development and regeneration

Key Findings:

- Embryonic Hox-expressing cells contribute predominantly to posterior connective tissue compartments [12]

- During regeneration, most Shh-expressing cells arise from outside the embryonic Shh lineage, indicating activation of Hox signaling in new cell populations [12]

- Hox-expressing stromal cells retain positional memory and can reactivate developmental programs during regeneration [12]

Analysis of Hox Mutant Phenotypes

Detailed characterization of compound Hox mutants has revealed the essential role of stromal Hox expression in musculoskeletal integration:

Methodology:

- Generation of compound mutants targeting multiple paralogous group members to overcome functional redundancy

- Histological analysis of skeletal, muscle, and tendon patterning using tissue-specific markers

- Expression analysis of key patterning signals (Shh, Fgfs, BMPs) in mutant backgrounds

- Transplantation experiments to test cell autonomy of Hox function

Key Findings:

- Hox11 paralogue mutants show disrupted muscle and tendon patterning independent of skeletal defects [15]

- Connective tissue-specific deletion of Hox genes recapitulates musculoskeletal patterning defects observed in conventional knockouts

- Hox genes in stroma regulate the expression of signaling molecules that coordinate tissue assembly [1]

Technical Approaches and Research Reagents

The investigation of Hox function in stromal connective tissue requires specialized experimental approaches and reagents. The table below summarizes key methodologies and tools essential for this research domain.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Hox Function in Stromal Tissue

| Research Reagent | Specification/Example | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|

| Knock-in Alleles | Hoxa11eGFP; Hand2:EGFP | Labeling of Hox-expressing cells for lineage tracing and isolation |

| Inducible Cre Lines | Prrx1-CreERT2; Hox-CreERT2 | Temporal-spatial control of genetic recombination in stromal cells |

| Transgenic Reporters | ZRS>TFP (Shh reporter) | Visualization of signaling center activation |

| Compound Mutants | Hoxa11-/-;Hoxd11-/-;Hoxc11-/- | Overcoming functional redundancy to reveal Hox function |

| Isolation Methods | FACS sorting of GFP+ stromal cells | Purification of Hox-expressing populations for transcriptomic analysis |

Visualization of Signaling Networks

The regulatory networks controlled by Hox genes in stromal tissue can be visualized using the following DOT language representation:

Figure 1: Hox-Controlled Signaling Network in Limb Stroma. Hox genes in stromal tissue establish positional identity through regulation of key signaling pathways including Hand2-Shh and Fgf signaling, which together coordinate tissue patterning and musculoskeletal integration.

Experimental Workflow for Stromal Hox Analysis

The investigation of Hox function in stromal connective tissue follows a systematic experimental pipeline:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Stromal Hox Research. A cyclic research approach begins with expression analysis to identify Hox expression domains, followed by lineage tracing, functional manipulation, assessment of integration defects, and mechanistic studies of downstream pathways.

Implications for Regenerative Medicine and Therapeutics

The recognition of stromal connective tissue as the primary site of Hox patterning activity has significant implications for regenerative medicine approaches. The maintenance of positional memory in adult stromal cells provides a mechanistic basis for the limited regenerative capacity of many mammalian tissues and suggests potential strategies for enhancing regeneration.

Hox-positive mesenchymal stromal cells represent a unique regenerative reserve in postnatal tissues [21]. These cells retain location-specific information that enables them to coordinate appropriate tissue reconstruction after injury. In successful digit tip regeneration in mice, temporary reactivation of Hoxa13 and Hoxd13 expression accompanies regeneration, recapitulating their embryonic expression patterns [21]. Conversely, mismatched Hox expression between grafts and host tissue decreases graft survival, highlighting the importance of positional compatibility [21].

The therapeutic manipulation of Hox expression in stromal cells represents a promising avenue for improving regenerative outcomes. For example, exogenous delivery of Hoxd3 to wound beds in diabetic mice accelerated wound closure through increased fibroblast collagen production [21]. Similarly, modulation of the Hand2-Shh feedback loop in axolotl regeneration demonstrates the potential for reprogramming positional memory to enhance regenerative capacity [12].

The paradigm shift recognizing stromal connective tissue as the primary site of Hox patterning activity has fundamentally transformed our understanding of limb musculoskeletal development. Rather than acting directly on skeletal differentiation, Hox genes function within stromal compartments to establish positional identity and coordinate the integration of muscle, tendon, and bone into functional units. This stromal Hox code is established during early embryogenesis, maintained throughout life, and reactivated during regeneration.

Future research directions include elucidating the epigenetic mechanisms that maintain positional memory, identifying the downstream effectors that execute Hox-dependent patterning, and developing therapeutic approaches to modulate Hox expression for regenerative applications. The continued investigation of Hox function in stromal tissue will not only advance fundamental understanding of developmental patterning but also open new avenues for treating congenital limb defects and enhancing regenerative capacity.

The patterning of the anteroposterior (AP) axis in the developing limb is a precisely coordinated process fundamental to the correct formation of musculoskeletal structures. This whitepaper delineates the critical and distinct roles played by Hox5 and Hox9 paralogous groups in regulating Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signaling, the primary morphogen orchestrating this axis. While Hox9 genes are established as essential initiators of the Shh expression domain in the posterior limb bud, recent findings confirm that anterior Hox5 genes function as crucial repressors, restricting Shh to the posterior zone of polarizing activity (ZPA). Disruption of the intricate balance between these Hox codes leads to severe AP patterning defects, underscoring their collective importance in limb musculoskeletal development. This document provides a comprehensive technical overview of the molecular mechanisms, key experimental evidence, and essential research methodologies defining this regulatory network.

The vertebrate limb bud is patterned along three principal axes: proximodistal (PD), dorsoventral (DV), and anteroposterior (AP). The AP axis, running from the thumb (anterior) to the little finger (posterior), is specified by a signaling center located in the posterior mesenchyme known as the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) [23]. The ZPA secretes Sonic Hedgehog (Shh), which acts as a morphogen to determine the identity and pattern of the developing digits [24].

Hox genes, a family of evolutionarily conserved transcription factors, are master regulators of embryonic patterning. In the limb, members of the posterior HoxA and HoxD clusters (paralog groups 9-13) are well-known for their roles in PD patterning, where they govern the formation of specific limb segments in a non-overlapping manner: Hox9/Hox10 genes pattern the stylopod (e.g., humerus), Hox11 genes pattern the zeugopod (e.g., radius/ulna), and Hox12/Hox13 genes pattern the autopod (hand/foot) [1] [25]. Furthermore, these posterior Hox genes are collectively required for the activation and maintenance of Shh expression [26]. Beyond this well-established role, emerging research has unveiled critical functions for more anterior Hox genes, specifically Hox5 and Hox9 paralog groups, in the initial establishment and precise spatial restriction of the Shh expression domain, thereby governing the fundamental blueprint of the AP axis [26] [7].

Molecular Mechanisms of Hox5, Hox9, and Shh Interaction

The Initiator: Hox9 and Shh Activation

The Hox9 paralogous group (including Hoxa9, Hoxb9, Hoxc9, and Hoxd9) acts as a critical upstream regulator that sets the stage for Shh expression in the posterior limb bud.

- Regulation of Hand2: Hox9 genes control the onset of expression of the transcription factor Hand2 in the posterior forelimb compartment [26] [1].

- Inhibition of Gli3: Hand2, in turn, inhibits the expression of Gli3, a key repressor of the Shh pathway. In the posterior limb bud, repression of Gli3 is permissive for the initiation of Shh expression [1].

- Functional Consequence: Complete loss of all four Hox9 genes in mice results in a failure to initiate Shh expression. This leads to a severe limb phenotype characterized by the absence of posterior skeletal elements, mirroring the defects observed in Shh null mutants, where only a single, anterior digit forms [1].

The following diagram illustrates this sequential pathway of Shh activation by Hox9.

The Restrictor: Hox5 and Shh Repression

Contrary to the posterior-specific role of Hox9, the more anteriorly expressed Hox5 paralogous group (Hoxa5, Hoxb5, Hoxc5) plays a complementary and equally critical role in confining the Shh expression domain.

- Phenotype of Hox5 Loss-of-Function: Triple mutant mice lacking all six alleles of Hoxa5, Hoxb5, and Hoxc5 exhibit severe anterior forelimb defects, including a missing or transformed thumb (digit 1), a truncated radius, and preaxial polydactyly [26].

- Ectopic Shh Expression: These patterning defects are driven by a dramatic molecular change: the derepression and anterior expansion of Shh expression in the limb bud. This results in ectopic activation of the Shh pathway, as evidenced by anteriorized expression of downstream targets like Ptch1 and Gli1 [26].

- Genetic Redundancy: The limb phenotype is only apparent upon deletion of all three Hox5 genes, demonstrating a high degree of functional redundancy within this paralogous group [26].

- Interaction with Plzf: Mechanistically, Hox5 proteins were found to biochemically and genetically interact with the transcriptional regulator Promyelocytic Leukemia Zinc Finger (Plzf). This collaboration is essential for restricting Shh expression to the posterior ZPA. Mutations in Plzf in both humans and mice result in similar anterior limb defects, reinforcing the importance of this repressive complex [26].

The diagram below summarizes the repressive mechanism of Hox5 and its functional outcome.

Integrated Hox Code for AP Patterning

The concerted actions of Hox5 and Hox9 establish a precise domain of Shh signaling. This interaction is part of a broader "Hox code" that patterns the limb field. Recent research elucidates that this code involves both permissive and instructive signals [7]:

- Permissive Role of Hox4/5: Hox4 and Hox5 genes are expressed in a broad domain that establishes a permissive territory where forelimb development can occur.

- Instructive Role of Hox6/7: Within this permissive field, the expression of Hox6 and Hox7 genes provides an instructive signal that determines the precise anterior-posterior position of the forelimb bud, in part by regulating Tbx5 expression [7].

Table 1: Summary of Hox Gene Functions in Limb AP Patterning

| Hox Paralog Group | Primary Role in AP Patterning | Molecular Function | Phenotype of Loss-of-Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox5 | Anterior restrictor | Interacts with Plzf to repress Shh expression in the anterior limb bud. | Ectopic anterior Shh; loss/transformation of anterior structures (e.g., digit 1). |

| Hox9 | Posterior initiator | Activates posterior Hand2; inhibits Gli3 to permit Shh expression. | Failure to initiate Shh; loss of posterior skeletal elements. |

| Hox4/5 (combined) | Permissive signal | Demarcates territory permissive for forelimb formation. | Necessary but insufficient for forelimb formation [7]. |

| Hox6/7 | Instructive signal | Determines final forelimb position within permissive field. | Ectopic limb induction when misexpressed anteriorly [7]. |

Key Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

The models described above are supported by rigorous genetic and molecular experiments in model organisms, primarily mice and chicks.

Genetic Loss-of-Function Studies

The most compelling evidence for the roles of Hox5 and Hox9 comes from the analysis of compound mutant embryos.

Table 2: Key Genetic Mutant Models in Mice

| Genotype | Experimental Model | Key Phenotypic Outcomes | Molecular Readouts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox5 TKO (Hoxa5â»/â»; Hoxb5â»/â»; Hoxc5â»/â») | Mouse [26] | Severe anterior forelimb defects: missing/transformed digit 1, truncated radius, bifurcated digit 2. Hindlimb unaffected. | Ectopic and anteriorly expanded expression of Shh, Ptch1, Gli1, and Fgf4 in forelimb buds. |

| Hox9 QKO (Hoxa9â»/â»; Hoxb9â»/â»; Hoxc9â»/â»; Hoxd9â»/â») | Mouse [1] | Loss of posterior limb elements; single digit in each limb segment. | Failure to initiate Shh expression; loss of posterior Hand2 expression. |

| Plzf â»/â» | Mouse [26] | Anterior forelimb defects similar to Hox5 TKO. | Genetic interaction with Hox5 mutants; proposed part of Shh-repressing complex. |

Detailed Protocol: Generation and Analysis of Hox5 Triple Mutants [26]

- Animal Crosses: Generate compound heterozygous mice for Hoxa5, Hoxb5, and Hoxc5 null alleles through sequential breeding.

- Genotyping: Perform PCR-based genotyping on embryonic or tail clip DNA to identify embryos carrying mutations in all three Hox5 genes.

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Skeletal Staining: Fix E18.5 embryos, clear soft tissue with KOH, and stain bone with Alizarin Red and cartilage with Alcian Blue to visualize the skeletal phenotype.

- Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WMISH): Fix earlier stage embryos (e.g., E10.5-E11.5). Use digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes for genes of interest (e.g., Shh, Ptch1, Gli1, Gli3, Hand2). Develop color reaction to visualize spatial gene expression patterns.

- Biochemical Interaction Studies:

- Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP): Transfect cultured cells with expression vectors for Hox5 proteins and Plzf. Immunoprecipitate one protein with a specific antibody and probe the immunoprecipitate via Western blot for the other to test for physical interaction.

Gain-of-Function and Lineage Tracing Experiments

Experimental Model: Chicken embryo electroporation [7]. Objective: To test the sufficiency of Hox genes to reprogram limb position and confirm cell lineage contributions. Protocol:

- Construct Preparation: Clone full-length or dominant-negative (DN) forms of Hox genes (e.g., Hoxa4, a5, a6, a7) into expression vectors with a constitutive promoter and an EGFP reporter.

- Embryo Electroporation: Window fertile chick eggs at Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stage 12-14. Inject plasmid DNA into the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) and apply electrical pulses to drive DNA into the cells.

- Analysis:

- Lineage Tracing: The co-expressed EGFP marks transfected cells and their progeny, allowing their fate to be followed.

- Gene Expression Analysis: Harvest embryos 24-48 hours post-electroporation. Analyze changes in target gene expression (e.g., Tbx5, Shh) using WMISH or immunohistochemistry. Ectopic Tbx5 expression indicates reprogramming of the LPM to a limb fate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogues critical reagents used in the experiments cited herein, providing a resource for researchers aiming to investigate this pathway.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Hox-Shh Interactions in Limb Patterning

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox5 Triple Mutant Mice | Genetic Model | In vivo model to study functional redundancy and the role of Hox5 in Shh repression. | Defining the requirement for Hox5 in anterior limb patterning [26]. |

| Hox9 Quadruple Mutant Mice | Genetic Model | In vivo model to dissect the role of Hox9 in initiating the Shh expression domain. | Establishing Hox9 as an upstream regulator of Shh [1]. |

| Plzf Mutant Mice | Genetic Model | Model to study the interaction between Plzf and Hox genes in Shh restriction. | Genetic interaction studies with Hox5 mutants [26]. |

| Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs | Molecular Tool | Suppresses the function of specific Hox genes and their paralogs by sequestering co-factors. | Loss-of-function studies in chick electroporation models [7]. |

| Shh, Ptch1, Gli1 RNA Probes | Molecular Tool | Detect spatial mRNA expression of key pathway components via in situ hybridization. | Molecular phenotyping of mutant embryos [26]. |

| Anti-GFP Antibodies | Immunological Reagent | Visualize and trace electroporated or genetically labeled cells and their progeny. | Lineage tracing in chick embryo experiments [7]. |

| BI 653048 phosphate | BI 653048 phosphate, MF:C23H28F4N3O8PS, MW:613.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Buxbodine B | Buxbodine B, MF:C26H41NO2, MW:399.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The precise specification of the limb's AP axis is a paradigm of coordinated gene regulation during organogenesis. The antagonistic interplay between the posterior Hox9-Shh activation module and the anterior Hox5/Plzf-Shh repression module is fundamental to establishing a robust morphogen gradient. Disruption of this balance leads to congenital limb malformations, such as those seen in human syndromes associated with mutations in the SHH regulatory sequence (ZRS) or its interacting factors [26] [24]. A deeper understanding of this Hox-Shh network not only illuminates fundamental principles of developmental biology but also provides a mechanistic framework for interpreting the genetic basis of limb defects. Future research, leveraging single-cell omics and advanced CRISPR screening in model systems, will further decode the regulatory logic of this network and its downstream effectors in patterning the limb musculoskeletal system.

From Development to Repair: Techniques for Studying Hox Function

Genetic Fate Mapping and Lineage Tracing of Hox-Expressing Cells

The patterning of the limb musculoskeletal system is a complex process requiring the precise integration of bone, tendon, and muscle tissues into a functional unit. Hox genes, a family of highly conserved developmental regulators, play a critical role in establishing positional identity along the body axes and are fundamental to this integration process [1]. Within the limb, different Hox paralogous groups exhibit non-overlapping functions in patterning specific segments: Hox10 paralogs pattern the stylopod (humerus/femur), Hox11 the zeugopod (radius/ulna, tibia/fibula), and Hox13 the autopod (hand/foot bones) [1]. Unexpectedly, these genes are not expressed in differentiated skeletal cells but are highly expressed in the associated stromal connective tissues, as well as regionally in tendons and muscle connective tissue [1]. This technical guide details the methodologies for genetically tracing Hox-expressing cell lineages, providing a foundational toolkit for researchers investigating how these genes orchestrate musculoskeletal patterning.

Core Principles of Genetic Fate Mapping

Conceptual Foundation

Genetic fate mapping is a powerful approach that establishes hierarchical relationships between cells by permanently labeling progenitor cells and all their progeny [27]. When applied to Hox-expressing cells, this technique allows researchers to determine the developmental fate of cells based on their historical expression of specific Hox genes, answering fundamental questions about cellular origins, proliferation, and differentiation within the limb musculoskeletal system [27] [28].

The core principle involves two essential genetic components: (1) a tissue-specific driver that controls the expression of a recombinase (e.g., Cre) in Hox-expressing cells, and (2) a conditional reporter allele that undergoes permanent, heritable activation upon encountering this recombinase [27] [28]. This system capitalizes on the precise spatial control offered by Hox gene regulatory elements and the irreversible nature of the genetic recombination, creating a permanent lineage trace.

Hox-Specific Considerations

The genomic organization of Hox genes into four clusters (A-D) and their spatiotemporal collinearity present unique considerations for fate mapping [1] [6]. Different paralog groups confer positional identity along the anterior-posterior and proximodistal axes, necessitating careful selection of the specific Hox gene or combinatorial approach relevant to the musculoskeletal compartment under investigation. Furthermore, the dynamic expression of Hox genes during development requires temporal control strategies to pinpoint the specific developmental window of interest for lineage tracing [27].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Basic Genetic Tracing of Hox-Expressing Progeny

This protocol describes the foundational method for performing genetic fate mapping of Hox-expressing cells, as applied in studies of anterior Hox genes [28].

Key Reagents:

- Hox-IRES-Cre mice: Transgenic mice where Cre recombinase is expressed under the control of a specific Hox gene promoter/enhancer (e.g., Hoxb1 or Hoxa1-enhIII) [28].

- ROSA26R reporter mice: A conditional reporter strain containing a loxP-flanked STOP cassette preventing the expression of a reporter gene (e.g., LacZ) at the ubiquitously expressed ROSA26 locus [28].

Workflow:

- Mouse Crossing: Cross Hox-IRES-Cre mice with ROSA26R reporter mice to generate double-heterozygous embryos or adults for analysis [28].

- Tissue Collection: Collect embryos or dissected organs (e.g., the developing heart) at the desired developmental stage.

- Fixation: Fix tissues in paraformaldehyde.

- Detection of Lineage-Traced Cells: Perform X-gal staining on whole-mount embryos or dissected organs to detect β-galactosidase activity in cells derived from the original Hox-expressing progenitors [28].

- Analysis: Observe and document the distribution of X-gal-positive cells to determine the lineage contribution of the Hox-expressing population.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this core genetic strategy:

Protocol 2: Inducible Lineage Tracing for Temporal Control

For precise temporal control over the initiation of lineage tracing, which is crucial for dissecting dynamic Hox functions, an inducible system is required.

Key Reagents:

- Hox-CreERT2 mice: Transgenic mice expressing a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase (CreERT2) under the control of a Hox regulatory element.

- Inducible Reporter mice: Reporter mice with a loxP-flanked STOP cassette (e.g., R26R-Confetti for multicolor fate mapping) [27].

- Tamoxifen or 4-Hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT): The inducing agent that activates CreERT2.

Workflow:

- Mouse Crossing: Generate Hox-CreERT2; Reporter double-heterozygous mice.

- Induction: Administer tamoxifen or 4-OHT at the precise developmental timepoint via intraperitoneal injection to the pregnant dam or by direct embryo culture. The timing of induction is critical for fate mapping specific progenitor pools [12].

- Chase Period: Allow a defined period for development to proceed, enabling the labeled progenitor cells to proliferate and differentiate.

- Tissue Harvest and Analysis: Harvest tissues at the desired endpoint. Analyze using fluorescence microscopy (for fluorescent reporters), immunohistochemistry, or single-cell RNA sequencing to determine the fates of the initially labeled Hox-expressing cells [27] [29].

Advanced Workflow: Integrating Single-Cell Transcriptomics

Modern lineage tracing increasingly integrates with single-cell technologies to correlate lineage history with cellular states [27] [29] [6].

Key Reagents:

Workflow:

- Sparse Labeling: Induce low-dose tamoxifen in Hox-CreERT2; R26R-Confetti mice to achieve sparse labeling of Hox-expressing progenitors, facilitating clonal resolution [27].

- Tissue Dissociation: Harvest the limb or other tissue of interest and create a single-cell suspension.

- Single-Cell Sequencing: Perform single-cell RNA-seq, capturing both the transcriptome and the lineage barcode (e.g., the specific fluorescent protein or DNA barcode) for each cell.

- Computational Analysis: Use computational tools (e.g., Decipher, clone2vec) to reconstruct lineage relationships and correlate them with transcriptional cell states, identifying gene regulatory networks underlying fate decisions [30] [29].

Quantitative Data and Analysis

Hox Gene Expression in Musculoskeletal Tissues

The table below summarizes the expression patterns and functional roles of key Hox genes in the developing limb musculoskeletal system, based on loss-of-function studies and expression analyses [1] [17] [6].

Table 1: Hox Gene Functions in Limb Musculoskeletal Patterning

| Hox Paralog Group | Limb Segment | Expression Domain | Loss-of-Function Phenotype | Key Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hox5 | Forelimb (AP Axis) | Anterior limb bud mesenchyme | Ectopic anterior Shh expression; anterior patterning defects [1] | Represses Shh via interaction with Plzf [1] |

| Hox9 | Forelimb (AP Axis) | Posterior limb bud | Failure to initiate Shh expression; loss of AP patterning [1] | Promotes posterior Hand2; inhibits Gli3 [1] |

| Hox10 | Stylopod | Proximal limb connective tissues | Severe stylopod (e.g., humerus/femur) mis-patterning [1] | Non-overlapping with Hox11/13 [1] |

| Hox11 | Zeugopod | Medial limb connective tissues | Severe zeugopod (e.g., radius/ulna) mis-patterning [1] | Non-overlapping with Hox10/13 [1] |

| Hox13 | Autopod | Distal limb connective tissues | Complete loss of autopod (hand/foot) skeletal elements [1] | Non-overlapping with Hox10/11 [1] |

Analysis of Lineage Tracing Data

The quantitative analysis of lineage tracing data involves characterizing clone size, composition, and spatial distribution to infer progenitor behaviors such as potency, proliferation, and fate biases [29].

Table 2: Key Metrics for Quantitative Clonal Analysis

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Clonal Size | Number of cells per clone. | Indicates proliferative potential of the progenitor. |

| Clonal Composition | Diversity of cell types within a clone (e.g., chondrocytes, tenocytes). | Reveals the potency (multipotent vs. unipotent) of the progenitor. |

| Clone Dispersion | Spatial spread of a clone within a tissue. | Informs on cell migration patterns during development. |

| Fate Bias | Relative frequency of specific cell types among a clone's progeny. | Identifies influences of extrinsic signals or intrinsic biases on fate decisions [29]. |

Advanced computational methods like clone2vec can embed clones in a low-dimensional space based on their fate distributions, enabling the identification of continuous gradients of clonal variation and the gene regulatory networks that bias cell fate [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Hox Genetic Fate Mapping

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cre Drivers | Hoxb1-IRES-Cre, Hoxa1-enhIII-Cre, Hox-CreERT2 [28] | Provides spatial and/or temporal control of Cre recombinase activity for lineage labeling. |

| Reporter Mice | ROSA26-loxP-STOP-loxP-LacZ (R26R), R26R-Confetti, R26R-tdTomato [27] [28] | Conditional alleles that, upon Cre-mediated recombination, express a detectable marker in all progeny. |

| Inducing Agents | Tamoxifen, 4-Hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) | Activates the CreERT2 fusion protein for inducible, temporal control of lineage tracing. |

| Detection Reagents | X-gal (for LacZ), Antibodies (for GFP, tdTomato) | Used to visualize the lineage-traced cells and their spatial context in tissues. |

| Barcoding Systems | Confetti, CARLIN, TREX [27] [29] | Enables multiplexed lineage tracing by labeling individual progenitors with unique, heritable markers. |

| Phenothiazine-d8 | Phenothiazine-d8, MF:C12H9NS, MW:207.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Dodecanol-d1 | 1-Dodecanol-d1, MF:C12H26O, MW:187.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathways in Hox-Limb Patterning

Hox genes operate within complex signaling networks to pattern the limb. A key pathway involves the establishment of the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis, where Hox genes interact with critical morphogens like Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) [1] [12].

The following diagram summarizes the core genetic interactions in the posterior limb bud that are crucial for initiating and maintaining limb patterning, a system relevant to understanding the origin of cells traced in fate-mapping studies.

This positive-feedback loop between Hand2 and Shh is essential for establishing and maintaining posterior identity in the developing limb, a mechanism that appears to be conserved in limb regeneration contexts as well [12]. Genetic fate mapping of cells within this network can reveal their contribution to the forming musculoskeletal tissues.

CRISPR-Cas9 and Paralogous Group Knockout Strategies