ICE vs. CRISPR-STAT: A Comparative Analysis of Indel Detection Methods for CRISPR Genome Editing

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of two prominent indel detection methods, ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) and CRISPR-STAT (Somatic Tissue Activity Test).

ICE vs. CRISPR-STAT: A Comparative Analysis of Indel Detection Methods for CRISPR Genome Editing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of two prominent indel detection methods, ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) and CRISPR-STAT (Somatic Tissue Activity Test). Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, methodological workflows, and key applications of each technique. The content delves into optimization strategies and troubleshooting common challenges, supported by recent survey data on CRISPR experimental success rates. Finally, it offers a rigorous validation and comparative framework, evaluating critical performance metrics such as cost, throughput, sensitivity, and specificity to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate method for their specific experimental and clinical goals.

Understanding the Basics: Core Principles of ICE and CRISPR-STAT Indel Detection

The advent of CRISPR-Cas systems has revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development by enabling precise genome editing. This process relies on creating double-strand breaks in DNA at specific locations guided by RNA sequences. When the cell repairs these breaks, insertions or deletions of nucleotides—collectively known as indels—frequently occur, potentially disrupting gene function. Accurate detection and quantification of these indels is therefore a critical step in evaluating the success and efficiency of any CRISPR experiment, serving as a fundamental metric for assessing editing outcomes across basic research and clinical applications [1] [2].

As CRISPR technology has advanced from a laboratory tool to clinical application—including the first FDA-approved CRISPR-based medicine for sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia—the need for robust, accurate indel analysis has become increasingly important for both quality control and safety assessment [3]. The landscape of analysis methods has evolved significantly, ranging from simple electrophoresis-based techniques to sophisticated computational tools and single-cell sequencing approaches.

Comparative Analysis of Major Computational Tools

For most researchers, computational analysis of Sanger sequencing data represents the primary method for indel detection due to its balance of cost, accessibility, and information content. These tools use decomposition algorithms to compare sequencing trace data from edited samples against wild-type controls, estimating both the overall editing efficiency and the spectrum of specific indel sequences generated [1].

Performance Comparison of Leading Tools

A systematic comparison of four prominent web tools—TIDE, ICE, DECODR, and SeqScreener—using artificial sequencing templates with predetermined indels reveals both their capabilities and limitations [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Computational Indel Analysis Tools

| Tool | Accuracy with Simple Indels | Performance with Complex Edits | Key Strengths | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIDE | Acceptable accuracy [1] | Variable performance; struggles with complex indels and knock-ins [1] | User-friendly; provides statistical significance for identified indels [2] | Limited capability for detecting longer insertions; requires manual setting adjustments [2] |

| ICE (Synthego) | Acceptable accuracy [1] | Better detection of large insertions/deletions compared to TIDE [2] | High correlation with NGS (R² = 0.96); batch upload capability; knockout score [2] | Web-based interface with some feature limitations [4] |

| DECODR | Acceptable accuracy [1] | Most accurate for majority of samples, particularly with complex indels [1] | Superior indel sequence identification; effective with complex editing patterns [1] [4] | Web-based interface [4] |

| SeqScreener | Acceptable accuracy [1] | Variable performance with complex edits [1] | Part of integrated commercial platform [1] | Less documented in independent comparisons |

The comparative study demonstrated that all four tools could estimate indel frequency with reasonable accuracy when the indels were simple and contained only a few base changes. However, the estimated values became more variable among the tools when the sequencing templates contained more complex indels or knock-in sequences [1]. Among the tools evaluated, DECODR provided the most accurate estimations of indel frequencies for the majority of samples, a finding consistent across multiple studies [1] [4].

Critical Considerations for Tool Selection

The divergence in tool performance becomes particularly pronounced in complex biological contexts. Analysis of somatic CRISPR/Cas9 tumor models revealed high variability in the reported number, size, and frequency of indels across different software platforms [4]. This discrepancy is especially evident when samples contain larger indels, which are common in somatic, in vivo CRISPR/Cas9 tumor models [4].

These findings underscore the importance of:

- Context-specific platform selection based on the biological model and editing approach [4]

- Validation with complementary methods when analyzing complex editing outcomes

- Tool-specific awareness, as algorithms employ different regression models (non-negative regression for TIDE versus lasso regression for ICE) that impact indel quantification [4]

Experimental Protocols for Indel Detection

Standard Workflow for Computational Tool Analysis

The fundamental workflow for CRISPR indel analysis using computational tools follows a consistent pattern across most methodologies, beginning with sample preparation and culminating in computational decomposition.

The protocol involves several critical stages [1] [4]:

- Sample Preparation: Extract genomic DNA from edited cells or tissues, then perform PCR amplification of the target region flanking the CRISPR cut site using high-fidelity DNA polymerase.

- Sequencing: Submit PCR products for Sanger sequencing using either forward or reverse primers.

- Data Analysis: Upload the resulting sequencing chromatogram files (.ab1 or .scf formats) along with the wild-type control sequence and gRNA target sequence to the chosen analysis tool.

- Interpretation: Review the output, which typically includes overall editing efficiency, specific indel sequences with frequencies, and quality metrics.

Advanced Single-Cell Multi-Omic Approaches

While bulk sequencing methods provide population-level data, emerging single-cell technologies offer unprecedented resolution for characterizing editing outcomes. The CRAFTseq method represents a significant advancement by enabling quad-modal analysis at single-cell resolution [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Indel Detection Methodologies

| Method Type | Key Features | Resolution | Best Use Cases | Throughput | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools (TIDE, ICE, DECODR) | Analysis of Sanger sequencing traces; indel frequency and distribution [1] | Bulk population | Routine editing validation; gRNA screening [2] | Medium | Low |

| Capillary Electrophoresis | Fragment size analysis; precise indel sizing to 1bp resolution [6] | Bulk population | Polyploid species; large screening projects [6] | High | Medium |

| T7E1 / Cas9 RNP Assay | Mismatch cleavage; no sequencing information [2] [6] | Bulk population | Initial screening; low-budget validation [2] | High | Very Low |

| Single-Cell Multi-omic (CRAFTseq) | Parallel DNA, RNA, protein profiling; identifies genotype-phenotype links [5] | Single-cell | Complex biological systems; heterogeneous populations [5] | Low | High |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Comprehensive sequence data; detects all mutation types [2] | Bulk population (can be single-cell) | Gold standard validation; complex editing analysis [2] | Variable | High |

CRAFTseq enables researchers to [5]:

- Amplify and sequence genomic DNA from targeted loci in individual cells

- Profile whole transcriptome mRNA expression

- Measure cell-surface protein expression simultaneously

- Correlate specific editing outcomes with functional consequences in the same cell

This method is particularly valuable for identifying the functional consequences of non-coding variants and detecting subtle, cell-state-specific effects of genome editing that might be obscured in bulk populations [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Analysis

Successful indel detection requires specific reagents and materials at each stage of the experimental workflow. The following table outlines essential components for a typical CRISPR analysis pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Edit Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | PCR amplification of target region with minimal errors | Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase [4] |

| PCR Purification Kit | Cleanup of amplified products before sequencing | Monarch PCR and DNA Cleanup Kit [4] |

| Sanger Sequencing Services | Generation of sequencing trace files | Commercial providers (Genewiz, Eurofins) [4] |

| crRNA/tracrRNA | For Cas9 RNP assays to validate editing | Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA and tracrRNA [1] [7] |

| Cas9 Nuclease | For Cas9 RNP assays | Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease V3 [1] [7] |

| Capillary Electrophoresis System | Precise fragment size analysis for indel detection | Applied Biosystems systems [6] |

| Single-Cell Sequencing Platform | High-resolution multi-omic analysis | Tapestri platform for single-cell genotyping [8] |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of CRISPR analysis continues to evolve with several emerging technologies addressing current limitations:

Single-Cell Resolution Platforms: Technologies like Tapestri enable precise measurement of CRISPR genome editing outcomes at single-cell resolution, allowing researchers to characterize the genotype of triple-edited cells simultaneously at more than 100 loci, including editing zygosity and structural variations [8].

Multi-Omic Integration: Approaches like CRAFTseq represent the next frontier in CRISPR analysis, bridging DNA editing outcomes with functional transcriptomic and proteomic consequences in the same cell [5].

Optimized Screening for Challenging Systems: Protocol improvements continue to emerge for specific applications, such as cost-effective PCR-based screening in Chlamydomonas that detects both large insertions and small indels as small as one base pair [7].

As CRISPR applications expand into more complex biological systems and clinical applications, the demand for more accurate, comprehensive, and accessible indel detection methods will continue to drive innovation in this critical area of genome editing research.

The advent of CRISPR-based genome engineering has revolutionized functional genomics, but its success is entirely dependent on accurate, reliable validation of editing outcomes. The post-editing phase presents a significant bottleneck for researchers who must navigate a complex landscape of analysis methods, each with distinct trade-offs between cost, throughput, and informational depth. Within this context, Sanger sequencing has remained an accessible, cost-effective tool, but its traditional analysis limitations have constrained its utility for quantifying complex editing outcomes. The development of sophisticated computational tools like ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) has fundamentally altered this landscape by bridging the critical gap between low-cost Sanger sequencing and the rich, quantitative data previously only attainable through next-generation sequencing (NGS). This guide provides a comparative analysis of indel detection methods, focusing on how ICE transforms Sanger sequencing into a powerful tool for NGS-quality analysis, empowering researchers to make informed decisions in their CRISPR workflow.

Comparative Landscape of CRISPR Analysis Methods

Before delving into the specifics of ICE, it is essential to understand the broader ecosystem of CRISPR analysis techniques. Methods vary from simple, non-sequencing based assays to sophisticated high-throughput sequencing, each serving different needs based on required detail, throughput, and budget.

Overview of Key Methods:

T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay: This non-sequencing method detects the presence of indels by exploiting the ability of the T7E1 enzyme to cleave mismatched DNA in heteroduplex formations. Following PCR amplification, products are denatured and re-annealed. If edits are present, heteroduplexes form and are cleaved by T7E1, producing smaller fragments visible on an agarose gel. While fast and inexpensive, it is only semi-quantitative and provides no sequence-level information on the types of indels generated [2] [9].

Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE): An early computational tool that analyzes Sanger sequencing chromatograms from both edited and control samples. It decomposes the complex sequencing trace data to estimate the spectrum and frequency of indels. While a cost-effective alternative to NGS, TIDE has limitations, particularly in analyzing complex edits like large insertions or multiple simultaneous edits [2] [1].

Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE): A more advanced Sanger sequencing-based analysis tool developed by Synthego. ICE uses a sophisticated algorithm to compare Sanger sequencing data from edited samples against a control, providing a detailed breakdown of editing efficiency (ICE Score), indel spectrum, and specific metrics like Knockout Score. Its key advantage is delivering NGS-level analysis from Sanger data at a fraction of the cost [2] [10].

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): The gold standard for CRISPR analysis, NGS (often via targeted amplicon sequencing) provides the most comprehensive, sensitive, and quantitative data on editing outcomes. It can detect all indel types and their frequencies with high accuracy. However, it is the most expensive and time-consuming option, requiring significant bioinformatics expertise, making it less practical for small-scale or rapid screening projects [2] [11].

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR): This method uses differentially labeled fluorescent probes to quantitatively measure the frequency of specific edits. It is highly precise and is particularly useful for applications like discriminating between NHEJ and HDR products. However, it requires prior knowledge of the expected edit to design specific probes [9].

Table 1: High-Level Comparison of Primary CRISPR Analysis Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Outputs | Cost | Throughput | Informational Depth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7E1 Assay | Mismatch cleavage of heteroduplex DNA | Presence/Absence of editing; Semi-quantitative efficiency | Very Low | Low | Low (No sequence data) |

| TIDE | Decomposition of Sanger sequencing traces | Indel frequency, limited indel spectrum | Low | Medium | Medium |

| ICE | Advanced decomposition of Sanger traces | Editing efficiency (ICE Score), full indel spectrum, Knockout/Knock-in Scores | Low | Medium | High (NGS-quality) |

| ddPCR | Quantitative PCR with fluorescent probes | Precise frequency of a pre-defined edit | Medium | High | Low (Target-specific) |

| NGS (Amplicon) | Deep sequencing of target amplicons | Comprehensive indel spectrum and frequency with high sensitivity | High | High | Very High (Gold standard) |

Benchmarking ICE Against Alternative Methods: Performance and Experimental Data

Independent, comparative studies provide the most objective data for evaluating the real-world performance of ICE against other common techniques.

Quantitative Comparison of Accuracy and Sensitivity

A systematic 2024 study compared the performance of computational tools, including ICE, TIDE, and DECODR, using artificial sequencing templates with predetermined indels [1]. The findings revealed that while all tools could estimate indel frequency with reasonable accuracy for simple indels, their performance varied with complexity.

Key Experimental Findings:

- For samples with a few base changes and mid-range indel frequencies, all tools performed acceptably.

- The estimated values became more variable among the tools when the sequencing templates contained more complex indels.

- DECODR was noted as providing the most accurate estimations for the majority of samples, though ICE remained highly competitive.

- All tools accurately estimated net indel sizes, but their capability to deconvolute exact indel sequences exhibited variability, with DECODR having an edge for identifying specific sequences.

Another comprehensive benchmarking study in plants, which used targeted amplicon sequencing (AmpSeq) as the gold standard, evaluated T7E1, ICE, TIDE, and other methods across 20 sgRNA targets [11]. The results demonstrated that methods like PCR-capillary electrophoresis and ddPCR were highly accurate when benchmarked against AmpSeq. The study also highlighted that the base-calling software used for Sanger sequencing could affect the sensitivity of tools like ICE and TIDE for detecting low-frequency edits.

ICE vs. NGS: A Direct Correlation

Synthego's internal validation, as presented in their guide, demonstrates that ICE analysis results are highly comparable to NGS, with a reported correlation of R² = 0.96 [2]. This high degree of accuracy means researchers can achieve a level of analysis approaching that of NGS without the associated cost and complexity. The ICE score, which represents the overall indel frequency, provides a reliable metric for editing efficiency that is validated by this NGS correlation.

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Benchmarking Results from Independent Studies

| Comparison | Experimental Setup | Key Finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICE vs. TIDE vs. DECODR | Artificial sequencing templates with predefined indels of varying complexity. | All tools were accurate for simple indels; variability increased with complexity. DECODR was most accurate for frequency, but all estimated size well. | [1] |

| Multiple Methods vs. AmpSeq | 20 sgRNA targets in N. benthamiana; benchmarked against AmpSeq. | PCR-CE/IDAA and ddPCR were most accurate vs. AmpSeq. Sanger tool sensitivity can be affected by base-caller software. | [11] |

| ICE vs. NGS | Internal comparison of ICE analysis to NGS data. | ICE results were highly comparable to NGS (R² = 0.96). | [2] |

| T7E1 Limitations | General assessment and comparison of methods. | T7E1 is semi-quantitative and provides no sequence-level data; signals can be influenced by indel complexity. | [2] [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Benchmarking Studies

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of the data's foundation, here are the detailed methodologies from two critical comparative studies.

Protocol: Systematic Comparison of Computational Tools (2024)

This study [1] was designed to quantitatively assess the performance of ICE, TIDE, DECODR, and SeqScreener.

- Sample Generation: CRISPR-Cas9 or Cas12a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes were microinjected into zebrafish embryos at the 1-cell stage.

- DNA Extraction and Cloning: Embryos were lysed, and genomic regions encompassing the target sites were PCR-amplified. The resulting PCR products were cloned into a pUC19 vector.

- Creation of Artificial Templates: Sanger sequencing of individual clones identified specific indel sequences. These predefined indels were then mixed in various ratios to create artificial sequencing templates with known indel frequencies and complexities.

- Data Analysis: Sanger sequencing chromatograms (.ab1 files) of these mixed templates were generated and uploaded to the respective web tools (ICE, TIDE, DECODR, SeqScreener) for analysis using each tool's default parameters.

- Data Comparison: The indel frequencies and spectra reported by each tool were compared against the known, pre-determined values in the artificial templates to assess accuracy.

Protocol: Benchmarking in Plant Genome Editing (2025)

This study [11] evaluated eight different quantification methods, including ICE and TIDE, against the gold standard of AmpSeq.

- sgRNA Design and Selection: 20 sgRNA targets across six endogenous genes in Nicotiana benthamiana were selected using CRISPOR, aiming for a range of predicted editing efficiencies.

- Transient Expression: A dual geminiviral replicon (GVR) system was used for the transient co-expression of SpCas9 and individual sgRNAs in N. benthamiana leaves via agroinfiltration.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA was extracted from the infiltrated leaf tissue seven days post-infiltration.

- Multi-Method Analysis: The same DNA samples were analyzed using:

- T7E1: PCR products were purified, treated with T7 Endonuclease I, and run on a gel. The ratio of cleaved to uncleaved bands was analyzed.

- Sanger Sequencing: PCR products were sequenced. The resulting chromatograms were analyzed by the ICE and TIDE web tools.

- AmpSeq (Benchmark): PCR amplicons were prepared for high-throughput sequencing on an Illumina platform to determine the "true" editing efficiency and spectrum.

- Benchmarking: The editing efficiencies and outcomes calculated by T7E1, ICE, and TIDE were directly compared to the AmpSeq results to evaluate their accuracy, sensitivity, and limitations in a plant system.

The ICE Analysis Workflow: From Sanger Sequencing to Comprehensive Report

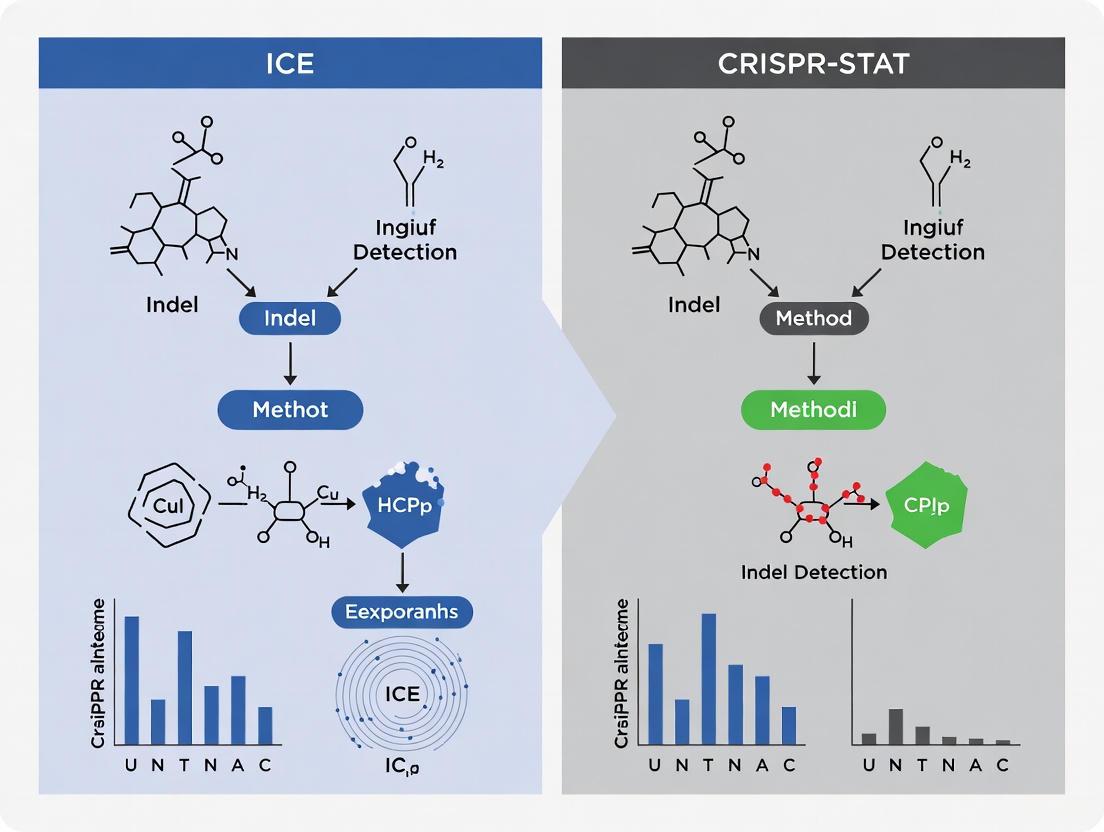

The power of ICE lies in its streamlined workflow that converts standard Sanger sequencing data into a rich, quantitative report. The following diagram illustrates this process and its position within the broader context of CRISPR analysis methodologies.

The ICE analysis process involves a clear, step-by-step protocol that researchers can follow to generate these comprehensive reports [10]:

Sample Preparation & Sequencing:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Extract gDNA from edited cells and a wild-type control.

- PCR Amplification: Design and use primers to amplify the genomic region surrounding the CRISPR target site.

- Sanger Sequencing: Purify the PCR product and submit it for Sanger sequencing, ensuring high-quality chromatograms (.ab1 files).

Data Upload to ICE Platform:

- Upload the control and edited sample Sanger sequencing files.

- Input the gRNA target sequence (excluding the PAM sequence).

- Select the nuclease used (e.g., SpCas9, Cas12a).

- For knock-in analysis, also provide the donor DNA sequence (up to 300 bp).

Automated Analysis and Output: The ICE algorithm performs a sequence alignment and decomposition, generating a report with several key metrics:

- Indel Percentage (ICE Score): The overall editing efficiency, representing the percentage of sequences with any indel.

- Knockout Score: The proportion of edits that are likely to cause a functional knockout (frameshifts or large 21+ bp indels).

- Knock-in Score: The proportion of sequences with the desired knock-in edit.

- Model Fit (R²): Indicates the confidence in the ICE score based on how well the data fits the computational model.

- Indel Spectrum: A detailed visualization and list of all detected indel sequences and their relative abundances.

Successful CRISPR analysis with ICE or any other method relies on a foundation of high-quality molecular biology reagents and resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Analysis

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Workflow | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix | Amplifies the target genomic locus from extracted DNA with minimal errors. | Critical for generating clean, accurate Sanger sequencing traces and NGS amplicons. Use proofreading enzymes. |

| Gel & PCR Clean-Up Kit | Purifies PCR products before sequencing or enzymatic assays. | Removes primers, enzymes, and salts that can interfere with downstream steps. |

| Sanger Sequencing Service | Generates the sequencing chromatograms (.ab1 files) for analysis. | Ensure the service provides high-quality trace files, as base-caller software can impact analysis sensitivity [11]. |

| ICE Web Tool (Synthego) | The computational platform for analyzing Sanger data. | Free, user-friendly online tool. Compatible with batch analysis and multiple nucleases. |

| TIDE Web Tool | An alternative computational platform for Sanger data analysis. | Useful for comparison; has limitations with complex edits compared to ICE [2]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I | Mismatch-specific nuclease for the T7E1 cleavage assay. | A fast, low-cost option for initial confirmation where sequence data is not needed. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Prepares PCR amplicons for high-throughput sequencing. | Required for gold-standard AmpSeq; choose kits optimized for targeted amplicon sequencing. |

The choice of a CRISPR analysis method is not one-size-fits-all but should be guided by the specific goals and constraints of the research project.

When to choose ICE: ICE is the recommended solution for the majority of routine CRISPR knockout and knock-in validation experiments where a balance of cost, speed, and informational depth is required. It is particularly advantageous when:

- Your budget does not allow for NGS.

- You require sequence-level detail and quantitative efficiency metrics beyond what T7E1 offers.

- You need to analyze edits from multiple gRNAs or non-SpCas9 nucleases.

- Your experimental workflow benefits from a rapid turnaround time.

When other methods are preferable:

- NGS: Choose NGS when you require the absolute highest sensitivity and comprehensiveness, such as for detecting very low-frequency edits, characterizing highly complex heterogeneous populations, or for definitive validation in a therapeutic context [2] [11].

- T7E1: This method remains a viable, ultra-low-cost option for the initial stages of gRNA screening or when you only need a binary "yes/no" answer about the presence of editing [2].

- ddPCR: This is the ideal tool for longitudinal studies or when you need to track the frequency of a single, specific known edit with extreme precision over many samples [9].

In conclusion, ICE has firmly established itself as a transformative tool in the CRISPR workflow. By effectively bridging the gap between the accessibility of Sanger sequencing and the analytical power of NGS, it empowers a broader range of researchers to perform robust, quantitative validation of their genome editing experiments, thereby accelerating the pace of discovery in functional genomics and drug development.

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 as a versatile genome-engineering tool has revolutionized biological research, enabling targeted mutagenesis across diverse model systems. This technology relies on a single guide RNA (sgRNA) to direct the Cas9 enzyme to specific genomic loci, where it induces double-strand breaks. However, a significant challenge persists: not all sgRNAs exhibit equivalent activity at their target sites. Pre-screening sgRNAs for efficacy is crucial for successful mutagenesis and for minimizing wasted resources on poorly performing targets [12] [13].

Several methods have been developed to quantify CRISPR editing efficiency. The traditional "gold standard" involves polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the target region followed by cloning and sequencing of a large number of clones. While sensitive and specific, this approach is expensive and labor-intensive [12]. Alternatives like mismatch cleavage assays (e.g., T7E1) are cost-effective but can lack specificity, particularly in organisms with high genomic polymorphism, and may underestimate true activity [12] [14]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) offers comprehensive data but remains costly and requires complex bioinformatics analysis [15] [2].

Within this landscape, CRISPR-STAT (CRISPR Somatic Tissue Activity Test) was developed as an easy, quick, and cost-effective fluorescent PCR-based method to determine target-specific sgRNA efficiency [12] [13]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of CRISPR-STAT against other prevalent indel detection methods, focusing on their principles, applications, and performance to inform researchers in selecting the optimal tool for their experimental needs.

Principle and Workflow of CRISPR-STAT

CRISPR-STAT is a fluorescent PCR-based assay designed to evaluate the somatic activity of sgRNAs in injected embryos or transfected cells. Its core principle involves using fluorescently-labeled primers to amplify the genomic target region. The resulting amplicons are then separated by size via capillary electrophoresis. The key differentiator of CRISPR-STAT is its ability to detect and quantify the spectrum of insertion and deletion (indel) mutations caused by CRISPR-Cas9 activity, which manifest as a series of peaks downstream of the main, wild-type peak in the electrophoregram [12].

The protocol involves specific primer design with adapter sequences. The forward primer is typically modified with an M13F adapter, while the reverse primer includes a PIGtail adapter to facilitate accurate sequencing and minimize artifacts during capillary electrophoresis [12]. The assay is sensitive enough to evaluate multiplex gene targeting and has demonstrated a strong positive correlation between its fluorescent PCR profiles in injected zebrafish embryos and the subsequent germline transmission efficiency of the sgRNAs [12] [13].

Experimental Protocol for CRISPR-STAT

The following workflow details the key steps in performing the CRISPR-STAT assay, from sgRNA design to data interpretation.

CRISPR-STAT Experimental Workflow

- sgRNA and Cas9 Preparation: Synthesize sgRNAs for each target, for example, using an oligonucleotide assembly method and the HiScribe T7 Quick High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit. Cas9 mRNA can be synthesized from an appropriate plasmid (e.g., pT3TS-nCas9n) using an mMessage mMachine T3 Transcription Kit [12].

- Delivery and Tissue Collection: Microinject one-cell stage embryos (e.g., zebrafish) with a mixture of Cas9 mRNA (e.g., 300 pg) and sgRNA (e.g., 50 pg). Incubate injected embryos and euthanize them at the desired endpoint (e.g., 48 hours post-fertilization). Extract genomic DNA from pooled injected embryos and uninjected controls using a commercial kit [12].

- Fluorescent PCR and Analysis: Design primers to amplify a 180-300 bp fragment with the target site roughly in the middle. The forward primer should have an M13F adapter (5′-TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT-3′), and the reverse primer should have a PIGtail adapter (5′-GTGTCTT-3′). Perform PCR using a fluorescently-labeled primer and a DNA polymerase such as AmpliTaq Gold. Dilute the PCR products and analyze them via capillary electrophoresis on a genetic analyzer [12].

- Data Interpretation: The analysis focuses on the electrophoregram profile. A clean, single peak indicates no editing. A main peak with a series of smaller, staggered peaks downstream indicates successful indel formation. The complexity and intensity of these secondary peaks correlate with sgRNA activity and diversity of edits [12].

Comparative Analysis of Key Indel Detection Methods

CRISPR-STAT exists within a ecosystem of CRISPR analysis tools. The table below provides a high-level comparison of its features against other common methods.

Table 1: Overview of Common CRISPR Analysis Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Readout | Best For | Major Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-STAT | Fluorescent PCR & capillary electrophoresis | Electrophoregram peak profile | Pre-screening sgRNA efficacy in vivo; predicting germline transmission | Requires access to a capillary sequencer [12] |

| ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) | Decomposition of Sanger sequencing traces | Indel %, KO Score, R² value | High-throughput, cost-effective analysis with NGS-like data from Sanger [10] [2] | Analysis is constrained by the quality of Sanger sequencing data [2] |

| TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Decomposition) | Decomposition of Sanger sequencing traces | Indel frequency, p-value | Quick, inexpensive initial assessment of editing efficiency | Struggles with complex edits and rare alleles; less accurate than ICE [14] [2] [16] |

| T7E1 Assay | Mismatch cleavage of heteroduplex DNA | Gel banding pattern | Fast, low-cost confirmation of editing presence | Semi-quantitative; cannot identify specific indel sequences [14] [2] [16] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | High-throughput sequencing of amplicons | Exact sequences and frequencies of all indels | Comprehensive, gold-standard analysis for final validation | Expensive, time-consuming, requires bioinformatics expertise [15] [2] |

Performance and Quantitative Data

A core validation study for CRISPR-STAT tested 28 sgRNAs with known germline transmission rates in zebrafish. The assay demonstrated a strong positive correlation between the fluorescent PCR profiles in somatic tissue (injected embryos) and the ultimate germline transmission efficiency of those sgRNAs. This makes it a powerful predictive tool [12].

Table 2: Correlation of CRISPR-STAT with Germline Transmission (Selected Data) [12]

| Gene Target | Germline Transmission Rate (%) | CRISPR-STAT Result (Positive/Negative) | CRISPR-STAT Fold Change (Relative to control) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pou4f3 | 100 | Yes | 4000.08 |

| grhl2a | 100 | Yes | 4623.64 |

| msrb3 | 100 | Yes | 1710.94 |

| coch | 77.78 | Yes | 8.55 |

| slc26a4 | 50 | Yes | 454.96 |

| marveld2b | 33.33 | Yes | 1.19 |

| krt15 | 20 | Yes | 3.27 |

| tmc1 | 16.67 | No | 0.99 |

| lhfpl5a | 0 | No | 0.97 |

| ptprq | 0 | No | 0.91 |

Comparative studies between other methods highlight key performance differences. When benchmarked against NGS, the ICE tool showed a high correlation (R² = 0.96), validating its accuracy for quantifying editing efficiency from Sanger data [2]. In a systematic comparison using mixed plasmid standards to simulate known editing rates, T7E1 consistently underestimated editing frequencies compared to sequencing-based methods (TIDE and ICE). Meanwhile, TIDE and ICE showed good agreement at medium to high editing efficiencies, but TIDE's performance could degrade with lower quality sequencing data or more complex indel patterns [16].

Successful implementation of CRISPR efficiency assays requires specific reagents and resources. The following table details key solutions for setting up the CRISPR-STAT method and other comparative techniques.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Analysis

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Capillary Sequencer | Instrument for separating and detecting fluorescently-labeled DNA fragments by size. | Essential for the final readout step of the CRISPR-STAT protocol [12]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes/Primers | Primers tagged with fluorophores for PCR amplification and subsequent fragment analysis. | Required for generating the labeled amplicons in CRISPR-STAT [12]. |

| Cas9 Nuclease & sgRNA Synthesis Kits | In vitro transcription or chemical synthesis of high-quality CRISPR components. | Generating consistent and active Cas9 mRNA and sgRNAs for initial editing in any validation assay [12] [17]. |

| ICE Analysis Software (Synthego) | A web-based tool for deconvoluting Sanger sequencing data to quantify CRISPR edits. | Provides an ICE Score (indel %), KO Score, and edit spectrum from standard Sanger files, serving as a key comparative tool [10] [2]. |

| TIDE Web Tool | An online software for Tracking of Indels by Decomposition from Sanger sequencing chromatograms. | Used for a rapid, initial quantitative assessment of editing efficiency, often compared against ICE and CRISPR-STAT [16]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I | An enzyme that cleaves mismatched DNA in heteroduplexes, forming the basis of the T7E1 assay. | A low-cost, non-sequencing-based method to confirm the presence of edits [14] [16]. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix | Enzyme mix for accurate and efficient amplification of the target genomic locus from extracted DNA. | Critical first step for almost all analysis methods, including CRISPR-STAT, ICE, TIDE, and T7E1 [16]. |

The choice of a CRISPR analysis method involves a careful balance between cost, time, required information detail, and available laboratory infrastructure. CRISPR-STAT stands out for its unique application in pre-screening sgRNA activity in somatic tissues to reliably predict heritable mutagenesis, particularly in animal models like zebrafish. Its reliance on capillary electrophoresis differentiates it from sequencing-based protocols.

For most routine in vitro applications, ICE analysis provides an excellent balance of cost and information, delivering NGS-quality data from standard Sanger sequencing. In contrast, the T7E1 assay remains a viable option for initial, low-cost confirmation when precise quantification or identification of specific indels is not required. NGS retains its place as the gold standard for final, comprehensive validation, especially in clinical or therapeutic contexts.

As CRISPR technology evolves, the development of more sensitive, affordable, and streamlined analysis tools will continue. Understanding the comparative strengths of existing methods like CRISPR-STAT, ICE, TIDE, and T7E1 empowers researchers to design more efficient and cost-effective gene-editing workflows, accelerating discovery and therapeutic development.

The advent of CRISPR–Cas systems has revolutionized biological research, making efficient and precise genome editing accessible. A critical step in any CRISPR experiment is the accurate quantification of editing efficiency and characterization of the resulting insertion and deletion profiles (indels). Successful genome editing hinges on the cleavage efficiency of programmable nucleases, which is typically assessed by measuring the degree of indels induced at the target sites [1]. While next-generation sequencing offers the most comprehensive data, Sanger sequencing followed by computational analysis has gained popularity due to its user-friendly nature and cost-effectiveness, enabling researchers to estimate indel frequencies by computationally decomposing sequencing trace data from edited samples [18].

Several computational tools have been developed to deconvolve complex Sanger sequencing chromatograms from edited cell populations. These include Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE), Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) by Synthego, DECODR (Deconvolution of Complex DNA Repair), and SeqScreener from Thermo Fisher Scientific [1] [18]. Each tool employs specific algorithms to compare sequencing traces from wild-type control and genome-edited samples, estimating total editing efficiency and quantifying the spectrum of different indel sequences present. Understanding the relative performance characteristics of these tools is essential for researchers to select the most appropriate method for their specific experimental context and to correctly interpret the resulting data.

Systematic Performance Comparison of Computational Tools

Quantitative Analysis of Tool Performance

Recent studies have systematically evaluated the performance of CRISPR analysis tools using artificial sequencing templates with predetermined indels, providing crucial insights into their accuracy and limitations. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from controlled comparisons:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CRISPR Editing Analysis Tools

| Tool | Best Use Case | Strengths | Limitations | Correlation with NGS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICE (Synthego) | Rapid knockout efficiency screening | User-friendly interface, fast analysis, good for small indels | Variable performance with complex indels | Pearson's r = 0.90 in zebrafish models [19] |

| DECODR | Identifying precise indel sequences | Most accurate indel frequency estimation for majority of samples | - | Superior accuracy in controlled studies [1] [18] |

| TIDE | Knock-in efficiency analysis | TIDER module outperforms others for knock-in assessment | Less accurate for complex editing patterns | Variable performance depending on edit type [1] |

| SeqScreener | Basic editing efficiency screening | Accessible web interface | Limited capability for deconvoluting complex indel sequences | - |

These tools demonstrate acceptable accuracy when analyzing simple indels containing only a few base changes, making them suitable for routine knockout efficiency assessment [1]. However, as editing patterns become more complex, significant variability emerges in the performance of different algorithms. A particularly important finding from comparative studies is that DECODR consistently provides the most accurate estimations of indel frequencies for the majority of samples, while TIDE's TIDER module outperforms other tools specifically for assessing knock-in efficiency [1] [18].

Performance in Specialized Research Contexts

The reliability of computational tools varies considerably when applied to different experimental models and editing approaches. Research using somatic CRISPR/Cas9 tumorigenesis models has revealed high variability in the reported number, size, and frequency of indels across software platforms [4]. This is particularly evident when analyzing larger indels, which are common in somatic in vivo editing contexts but pose challenges for decomposition algorithms. Similarly, studies in zebrafish models demonstrate that while both ICE and CRISPR-STAT show significant correlation with NGS data, ICE provides more objective results, performs faster, and leads to fewer errors in estimating small (1-2 bp) indels [19].

The fundamental challenge common to all these tools lies in the mathematical decomposition of mixed Sanger sequencing signals, which becomes increasingly complex as the number and diversity of edits grow. All tools effectively estimate net indel sizes, but their capability to deconvolute specific indel sequences exhibits considerable variability with certain limitations [1]. This underscores the importance of selecting analysis tools that have been validated in specific experimental contexts similar to one's own research.

Experimental Protocols for Tool Evaluation

Controlled Assessment Using Artificial Sequencing Templates

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of indel analysis tools, researchers have developed rigorous experimental protocols using artificial templates with predefined edits:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Editing Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Protein | Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease V3 | Creates double-strand breaks at target DNA sequences |

| Guide RNA | Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA and tracrRNA | Targets Cas9 to specific genomic loci |

| CRISPR-Cas12a RNP | Alt-R A.s. Cas12a Nuclease Ultra with crRNA | Alternative nuclease for creating DNA breaks |

| Cloning Vector | pUC19 plasmid | For cloning indel fragments for sequencing validation |

| DNA Polymerase | KOD One PCR Master Mix | High-fidelity amplification of target regions |

| Zebrafish Embryos | Tüpfel long-fin strain | In vivo model for evaluating editing efficiency |

Methodology Overview: The evaluation begins with microinjection of CRISPR-Cas9 or Cas12a ribonucleoprotein complexes into zebrafish embryos at the 1-cell stage [1]. After incubation until 1-day post-fertilization, embryos are lysed and genomic DNA is extracted using proteinase K digestion followed by heat inactivation. Target sites are amplified using PCR with specific primers, and the resulting fragments are cloned into pUC19 vectors for Sanger sequencing to identify individual indel sequences [1].

Artificial Template Preparation: Researchers create defined mixtures of wild-type and edited sequences by combining cloned plasmids with predetermined indels in specific ratios [18]. These artificial templates serve as gold standards for evaluating the accuracy of computational tools because the exact composition and frequency of indels in each sample is known. Sanger sequencing is performed on these defined mixtures, and the resulting chromatogram files are analyzed with each computational tool (TIDE, ICE, DECODR, SeqScreener) to compare their estimated indel frequencies against the known values [1] [18].

Analysis and Validation: The performance of each tool is assessed by calculating the deviation between computational estimates and known indel frequencies across a range of editing complexities. This approach has revealed that while all tools perform reasonably well with simple edits, their accuracy diverges significantly when analyzing complex indel patterns or knock-in sequences [1].

Workflow for Editing Efficiency Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for preparing and analyzing CRISPR-edited samples, from embryo injection to computational analysis:

Implications for Research and Development

Strategic Tool Selection for Different Editing Applications

The comparative performance data enables researchers to make informed decisions when selecting analysis tools for specific genome editing applications:

For basic knockout efficiency screening where the primary need is rapid assessment of overall editing efficiency, ICE provides a good balance of speed, usability, and reasonable accuracy [10] [19]. Its web-based interface and automated analysis workflow are particularly advantageous for researchers without bioinformatics expertise. When the research goal requires precise characterization of specific indel sequences, as needed for understanding genotype-phenotype relationships, DECODR demonstrates superior performance in identifying exact indel sequences [1] [18]. For knock-in efficiency assessment, the TIDER module of TIDE outperforms other tools, making it the preferred choice for experiments involving homology-directed repair [1].

The experimental context must also guide tool selection. Analysis of simple editing patterns in cell lines can yield consistent results across most platforms, while complex in vivo editing models – particularly those involving somatic tissue or tumor samples – require more cautious interpretation due to higher variability between tools [4]. In these complex scenarios, researchers should consider using multiple complementary analysis methods or validating key findings with targeted next-generation sequencing.

Methodological Recommendations and Future Directions

Based on the comparative performance data, researchers should adopt several best practices to ensure accurate quantification of editing efficiency. Corroborating findings with multiple analysis tools can help identify potential inaccuracies, particularly when working with complex editing patterns. When precise indel sequences are critical, DECODR should be prioritized for its demonstrated accuracy in sequence deconvolution [1]. For projects involving knock-in edits, TIDE's TIDER module provides the most reliable assessment of precise genome modifications [1].

The consistent observation that all tools struggle with highly complex editing patterns highlights the need for continued method development. Future algorithmic improvements should focus on better handling of diverse editing outcomes, particularly in heterogeneous cell populations. Until then, researchers working with challenging samples should consider targeted NGS validation for critical findings, despite the higher cost and computational requirements [20]. The field would also benefit from standardized reference materials and benchmarking protocols to enable more systematic comparison of existing and future analysis tools.

The shared goal of accurately quantifying editing efficiency and characterizing indel profiles unites CRISPR researchers across diverse applications. While computational tools like ICE, DECODR, TIDE, and SeqScreener have dramatically simplified the analysis of CRISPR editing experiments, their variable performance characteristics necessitate careful tool selection based on specific experimental needs. The comprehensive comparison presented here provides researchers with a evidence-based framework for selecting appropriate analysis methods and interpreting results with appropriate caution. As CRISPR technologies continue evolving toward therapeutic applications, robust and standardized editing assessment will become increasingly critical for translating laboratory findings into clinical breakthroughs.

Positioning ICE and CRISPR-STAT within the Broader Landscape of Gene Editing Validation

In the decade since its discovery, CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has revolutionized biological research, drug discovery, and therapeutic development. However, the reliability of CRISPR experiments hinges entirely on accurate measurement and validation of editing outcomes. The highly variable efficiency reported across studies—ranging from less than 0.1% to over 30% across different sgRNA targets—emphasizes the critical need for robust, quantitative validation methods [11]. Within this landscape, bioinformatics tools that analyze Sanger sequencing data, particularly the Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE), have emerged as accessible solutions that bridge the gap between simple gel-based assays and expensive next-generation sequencing [10]. Meanwhile, CRISPR-STAT represents another approach in the evolving toolkit for editing validation. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods within the broader context of indel detection technologies, enabling researchers to select optimal validation strategies for their specific applications in pharmaceutical development and basic research.

The ICE Algorithm: Deconvoluting Sanger Sequencing Traces

ICE operates on the principle that Sanger sequencing chromatograms from edited cell populations represent an overlapping mixture of sequence traces from different alleles. The algorithm uses decomposition mathematics to resolve this complex signal into its constituent sequences and their relative abundances [10]. The process begins by aligning the edited sample sequence trace against a control (non-edited) reference sequence. The software then computationally generates a comprehensive set of potential insertion and deletion (indel) variants and calculates the optimal combination of these variants that would produce the observed mixed-sequence chromatogram [21]. Key outputs include the Indel Percentage (overall editing efficiency), Knockout Score (proportion of edits likely to cause functional gene knockout), and R² value (goodness-of-fit between the model and actual data) [10]. ICE supports analysis of edits generated by multiple nucleases, including SpCas9, Cas12a, and MAD7, and can handle complex editing scenarios involving multiple guide RNAs [21].

CRISPR-STAT and the Broader Methodological Landscape

While comprehensive experimental data on CRISPR-STAT was limited in the searched literature, it exists within a broader ecosystem of indel detection methods that can be categorized by their underlying biochemical or computational principles:

- Enzyme-based Mismatch Detection Methods: The T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay and SURVEYOR assay operate on the principle of recognizing and cleaving heteroduplex DNA formed when edited and wild-type sequences hybridize. The cleavage products are separated by gel electrophoresis, and editing efficiency is estimated semi-quantitatively through densitometric analysis [16].

- High-Resolution Fragment Analysis: PCR-capillary electrophoresis (PCR-CE) methods, also known as Indel Detection by Amplicon Analysis (IDAA), utilize fluorescently labeled PCR primers followed by precise fragment sizing through capillary electrophoresis. This approach provides quantitative data with 1-base pair resolution but cannot determine exact sequence changes [22].

- Digital PCR Methods: Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) uses a microfluidics system to partition PCR reactions into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets. By employing fluorescent probes that distinguish between edited and wild-type sequences, ddPCR provides absolute quantification of editing frequencies without requiring standard curves [16].

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Targeted amplicon sequencing (AmpSeq) is widely considered the "gold standard" for editing validation, providing comprehensive sequence-level data with high sensitivity and accuracy across a wide dynamic range of editing efficiencies [11].

Table 1: Classification of Indel Detection Methods by Fundamental Principle

| Method Category | Examples | Fundamental Principle | Quantitative Capability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Cleavage | T7E1, SURVEYOR | Mismatch recognition in heteroduplex DNA | Semi-quantitative |

| Fragment Analysis | PCR-CE/IDAA, HMA | Size separation of DNA fragments | Quantitative |

| Sanger Deconvolution | ICE, TIDE, CRISPR-STAT | Computational decomposition of mixed traces | Quantitative |

| Digital PCR | ddPCR | Endpoint partitioning and fluorescence detection | Absolute quantification |

| Sequencing-Based | AmpSeq, NGS | High-throughput sequence reading | Quantitative with sequence context |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Sample Preparation Workflow for ICE Analysis

The ICE analysis workflow begins with critical wet-lab procedures that significantly impact result accuracy [10]:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection and extract genomic DNA using standard phenol-chloroform or commercial kit-based methods. DNA quality should be verified by spectrophotometry or gel electrophoresis.

- PCR Amplification: Design primers flanking the target site to generate amplicons of 300-500 bp. Use high-fidelity DNA polymerase to minimize PCR errors. Validate amplification specificity by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Sanger Sequencing: Purify PCR products and submit for Sanger sequencing with the forward or reverse primer used for amplification. Ensure adequate sequencing coverage across the target site.

- Data Analysis: Upload the resulting chromatogram (.ab1 file) along with the guide RNA sequence to the ICE web tool (ice.synthego.com). The control (unmodified) sample sequence should be included for reference.

Reference Methodologies for Comparative Validation

To benchmark ICE performance against established methods, researchers can employ these protocols:

Targeted Amplicon Sequencing (AmpSeq) Protocol [11]:

- Amplify the target region using primers with Illumina adapter overhangs

- Purify PCR products and quantify using fluorometric methods

- Prepare sequencing libraries with dual indexing to enable multiplexing

- Sequence on Illumina platforms (MiSeq or MiniSeq) with minimum 10,000 reads per sample

- Process data using bioinformatics pipelines like CRISPResso2 to quantify indel frequencies

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) Protocol [16]:

- Design two TaqMan probes: one targeting the wild-type sequence and one targeting a predicted common indel

- Partition the PCR reaction into 20,000 droplets using a QX200 Droplet Generator

- Amplify using touchdown PCR protocols

- Read droplets on a QX200 Droplet Reader and analyze with QuantaSoft software

- Calculate editing efficiency from the ratio of positive to negative droplets

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for CRISPR validation methods

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons Across Methods

Sensitivity and Accuracy Metrics

Recent systematic comparisons have revealed significant differences in the performance of indel detection methods. When benchmarked against targeted amplicon sequencing (AmpSeq) as the gold standard, different methods show varying degrees of accuracy and sensitivity across the editing efficiency spectrum [11].

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Indel Detection Methods Relative to AmpSeq

| Method | Quantitative Accuracy | Effective Sensitivity Range | Detection Limitations | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICE | High (R² > 0.95 with AmpSeq) [23] | 5% - 95% editing | Limited detection of variants <1% frequency | Model Fit (R²) 0.85-0.99 [10] |

| T7E1 | Semi-quantitative [16] | 10% - 80% editing | Cannot detect homozygous edits; misses small indels | Band intensity ratio analysis |

| PCR-CE/IDAA | High [11] | 1% - 95% editing | Cannot determine exact sequence changes | 1-bp resolution size detection |

| ddPCR | Absolute quantification [16] | 0.1% - 99.9% editing | Requires prior knowledge of expected edits | Linear dynamic range >5 logs |

| AmpSeq (Reference) | Gold standard [11] | 0.01% - 100% editing | Cost and computational requirements | >10,000 reads per amplicon |

Technical Requirements and Practical Considerations

The selection of an appropriate validation method often involves trade-offs between technical requirements, cost, and throughput needs.

Table 3: Technical and Operational Comparison of Validation Methods

| Method | Equipment Requirements | Hands-on Time | Cost per Sample | Throughput Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICE | Sanger sequencer, computer | 2-3 hours | $10-$20 [10] | Medium (batch analysis available) |

| T7E1 | Thermal cycler, gel electrophoresis | 4-5 hours | $5-$10 | Low to medium |

| PCR-CE/IDAA | Capillary electrophoresis system | 3-4 hours | $15-$25 | Medium |

| ddPCR | Droplet generator, reader | 3-4 hours | $20-$30 | Medium |

| AmpSeq | NGS platform, bioinformatics | 6-8 hours | $50-$100 | High (multiplexing) |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

Validation in Different Biological Contexts

The performance of editing validation methods varies significantly across different biological systems, an important consideration for drug development applications:

- Human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs): In optimized iCas9 hPSC systems, ICE analysis confirmed INDEL efficiencies of 82-93% for single-gene knockouts and over 80% for double-gene knockouts, correlating well with protein validation by Western blot [23].

- Primary vs. Immortalized Cells: Survey data reveals that CRISPR editing is perceived as more difficult in primary cells (particularly T-cells) compared to immortalized cell lines, potentially impacting validation method selection [24].

- Plant Systems: Complex plant genomes with high sequence variation between homeologs present unique challenges for editing detection, with methods like ICE potentially struggling with highly heterogeneous samples [11].

Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Validation

Table 4: Key Reagents and Resources for Editing Validation Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Products/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | PCR amplification of target locus | Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity (NEB) [16] |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Genomic DNA isolation | Extract-N-Amp (Sigma), DNeasy (Qiagen) [22] |

| Sanger Sequencing Service | Sequence generation for ICE | Commercial providers (Macrogen) [16] |

| T7 Endonuclease I | Mismatch detection enzyme | M0302 (New England Biolabs) [16] |

| Fluorescent Probes | ddPCR detection | TaqMan probes (ThermoFisher) [16] |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | AmpSeq library construction | Illumina DNA Prep kits [11] |

Integrated Analysis and Future Directions

The CRISPR validation landscape continues to evolve with emerging technologies that address current limitations. Single-cell sequencing technologies, such as Tapestri, now enable characterization of editing outcomes at single-cell resolution, revealing editing patterns in nearly every edited cell that were obscured by bulk measurement methods [8]. For comprehensive project support, repositories like CRISPR-GATE consolidate publicly available tools for genome editing research, providing categorized access to gRNA design, efficiency prediction, and outcome analysis resources [25].

Diagram 2: Method comparison by cost and complexity versus information depth

The comprehensive comparison of gene editing validation methods reveals a clear trade-off between technical accessibility and analytical depth. ICE occupies a strategic position in this landscape, providing NGS-quality analysis from low-cost Sanger sequencing data with ~100-fold cost reduction compared to AmpSeq [10]. Its quantitative capabilities, when properly validated with high R² scores (>0.85), make it suitable for most routine editing experiments in research and early drug discovery. However, for clinical applications requiring absolute quantification or detection of low-frequency edits, ddPCR and AmpSeq remain essential. For the highest safety standards in therapeutic development, emerging single-cell approaches provide previously unattainable resolution of editing patterns in heterogeneous cell populations [8]. The optimal validation strategy often employs a tiered approach: using ICE for rapid screening and optimization, followed by orthogonal confirmation with AmpSeq or ddPCR for critical applications. As CRISPR therapeutics advance toward clinical use, this multi-layered validation approach will become increasingly essential for ensuring both efficacy and safety.

A Guide to Implementation: Step-by-Step Workflows and Applications

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, accurately quantifying the outcomes of CRISPR genome editing experiments is a critical step in both basic research and therapeutic development. While next-generation sequencing (NGS) is considered the gold standard for comprehensive analysis, its cost and complexity can be prohibitive for many applications [2]. In response, several computational methods have been developed to derive quantitative insights from more accessible Sanger sequencing data. Among these, the Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) tool from Synthego has emerged as a widely adopted solution. This guide provides an objective analysis of the ICE workflow, its key output metrics, and its performance relative to other common indel analysis methods, providing a clear framework for selecting the appropriate tool in a research or development context.

The ICE Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

The ICE tool is designed to analyze CRISPR editing results from Sanger sequencing data, transforming chromatograms into quantitative, NGS-quality analysis [10]. The process is streamlined into several key stages, as illustrated below.

Diagram 1: The end-to-end ICE analysis workflow, from initial sample preparation to final result export.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for ICE Analysis

The methodology for a typical ICE analysis involves the following steps, which are consistent with those used in comparative studies [11] [16]:

Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from both edited and control (non-edited) cell populations or tissues.

- PCR Amplification: Design primers to amplify a region of 500-1200 bp flanking the CRISPR target site. The target site should be positioned with a minimum distance of ≥150 bp from the primers. Use a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Phusion) to minimize PCR-introduced errors [26].

- Sanger Sequencing: Purify the PCR amplicons and submit them for Sanger sequencing. The resulting chromatogram files (typically in

.ab1format) for both control and edited samples are the primary inputs for ICE.

Data Upload and Tool Configuration:

- Access the web-based ICE tool (provided by Synthego).

- Upload the control and edited sample sequencing files.

- Input the gRNA target sequence (excluding the PAM sequence).

- Select the specific nuclease used in the experiment (e.g., SpCas9, Cas12a, MAD7) [10].

Analysis and Data Interpretation:

- The ICE algorithm automatically performs sequence alignment, compares the edited trace to the control trace, and deconvolutes the mixed signals using a lasso regression model [10] [4].

- Upon completion, the software provides a summary table and detailed views for each sample. Key output metrics to review include:

- Indel Percentage (ICE Score): The overall editing efficiency.

- R² (Model Fit) Score: A measure of confidence in the ICE score.

- Knockout (KO) Score: The proportion of edits likely to cause a gene knockout.

- Knock-in (KI) Score: For knock-in experiments, the proportion of sequences with the desired insertion [10].

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR Indel Detection Methods

To objectively place ICE's performance in context, it is essential to compare it with other commonly used methods. The following table and analysis synthesize data from recent benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Key characteristics and performance metrics of major CRISPR analysis methods.

| Method | Principle | Data Input | Key Metrics | Reported Correlation with NGS (R²) | Cost & Time | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICE (Synthego) | Sequence deconvolution via lasso regression [4] | Sanger .ab1 files |

Indel %, KO Score, KI Score, R² fit | 0.96 (Synthego claim) [2] | Low cost, rapid turnaround [2] | High-accuracy screening without NGS cost |

| TIDE | Sequence decomposition via non-negative regression [4] [16] | Sanger .ab1 or .scf files |

Indel %, p-value, efficiency | N/A | Low cost, rapid turnaround | Basic indel efficiency estimation |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) | Cleavage of heteroduplex DNA [16] | PCR amplicons | Cleavage band intensity | N/A | Very low cost, quick results [2] | Initial, low-cost confirmation of editing |

| ddPCR | Fluorescent probe-based absolute quantification [11] | Genomic DNA | Absolute edit frequency | High (benchmarked to AmpSeq) [11] | Medium cost, medium complexity | Precise quantification of specific edits |

| AmpSeq (NGS) | High-throughput sequencing [11] | PCR amplicons | Full sequence-level characterization | Gold Standard (1.00) | High cost, long turnaround, complex analysis [2] | Comprehensive, gold-standard validation |

Experimental Performance Benchmarking

Independent studies have benchmarked these methods against the gold standard of targeted amplicon sequencing (AmpSeq). One comprehensive study in plant systems compared multiple techniques across 20 sgRNA targets and found that ICE, along with ddPCR and PCR-CE/IDAA, provided accurate quantification when benchmarked against AmpSeq [11]. Another comparative study using plasmid mixtures to simulate defined editing frequencies concluded that ICE and TIDE offer more quantitative analysis than T7E1 assays, though their accuracy is dependent on the quality of PCR and sequencing [16].

A critical finding for researchers working with complex editing outcomes, such as those from in vivo tumor models, comes from a 2023 cross-platform comparison. This study revealed high variability in the reported number, size, and frequency of indels across software platforms (TIDE, Synthego ICE, DECODR, and Indigo), especially when larger indels were present [4]. This highlights that the choice of analysis software must be tailored to the specific experimental context, as algorithms perform differently with complex indel profiles.

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful ICE analysis relies on several key reagents and tools throughout the experimental pipeline.

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for the CRISPR analysis workflow.

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate PCR amplification of the target locus from genomic DNA. | Phusion Hot Start High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [11] |

| Gel and PCR Clean-Up Kit | Purification of PCR amplicons prior to sequencing. | Monarch PCR & DNA Cleanup Kit [4] |

| Sanger Sequencing Service | Generation of sequencing chromatograms for ICE analysis. | Requires output in .ab1 file format [4] |

| ICE Analysis Tool | Web-based software for deconvoluting Sanger sequencing data and quantifying indels. | Synthego's ICE tool (publicly available) [10] |

| Control Genomic DNA | Non-edited sample crucial for establishing a reference sequence for ICE. | Wild-type cell line or tissue [4] |

The ICE workflow provides a robust and cost-effective bridge between simple, low-information assays and comprehensive but expensive NGS analysis. Its strength lies in delivering quantitative, sequence-level data from standard Sanger sequencing, with a reported high correlation to NGS results [2]. For researchers screening gRNA efficiency, validating gene knockouts, or performing initial characterization of editing experiments, ICE offers an excellent balance of accuracy, accessibility, and depth of information.

However, evidence shows that no single analysis method is universally superior. The choice between ICE, TIDE, T7E1, ddPCR, or AmpSeq should be guided by the specific experimental needs, the required level of quantification, the complexity of the expected edits, and available resources [11] [4] [16]. For critical applications, particularly in therapeutic development where accuracy is paramount, confirming key results with a gold-standard method like AmpSeq remains a best practice.

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic engineering, making targeted genome editing accessible across model organisms and cell lines. A critical component of any CRISPR workflow is the detection and quantification of insertion-deletion mutations (indels) resulting from non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair of Cas9-induced double-strand breaks. Efficient and accurate genotyping methods are essential for evaluating guide RNA (gRNA) efficacy, screening for successful mutagenesis, and establishing genetically modified lines. Among the available techniques, CRISPR-STAT (Somatic Tissue Activity Test) has emerged as a reliable fluorescent PCR-based method that enables researchers to pre-screen gRNA activity before committing extensive resources to animal husbandry or clonal expansion [12] [22].

The broader landscape of indel detection methods encompasses a spectrum of technologies ranging from simple gel-based approaches to sophisticated next-generation sequencing. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations in terms of sensitivity, throughput, cost, and technical requirements. While traditional methods like T7 endonuclease I (T7E1) assays and heteroduplex mobility assays (HMA) provide accessible options for many laboratories, they often lack the sensitivity to detect smaller indels or precisely quantify editing efficiency [22] [27]. Sequencing-based approaches, including Sanger sequencing and next-generation sequencing (NGS), offer high resolution but at greater cost and computational burden [10].

CRISPR-STAT occupies a strategic middle ground in this landscape, combining the sensitivity and resolution of capillary electrophoresis with the practicality and throughput required for rapid screening. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of CRISPR-STAT against alternative indel detection methods, with particular emphasis on its experimental workflow, performance characteristics, and applications in both knockout and knock-in screening scenarios.

Table 1: Overview of Major Indel Detection Methods

| Method | Principle | Detection Limit | Throughput | Equipment Needs | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-STAT | Fluorescent PCR + capillary electrophoresis | 1 bp [22] | High [12] | Capillary sequencer [12] | $$ |

| ICE Analysis | Sanger sequencing + computational decomposition | Varies with editing complexity [10] | Medium-High [10] | Standard sequencer + software [10] | $ |

| Heteroduplex Assay | Gel separation of mismatched DNA duplexes | >2-3 bp [22] [27] | Low-Medium [27] | Standard gel electrophoresis [27] | $ |

| T7E1/SURVEYOR | Enzyme cleavage of mismatched DNA | >3-5 bp [12] | Low-Medium | Standard gel electrophoresis | $ |

| Sanger Sequencing | Direct sequence analysis | 1 bp (but requires cloning) [12] | Low | DNA sequencer | $$$ |

| NGS | High-throughput sequencing | 1 bp [12] | Very High | NGS platform | $$$$ |

The CRISPR-STAT Methodology: A Detailed Experimental Protocol

CRISPR-STAT employs fluorescently labeled primers to amplify the genomic region flanking the CRISPR target site, followed by high-resolution fragment separation via capillary gel electrophoresis. The fundamental principle underlying this technique is that insertions or deletions of even a single base pair will alter the migration time of DNA fragments through the capillary matrix, enabling precise sizing of indels with single-base-pair resolution [12] [22]. This approach provides both quantitative data on editing efficiency (percentage of indels) and qualitative information about the specific types of mutations generated.

The method was originally validated in zebrafish using 28 sgRNAs with known germline transmission efficiency, demonstrating a strong positive correlation between somatic activity in injected embryos and germline transmission rates [12]. The assay's sensitivity enables evaluation of multiplex gene targeting, making it particularly valuable for complex genetic engineering projects requiring simultaneous targeting of multiple loci [12]. Furthermore, the technique has been successfully adapted for mammalian cell culture systems, demonstrating its versatility across model organisms [28] [29].

Step-by-Step Experimental Procedure

The standard CRISPR-STAT protocol can be divided into four main phases: (1) sample preparation and DNA extraction, (2) fluorescent PCR amplification, (3) capillary electrophoresis, and (4) data analysis.

Phase 1: Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- For zebrafish embryos: Inject one-cell stage embryos with Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA, incubate for 48 hours post-fertilization, then euthanize for DNA extraction [12].

- For mammalian cells: Transfert cells with CRISPR components, sort successfully transfected cells (e.g., GFP-positive if using a fluorescent reporter), culture until single-cell colonies form, and transfer individual clones to multi-well plates [28] [29].

- DNA extraction uses a simplified direct lysis approach. For zebrafish embryos, the Extract-N-Amp Tissue PCR Kit with one-fourth recommended volumes suffices [12]. For mammalian cells, a homemade Direct-Lyse buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 2.5 mM EDTA, 0.2 M NaCl, 0.15% SDS, and 0.3% Tween-20) can be used with thermal cycling to ensure complete cell lysis and genomic DNA release [29]. The lysate is typically diluted 1:10 with nuclease-free water before PCR [12].

Phase 2: Fluorescent PCR Amplification

- Primer Design: Design primers to amplify a 180-300 bp fragment with the target site positioned roughly in the middle. The forward primer should include the M13F adapter sequence (5′-TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT-3′) at its 5′ end, while the reverse primer should include a PIGtail sequence (5′-GTGTCTT-3′) to ensure uniform adenylation of PCR products [12] [30].

- PCR Reaction: Set up reactions using a robust DNA polymerase such as AmpliTaq Gold. The reaction includes the M13F-tailed forward primer, PIG-tailed reverse primer, and a fluorescently labeled M13F primer (labeled with 6-FAM, HEX, or similar fluorophores). Use 1.5-3 μL of diluted lysate as template in a 20 μL reaction [12] [29].

- Thermal Cycling: Standard conditions include initial denaturation at 94°C for 10 min; followed by touchdown cycles (e.g., 4 cycles each at 64°C, 61°C, and 58°C annealing); and final extension at 68°C [28].

Phase 3: Capillary Gel Electrophoresis

- Sample Preparation: Mix fluorescent PCR products with an internal size standard (e.g., GeneScan 400HD ROX) and Hi-Di formamide according to capillary sequencer manufacturer recommendations [30].

- Fragment Separation: Run samples on a capillary electrophoresis instrument such as an Applied Biosystems Genetic Analyzer using appropriate polymer and run conditions [12] [29].

- Data Collection: Instrument software detects fluorescence signals and generates electrophoretograms showing peak patterns for each sample.

Phase 4: Data Analysis

- Using software such as Genemapper or Peak Studio, analyze fragment sizes by comparing to the internal standard [22].

- Wild-type samples display a single peak at the expected amplicon size, while successfully edited samples show additional peaks corresponding to indel mutations [29].

- Editing efficiency is calculated based on the relative peak heights or areas of mutant versus wild-type fragments [12].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Direct Comparison of Key Methodologies

When evaluating CRISPR-STAT against alternative indel detection methods, several performance parameters must be considered, including resolution, sensitivity, throughput, and practical implementation requirements. The following comparative analysis draws from experimental data across multiple studies to provide a comprehensive assessment.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of CRISPR-STAT Versus Alternatives

| Parameter | CRISPR-STAT | ICE Analysis | Heteroduplex Assay | T7E1/SURVEYOR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | 1 bp [22] | Single base (when clean sequence) [10] | >2-3 bp [22] [27] | >3-5 bp [12] |

| Sensitivity | High (detects mosaicism) [12] | Medium-High (depends on R² value) [10] | Medium [22] | Low-Medium [12] |

| Quantitation Accuracy | High (direct peak measurement) [29] | Medium (computational inference) [10] | Low (band intensity estimation) | Low (band intensity estimation) |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Yes (multiple fluorophores) [12] [29] | Limited (single target per sequence) | Limited | Limited |

| Handling of Complex Edits | Excellent (direct size detection) [12] | Good (with high-quality data) [10] | Poor | Poor |

| Throughput | High (96-well format) [29] | Medium-High (batch upload) [10] | Low-Medium | Low-Medium |