Key Factors Influencing Mouse Embryo Implantation Success: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article synthesizes current research on the molecular, cellular, and technical factors determining mouse embryo implantation success, a critical model for reproductive biology and drug development.

Key Factors Influencing Mouse Embryo Implantation Success: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the molecular, cellular, and technical factors determining mouse embryo implantation success, a critical model for reproductive biology and drug development. It explores foundational biological mechanisms, including the roles of the LIF/STAT3 pathway, blastocyst hatching dynamics, and immune gene regulation. The content further details advanced methodological approaches for improving embryo quality in vitro, troubleshooting common challenges like recurrent implantation failure, and validating embryo potential through novel imaging and biomarkers. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this review provides a framework for optimizing experimental design and translating findings to enhance clinical outcomes in assisted reproductive technologies.

Decoding the Core Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Implantation

In eutherian mammals, the successful establishment of pregnancy hinges on embryo implantation, a complex biological process representing the first critical point of interaction between the maternal endometrium and the developing blastocyst. The molecular dialogue between a receptive uterus and an implantation-competent blastocyst must be exquisitely synchronized, with disruptions in this process representing a significant cause of infertility in both humans and model organisms. Central to this dialogue is the Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) receptor/Glycoprotein 130-Janus Kinase-Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (LIFR/Gp130-JAK/STAT3) signaling axis, which has emerged as a master regulator of uterine receptivity. Within the context of mouse embryo implantation success rates, this signaling pathway integrates hormonal cues with cellular responses to orchestrate the transition of the endometrium from a pre-receptive to a receptive state, enabling blastocyst attachment and subsequent decidualization. This technical guide synthesizes current research to provide an in-depth analysis of this critical signaling axis, its molecular mechanisms, experimental evidence of its functions, and the technical approaches used to investigate its role in embryo implantation.

Molecular Architecture of the LIFR/Gp130-JAK/STAT3 Signaling Axis

Core Signaling Components and Pathway Activation

The LIFR/Gp130-JAK/STAT3 pathway constitutes a highly specialized signaling cascade that translates extracellular cytokine signals into specific gene expression programs within uterine cells. The molecular architecture begins with LIF, a member of the interleukin-6 (IL-6) family of cytokines, binding to its heterodimeric receptor complex composed of the LIF-specific receptor (LIFR) and the signal-transducing subunit glycoprotein 130 (Gp130) [1]. This ligand-receptor interaction induces conformational changes that activate receptor-associated Janus kinases (JAKs), leading to tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptors and creation of docking sites for Src homology-2 (SH2) domain-containing proteins, most notably STAT3 [1]. Once recruited to the receptor complex, STAT3 molecules are phosphorylated on tyrosine 705 residues, inducing their dimerization and subsequent nuclear translocation. Within the nucleus, STAT3 dimers bind to specific promoter and enhancer regions of target genes, initiating transcriptional programs essential for uterine receptivity and embryo implantation [1] [2].

Parallel to the JAK/STAT3 pathway, LIF binding to the LIFRβ/gp130 receptor can also activate secondary signaling cascades, including the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol-3 phosphate kinase (PI3K) pathways [1]. The activated gp130 receptor associates with the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, which serves as a positive effector of the MAPK signaling cascade through recruitment of Gab1 adaptor protein, ultimately leading to activation of ERK1 and ERK2 kinases [1]. Similarly, PI3K activation leads to phosphorylation of AKT/PKB, influencing multiple cellular processes including cell survival, metabolism, and adhesion. This signaling diversification enables the LIF pathway to coordinate multiple aspects of uterine remodeling necessary for successful implantation.

Pathway Visualization

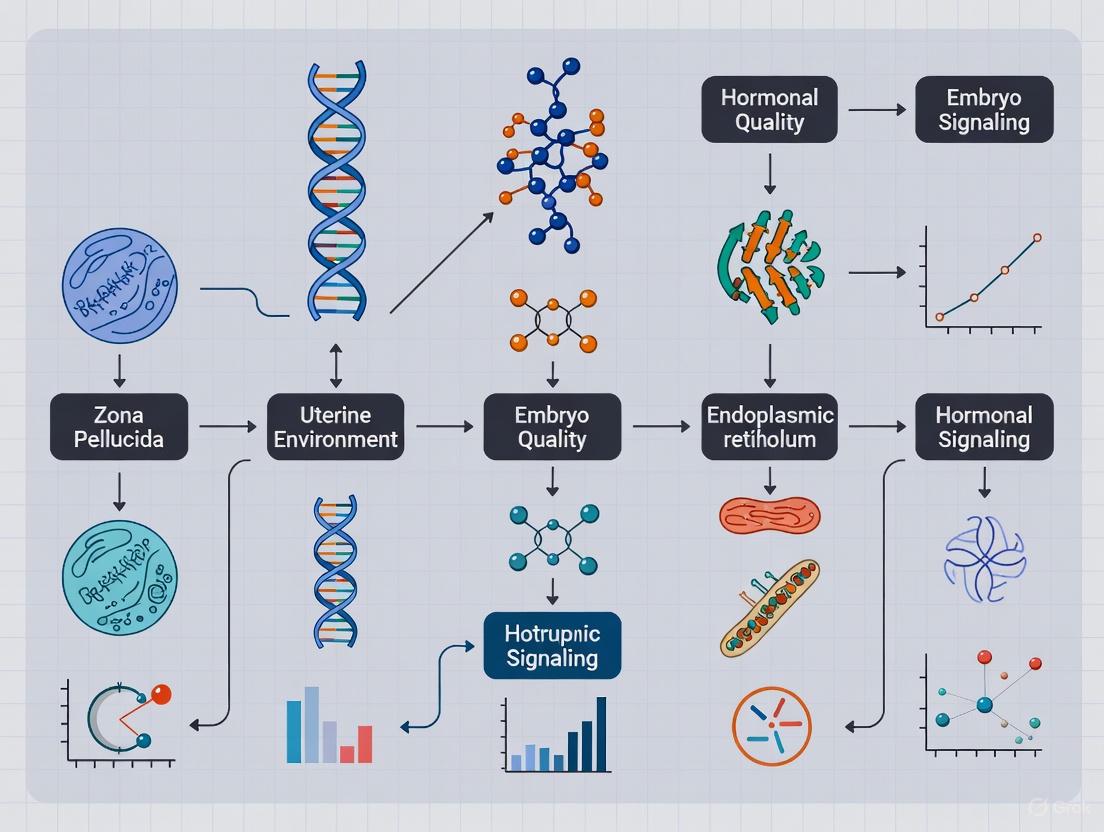

The following diagram illustrates the core LIFR/Gp130-JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway and its role in uterine receptivity:

Figure 1: The LIFR/Gp130-JAK/STAT3 Signaling Pathway in Uterine Receptivity. This diagram illustrates the core signaling cascade from LIF binding to transcriptional regulation of genes essential for uterine receptivity and embryo implantation. The negative feedback loop mediated by SOCS3 provides regulatory control.

Experimental Evidence: Establishing Essential Roles in Implantation

Genetic Knockout Models Reveal Non-Redundant Functions

The development of tissue-specific conditional knockout mouse models has been instrumental in elucidating the essential, non-redundant functions of the LIFR/Gp130-JAK/STAT3 signaling axis in uterine receptivity and embryo implantation. These genetic approaches have demonstrated that each component of this pathway plays indispensable but distinct roles in the implantation process.

Table 1: Phenotypes of Uterine Epithelium-Specific Knockout Mice in the LIFR/Gp130-JAK/STAT3 Pathway

| Genetic Model | Fertility Status | Primary Defect | Additional Phenotypic Features | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifr eKO | Completely infertile | Implantation failure | Altered epithelial gene expression; Disrupted ERBB2 signaling | [3] [4] |

| Gp130 eKO | Completely infertile | Implantation failure | Defective epithelial remodeling; Reduced hormone responsiveness; Immune cell infiltration | [5] [3] |

| Stat3 eKO | Completely infertile | Implantation failure | Disrupted epithelial transition to attachment phase; Impaired decidualization | [5] [2] |

| Lif eKO | Completely infertile | Embryo attachment failure | Failure of luminal closure and crypt formation; Disrupted epithelial gene expression | [2] |

| Lif uKO | Completely infertile | Embryo attachment failure | Unrescued by recombinant LIF; Severe defects in implantation chamber formation | [2] |

The distinct expression patterns of LIFR and Gp130 in the uterine epithelium immediately prior to implantation initially suggested potential functional divergence, yet both receptors prove essential for successful implantation [3] [4]. While these receptors typically function as heterodimers, their non-overlapping knockout phenotypes indicate they may activate partially distinct downstream signaling effectors or interact with different co-receptors in uterine tissue.

Quantitative Analysis of Implantation Success in Intervention Studies

Pharmacological and biochemical interventions have further elucidated the functional significance of the LIFR/Gp130-JAK/STAT3 pathway and explored potential therapeutic applications for implantation failure.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Implantation Success Following Experimental Interventions

| Experimental Intervention | Model System | Effect on Implantation | Molecular Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RO8191 (STAT3 activator) | Delayed implantation model | Induced implantation; Rescue of implantation in Lifr eKO mice | Selective STAT3 activation in epithelial and stromal compartments; Partial decidual response in Stat3/Gp130 eKO | [5] |

| Recombinant LIF protein | Lif eKO mice | Rescued reproductive phenotype | Restoration of epithelial gene expression; Activation of nuclear STAT3 | [2] |

| Recombinant LIF protein | Lif uKO mice | Did not rescue attachment failure | Inability to restore implantation chamber formation | [2] |

| ERBB2 inhibitors (Tucatinib/Sapitinib) | Wild-type mice | Prevented embryo implantation | Disruption of LIFR-ERBB2 signaling axis | [3] [4] |

| Cardiotrophin-1 (CT-1) | Delayed implantation model | Induced implantation | Activation of STAT3 signaling in uterine epithelium | [3] |

The experimental compound RO8191, identified as a potent STAT3 activator, has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in inducing embryo implantation and decidual reaction in delayed implantation models through selective activation of STAT3 (but not STAT1) signaling in both epithelial and stromal compartments [5]. Notably, RO8191 administration was able to rescue implantation and establish pregnancy even in uterine epithelial-specific Lifr conditional knockout mice, which typically exhibit complete infertility due to implantation failure [5]. This suggests that direct STAT3 activation can bypass the requirement for upstream LIF-LIFR signaling. However, in uterine epithelial-specific Stat3 or Gp130 conditional knockout mice, RO8191 induced only a partial decidual response, indicating that both STAT3 and Gp130 are essential for the complete implantation response [5].

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating the Pathway

Delayed Implantation Model and RO8191 Treatment Protocol

The delayed implantation (DI) mouse model provides a valuable experimental system for investigating molecular mechanisms underlying embryo implantation and testing potential therapeutic compounds [5]. The following workflow and protocol detail the establishment of this model and the testing of STAT3 activators:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Delayed Implantation Model and RO8191 Treatment. This diagram outlines the key procedural steps for establishing delayed implantation and testing STAT3 activators like RO8191.

Detailed Protocol:

- Ovariectomy Timing: Perform ovariectomy on plug-positive ICR females between 1300 and 1530 h on day 3 (D3) of pregnancy under sevoflurane anesthesia [5].

- Progesterone Administration: Administer siliconized medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, 100 µl/head) subcutaneously in the ventral region immediately following ovariectomy to maintain delayed implantation [5].

- Compound Treatment: On D7, prepare RO8191 (400 µg/head) dissolved in sesame oil and administer via single intraperitoneal injection at 1300 h. Use sesame oil alone as a negative control and E2 (25 ng/head) as a positive control [5].

- Tissue Collection and Analysis: Euthanize mice in a carbon dioxide chamber and dissect at 1300 h on D10 to count implantation sites. For molecular analysis, collect uterine tissues at 6 h (for immunohistochemistry) and 24 h (for Western blot analysis) after treatment [5].

- Exclusion Criteria: Exclude from statistical analysis any DI mice that have no implantation sites and from which no blastocyst can be recovered via uterine flushing with saline solution [5].

Conditional Knockout Mouse Generation and Validation

The generation of tissue-specific conditional knockout mice has been critical for delineating the uterine-specific functions of pathway components without the confounding effects of systemic knockout phenotypes:

Genetic Engineering Protocol:

- Mouse Strains: Utilize the following commercially available strains: LtfiCre/+ (JAX: 026030) for uterine epithelium-specific deletion, Stat3flox/flox, Gp130flox/flox, and Lifrflox/flox mice [5] [3].

- Crossing Strategy: Cross floxed mice with LtfiCre/+ mice to generate uterine epithelial-specific conditional knockout (cKO) models (Stat3 cKO, Gp130 cKO, or Lifr cKO) [5].

- Genotyping Primers:

- LtfiCre: 5'-GTTTCCTCCTTCTGGGCTCC-3', 5'-TTTAGTGCCCAGCTTCCCAG-3', and 5'-CCTGTTGTTCAGCTTGCACC-3' [5]

- Stat3flox: 5'-CCTGAAGACCAAGTTCATCTGTGTGAC-3', 5'-CACACAAGCCATCAAACTCTGGTCTCC-3', and 5'-GATTTGAGTCAGGGATCCTTATCTTCG-3' [5]

- Gp130flox: 5'-GGCTTTTCCTCTGGTTCTTG-3' and 5'-CAGGAACATTAGGCCAGATG-3' [5]

- Lifrflox: 5'-TGAGAGCACGGAAGCTCTTT-3' and 5'-ACTGCCCGACAAGGTTTTTA-3' [5]

- Phenotypic Validation: Confirm knockout efficiency through quantification of implantation sites following blue dye injection, histological analysis of uterine tissues, and molecular analysis of pathway component expression [3] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating the LIFR/Gp130-JAK/STAT3 Pathway

| Reagent / Model | Specific Application | Function / Purpose | Source / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RO8191 | STAT3 pathway activation | Small molecule STAT3 activator; induces implantation in delayed models | TargetMol (T22142) or Sigma-Aldrich (SML1200) [5] |

| Delayed Implantation Model | Implantation timing studies | Allows synchronization of implantation events; tests implantation competence | [5] |

| LtfiCre/+ mouse | Tissue-specific knockout | Enables uterine epithelium-specific gene deletion | JAX: 026030 [5] [3] |

| Recombinant LIF protein | Pathway stimulation | Rescues implantation in Lif-deficient models; tests LIF sufficiency | [2] |

| ERBB2 inhibitors (Tucatinib/Sapitinib) | Signaling inhibition | Blocks LIFR-ERBB2 signaling axis; tests pathway necessity | TargetMol (T2346); Selleck Chemicals (AZD8931) [3] [4] |

| Conditional knockout mice (Stat3, Gp130, Lifr floxed) | Genetic pathway dissection | Enables cell-type specific deletion of pathway components | [5] [3] |

| UT-B-IN-1 | UT-B-IN-1, MF:C20H17N5O2S3, MW:455.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 5-Methyl-4-phenyl-2-pyrimidinethiol | 5-Methyl-4-phenyl-2-pyrimidinethiol|CAS 857412-75-0 | High-purity 5-Methyl-4-phenyl-2-pyrimidinethiol for pharmaceutical research. CAS 857412-75-0. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Concepts and Emerging Research Directions

Spatiotemporal Regulation of Uterine Receptivity

Recent research has revealed sophisticated spatiotemporal regulation of LIF signaling within the uterine environment. LIF exhibits dynamic expression patterns, being abundantly expressed in the glandular epithelium during the blastocyst-receptive phase and subsequently induced in the stroma surrounding attached blastocysts [2]. This patterned expression suggests distinct functional roles for epithelial versus stromal LIF signaling. Studies using uterine epithelial-specific Lif knockout (Lif eKO) and uterine-specific Lif knockout (Lif uKO) mice demonstrate that epithelial LIF is sufficient for embryo attachment, while stromal LIF is essential for the formation of proper implantation chambers [2].

Three-dimensional imaging of the uterine epithelium has revealed that luminal closure and crypt formation—critical architectural changes required for embryo implantation—are regulated by the uterine LIF-STAT3 axis in coordination with the presence of blastocysts [2]. RNA sequencing analyses of luminal epithelia from Lif eKO mice have further identified that LIF governs the transition of uterine epithelium from the receptive to embryo-attaching phase by activating nuclear STAT3 and regulating genes associated with cytokine signaling and angiogenesis [2].

Cross-Talk with Other Signaling Pathways

The LIFR/Gp130-JAK/STAT3 axis does not function in isolation but engages in extensive cross-talk with other signaling pathways critical for uterine receptivity:

ERBB2 Signaling: Recent research has identified LIFR-mediated ERBB2 signaling as essential for successful embryo implantation [3] [4]. Hub gene analysis of differentially expressed genes in both Lifr eKO and Gp130 eKO mice identified Erbb2 and c-Fos as key regulators, suggesting novel signaling connections beyond the canonical JAK/STAT3 pathway [3].

Hormonal Signaling Pathways: The LIF-STAT3 axis interfaces with progesterone and estrogen signaling in complex ways. LIF appears to suppress Pgr-induced genes in the luminal epithelium, facilitating the transition to an attachment-competent state [2]. This interaction is critical given that sustained or excessive P4-Pgr signaling can disturb embryo attachment [2].

Immune Regulation: Gp130 eKO mice display defective epithelial remodeling accompanied by immune cell infiltration in the endometrium, suggesting connections between LIF signaling and immune regulation during implantation [3].

The LIFR/Gp130-JAK/STAT3 signaling axis represents a master regulatory circuit that coordinates uterine receptivity and embryo implantation through precise spatiotemporal control of gene expression programs in the uterine epithelium and stroma. Genetic evidence firmly establishes that each component of this pathway—LIF, LIFR, Gp130, and STAT3—is indispensable for successful implantation in murine models. The development of pharmacological activators like RO8191 that can bypass upstream signaling defects to directly activate STAT3 offers promising therapeutic avenues for addressing implantation failure in clinical contexts.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the complete transcriptional networks downstream of STAT3 in uterine cells, understanding the molecular basis of sexual dimorphism in pathway regulation, and exploring potential cross-species conservation of these mechanisms to inform human fertility treatments. The continued investigation of this critical signaling axis will not only enhance our fundamental understanding of reproductive biology but may also yield novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for addressing infertility in human patients.

Blastocyst hatching, the process whereby the mammalian embryo escapes its zona pellucida (ZP), is a critical prerequisite for successful implantation. While traditionally viewed as a mechanical event, recent research reveals that hatching is a biologically nuanced process, with the specific site of ZP exit playing a potentially decisive role in subsequent implantation success. This review synthesizes emerging evidence from mouse models, demonstrating that the location of the hatching aperture is non-random and is linked to distinct molecular programs that influence embryonic developmental potential. We delve into the molecular mechanisms, including ion transporters, proteases, and immune-related gene expression, that underpin these site-specific dynamics. Furthermore, we evaluate the translational implications of these findings for assisted reproductive technologies (ART), particularly regarding the efficacy and methodology of assisted hatching. The synthesis of quantitative data, experimental protocols, and key signaling pathways provided herein aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive toolkit for advancing this critical area of reproductive biology.

In mammalian embryonic development, blastocyst hatching represents the crucial transition from a free-floating entity to one capable of direct interaction with the maternal endometrium. This process, essential for implantation and the establishment of pregnancy, involves a combination of blastocoel cavity expansion, ZP thinning, and proteolytic degradation [6]. Historically, the focus has been on the timing and mere occurrence of hatching; however, a growing body of evidence suggests that the precise location of the hatching site relative to the inner cell mass (ICM) is a significant determinant of embryonic fate [7]. This technical guide explores the sophisticated dynamics of site-specific ZP exit, integrating foundational knowledge with recent breakthroughs that have begun to decipher how the hatching site governs implantation potential. Framed within broader research on factors affecting mouse embryo implantation success, this review provides an in-depth analysis of the mechanisms, consequences, and research methodologies central to understanding blastocyst hatching dynamics.

Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Hatching

The process of blastocyst hatching is governed by a concert of biophysical and biochemical mechanisms. The trophectoderm (TE), the outer cell layer of the blastocyst, plays the lead role in executing this escape.

- Biophysical Forces: A primary driver is the elevated osmotic pressure within the blastocoel cavity, created by the active transport of ions, particularly through Na+/K+ ATPase pumps located on TE cells. This pumping action draws water into the cavity, increasing internal pressure and exerting a mechanical force against the ZP [6] [7].

- Biochemical Degradation: Concurrently, TE cells produce and secrete a repertoire of proteases that hydrolyze the glycoprotein matrix of the ZP. These enzymes locally weaken the ZP, creating a focal point where the combined pressure and enzymatic activity can lead to rupture and embryo extrusion [6]. The site where the TE initially herniates through the ZP is defined as the hatching site.

The interplay between global pressure and localized degradation suggests an inherent capacity for the blastocyst to regulate the location of its exit, a process that appears to have significant developmental consequences.

Site-Specific Hatching and Its Impact on Implantation Potential

The hypothesis that the hatching site is random has been challenged by detailed morphological and transcriptomic analyses. Evidence from mouse models indicates a site preference that correlates strongly with subsequent implantation success and pregnancy outcomes.

A 2020 study by Liu et al. classified over 1,800 mouse hatching blastocysts based on the angle (θ) between the hatching site and the arc midpoint of the ICM. Their analysis revealed a non-random distribution [8]. The table below summarizes their key findings on site distribution and developmental outcomes after transfer.

Table 1: Distribution of Hatching Sites and Resulting Developmental Outcomes in Mice

| Hatching Site Category (Angle θ) | Distribution of Blastocysts | Implantation Rate | Development to Term |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0° ≤ θ ≤ 30° (near ICM) | 30.60% | No significant difference | ~30% (No significant difference) |

| 30° < θ ≤ 60° | 43.84% | No significant difference | ~30% (No significant difference) |

| 60° < θ ≤ 90° (opposite ICM) | 21.67% | No significant difference | ~30% (No significant difference) |

| Multiple Hatching Sites | 3.89% | Not reported | Not reported |

This study concluded that while hatching site distribution was not random, the site itself had no measurable impact on implantation rates, pregnancy maintenance, litter size, or offspring health [8].

In contrast, a more recent study by An et al. (2025) presented a different classification system and reached a contrasting conclusion. They classified hatching into sites relative to an "ICM clock" and found a strong correlation between hatching site and birth rate [7].

Table 2: Hatching Site Classification and Birth Rates by An et al.

| Hatching Site | Description | Birth Rate After Transfer |

|---|---|---|

| B-site | 3 o'clock (beside ICM) | 65.6% |

| A-site | 1-2 o'clock (near ICM) | 55.6% |

| C-site/D-site | 4-6 o'clock (opposite ICM) | 21.3% |

| Failure to Hatch | Non-hatching blastocysts | 5.1% |

This work demonstrated that blastocysts hatching from sites near or beside the ICM (A and B sites) had significantly higher developmental potential than those hatching from sites opposite the ICM [7].

Transcriptomic Underpinnings of Site-Specific Potential

The disparity in developmental outcomes is rooted in distinct gene expression profiles. RNA-seq analysis of blastocysts grouped by hatching site revealed that embryos with high implantation potential (A and B sites) cluster closely together, while those with poor potential (C site and non-hatching) form a separate cluster [7].

- Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs): A comparison between B-site (high success) and C-site (low success) blastocysts identified 178 differentially expressed genes. These genes were significantly enriched in immune-related pathways [7].

- Key Regulators: Transcription factors TCF24 and DLX3 were identified as primary regulators of these DEGs. Furthermore, a specific transcriptional switch, involving upregulation by transcription factor ATOH8 and downregulation by SPIC, activates immune pathways as the blastocyst progresses from expansion to full hatching [7].

- Critical Immune Genes: Upregulated genes in successfully hatching blastocysts included

Ptgs1,Lyz2,Il-α, andCfb, whileCd36was downregulated. Immunofluorescence confirmed the presence of immune factors like C3 and IL-1β on the extra-luminal surface of the TE, suggesting their role in preparing for maternal-fetal crosstalk [7].

This work provides a molecular rationale for the observed phenotypic differences, positioning the immune properties of the preimplantation embryo as a major determinant of hatching success and subsequent implantation competence.

Essential Signaling Pathways Governing Implantation

Successful implantation depends on a synchronized dialogue between a receptive endometrium and a mature, hatched blastocyst. Key signaling pathways, particularly in the uterus, are essential for this process.

The LIFR/GP130-JAK-STAT3 Axis

The Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) signaling pathway is a master regulator of implantation in mice.

- LIF, expressed in the uterine glandular epithelium in response to estrogen, binds to a heterodimeric receptor complex composed of LIFR (LIF receptor) and GP130 on the luminal epithelium [9] [3].

- This binding activates the associated JAK kinases, which phosphorylate the transcription factor STAT3.

- Phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3) dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, driving the expression of genes essential for endometrial receptivity and embryo adhesion [9].

The non-redundant criticality of this pathway is demonstrated by the complete infertility observed in mouse models with uterine epithelial-specific knockout of Lif, Lifr, Gp130, or Stat3, all of which result in implantation failure [9] [3].

Figure 1: The LIFR/GP130-JAK-STAT3 Signaling Pathway in Implantation. This pathway is essential for establishing uterine receptivity in mice.

Novel Pharmacological Activation and Cross-Talk

Recent research has identified RO8191, a small-molecule interferon agonist that also acts as a potent STAT3 activator. In mouse delayed implantation models, RO8191 was able to induce embryo implantation and decidualization, even in uterine epithelial-specific Lifr conditional knockout mice [9]. This suggests that RO8191 can bypass the need for the LIF ligand and LIFR component to trigger the critical downstream STAT3 signaling.

Further investigation into Lifr and Gp130 knockout models revealed that while both receptors are required for fertility, they mediate non-identical signaling outputs. Hub gene analysis identified ERBB2 (a receptor tyrosine kinase) and c-Fos as key downstream regulators, outlining a crucial role for LIFR-mediated ERBB2 signaling in successful implantation [3].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

This section details key experimental approaches for studying blastocyst hatching and implantation in mouse models.

The following methodology, adapted from An et al. and Liu et al., is used to investigate the relationship between hatching site and developmental potential [8] [7].

- Embryo Collection: Superovulate 6-8 week old CD-1 or ICR female mice using PMSG and hCG. Mate with fertile males and check for vaginal plugs (designated 0.5 dpc). Flush expanding blastocysts from the uterus at 3.5 dpc using M2 medium.

- In Vitro Culture: Culture flushed blastocysts in KSOM medium under mineral oil in a standard cell culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2).

- Site Classification: After 6-8 hours of culture, observe blastocysts and classify the hatching site based on the relative position to the ICM.

- Embryo Transfer: Use a non-surgical embryo transfer (NSET) device to transfer classified, hatching blastocysts into pseudopregnant recipient females.

- Outcome Assessment: Monitor recipients for implantation sites, pregnancy rates, litter size, and offspring health to correlate with the initial hatching site.

Protocol: The Delayed Implantation (DI) Model

The DI model is a powerful tool for dissecting the molecular requirements for implantation, as it uncouples embryo development from uterine receptivity [9].

- Ovariectomy: On day 3 of pregnancy (D3), perform ovariectomy on plug-positive female mice under anesthesia.

- Progesterone Maintenance: Administer medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) subcutaneously daily to maintain a state of delayed implantation. In this state, blastocysts hatch but remain dormant in the uterus.

- Experimental Intervention: On D7, administer a single injection of the experimental stimulus. This can be:

- Positive Control: Estradiol (E2, 25 ng/head).

- Test Compound: e.g., RO8191 (400 µg/head, i.p.) [9].

- Vehicle Control: Sesame oil.

- Tissue Collection: Euthanize mice 24-72 hours post-injection. Collect uterine tissue to:

- Count implantation sites visualized by Chicago Blue dye injection.

- Analyze molecular changes via Western blot or immunohistochemistry (e.g., p-STAT3 levels).

- Perform RNA sequencing for transcriptomic profiling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The table below catalogues essential reagents and their applications in studying blastocyst hatching and implantation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Embryo Implantation Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Details / Example |

|---|---|---|

| RO8191 | A small-molecule STAT3 activator used to induce implantation in mouse models. | Can rescue implantation in Lifr cKO mice; useful for studying STAT3-dependent pathways [9]. |

| Tucatinib / Sapitinib | ERBB2 inhibitors used to probe the role of LIFR-ERBB2 signaling in implantation. | Orally administered; experiments with these inhibitors underscore the importance of ERBB2 signaling downstream of LIFR [3]. |

| SCADS Inhibitor Kits | Standardized libraries of low-molecular-weight inhibitors for screening novel developmental factors. | Used in high-throughput screens to identify proteins like Cathepsin D and CXCR2 as regulators of early development [10]. |

| Non-Surgical Embryo Transfer (NSET) Device | A device for transferring embryos into recipient mice without invasive surgery. | Minimizes stress and surgical complications; improves animal welfare and live birth rates in transfer experiments [8]. |

| Laser-Assisted Hatching (LAH) System | A microscopic laser used to create a precise opening in the ZP for assisted hatching studies. | Laser power ~400 mW, wavelength 1480 nm; used to study the effects of artificial hatching on re-expansion and implantation [11]. |

| ST-193 hydrochloride | ST-193 hydrochloride, MF:C24H26ClN3O, MW:407.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Cyclopropylethane-1-sulfonamide | 2-Cyclopropylethane-1-sulfonamide|CAS 1487784-84-8 | 2-Cyclopropylethane-1-sulfonamide for research. This sulfonamide derivative is for Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Discussion and Synthesis

The investigation into blastocyst hatching dynamics reveals a complex picture where the location of ZP exit is a biomarker of the embryo's underlying health and developmental potential. The apparent contradiction between studies finding no effect of hatching site [8] and those finding a strong correlation [7] may be reconciled by considering the molecular heterogeneity of blastocysts. The transcriptomic evidence from An et al. suggests that the hatching site itself may be a manifestation of pre-existing, global gene expression patterns, particularly in immune-related pathways, that ultimately dictate both the site selection and the capacity for successful maternal-fetal interaction [7].

From a translational perspective, these findings have significant implications for ART. The development of a predictive model for implantation success based on DEGs like Lyz2, Cd36, Cfb, and Cyp17a1 offers a potential new tool for embryo selection [7]. Furthermore, the nuanced effects of assisted hatching (AH)—where it may benefit poor-quality blastocysts (TE grade C) while potentially impairing the re-expansion of competent vitrified-warmed blastocysts—argues for a more refined, patient-specific application of this technique [11]. The discovery of pharmacological agents like RO8191 that can activate key implantation pathways also opens avenues for therapeutic intervention in cases of recurrent implantation failure [9].

The journey of the mammalian blastocyst out of its zona pellucida is far from a simple escape. It is a dynamic, biologically programmed event where the site of exit provides a critical window into the embryo's molecular constitution and future developmental potential. Research in mouse models has been instrumental in uncovering the intricate relationships between hatching location, immune gene activation, and implantation success. As the molecular players and signaling pathways continue to be elucidated, the opportunity to develop more sophisticated diagnostic tools and targeted interventions for human infertility grows. The ongoing challenge for researchers and clinicians is to translate these dynamic biological principles into strategies that improve outcomes in assisted reproduction and regenerative medicine.

The success of mouse embryo implantation is a complex biological process dependent on precise orchestration of immune-related gene expression at the maternal-fetal interface. This intricate crosstalk between maternal decidua and fetal trophoblast cells establishes a unique immunological microenvironment that facilitates embryonic acceptance while maintaining host defense capabilities. Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics have revealed unprecedented details about the transcriptional dynamics governing this relationship, providing new insights into the molecular mechanisms that determine implantation success. The maternal immune system undergoes remarkable adaptations during pregnancy, transitioning through pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, and again pro-inflammatory phases to accommodate implantation, fetal development, and parturition [12] [13]. Understanding how immune-related gene networks coordinate these phases offers significant potential for improving outcomes in assisted reproductive technologies and addressing implantation failure.

Within the context of mouse embryo implantation research, this whitepaper examines how transcriptional regulation of immune mediators—including cytokines, growth factors, and epigenetic regulators—shapes the uterine environment for embryonic acceptance. We focus specifically on the molecular dialogue between maternal immune cells and developing embryos, highlighting technical approaches for quantifying these interactions and their implications for developmental success.

Quantitative Landscape of Immune-Mediated Implantation Success

Analysis of multiple studies reveals consistent quantitative relationships between specific immune-related gene expression patterns and embryo implantation outcomes in mouse models. The data demonstrate that transcriptional stability and specific immune signatures strongly correlate with implantation success rates.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Relationships in Immune-Related Gene Expression and Implantation Outcomes

| Experimental Factor | Measured Parameter | Impact on Implantation | Reference Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allogeneic MHC combinations | 25-30% reduction in "intrinsic" gene noise | Positive impact on embryonic mass | C57BL/6J embryos in surrogate mothers [14] |

| Maternal HFD-induced sncRNA alterations | 72.3% rsRNAs in UF vs 58.3% in controls (P=0.036) | Impaired blastocyst metabolic gene expression | Pre-implantation maternal HFD mouse model [15] |

| Ex vivo uterine culture system | >90% embryonic attachment efficiency | Enables implantation and embryogenesis | Air-liquid interface culture with PDMS devices [16] |

| Sequential embryo transfer | Significantly higher CPR and IR (P<0.01) | Beneficial for patients with repeated implantation failures | Frozen embryo transfer cycles [17] |

| "Intrinsic" gene noise | Negative correlation with embryonic mass & PLGF | Associated with phenotypic growth instability | C57BL/6J in NOD-SCID/BALB/c mothers [14] |

Table 2: Immune Cell Populations at the Maternal-Fetal Interface in Normal vs RM Conditions

| Cell Type | Normal Pregnancy (%) | Recurrent Miscarriage (RM) (%) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dendritic Cells (DCs) | Lower proportion | Higher proportion | Antigen presentation, immune tolerance |

| Macrophages | Lower proportion | Higher proportion | Tissue remodeling, immune regulation |

| Villous Cytotrophoblasts (VCTs) | Lower proportion | Higher proportion | Trophoblast stem cells |

| Extravillous Trophoblasts (EVTs) | Higher proportion | Lower proportion | Spiral artery remodeling, invasion |

| Uterine Natural Killer (uNK) cells | 60-90% of decidual immune cells | Altered proportions | Vascular remodeling, cytokine secretion |

Methodologies for Assessing Transcriptional Landscapes

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Analysis

Protocol Overview: Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables comprehensive profiling of transcriptional heterogeneity at the maternal-fetal interface. The standard protocol involves: (1) tissue collection and dissociation into single-cell suspensions from paired placental and decidual tissues; (2) cell partitioning and barcoding using microfluidic devices; (3) library preparation and sequencing; (4) bioinformatic analysis using Seurat and CellChat pipelines [18].

Technical Specifications: Cells with <600 detected genes or total mitochondrial gene expression >5% are typically removed during quality control. Differential expression analysis employs the FindMarkers function in Seurat with test.use = MAST, setting significance thresholds at p-value <0.05 and |log2(fold change)| >0.58. Cell communication analysis utilizes the CellChat R package to predict major signaling inputs and outputs and identify differentially expressed ligand-receptor pairs between normal and pathological pregnancies [18].

Application: This approach has revealed alterations in the cellular organization of the decidua and placenta in recurrent miscarriage (RM), identifying dysregulated interactions between trophoblast cells and decidual immune cells that contribute to implantation failure [18].

Statistical Framework for Developmental Instability Components

Protocol Overview: A specialized statistical framework dissects "extrinsic" (canalization) and "intrinsic" (fluctuating asymmetry, FA) components of developmental instability from bilateral trait measurements [14].

Technical Specifications: The method employs Principal Component Analysis (PCA) projection of left/right measurements on eigenvectors followed by Generalized Additive Models for Location Scale and Shape (GAMLSS) modeling of eigenvalues. The first eigenvalue represents "extrinsic" developmental instability, while the second represents "intrinsic" components. For a bilateral trait measured on left (l) and right (r) sides, "extrinsic" variance is calculated as Var[E(x|ξ)] = Var(l+r/2) ≈ ¼σ²l+r, while "intrinsic" variance is E[Var(x|ξ)] ≈ ¼FA = ¼σ²l-r [14].

Application: This framework demonstrated that allogeneic MHC combinations in C57BL/6J embryos developing in surrogate NOD-SCID and BALB/c mothers decreased both "extrinsic" and "intrinsic" gene expression noise, correlating with improved embryonic growth and developmental stability [14].

Ex Vivo Uterine Culture System

Protocol Overview: An ex vivo uterine system recapitulates bona fide implantation at >90% efficiency using authentic mouse embryos and uterine tissue [16].

Technical Specifications: The system utilizes air-liquid interface (ALI) culture with originally developed polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) devices manufactured for optimal gas permeability. Day post coitum (dpc) 3.75 endometria are isolated and co-cultured with E3.75 blastocysts. The optimized EXiM medium, based on IVC2 medium containing KnockOut Serum Replacement (KSR) instead of Fetal Calf Serum (FCS), maintains physiological ovarian hormone levels (3 pg/mL for 17β-estradiol and 60 ng/mL for progesterone). The system uses 750 μm-thick PDMS ceilings, which produce optimal attachment efficiency (95.8%) while facilitating observation under fluorescent upright microscopes [16].

Application: This system has replicated the robust induction of maternal implantation regulator COX-2 at the attachment interface, accompanied by trophoblastic AKT activation, suggesting possible signaling mediating maternal-embryonic communication that accelerates implantation [16].

Signaling Pathways in Maternal-Fetal Crosstalk

Immune Signaling Pathways at Maternal-Fetal Interface

The diagram illustrates key signaling pathways mediating maternal-fetal crosstalk, highlighting how allogeneic MHC combinations decrease transcriptional noise to promote developmental stability and embryonic growth. Critical interactions include: (1) PVR-CD226/TIGIT signaling between extravillous trophoblasts and T cells/dendritic cells; (2) VEGF/PLGF secretion by uterine NK cells to promote vascular remodeling; (3) ADM-CALCRL signaling between EVTs and dendritic cells to promote immune tolerance; and (4) cytokine-mediated facilitation of trophoblast invasion by macrophages [14] [12] [18].

Epigenetic Regulation of Immune Gene Expression

Epigenetic mechanisms serve as critical interfaces between environmental signals and transcriptional responses at the maternal-fetal interface. DNA methylation patterns significantly influence immune cell function and trophoblast development through gene silencing mechanisms. DNMT1 maintains methylation status, while DNMT3A and DNMT3B act on unmethylated DNA, with TET proteins mediating demethylation processes. At the maternal-fetal interface, abnormal DNA methylation regulation affects embryonic development ability and interferes with the immune microenvironment, contributing to adverse pregnancy outcomes [13].

Histone modifications, including acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation, provide another layer of epigenetic control that modulates chromatin structure and accessibility. Histone acetylation by HAT and HDAC enzymes balances transcriptional activation and repression, with specific HDACs (HDAC8, HDAC9) regulating M1/M2 macrophage polarization. Histone methylation at various lysine residues (H3K4, H3K9, H3K27, H3K36) either activates or represses transcription depending on the specific site and methylation level [13].

Non-coding RNAs, particularly small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs) in reproductive fluids, have emerged as important mediators of maternal-embryonic communication. PANDORA-seq analysis revealed that tRNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) and rRNA-derived small RNAs (rsRNAs) comprise over 80% of sncRNAs in oviduct and uterine fluids, exhibiting dynamic changes in response to maternal dietary factors like high-fat diet. These sncRNAs may reflect maternal metabolic status and transmit dietary information to early embryos, influencing implantation success and offspring health [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Maternal-Fetal Transcriptional Landscapes

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Markers | CD56, CD16, CD11c, KLRK1, NCR3 | Immune cell phenotyping | Distinguish uNK (CD56bright CD16-) from pbNK (CD56dim CD16+) cells [12] |

| Cytokines/Growth Factors | VEGF, PLGF, CSF1, CSF2, IL15 | Functional assays | uNK-derived angiogenic factors; stromal cell-mediated NK expansion [14] [12] |

| Epigenetic Tools | DNMT inhibitors, HDAC inhibitors, HAT activators | Epigenetic regulation studies | Modulate DNA methylation and histone acetylation at interface [13] |

| sncRNA Analysis | PANDORA-seq, LC-MS | sncRNA profiling | Comprehensive tsRNA/rsRNA detection with modification analysis [15] |

| Culture Media | EXiM medium, IVC2 with KSR | Ex vivo implantation models | Supports embryo development with optimized hormone levels [16] |

| Animal Models | C57BL/6J, NOD-SCID, BALB/c | MHC interaction studies | Allogeneic vs syngeneic maternal-fetal immune interactions [14] |

Experimental Workflow for Transcriptional Analysis

Workflow for Maternal-Fetal Interface Transcriptomics

The workflow outlines a comprehensive pipeline for analyzing transcriptional landscapes at the maternal-fetal interface, beginning with tissue collection and progressing through single-cell sequencing, bioinformatic analysis, and functional validation. Critical quality control metrics include filtering cells with fewer than 600 detected genes or greater than 5% mitochondrial gene expression. The analytical phase utilizes Seurat for cell clustering and differential expression analysis with MAST test, followed by CellChat for predicting cell-cell communication networks. Functional validation employs ex vivo uterine systems or targeted gene modulation to confirm identified pathways [16] [18].

The transcriptional landscape of immune-related gene expression at the maternal-fetal interface represents a sophisticated regulatory network that determines implantation success in mouse models. Key determinants include MHC-mediated interactions that reduce transcriptional noise and stabilize development, epigenetic mechanisms that fine-tune immune responses, and sncRNA-mediated communication that transmits maternal metabolic information to embryos. The integrated analysis of these elements through advanced technologies like scRNA-seq and ex vivo culture systems provides unprecedented insights into the molecular dialogue governing implantation. These findings not only illuminate fundamental biological processes but also offer promising avenues for developing targeted interventions to address implantation failure in clinical settings. Future research should focus on translating these mechanistic insights into diagnostic and therapeutic strategies that can improve pregnancy outcomes in assisted reproduction.

{/* Main content of the technical guide begins */}

Endocannabinoids and Other Signaling Molecules: Exploring the Uterine Milieu

The success of mouse embryo implantation is not an autonomous process but is critically dependent on a synchronized dialogue between the developing blastocyst and a receptive uterine environment. This review delves into the intricate signaling networks within the uterine milieu, with a particular focus on the endocannabinoid system as a pivotal regulator. We explore how molecules such as anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), signaling through their cognate receptors CB1 and CB2, create a precise biochemical landscape that guides preimplantation embryo development, oviductal transport, and decidualization. Disruption of this finely tuned system, through either genetic ablation of its components or pharmacological manipulation, leads to asynchronous development and implantation failure, ultimately compromising pregnancy rates. This whitepaper synthesizes key quantitative data and experimental methodologies from foundational studies, providing a technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals working to elucidate the fundamental mechanisms governing reproductive success.

Embryo implantation is a complex and critically timed biological process that represents a major rate-limiting step in mammalian pregnancy. In mice, successful implantation requires the simultaneous achievement of two key milestones: the development of the preimplantation embryo to the blastocyst stage, and the differentiation of the uterine endometrium into a receptive state, often termed the "window of implantation" [19]. A failure in this synchrony is a significant cause of early pregnancy loss. The uterine milieu, composed of a dynamic mix of signaling molecules, is the medium through which this maternal-embryonic cross-talk occurs. Among these signals, endocannabinoids—a class of endogenous lipid-based neurotransmitters—have emerged as crucial directors of early pregnancy events [20] [21]. Historically, the adverse effects of cannabis (marijuana) on female fertility were observed for decades, but the underlying molecular mechanisms remained elusive until the discovery of the endocannabinoid system [20]. This system, comprising endogenous ligands (e.g., AEA and 2-AG), their synthetic and degradative enzymes, and cannabinoid receptors, provides a molecular framework for understanding how the uterine environment is actively shaped to support reproduction. Framed within broader research on factors affecting mouse embryo implantation success, this review examines the endocannabinoid system as a central, model component of the signaling uterine milieu.

The Molecular Players: Composition of the Uterine Milieu

The biochemical environment of the uterus during the periimplantation period is defined by a precise balance of numerous factors, with the endocannabinoid system playing a prominent role.

Core Components of the Endocannabinoid System

The two most well-characterized endocannabinoids are anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG). Both are lipid-derived molecules synthesized on demand that activate G-protein coupled cannabinoid receptors [20]. Despite their similar functions, they possess distinct biochemical properties and signaling efficacies. AEA often acts as a partial agonist of cannabinoid receptors, while 2-AG acts as a full agonist. However, the binding affinity of 2-AG to these receptors is approximately 24 times less than that of AEA [20].

Their levels are tightly regulated by specialized synthetic and degradative enzymes:

- AEA Synthesis and Degradation: AEA is primarily derived from the precursor N-arachidonoylphosphatidylethanolamine (NAPE). The canonical pathway involves cleavage by NAPE-hydrolyzing phospholipase D (NAPE-PLD) [20]. Alternative pathways via α/β-hydrolase 4 (Abh4) and a phospholipase C/protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN22) pathway also contribute [20] [21]. Its degradation is predominantly mediated by a membrane-bound fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), which hydrolyzes AEA into ethanolamine and arachidonic acid [20] [22].

- 2-AG Synthesis and Degradation: 2-AG is produced from diacylglycerol (DAG) by sn1-diacylglycerol lipase (DAGL), which has two isoforms, DAGLα and DAGLβ [20]. It is degraded primarily by monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL), and to a lesser extent by FAAH [20] [22].

The primary receptors for endocannabinoids are:

- Cannabinoid Receptor 1 (CB1): Encoded by the Cnr1 gene, CB1 is widely expressed in the central nervous system but is also found in peripheral tissues, including the uterus, oviduct, and preimplantation embryo [20] [21]. In blastocysts, CB1 is localized primarily in the trophectoderm [21].

- Cannabinoid Receptor 2 (CB2): Encoded by the Cnr2 gene, CB2 is predominantly expressed in immune cells but is also present in the preimplantation embryo, specifically in the inner cell mass (ICM) from the one-cell stage [20] [21].

Interaction with Other Signaling Pathways

The endocannabinoid system does not operate in isolation. It exhibits cross-talk with other critical pathways in the uterus:

- Vanilloid Receptors: AEA can also activate the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), a ligand-gated ion channel, triggering calcium influx and distinct cellular responses [20].

- Angiogenic Factors: Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor FLK1 are key regulators of uterine blood vessel remodeling. Their expression is intricately linked to endocannabinoid signaling during decidualization [23].

- Decidualization Markers: Morphogens and transcription factors such as BMP2 and HOXA10 are critical for stromal cell differentiation and are downstream of proper endocannabinoid signaling [23].

- Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) / Prostaglandin Pathway: This enzyme, critical for implantation, also participates in metabolizing 2-AG, creating a direct biochemical link between the endocannabinoid and prostaglandin systems in the uterus [22].

The following diagram illustrates the core synthesis, signaling, and degradation pathways of the two major endocannabinoids.

Endocannabinoid Synthesis and Signaling Pathways

Quantitative Data: Concentrations, Localization, and Phenotypes

A comprehensive understanding of the uterine milieu requires an integration of quantitative data on endocannabinoid levels, spatiotemporal expression patterns, and the phenotypic outcomes of experimental manipulations. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from foundational studies in mouse models.

Table 1: Endocannabinoid Levels and Receptor Expression in the Mouse Uterine Milieu

| Parameter | Measurement / Localization | Biological Significance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uterine 2-AG Level | One order of magnitude higher than AEA [22] | High basal level suggests 2-AG has distinct, non-redundant functions in uterine physiology. | Day 5-6 of pregnancy in mice [22]. |

| Uterine AEA Gradient | Lower at implantation sites; higher at interimplantation sites [22] | Creates a localized environment permissive for blastocyst implantation. | Day 5 of pregnancy in mice [22]. |

| CB1 Receptor Expression | Oviduct & uterus; Trophectoderm of blastocyst [20] [21] | Mediates effects on oviductal embryo transport and trophectoderm development. | Immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, RT-PCR [20] [21]. |

| CB2 Receptor Expression | Inner Cell Mass (ICM) of blastocyst [21] | Suggests a specific role in regulating development of the embryo proper. | Immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, RT-PCR [20] [21]. |

| AEA Trophic Effect | Trophoblast outgrowth promoted at 7 nM; retarded at 28 nM [21] | Demonstrates the biphasic, concentration-dependent effect of AEA on embryonic development. | In vitro blastocyst culture assay [21]. |

Table 2: Phenotypic Outcomes in Cannabinoid Receptor Mutant Mice

| Genotype | Embryo Development Phenotype | Implantation / Decidualization Phenotype | Key Molecular Alterations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cnr1-/- | Retarded development in vivo; Resistant to AEA-induced arrest in vitro [19] [21] | Compromised primary decidual zone (PDZ) formation; retained blood vessels & macrophages [23]. | Dysregulated angiogenic factors (VEGFA, FLK1) in PDZ [23]. |

| Cnr2-/- | Mild developmental aberrations [21] | Less severe decidual defects compared to Cnr1-/- [23]. | Increased uterine edema before implantation [23]. |

| Cnr1-/- Cnr2-/- (Double KO) | Severely retarded development; oviductal retention [19] [21] | Severely compromised PDZ; defective Bmp2/Hoxa10 expression; flat uterine lumen [23]. | Significant retention of F4/80+ macrophages and CD45+ hematopoietic cells near embryo [23]. |

| Wild-type | Normal development to blastocyst | Normal formation of an avascular PDZ; proper embryo-uterine synchrony. | Normal spatiotemporal expression of Ptgs2, Bmp2, and Vegfa [23]. |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Investigating the Uterine Milieu

To enable replication and critical evaluation, this section outlines detailed protocols for key experiments that have elucidated the role of endocannabinoids in mouse embryo implantation.

Assessing Preimplantation Embryo Development In Vitro

Objective: To determine the direct effects of endocannabinoids on the developmental competence of preimplantation embryos.

Materials:

- Research Reagents:

- Cannabinoid Agonists: Anandamide (AEA), 2-Arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), synthetic agonist WIN55212-2.

- Receptor Antagonists: SR141716A (CB1-selective), AM251 (CB1-selective), SR144528 (CB2-selective).

- Culture Media: HEPES-buffered medium for handling; specific culture media like HTF (Human Tubal Fluid) under oil for extended culture [24].

- Embryos: One-cell or two-cell stage mouse zygotes collected from superovulated females.

Methodology:

- Embryo Collection: Sacrifice mated female mice and flush one-cell or two-cell embryos from the oviducts.

- Experimental Groups: Randomize and allocate embryos into control and treatment groups.

- Control: Culture medium with vehicle (e.g., DMSO, ethanol).

- Treatment: Culture medium supplemented with specific concentrations of cannabinoid agonists (e.g., 7 nM, 28 nM AEA) [21].

- Antagonist Co-treatment: Include groups with agonist plus a receptor antagonist (e.g., AEA + SR141716A) to confirm receptor specificity.

- Culture Conditions: Culture embryos in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 72-96 hours.

- Outcome Assessment: Monitor and record embryo development every 24 hours. Key endpoints include:

- Rate of development to the morula and blastocyst stages.

- Blastocyst cell number (e.g., by differential staining of ICM and TE).

- Blastocyst zona hatching rate [21].

In Vivo Analysis of Embryo Transport and Uterine Receptivity

Objective: To investigate the role of maternal cannabinoid signaling in transporting embryos from the oviduct to the uterus and preparing the uterus for implantation.

Materials:

- Animal Models: Wild-type and cannabinoid receptor knockout (e.g., Cnr1-/-, Cnr2-/-, Cnr1-/-Cnr2-/-) mice.

- Reagents: Miniosmotic pumps for sustained delivery of (-)THC [19].

- Detection Tools: Specific RNA probes for in situ hybridization (e.g., for Ptgs2, Bmp2, Hoxa10); antibodies for immunohistochemistry (e.g., against FLK1, F4/80, Scribble) [23].

Methodology:

- Mating and Drug Administration: Mate female mice with proven males. Confirm mating by vaginal plug (day 1 of pregnancy). Implant miniosmotic pumps containing vehicle or (-)THC from day 2 to day 5 [19].

- Tissue Collection: Sacrifice mice on specific days of pregnancy (e.g., day 4 for embryo location; day 5-6 for implantation site analysis).

- Embryo Recovery and Localization: Flush embryos from the oviducts and uterus on day 4. The number and location of embryos are recorded. Fewer embryos in the uterus of knockout females indicates oviductal retention [21].

- Analysis of Uterine Receptivity and Decidualization:

- In situ hybridization: Analyze the expression patterns of receptivity (Ptgs2) and decidualization (Bmp2, Hoxa10) markers in uterine sections [23].

- Immunohistochemistry: Stain uterine sections from day 6 of pregnancy to assess PDZ integrity (Scribble), vascularization (FLK1), and immune cell presence (F4/80 for macrophages) [23].

In Vitro Decidualization Assay

Objective: To model stromal cell differentiation in culture and dissect the cell-autonomous role of endocannabinoid signaling in decidualization.

Materials:

- Cell Source: Primary uterine stromal cells isolated from day 4 pregnant wild-type or Cnr1-/- mice.

- Decidualization Cocktail: Culture media containing progesterone (P4) and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) to induce decidualization [23].

- Neutralizing Agents: CB1 receptor neutralizing antibody or specific antagonists.

Methodology:

- Stromal Cell Isolation: Dissect uteri from day 4 pregnant mice, enzymatically digest, and isolate the stromal cell fraction.

- Induction of Decidualization: Plate stromal cells and treat with control media or decidualization media (P4 + cAMP) for 5-7 days.

- Experimental Intervention: Include treatment groups with CB1 antagonists or neutralizing antibodies during the decidualization process.

- Assessment of Decidualization:

- Morphological: Observe transformation from fibroblastic to epithelioid morphology.

- Molecular: Quantify mRNA or protein levels of decidual markers (e.g., Bmp2, Hoxa10) via qRT-PCR or western blot.

- Functional: Measure the expression of angiogenic factors (e.g., VEGFA) in the culture supernatant [23].

The workflow for these key methodologies is summarized in the following diagram.

Experimental Workflow for Key Methodologies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A systematic investigation of endocannabinoids in the uterine milieu relies on a specific toolkit of reagents, animal models, and detection methods. The following table catalogs essential resources for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Endocannabinoid Studies

| Reagent / Model Category | Specific Example | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists | Anandamide (AEA), 2-Arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), Δ9-THC, WIN55212-2 | Activate CB1 and/or CB2 receptors to mimic elevated endocannabinoid signaling and test effects on embryo development and uterine function [20] [21]. |

| Cannabinoid Receptor Antagonists | SR141716A (Rimonabant), AM251 (CB1-selective); SR144528 (CB2-selective) | Block specific cannabinoid receptors to elucidate their individual roles and confirm receptor-mediated effects [19] [21]. |

| Genetic Mouse Models | Cnr1-/- (CB1 KO), Cnr2-/- (CB2 KO), Cnr1-/- Cnr2-/- (Double KO) | Provide loss-of-function models to study the physiological roles of cannabinoid receptors in embryo transport, implantation, and decidualization without pharmacological confounding [19] [23] [21]. |

| Key Enzymatic Targets | FAAH inhibitors (e.g., URB597), MAGL inhibitors (e.g., JZL184) | Elevate endogenous levels of AEA or 2-AG, respectively, by blocking their degradation, allowing study of tonic endocannabinoid signaling [20]. |

| Molecular Detection Tools | RNA probes for Ptgs2, Bmp2, Hoxa10; Antibodies for FLK1, F4/80, Scribble | Used in in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry to visualize spatial and temporal patterns of gene expression and protein localization in uterine tissues [23]. |

| Culture Media & Supplements | HEPES-buffered handling media; HTF (Human Tubal Fluid) culture media; Hormones (Progesterone, Estrogen) | Ensure optimal embryo viability during manipulation and culture, and for preparing the uterus in experimental models [24]. |

| Phenamil methanesulfonate | Phenamil methanesulfonate, CAS:1161-94-0; 2038-35-9, MF:C13H16ClN7O4S, MW:401.83 | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-(azidomethoxy)-2-methoxyethane | 1-(Azidomethoxy)-2-methoxyethane|Research Chemical | 1-(Azidomethoxy)-2-methoxyethane is a valuable azide-containing building block for research applications. This product is for research use only (RUO). |

The evidence from mouse models unequivocally establishes the endocannabinoid system as a central rheostat in the uterine milieu, fine-tuning the critical stages of early pregnancy. The precise spatiotemporal gradients of AEA and 2-AG, achieved through the regulated expression of their synthetic and catabolic enzymes, create a conducive environment for synchronized embryo-uterine dialogue. The concentration-dependent, biphasic effects of ligands like AEA, coupled with the distinct but complementary roles of CB1 and CB2 receptors, highlight the exquisite sensitivity of reproductive processes to this signaling system. Disruption of this balance, as evidenced by studies in knockout mice, leads to a cascade of failures including oviductal embryo retention, defective decidualization, impaired formation of the protective PDZ, and ultimately, pregnancy loss.

Future research must bridge the gap between these detailed mechanistic studies in mice and human reproductive health. While mice have been invaluable models, differences in reproductive physiology and placentation necessitate careful extrapolation [25]. Investigating the role of endocannabinoids in human endometrial stromal cell decidualization and trophectoderm invasion is a critical next step. Furthermore, the interplay between endocannabinoids and other signaling pathways, such as prostaglandins and angiogenic factors, represents a complex regulatory network that is only beginning to be understood. From a translational perspective, components of the endocannabinoid system, such as FAAH in lymphocytes, have been implicated in human miscarriage [19], suggesting potential as diagnostic biomarkers or therapeutic targets for treating infertility. As our understanding deepens, manipulating the endocannabinoid tone may emerge as a novel strategy to improve outcomes in assisted reproductive technologies by optimizing the embryonic environment.

The use of mice as model organisms to study human biology is predicated on the genetic and physiological similarities between the species. Nonetheless, mice and humans have evolved in and become adapted to different environments and, despite their phylogenetic relatedness, have become very different organisms [26]. This is particularly true in the field of reproductive physiology, where the limitations of mouse models are critical for researchers to understand when investigating complex processes such as embryo implantation. Within the context of a broader thesis on factors affecting mouse embryo implantation success rates, this review synthesizes the fundamental genetic, physiological, and anatomical differences that complicate the extrapolation of mouse data to human reproductive biology. It further provides detailed experimental protocols and reagent solutions to guide rigorous research design in this field.

Evolutionary, Anatomical, and Physiological Divergence

Fundamental Evolutionary Differences

Since the lineages leading to modern rodents and primates diverged from a common ancestor approximately 85 million years ago, they have evolved distinct biological strategies [26]. The most fundamental difference is body size: humans are roughly 2,500 times larger than mice. Size is not merely a physical attribute but a major target of natural selection that correlates with a suite of metabolic and life history traits [26].

This size difference drives profound physiological divergence. The specific metabolic rate (metabolic rate per gram of tissue) of a mouse is roughly seven times that of a human [26]. This elevated metabolic rate is correlated with anatomic and biochemical differences, including:

- Higher mitochondrial density and capillary density in mouse tissues.

- Higher rates of reactive oxygen species production and oxidative damage.

- Differences in membrane phospholipid composition, with mouse cells having a higher content of readily oxidizable docosahexaenoic acid [26].

These underlying metabolic disparities can significantly influence cellular processes, including those critical for embryonic development and implantation.

Life History and Reproductive Strategies

Mice and humans exhibit vastly different life history strategies, which are tightly linked to their differences in body size and metabolic rate. These strategies directly impact reproductive physiology and experimental design.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Life History and Reproductive Traits Between Mice and Humans

| Trait | Mouse | Human |

|---|---|---|

| Time to Sexual Maturity | 6-8 weeks [26] | >12 years |

| Gestation Length | 19-20 days [26] | ~40 weeks |

| Litter Size | 5-8 pups [26] | Typically 1 |

| Life Span | 3-4 years (lab strains) [26] | >70 years |

| Energy Investment in Reproduction | High proportion [26] | Lower proportion |

These differences underscore that mice are selected for rapid, high-quantity reproduction, whereas humans invest heavily in a few, highly developed offspring. These divergent evolutionary pressures inevitably shape the molecular and physiological mechanisms governing reproduction.

Anatomical Differences in the Reproductive Tract

Significant anatomical differences exist between the reproductive tracts of mice and humans, which must be considered when studying implantation.

- Uterine Anatomy: The human uterus is a single, pear-shaped organ (simplex), while the mouse uterus is bipartite, consisting of two separate uterine horns (bicornuate). This fundamental structural difference affects the spatial context of implantation.

- Placentation: The type and invasiveness of placentation differ between the species, affecting the nature of the maternal-fetal interface.

- Penile Anatomy: The mouse penis contains a bone (os penis) and a substantial fibrocartilaginous projection (the male urogenital mating protuberance, MUMP), both absent in humans. Mice also have six penile erectile bodies, compared to two in humans [27]. These differences highlight divergent developmental pathways for structures dependent on androgen signaling.

Critical Differences in Embryo Implantation

Molecular Signaling in Implantation

A critical window for embryo implantation exists in both mice and humans, but the key molecular regulators, while sometimes sharing nomenclature, often play distinct roles. The leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) pathway is a prime example.

In mice, LIF is considered a master regulator of implantation. Uterine LIF expression is induced by a transient surge of nidatory estrogen on day 4 of pregnancy [9] [3]. LIF binds to a heterodimeric receptor complex of LIFR and GP130 on the uterine luminal epithelium, activating the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway. This activation is absolutely essential for embryo implantation in mice; genetic deletion of Lif, Lifr, Gp130, or Stat3 in the uterine epithelium results in complete implantation failure and infertility [9] [3].

However, the role of LIF in human implantation is less clear-cut and appears to be more modulatory than essential. While LIF is present in the human endometrium, its functional redundancy with other cytokines and its absolute necessity are not fully established. Recent research highlights further complexity within the mouse model itself. While LIFR and GP130 were thought to function solely as a heterodimer, their distinct expression patterns in the uterus suggest potential independent roles. A 2025 study using uterine epithelium-specific Lifr knockout (Lifr eKO) mice confirmed complete infertility but, through comprehensive gene expression analysis, identified ERBB2 (HER2/neu) as a key downstream signaling hub essential for implantation [3]. This reveals a more complex signaling network than previously appreciated.

The following diagram illustrates this essential signaling pathway for mouse embryo implantation:

Experimental Models for Studying Implantation

Researchers have developed several sophisticated mouse models to dissect the mechanics of implantation. Two key protocols are detailed below.

The Delayed Implantation (DI) Model

This model is invaluable for uncoupling embryo viability from uterine receptivity, allowing researchers to study the window of implantation directly [9].

Experimental Workflow: Delayed Implantation Model

Detailed Protocol:

- Timed Mating: House female mice with fertile males and check for vaginal plugs each morning. The day a plug is found is designated as day 1 of pregnancy (D1) [9] [3].

- Ovariectomy (OVX): On D3 (between 1300 and 1530 hours), anesthetize plug-positive females and perform ovariectomy to remove the primary source of endogenous hormones [9].

- Hormonal Maintenance: Immediately following OVX, administer a subcutaneous injection of the synthetic progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, 100 µl/head) to maintain the uterus in a neutral, non-receptive state [9].

- Implantation Arrest: With only P4 present, embryos will develop to the blastocyst stage but enter a state of "diapause" or developmental arrest. They can remain viable in the uterus for several days.

- Experimental Trigger: On D7, administer the experimental stimulus to initiate implantation. In a control group, a single injection of estradiol (E2, 25 ng/head) is given to mimic the natural nidatory E2 surge. In the test group, the compound of interest (e.g., RO8191, 400 µg/head, dissolved in sesame oil) is administered via intraperitoneal injection [9].

- Assessment: Sacrifice mice 72 hours post-injection (D10) and count the number of implantation sites, visible as distinct blue bands if a dye like Chicago Blue is injected intravenously prior to sacrifice [3]. Uterine horns can be flushed to recover embryos if no implantation sites are visible.

Conditional Knockout (cKO) Models

To define the cell-specific role of a gene, researchers use uterine epithelium-specific conditional knockout mice.

Detailed Protocol for Validating Gene Function in Implantation:

- Mouse Generation: Cross mice carrying a "floxed" allele of the target gene (e.g., Lifrflox/flox, Stat3flox/flox, Gp130flox/flox) with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of a uterine epithelial-specific promoter (e.g., *LtfiCre/+) [9] [3].

- Genotyping: Confirm the genotypes of offspring via PCR using tail clip DNA and specific primers for the Cre transgene and the floxed allele.

- Phenotyping:

- Fertility Test: House adult female cKO mice with proven fertile wild-type males for 4-6 months. Record the number of litters and pups born to assess long-term fertility [3].

- Implantation Site Analysis: Set up timed matings with cKO and control females. On D5 or D6, visualize implantation sites by intravenous injection of 1% Chicago Blue dye. The absence of blue bands indicates implantation failure [3].

- Rescue Experiments: To test if a pathway is sufficient to overcome a genetic defect, administer a candidate compound (e.g., RO8191) to pregnant cKO mice on D4 and assess implantation outcomes as in the DI model [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Models

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Models for Mouse Implantation Studies

| Reagent / Model | Function / Purpose | Key Consideration / Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| RO8191 [9] | A small-molecule interferon agonist that acts as a potent STAT3 activator; can induce implantation in delayed implantation models. | Its effect is partial in Stat3 or Gp130 cKO mice, indicating it requires a functional GP130/STAT3 axis. |

| Lifr eKO / Gp130 eKO Mice [3] | Genetically engineered models to study the specific role of LIF signaling in the uterine epithelium. | Reveals distinct and overlapping gene networks downstream of LIFR and GP130, complicating the simple heterodimer model. |

| Delayed Implantation Model [9] | Allows precise temporal control over the implantation process, useful for testing specific agonists/antagonists. | An artificial system that may not fully recapitulate the dynamics of natural conception. |

| Tucatinib / Sapitinib [3] | ERBB2 (HER2) inhibitors; used to pharmacologically validate the role of ERBB2 signaling in implantation. | Demonstrates the critical role of the LIFR-ERBB2 axis beyond the classic JAK-STAT3 pathway. |

| SCADS Inhibitor Kits [10] | Standardized libraries of chemical inhibitors for high-throughput screening of factors involved in early embryonic development. | Identified novel regulators like Cathepsin D and CXCR2, whose roles in human implantation are unknown. |

| JMJD7-IN-1 | JMJD7-IN-1, CAS:311316-96-8, MF:C16H8Cl2N2O4, MW:363.15 | Chemical Reagent |

| DMPQ Dihydrochloride | DMPQ Dihydrochloride, CAS:1123491-15-5; 137206-97-4, MF:C16H16Cl2N2O2, MW:339.22 | Chemical Reagent |

Impact of Assisted Reproduction and Staging on Data Fidelity

Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) and Genetic Integrity

The use of in vitro fertilization (IVF) and embryo transfer in mouse models is common. However, a 2025 study indicates that mouse pups conceived via IVF have about 30% more de novo single-nucleotide variants in their DNA compared to naturally conceived pups [28]. While the absolute risk of a harmful mutation remains low, this finding highlights that ART procedures can alter the genetic landscape of the model organism, potentially introducing a confounding variable in studies of embryonic development and implantation.

Embryo Staging and Developmental Asynchrony

A significant technical challenge in mouse embryology is accurate developmental staging. Relying solely on harvesting age (time post-conception) is unreliable due to uncertainties in fertilization timing and developmental asynchrony between embryos, even within the same litter [29]. The eMOSS (embryonic mouse ontogenetic staging system) provides a solution. This tool determines the developmental stage (morphometric age) with a typical uncertainty of only 2 hours, based on a geometric morphometric analysis of the hindlimb bud shape from 2D images [29]. Using precise staging tools is critical for obtaining reproducible data when analyzing molecular events during the peri-implantation period.

Mouse models provide indispensable, experimentally tractable systems for investigating the fundamental mechanisms of embryo implantation. However, their utility is bounded by significant limitations arising from evolutionary divergence in size, life history, anatomy, and the specific molecular wiring of key pathways like LIF signaling. The essential role of the LIF-STAT3 axis in mice is not directly transferable to humans, and recent work revealing complex downstream hubs like ERBB2 further underscores the intricacy of these networks. Researchers must therefore exercise caution when extrapolating findings from mouse to human. The future of implantation research lies in leveraging sophisticated mouse models—such as conditional knockouts and the delayed implantation protocol—with a clear understanding of their inherent limitations, while increasingly seeking validation through human endometrial cell and tissue models to bridge the translational gap.

Advanced Techniques for Culturing and Manipulating Embryo Viability