Mastering Background Control: Whole-Mount vs. Section In Situ Hybridization for Precision Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing background noise in whole-mount versus sectioned in situ hybridization (ISH).

Mastering Background Control: Whole-Mount vs. Section In Situ Hybridization for Precision Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing background noise in whole-mount versus sectioned in situ hybridization (ISH). We explore the fundamental principles governing background challenges in each method, detail optimized protocols from recent studies including bleaching, probe design, and optical clearing techniques, present systematic troubleshooting approaches for common problems, and establish validation frameworks using proper controls and comparative analysis. By synthesizing current methodological advances, this resource enables scientists to select appropriate ISH formats and implement robust background suppression strategies for accurate spatial gene expression analysis in biomedical research.

Understanding Background Challenges: Fundamental Principles of Whole-Mount vs. Section ISH

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a cornerstone technique in molecular biology that enables the detection of specific nucleic acid sequences within their native cellular context. This powerful method provides invaluable spatial and, in some cases, temporal information about gene expression patterns that bulk sequencing techniques cannot offer. The core principle of ISH relies on the complementary binding of a labeled nucleic acid probe to a specific DNA or RNA target sequence within fixed cells or tissues [1]. The ISH landscape is primarily divided into two methodological approaches: section ISH and whole-mount ISH (WMISH). The fundamental distinction lies in the sample preparation: section ISH is performed on thin slices of tissue, while WMISH is applied to intact, three-dimensional specimens, typically entire embryos or small tissues [2]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two methodologies, focusing on their technical parameters, performance characteristics, and suitability for different research scenarios, with a particular emphasis on background control and signal integrity.

Core Principles and Technical Comparison

The choice between section and whole-mount ISH dictates the entire experimental workflow, from sample preparation to image analysis. Section ISH involves embedding a tissue sample in a medium like paraffin or OCT compound, then cutting it into thin sections (typically 5-6 µm) using a microtome or cryostat [2] [3]. These sections are mounted on glass slides for the hybridization procedure. In contrast, WMISH processes the entire specimen intact through all steps of fixation, permeabilization, hybridization, and washing [2]. This key difference drives all subsequent variations in protocol and performance.

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between Section ISH and Whole-Mount ISH

| Parameter | Section ISH | Whole-Mount ISH |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Thin tissue sections (5-6 µm) mounted on slides [2] | Intact embryos or small tissues [2] |

| Spatial Context | Two-dimensional; 3D requires reconstruction from serial sections [2] | Three-dimensional; preserves native spatial relationships [2] |

| Tissue Permeability | High; achieved physically by sectioning [3] | Challenging; requires chemical and/or enzymatic permeabilization [2] [4] |

| Probe Penetration | Uniform and efficient [3] | Limited; can be uneven in dense core tissues [5] |

| Background Control | Generally lower; easier wash steps [3] | More challenging; requires extensive washing to reduce background [5] [6] |

| Protocol Duration | Shorter fixation and washing times [3] | Longer; includes extended permeabilization and wash steps [2] |

| Primary Applications | Histological analysis, high-resolution cellular localization, archived (FFPE) samples [3] | Developmental biology, analysis of gene expression in 3D context, embryonic patterning [2] [7] |

A critical challenge specific to WMISH is background staining, often caused by probe trapping in loose tissues like tadpole tail fins or incomplete removal of unbound probe [5]. Optimized protocols address this through physical (e.g., notching fin tissues) and chemical (e.g., adjusted stringency washes) means to improve the signal-to-noise ratio [5] [6]. For section ISH, background is more frequently managed through optimized protease digestion times and stringent post-hybridization washes [3].

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Empirical data from published studies highlights the performance characteristics of each method. A study on Xenopus laevis tadpole tail regeneration optimized WMISH to detect low-abundance mRNAs like mmp9. The optimized protocol, which included tissue bleaching and fin notching, successfully revealed distinct expression patterns during early regeneration stages (0, 3, 6, and 24 hours post-amputation) [5]. This demonstrates WMISH's capability for sensitive temporal-spatial analysis in complex, regenerating tissues. In a different application, an optimized WMISH protocol for paradise fish (Macropodus opercularis) enabled a direct comparison of conserved developmental genes (e.g., chordin, goosecoid, myod1) with the zebrafish model, providing insights into evolutionary developmental biology [7].

For section ISH, a standard protocol for paraffin-embedded tissues involves deparaffinization in xylene, rehydration through an ethanol series, proteinase K digestion for antigen retrieval (e.g., 20 µg/mL for 10-20 minutes), and hybridization with DIG-labeled probes [3]. The performance is reliably quantified by the clarity of cellular resolution and the low background, facilitating precise mRNA localization.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Based on Experimental Applications

| Experimental Goal | Performance in Section ISH | Performance in Whole-Mount ISH | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mapping 3D Expression Patterns | Poor; requires serial sectioning and complex reconstruction [2] | Excellent; preserves native 3D architecture of embryos [2] | Visualization of gene expression over entire embryo without sectioning [2] |

| Cellular/Sub-cellular Resolution | Excellent; high-resolution on thin sections [3] | Variable; can be limited by probe penetration and sample opacity [8] | Single-molecule detection achieved in sectioned or squashed samples [8] |

| Analysis of Delicate Tissues | Good; structural support from embedding medium [3] | Challenging; harsh permeabilization can damage tissue [4] | New NAFA fixation for planarians preserves blastema integrity [4] |

| Handling Opaque/Pigmented Samples | Manageable; pigment may be localized to specific layers | Challenging; pigment can obscure signal throughout sample [5] | Bleaching steps required for Xenopus tadpoles to clear melanin [5] |

| Compatibility with Genotyping | Standard; DNA extracted from adjacent sections | Possible with protocol adjustments; dextran sulfate inhibits PCR [6] | Reliable genotyping after WMISH achieved by omitting dextran sulfate [6] |

Advanced Techniques and Protocol Optimizations

Whole-Mount ISH Protocol for Challenging Tissues

Advanced WMISH protocols have been developed to address specific challenges. A study on regenerating Xenopus laevis tails introduced key optimizations to minimize background in loose, pigmented tissues [5]:

- Sample Bleaching: Performed after fixation to decolorize melanosomes and melanophores that interfere with chromogenic stain detection.

- Tail Fin Notching: Making incisions in the fin fringe improved the diffusion of reagents and washes, preventing trapping of the chromogen (BM Purple) and reducing non-specific background, even after 3-4 days of staining.

- Proteinase K Optimization: While extended proteinase K digestion can aid permeabilization, it was found to be less effective than physical notching for background reduction in this model [5].

A Novel Fixation Protocol for Delicate Tissues

The Nitric Acid/Formic Acid (NAFA) protocol represents a significant advancement for WMISH and immunostaining in fragile specimens like planarians and killifish fin tissues [4]. Its key features include:

- Superior Tissue Preservation: It eliminates the need for proteinase K digestion, which often damages delicate structures like the regeneration blastema and epidermis.

- Enhanced Compatibility: The protocol robustly preserves antigen epitopes, enabling high-quality tandem fluorescent ISH (FISH) and immunostaining.

- Effective Probe Penetration: Despite the absence of harsh proteolytic digestion, the NAFA treatment allows sufficient penetration of riboprobes for sensitive detection of markers in both internal (e.g., piwi-1+ neoblasts) and external (e.g., zpuf-6+ epidermal progenitors) cell populations [4].

Optical Clearing for 3D Imaging

A major limitation of WMISH in thicker samples is light scattering. The 3D-LIMPID-FISH protocol overcomes this via a simple, aqueous clearing method that preserves lipids and minimizes tissue deformation [9]. This hydrophilic technique uses saline-sodium citrate, urea, and iohexol for refractive index matching. It is compatible with FISH probes and enables high-resolution confocal imaging deep within thick tissues (e.g., a 250 µm adult mouse brain slice), allowing for 3D mapping of RNA and simultaneous protein detection [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for In Situ Hybridization Protocols

| Reagent Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MEMPFA Fixative | Cross-links proteins and nucleic acids to preserve tissue morphology and RNA integrity [5]. | Standard fixative for Xenopus and zebrafish embryos; requires careful pH adjustment. |

| Proteinase K | Enzymatically digests proteins to increase tissue permeability for probe entry [3]. | Concentration and time must be titrated; over-digestion damages morphology [3]. |

| Formamide | Denaturant that lowers the thermal stability of nucleic acid duplexes [6]. | Allows hybridization to occur at lower, less destructive temperatures (e.g., 55-65°C) [6]. |

| Dextran Sulfate | A volume-excluding polymer that increases the effective concentration of the probe [6]. | Accelerates stain development and enhances contrast but inhibits PCR-based genotyping [6]. |

| Hybridization Buffer | The solution for probe application, containing formamide, salts, and blocking agents [3]. | Standard salts are SSC (Saline-Sodium Citrate); Denhardt's solution and heparin block non-specific binding [3]. |

| NBT/BCIP | Chromogenic substrate for alkaline phosphatase. Precipitates as an insoluble purple-blue product [6]. | Used for colorimetric detection of DIG-labeled probes; reaction monitored under a microscope. |

| Anti-DIG-AP Antibody | Conjugate that binds to digoxigenin on the hybridized probe. Alkaline phosphatase (AP) enzyme produces the signal [6]. | The standard detection method for chromogenic WMISH in model organisms. |

| KML29 | KML29, CAS:1380424-42-9, MF:C24H21F6NO7, MW:549.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| LP-935509 | LP-935509, CAS:1454555-29-3, MF:C20H24N6O3, MW:396.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between section and whole-mount ISH is not a matter of one method being superior to the other, but rather a strategic decision based on the biological question and sample type. Section ISH remains the gold standard for achieving high cellular resolution, working with archived tissues, and when 3D reconstruction is a manageable secondary step. Whole-mount ISH is indispensable for visualizing gene expression patterns within the intact three-dimensional architecture of an embryo or small tissue, providing an unrivaled holistic view. Recent innovations—such as the NAFA fixation protocol for superior preservation of delicate tissues [4], physical notching techniques to reduce background [5], and advanced optical clearing like LIMPID for deep-tissue imaging [9]—continue to expand the capabilities and applications of WMISH. By carefully considering the trade-offs outlined in this guide and leveraging the appropriate optimized protocols, researchers can effectively harness the power of ISH to uncover the spatial dynamics of gene expression.

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, enabling the precise localization of specific nucleic acid sequences within cells, tissue sections, or whole-mount preparations. However, the accuracy and clarity of ISH are perpetually challenged by various sources of background noise, which can obscure specific signals and lead to erroneous interpretation. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding and mitigating this noise is crucial for generating reliable data, particularly in the context of comparing whole-mount versus section ISH methodologies. The principal sources of background interference are tissue autofluorescence, limitations in probe penetration, and non-specific probe binding. Tissue autofluorescence, caused by endogenous fluorophores like collagen and elastin, is a pervasive issue in fluorescence-based techniques, emitting light across a broad spectrum that can mask the specific signal from probes [10] [11]. Probe penetration presents a different challenge, especially in thicker whole-mount samples, where dense cellular matrices can prevent uniform access of probes to their targets, resulting in uneven or false-negative signals [10] [12]. Finally, non-specific binding occurs when probes interact with non-target sequences or cellular components, a problem exacerbated by factors such as insufficient hybridization stringency or the presence of fragmented nucleic acids in dying cells [13] [14]. This guide objectively compares how whole-mount and section ISH protocols perform in controlling these background sources, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform best practices in experimental design.

Tissue Autofluorescence: Mechanisms and Mitigation

Tissue autofluorescence is a significant impediment in fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), arising from endogenous molecules such as collagen, elastin, and lipofuscin upon excitation by light [10] [11]. This intrinsic fluorescence emits a broad-spectrum glow that can severely obscure the specific signal from fluorescently labeled RNA or DNA probes, compromising the signal-to-noise ratio. While this issue affects all fluorescence-based techniques, its impact and the strategies for its reduction differ markedly between section and whole-mount ISH.

In section ISH, particularly using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, enzymatic pre-treatment is a standard method for reducing autofluorescence. A recent comparative study demonstrated that elastase is highly effective for lung tissue, which is notoriously autofluorescent. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) samples, a novel elastase-based pretreatment protocol reduced the retest rate for ALK FISH assays from 86.7% to 0%, while also preserving nuclear morphology better than traditional pepsin treatment [11]. This specificity highlights that the optimal enzyme can be tissue-dependent.

Conversely, whole-mount ISH, used for intact tissues or embryos, requires different approaches due to the sample's thickness. The OMAR (Oxidation-Mediated Autofluorescence Reduction) protocol has been developed to address this. OMAR employs a photochemical bleaching method using high-intensity cold white light in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and ammonia to chemically oxidize and bleach endogenous fluorophores prior to hybridization. This method has been successfully applied to mouse embryonic limb buds, effectively eliminating autofluorescence without the need for digital post-processing [10].

The table below summarizes key experimental findings from recent studies on autofluorescence reduction:

Table 1: Comparative Effectiveness of Autofluorescence Reduction Techniques

| Technique | Sample Type | Key Reagent | Experimental Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OMAR Protocol | Mouse embryonic limb buds (Whole-mount) | Hydrogen Peroxide, Ammonia, LED Light | Eliminated tissue autofluorescence, eliminating the need for digital post-processing. | [10] |

| Elastase Pretreatment | NSCLC tissue sections | Elastase | Reduced FISH retest rate from 86.7% to 0%; detected two additional ALK translocations missed with pepsin. | [11] |

| Hypotonic Solution | Blood smear slides | Potassium Chloride | Recommended during fixation to reduce background fluorescence. | [15] |

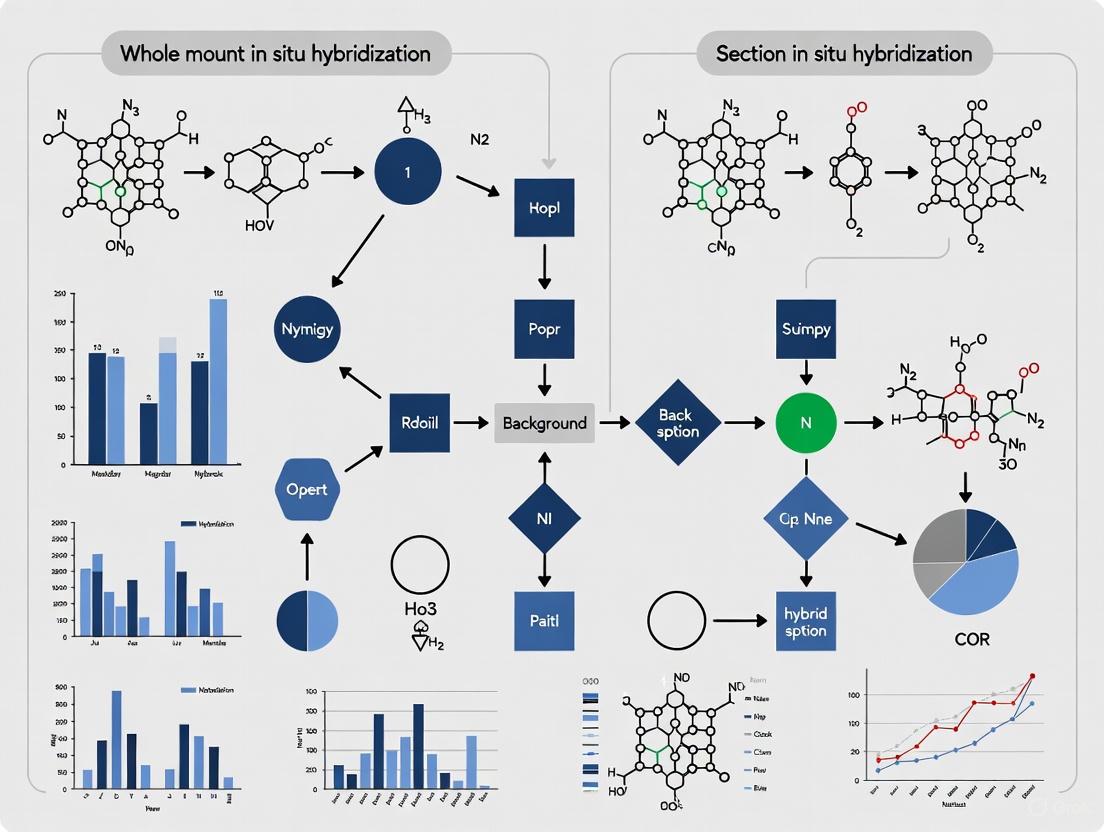

Figure 1. Sources and mitigation strategies for tissue autofluorescence in ISH.

Probe Penetration and Non-Specific Binding

Beyond autofluorescence, probe penetration and non-specific binding are two interrelated technical challenges that contribute significantly to background noise. Probe penetration refers to the physical ability of the nucleic acid probe to access all target sequences throughout the sample. Non-specific binding occurs when the probe anneals to sequences with partial complementarity or interacts with cellular components other than the target mRNA or DNA [13] [14].

The physical nature of the sample creates a fundamental trade-off. Section ISH (typically 3-4µm thick) offers minimal resistance to probe diffusion, allowing for efficient penetration even with standard protocols [15]. However, the cutting process can expose fragmented nucleic acids from damaged or dying cells. These fragments create abundant non-target binding sites, leading to pervasive non-specific signals that are challenging to eliminate [14]. In whole-mount ISH, the sample is intact, which better preserves native tissue architecture and can reduce exposure to fragmented nucleic acids. The primary barrier here is the sample's thickness and density, which can hinder probe access to internal structures, potentially causing weak or absent signals in deeper regions [10] [12].

A critical source of non-specificity in both methods, but particularly problematic in sections, is the presence of fragmented DNA from cells undergoing programmed cell death (PCD). A study on Scots pine seeds demonstrated that sense and antisense probes alike hybridized non-specifically to zones with extensive nucleic acid fragmentation, such as the embryo surrounding region and degenerated suspensors. This confirms that non-specific signals can originate from degraded DNA rather than true mRNA expression, a pitfall that requires careful control [14].

The stringency of the hybridization and post-hybridization washes is paramount for minimizing non-specific binding. Key parameters include temperature, salt concentration, and detergent presence. Inadequate stringency washing fails to remove imperfectly matched probe hybrids, elevating background [16] [15]. Furthermore, the choice of probe itself is crucial; probes containing repetitive sequences (e.g., Alu elements) must be blocked with COT-1 DNA to prevent widespread non-specific binding [16].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Probe Penetration and Non-Specific Binding

| Problem | Common Causes | Recommended Solutions | Applicable to Section/Whole-Mount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Probe Penetration | Over-fixation, dense tissue matrix, large probe size. | Optimize permeabilization (e.g., with Triton X-100, proteinase K); use smaller probes or fragment larger ones. | Primarily Whole-Mount |

| High Background from Non-Specific Binding | Low hybridization stringency, repetitive sequences in probe, fragmented nucleic acids. | Increase wash stringency (temperature & low salt); use COT-1 DNA blocking; include DNase/RNase controls. | Both |

| Weak Specific Signal | Under-fixation, target degradation, insufficient denaturation. | Ensure fresh fixatives; optimize denaturation temperature/time; use positive controls. | Both |

Figure 2. Logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving non-specific binding in ISH.

Direct Comparison: Whole-Mount vs. Section ISH

Choosing between whole-mount and section ISH requires a careful balance, as each method presents distinct advantages and disadvantages for controlling background noise. A direct comparative study on pinewood nematodes (PWN) quantitatively evaluated whole-mount and a "cut-off" section method for localizing a pathogenicity gene (Bx-vap-2) and a sex-determination gene (fem-2) [17]. The findings, combined with insights from other studies, provide a clear, data-driven comparison.

The whole-mount method demonstrated a significant advantage in sensitivity, achieving higher staining rates and correct staining rates for both genes. This makes it particularly suitable for studying developmental processes, as the intact sample allows for the visualization of gene expression patterns in a continuous, three-dimensional context [17]. However, this sensitivity can come at the cost of precision. The study noted that whole-mount samples could exhibit more diffuse staining and greater non-specific background, likely due to challenges in achieving complete and even probe penetration and wash throughout the entire sample [17].

In contrast, the cut-off section method excelled in precision and clarity. Although the overall staining rate was lower, the method produced clearer hybridization signals with more precise localization and less non-specific staining. The physical sectioning of the nematode likely facilitated better probe access and, more importantly, more effective removal of non-specifically bound probes during washing steps, resulting in a superior signal-to-noise ratio for localizing gene expression to specific tissues [17].

The table below synthesizes the core findings of this comparison:

Table 3: Objective Comparison of Whole-Mount vs. Cut-Off Section ISH Methods in Pinewood Nematodes

| Parameter | Whole-Mount ISH | Cut-Off Section ISH | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staining Rate (Success) | Higher | Lower | Higher staining rate for Bx-vap-2 and fem-2 genes [17]. |

| Correct Staining Rate | Higher | Lower | Higher correct staining rate for Bx-vap-2 and fem-2 genes [17]. |

| Signal Precision & Localization | More diffuse, less precise | Sharper, more precise | Cut-off method showed clearer signal locations [17]. |

| Non-Specific Staining | Higher | Lower | Cut-off method resulted in less non-specific staining [17]. |

| Recommended Application | Developmental gene expression | Disease-related genes | Whole-mount preferred for continuous development; cut-off for precise localization [17]. |

This comparative data leads to a clear methodological recommendation: the whole-mount method is more appropriate for analyzing development-related genes where understanding the expression pattern in the context of the entire organism is paramount. Conversely, the cut-off section method is better suited for studying disease-related genes, where precise cellular localization is critical for diagnostic or mechanistic insights [17].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Background Control

To achieve publication-quality results, the integration of robust protocols for background control is essential. Below are detailed methodologies for two key techniques: the OMAR protocol for reducing autofluorescence in whole-mount samples and a standard ISH protocol with optimized stringency washes.

The OMAR protocol is designed to oxidize and bleach endogenous fluorophores in whole-mount samples like mouse embryonic limb buds prior to hybridization.

- Sample Fixation: Collect and fix samples in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C.

- Photochemical Bleaching:

- Prepare OMAR working solution: 1% hydrogen peroxide, 5mM ammonium chloride, in a 0.1% Tween 20-PBS solution.

- Transfer fixed samples to a glass vial containing the OMAR solution.

- Place the vial under a high-intensity cold white light source (e.g., 20,000 lumen LED panels or flexible gooseneck LED spotlights). Ensure the sample is fully submerged.

- Irradiate for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Successful reaction is indicated by the appearance of bubbles.

- Protect the sample from light during this process to prevent potential photobleaching of future fluorophores.

- Post-OMAR Wash: Rinse the samples thoroughly with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20.

- Proceed with Standard FISH: Continue with standard permeabilization, probe hybridization, and washing steps as required by your specific FISH protocol.

This protocol outlines critical steps for minimizing non-specific binding in both section and whole-mount ISH, highlighting controls for false positives.

- Tissue Preparation and Permeabilization:

- For FFPE sections: Deparaffinize and rehydrate slides. Perform antigen retrieval.

- Permeabilization: Digest with Proteinase K (e.g., 20 µg/mL) for 10-20 minutes at 37°C. Titrate concentration and time for each tissue type to avoid over-digestion (damages morphology) or under-digestion (reduces signal) [3].

- Pre-hybridization and Blocking: Incubate samples in a pre-hybridization buffer (e.g., containing formamide, salts, and blocking agents like BSA) for 1 hour at the hybridization temperature to reduce non-specific probe attachment.

- Hybridization:

- Denature the probe (e.g., at 95°C for 2 minutes) and chill on ice.

- Apply the diluted probe in hybridization buffer to the sample.

- Hybridize overnight at the appropriate temperature (e.g., 55-65°C) in a humidified chamber to prevent evaporation.

- Stringency Washes (Critical Step):

- First Wash: 50% formamide in 2x SSC, 3 times for 5 minutes each at 37-45°C.

- Second Wash (High Stringency): 0.1x to 2x SSC, 3 times for 5 minutes each. The temperature and salt concentration here are crucial. For unique targets, use higher temperature (up to 65°C) and lower salt (e.g., 0.1x SSC). Adjust for probe type and complexity [3].

- Detection and Mounting: Proceed with immunological detection (e.g., using anti-DIG antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase or a fluorophore) according to standard protocols. Mount for imaging.

- Mandatory Controls:

- No-Probe Control: Incubate a sample without any probe to check for endogenous alkaline phosphatase activity or non-specific antibody binding.

- Sense Probe Control: Use a sense (non-complementary) RNA probe to identify areas of non-specific hybridization, particularly in tissues undergoing cell death [14].

- DNase/RNase Control: Pre-treat samples with nucleases to help distinguish if non-specific signal originates from DNA or RNA fragments [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Background Control

Successful ISH with low background relies on a suite of specific reagents, each serving a distinct function in sample preparation, hybridization, and washing.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Background Control in ISH

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Key Consideration for Background Control |

|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K | Enzyme digestion for tissue permeabilization. | Concentration and time must be titrated; over-digestion damages tissue, under-digestion reduces signal and increases background. [3] |

| Formamide | Denaturant in hybridization buffer to lower melting temperature. | Enables lower hybridization temperatures, preserving morphology but is toxic. New, less toxic solvents are emerging. [18] |

| COT-1 DNA | Blocking agent for repetitive DNA sequences. | Essential when using genomic DNA probes to prevent non-specific binding to repetitive elements (e.g., Alu, LINE). [16] |

| Deionized Formamide | Solvent for hybridization buffers. | Must be of high purity; impurities can increase background noise and degrade sample RNA. |

| SSC Buffer (Saline-Sodium Citrate) | Buffer for stringency washes. | Higher temperature and lower concentration (e.g., 0.1x SSC at 65°C) increase stringency, removing imperfectly matched hybrids. [3] |

| Tween 20 | Detergent in wash buffers (e.g., PBST, MABT). | Helps reduce non-specific hydrophobic interactions and prevents slides from drying. Washing with PBS without Tween can elevate background. [16] [3] |

| Elastase | Enzymatic pre-treatment for autofluorescence reduction. | Particularly effective in tissues with high elastin content (e.g., lung); preserves nuclear morphology better than pepsin. [11] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide & Ammonia (OMAR) | Chemical agents for photochemical bleaching. | Core components of the OMAR protocol for oxidizing and reducing autofluorescence in whole-mount samples. [10] |

| LX7101 | ||

| M-110 | M-110, MF:C22H28ClN5O3, MW:445.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The shift from traditional thin-section analysis to three-dimensional whole-mount imaging represents a paradigm change in molecular histology, offering unprecedented capability to visualize gene expression patterns within intact tissue contexts. However, this transition introduces significant technical challenges, with background staining emerging as a particularly complex obstacle that varies directly with tissue architecture. Unlike thin sections where background can be minimized through simple washing steps, the three-dimensional nature of whole-mount samples creates diffusion barriers that trap reagents within deep tissue layers and optical barriers that scatter light, compounding signal detection problems [9]. This article objectively compares the performance of leading whole-mount methodologies against traditional sectioning approaches, providing experimental data and protocols to guide researchers in selecting appropriate background control strategies for their specific tissue types and research questions.

The fundamental challenge in whole-mount samples stems from their intact tissue architecture, which preserves valuable spatial relationships but creates both diffusion-limited reagent trapping and light-scattering effects that elevate background signals. In whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH), the problem is particularly pronounced in loose, porous tissues such as amphibian tail fins, where trapping of chromogenic substrates generates substantial non-specific staining that obscures legitimate signal [19]. Similarly, in optically dense tissues like mammalian brain or organoids, light scattering produces fluorescence background that increases with imaging depth, compromising signal-to-noise ratios [9] [20]. Understanding these architectural influences is essential for selecting appropriate methodological approaches.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Whole-Mount Methodologies

Whole-Mount FISH with Optical Clearing vs. Traditional Section FISH

Table 1: Performance comparison between 3D-LIMPID-FISH and traditional section FISH

| Performance Metric | 3D-LIMPID-FISH (Whole-Mount) | Traditional Section FISH |

|---|---|---|

| Background Sources | Light scattering in deep tissue; reagent trapping | Section edge artifacts; minimal reagent trapping |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | 3-8x intensity improvement with clearing [20] | Limited by section thickness |

| Spatial Context | Preserved 3D architecture; subcellular localization | 2D reconstruction required; potential distortion |

| Processing Time | 4-7 days (including clearing) [9] | 1-2 days (including sectioning) |

| Multiplexing Capability | Simultaneous mRNA/protein detection [9] | Sequential staining challenging |

| Tissue Integrity | Minimal shrinkage/swelling [9] | Potential tears/folds during sectioning |

The 3D-LIMPID-FISH (Lipid-preserving index matching for prolonged imaging depth) method represents an advanced aqueous clearing approach that addresses key background challenges in whole-mount samples. This technique employs a refractive index matching strategy using saline-sodium citrate, urea, and iohexol to render tissues transparent while preserving lipid structures [9]. Unlike organic solvent-based methods that can shrink tissues and denature fluorophores, LIMPID's aqueous composition maintains tissue architecture and fluorescence integrity, crucial for accurate background discrimination. The method enables high-resolution confocal imaging through 250μm thick adult mouse brain slices with minimal aberration across all z-sections, demonstrating effective background suppression even at depth [9].

A key advantage of 3D-LIMPID-FISH is its compatibility with multiple detection modalities. Researchers have successfully combined FISH probes with antibody staining against proteins such as beta-tubulin III (TUJ1), enabling simultaneous mapping of mRNA and protein landscapes within the same sample [9]. This multiplexing capability is particularly valuable for distinguishing between protein expression in nerve fibers and RNA expression in ganglion cell bodies, a distinction often blurred by background in traditional methods. The protocol's single-step clearing process significantly simplifies workflow compared to multi-step section reconstruction approaches, though it requires optimization of iohexol concentration to match the refractive index of specific objective lenses [9].

Optimized Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization vs. Standard WISH

Table 2: Background reduction in optimized Xenopus laevis WISH protocol

| Parameter | Standard WISH Protocol | Optimized WISH Protocol [19] |

|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K Treatment | 10-15 minutes | 30 minutes extended time |

| Bleaching Approach | Post-staining bleaching | Pre-hybridization bleaching |

| Fin Modification | None | Fringe-like notching |

| Background in Loose Tissues | Severe | Minimal even after 3-4 days staining |

| Melanophore Interference | High | Eliminated through pre-bleaching |

| Target Accessibility | Limited | Enhanced through tissue permeabilization |

For chromogenic whole-mount in situ hybridization in challenging model organisms like Xenopus laevis tadpoles, background control requires specialized strategies tailored to specific tissue properties. Researchers developing an optimized WISH protocol for regenerating tadpole tails identified two primary background sources: melanophore pigmentation that obscures chromogenic signal and loose fin architecture that traps BM Purple substrate [19]. Their systematic optimization tested four protocol variants, ultimately demonstrating that a combination of pre-hybridization bleaching and fin notching reduced background to negligible levels even with extended staining times [19].

The optimized protocol addresses tissue-specific challenges through strategic modifications. Pre-hybridization bleaching immediately after fixation effectively decolors melanosomes and melanophores that would otherwise mask specific staining [19]. The fringe-like fin notching procedure creates escape pathways for reagents trapped in the loose fin tissues, preventing accumulation of background stain that occurs in intact fins [19]. Additionally, extended proteinase K treatment (30 minutes) enhances probe accessibility to target sequences in dense tissues, improving signal strength without increasing background when combined with the other optimizations [19]. This comprehensive approach enabled the first detailed visualization of mmp9 expression patterns during early tail regeneration at stage 40, revealing expression dynamics previously obscured by background.

Experimental Protocols for Background Control

3D-LIMPID-FISH Protocol for Thick Tissues

The 3D-LIMPID-FISH protocol employs a streamlined five-step workflow designed to minimize background while preserving signal integrity in thick tissues [9]:

Sample Extraction and Fixation: Harvest tissues and fix with appropriate fixative (e.g., 4% PFA). Avoid overfixation, which can reduce FISH signals by excessive cross-linking [9].

Bleaching: Incubate tissues in Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ solution to reduce autofluorescence. Addition of formamide can further enhance fluorescence intensity [9].

Delipidation (Optional): For enhanced clearing, perform partial lipid removal. This step can be omitted to preserve lipid structures or lipophilic dyes.

Staining: Apply HCR FISH probes following established protocols. For single-molecule detection, limit amplification time to 2 hours to visualize discrete fluorescent dots [9]. Co-staining with antibody markers can be performed simultaneously.

Clearing and Refractive Index Matching: Immerse samples in LIMPID solution. Adjust iohexol concentration based on calibration curves to match the refractive index of the objective lens (typically 1.515 for high-NA oil immersion objectives) [9].

The protocol includes critical stop points after delipidation and amplification steps where tissues can be stored temporarily in cold storage. For optimal results, image stained tissues within one week of amplification to preserve signal integrity [9].

Optimized WISH Protocol for Pigmented and Loose Tissues

The optimized WISH protocol for Xenopus laevis tadpole tails addresses background challenges through specific modifications to standard procedures [19]:

Fixation: Fix samples in MEMPFA (4% paraformaldehyde, 2mM EGTA, 1mM MgSOâ‚„, 100mM MOPS, pH 7.4) [19].

Pre-hybridization Bleaching: Immediately after fixation and dehydration, bleach samples to remove melanophores and melanosomes. This critical step prevents pigment interference with subsequent chromogenic detection.

Fin Notching: Create fringe-like incisions in tail fins at a distance from the area of interest. This prevents trapping of BM Purple in loose fin tissues, eliminating a major source of background staining.

Enhanced Permeabilization: Extend proteinase K treatment to 30 minutes to improve probe accessibility while maintaining tissue integrity.

Hybridization and Staining: Apply antisense RNA probes and develop with BM Purple. The optimized washing conditions prevent non-specific chromogenic reactions even with extended staining times.

This protocol combination enables high-contrast detection of low-abundance transcripts like mmp9 during early regeneration stages, revealing spatial and temporal expression patterns that were previously obscured by background [19].

Figure 1: Experimental Design Logic for Background Reduction. This workflow outlines the systematic approach to identifying background sources in whole-mount samples and selecting appropriate methodological solutions.

Research Reagent Solutions for Background Control

Table 3: Essential reagents for background control in whole-mount studies

| Reagent | Function | Application Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Iohexol | Refractive index matching | Adjust concentration (20-40%) to match objective lens RI (1.515) [9] |

| Urea | Hyperhydration & clearing | Component of LIMPID; enhances penetration of aqueous solutions [9] |

| Proteinase K | Tissue permeabilization | Extended treatment (30min) enhances probe accessibility [19] |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Bleaching autofluorescence | Reduces tissue autofluorescence before hybridization [9] |

| BM Purple | Chromogenic detection | Prone to trapping in loose tissues; requires fin notching [19] |

| Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) Probes | Signal amplification | Linear amplification preserves quantitative capability [9] |

| MEMPFA Fixative | Tissue preservation | Maintains morphology while preserving RNA integrity [19] |

The evolution of whole-mount methodologies has transformed our ability to visualize gene expression within architecturally intact tissues, but has simultaneously introduced complex background challenges intrinsically linked to tissue properties. Through comparative analysis of leading techniques, several key principles emerge for effective background control. Optical clearing methods like 3D-LIMPID-FISH and ADAPT-3D address background from light scattering in optically dense tissues through refractive index matching, while tissue-specific modifications like fin notching and extended permeabilization control background in loose or pigmented tissues [9] [19]. The selection of appropriate background control strategies must be guided by specific tissue properties, target molecules, and imaging requirements.

For researchers navigating the transition from traditional sections to whole-mount approaches, the methodological frameworks presented here provide validated pathways for maintaining signal fidelity while suppressing background. As whole-mount technologies continue to advance, particularly through improvements in clearing efficiency, probe design, and computational analysis, the balance between architectural preservation and background control will increasingly favor three-dimensional imaging approaches. By applying the principles and protocols outlined in this comparison, researchers can effectively address the 3D complexity challenge, unlocking deeper insights into gene expression patterns within their native tissue contexts.

The choice between whole mount and sectioned samples for in situ hybridization (ISH) represents a fundamental trade-off between morphological context and technical artifact susceptibility. While thin sections provide superior resolution for complex tissues, they introduce unique artifacts not encountered in whole mount preparations. Edge effects and processing-induced background constitute two predominant challenges that can compromise data interpretation in section-based ISH. These artifacts arise from the physical cutting of tissues and the chemical processing required for sectioning, creating binding sites for non-specific probe adhesion that are less prevalent in intact three-dimensional whole mount samples [21]. Understanding the origins and characteristics of these artifacts is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on accurate spatial gene expression data for their investigative and diagnostic work.

This guide objectively compares the performance of whole mount versus section ISH methodologies, with particular emphasis on background control. The analysis is framed within a broader thesis that optimal background suppression requires technique-specific optimization strategies tailored to each preparation method. We present experimental data quantifying these artifacts and provide detailed protocols for their identification and suppression, enabling researchers to make informed methodological choices based on their specific experimental requirements.

Fundamental Differences in Whole Mount vs. Section ISH

Artifact Profiles by Sample Type

The physical state of the sample creates distinct technical challenges and artifact profiles. The table below systematizes the primary background sources in each methodology:

Table 1: Characteristic Background Artifacts in Whole Mount vs. Section ISH

| Background Source | Whole Mount ISH | Section ISH |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Origin | Probe trapping in 3D matrix [21] | Exposed intracellular components at cut edges [21] |

| Morphological Impact | Potential internal masking | Edge-specific false positives |

| Processing Link | Less dependent on dehydration/clearing [22] | Highly dependent on fixation and processing quality [15] [23] |

| Probe Penetration | Rate-limiting step [24] | Facilitated by sectioning |

| Spatial Pattern | Diffuse, internal background | Localized to tissue section peripheries |

Visualization of Artifact Generation Pathways

The diagram below illustrates how sample processing diverges to generate these technique-specific artifacts:

Experimental Data: Quantifying Section-Specific Artifacts

Systematic Analysis of Edge Effect Intensity

Experimental comparisons using controlled probe systems demonstrate that sectioned tissues consistently exhibit elevated non-specific signal at tissue edges compared to internal regions. Research indicates that this edge effect can increase background signal by 3 to 8-fold compared to central regions of the same section, severely compromising signal-to-noise ratio for targets located near section boundaries [21]. The table below summarizes quantitative findings from these investigations:

Table 2: Experimental Quantification of Section-Specific Artifacts

| Artifact Type | Experimental System | Quantitative Impact | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edge Effects | Mouse urogenital tissue sections [21] | 3-8x background increase at edges | Exposed cellular components from cutting |

| Processing Background | Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues [15] | High variation (15-60% false positives) | Over-fixation crosslinking masking targets |

| Probe Penetration | Drosophila embryos [25] | 10x signal improvement with optimized probes | Removal of repetitive sequence elements |

| Under-Fixation | Blood smears & FFPE tissues [15] | Significant non-specific binding | Incomplete tissue preservation |

Experimental Protocol for Artifact Assessment

The following detailed methodology, adapted from a high-throughput ISH technique for fetal mouse tissues, allows systematic evaluation of edge effects in section ISH [21]:

Tissue Preparation and Sectioning:

- Dissect fresh mouse urogenital tract (bladder, pelvic urethra, and associated ductal structures) and incubate overnight at 4°C in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde.

- Dehydrate tissues through a graded methanol/PBSTw series (1:3, 1:1, 3:1 v/v), 10 minutes each at 25°C.

- Store samples at -20°C in 100% methanol for at least overnight (archived tissues may be kept up to 2 years).

- Rehydrate through graded methanol/PBSTw (3:1, 1:1, 1:3 v/v), 10 minutes each at 25°C.

- Embed in 4% low-melt agarose in PBS and section at 50μm thickness using a vibrating microtome with reinforced Wilkinson blade.

Probe Synthesis and Hybridization:

- Design gene-specific PCR primers against the 3'-region of the cDNA sequence. Verify specificity using MegaBLAST Program with an EXPECT threshold of 0.01.

- PCR amplify riboprobe template: 50μL reaction containing 1X buffer, 2mM MgCl₂, 0.2mM dNTPs, 1X Q solution, 1μg cDNA, 2.5U Taq DNA polymerase, 0.25μm primers.

- Transcribe purified PCR product (400ng) into digoxigenin-11-UTP-labeled riboprobe in 40μL reaction with 1X nucleotide labeling mix, 1X transcription buffer, 5U RNase inhibitor, 80U T7 RNA polymerase. Incubate 3-4 hours at 37°C with agitation every 30 minutes.

- Purify using RNEASY Mini kit with on-column DNase digestion. Expected yield: 4-20μg.

Hybridization and Signal Detection:

- Transfer tissue sections to custom microcentrifuge tube baskets with polyester mesh bottoms for efficient fluid exchange.

- Hybridize with diluted riboprobes in hybridization buffer overnight.

- Perform stringent washes with SSC buffer at 75-80°C for 5 minutes to reduce non-specific background [16].

- Detect hybridized probes with anti-DIG antibodies conjugated to enzymatic or fluorescent reporters.

Critical Controls for Background Identification

Implementing appropriate controls is essential for distinguishing technical artifacts from genuine signals. The following control experiments should be incorporated into every section ISH study:

Table 3: Essential Control Experiments for Background Assessment

| Control Type | Purpose | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Sense Probe | Detects non-specific "sticking" to cellular matrix [25] | Not appropriate for sequence-based off-target hybridization |

| Housekeeping Gene | Technical workflow verification [26] | Should show consistent staining across tissue |

| Bacterial Gene (dapB) | Negative control for non-specific binding [26] | Should display no staining in successful assay |

| No-Probe Control | Identifies autofluorescence | Distinguishes true signal from tissue fluorescence |

| Edge-to-Center Comparison | Quantifies edge-specific artifacts | Internal control within each section |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Background Suppression

Successful background control in section ISH depends on utilizing specific reagents with optimized functions:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Background Control

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Background Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 4% Paraformaldehyde [22] | Preserves morphology while maintaining target accessibility |

| Permeabilization Agents | Proteinase K [27] | Removes crosslinked proteins that mask target sequences |

| Blocking Reagents | PerkinElmer Blocking Reagent [22] | Prevents non-specific antibody binding |

| Stringent Wash Buffers | SSC buffer (75-80°C) [16] | Removes non-specifically bound probes |

| Probe Design Tools | k-mer uniqueness algorithms [25] | Identifies and removes repetitive sequences causing off-target binding |

| Detection Systems | Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) [16] | Enhances sensitivity for low-abundance targets |

| MEB55 | MEB55, CAS:1323359-63-2, MF:C22H17NO4S, MW:391.44 | Chemical Reagent |

| MF-094 | BCL6 Inhibitor|N-[(2S)-1-[[5-(tert-butylsulfamoyl)naphthalen-1-yl]amino]-1-oxo-3-phenylpropan-2-yl]cyclohexanecarboxamide | High-purity BCL6 inhibitor for cancer research. Compound: N-[(2S)-1-[[5-(tert-butylsulfamoyl)naphthalen-1-yl]amino]-1-oxo-3-phenylpropan-2-yl]cyclohexanecarboxamide. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

Optimized Protocol for Background Suppression in Sections

Integrated Workflow for Minimal Background

The following workflow synthesizes optimal practices for minimizing artifacts in section ISH, integrating critical steps identified from experimental data:

Critical Optimization Parameters

- Fixation Control: Maintain fixation between 6-24 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde. Under-fixation results in incomplete tissue preservation, while over-fixation causes excessive cross-linking that masks target sequences and increases background [15].

- Probe Design Specificity: Remove repetitive sequences from probes. Studies demonstrate that perfect repeated sequences as short as 20bp within longer probes (350-1500nt) can produce significant off-target signals. Probe uniqueness checking improves signal-to-noise ratio by orders of magnitude [25].

- Stringency Optimization: Adjust SSC concentration and temperature during post-hybridization washes. Increasing temperature to 75-80°C with SSC buffer significantly reduces background without eliminating specific signals [16].

- Tissue Section Quality: Prepare sections of optimal thickness (3-4μm for FFPE tissues) to avoid issues with probe penetration and interpretation [15].

The methodological choice between whole mount and section ISH represents a strategic decision balancing morphological preservation against technical artifact susceptibility. Whole mount preparations excel in preserving three-dimensional context but face probe penetration challenges and internal trapping artifacts. Section ISH provides superior resolution for complex tissues but introduces characteristic edge effects and processing-induced background. The experimental data and protocols presented herein provide researchers with a systematic framework for identifying, quantifying, and suppressing these technique-specific artifacts. Through implementation of optimized fixation protocols, stringent probe design criteria, controlled hybridization conditions, and appropriate validation controls, researchers can achieve the high signal-to-noise ratios essential for accurate spatial gene expression analysis in both basic research and drug development applications.

Impact of Fixation and Permeabilization on Background Signal in Both Formats

In the intricate methodology of in situ hybridization (ISH), the dual processes of fixation and permeabilization represent a fundamental trade-off. Effective fixation is essential for preserving tissue architecture and nucleic acid integrity, while thorough permeabilization is required to grant probe access to target sequences. However, imprecise execution of either step is a primary contributor to elevated background noise, compromising signal clarity in both whole-mount and sectioned samples [12] [28]. This guide objectively compares how different fixation and permeabilization strategies impact background signal across experimental formats, drawing on current experimental data to inform best practices for researchers and drug development professionals.

The physical and molecular characteristics of whole-mount versus sectioned samples dictate distinct challenges in background control. The table below summarizes the primary sources of background signal in each format.

Table 1: Format-Specific Sources of Background Signal

| Sample Format | Key Background Sources | Influence of Fixation | Influence of Permeabilization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Mount | High autofluorescence in deep tissue [29]; probe trapping; endogenous phosphatase activity [30]. | Over-fixation (e.g., prolonged PFA) increases autofluorescence and masks epitopes [4]. | Incomplete permeation causes uneven probe access; excessive digestion damages tissue integrity [4]. |

| Sectioned | Non-specific probe binding to cellular components; sample drying during processing [28]. | Under-fixation fails to preserve RNA and structure, leading to diffusion and high background [12]. | Harsh detergents (e.g., SDS) can disrupt morphology and increase non-specific binding [28]. |

Quantitative Data from Protocol Comparisons

Recent studies have directly compared novel protocols against established methods, providing quantitative measures of background reduction. The following table summarizes key experimental findings.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Protocol Comparisons

| Protocol Name | Format & Sample | Key Innovation | Quantified Outcome | Reported Cause of Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAFA Fixation [4] | Whole-mount planarian | Acid-based fixation without proteinase K digestion. | Near-complete preservation of delicate epidermis; 2-3x brighter immunofluorescence signal. | Elimination of proteinase K digestion preserves epitopes and tissue integrity. |

| Optimized RNAscope [31] | Whole-mount zebrafish embryo | Substitution of lithium dodecyl sulfate with 0.2x SSCT wash buffer. | Preserved embryo integrity; high signal-to-noise ratio for low-abundance transcripts. | Gentler wash buffers preserve morphology; optimized fixation prevents sample dissociation. |

| HCR with Random Oligos [32] | Whole-mount X. tropicalis | Addition of random oligonucleotides during pre-hybridization/hybridization. | 3 to 90-fold reduction in background signals. | Random oligonucleotides outcompete non-specific binding of single probes to hairpin DNAs. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The NAFA Fixation Protocol for Whole-Mount Samples

Developed for fragile planarian tissues but adaptable to other species, the NAFA (Nitric Acid/Formic Acid) protocol aims to permeabilize without proteinase K, thereby preserving tissue integrity and reducing background [4].

- Fixation Solution: The primary fixative is 1X MEMFA, which contains 3.7% formaldehyde, 0.1M MOPS (pH 7.4), 2mM EGTA, and 1mM MgSOâ‚„ [33]. The inclusion of the calcium chelator EGTA helps inhibit nucleases and preserve RNA integrity [4].

- Acid-Based Permeabilization: Following fixation and dehydration, samples are treated with a permeabilization solution containing nitric acid and formic acid. This critical step replaces traditional proteinase K digestion, thereby avoiding the associated tissue damage and disruption of protein epitopes that can contribute to background [4].

- Workflow Application: This protocol is compatible with both chromogenic and fluorescent detection methods. It has been validated for combined RNA in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence, demonstrating its utility for co-localization studies [4].

Optimized RNAscope for Embryonic Whole-Mounts

This protocol adapts the highly specific RNAscope technology for intact embryos, focusing on preserving sample integrity to maintain a low background [31].

- Gentle Wash Buffers: The original RNAscope wash buffers, which contain lithium dodecyl sulfate, are replaced with 0.2x SSCT (saline-sodium citrate buffer with 0.01% Tween-20) or 1x PBT (phosphate buffer with 0.01% Tween-20). This modification is crucial for preventing embryo disintegration during stringent washes [31].

- Critical Fixation & Drying Steps:

- Fixation: Embryos are fixed in 4% PFA for 1 hour at room temperature. Shorter fixation times can lead to sample dissociation.

- Drying: An initial air-drying step of 30 minutes after methanol removal significantly improves embryo integrity throughout the subsequent procedure [31].

- Hybridization Temperature: A lower hybridization temperature of 40-50°C is used instead of the standard 65°C for zebrafish, which was found to provide a specific signal with low background [31].

In Situ HCR with Background Suppression

Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) is a powerful signal amplification method. A recent modification effectively tackles its inherent background issue [32].

- Background Mechanism: Even in the absence of target mRNA, a single "split probe" can occasionally bind non-specifically to tissue and partially open a fluorescent hairpin DNA, causing a background signal [32].

- Competitive Inhibition: The addition of an excess of random oligonucleotides (e.g., random 20-mers) during the pre-hybridization and hybridization steps is the key innovation. These oligonucleotides act as competitors, binding to the non-specific sites on the hairpin DNA or tissue that would otherwise cause spurious amplification [32].

- Outcome: This simple and low-cost addition can reduce background signals by 3 to 90 times, dramatically improving the signal-to-noise ratio for detecting low-abundance mRNAs without modifying the core HCR chemistry [32].

Visual Guide to Workflow and Background Mitigation

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows and a key mechanism for background reduction discussed in this guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Background Control

The following table lists key reagents mentioned in the cited studies that are critical for managing background signal during fixation and permeabilization.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Background Control

| Reagent | Function | Role in Background Control |

|---|---|---|

| Formic Acid (in NAFA) [4] | Acid-based permeabilizer. | Replaces proteinase K, preserving tissue integrity and preventing false binding sites. |

| EGTA [4] | Calcium chelator in MEMFA fixative. | Inhibits nucleases, protecting RNA integrity and preventing degradation-related background. |

| Random Oligonucleotides [32] | Competitive inhibitor in HCR. | Blocks non-specific binding of probes to hairpins and tissue, drastically reducing background. |

| Tween-20 / CHAPS [28] [34] | Mild detergents in wash buffers. | Enhance removal of unbound probes without damaging morphology, lowering background. |

| Triethanolamine / Acetic Anhydride [33] | Acetylation mixture. | Chemically blocks positively charged tissue amines to prevent non-specific electrostatic probe binding. |

| Lithium Dodecyl Sulfate Substitute [31] | Gentle wash buffer (0.2x SSCT). | Prevents embryo disintegration, a source of high background, during stringent washes. |

| ML-323 | ML-323, CAS:1572414-83-5, MF:C23H24N6, MW:384.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MLT-747 | BTK Inhibitor|1-[2-chloro-7-[(1S)-1-methoxyethyl]pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-6-yl]-3-[5-chloro-6-(pyrrolidine-1-carbonyl)pyridin-3-yl]urea |

Concluding Analysis and Outlook

The experimental data clearly demonstrate that background signal in ISH is not an inevitable artifact but a manageable variable. The most significant advancements in background control stem from re-engineering the initial sample preparation steps—specifically, moving away from harsh, disruptive chemicals like proteinase K and strong ionic detergents towards gentler, more specific alternatives [4] [31]. Furthermore, strategic methods that use competitive inhibition, such as adding random oligonucleotides in HCR, showcase a powerful biochemical approach to suppressing noise at its source [32].

For the researcher, the choice between whole-mount and sectioned ISH, and the selection of a specific protocol, should be guided by the biological question and the sensitivity required. For high-resolution, multiplexed detection of low-abundance targets in intact tissues, optimized whole-mount methods like HCR and RNAscope are increasingly powerful. For rapid screening or when dealing with dense, autofluorescent tissues, well-optimized section-based ISH remains a robust and effective option. Ultimately, a deep understanding of how fixation and permeabilization reagents interact with one's specific sample type is the most critical factor in achieving a clear, publishable signal with minimal background.

Advanced Protocols: Optimized Techniques for Background Suppression in Both Formats

Within the broader methodological debate comparing whole-mount versus sectioned samples for in situ hybridization, a central challenge persists: achieving high signal-to-noise ratios in intact, three-dimensional tissues. Whole-mount approaches preserve invaluable spatial context and three-dimensional relationships but are often plagued by inherent background interference. Two physical barriers—pigmentation (like melanin) and loose, porous tissue structures—routinely trap reagents and cause non-specific staining, obscuring true hybridization signals [5]. This comparison guide objectively analyzes two targeted solutions—tissue notching and photo-bleaching—detailing their performance in enhancing signal clarity based on direct experimental evidence.

Solution Comparison: Performance and Experimental Data

The following solutions were systematically tested on regenerating tails of Xenopus laevis tadpoles to improve the detection of the low-abundance mRNA marker, mmp9 [5]. The table below summarizes the core findings.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Signal Enhancement Solutions

| Solution | Protocol Variant | Key Experimental Findings | Impact on Signal Clarity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extended Proteinase K | Prolonged incubation (30 min) during pre-hybridization [5] | Unimpressive staining; mmp9+ cells overlapped with strong background staining [5] | Minimal improvement |

| Tail Fin Notching & Post-Staining Bleaching | Notching fins before WISH; bleaching after BM Purple staining [5] | Enabled observation of "many more mmp9+ cells"; melanophores faded to brown, improving imaging but not fully eliminating pigment interference [5] | Moderate improvement |

| Early Photo-Bleaching | Bleaching immediately after fixation and dehydration [5] | Resulted in "perfectly albino tails"; some samples developed large bubbles filled with non-specific stain in the tail fin [5] | High improvement in pigment removal, but introduced new artifacts |

| Early Bleaching + Tail Fin Notching (Optimized) | Combining early bleaching with fin notching before hybridization [5] | Produced "very clear images of the specific staining of mmp9+ cells"; no background staining detected even after 3–4 days of staining [5] | Superior, synergistic improvement |

The optimized protocol's efficacy is quantifiable. It enabled the first high-contrast visualization of the detailed mmp9 expression pattern during the early stages (0, 3, 6, and 24 hours post-amputation) of tail regeneration, revealing significant differences correlated with regeneration competence [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Optimized Whole-Mount Protocol: Early Bleaching and Tissue Notching

The most effective variant combines early bleaching and strategic tissue notching. The workflow is as follows.

Key Steps Explained:

Early Photo-Bleaching:

- Timing: Performed after fixation in MEMPFA and a dehydration step, but before the pre-hybridization stages of WISH [5].

- Procedure: The protocol follows the photo-bleaching method recommended by Harland (1991), which typically involves incubating samples in a peroxide-based solution under bright light to decolorize melanosomes and melanophores [5].

- Outcome: This step results in "perfectly albino tails," removing pigment interference that can obscure or be mistaken for a positive stain [5].

Tail Fin Notching:

- Procedure: Before hybridization, partial incisions are made in a "fringe-like pattern" at the edges of the tail fin, specifically at a distance from the primary area of interest (e.g., the regenerating tip) [5].

- Mechanism: This physical modification drastically "improved the washing out of all solutions," preventing trapping of reagents like BM Purple in the loose fin tissues. This addresses the problem of "non-specific autocromogenic reactions" that cause high background [5].

- Outcome: When combined with early bleaching, this procedure resulted in clear images with no detected background staining, even after prolonged staining incubation periods of 3–4 days [5].

Complementary Advanced Solutions

Other advanced methods can be integrated with the above physical techniques for further signal enhancement.

Optical Clearing with LIMPID: The LIMPID (Lipid-preserving index matching for prolonged imaging depth) method is a single-step aqueous clearing protocol that uses iohexol, urea, and saline-sodium citrate to render tissues transparent by refractive index matching [9]. It preserves fluorescence and is compatible with FISH and immunohistochemistry, enabling high-resolution 3D imaging deep within thick tissues (e.g., 250 μm mouse brain slices) with conventional confocal microscopes [9].

Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR): HCR is a powerful signal amplification technique that uses split initiator probes and fluorophore-tagged DNA hairpins to self-assemble into amplification polymers upon binding to target mRNA [35]. This method provides linear signal amplification, which allows for better quantification of RNA abundance and enables highly multiplexed imaging in whole-mount tissues like mosquito brains [9] [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protocol | Specific Example/Application |

|---|---|---|

| MEMPFA Fixative | Sample fixation to preserve tissue morphology and RNA integrity [5] | Standard fixative for Xenopus tadpole tails [5] |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme treatment to increase tissue permeability for probe access [5] | Used during pre-hybridization; timing requires optimization to avoid background [5] |

| BM Purple | Alkaline phosphatase substrate producing a colorimetric precipitate [5] | Used for chromogenic detection in WISH [5] |

| H2O2-based Bleaching Solution | Chemical decoloration of pigments like melanin [5] | Key component of the photo-bleaching step for pigment removal [5] |

| LIMPID Solution | Aqueous optical clearing medium for refractive index matching [9] | Contains iohexol, urea, SSC; preserves lipids and fluorescence for deep imaging [9] |

| HCR Probe Sets & Hairpins | For multiplexed, amplified RNA detection via hybridization chain reaction [35] | Custom DNA oligos designed for target mRNA; fluorophore-labeled hairpins for signal amplification [35] |

| ClearSee | Commercial clearing solution for reducing autofluorescence [8] | Used in plant WM-smFISH protocols to improve signal-to-noise ratio [8] |

| Mps-BAY2b | Mps-BAY2b, MF:C20H23N5O, MW:349.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MS-1020 | MS-1020, CAS:1255516-86-9, MF:C21H18N2O3, MW:346.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

For researchers committed to the whole-mount paradigm, the combination of strategic tissue notching and early photo-bleaching provides a robust, experimentally validated solution to the persistent problem of background staining. These physical and chemical enhancements directly address the core sources of noise—pigment interference and reagent trapping—without compromising the intricate spatial information that makes whole-mount studies invaluable. When integrated with advanced methods like optical clearing and linear signal amplification, these solutions empower researchers to achieve a level of signal clarity in intact tissues that rivals, and in some contexts surpasses, the traditional sectioning approach.

In the evolving field of spatial biology, the precision of in situ hybridization (ISH) experiments is fundamentally governed by probe design excellence. The selection of optimal probes and labels represents a critical frontier in minimizing background noise, thereby enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio essential for accurate gene expression visualization. This challenge is particularly pronounced when comparing whole mount versus sectioned ISH methodologies, where tissue complexity and permeability barriers differentially impact background phenomena. While whole mount techniques preserve three-dimensional architectural context, they often contend with heightened autofluorescence and probe penetration issues. Conversely, sectioned specimens, though more amenable to probe access, face challenges with structural integrity and potential signal loss during processing. Across both approaches, background signals originating from non-specific probe binding, imperfect hybridization kinetics, or suboptimal label detection can compromise data interpretation, especially for low-abundance transcripts. The emergence of sophisticated signal amplification technologies, including hybridization chain reaction (HCR), multiplexed error-robust fluorescence in situ hybridization (MERFISH), and single-molecule FISH (smFISH), has intensified the need for refined probe design strategies that maximize specificity while minimizing artifactual signals. This guide systematically compares contemporary probe design platforms and labeling strategies, providing experimental data and methodological frameworks to empower researchers in selecting optimal reagents for their specific spatial transcriptomics applications.

Comparative Analysis of Probe Design Platforms

Computational Design Strategies and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Probe Design Platforms for Background Minimization

| Platform/Method | Design Strategy | Specificity Validation | Key Advantages | Limitations | Experimental Background Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TrueProbes [36] | Genome-wide BLAST with thermodynamic modeling and kinetic simulation | Gibbs free energy calculations; expressed off-target binding assessment | Ranks probes by predicted specificity; incorporates expression data | Requires computational expertise; longer processing time | Superior target selectivity; enhanced signal-to-noise in validation assays |

| HCR Probe Designer [35] | Splits target mRNA into oligos with filters for Tm, GC content, and specificity | BLAST alignment against reference genome | Cost-effective; customized for non-model organisms | Limited to HCR methodology; requires in-house design work | 3-90x background reduction with random oligonucleotide addition [32] |

| Conventional MERFISH [37] | GC/Tm filtering with hashing into 15/17-mers for off-target indexing | Transcriptome and rRNA screening | Error-robust barcoding; high multiplexing capability | Narrow heuristic windows; minimal expression integration | Performance varies with encoding probe hybridization conditions |

| Stellaris [36] | Sequential 5' to 3' tiling with GC-content filtering | Five masking levels for repetitive sequences | User-friendly; widely adopted | "First-pass" design approach; limited off-target assessment | Can yield insufficient probes for atypical genes |

| Repetitive Sequence Targeting [38] | Genome-wide scan for high-copy number repetitive elements | BLAST analysis against host genome for cross-reactivity | Intrinsic signal amplification without PCR | Potential cross-strain variability; not gene-specific | Higher sensitivity but requires careful specificity validation |

Experimental Validation of Platform Performance

Recent benchmarking studies demonstrate that probe design platforms incorporating comprehensive off-target prediction significantly outperform conventional tools. The TrueProbes platform, which employs genome-wide BLAST analysis combined with thermodynamic modeling of binding interactions, consistently generates probe sets with enhanced specificity across diverse cell types and experimental conditions [36]. This approach conceptually optimizes the balance between on-target spot intensity and off-target background, a critical determinant of final image quality. In direct experimental comparisons, probes designed with advanced algorithms demonstrate significantly reduced false-positive rates in knockout validation assays, where background signal should be minimal in the absence of the target transcript.

For researchers working with non-model organisms or with limited budgets, custom HCR probe design tools offer a viable alternative. The HCR Probe Designer specifically developed for Anopheles gambiae provides a cost-effective solution that maintains high specificity through stringent BLAST alignment against the reference genome and filtering based on melting temperature and GC content [35]. This approach has been successfully applied to both whole-mount and sectioned samples, demonstrating its versatility across different sample preparation methodologies.

Experimental Protocols for Background Reduction

Optimized Whole-Mount HCR RNA-FISH with Background Suppression

Protocol Overview: This 3-day protocol adapts HCR RNA-FISH for plant and animal whole-mount specimens with enhanced signal-to-noise ratio [35] [24].

Day 1: Sample Preparation and Pre-hybridization

- Fixation: Fix tissues in 4% paraformaldehyde with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 45 minutes at room temperature [35].

- Permeabilization: For plant tissues, employ enzymatic cell wall digestion (1% cellulase, 1% pectolyase) for 30 minutes followed by methanol and ethanol dehydration series [24]. For animal tissues, proteinase K treatment (10-30 μg/mL) for 15-30 minutes improves probe accessibility [5].

- Pre-hybridization: Incubate samples in hybridization buffer for 30 minutes at the hybridization temperature. Critical addition: Include random oligonucleotides (50-100 ng/μL) during pre-hybridization and hybridization steps, which reduces background by 3-90 times by competing for non-specific binding sites [32].

Day 2: Probe Hybridization and Amplification

- Hybridization: Add HCR probe sets (1-10 nM final concentration) in hybridization buffer. Incubate at 37°C for 12-36 hours. Each probe set should contain 15-20 probe pairs per transcript for optimal signal amplification [35].

- Washes: Perform 4 × 15-minute washes with probe wash buffer at 37°C, followed by 2 × 5-minute washes with 5× SSCT at room temperature [24].

- Signal Amplification: Incubate with snap-cooled HCR hairpins (30-60 nM) in amplification buffer overnight at room temperature. Use fluorophores with minimal spectral overlap to reduce channel crosstalk.

Day 3: Washes and Imaging

- Final Washes: Perform 4 × 15-minute washes with 5× SSCT at room temperature.

- Mounting: Mount samples in anti-fade mounting medium. For plant tissues with high autofluorescence, ClearSee treatment significantly improves signal-to-noise ratio [8].

- Imaging: Acquire images using confocal microscopy with optimal z-stacking for whole-mount samples. Protect samples from direct light throughout the protocol to prevent fluorophore photobleaching [35].

MERFISH Optimization for Tissue Sections

Protocol Modifications for Enhanced Performance [37]:

- Encoding Probe Design: Utilize 30-50 nt target regions for optimal hybridization efficiency. Screening formamide concentrations (15-40%) with fixed hybridization temperature (37°C) identifies ideal stringency conditions.

- Hybridization Acceleration: Implement changes to encoding probe hybridization to substantially enhance the rate of probe assembly, providing brighter signals.

- Buffer Composition: Employ newly developed imaging buffers that improve photostability and effective brightness for commonly used MERFISH fluorophores.

- Readout Probe Validation: Prescreen readout probes against the sample of interest to identify and mitigate tissue-specific non-specific binding that can introduce false positive counts.

Diagram Title: Background Minimization Workflow for Probe Hybridization

Research Reagent Solutions for Background Control

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Background Minimization in ISH Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Products/Components | Function in Background Control | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Design Tools | TrueProbes [36], HCR Probe Designer [35], MERFISH Designer [37] | Computational selection of high-specificity probes | Incorporate expression data for tissue-specific designs |

| Blocking Agents | Random oligonucleotides [32], tRNA, sheared salmon sperm DNA | Competes for non-specific binding sites | 50-100 ng/μL during pre-hybridization and hybridization |

| Permeabilization Reagents | Proteinase K [5], Triton X-100 [35], cellulase/pectolyase (plants) [24] | Enhances probe accessibility while preserving morphology | Titrate concentration and time to balance access vs integrity |

| Hybridization Enhancers | Formamide, dextran sulfate, Denhardt's solution | Increases specificity and efficiency of hybridization | Formamide concentration (15-40%) critical for stringency [37] |

| Stringency Wash Buffers | Saline-sodium citrate (SSC) with Tween-20 | Removes imperfectly matched probes | Temperature and salt concentration determine stringency |

| Signal Amplification Systems | HCR hairpins [35], bDNA amplifiers [39] | Amplifies specific signal over background | Optimize hairpin concentration (30-60 nM) to minimize self-amplification |