Mechanical Cues in Bone Organoid Development: From Biomechanical Sensing to Advanced Biofabrication

Bone organoids represent a transformative platform for studying bone development, disease modeling, and drug screening.

Mechanical Cues in Bone Organoid Development: From Biomechanical Sensing to Advanced Biofabrication

Abstract

Bone organoids represent a transformative platform for studying bone development, disease modeling, and drug screening. This article comprehensively explores the critical yet underexplored role of mechanical cues—including substrate stiffness, shear stress, and dynamic loading—in guiding the differentiation and maturation of these 3D biomimetic constructs. We examine foundational mechanobiology principles, advanced methodologies for applying mechanical stimulation, strategies for overcoming technical bottlenecks like vascularization and standardization, and the validation of bone organoids against traditional models. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes cutting-edge advancements to provide a roadmap for harnessing biomechanical forces to create more physiologically relevant and clinically translatable bone organoid systems.

The Mechanobiology of Bone: How Cells Sense and Respond to Physical Forces

The Bone Niche: Composition and Function

The bone niche is a dynamic and organizationally complex microenvironment essential for maintaining bone health, regulating stem cell fate, and facilitating regeneration after injury [1] [2]. This specialized niche consists of a intricate network of cellular components, extracellular matrix (ECM), and signaling molecules that work in concert to orchestrate bone homeostasis [2]. The bone marrow niche, a key part of this system, provides both structural and biochemical support, predominantly to regulate hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function, differentiation, and self-renewal, ensuring a delicate balance between quiescence, proliferation, and lineage commitment [3].

The core function of this niche is to send biochemical and mechanical signals to maintain the stem cell pool and prevent its early depletion [3]. It acts as a protective barrier, shielding stem cells from external stressors such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and toxic insults, which is crucial for preventing DNA damage and mutations that could lead to hematological malignancies [3]. Furthermore, the bone microenvironment plays a critical role in disease processes, including the formation of pre-metastatic niches that facilitate cancer spread [1].

Table 1: Major Cellular Components of the Bone Niche

| Cell Type | Primary Function | Key Signaling Molecules Produced |

|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes; support HSCs by secreting regulatory factors. | SCF, CXCL12 [3] [2] |

| Osteoblasts | Bone formation; synthesize and deposit bone matrix; regulate HSC quiescence. | Osteopontin, Angiopoietin-1, Wnt, BMP [3] [2] |

| Osteoclasts | Bone resorption; regulate ECM turnover and niche remodeling. | Digestive enzymes, factors influencing HSC function [2] |

| Osteocytes | Regulate mineral homeostasis and respond to mechanical signals; embedded in the bone matrix. | Signals influencing osteoblast/osteoclast activity [2] |

| Endothelial Cells | Form the vascular niche; regulate HSC migration, maintenance, and activation. | VEGF, Notch ligands, Angiocrine factors [3] [2] |

| Macrophages | Support HSC maintenance; clear debris; preserve niche homeostasis. | IL-6, TGF-β [3] |

The extracellular matrix provides structural and biochemical support, with collagen, fibronectin, and proteoglycans influencing HSC adhesion, migration, and retention [3]. A network of signaling molecules, including CXCL12, SCF, VEGF, and TGF-β, regulates HSC retention, survival, self-renewal, and quiescence [3]. Disruptions in the niche, whether due to aging, disease, or external factors like chemotherapy, can lead to dysfunction, contributing to conditions such as anemia, immunodeficiency, or hematological malignancies [3].

Biomechanical Cues and Signaling Pathways

Mechanical stimuli are pivotal environmental cues within the bone niche, profoundly influencing bone adaptation, regeneration, and cellular differentiation. The stiffness, density, and architecture of the bone matrix directly influence cell behavior and fate decisions [2]. Mechanical forces, such as those from weight-bearing activities and muscle contractions, are sensed by osteoblasts and osteocytes, which in turn regulate bone formation and remodeling processes [2].

These biomechanical signals are transduced into biochemical responses through several evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways. Key among these are the Wnt/β-catenin, BMP, and Hippo (YAP/TAZ) pathways, which integrate mechanical cues to direct MSC differentiation toward the osteoblastic lineage [2].

Diagram 1: Mechanical Signaling to Osteoblastogenesis. Mechanical cues are transduced via integrins and the cytoskeleton, leading to YAP/TAZ nuclear translocation and activation of osteogenic genes.

The Hippo signaling pathway and its transcriptional co-activators YAP and TAZ are critical mechanotransducers. On a stiff substrate—mimicking the natural bone matrix—increased integrin clustering and F-actin polymerization promote the nuclear translocation of YAP/TAZ. Inside the nucleus, YAP/TAZ stimulate osteogenesis by upregulating the master osteogenic transcription factor RUNX2 while downregulating the adipogenic transcription factor PPARγ [2]. Conversely, a soft substrate leads to cytosolic sequestration of YAP/TAZ, promoting adipogenesis over bone formation [2]. This mechanism ensures that MSCs differentiate into osteoblasts in mechanically favorable environments.

Bone Organoids: Modeling the NicheIn Vitro

Bone organoids are three-dimensional (3D) biomimetic constructs that have emerged as a transformative platform for studying bone development, disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine [4]. These miniature, self-organized tissues are typically derived from stem cells—such as pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), or mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)—and are designed to recapitulate the intricate 3D architecture and multicellular composition of native bone tissue [4] [5]. Compared to conventional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures, bone organoids provide a more physiologically relevant system for investigating the complex cellular interactions and biological processes within the bone niche [5].

Key Construction Methodologies

The construction of a bone organoid involves the careful combination of cells, matrix scaffolds, and biochemical cues to guide self-organization and differentiation.

- Cell Sources: iPSCs and MSCs are the most commonly used cell sources due to their differentiation potential. MSCs can directly differentiate into osteoblasts, while iPSCs offer the ability to generate patient-specific models [4] [6] [7].

- Scaffolds/Matrix: Matrigel is a common but suboptimal scaffold due to its tumor origin and batch variability. Research is exploring alternative biomaterials, including collagen-based hydrogels and 3D-bioprinted scaffolds, to provide better mechanical support and osteoinductive properties [4].

- Biochemical Inducers: A combination of growth factors and morphogens is used to direct osteogenic differentiation. These include Bone Morphogenetic Proteins (BMPs, notably BMP-2), ascorbic acid, β-glycerophosphate, and dexamethasone [7] [5]. Neuropeptides like Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) have also been shown to synergistically promote osteogenesis with BMP-2 at physiological doses [7].

Advanced technologies are being integrated to overcome the limitations of traditional organoid culture. 3D bioprinting enhances spatial precision and structural complexity, allowing for the creation of organoids with defined architectures [4] [7]. Assembloid techniques enable the assembly of multiple, distinct cellular components—such as vascular endothelial cells and osteoblasts—to better replicate the multicellular microenvironment of native bone [4]. Furthermore, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are being leveraged to optimize organoid culture conditions and analyze complex single-cell RNA sequencing data from organoid-based regeneration studies [4] [7].

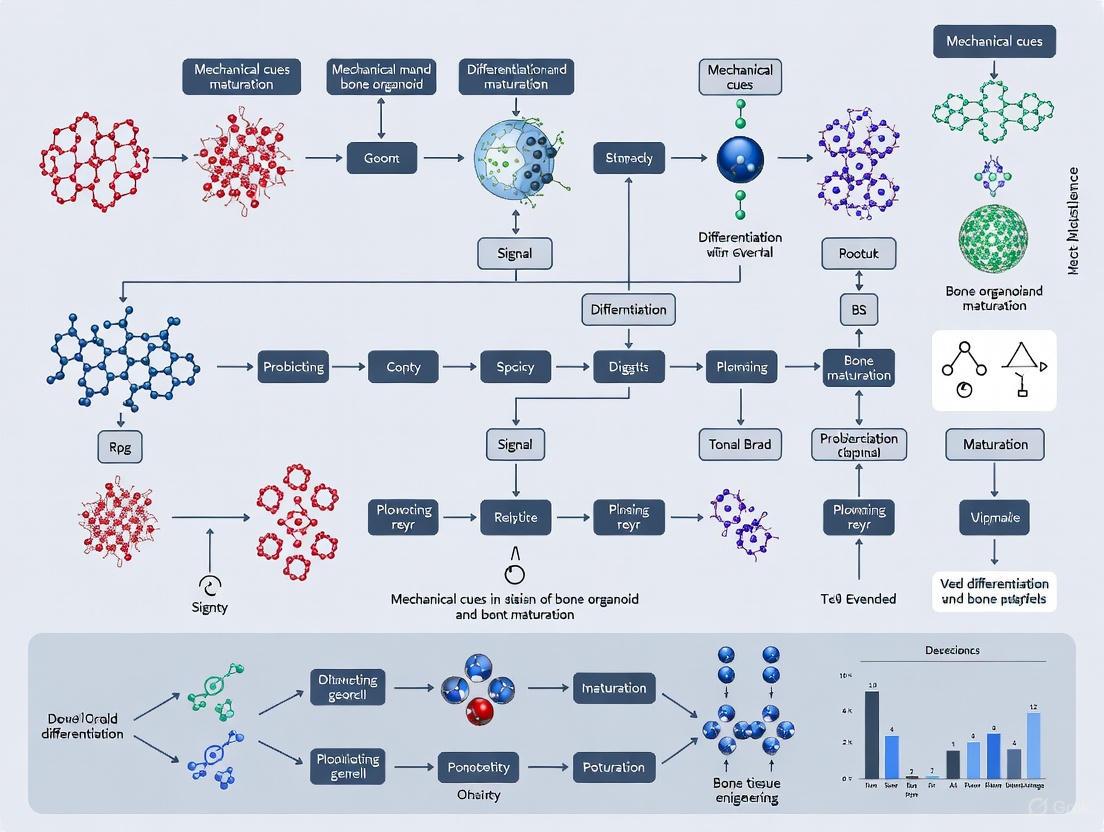

Diagram 2: Bone Organoid Construction Workflow. Key inputs and technologies are combined through 3D culture to generate functional organoids for diverse applications.

Current Challenges and Limitations

Despite their promise, bone organoid technology faces several significant hurdles. A primary challenge is the lack of vascularization, which restricts nutrient and oxygen exchange, limits the size of organoids, and impairs their ability to mimic large-scale bone structures [4] [5]. Another major limitation is the insufficient replication of the native biomechanical environment. Most organoid cultures are maintained in static conditions, lacking the dynamic mechanical loading that is critical for regulating bone cell differentiation, matrix deposition, and tissue maturation in vivo [4]. Additional challenges include the lack of standardized protocols across laboratories, the suboptimal nature of common scaffold materials like Matrigel, and the difficulty in replicating the full cellular complexity of the bone niche [4] [5].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Biomechanics in Bone Organoids

To effectively model the bone niche in vitro, researchers are developing sophisticated experimental methods to introduce and control mechanical stimuli within bone organoid cultures. The protocols below outline key methodologies for applying and assessing the effects of biomechanical cues.

Protocol: Applying Dynamic Mechanical Stimulation via Bioreactors

Purpose: To mimic the in vivo mechanical environment and promote osteogenic maturation of bone organoids. Materials:

- Pre-differentiated bone organoids (e.g., from MSCs in a 3D hydrogel).

- Bioreactor system capable of applying cyclic mechanical load or vibrational forces.

- Control culture vessel (static).

- Osteogenic medium.

Procedure:

- Organoid Preparation: Generate bone organoids using a standard protocol. Encapsulate MSCs in an appropriate hydrogel (e.g., collagen-based or a synthetic polymer) and pre-culture in osteogenic medium for 7-14 days to initiate differentiation.

- Experimental Setup: Divide organoids into two groups: an experimental group and a static control group.

- Mechanical Stimulation:

- Place the experimental group of organoids into the bioreactor chamber.

- Apply a defined cyclic mechanical stimulus. A representative regimen could be a uniaxial or compressive strain of 1-5% at a frequency of 1 Hz, for 1-2 hours per day.

- Maintain the static control group in the same osteogenic medium but without mechanical stimulation.

- Culture Duration: Continue the culture with daily stimulation for a period of 14-28 days, refreshing the medium as required.

- Endpoint Analysis: Assess osteogenic differentiation and matrix maturation (see Protocol 4.2).

Protocol: Assessing Osteogenic Differentiation and Matrix Maturation

Purpose: To quantify the biochemical and functional outcomes of mechanical stimulation on bone organoids. Materials:

- Stimulated and control organoids.

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Paraformaldehyde (4% in PBS).

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) staining kit.

- Alizarin Red S (ARS) solution.

- RNA extraction kit, cDNA synthesis kit, and qPCR reagents.

- Primary antibodies for osteogenic markers (e.g., anti-OSTEOCALCIN, anti-RUNX2).

Procedure:

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Staining (Early osteogenic marker):

- Fix a subset of organoids with 4% PFA for 15-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash with PBS and incubate with an ALP staining solution according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- Quantify ALP activity via image analysis or by measuring absorbance after elution of the dye.

- Alizarin Red S (ARS) Staining (Mineralized matrix deposition):

- Fix organoids as above.

- Incubate with 2% ARS solution (pH 4.2) for 20-45 minutes.

- Wash extensively with distilled water to remove non-specific staining.

- To quantify, elute the bound dye with 10% cetylpyridinium chloride and measure the absorbance at 562 nm.

- Gene Expression Analysis (qPCR):

- Homogenize organoids and extract total RNA.

- Synthesize cDNA and perform qPCR for key osteogenic genes (e.g., RUNX2, ALPL/Alp, SP7/Osterix, COL1A1). Normalize data to a housekeeping gene (e.g., GAPDH).

- Immunofluorescence (Protein-level analysis):

- Fix, permeabilize, and block organoids.

- Incubate with primary antibodies against osteogenic markers (e.g., OSTEOCALCIN) overnight at 4°C.

- Incubate with fluorescently conjugated secondary antibodies.

- Image using confocal microscopy to visualize the spatial distribution of protein expression.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Assessments for Bone Organoid Maturation

| Analysis Method | Target Readout | Interpretation of Results |

|---|---|---|

| ALP Staining/Activity | Early osteogenic differentiation | Increased staining/activity indicates commitment to the osteoblast lineage. |

| ARS Staining & Quantification | Calcium deposition and mineralization | Higher absorbance confirms the formation of a mineralized bone-like matrix. |

| qPCR for RUNX2, ALPL | Osteogenic gene expression | Upregulation confirms activation of the genetic program for bone formation. |

| Immunofluorescence for Osteocalcin | Late osteogenic marker protein | Positive staining indicates mature, matrix-producing osteoblasts. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in the construction and analysis of bone organoids, particularly in the context of biomechanical research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Bone Organoid Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Patient-specific cell source for generating bone lineage cells; enable disease modeling. | Differentiate into MSCs and subsequently into osteoblasts within organoids [4] [6]. |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Primary progenitor cells capable of osteogenic differentiation; workhorse for organoid formation. | Form the core cellular component of ossification center-like organoids (OCOs) [7] [2]. |

| Recombinant Human BMP-2 | Potent osteo-inductive growth factor; drives MSC commitment to the osteoblast lineage. | Used at low (physiological) doses in combination with CGRP to synergistically enhance osteogenesis [7]. |

| Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) | Neuropeptide that synergistically promotes osteogenesis with BMP-2. | Incorporated into organoid culture to enhance osteogenic differentiation and matrix mineralization [7]. |

| 3D Bioprinting Scaffolds | Provides tunable structural and mechanical support for 3D cell growth and organization. | Printing MSC-laden hydrogels to create spatially defined "ossification center-like organoids" (OCOs) [4] [7]. |

| Collagen-Based Hydrogels | Biomimetic ECM scaffold that supports cell adhesion, migration, and 3D organization. | Serve as the primary matrix for encapsulating MSCs during organoid self-assembly [4]. |

| Osteogenic Induction Cocktail | Standardized medium supplement to induce osteoblast differentiation. | Typically contains ascorbic acid, β-glycerophosphate, and dexamethasone [5]. |

| Oleonuezhenide | Oleonuezhenide, CAS:112693-21-7, MF:C48H64O27, MW:1073.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Urease-IN-6 | N-[2-(1H-Indol-3-yl)ethyl]-N'-(4-methoxyphenyl)thiourea | High-purity N-[2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]-N'-(4-methoxyphenyl)thiourea for research use only (RUO). Explore its potential in pharmaceutical and biological applications. Not for human consumption. |

The bone niche is a complex biomechanical microenvironment where cellular components, signaling pathways, and physical forces interact to maintain homeostasis and drive regeneration. Bone organoids represent a powerful and evolving technology to model this niche in vitro. The integration of advanced techniques such as 3D bioprinting for spatial patterning, bioreactors for applying mechanical stimuli, and AI-driven data analysis is rapidly enhancing the physiological relevance and utility of these models [4] [7].

Future progress in the field hinges on overcoming the key challenges of vascularization, innervation, and the replication of native tissue biomechanics. As these hurdles are addressed, bone organoids will become an indispensable tool for unraveling the fundamental role of mechanical cues in bone biology, advancing drug discovery for skeletal diseases, and ultimately, creating personalized regenerative therapies.

Bone is a dynamic, highly specialized tissue that continuously adapts to its mechanical environment through a process known as remodeling. This process involves the coordinated activity of bone-forming osteoblasts, bone-resorbing osteoclasts, and mechanosensitive osteocytes that orchestrate cellular responses to physical forces [8]. The mechanical environment of bone consists of multiple biophysical cues including substrate stiffness, topographical features, and fluid shear stress (FSS), all of which play critical roles in directing cellular behavior and tissue maturation [4] [8]. Understanding these mechanical determinants is particularly crucial in the emerging field of bone organoid development, where recreating a physiologically relevant microenvironment is essential for producing functional tissue models that accurately mimic native bone properties [4] [9].

Bone organoids—three-dimensional, miniaturized, and simplified in vitro versions of bone tissue—have emerged as promising platforms for studying bone development, disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine [4] [9]. However, a significant challenge in bone organoid technology lies in replicating the native mechanical microenvironment of bone tissue, which profoundly influences cellular differentiation and function [4]. Traditional culture systems often fail to incorporate these critical mechanical signals, resulting in organoids that lack key structural and functional characteristics of native bone [4] [10]. This technical gap underscores the importance of understanding and applying fundamental mechanical principles, particularly the interplay between substrate stiffness, topography, and fluid dynamics, to advance bone organoid research and its translational applications.

Substrate Stiffness in Bone Cell Differentiation

Fundamental Principles and Biological Significance

Substrate stiffness, defined as the resistance of a material to deformation, is a potent regulator of cell behavior through a process called mechanotransduction—how cells convert mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals. Cells sense substrate stiffness through integrin-mediated adhesion sites and respond by adjusting their cytoskeletal organization, gene expression, and differentiation pathways [11]. In native bone tissue, the extracellular matrix (ECM) undergoes dynamic changes in stiffness during development, healing, and remodeling processes, with stiffness values ranging from the soft granulation tissue in early healing phases to the rigid mineralized bone matrix in mature tissue [11]. The profound dependence of cell behavior on microenvironmental stiffness makes this parameter particularly critical for directing osteogenic commitment in bone organoid systems.

Quantitative Effects on Osteogenic Differentiation

Table 1: Effects of Substrate Stiffness on Bone Cell Behavior

| Stiffness Range | Biological Correlate | Cell Types Studied | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.46 kPa | Soft tissue-like | Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) | Reduced osteogenic differentiation compared to stiff substrates | [12] |

| 15 kPa | Granulation tissue | Pre-osteoblasts (MC3T3-E1), Fibroblasts (NIH3T3) | Enhanced fibronectin (Fn1) and collagen type I (Col1a1) expression in fibroblasts | [11] |

| 26.12 kPa | Stiff tissue | Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) | Enhanced osteogenic differentiation with increased ALP activity, osteocalcin, Runx2 expression, and mineralization | [12] |

| 35 kPa | Osteoid tissue | Pre-osteoblasts (MC3T3-E1), Fibroblasts (NIH3T3) | Intermediate osteogenic response; decreased Fn1 and Col1a1 in fibroblasts compared to softer substrates | [11] |

| 150 kPa | Calcified bone matrix | Pre-osteoblasts (MC3T3-E1), Fibroblasts (NIH3T3) | Highest Runx2 expression in pre-osteoblasts; lowest Fn1 and Col1a1 in fibroblasts | [11] |

Research has demonstrated that osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) is significantly enhanced on stiffer substrates (∼26 kPa) compared to softer ones (∼1.5 kPa), as evidenced by increased alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, elevated expression of osteoblast-specific markers including osteocalcin, Runx2, and collagen type I, and enhanced mineralization capacity [12]. Interestingly, the effect of substrate stiffness appears to be cell-type specific. While BM-MSCs show stiffness-dependent osteogenic differentiation, more committed bone-derived cells (BDCs) exhibit less variation in their differentiation capacity across different stiffness values [12]. This distinction highlights the importance of considering cell source and commitment state when designing biomaterials for bone organoid development.

The mechanism behind stiffness-dependent differentiation involves increased cell traction forces generated on stiffer substrates, which promote cytoskeletal tension and activation of mechanosensitive transcription factors such as Runx2, a master regulator of osteogenesis [11]. In pre-osteoblasts, Runx2 expression increases with increasing substrate stiffness, while genes associated with fibroblastic activity (Fn1 and Col1a1) decrease correspondingly [11]. This mechanical regulation helps explain why stiffer environments promote osteogenic lineage commitment while softer environments may maintain stemness or direct cells toward softer tissue lineages.

Experimental Protocol: Substrate Stiffness Testing

Polyacrylamide Substrate Preparation Protocol:

- Material Preparation: Prepare polyacrylamide (PAAm) solutions with varying acrylamide and bis-acrylamide concentrations to achieve target stiffness values (e.g., 15, 35, and 150 kPa) as outlined in Table 1 [11].

- Polymerization: Activate polymerization using ammonium persulfate (APS) and tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED).

- Surface Functionalization: Treat polymerized substrates with sulfosuccinimidyl-6-[4'-azido-2'-nitrophenylamino] hexanoate (Sulfo-SANPAH) under UV light for 15 minutes to enable covalent binding of extracellular matrix proteins [11].

- ECM Coating: Incubate substrates with type I collagen (0.1 mg/mL) overnight at 4°C to create a bioactive surface for cell adhesion [11].

- Mechanical Validation: Characterize Young's moduli of resulting substrates using universal testing equipment with a spherical indenter probe to confirm target stiffness values [11].

- Cell Seeding: Plate cells (e.g., MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblasts or NIH3T3 fibroblasts) at appropriate densities (e.g., 2×10â´/mL for immunostaining, 8×10â´/mL for PCR analysis) and culture under standard conditions [11].

- Analysis: Assess osteogenic differentiation using quantitative PCR for markers (Runx2, OPN, Col1a1), immunostaining, and mineralization assays (Alizarin Red S staining) [12] [11].

Topographical Cues in Bone Tissue Engineering

Biological Role of Surface Topography

Surface topography encompasses the physical features and nanoscale to microscale patterns on a material surface that influence cell behavior through contact guidance. In native bone, cells interact with a complex topographic landscape including collagen fibrils, mineral crystals, and macroporous structures that direct cell adhesion, migration, and tissue organization [4]. The hierarchical organization of bone tissue, ranging from nanoscale collagen fibrils to trabecular and cortical architectures, provides topographic cues that are essential for proper cell functioning and tissue-level mechanical properties [4]. Recreating these features in bone organoid systems is critical for achieving physiological relevance in vitro.

Implementation in Bone Organoid Design

Advanced fabrication techniques such as 3D bioprinting have enabled unprecedented control over topographical features in bone tissue engineering scaffolds [4]. These technologies allow for the creation of complex geometries with precise spatial patterning that can direct cellular self-organization and tissue maturation in bone organoids. Bioprinted constructs can incorporate microarchitectural features resembling native bone trabeculae, facilitating the development of more physiologically relevant organoid models [4]. The integration of topographical cues with biochemical signaling in these systems enhances the fidelity of bone organoids, enabling better replication of native tissue properties.

While specific quantitative data on topographical parameters was limited in the search results, the consensus literature emphasizes that topographical design is a critical consideration in bone organoid construction [4] [9]. The mechanical properties provided by topographic features interact with other mechanical cues, particularly substrate stiffness, to regulate cell fate decisions and tissue development in evolving organoid systems.

Fluid Shear Stress in Bone Mechanobiology

Physiological Role in Bone Tissue

Fluid shear stress (FSS) is the frictional force generated by interstitial fluid flow within the lacunar-canalicular network of bone tissue, primarily resulting from external loading during physical activity [8]. This mechanical cue plays a fundamental role in bone maintenance, adaptation, and healing processes. Osteocytes, the most abundant bone cells embedded within the mineralized matrix, are particularly sensitive to FSS and function as mechanosensors that coordinate the activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts in response to mechanical loading [8]. In bone organoid systems, incorporating physiologically relevant fluid dynamics remains a significant challenge but is essential for creating functional tissue models.

Quantitative Effects on Osteogenic Differentiation

Table 2: Effects of Fluid Shear Stress on Bone Cell Behavior

| FSS Magnitude | Temporal Profile | Cell Type | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-30 dynes/cm² | Physiological range | Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) | Promotes osteogenic differentiation | [13] |

| 16 dynes/cm² | Intermittent vs. Continuous | Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) | Intermittent FSS preserves mechanical sensitivity and enhances osteogenic differentiation compared to continuous FSS | [13] |

| 12 dynes/cm² | 2 hours | BMSCs at different differentiation phases | Enhanced osteogenic differentiation at early matrix maturation phase; suppressed expression at proliferation phase; decreased mineralization at late mineralization phase | [13] |

Fluid shear stress within the physiological range (8-30 dynes/cm²) significantly enhances osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) [13]. The temporal pattern of FSS application is crucial, with intermittent stimulation proving more effective than continuous flow for promoting osteogenic commitment [13]. This mimics the natural loading patterns experienced by bone tissue during daily activities.

The effect of FSS is highly dependent on the differentiation stage of target cells. When applied to BMSCs at the early matrix maturation phase (approximately 7 days of osteogenic induction), FSS (12 dynes/cm², 2 hours) significantly promotes osteogenic differentiation, evidenced by enhanced expression of Runx2, ALP, OPN, and OCN genes [13]. In contrast, the same stimulus applied during the proliferation phase suppresses osteogenesis-related gene expression, while application during the late mineralization phase decreases nodule mineralization [13]. This stage-specific responsiveness highlights the importance of temporal considerations when applying mechanical stimulation in bone organoid culture protocols.

Molecular Mechanisms of FSS Signaling

Diagram Title: FSS Mechanotransduction Pathway in BMSCs

The molecular mechanism by which FSS promotes osteogenesis involves sophisticated mechanotransduction pathways. FSS initially induces cytoskeletal reorganization and actin stress fiber formation in BMSCs [13]. This mechanical stimulation enhances the expression of Lamin A, a key component of the nuclear lamina that stabilizes nuclear structure and regulates gene expression [13]. Upregulated Lamin A interacts with METTL3 (methyltransferase-like 3), the catalytic core of the N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methyltransferase complex, promoting its nuclear localization and stability [13].

The Lamin A/METTL3 interaction enhances m6A methylation on target mRNAs, an epigenetic modification that regulates their stability and translation efficiency [13]. This mechanosensitive epigenetic regulation ultimately promotes the expression of osteogenic genes, creating a direct link between mechanical stimulation and gene expression programming in bone cells. This pathway represents a crucial mechanism whereby physical forces are transduced into biochemical signals that direct cell fate decisions in bone tissue and organoid systems.

Experimental Protocol: Fluid Shear Stress Application

Fluid Shear Stress Application Protocol:

- Device Setup: Utilize a parallel-plate flow chamber system connected to a peristaltic pump and medium reservoir, maintaining constant temperature at 37°C and 5% CO₂ [13].

- Cell Preparation: Culture BMSCs in osteogenic induction medium for varying durations to achieve different differentiation phases: proliferation phase (1 day), early matrix maturation phase (7 days), and late mineralization phase (14 days) [13].

- Flow Application: Apply pulsatile fluid flow at physiological magnitude (e.g., 12 dynes/cm²) for specified durations (e.g., 2 hours) [13].

- Post-Stimulation Analysis:

- Assess cytoskeletal organization via F-actin staining using phalloidin.

- Evaluate osteogenic gene expression (Runx2, ALP, OPN, OCN) using quantitative RT-PCR.

- Analyze protein expression and localization via immunofluorescence and western blot.

- Examine mineralized nodule formation using Alizarin Red S staining [13].

- Mechanistic Studies: For pathway inhibition studies, employ specific inhibitors targeting actin polymerization (e.g., cytochalasin D) or METTL3 function (e.g., siRNA knockdown) to confirm mechanism [13].

Integration of Mechanical Cues in Bone Organoid Development

Current Challenges and Limitations

The integration of multiple mechanical cues into bone organoid systems presents several significant challenges. The complex hierarchical organization of native bone tissue, which confers exceptional mechanical strength and load-bearing capacity, is difficult to replicate in vitro [4]. Most current organoid cultures are maintained in static conditions or simple hydrogels that lack the dynamic mechanical stimulation inherent to living bone [4]. This mechanical deficiency likely contributes to the observed morphological and functional differences between current bone organoid models and native skeletal tissue.

Vascularization represents another major challenge, as native bone is highly vascularized while existing bone organoids typically lack mature vascular networks [4]. This limitation restricts nutrient exchange and organoid size, ultimately impairing long-term viability and functional maturation. Additionally, standardization issues across different laboratories, including variations in cell sources, scaffold materials, and culture conditions, have led to substantial batch-to-batch variability, complicating comparative analyses and clinical translation [4] [9].

Advanced Engineering Approaches

Emerging technologies are providing new solutions for incorporating mechanical cues into bone organoid development. Three-dimensional bioprinting enables precise spatial patterning of cells and biomaterials, allowing creation of complex structures with anatomically relevant topographical features [4]. Perfusion bioreactors can deliver physiological fluid shear stress to organoid cultures, promoting nutrient exchange and providing mechanical stimulation [8] [13]. These systems can apply controlled intermittent flow patterns that mimic natural loading cycles in bone tissue.

Assembloid technologies, which involve the assembly of multiple organoid units or different cell types, enable reconstruction of more complex tissue microenvironments with heterogeneous mechanical properties [4]. These approaches facilitate the creation of organoid systems that better replicate the multicellular composition and structural complexity of native bone. Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in organoid culture optimization offers promising avenues for systematically analyzing the combined effects of multiple mechanical parameters and identifying optimal culture conditions [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Mechanical Cue Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engineered Substrates | Polyacrylamide (PAAm) hydrogels; Collagen-coated surfaces | Mimic variable stiffness of bone microenvironment; Study stiffness-dependent cell behavior | [12] [11] |

| 3D Scaffold Materials | Matrigel; Collagen-based hydrogels; Synthetic polymers | Provide three-dimensional support for organoid formation; Can be engineered with specific mechanical properties | [4] |

| Mechanotransduction Inhibitors | Cytochalasin D (actin disruptor); METTL3 siRNA; ROCK inhibitors | Probe specific mechanosensing pathways; Validate mechanism of mechanical cue response | [13] |

| Osteogenic Markers | Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP); Runx2; Osteocalcin; Osteopontin | Quantify osteogenic differentiation response to mechanical cues; Assess functional maturation | [12] [11] [13] |

| Flow Systems | Parallel-plate flow chambers; Perfusion bioreactors | Apply controlled fluid shear stress to cells; Mimic interstitial fluid flow in bone | [8] [13] |

| Ac2-26 | Ac2-26, MF:C141H210N32O44S, MW:3089.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| CTCE-9908 | CTCE-9908, CAS:1030384-98-5, MF:C86H147N27O23, MW:1927.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Substrate stiffness, topography, and fluid shear stress represent three fundamental mechanical cues that collectively direct bone cell fate and tissue maturation. The integration of these mechanical principles into bone organoid development is essential for creating physiologically relevant models that accurately recapitulate native bone properties. While significant progress has been made in understanding individual mechanical parameters, future research should focus on their synergistic integration and temporal application throughout organoid development and maturation processes. Advanced bioengineering approaches such as 3D bioprinting, perfusion bioreactors, and assembloid technologies offer promising avenues for addressing current limitations in bone organoid technology. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly enhance the fidelity and functionality of bone organoids, ultimately advancing their applications in disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine.

Cellular mechanosensors, comprising integrins, focal adhesions (FAs), and the cytoskeleton, constitute a sophisticated mechanotransduction network that enables cells to perceive and respond to physical cues from their microenvironment. Within the context of bone biology, this mechanosensory apparatus is indispensable for directing osteogenic differentiation, bone remodeling, and maintaining skeletal homeostasis. This technical review delineates the core components, molecular architectures, and dynamic signaling pathways of these mechanosensors, with a specific emphasis on their integrated function in bone organoid differentiation and maturation. We synthesize current mechanistic insights, present quantitative data on mechanosensitive signaling, and provide detailed experimental protocols for investigating these processes. Furthermore, we outline a toolkit of research reagents and engineered platforms essential for advancing the field of bone organoid engineering, thereby offering a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to harness mechanobiology for regenerative medicine.

Bone is a quintessential mechanoresponsive tissue, whose mass and architecture are dynamically regulated by mechanical loading. The adaptation of bone to physical force is orchestrated by resident bone cells—osteocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts—that translate mechanical signals into biochemical responses, a process known as mechanotransduction [14]. The emergence of bone organoids as three-dimensional, self-organizing model systems presents an unprecedented opportunity to study these complex processes in vitro. However, the fidelity of these organoids is critically dependent on the recapitulation of the native mechanical niche [5].

The extracellular matrix (ECM) provides more than just structural support; it is a biomechanical information reservoir. Cells probe this environment through a triad of interconnected mechanosensors: integrins, which are transmembrane receptors binding ECM ligands; focal adhesions, which are macromolecular assemblies that link integrins to the intracellular machinery; and the cytoskeleton, a dynamic network of filaments that confers cellular structure and transmits force [15] [14] [16]. In bone organoid engineering, the static, poorly defined nature of conventional matrices like Matrigel poses a significant limitation, often failing to provide the precise, dynamic mechanical cues necessary for robust organoid maturation [17] [18]. A deep understanding of these mechanosensors is therefore paramount for designing next-generation biomimetic environments that can guide organoid development with high physiological relevance and reproducibility. This review dissects the roles of this mechanosensory triad, framing their function within the specific context of bone organoid differentiation and maturation.

Core Components of Cellular Mechanosensing

Integrins: The Primary Mechanoreceptors

Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors, composed of α and β subunits, that serve as the primary link between the ECM and the intracellular cytoskeleton. They exist in a range of affinities, and their activation is a tightly regulated process crucial for mechanosensation [15] [19].

- Structure and Activation: Integrins transition between bent-closed (low affinity), extended-closed (intermediate affinity), and extended-open (high affinity) conformations. This activation can be triggered by ligand binding from the outside (outside-in activation) or by intracellular proteins binding the β-subunit's cytoplasmic tail (inside-out activation) [15]. The α5β1 integrin, the principal receptor for fibronectin, is of particular significance in bone. It recognizes the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide sequence within fibronectin, and its expression is upregulated during osteogenic differentiation [20].

- Mechanosensation: Integrins are force-sensitive. Applied force stabilizes the high-affinity conformation and promotes clustering, which in turn initiates the assembly of focal adhesion complexes. Clinical and experimental data underscore its importance: expression of α5β1 is downregulated in osteoporotic bone but upregulated in osteoarthritic chondrocytes, highlighting its context-dependent role in skeletal pathology [20].

- Role in Bone Organoids: The specific repertoire of integrins expressed by stem cells dictates their response to the surrounding engineered matrix. Providing appropriate RGD-containing ligands within synthetic hydrogels is a key strategy to engage α5β1 and other RGD-binding integrins, thereby promoting osteogenic differentiation and bone organoid development [17] [18].

Focal Adhesions: The Mechanotransduction Hub

Focal adhesions are dynamic, layered protein complexes that form at the interface between ligated integrins and the actin cytoskeleton. They act as central signaling platforms, facilitating bidirectional mechanical communication [15].

- Layered Architecture: FAs are organized into functional layers:

- Structural Layer: Comprises proteins like talin and kindlin, which directly bind integrin β-tails and recruit vinculin and α-actinin, providing a mechanical link to actin [15].

- Signaling Layer: Includes kinases such as Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) and Src, which are activated by integrin clustering and mechanical force, initiating downstream signaling cascades [15] [19].

- Actin Cross-linking Layer: Contains proteins like α-actinin and VASP that regulate actin polymerization and bundling, reinforcing the mechanical connection [15].

- Mechanotransduction: Force-dependent unfolding of proteins like talin exposes cryptic binding sites for vinculin, reinforcing the adhesion and amplifying downstream signaling. This process is critical for the activation of pathways like MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT, which drive osteogenic gene expression [15] [21] [19].

The Cytoskeleton: The Intracellular Mechanoscaffold

The cytoskeleton is an integrated network of three primary filament systems that collectively define cell shape, provide mechanical stability, and serve as a conduit for intracellular force transmission.

- Actin Filaments: Actin networks, particularly stress fibers, generate contractile forces via myosin II and are directly attached to focal adhesions. This actomyosin contractility is a primary driver of cellular tension and a key regulator of mechanosensitive transcription factors like YAP/TAZ [14] [16].

- Microtubules: These hollow tubes provide compressive resistance and serve as tracks for intracellular transport. Their mechanosensory role is fine-tuned by post-translational modifications. Acetylation and detyrosination enhance microtubule flexibility and stability, allowing them to withstand mechanical stress and influence mechanosignaling [14].

- Intermediate Filaments: Networks of vimentin or keratins provide mechanical integrity and contribute to the viscoelastic response of the cell, distributing stresses and protecting the nucleus from deformation [14].

The interconnectedness of these three systems means that force applied at an integrin receptor is transmitted and distributed throughout the entire cellular architecture, ultimately influencing nuclear shape and gene expression.

Integrated Mechanotransduction Signaling in Bone

The mechanosensory components collaborate to activate specific signaling pathways that dictate bone cell fate. The following diagram illustrates the core integrated pathway from force sensing to osteogenic response, particularly in the context of bone organoid maturation.

Diagram 1: Integrated mechanotransduction pathway from initial force sensing to osteogenic response in bone cells, relevant to organoid maturation.

The pathway depicted above is driven by several key molecular players, whose activities and relationships have been quantified through experimental studies. The table below summarizes critical quantitative data on these mechanosensitive signaling dynamics.

Table 1: Quantitative Dynamics of Mechanosensitive Signaling in Osteoblasts

| Parameter | Value / Dynamic Range | Biological Context & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Integrin Mechanosensitivity Threshold (MT) | 1% of Applied Force (Ultra-Sensitive) vs. 10% (Sensitive) | Ultra-sensitive (1%) threshold leads to sustained ERK activation beyond 4 days, while sensitive (10%) threshold leads to signal termination within 6 hours [21]. |

| pERK Activation Duration | > 4 days (Ultra-Sensitive MT) vs. ~6 hours (Sensitive MT) | Sustained pERK is linked to long-term osteogenic commitment and the emergence of a "mechanical memory" [21]. |

| Matrix Stiffness for Osteogenesis | ~25-40 kPa (for 2D culture) | Mimics the stiffness of collagenous bone matrix; promotes osteogenic differentiation of MSCs via enhanced integrin clustering and actomyosin contractility [16]. |

| YAP/TAZ Nuclear Translocation | Increased on stiff (>10 kPa) 2D substrates & in stiff 3D matrices | Serves as a key mechanosensitive readout; nuclear YAP/TAZ upregulates osteogenic transcription factors like Runx2 [17] [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Mechanosensor Analysis

Protocol: Quantifying Integrin-Mediated Mechanotransduction via pERK Dynamics

Objective: To measure the duration and intensity of ERK activation (phosphorylation) in response to mechanical stimulation, as a readout of integrin-mediated mechanotransduction and its sensitivity.

Materials:

- Osteoblast precursor cells (e.g., MC3T3-E1 or human MSCs)

- Flexible-bottomed culture plates (e.g., from FlexCell International)

- Standard cell culture equipment

- Phospho-specific antibody against pERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204)

- Flow cytometer or Western blot apparatus

Method:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells at a defined density on flexible membranes coated with a defined ECM protein (e.g., fibronectin for α5β1 integrin studies).

- Serum Starvation: Incubate cells in low-serum (e.g., 0.5% FBS) medium for 12-16 hours to synchronize cells and reduce background signaling.

- Mechanical Stimulation: Apply a defined cyclic uniaxial or equiaxial strain (e.g., 10% elongation at 1 Hz) using the strain device. Include static controls.

- Inhibition (Optional): Pre-treat a subset of cells with function-blocking anti-α5β1 integrin antibody or a FAK inhibitor (e.g., PF-573228) to confirm the specificity of the response.

- Cell Lysis and Analysis: At defined time points post-stimulation onset (e.g., 15, 30, 60, 90 mins, 4h, 24h), lyse cells.

- For Western Blot, probe lysates with anti-pERK and total ERK antibodies to quantify the pERK/ERK ratio.

- For Flow Cytometry, fix and permeabilize cells, then stain intracellularly with pERK antibody and a fluorescent secondary antibody. Analyze the geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI) of the cell population.

- Data Interpretation: Plot pERK levels over time. As demonstrated in computational models, observe if the signal is transient (sensitive integrin response) or sustained for days (ultra-sensitive response), indicating a potential for long-term osteogenic commitment [21].

Protocol: Modulating Cytoskeletal Mechanics to Probe Osteocyte Response

Objective: To dissect the contribution of specific cytoskeletal elements to mechanosensing by using pharmacological agents and assessing downstream effector expression.

Materials:

- Osteocyte-like cells (e.g., MLO-Y4)

- Pharmacological agents: Nocodazole (microtubule destabilizer), Paclitaxel (Taxol, microtubule stabilizer), Latrunculin B (actin polymerization inhibitor), Jasplakinolide (actin stabilizer).

- ELISA or Western blot kits for Sclerostin (SOST) and Nitric Oxide (NO) detection.

Method:

- Cell Culture: Culture MLO-Y4 cells on type I collagen-coated plates until they develop dendritic processes.

- Pharmacological Perturbation: Pre-treat cells with cytoskeletal-modulating drugs for a predetermined duration (e.g., 2-4 hours). Use appropriate vehicle controls.

- Example:

- Microtubule Destabilization: 1 µM Nocodazole

- Microtubule Stabilization: 1 µM Paclitaxel

- Actin Depolymerization: 100 nM Latrunculin B

- Example:

- Mechanical Stimulation: Apply oscillatory fluid flow shear stress (e.g., 1 Pa, 1 Hz) to the cells for 30-60 minutes. Include static and drug-only controls.

- Assessment of Mechanoresponse:

- Sclerostin Downregulation: Collect cell lysates or supernatant after 1-6 hours post-flow. Quantify sclerostin protein levels via ELISA. Intact microtubules and actin are required for the flow-induced downregulation of sclerostin [14].

- Nitric Oxide Release: Measure NO in the culture medium immediately after flow cessation using a Griess assay. NO release is an early, rapid response to fluid shear stress.

- Data Interpretation: Compare the ability of mechanically stimulated cells to downregulate sclerostin and upregulate NO release in the presence of cytoskeletal perturbations. This reveals the relative contribution of each filament system to the transduction of the anabolic mechanical signal [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Advancing research in bone organoid mechanobiology requires a specific toolkit of reagents and engineered materials. The following table details essential solutions for probing and controlling the mechanosensory environment.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Mechanobiology Studies in Bone Organoids

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Hydrogels | PEG-based hydrogels; Alginate-DNA viscoelastic hydrogels; Decellularized ECM (dECM) hydrogels. | Provide a mechanically tunable 3D microenvironment with definable stiffness, viscoelasticity, and adhesive ligand presentation to study their impact on organoid morphogenesis [17] [18]. |

| Mechanosensing Agonists/Inhibitors | Function-blocking anti-Integrin antibodies (e.g., α5β1); FAK inhibitor (PF-573228); RGD motif peptides. | Used to perturb specific components of the mechanotransduction pathway to establish causal links between sensor activity and osteogenic outcomes [20] [15]. |

| Biosensors & Reporters | FRET-based tension biosensors (e.g., for Vinculin, Talin); YAP/TAZ localization reporters; Sclerostin-promoter driven fluorescent reporters. | Enable real-time visualization and quantification of molecular forces, pathway activation, and mechanosensitive gene expression in live cells [14] [19]. |

| Advanced 3D Culture Platforms | Organ-on-a-Chip devices with integrated mechanical actuation; 3D Bioprinting systems. | Allow for the application of physiologically relevant mechanical forces (e.g., fluid shear, compression) within complex 3D tissue constructs, enabling vascularized bone organoid models [5] [16]. |

| AC 187 | AC 187, MF:C127H205N37O40, MW:2890.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MEN 11270 | B2 Receptor Research Peptide | High-purity H-D-Arg-Arg-Pro-Hyp-Gly-2Thi-Dab(1)-D-Tic-Oic-Arg-(1) for bradykinin B2 receptor studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

The strategic use of these tools, particularly the integration of tunable hydrogels into advanced 3D platforms, is revolutionizing bone organoid engineering. The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for employing these materials to build and test bone organoids with defined mechanical properties.

Diagram 2: Workflow for engineering bone organoids using tunable hydrogel platforms, from material formulation to functional analysis.

Bone tissue exists in a constant state of dynamic equilibrium, continuously adapting its structure in response to mechanical demands—a principle encapsulated by Wolff's Law [22]. At the molecular heart of this phenomenon lies the YAP/TAZ signaling axis, which serves as a primary mechanotransduction pathway converting physical stimuli into biochemical signals that direct osteogenic gene expression [23] [24]. These transcriptional co-activators have emerged as central regulators of bone homeostasis, stem cell differentiation, and tissue regeneration [25] [22]. In the context of bone organoid engineering, understanding YAP/TAZ mechanobiology is paramount for creating physiologically relevant models that accurately mimic the native bone microenvironment [4] [26]. This technical guide comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms of YAP/TAZ-mediated mechanotransduction, details experimental methodologies for its investigation in bone organoids, and synthesizes quantitative findings that underscore its pivotal role in osteogenic differentiation.

Molecular Mechanisms of YAP/TAZ Mechanotransduction

Core Hippo Pathway and Alternative Regulation

The Hippo pathway represents the canonical regulatory circuit controlling YAP/TAZ activity. This kinase cascade centers on MST1/2 and LATS1/2 kinases, which phosphorylate YAP/TAZ, promoting their cytoplasmic retention and proteasomal degradation [25] [27]. When the Hippo pathway is inactive, dephosphorylated YAP/TAZ translocate to the nucleus, associate with TEAD transcription factors, and activate genes controlling cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation [27]. However, in mechanical signaling, YAP/TAZ regulation often occurs through Hippo-independent mechanisms that respond directly to cytoskeletal tension and cell shape changes [25] [23].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated signaling pathways through which mechanical cues regulate YAP/TAZ activity to direct osteogenic gene expression:

Cytoskeletal Dynamics as a Mechanical Integrator

The actin cytoskeleton serves as a central mediator of YAP/TAZ mechanical responsiveness [25] [23]. Mechanical stimuli—including substrate stiffness, fluid shear stress, and cellular deformation—are transmitted to the actin cytoskeleton through mechanosensitive structures, resulting in actin polymerization and increased tension [25]. This tension directly influences YAP/TAZ activity, as evidenced by experiments showing that F-actin disrupting drugs (e.g., latrunculin A, cytochalasin D) prevent YAP/TAZ nuclear localization even on stiff substrates [23]. Importantly, the regulatory input stems not from total F-actin content but from specific actin architectures generated under mechanical load; rounded cells may contain more F-actin than spread cells yet exhibit cytoplasmic YAP/TAZ localization [23]. Key actin regulatory proteins including actin-capping proteins (CAPZ), cofilin (CFL), and angiomotin (AMOT) family members have been demonstrated to exert significant control over YAP/TAZ activity [23].

Experimental Analysis of YAP/TAZ in Bone Organoids

Methodologies for Mechanotransduction Investigation

Studying YAP/TAZ mechanobiology in bone organoids requires specialized approaches that enable precise control and measurement of mechanical parameters while assessing molecular responses. The following experimental workflow outlines key methodologies:

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The following table catalogs crucial reagents and methodologies for investigating YAP/TAZ mechanobiology in bone organoid systems:

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal Modulators | Latrunculin A, Cytochalasin D (F-actin disruptors); Jasplakinolide (F-actin stabilizer); Blebbistatin (myosin II inhibitor) | Dissect actin cytoskeleton contribution to YAP/TAZ regulation | F-actin disruption prevents YAP/TAZ nuclear localization even on stiff substrates [23] |

| Substrate Engineering | Tunable hydrogels (polyacrylamide, PEG); Stiffness gradients; Matrigel; Collagen-based scaffolds | Control mechanical microenvironment independent of biochemical cues | Stiff substrates (>5-10 kPa) promote nuclear YAP/TAZ while soft substrates (<1.5 kPa) retain YAP/TAZ in cytoplasm [23] [24] |

| Genetic Manipulation Tools | YAP/TAZ siRNA/shRNA; CRISPR/Cas9 knockout; Constitutively active YAP/TAZ mutants (S127A); YAP/TAZ fluorescent reporters | Establish causal relationship between YAP/TAZ and osteogenic outcomes | YAP/TAZ depletion prevents osteogenic differentiation even on osteoinductive stiff substrates [25] [22] |

| Mechanical Stimulation Systems | Cyclic stretch devices; Compression bioreactors; Fluid shear systems; Acoustic stimulators | Apply controlled mechanical forces mimicking physiological conditions | Cyclic stretching promotes nuclear YAP/TAZ and enhances osteogenic differentiation in MSCs [25] |

| Analysis & Detection | YAP/TAZ phosphorylation-specific antibodies; Immunofluorescence imaging; TEAD luciferase reporters; Osteogenic markers (RUNX2, ALPL, OCN) | Quantify YAP/TAZ activity and downstream osteogenic responses | Subcellular fractionation reveals mechanical regulation operates largely through nuclear translocation rather than total protein abundance [23] |

Quantitative Effects of Mechanical Cues on YAP/TAZ and Osteogenesis

The relationship between mechanical inputs, YAP/TAZ activation, and osteogenic outcomes has been quantitatively characterized across numerous experimental systems. The following table synthesizes key quantitative findings:

| Mechanical Input | Experimental System | YAP/TAZ Response | Osteogenic Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Stiffness | MSCs on tunable hydrogels [25] [23] | Nuclear localization: <10% on soft (0.5-1 kPa) vs >80% on stiff (30-40 kPa) substrates | Stiff substrates (25-40 kPa): osteogenic differentiation; Soft substrates (0.5-1 kPa): adipogenic differentiation [25] |

| Cell Spreading Area | Micropatterned islands [23] [24] | Cytoplasmic on small islands (300 μm²); Nuclear on large islands (3000 μm²) | Apoptosis on small islands; Proliferation on large islands [23] |

| Fluid Shear Stress | Endothelial cells [25] [23] | Flow-induced nuclear translocation (2-20 dyn/cm²) | Enhanced vascular stability and angiogenesis [25] |

| Cyclic Stretch | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts [25] | Stretch-induced nuclear localization and target gene activation | Enhanced proliferation and stress fiber formation [25] |

| Cell Density | Epithelial and mesenchymal cells [25] [23] | High density: cytoplasmic; Low density: nuclear | Contact inhibition of proliferation at high density [25] [23] |

YAP/TAZ in Bone Organoid Engineering and Therapeutic Applications

Advancing Bone Organoid Technology Through Mechanobiology

The integration of YAP/TAZ mechanobiology principles has catalyzed significant advances in bone organoid engineering [4] [26]. Traditional organoid culture systems often fail to recapitulate the mechanical milieu of native bone tissue, limiting their physiological relevance [4] [5]. However, emerging approaches now deliberately incorporate mechanical cues known to activate YAP/TAZ signaling. For instance, researchers are employing 3D bioprinting to create organoids with controlled architectural features that direct cellular mechanical forces, and utilizing tunable biomaterials with bone-mimetic stiffness to promote osteogenic differentiation through YAP/TAZ activation [4] [26]. These engineered microenvironments have demonstrated that nuclear YAP/TAZ localization is a hallmark of the growing, stem-like compartments within organoids, while differentiated regions show predominantly cytoplasmic localization [23]. This spatial patterning mirrors the in vivo distribution observed in intestinal crypt-villus systems and suggests conserved mechanical regulation of stem cell maintenance across tissues [23].

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The central role of YAP/TAZ in bone mechanobiology presents compelling therapeutic opportunities for bone regeneration and disease treatment [22] [27]. In bone repair contexts, YAP/TAZ activation represents a promising strategy to enhance fracture healing and combat disuse osteoporosis [22]. Recent innovations include the development of "ossification center-like organoids" (OCOs) that harness YAP/TAZ-mediated mechanical signaling to drive rapid bone regeneration in critical-sized defects [7]. These OCOs employ a "divide-and-conquer" strategy, where multiple organoid units collectively facilitate bone bridging through coordinated activation of developmental mechanosensitive programs [7]. For clinical translation, targeting YAP/TAZ signaling could revolutionize treatment for osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and bone defects [22] [27]. Future research directions should focus on delineating the precise mechanical thresholds for therapeutic YAP/TAZ activation, developing biomaterials with spatially patterned mechanical properties to guide organoid maturation, and establishing standardized protocols that integrate mechanical conditioning as a fundamental aspect of bone organoid culture [4] [26] [5].

YAP/TAZ signaling represents the fundamental molecular bridge connecting mechanical cues with osteogenic gene expression programs. In bone organoid engineering, deliberate manipulation of this mechanosensitive axis enables the creation of more physiologically relevant models that faithfully recapitulate the mechanical aspects of bone development, homeostasis, and pathology. As the field advances, integrating increasingly sophisticated mechanical controls with emerging technologies—including 3D bioprinting, artificial intelligence-driven optimization, and multi-organoid assembloids—will further enhance our ability to harness YAP/TAZ biology for both fundamental discovery and therapeutic innovation in skeletal health and disease [4] [26].

The motor-clutch model is a fundamental theoretical framework in cellular mechanobiology that describes how cells transmit and sense mechanical forces through their environment. This model provides a mechanistic understanding of how cells sense extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness through myosin-generated pulling forces acting on F-actin, which is mechanically coupled to the environment via adhesive proteins, functioning similarly to a clutch in a drivetrain [28]. At its core, the model consists of three essential components: myosin molecular motors that generate tension on actin filaments, integrin-based molecular clutches that transiently link these filaments to the extracellular substrate, and the substrate itself with its specific mechanical properties [29] [30]. The complex interplay between these components determines the force transmitted to the substrate, influencing fundamental cellular processes including migration, spreading, differentiation, and tissue remodeling [28] [31].

The mechanical stiffness of a cell's environment exerts a strong, but variable, influence on cell behavior and fate [32]. Different cell types cultured on compliant substrates show opposite trends of cell migration and traction as a function of substrate stiffness, which the motor-clutch model helps explain mechanistically [32] [33]. The model exhibits distinct regimes: at high substrate stiffness, clutches quickly build force and fail (frictional slippage), whereas at low substrate stiffness, clutches fail spontaneously before motors can load the substrate appreciably (a second regime of frictional slippage) [32]. Between these extremes lies a stiffness optimum where traction force is maximized—when the substrate load-and-fail cycle time equals the expected time for all clutches to bind [32]. At this optimal stiffness, clutches are used to their fullest extent, and motors are resisted to their fullest extent [32].

Core Mathematical Framework

Fundamental Equations

The motor-clutch system is governed by a set of equations that describe the mechanical interactions and stochastic binding dynamics. The velocity of actin retrograde flow (V_actin) is determined by a linear force-velocity relationship:

V_actin = V_u (1 - (∑F_clutch) / (n_m × F_m)) [29]

Where Vu is the unloaded velocity of the actin bundle, ∑Fclutch is the sum of forces from all bound clutches, nm is the number of motors, and Fm is the force per motor [29]. Each clutch acts as a Hookean spring with force calculated as:

F_clutch(i) = K_c × (X_i - X_sub) [29]

Where Kc is the clutch spring constant, Xi is the position of the ith clutch, and X_sub is the position of the substrate [29]. The substrate position is determined through an elastic force balance:

K_sub × X_sub = K_c × ∑(X_i - X_sub) [30]

The stochastic binding and unbinding of clutches follows first-order kinetics, with the Bell model describing force-dependent unbinding:

k_off* = k_off × exp(F_clutch / F_b) [30]

Where koff is the unloaded off-rate, and Fb is the characteristic bond rupture force [30].

Master Equation Formulation

A master equation-based ordinary differential equation (ODE) approach provides a mean-field treatment of the stochastic motor-clutch model, enabling more computationally efficient analysis of system behavior [30]. The change in probability that a clutch is bound (p_b) is given by:

dp_b/dt = (1 - p_b) × k_on - p_b × 〈k_off*〉 [30]

This formulation allows derivation of an analytical expression for a cell's optimum stiffness (the stiffness at which traction force is maximal) as a function of key cell-specific parameters [30]. The fundamental controlling parameters are the numbers of motors and clutches (constrained to be nearly equal), and the time scale of the on-off kinetics of the clutches (constrained to favor clutch binding over clutch unbinding) [30].

Table 1: Core Parameters in Motor-Clutch Models

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of motors | n_m | Myosin II motors generating tension | dimensionless |

| Number of clutches | n_c | Integrin-based adhesion complexes | dimensionless |

| Clutch spring constant | K_c | Stiffness of individual clutches | pN/nm |

| Substrate spring constant | K_sub | Stiffness of extracellular substrate | pN/nm |

| Unloaded actin velocity | V_u | Maximum retrograde flow velocity | nm/s |

| Motor stall force | F_m | Force at which motor velocity reaches zero | pN |

| Bond rupture force | F_b | Characteristic force for clutch failure | pN |

| Clutch on-rate | k_on | Rate of clutch binding | sâ»Â¹ |

| Clutch off-rate | k_off | Unloaded rate of clutch unbinding | sâ»Â¹ |

Advanced Model Developments

Generalized Motor-Clutch Framework

Recent work has generalized the motor-clutch analytical framework to include imbalanced motor-clutch regimes, clutch reinforcement, and catch bond behavior [28]. This generalized approach investigates optimality with respect to all parameters and reveals that traction force is strongly influenced by clutch stiffness, with the discovery of an optimal clutch stiffness that maximizes traction force [28]. This suggests cells could tune their clutch mechanical properties to perform specific functions. On rigid substrates, the mean-field analysis identifies optimal motor properties, suggesting cells could regulate their myosin repertoire and activity to maximize force transmission [28]. Additionally, clutch reinforcement shifts the optimum substrate stiffness to larger values, whereas the optimum substrate stiffness is insensitive to clutch catch bond properties [28].

Whole-Cell Migration Simulator

To bridge the gap between molecular-scale clutch dynamics and whole-cell behavior, researchers have developed a stochastic whole-cell migration simulator built from the motor-clutch model [33]. This simulator links together multiple motor-clutch "modules" that each exert force on a central cell body, with cell migration arising from force balances among these modules [33]. The simulator predicts a stiffness optimum for cell migration that can be shifted by altering the numbers of active molecular motors and clutches [33]. Experimental tests with U251 glioma cells and embryonic chick forebrain neurons confirmed these predictions, showing that coordinate changes in motor and clutch numbers can shift the optimal stiffness for migration by orders of magnitude [33].

Table 2: Motor-Clutch Model Predictions and Experimental Validations

| Cell Type | Predicted Optimal Stiffness | Experimentally Confirmed Optimum | Key Regulators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embryonic chick forebrain neurons | ~1 kPa | ~1 kPa | Low numbers of motors and clutches |

| U251 glioma cells | ~100 kPa | ~100 kPa | High numbers of motors and clutches |

| Drug-inhibited U251 cells | Shift to lower stiffness | Confirmed shift | Reduced myosin II and integrin activity |

Experimental Methodologies

Traction Force Microscopy

Traction force microscopy provides essential experimental validation for motor-clutch model predictions. This technique involves culturing cells on compliant substrates with embedded fluorescent beads, then imaging bead displacements as cells exert traction forces [33]. Computational algorithms calculate traction vectors from displacement fields, allowing quantification of total strain energy and force magnitudes [33]. For U251 glioma cells, this method confirmed they transmit approximately two orders of magnitude more force than embryonic chick forebrain neurons, consistent with predictions of increased motors and clutches in glioma cells [33].

F-Actin Retrograde Flow Measurement

Measuring F-actin retrograde flow rate provides critical insights into motor-clutch dynamics. This typically involves transfection with EGFP-actin and time-lapse imaging of actin dynamics at cell edges [33]. Kymograph analysis from these images quantifies flow rates, with the motor-clutch model predicting minimal flow at optimal stiffness [33]. Experimental measurements show ECFNs have minimal flow at ~1 kPa, while U251 glioma cells exhibit minimal flow at ~100 kPa, consistent with their different motor-clutch compositions [33].

Modulating Motor and Clutch Activity

Drug inhibition studies provide direct experimental manipulation of motor-clutch components. Simultaneous inhibition of myosin II motors (e.g., with blebbistatin) and integrin-mediated adhesions (e.g., with RGD peptides or integrin-blocking antibodies) shifts the stiffness optimum of U251 glioma cell migration, morphology, and F-actin retrograde flow rate to lower stiffness values [33]. This experimental approach directly tests model predictions about coordinate regulation of motors and clutches.

Application to Bone Organoid Research

Bone Organoid Development Framework

Bone organoid technology has evolved through a systematic five-stage iterative framework: 1.0 (physiological model), 2.0 (pathological model), 3.0 (structural model), 4.0 (composite model), and 5.0 (applied model) [26]. This progression represents advancement from basic physiological modeling to advanced, clinically applicable systems. The motor-clutch model provides theoretical guidance for optimizing mechanical cues at each stage, particularly in stages 3.0 and 4.0 where structural complexity and multi-tissue interactions are introduced [26].

Recent methodology developments have established cost-effective, well-characterized three-dimensional bone organoid models derived from murine cell lines [34]. These 3D murine-cell-derived bone organoid models (3D-mcBOM) use pre-osteoblast murine cell lines seeded into hydrogel extracellular matrices that differentiate into functional osteoblasts, mineralizing the hydrogel ECM and depositing hydroxyapatite into bone-like organoids [34]. The mechanical properties of these hydrogel systems directly influence osteogenic differentiation through motor-clutch mediated mechanosensing.

Mechanoregulation of Bone Cell Differentiation

The motor-clutch framework explains how osteoblasts and osteoclasts sense and respond to mechanical cues during bone organoid development. Osteoblasts derived from mesenchymal stromal/stem cells migrate to bone remodeling sites and differentiate under influence of various factors including bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) and phosphate-containing compounds [34]. When osteoblasts become surrounded by bone matrix, they differentiate into osteocytes that maintain important mechano-sensing capabilities and regulate bone structure and remodeling in a load/stress-dependent manner [34].

In the 3D-mcBOM system, osteoblastogenic conditioning significantly increases levels of the transcription factor Runx2, with BMP2 identified as necessary for osteoblast differentiation [34]. Similarly, osteoclastogenic conditioning of RAW 264.7 cells significantly increases levels of TRAP protein, indicating phenotypic differentiation to osteoclasts [34]. These differentiation processes are mechanically regulated through motor-clutch mechanisms that sense substrate stiffness and viscoelasticity.

Optimizing Organoid Mechanical Properties

The generalized motor-clutch model provides specific guidance for maximizing accuracy of cell-generated force measurements in molecular tension sensors by designing mechanosensitive linker peptides to be as stiff as possible [28]. For bone organoid construction, this suggests that clutch stiffness optimization could enhance mechanical signaling fidelity. Additionally, the finding that cells can tune their motor-clutch parameters to sense specific stiffness ranges [28] [33] informs the design of biomaterials that match the mechanical properties of native bone tissue (which varies from ~100s of Pascals in trabecular bone to 10s of GPa in cortical bone) [35].

The recognition that tissues exhibit complex viscoelastic behavior rather than simple elasticity [35] further refines application of the motor-clutch model to bone organoids. As bone organoids advance through the developmental framework, incorporating viscoelastic matrices that better mimic native tissue mechanics will enhance their physiological relevance and predictive power for studying bone diseases and regenerative therapies [35] [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Motor-Clutch and Bone Organoid Research

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Polyacrylamide hydrogels | Tunable elastic substrates for stiffness screening | Testing cell migration, spreading, and traction forces across stiffness gradients [35] [33] |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Elastic polymer for cell culture substrates | Creating substrates with defined mechanical properties [35] |

| Matrigel | Basement membrane matrix for 3D culture | Supporting organoid development and cell-ECM interactions [34] |

| Gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable hydrogel for bioprinting | Creating 3D bone organoids with tunable mechanical properties [26] |

| Hydroxyapatite-blended bioinks | Mineralized matrix for bone tissue engineering | Recapitulating bone ECM architecture and mineralization [26] |

| Blebbistatin | Myosin II inhibitor for motor perturbation | Testing motor-clutch predictions by reducing motor activity [33] |

| RGD peptides | Integrin-binding adhesion blockers | Inhibiting clutch engagement to test model predictions [33] |

| BMP2 | Osteogenic differentiation factor | Promoting osteoblast differentiation in bone organoids [34] |

| RANKL | Osteoclast differentiation factor | Inducing osteoclast formation in bone organoid systems [34] |

| BOC-FlFlF | Boc-Phe-Leu-Phe-Leu-Phe|FPR Antagonist | |

| GRGDSPK | GRGDSPK, CAS:111119-28-9, MF:C28H49N11O11, MW:715.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The motor-clutch model continues to evolve, with recent generalizations incorporating more biological complexity such as clutch reinforcement and catch bond behavior [28]. These advances reveal novel features that can affect the design of molecular tension sensors and provide a generalized analytical framework for predicting and controlling cell adhesion and migration in immunotherapy and cancer [28]. For bone organoid research, integrating these refined motor-clutch principles will enhance the physiological relevance of engineered bone tissues.

The five-stage iterative framework for bone organoid development [26] provides a systematic approach for advancing from basic physiological models to clinically applicable systems. Throughout this progression, the motor-clutch model offers theoretical guidance for optimizing mechanical cues that drive osteogenic differentiation and bone tissue formation. As bone organoid technology incorporates advanced technologies like artificial intelligence and 3D bioprinting [26], motor-clutch principles will inform the design of systems that better recapitulate native bone mechanobiology.

In conclusion, the motor-clutch model provides an essential theoretical framework for understanding cellular force transmission that directly applies to the evolving field of bone organoid research. By elucidating how cells sense and respond to mechanical cues through coordinated motor-clutch interactions, this model guides the optimization of biomaterial properties and culture conditions for developing physiologically relevant bone organoids with enhanced translational potential for regenerative medicine and orthopedic therapies.

Engineering Mechanical Stimulation: Techniques for Directing Bone Organoid Fate

The emergence of bone organoid technology represents a transformative advance in the study of skeletal biology, disease modeling, and drug screening. These three-dimensional (3D) biomimetic constructs recapitulate key aspects of bone architecture and function, providing an unprecedented platform for investigating bone development and pathology in vitro [4]. However, a significant technical barrier has been the difficulty in replicating the native bone mechanical microenvironment within these model systems. Bone is a dynamic tissue whose development, homeostasis, and regenerative capacity are profoundly regulated by mechanical cues [4]. Conventional 3D culture systems, including those utilizing Matrigel, lack the spatiotemporal control of mechanical properties necessary to dissect mechanotransductive mechanisms in organoids [18]. This limitation impedes the formation of fully functional bone organoids that can accurately model the complexity of native bone tissue.