Molecular and Mechanical Mechanisms of Neural Crest Cell Migration: From Embryonic Guidance to Disease Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sophisticated mechanisms governing neural crest cell migration, a cornerstone of vertebrate development.

Molecular and Mechanical Mechanisms of Neural Crest Cell Migration: From Embryonic Guidance to Disease Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sophisticated mechanisms governing neural crest cell migration, a cornerstone of vertebrate development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational concepts with cutting-edge discoveries, including the novel role of mechanosensitive protein PIEZO1 in cell detachment via extrusion. We explore the experimental models and live imaging technologies that decode collective cell behaviors, examine how migration errors cause neurocristopathies and inform cancer metastasis, and validate findings through comparative studies across model organisms. The review concludes by highlighting emerging paradigms and translational opportunities for therapeutic intervention in congenital disorders and cancer.

Blueprints of a Journey: Delamination, Guidance Cues, and the Neural Crest Gene Regulatory Network

The study of neural crest cell migration represents a cornerstone of developmental biology, illustrating the exquisite interplay between cellular potential and environmental guidance. This field rests on a historical foundation paved by pioneering embryologists who first identified and traced the fate of these remarkable cells. Wilhelm His (1831–1904), in a landmark discovery 150 years ago, first described the "Zwischenstrang" (intermediate cord)—a distinct cell population we now know as the neural crest [1] [2]. His's work was foundational not only for identifying this cell lineage but also for making its study possible through his introduction of the first microtome with micrometer advance in 1866, enabling precise comparative cellular anatomy [1]. His's detailed observations on the origin, migration, and fate of neural crest cells were instrumental in establishing the neuron doctrine and framing the core questions that would drive neuroembryology for the next century [1] [2]. His's legacy extends to his profound insights into hindbrain development, ideas that continue to inform modern molecular investigations of hindbrain regionalization and evolution [2]. This whitepaper traces the critical technological and conceptual advancements in neural crest research, from these initial histological descriptions to the sophisticated experimental models that now allow researchers to dissect the molecular and mechanical mechanisms guiding neural crest migration.

Foundational Discoveries and Key Questions

The recognition of the neural crest as a discrete embryonic population opened fundamental questions about its capabilities and migratory behavior. Early embryologists sought to reconcile the embryonic layers theory, cell theory, and evolution theory through the study of these cells [1]. Wilhelm His stood at the junction of two embryological traditions—the descriptive morphological approach and the emerging experimental approach—thereby enabling a transition in how neural crest development was investigated [1].

His's work in the 1890s on the human hindbrain provided novel ideas about the regionalization of the hindbrain neural tube and the migration of its neuronal populations [2]. A central proposition from His's writings, that a primordial spinal cord-like organization was molecularly supplemented to generate hindbrain 'neomorphs,' continues to influence modern evolutionary developmental biology [2]. The subsequent development of cell marking techniques, particularly the quail-chick chimera system, provided the critical tool needed to move from descriptive observation to experimental fate mapping, enabling researchers to definitively trace the migratory pathways and derivatives of neural crest cells.

Table: Historical Foundations of Neural Crest Research

| Investigator/Innovation | Time Period | Key Contribution | Impact on the Field |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wilhelm His | 1868-1904 | Discovery of the "Zwischenstrang" (neural crest); invention of the microtome; foundational insights into hindbrain development [1] [2]. | Made neuroembryology at a cellular level possible; established core principles of neural crest origin and migration [1] [2]. |

| Quail-Chick Chimera | 20th Century | Stable labeling technique allowing precise tracing of cell lineages and fate mapping in avian embryos [3]. | Enabled functional studies of neural crest migration and derivatives; resolved questions of embryonic origin [3]. |

| Live Imaging & Quantitative Analysis | Early 21st Century | High-resolution time-lapse microscopy coupled with computational analysis (e.g., Optical Flow) to quantify dynamic cell behaviors [4] [5]. | Revealed distinct migratory modes (individual vs. collective); allowed quantification of speed, directionality, and contact dynamics [4] [5]. |

| Modern Synthesis | Present / 2025 | Integration of molecular guidance cues (chemotaxis) with biomechanical signals (durotaxis, mechanosensing) [6]. | Elucidates how chemical and mechanical cues interact to guide neural crest cells over large distances in the embryo [6]. |

The Experimental Paradigm: Quail-Chick Chimeras

The quail-chick chimera technique, developed by Nicole Le Douarin, represents a monumental advance in experimental embryology, providing a stable and precise method for tracing definite cells and their progeny without interfering with normal development [3]. This system exploits the evolutionary relatedness of two avian species, the quail and the chick, to create chimeric embryos where the developmental fate of transplanted cells can be followed with certainty.

Detailed Methodology

The core protocol involves the surgical transplantation of quail tissues into a stage-matched chick embryo host (or vice versa) [3]. The specific steps for studying neural crest-derived components of the eye are as follows [3]:

- Donor Preparation: Identify and isolate the region of interest (the graft) containing premigratory neural crest cells from a quail donor embryo. This typically involves microdissection of the dorsal neural tube at the desired axial level (e.g., cranial for eye studies).

- Host Preparation: In a stage-matched chick host embryo, create a recipient site by surgically removing the equivalent tissue region. Care must be taken to minimize damage to surrounding tissues.

- Transplantation: Precisely place the quail graft into the prepared host site, ensuring proper anatomical orientation. The graft is integrated into the host embryo.

- Incubation & Analysis: Allow the chimera to develop for the desired period. The chimeras can then be analyzed by:

- Immunolabeling: Using species-specific antibodies (e.g., QCPN or QH1 that recognize quail antigens) to selectively label donor-derived cells [3].

- Differential Staining: Utilizing the distinct nuclear morphology of quail cells (with prominent heterochromatin condensations) compared to chick cells for histological identification [3].

This technique is particularly powerful for eye development studies because the eye forms from tissues of different embryonic origins: surface ectoderm, neuroectoderm, and neural crest cells. The quail-chick system allows researchers to determine the contribution of neural crest cells to structures such as the cornea, iris, and sclera, and to investigate the cellular interactions required for normal ocular morphogenesis [3]. The technique can be combined with molecular biology for functional studies, such as by grafting tissues that have been genetically manipulated prior to transplantation.

Quantitative Live Imaging: A Modern Revolution

The advent of high-resolution, long-term live imaging transformed the study of neural crest migration from a static, inferential science to a dynamic, quantitative one. While fixed tissue analysis suggested trunk neural crest cells migrated as individuals, live imaging confirmed this and revealed the complex, stochastic dynamics of their movement [4]. Researchers coupled advanced imaging with custom computational software to quantify migratory behavior in unprecedented detail.

Live Imaging Protocol for Trunk Neural Crest

The following methodology, adapted for chick embryos, allows for the visualization of complete neural crest cell trajectories [4]:

- Tissue Preparation: Generate a thick transverse slice (approximately 500 µm, 2-somite wide) through the trunk region (e.g., forelimb level) of a Stage HH18-19 chick embryo.

- Tissue Stabilization: Place the slice on a mold with a nylon grid, attaching it only to structures ventral to the dorsal aortas to leave dorsal migratory routes unperturbed.

- Fluorescent Labeling: Infect premigratory neural crest cells with a replication-incompetent avian retrovirus (RIA) encoding cytoplasmic mCherry and nuclear H2B-GFP. A high viral titer (10â¶â€“10â· PFU/mL) ensures a large number of cells are labeled with uniform intensity, facilitating precise 3D segmentation and 4D trajectory mapping [4].

- Image Acquisition: Perform time-lapse imaging using confocal microscopy with a 20×/0.8 NA objective. Capture a large field of view (e.g., 240 × 100 × 80 µm³) from the dorsal neural tube to the dorsal aorta at regular intervals (e.g., every 8 minutes) for up to 13 hours.

- Validation: After imaging, confirm the identity of infected cells via immunofluorescence for specific neural crest markers, such as the HNK-1 epitope, to ensure normal development under the experimental conditions [4].

Quantitative Analysis of Cell Migration

The rich datasets generated by live imaging require sophisticated computational tools for analysis. Two prominent approaches are:

- Single-Cell Trajectory Analysis: This involves tracking the 3D positions of individual cell nuclei over time. The data is used to calculate metrics like speed, directionality, and mean square displacement (MSD). In trunk neural crest, this analysis revealed a "long-range biased random walk" where cells move as individuals with a net ventral bias but significant short-term stochasticity [4].

- Optical Flow Analysis: This image processing method quantifies the motion of entire cell populations in time-lapse movies without tracking individual cells. It generates a vector field representing the magnitude and direction of movement for all pixels, which can be summed to analyze population-wide dynamics, such as left-right asymmetry or overall directionality [5]. This method is powerful for detecting subtle changes in population migration caused by genetic or environmental perturbations [5].

Table: Quantitative Metrics of Trunk Neural Crest Cell Migration from Live Imaging

| Metric | Description | Experimental Finding in Trunk Neural Crest | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migratory Mode | The spatial relationship and coordination between moving cells. | Individual cell migration, not tightly coordinated with neighbors [4]. | Distinct from collective chain migration in other axial regions (e.g., cranial). |

| Mean Square Displacement (MSD) | A measure of the deviation of a cell's position over time, indicating the spatial extent of its movement. | Analysis confirms a "biased random walk" pattern [4]. | Migration is stochastic but with a net directional bias toward ventral targets. |

| Leading Edge Dynamics | Behavior of the protrusive front of a migrating cell. | Fan-shaped lamellipodium that reorients upon cell-cell contact [4]. | Lamellipodia are key sensors and actuators for navigation. |

| Contact Behavior | The outcome of a physical collision between two cells. | "Contact attraction": cells often move together after contact, then separate via lamellipodial pulling [4]. | Transient contact helps organize local cell movements without stable adhesion. |

| Density Dependence | How local cell density influences migratory parameters. | Cells move from high to low density, generating a long-range directional bias [4]. | Contact inhibition or local repulsion helps drive ventral dispersal. |

Signaling Pathways Guiding Migration

Neural crest cell migration is orchestrated by a complex interplay of molecular and mechanical signals that guide cells along precise pathways to their final destinations. Recent research synthesizes these cues into a coherent model of navigation.

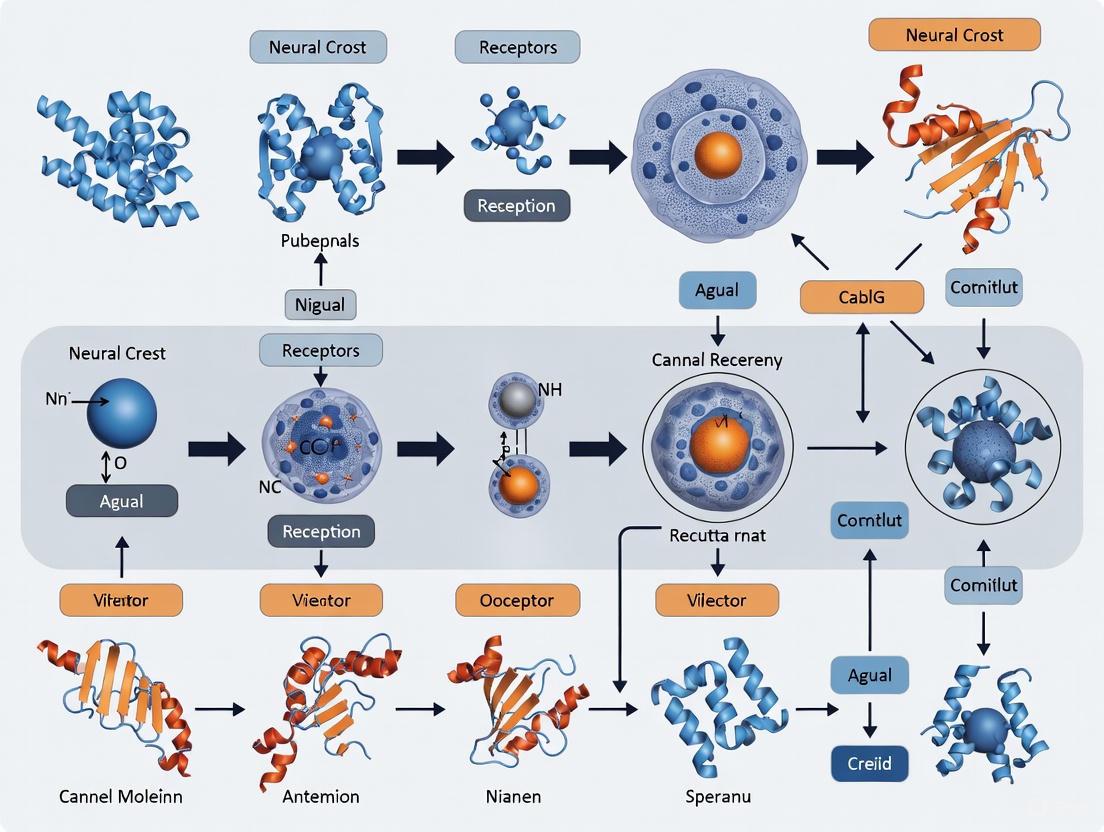

The diagram above summarizes the integrated guidance system. Chemical guidance involves classic morphogens and chemotropic factors. For example, in the trunk, Semaphorin 3F and ephrins in the posterior half of each somite create a repulsive barrier, constraining neural crest cells to the anterior somitic sclerotome [4] [6]. Meanwhile, cells may also generate their own local chemical gradients (e.g., via degradation of extracellular ligands) to facilitate robust, self-sustained migration [6]. Mechanical guidance is equally critical. Neural crest cells exhibit durotaxis (migration toward stiffer substrates) and respond to physical confinement by channels in the extracellular matrix [6]. Furthermore, contact inhibition of locomotion, where cells change direction upon colliding, is a key behavior for individual cell migration, preventing aggregation and promoting dispersal [4] [5]. The combination of these chemical and mechanical cues, interpreted by the cell's cytoskeletal machinery, results in the actin polymerization and force generation that powers directional migration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting advanced research on neural crest cell migration, as featured in the cited studies.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Crest Cell Migration Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quail & Chick Embryos | Donor and host organisms for creating chimeras. Their species-specific differences allow for stable, long-term cell lineage tracing [3]. | Fate mapping of neural crest derivatives in the eye and other tissues [3]. |

| Species-Specific Antibodies | Immunological detection of donor-derived quail cells within a chick host environment. | QCPN or QH1 antibodies used to identify quail neural crest cells in chimeric embryos after transplantation [3]. |

| Replication-Incompetent Avian Retrovirus (RIA) | Fluorescent labeling of neural crest cells for live imaging. Provides stable, uniform expression of reporters. | Cytoplasmic mCherry and nuclear H2B-GFP expressed in chick trunk neural crest for high-resolution time-lapse imaging [4]. |

| HNK-1 Antibody | Immunohistochemical marker for identifying migrating neural crest cells. | Validation of neural crest cell identity in fixed tissue samples and post-imaging analysis [4]. |

| Optical Flow Algorithm | Computational tool for quantifying population-wide cell movements from time-lapse movies in an unbiased manner. | Detecting subtle changes in directionality and left-right asymmetry of cranial neural crest streams in zebrafish after ethanol exposure [5]. |

| RK-2 | RK-2 | Chemical Reagent |

| Im-1 | Im-1|Chemical Reagent|For Research Use | The compound 'Im-1' is not uniquely identified. Please verify the specific compound structure or intended application. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The delamination of neural crest cells (NCC) from the neuroepithelium represents a fundamental process in vertebrate embryogenesis, with failures leading to severe neurocristopathies. For decades, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) has been regarded as the exclusive mechanism driving NCC delamination, characterized by progressive loss of epithelial adhesion and acquisition of migratory mesenchymal properties. However, recent research has uncovered cell extrusion as a parallel delamination mechanism, revealing unprecedented complexity in developmental biology. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of both classical EMT and the novel extrusion model, highlighting the mechanosensitive ion channel PIEZO1 as a key regulator of extrusion, and the discovery of intermediate cell states during EMT. These findings not only reshape fundamental concepts of neural crest development but also offer new perspectives for understanding cancer metastasis and designing therapeutic interventions.

Neural crest cells constitute a transient, multipotent stem cell population unique to vertebrates, contributing to diverse tissues including the craniofacial skeleton, peripheral nervous system, and cardiac outflow tract [7] [8]. Their development progresses through four phases: formation, delamination, migration, and differentiation. Delamination—the physical exit of NCC from the neuroepithelium—has long been considered synonymous with EMT [9].

Traditional EMT involves coordinated molecular changes: downregulation of epithelial markers (E-cadherin), upregulation of mesenchymal markers (vimentin, N-cadherin), cytoskeletal reorganization, and acquisition of migratory capacity [9] [10]. This process is regulated by core transcription factors including Snai1/2, Twist, and Zeb2 within a well-characterized gene regulatory network [11] [9]. However, emerging evidence reveals significant mechanistic differences between species and the existence of non-EMT delamination pathways in mammals [8] [12].

Table: Key Characteristics of Neural Crest Cell Delamination Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Classical EMT | Cell Extrusion |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Process | Progressive transformation | Forceful expulsion |

| Cell Morphology | Elongated, mesenchymal | Round, apolar |

| Primary Drivers | Transcriptional reprogramming | Biomechanical pressure |

| Key Regulators | Snai1/2, Twist, Zeb2 | PIEZO1 |

| Temporal Dynamics | Gradual (hours) | Rapid (minutes) |

| Species Prevalence | Avian, aquatic species | Mammals |

Classical EMT: The Established Paradigm of NCC Delamination

Molecular Regulation of EMT

The EMT program initiates with external signaling cues (WNT, BMP, FGF, NOTCH) that activate master transcription factors. These include Snai1/2, Twist, and Zeb2, which collectively repress epithelial genes while activating mesenchymal genes [11] [9]. A critical event is the "cadherin switch"—downregulation of epithelial cadherins (E-cadherin, Cadherin-6B) and upregulation of mesenchymal cadherins (Cadherin-7, Cadherin-11) [11] [10].

In avian and aquatic models, Snai1/2 are essential for NCC delamination; their knockdown severely disrupts EMT [9]. Similarly, Zeb2 functions as a critical EMT regulator in Xenopus and chicken embryos [9]. These transcription factors directly suppress E-cadherin expression and activate mesenchymal genes including vimentin and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [9].

Cytoskeletal and Adhesion Remodeling

During EMT, NCC undergo profound cytoskeletal reorganization to acquire migratory capacity. Epithelial cells transform their static apical-basal polarity into fluid front-back polarity essential for migration [11] [10]. Small GTPases (Rac1, Cdc42, RhoA) become asymmetrically localized—Rac1/Cdc42 at the leading edge promote actin polymerization and lamellipodia formation, while RhoA at the trailing edge activates myosin contractility [11].

Proteolytic enzymes facilitate delamination by degrading cell-cell junctions and remodeling the basement membrane. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP-14) and ADAM proteases (ADAM-10, ADAM-19) cleave cadherins (N-cadherin, Cadherin-6B) and extracellular matrix components (fibronectin, laminin) [11]. Interestingly, the cleaved ectodomain of Cadherin-6B further activates MMP-2, creating a positive feedback loop that promotes delamination [11].

EMT as a Spectrum and Migratory Strategies

Rather than a binary switch, EMT is now recognized as a spectrum of intermediate states with varying degrees of mesenchymalization [11] [12]. Single-cell RNA sequencing has identified multiple intermediate populations during mammalian NCC delamination, characterized by distinct combinations of epithelial and mesenchymal markers [12]. This epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity (EMP) enables diverse migratory strategies.

Migratory strategies vary significantly between species: anamniotes (Xenopus, zebrafish) predominantly utilize collective migration with maintained cell-cell contacts, while amniotes (chick, mouse) favor individual cell migration [11] [10]. These differences reflect species-specific adaptations in the EMT program.

Diagram: Molecular Regulation of Classical EMT in Neural Crest Cells

Cell Extrusion: A Novel Mechanism for NCC Delamination

Discovery of Extrusion in Mammalian NCC

Recent live timelapse imaging of mouse embryos revealed a previously uncharacterized subpopulation of round NCC that delaminate without typical mesenchymal morphology [7] [8]. These cells exit the neuroepithelium as isolated, apolar cells and pause briefly before acquiring migratory morphology. High-resolution imaging and cytoskeletal analysis demonstrated that these round NCC lack the front-back polarity and elongated shape characteristic of EMT, instead exhibiting features of live cell extrusion [8].

Cell extrusion represents a distinct delamination mechanism where cells are forcibly expelled from epithelial sheets due to mechanical pressures from neighboring cells [7] [8]. This process reduces tissue stress in overcrowded regions and occurs independently of classical EMT programs. Measurements of internal pressure and edge tension in the neuroepithelium confirmed that regions undergoing NCC delamination exhibit elevated tissue stress—a prerequisite for extrusion [8].

PIEZO1 as a Mechanical Sensor in NCC Extrusion

The mechanosensitive ion channel PIEZO1 emerged as the key molecular mediator of NCC extrusion [7] [8]. Single-cell RNA sequencing and immunostaining confirmed PIEZO1 expression in delaminating NCC. Functional experiments using pharmacological modulators demonstrated its necessity and sufficiency for extrusion:

- PIEZO1 inhibition (GsMTx4) reduced delamination and eliminated round NCC

- PIEZO1 activation (Yoda1) increased delamination and round NCC numbers [8]

PIEZO1 activation likely triggers calcium signaling that reorganizes the cytoskeleton in both the extruding cell and its neighbors, facilitating expulsion from the neuroepithelium [8]. This represents a novel role for PIEZO1 in neural crest development beyond its established functions in vascular development and erythrocyte volume regulation.

Table: Experimental Evidence for PIEZO1-Mediated Extrusion

| Experimental Approach | Key Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Live timelapse imaging | Identification of round, apolar NCC population | Existence of non-EMT delamination mechanism |

| Cytoskeletal analysis | Distinct actin organization in round vs. elongated NCC | Different structural requirements for extrusion vs. EMT |

| Pressure/tension measurements | Elevated tissue stress in delaminating regions | Mechanical drivers of extrusion |

| scRNA-seq + immunostaining | PIEZO1 expression in delaminating NCC | Molecular mediator identification |

| Pharmacological modulation | Altered NCC delamination with PIEZO1 agonists/antagonists | Functional validation of PIEZO1 role |

Relationship Between EMT and Extrusion

EMT and extrusion operate as parallel delamination mechanisms in mammalian NCC, potentially yielding distinct migratory populations [8]. The relative contribution of each pathway may vary by embryonic region, developmental timing, and species. This dual-mechanism model explains previous observations that genetic ablation of classic EMT regulators (Snai1/2, Twist) does not completely abolish NCC delamination in mice [9].

The emerging paradigm suggests that biomechanical constraints and tissue microenvironment influence which delamination mechanism predominates. Regions of high neuroepithelial pressure and crowding favor extrusion, while other regions may utilize classical EMT [8]. This mechanistic diversity may enhance the robustness of NCC development across varying embryonic contexts.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Visualizing NCC Delamination Dynamics

Live timelapse imaging of transgenic mouse embryos (Wnt1-Cre;R26R-mTmG) enabled direct observation of delamination dynamics [8]. This approach revealed the previously unappreciated population of round NCC and their temporal sequence of delamination followed by mesenchymal transformation.

High-resolution confocal microscopy coupled with immunostaining for cytoskeletal markers (actin, myosin) and junctional proteins delineated structural differences between EMT and extrusion. Quantitative analysis of cell morphology, coupled with measurements of intracellular pressure and membrane tension, provided biophysical evidence for distinct delamination mechanisms [8].

Molecular Manipulation Strategies

Pharmacological approaches using PIEZO1 modulators (GsMTx4 antagonist, Yoda1 agonist) established the functional role of this mechanosensitive channel in extrusion [8]. These small molecule interventions allowed precise temporal control to test necessity and sufficiency during the delamination window.

Genetic approaches including conditional knockout of EMT transcription factors and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing have elucidated requirements for specific molecular pathways. Single-cell RNA sequencing has been particularly powerful for identifying intermediate EMT states and novel molecular markers [12].

Biophysical Measurement Techniques

Laser ablation assays enabled quantification of cortical tension in neuroepithelial cells and delaminating NCC [8]. By measuring recoil velocity after targeted cytoskeletal disruption, researchers inferred relative tension values that support the extrusion model.

Atomic force microscopy has been applied to measure tissue stiffness in the neuroepithelium and surrounding microenvironment. These measurements revealed correlations between matrix stiffness, tissue tension, and NCC delamination patterns [11].

Diagram: Experimental Approaches for Studying NCC Delamination Mechanisms

Post-Transcriptional Regulation of NCC Delamination

Beyond transcriptional control, post-transcriptional mechanisms fine-tune EMT and delamination timing. RNA-binding proteins, microRNAs, and RNA modifications provide additional regulatory layers that modulate gene expression output [13] [14].

RNA Modifications and Processing

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA methylation regulates NCC development through transcript stability control. In zebrafish, METTL3-mediated m6A modification stabilizes psen1 mRNA, enhancing Wnt signaling and promoting NCC migration [13]. The m6A reader protein YTHDF1 recognizes this modification and stabilizes target transcripts, while YTHDF2 promotes mRNA decay [13].

Processing bodies (P-bodies) function as conserved regulators of NCC migration through controlled mRNA storage and decay. The RNA helicase DDX6 recruits Draxin mRNA to P-bodies for degradation, relieving inhibition of Wnt signaling and facilitating EMT [13]. Similarly, the RNA-binding protein ELAVL1 stabilizes Draxin mRNA in premigratory NCC, preventing premature delamination [13] [14].

MicroRNA-Mediated Regulation

MicroRNAs provide precise temporal control of EMT effectors. miR-34a directly targets Snai1 mRNA in zebrafish NCC, creating a negative feedback loop that limits EMT progression [14]. Similarly, miR-203 represses Snai2 expression in chick embryos, while let-7 family miRNAs regulate FoxD3, Pax7, and cMyc [14].

These post-transcriptional mechanisms enable rapid response to environmental signals and fine-tuning of delamination timing, complementing the slower transcriptional regulatory programs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagents for Studying NCC Delamination Mechanisms

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Transgenic Models | Wnt1-Cre;R26R-mTmG, Mef2c-F10N-LacZ | Lineage tracing, live imaging of NCC delamination |

| Pharmacological Modulators | GsMTx4 (PIEZO1 antagonist), Yoda1 (PIEZO1 agonist) | Functional testing of mechanosensitive channels |

| Molecular Markers | Antibodies: Snai1/2, Twist, Zeb2, PIEZO1, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin | Immunostaining, Western blot, protein localization |

| RNA-seq Technologies | Single-cell RNA sequencing, Spatial transcriptomics | Identification of intermediate states, transcriptional profiling |

| Cytoskeletal Probes | Phalloidin (F-actin), Myosin II antibodies, Live-cell actin markers | Visualization of cytoskeletal dynamics during delamination |

| Biophysical Tools | Atomic force microscopy, Laser ablation systems | Measurement of tissue stiffness, cortical tension |

| Post-transcriptional Regulators | METTL3 inhibitors, DDX6 mutants, miRNA mimics/inhibitors | Studying RNA modification, processing, and stability |

| HaA4 | HaA4 | Chemical Reagent |

| EP3 | EP3 Receptor Agonist / Antagonist | Explore high-purity EP3 ligands for cardiovascular, metabolic, and neuro research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Implications for Disease and Therapeutic Development

Understanding NCC delamination mechanisms has profound implications for neurocristopathies and cancer metastasis. Neurocristopathies like Treacher Collins syndrome and Hirschsprung disease result from defective NCC development, potentially involving dysregulated delamination [9] [12].

The discovery of extrusion and EMP in NCC provides new perspectives on cancer metastasis, where tumor cells co-opt developmental EMT programs for dissemination [13] [12]. Hybrid E/M states may enhance metastatic potential by balancing stemness, plasticity, and migratory capabilities. Circulating tumor cells often exhibit partial EMT signatures similar to intermediate NCC states [12].

PIEZO1-mediated extrusion represents a potential therapeutic target for controlling cell dissemination in both developmental disorders and cancer. The mechanosensitive nature of this pathway offers opportunities for physical or pharmacological intervention distinct from traditional biochemical targets.

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The recognition of multiple delamination mechanisms (EMT, extrusion) and intermediate states along the EMT spectrum has transformed our understanding of NCC development. Key future directions include:

- Determining the functional consequences of different delamination mechanisms on NCC fate and migratory behavior

- Elucidating cross-talk between biomechanical (extrusion) and molecular (EMT) pathways

- Exploring conservation of extrusion across vertebrate species and NCC axial levels

- Developing advanced tools for simultaneous visualization of mechanical forces and molecular events in live embryos

The integration of biophysical, molecular, and genomic approaches will continue to reveal unprecedented complexity in NCC delamination. These insights will enhance our fundamental understanding of developmental cell biology while providing new paradigms for addressing disease processes involving aberrant cell migration and plasticity.

In conclusion, NCC delamination employs both classical EMT and novel extrusion mechanisms, regulated by interconnected molecular, cellular, and biophysical processes. The continued dissection of these pathways will undoubtedly yield exciting discoveries at the intersection of developmental biology, biophysics, and disease pathogenesis.

The neural crest is a transient, multipotent stem/progenitor cell population unique to vertebrate embryos, renowned for its extensive migration and ability to differentiate into a vast array of cell types [15] [16]. Originating from the ectodermal germ layer, these cells are specified at the neural plate border and subsequently undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to embark on long-distance migrations throughout the embryo [15]. The neural crest contributes to diverse structures that define vertebrates, including the craniofacial skeleton, peripheral nervous system, cardiac outflow tract, and skin pigment cells [17] [16]. The exceptional developmental plasticity and migratory capacity of neural crest cells (NCCs) are orchestrated by a hierarchically organized Gene Regulatory Network (GRN)—a complex circuitry of transcription factors (TFs), signaling molecules, and epigenetic regulators [16]. This review dissects the core architecture of the Neural Crest Gene Regulatory Network (NC-GRN), with a specific focus on the transcriptional mechanisms controlling migratory potential, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals working in this field.

The Architecture of the Neural Crest Gene Regulatory Network (NC-GRN)

The NC-GRN is a hierarchical system that unfolds in a sequential manner, directing the formation, delamination, migration, and ultimate differentiation of neural crest cells. The network can be segmented into discrete, interconnected functional modules.

Core Modules of the NC-GRN

- Neural Plate Border Specification: This initial module establishes the territory from which NCCs arise. It is defined by the combined action of signaling gradients—BMP, Wnt, and FGF—which exhibit a medial-to-lateral distribution in the embryo [16]. Intermediate levels of these signals activate a set of neural plate border specifier genes, including Msx1/2, Pax3/7, and Zic1 [16]. These TFs act in a reinforcing network to define a progenitor domain distinct from the neural plate and non-neural ectoderm.

- Neural Crest Specification: Within the broader neural plate border, a subsequent regulatory state defines bona fide NCCs. Specifier genes such as Sox8/9/10, FoxD3, and Snai1/2 are activated by the combinatorial input of the border specifiers [16]. This module confers neural crest identity and multipotency. As one review notes, "neural crest development is thought to be controlled by a suite of transcriptional and epigenetic inputs arranged hierarchically in a gene regulatory network" [16].

- NC-GRN and Migratory Activation: The specifier genes directly activate effectors responsible for EMT and migration. Key among these are TFs like Snail1/2 and Twist, which repress epithelial adhesion molecules (e.g., E-cadherin) and upregulate mesenchymal genes (e.g., N-cadherin, vimentin) [16]. This module equips NCCs with the cytoskeletal machinery, motility, and guidance receptor expression necessary for their extensive journeys.

The logical relationships and regulatory flow between these core modules are illustrated in the following diagram:

Transcriptional Control of Migration and Guidance

The migratory phase of NCCs is a highly dynamic and regulated process. The NC-GRN governs not only the initiation of motility but also the spatiotemporal precision of pathway selection, a process critical for proper colonization of target tissues.

Axial Patterning of Migratory Potential

The transcriptional program and resultant migratory capacity of NCCs vary significantly along the anterior-posterior axis, reflecting distinct regulatory states established by the GRN [17] [15].

- Cranial NCCs originate from the midbrain/hindbrain region and contribute to craniofacial structures. They are characterized by the expression of TFs such as Sox8/9 and possess the unique ability to form mesenchymal derivatives like bone and cartilage—a potential not shared by trunk NCCs under normal conditions [17] [15]. Heterotopic grafting experiments, where cranial crest is transplanted to the trunk, confirm this intrinsic difference, as the transplanted cells maintain their ability to form ectopic cartilage [15].

- Vagal and Cardiac NCCs (from mid-otic placode to somite 7) express a transcriptional profile enabling colonization of the pharyngeal arches, cardiac outflow tract, and the entire gastrointestinal tract to form the enteric nervous system [17] [18]. Key factors here include Pax3 and FoxD3.

- Trunk NCCs contribute to dorsal root ganglia, sympathetic ganglia, melanocytes, and the adrenal medulla [17]. Their migration is segmental, guided by repulsive cues from the somites. The trunk NCC GRN lacks the full complement of TFs required for skeletogenesis.

Table 1: Axial-Level Specific Derivatives and Key Transcription Factors

| Axial Level | Major Derivatives | Key Transcription Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Cranial | Craniofacial skeleton, cranial ganglia, teeth, cornea | Sox8, Sox9, FoxD3, Twist1 |

| Vagal/Cardiac | Enteric nervous system, aorticopulmonary septum, cardiac ganglia | Pax3, FoxD3, Phox2b |

| Trunk | Dorsal root ganglia, sympathetic ganglia, melanocytes, adrenal medulla | Sox10, FoxD3, Ets1 |

Signaling Pathways and Transcriptional Integration in Migration

The migration of NCCs, particularly the enteric neural crest cells (ENCCs), is a multi-stage process—craniocaudal, radial, and transmesenteric—each under precise transcriptional control guided by extracellular signals [18].

Craniocaudal Migration: The directed colonization of the gut by vagal NCCs is governed by a wavefront of cells with distinct transcriptional and behavioral properties. Wavefront cells exhibit high migratory speed and low directional persistence, organized in chain-like structures [18]. This process is regulated by:

- Retinoic Acid (RA) Signaling: Promotes collective chain migration by upregulating the transcription factor Meis3 and the RET tyrosine kinase receptor [18].

- PKA Activity Gradient: Low PKA activity in the wavefront promotes migration, while high PKA activity in trailing cells reduces Rac1 activity and migration speed [18].

- DUSP6 Expression: This dual-specificity phosphatase is specifically upregulated in the wavefront, creating a negative feedback loop that fine-tunes ERK signaling to maintain the migratory phenotype [18].

Radial Migration: The inward movement of NCCs from the myenteric plexus to form the submucosal plexus is guided by a balance of attractive and repulsive signals that are interpreted transcriptionally [18]. Key pathways include:

- Netrin attraction from the epithelium.

- Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) repression from the epithelium to prevent over-invasion.

- BMP suppression of Netrin attraction to stabilize the migratory pathway.

The integration of these extracellular signals with the core NC-GRN to direct cell motility is summarized below:

Experimental Dissection of the NC-GRN: Methods and Protocols

Understanding the NC-GRN's structure and function relies on a suite of sophisticated molecular and cellular techniques. The following table outlines key experimental approaches and their applications in studying the transcriptional control of NCC migration.

Table 2: Key Experimental Methods for NC-GRN Analysis

| Method | Core Function | Application in NC Migration Research | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-Seq [19] [20] | Identifies genome-wide binding sites for TFs. | Mapping direct targets of migratory TFs (e.g., Snail, SoxE). | Catalog of TF-bound genomic regions and associated genes. |

| DAP-Seq [20] | In vitro profiling of TF binding sites. | Rapidly characterizes binding landscape of many TFs; useful for crops/custom TFs. | TF binding motifs and putative target genes. |

| Single-Cell Multiomics (scRNA-seq + scATAC-seq) [21] | Paired measurement of gene expression and chromatin accessibility in single cells. | Resolving heterogeneity in migratory NCC populations; inferring TF activity. | Cell-type specific regulatory landscapes and active GRNs. |

| Quail-Chick Chimeras [15] | Lineage tracing and fate mapping via interspecies grafting. | Defining migration pathways and axial-level potential of NCCs. | Maps of NCC migration routes and derivative contributions. |

| In Vivo Lineage Tracing (e.g., Confetti mice) [15] | Genetic labeling of single cells and their progeny within the embryo. | Clonal analysis of individual NCCs to assess multipotency and migratory divergence. | Fate maps demonstrating multipotency of single NCCs. |

Detailed Protocol: DAP-Seq for Profiling TF Binding Landscapes

DNA Affinity Purification sequencing (DAP-seq) is a powerful in vitro method for mapping the cistrome of hundreds of TFs, as demonstrated in soybean and other systems [20]. The following workflow is adapted from high-throughput studies.

1. Library Design and Cloning:

- TF Cloning: Clone the open reading frame of the TF of interest into an expression vector with an N- or C-terminal affinity tag (e.g., His-tag, FLAG-tag).

- Genomic DNA Library Preparation: Fragment genomic DNA (e.g., from the model organism of choice) by sonication or enzymatic digestion to sizes of 100-500 bp.

2. Protein Expression and DNA Capture:

- Express the recombinant TF in a system like E. coli or using in vitro transcription/translation.

- Incubate the tagged TF with the fragmented genomic library. The TF binds to its cognate sites in the DNA.

- Use affinity resin (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tags, anti-FLAG beads) to pull down the TF-DNA complexes.

- Wash the resin thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound DNA.

3. Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Elute the bound DNA from the resin.

- Amplify the eluted DNA via PCR and prepare the library for high-throughput sequencing (Illumina platforms).

4. Data Analysis:

- Peak Calling: Align sequencing reads to the reference genome and identify statistically significant regions of enrichment (peaks) using tools like MACS2. These peaks represent putative TF binding sites (TFBSs).

- Motif Discovery: Use tools like MEME-ChIP to identify the de novo DNA binding motif of the TF from the peak sequences.

- Target Gene Annotation: Assign peaks to candidate target genes based on genomic proximity (e.g., within promoters, enhancers).

Detailed Protocol: Single-Cell Multiomics with Epiregulon Analysis

The Epiregulon method constructs GRNs from single-cell multiomics data to infer TF activity at single-cell resolution, which is crucial for understanding heterogeneity in migratory NCC populations [21].

1. Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- Dissociate migratory NCCs or whole embryos at the relevant developmental stage into a single-cell suspension.

- Process the cells using a single-cell multiome platform (e.g., 10x Genomics Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression) to generate paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data from the same cell.

2. Data Preprocessing and Integration:

- scRNA-seq Data: Align reads to the genome, quantify gene expression counts, and perform standard normalization and clustering.

- scATAC-seq Data: Align reads, call peaks, and create a cell-by-peak matrix quantifying chromatin accessibility.

- Integration: Use tools like Seurat or Signac to co-embed the RNA and ATAC modalities based on common cellular identities.

3. GRN Inference with Epiregulon:

- Define Regulatory Elements (REs): Use scATAC-seq data to identify accessible REs (promoters, enhancers).

- Assign REs to TFs: Overlap REs with pre-compiled ChIP-seq binding sites for specific TFs or with known TF motifs.

- Link REs to Target Genes (TGs): Correlate RE accessibility with the expression of potential target genes within a defined genomic distance (e.g., ±500 kb from the TSS) across metacells (groups of similar cells).

- Calculate TF Activity: For each cell, the activity of a TF is computed as the RE-TG-edge-weighted sum of its target genes' expression levels. This metric can detect changes in TF activity even when its mRNA expression is unchanged, such as after post-translational modification [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating the NC-GRN

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| DAP-seq Library [20] | High-throughput in vitro mapping of TF binding sites. | Rapidly profiling the cistrome of 148+ TFs in a single study. |

| Quail-Chick Chimeras [15] | Classic fate-mapping and lineage tracing. | Defining the contribution of grafted NCC populations to specific derivatives. |

| Conditional Transgenic Mice (e.g., Confetti) [15] | Sparse, heritable labeling of single cells and their progeny in vivo. | Clonal analysis to trace the lineage and migratory routes of individual NCCs. |

| Sir4p-TF Fusion Plasmid [19] | Part of the "Calling Cards" system; directs transposon integration to TF binding sites for recording TF activity. | Tracking historical TF binding events in yeast models of gene regulation. |

| SMARCA2/4 Degrader (e.g., SMARCA2_4.1) [21] | Pharmacologically disrupts the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeler complex. | Probing the role of chromatin remodeling in NCC migration and TF function. |

| Morpholinos / siRNA [17] | Knocks down gene expression transiently. | Functional assessment of specific TFs (e.g., Sox10, FoxD3) in NCC migration in zebrafish/Xenopus. |

| PsD1 | Psd1 Pea Defensin | Psd1 is a plant defensin for antifungal mechanism research. It targets fungal membrane glucosylceramide. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| DP1 | DP1 Synthetic Antimicrobial Peptide | DP1 is a synthetic antimicrobial peptide (RUO) for studying broad-spectrum anti-bacterial mechanisms, membrane disruption, and wound healing. Not for human use. |

The Neural Crest Gene Regulatory Network represents a sophisticated and robust system that translates developmental cues into precise cellular behaviors, most notably the extensive migration that defines the neural crest lineage. The hierarchical, modular architecture of the NC-GRN, progressing from border specification to migratory activation, ensures the faithful execution of this complex developmental program. Current research, powered by high-throughput technologies like DAP-seq and single-cell multiomics, is moving beyond cataloging network components to quantitatively understanding the dynamic interactions and kinetic parameters that govern TF binding and target gene regulation [19] [21] [20]. Future work will focus on integrating quantitative GRN models with live imaging data to predict migratory behaviors, and on elucidating the role of epigenetic modifications in refining the network's output. A deeper understanding of the NC-GRN not only illuminates fundamental developmental biology but also provides a critical framework for diagnosing and treating neurocristopathies like Hirschsprung's disease and for advancing regenerative medicine strategies aimed at harnessing the potential of neural crest-derived stem cells.

The directed migration of neural crest cells (NCCs) is a cornerstone of vertebrate embryogenesis, enabling the formation of diverse structures from facial bones to peripheral nerves. This complex journey is orchestrated by a sophisticated interplay of molecular guidance cues, including classical chemotactic signals, Ephrins, and Semaphorins. These molecules function not in isolation but as an integrated guidance system, directing NCC pathfinding through contact inhibition, chemotaxis, and chemorepulsion. Recent research continues to refine our understanding of how these chemical signals are interpreted by NCCs in conjunction with mechanical inputs from the embryonic environment. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the core molecular players and mechanistic principles governing neural crest cell navigation, serving as a critical resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to manipulate cell migration in regenerative medicine or combat pathological processes like cancer metastasis.

The neural crest is a transient, multipotent embryonic stem cell population that undergoes a remarkable epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to embark on long-range migration throughout the embryo [22]. NCCs contribute to a vast array of cell types and tissues, including neurons and glia of the peripheral nervous system, craniofacial cartilage and bone, melanocytes, and smooth muscle [22]. The cranial neural crest, in particular, undergoes collective cell migration, a highly coordinated and directional movement that has been likened to cancer metastasis [22]. The successful execution of this migratory program is foundational to normal development, and errors in NCC guidance underlie a range of congenital disorders and disease states. The directed migration of NCCs is not random but is channeled along precise pathways by a combination of attractive and repulsive molecular signals present in the embryonic microenvironment. These cues are detected by receptors on NCCs, triggering intracellular signaling cascades that ultimately reorganize the cytoskeleton to propel cell movement.

Core Guidance Cue Families and Their Mechanisms

Neural crest cells integrate a multitude of extracellular signals to navigate the embryo. The major families of guidance cues and their specific roles in NCC migration are detailed below.

Molecular Guidance Cues in Neural Crest Cell Migration

Table 1: Key Molecular Guidance Cues and Their Functions in Neural Crest Migration

| Guidance Cue Family | Specific Member | Role in NCC Migration | Receptors on NCC | Type of Signal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semaphorin | Sema3A | Chemorepulsion; prevents NCCs from entering inappropriate regions [23] | Neuropilin-1 (NRP1)/Plexin-A complex [24] | Repulsive |

| Ephrin | EphrinB2 | Establishes exclusion boundaries; mediates contact inhibition of locomotion (CIL) with placodal cells [22] | EphB4 [22] | Repulsive |

| Complement Factor | C3a | Prevents NCC dispersion via short-range co-attraction [22] | C3aR [22] | Attractive |

| Chemokine | SDF1 | Chemoattraction toward placodal cells [22] | CXCR4 [22] | Attractive |

| Growth Factor | VEGF | Chemoattraction [22] | VEGFR (likely) | Attractive |

| Growth Factor | FGF8 | Chemoattraction [22] | FGFR (likely) | Attractive |

| Extracellular Matrix | Versican | Inhibits migration into boundaries; promotes confinement within streams [22] | Integrins (indirect) | Repulsive/Permissive |

Intracellular Signaling Machinery

The binding of guidance cues to their transmembrane receptors activates a conserved set of intracellular signaling proteins that direct cytoskeletal remodeling. The Rho family of GTPases acts as a central signaling hub.

Table 2: Key Intracellular Signaling Proteins in Neural Crest Guidance

| Protein | Function in Neural Crest Guidance | References |

|---|---|---|

| RhoA | Small GTPase; accumulates at cell-cell contacts to mediate actomyosin contractility and retraction during CIL. | [22] |

| Rac1 | Small GTPase; activated at the cell's free edge to promote actin polymerization and protrusion formation. | [22] |

| N-Cadherin | Cell-cell adhesion molecule; mediates CIL by locally inhibiting Rac1 at contact sites. | [22] |

| Src & FAK | Non-receptor tyrosine kinases; involved in the disassembly of cell-matrix adhesions during CIL. | [22] |

| GSK3 | Serine/threonine kinase; central regulator of migration; controls Rac1, lamellipodin, and FAK. | [22] |

| TBC1d24 | Rab35-GTPase activating protein; interacts with EphrinB2 to control CIL. | [22] |

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core signaling pathways and their integration during neural crest cell guidance.

Diagram 1: Semaphorin 3A Repulsive Signaling Pathway

Diagram 2: Integrated Neural Crest Guidance System

Experimental Protocols for Studying Guidance

Understanding the mechanistic action of guidance cues requires robust in vitro and ex vivo assays that allow for precise control of the cellular microenvironment.

Modified Zigmond Chamber Assay for Trunk Neural Crest

This protocol describes an advanced method for analyzing chemotaxis in primary trunk NCCs, capable of distinguishing true chemotaxis from other influences like chemokinesis [23].

Workflow Diagram: Modified Zigmond Chamber Assay

Detailed Protocol:

- Day 1: Neural Tube Explant Culture: Isolate trunks from HH15-HH17 chick embryos. Digest in Dispase (0.24 U/ml DMEM) for 75 minutes at 37°C. Dissect out neural tubes using fine forceps and a tungsten needle. Transfer individual neural tubes to fibronectin-coated (10 µg/ml) coverslips and culture overnight in DMEM with 8% FBS [23].

- Day 2: Chamber Assembly and Imaging: Select neural crest cultures with a long, straight edge for analysis. Remove the central neural tube, leaving migrated NCCs attached. Mount the coverslip onto a modified Zigmond chamber coated with petroleum jelly, ensuring the straight NCC border is centered over the bridge and perpendicular to it. Load the reservoir opposite the NCCs with control medium. Load the reservoir facing the NCCs with the test chemotactant solution. Seal the chamber and acquire time-lapse images to quantify alterations in NCC migratory polarity toward the chemotactant gradient [23].

Key Advantages: This method is inexpensive, avoids harsh cell lifting (e.g., trypsinization), maintains NCCs in a distribution more similar to in vivo conditions, and allows simultaneous evaluation of multiple migratory parameters [23].

High-Throughput 3D Chemotactic Assay (HT-ChemoChip)

For more systematic, high-resolution investigation, microfluidic platforms like the HT-ChemoChip enable high-throughput 3D chemotactic assays under highly controlled conditions [25].

Workflow Diagram: HT-ChemoChip Workflow

Application to Guidance Cues: This platform has been used to reveal complexity in neuronal sensation to gradients. For example, studies with Sema3A showed that the STK11 and GSK3 signaling pathways are differentially involved in steepness-dependent chemotactic regulation, with GSK3 activity being critical for sensing Sema3A gradient steepness in neuronal migration [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Neural Crest Guidance Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use in Guidance Research |

|---|---|---|

| Modified Zigmond Chamber | Creates stable linear chemical gradients for chemotaxis assays. | Used to test the chemotactic/chemorepulsive effect of candidate molecules like Semaphorins on trunk NCC migration [23]. |

| HT-ChemoChip Microfluidic Device | High-throughput generation of a large-scale library of 3D molecular gradients with distinct steepness. | Enables systematic study of steepness-dependent neuronal/NCC response to Netrin-1, NGF, and Sema3A [25]. |

| Recombinant Guidance Cues (e.g., Sema3A, Netrin-1) | Purified proteins used to create defined gradients in vitro. | Applied in chambers or microfluidic devices to elicit and quantify cellular responses [25]. |

| Function-Blocking Antibodies | Inhibits the function of specific cell-surface receptors or ligands. | Antibodies against NRP1 used to demonstrate its role in mediating Sema3A's effects on CD8+ T cells (analogous to NCC studies) [24]. |

| Conditional Knockout Mice (e.g., Cd4Cre x Nrp1Flox/Flox) | Enables cell-type-specific deletion of genes of interest in vivo. | Used to demonstrate that NRP1-deficiency in T cells enhances anti-tumor activity by improving infiltration into SEMA3A-rich tumors [24]. |

| Dispase Enzyme | Neutral protease used for the clean isolation of embryonic tissues like neural tubes. | Critical for dissecting neural tubes from chick embryos for explant culture in migration assays [23]. |

| Fibronectin from Bovine Plasma | Extracellular matrix protein used as a coated substrate to support cell adhesion and migration. | Coated on coverslips to facilitate neural tube attachment and subsequent neural crest cell migration [23]. |

| PhD1 | PHD1 Inhibitor | Explore PHD1 (EGLN2), a key oxygen-sensing enzyme. This HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor is for research use only (RUO). Not for human use. |

| RFIPPILRPPVRPPFRPPFRPPFRPPPIIRFFGG | RFIPPILRPPVRPPFRPPFRPPFRPPPIIRFFGG | Chemical Reagent |

The navigation of neural crest cells through the embryo is a paradigm of directed cell migration, masterfully controlled by the integrated signaling of molecular guidance cues like Semaphorins, Ephrins, and chemotactic factors. The field has moved beyond simply cataloging these molecules to understanding how they signal through core intracellular machinery like the Rho GTPases to dynamically regulate the cytoskeleton. Furthermore, the interplay between these chemical signals and mechanical inputs from the extracellular environment is an area of intense and ongoing investigation [22] [6]. The development of sophisticated tools, such as high-throughput 3D microfluidic assays, is pushing the boundaries of our understanding, allowing researchers to dissect the role of complex parameters like gradient steepness. For drug development professionals, this deep mechanistic knowledge opens avenues for therapeutic intervention, whether by promoting regenerative neural crest pathways, blocking metastatic cancer cell migration that co-opts these same cues, or modulating immune cell trafficking in the tumor microenvironment [24]. The future of neural crest guidance research lies in further elucidating this complex signaling network in vivo and leveraging this knowledge to develop precise cell-based therapeutics.

The directed migration of neural crest (NC) cells is a fundamental process in vertebrate embryogenesis, giving rise to diverse cell types and structures. The precise coordination of this complex journey is governed by intricate molecular networks, with small GTPases and the Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) complex acting as central regulators. This review delves into the mechanisms by which these signaling systems control polarized cytoskeletal organization, cell adhesion, and directional motility in cranial and cardiac NC cells. We synthesize current findings from genetic, cell biological, and biochemical studies, framing them within the context of congenital disease etiology. Furthermore, we provide a detailed methodological toolkit for investigating these pathways, including standardized protocols and essential research reagents, to advance the study of NC-related developmental disorders and potential therapeutic interventions.

The neural crest is a transient, multipotent progenitor cell population that originates at the neural plate border. NC cells undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), delaminate, and embark on extensive migration throughout the embryo to differentiate into a wide array of cell types, including craniofacial cartilage and bone, neurons and glia of the peripheral nervous system, and cardiac outflow tract structures [26]. The directional migration and correct positioning of NC cells at their target sites are absolutely essential for proper embryonic development. Defects in these processes result in severe congenital diseases known as neurocristopathies, which include Treacher Collins syndrome, Hirschsprung's disease, and cardiac outflow tract anomalies [26].

The molecular mechanisms steering NC cell migration are multifaceted, involving a combination of contact inhibition of locomotion, co-attraction, chemotaxis, and responses to mechanical cues from the extracellular environment [26]. Underpinning all these guidance mechanisms is the fundamental cellular capacity to establish and maintain polarity—the asymmetric organization of cellular components that defines a leading and trailing edge. This review focuses on two pivotal families of proteins that orchestrate this polarity: the small GTPases and the components of the Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) complex.

The Central Role of Small GTPases in Cell Polarity and Motility

Small GTPases of the Ras superfamily function as molecular switches, cycling between an active GTP-bound state and an inactive GDP-bound state. This cycling is tightly regulated by Guanine nucleotide Exchange Factors (GEFs), which promote GTP loading, and GTPase-Activating Proteins (GAPs), which enhance GTP hydrolysis [27]. They are crucial signaling nodes in a remarkable range of cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and adhesion. In the context of cell polarity and migration, the Rho family of small GTPases—particularly Cdc42, Rac, and Rho—are the master regulators.

Cdc42: A Conserved Master Regulator of Polarity

The Rho family GTPase Cdc42 is a highly conserved polarity protein, identified first in S. cerevisiae and found to be critical for bud site selection [28]. Its function and structure are conserved from yeast to humans, with 80-95% identity in the predicted amino acid sequence [28]. Cdc42 orchestrates polarized growth by:

- Triggering Actin Polarization: Active, GTP-bound Cdc42 interacts with effector proteins containing the Cdc42/Rac Interactive Binding (CRIB) domain, such as the p21-activated kinase (PAK) family, to reorganize the actin cytoskeleton [28].

- Regulating Exocytosis: Cdc42 guides secretory vesicles to sites of polarized growth, ensuring targeted membrane addition and protein delivery [28].

- Membrane Localization: The membrane targeting of Cdc42 is dependent on a C-terminal CAAX box (e.g., CTIL in yeast) that undergoes geranylgeranylation, a lipid modification essential for its function [28].

In NC cells, this ancient mechanism is co-opted to establish a leading edge. The accumulation of active Cdc42 at the front of a cell nucleates actin polymerization and directs protrusion formation, a prerequisite for directional migration.

Rap1 and Ral: Expanding the GTPase Network in Polarity

Beyond the Rho family, other small GTPases play critical and evolutionarily conserved roles in polarity. The Ras-like GTPases Rap1 and Ral have been identified as key regulators of cortical polarity and spindle orientation during asymmetric cell division in Drosophila neuroblasts [27]. This signaling network (Rap1-Rgl-Ral) influences the apical localization of polarity proteins like aPKC and Bazooka/Par3 and regulates spindle orientation through interactions with the apical protein Canoe/AF-6 [27].

The role of Rap1 in polarity is conserved in vertebrates. In developing mammalian neurons, Rap1B activation in a single neurite promotes local activation of Cdc42 and the Par complex (Par3/Par6/aPKC), leading to the specification of that neurite as the axon [27]. This demonstrates a conserved principle where small GTPases act in a positive feedback loop with polarity complexes to break cellular symmetry and establish a stable polarized axis—a process directly analogous to the polarization of migrating NC cells.

Table 1: Key Small GTPases Regulating Cell Polarity and Motility

| GTPase | Family | Primary Function in Polarity/Motility | Key Regulators | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cdc42 | Rho | Master polarity regulator; nucleates actin polymerization at leading edge; guides exocytosis. | Cdc24 (GEF in yeast), Intersectin (GEF in mammals) | Bud site selection in yeast; Axon specification in neurons; Leading-edge formation in NC cells. |

| Rac1 | Rho | Promotes lamellipodia formation and membrane protrusion at the leading edge. | Tiam1, Vav2 (GEFs) | NC cell migration; Collective cell migration. |

| RhoA | Rho | Regulates actomyosin contractility at the cell body and trailing edge. | p115RhoGEF, LARG | Cell body contraction; Retraction fiber formation. |

| Rap1 | Ras | Regulates cell-cell adhesion, integrin signaling, and cortical polarity. | Epac, PDZ-GEF | Spindle orientation in asymmetric division; Neuronal polarity; NC cell adhesion and migration. |

| Ral | Ras | Regulates exocyst complex function in vesicle trafficking. | Rgl, RalGDS (GEFs) | Partner of Rap1 in polarity; Exocytosis during polarized growth. |

The Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) Signaling Pathway

Planar Cell Polarity refers to the coordinated polarization of cells within the plane of a tissue, a phenomenon distinct from apical-basolateral polarity. While historically studied in Drosophila (e.g., in the oriented hairs of the wing and ommatidia of the eye), PCP is a conserved feature of vertebrate development and is critically important in mesenchymal cells like NC cells for regulating directed migration and cell intercalation [29].

The Core PCP Molecular Machinery

The principal PCP signaling pathway is the noncanonical Wnt/Frizzled pathway, which operates independently of β-catenin. The core components form two opposing complexes at the cell membrane that transmit directional information between cells.

Core Frizzled/PCP Components:

- Frizzled (Fz): A seven-pass transmembrane receptor that binds Wnt ligands (e.g., Wnt5a, Wnt11) and recruits Dishevelled to the membrane [29] [30].

- Flamingo (Fmi/Celsr in vertebrates): An atypical cadherin that mediates homophilic adhesion between adjacent cells, facilitating the propagation of polarity signals [29] [30].

- Dishevelled (Dsh/Dvl in vertebrates): A cytoplasmic multi-domain protein that is recruited by Fz and serves as a central hub for downstream signaling [29] [30].

- Strabismus/Van Gogh (Stbm/Vangl in vertebrates): A four-pass transmembrane protein that localizes to the opposite side of the cell from Fz and can antagonize Fz/Dvl signaling [29] [30].

- Prickle (Pk): A cytoplasmic LIM-domain protein that binds Stbm and also antagonizes Dvl [29] [30].

- Diego (Dgo/Ankrd6 and Invs in vertebrates): A cytoplasmic ankyrin-repeat protein that stabilizes the Fz-Dvl complex [29].

This asymmetric localization of core PCP components (e.g., Fz-Dvl on one side and Vangl-Pk on the opposite side of a cell) creates a molecular compass that defines the axis of polarity within the tissue plane.

PCP Signaling in Cell Migration and Neural Tube Closure

A primary function of PCP signaling in vertebrate morphogenesis is to regulate convergent extension (CE) movements, during which a tissue narrows (converges) and lengthens (extends). This process is driven by mediolateral cell intercalation and is essential for gastrulation and neural tube closure [29] [30]. During neural tube formation, PCP-dependent CE narrows the distance between the elevating neural folds, allowing their apposition and fusion [30]. Time-lapse studies in Xenopus and zebrafish have shown that PCP signaling orients the protrusive activity of cells, enabling them to intercalate between their neighbors [31].

The link between PCP and human disease is starkly evident in neural tube defects (NTDs), which are severe birth defects arising from a failure in neural tube closure. Mutations in core PCP genes such as VANGL1 and VANGL2 are strongly associated with NTDs like craniorachischisis in both mice and humans [30]. This underscores the non-redundant role of PCP signaling in coordinating cell polarity and movement during embryonic development.

Integration of Small GTPase and PCP Signaling in Neural Crest Cell Migration

The small GTPase and PCP pathways are not isolated systems; they converge to direct the collective migration of NC cells. The PCP pathway acts upstream to interpret tissue-level polarity cues, which are then executed at the cellular level through the localized activation of small GTPases.

The core PCP component Dishevelled (Dvl) directly engages the cytoskeletal machinery by activating small GTPases RhoA and Rac1 [29] [30]. In the PCP context, Dvl can form a complex with the formin protein Daam1, which in turn activates RhoA [29]. Active RhoA then signals through its effector Rho kinase (ROCK) to regulate actomyosin contractility, a force essential for cell body translocation and intercalation. Simultaneously, Dvl can activate Rac1 to promote the formation of lamellipodial protrusions in the direction of migration [29]. This coordinated regulation of Rho and Rac family GTPases ensures that protrusive forces at the front and contractile forces at the rear are spatially coordinated.

Recent research underscores the role of PCP signaling in NC cell migration itself. It has been shown that PCP genes regulate the polarity and migration of cranial and cardiac NC cells, and that disturbances in this pathway, involving small GTPases, heterotrimeric G proteins, and the PCP complex, can lead to congenital diseases [26]. For instance, in zebrafish, the loss of the core PCP gene prickle1 disrupts EMT and the migration of cranial neural crest cells [26].

Table 2: Core Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) Pathway Components

| Gene (Drosophila) | Vertebrate Homolog | Molecular Features | Role in PCP Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| frizzled (fz) | Fz3, Fz6, Fz7 | Seven-pass transmembrane receptor; binds Wnt ligands. | Forms core complex with Dvl; defines one pole of the polarity axis. |

| dishevelled (dsh) | Dvl1, Dvl2, Dvl3 | Cytoplasmic protein with DIX, PDZ, DEP domains. | Central adaptor; transduces signal from Fz to small GTPases RhoA/Rac. |

| prickle (pk) | Pk1, Pk2 | Cytoplasmic protein with LIM domains. | Antagonizes Dvl; part of the opposing complex with Vangl. |

| strabismus (stbm) | Vangl1, Vangl2 | Four-pass transmembrane protein. | Forms core complex with Pk; defines the opposite pole from Fz/Dvl. |

| flamingo (fmi) | Celsr1 | Atypical cadherin, seven-pass transmembrane. | Mediates intercellular communication; stabilizes Fz-Vangl asymmetry. |

| diego (dgo) | Ankrd6, Inversin | Cytoplasmic ankyrin repeat protein. | Stabilizes the Fz-Dvl complex; promotes PCP signaling. |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Studying the dynamic and integrated nature of polarity signaling requires a combination of genetic, cell biological, and biochemical techniques. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments cited in this field.

Protocol 1: Analyzing Small GTPase Activity in Migrating Neural Crest Cells

This protocol outlines a method to assess the spatiotemporal activation of Cdc42 and Rac1 during NC cell migration using FRET-based biosensors.

Workflow:

- Biosensor Electroporation: Dissect avian (chicken/quail) or murine neural tubes at the premigratory NC stage. Electroporate the tissue with plasmids encoding Raichu- or FRET-based Cdc42 or Rac1 activity biosensors.

- Explant Culture: Culture the electroporated neural tubes on fibronectin-coated glass-bottom dishes in serum-free medium to allow NC cell emigration.

- Time-Lapse Imaging: Place the explant culture on a confocal or TIRF microscope with an environmental chamber (37°C, 5% CO2). Acquire FRET and CFP images at 30-second to 2-minute intervals over 2-4 hours to track migrating NC cells.

- Image Analysis:

- Calculate the FRET/CFP ratio for each time point to generate an activity map.

- Use kymograph analysis to correlate protrusion dynamics with localized GTPase activity at the leading edge.

- Quantify the asymmetry index of GTPase activity between the front and rear of the cell.

Protocol 2: Functional Genetics of PCP Signaling in Neural Crest Migration

This protocol describes the use of antisense morpholinos in zebrafish to determine the role of a PCP gene (e.g., prickle1) in cranial NC cell migration.

Workflow:

- Morpholino Design and Injection: Design a splice-blocking or translation-blocking morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) against the target PCP gene (e.g., prickle1). Inject 1-2 nL of MO (e.g., 500 µM) into the yolk of 1-4 cell stage zebrafish embryos. Include a standard control MO-injected group.

- In Situ Hybridization (ISH): At 24-48 hours post-fertilition (hpf), fix embryos and perform whole-mount ISH using riboprobes for NC markers such as sox10, foxd3, or crestin.

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Migration Scoring: Score the extent and pattern of cranial NC cell migration under a stereomicroscope. A positive phenotype may show delayed, dispersed, or truncated NC streams.

- Morphometric Measurement: Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to measure the area and distance migrated by the most anterior NC stream.

- Rescue Experiment: Co-inject the MO with synthetic, MO-resistant mRNA of the target gene to confirm phenotype specificity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Polarity and Migration

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| FRET-based GTPase Biosensors (e.g., Raichu-Cdc42) | Live-cell Biosensor | Visualizes spatiotemporal activity of specific GTPases (Cdc42, Rac, Rho) in live cells. | Protocol 1: Mapping Cdc42 activation zones in protrusions of migrating NC cells. |

| Antisense Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Functional Genomics Tool | Knocks down specific gene expression by blocking mRNA splicing or translation. | Protocol 2: Rapidly assessing loss-of-function phenotypes of PCP genes in zebrafish NC. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Gene Editing Tool | Creates stable, heritable gene knockouts or knock-ins in model organisms. | Generating mutant mouse lines for Vangl2 to study its role in cardiac NC and NTDs. |

| Specific Chemical Inhibitors (e.g., Y-27632 for ROCK) | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Pharmacologically inhibits specific signaling proteins to probe function. | Testing the role of ROCK-mediated contractility in NC cell migration ex vivo. |

| Antibodies against Phospho-Myosin Light Chain | Immunological Reagent | Marks sites of actomyosin contractility; readout for Rho/ROCK signaling. | Immunofluorescence staining to visualize contractile regions in NC cells and tissues. |

| P-18 | P-18 Hybrid Peptide|Anti-melanoma Research | P-18 hybrid peptide for research on melanoma cytotoxicity. Product is For Research Use Only. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. | Bench Chemicals |

| P15 | P15 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Small GTPase Coordination in Cell Polarity

Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) Core Signaling

Decoding Movement: Live Imaging, Computational Modeling, and Translational Bridges to Disease

State-of-the-Art In Vivo Imaging: Quantitative Analysis of Trunk Neural Crest Migration

An technical guide for investigating cell migration within developing embryos

The migration of trunk neural crest (TNC) cells is a fundamental process in vertebrate development, giving rise to diverse structures including the peripheral nervous system, melanocytes, and adrenal medulla [4] [32]. Unlike cranial neural crest cells that often migrate collectively, TNC cells primarily navigate the complex embryonic environment as individuals, exhibiting distinct migratory behaviors [4] [33]. Understanding the mechanisms governing their journey from the dorsal neural tube to distant targets requires the ability to visualize and quantify their dynamic behaviors in a living organism.

For decades, inferences about TNC migration were drawn from static images, which provided snapshots of the process but failed to capture its dynamic nature [4]. The emergence of advanced in vivo live imaging, coupled with sophisticated computational tools, has revolutionized the field. These technologies now enable researchers to observe the complete migratory journey of TNC cells with high spatiotemporal resolution, transforming our understanding from a model of coordinated, directed migration to one characterized by stochastic and biased random walk behavior [4]. This guide details the state-of-the-art methodologies for the quantitative imaging and analysis of trunk neural crest migration, providing a framework for researchers to investigate the cellular and molecular mechanisms that orchestrate this complex morphogenetic event.

Core Quantitative Imaging Methodology

The acquisition of high-quality, quantitative data on TNC migration hinges on a refined ex vivo tissue slice culture system that preserves the native cellular environment while allowing for optical accessibility.

Tissue Preparation and Live Imaging Protocol

Experimental Workflow: Trunk Neural Crest Live Imaging

- Biological Model and Fluorescent Labeling: The protocol utilizes stage HH18-19 chick embryos. Premigratory neural crest cells are fluorescently tagged using a replication-incompetent avian retrovirus (RIA) encoding both nuclear H2B-GFP and cytoplasmic mCherry [4] [34]. A high viral titer (10â¶â€“10â· PFU/mL) ensures a large number of cells are labeled with nearly uniform intensity, which is critical for precise 3D segmentation and 4D tracking [4].

- Tissue Slice Culture and Stabilization: A 2-somite-wide transverse slice (~500 μm thick) is prepared from the forelimb level of the embryo. A key innovation is the use of a nylon grid mold placed on the slice, which attaches only to structures ventral to the dorsal aortas. This stabilizes the culture for long-term imaging without perturbing the dorsal migratory routes of the neural crest cells [4].

- Image Acquisition Parameters: Imaging is performed using confocal microscopy with a 20×/0.8 NA objective, providing a large field of view (240 × 100 × 80 μm³) at cellular resolution (10-μm scale). Images are captured at 8-minute intervals for up to 13 hours to resolve complete cell trajectories from the dorsal neural tube to the dorsal aorta [4]. Post-imaging immunofluorescence with the HNK-1 antibody confirms the identity of the migrating neural crest cells [4].

Key Quantitative Metrics and Analytical Tools

The dynamic 4D data (x, y, z, t) generated requires specialized computational tools for objective analysis. Custom software has been developed for 3D cell segmentation and 4D trajectory mapping, enabling the extraction of key migratory parameters [4] [34].

Table 1: Core Quantitative Metrics for Analyzing Trunk Neural Crest Migration

| Metric | Description | Biological Insight | Typical Findings from In Vivo Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) | Measures the square of the distance a cell travels over time; MSD(Ï„) ~ Ï„â¿ [4] | Reveals the mode of migration (n=1: random walk; n>1: directed migration). | TNC migration exhibits a biased random walk (1 < n < 2) [4]. |