Navigating Pluripotency: How Pre-Growth Conditions Dictate Stem Cell Fate and Function

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how pre-growth conditions fundamentally shape the pluripotency state of stem cells, with direct consequences for their stability, differentiation potential, and utility in research...

Navigating Pluripotency: How Pre-Growth Conditions Dictate Stem Cell Fate and Function

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how pre-growth conditions fundamentally shape the pluripotency state of stem cells, with direct consequences for their stability, differentiation potential, and utility in research and therapy. We explore the foundational biology of the pluripotency continuum, from naive to primed states, and detail the specific culture parameters—including signaling pathways, medium components, and cell handling—that establish and maintain these states. A significant focus is placed on practical methodologies for controlling pluripotency and troubleshooting common sources of variability, such as batch effects and cell line-specific responses. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of pluripotency regulation across species, validating key concepts while highlighting critical differences that impact the translation of findings from model systems to human applications. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to optimize stem cell systems for robust and reproducible outcomes.

The Pluripotency Spectrum: From Naive to Primed States and Their Molecular Hallmarks

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My primed hPSCs are failing to convert to a naive state in RSeT medium. What could be the cause? A1: This is an expected finding, not a protocol failure. Research indicates that RSeT medium does not support the conversion of primed hESCs to a naive state. Instead, it maintains a distinct pluripotent state between naive and primed [1]. Your cells are likely in this previously unrecognized intermediate state, which lacks many transcriptomic hallmarks of naive pluripotency and shows differential signaling dependencies [1].

Q2: How does oxygen tension affect the growth of different pluripotent states, and what are the practical implications for my culture conditions? A2: Sensitivity to oxygen tension is state-dependent. While many naive hPSCs require hypoxic conditions (e.g., 3% Oâ‚‚), RSeT hPSCs can circumvent the need for hypoxic growth and proliferate under both normoxia (20% Oâ‚‚) and hypoxia [1]. However, cell line-specific differences exist; some lines (e.g., H1 cells) may exhibit significantly retarded growth under both conditions [1]. Optimize conditions based on your specific cell line and target state.

Q3: I am observing significantly low single-cell plating efficiency with my H1 RSeT hPSCs. How can I improve cell survival? A3: Low single-cell plating efficiency is a documented characteristic of some RSeT cell lines, including H1 [1]. To enhance survival:

- Use the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (10 µM) in the medium for at least the initial passages after single-cell dissociation [1].

- Consider alternative cell lines if clonal expansion is critical, as this appears to be a cell line-specific phenomenon [1].

Q4: What are the key signaling pathway dependencies I should monitor when characterizing an unknown pluripotent state? A4: Signaling dependencies are a primary diagnostic tool. The table below summarizes core pathway requirements for different states, which can be assessed using specific inhibitors [1] [2].

| Pluripotency State | Core Signaling Dependencies | Key Inhibitors for Experimental Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Naive (Mouse, in 2i/LIF) | LIF/STAT3, GSK3β inhibition, MEK/ERK inhibition [3] [2] | PD0325901 (MEKi), CHIR99021 (GSK3βi) [2] |

| Primed (Mouse EpiSC) | FGF/ERK, Activin/TGFβ [2] | SB431542 (TGFβi), FGF receptor inhibitors [2] |

| Intermediate (hPSC in RSeT) | Co-dependency on JAK/STAT and TGFβ, with sustained FGF2 activity (cell line-specific) [1] | Ruxolitinib (JAKi), SB431542 (TGFβi), FGF receptor inhibitors [1] |

Q5: My cells are in RSeT medium but do not express the naive surface markers SUSD2 or CD75. Does this mean the conversion failed? A5: No. RSeT hPSCs do not express classic naive surface markers like SUSD2 and CD75 at significant levels [1]. The absence of these markers is consistent with the established phenotype for this intermediate state and should not be used as the sole criterion for failure. Focus on a multi-parameter characterization, including transcriptomics and signaling dependencies [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Failure to Achieve Naive Conversion in RSeT Medium

- Problem: Primed hPSCs cultured in RSeT medium do not acquire naive characteristics.

- Explanation: RSeT medium sustains FGF2 activity and maintains a pluripotent state downstream of naive pluripotency, restricting full conversion to the naive state [1].

- Solution:

- For RSeT Intermediate State: Continue characterization to confirm the unique RSeT state. This state is insensitive to hypoxia and has its own transcriptomic signature [1].

- For True Naive State: Switch to a dedicated naive reprogramming medium, such as the PXGL protocol (containing PD0325901, XAV939, Gö6983, and LIF), which is explicitly designed to induce and maintain naive pluripotency [1].

Problem 2: Poor Cell Survival and Altered Growth Rates in RSeT Culture

- Problem: Cells, particularly specific lines like H1, show significantly retarded growth or low viability under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

- Explanation: This is a documented, cell line-specific phenomenon for some RSeT hPSCs [1].

- Solution:

- Use ROCK Inhibitor: Routinely include Y-27632 (10 µM) during passaging to improve single-cell survival [1].

- Test Multiple Cell Lines: If possible, use a cell line less affected by this issue, such as H9 or an iPSC line [1].

- Confirm State Identity: Verify that the altered growth is not due to unintended differentiation by checking for the maintenance of pluripotency markers specific to the RSeT state.

Problem 3: Spontaneous Differentiation in Pluripotent Stem Cell Cultures

- Problem: Excessive differentiation (>20%) is observed in cultures.

- Explanation: This is a common issue in hPSC culture often related to suboptimal culture conditions or handling [4].

- Solution [4]:

- Ensure culture medium is fresh and has been stored correctly (at 2-8°C for less than 2 weeks).

- Manually remove differentiated areas from colonies before passaging.

- Avoid leaving culture plates outside the incubator for extended periods (>15 minutes).

- Ensure cell aggregates after passaging are evenly sized and cultures are not allowed to overgrow.

- Decrease colony density by plating fewer aggregates during passaging.

Problem 4: Adaptation to Feeder-Free Conditions Results in High Differentiation and Apoptosis

- Problem: When switching iPSCs from feeder-dependent to feeder-free culture systems, cells experience high rates of differentiation and death.

- Explanation: Pluripotent cells need to adapt to new systems to regain homeostasis, and this process can be stressful, especially for newly derived lines [5].

- Solution [5]:

- Use ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) or RevitaCell Supplement during the initial passages in the new system to suppress apoptosis.

- Test different matrix and media combinations (e.g., Matrigel with mTeSR1 or Geltrex with StemFlex) to find the optimal condition for your specific cell line.

- Pre-rinse materials with culture medium, not PBS, to avoid subjecting fragile cells to unnecessary stress.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use in Pluripotency Research |

|---|---|---|

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Improves single-cell survival by inhibiting apoptosis following dissociation [1] [5]. | Used in single-cell passaging and during adaptation to new culture conditions [1]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors (2i: PD0325901, CHIR99021) | PD0325901 inhibits MEK; CHIR99021 inhibits GSK3β. Together, they help maintain mouse ESCs in a ground-state naive pluripotency [3] [2]. | Key components of 2i/LIF medium for deriving and maintaining naive mESCs [2]. |

| RSeT Medium | A defined commercial medium used to convert and maintain primed hPSCs in a "naive-like" state, which research shows is actually a distinct intermediate state [1]. | Used to study pluripotent states between naive and primed, and for culturing cells insensitive to oxygen tension [1]. |

| LIF (Leukemia Inhibitory Factor) | Cytokine that activates JAK/STAT3 signaling to support self-renewal and inhibit differentiation in naive mouse ESCs [2]. | A core component of naive (2i/LIF) and ground-state mouse ESC culture media [2]. |

| TGFβ/Activin A Pathway Inhibitor (SB431542) | Inhibits the TGFβ and Activin Nodal signaling pathways, which are critical for maintaining the primed state [6] [2]. | Used to promote ground-state pluripotency in mESCs and to test signaling dependencies in intermediate states [1] [2]. |

| ReLeSR / Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent | Non-enzymatic, gentle passaging reagents used to harvest hPSCs as small aggregates for routine maintenance [4]. | Maintains pluripotent cultures by generating evenly-sized cell aggregates, helping to minimize spontaneous differentiation [4]. |

| A-80987 | A-80987, CAS:144141-97-9, MF:C37H43N5O6, MW:653.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Abametapir | Abametapir|Metalloproteinase Inhibitor|CAS 1762-34-1 | Abametapir is a metalloproteinase inhibitor for lice research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

- Starting Culture: Culture primed hESCs on mitomycin-C-treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in mTeSR1 medium.

- Chemical Resetting: After two days, replace the medium with a chemical resetting medium for three days.

- Naive Induction: Switch the culture medium to PXGL, an N2B27-based medium containing PD0325901 (MEKi), XAV939 (WNTi), Gö6983 (PKCi), and human LIF.

- Maintenance: Culture the cells in PXGL for 10-12 days.

- Passaging: Dissociate cells with Accutase and passage onto fresh MEFs in the presence of 10 µM Y-27632.

- Monitoring: Over several passages (e.g., seven), cells gradually acquire naive characteristics. Monitor changes in colony morphology (e.g., dome-shaped) and the expression of naive pluripotency markers (e.g., SUSD2+CD24− via flow cytometry).

Quantitative Data: Transcriptional Profiles of Pluripotency States

The following table consolidates key gene ontology (GO) terms and characteristics derived from transcriptional profiling of different mouse pluripotent states originating from the same genetic background [2]. This allows for a direct comparison without genetic variability.

| Pluripotency State | Enriched GO Terms (Upregulated) | Key Functional & Culture Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Naive (LS: LIF + Serum) | Nucleosome & chromatin assembly [2] | Derived from pre-implantation embryos. Metastable, correlating with both pre- and post-implantation embryonic stages [3] [2]. |

| Ground State (2i: 2i + LIF) | Regulation of transcription & RNA metabolic processes [2] | Derived from pre-implantation embryos. Resembles the pre-implantation epiblast. Shows increased polysome density and translation efficiency [3] [2]. |

| Primed (EpiSCs) | Developmental processes [2] | Derived from post-implantation epiblast. Dependent on FGF and Activin signaling. Transcriptionally distinct from naive and ground states [2]. |

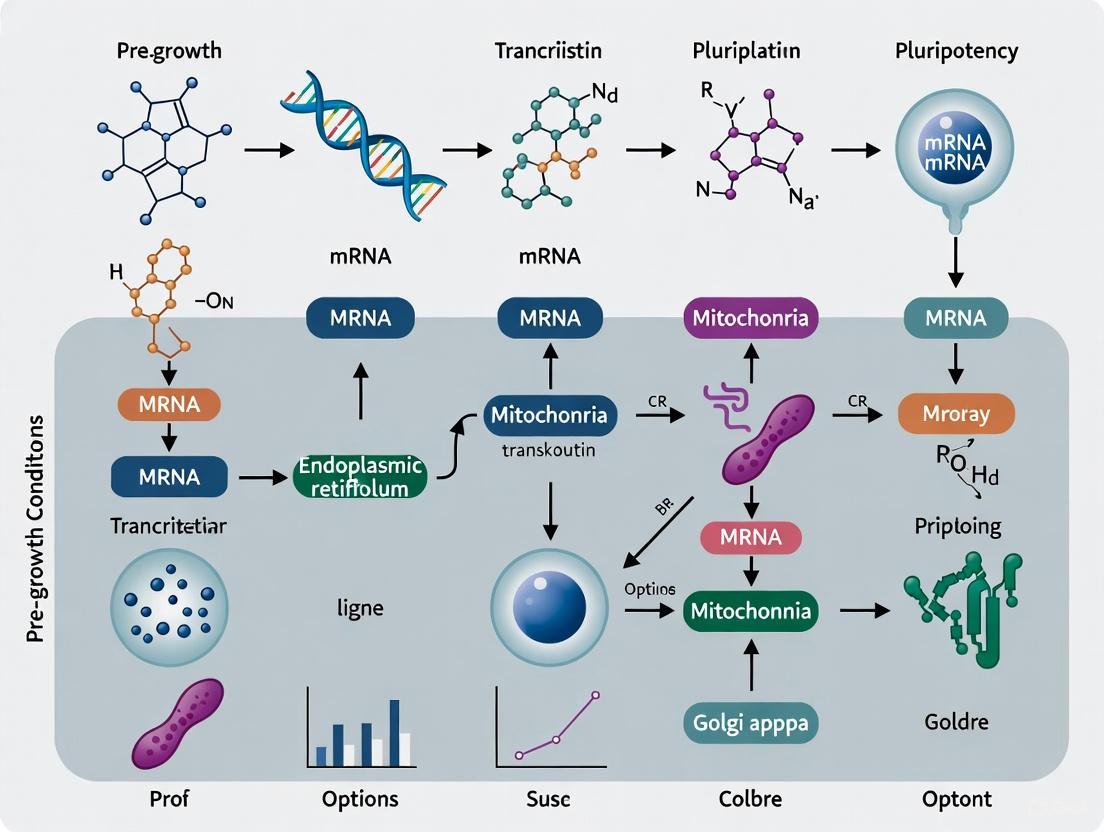

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Signaling Pathway Dependencies Across Pluripotency States

The following diagram summarizes the core signaling pathway dependencies that define and can be used to diagnose the three main pluripotency states.

Experimental Workflow for Pluripotent State Characterization

This workflow outlines a systematic approach for characterizing an unknown pluripotent stem cell state, integrating key experiments from the cited research [1] [6] [2].

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

FAQ: General Pathway Interactions

Q: My cells are spontaneously differentiating even with LIF supplementation. What could be wrong?

- A: Uncontrolled differentiation despite LIF often indicates a dominance of competing differentiation signals.

- Check BMP4 levels: In murine cells, high BMP4 can induce differentiation via Id genes. Titrate BMP4 or use a BMP inhibitor (e.g., Dorsomorphin) at low concentrations to rebalance the network towards self-renewal.

- Assess FGF/ERK activity: High FGF2/ERK signaling drives differentiation. Incorporate an ERK inhibitor (e.g., PD0325901) into your medium to enforce naïve pluripotency.

- Confirm LIF bioavailability: Ensure your LIF is fresh and stored correctly. Test different batches or suppliers.

- A: Uncontrolled differentiation despite LIF often indicates a dominance of competing differentiation signals.

Q: How do I determine if I am maintaining naïve or primed pluripotency?

- A: The state is defined by the signaling balance. Use this table for key differentiators:

| Feature | Naïve Pluripotency | Primed Pluripotency |

|---|---|---|

| Key Signaling | High LIF/STAT3; Low FGF/ERK; BMP4 (mouse) | High FGF/ERK; TGF-β/Activin A |

| Inhibitors Used | ERKi (PD0325901), MEKi, GSK3βi (CHIR) | Often none, or BMPi for human |

| Common Markers | Nanog, Klf4, Rex1, Stella | Otx2, Fgf5, Dnmt3a,b |

| Colony Morphology | Dome-shaped, compact | Flat, spread-out |

- Q: I am getting high cell death when switching to a defined medium. What is the cause?

- A: Acute cell death is often due to the withdrawal of survival factors.

- Increase FGF2 concentration: FGF is a critical survival factor, especially for primed-state human iPSCs. Start with a higher dose (e.g., 100 ng/mL) and titrate down.

- Optimize Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor: Add a ROCK inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632) to the medium for the first 24-48 hours after passaging to suppress anoikis.

- Check Insulin/IGF-1 levels: Ensure your defined medium contains sufficient insulin or IGF-1 for PI3K/Akt-mediated survival.

- A: Acute cell death is often due to the withdrawal of survival factors.

Troubleshooting: Experimental Issues

Q: My phospho-STAT3 western blot shows no signal in the LIF-treated group.

- A: This indicates a failure in the LIF/STAT3 pathway activation.

- Positive Control: Include a cell line known to have strong STAT3 activation (e.g., HepG2 with IL-6 treatment).

- Starvation Step: Serum-starve cells for 4-6 hours before LIF stimulation to reduce basal phosphorylation.

- Timing: Harvest cells 15-30 minutes after LIF addition for peak phosphorylation. Perform a time-course experiment.

- Antibody Validation: Confirm antibody specificity using a STAT3 knockout cell line or siRNA knockdown.

- A: This indicates a failure in the LIF/STAT3 pathway activation.

Q: How can I precisely modulate TGF-β/Activin/Nodal vs. BMP signaling independently?

- A: Use specific small molecule inhibitors and recombinant proteins. See the table below for precise tools.

| Pathway | Activator (Function) | Inhibitor (Function) |

|---|---|---|

| TGF-β/Activin/Nodal | Activin A (Activates Smad2/3) | SB431542 (Selectively inhibits ALK4,5,7) |

| BMP | BMP4 (Activates Smad1/5/8) | Dorsomorphin (Inhibits BMPR: ALK2,3,6) |

| FGF/ERK | FGF2 (Promotes proliferation/differentiation) | PD0325901 (MEK inhibitor, blocks ERK phosphorylation) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Pluripotency State via Immunofluorescence

- Objective: To qualitatively determine the expression of naïve (e.g., NANOG) and primed (e.g., OTX2) markers.

- Procedure:

- Culture cells on Matrigel-coated glass coverslips.

- Fix with 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 minutes at room temperature (RT).

- Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes.

- Block with 3% BSA in PBS for 1 hour.

- Incubate with primary antibody (e.g., anti-NANOG, 1:500) diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Wash 3x with PBS.

- Incubate with fluorescently-labeled secondary antibody (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488, 1:1000) for 1 hour at RT in the dark.

- Counterstain nuclei with DAPI (1 µg/mL) for 5 minutes.

- Mount on slides and image with a fluorescence microscope.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Signaling Activity via qPCR

- Objective: To quantitatively measure the transcriptional output of pathways (e.g., STAT3 target genes).

- Procedure:

- Treat cells with experimental conditions (e.g., ±LIF, ±Inhibitor) for 24 hours.

- Lyse cells and extract total RNA using a commercial kit.

- Synthesize cDNA from 1 µg of RNA using a reverse transcription kit.

- Prepare qPCR reactions with SYBR Green master mix, gene-specific primers (e.g., for Socs3, Klf4), and a housekeeping gene (e.g., Gapdh, Hprt).

- Run the qPCR program: 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10s and 60°C for 30s.

- Analyze data using the ΔΔCt method to calculate relative gene expression.

Pathway & Workflow Diagrams

LIF/STAT3 Signaling Pathway

Pluripotency Signaling Network

State Maintenance Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Recombinant LIF | Cytokine for activating JAK/STAT3 signaling to maintain self-renewal. |

| Recombinant FGF2 (bFGF) | Growth factor for promoting cell survival and priming/ differentiation. |

| CHIR99021 | GSK3β inhibitor; activates Wnt signaling, used in 2i/LIF naïve medium. |

| PD0325901 | MEK inhibitor; suppresses FGF/ERK signaling to stabilize naïve state. |

| SB431542 | TGF-β/Activin/Nodal pathway inhibitor; blocks ALK4,5,7 receptors. |

| Dorsomorphin | BMP pathway inhibitor; blocks ALK2,3,6 receptors. |

| Y-27632 | ROCK inhibitor; reduces apoptosis during single-cell passaging. |

| Matrigel | Extracellular matrix providing adhesion signals for cell growth. |

| mTeSR1 / E8 Medium | Defined, xeno-free culture media for human PSCs. |

| ABT-963 | ABT-963, CAS:266320-83-6, MF:C22H22F2N2O5S, MW:464.5 g/mol |

| AG-012986 | AG-012986, CAS:223784-75-6, MF:C16H12F2N4O3S2, MW:410.4 g/mol |

FAQ: Core Pluripotency Factor Functions

Q1: What are the core functional roles of Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, and Klf4 in pluripotency? These factors form a core transcriptional network that establishes and maintains pluripotency. Oct4, a POU-family transcription factor, is a master regulator essential for the initiation and maintenance of pluripotent cells; its precise expression level is a critical determinant of cell fate [7]. Sox2, an HMG-box transcription factor, frequently partners with Oct4, binding to composite DNA elements to co-activate target genes [8] [7]. Nanog functions to stabilize the pluripotent state, and its forced expression can convert partially reprogrammed cells to a fully reprogrammed state [8]. Klf4 contributes to the repression of somatic gene programs and supports the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), an important early step in reprogramming [8].

Q2: Can any of these core factors be replaced, and what does this tell us about the network? Yes, the network demonstrates a degree of flexibility. Replacement factors can substitute for a core factor's function in reprogramming, providing insight into the network's logic. For example:

- Klf4 can be replaced by the orphan nuclear receptor Esrrb or by p53 knockdown [8].

- Sox2 can be replaced using specific small molecules [8].

- Oct4 can be replaced by another nuclear receptor, Nr5a2 [8]. These replacements indicate that the core function of maintaining the pluripotent state can be achieved through multiple molecular paths that converge on key downstream genes and pathways.

Q3: What epigenetic barriers impede reprogramming, and how do the core factors overcome them? Somatic cells have a stable chromatin state that resists dedifferentiation. Major barriers include:

- Repressive chromatin marks: High levels of H3K9me3 and DNA methylation silence pluripotency genes like Oct4 [7] [9].

- Polycomb-mediated repression: The PRC2 complex deposits H3K27me3 at developmental genes, which in ESCs exist in a "bivalent" state with H3K4me3, poising them for activation [10]. The core factors work to reset this epigenetic landscape by recruiting chromatin-remodeling complexes, leading to demethylation of pluripotency gene promoters and establishing a transcriptionally permissive environment [9].

Troubleshooting Guide for Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Common Reprogramming Challenges and Solutions

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Solution / Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Low reprogramming efficiency | Presence of epigenetic barriers | Inhibit repressive pathways with small molecules (e.g., G9a or DNA methyltransferase inhibitors) [7] [9]. |

| Inefficient cell cycle progression | Knockdown of cell cycle checkpoints (e.g., p53, p21) can enhance efficiency [8]. | |

| Accumulation of partially reprogrammed cells | Failure to activate endogenous pluripotency network | Overexpression of late-stage factors like Nanog or Glis1 can drive conversion to full pluripotency [8]. |

| Failure to downregulate somatic genes | Incomplete MET | Ensure culture conditions support MET; BMP/Smad signaling promotes this transition while TGF-β pathway activation inhibits it [8]. |

| Heterogeneous cell populations in ESC cultures | Culture conditions not stabilizing the "ground state" | Use 2i/LIF culture conditions (MEK and GSK3 inhibitors with LIF) to maintain a homogenous, naïve pluripotent state [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Pluripotency Factor Activity

Method: Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for Mapping Transcription Factor Binding

- Cell Fixation: Cross-link proteins to DNA in your cell population (e.g., ESCs or reprogramming intermediates) using formaldehyde.

- Cell Lysis and Chromatin Shearing: Lyse cells and fragment the chromatin by sonication to an average size of 200-500 bp.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the sheared chromatin with a specific antibody against your target transcription factor (e.g., anti-Oct4, anti-Sox2). Use a non-specific IgG antibody as a negative control.

- Washing and Elution: Wash the antibody-protein-DNA complexes to remove non-specifically bound material, then reverse the cross-links to elute the DNA.

- DNA Analysis: Purity the DNA and analyze by quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) for specific genomic loci or by high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-Seq) for genome-wide binding maps [10]. ChIP-Seq in ESCs has revealed that these core factors co-bind at many genomic locations, forming a interconnected regulatory circuitry [8].

Key Signaling Pathways in Pluripotency

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways that support the naïve pluripotent state, in which the core transcription factor network operates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating Pluripotency Networks

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| 2i/LIF Medium | Maintains mouse ESCs in a homogenous "ground state" of naïve pluripotency. | Combination of MEK inhibitor (PD0325901) and GSK3 inhibitor (CHIR99021) with Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) [11]. |

| Chromatin Modifying Inhibitors | Overcome epigenetic barriers to reprogramming. | Includes DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (5-aza-cytidine) and histone deacetylase inhibitors (e.g., VPA, TSA) [7] [9]. |

| Defined Feeder-Free Culture | Provides a controlled environment for human PSC culture. | Uses defined matrices (e.g., Vitronectin, Laminin-521) and media formulations to eliminate variability from feeder cells and serum [11]. |

| scRNA-seq & GRN Analysis Tools | Decodes cellular heterogeneity and infers gene regulatory networks. | Technologies like scHGR and GRLGRN use computational methods to infer regulatory relationships from single-cell transcriptome data [12] [13]. |

| AG-494 | AG-494, CAS:139087-53-9, MF:C16H12N2O3, MW:280.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AG-494 | AG-494, CAS:133550-35-3, MF:C16H12N2O3, MW:280.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Core Transcriptional Regulatory Circuitry

The core factors Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog form an interconnected autoregulatory loop that stabilizes the pluripotent state. The following diagram illustrates this network and its key outputs.

Troubleshooting Common Epigenetic Assays

This guide addresses frequent experimental challenges in key epigenetic techniques, providing targeted solutions for researchers studying pluripotency states.

DNA Methylation Analysis

Issue: Inconsistent or failed bisulfite conversion during DNA methylation analysis.

- Problem Explanation: Bisulfite conversion is a critical but harsh chemical process that can degrade DNA and lead to incomplete conversion, resulting in inaccurate methylation data [14].

- Solution:

- Ensure DNA Purity: Use high-quality, pure DNA. If particulate matter is present after adding conversion reagent, centrifuge at high speed and use only the clear supernatant [15].

- Verify Reaction Conditions: Ensure all liquid is at the bottom of the reaction tube and not on the cap or walls before starting the conversion reaction [15].

- Amplification Follow-up:

- Primer Design: Design primers (24-32 nt) to specifically amplify the converted template. Avoid more than 2-3 mixed bases and ensure the 3' end does not end in a residue whose conversion state is unknown [15].

- Polymerase Selection: Use a hot-start Taq polymerase (e.g., Platinum Taq). Avoid proof-reading polymerases as they cannot read through uracil in the converted DNA [15].

- Amplicon Size: Target ~200 bp amplicons. Larger fragments are possible but require protocol optimization due to potential strand breaks from bisulfite treatment [15].

Issue: Low or no enrichment of methylated DNA in enrichment-based protocols (e.g., MeDIP).

- Problem Explanation: Methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD) proteins or antibodies can bind non-specifically to unmethylated DNA, especially with low DNA input, reducing assay specificity [15].

- Solution: Strictly follow the product manual's protocol for different DNA input amounts. Using the correct protocol for your specific DNA quantity minimizes non-specific binding and improves enrichment efficiency [15].

Chromatin Accessibility Profiling

Issue: High background noise or unclear nucleosome patterning in ATAC-seq data.

- Problem Explanation: This often stems from suboptimal cell viability or an over-digestion of chromatin by the Tn5 transposase, which obscures the clear fragment size periodicity indicative of nucleosome positioning [16].

- Solution:

- Cell Viability: Use fresh cells or nuclei with high viability (>90%) to minimize background from apoptotic DNA.

- Titrate Transposase: Optimize the amount of Tn5 enzyme and reaction time to prevent over-digestion. A pilot assay can help determine the ideal conditions.

- Paired-End Sequencing: Use paired-end sequencing, which provides higher unique alignment rates and more precise categorization of fragments as nucleosome-free, mono-nucleosomal, or di-nucleosomal [16].

Issue: Biased sampling in MNase-seq data.

- Problem Explanation: Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) has a sequence cleavage bias (preference for AT-rich regions) and can differentially digest distinct classes of nucleosomes, leading to an inaccurate picture of nucleosome occupancy and positioning [17] [18].

- Solution: Perform extensive digestion of crosslinked chromatin to ~95-100% mononucleosomes. At this level, all linker DNA is cut, reducing bias related to internucleosomal linker length and providing a more accurate and reproducible assessment [18]. Using spike-in controls and standardized MNase titration can also help mitigate this issue [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ: How does chromatin accessibility relate to the naive pluripotency state? The naive pluripotent state, considered a "ground state" of pluripotency, is characterized by a distinct epigenetic landscape. Research in mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (mESCs) shows that maintaining this state in defined "2i" culture conditions (using MEK and GSK3 inhibitors) results in a more uniform chromatin architecture and reduced expression of early differentiation genes compared to serum-cultured cells [11]. A key feature of the transition from a naive pluripotent state toward a more differentiated "2-cell-like" (2CLC) state is widespread chromatin decompaction, increased nucleosome mobility, and a global reduction in DNA methylation [19]. These accessibility changes are prerequisites for the massive zygotic genome activation that defines this developmental window.

FAQ: What is the recommended sequencing depth for bulk ATAC-seq experiments? The required depth depends on your research goal. Below are general guidelines using paired-end reads for superior alignment and duplicate removal [16].

Table: ATAC-seq Sequencing Depth Recommendations

| Research Goal | Recommended Depth |

|---|---|

| Identification of open chromatin regions | ≥ 50 million paired-end reads |

| Transcription factor footprinting | > 200 million paired-end reads |

FAQ: What alternative methods exist for DNA methylation sequencing besides bisulfite sequencing? Bisulfite sequencing is the gold standard but can degrade DNA. Several alternative and complementary methods are available.

Table: DNA Methylation Sequencing Methods Comparison

| Method | Principle | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) [14] | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracil | Base-pair resolution; high coverage; widely used | Harsh treatment degrades DNA; requires deep sequencing; computationally intensive | Whole-genome methylation analysis in high-quality DNA |

| Enzymatic Methyl-seq [14] | Enzymatic conversion of unmethylated cytosines | Gentler on DNA (less damage); works with low-input/FFPE samples; can distinguish 5mC/5hmC | Still requires deep sequencing; newer method with fewer comparative studies | High-precision profiling in low-input or degraded samples |

| Long-Read Sequencing (PacBio/Nanopore) [14] | Direct detection of methylation on native DNA | No conversion needed; long reads allow phasing of modifications | Higher error rates; more DNA input; less established analysis pipelines | Phasing methylation with genetic variants; repetitive regions |

| meCUT&RUN [14] | Enrichment of methylated DNA using an MBD protein | Low sequencing depth (20-50M reads); cost-effective; works with low cell numbers (10,000) | Non-quantitative; no base-pair resolution (without conversion) | Cost-sensitive studies to identify methylated regulatory regions |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Seq (RRBS) [14] | Restriction enzyme digestion followed by bisulfite sequencing | Cost-effective; focused on CpG islands and promoters | Limited genome coverage (~5-10% of CpGs); biased toward high CpG density | Cost-sensitive studies focusing on CpG islands and promoters |

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Protocol: ATAC-seq for Mapping Chromatin Accessibility

This protocol outlines the method for Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq), a rapid and sensitive technique to profile genome-wide chromatin accessibility [16].

- Cell Preparation: Isolate 50,000 - 100,000 viable cells (fresh or cryopreserved). High viability is critical.

- Nuclei Isolation: Pellet cells and lyse with a cold lysis buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630). Immediately pellet nuclei and resuspend in transposase reaction mix.

- Tagmentation: Incubate nuclei with the Tn5 transposase (e.g., Illumina Tagment DNA TDE1 Enzyme) at 37°C for 30 minutes. The Tn5 enzyme simultaneously fragments DNA and inserts sequencing adapters into accessible chromatin regions.

- DNA Purification: Purify the tagmented DNA using a DNA cleanup kit (e.g., Qiagen MinElute PCR Purification Kit).

- Library Amplification: Amplify the purified DNA by PCR (e.g., 12 cycles) using indexing primers to barcode samples for multiplexing.

- Library Purification & Sequencing: Purify the final library and quantify. Sequence using paired-end chemistry on an appropriate Illumina sequencing platform [16].

ATAC-seq Experimental Workflow

Protocol: Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS)

This protocol describes Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS), the gold-standard method for base-pair resolution mapping of DNA methylation across the entire genome [14].

- DNA Extraction & Quality Control: Extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA. Verify integrity and purity (A260/280 ratio ~1.8).

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat 100-500 ng of DNA with sodium bisulfite. This reaction deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged.

- Desalting & Purification: Purify the bisulfite-converted DNA to remove salts and reagents. This is typically done using a column-based or bead-based cleanup kit.

- Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries from the converted DNA. Standard Illumina library prep protocols can be used, but the polymerase must be uracil-insensitive.

- Amplification & Indexing: Amplify the library with a limited number of PCR cycles and add dual-index barcodes for multiplexing.

- Sequencing: Sequence the library on an Illumina platform. Due to the reduced sequence complexity after bisulfite conversion, higher sequencing depth is required for full genome coverage compared to standard DNA-seq.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Epigenetic Research in Pluripotency

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Tn5 Transposase [16] | Enzymatic fragmentation and tagging of accessible chromatin in ATAC-seq. | Hyperactive mutant Tn5 ensures efficient tagmentation. Commercial kits (e.g., Illumina Tagment DNA TDE1) are optimized. |

| Sodium Bisulfite [14] | Chemical conversion of unmethylated C to U for methylation detection in WGBS/RRBS. | Purity is critical. Harsh treatment degrades DNA; optimize conversion time and temperature. |

| Methylation-Specific Restriction Enzymes (e.g., Mspl) [14] | Digest genome to create reduced representation fragments for RRBS. | Enzyme selection determines genomic coverage; biased toward CpG-rich regions. |

| Methyl-Binding Domain (MBD) Proteins [14] | Enrichment of methylated DNA fragments in protocols like meCUT&RUN. | Offers a gentler alternative to bisulfite conversion for genome-wide methylation profiling. |

| Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) [11] [19] | Cytokine used in cell culture to maintain mouse embryonic stem cell (mESC) self-renewal and pluripotency. | Activates the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway to suppress differentiation. |

| 2i/LIF Culture System [11] | Defined culture condition (MEK + GSK3 inhibitors + LIF) to maintain mESCs in a naive "ground state" of pluripotency. | Blocks prodifferentiation signaling pathways (FGF4/Erk), promoting a more homogeneous pluripotent population. |

| AK 295 | AK 295, CAS:160399-35-9, MF:C26H40N4O6, MW:504.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (S)-Alaproclate | Alaproclate, (S)-|High-Quality SSRI for Research | Alaproclate, (S)- is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for neuroscience research. This product is for Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key in vivo correlates for the naive and primed pluripotent states?

The naive pluripotent state corresponds to the pre-implantation epiblast of the blastocyst, captured in vitro by naive human pluripotent stem cells (hnPSCs). In contrast, the primed pluripotent state corresponds to the post-implantation epiblast, captured in vitro by epiblast stem cells (EpiSCs) or conventional human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). The transition between these states involves significant transcriptional, epigenetic, and functional changes [20] [6].

FAQ 2: How can I experimentally validate the pluripotency state of my stem cell culture?

Validation is multi-faceted and should assess molecular and functional characteristics:

- Molecular Markers: Analyze key transcription factors. Naive cells typically express KLF2, KLF4, TFCP2L1, and NANOG. Primed cells maintain OCT4 but show different surface markers and may express OTX2 [21] [20].

- Functional Assays: Naive pluripotent cells, like mouse ESCs, are capable of forming high-efficiency blastocyst chimeras. Primed cells, like EpiSCs, lack this capability for naive chimeras but can contribute to teratomas [20] [6].

- Signaling Dependence: Naive pluripotency can be maintained with LIF and 2i inhibitors (MEK and GSK3 inhibition). Primed pluripotency relies on FGF2 and Activin A signaling [21] [20].

FAQ 3: What critical signaling pathway governs epiblast versus hypoblast specification in the human blastocyst?

ERK signaling is a critical pathway. Suppressing ERK signaling in human blastocysts expands the NANOG-positive epiblast population and blocks GATA4-positive hypoblast formation. Conversely, FGF stimulation, which activates ERK, promotes hypoblast specification at the expense of the epiblast [22].

FAQ 4: My blastoid formation efficiency is low. What are potential molecular culprits?

Recent research implicates species-specific regulatory elements. The repression of HERVK LTR5Hs, a hominoid-specific endogenous retrovirus active in the pre-implantation epiblast, leads to a dose-dependent failure in blastoid formation. High repression causes widespread apoptosis and formation of non-cavitating "dark spheres" [23]. Ensuring the integrity of this pathway is essential for efficient model generation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Failure to Maintain a Naive Pluripotent State

Problem: Cells spontaneously differentiate or adopt a primed-like identity during naive culture.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient signaling inhibition | Check expression of naive markers (e.g., KLF4) and primed markers (e.g., OTX2) via qPCR/IF. | Ensure MEK (e.g., PD0325901) and GSK3 (e.g., CHIR99021) inhibitors are fresh and used at correct concentrations in 2i/LIF medium [20]. |

| Epigenetic instability | Perform RNA-seq to assess transcriptomic fidelity to the naive state. Long-term 2i/LIF culture can cause aberrations [20]. | Consider using alternative naive culture conditions or limiting long-term passaging in 2i/LIF. |

| Incorrect starting population | Validate that the initial cell population is genuinely naive, not primed. | Re-derive naive cells from primed PSCs using a established reprogramming protocol [20]. |

Issue 2: Inefficient Differentiation or Guided Differentiation Yielding Incorrect Lineages

Problem: When exiting naive pluripotency, cells do not efficiently form desired post-implantation lineages or embryo models.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous starting population | Use single-cell RNA sequencing or flow cytometry to check for uniformity of key pluripotency factors like NANOG and SOX2. | Pre-sort the naive population for homogeneous marker expression before initiating differentiation [21]. |

| Dysregulated core pluripotency network | After silencing a pluripotency factor, use RNA-seq to analyze the activity of other master regulators (e.g., from the known 132 MRs in EpiSCs) [6]. | The exit from pluripotency relies on a complex network. Target "Mediator" or "Speaker" master regulators identified in primed-state networks to unblock differentiation [6]. |

| Inadequate activation of new enhancers | Perform ChIP-seq for key TFs (e.g., OTX2) and histone marks (e.g., H3K27ac) during differentiation. | Ensure the correct induction of formative/primed-state TFs like OTX2, which helps rewire the enhancer landscape away from the naive state [21]. |

Key Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Characteristics of Key Pluripotency States

| Feature | Naive Pluripotency | Formative Pluripotency | Primed Pluripotency |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Correlate | Pre-implantation epiblast | Pre-streak post-implantation epiblast | Post-implantation epiblast [20] [6] |

| Key Transcription Factors | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, KLF2, KLF4, TFCP2L1 | (Emerging: responds to germ cell induction) | OCT4, OTX2; distinct network of 132 Master Regulators [21] [6] |

| Signaling Requirements | LIF/STAT3, MEKi, GSK3i (2i/LIF) | FGF2, TGF-β/Activin, WNT modulation | FGF2, Activin A/TGF-β [20] |

| Chimera Competency | High (mouse) | Not well-established | Low/None [20] |

| Representative Cell Lines | Mouse ESCs, hnPSCs | Mouse EpiLCs, formative ESCs | Mouse EpiSCs, conventional hPSCs [20] [6] |

Key Quantitative Findings from Recent Studies

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Signaling Modulation on Lineage Specification

| Experimental Manipulation | System | Effect on Epiblast | Effect on Hypoblast | Key Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGF4 (750 ng/ml) treatment | Human blastocyst | ↓ 2-fold (mean 3 vs 8 cells/embryo) | ↑ 1.5-fold (mean 12 vs 8 cells/embryo) | [22] |

| ERK inhibition (Ulixertinib) | Human blastocyst | Modest increase (mean 15 vs 12 cells/embryo); becomes predominant | Near-total loss (mean 2 vs 13 cells/embryo) | [22] |

| LTR5Hs high repression | Human blastoid model | Failure to form; apoptosis (29 vs 3 cleaved CASP3+ cells) | Failure to form | [23] |

Detailed Protocol: Investigating ERK Dependence in Human Blastocysts

This protocol is adapted from functional studies on human blastocysts [22].

Objective: To determine the role of ERK signaling in lineage specification within the human inner cell mass (ICM).

Materials:

- Inhibitor: Ulixertinib (ERKi), reconstituted in DMSO.

- Control: Volume-matched DMSO.

- Culture Medium: Pre-equilibrated human embryo culture medium.

- Day 5 Human Blastocysts: Obtained from donated IVF surplus embryos with informed consent and ethical approval.

Workflow:

- Preparation: On Day 5 post-fertilization, select morphologically normal blastocysts.

- Treatment: Randomize embryos into two groups:

- Control Group: Culture in medium containing DMSO.

- ERKi Group: Culture in medium containing 5 µM Ulixertinib.

- Culture: Maintain embryos in culture for 36 hours under standard conditions (37°C, 5% O₂, 6% CO₂).

- Fixation and Staining: At the end of the culture period, fix embryos and perform immunofluorescence staining for key lineage markers:

- Epiblast: NANOG

- Hypoblast: GATA4

- Trophectoderm: GATA3

- Imaging and Quantification: Acquire high-resolution confocal images. Count the number of NANOG+ and GATA4+ cells in the ICM of each embryo.

- Statistical Analysis: Compare the average number of epiblast and hypoblast cells, and the hypoblast:epiblast ratio between control and ERKi-treated groups using an appropriate statistical test (e.g., t-test).

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for ERK inhibition in human blastocysts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying Pluripotency States

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Detail |

|---|---|---|

| PD0325901 | MEK inhibitor. Component of "2i" cocktail to maintain naive pluripotency by suppressing differentiation signals [20]. | Used at concentrations typically in the µM range. Critical for maintaining mouse and human naive PSCs. |

| LIF (Leukemia Inhibitory Factor) | Cytokine. Activates STAT3 signaling to support self-renewal in naive pluripotency [20]. | Used in combination with 2i (2i/LIF) for naive culture. |

| FGF2 (bFGF) | Growth Factor. Key signaling component for maintaining primed pluripotency (in EpiSCs and hPSCs) and for driving differentiation [20]. | Used in conjunction with Activin A in FA culture condition for primed state. |

| Ulixertinib | ERK1/2 inhibitor. Used to functionally test the role of ERK signaling in epiblast/hypoblast specification in embryo models [22]. | Used at 5 µM in human blastocyst cultures to block hypoblast formation. |

| Activin A | TGF-β family cytokine. Supports self-renewal in primed pluripotency and is involved in endoderm differentiation [20]. | A key component in formative (AloXR) and primed (FA) culture conditions. |

| CARGO-CRISPRi | Targeted epigenetic repression system. Enables simultaneous repression of multiple genomic loci (e.g., HERVK LTR5Hs elements) to study function in blastoids [23]. | Uses a 12-mer gRNA array and KRAB-dCas9 to deposit repressive H3K9me3 marks. |

| NSC111552 | NSC111552, CAS:40420-48-2, MF:C12H10O3, MW:202.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tectoquinone | Tectoquinone, CAS:84-54-8, MF:C15H10O2, MW:222.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Core Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The Role of ERK in Early Lineage Specification

The FGF/ERK pathway is a master regulator of the first cell fate decision within the inner cell mass. The core mechanism, conserved in humans, involves epiblast-derived FGF4 signaling to uncommitted ICM cells, activating ERK to promote hypoblast fate. Inhibiting this pathway locks the ICM into an epiblast state [22].

Diagram 2: ERK signaling pathway in ICM lineage specification.

The NANOG-SOX2 Regulatory Switch During the Naive-to-Primed Transition

A key molecular event in exiting naive pluripotency is the rewiring of the core pluripotency network. In the post-implantation mouse embryo, NANOG and SOX2 expression become segregated. Surprisingly, NANOG represses Sox2 in the posterior epiblast, facilitating the loss of pluripotency and entry into gastrulation. This represents a repurposing of NANOG from a pluripotency sustainer to a differentiation promoter [24].

Diagram 3: NANOG-SOX2 dynamics during pluripotency transition.

A Practical Guide to Controlling Pluripotency Through Culture Conditions

Media System Comparison & Selection Guide

Key Characteristics at a Glance

The choice between serum-containing and defined, feeder-free media systems is fundamental to experimental design, significantly impacting reproducibility, cell phenotype, and applicability to regulatory pathways.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each system:

| Feature | Serum-Containing Media | Defined, Feeder-Free Media |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Complex, undefined mixture of growth factors, hormones, and proteins [25] [26]. | Chemically defined, known concentrations of components [25] [27]. |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability | High, due to biological source variations [26]. | Low, designed for high consistency [26] [28]. |

| Regulatory & Safety Profile | Higher risk of pathogen contamination; ethical concerns regarding animal welfare [25] [26]. | Xeno-free options available; safer for clinical applications; reduced contamination risk [25] [26]. |

| Experimental Control | Low, undefined components can interfere with cellular responses [26]. | High, allows precise evaluation of cellular functions [28]. |

| Downstream Processing | Difficult due to undefined serum components [28]. | Simplified purification and processing [28]. |

| Cost | Generally lower media cost, but variability can incur hidden costs [25]. | Significantly higher media cost, but can be offset by improved consistency [25] [26]. |

| Typical Applications | Routine cell culture; initial cell establishment [26]. | Biopharmaceutical production; clinical-grade cell manufacturing; toxicology studies; precise mechanistic research [25] [26] [28]. |

Quantitative Performance Data

Performance metrics vary significantly based on cell type and media formulation. The following table provides examples from recent research:

| Cell Type | Media Supplement | Key Performance Metric | Reported Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | 7 Commercial SFM | Growth Support | Most, but not all, supported expansion well [25]. | |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | 5 hPL preparations | Growth Support | All supported MSC growth [25]. | |

| Natural Killer (NK) Cells | Cytokine Combination (IL-2, IL-18, rIL-27) | Fold Expansion | 17.19 ± 4.85-fold [29]. | |

| Natural Killer (NK) Cells | Genetically Engineered K562 Feeder Cells | Fold Expansion | Ranged from ~842-fold to over 12,000-fold, depending on membrane-bound ligands [30] [29]. | |

| Natural Killer (NK) Cells | Antibody Stimulation (OKT-3 + anti-CD52) | Fold Expansion / Purity | ~1,000-fold / ~60% purity [29]. | |

| Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (mESCs) | DARP Medium (Novel SFM) | Functionality | Supported normal transcriptome, differentiation into teratomas, and establishment of new lines from blastocysts [27]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: Problem Resolution in Media Transitions and Culture

Q1: My cells are undergoing increased cell death during the adaptation from serum-containing to serum-free media. What is the cause and how can I mitigate this?

- Cause: Serum withdrawal can induce apoptosis, as cells are suddenly deprived of survival factors and adhesion signals they were dependent upon [31].

- Solution:

- Gradual Adaptation: Do not switch directly. Gradually reduce the percentage of serum while increasing the percentage of the new serum-free medium over several passages.

- Supplement with Anti-Apoptotics: Supplement the medium with a Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor during the initial adaptation phase. Research shows that the Fyn-RhoA-ROCK pathway is a major pathway for cell death in hiPSCs upon dissociation, and its inhibition can dramatically improve survival [31].

- Ensure Proper Scaffolding: In feeder-free systems, the choice of extracellular matrix (ECM) is critical. For example, signaling through laminin-511/α6β1 integrin is known to protect against apoptosis in hiPSCs [31]. Confirm your cells are plated on an optimal, defined ECM.

Q2: I am observing high differentiation rates in my pluripotent stem cell cultures after moving to a feeder-free system. How can I maintain pluripotency?

- Cause: The loss of supportive signals previously provided by feeder cells or undefined serum components. Feeder cells secrete critical products like activin A, TGF-β, and IGFs that help maintain pluripotency [31].

- Solution:

- Optimize Small Molecule Inhibitors: For naïve-state pluripotent cells like mESCs, use "2i" culture conditions containing small molecule inhibitors PD0325901 (MEK inhibitor) and CHIR99021 (GSK3 inhibitor) to support self-renewal [27].

- Supplement Key Growth Factors: Ensure your medium contains essential cytokines. For naïve cells, Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) is critical. For primed-state cells, basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF2) and TGF-β signaling are often required [31] [27].

- Check Component Quality: Use high-purity, recombinant growth factors to ensure consistent and effective signaling.

Q3: My experimental results are inconsistent between replicates, and I suspect my culture media. What should I investigate?

- Cause: Batch-to-batch variability of serum is a classic source of irreproducibility [26] [27].

- Solution:

- Switch to Defined Media: The most effective long-term solution is to transition to a serum-free, chemically defined medium, which offers more consistent performance [28].

- Use a Single Serum Batch: If serum is necessary, purchase a large, single batch of serum that is pre-screened for your specific cell type. Use this same batch for an entire project or series of experiments.

- Implement Quality Control: Perform regular quality control tests on your media supplements, such as growth factor ELISAs, to monitor key component levels [25].

Q4: I am expanding NK cells for adoptive cell therapy but want to avoid the risks of feeder cells. What are my options?

- Cause: Feeder-based NK cell expansion, while efficient, poses challenges for clinical translation, including risks of contamination and difficulties in standardizing production [30] [29].

- Solution: Several feeder-free strategies are in development:

- Cytokine Combinations: Use optimized combinations of cytokines. IL-2 and IL-15 are "essential" for mild proliferation, while IL-18, IL-21, and IL-27 are "supportive" and enhance expansion when combined with the essential cytokines [29].

- Agonistic Antibody Stimulation: Stimulate NK cells with combinations of agonist antibodies, such as low-dose OKT-3 with anti-CD52 or anti-CD16 antibodies, to mimic activation signals [29].

- Emerging Technologies: Novel approaches like nanoparticle-based stimulation show strong potential for safe, scalable, and standardized NK cell expansion [30] [29].

Essential Signaling Pathways in Feeder-Free Systems

Understanding the intracellular signaling cascades is key to troubleshooting feeder-free cultures. The diagram below illustrates the core pathways maintaining pluripotency and viability in human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) under serum-free conditions on a laminin-511 scaffold.

Pathway Logic and Experimental Implications

The diagram illustrates how extracellular cues from the culture medium and scaffold integrate to control cell fate:

- Growth Factor Signaling (FGF2 & Insulin/IGF): Binding of FGF2 to its receptor (FGFR1) and insulin/IGF to IGF-1R activates two major pathways: the Ras/MAPK pathway and the PI3K/AKT pathway [31]. The PI3K/AKT pathway is a critical nexus, also activated by integrin signaling, and is essential for cell survival.

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Signaling: Attachment to a defined ECM, such as laminin-511, via α6β1 integrin, converges on the same PI3K/AKT pathway and also activates the Fyn-RhoA-ROCK pathway [31]. This latter pathway is a major mediator of cell death upon dissociation; its inhibition through signaling is crucial for cell survival.

- Signal Integration & Pluripotency: The Activin A/ALK4 pathway activates SMAD2/3. The PI3K/AKT pathway enables this SMAD2/3 signaling, which in turn promotes the expression of pluripotency genes like Nanog [31]. This cooperation between growth factor, ECM, and cytokine signals is fundamental for maintaining the undifferentiated state.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Defined Systems

Successful implementation of defined, feeder-free cultures relies on a specific set of reagents. This table details essential components and their functions.

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Basal Media | DMEM/F12, RPMI-1640 [28] | Provides fundamental inorganic salts, amino acids, vitamins, and a carbon source. DMEM/F12 is commonly used for its rich composition. |

| Carrier Proteins | Albumin (BSA) [31] [27] | Acts as a lipid carrier, provides physical protection, and prevents toxic effects of other components. |

| Essential Nutrients | Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (ITS) [31] [27] | Insulin promotes growth and metabolism; Transferrin transports iron; Selenium is an antioxidant essential for cell defense. |

| Growth Factors & Cytokines | FGF2, LIF, TGF-β, IL-2, IL-15 [31] [30] [29] | Provide specific mitogenic and survival signals. FGF2 and LIF are critical for stem cells; IL-2/IL-15 are essential for lymphocyte expansion. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | PD0325901 (MEKi), CHIR99021 (GSK3i), ROCK inhibitor [31] [27] | "2i" (PD0325901 & CHIR99021) maintain naïve pluripotency. ROCK inhibitor dramatically improves single-cell survival after passaging. |

| Defined Extracellular Matrix | Recombinant Laminin-511/E8, Vitronectin, Fibronectin [31] [27] | Replaces feeder cells and animal-derived gels like Matrigel. Provides a defined scaffold for cell attachment and activates key integrin signaling. |

| Specialized Supplements | Cholesterol, Lipids, Non-essential Amino Acids [27] | Specific components like cholesterol were identified as essential for robust growth of naïve mESCs in fully defined media [27]. |

| Tyrphostin AG1296 | Tyrphostin AG1296, CAS:146535-11-7, MF:C16H14N2O2, MW:266.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| A25822B | UCA 1064-A|Bioactive Fungal Metabolite for Research | UCA 1064-A is a sterol compound fromWallemia sebiwith antitumor and antimicrobial activity. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Experimental Workflow: Transitioning to a Defined Feeder-Free System

The following diagram outlines a general methodology for adapting cells and establishing cultures in a defined, feeder-free environment, drawing from specific protocols for stem cells and other lineages.

Protocol Details

- Step 1: Surface Coating. Prepare culture vessels by coating with a defined extracellular matrix (ECM). For example, use recombinant Laminin-511-E8 fragments at 0.5 µg/cm² or other matrices like Vitronectin, following the manufacturer's instructions for dilution and incubation (typically 1 hour at 37°C) [27].

- Step 2: Gradual Media Adaptation. Do not switch media abruptly. Upon the first passage, culture cells in a 1:1 mixture of the old serum-containing medium and the new serum-free medium (SFM). Over subsequent passages (e.g., 3-5 passages), progressively increase the ratio of SFM to serum-medium (e.g., 3:1, then 100% SFM) [26].

- Step 3: Dissociation & Seeding. Use a mild dissociation reagent like Accutase or TrypLE instead of trypsin to better preserve cell surface proteins [32]. To combat the dramatic decrease in viability often seen after passaging in SFM, supplement the medium with a ROCK inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632) for the first 24-48 hours after seeding [31].

- Step 4: Culture & Monitor. Change the medium regularly, taking care to pre-warm it to 37°C before use to avoid thermal shock [28]. Closely monitor cell morphology, confluency, and doubling time. Be prepared for an initial adjustment period where growth may be slower.

- Step 5: Characterize Output. Once the culture is stabilized, perform quality control checks. This includes cell line authentication (e.g., STR profiling) [32] and functional assays to confirm the desired cell state is maintained (e.g., flow cytometry for pluripotency markers, differentiation potential assays) [27].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: My mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) are spontaneously differentiating even when cultured with LIF. What could be wrong? A: LIF alone is often insufficient to fully suppress differentiation. Spontaneous differentiation, particularly into primitive endoderm, is common. This is because LIF primarily activates the JAK-STAT3 pathway but does not inhibit pro-differentiation MAPK/ERK signaling. The solution is to supplement your medium with the 2i inhibitor cocktail (MEKi + GSK3i), which actively blocks these differentiation signals and enforces ground-state pluripotency.

Q2: How do I choose between using LIF alone, LIF+2i, or adding BMP4 for my pluripotency experiments? A: The choice depends on the pluripotency state you wish to maintain or induce. See the table below for a comparison.

Table 1: Culture Conditions and Resulting Pluripotency States

| Condition | Key Signaling | Pluripotency State | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIF + Serum | STAT3 Active, ERK Variable | Naive (Unstable) | Heterogeneous, prone to spontaneous differentiation. |

| LIF + 2i | STAT3 Active, ERK & GSK3 Inhibited | Ground-State Naive | Homogeneous, minimal differentiation, hypomethylated genome. |

| LIF + BMP4 | STAT3 & SMAD1/5/9 Active | Naive (Serum-Free) | Supports self-renewal in absence of serum; can prime for specific fates. |

Q3: What is the precise mechanism by which 2i maintains pluripotency? A: The 2i cocktail targets two key pathways:

- MEK Inhibitor (e.g., PD0325901): Blocks the MAPK/ERK pathway, which is a potent driver of differentiation.

- GSK3 Inhibitor (e.g., CHIR99021): Inhibits GSK3β, leading to the stabilization of β-catenin. This activates Wnt pathway target genes that support self-renewal and represses pro-differentiation factors.

Diagram 1: 2i Inhibition Mechanism

Q4: I am working with human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). Can I use these same factors? A: Caution is required. While MEK inhibition is beneficial, GSK3 inhibition alone can promote hPSC differentiation. The standard for naive hPSC culture often involves different inhibitor combinations (e.g., 5i/L/A). LIF is not typically used for primed hPSCs. BMP4 generally induces differentiation in hPSCs rather than supporting self-renewal. Always consult literature specific to your cell type.

Q5: My cells are dying in 2i/LIF conditions. What should I check? A:

- Inhibitor Concentration: Confirm you are using the correct dose. Common ranges are PD0325901 (0.5-1 µM) and CHIR99021 (1-3 µM). Perform a dose-response curve.

- Cell Density: Plate cells at an optimal density. Too low density can lead to apoptosis. A recommended seeding density is 10,000-20,000 cells/cm².

- Base Medium: Ensure you are using a defined, serum-free base medium like N2B27, which is optimized for 2i culture.

- Inhibitor Stock: Check that your inhibitor stocks are fresh and have been stored correctly (-20°C, protected from light and moisture).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Pluripotency by Immunofluorescence Objective: To validate the pluripotent state of mESCs cultured in LIF+2i. Reagents:

- 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA)

- Permeabilization Buffer (0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS)

- Blocking Buffer (5% BSA in PBS)

- Primary Antibodies: Anti-Nanog, Anti-Oct4

- Fluorescently-labeled Secondary Antibodies

- DAPI (for nuclear staining) Method:

- Culture mESCs on gelatin-coated coverslips in LIF+2i medium for 48 hours.

- Fix cells with 4% PFA for 15 minutes at room temperature (RT).

- Permeabilize with Permeabilization Buffer for 10 minutes at RT.

- Block with Blocking Buffer for 1 hour at RT.

- Incubate with primary antibodies diluted in Blocking Buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Wash 3x with PBS.

- Incubate with secondary antibodies and DAPI for 1 hour at RT in the dark.

- Wash 3x with PBS and mount on slides.

- Image using a fluorescence microscope. Co-expression of Nanog and Oct4 indicates a naive pluripotent state.

Protocol 2: Testing the Effect of BMP4 on Lineage Priming Objective: To evaluate early differentiation priming by BMP4 in naive mESCs. Reagents:

- mESCs maintained in LIF+2i

- N2B27 medium

- Recombinant BMP4

- RNA extraction kit

- qPCR reagents Method:

- Split mESCs from LIF+2i conditions and plate in N2B27 medium supplemented with LIF+2i (control) or LIF+2i + BMP4 (e.g., 10-50 ng/mL).

- Culture for 48-72 hours.

- Harvest cells and extract total RNA.

- Perform reverse transcription and quantitative PCR (qPCR).

- Analyze the expression of pluripotency markers (Nanog, Rex1) and early lineage markers (e.g., T for mesoderm, Sox17 for endoderm). BMP4 is expected to maintain self-renewal but may induce a subtle priming bias.

Diagram 2: BMP4 Priming Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function | Example | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIF (Leukemia Inhibitory Factor) | Cytokine that activates JAK-STAT3 signaling. | Recombinant mouse or human LIF. | Supports self-renewal in mouse ESC and iPSC culture. |

| MEK Inhibitor | Small molecule that inhibits MEK1/2, blocking ERK signaling. | PD0325901, PD184352. | Component of 2i; suppresses differentiation. |

| GSK3 Inhibitor | Small molecule that inhibits GSK3α/β, stabilizing β-catenin. | CHIR99021, BIO. | Component of 2i; activates Wnt-driven self-renewal. |

| BMP4 (Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4) | Cytokine that activates SMAD1/5/9 signaling. | Recombinant BMP4. | In mESCs, supports self-renewal with LIF; induces differentiation in other contexts. |

| N2B27 Medium | Defined, serum-free medium formulation. | 1:1 mix of DMEM/F12 with Neurobasal medium + supplements. | Base medium for robust and consistent 2i/LIF culture. |

| A-286501 | A-286501, CAS:483341-15-7, MF:C11H14BrN5O2, MW:328.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| AC1903 | AC1903, CAS:831234-13-0, MF:C19H17N3O, MW:303.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Troubleshooting Guides

Feeder Cell Performance Issues

Problem: Poor attachment and growth of pluripotent stem cells on feeder layers.

- Potential Cause: Incomplete growth arrest of feeder cells, allowing them to proliferate and compete with your stem cells.

- Solution: Validate the inactivation process. For Mitomycin-C treatment, ensure a concentration of 2-4 µg/ml for 2 hours is used and followed by thorough washing. For γ-irradiation, confirm the dose is 30 Gy (3000 rads) [33].

- Prevention: Use freshly prepared and quality-tested Mitomycin-C. After treatment, confirm inactivation by plating a test sample of feeder cells and monitoring for proliferation over 5-7 days [34].

Problem: Rapid decline in feeder cell supportive capacity.

- Potential Cause: Feeder cells are dying too quickly or were over-treated during inactivation.

- Solution: Optimize the plating density. For mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeders, a density of 8×10â´â€“1.1×10âµ cells/cm² is recommended. Low density can cause premature senescence [34].

- Prevention: Use early passage MEFs (passage 3-5) and ensure they are not grown to 100% confluence before inactivation, as this can reduce their supportive quality [34].

Culture Media and Pluripotency State Problems

Problem: Spontaneous differentiation in defined culture systems.

- Potential Cause: The base media formulation may not support the specific pluripotency state you are targeting (naive, formative, or primed).

- Solution: Select a media system validated for your desired pluripotency state. For example, RSeT medium sustains a state downstream of naive pluripotency, while PXGL supports a naive state. mTeSR1 and STEMPRO have demonstrated success in maintaining most human embryonic stem cell lines in a primed state [35] [1].

- Prevention: Pre-adapt your cell line to the new medium over 3-5 passages. Include ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (10 µM) during passaging to enhance single-cell survival, which is critical for media adaptation [1].

Problem: Inconsistent results across different cell lines with the same media.

- Potential Cause: Cell-line specific variations in dependency on signaling pathways.

- Solution: Characterize your cell line's signaling dependencies. RSeT hPSCs, for instance, show variable co-dependency on JAK and TGFβ signaling in a cell line-specific manner, despite the base medium lacking FGF2 and TGFβ [1].

- Prevention: When establishing a new cell line, perform pilot studies with multiple media (e.g., mTeSR1, STEMPRO, RSeT) to identify the most robust one for your specific line [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages and disadvantages of using feeder-free versus feeder-based systems for pluripotent stem cell culture? Feeder-free systems (e.g., using mTeSR1 or STEMPRO on defined matrices) offer a more standardized, xeno-free environment which is beneficial for clinical applications and reduces variability. However, they can be prohibitively expensive for large-scale culture and some cell lines may lose specific characteristics or growth efficiency without feeder-derived signals. Feeder-based systems using MEFs are often more robust for difficult-to-culture primary cells or establishing new lines, as they provide a complex mix of substratum, growth factors, and cytokines that are not fully replicated in defined media [35] [33]. The choice depends on the application: feeder-free for defined regulatory paths, and feeder-based for challenging primary cultures.

Q2: How does serum percentage in the medium influence the pluripotency state? The shift from serum-containing to serum-free or serum-replacer containing conditions has been pivotal in defining pluripotency states. High serum percentages can promote spontaneous differentiation and make it difficult to maintain a uniform pluripotency state. Modern defined media often use Knockout Serum Replacer (KSR) at 20% in combination with specific growth factors like bFGF to support a "primed" pluripotent state, which is the default for most human ESCs and iPSCs. Removing serum helps in achieving and maintaining more naive pluripotent states, which require different signaling environments, such as those provided by RSeT or PXGL media [35] [1].

Q3: My cells are not detaching properly during passaging. What should I do? The choice of dissociation enzyme is critical. For strongly adherent cells, trypsin or TrypLE Express is effective. For cells that are sensitive to proteases or when you need to keep cell surfaces intact, use a non-enzymatic cell dissociation buffer. For delicate cultures or when detaching cells as intact sheets (e.g., for epithelial cultures), Dispase is the recommended agent [36]. Always ensure the dissociation solution covers the cell monolayer completely and monitor the process under a microscope to avoid over-digestion, which can damage cells.

Data Presentation

Comparison of Defined Culture Systems

The following table summarizes the performance of different culture systems as identified in a multi-laboratory comparative study [35].

Table 1: Performance of Defined Culture Systems for Human Pluripotent Stem Cells

| Culture System | Ability to Maintain Most hESC Lines for 10 Passages | Key Signaling Pathway Components | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (KSR + FGF2 + MEFs) | Yes | FGF2, factors from MEFs and serum replacer | Positive control; contains undefined components. |

| mTeSR1 | Yes | FGF2, TGFβ, GABA agonist, Lithium Chloride | Robust commercial formulation; supports primed pluripotency. |

| STEMPRO | Yes | FGF, Activin A, HRG1β, LR3-IGF1 | Robust commercial formulation; supports primed pluripotency. |

| hESF9 | No (Failed before 10 passages) | FGF2, Heparin Sulfate | Relatively simple formulation. |

| Other Academic Formulations (Li 2005, Vallier 2005, etc.) | No (Failed before 10 passages) | Varied | Failed due to lack of attachment, cell death, or overt differentiation. |

Feeder Cell Inactivation Methods

The table below compares the two primary methods for inactivating feeder cells [33] [34].

Table 2: Comparison of Feeder Cell Inactivation Methods

| Parameter | Mitomycin-C (MC) Treatment | γ-Irradiation (GI) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Double-stranded DNA alkylating agent, causing mitotic inactivation. | Introduces double-stranded DNA breaks, suspending replication. |

| Typical Protocol | 2-4 µg/ml for 2 hours at 37°C. | Single dose of 30 Gy (3000 rads). |

| Key Advantages | Cost-effective; readily available reagents; no specialized equipment needed. | Considered highly efficient; can treat large volumes of cells at once. |

| Key Disadvantages | Requires thorough washing to remove residual toxin; potential for incomplete inactivation if not applied properly. | Requires access to a radiation source (e.g., Cobalt-60), which is costly and less common. |

| Efficiency | Effective when protocol is followed precisely; supportive capacity may be slightly lower than GI-treated feeders. | Considered the gold standard for complete and reliable inactivation. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Preparation of Feeder Cells using Mitomycin-C

This protocol describes the Suspension-Adhesion Method (SAM) for preparing mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeders, which offers higher adherent and recovery rates compared to the conventional method [34].

Materials:

- CF-1 MEFs (or other suitable strain) at passage 3.

- MEF medium: DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids, 1 mM L-glutamine.

- Mitomycin-C (MMC) stock solution.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), without Ca²⺠and Mg²âº.

- 0.25% Trypsin/EDTA.

Procedure:

- Culture CF-1 MEFs for four days to expand the population.

- Wash the cells with PBS and digest to a single-cell suspension using 0.25% trypsin/EDTA. Neutralize the trypsin with MEF medium and collect the cells in a centrifuge tube.

- Seed the cells densely at 8×10â´â€“1.1×10âµ cells/cm² into new culture dishes.

- Allow the cells to adhere for 2-3 hours in an incubator at 37°C.

- Add MMC to a final concentration of 10 µg/ml directly to the medium.

- Incubate for 0.5 to 3.5 hours at 37°C. Note: The study found that 0.5 hours was sufficient for full inhibition with this method [34].

- Discard the MMC-containing medium completely. Wash the cell layer 6 times with PBS to ensure all traces of MMC are removed.

- Trypsinize the inactivated cells, centrifuge at 180 × g for 5 minutes, and resuspend in MEF medium.

- Count the cells and plate immediately for co-culture or freeze for later use. The recommended plating density for supporting iPSC growth is specific to the cell type but often ranges from 1×10ⵠto 2×10ⵠcells/cm².

Detailed Protocol: Enzymatic Passaging of Pluripotent Stem Cells

This is a general procedure for subculturing adherent pluripotent stem cell colonies using TrypLE Express, an animal-origin-free enzyme [36].

Materials:

- Pluripotent stem cell culture.

- Pre-warmed DPBS (without calcium and magnesium).

- Pre-warmed TrypLE Express enzyme.

- Pre-warmed complete growth medium.

- ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) stock solution.

Procedure:

- Pre-warm TrypLE Express and complete growth medium to 37°C.

- Aspirate and discard the spent cell culture medium from the culture vessel.

- Wash the cell monolayer with 5 mL of DPBS to remove residual calcium and magnesium, which can inhibit enzyme activity. Aspirate and discard the wash solution.

- Add an appropriate volume of TrypLE Express to the flask to ensure complete coverage of the cell monolayer (e.g., 5 mL for a T-75 flask).

- Incubate at 37°C for 5-15 minutes. Monitor the cells under an inverted microscope until the cells round up and detach. Gently tap the flask to dislodge any remaining cells.

- Add 5-10 mL of pre-warmed complete growth medium to the flask to neutralize the enzyme. Tilt the flask to rinse the surface and transfer the cell suspension to a 15 mL conical tube.

- Centrifuge the tube at 100 × g for 5-10 minutes.

- Carefully discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in a fresh, pre-warmed complete medium.

- For critical applications, especially when working with single cells, add a ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) to a final concentration of 10 µM to the medium to enhance cell survival [1].

- Determine viable cell density and percent viability using an automated cell counter or hemocytometer.

- Seed cells into new culture vessels pre-coated with the appropriate matrix at the desired density.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Signaling in Defined Culture Media

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways targeted by key components in defined culture media like mTeSR1 and STEMPRO, which are critical for maintaining pluripotency [35].

Feeder Cell Preparation Workflow

This workflow outlines the efficient Three-Dimensional Suspension Method (3DSM) for large-scale preparation of feeder cells, as an optimization over the conventional method [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Pre-Growth Condition Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs) | Serves as a feeder layer; provides physical support, secretes essential growth factors and extracellular matrix proteins for stem cell growth. | Use early passages (P3-P5); ensure complete mitotic inactivation via Mitomycin-C or γ-irradiation [33] [34]. |

| Mitomycin-C | Chemical agent used for the mitotic inactivation of feeder cells. | Requires careful handling and thorough washing post-treatment to remove all traces of the toxin [33]. |

| Defined Culture Media (mTeSR1, STEMPRO) | Serum-free, defined formulations for feeder-free culture of pluripotent stem cells. Supports a "primed" state of pluripotency. | Robust and standardized but can be costly. Quality can vary between batches from different vendors [35]. |

| Specialized Media (RSeT, PXGL) | Supports alternative pluripotency states. RSeT maintains a state between naive and primed, while PXGL supports a "naive" state. | Requires pre-adaptation of cell lines. Signaling dependencies (JAK, TGFβ) can be cell-line specific [1]. |

| TrypLE Express | Recombinant fungal protease, animal-origin-free, used for enzymatic dissociation of cells into single cells. | Direct substitute for trypsin; gentler on some cell types. Incubation time needs to be optimized [36] [1]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Small molecule inhibitor that dramatically improves the survival of single pluripotent stem cells after dissociation. | Use at 10 µM in the medium for 24-48 hours after passaging. Critical for single-cell cloning and media adaptation [1]. |

| Dispase | Proteolytic enzyme used for the gentle dissociation of cell colonies as intact clumps. | Ideal for passaging cells when single-cell survival is low. Not suitable for generating single-cell suspensions [36]. |

| 17-ODYA | 17-ODYA, CAS:34450-18-5, MF:C18H32O2, MW:280.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |