Navigating the Challenges of Low Input RNA Sequencing in Embryonic Research: From Technical Hurdles to Biological Insights

Low input RNA sequencing has become indispensable for studying embryonic development, where sample material is extremely limited. This article explores the foundational challenges, including RNA degradation and the complexities of early developmental transcriptomes. It reviews methodological advancements in library preparation and rRNA depletion, alongside practical troubleshooting strategies for optimizing yields from precious samples. Furthermore, it highlights the critical role of sophisticated computational tools and rigorous validation in ensuring data reliability. By synthesizing current research and technical evaluations, this guide provides a comprehensive resource for researchers aiming to leverage low input RNA-seq to unlock the molecular mysteries of embryogenesis, with significant implications for understanding developmental disorders and improving regenerative medicine.

Navigating the Challenges of Low Input RNA Sequencing in Embryonic Research: From Technical Hurdles to Biological Insights

Abstract

Low input RNA sequencing has become indispensable for studying embryonic development, where sample material is extremely limited. This article explores the foundational challenges, including RNA degradation and the complexities of early developmental transcriptomes. It reviews methodological advancements in library preparation and rRNA depletion, alongside practical troubleshooting strategies for optimizing yields from precious samples. Furthermore, it highlights the critical role of sophisticated computational tools and rigorous validation in ensuring data reliability. By synthesizing current research and technical evaluations, this guide provides a comprehensive resource for researchers aiming to leverage low input RNA-seq to unlock the molecular mysteries of embryogenesis, with significant implications for understanding developmental disorders and improving regenerative medicine.

Why Embryos Pose a Unique Challenge: The Foundations of Low Input RNA-Seq

The scarcity of human embryonic material represents a fundamental bottleneck in developmental biology and reproductive medicine. This scarcity stems from a confluence of significant ethical considerations and formidable technical challenges associated with the acquisition and analysis of these precious samples. Research on early human development is essential for advancing knowledge of human genetics, the origins of life, and the causes of congenital diseases, early miscarriages, and infertility [1]. The initial phase of human embryonic development offers crucial insights into the processes that transform a single fertilized cell into a complex multicellular organism [1]. However, thorough research is severely hampered by the ethical, technical, and legal difficulties associated with studying human embryonic development, creating a pressing need for alternative models and sophisticated low-input analytical techniques [1]. This guide examines the core limitations and the advanced methodologies being developed to overcome them, with a specific focus on the challenges and solutions for low-input RNA sequencing in embryo research.

Ethical and Regulatory Landscape

The use of human embryos in research is governed by a complex framework of ethical principles and regulatory guidelines that directly limit the availability of embryonic material.

Core Ethical Restrictions

- The 14-Day Rule: A cornerstone of international regulations, this rule prohibits the culture of human embryos for research beyond 14 days or the appearance of the primitive streak, which signifies the onset of gastrulation and the emergence of the body plan [1] [2]. This restriction leaves post-implantation development, gastrulation, and early organ formation in humans poorly understood [1].

- Restrictions on Embryo Creation: The creation of embryos specifically for research is permitted in relatively few jurisdictions, further limiting supply [3].

- Oversight of Stem Cell-Based Embryo Models (SCBEMs): The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) has issued stringent guidelines stating that researchers should not use stem cell-based embryo models to try to start a pregnancy or grow them in an artificial womb to the point of viability, deeming such experiments unethical [4] [3].

Regulatory Oversight Framework

All research involving preimplantation human embryos, in vitro human embryo culture, or the generation of stem cell-based embryo models must undergo a specialized scientific and ethics oversight process [3]. This oversight is typically conducted by a committee comprising scientists, ethicists, legal experts, and community members, who are responsible for assessing the scientific merit, ethical justification, and the provenance of the materials used [3].

Technical Challenges in Acquisition and Analysis

Beyond ethical constraints, the physical and molecular characteristics of embryonic material present significant technical hurdles.

Scarcity of Biological Material

The very nature of early embryogenesis involves a limited number of cells. For instance, a human blastocyst contains only about 200-300 cells, making it a quintessentially low-input system [1]. This scarcity is compounded by the challenges of obtaining donated embryos from IVF procedures, which are themselves limited resources.

Low RNA Content and Quality

Sequencing the transcriptome of embryonic or gamete-derived material is particularly challenging due to the inherently low RNA content. This is especially true for spermatozoa, where RNA is highly fragmented and conventional RNA quality metrics, such as the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) and the 28S/18S ratio, are often unreliable [5]. One study attempting sperm transcriptome sequencing started with 83 semen samples, but only 37 had sufficient RNA content for sequencing, and a mere 15 met standard quality thresholds (RIN > 6) [5].

Challenges of Single-Cell Analysis

While single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized the study of embryonic development by allowing researchers to analyze individual cells from rare samples [1] [2], the technique is vulnerable to technical noise and batch effects. Creating a unified reference map from multiple datasets requires sophisticated computational integration to minimize these effects and ensure robust comparisons [2].

Table 1: Key Technical Challenges in Low-Input Embryonic RNA Sequencing

| Challenge | Description | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Number Limitation | Early embryos consist of a very small number of cells (e.g., ~200-300 in a blastocyst) [1]. | Severely restricts the total RNA yield, necessitating highly sensitive amplification methods that can introduce bias. |

| Low RNA Integrity in Gametes | Sperm RNA is highly fragmented; standard quality metrics like RIN can be misleading [5]. | Challenges accurate transcriptome quantification; requires alternative quality assessments (e.g., RNA IQ, DV200). |

| Sample Attrition | A high percentage of collected samples may fail to yield sequencable RNA. | Reduces effective sample size and statistical power; one study had a 55% attrition rate (83 to 37 samples) [5]. |

| Batch Effects in scRNA-seq | Technical variation between experiments conducted on different embryos or different days [2]. | Can obscure true biological signals; requires advanced computational integration for cross-study comparisons. |

Table 2: Comparison of Alternative Research Models to Overcome Scarcity

| Model System | Description | Utility in Transcriptomics | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell-Based Embryo Models (SCBEMs) | Structures built from stem cells to mimic aspects of embryonic development [1] [2]. | Serves as a scalable source for scRNA-seq; enables experimental perturbation [1] [2]. | Fidelity to natural embryos must be rigorously validated using integrated reference atlases [2]. |

| Blastoids & Gastruloids | In vitro models that mimic the blastocyst or gastrulating embryo [1]. | Provides insights into pre- and post-implantation gene expression dynamics [1]. | Not a perfect replica; may lack some cell types or spatial organization found in vivo. |

| Reproductive Mini-Organoids | In vitro models of reproductive tissues (e.g., placental structures, ovarian tissue) [6]. | Ideal platform for investigating causes of infertility and testing interventions under controlled conditions [6]. | Complexity and long-term maturation challenges remain. |

Advanced Methodologies for Low-Input Sequencing

To address the challenges of scarcity, researchers have developed specialized protocols and computational tools.

Experimental Protocol: Small-Scale In Situ Hi-C for Chromatin Architecture

This protocol demonstrates key principles for working with ultra-low cell inputs, applicable to RNA-seq library preparation.

- Step 1: Cell Collection and Fixation. Transfer a small number of embryonic cells (50-100) using glass capillaries and fix them with formaldehyde in droplets on disposable plastic culture dishes. This minimizes cell loss compared to conventional fixation in centrifuge tubes [7].

- Step 2: Lysis and Digestion. Lyse cells and digest chromatin with a restriction enzyme (e.g., AluI). Using enzymatic digestion instead of sonication enables more controlled fragmentation and reduces material loss [7].

- Step 3: Proximity Ligation. Perform end-repair with biotin labeling and intra-chromosomal ligation in a scaled-down reaction volume to maintain high concentrations of molecules [7].

- Step 4: DNA Purification and Sequencing. Decrosslink DNA, purify it, and perform size selection to enrich for ligation products. Generate sequencing libraries for high-throughput sequencing [7].

Computational Validation of Embryo Models

Given the limitations of natural embryos, authenticating stem cell-based models is crucial. This is achieved by:

- Creating an Integrated Reference: Assembling a comprehensive transcriptional reference map from all available scRNA-seq datasets of human embryos, from zygote to gastrula [2].

- Projection and Annotation: Using this reference as a universal benchmark. Query datasets from embryo models are projected onto the reference to annotate cell identities and assess transcriptional fidelity [2]. This process helps avoid misannotation and ensures the models' usefulness [2].

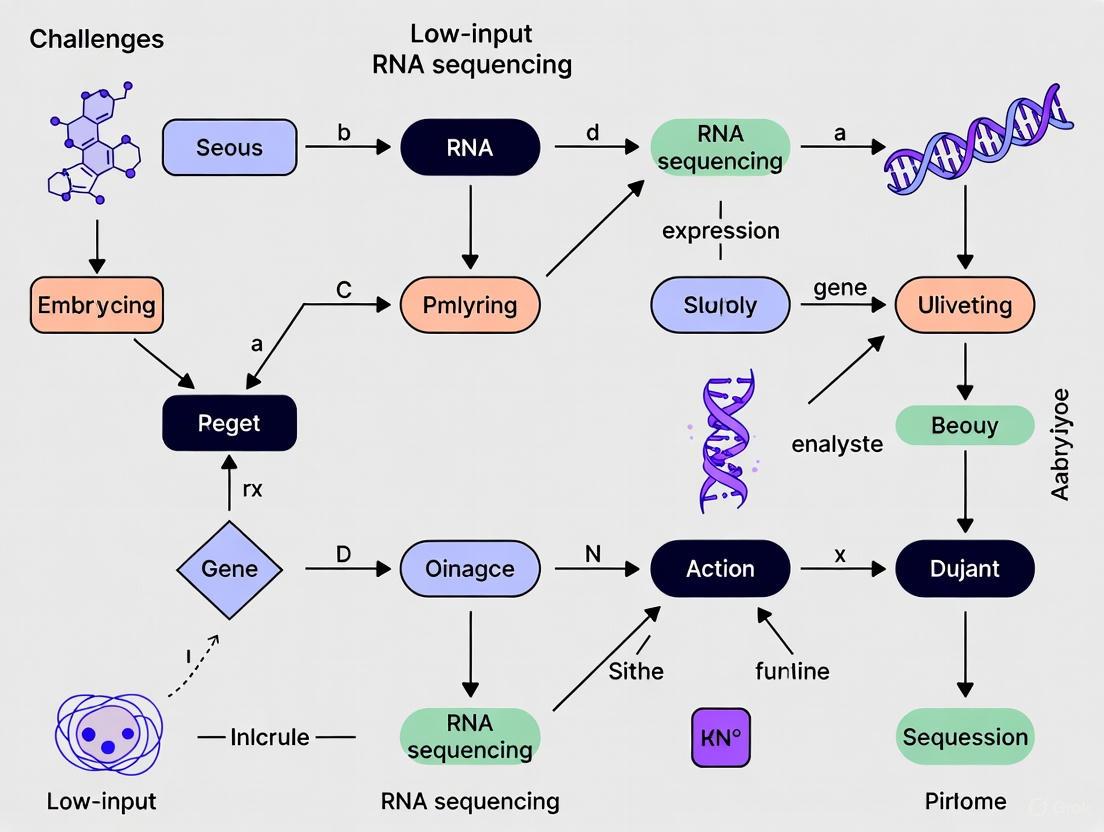

Diagram 1: Research workflow for overcoming embryonic material scarcity. The central challenge of scarcity drives the development of alternative models and specialized protocols, which are validated against an integrated computational reference.

Direct RNA Sequencing for Modification Detection

Nanopore-based Direct RNA Sequencing (DRS) bypasses cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification, allowing for the direct sequencing of native RNA molecules. This is particularly valuable for detecting RNA modifications like m6A, which is essential for regulating gene expression, and for sequencing highly fragmented RNA. Deep learning models such as SingleMod use a multiple instance regression framework to detect these modifications on individual RNA molecules from DRS data with high accuracy, providing another tool for analyzing low-quality or low-quantity samples [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Input Embryo Research

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde | Crosslinking agent for fixing chromatin structure. | Used in small-scale in situ Hi-C to preserve 3D chromatin architecture in low cell numbers [7]. |

| AluI Restriction Enzyme | Digests chromatin at specific sequences for Hi-C. | Preferred over sonication in low-input protocols for controlled fragmentation and reduced material loss [7]. |

| VAHTS Universal V6 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries from total RNA. | Used for constructing libraries from low-input sperm RNA samples for transcriptome analysis [5]. |

| TRIzol Reagent | Monophasic solution for RNA isolation from cells and tissues. | Standard method for extracting total RNA from challenging samples like spermatozoa [5]. |

| Stabilized UMAP (sUMAP) | Computational tool for dimensionality reduction and visualization. | Creates a stable, integrated reference map from multiple human embryo scRNA-seq datasets for benchmarking models [2]. |

| SingleMod Software | Deep learning model for detecting RNA modifications from Nanopore DRS data. | Enables precise detection of m6A modification on individual RNA molecules, leveraging quantitative benchmarks [8]. |

| Thalibealine | Thalibealine | Thalibealine is a novel dimeric alkaloid for cancer research. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human consumption. |

| Hemiphroside B | Hemiphroside B | Hemiphroside B is a natural phenylpropanoid glycoside for ulcerative colitis research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO), not for human or veterinary use. |

Diagram 2: Two-pronged strategy to overcome material scarcity. Researchers address the core problem through both advanced technical methods for handling minimal samples and the creation of scalable synthetic embryo models.

The scarcity of human embryonic material, shaped by profound ethical boundaries and technical realities, continues to challenge and inspire the field of developmental biology. While these limitations constrain direct research on human embryos, they have catalyzed significant innovation. The development of low-input sequencing protocols, sophisticated stem cell-based embryo models, and comprehensive computational reference tools collectively provide a viable path forward. The ongoing refinement of these ethical and technical workarounds promises to deepen our understanding of human life's earliest stages, ultimately addressing critical issues in infertility, congenital diseases, and prenatal health. The future of the field lies in the continued interdisciplinary integration of biology, engineering, and bioinformatics to extract maximal knowledge from minimal material.

Zygotic Genome Activation (ZGA) represents the inaugural transcriptional event in embryonic development, marking the critical transition when the newly formed embryonic genome assumes control of development from maternally deposited factors [9]. This process initiates the embryonic program that guides the transformation of a totipotent zygote into a complex multicellular organism [10]. For decades, the molecular mechanisms governing ZGA remained poorly understood due to technical limitations in analyzing the minute biological material available from early embryos [9]. However, with recent advances in single-cell and low-input technologies, remarkable progress has been made in elucidating the dramatic transitions in epigenomes, transcriptomes, proteomes, and metabolomes associated with ZGA [9] [11].

This technical guide examines the transcriptional dynamics from ZGA through the first lineage specifications, with particular emphasis on the challenges and solutions associated with low-input RNA sequencing in embryonic research. We synthesize current understanding of the molecular regulators, epigenetic reprogramming, and transcriptional networks that orchestrate this foundational period of mammalian development, providing both conceptual frameworks and practical methodological guidance for researchers investigating early embryogenesis.

The Phases of Embryonic Genome Activation

Historical Classification and Contemporary Refinements

Traditional models divided ZGA into two distinct waves: minor and major activation. However, recent high-resolution temporal studies have revealed a more complex and continuous transcriptional initiation process.

Table 1: Waves of Embryonic Genome Activation Across Species

| Activation Phase | Developmental Stage | Key Characteristics | Representative Genes/Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate EGA (iEGA) | Mouse: Within 4h post-fertilization; Human: 1-cell stage | First transcription from maternal genome; paternal genome follows ~10h post-fertilization; canonically spliced transcripts [12] | MYC/c-Myc; predicts embryonic processes and regulatory TFs associated with cancer [12] |

| Minor ZGA | Mouse: Middle 1-cell stage; Human: Continuation of iEGA | Small set of genes activated; continuous with iEGA [9] [12] | Transcription factors including NR family members [13] |

| Major ZGA | Mouse: Late 2-cell stage; Human: 4-8-cell stage | Thousands of genes transcribed; higher amplitude wave [9] [12] | Pluripotency factors; lineage specification genes [13] [14] |

Recent evidence challenges the traditional view that ZGA occurs predominantly at the 2-cell stage in mice and 4-8-cell stage in humans. Precise time-course single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) of mouse 1-cell embryos revealed an immediate EGA (iEGA) program initiating within 4 hours of fertilization, primarily from the maternal genome, with paternal genomic transcription beginning approximately 10 hours post-fertilization [12]. Significant low-magnitude upregulation occurs similarly in healthy human 1-cell embryos, suggesting conservation of this immediate activation mechanism across mammals [12].

The regulatory distinction between immediate/minor EGA and major EGA appears fundamental. Inhibition studies demonstrate that immediate EGA is uniquely sensitive to perturbation of specific transcription factors like c-Myc, whose blockade induces acute developmental arrest and disrupted iEGA, while unexpectedly causing upregulation of hundreds of genes—a phenomenon termed "embryonic genome repression" (EGR) [12].

Technical Considerations for Transcriptional Phase Analysis

Accurate characterization of these transcriptional phases presents significant technical challenges:

Temporal Precision: Traditional studies using pooled embryos with indeterminate fertilization timing potentially smooth critical transcriptional signals [12]. Time-stamped collection systems and live imaging coupled with scRNA-seq provide superior temporal resolution.

Transcript Detection Sensitivity: Poly(A) capture-based methods may skew results due to controlled poly(A) tail length regulation in early embryos [12]. Full-length transcript protocols and specialized normalization approaches are essential for accurate quantification.

Species-Specific Considerations: While fundamental principles are conserved, precise timing varies between model organisms. Guinea pig embryos recently emerged as a valuable model showing preimplantation development surprisingly similar to humans in both timing and regulatory circuitry [15].

Molecular Regulators of ZGA: Licensors and Specifiers

The molecular control of ZGA involves two emerging classes of regulators: licensors that control the permission and timing of transcription, and specifiers that instruct the activation of specific genes [9].

Licensors: Gatekeepers of Transcriptional Competence

Licensors generate competency for ZGA by creating a permissive environment for transcription without strong gene selectivity [9]. These include:

- Regulators of the transcription apparatus: Components that establish the basal transcriptional machinery and overcome initial repression.

- Nuclear gatekeepers: Factors controlling nuclear import, chromatin state, and accessibility.

- Epigenetic modifiers: Enzymes that establish permissive chromatin environments, including histone acetyltransferases (e.g., P300/CBP) and chromatin remodelers [9].

Functional evidence demonstrates that chemical inhibition of CBP/P300 disrupts ZGA, causes loss of chromatin accessibility, and leads to 2-cell arrest in mouse embryos [9]. Similarly, artificial recruitment of p300 can activate ZGA genes and bypass the need for certain transcription factors [9]. Interestingly, histone deacetylation also contributes to ZGA, as HDAC inhibition or NAD+ depletion (cofactor for deacetylation) causes precise timing defects during minor ZGA [9].

Specifiers: Instructors of Gene-Specific Activation

Specifiers determine which specific genes are activated during ZGA and include key transcription factors present at this stage, often facilitated by epigenetic regulators [9]. Among the most critical specifiers are nuclear receptor transcription factors, whose motifs are highly enriched in accessible regulatory elements from the 2-cell to 8-cell stages [13].

Table 2: Key Transcription Factor Families in Early Embryonic Development

| TF Family | Representative Members | Expression Peak | Functional Role | Validation Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Receptors | NR5A2, RARG, NR2F2 | 2-cell to 8-cell stages | Bridge ZGA to first lineage specification; regulate pluripotency genes [13] [14] | Knockout causes morula arrest; directly activates Oct4, Nanog [13] |

| Pluripotency TFs | NANOG, SOX2, OCT4 (NSO) | Inner cell mass | Core pluripotency network; cooperatively regulate intrinsic pluripotency circuits [13] | Motifs enriched in ICM and ESCs; essential for pluripotency establishment [13] |

| Zf-C2H2 | Various | Chicken early embryogenesis | Early cell differentiation and specification [16] | Dominant TF family in early chicken embryogenesis [16] |

| Homeobox | Various | Chicken early embryogenesis | Body patterning and tissue formation [16] | Appears in early embryogenesis across species [16] |

NR5A2 emerges as a particularly critical specifier, with functional studies demonstrating that its knockdown or knockout allows development beyond the 2-cell stage but substantially impairs 4-8C-specific gene activation, resulting in embryonic arrest at the morula stage [13]. NR5A2 directly regulates key pluripotency genes including Nanog and Pou5f1/Oct4, as well as primitive endoderm regulatory genes including Gata6 and trophectoderm regulators including Tead4 and Gata3 [13].

Epigenetic Reprogramming During ZGA

Epigenetic landscapes undergo drastic reprogramming during ZGA to accommodate the first transcriptional events [9]. This reprogramming involves coordinated changes in DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin accessibility, and 3D chromatin organization.

DNA Methylation Dynamics

In both mouse and human embryos, the paternal genome undergoes rapid global DNA demethylation after fertilization, while the maternal genome gradually loses methylation, leaving only 20-40% of CpG sites with gamete-inherited methylation in blastocysts [9]. Exceptions include imprinting control regions and certain repeats that retain high methylation levels [9]. Proper DNA methylation reprogramming promotes fidelity of gene expression during and after ZGA, as demonstrated by defects in embryos with aberrant DNMT1/UHRF1 retention or impaired passive demethylation [9].

Histone Modification Transitions

Histone acetylation, particularly H3K27ac, marks active promoters and enhancers before ZGA in multiple species [9]. In mouse embryos, major ZGA genes are primed with histone acetylation in zygotes and early 2-cell embryos [9]. H3K27ac exhibits a non-canonical broad pattern that correlates with H3K4me3 and chromatin accessibility before being reprogrammed during the 2-cell stage [9].

H3K4me3, a classic transcription-permissive histone mark, also undergoes developmental stage-specific regulation [9]. The functional significance of these modifications is demonstrated by inhibition studies showing that disruption of acetylation writers or readers reduces zygotic transcription and causes developmental arrest [9].

Experimental Approaches and Technical Challenges

Low-Input RNA Sequencing Methodologies

Advanced single-cell RNA sequencing technologies have revolutionized embryonic transcriptomics by enabling high-throughput profiling of transcriptomic information at individual cell resolution [11]. However, several methodological considerations are critical for obtaining accurate data:

Cell Capture Efficiency: Different scRNA-seq platforms offer complementary strengths. High-sensitivity methods (e.g., SMART-seq) provide superior transcript detection for small cell numbers, while high-throughput approaches (e.g., 10x Genomics) capture larger cell numbers at lower detection efficiency [17].

Batch Effect Management: Integration of multiple datasets requires careful normalization. Standardized processing pipelines using the same genome reference and annotation minimize batch effects in integrated analyses [14].

Spatial Context Preservation: Emerging spatial transcriptomic technologies preserve architectural information that is crucial for understanding lineage specification [11].

Analytical Frameworks for Embryonic Transcriptomics

Several computational approaches have been developed specifically for embryonic transcriptome analysis:

- Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA): Identifies gene modules with stage-specific characteristics and hub genes [18].

- Trajectory Inference: Tools like Slingshot reconstruct developmental trajectories and identify transcription factors with modulated expression across pseudotime [14].

- Regulatory Network Inference: SCENIC analysis identifies active transcription factor regulons based on corrected expression values [14].

- Reference Atlas Integration: Stabilized UMAP projection enables annotation of query datasets against integrated reference embryos [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Embryonic Transcriptomics Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq Library Kits | NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit; SMART-seq | cDNA library construction from low-input RNA | Full-length coverage vs. 3'-end tradeoffs [18] [17] |

| Epigenetic Inhibitors | CBP/P300 inhibitors; HDAC inhibitors; BRD4 inhibitors | Functional validation of epigenetic mechanisms | Dose-response critical; developmental stage-specific effects [9] |

| Gene Perturbation Tools | siRNA pools; base editors (e.g., CRISPR/dCas9-epigenetic editors) | Loss/gain-of-function studies | Multi-gene targeting often necessary due to redundancy [13] |

| Antibodies for Chromatin Analysis | H3K27ac; H3K4me3; NR5A2 | Immunofluorescence; CUT&RUN profiling | Validation in embryonic material essential [9] [13] |

| Reference Datasets | Human embryo integrated atlas (zygote to gastrula) | Benchmarking embryo models and experimental data | Must include relevant developmental stages [14] |

| Curcumaromin C | Curcumaromin C | 96% Purity | Curcumaromin C (CAS 1810034-40-2), 96% purity. A natural phenol for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human or animal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Taxilluside A | Taxilluside A, MF:C18H24O10, MW:400.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

The diagrams below visualize key regulatory relationships and experimental workflows described in this field.

Diagram 1: Regulatory Control of ZGA and Lineage Specification

Diagram 2: Low-Input RNA-seq Experimental Workflow

The integration of single-cell and spatial multi-omic technologies continues to transform our understanding of transcriptional dynamics during early embryonic development [11]. Future research directions will likely focus on:

- Multi-omic Integration: Simultaneous profiling of transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic information from the same embryonic cells [11] [10].

- Enhanced Spatial Resolution: Application of spatial transcriptomics to preserve architectural context during lineage decisions [11].

- Functional Screening Platforms: CRISPR-based screens in embryo models to systematically identify regulatory components [13] [10].

- Cross-Species Comparisons: Leveraging conserved and divergent mechanisms across model organisms to identify fundamental principles [15] [14].

- Clinical Translation: Understanding how transcriptional dysregulation contributes to developmental disorders and implantation failure [15] [10].

The molecular dissection of ZGA and lineage specification not only advances fundamental knowledge of embryogenesis but also provides critical insights for regenerative medicine, assisted reproductive technologies, and developmental disorders. As low-input sequencing technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly reveal further complexity in the transcriptional programs that launch new life.

In the field of developmental biology, particularly in embryonic research, the study of the transcriptome is often constrained by a fundamental limitation: the scarcity of sample material. Early preimplantation embryos are precious and contain limited numbers of cells, creating significant challenges for quantitative gene expression analyses [19]. In these low-input contexts, the integrity of RNA transitions from a routine consideration to a pivotal factor determining experimental success or failure. RNA quality directly impacts the accuracy, reliability, and interpretability of sequencing data, especially when working with picogram to nanogram quantities of RNA [20]. Degraded RNA can introduce substantial biases in transcript representation, skew expression profiles, and ultimately lead to erroneous biological conclusions. This technical guide examines the multifaceted challenges of RNA degradation in low-input sequencing workflows, provides actionable methodologies for quality assessment and preservation, and presents advanced solutions tailored to embryonic research where sample preservation is paramount.

RNA Quality Assessment in Low-Input Contexts

Quantitative Metrics for RNA Integrity Evaluation

The accurate assessment of RNA quality is a critical first step in any low-input sequencing workflow. For embryonic samples, where material is extremely limited, traditional quantification methods may need adaptation or replacement with more sensitive approaches.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing RNA Quality in Low-Input Contexts

| Metric | Description | Target Value | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | Quantitative measure of RNA integrity based on ribosomal RNA ratios [21] | >7.0 for high-quality sequencing [21] | Less reliable for low-input samples; requires specialized equipment (Bioanalyzer/TapeStation) |

| 260/280 Ratio | Assesses protein contamination | ~1.8-2.0 [22] | Can be influenced by extraction method; critical for low-concentration samples |

| 260/230 Ratio | Indicates chemical contamination (e.g., salts, solvents) | >1.8 [22] | Particularly important when working with purified cell populations |

| Visual Electropherogram | Qualitative assessment of 28S and 18S rRNA peaks | Distinct 2:1 ratio of 28S:18S peaks [21] | Provides visual confirmation of degradation patterns; challenging with ultra-low input |

For embryonic samples, where material is often limited to single embryos or even single blastomeres, the standard RIN measurement may be impractical due to insufficient material. In these cases, alternative quality control methods such as qPCR-based assays targeting housekeeping genes or spike-in controls can provide indirect assessments of RNA quality [19]. Additionally, the implementation of external RNA controls consortium (ERCC) RNA spike-ins can help monitor technical variability and assess amplification efficiency in degraded samples [23].

Impact of Degradation on Low-Input RNA-Seq Data

RNA degradation manifests differently in low-input contexts compared to conventional RNA-seq. The combination of minimal starting material and RNA degradation can compound technical artifacts, leading to:

- 3' Bias Amplification: In degraded samples, protocols relying on poly(A) selection exhibit pronounced 3' bias, as the 5' ends of transcripts are more susceptible to degradation [21]. This effect is magnified in low-input workflows that involve cDNA amplification.

- Gene Detection Loss: Degradation preferentially affects longer transcripts, leading to their underrepresentation in sequencing libraries [21]. In embryonic research, this could mean missing critical long transcripts involved in developmental processes.

- Quantitative Inaccuracies: Comparison between samples with varying degradation levels can produce false differential expression results, potentially misdirecting biological interpretations [21].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of RNA-Seq Methods with Suboptimal RNA Quality

| Method | Minimum Input | Degraded RNA Compatibility | Key Advantages for Compromised Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Poly(A) Selection | Varies | Poor [21] | Not recommended for degraded samples |

| rRNA Depletion with Random Priming | 10pg-1ng [23] | Good [21] | Does not require intact poly(A) tail; more representative coverage |

| Uli-epic Strategy | 100pg-1ng [20] | Excellent | Specifically designed for compromised samples; integrates RNA modification profiling |

| SMART-seq Variants | 20pg-1ng [22] | Moderate | Full-length transcript recovery; better for intact RNAs |

Methodological Approaches for Challenging Samples

Specialized Library Preparation Techniques

Advanced library preparation methods have been developed specifically to address the dual challenges of low input and suboptimal RNA quality. These techniques often incorporate strategic modifications to standard protocols to enhance robustness against degradation.

The Uli-epic method represents a significant advancement for profiling epitranscriptomic modifications using only 100 pg to 1 ng of RNA [20]. This innovative library construction strategy integrates poly(A) tailing, reverse transcription coupled with template switching, and T7 RNA polymerase-mediated in vitro transcription to enable precise RNA modification profiling at single-nucleotide resolution even with severely limited input. The method has been successfully applied to study pseudouridine (Ψ) sites in neural stem cells and sperm RNA using only 500 pg of rRNA-depleted RNA [20].

For embryonic development research, a combined analysis approach enabling both transcriptome and genome sequencing from the same ultra-low input sample has been demonstrated [24]. This method allows preparation of amplified cDNA and whole-genome amplified DNA from sub-colonies of human embryonic stem cells containing only 150-200 cells, preserving precious embryonic material while maximizing data output [24].

Experimental Workflow for Low-Input Embryonic Samples

The following diagram illustrates a robust experimental workflow optimized for low-input embryonic samples where RNA quality is a concern:

This workflow emphasizes critical decision points based on RNA quality assessment results. For embryonic samples where material is extremely limited, the choice between poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion with random priming should be guided by RNA integrity metrics [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Input RNA Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo-dT Magnetic Beads | mRNA capture via poly(A) tail selection [24] | Requires intact poly(A) tails; not suitable for degraded samples [21] |

| ERCC RNA Spike-Ins | External RNA controls for normalization [23] | Critical for low-input studies to monitor technical variability and normalization |

| rRNA Depletion Probes | Removal of ribosomal RNA [21] | Essential for degraded samples or non-polyadenylated RNAs; reduces sequencing costs |

| Template Switching Oligos | cDNA amplification for full-length transcripts [20] | Enables whole-transcriptome amplification from minimal input |

| UMIs (Unique Molecular Identifiers) | Correction for amplification biases [23] | Improves quantification accuracy in amplified libraries |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preservation of RNA integrity during collection | Critical for clinical or precious embryonic samples |

| Mbamiloside A | Mbamiloside A|RUO | Mbamiloside A (CAS 1356388-55-0) is a natural isoflavonoid for research. This product is for Research Use Only, not for human use. |

| 24-Methylenecycloartanone | 24-Methylenecycloartanone, MF:C31H50O, MW:438.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Protocols for Embryonic Research

Low-Input RNA-Seq Protocol for Embryonic Cells

The following detailed protocol has been specifically adapted for embryonic research applications, incorporating quality preservation measures at each step:

Sample Collection and Lysis

- For embryonic stem cell sub-colonies (150-200 cells), mechanically dissociate and immediately transfer to lysis buffer containing RNase inhibitors [24].

- Use oligo-dT coupled magnetic beads for mRNA capture. For degraded samples or those with suspected integrity issues, proceed directly to total RNA extraction with rRNA depletion.

- Include ERCC RNA spike-in controls at this stage to enable subsequent normalization and quality assessment.

cDNA Synthesis and Amplification

- Perform reverse transcription using template-switching oligonucleotides to ensure full-length cDNA representation [20].

- For ultra-low inputs (100pg-1ng), employ strategies like Uli-epic that incorporate in vitro transcription amplification: "The double-stranded cDNA template with the T7 promoter is then subjected to linear amplification via T7 RNA polymerase-mediated IVT" [20].

- Incorporate UMIs during cDNA synthesis to correct for PCR amplification biases in downstream analysis [23].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- For embryonic studies requiring detection of non-coding RNAs and strand information, use stranded library preparation protocols [21].

- Employ ribosomal depletion methods for samples where RNA integrity is compromised: "alternative methods that utilize random priming and include steps like ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion can enhance performance significantly with degraded samples because they do not depend on an intact polyA tail" [21].

- Sequence with sufficient depth (typically 20-100 million reads depending on application) to compensate for potential 3' bias and ensure detection of low-abundance transcripts.

Quality Control Checkpoints

Implement rigorous QC checkpoints throughout the experimental workflow:

- Post-Extraction: Assess RNA integrity using appropriate methods (RIN, DV200, or qPCR for low-input samples).

- Post-Amplification: Evaluate cDNA quality and size distribution using capillary electrophoresis.

- Post-Library Preparation: Quantify library concentration and validate insert size distribution.

- Post-Sequencing: Monitor alignment rates, ribosomal content, and 3' bias metrics.

In embryonic research, where sample material is inherently limited and often irreplaceable, maintaining RNA integrity is not merely a technical consideration but a fundamental determinant of experimental success. The challenges of RNA degradation in low-input contexts require specialized approaches from sample collection through data analysis. By implementing rigorous quality assessment, selecting appropriate library preparation strategies based on RNA quality, and utilizing specialized reagents designed for challenging samples, researchers can overcome these hurdles. The continued development of ultra-sensitive methods like Uli-epic that push the boundaries of input requirements while maintaining data quality promises to further advance our understanding of embryonic development through transcriptomic analysis. As these methodologies evolve, they will undoubtedly yield new insights into the molecular mechanisms governing early development while providing frameworks for addressing the universal challenges of working with precious, limited samples.

High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become an indispensable tool for profiling transcriptomes, offering unparalleled insights into gene expression dynamics. However, its application to rare and biologically precious samples, such as human embryos or limited clinical specimens, is fraught with significant technical challenges. In the context of a broader thesis on low-input RNA sequencing for embryo research, three core obstacles consistently emerge as critical bottlenecks: the stringent limitations on input RNA amount, the pervasive biases introduced during amplification, and the incomplete coverage of complex transcripts. These challenges are particularly acute in embryonic development studies, where sample availability is extremely limited and the accurate quantification of low-abundance and full-length transcripts is paramount for understanding lineage specification. This review dissects these obstacles, presents current methodological solutions, and provides a resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complexities of modern transcriptomics.

Core Obstacle 1: The Challenge of Low Input RNA Amount

The fundamental requirement for standard RNA-seq protocols is a microgram-scale quantity of high-quality input RNA. However, in fields such as embryonic research and single-cell analysis, the available material often falls into the nanogram or even picogram range, presenting a major hurdle.

- Sample Degradation and Quality: The integrity of starting RNA is a primary determinant of data quality. This is a particular concern for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, a common source of archival clinical samples. Nucleic acids from FFPE tissues are prone to fragmentation, cross-linking, and chemical modification, leading to poor sequencing libraries [25]. Even with frozen specimens, the success of RNA purification is challenged by the ubiquitous presence of RNases [25].

- Impact on Library Complexity and Quantification: Low amounts of starting RNA directly result in reduced library complexity, meaning the number of unique RNA molecules represented in the final sequencing library is low. This has a pronounced effect on the reliable quantification of transcripts, especially those expressed at low levels. As shown in Table 1, the bias associated with low input RNA has strong and harmful effects on downstream analysis, potentially leading to significant impacts on subsequent biological interpretation [25]. This is critically relevant for embryo research, where key regulatory genes, such as transcription factors and long non-coding RNAs, are often expressed at low levels [26].

Table 1: Impact of Input RNA on Sequencing and Proposed Mitigation Strategies

| Challenge | Impact on Data | Suggested Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Low-input RNA Quantity | Reduced library complexity; inaccurate quantification, especially for low-abundance transcripts [25]. | Use of high sample input for degraded samples; molecular barcoding (UMIs) to account for amplification bias [25] [27]. |

| FFPE-derived RNA | Fragmentation, cross-linking, and chemical modifications of nucleic acids [25]. | Use of non-cross-linking organic fixatives; random priming in reverse transcription instead of oligo-dT [25]. |

| General RNA Degradation | Loss of RNA integrity, particularly affecting 5'-end of transcripts [25]. | Minimize sample processing and freeze-thaw cycles; use of random primers for reverse transcription [25]. |

Core Obstacle 2: Amplification Bias and Library Preparation Artifacts

To generate sequencing-ready libraries from minute amounts of RNA, amplification is a necessary but problematic step. The enzymatic processes involved can stochastically and systematically distort the true representation of transcripts in the final data.

- PCR Amplification Bias: PCR is the most common amplification method but is known to amplify different molecules with unequal probabilities, leading to uneven coverage [25]. This bias is often sequence-dependent, with GC-rich or AT-rich regions being particularly problematic [25]. Furthermore, the number of PCR cycles is a key factor, with higher cycle numbers exacerbating these biases [25] [27].

- The Duplicate Reads Dilemma: A significant challenge in data analysis is handling reads that map to the same genomic location. These are often computationally removed as presumed PCR duplicates. However, a landmark study demonstrated that a large fraction of these so-called duplicates are actually "natural duplicates" stemming from the fragmentation of highly expressed transcripts or sampling bias, rather than from PCR amplification [27]. Computationally removing these reads does not improve accuracy or precision and can actually worsen the power and false discovery rate in differential expression analysis [27]. The use of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) is the definitive solution, as they allow for the bioinformatic correction of amplification bias by tagging each original RNA molecule before amplification [27].

- Fragmentation and Priming Bias: The method used to fragment RNA for sequencing can also introduce bias. For instance, RNase III fragmentation is not completely random and can reduce library complexity [25]. Similarly, the use of random hexamers in reverse transcription can introduce priming bias, where certain sequences are favored over others [25].

Figure 1: Workflow of amplification and fragmentation biases in low-input RNA-seq. PCR amplification and non-random fragmentation introduce distortions before sequencing. Computational duplicate removal is an imperfect solution, whereas UMI-based correction directly addresses amplification bias.

Table 2: Sources of Library Preparation Bias and Recommended Solutions

| Bias Source | Description | Suggestion for Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Amplification | Preferential amplification of sequences with neutral GC%; propagated through cycles [25]. | Reduce number of PCR cycles; use polymerases like Kapa HiFi; for extreme GC%, use additives like TMAC or betaine [25]. |

| Primer Bias (Random Hexamer) | Non-uniform reverse transcription initiation [25]. | Direct ligation of adapters to RNA fragments; bioinformatic read count reweighing schemes [25]. |

| Adapter Ligation | Substrate preferences of T4 RNA ligases [25]. | Use adapters with random nucleotides at the ligation extremities [25]. |

| Fragmentation Bias | Non-random breakage sites reduce complexity [27]. | Use chemical treatment (e.g., zinc) over enzymatic fragmentation; fragment cDNA post-synthesis [25]. |

Core Obstacle 3: Incomplete and Inaccurate Transcript Coverage

A primary advantage of RNA-seq is its ability to characterize the full complexity of the transcriptome, including alternative isoforms and non-coding RNAs. However, standard short-read sequencing often fails to deliver on this promise.

- The Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA) Problem: LncRNAs are generally expressed at approximately tenfold lower levels than messenger RNAs (mRNAs) [26]. At these low levels, RNA-seq quantification is unacceptably poor and not sufficient for reliable differential expression analysis. Even a substantial increase in sequencing depth does not resolve this issue for a large proportion of low-abundance transcripts, making it an inefficient and costly strategy [26]. Furthermore, accurate quantification depends on complete transcript model annotations, which are often lacking for lncRNAs [26].

- The Isoform Resolution Challenge: Accurate profiling of transcript isoforms is critical, as different isoforms from the same gene can have distinct functions. Short-read RNA-seq provides weak and non-uniform coverage across splice junctions, making the accurate reconstruction of full-length transcript isoforms inherently difficult [26] [28]. This is because short reads cannot span multiple distant exons, leading to "missing connectivity information" [26].

- The Rise of Long-Read Sequencing: Technologies like Oxford Nanopore and PacBio IsoSeq are revolutionizing transcriptome analysis by sequencing entire RNA molecules or full-length cDNAs. A systematic benchmark demonstrated that long-read RNA sequencing more robustly identifies major isoforms and facilitates the analysis of complex transcriptional events, such as alternative promoters, gene fusions, and RNA modifications [28]. As shown in Table 3, different long-read protocols offer trade-offs between input requirements, throughput, and the ability to detect base modifications, providing researchers with a toolkit to match their experimental needs.

Table 3: Comparison of Long-Read RNA-Sequencing Protocols for Transcript Coverage

| Protocol | Description | Key Advantages | Typical Input Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanopore Direct RNA-seq | Sequences native RNA directly. | Detects RNA modifications (e.g., m6A); no reverse transcription or amplification bias [28]. | High (µg scale) [28]. |

| Nanopore Direct cDNA | Sequences full-length cDNA without PCR. | Avoids PCR biases; provides full-length transcript information [28]. | Moderate [28]. |

| Nanopore PCR-cDNA | PCR-amplified cDNA sequencing. | Highest throughput; lowest input requirement [28]. | Low (compatible with single cells) [28]. |

| PacBio Iso-Seq | Circular consensus sequencing of cDNA. | Very high single-read accuracy; excellent for isoform discovery [28]. | Moderate to High [28]. |

Application in Embryo Research and Emerging Solutions

The challenges of low-input RNA-seq are acutely felt in human embryonic research, where material is exceedingly rare and subject to ethical constraints. Here, the push towards single-cell and low-cell-number transcriptomics is paramount.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has completely transformed our knowledge of human embryonic development by enabling the profiling of individual cells from rare embryo samples and stem cell-derived embryo-like models [1] [14]. However, these applications represent the ultimate low-input scenario, amplifying all the aforementioned obstacles. To authenticate embryo models, scRNA-seq data is compared to in vivo reference transcriptomes. Recent efforts have focused on creating integrated human embryo scRNA-seq reference datasets, spanning from the zygote to the gastrula stage, which serve as essential benchmarks for ensuring the fidelity of in vitro models [14].

Methodological innovations are key to progress. For example, a 2025 study on gut bacteria employed a low-input RNA-seq approach based on MATQ-seq to successfully profile sorted bacterial subpopulations, leading to the discovery of marker genes associated with cell morphology [29]. This demonstrates the power of ultra-sensitive methods for revealing heterogeneity in limited samples—a goal directly analogous to dissecting cellular diversity in embryonic development.

Figure 2: Method selection impacts transcriptome coverage in embryo research. The choice between standard short-read and advanced long-read sequencing directly influences the ability to resolve key transcriptional features like full-length isoforms and lncRNAs in precious embryo samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Navigating the technical landscape of low-input RNA-seq requires a carefully selected set of reagents and methodologies. The following toolkit outlines key solutions for addressing the core obstacles discussed in this review.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Input RNA-Seq Challenges

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Relevance to Core Obstacles |

|---|---|---|

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences that uniquely tag each original RNA molecule before amplification [27]. | Corrects for amplification bias and enables accurate digital counting of transcripts, overcoming Obstacle 2 [27]. |

| ERCC & SIRV Spike-Ins | Exogenous RNA controls with known sequences and concentrations spiked into the sample [27] [28]. | Assesses technical accuracy, sensitivity, and dynamic range of the entire workflow; crucial for benchmarking performance in low-input scenarios (Obstacles 1 & 3) [27] [28]. |

| Kapa HiFi Polymerase | A high-fidelity PCR enzyme designed for robust amplification of GC-rich templates with low error rates [25]. | Reduces PCR bias and improves library representation during the amplification step (Obstacle 2) [25]. |

| Poly(A) Selection / rRNA Depletion | Enriches for polyadenylated mRNA or depletes abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) [25]. | Increases sequencing efficiency for target transcripts. Note: oligo-dT selection can introduce 3'-bias and miss non-polyA RNAs (Obstacle 3) [25]. |

| Strand-Specific Library Kits | Preserves the original strand orientation of the RNA transcript during library construction [30]. | Enables accurate annotation of antisense transcription and overlapping genes, improving transcriptome coverage (Obstacle 3) [30]. |

| Methylated RNA Immunoprecipitation (MeRIP) | Antibody-based pulldown of RNA containing specific modifications, such as N6-methyladenosine (m6A) [28]. | When combined with sequencing (e.g., from direct RNA-seq data), allows functional study of the epitranscriptome (Obstacle 3) [28]. |

| Securinol A | Securinol A, MF:C13H17NO3, MW:235.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Taccaoside E | Taccaoside E, MF:C47H74O17, MW:911.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The journey to robust and biologically meaningful results from low-input RNA-seq, particularly in demanding fields like embryo research, requires a clear understanding of three interconnected obstacles: input amount, amplification bias, and transcript coverage. While the limitations posed by minimal starting material are fundamental, the field has responded with powerful solutions. These include the use of UMIs to control for amplification artifacts and the advent of long-read sequencing technologies to fully capture transcriptome complexity. As integrated reference datasets and standardized analysis pipelines continue to mature, the path forward involves the thoughtful selection and combination of these tools. By doing so, researchers can transform these core obstacles from roadblocks into stepping stones, unlocking deeper insights into the fundamental processes of life and disease.

Overcoming Limitations: Advanced Library Prep and Strategic Method Selection

In the field of transcriptomics, particularly when working with rare and precious samples such as human embryos, the quality and quantity of input RNA can profoundly impact research outcomes. A significant challenge faced by researchers is the high abundance of ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which constitutes approximately 80-90% of total RNA in most cells, leaving only a small fraction for the coding and non-coding transcripts of actual interest [31] [32]. To economize sequencing efforts and focus on biologically relevant RNA species, scientists must employ strategies to remove or circumvent this rRNA. The two predominant methods for achieving this are poly(A) selection and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion. However, these techniques differ dramatically in their performance characteristics, especially when applied to degraded samples or low-input scenarios common in embryo research [33] [21].

When embryos are donated for research, they often undergo freezing, thawing, and potentially suboptimal fixation methods such as formalin-fixed paraffin-embedding (FFPE), leading to RNA degradation, fragmentation, and cross-linking [25]. Under these conditions, the choice between poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion becomes critical, as it directly determines which RNA species will be captured, the accuracy of quantification, and ultimately, the biological conclusions that can be drawn. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these two approaches, with a specific focus on their application to degraded samples and low-input RNA sequencing in the context of embryo research.

Fundamental Mechanisms: How Poly(A) Selection and rRNA Depletion Work

Poly(A) Selection: A Positive Enrichment Strategy

Poly(A) selection operates as a positive enrichment strategy, specifically targeting RNA molecules that contain polyadenylated tails for capture and sequencing. The process relies on the biological fact that most mature eukaryotic messenger RNAs (mRNAs) undergo polyadenylation, acquiring a tail of approximately 200 adenine nucleotides at their 3' end [34].

The standard poly(A) selection protocol involves several key steps. First, total RNA is denatured by heating to 65-70°C in a high-salt binding buffer to remove secondary structures and make the poly(A) tails accessible for hybridization [34]. The denatured RNA is then incubated with magnetic beads coated with oligo(dT) strands, where the thymine bases base-pair specifically with the adenine bases in the poly(A) tail. This hybridization typically occurs over 30-60 minutes at room temperature [34]. After binding, the bead-mRNA complex is immobilized using a magnet, and the supernatant containing non-polyadenylated RNA (including rRNA, tRNA, and other non-coding RNAs) is discarded. The beads are subsequently washed several times with high-salt buffer to remove any residual contaminants. Finally, the purified poly(A)+ RNA is eluted by adding a warm elution buffer (60-80°C), which breaks the A-T bonds, releasing the mRNA into solution for downstream library preparation [34].

rRNA Depletion: A Negative Selection Approach

In contrast to poly(A) selection, rRNA depletion employs a negative selection strategy, specifically removing ribosomal RNA while leaving the remainder of the transcriptome intact. This approach can be achieved through several mechanisms, with hybridization/capture methods and RNase H-mediated degradation being the most common [32].

In the hybridization/capture method, single-stranded DNA probes complementary to rRNA sequences are hybridized to the total RNA. These probes contain affinity tags (typically biotin) that allow capture using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads [31]. The bead-probe-rRNA complexes are then removed magnetically, leaving the desired non-rRNA transcripts in the supernatant. Alternatively, the RNase H method uses DNA probes that hybridize to rRNA sequences, forming RNA-DNA hybrids. The enzyme RNase H then specifically cleaves the RNA within these hybrids, degrading the rRNA [31] [32]. The remaining RNA, which includes both coding and non-coding RNA species, is then recovered for library preparation.

A critical advancement in rRNA depletion has been the development of species-specific probe sets. Early depletion methods optimized for mammalian rRNA performed poorly on non-mammalian samples, such as C. elegans, retaining high levels of rRNA in final libraries [35]. Custom-designed probes matching the target organism's rRNA sequences significantly improve depletion efficiency. For example, one study used a custom kit of 200 probes designed specifically for C. elegans rRNA, which resulted in improved detection of noncoding RNAs, reduced noise in lowly expressed genes, and more accurate counting of long genes compared to polyA selection methods [35].

Technical Comparison: Performance Metrics for Degraded Samples

Quantitative Performance Differences

The choice between poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion has profound implications for sequencing efficiency, cost, and data quality, particularly with degraded samples. The table below summarizes key performance differences based on empirical comparisons:

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between Poly(A) Selection and rRNA Depletion

| Performance Metric | Poly(A) Selection | rRNA Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| Usable Exonic Reads (Blood) | 71% | 22% |

| Usable Exonic Reads (Colon Tissue) | 70% | 46% |

| Extra Reads Needed for Same Exonic Coverage | — | +220% (blood), +50% (colon) |

| Transcript Types Captured | Mature, coding mRNAs | Coding + noncoding (lncRNAs, snoRNAs, pre-mRNA) |

| 3′–5′ Coverage Uniformity | Pronounced 3′ bias | More uniform coverage |

| Performance with Low-Quality/FFPE Samples | Reduced efficiency | Robust—even with degraded RNA |

| Sequencing Cost per Usable Read | Lower (fewer total reads needed) | Higher (due to extra sequencing depth) |

| Bioinformatics Complexity | Lower (mostly exonic reads) | Higher (includes intronic/noncoding reads) |

As evidenced by the data, poly(A) selection provides a much higher fraction of usable exonic reads, making it significantly more cost-efficient for standard mRNA sequencing projects [36]. However, this advantage disappears when working with degraded samples, as the method depends on intact poly(A) tails that are often lost in fragmented RNA.

Both methods introduce specific biases that can affect data interpretation, though the nature of these biases differs substantially. Poly(A) selection exhibits a pronounced 3' bias because the oligo(dT) primers bind at the 3' end of transcripts [36]. In degraded samples, this bias is exacerbated because RNA fragmentation creates molecules with missing 5' regions, leading to even stronger 3' enrichment and potentially misleading quantification [32] [25].

rRNA depletion, while providing more uniform transcript coverage, typically yields a lower fraction of exonic reads because it captures both exonic and intronic sequences [36]. This necessitates deeper sequencing to achieve the same exonic coverage, increasing costs. Additionally, rRNA depletion methods can show variability in efficiency, with potential for residual rRNA contamination (often 5-30% of reads) if probes are not perfectly matched to the target species or if the protocol is not rigorously optimized [35] [21].

Experimental Protocols for Low-Input and Degraded Samples

Low-Input RNA-seq Library Construction for Embryo Research

Research on human embryos presents unique challenges, including extremely limited biological material and often compromised RNA quality. A 2019 study established a proof-of-principle protocol for RNA-seq from embryo biopsies, which can be adapted for degraded samples [33]. The workflow begins with embryo collection and trophectoderm (TE) biopsy using standard clinical techniques. Both the TE biopsy and the remaining whole embryo are harvested separately for RNA extraction. RNA is extracted using phase separation methods (e.g., TRIzol) followed by clean-up and concentration using silica-based columns. DNase I treatment is recommended to remove genomic DNA contamination. For low-input scenarios, the Smart-seq2 protocol is employed for library preparation, as it has demonstrated efficacy with minimal RNA input [33]. The resulting libraries are then sequenced to an appropriate depth (approximately 44 million reads in the referenced study), followed by bioinformatic analysis including principle component analysis to assess sample relationships and quality control metrics.

Ribodepletion Protocol Optimized for Low-Input Samples

For researchers specifically choosing ribodepletion for challenging samples, the following protocol, adapted from a C. elegans neuron study, provides a robust framework [35]:

Sample Collection and RNA Extraction: Collect FACS-sorted cells directly into TRIzol LS. Perform chloroform extraction using Phase Lock Gel-Heavy tubes. Clean and concentrate RNA using the RNA Clean and Concentrator Kit, including an on-column DNase I treatment step. Elute RNA in a minimal volume (e.g., 15 µL).

Probe-Based rRNA Depletion: Use a commercially available ribodepletion kit such as the SoLo Ovation system (Tecan Genomics). For non-model organisms or specific applications, consider custom-designed rRNA probes. For C. elegans, researchers used a custom set of 200 probes designed to match C. elegans rRNA gene sequences, which significantly improved depletion efficiency compared to generic kits [35].

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Proceed with library construction using the depleted RNA. The referenced study used SoLo Ovation (Tecan Genomics) for ribodepletion-based libraries, compared against SMARTSeq V4 (Takara) for polyA-selected libraries. Sequence the resulting libraries at high depth to ensure adequate coverage of non-ribosomal transcripts.

Decision Framework and Recommendations for Embryo Research

Strategic Selection Guide

Choosing between poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion requires careful consideration of research goals, sample quality, and resource constraints. The following decision framework provides guidance:

Table 2: Decision Matrix for Method Selection

| Sample or Goal | Poly(A) Selection | rRNA Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality RNA (RIN ≥8) | Ideal—efficient capture of mature mRNA | Works, but yields more non-coding reads |

| Degraded RNA / FFPE Samples (RIN <7) | Not recommended—strong 3′ bias, low yield | Recommended—handles fragmented RNA |

| Protein-Coding mRNA Quantification | Best choice—high exonic read fraction | Less efficient—requires deeper sequencing |

| Non-Coding RNA Profiling | Misses non-polyadenylated RNAs | Captures both polyA and non-polyA transcripts |

| Low-Input Embryo Samples | Works well with optimized kits | Also effective, but verify input requirements |

For embryo research specifically, where sample quality is often compromised and the biological material is extremely limited, rRNA depletion generally offers significant advantages. A study on human embryo competence demonstrated that RNA-seq could be successfully performed from trophectoderm biopsies, which inherently provide minimal RNA input [33]. In such cases, rRNA depletion's ability to work with degraded RNA and capture a broader spectrum of transcript types provides a more comprehensive view of the embryonic transcriptome.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Input RNA-seq

| Reagent/Method | Function | Considerations for Embryo Research |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Captures polyadenylated RNA through complementary base pairing | Efficient for intact mRNA but fails with degraded samples; suitable for high-quality embryo samples only |

| Species-Specific rRNA Depletion Probes | Removes ribosomal RNA via hybridization to complementary sequences | Custom design recommended for optimal efficiency; essential for non-model organisms |

| Smart-seq2 Protocol | Library preparation method for ultra-low-input RNA | Ideal for embryo biopsies; provides full-length transcript information |

| RNA Clean & Concentrator Kits | Purifies and concentrates low-abundance RNA | Critical step after RNA extraction from limited embryo material |

| Phase Lock Gel Tubes | Improves RNA recovery during phase separation | Maximizes yield during TRIzol-based extraction from precious samples |

| Tutin,6-acetate | Tutin,6-acetate|High-Purity Research Neurotoxin | Tutin,6-acetate is a neuroactive research compound. It is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Alstolenine | Alstolenine|RUO | Alstolenine is a natural alkaloid for anti-psoriatic research. This product is for Research Use Only, not for human or veterinary diagnostics. |

In the challenging realm of embryo research, where sample degradation and limited input are frequently unavoidable constraints, the selection between poly(A) enrichment and rRNA depletion is not merely a technical choice but a strategic one that fundamentally shapes experimental outcomes. While poly(A) selection offers cost efficiency and simplicity for intact, high-quality RNA samples, rRNA depletion emerges as the more robust and comprehensive approach for degraded samples typical of embryo research contexts. The ability of rRNA depletion to capture both coding and non-coding RNAs, coupled with its tolerance for RNA fragmentation, provides researchers with a more complete picture of the transcriptional landscape in precious embryonic samples. As single-cell and low-input RNA sequencing technologies continue to advance, the development of even more efficient depletion methods and optimized protocols will further empower embryo researchers to extract maximal biological insight from minimal material, ultimately enhancing our understanding of early human development and improving clinical outcomes in reproductive medicine.

Transcriptomic analysis of embryonic material represents one of the most biologically informative yet technically challenging applications in modern genomics. Embryo research is fundamentally constrained by extremely limited starting RNA quantities, often falling below 100 ng total RNA, creating a critical tension between protocol selection and data integrity. Within this context, the choice between stranded and non-stranded RNA sequencing protocols moves from a mere technical consideration to a pivotal decision that directly impacts data accuracy, biological interpretation, and resource allocation. Stranded RNA-Seq, which preserves the original orientation of transcripts, provides superior transcriptional resolution but traditionally requires more complex workflows. Non-stranded protocols offer simplicity and cost efficiency but sacrifice critical strand information. This technical guide examines this balance through the specific lens of low-input challenges faced by embryo researchers, providing a structured framework for protocol selection based on empirical data and theoretical principles, with particular emphasis on how to maximize information content when sample material is severely limited.

Fundamental Technical Differences Between Stranded and Non-Stranded RNA-Seq

Library Preparation Mechanisms

The fundamental distinction between stranded and non-stranded RNA-Seq protocols lies in the molecular biology of cDNA library preparation and how strand-of-origin information is either preserved or lost.

Non-stranded protocols follow a relatively straightforward workflow where RNA is fragmented, followed by cDNA synthesis using random primers for both first and second strand synthesis. Critically, the resulting sequencing libraries contain reads from both original transcript strands without distinction. When two antisense transcripts from the same genomic locus are sequenced, their sequencing products become identical, irrevocably losing directional information [37]. This information loss occurs during double-stranded cDNA synthesis where adaptors are ligated without tracking original strand orientation.

Stranded protocols incorporate specific modifications to preserve strand information. The most prevalent method, the dUTP second-strand marking technique, uses dUTPs instead of dTTPs during second-strand cDNA synthesis [38] [39]. Following adapter ligation, the second strand (containing uracils) is enzymatically degraded using uracil-N-glycosylase before PCR amplification. This ensures only the first strand is amplified, preserving the original transcript orientation throughout sequencing [39]. Alternative approaches include direct RNA ligation methods, where adapters are ligated directly to RNA molecules before cDNA synthesis, and template-switching technologies that use specialized primers and enzymes to preserve directionality [40].

Impact on Data Interpretation and Analytical Resolution

The preservation of strand information in stranded protocols fundamentally enhances transcriptional resolution in ways particularly relevant to complex embryonic transcriptomes:

Resolution of Overlapping Genes: Genomic loci where both DNA strands encode distinct genes with overlapping regions are common, affecting approximately 19% (∼11,000) of annotated genes in Gencode Release 19 [39]. Stranded RNA-Seq unambiguously assigns reads to the correct transcriptional unit, whereas non-stranded protocols attribute reads to both genes, artificially inflating expression estimates for both loci and complicating differential expression analysis.

Antisense Transcription Profiling: Embryonic development involves intricate regulatory networks where antisense non-coding RNAs frequently modulate sense transcript activity through various mechanisms including transcriptional interference, RNA duplex formation affecting stability, and chromatin modification [41]. Stranded protocols exclusively detect these antisense regulators, while non-stranded protocols simply aggregate them with sense transcription.

Accurate Transcript Assembly and Annotation: For de novo transcriptome assembly without a reference genome—common in non-model organism embryology—stranded information is indispensable for correctly determining exon-intron structures and distinguishing overlapping transcripts on opposite strands [42].

The following diagram illustrates the core methodological differences that create these analytical distinctions:

Diagram: Core methodological differences between non-stranded and stranded RNA-Seq protocols. The dUTP method preserves strand information by selectively degrading the second cDNA strand.

Quantitative Comparison: Strandedness Significantly Enhances Measurement Accuracy

Empirical comparisons between stranded and non-stranded protocols demonstrate substantial differences in data quality and analytical accuracy, with particular implications for embryonic transcriptomes characterized by complex regulatory architecture.

Resolution of Ambiguous Mapping

The most quantitatively demonstrable advantage of stranded protocols is the resolution of ambiguous read assignments. In comparative analyses of whole blood RNA samples:

- Non-stranded RNA-Seq exhibited approximately 6.1% ambiguous reads that could not be uniquely assigned to specific genes [39].

- Stranded RNA-Seq reduced this ambiguity to approximately 2.94%—a relative reduction of 3.1% that directly corresponds to reads originating from overlapping genes on opposite strands [38] [39].

- This reduction in ambiguity has direct consequences for expression quantification, with studies identifying 1,751 genes as differentially expressed when comparing the same samples processed with stranded versus non-stranded protocols, with antisense genes and pseudogenes significantly enriched among these differences [39].

Theoretical and Empirical Overlap Considerations

Theoretical analysis of genome annotation confirms these empirical observations. In Gencode Release 19, approximately 3% of nucleotide bases feature genes overlapping on the same strand, while 3.6% involve genes overlapping from opposite strands [39]. These proportions align closely with the 3.1% reduction in ambiguous reads observed empirically, confirming that stranded protocols specifically resolve the opposite-strand overlap component.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Stranded RNA-Seq on Read Assignment Accuracy

| Metric | Non-Stranded Protocol | Stranded Protocol | Relative Change | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambiguous Reads | 6.1% [39] | 2.94% [39] | -3.1% [39] | Resolution of opposite-strand gene overlaps |

| Opposite-Strand Overlaps | Not resolved | Completely resolved | N/A | Enables accurate quantification of ~11,000 overlapping genes [39] |

| Differential Expression Calls | Inflated false positives/negatives | Accurate quantification | ~10% false positives, ~6% false negatives without strand info [43] | Correct identification of regulatory relationships |

| Antisense Transcription | Not detectable | Precisely quantifiable | N/A | Reveals regulatory antisense RNAs [41] |

Protocol Selection Framework for Low-Input Embryo Research

Decision Matrix: Balancing Information Content and Practical Constraints

For embryo researchers facing material limitations, protocol selection requires balancing multiple competing factors. The following decision matrix provides a structured framework for this selection process:

Table 2: Protocol Selection Guide for Embryo Research Applications

| Research Objective | Recommended Protocol | Key Advantages | Input Requirements | Embryonic Development Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptome Annotation & Novel Transcript Discovery | Stranded | Correct strand assignment essential for de novo assembly [42] [37] | Higher (≥100 ng) | Mapping developmental stage-specific isoforms, novel non-coding RNAs |

| Antisense & Non-Coding RNA Regulation | Stranded | Unambiguous identification of antisense transcripts [41] | Moderate (50-100 ng) | Epigenetic regulation, imprinting control, X-chromosome inactivation |

| Differential Expression (Well-Annotated Organisms) | Either (Context-dependent) | Sufficient for overall expression trends [37] | Flexible (10-500 ng) [40] | Expression trajectory analysis across developmental stages |

| High-Throughput Screening | Non-stranded | Cost-effective for large sample numbers [42] [37] | Lower (10-50 ng) [40] | Chemical/genetic screening in mutant embryos |

| Degraded/FFPE Embryonic Samples | Non-stranded or 3' mRNA-Seq | Simplified workflow, less technical variation [44] | Most flexible (1-100 ng) | Archival clinical embryo specimens |

Low-Input Protocol Performance and Modern Kit Options

Recent systematic evaluations of strand-specific RNA-seq library preparation methods for low input samples provide critical guidance for embryo research. Comprehensive testing of commercial technologies demonstrates that:

- Swift RNA libraries maintain strand specificity at inputs as low as 10 ng total RNA while showing high agreement (Pearson correlation >0.97) with standard Illumina TruSeq stranded mRNA references [40].

- Swift Rapid RNA libraries provide an even faster workflow (3.5 hours) while maintaining strand specificity at 50 ng inputs, offering a valuable balance between speed and information content for precious embryonic samples [40].

- All three stranded methods (TruSeq, Swift, Swift Rapid) demonstrated >90% of reads mapping to the correct strand, even at lowest input levels, confirming that strand specificity can be maintained despite limited starting material [40].

For extremely scarce embryonic material where even 10 ng is unattainable, 3' mRNA-Seq methods (e.g., QuantSeq) provide a viable alternative, though they sacrifice comprehensive transcript coverage for extreme sensitivity and cost-effectiveness, focusing sequencing on 3' transcript ends [44].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies