Optimizing Germline Transmission in Zebrafish CRISPR Mutants: A Guide for Functional Genomics and Disease Modeling

This article provides a comprehensive overview of strategies for achieving efficient germline transmission of CRISPR-Cas9-induced mutations in zebrafish, a critical vertebrate model for functional genomics and drug discovery.

Optimizing Germline Transmission in Zebrafish CRISPR Mutants: A Guide for Functional Genomics and Disease Modeling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of strategies for achieving efficient germline transmission of CRISPR-Cas9-induced mutations in zebrafish, a critical vertebrate model for functional genomics and drug discovery. We explore the foundational principles of CRISPR in zebrafish, detail high-throughput methodologies for mutagenesis and screening, and address common challenges with advanced optimization and troubleshooting techniques. Furthermore, we compare the efficacy of different genome-editing tools and discuss the validation of mutant lines for modeling human diseases, offering a complete resource for researchers and drug development professionals to accelerate their genetic studies.

Understanding Germline Transmission: Core Concepts of Zebrafish CRISPR

The Critical Role of Germline Transmission in Functional Genomics

In the field of vertebrate functional genomics, the ability to create stable, heritable genetic lines is paramount for rigorous biological investigation. Germline transmission—the process by which induced genetic modifications are passed from founder animals to their offspring—transforms transient, somatic edits into stable, research-grade animal models. This process is the critical bridge between initial gene perturbation and the establishment of reproducible genetic lines for functional analysis. In zebrafish (Danio rerio), the combination of CRISPR-based genome editing and germline transmission has revolutionized our capacity to model human diseases and perform systematic genetic screens. The zebrafish model offers unique advantages for high-throughput genetics, including external fertilization, high fecundity, and rapid embryonic development, making it particularly suited for large-scale functional genomics efforts [1] [2]. This technical guide examines the methodologies, challenges, and applications of germline transmission in zebrafish CRISPR research, providing a comprehensive framework for researchers pursuing functional genomic studies.

Germline Transmission as a Validation Gateway in High-Throughput Mutagenesis

The scalability of CRISPR-Cas9 technology in zebrafish has enabled mutagenesis rates previously unimaginable in vertebrate model organisms. Early demonstrations of this capability showed that CRISPR-based mutagenesis could achieve a 99% success rate for generating mutations across 162 targeted loci, with an average germline transmission rate of 28% from founder fish [2]. This efficiency is approximately sixfold higher than previous technologies such as TALENs and ZFNs, positioning CRISPR as the preferred technology for large-scale functional genomics [2].

The standard workflow for establishing heritable mutations begins with microinjection of CRISPR components (Cas9 nuclease and gene-specific guide RNA) into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos. These injected founders (F0 generation) develop as genetic mosaics, with mutations present in only a subset of cells. To identify founders carrying mutations in their germ cells, these F0 fish are outcrossed to wild-type partners, and their F1 progeny are screened for the presence of induced mutations [3] [2]. The successful identification of mutant alleles in the F1 generation confirms germline transmission, enabling the establishment of stable lines for phenotypic analysis.

Table 1: Key Stages in a High-Throughput Zebrafish Mutagenesis Pipeline

| Stage | Timeline | Key Activities | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Selection & sgRNA Synthesis | 3 days | Bioinformatics design; cloning-free sgRNA synthesis via overlapping oligonucleotides | Target-specific, functional sgRNAs |

| Microinjection & Mosaic Founder Generation | 1 day | Co-injection of Cas9 mRNA/protein + sgRNA into one-cell embryos | Genetically mosaic F0 generation |

| Germline Transmission Screening | 3 months | Outcross F0 founders; screen F1 embryos via fluorescence PCR or sequencing | Identification of germline-transmitting founders |

| Stable Line Establishment | 6 months | Inbreeding F1 carriers to generate F2 homozygous mutants | Stable, genetically defined mutant lines |

A significant innovation in increasing the throughput of phenotypic screening is the demonstration that F1 phenotyping can be performed by inbreeding two injected founder fish, effectively reducing the timeline for phenotypic analysis by an entire generation (approximately 3-4 months) [2]. This approach requires careful experimental design and validation but offers substantial efficiency gains for large-scale functional genomics projects.

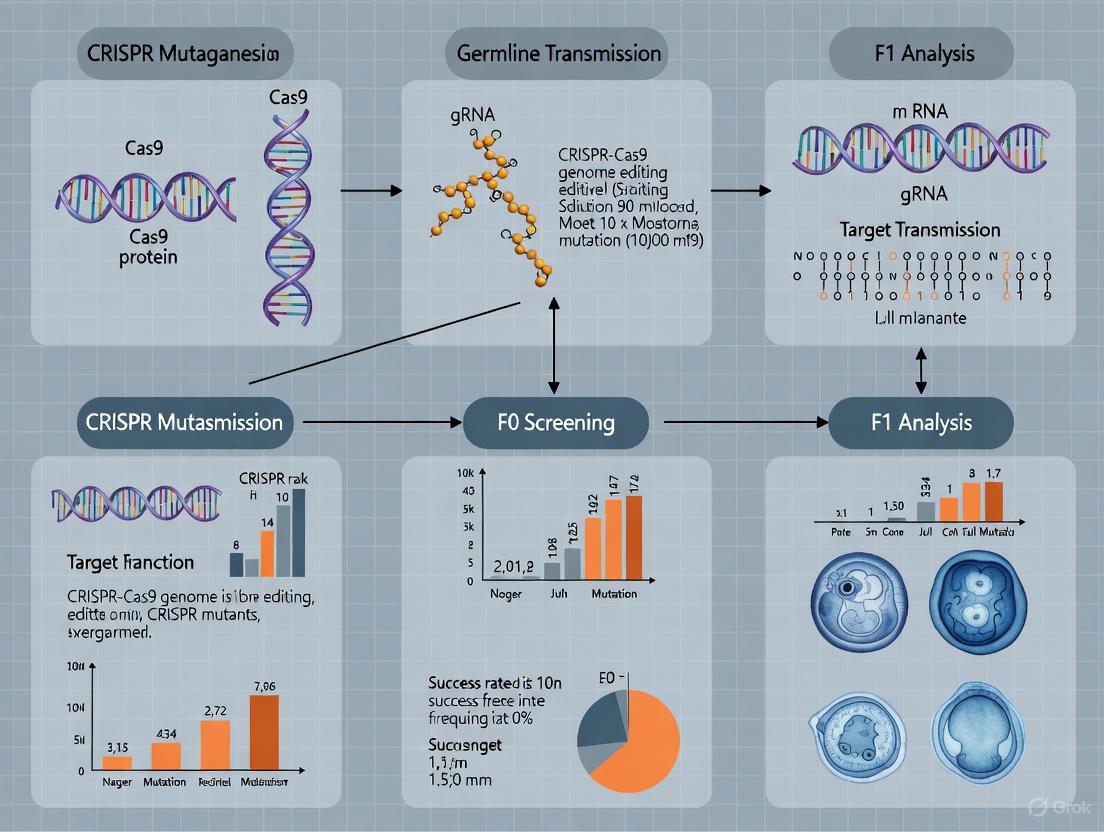

Figure 1: Workflow for establishing zebrafish mutant lines through germline transmission. The process begins with CRISPR design and culminates in stable line establishment, with germline transmission confirmation as the critical validation step.

Quantitative Benchmarks and Efficiency Optimization

Establishing Baseline Efficiency Metrics

Understanding expected efficiency rates is crucial for experimental planning in functional genomics. Large-scale zebrafish CRISPR studies have established key quantitative benchmarks for germline transmission. In one comprehensive study targeting 162 loci across 83 genes, researchers documented a 99% success rate in generating mutations, with an average germline transmission rate of 28% from founder fish [2]. This transmission rate represents the percentage of F0 founders that successfully pass induced mutations to their F1 progeny. The study further verified 678 unique alleles from 58 genes through high-throughput sequencing, demonstrating the rich genetic diversity that can be achieved through CRISPR mutagenesis [2].

Efficiency varies substantially based on the specific sgRNA design and target locus. While many published "rules" for efficient sgRNA design show limited predictive value for germline transmission rates in zebrafish, the presence of a GG or GA dinucleotide genomic match at the 5′ end of the sgRNA does correlate with improved efficiency [2]. This finding highlights the continued importance of empirical testing over purely computational predictions.

Advanced Strategies for Enhancing Germline Transmission

Knock-in and Precision Editing

While standard CRISPR knockout approaches rely on non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), more precise homology-directed repair (HDR) enables knock-in of specific point mutations—a critical capability for modeling human disease variants. However, HDR efficiency is typically much lower than NHEJ, creating significant challenges for obtaining germline transmission [4] [5].

Systematic optimization has identified several key factors that improve HDR-mediated germline transmission:

- Cas9 delivery method: Using Cas9 protein instead of mRNA significantly increases editing efficiency, with one study showing a rise from 1.04% to 2.83% somatic editing efficiency at one locus [5]

- Repair template design: Non-target asymmetric PAM-distal (NAD) single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) templates outperform other conformations [5]

- Small molecule enhancement: Inhibiting NHEJ with SCR7 (a DNA ligase IV inhibitor) and stimulating HDR with RS-1 (a Rad51 stimulator) can significantly improve HDR efficiency—with SCR7 increasing point mutation rates from 16% to 58% in one study [4]

Table 2: Efficiency Benchmarks for Different CRISPR Editing Approaches in Zebrafish

| Editing Approach | Typical Somatic Efficiency | Germline Transmission Rate | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ-Mediated Knockout | Up to 80% indel formation [6] | ~28% average [2] | Gene function loss studies, reverse genetics |

| HDR-Mediated Point Mutation | 1-5% without optimization [5] | 2-25% with optimization [4] | Disease-associated point mutation modeling |

| Base Editing | 9-90% depending on system [7] | Comparable to knockout approaches [7] | Precise nucleotide conversion without DSBs |

Early Genotyping and Selection

A powerful strategy for improving germline transmission outcomes involves early genotyping of mosaic founders to identify those with the highest editing rates. The Zebrafish Embryo Genotyper (ZEG) device enables minimally invasive DNA extraction from 72 hours post-fertilization embryos, allowing researchers to selectively raise only those embryos with the highest mutation rates [5]. This approach has demonstrated a 17-fold increase in somatic editing efficiency for some alleles, particularly benefiting those with lower inherent editing efficiencies [5]. By reducing the number of animals that need to be raised to adulthood and focusing resources on the most promising founders, this method addresses both efficiency and ethical concerns in zebrafish functional genomics.

Technical Protocols and Methodologies

High-Throughput Mutagenesis Workflow

A complete high-throughput functional genomics workflow encompasses the following key methodologies [3]:

Target Selection and sgRNA Design: Identify target sites with appropriate specificity considerations. Computational tools like CRISPRscan can assist, though empirical validation remains essential [6]

Cloning-Free sgRNA Synthesis: Using two partially overlapping oligonucleotides (one target-specific, one generic) that form a double-stranded template through annealing and extension via Taq DNA polymerase, followed by in vitro transcription directly from the linear DNA template [2]

Microinjection: Co-inject Cas9 mRNA or protein with synthesized sgRNA into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos. Protein delivery often yields higher efficiency [5]

Germline Transmission Screening: Outcross adult F0 founders to wild-types and screen seven F1 embryos per founder using fluorescence PCR or sequencing-based methods to identify germline-transmitting events [2]

Mutation Verification: Confirm exact lesions in transmitting founders by Sanger or next-generation sequencing, followed by establishment of stable lines

Mutation Detection and Verification

Accurate detection of induced mutations is crucial for identifying germline transmission events. Several methods have been systematically compared for their reliability:

- NGS-based approaches: Provide the most precise quantification of editing efficiency but at higher cost [6]

- ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits): Analysis of Sanger sequencing data shows strong correlation (r = 0.90) with NGS data and offers a cost-effective alternative [6]

- TIDE (Tracking of Indels by Decomposition): Another Sanger-based tool with good correlation to NGS (r = 0.59) but greater tendency to underestimate efficiency [6]

- Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE): The most affordable approach but with weaker correlation to NGS data (r = 0.37), making it less reliable for quantitative assessments [6]

For challenging HDR-mediated point mutations, specific strategies improve identification:

- Incorporate blocking mutations in the repair template to prevent re-cleavage by Cas9 and enable design of mutant-specific primers [4]

- Implement nested PCR with external primers outside the donor DNA region to avoid amplification of residual donor template [4]

- Use mutant-specific primers in quantitative PCR reactions to selectively amplify HDR-induced mutations while excluding indels and wild-type sequences [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Zebrafish CRISPR Germline Transmission Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | Cas9 mRNA, Cas9 protein, ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes | Induces double-strand breaks at target loci | Protein delivery often increases efficiency and reduces mosaicism [5] |

| Guide RNA Design | CRISPRscan, CHOPCHOP, ZiFiT Targeter | Bioinformatics tools for target selection | Most "rules" show limited predictive value except GG/GA at 5' end [2] |

| Repair Templates | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs), plasmid donors | Homology-directed repair for precise editing | Non-target asymmetric PAM-distal (NAD) design outperforms other conformations [5] |

| Efficiency Enhancers | SCR7 (NHEJ inhibitor), RS-1 (HDR stimulator) | Modulate DNA repair pathways to favor desired outcome | SCR7 increased HDR efficiency from 16% to 58% in one study [4] |

| Screening Tools | ZEG device, fluorescence PCR, ICE analysis, NGS platforms | Identify and quantify germline transmission events | Early genotyping with ZEG enabled 17-fold efficiency increase [5] |

| Ampelopsin F | Ampelopsin F, MF:C28H22O6, MW:454.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Panaxcerol B | Panaxcerol B, MF:C27H46O9, MW:514.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Advanced Editing Platforms

Beyond standard CRISPR-Cas9 systems, several innovative technologies show significant promise for enhancing germline transmission studies:

Base editing technologies represent a particularly exciting advancement, enabling direct chemical conversion of one DNA base to another without inducing double-strand breaks. Both cytosine base editors (CBEs) and adenine base editors (ABEs) have been successfully implemented in zebrafish, achieving editing efficiencies ranging from 9.25% to 90% depending on the specific system and target locus [7]. The development of "near PAM-less" editors such as CBE4max-SpRY further expands the targeting scope, potentially increasing the range of genes accessible to germline modification [7].

Prime editing offers another promising approach, combining a Cas9 nickase with a reverse transcriptase to enable precise edits without double-strand breaks. While not yet as widely adopted in zebrafish as base editors, this technology addresses some of the limitations of both traditional HDR and base editing approaches [1].

Induced Germ Cell Technologies

A particularly innovative approach addresses the fundamental challenge of limited primordial germ cells (PGCs) in early embryos. Researchers have identified a combination of nine germplasm factors (9GMs: vasa, dazl, piwil1, dnd1, nanos3, tdrd6, tdrd7a, dazap2, and buc) that can efficiently convert blastomeres into induced PGCs (iPGCs) [8]. These iPGCs demonstrate functional capability, migrating to genital ridges and developing into functional gametes when transplanted into germ cell-deficient hosts [8].

This technology enables a novel workflow combining genome editing with iPGC transplantation:

- Perform gene editing in donor embryos

- Induce PGC formation using germplasm factors

- Transplant iPGCs into germ cell-deficient hosts

- Obtain functional gametes from the host animals

This approach "resolves the contradiction between high knock-in efficiency and early lethality" that often plagues studies of essential genes, as edited embryos that would otherwise die before reproductive maturity can still contribute to the germline through iPGC transplantation [8].

Figure 2: Innovative germline transmission workflow using induced primordial germ cells (iPGCs). This approach bypasses embryonic lethality and enhances transmission efficiency for challenging genetic edits.

Germline transmission represents the critical juncture in functional genomics where targeted genetic modifications transition from transient experimental observations to stable, research-grade biological tools. The continuous refinement of CRISPR-based technologies in zebrafish—from high-throughput mutagenesis pipelines to precision base editing and induced germ cell formation—has dramatically expanded our capacity to model genetic diseases and perform systematic functional genomic studies. As these technologies mature, they promise to further accelerate the pace of discovery in vertebrate functional genomics, enabling increasingly sophisticated investigations into gene function, genetic interactions, and the molecular basis of human disease. The ongoing optimization of germline transmission methodologies ensures that zebrafish will remain at the forefront of these efforts, providing an essential platform for connecting genetic variation to biological function.

Zebrafish as a Premier Vertebrate Model for CRISPR Screening

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) have emerged as a premier vertebrate model for high-throughput CRISPR screening, occupying a unique experimental niche between in vitro cell culture systems and low-throughput mammalian models. This position is powered by specific biological advantages: approximately 70% of human genes have at least one zebrafish ortholog, and an even higher percentage (approximately 84%) of genes known to be associated with human diseases have functional counterparts in zebrafish [9]. The external fertilization, optical transparency of embryos, and rapid development—with major organ systems formed within 24–48 hours post-fertilization—enable direct observation of phenotypic consequences in a whole vertebrate organism [9]. Furthermore, their small size, high fecundity, and cost-effectiveness facilitate large-scale genetic studies that would be prohibitively expensive or ethically challenging in mammalian systems [9] [10]. The combination of these inherent advantages with CRISPR-Cas9 technologies has revolutionized approaches to functional genomics, disease modeling, and drug discovery.

Technical Foundations: CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow in Zebrafish

The implementation of CRISPR-based screening in zebrafish follows a streamlined workflow designed for scalability and efficiency, from sgRNA design to phenotypic analysis.

sgRNA Design and Validation

The process begins with the careful design of guide RNAs (sgRNAs). While multiple computational tools exist for predicting sgRNA efficiency (e.g., CRISPRScan), studies have revealed large discrepancies between different prediction methods, underscoring the importance of empirical validation [6]. Target sites are typically selected to minimize potential off-target effects by searching for sequences with low homology to other genomic regions. The most common target site consensus for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 is N21GG, though designs are often adjusted to accommodate promoter requirements for in vitro transcription, such as GGN19GG [11]. Tools are available to batch-design sgRNAs and corresponding PCR primers for amplicon sequencing, enabling high-throughput pipeline development.

Delivery and Screening Strategies

CRISPR components are commonly introduced into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos via microinjection. This can be achieved using Cas9 protein mRNA in combination with sgRNAs, or as pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes [6] [10]. A significant innovation in the field is the use of mosaic G0 mutant screens, where injected individuals (G0) are phenotypically screened without raising stable mutant lines, dramatically increasing throughput [6] [12]. To accurately identify germline-transmitting mutations, researchers increasingly employ amplicon sequencing of sperm samples from G0 founder males. This approach simultaneously provides information on transmission rates and specific indel sequences, facilitates cryopreservation of sperm archives, and enables the design of efficient genotyping assays for identifying F1 carriers [11].

Table 1: Key Phases of a Zebrafish CRISPR Screening Workflow

| Phase | Key Activities | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Design & Construction | sgRNA design, oligo synthesis, in vitro transcription of sgRNAs/Cas9 mRNA | Validated sgRNAs with high predicted and empirical efficiency |

| Delivery & Mutation Generation | Microinjection into one-cell embryos, raising injected embryos | Mosaic G0 founder fish |

| Germline Screening | Sperm collection, amplicon sequencing of target loci, cryopreservation | Identification of founders transmitting desired mutations, archived sperm |

| Phenotypic Analysis | Raising F1 families, genotyping, morphological/behavioral/molecular phenotyping | Functional association between genetic perturbation and phenotype |

Quantitative Analysis of Editing Efficiency and Confounders

Understanding the efficiency and precision of CRISPR editing is crucial for experimental design and data interpretation. A systematic evaluation of 50 different gRNAs targeting 14 genes in zebrafish revealed that experimental in vivo editing efficiencies in mosaic G0 embryos often diverged significantly from computational predictions [6]. The same study provided reassuring evidence that off-target mutation rates in vivo are generally low, with the majority of tested loci showing frequencies below 1% [6].

However, researchers must be aware of potential confounders. RNA-seq analysis of "mock" injected control larvae (injected with Cas9 enzyme or mRNA without gRNA) revealed hundreds of differentially expressed genes compared to uninjected siblings [6]. These genes were associated with processes such as "response to wounding" and "cytoskeleton organization," highlighting a potentially lasting effect from the microinjection process itself that could confound phenotypic analysis if not properly controlled [6].

Table 2: Efficiency of Precision Genome Editing Technologies in Zebrafish

| Editing Technology | Editing Type | Key Features | Reported Efficiency | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 (NHEJ) | Indels (knockout) | Creates double-strand breaks, repaired by NHEJ | High efficiency, germline transmission up to 28% | [1] [11] |

| HDR-Mediated Knock-in | Point mutations, small insertions | Requires donor DNA template; lower efficiency | Challenging; germline transmission traditionally <2% | [13] |

| Base Editors (BE3, AncBE4max) | Single-base substitutions (C>T, A>G) | No double-strand breaks; reduced indels | BE3: 9-28%; AncBE4max: ~3x BE3 efficiency | [7] |

| Prime Editing (PE2, PEn) | All 12 possible base-to-base conversions, small insertions/deletions | No double-strand breaks; uses pegRNA and reverse transcriptase | PE2: 8.4% for substitution; PEn: superior for insertions up to 30bp | [14] |

Advanced Tools: Precision Editing with Base and Prime Editors

Beyond conventional CRISPR-Cas9, more precise genome editing tools have been successfully adapted for zebrafish research, significantly expanding the scope of disease modeling.

Base Editors enable single-nucleotide changes without inducing double-strand breaks, addressing a key limitation of traditional CRISPR-Cas9. Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) catalyze C•G to T•A conversions, while Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) facilitate A•T to G•C changes [7]. Continuous development has yielded improved editors with expanded capabilities. For instance, the AncBE4max system, optimized for zebrafish codon usage, demonstrated approximately threefold higher editing efficiency compared to the original BE3 system [7]. More recently, a "near PAM-less" cytidine base editor (CBE4max-SpRY) was developed, bypassing the traditional NGG PAM requirement and enabling targeting of virtually all PAM sequences with efficiencies reaching up to 87% at some loci [7].

Prime Editors represent a further advancement, capable of implementing all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, without requiring double-strand breaks or donor DNA templates. A comparative study in zebrafish demonstrated that the nickase-based PE2 editor was more efficient for precise base pair substitutions (8.4% vs. 4.4% for PEn), while the nuclease-based PEn editor was superior for inserting short DNA fragments (up to 30 bp) [14]. This versatility enables the precise modeling of human disease-associated point mutations and the insertion of functional sequences like nuclear localization signals [14].

Diagram 1: Zebrafish CRISPR screening workflow, showing parallel paths for direct G0 phenotypic analysis and germline transmission for stable line generation.

Successful implementation of zebrafish CRISPR screening requires a collection of well-characterized reagents and resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Zebrafish CRISPR Screening

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Vector or Cas9 Protein | Engineered nuclease that cleaves target DNA | Can be delivered as mRNA, protein, or plasmid; codon-optimized versions enhance efficiency |

| sgRNA Design Tools (e.g., CRISPRScan, ACEofBASEs) | Bioinformatics design of specific guide RNAs | Predict on-target efficiency and potential off-target effects; species-specific tools available |

| Target-Specific sgRNAs | Guides Cas9 to specific genomic loci | Chemically synthesized or in vitro transcribed; modified sgRNAs can enhance stability |

| Amplicon Sequencing Primers | Amplification of target regions for NGS validation | Nested primer designs improve specificity for sequencing-based efficiency quantification |

| Microinjection Equipment | Delivery of CRISPR components into embryos | Standard zebrafish microinjection setup with fine-needle pipettes |

| Phenotypic Assay Reagents (e.g., Nile Red, antibodies) | Detection and quantification of phenotypic outcomes | Cell-type specific reporters, lipophilic dyes for adiposity, behavioral tracking systems |

Case Study: In Vivo CRISPR Screening for Adipose Tissue Regulators

A compelling demonstration of zebrafish's power for CRISPR screening comes from a study investigating regulators of adipose tissue remodeling [12]. Researchers developed a quantitative imaging pipeline to assess hyperplastic (many small adipocytes) versus hypertrophic (few large adipocytes) morphology in zebrafish subcutaneous adipose tissue. They then applied this platform in an F0 CRISPR mutagenesis screen targeting 25 candidate genes derived from human genetic and transcriptomic data on adipocyte size [12].

The screen successfully identified six genes that significantly altered adipose morphology. Three genes (foxp1b, txnipa, mmp14b) disruption induced hypertrophic morphology, while three others (ptenb, cxcl14, srpx) induced hyperplastic morphology [12]. Notably, Sushi Repeat Containing Protein (Srpx) had no previously characterized role in adipose biology. Follow-up studies on foxp1b revealed that mutants displayed a developmental bias toward hypertrophic growth but failed to undergo further hypertrophic remodeling in response to a high-fat diet, suggesting that early developmental patterning constrains later adaptive responses to nutritional challenge [12]. This case study exemplifies the power of combining zebrafish CRISPR screening with quantitative phenotyping to uncover novel genetic regulators of physiological processes with direct relevance to human metabolic health.

Zebrafish have firmly established their position as a premier vertebrate model for CRISPR screening, combining genetic tractability with physiological relevance in a scalable format. The continuous refinement of genome editing tools—from efficient Cas9 variants to base and prime editors—is expanding the range of genetic questions that can be addressed. These technologies enable everything from large-scale knockout screens to precise modeling of human disease-associated point mutations.

Future directions in the field will likely focus on increasing the throughput and sophistication of both genetic perturbations and phenotypic readouts. Methods such as MIC-Drop and Perturb-seq, which increase screening scalability and enable single-cell transcriptional profiling of CRISPR perturbations, respectively, hold significant promise for dissecting complex biological mechanisms [1]. Furthermore, the integration of single-cell transcriptomics, computational modeling, and machine learning with zebrafish CRISPR screening data is enhancing the translational relevance of findings [9]. As these technologies mature and datasets expand, zebrafish will continue to provide invaluable insights into gene function, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic strategies, solidifying their role in the functional genomics landscape.

In the field of functional genomics, the advent of CRISPR-Cas technology has revolutionized our ability to perform targeted genome editing in model organisms. Central to this process are the DNA repair mechanisms that resolve the CRISPR-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs). In zebrafish (Danio rerio), a premier model for vertebrate biology and human disease, understanding these pathways is paramount for improving the efficiency of precise gene editing, particularly in the context of germline transmission of genetic modifications. The three primary pathways—Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ), Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), and Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ)—compete to repair DSBs, each resulting in distinct mutational outcomes [15] [16]. Their complex interplay directly influences the success of CRISPR knock-in strategies, where the goal is the precise integration of exogenous DNA sequences over error-prone mutagenesis [17]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these mechanisms, framed within the context of zebrafish CRISPR research, to empower scientists in the design and interpretation of their genome editing experiments.

Core DNA Repair Pathways in Zebrafish

In zebrafish, as in other vertebrates, the repair of CRISPR-Cas9-induced DSBs is a competitive process between several conserved pathways. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three major pathways.

Table 1: Core DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways in Zebrafish CRISPR Mutagenesis

| Pathway | Key Proteins | Template Requirement | Mutagenic Outcome | Typical Efficiency in Zebrafish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs, DNA Ligase IV [15] | None (error-prone) | Small insertions/deletions (indels); imperfect knock-in [16] | High (dominant pathway) [18] |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | Rad51, BRCA2, RAD52 [17] [15] | Homologous donor DNA (precise) | Precise nucleotide changes; accurate knock-in [18] | Low (typically <10% without optimization) [18] [16] |

| Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) | POLQ (DNA Polymerase Theta), PARP1 [17] | Microhomology sequences (5-25 bp) | Deletions flanked by microhomology regions [17] | Variable; contributes to imprecise repair [17] |

The NHEJ pathway is the most active in zebrafish embryos and is often considered a major barrier to precise HDR-mediated knock-in. It functions throughout the cell cycle by directly ligating broken DNA ends, a process that frequently results in small insertions or deletions (indels) [16]. In CRISPR experiments, this typically leads to gene knockouts.

HDR is the only pathway that can facilitate precise knock-in, such as the introduction of fluorescent protein tags or specific disease-associated point mutations. It requires a donor DNA template with homology arms and is active primarily in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle. Its low efficiency in zebrafish is a significant technical challenge, often resulting in mosaic embryos where only a subset of cells carries the desired modification [18] [16].

MMEJ is an alternative, error-prone repair pathway that operates in a microhomology-dependent manner. It typically results in larger deletions than NHEJ. Recent studies have shown that even with NHEJ inhibition, imprecise repair persists due to the activity of MMEJ and the related Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) pathway, complicating knock-in efforts [17].

The following diagram illustrates the competitive interplay between these pathways following a CRISPR-induced double-strand break in a zebrafish cell.

Diagram 1: Competitive DNA Repair Pathways Activated by CRISPR/Cas9. Following a double-strand break (DSB), the cell utilizes different repair mechanisms based on template availability, leading to distinct mutational outcomes with varying efficiencies.

Quantitative Analysis of Repair Outcomes

Understanding the relative efficiency and outcomes of these pathways is critical for experimental design. Recent quantitative studies in zebrafish and human cells have shed light on the distribution of repair events.

Table 2: Quantitative Distribution of CRISPR-Mediated Repair Outcomes in RPE1 Cells (with NHEJ Inhibition)

| Repair Outcome | Approximate Frequency | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Perfect HDR | Variable; increased with pathway suppression | Precise integration of the donor sequence [17] |

| Small Deletions (<50 nt) | Significantly reduced | Typically associated with NHEJ [17] |

| Large Deletions (≥50 nt) & Complex Indels | ~50% of integration events | Associated with MMEJ and other alternative pathways [17] |

| Asymmetric HDR | Reduced by SSA suppression | Only one end of the donor is precisely integrated [17] |

A key finding from recent research is that inhibiting the predominant NHEJ pathway, while boosting the proportion of perfect HDR, is not sufficient to completely suppress non-HDR repairs. In human RPE1 cells, even with NHEJ inhibition, imprecise integration still accounted for nearly half of all integration events, underscoring the significant role of alternative pathways like MMEJ and SSA in CRISPR knock-in [17].

Advanced Strategies to Modulate Repair Pathways

A primary focus in zebrafish CRISPR research is to shift the repair equilibrium away from error-prone pathways and toward HDR. Both genetic and chemical modulation strategies have been successfully employed.

Chemical Reprogramming of DNA Repair

The use of small-molecule inhibitors to transiently modulate key repair proteins has proven highly effective in zebrafish embryos. The table below summarizes key reagents used to enhance HDR efficiency.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enhancing HDR in Zebrafish

| Reagent / Solution | Target Pathway | Molecular Function | Effect on Genome Editing |

|---|---|---|---|

| NU7441 [18] | NHEJ inhibitor | DNA-PK inhibitor [18] | Enhanced HDR efficiency up to 13.4-fold in zebrafish embryos [18] |

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 [17] | NHEJ inhibitor | Potent, commercially available NHEJ inhibitor | Increased knock-in efficiency approximately 3-fold in human cell studies [17] |

| ART558 [17] | MMEJ inhibitor | Selective inhibitor of POLQ (DNA Polymerase Theta) [17] | Reduces large deletions and complex indels; increases perfect HDR frequency [17] |

| SCR7 [18] | NHEJ inhibitor | DNA Ligase IV inhibitor | Shows species-specific effects; no significant HDR enhancement in zebrafish [18] |

| RS-1 [18] | HDR enhancer | RAD51 stimulator | Modest but significant increase in HDR efficiency [18] |

The experimental workflow for a typical chemical enhancement experiment in zebrafish is illustrated below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Enhanced HDR in Zebrafish Embryos. The protocol involves co-injection of CRISPR components and a donor template into one-cell stage embryos, followed by immediate treatment with small molecules to modulate DNA repair pathways, ultimately leading to screening and validation of precisely edited animals.

Inhibition of Alternative Repair Pathways

Beyond NHEJ, targeting the MMEJ and SSA pathways is a novel strategy to further enhance precision. Suppressing POLQ, the central effector of MMEJ, reduces the occurrence of large deletions and complex indels at the target site [17]. Similarly, inhibiting RAD52, a key protein in the SSA pathway, reduces imprecise donor integration, particularly a faulty repair pattern known as "asymmetric HDR" where only one end of the donor DNA integrates correctly [17]. Combined inhibition of NHEJ and these alternative pathways represents the cutting edge for improving precise knock-in efficiency.

Experimental Protocols for Zebrafish

Visual HDR Reporter Assay

A quantitative in vivo reporter system was developed to screen for HDR-enhancing conditions in zebrafish at single-cell resolution [18].

- Principle: A transgenic zebrafish line expresses eBFP2 (blue fluorescent protein) specifically in fast-muscle cells. A donor template containing the tdTomato (red fluorescent protein) gene flanked by homology arms is designed to replace eBFP2 upon successful HDR.

- Method: Embryos are co-injected with Cas9 protein, a guide RNA targeting eBFP2, and the tdTomato donor DNA. Successful HDR converts individual muscle fibers from blue to red fluorescence.

- Quantification: The number of red fluorescent fibers in living embryos is counted at 72 hours post-fertilization (hpf). This provides a quantitative and rapid readout of HDR efficiency, allowing for the testing of chemical modulators like NU7441, which was shown to increase HDR events from 4.0 to 53.7 red fibers per embryo on average [18].

Optimized Protocol for HDR-Mediated Knock-In

The following is a detailed methodology for achieving precise knock-in in zebrafish, incorporating best practices and chemical enhancement [18] [16]:

- sgRNA Design: Select a sgRNA with very high efficiency (indel frequency >70% in pooled embryos). The target site should be as close as possible to the intended insertion point [16].

- Donor Template Design: For linear dsDNA donors, use homology arms of 300-1000 bp. Incorporating the sgRNA target sequence within the homology arm can promote "self-linearization" of the donor and enhance HDR efficiency [18].

- Microinjection Cocktail: Co-inject into the cytoplasm of one-cell stage embryos:

- CRISPR Component: High-quality Cas9 protein pre-complexed with sgRNA as a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex for rapid activity.

- Donor DNA: 50-100 ng/μL of purified, linearized donor template.

- Chemical Modulators: Add 50 μM NU7441 directly to the injection mix or incubate embryos in the solution immediately after injection [18].

- Screening and Validation: Raise injected embryos (F0) and screen for somatic editing using fluorescence, PCR, or restriction fragment analysis. Cross founder F0 fish to wild-types and screen the F1 offspring for germline transmission of the precise edit.

The competition between NHEJ, HDR, and MMEJ pathways fundamentally shapes the outcomes of CRISPR genome editing in zebrafish. While NHEJ remains the dominant and most efficient pathway, leading to high knockout rates, HDR's inefficiency has been a major bottleneck for precise knock-in. The strategic inhibition of NHEJ and the emerging targeting of alternative pathways like MMEJ and SSA provide powerful chemical-genetic strategies to reprogram the zebrafish embryo's repair landscape. Quantitative assays and optimized protocols are crucial for evaluating these strategies and achieving seamless integration of genetic material. As the field moves forward, a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between these DNA repair mechanisms will continue to enhance the precision and efficiency of generating zebrafish models with germline-transmitted mutations, thereby accelerating functional genomics and the modeling of human disease.

The establishment of heritable mutant lines is the cornerstone of genetic research in model organisms. In zebrafish (Danio rerio), the efficiency with which CRISPR-induced mutations are transmitted through the germline to subsequent generations fundamentally determines the practicality and scale of functional genomics studies. The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized targeted mutagenesis in zebrafish, offering unprecedented capabilities for high-throughput functional genomics and disease modeling [19]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical benchmark of germline transmission rates in zebrafish CRISPR mutants, tracing the evolution of these critical efficiency metrics from foundational studies to contemporary precision editing approaches. Within the broader context of zebrafish CRISPR research, understanding these benchmarks enables researchers to design appropriately powered experiments, allocate resources efficiently, and advance therapeutic discovery through robust in vivo validation of candidate genes.

Historical Benchmarks: Establishing CRISPR-Cas9 in Zebrafish

Foundational High-Throughput Mutagenesis

Early large-scale efforts to establish CRISPR-Cas9 as a robust tool in zebrafish provided critical baseline metrics for germline transmission. A seminal 2015 study by Varshney et al. established a high-throughput pipeline that would serve as a benchmark for years to come [2]. This groundbreaking work reported:

Key Historical Germline Transmission Data (Varshney et al., 2015) [2]

| Metric | Result |

|---|---|

| Overall Success Rate for Generating Mutations | 99% (across 162 loci targeting 83 genes) |

| Average Germline Transmission Rate | 28% |

| Unique Alleles Verified | 678 from 58 genes |

| Comparative Efficiency vs. TALENs/ZFNs | ~6-fold more efficient |

This study demonstrated that CRISPR/Cas9 was not only highly efficient at inducing mutations but also reliably transmitted these mutations through the germline. The authors employed a cloning-free single-guide RNA (sgRNA) synthesis method that significantly increased throughput, enabling the synthesis of hundreds of sgRNAs in a few hours [2]. Their strategy involved crossing founder fish (F0) to wild-type fish and analyzing F1 progeny for insertions or deletions (indels) using fluorescence PCR or sequencing, establishing a protocol that would become standard for germline transmission assessment.

Technical Workflows for Germline Identification

The development of streamlined protocols was instrumental in standardizing the identification of germline-transmitting founders. A 2018 protocol by Boel et al. detailed a robust, economical CRISPR-Cas9 strategy specifically designed to minimize equipment needs and enable participation by personnel across experience levels [20]. This protocol emphasized:

- Efficient sgRNA Synthesis: Using target-specific and generic oligonucleotides to form double-stranded templates for in vitro transcription.

- Cas9 Delivery: Employing Cas9 protein rather than mRNA, with injection-ready aliquots stored at -80°C to minimize freeze-thaw cycles.

- Mutation Identification: Implementing a PCR-based heteroduplex mobility assay (HMA) for initial screening, followed by next-generation sequencing (NGS) for comprehensive characterization of indels in heterozygous fish [20].

This workflow demonstrated that careful optimization of reagent preparation and delivery could yield consistent germline transmission without requiring highly specialized expertise, thus democratizing the generation of zebrafish knockout lines.

Current Benchmarks: Precision Genome Editing and Transmission Efficiencies

Advanced Editing Platforms: Base and Prime Editors

Recent advances have shifted from simple knockout approaches to precise nucleotide-level editing, with corresponding developments in germline transmission metrics.

Base Editors enable direct conversion of one nucleotide to another without double-strand breaks through fusion of catalytically impaired Cas proteins with deaminase enzymes [7]. Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) facilitate C:G to T:A conversions, while Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) catalyze A:T to G:C changes [7]. The evolution of these tools in zebrafish has seen progressive efficiency improvements:

- BE3 System: Initial cytosine base editing with efficiencies of 9.25% to 28.57% in somatic cells [7].

- AncBE4max: A codon-optimized system showing approximately threefold enhanced editing efficiency compared to BE3 [7].

- CBE4max-SpRY: A "near PAM-less" cytidine base editor achieving efficiencies up to 87% at some loci, bypassing traditional NGG PAM requirements [7].

Prime Editors represent a more versatile precise editing technology that uses a Cas9 nickase-reverse transcriptase fusion and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) to directly write new genetic information into a target site [14]. A 2025 study systematically compared nickase-based (PE2) and nuclease-based (PEn) prime editors in zebrafish, with significant implications for germline transmission:

Prime Editing Efficiency Comparison [14]

| Editor Type | Application | Precision Editing Efficiency | Indel Rate | Precision Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE2 (Nickase) | Nucleotide substitution | 8.4% | Lower | 40.8% |

| PEn (Nuclease) | Nucleotide substitution | 4.4% | Higher | 11.4% |

| PEn (Nuclease) | Short sequence insertion (3-30 bp) | Higher than PE2 | Variable | Not specified |

This study further demonstrated that both somatic precision editing and germline transmission of these precise modifications could be achieved, with the editing mode (substitution vs. insertion) dictating the optimal editor choice [14].

Optimized Knock-In Strategies for Germline Transmission

Recent methodological refinements have significantly improved knock-in efficiency, which traditionally lagged behind knockout approaches. A 2023 study described the "S-NGG-25" strategy—an optimized MMEJ-mediated knock-in approach using donors with shortened microhomology arms (25 bp) and reduced Cas9/sgRNA consensus sites [21]. This method demonstrated:

- High-Efficiency Germline Transmission: Successfully applied to 33 connexin genes, with germline transmission rates ranging from 5.8% to 35.4% across founders [21].

- Streamlined Screening: Implementation of a combined fluorescence enrichment and caudal-fin junction-PCR protocol to expedite the identification of germline-transmitting founders [21].

- Reduced Mosaicism: Improved rates of obtaining seamless F1 carriers with precise integrations [21].

This optimized platform addresses one of the most challenging aspects of zebrafish genome engineering—efficient and precise protein tagging—with direct implications for improving germline transmission rates of complex alleles.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Germline Transmission

Foundational Workflow for Germline Transmission Assessment

The following experimental workflow visualizes the standard process for generating and identifying zebrafish with germline-transmitted mutations:

Diagram 1: Standard workflow for assessing germline transmission in zebrafish CRISPR mutants.

Step 1: sgRNA Design and Synthesis

- Design: Select target sites in early exons near the 5' end of coding sequences to maximize likelihood of gene disruption. Ideal sgRNA sequences contain 40-80% GC content with a G at the 5′ position for efficient T7 transcription [20].

- Synthesis: Employ cloning-free methods using partially overlapping oligonucleotides (target-specific + generic scaffold) annealed and extended to form dsDNA templates for in vitro transcription [2].

Step 2: Microinjection

- Preparation: Combine sgRNA with Cas9 protein (1 mg/mL) in injection-ready aliquots [20].

- Delivery: Microinject into the yolk or cell cytoplasm of one-cell stage embryos [20].

- Controls: Include uninjected embryos from the same clutch as critical controls [6].

Step 3: Founder Raising

- Rearing: Raise injected embryos (F0) to sexual maturity (approximately 3 months).

- Mosaicism Expectation: F0 founders are highly mosaic, carrying multiple different editing events in different germ cells [22].

Step 4: Outcrossing

- Breeding: Outcross individual F0 founders to wild-type fish.

- Germline Assessment: The resulting F1 embryos represent the genetic composition of the germline of the F0 founder.

Step 5: Mutation Screening

- Initial Screening: Use heteroduplex mobility assays (HMA) or T7 endonuclease I (T7E1) assays to identify potential mutants [20].

- Advanced Screening: Implement fluorescence enrichment strategies when fluorescent reporters are co-injected [21].

Step 6: Sequence Verification

- Amplification: PCR-amplify target regions from pooled F1 embryos or fin clips from adult F1 fish.

- Sequencing: Utilize Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing (NGS) to characterize specific indel patterns or precise edits [20] [2].

- Transmission Rate Calculation: Calculate as the percentage of F1 offspring carrying the mutation derived from a specific F0 founder.

Advanced Methodologies for Precision Editing

For base and prime editing applications, modified protocols are required:

Base Editing Workflow [7]

- Component Preparation: Synthesize mRNA for base editor (BE) constructs (e.g., BE3, AncBE4max) or prepare ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes.

- Microinjection: Inject BE mRNA/sgRNA complexes or RNP into one-cell stage embryos.

- Efficiency Optimization: Modify PAM recognition using engineered Cas variants (e.g., VQR, SpRY) to expand targetable sites.

- Temperature Control: Incubate injected embryos at elevated temperatures (e.g., 32°C) to enhance base editing efficiency in some systems [14].

Prime Editing Workflow [14]

- pegRNA Design: Design prime editing guide RNAs with reverse transcription template and primer binding site sequences.

- Component Delivery: Co-inject PE mRNA or protein with pegRNA into zebrafish embryos.

- Editing Validation: Use amplicon sequencing of target regions to quantify precise edit incorporation rates and identify potential byproducts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Zebrafish CRISPR Germline Transmission Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Protein | CRISPR endonuclease that creates DSBs at target sites | Using protein instead of mRNA can increase efficiency and reduce mosaicism [20] |

| sgRNA In Vitro Transcription Kit | High-throughput sgRNA synthesis | Enables cloning-free production of hundreds of sgRNAs [2] |

| Heteroduplex Mobility Assay (HMA) | Initial mutation screening | Rapid, inexpensive method to detect indels in pooled embryos [20] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Comprehensive mutation characterization | Precisely identifies and quantifies mutant alleles; essential for assessing complex editing outcomes [20] |

| Fluorescence Enrichment | Screening for knock-in events | Uses co-injected fluorescent markers or integrated tags to identify potential founders [21] |

| Caudal-Fin Junction PCR | Germline transmission screening | Enables non-lethal genotyping of potential F0 founders before breeding [21] |

| Long-Read Sequencing (PacBio/Nanopore) | Detecting structural variants | Identifies large, complex on-target and off-target edits missed by short-read methods [22] |

| GS-443902 trisodium | GS-443902 trisodium, MF:C12H14N5Na3O13P3+, MW:598.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TRAP-14 amide | TRAP-14 amide, MF:C81H119N21O22, MW:1738.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Factors Influencing Germline Transmission Efficiency

Technical and Biological Determinants

Germline transmission rates are influenced by multiple interconnected factors:

sgRNA Design: Optimal sgRNAs feature high GC content (40-80%), a G at the 5′ position, and minimal predicted off-target effects [20]. However, historical data suggests that most published "rules" for sgRNA design poorly predict germline transmission rates, with the exception of a GG or GA dinucleotide at the 5′ end [2].

Delivery Method and Timing: Microinjection at the one-cell stage is critical. Delivery of preassembled Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes generally yields higher editing and germline transmission rates compared to mRNA injection [20] [22].

Biological Constraints: The inherent mosaicism of F0 founders remains a fundamental challenge. Studies demonstrate that adult founder zebrafish are mosaic in their germ cells, with individual founders carrying multiple different editing events [22].

Addressing Unintended Mutagenesis

A comprehensive 2022 study revealed that CRISPR-Cas9 can introduce large structural variants (SVs ≥50 bp) at both on-target and off-target sites, with 6% of editing outcomes in founder larvae representing such SVs [22]. Critically, these SVs can be transmitted to the next generation, with 9% of F1 offspring carrying an SV [22]. This highlights the importance of:

- Comprehensive Validation: Using long-read sequencing technologies to detect large structural variants missed by conventional methods.

- Off-Target Assessment: Employing genome-wide methods like Nano-OTS to identify potential off-target sites before germline transmission studies [22].

The benchmarking data presented in this whitepaper trace a trajectory of remarkable progress in zebrafish CRISPR germline transmission efficiency. From the foundational average of 28% transmission in early high-throughput studies [2] to the sophisticated precision editing systems now achieving efficiencies above 80% at optimized loci [7], the field has witnessed substantial methodological refinement. Current research priorities include improving the fidelity of complex knock-in approaches [21], minimizing structural variants [22], and expanding the target scope of precision editors [7] [14]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these benchmarks provide critical reference points for experimental design, highlighting both the capabilities and limitations of current zebrafish genome engineering platforms. As these technologies continue to mature, they promise to further accelerate the use of zebrafish in functional genomics and therapeutic discovery.

Within vertebrate biomedical research, the zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a preeminent model that uniquely combines high experimental throughput with ethical husbandry and robust 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) compliance. This technical whitepaper examines these advantages within the specific context of generating and analyzing germline transmission in zebrafish CRISPR mutants. We detail how the zebrafish model enables rapid, large-scale genetic screens and detailed functional validation of gene edits with significantly reduced animal usage, lower costs, and diminished ethical concerns compared to traditional mammalian models. The integration of CRISPR/Cas9 technology with the inherent biological features of zebrafish creates a powerful platform for accelerating preclinical research, particularly in the validation of disease-associated genetic variants and drug discovery pipelines.

The generation of stable, heritable mutant lines through germline transmission is a fundamental requirement for functional genomics and disease modeling. In this context, the zebrafish offers a compelling alternative to mammalian models. The external fertilization and development of zebrafish embryos provide direct access to the germline from the earliest stages, enabling high-efficiency CRISPR/Cas9 editing and simplifying the recovery of mutant alleles [23] [24]. Furthermore, approximately 70% of human genes have at least one zebrafish ortholog, and 84% of genes known to be associated with human disease have a zebrafish counterpart, making it a highly relevant model for human biology and pathology [9]. This high degree of genetic conservation, combined with its practical advantages, positions the zebrafish as an ideal system for studying the functional consequences of genetic alterations in a vertebrate system. The following sections will dissect the specific advantages of throughput, husbandry, and 3Rs compliance, providing a technical foundation for leveraging the zebrafish model in sophisticated germline transmission studies.

Quantitative Advantages in Throughput and Scale

The experimental throughput achievable with zebrafish is orders of magnitude greater than that of mammalian models, a critical factor in large-scale genetic screens and drug discovery initiatives.

Table 1: Comparative Throughput and Husbandry of Animal Models

| Feature | Zebrafish | Mice | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embryos/Clutch | 70 - 300 | 2 - 12 (litter size) | [24] [25] |

| Time to Sexual Maturity | 2 - 3 months | ~2 months | [24] |

| Developmental Timeline | Major organs formed in 24-48 hours | Several weeks | [9] |

| High-Throughput Screening | Very high (larvae in multi-well plates) | Moderate | [9] |

| Husbandry Cost | Low | High | [9] |

The data in Table 1 underscores the scalability of the zebrafish system. A single mating pair can produce hundreds of embryos weekly, enabling high-throughput phenotypic assays and large-scale mutagenesis screens that would be logistically and financially prohibitive in mice [9] [24]. This fecundity is crucial for germline transmission studies, as it allows researchers to screen large numbers of F1 offspring to identify those carrying the desired mutation, even when transmission rates are low.

The rapid development of zebrafish is another key throughput accelerator. Major organ systems are formed within 24 to 72 hours post-fertilization (hpf), allowing for the rapid assessment of phenotypic outcomes in a vertebrate system [9]. This speed, combined with the ability to house many animals in a small space, significantly compresses research timelines from gene editing to phenotypic analysis in stable lines.

Husbandry and Economic Efficiency

The practical aspects of zebrafish husbandry contribute directly to its status as a cost-effective and efficient model.

- Size and Space Efficiency: The small size of zebrafish (larval and adult stages) allows for high-density housing in aquarium systems, drastically reducing the physical footprint and maintenance costs compared to mammalian facilities [9] [25].

- Cost-Effectiveness: Overall husbandry costs for zebrafish are significantly lower than for mice. This includes expenses related to housing, feeding, and husbandry labor, making large-scale experiments more feasible [9].

- Genetic Diversity: Unlike highly inbred mammalian models, common laboratory zebrafish strains are genetically heterogeneous. This diversity more accurately models human genetic variation and can provide more translatable results, particularly in drug response studies [24]. While this requires careful experimental design and appropriate sample sizes, the large number of available embryos makes this manageable.

Adherence to the 3Rs Principles in Zebrafish CRISPR Research

The zebrafish model aligns powerfully with the ethical principles of Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement (3Rs), a cornerstone of modern humane science.

Replacement

A paramount ethical advantage is the classification of zebrafish embryos and larvae before 5 days post-fertilization (dpf). According to EU Directive 2010/63/EU, they are not considered protected animals as they have not begun independent feeding [26]. This allows researchers to gather systemic in vivo data from a whole vertebrate organism under an in vitro classification, effectively replacing the use of protected animals in early-stage toxicity screens, disease modeling, and drug discovery [26] [25].

Reduction

Zebrafish are inherently suited to reducing animal numbers:

- Sequential Assessment: The optical transparency of larvae enables researchers to non-invasively measure multiple parameters (e.g., organ function, behavior) in the same animal over time, reducing variability and the need for separate cohorts for each measurement [26].

- Pipeline Impact: Using zebrafish in early-stage discovery helps narrow down the most promising compounds or genetic targets, reducing the number of mammals required for subsequent regulatory testing phases [26] [25].

Refinement

Zebrafish research naturally refines experimental approaches to minimize suffering.

- Non-Invasive Imaging: The transparency of embryos and larvae (including genetically transparent lines like casper) allows for high-resolution, real-time imaging of internal processes without invasive surgical procedures, minimizing stress and harm [9] [26] [24].

- Minimal Intervention: This transparency reduces or eliminates the need for invasive techniques that are common in mammalian research, leading to less stressful experimental procedures and more accurate, artifact-free data [26].

Experimental Protocols for Germline Transmission

Efficient germline transmission of CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutations is critical for establishing stable lines. The following protocols detail optimized methodologies.

Optimized CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery for High-Efficiency Editing

The choice of reagents and delivery methods significantly impacts mutagenesis efficiency and mosaicism in G0 embryos, which in turn influences germline transmission rates.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Zebrafish CRISPR

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application in Germline Transmission |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Protein | Pre-complexed ribonucleoprotein; enables immediate activity upon injection. | Superior to Cas9 mRNA; leads to higher editing efficiency and reduced mosaicism [5] [27]. |

| sgRNA (single guide RNA) | Synthetic RNA guiding Cas9 to specific genomic loci. | Target-specific cleavage. Efficiency can be predicted using tools like CRISPRScan [23] [6]. |

| ssODN (single-stranded Oligodeoxynucleotide) | Short, single-stranded DNA template for Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). | Used for introducing precise point mutations (knock-ins). Non-target asymmetric PAM-distal (NAD) conformations are recommended [5]. |

| Zebrafish Embryo Genotyper (ZEG) | Device for minimally invasive biopsy of 72 hpf embryos. | Allows early genotyping and selective raising of embryos with high editing efficiency, reducing animals raised and screened [5]. |

| NHEJ Inhibitors | Chemical compounds that suppress the error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining pathway. | Can be used to favor HDR, improving knock-in efficiency [27]. |

Protocol Steps:

- Component Preparation: Synthesize sgRNA via in vitro transcription from a DNA template or use pre-designed crRNA:tracrRNA duplexes. Use purified Cas9 protein.

- Microinjection Mix Preparation: Co-complex the sgRNA and Cas9 protein to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex prior to injection. For knock-ins, include an ssODN repair template with a NAD conformation [5].

- Zygote Microinjection: Inject 1-2 nL of the RNP mixture directly into the cytoplasm of single-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

- Temperature Manipulation (Optional): Incubate injected embryos at a reduced temperature (e.g., 12°C) for 30-60 minutes post-injection. This extends the single-cell stage, significantly increasing mutagenesis efficiency by providing more time for Cas9 to act before DNA replication and cell division [28].

Screening for Germline Transmission

Identifying founders (F0 fish that transmit mutations through their germline) is a critical step.

- Early Somatic Screening: At 3-5 dpf, use the ZEG device to extract a small amount of genomic DNA from embryos with minimal lethality. Analyze this DNA via next-generation sequencing (NGS) to quantify somatic editing efficiency [5].

- Founder Selection and Raising: Select and raise only the embryos showing the highest levels of correct editing to adulthood. This pre-selection can lead to a 17-fold increase in somatic editing efficiency in the raised cohort, dramatically improving the odds of obtaining germline transmission [5].

- Outcrossing and F1 Screening: Outcross the adult pre-selected F0 fish to wild-type partners. Collect and raise F1 embryos.

- Genotyping F1 Progeny: At an appropriate stage, genotype individual F1 larvae to identify those that are heterozygous for the desired mutation, confirming successful germline transmission from the F0 founder.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this optimized pipeline for achieving germline transmission.

The zebrafish model provides an unparalleled combination of high throughput, cost-effective husbandry, and robust 3Rs compliance, making it an indispensable tool for modern biomedical research, particularly in the realm of CRISPR/Cas9 germline transmission studies. Its capabilities enable the rapid functional validation of human disease-associated genes and the acceleration of drug discovery pipelines. By adopting the optimized protocols outlined herein—including the use of Cas9 protein, early genotyping with the ZEG device, and temperature modulation—researchers can significantly enhance the efficiency of generating stable mutant lines. As the demand for genetically accurate disease models and ethical research practices grows, the zebrafish stands as a powerful and strategic platform for advancing our understanding of vertebrate biology and disease.

High-Throughput Workflows: From sgRNA Design to Stable Lines

Cloning-Free sgRNA Synthesis for Scalable Mutagenesis

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic engineering, enabling precise genome manipulations across model organisms. For zebrafish researchers, this technology has been particularly transformative for studying gene function through targeted mutagenesis. Early CRISPR implementations relied on plasmid-based sgRNA expression, requiring days to weeks of molecular cloning for each new target [29]. This bottleneck significantly constrained scalability, especially for large-scale functional genomics screens. The development of cloning-free sgRNA synthesis methods has dramatically accelerated this process, allowing researchers to proceed from target selection to embryo injection in a single day [30] [31].

These technical advances are particularly crucial in the context of germline transmission research, where efficiency and precision directly impact successful establishment of stable mutant lines. Traditional approaches often produced mosaic founders, complicating germline transmission and requiring extensive outcrossing [31]. Cloning-free methods, particularly those utilizing synthetic sgRNAs or pre-complexed ribonucleoproteins (RNPs), have demonstrated superior efficiency in generating non-mosaic mutants with high germline transmission rates [32] [31]. This technical guide examines current cloning-free sgRNA synthesis methodologies, their application in zebrafish mutagenesis, and their critical role in advancing germline transmission studies.

sgRNA Formats: From Plasmid-Based to Cloning-Free Systems

Traditional vs. Modern sgRNA Synthesis Approaches

CRISPR guide RNAs exist in multiple formats, each with distinct advantages for specific applications. Understanding these formats is essential for selecting the optimal approach for scalable mutagenesis.

Two-Component System (crRNA:tracrRNA): This natural bacterial system utilizes a target-specific CRISPR RNA (crRNA) complexed with a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) that serves as a scaffold for Cas9 binding [31]. This system is commercially available as chemically synthesized oligonucleotides, requiring no cloning and offering immediate use after complexing.

Single-Guide RNA (sgRNA): Researchers have engineered a chimeric RNA molecule that combines crRNA and tracrRNA into a single transcript via a linker loop [29]. While this format can be expressed from plasmids requiring cloning, it can also be synthesized chemically or produced via in vitro transcription (IVT) without cloning.

The evolution toward cloning-free methods represents a significant advancement for high-throughput applications. As evidenced by recent studies in zebrafish, direct delivery of synthetic sgRNAs or RNPs has demonstrated remarkable efficiency in generating biallelic mutations in F0 embryos, with some approaches achieving over 99% edited alleles in germline tissues [32].

Comparison of sgRNA Synthesis Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Cloning-Free sgRNA Synthesis Methods

| Method | Procedure | Time Required | Key Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Synthesis | Commercially produced via solid-phase synthesis | Immediate shipment | High purity; chemical modifications available; minimal batch variation | Cost at small scale; limited length options | High-precision editing; screening; therapeutic development |

| In Vitro Transcription (IVT) | DNA template with promoter + in vitro transcription | 1-3 days | Cost-effective for large-scale production; customizable targets | RNA contamination risk; 5' end heterogeneity; purification required | Large-scale screens; testing multiple targets |

| crRNA:tracrRNA Duplex | Commercial oligonucleotides complexed with tracrRNA | 1 day (including complexing) | High efficiency; reduced off-target effects; flexible target switching | Higher cost than IVT; requires complexing step | RNP delivery; precision editing; reduced mosaicism |

Cloning-Free sgRNA Synthesis Methodologies

Chemically Synthesized sgRNAs

Synthetic sgRNAs are produced through solid-phase chemical synthesis, where individual ribonucleotides are sequentially added to a growing RNA chain [29]. This method offers several advantages for germline transmission studies:

- Chemical modifications: Incorporation of 2'-O-methyl analogs at the three terminal nucleotides and phosphorothioate bonds can dramatically enhance RNA stability and editing efficiency [7].

- High purity: High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) purification ensures removal of incomplete transcripts and contaminants.

- Reproducibility: Minimal batch-to-batch variation provides consistent editing efficiency across experiments.

A recent zebrafish study utilizing extended, GC-rich, chemically modified sgRNAs reported exceptional germline transmission efficiency, with edited alleles accounting for over 99% of alleles in testes and 100% inheritance in offspring [32].

In Vitro Transcription (IVT)

The IVT method utilizes bacteriophage RNA polymerases (T7, SP6, or T3) to transcribe sgRNAs from DNA templates containing the appropriate promoter [29]. The typical workflow includes:

- Template design: PCR amplification or oligonucleotide annealing to create DNA templates with promoter sequences

- In vitro transcription: RNA synthesis using ribonucleotide mixes and RNA polymerase

- Purification: Removal of proteins, unincorporated nucleotides, and aborted transcripts

- Quality control: Quantification and integrity assessment

While cost-effective for large-scale screening, IVT-synthesized sgRNAs may exhibit 5' end heterogeneity, potentially affecting editing efficiency. For germline transmission studies, IVT is particularly valuable when testing numerous target sites before committing to synthetic sgRNAs for critical experiments.

crRNA:tracrRNA Complexes

The two-component system represents perhaps the most straightforward cloning-free approach. The method typically involves:

- Commercial procurement: Chemically synthesized crRNA and tracrRNA

- Complex formation: Annealing of crRNA with tracrRNA to form functional guide RNAs

- RNP complex assembly: Combination with purified Cas9 protein before delivery

This approach was successfully employed in a cloning-free mouse genome editing study, which reported high-efficiency generation of non-mosaic mutants with germline transmission rates averaging 52.8% [31]. The reduced mosaicism is particularly advantageous for germline transmission studies, as founders more reliably transmit edited alleles to the next generation.

Experimental Protocols for Zebrafish Germline Transmission Studies

Optimized RNP Microinjection Protocol for High-Efficiency Germline Editing

Based on recent successful approaches in zebrafish [32], the following protocol has been optimized for maximal germline transmission:

Reagents and Equipment:

- Purified recombinant SpCas9 protein (commercial source)

- Chemically synthesized sgRNA (target-specific) or crRNA:tracrRNA duplex

- Nuclease-free water

- Phenol red solution (0.5% for injection tracking)

- Microinjection system with needle puller and injector

- Zebrafish embryos at 1-cell stage

Procedure:

- RNP Complex Assembly:

- Prepare 5µg/µL Cas9 protein working concentration

- Mix with sgRNA at 1:2 molar ratio (Cas9:sgRNA)

- Incubate at 37°C for 10 minutes to form RNP complexes

Injection Mix Preparation:

- Combine RNP complexes with phenol red (final concentration 0.05%)

- Centrifuge at 14,000g for 10 minutes to remove aggregates

Zebrafish Embryo Injection:

- Collect 1-cell stage embryos within 20 minutes post-fertilization

- Inject 1-2nL of RNP mix into the yolk sac directly adjacent to the cell

- Maintain injected embryos at 28.5°C in embryo medium

Germline Transmission Assessment:

- Raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood

- Outcross F0 founders to wild-type fish

- Screen F1 embryos for edited alleles via PCR and sequencing

A critical optimization in recent protocols involves yolk sac injection at the 1-cell stage rather than cytoplasmic injection, which has demonstrated improved biallelic editing and germline transmission [32].

ssODN HDR Protocol for Precise Editing

For precise knock-in mutations, single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) can be co-injected with RNP complexes:

Additional Reagents:

- Ultramer ssODN repair template (IDT) with 30-40bp homology arms

- Target-specific modifications flanked by PAM-disrupting silent mutations

Procedure:

- Design ssODN with homologous arms complementary to target region

- Prepare injection mix containing:

- 30 ng/μL Cas9 protein

- 0.6 pmol/μL sgRNA

- 20 ng/μL ssODN repair template

- Inject into pronucleus of zebrafish embryos

- Screen for precise edits using restriction fragment length polymorphism or sequencing assays

This approach has achieved 35% HDR efficiency in mouse models [31], suggesting similar potential in zebrafish with protocol optimization.

Quantitative Analysis of Editing Efficiencies

Comparative Performance of Editing Platforms

Table 2: Editing Efficiencies Across Cloning-Free Platforms in Vertebrate Models

| Editing Platform | Typical Efficiency Range | Key Applications in Germline Studies | Mosaicism Rate | Germline Transmission Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 RNP (NHEJ) | 70-99% [32] | Gene knockouts; large deletions | Low with optimized injection | 28-100% with biallelic editing [32] |

| Cas9 RNP (HDR) | 20-35% [31] | Point mutations; small insertions | Moderate | ~50% in non-mosaic founders [31] |

| Base Editors | 9-87% [7] | Single nucleotide conversions | Variable | 28% average (zebrafish) [1] |

| Prime Editors | 4-8% (substitution) [14] | Precise edits without donors | Low | Successfully demonstrated [14] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Cloning-Free sgRNA Synthesis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations for Germline Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Proteins | Recombinant SpyCas9 (IDT), Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease | DNA cleavage at target sites | High-purity grades reduce toxicity; protein concentration affects mosaicism |

| Synthetic sgRNAs | Synthego EZ sgRNA, Sigma Custom CRISPR sgRNA | Target-specific guidance for Cas9 | Chemical modifications enhance stability and editing efficiency [7] |

| crRNA:tracrRNA Systems | IDT Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA and tracrRNA | Two-component guide system | Flexible target switching; demonstrated reduced off-target effects [31] |

| Template DNA for IVT | Custom oligonucleotides with T7 promoter | Template for in vitro transcription | Cost-effective for screening multiple targets; requires purification |

| Delivery Reagents | Alt-R Cas9 Electroporation Enhancer | Improves cellular delivery | Critical for hard-to-transfect primordial germ cells |

| Quality Control Tools | Bioanalyzer RNA chips, UV spectrophotometry | Assess sgRNA integrity and concentration | Essential for reproducible editing efficiency |

| OXA-06 | OXA-06, MF:C21H18FN3, MW:331.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Epimedonin J | Epimedonin J, MF:C25H26O6, MW:422.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

Cloning-Free sgRNA Synthesis and Screening Pipeline

Germline Transmission Pipeline for Zebrafish Mutants

Cloning-free sgRNA synthesis represents a transformative advancement for scalable mutagenesis in zebrafish germline transmission studies. The methods detailed in this guide—from chemically synthesized sgRNAs to crRNA:tracrRNA systems—provide researchers with powerful tools to accelerate functional genomics research. The quantitative data presented demonstrates that these approaches achieve editing efficiencies compatible with high-throughput screening while maintaining the precision required for disease modeling.

As CRISPR technology continues to evolve, cloning-free methods will undoubtedly remain central to large-scale functional genomics initiatives in zebrafish and other model organisms. Their simplicity, efficiency, and compatibility with germline transmission studies position them as essential tools for unraveling gene function in vertebrate development and disease.

In the field of zebrafish genome engineering, the choice between delivering the CRISPR-Cas9 system as mRNA or as a purified protein complex is a critical decision that directly impacts editing efficiency, mutagenesis rates, and ultimately, the success of germline transmission in mutant lines. Within the broader context of establishing heritable genetic mutations, the method of CRISPR component delivery influences the timing, precision, and consistency of genomic edits in founder (F0) generations. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of mRNA and Cas9 protein microinjection protocols, synthesizing current research to empower researchers in making evidence-based decisions for their specific experimental goals in functional genomics and drug development.

Molecular Mechanisms and Delivery Strategies