Optimizing Hox Gene Expression Detection in Early Limb Buds: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Single-Cell Resolution

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of detecting Hox gene expression during early limb bud development, where precise spatiotemporal patterns establish anterior-posterior positioning.

Optimizing Hox Gene Expression Detection in Early Limb Buds: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Single-Cell Resolution

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of detecting Hox gene expression during early limb bud development, where precise spatiotemporal patterns establish anterior-posterior positioning. We synthesize foundational principles of Hox collinearity and limb positioning with cutting-edge methodological approaches, including single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics. The article provides practical troubleshooting guidance for overcoming sensitivity and resolution limitations in traditional assays while establishing rigorous validation frameworks for emerging technologies. By integrating recent breakthroughs from multiple model organisms and human developmental studies, this resource equips researchers and drug development professionals with optimized strategies to advance understanding of limb development, congenital defects, and evolutionary adaptations.

Hox Gene Blueprint: Decoding Positional Memory in Limb Bud Development

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the Hox code and why is it fundamental to patterning the limb bud? The Hox code refers to the combinatorial expression of Hox genes along the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis that provides positional information to specify the correct arrangement of body parts [1]. In the limb bud, this code is established by the spatial collinearity of Hox genes, particularly from the HoxA and HoxD clusters [2]. Their expression domains are laid down in a temporal manner, with 'anterior' genes (e.g., paralogy groups 1 and 2) activated earlier than 'posterior' genes (e.g., groups 11 and 12) [2]. This results in a nested, "Russian dolls" pattern of expression that is crucial for assigning unique identities to different limb segments [2] [1]. Disruption of this code leads to homeotic transformations, where one limb segment develops the identity of another [1].

FAQ 2: What is the principle of posterior prevalence and how does it impact limb patterning? Posterior prevalence (also known as posterior dominance) is a functional hierarchy in which the protein products of more posteriorly expressed Hox genes (e.g., Hox group 13) prevail over the functions of more anteriorly expressed genes (e.g., Hox group 11) [2] [3] [4]. In the limb, this principle is evident in the distal areas, where the function of 'posterior' genes is prevalent [2]. For example, gain-of-function experiments show that group 13 Hox proteins can antagonize the function of group 11 proteins, leading to a reduction in bony elements [2]. This functional dominance ensures that posterior limb structures are correctly specified despite the overlapping expression of multiple Hox genes.

FAQ 3: How is the early phase of Hoxd gene expression in the limb bud regulated? The early phase of Hoxd gene expression in the limb bud is controlled by a mechanism exhibiting temporal and spatial collinearity, which bears strong similarities to the strategy used during trunk development [2]. This phase involves a progressive restriction of expressing cells towards the posterior margin of the bud [2]. The regulatory logic for this early phase is distinct from the later phase of Hoxd expression and is controlled by enhancer systems located on one side of the gene cluster [2]. This collinear regulation is thought to have been co-opted from the trunk into the limbs during evolution [2].

FAQ 4: Why is it challenging to identify specific Hox gene binding sites and target genes? This challenge is known as the "Hox Specificity Paradox" [5]. All Hox proteins have very similar DNA-binding domains and can bind to the same high-affinity DNA sequences in test-tube experiments [5]. However, in vivo specificity is achieved through weak interactions at clusters of low-affinity binding sites that do not resemble classic Hox binding sequences [5]. These clusters of low-affinity sites are essential for robust gene activation under varying physiological conditions, explaining why bioinformatic analyses based on high-affinity sites have often been unsuccessful [5].

FAQ 5: What are the key upstream regulators that initiate Hox gene expression in the limb-forming region? The initiation of limb buds and the subsequent activation of the Hox code are governed by a network of transcription factors and signaling molecules [6]. A key upstream regulator for the forelimb is Tbx5, which is directly induced by Hox genes at the forelimb level and, in turn, directly induces expression of Fgf10 in the lateral plate mesoderm [6]. For the hindlimb, the OTX-related homeobox gene Pitx1 acts upstream of Tbx4, which then contributes to Fgf10 activation [6]. The establishment of this Fgf10 feedback loop is a pivotal event in limb initiation [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Weak Hox Gene Expression Patterns in Early Limb Buds

- Potential Cause 1: Inefficient detection of low-affinity binding sites.

- Solution: Focus on identifying clusters of potential binding sites rather than isolated, high-affinity sites. Use biochemical methods to scan enhancer regions for physical evidence of Hox binding, as classic sequence analysis may be insufficient [5].

- Potential Cause 2: Disruption of the temporal collinearity sequence.

- Potential Cause 3: Inadequate fixation or permeabilization of limb bud tissue.

- Solution: Optimize fixation protocols for early mesenchymal tissue. The limb bud is a dense mass of cells, and standard protocols may not allow probes or antibodies to penetrate effectively, leading to weak signal.

Problem: Failure to Observe Expected Homeotic Transformations in Loss-of-Function Experiments

- Potential Cause 1: Functional redundancy between Hox paralogs.

- Solution: Implement paralogous knockout strategies. Due to the overlapping expression and function of Hox genes from different clusters (e.g., HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, HoxD), knocking out a single gene may not yield a phenotype [1]. Simultaneously target all genes within a paralogy group (e.g., HoxA5, HoxB5, HoxC5) to observe a complete transformation [1].

- Potential Cause 2: Incomplete gene inactivation.

- Solution: Use multiple methods to confirm knockout efficiency (e.g., RT-qPCR, Western blot, and functional assays). Consider using dominant-negative forms of Hox genes, but ensure to include controls for specificity [7].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Phenotypic Outcomes of Hox Paralogous Mutations in the Mouse Axial Skeleton

This table synthesizes data from large-scale knockout studies, showing how the simultaneous deletion of all Hox genes within a paralogy group leads to specific homeotic transformations. These principles also apply to the understanding of limb patterning [1].

| Paralogy Group Targeted | Vertebral Element Analyzed | Observed Phenotype (Transformation) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox5 | First Thoracic Vertebra (T1) | Partial transformation; incomplete ribs | Towards a more cervical morphology |

| Hox6 | First Thoracic Vertebra (T1) | Complete transformation to a C7 vertebra | T1 assumes the identity of the last cervical vertebra |

| Hox10 | Lumbar and Sacral Vertebrae | Suppression of rib formation | Ground state is thoracic-like; Hox10 suppresses ribs |

| Hox10 & Hox11 | Sacral Vertebrae | Loss of sacral identity | Combinatorial expression is required for joint formation with the pelvis |

Table 2: Correlation between Histone Modifications and Hox Gene Transcriptional Status

This table, derived from studies in C. elegans and mammals, provides a guide for using epigenetic marks to infer the activation status of Hox clusters, which is crucial for their collinear expression [8].

| Methylation State | H3K4 | H3K9 | H3K27 | H3K36 | Transcriptional Status & Chromatin State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Unmethylated) | Off | On | On | Off | Off: Constitutive heterochromatin |

| 1 (Mono-) | On | Off | Off | On | On: Transcriptionally competent euchromatin |

| 2 (Di-) | On | Off | Off | On | On: Transcriptionally competent euchromatin |

| 3 (Tri-) | On | Off | Off | On | On: Transcriptionally competent euchromatin |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Analyzing Hox Gene Function via Dominant-Negative Electroporation in Chick Limb Buds This protocol is adapted from gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies in chick embryos [7].

- Construct Design: Create a dominant-negative form of the Hox gene of interest (e.g., Hoxa4, Hoxa5, Hoxa6, Hoxa7) by removing the DNA-binding domain.

- Embryo Preparation: Incubate fertilized chick eggs to Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stage 12. Window the eggs under sterile conditions to access the embryo.

- Electroporation: Inject the plasmid DNA into the prospective wing field of the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM). Use electrodes to apply precise electrical pulses, facilitating DNA uptake into the cells.

- Incubation: Allow the embryos to develop for a further 24-48 hours to observe the effects on limb bud initiation and patterning.

- Analysis:

- Use in situ hybridization to assess the expression of downstream markers like Tbx5 and Fgf10.

- Analyze limb bud morphology and size.

- Critical Control: Include a control electroporated with an empty vector to account for non-specific effects of the procedure.

Protocol 2: Investigating Hox Specificity via Low-Affinity Binding Site Mutation This protocol is based on the research that solved the Hox specificity paradox [5].

- Identify Target Enhancer: Select a Hox-regulated enhancer (e.g., from the shavenbaby gene) suspected to contain low-affinity binding sites.

- Biochemical Scanning: Use methods like SELEX or EMSA in the presence of the Hox protein and its cofactor to identify physical binding to enhancer sub-regions. Focus on sites with weak binding affinity.

- Cluster Mutation: Using site-directed mutagenesis, create mutations in the identified clusters of low-affinity binding sites within the enhancer.

- In Vivo Testing:

- Create transgenic fruit flies carrying the wild-type or mutated enhancer linked to a reporter gene (e.g., LacZ).

- Quantify reporter gene expression (e.g., by counting trichomes in the case of shavenbaby) in the relevant Hox expression domain.

- Robustness Testing: Challenge the system by raising flies at sub-optimal temperatures or with genetically reduced levels of the Hox protein to demonstrate the functional importance of the binding site cluster for robust expression.

Signaling Pathway and Regulatory Logic Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Hox Gene and Limb Patterning Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Paralogous Knockout Mice (e.g., HoxA5/B5/C5 null) | To study gene function without redundancy; reveals complete homeotic transformations [1]. | Requires breeding of multiple mutant alleles; phenotypic analysis must be precise (e.g., vertebral identity). |

| Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs | For loss-of-function studies in model systems like chick to block endogenous Hox protein function [7]. | Must remove the DNA-binding domain; critical to include specificity controls for interpretation. |

| Fgf8/Fgf10 Soaked Beads | To test limb-inducing capability and study the Fgf feedback loop by applying protein ectopically [6]. | Bead concentration and placement are critical; can test competence of non-limb tissues (e.g., neck). |

| Hox Protein-Specific Antibodies | For detecting protein expression and localization via immunohistochemistry (IHC). | Cross-reactivity with paralogs can be an issue; validation via knockout tissue is essential. |

| Epigenetic Marker Antibodies (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27me3) | To assess the open/closed state of Hox cluster chromatin via ChIP-seq or immunofluorescence [8]. | Correlate marks with transcriptional activity (see Table 2). |

| Low-Affinity Binding Site Reporter Constructs | To validate functional Hox enhancers and test the role of specific site clusters in vivo [5]. | Requires quantitative readouts (e.g., trichome counting) to detect subtle effects of mutations. |

| E722-2648 | E722-2648, MF:C21H30N2OS2, MW:390.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| C450-0730 | C450-0730, MF:C23H28ClN3O4S, MW:478.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Hox Gene Function in Limb Development

Q1: What is the conclusive genetic evidence that Hox genes are essential for initiating limb formation, rather than just patterning existing buds?

Strong genetic evidence comes from zebrafish models. Deletion of both hoxba and hoxbb clusters (derived from HoxB) results in a complete absence of pectoral fin buds, accompanied by a failure to induce tbx5a expression in the lateral plate mesoderm. This demonstrates that these Hox genes are required upstream for the initial specification of the limb field itself [9] [10].

Q2: How functionally redundant are the different Hox clusters during limb development?

Evidence shows both redundancy and specialization. In zebrafish, deleting all three HoxA- and HoxD-related clusters (hoxaa, hoxab, hoxda) causes severe pectoral fin truncation, more severe than any single or double deletion, confirming redundant roles in fin growth [11]. However, HoxB-related clusters have a unique, non-redundant role in limb positioning [10], showing that redundancy is not absolute.

Q3: What are the key phenotypic differences in limb defects when comparing HoxA/HoxD mutants versus HoxB mutants? The phenotypes are distinct and relate to different stages:

- HoxA/HoxD-related mutants (Zebrafish

hoxaa,hoxab,hoxda; MouseHoxA,HoxD): Display defects in the outgrowth and patterning of existing limb buds. Phenotypes include significant shortening of the endoskeletal disc and fin-fold, and in mice, severe truncation of distal limb elements [11] [12]. - HoxB-related mutants (Zebrafish

hoxba,hoxbb): Exhibit a failure in the very first step—the limb buds do not form in the correct anterior-posterior position, or are absent altogether, due to a failure to inducetbx5a[9] [10].

Q4: Why have traditional mouse knockout studies had difficulty revealing the role of Hox genes in limb positioning? The high degree of functional redundancy between Hox genes, especially within the same paralogy group, has made it difficult to uncover their full roles through single-gene knockouts. The clearest genetic evidence has emerged from more extensive cluster deletions in zebrafish, which circumvent this redundancy and reveal the essential cooperative functions of multiple Hox genes [11] [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Hox Gene Expression and Phenotype Analysis

| Problem & Phenomenon | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

No limb bud formation; absence of tbx5 expression. |

Loss of function in genes specifying limb position (e.g., HoxB-related genes). | Analyze expression of hoxb4, hoxb5, and tbx5 at early stages (e.g., 24-30 hpf in zebrafish) to pinpoint the failure in the initial specification cascade [10]. |

| Severe limb/fin truncation with normal bud initiation. | Loss of function in genes controlling limb outgrowth and patterning (e.g., HoxA/HoxD-related genes). | Examine later markers of proliferation and patterning (e.g., shha). In zebrafish, analyze cartilage staining at 5 dpf to quantify truncation of the endoskeletal disc [11]. |

| Weak or variable phenotypes in single Hox gene mutants. | Functional redundancy from paralogous genes within or across clusters. | Generate compound mutants targeting multiple genes or entire clusters (e.g., hoxaa;hoxab;hoxda) [11]. |

| Ectopic or shifted limb bud position in avian models. | Misexpression of key Hox genes (e.g., Hoxa6, Hoxa7) altering positional identity in the lateral plate mesoderm [7]. |

Precisely map the anterior expression boundaries of multiple Hox genes via in situ hybridization to confirm alterations in the Hox code. |

Table 2: Quantitative Phenotypes in Hox Cluster Mutants

| Model Organ | Genotype | Key Phenotypic Outcome | Quantitative Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish | hoxba-/-; hoxbb-/- |

Complete absence of pectoral fins [9] [10]. | Penetrance: 100% in double homozygotes (15/15 embryos) [10]. |

| Zebrafish | hoxaa-/-; hoxab-/-; hoxda-/- |

Severe shortening of pectoral fins [11]. | Significant shortening of endoskeletal disc and fin-fold length at 5 dpf [11]. |

| Zebrafish | hoxab-/-; hoxda-/- |

Shortening of pectoral fins [11]. | Significant shortening of both endoskeletal disc and fin-fold [11]. |

| Mouse | HoxA and HoxD cluster deletion |

Severe truncation of forelimbs [11]. | Loss of distal limb elements [11] [12]. |

| Chick | Misexpression of Hoxa6/a7 in neck |

Ectopic limb budding [7]. | Ectopic bud formation; however, buds arrest early without AER formation [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Experiments

Protocol 1: Analyzing the Role of Hox Clusters in Zebrafish Fin Development

- Objective: To determine the functional requirement of Hox clusters in pectoral fin development using CRISPR-Cas9-generated cluster mutants.

- Key Reagents: Zebrafish mutants for

hoxaa,hoxab,hoxda,hoxba,hoxbbclusters [11] [10]. - Methodology:

- Genotyping: Perform PCR and sequencing to identify homozygous, heterozygous, and compound mutant larvae [11].

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Quantification: Measure lengths of endoskeletal discs and fin-folds from stained or imaged specimens for statistical comparison [11].

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of Hox Genes in Avian Limb Positioning

- Objective: To test the sufficiency of Hox genes in specifying limb position via electroporation in chick embryos.

- Key Reagents: Full-length

Hoxa6andHoxa7expression constructs; Dominant-negative constructs forHoxa4-a7; FGF beads [7]. - Methodology:

- Electroporation: Introduce constructs into the neck lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) of HH12 chick embryos, a region normally incompetent to form limbs [7].

- Analysis:

- In situ Hybridization: Analyze the expression of

Tbx5,Fgf10, andFgf824-48 hours post-electroporation. - Phenotypic Tracking: Monitor embryos for the formation of ectopic limb buds.

- Transcriptomics: Use RNA-seq to compare the transcriptomes of ectopic buds, normal forelimb buds, and neck tissue to identify differentially expressed genes [7].

- In situ Hybridization: Analyze the expression of

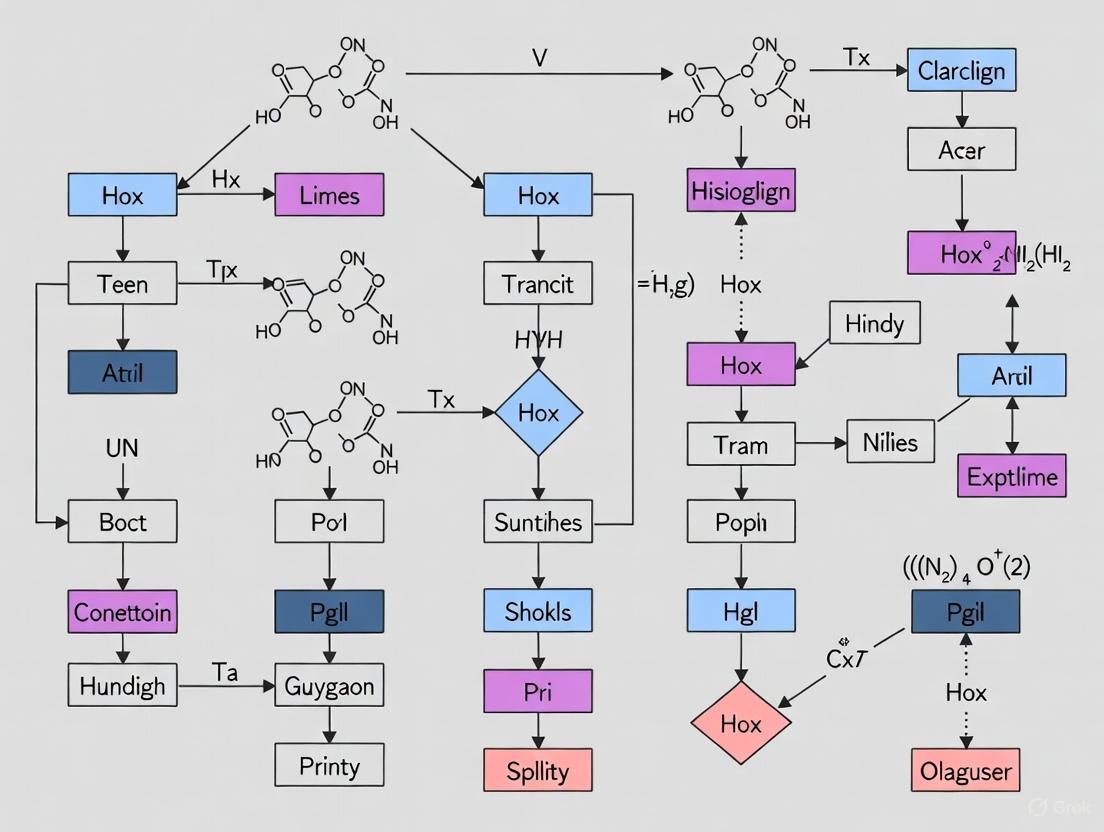

Signaling Pathways and Genetic Hierarchies

Diagram 1: Hox Gene Genetic Hierarchy in Zebrafish Fin Development

Diagram Title: Hox Gene Hierarchy in Fin Development

Diagram 2: Hox Gene Functional Specialization Across Models

Diagram Title: Hox Gene Functional Roles

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Hox Genes in Limb Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | For generating targeted knockouts of specific Hox genes or entire clusters. | Creating zebrafish hox cluster deletion mutants (e.g., hoxaa-/-;hoxab-/-;hoxda-/-) to study functional redundancy [11]. |

| Hox Expression Plasmids | For gain-of-function studies via electroporation or injection. | Electroporating Hoxa6/Hoxa7 into chick neck LPM to test sufficiency in limb bud induction [7]. |

| Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs | To inhibit the function of specific Hox proteins and their paralogs. | Electroporating dnHoxa4-7 into chick wing fields to test necessity in limb specification [7]. |

| Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization (WISH) | To visualize the spatial expression patterns of genes. | Detecting tbx5a expression in zebrafish fin fields or shha in fin buds to assess genetic hierarchies [11] [10]. |

| Alcian Blue Stain | To stain cartilaginous structures in developing embryos. | Visualizing and measuring the endoskeletal disc in zebrafish larval pectoral fins at 5 dpf [11]. |

| F7H | 4-fluoro-N-[4-[2-oxo-2-[(4-phenyl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]ethyl]sulfanylphenyl]benzamide | Research-grade 4-fluoro-N-[4-[2-oxo-2-[(4-phenyl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]ethyl]sulfanylphenyl]benzamide for laboratory use. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic applications. |

| GST-FH.1 | GST-FH.1, MF:C15H13N3O3S, MW:315.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQ: The Core Regulatory Network

What is the primary functional role of Hoxb4a, Hoxb5a, and Hoxb5b in limb development?

Hoxb4a, Hoxb5a, and Hoxb5b are transcription factors that cooperatively provide positional cues along the anterior-posterior axis within the lateral plate mesoderm. Their primary role is to specify the initial position for limb bud formation by directly inducing the expression of tbx5a, a master regulator of forelimb initiation [10] [13]. In zebrafish, the combined deletion of the hoxba and hoxbb clusters (which contain these genes) results in a complete absence of pectoral fins, demonstrating their essential function [13].

How does retinoic acid (RA) signaling interact with this Hox gene network?

Retinoic acid (RA) signaling acts upstream of these Hox genes. Evidence from zebrafish indicates that hoxb5b is an RA-responsive gene [14]. Furthermore, the competence of the lateral plate mesoderm to respond to retinoic acid and subsequently induce tbx5a expression is lost in hoxba;hoxbb cluster mutants, placing these Hox genes as crucial mediators of RA signaling in limb positioning [10] [13].

The following diagram illustrates the core genetic pathway and the phenotypic consequence of its disruption.

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Challenges

Issue: Failure to Detect Hox Gene Expression or Function

| Problem Area | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Redundancy | Functional compensation by paralogous genes (e.g., between hoxba and hoxbb clusters) [10] [13]. |

Generate compound mutants targeting multiple genes or entire clusters (e.g., hoxba;hoxbb double mutants) using CRISPR-Cas9 [13]. |

| Low Phenotype Penetrance | Incomplete penetrance observed with single-gene frameshift mutations [10] [13]. | Use genomic locus deletion mutants instead of single-gene mutants to fully abolish regulatory elements and gene function. Analyze large sample sizes for statistical significance [10]. |

| Upstream Signaling Defects | Disruption in the retinoic acid (RA) signaling pathway, which lies upstream of Hox genes [14]. | Verify RA pathway integrity. Use pharmacological inhibitors (e.g., DEAB, BMS189453) as a control to mimic RA deficiency and compare with Hox mutant phenotypes [14]. |

Issue: Disrupted Downstream Limb Bud Initiation

| Problem Area | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Absence of tbx5a Expression | Failure of Hox genes to activate the key downstream effector tbx5a in the lateral plate mesoderm [10] [13]. |

Perform whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) for tbx5a at early stages (e.g., 30 hpf in zebrafish) as a primary readout for Hox gene function in limb positioning [13]. |

| Heart Field Expansion | Loss of non-autonomous restriction signals from the forelimb field, leading to an enlarged heart, a converse phenotype to limb loss [14]. | Extend analysis beyond the limb field. Examine cardiac progenitor markers (e.g., amhc, vmhc) to assess potential field expansion due to loss of Hox-mediated signaling [14]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Genetic Validation of Hox Gene Function in Zebrafish

Objective: To confirm the essential role of hoxb4a, hoxb5a, and hoxb5b in pectoral fin positioning via cluster deletion.

Workflow Summary:

- Mutant Generation: Use CRISPR-Cas9 to create large deletion mutants encompassing the

hoxbaandhoxbbgenomic loci [13]. - Genotypic Validation: Confirm homozygous double mutants via PCR and sequencing.

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Morphology: Score for the presence or absence of pectoral fins at 3 days post-fertilization (dpf).

- Molecular Marker: Perform WISH for

tbx5aat ~30 hours post-fertilization (hpf) on progeny from incrosses of double heterozygotes [13].

- Functional Rescue: Test the requirement of specific genes by co-injecting mRNA (e.g.,

hoxb5b) into mutant embryos and assessingtbx5arescue.

The workflow for this genetic analysis is detailed below.

Protocol: Inhibiting Retinoic Acid Signaling

Objective: To probe the upstream relationship between RA signaling and Hox gene function.

Methodology:

- Treatment Window: Expose zebrafish embryos to RA signaling inhibitors starting at 40% epiboly (just before gastrulation) for early roles, or at the 6-8 somite stage to assess atrial-specific effects [14].

- Reagents:

- DEAB (Diethylaminobenzaldehyde): A retinaldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor, used at 10-50 µM to block RA synthesis.

- BMS189453: A pan-RAR antagonist, used at 1-10 µM to block RA receptor signaling [14].

- Analysis: Examine the resulting phenotypes, which should include fin loss and heart enlargement, and compare them to Hox cluster mutant phenotypes [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Generation of cluster deletion mutants to overcome genetic redundancy [10] [13]. | Target multiple guide RNAs to flank the entire genomic locus of a hox cluster for complete deletion. |

| DEAB (RA Synthesis Inhibitor) | To chemically inhibit retinoic acid synthesis and mimic upstream signaling defects [14]. | Use during early gastrulation (40% epiboly) to observe the most severe effects on both limb and heart fields. |

| BMS189453 (RAR Antagonist) | To block retinoic acid receptor function and validate RA-dependent processes [14]. | Can be used at later stages (e.g., 6-8 somites) to dissect stage-specific requirements. |

| tbx5a RNA Probe (for WISH) | Essential molecular marker for visualizing and quantifying the initiation of the limb field [10] [13]. | A significant reduction or absence of tbx5a signal is the primary indicator of successful Hox pathway disruption. |

| Cardiac Myosin Heavy Chain Probes (amhc, vmhc) | Markers for analyzing the non-autonomous effect on heart field size [14]. | An expansion of cardiac progenitor domains is a converse phenotype confirming field regulation. |

| ICMT-IN-49 | ICMT-IN-49, MF:C27H31NO3, MW:417.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| CDA-IN-2 | CDA-IN-2, MF:C17H16N2O7, MW:360.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the musculoskeletal system, bone, tendon, and muscle tissues develop in a spatially and temporally coordinated manner, integrating into a cohesive functional unit. Hox genes, a family of highly conserved developmental regulators, play critical roles in patterning this system along the anterior-posterior (A-P) and proximodistal (PD) axes [15]. A fundamental concept in this process is temporal collinearity, where Hox genes are activated sequentially during mid-gastrulation following their chromosomal order, from 3' to 5' within the Hox clusters [16] [3]. This "Hox timer" mechanism translates temporal activation sequences into precise spatial organization along the extending body axis [16]. In limb development, this translates into distinct roles for posterior Hox paralogs (Hox9-13) in patterning the limb skeleton along the PD axis, with non-overlapping functions that determine the identity of the stylopod (upper limb), zeugopod (lower limb), and autopod (hand/foot) [15]. Understanding the gastrulation origins and precisely timed activation windows of these genes is therefore fundamental for researchers aiming to optimize detection and manipulation of Hox gene expression in early limb buds.

Key Concepts and Definitions

Temporal Collinearity (TC): The sequential activation of Hox genes in time, matching their genomic order within a cluster. This precedes and leads to spatial collinearity [3].

Spatial Collinearity (SC): The spatial sequence of Hox gene expression along the anterior-posterior body axis that matches their genomic order [3].

Hox Timer / Hox Clock: A timing mechanism that implements a time-sequenced activation of Hox genes, believed to be responsible for patterning the vertebrate A-P axis [16] [3].

Posterior Prevalence (PP) / Posterior Dominance (PD): A phenomenon where more 5' (posterior) Hox genes functionally dominate over more 3' (anterior) genes, repressing their expression or function [3].

Technical FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the critical temporal windows for detecting Hox gene activation during early limb development?

The initiation of Hox gene expression in the limb bud is a tightly regulated, multi-phase process. Research indicates two critical waves of transcriptional activation, controlled by different mechanisms [17].

- First Wave (Proximal Patterning): This initial, time-dependent wave is essential for the growth and polarity of the proximal limb up to the forearm (stylopod and zeugopod). It is controlled by opposite regulatory modules and exhibits classical temporal collinearity [17].

- Second Wave (Distal Patterning): This subsequent phase involves different regulatory mechanisms and is required for the morphogenesis of distal structures, the digits (autopod) [17]. The posterior HoxA and HoxD clusters (specifically Hox9-13 paralogs) are expressed in both forelimbs and hindlimbs, with HoxC expression restricted to the hindlimb [15].

FAQ 2: Why is my spatial detection of Hox expression patterns weak or non-collinear?

Weak or non-collinear spatial patterns often stem from issues related to the developmental stage or the molecular signals that coordinate the translation of temporal into spatial collinearity.

- Incorrect Developmental Staging: Hox spatial collinearity (SC) is a direct result of prior temporal collinearity (TC) [3]. Sampling embryos too early or too late relative to the gastrulation and early limb bud stages will miss the establishment of this pattern. In mouse models, the forelimb bud emerges at approximately embryonic day 9 (E9) [15].

- Disrupted Signaling Pathways: Evidence from multiple vertebrate models (Xenopus, chicken, zebrafish) shows that the BMP/anti-BMP signaling antagonism is a general regulator of Hox collinearity [3]. The conversion of TC to SC is regulated by these signals; BMP-rich environments may only show TC, while the introduction of anti-BMP signals (e.g., Noggin) is required to stabilize nascent Hox codes and generate the spatially collinear axial pattern [3]. Ensure that experimental conditions or model systems have not disrupted this critical pathway.

FAQ 3: How does the origin of musculoskeletal tissues impact Hox gene detection?

The different components of the musculoskeletal system have distinct embryonic origins, which can influence Hox expression profiles and detection strategies.

- Lateral Plate Mesoderm: Gives rise to the limb bud itself, including the cartilage and tendon precursors [15]. Hox genes are highly expressed in the stromal connective tissues derived from this mesoderm and are regionally expressed in tendons and muscle connective tissue [15].

- Somitic Mesoderm: Gives rise to the muscle precursors, which migrate into the limb bud [15]. Crucially, studies show that early patterning of connective tissue and skeletal elements occurs autonomously and does not require the presence of muscle, as demonstrated in muscle-less limb models [15]. Therefore, your cell type of interest and its embryonic origin must be carefully considered when interpreting Hox detection assays.

Table 1: Functional Roles of Hox Paralogs in Vertebrate Limb Patterning

| Paralog Group | Primary Limb Segment Affected | Phenotype of Loss-of-Function | Key Regulatory Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hox5 | Anterior-Posterior (AP) Axis of Forelimb | Anterior patterning defects; loss of repression of anterior Shh expression [15]. | Interacts with Plzf to restrict Shh to the posterior limb bud [15]. |

| Hox9 | Initiation of AP Patterning | Shh expression not initiated; disruption of AP patterning [15]. | Promotes posterior Hand2 expression, inhibiting Gli3 to allow Shh induction [15]. |

| Hox10 | Proximal Stylopod (e.g., Humerus/Femur) | Severe mis-patterning of the stylopod [15]. | Non-overlapping function; critical for proximal segment identity [15]. |

| Hox11 | Medial Zeugopod (e.g., Radius/Ulna) | Severe mis-patterning of the zeugopod [15]. | Non-overlapping function; critical for medial segment identity [15]. |

| Hox12/Hox13 | Distal Autopod (Hand/Foot) | Complete loss of autopod skeletal elements [15]. | Required for initiating and maintaining Shh expression; critical for distal structures [15]. |

Table 2: Key Signaling Pathways Regulating Hox Collinearity and Limb Patterning

| Signaling Pathway | Role in Hox Expression & Limb Patterning | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| BMP / anti-BMP | General regulator of Hox collinearity; translates temporal collinearity (TC) into spatial collinearity (SC) [3]. | In Xenopus, anti-BMP (Noggin) challenges generate parts of the spatially collinear Hox pattern. Similar findings in chicken and zebrafish [3]. |

| Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) | Critical for AP patterning and maintained expression of posterior Hox genes in the limb [15]. | Loss of Hox9 or Hox5 paralogs disrupts Shh initiation or restriction. Loss of posterior HoxA/D results in failed Shh initiation/maintenance [15]. |

| FGF Signaling | Part of the Fgf10-Fgf8 feedback loop essential for limb bud initiation and outgrowth [7]. | Hoxa6/a7 are sufficient to induce Tbx5 and Fgf10 in the neck region, initiating this loop [7]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Gain/Loss-of-Function Analysis for Hox Gene Function in Limb Patterning

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the necessity and sufficiency of Hox genes in specifying forelimb position [7].

1. Research Objective: To determine if a specific Hox gene is necessary and/or sufficient for limb field specification and budding.

2. Key Reagents:

- For Loss-of-Function (LOF): Dominant-negative forms of Hox genes (e.g., lacking the DNA-binding domain), siRNA, or CRISPR-Cas9 knockout constructs.

- For Gain-of-Function (GOF): Full-length Hox gene expression constructs.

- Model System: Chick embryos at pre-limb bud stage (e.g., HH12).

- Electroporation System: For precise delivery of constructs into the target tissue (e.g., lateral plate mesoderm).

- Marker Genes: Antibodies or RNA probes for Tbx5, Fgf10, Fgf8, and Shh.

3. Methodology:

- LOF Experimental Arm:

- Electroporate dominant-negative Hox constructs into the prospective wing field of the lateral plate mesoderm.

- Culture embryos and analyze for down-regulation of early limb markers (Tbx5, Fgf10, Fgf8) via in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry.

- Assess the resulting limb bud size and morphology.

- GOF Experimental Arm:

- Electroporate full-length Hox constructs into a non-limb forming region (e.g., neck lateral plate mesoderm).

- Assess for ectopic expression of Tbx5 and Fgf10, indicating a posteriorization of cell identity.

- Examine whether an ectopic limb bud forms and analyze its molecular signature (e.g., via RNA-seq) to determine which limb development circuits are activated or missing.

4. Critical Controls:

- Validate the specificity of dominant-negative constructs to ensure effects are due to disruption of the targeted Hox proteins [7].

- Co-electroporation experiments (e.g., GOF Hoxa6/a7 with dnHoxA4/a5) to test the interplay and specificity between different Hox paralogs [7].

Protocol 2: Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomic Profiling of Hox Codes

This protocol leverages advanced sequencing technologies to create a high-resolution atlas of Hox gene expression in the developing spine and limb, as demonstrated in recent human fetal studies [18].

1. Research Objective: To delineate the precise rostrocaudal and cell-type-specific expression of HOX genes during development.

2. Key Reagents & Platforms:

- Tissue: Human or mouse fetal spines/limbs from precisely defined developmental stages and anatomical segments.

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNAseq): Droplet-based method (e.g., 10X Genomics Chromium).

- Spatial Transcriptomics (ST): Visium spatial gene expression slides.

- In-Situ Sequencing (ISS): High-plex, single-cell resolution method (e.g., Cartana).

- Bioinformatics Tools: Cell type clustering algorithms (e.g., Seurat), spatial mapping algorithms (e.g., cell2location).

3. Methodology:

- Tissue Processing: Dissect spines or limbs into precise anatomical segments along the rostrocaudal axis. Generate single-cell suspensions for scRNAseq.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare scRNAseq, ST, and ISS libraries according to platform-specific protocols.

- Data Integration & Analysis:

- Cluster scRNAseq data to define cell types.

- Use spatial transcriptomics (ST) to validate and map cell types to anatomical locations.

- Apply in-situ sequencing (ISS) for single-cell resolution of a targeted gene panel, including key HOX genes.

- Perform differential expression testing to identify position-specific HOX codes, excluding genes with low segment-specificity or ubiquitous expression in certain cell types.

4. Key Outputs:

- A validated rostrocaudal HOX code comprising the most position-specific genes across stationary cell types [18].

- Identification of HOX gene expression peculiar to specific cell lineages (e.g., tendon cells expressing HOXA6, HOXD3, HOXD4, HOXD8 ubiquitously) [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hox Gene Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant-Negative Hox Constructs | To inhibit the function of specific Hox proteins in loss-of-function studies. | Constructs lacking the DNA-binding domain; requires careful validation of specificity [7]. |

| Full-Length Hox Expression Constructs | For gain-of-function studies to test sufficiency in cell fate transformation. | Used to induce ectopic gene expression and patterning, e.g., in non-limb forming regions [7]. |

| In Situ Hybridization (ISH) Probes | To visualize the spatiotemporal expression patterns of Hox mRNAs in tissue sections. | Considered a gold standard for avoiding confusion from whole-embryo analyses; allows tissue and location distinction [3]. |

| scRNAseq & Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms | To profile gene expression at single-cell resolution and map it to anatomical context. | 10X Genomics Chromium (scRNAseq, Visium); Cartana (ISS) [18]. |

| BMP Pathway Modulators | To manipulate the BMP/anti-BMP signaling that regulates Hox collinearity. | Recombinant BMP4 (agonist); Noggin (antagonist) [3]. |

| Markers for Limb Patterning | To assess the molecular and morphological outcomes of Hox perturbation. | Antibodies/RNA probes for Tbx5, Fgf10, Fgf8, Shh, and skeletal stains [15] [7]. |

| Dihydroartemisinin | Dihydroartemisinin, MF:C15H24O5, MW:284.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AAL-149 | (S)-2-Amino-4-(4-(heptyloxy)phenyl)-2-methylbutan-1-ol | Research compound (S)-2-Amino-4-(4-(heptyloxy)phenyl)-2-methylbutan-1-ol, a PP2A activator for pulmonary fibrosis studies. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Visualizing Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Logic

FAQ: Core Concepts and Definitions

What is positional memory in the context of developmental biology? Positional memory is the mechanism by which cells retain information about their original spatial location within a tissue or along a body axis. This information, often established during embryonic development by transcription factors like HOX genes, instructs cells during processes like tissue repair, regeneration, and homeostasis, ensuring new structures integrate correctly with existing ones [19] [20]. In limb regeneration, for instance, connective tissue cells maintain distinct anterior and posterior identities that are crucial for launching the correct regenerative program [19].

How do HOX genes establish and maintain positional identity? HOX genes encode a family of transcription factors that are master regulators of the body plan during embryogenesis. They are organized into four clusters (HOXA, HOXB, HOXC, HOXD) in mammals and are expressed in a spatiotemporally collinear fashion—genes at the 3' end of a cluster are expressed earlier and in more anterior regions, while genes at the 5' end are expressed later and in more posterior regions [21] [18] [22]. This creates a "HOX code" that provides each cell with its positional address. This code is maintained in many adult tissues, including the skeleton, where it continues to regulate stem cell function and repair in a location-specific manner [20] [22].

What is the relationship between positional memory and cellular plasticity? Positional identity, established by HOX genes and their MEINOX cofactors, is a key determinant of cellular plasticity—the ability of a cell to change its phenotype. This plasticity is essential for both normal tissue homeostasis and regenerative responses. However, the dysregulation of this system can lead to pathological conditions. Altered HOX-MEINOX expression can promote excessive cellular plasticity, facilitating processes like epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) that drive fibrosis and cancer metastasis [21].

FAQ: Technical Challenges and Experimental Troubleshooting

What are the major technical hurdles in detecting HOX gene expression, especially in archived tissues? A primary challenge is that standard fixation protocols often over-fix tissues, which can mask the target mRNA and trap it within ribosomes, making it inaccessible for detection by standard in situ hybridization (ISH) protocols. One study noted that with standard methods, less than 20% of archived human tissue samples yielded reliable labeling [23]. This is a significant obstacle for leveraging valuable biobanks.

How can I optimize my in situ hybridization protocol for HOX mRNA detection in fixed tissues? An optimized, non-radioactive ISH protocol was developed to overcome fixation barriers [23]. The key modifications are summarized in the table below, focusing on enhanced target retrieval and detection.

Table 1: Key Modifications in an Optimized ISH Protocol for HOX Gene Detection

| Protocol Step | Standard Protocol Challenge | Optimized Solution | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dewaxing & Rehydration | Standard times may be insufficient. | Extended dewaxing (overnight in xylene) and rehydration. | Complete paraffin removal improves probe penetration. |

| Post-fixation | Not always included. | Refix in 2% PFA for 10 min at 4°C. | Stabilizes superficial tissue layers without hindering mRNA detection. |

| HCl Treatment | Often omitted. | Incubate with 2M HCl for 10 min at 30°C. | Helps break down crosslinks and improve mRNA accessibility. |

| Proteolysis | Concentration and time are critical. | Use Proteinase K (50 µg/mL) for 30 min at 37°C. | Digests proteins cross-linked to mRNA. |

| Lipid Removal | Not typically performed. | Incubate with chloroform for 5 min after dehydration. | Removes lipids that can block probe access. |

| Hybridization Buffer | Standard buffers may lack penetration enhancers. | Supplement with Triton X-100 (0.2-0.4%). | A detergent that enhances probe penetration into fixed tissue. |

| Detection | Fluorescent methods may lack sensitivity. | Use an anti-FITC antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase with NBT/BCIP chromogenic stain. | Provides high-sensitivity, permanent staining. |

Why might my experiments fail to show a phenotype after perturbing a single HOX gene, and how can I address this? This is a common issue due to the high degree of functional redundancy between HOX genes. During development, paralogous genes (those in the same position in different clusters, e.g., HOXA9, HOXB9, HOXC9, HOXD9) often have overlapping functions and expression patterns. A loss-of-function in one may be compensated for by its paralogs [22]. To address this:

- Target multiple paralogs: Use genetic approaches to create compound mutants of two or more paralogous genes.

- Analyze specific cell types: Phenotypes might be cell-type-specific. Employ single-cell RNA sequencing or conditional knockout models targeting specific tissues or developmental timepoints [18] [22].

- Look beyond gross morphology: Subtle phenotypes may exist in cellular behavior, proliferation, or molecular pathways that are not immediately visible.

How is positional memory studied in a regenerating system like the axolotl limb? Research on axolotls has identified specific molecular circuits that maintain positional memory. A key mechanism is a positive-feedback loop involving the transcription factor Hand2 and the signaling molecule Sonic hedgehog (Shh) [19].

- In posterior cells, residual Hand2 from development primes them to express Shh after amputation.

- During regeneration, Shh signaling, in turn, maintains Hand2 expression.

- After regeneration, Shh is turned off, but Hand2 expression persists, preserving the posterior memory state. This circuit can be experimentally manipulated; for example, transiently exposing anterior cells to Shh can kick-start this loop and convert them to a stable posterior identity [19].

Diagram: The Hand2-Shh Positive-Feedback Loop Maintaining Posterior Positional Memory

What role does retinoic acid (RA) play in positional identity, and how can I modulate its signaling? RA is a critical morphogen for specifying proximal identity along the proximodistal (PD) limb axis. In regeneration, higher RA signaling in proximal blastemas activates genes like Meis1/2, which confer a proximal identity. The level of RA signaling is actively controlled not just by synthesis but also by its breakdown via the enzyme CYP26B1 [24].

- Distal blastemas have higher CYP26B1 activity, breaking down RA to maintain a distal identity.

- Inhibiting CYP26B1 (e.g., with pharmacological inhibitors) in a distal blastema increases RA signaling, reprogramming it to a more proximal identity and causing serial duplications of limb segments [24].

- Key genes like Shox and Shox2 are RA-responsive and help confer proximal positional identity [24].

Diagram: Retinoic Acid Signaling Determines Proximodistal Identity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Models for Studying Positional Memory

| Reagent / Model | Function / Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|

| ZRS (MFCS1) Enhancer Reporters | Drives expression of reporters (e.g., TFP, Cre) in Shh-expressing cells. Used for lineage tracing. | Revealed that embryonic Shh-lineage cells are dispensable; other posterior cells can activate Shh during regeneration [19]. |

| Hand2:EGFP Knock-in Axolotl | Reports and tracks endogenous Hand2 expression. | Identified Hand2 as a key priming factor for posterior identity, expressed before Shh after injury [19]. |

| CYP26B1 Inhibitors | Pharmacologically blocks RA breakdown, increasing local RA signaling. | Demonstrated that RA degradation is required for distal identity; its inhibition reprograms distal blastemas to a proximal fate [24]. |

| Conditional HOX Knockout Mice | Enables tissue-specific or time-specific deletion of Hox genes. | Revealed Hox gene functions in adult tissue maintenance, stem cell regulation, and location-specific bone repair [20] [22]. |

| Optimized ISH Probe Sets | FAM-labeled DNA oligomers for high-sensitivity chromogenic detection. | Enabled reliable HOX mRNA detection in a wide range of fixed human tissues, including over-fixed archives [23]. |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | Profiles gene expression (including the "HOXOME") at single-cell resolution. | Mapped HOX codes with high spatial precision in complex tissues like the developing human spine [18]. |

| HIV-1 inhibitor-69 | HIV-1 inhibitor-69, CAS:257891-65-9, MF:C16H20ClN3S, MW:321.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ELA-11(human) | 4-Iodo-5-(o-tolyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-amine | 4-Iodo-5-(o-tolyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-amine for research. Explore its applications in medicinal chemistry. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Advanced Detection Platforms: From Single-Cell Genomics to Spatial Mapping

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to study complex biological systems by enabling the profiling of gene expression at the resolution of individual cells. This technology is particularly valuable for investigating the limb mesenchyme, a highly heterogeneous population of mesenchymal progenitor cells that give rise to the diverse skeletal elements, tendons, and connective tissues of the vertebrate limb. The application of scRNA-seq to early limb buds allows researchers to resolve the cellular heterogeneity within the mesenchyme and decipher the molecular mechanisms controlling limb patterning and morphogenesis.

A key aspect of limb patterning along the anterior-posterior axis is regulated by HOX genes, which exhibit a spatially restricted expression pattern that correlates with their position within the HOX clusters. The 3' to 5' expression of HOX genes in the clusters corresponds to their expression along the anterior-posterior axis of the developing limb [18]. Creating a detailed atlas of the murine limb skeleton through scRNA-seq has revealed 39 distinct cell types and states, with 26 clusters originating from the mesenchymal lineage, providing an invaluable resource for understanding limb development [25].

Technical Challenges and Solutions for Limb Mesenchyme Studies

Key Technical Challenges in scRNA-seq

| Challenge | Impact on Data Quality | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low RNA Input [26] | Incomplete reverse transcription, technical noise, inadequate coverage [26] | Standardize cell lysis/RNA extraction; implement pre-amplification methods [26] |

| Amplification Bias [26] | Skewed gene representation, overestimated expression levels [26] | Use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs); incorporate spike-in controls [26] |

| Dropout Events [26] | False negatives, particularly problematic for lowly expressed genes like some HOX genes [26] | Apply computational imputation methods; use targeted approaches (SMART-seq) for higher sensitivity [26] |

| Cell Doublets [26] | Misidentification of cell types, confounding of downstream analysis [26] | Implement cell hashing; utilize computational doublet detection tools (DoubletFinder, Scrublet) [26] |

| Batch Effects [26] | Systematic technical variations confound biological signals [26] | Apply batch correction algorithms (Combat, Harmony, Scanorama) [26] |

Methodological and Biological Challenges Specific to Limb Research

Cell Dissociation and Viability: The process of generating single-cell suspensions from limb bud tissue can induce cellular stress and alter gene expression profiles. This is particularly problematic for studying precise expression patterns of key developmental regulators like HOX genes. Optimization of dissociation protocols is essential to minimize these effects and maintain RNA integrity [26].

Spatial Context Loss: scRNA-seq provides detailed transcriptomic information but loses the native spatial organization of cells within the limb bud. This is a significant limitation for studying patterning mechanisms. Solutions include combining scRNA-seq with spatial transcriptomics techniques such as Visium spatial transcriptomics or in-situ sequencing (ISS) to preserve spatial information [26] [18].

Rare Cell Populations: Identifying rare but biologically important progenitor populations in the limb mesenchyme can be challenging due to low cell numbers and potentially low expression levels of marker genes. Targeted approaches with higher sensitivity, such as SMART-seq, can help detect these populations and low-abundance transcripts [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q: How does dead cell percentage impact data quality in limb mesenchyme studies, and what viability threshold is recommended? A: Dead cells release ambient RNA, which increases background noise and can lead to missed sequencing targets and suboptimal results. This is particularly problematic when trying to detect the expression of key regulators like HOX genes. We recommend maintaining cell viability above 90% for optimal results [27].

Q: What sequencing depth is recommended for detecting lowly expressed transcription factors like HOX genes in limb mesenchyme? A: For standard 10x Genomics workflows, we recommend a minimum of 100,000 reads per cell to maximize the identification of transcripts, including those with low expression levels [27]. However, for more comprehensive coverage, especially when studying rare cell populations or low-abundance transcripts, deeper sequencing may be beneficial.

Q: How can I accurately resolve the distinct mesenchymal subpopulations present in the developing limb bud? A: Successfully resolving limb mesenchymal subpopulations requires careful experimental design and analysis:

- Ensure adequate cell numbers: Profiling a sufficient number of cells increases the likelihood of capturing rare populations.

- Use appropriate clustering parameters: Over-clustering can split biologically homogeneous populations, while under-clustering can mask important heterogeneity.

- Validate findings with orthogonal methods: Confirm key findings using spatial transcriptomics or in-situ hybridization to verify both identity and spatial localization of clusters [25].

Q: What are the key quality control metrics I should check after scRNA-seq data generation? A: The three primary QC metrics are:

- Count depth: The total number of UMIs per cell; low values may indicate poor-quality cells.

- Number of detected genes: The number of genes expressed per cell; low values may indicate damaged cells.

- Mitochondrial fraction: The fraction of counts from mitochondrial genes; high values (>10-20%) often indicate stressed or dying cells [28] [29].

Additionally, for limb studies, examine the expression of housekeeping genes and check for unexpected expression of hemoglobin genes (HBB) which may indicate red blood cell contamination [29].

Experimental Workflow and Protocol Optimization

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

Tissue Dissociation Protocol for Limb Buds:

- Work quickly with fresh tissue when possible, using pre-chilled solutions to maintain RNA integrity.

- Use gentle enzymatic digestion cocktails suitable for mesenchymal tissues (e.g., collagenase-based enzymes).

- Continuously monitor dissociation progress to avoid over-digestion which can reduce cell viability and alter gene expression.

- Filter the cell suspension through appropriate mesh (30-40μm) to remove debris and cell clumps.

- Always assess viability and cell concentration before proceeding to library preparation. Cell viability should exceed 90% for optimal results [27].

Sample Requirements:

- For tissue samples: ~100 mg of frozen tissue is typically sufficient.

- For cell suspensions: 5×10ⵠto 1×10ⶠcells in 1 ml of appropriate freezing media.

- Use standard freezing media without Mg²⺠and Ca²⺠as these can inhibit downstream processing [27].

Library Preparation and Sequencing Strategies

SC RNA-seq Workflow

Several library preparation methods are available, each with advantages for developmental studies:

Droplet-Based Methods (10x Genomics): Enable high-throughput profiling of thousands of cells, ideal for capturing the full heterogeneity of limb mesenchyme. These methods typically use UMIs to correct for amplification bias [28].

Combinatorial Indexing (Parse Biosciences Evercode): Uses split-pool combinatorial barcoding without specialized instrumentation, allowing for fixation of samples which can simplify time-course experiments [30].

Plate-Based Methods (SMART-seq): Provide full-length transcript coverage which can be advantageous for detecting isoform-level differences, but with lower throughput.

For HOX gene expression studies specifically, consider using 3'-end enriched protocols as many HOX genes are located near the 3' end of transcripts, making them more amenable to detection with these methods [31].

Data Analysis Guidelines for Limb Mesenchyme Studies

Quality Control and Preprocessing

Cell Quality Control:

- Remove cells with low UMI counts (<500-1000 depending on protocol)

- Exclude cells with high mitochondrial content (>10-20%)

- Filter out cells with unusually high UMI counts/gene counts (potential doublets)

- Eliminate cells with high hemoglobin gene expression (indicates red blood cell contamination) [29]

Gene Quality Control:

- Remove genes detected in very few cells (<10 cells)

- Filter out genes with consistently low expression across all cells

Special Considerations for HOX Gene Analysis

HOX genes present specific challenges for scRNA-seq analysis due to their:

- Low to moderate expression levels

- High degree of sequence similarity between paralogs

- Precise spatial expression patterns that may be lost upon tissue dissociation

To optimize HOX gene detection:

- Targeted Analysis: Include HOX genes in your feature selection rather than relying solely on highly variable gene detection.

- Spatial Validation: Use spatial transcriptomics or in-situ hybridization to validate HOX expression patterns observed in scRNA-seq data [18].

- Pseudospatial Reconstruction: Apply trajectory inference algorithms to reconstruct proximal-distal patterning based on HOX gene expression gradients [25].

Hox Gene Analysis Pipeline

Research Reagent Solutions for Limb Mesenchyme Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3' (10x Genomics) [18] | Droplet-based single cell partitioning and barcoding | Ideal for high-throughput profiling of limb bud cells; uses UMIs to minimize amplification bias |

| Evercode Whole Transcriptome (Parse Biosciences) [30] | Combinatorial barcoding without specialized instrumentation | Enables sample fixation; useful for time-course experiments of limb development |

| Cell Ranger [28] | Raw data processing pipeline | Performs demultiplexing, barcode processing, and UMI counting for 10x Genomics data |

| Seurat [28] | R package for scRNA-seq analysis | Provides comprehensive toolkit for QC, normalization, clustering, and differential expression |

| CellPhoneDB [25] | Cell-cell communication analysis | Considers multimeric receptor complexes; useful for studying signaling in limb patterning |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Spatial Transcriptomics

Integrating scRNA-seq with spatial transcriptomics approaches is particularly powerful for limb development studies, as it preserves the critical spatial context of gene expression patterns. The Limb Skeletal Cell Atlas (LSCA) demonstrates how this integration can reveal the spatial organization of mesenchymal subpopulations and their relationship to signaling centers like the Zone of Polarizing Activity (ZPA) and Apical Ectodermal Ridge (AER) [25].

For HOX gene studies specifically, spatial transcriptomics and in-situ sequencing can validate and refine the expression patterns observed in dissociated cells. Research has shown that HOX gene expression can define proximal-distal patterning in the limb bud, with genes like Hoxa9 and Hoxd9 expressed more proximally, while Hoxa13 and Hoxd13 mark distal regions [25] [18].

This integrated approach allows researchers to not only identify mesenchymal subpopulations but also understand their positional identities and potential roles in patterning the developing limb.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Experimental Design and Platform Selection

Q: What are the key considerations when selecting a spatial transcriptomics platform for studying Hox expression domains in early limb buds?

A: The choice of platform involves trade-offs between resolution, gene throughput, and sample compatibility. For mapping precise Hox expression boundaries in early limb buds, which require single-cell or subcellular resolution, high-resolution in situ profiling platforms are recommended. The lessons from profiling over 1,000 spatial samples indicate that platform selection should be driven by the specific research question, with a need to balance resolution, spatial capture area, and multiplexing capability [32].

Q: How can I mitigate the challenges of working with limited or precious clinical samples, such as early embryonic tissues?

A: Robust tissue handling is critical. Best practices informed by large-scale spatial studies include [32]:

- Optimal Freezing: Snap-freeze tissues in OCT compound using a dry ice-ethanol or liquid nitrogen bath to prevent RNA degradation and preserve tissue morphology.

- Cryosectioning: Section tissues at a recommended thickness (e.g., 10-14 µm for Visium) and minimize air exposure. Maintain a consistent temperature in the cryostat.

- Quality Control: Always perform RNA Quality Number (RQN) assessment via bioanalyzer. Tissues with an RQN > 7 are generally suitable for spatial transcriptomics.

Wet-Lab Protocols and Optimization

Q: My negative control shows high background noise during the hybridization chain reaction (HCR) for Hox genes. What could be the cause?

A: High background in HCR can stem from several factors. Based on protocols for multiplexed whole-mount HCR in complex tissues like the zebrafish gut, you can troubleshoot the following [33]:

- Probe Specificity: Re-BLAST your HCR probe sequences against the latest genome assembly to ensure they are specific to your target Hox mRNA.

- Hybridization Stringency: Increase the hybridization temperature or formamide concentration in a step-wise manner to enhance stringency and reduce non-specific binding.

- Wash Stringency: Increase the number and duration of post-hybridization washes. Using a buffer with added SDS can help reduce background.

- Amplification Time: Optimize the HCR hairpin amplification time; over-amplification can lead to diffuse background signal.

Q: What is a detailed protocol for multiplexed spatial genomic analysis of a developing tissue?

A: The following protocol, adapted from a study of the enteric nervous system, provides a robust workflow for spatial gene expression analysis [33]:

| Step | Procedure | Key Parameters | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Tissue Fixation | Fix samples with 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA). | 4% PFA, overnight at 4°C | Preserve tissue architecture and RNA. |

| 2. Mounting | Position tissue permanently on silanized, poly-L-lysine-treated slides with sealing chambers. | Use of HybriWell sealing system | Secure tissue for multiple processing rounds. |

| 3. Multiplexed HCR | Perform sequential rounds of hybridization. | - Probe hybridization: 37°C overnight.- Washes: Post-hybridization and post-amplification.- Fluorophore: 488, 546, 647. | Detect multiple mRNA targets in the same sample. |

| 4. Imaging | Acquire images using high-content semi-automated confocal microscopy. | - 20x objective.- Z-stack acquisition.- Multi-area time-lapse for reference maps. | Capture full 3D spatial and expression data. |

| 5. Data Processing | Import stitched images for 3D cell segmentation and curation. | Use of IMARIS AI-powered segmentation tool. | Identify individual cells and extract position/intensity data. |

Data Analysis and Computational Integration

Q: How can I integrate multiple spatial transcriptomics slices to reconstruct a 3D Hox expression pattern in the developing limb bud?

A: Computational integration of multiple slices is essential for 3D reconstruction. Frameworks like GRASS (Graph Representation Learning for Integration and Alignment of Spatial Slices) are specifically designed for this task. GRASS uses a heterogeneous graph contrastive learning approach to integrate multislice ST data and perform spot-level alignment, which enables accurate 3D tissue reconstruction [34]. The process involves:

- Preprocessing: Mitigating batch effects while preserving biological signals.

- Integration: Using contrastive learning to align spots from different slices into a shared latent space based on gene expression and spatial relationships.

- Alignment & 3D Reconstruction: Employing a dual-perception similarity metric and the Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithm to align spatial coordinates and reconstruct the 3D volume [34].

Q: What methods can accurately map single-cell RNA-seq data onto a spatial transcriptomics map to infer the location of rare cell populations defined by Hox codes?

A: SEU-TCA (Spatial Expression Utility—Transfer Component Analysis) is a method developed for precisely this purpose. It leverages Transfer Component Analysis (TCA) to find a shared latent space between scRNA-seq data (the query) and ST data (the reference). By minimizing the Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) between datasets in this space, it can predict the spatial location of single cells with high accuracy, which is ideal for locating rare Hox-defined progenitors [35].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and computational tools used in spatial transcriptomics for developmental studies, as cited in recent literature.

| Reagent/Tool Name | Category | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCR Probes [33] | Wet-lab Reagent | Detect specific mRNA targets via hybridization and amplified fluorescence. | Multiplexed detection of Hox genes (e.g., Hoxb5b, Hoxa4a) in whole-mount zebrafish gut [33]. |

| Visium Spatial Gene Expression [36] | Platform | Whole transcriptome analysis at 50-100 µm resolution on a tissue section. | Creating a developmental atlas of the human fetal spine and mapping HOX gene expression [18]. |

| Xenium In Situ [36] | Platform | Targeted in situ gene expression profiling at subcellular resolution. | High-resolution mapping of the tumor microenvironment and cell-type annotation [36]. |

| GRASS [34] | Computational Tool | Integration, alignment, and 3D reconstruction of multiple ST slices. | Building a 3D model of gene expression from consecutive 2D tissue slices [34]. |

| SEU-TCA [35] | Computational Tool | Mapping single-cell transcriptomes onto spatial data to infer cell locations. | Predicting the spatial origin of early cardiac progenitors during mouse gastrulation [35]. |

| STAIG [37] | Computational Tool | Integrates gene expression, spatial coordinates, and histology images to identify spatial domains. | Precise identification of layered brain structures (e.g., cortical layers) in human DLPFC [37]. |

| spCLUE [38] | Computational Tool | A unified framework for spatial domain analysis across single- and multi-slice data. | Identifying biologically consistent spatial domains across multiple tissue slices and conditions [38]. |

Visualized Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Workflow for Spatial Genomic Analysis of Hox Expression

The diagram below outlines the integrated experimental and computational pipeline for mapping Hox gene expression, as derived from established protocols [33].

Simplified Hox Gene Regulatory Logic

This diagram illustrates the fundamental regulatory principles of Hox genes that underpin their spatially collinear expression patterns, a key concept for interpreting data [18].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most critical steps to ensure a strong, specific signal in my ISH experiment? A strong, specific signal depends on three pillars: optimal sample preparation, appropriate probe design, and precise hybridization and washing conditions. Ensure tissue is fixed promptly in fresh fixative to preserve RNA integrity, use a probe with confirmed sensitivity and specificity for your target, and strictly control the temperatures and durations of the hybridization and stringent wash steps to balance signal and background [39] [40].

My positive control shows staining, but my test sample does not. What could be the cause? This typically indicates an issue with the test sample itself or how it was handled. The sample might be under-fixed, leading to RNA degradation, or it may have been over-digested with pepsin or proteinase K during pretreatment, which can destroy the target nucleic acids. Re-optimize the enzyme pretreatment conditions for your specific tissue type and ensure fixation times are consistent and adequate [41] [39].

I am experiencing high, diffuse background staining across my entire section. How can I fix this? High background is often a result of inadequate stringent washing or non-specific binding of the probe. Ensure you are using the correct SSC buffer and that the temperature during the stringent wash is precisely controlled (typically between 75-80°C). Also, verify that your probe does not contain repetitive sequences (like Alu elements); if it does, these must be blocked with COT-1 DNA during hybridization. Finally, avoid allowing sections to dry out at any point during the procedure after hybridization has begun [41].

The signal in my sample is weak, even with long substrate incubation times. What should I optimize? Weak signal can be caused by several factors. First, check the integrity of your detection reagents by performing a conjugate/subactivity check. Second, review your antigen retrieval or permeabilization step; under-digestion can prevent the probe from accessing its target. Third, consider the sensitivity of your detection system; for low-abundance targets, you may need to switch to a more sensitive method, such as tyramide signal amplification (TSA) [41] [39].

Why is my staining uneven, with some areas of the section darker than others? Uneven staining is frequently traced to section quality and reagent application. Ensure sections are thin, flat, and thoroughly adhered to charged slides. Incomplete dewaxing can also create unstained patches. During incubation steps, make sure the probe and other reagents are applied evenly across the section and that evaporation is prevented by using a humidified chamber, as drying of reagents causes heavy, non-specific staining at the edges [39].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

Table: Common ISH Issues, Causes, and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal |

|

|

| High Background |

|

|

| Uneven Staining |

|

|

| Unexpected Signal Localization |

|

|

Experimental Protocol: Optimized Chromogenic ISH for Hox Gene Detection

The following protocol is adapted from established methods and troubleshooting guidelines for detecting mRNA in embryonic tissue [41] [42] [39].

1. Sample Preparation and Fixation

- For embryonic limb buds or whole embryos, fix immediately after dissection in fresh 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M PBS for 1 hour at room temperature [42].

- For larger tissues, block to 3-4 mm thickness and fix in 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) for 16-32 hours at room temperature [40].

- Dehydrate through a graded ethanol series, clear in xylene, and embed in paraffin.

- Section tissue at 5 ±1 μm thickness using a microtome and mount on charged slides. Air-dry slides overnight [40].

2. Pretreatment and Permeabilization

- Dewaxing: Deparaffinize slides in fresh xylene (2 changes, 10 min each) and rehydrate through a graded ethanol series to distilled water.

- Antigen Retrieval: Perform heat-induced epitope retrieval by heating slides in an appropriate buffer (e.g., citrate buffer) to 98°C for 15 minutes [41].

- Proteinase Digestion: Digest sections with pepsin (e.g., 3-10 minutes at 37°C) to expose target nucleic acids. Critical: Optimize this time for your specific tissue; over-digestion destroys morphology and target, while under-digestion reduces signal [41].

3. Hybridization

- Denaturation: Denature target and probe simultaneously at 95 ± 5°C for 5-10 minutes on a hot plate with a coverslip in place. Use a humidified chamber to prevent drying [41].

- Hybridization: Immediately transfer slides to a pre-warmed humidified chamber and hybridize with the specific probe (e.g., digoxigenin-labeled anti-sense RNA probe) at 37°C for 16 hours (overnight) [41] [42].

4. Post-Hybridization Washes and Stringency

- Remove coverslips by soaking in PBST or SSC buffer.

- Stringent Wash: Wash slides in 1X SSC buffer at 75-80°C for 5 minutes. This is a critical step for removing unbound probe and reducing background. Increase the temperature by 1°C per slide if processing more than 2 slides, but do not exceed 80°C [41].

- Rinse slides with TBST or PBST.

5. Immunological Detection

- Block sections with an appropriate blocking reagent.

- Incubate with an enzyme conjugate (e.g., anti-digoxigenin-AP for NBT/BCIP) at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Wash slides thoroughly with PBS buffer.

- Chromogenic Reaction: Develop color by incubating with substrate (e.g., NBT/BCIP for alkaline phosphatase). Monitor the reaction microscopically every 2-5 minutes and stop the moment background begins to appear by rinsing in distilled water [41].

- Counterstaining: Apply a light counterstain (e.g., Mayer’s hematoxylin for 5-60 seconds) to avoid masking the specific signal [41].

- Mount sections with an aqueous mounting medium.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for ISH Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples & Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | Preserves tissue morphology and immobilizes nucleic acids. | 4% PFA: Ideal for embryos and small tissues [42]. 10% NBF: Standard for larger tissue blocks; fixation time is critical [40]. |

| Permeabilization Enzymes | Breaks down proteins to allow probe access to the target. | Pepsin, Proteinase K: Concentration and incubation time must be empirically optimized for each tissue type to balance signal and morphology [41]. |

| Nucleic Acid Probes | Binds specifically to the target mRNA for detection. | DIG-labeled RNA probes: Commonly used for high sensitivity. Specificity must be validated. For DNA FISH, probe length should cover ~10 kbp for robust imaging [41]. |

| Stringent Wash Buffers | Removes imperfectly matched or unbound probe to reduce background. | SSC (Saline-Sodium Citrate) Buffer: Used at 75-80°C. Precise temperature control is essential for signal-to-noise ratio [41]. |

| Detection Systems | Visualizes the bound probe. | Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) + NBT/BCIP: Yields a purple-blue precipitate. Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) + DAB: Yields a brown precipitate. DAB is solvent-insoluble [41]. |

| Signal Amplification | Enhances signal for low-abundance targets. | Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA): Can dramatically increase sensitivity for challenging targets [41]. |

| NCGC00262650 | NCGC00262650, MF:C18H20N4O, MW:308.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 25-NBD Cholesterol | 25-NBD Cholesterol, MF:C33H48N4O4, MW:564.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

ISH Experimental Workflow

Factors Affecting Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main advantages of using an endogenous Hox reporter system compared to transgenic overexpression? Endogenous reporter systems, where a fluorescent protein (e.g., eGFP) is knocked into the native Hox gene locus, express the fusion protein under the control of the authentic genetic regulatory elements. This ensures that the reporter's expression mirrors the precise spatial, temporal, and quantitative dynamics of the endogenous Hox gene, avoiding the potential misrepresentation of cell fates that can occur with transgenic insertions or mRNA injections [43].

Q2: Why is my live Hox reporter signal weak or undetectable in early-stage embryos, even though immunohistochemistry data exists? This is a common discrepancy. Immunohistochemistry is highly sensitive and can amplify minuscule amounts of protein, making it capable of detecting very low initial expression. In live imaging, if the Hox protein undergoes rapid turnover at early stages, the transient fluorescent signal may be difficult to visualize. This highlights the importance of live reporters for revealing authentic protein dynamics and stability, which might be masked in fixed-tissue analyses [43].

Q3: What microscopy setup is most suitable for long-term live imaging of pre-implantation embryos or early limb buds? Two-photon laser scanning microscopy (TPLSM) is an excellent technique for this purpose. It provides high spatiotemporal resolution and allows for full-thickness imaging of dense tissues like embryos with negligible phototoxicity or developmental delays. Unlike conventional confocal microscopy, TPLSM uses longer-wavelength light, which penetrates deeper into tissue and reduces scattering, making it ideal for tracking fluorescent reporters over extended periods [43].