Optimizing Organoid Size and Shape: Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Differentiation and Function

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced strategies for controlling organoid size and shape to improve differentiation efficiency, functionality, and reproducibility.

Optimizing Organoid Size and Shape: Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Differentiation and Function

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced strategies for controlling organoid size and shape to improve differentiation efficiency, functionality, and reproducibility. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the critical link between physical morphology and biological outcomes, covering foundational principles, innovative engineering methodologies, practical optimization techniques, and rigorous validation frameworks. By integrating insights from cutting-edge research on platforms like geometrically-engineered membranes, AI-driven prediction models, and vascularization techniques, this resource serves as a guide for overcoming key challenges in organoid culture to advance disease modeling, drug screening, and regenerative medicine applications.

Why Size and Shape Matter: The Fundamental Impact of Morphology on Organoid Development and Function

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the direct relationship between organoid size and the formation of a necrotic core? As organoids grow beyond a critical size, typically a few millimeters in diameter, the diffusion distance for oxygen and nutrients becomes insufficient to reach the core regions. Most cells can only survive approximately 200 µm away from a nutrient and oxygen source [1]. In larger organoids, the core regions experience severe hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) and nutrient deprivation, leading to cell death and the formation of a necrotic core [2] [1]. This negatively impacts cell viability, alters cellular behavior, and compromises the organoid's ability to accurately model tissue function [2].

FAQ 2: Why is preventing a necrotic core critical for differentiation research? A necrotic core fundamentally compromises the integrity of an organoid model. The resulting cell death and metabolic stress pathways can:

- Disrupt Signaling Gradients: Endogenous morphogen gradients essential for patterning and cell fate decisions are altered.

- Skew Experimental Results: The presence of dying cells releases factors that can influence the behavior of surrounding healthy cells.

- Limit Maturity: Organoids with necrotic cores are often trapped in an immature, fetal-like state because prolonged culture required for maturation is not possible [1]. For reliable differentiation studies, a healthy, uniformly viable structure is paramount.

FAQ 3: What are the primary strategies to overcome diffusion barriers in organoid culture? Researchers employ two main strategies, which can be used in combination:

- Physical Intervention: Reducing the physical size of organoids through mechanical cutting or dissociation to directly decrease the diffusion distance for nutrients and oxygen [2].

- Vascularization: Engineering organoids to include a network of blood vessels. This is the most physiologically relevant approach, as it mimics the body's own solution for nourishing tissues [1] [3]. Integrated blood vessels allow organoids to grow larger and reach a more mature state [3].

FAQ 4: My organoids are already forming necrotic cores. What troubleshooting steps should I take? First, assess the size of your organoids. If they exceed 500 µm in diameter, size is likely the primary issue. You can:

- Initiate a Cutting Protocol: Use a sterile scalpel or a 3D-printed cutting jig to slice existing organoids into smaller fragments, effectively removing the necrotic core and restoring health to the outer parts [2].

- Re-evaluate Your Differentiation Protocol: For future cultures, incorporate regular, scheduled cutting (e.g., every 3 weeks) to maintain an optimal size from the beginning [2].

- Consider Co-culture: Introduce endothelial cells during the initial stages of organoid formation to promote the self-organization of vascular networks [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Necrotic Core Formation in Maturing Organoids

Issue: During extended culture periods necessary for maturation, organoids develop a dark, central necrotic core, leading to loss of cellular material and compromised functionality.

Root Cause Analysis

- Primary Cause: The core pathology is the diffusion limit of oxygen and nutrients. As organoids grow, the center exceeds the ~200 µm diffusion threshold, leading to hypoxia and necrosis [1].

- Contributing Factors:

- Lack of Perfusion System: Traditional static culture systems lack any mechanism for convective transport of media, relying entirely on passive diffusion.

- Absence of Vasculature: Most standard organoid protocols do not include mesoderm-derived endothelial cells, which are needed to form a perfusable vascular network [1].

- High Metabolic Demand: Tissues with high metabolic activity, such as neuronal or cardiac organoids, are particularly susceptible [1] [3].

Recommended Solutions and Protocols

Solution A: Mechanical Sectioning for Long-Term Culture

This protocol involves physically cutting organoids into smaller pieces to maintain viability over months.

Experimental Protocol: Adapted from an Efficient Organoid Cutting Method [2]

- Preparation: Sterilize all tools. Collect organoids from the bioreactor and place them in a dish.

- Transfer to Jig: Aspirate about 30 organoids using a cut pipette tip and deposit them into the channel of a pre-sterilized, 3D-printed cutting jig base.

- Alignment: Use a fine-point tweezer to gently align organoids at the bottom of the channel without contacting each other.

- Sectioning: Position the blade guide onto the jig base. Push a sterile razor blade down through the guide slots to slice all organoids uniformly.

- Collection: Flush the cut organoid fragments out with fresh medium into a new dish. Collect any fragments stuck to the guide.

- Culture: Transfer the sliced organoids into a fresh culture system (e.g., mini-spin bioreactor). Repeat cutting every 3 weeks (± 3 days).

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

Solution B: Inducing Self-Vascularization

This method modifies the differentiation protocol to co-induce vascular cell types, creating organoids with an internal capillary network.

Experimental Protocol: Adapted from Vascularized Cardiac Organoid Generation [3]

- Cell Line: Use human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs), either embryonic (hESCs) or induced (hiPSCs).

- Optimized Recipe Screening: The protocol involves testing multiple chemical recipes (growth factor combinations) to simultaneously differentiate cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells. The winning "condition 32" reliably produced all three lineages.

- 3D Culture: Culture cells using a 3D aggregation method (e.g., serum-free floating culture of embryoid body-like aggregates with quick aggregation).

- Validation: After about two weeks, analyze organoids via 3D microscopy for the presence of branching, tubular structures expressing endothelial markers (e.g., CDH5). Use single-cell RNA sequencing to confirm the presence of multiple cardiac cell types.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Specialized Growth Factors: A specific combination of growth factors and small molecules to guide differentiation into cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells concurrently. The exact recipe is critical and was identified from 34 tested conditions [3].

- Synthetic Matrices: Gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) or other defined hydrogels can provide a consistent 3D environment, superior to variable, animal-derived Matrigel for vascular morphogenesis [2] [4].

Solution Comparison Table

| Solution | Key Principle | Best For | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Sectioning | Physical reduction of organoid size [2] | Long-term maintenance of existing protocols; complex organoids (e.g., cerebral, gonad) [2] | Immediate restoration of viability; high throughput with specialized jigs [2] | Invasive, can disrupt structure; requires repeating; not a physiological solution |

| Induced Self-Vascularization | In vitro recreation of developmental angiogenesis [3] | Creating next-generation models for disease modeling & drug testing; enhancing maturity [3] | Physiologically relevant; enables larger, more mature organoids; allows connection to host vasculature in transplants [3] | Protocol complexity; requires extensive optimization; potential for heterogeneous outcomes |

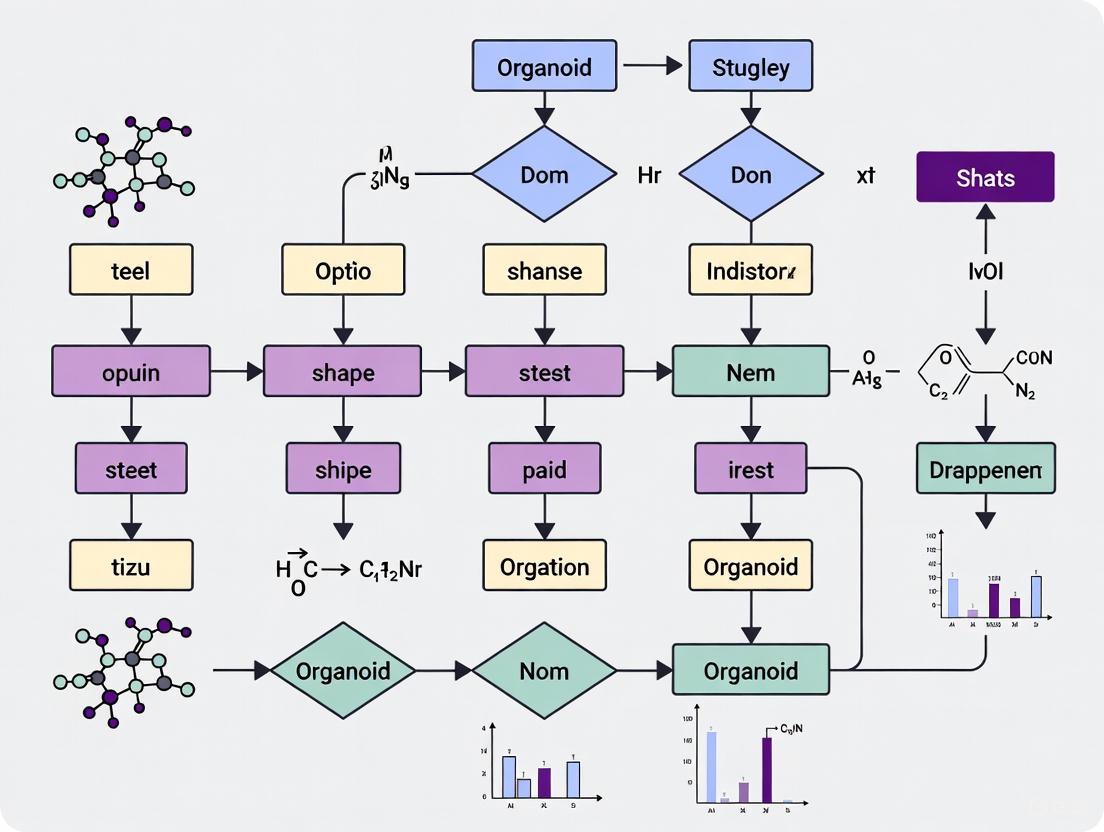

Visualizing the Core Problem and Key Solution

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationship between organoid size, nutrient diffusion, and the two primary solutions discussed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Overcoming Diffusion Barriers

The following table details key materials and reagents used in the experimental protocols cited for preventing necrotic cores.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 3D-Printed Cutting Jig [2] | Provides a sterile, high-throughput platform for uniformly sectioning multiple organoids to reduce their size. | A flat-bottom design was found to have superior cutting efficiency. Designs should be published in open databases for reproducibility. |

| BioMed Clear Resin [2] | Biocompatible material for sterilizable 3D printing of cutting jigs and custom molds. | Ensures tool sterility and compatibility with cell culture environments. |

| GelMA (Gelatin Methacrylate) [2] [4] | A synthetic, tunable hydrogel used as an extracellular matrix (ECM) to support organoid growth and vascular network formation. | Offers more consistent chemical and physical properties compared to animal-derived Matrigel, improving reproducibility. |

| Specialized Growth Factor Cocktails [3] | A defined combination of factors to co-differentiate parenchymal cells (e.g., neurons, cardiomyocytes) and vascular cells (endothelial, smooth muscle) from hPSCs. | The specific combination and timing are critical. Optimal recipes must be empirically determined for different organoid types. |

| Mini-Spin Bioreactors [2] | Dynamic culture system that improves nutrient and gas exchange for organoids during recovery after cutting or during long-term expansion. | Provides a low-shear stress environment that is superior to static culture for larger organoid masses. |

| MK2-IN-3 | MK2-IN-3, MF:C21H16N4O, MW:340.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (Rac)-Anemonin | (Rac)-Anemonin, CAS:90921-11-2, MF:C10H8O4, MW:192.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key mechanical cues that influence cell fate in organoid cultures? The primary mechanical cues include substrate stiffness (the rigidity of the growth surface), viscoelasticity (the time-dependent mechanical response of the matrix), spatial confinement (physical restrictions on cell movement and space), and cell shape changes induced by the microenvironment. These physical signals are sensed by cells and transduced into biochemical responses that direct differentiation and self-organization [5] [6] [7].

FAQ 2: How does substrate stiffness direct stem cell differentiation? Substrate stiffness is a potent regulator of stem cell lineage specification. Foundational studies have shown that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) differentiate into different lineages based on stiffness:

- Soft matrices (0.1–1 kPa): Promote neurogenic differentiation.

- Intermediate stiffness (8–17 kPa): Promote myogenic differentiation.

- Stiff matrices (>34 kPa): Promote osteogenic differentiation [5] [7]. This occurs because cells exert forces on their substrate, and the resistance they meet regulates signaling pathways that control fate decisions [8] [5].

FAQ 3: Why is my organoid culture highly variable in size and shape? A major source of variability is the lack of control over the biophysical microenvironment in traditional culture systems. Standard matrices like Matrigel, while supportive, are mechanically ill-defined and exhibit batch-to-batch variability. This randomness results in heterogeneous mechanical forces acting on the stem cells, which in turn leads to organoids with divergent morphology, size, and cellular composition [9] [6]. Employing synthetic, tunable hydrogels can significantly improve reproducibility [10] [11].

FAQ 4: Can physical constraints alone trigger differentiation without chemical inducers? Yes, emerging research shows that physical confinement alone can be a powerful trigger for differentiation. For instance, human MSCs forced to migrate through narrow microchannels (as tight as 3 micrometers) undergo sustained changes in cell shape and show increased activity of the osteogenic master regulator gene RUNX2, even in the absence of chemical induction agents [12]. This suggests cells can develop a "mechanical memory" of their physical experiences.

FAQ 5: What is the role of viscoelasticity versus elasticity in guiding cell behavior? While elasticity (stiffness) measures a material's immediate, solid-like resistance to deformation, viscoelasticity describes a material's time-dependent, fluid-like response.

- Elastic cues are often linked to fate decisions, as in the classic stiffness-differentiation relationship [5].

- Viscoelastic cues regulate processes like cell migration and tissue remodeling. A matrix that exhibits stress relaxation allows cells to reshape their environment more easily, which can enhance differentiation and function. For example, viscoelastic matrices have been shown to improve the development of functional blood vessels and healing after heart injury [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Control Over Organoid Differentiation Outcomes

Potential Cause: The mechanical properties of the culture substrate do not match the target tissue's physiology.

Solution:

- Characterize the Target Tissue: First, determine the approximate stiffness (Young's modulus) of the native tissue you are modeling. Use the table below as a guide.

- Select a Tunable Hydrogel: Move away from ill-defined matrices like Matrigel. Instead, use synthetic hydrogels such as Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) or tunable collagen, which allow independent control over stiffness and biochemical cues [10].

- Validate Mechanosensing: Confirm that your cells are responding to the substrate by checking for the nuclear localization of mechanosensitive transcription factors like YAP/TAZ, which is a key readout of mechanical signaling [10].

Representative Tissue Stiffness for Culture Optimization

| Tissue Type | Approximate Stiffness (Elastic Modulus) | Reference for Lineage Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Brain | 0.1 - 1 kPa | Neurogenic [5] [7] |

| Muscle | 8 - 17 kPa | Myogenic [5] |

| Bone | > 34 kPa | Osteogenic [5] [7] |

| Pre-fibrotic Liver | ~20 kPa | (Indicates disease state) [5] |

Problem 2: Inconsistent Organoid Size and Morphology

Potential Cause: Uncontrolled and heterogeneous mechanical forces during self-organization.

Solution:

- Utilize Microfabrication: Employ 3D bioprinting or microwell arrays to define the initial spatial constraints and geometry for organoid formation. This provides a uniform physical template, reducing randomness [9] [6].

- Incorporate Dynamic Mechanics: Use hydrogels with dynamic properties that can degrade or soften in response to cellular activity or an external trigger. This allows the mechanical environment to evolve with the organoid, preventing physical confinement from limiting growth and maturation [10].

- Monitor Mechanical Stress: Implement tools like traction force microscopy to map the forces generated by the organoid. High levels of internal stress can lead to necrosis and heterogeneity.

Problem 3: Limited Organoid Growth and Necrotic Core Formation

Potential Cause: Diffusional limitations due to the lack of a vascular network and physical size constraints.

Solution:

- Induce Vascularization: Co-culture organoids with endothelial cells to encourage the formation of primitive vessel networks. This can be further enhanced by using microfluidic "organ-on-a-chip" platforms that provide perfusable channels, mimicking blood flow and improving nutrient/waste exchange [13] [11].

- Apply Bioreactors: Culture organoids in stirred bioreactors. The dynamic fluid flow enhances nutrient diffusion and reduces the formation of necrotic cores, enabling organoids to grow larger and more uniformly [11].

Experimental Protocols for Key Mechanobiology Assays

Protocol 1: Directing Fate via Substrate Stiffness

Objective: To direct mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) differentiation by culturing on hydrogels of defined stiffness.

Materials:

- Polyacrylamide (PA) Hydrogel Kits or PEG-based Hydrogels: For creating substrates with tunable elastic modulus.

- Stiffness Tuner: Such as a variable crosslinker concentration.

- Fibronectin or Collagen: For coating the hydrogel surface to ensure cell adhesion.

- Standard Cell Culture Equipment.

Method:

- Prepare Hydrogels: Fabricate a series of hydrogels with stiffness values spanning 0.1 kPa to 50 kPa by adjusting the concentration of the polymer and crosslinker according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Functionalize Surfaces: Coat the hydrogel surfaces with an ECM protein (e.g., 10 µg/mL fibronectin) for 1 hour at 37°C.

- Plate Cells: Seed human MSCs at a defined density (e.g., 5,000 cells/cm²) onto the coated hydrogels.

- Maintain Culture: Culture cells in a base growth medium without specific differentiation inducers for 7-14 days.

- Analyze Outcomes:

- Immunofluorescence: Stain for lineage-specific markers (e.g., β-III tubulin for neurons, MyoD for muscle, Runx2 for bone).

- qPCR: Quantify gene expression of the same markers.

- Mechanosensing Validation: Stain for YAP and visualize its localization (nuclear = mechano-active, cytoplasmic = mechano-inactive) [5] [7].

Protocol 2: Investigating Differentiation via Physical Confinement

Objective: To assess the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs induced by migration through physically confined spaces.

Materials:

- Microfabricated Channel Device: Featuring channels with heights/widths ranging from 3 µm to 20 µm.

- Time-Lapse Microscope: To track cell migration and morphology.

- Cell Tracking Software.

Method:

- Seed Cells: Introduce a suspension of MSCs into the reservoir of the microchannel device.

- Apply Chemoattractant: Create a chemokine gradient (e.g., with PDGF or serum) across the microchannels to encourage migration.

- Image and Track: Use time-lapse microscopy to monitor cell migration through the channels over 12-24 hours. Track parameters like migration speed and cell shape deformation.

- Recover and Culture: Collect cells that have migrated through the narrowest (3 µm) channels and plate them on a standard tissue culture surface.

- Analyze Differentiation:

- qPCR: Measure the expression of osteogenic genes (e.g., RUNX2, Osteocalcin) compared to control cells that were not confined.

- Immunostaining: Confirm the presence of early osteogenic proteins [12].

Signaling Pathways in Mechanotransduction

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways through which cells sense and transduce mechanical cues into biochemical signals and gene expression changes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Key solutions for controlling and interrogating the mechanical microenvironment.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Mechanobiology | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polyacrylamide (PA) Hydrogels | Provides 2D substrates with finely tunable stiffness for studying the effect of elasticity on cell fate. | Stiffness is decoupled from adhesion ligand density; requires surface coating with ECM proteins [5] [7]. |

| Synthetic PEG-based Hydrogels | Serves as a defined, bio-inert 3D artificial ECM (aECM). Mechanical properties (stiffness, viscoelasticity) and degradability can be precisely controlled. | Highly reproducible; allows incorporation of specific adhesive peptides (e.g., RGD) and MMP-sensitive degradation sites [10] [6]. |

| Tunable Viscoelastic Hydrogels | Models the time-dependent mechanical behavior of native tissues. Used to study the effects of stress relaxation on cell spreading, migration, and differentiation. | Properties can be designed to mimic healthy or diseased tissues (e.g., fibrotic liver) [5]. |

| Microfabricated Devices | Creates precisely defined physical constraints (channels, wells) to study the effects of confinement, shear stress, and geometry on cell behavior. | Enables high-resolution imaging and quantitative analysis of single-cell responses to physical cues [12]. |

| Mechanosensitive Protein Reporters | Antibodies or biosensors for proteins like YAP/TAZ. Readout of pathway activity via nuclear/cytoplasmic localization. | A central, widely-used indicator of mechanical signaling; nuclear YAP indicates active mechanotransduction [10] [14]. |

| Isoanhydroicaritin | Isoanhydroicaritin|Tyrosinase Inhibitor|RUO | Isoanhydroicaritin is a potent prenylated flavonoid and tyrosinase inhibitor for research on melanogenesis. This product is for Research Use Only, not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapy. |

| Stachyose | Stachyose Tetrasaccharide|High-Purity Research Grade | Research-grade Stachyose for gut microbiota, metabolic disease, and diabetes studies. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO), not for human consumption. |

Technical Support Center: Organoid Morphology & Standardization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary sources of morphological variability in organoid cultures? Morphological variability in organoid cultures arises from multiple technical sources. Extracellular matrix (ECM) batch effects are a major contributor; commonly used animal-derived matrices like Matrigel demonstrate significant batch-to-batch variability in their mechanical and biochemical properties, directly impacting organoid development and shape [4] [15]. Non-standardized medium formulations are another key source, as ill-defined and non-specific compositions of growth factors, cytokines, and small molecules can lead to inconsistent growth patterns and cellular differentiation [15]. Furthermore, variability in the initial tissue source and subsequent processing techniques—such as differences in dissociation methods, tissue fragment sizes, and sampling from different tumor regions—introduces irreproducibility from the very start of culture establishment [15].

FAQ 2: How does organoid size impact experimental outcomes and reproducibility? Uncontrolled organoid size directly leads to inconsistent experimental results and poor reproducibility. There is an upper limit to organoid growth dictated by the diffusion of nutrients throughout the 3D structure. When a certain size limit is reached, organoids frequently develop a necrotic core due to inaccessibility of nutrients and oxygen, which alters cell viability, metabolic activity, and drug response data [11]. This lack of control over organoid size and shape also generates intra-organoid heterogeneity, making it difficult to distinguish true biological signals from technical artifacts [11].

FAQ 3: What strategies can reduce batch-to-batch variability in organoid morphology? Implementing synthetic matrix materials is a promising strategy to reduce ECM-related variability. Synthetic hydrogels and gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) provide consistent chemical compositions and physical properties, enabling more stable and reproducible organoid growth [4] [15]. Automation and high-throughput platforms standardize protocols and remove human bias from cell culture processes, significantly improving consistency [13] [11]. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) with automated systems further standardizes protocols and reduces variability by ensuring cells receive precisely optimized culture parameters [4] [11]. Finally, employing defined, GMP-grade culture components instead of poorly characterized, animal-derived materials helps minimize lot-to-lot variability [11].

FAQ 4: Can organoid-immune cell co-culture affect morphological consistency, and how can it be standardized? Yes, introducing immune cells into organoid cultures adds complexity that can impact morphological consistency. Two main co-culture approaches present different standardization challenges. Innate immune microenvironment models (e.g., ALI cultures, tissue-derived organoids) preserve a tumor's native immune cells but struggle with long-term stability and immune cell retention [4] [15]. Immune reconstitution models involve adding exogenous immune cells to tumor organoids, requiring precise control over immune cell type, ratio, and activation state to achieve reproducible interactions and morphology [4]. Standardization efforts include using microfluidic systems to precisely control cell interactions and developing defined protocols for immune cell addition [4] [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Organoid Size and Shape Within and Between Batches

| Root Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Variable ECM [4] [15] | Check lot numbers; test mechanical properties. | Switch to synthetic hydrogels; standardize matrix concentration. |

| Undefined Medium [15] | Audit growth factor sources/concentrations. | Use commercially defined media; document all components. |

| Uncontrolled Culture Initiation [15] | Standardize tissue dissociation protocol; measure initial fragment size. | Use tissue sieves for uniform size; automate cell seeding density. |

Recommended Experimental Workflow:

- Tissue Processing: Mince fresh tumor tissue into fragments of approximately 0.3 mm³ or smaller on ice to prevent cell damage [15].

- Enzymatic Digestion: Digest tissue pieces with collagenase/DNase solution, followed by vigorous pipetting. Centrifuge the supernatant to obtain a cell pellet [15].

- Inoculation: Suspend the cell pellet or tissue fragments in a synthetic, well-defined hydrogel (e.g., GelMA) at a standardized concentration [4] [15].

- Culture: Plate the matrix-cell mix and culture in a defined medium, supplemented with a ROCK inhibitor (e.g., Y-27632) for the first 2-4 days to inhibit anoikis [15].

- Quality Control: Routinely monitor organoid size and morphology using automated, AI-driven imaging systems to ensure consistency and flag aberrant cultures early [11].

Standardized Organoid Culture Workflow

Problem: Development of Necrotic Cores in Large Organoids

| Root Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Limit [11] | Section and stain organoids; check for central cell death. | Control initial seeding density; use stirred-tank bioreactors. |

| Lack of Vasculature [11] | Image for endothelial networks; assess hypoxia markers. | Co-culture with endothelial cells; use microfluidic organ-chips. |

Recommended Experimental Protocol for Vascularization:

- Co-culture Setup: Co-culture organoids with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and mesenchymal stem cells in a defined ratio within a collagen-Matrigel mix [11].

- Microfluidic Integration: Load the co-culture mix into a microfluidic organ-chip device to provide dynamic fluid flow, which enhances endothelial network formation and maturity by providing physiological shear stress [11].

- Validation: Confirm the formation of perfusable endothelial networks by immunostaining for CD31 and measuring the improved penetration of fluorescent dextran into the organoid core [11].

Solving the Necrotic Core Problem

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Standardizing Organoid Culture

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Standardization |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Matrices | Synthetic hydrogels, Gelatin Methacrylate (GelMA) | Provides consistent mechanical/ biochemical cues; reduces batch variability vs. Matrigel [4] [15]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor | Y-27632 | Inhibits anoikis; increases initial cell survival and organoid generation success rate post-dissociation [15]. |

| Key Growth Factors | R-spondin-1, Noggin, Wnt3a, EGF, FGF10 | Maintains stemness and promotes growth in various organoid types; requires precise concentration control [4] [16]. |

| Medium Supplements | N2, B27, N-acetylcysteine | Provides essential nutrients, hormones, and antioxidants; defined formulations enhance reproducibility [4] [16]. |

| Sedanolide | Sedanolide, CAS:4567-33-3, MF:C12H18O2, MW:194.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4,4-Dimethoxy-2-butanone | 4,4-Dimethoxy-2-butanone, CAS:5436-21-5, MF:C6H12O3, MW:132.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Establishing a Standardized Liver Cancer Organoid Line

This protocol is adapted for a reconstituted model focusing on standardization [15].

Materials:

- Tissue Source: Primary liver tumor sample, obtained via surgical resection or biopsy and kept on ice in transport medium [15].

- Digestion Buffer: Collagenase/DNase solution in PBS.

- Basal Medium: Advanced DMEM/F12.

- Complete Growth Medium: Basal medium supplemented with defined components including B27, N2, N-acetylcysteine, 50 ng/mL EGF, 10% R-spondin-1-conditioned medium, 100 ng/mL Noggin, 10 mM Nicotinamide, 5 μM A-83-01, and 10 μM Y-27632 (for first 4 days) [15] [16].

- Matrix: Synthetic hydrogel or reduced-growth-factor Basement Membrane Extract.

Method:

- Processing: Wash the tissue sample in ice-cold PBS. Mince thoroughly with sterile scissors to fragments <0.5 mm³.

- Digestion: Incubate the fragments in digestion buffer for 30-60 minutes at 37°C with gentle agitation. Quench with complete medium.

- Dissociation: Pipet the mixture vigorously to dissociate cells. Filter the suspension sequentially through 100 μm and 40 μm cell strainers.

- Seeding: Centrifuge the filtrate. Resuspend the cell pellet in cold matrix. Plate 30-50 μL droplets in a pre-warmed culture plate. Polymerize at 37°C for 20-30 minutes.

- Culture: Overlay the matrix droplets with pre-warmed complete medium, including Y-27632. Refresh medium every 2-3 days, omitting Y-27632 after the first 4 days.

Table: Quantitative Assessment of Standardization Success in Liver Cancer Organoids

| Standardization Parameter | Non-Standardized Protocol (Typical Range) | Standardized Protocol (Target) | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organoid Formation Efficiency | 5 - 40% [15] | >50% [15] | (No.. of organoids / No. of cells seeded) x 100 |

| Size Uniformity (Diameter) | High variability (50 - 500 μm) [11] | Coefficient of variation <15% | Automated brightfield imaging & analysis |

| Batch-to-Batch Transcriptomic Correlation | R² = 0.85 - 0.95 [17] | R² > 0.98 [17] | RNA sequencing & Pearson correlation |

| Passage Stability (Key Markers) | Loss after 5-10 passages [15] | Retention beyond 15 passages [15] | Immunofluorescence / qPCR |

Protocol 2: Integrating Organoids with Microfluidic Organ-Chips for Enhanced Maturity

This protocol enhances organoid physiological relevance and reduces size-dependent necrosis [11].

Materials:

- Device: Commercial or fabricated PDMS-organ-chip.

- Cells: Pre-formed organoids (from Protocol 1) and endothelial cells (e.g., HUVECs).

- Collagen I: Acid-soluble rat tail collagen I.

Method:

- Preparation: Pre-treat the organ-chip according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Loading: Mix pre-formed organoids (100-200 μm in diameter) with endothelial cells in neutralized collagen I gel. Pipet the mixture into the top channel of the organ-chip.

- Perfusion: After gel polymerization, connect the chip to a perfusion system and begin flowing medium through the endothelialized bottom channel at a low, physiological shear stress.

- Culture: Maintain the system under continuous flow for 7-14 days, allowing for vascular invasion and interconnection.

- Analysis: Assess vascular network formation via live imaging and endpoint immunostaining.

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common experimental challenges in linking organoid morphology to differentiation outcomes, providing evidence-based solutions for researchers.

FAQ 1: How can I reliably quantify organoid morphology to establish correlations with differentiation?

- Challenge: Inconsistent morphological measurements lead to unreliable correlation data.

- Solution: Implement automated AI-driven image analysis pipelines. A multiscale light-sheet organoid imaging framework combined with deep learning segmentation can turn long-term imaging into digital organoids, enabling precise 3D quantification of organoid size, lumen formation, and cellular organization [18]. The 3DCellScope software provides a user-friendly interface for this purpose, segmenting nuclei, cells, and whole organoids in 3D [19].

- Protocol:

- Culture organoids expressing fluorescent markers (e.g., H2B-mCherry for nuclei, mem9-GFP for membrane)

- Image using light-sheet microscopy every 10min over several days

- Process images using LSTree workflow for cropping, denoising, and deconvolution

- Segment using convolutional neural networks (RDCNet instance segmentation)

- Extract multivariate features (organoid volume, nuclei density, cell volume ratios) [18]

FAQ 2: Why do my organoids develop necrotic cores despite optimal culture conditions?

- Challenge: Nutrient diffusion limitations impair differentiation and viability.

- Solution: Control organoid size and promote vascularization. Studies show that exceeding ~500μm diameter often causes central necrosis due to diffusion limitations [11]. Integrate endothelial cells to form primitive vascular networks, or use microfluidic platforms to enhance nutrient access [20] [11].

- Protocol for Vascularization:

- Co-culture organoids with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in 3:1 ratio

- Supplement with VEGF (50ng/mL) and FGF2 (25ng/mL)

- Embed in fibrin hydrogel (5mg/mL) with aprotinin (2μg/mL)

- Culture in vascularization medium for 14-21 days [20]

FAQ 3: How can I minimize batch-to-batch variability in organoid differentiation?

- Challenge: Uncontrolled variability obscures morphology-differentiation relationships.

- Solution: Standardize protocols using automated systems and validated matrices. Nearly 40% of scientists report reproducibility as a major challenge [11]. Implement automated bioreactor systems with AI monitoring to control culture parameters consistently [11].

- Protocol:

- Use GMP-grade extracellular matrices instead of research-grade Matrigel

- Employ automated cell culture systems for consistent seeding density

- Monitor organoid size and morphology in real-time using integrated imaging

- Apply AI-based classification to sort organoids by morphological criteria before differentiation assays [11]

FAQ 4: What morphological features best predict successful differentiation across organoid types?

- Challenge: Identifying universal versus tissue-specific morphological predictors.

- Solution: The differentiation state significantly influences morphological predictors. Studies show proliferative and differentiated intestinal organoids respond differently to identical toxic compounds, highlighting how cellular composition affects functional outcomes [21].

- Tissue-Specific Indicators:

- Brain organoids: Formation of polarized cortical structures and fluid-filled ventricles indicates successful regional patterning [22] [23]

- Intestinal organoids: Crypt-villus architecture with clear lumen formation predicts proper epithelial organization [24] [21]

- Hepatic organoids: Formation of bile canaliculi-like structures and albumin secretion correlates with functional maturation [13]

Quantitative Morphology-Differentiation Correlations

Table 1: Experimentally Measured Correlations Between Morphological Features and Differentiation Outcomes

| Organoid Type | Morphological Feature | Quantitative Measure | Correlation with Differentiation | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intestinal | Organoid diameter | 150-200μm | Optimal for crypt formation (p<0.01) | Brightfield imaging + LGR5 staining [21] |

| Intestinal | Lumen size | 30-50μm | Predicts polarized epithelium (p<0.05) | Immunofluorescence for ZO-1 [21] |

| Brain | Ventricular structure | Presence/absence | Correlates with cortical organization (p<0.001) | PAX6 staining + spatial transcriptomics [22] |

| Bone | Mineralization area | >15% of total area | Indicates osteogenic maturation (p<0.01) | Alizarin Red staining + calcium quantification [20] |

| General | Nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio | 1:3-1:4 steady state | Indicates proper cellular maturation | Live imaging of H2B-mCherry/mem9-GFP [18] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Matrix for Common Morphology-Differentiation Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Validation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous size distribution | Uneven seeding density; variable matrix composition | Use automated dispensing; standardize matrix lots | Brightfield imaging + size distribution analysis [11] [19] |

| Inconsistent patterning | Suboptimal growth factor gradients; incorrect timing | Implement microfluidic gradient generators; optimize differentiation window | Immunostaining for regional markers; spatial transcriptomics [22] [23] |

| Premature differentiation | Excessive constitutive signaling; overmature starting cells | Use inducible expression systems; validate stem cell potency | qPCR for early vs. late markers; flow cytometry [13] [21] |

| Poor structural complexity | Lack of mechanical cues; insufficient multicellular interactions | Incorporate biomechanical stimulation; co-culture with stromal cells | 3D reconstruction; electron microscopy; functional assays [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Morphological Analysis

Protocol 1: Multiscale Light-Sheet Imaging and Analysis

This protocol enables quantitative tracking of morphology-differentiation relationships over time [18].

Materials:

- Light-sheet microscope with multi-positioning sample holder

- FEP foil patterned with microwells

- Organoids expressing nuclear (H2B-mCherry) and membrane (mem9-GFP) markers

- Image processing workstation with LSTree pipeline [18]

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- FACS sort single cells from mature organoids

- Mount as 5μL Matrigel drops on patterned FEP foil

- Culture in appropriate differentiation medium

Imaging Optimization:

- Perform position-dependent illumination alignment for each sample

- Set imaging interval to 10 minutes for 4+ days

- Acquire multiscale data from whole organoid to single cells

Image Processing:

- Correct for 3D sample drifting using automated cropping tool

- Denoise images using Noise2Void scheme

- Apply tensor-flow based image deconvolution

- Segment using RDCNet instance segmentation network

- Generate 3D segmentation meshes for each organoid

Data Integration:

- Link lineage trees with 3D segmentation data

- Extract multivariate features (organoid volume, nuclei count, cell volume ratios)

- Visualize using Digital Organoid Viewer tool

Protocol 2: AI-Powered 3D Morphological Analysis

This protocol uses the 3DCellScope platform for high-throughput morphological quantification [19].

Materials:

- 3DCellScope software (https://github.com/quantacell/3DcellScope/)

- Standard fluorescence microscope

- Organoids stained with DAPI/NucBlue and actin/membrane markers

- Standard laptop computer (8GB+ RAM)

Procedure:

- Image Acquisition:

- Acquire 3D z-stacks of organoids (minimum 10μm depth)

- Ensure adequate signal-to-noise ratio for segmentation

- Include both nuclear and cytoplasmic markers

Segmentation Workflow:

- Import images into 3DCellScope interface

- Run DeepStar3D CNN for nuclear segmentation

- Apply grayscale 3D watershed for cell surface detection

- Use thresholding and morphological filtering for organoid contours

Morphological Quantification:

- Extract nuclear morphology descriptors (volume, sphericity)

- Calculate cell positioning and neighborhood relationships

- Quantify organoid-scale features (size, symmetry, complexity)

- Export data for statistical analysis

Correlation Analysis:

- Integrate morphological data with differentiation markers

- Perform multivariate regression analysis

- Identify significant morphology-differentiation relationships

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Morphology-Differentiation Analysis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Morphology-Differentiation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Morphology Studies | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrices | Cultrex Reduced Growth Factor BME, Type II; Matrigel | Provides 3D scaffold for self-organization | Batch variability affects morphology; use GMP-grade for consistency [24] [21] |

| Cell Lineage Reporters | LGR5-GFP; H2B-mCherry; mem9-GFP | Enables live tracking of differentiation and morphology | Combine nuclear and membrane markers for complete segmentation [18] |

| Differentiation Media | IntestiCult Organoid Differentiation Medium; Region-specific neural induction media | Directs fate specification | Timing of application crucial for morphology-differentiation coupling [21] |

| Imaging Reagents | NucBlue Live; Actin stains; Immunofluorescence antibodies | Enables morphological quantification | Balance signal intensity with toxicity for long-term imaging [19] |

| Segmentation Tools | 3DCellScope; LSTree workflow; DeepStar3D CNN | Quantifies morphological features | Choose based on imaging modality and computational resources [18] [19] |

Engineering Uniformity: Advanced Platforms and Protocols for Precise Size and Shape Control

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Size Variability in Recovered Organoids

- Problem: Organoids harvested from the UniMat scaffold show a wide distribution of diameters, undermining experimental uniformity.

- Potential Cause 1: Seeding cell density was not optimized for the specific cell type.

- Solution: Perform a seeding density gradient experiment (e.g., 1x10^6, 2x10^6, 4x10^6 cells/mL) to identify the density that yields the most uniform organoids within the scaffold pores.

- Potential Cause 2: Incomplete cell aggregation due to excessive media flow or agitation during the initial 24-48 hours.

- Solution: Ensure the culture plate is placed on a stable, level surface in the incubator. Minimize agitation and disturbance for the first 48 hours post-seeding.

- Potential Cause 3: Scaffold pore size is inappropriate for the target organoid size.

- Solution: Select a UniMat scaffold with a pore size that physically constrains growth to the desired final diameter.

Issue 2: Poor Organoid Differentiation Outcomes

- Problem: Organoids are viable but do not express expected differentiation markers.

- Potential Cause 1: Nutrient or morphogen gradient formation within the scaffold, leading to heterogeneous microenvironments.

- Solution: Increase media change frequency or volume to ensure uniform nutrient and signaling molecule distribution. Consider using a rocker platform to enhance perfusion.

- Potential Cause 2: The scaffold material is adsorbing critical small molecules or growth factors from the media.

- Solution: Pre-condition the scaffold by incubating with base media for 1-2 hours prior to seeding. Increase the concentration of critical, labile factors in the differentiation cocktail.

- Potential Cause 3: Organoids are overgrown and develop necrotic cores before differentiation induction.

- Solution: Shorten the proliferation phase or initiate differentiation protocols at a smaller organoid size.

Issue 3: Low Cell Seeding Efficiency & Viability

- Problem: A significant proportion of cells fail to incorporate into organoids and are found dead in the supernatant.

- Potential Cause 1: Cell clumping in the initial single-cell suspension.

- Solution: Filter the cell suspension through a sterile 40μm cell strainer immediately before seeding.

- Potential Cause 2: Cytotoxicity during scaffold handling or due to residual processing reagents.

- Solution: Ensure all washing steps (e.g., with PBS) are thoroughly performed as per the manufacturer's protocol. Perform a viability assay using a control scaffold.

- Potential Cause 3: Excessive force used during seeding, damaging cells.

- Solution: Use gentle pipetting techniques. Allow the cell suspension to wick into the scaffold via capillary action rather than forced pipetting.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I select the appropriate UniMat pore size for my intestinal organoid model? A: The pore size dictates the final organoid diameter. For standard intestinal organoids aiming for a 100-150μm diameter, a 150μm pore scaffold is ideal as it provides physical constraint. Use the following table as a guide:

| Target Organoid Type | Recommended Pore Size (μm) | Expected Organoid Diameter (μm) |

|---|---|---|

| Intestinal (Proliferation) | 150 | 100 - 150 |

| Cerebral (Neural) | 200 | 150 - 200 |

| Hepatic (Liver Bud) | 250 | 200 - 250 |

| Pancreatic | 150 | 100 - 150 |

Q2: What is the recommended protocol for harvesting organoids from the UniMat scaffold? A: The standard protocol involves a gentle enzymatic dissociation. Briefly:

- Transfer the scaffold to a new well.

- Incubate with Accutase or TrypLE (200-300μL per scaffold) for 10-15 minutes at 37°C.

- Gently pipette the solution up and down across the scaffold surface 5-10 times to dislodge organoids.

- Transfer the cell suspension containing organoids to a tube containing complete media to neutralize the enzyme.

- Centrifuge at low speed (100-200 x g) for 3 minutes to pellet organoids.

Q3: Can I image organoids directly within the UniMat scaffold? A: Yes, the transparent nature of the UniMat allows for real-time, high-resolution imaging using confocal or light-sheet microscopy. For best results, use a glass-bottom dish and a long-working-distance objective.

Q4: How does media composition differ when using UniMat compared to traditional Matrigel domes? A: The core media formulation remains the same. However, due to the increased surface area and perfusion in the 3D scaffold, evaporation can be slightly higher. It is recommended to ensure adequate media volume and consider using a humidity-controlled incubator tray. No specific additive changes are required.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Seeding of Intestinal Stem Cells into UniMat Objective: To achieve consistent and high-efficiency formation of uniform intestinal organoids. Materials: Single-cell suspension of intestinal crypts or stem cells, UniMat scaffold (150μm pore), complete IntestiCult Organoid Growth Medium, 24-well plate, PBS. Procedure:

- Hydration: Place the UniMat scaffold in a well of a 24-well plate. Add 500μL of PBS to cover the scaffold and incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Preparation: Aspirate PBS. Wash once with 500μL of base media.

- Seeding: Prepare a cell suspension at 2x10^6 cells/mL in cold complete growth medium. Gently pipette 150μL of the cell suspension onto the center of the scaffold.

- Incubation: Allow the scaffold to sit in the incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) for 30 minutes to let cells settle into the pores.

- Feeding: Carefully add 1 mL of pre-warmed complete growth medium to the well surrounding the scaffold. Do not disturb the scaffold surface.

- Culture: Refresh 70% of the media every 2-3 days.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Analysis of Organoid Size Uniformity Objective: To quantify the coefficient of variation (CV) in organoid diameter as a measure of production uniformity. Materials: Harvested organoids, PBS, glass-bottom dish, inverted microscope with camera, ImageJ software. Procedure:

- Image Acquisition: Harvest organoids as per FAQ A2. Place a 50μL drop on a glass-bottom dish and acquire bright-field images at 10x magnification. Capture at least 10 non-overlapping fields.

- Image Analysis:

- Open images in ImageJ.

- Set scale (Analyze > Set Scale).

- Convert image to 8-bit (Image > Type > 8-bit).

- Adjust threshold (Image > Adjust > Threshold) to highlight organoids.

- Analyze particles (Analyze > Analyze Particles). Set size limit (e.g., 50μm^2 - Infinity) and circularity (0.70-1.00) to exclude debris and non-spherical objects.

- Data Calculation: Export the "Area" results. Calculate the diameter from the area (Diameter = 2 * √(Area/π)). Calculate the mean diameter and standard deviation. Uniformity is reported as Coefficient of Variation (CV) = (Standard Deviation / Mean) * 100%.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Seeding Density on Intestinal Organoid Formation in 150μm UniMat

| Seeding Density (cells/mL) | Seeding Efficiency (%) | Mean Organoid Diameter (μm) | Coefficient of Variation (CV%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 x 10^6 | 45% ± 5 | 115 ± 25 | 21.7% | Low yield, some empty pores |

| 2.0 x 10^6 | 85% ± 4 | 132 ± 18 | 13.6% | Optimal density |

| 4.0 x 10^6 | 90% ± 3 | 148 ± 30 | 20.3% | High yield but increased fusion events |

Table 2: Differentiation Marker Expression vs. Organoid Size in Cerebral Organoids

| Organoid Size Category (μm) | PAX6 (Neural Progenitor) | TBR1 (Neuronal) | GFAP (Astrocytic) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100-150 | High | Low | Absent | Proliferative state |

| 150-200 | Medium | High | Low | Balanced differentiation |

| >200 | Low (Necrotic Core) | Medium | High | Increased heterogeneity, necrosis |

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent / Material | Function |

|---|---|

| UniMat Scaffold (150μm pore) | The geometrically-engineered 3D membrane that provides physical constraints for uniform organoid growth. |

| Accutase Enzyme Solution | A gentle cell detachment solution used for harvesting intact organoids from the scaffold. |

| Y-27632 (ROCK Inhibitor) | Enhances single-cell survival and viability during the initial seeding phase by inhibiting apoptosis. |

| IntestiCult / STEMdiff Media | Specialized, defined media kits for the proliferation and differentiation of specific organoid types. |

| Cell Strainer (40μm) | Used to generate a single-cell suspension by removing pre-existing clumps before seeding. |

| Matrigel, Geltrex | Basement membrane extracts; sometimes used in a thin coating below the scaffold to aid initial cell attachment. |

| 2-PMPA | 2-PMPA, CAS:173039-10-6, MF:C6H11O7P, MW:226.12 g/mol |

| Dicaprylyl Carbonate | Dicaprylyl Carbonate Reagent|CAS 1680-31-5|RUO |

Visualizations

UniMat Organoid Culture Workflow

How UniMat Enhances Differentiation

Troubleshooting Guides

This section addresses common technical challenges in 3D bioprinting that can impact the controlled self-organization of organoids, such as viability, structural integrity, and printing fidelity.

Troubleshooting Cell Viability

Low cell viability is a critical failure point that disrupts self-organization and differentiation. The table below summarizes common causes and solutions.

| Issue | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution | Relevant Control Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low post-print viability | High shear stress from small needle diameter or high print pressure [25] | Test tapered needles and lower print pressures; conduct a 24-hour viability study [25]. | 3D Printed Thin-Film Control [25] |

| Harsh crosslinking process (chemicals, UV) [25] | Optimize crosslinking degree (concentration, time, intensity) to balance mechanics and cell health [25]. | 3D Pipetted Control [25] | |

| Viability loss during culture | Contamination from non-sterile equipment or bioink [26] | Sterilize all components (autoclave, UV, filters); work in a biosafety cabinet; use 70% ethanol [26]. | 2D Cell Culture Control [25] |

| Nutrient/Waste diffusion issues from high cell density or thick constructs [25] | Optimize initial cell concentration; design constructs with microchannels to enhance transport [25]. | Encapsulation Study [25] | |

| Needle Clogging | Bioink inhomogeneity or particle size larger than nozzle [26] | Ensure bioink homogeneity; characterize particle size; increase pressure (≤2 bar for cells) or use larger needle [26]. | - |

Troubleshooting Print Fidelity and Structural Integrity

Poor print fidelity compromises the defined microenvironment necessary for guiding self-organization. The following table addresses these issues.

| Issue | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Layer Collapse/Merging | Bioink viscosity too low; insufficient or slow crosslinking [26] | Perform rheological tests; optimize crosslinking time (ionic, thermal, UV) for faster gelation [26]. |

| Lack of Structural Integrity | Inadequate crosslinking (wrong method, concentration, or parameters) [26] | Characterize and select the correct crosslinking method (ionic, photo, thermal) and its optimal parameters [26]. |

| Needle Dragging Material | Print speed is too high [26] | Lower the print speed to allow deposited bioink to adhere properly [26]. |

| Air Bubbles in Bioink | Trituration or loading technique introduces air [26] | Centrifuge bioink at low RPM; triturate gently along the wall of the tube to prevent bubble formation [26]. |

| Gaps Between Struts/Under-Extrusion | Nozzle too small for cell clusters [27] | Select a nozzle diameter larger than 85% of the cell clusters in the bioink [27]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I quickly identify and correct print defects during a bioprinting run? A modular, AI-based monitoring technique can be implemented. A digital microscope captures high-resolution, layer-by-layer images of the printed tissue and rapidly compares them to the intended digital design using an AI analysis pipeline. This allows for real-time identification of defects like over- or under-extrusion and enables adaptive correction and parameter tuning [28].

Q2: Why are my bioprinted layers not stacking properly and collapsing into a 2D structure? This is typically due to insufficient bioink viscosity or an overly slow crosslinking process. The bottom layer must gain enough structural integrity quickly to support the weight of subsequent layers. Optimize your bioink's rheological properties and crosslinking time (e.g., using a higher concentration of crosslinker or a more efficient photoinitiator) to ensure immediate stabilization of each printed layer [26].

Q3: What is the single most important control experiment for a new bioprinting study? While multiple controls are crucial, a 3D pipetted control (or thin film) is essential. This control involves pipetting your bioink into a well-plate or similar container and crosslinking it alongside your bioprinted constructs. It allows you to decouple the effects of your bioink formulation and crosslinking process from the stresses specific to the printing process (e.g., shear stress), helping you pinpoint the source of viability or structural issues [25].

Q4: My cells are viable after printing but die in long-term culture. What might be wrong? The issue likely lies in the post-printing microenvironment. First, check for sufficient nutrient perfusion; high cell density in thick constructs can lead to core necrosis, so consider redesigning your construct with microchannels [25]. Second, ensure your crosslinked material has appropriate permeability for nutrient and waste diffusion. Finally, rigorously maintain sterility throughout the printing and culture process [26].

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Conducting a 24-Hour Viability Study for Printing Parameters

Purpose: To systematically characterize the impact of printing parameters (needle type, pressure) on short-term cell viability, a critical factor for successful self-organization.

Materials:

- Standard bioink with characterized cells.

- Bioprinter.

- Multiple needle types (e.g., varying gauge diameters, tapered vs. non-tapered).

- Live/Dead cell viability assay kit.

- Confocal or fluorescence microscope.

Method:

- Prepare Bioinks: Prepare a single batch of cell-laden bioink and aliquot it into sterile syringes.

- Print Constructs: Print multiple simple constructs (e.g., thin films or small grids) for each combination of needle type and print pressure you wish to test.

- Culture: Transfer all printed constructs into a cell culture incubator and maintain for 24 hours.

- Assay: After 24 hours, stain the constructs with a Live/Dead assay according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Image & Analyze: Image the constructs using microscopy and quantify the percentage of live cells. Compare results across different parameter sets to identify the optimal conditions that maximize viability [25].

Protocol 2: Running an Encapsulation Study for Bioink Characterization

Purpose: To evaluate the biocompatibility of a new biomaterial or cell concentration before introducing the complexity of the printing process.

Materials:

- Biomaterial(s) of interest.

- Cell line of interest.

- Crosslinking agent.

- Multi-well plate.

Method:

- Mix Bioink: Mix your cells into the biomaterial at the desired concentration(s).

- Pipette Controls: Pipette small droplets of the cell-laden bioink into the wells of a multi-well plate (creating "thin films").

- Crosslink: Crosslink the droplets using your standard method.

- Culture and Assess: Add culture media and maintain the constructs. Assess cell viability, morphology, and proliferation over several days using standard assays. This study helps identify toxic materials or non-permissive cell densities early in the optimization process [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key materials used in 3D bioprinting for creating defined microenvironments.

| Item | Function in Microfabrication & Bioprinting |

|---|---|

| Natural Polymers (Alginate, Gelatin, Collagen, Hyaluronic Acid) | Serve as the primary base for bioinks, providing a biocompatible, hydrogel-based mimic of the native extracellular matrix (ECM) that supports cell encapsulation and self-organization [29] [30]. |

| Synthetic Polymers (PEGDA, PU, PLA) | Provide tunable mechanical properties and structural integrity to printed constructs. They are often used to reinforce softer natural hydrogels or create stable, long-lasting scaffolds [29]. |

| Crosslinkers (Ionic (e.g., CaClâ‚‚), Photoinitiators (for UV), Thermal) | Agents that induce the gelation of bioinks, transforming them from a liquid to a solid gel. They are critical for achieving and controlling the structural fidelity of the printed construct [25] [26]. |

| GelMA (Gelatin Methacryloyl) | A versatile, photo-crosslinkable hydrogel that combines the biocompatibility and cell-adhesive motifs of gelatin with the tunable mechanical properties of a synthetic polymer. Widely used for creating cell-laden structures [29]. |

| Decellularized Extracellular Matrix (dECM) | A bioink component derived from native tissues, providing a complex, tissue-specific biochemical microenvironment that can significantly enhance cell differentiation and function [30]. |

| Gancaonin I | Gancaonin I, CAS:126716-36-7, MF:C21H22O5, MW:354.4 g/mol |

| Hydroxyanigorufone | Hydroxyanigorufone, CAS:56252-02-9, MF:C19H12O3, MW:288.3 g/mol |

Workflow and Parameter Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for optimizing a bioprinting process, from problem identification to solution, highlighting the key parameters that influence the final outcome of viability and fidelity.

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary purpose of using a 3D-printed cutting jig for organoid culture? The primary purpose is to enable long-term maintenance of organoids by periodically sectioning them to improve nutrient diffusion and oxygen supply, thereby preventing central hypoxia and necrosis that occur as organoids grow large. This cutting process enhances cell proliferation, viability, and overall organoid health during extended culture periods [31] [32].

Q2: What design of cutting jig was found to be most effective? Among several 3D-printed jig designs tested, a flat-bottom cutting jig demonstrated superior cutting efficiency compared to other models [31] [32].

Q3: How often should organoids be cut for long-term culture? The cited study implemented a protocol where organoids were cut every three weeks, beginning on day 35 of culture [31].

Q4: Does the cutting process affect the utility of organoids for downstream analysis? No, the method enhances downstream applications. It enables the creation of densely packed organoid arrays and cryosections for techniques like high-throughput drug screening and single-cell spatial transcriptomics [31].

Q5: What are the advantages of this method over traditional organoid cutting techniques? This method offers high throughput, maintains sterility to reduce contamination risk, and provides uniform sectioning for consistent and reproducible results, overcoming the limitations of low-throughput and contamination-prone manual methods [31].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Organoid Sectioning | Jig blade is dull or damaged; Jig not properly calibrated. | Regularly inspect and replace blades; Ensure jig is 3D-printed with high precision and validate cutting uniformity with test materials. |

| Contamination After Cutting | Break in sterile technique during transfer; Inadequate sterilization of jig. | Perform all steps in a biosafety cabinet; Sterilize the 3D-printed jig (e.g., via autoclaving or ethanol immersion) before use. |

| Poor Organoid Viability Post-Cutting | Excessive mechanical force during cutting; Overly small section sizes. | Optimize cutting pressure; Ensure section sizes are large enough to retain viability while improving diffusion. |

| Low Throughput | Reliance on manual cutting methods. | Adopt the 3D-printed jig system with integrated blade guides to process multiple organoids rapidly and uniformly. |

Experimental Data and Protocols

Table 1: Performance Metrics of 3D-Printed Organoid Cutting Jigs

| Jig Design | Cutting Efficiency | Ease of Sterilization | Uniformity of Sections | Throughput (Organoids/Hour) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flat-Bottom | Superior | High | High | >100 |

| Other Designs (e.g., Angled-Bottom) | Standard | High | Moderate | 50-70 |

Table 2: Impact of Regular Cutting on Long-Term Organoid Culture

| Culture Metric | Uncut Organoids | Organoids Cut Every 3 Weeks |

|---|---|---|

| Proliferative Marker Expression | Low | High [31] |

| Incidence of Central Necrosis | High | Low [31] [32] |

| Average Size Consistency | Low (High Variability) | High (Low Variability) [31] |

| Maximum Culture Duration | Limited | Extended [31] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Method: Efficient Organoid Cutting Using a 3D-Printed Jig

1. Fabrication of the Cutting Jig:

- Design and fabricate the cutting jig using a high-resolution 3D printer.

- The study tested and optimized four classes of jigs with blade guides.

- The recommended design is a flat-bottom cutting jig for superior efficiency [31].

2. Sterilization:

- Sterilize the 3D-printed jig before use. Acceptable methods include autoclaving or immersion in 70% ethanol, followed by UV irradiation in a biosafety cabinet.

3. Organoid Harvesting and Embedding:

- Harvest the mature organoids (e.g., hPSC-derived, from day 35 onwards) from their culture matrix.

- Gently wash to remove residual extracellular matrix.

- Place the organoids in a small droplet of a neutral buffer or embedding material on the cutting surface of the jig.

4. Sectioning Process:

- Using a sterile surgical blade or scalpel, follow the blade guides on the jig to make precise, uniform cuts through the organoid mass.

- This typically results in organoids being sectioned into halves or quarters.

5. Re-embedding and Continued Culture:

- Transfer the freshly cut organoid fragments into a fresh culture environment, such as a mini-spin bioreactor, embedded in a new droplet of Geltrex or a GelMA hydrogel [31].

- Return the culture to the incubator for continued growth. This cutting process should be repeated every three weeks.

6. Creating Organoid Arrays (Optional):

- For high-throughput analysis, use 3D-printed molds to create GelMA or Geltrex-embedded organoid arrays, which position organoids in a dense, regular pattern [31].

- Similarly, silicone molds can be used to create organoid arrays for optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound embedding, facilitating even cryosectioning [31].

Workflow and Signaling Visualization

Organoid Culture & Analysis Workflow

Impact of Cutting on Organoid Health

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for the Organoid Cutting Protocol

| Item | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| 3D-Printed Flat-Bottom Jig | Provides a sterile, reusable platform with blade guides to ensure uniform and consistent sectioning of organoids [31]. |

| Human Pluripotent Stem Cell (hPSC)-Derived Organoids | The self-assembled, 3D tissue models that are the subject of the long-term culture and cutting experiments [31]. |

| Mini-Spin Bioreactors | A dynamic culture system used to maintain the organoids after cutting, potentially improving gas and nutrient exchange [31]. |

| Geltrex / GelMA Hydrogel | Extracellular matrix substitutes used to re-embed the cut organoid fragments, providing a 3D scaffold for growth [31]. |

| Silicone Molds for OCT | Used to create organized arrays of organoids before embedding in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound for uniform cryosectioning [31]. |

| Xanthomegnin | Xanthomegnin, CAS:1685-91-2, MF:C30H22O12, MW:574.5 g/mol |

| MK2-IN-3 hydrate | MK2-IN-3 hydrate, MF:C21H18N4O2, MW:358.4 g/mol |

Fundamental Concepts: The Role of Dynamic Culture in Organoid Research

Why are bioreactors and dynamic culture conditions important for organoid research?

Dynamic culture in bioreactors provides significant advantages over static culture by enhancing nutrient delivery and waste removal through active perfusion. This is crucial for supporting the viability and growth of larger, more complex 3D organoid structures. Furthermore, bioreactors enable the application of controlled mechanical stimulation, which activates essential mechanotransduction pathways that guide cell differentiation and tissue maturation, more closely mimicking the in vivo environment [33]. These systems are particularly valuable for scaling up organoid production for drug screening and regenerative medicine applications.

What types of mechanical stimulation can bioreactors provide?

Bioreactors are designed to deliver various types of mechanical stimuli to cultured tissues, broadly categorized as passive and active stimulation.

- Passive Stimulation: Includes cues from the underlying substrate, such as topography and stiffness, which can modulate cell migration, gene expression, and fate [33].

- Active Stimulation: Involves externally applied forces, including:

- Tension: Uniaxial or multiaxial stretching.

- Compression: Direct pressure on the tissue construct.

- Shear Stress: Frictional forces from fluid flow over the cell surface.

- Torsion: Twisting forces [33].

Advanced "soft bioreactor" systems are now emerging to apply complex, multiaxial loading patterns that better replicate physiological conditions [33].

Troubleshooting Common Bioreactor and Organoid Culture Challenges

Why is my organoid culture showing high heterogeneity in size and shape, and how can I control it?

High heterogeneity in organoid populations often stems from inconsistent nutrient gradients, uneven mechanical stimulation, or suboptimal initial seeding conditions. To address this:

- Implement Quality Control: Use automated imaging technologies like Flow Imaging Microscopy (FlowCam) for real-time, high-throughput assessment of 3D cell cluster size, shape, and morphology. This provides an objective, complete assessment of the aggregate population, enabling rapid adjustments to culture parameters [34].

- Optimize Seeding: For homogenous cell distribution, use perfusion-based seeding in bioreactors. One protocol involves installing scaffolds in flow perfusion bioreactors, injecting a cell suspension, and maintaining a superficial media velocity of 3 mL/min for 15–18 hours [35].

- Control Geometry: Employ micropatterning techniques to create organoids with defined 2D geometric designs (e.g., circles, rectangles, stars). This provides precise control over the initial organoid structure, which influences subsequent physiological function and reduces inherent heterogeneity [36].

My organoids show central necrosis. How can I improve nutrient perfusion?

Central necrosis indicates that oxygen and nutrients are not sufficiently penetrating the core of the organoid.

- Increase Perfusion Rate: Systematically adjust the perfusion flow rate to enhance convective transport. However, avoid excessively high rates that could generate damaging shear stresses.

- Optimize Scaffold Properties: Ensure your scaffold has high pore connectivity to facilitate fluid permeation. You can measure the permeation velocity of fluid flow through acellular scaffolds using a derivative of Darcy's Law as an indicator of pore connectivity and an indirect measure of the fluid shear stress cells will experience [35].

- Incorporate Mechanical Stimulation: Apply cyclic strain to the construct. This can enhance nutrient exchange by actively pumping fluid through the tissue matrix and has been shown to upregulate matrix-remodeling genes that can improve permeability [33].

My tissue constructs lack functional maturity. How can mechanical stimulation help?

Insufficient functional maturity often results from a lack of physiologically relevant mechanical cues.

- Mimic In Vivo Signals: Program your bioreactor to deliver displacement waveforms that replicate native tissue strains. For example, one study designed a bioreactor to replicate frequencies and peak in vivo patellar tendon strains, which improved the stiffness of both the engineered construct and the subsequent in vivo repair [37].

- Apply Complex Loading: Move beyond simple uniaxial tension. Explore combinations of stimuli (e.g., tension with torsion or compression with shear) to better mimic the in vivo cellular environment. Studies have shown that such complex loading conditions improve biological and biochemical outcomes over single-type stimuli [33].

- Optimize Culture Duration: Do not under-culture your constructs. A study on mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-seeded scaffolds found that culturing under perfusion for at least 14 days in vitro was necessary to achieve significantly greater bone volume fraction, bone mineral density, and osteoblastic markers upon implantation in vivo, compared to shorter 1- or 7-day culture periods [35].

Quality Control and Optimization Protocols

How can I systematically monitor and analyze organoid morphology and function?

A combination of imaging, molecular analysis, and data science techniques is most effective.

- High-Throughput Imaging: Use Flow Imaging Microscopy (FlowCam) to automatically analyze thousands of organoids, providing quantitative data on size (e.g., equivalent spherical diameter) and shape (e.g., circularity, aspect ratio) to replace subjective manual microscopy [34].

- Functional Assessment: For cardiac organoids, simultaneously record calcium transients (e.g., using a GCaMP6f reporter) and contractile motion from bright-field videos. This yields key functional parameters like beat rate, contraction velocity, calcium rising time (t0), and decay time (t50, t75) [36].

- Leverage Machine Learning: Apply unsupervised machine learning algorithms like t-SNE and UMAP to reduce high-dimensional physiological data (e.g., 10 functional parameters) into 2D space. This allows for the visualization of organoid heterogeneity and the identification of functional clusters associated with specific culture conditions or geometric designs [36].

What is a step-by-step protocol for establishing a perfusion culture for bone-forming constructs?

The following protocol, adapted from a study using human MSCs in HA-PLG scaffolds, can serve as a template for osteogenic culture [35].

- Scaffold Preparation: Fabricate composite scaffolds (e.g., hydroxyapatite and PLG) using a gas foaming/particulate leaching method. Sterilize with 70% ethanol and pre-wet in cell culture medium.

- Cell Seeding in Bioreactor:

- Install scaffolds in flow perfusion bioreactors (e.g., U-CUP style).

- Inject 10 mL of growth medium (GM) through the bottom port.

- Inject a suspension of 1.2 x 10^6 MSCs in 2 mL of GM via the top port.

- Connect bioreactors to a syringe pump and perfuse at a superficial velocity of 3 mL/min for 15-18 hours to ensure homogenous cell distribution.

- Osteogenic Induction and Maintenance:

- After the seeding phase, replace GM with osteogenic medium (OM: GM supplemented with 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μg/mL ascorbate-2-phosphate, and 100 nM dexamethasone).

- Maintain constructs under continuous perfusion culture. Change the osteogenic medium every 3-4 days.

- Harvesting and Analysis:

- After the desired culture duration (e.g., 14 days for in vivo bone formation), harvest constructs.

- Assess DNA content, calcium deposition, and expression of osteogenic markers (e.g., via RT-qPCR for Runx2, Osteocalcin).

The diagram below illustrates the experimental workflow for perfusion culture of tissue engineered constructs.

Perfusion Culture Workflow for Bone Constructs

Essential Reagents and Materials for Organoid and Bioreactor Research

The table below lists key reagents and their functions for organoid and bioreactor-based research, compiled from various protocols [24] [35] [38].

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) Matrix | An undefined extracellular matrix (e.g., Matrigel) providing a 3D scaffold for embedded organoid culture, essential for growth and self-organization [38]. |

| Advanced DMEM/F12 | A common basal medium for many organoid culture systems, including those for colon, esophagus, and pancreas [24] [38]. |

| Noggin | A BMP inhibitor used in various organoid media (at 100 ng/mL) to promote epithelial growth and suppress differentiation [38]. |

| R-spondin1 Conditioned Medium | A critical niche component that potentiates Wnt signaling, essential for stem cell maintenance in intestinal, esophageal, and pancreatic organoids [38]. |

| A83-01 | A TGF-β signaling inhibitor (used at 500 nM) that supports the growth of epithelial organoids by preventing differentiation [38]. |

| Y-27632 (ROCK Inhibitor) | Enhances cell survival after dissociation and thawing by inhibiting apoptosis; used in some protocols (e.g., Mammary at 5 μM) [38]. |

| Hydroxyapatite-PLG Scaffold | A composite biomaterial scaffold used in bone tissue engineering; provides osteoconductivity and tunable porosity for MSC growth under perfusion [35]. |

| B-27 Supplement | A serum-free supplement used in various organoid media to support neuronal and epithelial cell survival and growth [38]. |

| EGF (Epidermal Growth Factor) | A mitogen that promotes proliferation of epithelial stem and progenitor cells in organoids (typically used at 50 ng/mL) [38]. |

Optimizing Bioreactor Performance and Process Control

How can I optimize multiple bioreactor parameters efficiently?

Traditional one-variable-at-a-time optimization is inefficient due to variable interdependence.

- Use Design of Experiments (DOE): Proactively design small-scale culture systems (e.g., 10-50 samples) to manipulate multiple variables (e.g., pH, dissolved Oâ‚‚, temperature, perfusion rate) simultaneously. Statistical analysis of the results allows you to efficiently identify the optimal set of critical process parameters [39].

- Implement Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Increase sensorization in your bioreactor system. On-line sensors for parameters like pH, oxygen, and cell density provide real-time data, leading to a deeper understanding of the system and enabling real-time adjustments [39].

- Automate Testing and Control: Use benchtop devices that automatically take small-volume samples from cultures to analyze pH, cell density, and nutrient levels. When combined with DOE-based software, this creates a closed-loop feedback control system, offering unprecedented real-time control and ensuring that scale-up parameters are accurately measured [39].