Optimizing SDS Reduction Solutions for Whole Mount Hybridization in Spiralian Model Systems

Whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) is an indispensable technique for visualizing spatial gene expression, yet its application in Spiralian models presents unique challenges due to complex tissue biochemistry and...

Optimizing SDS Reduction Solutions for Whole Mount Hybridization in Spiralian Model Systems

Abstract

Whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) is an indispensable technique for visualizing spatial gene expression, yet its application in Spiralian models presents unique challenges due to complex tissue biochemistry and morphology. This article provides a comprehensive guide on the use and optimization of SDS-based reduction solutions to overcome these hurdles. We explore the foundational principles of SDS chemistry, detail a step-by-step optimized protocol for diverse Spiralian species, address common troubleshooting scenarios like background staining and autofluorescence, and validate the method's efficacy through comparative analysis and its application in discovering novel, lineage-specific genes. This resource is tailored for researchers in evolutionary developmental biology and drug discovery, aiming to enhance the consistency, signal-to-noise ratio, and success of WMISH in these critical non-model organisms.

The Spiralian Challenge: Why SDS Reduction is a Game-Changer for Whole Mount Hybridization

Spiralia represents one of the three major ancient bilaterian lineages, alongside ecdysozoans and deuterostomes, comprising approximately 11 of the 25 animal phyla [1] [2]. This diverse clade includes molluscs, annelids, brachiopods, phoronids, nemerteans, bryozoans, platyhelminths, and rotifers [1]. Spiralia arose shortly after the origin of bilaterians, likely at the beginning of the Cambrian period, making them a crucial group for understanding early animal evolution [1] [2]. A subset of Spiralia is also referred to as Lophotrochozoa, reflecting the two major larval types found within the group: the lophophore (a feeding structure) and the trochophore larva [3]. Despite extraordinary diversity in adult morphology, many spiralians share conserved early developmental programs and morphological traits, making them exceptionally valuable for evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) research [1].

Key Biological Features of Spiralia

Spiral Cleavage and Embryonic Development

A defining characteristic of many spiralians is their highly conserved pattern of early development called spiral cleavage [1] [4]. This stereotypic embryonic program is shared by molluscs, annelids, nemerteans, and polyclad flatworms [1]. In spiral cleavage, the cell divisions are oblique to the polar axis, resulting in a characteristic spiral arrangement of blastomeres [4]. Another significant feature is the determinant specification of the D quadrant, which becomes specialized for mesoderm production in most spiralians through the mesentoblast cell (4d) [4]. This embryonic cell lineage conservation across diverse phyla provides a powerful framework for comparative evolutionary studies.

Ciliary Bands and Lophotrochin Genes

Many spiralians possess prominent ciliary bands used for locomotion and feeding, with striking similarities in structure and function across the group [1]. The trochophore larva, shared by annelids and molluscs, features a main ciliary band called the prototroch composed of cells with multiple large cilia [1] [2]. Research has identified spiralian-specific genes with conserved expression in these ciliary structures. Lophotrochin and trochin are genes containing protein motifs strongly conserved within Spiralia but not detectable outside it [1] [4] [2]. Lophotrochin appears to have evolved from a DUF4476 domain-containing protein in the spiralian common ancestor, acquiring a novel C-terminal spiralian-specific motif, while trochin shows no detectable similarity to any non-spiralian genes, suggesting possible de novo gene formation [1] [2].

Table 1: Key Spiralian-Specific Genes and Their Characteristics

| Gene Name | Sequence Characteristics | Evolutionary Origin | Expression Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lophotrochin | Contains novel C-terminal spiralian-specific motif; N-terminal has similarity to DUF4476 | Evolved from DUF4476 domain-containing protein in spiralian ancestor | Specifically expressed in ciliary bands across multiple spiralian phyla |

| Trochin | No detectable similarity to non-spiralian genes or protein domains | De novo formation or rapid evolution in spiralian ancestor | Restricted to main ciliary bands and subset of other ciliated structures |

Regeneration Capabilities

Spiralians exhibit remarkable diversity in regeneration abilities, with some groups displaying exceptional regenerative capacity [5] [6]. Annelids, nemerteans, and platyhelminths include species capable of regenerating complete individuals from small body fragments, while most molluscs have more limited abilities [5]. This variation makes Spiralia an excellent system for studying the evolution of regenerative mechanisms, with recent advances in molecular tools enabling investigations into the developmental basis of regeneration across different spiralian groups [5].

Genomic and Evolutionary Significance

Recent developments in sequencing technologies have revolutionized our understanding of spiralian genomics and genome architecture [7]. Comparative genomic analyses reveal that although spiralian genomes have undergone substantial changes over 500 million years, they exhibit both conserved and lineage-specific features [7]. Chromosome-level assemblies have highlighted key genomic features including karyotype, synteny, and Hox gene organization [7]. The strong evolutionary constraint on spiralian-specific genes like lophotrochin and trochin since the Cambrian indicates significant functional roles, highlighting the importance of lineage-specific genes for understanding phenotypic evolution [1] [2].

Application Notes: SDS-Based Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization for Spiralia

Protocol Background and Optimization Challenges

Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) is an invaluable technique for developmental and evolutionary biologists, allowing visualization of gene expression patterns in developing embryos and larvae [8]. However, WMISH protocols often require significant optimization for different species and developmental stages due to variation in the biochemical and biophysical properties of cells and tissues [8]. For spiralian embryos, several technical challenges exist, including viscous intra-capsular fluid that can interfere with procedures, and non-specific background signal from shell formation in molluscan larvae [8]. The SDS-based WMISH protocol addresses these challenges through strategic use of detergents and permeabilization treatments.

Optimized SDS-Based WMISH Protocol for Spiralians

The following protocol has been optimized for spiralian embryos, particularly molluscs like Lymnaea stagnalis, but can be adapted for other spiralian taxa:

Critical Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spiralian WMISH

| Reagent/Solution | Concentration/Formula | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) | 2.5-5% in PBS | Mucolytic agent that degrades viscous intra-capsular fluid |

| SDS Reduction Solution | 0.1-1% SDS in PBS | Detergent that permeabilizes membranes without disrupting morphology |

| Paraformaldehyde Fixative | 4% PFA in PBS | Cross-linking fixative that preserves tissue morphology and RNA integrity |

| Proteinase K | Species- and stage-dependent concentration | Enzymatic permeabilization through partial protein digestion |

| Triethanolamine/Acetic Anhydride | 0.1M TEA + 0.25% acetic anhydride | Acetylation treatment that reduces non-specific background staining |

| Hybridization Buffer | Standard WMISH formulation with 50% formamide | Provides optimal stringency for specific riboprobe binding |

Technical Considerations for Spiralian Embryos

The optimal SDS concentration and treatment duration vary with developmental stage. Earlier embryos (2-3 days post first cleavage) typically require milder treatment (0.1% SDS for 10 minutes), while later stages (3-5 days post first cleavage) tolerate higher concentrations (0.5-1% SDS for 10 minutes) [8]. The reduction solution (containing DTT and detergents like SDS and NP-40) can be used as an alternative to SDS alone, particularly for tougher embryonic stages, though embryos become extremely fragile during this treatment and require careful handling [8]. For spiralian species with developing shell fields, acetylation with triethanolamine and acetic anhydride is essential to eliminate tissue-specific background signal in these mineralizing tissues [8].

Research Applications and Future Directions

The combination of spiralian-specific molecular tools and optimized techniques like SDS-based WMISH enables diverse research applications. These include investigating the evolution of novel traits through lineage-specific genes, comparing regenerative mechanisms across related phyla, and understanding the developmental basis of diverse body plans [1] [5]. Future research directions recommended by current literature include increasing sequencing efforts to improve genomic resources, expanding functional genomics research, and developing more targeted approaches for manipulating gene function in diverse spiralian species [7]. These approaches will deepen insights into spiralian biology and provide broader understanding of animal evolution and development.

Application Notes

Whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) is an indispensable technique for spatial gene expression analysis in evolutionary developmental biology. Within the Spiralia, a clade encompassing mollusks, annelids, and other lophotrochozoans, the pulmonate freshwater gastropod Lymnaea stagnalis serves as a key model organism for studies on shell formation, chirality, and ecologically regulated development [8]. However, researchers employing WMISH in L. stagnalis and other spiralians encounter unique biochemical and biophysical obstacles that can compromise signal clarity and morphological integrity. Two principal challenges are the presence of viscous intra-capsular fluid and the onset of larval biomineralization, which collectively necessitate specific pre-hybridization treatments for successful gene visualization [8]. The application of an optimized SDS reduction solution is a critical step in overcoming these barriers, enabling robust and reproducible results.

The table below summarizes the core obstacles and the specific solutions required to mitigate them.

Table 1: Primary Obstacles in Spiralian WMISH and Corresponding Solutions

| Obstacle | Origin & Nature | Impact on WMISH | Required Pre-Treatment Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-Capsular Fluid [8] | Viscous nutritive fluid within egg capsules; complex mix of ions, polysaccharides, and proteoglycans. | Sticks to embryo post-decapsulation; physically blocks probe penetration and non-specifically binds reagents. | Mucolytic agent (N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine, NAC) and detergent-based permeabilization (SDS). |

| Larval Biomineralization [8] | Secretion of first insoluble shell material, starting from ~52 hours post-first cleavage. | Material non-specifically binds nucleic acid probes, creating severe background staining in the shell field. | High-stringency washes and acetylation treatment with Triethanolamine (TEA) and Acetic Anhydride (AA). |

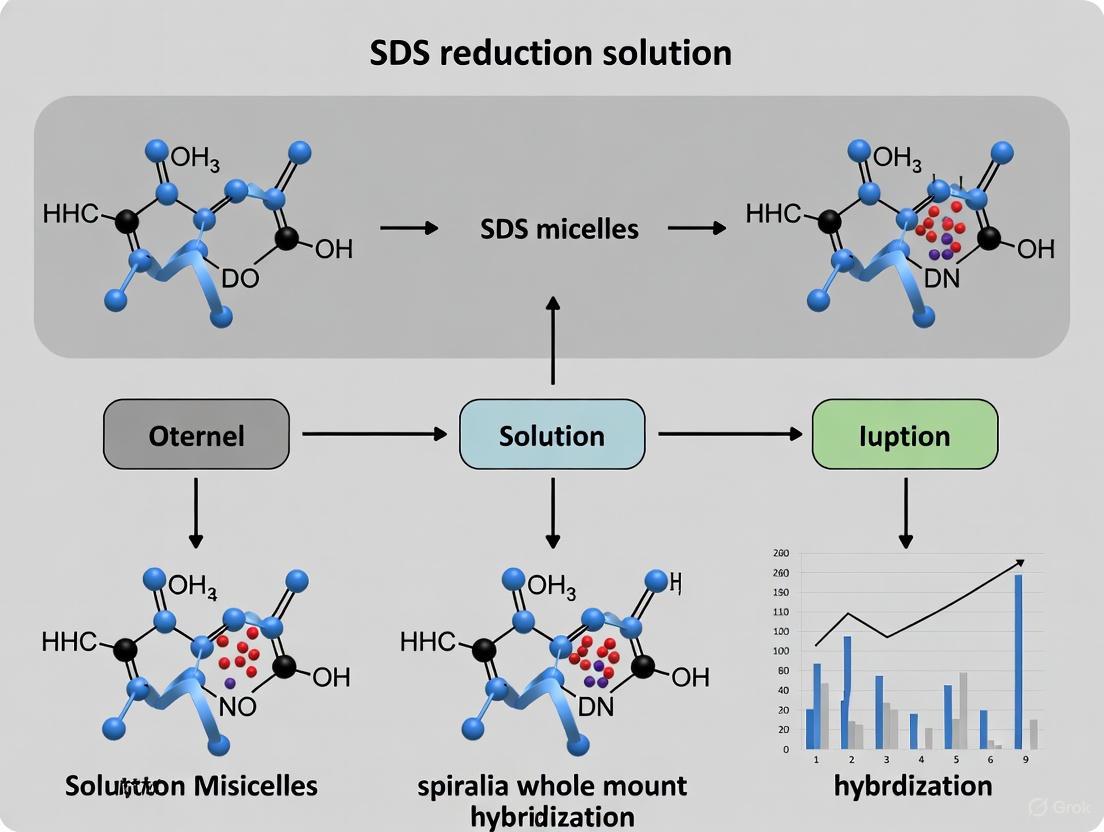

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these obstacles, the solutions employed, and the desired outcome in the WMISH workflow.

Quantitative Analysis of Pre-hybridization Treatments

The efficacy of WMISH is highly dependent on the precise conditions of pre-hybridization treatments. Systematic comparisons have identified optimal parameters for key steps, which vary according to larval developmental stage [8]. The data in the following table provide a foundational guide for protocol optimization.

Table 2: Optimized Pre-hybridization Treatments for Different Larval Stages of L. stagnalis

| Treatment | 2-3 Days Post-First Cleavage (dpfc) | 3-5+ Days Post-First Cleavage (dpfc) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC) | 5 min in 2.5% NAC [8] | 2x 5 min in 5% NAC [8] | Degrades mucosal intra-capsular fluid; increases tissue accessibility. |

| SDS Treatment | 10 min in 0.1% SDS [8] | 10 min in 0.5%-1% SDS [8] | Permeabilizes tissues by dissolving membranes and denaturing proteins. |

| Reduction Solution | 10 min in 0.1X Solution [8] | 10 min in 1X Solution at 37°C [8] | Uses DTT and detergents (SDS, NP-40) to break disulfide bonds and permeabilize. |

| Proteinase K (Pro-K) | 5 min [9] | 10-20 min [9] | Digests proteins cross-linked by fixation, further enhancing probe penetration. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

High-Throughput Decapsulation and Initial Processing

The initial steps are critical for obtaining morphologically intact, accessible embryos free of obstructive capsules and jelly [9].

- Apparatus Assembly: Construct a decapsulation device by connecting a 20 ml syringe to silicone tubing. A pulled glass needle is fixed adjacent to a microscope slide and inserted into the tubing so its tip protrudes slightly into the lumen.

- Sample Collection & Relaxation: Collect egg strings from aquaria and de-jelly individual capsules on a damp paper towel. For larvae 5 dpfc and older, anaesthetize by relaxing in 2% MgCl₂•6H₂O for 30 minutes to prevent muscle contraction during fixation [9].

- Fixation & Decapsulation: Fix embryos/larvae in 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. After washing with PBTw (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20), pass the fixed capsules through the decapsulation device. The glass needle ruptures the capsule membrane, releasing the embryo. Process material multiple times if necessary to achieve >90% decapsulation [9].

- Storage: Dehydrate decapsulated samples through a graded ethanol series (33%, 66%, 100%) in PBTw and store at -20°C in 100% ethanol until use [8] [9].

Pre-Hybridization Treatments for Intra-capsular Fluid and Biomineralization

This core protocol details the use of SDS reduction and acetylation to overcome the specific obstacles of fluid and shell background.

- Rehydration: Rehydrate stored samples through a descending ethanol series (66%, 33%) into PBTw [9].

- Mucolysis & Permeabilization with NAC and SDS:

- Treat samples with the age-appropriate NAC concentration and duration (see Table 2) [8].

- Immediately following NAC, perform an SDS treatment. Incubate samples in the age-adjusted SDS solution (0.1% for 2-3 dpfc, 0.5-1% for 3-5+ dpfc) in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature [8].

- Alternative: Reduction Solution. In some protocols, the SDS step is replaced or complemented by a "reduction" step using a solution containing DTT, SDS, and NP-40. This treatment is particularly effective but makes samples extremely fragile and must be handled with care [8].

- Proteinase K Digestion: Treat rehydrated samples with Proteinase K (e.g., 5-20 minutes, depending on stage) to digest surface proteins and further enhance probe access to the tissue [9].

- Post-fixation & Acetylation:

- Re-fix samples in 4% PFA for 30 minutes to restore morphological stability after protease digestion.

- To eliminate background from non-specific probe binding to shell material, acetylate the samples. Incubate in 0.1M Triethanolamine (TEA) with 0.25% acetic anhydride (AA) for 10 minutes. This treatment neutralizes positive charges on the tissue that can bind anionic nucleic acid probes [8].

- Hybridization and Detection: Proceed with standard WMISH steps: pre-hybridization, hybridization with DIG-labelled riboprobes, high-stringency post-hybridization washes, and immunodetection using an Alkaline Phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-DIG antibody with NBT/BCIP as a colorimetric substrate [8].

The following workflow provides a visual summary of the complete protocol, integrating the specialized pre-hybridization treatments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table catalogues the essential reagents discussed and their critical functions in overcoming spiralian WMISH challenges.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Spiralian WMISH Obstacles

| Research Reagent | Function in Protocol | Role in Overcoming Obstacles |

|---|---|---|

| N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC) | Mucolytic agent applied immediately after decapsulation [8]. | Degrades the viscous polysaccharide-rich intra-capsular fluid, preventing probe penetration blockage. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ionic detergent used in pre-hybridization permeabilization [8]. | Dissolves lipid membranes and denatures proteins, creating pores for probe entry. Used alone or in "reduction" solution. |

| Reduction Solution (DTT/SDS/NP-40) | A potent permeabilization cocktail containing a reducing agent and detergents [8]. | DTT breaks disulfide bonds in proteins, while SDS and NP-40 solubilize lipids. Synergistically enhances tissue permeability. |

| Proteinase K | Serine protease for controlled enzymatic digestion [8] [9]. | Cleaves peptide bonds in proteins cross-linked by fixation, allowing deeper probe penetration into the tissue. |

| Triethanolamine (TEA) & Acetic Anhydride | Acetylation reagents applied before hybridization [8]. | Acetylates positively charged amino groups in proteins, eliminating electrostatic non-specific binding of probes to shell material and other tissues. |

| MgCl₂•6H₂O | Anaesthetic agent for older larvae [9]. | Relaxes larval muscles, preventing contraction during fixation that would distort morphology and complicate interpretation of gene expression patterns. |

| SR7826 | SR7826, MF:C22H21N5O2, MW:387.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TH1338 | TH1338, MF:C22H21N3O4, MW:391.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the field of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), research on Spiralia—a vast and morphologically diverse clade of invertebrates including mollusks, annelids, and flatworms—provides crucial insights into the evolutionary history of animal body plans. Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) has emerged as an indispensable technique for visualizing spatial gene expression patterns in these organisms, enabling scientists to correlate gene function with morphological development. However, a significant technical challenge persists: the biochemical and biophysical properties of spiralian tissues often impede reagent penetration, resulting in weak or inconsistent signals [8].

The integration of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and reducing agents into tissue permeabilization protocols has dramatically improved WMISH outcomes for Spiralia research. These chemical treatments function synergistically to disrupt lipid membranes and break disulfide bonds in proteins, thereby overcoming the natural barriers that would otherwise prevent uniform probe access. This application note details the chemical basis, optimized protocols, and practical applications of these permeabilization strategies, providing a structured framework for their implementation in spiralian WMISH studies as part of a broader thesis investigation.

Chemical Mechanisms of Permeabilization

SDS: A Powerful Ionic Detergent

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is an anionic surfactant characterized by a hydrophobic 12-carbon tail and a hydrophilic sulfate head group. In biological applications, its primary function is to solubilize lipid membranes and denature proteins through multiple mechanisms. The hydrophobic tail inserts into lipid bilayers, while the charged head group interacts with aqueous environments, effectively disrupting membrane integrity [10]. This membrane dissolution creates microscopic channels through which nucleic acid probes and antibodies can diffuse into tissues.

At the molecular level, SDS binds to proteins via hydrophobic interactions, unfolding tertiary structures and exposing previously buried domains. This denaturation not only facilitates penetration but also inactivates nucleases that might otherwise degrade RNA probes or target mRNAs. However, the potent action of SDS requires careful optimization, as excessive concentrations or incubation times can compromise tissue morphology through over-digestion of cellular structures [8].

Reducing Agents: Breaking Disulfide Bridges

Reducing agents such as dithiothreitol (DTT) complement SDS-mediated permeabilization by targeting the covalent disulfide bonds that stabilize extracellular matrices and protein tertiary structures. The "reduction" solution, typically containing DTT and additional detergents like SDS or NP-40, breaks these sulfur-sulfur bonds, effectively loosening the dense meshwork of structural proteins that constrains tissue architecture [8].

This combination is particularly valuable for spiralian embryos, which often possess tough egg capsules and complex extracellular matrices that resist standard permeabilization methods. By disrupting both lipid membranes and protein networks, SDS-reducing agent combinations achieve superior penetration while maintaining morphological integrity—a balance crucial for accurate spatial localization of gene expression patterns.

Table 1: Key Permeabilization Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent | Chemical Class | Primary Mechanism | Typical Working Concentration | Effect on Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDS | Ionic detergent | Solubilizes lipids, denatures proteins | 0.1-1% in PBS [8] | Creates permeable channels in membranes |

| DTT | Thiol-based reducing agent | Breaks protein disulfide bonds | 0.1X-1X reduction solution [8] | Loosens extracellular matrix |

| N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC) | Mucolytic compound | Degrades mucopolysaccharides | 2.5-5% in PBS [8] | Removes viscous coatings |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent | Solubilizes lipids | 0.1-2% [11] [10] | Gentle membrane permeabilization |

| Proteinase K | Serine protease | Digests proteins | 10-100 μg/ml [8] | Enzymatic tissue digestion |

Optimized Protocols for Spiralia WMISH

Sample Preparation and Fixation

Proper sample preparation establishes the foundation for successful WMISH. For the freshwater gastropod Lymnaea stagnalis, a key spiralian model, carefully release embryos from egg capsules using fine forceps and mounted needles. The viscous intracapsular fluid—a complex mixture of polysaccharides, proteoglycans, and other polymers—often adheres to embryos and interferes with subsequent steps [8].

Immediately treat dissected embryos with N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), a mucolytic agent that degrades this obstructive mucosal layer. For embryos between two and three days post first cleavage (dpfc), incubate in 2.5% NAC for five minutes. For older embryos (three to six dpfc), use 5% NAC with two five-minute treatments. Following NAC treatment, fix samples in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 minutes at room temperature [8].

SDS and Reduction-Based Permeabilization

After fixation, proceed with permeabilization using either SDS or reduction solution based on experimental requirements and embryonic age:

SDS Treatment Protocol:

- Wash fixed samples once in PBTw (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20) for five minutes

- Incubate in SDS solution (0.1%, 0.5%, or 1% SDS in PBS) for ten minutes at room temperature

- Rinse in PBTw and dehydrate through graded ethanol series (33%, 66%, 100%) [8]

Reduction Solution Protocol:

- Wash fixed samples once in PBTw for five minutes

- For embryos between two and three dpfc: treat with 0.1X reduction solution for ten minutes at room temperature

- For embryos between three and five dpfc: incubate in preheated 1X reduction solution at 37°C for ten minutes

- Briefly rinse with PBTw before dehydration through graded ethanol series [8]

Table 2: Age-Dependent Permeabilization Parameters for Lymnaea stagnalis

| Developmental Stage | Permeabilization Method | Concentration | Incubation Conditions | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-3 days post first cleavage | SDS Treatment | 0.1% SDS | 10 min, room temperature | Preserves delicate tissues |

| 2-3 days post first cleavage | Reduction Solution | 0.1X strength | 10 min, room temperature | For resistant tissues |

| 3-5 days post first cleavage | SDS Treatment | 0.5-1% SDS | 10 min, room temperature | Increased toughness |

| 3-5 days post first cleavage | Reduction Solution | 1X strength | 10 min, 37°C | Enhanced penetration needed |

| All stages | NAC Pre-treatment | 2.5-5% | 5-10 min, room temperature | Removes mucosal coatings |

Alternative Permeabilization Strategies

For particularly challenging tissues or when optimizing for specific spiralian species, consider these alternative approaches:

Proteinase K Digestion: Following rehydration, incubate samples in Proteinase K (10-100 μg/ml in 2X SSC) for 30 minutes at 37°C. This enzymatic treatment digests proteins and enhances probe accessibility, particularly for internal tissues [8].

Nitric Acid/Formic Acid (NAFA) Method: For delicate regenerating tissues, as demonstrated in planarian studies, a NAFA fixation and permeabilization approach can preserve tissue integrity while allowing sufficient probe penetration. This method eliminates the need for proteinase K digestion, potentially preserving antigen epitopes for subsequent immunoassays [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of SDS and reducing agent protocols requires carefully formulated solutions. The following table details key reagents used in spiralian WMISH permeabilization:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Tissue Permeabilization

| Reagent Solution | Composition | Primary Function | Protocol Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detergent Solution | 1% SDS, 0.5% Tween-20, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl [13] | Membrane solubilization and lipid removal | Initial tissue permeabilization |

| Reduction Solution | DTT, SDS, NP-40 in appropriate buffer [8] | Disruption of disulfide bonds in extracellular matrix | Enhanced penetration for tough tissues |

| Hybridization Buffer (Hyb) | 50% deionized formamide, 5× SSC, 50 μg/mL heparin, 0.1% Tween-20 (pH 5.0) [13] | Creates optimal hybridization conditions | RNA probe incubation |

| Hybridization Buffer with DNA and SDS | Hyb buffer with 0.1 mg/mL sonicated salmon sperm DNA, 0.3% SDS [13] | Blocks non-specific binding and reduces background | Pre-hybridization and probe hybridization |

| Proteinase K Solution | 10-100 μg/mL Proteinase K in 2× SSC [8] | Enzymatic digestion of proteins | Alternative permeabilization method |

| NAC Solution | 2.5-5% N-acetyl-L-cysteine in PBS [8] | Degradation of mucopolysaccharides | Removal of viscous coatings from embryos |

| TH-257 | TH-257, MF:C24H26N2O3S, MW:422.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| TP-3654 | TP-3654, CAS:1361951-15-6, MF:C22H25F3N4O, MW:418.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Workflow and Mechanism of Action

The following diagram illustrates the sequential steps and underlying mechanisms of SDS and reducing agent-mediated tissue permeabilization in spiralian WMISH:

The strategic application of SDS and reducing agents has revolutionized tissue permeabilization for WMISH in Spiralia research, enabling precise spatial localization of gene expression patterns in these evolutionarily significant organisms. The protocols detailed in this application note provide a systematic framework for balancing permeabilization efficacy with morphological preservation—a critical consideration for thesis research and broader scientific investigations. Through continued optimization of these chemical approaches, researchers can further unlock the potential of spiralian models for addressing fundamental questions in evolutionary developmental biology.

While sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is widely recognized as a detergent for permeabilizing tissues in molecular techniques, its critical function in reducing non-specific background in nucleic acid hybridization assays is less appreciated. This application note details the specialized role of SDS in hybridization workflows, framing it within a broader thesis on optimizing whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) for Spiralia research. We synthesize data demonstrating that SDS in hybridization buffers substantially lowers background signals by blocking non-specific probe adherence to membranes and tissues. The quantitative and mechanistic evidence presented provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a validated strategy to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio in challenging model systems, including the mollusc Lymnaea stagnalis.

In molecular biology protocols, SDS is a ubiquitous component of lysis and loading buffers, primarily valued for its potent anionic detergent properties that solubilize membranes and denature proteins. However, its application in hybridization-based techniques like WMISH and filter hybridizations extends beyond mere permeabilization. High concentrations of SDS in hybridization buffers serve a distinct and critical function: to block non-specific binding sites on blotting membranes and complex embryonic tissues, thereby minimizing background signal and improving the clarity and reliability of experimental results [14] [15].

This application note explores this specific role of SDS, placing it within the context of overcoming technical challenges in Spiralian research. Organisms like the mollusc Lymnaea stagnalis present particular difficulties for WMISH, including sticky intra-capsular fluid and biophysical tissue properties that can foster non-specific probe binding [8]. We will demonstrate that incorporating SDS into the experimental workflow is a key solution to these problems, enabling high-fidelity gene expression analysis in these scientifically valuable but technically demanding systems.

The Core Mechanism: How SDS Minimizes Background

The primary function of SDS in reducing non-specific background is attributed to its ability to coat surfaces and prevent the direct, undesired adherence of nucleic acid probes.

- Blocking Agent: SDS acts as a powerful blocking reagent during prehybridization and hybridization steps. Its high concentration in the buffer ensures that it saturates charged or hydrophobic sites on the solid support (e.g., nylon membranes) or within complex tissue samples that might otherwise bind the labeled probe indiscriminately [14] [15].

- Impact on Hybridization Stringency: While salt concentration and temperature are the primary determinants of hybridization stringency, SDS also exerts a modest effect. Research by Rose et al. showed that the presence of 1% (w/v) SDS in a hybridization buffer is equivalent to a reduction in salt concentration of approximately 8 mM NaCl in terms of its effect on the dissociation temperature (Tm*). This slight destablizing effect on duplex formation may further contribute to cleaner results by favoring the formation of only perfectly matched, specific hybrids [16].

The following diagram illustrates how SDS integrates into a standard hybridization workflow and exerts its background-reducing effects at key stages.

Quantitative Evidence: Experimental Data on SDS Efficacy

The inclusion of SDS in hybridization buffers is not merely a theoretical recommendation; it is grounded in empirical data. The table below summarizes key findings from the literature on the quantitative and qualitative effects of SDS.

Table 1: Experimental Evidence Supporting the Use of SDS in Hybridization Protocols

| Evidence Type | Key Finding | Experimental Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Background Reduction | Buffers containing SDS yielded "reproducibly low backgrounds," while those lacking SDS or with low salt gave "high hybridization backgrounds." | Filter hybridization with targets on nylon membranes and PCR-generated probes. | [16] |

| Signal Consistency | SDS pre-treatment was identified as a key step that "greatly increases both WMISH signal intensity and consistency" while preserving morphology. | Whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) on early larval stages of Lymnaea stagnalis. | [8] |

| Stringency Effect | 1% (w/v) SDS was found to be equivalent to ~8 mM NaCl in its effect on dissociation temperature (Tm*), a modest but measurable impact. | Investigation of hybridization parameters in solutions containing SDS. | [16] |

| Protocol Adoption | A hybridization mix containing 1% SDS is specified as a standard component for sensitive in situ hybridization in mouse embryos. | Whole mount and section in situ hybridization for mouse embryonic tissues. | [17] |

The data from Rose et al. is particularly compelling. Their systematic investigation revealed that SDS has a more pronounced effect on controlling background than on altering the fundamental stringency of the hybridization itself [16]. This underscores its primary role as a blocking agent rather than a stringency modulator.

Application in Spiralian Research: A Case Study inLymnaea stagnalis

The value of SDS is clearly demonstrated in the development of an optimized WMISH protocol for the mollusc Lymnaea stagnalis, a key spiralian model. Researchers faced challenges with inconsistent signals and background staining, partly attributed to sticky intra-capsular fluid and the developing larval shell field that non-specifically bound nucleic acid probes [8].

To address this, an SDS-based permeabilization step was systematically tested and integrated into the workflow. Following fixation, samples were incubated in a solution of 0.1% to 1% SDS in PBS before dehydration and storage. This treatment was found to be highly effective in enhancing the final WMISH outcome [8]. The protocol for this critical step is detailed below.

SDS Treatment Protocol for L. stagnalis Larvae

- Following Fixation: After dissection and fixation in 4% PFA, wash samples once in PBTw (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20) for five minutes.

- SDS Incubation: Incubate the samples in SDS solution (0.1%, 0.5%, or 1% SDS in PBS) for ten minutes at room temperature.

- Rinse and Dehydrate: Remove the SDS solution and rinse the samples once with PBTw. Subsequently, dehydrate through a graded ethanol series (e.g., 33%, 66%, 100%) and store at -20°C until ready for the hybridization experiment [8].

This optimized step contributed significantly to achieving consistent, high-intensity WMISH signals for genes with varying expression levels, such as beta tubulin, engrailed, and COE, thereby enabling more precise gene expression characterization in this spiralian model [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key reagents discussed in this note that are essential for designing hybridization experiments with low background.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hybridization Experiments

| Reagent | Function in Hybridization | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Blocking agent to reduce non-specific probe binding to membranes and tissues; also aids in permeabilization. | Often used at 0.1-1% concentration. High concentrations require UV crosslinking for nucleic acids immobilized on nylon membranes [14]. |

| Formamide | Denaturing agent that reduces hybridization temperature and solution viscosity. | Commonly used at 50% in hybridization mix. Allows for lower, more biologically compatible incubation temperatures [14] [17]. |

| SSC (Saline Sodium Citrate) | Provides ionic strength for hybridization; critical for controlling stringency during washes. | Low SSC concentration and high temperature during washes increase stringency, removing imperfectly matched hybrids [15]. |

| Blocking Reagent (e.g., Casein, BSA) | Protein-based blocker used to occupy non-specific binding sites on membranes and tissues. | Often used in combination with denatured salmon sperm DNA and detergent in prehybridization steps [15]. |

| Proteinase K | Proteolytic enzyme that digests proteins, increases tissue permeability, and removes nucleases. | Concentration and incubation time must be optimized for each tissue type to avoid destroying morphology [8] [17]. |

| UAMC-1110 | UAMC-1110, CAS:1448440-52-5, MF:C17H14F2N4O2, MW:344.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| UNC0642 | UNC0642, CAS:1481677-78-4, MF:C29H44F2N6O2, MW:546.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Experimental Workflow

The diagram below synthesizes the key steps and reagents into a comprehensive workflow for a whole mount in situ hybridization experiment, highlighting stages where SDS and other critical reagents are applied to ensure a high-quality, low-background outcome.

SDS is a cornerstone reagent for achieving low-background hybridization in molecular applications. Its critical function extends beyond permeabilization to actively blocking non-specific binding sites on membranes and complex tissues. As demonstrated in the challenging context of spiralian WMISH, integrating a dedicated SDS treatment step is a powerful strategy to enhance signal consistency and intensity. By understanding and applying the principles and protocols outlined in this note, researchers can significantly improve the quality and reliability of their gene expression data.

The Spiralia, a vast and diverse clade of animals including molluscs, annelids, brachiopods, and nemerteans, represents one of the three major bilaterian lineages alongside ecdysozoans and deuterostomes [18]. Despite extraordinary diversity in adult morphology, spiralians share conserved early developmental programs and frequently possess ciliary bands used for locomotion and feeding [18]. These ciliary bands, particularly the prototroch found in trochophore larvae of molluscs and annelids, represent a fundamental spiralian trait whose molecular underpinnings have remained partially elusive. The homology of these structures across spiralian phyla has been controversial due to variations in their structure, function, and embryonic origin [18].

Recent investigations have revealed that lineage-specific genes—those conserved within a particular lineage but absent in outgroups—may hold the key to understanding the evolution of spiralian-specific traits [18]. These genes can arise through various mechanisms including segmental duplication, transposition, or de novo origin from previously non-coding sequences [18]. For spiralians, genes containing protein motifs strongly conserved within the clade but undetectable outside it represent promising candidates for investigating the molecular basis of shared morphological features. This application note explores the discovery and validation of two such genes, lophotrochin and trochin, and details optimized methodologies for their investigation using whole mount in situ hybridization with SDS reduction solutions.

Background: The Spiralian Clade and Ciliary Band Diversity

Spiralia encompasses approximately 11 of the 25 bilaterian animal phyla, arising at the beginning of the Cambrian period approximately 500 million years ago [18]. While adult body plans show remarkable diversity, many spiralians share distinctive larval forms with prominent ciliary bands. The trochophore larva, characterized by its prototroch ciliary band, is shared by molluscs and annelids and derives from homologous embryonic cells (1q2, the vegetal daughters of the 1st quartet of micromeres) [18]. However, other ciliary bands across spiralian phyla show considerable variation in structure and function, and do not necessarily derive from clearly homologous cell lineages [18].

Ciliary bands represent crucial functional structures for spiralian larvae, serving both locomotor and feeding functions. Their fundamental composition of cells with multiple large cilia creates water currents for propulsion and particle capture [18]. The investigation of these structures has been challenging due to the lack of molecular markers that unambiguously identify them across diverse spiralian taxa. The discovery of spiralian-specific genes expressed specifically in these bands provides unprecedented tools for understanding their developmental genetics and evolutionary history.

Table 1: Spiralian Phyla and Ciliary Band Characteristics

| Phylum | Representative Species | Larval Type | Ciliary Band Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mollusca | Tritia obsoleta (gastropod) | Trochophore | Prototroch from 1q2 cells |

| Annelida | Capitella teleta (polychaete) | Trochophore | Prototroch, telotroch, neurotroch |

| Nemertea | Not specified | Various | Diverse ciliated structures |

| Brachiopoda | Not specified | Various | Ciliated bands |

| Phoronida | Not specified | Actinotroch | Ciliated tentacles |

| Rotifera | Not specified | Not applicable | Corona with ciliary bands |

Discovery of Spiralian-Specific Genes Lophotrochin and Trochin

Bioinformatic Identification

A comprehensive bioinformatic screen identified 37 genes containing protein motifs strongly conserved within the Spiralia but not recognizable outside the clade [18]. The screening methodology required genes to be detectable at a BLAST e-value below 10e-7 in at least one genome each of molluscs, annelids, and platyhelminths, while being absent from any non-spiralian outgroup genome or the NCBI nr database at an e-value below 10e-5 [18]. This approach specifically targeted genes with spiralian-restricted conservation rather than lineage-specific paralogs of known gene families.

From the initial candidates, 20 genes were selected for expression analysis during embryonic and larval development of the gastropod Tritia obsoleta (formerly Ilyanassa obsoleta) [18]. Surprisingly, two genes with no sequence similarity to each other demonstrated specific expression in the primary ciliary band (prototroch) cells, unlike the general ciliary marker axonemal dynein which was detected in all ciliary structures including ciliated cells on the foot and apical plate [18]. Based on their expression patterns, these genes were named lophotrochin and trochin.

Molecular Characteristics

Lophotrochin possesses an N-terminal region with similarity to the uncharacterized DUF4476 domain (pfam14771) found in some non-spiralian genes, but contains a novel C-terminal motif specific to spiralians that is strongly conserved [18]. This suggests the protein originated from a DUF4476 domain-containing protein in the spiralian common ancestor that underwent rapid evolution or a fusion event to generate the novel C-terminal motif. Importantly, no DUF4476 domain was detected in echinoderm sequences despite the similarity of their larval ciliary bands to spiralian bands [18].

In contrast, trochin shows no detectable sequence similarity to any non-spiralian genes or protein domains, even using sensitive methods like PSI-BLAST or HMMER [18]. This suggests trochin may represent a de novo gene formation or the product of rapid evolution in the spiralian ancestor. The strong evolutionary constraint on both genes over approximately 500 million years indicates significant functional importance.

Expression Patterns Across Spiralia

Expression analysis of lophotrochin across multiple spiralian phyla reveals conserved expression in ciliary bands:

- In the gastropod Tritia obsoleta, both lophotrochin and trochin are specifically expressed in the prototroch cells as cilia begin to appear during early organogenesis [18].

- In the polychaete annelid Capitella teleta, both genes are restricted to the main ciliary bands (prototroch, telotroch, neurotroch) and a subset of other ciliated structures in the larva, but not all ciliated cells [18].

- Expression patterns in nemerteans, phoronids, brachiopods, and rotifers demonstrate that lophotrochin shows conserved expression in particular ciliated structures, most consistently in ciliary bands [18].

Table 2: Expression Patterns of Spiralian-Specific Genes

| Gene | Sequence Features | Expression in Tritia obsoleta | Conservation Across Spiralia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lophotrochin | Novel C-terminal spiralian-specific motif fused to DUF4476 domain | Specific to prototroch cells | Expressed in ciliary bands of annelids, nemerteans, phoronids, brachiopods, rotifers |

| Trochin | No detectable similarity to non-spiralian sequences | Specific to prototroch cells | Expressed in ciliary bands of annelids (limited sampling in other phyla) |

Optimized Whole MountIn SituHybridization Protocol for Spiralians

Protocol Background and Challenges

Whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) presents particular challenges for spiralian embryos, especially for the freshwater gastropod Lymnaea stagnalis, which has served as a key model for molluscan development [8]. Technical obstacles include:

- Intra-capsular fluid: Viscous nutritive fluid within egg capsules sticks to embryos following decapsulation and likely interferes with WMISH procedures [8].

- Shell formation: From 52 hours post first cleavage, insoluble shell material is secreted that non-specifically binds nucleic acid probes, creating background signal [8].

- Ontogenetic changes: Significant morphometric and biophysical tissue changes during early development require stage-specific protocol adaptations [8].

Previously described WMISH protocols for L. stagnalis larvae produced signals with low signal-to-noise ratios, making gene expression patterns difficult to interpret [8]. The optimized protocol presented here addresses these challenges through systematic evaluation of pre-hybridization treatments.

Reagent Preparation

Key Solutions:

- Fixative: 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 1X PBS

- PBTw: PBS with 0.1% Tween-20

- NAC Solution: 2.5-5% N-acetyl-L-cysteine in PBS (concentration age-dependent)

- Reduction Solution: 1% dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% SDS in PBS

- Proteinase K (Pro-K): 10-100 μg/ml in 2X SSC

- Triethanolamine-Acetic Anhydride (TEA-AA): 0.1M triethanolamine with 0.25% acetic anhydride

Step-by-Step Protocol

Embryo Preparation and Fixation

- Collect egg masses of appropriate developmental stages (1-5 days post first cleavage).

- Free individual egg capsules from surrounding jelly by rolling over moist filter paper.

- Manually dissect embryos from egg capsules using forceps and mounted needles.

- Immediately treat with NAC solution (duration and concentration age-dependent):

- Embryos 2-3 dpfc: 5 minutes in 2.5% NAC

- Embryos 3-6 dpfc: Two 5-minute treatments in 5% NAC

- Fix embryos in freshly prepared 4% PFA in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash once in PBTw for 5 minutes.

SDS Reduction Treatment

- Incubate embryos in SDS reduction solution:

- Embryos 2-3 dpfc: 0.1X reduction solution for 10 minutes at room temperature

- Embryos 3-5 dpfc: 1X reduction solution for 10 minutes at 37°C

- Handle with extreme care as samples become fragile during this treatment.

- Briefly rinse with PBTw.

Permeabilization and Background Reduction

- Dehydrate through graded ethanol series (33%, 66%, 100%) in PBTw, 5-10 minutes per step.

- Store at -20°C or proceed immediately with protocol.

- Rehydrate through graded ethanol series into PBTw.

- Digest with Proteinase K (10-100 μg/ml in 2X SSC) for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Wash five times in PBTw for 5 minutes each.

- Acetylate with TEA-AA solution for 10 minutes to reduce tissue-specific background.

Hybridization and Detection

- Pre-hybridize with appropriate hybridization buffer for 1-4 hours at hybridization temperature.

- Hybridize with DIG-labeled riboprobes for lophotrochin or trochin overnight at hybridization temperature.

- Perform stringency washes with SSC solutions of decreasing concentration.

- Detect hybridization signals using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibodies and colorimetric substrates (NBT/BCIP) or fluorescent detection systems.

- Clear samples and image using appropriate microscopy systems.

Critical Protocol Notes

- The SDS reduction treatment significantly enhances probe penetration while maintaining morphological integrity, but requires careful handling as embryos become fragile [8].

- NAC treatment is essential for removing residual intracapsular fluid that would otherwise interfere with hybridization [8].

- Proteinase K concentration and duration must be optimized for each developmental stage to balance permeabilization with tissue preservation.

- TEA-AA acetylation is particularly important for reducing non-specific background in shell-forming tissues [8].

- This protocol has been validated for both colorimetric and fluorescent WMISH and functions well for genes with different expression levels [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Spiralian WMISH

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) | Mucolytic agent degrading intracapsular fluid | Critical for removing viscous fluid that interferes with hybridization; concentration age-dependent |

| SDS Reduction Solution (DTT, NP-40, SDS) | Permeabilization and enhancement of probe accessibility | Dramatically improves signal intensity; embryos become fragile during treatment |

| Proteinase K | Enzymatic permeabilization of tissues | Must be optimized for each developmental stage; overtreatment damages morphology |

| Triethanolamine-Acetic Anhydride (TEA-AA) | Acetylation to reduce non-specific background | Essential for eliminating tissue-specific background in shell-forming regions |

| DIG-labeled Riboprobes | Nucleic acid probes for target detection | Optimized for lophotrochin and trochin detection in ciliary bands |

The discovery of spiralian-specific genes lophotrochin and trochin provides unprecedented molecular tools for investigating the evolution and development of ciliary bands across this diverse animal clade. Their specific expression in these functionally crucial structures highlights the potential importance of lineage-specific genes for understanding the evolution of novel morphological features. The optimized WMISH protocol with SDS reduction solution enables robust detection of these genes' expression patterns while overcoming the technical challenges presented by spiralian embryos.

This integrated approach—combining bioinformatic identification of lineage-specific genes with optimized morphological techniques—represents a powerful strategy for evolutionary developmental biology. It allows researchers to move beyond the constraints of conserved gene families and investigate truly novel genetic elements that may underlie clade-specific morphological innovations. For the spiralian research community, these tools facilitate more detailed investigations into the molecular basis of development across diverse taxa, from establishing body asymmetry to understanding the evolution of shell formation and ecological developmental processes.

A Step-by-Step Optimized Protocol for SDS-Based Whole Mount Hybridization in Spiralia

Within the specialized field of whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) for spiralian research, sample pre-treatment is a critical determinant of experimental success. The complex biochemical and biophysical properties of spiralian embryos, particularly their mucosal layers and proteinaceous structures, present significant barriers to probe penetration and specific hybridization. This application note details the synergistic use of two essential pre-treatment agents: N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) for mucolysis and Proteinase K (ProK) for controlled protein digestion. Framed within a broader thesis on SDS reduction solutions for Spiralia WMISH research, we provide a standardized, quantitative framework for implementing these treatments to enhance signal-to-noise ratios while preserving morphological integrity in challenging model systems such as Lymnaea stagnalis.

Background and Mechanism of Action

The Biochemical Challenge in Spiralia WMISH

Spiralian embryos, including the key model Lymnaea stagnalis, possess unique characteristics that complicate WMISH. They develop within egg capsules filled with a viscous, polysaccharide-rich fluid that adheres to the embryo and can non-specifically bind nucleic acid probes [19]. Furthermore, the onset of shell formation introduces insoluble material that acts as a source of significant background signal. These obstacles often result in poor probe accessibility and high non-specific staining, necessitating robust pre-hybridization treatments.

Pharmacological and Biochemical Foundations

N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC) is a mucolytic agent whose free sulfhydryl (-SH) group cleaves disulfide bonds in glycoproteins within mucus, reducing its viscosity and structural integrity [20] [21]. In a WMISH context, this action disrupts the protective mucosal layers and residual capsule fluid, thereby increasing tissue permeability and probe accessibility [19].

Proteinase K (ProK) is a broad-spectrum serine protease that cleaves peptide bonds adjacent to carboxylic groups of aliphatic and aromatic amino acids. It is highly stable and retains activity in the presence of SDS and urea, making it ideal for digesting cellular proteins in fixed tissues [22] [23]. This digestion reduces non-specific protein binding and degrades cellular components that may physically block probe access to the target mRNA.

When sequenced appropriately—typically NAC followed by ProK—these treatments work synergistically to permeabilize the sample. NAC dismantles the extracellular matrix, allowing Proteinase K to penetrate more effectively for controlled internal protein digestion.

Quantitative Data and Solution Formulations

Standardized preparation of stock and working solutions is fundamental to experimental reproducibility. The following tables summarize critical formulations and optimized treatment parameters.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Sample Pre-Treatment

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Key Components & Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| NAC Stock Solution | Mucolytic agent; disrupts disulfide bonds in mucus and viscous capsules. | 2.5% or 5% (w/v) N-acetyl-L-cysteine in buffer or water [19]. |

| Proteinase K Stock | Proteolytic digestion; digests proteins for tissue permeabilization. | 10-100 mg/mL in Tris-HCl, EDTA, or TE buffer; stored at -20°C [22]. |

| SDS Reduction Solution | Permeabilization; treatment to increase probe accessibility. | 1% SDS, 50 mM DTT, 1% NP-40 [19]. |

| Proteinase K Working Solution | Controlled digestion of tissue proteins. | 50-100 µg/mL in PBTw or Tris-EDTA buffer [22] [23]. |

| PBTw (PBS + Tween-20) | Standard washing and dilution buffer. | 1X PBS, 0.1% Tween-20. |

Table 2: Optimized Pre-Treatment Parameters for Spiralian Embryos

| Treatment | Concentration | Incubation | Temperature | Application & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) | 2.5% - 5.0% | 5 min (single or double treatment) | Room Temperature | Age-dependent dosage. For 2-3 dpfc* embryos: 2.5%. For 3-6 dpfc embryos: 5%, two 5-min treatments [19]. |

| Proteinase K | 50 - 100 µg/mL | 30 minutes | Room Temperature | Must be empirically optimized for each new organism, fixation, and developmental stage [22] [13]. |

| SDS Reduction | 0.1X - 1X | 10 minutes | 37°C or Room Temperature | Embryos are fragile; handle with care. Can replace SDS treatment [19]. |

*dpfc = days post first cleavage

Detailed Experimental Protocols

N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC) Treatment for Mucolysis

This protocol is designed for L. stagnalis but is adaptable to other spiralians with mucinous coatings or capsules.

- Sample Preparation: Manually dissect embryos from egg capsules and pool them in a suitable container [19].

- NAC Incubation: Immediately incubate embryos in the pre-prepared NAC solution (Table 2). Gently agitate.

- For embryos 2-3 dpfc, use 2.5% NAC for 5 minutes.

- For embryos 3-6 dpfc, use 5% NAC for two rounds of 5 minutes each.

- Termination and Fixation: Carefully remove the NAC solution. Immediately transfer samples into freshly prepared 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Fix for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash: Remove the fixative with one 5-minute wash in 1X PBTw.

- Post-Treatment Processing: Proceed directly to an SDS treatment or dehydration for storage at -20°C.

Proteinase K Digestion for Tissue Permeabilization

This step must follow fixation and washing. Optimal concentration and time must be determined empirically.

- Rehydration: If samples are stored in ethanol, rehydrate through a graded series (100% -> 66% -> 33% EtOH, 5 minutes each) into PBTw.

- Digestion: Incubate samples in the pre-diluted Proteinase K working solution (50-100 µg/mL in PBTw) for 30 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation. Note: Over-digestion will destroy morphology, while under-digestion will limit probe access.

- Enzyme Inactivation: Remove the Proteinase K solution and rinse samples briefly with PBTw.

- Post-Fixation (Critical): Re-fix samples in 4% PFA for 20-30 minutes to stabilize morphology after digestion.

- Washing: Perform 2-3 washes, 5 minutes each, in PBTw to remove traces of fixative.

- Hybridization: Samples are now ready for the pre-hybridization and probe hybridization steps of your WMISH protocol.

Workflow Integration and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the sequential integration of NAC and Proteinase K treatments into a comprehensive WMISH workflow for Spiralia, highlighting its position relative to the SDS reduction solution.

Diagram: Integrated Pre-Hybridization Workflow for Spiralia WMISH. Critical pre-treatments (NAC, Proteinase K) and their relationship with the SDS reduction solution are shown in blue and red. NAC treatment for mucolysis precedes Proteinase K digestion for tissue permeabilization, with an optional SDS reduction step in between. All pre-treatments must be followed by a post-fixation step to preserve morphology.

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- Optimization is Mandatory: The provided concentrations and times are a starting point for L. stagnalis. Each new species, developmental stage, and fixation condition requires empirical optimization of Proteinase K concentration and incubation time [22] [19].

- Proteinase K Inhibitors: Be aware that Proteinase K can be inhibited by high concentrations of SDS, EDTA, urea, and specific protease inhibitors like PMSF [22]. Ensure compatibility with other buffers in your protocol.

- Handling Fragile Samples: Treatments, especially with SDS reduction solution, make embryos extremely fragile. Handle with extreme care, avoiding vigorous pipetting [19].

- Background Control: Persistent background, particularly in shell-forming regions, may be mitigated by acetylation treatments (e.g., with triethanolamine and acetic anhydride) to block electrostatic probe binding [19].

The sequential application of NAC for mucolysis and Proteinase K for controlled proteolysis is a powerful strategy to overcome the inherent barriers of spiralian embryos in WMISH. This protocol, designed to integrate with SDS-based reduction methods, provides a robust foundation for achieving high-quality gene expression data with excellent signal intensity and morphological preservation. By systematically applying these critical pre-treatments, researchers can reliably advance the study of developmental gene expression in these ecologically and evolutionarily vital organisms.

Within the field of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), research on Spiralia—a vast and morphologically diverse clade of invertebrates including mollusks and annelids—relies heavily on techniques that can reveal the spatial expression of genes. Whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) is one such foundational technique. A significant technical challenge in applying WMISH to Spiralian embryos, which are often rich in yolk and protected by complex extracellular coatings, is achieving sufficient probe penetration while preserving morphological integrity. The use of a reduction solution containing Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) and Dithiothreitol (DTT) has been established as a critical pre-hybridization treatment to overcome these barriers. This application note details the formulation, optimization, and integration of this reduction solution within the context of a broader thesis on WMISH methodology for Spiralia research, providing a standardized protocol for scientists and drug development professionals investigating gene expression in non-model organisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential reagents required for the preparation and use of the SDS-DTT reduction solution in WMISH protocols.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Reduction Solution Formulation

| Reagent | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reducing agent that cleaves disulfide bonds in proteins, permeabilizing tissues and dissolving mucinous layers. | Critical for disrupting the structure of the intracapsular fluid in species like Lymnaea stagnalis [19]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ionic detergent that solubilizes lipids and proteins, thereby permeabilizing cell and tissue membranes. | Facilitates probe penetration; concentration must be optimized to balance permeabilization with tissue integrity [19]. |

| N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC) | Mucolytic agent that degrades viscous polysaccharides and proteoglycans in extracellular fluids. | Pre-treatment is often necessary to remove nutritive egg capsule fluid that can non-specifically bind probes [19]. |

| Proteinase K | Proteolytic enzyme that digests proteins to further permeabilize fixed tissues. | Use requires careful titration, as over-digestion can destroy morphology; may be omitted in optimized reduction-based protocols [13]. |

| Triethanolamine (TEA) and Acetic Anhydride | Acetylating agents that reduce non-specific electrostatic binding of negatively charged probes to tissues. | Effective in eliminating tissue-specific background staining, for instance, in the larval shell field of mollusks [19]. |

| VCH-286 | VCH-286|Potent CCR5 Inhibitor|CAS 891824-47-8 | VCH-286 is a potent CCR5 inhibitor for anti-HIV-1 research. This product is for research use only and is not intended for human use. |

| BML-280 | BML-280, MF:C25H27N5O2, MW:429.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Composition and Mechanism of the Reduction Solution

The reduction solution functions through the synergistic action of its key components. DTT is a potent reducing agent that acts on disulfide bonds via a thiol-disulfide exchange reaction. Its intramolecular ring structure upon oxidation drives the equilibrium towards the reduced state, making it highly effective at lower concentrations compared to other agents like 2-mercaptoethanol [24]. In the context of WMISH, this activity helps break down the complex, often cross-linked, proteinaceous and mucinous barriers surrounding many Spiralian embryos [19].

SDS, an ionic detergent, complements DTT's action by solubilizing lipid membranes and denaturing proteins, thereby creating channels for the nucleic acid probes to diffuse into the tissue. The combination of these agents in a single solution achieves a level of permeabilization that is often unattainable with either one alone. The efficacy of this solution is so pronounced that it has allowed for the omission of other, more harsh permeabilization treatments like extensive Proteinase K digestion in some protocols [13]. The graph below illustrates the mechanism of this solution and its role in the broader WMISH workflow.

Quantitative Optimization of Reagent Concentrations

The performance of the reduction solution is highly dependent on reagent concentration and treatment duration, which must be optimized for specific tissues and developmental stages. Based on empirical data from related biochemical and embryological studies, we can establish effective concentration ranges.

Table 2: Optimization of Reduction Solution Components

| Component | Concentration Range | Effect and Rationale | Supporting Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTT | 10 mM - 100 mM | Higher concentrations (e.g., 100 mM) ensure complete reduction of disulfide bonds, preventing their reformation and minimizing streaking or artifacts in subsequent assays. Lower concentrations may be sufficient for less robust tissues. [24] | In proteomics, 100 mM DTT + 5 mM TBP was optimal for proteoform reduction [24]. |

| SDS | 0.1% - 1.0% (w/v) | Lower concentrations (0.1%) are suitable for delicate early-stage embryos, while higher concentrations (up to 1%) can be used for more resilient, later-stage larvae to maximize permeabilization. [19] | A study on L. stagnalis tested 0.1%, 0.5%, and 1.0% SDS for WMISH [19]. |

| Treatment Duration | 10 - 30 minutes | Shorter durations (10 min) at room temperature are used for younger, more fragile embryos. Longer or warmer incubations (30 min at 37°C) can be applied to older, tougher specimens. [19] | A 10-minute incubation in reduction solution was used for L. stagnalis larvae [19]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Whole Mount In Situ Hybridization with Reduction Treatment

Sample Preparation and Pre-Treatment

- Dissection and Fixation: Manually release embryos from egg capsules and immediately fix in freshly prepared 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 1X PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Mucolytic Treatment (If required): For embryos with significant mucinous capsules (e.g., Lymnaea stagnalis), incubate freshly dissected specimens in a 2.5%-5% N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC) solution for 5-10 minutes post-dissection, then proceed to fixation [19].

- Dehydration and Storage: Wash fixed samples once in 1X PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBTw). Dehydrate through a graded ethanol series (33%, 66%, 100%) and store in 100% ethanol at -20°C.

Reduction Solution Treatment and Permeabilization

- Rehydration: Rehydrate stored samples through a descending ethanol series (100%, 66%, 33%) into PBTw.

- Application of Reduction Solution: Prepare the reduction solution immediately before use. A recommended starting formulation is:

- 1X Reduction Solution: 50 mM DTT, 0.5% SDS in PBS.

- Remove PBTw from samples and incubate in the reduction solution. For embryos between two and three days post-first cleavage, treat for 10 minutes at room temperature. For older, more robust embryos (three to five days post-first cleavage), incubate for 10 minutes in preheated solution at 37°C [19].

- Critical Note: Samples become extremely fragile during this treatment. Handle with care, avoiding vigorous pipetting or shaking.

- Post-Reduction Wash: Carefully remove the reduction solution and briefly rinse samples with PBTw to terminate the reaction.

- Dehydration for Hybridization: Wash samples once in 50% ethanol/PBTw, followed by two washes in 100% ethanol, each for 5-10 minutes. Samples can be stored at -20°C or proceed directly to hybridization.

Hybridization and Detection

- Pre-hybridization and Probe Application: Rehydrate samples and pre-hybridize in an appropriate hybridization buffer (e.g., containing 50% formamide, 5x SSC, 0.1% Tween-20) for 1-4 hours at the hybridization temperature (e.g., 60°C). Replace with fresh hybridization buffer containing the heat-denatured, DIG-labeled riboprobe and hybridize overnight [13].

- Post-Hybridization Washes: The following day, perform stringent washes to remove unbound probe:

- 1x 30 min with pre-warmed hybridization buffer at 60°C.

- 5x 30 min with PTw at 60°C.

- 1x 30 min with PT at room temperature.

- Antibody Binding and Color Reaction:

- Incubate samples with anti-DIG-Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) antibody (typical dilution 1:2000) for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C [13].

- Wash 4x 30 min with PT to remove unbound antibody.

- Rinse 3x 5 min in AP buffer (100 mM Tris pH 9.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgClâ‚‚, 0.1% Tween-20).

- Develop color by incubating in AP-NBT/BCIP solution in the dark. Monitor the reaction periodically under a dissection microscope and stop by washing with PT once sufficient signal-to-noise is achieved [13].

- Post-staining and Mounting: Wash samples 1x 5 min with PBS. Clear and mount tissues in a graded glycerol series (50%, 70%) for imaging and analysis.

The complete workflow, from sample preparation to imaging, is summarized below.

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- Excessive Tissue Fragility: This is the most common issue and indicates the reduction solution is too harsh. Remedies include: reducing the SDS concentration to 0.1%, shortening the incubation time, performing the entire step at room temperature, or eliminating agitation.

- High Background Staining: Non-specific probe binding can persist. Incorporate a acetylation step (treatment with 0.1M Triethanolamine and 0.25% acetic anhydride) after the reduction step to neutralize positive charges on the tissue [19]. Ensure stringent post-hybridization wash conditions are followed.

- Poor or No Signal: Inadequate permeabilization may occur with very resilient tissues. Solutions include: increasing the SDS concentration to 1%, extending the incubation time, or raising the temperature to 37°C. Simultaneously, verify the quality and concentration of the riboprobe.

- Tissue-Specific Background: Specific tissues, such as the molluscan shell field, can exhibit high endogenous background. This can often be abolished with the TEA/acetic anhydride treatment mentioned above [19].

Stage-Specific and Species-Specific Application Guidelines

Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) is an indispensable technique for visualizing spatial gene expression patterns in developing embryos, providing critical insights into gene function and evolutionary biology. For spiralian species—a large, diverse clade of animals including molluscs, annelids, and brachiopods—achieving high-quality WMISH results has historically been challenging due to unique morphological and biochemical characteristics [8]. The viscous intra-capsular fluid in molluscs like Lymnaea stagnalis and the onset of shell formation can interfere with probe penetration and cause non-specific background staining [8].

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), an ionic detergent, has emerged as a crucial component in pre-hybridization treatments to overcome these challenges. SDS functions as a potent surfactant that permeabilizes tissues by dissolving membranes and disrupting hydrophobic interactions, thereby facilitating nucleic acid probe access to target sequences [8] [25]. However, SDS must be carefully removed or reduced post-permeabilization as residual detergent can interfere with hybridization and detection steps. This protocol establishes standardized, optimized guidelines for SDS application and removal across diverse spiralian taxa and developmental stages, ensuring reproducible, high-fidelity WMISH results while preserving morphological integrity.

Systematic evaluation of SDS concentration, exposure time, and complementary treatments across developmental stages is essential for optimizing WMISH in spiralians. The tables below consolidate quantitative data from empirical testing.

Table 1: Stage-Specific SDS Treatment Parameters for L. stagnalis

| Developmental Stage | Optimal SDS Concentration | Treatment Duration | Complementary Treatments | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Larvae (2-3 dpfc) | 0.1% in PBS | 10 minutes | 5 minutes 2.5% NAC | Enhanced probe access with maintained structural integrity |

| Mid-Stage Larvae (3-5 dpfc) | 0.5%-1% in PBS | 10 minutes | Two 5-minute 5% NAC treatments | Effective permeabilization of developing shell field |

| Late Larvae (3-6 dpfc) | 1% in PBS | 10 minutes | Proteinase K (age-dependent) | Balanced permeabilization for complex tissues |

Table 2: SDS Removal Efficiency Across Methodologies

| Removal Method | Reported Efficiency | Residual SDS Concentration | Protein/RNA Recovery | Compatibility with WMISH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCl Precipitation (Basic pH) | >99.99% | <0.01% | >96% | High - maintains sample integrity |

| Vacuum Washing (VW12h) | High | Significantly reduced (P≤0.001) | High cell survival | Moderate - for tissue scaffolds |

| Organic Solvent Precipitation | Variable | Variable | Potential sample loss | Low - can compromise morphology |

| Commercial Kits (Minute SDS-Remover) | Superior to columns | Minimized with <20% protein loss | High concentration maintained | Untested for WMISH |

Experimental Protocols for SDS-Integrated WMISH

Optimized WMISH Protocol with SDS Permeabilization for Spiralians

Fixation and Pre-Treatment:

- Dissection and Initial Fixation: Manually dissect embryos from egg capsules and immediately transfer to freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 1X PBS. Fix for 30 minutes at room temperature [8].

- Mucolytic Treatment: For stages 2-6 days post first cleavage (dpfc), incubate embryos in N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC): 2.5% for 5 minutes (2-3 dpfc) or two treatments of 5% for 5 minutes each (3-6 dpfc) to dissolve viscous intra-capsular fluid [8].

- SDS Permeabilization: Wash samples once in PBTw (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20) for 5 minutes. Incubate in optimal SDS concentration (see Table 1) in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature [8].

- Dehydration and Storage: Rinse samples in PBTw and dehydrate through graded ethanol series (33%, 66%, 100%), 5-10 minutes per wash. Store at -20°C in 100% ethanol until use [8].

Hybridization and Detection:

- Rehydration and Proteinase Digestion: Rehydrate through graded ethanol series to PBTw. Digest with age-appropriate Proteinase K concentration (e.g., 10-100 μg/mL) for precise duration determined empirically for each stage [8].

- Acetylation: Incubate in 0.1M triethanolamine (TEA) with 0.25% acetic anhydride (AA) for 10 minutes to reduce non-specific probe binding [8].

- Hybridization: Replace solution with hybridization buffer containing DIG-labeled antisense RNA probes. Hybridize overnight at appropriate temperature (typically 55-65°C) [26].

- Post-Hybridization Washes: Perform stringent washes with SSC solutions of decreasing salinity (e.g., 2X SSC to 0.2X SSC) with 0.1% CHAPS to remove unbound probe [8].

- Immunological Detection: Block with appropriate serum (1-5%), then incubate with anti-DIG-AP antibody (typically 1:2000-1:5000 dilution). Wash thoroughly with PBTw [8].

- Colorimetric Development: Develop color reaction with NBT/BCIP in staining buffer. Monitor development microscopically, then stop with PBTw washes [8].

- Post-Processing: Post-fix in 4% PFA, clear in glycerol series, and mount for microscopy [8].

SDS Removal Protocol via KCl Precipitation

For procedures requiring complete SDS removal after permeabilization:

- Adjust pH: Raise pH to 12 using NaOH for optimal SDS precipitation [27].

- Add KCl: Introduce KCl to final concentration of 180-300 mM while gently mixing [27].

- Precipitate: Incubate 10-15 minutes at room temperature to allow potassium dodecyl sulfate (KDS) precipitation [27].

- Pellet Precipitate: Centrifuge at 10,000×g for 10 minutes to pellet KDS [27].

- Recover Sample: Carefully transfer supernatant (containing proteins/RNA) to new tube [27].

- Verify Removal: Confirm SDS depletion before proceeding to hybridization [27].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

SDS-Mediated Permeabilization in WMISH Workflow

SDS Integration in Spiralian WMISH Workflow. This workflow highlights the critical position of SDS permeabilization in the optimized WMISH protocol for spiralians, occurring after mucolytic treatment and before dehydration steps.

Spiralian Ciliary Band Gene Regulation Context

Evolutionary Context for Spiralian-Specific Gene Expression. This diagram illustrates the biological context where SDS-optimized WMISH reveals expression of spiralian-specific genes like lophotrochin and trochin in ciliary bands, supporting hypotheses about their functional conservation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for SDS-Optimized Spiralian WMISH

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes | Stage-Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS (0.1-1%) | Membrane permeabilization via surfactant action | Critical for probe penetration; requires optimization | Lower concentrations (0.1%) for early stages; higher (1%) for later stages with shell formation |

| N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (2.5-5%) | Mucolytic agent degrading intra-capsular fluid | Reduces viscous barriers to probe access | Multiple treatments needed for later developmental stages |

| Proteinase K (10-100 μg/mL) | Enzymatic permeabilization through protein digestion | Enhances tissue accessibility; overtreatment destroys morphology | Concentration and duration must be empirically determined for each stage |

| Triethanolamine/Acetic Anhydride | Acetylation to reduce non-specific probe binding | Critical for minimizing background in ciliary bands | Particularly important for shell-forming regions prone to non-specific staining |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | SDS precipitation agent for removal | Efficiently removes SDS after permeabilization | Use at basic pH (12) for optimal precipitation efficiency |

| Anti-DIG-AP Antibody | Immunological detection of hybridized probes | Colorimetric or fluorescent detection | Typical dilutions 1:2000-1:5000; concentration affects signal intensity |

| WM-1119 | WM-1119, CAS:2055397-28-7, MF:C18H13F2N3O3S, MW:389.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| WZ-3146 | WZ-3146, CAS:1214265-56-1, MF:C24H25ClN6O2, MW:464.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |