Optimizing ssODN Repair Templates for High-Efficiency CRISPR Genome Editing

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on designing single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) repair templates to maximize the efficiency of precise CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing via Homology-Directed...

Optimizing ssODN Repair Templates for High-Efficiency CRISPR Genome Editing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on designing single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) repair templates to maximize the efficiency of precise CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing via Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). It covers foundational principles of DNA repair pathways, detailed methodological design for ssODNs, advanced troubleshooting and optimization strategies to overcome low HDR efficiency, and validation techniques for confirming edit precision. By synthesizing the latest research and practical insights, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to design robust editing experiments, from basic knock-ins to complex therapeutic applications, while navigating common pitfalls like off-target integration and competition from error-prone repair pathways.

Understanding ssODNs and the Cellular Battlefield of DNA Repair

What are ssODNs? Defining the Key Tool for Precision Editing

What are ssODNs? Defining the Key Tool for Precision Editing

Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) are synthetic, short, single-stranded DNA molecules that serve as versatile tools in modern genetic research and therapeutic development. When used as repair templates in conjunction with genome-editing technologies like CRISPR-Cas9, they enable the introduction of precise, user-defined genetic alterations into a genome. These alterations can range from single nucleotide changes to the insertion or deletion of small sequences, making ssODNs indispensable for creating precise disease models, studying gene function, and developing gene therapies [1] [2].

The utility of ssODNs lies in their ability to direct the cell's own DNA repair machinery. When a CRISPR-Cas9 system creates a double-strand break (DSB) at a targeted genomic location, the cell can repair this break using a provided ssODN as a template via the Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) pathway. This process allows researchers to rewrite the genetic code with high precision at the site of the break [3].

Mechanism of Action: How ssODNs Enable Precision Editing

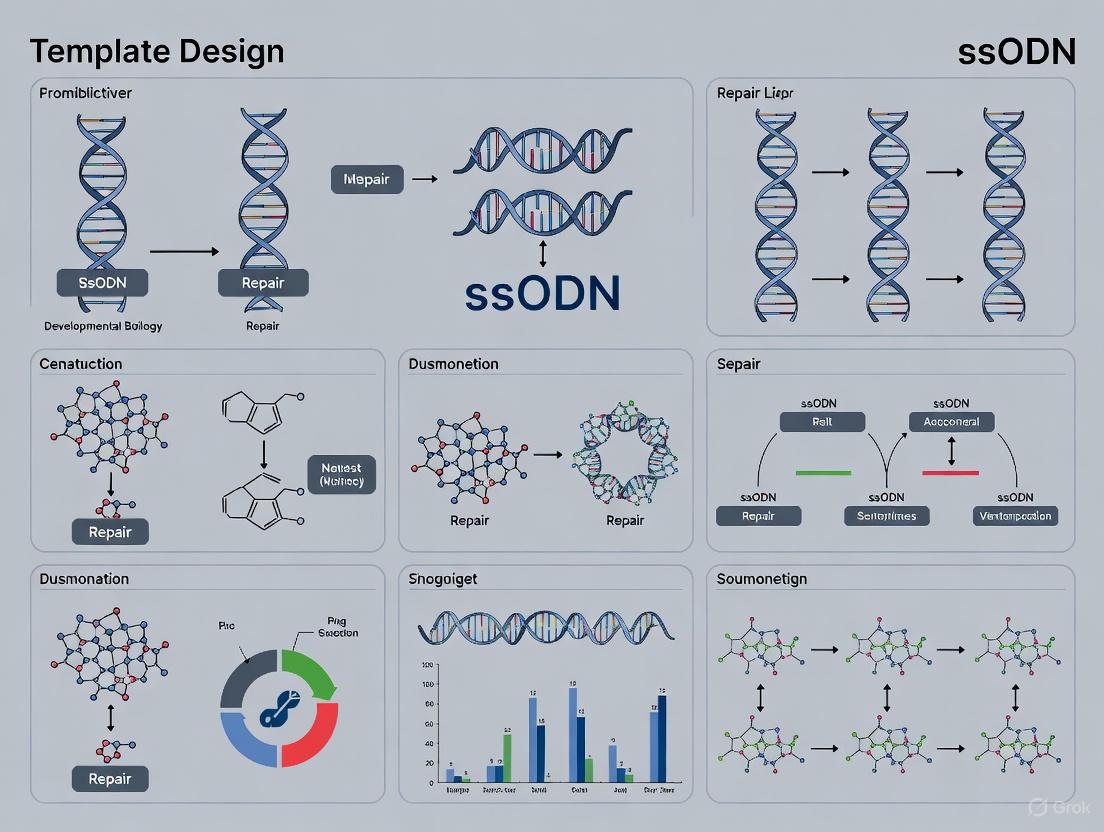

The fundamental principle behind ssODN-mediated editing is the exploitation of the cell's natural HDR pathway. The process can be broken down into a series of key steps, which are illustrated in the diagram below.

Key Applications in Research and Therapy

ssODNs have become a cornerstone technology in molecular biology due to their precision. Their applications span from basic research to advanced therapeutic development.

Creating Disease Models

ssODNs are used to introduce specific disease-associated mutations into the genomes of stem cells or animal models. This allows scientists to study the mechanism of diseases in a controlled setting and provides a platform for drug screening. A prominent example is the introduction of mutations into the GBA1 gene, which is associated with Gaucher disease and Parkinson's disease, in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to model pathology [2].

Protein Tagging for Functional Studies

Researchers can use ssODNs to knock-in sequences that tag a protein of interest with a fluorescent marker (like GFP). This enables the visualization of protein localization, dynamics, and interactions in living cells, providing critical insights into their function [4].

Gene Therapy and Correction

Therapeutically, ssODNs offer the potential to correct genetic defects at their source. By providing a correct version of a mutated sequence, ssODNs can guide the repair of a faulty gene, paving the way for treatments for a wide range of genetic disorders [3].

Key Advantages Over Alternative Methods

- High Precision: Ideal for introducing single-nucleotide changes with minimal collateral sequence alterations.

- Reduced Off-Target Integration: Compared to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) donors, ssODNs have a significantly lower risk of random integration into the genome, making them safer for therapeutic applications [5].

- Simplicity and Speed: ssODNs are chemically synthesized and do not require complex cloning procedures for vector construction, which streamlines the experimental workflow.

Optimizing ssODN Design: A Data-Driven Approach

The efficiency of ssODN-mediated editing is highly dependent on the design of the oligonucleotide itself. Key parameters include length, modification, and the position of these modifications. Recent research provides quantitative guidance for optimal design.

Impact of Length and LNA Modifications on Editing Efficiency

Table 1: The effect of ssODN length and Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) modifications on genome editing efficiency in HEK293T cells. Efficiency is measured by the successful deletion of an 8-base sequence from an EGFP reporter cassette [6].

| ssODN Length (nt) | Modification Details | Relative Editing Efficiency | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 nt | Unmodified | Baseline (0.0001%) | Efficiency increases with ssODN length |

| 40 nt | Unmodified | 2x Baseline | |

| 60 nt | Unmodified | 19x Baseline | |

| 80 nt | Unmodified | 91x Baseline | |

| 100 nt | Unmodified | 154x Baseline | |

| 80 nt | 10 LNAs (80-10L) | 1.23x (vs. 80nt unmodified) | LNA modifications boost efficiency |

| 80 nt | 12 LNAs (80-12L) | 1.5x (vs. 80nt unmodified) | |

| 80 nt | 14 LNAs (80-14L) | 3.77x (vs. 80nt unmodified) | Optimal number |

| 80 nt | 12 LNAs + 2 extra at 25nt from center | ~2x (vs. 80-12L) | Optimal position is 20-27nt from the center |

Critical Design Parameters

- Homology Arm Length: The regions of the ssODN that are homologous to the genomic sequence flanking the cut site are critical. While early studies used arms of 60 nucleotides [4], a common design incorporates 60-base homology arms on each side of the desired edit [2].

- Backbone Modifications: To protect the ssODN from degradation by cellular exonucleases, stability-enhancing modifications are added. A standard practice is the incorporation of phosphorothioate (PS) bonds at the terminal 5' and 3' ends [7] [2].

- Strand Selection: The ssODN can be designed to be homologous to either the strand that is cleaved by Cas9 ("target" strand) or the uncut strand. Empirical testing is often required to determine which strand gives higher HDR efficiency for a specific target.

Protocol: ssODN-Mediated Knock-in to Compete with Pseudogene Conversion

A critical application of ssODNs is to edit a specific gene when a highly homologous pseudogene is present. The following protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, demonstrates how to outcompete natural gene conversion using ssODN donors to knockout the GBA1 gene [2].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential research reagents for ssODN-mediated knock-in experiments in iPSCs [2].

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| ssODN Donor | Homology-directed repair template with desired edit | 120-140 nt, phosphorothioate bonds at 5'/3' ends, 60-nt homology arms |

| Cas9 Protein | Engineered nuclease that creates DSB | Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease V3 |

| sgRNA | Synthetic guide RNA for target specificity | Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 sgRNA, target: 5'-CCATTGGTCTTGAGCCAAGT-3' |

| Cell Line | Genetically stable host for editing | Human induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) |

| Transfection Reagent | Method for delivering RNP and ssODN | Electroporation (e.g., Neon Transfection System) |

| Culture Medium | Supports growth and maintenance of iPSCs | mTeSR Plus medium on Matrigel-coated plates |

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Design and Synthesize ssODN Donors: Design two ssODN donors containing the desired out-of-frame deletions (e.g., 7 bp or 10 bp) within the region homologous to the Cas9 cut site in GBA1 exon 6. Each ssODN should have 60-nucleotide homology arms and phosphorothioate modifications at the 5' and 3' ends to enhance stability [2].

- Prepare RNP Complex: Complex the purified Cas9 protein with the synthetic sgRNA targeting GBA1 exon 6 to form the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex.

- Cell Transfection: Co-electroporate the pre-formed RNP complex and the two ssODN donors into human iPSCs. This simultaneous delivery is crucial for competing with the endogenous gene conversion mechanism.

- Culture and Expand: Plate the transfected cells and culture them in conditions that maintain pluripotency. Allow the cells to recover and expand for several days.

- Screen and Validate Clones: Extract genomic DNA from a pool of cells or individual clones. Use PCR to amplify the targeted region and sequence the amplicons to identify successfully edited alleles. The desired outcome is the incorporation of the out-of-frame deletion from the ssODN, which disrupts the GBA1 gene without transferring sequence from the GBAP1 pseudogene.

ssODNs represent a powerful and refined tool in the genome editing arsenal, enabling a level of precision that is essential for advanced research and therapeutic applications. By understanding their mechanism of action and following data-optimized design principles—such as incorporating LNA modifications at specific positions (20-27 nt from the center) and using ~60 nt homology arms—researchers can significantly enhance editing efficiency. As demonstrated in complex scenarios like editing the GBA1 locus, the strategic use of ssODNs can overcome significant biological challenges, paving the way for more accurate disease models and the future of genetic medicine.

In CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing, the introduction of a precise double-strand break (DSB) creates a crossroads where multiple cellular repair pathways compete to resolve the DNA lesion. The ultimate editing outcome is determined by which pathway the cell employs, making the understanding and control of these mechanisms paramount for precise genome engineering [8]. The four primary pathways include the error-free homology-directed repair (HDR) and three error-prone pathways: classical non-homologous end joining (cNHEJ), microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), and single-strand annealing (SSA) [9] [8].

For researchers aiming to incorporate specific genetic changes using single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) templates, the dominance of the error-prone NHEJ pathway and the complex interplay between all these pathways present a significant challenge. While HDR is the only pathway that can use an exogenous donor template for precise repair, its efficiency is often low, especially in non-dividing cells [10] [3]. Recent advances have revealed that the competing MMEJ and SSA pathways, which rely on microhomology and longer homologous sequences respectively, also play crucial roles in determining the fidelity of editing outcomes, even when NHEJ is suppressed [9]. This application note examines the characteristics of these repair pathways, provides quantitative comparisons, and details experimental strategies for enhancing precise editing via HDR, with a specific focus on ssODN repair template design.

DNA Repair Pathways: Mechanisms and Outcomes

Comparative Pathway Analysis

Table 1: Characteristics of Major DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

| Pathway | Template Required | Key Effector Proteins | Repair Fidelity | Primary Role in Genome Editing | Cell Cycle Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDR (Homology-Directed Repair) | Yes (homologous donor) | Rad51, BRCA2 | Error-free | Precise knock-in of desired sequences [10] | Late S and G2 [11] |

| cNHEJ (Classical Non-Homologous End Joining) | No | Ku70/Ku80, DNA-PKcs, DNA Ligase IV | Error-prone (indels common) | Dominant pathway; leads to gene knockouts [10] [11] | Active throughout cell cycle |

| MMEJ (Microhomology-Mediated End Joining) | No (uses 5-25 bp microhomology) | POLQ (DNA polymerase theta), PARP1 | Error-prone (deletions) | Predictable deletions; alternative knock-in strategy (e.g., PITCh) [12] [13] | M and early S phase [13] |

| SSA (Single-Strand Annealing) | No (uses >30 bp homology) | Rad52, ERCC1 | Error-prone (large deletions) | Imprecise integration; contributor to asymmetric HDR [9] | Not well defined |

Visualizing the Repair Pathway Decision Network

The following diagram illustrates the complex cellular decision-making process at the site of a CRISPR-Cas9-induced double-strand break, highlighting the competition between the four major repair pathways.

Quantitative Analysis of Repair Pathway Dynamics

Pathway Kinetics and Efficiency Metrics

Understanding the temporal dynamics and efficiency of each repair pathway is crucial for experimental planning and timing of interventions. Research has demonstrated that different repair pathways operate at distinct speeds and with varying efficiencies across cell types.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of DNA Repair Pathway Kinetics and Outcomes

| Pathway | Kinetics (T50) | Editing Efficiency Range | Key Influencing Factors | Impact on ssODN Editing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDR | Intermediate (between NHEJ and MMEJ) [14] | Highly variable: 5% to >98.5% with optimized lssDNA [15] | Cell cycle, donor concentration & form, homology arm length [11] [15] | Critical for precise ssODN incorporation; generally low efficiency |

| NHEJ | Fastest (short indels especially +A/T) [14] | Typically 75-99% knockout efficiency [15] | Ku70/80 complex activity; dominant in most cells [10] | Primary competitor; causes random indels at target site |

| MMEJ | Slower than NHEJ [14] | ~80% correct 5' junction, ~50% correct 3' junction with PITCh [13] | POLQ activity; 5-25 bp microhomology regions [9] [13] | Can be harnessed as alternative to HDR for specific insertions |

| SSA | Not well characterized | Significant contributor to imprecise integration [9] | Rad52 activity; long homologous repeats [9] | Source of asymmetric HDR where only one end integrates precisely [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Modulation

Enhancing HDR Efficiency for ssODN Integration

Principle: Suppressing competing NHEJ and modulating alternative repair pathways to favor HDR-mediated precise integration of ssODN templates.

Materials:

- Cas9 nuclease (as protein, mRNA, or encoded in plasmid)

- Target-specific sgRNA

- Purified ssODN repair template with appropriate homology arms

- Delivery system (electroporation, lipofection, or microinjection)

- Pathway-specific small molecule inhibitors/enhancers

Procedure:

Design and Preparation of ssODN Template:

- For point mutations: Design symmetric or asymmetric ssODNs with 30-100 nt homology arms flanking the desired edit [15].

- For larger insertions: Consider long ssDNA (lssDNA) templates (>200 nt) which have shown significantly higher HDR efficiency in multiple models [15].

- Incorporate phosphorothioate modifications at ends to enhance nuclease resistance if needed.

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation:

- Complex purified Cas9 protein with sgRNA at molar ratio of 1:2 to 1:3.

- Incubate at 25°C for 10-20 minutes to allow proper RNP formation.

Co-delivery of Editing Components:

- Combine RNP complexes with ssODN template at optimal concentration.

- Delivery method varies by cell type:

- Electroporation: For mammalian cell lines (e.g., HEK293T, RPE1), use Neon or Amaxa systems with manufacturer's optimized protocols [9].

- Microinjection: For zebrafish embryos and other model systems, inject into one-cell stage embryos [15].

- Lipofection: For hard-to-transfect cells, use commercial lipid-based transfection reagents.

Pathway Modulation with Small Molecules:

- NHEJ Inhibition: Treat cells with Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 or M3814 (DNA-PKcs inhibitor) + Trichostatin A (histone deacetylase inhibitor) for 24-48 hours post-editing to increase HDR efficiency 3-fold [9] [14].

- MMEJ Inhibition: Add ART558 (POLQ inhibitor) to reduce large deletions and complex indels [9].

- SSA Inhibition: Use D-I03 (Rad52 inhibitor) to decrease asymmetric HDR and other imprecise integration events [9].

Validation and Screening:

- Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-editing for initial assessment.

- Use restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) if new site introduced.

- Perform targeted amplicon sequencing to quantify precise HDR efficiency and identify editing signatures of different pathways.

- For phenotypic screening (e.g., pigment restoration in zebrafish tyr model), score at appropriate developmental timepoints [15].

MMEJ-Mediated Knock-in Using PITCh System

Principle: Harnessing the predictable nature of MMEJ for DNA integration using very short homologies (5-25 bp), bypassing the need for traditional long homology arms.

Procedure:

Vector Design:

- Clone your gene of interest into a PITCh vector.

- Add 5' and 3' microhomology arms (~20 bp each) matching the target locus via PCR or direct synthesis.

gRNA Design:

- Design a locus-specific gRNA targeting the genomic integration site.

- Include a second PITCh-gRNA targeting the vector boundaries.

Delivery and Selection:

- Co-transfect PITCh vector with plasmids expressing Cas9, PITCh-gRNA, and locus-specific gRNA.

- Select with puromycin or appropriate antibiotic starting 24-48 hours post-transfection.

Screening:

- PCR amplification of integration junctions using primers flanking the target site.

- Sequence verification of both 5' and 3' junctions [13].

Research Reagent Solutions for Repair Pathway Studies

Table 3: Essential Reagents for DNA Repair Pathway Manipulation and Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations for ssODN Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Inhibitors | Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 (NHEJi), ART558 (POLQ inhibitor), D-I03 (Rad52 inhibitor) [9] | Shifts repair balance toward HDR; reduces specific imprecise outcomes | 24-hour treatment post-editing is typically sufficient [9] |

| Donor Templates | ssODN (symmetric/asymmetric), lssDNA (zLOST, Easi-CRISPR) [15] | Provides homology for HDR; lssDNA shows superior efficiency for longer inserts | lssDNA templates show order-of-magnitude improvement in HDR efficiency [15] |

| Analysis Tools | knock-knock computational framework, inDelphi deep learning model [9] [12] | Classifies editing outcomes; predicts MMEJ repair patterns | Enables quantitative analysis of perfect HDR vs. imprecise integration [9] |

| Specialized Cloning Systems | PITCh vectors, PaqMan plasmids with type IIS sites [12] [13] | Facilitates MMEJ-mediated knock-in; enables precise donor linearization | Reduces random integration compared to non-linearized plasmids [12] |

Strategic Application Notes for ssODN Template Design

Optimizing Template Design and Delivery

The success of precise genome editing experiments critically depends on evidence-based optimization of ssODN design parameters. Based on comparative studies in multiple model systems:

Template Length and Symmetry: In zebrafish models, lssDNA templates (299-512 nt) demonstrated dramatically higher HDR efficiency (98.5% phenotypic rescue) compared to shorter ssODN templates, despite having similar total homology arm lengths [15]. For traditional ssODN designs, asymmetric templates often show superior performance, though results are locus-dependent.

Homology Arm Optimization: While HDR traditionally uses long homology arms (several hundred base pairs), MMEJ-based strategies achieve efficient integration with only 5-25 bp microhomology regions [13]. The emerging approach of using microhomology tandem repeats (5× 3-bp µH) at donor edges can safeguard genome-transgene boundaries from extensive deletions, with the optimal number of repeats being predictable by deep learning models like inDelphi [12].

Critical Timing Considerations: HDR-mediated knock-in efficiency is highly dependent on cell cycle stage, with the highest efficiency occurring in late S and G2 phases when sister chromatids are available as natural repair templates [11]. Controlled timing of CRISPR/Cas9 delivery to coincide with these phases can significantly enhance HDR outcomes.

Pathway Interplay and Co-targeting Strategies

The conventional view of HDR versus NHEJ competition has expanded to include the significant roles of MMEJ and SSA in determining editing outcomes. A key finding from long-read amplicon sequencing studies is that imprecise integration persists even with effective NHEJ inhibition, with SSA specifically contributing to asymmetric HDR events where only one end of the donor integrates precisely [9]. This suggests that combined inhibition of NHEJ and SSA may provide the most effective strategy for maximizing perfect HDR when using ssODN templates.

Furthermore, the predictable nature of MMEJ repair outcomes, guided by local sequence context, enables rational design of donor templates that channel repair toward predictable outcomes. Deep learning models pretrained on DNA repair outcomes can now inform the design of microhomology-based repair arms that maximize on-target integration while minimizing both genomic and transgene deletions [12]. This approach is particularly valuable in cell types with low HDR activity, such as non-dividing neurons or specific fungal species where NHEJ dominates the repair landscape [13].

Why ssODNs? Advantages Over Double-Stranded DNA Donors

Precise gene editing, essential for both basic research and clinical applications, often requires the use of a donor repair template (DRT) to introduce specific changes into a genomic target site. When a CRISPR-Cas nuclease creates a double-stranded break (DSB) in the DNA, the cell activates repair pathways. The presence of a donor template enables the homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway to precisely insert or substitute DNA sequences, facilitating precise genetic modifications [16] [17]. The structure and properties of the DRT are critical determinants of editing success. Donor templates are broadly categorized as either double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) or single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), the latter often in the form of single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs). This application note examines the comparative advantages of ssODNs over traditional dsDNA donors, providing evidence-based protocols for their implementation in precise editing research.

Key Advantages of ssODNs Over dsDNA Donors

Enhanced Editing Efficiency and Specificity

ssODNs consistently demonstrate superior HDR efficiency and specificity compared to dsDNA donors. Research in primary human T cells shows that ssDNA templates achieve high gene knock-in efficiency while significantly reducing off-target integration. In a direct comparison, dsDNA templates induced readily detectable off-target integration, whereas ssDNA templates reduced this to the limit of detection, a level comparable to negative controls with no nuclease activity [18]. This high specificity is crucial for therapeutic applications where precise on-target editing is paramount.

Reduced Cytotoxicity and Improved Cell Viability

A significant practical advantage of ssODNs is their lower cytotoxicity. In T-cell engineering experiments, cells electroporated with ssDNA templates maintained higher viability across a range of concentrations (0.5-3 µg) compared to those treated with dsDNA templates [18]. Only at the highest concentration tested (4 µg) did viability become similar between the two donor types. Improved cell health following transfection enables more robust experimental outcomes and is particularly valuable when working with precious primary cell samples or when scaling therapeutic manufacturing.

Favorable Performance with Short Homology Arms

Unlike dsDNA donors, which typically require long homology arms (often hundreds to thousands of base pairs) for optimal HDR efficiency, ssODNs perform robustly with short homology arms of 30-100 nucleotides [16] [17] [19]. Research in potato protoplasts demonstrated that ssDNA donors with homology arms as short as 30 nucleotides facilitated targeted insertions in up to 24.89% of sequencing reads on average [16] [19]. This simplifies donor synthesis and reduces costs, especially for introducing point mutations or short inserts.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ssODNs vs. dsDNA Donors

| Parameter | ssODN Donors | dsDNA Donors |

|---|---|---|

| HDR Efficiency | High, especially for short edits [17] [18] | Variable, can be lower [18] |

| Off-Target Integration | Greatly reduced [18] | Significantly higher [18] |

| Cytotoxicity | Lower, supports higher cell viability [18] | Higher, can impact cell health [18] |

| Optimal Homology Arm Length | 30-100 nt [16] [17] | 200-2000+ bp [16] [19] |

| Theoretical Risk of Insertional Mutagenesis | Lower [20] | Higher with viral vectors [20] |

Mechanistic Insights: The Cellular Repair Pathway Advantage

The superior performance of ssODNs is rooted in the cellular mechanisms of DNA repair. Evidence suggests that ssODNs are utilized primarily through synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) and single-stranded DNA incorporation pathways, which are inherently precise and generate short, predictable conversion tracts [21]. Furthermore, the single-stranded nature of ssODNs may more closely resemble the natural intermediates processed during HDR, making them more accessible to the cellular repair machinery than blunt-ended dsDNA fragments. Recent advances have leveraged this understanding by engineering RAD51-preferred sequences into ssODNs, creating "HDR-boosting" modules that augment the donor's affinity for key repair proteins and further enhance HDR efficiency [22].

Experimental Protocols for ssODN-Mediated Editing

General Workflow for RNP and ssODN Delivery in Mammalian Cells

The following protocol, adapted from successful gene editing in T cells [18] and HEK293T cells [22], outlines a standard methodology for achieving precise editing with CRISPR RNP and ssODN donors.

Design and Synthesis

- sgRNA Design: Design sgRNAs with high on-target efficiency. Tools like CRISPOR or similar are recommended.

- ssODN Design: Design the ssODN donor with the desired edit flanked by homology arms. For point mutations or small insertions, 30-60 nucleotide arms are typically sufficient. The "target" strand (complementary to the sgRNA) often shows higher efficiency [16] [19]. Consider adding 5' HDR-boosting modules (e.g., RAD51-binding sequences like SSO9 or SSO14) to enhance efficiency without chemical modification [22].

- Synthesis: Obtain high-purity, sequence-verified ssODNs from a commercial supplier.

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation

- Complex purified Cas9 protein with synthetic sgRNA at a molar ratio of 1:2 to 1:3 (e.g., 10 µg Cas9 + 4 µg sgRNA).

- Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to form active RNP complexes.

Cell Transfection/Electroporation

- For suspension cells (e.g., T cells): Mix cells with RNP complexes and ssODN donor (e.g., 2-4 µg per 100 µL reaction). Electroporate using a specialized system (e.g., Neon or Nucleofector).

- For adherent cells (e.g., HEK293T): Trypsinize, resuspend, and electroporate as above. Lipid-based transfection can also be used but is generally less efficient for RNP delivery.

Post-Transfection Culture and Analysis

- Allow cells to recover in complete medium. Assess editing efficiency 48-96 hours post-transfection via flow cytometry (for fluorescent reporters), next-generation sequencing (NGS), or digital droplet PCR (ddPCR).

Optimized Co-Conversion Protocol in C. elegans

The following detailed protocol uses the sid-1 gene as a co-conversion marker for highly efficient editing in C. elegans [23], demonstrating the application of ssODNs in a complex animal model.

Diagram 1: C. elegans ssODN editing workflow.

Key Reagents:

- sid-1 LOF ssODN: A 117 nt anti-sense ssODN with ~35 nt homology arms directing insertion of a universal cassette containing stop codons and an exogenous crRNA target sequence [23].

- Edit of Interest (EOI) ssODN: A custom-designed ssODN for the target gene, with ~35 nt homology arms.

- CRISPR Reagents: crRNAs targeting the sid-1 locus and the EOI, tracrRNA, and purified Cas9 protein.

Detailed Procedure:

- Reagent Preparation: Co-inject C. elegans gonads with a mixture of:

- RNP complexes for sid-1 LOF (1 part).

- RNP complexes for the EOI (9 parts).

- sid-1 LOF ssODN and EOI ssODN.

- pRF4::rol-6 marker plasmid (optional, for identifying injected animals).

- Screening for Loss-of-Function (LOF):

- After injection, transfer individual P0 animals to fresh plates and allow them to produce F1 progeny.

- Transfer F1 progeny to plates containing RNAi food targeting an essential gene (e.g., unc-22 or act-5).

- Selection: Wild-type animals are sensitive to RNAi and will show a phenotype or die. Animals with successful sid-1 LOF co-conversion will be RNAi-resistant and healthy. This enriches for animals that have taken up the editing reagents.

- Genotyping: Screen the RNAi-resistant F1 animals for the desired edit in the gene of interest via PCR and sequencing. The majority of animals with sid-1 co-conversion will also harbor the EOI [23].

- Restoration-of-Function (ROF) Cycling (Optional): To remove the sid-1 LOF mutation for iterative editing, inject animals with an RNP complex targeting the inserted exogenous sequence and a short 73 nt "restoration" ssODN to revert sid-1 to wild-type [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for ssODN-Based Editing

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Providers / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity ssODNs | Serves as the repair template; requires high purity and sequence verification. | GenScript (GenExact), Takara Bio, Moligo Technologies [20] [18] |

| Cas9 Nuclease | Forms the RNP complex with sgRNA to induce the DSB. | Commercial suppliers of recombinant Cas9 protein. |

| Synthetic sgRNA | Guides Cas9 to the specific genomic target. | Commercial synthesis of crRNA and tracrRNA or single-guide RNA. |

| Electroporation System | Enables efficient delivery of RNP and ssODNs into cells. | Neon (Thermo Fisher), Nucleofector (Lonza) |

| HDR-Boosting Modules | Short sequence motifs (e.g., SSO9, SSO14) added to the 5' end of the ssODN to enhance RAD51 binding and HDR efficiency. | Can be incorporated into custom ssODN synthesis [22] |

| NHEJ Inhibitors | Small molecules (e.g., M3814) that can be combined with modular ssODNs to further enhance HDR efficiency. | Used in research protocols [22] |

| RA375 | RA375, MF:C30H25ClN4O7, MW:589.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SW-034538 | SW-034538, MF:C18H20N4O3S2, MW:404.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

ssODNs represent a superior donor template choice for precise genome editing across a wide range of applications, from plant bioengineering [16] [19] to mammalian cell therapy [18] and animal model generation [23]. Their key advantages—high HDR efficiency, reduced off-target integration, lower cytotoxicity, and the ability to function with short homology arms—make them indispensable tools for modern genetic research and therapeutic development. The provided protocols and toolkit offer a foundation for researchers to effectively implement ssODN-based strategies, while emerging innovations like HDR-boosting modules [22] and deep-learning-assisted design [12] promise to further enhance the precision and efficacy of this powerful technology.

Homology-directed repair (HDR) is a high-fidelity cellular pathway that repairs DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) using a homologous DNA template, enabling precise genetic modifications for research and therapeutic applications. In CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, HDR leverages exogenous donor templates to facilitate precise gene modifications, including targeted insertions, deletions, and nucleotide substitutions [24]. This mechanism stands in contrast to error-prone repair pathways like non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) that often result in disruptive insertions or deletions (indels) [25] [24]. The ability to guide DSB repair toward HDR has become a major focus in genome engineering, particularly for correcting disease-causing mutations where precision is critical [25].

Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) have emerged as favored donor templates due to their lower cytotoxicity, higher specificity, and greater efficiency in precise gene editing compared to double-stranded DNA donors [17]. Optimal ssODN design is crucial for enhancing HDR efficiency, with studies indicating that donor length of approximately 120 nucleotides and homology arms of at least 40 bases typically achieve robust HDR outcomes [17]. The strategic design of these ssODN templates represents a critical area of investigation for researchers seeking to maximize precise editing efficiency while minimizing unintended genetic consequences.

Molecular Mechanism of HDR

The HDR pathway initiates when a DSB is recognized by the MRN complex (MRE11–RAD50–NBS1), which coordinates the initial steps of repair [24]. Subsequently, coordinated resection of DNA ends generates 3' single-stranded overhangs that become protected by replication protein A (RPA), preventing secondary structure formation [24]. The central recombinase RAD51 then displaces RPA to form nucleoprotein filaments that perform strand invasion into a homologous donor sequence, establishing a displacement loop (D-loop) that serves as the foundation for precise DNA synthesis using the provided template [24].

The competition between DNA repair pathways fundamentally depends on whether DNA ends undergo resection and whether a homologous donor is available [24]. Proteins including 53BP1 and the Shieldin complex stabilize DNA ends against resection, favoring NHEJ, whereas BRCA1 and CtIP promote resection and HDR [24]. This delicate balance creates opportunities for experimental intervention to bias repair toward HDR, particularly through temporal control strategies and modulation of key pathway components.

HDR Pathway Diagram

Quantitative Analysis of HDR Efficiency

HDR Efficiency Across Experimental Conditions

Table 1: HDR Efficiency Metrics Across Different Experimental Approaches

| Experimental System | Target Gene | Baseline HDR Efficiency | Enhanced HDR Efficiency | Methodology for Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H9 hESCs [25] | TTLL5 | 21% | 80% | DNA-PKcs K3753R + Polθ V896* |

| H9 hESCs [25] | RB1CC1 | 19% | 63% | DNA-PKcs K3753R mutation |

| H9 hESCs [25] | VCAN | 7% | 33% | DNA-PKcs K3753R + Polθ V896* |

| H9 hESCs [25] | SSH2 | 10% | 37% | DNA-PKcs K3753R + Polθ V896* |

| K562 Cells [25] | FRMD7 | Not specified | 89% | DNA-PKcs K3753R + Polθ V896* |

| HEK293T [12] | AAVS1 | Not applicable | 5.2% GFP+ | µH tandem repeat repair arms |

| iPSCs [2] | GBA1 | 30% (NHEJ) | >10% HDR | ssODN donors to outcompete pseudogene |

HDR Enhancement Strategies and Outcomes

Table 2: Comparison of HDR Enhancement Strategies and Their Outcomes

| Enhancement Strategy | Molecular Target | Key Effect | Efficiency Impact | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymerase theta inhibition [25] | POLQ (MMEJ pathway) | Reduces MMEJ-mediated deletions | Increases HDR to 80% in some loci | Increased cell death without donor template |

| DNA-PKcs inhibition [25] | NHEJ pathway | Suppresses error-prone NHEJ | Increases HDR to 63-89% | Cell cycle restrictions remain |

| Combined NHEJ+MMEJ inhibition [25] | DNA-PKcs + POLQ | Synergistic pathway suppression | 91% outcome purity | Reduced cell proliferation |

| Microhomology tandem repeats [12] | Repair arm design | Promotes frame-retentive integration | 5.2% on-target integration | Sequence context dependency |

| ssODN design optimization [17] | Donor template | Enhances HDR template efficiency | >10% KI efficiency | Requires careful homology arm design |

| Cell cycle synchronization [24] | S/G2 phase targeting | Exploits HDR-permissive phases | Variable | Technically challenging |

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced HDR

HDRobust Method for High-Efficiency Precision Editing

The HDRobust protocol employs combined transient inhibition of NHEJ and MMEJ to achieve HDR efficiencies up to 93% (median 60%) of chromosomes in cell populations [25]. This method significantly reduces indels, large deletions, rearrangements at the target site, and unintended changes at other genomic locations.

Materials Required:

- CRISPR-Cas9 components (gRNA, Cas9 protein)

- Single-stranded DNA donor template (ssODN)

- HDRobust substance mix (NHEJ and MMEJ inhibitors)

- Appropriate cell culture reagents

- Transfection reagents

Procedure:

- Design and prepare ssODN donor templates with approximately 120 nucleotides total length, including at least 40-base homology arms on each side [17].

- Complex CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) by incubating gRNA with Cas9 protein at room temperature for 10-15 minutes.

- Transfect cells with RNP complexes and ssODN donors using preferred transfection method appropriate for cell type.

- Apply HDRobust substance mix containing NHEJ and MMEJ inhibitors immediately after transfection.

- Incubate cells for 48-72 hours to allow for genome editing and repair.

- Analyze editing outcomes using targeted amplicon sequencing of boundary PCR products to quantify HDR efficiency and precision [25].

Microhomology-Based Template Design Protocol

This protocol utilizes deep-learning-assisted design of microhomology-based templates to achieve precise, predictable genome integrations [12].

Materials Required:

- PaqCI type IIS endonuclease restriction sites

- Donor cassette (e.g., pCMV:eGFP)

- Design tool Pythia for µH predictions [12]

Procedure:

- Identify microhomology regions using deep learning model inDelphi to predict repair outcomes based on local sequence context [12].

- Design µH tandem repeat repair arms with five tandem repeats of 3-bp µH matching sequence context left and right of the cut site [12].

- Clone donor cassette with invertedly flanked PaqCI type IIS endonuclease restriction sites for in vitro release of linear DNA.

- Linearize donor plasmid using PaqCI to create PaqMan linearized donors.

- Co-transfect linearized donor with CRISPR RNP targeting desired genomic locus.

- Validate on-target integration through boundary PCR analysis and amplicon sequencing [12].

Experimental Workflow for ssODN-Mediated HDR

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for HDR-Based Genome Editing Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Design Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Components | Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 sgRNA [2], Cas9-HiFi [25] | Target-specific DSB induction | High specificity scores, activity prediction, SNP checking |

| Donor Templates | ssODN with phosphorothioate bonds [2] | HDR template for precise editing | 60-base homology arms, 2 PTO bonds at each terminal |

| Repair Pathway Modulators | DNA-PKcs inhibitors [25], Polθ inhibitors [25] | Bias repair toward HDR | Transient inhibition avoids complete pathway knockout |

| Cell Lines | H9 hESCs [25], HEK293T [12] [26], iPSCs [2] | Editing platforms | PDL coating improves HEK293T adhesion [26] |

| Delivery Tools | RNP transfection [25] [2] | Efficient component delivery | Ribonucleoprotein complexes reduce off-target effects |

| Analysis Tools | inDelphi [12], boundary PCR [12] | Outcome prediction and validation | Deep learning models predict repair outcomes |

Technical Applications and Considerations

Advanced Applications in Disease Modeling

HDR-mediated editing with ssODNs has demonstrated particular utility in challenging genomic contexts, such as editing genes with highly homologous pseudogenes. In one notable application, researchers successfully edited the GBA1 gene despite the presence of GBAP1 pseudogene with 96% sequence identity located 16 kb downstream [2]. By transferring Cas9/gRNA RNP with two ssODN donors carrying out-of-frame deletions as HDR templates, they achieved >10% knock-in efficiency while reducing the gene conversion rate from 70% to manageable levels, ultimately enabling isolation of biallelic out-of-frame clones [2].

The HDRobust approach has validated efficient correction of pathogenic mutations in cells derived from patients suffering from anemia, sickle cell disease, and thrombophilia [25]. This method achieved predominant HDR in 58 different target sites, demonstrating its broad applicability across diverse genomic contexts and target genes [25].

Critical Technical Considerations

Cell Cycle Dependence: HDR is restricted to S/G2 phases while NHEJ operates throughout all cell cycle phases, creating inherent efficiency limitations [24]. Strategic approaches to address this include synchronizing cells in HDR-permissive phases or using postmitotic cells with alternative strategies.

Template Design Optimization: Effective ssODN design incorporates phosphorothioate (PTO) modifications at terminal ends to protect from exonuclease activity [2]. Additionally, strategic placement of blocking mutations in the donor template prevents recutting after successful HDR [25].

Pathway Competition Management: The predictable nature of DSB repair enables strategic intervention. Deep learning models like inDelphi can predict repair outcomes based on local sequence context, allowing researchers to design optimal repair arms that promote intended edits and integrations [12].

A Step-by-Step Guide to ssODN Design and Delivery

Homology-directed repair (HDR) represents a powerful pathway for precise genome editing, enabling researchers to insert, replace, or modify genetic sequences with high fidelity. The design of the donor DNA template, particularly the homology arms—sequences flanking the desired edit that are homologous to the genomic target—is a critical determinant of HDR efficiency. This application note synthesizes current research to provide detailed protocols and design principles for optimizing homology arm length and sequence composition, specifically within the context of single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) repair templates. The recommendations are framed to support a broader thesis on achieving precise editing outcomes in therapeutic and research applications.

Core Principles of Homology Arm Design

The Impact of Homology Arm Length

The length of homology arms is a primary factor influencing the efficiency of HDR. The relationship between length and efficiency is not linear but follows a threshold pattern, where increasing arm length beyond a certain point yields diminishing returns. The optimal length is also influenced by the template type (single-stranded vs. double-stranded DNA) and the size of the intended genetic modification.

For ssODN templates, which are typically used for small edits such as point mutations or short insertions (under 50 nucleotides), effective design can utilize relatively short homology arms. Practical guidelines suggest that for small insertions or point mutations, arms of 30 to 100 base pairs can be sufficient [27]. Protocols utilizing ssODNs in C. elegans have successfully employed homology arms as short as 35 nucleotides on each side of the edit [23]. Research indicates that ssDNA templates with homology arms ranging from 350 to 700 nucleotides provide optimal performance for knock-in experiments in human cells [28].

For double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) templates, which are necessary for larger insertions like gene cassettes, longer homology arms are generally required. A study investigating the integration of an EGFP cassette into the CCR5 locus in human HT1080 cells demonstrated that 150 bp arms yielded the lowest efficiency, while arms of 600 bp to 1000 bp showed significantly improved results [29]. Another critical finding is that the cellular mismatch repair (MMR) system, through the protein Msh2, can suppress HDR-mediated targeted integration when homology arms are too short. This suppression is particularly pronounced when a homology arm is 1.7 kb or shorter, a length that appears linked to the average extent of DNA end resection at double-strand breaks [30].

Table 1: Recommended Homology Arm Lengths by Application

| Template Type | Edit Size | Recommended Arm Length | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ssODN | Point mutations, small insertions (<50 nt) | 30 - 100 bp | Shorter arms (30-100 bp) suffice; 35 nt used in validated protocols [27] [23]. |

| Long ssDNA | Larger insertions | 350 - 700 bp | Exponential relationship between length and efficiency; 350 nt is a effective minimum [28]. |

| dsDNA (Plasmid, Viral Vector) | Large cassettes (e.g., reporter genes) | 600 - 1000 bp | 150 bp arms are significantly less efficient than longer arms; 600 bp can achieve high integration rates [29]. |

Sequence Composition and Structural Considerations

Beyond length, the sequence composition and structural properties of homology arms are crucial for maximizing HDR efficiency and ensuring precise editing outcomes.

- GC Content and Stability: GC-rich homology arms can enhance recombination efficiency by stabilizing the DNA interactions during the strand invasion step of HDR [27].

- Sequence Imperfections and MMR: While MMR suppresses recombination with divergent (non-isogenic) sequences, it also conditionally affects editing with isogenic DNA. The absence of Msh2 can significantly increase targeted integration frequency for vectors with short homology arms (≤1.7 kb), highlighting an interaction between arm length and the cellular MMR status [30].

- Disrupting Cas9 Binding to Prevent Re-cleavage: A key strategy for improving the yield of precise edits is to incorporate silent mutations in the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) or the sgRNA seeding region within the repair template. This prevents the Cas9-sgRNA complex from re-cleaving the genome after the desired edit has been incorporated, thereby favoring HDR products over indel mutations [28].

- Avoiding Problematic Sequences: Designers should avoid repetitive sequences or regions with high potential for secondary structure (e.g., hairpins), as these can hinder the strand invasion process [27]. Furthermore, recent evidence shows that extensive homologous regions in pool-packaged AAV libraries can lead to pervasive molecular chimerism through barcode swapping, a phenomenon that is both length- and homology-dependent [31].

The following workflow summarizes the key decision points and considerations for designing effective homology arms.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol: Gene-Targeting Assay with Variable-Length Homology Arms

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to investigate the impact of Msh2 loss on targeted integration efficiency with isogenic donor DNA, which revealed the homology arm length dependency of MMR suppression [30]. It provides a framework for empirically testing arm length efficiency.

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Gene-Targeting Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting Vectors | Donor DNA templates with varying homology arm lengths. | Constructed using systems like MultiSite Gateway or In-Fusion cloning [30]. |

| Cas9 Nuclease & sgRNA | To induce a site-specific double-strand break (DSB) at the genomic locus. | Delivered as a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. |

| Cell Line | Model system for the editing experiment. | Nalm-6 (human pre-B cell line) used in foundational studies [30]. |

| Selection Antibiotic | To select for cells that have integrated the donor template. | e.g., Puromycin, if the vector contains a puromycin-resistance gene. |

| PCR Reagents & Primers | To amplify and sequence the edited genomic locus for validation. | Used for calculating TI (Targeted Integration) and RI (Random Integration) frequency. |

II. Step-by-Step Methodology

- Vector Construction: Design and construct a series of targeting vectors (e.g., plasmid-based) for the desired genomic locus (e.g., HPRT). These vectors should share an identical internal cassette (e.g., a puromycin-resistance gene) but differ in the total length of their homology arms. For example, create vectors with total arm lengths of 1.7 kb, 3.0 kb, 4.5 kb, 5.1 kb, 6.6 kb, 6.8 kb, and 8.9 kb to establish a clear length-efficiency relationship [30].

- Cell Transfection: Transfert the targeting vector along with CRISPR-Cas9 components (e.g., Cas9 protein and in vitro transcribed sgRNA) into the chosen cell line. Include appropriate controls (e.g., no nuclease, empty vector).

- Selection and Outgrowth: At 24-48 hours post-transfection, plate cells in media containing the appropriate selection antibiotic (e.g., puromycin). Allow the cells to grow for a sufficient period (e.g., 7-10 days) to form stable colonies.

- Data Collection and Analysis:

- Count the number of antibiotic-resistant colonies to determine the total number of integration events.

- Calculate the Gene-Targeting Efficiency as the number of colonies with targeted integration divided by the total number of viable cells transfected.

- Use PCR and/or Southern blotting on genomic DNA from pooled colonies to distinguish between targeted integration (TI) and random integration (RI).

- Calculate TI Frequency and RI Frequency as follows [30]:

- TI Frequency = (Number of TI colonies) / (Number of viable cells transfected)

- RI Frequency = (Number of RI colonies) / (Number of viable cells transfected)

- Data Interpretation: Plot the TI frequency against the homology arm length for each vector. The data should reveal the correlation between arm length and editing efficiency, potentially showing a significant drop in efficiency below a specific threshold (e.g., 1.7 kb) in MMR-proficient cells.

Protocol: ssODN-Mediated Point Mutation with Short Homology Arms

This protocol details the use of short-homology arm ssODNs for introducing precise point mutations or small tags, a common application in model organisms and cell lines.

I. Research Reagent Solutions

- ssODN Repair Template: A chemically synthesized single-stranded DNA oligo. The desired edit (e.g., point mutation) is flanked by homology arms (e.g., 35-50 nucleotides each). The template should be designed to introduce silent mutations in the PAM site to prevent re-cleavage [23] [28].

- CRISPR Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex: Consists of purified Cas9 protein and a target-specific crRNA complexed with a tracrRNA.

- Co-conversion Marker Plasmids: (Optional) Plasmids like pRF4::rol-6 can be co-injected to mark successfully injected animals and help assess reagent functionality [23].

II. Step-by-Step Methodology

- ssODN Design: Design an ssODN template of approximately 70-110 nucleotides, with the intended edit positioned in the middle. Flank the edit with homology arms of equal length (e.g., 35 nt each). Ensure the template's polarity (sense or antisense) is considered, as it can affect efficiency [23] [28].

- RNP Complex Formation: In vitro, complex the Cas9 protein with the crRNA:tracrRNA duplex to form the RNP according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Reagent Injection: Prepare the injection mixture containing the RNP complex (at a recommended concentration) and the ssODN repair template. For C. elegans, this mixture is microinjected into the gonad of young adult animals [23]. For mammalian cells, deliver via electroporation or other transfection methods.

- Screening and Validation:

- (For C. elegans) Allow injected P0 animals to lay eggs on separate plates. Screen the F1 progeny for the presence of the co-conversion marker (e.g., Rol phenotype) or directly for the desired edit.

- Pick candidate F1 animals and allow them to produce F2 progeny. Genotype the F2 population to identify homozygous lines carrying the precise edit.

- Use PCR amplification followed by Sanger sequencing of the target locus to confirm the precise incorporation of the mutation and the absence of unintended indels.

Advanced Design Strategies and Future Directions

Leveraging Microhomology and Machine Learning

Emerging strategies move beyond traditional HDR by exploiting alternative repair pathways. One promising approach uses microhomology (µH)-mediated end joining (MMEJ). A recent study demonstrated that designing donor templates with tandem repeats of 3-6 bp microhomologies matching the sequences flanking the Cas9 cut site can facilitate precise, predictable integrations. This method, which uses tools like inDelphi to predict optimal repair outcomes, promotes frame-retentive cassette integration and reduces deletions at the genome-cargo interface. It is particularly useful in non-dividing cells where HDR is inefficient [12].

Furthermore, artificial intelligence and deep learning are being harnessed to design entirely novel CRISPR-Cas proteins and predict repair outcomes. Large language models trained on vast datasets of CRISPR operons can now generate functional Cas9-like effectors with sequences highly divergent from natural proteins [32]. These AI-generated editors, along with predictive models for DNA repair, are paving the way for more precise and efficient genome editing tools, potentially overcoming some of the limitations associated with homology arm design.

The application of single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) as repair templates for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated homology-directed repair (HDR) represents a powerful approach for achieving precise genome engineering, enabling the introduction of single-nucleotide changes, epitope tags, and other subtle modifications. Despite its conceptual simplicity, this method is often hampered by low efficiency, largely because the desired HDR process must compete with the more dominant and error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway [3]. A critical, and often underappreciated, factor determining the success of these experiments is the strategic placement of the desired edit within the repair template relative to the Cas9-induced double-strand break (DSB). Optimal design, positioning the edit in close proximity to the cut site and incorporating PAM-disrupting changes, can significantly enhance the recovery of correctly modified cells by minimizing continued Cas9 activity at the successfully edited locus. This application note details the experimental rationale and protocols for designing ssODNs that leverage these principles, providing a structured framework for researchers in drug development and biomedical science to improve the precision and efficiency of their genome editing workflows.

Theoretical Framework: The Rationale for Strategic Placement

The Re-Cutting Problem

Upon the successful introduction of a desired point mutation via HDR, the CRISPR-Cas9 system remains active in the cell and can recognize and re-cleave the newly modified genomic sequence. This occurs because Cas9, complexed with the single-guide RNA (sgRNA), can still bind to and cut at target sites that bear a small number of mismatches to the original protospacer sequence [33]. A single base-pair substitution introduced by HDR may be insufficient to prevent this recognition, leading to repeated cycles of cutting and repair. Subsequent repair via NHEJ often introduces insertion or deletion mutations (indels) that destroy the precise edit the researcher intended to create, thereby drastically reducing the final yield of correctly modified clones [33]. This "re-cutting" phenomenon represents a major bottleneck in the generation of clean, precise mutations, particularly single-nucleotide substitutions.

PAM Disruption as a Primary Strategy

The most effective strategy to prevent re-cutting is to disrupt the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) in the edited allele. The PAM (e.g., NGG for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) is absolutely required for Cas9 recognition and cleavage [34]. A mutation that alters the PAM sequence, even by a single nucleotide, renders the locus largely invisible to Cas9 and thus protects the HDR-generated edit from destruction. When designing an ssODN to introduce a specific nucleotide change, incorporating an additional, silent mutation to disrupt the PAM is a highly reliable method to enhance editing efficiency.

The Imperative of Proximal Placement

The efficiency of HDR is not uniform across the region surrounding a DSB. The cellular repair machinery exhibits a distance-dependent decline in its ability to incorporate genetic information from a donor template. The highest HDR efficiency is achieved when the desired edit is located as close as possible to the Cas9 cut site, which is typically within 10 base pairs or fewer [35]. Placing an edit or a PAM-disruption mutation distal to the cut site, for instance, more than 20-30 base pairs away, can lead to a significant drop in the incorporation rate of that change. Therefore, the strategic placement of both the desired mutation and any protective PAM disruption near the DSB is paramount for success.

Quantitative Data and Design Parameters

The following tables summarize key experimental findings and design rules for optimizing ssODN templates.

Table 1: Impact of PAM Disruption and hideRNA Co-delivery on HDR Efficiency in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells [33]

| Experimental Condition | Puromycin Selection (μg/ml) | Relative HDR Efficiency (GFP+ Cells) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| ssODN (AAG>ATG only) | 1.2 | Baseline | Re-cutting occurs, limiting HDR output. |

| ssODN (AAG>ATG only) | 3.6 | ~2.5x Baseline | Higher Cas9/gRNA levels increase initial HDR but also re-cutting. |

| ssODN (AAG>ATG + PAM disruption) | 3.6 | ~5x Baseline | PAM disruption prevents re-cutting, maximizing yield. |

| ssODN (AAG>ATG only) + hideRNA | 3.6 | ~4x Baseline | hideRNA protects the edited site, boosting yield without extra coding changes. |

Table 2: Critical Design Parameters for ssODN Repair Templates [36] [35] [33]

| Parameter | Optimal Design Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Edit Proximity to DSB | Within 10 bp of the Cas9 cut site, ideally < 6 bp. | HDR efficiency is highest closest to the break; minimizes "scarless" DNA synthesis. |

| PAM Disruption | Incorporate a silent mutation (if possible) to alter the NGG sequence. | The most effective method to prevent Cas9 re-cleavage of the successfully edited allele. |

| Homology Arm Length | 30-60 bp on each side for short ssODNs; can be asymmetric (e.g., 91 bp/36 bp). | Provides sufficient homology for the HDR machinery without reducing synthesis yield. |

| Template Strand | ssODN should be complementary to the Cas9-cut strand (the "non-target" strand). | Reported to improve HDR efficiency by making the homologous region more accessible. |

| Synergistic Protection | Combine proximal PAM disruption with hideRNA co-delivery for difficult edits. | hideRNAs (truncated gRNAs) can block re-cutting where PAM disruption is not feasible. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing an ssODN with Integrated PAM Disruption

This protocol guides the design of a "PAM-disrupting" ssODN for introducing a single nucleotide variant (SNV).

Materials:

- CRISPR design tool (e.g., CHOPCHOP, CRISPR Design Tool) [35]

- DNA sequence of the target genomic locus

- sgRNA sequence and known Cas9 cut site (3 bp upstream of PAM) [34]

Workflow:

- Identify the PAM and Cut Site: Locate the NGG PAM sequence targeted by your sgRNA and note the Cas9 cut site ~3-4 bp upstream.

- Position the Primary Edit: Center your desired nucleotide change within the ssODN, ensuring it is placed as close as possible to the predicted cut site (aim for < 10 bp away).

- Design the PAM Disruption: Introduce a second, silent mutation within the PAM sequence (e.g., change "GG" to "GC", "GT", or "GA"). If this is not possible without altering the amino acid sequence, consider introducing a synonymous mutation in the protospacer region closest to the PAM.

- Finalize ssODN Sequence:

- The final ssODN should be 100-200 nucleotides in total length.

- It should contain the primary edit and the PAM-disrupting mutation, flanked by homology arms of 30-60 bp on each side.

- Ensure the ssODN is complementary to the strand that Cas9 cuts (the non-target strand) to improve efficiency [36].

Protocol 2: Co-delivery of ssODN with hideRNAs for Enhanced Protection

When PAM disruption is not feasible, hideRNAs can be used to protect the edited allele. This protocol outlines this alternative strategy [33].

Materials:

- Plasmid or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex for expressing the full-length sgRNA and Cas9.

- Custom-designed hideRNA (as a plasmid, PCR amplicon, or synthetic RNA).

- ssODN template containing only the primary edit (without PAM disruption).

Workflow:

- Design hideRNAs: Design truncated guide RNAs (typically 10-16 nt in length) that are perfectly complementary to the successfully edited genomic sequence, including the new nucleotide. The hideRNA spacer should be positioned to bind over the region where the original sgRNA would bind, effectively "hiding" the site.

- Prepare Reagents: Synthesize the ssODN and the hideRNA expression construct (or synthetic hideRNA for RNP formation).

- Co-transfect/Co-inject: Deliver the following components simultaneously into your target cells (e.g., via electroporation) or zygotes (via microinjection):

- Cas9 protein or mRNA.

- Full-length sgRNA (as RNP or expressed from a plasmid).

- hideRNA (as RNP or expressed from a plasmid).

- ssODN repair template (containing only the primary edit).

- Screen and Validate: Screen the resulting clones or organisms by PCR and Sanger sequencing to identify those with the precise, desired edit and no secondary mutations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ssODN-Mediated Precise Editing

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Example / Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 | Induces the target DSB with reduced off-target activity. | eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9 [34]. |

| Chemically Synthesized ssODN | Serves as the repair template for HDR. | 100-200 nt, PAGE-purified, designed with proximal edits and/or PAM disruption. |

| hideRNA Expression Vector | Expresses truncated gRNA to protect the edited site from re-cutting. | Plasmid encoding a 10-16 nt guide sequence matching the edited allele [33]. |

| HDR Enrichment System | Improves the odds of isolating HDR-edited cells. | Fluorescent reporters (e.g., GFP) or co-selection with puromycin resistance [33]. |

| NHEJ Inhibitors | Shifts repair balance from NHEJ toward HDR. | Small molecules like Scr7 or Alt-R HDR Enhancer. |

| In Silico Off-Target Predictor | Nominates potential off-target sites for assessment. | Cas-OFFinder, CCTop (for sgRNA-dependent sites) [37]. |

| Mytoxin B | Mytoxin B, MF:C29H36O9, MW:528.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Acetaminophen-d7 | Acetaminophen-d7, MF:C8H9NO2, MW:158.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Strategic placement of edits within ssODN repair templates is not a minor detail but a foundational principle for successful precise genome engineering. Positioning the desired mutation near the Cas9 cut site and incorporating PAM-disrupting changes directly address the two major bottlenecks of HDR: its inherently low efficiency and the threat of Cas9-mediated re-cleavage. The quantitative data and detailed protocols provided herein offer researchers a clear, actionable path to significantly improve the yield of precise edits in their models. As the field advances toward therapeutic applications, the rigorous application of these design principles will be indispensable for generating clean, reliable, and clinically relevant genetic models.

Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) serve as crucial donor repair templates (DRTs) for achieving precise genome edits via homology-directed repair (HDR). The strategic design of these ssODNs is a fundamental determinant of editing success. Among the critical design parameters, strand polarity—the choice of whether the ssODN is homologous to the sense (target) or antisense (non-target) strand at the genomic target site—has emerged as a significant factor influencing HDR efficiency. While the impact of other factors like homology arm (HA) length is well-documented, strand polarity presents a more nuanced and context-dependent variable. This Application Note synthesizes current empirical evidence to provide a structured framework for selecting strand polarity, thereby enhancing the precision and efficiency of genome editing workflows for research and therapeutic development.

Quantitative Analysis of Strand Polarity Impact

Recent investigations across various model systems have quantified the effect of ssODN strand orientation on HDR outcomes. The consensus indicates a preferential efficiency for one orientation, though the optimal choice can be locus-specific.

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings on strand polarity from recent studies:

Table 1: Experimental Data on ssODN Strand Polarity and HDR Efficiency

| Experimental System | Locus/Target | ssODN Length & Design | Optimal Strand | Reported HDR Efficiency | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potato Protoplasts | Soluble Starch Synthase 1 (SS1) | ssDNA DRTs of varying lengths | Target (sense) orientation | Achieved 1.12% HDR in protoplast pool | Outperformed "non-target" (antisense) orientation at 3 out of 4 tested loci. | [19] [16] |

| General ssODN Design | N/A | < 200 nucleotides | Polarity has a demonstrated effect | Not Specified | The effect of template polarity is more pronounced for shorter ssODN templates. | [38] |

| Human iPSCs (GBA1 editing) | GBA1 Exon 6 | 60-nt homology arms, PTO modifications | Protocol successful with designed ssODNs | >10% Knock-in efficiency | Used two ssODNs to outcompete pseudogene-mediated gene conversion, confirming functional HDR. | [2] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rapid Assessment of Strand Polarity in Plant Protoplasts

This protocol, adapted from a study in potato, provides a high-throughput method for evaluating editing components, including strand polarity [19] [16].

Key Reagents and Equipment

- Solanum tuberosum cultivar Kuras or other relevant plant line.

- Protoplast isolation enzymes (e.g., cellulase, macerozyme).

- CRISPR/Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex: pre-complexed Cas9 nuclease and target-specific sgRNA.

- Experimental ssODN DRTs: Designed in both target (sense) and non-target (antisense) orientations.

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution for transfection.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) library preparation kit and sequencer.

Step-by-Step Workflow

- Protoplast Isolation: Isolate protoplasts from plant leaves using enzymatic digestion. Purify and quantify the protoplast yield.

- RNP/DRT Transfection:

- Prepare two main reaction mixtures:

- Reaction A: RNP complex + Target-oriented ssODN DRT.

- Reaction B: RNP complex + Non-Target-oriented ssODN DRT.

- Include appropriate controls (e.g., RNP only, no treatment).

- Transfect the protoplasts using PEG-mediated delivery.

- Prepare two main reaction mixtures:

- Incubation and DNA Extraction: Incubate transfected protoplasts for 48-72 hours to allow for genome editing and repair. Harvest cells and extract genomic DNA.

- NGS and Data Analysis:

- Amplify the target genomic region by PCR and prepare libraries for NGS.

- Sequence the amplicons and use bioinformatic pipelines to quantify the frequency of precise HDR events from the sequencing reads.

- Compare the HDR efficiency between Reaction A and Reaction B to determine the optimal strand polarity for the target locus.

Figure 1: Workflow for assessing ssODN strand polarity in plant protoplasts.

Protocol 2: Competing with Pseudogene Conversion in Human iPSCs

This protocol demonstrates the use of ssODNs to achieve precise editing in a challenging genomic context with high pseudogene homology [2].

Key Reagents and Equipment

- Human induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs).

- Cas9 protein and synthetic sgRNA (e.g., Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 sgRNA from IDT).

- ssODN DRTs: Two donors designed with out-of-frame deletions. Key design features include:

- 60-nucleotide homology arms on each side.

- Phosphorothioate (PTO) bonds at the 5' and 3' termini to protect from exonuclease degradation.

- Electroporation system (e.g., Neon System).

- Karyotyping and Mycoplasma testing services.

Step-by-Step Workflow

- gRNA and ssODN Design:

- Design a sgRNA with high specificity for the target gene (e.g., GBA1), avoiding the pseudogene.

- Design two ssODN DRTs to introduce small, out-of-frame deletions at the cut site. The goal is to disrupt the reading frame to trigger nonsense-mediated decay (NMD).

- RNP Complex Formation:

- Pre-complexe the Cas9 protein and sgRNA to form the RNP complex. Incubate for 10-20 minutes at room temperature.

- Cell Preparation and Electroporation:

- Culture and maintain iPSCs in an undifferentiated state.

- Harvest iPSCs and resuspend them in an electroporation buffer.

- Mix the cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complex and the two PTO-modified ssODN DRTs.

- Electroporate the mixture using optimized parameters for iPSCs.

- Post-Electroporation Culture and Clonal Isolation:

- Plate the electroporated cells on Matrigel-coated plates in recovery medium.

- After 5-7 days, pick individual colonies and expand them for genotyping.

- Genotyping and Validation:

- Screen clonal lines by PCR and Sanger sequencing to identify precise HDR events.

- Confirm the absence of large structural variations via long-read sequencing (e.g., LOCK-seq) and validate normal karyotype.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for ssODN-Mediated HDR

Successful execution of strand polarity optimization requires specific, high-quality reagents. The following table details essential components and their functions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ssODN-Mediated HDR

| Reagent / Material | Function & Importance | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Complex | Induces a clean double-strand break at the target locus. RNP delivery offers high efficiency and reduced off-target effects compared to plasmid delivery. | Commercially available as Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease V3 and Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 sgRNA (IDT). |

| High-Purity ssODN DRTs | Serves as the template for precise HDR. Strand polarity is the key variable under investigation. | Should be HPLC-purified. For difficult edits or longer cultures, specify phosphorothioate (PTO) modifications on terminal bases to enhance stability [2]. |

| Cell Type-Specific Transfection System | Delivers RNP and ssODN into the target cells with high efficiency and low toxicity. | Plant Protoplasts: PEG-mediated transfection [19] [16]. Human iPSCs: Electroporation systems like the Neon Transfection System (Thermo Fisher). |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Enables quantitative and unbiased assessment of HDR efficiency and other editing outcomes in pooled populations. | Kits such as Illumina's DNA Prep kits are standard. Analysis requires specialized bioinformatics pipelines. |

| RM-018 | RM-018, MF:C56H72N8O8, MW:985.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Y13g | Y13g, MF:C16H24N2O4, MW:308.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

A Decision Framework for Strand Selection

Based on the synthesized evidence, the following workflow provides a strategic guide for researchers selecting ssODN strand polarity.

Figure 2: Decision framework for selecting ssODN strand polarity.

The selection of sense versus antisense orientation for ssODN repair templates is a critical, though often overlooked, component of precise genome editing experimental design. Current evidence strongly indicates that the target (sense) strand orientation frequently yields superior HDR efficiency, particularly for shorter ssODNs. However, the potential for locus-specific variation necessitates a strategic approach. For robust and reproducible results, especially in novel or challenging editing contexts, empirical testing of both polarities remains the gold standard. By integrating the quantitative data, detailed protocols, and the decision framework provided in this Application Note, researchers can make informed decisions on strand polarity, thereby optimizing the efficiency and success of their precise genome editing endeavors.

Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) serve as vital repair templates in CRISPR-Cas9-mediated homology-directed repair (HDR), enabling precise genetic modifications from single-base substitutions to short insertions. Achieving high HDR efficiency remains a major challenge in many cell types, partly due to the rapid degradation of exogenous DNA templates by cellular nucleases before they can engage in the repair process [39]. The phosphorothioate (PS) bond modification, where one of the non-bridging oxygen atoms in the phosphate backbone is replaced by sulfur, has emerged as a critical chemical innovation to enhance the stability and efficacy of ssODNs [40]. This application note details the use of phosphorothioate modifications within the context of ssODN repair template design, providing structured data, optimized protocols, and visual guides for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to achieve precise genome editing.

Chemical Basis and Protective Mechanism of Phosphorothioate Modifications

The substitution of oxygen with sulfur in the phosphate backbone fundamentally alters the properties of the oligonucleotide. This modification renders the internucleotide linkage resistant to degradation by ubiquitous cellular nucleases, thereby increasing the half-life of ssODNs within the cell [40]. Furthermore, the enhanced hydrophobicity of the PS bond can improve cellular uptake and facilitate interaction with proteins involved in the DNA repair machinery [41] [40].

Recent research has identified specific nucleases that pose a significant barrier to HDR. The endoplasmic reticulum-associated exonuclease TREX1, for instance, has been shown to physically interact with and degrade electroporated ssODN templates, severely limiting HDR efficiency in various cell types, including primary T cells and hematopoietic stem cells [39]. Phosphorothioate modifications protect the ssODN from TREX1 activity, with studies demonstrating that TREX1 knockout or the use of chemically protected ssODN templates can rescue HDR efficiency with improvements ranging from two-fold to eight-fold [39].

Table 1: Key Properties of Phosphorothioate-Modified ssODNs vs. Unmodified ssODNs

| Property | Unmodified ssODN | Phosphorothioate-Modified ssODN | Experimental Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Resistance | Low | High | Increased half-life in cellulo [40] |

| Binding Affinity to Proteins | Standard | Enhanced | Can improve engagement with repair machinery but may increase non-specific binding [41] [40] |

| Cellular Uptake | Standard | Improved | Aided by increased hydrophobicity [40] |

| HDR Efficiency (in high TREX1 contexts) | Low | High (2- to 8-fold increase) | Enables efficient editing in resistant cell types [39] |

| Potential for Non-Specific Toxicity | Low | Moderate | Dose-dependent effects; requires optimization [40] |

Visualizing the Protective Mechanism of Phosphorothioate Modifications

The following diagram illustrates how phosphorothioate bonds protect ssODN repair templates from exonuclease degradation, a key barrier to efficient homology-directed repair.

Application Notes: Designing Phosphorothioate-Modified ssODNs for HDR

Strategic Placement of Phosphorothioate Linkages

While full phosphorothioate backbone modification is possible, it can increase non-specific binding and toxicity [40]. A common and effective strategy is end-protection, where 3-5 nucleotides at both the 5' and 3' termini are synthesized with PS bonds. This configuration shields the ssODN from processive exonucleases like TREX1, which is a primary cause of template degradation [39] [42]. For applications requiring extreme stability, a limited number of internal PS linkages can be added, though this should be evaluated on a case-specific basis.

Combination with Other Optimization Strategies

Phosphorothioate modification is one component of a comprehensive ssODN design strategy. Its efficacy is synergistic with other optimizations:

- Homology Arm (HA) Length: ssODNs with HAs as short as 30-50 nucleotides can support high frequencies of targeted insertion, though the optimal length may be locus-dependent [19].

- Strand Orientation: The "target" strand (complementary to the sgRNA-recognized strand) often outperforms the "non-target" strand as an ssODN template [19].

- Silent PAM Disruption: Introducing silent mutations in the repair template to disrupt the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence can prevent re-cleavage of the edited locus by Cas9, thereby enriching for HDR-derived cells [43].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of ssODN Design on Editing Outcomes in Various Systems

| ssODN Design Parameter | System/Cell Type | Key Quantitative Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|