PAR Proteins and Gastrulation: Orchestrating Cell Polarity and Movement in C. elegans Development

This article synthesizes current research on the fundamental role of PAR proteins in controlling gastrulation in C.

PAR Proteins and Gastrulation: Orchestrating Cell Polarity and Movement in C. elegans Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the fundamental role of PAR proteins in controlling gastrulation in C. elegans. We explore how this conserved polarity module, first identified for regulating asymmetric cell division, is co-opted to drive the cell shape changes and ingression movements of gastrulation. The content details the molecular circuitry of PAR proteins, their regulation by phosphorylation cycles, and their downstream control of the actomyosin cytoskeleton to power apical constriction. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review covers foundational principles, advanced imaging and modeling methodologies, common experimental challenges, and comparative analyses that validate PAR protein functions across biological contexts, highlighting their broader implications for understanding cell movement in development and disease.

The PAR Polarity Module: From Asymmetric Division to Gastrulation Control

The discovery of the par (partitioning defective) genes in Caenorhabditis elegans represents a foundational milestone in developmental biology, revealing an ancient and conserved machinery for cell polarization. This whitepaper delineates the historical identification of these genes through innovative genetic screens and explores their profound role in cytoplasmic partitioning and embryonic patterning. Within the broader context of PAR protein function in C. elegans gastrulation research, we examine how these proteins orchestrate critical morphogenetic events, such as endoderm precursor cell (EPC) ingression, via the regulation of apical constriction and actomyosin dynamics. The content is structured to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a rigorous technical guide, encompassing quantitative data summaries, detailed experimental methodologies, and essential research tools that have propelled this field forward.

The establishment of cellular polarity is a fundamental process governing asymmetric cell division, cell fate specification, and tissue morphogenesis during embryonic development. In the nematode C. elegans, this process is controlled by an evolutionarily conserved set of proteins known as the PAR (partitioning defective) proteins. The historical discovery of the par genes emerged from a quest to understand how maternal-effect genes control the earliest stages of embryogenesis, particularly the asymmetric partitioning of cytoplasmic components that precedes cell fate determination [1]. These proteins form a core signaling pathway that enables cells to establish and maintain polarized domains, a necessity for processes ranging from asymmetric stem cell divisions to gastrulation movements [1] [2].

Within the specific context of C. elegans gastrulation, PAR proteins play a critical role in coordinating cell ingression and tissue reorganization. Gastrulation involves the internalization of cells that will form internal tissues and organs, with the endoderm precursor cells (EPCs) being the first to ingress at the 26-cell stage [3]. The proper execution of this process relies on the PAR-dependent establishment of cellular asymmetry, which regulates downstream effectors such as the actomyosin cytoskeleton to drive apical constriction and cell movement [3]. This whitepaper will explore the historical linkage between the par genes and cytoplasmic partitioning, and how this foundational polarity system is co-opted to control gastrulation, providing a mechanistic understanding of early embryonic patterning.

Historical Discovery of par Genes

The Genetic Screen: A Landmark Approach

The initial discovery of the par genes was rooted in a pioneering genetic screen conducted by Ken Kemphues and Jim Priess in 1983. The screen was designed to identify maternal-effect genes essential for early embryonic development in C. elegans. A key innovation that enabled this large-scale endeavor was the strategic use of mutant strains with an egg-laying defective (Egl) phenotype. In such strains, embryos that are not released hatch inside their mother and consume her, resulting in a "bag of worms" phenotype. Priess reasoned that by mutagenizing Egl strains, any worm harboring a penetrant maternal embryonic lethal mutation would be spared from being devoured—making it easily identifiable as a surviving, crawling adult on the culture plate [1].

This screening methodology was further streamlined by incorporating a high incidence of males (Him) mutation, which facilitated the maintenance of recessive lethal mutations through heterozygous siblings. In the very first screen employing this strategy, Kemphues and technician Nurit Wolf isolated six embryonic lethal mutants. One strain exhibited a particularly striking phenotype: embryos underwent abnormally equal and synchronous cell divisions, suggesting a profound failure in partitioning cytoplasmic components during early cleavages [1]. This gene was designated par-1, and subsequent screens ultimately identified a total of six core par genes (par-1 to par-6), with multiple alleles isolated for each [1].

Initial Phenotypic Analysis: Revealing the Core Function

Mutant analyses of the identified par genes revealed their fundamental role in two interconnected aspects of cell polarization in the one-cell embryo:

- Asymmetric spindle positioning: The par genes were required for the asymmetric positioning of the mitotic spindle, which results in an unequal first cell division.

- Asymmetric cargo localization: They were essential for the asymmetric positioning of specific proteins and RNAs, such as the germline-specific P-granules, which are critical for establishing distinct cell fates in the daughter cells [1].

Because most par genes functioned upstream of both processes, it was concluded that they encode the core machinery responsible for initiating cell polarization in the C. elegans zygote [1]. This foundational polarity system was later found to operate in numerous other cell types, including those involved in gastrulation, epithelia, and cell migration [1].

Molecular Identities and Conservation of PAR Proteins

The molecular cloning of the six par genes between 1994 and 2002 revealed that they encode components of a novel intracellular signaling pathway, illuminating their potential mechanisms of action [1].

Table 1: Molecular Identities of the Core C. elegans PAR Proteins

| Protein | Molecular Identity | Proposed Function in Polarity |

|---|---|---|

| PAR-1 | Serine/threonine kinase | Posterior determinant; phosphorylates downstream substrates |

| PAR-2 | RING finger domain protein | Potential role in ubiquitination pathway; posterior cortex |

| PAR-3 | PDZ domain protein | Scaffold protein; anterior determinant |

| PAR-4 | Serine/threonine kinase | Kinase; symmetrically localized |

| PAR-5 | 14-3-3 protein | Binds phosphorylated serines/threonines |

| PAR-6 | PDZ domain protein | Scaffold protein; anterior determinant |

| aPKC (PKC-3) | Atypical Protein Kinase C | Kinase; anterior determinant |

The identities of these proteins suggested they formed a complex signaling network. PAR-3 and PAR-6, with their PDZ domains, could function as a scaffold. PAR-1 and PAR-4 are kinases, and PAR-5, a 14-3-3 protein, often recognizes phospho-epitopes, indicating a network regulated by phosphorylation [1]. A critical turning point was the discovery that the fly polarity protein Bazooka is a PAR-3 homolog, and that mammalian PAR-3 binds to an atypical PKC (aPKC) [1]. This was swiftly followed by the identification of C. elegans aPKC (PKC-3) as a protein with a Par phenotype and asymmetric localization [1]. Subsequently, PAR-3, PAR-6, and aPKC were found to form a physical complex with the small GTPase CDC-42, an ancient polarity protein [1] [2]. The high conservation of all PAR proteins across animal species underscored their status as fundamental players in cell polarization [1].

PAR Protein Dynamics and Domain Maintenance

A key question in the field has been how the asymmetric distributions of PAR proteins are maintained stably over time. Research has revealed that PAR proteins are not statically anchored but exist in a dynamic steady state.

A Dynamic Steady State Governed by Diffusion and Antagonism

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) experiments during the maintenance phase of polarity demonstrated that both anterior (PAR-6) and posterior (PAR-2) PAR proteins undergo rapid exchange between the cytoplasm and the membrane, and are free to diffuse laterally within the membrane [4]. This creates a continuous flux of molecules across the boundary between the anterior and posterior domains due to diffusion down their concentration gradients. The stable maintenance of these domains, therefore, does not rely on diffusion barriers or active transport but is instead achieved by a balance of diffusive flux and actin-independent differences in the effective membrane affinities of the PAR proteins between the two domains [4]. Essentially, mutual antagonism between the anterior and posterior PAR complexes creates regional differences in net association and dissociation rates, counteracting the homogenizing effect of lateral diffusion.

Network of Mutual Antagonism

The stable polarization of the PAR domains is enforced by a network of mutually antagonistic interactions:

- The anterior PAR complex (PAR-3/PAR-6/PKC-3) promotes the dissociation of posterior PAR proteins (PAR-1, PAR-2) from the membrane [2].

- Conversely, the posterior PAR proteins promote the dissociation of the anterior complex from the membrane [2]. For instance, PAR-1 phosphorylates PAR-3 to exclude it from the posterior cortex, and PAR-2 plays a role in dissociating PAR-6 and CDC-42 [2].

- This mutual inhibition is complemented by within-group positive feedback, such as the cooperative membrane binding of PAR-3 and its association with PAR-6 and CDC-42 [2] [5].

This network of interactions allows the system to function as a bistable switch, reinforcing initial asymmetries to create and maintain two distinct cortical domains.

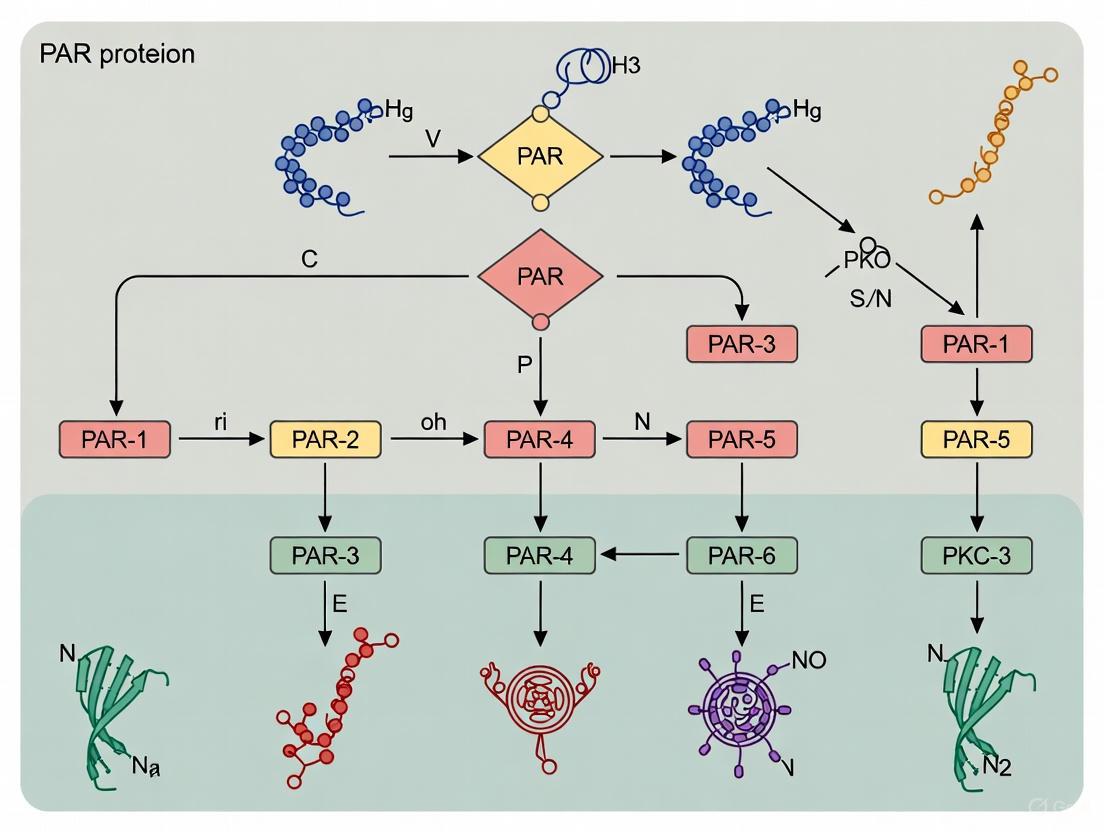

Diagram 1: PAR Protein Mutual Antagonism Network. The core signaling network showing mutual exclusion between anterior and posterior PAR proteins, and the stabilizing role of CDC-42.

PAR Proteins in Gastrulation Control

Within the context of C. elegans gastrulation, the PAR polarity system is co-opted to control the intricate cell movements required for internalizing the endoderm and mesoderm precursors. The gastrulation of the EPCs serves as a paradigm for understanding this control.

Cell Biology of Endoderm Precursor Cell (EPC) Ingression

The internalization of the two EPCs at the 26-cell stage involves several coordinated cell biological events:

- Apical Constriction: The EPCs undergo a dramatic flattening and constriction of their contact-free apical surfaces, driving the cytoplasm towards the inner side of the cell. This process is powered by the actomyosin cytoskeleton, specifically the accumulation and contraction of non-muscle myosin II (NMY-2) and phosphorylated regulatory myosin light chain (p-rMLC) at the apical cortex [3].

- Spreading of Neighboring Cells: As the EPCs constrict apically, neighboring cells (MS mesodermal precursors and the P4 germline precursor) migrate over them to cover the space they vacate. This redistribution of embryonic mass is crucial for liberating interior space within the small blastocoel cavity, accommodating the ingressing cells [3].

- Cell Cycle Expansion: The EPCs exhibit a characteristically extended cell cycle, dividing only after they are fully internalized. This extended cycle is pre-programmed and is critical for efficient ingression, as it allows sufficient time for the cytoskeletal rearrangements to occur. Mutants like gad-1, which cause premature division of the EPCs, result in gastrulation failure [3].

Linking PAR Polarity to Gastrulation Movements

The PAR proteins influence gastrulation through multiple mechanisms. They are involved in contact-induced cell polarity, which helps specify the fate of cells like the EPCs. Furthermore, the PAR pathway regulates the actomyosin forces required for apical constriction. The PAR-6/PKC-3 complex is instrumental in this process. PAR-6, in a complex with PKC-3 and CDC-42, directly or indirectly regulates the activity and localization of non-muscle myosin II, thereby controlling the apical constriction that drives EPC ingression [3]. This demonstrates a direct functional link between the embryonic polarity apparatus and the execution of morphogenetic movements during gastrulation.

Table 2: Key Cell Biological Events in C. elegans EPC Ingression

| Event | Description | Molecular Mediators | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apical Constriction | Flattening and constriction of the apical cell surface | NMY-2 (Myosin II), p-rMLC, Actin microfilaments, PAR-6/PKC-3 | Generates force to drive cell internalization |

| Spreading of Neighbors | Migration of MS and P4 cells over ingressing EPCs | Unknown guidance cues from EPCs | Creates interior space for ingressing cells |

| Cell Cycle Expansion | Extended cell cycle duration specific to E lineage | GAD-1 (WD repeat protein) | Provides time for cytoskeletal changes to complete |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Key Historical and Contemporary Techniques

The study of PAR proteins and gastrulation has relied on a suite of genetic, cell biological, and quantitative imaging techniques.

1. Original Genetic Screening Protocol:

- Strain Construction: Generate a strain with an egg-laying defective (egl) mutation and a high incidence of males (him) mutation.

- Mutagenesis: Treat worms with a chemical mutagen (e.g., ethyl methanesulfonate).

- Phenotypic Screening: Scan culture plates for surviving, crawling adults (potential carriers of maternal-effect lethal mutations).

- Clone Isolation and Characterization: Isolate putative mutants and characterize their embryonic phenotypes using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy to assess defects in asymmetric division and cytoplasmic partitioning [1].

2. FRAP Protocol for PAR Protein Dynamics:

- Sample Preparation: Create a strain expressing a functional GFP-tagged PAR protein (e.g., GFP::PAR-6 or GFP::PAR-2).

- Image Acquisition: Use a confocal or spinning-disk microscope to image live embryos during the polarity maintenance phase.

- Photobleaching: Apply a high-intensity laser pulse to a defined region of interest (ROI) within either the anterior or posterior domain, bleaching the GFP fluorescence.

- Recovery Monitoring: Acquire time-lapse images at short intervals post-bleach to monitor fluorescence recovery.

- Data Analysis: Quantify fluorescence intensity within the bleached ROI over time. Analyze the spatial characteristics of recovery (e.g., edge-first vs. uniform) to determine the mode of mobility (lateral diffusion vs. cytosolic exchange) [4].

3. Quantitative Perturbation-Phenotype Mapping:

- Dosage Perturbation: Use genetic tools (e.g., RNAi, CRISPR-engineered alleles) to create a series of strains with varying dosages of a specific PAR protein.

- Live Imaging: Record high-resolution movies of embryonic development in these strains, focusing on polarity markers, spindle positioning, and cell division asymmetry.

- Image Quantitation: Employ automated or semi-automated image analysis workflows to extract quantitative metrics such as PAR domain size and intensity, asymmetry index (ASI) for cell division, and cell cycle timing.

- Phenotype Mapping: Correlate the quantitative changes in protein dosage with the resulting phenotypic outcomes for individual embryos to build perturbation-phenotype maps and assess robustness [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for PAR and Gastrulation Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Key Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PAR Mutants | Loss-of-function alleles to define gene function | Six core par genes (par-1 to par-6); maternal-effect lethal [1]. |

| GFP/RFP Fusion Proteins | Live imaging of protein localization and dynamics | Functional fusions of PAR-2, PAR-6, NMY-2::GFP [3] [4]. |

| RNA Interference (RNAi) | Targeted gene knockdown | Feeding or injection RNAi to deplete specific PAR proteins [2] [5]. |

| FRAP Setup | Analyzing protein kinetics and mobility | Confocal microscope with laser bleaching capability [4]. |

| Actin/Myosin Inhibitors | Probing cytoskeletal requirements | Latrunculin A (actin depolymerizer); Blebbistatin (myosin inhibitor) [3]. |

| Mathematical Models | Theoretical framework for polarity | PDE models simulating PAR network interactions and feedback [2]. |

| CBS-3595 | CBS-3595, CAS:908380-97-2, MF:C18H17FN4O2S, MW:372.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| CCT036477 | CCT036477, CAS:305372-78-5, MF:C21H18ClN3, MW:347.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The historical discovery of the par genes opened a critical window into the molecular mechanisms of cell polarity. From the initial genetic screens that identified mutants defective in cytoplasmic partitioning, to the modern quantitative analyses of protein dynamics and network robustness, research on PAR proteins has consistently provided fundamental insights. This body of work has firmly established that an evolutionarily conserved machinery, centered on the PAR proteins, is fundamental for breaking cellular symmetry and orchestrating subsequent developmental events. In C. elegans, this machinery is not only essential for the first asymmetric division but is also intricately linked to the control of gastrulation movements, such as EPC ingression, by regulating the actomyosin cytoskeleton. The experimental paradigms and reagents developed in this system continue to serve as a powerful toolkit for dissecting the principles of cell polarization, with broad implications for understanding development and disease across metazoans.

The PAR (Partitioning-defective) proteins constitute an ancient and fundamental mechanism for cell polarization, first discovered in genetic screens for regulators of cytoplasmic partitioning in the early embryo of C. elegans [1]. These proteins are essential for asymmetric cell division, a process critical for generating cell diversity during development. In the C. elegans zygote, PAR proteins become asymmetrically localized to define two opposing cortical domains: an anterior domain (aPAR) containing PAR-3, PAR-6, and PKC-3, and a posterior domain (pPAR) containing PAR-1 and PAR-2 [1] [3]. This polarization establishes a fundamental cellular asymmetry that directs the asymmetric positioning of the mitotic spindle and the unequal segregation of cell fate determinants [1]. The process is not only crucial for the first cell divisions but also for subsequent developmental events, including gastrulation, where contact-induced cell polarity and PAR proteins guide the ingression of endodermal and mesodermal precursor cells [3]. This guide will provide an in-depth technical overview of the core molecular players—the aPAR and pPAR complexes—detailing their conserved domains, functions, and roles in gastrulation, complete with structured data and methodological protocols for researchers.

The Core Molecular Components: aPAR vs. pPAR Complexes

Molecular Identities and Conserved Domains

The six core PAR proteins encoded by the par genes were cloned between 1994 and 2002, revealing that they form a novel intracellular signaling pathway [1]. Their sequences and domain architectures provide critical insight into their functions.

Table 1: Core PAR Proteins and Their Conserved Domains

| Protein | Complex | Conserved Domain(s) | Molecular Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAR-3 | aPAR | PDZ domains (multiple) | Acts as a scaffolding protein for complex assembly [1] |

| PAR-6 | aPAR | PDZ domain | Scaffolding protein; binds CDC-42 and PKC-3 [1] |

| PKC-3 | aPAR | Protein Kinase Domain (aPKC) | Serine/Threonine kinase; phosphorylates downstream targets [1] |

| PAR-1 | pPAR | Protein Kinase Domain (Serine/Threonine) | Serine/Threonine kinase; phosphorylates downstream targets [1] |

| PAR-2 | pPAR | RING Finger Domain | Potential E3 ubiquitin ligase activity [1] |

| PAR-5 | Symmetric | 14-3-3 protein domain | Binds phosphorylated serines/threonines; required for mutual exclusion of PAR domains [1] |

| PAR-4 | Symmetric | Protein Kinase Domain (Serine/Threonine) | Serine/Threonine kinase; involved in cell fate specification [1] |

Asymmetric Localization and Mutual Exclusion

The establishment of polarity relies on the mutual exclusion of the aPAR and pPAR complexes from opposing cortical domains. In the one-cell C. elegans embryo, the aPAR complex (PAR-3, PAR-6, PKC-3) becomes enriched in the anterior cortex, while the pPAR complex (PAR-1, PAR-2) localizes to the posterior cortex [1]. PAR-4 and PAR-5 are symmetrically localized, both cortically and cytoplasmically [1]. Genetic analyses have ordered these components into a functional pathway:

- The anterior PAR proteins are required to prevent the posterior PAR proteins from localizing to the anterior.

- Conversely, the posterior PAR proteins prevent the anterior proteins from localizing to the posterior [1].

- PAR-5 is required for the mutual exclusion of these two domains, likely by binding phosphorylated residues generated by the opposing kinases [1].

- In the posterior, the membrane association of PAR-1 is partially dependent on PAR-2 [1].

This antagonistic relationship creates a bistable system that ensures clear demarcation of cellular fronts, a prerequisite for asymmetric division and cell fate specification.

PAR Protein Function in C. elegans Gastrulation

Gastrulation is a critical developmental event during which cells destined to form internal tissues move from the embryo's surface into the interior. In C. elegans, this process begins at the 26-cell stage with the ingression of the two endoderm precursor cells (EPCs) [3]. PAR proteins play a direct role in regulating this cell movement.

The EPCs undergo apical constriction, a process driven by the actomyosin cytoskeleton, which is regulated by PAR proteins. Non-muscle myosin II (NMY-2) and its phosphorylated regulatory light chain (p-rMLC) accumulate at the apical surfaces of the ingressing EPCs [3]. This asymmetric activation of myosin causes cortical microfilaments to contract, flattening and constricting the apical surface and pushing the cytoplasm inward [3]. The regulation of this process is linked to contact-induced cell polarity, which involves PAR proteins. Furthermore, an extended cell cycle in the EPCs, which is crucial for successful ingression, is controlled by genes like gad-1, and this cell cycle expansion is a conserved feature of ingressing cells across species [3].

Experimental Protocols for Key PAR Analyses

Genetic Screens and Mutant Analysis

The original par mutants were identified in maternal embryonic lethal screens in C. elegans [1].

- Methodology: Mutagenized strains with pre-existing egg-laying defective (Egl) and high incidence of male (Him) phenotypes were screened for worms that survived instead of being devoured by their internal progeny. These "escapers" were potential carriers of recessive maternal-effect embryonic lethal mutations [1].

- Phenotypic Analysis: Embryos from identified mutants were examined for defects in early cell divisions. The hallmark "Par" phenotype includes abnormally equal and synchronous early cell divisions, indicating a failure in cytoplasmic partitioning and asymmetric cell division [1].

- Epistasis Analysis: The functional hierarchy of PAR proteins was determined by examining the localization of each PAR protein in the mutant background of others. For example, PAR-1 localization is dependent on PAR-2, and the mutual exclusion of anterior and posterior domains requires PAR-5 [1].

Cell Biological Analysis of Gastrulation

The role of PAR proteins in EPC ingression during gastrulation can be studied using cell biological techniques.

- Cytoskeletal Drug Inhibition: To test the requirement of the actomyosin cytoskeleton in EPC ingression, embryos can be treated with drugs that depolymerize microfilaments (e.g., Latrunculin A) or inhibit myosin activity (e.g., Blebbistatin). These treatments block apical constriction and prevent ingression [3].

- Immunofluorescence and Live Imaging: The apical enrichment of myosin (NMY-2, p-rMLC) in EPCs can be visualized by immunofluorescence. Live imaging of embryos expressing fluorescently tagged PAR proteins, myosin, and actin allows for the real-time observation of polarization and ingression dynamics [3].

- Laser Ablation and Blastomere Manipulation: To understand the role of neighboring cells, the P4 cell (a germline precursor) can be removed via laser ablation. Experiments show that MS cells (mesodermal precursors) can still migrate over the EPCs in the absence of P4, indicating that convergence is guided by cues from the EPCs themselves and not merely by chemotaxis between MS and P4 [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for PAR Protein and Gastrulation Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application in PAR Research |

|---|---|

| PAR Mutants (e.g., par-1, par-2, par-3) | Used for genetic epistasis analysis and to determine the function of each PAR protein in polarization and gastrulation [1]. |

| Anti-PAR Antibodies | Essential for visualizing the asymmetric localization of PAR proteins via immunofluorescence microscopy [1]. |

| Fluorescent Protein Tags (e.g., GFP::PAR-2) | Enable live imaging of PAR protein dynamics and cortical flows in real-time within developing embryos. |

| Cytoskeletal Inhibitors (e.g., Latrunculin A, Blebbistatin) | Used to dissect the functional role of actin and myosin in PAR-dependent processes like apical constriction during gastrulation [3]. |

| Laser Ablation System | Allows for precise killing or cutting of specific cells (e.g., P4) to study their role in cell migration and ingression during gastrulation [3]. |

| K00546 | K00546, CAS:443798-55-8, MF:C15H13F2N7O2S2, MW:425.4 g/mol |

| Cardionogen 1 | Cardionogen 1, CAS:577696-37-8, MF:C13H14N4OS, MW:274.34 g/mol |

Visualizing the PAR Network and Gastrulation

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core relationships and processes described in this guide.

PAR Protein Polarity Network

PAR Proteins in Gastrulation

The establishment of cellular asymmetry is a fundamental process in developmental biology, directing cell fate specification, tissue morphogenesis, and embryonic patterning. In C. elegans gastrulation, this process is governed by an evolutionarily conserved system of partitioning defective (PAR) proteins, which segregate into antagonistic cortical domains to define the anterior-posterior axis of the embryo [1]. The PAR network, discovered through genetic screens for regulators of cytoplasmic partitioning, comprises six core proteins (PAR-1 to PAR-6) that form a biochemical signaling pathway capable of self-organizing into stable, mutually exclusive membrane domains [1]. This whitepaper examines the principles of mutual antagonism and cortical domain segregation that underpin PAR protein function, focusing on their role in C. elegans gastrulation research and their implications for biomedical applications.

Core Principles of the PAR Polarity System

The Molecular Composition of the PAR Network

The PAR proteins form two functionally and spatially opposed complexes that exhibit mutual antagonism to establish and maintain cellular polarity (Table 1).

Table 1: Core PAR Protein Complexes and Their Functions

| Protein Complex | Component Proteins | Molecular Function | Cortical Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| anterior PARs (aPARs) | PAR-3, PAR-6, PKC-3 (aPKC) | Scaffold with PDZ domains; serine-threonine kinase; binds CDC-42 | Anterior cortex |

| posterior PARs (pPARs) | PAR-1, PAR-2 | Serine-threonine kinase; RING finger domain | Posterior cortex |

| Ubiquitous PARs | PAR-4, PAR-5 | Serine-threonine kinase; 14-3-3 protein family | Cortical and cytoplasmic |

The anterior PAR complex (PAR-3, PAR-6, and aPKC) localizes to the anterior cortex, while the posterior complex (PAR-1 and PAR-2) occupies the posterior cortex. PAR-4 and PAR-5 remain symmetrically distributed, playing modulatory roles [1]. This asymmetric distribution is established through a combination of mechanical cues and biochemical interactions, culminating in a stable boundary at mid-embryo that persists until cell division.

The Principle of Mutual Antagonism

Mutual antagonism represents the core biochemical principle enabling PAR domain segregation and stability. This reciprocal inhibition occurs through phosphorylation-mediated membrane dissociation:

Anterior-to-posterior inhibition: Membrane-bound aPAR complexes (PAR-3/PAR-6/PKC-3) phosphorylate pPARs (PAR-1 and PAR-2), promoting their dissociation from the membrane and subsequent cytoplasmic localization [2] [6].

Posterior-to-anterior inhibition: Conversely, membrane-associated pPARs phosphorylate aPAR components, triggering their displacement from the cortex [2] [6].

This cross-inhibition creates a self-sustaining system where each complex reinforces its own domain by excluding the opposing complex, forming a sharp boundary at the interface between domains. Genetic evidence demonstrates that disruption of either complex leads to expansion of the other throughout the cortex [4].

Diagram Title: Mutual Antagonism Between PAR Protein Complexes

Dynamic Equilibrium Model of Domain Segregation

The PAR system maintains polarity through a dynamic equilibrium rather than static association. Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) experiments reveal that both PAR-2 and PAR-6 undergo continuous exchange between cytoplasmic pools and laterally diffusing membrane-associated states [4]. Several kinetic principles govern this equilibrium:

Free lateral diffusion: PAR proteins freely diffuse within membrane domains, with continuous flux across the boundary due to concentration gradients [4].

Balanced membrane affinity: Spatial differences in effective membrane affinity counterbalance the equalizing effects of lateral diffusion [4].

Actin-independent stabilization: During the maintenance phase, PAR domains remain stable without active actin flows, relying on differences in membrane association/dissociation kinetics [4].

This dynamic system represents a steady state where molecules undergo continuous exchange between regions of net association and dissociation, maintaining stable domains despite constant molecular turnover.

Quantitative Analysis of PAR Protein Dynamics

FRAP Measurements of PAR Protein Kinetics

FRAP experiments provide crucial quantitative insights into PAR protein dynamics during the maintenance phase of polarity (Table 2).

Table 2: Kinetic Parameters of PAR Proteins in C. elegans Embryos

| PAR Protein | Recovery Time (s) | Mobility Mechanism | Dependence on Antagonistic PARs |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAR-6 | ~60 | Lateral diffusion + membrane-cytoplasmic exchange | Requires PAR-2 for anterior restriction |

| PAR-2 | ~60 | Lateral diffusion + membrane-cytoplasmic exchange | Requires PAR-6 for posterior restriction |

| aPKC (PKC-3) | N/A | Complex with PAR-3/PAR-6 | Phosphorylates PAR-1 and PAR-2 |

| PAR-1 | N/A | Membrane association regulated by PAR-2 | Dependent on PAR-2 for cortical localization |

Both PAR-6 and PAR-2 exhibit rapid fluorescence recovery, typically reaching near-complete recovery within 60 seconds post-bleaching. Spatial analysis of recovery patterns demonstrates that both proteins recover more rapidly at the edges of bleached zones than at the center, indicating significant lateral diffusion along the membrane plane [4].

Geometric Control of PAR Domain Positioning

Cell geometry influences PAR patterning through the local membrane-to-cytoplasm ratio, which affects the probability of protein rebinding after dissociation. In prolate spheroid C. elegans embryos (semi-axes: 27 μm major, 15 μm minor), long-axis polarization is favored because it minimizes the interface length between aPAR and pPAR domains, reducing the energetic cost of maintaining the boundary [6]. This geometric sensing is mediated by:

Local surface-to-volume ratio: Higher local membrane curvature affects rebinding probability of dissociated proteins [6].

Interface length minimization: The system naturally evolves toward configurations that minimize the aPAR-pPAR boundary length [6].

Cytosolic dephosphorylation rates: The kinetics of the phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycle significantly impact axis selection [6].

Experimental Approaches for Investigating PAR Polarity

Genetic Perturbation and Mutant Analysis

Table 3: Key Genetic Approaches in PAR Polarity Research

| Method | Application | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal-effect mutant screens | Identification of core par genes | Discovery of 6 essential par genes [1] |

| RNAi-mediated depletion | Functional analysis of individual PAR proteins | Demonstration of mutual exclusion requirements [4] |

| Transgenic rescue | Structure-function analysis | Determination of functional domains and interactions |

| Conditional mutants (temperature-sensitive) | Analysis of temporal requirements | Separation of establishment vs. maintenance functions [7] |

The initial par mutants were identified through maternal-effect screens in C. elegans, using inventive genetic schemes that took advantage of egg-laying defective (Egl) mutants. In these screens, embryos that failed to hatch inside their mothers would devour them, resulting in "bags of worms" that were easily identifiable [1]. This approach enabled the discovery of the six core par genes, whose mutant phenotypes included abnormally equal and synchronous cell divisions, indicating failed partitioning of cytoplasmic components [1].

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) Protocol

Objective: Quantify mobility and exchange kinetics of PAR proteins during polarity maintenance.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Generate C. elegans strains expressing functional GFP-tagged PAR proteins (GFP::PAR-6 or GFP::PAR-2) that complement native mutations [4].

Imaging Setup:

- Use confocal microscopy with high-sensitivity detectors

- Maintain embryos at 20-25°C during imaging

- Select embryos in maintenance phase (after establishment of PAR domains)

Photobleaching:

- Define region of interest (ROI) within PAR domain

- Apply high-intensity laser pulse (typically 488nm) to bleach fluorescence in ROI

- Ensure bleaching covers entire depth of cortical region

Recovery Imaging:

- Acquire time-lapse images at 1-5 second intervals post-bleach

- Continue imaging for 2-5 minutes to capture complete recovery

- Use low laser power to minimize additional photobleaching

Data Analysis:

- Quantify fluorescence intensity in bleached ROI over time

- Normalize to pre-bleach intensity and correct for background

- Compare recovery kinetics at center vs. edges of bleached zone

- Fit recovery curves to determine diffusion coefficients and exchange rates

Key Controls:

- Perform experiments in wild-type and mutant backgrounds (e.g., par-2(RNAi) for PAR-6 FRAP)

- Verify protein functionality of GFP fusions through complementation tests

- Account for overall photobleaching during time-lapse imaging

Quantitative Imaging and Computational Modeling

Modern analysis of PAR dynamics combines high-throughput imaging with computational modeling. Recent approaches include:

Reaction-diffusion modeling: Partial differential equation models that incorporate realistic cell geometry and biomolecular reactions [2] [6].

Stochastic simulations: Models that account for fluctuations in low-copy number regimes [8].

Sensitivity analysis: Computational approaches to identify critical parameters controlling system behavior [2].

These models have revealed that the phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycle kinetics and the ratio of membrane-binding to cytosolic diffusion are crucial for robust long-axis polarization [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for PAR Polarity Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| GFP::PAR-2/6 fusions | FRAP and live imaging | Functional transgenic fusions for dynamics studies [4] |

| par-2(it5ts) | Temperature-sensitive mutant | Allows temporal control of PAR-2 function [7] |

| RNAi feeding clones | Gene-specific depletion | Enables systematic analysis of protein requirements |

| Anti-PAR antibodies | Immunofluorescence | Fixed analysis of protein localization |

| pMindGFP vector | Conditional antisense expression | Tunable gene suppression [9] |

| Mathematical models | Computational analysis | PDE frameworks for testing hypotheses [2] [6] |

| CE-245677 | CE-245677, CAS:717899-97-3, MF:C24H22Cl2N6O3, MW:513.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (R)-CE3F4 | (R)-CE3F4, CAS:143703-25-7, MF:C11H10Br2FNO, MW:351.01 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for C. elegans Gastrulation and Beyond

During C. elegans gastrulation, PAR proteins continue to function in polarizing various cell types, including migrating cells and epithelial cells [1]. The balance between different PAR species can specify both asymmetric and symmetric division modes, providing a mechanism for generating cellular diversity during development [10]. Disruption of this balance reprograms division modes independently of cell-size asymmetry or cell-cycle asynchrony, highlighting the fundamental role of PAR-mediated polarity in developmental patterning [10].

The principles of mutual antagonism and cortical domain segregation extend beyond early embryonic patterning to multiple aspects of C. elegans development, including spindle orientation in blastomeres [11] and the regulation of asymmetric cell division by PAR protein modifiers [7]. The conservation of these mechanisms across species underscores their fundamental importance in cell biology and their potential as targets for therapeutic intervention in diseases involving polarized cell processes.

The PAR protein system constitutes an evolutionarily conserved molecular machinery that establishes cellular asymmetry and governs polarized cell behaviors essential for morphogenesis. In C. elegans embryogenesis, PAR proteins not only pattern the anterior-posterior axis in the one-cell embryo but also function reiteratively in subsequent divisions to direct cell fate decisions that ultimately drive gastrulation movements. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of how the dynamic interplay between anterior PAR complexes (PAR-3/PAR-6/PKC-3) and posterior PAR proteins (PAR-1/PAR-2) generates molecular asymmetries that specify distinct cell fates, thereby creating the coordinated cellular forces necessary for gastrulation. We present quantitative analyses of PAR protein interactions, detailed experimental frameworks for investigating PAR-mediated morphogenesis, and visualizations of the core regulatory networks that translate cell polarity into tissue remodeling.

Molecular Mechanisms of PAR Protein Function in Cell Polarization

Core PAR Protein Complexes and Their Conserved Roles

The PAR protein network comprises six fundamental components (PAR-1 to PAR-6) that function as master regulators of cell polarity across metazoans. These proteins form two functionally antagonistic groups that establish complementary cortical domains: the anterior PAR complex (PAR-3, PAR-6, and PKC-3) localizes to anterior cortical regions, while the posterior PAR proteins (PAR-1 and PAR-2) occupy posterior domains, with PAR-4 and PAR-5 functioning throughout the cortex and cytoplasm [1]. The molecular identities of these proteins reveal their signaling capabilities: PAR-1 and PAR-4 encode serine-threonine kinases, PAR-5 belongs to the 14-3-3 family of phospho-binding proteins, while PAR-3 and PAR-6 contain PDZ domains that facilitate scaffolding functions [1]. This composition enables the PAR system to integrate spatial information with downstream effector mechanisms.

The evolutionary conservation of PAR proteins underscores their fundamental importance in polarization processes. Following their initial discovery in C. elegans, homologous proteins were identified in Drosophila, where Bazooka (PAR-3 homolog) regulates embryonic polarity, and in mammalian systems, where PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC complexes control apical-basal polarization in epithelial cells [1]. The core mechanism involves reciprocal inhibition between anterior and posterior PAR complexes, creating a self-reinforcing bistable system that amplifies stochastic fluctuations into stable asymmetries [2].

Downstream Effector Pathways Linking Polarity to Cell Fate

PAR proteins direct cell fate specification through multiple downstream mechanisms that asymmetrically localize cell fate determinants. In the C. elegans embryo, the PAR-1 kinase phosphorylates and regulates the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding (CPEB) protein MEX-5, creating a MEX-5/PIE-1 gradient that patterns the anterior-posterior axis [12]. This cytoplasmic asymmetry ensures the differential inheritance of cell fate determinants during successive divisions, ultimately establishing the founder cells that will execute gastrulation movements.

The PAR network also interfaces with cytoskeletal regulators to position mitotic spindles along polarized axes, ensuring asymmetric divisions that generate daughter cells with different sizes and developmental potentials. Recent research has revealed that PAR proteins form apical caps that orient the mitotic spindle in early C. elegans embryos, functioning independently of cell contacts [11]. This spindle orientation mechanism operates in cooperation with the key polarity kinase aPKC (PKC-3 in C. elegans) to coordinate division orientation with the established polarity axis [11].

Quantitative Analysis of PAR Protein Interactions and Dynamics

PAR Protein Localization and Mutual Exclusion Parameters

Table 1: Quantitative Dynamics of PAR Protein Localization in C. elegans Embryos

| PAR Protein | Cortical Localization | Cytoplasmic Pool | Establishment Time | Key Regulators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAR-3 | Anterior cortex | 40-50% | 3-5 minutes | PKC-3, CDC-42 |

| PAR-6 | Anterior cortex | 30-40% | 3-5 minutes | PKC-3, CDC-42, PAR-3 |

| PKC-3 | Anterior cortex | 20-30% | 3-5 minutes | PAR-6, CDC-42 |

| PAR-1 | Posterior cortex | 50-60% | 4-6 minutes | PAR-2, PAR-4 |

| PAR-2 | Posterior cortex | 40-50% | 4-6 minutes | PAR-1, PAR-5 |

| PAR-4 | Uniform cortical | 60-70% | Constitutive | - |

| PAR-5 | Uniform cortical | 70-80% | Constitutive | - |

The dynamic localization patterns of PAR proteins create a molecular asymmetry that guides subsequent developmental processes. During polarization of the one-cell C. elegans embryo, anterior PAR proteins become restricted to the anterior cortex within 3-5 minutes following actomyosin contraction, while posterior PAR proteins occupy the posterior cortical region within 4-6 minutes [13]. The mutual exclusion between these domains is maintained through reciprocal inhibition mechanisms, with PAR-5 (14-3-3 protein) playing a particularly important role in preventing the coexistence of anterior and posterior PAR complexes in the same cortical regions [1].

Biochemical Interaction Network and Feedback Loops

Table 2: Biochemical Interactions in the PAR-CDC-42 Polarity Network

| Interaction | Molecular Mechanism | Functional Outcome | Required Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| aPAR → pPAR inhibition | PKC-3 phosphorylation of PAR-1/PAR-2 | Dissociation of pPAR from membrane | PAR-3, PAR-6, PKC-3 |

| pPAR → aPAR inhibition | PAR-1 phosphorylation of PAR-3 | Dissociation of aPAR from membrane | PAR-1, PAR-2 |

| CDC-42 → aPAR stabilization | GTP-CDC-42 binding to PAR-6 | Enhanced membrane association of aPAR | CDC-42(GTP), PAR-6 |

| aPAR → CDC-42 activation | PAR-6 recruitment of CDC-42 GEF | Local CDC-42 activation | PAR-6, CDC-42 GEF |

| PAR-2 → PAR-1 protection | PAR-2 binding to PAR-1 | Prevents PAR-1 dissociation by aPAR | PAR-2, PAR-1 |

The PAR protein network operates through interconnected feedback loops that create self-sustaining asymmetry. Computational modeling reveals that CDC-42 reinforces maintenance of anterior PAR protein polarity, which in turn feedbacks to maintain CDC-42 polarization, while also supporting posterior PAR protein polarization maintenance [2]. These mutual reinforcement mechanisms create robustness against fluctuations, ensuring stable maintenance of the polarized state throughout critical developmental windows, including the period leading to gastrulation.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating PAR Function in Gastrulation

Genetic Perturbation Strategies

Elucidating PAR protein functions in gastrulation requires precise genetic interventions that disrupt specific components while preserving overall embryonic viability. The following experimental approaches have proven particularly effective:

3.1.1 RNAi-Mediated Gene Knockdown

- Protocol: Feed C. elegans L4-stage larvae with HT115 E. coli expressing dsRNA targeting specific par genes. Transfer P0 animals to fresh RNAi plates after 24 hours and collect embryos from the F1 generation for analysis.

- Key Parameters: dsRNA design should target unique gene regions; include control RNAi against non-essential genes; monitor embryonic lethality and gastrulation defects.

- Applications: This method enables rapid assessment of maternal-effect phenotypes and has been instrumental in establishing the requirements for specific PAR proteins in gastrulation movements [1].

3.1.2 CRISPR/Cas9-Generated Mutants

- Protocol: Inject C. elegans adults with Cas9 protein, gene-specific sgRNAs, and a co-injection marker (e.g., rol-6). Select F1 rollers and establish mutant lines from their progeny. Outcross homozygous mutants to remove off-target mutations.

- Key Parameters: Design sgRNAs to target functional domains; use temperature-sensitive alleles for lethal mutations; employ balancer chromosomes to maintain lethal mutations.

- Applications: Generation of null alleles and precise domain-specific mutations has revealed structure-function relationships for PAR proteins in gastrulation [11].

3.1.3 Auxin-Inducible Degradation System

- Protocol: Express the plant-specific F-box protein TIR1 under tissue-specific promoters in worms carrying AID-tagged PAR proteins. Apply auxin to embryos at specific developmental stages to trigger targeted protein degradation.

- Key Parameters: Titrate auxin concentration (typically 0.5-1.0 mM) to achieve complete degradation without off-target effects; include non-degradable controls; time treatments to specific gastrulation stages.

- Applications: This system enables temporal control of protein function, allowing researchers to define precisely when PAR proteins are required for gastrulation events [11].

Live Imaging and Quantitative Analysis

Visualizing PAR protein dynamics during gastrulation requires high-resolution live imaging coupled with computational analysis:

3.2.1 Fluorescent Tagging of PAR Proteins

- Protocol: Generate transgenic lines expressing endogenously tagged PAR proteins (e.g., PAR-2::GFP, PAR-6::mCherry) using CRISPR/Cas9. For simultaneous visualization of multiple proteins, combine tags with distinct spectral properties.

- Key Parameters: Validate functionality of tagged proteins; minimize tag size to reduce perturbation; confirm expression levels match endogenous patterns.

- Applications: Live tracking of PAR protein localization during gastrulation movements reveals dynamic redistribution in response to cellular rearrangements [12].

3.2.2 Quantitative Image Analysis

- Protocol: Acquire time-lapse images of developing embryos expressing fluorescently tagged PAR proteins. Use computational tools to quantify cortical fluorescence intensity, domain boundaries, and protein redistribution rates.

- Key Parameters: Maintain consistent imaging conditions; correct for photobleaching; normalize fluorescence intensities to cytoplasmic background; analyze multiple embryos (n≥10) for statistical power.

- Applications: This approach has revealed the kinetics of PAR domain establishment in the P1 cell, with posterior PAR-2 domains forming within 4 minutes of division [12].

Visualization of PAR Protein Signaling Networks

Core PAR Protein Interaction Network

PAR Protein Regulatory Network: This diagram illustrates the core interactions between anterior PAR complexes (blue), posterior PAR complexes (red), and CDC-42 (yellow) that establish and maintain cellular asymmetry. The network highlights how mutual exclusion between anterior and posterior PAR domains creates stable polarity, which then directs downstream processes including spindle orientation and cell fate specification—both critical for gastrulation.

Experimental Workflow for PAR Protein Functional Analysis

PAR Protein Experimental Workflow: This workflow outlines the key steps for investigating PAR protein function in gastrulation, from genetic manipulation to phenotypic analysis. The sequential process ensures comprehensive assessment of how polarity disruptions impact morphogenetic movements.

Research Reagent Solutions for PAR Protein Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating PAR Proteins in Gastrulation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Tools | par-2(lt1), par-3(zu310), pkc-3(RNAi) | Loss-of-function studies | Maternal-effect embryonic lethal phenotypes |

| Live Imaging Reagents | PAR-2::GFP, PAR-6::mCherry, PH::GFP | Protein localization and dynamics | Endogenous tagging, minimal perturbation |

| Perturbation Systems | AID::PAR-3, TIR1 expression | Temporal protein degradation | Stage-specific inactivation |

| Cell Biology Probes | Anti-PAR-1 antibody, Rhodamine-phalloidin | Cytoskeletal coordination | F-actin visualization with PAR protein staining |

| Computational Tools | PAR protein domain quantification scripts | Quantitative analysis of polarity | Automated boundary detection, intensity profiling |

The reagents listed in Table 3 represent essential tools for dissecting PAR protein functions during gastrulation. Genetic tools enable researchers to disrupt specific PAR components and assess the functional consequences. Live imaging reagents facilitate direct visualization of protein dynamics throughout the polarization process. Importantly, recent advances in conditional perturbation systems, such as the auxin-inducible degradation (AID) system, allow precise temporal control over protein function, enabling researchers to define precisely when PAR proteins are required for specific gastrulation events [11]. These tools collectively provide a comprehensive toolkit for investigating how PAR-mediated polarity directs morphogenesis.

The PAR protein network represents a fundamental mechanism for translating molecular asymmetries into coordinated cell behaviors during embryogenesis. In C. elegans, PAR proteins not only establish the anterior-posterior axis in the one-cell embryo but also continue to function in descendant cells to direct the cell fate decisions and polarized divisions that enable gastrulation. The mutual inhibition between anterior and posterior PAR complexes, reinforced by feedback loops involving CDC-42 and cytoskeletal networks, creates robust polarity that withstands developmental perturbations. Continued investigation of PAR protein dynamics using the experimental approaches outlined herein will further elucidate how cellular polarity is harnessed to drive the complex tissue rearrangements that characterize gastrulation across metazoans.

Decoding Polarity Dynamics: Biochemical, Biophysical, and Computational Approaches

This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for applying Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) to investigate the dynamics of PAR proteins in living C. elegans embryos. Within the context of gastrulation research, understanding PAR protein dynamics is essential as these conserved regulators establish apical-basal polarity required for proper cell ingression movements. We present detailed methodologies for quantifying PAR protein membrane affinity, diffusion coefficients, and turnover rates, along with analytical approaches for interpreting recovery kinetics within the framework of PAR network interactions. The protocols and data analysis pipelines enable researchers to decipher how balanced antagonism between anterior and posterior PAR complexes patterns embryonic cells for asymmetric division and morphogenetic events during gastrulation.

PAR Protein Fundamentals

The partitioning-defective (PAR) proteins form an evolutionarily conserved system that establishes cellular polarity across animal species. Initially discovered in genetic screens for regulators of cytoplasmic partitioning in the early C. elegans embryo [1], the six core PAR proteins organize into two functionally antagonistic groups: the anterior complex (PAR-3, PAR-6, and aPKC) and the posterior complex (PAR-1, PAR-2, and PAR-5/14-3-3) [1] [10]. These proteins segregate into mutually exclusive cortical domains, creating a fundamental polarity axis that directs asymmetric cell division and cell fate determination.

During C. elegans gastrulation, which begins at the 26-cell stage, PAR proteins undergo a remarkable transition from anterior-posterior polarization in the one-cell embryo to apical-basal polarization in somatic cells [14]. PAR-3, PAR-6, and PKC-3 become enriched on apical surfaces, while PAR-1 and PAR-2 localize to basolateral surfaces [14]. This apical-basal polarization is essential for proper blastocoel formation and guides the ingression movements of endodermal precursors (Ea and Ep) and other cells during gastrulation [14]. The PAR network thus provides the structural and signaling framework that enables gastrulation movements by regulating cell adhesion properties and actomyosin contractility.

Significance of PAR Protein Dynamics

PAR domains maintain remarkable stability despite constant molecular turnover, suggesting that these systems exist in a dynamic steady state rather than a static configuration. Understanding how polarity is maintained requires quantitative analysis of PAR protein kinetics, including their membrane association/dissociation rates, lateral mobility, and response to perturbation. FRAP has emerged as a powerful method for quantifying these dynamics in living embryos, revealing that PAR proteins undergo continuous exchange between cytoplasmic and membrane-associated states while maintaining sharp domain boundaries [4].

The balance between antagonizing PAR complexes not only specifies asymmetric division patterns but also regulates the transition to symmetric divisions during embryonic development [10]. Quantitative measurements of PAR dynamics are therefore essential for understanding how embryonic cells interpret and remodel polarity information during gastrulation and subsequent morphogenetic events.

FRAP Fundamentals and Experimental Design

Principles of FRAP

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) is a powerful method to investigate the dynamics of molecules in living cells [15]. In a FRAP experiment, fluorescent molecules in a defined region are irreversibly photobleached using a high-power laser, and the subsequent recovery of fluorescence into the bleached area is monitored over time [15]. The recovery kinetics provide quantitative information about molecular mobility, binding interactions, and transport mechanisms.

For membrane-associated proteins like PAR components, FRAP can distinguish between several potential mobility mechanisms:

- Lateral diffusion: Movement along the membrane plane

- Cytoplasmic exchange: Rapid association/dissociation with the membrane

- Directed transport: Active movement via motor proteins or flow

The spatial pattern of recovery is particularly informative: lateral diffusion produces faster recovery at the edges of the bleached region, while pure cytoplasmic exchange results in spatially uniform recovery [4].

PAR-Specific FRAP Considerations

When designing FRAP experiments for PAR proteins, several specialized considerations apply:

Developmental Timing: PAR protein dynamics differ significantly between polarity establishment and maintenance phases. The maintenance phase (after the PAR domains have formed) is particularly suitable for quantitative measurements due to the absence of large-scale cortical flows and relative stability of domain boundaries [4].

Genetic Background: To isolate the intrinsic behavior of individual PAR proteins, experiments may be performed in embryos depleted of opposing PAR factors (e.g., analyzing GFP-PAR-6 in PAR-2 depleted embryos) [4]. This eliminates the confounding effects of mutual antagonism during recovery.

Spatial Positioning: The location of bleaching regions relative to domain boundaries provides information about potential diffusion barriers and directional biases in recovery.

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters for PAR Protein FRAP

| Parameter | Consideration | Typical Setting for PAR Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| Bleaching Region | Size and shape | Circular spot, 7-pixel radius [15] |

| Background Regions | Reference for bleaching correction | Non-bleached area in same domain [15] |

| Temporal Resolution | Balance between kinetics and phototoxicity | 0.242 sec/cycle for PAR-2/PAR-6 [4] |

| Laser Power | Sufficient bleaching without damage | 50% transmission, 20 iterations [15] |

| Developmental Stage | Maintenance phase preferred | After polarity establishment, before gastrulation |

Experimental Protocols for C. elegans Embryos

Sample Preparation and Mounting

C. elegans Strains and Transgenes

- Use transgenic strains expressing functional GFP-tagged PAR proteins (e.g., GFP::PAR-6 or GFP::PAR-2) that complement null mutations [4]

- Maintain transgenes in appropriate genetic backgrounds; for extrachromosomal arrays, select GFP-positive worms for experiments [15]

- For membrane fluidity studies, utilize strains expressing membrane-targeted FPs (e.g.,

glo-1p::GFP::ras-2 CAAXfor intestinal plasma membranes) [15]

Synchronization and Preparation

- Bleach gravid hermaphrodites to obtain synchronized eggs [15]

- Allow eggs to hatch overnight in M9 buffer to collect synchronized L1 larvae [15]

- Transfer L1 larvae to NGM plates seeded with OP50 E. coli, potentially supplemented with experimental compounds (e.g., 20 mM glucose for membrane rigidity studies) [15]

- Incubate at 20°C for 16 hours until worms reach desired developmental stage (L2 for intestinal studies) [15]

Embryo Mounting

- Prepare 2% agarose pads on microscope slides [15]

- Transfer transgenic worms (20-25) to agarose pad in 1-1.5 μL of 100 mM levamisole to paralyze without complete immobilization [15]

- Apply cover glass gently to avoid compression artifacts

- Verify embryo viability and developmental stage before imaging

Microscope Configuration

Hardware Requirements

- Confocal microscope with 40x water immersion objective (Numerical Aperture 1.1 recommended) [15]

- 488 nm laser for GFP excitation [15]

- Temperature control to maintain embryos at 20-25°C during imaging

Software Settings

- Use frame mode with 12-bit intensity resolution over 256 × 256 pixels [15]

- Set digital zoom to 4x and pixel dwell time to 1.58 μsec [15]

- Use unidirectional scanning with pinhole set to 1 Airy Unit [15]

- Configure time series with 200 cycles at 242.04 msec/cycle [15]

- Set up bleaching parameters: 20 iterations at 50% laser power transmission [15]

- Adjust master gain and digital offset to avoid signal saturation [15]

FRAP Execution Protocol

- Localization: Using bright field or low-intensity fluorescence, identify a suitable embryo with clear PAR protein localization

- Baseline Acquisition: Acquire 10 pre-bleach scans to establish baseline fluorescence [15]

- Photobleaching: Bleach a circular region (7-pixel radius) using high-power laser settings [15]

- Recovery Monitoring: Continuously scan the region for 200 cycles to monitor fluorescence recovery [15]

- Data Export: Save both images and fluorescence intensity tables (.txt format) for subsequent analysis [15]

Quantitative Analysis of FRAP Data

Data Preprocessing

FRAP recovery curves require three correction steps before quantitative analysis:

1. Background Subtraction

- Subtract background intensity from non-cellular regions

- Apply to all frames in the time series

2. Bleaching Correction

- Select a reference region in the non-bleached area of the same domain [15]

- Calculate the slope of fluorescence decrease in the reference region

- Compensate for global bleaching during acquisition: divide each FRAP measurement by [1 - (bleaching_rate × time)] [15]

3. Normalization

- Identify the minimum intensity value immediately after bleaching and subtract from all values [15]

- Calculate average intensity of 5 pre-bleach measurements and divide all intensities by this value [15]

- Express recovery as normalized intensity from 0 (immediately post-bleach) to 1 (full recovery)

Kinetic Parameter Extraction

The corrected recovery curve can be fit to appropriate models to extract quantitative parameters:

Mobile Fraction (Mf)

- Mf = (I∞ - I0) / (Ii - I0)

- Where I∞ is plateau intensity, I0 is immediate post-bleach intensity, Ii is initial pre-bleach intensity

- Represents the proportion of molecules free to exchange during the experimental timeframe

Half-Time of Recovery (tâ‚/â‚‚)

- Time required to reach half of maximum recovery

- Inversely related to exchange kinetics

Diffusion Coefficient (D)

- For lateral diffusion, D can be estimated from recovery half-time: D = 0.224 × r² / tâ‚/â‚‚

- Where r is the radius of the bleached spot

Table 2: Quantitative FRAP Parameters for PAR Proteins

| PAR Protein | Mobile Fraction | Recovery Half-Time (tâ‚/â‚‚) | Diffusion Coefficient | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAR-6 | High (~80-90%) | Rapid (~seconds) | ~0.1 μm²/s | PAR-2 depleted embryos [4] |

| PAR-2 | High (~80-90%) | Rapid (~seconds) | ~0.1 μm²/s | PAR-6 depleted embryos [4] |

| Membrane Marker | Variable | Dependent on fluidity | Environment-dependent | Varies with lipid composition [15] |

Spatial Analysis of Recovery Patterns

The spatial characteristics of FRAP recovery provide critical information about mobility mechanisms:

Edge-Enhanced Recovery: Indicates significant lateral diffusion component, as molecules diffuse into the bleached area from adjacent regions [4]

Uniform Recovery: Suggests exchange-dominated kinetics, with molecules arriving from the cytoplasm rather than adjacent membrane regions

For PAR proteins, both PAR-6 and PAR-2 demonstrate edge-enhanced recovery, indicating substantial lateral diffusion along the membrane plane [4]. This spatial signature is consistent with free diffusion of molecules across domain boundaries, countered by spatially varying membrane affinities rather than diffusion barriers.

PAR Protein Dynamics in Gastrulation Context

Apical-Basal Polarization

During gastrulation, PAR proteins transition from anterior-posterior polarization to apical-basal polarization in somatic cells [14]. By the end of the four-cell stage, PAR-3 becomes restricted to apical surfaces while PAR-2 localizes to basolateral surfaces [14]. This apical-basal asymmetry depends on cell contacts and directs the pattern of cell adhesions that form the blastocoel cavity [14].

FRAP analysis reveals that PAR proteins maintain dynamic exchange even while stably localized to specific membrane domains. This dynamic steady state enables cells to remodel polarity during gastrulation as they change shape, position, and contacts.

Regulation of Cell Ingression

PAR proteins directly regulate the actomyosin dynamics that drive cell ingression during gastrulation. The endodermal precursors Ea and Ep accumulate non-muscle myosin NMY-2 at their apical surfaces as they ingress [14]. PAR proteins localized to apical surfaces are required for this apical accumulation of myosin [14].

The balance between anterior and posterior PAR complexes determines division mode (asymmetric vs. symmetric) during development [10]. Changes in the PAR-2/PAR-6 balance can reprogram division modes independently of other asymmetries [10], highlighting how PAR protein dynamics directly influence cell behavior during gastrulation.

Diagram 1: PAR Protein Network in Gastrulation Context. PAR proteins establish both anterior-posterior and apical-basal polarity through mutual antagonism, then regulate gastrulation processes including myosin localization and cell adhesion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for PAR Protein FRAP Studies

| Reagent/Condition | Function/Application | Example Use in PAR Studies |

|---|---|---|

| GFP-tagged PAR strains | Functional fusions for live imaging | QC114 for membrane dynamics; endogenous CRISPR-tagged PAR proteins [15] [16] |

| par-2(RNAi) | Deplete posterior PAR domain | Study PAR-6 dynamics without antagonism [4] |

| par-6(RNAi) | Deplete anterior PAR domain | Study PAR-2 dynamics without antagonism [4] |

| Levamisole (100 mM) | Reversible immobilization | Paralyze embryos without fixation [15] |

| Agarose pads (2%) | Physiological mounting substrate | Support embryos during imaging [15] |

| NMY-2::GFP | Monitor actomyosin dynamics | Visualize apical constriction during ingression [14] |

| FRAP configuration | Standardized bleaching protocol | 7-pixel radius, 20 iterations, 50% laser power [15] |

| Temperature control | Maintain physiological conditions | 20°C during imaging for normal development |

| Cefmatilen | Cefmatilen, CAS:140128-74-1, MF:C15H14N8O5S4, MW:514.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| LY 121019 | Cilofungin CAS 79404-91-4|For Research | Cilofungin is a first-generation echinocandin antifungal agent for research. It inhibits β-(1,3)-D-glucan synthase. This product is For Research Use Only. |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Interactions

The PAR protein network operates through a system of mutual antagonism and spatially regulated kinase-phosphatase activities:

Anterior Complex Signaling

- PAR-3, PAR-6, and aPKC form a stable complex [1]

- CDC-42 binds PAR-6 and promotes cortical association [1]

- aPKC phosphorylates posterior PAR proteins to exclude them from the anterior domain

Posterior Complex Signaling

- PAR-1 and PAR-2 form a mutually reinforcing complex [1]

- PAR-1 phosphorylates anterior components to exclude them from the posterior

- PAR-5/14-3-3 facilitates mutual exclusion by binding phosphorylated residues [1]

Integration with Gastrulation Machinery

- PAR proteins regulate apical accumulation of non-muscle myosin II [14]

- Myosin contraction drives apical constriction of ingressing cells

- PAR-dependent adhesion patterning controls blastocoel formation [14]

Diagram 2: PAR Protein Signaling Network. Anterior and posterior PAR complexes mutually exclude each other through phosphorylation events, then regulate effectors for gastrulation including myosin and adhesion proteins.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Integration with Other Biophysical Techniques

FRAP data becomes more powerful when combined with complementary approaches:

FLIP (Fluorescence Loss in Photobleaching): Assesses intercompartmental connectivity by repeatedly bleaching an area and monitoring fluorescence loss in adjacent regions

FCS (Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy): Measures diffusion coefficients and concentrations at very small spatial scales

FRET (Förster Resonance Energy Transfer): Probes molecular interactions and conformational changes in living embryos

Computational Modeling Approaches

Quantitative FRAP data enables computational modeling of PAR network dynamics:

Reaction-Diffusion Models: Test whether proposed interaction networks can generate and maintain polarized states

Stochastic Simulations: Account for low copy numbers of some PAR components and potential noise in the system

Parameter Optimization: Use FRAP recovery curves to constrain unknown kinetic parameters in mathematical models

Future Technical Developments

Emerging technologies will enhance PAR protein dynamics studies:

Improved FP Variants: Brighter, more photostable fluorescent proteins (e.g., mNeonGreen, mScarlet) enable longer imaging with reduced phototoxicity [16]

CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing: Precise endogenous tagging eliminates artifacts from overexpression and ensures proper regulation [16]

Light Sheet Microscopy: Reduces photobleaching and enables long-term 3D imaging of PAR dynamics during entire gastrulation process

Super-Resolution Techniques: Reveal nanoscale organization of PAR domains beyond diffraction limit

FRAP provides a powerful quantitative approach for investigating PAR protein dynamics in living C. elegans embryos. The methodologies outlined in this guide enable researchers to measure key kinetic parameters that govern the establishment and maintenance of cellular polarity during gastrulation. The dynamic nature of PAR proteins, with continuous exchange between membrane and cytoplasmic pools coupled with free lateral diffusion, reveals that polarity maintenance is an active process requiring balanced antagonism rather than a static distribution. As technical capabilities advance, integrating FRAP with complementary approaches will further elucidate how PAR protein dynamics regulate the cell behaviors that drive gastrulation and embryonic morphogenesis.

Cell polarization, the process by which cells establish spatial asymmetry, is a fundamental biological phenomenon governing critical processes including embryonic development, cell division, and cell fate specification. In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans embryo, this polarization is orchestrated by partitioning-defective (PAR) proteins, which form opposing domains on the cell membrane and control asymmetric cell divisions [17] [18]. These divisions are crucial for patterned tissue growth and cell fate specification during gastrulation, the complex morphological rearrangement where embryonic cells form the three germ layers [11]. Understanding the role of PAR proteins in gastrulation requires uncovering how their spatiotemporal dynamics influence downstream cell behaviors. Reaction-diffusion modeling provides a powerful computational framework to simulate these dynamics, offering insights into how biochemical networks and physical constraints interact to generate robust polarization patterns in realistic cellular geometries. This technical guide explores current methodologies for simulating PAR network behavior, with emphasis on applications to gastrulation research in C. elegans.

Biological Foundation: The PAR Protein Network

Core PAR Protein Components and Interactions

The core PAR polarization system in the C. elegans zygote consists of two antagonistic groups localized to opposite membrane domains. The anterior complex includes PAR-3, PAR-6, and atypical protein kinase C (PKC-3), while the posterior complex comprises PAR-1 and PAR-2 [17] [18]. Following fertilization, the sperm entry point defines the posterior pole, triggering a contraction of cortical actomyosin that excludes the anterior PAR complex from the posterior region, allowing the posterior PAR complex to establish its domain [18]. During the maintenance phase, these two groups engage in mutual inhibition: membrane-associated PAR-3/PAR-6/PKC-3 inhibits the recruitment of PAR-1/PAR-2, and vice versa [17]. This reciprocal exclusion forms the backbone of a robust reaction-diffusion system that maintains stable polarized states.

Expanded Network Complexity

Recent research has identified additional proteins that significantly interact with the core PAR network, increasing its complexity and robustness. Key players include CDC-42, LGL-1, and CHIN-1, which modify the network's dynamics during the maintenance phase [17] [18]. These components introduce additional regulatory pathways, such as mutual activation in the anterior and additional mutual inhibition between anterior and posterior domains [18]. This expanded connectivity forms a 5-node network that enhances stability and enables precise control over the boundary position between anterior and posterior domains, crucial for proper asymmetric cell divisions during gastrulation.

Table 1: Core PAR Protein Complexes in C. elegans

| Domain | Protein Components | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior | PAR-3, PAR-6, PKC-3 | Forms apical caps; inhibits posterior complex; orient mitotic spindle [11] |

| Posterior | PAR-1, PAR-2 | Excludes anterior complex; regulates spindle orientation [11] |

| Regulatory | CDC-42, LGL-1, CHIN-1 | Modifies network stability and asymmetry; provides robustness [18] |

Computational Modeling Approaches

Reaction-Diffusion Principles for PAR Networks

Reaction-diffusion models describe how the concentrations of PAR protein complexes evolve in space and time through the combined effects of chemical reactions (association/dissociation, mutual inhibition) and spatial diffusion. The dynamics of each molecular species ( X ) can be captured through conservation equations that account for its membrane association rate ( F{on}^X(x,t) ), dissociation rate ( F{off}^X(x,t) ), and diffusion along the membrane and in the cytosol [18]. The mutual inhibition between anterior and posterior PAR complexes creates a nonlinear feedback that enables pattern formation, while the significant difference in diffusion rates between cytosolic and membrane-bound states (approximately two orders of magnitude higher in the cytosol) contributes to the stability of the polarized pattern [18].

Modeling Workflow for Realistic Cell Geometries

Implementing reaction-diffusion models for PAR networks in realistic cell geometries involves several key stages. First, cellular and subcellular geometries must be discretized using appropriate meshing techniques. The Spatial Modeling Algorithms for Reactions and Transport (SMART) software package utilizes tetrahedral meshes derived from microscopy images to accurately represent complex cellular morphologies [19]. Next, reaction-diffusion equations are defined over these computational domains, with careful attention to mixed-dimensional couplings (e.g., bulk-surface reactions at organelle membranes). Finally, numerical solutions are obtained using finite element methods, which provide high accuracy and geometric flexibility while conserving mass and momentum [19].

Diagram 1: Computational Modeling Workflow for PAR Networks. This workflow illustrates the key stages in developing realistic reaction-diffusion models of PAR protein dynamics, from geometry acquisition to results analysis.

Implementing PAR Network Simulations

Network Topologies and Their Properties

The simplest representation of the PAR system is an antagonistic 2-node network comprising mutual inhibition between anterior and posterior complexes. While this minimal model can generate polarization, it exhibits translational symmetry, meaning the boundary between domains can be stabilized at any location [18]. Realistic PAR networks incorporate additional components that break this symmetry and stabilize the boundary at specific positions. Research shows that unbalanced modifications—such as single-sided self-regulation, single-sided additional regulation, or unequal system parameters—can cause polarized patterns to collapse into homogeneous states. However, combining two or more unbalanced modifications with opposing effects can restore pattern stability through fine-tuning of kinetic parameters [18].

Spatial Considerations and Boundary Control

In realistic cell geometries, the PAR network interface can be stabilized at designated locations using spatially inhomogeneous parameters that favor respective domains. This strategy is employed in the C. elegans cell polarization network to maintain pattern stability while controlling interface localization [18]. Computational studies demonstrate that a step-like spatial profile of kinetic parameters, with values leading to opposing velocities when the interface is displaced, can effectively pin the boundary at specific positions. This mechanism enables the robust asymmetry required for proper cell positioning during embryonic development, including gastrulation events [11].

Table 2: Modeling Approaches for PAR Networks

| Approach | Key Features | Applications | Tools/Software |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Node Network | Mutual inhibition; minimal model; translational symmetry | Basic pattern formation studies; theoretical analysis | Custom simulations [18] |