Producing Germ-Free Mice via Embryo Transfer: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the production of germ-free mice through embryo transfer, a critical technology for studying host-microbiome interactions.

Producing Germ-Free Mice via Embryo Transfer: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the production of germ-free mice through embryo transfer, a critical technology for studying host-microbiome interactions. It covers the foundational principles of germ-free life, detailing the profound physiological and immunological differences in these models. A step-by-step methodological breakdown of the embryo transfer procedure is presented, from donor embryo collection to surgical implantation in germ-free surrogates. The guide further addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies to maximize success rates and maintain sterility. Finally, it validates the embryo transfer technique by comparing it to alternative derivation methods and outlining rigorous protocols for confirming the germ-free status, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the essential knowledge to implement this powerful model system.

Germ-Free Mice: Defining a Critical Model for Microbiome Research

What are Germ-Free Mice? Understanding Axenic Life and the Gnotobiotic Niche

Germ-free (GF) mice, also known as axenic mice, are laboratory-bred organisms that are entirely devoid of all microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microbes. These animals are raised in sterile isolators and serve as a fundamental tool for discerning the role of the microbiome in host physiology, immunity, and disease. Their production primarily relies on rigorous aseptic techniques, with embryo transfer being a gold-standard method for deriving new GF colonies. This technical guide explores the core concepts of axenic life, details the methodology behind germ-free mouse production, and examines their application in biomedical research, providing scientists with a comprehensive resource for gnotobiotic experimentation.

Defining the Germ-Free Condition and Gnotobiotic Systems

Germ-free (GF) or axenic animals are defined as those raised in the absence of all microorganisms [1]. This status is maintained from birth through adulthood by housing them in specialized sterile environments called gnotobiotic isolators—flexible film, plastic, or metal containers ventilated with sterile air [1]. The term "gnotobiotic" is derived from the Greek words 'gnosis' (knowledge) and 'bios' (life), referring to an experimental environment where all microorganisms are either defined or excluded [1].

The foundation of gnotobiotic experiments is the ability to raise GF animals and then colonize them with specific microbial species or complex consortia to study host-microbe interactions [1]. Animals that are derived germ-free and later colonized with a defined microbial community are termed conventionalized (CONVD), while those raised under standard laboratory conditions with a normal microbiota are called conventionally-raised (CONV-R) [1]. This precise control over microbial exposure allows researchers to investigate the specific contributions of microbiota to host biology.

Production of Germ-Free Mice via Embryo Transfer

The most reliable method for generating a new germ-free mouse line is through sterile embryo transfer, which bypasses the non-sterile birth canal and ensures embryos are free of contaminants [2] [3]. This process involves transferring embryos from a donor mouse into a germ-free surrogate mother who will give birth to and rear the offspring within a sterile isolator.

Key Steps in Embryo Transfer for GF Mouse Derivation

The following workflow outlines the core procedures for generating germ-free mice through embryo transfer:

Embryo Donor Preparation: Donor female mice (e.g., BALB/c) are typically superovulated through intraperitoneal injection with pregnant mare's serum gonadotropin (PMSG, 5 IU) followed by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG, 5 IU) 48 hours later [4]. The superovulated females are then mated with stud males overnight. Successfully mated females, identified by the presence of a vaginal plug the following morning, serve as embryo donors [4].

Embryo Collection: On gestational day 2.5-3.5, donor females are humanely culled, and their uterine horns and oviducts are flushed with specialized media (e.g., M2 media) to collect blastocysts [4]. The blastocysts are often cultured overnight in M2 media before transfer to ensure developmental competence [4].

Recipient Preparation and Surgery: Simultaneously, recipient female mice (commonly C57BL/6J, Swiss, or F1 crosses) undergo ovariectomy to eliminate endogenous hormone production and ensure precise control of the reproductive cycle [4]. After a recovery period of approximately two weeks, recipients receive exogenous hormone replacement: typically 100 ng estradiol on Day 0, followed by 2 mg progesterone on Day 2 [4]. On Day 3, embryo transfer is performed under isoflurane anesthesia. A paralumbar incision is made, the uterine horn is exposed, and approximately five blastocysts are transferred into each horn [4]. Post-surgery, recipients receive supplemental progesterone (2 mg daily) to support pregnancy until collection [4].

Sterile Rearing and Validation: The recipient female is housed in a gnotobiotic isolator for the duration of pregnancy and pup rearing. The germ-free status of the resulting offspring is rigorously and routinely monitored through a combination of aerobic and anaerobic culturing, Gram staining, and PCR analysis of freshly passed fecal pellets [2]. This multi-faceted approach ensures the complete absence of bacterial, fungal, and viral contaminants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Germ-Free Research

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Germ-Free Mouse Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Isolator | Provides a sterile barrier environment for housing GF animals; ventilated with HEPA-filtered air. | Flexible film isolator [1] |

| Hormones for Synchronization | Controls and synchronizes the estrous cycle of embryo recipients to ensure uterine receptivity. | Estradiol (Sigma E8875), Progesterone (Sigma P0130) [4] |

| Embryo Handling Media | Supports embryo viability during collection, culture, and transfer procedures. | M2 Media [4] |

| Sterility Testing Reagents | Validates the axenic status of the colony through multiple detection methods. | Culture media for aerobic/anaerobic bacteria, Gram stain kits, PCR primers for bacterial 16S rRNA gene [2] |

| Defined Microbial Consortia | Used to conventionalize GF mice with known communities to study specific host-microbe interactions. | e.g., Human microbiota harvests, specific bacterial strains like Lactobacillus or Acinetobacter [1] [5] |

| Chlorhexidine diacetate | Chlorhexidine diacetate, CAS:206986-79-0, MF:C26H40Cl2N10O5, MW:643.57 | Chemical Reagent |

| eIF4A3-IN-1 | eIF4A3-IN-1, MF:C29H23BrClN5O2, MW:588.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Research Applications and Key Phenotypes of Germ-Free Mice

Germ-free mice exhibit distinct physiological and neurological differences compared to conventionally-raised counterparts, making them invaluable for dissecting the microbiome's role in health and disease.

Neurological and Behavioral Alterations

Research has consistently demonstrated that the absence of gut microbiota significantly influences brain development and behavior, a key aspect of the gut-brain axis.

- Behavioral Phenotypes: GF mice display increased motor activity and reduced anxiety-like behavior compared to specific pathogen-free (SPF) controls [6]. This is evidenced by spending more time in the open arms of an elevated plus maze and the light compartment of a light-dark box [6].

- Neurochemical Changes: These behavioral changes are associated with altered neurochemistry. GF mice have an elevated turnover rate of key neurotransmitters, including noradrenaline (NA), dopamine (DA), and serotonin (5-HT), specifically in the striatum—a brain region critical for motor control and reward [6].

- Gene Expression and Neurogenesis: The gut microbiome modulates hippocampal neurogenesis in an age-dependent and sex-dependent manner [3]. Furthermore, GF mice show altered expression of synaptic plasticity-related genes, including significantly lower levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and NGFI-A mRNA in key brain regions like the hippocampus, amygdala, and cortex [6].

Table: Documented Behavioral and Neurobiological Differences in Germ-Free Mice

| Parameter | Observation in GF Mice vs. CONV-R | Experimental Test | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety-like Behavior | ↓ Decreased (Spent more time in open/light areas) | Elevated Plus Maze, Light-Dark Box | [6] |

| Motor Activity | ↑ Increased (Greater total distance traveled) | Open Field Test | [6] |

| Monoamine Turnover | ↑ Increased in striatum | HPLC analysis of neurotransmitters | [6] |

| Hippocampal Neurogenesis | Altered (Age and sex-dependent effects) | BrdU/DCX labeling | [3] |

| BDNF Expression | ↓ Decreased in hippocampus and amygdala | In situ hybridization | [6] |

Modeling Human-Specific Infections

GF mice, particularly when humanized, provide a powerful platform for studying the role of microbiota in human-specific pathogen infections.

- GF Humanized BLT Mice: The Bone Marrow/Liver/Thymus (BLT) model involves implanting immune-deficient GF mice with human hematopoietic stem cells and tissues, creating a system with a human-like immune system in a microbe-free context [2].

- Enhanced Pathogenesis: Studies using this model have shown that resident microbiota dramatically enhance infection by human-specific viruses. For instance, compared to GF-BLT mice, conventionalized (CV)-BLT mice exhibited higher incidence of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) infection and EBV-induced tumorigenesis [2]. Similarly, oral HIV acquisition and subsequent systemic viral replication were significantly augmented in the presence of microbiota, linked to an increased frequency of CCR5+ CD4+ T cells—the primary target for HIV—in the intestinal tract [2].

Host-Microbe Specificity and Dynamics

Research in simpler models like Drosophila melanogaster has revealed fundamental principles of host-microbe interactions that are relevant to mammalian systems. Studies show that stable microbial association often relies on host-constructed physical niches that selectively bind bacteria with strain-level specificity [5]. For example, specific strains of Lactobacillus and Acinetobacter colonize a physical niche in the Drosophila foregut, where bacterial colonization saturates at a fixed population size and resists displacement, demonstrating clear priority effects in community assembly [5].

Advanced Technical Considerations

Quantitative Microbial Analysis

A significant methodological advancement in gnotobiotic research is the shift from relative to absolute quantification of microbial abundance. Standard 16S rRNA gene sequencing provides only relative data, where an increase in one taxon's abundance forces an apparent decrease in others [7]. A digital PCR (dPCR) anchoring framework overcomes this by providing absolute quantification, enabling accurate measurement of microbial loads across different gastrointestinal locations (e.g., lumen vs. mucosa) and under different dietary conditions, such as a ketogenic diet [7]. This is critical for accurately interpreting how experimental manipulations truly affect specific microbial populations.

Embryo Transfer as a Research Model

Beyond its use for generating GF lines, the embryo transfer model itself is a powerful tool for reproductive research. Using ovariectomized recipients allows researchers to study the uterine-specific contributions to pregnancy independent of ovarian function [4]. This model enables the investigation of how external factors (e.g., diet, drugs, environmental toxins) specifically impact uterine receptivity, implantation, and subsequent fetal development [4].

Germ-free mice are an indispensable resource in modern biomedical research, providing a controlled system to elucidate the profound influence of the microbiome on host physiology. The rigorous process of deriving and maintaining axenic colonies via embryo transfer is foundational to gnotobiotic science. The distinct phenotypes observed in these animals—from altered behavior and neurochemistry to modified immune responses to pathogens—underscore the microbiota's critical role in shaping the host. As techniques for absolute microbial quantification and complex humanized modeling continue to evolve, germ-free mice will remain at the forefront of efforts to understand and harness host-microbe interactions for therapeutic benefit.

The development of germ-free (GF) mice represents a cornerstone of modern biomedical research, enabling precise exploration of the microbiome's role in health and disease. These animals, devoid of all living microorganisms, provide a "clean slate" for investigating host-microbe interactions [8]. The journey to establish and maintain these vital models spans over a century, marked by technological innovations that have transformed gnotobiotic science from a theoretical possibility to a reproducible methodology. This evolution has progressed from initial sterile cesarean sections to the sophisticated embryo transfer techniques and isolator environments that define contemporary practice [9] [8]. The historical development of these methods is not merely of academic interest but provides critical context for the standardized protocols used in today's leading research institutions. Understanding this progression—from early germ-free animal attempts in the 19th century to the current integration of in vitro fertilization (IVF) with advanced isolator technology—reveals how technical challenges were systematically addressed to enhance reliability, efficiency, and scalability in GF mouse production [9] [8].

The Pioneering Era: First Germ-Free Mammals and Technical Barriers

The conceptual foundation for germ-free life was laid in the 19th century. In 1885, Louis Pasteur initially proposed the concept of GF animals, though the prevailing scientific opinion at the time held that bacteria-free life was impossible [9]. A decade later, researchers at Berlin University achieved the first documented germ-free mammal—a guinea pig—in 1895. However, this early success was short-lived; the animal survived only 13 days due to inadequate sterile techniques and nutritional support [9]. This attempt highlighted the two principal challenges that would occupy researchers for decades: preventing microbial contamination and meeting the unique physiological needs of germ-free organisms.

The true breakthrough came when Gustafsson successfully obtained GF rats via sterile cesarean section in the mid-20th century, followed by Pleasants' production of GF mice in 1959 [9]. These achievements were made possible by Gustafsson's pioneering isolator technology, which he specifically designed to maintain a sterile environment for the animals [10] [9]. The stainless steel isolators Gustafsson developed in 1959 created a physical barrier against environmental microbes, allowing researchers to control the gnotobiotic status of the animals within [10]. This technology formed the basis for maintaining GF colonies and paved the way for subsequent advancements in microbiome research [9].

Table: Key Milestones in Early Germ-Free Animal Research

| Year | Development | Key Researcher/Institution | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1885 | Conceptual proposal of GF animals | Louis Pasteur | Initial theoretical foundation |

| 1895 | First germ-free mammal (guinea pig) | Berlin University | Proof of concept; survived 13 days |

| Mid-20th century | First GF rats via sterile C-section | Gustafsson | Established viable GF model system |

| 1959 | First GF mice | Pleasants | Expanded GF models to key research species |

| 1959 | Stainless steel isolator design | Gustafsson | Enabled long-term maintenance of GF status |

Technical Evolution: From Cesarean Section to Embryo Transfer

The initial success in producing germ-free rodents relied exclusively on sterile cesarean section techniques, which remained the gold standard for decades [9]. This method is predicated on the "sterile womb hypothesis," which posits that the placental epithelium serves as an effective barrier protecting the fetus from microbial exposure [9]. In practice, fetuses are delivered via sterile C-section from specific pathogen-free (SPF) donor females, after which the uterine sac is removed and transferred into a sterile isolator where pups are carefully extracted, resuscitated, and introduced to GF foster mothers [9].

While effective, the traditional C-section approach (T-CS) presented significant limitations, including variability in donor mating times, difficulty in precisely predicting delivery dates, and uncertainty in ensuring adequate maternal care from foster mothers [9]. These factors contributed to inconsistent success rates in obtaining viable GF pups.

A critical advancement came with the introduction and refinement of embryo transfer techniques. First successfully applied to GF mouse production in 1999 [11], this method involves harvesting embryos from superovulated mice and transferring them aseptically into the uterus of GF recipient females that have been mated with vasectomized GF males [11]. This approach offered a fundamental advantage: by bypassing the potential for microbial transmission that could occur during C-section, it provided a more reliable method for establishing GF colonies.

Research has demonstrated that embryo transfer in an isolator environment allows for the "reproducible and quality-assured conversion of animals to those which are negative for the presence of microorganisms" [10]. This method enables the implantation of cleansed embryos into GF recipients under well-controlled conditions, with recipient females typically giving birth normally and providing adequate maternal care that enhances offspring survival rates [10].

Table: Comparison of Traditional C-Section vs. Embryo Transfer for GF Mouse Production

| Parameter | Traditional C-Section (T-CS) | Female Reproductive Tract-Preserved C-Section (FRT-CS) | Embryo Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical basis | Sterile womb hypothesis | Sterile womb hypothesis | Pre-implantation embryo sterility |

| Technical complexity | Moderate | Moderate to high | High (requires microsurgery) |

| Risk of contamination | Higher (placental crossers possible) | Higher (placental crossers possible) | Lower when properly executed |

| Fetal survival rate | Variable | Significantly improved [9] | Approximately 50% of transferred embryos [9] |

| Control over timing | Low (dependent on natural mating) | Low (dependent on natural mating) | High (enabled by IVF) [9] |

| Required resources | Surgical equipment, isolator | Surgical equipment, isolator | Stereomicroscope, IVF equipment, isolator [10] |

Modern Optimizations and Technical Refinements

Contemporary research has focused on optimizing both cesarean and embryo transfer techniques to improve efficiency and reproducibility in GF mouse production. Recent studies have demonstrated that optimizing surgical methods can significantly impact outcomes. The female reproductive tract-preserved C-section (FRT-CS), which selectively clamps only the cervix base while preserving the entire reproductive tract, has shown significantly improved fetal survival rates while maintaining sterility compared to traditional C-section approaches [9].

The integration of in vitro fertilization (IVF) has addressed one of the most persistent challenges in GF mouse production: precise control over developmental timing. IVF enables researchers to obtain donor mice with precisely controlled delivery dates, dramatically enhancing experimental reproducibility and planning [9]. This approach allows for pre-labor C-sections on predicted delivery dates, reducing the variability inherent in natural mating cycles.

Another critical area of optimization involves foster mother selection. Systematic evaluation of different GF foster strains has revealed significant differences in maternal care capabilities. Studies show that BALB/c and NSG mice exhibit superior nursing and weaning success, whereas C57BL/6J strains demonstrate the lowest weaning rates among GF foster mothers—a finding that contrasts strikingly with observations of maternal care in SPF C57BL/6J foster mothers [9]. This highlights the importance of strain-specific considerations in GF mouse production protocols.

Table: Strain-Specific Performance of GF Foster Mothers

| Mouse Strain | Type | Weaning Success | Maternal Care Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | Inbred | Superior | Exhibits active maternal behaviors [9] |

| NSG | Inbred | Superior | Effective nursing of cross-fostered pups [9] |

| KM | Outbred | Moderate | Adequate maternal care performance [9] |

| C57BL/6J | Inbred | Lowest | Poor GF foster performance despite good care in SPF conditions [9] |

Modern isolator technology has also evolved substantially from Gustafsson's original stainless steel designs. Current systems typically use polyvinyl chloride (PVC) isolators that require specialized husbandry protocols, including thermal regulation to prevent hypothermia in neonates [9]. The integration of stereomicroscopes mounted within these isolators has facilitated the performance of delicate embryo transfer procedures entirely within the sterile environment [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Producing germ-free mice requires specialized materials and equipment designed to establish and maintain a sterile environment throughout the process. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for successful GF mouse derivation via embryo transfer.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for GF Mouse Production via Embryo Transfer

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) Isolators | Primary sterile housing environment | Requires heating pads (40-45°C) to prevent neonatal hypothermia [9] |

| Clidox-S | Chlorine dioxide disinfectant | Used for sterilizing tissue samples and disinfecting the isolator environment [9] |

| Vasectomized GF Males | Induction of pseudopregnancy in recipients | Mated with GF females to prepare them as embryo recipients [11] |

| Specific Pathogen-Free (SPF) Donors | Source of embryos | Provide embryos that are cleansed before transfer [9] |

| Stereomicroscope | Visualization for embryo transfer | Mounted inside isolator for micromanipulation in sterile conditions [10] |

| Germ-Free Foster Mothers | Care for derived pups | Strain selection critical; BALB/c and NSG show superior success [9] |

| GSK620 | GSK620, CAS:2088410-46-0, MF:C18H19N3O3, MW:325.368 | Chemical Reagent |

| Mito-apocynin (C2) | Mito-apocynin (C2), MF:C28H27BrNO3P, MW:536.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Current Workflows and Experimental Approaches

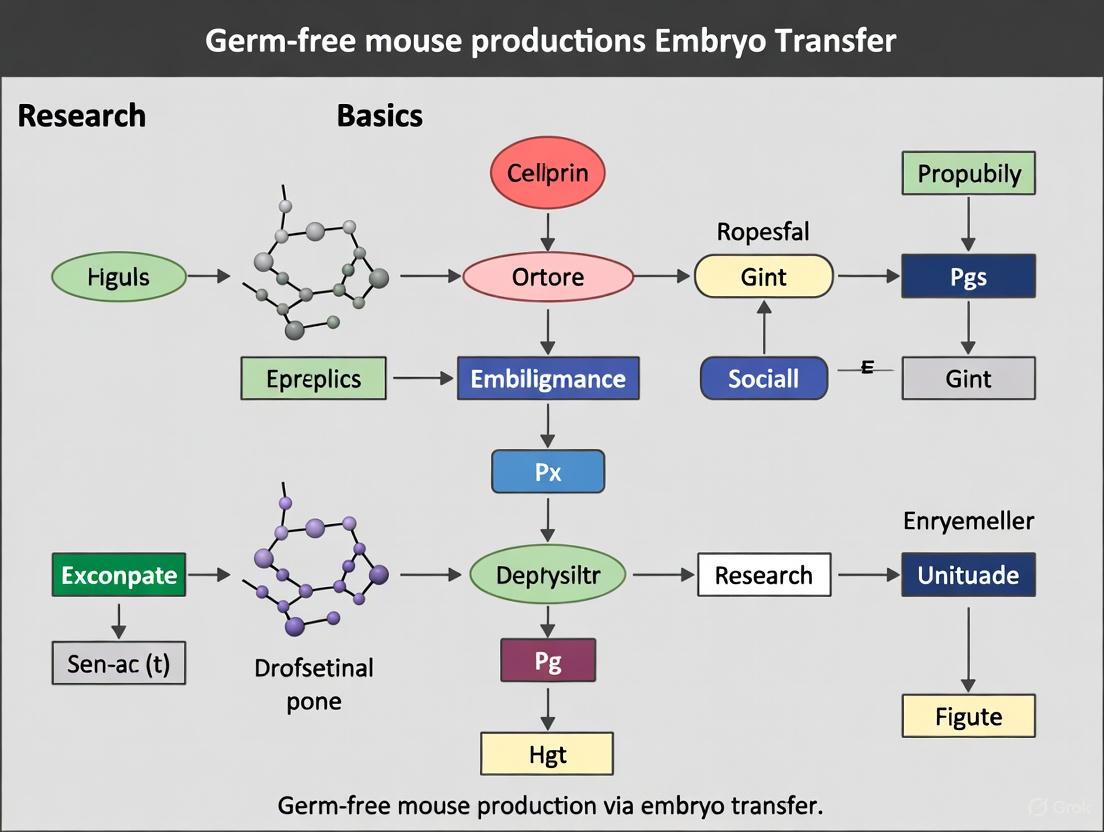

The modern workflow for establishing germ-free mice via embryo transfer integrates multiple sophisticated techniques within a sterile isolator environment. The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and procedural flow in contemporary GF mouse production:

Contemporary embryo transfer protocols typically follow a standardized sequence: (1) embryo collection from superovulated SPF donors, (2) aseptic transfer of cleansed embryos into GF recipients within a sterile isolator environment, (3) birth and care by recipient females, and (4) rigorous sterility testing to confirm germ-free status [10] [11]. This workflow leverages the combined advantages of IVF for temporal precision and embryo transfer for contamination control.

For C-section approaches, the optimized FRT-CS method involves: (1) euthanizing pregnant SPF donors at term, (2) performing C-section with preservation of the female reproductive tract, (3) rapid transfer of the intact uterine horn into sterile disinfectant, (4) extraction of pups inside the isolator within 5 minutes to ensure viability, and (5) resuscitation and transfer to pre-selected GF foster mothers [9].

The production of germ-free mice has evolved substantially from the early germ-free guinea pig that survived merely 13 days to today's sophisticated embryo transfer protocols in advanced isolator environments [9]. This journey has been marked by critical innovations: Gustafsson's initial isolator design, the shift from C-section to embryo transfer as the preferred method, the integration of IVF for precise timing control, and the optimization of foster mother selection based on strain-specific performance [10] [9] [11]. These historical developments have collectively addressed the fundamental challenges of maintaining sterility while ensuring viable, reproductively stable GF mouse colonies.

The continued refinement of these techniques remains essential for advancing microbiome research. As the field progresses toward increasingly complex gnotobiotic models—including monoxenic and polyxenic animals with defined microbial communities—the historical context of germ-free mouse production provides a foundation for future innovation [10]. Current methods enable researchers to explore host-microbe interactions with unprecedented precision, facilitating discoveries across immunology, metabolism, oncology, and neuroscience [8]. The evolution from early experiments to modern isolator technology exemplifies how methodological advances can unlock new frontiers in biological understanding, making germ-free mice powerful tools for deciphering the complex relationships between microorganisms and their mammalian hosts.

Germ-free (GF) animal models are indispensable tools for dissecting the intricate relationship between host physiology and commensal microorganisms. Studies utilizing these models consistently demonstrate that the absence of a microbiota has profound and systemic consequences, leading to significant impairments in immune system maturation and marked alterations in organ function. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to detail the specific immunological deficits observed in GF mice, including the underdevelopment of lymphoid structures and altered T-cell populations, and further describes the associated metabolic perturbations in distal organs such as the liver, lungs, and kidneys. The presented data, structured for clear comparison, alongside detailed experimental methodologies and visual summaries of affected pathways, provides a comprehensive technical guide for researchers in the field of gnotobiology and preclinical drug development.

The germ-free mouse is a critical in vivo model for studying the microbiome's role in host physiology. Produced via sterile cesarean section or aseptic embryo transfer to eliminate microbial exposure, these animals are maintained in isolators to preserve their axenic status [12]. Research comparing GF mice to their conventional or colonized counterparts has revealed that the microbiome is not merely a passive resident but an active participant in programming host systems. The absence of these microbial signals results in a distinct physiological state, often termed "germ-free syndrome," characterized by immature immune defenses and systemic molecular alterations [13]. This review systematically examines the physiological impact of the germ-free state, focusing on its foundational role in immune maturation and organ function, a knowledge essential for advancing germ-free mouse production via embryo transfer research.

Immune System Deficits in Germ-Free Mice

The immune system of germ-free mice exhibits widespread immaturity, affecting both its structural development and cellular functionality. The deficits span innate and adaptive immunity and are largely attributable to the lack of continuous microbial stimulation.

Key Immunological Deficiencies

The table below summarizes the major immunological abnormalities identified in GF mice.

Table 1: Immune System Deficiencies in Germ-Free Mice

| Immune Component | Observed Deficiency in GF Mice | Physiological Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissues (GALT) | Impaired development of Peyer's patches and isolated lymphoid follicles [14]. | Reduced capacity for immune surveillance and response initiation in the intestinal mucosa. |

| CD4+ T Helper Cells | Marked reduction in intestinal lamina propria Th17 cells; diminished Th1 responses [14]. | Compromised clearance of intracellular pathogens and altered immune regulation. |

| Regulatory T Cells (Tregs) | Reductions in microbiome-dependent RORγt+ Treg populations [15]. | Disrupted balance between immune tolerance and inflammation. |

| Intraepithelial Lymphocytes (IELs) | 30% reduction in αβ/γδ IELs [14]. | Weakened first-line barrier defense at the intestinal epithelium. |

| Secretory IgA (sIgA) | Markedly reduced IgA secretion [14]. | Impaired mucosal defense and uncontrolled microbial colonization. |

| Systemic Innate Immunity | Alterations in immune cell numbers at distal sites, indicative of an aberrant immune response [16]. | Reduced priming and readiness of systemic immune defenses. |

Experimental Evidence and Protocol: Immune Phenotyping

A typical methodology for characterizing the immune status of GF mice involves comparative flow cytometry analysis of tissues from GF, colonized, and specific-pathogen-free (SPF) controls [16] [15].

Detailed Protocol:

- Animal Models: Utilize age- and sex-matched GF mice and SPF controls. Gnotobiotic models, such as mice colonized with a defined microbial consortium (e.g., OMM12), are often included to establish causality [15].

- Tissue Collection: Euthanize mice via CO2 asphyxiation. Harvest immune-relevant tissues, including the spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes, intestinal lamina propria, and lung tissue [16].

- Cell Isolation: Mechanically dissociate and enzymatically digest solid tissues (e.g., spleen, lungs) to create single-cell suspensions. For intestinal lamina propria lymphocytes, a more extensive digestion protocol is required post-epithelial cell removal.

- Cell Staining & Flow Cytometry: Stain cells with fluorescently labeled antibodies against key surface markers (e.g., CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19) and intracellular markers (e.g., RORγt, T-bet, FoxP3, cytokines like IFNγ and TNFα). Intracellular cytokine staining requires prior cell restimulation with a mitogen or specific antigens [15].

- Data Analysis: Compare the frequency and absolute numbers of immune cell populations (e.g., Th1, Th17, Tregs, cytotoxic T cells, innate lymphoid cells) between GF and control groups.

The following diagram illustrates the core immune deficiencies and their relationships in the germ-free state.

Impact on Distal Organ Function and Metabolism

The influence of the germ-free state extends far beyond the immune system, significantly affecting the physiology of systemic organs. These effects are largely mediated by the absence of microbial metabolites, which serve as key signaling molecules.

Systemic Metabolic and Phenotypic Alterations

Spatial metabolomics and phenotypic characterization reveal significant molecular and cellular changes in distal organs of GF mice.

Table 2: Organ-Specific Alterations in Germ-Free Mice

| Organ | Observed Molecular/Cellular Alterations | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Liver | Highest number of significantly changed molecular species; dysfunctional hepatic lipid accumulation [16]. | Increased susceptibility to metabolic disorders like non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [16]. |

| Lung, Kidney, & Spleen | Significant alterations in small molecule abundance and immune cell numbers [16]. | Disrupted local immune priming and homeostatic function, underscoring microbiome's role at sites distal from the intestine. |

| Intestinal Tract | Altered levels of microbial metabolites (e.g., SCFAs, indoles) and host molecules; reduced colonic 5-HT biosynthesis; compromised epithelial barrier [17]. | Dysregulated gut-brain communication, immune function, and nutrient absorption. |

Experimental Protocol: Spatial Metabolomics and Phenotyping

A comprehensive approach to mapping systemic impacts involves combining mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) with imaging mass cytometry (IMC) [16].

Detailed Protocol:

- Tissue Preparation: Sacrifice GF and SPF control mice. Collect tissues (ileum, colon, spleen, lung, liver, kidney), snap-freeze in a slurry of dry ice and isopentane, and store at -80°C. Cryosection tissues at 10µm thickness and mount onto slides for analysis [16].

- Desorption Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry Imaging (DESI-MSI):

- Perform DESI-MSI on the tissue sections using a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Orbitrap).

- Use a spray solvent (e.g., methanol/water) to desorb and ionize molecules from the tissue surface.

- Acquire full mass spectra in a defined range (e.g., m/z 100-1000) at a specific spatial resolution (e.g., 60µm for gut, 100µm for other tissues) [16].

- Data Analysis for MSI: Convert raw data files and analyze using specialized software (e.g., SCiLS Lab). Use multivariate analysis (e.g., PCA, PLS-DA) and univariate analysis to identify metabolites that significantly discriminate between GF and SPF tissues [16].

- Imaging Mass Cytometry (IMC):

- Stain consecutive tissue sections with a panel of metal-tagged antibodies targeting phenotypic markers (e.g., immune cell markers).

- Use a laser to ablate stained regions, and a mass cytometer to detect the metal tags.

- This allows for high-dimensional, spatial characterization of cell types in the same tissues analyzed by MSI [16].

- Integration: Correlate the spatial localization of discriminatory metabolites with alterations in neighboring cell phenotypes to infer functional relationships.

The workflow for this integrated spatial analysis is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successfully conducting germ-free research requires specialized reagents and tools to maintain sterility, validate models, and analyze outcomes.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Germ-Free Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sterilized Diet (e.g., Labdiet 5CJL) | Provides nutrition without introducing microbes. | Must be sterilized by irradiation (e.g., 50 kGy) [12]. |

| Chlorine Dioxide Disinfectant (e.g., Clidox-S) | Surface and instrument sterilant for entry into isolators. | Used in a specific dilution (e.g., 1:3:1) and activated before use [12]. |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) Isolators | Primary housing for GF mice, maintaining a sterile barrier. | Require pre-sterilization with disinfectant and continuous supply of sterile air [12]. |

| Antibody Panels for Flow Cytometry | Immune phenotyping of tissues from GF and control mice. | Panels must include markers for T-cell subsets (CD4, CD8), differentiation states (CD44, CD62L), and key cytokines (IFNγ, TNFα) [15] [14]. |

| Metal-Tagged Antibody Panels for IMC | High-plex spatial phenotyping of tissue sections. | Allows simultaneous detection of 40+ markers on a single tissue section when combined with IMC [16]. |

| Defined Microbial Consortium (e.g., OMM12) | Used to colonize GF mice to establish causality in gnotobiotic studies. | A low-complexity bacterial community that allows study of structured host-microbe interactions [15]. |

| Sterile Aspen Wood Shavings | Bedding material for GF mouse cages. | Must be autoclaved before introduction into the isolator to maintain sterility [12]. |

| Oxfbd04 | Oxfbd04, MF:C17H16N2O3, MW:296.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| USP30 inhibitor 11 | USP30 inhibitor 11, MF:C17H16N6O2S, MW:368.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The germ-free mouse model unequivocally demonstrates that microbial colonization is a fundamental requirement for normal physiological development. The absence of microbiota leads to a comprehensive "germ-free syndrome" characterized by an immature immune system with defective lymphoid structures, altered T-cell landscapes, and weakened mucosal defenses. Furthermore, these immunological deficits are accompanied by significant metabolic perturbations in distal organs, including the liver, lungs, and kidneys, mediated by the absence of key microbial metabolites. For researchers engaged in germ-free mouse production via embryo transfer, a deep understanding of these physiological impacts is crucial. It not only informs the interpretation of experimental data generated using these models but also underscores the importance of rigorous protocols in producing and maintaining a truly axenic animal colony for reproducible and translatable research outcomes.

Germ-free (GF) mice, also known as axenic mice, are laboratory-bred mice that are completely free of all detectable microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microbes [18]. These specialized animal models provide a biological model system to study either the complete absence of microbes or to verify the effects of colonization with specific and known microbial species [18]. The fundamental value of GF mice in biomedical research lies in their ability to enable researchers to establish causal relationships between the microbiome and various aspects of physiology, normal aging, and the functioning of the nervous, digestive, immune, and metabolic systems [18].

The historical development of GF technology dates back to 1896, when Nuttall and Thierfelder generated the first GF mammals (guinea pigs) at the University of Berlin, though these early specimens survived only 13 days due to technological constraints [18]. The field advanced significantly in the mid-twentieth century when James Reyniers and his colleagues at the University of Notre Dame established the first successful colonies of GF rodents, proving conclusively that life without microbes is possible [18] [19]. Subsequent technological innovations, particularly the development of flexible film isolator systems by Philip C. Trexler, made GF mouse research more practical and accessible [19]. Today, GF mice are considered irreplaceable animal models for studying the interaction between the microbiome and human genes on health and disease, serving as a cornerstone for mechanistic investigations into microbiota-host interactions [20] [21].

Germ-Free Mouse Production Methods

Core Production Techniques

The production of germ-free mice relies on two primary methods, each with distinct advantages and limitations. These approaches share the common goal of generating mice free of microorganisms while maintaining viability.

Table 1: Comparison of Germ-Free Mouse Production Methods

| Method | Key Procedure | Advantages | Limitations | Efficiency/Success Rates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sterile Cesarean Section (C-section) | Uterus containing pups is aseptically removed from SPF donor and transferred to germ-free isolator via disinfectant tank [19] [20] | Considered the "gold standard" method; based on "sterile womb hypothesis" that fetuses develop in sterile intrauterine environment [20] | Variable mating times; difficult to predict delivery dates; uncertainty in maternal care [20] | Optimized FRT-CS technique significantly improves fetal survival rates while maintaining sterility [20] |

| Aseptic Embryo Transfer | Embryos in two-cell state are implanted into oviduct of germ-free surrogate mother who gives birth inside sterile isolator [22] [19] | Enables precise control over donor delivery dates, enhancing experimental reproducibility [20] | Requires integration of stereomicroscope within isolator; lower embryo survival rates (~50% of transferred embryos result in live births) [20] | IVF-generated germ-free cohorts available from 10-40 mice with same week of birth [22] |

The sterile cesarean section technique has been refined through various approaches. The female reproductive tract preserved C-section (FRT-CS) method, which selectively clamps only the cervix base while preserving the entire reproductive tract, has demonstrated significantly improved fetal survival rates compared to traditional C-section techniques [20]. This optimization is critical as the entire surgical procedure must be completed within 5 minutes to ensure both sterility and pup viability [20].

Foster Mother Selection and Maternal Care

The successful rearing of GF pups depends heavily on the selection of appropriate foster mothers. Different mouse strains exhibit varying capabilities in maternal care, which significantly impacts weaning success rates.

Table 2: Comparison of Germ-Free Foster Mother Strains

| Strain | Type | Maternal Care Performance | Weaning Success | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | Inbred | Superior nursing capabilities; milk contributes significantly to pup weight gain [20] | High weaning success | One of the most used inbred strains for GF foster care [20] |

| NSG (NOD/SCID Il2rg–/–) | Inbred | Exhibits superior nursing capabilities [20] | High weaning success | Requires biological decontamination by cesarean section [20] |

| KM (Kunming) | Outbred | Moderate maternal care performance | Moderate weaning success | Original GF strain bred in specialized facilities [20] |

| C57BL/6J | Inbred | Lowest nursing capability among tested strains [20] | Lowest weaning rate | Contrasts with findings on maternal care in SPF C57BL/6J foster mothers [20] |

Research indicates that BALB/c and NSG strains exhibit superior nursing capabilities and weaning success when serving as GF foster mothers [20]. This finding is particularly notable for C57BL/6J, which demonstrates the lowest weaning rate in GF conditions despite more active maternal behaviors in specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions [20]. This discrepancy highlights the importance of selecting appropriate foster strains specifically for GF applications rather than relying on data from conventional mouse husbandry.

Housing and Maintenance

GF mice require specialized housing in flexible-film isolators made of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) that create an impermeable mechanical barrier separating the sterile inner environment from the outside [19]. These isolators maintain positive pressure and contain essential components including an isolation chamber, air filter system, port system, blower, and gloves [19]. All life supplements—including food, water, and bedding—must be autoclaved at 121°C for 1200 seconds before introduction to the isolator [20]. Additionally, chlorine dioxide disinfectants (e.g., Clidox-S) are used to sterilize tissue samples and maintain the disinfected environment, typically applied in a 1:3:1 dilution and activated for 15 minutes before use [20].

Experimental Applications of Germ-Free Mice

Establishing Causal Links in Disease

GF mice serve as powerful tools for moving beyond correlational observations to establishing causal mechanisms in microbiome-related diseases. This approach is particularly valuable in neurodegenerative diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS), where gut bacteria have been implicated but causal factors remain poorly understood [21]. In a recent pre-clinical study of MS using experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), GF mice colonized with different synthetic microbial communities enabled researchers to identify specific microbial risk factors for severe neuroinflammation [21]. This research demonstrated that the presence of Akkermansia muciniphila represents a potential microbial risk factor for severe EAE when combined with certain other bacterial strains, though changes in its relative abundance alone negligibly impact disease course [21].

The application of GF mice extends beyond neurological diseases to various intestinal and non-intestinal disorders. GF animal models have been instrumental in linking gut microbiota dysbiosis with conditions including irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic syndrome, cancers, and brain diseases [18]. These models help elucidate the role of commensal microbiota in the development and function of organisms, providing insights that would be impossible to obtain through human observational studies alone.

Gnotobiotic Experimentation

Gnotobiotic experimentation involves the intentional colonization of GF mice with defined microorganisms, enabling precise investigation of host-microbe interactions. This approach includes:

- Monocolonization: Association of GF mice with individual microbial species to study their specific effects [19]

- Synthetic Communities (Syncoms): Colonization with defined sets of selected bacteria from pure cultures to limit experimental variability and improve reproducibility [19]

- Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT): Transplantation of complex microbiomes from human donors or other species to study disease transmission [19]

The altered Schaedler flora (ASF), consisting of eight culturable and quantifiable bacterial species, represents one of the most prominent examples of a standardized model microbiome [19]. Additional synthetic communities like the Oligo-Mouse Microbiota (OMM), Simplified Human Intestinal Microbiota (SIHUMI), and Simplified Intestinal Microbiota (SIM) have expanded the toolbox for gnotobiotic research [19]. These defined communities enable researchers to move from association-based evidence to causality, pinpointing the exact molecular mechanisms underlying microbiota-host interactions in health and disease.

Humanized Gnotobiotic Mouse Models

Humanized gnotobiotic models involve transplanting human gut microbiota into GF mice to study donor-specific physiological or disease phenotypes [19]. These models are particularly valuable for preclinical studies aimed at understanding how human microbial communities influence host physiology. However, it is important to note that the genetic background of the recipient rodent system strongly influences the composition of the transferred microbiota, adding an important consideration for experimental design [19].

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Sterility Testing and Quality Control

Maintaining and verifying the germ-free status of mice requires rigorous and standardized monitoring protocols. As noted by James A. Reyniers in 1959, "the science or art of detecting contamination is always the limiting factor and is at best a temporary situation" [19]. Modern gnotobiotic facilities implement comprehensive sterility testing procedures that include:

- Weekly microbial monitoring of isolators to certify Germ-Free Health Standard [22]

- Twelve weeks of negative reports required before an isolator holding rederived offspring is considered germ-free [22]

- Dual isolator redundancy to ensure backup systems in case of contamination [22]

- Culture-based and molecular methods to detect bacterial, fungal, and other microbial contaminants [19]

These procedures must account for variations in diet batch-to-batch composition, irradiation procedures (gamma vs. electron beam radiation, radiation dose), and autoclaving protocols, all of which may vary between facilities and influence sterility testing outcomes [19].

Experimental Workflow for Causality Establishment

The following diagram illustrates a typical experimental workflow for using GF mice to establish causal links in disease:

Metabolic Pathway Analysis in GF Studies

Metabolomic analyses of GF mice provide critical insights into microbial influences on host physiology. In EAE studies, researchers have identified γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) as a metabolite of interest showing positive association with disease severity [21]. The following diagram illustrates how microbial factors influence host metabolism in GF models:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Germ-Free Mouse Studies

| Category | Specific Item/Technique | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germ-Free Animals | Commercial GF mice | Provide validated germ-free models for research | Taconic Biosciences offers germ-free rederivation services and commercially available GF mice [22] |

| Sterilization Equipment | Flexible-film isolators | Maintain sterile environment for housing GF mice | PVC isolators with positive pressure, air filters, port systems [19] |

| Germ-free shippers | Transport GF animals while maintaining sterility | Specialized containers that ensure germ-free status during transport [22] [19] | |

| Sterilization Agents | Clidox-S | Chlorine dioxide disinfectant for sterility maintenance | Used in 1:3:1 dilution, activated for 15 minutes before use [20] |

| Autoclaving | Sterilization of life supplements | 121°C for 1200 seconds for food, water, bedding [20] | |

| Microbial Monitoring | Culture-based methods | Detect bacterial and fungal contamination | Weekly monitoring of isolators [22] [19] |

| Molecular methods | Comprehensive detection of contaminants | Next-generation sequencing approaches [19] | |

| Defined Microbial Communities | Altered Schaedler Flora (ASF) | Standardized model microbiome | 8 culturable and quantifiable bacterial species [19] |

| Oligo-Mouse Microbiota (OMM) | Synthetic microbiome for reduced complexity | Limited bacterial species for controlled studies [19] | |

| Analytical Tools | Metabolomics | Analysis of microbial metabolites | Identification of metabolites like GABA linked to disease [21] |

| Immunoglobulin A (IgA) coating index | Predictor of disease development | Robust individualized predictor of neuroinflammation [21] | |

| Foster Strains | BALB/c and NSG mice | Superior GF foster mothers | Enhanced nursing capabilities and weaning success [20] |

| LDN-192960 | LDN-192960, CAS:184582-62-5; 184582-62-5, MF:C18H20N2O2S, MW:328.43 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| PKC-iota inhibitor 1 | PKC-iota inhibitor 1, MF:C21H22N6O, MW:374.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Germ-free mice represent an indispensable tool in modern biomedical research for establishing causal links between the microbiome and disease pathogenesis. The rigorous production methods, including optimized cesarean techniques and embryo transfer, combined with appropriate foster strain selection, enable the generation of high-quality GF models for mechanistic studies. Through gnotobiotic experimentation involving controlled colonization with defined microbial communities, researchers can move beyond correlational observations to identify specific microbial factors and mechanisms influencing host physiology in health and disease. As the field advances, standardized protocols for GF mouse generation, maintenance, and sterility testing will be crucial for ensuring reproducibility and translational relevance of findings. The continued refinement of GF mouse models promises to deepen our understanding of host-microbe interactions and open new avenues for therapeutic interventions targeting the microbiome.

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Germ-Free Mouse Derivation via Embryo Transfer

This technical guide elucidates the core principle of using embryo transfer to bypass vertical microbial transmission in the establishment of germ-free (GF) mouse colonies. Within the context of GF animal production, vertical transmission refers to the transfer of microorganisms from the mother to her offspring during vaginal birth. This document provides a comprehensive overview of the scientific rationale, detailed experimental protocols, and key reagents, framing embryo transfer as a superior alternative to sterile cesarean section for ensuring the germ-free status of offspring. The content is designed to support researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in implementing robust and reproducible methodologies for generating high-quality animal models.

The concept of a "sterile womb" has long been a foundational hypothesis in germ-free research, positing that the placental epithelium acts as a barrier, protecting the fetus from microbial exposure and supporting the consensus that term fetuses develop in a sterile intrauterine environment [12]. This theory forms the basis for cesarean section rederivation, which has been considered the gold standard for obtaining germ-free mice. The procedure involves delivering fetuses via sterile C-section from specific pathogen-free (SPF) donor females, disinfecting the uterine sac, and immediately transferring the pups into a sterile isolator where they are hand-reared or fostered by a GF mother [12].

However, this method presents significant challenges. Vertical transmission of microbes can occur during the birthing process itself, potentially compromising the germ-free status of the newborns. Furthermore, the "sterile womb" hypothesis is continually re-evaluated, with ongoing research investigating potential microbial presence at the maternal-fetal interface [23]. While the placenta has evolved robust mechanisms of microbial defence, the risk of contamination during C-section derivation remains non-negligible.

Aseptic embryo transfer addresses this fundamental problem by completely bypassing the birth canal and any associated vertical transmission. By transferring embryos that have been surgically collected or produced via in vitro fertilization (IVF) directly into the uterus of a pseudopregnant GF surrogate, the developing offspring are never exposed to the maternal microbiota of the biological donor mother. This method offers a more controlled and secure pathway for establishing authentic germ-free animal models, which are indispensable for studying host-microbe interactions in health and disease [18] [24].

Comparative Analysis: Embryo Transfer vs. Caesarean Section

When establishing germ-free colonies, researchers primarily rely on two core techniques: sterile cesarean section and aseptic embryo transfer. The following table summarizes the key distinctions between these methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Germ-Free Mouse Generation Techniques

| Feature | Sterile Cesarean Section (C-Section) | Aseptic Embryo Transfer |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Intercepts and surgically removes fetuses at term, just before natural birth. | Bypasses the birth canal entirely by transferring early-stage embryos into a GF surrogate. |

| Primary Mechanism for Preventing Microbial Transfer | Physical removal of pups from the uterine environment before contact with the vaginal canal. | Complete avoidance of the vaginal birth process and associated microflora. |

| Control Over Timing | Variable; dependent on natural mating cycles and precise prediction of delivery [12]. | High; enables precise scheduling via IVF or timed mating of donors [12]. |

| Fetal/Neonatal Survival Rate | Can be optimized (e.g., FRT-CS method improves survival) but is generally variable [12]. | Historically lower (~50% of transferred embryos result in live births [12]), but highly protocol-dependent. |

| Technical Complexity & Required Expertise | Requires advanced surgical skill for rapid, aseptic pup extraction and revival. | Requires sophisticated skills in embryo handling, transfer surgery, and often IVF. |

| Risk of Microbial Contamination | Moderate; risk exists during uterine extraction and pup revival. | Low; embryos are typically washed in sterile media before transfer, minimizing contaminant carryover. |

| Impact on Surrogate's Reproductive Tract | The female reproductive tract can be preserved with optimized techniques (FRT-CS) [12]. | Minimally invasive procedure for the surrogate. |

As illustrated, embryo transfer provides a fundamentally more direct method for circumventing vertical transmission, though it requires a different set of technical competencies and can present challenges in achieving high survival rates.

Experimental Protocol: Aseptic Embryo Transfer for GF Mouse Production

The following section details a standardized protocol for generating germ-free mice via embryo transfer, integrating best practices and insights from current research.

The entire process, from donor selection to weaning, must be meticulously planned and executed under strict aseptic conditions. The following diagram visualizes the core workflow.

Detailed Methodologies

1. Donor Selection and Embryo Production:

- Donor Mice: Use healthy SPF female mice (e.g., C57BL/6, BALB/c) as embryo donors. Their microbial status should be thoroughly characterized.

- Embryo Source: Embryos can be obtained via natural mating (NM) with SPF males or, preferably, in vitro fertilization (IVF). IVF offers superior control over the timing of embryo development, which enhances experimental reproducibility and allows for precise scheduling of the transfer procedure [12]. Superovulation of donors with gonadotropins may be employed to increase embryo yield.

2. Embryo Collection and Preparation:

- Collection: At the appropriate developmental stage (e.g., two-cell stage), euthanize donor females and surgically flush embryos from the oviducts using sterile flushing media.

- Washing: A critical step for decontamination. Embryos must be washed through several drops of sterile, pre-equilibrated culture medium to remove any potential adherent contaminants from the reproductive tract. This process leverages a significant dilution factor to minimize the risk of pathogen carryover [25].

3. Preparation of Germ-Free Surrogate:

- Surrogate Mothers: Use proven GF female mice that have successfully given birth previously. Strains like BALB/c and NSG have been shown to exhibit superior nursing and weaning success compared to others like C57BL/6J in a GF environment [12].

- Pseudopregnancy: Mate GF females with vasectomized GF males to induce a pseudopregnant state, which provides a receptive uterine environment for embryo implantation. The day of observing a vaginal plug is designated as E0.5 (embryonic day 0.5).

4. Surgical Embryo Transfer:

- Aseptic Technique: The entire procedure must be performed within a sterile isolator or using a laminar flow hood with strict aseptic surgical protocol.

- Procedure: Anesthetize the pseudopregnant surrogate. Make a small midline incision, exteriorize the uterine horn, and carefully transfer the washed embryos into the uterine lumen using a glass transfer pipette. The surgical field and instruments must be sterile to prevent introduction of contaminants.

5. Post-Transfer Care and Validation:

- Gestation and Birth: Following surgery, the surrogate is returned to the sterile isolator and monitored throughout gestation. The resulting pups are born naturally to the GF surrogate, thereby bypassing any vertical transmission from the biological SPF mother.

- Germ-Free Validation: The germ-free status of the offspring must be rigorously confirmed post-weaning using a combination of culture-based methods, 16S rRNA gene PCR, and serological testing to ensure the absence of bacteria, viruses, and fungi [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of this technique relies on the use of specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The following table catalogues the essential components.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Germ-Free Embryo Transfer

| Reagent / Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SPF Donor Mice | Source of high-quality, pathogen-free oocytes and embryos. | Select strains with known high response to superovulation. Maintain strict SPF housing conditions. |

| Hormones for Superovulation | (e.g., PMSG, hCG) to stimulate production of multiple oocytes in donor females. | Timing and dosage are critical for optimal yield and developmental competence of embryos. |

| Sterile Embryo Flushing & Culture Media | For collection, washing, and short-term in vitro culture of embryos. | Media must be pre-warmed and equilibrated for pH and osmolality. Washing is a key decontamination step. |

| Germ-Free Surrogate Dams | To carry and give birth to the derived GF pups. | BALB/c and NSG strains are recommended for superior maternal care in isolators [12]. |

| Liquid Nitrogen Storage System | For long-term cryopreservation and banking of embryos. | Use high-security straws/vials to mitigate cross-contamination risks [25]. |

| Sterile Surgical Suite & Isolator | Provides the controlled, aseptic environment for all procedures involving GF animals. | Includes isolators, laminar flow hoods, and sterilized surgical instruments. |

| Disinfectants (e.g., Clidox-S) | For sterilizing the exterior of materials entering the isolator and the surgical field. | Must be freshly prepared and activated according to manufacturer specifications [12]. |

| SCD1 inhibitor-1 | SCD1 inhibitor-1, MF:C21H22N3NaO3S2, MW:451.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| GSK717 | GSK717, MF:C28H28N4O2, MW:452.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Embryo transfer stands as a powerful and principled biological strategy for bypassing vertical microbial transmission in the production of germ-free mice. While the sterile cesarean section remains a valuable tool, the embryo transfer technique offers a more direct and secure method for ensuring that offspring are free from maternal microbiota from the moment of "birth" within the germ-free isolator. By adhering to the detailed protocols and utilizing the essential reagents outlined in this guide, researchers can reliably generate authentic germ-free models. These models are crucial for advancing our mechanistic understanding of host-microbe interactions across fields including immunology, neurology, and reproductive biology [18] [24] [26]. As the field progresses, refining these protocols to improve efficiency and survival rates will further solidify embryo transfer as a cornerstone technique in germ-free science.

The production of germ-free mice is a cornerstone of modern microbiome research, enabling scientists to move from correlative observations to causal mechanistic studies of host-microbiome interactions [8] [19]. The process begins with the acquisition of sterile embryos, making superovulation and embryo harvesting the critical first step in this sophisticated pipeline. Superovulation is a technique designed to induce female mice to produce a higher-than-normal number of oocytes, thereby maximizing embryo yield for subsequent procedures [27]. These embryos serve as the foundational material for either embryo transfer into germ-free surrogate dams or for in vitro fertilization (IVF) techniques, both established methods for deriving germ-free mouse colonies [12] [28] [8].

This initial step is paramount for the entire germ-free production workflow. The quality, quantity, and sterility of the harvested embryos directly influence the success rate of establishing a germ-free colony. Consistent with the broader thesis on germ-free mouse production, this guide details the technical protocols for superovulation and embryo harvesting, framing them within the stringent requirements of gnotobiotic research [12].

The Role of Superovulation in Germ-Free Mouse Production

Superovulation is a critical technique for obtaining a sufficient number of embryos for germ-free derivation. In the context of germ-free mouse production, two primary methods are employed: aseptic embryo transfer and sterile cesarean section [12] [28]. Superovulation directly feeds into the first method and enhances the efficiency of the second by ensuring a robust supply of embryos.

While cesarean section has traditionally been the "golden method," embryo transfer is increasingly favored for germ-free derivation because it eliminates the risk of transplacental contamination from pathogens such as Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV) and Pasteurella pneumotropica [8]. Furthermore, integrating IVF with superovulation allows for precise control over donor delivery dates, significantly enhancing experimental reproducibility and scheduling efficiency in a germ-free facility [12].

The following workflow illustrates how superovulation and embryo harvesting integrate into the comprehensive process of germ-free mouse production:

Superovulation Protocol: A Detailed Methodology

The superovulation protocol involves the coordinated administration of exogenous hormones to synchronize and amplify the natural ovulatory cycle [27]. The following section outlines the standard reagents, animals, and a step-by-step procedure.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful superovulation requires precise preparation and use of specific hormonal reagents.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Mouse Superovulation

| Reagent/Material | Function and Key Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Pregnant Mare's Serum Gonadotropin (PMSG) | Acts as a follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) analog, initiating the recruitment and development of multiple ovarian follicles [27]. |

| Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) | Mimics luteinizing hormone (LH), triggering final oocyte maturation and ovulation approximately 48 hours after PMSG administration [27]. |

| Sterile Saline or PBS | Diluent used for reconstituting lyophilized hormone powders and for preparing injection aliquots [27]. |

| Young Female Mice (4-5 weeks old) | Donor animals at this pre-pubertal age are highly responsive to exogenous gonadotropins, leading to higher oocyte yields [27]. |

Hormone Preparation and Injection Protocol

The protocol below is adapted from established, high-efficiency methods used for the C57BL/6 background, a common strain in germ-free research [27].

Hormone Reconstitution and Aliquot Preparation:

- PMSG: Reconstitute a lyophilized vial (2000 IU) with 2 mL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or 0.9% saline. This creates a stock concentration of 1000 IU/mL. Aliquot 50 µL (50 IU) into individual conical tubes and store at -80°C [27].

- hCG: Reconstitute a lyophilized vial (10,000 IU) with 10 mL of sterile PBS or saline. This creates a stock concentration of 1000 IU/mL. Aliquot 50 µL (50 IU) into individual conical tubes and store at -80°C [27].

Injection Preparation and Administration:

- For use, thaw one aliquot each of PMSG and hCG.

- Dilute each 50 µL aliquot with 950 µL of sterile PBS, resulting in a final concentration of 5 IU per 0.1 mL injection volume.

- Administer all injections intraperitoneally (IP) [27].

Timing and Scheduling

Coordinating the injection schedule with the animal's light cycle is critical for maximizing the superovulation response. The timing of hormone injections relative to the light-dark cycle must be meticulously planned.

Table 2: Example Superovulation Schedules for Donor Mice

| Schedule Option | PMSG Injection | hCG Injection | Mating with Males | Embryo Collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Option 1 | Day 1, 1:00 p.m. | Day 3, 11:00 a.m. | Day 3, 2:30 p.m. | Morulae: Day 2.5 dpcBlastocysts: Day 3.5 dpc [27] |

| Option 2 | Day 1, 3:00 p.m. | Day 3, 1:00 p.m. | Day 3, immediately post-hCG | Morulae: Day 2.5 dpcBlastocysts: Day 3.5 dpc [27] |

| Notes | Initiates follicular growth. | Triggers ovulation ~48 hours after PMSG. | Females are placed with fertile males; check for vaginal plug the next morning. | dpc = days post coitum. Collection timing depends on desired embryonic stage [27]. |

Embryo Harvesting and Post-Collection Processing

Following successful mating, embryos are harvested at specific developmental stages suitable for germ-free derivation.

- Harvesting Morulae (2.5 dpc): Embryos are typically collected from the oviducts by flushing with a suitable medium. They can be incubated in vitro overnight to develop into blastocysts for injection the following day [27].

- Harvesting Blastocysts (3.5 dpc): Embryos are collected from the uterus. These can be used shortly after collection for injections or other procedures [27].

- Sterility Considerations: For germ-free production, all collection media and instruments must be sterile. The collected embryos are handled under aseptic conditions in preparation for the next step, which is either surgical transfer into a germ-free pseudopregnant dam or aseptic loading into a germ-free shipper for transport to a gnotobiotic facility [8].

Troubleshooting and Optimization for Germ-Free Research

Several factors can influence the efficiency of superovulation and the quality of harvested embryos, which is crucial for downstream germ-free derivation.

- Strain Variability: The C57BL/6 strain is commonly used, but response to superovulation can vary between genetic backgrounds. Protocols may require optimization for different strains [27] [12].

- Donor Age and Health: Using females that are ~4-5 weeks of age (12-16 grams) is optimal. Donors must be healthy and free from pathogens that could compromise embryo viability or sterility [27].

- Hormone Quality and Storage: Proper reconstitution, aliquoting, and storage at -80°C are essential to maintain hormone efficacy. Repeated freeze-thaw cycles should be avoided [27].

- Integration with IVF: To achieve precise control over delivery timing for cesarean derivation, using IVF-derived donor mothers is highly effective. This involves creating embryos via IVF from superovulated donors and then implanting them into synchronized recipients, allowing for scheduled pre-labor C-sections [12].

Superovulation and the subsequent harvesting of donor embryos represent the foundational first step in the multi-stage process of germ-free mouse production. A meticulously executed protocol, paying close attention to hormone preparation, timing, and animal selection, ensures a high yield of quality embryos. These embryos are the primary source material for either aseptic embryo transfer or timed cesarean section, the two principal methods for establishing a germ-free colony. By mastering this initial step, researchers can significantly enhance the efficiency and reproducibility of generating these invaluable animal models, thereby powering rigorous investigations into the causal relationships between the microbiome and host physiology, immunology, and disease.

This guide details the procedures for the aseptic handling and in vitro culture (IVC) of embryos, a critical step in the production of germ-free mice via embryo transfer. The successful generation of germ-free mice is paramount for studying host-microbiome interactions, and the use of in vitro fertilization (IVF) has been shown to enhance the efficiency of this process by providing precise control over embryo development and donor delivery dates [12]. Mastery of these techniques allows researchers to obtain contamination-free embryos and cultivate them to a stage suitable for transfer into germ-free recipients, thereby ensuring the integrity of the germ-free status.

The following sections provide a comprehensive technical protocol, from the core principles of aseptic technique to the detailed methodology of embryo culture, culminating in the surgical transfer of embryos into pseudopregnant germ-free dams.

Core Concepts and Workflow

The entire process, from oocyte collection to the preparation of embryos for transfer, must be conducted under strict aseptic conditions to prevent microbial contamination that would compromise the germ-free status of the resulting offspring [29]. The workflow involves the collection of oocytes and sperm, in vitro fertilization, and the subsequent culture of the resulting embryos to the blastocyst stage, at which point they are ready for transfer.

The diagram below illustrates the complete experimental workflow for the aseptic handling and culture of embryos.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Aseptic Technique and Setup

Maintaining a sterile environment is the foundation of germ-free research. All procedures must be performed within a laminar flow hood to ensure an aseptic work area [30]. All instruments that will contact the embryos, such as forceps and scissors, must be sterilized by autoclaving before use [29]. Similarly, all solutions, including media and sterilants, must be filtered through a 0.22 μm filter [30]. Personnel must wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), and the use of a stereomicroscope within the sterile field is essential for all manipulations of oocytes and embryos [12] [30].

Protocol for In Vitro Culture (IVC) of Embryos

This protocol describes the method for culturing presumptive zygotes through to the blastocyst stage, adapted for the production of germ-free mice.

1. Preparation of Culture Media and Dishes

- Prepare culture media appropriate for pre-implantation mouse embryo development.

- Equilibrate all media in a CO₂ incubator set to 5% CO₂ and 37°C for at least 4 hours, and preferably overnight, before use [30].

- Prepare culture dishes, such as 4-well dishes, by placing microdrops of equilibrated culture medium under pre-warmed mineral oil to prevent evaporation [30].

2. Washing and Placing Embryos

- Following IVF and confirmation of fertilization, presumptive zygotes must be washed to remove any residual components.

- Using a cell strainer (e.g., 70 μm or 100 μm) can provide a unique and efficient method for washing and moving a large number of zygotes between dishes [30].

- After washing, transfer groups of zygotes into the pre-equilibrated culture microdrops. A typical group size is 10-30 embryos per drop.

3. Incubation and Monitoring

- Place the culture dish into the CO₂ incubator (5% CO₂, 37°C).

- Culture the embryos for approximately 3.5 to 5 days, monitoring development at 24-hour intervals.

- Expected developmental milestones:

- Day 1: Cleavage to the 2-cell stage.

- Day 2-3: Progression to the morula stage.

- Day 4-5: Formation of the blastocyst.

- Assess and record the rates of cleavage and blastocyst formation to evaluate the success of the IVC system.

Quantitative Outcomes and Performance Metrics

The efficiency of the IVC process is critical for planning subsequent embryo transfers. The table below summarizes typical performance metrics for in vitro embryo production systems.

Table 1: Expected Performance Metrics for Bovine and Mouse Embryo Culture*

| Metric | Bovine Model Performance [30] | Expected Mouse Model Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Cleavage Rate | >70% | >80% |

| Blastocyst Rate | >20% | 30-60% |

| Key Technique | Use of cell strainer for washing | Aseptic technique throughout |

| Culture Duration | Up to blastocyst stage (~7-9 days) | Up to blastocyst stage (~3.5-5 days) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following reagents and materials are essential for executing the aseptic handling and culture of embryos.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Embryo Handling and Culture

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Oocyte Washing Medium | To wash and handle oocytes after collection. | Often contains Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [30]. |

| Fertilization Medium | To support the process of in vitro fertilization. | Typically includes compounds like caffeine and heparin to enhance sperm capacitation [30]. |

| Culture Medium | To support embryonic development from zygote to blastocyst. | Sequential media may be used for different pre-implantation stages. |

| Mineral Oil | To overlay culture media drops preventing evaporation and pH shifts. | Should be equilibrated with the culture media [30]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A common protein supplement in media to support embryo development. | Used in washing and culture media [30]. |

| Cell Strainers (70-100 μm) | To efficiently wash and transfer groups of oocytes/zygotes between dishes. | A unique protocol step for handling large numbers of embryos [30]. |

| Water-Jacketed CO₂ Incubator | To provide a stable environment (37°C, 5% CO₂) for embryo culture. | Critical for maintaining correct pH and temperature [30]. |

| RSV-IN-4 | RSV-IN-4, CAS:862825-89-6, MF:C18H18N2O2S, MW:326.41 | Chemical Reagent |

| Helioxanthin 8-1 | Helioxanthin 8-1, MF:C20H12N2O6, MW:376.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integration with Germ-Free Mouse Production

The culmination of this step is the transfer of the in vitro-produced blastocysts into a prepared germ-free recipient female. This requires a pseudopregnant germ-free dam, which is generated by mating a germ-free female with a vasectomized germ-free male [12] [28]. The embryo transfer itself is a surgical procedure that must be performed with strict aseptic technique, either entirely within a sterile isolator or in a biosafety cabinet with subsequent return of the animal to the isolator [28]. The success of this integrated approach is evidenced by studies where IVF-derived donor mothers successfully underwent cesarean section to obtain germ-free pups, highlighting the role of IVF in providing precise control over delivery timing for germ-free production [12].

This section details the preparation of two essential components for germ-free mouse production via embryo transfer: sterile males to induce pseudopregnancy and recipient females that will carry the transplanted embryos.

Production of Sterile Males

Sterile males are required to mate with recipient females to induce a pseudopregnant state, creating a receptive uterine environment for transferred embryos. Two primary methods are employed.

Table: Comparison of Sterile Male Production Methods

| Method | Key Feature | Procedure | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical Vasectomy | Physical interruption of sperm delivery [31] | Ligation/cauterization of vas deferens [31] | Well-established, reliable protocol [31] | Invasive surgery, requires analgesia, post-op recovery [31] |