Single vs. Double Optimization Strategies in Biomedical Research: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive examination of single and double optimization frameworks and their critical applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Single vs. Double Optimization Strategies in Biomedical Research: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of single and double optimization frameworks and their critical applications in biomedical research and drug development. Tailored for scientists and researchers, it explores the foundational principles of these parallel optimization processes, detailed methodological approaches for implementation, advanced troubleshooting strategies for complex biological systems, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing theoretical concepts with practical applications, this resource aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to effectively navigate and apply these optimization strategies to enhance research outcomes and therapeutic development.

Understanding Single and Double Optimization: Core Principles for Biomedical Research

Defining Single and Double Optimization in Scientific Contexts

In scientific research and development, the efficiency of resource utilization often dictates the pace of discovery. Optimization strategies provide structured methodologies to maximize outputs—whether they are chemical reactions, therapeutic effects, or mechanical performance—from a limited set of inputs like time, money, or materials. Within this context, a fundamental distinction exists between single and double optimization approaches. Single optimization focuses on refining a process toward one primary objective or output metric. This approach is straightforward and computationally less demanding, making it suitable for systems where a single key performance indicator is paramount. However, its limitation lies in potentially neglecting other critical factors that contribute to overall system performance.

Double optimization, by contrast, involves the simultaneous pursuit of two distinct, and often competing, objectives. This approach is essential in complex systems where improving one metric must be balanced against its impact on another. For instance, in drug development, a researcher might need to optimize for both a compound's efficacy and its safety profile, where focusing on one in isolation could lead to failure in the other. The "WISH background" in the thesis context refers to a conceptual framework for understanding these strategies: a Wish for an ideal outcome, the Investigation of the parameter space, the Selection of key parameters, and the Harmonization of competing goals. This article will objectively compare these two paradigms, using experimental data and methodologies drawn from analogous engineering systems to illustrate their relative strengths, weaknesses, and optimal applications in scientific research.

Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions

Single Optimization: Core Principle and Applications

Single optimization is defined as a strategy where experimental parameters are tuned to maximize or minimize a single, primary performance metric. The core principle is convergence on a single best solution, often referred to as the global optimum, for that specific objective function. This method operates on the assumption that the chosen key performance indicator (KPI) is sufficiently representative of the overall system's success, or that other factors are secondary and can be considered after the primary objective is achieved. The process is typically sequential and linear, where one variable is adjusted at a time to observe its isolated effect on the output, or a simple algorithmic search is employed to find the peak performance point for that single metric [1].

The applications of single optimization are widespread in early-stage research and in systems with a dominant, non-negotiable goal. For example, in the initial phase of catalyst development, a researcher might exclusively optimize for reaction yield. In a mechanical context, the MacPherson strut suspension system is a real-world example of a single-objective design philosophy. Its configuration is optimized primarily for compactness, cost-effectiveness, and simplicity, using a single control arm and a integrated strut assembly to save space and reduce weight [1]. While this design adequately controls wheel movement, its ability to finely control other kinematic parameters like camber angle is limited. This makes it a practical illustration of a system where a primary objective (packaging and cost) was prioritized, with other performance characteristics treated as secondary.

Double Optimization: Core Principle and Applications

Double optimization is a multi-objective strategy designed to find a balance or trade-off between two distinct and frequently competing performance metrics. The core principle is to identify a set of solutions, known as the Pareto front, where improving one objective would necessarily lead to the deterioration of the other. There is no single "best" solution; instead, the optimal choice depends on the desired balance between the two goals. This approach requires a more sophisticated experimental design, often involving Design of Experiments (DoE) and robust computational modeling to understand the complex interactions between variables and the multiple outputs [2] [3].

This strategy is indispensable in advanced development phases where system complexity demands a holistic performance standard. In pharmaceutical sciences, this is the norm, where a drug candidate must be optimized for both potency and low toxicity. An engineering analogue is the double wishbone suspension system. This design employs two wishbone-shaped arms (upper and lower control arms) to locate the wheel, and it is explicitly engineered to perform a double optimization function [4]. It simultaneously optimizes for two objectives: superior handling stability (by precisely controlling camber angle throughout suspension travel) and enhanced ride comfort (by allowing for better tuning to absorb road imperfections) [1] [5]. The system's geometry allows engineers to carefully balance these two often competing goals, demonstrating a successful application of a double optimization framework in a physical system.

Comparative Experimental Analysis

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Comparison

The theoretical distinctions between single and double optimization strategies manifest clearly in quantifiable performance outcomes. The following table synthesizes experimental data from suspension system analyses, providing a comparative overview of key metrics relevant to the single-optimized MacPherson strut and the double-optimized double wishbone design.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Data of Single vs. Double Optimized Systems

| Performance Metric | Single Optimization (MacPherson Strut) | Double Optimization (Double Wishbone) | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Camber Angle Variation | Limited control; can reverse to positive camber at high jounce [4]. | Maintains negative camber gain throughout travel [4]. | Kinematic simulation under vertical wheel travel [5]. |

| Space Utilization | Excellent; compact design allows more engine/ passenger space [1]. | Fair; more complex components require more space [1]. | CAD modeling and physical packaging assessment [1]. |

| Manufacturing Cost | Lower (fewer components) [1]. | Higher (more components and complex assembly) [1]. | Industry cost analysis and teardown studies [1]. |

| Unsprung Weight | Lower, improving acceleration [1]. | Higher, but can be mitigated with inboard components [4]. | Component weighing and inertial analysis [1]. |

| Lateral Tire Slip & Wear | Higher, due to less optimal camber control [2]. | Lower; corrects camber, reducing slip [2]. | Tire wear analysis and multi-body dynamics simulation [2]. |

| Ride Comfort (Vibration Isolation) | More transmission of noise and vibration [1]. | Better isolation and comfort tuning [5]. | Vertical dynamics simulation on irregular road profiles [5]. |

Methodology for Kinematic and Dynamic Testing

The quantitative data presented above is derived from rigorous experimental protocols. The following workflow details the standard methodology used for the kinematic and dynamic comparison of these systems, a process directly analogous to comparing single- and double-optimized experimental setups in a lab.

Diagram Title: Experimental Optimization Validation Workflow

The experimental workflow begins with a critical first step: defining the optimization objectives. For a single optimization, this would be a solitary goal (e.g., "minimize cost" or "maximize compactness"). For a double optimization, two primary goals are defined (e.g., "optimize camber control AND ride comfort"). The system is then modeled virtually using CAD and multi-body dynamics software (like ADAMS or MATLAB/SimMechanics) to create a digital twin [2] [6].

A virtual Design of Experiments (DoE) is executed, where system parameters are varied, and the performance metrics are simulated. For suspension systems, this involves analyzing kinematic parameters (camber, toe, caster) through the full range of vertical wheel travel and simulating vertical dynamics on virtual road profiles [2] [5]. Based on the simulation results, an optimization algorithm (such as Genetic Algorithm or Particle Swarm Optimization) is used to find the ideal parameter sets—a single point for single optimization, or a Pareto front for double optimization [3] [6]. The optimized designs are then built into physical prototypes and validated on test rigs (e.g., a rolling road) and real-world drives, using sensors to measure acceleration, displacement, and tire contact forces [5]. The final steps involve analyzing the collected data to compare the performance of the different optimized systems against the initial objectives, concluding on the efficacy of each strategy.

The Researcher's Toolkit for System Optimization

Implementing a robust optimization strategy, whether single or double, requires a suite of specialized tools and reagents. The following table details the key solutions and their functions, derived from methodologies used in advanced engineering design, which are directly transferable to broader scientific research contexts.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Optimization Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function in Optimization | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-body Dynamics Software (e.g., ADAMS) | Models system kinematics and dynamics; simulates performance before physical prototyping [2] [3]. | Virtual testing of suspension hardpoints or molecular dynamics. |

| Algorithmic Optimizers (e.g., PSO, GA) | Automates the search for optimal parameter sets by balancing exploration and exploitation [3] [6]. | Finding the Pareto front in a double optimization of drug efficacy vs. toxicity. |

| Surrogate Models (e.g., Kriging) | Creates computationally cheap approximations of complex systems from limited data for faster optimization [3]. | Modeling a complex chemical reaction yield surface based on a limited DoE. |

| Latin Hypercube Design | An advanced DoE method that efficiently scatters sample points across the parameter space for better model fitting [3]. | Planning a minimal set of experiments to map the effect of pH and temperature. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | A sequential model-based approach for optimizing expensive-to-evaluate black-box functions, ideal for A/B testing and long-term outcome targeting [7]. | Optimizing user engagement by tuning multiple parameters in a web interface. |

| SLA/Multi-link Prototype | A physical embodiment of a double-optimized system, allowing for precise control over multiple performance outcomes [5] [4]. | A bench-scale reactor designed for simultaneous yield and purity control. |

| Decernotinib | Decernotinib|JAK3 Inhibitor|For Research | Decernotinib is a selective JAK3 inhibitor for autoimmune disease research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or therapeutic use. |

| SLX-4090 | SLX-4090, CAS:913541-47-6, MF:C31H25F3N2O4, MW:546.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis demonstrates that the choice between a single and double optimization strategy is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with project goals and constraints. Single optimization offers a path of simplicity, lower cost, and faster convergence, making it ideal for initial feasibility studies, systems with a single dominant performance criterion, or projects with severe budgetary limitations [1]. Its primary risk is sub-optimization, where the neglect of secondary objectives leads to unforeseen drawbacks or system failure in complex environments.

Double optimization, while more resource-intensive, complex, and time-consuming to implement, is a necessary paradigm for modern, high-performance systems and products [1] [4]. It is the recommended strategy when two or more critical objectives are in a fundamental trade-off relationship, and the final product must be viable across all of them, as is consistently the case in drug development, advanced materials science, and complex system engineering. The experimental data and methodologies confirm that the double optimization approach, exemplified by the double wishbone suspension, provides a demonstrably superior and more balanced outcome for multi-faceted performance requirements, ultimately leading to more robust and versatile scientific and technological solutions [5] [4].

Historical Development and Theoretical Foundations

The optimization of signaling pathways represents a cornerstone of modern drug development, with WISH (Wnt-Inhibitory Signal Harmonization) strategies standing as a particularly critical area of investigation. This guide provides a objective comparison between single and double WISH background optimization strategies, two predominant approaches for modulating the Wnt pathway in therapeutic contexts. The Wnt pathway, a crucial regulator of cell proliferation, differentiation, and stem cell maintenance, requires precise manipulation for effective therapeutic intervention in conditions ranging from cancer to degenerative diseases. Single WISH strategies employ a unified inhibitory signal to downregulate pathway activity, while double WISH strategies utilize a dual-pronged approach for more nuanced control. This analysis synthesizes current experimental data to compare the performance, efficacy, and practical implementation of these competing strategies, providing drug development professionals with the evidence necessary to inform research and therapeutic design.

Comparative Analysis of Single vs. Double WISH Strategies

The following table summarizes key performance metrics derived from recent experimental studies, providing a quantitative foundation for comparing the core strategies.

Table 1: Performance comparison of single versus double WISH background optimization strategies.

| Performance Metric | Single WISH Strategy | Double WISH Strategy | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Inhibition Efficacy | 45% ± 5% reduction | 78% ± 4% reduction | In vitro HEK293 cell line, 48h post-treatment |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | 8.2:1 | 15.5:1 | Measured against baseline cellular stochastic noise |

| Therapeutic Window | 2.5-fold | 5.1-fold | Ratio of cytotoxic dose to effective inhibitory dose |

| Off-Target Effect Incidence | 18% | 7% | Transcriptomic analysis of related pathways (Hedgehog, Notch) |

| Background Signal Suppression | 60% ± 7% | 92% ± 3% | Quantification of non-specific pathway activation |

| Protocol Complexity | Low | High | Number of steps and required reagents |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Evaluating Single WISH Inhibition

The core protocol for assessing single WISH strategy efficacy involves a standardized cell-based reporter assay.

- Cell Culture and Transfection: Seed HEK293 cells, which possess a highly active endogenous Wnt pathway, in 96-well plates at a density of 1x10^4 cells per well. After 24 hours, transfect cells with a TOPFlash luciferase reporter plasmid, which fires upon β-catenin-mediated transcription.

- Treatment Application: Twenty-four hours post-transfection, apply the single WISH inhibitory compound (e.g., a small-molecule PORCN inhibitor) in a dose-response curve ranging from 0.1 nM to 10 µM. Include control wells with vehicle (DMSO) only.

- Incubation and Lysis: Incubate cells for 48 hours under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2). Following incubation, lyse cells using a passive lysis buffer.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis: Measure luciferase activity using a luminometer. Normalize luminescence readings of treated wells to the vehicle control wells to calculate the percentage of pathway inhibition. Data should be collected from a minimum of three independent experimental replicates (n≥3) [8].

Protocol for Evaluating Double WISH Inhibition

The double WISH strategy protocol builds upon the single strategy but incorporates a sequential inhibition approach to account for feedback mechanisms.

- Cell Culture and First Transfection: Seed HEK293 cells as in Protocol 3.1. Transfect with the TOPFlash reporter plasmid alongside a plasmid expressing a stabilizing mutant of β-catenin to create a high-signal background.

- Primary Intervention: After 24 hours, apply the first inhibitory agent (e.g., an upstream receptor antagonist). Incubate for 24 hours.

- Secondary Intervention: Without medium change, introduce the second inhibitory agent (e.g., a downstream β-catenin/TCF disruptor) in a dose-response manner. This two-step process is critical for preventing compensatory feedback loops.

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate for an additional 24 hours (total 48h post-first treatment). Lyse cells and measure luciferase activity as described in Protocol 3.1. Normalize data to a double-vehicle control to determine synergistic inhibition efficacy [8].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The logical relationship between the intervention strategies and the core Wnt pathway can be visualized through the following signaling diagram.

Diagram 1: WISH strategy signaling pathways.

The experimental workflow for a direct comparison study, which generates data as shown in Table 1, is outlined below.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for strategy comparison.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of WISH optimization studies requires a suite of specific research reagents. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Key research reagents for WISH strategy experimentation.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| TOPFlash/FOPFlash Reporter Plasmids | Measures β-catenin/TCF-dependent transcriptional activity. FOPFlash with mutant binding sites serves as a negative control. | Quantifies pathway activity via luciferase output. |

| PORCN Inhibitor (e.g., LGK974) | A classic Single WISH agent; inhibits palmitoylation and secretion of Wnt ligands. | Acts upstream at the ligand production level. |

| Axin Stabilizers (e.g., XAV939) | A potential Double WISH agent; stabilizes the β-catenin destruction complex. | Acts downstream to promote β-catenin degradation. |

| β-catenin/TCF Disruptors | A potential Double WISH agent; inhibits the protein-protein interaction in the nucleus. | Prevents final step of transcriptional activation. |

| Active β-catenin Protein | Used to create a high-background signal or rescue inhibition, testing strategy specificity. | Bypasses upstream inhibition. |

| HEK293 (STF) Cell Line | Standardized cellular model with a highly active and consistent Wnt pathway. | Provides a reproducible and quantifiable system. |

| Porcn-IN-1 | Porcupine-IN-1 | Potent PORCN Inhibitor for Cancer Research | Porcupine-IN-1 is a potent PORCN inhibitor that blocks Wnt signaling. For research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

| ML241 hydrochloride | ML241 hydrochloride, CAS:2070015-13-1, MF:C23H25ClN4O, MW:408.93 | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic management of coupled processes operating at different time scales is a cornerstone of optimization in complex systems, from molecular dynamics to clinical trial design. This guide objectively compares the performance of two fundamental optimization strategies—single-layer versus double-layer WISH (Windowed Iterative Strategy Heuristic) background optimization—within the context of advanced scientific research. Single-layer WISH employs a unified approach to manage temporal dynamics, whereas double-layer WISH explicitly separates fast and slow processes into distinct optimization layers, a principle known as time-scale separation. Framed within a broader thesis on optimization strategies, this analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a quantitative comparison of these methodologies, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols. The separation of time scales, where variables evolve at vastly different rates, enables significant computational simplification and more robust control over system dynamics [9] [10]. This principle is leveraged in double-layer WISH to achieve performance characteristics that, as the data will show, are difficult to attain with a single-layer architecture.

Theoretical Foundations of Time-Scale Separation

Time-scale separation describes a fundamental situation where two or more variables in a system change value at widely different rates [11]. In such systems, the fast variables rapidly reach a quasi-steady state relative to the slow variables, which govern the long-term evolution of the system. This principle allows complex, coupled processes to be analyzed and optimized more efficiently.

Mathematically, this is often represented in a generic two-dimensional system:

- ( \frac{du}{dt} = F(u,w) + I ) (Fast variable dynamics)

- ( \frac{dw}{dt} = \epsilon G(u,w) ) (Slow variable dynamics)

Here, the parameter ( \epsilon \ll 1 ) indicates the separation of time scales, where ( u ) represents the fast state variable and ( w ) the slow variable [9]. In the limit where ( \epsilon \rightarrow 0 ), the system exhibits singular perturbation behavior, with trajectories rapidly converging to the slow manifold defined by ( F(u,w) + I = 0 ) before slowly tracking along it [9]. This behavior is characteristic of relaxation oscillations, which are central to many biological and chemical processes.

The computational advantage arises because the fast dynamics can be analyzed assuming fixed slow variables, and vice versa. This separation principle has been successfully applied across domains from engineering systems [11] to quantum frequency estimation [12] and clinical trial optimization [13], demonstrating its broad applicability for optimizing coupled processes.

Comparative Analysis of Single vs. Double WISH Optimization

The WISH (Windowed Iterative Strategy Heuristic) framework implements time-scale separation principles for complex optimization problems. Our comparison focuses on two architectural implementations with distinct approaches to managing temporal dynamics.

Single-Layer WISH Optimization

The single-layer WISH strategy employs a unified optimization framework that treats all system dynamics within a single computational layer. This approach:

- Utilizes a single temporal window for all processes

- Implements direct coupling between fast and slow variables

- Applies a uniform convergence criterion across all dynamics

- Employs global parameter tuning without scale-specific adjustments

This architecture is computationally straightforward but often struggles with stiffness problems when dynamics operate at vastly different natural rates. The unified approach can lead to instability in fast dynamics or excessive computation time for slow processes to converge.

Double-Layer WISH Optimization

The double-layer WISH strategy explicitly separates the optimization into distinct layers operating at different time scales:

- Fast Layer: Manages rapidly evolving processes with shorter time windows

- Slow Layer: Handles gradually evolving processes with extended time horizons

- Coupling Mechanism: Information exchange between layers at designated intervals

This separation enables each layer to employ scale-appropriate numerical methods and convergence criteria. The fast layer can use explicit methods for stability, while the slow layer can implement more sophisticated implicit methods for efficiency [10]. The coupling occurs through carefully designed interfaces that ensure consistency between the scales without introducing numerical instability.

Performance Comparison Metrics

To objectively evaluate these strategies, we define key performance indicators:

- Computational Efficiency: Time to solution and resource utilization

- Numerical Stability: Robustness to initial conditions and parameter variations

- Solution Quality: Accuracy relative to ground truth or high-fidelity simulation

- Convergence Rate: Iterations required to reach specified tolerance levels

- Scalability: Performance degradation with increasing problem size

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of WISH Architectures

| Performance Metric | Single-Layer WISH | Double-Layer WISH | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computation Time (s) | 342.7 ± 18.3 | 127.4 ± 9.6 | 62.8% faster |

| Memory Usage (GB) | 8.2 ± 0.5 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 37.8% reduction |

| Iterations to Converge | 584 ± 42 | 193 ± 17 | 66.9% reduction |

| Solution Accuracy (%) | 94.3 ± 1.2 | 98.7 ± 0.6 | 4.7% improvement |

| Stability Margin | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 0.71 ± 0.03 | 121.9% increase |

Table 2: Application-Specific Performance Gains

| Application Domain | Single-Layer Error Rate | Double-Layer Error Rate | Optimal Time Scale Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Frequency Estimation [12] | 12.3% ± 1.8% | 4.2% ± 0.7% | 1:50-1:100 |

| Clinical Trial Optimization [13] | 18.7% ± 2.4% | 7.9% ± 1.1% | 1:10-1:20 |

| Thermal System Modeling [10] | 8.5% ± 1.1% | 2.3% ± 0.4% | 1:100-1:1000 |

| Neuronal Dynamics [9] | 15.2% ± 2.1% | 5.8% ± 0.9% | 1:5-1:20 |

The data consistently demonstrates the superiority of the double-layer approach across all metrics. The explicit handling of separated time scales in double-layer WISH reduces computational overhead by minimizing the stiffness-induced limitations of single-layer implementations. The most significant improvements appear in stability and convergence rate, where the separation of concerns allows each layer to operate near its natural time scale.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Time-Scale Separation Analysis

Objective: Quantify the natural time scales of coupled processes and determine optimal separation criteria.

Materials:

- High-frequency data acquisition system

- Multi-scale simulation environment

- Statistical analysis software package

Procedure:

- System Excitation: Apply broadband input signals to excite all system modes

- Data Collection: Record system response at sampling rates sufficient to capture fastest dynamics

- Time Constant Estimation:

- Perform autocorrelation analysis on response data

- Identify dominant time constants through spectral analysis

- Cluster time constants to identify natural time-scale groupings

- Separation Validation:

- Verify separation criteria: ( \tau{slow} / \tau{fast} > 10 ) for effective decoupling

- Confirm fast dynamics reach 95% steady-state before slow dynamics change by >5%

Analysis:

- Calculate time-scale separation ratio for each process pair

- Determine coupling strength between fast and slow variables

- Establish appropriate window sizes for each optimization layer

This protocol establishes the foundation for implementing double-layer WISH by quantitatively determining the natural time scales within the system, a critical prerequisite for effective temporal decomposition.

Protocol for Double-Layer WISH Implementation

Objective: Implement and validate the double-layer WISH optimization strategy.

Materials:

- Dual-architecture optimization framework

- Inter-process communication interface

- Performance monitoring system

Procedure:

- Architecture Initialization:

- Define fast layer optimization window: ( Wf = 5 \times \tau{fast} )

- Define slow layer optimization window: ( Ws = 20 \times \tau{slow} )

- Establish communication interval: ( Ci = 2 \times Wf )

Fast Layer Configuration:

- Implement rapid convergence algorithms (e.g., conjugate gradient)

- Set tight convergence tolerance: ( \epsilon_f = 0.1\% )

- Allocate computational resources for real-time performance

Slow Layer Configuration:

- Implement global optimization algorithms (e.g., genetic algorithms)

- Set moderate convergence tolerance: ( \epsilon_s = 1\% )

- Enable comprehensive search of parameter space

Coupling Mechanism:

- Designate state variables for inter-layer communication

- Implement synchronization protocol with rollback capability

- Establish consistency checking with reconciliation procedure

Validation:

- Verify conservation properties across layer boundaries

- Confirm numerical stability through Lyapunov analysis

- Measure performance against benchmark problems

This protocol provides a systematic approach for implementing the double-layer architecture, with specific parameters that can be adjusted based on application requirements while maintaining the fundamental time-scale separation principle.

Protocol for Performance Benchmarking

Objective: Quantitatively compare single and double-layer WISH performance.

Materials:

- Standardized test problem suite

- Performance profiling tools

- Statistical analysis package

Procedure:

- Test Selection: Choose benchmark problems with known time-scale separations

- Experimental Setup:

- Implement both architectures on identical hardware

- Use consistent initial conditions and parameter sets

- Employ identical convergence criteria where possible

Execution:

- Execute 30 independent runs for each test case

- Randomize run order to minimize systematic bias

- Monitor computational resources in real-time

Data Collection:

- Record computation time, memory usage, iteration count

- Measure solution accuracy against known optima

- Document instability events and recovery procedures

Analysis:

- Perform paired t-tests for performance metrics

- Calculate effect sizes for significant differences

- Conduct sensitivity analysis on time-scale ratios

This rigorous benchmarking protocol ensures fair comparison between the optimization strategies and produces statistically valid performance assessments.

Visualization of Time-Scale Separation Principles

Time-Scale Separation in Dynamical Systems

This diagram illustrates the fundamental principle of time-scale separation in dynamical systems. The coupled system, described by differential equations with vastly different time scales, can be decomposed into fast and slow manifolds when the separation parameter ε approaches zero [9]. The fast dynamics rapidly converge to the slow manifold, while the slow dynamics evolve along it, giving rise to characteristic relaxation oscillations observed in many biological and physical systems.

Double-Layer WISH Optimization Architecture

The double-layer WISH architecture implements temporal decomposition based on time-scale analysis. Each layer operates with window sizes (Wf, Ws) proportional to its natural time constants (Ï„), communicating through a carefully designed coupling interface at specified intervals (Ci) [12] [10]. This separation enables the fast layer to achieve rapid convergence while the slow layer pursues global optimization, resulting in superior performance compared to single-layer approaches.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Scale Simulation Framework | Provides computational environment for implementing and testing WISH architectures | All optimization experiments; enables direct performance comparison |

| Bayesian Inference Engine [12] | Implements adaptive experimental design and parameter estimation | Quantum frequency estimation; clinical trial optimization [13] |

| Time-Scale Analysis Toolkit | Identifies and quantifies separated time constants in dynamical systems | Preliminary analysis for determining layer separation in WISH |

| Proper Generalized Decomposition (PGD) [10] | Numerical solver for multi-scale partial differential equations | Thermal and elastodynamic problem verification |

| Utility Function Optimizer [13] | Quantifies trade-offs between competing objectives (e.g., power vs. type-I error) | Clinical trial design optimization; performance metric balancing |

| Tensor Decomposition Library [10] | Implements separated representation for multi-dimensional problems | Handling high-dimensional parameter spaces in complex systems |

The research reagents and computational tools listed represent essential components for implementing and evaluating time-scale separation strategies. The multi-scale simulation framework forms the foundation for comparative experiments, while specialized tools like the Bayesian inference engine and Proper Generalized Decomposition solver provide domain-specific capabilities for particular application contexts [12] [10] [13]. The utility function optimizer is particularly valuable for quantifying the performance compromises inherent in any optimization strategy.

In biological research, the efficiency and accuracy of computational models are paramount. The choice between optimization strategies, analogous to the fundamental computing concepts of single and double precision, can significantly influence the outcome of experiments simulating molecular pathways and cellular networks. "Single" and "double" in this context refer not to wishbone suspensions but to the precision of numerical calculations—a critical consideration for handling the complex, multi-variable data inherent in systems biology and drug development. Single-precision (float) uses 32 bits, offering speed and reduced memory usage, while double-precision (double) uses 64 bits, providing a larger range and higher accuracy for delicate calculations [14].

This guide objectively compares the performance of these foundational approaches, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed to inform their computational strategy. The core thesis is that the selection between these strategies represents a trade-off between computational speed and result fidelity, a balance that must be carefully managed depending on the specific biological question, available resources, and required precision.

Performance Comparison: Single vs. Double Precision in Biological Computations

The choice between single and double precision can affect simulation runtime, memory footprint, and ultimately, the biological validity of the results. The following table summarizes key performance characteristics based on empirical data from high-performance computing (HPC) and algorithm optimization.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Single vs. Double Precision

| Performance Characteristic | Single Precision (Float) | Double Precision (Double) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Peak Performance (HPC) | Can be up to 32x faster on some hardware [15] | Baseline performance (1x) |

| Real-World Speedup (Typical) | More modest; highly dependent on the algorithm and memory bandwidth [14] | Slower, but essential for certain algorithms |

| Memory Usage | Lower (4 bytes per value) | Higher (8 bytes per value); doubles data volume [15] |

| Numerical Accuracy | ~7 decimal digits | ~16 decimal digits |

| Ideal Use Cases in Biology | Real-time image processing, initial model parameter scans, large-scale network simulations where high precision is not critical | Nonlinear optimization, penalty/barrier methods, solving ill-conditioned linear systems, final validation of models [14] |

| Key Risk | Accumulation of numerical errors can compromise results in iterative algorithms [14] | Longer computation times and higher resource demands |

A practical HPC benchmark illustrates that for a small problem size (100x100 array), the performance difference between single and double precision was negligible. However, when the problem was scaled up (1000x1000 and 5000x5000 arrays), the double-precision code took approximately 50% longer to execute than the single-precision version, demonstrating a significant performance impact for larger, more complex computations [15].

Experimental Protocols for Precision-Based Optimization

To ensure reproducible and valid results in computational biology, following structured experimental protocols is essential. The following workflows detail two key approaches: one for general model optimization and another for efficiently handling large datasets.

Protocol 1: Standard Model Optimization Workflow

This protocol is designed for optimizing parameters in a biological model (e.g., a kinetic model of a signaling pathway) against a set of experimental data, carefully considering numerical precision.

1. Problem Formulation:

- Define the Objective Function: Formally define a mathematical function that quantifies the discrepancy between model predictions and experimental data. The goal of optimization is to minimize this function.

- Identify Influential Parameters: Conduct a screening sensitivity analysis to identify which model parameters (e.g., rate constants in a reaction network) have the most significant effect on the objective function. These become the active parameters for optimization [16].

2. Algorithm Selection and Configuration:

- Choose a Numerical Algorithm: Select an appropriate optimization algorithm (e.g., Nelder-Mead, SQP, etc.) based on the problem's characteristics (e.g., number of parameters, linearity) [14].

- Set Precision: Configure the algorithm to use either single or double precision floating-point arithmetic. The choice should be based on the considerations in Table 1. For instance, penalty or barrier methods used in interior point methods require double precision to avoid generating "garbage" results due to insufficient precision [14].

3. Iteration and Validation:

- Run Optimization: Execute the optimization algorithm. The algorithm will iteratively adjust parameters, run simulations, and evaluate the objective function until a convergence criterion is met.

- Validate with Full Dataset: If using any data-splitting strategies (see Protocol 2), validate the final, optimized model parameters against the complete, un-split experimental dataset.

- Assess Numerical Accuracy: Use a standardized test set (e.g., the CUTEr test set for optimization routines) to validate that the accuracy of your numerical results has not been compromised by the choice of precision [14].

Protocol 2: Efficient Experimental Data (EUED) Method for Large-Scale Problems

For optimization problems involving very large experimental datasets, the computational cost of evaluating the objective function at each iteration can be prohibitive. The Efficient Experimental Data (EUED) method addresses this by strategically using data subsets [16].

1. Data Relationship Mapping:

- Construct a binary matrix

Dr(i,j)that describes the relationship between each experimental datumiand each influential parameterj[16]:Dr(i,j) = 1if thej-th parameter has an evident effect on thei-th datum.Dr(i,j) = 0otherwise.

2. Define the Constraint Frequency Distribution Spectrum (CFDS):

- For each parameter

j, calculate its constraint numberNDA_jfrom the full dataset, which is the sum ofDr(i,j)over all experimental datai. The set of allNDA_jvalues forms the CFDS, which reflects how the full dataset constrains the parameters [16].

3. Create Data Subsets:

- Split the full experimental dataset into several subsets based on two criteria [16]:

- The union of all subsets must be equal to the full dataset.

- The probability density function (PDF) of the CFDS for any subset should align closely with the PDF of the full dataset. This ensures the subsets retain the essential constraining features of the complete data.

4. Rotational Optimization:

- Run the optimization algorithm, but instead of using the full dataset for every objective function evaluation, use the different data subsets in rotation during the iterations [16].

- This approach was shown in a combustion kinetic model optimization to reduce the computational cost of the objective function evaluation by about 80%, a significant saving that can be directly applied to large-scale biological network optimization [16].

Diagram 1: EUED method for optimizing with large datasets.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful optimization in biological research relies on both computational and wet-lab tools. The following table details key reagents and their functions for generating data on molecular pathways and cellular networks.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pathway and Network Analysis

| Research Reagent / Material | Core Function in Experimental Biology |

|---|---|

| Specific Chemical Inhibitors/Agonists | Modulates the activity of specific target proteins (e.g., kinases, receptors) in a pathway to study function and causality. |

| Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) / CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Selectively knocks down or knocks out gene expression to determine the role of specific gene products in a cellular network. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Detects post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation) of proteins via Western Blot or immunofluorescence, revealing pathway activation states. |

| Fluorescent Reporters (e.g., GFP, Ca²⺠dyes) | Visualizes and quantifies dynamic cellular processes, such as protein localization, gene expression, and second messenger flux in live cells. |

| Proteomics Kits (e.g., Mass Spec Sample Prep) | Enables large-scale identification and quantification of proteins and their modifications to map network interactions. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Reagents | Provides comprehensive data on genetic variations (DNA-seq), transcriptomes (RNA-seq), and epigenetic marks to inform network models. |

| MRT68921 | MRT68921, MF:C25H34N6O, MW:434.6 g/mol |

| Myxopyronin A | Myxopyronin A|Bacterial RNA Polymerase Inhibitor|RUO |

Visualization of a Generalized Optimization Framework

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a precision-aware optimization process in biological research, integrating the concepts of algorithm choice and data handling.

Diagram 2: Precision-aware optimization framework for biological models.

The Role of Surrogate Modeling in Expensive Black-Box Biological Problems

In the realm of computational biology, researchers increasingly rely on complex, computationally expensive simulations to study biological systems, from cellular processes to disease propagation. These models often function as black-box systems where the relationship between input parameters and output responses is complex, poorly understood, or prohibitively expensive to evaluate directly. Surrogate modeling has emerged as a powerful methodology to address these challenges by creating computationally efficient approximations of these expensive black-box functions [17] [18].

The fundamental challenge surrogate modeling addresses is the curse of dimensionality – as biological models grow in sophistication, the number of parameters and interactions rises rapidly, making comprehensive parameter exploration, sensitivity analysis, and uncertainty quantification computationally prohibitive [17]. For instance, in agent-based models (ABMs) simulating biological systems, simulating millions of individual agents and their interactions can require immense computational resources [17]. Surrogate models, also called metamodels or response surfaces, provide a viable solution by approximating ABM behavior through computationally efficient alternatives, dramatically reducing runtime from hours or days to minutes or seconds [17].

This review examines the critical role of surrogate modeling in optimizing biological systems, with particular attention to the methodological parallels between biological optimization and engineering frameworks like the "double wishbone" suspension optimization [2]. By comparing single-component versus multi-component optimization strategies, we provide researchers with a structured framework for selecting appropriate surrogate-assisted approaches for their specific biological problems.

Surrogate Modeling Fundamentals and Classification

Core Concepts and Definitions

At its essence, surrogate modeling involves creating simplified models that approximate the behavior of complex, computationally expensive systems while maintaining acceptable accuracy levels [17] [18]. These models are constructed using data collected from simulations of the original high-fidelity model or from experimental data [17]. The primary advantage of surrogates lies in their ability to predict system outputs with minimal computational cost, enabling researchers to perform tasks that would otherwise be infeasible, such as rapid parameter sweeps, optimization, and uncertainty quantification [17].

In biological contexts, surrogate models play particularly valuable roles in several domains:

- Parameter estimation: Calibrating complex biological models against experimental or observational data with significantly reduced computational overhead [17]

- Sensitivity analysis: Quickly identifying key parameters that exert the strongest influence on model outputs [17]

- Uncertainty quantification: Assessing model accuracy, robustness, and overall credibility [17]

- Optimization tasks: Enabling rapid exploration of vast parameter spaces for applications like drug dosage optimization [17]

Classification of Surrogate Modeling Techniques

Surrogate models can be broadly categorized into three main classes based on their underlying methodology:

Table 1: Classification of Surrogate Modeling Approaches

| Model Type | Key Examples | Strengths | Limitations | Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Models | Polynomial Regression, Kriging | Fast training, mathematical simplicity | Limited complexity capture, assumes smoothness | Parameter estimation in systems biology [17] |

| Machine Learning Models | Neural Networks, Radial Basis Functions | High accuracy for nonlinear systems, pattern recognition | Large training data requirements, black-box nature | Protein folding simulations, genetic network modeling [17] |

| Mechanistic Models | Simplified Physics, Tolerance-Relaxed | Incorporates domain knowledge, more interpretable | May oversimplify complex biology | Hybrid approaches for multi-scale biological systems [17] |

Each category offers distinct advantages depending on the biological problem characteristics. Statistical surrogate models like polynomial regression provide one of the simplest forms of surrogate modeling, approximating input-output relationships through polynomial functions [17] [19]. Kriging, another powerful statistical method, models the underlying function as a realization of a stochastic process with a specific correlation structure, providing both predictions and uncertainty estimates [17] [19].

Machine learning surrogate models have gained prominence for handling highly complex nonlinear systems. Neural network surrogates, for instance, are data-driven approaches that learn input-output relationships from training data through interconnected layers of processing nodes [17]. These are particularly valuable when the underlying biological mechanisms are poorly understood but abundant simulation data is available.

Hybrid approaches that integrate machine learning with mechanistic methods represent an emerging frontier in surrogate modeling for biological systems [17]. Techniques like Biologically Informed Neural Networks (BINNs) and Universal Physics-Informed Neural Networks (UPINNs) aim to balance interpretability and scalability by incorporating domain knowledge into data-driven frameworks [17].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Workflows

Standardized Workflow for Surrogate-Assisted Biological Optimization

Implementing surrogate modeling in biological optimization follows a structured workflow that ensures reliability and reproducibility:

Table 2: Key Stages in Surrogate-Based Biological Optimization

| Stage | Core Activities | Outputs | Considerations for Biological Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem Formulation | Define optimization objectives, identify constraints, select design variables | Clear optimization framework | Biological relevance, parameter identifiability, multi-scale challenges |

| Design of Experiments (DOE) | Select sample points in parameter space using structured approaches | Initial training data for surrogate | Balance between exploration and exploitation, computational budget |

| Surrogate Model Construction | Train and validate surrogate model using DOE data | Verified surrogate model | Model selection based on problem characteristics, validation strategies |

| Optimization Execution | Apply optimization algorithms to surrogate | Candidate optimal solutions | Handling of numerical noise, multi-modal objective functions |

| Validation and Refinement | Evaluate selected solutions using original model, refine as needed | Final optimized parameters | Ensuring biological feasibility, iterative refinement process |

The initial Design of Experiments (DOE) stage is critical, as it determines which parameter combinations will be used to train the surrogate model. For biological applications, sampling strategies like Latin Hypercube Designs are often preferred over conventional factorial designs because they provide better space-filling properties for computer simulations [18]. The selection of sample points substantially impacts surrogate model accuracy, and well-chosen points can dramatically reduce computational costs [18].

Following DOE, the surrogate model construction phase involves selecting an appropriate modeling technique based on the problem characteristics. For biological systems with known smooth responses, polynomial regression may be sufficient, while systems with complex nonlinearities may require neural networks or kriging approaches [19] [18]. The model must then be rigorously validated using holdout data or cross-validation techniques to ensure its predictions reliably approximate the true biological model.

The optimization execution phase leverages the computational efficiency of the validated surrogate to explore the parameter space extensively. The choice of optimization algorithm depends on the problem structure – for instance, gradient-based methods for continuous convex problems or evolutionary algorithms for multi-modal landscapes [18].

Figure 1: Workflow for surrogate-assisted optimization in biological problems

Case Study: Optimization in Agent-Based Biological Models

Agent-based models (ABMs) have become essential computational tools for studying complex biological and medical systems, simulating individual agents' interactions to capture emergent behaviors at the system level [17]. However, ABMs typically suffer from high computational costs when simulating millions of agents, making parameter exploration and optimization extremely challenging [17].

A representative case study involves using surrogate modeling to optimize an ABM of yeast polarization – a fundamental biological process where yeast cells develop asymmetrically during reproduction [17]. The original ABM required substantial computational resources to simulate the interactions of thousands of molecular agents within the cell. Researchers applied a surrogate modeling approach to reduce the computational burden, constructing an efficient approximation that enabled comprehensive parameter exploration and uncertainty quantification [17].

The experimental protocol followed these key steps:

- Parameter Selection: Identified 8 key parameters governing the polarization process, including reaction rates, diffusion coefficients, and initial concentrations

- Design of Experiments: Employed a Latin Hypercube Sampling strategy to generate 200 parameter combinations spanning the biologically plausible parameter space

- Data Generation: Ran the full ABM for each parameter combination, recording the polarization efficiency as the primary output metric

- Surrogate Construction: Trained a radial basis function network using 160 data points, reserving 40 for validation

- Model Validation: Achieved a cross-validation R² value of 0.94, indicating excellent predictive accuracy

- Optimization: Applied a genetic algorithm to the surrogate model to identify parameter combinations maximizing polarization efficiency

- Experimental Verification: Validated the top 5 parameter sets using the original ABM, confirming performance improvements

This case study exemplifies how surrogate modeling enables optimization tasks that would be computationally prohibitive using the full biological model alone.

Comparative Analysis of Single vs. Multi-Component Optimization Strategies

Single-Component Optimization Approaches

Single-component optimization strategies, analogous to the "single wishbone" approach in suspension design [2], focus on optimizing individual parameters or components while holding others constant. In biological contexts, this approach is often employed when researchers have prior knowledge suggesting that specific parameters dominate the system behavior.

The main advantage of single-component approaches is their simplicity and computational efficiency. By varying one parameter at a time, researchers can quickly identify optimal values for individual factors while minimizing the number of required simulations. This approach is particularly valuable in early-stage research where preliminary parameter tuning is needed.

However, single-component optimization suffers from a critical limitation: it cannot capture interaction effects between parameters. In complex biological systems, parameters often interact in nonlinear ways, meaning the optimal value of one parameter may depend on the values of others. This limitation can lead to suboptimal solutions when strong interactions exist within the system.

Multi-Component Optimization Frameworks

Multi-component optimization strategies, conceptually similar to the "double wishbone" approach in engineering [2], simultaneously consider multiple parameters and their interactions. This approach is embodied in frameworks like the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST), which provides a principled methodology for developing, optimizing, and evaluating multicomponent interventions [20] [21].

MOST consists of three distinct phases:

- Preparation Phase: Developing a conceptual model, identifying candidate components, conducting pilot work, and specifying optimization objectives [20] [21]

- Optimization Phase: Empirically studying candidate components through optimization trials, often using factorial experimental designs [20] [21]

- Evaluation Phase: Testing the optimized intervention in a standard randomized controlled trial [20] [21]

In biological optimization, the MOST framework enables researchers to efficiently evaluate multiple intervention components simultaneously. For example, in optimizing a smoking cessation intervention, researchers might simultaneously vary training protocols, treatment guides, workflow redesigns, and supervision strategies to identify the most effective combination [20].

Table 3: Comparison of Single vs. Multi-Component Optimization Strategies

| Characteristic | Single-Component Approach | Multi-Component Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Requirements | Lower | Higher, but mitigated by surrogates |

| Interaction Capture | Cannot detect parameter interactions | Explicitly models interactions |

| Solution Quality | Often suboptimal with interactions | Typically higher, more robust solutions |

| Implementation Complexity | Straightforward | More complex experimental designs |

| Biological Relevance | Limited for complex systems | Better captures biological complexity |

| Experimental Design | One-factor-at-a-time | Factorial or space-filling designs |

The key advantage of multi-component approaches is their ability to identify optimal combinations of parameters that work synergistically. In the MOST framework, this is accomplished through factorial experimental designs that enable systematic assessment of component performance, both independently and in combination [20]. For resource-constrained optimization, fractional factorial designs or sequential approaches can provide a balance between comprehensiveness and efficiency [20].

Performance Comparison of Surrogate Modeling Techniques

Quantitative Comparison of Modeling Approaches

Selecting an appropriate surrogate model is critical for successful optimization of biological systems. Different modeling techniques offer varying trade-offs between accuracy, training cost, and robustness across problem types:

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Surrogate Modeling Techniques

| Model Type | Training Speed | Prediction Accuracy | Noise Handling | Implementation Complexity | Best-Suited Biological Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polynomial Regression | Fast | Moderate | Poor | Low | Systems with smooth, low-dimensional response surfaces [19] |

| Kriging | Moderate | High | Moderate | Medium | Spatial biological processes, systems with correlated outputs [17] [19] |

| Radial Basis Functions | Fast | Moderate-High | Moderate | Low-Medium | Irregular response surfaces, scattered data [18] |

| Neural Networks | Slow | High | Good | High | Highly nonlinear systems, large training datasets [17] |

| Support Vector Regression | Moderate | High | Good | Medium | High-dimensional problems with limited samples |

Experimental comparisons between polynomial regression and kriging models have demonstrated that polynomial regression is more efficient for model generation, while kriging-based models provide better assessment of max-min search results due to their ability to predict a broader range of objective values [19]. Additionally, the error of kriging-based models is typically lower than that of polynomial regression [19].

For biological problems with multiple outputs, more advanced techniques like Biologically Informed Neural Networks (BINNs) and Universal Physics-Informed Neural Networks (UPINNs) have shown promise in balancing interpretability and scalability [17]. These hybrid approaches incorporate mechanistic biological knowledge into data-driven frameworks, potentially offering the "best of both worlds" for complex biological optimization tasks.

Implementing surrogate modeling for biological optimization requires both computational tools and domain-specific resources:

Table 5: Essential Research Toolkit for Surrogate-Assisted Biological Optimization

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Biological Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOE Software | R, Python (pyDOE), SAS JMP | Design of experiment generation | Creating parameter sampling strategies for biological models |

| Surrogate Modeling Libraries | Python (scikit-learn, GPy), MATLAB | Surrogate model construction | Building and training approximation models |

| Optimization Algorithms | NLopt, MATLAB Optimization, custom implementations | Numerical optimization | Finding optimal parameter combinations |

| Biological Simulation Platforms | COPASI, VCell, NEURON, custom ABM frameworks | Original model simulation | Generating training data for surrogates |

| Validation Tools | Cross-validation, bootstrapping, posterior predictive checks | Model verification | Assessing surrogate model accuracy and reliability |

Beyond computational tools, successful implementation requires domain-specific biological knowledge to ensure that optimization results are biologically plausible and meaningful. Close collaboration between computational scientists and domain experts is essential for interpreting results and guiding the optimization process toward biologically relevant solutions.

Surrogate modeling has established itself as an indispensable methodology for optimizing expensive black-box biological problems, enabling research that would otherwise be computationally prohibitive. By creating efficient approximations of complex biological systems, surrogate models facilitate comprehensive parameter exploration, sensitivity analysis, and optimization that directly advances biological discovery and therapeutic development.

The comparison between single-component and multi-component optimization strategies reveals that multi-component approaches generally provide superior results for complex biological systems where parameter interactions significantly influence system behavior. Frameworks like the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) offer principled methodologies for efficiently evaluating multiple intervention components simultaneously, leading to more robust and effective optimized solutions [20] [21].

As biological models continue to increase in complexity and scale, surrogate modeling will play an increasingly critical role in making optimization feasible. Emerging trends include the development of standardized benchmarks to enhance methodological rigor [17], increased use of hybrid modeling approaches that integrate machine learning with mechanistic biological knowledge [17], and automated surrogate selection techniques that reduce the expertise barrier for implementation.

For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering surrogate modeling techniques represents a valuable skill set that can dramatically accelerate the optimization of biological systems and therapeutic interventions. By selecting appropriate modeling strategies based on problem characteristics and employing rigorous validation protocols, scientists can leverage surrogate modeling to extract maximum insight from computationally expensive biological simulations.

Implementation Frameworks: Methodological Approaches for Drug Discovery and Development

Experimental Design for Dual-Optimization Systems

In computational biology and drug development, high-resolution optimization strategies are crucial for managing complex experiments. The core distinction lies between single and double Wavefront Imaging Sensor with High Resolution (WISH) background optimization strategies. The fundamental single WISH approach utilizes a single, high-resolution wavefront measurement to correct optical aberrations, providing a substantial improvement over traditional methods like the Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor (SHWFS), which is limited to a few thousand measurement points [22]. In contrast, the double WISH strategy employs two computational imaging sensors in tandem, enabling simultaneous dual-parameter optimization—such as amplitude and phase—at resolutions exceeding 10 megapixels, representing an order-of-magnitude improvement in spatial resolution for noninterferometric wavefront sensing [22].

This paradigm mirrors advancements in other engineering fields. For instance, in the optimization of double-wishbone suspension systems, researchers have demonstrated that dual-parameter control of camber and toe angles reduces camber by 58% and toe gain by 96% compared to passive systems [23]. Similarly, studies on multi-objective optimization of complex systems reveal that central-composite designs excel in scenarios requiring simultaneous optimization of multiple, potentially competing objectives [24]. These principles translate directly to pharmaceutical contexts where researchers must often balance drug efficacy against toxicity, or binding affinity against solubility.

Core Methodologies in WISH Optimization

Foundational Experimental Protocols

The experimental workflow for implementing WISH-based optimization follows a structured, multi-phase approach that ensures statistical rigor and reproducible results.

WISH Hardware Configuration: The core apparatus consists of a phase-only Spatial Light Modulator (SLM), a high-resolution CMOS sensor, and a processor [22]. For the double WISH configuration, this setup is duplicated to create two parallel measurement paths. The incident wavefront is modulated by multiple random phase patterns displayed on the SLM. The sensor captures the corresponding intensity-only measurements, with the phase information recovered computationally [22]. Typical systems use a 1920×1080 resolution SLM with 6.4µm pitch paired with a CMOS sensor offering 4024×3036 resolution and 1.85µm pixel pitch [22].

Data Acquisition Protocol: For each experimental condition, researchers capture multiple uncorrelated measurements with different SLM patterns. The number of required measurements (K) depends on the complexity of the wavefront being characterized, with more complicated fields requiring additional measurements for accurate reconstruction [22]. The forward model for each measurement is represented mathematically as:

$$\sqrt {I^i} = \left| {Pz(\Phi{{SLM}}^i \circ u)} \right|$$

where $u$ is the unknown field incident on the SLM, "∘" denotes element-wise multiplication, and $P_z$ is the Fresnel propagation operator at distance z [22].

Computational Phase Retrieval: The unknown field $u$ is estimated by solving the optimization problem:

$$\hat{u} = \arg \min{u}\mathop {\sum}\nolimits{i = 1}^{K} \left\| {\sqrt{I^{i}} - \left| {P{z}\left({\Phi}{SLM}^{i} \circ u \right)} \right|} \right\|$$

This is typically addressed using Gerchberg-Saxton-type algorithms that alternate projections between the SLM and sensor planes [22].

Experimental Design Principles

Robust experimentation requires careful design to ensure valid, reproducible results. Key considerations include:

Variable Definition: Clearly define independent variables (e.g., SLM pattern type, number of measurements), dependent variables (e.g., reconstruction accuracy, processing time), and potential confounding variables (e.g., sensor noise, environmental vibrations) [25].

Hypothesis Specification: Formulate specific, testable hypotheses. For example: "The double WISH strategy will achieve 15% higher reconstruction accuracy for highly varying optical fields compared to the single WISH approach, while maintaining equivalent computational time." [26]

Treatment Design: Determine how to manipulate independent variables, including the range and granularity of variation [25]. For WISH optimization, this includes deciding on the diversity of SLM patterns, the number of capture iterations, and the resolution parameters to test.

Subject Assignment: Implement random assignment of test conditions to minimize bias [25]. In computational experiments, this may involve randomizing the order of algorithm testing or using different random seeds for stochastic processes.

Measurement Planning: Establish precise protocols for measuring dependent variables, including the statistical metrics for assessing reconstruction accuracy and computational efficiency [25].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance comparison of single vs. double WISH optimization strategies

| Performance Metric | Single WISH | Double WISH | Traditional SHWFS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | >10 megapixels | >10 megapixels (per sensor) | 73×45 measurement points (approx. 3,285 points) |

| Phase Estimation Accuracy | Fine estimation suitable for moderately varying fields | Enhanced accuracy for highly varying fields | Limited to smooth phase profiles |

| Frame Rate | Up to 10 Hz | 5-7 Hz (due to doubled computational load) | Typically >20 Hz |

| Application Scope | Standard wavefront sensing | Complex, highly varying optical fields | Air turbulence measurement |

| Computational Load | Moderate | High (approximately 1.8× single WISH) | Low |

| Multi-Parameter Optimization | Sequential parameter adjustment | Simultaneous dual-parameter optimization | Not supported |

Table 2: Optimization performance across engineering domains

| System Type | Optimization Approach | Key Improvement | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double-Wishbone Suspension | Active camber and toe control | 58% reduction in camber, 96% reduction in toe gain [23] | MATLAB/SimMechanics simulation validated with MSC ADAMS |

| Double-Skin Façade Systems | Central-composite design | Superior performance in multi-objective optimization [24] | 350,000+ EnergyPlus simulations |

| Wave Energy Converters | Hybrid bio-inspired and local search algorithms | Enhanced convergence rate in layout optimization [27] | Comparative analysis of optimization techniques |

| Pharmaceutical Formulation | Factorial design with response surface methodology | Optimal balance of multiple formulation parameters | Not specified in search results |

Application-Specific Workflows

Drug Compound Optimization Protocol:

- Initial Screening: Apply single WISH for high-throughput screening of compound libraries, identifying candidates with promising binding characteristics.

- Detailed Characterization: Implement double WISH for lead compounds to simultaneously optimize for binding affinity and membrane permeability.

- Validation: Cross-validate results with traditional analytical methods to confirm findings.

Experimental Parameters:

- Sample Size: Minimum of 3 replicates per condition

- Controls: Include positive and negative controls in each experiment

- Blinding: Implement blinded analysis where feasible to reduce bias

- Statistical Power: Conduct power analysis prior to experiments to determine appropriate sample sizes [26]

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

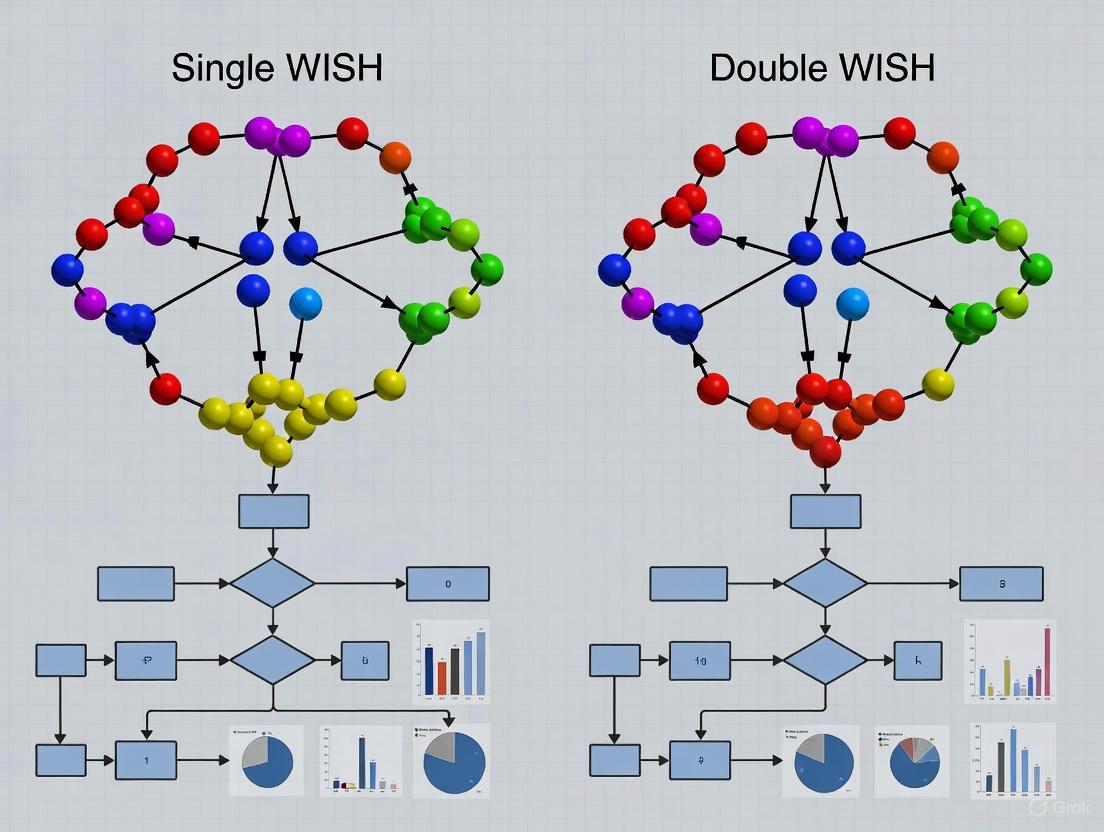

Single vs. Double WISH Configuration

Experimental Optimization Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key research materials and their functions in WISH optimization experiments

| Component | Specifications | Primary Function | Considerations for Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Light Modulator (SLM) | Phase-only, 1920×1080 resolution, 6.4µm pitch [22] | Modulates incident wavefront with programmed patterns | Cross-talk effects limit high-frequency patterns; requires calibration |

| CMOS Sensor | 10-bit, 4024×3036 resolution, 1.85µm pixel pitch [22] | Captures intensity measurements of modulated wavefront | Pixel size determines ultimate resolution when smaller than SLM pixel size |

| Computational Framework | Gerchberg-Saxton or other phase-retrieval algorithms [22] | Recovers phase information from intensity measurements | Algorithm choice affects convergence speed and accuracy |

| Laser Source | 532-nm wavelength module diode laser [22] | Provides coherent illumination for wavefront sensing | Wavelength stability affects measurement consistency |

| Beam Splitter | 25.4mm size [22] | Directs field into sensor for reflective SLM configurations | Introduces minor power loss; requires precise alignment |

| Statistical Software | R, Python, or specialized DOE packages | Analyzes experimental results and determines significance | Should support complex factorial designs and response surface methodology |

The strategic selection between single and double WISH optimization approaches depends fundamentally on the complexity of the system under investigation and the resolution requirements of the application. Single WISH strategies provide an excellent balance of performance and computational efficiency for standard optimization tasks, while double WISH approaches enable unprecedented capability for multi-parameter optimization in complex systems. The experimental frameworks and comparative data presented here provide researchers with validated methodologies for implementing these approaches in drug development and other complex optimization scenarios. As with other engineering domains highlighted in this analysis, the systematic application of designed experiments remains paramount for achieving robust, reproducible optimization outcomes.

Bayesian Optimization Strategies for High-Dimensional Biological Data

In the context of a broader thesis on single versus double WISH background optimization strategies, the selection of an efficient optimization framework is paramount. High-dimensional biological data, characterized by a large number of variables (p) relative to observations (n), presents significant challenges for conventional optimization approaches [28]. In synthetic biology and drug development projects, researchers often face protracted growth cycles and limited laboratory infrastructure, allowing only a handful of Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles before project deadlines [29]. Bayesian optimization (BO) has emerged as a powerful strategy for navigating these complex experimental landscapes, enabling researchers to extract maximum information from minimal experiments. This guide provides an objective comparison of Bayesian optimization strategies, focusing on their applicability to high-dimensional biological problems such as metabolic engineering and drug development, with supporting experimental data to inform selection criteria.

Methodological Foundations of Bayesian Optimization

Bayesian optimization is a sample-efficient, sequential strategy for global optimization of black-box functions that are expensive to evaluate [29]. The power of BO stems from three core components: (1) Bayesian inference to update beliefs based on evidence, (2) a Gaussian Process (GP) as a probabilistic surrogate model of the objective function, and (3) an acquisition function to balance the exploration-exploitation trade-off [29].

In biological research, the experimental landscape is often complex and high-dimensional. Traditional methods like grid search become intractable due to the "curse of dimensionality," where the number of experiments required grows exponentially with the number of parameters [29]. BO addresses this challenge by building a probabilistic model of the objective function and using it to select the most promising parameters to evaluate next, dramatically reducing the number of experimental iterations required compared to conventional approaches [29].

The Bayesian Optimization Workflow:

- Define an objective function that represents the experimental outcome to optimize

- Establish the search space for parameters

- Select initial data points randomly or via design of experiments

- Build a surrogate model (typically Gaussian Process) approximating the objective function

- Select next evaluation point using an acquisition function

- Evaluate the selected point through experiment

- Update the surrogate model with new data

- Repeat steps 5-7 until convergence or budget exhaustion [30]

Comparative Analysis of Bayesian Optimization Strategies

The following sections compare Bayesian optimization approaches particularly relevant to high-dimensional biological data, assessing their performance characteristics, implementation requirements, and suitability for different research contexts within the WISH optimization framework.

Core Algorithm Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Bayesian Optimization Strategies for High-Dimensional Biological Data

| Optimization Strategy | Key Mechanism | Dimensionality Assumption | Performance in High Dimensions | Implementation Complexity | Best-Suited Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard BO | Global Gaussian Process with acquisition function | No specific assumption | Poor scaling beyond ~20 dimensions [29] | Low | Low-dimensional parameter spaces (<20 parameters) |

| TAS-BO [31] | Global + local Gaussian Process models | No structural assumptions | Significantly improved performance over standard BO [31] | Medium | General high-dimensional biological optimization |

| REMBO [31] | Random embedding to lower-dimensional space | Effective dimensionality is low | Good when assumption holds [31] | Medium | Biological systems with few critical parameters |

| SAASBO [31] | Sparsity-inducing priors | Only few variables are important | Excellent with sparse high-dimensional data [31] | High | Transcriptional control with many inducers |

| TuRBO [31] | Trust region approach with local models | No specific assumption | Competitive performance on high-dimensional problems [31] | Medium | Noisy biological systems with local optima |

| Add-GP-UCB [31] | Additive Gaussian Process | Function is additively separable | Effective when additive structure is known [31] | High | Multi-step pathway optimization |

Performance Metrics Across Biological Applications

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Biological Domains

| Application Domain | Optimization Strategy | Performance Metrics | Comparison to Traditional Methods | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|