Solving High Background in Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization: A Comprehensive Troubleshooting Guide for Researchers

High background staining is a common and frustrating challenge in whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) that can obscure genuine gene expression signals.

Solving High Background in Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization: A Comprehensive Troubleshooting Guide for Researchers

Abstract

High background staining is a common and frustrating challenge in whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) that can obscure genuine gene expression signals. This article provides a systematic guide for scientists to diagnose and resolve the causes of high background, drawing on current, optimized protocols from multiple model organisms. We cover foundational principles of WISH, methodological best practices for probe design and hybridization, a step-by-step troubleshooting framework for immediate problem-solving, and advanced validation techniques to confirm results. By integrating foundational knowledge with practical optimization strategies, this resource aims to empower researchers to achieve clear, publication-quality in situ hybridization data, thereby enhancing the reliability of spatial gene expression analysis in developmental biology and biomedical research.

Understanding the Core Principles: What Causes High Background in WISH?

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a foundational technique in molecular biology that enables the localization of specific nucleic acid sequences within tissues, cells, or entire organisms. The core principle relies on the ability of a labeled nucleic acid probe to find and bind to its complementary target sequence through Watson-Crick base pairing, a process known as hybridization. However, the theoretical elegance of this process belies a significant practical challenge: achieving specific hybridization while minimizing non-specific probe binding. This balance is particularly critical in whole-mount in situ hybridization (WMISH), where the three-dimensional structure of samples creates numerous opportunities for background signals that can obscure true biological signals.

The fundamental issue stems from the dual nature of hybridization forces. The same hydrogen bonding and base-stacking interactions that facilitate precise complementarity between probe and target can also mediate weaker, non-specific interactions between the probe and non-target sequences or other cellular components. When these non-specific interactions occur, they generate high background staining that compromises experimental interpretation. For researchers investigating spatial gene expression patterns, this background problem can lead to false positives, reduced signal-to-noise ratio, and ultimately, erroneous conclusions about gene function and localization. Understanding the molecular basis of this balance and implementing strategies to control it is therefore essential for generating reliable, publication-quality WMISH data.

The Molecular Mechanisms: Specific Versus Non-Specific Interactions

Molecular Signatures of Hybridization Events

At the molecular level, specific and non-specific hybridization events exhibit distinct characteristics that can be identified and measured. Research on oligonucleotide probe hybridization has revealed that these two types of binding produce different relationships between perfect match (PM) and mismatch (MM) probe intensities based on the middle base of the probe sequence.

Specific hybridization follows a triplet-like pattern (C > G ≈ T > A > 0) of the PM-MM log-intensity difference when specific RNA fragments bind to their intended targets [1]. This pattern arises from the combination of a Watson-Crick (WC) pairing in PM probes and a self-complementary (SC) pairing in MM probes. The Gibbs free energy contribution of WC pairs to duplex stability is asymmetric for purines and pyrimidines and decreases according to C > G ≈ T > A [1].

Non-specific hybridization produces a duplet-like pattern (C ≈ T > 0 > G ≈ A) of the PM-MM log-intensity difference upon binding of non-specific RNA fragments [1]. This systematic behavior is characterized by the reversal of the central WC pairing for each PM/MM probe pair, with SC pairings contributing only weakly to overall duplex stability.

The binding free energy (ΔG) for specific hybridization is significantly more negative than for non-specific binding, leading to more stable duplex formation. The equilibrium temperature dependence follows the Boltzmann factor, exp(-ΔG/kBT), where kB is the Boltzmann constant and T is the effective hybridization temperature [2]. This thermodynamic understanding provides the foundation for optimizing experimental conditions to favor specific over non-specific interactions.

Several biological and technical factors contribute to non-specific probe binding in WMISH experiments:

Fragmented nucleic acids in tissues undergoing cell death processes are a major source of non-specific signals [3]. During programmed cell death (PCD), nuclear DNA is fragmented into nucleosomal units, creating numerous short nucleic acid sequences that can bind probes non-specifically. This has been demonstrated in Scots pine seeds, where non-specific signals consistently appeared in tissues with fragmented DNA, such as the embryo surrounding region of the megagametophyte and remnants of degenerated suspensors [3].

Electrostatic interactions between charged probe molecules and cellular components can cause retention of probes in specific tissue regions. The phosphate backbone of nucleic acid probes carries a negative charge that can interact with positively charged cellular structures.

Hydrophobic interactions between probes and cellular lipids or proteins may contribute to background, particularly when using certain labeling techniques or detection systems.

Endogenous biomarkers such as alkaline phosphatases or other enzymes used in detection systems can generate background if not adequately blocked or inhibited [4].

Table 1: Characteristics of Specific vs. Non-Specific Hybridization

| Characteristic | Specific Hybridization | Non-Specific Hybridization |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular pattern | Triplet-like (C > G ≈ T > A) | Duplet-like (C ≈ T > 0 > G ≈ A) |

| Base pairing | Watson-Crick in PM, self-complementary in MM | Reversed central WC pairing |

| Thermodynamic stability | High (more negative ΔG) | Lower (less negative ΔG) |

| Dependence on stringency | High at optimal stringency | Decreases with increasing stringency |

| Localization | Tissue- and cell-specific | Widespread, often in dying cells |

Quantitative Impact: The Cost of Suboptimal Conditions

The consequences of suboptimal hybridization conditions extend beyond mere background signals to significantly impact biological interpretations. Research has demonstrated that even minor deviations from optimal conditions can dramatically reduce data quality and experimental sensitivity.

Temperature optimization studies reveal that a deviation of just one degree Celsius from the optimal hybridization temperature can lead to a loss of up to 44% of differentially expressed genes that would otherwise be identified [2]. This sensitivity loss is not uniform across all gene categories—transcription factors and other low-copy-number regulators are disproportionately affected by suboptimal conditions [2]. This bias occurs because these transcripts are already present at low concentrations, making their detection more vulnerable to signal-to-noise ratio reductions caused by non-specific binding.

The relationship between hybridization temperature and probe behavior follows a fundamental thermodynamic principle. For each probe, depending on its structure and potential binding partners, there exists an optimal condition where it binds the intended target strongly while minimally binding non-targets [2]. Hybridization below this temperature increases cross-hybridization, reducing signal specificity, while hybridization above this temperature decreases signal intensities, degrading the signal-to-noise ratio [2].

Table 2: Impact of Suboptimal Hybridization Conditions on Detection Sensitivity

| Condition | Impact on Sensitivity | Effect on Specificity | Consequence for Low-Copy Transcripts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature -1°C below optimum | Minimal change | Up to 44% loss of differential expression detection | Disproportionate loss of transcription factors |

| Temperature +1°C above optimum | Reduced signal intensity | Potential improvement | Decreased detection due to reduced signal |

| Low stringency washes | Potential increase | Significant decrease | Masked by background noise |

| High stringency washes | Potential decrease | Significant improvement | Potential loss of authentic signal |

| Suboptimal probe design | Variable | Consistently decreased | Detection compromised |

Optimizing Experimental Parameters: A Quantitative Framework

Temperature and Stringency Optimization

The empirical determination of optimal hybridization conditions represents one of the most critical steps in minimizing non-specific binding. A systematic approach to this optimization involves using a comparison of two typical biologically distinct samples to quantitatively assess how much information about sample differences can be extracted under different conditions [2].

The Boltzmann factor [exp(-ΔG/kBT)] describes the equilibrium temperature dependence of hybridization, where ΔG(p, π) < 0 represents the Gibbs binding free energy for a pair of nucleotide strands (p, π) that bind exergonically at the effective hybridization temperature T [2]. For a well-designed probe set, the Boltzmann factors should be similar for all probes, with a temperature T existing where for most probes γT(p, π) ≫ γT(p, π') for all non-targets π' ≠π [2].

The protocol for temperature optimization should include:

- Testing a range of temperatures (typically 55-65°C) using biologically distinct but related samples

- Quantifying the amount of differential expression detected at each temperature

- Selecting the temperature that maximizes the reliable detection of differentially expressed genes

- Verifying that the optimal conditions are independent of the specific samples used for calibration

This optimization approach maximizes both the sensitivity and specificity of the measurement process by quantifying the differential expression at different hybridization temperatures [2].

Probe Design and Selection Considerations

Proper probe design is fundamental to minimizing non-specific hybridization:

RNA probes should be 250-1500 bases in length, with probes of approximately 800 bases exhibiting the highest sensitivity and specificity [5]. The probe sequence must have high complementarity to the target, as even >5% non-complementary base pairs can result in loose hybridization that washes away during stringency steps [5].

For WMISH, single-molecule RNA FISH (smFISH) approaches utilize multiple short singly labeled oligonucleotide probes (20-50 oligonucleotide pairs) targeting different regions of the same transcript [6]. The binding of up to 48 fluorescent labeled oligos to a single mRNA molecule provides sufficient fluorescence for accurate detection while ensuring that probes not binding to the intended sequence don't achieve sufficient localized fluorescence to be distinguished from background [6].

Control probes are essential, including sense strand probes to assess non-specific binding and probes for housekeeping genes to verify RNA integrity and procedure effectiveness [3] [7].

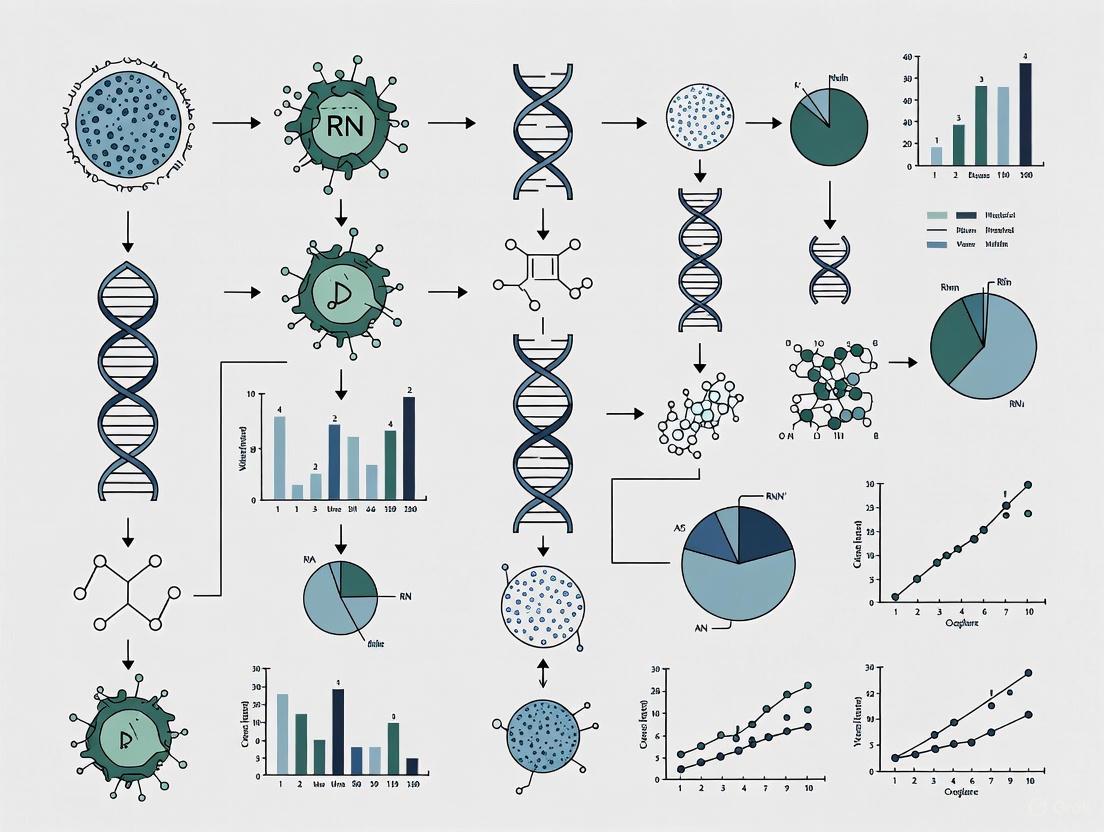

Diagram 1: Hybridization Optimization Workflow

Technical Protocols: Minimizing Non-Specific Binding in Practice

Sample Preparation and Pre-Treatment

Proper sample preparation is the first defense against non-specific background:

Fixation should use 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight at 4°C to preserve tissue architecture while maintaining nucleic acid accessibility [4]. Incomplete or excessive fixation can either reduce signal or increase background.

Permeabilization techniques include:

- Proteinase K digestion (10 μg/ml in PBST for 5-12 minutes at room temperature for embryos) [4]

- Detergents such as Tween-20 or Triton X-100 at 0.1% concentration to enhance tissue permeability [6]

- Acetic anhydride treatment (2.5 μl in 1 ml of 0.1M triethanolamine for 10-60 minutes) to reduce background from endogenous phosphatases [4]

Autofluorescence reduction using techniques like OMAR (oxidation-mediated autofluorescence reduction) with high-intensity cold white light source treatment can significantly improve signal-to-noise ratio without digital post-processing [8]. This photochemical pre-treatment creates bubbles in the solution around the sample, indicating successful oxidation reaction [8].

Hybridization and Washes: The Critical Steps

The hybridization and washing steps represent the point where strategic decisions most directly impact the specific versus non-specific binding balance:

Prehybridization should be performed for 1-48 hours at 55°C in hybridization buffer containing blocking agents such as torula RNA (5 mg/ml) and heparin (50 μg/ml) to saturate non-specific binding sites [4].

Hybridization temperature must be optimized for each probe and tissue type. Standard temperatures range between 55-65°C [5]. For oligonucleotide microarrays, the effective hybridization temperature in probe design computations often differs from the optimized physical temperature that should be used for hybridizations due to complex effects like surface interactions and buffer additives [2].

Stringency washes are critical for removing non-specifically bound probes. The parameters can be systematically adjusted:

Post-hybridization treatments may include RNase digestion (RNase A 20 μl/ml plus RNase T1 100 U/ml in PBST for 30 minutes at 37°C) to reduce background, though this should be tested as it decreases signal intensity for some probes [4].

Diagram 2: Stringency Control Outcomes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Their Functions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Controlling Hybridization Specificity

| Reagent | Function | Optimization Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Formamide | Denaturing agent that lowers effective melting temperature, allowing specific hybridization at lower temperatures | Typically used at 50% concentration in hybridization buffer; higher concentrations increase stringency |

| SSC (Saline Sodium Citrate) | Provides ionic strength for hybridization; lower concentrations increase stringency | Standard concentrations from 0.1x to 2x SSC; lower concentrations remove imperfect hybrids |

| Blocking Reagents (BSA, milk, serum, torula RNA, heparin) | Block non-specific probe attachment to membrane and cellular components | Combination approaches often most effective; torula RNA at 5 mg/ml with heparin at 50 μg/ml recommended for WMISH |

| Proteinase K | Digest proteins to increase tissue permeability and nucleic acid accessibility | Concentration and time critical (10-20 μg/mL, 10-20 min at 37°C); overtreatment damages morphology |

| Detergents (Tween-20, Triton X-100) | Enhance tissue permeability by dissolving membranes | Typically used at 0.1% concentration; help reduce background in washing steps |

| Formamide in Washes | Increases stringency of post-hybridization washes | 50% formamide in 2x SSC at 55°C effectively removes non-specific binding |

| Acetic Anhydride | Acetylates proteins to reduce non-specific electrostatic probe binding | Particularly important for reducing background from endogenous phosphatases |

| c-JUN peptide | c-JUN peptide, CAS:610273-01-3, MF:C121H210N36O34S, MW:2743.55 | Chemical Reagent |

| L-NIL | L-NIL, CAS:53774-63-3, MF:C8H17N3O2, MW:187.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting High Background: A Systematic Approach

When faced with persistent non-specific signals in WMISH experiments, a systematic troubleshooting approach is essential:

Determine the pattern of background staining:

- Uniform background suggests insufficient blocking or overall low stringency

- Specific tissue localization (particularly in dying cells) indicates interaction with fragmented nucleic acids [3]

Verify probe specificity:

- Always include sense probe controls

- Test multiple different probe sequences targeting the same transcript

- For WMISH, use single-molecule FISH approaches with ~20 oligonucleotide pairs per target [6]

Assess nucleic acid integrity in problematic tissues:

Systematically adjust stringency:

- Increase hybridization temperature in 2°C increments

- Decrease salt concentration in washing solutions

- Add additional post-hybridization washes with increased stringency

Incorporate specialized treatments for persistent background:

For tissues with known high levels of cell death or nucleic acid fragmentation, additional controls including DNase and RNase treatments alongside TUNEL assays may be necessary to distinguish specific from non-specific signals [3].

The challenge of balancing specific hybridization against non-specific probe binding in whole-mount in situ hybridization represents both a technical hurdle and an opportunity for experimental refinement. By understanding the molecular mechanisms that differentiate these interactions, researchers can implement strategic approaches that maximize signal-to-noise ratio while maintaining biological relevance. The critical insights are that even minor deviations from optimal conditions disproportionately affect the detection of biologically important low-copy-number transcripts, and that systematic optimization using quantitative measures provides a pathway to reproducible, high-quality results. As WMISH continues to evolve with advanced detection methods and computational analysis frameworks, the fundamental principles of hybridization specificity remain essential for extracting meaningful biological information from spatial gene expression patterns.

Whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH) is an indispensable technique in developmental biology and regenerative research, enabling the visualization of gene expression patterns in whole, three-dimensional samples. The power of this method lies in its ability to provide spatial and temporal dynamics of target mRNA within the complex architecture of intact tissues, supporting the "seeing is believing" concept in molecular biology [10]. However, a frequent and formidable challenge faced by researchers is high background staining, which can obscure specific signals and compromise data interpretation. This high background stems from multiple sources, broadly categorized as endogenous background originating from the biological sample itself and technical background arising from methodological procedures or reagent interactions.

For researchers investigating why their WISH experiments exhibit high background, understanding these culprits is the first critical step toward troubleshooting. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of these sources, complete with diagnostic strategies and optimized protocols to achieve clear, high-contrast results, specifically framed within the context of a broader thesis on resolving high background in whole mount in situ hybridization research.

Endogenous background originates from the intrinsic properties of the biological sample itself. These sources are not introduced by the experimental protocol but must be actively blocked or mitigated to achieve a clean signal.

Pigmentation and Autofluorescence

A primary challenge in many model organisms, particularly in regeneration studies using Xenopus laevis tadpoles, is the presence of melanosomes and melanophores. These pigment granules actively migrate to sites of injury, such as a tail amputation site, and can severely interfere with the visualization of chromogenic or fluorescent stains [10]. The problem is twofold: pigments can physically obscure the specific stain and exhibit intrinsic autofluorescence, emitting light in the green and red channels commonly used for detection [11].

Mitigation Strategy: A highly effective solution is a photo-bleaching step implemented after fixation and before pre-hybridization. This procedure decolors melanosomes and melanophores, resulting in perfectly albino tails that no longer interfere with signal detection [10].

Endogenous Enzyme Activity

Many detection systems rely on reporter enzymes like Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) or Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP). However, some tissues possess high levels of endogenous enzymatic activity. For instance, blood-rich tissues such as the spleen and kidney have high endogenous peroxidases, while the kidney, intestine, and liver can have high phosphatase levels [11]. These endogenous enzymes will react with the chromogenic substrate, producing a false-positive, high-background signal across the tissue.

Mitigation Strategy: It is crucial to block these endogenous enzymes prior to the immunostaining step. This can be achieved by treating samples with specific inhibitors [11] [12]:

- For HRP, use Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) at 0.3% (v/v).

- For AP, use Levamisol (2 mM).

Endogenous Biotin and Immunoglobulins

Endogenous biotin (Vitamin B7) is a cofactor in metabolism and is found at high levels in tissues with high mitochondrial activity, such as the liver, kidney, and certain tumors [11]. When using the highly sensitive Avidin-Biotin Complex (ABC) detection method, endogenous biotin will bind to streptavidin, causing widespread non-specific staining.

Furthermore, in systems where the primary antibody is derived from the same species as the sample (e.g., mouse-on-mouse), endogenous immunoglobulins within the tissue can be bound by the secondary antibody, leading to high background [11].

Mitigation Strategy:

- For biotin-based detection, use a commercial Avidin/Biotin Blocking Kit prior to applying the detection system [11] [12].

- For endogenous immunoglobulin issues, ensure thorough blocking with normal serum from the species of the secondary antibody and consider using secondary antibodies that have been pre-adsorbed against the immunoglobulins of the sample species [11] [12].

Table 1: Summary of Endogenous Background Sources and Solutions

| Endogenous Source | Tissues/Models Affected | Impact on WISH | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pigmentation (Melanophores) | Xenopus laevis tadpoles, zebrafish embryos | Obscures signal, causes autofluorescence | Photo-bleaching after fixation [10] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) | Kidney, intestine, liver | High background with AP-conjugated antibodies | Block with Levamisol (2 mM) [11] [12] |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | Spleen, kidney (blood-rich tissues) | High background with HRP-conjugated antibodies | Block with Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ (0.3% v/v) [11] [12] |

| Endogenous Biotin | Liver, kidney, spleen, tumors | Non-specific staining with ABC detection kits | Use Avidin/Biotin Blocking Kit [11] [12] |

| Endogenous Immunoglobulins | Mouse-on-mouse, human-on-human systems | Secondary antibody binds to host IgGs | Use pre-adsorbed secondary antibodies; increase blocking [11] |

Technical background arises from suboptimal experimental conditions, reagent choices, or procedural errors during the WISH protocol.

Probe-Related Issues

The probe is a central player, and its mishandling is a common source of background.

- Cross-reactivity: This occurs when the primary probe or, more commonly, the secondary antibody binds to unintended epitopes on non-target mRNAs or tissue components [11].

- Probe Concentration: Using a probe concentration that is too high is a frequent mistake. While a high concentration can increase signal, it also promotes non-specific binding to non-target sites that would otherwise be washed away, resulting in pervasive background [11] [13]. Research with LNA probes has shown that effective hybridization occurs over a narrow concentration range (e.g., 0.5–25 nM), beyond which background increases significantly [13].

- Non-specific Binding: Weak, non-specific interactions between the probe and the sample can persist if washing steps are insufficiently stringent.

Suboptimal Tissue Permeability and Washing

The dense nature of many whole-mount samples poses a significant challenge. Loose tissues, such as the tail fins of tadpoles, are particularly problematic as they can trap reagents, including the chromogenic substrate BM Purple, leading to high background staining that can be mistaken for a true signal [10]. Inadequate washing between steps fails to remove unbound probes and antibodies, leaving them in the tissue to contribute to a false-positive signal during development [12].

Mitigation Strategy: A simple but effective mechanical method is tail fin notching. Making incisions in a fringe-like pattern at a distance from the area of interest dramatically improves the diffusion of all solutions in and out of the tissue, preventing the trapping of substrates and eliminating non-specific autocromogenic reactions, even after prolonged staining [10].

Detection System and Incubation Parameters

The detection phase is another critical point where background can be introduced.

- Over-amplification: When using signal amplification techniques (e.g., biotin-tyramide), over-amplification can lead to high background across the entire sample [12].

- Substrate Precipitation: Excessive substrate concentration or prolonged substrate incubation time can cause the precipitate to form non-specifically throughout the sample and on its surface [12].

- Sample Drying: If tissue sections or whole mounts partially dry out at any point during the procedure, it can concentrate reagents nonspecifically, often leading to a characteristic higher background at the edges of the sample [12].

Table 2: Summary of Technical Background Sources and Solutions

| Technical Source | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Probe Concentration | Non-specific binding to off-target sites | Titrate probe; use optimal concentration (e.g., 0.5-25 nM for LNAs) [11] [13] |

| Insufficient Washing | Unbound probes/antibodies not removed | Increase washing time and volume; use detergents (Tween-20, CHAPS) [13] [12] |

| Trap Reagents | Loose tissues (e.g., fins) trap substrates | Mechanically notch fins to improve reagent flow [10] |

| Over-amplification | Too much signal amplification | Reduce amplification level (e.g., less biotin on secondary) [12] |

| Long Substrate Incubation | Non-specific precipitate formation | Dilute substrate; reduce incubation time; monitor reaction [12] |

| Sample Drying | Concentration of reagents on tissue | Always keep samples in a humidified chamber [12] |

An Optimized WISH Protocol for Low Background

Based on the identified culprits, below is a detailed optimized protocol incorporating specific treatments to minimize background, particularly for challenging samples like regenerating Xenopus laevis tails [10].

Specialized Pre-Treatment Steps

- Fixation and Rehydration: Fix samples in MEMPFA. Subsequently, dehydrate through a graded series of methanol (e.g., 25%, 50%, 75% in PBS-Tween, then 100% methanol) and store at -20°C. Rehydrate by reversing the methanol series to PBS-Tween.

- Early Photo-bleaching (Critical for pigmented samples): After rehydration, place samples in a transparent dish filled with a bleaching solution (e.g., 3% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ in PBS under strong light). Bleach until pigmentation is fully removed (1-3 hours). This step is performed before pre-hybridization [10].

- Tail Fin Notching (Critical for loose tissues): Using a fine scalpel or razor blade, make small, careful incisions along the edge of the tail fin in a fringe-like pattern, ensuring you do not damage the main area of interest (e.g., the regenerating tip) [10].

Hybridization and Washing

- Pre-hybridization: Incubate samples in hybridization buffer for at least 1-4 hours at the hybridization temperature (e.g., 60-70°C) to block non-specific sites.

- Hybridization: Replace the pre-hybridization buffer with fresh buffer containing the labeled probe (antisense RNA or LNA) at an optimized concentration. Hybridize for 48 hours at the appropriate temperature. Note that longer hybridization times (e.g., up to 120 hours) can yield a graded increase in specific signal for low-abundance targets [13].

- Stringent Washes: Perform a series of post-hybridization washes with buffers containing SDS and/or detergents. The inclusion of Tween-20 and CHAPS in wash solutions has been shown to significantly reduce background by enhancing the removal of unbound LNA probes [13]. Wash conditions (temperature and salt concentration) should be optimized for stringency.

Immunological Detection and Staining

- Blocking: Prior to applying the antibody, block samples for several hours in a blocking solution (e.g., 2% Blocking Reagent and 10% normal serum from the secondary antibody species in PBS-Tween).

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate with the anti-label antibody (e.g., Anti-DIG-AP) diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C.

- Final Washes: Perform extensive washes over several hours to remove any unbound antibody completely.

- Staining Reaction: Develop the color reaction using BM Purple or NBT/BCIP substrate. Monitor the reaction closely to stop it as soon as the desired signal-to-noise ratio is achieved, thus preventing background from developing.

- Post-Staining: Stop the reaction by washing with PBS-Tween and fix the stain by re-fixing in MEMPFA. Store samples in the dark.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps of the optimized protocol, highlighting the critical additions for background reduction.

Diagram Title: Optimized WISH Workflow for Low Background

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Background Reduction

Success in WISH relies on a suite of specific reagents, each designed to address a particular aspect of the technique. The following table details key solutions for mitigating background.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Background Reduction in WISH

| Reagent | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | Blocks endogenous peroxidase (HRP) activity. | Use at 0.3% (v/v) prior to applying HRP-conjugated antibodies [12]. |

| Levamisol | Inhibits endogenous alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity. | Use at 2 mM concentration in the staining reaction to prevent background from tissue phosphatases [12]. |

| Normal Serum | Blocks non-specific binding sites on the tissue. | Use 10% serum from the species of the secondary antibody during a 1-hour blocking step [12]. |

| Avidin/Biotin Blocking Kit | Saturates endogenous biotin to prevent binding to streptavidin. | Essential for tissues with high mitochondrial activity (liver, kidney) when using ABC detection [11] [12]. |

| Proteinase K | Increases tissue permeability for reagents. | Treatment time must be optimized; over-digestion can damage tissue morphology [10]. |

| Tween-20 & CHAPS | Detergents that improve washing efficiency. | Adding these to wash buffers helps remove unbound probes, significantly reducing background [13]. |

| Pre-adsorbed Secondary Antibodies | Secondary antibodies purified to remove cross-reactivity. | Critical for reducing non-specific binding, especially in complex tissues or cross-species experiments [11] [12]. |

| Denotivir | Denotivir, CAS:51287-57-1, MF:C18H14ClN3O2S, MW:371.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| EIDD-1931 | EIDD-1931, CAS:3258-02-4, MF:C9H13N3O6, MW:259.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Achieving a low-background, high-contrast whole mount in situ hybridization requires a methodical approach that anticipates and counters both endogenous and technical sources of noise. The journey from a messy, high-background stain to a publication-quality image hinges on understanding the common culprits: endogenous pigments and enzymes, suboptimal probe handling, and inadequate tissue processing. By integrating strategic pre-treatments like photo-bleaching and fin notching, employing specific blocking agents, and meticulously optimizing hybridization and washing conditions, researchers can systematically overcome these challenges. This comprehensive overview provides a actionable framework for troubleshooting, ensuring that the true signal of gene expression can be visualized with the clarity and specificity that the WISH technique promises.

The Role of Tissue Permeability and Fixation in Background Staining

Whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH) is a foundational technique in developmental biology and regeneration research, enabling the spatial visualization of gene expression patterns within intact tissues. However, a pervasive challenge that can compromise experimental results is high background staining. This issue is intrinsically linked to two critical technical aspects: tissue fixation, which preserves morphological integrity and nucleic acid targets, and tissue permeability, which governs reagent access. Inadequate fixation can lead to RNA degradation and non-specific probe trapping, while excessive or improper permeabilization can damage tissue architecture, creating voids that trap staining reagents. This technical guide examines the mechanisms by which fixation and permeability protocols influence background staining and provides detailed, updated methodologies to achieve high-signal, low-noise results in WISH experiments.

Core Mechanisms: How Fixation and Permeability Govern Background

The journey of a probe from application to its target mRNA is fraught with opportunities for non-specific interactions. The physical and chemical state of the tissue, determined by fixation and permeabilization, is the primary factor controlling these interactions.

Fixation's Dual Role: Effective fixation performs two vital functions. First, it rapidly preserves tissue architecture by cross-linking proteins, locking cellular components in place. Second, it immobilizes the target RNA molecules, preventing their diffusion and degradation. Incomplete fixation results in the leakage of endogenous RNAses and cellular debris, which can bind probes non-specifically. Conversely, over-fixation can create an excessive network of cross-links, not only hindering probe penetration but also generating hydrophobic pockets that promote the non-specific binding of probes and antibodies via charge-based interactions [14].

Permeability's Delicate Balance: Permeabilization is essential for allowing probes and antibodies to reach their intracellular targets. However, the process is a double-edged sword. Chemical permeabilization agents like detergents (e.g., Tween-20, Triton X-100) work by dissolving lipid membranes. Over-treatment can lyse cells and destroy the very tissue structures—such as the delicate epidermis and blastema in regenerating planarians—that researchers aim to study [15]. Enzymatic permeabilization, typically with Proteinase K, digests proteins to loosen the tissue matrix. While this can improve probe access, it also risks destroying antigen epitopes for subsequent immunofluorescence and can create a porous, sponge-like tissue that avidly traps developing substrate, leading to pervasive background signal [15] [16].

The table below summarizes the primary causes of background staining and their underlying mechanisms.

Table 1: Primary Causes of Background Staining in WISH

| Cause | Impact on Tissue | Resulting Background Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Fixation | Poor RNA immobilization; cellular leakage | Non-specific probe binding to degraded nucleic acids and cellular debris |

| Over-Fixation | Excessive protein cross-linking; masked targets | Hydrophobic trapping of probes; reduced specific signal |

| Over-Permeabilization | Physical damage to tissue integrity; creation of voids | Trapping of chromogenic/fluorescent substrate in tissue interstices |

| Inadequate Washing | Residual unbound probe and reagents | Non-specific signal development during substrate reaction |

Quantitative Comparison of Fixation and Permeabilization Strategies

Recent research has yielded new protocols designed to optimize the balance between tissue preservation and permeability. The following table provides a comparative analysis of established and novel methods, highlighting their impact on background staining and tissue integrity.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of WISH Permeabilization and Fixation Protocols

| Protocol Name | Key Components | Impact on Background & Tissue Integrity | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional NAC Protocol [15] | N-Acetyl Cysteine (mucolytic), Proteinase K | High background; damages epidermis and blastema; disrupts epitopes | Robust tissues where antigen preservation is not a priority |

| NA (Rompolas) Protocol [15] | Nitric Acid, EGTA | Excellent tissue preservation; low background but poor probe penetration for many internal targets | Primarily for immunofluorescence; less ideal for RNA ISH |

| NAFA Protocol (2024) [15] | Nitric Acid, Formic Acid, EGTA | Low background; superior preservation of epidermis/blastema; high compatibility with immunofluorescence | Delicate tissues (e.g., planarians, regenerating fins); combined FISH/immunostaining |

| Optimized Xenopus Protocol [16] | MEMPFA fixation, Photo-bleaching, Fin notching | Significantly reduces pigment interference and background in loose fin tissues | Pigmented and loose connective tissues (e.g., Xenopus tadpole tail) |

The NAFA (Nitric Acid/Formic Acid) protocol represents a significant advance. By avoiding Proteinase K digestion and using a specific acid combination, it preserves the integrity of fragile structures like the planarian epidermis and regeneration blastema far better than the traditional NAC protocol [15]. This preservation directly correlates with reduced background, as the tissue is less physically disrupted and therefore less prone to trapping stain. Furthermore, the avoidance of protease treatment makes the NAFA protocol highly compatible with subsequent immunostaining, as protein antigen epitopes remain intact [15].

For tissues with specific challenges, such as the pigmented and loose-finned regenerating tails of Xenopus laevis tadpoles, a tailored approach is necessary. The optimized protocol combining photo-bleaching to remove melanin interference and precise fin notching to allow thorough washing of loose tissues proved essential for obtaining clear, high-contrast images of mmp9-expressing cells with minimal background [16].

Detailed Experimental Methodologies

The NAFA Protocol for Planarian WISH and Immunostaining

The following workflow diagrams the NAFA protocol, which is designed for optimal preservation and low background.

Diagram 1: NAFA Protocol Workflow for Low-Background WISH.

Key Reagents and Steps:

- Fixation Solution: The NAFA fixative is pivotal. It consists of 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in a solution containing nitric acid, formic acid, and the calcium chelator EGTA. EGTA is included to inhibit nucleases and preserve RNA integrity during sample preparation [15].

- Permeabilization: This protocol deliberately omits Proteinase K. Permeabilization is achieved through the action of the acids in the fixation solution, which is sufficient for probe penetration without causing the physical damage associated with enzymatic digestion [15].

- Hybridization and Washes: Following standard hybridization with a labeled antisense RNA probe, stringent washes are critical. The temperature and salt concentration (e.g., of SSC buffer) should be optimized for each probe to remove unbound and weakly-bound probes without stripping the specific signal [14].

- Blocking and Detection: Prior to antibody incubation, samples should be treated with a blocking agent like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or casein to occupy non-specific binding sites. Detection then proceeds with either a chromogenic (e.g., NBT/BCIP) or fluorescent substrate [14].

Optimized Protocol for Challenging Tissues: Xenopus Tadpole Tail

Regenerating Xenopus tadpole tails present dual challenges: dense pigment and loose fin tissue. This protocol specifically addresses these issues.

Diagram 2: Specialized Workflow for Pigmented and Loose Tissues.

Key Modifications:

- MEMPFA Fixation: Fix samples in MEMPFA (4% PFA, 2mM EGTA, 1mM MgSOâ‚„, 100mM MOPS, pH 7.4). This formulation is excellent for preserving morphology and nucleic acids [16].

- Early Photo-bleaching: Immediately after fixation and dehydration, expose the samples to strong light to bleach melanosomes and melanophores. This step is performed before pre-hybridization to prevent pigment from obscuring the specific stain [16].

- Caudal Fin Notching: Making small, fringe-like incisions in the tail fin at a distance from the area of interest is a critical mechanical step. It allows reagents to wash in and out of the loose fin tissue efficiently, preventing the trapping of the chromogenic substrate (e.g., BM Purple) that would otherwise cause severe, non-specific background [16]. The combination of these two steps was proven essential for achieving high-quality, low-background visualization of mmp9 expression in this model system [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Background Reduction

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Optimizing WISH

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Role in Background Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | Paraformaldehyde (PFA) (4%), MEMPFA, NAFA Fixative | Preserves tissue structure and immobilizes RNA; optimal formulation prevents probe trapping. |

| Permeabilizers | Proteinase K, Tween-20, Triton X-100, Formic Acid (in NAFA) | Enables probe access to target; concentration and type must be carefully titrated to avoid tissue damage. |

| Blocking Agents | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Casein, Salmon Sperm DNA, tRNA | Occupies non-specific binding sites on tissue and on the probe to prevent off-target binding. |

| Hybridization Buffers | Formamide (50%), SSC (Saline Sodium Citrate), Denhardt's Solution | Creates optimal ionic and chemical environment for specific probe-target hybridization. |

| Stringency Wash Buffers | SSC at varying concentrations (e.g., 2X, 0.2X), SDS | Removes unbound and non-specifically bound probe through controlled temperature and ionic strength. |

| Detection Substrates | NBT/BCIP (Chromogenic), Fluorescent tyramides | Produces the detectable signal; using fresh, high-quality substrate reduces precipitate-based background. |

| PNU-177864 | PNU-177864, CAS:250266-51-4, MF:C18H21F3N2O3S, MW:402.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Stavudine sodium | Stavudine sodium, MF:C10H11N2NaO4, MW:246.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Analysis and Quantification of Background and Signal

Modern image analysis tools provide objective methods to quantify signal and background, moving beyond subjective visual assessment. The QuantISH framework is an open-source pipeline designed to quantify RNA-ISH signals from chromogenic or fluorescent images, even on complex backgrounds [7].

- Image Processing: The pipeline involves critical pre-processing steps such as color deconvolution to separate the chromogenic stain (e.g., brown DAB or NBT/BCIP) from the nuclear counterstain (e.g., hematoxylin). This allows for independent analysis of the expression signal [7].

- Cell Segmentation and Classification: Using the nuclear channel, cells are segmented. They can then be classified into types (e.g., carcinoma, immune, stromal) based on nuclear morphology, enabling cell type-specific expression quantification [7].

- Quantification of Expression and Heterogeneity: QuantISH can measure the average expression level of a target RNA within a cell population. Furthermore, it can calculate a variability factor, which characterizes biological heterogeneity of gene expression independently of the mean expression level. This is a powerful application of RNA-ISH technology that bulk extraction methods cannot provide [7].

High background staining in whole mount in situ hybridization is not an insurmountable obstacle but a solvable problem rooted in the technical interplay of fixation and permeability. The advent of novel protocols like NAFA, which forgoes destructive proteinase digestion, alongside targeted strategies for challenging tissues, provides researchers with a refined toolkit. By understanding the mechanisms of background generation and rigorously applying optimized, tissue-appropriate methodologies, scientists can achieve the ultimate goal of WISH: clear, specific, and quantifiable visualization of gene expression that faithfully reflects underlying biological processes.

How Probe Characteristics (Length, Concentration, Purity) Influence Signal-to-Noise Ratio

In molecular hybridization techniques such as whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH), achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is paramount for accurate detection of gene expression. The biochemical characteristics of the nucleic acid probes themselves—specifically their length, concentration, and purity—are fundamental determinants of assay performance. This technical guide explores the mechanistic relationships between these probe parameters and the resulting SNR, providing evidence-based optimization strategies and detailed protocols to enable researchers to systematically reduce high background in their experiments. By integrating quantitative data and experimental methodologies, this whitepaper serves as an essential resource for improving the clarity and reliability of hybridization-based research.

High background fluorescence is a critical obstacle in whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH), obscuring specific signals and complicating data interpretation. The signal-to-noise ratio is a key metric that quantitatively compares the level of a target-specific signal to the level of background noise; a higher SNR indicates a clearer, more reliable detection. Noise often originates from non-specific binding of probes to off-target sites, incomplete washing that fails to remove unbound probes, and endogenous autofluorescence.

While factors like fixation conditions, washing stringency, and detection methods are frequently optimized, the intrinsic properties of the probe are equally critical. The length of the probe influences its penetration efficiency and binding kinetics; its concentration directly affects the balance between specific hybridization and non-specific background; and its purity determines the fraction of molecules capable of target-specific binding. This guide details how a methodical approach to optimizing these three probe characteristics can significantly enhance SNR, thereby resolving the pervasive issue of high background in WISH.

Theoretical Foundations: How Probe Parameters Govern SNR

Probe Length and Hybridization Dynamics

Probe length directly governs binding stability, tissue penetration, and hybridization specificity. Overly long probes can increase non-specific binding, while very short probes may lack the avidity for stable target binding.

- Optimal Length Range: Research indicates that long RNA probes (up to 2.61 kilobases) can readily permeate cryosections and yield stronger specific hybridization signals than shorter, hydrolyzed probes of equivalent complexity [17]. This challenges the conventional practice of hydrolyzing long probes and suggests that full-length probes can be optimal for detecting rare mRNAs.

- Penetration and Stability Trade-off: A longer probe carries more label, potentially increasing signal. However, in dense whole-mount tissues, excessive length can hinder probe diffusion. Therefore, a balance must be struck to ensure sufficient avidity without compromising access to the target site.

Probe Concentration and Its Dual Role

Probe concentration is a decisive factor for SNR. An optimal concentration saturates all target sites, whereas deviations lead to high background or weak signal.

- Signal and Noise Relationship: As concentration increases, the specific signal strength rises as more target molecules are bound. However, beyond an optimal point, non-specific binding rises disproportionately, elevating background noise [18]. This non-specific binding is a primary contributor to low SNR.

- Key Optimization Parameter: Studies have explicitly highlighted probe concentration as a critical parameter for improving the signal-to-noise ratio in in situ hybridization [17]. Empirical titration is necessary to identify the concentration that maximizes specific binding while minimizing background.

Probe Purity and Functional Integrity

Probe purity ensures that a high proportion of molecules in the hybridization solution are the intended sequence. Impurities are a direct source of noise.

- Consequences of Impurities: Contaminants such as free nucleotides, truncated probe fragments, or salts can bind non-specifically to tissue components, creating a diffuse background signal. Furthermore, incomplete purification can leave behind enzymes and buffers that interfere with the hybridization chemistry.

- Impact on SNR: A pure probe preparation ensures that the observed signal originates from a successful hybridization event. The presence of impurities effectively dilutes the functional probe concentration, often forcing researchers to use higher total concentrations to achieve a signal, which in turn exacerbates background noise [19].

The following diagram illustrates the foundational theory of how these probe characteristics influence the final assay outcome through distinct mechanistic pathways.

Quantitative Data and Experimental Evidence

SNR Calculation Methods

To objectively optimize probe parameters, a consistent method for calculating SNR is required. Different methodological approaches exist, and the choice of formula can influence the perceived performance.

Table 1: Common Methods for Calculating Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

| Calculation Method | Formula | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Standard-Deviation Ratio (SSR) [20] | SNR = (Mean_Signal - Mean_Background) / SD_Background |

Microarray analysis; general signal processing | Common threshold: 2.0-3.0. Considers background variability. |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR) [20] | SNR = Median_Signal / Median_Background |

Fluorescence imaging & microscopy | Common threshold: ~1.60. Simple but ignores data spread. |

| Signal-to-Both-Standard-Deviations Ratio (SSDR) [20] | SNR = (Mean_Signal - Mean_Background) / √(SD_Signal² + SD_Background²) |

Microarray analysis (recommended) | Incorporates both signal and background variance for higher accuracy. |

| First Standard Deviation (FSD) / SQRT Method [21] | SNR = (Peak_Signal - Background) / √(Background) |

Photon-counting spectrofluorometry | Assumes Poisson statistics of light detection. |

| Root Mean Square (RMS) Method [21] | SNR = (Peak_Signal - Background) / RMS_Noise |

Analog detection systems (e.g., fluorometers) | RMS noise is measured from kinetic data at an off-peak wavelength. |

The SSDR method has been shown to provide a more accurate determination of SNR thresholds with the lowest percentage of false positives and false negatives in microarray studies [20]. For fluorescence imaging, the SBR is widely used due to its simplicity, though it is less statistically robust.

Impact of Probe Characteristics on SNR: Empirical Findings

Experimental data across different hybridization techniques provides quantitative insights into how probe parameters should be controlled.

Table 2: Experimental Impact of Probe Parameters on SNR and Assay Performance

| Probe Parameter | Experimental Finding | Effect on SNR | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Concentration | Identified as a key parameter for improving SNR [17]. | Directly optimized; insufficient concentration lowers signal, excess increases background. | ISH for rare mRNAs |

| Long Probe Length | Long RNA probes (up to 2.61 kb) yielded stronger signals than hydrolyzed probes without increasing background [17]. | Increased | ISH on cryosections |

| Probe Purity & Conjugation | An under-conjugated probe may provide a false-negative result, while over-conjugation can cause steric hindrance and self-quenching of the signal [19]. | Decreased (if non-optimal) | Characterization of optical imaging probes |

| Hybridization Stringency | SNR thresholds were affected by hybridization stringency, requiring adjustment of optimal conditions [20]. | Requires re-optimization of other parameters | Microarray analysis with gDNA |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining Optimal Probe Concentration

This protocol is adapted from methods used to optimize in situ hybridization for rare mRNAs [17].

- Prepare Probe Dilutions: Serially dilute your purified probe in hybridization buffer to create a concentration series (e.g., 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 ng/μL).

- Hybridize Parallel Samples: Apply each dilution to parallel tissue samples (or sections) under identical conditions.

- Standardize Detection: Perform all subsequent washing and detection steps simultaneously and with identical parameters (e.g., time, temperature, buffer volumes).

- Quantify Signal and Background: Using image analysis software, measure the mean signal intensity within the specific expression domain and an adjacent background region with no expected expression.

- Calculate SNR: For each sample, calculate the Signal-to-Background Ratio (SBR):

SBR = Mean_Signal_Intensity / Mean_Background_Intensity. - Identify Optimal Point: Plot SBR against probe concentration. The optimal concentration is at the point where the SBR plateaus or begins to decline, indicating maximal specific signal without a proportional increase in background.

Protocol: Probe Purification and Quality Control

High purity is critical. This protocol outlines steps based on guidelines for characterizing optical imaging probes, which are equally relevant for fluorescent in situ hybridization probes [19].

- Synthesis: Synthesize probes with appropriate labels (e.g., DIG, Fluorescein, Cy dyes).

- Purification: Use HPLC or column chromatography to separate the full-length conjugated probe from free dyes, truncated sequences, and unincorporated nucleotides.

- Quality Control:

- Assess Purity: Analyze the purified product by analytical HPLC or capillary electrophoresis. A single, sharp peak indicates high purity.

- Verify Structure: Confirm the probe's identity using mass spectrometry.

- Determine Concentration: Accurately quantify the probe using UV-Vis spectrophotometry. Calculate the number of dye molecules per probe to ensure it is neither under- nor over-conjugated.

- Functional Validation: Test the performance of the purified probe against a known positive control sample in a standardized assay.

The following workflow diagram integrates the optimization of probe length, concentration, and purity into a cohesive experimental strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following reagents are critical for implementing the protocols and optimization strategies described in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Probe-Based Hybridization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Probe | The primary agent for specific target detection. | Prioritize suppliers that provide mass spectrometry and HPLC validation data. |

| Hybridization Buffer | Creates the chemical environment for specific probe-target binding. | Formulation (pH, salt, formamide concentration) dictates stringency and must be optimized. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Casein) | Reduce non-specific binding of probes and detection antibodies to the tissue. | Using normal serum from the host species of secondary antibodies can block Fc receptors [22]. |

| Stringent Wash Buffers | Remove probes that are non-specifically or weakly bound. | Freshly prepared SSC-based buffers with controlled pH and temperature are critical [18]. |

| Tissue Pretreatment Kit | Enzymatically treats tissues to unmask target sequences and reduce autofluorescence. | Kits like CytoCell LPS 100 standardize the pre-treatment of FFPE tissues [18]. |

| Autofluorescence Quenchers | Chemically reduces inherent tissue fluorescence. | Reagents like TrueBlack are specifically designed to quench lipofuscin autofluorescence without affecting the specific signal [22]. |

| Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibodies | For immunodetection of labeled probes, these minimize cross-reactivity. | Affinity-purified against immunoglobulins of multiple species to reduce background [22]. |

| AR-C102222 | AR-C102222, MF:C19H17ClF2N6O, MW:418.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N3PT | N3PT, CAS:13860-66-7, MF:C13H19Cl2N3OS, MW:336.28 | Chemical Reagent |

The characteristics of nucleic acid probes are not merely preliminary details but are active and powerful levers for controlling the signal-to-noise ratio in whole mount in situ hybridization. Evidence demonstrates that probe length dictates hybridization kinetics and specificity, probe concentration directly governs the equilibrium between signal and background, and probe purity is the bedrock upon which specific binding is built. By systematically optimizing these parameters using the quantitative protocols and reagents outlined in this guide, researchers can effectively diagnose and resolve the persistent challenge of high background.

Future advancements in probe chemistry, such as the development of locked nucleic acids (LNAs) with higher affinity and specificity, and the refinement of in situ amplification techniques like Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) [22], will provide even more tools to push the boundaries of SNR. However, a foundational and rigorous approach to the basic principles of probe design, preparation, and quantification will remain essential for achieving clear and meaningful scientific images.

Optimizing Your WISH Protocol: Methodological Choices to Minimize Background

In whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH), high background staining is a frequent challenge that can obscure specific signals and compromise data interpretation. A primary factor contributing to this noise is suboptimal probe design, particularly concerning probe length and labeling efficiency. The design of nucleic acid probes is a fundamental step that directly influences hybridization specificity, signal intensity, and ultimately, the signal-to-noise ratio. Within the context of a broader thesis on resolving high background in WISH, this guide details the core principles of designing probes within the 250-1500 base range, ensuring that researchers can generate clean, interpretable results. Properly designed probes minimize non-specific binding to off-target sequences and ensure that the hybridization signal originates authentically from the gene of interest.

Core Guidelines for Probe Length

Selecting an appropriate probe length is a balance between achieving sufficient sensitivity (signal intensity) and maintaining high specificity to avoid background. The following table summarizes key considerations for different probe length ranges:

Table 1: Probe Length Guidelines for In Situ Hybridization

| Length Range | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shorter Oligos (20-30 bases) | Typically used in FISH; high specificity required [23]. | High specificity for distinguishing closely related sequences. | Lower sensitivity; may require complex signal amplification systems [23]. | Single-molecule FISH (smFISH), mutation detection. |

| Medium Length (50-150 bases) | Often considered "long oligonucleotides"; a balance of sensitivity and specificity. | Good signal intensity; can be designed for gene-specific targeting [24]. | May require experimental validation to identify optimal probes [24]. | Standard FISH and WISH applications. |

| Long Probes (150-1000+ bases) | Typical for riboprobes generated by in vitro transcription. | High sensitivity; robust signal intensity; less dependent on experimental validation [24]. | Increased risk of cross-hybridization to non-target sequences if not carefully designed [24]. | Detecting low-abundance targets; whole-mount specimens. |

For probes in the 250-1500 base range, which are commonly used in WISH, the following specific recommendations apply:

- Optimal Sensitivity: Longer probes within this range generally yield better signal intensity than shorter probes [24]. This is because a longer probe provides more binding sites for the labeled nucleotides or subsequent detection molecules.

- Specificity Assurance: To mitigate the risk of cross-hybridization with long probes, a computational design approach is crucial. This involves masking any part of a gene with >75% local sequence similarity over a 50-base window with other genes. The remaining unmasked sequences are considered unique and should be used for probe design [24].

- Sequence Composition: The GC content of the probe should be ideally maintained between 45% and 55% to ensure uniform hybridization behavior. Probes should also be screened for secondary structures and repetitive elements, which can elevate background staining [24] [25].

Probe Labeling Strategies for Optimal Detection

The choice of label and detection system is equally critical for minimizing background.

Label Type (Direct vs. Indirect):

- Direct Labeling: Probes are conjugated directly to a fluorophore (for FISH) or hapten. This allows for faster protocols but may offer lower signal amplification [26] [23].

- Indirect Labeling: Probes are labeled with a hapten (e.g., digoxigenin or biotin). This requires a detection step with an enzyme-conjugated antibody (e.g., anti-digoxigenin) followed by a chromogenic or fluorescent substrate. Indirect methods provide significant signal amplification, which is beneficial for detecting low-abundance targets [26].

Critical Considerations for Labeling:

- Biotin Awareness: Endogenous biotin present in many tissues can cause non-specific staining. For tissues high in biotin, digoxigenin is the preferred label due to its plant origin and lack of endogenous interference [26].

- Repetitive Sequence Blocking: If the probe template contains repetitive sequences (e.g., Alu or LINE elements), background can be elevated. This must be blocked by adding unlabeled competitor DNA like COT-1 DNA to the hybridization mixture [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Probe-Based Experiments

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for In Situ Hybridization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Digoxigenin-dUTP | A non-radioactive label incorporated into probes via transcription or labeling kits; highly specific antibodies allow for sensitive detection with low background [26]. |

| Proteinase K | A critical enzyme for digesting proteins and increasing tissue permeability to probes. Concentration and time must be optimized to avoid tissue damage [16]. |

| COT-1 DNA | Unlabeled genomic DNA used to block non-specific hybridization of probe repetitive sequences to genomic DNA, thereby reducing background [25]. |

| Formamide | A component of hybridization buffers that allows the reaction to occur at lower temperatures (e.g., 37-65°C), preserving tissue morphology while maintaining stringency [26]. |

| Blocking Reagent | (e.g., sheep serum, BSA) Prevents non-specific binding of antibodies during the detection steps. |

| Chromogenic Substrate | (e.g., NBT/BCIP, DAB) Enzymatic conversion produces an insoluble, colored precipitate at the site of probe hybridization [25]. |

| EMD638683 S-Form | EMD638683 S-Form, CAS:1184940-46-2, MF:C18H18F2N2O4, MW:364.3 g/mol |

| EMD638683 R-Form | EMD638683 R-Form, CAS:1184940-47-3, MF:C18H18F2N2O4, MW:364.3 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Low-Background WISH

The following diagram illustrates a robust WISH protocol that incorporates key steps for background reduction, particularly for challenging samples like regenerating tadpole tails [16].

WISH Workflow with Background Optimization

Detailed Methodology for Key Steps

Step 1: Sample Fixation and Preparation

- Fixation: Fix samples in 4% MEMPFA (4% paraformaldehyde in MOPS, EGTA, MgSOâ‚„ buffer, pH 7.4) for optimal tissue preservation [16].

- Photobleaching (for pigmented samples): To eliminate masking by melanin, perform a bleaching step after fixation and dehydration. This creates "perfectly albino tails" for clear signal visualization [16].

- Fin Notching: For loose tissues like tail fins, make small incisions in a fringe-like pattern. This dramatically improves reagent penetration and washing, preventing trapped chromogen from causing background [16].

Step 2: Permeabilization and Hybridization

- Proteinase K Treatment: Digest with 1-5 µg/mL Proteinase K for 10 minutes at room temperature. Titrate this concentration for your tissue type; over-digestion destroys morphology, while under-digestion reduces signal [26] [16].

- Hybridization: Hybridize with the specific, labeled probe at 37°C overnight in a humidified chamber. Ensure the probe is denatured (if double-stranded) and well-mixed before application [25].

Step 3: Post-Hybridization Washes and Detection

- Stringent Washes: This is a critical step. After hybridization, rinse slides briefly and then perform a stringent wash in SSC buffer (e.g., 1X SSC) at 75-80°C for 5 minutes. This dissociates imperfectly matched probes, drastically reducing background [25].

- Detection and Staining:

- For digoxigenin-labeled probes, incubate with an alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody.

- Wash thoroughly to remove unbound antibody.

- Incubate with the chromogenic substrate BM Purple or NBT/BCIP.

- Monitor the staining reaction under a microscope every 2-3 minutes and stop the reaction by rinsing in distilled water the moment background staining appears [25] [16].

- Counterstaining: If required, apply a light counterstain (e.g., Mayer's hematoxylin for 5-60 seconds), as a dark counterstain can mask the specific signal [25].

Advanced Enhancement Strategies

For particularly challenging targets, such as low-abundance transcripts, consider these advanced strategies to enhance signal-to-noise:

- Signal Amplification: Employ methods like Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) or tyramide signal amplification (TSA). These techniques can significantly boost the signal at the site of hybridization, making faint signals detectable without increasing background [23].

- Tissue Clearing: For thick tissues or whole mounts, tissue clearing methods can reduce light scattering and autofluorescence, improving signal access and visualization while lowering background [23].

Achieving low-background, high-quality results in whole mount in situ hybridization is intimately linked to rigorous probe design and protocol optimization. By selecting a probe length of 150 bases or longer from unique genomic regions, using a non-interfering label like digoxigenin, and adhering to a protocol that emphasizes stringent washes and controlled development, researchers can effectively address the challenge of high background. This disciplined approach ensures that the resulting expression patterns are a true and clear representation of underlying biological reality.

In whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH), effective tissue preparation is the foundational step that determines the success of the entire experiment. The critical challenge researchers face—high background staining—often originates from improper handling of fixation, permeabilization, and Proteinase K digestion long before detection steps begin. This guide examines these core preparatory techniques within the context of a broader thesis on troubleshooting high background in WISH, providing researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based protocols to preserve tissue integrity while ensuring specific hybridization.

The balance between preserving tissue morphology and allowing sufficient probe penetration represents a significant technical hurdle. Inadequate fixation compromises cellular structure, while over-fixation creates excessive cross-links that mask target sequences and promote non-specific binding [27]. Similarly, improper permeabilization either leaves target nucleic acids inaccessible or destroys tissue architecture [15] [28]. This guide synthesizes current methodologies and introduces innovative approaches to overcome these persistent challenges in molecular histology.

Fundamental Principles of Tissue Fixation

Fixation serves the dual purpose of preserving tissue architecture and immobilizing nucleic acids while maintaining their accessibility for hybridization. The fixation process represents a delicate balance; understanding the chemistry behind common fixatives is essential for optimizing WISH outcomes.

Fixative Selection and Formulation

Paraformaldehyde (PFA) remains the gold standard fixative for WISH due to its excellent preservation of cellular ultrastructure and RNA integrity. PFA works by creating cross-links between proteins, effectively "locking" cellular components in place. For most applications, a concentration of 4% PFA in phosphate-buffered saline provides optimal results [29]. The critical importance of using freshly prepared PFA cannot be overstated, as degraded PFA contains formic acid that can hydrolyze RNA targets.

Recent research has introduced alternative acidic fixatives that may offer advantages for specific applications. The Nitric Acid/Formic Acid (NAFA) protocol demonstrates particular utility for delicate regenerating tissues, effectively preserving fragile structures like planarian epidermis and blastema while maintaining compatibility with both chromogenic and fluorescent detection systems [15]. This approach eliminates the need for Proteinase K digestion, thereby preserving antigen epitopes for subsequent immunostaining.

Table 1: Common Fixatives for Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization

| Fixative | Concentration | Mechanism | Optimal Tissue Types | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | 4% in PBS | Protein cross-linking | Most tissues, especially embryos | Excellent morphology preservation, maintained RNA integrity |

| NAFA Fixative | Nitric + Formic Acid | Not specified | Delicate regenerating tissues | Preserves fragile epithelia, no Proteinase K needed |

| MEMPFA | 4% PFA + MOPS, EGTA, MgSOâ‚„ | Cross-linking with cation chelation | Xenopus tadpole tails | Enhanced RNA preservation, reduces background |

Fixation Protocol Optimization

Standardized fixation protocols must be adapted to specific tissue types and experimental requirements. For zebrafish embryos, fixation in 4% PFA for 1 hour at room temperature typically yields optimal results, while shorter fixation times (30 minutes) may suffice for older embryos [29]. Inconsistent fixation represents a frequent source of variability; tissues must be completely submerged in an adequate volume of fixative (typically 10:1 fixative-to-tissue ratio) to ensure uniform preservation.

The inclusion of additives can significantly enhance fixation outcomes. EGTA (ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid) chelates calcium ions, inhibiting calcium-dependent nucleases that degrade RNA during sample preparation [15]. Similarly, fixation buffers with MgSO₄ help maintain cellular structure while preserving RNA accessibility.

Tissue Permeabilization Strategies

Effective permeabilization enables probe access to target nucleic acids while maintaining tissue integrity. This balance is particularly challenging in whole-mount specimens where reagents must penetrate three-dimensional structures.

Proteinase K Digestion

Proteinase K remains the most widely used enzymatic method for tissue permeabilization in WISH protocols. This serine protease digests proteins surrounding target nucleic acids, increasing probe accessibility. However, the digestion must be carefully optimized, as insufficient treatment limits probe penetration while excessive digestion damages tissue morphology and can create binding sites for non-specific probe attachment [27].

The optimal Proteinase K concentration must be empirically determined for each tissue type and fixation condition. A general starting point ranges from 1-20 µg/mL, with incubation times typically between 10-30 minutes at room temperature [28]. As noted in established protocols, "the amount of proteinase K used needs to be optimized for each lot of proteinase K" [28]. Some researchers recommend performing mock hybridizations with a range of Proteinase K concentrations to identify conditions that preserve tissue morphology while permitting adequate probe access.

Alternative Permeabilization Approaches

Recent methodological advances have introduced Proteinase K-free permeabilization strategies that overcome limitations of enzymatic digestion. The NAFA protocol achieves effective permeabilization through acid treatment, significantly improving preservation of delicate tissues like regenerating planarian epidermis and blastema [15]. This approach demonstrates that "the NAFA protocol does not include a protease digestion, providing increased compatibility with immunological assays, while not compromising ISH signal" [15].

Mechanical permeabilization methods can further enhance reagent penetration in challenging tissues. For Xenopus tadpole tail regenerates, creating fin incisions in a fringe-like pattern at a distance from the area of interest dramatically improves washing efficiency, preventing trapping of detection reagents in loose fin tissues that causes non-specific chromogenic reactions [10]. This simple modification enables extended staining incubation without increased background.

Table 2: Permeabilization Methods for Whole-Mount Tissues

| Method | Mechanism | Key Parameters | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K | Enzymatic protein digestion | Concentration (1-20 µg/mL), time (10-30 min), temperature (RT) | Well-established, effective for most tissues | Can damage delicate tissues, requires optimization |

| Acid Treatment (NAFA) | Not specified | Nitric acid/formic acid combination | Preserves delicate structures, compatible with immunoassay | May not suit all tissue types |

| Mechanical Notching | Physical disruption | Incisions in non-critical areas | No chemical treatment, improves reagent exchange | Limited to areas where cutting won't disrupt biology |

| Detergent Treatment | Membrane solubilization | Concentration, duration | Mild treatment, preserves epitopes | May not provide sufficient penetration for dense tissues |

Experimental Protocols

NAFA Fixation Protocol for Delicate Tissues

The NAFA (Nitric Acid/Formic Acid) protocol represents a significant advancement for WISH on fragile regenerating tissues, effectively preserving delicate structures while permitting probe penetration without Proteinase K digestion [15]:

- Fixation: Fix samples in NAFA fixative (composition optimized for specific tissue type) for prescribed duration

- Permeabilization: Treat with NAFA permeabilization solution containing nitric and formic acids

- Washing: Rinse thoroughly with appropriate buffer (0.2× SSCT or 1× PBT recommended)

- Hybridization: Proceed directly to hybridization with target-specific probes

This protocol demonstrates particular efficacy for planarian tissues and regenerating killifish tail fins, preserving "the integrity of the epidermis and regeneration blastema" while facilitating "probe and antibody penetration into internal tissues" [15].

Proteinase K Titration Experiment

Systematic optimization of Proteinase K concentration is essential for minimizing background while maintaining signal intensity:

- Sample Preparation: Divide fixed tissue samples into 6-8 equivalent groups

- Digestion Series: Prepare Proteinase K solutions across a concentration gradient (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 µg/mL) in appropriate buffer

- Controlled Digestion: Treat sample groups with respective solutions for fixed duration (typically 15-30 minutes) at room temperature

- Enzyme Inactivation: Terminate digestion by rinsing in PBS containing 2 mg/mL glycine or by post-fixing in 4% PFA for 10 minutes

- Parallel Processing: Subject all samples to identical WISH procedure using a well-characterized probe

- Assessment: Evaluate samples for tissue integrity, specific signal intensity, and non-specific background

Researchers should note that "if tissue retention on the slide is a serious problem the first thing to do is eliminate the proteinase K step" [28], though this may reduce signal intensity.

RNAscope-Based WISH for Embryos

The RNAscope technology, adapted for whole-mount embryos, provides exceptional signal-to-noise ratio through specialized probe design and signal amplification [29]:

- Fixation: Fix embryos in 4% PFA for 1 hour at room temperature (20 hpf zebrafish embryos)

- Dehydration: Gradually dehydrate through methanol series (25%, 50%, 75% in PBS) followed by 100% methanol

- Rehydration: Air-dry embryos for 30 minutes after methanol removal, then rehydrate through descending methanol series

- Permeabilization: Digest with Pretreat solution (commercially available) for 20 minutes

- Hybridization: Hybridize with target probes at 40°C overnight

- Signal Amplification: Perform RNAscope amplification steps per manufacturer instructions

- Detection: Visualize using chromogenic or fluorescent substrates

This method enables "simultaneous high-resolution detection of multiple transcripts combined with localization of proteins in whole-mount embryos" with superior preservation of morphology [29].