Sonic Hedgehog in Neural Tube Patterning: From Morphogen Gradient to Therapeutic Target

This article synthesizes current knowledge on the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway, a master regulator of neural tube patterning.

Sonic Hedgehog in Neural Tube Patterning: From Morphogen Gradient to Therapeutic Target

Abstract

This article synthesizes current knowledge on the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway, a master regulator of neural tube patterning. It explores the foundational mechanisms by which SHH, as a morphogen, establishes dorsoventral neuronal identities through concentration and duration gradients. The content delves into methodological approaches for studying SHH, including explant assays and stem cell differentiation models, and addresses challenges in pathway modulation and optimization. Furthermore, it examines the pathway's validation in disease contexts, linking its dysregulation to neural tube defects and cancers, and discusses the translational potential of SHH pathway modulators in regenerative medicine and oncology for a specialized audience of researchers and drug development professionals.

The SHH Morphogen: Decoding a Gradient that Builds the Nervous System

The Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway functions as a classical morphogen, orchestrating the pattern of the ventral neural tube through a concentration-dependent gradient that instructs progenitor cells to adopt distinct fates. Originating from the notochord and floor plate, the SHH gradient activates specific genetic programs in a dose-dependent manner, leading to the precise spatial arrangement of motor neurons, oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), and various interneurons. This whitepaper delves into the molecular mechanisms of SHH gradient formation, its interpretation by neural progenitors, and the experimental methodologies used to elucidate these processes. Furthermore, it explores the therapeutic implications of targeting this pathway, given its critical role in both development and disease. Framed within broader research on neural tube patterning, this review synthesizes foundational and contemporary findings to serve as a technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

The concept of a morphogen, a substance that governs the fate of cells in a concentration-dependent manner, provides a fundamental framework for understanding embryonic development. Lewis Wolpert's "French Flag Model" posits that a signal emitted from a localized source forms a concentration gradient across a field of cells, and these cells interpret different threshold levels of the signal to adopt distinct, discrete fates [1]. In the developing vertebrate neural tube, Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) represents a quintessential morphogen. Secreted initially by the notochord and subsequently by the floor plate cells at the ventral midline, SHH patterns the ventral neural tube by specifying the identity of progenitor domains arrayed along the dorso-ventral axis [2] [1] [3].

The establishment of this pattern is a prerequisite for the generation of diverse neuronal and glial cell types, including motor neurons (MNs), V3 interneurons, and oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs). The neural tube's response to the SHH gradient is not merely spatial but also temporal; the duration of SHH exposure works in concert with concentration to refine cellular identities [4]. The critical role of SHH signaling is underscored by the severe congenital anomalies, such as holoprosencephaly and neural tube defects, that arise from its disruption [5] [3]. Moreover, aberrant reactivation of the SHH pathway in adulthood is a driver of several malignancies, including medulloblastoma and basal cell carcinoma, making it a significant therapeutic target [6] [7] [8]. This paper details the mechanisms by which SHH fulfills its role as a morphogen, focusing on its function in neural tube patterning.

SHH Gradient Formation and Interpretation

Establishment of the Morphogen Gradient

The SHH morphogen gradient is established from two primary signaling centers. During early embryogenesis, the notochord, located beneath the neural tube, is the first source of SHH. This signal induces the formation of the floor plate at the ventral midline of the neural tube itself. Once specified, the floor plate becomes a secondary, sustained source of SHH, reinforcing and shaping the gradient [1] [3]. The SHH protein is synthesized as a precursor that undergoes autocatalytic cleavage to produce a biologically active N-terminal fragment, which is then modified by the addition of a cholesterol moiety. This lipid modification is crucial for its ability to form a steep, long-range gradient, as it influences the molecule's diffusion and distribution through the extracellular matrix [3].

The propagation of SHH is not a simple matter of free diffusion. It is actively regulated by interactions with heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) on the cell surface. Enzymes like Sulf1 and Sulf2 remodel these HSPGs by removing 6-O-sulfate groups, which in turn modulates the binding and distribution of SHH. For instance, Sulf2a, expressed in neural progenitors, acts to reduce the sensitivity of target cells to SHH, thereby fine-tuning the morphogen's effective signaling range and ensuring proper progenitor domain specification [9].

Intracellular Interpretation of the SHH Gradient

The cellular interpretation of the SHH gradient begins with its binding to the Patched1 (PTCH1) receptor on target cells. In the absence of SHH, PTCH1 constitutively represses the activity of the seven-transmembrane protein Smoothened (SMO). Binding of SHH to PTCH1 relieves this repression, allowing SMO to accumulate and initiate an intracellular signaling cascade that ultimately leads to the activation of the GLI family of transcription factors (GLI1, GLI2, GLI3) [6] [7] [8].

The key to morphogen function lies in how different concentration thresholds of SHH lead to differential GLI activity and, consequently, differential gene expression. In the ventral neural tube, progenitor domains are defined by the combinatorial expression of transcription factors. The concentration and duration of SHH signaling dictate which genes are activated or repressed. Progenitors exposed to the highest SHH levels activate Nkx2.2 and become the p3 domain, which gives rise to V3 interneurons. Slightly lower levels promote the expression of Olig2 in the pMN domain, which produces motor neurons. Even lower thresholds specify other interneuron subtypes [2] [9] [1]. This process ensures that a continuous gradient of SHH is interpreted to generate discrete blocks of cellular identity.

Table 1: SHH Concentration Thresholds and Ventral Neural Tube Patterning

| Progenitor Domain | Neural Cell Fate Produced | Key Transcription Factor | Required SHH Signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| p3 | V3 Interneurons | Nkx2.2 | High concentration/threshold [9] |

| pMN | Somatic Motor Neurons (MNs) | Olig2 | Intermediate concentration/threshold [9] [10] |

| p* | Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells (OPCs) | Olig2 & Nkx2.2 | Late, high signal (from lateral floor plate) [9] |

| p2, p1, p0 | V2, V1, V0 Interneurons | Irx3, Pax6, Dbx1/2, etc. | Low concentrations/thresholds [2] [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating SHH Morphogen Function

A combination of in vitro and in vivo approaches has been instrumental in defining SHH as a morphogen. The following protocols represent key methodologies in the field.

In Vitro Neural Differentiation Assay

This assay tests the direct concentration-dependent effect of SHH on naive neural progenitor cells.

Materials:

- Reagent: Recombinant Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) N-terminal peptide (e.g., R&D Systems).

- Cells: Neuralized embryonic stem cells or primary neural tube progenitors.

- Media: Defined neural differentiation medium (e.g., DMEM/F12 with N2 and B27 supplements).

Methodology:

- Neural Induction: Differentiate pluripotent stem cells into primitive neural progenitor cells using dual-SMAD inhibition (e.g., with SB431542 and LDN-193189).

- SHH Titration: Plate neuralized progenitors and treat them with a range of recombinant SHH concentrations (e.g., from 1 nM to 500 nM). Include a control with no SHH (ventralizing factor).

- Ventral Patterning: Co-administer a caudalizing factor like retinoic acid (RA) to direct progenitors toward a spinal cord identity.

- Analysis: After 3-7 days, analyze the cells by immunocytochemistry or quantitative PCR (qPCR) for domain-specific markers.

In Vivo Morpholino Knockdown in Zebrafish

Zebrafish are an ideal model for functional genetics due to their external development and optical clarity. This protocol assesses the consequence of loss-of-function of SHH pathway components.

Materials:

- Reagent: Gene-specific morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) designed to block translation or splicing of a target gene (e.g., sulf2a, shha).

- Model: Wild-type zebrafish embryos.

Methodology:

- Microinjection: At the 1-4 cell stage, inject morpholinos into the yolk of zebrafish embryos. Use a standard control morpholino for comparison.

- Incubation: Allow embryos to develop to desired stages (e.g., 24 hpf for early patterning, 48 hpf for neuronal specification, 72 hpf for gliogenesis).

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- In Situ Hybridization (ISH): Fix embryos and perform ISH with riboprobes for specific cell fate markers.

- sulf2a MO: Analyze for an increase in sim1a+ V3 interneurons and a decrease in olig2+ MNs and OPCs at 48 hpf and 72 hpf, respectively [9].

- Immunohistochemistry: Use antibodies against proteins like Olig2 or Islet1 to visualize motor neuron populations.

- In Situ Hybridization (ISH): Fix embryos and perform ISH with riboprobes for specific cell fate markers.

- Validation: Confirm knockdown efficacy through RT-PCR to detect mis-spliced transcripts or Western blotting if antibodies are available [9].

Regulatory Modulation of SHH Signaling

The SHH gradient is not static, and its interpretation is finely tuned by multiple regulatory mechanisms. As highlighted in the experimental protocols, the extracellular sulfatase Sulf2a plays a critical role in shaping the SHH response. Expressed in neural progenitors, Sulf2a remodels heparan sulfates to reduce the sensitivity of responding cells to the SHH signal. This activity is essential for preventing progenitor cells like those in the pMN domain from inappropriately adopting a high-threshold p3 (V3 interneuron) fate, thereby ensuring the proper balance between motor neuron and interneuron production [9]. This represents a key mechanism where the responding cell's capacity to interpret the morphogen is actively regulated.

Furthermore, the duration of SHH exposure is a critical parameter in cell fate specification. Studies in the limb bud and neural tube have demonstrated that prolonged exposure to SHH can specify more posterior limb identities and contribute to the late specification of cell types like OPCs. The pMN domain, after generating motor neurons, receives a new, high-level SHH signal from the lateral floor plate. This sustained signal, facilitated by Sulf1, induces the formation of a new progenitor domain (p*) where cells co-express Olig2 and Nkx2.2 and are fated to become OPCs [9] [4]. This illustrates how temporal dynamics work alongside concentration to expand the patterning capacity of a single morphogen.

Therapeutic Implications and Pathway Targeting

The critical role of SHH in development is mirrored by its pathogenic potential when dysregulated in adulthood. Constitutive, ligand-independent activation of the SHH pathway, often through inactivating mutations in PTCH1 or activating mutations in SMO, is a hallmark of cancers like basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and a subset of medulloblastoma (SHH-MB) [6] [8]. This has led to the development of targeted therapies that inhibit pathway components.

Table 2: FDA-Approved Hedgehog Pathway Inhibitors in Cancer

| Drug Name | Molecular Target | Primary Indication | Key Challenge in CNS Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vismodegib (GDC-0449) | Smoothened (SMO) | Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma [6] | Poor blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability [7] |

| Sonidegib (LDE225) | Smoothened (SMO) | Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma [6] | Poor blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability [7] |

| Arsenic Trioxide (ATO) | GLI proteins (& PML-RARα) | Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia [6] | Suppresses GLI activity; used in APL, efficacy in SHH-MB being investigated |

A significant challenge in treating CNS tumors like SHH-MB with SMO inhibitors is their limited penetration of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Current research focuses on novel drug delivery systems to overcome this hurdle. Strategies include encapsulating drugs like sonidegib in engineered HDL-mimetic nanoparticles (eHNPs) or polymeric nanoparticles, which can enhance BBB transit and improve tumor-specific delivery [7]. For tumors resistant to SMO inhibition, downstream inhibitors targeting the GLI transcription factors represent an alternative strategy, though their clinical development is less advanced [6] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SHH Morphogen Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SHH Protein | Purified active ligand for in vitro stimulation; used to create concentration gradients. | Titrating SHH in stem cell differentiation protocols to induce specific neuronal fates [10]. |

| SMO Inhibitors (e.g., Vismodegib, Sonidegib) | Small molecule antagonists of Smoothened; used to inhibit canonical pathway signaling. | Testing pathway dependence in cancer models or probing the requirement of SHH signaling at specific developmental timepoints [6] [7]. |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Gene-specific knockdown tools for loss-of-function studies in model organisms like zebrafish. | Rapidly assessing the in vivo function of genes like sulf2a in spinal cord patterning [9]. |

| Antibody Panels (Olig2, Nkx2.2, Pax6, Islet1) | Markers for immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry to identify progenitor domains and neuronal subtypes. | Analyzing the pattern of the neural tube in mutant embryos or differentiated cell cultures [2] [9]. |

| SHH-Reporting Cell Lines | Cell lines with a GLI-responsive reporter (e.g., GFP or Luciferase) to quantify pathway activity. | High-throughput screening for SHH pathway agonists or inhibitors [6]. |

| POPSO | Popso (Poplar Propolis Extract) | Popso, a poplar-type propolis extract rich in flavonoids. For Research Use Only (RUO). Supports studies in microbiology, oxidative stress, and phytochemistry. |

| 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid | 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, CAS:7365-45-9, MF:C8H18N2O4S, MW:238.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

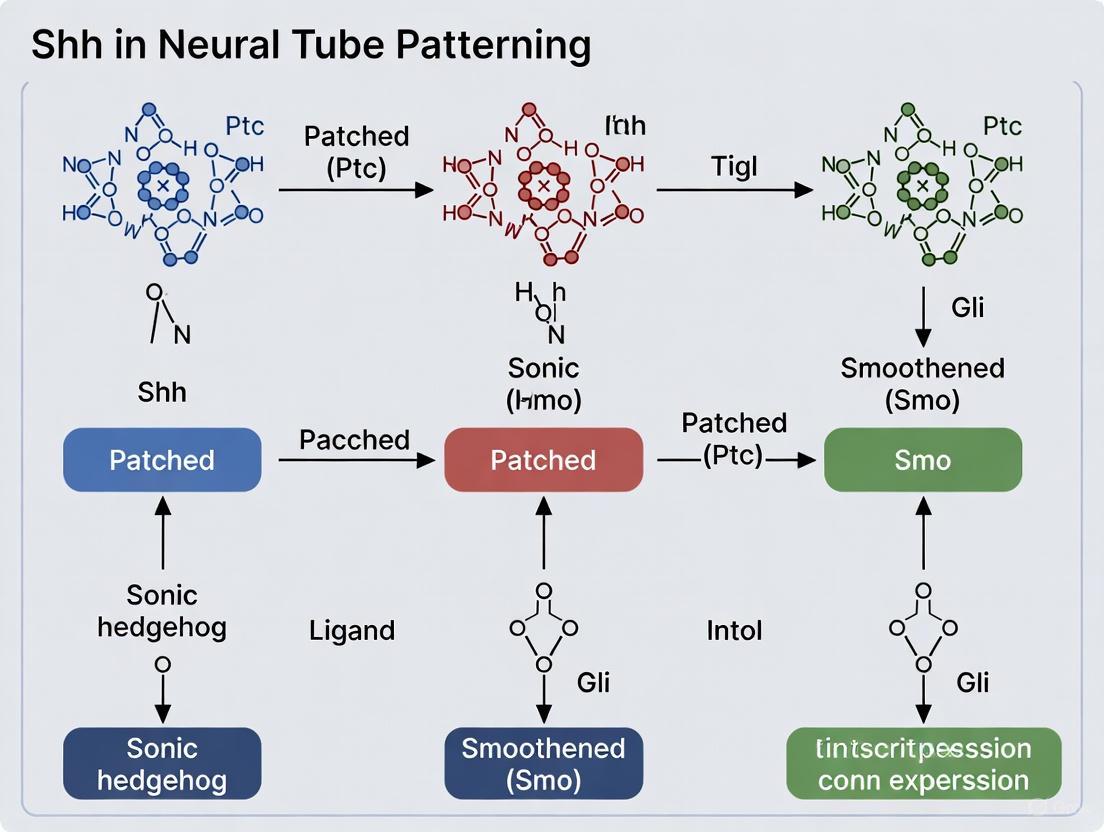

Visualizing the SHH Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core SHH signaling mechanism and a typical experimental workflow.

Diagram 1: SHH Signaling Pathway in Neural Patterning

(SHH Signaling Pathway: This diagram illustrates the core mechanism. SHH binding to PTCH1 releases the inhibition on SMO. Activated SMO prevents the proteolytic processing of GLI proteins into repressors and promotes their activation. The active GLI transcription factors then translocate to the nucleus to regulate the expression of target genes, which specify distinct neural progenitor fates in a concentration-dependent manner.)

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for SHH Morphogen Study

(SHH Experimental Workflow: A generalized workflow for studying SHH morphogen function. Research begins with a defined objective, leading to the selection of an in vitro or in vivo model system. The pathway is perturbed through methods like SHH protein titration or genetic knockdown. The resulting phenotypic changes are analyzed using molecular and cellular techniques, culminating in data interpretation.)

Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signaling constitutes a cornerstone of embryonic development, serving as a master regulator of ventral neural tube patterning. The establishment of distinct neuronal progenitor domains and subsequent cell fates along the dorsoventral axis is orchestrated by a gradient of Shh protein, meticulously organized from its primary secretion sources. This whitepaper delineates the precise cellular origins of the Shh signal—the notochord and the floor plate—and explores the sophisticated mechanisms governing its dissemination and interpretation. Within the broader context of Shh research in neural tube patterning, understanding these foundational signaling sources is critical for elucidating the etiology of congenital neural defects and developing therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative diseases and spinal cord injuries.

Molecular Mechanisms of Shh Production and Signaling

The Shh signaling pathway is a highly conserved system initiated by the production and processing of the Shh ligand. The human SHH gene encodes a precursor protein that undergoes autocatalytic cleavage to yield a 19 kDa N-terminal fragment (Shh-N) and a 26 kDa C-terminal fragment (Shh-C) [11] [12]. This processing event, catalyzed by Shh-C, results in the covalent attachment of a cholesterol moiety to the C-terminus of Shh-N, producing the biologically active ligand. Subsequent palmitoylation of the N-terminal cysteine residue by acyl transferase yields the fully active, dually lipid-modified Shh protein [12]. These lipid modifications are crucial for regulating the spatial distribution and signaling range of Shh by tethering the ligand to cell membranes, thus preventing uncontrolled diffusion [13].

The canonical Shh signaling cascade is initiated when the active Shh ligand binds to its transmembrane receptor Patched1 (Ptch1). In the absence of Shh, Ptch1 constitutively inhibits the G protein-coupled receptor Smoothened (Smo) [14] [11]. Shh binding to Ptch1 relieves this inhibition, allowing Smo to accumulate in primary cilia and transduce an intracellular signal that prevents the proteolytic processing of Gli transcription factors into their repressor forms [14] [15]. This leads to the nuclear translocation of full-length Gli activators (primarily Gli1 and Gli2) and the transcriptional activation of target genes, including Ptch1 and Gli1 themselves, creating a feedback loop [15] [12].

Diagram 1: Canonical Shh Signaling Pathway. The pathway shows inhibition of Smo by Ptch1 in the absence of Shh, leading to Gli repressor formation and suppression of target genes. Shh binding releases Smo inhibition, enabling Gli activator formation and target gene transcription.

Primary Signaling Centers: Notochord and Floor Plate

The ventral neural tube is patterned by Shh secreted from two principal signaling centers: the notochord and the floor plate. The notochord, a transient mesodermal structure underlying the neural tube, serves as the initial source of Shh during early embryogenesis [16] [10]. This notochord-derived Shh is responsible for the induction of the floor plate, a specialized group of glial cells at the ventral midline of the neural tube [17]. Once specified, the floor plate itself becomes a secondary source of Shh, maintaining and refining the Shh gradient that patterns ventral neuronal progenitors [17].

The development of distinct neuronal subtypes in the ventral neural tube occurs in a precise spatial order that corresponds to their requirement for different Shh concentrations and exposure durations. Progenitors close to the signaling sources, exposed to high Shh levels, adopt ventral fates such as floor plate and V3 interneurons, while those at progressively greater distances, exposed to lower concentrations, form motor neurons and more dorsal interneuron subtypes [17]. This concentration-dependent patterning extends to the specification of Olig2+ motoneuron progenitors and Hb9+ motoneurons, which require sustained Shh signaling for their development and maintenance [16].

Sclerotome as a Transit Pathway

Recent research has revealed that the sclerotome, the ventral compartment of the somites, serves as a crucial transit pathway for Shh dissemination. Notochord-derived Shh must traverse the sclerotome to reach both the myotome and the basal aspect of the neural tube [16]. Reduction of Shh in the sclerotome through targeted expression of membrane-tethered Hedgehog-interacting protein (Hhip:CD4) significantly decreases the number of Olig2+ motoneuron progenitors and Hb9+ motoneurons, demonstrating that sclerotomal Shh is necessary for proper neural tube development [16].

Notably, notochord grafting experiments have demonstrated that Shh presentation to the basal side of the neuroepithelium, corresponding to the sclerotome-neural tube interface, profoundly affects motoneuron development compared to apical grafting [16]. This suggests that initial ligand presentation occurs preferentially at the basal side of epithelia, revealing the sclerotome as a novel pathway through which notochord-derived Shh disperses to coordinate the development of both mesodermal and neural progenitors.

Dynamics of Gradient Interpretation

The interpretation of the Shh gradient involves not only concentration thresholds but also temporal dynamics of signaling. Floor plate specification exemplifies this sophisticated mechanism, involving a biphasic response to Shh signaling [17]. During gastrulation and early somitogenesis, floor plate induction depends on high levels of Shh signaling. Subsequently, prospective floor plate cells become refractory to Shh signaling, a prerequisite for the elaboration of their definitive non-neuronal identity [17]. This dynamic response expands the patterning capacity of a single ligand, enabling the specification of multiple cell types.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Shh Pathway Manipulations on Neural Development

| Experimental Manipulation | Biological System | Quantitative Effect | Biological Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hhip1 misexpression in sclerotome | Chick embryo | 40% reduction in Hb9+ motoneurons | Impaired motoneuron differentiation | [16] |

| Shh-P150 exosome application | Neural explant assay | Induction of Nkx2.2+ ventral progenitors | Ventral neural tube patterning | [14] |

| Shh-P450 exosome application | Neural explant assay | Increased progenitor proliferation | Expansion of neural progenitor pool | [14] |

| Floor plate deletion | Chick/mouse embryo | Altered FoxA2+ floor plate cells | Disrupted ventral patterning | [17] |

Novel Secretion Mechanisms and Signaling Dynamics

Distinct Exosomal Pools for Patterning versus Proliferation

Emerging evidence indicates that Shh is secreted on biochemically distinct exosomal pools that mediate different aspects of neural development. Ultracentrifugation studies have identified two principal exosomal fractions: Shh-P150 and Shh-P450, distinguished by their differential pelletability [14]. These pools possess unique protein and miRNA cargo and execute distinct biological functions.

The Shh-P150 exosome fraction mediates canonical signaling and neural tube patterning, inducing the expression of ventral spinal cord markers including Nkx2.2 [14]. Conversely, the lighter Shh-P450 pool drives progenitor proliferation through Gαi-mediated signaling but is incapable of patterning ventral neuronal progenitors [14]. The identification of Rab7 as a regulator of Shh-P150 biogenesis suggests that differential packaging of Shh into distinct exosomal pools provides a molecular switch between its morphogenetic and mitogenic outputs, resolving the long-standing question of how Shh segregates these distinct functions.

Spatiotemporal Control of Signaling

The deployment of Shh from different sources follows precise spatiotemporal dynamics that are essential for proper neural tube patterning. The notochord provides the initial Shh signal during early developmental stages, establishing the foundation for ventral patterning [16] [10]. As development proceeds, the floor plate assumes the role of the dominant Shh source, maintaining and refining the patterning signal [17]. This transition ensures the proper temporal coordination of ventral neuronal specification.

Recent technological advances, including optogenetic control of morphogen production, have enabled unprecedented precision in investigating Shh gradient formation and dynamics [18]. These approaches allow researchers to manipulate the timing, duration, and location of Shh production with high spatial and temporal resolution, providing new insights into how gradient interpretation translates into precise patterns of gene expression and cell fate specification.

Diagram 2: Shh Secretion and Gradient Formation. The diagram illustrates how Shh from notochord and floor plate creates a ventral-to-dorsal concentration gradient through direct secretion and sclerotomal transit, leading to specification of distinct ventral neuronal subtypes.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Experimental Paradigms

Research elucidating the origins and mechanisms of Shh signaling has employed sophisticated experimental approaches, including loss-of-function and gain-of-function studies in model organisms. Electroporation-based gene manipulation in chick embryos has been particularly instrumental for spatially and temporally controlled perturbation of Shh signaling [16]. At 23- to 25-somite stages, electroporation at the level of epithelial somites enables targeted manipulation of the prospective sclerotome, allowing researchers to investigate Shh transit through this compartment without affecting earlier patterning events [16].

Notochord grafting experiments have provided critical insights into the directional nature of Shh presentation. Studies demonstrate that grafting notochord fragments adjacent to the basal sclerotomal side of the neural tube profoundly affects motoneuron development compared to apical grafts [16]. Similarly, basal grafting with respect to the dermomyotome significantly enhances myotome formation, suggesting a general requirement for initial ligand presentation at the basal side of epithelia [16].

Neural Explant Assays

Neural explant assays have served as a foundational methodology for investigating Shh patterning activity [14]. In this protocol, neural tube explants are cultured in three-dimensional matrices and exposed to purified Shh or exosomal fractions. The explants are typically cultured for 48-72 hours, then processed for immunohistochemistry or RNA analysis to assess the induction of ventral markers such as Nkx2.2, Olig2, and FoxA2 [14]. This assay has been crucial for demonstrating the differential activities of Shh-P150 and Shh-P450 exosomal fractions, with Shh-P150 inducing ventral progenitor markers while Shh-P450 promotes proliferation without patterning activity [14].

Exosome Isolation and Characterization

The identification of distinct Shh-containing exosomal pools relied on sophisticated fractionation techniques [14]. The standard protocol involves sequential ultracentrifugation of conditioned media from Shh-expressing cells. Initial low-speed centrifugation (10,000 × g) removes cellular debris, followed by high-speed centrifugation (150,000 × g) to pellet the P150 exosomal fraction. The resulting supernatant is then subjected to ultracentrifugation at 450,000 × g to pellet the P450 fraction [14]. These biochemically distinct pools are further characterized by electron microscopy, western blotting for exosomal markers (e.g., Alix, Tsg101), and functional assays in neural explants or stem cell differentiation systems.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Shh Signaling Studies

| Research Tool | Type | Primary Application | Key Features & Function | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hhip:CD4 | Membrane-tethered antagonist | Loss-of-function studies | Sequesters Shh in sclerotome; reduces motoneuron differentiation | [16] |

| Shh-P150 & Shh-P450 | Distinct exosomal fractions | Functional segregation studies | P150 patterns ventral neural tube; P450 drives proliferation | [14] |

| ShhN:YFP | Fluorescent Shh construct | Ligand trafficking studies | Palmitoylated but not cholesterol-modified; tracks Shh movement | [16] |

| Neural Explant Assay | Ex vivo culture system | Pattering activity testing | Measures induction of ventral markers by Shh sources | [14] |

| Optogenetic Shh Control | Spatiotemporal manipulation | Gradient dynamics studies | Precise control over timing and location of Shh production | [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The investigation of Shh secretion and function relies on a specialized toolkit of reagents and methodologies. Membrane-tethered Hhip (Hhip:CD4) serves as a critical tool for cell-autonomous sequestration of Shh ligand, specifically designed to prevent Shh movement through the sclerotome without the confounding effects of secreted Hhip [16]. Fluorescently tagged Shh constructs (ShhN:YFP) enable visualization of ligand distribution and trafficking, particularly valuable for studying the transit of Shh through various compartments [16].

For functional studies, specific Shh pathway agonists (SAG, Purmorphamine) and antagonists (Cyclopamine, Vismodegib) allow precise pharmacological manipulation of signaling activity [11] [12]. The development of optogenetic systems for controlling Shh production represents a cutting-edge approach for investigating morphogen dynamics with high spatiotemporal precision [18]. These tools, combined with traditional embryological techniques such as notochord grafting and neural explant cultures, provide a comprehensive methodological framework for dissecting the complexity of Shh signaling from its origins in the notochord and floor plate.

The notochord and floor plate serve as the primary signaling centers that establish and maintain the Shh gradient responsible for ventral neural tube patterning. Through sophisticated mechanisms including sclerotomal transit, differential exosomal packaging, and dynamic cellular responses, Shh from these sources orchestrates the precise spatial and temporal patterning of neuronal progenitors. The evolving understanding of these processes, facilitated by advanced experimental approaches and reagents, continues to reveal unexpected complexity in how a single morphogen coordinates the development of multiple tissue types. As research progresses, these insights promise to inform therapeutic strategies for neural developmental disorders and regenerative medicine approaches for neurological injuries.

The French Flag model, a foundational concept in developmental biology, posits that cells acquire distinct identities in response to different concentrations of a diffusible morphogen. This whitepaper explores the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) protein as a quintessential morphogen that patterns the ventral neural tube along the dorsoventral axis. We detail the mechanisms of SHH gradient formation, the dynamic interpretation of this gradient by neural progenitor cells, and the quantitative precision that ensures robust patterning. Furthermore, we discuss cutting-edge methodologies for investigating SHH signaling and its implications for neurodevelopmental disorders and therapeutic strategies. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical overview of SHH-mediated patterning, underscoring its critical role in neural development.

The French Flag model, introduced by Lewis Wolpert, provides a theoretical framework for understanding how a uniform field of cells can differentiate into distinct spatial domains [19]. According to this model, a secreted signaling molecule—a morphogen—forms a concentration gradient across a developing tissue. Cells respond to this gradient by adopting specific fates based on the local morphogen concentration, effectively dividing the tissue into discrete regions analogous to the stripes of the French flag [19] [20]. Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) is a paradigmatic morphogen that executes this model during ventral patterning of the vertebrate neural tube [20] [3]. The neural tube, the embryonic precursor to the spinal cord and brain, exhibits a remarkably organized structure where distinct neuronal subtypes arise at precise positions along the dorsoventral (DV) axis. This patterning is largely governed by a SHH concentration gradient, which emanates from ventral signaling centers—the notochord and the floor plate [19] [3]. Cells exposed to the highest SHH concentrations become ventral floor plate cells, while progressively lower concentrations specify more dorsal progenitor domains, giving rise to different neuronal subtypes [20]. The interpretation of the SHH gradient is a dynamic process, integrating both the concentration of the signal and the duration of cellular exposure, and is refined by intricate feedback mechanisms within the receiving cells [20].

The SHH Signaling Pathway: From Ligand to Transcriptional Response

The SHH signaling pathway is the molecular machinery that transmits the extracellular morphogen signal into intracellular gene expression changes. The core components and sequence of events are as follows:

Canonical Pathway Activation:

- Ligand Processing and Secretion: SHH is synthesized as a precursor protein that undergoes autocatalytic cleavage and dual lipid modification: cholesterol at its C-terminus and palmitate at its N-terminus [19] [21]. These modifications are critical for its potency and range of diffusion. The processed and modified SHH ligand is secreted from the source cells via the transmembrane protein Dispatched [19].

- Receptor Binding and Signal Initiation: The secreted SHH ligand binds to its primary receptor, Patched1 (PTCH1), on the target cell membrane. PTCH1 constitutively inhibits a second transmembrane protein, Smoothened (SMO). Binding of SHH to PTCH1 relieves this inhibition [19] [22].

- Ciliary Transduction and Transcriptional Activation: SMO then accumulates in the primary cilium, a key signaling organelle. This leads to the activation and nuclear translocation of the GLI family of transcription factors (GLI1, GLI2, GLI3), which subsequently induce or repress the expression of target genes, including PTCH1 itself and GLI1, creating a negative feedback loop [19] [20] [22].

Non-Canonical Pathways: SHH can also signal independently of the canonical PTCH1-SMO-GLI axis. These non-canonical pathways may be SMO-dependent but GLI-independent, or operate completely independently of SMO, and are involved in processes like axon guidance and cell migration [19] [22].

Table 1: Core Components of the SHH Signaling Pathway

| Component | Type | Function in SHH Signaling |

|---|---|---|

| SHH | Ligand | Lipid-modified morphogen; binds to PTCH1 to initiate signaling. |

| PTCH1 | Receptor | Transmembrane receptor that inhibits SMO in the absence of SHH. |

| SMO | Transducer | Seven-pass transmembrane protein; transduces signal upon PTCH1 inhibition relief. |

| GLI1/2/3 | Transcription Factors | Terminal effectors; regulate transcription of target genes (GLI1/2 activators, GLI3 repressor). |

| Primary Cilium | Organelle | Specialized cellular compartment where key signaling events (SMO/GLI activation) occur. |

| BOC/GAS1/CDON | Coreceptors | Enhance SHH binding and signaling efficiency [19] [23]. |

| SUFU | Negative Regulator | Cytosolic protein that inhibits GLI protein activity [22]. |

| SN003 | SN003, MF:C19H25N5O2, MW:355.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| C-021 | CCR4 Antagonist C-021|Research Compound |

The following diagram illustrates the core canonical SHH signaling pathway and its key outputs.

Diagram 1: Canonical SHH Signaling Pathway. When SHH is absent (left), PTCH1 inhibits SMO, leading to the proteolytic processing of GLI factors into repressors and suppression of target gene expression. When SHH is present (right), it binds PTCH1, relieving inhibition of SMO. SMO activation promotes the formation of GLI activators, which translocate to the nucleus and induce target gene transcription.

Establishing the SHH Morphogen Gradient

The formation of the SHH concentration gradient is a highly regulated process involving specialized signaling centers, unique biochemical properties of the ligand, and active transport mechanisms.

Signaling Centers and Spatiotemporal Dynamics

The primary sources of SHH in the developing neural tube are the notochord (a mesodermal structure underlying the neural tube) and the floor plate (the ventral-most structure of the neural tube itself) [19] [20] [3]. Signaling initiates with SHH secretion from the notochord, which is responsible for the initial induction of the floor plate. Once established, the floor plate itself becomes a secondary source of SHH, reinforcing and maintaining the gradient [20]. The gradient is not static; it evolves over time. The amplitude of the SHH gradient increases as development progresses, meaning cells near the source are exposed to progressively higher concentrations for longer durations [20]. This temporal dynamics is crucial for the sequential induction of ventral progenitor identities.

Biochemical Mechanisms of Gradient Formation

The range and shape of the SHH gradient are profoundly influenced by the molecule's biochemistry:

- Dual Lipid Modification: The covalent attachment of cholesterol and palmitate makes SHH highly hydrophobic [19] [21]. This hydrophobicity traditionally suggested a limited capacity for free diffusion, promoting the formation of steep, short-range gradients. However, it also facilitates the assembly of SHH into larger multimeric complexes or micelles and its association with lipoprotein particles, which can enable long-range distribution [20].

- Feedback Regulation: The SHH gradient is shaped by feedback loops from the responding cells. The pathway targets PTCH1 and GLI1 are themselves transcriptional targets of SHH signaling. Upregulation of PTCH1 at the site of ligand reception creates a sink that can limit further spread of the SHH ligand, thereby sharpening the gradient in a non-cell-autonomous manner [20].

Interpreting the Gradient: From Signal to Cell Fate

The conversion of a continuous SHH concentration gradient into discrete cellular domains is a complex process of signal interpretation involving temporal integration and transcriptional networks.

Concentration and Duration Dependence

Neural progenitor cells translate different SHH signal intensities and exposure times into distinct fate choices. In vitro studies using chick neural explants have demonstrated that a two- to threefold increase in SHH concentration is sufficient to switch progenitor identity from one subtype to the next, more ventral one [20]. For instance, lower concentrations specify motor neuron (pMN) progenitors, while higher concentrations specify V3 interneurons [19] [20]. Furthermore, the duration of SHH exposure is equally critical. Prolonged signaling is required to activate genes that require high levels of SHH, leading to a progressive ventralization of cell fate over time [20].

Intracellular Interpretation and Network Architecture

The cellular response to SHH is not a simple passive reception but an active process of refinement:

- Temporal Adaptation and Negative Feedback: The concept of "temporal adaptation" describes how cells continuously adjust their response to a persistent SHH signal. Key to this is the induction of negative regulators like PTCH1 and SUFU. This feedback creates a system where the initial level of signaling is strong, but adapts over time, allowing cells to effectively measure and lock in a positional identity based on the signal history [20].

- Transcriptional Cross-Repression: The boundaries between different progenitor domains are sharpened by a network of transcription factors that mutually repress each other's expression. For example, in the ventral neural tube, the domain of Pax6 (dorsal) is separated from Nkx2.2 (ventral) by cross-repressive interactions, ensuring a clean switch between domains rather than a blended mixture of cell types [19].

Table 2: Progenitor Domains in the Ventral Neural Tube

| Progenitor Domain | Key Transcription Factor | Neuronal Output | Relative SHH Exposure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Floor Plate (FP) | FoxA2 | Specialized non-neuronal signaling cells | Highest |

| p3 | Nkx2.2 | V3 interneurons | High |

| pMN | Olig2 | Motor neurons | Medium-High |

| p2 | Irx3, Pax6 | V2 interneurons | Medium |

| p1 | Dbx1, Pax6 | V1 interneurons | Low |

| p0 | Dbx2, Pax6 | V0 interneurons | Lowest |

| Dorsal Domains | Pax3, Pax7 | Sensory interneurons | None / BMP signal |

Quantitative Analysis of Gradient Precision

Recent quantitative studies have reshaped our understanding of the precision of morphogen gradients, moving away from the idea of highly variable gradients requiring combinatorial readouts.

A 2022 re-analysis of gradient precision in the mouse neural tube demonstrated that the positional error of the SHH gradient had been previously overestimated due to methodological limitations in data fitting [24]. The study concluded that:

- A single SHH gradient is sufficiently precise to define the boundaries of central progenitor domains (like the NKX6.1 and PAX3 boundaries) with the accuracy observed biologically, which is within 1-3 cell diameters [24].

- The patterning mechanism is robust to changes in gradient amplitude. Because domain boundaries are defined by specific concentration thresholds, a change in the overall amplitude of the SHH gradient shifts the absolute position of all boundaries but can leave the relative sizes of the interior progenitor domains largely unchanged. This ensures a precise number of progenitor cells for each neuronal type, even in the face of natural embryo-to-embryo variation [24].

Table 3: Key Quantitative Findings on SHH Gradient Precision

| Parameter | Historical Estimation | Revised Estimation (2022) | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positional Error | Up to 30+ cell diameters in neural tube center [24] | 1-3 cell diameters [24] | Single gradient is sufficiently precise for patterning. |

| Gradient Shape | Assumed to be a perfect exponential [24] | Mean of multiple exponentials is non-exponential [24] | Fitting a single exponential to averaged data overestimates variability. |

| Domain Sizing | Assumed to be affected by amplitude noise | Robust to amplitude changes [24] | Progenitor cell numbers are precisely controlled. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Investigating the SHH gradient requires a multidisciplinary approach combining embryology, molecular biology, and advanced imaging.

Classical Embryological Manipulations

- Neural Tube/Notochord Explant Co-culture: This protocol involves isolating the neural tube and notochord from model organisms like chick or mouse embryos. The tissues are cultured in close proximity, and the differentiation of neural progenitors is assessed via immunohistochemistry for domain-specific markers (e.g., Olig2, Nkx2.2) [20].

- Microparticle/Bead Implantation: Beads soaked in purified SHH-N protein (the active N-terminal fragment) or in specific inhibitors (e.g., cyclopamine, an SMO antagonist) are implanted into the developing neural tube or limb bud in vivo. This creates a localized source or sink of signaling, allowing researchers to observe changes in patterning and gene expression around the bead [25].

Live Imaging and Single-Cell Analysis

- Fluorescent Reporter Lines: Transgenic animals (e.g., zebrafish, mice) expressing fluorescent proteins under the control of SHH-responsive promoters (e.g., Gli1 or Ptc1 promoters) enable real-time visualization of pathway activity in vivo [26].

- Single-Cell Resolution Tracking: A 2023 reviewed preprint detailed a protocol using a photoactivatable SHH reporter (Kaede) in zebrafish embryos. This allows for tracking of SHH signaling dynamics in single neural progenitor cells over time and correlating these dynamics with the final transcriptional identity of the cell, revealing significant heterogeneity in response dynamics at the single-cell level that still results in robust fate specification at the population level [26].

The workflow for such a single-cell analysis is complex and involves multiple steps, as summarized below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Single-Cell SHH Signaling Analysis. This pipeline enables the correlation of dynamic SHH signaling history with the ultimate fate of individual neural progenitor cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogues critical reagents and models used in SHH gradient and neural tube patterning research.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Models for SHH Studies

| Reagent / Model | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SHH-N Protein | Protein | The active, N-terminal fragment of SHH; used for in vitro and in vivo (bead implantation) gain-of-function studies to mimic pathway activation [25]. |

| 5E1 Anti-SHH Antibody | Monoclonal Antibody | Function-blocking antibody; used for in vivo neutralization of SHH ligand to create loss-of-function conditions and study patterning defects [25]. |

| Cyclopamine / SANT-1 | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Specific inhibitors of Smoothened (SMO); used to chemically inhibit the canonical SHH pathway in a dose-dependent manner [22]. |

| SAG (Smoothened Agonist) | Small Molecule Agonist | Activates SMO; used to experimentally stimulate the SHH pathway downstream of PTCH1 [22]. |

| SHH-GFP Knock-in Mice | Genetic Model | Mouse line expressing a biologically active SHH-GFP fusion protein from the endogenous Shh locus; enables direct visualization and quantification of the SHH protein gradient [20]. |

| Avian Embryo (Chick/Quail) | Model System | Classic model for embryological manipulations due to easy accessibility; ideal for microsurgery, electroporation, and bead implantation experiments [25]. |

| Zebrafish Reporter Lines | Transgenic Model | Transgenic fish with GFP or other reporters under SHH-pathway control; excellent for live, real-time imaging of signaling dynamics at single-cell resolution [26]. |

| Human Cerebral Organoids | In Vitro 3D Model | Stem cell-derived models that recapitulate aspects of human brain development; used to study human-specific SHH functions and neurodevelopmental disorders [19]. |

| Isrib | ISRIB|Integrated Stress Response Inhibitor|eIF2B Activator | ISRIB is a potent small molecule inhibitor of the integrated stress response (ISR) that reverses the effects of eIF2α phosphorylation. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| OU749 | OU749 CAS 519170-13-9|GGT Inhibitor | OU749 is a non-glutamine, uncompetitive, and species-specific GGT inhibitor for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Implications in Development and Disease

Dysregulation of the precisely controlled SHH signaling pathway leads to severe congenital disorders and cancers.

- Holoprosencephaly (HPE): HPE is a spectrum of brain malformations caused by a failure of the forebrain to separate into two hemispheres. Mutations in the SHH gene are a major genetic cause of HPE, highlighting the critical role of SHH in ventral forebrain patterning and midline development [23] [21] [3]. Dose-dependent effects are evident, where reduced SHH signaling leads to a spectrum of facial and brain midline defects, ranging from hypotelorism (close-set eyes) to cyclopia [25].

- Cancer: Aberrant activation of the SHH pathway in adulthood is a driver of several cancers. The most well-established link is with medulloblastoma, where constitutive SHH signaling promotes tumor growth in the cerebellum [22] [3]. Mutations in pathway components like PTCH1 and SUFU are also associated with Gorlin syndrome, which predisposes individuals to basal cell carcinomas and medulloblastomas [21] [22].

- Aging-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases: Emerging evidence implicates altered SHH signaling in the pathogenesis of diseases like Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The pathway's role in adult neurogenesis, neuronal maintenance, and protection against oxidative stress and inflammation is now being explored as a potential therapeutic avenue [22].

The patterning of the neural tube by the SHH morphogen gradient remains a premier example of the French Flag model in action. The process is remarkably sophisticated, involving the dynamic formation of a concentration gradient, its interpretation through a network of intracellular feedback mechanisms, and the translation of this information into discrete, precisely positioned cellular domains. While the core principles are well-established, advances in live imaging, single-cell analysis, and quantitative modeling continue to reveal new layers of complexity, including heterogeneity in single-cell responses and unexpected robustness mechanisms. A deep understanding of SHH biology is therefore indispensable, not only for deciphering the fundamental rules of embryonic development but also for informing novel therapeutic strategies for a wide range of human diseases, from severe birth defects to cancer and neurodegenerative disorders.

The Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway is a master regulator of embryonic development, with a particularly crucial role in the precise patterning of the vertebrate neural tube. The efficacy and range of the SHH morphogen are not solely dictated by its amino acid sequence but are profoundly regulated by a unique post-translational modification: the covalent attachment of two lipid moieties, cholesterol and palmitate. This dual-lipid modification is indispensable for orchestrating the complex cell fate decisions that generate distinct neuronal progenitor domains along the dorsoventral axis. This whitepaper delves into the molecular machinery behind these modifications, their direct impact on SHH ligand biogenesis, distribution, and signaling potency, and outlines the essential experimental tools for probing their functions. Understanding these mechanisms is paramount for developing therapeutic interventions for congenital disorders and cancers driven by aberrant Hedgehog signaling.

The vertebrate neural tube, the embryonic precursor to the central nervous system, exhibits a highly organized structure where distinct neuronal subtypes emerge in specific spatial order. This dorsoventral (DV) patterning is primarily directed by a gradient of SHH protein secreted from two key signaling centers: the notochord and, subsequently, the floor plate cells within the neural tube itself [20]. SHH operates as a classical morphogen—a secreted molecule that conveys positional information through its concentration and the duration of exposure. Progenitor cells exposed to different SHH levels activate distinct transcriptional programs, leading to the establishment of six primary progenitor domains (p0, p1, p2, pMN, p3, and the floor plate), each giving rise to a specific class of neurons [20]. The emergence of these domains is a dynamic process; genes requiring progressively higher levels or longer durations of SHH signaling are sequentially induced at the ventral midline [20]. The formation of this exquisite pattern raises a fundamental question: how is the distribution and perception of the SHH gradient so precisely controlled? The answer lies in the unique biochemical tethering of the SHH ligand itself via cholesterol and palmitate modifications.

The Biochemistry of SHH Lipid Modification

The SHH protein is synthesized as a ~45 kDa precursor that undergoes a series of critical processing steps within the secretory pathway to become the active, lipid-modified morphogen.

Cholesterol Modification: An Unusual Autoprocessing Event

Cholesterol modification is an autocatalytic process that occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum. The C-terminal domain of the SHH precursor catalyzes an intramolecular cleavage reaction. This proceeds through a thioester intermediate that is resolved by nucleophilic attack from the hydroxyl group of a cholesterol molecule [27] [28]. The result is a covalent ester bond linking cholesterol to the C-terminal glycine (Gly-198 in mouse SHH) of the newly formed ~19 kDa N-terminal signaling fragment (SHH-N) [29] [28]. This reaction is essential for the correct formation of SHH gradients in vivo.

Palmitoylation: A Catalytic Addition by Hhat

The second lipid modification is the attachment of a palmitate group, a 16-carbon saturated fatty acid. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme Hedgehog acyltransferase (Hhat) (known as Skinny hedgehog or Rasp in Drosophila), a member of the membrane-bound O-acyltransferase (MBOAT) family [27] [30]. Hhat transfers palmitate from palmitoyl-Coenzyme A to the alpha-amino group of the N-terminal cysteine (Cys-25 in human SHH) of the cholesterol-modified SHH-N fragment, forming a stable amide bond [30] [29]. Unlike cholesterol modification, palmitoylation is a purely enzymatic process and is absolutely required for full SHH signaling activity.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of SHH Lipid Modifications

| Feature | Cholesterol Modification | Palmitate Modification |

|---|---|---|

| Modification Type | Autocatalytic | Enzymatic (Hhat) |

| Bond Type | Ester | Amide |

| Attachment Site | C-terminal Glycine | N-terminal Cysteine |

| Enzyme/Mechanism | C-terminal domain of SHH precursor | Hedgehog acyltransferase (Hhat) |

| Cellular Location | Endoplasmic Reticulum | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

Functional Consequences of Dual Lipidation on SHH Signaling

The attachment of two hydrophobic anchors fundamentally shapes the behavior of the SHH ligand, influencing its membrane association, distribution, and ultimate signaling potency.

Membrane Tethering and Solubilization

The dual lipid moieties render the mature SHH protein highly hydrophobic, causing it to be firmly associated with the plasma membrane of the producing cell [31] [32]. This membrane tethering poses a challenge for a morphogen that must signal at a distance. The resolution of this paradox involves specialized machinery for ligand solubilization and release. The 12-pass transmembrane protein Dispatched (Disp) is critical for releasing lipidated SHH from the cell surface [27] [32]. Recent models suggest a collaborative process where Disp, potentially assisted by the secreted glycoprotein Scube2, facilitates the transfer of cholesterol-modified SHH to extracellular carriers like high-density lipoproteins (HDL) [33] [32]. This process may be completed by proteolytic shedding of the palmitoylated N-terminus, generating a soluble, mono-lipidated SHH form with high bioactivity [32].

Formation of Gradients and Signaling Range

The lipid modifications are crucial for shaping the SHH gradient in the target field, such as the neural tube. The hydrophobic nature of the ligand limits its free diffusion, contributing to a steep, stable concentration gradient that is essential for patterning multiple cell types. Visualization of a SHH-GFP fusion protein in the neural tube reveals an exponentially decaying gradient from the ventral midline, with punctate structures enriched near ciliary basal bodies [20]. The cholesterol moiety, in particular, is vital for long-range signaling activity and for the formation of large, multimeric SHH complexes [34] [31]. In Drosophila, Hh ligands associate with lipoprotein particles (lipophorins), and reducing lipophorin levels impairs long-range signaling [33].

Signaling Potency and Cellular Reception

Lipid modifications are not merely for distribution; they directly enhance the ligand's ability to activate its receptor. Studies comparing the signaling potency of different SHH forms have demonstrated that the dually lipidated protein is significantly more potent than forms lacking one or both lipids [29] [31]. The lipids govern cellular reception by controlling the ligand's association with target cell membranes. Research shows that either lipid adduct is sufficient to confer cellular association, with the cholesterol adduct primarily anchoring the ligand to the plasma membrane and the palmitate adduct augmenting ligand internalization [31]. Crucially, signaling potency directly correlates with the cellular concentration of the SHH ligand, which is maximized by the presence of both lipids [31].

Experimental Analysis of SHH Lipidation

Investigating the roles of SHH lipid modifications requires a suite of well-established biochemical and cell-based assays.

Key Experimental Protocols

1. Assessing Hhat Activity and SHH Palmitoylation in Cells:

- Method: Co-transfect cells (e.g., HEK293T) with cDNAs encoding Hhat and SHH.

- Labeling: Incubate cells with palmitate analogues, such as

125I-Iodopalmitateor azide/alkyne-modified palmitate (e.g., 17-octadecynoic acid). - Detection: Immunoprecipitate SHH from cell lysates. For radioactive labels, quantify incorporation via phosphorimaging after SDS-PAGE. For click-compatible labels, use a copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction to conjugate a fluorescent or biotin tag, followed by detection [30].

2. In Vitro Hhat Enzymatic Assay:

- Enzyme Source: Use detergent-solubilized or purified Hhat protein.

- Substrate: An N-terminal Shh peptide (as short as 10-11 amino acids) with a C-terminal biotin tag.

- Reaction: Incubate with

125I-Iodopalmitoyl-CoAor an alkyne-labeled palmitoyl-CoA. - Detection: Capture the biotinylated peptide on streptavidin beads and measure incorporated radiolabel or perform click chemistry for fluorescence-based detection [30] [20].

3. Functional Patterning Assay (Neural Explant):

- Tissue Source: Isolate neural tube explants from chick or mouse embryos.

- Treatment: Expose explants to purified SHH proteins (wild-type or lipid-mutant forms) or to distinct SHH-carrying exosomal pools (e.g., Shh-P150 vs. Shh-P450) [14].

- Readout: After culture, analyze the expression of ventral progenitor markers (e.g., Nkx2.2, Olig2) by in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry to assess patterning competence [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Studying SHH Lipidation and Function

| Reagent/Category | Example Specific Items | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Tools | SHH cDNA constructs (wild-type, C25A/S, ShhN) | To express defined lipid-mutant forms of SHH in cells [31]. |

| Chemical Inhibitors | RU-SKI 43 (Hhat inhibitor); Lovastatin (cholesterol synthesis inhibitor) | To pharmacologically block palmitoylation or deplete cellular cholesterol pools, respectively [33] [30]. |

| Palmitate Analogues | 17-ODYA (Alkynyl-palmitate); 125I-Iodopalmitate | For metabolic labeling and detection of palmitoylated SHH [30]. |

| Assay Systems | C3H10T1/2 cell line (alkaline phosphatase induction); Gli-luciferase reporter assay | Cell-based bioassays to quantify SHH signaling potency [29] [31]. |

| Carrier Molecules | Purified High-Density Lipoproteins (HDL) | To study the role of lipoprotein particles in SHH solubilization and transport [32]. |

| Symmetric Dimethylarginine | SDMA (Symmetric Dimethylarginine) Research Chemical | High-purity SDMA for renal and cardiovascular disease research. This product is for Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. |

| 2-Acetyl-4-tetrahydroxybutyl imidazole | 2-Acetyl-4-tetrahydroxybutyl imidazole, CAS:94944-70-4, MF:C9H14N2O5, MW:230.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of SHH Biogenesis, Release, and Reception

The following diagram summarizes the key stages of SHH processing, from its biogenesis to its reception on a target cell, highlighting the central role of its dual lipid modifications.

The dual lipid modification of Sonic Hedgehog is a quintessential example of how fundamental biochemistry directs high-order biological patterning. The covalent attachment of cholesterol and palmitate is not a mere ancillary feature but is integral to the morphogen's function, governing its release from producing cells, its distribution through developing tissues, and its potent activation of signal transduction in target cells. Within the context of neural tube patterning, these modifications ensure the formation of a robust and precise gradient that is interpreted by progenitor cells to generate the diverse neuronal subtypes of the central nervous system.

Future research will continue to elucidate the precise structural mechanisms of Hhat and Dispatched, and the dynamic interplay between different SHH carriers (exosomes, lipoproteins) in specific developmental contexts. Furthermore, the direct implication of Hedgehog signaling in multiple cancers and its regulation by lipids presents a compelling therapeutic avenue. The development of specific inhibitors targeting Hhat or the lipid-dependent release machinery, alongside already approved SMO inhibitors, holds promise for a new generation of targeted therapies with potentially greater efficacy and reduced resistance. The study of SHH lipidation remains a rich field at the intersection of biochemistry, developmental biology, and medicine.

The Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signaling pathway is a master regulator of embryonic development, with its canonical pathway comprising PTCH1, SMO, and GLI transcription factors serving critical functions in neural tube patterning. This canonical cascade translates extracellular morphogen gradients into precise intracellular transcriptional responses that dictate ventral neural progenitor fates. Through quantitative analysis of Shh gradient dynamics and intracellular signaling adaptations, this whitepaper elucidates the fundamental mechanisms governing pathway operation. We detail experimental methodologies for quantifying Shh gradient formation and GLI activity dynamics, providing researchers with robust protocols for investigating pathway mechanics. The intricate feedback regulation and cross-pathway interactions discussed herein offer valuable insights for therapeutic targeting in developmental disorders and cancers characterized by pathway dysregulation.

The canonical Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) pathway represents one of the fundamental signaling cascades governing vertebrate embryonic development, with particularly crucial roles in neural tube patterning. This pathway operates through a highly conserved membrane-to-nucleus signaling relay involving three key components: the Patched1 (PTCH1) receptor, the Smoothened (SMO) transducer, and the GLI family of transcription factors. In the developing neural tube, Shh secreted from the notochord and floor plate establishes a concentration gradient along the ventral-dorsal axis, providing positional information that determines the identity of distinct neural progenitor domains [35]. The accurate interpretation of this gradient through the canonical PTCH1-SMO-GLI axis ensures proper specification of motor neurons and various interneurons, with pathway dysfunction resulting in severe neural tube defects.

The canonical pathway is distinguished by its dependence on the primary cilium, a specialized organelle that serves as a signaling hub for pathway component trafficking and activation. The pathway features multiple regulatory layers, including transcriptional feedback loops, post-translational modifications, and protein stability control, which collectively ensure precise spatiotemporal regulation of signaling activity [36] [37]. These regulatory mechanisms enable the pathway to exhibit adaptive dynamics in response to sustained Shh exposure, a property crucial for its morphogenetic functions in neural tube patterning [35].

Core Pathway Mechanics

The Membrane Signaling Complex

In the absence of Shh ligand, PTCH1 localizes to the primary cilium and constitutively suppresses SMO activity through indirect means. While the precise mechanism remains under investigation, current evidence suggests that PTCH1, which shares structural homology with bacterial transmembrane transporters, may prevent the accumulation of activating sterol lipids near SMO or actively transport endogenous SMO inhibitors [36] [38]. The SMO receptor possesses two distinct sterol-binding domains: an extracellular cysteine-rich domain (CRD) and a site within its seven-transmembrane domain (7TMD). Recent structural analyses indicate that SMO activation involves the opening of a tunnel that enables cholesterol movement from the membrane inner leaflet to the CRD, though the exact activation mechanism continues to be elucidated [36].

Upon Shh binding, PTCH1 undergoes conformational changes that relieve its inhibition of SMO. This binding event requires cooperation from multiple co-receptors, including CAM-related/downregulated by oncogenes (CDO), brother of CDO (BOC), and growth-arrest-specific 1 (GAS1), which form a multimolecular complex with PTCH1 to facilitate high-affinity Shh binding and promote signal transduction [36]. Additionally, glypicans (membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycans) enhance Shh stability and promote its internalization with PTCH1, while Hedgehog-interacting protein (HHIP) acts as a negative regulator by sequestering Shh ligand and making it unavailable for PTCH1 binding [36].

Following Shh binding, PTCH1 is internalized and removed from the cilium, abolishing its inhibition of SMO. This allows SMO to accumulate within the ciliary membrane, where its C-terminal tail becomes phosphorylated by casein kinase 1α (CK1α) and G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) [36]. These phosphorylation events trigger conformational changes that promote SMO dimerization and activation, enabling it to relay the signal to downstream cytoplasmic components.

Cytoplasmic Signal Transduction

The downstream cytoplasmic events of the canonical Shh pathway center on the regulation of GLI transcription factors, which exist in three vertebrate variants (GLI1, GLI2, and GLI3) that display both overlapping and distinct functions. In the absence of pathway activation, GLI proteins are sequestered in the cytoplasm through binding to Suppressor of Fused (SUFU), a major negative regulator of the pathway [36] [37]. SUFU binding not only prevents GLI nuclear translocation but also promotes the proteolytic processing of GLI2 and GLI3 into their repressor forms (GLI2-R, GLI3-R).

The processing of full-length GLI proteins into repressor forms involves sequential phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA), glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β), and casein kinase 1 (CK1) within a cytoplasmic complex [36] [37]. This phosphorylation targets GLI2/3 for ubiquitination by the SCFβ-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, leading to partial proteasomal degradation that generates N-terminal repressor fragments. These truncated GLI repressors then translocate to the nucleus and suppress the expression of Shh target genes.

Upon pathway activation, the signal from ciliary SMO triggers the dissociation of the SUFU-GLI complex. The mechanism involves the displacement of GPR161 (a negative regulator that promotes GLI3 repressor formation) from the cilium and the recruitment of proteins such as EVC/EVC2 that facilitate GLI activation [36]. The liberated full-length GLI2 and GLI3 proteins then undergo additional post-translational modifications and translocate to the nucleus as transcriptional activators (GLI2-A, GLI3-A). Notably, GLI1 differs from GLI2 and GLI3 in that it functions primarily as a transcriptional activator and is not subject to proteolytic processing into a repressor form [37].

Nuclear Transcriptional Regulation

Within the nucleus, activated GLI proteins bind to specific consensus sequences (5'-GACCACCCA-3') in the promoter regions of target genes, thereby initiating or repressing transcription. The transcriptional output is determined by the balance between activator (primarily GLI1 and GLI2-A) and repressor (primarily GLI3-R) forms [37] [39]. GLI1 possesses the strongest transcriptional activation capacity but lacks a repressor domain, while GLI2 serves as the primary transcriptional activator in response to Shh signaling, and GLI3 predominantly functions as a repressor [39].

Key target genes of the canonical pathway include PTCH1 and GLI1 themselves, creating critical feedback regulatory loops. The upregulation of PTCH1 establishes a negative feedback loop that dampens pathway activity, while GLI1 induction creates a positive feedback loop that amplifies the signaling response [35] [37]. Other important target genes include regulators of cell cycle progression (CYCLIN D1, MYC), apoptosis regulators (BCL2), and transcription factors involved in neural patterning (NKX2.2, OLIG2) [35] [37].

Table 1: GLI Transcription Factor Functions in Canonical Shh Signaling

| Transcription Factor | Primary Function | Processing | Regulatory Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLI1 | Transcriptional activator | No proteolytic processing | Target gene; positive feedback regulator |

| GLI2 | Primary transcriptional activator | Proteolytic processing to repressor form | Main mediator of Shh signal; regulated by SUFU and SPOP |

| GLI3 | Primarily functions as repressor | Proteolytic processing to repressor form | Constitutive repressor in absence of signal; ratio of GLI3R/GLI3A determines output |

Quantitative Dynamics in Neural Tube Patterning

The operation of the canonical Shh pathway during neural tube patterning exhibits sophisticated temporal and spatial dynamics that enable precise control of progenitor domain specification. Quantitative analysis of Shh gradient formation and intracellular signaling activity has revealed complex adaptive behaviors critical for proper neural patterning.

Table 2: Quantitative Dynamics of Shh Signaling in Mouse Neural Tube Patterning

| Parameter | Early Development (E8.5) | Late Development (E10.5) | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shh Gradient Amplitude (Câ‚€) | Baseline | >10-fold increase | Immunofluorescence intensity profiling |

| Gradient Decay Length (λ) | 19.6 ± 4.2 μm | Remains constant | Exponential curve fitting to Shh intensity profiles |

| Gli Activity Levels | Increases rapidly | Decreases after peak (adaptation) | Transcriptional reporter (GBS-GFP) quantification |

| Ptch1 Expression | Induced by Shh signaling | Undergoes adaptation | Immunostaining and transcript quantification |

Research quantifying the Shh gradient in developing mouse neural tube revealed that while gradient amplitude increases more than 10-fold between E8.5 and E10.5, the decay length remains relatively constant at approximately 19.6±4.2 μm [35]. This expanding amplitude exposes neural progenitor cells to increasing Shh concentrations over time. Surprisingly, intracellular signaling activity measured through GLI transcriptional reporters demonstrates adaptive behavior, initially increasing to peak levels around E9 before declining despite the continuously rising Shh concentration [35].

This adaptation phenomenon involves at least three distinct mechanisms: transcriptional upregulation of PTCH1 creating negative feedback, transcriptional downregulation of GLI genes reducing pathway capacity, and differential stability between active and repressive GLI isoforms [35]. The stability of activated GLI proteins is reduced compared to their repressive forms, creating an integral feedback mechanism that contributes to adaptation. Notably, this adaptive behavior differs between cell types, with NIH3T3 fibroblasts showing sustained signaling compared to neural progenitors, potentially due to maintained GLI2 expression [35].

Experimental Methodologies

Quantifying Shh Gradient Formation

Objective: To measure the spatiotemporal dynamics of Shh morphogen gradient formation in the developing neural tube.

Materials:

- Mouse embryos spanning developmental stages (E8.5-E10.5)

- Anti-Shh primary antibodies

- Fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies

- Tissue fixation and permeabilization solutions

- Confocal microscopy equipment

- Image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, Imaris)

Procedure:

- Collect mouse embryos at precise developmental stages (accurately staged by somite count).

- Fix embryos in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2-4 hours at 4°C, followed by cryopreservation in sucrose solution and embedding in OCT compound.

- Section brachial region neural tubes transversely at 10-16μm thickness using a cryostat.

- Perform immunohistochemistry with anti-Shh antibodies using standardized conditions across all samples to enable quantitative comparison.

- Image sections using confocal microscopy with identical laser power, gain, and exposure settings across all samples.

- Measure fluorescence intensity along the dorsal-ventral axis in a defined region (e.g., 16μm adjacent to the apical lumen) using image analysis software.

- Determine the position of peak Shh intensity, typically occurring 5-13μm from the ventral midline, which defines the boundary between Shh source and target tissue.

- Fit an exponential function (C = C₀e^(-x/λ)) to intensity profiles to derive gradient amplitude (C₀) and decay length (λ) parameters.

- Correlate gradient parameters with developmental time and tissue size.

Technical Considerations: The Shh gradient measurement protocol requires meticulous standardization of immunohistochemistry and imaging conditions to enable valid quantitative comparisons. Staging accuracy is critical, and dorsal-ventral length of the neural tube can serve as a proxy for developmental stage [35]. The position of the Nkx2.2 expression domain boundary provides a valuable landmark for validating gradient measurements.

Monitoring GLI Activity Dynamics

Objective: To quantify the temporal adaptation of intracellular GLI activity in response to Shh signaling.

Materials:

- Tg(GBS-GFP) transgenic mouse line (GLI-binding site transcriptional reporter)

- Anti-GFP antibodies

- Anti-Ptch1 antibodies (for correlation with endogenous pathway activity)

- Tissue processing reagents as above

- Quantitative PCR equipment and reagents

Procedure:

- Collect Tg(GBS-GFP) embryo neural tubes at multiple developmental timepoints (E8.5-E10.5).

- Process tissue for either immunohistochemistry or RNA extraction.

- For protein-level assessment, perform co-immunostaining for GFP and Ptch1 to compare reporter activity with endogenous pathway output.

- Quantify nuclear GFP intensity across neural progenitor domains using fluorescence microscopy and image analysis.

- For transcript-level assessment, perform quantitative RT-PCR for GFP mRNA alongside endogenous targets (Gli1, Ptch1, Hip1).

- Normalize measurements to internal controls and plot temporal profiles of GLI activity.

- Compare activity dynamics with simultaneous measurements of Shh ligand concentration.

Technical Considerations: The Tg(GBS-GFP) reporter provides a direct readout of net GLI transcriptional activity, reflecting the balance between activator and repressor forms [35]. Combining reporter analysis with endogenous target measurement (Ptch1, Gli1) enables validation of pathway activity status. Adaptation kinetics can be quantified by calculating the ratio of peak to steady-state activity levels.

Pathway Visualization

Figure 1: Canonical Shh Pathway Mechanism. The diagram illustrates the core signaling cascade from Shh binding to PTCH1 through GLI-mediated transcriptional regulation. Key regulatory steps include SMO ciliary translocation, SUFU-GLI complex dissociation, and feedback regulation of target genes.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Analyzing Shh Pathway Dynamics. The flowchart outlines the integrated methodology for quantifying both Shh gradient formation and intracellular signaling activity during neural tube patterning.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Canonical Shh Signaling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Reporters | Tg(GBS-GFP) mice | Monitoring GLI transcriptional activity in live tissues | Reports net balance of GLI activator/repressor forms |

| Chemical Modulators | Cyclopamine (SMO inhibitor), SAG (SMO agonist), Forskolin (PKA activator) | Pathway perturbation studies | Dose-response characterization essential for specificity |

| Antibody Reagents | Anti-Shh, Anti-Ptch1, Anti-GLI1/2/3, Anti-SUFU | Protein localization and quantification | Validation for specific applications required |

| Cell Models | Gli mutant MEFs, NIH3T3 fibroblasts | Mechanistic studies in controlled environments | Context-dependent signaling differences observed |

| Computational Tools | Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) | Inferring pathway parameters from quantitative data | Requires accurate prior knowledge of system |

The canonical Shh pathway comprising PTCH1, SMO, and GLI transcription factors represents a sophisticated signaling system that converts graded morphogen information into precise transcriptional responses during neural tube patterning. The quantitative dynamics of this pathway, including its adaptive properties and feedback regulation, enable robust patterning despite biological noise and variability. The experimental methodologies outlined provide researchers with robust tools for investigating pathway mechanics, while the reagent toolkit facilitates standardized investigation across model systems. Continuing elucidation of pathway regulation, including cross-talk with other developmental signaling pathways and cell-type-specific modulations, will further enhance our understanding of its roles in development and disease, potentially revealing new therapeutic opportunities for neural tube defects and cancers driven by pathway dysregulation.