The Embryo's Blueprint

How Embryology Blended Classic Science with DNA Discovery

The intricate dance of a single cell transforming into a complex human body has captivated scientists for centuries. Today, this mystery is being unraveled through a powerful synthesis of old and new scientific traditions.

Imagine a master architect's blueprint, one that not only outlines the structure of a magnificent building but also contains the very construction crews, their instruction manuals, and the precise timing for every single task. The development of an embryo is infinitely more complex than this. For centuries, scientists have strived to decode this biological blueprint, and their journey—from simply describing what they saw under a microscope to manipulating the fundamental genetic instructions of life—has revolutionized our understanding of existence itself.

This field, embryology, has not evolved in a straight line but has blossomed through the integration of three powerful perspectives: the classic, the experimental, and the molecular. It's a story that begins with careful observation, progresses to probing the 'how' and 'why,' and culminates in today's era of molecular mastery, where we can read and edit the text of life itself 1 .

The Classical Period: Charting the Unknown Map

Before we could ask why or how an embryo develops, we first needed to know what happens. The classical period of embryology, spanning the 19th century to the 1940s, was a golden age of exploration and description 1 . Scientists, armed with increasingly powerful microscopes, meticulously documented the breathtaking transformation of a fertilized egg into a complete organism.

Their work was akin to creating the first accurate maps of a new continent. They established a foundational timeline of human development, categorizing the early weeks into a meticulous sequence of events.

Key Insight

Classical embryology established the fundamental "what" of development through meticulous observation and description, creating the essential framework for all future research.

Key Concepts of Descriptive Embryology

Cleavage and Blastocyst Formation

The journey begins with a fertilized egg, or zygote, which starts dividing rapidly. This process, called cleavage, leads to a solid ball of cells known as a morula. Soon, a fluid-filled cavity forms, creating a blastocyst—a structure with an outer layer that will become the placenta (trophoblast) and an inner cell mass that will form the embryo itself (embryoblast) 6 .

Germ Layer Formation

In the second week, the inner cell mass rearranges into two layers (the bilaminar embryo), and soon after, a third layer is established through a process called gastrulation. These three germ layers—the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—are the primary tissues from which all the body's organs and systems will arise 2 .

Implantation

Around day 6-7, the blastocyst "hatches" from its protective shell and adheres to the uterine wall, burrowing in to establish a connection with the mother's blood supply—a process called implantation 6 .

Carnegie Stages

To make sense of the rapid and complex changes, embryologists developed a standardized system of 23 Carnegie stages, which provide a detailed "week-by-week" timeline of embryonic development, from fertilization to the end of the eighth week 2 .

This descriptive work was vital. It provided the essential framework, the basic narrative of development, upon which all future questions would be built.

The Experimental Period: Probing the Causes

By the mid-20th century, the "what" was largely established. The next generation of embryologists, unsatisfied with mere description, began asking deeper questions. The period from 1940 to 1970 became the era of experimental or causal embryology 1 . Their goal was to uncover the secondary causes—the forces, signals, and interactions—that guide the development process.

This was a shift from cartography to engineering. Instead of just mapping the terrain, scientists began poking and prodding the embryo to see how it responded. They asked: Is development pre-determined from the start, or is it a flexible process where cells communicate and adjust their fates based on their neighbors?

Principles of Developmental Regulation

Experimental embryologists uncovered several core principles that govern how embryos build themselves 8 :

Autonomous Specification

In some cases, a cell's fate is determined early on by factors contained within itself. If you remove that cell, it will still develop according to its original plan, and the embryo will be missing the tissues that cell would have produced.

Conditional Specification

In many other cases, particularly in mammals, a cell's fate is not fixed but depends on signals from its neighbors. This is a regulative pattern of development; if a cell is removed, other cells can change their fates to compensate, and the embryo still develops normally 8 .

The Organizer

One of the most famous experiments in all of biology came from Hans Spemann and Hilde Mangold in 1924. They discovered that a specific group of cells in a newt embryo, when transplanted to another embryo, could induce the formation of a complete second body axis. They called this region the "organizer," demonstrating that certain cells act as signaling centers, directing the development of those around them .

These experiments revealed that development is a delicate dance between intrinsic cellular programs and extrinsic signals—a conversation where "whom a cell meets" can determine its ultimate destiny 8 .

The Molecular Revolution: Reading the Text of Life

The stage was now set for the most profound revolution yet. Beginning in the 1980s, the tools of molecular biology and genetics stormed the field, allowing scientists to peer into the very machinery driving development 1 . Embryology fused with genetics to form the broader discipline of developmental biology, concerned with the activation and transcription of DNA sequences that represent the "first causes" of development 1 .

This molecular perspective did not replace the classical or experimental ones; instead, it provided the underlying explanation for their observations. The organizer, for instance, was found to work by secreting specific signaling proteins like BMP (Bone Morphogenetic Protein) inhibitors. The dramatic transformation of a flat sheet of cells into the intricate structures of the brain and spinal cord (neurulation) is directed by the precise, timed expression of genes such as Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) and Noggin 2 .

Modern Tools and Future Horizons

The molecular toolkit is constantly evolving, pushing the boundaries of what is possible:

CRISPR-Cas9

This powerful gene-editing technology allows scientists to make precise changes to the genome, enabling them to test the function of specific genes with unprecedented accuracy 3 .

Stem Cell Research and Organoids

The discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) allowed researchers to create embryo-like models and mini-organs (organoids) in a dish. These provide an ethical and accessible platform to study human development and the causes of infertility 3 .

Interdisciplinary Fusion

Today, progress is driven by collaboration. Artificial intelligence is being used to analyze embryo development and predict the success of in vitro fertilization (IVF). Biophysics helps us understand how mechanical forces influence cell fate, and bioinformatics allows us to process vast amounts of genetic data 3 .

In-Depth Look: The Spemann-Mangold Organizer Experiment

To truly appreciate the synthesis of these perspectives, let's examine one of the most crucial experiments in embryology, conducted by Hans Spemann and Hilde Mangold in the early 1920s—a masterpiece of experimental embryology whose molecular basis would only be understood decades later.

Methodology: A Delicate Transplantation

Spemann and Mangold worked with embryos of the newt, Triturus taeniatus. Their experimental procedure was elegant in design but required immense technical skill :

- Donor and Host Selection: They selected two embryos of different colorings—a light-pigmented one as the host and a dark-pigmented one as the donor. This pigmentation difference would later be crucial for tracking the fate of the transplanted cells.

- Tissue Extraction: Using a fine glass needle and a hair loop, they carefully excised a small piece of tissue from the dorsal lip of the blastopore (the opening of the primitive groove) from the donor embryo.

- Transplantation: This donor tissue was then transplanted into a region on the opposite side of the host embryo, an area that would normally become ventral (belly) skin.

- Observation: The host embryo was then allowed to continue its development, and the researchers observed the consequences of this surgical manipulation.

Results and Analysis: The Discovery of Induction

The results were astonishing. The host embryo developed not one, but two neural tubes. Even more remarkably, it began to form a complete, albeit conjoined, secondary embryo with its own head, trunk, and tail structures.

Upon closer examination, Spemann and Mangold made a critical observation using the pigment as a natural cell tracker: the transplanted donor tissue (the dorsal lip) did not itself form the bulk of the new structures. Instead, it acted as an "organizer," instructing the host's own cells—cells that were destined to become mundane belly skin—to change their fate and form complex neural and structural tissues like the brain, spinal cord, and somites (precursors to muscle and vertebra) .

| Experimental Component | Observation | Scientific Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Transplanted Dorsal Lip | Developed into notochord and somites of the secondary axis. | The organizer contributes to primary structures but its true power is signaling. |

| Host Ventral Cells | Formed the neural tube and other complex tissues of the secondary axis. | Embryonic cells are naive; their fate can be redirected by signals from neighbors (induction). |

| Formation of Secondary Axis | A complete but conjoined twin embryo developed. | A specific group of cells can orchestrate the formation of an entire body plan. |

The profound importance of this experiment was its demonstration of embryonic induction—the process by which one group of cells directs the development of another. It showed that development is not purely mosaic (pre-formed) but is highly regulative, dependent on communication between cell groups. This work earned Spemann the Nobel Prize in 1935 and laid the groundwork for the entire field of experimental embryology. Decades later, molecular biology would identify the specific proteins (like growth factors) that the organizer cells secrete to perform this remarkable feat, perfectly synthesizing the experimental and molecular perspectives.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents in Modern Embryology

Modern developmental biology relies on a sophisticated array of tools to interrogate the embryo. The table below details some essential "research reagents" and their functions.

Morpholinos

Synthetic molecules that block the translation of specific messenger RNAs (mRNA), allowing scientists to temporarily "knock down" a gene's function and observe the developmental defects.

CRISPR-Cas9

A gene-editing system that acts like molecular scissors. It allows for the precise knockout or alteration of specific DNA sequences to study gene function.

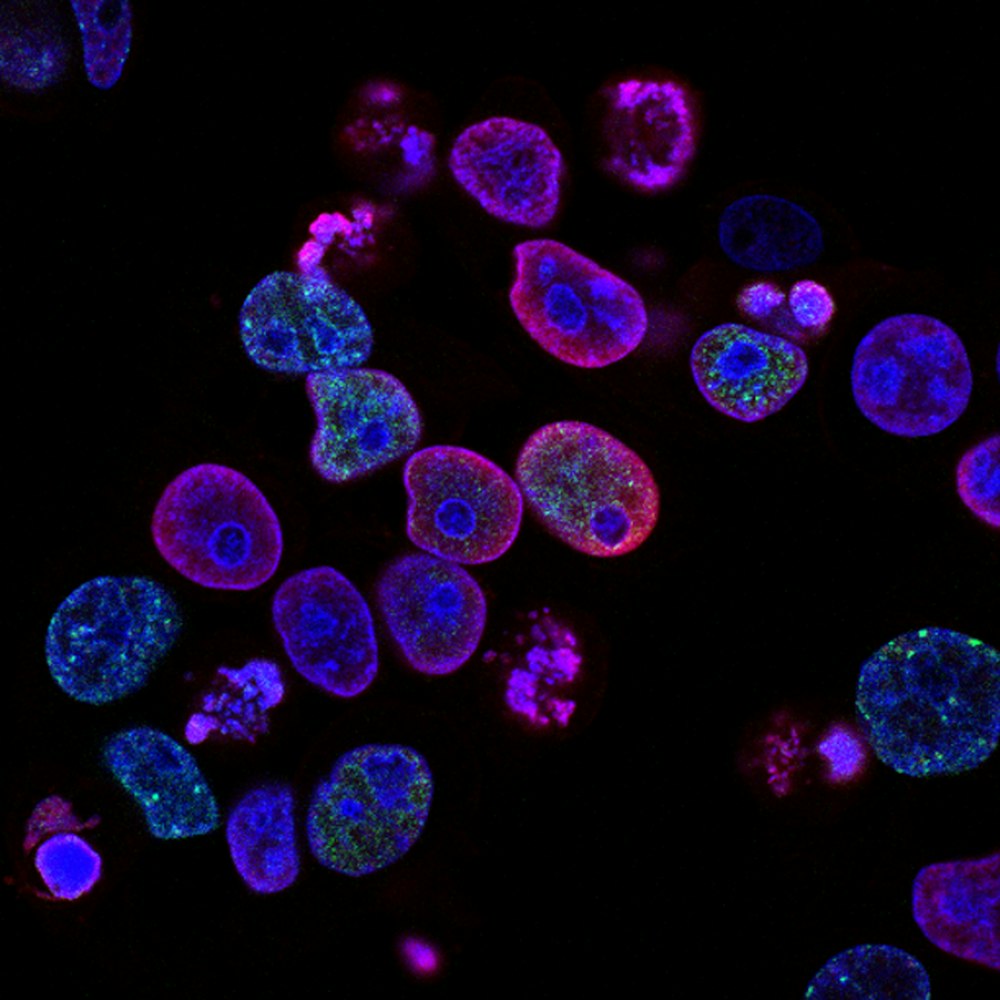

Fluorescent Antibodies

Antibodies tagged with fluorescent dyes that bind to specific proteins, allowing researchers to visualize the location and amount of that protein within a cell or tissue.

Lineage Tracing Dyes

Fluorescent dyes (e.g., DiI) that are injected into individual cells. The dye is passed on to all the descendant cells, allowing scientists to track the ultimate fate of that original cell's progeny.

Conclusion: A Synthesis for the Future

The evolution of embryology from a classical, descriptive science to an integrated molecular discipline is a powerful testament to the cumulative nature of scientific progress. The classical period provided the essential map, the experimental period taught us how to perturb the system to understand its rules, and the molecular period gave us the lexicon to read the fundamental text of life 1 .

This synthesis is not just academic. It has profound real-world implications, driving advances in assisted reproductive technologies (ART) like IVF, which has led to the birth of millions of children 3 . It fuels the promise of regenerative medicine and provides insights into the causes of birth defects and diseases.

As we look to the future, the lines will continue to blur. The integration of artificial intelligence, advanced bioimaging, and ethical gene therapy promises to deepen our understanding even further. The journey to decipher the embryo's blueprint, which began with scientists simply sketching what they saw, is now powered by the ability to read and edit its underlying code—a beautiful synthesis of classical, experimental, and molecular perspectives that continues to reveal the magnificent logic of life.

Three Perspectives of Embryology

Classical

Observation & DescriptionExperimental

Manipulation & CausationMolecular

Genetic & Molecular MechanismsReferences

References to be added separately.