Tissue Permeability in Biomedical Research: Mechanisms, Assessment, and Impact on Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role tissue permeability plays in physiological function, disease pathogenesis, and therapeutic development.

Tissue Permeability in Biomedical Research: Mechanisms, Assessment, and Impact on Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role tissue permeability plays in physiological function, disease pathogenesis, and therapeutic development. We explore foundational concepts of paracellular and transcellular transport mechanisms across different tissue barriers, including intestinal and vascular endothelium. The content details state-of-the-art methodologies for assessing permeability in research and clinical settings, addresses common challenges in permeability modulation, and examines regulatory considerations for permeability-targeting therapies. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current evidence and emerging trends to inform research design and therapeutic innovation in this rapidly evolving field.

Fundamental Principles of Tissue Permeability: From Cellular Mechanisms to Systemic Impact

Tissue permeability refers to the regulated movement of substances—including fluids, ions, nutrients, and pharmaceuticals—across biological barriers formed by cellular layers. These semi-permeable barriers, primarily constituted by endothelial and epithelial cell linings, separate distinctive physiological compartments and maintain compartment-specific homeostasis [1]. The controlled passage of materials occurs through two principal pathways: the paracellular route (between adjacent cells) and the transcellular route (through the cells themselves) [2] [3]. The permeability of a tissue barrier is not a static property but is dynamically regulated by complex molecular mechanisms and can be disrupted in various disease states, leading to pathological conditions such as edema (in the case of vascular endothelium) or compromised drug absorption (in the case of intestinal epithelium) [1] [2].

The study of tissue permeability is fundamental to multiple scientific and clinical disciplines. In drug development, understanding and predicting intestinal permeability is critical for estimating the oral bioavailability of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [4] [5]. In toxicology and physiology, the breakdown of barrier function in organs like the lung or gut is a key event in inflammatory diseases [6] [2]. Consequently, accurate assessment and a deep mechanistic understanding of tissue permeability are prerequisites for advances in therapeutics and disease management.

Core Concepts and Pathways of Transport

The Paracellular Pathway

The paracellular pathway is a major route for the passive movement of water, solutes, and immune cells through the intercellular space between adjacent endothelial or epithelial cells [2]. This pathway is governed by specialized junctional complexes that bridge the cells, which together form a selectively permeable "gate" in the paracellular space [6].

- Tight Junctions (TJs): These are the most apical component of the junctional complex and represent the primary determinant of paracellular permeability. TJs are multimolecular structures composed of proteins such as claudins and occludins, which create a seal that can be tuned to allow selective passage based on size and charge [6] [3].

- Adherens Junctions (AJs): Located just below the tight junctions, AJs are crucial for initiating and maintaining cell-cell adhesion, primarily through E-cadherin proteins. They provide structural integrity to the epithelial layer and are connected to the actin cytoskeleton, playing a supportive role in barrier regulation [6].

- The Perijunctional Actomyosin Ring (PAMR): This is a contractile ring of actin and myosin filaments that is intimately associated with the TJs and AJs. The equilibrium between contractile forces generated by the PAMR and the tethering forces of the junctional complexes determines the tightness of the paracellular gate. An increase in PAMR tension, often mediated by the phosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC), leads to junctional opening and increased permeability [2] [3].

The permeability conferred by this pathway can be experimentally enhanced by agents like ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), which acts as a chelator of divalent cations (e.g., Ca²âº). By sequestering these ions, EDTA disrupts the integrity of tight junctions, leading to a "bulging" of the enterocyte apex and a pronounced increase in the paracellular flux of both polar and lipophilic probes [3].

The Transcellular Pathway

The transcellular pathway involves the movement of substances directly across the cell's membrane and cytoplasm. This pathway can be passive or active and is highly dependent on the physicochemical properties of the permeating molecule [2] [3].

- Passive Diffusion: Small, nonpolar molecules can diffuse freely through the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane. The rate of this passive transcellular transport is governed by the molecule's size, lipophilicity, and polarity [7].

- Transporter-Mediated Uptake: Numerous nutrients and drugs rely on specific membrane transporters (e.g., for amino acids, sugars) to facilitate their entry into cells.

- Transcytosis: This is an active process for transporting larger molecules (such as albumin) or even entire complexes across the cell. It involves vesicle formation at one cell membrane, transport of the vesicle through the cytoplasm, and exocytosis at the opposite membrane. A key structure involved in transcytosis is the caveolae, a type of lipid raft plasma membrane microdomain enriched with the scaffolding protein caveolin-1 [2].

The transcellular pathway can be compromised by surfactants like sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). SDS inserts into the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, increasing its fluidity and compromising its integrity. At the ultrastructural level, this leads to the formation of vacuoles and vesicle-like structures, which increases passive transcellular leakage and can also block constitutive endocytosis from the brush border [3].

Selective Permeability and Membrane Permeability Coefficients

The concept of selective permeability describes the ability of a biological membrane to differentiate between different types of molecules, allowing some to pass while blocking others [7]. This selectivity stems from both the intrinsic physicochemical properties of the membrane's lipid bilayer and the activity of various protein-based channels and transporters.

The permeability of a substance across a membrane can be quantified experimentally and reported as a Membrane Permeability Coefficient (MPC), typically in units of cm/s. The MPC is proportional to the molecule's partition coefficient and inversely proportional to the membrane thickness. The table below summarizes the vast range of MPCs for different types of compounds, illustrating the basis for selective permeability [7].

Table 1: Membrane Permeability Coefficients for Various Compounds

| Compound | Membrane Permeability Coefficient (cm/s) | Relative Permeability |

|---|---|---|

| Hexanoic Acid | 0.9 | Very High |

| Acetic Acid | 0.01 - 0.001 | Moderate |

| Water | 0.01 - 0.001 | Moderate |

| Ethanol | 0.01 - 0.001 | Moderate |

| Sodium Ion (Naâº) | 10â»Â¹Â² | Very Low |

Quantitative Assessment of Tissue Permeability

Key Quantitative Parameters

The permeability of tissue barriers is characterized using specific, measurable parameters that allow for the comparison of different barriers, substances, and experimental or pathological conditions.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters in Tissue Permeability Studies

| Parameter | Description | Typical Units | Application & Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Permeability Coefficient (MPC) | The rate of simple diffusion of a solute across a membrane. | cm/s | A fundamental biophysical property used to compare intrinsic permeability of different molecules [7]. |

| Apparent Permeability (P_app) | The measured permeability of a compound across a cellular barrier (e.g., Caco-2 monolayer). Often reported as log P_app. | cm/s | A standard metric in drug development for predicting human intestinal absorption [4]. |

| Human Intestinal Absorption (HIA) | The percentage of an orally administered dose that is absorbed through the intestinal wall. | % | A direct physiological and clinical endpoint; compounds with >85% HIA are classified as highly permeable [4]. |

| Elimination Half-Life | The time required for the plasma concentration of a substance to reduce by half. | hours (h) | A key pharmacokinetic parameter indicating the persistence of a compound in the body, influenced by its distribution and clearance [8]. |

| Volume of Distribution (Vd) | A theoretical volume that a drug would need to occupy to achieve the current blood concentration. | L/kg | Reflects the extent of a drug's distribution into tissues; a high Vd suggests extensive tissue penetration beyond the plasma compartment [8]. |

In Vivo Pharmacokinetic and Tissue Distribution Studies

In vivo studies provide the most physiologically relevant data on tissue permeability and barrier penetration. These studies involve administering a compound to a live animal and then measuring its concentration over time in the blood (pharmacokinetics) and in various harvested tissues (tissue distribution).

A recent study on Ginsenoside Rh3 (GRh3) in rats provides a clear example. Researchers used a validated LC-MS/MS method to quantify GRh3 after oral administration. The study revealed that GRh3 had a prolonged elimination half-life of 14.7 ± 1.7 hours and a high volume of distribution of 280.4 ± 109.3 L/kg, indicating extensive tissue penetration. The tissue distribution analysis at the time of peak plasma concentration (T~max~) showed the highest levels in the intestine, stomach, and liver. Critically, it demonstrated that GRh3 could cross the blood-brain barrier, with significant accumulation in the hippocampus (520.0 ng/g), suggesting potential for central nervous system activity [8].

Table 3: Tissue Distribution of Ginsenoside Rh3 in Rats Following Oral Administration (100 mg/kg)

| Tissue | Concentration (ng/g) |

|---|---|

| Intestine | 15445.2 |

| Stomach | 2906.7 |

| Liver | 1930.8 |

| Hippocampus | 520.0 |

| Other Tissues (e.g., kidney, lung, heart, spleen) | Analyzed, specific values not listed in excerpt |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vitro and Ex Vivo Models

A variety of models are employed to study tissue permeability in a controlled setting, each with its own advantages and limitations.

- Cell-Based Monolayers:

- Caco-2: A human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line that, upon differentiation, forms a monolayer with morphology and functionality similar to human enterocytes. It is the most widely used in vitro model for predicting human intestinal permeability and is recommended by regulatory agencies [4] [5].

- MDCK & LLC-PK1: Canine and porcine kidney epithelial cell lines, respectively, also used for permeability screening [4].

- Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay (PAMPA): This is a non-cell-based, high-throughput assay that uses an artificial membrane to measure passive transcellular permeability [4].

- Mucosal Explant Systems: Cultured intestinal mucosal tissues, as used in studies with SDS and EDTA, offer a more in-vivo-like environment than simple cell lines while remaining simpler than whole-animal models. They allow for easy visualization of probe uptake and differentiation between paracellular and transcellular mechanisms [3].

- Membrane Insert Systems with Engineered Tissues: Advanced systems cultivate skin or other tissue models on permeable membrane inserts. A specific protocol uses 96-well or 12-well Transwell systems to determine permeability coefficients for fluorescently-labeled substances directly in the insert, providing a compact and cost-effective alternative to larger systems like the Franz diffusion cell [9].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Permeability Measurement in Membrane Insert Systems

This protocol, adapted from a 2018 study, details a method for determining permeability coefficients in small membrane-insert systems, suitable for engineered skin or mucosal models [9].

- Sample Preparation:

- For a collagen gel barrier, mix 125 µL of HBSS with 1 mL of 0.4% collagen R solution on ice.

- Titrate with ~6 µL of 1 M NaOH until the color of phenol red changes from yellow to red.

- Add 125 µL of DMEM + 10% FCS and mix carefully.

- Apply 28.6 µL of the collagen gel to the membrane of a 96-well membrane insert system (4.26 mm diameter).

- Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 30 min to allow polymerization.

- Permeation Experiment:

- Apply the donor substance (e.g., fluorescent tracer like sodium fluorescein) in solution to the top (apical side) of the sample.

- Ensure the bottom (basolateral) chamber is filled with an appropriate acceptor medium.

- Incubate the system at a constant temperature (e.g., 37°C).

- Sample Collection and Analysis:

- At predetermined time points, measure the concentration of the permeated substance in the acceptor chamber using a method suitable for the tracer (e.g., fluorescence plate reader).

- Data Calculation:

- The permeability coefficient can be calculated from the time-dependent concentration change in the acceptor compartment. Supporting simulations using computational fluid dynamics can be used to fit the experimental data and determine the diffusion coefficient [9].

Protocol: Differentiating Paracellular vs. Transcellular Pathways in Mucosal Explants

This protocol uses fluorescent probes to visually distinguish the mechanism of action of permeation enhancers in a porcine jejunal mucosal explant system [3].

- Tissue Preparation:

- Surgically remove segments of porcine jejunum and place in ice-cold RPMI medium.

- Excise small mucosal specimens (~0.1 g) and transfer them to metal grids in organ culture dishes with 1 mL of RPMI medium.

- Treatment and Incubation:

- Pre-incubate explants for 15 minutes at 37°C.

- Add the permeation enhancer (e.g., 0.05% SDS for transcellular study, 0.05% EDTA for paracellular study) along with fluorescent probes to the culture medium.

- Key Probes: Lucifer Yellow (small polar), Texas Red-conjugated dextrans of varying sizes (3kDa, 70kDa), and lipophilic FM dyes (e.g., FM 1–43).

- Culture the explants with probes for 1 hour at 37°C.

- Post-Incubation Processing:

- Rinse explants carefully in fresh medium.

- Fix overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C.

- Cryoprotect by immersing in 25% sucrose overnight, then embed and section (~7 µm thickness) using a cryostat.

- Visualization and Analysis:

- Analyze sections using fluorescence microscopy.

- Expected Outcomes:

- EDTA (Paracellular): Increased paracellular flux is visualized as distinct stripy lateral staining of enterocytes and accumulation of probes (including larger dextrans) in the lamina propria. It may also cause a loss of cell polarity.

- SDS (Transcellular): Renders cell membranes leaky to small polar tracers and conspicuously blocks constitutive endocytosis. It causes vacuolization at the ultrastructural level.

In Silico and AI-Based Prediction Models

Computational approaches are increasingly important for predicting permeability, especially in early drug discovery. Quantitative Structure-Permeability Relationship (QSPR) models use machine learning to predict permeability based on molecular descriptors derived from a compound's chemical structure [4].

A recent advanced approach used an Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based system—a hierarchical combination of classification and regression models—to predict Human Intestinal Absorption (HIA) for compounds with serotonergic activity. This system widened the space of molecules classified as highly permeable with high accuracy and, in external validation, correctly selected 38% of highly permeable molecules without any false positives. Such AI-based tools represent a promising strategy for in silico screening of oral drug candidates at early development stages [4].

Molecular Regulation and Signaling Pathways

The permeability of tissue barriers is dynamically regulated by a complex interplay of signaling pathways that control the cytoskeleton and intercellular junctions.

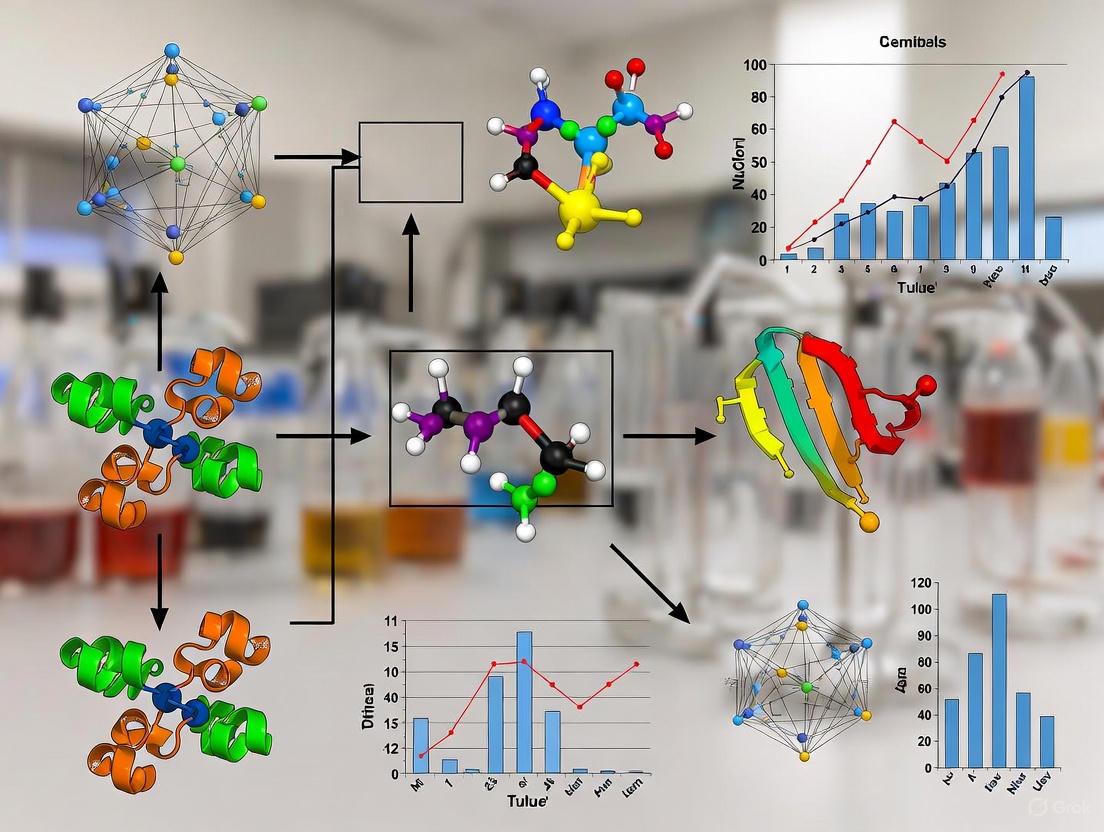

Diagram Title: Signaling Pathways in Endothelial Barrier Regulation

The diagram above illustrates the core signaling pathways that regulate endothelial permeability, particularly in the context of conditions like Acute Lung Injury (ALI) [2].

Barrier-Disruptive Signaling (Red):

- Edemagenic Agonists such as thrombin, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) trigger the pathway.

- They lead to microtubule (MT) destabilization, either directly or through activation of histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6), which deacetylates tubulin.

- Microtubule disassembly releases the Rho-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor GEF-H1.

- GEF-H1 activates the small GTPase RhoA, which in turn activates its effector ROCK (Rho-associated protein kinase).

- ROCK promotes the phosphorylation of Myosin Light Chain (MLC), which increases the tension of the Perijunctional Actomyosin Ring (PAMR).

- This contraction pulls apart the tight and adherens junctions, resulting in increased paracellular permeability [2].

Barrier-Protective Signaling (Green):

- Conversely, microtubule stabilization (e.g., by the drug paclitaxel or by tubulin acetylation) promotes activation of the small GTPase Rac1.

- Rac1 activation generally opposes RhoA signaling and promotes barrier enhancement and restoration. Factors that increase cAMP or inhibit HSP90 and p38 MAPK also exert their barrier-protective effects partly through MT stabilization [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Models for Tissue Permeability Research

| Tool Name | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | In Vitro Model | Gold-standard human cell line for predicting intestinal drug permeability and absorption studies [4] [5]. |

| Transwell / Membrane Insert Systems | Experimental Apparatus | Permeable supports for cultivating cell monolayers or tissue models to study directional solute flux (e.g., apical-to-basolateral) [9]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Transcellular Permeation Enhancer | Surfactant used to investigate transcellular transport pathways by perturbing plasma membrane integrity [3]. |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA) | Paracellular Permeation Enhancer | Chelator of divalent cations used to disrupt tight junctions and study the paracellular transport pathway [3]. |

| Fluorescent Tracers (e.g., Lucifer Yellow, FITC-Dextrans) | Research Reagents | A suite of probes of varying size and charge used to visualize and quantify permeability across biological barriers and determine pore sizes [9] [3]. |

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | Analytical Instrument | Highly sensitive and specific technology for quantifying drug concentrations in complex biological matrices (e.g., plasma, tissue homogenates) for pharmacokinetic and tissue distribution studies [8]. |

| GEF-H1, RhoA/ROCK, MLC Pathway Inhibitors | Pharmacological/Signaling Tools | Chemical inhibitors (e.g., ROCK inhibitor Y-27632) used to dissect the molecular mechanisms controlling actomyosin-based contraction and paracellular permeability [2]. |

| HDAC6 Inhibitors (e.g., Tubastatin A) | Pharmacological/Signaling Tools | Used to investigate the role of microtubule acetylation and stability in maintaining endothelial barrier function; potential therapeutic agents for ALI/ARDS [2]. |

| Rat CGRP-(8-37) | Rat CGRP-(8-37), MF:C138H224N42O41, MW:3127.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Monomyristin | 1-Monomyristin, CAS:27214-38-6, MF:C17H34O4, MW:302.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The permeation of substances across cellular barriers is a fundamental process in physiology and drug development. Two primary pathways facilitate this movement: the paracellular and transcellular routes. The paracellular pathway involves the transport of substances between adjacent cells, passing through intercellular spaces sealed by tight junctions [10] [11]. In contrast, the transcellular pathway involves the transport of substances through the cell, requiring translocation across both the apical and basolateral membranes [12] [13]. The distinct structural components, regulatory mechanisms, and functional characteristics of these pathways collectively define the permeability of biological tissues, a critical parameter in therapeutic agent absorption and distribution. Within the context of WISH background research, a precise understanding of these pathways is paramount for predicting drug bioavailability and designing novel delivery strategies that can navigate or modulate biological barriers.

Core Structural and Mechanistic Distinctions

The paracellular and transcellular pathways are distinguished by their unique architectural designs and the physical forces that govern solute movement.

The Paracellular Pathway

This is a passive, energy-independent process where solutes move diffusively through the intercellular space, driven by concentration, osmotic, or electrochemical gradients [10] [11]. The rate-limiting step is passage through the tight junction (TJ), a multi-protein complex that forms a selective seal at the most apical part of the intercellular space [12] [11]. The TJ's barrier and pore functions are defined by specific transmembrane proteins, primarily claudins and occludin, which form a branching network of strands [10] [11]. These strands are anchored intracellularly to the actin cytoskeleton via plaque proteins like ZO-1, allowing for dynamic regulation [11]. The paracellular pathway is generally size-selective and charge-selective. It is most relevant for small, hydrophilic molecules (typically under 0.6 kDa) and demonstrates a preference for cations over anions due to the net negative charge of the tight junctions [10] [11].

The Transcellular Pathway

This pathway entails solute traversal across the cell's membrane structures. Transcellular transport can occur via several mechanisms, which can be either passive or active [13] [14]:

- Passive Transcellular Diffusion: A passive process where lipophilic solutes dissolve into and diffuse across the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane, moving down their concentration gradient [13].

- Carrier-Mediated Transport: An active, energy-dependent process that utilizes specific membrane-bound transporters to move solutes, often against a concentration gradient [13] [14].

- Transcytosis: A process where large molecules, such as proteins or nanoparticles, are engulfed by the cell via endocytosis, transported across the cytoplasm in vesicles, and expelled on the opposite side via exocytosis [13] [14].

A prerequisite for vectorial transcellular transport is cell polarity, the asymmetric distribution of transporters, channels, and enzymes between the apical and basolateral membranes, which is maintained by the fence function of the tight junctions [12].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Paracellular and Transcellular Transport Pathways

| Feature | Paracellular Transport | Transcellular Transport |

|---|---|---|

| Route | Between adjacent cells (through tight junctions) [10] [11] | Through the cell body (across apical and basolateral membranes) [12] [13] |

| Energy Requirement | Passive (no energy required) [10] | Can be passive or active (energy-requiring) [13] [14] |

| Primary Driving Force | Concentration, osmotic, or electrochemical gradients [10] [11] | Concentration gradient (passive) or ATP (active) [13] |

| Key Molecular Structures | Tight junction proteins (claudins, occludin, ZO proteins) [10] [11] | Membrane lipids, channels, carriers, and endocytic machinery [13] |

| Typical Solutes | Small, hydrophilic molecules and ions (e.g., acyclovir) [10] [15] | Lipophilic molecules (passive); specific nutrients/drugs (carrier-mediated); macromolecules (transcytosis) [13] [15] |

| Saturability | Generally non-saturable [10] | Carrier-mediated transport is saturable [13] |

| Influencing Factors | Tight junction integrity and dynamic regulation [11] | Solute lipophilicity, molecular size, and affinity for specific transporters [13] |

Diagram 1: Overview of Transport Pathways

Molecular Architecture and Regulation

The functional distinction between the two pathways is rooted in their unique molecular architectures.

Tight Junctions: Gatekeepers of the Paracellular Route

The tight junction is not a static seal but a dynamic, regulated structure. Its core transmembrane components are:

- Claudins: A large family of proteins that form the primary seal and create charge- and size-selective pores within the tight junction strands [10]. Different claudin isoforms determine the specific permeability properties of a given tissue [10].

- Occludin: A regulatory protein that contributes to the barrier function and is involved in the response to various physiological stimuli [11].

- Junctional Adhesion Molecules (JAMs): These proteins play a role in the initial formation of tight junctions and in cell-cell adhesion [12].

Intracellularly, these proteins are linked to the actin cytoskeleton by scaffolding proteins like zonula occludens (ZO-1, -2, -3) [11]. This connection is crucial, as it allows the cell to rapidly modulate paracellular permeability in response to physiological demands; for instance, the phosphorylation of myosin light chains can trigger actin-myosin contraction and open the junctions [12].

Cellular Machinery for Transcellular Transport

The transcellular route relies on the polarized distribution of various transport systems across the cell:

- Lipid Bilayer: Serves as the conduit for passive diffusion of lipophilic solutes [13].

- Transport Proteins: Include channels, carriers, and pumps that facilitate the movement of specific solutes. For example, the Na-K-ATPase pump on the basolateral membrane actively maintains the sodium gradient that drives many secondary active transporters on the apical membrane [12].

- Endocytic and Exocytic Machinery: A complex system of vesicles, receptors, and cytoskeletal elements that facilitates transcytosis, enabling the transport of nanoparticles and macromolecules [13] [16].

Diagram 2: Molecular Architecture of Transport Pathways

Experimental Methods for Assessing Pathway Permeability

Distinguishing the contribution of each pathway and measuring tissue permeability are essential in research and development. The following are established methodologies.

In Vitro Barrier Models and Permeability Studies

A common approach involves using cell monolayers grown on permeable transwell inserts. The apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) of a solute is calculated from its rate of transport from the donor to the acceptor compartment [17].

Protocol 1: Standard Permeability Assay Using Transwell Inserts

- Cell Culture: Seed relevant epithelial cells (e.g., Caco-2 for intestine, Calu-3 for lung) on porous membrane inserts and culture until a fully differentiated, confluent monolayer with high transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) is formed [17].

- TEER Measurement: Measure TEER before the experiment to verify monolayer integrity. TEER is a sensitive indicator of tight junction integrity and thus paracellular permeability [12].

- Dosing and Sampling: Apply the test compound in buffer to the donor compartment (e.g., apical side). Collect samples from the acceptor compartment (e.g., basolateral side) at predetermined time points over the course of several hours [15] [17].

- Analytical Quantification: Analyze samples using a suitable method (e.g., HPLC, MS, fluorescence spectroscopy) to determine the concentration of the transported compound.

- Papp Calculation: Calculate the apparent permeability coefficient using the formula:

Papp = (dQ/dt) / (A * C0), where dQ/dt is the steady-state flux, A is the membrane surface area, and C0 is the initial donor concentration [17].

Pharmacological Modulation of Pathways

Specific inhibitors or manipulative techniques can be used to delineate the contribution of each pathway.

Protocol 2: Pathway Differentiation Using Inhibitors and Osmotic Manipulation

- Inhibiting Transcellular Transport:

- Modulating Paracellular Transport:

- Osmotic Manipulation: Pre-treat barriers with hypo-osmotic solutions. This can cause swelling of cells or vesicles, physically altering the intercellular spaces and increasing paracellular flux of hydrophilic markers, as demonstrated in PermeaPad models [15].

- TJ Modulators: Use agents that directly affect tight junctions, such as calcium chelators (EGTA) or specific peptides targeting claudins.

Advanced Microphysiological Systems (MPS)

More complex in vitro models, such as organ-on-a-chip systems, incorporate fluid flow and multiple cell types to better recapitulate in vivo physiology. For instance, a small airway MPS with primary human lung epithelial and endothelial cells has been used to study the permeability of inhaled drugs like albuterol and formoterol [17]. These systems allow for real-time monitoring of solute transport in a more physiologically relevant context.

Table 2: Experimental Reagents for Pathway Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Experimental Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Dynasore [16] | Inhibitor of dynamin, a GTPase | Blocks clathrin- and caveolin-mediated endocytosis; used to inhibit transcellular transport via endocytosis. |

| Amiloride [16] | Inhibitor of Na+/H+ exchange | Blocks macropinocytosis, a form of fluid-phase endocytosis; used to study transcellular particle uptake. |

| EGTA (Ca2+ Chelator) | Depletes extracellular calcium | Disrupts calcium-dependent cell adhesion, leading to the opening of tight junctions; used to probe paracellular pathway. |

| Hypo-/Hyper-osmotic Solutions [15] | Alters cellular and vesicular volume via osmosis | Modifies the width of paracellular water channels; used to manipulate paracellular permeability. |

| TEER Measurement [12] | Measures electrical resistance across a monolayer | A non-invasive, quantitative readout of tight junction integrity and paracellular permeability. |

| Fluorescent Tracers (e.g., Calcein, FD-4) | Inert, detectable molecules | Serve as markers for paracellular (small/charged) or transcellular (lipophilic) transport. |

Diagram 3: Permeability Experiment Workflow

Implications for Drug Delivery and Permeability Research

The strategic exploitation of these pathways is central to modern drug delivery, particularly within the WISH research framework focused on tissue permeability.

Designing Molecules for Targeted Pathways

- Transcellular Route Optimization: For drugs with low oral bioavailability, chemical modification to increase lipophilicity (e.g., prodrug approaches) can enhance passive transcellular diffusion [13]. Alternatively, designing molecules to be substrates for active transporters expressed in the target tissue can facilitate efficient uptake [13].

- Paracellular Route Considerations: The paracellular route is particularly important for hydrophilic, charged drugs that poorly cross cell membranes (e.g., acyclovir, atenolol) [10] [11]. However, its utility is limited by molecular size and the restricted surface area of the intercellular space. Strategies to safely and transiently enhance paracellular permeability using permeation enhancers (e.g., medium-chain fatty acids, chitosan) are an active area of research [10].

Nanoparticle Delivery Systems

Nanoparticles (NPs) can be engineered to exploit specific transport mechanisms. Their size, surface charge, and coating dictate their pathway.

- Transcellular Dominance: Most nanoparticles are taken up by lymphatic endothelial cells and other barriers primarily via transcellular mechanisms such as micropinocytosis and macropinocytosis [16]. PEGylation of nanoparticles can steer their transport toward these mechanisms [16].

- Paracellular Potential: Smaller nanoparticles with positive surface charges may more readily undergo paracellular transport by interacting with the negatively charged tight junction proteins [11]. Computational kinetic modeling, using systems of differential equations, can help deconvolute the contributions of para- and transcellular mechanisms to overall NP transport [16].

The paracellular and transcellular routes represent two structurally and functionally distinct biological systems for solute transport. The paracellular pathway is a passive conduit between cells, rigorously governed by the dynamic tight junction complex, while the transcellular pathway is a multifaceted cellular traversal system capable of both passive and active transport. The distinction is not merely academic; it provides a critical framework for understanding tissue permeability, predicting drug absorption, and innovating drug delivery platforms. For WISH background research, a deep and nuanced grasp of these pathways, their interactions, and the methods to study them is indispensable for advancing therapeutic efficacy and navigating the complex landscape of biological barriers.

Tight junctions (TJs) represent the primary determinant of paracellular permeability, forming selective seals between epithelial and endothelial cells that control the passage of ions, molecules, and cells across tissue compartments [18]. These dynamic structures function not merely as static barriers but as sophisticated signaling hubs that integrate environmental cues, microbial signals, and metabolic information to regulate tissue homeostasis [19]. The molecular architecture of TJs encompasses multiple protein families including claudins, zonula occludens (ZO) proteins, occludin, and regulatory mediators like zonulin [20] [21]. Within the context of tissue permeability research, understanding the precise mechanisms governing these key molecular regulators provides critical insights into numerous pathological conditions including inflammatory disorders, autoimmune diseases, cancer metastasis, and infectious diseases [22] [19]. This technical guide comprehensively examines the structure, function, and experimental methodologies for investigating these crucial molecular determinants of barrier function.

Molecular Architecture of Tight Junctions

Core Protein Components and Their Functions

The tight junction complex comprises transmembrane proteins, cytoplasmic plaque proteins, and cytoskeletal linkers that collectively regulate paracellular permeability [20] [21].

Table 1: Core Protein Components of Tight Junctions

| Protein Category | Key Members | Primary Functions | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmembrane Proteins | Claudin family (27 members) | Forms paracellular barrier & selective pores; determines ion selectivity [18] | Tetraspan proteins with 2 extracellular loops, short N-terminus, long C-terminal cytoplasmic domain [18] |

| Occludin | TJ regulation & stabilization; modulates leak pathway [21] | Tetraspan protein with 2 extracellular loops, C-terminal OCEL domain [21] | |

| Junctional Adhesion Molecules (JAMs) | Cell-cell adhesion; immune cell migration [23] | Immunoglobulin-like fold with single transmembrane domain [23] | |

| Cytoplasmic Plaque Proteins | Zonula Occludens (ZO-1, ZO-2, ZO-3) | Scaffolding proteins linking transmembrane proteins to actin cytoskeleton [21] | PDZ domains, SH3 domain, guanylate kinase domain, actin-binding region [21] |

| Regulatory Mediators | Zonulin | Reversibly regulates intestinal permeability by modulating intercellular TJs [24] [25] | Serum protein that activates PAR-2/EGFR signaling leading to actin rearrangement [26] |

Claudin Family: Masters of Paracellular Selectivity

The claudin (CLDN) protein family represents the fundamental building blocks of tight junction strands, with at least 27 members identified in mammals [18]. These four-pass transmembrane proteins create the characteristic tight junction strands observed via freeze-fracture microscopy and establish the paracellular charge and size selectivity [18]. Several structural features dictate claudin functionality:

- Extracellular Loop 1 (ECL1): This larger extracellular domain contains critical conserved amino acid motifs that directly determine ion selectivity and paracellular permeability. The distribution pattern of acidic and basic amino acids in ECL1 creates charge-selective channels [18].

- Extracellular Loop 2 (ECL2): The smaller second extracellular loop contributes to strand organization and barrier integrity [18].

- C-terminal PDZ-binding domain: This cytoplasmic domain interacts with scaffold proteins of the ZO family and MUPP1, enabling connection to the actin cytoskeleton and facilitating intracellular signaling [18].

Claudins can be functionally categorized as "barrier-forming" (e.g., claudin-1, -3, -4, -5, -8, -11) or "pore-forming" (e.g., claudin-2, -10, -15, -16), with the specific claudin composition of a tissue determining its paracellular transport properties [18] [26]. The expression balance between sealing and pore-forming claudins is dynamically regulated in physiological and pathological states; inflammation typically decreases sealing claudins while increasing pore-forming claudins like claudin-2, disrupting barrier function [26].

Quantitative Assessment of Tight Junction Regulators

Recent clinical studies have established the diagnostic and prognostic value of specific tight junction proteins as serum biomarkers for barrier dysfunction.

Table 2: Diagnostic Performance of TJ Protein Biomarkers in Clinical Studies

| Biomarker | Condition Assessed | Population | Key Findings | Diagnostic Performance (AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claudin-3 | Post-abdominal surgery intestinal barrier dysfunction [24] | Patients undergoing abdominal surgery | Significantly increased at 24h post-operation; positively correlated with intestinal injury severity [24] | AUC = 0.934 [24] |

| Zonulin | Post-abdominal surgery intestinal barrier dysfunction [24] | Patients undergoing abdominal surgery | Significantly increased at 24h post-operation; peaks at 24h post-reperfusion [24] | AUC = 0.826 [24] |

| Occludin | Inflammatory Bowel Disease [26] | IBD patients (UC & CD) | Decreased serum levels compared to healthy controls; improved with anti-TNF-α treatment [26] | UC: AUC = 0.959; CD: AUC = 0.948 [26] |

| Claudin-2 | Inflammatory Bowel Disease [26] | IBD patients (UC & CD) | Increased serum levels compared to healthy controls [26] | UC: AUC = 0.864; CD: AUC = 0.896 [26] |

| Zonulin | Crohn's Disease [26] | CD patients | Increased concentration compared to control group [26] | AUC = 0.74 [26] |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Interactions

Zonulin Signaling Pathway

Zonulin serves as a key physiological regulator of intestinal permeability through its reversible modulation of intercellular tight junctions [24] [25]. The zonulin signaling cascade involves:

- Receptor Binding: Zonulin binds to specific apical membrane receptors on enterocytes [22]

- Intracellular Activation: Triggers activation of protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling [26]

- Cytoskeletal Rearrangement: Leads to protein kinase C (PKC)-dependent phosphorylation and subsequent actin polymerization and contraction [22]

- Tight Junction Disassembly: Causes dislocation of zonula occludens-1 and rearrangement of TJ proteins, increasing paracellular permeability [26]

This pathway is physiologically upregulated in response to bacterial exposure and intestinal dysbiosis, highlighting its role in host-microbe interactions [26]. In pathological states, zonulin upregulation is associated with increased intestinal permeability in autoimmune, inflammatory, and neoplastic diseases [22] [20].

Claudin Cross-Regulation and Signaling

Claudin proteins participate in complex regulatory networks, including cross-regulation between family members. A significant mechanistic insight reveals that one claudin can influence the ability of another claudin to interact with the tight junction scaffold [27]. For instance:

- Claudin-5 and Claudin-18 Interaction: In alveolar epithelial cells, alcohol exposure upregulates claudin-5 expression, which impairs barrier function by displacing claudin-18 from ZO-1 interactions [27]. This claudin-5 mediated disruption is both necessary and sufficient for barrier compromise.

- Scaffold Protein Competition: Claudins compete for binding sites on ZO proteins; phosphorylation events regulate these interactions and consequently affect paracellular permeability [27] [21].

- Signaling Pathway Integration: Claudins modulate critical signaling pathways including:

- PI3K/AKT: Regulates cell survival and proliferation

- Wnt/β-catenin: Influences cell polarity and differentiation

- Small GTPases (Rac1/RhoA): Controls cytoskeletal reorganization

- Notch and Hippo pathways: Potential roles in proliferation and junction organization [18]

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Assessment of Intestinal Barrier Function in Animal Models

Intestinal Ischemia-Reperfusion (I/R) Injury Model [24] [25]

Objective: To establish a reproducible model of intestinal barrier dysfunction for evaluating TJ protein dynamics.

Materials:

- Sprague-Dawley rats (6-8 weeks, 180-220g)

- Anesthetic: 10% chloral hydrate solution

- Surgical instruments: microvascular clamps, sutures

- Sample collection: tubes for serum, 4% paraformaldehyde for tissue fixation

Procedure:

- Anesthetize rats with intraperitoneal chloral hydrate (0.3 ml/100g)

- Perform midline laparotomy (4cm incision) and exteriorize small intestine

- Identify superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and apply microvascular clamp for 40 minutes

- Confirm ischemia by pale intestinal coloration

- Remove clamp and confirm reperfusion by return of bright red color

- Close abdomen in layers

- Collect blood samples at predetermined timepoints (6h, 24h, 48h, 72h post-reperfusion)

- Euthanize animals and collect intestinal tissue samples 6cm from cecum

- Process samples for H&E staining and serum biomarker analysis

Assessment Parameters:

- Chiu's scoring system for intestinal mucosal injury: 0 (normal) to 5 (complete destruction with hemorrhage) [24] [25]

- Serum claudin-3 and zonulin levels via ELISA

- Peripheral blood E. coli 16sDNA detection via qPCR as translocation marker

Measurement of Serum Tight Junction Proteins by ELISA

Principle: Quantitative detection of soluble TJ proteins in serum samples using sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [24] [26].

Reagents:

- Pre-coated capture antibody plates

- Detection antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP)

- Protein standards for calibration curves

- Substrate solution (TMB or similar)

- Stop solution

Procedure:

- Coat wells with capture antibodies specific to target protein (claudin-3, zonulin, or occludin)

- Block remaining protein-binding sites

- Add serum samples and standards in duplicate

- Incubate with detection antibody (HRP-conjugated)

- Develop with substrate solution for 15-30 minutes

- Stop reaction and measure absorbance at appropriate wavelength

- Calculate concentrations from standard curve

Technical Notes:

- Optimal sample collection at 24h post-injury for peak biomarker levels [24]

- Centrifuge blood samples at 3500 rpm for 10 minutes for serum separation

- Store serum at -80°C until analysis to prevent protein degradation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Tight Junction Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Rat intestinal I/R model [24] | Studying dynamic changes in TJ proteins post-injury | Peak TJ protein release at 24h post-reperfusion; monitor via Chiu's scoring [24] |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary alveolar epithelial cells [27] | Mechanistic studies of claudin interactions | Alcohol exposure model demonstrates claudin-5/18 cross-regulation [27] |

| Detection Antibodies | Claudin-3, zonulin, occludin ELISA kits [24] [26] | Quantifying serum biomarkers of barrier dysfunction | Commercial kits available; validate with spike-recovery experiments [24] |

| Molecular Tools | Claudin-5 shRNA [27], YFP-claudin constructs [27] | Manipulating specific claudin expression | shRNA reverses alcohol-induced barrier defects; overexpression studies [27] |

| Permeability Assays | Transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) [27], paracellular flux markers [27] | Functional assessment of barrier integrity | Use multiple probe sizes (0.6-10 kDa) for comprehensive assessment [27] |

| Therapeutic Modulators | Claudin-5 peptide mimetic [27], anti-TNF-α [26] | Testing barrier-restoring interventions | Peptide mimetic reverses alcohol-induced dysfunction; anti-TNF-α improves occludin [27] [26] |

| Eupalinolide B | Eupalinolide B, CAS:877822-40-7, MF:C₂₄H₃₀O₉, MW:462.49 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Larsucosterol Sodium | Larsucosterol Sodium, CAS:1174047-40-5, MF:C27H45NaO5S, MW:504.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The molecular regulators of tight junctions—claudins, zonulin, and associated scaffolding proteins—represent sophisticated determinants of tissue permeability with far-reaching implications for human health and disease. The experimental methodologies outlined herein enable rigorous investigation of these regulatory systems, while the emerging toolkit of targeted modulators offers promising therapeutic avenues. Future research directions should prioritize the development of claudin-specific modulators, exploration of tissue-specific TJ protein isoforms, and translation of serum TJ biomarkers into clinical diagnostics for barrier-related pathologies. As our understanding of these key molecular regulators deepens, so too does our capacity to manipulate tissue permeability for therapeutic benefit across a spectrum of diseases.

Physiological Roles in Nutrient Absorption, Immune Surveillance, and Homeostasis

Tissue permeability is a fundamental biological property that governs the selective movement of molecules, fluids, and cells across biological barriers. This selective transport plays a critical role in maintaining organismal health by enabling nutrient absorption, facilitating immune surveillance, and ensuring tissue homeostasis. The controlled exchange between compartments allows for the delivery of essential nutrients, immune cell trafficking for pathogen detection, and communication signals for tissue repair and regeneration. Disruption of these finely tuned permeability barriers contributes significantly to disease pathogenesis, including inflammatory disorders, metabolic syndromes, and cancer. This whitepaper examines the physiological roles of tissue permeability through the lens of its core functions, integrating current scientific understanding with methodological approaches for research and drug development.

Tissue Barrier Structures and Permeability Fundamentals

Biological barriers throughout the body maintain compartmentalization while permitting selective exchange. These barriers share common design principles but exhibit specialized adaptations suited to their specific physiological contexts.

Structural Components of Major Biological Barriers

The intestinal barrier exemplifies a complex selective interface between the external environment and internal milieus. It consists of multiple integrated layers: a mucous layer containing commensal microbiota, a single layer of specialized epithelial cells, and the underlying lamina propria rich in immune cells [28]. The mucous layer itself is subdivided into an inner stratum firmly attached to the epithelium and an outer layer colonized by microorganisms [29]. This structural organization allows for nutrient processing while maintaining defense functions.

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) represents a highly specialized vascular interface that protects the central nervous system (CNS). The BBB is formed by specialized microvascular endothelial cells connected by complex tight junctions, an underlying basement membrane containing pericytes, and the glia limitans composed of astrocyte end-feet [30]. This multi-layered structure strictly limits paracellular transport while regulating transcellular passage of substances.

Pathways of Molecular and Cellular Transport

The transport of substances across biological barriers occurs through several distinct pathways:

- Paracellular pathway: Small hydrophilic compounds (400 Da to 10-20 kDa) pass between epithelial cells through tight junction complexes [29]

- Transcellular pathway: Small lipophilic compounds cross directly through the plasma membrane of epithelial cells [29]

- Transporter-mediated uptake: Nutrients including amino acids, vitamins, and sugars use specialized epithelial transporters [29]

- Endocytic pathways: Larger peptides, proteins, and bacteria cross via vesicular transport mechanisms [29]

Table 1: Transport Pathways Across Biological Barriers

| Pathway | Mechanism | Substances Transported |

|---|---|---|

| Paracellular | Movement between cells through tight junctions | Small hydrophilic compounds (400 Da - 20 kDa), ions, water |

| Transcellular | Passive diffusion through cell membranes | Small lipophilic compounds |

| Transporter-mediated | Active transport via membrane proteins | Nutrients (amino acids, sugars, vitamins) |

| Endocytic | Vesicular uptake and transcytosis | Large peptides, proteins, bacteria |

Nutrient Absorption and the Gastrointestinal Barrier

The gastrointestinal tract represents the primary interface for nutrient absorption, with its permeability tightly regulated to allow uptake of dietary components while excluding potential harmful substances.

Intestinal Architecture for Selective Permeability

The intestinal epithelium contains several specialized cell types that collectively mediate its absorptive and barrier functions. Enterocytes, the most abundant epithelial cells, are primarily responsible for nutrient absorption and form an effective physical barrier [29]. Goblet cells (approximately 10% of epithelial cells) secrete gel-forming mucins that generate the protective mucous layer [29] [28]. Paneth cells located at the crypt bases produce antimicrobial compounds, while enteroendocrine cells secrete gastrointestinal hormones and peptides [29]. Microfold (M) cells overlying Peyer's patches play important roles in intestinal immune sampling [29].

The tight junction complexes between epithelial cells constitute the primary determinant of paracellular permeability. Historically first described in 1976 as "occluding zonules" in gallbladder epithelium, these protein complexes create a selective seal that polarizes the intestinal epithelium and allows regulated passage of ions and molecules [29].

Regional Specialization for Nutrient Processing

The gastrointestinal tract exhibits remarkable regional specialization for nutrient processing and absorption:

- Stomach: Functions in food storage, acidification, and initial enzymatic digestion with antibacterial properties [29]

- Duodenum: Continues digestion with bile and pancreatic juices for nutrient preparation [29]

- Jejunum: Absorbs water, amino acids, sugars, and fatty acids [29]

- Ileum: Absorbs remaining digestion products (e.g., vitamin B12) and contains important immune structures (Peyer's patches) [29]

- Colon: Reabsorbs remaining water and prepares luminal content for elimination [29]

This functional specialization is reflected in varying pH gradients along the GI tract, from highly acidic in the stomach (pH 1.4-4.6) to nearly neutral in the distal small intestine (pH 7.4-7.8) and variable in the colon (pH 5-8) [29]. These chemical gradients significantly influence microbial distribution, enzyme activity, and nutrient absorption efficiency.

Regulation of Absorption Processes

Nutrient absorption is precisely regulated by multiple factors, including gastrointestinal hormones, neural signals, and local cellular responses. The presence of nutrients in the intestinal lumen stimulates the release of hormones such as cholecystokinin (CCK), glucagon-like peptides (GLP-1 and GLP-2), and peptide YY, which collectively regulate digestion and absorption processes [31]. GLP-2 specifically enhances nutrient absorption and has been shown to improve lean body mass in patients with functional short-bowel syndrome [31].

The rate of gastric emptying represents a primary determinant of absorption kinetics, particularly for compounds like alcohol that require no digestion and are absorbed passively [31]. Food in the stomach generally slows gastric emptying and consequently delays absorption, while strong alcoholic beverages can irritate the stomach and cause pyloric sphincter closure, further complicating absorption predictability [31].

Immune Surveillance and Tissue-Resident Immunity

The immune system maintains continuous monitoring of tissues through specialized resident cell populations that interface with permeability barriers to detect and respond to potential threats.

Tissue-Resident Immune Cells (TRICs)

Tissue-resident immune cells constitute a heterogeneous population of immune cells that reside in lymphoid or peripheral tissues without recirculation, endowed with distinct capabilities not shared by their circulating counterparts [32]. These cells include tissue-resident memory T cells (T~RM~), tissue-resident macrophages, tissue-resident innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), tissue-resident natural killer (trNK) cells, and tissue-resident memory B cells (B~RM~) [32].

TRICs are defined by their origins, phenotypic markers, and transcriptional profiles. Some TRICs, including tissue-resident macrophages and mast cells, acquire tissue-resident properties during embryogenesis, while others such as T~RM~ cells establish residency during effector stages postnatally [32]. Common phenotypic markers include CD69, CD103, and CD49a, though expression patterns vary significantly across different tissues [32].

Table 2: Major Tissue-Resident Immune Cell Populations and Functions

| Cell Type | Primary Markers | Main Functions | Tissue Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue-resident memory T cells (T~RM~) | CD69, CD103, CD49a | Local pathogen protection, immune surveillance | Mucosal sites, skin, various organs |

| Tissue-resident macrophages | F4/80, CD64, MerTK | Phagocytosis, homeostasis, tissue repair | All tissues, tissue-specific subtypes |

| Tissue-resident innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) | CD127, varying receptors | Barrier immunity, tissue remodeling, homeostasis | Mucosal barriers, various tissues |

| Tissue-resident natural killer (trNK) cells | CD49a, CXCR6 | Viral defense, antitumor immunity | Liver, uterus, salivary glands |

| Tissue-resident memory B cells (B~RM~) | CD69, CD80, CD73 | Local antibody production, antigen presentation | Mucosal tissues, lymphoid organs |

Immune Surveillance of Barrier Tissues

At barrier sites such as the skin and intestinal mucosa, immune surveillance involves close interaction between TRICs and the local tissue environment. Dendritic cells in tissue-draining lymph nodes process microenvironmental signals, including food-derived vitamin A in the gut and ultraviolet-induced vitamin D3 in the skin, to imprint tissue-specific homing programs in naïve lymphocytes [30]. This process ensures that immune cells are programmed to return to the specific tissue sites where they initially encountered antigens.

In the central nervous system, immune surveillance occurs despite the protective blood-brain barrier. Under physiological conditions, the BBB restricts immune cell trafficking primarily to activated T cells, which can reach the cerebrospinal fluid-filled compartments to perform CNS immune surveillance [30]. The CNS parenchyma itself maintains immune privilege, prioritizing neuronal function over robust immune responses, while the ventricular spaces and border compartments (subarachnoid and perivascular spaces) are dedicated to CNS immunity [30].

Immunosurveillance as a Homeostatic Mechanism

Beyond pathogen defense, immune surveillance plays crucial roles in tissue homeostasis by eliminating damaged, senescent, and potentially malignant cells [33]. This homeostatic immunosurveillance involves recognition of stress-induced ligands on compromised cells, followed by their removal through various immune mechanisms. Defects in these surveillance mechanisms accelerate the development of pathological conditions including cancer, fibrosis, post-ischemic tissue damage, and neurodegenerative diseases [33].

The immune system employs multiple recognition strategies for detecting aberrant cells:

- MHC-I-associated peptides that reflect intracellular alterations [33]

- Stress-induced ligands such as NKG2D ligands recognized by natural killer cells [33]

- Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released during cellular stress [33]

Tissue Homeostasis and Permeability Regulation

Tissue homeostasis involves the maintenance of microenvironmental variables within narrow ranges despite constant internal and external challenges. Permeability regulation represents a crucial aspect of this homeostatic maintenance across multiple tissue types.

Core Principles of Tissue Homeostasis

While cellular and organismal homeostasis are relatively well-understood, tissue homeostasis remains less comprehensively characterized [34]. Tissue homeostasis involves maintaining critical microenvironmental variables including oxygen and nutrient levels, cell number and composition, extracellular matrix composition and mechanical properties, and interstitial fluid characteristics (volume, pH, osmolarity) [34].

The maintenance of these variables depends on regulated processes including local blood perfusion, angiogenesis, cell proliferation and death, ECM production and degradation, vascular permeability, and lymphatic drainage [34]. The minimal composition of most vertebrate tissues comprises four core cell types: functional cells specific to the tissue (e.g., hepatocytes in liver, neurons in brain), microvascular endothelial cells, fibroblast-like stromal cells, and tissue-resident macrophages [34].

Cellular Circuits in Homeostatic Maintenance

Homeostatic regulation often involves reciprocal communication circuits between different cell types. A prime example is the macrophage-fibroblast two-cell circuit where fibroblasts produce colony stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) for macrophages, and macrophages synthesize platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) for fibroblasts [34]. This reciprocal exchange establishes a stable regulatory circuit that maintains appropriate cellular composition within tissues.

The cellular division of labor in tissues follows several organizational principles:

- Independent specialization: Different cell types perform distinct functions independently

- Collaborative function: Multiple cell types contribute to the same function

- Support relationships: One cell type performs primary functions while others provide essential support [34]

Impact of Permeability Dysregulation on Homeostasis

Disruption of normal tissue permeability barriers contributes significantly to disease pathogenesis. In the intestinal barrier, increased permeability permits translocation of luminal bacteria and microbial components such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) into the portal bloodstream [28]. This triggers metabolic endotoxemia characterized by chronic low-grade inflammation, which can promote atherosclerosis and thrombotic diseases through activation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on leukocytes and endothelial cells [28].

In the central nervous system, breaching of the glia limitans allows immune cells to access the CNS parenchyma, contributing to neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis [30]. The unique anatomical relationship between the brain barriers and the immune system creates compartments with differing accessibility to immune mediators, with the CNS parenchyma maintaining immune privilege while the ventricular and border compartments facilitate immune interactions [30].

Experimental Methods for Assessing Tissue Permeability

Accurate measurement of tissue permeability is essential for both basic research and drug development. Multiple experimental approaches have been developed to assess barrier function in various biological systems.

In Vivo Permeability Assessment

In vivo methods provide physiologically relevant data by preserving the complex interactions between different cell types and tissues. These approaches typically involve administering tracer substances and measuring their distribution across biological barriers [1]. Common methodologies include:

- Vascular permeability assays: Measuring leakage of intravenous tracers into tissues

- Intestinal permeability tests: Using non-metabolizable markers to assess gut barrier function

- Blood-brain barrier permeability evaluations: Quantifying CNS penetration of specific compounds

These in vivo approaches complement molecular findings and help establish the physiological significance of experimental observations [1]. The interaction of multiple cell types and tissues present in mammalian models allows for comprehensive testing of hypotheses regarding barrier function.

Ex Vivo and In Vitro Models

Reductionist systems provide controlled environments for mechanistic studies of permeability regulation:

- Using chamber systems: Measure transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) and molecular flux across epithelial barriers

- Cell culture models: Recreate simplified barrier systems using endothelial or epithelial cell monolayers

- Tissue explants: Maintain native tissue architecture while permitting controlled experimental manipulation

Specific Permeability Measurement Techniques

Different tissue types require specialized methodological approaches:

- Intestinal permeability: Lactose absorption tests, hydrogen breath tests, and sugar permeability assays [31]

- Vascular permeability: Tracer leakage assays using Evans blue or fluorescent dextrans [35]

- Blood-brain barrier permeability: In situ brain perfusion techniques, microdialysis

Table 3: Experimental Methods for Assessing Tissue Permeability

| Method Type | Specific Techniques | Measured Parameters | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo approaches | Vascular tracer leakage, intestinal permeability tests, BBB penetration assays | Leakage rate, absorption kinetics, distribution volume | Physiological relevance, therapeutic screening |

| Ex vivo systems | Using chamber experiments, tissue explant models | Transepithelial resistance, molecular flux, permeability coefficients | Mechanism investigation, toxin testing |

| Cellular assays | Cell monolayer permeability, transwell migration assays | Paracellular flux, transcellular transport, tight junction integrity | High-throughput screening, molecular studies |

| Clinical tests | Lactose tolerance tests, hydrogen breath tests | Blood glucose changes, expired hydrogen concentrations | Diagnostic applications, patient stratification |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This section details essential research tools for investigating tissue permeability, barrier function, and related physiological processes.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Tissue Permeability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Tight junction markers | Identify and quantify junctional complexes | Antibodies against ZO-1, occludin, claudin family proteins |

| Tracer molecules | Assess permeability in various systems | Fluorescent dextrans, Evans blue, HRP, sucrose isotopes |

| Cytokine and growth factors | Modulate barrier function experimentally | TNF-α, IFN-γ, TGF-β, VEGF for permeability manipulation |

| Immune cell markers | Characterize tissue-resident immune populations | Anti-CD69, CD103, CD49a for TRM cells; F4/80 for macrophages |

| TLR4 pathway reagents | Study innate immune activation by barrier disruption | LPS, TLR4 antagonists, MyD88/TRIF pathway inhibitors |

| Parabiosis setup | Distinguish tissue-resident vs. circulating cells | Surgical equipment for parabolic pairing, flow cytometry analysis |

| Intravascular labeling antibodies | Differentiate blood-borne and tissue-resident cells | Anti-CD45, CD3 antibodies administered intravenously |

| scRNA-seq reagents | Transcriptional profiling of tissue-resident cells | 10x Genomics platforms, droplet-based sequencing reagents |

| Guaiacol-d4 | Guaiacol-d4, MF:C7H8O2, MW:128.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (R)-Methotrexate-d3 | (R)-Methotrexate-d3, CAS:432545-63-6, MF:C20H22N8O5, MW:457.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Tissue permeability serves as a master regulator of physiological processes spanning nutrient absorption, immune surveillance, and tissue homeostasis. The intricate balance of selective barrier function enables organisms to maintain compartmentalization while permitting essential exchange processes. Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing permeability regulation across different tissue barriers provides critical insights for therapeutic development across a spectrum of diseases, including inflammatory disorders, metabolic syndromes, and cancer. Continued advancement in imaging technologies, single-cell analysis methods, and sophisticated experimental models will further elucidate the complex interplay between barrier function and physiological regulation, opening new avenues for targeted therapeutic interventions.

The regulation of molecular and cellular traffic across biological barriers is a cornerstone of physiological homeostasis and a critical consideration in drug development. Intestinal, vascular, and cutaneous barriers employ specialized structures and mechanisms to selectively control permeability. Disruption of this delicate balance is implicated in numerous disease states, from inflammatory conditions to metabolic disorders. This whitepaper provides a technical analysis of permeability regulation across these three fundamental tissue types, framing the discussion within research on barrier function assessment and its implications for therapeutic development. We synthesize contemporary research methodologies, quantitative permeability data, and experimental protocols to offer a consolidated resource for scientists and drug development professionals.

Intestinal Barrier Permeability

The intestinal epithelium forms a dynamic, selective barrier that facilitates nutrient absorption while preventing the translocation of pathogens, toxins, and undigested antigens. Its permeability is governed by complex cellular architectures and molecular systems.

Structure and Permeability Pathways

The intestinal barrier consists of a single layer of epithelial cells interconnected by tight junction (TJ) complexes, which are the primary regulators of paracellular permeability [36]. These TJs are composed of proteins including claudins, occludins, and zonula occludens (ZO) [37]. The transcellular pathway allows for the controlled transport of molecules through the epithelial cells themselves, via mechanisms such as carrier-mediated transport or transcytosis [37].

Advanced in vitro models have revealed significant segment-specific differences in human intestinal physiology. Enteroid-derived cells from human jejunum (J2) and duodenum (D109) demonstrate more physiologically relevant morphology and higher transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) compared to the traditional Caco-2 cell line (derived from colon adenocarcinoma) [36]. The EpiIntestinalTM model, a commercial engineered tissue, exhibits thicker, more uneven structures with lower TEER and correspondingly higher passive permeability [36].

Assessment Methods and Quantitative Data

The lactulose:mannitol (L:M) test is a widely used clinical and research method for assessing intestinal permeability in humans [37]. In this test, participants ingest a solution containing these two non-metabolized sugar molecules. Lactulose (larger molecule, ~0.62 nm) primarily crosses the intestinal barrier via the paracellular pathway, while mannitol (smaller molecule) primarily uses the transcellular pathway. Urinary excretion is measured over a 5-hour period, and the ratio of the two provides an indicator of barrier integrity, with a higher ratio suggesting increased paracellular permeability [37].

Table 1: Intestinal Permeability Assessment in an Elderly Population via L:M Test

| Parameter | Overall Population (n=54) | L:M ≤ P50 (n=27) | L:M > P50 (n=27) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median L:M Ratio | 0.037 (IQR: 0.014-0.060) | ≤0.037 | >0.037 | - |

| Hip Circumference (cm) | 99.00 (95.00-106.75) | 101.00 (97.00-108.00) | 96.50 (93.00-104.00) | 0.041 |

| Serum Retinol (mmol/L) | 1.19 (0.91-1.45) | 1.33 (1.19-1.52) | 0.95 (0.60-1.16) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes Prevalence | 25.9% | 22.2% | 29.6% | 0.75 |

| Hypertension Prevalence | 53.7% | 48.1% | 59.3% | 0.58 |

A study of an elderly population found the median L:M ratio was 0.037, and an L:M ratio above the 50th percentile was significantly associated with lower hip circumference and lower serum retinol levels, suggesting a link between intestinal hyperpermeability and nutritional status [37].

In vitro models provide comparative data for drug permeability assessment. The permeability of model small molecules like caffeine, propranolol, and indomethacin varies significantly across different intestinal models. Research shows that integrating data from traditional Caco-2 models with corrections from more physiologically relevant enteroid-derived cells can improve the accuracy of predicting human oral bioavailability using tools like the Physiologically based Gut Absorption Model (PECAT) [36].

Experimental Protocol: Lactulose:Mannitol Test

Purpose: To assess in vivo human intestinal permeability, specifically differentiating paracellular and transcellular absorption [37]. Materials:

- Lactulose and Mannitol Solution: 5.0 g lactulose and 1.0 g mannitol dissolved in 20 mL of water.

- Collection Supplies: Urine collection containers, 2.35% chlorhexidine solution for preservation.

- Analysis Equipment: High-performance liquid chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPLC-PAD). Procedure:

- Participants fast for a minimum of 2 hours and empty their bladder completely.

- Administer the oral lactulose/mannitol solution.

- Maintain fasting for an additional hour post-administration.

- Collect total urine output for a 5-hour period.

- Add 1 drop of 2.35% chlorhexidine per 50 mL of urine for preservation.

- Record total urine volume and store samples at -80°C until analysis.

- Analyze lactulose and mannitol concentrations using HPLC-PAD. Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of the administered dose of each sugar recovered in the urine. The primary outcome is the lactulose-to-mannitol ratio (L:M ratio). A higher ratio indicates increased paracellular permeability.

Vascular Barrier Permeability

Vascular endothelial barriers control the exchange of fluids, solutes, and cells between the bloodstream and tissues. Their permeability characteristics are highly specialized according to organ-specific requirements.

Structural Classification and Barrier Mechanisms

Blood vessels are structurally classified into three main types with distinct permeability properties [38]:

- Continuous Capillaries: Feature non-fenestrated endothelial cells with tight junctions and a continuous basement membrane (e.g., in skin, muscle, brain). They present the tightest barrier.

- Fenestrated Capillaries: Contain diaphragmed pores (fenestrae) that enhance permeability to small molecules and fluids (e.g., in endocrine glands, intestinal mucosa, kidney peritubular capillaries).

- Sinusoidal Capillaries: Have discontinuous endothelium with large intercellular gaps and an incomplete basement membrane, allowing passage of large proteins and even cells (e.g., in liver, spleen, bone marrow).

The vascular permeability barrier is maintained by two primary systems [38]:

- Size Barrier: Dictated by Interendothelial Junctions (IEJs) comprising adherens junctions (AJs, primarily VE-cadherin) and tight junctions (TJs, including claudins and occludin). The specific composition of these junctions determines the physical space available for paracellular transport.

- Charge Barrier: Formed by the glycocalyx, a negatively charged mesh of proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans on the endothelial luminal surface. This layer repels anionic molecules in the plasma.

Table 2: Vascular Barrier Types and Their Permeability Properties

| Vessel Type | Endothelial Characteristics | Junctional Complexes | Representative Organs | Estimated Size Limit (Paracellular) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous (non-fenestrated) | Continuous basement membrane, no fenestrae | Tight Junctions (TJs) & Adherens Junctions (AJs) | Brain, Retina, Spinal Cord | <1 nm [38] |

| Continuous (non-fenestrated) | Continuous basement membrane, no fenestrae | Adherens Junctions (AJs predominate) | Skin, Muscle, Heart, Lung | <5 nm [38] |

| Fenestrated | Fenestrations with diaphragm | Specialized diaphragms | Exocrine/Endocrine Glands, Intestinal Mucosa, Kidney (peritubular) | 6-12 nm [38] |

| Sinusoidal (Discontinuous) | Discontinuous basement membrane, large fenestrations | Few, loose junctions | Liver, Spleen | 50-280 nm (species-dependent) [38] |

Assessment and Pathophysiological Dynamics

Vascular permeability is dynamically regulated and increases significantly during inflammation. Histamine is a potent mediator of this response, and its effects are highly tissue-specific. A classic study demonstrated that after intravenous histamine injection, albumin permeation increased most dramatically in the cecum (4-fold), followed by the pancreas and small intestine, while skin permeability remained unchanged unless histamine was injected locally [39].

In the central nervous system, the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) is a highly specialized vascular barrier. Its integrity can be severely compromised after ischemic stroke. Research shows that vascular recanalization (reperfusion), while therapeutic, can exacerbate BBB disruption. This is characterized by a significant downregulation of TJ proteins occludin and ZO-1 (impairing the paracellular pathway) and an increase in the Caveolin-1/MFSD2a ratio (indicating enhanced transcytosis) [40]. This leads to increased leakage of IgG and FITC-dextran into brain tissue, worsening outcomes like hemorrhagic transformation [40].

Experimental Protocol: In Vivo Vascular Permeability Assay (Miles Assay)

Purpose: To assess changes in vascular permeability in response to vasoactive agents or inflammatory stimuli in an animal model [38] [39]. Materials:

- Tracers: Evans Blue dye (which binds to serum albumin) or fluorescent conjugates like FITC-dextran.

- Test Substances: Vasoactive agents (e.g., histamine).

- Equipment: Microinjection equipment, spectrophotometer or fluorescence microscope. Procedure:

- Administer the tracer (e.g., Evans Blue) intravenously to the animal.

- Inject the test substance (e.g., histamine) intradermally or subcutaneously at defined sites on the skin. A control site should be injected with vehicle alone.

- Allow circulation for a predetermined period (e.g., 20-30 minutes).

- Euthanize the animal and perfuse with saline to remove intravascular tracer.

- Excise the skin from the injection sites and control areas.

- Extract the Evans Blue dye from the tissue using formamide and quantify it spectrophotometrically. For fluorescent tracers, visualize and quantify leakage using fluorescence microscopy. Data Analysis: The amount of tracer extravasated at the test site is compared to the control site. A significant increase indicates induced vascular hyperpermeability.

Cutaneous Barrier Permeability

The skin is the body's outermost barrier, providing formidable protection against environmental insults and preventing water loss. Overcoming this barrier is a principal challenge for transdermal drug delivery.

Skin Architecture and Permeation Pathways

Human skin comprises three primary layers [41]:

- Epidermis: The outermost layer, containing the stratum corneum (SC), which is the rate-limiting barrier for most molecular permeation. The SC consists of cornified keratinocytes (corneocytes) embedded in a lipid matrix, often described as a "brick-and-mortar" structure.

- Dermis: A vascularized connective tissue layer housing nerves, hair follicles, and sweat glands.

- Hypodermis: The underlying adipose tissue.

There are three primary pathways for molecular penetration through the skin [41]:

- Transepidermal Pathway: Diffusion directly across the SC, which can be intercellular (through the lipid matrix) or transcellular (through corneocytes).

- Transfollicular (or Pilosebaceous) Pathway: Diffusion via hair follicles and associated sebaceous glands.