Understanding and Controlling Nonspecific Probe Binding: Sources, Impacts, and Solutions for Molecular Assays

Nonspecific probe binding is a critical challenge that compromises the accuracy and reliability of hybridization-based techniques essential to genomics, diagnostics, and drug development.

Understanding and Controlling Nonspecific Probe Binding: Sources, Impacts, and Solutions for Molecular Assays

Abstract

Nonspecific probe binding is a critical challenge that compromises the accuracy and reliability of hybridization-based techniques essential to genomics, diagnostics, and drug development. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and professionals, covering the fundamental mechanisms of nonspecific hybridization, its methodological impacts on assays from microarrays to hybrid capture, and established strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. It further explores advanced validation techniques, including computational counterselection and empirical analysis of dissociation curves, offering a holistic guide to improving data quality and assay specificity.

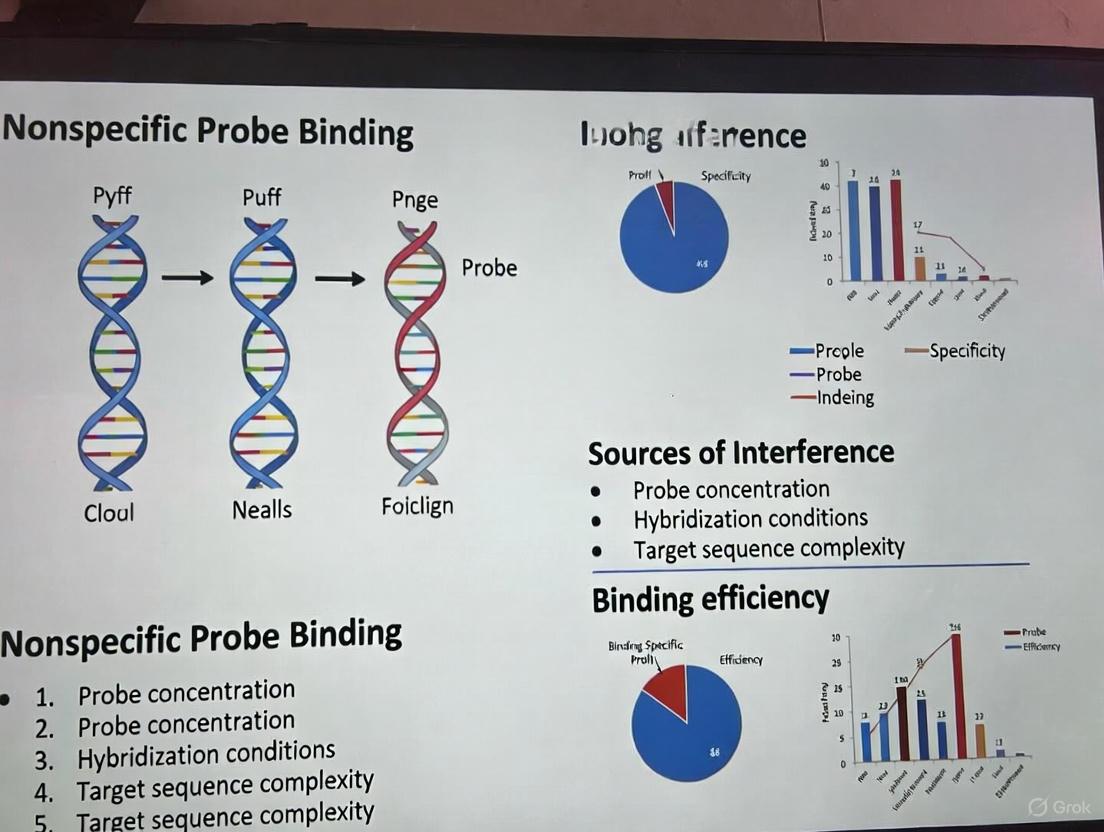

The Fundamental Mechanisms and Sources of Nonspecific Hybridization

Defining Specific vs. Nonspecific Binding in Molecular Contexts

In molecular biology and drug development, the reliability of data from hybridization-based techniques such as microarrays and quantitative PCR (qPCR) fundamentally depends on the specific binding of probes to their intended targets. Nonspecific binding refers to the association of a probe with molecules other than its perfectly matched, intended target, introducing a chemical background signal that can compromise data accuracy and lead to erroneous biological conclusions [1]. Within the broader context of a thesis on nonspecific probe binding, understanding these mechanisms is paramount for developing robust analytical methods. Such unintended binding events present significant challenges in gene expression analysis, diagnostic assay development, and the validation of therapeutic targets, making the distinction between specific and nonspecific interactions a critical focus for researchers and scientists [1] [2].

This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the mechanisms distinguishing specific from nonspecific hybridization, supported by quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and visualizations. It is structured to equip professionals with the knowledge to identify, quantify, and mitigate nonspecific binding in their experimental workflows, thereby enhancing the precision and reliability of their research outcomes in drug development and molecular diagnostics.

Molecular Mechanisms and Energetics

At its core, the hybridization process involves the formation of stable duplexes through Watson-Crick-Franklin base pairing. The journey of two complementary strands finding each other can be theorized as a three-stage process: diffusion, registry search, and zipping [3].

During the initial registry search, DNA strands sample numerous alignments to find the one that maximizes correct base pairing. Counterintuitively, non-specific binding in the form of mis-registered intermolecular binding can be beneficial at this stage, as it accelerates the hybridization rate by allowing strands to sample different alignments more rapidly [3]. However, once the correct alignment is found, the stability of the native structure is crucial to hold the molecules together long enough for non-native contacts to break and for the zipping stage to complete the formation of a stable, specific duplex [3].

The stability of the final duplex and the propensity for nonspecific binding are profoundly influenced by the DNA sequence. Non-native intramolecular structures (e.g., hairpins) can render portions of the molecule inert, limiting the alignments available for sampling and impeding the zipping process [3]. On the level of individual base pairings, specific and nonspecific binding give rise to distinct molecular signatures. Analyses of GeneChip microarrays reveal that specific hybridization, characterized by a perfect Watson-Crick (WC) pairing in the Perfect Match (PM) probe and a self-complementary (SC) pairing in the Mismatch (MM) probe, produces a triplet-like pattern (C > G ≈ T > A > 0) for the PM-MM log-intensity difference [1]. In contrast, nonspecific hybridization, often involving reversed central base pairings, results in a duplet-like pattern (C ≈ T > 0 > G ≈ A) [1]. The Gibbs free energy contribution of WC pairs to duplex stability is asymmetric for purines and pyrimidines, decreasing in the order C > G ≈ T > A, while SC pairings generally contribute only weakly to stability [1].

Quantitative Analysis of Binding Interactions

Thermodynamic Stability of Base Pairings

Table 1: Gibbs Free Energy Contributions of Central Base Pairings in DNA/RNA Duplexes

| Base Pairing Type | Central Base in Perfect Match (PM) Probe | Relative Gibbs Free Energy Contribution (Stability) | Observed Pattern in PM-MM Log-Intensity Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Watson-Crick (WC) - Specific | Cytosine (C) | Highest | Triplet-like pattern (C > G ≈ T > A > 0) |

| Watson-Crick (WC) - Specific | Guanine (G) | Medium | Triplet-like pattern (C > G ≈ T > A > 0) |

| Watson-Crick (WC) - Specific | Thymine (T) | Medium | Triplet-like pattern (C > G ≈ T > A > 0) |

| Watson-Crick (WC) - Specific | Adenine (A) | Lowest | Triplet-like pattern (C > G ≈ T > A > 0) |

| Self-Complementary (SC) - Mismatch | N/A | Very Low (Weak) | Contributes to background in MM probes |

| Reversed WC - Nonspecific | N/A | Variable, often destabilizing | Duplet-like pattern (C ≈ T > 0 > G ≈ A) |

The data in Table 1, derived from the analysis of perfect match and mismatch probes on GeneChip microarrays, quantifies the stability contributions of different central base pairings, which serve as a signature for the type of hybridization event [1].

Experimental Factors Influencing Specificity

Table 2: Impact of Experimental Parameters on Nonspecific Product Amplification in qPCR

| Experimental Parameter | Effect on Specific Product Amplification | Effect on Nonspecific Product Amplification (Artifacts) | Recommended Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Annealing Temperature | Increases | Decreases | Perform gradient PCR to determine optimal temperature. |

| Increased Primer Concentration | Can increase but plateaus | Increases (major factor) | Use checkerboard titration to find optimal concentration [2]. |

| High cDNA/DNA Template Input | Increases | Decreases (at fixed non-template concentration) | Standardize input amount; avoid extreme dilutions [2]. |

| High Non-Template cDNA Concentration | Can inhibit specific product (varies) | Increases (shifts balance) | Maintain consistent non-template background across samples [2]. |

| Long On-Bench Pipetting Time | No direct effect | Significantly Increases | Minimize time between reaction setup and PCR start; use hot-start enzymes [2]. |

| Post-Elongation Heating Step | No direct effect | Decreases fluorescence measurement from artifacts | Include a short heating step after elongation to melt primer-dimers [2]. |

The factors outlined in Table 2 were systematically identified through trouble-shooting experiments with validated qPCR assays, demonstrating that the balance between primer, template, and non-template concentrations is critical for reaction specificity [2].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Binding Specificity

Protocol: Specificity Analysis using Microarray Probe Intensities

This protocol is designed to characterize specific and nonspecific hybridization based on the signal intensities of Perfect Match (PM) and Mismatch (MM) probes, as derived from published microarray methodologies [1].

1. Key Materials:

- GeneChip Microarray or equivalent oligonucleotide array platform.

- Hybridized RNA sample(s) with fluorescent labels.

- Microarray scanner and associated data extraction software.

2. Procedure: A. Data Collection: Extract the raw fluorescence intensity values for all PM and MM probe pairs on the microarray. B. Calculation: For each probe pair, compute the log-intensity difference, PM-MM. C. Stratification: Group the calculated PM-MM differences based on the identity of the central base (A, T, G, C) in the PM probe sequence. D. Pattern Analysis: Analyze the grouped data for the presence of systematic patterns. A triplet-like pattern (C > G ≈ T > A > 0) is a signature of specific hybridization. A duplet-like pattern (C ≈ T > 0 > G ≈ A) indicates nonspecific hybridization [1].

3. Data Interpretation:

- The systematic behavior of the intensity difference can be rationalized by the energy contributions of WC and SC base pairings in the middle of the probe sequence.

- The MM intensity serves as a systematic source of variation and, if used for background correction, can decrease the precision of expression measures.

Protocol: Troubleshooting Nonspecific Amplification in qPCR

This protocol outlines a systematic procedure to identify and mitigate the amplification of nonspecific products (artifacts) in quantitative PCR, based on empirical investigations [2].

1. Key Materials:

- Validated primer pairs designed with limited 3' homology and analyzed for homo-/hetero-dimer formation (ΔG ≤ -9 kcal/mol).

- Hot-Start DNA Polymerase Master Mix (e.g., LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master mix).

- cDNA template.

- Real-Time PCR Instrument with melting curve analysis capability (e.g., LightCycler 480).

2. Procedure: A. Assay Validation: Always run controls, including a no-template control (NTC) and a minus-reverse-transcriptase (-RT) control, alongside test samples. B. Melting Curve Analysis: After amplification, perform a melting curve analysis. A single sharp peak typically indicates a specific product, while multiple or broad peaks suggest nonspecific amplification or primer-dimers. C. Gel Electrophoresis: If melting curve analysis is ambiguous, run the qPCR products on an agarose gel to verify the amplicon size. D. Checkerboard Titration: If artifacts persist, perform a checkerboard titration of primer concentrations (e.g., from 0.1 μM to 1 μM) against a dilution series of the template to identify the concentration window that maximizes specific product yield and minimizes artifacts [2]. E. Protocol Modification: To reduce the measurement of artifact-associated fluorescence, introduce a small heating step (e.g., 5-10 seconds at a temperature above the Tm of the primer-dimers but below the Tm of the specific product) immediately after the elongation phase in each amplification cycle [2].

3. Critical Notes:

- Bench Time: Long on-bench times during plate setup can lead to a significant increase in artifacts, even with hot-start enzymes. Minimize the time between pipetting the first and last well [2].

- Dilution Series Interpretation: Be cautious when interpreting dilution series, as both template and non-template concentrations decrease simultaneously, which can qualitatively and quantitatively affect the balance between specific and nonspecific amplification [2].

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

DNA Hybridization as a Three-Stage Process

The following diagram illustrates the theoretical pathway of DNA hybridization, highlighting the dual role of nonspecific interactions [3].

Diagram 1: DNA Hybridization Pathway. This flowchart depicts the three-stage process (diffusion, registry search, zipping). Green nodes represent the main stages, the red node is the successful outcome, and white diamonds represent factors influencing the pathway. Blue edges show the beneficial effect of mis-registered binding, while red edges show the detrimental effects of intramolecular structure [3].

Workflow for qPCR Assay Optimization

This diagram outlines a systematic workflow for optimizing a qPCR assay to minimize nonspecific amplification, based on detailed trouble-shooting procedures [2].

Diagram 2: qPCR Assay Optimization Workflow. This flowchart guides the user through the steps of developing a specific qPCR assay. Green nodes represent standard or successful steps, the red node indicates a critical decision/troubleshooting point, and white nodes detail specific optimization actions [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Hybridization Specificity Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Rationale | Key Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces primer-dimer formation and non-specific extension by inhibiting polymerase activity at low temperatures present during reaction setup [2]. | Essential for all SYBR Green qPCR assays. |

| Checkerboard Titration Plates | A systematic experimental design to simultaneously optimize two critical variables (e.g., primer and template concentration) to find the window that maximizes specificity [2]. | Use a multi-well plate layout to vary concentrations in two dimensions. |

| Oligonucleotide Microarrays (e.g., GeneChip) | Platform for high-throughput analysis of gene expression; enables dissection of specific vs. nonspecific hybridization via PM/MM probe pair analysis [1]. | The mismatch (MM) probe is key for estimating nonspecific background. |

| SYBR Green I Master Mix | Fluorescent dye that intercalates into double-stranded DNA, allowing for real-time monitoring of PCR amplification. Requires rigorous specificity checks. | Always paired with a post-amplification melting curve analysis. |

| In Silico Analysis Tools (e.g., Oligoanalyzer) | Software used during primer design to calculate thermodynamic properties, including homo-dimer and hetero-dimer strength (ΔG), and to check for 3' complementarity [2]. | Aim for hetero-dimer ΔG ≤ -9 kcal/mol and no extendable 3' ends. |

| GSK2334470 | GSK2334470, CAS:1227911-45-6, MF:C25H34N8O, MW:462.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ELR510444 | ELR510444, MF:C19H16N2O2S2, MW:368.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In molecular biology and diagnostic research, the specificity of nucleic acid hybridization is paramount. Techniques ranging from microarrays to quantitative PCR rely on the precise binding of probes to their intended target sequences. This process is governed by key molecular interactions, primarily Watson-Crick base pairing, electrostatic forces, and hydrophobic effects [4]. Understanding the delicate balance of these forces is crucial, not only for designing accurate assays but also for addressing the significant challenge of nonspecific probe binding, which can lead to false positives and compromised data integrity [5] [6]. Nonspecific hybridization introduces a chemical background signal unrelated to the actual presence of the target gene, posing a major obstacle in gene expression analysis, microbial diagnostics, and drug development [5] [7]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these core interactions, framed within the context of identifying and mitigating nonspecific binding in hybridization research.

Fundamental Molecular Interactions in Hybridization

Watson-Crick Base Pairing and Hydrogen Bonding

Watson-Crick (WC) base pairing is the foundational mechanism for specific nucleic acid recognition. It involves complementary hydrogen bonding between nucleobases: adenine (A) pairs with thymine (T) via two hydrogen bonds, and guanine (G) pairs with cytosine (C) via three hydrogen bonds [4]. This complementarity is the primary design principle for DNA probes and primers.

The role of hydrogen bonds in duplex stability is complex and context-dependent. In solution, DNA duplexes are significantly destabilized when Watson-Crick hydrogen bonds are eliminated, indicating their substantial role in stabilizing the helix [4]. However, studies with DNA polymerases have yielded surprising insights. Some high-fidelity polymerases replicate nonpolar nucleoside isosteres (which lack hydrogen-bonding capacity) with high efficiency and fidelity, suggesting that steric effects can play a larger role than hydrogen bonds in pairing selectivity for these enzymes [4]. Conversely, low-fidelity Y-family polymerases process non-hydrogen-bonding bases poorly, indicating a stronger reliance on Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding [4]. This paradox highlights that the fundamental rules of base recognition can vary dramatically depending on the biological or experimental context.

Electrostatic Interactions

Electrostatic interactions, particularly those involving hydrogen bonds and minor groove interactions, are critical for nucleic acid stability and specificity.

- Role of Hydrogen Bonds: Hydrogen bonding is an electrostatic interaction. In DNA, the energetic contribution of these bonds is tempered by the aqueous solvent, which has a high dielectric constant and competes for hydrogen-bonding groups [4]. The net stability gained from a WC hydrogen bond depends on the balance between the energy of the base-base bond and the cost of desolvating the participating groups.

- Minor Groove Interactions: The minor groove of DNA is lined with hydrogen bond acceptors, which are typically well-solvated. Studies with base analogs lacking these acceptors show a strong destabilizing effect on the DNA duplex [4]. In enzymatic contexts, such as with DNA polymerases, hydrogen bonds between the protein and the DNA in the minor groove can be even more critical for efficiency and fidelity than the Watson-Crick hydrogen bonds between the bases themselves [4]. The absence of minor groove acceptors in a probe can lead to poor replication or binding due to a costly desolvation penalty when placed opposite a polar amino acid in the enzyme's active site [4].

Hydrophobic Interactions

Hydrophobic interactions drive the burial of nonpolar surfaces and contribute to the stacking of nucleic acid bases. While hydrogen bonding provides directionality, the hydrophobic effect provides a major thermodynamic driving force for duplex formation.

The contribution of base stacking and hydrophobic packing to duplex stability is significant. Research into unnatural base pairs (UBPs),

Table 1: Key Interactions and Their Role in Nonspecific Binding

| Interaction Type | Molecular Basis | Contribution to Specificity | Role in Nonspecific Binding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Watson-Crick H-Bonding | Directional, complementary hydrogen bonds between bases (A-T, G-C). | High; provides primary sequence recognition code. | Loss of complementarity reduces binding, but mismatches with residual H-bonding can still cause binding. |

| Electrostatic (Minor Groove) | Interactions between backbone, base edges, and solvent/ions/proteins. | Moderate; stabilizes duplex and is critical for some protein recognition. | Can facilitate binding to non-target sequences that preserve minor groove electrostatics. |

| Hydrophobic | Entropy-driven burial of nonpolar surfaces; base stacking. | Low; provides general duplex stability but little sequence discrimination. | Major driver of nonspecific binding; allows probes to bind RNA/DNA with little sequence complementarity. |

Experimental Characterization of Interactions

Quantifying the strength and specificity of molecular interactions is essential for predicting and controlling hybridization behavior. The following section outlines key methodologies and parameters used in this characterization.

Thermodynamic Parameters and Melting Temperature (T~m~)

The stability of a nucleic acid duplex is commonly summarized by its melting temperature (T~m~), the temperature at which half of the duplexes dissociate into single strands. The T~m~ is a composite measure reflecting the net stability from all participating interactions. Probes with high GC content, which have more hydrogen bonds and enhanced stacking, typically exhibit higher T~m~ values. Theoretical T~m~ calculations are a standard part of probe design to ensure uniform hybridization conditions across a microarray [6].

Dissociation Curves and Specific Dissociation Temperature (T~d-w~)

While T~m~ is a theoretical predictor, the specific dissociation temperature (T~d-w~) is an experimental measure obtained from non-equilibrium dissociation curves (NEDCs). In this method, a post-hybridization microarray is subjected to a gradually increasing temperature while fluorescence is monitored, generating a dissociation profile [6]. The T~d-w~ is defined as the temperature at the maximum rate of dissociation (the negative peak of the first derivative of the dissociation curve) [6]. The T~d-w~/T~m~ ratio has been established as a robust parameter for identifying nonspecific hybridization. A low ratio (e.g., < 0.78) strongly indicates that the observed signal is due to nonspecific binding, which dissociates at a lower temperature than a perfect match duplex [6].

Table 2: Key Parameters for Differentiating Specific and Nonspecific Hybridization

| Parameter | Description | Application in Specificity Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical T~m~ | Calculated melting temperature for a perfect-match probe-target duplex. | Used as a benchmark for probe design and expected duplex stability. |

| Specific Dissociation Temperature (T~d-w~) | Experimentally measured temperature at maximum dissociation rate from NEDCs. | Directly measures the stability of the formed duplex on the array. |

| T~d-w~ / T~m~ Ratio | Ratio of experimental to theoretical stability. | Primary data filter: A ratio < 0.78 suggests nonspecific hybridization [6]. |

| PM-MM Log-Intensity Difference | Difference in log fluorescence between Perfect Match and Mismatch probes. | Positive value suggests specific binding; negative value suggests nonspecific binding [5]. |

Signature of Nonspecific Hybridization on Microarrays

The relationship between Perfect Match (PM) and Mismatch (MM) probe intensities provides a distinct signature for identifying the nature of hybridization. Naef and Magnasco demonstrated that the PM-MM log-intensity difference systematically correlates with the middle base of the PM probe [5].

- Specific Hybridization produces a triplet-like pattern (C > G ≈ T > A > 0) in the PM-MM log-intensity difference [5]. This can be rationalized by the asymmetric Gibbs free energy contribution of WC pairs, which decreases in the order C > G ≈ T > A [5].

- Nonspecific Hybridization produces a duplet-like pattern (C ≈ T > 0 > G ≈ A). Here, purines (A, G) in the PM middle position lead to "bright MM" probes (I~MM~ > I~PM~), a phenomenon known as the "riddle of bright MM" [5].

This systematic behavior indicates that nonspecific binding is characterized by a reversal of the central WC pairing, whereas specific binding combines a WC pairing in the PM with a self-complementary pairing in the MM [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful hybridization experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and tools designed to optimize specificity and signal detection.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Hybridization Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Perfect Match (PM) Probes | Oligonucleotide probes with a sequence perfectly complementary to the target nucleic acid. | The primary sensor for specific target binding. 25-mer probes are common in GeneChip arrays [5]. |

| Mismatch (MM) Probes | Control probes identical to the PM probe except for a single central base substitution. | Intended to measure nonspecific hybridization background; critical for data correction algorithms [5]. |

| Amino-allyl-dUTP | A modified nucleotide used for fluorescent labeling of cDNA or RNA targets. | Incorporated via Klenow polymerase; allows posterior coupling with fluorescent dyes for detection [6]. |

| Klenow Polymerase | A DNA polymerase I fragment used for DNA labeling and primer extension. | Used in the Bioprime DNA Labeling System to incorporate amino-allyl-dUTP into amplified targets [6]. |

| Poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (pHEMA) | A non-fouling polymer used to coat glass slides for cell and polymer microarrays. | Creates a non-adhesive background, confining cell and polymer spots to defined locations for HT screening [8]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Hydrogels | Tunable hydrogels used to create microwell arrays with variable stiffness. | Used in HT platforms to study the effect of substrate elasticity (1-50 kPa) on stem cell fate [8]. |

| GSK-1070916 | GSK-1070916, CAS:942918-07-2, MF:C30H33N7O, MW:507.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| BMS-833923 | BMS-833923, CAS:1059734-66-5, MF:C30H27N5O, MW:473.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: NEDC Analysis for Specificity

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for using Non-Equilibrium Dissociation Curves to discriminate between specific and nonspecific hybridization, as derived from established methods [6].

Microarray Synthesis and Probe Design

- Microarray Synthesis: Oligonucleotide probes are synthesized in situ on glass slides using a photolithographic or ink-jet style technology (e.g., from companies like Xeotron/Invitrogen). Probe density is typically optimized to approximately one molecule per 200 square angstroms [6].

- Probe Design: Probes should be designed to be complementary to the target gene of interest. Common lengths are 18-25 nucleotides. For validation, it is critical to include mismatch (MM) control probes. These can be designed with one or two randomly placed mismatches, or specifically with a mismatch in the central position (e.g., position 9 for an 18-mer) to maximally disrupt specific target binding [6].

Target Preparation and Labeling

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA or RNA from the sample (e.g., bacterial culture, tissue) using a standardized kit (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy Tissue Kit).

- Target Amplification (Optional): If targeting a specific gene (e.g., 16S rRNA), amplify the region using PCR with specific primers (e.g., 27F and 1525R for 16S rRNA). Use a high-fidelity DNA polymerase.

- Fluorescent Labeling: Label the target amplicon or RNA transcript. A standard method involves:

- Using the Bioprime DNA Labeling System (Invitrogen).

- Incubating 250 ng of DNA with Klenow polymerase and a nucleotide mix containing a 5:1 ratio of amino-allyl-dUTP to dTTP for 90 minutes.

- Purifying the labeled product.

- Chemically coupling a fluorescent dye (e.g., Cy3 or Cy5 NHS ester) to the incorporated amino-allyl groups.

Hybridization and Dissociation

- Hybridization: Apply the labeled target to the microarray under optimized buffer and temperature conditions for a sufficient period (e.g., several hours) to allow for duplex formation.

- Generate NEDC: After hybridization and a brief post-hybridization wash, place the microarray in a temperature-controlled flow cell.

- Use a fluorescent scanner to measure the initial fluorescence intensity.

- Gradually increase the temperature (e.g., from 20°C to 80°C) in small increments.

- At each temperature step, record the fluorescence intensity for every probe on the array.

Data Analysis and Specificity Filtering

- Curve Fitting: For each probe, fit the fluorescence vs. temperature data to a four-parameter, sigmoidally-shaped, asymmetric empirical equation using automated scripting.

- Calculate T~d-w~: From the fitted curve, determine the specific dissociation temperature (T~d-w~) as the temperature at the maximum rate of dissociation (the negative peak of the first derivative).

- Compute T~d-w~/T~m~ Ratio: For each probe, calculate the ratio of its experimentally determined T~d-w~ to its theoretical melting temperature (T~m~).

- Apply Filter: Use the T~d-w~/T~m~ ratio as a primary data filter. Based on empirical validation, hybridizations with a T~d-w~/T~m~ ratio of less than 0.78 can be confidently classified as nonspecific and filtered out from subsequent analysis [6].

The challenge of nonspecific probe binding in hybridization research necessitates a deep and practical understanding of the core molecular interactions that govern nucleic acid duplex formation. Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding provides the basis for specificity, but its contribution is modulated by the context, and it can be overshadowed by hydrophobic and steric effects in certain environments, leading to erroneous signals [5] [4]. The empirical and theoretical tools detailed in this whitepaper—ranging from the analysis of PM/MM intensity patterns and T~d-w~/T~m~ ratios to the strategic design of probes and experiments—provide researchers with a robust framework to identify, quantify, and mitigate nonspecific hybridization. As hybridization technologies continue to evolve and find applications in drug development, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring, a rigorous application of these principles will be fundamental to ensuring the generation of precise and reliable data.

DNA hybridization, the fundamental process whereby complementary nucleotide strands bind to form a duplex, is the cornerstone of countless molecular biology techniques, from diagnostic assays to advanced research methods. The fidelity of this process is paramount; however, it is persistently challenged by nonspecific probe binding, which can lead to false signals, reduced signal-to-background ratios, and compromised data integrity. A biophysical understanding of the hybridization mechanism is essential for diagnosing and mitigating these sources of error. Theoretical and computational models describe the association of DNA oligonucleotides as a three-stage process consisting of diffusion, registry search, and zipping [9]. This framework provides a powerful lens for analyzing the origins of nonspecific binding at the molecular level, thereby informing the design of more robust reagents and protocols. Within the context of a broader thesis on hybridization research, this whitepaper delineates this core mechanism, quantitatively analyzes its vulnerability to error, and presents advanced experimental strategies that leverage this understanding to achieve superior specificity.

The Molecular Mechanism of the Three-Stage Process

The formation of a stable DNA duplex from two single-stranded oligonucleotides is not a single, instantaneous event. Rather, it proceeds through a series of distinct, sequential stages, each with its own kinetic and thermodynamic constraints. The following diagram illustrates this coordinated three-stage mechanism.

Stage 1: Diffusion

The process initiates with diffusion, a passive, random walk during which the two single-stranded DNA molecules move through the solution and undergo rotational reorientation. The primary driver is Brownian motion, and the rate of association at this stage is governed by the Smoluchowski equation for diffusional encounter. The key vulnerability during this stage is that non-complementary sequences can collide with the same probability as perfectly matched partners [9]. There are no sequence-dependent discriminatory forces at work; any two strands can potentially come into close proximity, setting the stage for a nonproductive or nonspecific interaction. Factors such as viscosity, temperature, and molecular crowding agents can all influence the diffusion coefficient and thus the frequency of these initial encounters.

Stage 2: Registry Search

Following a collision, the strands enter the critical registry search (or nucleation) phase. The molecules, now in close proximity, undergo a series of transient, short-lived contacts, "searching" for a region of initial complementarity to form a stable nucleus from which zipping can proceed. This involves a precarious balance of internal displacement and zippering as the strands sample different translational and rotational alignments [9]. This stage is a significant kinetic bottleneck and a major source of specificity. The formation of the initial nucleus is highly sensitive to sequence; a few complementary base pairs in a row can provide a foothold, but even a single mismatch in this small nucleus can drastically reduce its stability and lifetime, causing the strands to dissociate and re-enter the search phase. It is here that the first line of defense against nonspecific binding is established.

Stage 3: Zipping

Once a stable nucleus of a few base pairs is formed, the process proceeds to the rapid zipping stage. The duplex elongates in a highly cooperative manner, with the free energy of each successive base pair stabilizing the next. This process is often described as a random walk along a one-dimensional free energy landscape [9]. While this stage is generally fast, it is not immune to errors. Mismatches can be kinetically trapped if the free energy cost of pausing to eject the mismatched base is higher than that of simply continuing to zip. Furthermore, secondary structures within the single strands, such as hairpins, can act as kinetic traps that pause or derail the zipping process, leading to incomplete hybridization or promoting off-target binding at sites with more accessible, though less complementary, sequences [9].

The three-stage model provides a framework for quantifying the impact of various factors that contribute to nonspecific probe binding. The table below summarizes key parameters and their influence on hybridization fidelity, drawing from experimental and computational studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Experimental Factors on Hybridization Specificity

| Factor | Stage Most Affected | Impact on Specificity | Quantitative Effect & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hybridization Temperature [10] | All, but especially Registry Search & Zipping | Critical for optimal specificity | Deviation of 1°C from optimum can lead to a loss of up to 44% of differentially expressed genes identified in microarray studies. |

| Probe Binding Affinity (ΔG) [10] | Registry Search & Zipping | Non-uniform affinities degrade overall performance | The Boltzmann factor ( e^{-\Delta G/RT} ) dictates equilibrium. A wide range of ΔG across a probe set makes finding a universally optimal temperature impossible. |

| Probe Length [11] | Zipping | Weak dependence for lengths >20-30 nt | smFISH experiments show minimal gains in single-molecule signal brightness for target regions increasing from 20 to 50 nt, suggesting other factors limit assembly. |

| Presence of Secondary Structure [9] | Registry Search & Zipping | Significantly destabilizes duplexes | DNA hairpins in single strands primarily promote melting (increasing dissociation rates) rather than just inhibiting hybridization. |

| Sequence Composition (GC vs. AT) [9] | Registry Search | Modulates association rates | GC-rich oligomers exhibit higher experimentally observed association rates than AT-rich equivalents due to more stable initial nucleation. |

The thermodynamic and kinetic parameters that govern each stage are not independent. For instance, the optimal hybridization temperature for a probe set is a compromise that balances the conflicting needs of sensitivity and specificity across all probes [10]. Hybridizing below the optimal temperature increases cross-hybridization during the registry and zipping stages for probes with higher binding affinity, as the thermal energy is insufficient to disrupt nonspecific complexes. Conversely, hybridizing above the optimal temperature reduces sensitivity for lower-affinity probes, as even perfectly matched duplexes may fail to form or stabilize. This trade-off underscores why a one-degree Celsius miscalibration can have such a dramatic effect on data quality, disproportionately affecting the detection of critical low-copy-number transcripts like transcription factors [10].

Experimental Protocols for Minimizing Nonspecific Binding

Leveraging the three-stage model, researchers have developed sophisticated protocols to suppress nonspecific binding. The following sections detail two such approaches: a foundational method for optimizing global hybridization conditions and a cutting-edge probe design that inherently enhances specificity.

Protocol 1: Empirical Optimization of Hybridization Conditions

This protocol is designed to find the best-compromise hybridization temperature for a given probe set, maximizing the detection of true differential expression while minimizing cross-hybridization [10].

- Principle: Systematically vary the hybridization temperature and use information-theoretic measures to identify the conditions that yield the maximum information about sample differences.

- Required Reagents & Equipment:

- Two biologically distinct but related samples (e.g., treated vs. untreated cells) with a balanced number of up- and down-regulated genes and many non-differentially expressed "house-keeping" genes.

- The full oligonucleotide microarray or FISH probe set to be calibrated.

- Thermocyclers or hybridization ovens with precise temperature control (±0.1°C).

- Standard labeling, washing, and imaging buffers.

- Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Hybridization Series: Hybridize the two samples with the probe set across a range of temperatures (e.g., from 45°C to 65°C in 1°C increments).

- Data Collection: Acquire gene expression data for all probes at each temperature.

- Information Quantification: For each temperature, calculate a protocol-dependent likelihood measure that aggregates the statistical significance (p-values) of all differentially expressed genes. This measure, derived from ANOVA models, reflects the total information content about the biological difference between the two samples [10].

- Optimum Identification: Plot the quantitative information measure against hybridization temperature. The temperature that maximizes this measure is identified as the globally optimal condition.

- Mitigated Nonspecific Binding: This protocol directly counteracts nonspecific binding in the registry search and zipping stages by ensuring the thermal energy is high enough to disrupt imperfect duplexes but low enough to permit stable formation of perfect matches.

Protocol 2: Split-Initiator Probes for In Situ HCR (v3.0)

This advanced protocol uses a novel probe architecture to eliminate amplified background in hybridization chain reaction (HCR) experiments, a major consequence of nonspecific binding [12].

- Principle: Replace single "standard" probes that carry a full HCR initiator with pairs of "split-initiator" probes that each carry half of the initiator. Full initiation only occurs when both probes bind adjacently to the correct target, providing automatic background suppression.

- Required Reagents & Equipment:

- Split-Initiator Probe Pairs: Two DNA oligonucleotides per target site, each with a 25-nt target-binding region and half of the HCR initiator sequence.

- HCR Hairpins (H1 & H2): Kinetically trapped, fluorophore-labeled DNA hairpins that undergo chain reaction assembly upon initiation.

- Fixed biological samples (e.g., whole-mount chicken embryos).

- Standard buffers for in situ hybridization and HCR amplification.

- Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Probe Hybridization: Hybridize the pool of split-initiator probe pairs to the fixed sample.

- Wash: Remove unbound probes.

- HCR Amplification: Introduce the H1 and H2 hairpins to initiate the amplification cascade.

- Imaging: Image the resulting fluorescent signals.

- Mitigated Nonspecific Binding: This design fundamentally addresses nonspecific binding at the diffusion and registry search stages. A single probe that diffuses to and binds a non-target site cannot initiate amplification. Only the co-localization of two probes via specific, adjacent binding on the intended target during the registry search generates a full initiator, triggering the zipping of the HCR amplifier [12]. This results in a typical 50-fold suppression of amplified background compared to standard probes, even when using large, unoptimized probe sets.

The mechanism of this advanced method is illustrated below, highlighting how it introduces a critical checkpoint to prevent nonspecific signal amplification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Controlled Hybridization

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hybridization Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Controlling Hybridization | Role in Mitigating Nonspecific Binding |

|---|---|---|

| Formamide [11] | Chemical denaturant that lowers the effective melting temperature of duplexes. | Allows for lower, gentler hybridization temperatures to be used while maintaining stringency, reducing nonspecific zipping. |

| Split-Initiator Probe Pairs [12] | DNA probes that only trigger signal amplification upon co-localization on a target. | Provides "automatic background suppression" by requiring two independent registry search events for signal generation. |

| HCR Hairpins (H1/H2) [12] | Kinetically trapped DNA hairpins that self-assemble into fluorescent polymers. | Provide isothermal, enzyme-free signal amplification. Individual hairpins that bind non-specifically do not trigger polymerization. |

| Encoding Probes (for MERFISH) [11] | Primary probes with a target-binding region and a readout sequence barcode. | Enable a two-step hybridization process, separating slow target-probe hybridization from fast, uniform readout, improving signal-to-noise. |

| Optimized Hybridization Buffers [11] [10] | Buffer systems with controlled ionic strength, pH, and denaturant concentration. | Stabilize reagents over long experiments and provide the correct chemical environment for stringent registry search and zipping. |

| GDC-0623 | GDC-0623, CAS:1168091-68-6, MF:C16H14FIN4O3, MW:456.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| XL-281 | XL-281, CAS:870603-16-0, MF:C24H19ClN4O4, MW:462.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The three-stage model of hybridization—diffusion, registry search, and zipping—provides an indispensable mechanistic framework for diagnosing and solving the pervasive challenge of nonspecific probe binding. By understanding that errors can originate from random collisions, faulty nucleation, or error-prone duplex elongation, researchers can move beyond trial-and-error. Quantitative optimization of traditional parameters like temperature remains a powerful, necessary strategy [10]. However, the most significant advances come from innovative molecular designs that build specificity directly into the system, as demonstrated by split-initiator probes that eliminate amplified background by demanding cooperative binding [12]. As hybridization techniques continue to evolve and find new applications in spatial transcriptomics and molecular diagnostics, a deep grounding in these core biophysical principles will be essential for developing the next generation of highly specific and reliable research and diagnostic tools.

Hybridization techniques, central to modern molecular biology and diagnostic applications, rely on the precise binding of nucleic acid probes to their complementary targets. The specificity of this interaction—the ability to discriminate intended targets from similar, non-target sequences—is paramount for data accuracy. This whitepaper examines the fundamental properties governing hybridization specificity, focusing on the influence of probe sequence, length, and nucleotide composition. Within the broader context of a thesis on nonspecific binding, we detail how these factors contribute to off-target interactions and provide evidence-based strategies for optimizing probe design. Supported by quantitative data and experimental protocols, this guide serves as a technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to enhance the reliability of their hybridization assays.

Nonspecific hybridization presents a significant challenge in techniques ranging from microarray-based gene expression analysis to real-time PCR and biosensing. It introduces a chemical background signal not related to the expression level or abundance of the intended target, thereby compromising data integrity [5]. The process of DNA strands finding their perfect match is complex, involving diffusion, a registry search for correct alignment, and zipping of the duplex; nonspecific binding can affect each of these stages [3]. The core of mitigating this issue lies in understanding and controlling the physiochemical properties of the probes and targets themselves. This paper delves into the molecular determinants of specificity, providing a framework for the rational design of hybridization probes that minimize off-target binding.

Molecular Determinants of Hybridization Specificity

The stability and specificity of a DNA duplex are governed by a combination of thermodynamic and kinetic parameters, which are directly influenced by the probe's sequence characteristics.

Probe Sequence and the Central Role of Mismatches

The position and type of a single base mismatch are critical for specificity. Research on Affymetrix GeneChips, which use Perfect Match (PM) and Mismatch (MM) probe pairs, reveals a distinct molecular signature for specific and nonspecific binding. Specific hybridization, characterized by the target binding to the PM probe, produces a triplet-like pattern (C > G ≈ T > A) in the PM-MM log-intensity difference. In contrast, nonspecific hybridization, where the target binds indiscriminately to both PM and MM probes, results in a duplet-like pattern (C ≈ T > 0 > G ≈ A) [5].

This systematic behavior can be rationalized by the base pairing at the probe's center. Nonspecific binding often involves the reversal of the central Watson-Crick pairing, while specific binding combines a Watson-Crick pair in the PM with a weaker self-complementary pairing in the MM. The Gibbs free energy contribution of Watson-Crick pairs is asymmetric, decreasing in the order C > G ≈ T > A, explaining the observed intensity patterns and the phenomenon of "bright MM" probes where mismatch intensities exceed those of their perfect match counterparts [5].

Probe Length: A Balance Between Sensitivity and Specificity

Probe length directly influences hybridization free energy and the availability of target molecules. While longer probes form more stable duplexes, they can suffer from finite availability of target molecules, leading to signal saturation and reduced specificity for single-nucleotide mismatches [13].

Table 1: The Effect of Probe Length on Specificity

| Probe Length | Hybridization Stability | Specificity for Single Mismatches | Risk of Cross-Hybridization | Optimal Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short (12-16 nt) | Lower | High | Lower (but risk of non-unique binding) | Detection of highly similar sequences |

| Medium (19-21 nt) | Balanced | Maximal [13] | Balanced | General purpose, high-specificity assays |

| Long (23-30 nt) | Higher | Lower (due to stability saturation) [13] | Higher | Applications where ultimate stability is required |

Experimental data comparing 14- to 25-mer probes indicates that the optimal length for maximizing single-nucleotide specificity is 19 to 21 nucleotides, shorter than the 25-mers used on some commercial platforms [13]. Furthermore, the optimal length is not universal; it varies for targets with high sequence variation. For highly variable genes, such as those in HIV and influenza, the optimal probe length can range from 12 nt to 19 nt and must be determined on a case-by-case basis [14].

GC Content and Secondary Structure

The GC content of a probe—the percentage of guanine and cytosine bases—profoundly impacts its stability and binding affinity. GC base pairs form three hydrogen bonds, compared to the two formed by AT base pairs, making GC-rich duplexes more stable. A balanced GC content (typically 30–80%) is recommended for TaqMan assays to ensure stable hybridization without promoting non-specific binding [15]. Probes with very high GC content may form overly stable secondary structures or exhibit non-specific binding, while those with very low GC content may not form stable duplexes.

Potential secondary structures, such as hairpins or self-dimers, within either the probe or the target sequence, can hinder hybridization by rendering portions of the molecule inaccessible [3] [16]. Tools like Primer Express software are often used to optimize probe sequences and minimize intra-molecular base pairing, which is crucial for efficient target binding [15].

The Impact of the Assay Environment

Surface Immobilization and Probe Density in Microarrays

When probes are immobilized on a surface, as in microarray technology, the local environment significantly alters hybridization behavior. Probe density—the number of oligonucleotide molecules per unit area—is a critical factor controlling both the efficiency of duplex formation and the kinetics of target capture [17].

At very low probe densities, hybridization efficiency can approach 100%, and binding follows Langmuir-like kinetics. In contrast, at high probe densities, efficiencies can drop to ~10%, and binding kinetics slow down significantly [17]. A densely packed layer of DNA can sterically hinder the access of target molecules to their complementary probes and increase the electrostatic repulsion due to the high concentration of negative charges from the phosphate backbones. The method of immobilization (e.g., single-stranded vs. duplex DNA) also affects the final probe density and the reproducibility of the film [17].

Solution Conditions and Thermodynamics

The stability of nucleic acid duplexes is highly dependent on the solution conditions. The thermal denaturation temperature (Tm), the temperature at which half of the duplexes dissociate, is a key parameter. An empirical relationship describes Tm as:

Tm = 16.6 log(Cs) + 41(χGC) + 81.5

where Cs is the total salt concentration and χGC is the mole fraction of GC base pairs [18].

This equation highlights that Tm increases with both ionic strength and GC content. Furthermore, duplexes with base-pair mismatches have lower Tm values than their fully complementary counterparts, with single mismatches often reducing Tm by about 8–10°C [18]. This difference provides a means to enhance specificity by stringency washing—performing washes at a temperature high enough to denature mismatched duplexes while leaving perfectly matched ones intact.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Specificity

Protocol: Determining Optimal Probe Length and Mismatch Discrimination

This protocol is adapted from a study that used a custom high-density oligonucleotide array to systematically evaluate probe behavior [13].

Objective: To empirically determine the optimal probe length for single-nucleotide mismatch discrimination under specific hybridization conditions.

Materials:

- Custom Microarray: Designed with probes of varying lengths (e.g., 14- to 25-mer) derived from a set of base sequences. For each length and sequence, include Perfect Match (PM) probes and all possible single-nucleotide mismatch (MM) probes.

- Targets: Artificially synthesized oligonucleotides complementary to the PM probes.

- Hybridization Buffer: Standard saline buffer (e.g., containing NaCl and TE buffer).

- Microarray Scanner: For fluorescence-based signal detection.

Method:

- Array Design: Generate 150 or more random 25-mer base sequences. For each base sequence, create truncated probes from 14- to 25-mer in length. For each length

n, design 3 PM probes and3nMM probes, covering all possible single-nucleotide substitutions at all positions [13]. - Target Hybridization: Hybridize the custom array with the synthesized oligonucleotide targets over a range of concentrations (e.g., from 1.4 fM to 1.4 nM) in the absence of a complex background.

- Signal Detection: Wash the array under stringent conditions to remove non-specifically bound target and scan to quantify signal intensity for each probe.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the average signal intensity of PM and MM probes as a function of probe length for each target concentration.

- Calculate the PM/MM signal intensity ratio for each probe pair. A higher ratio indicates better mismatch discrimination.

- Identify the probe length that yields the highest PM/MM ratio across the desired concentration range, indicating optimal specificity.

Protocol: Assessing the Effect of Surface Probe Density

This protocol utilizes Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) spectroscopy, a label-free method for in-situ kinetic analysis [17].

Objective: To quantify how the density of immobilized DNA probes affects target capture efficiency and kinetics.

Materials:

- SPR Instrument.

- Gold SPR substrates.

- Thiol-modified DNA oligonucleotide probes.

- Mercaptohexanol.

- Complementary and non-complementary DNA target sequences.

- Piranha solution (for cleaning gold substrates).

Method:

- Probe Immobilization: Prepare DNA films of varying density on gold SPR substrates using different strategies:

- Vary Immobilization Time: Expose the gold substrate to the DNA–thiol solution for different durations.

- Vary Ionic Strength: Immobilize probes using solutions of different salt concentrations (e.g., 0.05 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M NaCl).

- Use Duplex DNA: Immobilize a pre-hybridized duplex with a thiol linker on one strand, then denature to create a surface of ssDNA probes [17].

- Surface Passivation: Treat all probe films with mercaptohexanol to passivate unoccupied gold sites.

- Target Hybridization: Expose the probe surface to a solution containing a known concentration of complementary DNA target and monitor the association phase in real-time using SPR.

- Denaturation: Regenerate the probe surface by rinsing with hot water to denature the duplex.

- Data Analysis:

- Use SPR reflectance data to calculate the absolute probe coverage (molecules/cm²) and the target coverage after hybridization.

- Calculate the hybridization efficiency as: (Target Coverage / Probe Coverage) × 100%.

- Model the association phase to determine the kinetic rate constant for target capture.

- Correlate hybridization efficiency and kinetics with the calculated probe density.

Visualization of Hybridization Dynamics and Specificity

The following diagram illustrates the multi-stage process of DNA hybridization and the points at which key probe properties influence the pathway toward specific or nonspecific binding.

Diagram 1: Pathways and Pitfalls in DNA Hybridization. This diagram outlines the three-stage hybridization process (diffusion, registry search, zipping) and how probe properties and non-specific interactions can lead to a successful specific duplex or a failed binding event [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Hybridization Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Custom Oligonucleotide Microarrays | High-density arrays for parallel testing of thousands of probe sequences. | Used for systematic evaluation of probe length and mismatch position [13]. |

| Synthesized Oligodeoxyribonucleotide Targets | Pure, sequence-defined targets for controlled hybridization without cross-hybridization. | Essential for quantifying absolute signal intensity and specificity without background [13]. |

| Thiol-Modified DNA Oligonucleotides (DNA-C6-SH) | Allows covalent immobilization of probes onto gold surfaces via gold-thiol bond. | Critical for creating self-assembled monolayers for SPR biosensors [17]. |

| Mercaptohexanol | A passivating agent used to backfill unoccupied gold sites on a sensor surface. | Reduces non-specific adsorption of biomolecules to the surface [17]. |

| Locked Nucleic Acids (LNAs) | Modified nucleic acids with a bridged ribose ring, conferring high binding affinity and nuclease resistance. | Used in ISH probes to enhance specificity and stability [16]. |

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assays | Integrated system of primers and a hydrolyzed probe for highly specific qPCR. | Designed with bioinformatics pipelines to ensure transcript specificity and avoid SNPs [15]. |

| LY3009120 | LY3009120, CAS:1454682-72-4, MF:C23H29FN6O, MW:424.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| IDH-305 | IDH-305, CAS:1628805-46-8, MF:C23H22F4N6O2, MW:490.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Achieving high specificity in nucleic acid hybridization is a multifaceted challenge that requires careful consideration of probe and target properties. The probe's sequence, particularly the central base which dictates mismatch discrimination, its length, which must be optimized to balance stability and specificity, and its composition, including GC content and secondary structure potential, are fundamental design parameters. Furthermore, the assay environment, such as surface probe density and solution conditions, can profoundly influence the outcome. By applying the principles and experimental protocols outlined in this whitepaper, researchers can make informed decisions to design robust assays, minimize the detrimental effects of nonspecific binding, and generate more reliable and interpretable data in both basic research and drug development.

The Critical Role of Hybridization Buffers and Solution Conditions

In hybridization research, the specific binding of a nucleic acid probe to its intended target sequence is fundamental to the accuracy of techniques ranging from diagnostic assays to next-generation sequencing. A primary obstacle to achieving this specificity is nonspecific probe binding, which can lead to high background noise, false positives, and compromised data integrity. Nonspecific binding occurs when probes interact with non-target sequences, bind to the solid support membrane, or adhere to other components of the experimental setup. The strategic formulation of hybridization buffers and the careful control of solution conditions are the most powerful tools available to a researcher for suppressing these undesirable interactions. This guide examines the core components of these buffers, detailing their mechanistic roles in promoting specific hybridization while minimizing background, and provides actionable protocols for their use.

Core Components of a Hybridization Buffer

A hybridization buffer is not a single reagent but a carefully balanced mixture. Each component is included to control a specific aspect of the hybridization thermodynamics and kinetics, working in concert to favor specific probe-target duplex formation.

The table below summarizes the key components and their functions in preventing nonspecific binding.

Table 1: Core Components of a Hybridization Buffer and Their Roles

| Component | Primary Function | Common Examples | Mechanism in Preventing Nonspecific Binding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formamide | Lowers melting temperature (Tm) | Deionized formamide [19] | Destabilizes hydrogen bonding, allowing hybridization at lower temperatures that reduce non-specific duplex stability [20]. |

| Salts | Stabilizes nucleic acid structures; neutralizes phosphate backbone repulsion | Sodium Chloride (NaCl); Saline-sodium citrate (SSC) [20] | Shields the negative charges on the sugar-phosphate backbones, reducing electrostatic repulsion and facilitating proper annealing [20]. |

| Detergents | Reduces surface tension and prevents aggregation | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), Tween-20, Triton X-100 [20] | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions and removes excess probe that may stick to membranes or other surfaces [20]. |

| Blocking Agents | Minimizes non-specific binding to surfaces | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Salmon Sperm DNA, calf thymus DNA, yeast tRNA [20] [19] | Binds to and "blocks" positive or sticky sites on the membrane or tissue sample before the probe can bind to them [20]. |

| Buffering Agents | Regulates pH | Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE), Tris-HCl [20] [19] | Maintains an optimal pH for hybridization kinetics and ensures buffer component stability [20]. |

| Dextran Sulfate | Increases effective probe concentration | High molecular weight polymer [19] | Acts as a volume excluder, crowding the probe molecules and increasing the rate and efficiency of hybridization [19]. |

Optimization and Troubleshooting: An Experimental Framework

Simply combining the components in Table 1 is insufficient; their concentrations and the conditions of their use must be optimized for each specific application and probe. The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for developing and optimizing a hybridization protocol, with a focus on mitigating nonspecific binding.

Diagram 1: A logical workflow for troubleshooting nonspecific binding in hybridization experiments.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Solution Hybridization

The following protocol, adapted from current methodologies, provides a robust starting point for solution hybridization, a technique central to many advanced applications including smFISH [19] [21].

Hybridization Buffer Formulation (10 mL) [19]:

- Dextran Sulfate: 1 g (Volume excluder)

- E. coli tRNA: 10 mg (RNA-specific blocking agent)

- Vanadyl Ribonucleoside Complex: 100 µL of 200 mM stock (RNase inhibitor)

- BSA (RNase-free): 40 µL of 50 mg/mL solution (Protein-based blocking agent)

- 20x SSC: 1 mL (Salt source for ionic strength)

- Formamide: 1 mL for 10% final concentration (Stringency agent; can be adjusted from 10% to 25% as needed)

- Nuclease-free Water: to 10 mL final volume

Procedure:

- First, dissolve the dextran sulfate in approximately 4 mL of nuclease-free water with gentle agitation at room temperature. This may take several minutes to an hour.

- Once fully dissolved, add the remaining components to the solution.

- The final hybridization buffer can be aliquoted and stored at -20°C for future use.

Pre-hybridization Sample Preparation:

- Fixation: Prepare your cells or tissue sections. For intracellular targets, fixation is required. A common fixative is 1-4% paraformaldehyde, applied for 15-20 minutes on ice [22].

- Permeabilization: Incubate cells with a detergent solution for 10-15 minutes at room temperature to allow probe entry. The choice of detergent is critical:

- Equilibration: Centrifuge the fixed sample, aspirate the ethanol or previous buffer, and resuspend in 1 mL of wash buffer (see below) containing the same percentage of formamide as your hybridization buffer. Let stand for 2-5 minutes [19].

Hybridization and Washes:

- Prepare Hybridization Solution: For 100 µL of hybridization buffer, add 1-3 µL of your probe at an empirically determined concentration (often starting near 5-50 nM). Vortex and centrifuge [19].

- Hybridize: Aspirate the equilibration buffer from your sample and add the hybridization solution. Incubate in the dark overnight at 30°C (or a temperature optimized for your probe) [19].

- Post-Hybridization Washes: Stringent washing is critical for removing unbound and loosely bound probe.

- Wash Buffer (50 mL): 40 mL RNase-free water, 5 mL formamide, 5 mL 20x SSC [19]. The formamide concentration here can be increased to match or exceed that of the hybridization buffer for higher stringency.

- Add 1 mL of wash buffer to the sample, vortex, centrifuge, and aspirate.

- Resuspend in another 1 mL of wash buffer and incubate at 30°C for 30 minutes.

- Repeat this wash step as necessary.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful hybridization experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and tools beyond the buffer itself. The following table catalogs these essential items.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Hybridization Experiments

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Example Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formamide (deionized) | Stringency Agent | Lowers nucleic acid Tm, enabling lower temperature hybridization to preserve sample integrity [20] [19]. | Must be high-purity and nuclease-free. Concentration is a key optimization variable (e.g., 10-25%) [19]. |

| Saline-Sodium Citrate (SSC) | Salt Solution | Provides ionic strength to neutralize backbone charge and stabilize duplex formation [20]. | Used as 20x stock concentrate; dilution (e.g., to 2x) determines stringency in washes [20]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Blocking Agent | Binds to non-specific sites on membranes and tissues to prevent probe adsorption [20] [19]. | Often used at 1-5% concentration. RNase-free grade is essential for RNA work [19]. |

| tRNA or Salmon Sperm DNA | Nucleic Acid Blocking Agent | Competes with sample for non-specific binding of repetitive or common sequences [20]. | Sheared or denatured before use. Critical for reducing spot-like background in FISH [19]. |

| HybriWell Sealing System | Experimental Apparatus | Creates a sealed, defined chamber over a sample on a slide, minimizing hybridization volume [23]. | Various sizes available (e.g., 13mm-40mm) with usable volumes from 30µL to 200µL [23]. |

| Triton X-100 / Tween-20 | Detergent (Permeabilization) | Disrupts lipid membranes to allow probe entry for intracellular targets [22]. | Choice (harsh vs. mild) depends on target localization (nuclear vs. cytoplasmic) [22]. |

| Paraformaldehyde | Fixative | Preserves cellular morphology and immobilizes targets in situ [22]. | Typically used at 1-4%. Over-fixation can mask epitopes and reduce signal [22]. |

| Omaveloxolone | Omaveloxolone|CAS 1474034-05-3|Nrf2 Activator | Omaveloxolone is a potent Nrf2 activator for Friedreich's Ataxia research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| CEP-33779 | CEP-33779, CAS:1257704-57-6, MF:C24H26N6O2S, MW:462.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The path to a clean, specific, and reproducible hybridization experiment is paved with intentional buffer design and condition optimization. Nonspecific binding is not an inevitable nuisance but a controllable variable. By understanding the biochemical roles of components like formamide, salts, detergents, and blocking agents—and by applying systematic troubleshooting frameworks—researchers can deliberately engineer conditions that favor the single most important outcome in molecular detection: the unambiguous signal of a probe finding its true target. As hybridization techniques continue to evolve, pushing the limits of multiplexing and single-molecule sensitivity, these foundational principles of buffer composition will remain more critical than ever.

Methodological Impacts: How Nonspecific Binding Affects Key Technologies

Gene expression analysis using DNA microarrays is fundamentally based on the sequence-specific binding of RNA targets to DNA oligonucleotide probes attached to a solid surface. However, this process is complicated by nonspecific hybridization, where RNA fragments with sequences other than the intended target bind to the probes, adding a chemical background to the signal that does not reflect the actual expression level of the target gene [5] [24]. This phenomenon represents a significant challenge for accurate data interpretation, particularly in complex biological samples. To address this issue, the microarray community widely adopted the Perfect Match (PM) and Mismatch (MM) probe system, most famously implemented in Affymetrix GeneChip technology [5] [25]. The core premise is simple: while the PM probe perfectly complements a segment of the target transcript, the MM probe is identical except for a single base substitution at the central position, designed to measure nonspecific background hybridization. The difference in signal (PM-MM) should therefore represent specific binding. In practice, however, this system has revealed profound complexities that continue to challenge researchers and bioinformaticians.

The PM/MM System: Design and Theoretical Foundation

Fundamental Architecture

The standard Affymetrix design employs multiple 25-mer oligonucleotide probe pairs for each gene. Each probe set typically contains 11-20 PM/MM pairs representing different regions of the same transcript [26] [5]. The PM probe is perfectly complementary to a specific target sequence, while its corresponding MM probe contains a single base mismatch at the 13th (middle) position, theoretically disrupting specific binding while maintaining similar nonspecific hybridization characteristics [5] [1]. This design is predicated on two key assumptions: first, that nonspecific binding is identical for PM and MM probes, meaning nonspecific transcripts do not detect the single base change; and second, that the mismatch substantially reduces the affinity for specific target binding, ensuring that PM intensity should theoretically always equal or exceed MM intensity [5].

Thermodynamic Principles

The hybridization process on microarrays follows established biophysical principles. The binding affinity between probe and target can be modeled using the Langmuir isotherm and calculated using nearest-neighbor models that account for the changes in free energy (ΔG) during duplex formation [27] [28]. These thermodynamic calculations consider that the free energy of hybridization for any base pair depends not only on whether it is a C-G or A-T pair, but also on which base pairs occupy neighboring positions along the strand [27]. However, direct application of solution-based thermodynamics to the microarray environment is complicated by confined geometry, surface effects, and experimental variations that alter the entropic contributions to free-energy changes [27].

Table 1: Core Components of the PM/MM Probe System

| Component | Description | Intended Function | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect Match (PM) Probe | 25-mer oligonucleotide perfectly complementary to target sequence | Measure specific target binding plus nonspecific background | Watson-Crick base pairing with complete complementarity |

| Mismatch (MM) Probe | Identical to PM except for single central base substitution | Measure nonspecific background only | Disruption of specific binding while maintaining nonspecific hybridization profile |

| Probe Set | 11-20 PM/MM pairs per gene | Provide multiple independent measurements; improve reliability and statistical power | Sampling different regions of the same transcript minimizes regional hybridization artifacts |

Key Challenges and Systematic Artifacts

The "Bright Mismatch" Phenomenon

Contrary to theoretical expectations, empirical data consistently reveals that approximately 30% of MM probes exhibit higher fluorescence intensity than their corresponding PM partners [5] [25]. This "bright mismatch" phenomenon fundamentally challenges the core assumptions of the PM/MM system and complicates simple background subtraction approaches. Research has demonstrated that this effect follows a systematic pattern based on the central base of the PM probe. For specific hybridization, the PM-MM log-intensity difference follows a triplet-like pattern (C > G ≈ T > A > 0), whereas nonspecific binding produces a duplet-like pattern (C ≈ T > 0 > G ≈ A) [5] [24]. This systematic behavior can be rationalized at the molecular level: nonspecific binding is characterized by the reversal of the central Watson-Crick pairing for each PM/MM probe pair, while specific binding involves a combination of Watson-Crick and self-complementary pairing in PM and MM probes, respectively [1].

Widespread Data Quality Issues

A recent large-scale retrospective analysis employing deep learning to examine 37,724 published microarray datasets revealed an alarming prevalence of systematic defects [26]. The study found that 26.73% of microarray-based studies are affected by serious imaging defects, with 4.80% of individual microarrays containing significant contamination. Even more concerning, literature mining showed that publications associated with these problematic microarrays had disproportionately reported more biological discoveries for genes located in contaminated areas compared to other genes [26]. Overall, 28.82% of gene-level conclusions in these affected publications were based on measurements falling into contaminated areas, while these defects occupied only 2.78% of the total image area, indicating severe systematic problems where conclusions were based on contamination artifacts rather than biological reality [26].

Limitations in Complex Target Mixtures

The performance of the PM/MM system deteriorates further in complex target mixtures containing multiple nucleic acid species at varying concentrations. Evaluation of quantification methods in such environments has demonstrated that approaches relying on hidden correlations in microarray data are insufficient for accurate quantification of specific targets [29]. The fundamental issue is that signal intensity depends on both the binding energies of hybridized probe-target duplexes and the concentration of targets in solution, making physical interpretation of raw signal intensity extremely challenging [29]. This limitation is particularly problematic for clinical and environmental samples where accurate quantification of multiple targets is essential.

Diagram 1: Challenges in PM/MM Analysis

Experimental Insights and Methodological Approaches

Deep Learning for Defect Detection

To address systematic data quality issues, researchers have developed deep learning algorithms for automatic detection of microarray imaging defects [26]. This approach involves reconstructing fluorescence images from raw CEL files and using a U-Net convolutional neural network architecture to identify contaminated areas. The training process utilized a combination of cross-entropy and mean square error loss with Adam optimization, iterating over multiple epochs until stable performance was achieved [26]. This method has proven particularly valuable for retrospective analysis of existing datasets, allowing researchers to identify potentially compromised results and reanalyze data excluding problematic regions.

Optimization for Long Oligonucleotide Probes

While early PM/MM systems focused on 25-mer probes, research has extended to long oligonucleotide probes (50-70 mers) commonly used in spotted microarray platforms. Systematic evaluation of 50-mer MM probes revealed that evenly distributed mismatches provide better discrimination than randomly distributed mismatches or single central mismatches [25] [30]. The optimal number of mismatches depends on hybridization temperature: 3 mismatches at 50°C, 4 mismatches at 45°C, and 5 mismatches at 42°C [25]. Based on these findings, researchers developed a Modified Positional Dependent Nearest Neighbor (MPDNN) model that adjusts thermodynamic parameters for matched and mismatched dimer nucleotides in the microarray environment, significantly improving consistency for long MM probes [25] [30].

Physical Modeling of Hybridization

An alternative approach to empirical correction methods involves developing physical models based on hybridization thermodynamics [27] [28]. This methodology combines calculated free energies of hybridization with microarray data from known target concentrations to compute transcript concentration levels directly from raw data. The model uses nearest-neighbor parameters determined for nucleic acids in solution, incorporating corrections for initiation, termination, and stacking interactions [27]. When applied to controlled "spike-in" experiments, this approach demonstrates a clear correlation between calculated hybridization free energies and observed intensities, though it also reveals nonlinear responses at higher target concentrations due to saturation effects from finite probe sites [27].

Table 2: Experimental Approaches to Address PM/MM Challenges

| Methodology | Key Features | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning Defect Detection | U-Net architecture; combination of cross-entropy and MSE loss; image reconstruction from CEL files | Identification of systematic imaging defects; quality control for existing datasets | High accuracy in detecting localized contamination; scalable to large datasets | Requires substantial training data; computational intensive |

| Long Oligonucleotide Optimization | Evenly distributed mismatches; temperature-adjusted mismatch numbers; MPDNN model | Spotted microarrays with 50-70mer probes; environmental and clinical applications | Improved specificity over single central mismatch designs | Increased design complexity; position-specific effects must be considered |

| Physical Modeling | Nearest-neighbor thermodynamics; Langmuir isotherm; free energy calculations | Absolute quantification; spike-in experiments; model-based background correction | Physically interpretable parameters; less dependent on empirical adjustments | Sensitive to experimental variations; confined geometry effects not fully captured |

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Function/Benefit | Implementation Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affymetrix GeneChips | Commercial microarray platform | Standardized PM/MM system with 25-mer probes; extensive annotation databases | Genome-wide expression studies; standardized analytical pipelines |

| HG-U133 Plus 2.0 Array | Specific microarray design | 54,675 probe sets; 1,354,896 possible probe positions; 62 reference probe sets | Large-scale human transcriptome studies; data comparability across projects |

| Affymetrix Software Developer's Kit | Programming toolkit | API for reconstructing microarray images from CEL files; probe position mapping | Custom data analysis; image-based quality assessment |

| Langmuir Isotherm Models | Computational algorithm | Models binding kinetics based on physical principles; calculates equilibrium constants | Prediction of probe intensities; accounting for cross-hybridization effects |

| Nearest-Neighbor Parameters | Thermodynamic database | ΔH and ΔS values for perfect match and mismatch base pairs; initiation/termination values | Calculation of hybridization free energies; melting temperature prediction |