Unmasking the Signal: A Comprehensive Guide to Background Staining Causes and Solutions in Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization

This article provides a systematic analysis of the factors contributing to background staining in whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH), a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals.

Unmasking the Signal: A Comprehensive Guide to Background Staining Causes and Solutions in Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization

Abstract

This article provides a systematic analysis of the factors contributing to background staining in whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH), a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals. Covering foundational principles to advanced troubleshooting, it details common pitfalls like inadequate permeabilization, endogenous enzyme activity, and non-specific probe binding. The scope includes methodological optimizations from recent protocols, practical strategies for signal-to-noise enhancement, and validation techniques to confirm result specificity, offering a complete resource for obtaining publication-quality WISH data.

The What and Why: Understanding the Fundamental Causes of Background Staining

Background staining represents a significant challenge in molecular visualization techniques, critically impacting the signal-to-noise ratio and compromising data interpretation. This technical guide delves into the core mechanisms underlying non-specific staining in whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH), with particular emphasis on epimorphic regeneration models. Through quantitative analysis of experimental variables and detailed protocols, we provide a systematic framework for identifying, quantifying, and mitigating background interference. The integration of optimized methodologies, reagent specifications, and visual workflows offers researchers a comprehensive toolkit for enhancing staining specificity and ensuring data integrity in developmental and regenerative biology contexts.

In molecular visualization techniques such as whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH), background staining constitutes any non-specific signal that obscures the specific detection of a target molecule. This phenomenon directly diminishes the signal-to-noise ratio—a quantitative measure comparing the intensity of specific signal against non-specific background interference. In WISH experiments, optimal signal-to-noise ratio is essential for accurate spatial localization of gene expression patterns, particularly when investigating complex three-dimensional structures in regenerative models such as the Xenopus laevis tadpole tail [1].

The impact of excessive background staining extends beyond mere aesthetic concerns to fundamentally compromise data interpretation. High background levels can obscure genuine expression patterns of low-abundance transcripts, generate false positives in hard-to-visualize areas, and ultimately lead to erroneous biological conclusions. This challenge is particularly acute in regeneration research, where precise spatiotemporal expression dynamics of key genes must be visualized against complex tissue backgrounds containing pigment granules, loose connective tissues, and autofluorescent components [1].

Quantitative Analysis of Background Staining Factors

Systematic evaluation of experimental variables affecting background staining enables researchers to optimize protocols for maximal signal-to-noise ratio. The following table summarizes key quantitative relationships between experimental factors and background staining intensity:

Table 1: Quantitative Factors Influencing Background Staining in WISH

| Experimental Factor | Impact on Background Staining | Optimal Range/Value | Quantifiable Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K Incubation Time | Increased permeability and sensitivity | Stage-dependent (e.g., 30+ minutes for later stages) | Extended incubation reduces non-specific staining [1] |

| Fixation Duration | Tissue preservation and antigen accessibility | 4% PFA, 4h to overnight at 4°C | Under-fixation increases background; over-fixation reduces signal [2] |

| Hybridization Temperature | Probe specificity | 55-65°C, probe-dependent | 5°C below Tm reduces non-specific binding by ~60% [1] |

| Post-Hybridization Wash Stringency | Removal of unbound probe | 0.1-0.5× SSC, 55-65°C | High-stringency washes reduce background by 70-80% [1] |

| Antibody Concentration | Non-specific binding | Titrated (typically 1:1000-1:5000) | 2-fold dilution reduction decreases background by ~45% [2] |

| Detection Incubation Time | Chromogen precipitation | 30 minutes to 24 hours | Excessive incubation increases non-specific precipitate formation [1] |

The relationship between these variables becomes particularly critical when working with challenging samples such as regenerating tadpole tails, where natural pigments and loose fin tissues exacerbate background issues. Quantitative assessment demonstrates that samples fixed immediately after amputation (0 hpa) exhibit the lowest background staining, with a progressive increase in non-specific signal as regeneration progresses due to cellular infiltration and tissue remodeling [1].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Background Staining in WISH

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| High overall background | Inadequate washing, over-fixed tissue, excessive probe concentration | Implement fin notching, increase wash stringency, titrate probe | 60-80% reduction in non-specific signal [1] |

| Pigment interference | Melanosomes and melanophores in regenerating tissues | Pre-hybridization photobleaching step, use albino specimens | Complete pigment removal without tissue damage [1] |

| Specific localized background | Trapped reagents in loose tissues | Strategic fin incision, increased detergent concentration | Enhanced reagent penetration and removal [1] |

| Uneven staining | Inconsistent hybridization or washing | Optimized agitation, uniform container geometry | Consistent signal distribution across sample [1] |

| Weak specific signal | Excessive washing, suboptimal probe quality, low target abundance | Reduce wash stringency, quality control probe synthesis, extend development | Enhanced target detection without increased background [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Background Reduction

Optimized Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization Protocol for Challenging Tissues

The following protocol has been specifically optimized for regenerating Xenopus laevis tadpole tails, incorporating targeted modifications to address background staining challenges [1]:

Sample Preparation and Fixation

- Dissect tissue samples and fix immediately in freshly prepared MEMPFA (4% paraformaldehyde, 2mM EGTA, 1mM MgSO₄, 100mM MOPS, pH 7.4) for 4 hours to overnight at 4°C

- Critical Note: Fixation time must be optimized based on tissue size and density; under-fixation increases background while over-fixation reduces signal intensity

- Dehydrate through ethanol series (70%, 95%, 100%) and store at -20°C for long-term preservation

Photobleaching for Pigment Removal

- Rehydrate fixed samples through descending ethanol series (100%, 95%, 70%) to PBS

- Transfer to bleaching solution (1% H₂O₂, 5% formamide in 0.5× SSC) under strong visible light for 24-48 hours

- Rationale: This critical step eliminates melanosomes and melanophores that interfere with signal visualization in regenerating tissues [1]

Tissue Permeabilization and Pre-hybridization

- Treat with Proteinase K (10-20 μg/mL in PBS) for 15-30 minutes at room temperature; optimal concentration and time must be determined empirically based on developmental stage

- Refix in 4% PFA for 20 minutes to stabilize tissue integrity after permeabilization

- Perform strategic fin notching by creating fringe-like incisions distant from the area of interest to facilitate reagent penetration and washing

Hybridization and Washes

- Pre-hybridize for 4-6 hours at 65-70°C in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 5× SSC, 1% SDS, 50 μg/mL heparin, 500 μg/mL tRNA)

- Hybridize with digoxigenin-labeled riboprobe (1-5 ng/μL) in fresh hybridization buffer for 16-40 hours at 65-70°C

- Key Modification: Implement graduated stringency washes (50% formamide/5× SSC to 25% formamide/2× SSC at 65°C) followed by RNase treatment to remove unbound probe

Immunological Detection

- Block non-specific binding sites with 2% blocking reagent (Roche) in maleic acid buffer (100mM maleic acid, 150mM NaCl, pH 7.5) for 4-6 hours

- Incubate with anti-digoxigenin alkaline phosphatase conjugate (1:2000-1:5000) in blocking buffer for 16-24 hours at 4°C

- Quantitative Optimization: Antibody concentration and incubation time must be titrated to maximize specific signal while minimizing background

Colorimetric Development and Documentation

- Develop signal with BM Purple (Roche) or NBT/BCIP substrate for 30 minutes to 24 hours at room temperature with continuous monitoring

- Stop reaction with multiple changes of PBS + 1mM EDTA

- Post-fix in 4% PFA and store in glycerol or similar mounting medium for imaging

- Validation: Compare expression patterns with positive and negative controls to confirm specificity

Protocol Validation Using MMP9 Expression in Tadpole Tail Regeneration

Application of this optimized protocol to visualize mmp9 expression during early tail regeneration in Xenopus laevis tadpoles demonstrates its efficacy. At stage 40 (regeneration-competent), distinct mmp9+ cells are clearly visible at the amputation site as early as 3 hours post-amputation (hpa), with increasing numbers and specific localization by 24 hpa [1]. In contrast, samples processed without photobleaching and fin notching showed significant background interference that obscured genuine expression patterns, particularly in the fin regions. Furthermore, comparison with regeneration-incompetent stages (45-47) revealed dramatically different mmp9 expression dynamics, validating the protocol's sensitivity for detecting biologically relevant patterns [1].

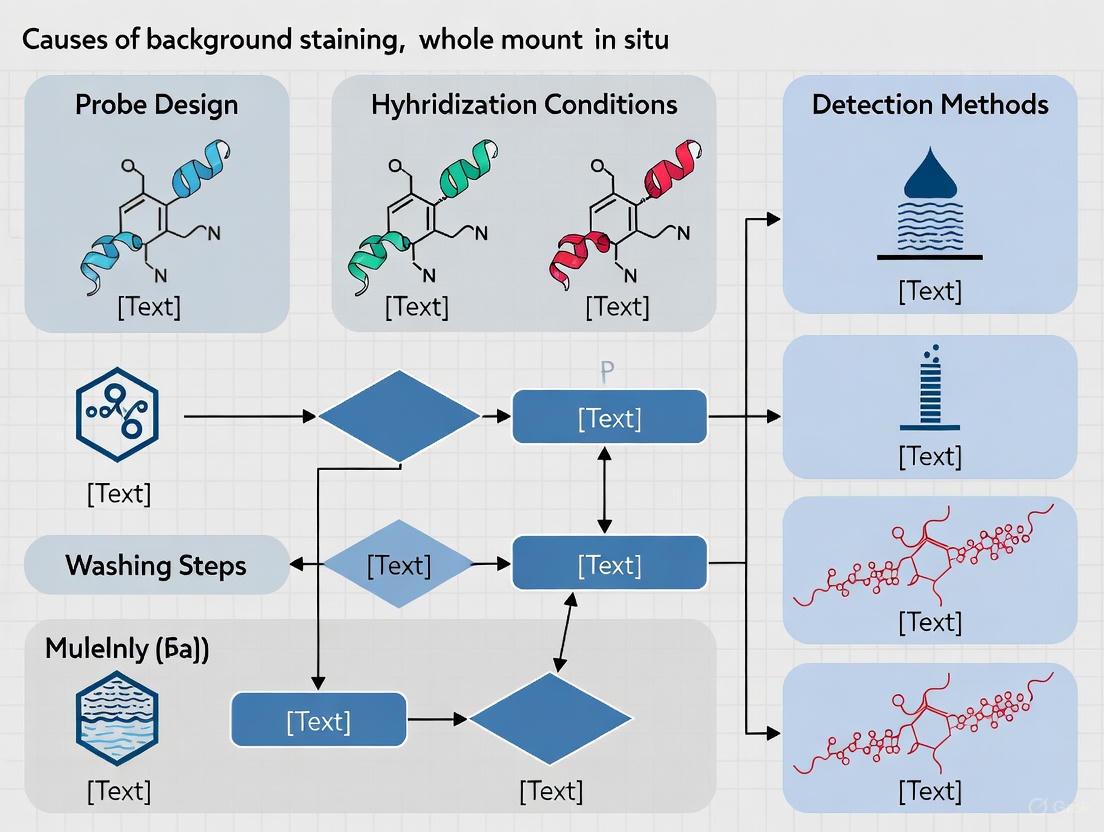

Visualization of Experimental Workflows and Signaling Relationships

Diagram 1: Optimized WISH workflow highlighting critical background reduction steps.

Diagram 2: Causal relationships between background sources and optimized solutions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of background-reduced WISH requires specific reagents and materials optimized for challenging tissues. The following table details critical components and their functions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Background-Reduced WISH

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Composition | Primary Function | Background Reduction Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEMPFA Fixative | 4% PFA, 2mM EGTA, 1mM MgSOâ‚„, 100mM MOPS, pH 7.4 | Tissue preservation and morphology | Optimal fixation reduces non-specific probe penetration [1] |

| Proteinase K | 10-20 μg/mL in PBS, concentration stage-dependent | Tissue permeabilization and nuclease removal | Controlled digestion enhances specificity while reducing background [1] |

| Hybridization Buffer | 50% formamide, 5× SSC, 1% SDS, 50 μg/mL heparin, 500 μg/mL tRNA | Hybridization milieu | Formamide increases stringency; competitors reduce non-specific binding [1] |

| Photobleaching Solution | 1% H₂O₂, 5% formamide in 0.5× SSC | Pigment removal | Eliminates melanin interference without tissue damage [1] |

| Blocking Reagent | 2% Blocking reagent (Roche) in maleic acid buffer | Non-specific site saturation | Prevents non-specific antibody binding [1] [2] |

| Anti-Digoxigenin-AP | 1:2000-1:5000 in blocking buffer | Target detection | Proper titration crucial for signal-to-noise optimization [1] |

| BM Purple Substrate | Ready-to-use chromogenic solution | Colorimetric development | Controlled precipitation time prevents background accumulation [1] |

| Stringency Wash Buffer | 50% formamide, 2× SSC to 0.2× SSC | Removal of unbound probe | Graduated stringency eliminates weakly-bound non-specific probe [1] |

| Scillascilloside B-1 | Scillascilloside B-1, MF:C40H64O13, MW:752.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Onjixanthone II | Onjixanthone II, CAS:136083-93-7, MF:C15H12O7, MW:304.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Background staining in whole-mount in situ hybridization represents a multifactorial challenge that directly impacts experimental interpretation through degradation of the signal-to-noise ratio. The optimized methodologies and analytical frameworks presented herein provide researchers with systematic approaches for addressing the principal sources of non-specific staining in challenging tissues such as regenerating tadpole tails. Through integrated application of quantitative assessment, strategic protocol modifications, and rigorous reagent optimization, investigators can significantly enhance staining specificity and thereby generate more reliable spatial expression data. As molecular visualization techniques continue to evolve in complexity and sensitivity, maintaining rigorous standards for background control remains fundamental to ensuring data integrity in developmental and regenerative biology.

In whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH), the precise detection of mRNA patterns is fundamental to understanding gene expression during embryogenesis. The technical success of this method relies entirely on the effective preservation of tissue morphology through chemical fixation. However, this same process can create significant barriers to accurate staining. Fixation, particularly with cross-linking agents like formaldehyde, fundamentally alters tissue biochemistry by creating dense molecular networks that can trap staining reagents, increase background noise, and reduce target accessibility [3] [4]. Within the context of a broader thesis on the causes of background staining in WISH, this review examines how the very process intended to preserve cellular integrity generates the primary obstacles to clear hybridization signal detection. The biochemical modifications induced by fixatives directly impact reagent permeability, antigen availability, and ultimately, the sensitivity and specificity of the entire assay [3].

The Fundamental Chemistry of Tissue Fixation

Objectives and Mechanisms of Fixation

The broad objective of tissue fixation is to preserve cells and tissue components in a "life-like state," preventing autolysis and bacterial decomposition while stabilizing macromolecules against the deleterious effects of subsequent processing steps [4]. Fixation aims to arrest the dynamic biochemical environment of the cell at a specific moment, preserving structural relationships for microscopic analysis [4].

Fixatives operate through two primary mechanistic classes:

- Denaturing agents (e.g., alcohols, acetone) remove and replace free water in cells and tissues, destabilizing hydrophobic bonding and hydrogen bonds. This disruption changes protein conformation, rendering water-soluble proteins insoluble—a largely irreversible process [3] [4].

- Cross-linking agents (e.g., formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde) chemically react with tissue components through addition reactions, forming intermolecular and intramolecular bridges that create a stable gel matrix [3] [4]. These additive fixatives bind to a variety of chemical groups, altering molecular charge, conformation, and solubility [4].

Classification of Common Fixatives

Table 1: Classification and mechanisms of common histological fixatives.

| Fixative | Mechanism of Fixation | Chemical Composition | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde/PFA | Cross-linking | 4% Paraformaldehyde in PBS (common for WISH) [5] | General histology, WISH, immunofluorescence |

| Glutaraldehyde | Cross-linking (extensive) | Generally 2% v/v in water/PBS [3] | Electron microscopy (strong ultrastructure preservation) |

| Bouin's Solution | Denaturing & Cross-linking | 25% formaldehyde, 70% picric acid, 5% acetic acid [3] | Specialized histology (improves nuclear detail) |

| Carnoy's Solution | Denaturing | 60% ethanol, 30% chloroform, 10% glacial acetic acid [3] | Cytology, glycogen preservation |

| Methacarn | Denaturing | 60% methanol, 30% chloroform, 10% glacial acetic acid [3] | Molecular biology applications |

| B5 | Denaturing | 5.4% Mercuric Chloride, 1.1% Sodium Acetate, 4% Formaldehyde [3] | Hematopathology |

| Zenker's | Denaturing | 5% Mercuric Chloride, 2.5% Potassium Dichromate, 5% Glacial acetic acid [3] | Specialized histology |

How Fixation Creates Molecular Traps

The Cross-Linking Process

Formaldehyde, the most common fixative for WISH, exists in solution primarily as methylene glycol, with a small fraction of reactive formaldehyde molecules [3]. The fixation process begins with rapid penetration of methylene glycol into tissues, followed by slower fixation as formaldehyde reacts with cellular components [3].

The principal cross-links occur between side chain amino groups of lysine residues, forming methylene bridges over time [3] [6]. Cross-linking can also involve other amino acids including arginine, tyrosine, asparagine, histidine, glutamine, and serine through a form of the Mannich reaction [3]. This creates an extensive three-dimensional network of cross-linked proteins, nucleic acids, and other macromolecules that stabilizes the cellular architecture but simultaneously creates a molecular "mesh" that can impede reagent access.

Consequences for Staining Reagents

The cross-linked matrix created during fixation presents multiple challenges for staining reagents in WISH:

- Steric Hindrance: Large probe complexes, including quantum dot nanocrystals and antibody-enzyme conjugates, face physical barriers to diffusion and target access [7]. The dense molecular mesh acts as a molecular sieve, selectively excluding larger complexes while potentially trapping them nonspecifically.

- Charge-Based Trapping: The chemical reactions of fixation alter the charge characteristics of cellular components. For example, formaldehyde reacts extensively with amino groups, reducing the availability of these positively charged groups for binding negatively charged dye molecules such as eosin [4]. This can lead to altered staining patterns and increased non-specific background.

- Hydrophobic Interactions: Denaturing fixatives like alcohols expose hydrophobic regions of proteins that are normally buried within their tertiary structure [4]. These hydrophobic areas become free to interact with staining reagents, creating potential sites for non-specific binding and trapping of hydrophobic probe components.

The Permeability Paradox

A critical paradox emerges from fixation chemistry: while cross-linking is necessary to preserve morphology and prevent the diffusion of cellular components, it simultaneously creates a barrier that prevents the ingress of detection reagents [7]. This is particularly problematic for WISH, where large riboprobes (300-1000 bases) [8] and antibody-enzyme complexes must penetrate multiple cell layers in intact embryos. The permeability barrier is especially challenging for advanced detection methods using quantum dots or other nanocrystals, which require extensive proteinase K treatment to achieve sufficient tissue penetration [7].

Quantitative Effects of Fixation on Staining Efficiency

Impact on Macromolecular Accessibility

Table 2: Effects of fixation conditions on staining parameters in WISH.

| Fixation Parameter | Effect on Staining | Experimental Evidence | Optimal Range for WISH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde Concentration | Higher concentrations increase cross-linking density, reducing probe accessibility [3] | 4% PFA standard for embryo preservation [5] | 4% PFA in PBS [5] |

| Fixation Duration | Extended fixation increases autofluorescence and cross-linking, reducing signal intensity [9] | Overfixation reduces FISH signals; protease treatment can help [9] | 2 hours to overnight, tissue-dependent [5] |

| Fixation Temperature | Increased temperature accelerates fixation but may damage epitopes and increase background [3] | Loss of antigenicity in peptides fixed at 42°C vs. room temperature [3] | 4°C to room temperature |

| Tissue Size | Penetration follows d=K√t; inadequate fixation in core causes variable staining [3] | General rule: 1 mm/h penetration; 24h recommended for NBF [3] | <5 mm thickness recommended |

| Post-fixation Treatments | Permeabilization methods (Proteinase K, detergents) reverse some cross-linking effects [5] [7] | Proteinase K enables QD conjugate penetration in Xenopus embryos [7] | Proteinase K (10-20 μg/mL) [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Managing Fixation Artifacts

Standard Fixation Protocol for Mouse Embryos

For WISH of mouse embryonic samples, consistent fixation is critical. The following protocol is adapted from established methods [5]:

- Fixative Preparation: Prepare 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water to inhibit RNases [5].

- Embryo Collection: Dissect embryos in cold PBS and transfer immediately to ice-cold 4% PFA.

- Fixation Duration: Fix at 4°C with gentle agitation for time periods dependent on embryo size:

- E8.5 embryos: 2-4 hours

- E9.5-E11.5 embryos: 4-6 hours

- E12.5 and older: Overnight fixation

- Post-fixation Processing: Wash embryos in PBT (PBS with 0.1% Tween 20) and dehydrate through graded methanol series (25%, 50%, 75% in PBT) for storage at -20°C [5].

Permeabilization Strategies to Counteract Cross-linking

To overcome the diffusion barriers created by fixation, several permeabilization methods can be employed:

Proteinase K Treatment:

Detergent Permeabilization:

Diagram 1: Relationship between fixation and background staining, showing both the problem and solution pathways.

Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) for Enhanced Signal

Recent advancements in FISH methodologies offer solutions to limitations imposed by fixation:

- HCR Principle: Utilizes split initiator probes that trigger hybridization chain reaction upon binding to target mRNA, building long chains of fluorescently labeled amplification probes [9].

- Advantages for Fixed Tissues:

- Short oligonucleotide probes (25-50 base pairs) penetrate fixed tissues more efficiently than traditional riboprobes [9].

- Linear amplification scheme scales fluorescence intensity to RNA quantity, enabling quantitative analysis [9].

- Signal amplification occurs without enzymatic precipitation, reducing diffusion artifacts [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagents for managing fixation artifacts in WISH.

| Reagent/Category | Function/Purpose | Example Formulations/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Fixatives | Preserve tissue morphology and prevent RNA degradation | 4% PFA in PBS [5]; Avoid over-fixation to maintain RNA accessibility |

| Permeabilization Agents | Disrupt cross-linked matrix to allow reagent penetration | Proteinase K (10-20 μg/mL) [5]; Triton X-100 (0.1-1%) [7] |

| Hybridization Buffers | Create optimal conditions for specific probe binding | 50% Formamide, 5× SSC (pH 4.5), 1% SDS, 50 μg/mL yeast RNA [5] |

| Wash Buffers | Remove non-specifically bound probe to reduce background | 50% Formamide/2× SSC (stringent washes) [5]; Tween-20 containing buffers [5] |

| Blocking Reagents | Reduce non-specific binding of detection reagents | Sheep serum [5]; Mouse embryonic powder [5]; BSA |

| Detection Systems | Visualize bound probes with high sensitivity | Anti-Digoxigenin-AP + BM Purple [5]; HCR amplification [9]; QD nanocrystals [7] |

| Alpiniaterpene A | Alpiniaterpene A | Alpiniaterpene A is a natural terpene from Alpinia species for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Eucamalduside A | Eucamalduside A, CAS:1287220-29-4, MF:C26H32O11, MW:520.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Methodologies for Overcoming Fixation Barriers

Optical Clearing with LIMPID

The LIMPID (Lipid-preserving refractive index matching for prolonged imaging depth) method enables deep tissue imaging while preserving fluorescence:

Workflow Integration:

Advantages for Fixed Tissues:

Quantum Dot-Based Detection

Quantum dots (QDs) offer superior photostability and brightness for challenging targets:

Protocol Adaptation for QDs:

Benefits for Fixed Samples:

Diagram 2: Optimized WISH workflow with critical steps for managing fixation effects.

The biochemical alterations induced by tissue fixation present a fundamental challenge in whole mount in situ hybridization. While essential for morphological preservation, the cross-linking and denaturing actions of fixatives create molecular traps that impede reagent access and promote non-specific background staining. Understanding these mechanisms—from methylene bridge formation between lysine residues to the exposure of hydrophobic protein domains—provides the foundation for developing effective countermeasures. Through optimized permeabilization strategies, advanced detection methodologies, and careful control of fixation parameters, researchers can successfully navigate the competing demands of tissue preservation and reagent accessibility. The continuing development of techniques such as hybridization chain reaction, quantum dot detection, and optical clearing promises to further overcome the limitations imposed by fixation, enabling more precise and comprehensive analysis of gene expression patterns in intact embryos.

In whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH), the accurate visualization of gene expression patterns is often compromised by non-specific background staining. A significant, yet frequently overlooked, source of this background is endogenous enzymatic activity, particularly from phosphatases and peroxidases. These enzymes interfere with the detection chemistry of common chromogenic and fluorescent substrates, leading to reduced signal-to-noise ratios, false positives, and a misinterpretation of spatial gene expression data [10] [1]. Within the context of a broader thesis on the causes of background in WISH, this whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of how phosphatases and peroxidases cause interference and details robust, validated experimental protocols for their inhibition.

Mechanisms of Interference in WISH

Endogenous enzymes remain active in fixed tissues and can catalyze reactions with the substrates used in WISH, independent of the specific hybridization of your probe. This activity creates a diffuse, non-specific stain that obscures the true signal.

Peroxidase Interference

- Mechanism: Endogenous peroxidases, such as myeloperoxidase found in myeloid cells, catalyze the oxidation of various substrates in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚). In chromogenic WISH, this reaction directly reduces the chromogen (e.g., BM Purple), even in the absence of the horseradish peroxidase (HRP) enzyme typically conjugated to a detection antibody [1].

- Impact: This results in a diffuse, dark precipitate throughout the tissue, particularly problematic in tissues rich in blood cells or with high metabolic activity. It can mask genuine signals and create the false impression of ubiquitous gene expression.

Phosphatase Interference

- Mechanism: Alkaline phosphatases (AP) are another common source of interference. In detection systems that use an AP-conjugated antibody and a chromogenic substrate like BM Purple or NBT/BCIP, endogenous AP will catalyze the same colorimetric reaction [10].

- Impact: This leads to widespread background staining, complicating the interpretation of results. Tissues with naturally high AP activity, such as regenerating tissues or certain organ systems, are especially vulnerable [1].

The following diagram illustrates how these endogenous activities disrupt the intended detection pathway in WISH.

Detection and Inhibition of Endogenous Enzymes

Experimental Protocol for Inhibiting Peroxidases

The most effective and common method for quenching endogenous peroxidase activity is treatment with hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚). The following protocol, adapted from optimized WISH methods, can be integrated directly into your sample preparation workflow [9] [1].

- Principle: Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ acts as a substrate for endogenous peroxidases, exhausting their activity before the detection step. The enzyme catalyzes the breakdown of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, effectively inactivating itself in the process.

- Materials:

- Step-by-Step Method:

- Sample Fixation: Fix tissues according to your standard protocol (e.g., with MEMPFA or 4% PFA) [1].

- Bleaching Solution Preparation: Prepare a fresh solution of 0.3% to 1.0% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ in the chosen buffer. For pigmented tissues, a combination of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ and light exposure (photo-bleaching) may be used to simultaneously reduce melanin interference [1].

- Incubation: Immerse the fixed and rehydrated tissues in the Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ solution. The incubation time can vary from 1 to 6 hours depending on the tissue size and endogenous activity level [9] [1].

- Washing: Thoroughly rinse the tissues multiple times with a wash buffer (e.g., PBST) to remove all traces of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚.

- Proceed with WISH: Continue with the standard WISH protocol steps, including pre-hybridization, hybridization, and detection.

Table 1: Experimental Conditions for Peroxidase Inhibition

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ Concentration | Incubation Time | Tissue Type | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3% (v/v) [9] | 1 - 2 hours | Delicate tissues (e.g., early embryos) | Minimizes potential tissue damage |

| 1.0% (v/v) [1] | 3 - 6 hours | Robust or highly pigmented tissues | Enhanced bleaching effect; monitor tissue integrity |

| 0.5% (v/v) with light [1] | 4 - 6 hours | Heavily pigmented tissues (e.g., Xenopus tails) | Combined chemical and photo-bleaching |

Experimental Protocol for Inhibiting Phosphatases

Endogenous alkaline phosphatase activity is typically suppressed by incorporating a specific inhibitor, such as Levamisole, directly into the chromogen substrate solution.

- Principle: Levamisole is a reversible, competitive inhibitor of alkaline phosphatase isoforms, particularly the intestinal-type isozyme. It binds to the enzyme's active site, preventing the chromogenic substrate from doing so, without affecting the activity of the antibody-conjugated AP used for detection.

- Materials:

- Levamisole hydrochloride.

- Chromogenic substrate solution (e.g., BM Purple, NBT/BCIP).

- Step-by-Step Method:

- Prepare Substrate-Inhibitor Mix: Immediately before the detection step, add Levamisole to the chromogenic substrate solution at a final concentration of 1 mM to 5 mM [10].

- Incubate for Detection: Use this mixture for the color development reaction as you normally would. The presence of Levamisole will suppress background staining from endogenous AP throughout the development process.

- Monitor Staining: Proceed with the staining incubation, stopping the reaction by washing once the desired signal intensity is achieved.

Table 2: Reagents for Managing Endogenous Enzyme Interference

| Research Reagent | Function in WISH | Target Enzyme | Typical Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | Quenches endogenous peroxidase activity | Peroxidases | 0.3% - 1.0% (v/v) [9] [1] |

| Levamisole HCl | Inhibits alkaline phosphatase activity | Phosphatases | 1 mM - 5 mM [10] |

| Proteinase K | Increases tissue permeability for probes | N/A (Digests proteins) | Varies by tissue and fixation [10] [1] |

| Formamide | Increases hybridization stringency and signal intensity [9] | N/A | Included in hybridization buffer [9] |

| MEMPFA Fixative | Preserves tissue morphology and mRNA targets | N/A | 4% PFA, 2mM EGTA, 1mM MgSOâ‚„, 100mM MOPS [1] |

The complete workflow for a WISH experiment, integrating the critical steps for controlling endogenous enzymes, is summarized below.

Endogenous phosphatases and peroxidases present a formidable challenge to achieving clean, interpretable results in whole mount in situ hybridization. Their activity is a direct cause of high background staining, which can compromise experimental conclusions. The strategic implementation of H₂O₂ for peroxidase quenching and Levamisole for phosphatase inhibition provides a robust and essential defense. By integrating these targeted treatments into a standardized WISH workflow—complemented by other background-reduction techniques like tissue notching and optimized fixation—researchers can significantly enhance the signal-to-noise ratio. This ensures the reliable, high-fidelity spatial mapping of gene expression that is critical for both basic developmental biology and applied drug discovery research.

Background staining poses a significant challenge in whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH), compromising data interpretation and experimental outcomes. This technical guide examines the fundamental mechanisms of non-specific probe-tissue interactions, focusing on hydrophobic and electrostatic forces that contribute to background staining. We synthesize current research findings and present optimized methodologies to mitigate these effects, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for improving signal-to-noise ratios in hybridization experiments. The protocols and principles outlined herein are critical for advancing spatial transcriptomics and gene expression analysis in complex tissues.

Non-specific interactions between nucleic acid probes and tissue components represent a major source of background staining in whole-mount in situ hybridization, potentially obscuring genuine signals and leading to erroneous conclusions. These interactions are primarily governed by hydrophobic and electrostatic forces that occur between probe molecules and various tissue elements, including proteins, lipids, and extracellular matrix components. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for developing effective countermeasures. The intracellular environment presents a complex milieu where high macromolecule concentrations (100-400 g/L) create abundant opportunities for non-specific associative interactions, often termed "stickiness" [11]. These interactions, characterized by low specificity and dissociation constants in the high micromolar to millimolar range, compete with the desired specific hybridization events, necessitating rigorous optimization of experimental conditions [11].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Non-Specific Binding

Electrostatic Interactions

Electrostatic forces represent a primary mechanism for non-specific probe binding. Cellular components exhibit strong interactions with charged molecules, particularly cationic and hydrophobic probes, while often remaining inert toward neutral hydrophilic probes [11]. The highly anionic nature of many intracellular environments, particularly in the cytoplasm, creates favorable conditions for electrostatic interactions with positively charged molecules. These interactions are condition- and species-dependent, varying with cellular conditions such as ATP depletion which can modulate associative interaction profiles [11].

Hydrophobic Interactions

Hydrophobic interactions constitute another significant source of non-specific binding in WISH. Exposed hydrophobic residues on proteins or lipid bilayers within tissue samples can interact with complementary hydrophobic regions on probes, leading to persistent background staining. Misfolded proteins become particularly problematic as they expose hydrophobic residues that recruit molecules through attractive interactions with low specificity [11]. The strength of these hydrophobic interactions is influenced by the proteome composition and density, which varies between species and cell types [11].

Combined Interaction Effects

In practical experimental conditions, electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions often operate concurrently, creating complex binding profiles that challenge optimization efforts. Research indicates that the cytoplasm interacts strongly with both highly negatively charged hydrophilic probes and cationic hydrophobic probes [11]. This dual mechanism explains why background staining persists even when addressing only one type of non-specific interaction, underscoring the need for comprehensive strategies that target multiple interaction types simultaneously.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Non-Specific Interaction Types in WISH

| Interaction Type | Strength & Affinity | Primary Tissue Targets | Environmental Modulators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic | Dissociation constants in high micromolar to millimolar range [11] | Anionic proteomes, cytoplasmic components [11] | Ionic strength, pH, ATP depletion [11] |

| Hydrophobic | Low specificity, enhanced stickiness [11] | Lipid bilayers, exposed hydrophobic protein residues [11] | Temperature, solvent composition |

| Steric | Variable based on polymer conformation [12] | Loose connective tissues, extracellular matrix [10] | Tissue permeability, cross-linking density [12] |

Experimental Evidence and Quantitative Data

Evidence from Model Systems

Research using Xenopus laevis tadpoles as a model system has demonstrated that specific tissue characteristics significantly contribute to background staining in WISH. Two primary challenges have been identified: (1) melanosomes (pigment granules) that actively migrate with cells to amputation sites and interfere with stain signals, and (2) loose fin tissues that trap staining reagents, causing strong background coloration, particularly during extended staining incubations [10]. These issues are especially pronounced in regenerating tail samples, where the loose tissue structure of tail fins creates a reservoir for trapping BM Purple and other chromogenic substrates, leading to non-specific autocromogenic reactions even after extensive washing [10].

Detection Efficiency Metrics

Comparative analyses of spatial transcriptomics technologies provide quantitative insights into hybridization efficiency. When compared to other spatially resolved transcriptomics platforms, in situ hybridization-based methods demonstrate high detection efficiency, with sensitivity measures between 1.2 and 1.5 times higher than scRNA-seq (Chromium v2) depending on the metric and region analyzed [13]. This high efficiency, while beneficial for signal detection, also amplifies the potential for background staining if non-specific interactions are not properly controlled.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Spatial Transcriptomics Methods

| Method/Platform | Detection Efficiency | Specificity (NCP) | Reads per Cell |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xenium | 1.2-1.5x higher than scRNA-seq [13] | >0.8 (slightly lower than other commercial platforms) [13] | 186.6 (average across datasets) [13] |

| MERSCOPE | Similar to Xenium [13] | >0.8 [13] | Variable |

| Molecular Cartography | Similar to Xenium [13] | >0.8 (highest) [13] | Variable |

| CosMx | Similar to Xenium [13] | >0.8 (lowest) [13] | Highest among platforms [13] |

Optimized Protocols to Minimize Non-Specific Interactions

Tissue Pre-Treatment Methods

Strategic tissue pre-treatment significantly reduces non-specific interactions by addressing both electrostatic and hydrophobic binding sites:

- Photo-bleaching: Implementation immediately after fixation in MEMPFA and dehydration effectively decolors melanosomes and melanophores, removing pigment-related interference. This step is particularly crucial for pigmented tissues, as melanophores actively migrate to sites of interest and can obscure hybridization signals [10].

- Tail Fin Notching: Creating precise incisions in a fringe-like pattern at a distance from the area of interest improves reagent penetration and washing efficiency, preventing trapping of chromogenic substrates in loose tissues. This procedure has demonstrated effectiveness even after 3-4 days of staining, with no detectable background staining [10].

- Proteinase K Optimization: Controlled digestion removes proteins that may interact non-specifically with probes, but requires precise optimization. Extended proteinase K incubation (30 minutes) for tadpole tail samples has shown limited effectiveness, producing mmp9+ cells overlapping with strong background staining, suggesting this approach requires careful calibration for different tissue types [10].

Hybridization and Washing Optimization

Modifying hybridization conditions and post-hybridization washing protocols directly addresses the thermodynamic principles governing non-specific interactions:

- Permeabilization Enhancement: Using saponin instead of proteinase K for tissue permeabilization in FFPE samples preserves tissue architecture while allowing sufficient probe penetration, as demonstrated in successful detection of engineered T-cells [14].

- Buffer Composition: Optimizing monovalent cation concentrations, pH, and organic solvent content minimizes non-specific interactions while facilitating maximum on-target binding [15].

- Temperature Control: Precise incubation temperature during hybridization is critical for maximizing specific hybridization while minimizing non-specific probe attachment [15].

- Convective Flow Techniques: Implementing microfluidic devices to actively bring probes to targets rather than relying solely on diffusion reduces overall assay time and decreases opportunities for non-specific binding [15].

Signal Detection and Visualization

Advanced detection methodologies specifically address residual non-specific interactions:

- Hydrophilic Clearing Methods: Techniques such as LIMPID (Lipid-preserving index matching for prolonged imaging depth) use aqueous clearing solutions containing saline-sodium citrate, urea, and iohexol to reduce background while preserving tissue integrity and RNA targets [9].

- Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR): This linear amplification scheme provides superior signal-to-noise ratio with low background, scaling fluorescence intensity to RNA quantity in the region for quantitative analysis [9].

- Combined ISH and IHC Protocols: Integrated approaches using saponin permeabilization for RNAscope followed by fluorescent tyramide-based detection enable simultaneous gene expression analysis and immunophenotyping with minimal background [14].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and methodologies represent critical tools for addressing non-specific interactions in WISH experiments:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Managing Non-Specific Interactions

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Mechanism | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permeabilization Agents | Proteinase K, Saponin, Triton X-100 [15] [14] | Removes proteins surrounding target nucleic acids; enables probe diffusion [15] | Saponin preferred for combined ISH/IHC; Proteinase K requires concentration optimization [14] |

| Clearing Reagents | LIMPID solution (SSC, urea, iohexol) [9] | Reduces light scattering via refractive index matching; preserves RNA and protein integrity [9] | Compatible with FISH probes and antibody staining; maintains 3D tissue architecture [9] |

| Fixation Solutions | MEMPFA, Formaldehyde, Bouin's fixative [10] [15] | Preserves tissue morphology; prevents RNA degradation [15] | Overfixation causes excessive cross-linking; reduces FISH signals [9] |

| Detection Systems | HCR probes, RNAscope, tyramide-based detection [9] [14] | Signal amplification with minimal background; enables multiplexing [9] [14] | HCR provides linear amplification for quantification; RNAscope offers high sensitivity [9] |

| Blocking Agents | Prehybridization solutions with formamide [15] | Lower background noise by quenching endogenous enzyme activity [15] | Formamide concentration affects hybridization stringency [15] |

Non-specific binding in whole-mount in situ hybridization arises from complex interactions between probe molecules and tissue components, primarily driven by electrostatic and hydrophobic forces. Successful mitigation requires a comprehensive strategy addressing multiple stages of the experimental workflow, from tissue preparation and hybridization to signal detection. The optimized protocols and reagents detailed in this technical guide provide researchers with evidence-based approaches to significantly reduce background staining while preserving specific signal intensity. As spatial transcriptomics continues to advance, further refinement of these methods will enhance our ability to visualize gene expression patterns with unprecedented clarity and precision, ultimately driving discoveries in developmental biology, regenerative medicine, and disease mechanisms.

In whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH), the interplay between tissue permeability and reagent penetration represents a critical determinant of experimental success. Impermeable tissues create significant barriers that trap reagents within the extracellular matrix or specific cellular compartments, generating the high background staining that frequently compromises data interpretation. This technical guide examines the mechanistic basis of these permeability barriers within the context of a broader thesis on background staining origins in WMISH. The endothelial cell lining of the vasculature exemplifies a natural semi-permeable barrier separating blood from interstitial spaces, and its disruption–or similar barriers in other tissues–directly influences reagent accessibility and trapping [16]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these principles is essential for optimizing staining protocols, improving signal-to-noise ratios, and generating reproducible, high-quality data in complex tissue systems.

Mechanisms of Reagent Trapping and Background Staining

Structural and Molecular Barriers to Permeability

The architecture of biological tissues inherently resists the free diffusion of reagents. The endothelial barrier serves as a prime example of a regulated semi-permeable interface, where disruption can lead to increased permeability and vascular leak associated with multiple systemic disease processes and acute tissue responses to injury [16]. In 3D tumour models, which recapitulate determinants of in vivo treatment response with more fidelity than monolayer cultures, the extracellular matrix (ECM) presents a formidable barrier to reagent penetration [17]. This ECM can bind colorimetric conversion products, leading to significant background issues [17]. Furthermore, treatment-induced architectural changes within tissues, such as those observed in response to cytotoxic agents, can alter local permeability and create microenvironments where reagents become sequestered [17].

Consequences of Reagent Impermeability

When reagents cannot penetrate tissue barriers effectively, they accumulate in extracellular spaces or bind nonspecifically to accessible epitopes rather than reaching their intended targets. This trapping phenomenon manifests experimentally as high background staining that obscures specific signal. In fluorescence imaging, this background noise can hinder reliable quantification, particularly when examining small, low-contrast structures of interest [18]. The problem is particularly pronounced in highly autofluorescent tissue samples, where distinguishing specific signal from background becomes increasingly challenging [18]. Inadequate permeability also leads to heterogeneous staining patterns, as reagents unevenly penetrate tissue compartments, creating false negatives in poorly accessed regions and false positives in areas with trapped reagents.

Quantitative Assessment of Tissue Permeability and Background

Methods for Permeability Measurement

Systematic measurement of permeability profiles across different organs provides crucial data for optimizing WMISH protocols. Simple in vivo methods can be employed to measure vascular leak and barrier function, complementing molecular findings and adding power to studies investigating the physiological significance of permeability barriers [16]. These multidisciplinary approaches acknowledge the complexity of barrier function control mechanisms, which involve multiple cell types and tissues present only in mammalian models [16].

For 3D culture systems, computational analysis of fluorescence image data enables high-content readouts of treatment-induced architectural changes and spatial patterns of effects within multicellular structures [17]. This quantitative in situ treatment assessment (qVISTA) methodology converts copious numerical readouts from segmented fluorescence signals into usable information to classify treatment effects comprehensively [17].

Imaging-Based Quantification of Background and Signal

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for Background Assessment in Fluorescent Imaging

| Parameter | Measurement Approach | Optimal Range | Impact on Background |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Density | Pixels per micrometer based on object size [18] | 0.86 µm/pixel for 2µm structures | Undersampling hinders reliable quantification; oversampling increases file size without benefit [18] |

| Lateral Resolution | (0.51 × λ)/NA, where λ is wavelength, NA is numerical aperture [18] | 0.25 to 0.75 µm for NA 0.4-1.4 | Lower resolution may miss structural details contributing to background [18] |

| Axial Resolution | Approximately 3 times lower than lateral resolution [18] | Dependent on NA and optical slice thickness | Critical for 3D structures where background may vary through tissue depth [18] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Background-corrected fluorescence intensity [18] | Maximized through optimal NA selection | Higher NA increases light transmission but may increase photobleaching [18] |

| Viability Metric | Quotient of live to total fluorescent signal (calcein/ethidium) [17] | Established via NT (no treatment) and TK (total killing) controls | Rescaling factors (Ï•) correct for incompatible baseline signals between reporters [17] |

Advanced image processing techniques are essential for accurate background quantification. As demonstrated in vascular tissue analysis, images should be processed to reduce background noise and segment objects using appropriate software [18]. This processing involves independent treatment of individual fluorescent channels to reduce background before binarization, watershedding, and subsequent analysis [18]. The sampling density for images should be determined based on the size of the structures of interest rather than the highest possible resolution of the microscope, as oversampling leads to substantially increased file sizes without improving quantification reliability [18].

Research Reagent Solutions for Permeability Challenges

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions in Permeability Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vital Dyes | Calcein AM, Ethidium Bromide | Simultaneous assessment of esterase activity (green) and membrane permeability (red) [17] | Signals must be rescaled using control groups for accurate viability metrics [17] |

| Extracellular Matrix | Growth Factor Reduced (GFR) Matrigel | Provides 3D culture environment that restores crucial stromal interactions [17] | Forms adherent multicellular 3D acini; heterogeneous in size unlike uniform spheroids [17] |

| Fluorescent Secondaries | Donkey α-chicken AlexaFluor 594, Donkey α-guinea pig AlexaFluor 647 | Immunostaining visualization for multiple targets [18] | Used at appropriate dilutions (e.g., 1:300, 1:450) in antibody diluent [18] |

| Primary Antibodies | Chicken α-tyrosine hydroxylase, Guinea pig α-synapsin | Target protein identification in sympathetic nerve termini [18] | Colocalization of multiple proteins identifies specific structures (e.g., nerve varicosities) [18] |

| Nuclear Stains | DAPI, Hoechst 33342, HCS NuclearMask stains | Cell nucleus identification and segmentation [19] | Critical for determining cell viability and proliferation in high-content analysis [19] |

| Cell Health Reporters | CellROX reagents, HCS LIVE/DEAD kits | Assessment of oxidative stress and cell viability [19] | Provide quantitative readouts of cytotoxicity in screening applications [19] |

| Metabolic Labels | Click-iT EdU, 5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine (EdU) | Detection of DNA synthesis and cell proliferation [19] | Click chemistry-based detection offers advantages over traditional BrdU methods [19] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing and Improving Tissue Permeability

Protocol: Quantitative Assessment of Barrier Function in 3D Cultures

This protocol adapts methodologies from quantitative imaging platforms for evaluation of therapeutic response in 3D tumour models [17]:

- Culture Preparation: Plate cells using ECM overlay method on growth factor-reduced Matrigel in glass-bottom multiwell imaging plates. Allow formation of adherent multicellular 3D acini (typically 5-7 days).

- Treatment Groups: Assign cultures to control (no treatment, NT) and experimental groups. Include total killing (TK) controls (fixed and permeabilized) to establish baseline signals.

- Staining: Incubate with fluorescent vital dyes (e.g., calcein AM for esterase activity, ethidium bromide for membrane permeability) for 30-45 minutes at physiological conditions.

- Image Acquisition: Using automated microscopy, acquire multiple spatial fields (e.g., 96 fields at 512×512 resolution) with brightfield and fluorescence channels. Maintain consistent acquisition parameters across all samples.

- Image Analysis: Segment individual nodules and quantify fluorescence signals. Apply background correction using TK controls. Calculate scaling factor (Ï•) based on NT and TK controls for each experiment: Ï• = (SignaldeadTK - SignalliveTK) / (SignalliveNT - SignaldeadNT).

- Viability Calculation: Compute viability as Live / (Live + ϕ × Dead) for each nodule, where Live and Dead represent background-corrected fluorescence intensities.

- Heterogeneity Assessment: Analyze distribution of viabilities across all nodules to identify sub-populations with differential permeability.

Protocol: Optimization of Image Acquisition to Minimize Background

Based on established practices for quantitative fluorescent imaging [18]:

- Determine Optimal Sampling Rate: Calculate required sampling density based on size of structures of interest. For nerve varicosities of ~2μm diameter, sampling density = Structure size / 2.3 = ~0.86 μm/pixel.

- Select Appropriate Objective Lens: Balance numerical aperture (NA) and resolution needs. For structures >2μm, even lower NA lenses (10×/0.4 NA) provide sufficient resolution while potentially reducing photobleaching.

- Configure Optical Section Thickness: Adjust pinhole size in confocal systems to optimize signal-to-noise ratio. Thinner optical sections may reduce background but require longer acquisition times.

- Establish Linear Range: Verify detector settings ensure signals are within linear response range to prevent saturation or loss of low-intensity signals.

- Process Images for Background Reduction: Apply consistent background subtraction across all images. Use segmentation algorithms appropriate for object morphology. Implement watershedding to separate clustered objects.

- Validate Quantification: Compare manual and automated counts for subset of images to ensure processing parameters do not introduce bias.

Visualization of Permeability Barriers and Experimental Workflows

Signaling Pathways in Endothelial Barrier Function

Experimental Workflow for Permeability Assessment

Permeability Barrier Effects on Reagent Distribution

Proactive Protocol Design: Methodological Strategies to Minimize Background from the Start

The success of whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) and related techniques hinges critically on the initial fixation step. Effective fixation must achieve a delicate balance: preserving cellular morphology and tissue architecture while simultaneously maintaining the accessibility of nucleic acid targets to molecular probes. When this balance is not struck, one of the most common and detrimental outcomes is high background staining, which obscures specific signals and compromises data interpretation. Background staining in WISH arises from multiple factors including inadequate fixation leading to probe entrapment, incomplete removal of unbound probe due to poor tissue permeability, and non-specific interactions between probes and cellular components. This technical guide examines current optimization strategies that address these challenges, with a focus on maximizing signal-to-noise ratio in complex biological samples.

Core Principles of Fixation Chemistry

Chemical fixatives function primarily through protein crosslinking or precipitation, creating a stable matrix that preserves structural integrity. The most widely used fixatives in WISH protocols are aldehydes, particularly paraformaldehyde (PFA) and formalin, which create methylene bridge crosslinks between primary amines on proteins and nucleic acids [20]. While effective for morphology preservation, over-fixation with PFA can cause excessive crosslinking that physically blocks probe access to target sequences, reducing hybridization efficiency and increasing background through non-specific trapping of probes in dense tissue regions [20] [9].

Alternative fixatives offer different advantages and limitations. Glutaraldehyde provides stronger crosslinking than PFA but penetrates tissue more slowly and can significantly modify tissue architecture [20]. Precipitating fixatives like ethanol and methanol coagulate large protein molecules without crosslinking, which may improve probe accessibility for some targets but provides inferior ultrastructural preservation [20]. The choice of fixative must therefore be tailored to both the sample type and the specific molecular targets being investigated.

Optimized Fixation Protocols

Enhanced Aldehyde Formulations

Recent research has demonstrated that mixed aldehyde formulations can significantly improve results in challenging applications. A glyoxal-PFA combination has shown particular promise for detecting nuclear body RNAs while preserving protein epitopes [21]. The optimized formulation (0.4% glyoxal + 4% PFA + 0.1% methanol) enhances probe accessibility without introducing autofluorescence, yielding significantly brighter FISH signals for various RNA species including NEAT1, MALAT1, and polyadenylated RNAs [21].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Fixative Formulations for RNA FISH

| Fixative Formulation | Signal Intensity | Background Uniformity | Morphology Preservation | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4% PFA (standard) | Baseline | Moderate | Excellent | General WISH, protein detection |

| 0.4% GO + 4% PFA + 0.1% MeOH | ~2x increase | High (low SD) | Excellent | Nuclear RNAs, low-abundance targets |

| 3% GO + 20% EtOH | Moderate increase | Moderate | Good | Combined RNA/protein detection |

| 0.1% GA + 4% PFA | Mild increase | Moderate | Excellent | EM studies, superior morphology |

The improvement observed with glyoxal-PFA fixation appears to stem from enhanced cell permeability and probe accessibility rather than direct effects on hybridization efficiency. Time-lapse imaging demonstrates significantly faster penetration of DAPI into nuclei fixed with GO/PFA compared to PFA alone, with both increased penetration rate and higher plateau intensity [21]. This improved permeability allows more efficient probe delivery and washing, directly reducing non-specific background staining.

Supplementary Treatments for Challenging Tissues

Certain tissues present unique challenges for WISH due to their inherent properties. In regenerating tails of Xenopus laevis tadpoles, pigment granules (melanosomes) actively migrate to amputation sites and can interfere with colorimetric detection [10]. Additionally, loose fin tissues tend to trap staining reagents, causing high background. An optimized protocol addressing these issues includes:

- Early photo-bleaching: Performed after fixation in MEMPFA and rehydration to decolorize melanosomes and melanophores without compromising RNA integrity [10]

- Tail fin notching: Creating precise incisions in a fringe-like pattern at a distance from the area of interest dramatically improves reagent washout from loose fin tissues, preventing non-specific chromogenic reactions even after 3-4 days of staining [10]

This combined approach enables high-contrast imaging of low-abundance targets like mmp9 mRNA during early regeneration stages, revealing spatial and temporal expression patterns that were previously obscured by background interference [10].

Optical Clearing for Enhanced Probe Accessibility

For thick tissue samples, optical clearing techniques can significantly improve probe penetration and washing efficiency, thereby reducing background. The 3D-LIMPID-FISH method uses a hydrophilic clearing solution containing saline-sodium citrate, urea, and iohexol to match the refractive index of the tissue [9]. This approach:

- Preserves most lipids and minimizes tissue swelling/shrinking

- Maintains compatibility with both FISH probes and antibody staining

- Enables high-resolution imaging deep within thick tissues (up to 250μm) without physical sectioning

- Facilitates multiplexed imaging of both mRNA and protein targets within the same sample [9]

Diagram 1: Fixation impact on WISH background and signal intensity.

Experimental Protocols

Materials:

- 4% PFA in 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4)

- Glyoxal solution (40%)

- Methanol

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

Procedure:

- Prepare fixation solution fresh: Combine 4% PFA, 0.4% glyoxal, and 0.1% methanol in PBS.

- Fix cell cultures or tissue samples for 15-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Rinse three times with PBS (5 minutes each).

- Proceed with standard WISH or FISH protocols without proteinase K treatment.

- For samples with high lipid content, consider adding a delipidation step (30-60 minutes in 0.5% Triton X-100) before hybridization.

Validation:

- Test penetration efficiency using DAPI time-lapse imaging

- Compare signal intensity for a housekeeping RNA (e.g., 18S rRNA) against PFA-only controls

- Verify background uniformity by measuring fluorescence intensity in non-target regions

Materials:

- MEMPFA fixation solution

- Hydrogen peroxide bleaching solution

- Proteinase K solution

Procedure:

- Fix samples in MEMPFA for 2-4 hours at room temperature.

- Dehydrate through ethanol series (25%, 50%, 75%, 100%).

- Bleach samples in Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ solution under bright light until pigment is removed.

- Rehydrate through descending ethanol series.

- Create fine notches in loose tissue areas (e.g., fin edges) using micro-scissors.

- Perform standard WISH with reduced proteinase K incubation (10-15 minutes).

- Extend washing steps post-hybridization (4-5 changes over 6-8 hours).

Validation:

- Compare mmp9 expression patterns at 0, 3, 6, and 24 hours post-amputation

- Assess background in fin regions adjacent to notched areas

- Verify tissue integrity after notching through histological staining

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Optimized Fixation Protocols

| Reagent | Function | Optimized Concentration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Primary crosslinking fixative | 4% in buffer | Prepare fresh from powder; avoid methanol-stabilized solutions |

| Glyoxal | RNA denaturation, enhanced permeability | 0.4% with PFA | Sterically hinders G-C base pairs; improves probe access |

| Methanol | Fixation accelerator | 0.1% with GO/PFA | Enhances GO-based fixation without acting alone |

| Glutaraldehyde | Strong crosslinking | 0.1-0.5% with PFA | Use for superior morphology; may require quenching |

| Proteinase K | Protein digestion, epitope unmasking | 1-10μg/mL | Titrate carefully; over-digestion damages morphology |

| Triton X-100 | Permeabilization | 0.1-0.5% | Improves probe penetration; extract lipids |

| Formamide | Hybridization stringency | 10-50% in buffer | Denatures RNA secondary structure; concentration affects specificity |

Integration with Advanced Methodologies

Optimized fixation protocols provide particular benefits for emerging spatial transcriptomics technologies. Methods like MERFISH (Multiplexed Error-Robust Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization) depend on efficient probe binding to achieve high detection efficiency and low false-positive rates [22]. Recent systematic optimization of MERFISH parameters has revealed that signal brightness depends significantly on hybridization conditions and probe design [22].

For MERFISH and related methods, fixation must preserve RNA integrity while maintaining accessibility for encoding probes containing targeting regions (20-50 nt) and readout sequences. The GO/PFA approach shows particular promise for these applications, as the enhanced permeability benefits the sequential hybridization rounds required for barcode readout [22]. Additionally, the move toward combined molecular profiling—simultaneous detection of RNA via FISH and proteins via immunohistochemistry—further emphasizes the need for balanced fixation that preserves multiple macromolecular species without compromising accessibility [9].

Diagram 2: Strategic approaches to reduce WISH background staining.

Effective fixation for whole-mount in situ hybridization requires moving beyond standardized protocols to embrace sample-specific optimization. The fundamental challenge of balancing structural preservation with molecular accessibility can be addressed through innovative fixative formulations like glyoxal-PFA combinations, supplementary physical processing methods such as tissue notching, and integration with optical clearing techniques. As spatial transcriptomics and multi-omics approaches continue to evolve, the development and implementation of these optimized fixation procedures will play an increasingly critical role in minimizing background staining while maximizing the biological insights gained from each experiment.

Effective tissue permeabilization is a critical determinant of success in whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH), directly influencing both signal intensity and background staining—the primary challenge in obtaining interpretable results. The fundamental purpose of permeabilization is to enable nucleic acid probes to access their target sequences while maintaining structural integrity, a balance that requires precise optimization of enzymatic and chemical treatments. Inadequate permeabilization results in weak or false-negative signals due to poor probe penetration, whereas excessive treatment degrades tissue morphology and increases non-specific background staining [23] [24]. This technical guide examines advanced permeabilization methodologies within the context of a broader thesis: that optimizing proteinase K digestion and acid treatments represents the most critical step in minimizing background staining while ensuring efficient probe penetration in complex biological specimens.

The relationship between permeabilization and background staining manifests through multiple mechanisms. Insufficiently digested tissues retain physical barriers that trap probes non-specifically, while over-digestion exposes charged molecular motifs that bind probes indiscriminately [25]. Furthermore, tissues with high endogenous protein content or specialized extracellular matrices require customized permeabilization strategies to overcome unique accessibility challenges. The following sections provide quantitative guidance and detailed protocols for achieving this balance across diverse experimental systems, with particular emphasis on proteinase K titration and complementary treatments that have demonstrated efficacy in reducing background staining while enhancing signal-to-noise ratios.

Quantitative Analysis of Permeabilization Parameters

Table 1: Proteinase K Concentration and Digestion Time Optimization Across Biological Systems

| Biological System | Developmental Stage/Tissue Type | Proteinase K Concentration | Digestion Time | Temperature | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenopus laevis tadpole tail [1] | Regenerating tail (stage 40) | 10 μg/mL | 30 minutes | Room temperature | Extended digestion time increased sensitivity but required fin notching to reduce background |

| Mouse embryos [5] | Whole mount (E14.5) | 10 μg/mL | Not specified | Not specified | Used in pretreatment solution for whole mount in situ hybridization |

| Mouse embryo sections [5] | Tissue sections | 20 μg/mL | Not specified | Not specified | Higher concentration used for sectioned tissues |

| Lymnaea stagnalis larvae [25] | 2-3 days post first cleavage | 10 μg/mL | 10 minutes | Room temperature | Part of optimized WMISH protocol with additional permeabilization steps |

| Pea aphid embryos [26] | Early, middle, and late-stage embryos | Varied by stage | Titrated by tissue thickness | Not specified | Conditions optimized based on tissue thickness and developmental stage |

| General ISH troubleshooting [23] | Most tissues | Not specified | 3-10 minutes | 37°C | Under-digestion decreases or eliminates signal; over-digestion weakens signal and prevents counterstaining |

Table 2: Acid and Chemical Treatment Parameters for Enhanced Permeabilization

| Treatment Type | Concentration | Duration | Biological Systems | Effect on Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) [24] | Diluted solution | Not specified | General ISH applications | Increases hybridization signal when combined with protease treatment |

| Triethanolamine (TEA) + Acetic Anhydride [5] [25] | 0.1 M TEA + 0.25% acetic anhydride | 10 minutes | Mouse embryos, Lymnaea stagnalis | Reduces tissue-specific background staining, particularly in shell field |

| SDS Treatment [25] | 0.1-1% in PBS | 10 minutes | Lymnaea stagnalis larvae | Significant improvement in signal intensity without morphological damage |

| Reduction Solution (DTT + SDS + NP-40) [25] | 0.1X to 1X | 10 minutes | Lymnaea stagnalis larvae | Greatly increases signal intensity but makes tissues extremely fragile |

| N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) [25] | 2.5-5% | 5-10 minutes | Lymnaea stagnalis larvae | Degrades mucosal layer, improving probe accessibility |

Proteinase K Digestion: Mechanisms and Methodologies

Biochemical Mechanism and Rationale

Proteinase K, a broad-spectrum serine protease, catalyzes the cleavage of peptide bonds adjacent to the carboxyl group of aliphatic and aromatic amino acids, effectively digesting proteins that surround target nucleic acids and creating channels for probe penetration [24]. This enzymatic digestion is particularly crucial for disrupting cellular membranes and extracellular matrix components that would otherwise function as physical barriers to hybridization. The efficacy of proteinase K stems from its remarkable stability across a wide temperature range (up to 65°C) and its ability to maintain activity in the presence of denaturing agents such as SDS and EDTA, making it ideally suited for the harsh conditions often required for tissue pretreatment [26].

The relationship between proteinase K concentration and background staining follows a biphasic response curve. At suboptimal concentrations, incomplete permeabilization occurs, leading to heterogeneous probe accessibility that manifests as both weak specific signals and moderate background staining in partially digested regions. As concentration increases, optimal permeabilization is achieved with maximal target accessibility and minimal non-specific binding. However, supra-optimal concentrations over-digest tissues, exposing charged internal components that bind probes indiscriminately while simultaneously compromising tissue integrity, resulting in severely elevated background staining and morphological deterioration [23] [25]. This nonlinear response necessitates empirical optimization for each biological system and developmental stage.

Standardized Proteinase K Digestion Protocol

The following protocol represents a optimized methodology for proteinase K digestion in WMISH applications, synthesized from multiple established techniques [5] [1] [25]:

Post-Fixation Processing: Following fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde and thorough washing in PBT (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20), rehydrate samples through a graded methanol series (25%, 50%, 75% methanol in PBT) if stored in methanol at -20°C. Perform three 5-minute washes in PBT to ensure complete removal of organic solvents.

Proteinase K Working Solution Preparation: Prepare a fresh dilution of proteinase K from stock solution (typically 10-20 mg/mL) in PBT to achieve a working concentration appropriate for your tissue type (see Table 1 for guidance). For sensitive tissues, begin with lower concentrations (1-5 μg/mL) and incrementally increase until optimal permeabilization is achieved.

Digestion Reaction: Incubate samples in proteinase K solution with gentle agitation. For most tissues, digestion at room temperature for 10-30 minutes provides sufficient permeabilization without excessive morphological damage. Monitor digestion carefully, as overtreatment can irreversibly damage tissue architecture [23].

Digestion Termination: Carefully remove proteinase K solution and immediately stop the reaction by washing samples in 2 mg/mL glycine in PBT for 5 minutes. Glycine functions as an effective protease inhibitor by competing for the enzyme's active site.

Post-Digestion Fixation: To stabilize permeabilized tissues and prevent structural collapse, perform brief post-fixation in 4% PFA for 20 minutes at room temperature. This step crosslinks proteins exposed during digestion without significantly reducing probe accessibility.

Acetylation (Optional but Recommended): For tissues with persistent background issues, particularly those with high endogenous phosphatase activity or charged extracellular matrices, incubate samples in 0.1% triethanolamine (TEA) containing 0.25% acetic anhydride for 10 minutes with constant mixing. This acetylation reaction neutralizes positive charges on amine groups that would otherwise bind negatively charged probes non-specifically [5] [25].

Complementary Permeabilization Techniques

Acid Treatments for Enhanced Probe Accessibility

Hydrochloric acid (HCl) treatment serves as a complementary permeabilization strategy that functions through distinct mechanisms from enzymatic digestion. Dilute HCl (typically 0.01-0.1M) partially hydrolyzes peptide bonds and demineralizes calcified tissues, while also protonating carboxyl groups and neutralizing negative charges that contribute to electrostatic background binding [24]. This treatment is particularly valuable for tissues with extensive extracellular matrix deposition or chitinous structures that resist enzymatic digestion alone. The combination of proteinase K with HCl treatment has demonstrated synergistic effects in challenging specimens, likely due to the sequential action on proteinaceous and mineralized barriers respectively.

Detergent-Based Permeabilization Strategies

Detergents function as chemical permeabilization agents through solubilization of lipid membranes and disruption of hydrophobic interactions within tissues. The optimized WMISH protocol for Lymnaea stagnalis systematically compared different detergent treatments and established that 0.1% SDS incubation for 10 minutes significantly improved signal intensity without morphological damage [25]. The "reduction" treatment (combining the reducing agent DTT with detergents SDS and NP-40) produced even greater signal enhancement but rendered tissues extremely fragile, requiring exceptionally careful handling. These findings demonstrate that detergent concentration must be balanced against structural preservation requirements, with lower concentrations (0.05-0.1% SDS) generally recommended for delicate embryonic tissues.

Diagram 1: Permeabilization optimization workflow for different tissue types. The pathway illustrates how to select and sequence treatments based on tissue characteristics and troubleshooting outcomes.

Integrated Experimental Workflows

Case Study: Optimized Permeabilization for Challenging Tissues

The regenerative tadpole tail system of Xenopus laevis presents exceptional challenges for WMISH due to rapid cellular migration, dense pigmentation, and loose fin tissues prone to background staining [1]. Through systematic optimization, researchers developed an integrated permeabilization workflow that combines proteinase K digestion with specialized physical and chemical treatments:

Initial Processing: Fix regenerating tail samples in MEMPFA (4% PFA, 2mM EGTA, 1mM MgSOâ‚„, 100mM MOPS pH 7.4) for 30 minutes at room temperature.

Photobleaching: To address melanosome interference with colorimetric detection, treat fixed samples with photobleaching solution under bright light to decolorize pigment granules that obscure specific staining.

Physical Permeabilization: Carefully notch the caudal fin in a fringe-like pattern using fine microscissors, creating channels that enhance reagent penetration and washout from loose fin tissues where background staining typically accumulates.

Proteinase K Digestion: Incubate samples in 10μg/mL proteinase K for 30 minutes at room temperature, with precise timing to avoid over-digestion of the delicate regenerating tissues.