Whole Mount Immunofluorescence for Mouse Embryos: A Complete Guide from Principles to 3D Analysis

This comprehensive overview details the application of whole-mount immunofluorescence (WM-IF) for the 3D spatial analysis of protein localization in mouse embryonic tissues.

Whole Mount Immunofluorescence for Mouse Embryos: A Complete Guide from Principles to 3D Analysis

Abstract

This comprehensive overview details the application of whole-mount immunofluorescence (WM-IF) for the 3D spatial analysis of protein localization in mouse embryonic tissues. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, the article covers foundational principles, optimized step-by-step protocols, advanced troubleshooting for common challenges, and rigorous validation techniques. It highlights the method's critical role in developmental biology, drug testing pipelines, and quantitative analysis of progenitor cell populations, providing a complete resource for implementing this powerful technique to study tissue architecture and cellular interactions in their native context.

Understanding Whole Mount Immunofluorescence: Principles and Power of 3D Imaging

The preservation of native three-dimensional architecture represents a fundamental prerequisite for meaningful spatial protein analysis in biological systems. Traditional methods that involve tissue sectioning inevitably disrupt structural context and spatial relationships, limiting our understanding of cellular interactions within their native microenvironment. This technical guide examines the core principles and methodologies for maintaining 3D integrity throughout the analytical pipeline, with specific application to whole mount immunofluorescence in mouse embryo research. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these techniques is essential for investigating protein expression patterns, cell signaling networks, and developmental processes in their authentic volumetric context. The integration of advanced tissue processing, imaging, and computational approaches discussed herein provides a framework for extracting high-fidelity spatial proteomic data from intact specimens.

Foundational Methodologies for 3D Analysis

Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence Protocol for Mouse Embryos

The whole-mount fluorescent immunostaining protocol for mouse embryos demonstrates a comprehensive approach to preserving 3D architecture while enabling protein localization studies. This method maintains structural integrity through carefully optimized fixation and processing steps [1].

Key Protocol Steps:

- Fixation: Embryos are fixed for 6 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) to preserve native protein localization and tissue structure

- Dehydration and Bleaching: Gradual methanol dehydration (25%, 50%, 75%, 100%) followed by 24-hour incubation in methanol at 4°C and 24-hour bleaching in methanol/hydrogen peroxide solution to reduce autofluorescence

- Permeabilization and Blocking: Post-fixation with Dent's Fixative (DMSO:methanol, 1:4) overnight at 4°C, followed by 1-hour blocking on ice in blocking solution (0.2% BSA, 20% DMSO in PBS) with 0.4% Triton

- Antibody Incubation: Extended primary antibody incubation for four days at room temperature, followed by secondary antibody incubation overnight in blocking solution

- Clearing and Imaging: Tissue clearing using BABB (benzyl alcohol:benzyl benzoate, 1:2) after methanol dehydration, with imaging performed using spinning disc confocal microscopy

Table 1: Key Reagents for Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence

| Reagent | Function | Concentration/Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Tissue fixation and antigen preservation | 4% for 6 hours |

| Methanol Series | Dehydration and tissue preparation | 25%, 50%, 75%, 100% |

| Hydrogen Peroxide/Methanol | Bleaching to reduce autofluorescence | 1:2 ratio for 24 hours at 4°C |

| Dent's Fixative | Post-fixation and permeabilization | DMSO:methanol (1:4) overnight at 4°C |

| BSA/DMSO/PBS/Triton | Blocking and permeabilization | 0.2% BSA, 20% DMSO, 0.4% Triton |

| BABB | Tissue clearing for deep imaging | Benzyl alcohol:benzyl benzoate (1:2) |

Tissue Clearing for 3D Imaging

Advanced tissue clearing techniques are essential for facilitating deep imaging within intact specimens. The CUBIC (Clear, Unobstructed Brain/Body Imaging Cocktails and Computational analysis) method enables visualization of internal structures without physical sectioning. This approach is particularly valuable for examining gene expression patterns through LacZ staining in cleared embryos and adult tissues, allowing spatial and temporal assessment of gene expression throughout development [2].

The CUBIC-1 reagent, containing 25 wt% N,N,N',N'-Tetrakis(2-hydroxypropyl)ethylenediamine, 25 wt% urea, and 15 wt% Triton X-100, enables effective tissue clearing by homogenizing refractive indices throughout the specimen. This process requires immersion for several hours until tissues become transparent, enabling comprehensive 3D analysis of protein distribution and gene expression patterns [2].

Computational Tools for 3D Spatial Analysis

Nuclear Segmentation Algorithms for Multiplexed Imaging

Accurate nuclear segmentation represents a critical first step in single-cell spatial analysis within 3D volumes. Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated the performance of various nuclear segmentation tools across multiple tissue types, providing guidance for algorithm selection based on specific research needs [3].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Nuclear Segmentation Platforms

| Segmentation Platform | Algorithm Type | F1-Score (IoU=0.5) | Tissue-Type Specific Performance | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesmer | Deep Learning | 0.67 | Best performance in skin and breast tissue | High computational requirements |

| Cellpose | Deep Learning | 0.65 | Superior performance in tonsil tissue | Moderate computational requirements |

| StarDist | Deep Learning | 0.63 | Performs well at high IoU thresholds (>0.75) | 12x faster with CPU, 4x with GPU vs. Mesmer |

| QuPath | Classical/Morphological | 0.55 | Consistent performance across tissue types | Low computational requirements |

| inForm | Proprietary | 0.54 | Moderate performance across tissue types | Commercial license required |

| CellProfiler | Classical/Morphological | 0.48 | Limited accuracy | Low computational requirements |

| Fiji | Classical/Morphological | 0.45 | Limited accuracy | Low computational requirements |

The benchmarking analysis encompassing approximately 20,000 labeled nuclei from seven human tissue types demonstrated that pre-trained deep learning models consistently outperform classical segmentation algorithms based on morphological operations. Mesmer emerged as the top-performing platform overall, exhibiting the highest nuclear segmentation accuracy with a 0.67 F1-score at an IoU threshold of 0.5. However, algorithm performance varied significantly across tissue types, highlighting the importance of selecting segmentation methods appropriate for specific experimental contexts [3].

3D Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction

SpatialPPI represents an advanced computational approach for predicting protein-protein interactions (PPIs) based on 3D structural information derived from AlphaFold Multimer predictions. This method leverages deep neural networks to analyze protein complex structures by transforming atomic coordinates and utilizing sophisticated image-processing techniques to extract vital 3D structural information [4].

The SpatialPPI pipeline employs both Densely Connected Convolutional Networks (DenseNet) and Deep Residual Networks (ResNet) within 3D convolutional networks to process protein 3D structure data. When benchmarked against leading PPI prediction methods including SpeedPPI, D-script, DeepTrio, and PEPPI, SpatialPPI exhibited superior efficacy, emphasizing the value of 3D spatial processing in advancing structural biology research [4].

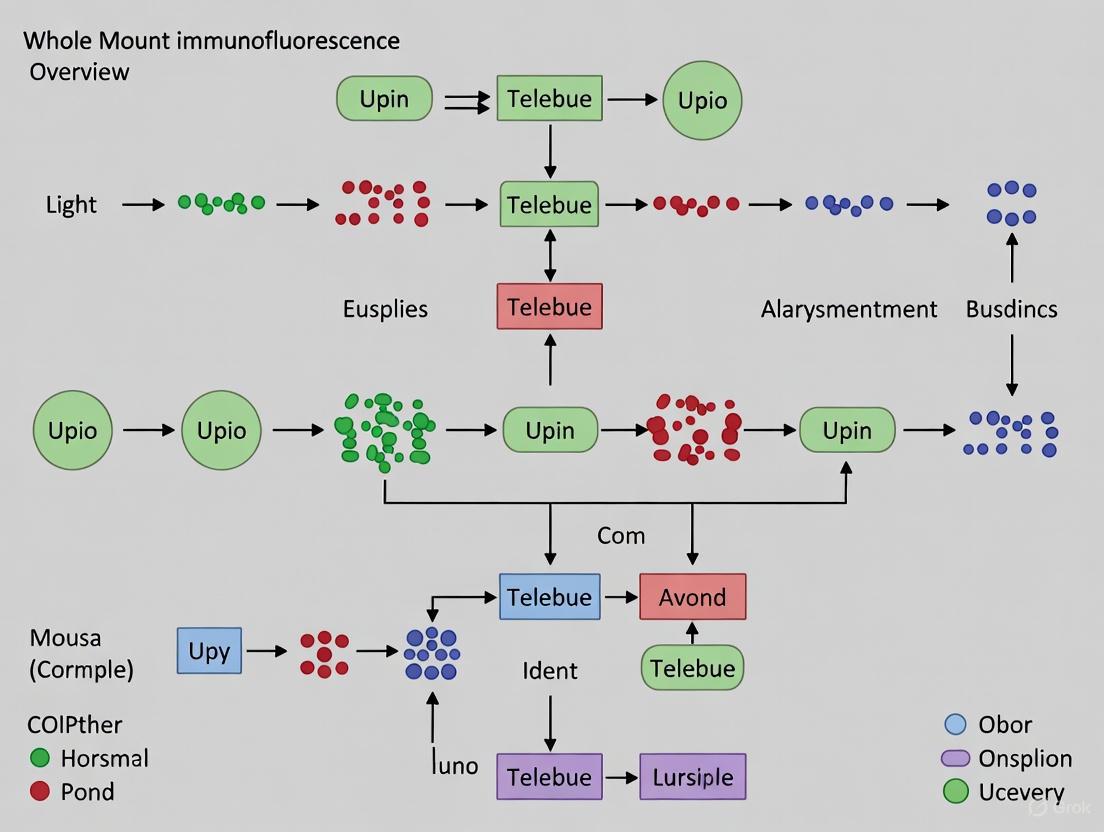

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for 3D spatial protein analysis in mouse embryos, highlighting critical steps for architecture preservation.

Advanced Spatial Analysis Techniques

Multiplexed Immunofluorescence for Single-Cell Heterogeneity

Multiplexed immunofluorescence (MxIF) enables quantitative, single-cell-based imaging of multiple protein markers within intact tissue contexts. This sequential staining approach involves applying fluorescent-labeled antibodies to tissue sections, followed by digital imaging and chemical bleaching of fluorophores between staining rounds. This methodology facilitates analysis of co-expression patterns and spatial distributions of numerous biomarkers at single-cell resolution, providing insights into cellular heterogeneity while maintaining architectural context [5].

In breast cancer research, MxIF has revealed significant heterogeneity in protein co-expression signatures and cellular arrangement within defined subtypes. Spatial analysis demonstrated variability in cellular neighborhoods within both cancer compartments and the tumor microenvironment, highlighting the value of this approach for understanding complex tissue organization [5].

Three-Dimensional Spatial Proteomics in Intact Specimens

Emerging spatial proteomics methodologies enable comprehensive protein mapping within three-dimensional intact specimens. These approaches combine tissue clearing methods with advanced mass spectrometry and artificial intelligence-driven analysis to characterize protein distribution throughout volumetric samples. Such techniques are particularly valuable for understanding spatial protein patterns in complex tissues and organs, including applications in Alzheimer's disease, traumatic brain injury, and human heart research [6].

The integration of robotics, deep learning, and spatial-omics technologies provides unprecedented capability to map protein distributions within their native 3D contexts, offering insights into organizational principles of biological systems that cannot be captured through traditional 2D approaches.

Computational Analysis Pipeline

Figure 2: Computational pipeline for 3D spatial analysis, from raw image processing to quantitative visualization.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 3D Spatial Protein Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in 3D Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA), Dent's Fixative (DMSO:methanol) | Preserve native protein positions and tissue architecture |

| Permeabilization Agents | Triton X-100, NP-40 Substitute | Enable antibody penetration throughout intact specimens |

| Blocking Solutions | BSA, DMSO in PBS | Reduce non-specific antibody binding in thick tissues |

| Tissue Clearing Reagents | BABB, CUBIC-1, CUBIC-2 | Homogenize refractive indices for deep imaging |

| Primary Antibodies | Mouse 2H3 (neurofilament), rabbit α-TFAP2A | Target-specific protein detection |

| Secondary Antibodies | Goat α-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 633, Goat α-Mouse Alexa Fluor 488 | Fluorescent detection with minimal spectral overlap |

| Mounting Media | BABB, specialized 3D media | Maintain tissue clarity and optical properties during imaging |

| Enzyme Substrates | X-gal (for LacZ detection) | Visualize gene expression patterns in cleared tissues |

The preservation of three-dimensional architecture represents an essential foundation for meaningful spatial protein analysis in complex biological systems. The integrated methodologies presented—encompassing specialized tissue processing, advanced imaging modalities, and sophisticated computational analysis—provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for investigating protein distribution and interactions within their native volumetric context. As these technologies continue to evolve, particularly through enhancements in tissue clearing, multiplexed imaging, and artificial intelligence-driven analysis, they promise to yield increasingly detailed insights into the spatial organization of biological systems. For mouse embryo research and drug development applications, these approaches enable unprecedented understanding of developmental processes, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic effects within physiologically relevant architectural contexts.

Key Advantages over Traditional Sectioning Methods

Whole-mount immunofluorescence (WMIF) represents a transformative approach in the study of biological specimens, particularly for complex three-dimensional structures like mouse embryos. Unlike traditional sectioning methods, which involve physically slicing tissues into thin sections, WMIF enables the entire intact specimen to be processed, stained, and imaged. This technical guide details the core advantages of WMIF over traditional histology, framing the discussion within mouse embryo research. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these benefits is crucial for designing more physiologically relevant and spatially accurate experiments.

Comparative Advantages of Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence

The transition from traditional sectioning to whole-mount techniques offers several distinct, quantifiable advantages that enhance data interpretation and experimental outcomes.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence over Traditional Sectioning

| Feature | Traditional Sectioning Methods | Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Spatial Context | Compromised; 3D architecture must be reconstructed from sequential 2D sections. [7] | Preserved; enables analysis of cellular relationships and protein localization in intact 3D space. [7] [8] | Accurate understanding of developmental gradients, cell migration, and tissue organization. |

| Tissue Integrity | Disrupted by physical cutting, potentially creating artifacts. [9] | Maintained; no physical sectioning required, preserving delicate structures. [9] | Reduced experimental artifacts, leading to more reliable data. |

| Single-Cell Resolution in Context | Limited to 2D plane; complete cell morphology may be lost. [10] | Achievable throughout the entire volume of the specimen with advanced microscopy. [10] | Comprehensive phenotyping and tracking of individual cells within their native microenvironment. |

| Workflow Efficiency | Requires sectioning, mounting, and often antigen retrieval for FFPE tissues. [11] | Eliminates sectioning and deparaffinization steps; a more streamlined protocol. [8] | Faster time-to-result and reduced sample manipulation, minimizing sample loss. |

| Compatibility with Advanced Imaging | Ideal for standard widefield microscopy and 2D analysis. | Essential for light-sheet microscopy and accurate 3D rendering/quantification. [10] | Enables high-resolution, rapid volumetric imaging of large, cleared samples. |

The paramount advantage of WMIF is the preservation of three-dimensional spatial information. In developmental biology, the position of a cell and its interactions with neighbors are often as critical as its molecular identity. Traditional sectioning irrevocably severs these connections, requiring complex and often error-prone reconstruction to infer 3D organization. In contrast, WMIF allows for the direct visualization of structures throughout the entire embryo, enabling a comprehensive interpretation of expression domains and cellular networks in their native configuration. [7]

Furthermore, WMIF avoids tissue processing artifacts inherent to sectioning. Physical cutting can crush, tear, or dislodge parts of a specimen, particularly in delicate, early-stage embryos. By processing the sample as a whole, these mechanical artifacts are eliminated, leading to a more faithful representation of the original tissue. [9] This preservation of integrity is crucial for accurately assessing morphology and structure.

Modern WMIF protocols, when combined with optical clearing and light-sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM), enable rapid, high-resolution volumetric imaging. A prominent example from immunology demonstrates that imaging a whole lymph node via confocal microscopy can take up to 12 hours, whereas the same sample can be imaged in 3D via light-sheet microscopy in approximately 30 minutes while conserving single-cell resolution. [10] This dramatic reduction in imaging time also minimizes photodamage and allows for the handling of larger sample cohorts.

Finally, the WMIF workflow can be more efficient for 3D analysis. Traditional methods for 3D reconstruction involve serial sectioning, immunohistochemistry on dozens of sections, and digital alignment. WMIF condenses this into a single processing and staining workflow for the entire sample, reducing hands-on time and potential error in alignment. [8]

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Mouse Embryos

This section outlines a generalized protocol for whole-mount immunofluorescence staining of early mouse embryos, synthesizing established methodologies. [7]

Sample Collection and Fixation

- Dissection: Isolate preimplantation to early postimplantation mouse embryos (up to E8.0) using standard surgical techniques. Perform all procedures in accordance with institutional animal care guidelines.

- Washing: Transfer embryos into a dish containing ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove residual blood and debris.

- Fixation: Immerse embryos in a fixative solution, typically 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. The fixation time must be optimized based on the size and age of the embryo (e.g., 30 minutes to several hours at 4°C). Critical: Over-fixation can mask antigen epitopes and reduce staining quality. [9] [7]

- Washing: After fixation, wash the embryos thoroughly with PBS (e.g., three washes for 15-30 minutes each) to remove all traces of PFA.

Permeabilization and Blocking

- Permeabilization: Incubate embryos in a permeabilization solution to allow antibodies to access intracellular targets. A common solution is 0.2% to 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS. Incubation times vary from 1 hour to overnight, depending on the specimen's size and density.

- Blocking: To prevent non-specific antibody binding, incubate embryos in a blocking buffer for several hours or overnight at 4°C. A standard buffer contains 0.1% BSA, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 10% normal serum (from the species in which the secondary antibody was raised) in PBS. [9]

Immunofluorescence Staining

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate embryos with the primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer. This incubation typically occurs for 20-48 hours at 4°C under gentle agitation to ensure even penetration. [7]

- Washing: Remove unbound primary antibody with multiple, prolonged washes (e.g., 5-6 washes over 12-24 hours) using a wash solution like PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBS-T).

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Incubate embryos with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies, diluted in blocking buffer, for 12-24 hours at 4°C in darkness.

- Nuclear Staining (Optional): A final incubation with a nuclear counterstain like Hoechst 33342 or DAPI can be performed for 1-16 hours. [9]

- Final Washes: Perform extensive final washes in PBS-T or PBS to reduce background fluorescence.

Optical Clearing and Mounting

For deep imaging, embryos may be rendered transparent using an optical clearing agent. A simple and effective clearing solution is a 1:2 mixture of Benzyl Alcohol and Benzyl Benzoate (BABB). After dehydration through an ethanol series, embryos are transferred to BABB, which makes them transparent and ready for imaging. [9] The cleared embryos are then mounted in the clearing medium within a specialized imaging chamber.

Image Acquisition

Image the stained and cleared embryos using a microscope capable of 3D capture, such as a confocal or light-sheet fluorescence microscope. Acquire Z-stacks with a step size appropriate for the resolution required to capture the full volume of the embryo.

Workflow for Whole-Mount Staining

Visualization and Data Analysis Tools

The complex 3D data generated by WMIF requires robust software and hardware for analysis and visualization.

Table 2: Key Reagent and Software Solutions for WMIF Research

| Category | Item | Function in WMIF | Example Products/Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation | Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-links proteins to preserve tissue structure and antigenicity. | 4% PFA in PBS [9] [7] |

| Permeabilization | Triton X-100 | Solubilizes lipid membranes to allow antibody penetration. | 0.2-0.5% in PBS [9] |

| Blocking | Normal Serum & BSA | Reduces non-specific background antibody binding. | 10% Goat Serum, 0.1% BSA [9] |

| Visualization | Fluorophore-conjugated Antibodies | Tag specific proteins for detection via microscopy. | Alexa Fluor 488, 555, 647, etc. [10] [9] |

| Nuclear Stain | Hoechst 33342 / DAPI | Labels DNA to identify all nuclei within the specimen. | [9] |

| Clearing Agent | BABB | Matches refractive index of tissue to render it transparent. | Benzyl Alcohol/Benzyl Benzoate [9] |

| Analysis Software | ImageJ/Fiji, Imaris | Processes, visualizes, and quantifies 3D image data. | Open-source (Fiji) [12], Commercial (Imaris) [10] |

| Advanced Analysis | CellProfiler, Icy, QuPath | Open-source platforms for automated cell segmentation and analysis. | [12] |

| AI-Driven Analysis | Machine Learning Segmentation | Automates identification and classification of complex structures in 3D. | [10] [13] |

A critical step in leveraging WMIF data is the use of optical clearing to reduce light scattering within the tissue. This process is essential for achieving high-resolution imaging deep within a specimen. Protocols using agents like BABB make tissues transparent, allowing light from the microscope to penetrate deeply with minimal distortion. [9]

For image analysis, open-source software like ImageJ/Fiji is a cornerstone of the field. Its ability to handle Z-stacks, perform 3D rendering, and its extensive plugin ecosystem make it an indispensable tool. [12] For more advanced and automated quantification, commercial software such as Imaris provides powerful segmentation and visualization tools, including machine learning capabilities that can identify and quantify specific cell types, like germinal center B cells or T follicular helper cells, within a whole immunized lymph node in 3D. [10] The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) is now pushing the boundaries further, enhancing image processing, automating analysis, and assisting in the interpretation of complex, multi-dimensional microscopy data. [13]

3D Image Analysis Pipeline

Whole-mount immunofluorescence offers a paradigm shift from traditional sectioning by providing an uncompromised, volumetric view of biological structures. The key advantages—preservation of 3D architecture, elimination of sectioning artifacts, compatibility with rapid volumetric imaging, and streamlined workflows—make it an indispensable technique for modern developmental biology, particularly in mouse embryo research. As optical clearing methods become more robust and image analysis software more powerful with the integration of AI, WMIF is poised to remain at the forefront of spatial biology, enabling deeper insights into the complex processes that govern development and disease.

Whole mount immunofluorescence represents a powerful technique for visualizing protein expression within the intact three-dimensional architecture of tissues, with mouse embryos serving as a critical model system in developmental biology, neurobiology, and embryology [14]. Unlike traditional methods that require physical sectioning, whole mount staining preserves the spatial relationships and tissue architecture essential for understanding complex biological processes such as organogenesis and neural circuit formation [14]. The successful application of this technique, however, hinges on the meticulous optimization of three interdependent components: fixation, permeabilization, and antibody penetration. These steps collectively ensure that the structural integrity of the specimen is maintained while allowing antibodies sufficient access to their target antigens throughout the thick tissue sample. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these core components, offering detailed methodologies and strategic frameworks tailored specifically for researchers working with mouse embryos to achieve reproducible and high-resolution staining outcomes suitable for advanced imaging modalities like confocal microscopy [14].

Component 1: Fixation

Fixation constitutes the foundational step in any whole mount immunofluorescence protocol, serving to preserve cellular morphology, prevent tissue degradation, and maintain the antigenicity of target proteins. For mouse embryos, this process must achieve a delicate balance: sufficient cross-linking or precipitation of cellular components to stabilize the tissue architecture without creating such dense networks that epitopes become masked and inaccessible to antibodies [14]. The chemical choice of fixative directly influences antibody binding capacity and thus represents a critical variable requiring empirical optimization for each antigen-antibody pair.

The mechanism of action varies significantly between different fixative classes. Aldehyde-based fixatives like paraformaldehyde (PFA) operate through protein cross-linking, creating stable covalent bonds between amino acid residues that effectively preserve cellular structures. In contrast, precipitating fixatives such as methanol act by dehydrating tissues and precipitating proteins, which can be advantageous for certain epitopes sensitive to aldehyde-induced masking [14]. For mouse embryos, which typically cannot withstand the aggressive antigen retrieval techniques used on sectioned samples (due to heat sensitivity), the initial fixation conditions become irreversibly consequential for experimental outcomes [14].

Experimental Protocol: Fixation for Mouse Embryos

The following protocol outlines a standardized yet adaptable approach to fixation of mouse embryos for whole mount immunofluorescence:

- Dissection and Collection: Dissect mouse embryos in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The recommended maximum age for effective whole mount staining is up to 12 days [14]. Transfer embryos to a suitable container, such as a glass vial or microcentrifuge tube, ensuring sufficient volume for immersion.

- Primary Fixation: Immerse embryos in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Two temporal approaches are commonly employed:

- Washing: Remove fixative and wash embryos 3-5 times in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBT) over 60-120 minutes to ensure complete removal of residual fixative. A final wash of at least 10 minutes is recommended before proceeding [14].

- Post-Fixation Handling: Fixed samples can be stored in PBS or PBT at 4°C for short-term use (days) or at -20°C in a cryoprotectant solution for long-term preservation.

Table 1: Fixation Agents for Whole Mount Mouse Embryo Staining

| Fixative | Mechanism | Concentration | Incubation Time | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [14] | Protein cross-linking | 4% in PBS [14] | 30 min at 20°C or overnight at 4°C [14] | Excellent structural preservation; most common choice | Can cause epitope masking for some antibodies |

| Methanol [14] | Protein precipitation | 100% (anhydrous) | 30-60 min at -20°C | Can unmask certain epitopes; improves permeabilization | May not preserve structure as well as PFA |

Component 2: Permeabilization

Permeabilization is the deliberate process of creating passages through cellular membranes to enable antibody access to intracellular targets. In whole mount specimens, this challenge is magnified because antibodies and reagents must diffuse through the entire thickness of the embryo, not just penetrate surface cells [14]. The fundamental challenge in whole mount permeabilization stems from the inverse relationship between tissue integrity and accessibility; insufficient permeabilization results in weak or absent staining, while excessive treatment can compromise morphological preservation and increase non-specific background.

The physics of diffusion dictate that reagent penetration time increases with the square of tissue thickness, making this a rate-limiting step for which extended incubation times are non-negotiable [14]. For mouse embryos beyond approximately 12 days of development, the size may necessitate physical dissection into segments before staining to facilitate adequate reagent penetration to the tissue core [14]. Permeabilization strategies typically employ detergents that solubilize lipid bilayers, with concentration and duration requiring optimization based on embryo age and size.

Experimental Protocol: Permeabilization for Mouse Embryos

- Post-Fixation Preparation: After thorough washing following fixation, transfer embryos to permeabilization solution.

- Detergent Treatment: Incubate embryos in PBS containing an appropriate detergent. Common options include:

- 0.1-1.0% Triton X-100: Incubate for 2-24 hours at 4°C with agitation. Duration depends on embryo size and age.

- 0.1-0.5% Tween-20: Often used in washing buffers (PBT) which provides mild permeabilization throughout subsequent steps.

- Combination Approaches: For challenging targets, a combination of detergent permeabilization followed by proteinase K treatment (at µg/mL concentrations for 5-30 minutes) may be employed, though this requires careful titration to avoid over-digestion.

- Washing: Following permeabilization, wash embryos 3 times in PBT over 60 minutes to remove detergents before proceeding to blocking.

Table 2: Permeabilization Methods for Whole Mount Staining

| Agent | Mechanism | Typical Concentration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent that solubilizes membranes | 0.1% - 1.0% | Stronger than Tween-20; optimal concentration and time must be determined empirically [14] |

| Tween-20 | Milder non-ionic detergent | 0.1% - 0.5% | Often included in wash buffers (PBT) for continuous mild permeabilization [14] |

| Methanol | Precipitates lipids and proteins | 100% (after PFA fixation) | Can be used as a fixative or as a permeabilization step after PFA fixation [14] |

| Proteinase K | Digests proteins to create access | µg/mL range | Harsh treatment that requires extensive optimization; use with caution [14] |

Component 3: Antibody Penetration

Antibody penetration represents the culmination of successful fixation and permeabilization, where specific immunoglobulin molecules traverse the tissue matrix to reach their target antigens. The kinetics of antibody diffusion through the fixed embryo follow Fickian principles, where the rate of penetration decreases exponentially with tissue depth and is influenced by antibody size, concentration, and the density of the extracellular matrix [14]. This physical limitation necessitates dramatically extended incubation times compared to section-based immunostaining, often requiring days rather than hours for full penetration, particularly to the core of larger specimens [14].

Molecular size significantly impacts penetration dynamics. Traditional IgG antibodies (approximately 150 kDa) diffuse more slowly than smaller recombinant fragments such as Fabs (approximately 50 kDa). This physical constraint has prompted the development of engineered antibody variants specifically designed for enhanced penetration in thick specimens. Furthermore, temperature manipulation serves as a critical control parameter, with lower temperatures (4°C) slowing degradation processes during extended incubations while potentially reducing non-specific binding, albeit at the cost of slower diffusion rates.

Experimental Protocol: Antibody Incubation for Mouse Embryos

- Blocking: After permeabilization and washing, incubate embryos in blocking solution for 6-24 hours at 4°C with agitation. A typical blocking solution is PBT containing 1-5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) or 5-10% normal serum from the host species of the secondary antibody.

- Primary Antibody Incubation:

- Dilute the primary antibody in fresh blocking solution. The optimal concentration must be determined empirically but is often 2-5 times higher than used for cryosections.

- Incubate embryos in primary antibody solution for 24-72 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation [14].

- For very large embryos, consider adding 0.01% sodium azide to prevent microbial growth.

- Washing: Remove unbound primary antibody with 5-8 washes in PBT over 12-24 hours, ensuring complete removal to minimize background.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation:

- Dilute fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibody in blocking solution, typically 2-5 times higher than manufacturer's recommendation for sections.

- Incubate for 24-48 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation, protecting from light.

- Final Washing: Perform extensive washing with PBT (6-10 changes over 24-48 hours) to ensure minimal background fluorescence before imaging.

Whole Mount Immunofluorescence Workflow for Mouse Embryos

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Whole Mount Immunofluorescence

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Fixatives [14] | 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA), Methanol | Preserves tissue architecture and antigenicity by cross-linking or precipitating proteins [14] |

| Permeabilization Agents [14] | Triton X-100, Tween-20 | Solubilizes cellular membranes to enable antibody penetration into the tissue [14] |

| Blocking Agents | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Normal Serum, Fish Skin Gelatin | Reduces non-specific antibody binding to minimize background staining |

| Antibodies | Primary Antibodies (validated for IHC-Fr), Fluorochrome-conjugated Secondary Antibodies | Primary antibody binds target antigen; secondary antibody (conjugated to a fluorophore) binds primary for detection [14] |

| Buffers | Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), PBS with Tween-20 (PBT) | Provides physiological pH and ionic strength; PBT used for washing and as a base for solutions [14] |

| Mounting Media | Glycerol-based media | Preserves fluorescence and provides appropriate refractive index for high-resolution microscopy [14] |

| Oleuropeic acid 8-O-glucoside | Oleuropeic acid 8-O-glucoside, MF:C16H26O8, MW:346.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methyl pyrimidine-4-carboxylate | Methyl pyrimidine-4-carboxylate, CAS:2450-08-0, MF:C6H6N2O2, MW:138.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Workflow and Strategic Optimization

The successful execution of whole mount immunofluorescence requires viewing fixation, permeabilization, and antibody penetration not as isolated steps but as an integrated system where each component influences the others. This interdependence creates a technical landscape where optimization must be approached systematically rather than through isolated parameter tuning. A strategic framework for troubleshooting common challenges in whole mount staining begins with pinpointing the failure point within this workflow, as each problem suggests distinct corrective pathways.

When troubleshooting weak or absent staining, consider whether the issue stems from upstream processing or the detection system itself. Inadequate staining throughout the embryo often indicates fixation-related epitope masking, insufficient permeabilization, or inappropriate antibody concentration/duration [14]. Conversely, staining only at the periphery of the embryo with a clear intensity gradient toward the core unequivocally indicates inadequate antibody penetration, requiring extended incubation times, increased antibody concentration, or enhanced permeabilization strategies [14]. Background staining, another common challenge, typically originates from insufficient blocking or inadequate washing between antibody steps, necessitating optimization of blocking agents and more rigorous washing protocols [14].

For mouse embryos specifically, specimen size remains a critical limiting factor. Embryos older than 12 days often become too large for effective reagent penetration to the core, requiring physical dissection into smaller segments before staining [14]. For these larger embryos, removal of surrounding muscle and skin may be required to facilitate effective staining and imaging [14]. Furthermore, antibody validation is paramount; an antibody that works successfully on cryosections (IHC-Fr) is likely suitable for whole mount staining, while antibodies validated only on paraffin-embedded sections (which undergo antigen retrieval) may fail in whole mount applications where such retrieval is typically not feasible in fragile embryos [14].

Troubleshooting Common Staining Problems

Ideal Applications in Mouse Embryonic Research

Whole-mount immunofluorescence (IF) staining has revolutionized mouse embryonic research by enabling the precise visualization of protein expression within the intact three-dimensional architecture of developing tissues. This technique preserves spatial context that is lost in traditional sectioning methods, allowing for a comprehensive analysis of expression domains and cellular relationships during critical developmental stages [7]. The ability to analyze protein localization and expression at cellular and sub-nuclear levels in whole embryos provides invaluable insights into the complex processes governing embryogenesis, from pre-implantation through to advanced organogenesis [7] [15]. This technical guide explores the ideal applications of whole-mount IF in mouse embryonic research, with a focus on practical methodologies, quantitative analytical approaches, and emerging techniques that enhance our understanding of developmental biology.

Core Applications in Embryonic Development

Analysis of Pre-implantation to Early Post-implantation Stages

Whole-mount IF is particularly valuable for studying mouse embryos from pre-implantation to early post-implantation stages (up to E8.0), as it allows researchers to visualize protein expression patterns across the entire embryo while maintaining crucial three-dimensional relationships [7]. During these early developmental windows, the embryo undergoes dramatic morphological changes including implantation, gastrulation, and early organogenesis. The preservation of 3D spatial information enables researchers to comprehensively interpret expression domains of key developmental regulators and signaling molecules that pattern the embryonic axes and germ layers.

The Hindbrain as a Model for Sprouting Angiogenesis

The embryonic mouse hindbrain has emerged as a premier model system for studying sprouting angiogenesis—the process by which new blood vessels form from pre-existing vessels. Its unique architecture and well-characterized developmental timeline make it ideally suited for whole-mount analysis [15]. Unlike postnatal models such as retinal angiogenesis, the hindbrain permits analysis of vascular development in embryos with genetic mutations that cause late embryonic or perinatal lethality, thus bypassing the limitations of studying non-viable mutants [15].

The hindbrain vasculature develops in a highly stereotypical pattern: vessels first sprout from the perineural vascular plexus around E9.75, growing centripetally toward the ventricular zone. From E10 onwards, these radial vessels extend sprouts that run parallel beneath the ventricular hindbrain surface, eventually forming a subventricular vascular plexus through anastomosis [15]. This predictable progression enables precise quantitative analysis of angiogenic sprouting, network density, and vessel calibre in both wild-type and genetically modified embryos.

Key advantages of the hindbrain model include:

- Simple geometric representation of 3D vessel networks after flat-mounting

- Temporal separation of arteriovenous specialization from sprouting phases

- Homogenous capillary networks suitable for accurate quantification

- Compatibility with genetic mutants that survive past E12.5 [15]

Seminal studies using this model have revealed how VEGF-A isoform gradients regulate vessel branching and caliber, how neuropilin-1 guides filopodia extension, and how tissue macrophages promote vascular anastomosis [15].

Multiplexed Imaging for Comprehensive Tissue Analysis

Recent advances in multiplexed imaging technologies have dramatically expanded the analytical power of whole-mount IF. Techniques such as cyclic immunofluorescence (CyCIF) enable researchers to visualize dozens of protein targets within the same embryonic sample, providing unprecedented insights into complex cellular landscapes and signaling networks [16] [17].

CyCIF operates through an iterative process where conventional fluorescence images are repeatedly collected from the same sample after each round of staining and fluorescence quenching [16]. These images are then assembled into high-dimensional representations that can simultaneously capture information about cell identity, signaling states, and spatial relationships. This method is particularly powerful for:

- Quantifying signal transduction cascades across different cell populations

- Characterizing tumor antigens and immune markers in cancer models

- Analyzing complex tissue microenvironments at single-cell resolution [16]

For embryonic studies, this multiplexing capability allows researchers to simultaneously track multiple developmental markers, creating comprehensive maps of differentiation states and lineage relationships within their native spatial contexts.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Angiogenic Parameters in the E10.5 Mouse Hindbrain

| Parameter | Measurement Method | Typical Wild-type Value | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sprouting Density | Number of endothelial tip cells per unit area | 15-25 sprouts/10,000 μm² [15] | Indicates pro-angiogenic signaling activity |

| Vessel Branching | Branch points per vascular segment | 3-5 branches/100 μm vessel length [15] | Reflects VEGF-A gradient sensing |

| Network Complexity | Total vessel length per unit area | 150-250 μm/1000 μm² [15] | Measures vascular network formation |

| Filopodia Dynamics | Filopodia number per tip cell | 10-20 filopodia/tip cell [15] | Indicates endothelial guidance activity |

Experimental Workflow and Methodologies

Standard Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence Protocol

The following protocol for whole-mount fluorescent immunostaining of mouse embryos has been adapted from established methods with minor modifications [1]:

Sample Preparation and Fixation

- Isolate embryos at desired developmental stage in cold PBS

- Fix in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 6 hours at 4°C

- Dehydrate through methanol gradient (25%, 50%, 75%, 100%)

- Incubate in 100% methanol for 24 hours at 4°C

Bleaching and Permeabilization

- Transfer to bleaching solution (1:2 ratio of 30% hydrogen peroxide:100% methanol) for 24 hours at 4°C

- Wash with 100% methanol (3 × 10 minutes at room temperature)

- Post-fix with Dent's Fixative (DMSO:methanol = 1:4) overnight at 4°C

Antibody Staining

- Block for 1 hour on ice in blocking solution (0.2% BSA, 20% DMSO in PBS) with 0.4% Triton

- Incubate with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution for four days at room temperature

- Wash extensively with PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100

- Incubate with secondary antibodies (e.g., Goat α-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 633; Goat α-Mouse Alexa Fluor 488) and DAPI overnight in blocking solution at room temperature

Clearing and Imaging

- Clear specimens using BABB (1 part benzyl alcohol:2 parts benzyl benzoate) after methanol dehydration

- Image using confocal or spinning disc microscopy

- Acquire confocal z-stacks through entire embryo (typically ~150 optical slices)

- Process using 3D visualization software (e.g., Bitplane IMARIS) for analysis [1]

Tissue Clearing for Enhanced Imaging

Traditional whole-mount IF faces limitations in penetration depth and image quality with thicker samples. Recent tissue clearing methods address these challenges by rendering tissues optically transparent while preserving fluorescence. The EZ Clear method represents a significant advancement in this area:

EZ Clear Protocol

- Step 1: Lipid removal with 50% tetrahydrofuran (THF) in water

- Step 2: Washing in sterile Milli-Q water for 4 hours

- Step 3: Refractive index matching with EZ View solution (RI=1.518) for 24 hours [18]

This simple three-step process clears whole adult mouse organs in 48 hours while maintaining sample size and preserving endogenous and synthetic fluorescence. Unlike methods that cause significant tissue shrinkage (e.g., 3DISCO shrinks to 59.3% of original size) or expansion (X-CLARITY expands to 160.8%), EZ Clear maintains relatively constant sample size (107.2% of original) [18]. This preservation of tissue architecture is crucial for accurate morphological analysis in embryonic studies.

Multiplexed Imaging with t-CyCIF

For highly multiplexed imaging, tissue-based cyclic immunofluorescence (t-CyCIF) enables visualization of up to 60 protein targets in the same specimen. The method works as follows:

- Sample Preparation: 5μm sections from FFPE blocks are dewaxed and subjected to antigen retrieval

- Pre-staining: Samples are incubated with secondary antibodies followed by fluorophore oxidation to reduce autofluorescence

- Staining Cycles: Each cycle includes:

This cyclic process progressively reduces background autofluorescence while building a comprehensive multiplexed dataset. The method is particularly valuable for characterizing complex tissue environments and rare cell populations during embryonic development.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixatives | 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [1] | Preserves tissue architecture and antigen integrity | Optimal fixation time varies by embryo age (typically 4-6 hours) |

| Permeabilization Agents | Triton X-100 [1], NP-40 [2] | Enables antibody penetration through membranes | Concentration critical (typically 0.1-0.5%); higher concentrations may damage epitopes |

| Blocking Solutions | BSA (0.2-5%) with DMSO (10-20%) [1] | Reduces non-specific antibody binding | DMSO enhances antibody penetration in thick samples |

| Tissue Clearing | BABB [1], EZ Clear [18], CUBIC [2] | Reduces light scattering for deeper imaging | BABB quenches GFP; EZ Clear preserves fluorescence |

| Primary Antibodies | Anti-neurofilament (2H3) [1], Anti-TFAP2A [1] | Binds specific target antigens | Validate for whole-mount applications; extended incubation (days) often needed |

| Secondary Antibodies | Alexa Fluor conjugates (488, 555, 647) [1] [19] | Detects primary antibodies with high sensitivity | Choose fluorophores with minimal emission overlap; consider bleaching characteristics |

Advanced Technical Considerations

Optimization of Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Several strategies can enhance signal quality in whole-mount IF:

Fluorophore Selection and Management When designing multicolor experiments, select fluorophores with minimal emission spectrum overlap to eliminate bleed-through effects [19]. For sequential staining methods like CyCIF, use fluorophores that can be effectively quenched between rounds (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488, 555, 647, 750) while avoiding resistant dyes like AF546 and fluorescein [17]. Optimal quenching employs 3% H2O2 in 20mM NaOH with incandescent light illumination for 30 minutes, which completely removes signal while reducing tissue autofluorescence by approximately 25% after the first quench [17].

Antibody Validation and Order Optimization Rigorously validate all antibodies for specificity in whole-mount applications. In multiplexed workflows, antibody application order significantly impacts results—stain less robust epitopes in earlier cycles when antigen integrity is highest. Include appropriate controls such as wild-type littermates, Cre-only controls, and floxed gene controls without Cre to account for potential confounding factors [15].

Three-Dimensional Analysis and Quantification

The power of whole-mount IF lies in quantifying three-dimensional structures:

Image Processing Pipeline Process confocal z-stacks using 3D visualization software (e.g., Bitplane IMARIS, mplexable Python library) [1] [17]. These tools enable:

- 3D reconstruction of entire embryonic structures

- Ortho/oblique sectioning for internal visualization

- Surface rendering to quantify expression intensity in specific regions

- Automated cell segmentation and feature extraction

Angiogenesis Quantification In hindbrain studies, quantify sprouting angiogenesis by measuring:

- Endothelial tip cell density at the vascular front

- Filopodia number and orientation per tip cell

- Vascular branch points per unit area

- Vessel diameter and network density [15]

These parameters provide quantitative readouts of genetic and pharmacological perturbations on vascular development.

Integration with Complementary Techniques

Combining Whole-Mount IF with Transcriptomic Analysis

Whole-mount IF provides spatial protein localization data that complements transcriptomic approaches. Recent studies have revealed sex-dependent gene expression differences in the embryonic mouse telencephalon as early as E14.5, preceding the influence of sex hormones [20]. These findings highlight the importance of correlating protein expression patterns with transcriptional profiles to understand the molecular mechanisms driving sexual dimorphism in brain development.

Methodology for integrated analysis:

- Perform bulk RNA-seq on microdissected embryonic regions

- Validate transcriptional differences using quantitative RT-PCR

- Localize protein products using whole-mount IF with specific antibodies

- Correlate spatial expression patterns with transcriptional data [20]

This integrated approach reveals how transcriptional differences manifest at the protein level within the context of embryonic tissue architecture.

Whole-Mount X-gal Staining and Tissue Clearing

For analyzing gene expression patterns in transgenic reporter strains, whole-mount X-gal staining can be combined with tissue clearing techniques. This approach visualizes LacZ activity reflecting endogenous gene expression across entire embryos [2].

Protocol highlights:

- Fix embryos in 1% PFA/0.05% glutaraldehyde

- Incubate in X-gal solution (1 mg/mL) for color development

- Clear samples using CUBIC reagents

- Image using light microscopy or combine with immunofluorescence [2]

This method enables comprehensive assessment of developmental stage-specific gene expression patterns both spatially and temporally, particularly valuable for characterizing novel genetic mouse models.

Whole-mount immunofluorescence represents a powerful methodology for mouse embryonic research, providing unparalleled insights into developmental processes within their native three-dimensional context. The ideal applications span from analysis of early pre-implantation stages through advanced organogenesis, with particular strength in modeling processes like hindbrain angiogenesis. When combined with emerging techniques in tissue clearing, multiplexed imaging, and computational analysis, whole-mount IF enables quantitative, high-dimensional characterization of embryonic development at single-cell resolution. As these methods continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly yield new discoveries about the fundamental mechanisms governing embryogenesis and provide platforms for evaluating developmental toxicities of pharmacological compounds.

A Step-by-Step WM-IF Protocol for Mouse Embryos with Advanced Applications

Within the framework of whole-mount immunofluorescence (WMIF) for mouse embryonic research, the initial stage of embryo harvesting, dissection, and fixation is the foundational pillar upon which all subsequent analysis is built. This phase is critical for preserving the delicate three-dimensional architecture of the embryo and the antigenicity of target proteins, enabling high-resolution qualitative and quantitative assessment of developmental processes [21] [22]. For studies focusing on early organogenesis, such as heart development at embryonic day 8.25 (E8.25), impeccable specimen preparation is paramount for visualizing progenitor cell populations and tissue-level dynamics [21]. This guide provides an in-depth technical protocol for this crucial first stage, designed to ensure the integrity of the embryo for advanced imaging and volumetric analysis.

Technical Protocol: Embryo Harvesting and Dissection

The following procedure describes the isolation of E8.25 mouse embryos, a key stage for observing structures like the cardiac crescent [22]. All procedures must be approved by the relevant Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IUCAC) and adhere to local institutional guidelines.

Materials and Equipment

- Pregnant Mouse: Timed to E8.25.

- Dissecting Microscope

- Fine Forceps (e.g., Fine Science Tools, #11252-00) [23]

- Spring Scissors (e.g., Fine Science Tools, #15000-08) [23]

- 35 mm and 60 mm Petri Dishes

- 1.5 mL Microcentrifuge Tubes

- Ice Bucket

- Dissecting Pins (optional, for pinning tissue) [23]

- PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline), ice-cold.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Euthanasia and Uterine Dissection: Euthanize the pregnant mouse according to approved protocols. Disinfect the abdomen with 70% ethanol. Make an abdominal incision through both the skin and body wall. Carefully dissect the entire uterus and transfer it to a 60 mm dish containing ice-cold PBS [22].

Isolation of Deciduoma: Under a dissecting microscope, use fine forceps to carefully remove the uterine muscle tissue surrounding each deciduom (the swollen structure containing the embryo) [22].

Embryo Extraction: Carefully slice the tip of the embryonic half of the deciduom. By gently pinching the deciduom, push and pull the embryo out. A visual guide from the JoVE protocol illustrates this delicate process [22].

Removal of Extra-Embryonic Tissues: Using fine forceps, meticulously dissect away the extra-embryonic membranes (e.g., Reichert's membrane, amniotic sac) without damaging the morphology of the embryo itself [22].

Transfer and Washing: Using a transfer pipette, place the harvested embryo into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube containing fresh, ice-cold PBS. Once all embryos are harvested, aspirate the PBS and rinse them once more with fresh PBS to remove any residual blood or debris [22].

Technical Protocol: Embryo Fixation

Fixation is crucial for preserving tissue morphology and preventing protein degradation. The choice of fixative and fixation time must be optimized to balance structural preservation with epitope recognition [24].

Materials and Reagents

- Fixative: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS is the most common fixative for WMIF [14] [22]. Alternative: Methanol can be used if PFA masks the target epitope [14] [24].

- Glycine (1 M): Can be used to quench unreacted aldehyde groups from PFA fixation [23].

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Fixative Application: Thoroughly aspirate the PBS from the tube containing the embryo. Add 1 mL of 4% PFA to the embryo.

- Fixation Incubation: Fix the embryo for 1 hour at room temperature [22]. Alternatively, fixation can be performed overnight at 4°C for some protocols [14].

- Washing: After fixation, aspirate the PFA and wash the embryo three times with fresh PBS to remove all traces of fixative. Washes can be performed for 5-10 minutes each [22]. A final wash with a quenching agent like 1 M glycine can be incorporated at this stage to reduce background [23].

- Storage: Fixed embryos can be stored in PBS at 4°C for subsequent immunostaining procedures [22]. For longer storage, consider using an antimicrobial agent in the buffer.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete embryo harvesting and fixation pipeline.

Key Data and Reagent Specifications

Table 1: Critical Fixation Parameters for E8.25 WMIF

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Stage | E8.25 | Ideal for visualizing early structures like the cardiac crescent; older/larger embryos require more complex processing [14] [22]. |

| Primary Fixative | 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-links proteins, preserving tissue structure excellently. May mask some epitopes [14] [24]. |

| Alternative Fixative | 100% Methanol (ice-cold) | Precipitates proteins; can preserve different epitopes. Can be more disruptive to morphology [24]. |

| Fixation Time (4% PFA) | 1 hour at Room Temperature | Optimal for E8.25 embryos; over-fixation can destroy epitopes, under-fixation leads to poor preservation [22] [24]. |

| Post-Fixation Storage | PBS at 4°C | Maintains tissue hydration and stability for short-term storage before immunostaining [22]. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Protocol | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Isotonic buffer for washes and dissections; base for other solutions. | Maintains pH and osmolarity to prevent tissue damage during processing [22] [23]. |

| 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Primary fixative. Forms cross-links to preserve cellular morphology and antigen position. | Always use fresh or freshly aliquoted. Concentration and time must be optimized to avoid epitope masking [14] [22] [24]. |

| Methanol | Alternative precipitating fixative. | Use ice-cold for best results. Can be less destructive for some antigens but may not preserve structure as well as PFA [24]. |

| Fine Forceps & Spring Scissors | Precision tools for micro-dissection of uterine tissue and embryonic membranes. | High-quality tools are essential for successful embryo extraction without mechanical damage [23]. |

| Ice Bath | Keeps solutions and samples cold during dissection. | Slows metabolic activity and degradation post-euthanasia, improving preservation [22]. |

Within the context of a whole-mount immunofluorescence overview for mouse embryo research, the stages of permeabilization and blocking are pivotal for successful experimental outcomes. This guide details the core principles and practical methodologies for these stages, which are essential for preserving the intricate three-dimensional architecture of mouse embryos while enabling specific antibody binding to intracellular targets [14]. Optimizing these steps ensures that researchers can achieve high-quality, reproducible data critical for developmental biology studies and drug development applications.

Core Concepts and Principles

The Role of Permeabilization

Permeabilization is the process of introducing pores into cellular membranes to allow antibodies access to intracellular epitopes. In whole-mount immunofluorescence, this step is particularly challenging due to the thickness and complex structure of intact embryos [14]. The primary goal is to disrupt lipid bilayers sufficiently to permit the passage of large immunoglobulin molecules without causing excessive structural damage or protein loss.

The Purpose of Blocking

Blocking serves to minimize non-specific antibody binding by occupying potential interaction sites before primary antibody application. This step dramatically improves the signal-to-noise ratio by preventing antibodies from adhering to hydrophobic patches, charged surfaces, or Fc receptors [25]. Effective blocking is essential for reducing high background staining, a common challenge in whole-mount preparations where thorough washing is more difficult compared to sectioned samples [14].

Experimental Protocols

Permeabilization Methodology for Mouse Embryos

The following protocol is optimized for mouse embryos up to 12 days old, as older embryos become too large for effective reagent penetration [14].

Materials Needed:

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Permeabilization agent (Triton X-100, Tween-20, Saponin, or Digitonin)

- Laboratory rocker or rotator

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Post-Fixation Wash: After fixation (typically with 4% paraformaldehyde), wash embryos three times with PBS for 15 minutes each at room temperature with gentle agitation [14].

Permeabilization Solution Preparation: Prepare an appropriate permeabilization solution in PBS. Common formulations include:

- 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 for general use

- 0.1-0.3% Tween-20 for milder permeabilization

- 0.1-0.5% Saponin for cholesterol-specific membrane disruption

- 0.001-0.05% Digitonin for nuclear membrane permeabilization [14]

Incubation: Incubate embryos in permeabilization solution for 1-24 hours at room temperature with constant gentle agitation. The exact duration must be optimized based on embryo size and the target antigen location [14].

Washing: Rinse embryos three times with PBS or blocking buffer for 15-30 minutes each to remove the permeabilization agent before proceeding to blocking.

Blocking Protocol for Mouse Embryos

Materials Needed:

- Blocking buffer (see formulations below)

- Laboratory rocker or rotator

- Incubation vessels

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Preparation of Blocking Buffer: Prepare 5-10 mL of fresh blocking buffer per embryo. Common formulations include:

- Standard blocking buffer: 1-5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or 5-10% normal serum in PBS

- Enhanced blocking buffer: 1% BSA, 0.1% Tween-20, and 5% normal serum in PBS

- Specialized blocking buffers may include additional components such as glycine to quench autofluorescence or sodium azide as a preservative [25]

Blocking Incubation: Transfer embryos to sufficient volume of blocking buffer to completely cover them. Incubate for 4-24 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation. Extended blocking times are often necessary for whole-mount samples to ensure complete penetration [14].

Primary Antibody Preparation: Dilute primary antibody in fresh blocking buffer. The optimal dilution should be determined empirically but typically ranges from 1:100 to 1:1000 for whole-mount samples.

Proceed to Staining: After blocking, transfer embryos directly to primary antibody solution without washing. Do not allow samples to dry out during transfer.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Permeabilization and Blocking

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Concentration Range | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detergents | Triton X-100, Tween-20 | Disrupts lipid bilayers to enable antibody entry | 0.1-0.5% (v/v) | Triton X-100 is stronger; Tween-20 is milder |

| Serum Blockers | Normal Goat Serum, Donkey Serum | Blocks Fc receptors and non-specific binding | 1-10% (v/v) | Should match host species of secondary antibody |

| Protein Blockers | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Blocks non-specific protein binding sites | 1-5% (w/v) | Inexpensive; compatible with most detection systems |

| Specialized Additives | Glycine, Sodium Azide | Reduces autofluorescence; prevents microbial growth | 0.1-0.3M (glycine); 0.02-0.05% (azide) | Azide inhibits peroxidase activity |

Quantitative Optimization Data

Table 2: Permeabilization Conditions for Different Mouse Embryo Ages

| Embryo Age (days) | Recommended Agent | Concentration | Incubation Time | Temperature | Efficacy Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-10 | Triton X-100 | 0.1% | 2-4 hours | Room Temperature | High |

| 10-12 | Triton X-100 | 0.2-0.3% | 6-8 hours | Room Temperature | Medium-High |

| >12 | Triton X-100 | 0.3-0.5% | 12-24 hours | Room Temperature | Medium (dissection recommended) |

| Nuclear Targets | Digitonin | 0.001-0.01% | 30-60 minutes | 4°C | Target-Dependent |

Table 3: Blocking Buffer Formulations and Applications

| Blocking Buffer Type | Composition | Incubation Time | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Serum-Based | 5% Normal Serum + 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS | 4-6 hours | General intracellular targets | Potential interference with certain antigens |

| Enhanced Protein-Based | 3% BSA + 0.3% Triton X-100 + 5% Serum in PBS | 12-24 hours | Phospho-specific antibodies; low abundance targets | More expensive; longer preparation |

| Simple Protein | 1-5% BSA in PBS | 2-4 hours | Fluorescent conjugates; direct detection | Less effective for Fc receptor blocking |

Workflow Visualization

Permeabilization and Blocking Workflow - This diagram illustrates the sequential steps from fixed embryo to ready-for-staining specimen, highlighting key decision points for optimization.

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

Common Challenges and Solutions

Poor Antibody Penetration: If staining is weak or uneven, increase permeabilization agent concentration or duration. For embryos older than 12 days, consider microdissection to expose internal tissues [14].

High Background Staining: Extend blocking time to 24 hours or increase serum concentration to 10%. Include 0.1% Tween-20 in all washing and antibody incubation buffers to reduce non-specific binding [25].

Structural Damage: Reduce permeabilization agent concentration or switch to a milder detergent (Tween-20 instead of Triton X-100). Perform permeabilization at 4°C instead of room temperature to preserve delicate structures.

Validation of Protocol Effectiveness

To confirm successful permeabilization and blocking, include control samples without primary antibody to assess non-specific background. Additionally, use antibodies against both intracellular and nuclear targets to verify adequate penetration through multiple membrane barriers [14]. The protocol is complete when negative controls show minimal background while positive signals are strong and specific.

In whole mount immunofluorescence for mouse embryo research, the incubation with primary and secondary antibodies represents the definitive stage for achieving specific and high-quality labeling of target proteins. This stage is pivotal, as suboptimal conditions can lead to weak signals, high background, or non-specific binding, ultimately compromising data interpretation [26]. Within the context of a broader immunofluorescence overview, this step follows critical preparatory phases such as sample fixation, permeabilization, and blocking. The strategies employed during antibody incubation must account for the unique challenges posed by the three-dimensional structure of whole mount embryos, which can impede antibody penetration and require extended incubation times compared to two-dimensional cell cultures or tissue sections. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of evidence-based incubation strategies, supported by quantitative data and detailed protocols, to enable researchers to optimize this crucial procedure for robust and reproducible results in mouse embryonic development studies.

Core Principles of Antibody Incubation

Effective antibody incubation in whole mount immunofluorescence hinges on achieving the optimal equilibrium between antibody binding and non-specific signal. For three-dimensional embryo samples, antibodies must diffuse throughout the entire tissue structure to reach their target epitopes. This process is influenced by multiple factors including antibody concentration, incubation duration, temperature, and the composition of the incubation buffer [26]. The fundamental goal is to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio through precise optimization of these parameters, ensuring specific antigen labeling while minimizing background fluorescence.

The affinity and specificity of the primary antibody for its target epitope constitute the foundation of successful immunofluorescence. Following primary antibody binding, the secondary antibody—conjugated to a fluorophore—must specifically recognize the Fc region of the primary antibody without cross-reacting with endogenous immunoglobulins or other tissue components. The selection of appropriate controls, including no-primary antibody controls and isotype controls, is essential for validating staining specificity [27]. For whole mount embryo staining, the inclusion of these controls is particularly crucial due to the increased potential for non-specific interactions within complex three-dimensional structures.

Optimization Strategies and Quantitative Data

Antibody Concentration Optimization

Optimizing antibody concentration represents the most critical parameter in achieving specific staining with minimal background. Suboptimal concentrations can lead to several common artifacts including weak signals, non-specific bands, and flecked or blotched background [26]. While traditional Western blot optimization methods require multiple time-consuming experiments, dot blot assays provide an efficient alternative for rapidly determining optimal concentrations before proceeding with whole mount staining procedures.

Table 1: Antibody Dilution Optimization Using Dot Blot Assay

| Component | Concentration Range | Incubation Parameters | Assessment Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibody | 1:50 - 1:2000 dilution | 1 hour, orbital shaker | Strong, lasting chemiluminescent signal (5-20 hours) |

| Secondary Antibody | Manufacturer's recommendation ± 2-fold | 1 hour, orbital shaker | Dark dots with minimal background |

| Protein Sample | Serial dilutions in assay buffer | 10-15 min drying post-application | Signal intensity proportional to dilution |

The dot blot protocol involves preparing a range of protein sample dilutions and applying them to nitrocellulose membrane strips. After blocking, primary antibody dilutions are applied followed by secondary antibody incubation with thorough washing between steps. Optimal concentrations are identified when the substrate development produces dark dots or strong chemiluminescent signal that persists for 5-20 hours [26].

Incubation Time and Temperature

The duration and temperature of antibody incubation significantly impact penetration depth and binding efficiency in three-dimensional embryo samples. While standard protocols often recommend overnight incubations at 4°C, the optimal conditions vary depending on antibody affinity and embryo developmental stage.

Table 2: Antibody Incubation Parameters for Whole Mount Embryo Staining

| Antibody Type | Concentration Range | Incubation Time | Temperature | Documented Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary (e.g., anti-STAT3) | 1:200 - 1:500 | Overnight | 4°C | Mouse preimplantation embryos [28] |

| Primary (e.g., anti-KI-67) | 1:500 | Overnight | 4°C | Embryonic day 14.25 mouse heads [29] |

| Primary (e.g., anti-CTSD) | 1:200 | Overnight | 4°C | Mouse fertilized eggs [27] |

| Secondary (Alexa Fluor conjugates) | 1:500 | 2 hours | Room temperature | Embryo heads and preimplantation embryos [28] [29] |

Extended incubation times at lower temperatures (4°C) often enhance primary antibody penetration and specificity for whole mount embryos, while secondary antibody incubations are typically conducted for shorter durations (2 hours) at room temperature to minimize fluorophore degradation [28] [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standardized Whole Mount Immunofluorescence Protocol

The following protocol delineates a standardized approach for whole mount immunofluorescence staining of mouse preimplantation embryos, incorporating optimized antibody incubation strategies based on established methodologies [28]:

- Post-fixation Processing: Following fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes at room temperature, remove the zona pellucida by brief treatment (approximately 10 seconds) with acid Tyrode's solution at room temperature.

- Permeabilization: Permeabilize embryos by incubation in 2% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 minutes at room temperature to facilitate antibody penetration.

- Blocking: Incubate embryos in blocking solution (4% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS) for a minimum of 1-2 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation to prevent non-specific antibody binding.

- Primary Antibody Incubation:

- Prepare primary antibody dilutions in blocking solution (e.g., 1:200 for anti-STAT3 antibodies C-20 (sc-482) and F-2 (sc-8019) or anti-GABPα antibody (sc-22810) [28].

- Incubate embryos with primary antibody solution overnight at 4°C with continuous gentle agitation to ensure even distribution.

- Washing: Thoroughly wash embryos 3-5 times in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.005% Triton X-100 over 1-2 hours to remove unbound primary antibody.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation:

- Prepare species-appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorophores (e.g., donkey anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (A-21206) or donkey anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 546 (A-10036) at 1:500 dilution in blocking solution [28].

- Include DAPI (1-5 µg/mL) in the secondary antibody solution for simultaneous nuclear counterstaining if compatible with the fluorophores.

- Incubate for 2 hours at room temperature protected from light.

- Final Washing: Perform 3-5 additional washes in PBS with 1% BSA and 0.005% Triton X-100 over 1-2 hours to remove unbound secondary antibody.

- Mounting: Mount stained embryos using ProLong Gold antifade reagent and proceed with imaging via laser scanning confocal microscopy [28].

Protocol for Early Postimplantation Embryos

For later-stage embryos (up to E8.0), modifications to the standard protocol are necessary to account for increased tissue size and complexity [7]:

- Extended Permeabilization: Increase Triton X-100 concentration to 0.5-1.0% and extend permeabilization time to 1-2 hours, or consider partial dissection to improve antibody accessibility.

- Prolonged Antibody Incubation: Extend primary antibody incubation to 24-48 hours at 4°C with continuous agitation to ensure adequate penetration throughout the larger tissue volume.

- Enhanced Washing: Implement extended washing steps (6-8 washes over 12-24 hours) following both primary and secondary antibody incubations to reduce background signal in denser tissues.

Research Reagent Solutions

The selection of appropriate reagents is fundamental to successful antibody incubation in whole mount immunofluorescence. The following table catalogues essential materials with documented efficacy in mouse embryo studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Whole Mount Immunofluorescence

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Anti-STAT3 C-20 (sc-482), F-2 (sc-8019); Anti-GABPα (sc-22810); Anti-KI-67 (CST, 12202); Anti-CTSD (55021-1-AP) | Target-specific binding; Validation for embryo samples is crucial [28] [29] [27] |

| Secondary Antibodies | Donkey anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (A-21206); Donkey anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 546 (A-10036) | Fluorophore-conjugated detection; Species-specific with minimal cross-reactivity [28] [29] |

| Blocking Reagents | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) at 4% in PBS | Reduces non-specific antibody binding; Superior for whole mount embryos [28] |

| Permeabilization Agents | Triton X-100 (0.5-2.0%) | Enables antibody penetration through membrane structures [28] |

| Mounting Media | ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent with DAPI | Preserves fluorescence and provides nuclear counterstain [28] |

| Wash Buffers | PBS with 1% BSA and 0.005% Triton X-100 | Maintains physiological pH while reducing background [28] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow for primary and secondary antibody incubation in whole mount immunofluorescence of mouse embryos, integrating key decision points and optimization strategies:

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Even with optimized protocols, researchers may encounter specific challenges during antibody incubation. The following table addresses common issues and provides evidence-based solutions:

Table 4: Troubleshooting Guide for Antibody Incubation

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Background | Inadequate blocking or washing; Antibody concentration too high | Increase blocking time to 2+ hours; Extend washing duration; Titrate down antibody concentration [26] |

| Weak or No Signal | Low antibody concentration or affinity; Inadequate permeabilization | Perform dot blot optimization; Increase primary antibody concentration; Extend permeabilization time [26] |

| Non-specific Staining | Antibody cross-reactivity; Insufficient specificity controls | Include isotype controls; Validate with knockout embryos if available; Try different antibody clones [27] |

| Incomplete Penetration | Short incubation time; Large embryo size | Extend primary antibody incubation to 24-48 hours; Consider tissue dissection or increased detergent concentration [7] |

Validation and Quality Control

Rigorous validation of antibody specificity is particularly crucial for whole mount embryo studies, where three-dimensional complexity can amplify non-specific signals. Several approaches should be employed concurrently:

- Isotype Controls: Use species- and isotype-matched immunoglobulins at the same concentration as the primary antibody to identify non-specific Fc receptor binding [27].

- Secondary Antibody Controls: Incubate embryos with secondary antibody alone to detect any cross-reactivity with endogenous immunoglobulins or non-specific tissue binding [30].

- Biological Controls: Include tissues or embryos known to express and not express the target antigen to verify antibody specificity.