Wnt Signaling in Early Embryogenesis: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targets

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Wnt signaling pathway's critical functions during early embryogenesis.

Wnt Signaling in Early Embryogenesis: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targets

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Wnt signaling pathway's critical functions during early embryogenesis. It explores the foundational biology of canonical and non-canonical Wnt pathways, their roles in cell fate determination, pluripotency, and body axis patterning. For a research and drug development audience, we examine advanced methodological approaches for studying Wnt signaling, address common experimental challenges and optimization strategies, and validate findings through cross-species comparisons and clinical implications. The synthesis of current research highlights Wnt signaling as a pivotal regulator of development and a promising therapeutic target, with future directions focusing on overcoming technical barriers for clinical translation.

Core Mechanisms of Wnt Signaling in Embryonic Development

Wnt signaling represents a cornerstone of cellular communication, governing fundamental processes in embryonic development and tissue homeostasis. The term "Wnt" originated as a merger of two homologous proteins: Drosophila Wingless (Wg) and mouse Int-1, ultimately coined by Nusse et al. in 1991 [1]. This evolutionarily conserved pathway regulates cell fate determination, proliferation, migration, and polarity across species from diploblastic cnidarians to mammals [2] [3]. The Wnt family comprises 19 highly conserved glycoproteins in humans that function as secreted signaling molecules [1] [3]. These proteins undergo extensive post-translational modifications including glycosylation and palmitoylation by the Porcupine protein, which are essential for their secretion and function [1] [4]. Wnt distribution occurs through various mechanisms—free diffusion, restricted diffusion, and active transport—forming concentration gradients that provide positional information during embryogenesis [5].

The broader thesis context of Wnt signaling in early embryogenesis research reveals its indispensable roles in axial patterning, gastrulation, neural specification, and organ formation [2] [5]. During mammalian embryogenesis, Wnt signaling specifies pattern formation and regulates the maintenance and differentiation of stem cells both in vivo and in vitro [2]. Disruption of Wnt signaling during embryonic development results in severe abnormalities, including spina bifida and other birth defects, while dysregulation in adults contributes to various pathologies including cancer, skeletal disorders, and metabolic diseases [1] [4]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of the canonical and non-canonical Wnt pathways, emphasizing their mechanisms, regulatory networks, and experimental approaches relevant to research in early embryogenesis.

Pathway Mechanisms and Molecular Components

Canonical Wnt/β-catenin Pathway

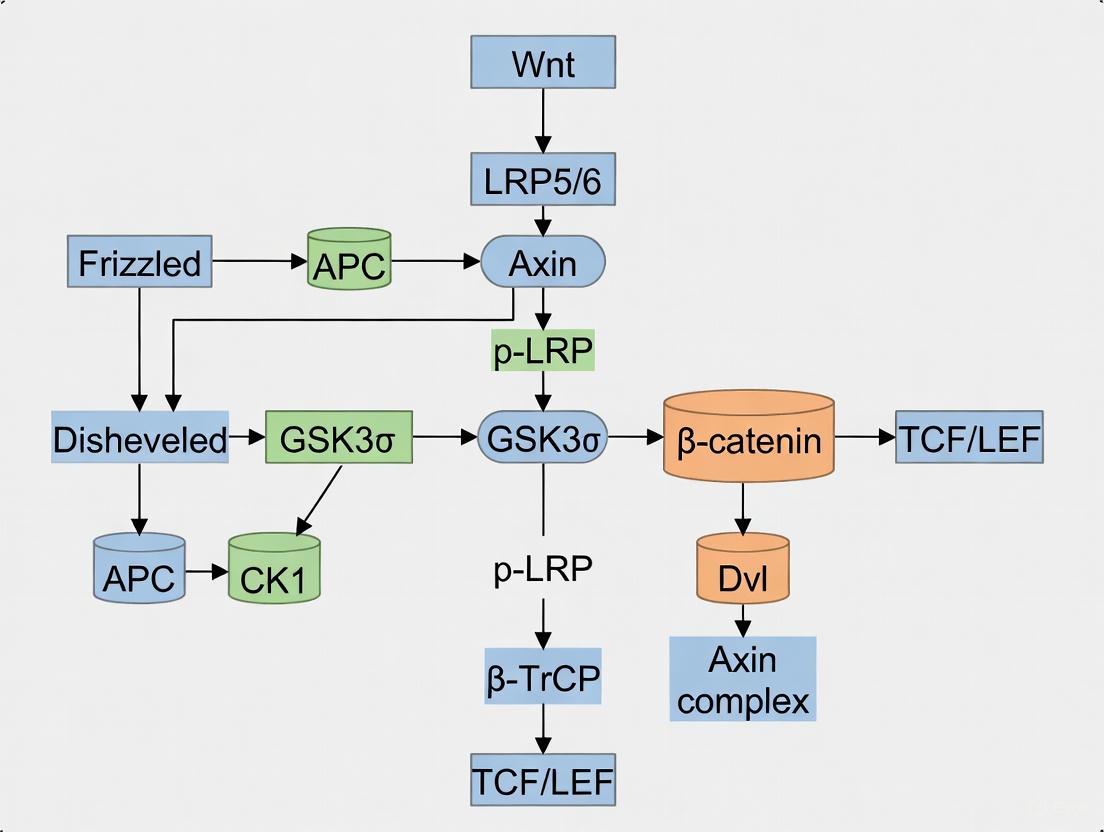

The canonical Wnt pathway, also known as the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, centers on the regulation of β-catenin stability and nuclear translocation. In the absence of Wnt ligand, a destruction complex composed of Axin, Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC), Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β (GSK3β), Casein Kinase 1α (CK1α), and β-transducin repeat containing protein (β-TrCP) constitutively targets β-catenin for proteasomal degradation [1] [3] [6]. This complex facilitates the phosphorylation of β-catenin by GSK3β, leading to its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation [1]. When canonical Wnt ligands (including Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt3, Wnt3a, Wnt8a, Wnt8b, Wnt10a, and Wnt10b) bind to Frizzled (Fz) receptors and LRP5/6 co-receptors, Dishevelled (Dsh/Dvl) is recruited to the membrane [1] [6]. This recruitment inhibits the destruction complex, allowing β-catenin to accumulate in the cytoplasm and translocate to the nucleus [1] [3]. Within the nucleus, β-catenin associates with T-cell factor (TCF)/lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF) transcription factors to activate target genes involved in cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation [1] [6] [4].

Table 1: Core Components of the Canonical Wnt Pathway

| Component | Function | Representative Members |

|---|---|---|

| Ligands | Activate pathway by binding receptors | Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt3, Wnt3a, Wnt8a, Wnt8b, Wnt10a, Wnt10b [1] [6] |

| Receptors | Bind Wnt ligands initiate signaling | Frizzled (Fz) family [1] [3] |

| Co-receptors | Essential for signal transduction | LRP5/6 [1] [3] |

| Intracellular Transducers | Relay signal from membrane | Dishevelled (Dsh/Dvl), β-catenin [1] [3] |

| Transcription Factors | Regulate target gene expression | TCF/LEF family [1] [6] |

| Target Genes | Execute cellular responses | MYC, CCND1 (Cyclin D1), WISP2 [7] |

Non-Canonical Wnt Pathways

Non-canonical Wnt pathways operate independently of β-catenin and LRP5/6 co-receptors, diversifying into two major branches: the Wnt/Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) pathway and the Wnt/Ca²⺠pathway [3] [4]. Non-canonical Wnt ligands include Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Wnt6, Wnt7a, Wnt7b, and Wnt11 [1] [6]. These ligands bind to Frizzled receptors along with alternative co-receptors such as ROR1/2, RYK, and CTHRC1 [1]. The diversity of receptor/co-receptor/ligand combinations creates context-specific signaling outcomes depending on cell type and receptor availability [1].

The Wnt/PCP pathway regulates coordinated cellular polarization and migration within the plane of epithelial sheets [3] [4]. Upon activation, Frizzled recruits Dishevelled, which then interacts with Dishevelled-associated activator of morphogenesis 1 (DAAM1) [3]. DAAM1 activates the small GTPase Rho through guanine exchange factors, leading to activation of Rho-associated kinase (ROCK)—a key regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics [3]. Simultaneously, Dishevelled can form complexes with Rac1, leading to Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation and actin polymerization [3].

The Wnt/Ca²⺠pathway triggers the release of intracellular calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum [3] [4]. This pathway involves Frizzled receptors along with co-receptors Knypek and Ror2 [4]. Activation leads to stimulation of G-proteins, phospholipase C (PLC), and protein kinase C (PKC) [4]. The resulting increase in intracellular calcium activates calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin, which dephosphorylates the transcription factor NF-AT (Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells), promoting its nuclear accumulation and subsequent regulation of target genes [3] [4].

Table 2: Core Components of Non-Canonical Wnt Pathways

| Component | Function | Representative Members |

|---|---|---|

| Ligands | Activate β-catenin-independent signaling | Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Wnt6, Wnt7a, Wnt7b, Wnt11 [1] [6] |

| Receptors | Bind non-canonical Wnt ligands | Frizzled (Fz) family [1] [3] |

| Co-receptors | Mediate alternative signaling | ROR1/2, RYK, CTHRC1, Knypek [1] [4] |

| PCP Effectors | Regulate cytoskeleton and polarity | DAAM1, Rho, Rac, ROCK, JNK [3] |

| Calcium Effectors | Mediate calcium signaling | PLC, PKC, Calcineurin, NF-AT [3] [4] |

Pathway Regulation and Cross-Talk

Extracellular and Intracellular Regulation

Wnt signaling is tightly regulated at multiple levels to ensure precise spatiotemporal control. Extracellular regulation occurs through various secreted antagonists that sequester Wnt ligands or block receptors [3] [6]. These include Secreted Frizzled-Related Proteins (sFRPs), Wnt Inhibitory Factor (WIF), and Dickkopf (DKK) family proteins [3] [6]. While sFRPs and WIF1 bind directly to Wnt ligands, preventing their interaction with Frizzled receptors, Dickkopf proteins specifically inhibit canonical signaling by binding to LRP5/6 co-receptors [6]. Conversely, R-spondin proteins enhance Wnt signaling by binding to LGR4/5/6 receptors and preventing Frizzled ubiquitination and degradation [6].

Intracellularly, multiple mechanisms fine-tune Wnt signaling responses. The destruction complex maintains low β-catenin levels in unstimulated cells [1]. Additionally, nuclear regulators such as ICAT and duplin directly interact with β-catenin to prevent its association with TCF/LEF transcription factors [4]. Recent findings also reveal intricate cross-talk between Wnt pathways and other signaling networks. For instance, non-canonical Wnt signaling interacts with the Hippo-YAP/TAZ pathway, forming an integrated signaling axis that regulates biological functions traditionally attributed to non-canonical Wnt signaling [1]. Furthermore, non-canonical signaling can inhibit canonical pathway activation through multiple mechanisms, including increased β-catenin degradation via GSK3β-independent mechanisms and enhanced secretion of canonical Wnt inhibitors such as DKK1 [1].

Integrated Wnt Signaling Model

The traditional binary classification of Wnt signaling has been challenged by proposals for an integrated Wnt signaling model that acknowledges the complexity of pathway cross-talk [1]. The emerging paradigm suggests that the cellular context—including specific receptor availability, cytoplasmic components, and nuclear mediators—determines the signaling outcome rather than a simple ligand-receptor coupling [1]. This perspective is particularly relevant in early embryogenesis, where Wnt signaling pleiotropy enables diverse context-dependent functions including mitogenic stimulation, cell fate specification, and differentiation [3].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Approaches

Key Quantitative Measurements

Advanced imaging and computational approaches have yielded quantitative insights into Wnt pathway dynamics. A study investigating β-catenin spatial dynamics in HEK293T cells developed a novel 3D confocal quantitation protocol to measure temporal and spatial changes in β-catenin concentrations following pathway perturbations [8]. The researchers acquired spatial data from two cellular compartments (nucleus and cytosol-membrane) and quantified target protein concentrations after treatments with cycloheximide (protein synthesis inhibitor) or Wnt3A (pathway activator) [8].

Table 3: Quantitative β-catenin Dynamics in HEK293T Cells After Perturbation [8]

| Treatment | Time Point | β-catenin Change (Whole Cell) | Compartmental Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cycloheximide | 0-4 hours | Decrease at constant rate | Similar decrease rate in both nuclear and cytosol-membrane compartments |

| Wnt3A | 0-1 hour | Initial increase | Faster increase in nuclear compartment |

| Wnt3A | 1-4 hours | Continued increase | Balanced increase across compartments |

This study demonstrated that with Wnt3A stimulation, the total cellular β-catenin rises throughout the cell, but the increase occurs initially faster in the nuclear compartment during the first hour [8]. When protein synthesis was inhibited with cycloheximide, β-catenin decreased at similar rates in both compartments, suggesting that diffusional transport is rapid compared to β-catenin degradation in the cytosol [8]. Computational modeling revealed that a two-compartment model with active transport mechanisms best reproduced the experimental data, highlighting the importance of spatial organization in Wnt signaling [8].

Experimental Protocols

3D Confocal Quantification of β-catenin Dynamics

The following methodology was adapted from the HEK293T study to quantify spatial and temporal protein dynamics in Wnt signaling [8]:

Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Culture HEK293T cells in appropriate medium under standard conditions.

- For perturbation experiments: apply either Wnt3A ligand (e.g., 100-200ng/mL) to activate signaling or cycloheximide (e.g., 10-100μg/mL) to inhibit protein biosynthesis.

- Include untreated controls at each time point.

- Incubate for predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4 hours).

Cell Staining and Fixation:

- Fix cells with paraformaldehyde (e.g., 4% for 15 minutes).

- Permeabilize with Triton X-100 (e.g., 0.1% for 10 minutes).

- Block with serum-based blocking buffer.

- Incubate with primary antibodies: anti-β-catenin, anti-N-cadherin (cell boundary marker).

- Incubate with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies.

- Counterstain nuclei with DAPI.

Image Acquisition and Calibration:

- Use confocal microscopy with consistent settings across samples.

- Include InSpeck microspheres (0.3% rated) as intensity calibration standards to enable quantitative comparisons between samples and time points.

- Acquire z-stacks to generate 3D volume data.

Image Analysis and Quantification:

- Use image processing software to identify cellular compartments based on marker signals (DAPI for nuclei, N-cadherin for cell boundary).

- Measure β-catenin intensity in each compartment.

- Normalize intensities using calibration standards.

- Perform statistical analysis across multiple cells and replicates.

This protocol enables quantitative analysis of protein localization and abundance changes in response to pathway perturbations, providing spatial and temporal resolution essential for understanding signaling dynamics.

Gene Expression Analysis in Pathological Contexts

To investigate Wnt pathway involvement in disease contexts, such as tumorigenesis, the following QPCR-based approach can be employed [7]:

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Obtain tissue samples (e.g., pituitary tumors) during surgical procedures.

- Microdissect to separate tumoral from non-tumoral tissues.

- Snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -70°C.

- Isolate total RNA using TRIzol reagent.

- Assess RNA integrity by spectrophotometry (260/280nm ratio) and agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcription kits.

Gene Expression Profiling:

- Design or select TaqMan assays for genes of interest covering:

- Canonical pathway components (WNT ligands, receptors, destruction complex members, target genes)

- Non-canonical pathway components (PCP and Ca²⺠pathway members)

- Endogenous controls (GUSβ, TBP, PGK1)

- Perform quantitative PCR with appropriate cycling conditions.

- Calculate gene expression using efficiency-corrected methods.

- Determine fold changes relative to control tissues.

Data Analysis:

- Use hierarchical clustering to identify expression patterns.

- Perform statistical comparisons between sample groups.

- Correlate expression patterns with clinical outcomes.

This approach revealed that most Wnt pathway components are not mis-expressed in pituitary tumors, contrasting with other tumors like colorectal cancer and craniopharyngioma where Wnt signaling plays established roles [7].

Research Tools and Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Wnt Signaling Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | HEK293T [8] | Pathway mechanism studies | Responsive to Wnt3A stimulation; no known Wnt pathway mutations |

| Wnt Ligands | Recombinant Wnt3A [8] | Canonical pathway activation | Binds Fz/LRP5/6 receptors to stabilize β-catenin |

| Pathway Inhibitors | Cycloheximide [8], IWP-2 [5] | Block protein synthesis or Wnt production | Inhibit global translation or Porcupine-mediated Wnt processing |

| Antibodies | anti-β-catenin, anti-N-cadherin [8] | Protein localization and quantification | Visualize and quantify target proteins in cellular compartments |

| Fluorescent Markers | DAPI [8] | Nuclear staining | Demarcate nuclear compartment for spatial analysis |

| Calibration Standards | InSpeck microspheres [8] | Intensity calibration | Enable quantitative comparisons between samples |

| Gene Expression Assays | TaqMan assays [7] | Expression profiling | Quantify transcript levels of pathway components |

Visualizing Wnt Signaling Pathways

Canonical Wnt/β-catenin Pathway

Non-Canonical Wnt Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Spatial Analysis

The canonical and non-canonical Wnt pathways represent sophisticated signaling networks that orchestrate critical processes in early embryogenesis and maintain tissue homeostasis throughout life. While the canonical pathway primarily regulates gene expression through β-catenin stabilization and nuclear translocation, the non-canonical pathways control cytoskeletal organization, cell polarity, and calcium-mediated signaling. The emerging paradigm of integrated Wnt signaling acknowledges the extensive cross-talk between these pathways and their context-dependent functions. Advanced experimental approaches, including 3D quantitative imaging and spatial modeling, continue to reveal new insights into the dynamic regulation of Wnt signaling. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these intricate mechanisms provides fertile ground for developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting Wnt-related pathologies while harnessing its regenerative potential.

The Wnt signaling pathway is a highly conserved, crucial system that governs fundamental aspects of embryonic development, including body axis patterning, cell fate specification, proliferation, and migration [9] [10]. Its function is paramount during early embryogenesis, directing processes from the establishment of the primary body axis to the formation of numerous tissues and organs [11]. The pathway's name is a portmanteau of the Drosophila segment polarity gene Wingless (Wg) and the vertebrate proto-oncogene Int-1, reflecting its evolutionary conservation and diverse functional roles [9] [12]. The intricate orchestration of Wnt signaling is achieved through a complex interplay between its core molecular components: the Wnt ligands, their cell surface receptors, and a suite of intracellular transducers that propagate the signal, ultimately leading to specific nuclear responses and changes in gene expression [9] [13]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of these key components, framing them within the context of embryogenesis research.

The Wnt Ligand Family

Wnt ligands constitute a large family of secreted, lipid-modified glycoproteins that are approximately 350-400 amino acids in length [9]. In humans, this family comprises 19 members, each playing distinct yet sometimes overlapping roles during development and homeostasis [9] [14]. A defining characteristic of all Wnts is a conserved palmitoleoylation event at a single cysteine residue. This modification, mediated by the Porcupine (PORCN) enzyme in the endoplasmic reticulum, is essential for the ligand's secretion via the Wntless (WLS) transporter and for its subsequent ability to bind to Frizzled receptors [9] [11]. Wnt proteins also undergo glycosylation, which further ensures their proper secretion and function [9].

While the functional classification of Wnt ligands can be context-dependent, they are often categorized based on their propensity to activate different downstream signaling branches. The table below summarizes the primary Wnt ligands found in Homo sapiens and their predominant signaling pathways.

Table 1: Major Wnt Ligands in Humans and Their Primary Signaling Pathways

| Wnt Ligand | Primary Signaling Pathway | Key Roles in Early Embryogenesis |

|---|---|---|

| WNT1 | Canonical [15] | Central nervous system development [9] |

| WNT2 | Canonical [15] | |

| WNT3 | Canonical [15] | Primitive streak formation, somiteogenesis [9] |

| WNT3A | Canonical [15] | |

| WNT4 | Non-canonical & Canonical [15] | Kidney, reproductive tract development [9] |

| WNT5A | Non-canonical [15] [12] | Limb bud patterning, cell migration [9] |

| WNT5B | Non-canonical [15] | |

| WNT6 | Non-canonical & Canonical [15] | |

| WNT7A | Non-canonical & Canonical [15] | Limb patterning, dorsoventral axis specification [9] |

| WNT7B | Non-canonical & Canonical [15] | |

| WNT8A | Canonical [15] | |

| WNT8B | Non-canonical & Canonical [15] | |

| WNT9A | Non-canonical & Canonical [15] | |

| WNT9B | Non-canonical & Canonical [15] | |

| WNT10A | Canonical [15] | |

| WNT10B | Canonical [15] | |

| WNT11 | Non-canonical [15] [12] | Cell movements during gastrulation [14] |

| WNT16 | Non-canonical & Canonical [15] |

Receptors and Co-receptors

The initiation of Wnt signaling occurs at the plasma membrane through the binding of a Wnt ligand to a receptor complex. The core of this complex is formed by receptors from the Frizzled (FZD) family, often in conjunction with various co-receptors that determine the specificity of the downstream signaling cascade [9] [11].

Frizzled (FZD) Receptors

Frizzled receptors are a family of G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR)-like proteins that span the plasma membrane seven times [9] [10]. In humans, there are 10 FZD genes (FZD1-FZD10) [14]. The extracellular N-terminal domain of FZD receptors features a characteristic cysteine-rich domain (CRD) that is responsible for direct binding to the Wnt ligand [9] [11]. The specific combination of Wnt ligand and the FZD receptor it engages with is a primary factor in channeling the signal into the canonical or a non-canonical pathway.

Co-receptors

Co-receptors are essential partners that work alongside FZD receptors to transduce the Wnt signal effectively.

- LRP5/6: The Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 are single-pass transmembrane proteins that act as the primary co-receptors for the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway [13] [10]. Their interaction with Wnt ligands and FZD receptors is crucial for initiating the intracellular events that lead to β-catenin stabilization.

- ROR1/ROR2 and RYK: For the non-canonical pathways, different co-receptors are employed. The tyrosine-protein kinase transmembrane receptors ROR1 and ROR2, as well as the RYK (Receptor-like tyrosine kinase), are key co-receptors for the Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) pathway [9] [15] [11]. These receptors help activate signaling cascades that regulate cytoskeletal organization and cell polarity.

Table 2: Primary Wnt Receptors and Co-receptors and Their Pathway Associations

| Receptor / Co-receptor | Family | Primary Signaling Pathway | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| FZD1-10 | 7-transmembrane GPCR | Canonical & Non-canonical [15] | Primary receptor for Wnt ligands [9] |

| LRP5/6 | Single-pass transmembrane | Canonical [15] | Co-receptor for β-catenin pathway [13] |

| ROR1 | Receptor tyrosine kinase | Non-canonical [15] | Co-receptor for PCP pathway [11] |

| ROR2 | Receptor tyrosine kinase | Non-canonical [15] | Co-receptor for PCP pathway [11] |

| RYK | Receptor tyrosine kinase | Non-canonical [15] | Co-receptor for PCP and Wnt/Ca2+ pathways [16] |

Intracellular Signal Transduction

Upon ligand-receptor binding, the Wnt signal is propagated inside the cell by a network of intracellular transducers. The central cytoplasmic node for all Wnt signaling branches is the Dishevelled (DVL/Dsh) protein.

The Central Mediator: Dishevelled (DVL)

Dishevelled is a multi-domain, cytoplasmic phosphoprotein that is directly recruited to the plasma membrane by the activated Frizzled receptor [9] [10]. It serves as a molecular hub, directing the signal into different pathways based on its specific protein domains [9]:

- DIX Domain: Essential for canonical pathway signaling. It facilitates interactions with the β-catenin destruction complex [11].

- PDZ Domain: Involved in both canonical and non-canonical pathways. It mediates protein-protein interactions with FZD and downstream effectors [11].

- DEP Domain: Primarily associated with non-canonical signaling, including the PCP and Wnt/Ca2+ pathways [11].

The Canonical Pathway: β-Catenin and the Destruction Complex

The hallmark of the canonical pathway is the regulation of the transcriptional co-activator β-catenin.

- "Off" State (No Wnt ligand): In the absence of a Wnt signal, cytoplasmic β-catenin is targeted for proteasomal degradation by a multi-protein "destruction complex." This complex includes the scaffold proteins Axin and Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC), and the kinases Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β (GSK3β) and Casein Kinase 1α (CK1α). These kinases sequentially phosphorylate β-catenin, marking it for ubiquitination by β-TrCP and subsequent degradation [13] [14]. This keeps cytoplasmic β-catenin levels low and prevents target gene transcription.

- "On" State (Wnt ligand present): Binding of a canonical Wnt (e.g., WNT3A) to FZD and LRP5/6 recruits DVL and Axin to the plasma membrane. This disrupts the destruction complex, preventing β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation. Stabilized β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm and translocates into the nucleus. There, it binds to transcription factors of the TCF/LEF (T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor) family, displacing transcriptional repressors and activating the expression of target genes (e.g., c-MYC, CYCLIN D1) that drive cell proliferation and fate decisions [9] [13] [11].

Non-Canonical Pathway Transducers

The non-canonical pathways operate independently of β-catenin/TCF/LEF-mediated transcription.

- Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) Pathway: This pathway regulates cytoskeletal organization and cell polarity. Activated DVL, via its PDZ domain, forms a complex with DAAM1 (Dishevelled-associated activator of morphogenesis 1). DAAM1 activates the small GTPase RhoA, which in turn activates ROCK (Rho-associated kinase). In a parallel branch, DVL activates the small GTPase Rac, which then activates JNK (Jun N-terminal kinase). These cascades ultimately lead to actin cytoskeleton remodeling, which is critical for convergent extension movements during gastrulation [9] [16] [3].

- Wnt/Ca2+ Pathway: Activation of this pathway (e.g., by WNT5A) leads to an increase in intracellular calcium ions (Ca2+). DVL, through its PDZ and DEP domains, can activate Phospholipase C (PLC) via G-proteins. PLC generates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), triggering the release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum. The elevated Ca2+ activates enzymes like Protein Kinase C (PKC) and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII), which can influence transcription through factors like NFAT (Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells), regulating processes such as cell adhesion and migration [16] [14].

Visualization of Wnt Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core components and signal flow of the canonical and non-canonical Wnt pathways.

Canonical Wnt/β-catenin Pathway

Non-Canonical Wnt Pathways

Experimental Analysis of Key Components

Studying the role of Wnt pathway components in embryogenesis requires a multifaceted experimental approach. The following section details key methodologies for analyzing the expression, localization, and functional involvement of ligands, receptors, and transducers.

Protocol: In Situ Hybridization for Mapping Wnt Ligand Expression in Embryo

Objective: To spatially localize the expression patterns of specific Wnt ligand mRNAs (e.g., Wnt3a, Wnt5a) in early-stage mouse embryos (e.g., E8.5-E12.5) [10].

Tissue Fixation and Sectioning:

- Dissect embryos in cold PBS and fix in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 12-24 hours at 4°C.

- Dehydrate through an ethanol series, clear in xylene, and embed in paraffin wax.

- Section the embedded embryos into 5-7 µm thick slices using a microtome and mount on positively charged glass slides.

Riboprobe Synthesis and Labeling:

- Clone a specific fragment of the target Wnt cDNA (e.g., 500-1000 bp) into a plasmid with opposing RNA polymerase promoters (e.g., T7, SP6).

- Linearize the plasmid and perform in vitro transcription with the appropriate RNA polymerase in the presence of digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled UTP to generate antisense (experimental) and sense (control) riboprobes.

Hybridization and Detection:

- Deparaffinize and rehydrate the sections. Treat with proteinase K (1-10 µg/mL) for permeabilization.

- Pre-hybridize sections with a hybridization buffer containing formamide, salts, and blocking agents (e.g., yeast tRNA, salmon sperm DNA) for 1-2 hours at 55-65°C.

- Hybridize with the DIG-labeled riboprobe (0.5-1.0 ng/µL) in hybridization buffer overnight at 55-65°C in a humidified chamber.

Washing and Signal Development:

- Perform stringent washes with SSC buffers (e.g., 2x SSC, 0.2x SSC) to remove non-specifically bound probe.

- Block non-specific binding sites with a blocking reagent (e.g., 2% normal sheep serum, 2% BSA).

- Incubate with an alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-DIG antibody for 1-2 hours.

- Wash thoroughly and incubate with the colorimetric AP substrates NBT/BCIP in the dark until a purple-blue precipitate forms. Stop the reaction with TE buffer.

- Counterstain with a nuclear fast red or eosin, dehydrate, clear, and mount with a permanent mounting medium.

Imaging and Analysis:

- Image sections using a bright-field microscope. The expression pattern of the target Wnt ligand will be visualized by the localized NBT/BCIP precipitate.

Protocol: Immunofluorescence for Localizing Intracellular Transducers

Objective: To visualize the subcellular localization and relative abundance of key intracellular transducers (e.g., β-catenin, DVL) in embryonic tissues or stem cell models of embryogenesis.

Sample Preparation:

- For embryos: Fix in 4% PFA, cryoprotect in 15-30% sucrose, embed in OCT compound, and section on a cryostat (8-12 µm thickness).

- For cultured cells: Grow on glass coverslips, treat with recombinant Wnt ligands (e.g., WNT3A) or inhibitors, and fix with 4% PFA.

Permeabilization and Blocking:

- Permeabilize samples with 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10-15 minutes.

- Block with 5-10% normal serum (from the species of the secondary antibody) and 1-5% BSA in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature to prevent non-specific antibody binding.

Antibody Incubation:

- Incubate samples with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Examples: Mouse anti-β-catenin (to assess nuclear accumulation), Rabbit anti-Dishevelled (to assess membrane recruitment), Rabbit anti-Axin.

- The next day, wash samples 3-4 times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST).

- Incubate with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488, 568) diluted in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature, protected from light.

- Incubate samples with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C.

Counterstaining and Mounting:

- Incubate with DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) for 5-10 minutes to stain nuclei.

- Wash extensively with PBS and mount coverslips onto glass slides using an anti-fade mounting medium (e.g., ProLong Gold).

Imaging and Analysis:

- Image using a confocal or epifluorescence microscope. Analyze images for changes in protein localization (e.g., β-catenin nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, DVL puncta formation at the membrane).

Protocol: Functional Knockdown using siRNA/shRNA

Objective: To assess the functional requirement of a specific Wnt component (e.g., FZD receptor, DVL) in a developmental process using in vitro models.

Design and Selection of RNAi Constructs:

- Design 2-3 different siRNA oligonucleotides or shRNA-encoding plasmids targeting distinct regions of the mRNA of the gene of interest (e.g., FZD5, DVL1). Include a non-targeting scrambled sequence as a negative control.

Cell Transfection/Transduction:

- Culture relevant cells (e.g., mouse embryonic stem cells, primary mesenchymal cells).

- For siRNA: Transfect cells at 40-60% confluency using a lipofection or electroporation reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- For shRNA: Transduce cells with lentiviral particles encoding the shRNA and select with puromycin (1-5 µg/mL) for 3-5 days to generate a stable knockdown pool.

Validation of Knockdown:

- 48-96 hours post-transfection (or after selection), harvest cells.

- Validate knockdown efficiency via quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) to measure mRNA levels and/or western blotting to assess protein depletion.

Phenotypic Analysis:

- Perform functional assays relevant to embryogenesis:

- Cell Migration/Invasion: Use Transwell or scratch/wound healing assays to model cell movements.

- Gene Expression Profiling: Analyze the expression of downstream Wnt target genes (e.g., Axin2, Sp5) by qRT-PCR.

- Cytoskeletal Analysis: Stain for F-actin with phalloidin and analyze cell morphology and polarity.

- Perform functional assays relevant to embryogenesis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and tools essential for investigating the Wnt signaling pathway in a research setting.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Wnt Pathway Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Wnt Proteins | Ligand | Activate Wnt signaling pathways [11] | Treatment of stem cells to direct differentiation; study of pathway activation in cell culture. |

| IWP-2 / LGK974 | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Inhibit Porcupine (PORCN), blocking Wnt ligand secretion and all downstream signaling [11] | Determine if a phenotypic effect is Wnt-dependent; create Wnt-free conditions. |

| XAV-939 / IWR-1 | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Stabilize the Axin/APC/GSK3β destruction complex, promoting β-catenin degradation (Canonical pathway specific) [11] | Probe the specific role of canonical signaling in a biological process. |

| Anti-β-catenin Antibodies | Antibody | Detect total and active (non-phospho) β-catenin protein levels and localization [14] | Immunofluorescence (nuclear vs. cytoplasmic), Western blot analysis. |

| Anti-FZD Antibodies | Antibody | Detect Frizzled receptor expression and localization [14] | Flow cytometry, immunoprecipitation, blocking receptor function. |

| Dkk-1 | Secreted Antagonist | Binds LRP5/6 co-receptors, specifically inhibiting the canonical Wnt pathway [13] [14] | Selectively block canonical signaling without affecting non-canonical pathways. |

| TOPFlash/FOPFlash | Reporter Assay | Luciferase-based reporters for β-catenin/TCF transcriptional activity [10] | Quantify the activity of the canonical Wnt pathway in cell-based screens. |

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | Functional Genomics | Knockdown expression of specific Wnt pathway genes [11] | Perform loss-of-function screens to identify essential pathway components. |

| KWKLFKKGIGAVLKV | KWKLFKKGIGAVLKV Cationic Antimicrobial Peptide | Research-grade cationic helical peptide "KWKLFKKGIGAVLKV" for antimicrobial mechanism studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Bmeda | BMEDA (N,N-bis(2-mercaptoethyl)-N',N'-diethylenediamine) | BMEDA is a chelating agent for Rhenium-186 in liposomal nanoliposome research (e.g., 186RNL for glioma). For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway constitutes an evolutionarily conserved system that plays a pivotal role in early embryonic development, tissue homeostasis, and cell fate determination. At the core of this pathway lies β-catenin, a dual-function protein that serves as both a transcriptional co-activator and a component of cell-cell adhesion complexes. This technical review comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms governing β-catenin dynamics, from its regulation by the cytoplasmic destruction complex to its nuclear translocation and transcriptional functions. Special emphasis is placed on the pathway's critical functions during early embryogenesis, including its established roles in maintaining pluripotency, regulating cell lineage specification, and facilitating implantation processes. Additionally, this review integrates recent advances in our understanding of nuclear translocation mechanisms and discusses emerging therapeutic strategies targeting β-catenin dynamics in disease contexts, particularly cancer. The information presented herein provides researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed framework for understanding β-catenin regulation and its implications in both developmental biology and pathogenesis.

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway, also known as the canonical Wnt pathway, represents a fundamental signaling cascade that is highly conserved across metazoan species, from Drosophila to humans [9]. The name "Wnt" originates from the fusion of two terms: the Drosophila segment polarity gene "Wingless" and the murine proto-oncogene "integration 1" [9] [17]. This pathway functions as a master regulator of various physiological processes, with particularly crucial functions during early embryonic development. The mammalian pre-implantation period constitutes one of the most critical and unique phases during early embryonic developmental processes, involving a precise transition from a single-cell zygote to the blastocyst stage through a series of meticulously regulated events [18]. These processes initiate cell lineage specification and differentiation into the inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm (TE), which are fundamentally regulated by the activation of several intracellular signaling cascades, with Wnt signaling playing a predominant role [18].

Wnt signaling is primarily categorized into two distinct branches: the canonical pathway (β-catenin-dependent) and non-canonical pathways (β-catenin-independent) [18] [19]. The canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway is distinguished by its reliance on the stabilization and nuclear translocation of β-catenin, which subsequently acts as a transcriptional co-activator for T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) family transcription factors [18] [19] [20]. During early embryogenesis, spatially defined and well-controlled Wnt signaling orchestrates normal embryonic development in a process that initiates at fertilization and continues throughout organism formation [18]. The pathway plays an indispensable role in maintaining pluripotency both in vivo and in vitro in human and mouse embryonic stem cell (ESC) cultures, primarily through regulation of core pluripotency factors such as Oct4, Nanog, Sox2, and Klf4 [18] [17].

Table 1: Key Components of the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

| Component Category | Key Elements | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Signals | Wnt proteins (Wnt1, Wnt3a, Wnt2, etc.) | Secreted ligands that initiate pathway activation by binding to receptors [19] [17] |

| Membrane Receptors | Frizzled (FZD), LRP5/6 | Seven-transmembrane receptors and co-receptors that transduce Wnt signals [19] [20] |

| Cytoplasmic Destruction Complex | APC, Axin, GSK-3β, CK1α | Phosphorylates β-catenin, targeting it for degradation in the absence of Wnt signaling [19] [20] [21] |

| Signal Transducers | Dvl (Dishevelled) | Recruited upon receptor activation; disrupts the destruction complex [19] [20] |

| Nuclear Components | β-catenin, TCF/LEF | Transcriptional co-activator complex that regulates target gene expression [18] [19] [20] |

Molecular Composition of the Destruction Complex

Architecture and Regulation

The β-catenin destruction complex represents a multi-protein machinery that maintains precise control over cytoplasmic β-catenin levels in the absence of Wnt signaling. This complex consists of several core components: adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), Axin, glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), and casein kinase 1α (CK1α) [19] [20] [21]. Under unstimulated conditions (Wnt-OFF state), this destruction complex facilitates the phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of β-catenin, thereby preventing its accumulation and nuclear translocation [19] [20].

Axin functions as a critical scaffolding protein within the destruction complex, containing binding domains that facilitate interactions with other complex components [19]. The regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) domain at the N-terminus of Axin specifically interacts with the APC protein, while the DIX domain at the C-terminus enables interaction with Dishevelled (Dvl) and also contributes to Axin oligomerization [19]. APC, a large multi-domain protein, serves as a scaffold in conjunction with Axin, promoting the sequential phosphorylation of β-catenin by the kinase components [19]. The destruction complex operates through a precisely coordinated phosphorylation cascade: CK1α initially phosphorylates β-catenin at serine 45 (Ser45), which serves as a priming phosphorylation event that enables subsequent phosphorylation by GSK-3β at threonine 41 (Thr41), serine 37 (Ser37), and serine 33 (Ser33) [19] [22].

Table 2: Phosphorylation Events in β-Catenin Regulation

| Residue | Kinase | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Ser45 | CK1α | Priming phosphorylation that enables subsequent GSK-3β-mediated phosphorylation [19] [22] |

| Thr41, Ser37, Ser33 | GSK-3β | Creates recognition site for β-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase; targets β-catenin for proteasomal degradation [19] [22] |

| Ser552 | AKT | Promotes dissociation from cell-cell contacts and enhances nuclear accumulation; independent of destruction complex [9] |

This multi-site phosphorylation creates a recognition motif for the E3 ubiquitin ligase β-TrCP (SCFβ-TrCP), which subsequently ubiquitinates β-catenin, marking it for proteasomal degradation [19] [20]. This meticulous regulatory mechanism ensures that cytoplasmic β-catenin levels remain low in the absence of Wnt signaling, thereby preventing inappropriate activation of target genes.

Wnt-Mediated Disassembly Mechanism

Upon Wnt ligand binding to the Frizzled receptor and LRP5/6 co-receptor, a series of intracellular events leads to the inhibition of the destruction complex [19] [20]. The transmembrane receptor complex recruits Dishevelled (Dvl) to the plasma membrane, which becomes activated through sequential phosphorylation, poly-ubiquitination, and polymerization [20]. Activated Dvl subsequently recruits Axin and the destruction complex to the plasma membrane through interactions with the intracellular domains of Frizzled and LRP5/6 [19] [20]. The phosphorylation of LRP5/6 at multiple PPPSPxS motifs creates docking sites for Axin, effectively sequestering the scaffolding protein away from the cytoplasmic destruction complex [19]. This redistribution and membrane localization of Axin disrupts the integrity and functionality of the destruction complex, thereby preventing β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation [19] [20]. Consequently, β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm and subsequently translocates to the nucleus to initiate transcriptional programs essential for embryonic development.

Diagram 1: Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway Regulation - illustrating the key molecular events in the destruction complex during Wnt OFF and ON states

Cytoplasmic Stabilization and Nuclear Translocation Mechanisms

Cytoplasmic Accumulation and Transport

Following disruption of the destruction complex, β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm through a tightly regulated process. The stability of β-catenin is significantly enhanced as it evades phosphorylation-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [19] [20]. This stabilized β-catenin then undergoes active transport toward the nucleus, a process recently discovered to involve specific motor proteins and adaptor complexes [22]. Recent research has revealed that the intraflagellar transport A complex (IFT-A) associates with Kinesin-2 to facilitate the nuclear translocation of β-catenin upon Wnt pathway activation [22]. IFT-A, traditionally known for its role in ciliogenesis, forms a complex with β-catenin via its N-terminal region, specifically through interaction with amino acid residues 24-79 in mammals (equivalent to Arm34-87 in Drosophila) [22]. This interaction is essential for the efficient nuclear translocation of β-catenin, as loss of function in either IFT-A components or Kinesin-2 results in impaired Wnt signaling and developmental defects despite normal cytoplasmic stabilization of β-catenin [22].

The molecular mechanism involves direct binding between IFT140 and the N-terminal region of β-catenin, which serves as a recognition site for the transport machinery [22]. Kinesin-2 interacts with IFT140 through Kap3 (kinesin-associated protein 3) and functions as the molecular motor that transports the IFT-A/β-catenin complex along cytoplasmic microtubules toward the nuclear envelope [22]. This active transport system ensures the efficient delivery of β-catenin to the nucleus, where it can execute its transcriptional functions. The critical nature of this process is demonstrated by experimental evidence showing that expression of a small N-terminal β-catenin peptide (β-catenin24-79) acts as a competitive inhibitor by binding to IFT140, thereby interfering with nuclear translocation of endogenous full-length β-catenin and attenuating Wnt signaling output [22].

Nuclear Import and Transcriptional Activation

Upon reaching the nuclear envelope, β-catenin translocates into the nucleus through the nuclear pore complex via mechanisms that involve Rac1 and other import factors [20]. Once inside the nucleus, β-catenin forms a transcriptional activation complex with T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) transcription factors [18] [19] [20]. This complex displaces transcriptional repressors, such as Groucho, that are bound to TCF/LEF in the absence of Wnt signaling [20] [17]. The formation of the β-catenin/TCF transcriptional complex recruits additional co-activators, including B-cell lymphoma 9 (BCL9), Pygopus, and CREB-binding protein (CBP)/p300, which possess histone acetyltransferase activity that modifies chromatin structure to facilitate transcription [19] [9].

The β-catenin/TCF complex activates the expression of numerous target genes that regulate fundamental processes during early embryogenesis, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and stem cell maintenance [18] [19]. Key target genes include c-Myc, Cyclin D1, Axin2, and CD44, many of which are associated with cell cycle progression and proliferation [19] [21]. Importantly, the specific transcriptional output of β-catenin is context-dependent and varies between cell types and developmental stages, influenced by the availability of co-factors and the epigenetic landscape [18] [9]. During early embryonic development, β-catenin also interacts with other transcription factors beyond TCF/LEF, including Oct4 and Yamanaka factors, to maintain pluripotency in embryonic stem cells [18]. This interaction enhances the expression of core pluripotency factors in a TCF-dependent manner, establishing a regulatory network that supports the pluripotent state in the inner cell mass of developing blastocysts [18].

Experimental Methodologies for Studying β-Catenin Dynamics

Live-Cell Imaging and Localization Assays

Advanced imaging techniques have revolutionized the study of β-catenin dynamics in living cells, enabling researchers to monitor its localization and movement in real time. The HiBiT Protein Tagging System represents a cutting-edge approach that allows for endogenous tagging of β-catenin with a small, luminescent tag [21]. When combined with LgBiT and Nano-Glo Live Cell substrate, the luminescent signal serves as a sensitive proxy for β-catenin abundance and subcellular location [21]. This methodology enables researchers to visualize β-catenin dynamics dynamically in live cells at single-cell resolution without the need for overexpression, fixation, or staining procedures that can introduce artifacts [21]. Experimental protocols typically involve:

- Endogenous Tagging: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated insertion of the HiBiT tag into the CTNNB1 gene locus, ensuring physiological expression levels and regulation [21].

- Live-Cell Imaging: Treated cells are imaged using systems such as the GloMax Galaxy Bioluminescence Imager, which captures spatial and temporal information over extended time courses [21].

- Quantitative Analysis: Image processing software quantifies the redistribution of β-catenin from cytoplasm to nucleus following pathway activation or inhibition [21].

This approach has demonstrated that in untreated cells, β-catenin remains predominantly cytoplasmic, while after treatment with GSK-3β inhibitors such as AZD2858, cells show clear nuclear accumulation of β-catenin over a five-hour time course [21]. The capability to track these dynamics in real time provides valuable insights for validating the mechanism of action of pathway modulators and identifying potential off-target effects early in the drug discovery process [21].

Reporter Assays and High-Throughput Screening

Luciferase-based reporter assays represent a cornerstone methodology for quantifying Wnt/β-catenin pathway activity and identifying regulatory compounds [21]. These assays typically utilize a β-catenin-responsive luciferase reporter construct containing multiple TCF/LEF binding sites upstream of a minimal promoter driving firefly or NanoLuc luciferase expression [21]. Standardized protocols include:

- Cell Line Development: Stable integration of the reporter construct into relevant cell lines (e.g., HEK293, HT-29, or primary stem cells) to ensure consistent expression and response [21].

- Compound Screening: High-throughput screening of chemical libraries using automated plate readers to measure Relative Luminescence Units (RLU) as a proxy for pathway activity [21].

- Validation Studies: Follow-up experiments using pathway activators (e.g., CHIR99021, Wnt3a conditioned medium) or inhibitors (e.g., iCRT compounds, XAV939) to confirm specificity [21].

In a landmark study, researchers employed a β-catenin-responsive luciferase reporter to screen nearly 15,000 compounds, leading to the discovery of the iCRT class of inhibitors that disrupt β-catenin/TCF interactions [21]. These compounds demonstrated selective toxicity toward colon cancer cells with constitutive Wnt activity and reduced tumor growth in mouse models, highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting nuclear β-catenin function [21]. While reporter assays provide population-level data on pathway activity, they are often combined with complementary approaches such as immunofluorescence, subcellular fractionation, and quantitative PCR to obtain a comprehensive understanding of β-catenin dynamics across molecular, cellular, and functional levels.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Studying β-Catenin Dynamics - outlining key methodological approaches

Research Reagent Solutions for β-Catenin Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating β-Catenin Dynamics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Activators | CHIR99021, AZD2858, Wnt3a conditioned medium, 6-Bio | GSK-3β inhibition; stabilizes β-catenin by preventing phosphorylation [18] [21] [23] | Chemical inhibitors provide temporal control; recombinant proteins offer physiological activation |

| Pathway Inhibitors | iCRT3, iCRT5, iCRT14, XAV939, GSK3787 | Disrupt β-catenin/TCF interactions; tankyrase inhibition stabilizes Axin [18] [21] | Target different pathway nodes; useful for mechanism studies and therapeutic development |

| Live-Cell Imaging Tools | HiBiT Protein Tagging System, Nano-Glo Live Cell Substrate, HaloTag-β-catenin fusions | Real-time tracking of β-catenin localization and dynamics [21] | Enable endogenous tagging; minimal perturbation to native protein function |

| Reporter Systems | TCF/LEF Luciferase Reporters (BAR, TOPFlash), GFP Reporters | Quantitative measurement of pathway activity; high-throughput screening [21] | Sensitive readouts; compatible with automated screening platforms |

| Antibodies | Phospho-specific β-catenin (Ser33/37/Thr41, Ser45), Total β-catenin, Non-phospho β-catenin (Active) | Immunofluorescence, Western blot, immunohistochemistry for detection and localization [22] [23] | Distinguish activation states; validate subcellular localization |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 editing constructs, siRNA/shRNA libraries, Dominant-negative peptides (β-catenin24-79) | Gene knockout, knockdown, and functional interference studies [22] | Enable mechanistic studies; assess requirement of specific pathway components |

β-Catenin in Embryonic Development and Therapeutic Implications

Roles in Early Embryogenesis

β-catenin dynamics play indispensable roles during early embryonic development, particularly in the critical stages surrounding blastocyst formation and implantation. During mammalian pre-implantation development, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is instrumental in maintaining pluripotency and regulating cell lineage specification [18]. The pathway is active from the earliest stages of development, with β-catenin detected from the 2-cell stage through to the blastocyst stage in mouse embryos [18]. The functional importance of this pathway is evidenced by experiments demonstrating that enhanced activation of Wnt signaling through GSK-3β inhibition (using compounds such as 6-Bio or CHIR99021) increases the inner cell mass (ICM) cell proliferation index and leads to improved quality and yield of bovine blastocysts [18] [23].

The trophectoderm (TE), which forms the outer cell layer of the blastocyst, exhibits particularly important dependence on proper β-catenin regulation [23]. Successful development of mammalian embryos relies on appropriate TE formation and function, as this tissue maintains blastocyst structure, forms the placenta to enable nutrient exchange between mother and embryo, and facilitates implantation [23]. Recent research has demonstrated that β-catenin accumulation in TE cells promotes their migratory and invasive capacities, which are essential for successful implantation [18] [23]. This function is mediated through the upregulation of key target genes such as c-Myc and PPARδ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta) [18]. The interplay between β-catenin and PPARδ establishes a regulatory network that coordinates cell proliferation and invasive capabilities during early development, with PPARδ strongly coupling with c-Myc expression in both ICM and trophoblast stem cells under elevated Wnt conditions [18].

Dysregulation in Disease and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysregulation of β-catenin dynamics contributes significantly to various human diseases, most notably cancer [19] [21] [17]. Aberrant activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway occurs through multiple mechanisms, including mutations in key pathway components such as APC, AXIN, CTNNB1 (encoding β-catenin), and other elements [19] [21]. In colorectal cancer, approximately 90% of cases involve mutations that disrupt normal β-catenin regulation, most commonly through loss-of-function mutations in APC or stabilizing mutations in CTNNB1 that prevent β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation [21]. These alterations lead to constitutive β-catenin signaling that drives uncontrolled proliferation and tumor progression [21] [24].

The clinical importance of targeting β-catenin dynamics is demonstrated by ongoing efforts to develop therapeutic interventions [19] [21] [17]. Several classes of inhibitors have been identified, including:

- Small molecule inhibitors that disrupt β-catenin/TCF interactions (iCRT compounds) [21]

- Tankyrase inhibitors (XAV939) that stabilize Axin and promote β-catenin degradation [19]

- Porcupine inhibitors that prevent Wnt secretion and ligand-mediated pathway activation [19]

- Antisense oligonucleotides that target pathway components [17]

- Peptide inhibitors that interfere with β-catenin nuclear translocation (β-catenin24-79) [22]

The β-catenin24-79 peptide represents a particularly promising therapeutic approach, as it acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor by competitively binding to IFT140 and preventing nuclear translocation of full-length β-catenin [22]. This mechanism effectively attenuates Wnt/β-catenin signaling output even in contexts with stabilized β-catenin, such as those caused by APC or CTNNB1 mutations [22]. While most of these therapeutic strategies are still in preclinical development, they offer considerable promise for targeting Wnt-driven cancers and other diseases characterized by aberrant β-catenin signaling.

The intricate regulation of β-catenin dynamics, from its controlled degradation by the cytoplasmic destruction complex to its regulated nuclear translocation and transcriptional functions, represents a cornerstone of embryonic development and tissue homeostasis. The molecular mechanisms governing these processes continue to be elucidated through advanced experimental approaches that enable real-time visualization and precise manipulation of pathway components. The essential functions of β-catenin during early embryogenesis—particularly in pluripotency maintenance, cell lineage specification, and implantation processes—highlight its fundamental importance in developmental biology. Furthermore, the frequent dysregulation of β-catenin dynamics in human diseases, especially cancer, underscores the therapeutic potential of targeting this pathway. Ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of β-catenin regulation and to develop innovative strategies for modulating its activity in pathological contexts, offering promising avenues for future therapeutic interventions.

TCF/LEF Transcription Factors as Gatekeepers of Gene Expression

Within the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) proteins function as the ultimate nuclear effectors, translating β-catenin signals into precise transcriptional programs that govern early embryogenesis. This whitepaper delineates the sophisticated molecular architecture of TCF/LEF transcription factors, their context-dependent regulation through alternative splicing and post-translational modifications, and their non-redundant functions in developmental processes such as nephron formation and axis patterning. We further present quantitative data on their DNA-binding properties, detailed experimental protocols for assessing Wnt pathway activity at single-cell resolution, and emerging therapeutic strategies targeting TCF/LEF regulatory kinases for cancer and fibrotic diseases. The integral role of these factors as binary molecular switches—mediating either repression or activation of Wnt target genes—establishes them as critical gatekeepers of gene expression during embryonic development and in stem cell niches.

The Wnt signaling pathway is a fundamental molecular pathway governing cell fate decisions, tissue patterning, and stem cell maintenance during embryonic development [25] [5]. At the core of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway are TCF/LEF transcription factors, which serve as the major endpoint mediators, translating the influx of β-catenin signals into discrete gene expression programs [26] [27]. The discovery of TCF/LEF genes as nuclear Wnt pathway components in the 1990s was a pivotal breakthrough that plugged a critical knowledge gap in understanding how nuclear β-catenin could regulate target genes despite lacking a DNA-binding domain [28]. The subsequent establishment of a model wherein Wnt-regulated β-catenin partners with DNA-binding TCF/LEF proteins on specific genomic sequences, known as Wnt Response Elements (WREs), provided the mechanistic link between extracellular signals and transcriptional outcomes [28].

TCF/LEF factors function as bimodal transcriptional switches that actively repress target genes in the absence of Wnt signaling and activate them when Wnt signaling is active [28]. This review examines the structure-function relationships of TCF/LEF proteins, their complex regulation, and their indispensable roles in early embryogenesis, with particular emphasis on their function as molecular gatekeepers of gene expression. We also explore experimental approaches for investigating TCF/LEF activity and the therapeutic potential of modulating their function in disease contexts.

Molecular Architecture of TCF/LEF Proteins

Domain Organization and Functional Motifs

TCF/LEF proteins possess a modular architecture consisting of highly conserved domains that enable their function as context-dependent transcription factors. Vertebrates have four TCF/LEF family members (TCF7, LEF1, TCF7L1, and TCF7L2) that arose through gene duplication, allowing for functional specialization beyond the single TCF/LEF ortholog found in invertebrates [26] [28].

Table 1: Functional Domains of TCF/LEF Transcription Factors

| Domain | Function | Conservation |

|---|---|---|

| N-terminal β-catenin binding domain | Recruits β-catenin for transcriptional activation; contains conserved motifs essential for the interaction | High across all vertebrate TCF/LEF members |

| Control region | Mediates transcriptional repression; contains binding sites for Groucho/TLE corepressors | Variable due to alternative splicing |

| DNA-binding HMG domain | Sequence-specific DNA binding to 5′-SCTTTGATS-3′ consensus; induces DNA bending | Extremely high; single amino acid changes can disrupt binding |

| C-clamp (CRARF domain) | Secondary DNA-binding domain recognizing GC-rich helper sites; not present in all isoforms | Limited to specific isoforms; absent in some family members |

The DNA-binding domain comprises a high-mobility group (HMG) box and a small peptide motif of basic residues that together recognize a specific DNA sequence (5′-SCTTTGATS-3′) with nanomolar affinity [26]. This HMG domain not only confers sequence specificity but also enforces a sharp bend in the DNA helix between 90° and 127°, likely facilitating the assembly of multi-protein complexes at regulatory elements [26].

The C-clamp domain, located carboxy-terminal to the HMG domain, is enriched in basic, cysteine, and aromatic residues and serves as a secondary DNA-binding domain with specificity for GC-rich "helper" sites [26]. This domain is not present in all TCF/LEF family members, with its inclusion or exclusion contributing to functional diversification and target gene specificity [26].

Structural Basis for Bimodal Transcriptional Regulation

TCF/LEF proteins function as binary switches that determine whether Wnt target genes are activated or repressed. This bimodal functionality is encoded within their structural domains:

Repression State: In the absence of Wnt signaling, TCF/LEF proteins interact with transcriptional corepressors from the Groucho/transducin-like enhancer of split (Gro/TLE) family via their control region, actively suppressing target gene expression [26] [28]. Additional corepressors include myeloid translocation gene-related 1 (Mtgr1) and corepressor of Pan (Coop) [26].

Activation State: Upon Wnt pathway activation, stabilized β-catenin translocates to the nucleus and binds to the N-terminal domain of TCF/LEF, displacing corepressors and recruiting coactivators to initiate transcription [26] [28]. The C-terminal transactivation domains of β-catenin then interact with additional transcriptional machinery to drive gene expression.

Diagram: Bimodal transcriptional regulation by TCF/LEF proteins. In the absence of Wnt signaling (OFF state), TCF/LEF associates with corepressors to silence target genes. When Wnt signaling is active (ON state), β-catenin translocates to the nucleus, binds TCF/LEF, displaces corepressors, and recruits coactivators to initiate transcription.

TCF/LEF in Early Embryogenesis

Roles in Nephron Development and Axis Patterning

During embryonic development, TCF/LEF transcription factors play indispensable roles in multiple morphogenetic processes. In kidney development, nephron formation depends critically on Wnt signaling, with two specific ligands—Wnt9b and Wnt4—required for nephron differentiation [25]. The canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway acts downstream of these ligands in metanephric mesenchymal progenitor cells, where forced activation triggers progression toward proto-epithelial aggregates, while selective antagonism inhibits differentiation [25]. Titration of pathway activity appears central for proper coordination of differentiation and morphogenesis, with transient activation of the pathway during epithelial differentiation [25].

Beyond organogenesis, TCF/LEF factors are essential for fundamental patterning processes. They contribute to anterior-posterior patterning of the developing central nervous system, neural crest development, and the initial induction of the dorsal body axis [28]. The vertebrate embryo utilizes different TCF/LEF family members to achieve spatial and temporal specificity in these diverse developmental contexts, with partial functional redundancy but also unique, non-overlapping functions [26] [28].

Isoform Diversity and Context-Dependent Functions

Functional diversification of TCF/LEF proteins occurs through several mechanisms:

Gene-specific specializations: The four mammalian TCF/LEF paralogs have evolved distinct expression patterns and functions, with genetic evidence indicating only partial redundancy [26] [28].

Alternative splicing: Extensive alternative splicing generates isoforms with different domain compositions, particularly in TCF7 and TCF7L2 genes. These include isoforms that lack the β-catenin binding domain (functioning as constitutive repressors) and isoforms with varying C-terminal domains that influence DNA-binding specificity and cofactor interactions [26] [28].

Post-translational modifications: Phosphorylation by kinases such as TNIK (TRAF2 and NCK-interacting kinase) and HIPK2 (homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2) dynamically regulates DNA-binding affinity and co-factor interactions [27]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system also contributes to regulation, particularly through UBR5-mediated clearance of Groucho/TLE corepressors [27].

Table 2: TCF/LEF Family Members in Vertebrates

| Gene Name | Common Aliases | Key Functions in Development | Notable Isoforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCF7 | TCF1 | T-cell development, Wnt pathway repression | Dominant-negative isoforms lacking β-catenin binding domain |

| LEF1 | TCF1α | Hair follicle development, neural crest specification | Multiple isoforms with varying transactivation potential |

| TCF7L1 | TCF3 | Pluripotency maintenance, neural patterning | Often functions as a transcriptional repressor |

| TCF7L2 | TCF4 | Central nervous system development, energy metabolism | Numerous splice variants with different C-terminal |

Experimental Analysis of TCF/LEF Function

Single-Cell RNA and DNA Sequencing for Pathway Activity Assessment

Advanced methodologies now enable simultaneous analysis of pathway activity and genetic mutations at single-cell resolution. A microfluidic-based approach allows differential extraction of RNA and DNA from individual cells through a two-stage lysis protocol [29]:

Protocol: Single-Cell RNA and DNA Extraction for Wnt Pathway Analysis

Cell Capture and Lysis:

- Capture individual calcein-stained cells in picoliter-volume traps within a microfluidic chip.

- Apply first lysis buffer (0.5× TBE with 0.5% Triton X-100) to lyse plasma membranes while keeping nuclear membranes intact.

- Collect cytoplasmic contents (including RNA) from separate outlets for off-chip cDNA synthesis and amplification.

- Apply second lysis buffer (0.5× TBE with 0.5% Triton X-100 and Proteinase K) to lyse nuclear membranes and release DNA.

- Perform on-chip whole genome amplification (WGA) at 30°C followed by heat inactivation at 60°C.

Pathway Activity Modeling:

- Construct a Bayesian network model representing the Wnt transcriptional program with three node types: transcription complex (TC), Wnt target genes, and expression level measurements.

- Calibrate the model using RNA-seq data from samples with known Wnt activity status (e.g., LS180 and SW1222 as Wnt-active; RKO as Wnt-inactive).

- Apply the calibrated model to single-cell RNA-seq data by entering measured expression values and using Bayesian reasoning to infer the probability of transcription complex activity.

Validation and Application:

- Verify model performance using control cell lines with established Wnt pathway status.

- Analyze single cells from experimental conditions to infer pathway activity states despite intercellular heterogeneity.

This approach successfully classified all seven analyzed single LS174T cells as Wnt-active and six RKO cells as Wnt-inactive, demonstrating robust pathway activity inference at single-cell resolution [29].

Diagram: Experimental workflow for single-cell analysis of Wnt pathway activity and genotype. Cells are captured in a microfluidic device, followed by sequential lysis to separate cytoplasmic RNA and nuclear DNA. Sequencing and Bayesian modeling enable correlation of pathway activity with mutational status.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TCF/LEF and Wnt Pathway Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| TCF/LEF Antibodies | Anti-Prep1, Anti-Pbx1 | Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP); protein localization |

| Wnt Pathway Modulators | CHIR (Wnt agonist), IWP-2 (Wnt antagonist) | Titration of pathway activity in progenitor cells |

| Microfluidic Systems | Custom picoliter-volume trap chips | Single-cell capture and processing |

| Lysis Buffers | Triton X-100 based buffers with Proteinase K | Differential extraction of RNA and DNA |

| Bayesian Model Components | 34 Wnt target gene panel | Inference of pathway activity from expression data |

Therapeutic Targeting and Future Perspectives

TCF/LEF Regulation as a Therapeutic Strategy

Direct targeting of TCF/LEF transcription factors has emerged as a promising therapeutic approach for Wnt-driven pathologies. Challenges in directly targeting the intrinsically disordered β-catenin binding domains have prompted innovative strategies:

Kinase inhibition: Targeting upstream regulatory kinases such as TNIK (TRAF2 and NCK-interacting kinase) offers an indirect approach to modulate TCF/LEF activity. The TNIK inhibitor INS018_055 has successfully completed Phase II clinical trials for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, demonstrating statistically significant attenuation of lung function decline over 52 weeks [27].

Advanced modalities: Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) and AI-designed protein scaffolds show promise for precise interaction with TCF/LEF proteins, potentially overcoming the limitations of conventional small-molecule approaches [27].

This therapeutic strategy represents a significant advance over broad Wnt pathway inhibition, which often carries substantial toxicity due to the pathway's fundamental roles in tissue homeostasis [27]. By targeting downstream regulatory nodes, these approaches aim to fine-tune rather than globally inhibit Wnt signaling, preserving physiological functions while correcting pathological activation.

Future Research Directions

The field continues to evolve with several emerging research priorities:

Enhanceosome dynamics: Recent evidence indicates that the Wnt enhanceosome is pre-assembled in a poised state before signal activation, enabling rapid transcriptional responses [27]. Understanding the composition and regulation of these enhanceosomes will provide deeper insights into context-specific Wnt responses.

Chromatin interactions: The interplay between TCF/LEF proteins and chromatin remodeling complexes creates a dynamic regulatory landscape that influences target gene accessibility [27]. Mapping these interactions in different developmental contexts remains a active area of investigation.

Synthetic biology approaches: Advances in computational protein design and synthetic biology may enable engineering of bespoke TCF/LEF modulators with unprecedented specificity, potentially heralding a new era of personalized molecular therapies [27].

TCF/LEF transcription factors serve as essential gatekeepers of gene expression in the Wnt signaling pathway, integrating multiple regulatory inputs to determine transcriptional outcomes during embryonic development. Their sophisticated domain architecture, isoform diversity, and context-dependent regulation enable precise control of fundamental processes including nephron formation, axis patterning, and stem cell maintenance. Experimental approaches such as single-cell RNA/DNA sequencing coupled with Bayesian modeling provide powerful tools to dissect their functions in heterogeneous cellular populations. Emerging therapeutic strategies that target TCF/LEF regulatory networks offer promising avenues for treating Wnt-driven diseases while minimizing toxicity. As our understanding of these transcriptional gatekeepers continues to deepen, so too will our ability to harness their regulatory potential for both basic research and clinical applications.

Wnt's Role in Cell Fate Specification and Pluripotency Maintenance

The Wnt signaling pathway is a complex, evolutionarily conserved network that functions as a master regulator of embryonic development, stem cell maintenance, and tissue homeostasis [5] [30]. This pathway coordinates critical cellular processes including proliferation, migration, cell fate specification, and the maintenance of pluripotency [31]. The name "Wnt" derives from the integration of two Drosophila phenotypes: wingless and int [5]. In mammalian systems, the pathway has generally been divided into the canonical (β-catenin-dependent) and non-canonical (β-catenin-independent) branches, with the canonical pathway being particularly implicated in cell fate decisions [5] [30]. Within early embryogenesis, WNT signaling activity is involved in the regulation of many cellular functions, including the maintenance of pluripotency and the induction of differentiation toward specific tissue lineages [31]. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms through which Wnt signaling governs cell fate specification and pluripotency maintenance, with particular emphasis on implications for therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Canonical Wnt Signaling

Core Pathway Components

The canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway initiates when Wnt ligands bind to Frizzled receptors and their co-receptors, Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 5/6 (LRP5/6) on the cell surface [32]. This interaction triggers a intracellular signaling cascade that prevents the phosphorylation and degradation of β-catenin [30]. In the absence of Wnt signaling, cytoplasmic β-catenin is phosphorylated by a destruction complex consisting of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), casein kinase I (CK I), Axin, and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) [33] [30]. This phosphorylation event targets β-catenin for ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation [30]. When Wnt ligands activate the pathway, they disrupt this destruction complex through the recruitment of cytosolic Disheveled (Dvl) protein, allowing β-catenin to accumulate in the cytoplasm and subsequently translocate to the nucleus [30]. Within the nucleus, β-catenin partners with T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (TCF/LEF) transcription factors to activate the expression of target genes governing cell fate decisions [32] [30].

Pathway Regulation and Feedback Loops

The Wnt signaling pathway is carefully controlled by multiple regulatory mechanisms, including feedback loops involving pathway agonists and antagonists [31]. Key negative regulators include RNF43 and ZNRF3, which are E3 ubiquitin ligases that promote Wnt receptor endocytosis and degradation, thereby dampening pathway activity [33]. Additionally, the Wnt target gene Axin2 functions as a negative feedback regulator by enhancing β-catenin degradation [33]. The availability of intracellular pools of active β-catenin and cross-regulation by β-catenin-independent pathways further fine-tune signaling output [31]. Recent research has revealed that the distribution of Wnt ligands occurs through various mechanisms, including free diffusion, restricted diffusion, active transport, and via filopodia extending to adjacent cells [5].

Wnt Signaling Pathway Diagram

Canonical Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Pathway

Wnt Signaling in Pluripotency States

Naive versus Primed Pluripotency

The role of Wnt signaling in pluripotent stem cells demonstrates remarkable context-dependency, particularly when comparing "naive" and "primed" states of pluripotency [34]. Mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) represent a naive pluripotent state similar to the pre-implantation inner cell mass, and in these cells, Wnt/β-catenin signaling supports self-renewal and prevents differentiation [34]. In contrast, human ESCs (hESCs) and mouse epiblast stem cells (EpiSCs) exist in a primed pluripotent state resembling the post-implantation epiblast, where Wnt signaling promotes differentiation toward definitive endoderm and mesoderm lineages [34]. This fundamental difference explains the seemingly contradictory effects of Wnt activation observed in different stem cell systems and underscores the importance of cellular context in determining Wnt functional outcomes.

Table 1: Characteristics of Pluripotent Stem Cell States

| Characteristic | Mouse ESC (Naive) | Human ESC (Primed) | Mouse EpiSC (Primed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Representative State | Pre-implantation | Post-implantation | Post-implantation |

| Culture Conditions for Self-renewal | Serum + LIF; Wnt3a/GSK3i | Fgf2 + Activin A | Fgf2 + Activin A |

| Effect of Wnt Activation | Self-renewal | Differentiation | Differentiation |

| Key Pluripotency Factors | High Klf4, Rex1, Stella | Low Klf4, Rex1, Stella | Low Klf4, Rex1, Stella |

| Developmental Potential | Broad (including germline) | Limited | Limited |

Molecular Mechanisms of Pluripotency Regulation