ZEB2 in Somitogenesis: Unraveling its Critical Role in Mouse and Human Development

This article synthesizes current research on the transcription factor ZEB2 and its indispensable function in mouse and human somitogenesis.

ZEB2 in Somitogenesis: Unraveling its Critical Role in Mouse and Human Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the transcription factor ZEB2 and its indispensable function in mouse and human somitogenesis. We explore the foundational biology of ZEB2, from its discovery as a SMAD-interacting protein to its role as a key regulator of paraxial mesoderm patterning. The content details advanced methodological approaches, including the use of gastruloid models and degron-based perturbation systems combined with single-cell omics, which have been pivotal in identifying ZEB2's critical role. We further address common challenges in ZEB2 research and discuss the validation of its functions across species, highlighting implications for understanding human developmental disorders like Mowat-Wilson Syndrome and potential translational applications. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking a comprehensive overview of ZEB2 in embryonic segmentation.

ZEB2: From Discovery to Fundamental Roles in Embryonic Patterning

Discovery of ZEB2 as a SMAD-Binding Transcription Factor

The discovery of Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2) as a SMAD-binding transcription factor marked a pivotal advancement in understanding embryonic development and disease pathogenesis. Initially identified in 1999 through yeast two-hybrid screening as a DNA-binding and SMAD-binding transcription factor that determines cell fate in amphibian embryos, ZEB2 emerged as a crucial nuclear fine-tuner of transcriptional responses to TGFβ/BMP signaling [1]. This discovery laid the foundation for comprehending ZEB2's multifaceted roles in neural development, neural crest cell formation, and its clinical significance in Mowat-Wilson syndrome [1] [2]. Subsequent research utilizing conditional knockout murine models and stem cell systems has further elucidated ZEB2's mechanism of action as a transcriptional repressor that integrates multiple signaling pathways, including BMP, Wnt, and Notch, during critical developmental processes such as somitogenesis [1] [3].

ZEB2, originally named SIP1 (SMAD Interacting Protein 1), represents one of two vertebrate members of the zinc-finger E-box binding homeodomain (ZEB) transcription factor family, characterized by their unique two-handed zinc finger/homeodomain structure [4] [3]. The discovery of its direct interaction with activated SMAD proteins positioned ZEB2 as a key nuclear effector in the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling pathway, which is essential during early fetal development [4]. This interaction mechanism provides a crucial link between extracellular signaling and transcriptional regulation, enabling precise control of developmental gene expression programs.

The structural configuration of ZEB2 includes eight zinc fingers and one homeodomain, which facilitate its DNA-binding capacity and protein-protein interactions [4]. As a transcription factor, ZEB2 predominantly functions as a transcriptional repressor but can also activate specific target genes depending on cellular context [2]. Its ability to interact with receptor-activated SMAD proteins allows ZEB2 to serve as a transcriptional corepressor that fine-tunes cellular responses to TGFβ/BMP signaling gradients, thereby influencing critical cell fate decisions during embryogenesis [1] [4].

Historical Context and Initial Discovery

The Original Experimental Approach

The initial identification of ZEB2 occurred through a yeast two-hybrid screening methodology using the transcription activation (MH2) domain of BMP-SMAD1 as bait against cDNA libraries derived from mid-gestation mouse embryos [1]. This approach was predicated on the hypothesis that receptor-activated SMADs required cooperation with DNA-binding transcription factors for their transcriptional regulatory functions in the nucleus. The screening identified several candidate SMAD-interacting proteins (SIPs), including a partial cDNA that exhibited significant sequence homology with the previously discovered transcription factor δEF1 (now known as ZEB1) [1].

Table 1: Key Experiments in ZEB2 Discovery

| Year | Experimental System | Key Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | Yeast two-hybrid screening | Identification of SIP1/ZEB2 as SMAD-binding protein | First demonstration of ZEB2-SMAD interaction [1] |

| 2001-2003 | Human genetic studies | ZEB2 mutations cause Mowat-Wilson syndrome | Established clinical relevance of ZEB2 [1] |

| 2003+ | Conditional KO mice | Embryonic lethality in full KO; tissue-specific functions | Revealed essential developmental roles [1] |

| 2016 | Zeb2 KO mouse ESCs | Defective exit from pluripotency | Identified role in stem cell differentiation [5] |

| 2020 | R26_Zeb2 mESCs | Positive regulation of myogenic differentiation | Demonstrated non-neural roles in mesodermal lineages [3] |

Technical Limitations and Methodological Considerations

The original yeast two-hybrid approach, while groundbreaking, presented several technical limitations that influenced the initial characterization of ZEB2. The screen identified partial cDNA clones rather than full-length transcripts, requiring subsequent complete cDNA isolation and sequencing. Additionally, the artificial environment of yeast cells may not have fully recapitulated the native nuclear context of mammalian cells, potentially missing certain post-translational modifications or protein co-factors essential for optimal SMAD-ZEB2 interactions. Despite these limitations, the initial discovery provided the crucial foundation for all subsequent functional studies of ZEB2 in development and disease.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vivo Model Systems

Mouse models have been instrumental in elucidating ZEB2 functions. General homozygous Zeb2-knockout mice exhibit early post-gastrulation embryonic lethality around E8.5, with severe defects in somitogenesis, neural plate formation, and neural crest development [5] [2]. This early lethality necessitated the development of conditional knockout strategies using Zeb2+/fl(Δex7) mice, enabling tissue-specific deletion of ZEB2 functions in the nervous system, neural crest derivatives, and other tissues [1]. These models have revealed both cell-autonomous and non-autonomous functions of ZEB2, particularly in brain development where ZEB2 determines neurogenic-to-gliogenic switching timing through paracrine signaling mechanisms [1].

Zebrafish models with zeb2 knockdown display early axial and neural patterning defects alongside neural crest abnormalities, establishing evolutionary conservation of ZEB2 functions and providing a complementary system for rapid functional screening [1]. The transparency and external development of zebrafish embryos facilitate live imaging of developmental processes affected by ZEB2 deficiency.

In Vitro and Stem Cell Systems

Embryonic stem cell systems have provided critical insights into ZEB2's molecular mechanisms. Zeb2 knockout mouse ESCs can exit naive pluripotency but stall in an early epiblast-like state, failing to properly differentiate into neural or mesendodermal lineages [5]. Transcriptomic and DNA methylome analyses of these systems revealed that ZEB2 regulates the silencing of pluripotency networks and establishment of DNA methylation patterns necessary for lineage commitment [5].

Human ESC studies demonstrate that ZEB2 knockdown promotes mesendodermal differentiation while its overexpression enhances neuroectoderm formation, highlighting its role in early cell fate decisions [5]. More recent gastruloid models provide three-dimensional in vitro systems that recapitulate aspects of somitogenesis and enable precise manipulation of ZEB2 function during mesoderm patterning [6].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Experimental Systems for ZEB2 Research

| System | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse KO | Developmental functions, tissue-specific roles | Physiologically relevant, enables tissue-specific analysis | Embryonic lethal in full KO, time-consuming [1] |

| Zebrafish KD | Neural crest, early patterning | Rapid screening, easy visualization | May not fully recapitulate mammalian development [1] |

| Mouse ESCs | Differentiation mechanisms, molecular pathways | Genetic manipulation, in vitro differentiation | May not capture all in vivo complexities [5] |

| Human ESCs | Human-specific mechanisms, disease modeling | Human-relevant, disease modeling | Ethical considerations, technical challenges [5] |

| Gastruloids | Somitogenesis, 3D patterning | 3D architecture, high-throughput capability | Still developing, may lack some tissue interactions [6] |

Molecular Mechanisms of ZEB2 Action

SMAD Interaction and Transcriptional Regulation

ZEB2 functions as a nuclear effector of TGFβ/BMP signaling through its direct interaction with receptor-activated SMAD proteins (R-SMADs). This interaction occurs primarily through the N-terminal domain of ZEB2 and the MH2 domain of SMADs, allowing ZEB2 to be recruited to SMAD-binding elements in target gene promoters [1] [4]. Once bound to DNA, ZEB2 typically functions as a transcriptional repressor through its recruitment of corepressor complexes, including CtBP and NCOR, which mediate histone deacetylation and chromatin compaction at target loci [2].

The transcriptional regulatory activity of ZEB2 exhibits context-dependent specificity, influenced by cellular environment, developmental stage, and interacting protein partners. In some contexts, ZEB2 can function as a transcriptional activator, though this represents a less common mode of action [2]. This functional versatility enables ZEB2 to integrate multiple signaling inputs and execute appropriate transcriptional outputs during complex developmental processes.

Signaling Pathway Integration

Beyond its canonical role in TGFβ/BMP signaling, ZEB2 interacts with multiple additional signaling pathways to coordinate developmental processes:

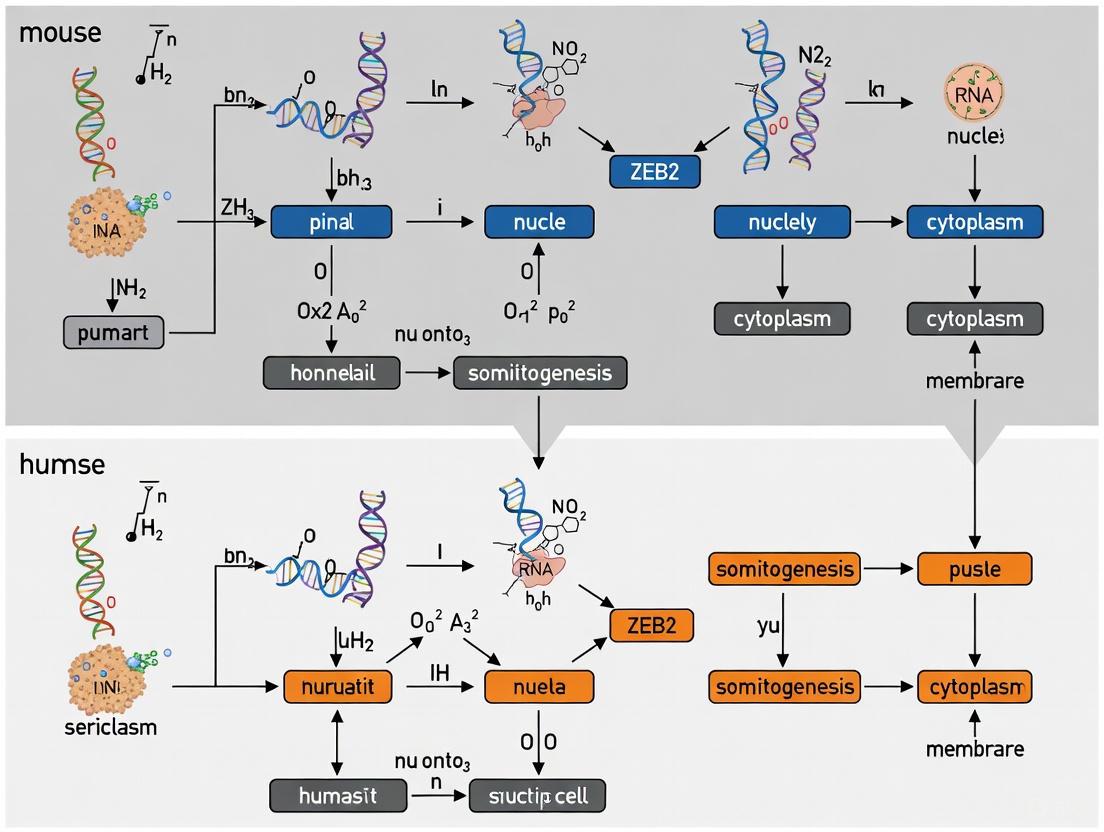

Figure 1: ZEB2 Integration of Multiple Signaling Pathways. ZEB2 directly interacts with SMAD proteins and integrates inputs from Wnt and Notch pathways to regulate target gene expression.

The anti-BMP activity of ZEB2 was among its first identified signaling modulatory functions, particularly evident in neural plate patterning where ZEB2 opposes BMP-mediated ventralization [1]. Additionally, ZEB2 modulates Wnt signaling through indirect mechanisms that remain to be fully elucidated, and regulates Notch signaling outcomes through transcriptional repression of Notch pathway components or effectors [1] [3]. This multifaceted signaling integration capacity positions ZEB2 as a central node in the regulatory networks controlling embryonic patterning and cell fate decisions.

Comparative Analysis of ZEB2 Functions Across Biological Contexts

Role in Neurodevelopment and Neural Crest

ZEB2 plays indispensable roles in nervous system development, functioning at multiple stages from initial neural induction through terminal differentiation. During early neurodevelopment, ZEB2 regulates the timing of neurogenic-to-gliogenic transition in the forebrain, serving as the first identified transcription factor that controls this critical switch in a cell non-autonomous manner [1]. In the developing cortex, ZEB2 determines the size and layering of cortical regions by controlling the relative proportions of different neuronal subtypes.

In neural crest development, ZEB2 orchestrates the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) required for neural crest cell delamination, followed by regulation of migration and differentiation into diverse derivatives, including enteric nervous system neurons, melanocytes, and craniofacial structures [1] [2]. These functions explain why ZEB2 haploinsufficiency in Mowat-Wilson syndrome affects both central and peripheral nervous systems, with clinical manifestations including Hirschsprung disease, intellectual disability, and distinctive facial features [1] [4].

Role in Somitogenesis and Mesodermal Differentiation

While initially characterized for its roles in neural development, ZEB2 also plays critical functions in mesodermal lineages, particularly during somitogenesis. Mouse embryos with complete Zeb2 knockout exhibit severe defects in somite formation and patterning, revealing essential requirements for ZEB2 in this process [1]. Recent studies using gastruloid models have further delineated ZEB2's role in regulating mouse and human somitogenesis, with degradation-tag (degron) mediated perturbation of ZEB2 function causing specific defects in somite patterning [6].

In pluripotent stem cell differentiation, ZEB2 positively regulates myogenic differentiation, with Zeb2-overexpressing mouse ESCs showing enhanced expression of myogenic markers (Pax3, Pax7, MyoD, Myogenin) and myomiRs (miR-1, miR-133b, miR-206, miR-208) compared to Zeb2-null counterparts [3]. This pro-myogenic function involves ZEB2's ability to modulate TGFβ/BMP signaling, which normally opposes myogenic differentiation, thereby creating a permissive environment for muscle-specific gene expression programs.

Table 3: ZEB2 Functional Roles Across Developmental Contexts

| Developmental Context | Main Functions | Key Target Genes/Pathways | Phenotype of Loss-of-Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forebrain Development | Timing of neuro-gliogenic switch, cortical layering | TGFβ/BMP signaling, paracrine factors | Microcephaly, intellectual disability [1] |

| Neural Crest | EMT, migration, differentiation | E-cadherin, TGFβ pathway | Hirschsprung disease, craniofacial defects [1] [2] |

| Somitogenesis | Somite patterning, segmentation | Unknown targets | Somitogenesis defects, axial patterning defects [1] [6] |

| Myogenic Differentiation | Enhancement of muscle differentiation | MyoD, Myogenin, myomiRs | Impaired muscle differentiation [3] |

| Stem Cell Pluripotency | Exit from naive pluripotency | Tet1, pluripotency factors | Stalling in epiblast-like state [5] |

Technical Approaches and Research Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Models

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ZEB2 Investigation

| Reagent/Model | Type | Key Applications | Specific Function in ZEB2 Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeb2+/fl(Δex7) mice | Animal model | Tissue-specific knockout studies | Enables Cre-mediated deletion of critical exon [1] |

| R26_Zeb2 mice | Animal model | Conditional overexpression | Rosa26 locus-driven cDNA expression [1] |

| Zeb2 KO mESCs | Cell line | Molecular mechanism studies | Elucidation of differentiation defects [5] |

| R26_Zeb2 mESCs | Cell line | Gain-of-function studies | Assessment of Zeb2 overexpression effects [3] |

| Anti-ZEB2 antibodies | Immunological reagent | Protein detection | Western blot, immunohistochemistry, ChIP [3] |

| Gastruloid systems | 3D in vitro model | Somitogenesis studies | Modeling early patterning events [6] |

| NIBR-17 | N6-(6-methoxypyridin-3-yl)-2-morpholino-[4,5'-bipyrimidine]-2',6-diamine | Get N6-(6-methoxypyridin-3-yl)-2-morpholino-[4,5'-bipyrimidine]-2',6-diamine (CAS 944396-88-7) for phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| McN5691 | McN5691, CAS:99254-95-2, MF:C30H35NO3, MW:457.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Key Methodological Approaches

Transcriptomic profiling through RNA-sequencing of wild-type versus Zeb2 mutant cells has identified comprehensive sets of ZEB2-dependent genes across multiple developmental contexts [1] [5]. These studies reveal that ZEB2 regulates diverse target genes involved in cell differentiation, signaling pathways, and metabolic processes.

Epigenomic analyses including reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) have elucidated ZEB2's impact on the epigenome, particularly its role in maintaining DNA methylation patterns during differentiation [5]. Zeb2 knockout ESCs initially acquire appropriate DNA methylation marks but fail to maintain them during neural differentiation, instead reverting toward a more naive methylome state [5].

Lineage tracing and fate mapping approaches in conditional knockout models have revealed cell-autonomous versus non-autonomous functions of ZEB2, particularly important in understanding its roles in tissue patterning and cell-cell communication [1].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for ZEB2 Functional Characterization. Comprehensive approaches combining multiple model systems and analytical methods are required to fully elucidate ZEB2 functions.

Implications for Human Development and Disease

Mowat-Wilson Syndrome

The discovery that heterozygous ZEB2 mutations cause Mowat-Wilson syndrome (MOWS) provided crucial clinical relevance to basic research on ZEB2 function [1] [4]. This rare autosomal dominant disorder (incidence 1:50,000-70,000 live births) exemplifies the pleiotropic effects of ZEB2 haploinsufficiency, affecting multiple organ systems including the central nervous system, neural crest derivatives, heart, and genitourinary tract [1]. The majority of MOWS cases result from complete gene deletions, nonsense mutations, or frameshift mutations that trigger nonsense-mediated decay of ZEB2 mRNA, effectively creating null alleles [1]. Rare missense mutations and C-terminal truncations typically cause milder phenotypes, providing structure-function insights into critical protein domains [1].

Hirschsprung Disease

Isolated Hirschsprung disease (aganglionic megacolon) can result from specific ZEB2 mutations that preferentially affect enteric nervous system development without the full spectrum of MOWS features [4]. This reflects the particular sensitivity of neural crest-derived enteric neurons to ZEB2 gene dosage, with compromised EMT, migration, or differentiation of enteric neural crest progenitors leading to incomplete colonization of the gastrointestinal tract [1] [2].

Cancer and Fibrosis

While beyond the scope of this developmental focus, ZEB2 has emerging roles in cancer progression and fibrotic diseases, primarily through its regulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [1] [7]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, a specific single-nucleotide polymorphism (rs3806475) in the ZEB2 promoter region associates with increased cancer risk under a recessive model [4]. These pathological contexts highlight the continued relevance of ZEB2 mechanisms in adult tissue homeostasis and disease.

Future Directions and Unanswered Questions

Despite significant advances since its initial discovery as a SMAD-binding transcription factor, numerous questions regarding ZEB2 biology remain unresolved. The complete repertoire of direct ZEB2 target genes across different developmental contexts requires further elucidation through combinatorial ChIP-seq and transcriptomic approaches. The precise mechanisms by which ZEB2 interacts with various chromatin-modifying complexes and how these interactions determine transcriptional outcomes need additional characterization.

The functional significance of ZEB2 protein isoforms generated through alternative splicing represents another area of limited understanding, as does the regulation of ZEB2 expression itself by transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. From a therapeutic perspective, strategies to modulate ZEB2 function in disease contexts, particularly Mowat-Wilson syndrome, remain largely unexplored and would benefit from continued research into ZEB2 structure-function relationships and downstream effector pathways.

The integration of emerging technologies such as single-cell multi-omics, CRISPR-based screening, and organoid models will undoubtedly provide new insights into ZEB2 functions in development and disease, building upon the foundational discovery of ZEB2 as a SMAD-binding transcription factor that coordinates complex transcriptional programs during embryogenesis.

ZEB2 Expression Dynamics During Early Embryogenesis

Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2) is a DNA-binding transcriptional repressor and critical developmental regulator essential for early embryonic patterning. As a nuclear fine-tuner of transcriptional responses to TGF-β/Nodal-Activin and BMP signaling, ZEB2 regulates cell fate decisions across multiple lineages during embryogenesis [3] [8]. Heterozygous mutations in ZEB2 cause Mowat-Wilson syndrome (MOWS), characterized by severe intellectual disability, Hirschsprung disease, epilepsy, and various structural anomalies including congenital heart defects and craniofacial dysmorphisms [9] [8]. This review synthesizes current understanding of ZEB2 expression dynamics and functional roles during early embryogenesis, with particular emphasis on its recently identified critical functions in mouse and human somitogenesis. We provide comprehensive experimental comparisons and methodological frameworks to guide future research into this pivotal developmental regulator.

Temporal and Spatial Expression Patterns of ZEB2

Early Embryonic Expression Dynamics

ZEB2 exhibits remarkably early and dynamic expression patterns during embryogenesis. In human embryonic stem cell (hESC) models of cranial neural crest induction, ZEB2 is among the earliest factors expressed in prospective human neural crest, with transcripts detectable as early as 12 hours after induction initiation and showing continuous increase over 5 days of differentiation [9]. This rapid activation positions ZEB2 as a primary responder to Wnt signaling during neural crest formation.

Comparative studies in chick embryos reveal conserved early expression patterns, with Zeb2 transcripts present throughout the entire epiblast of Hamburger-Hamilton stage 3 (HH3) gastrula embryos, prior to expression of the earliest neural crest specification marker Pax7 [9]. As development proceeds, Zeb2 becomes restricted to the prospective neural plate and neural crest at HH4+, and by HH8, expression localizes to neural folds with subsequent presence in neural tube and migrating neural crest streams at HH12 [9].

Table 1: Comparative ZEB2 Expression Dynamics Across Model Systems

| Developmental Stage | hESC Model | Chick Embryo | Mouse Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-gastrulation | Not applicable | Ubiquitous epiblast expression (HH3) | Not detected in naïve ESCs |

| Early specification | Detectable at 12h, increasing through day 5 | Restricted to neural plate/neural crest (HH4+) | Upregulated during exit from naïve pluripotency |

| Neural crest formation | Maintained throughout NC induction | Neural folds (HH8), migrating NC (HH12) | Critical for NC specification and differentiation |

| Somitogenesis | Not thoroughly investigated | Not thoroughly investigated | Essential for somite patterning and differentiation |

Expression in Pluripotency Transitions

In mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs), Zeb2 is undetectable in the naïve pluripotent state but demonstrates significant upregulation during the transition from primed pluripotency, accompanying efficient conversion of naïve ESCs into epiblast-like stem cells [5] [10]. This pattern establishes ZEB2 as a critical factor for exit from primed pluripotency and entry into general and neural differentiation programs.

Comparative Functional Analysis of ZEB2 in Early Lineage Specification

Neural Crest Specification

ZEB2 plays indispensable roles in neural crest formation through multiple mechanisms. Knockdown studies in hESC-based neural crest models reveal that ZEB2 promotes neural crest identity while repressing non-neural/pre-placodal ectodermal genes [9]. At day 3 of neural crest induction, ZEB2 knockdown results in upregulation of neural plate border genes (PAX7, MSX1/2, DLX5) and NC specifiers (FOXD3, SOX9, SNAI2), followed by subsequent downregulation at day 5, indicating failure of proper NC cell formation [9].

ZEB2 interacts with the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex to regulate the epigenetic landscape during neural crest development. Mutant ZEB2 lacking the N-terminal NuRD-interacting domain fails to properly recruit HDAC1 and displays derepressed enhancers during human neural crest induction, with compromised terminal differentiation into osteoblasts, peripheral neurons, and neuroglia [9].

Regulation of Pluripotency Exit

ZEB2 serves as a critical regulator of the transition from pluripotency to committed lineages. Zeb2 knockout mESCs can exit the naïve state but stall in an early epiblast-like state and demonstrate impaired neural and mesendodermal differentiation capacity [5]. These mutant cells maintain the ability to re-adapt to 2i+LIF conditions even after prolonged differentiation exposure, indicating failed irreversible commitment.

Mechanistically, Zeb2 knockout ESCs exhibit deregulated expression of genes involved in pluripotency, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and DNA methylation, including elevated Tet1 levels [5]. The aberrant maintenance of pluripotency networks and DNA methylation patterns in Zeb2-deficient cells establishes ZEB2 as a link between pluripotency networks and irreversible differentiation commitment.

Table 2: ZEB2 Functional Roles Across Developmental Contexts

| Developmental Context | Primary Function | Key Regulatory Targets | Phenotype of Perturbation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural crest formation | Specifies NC fate, represses non-neural lineages | PAX7, MSX1/2, FOXD3, SOX9, BMP pathway components | Failed NC differentiation, BMP signaling dysregulation |

| Pluripotency exit | Promotes irreversible commitment | Tet1, pluripotency factors, EMT genes | Stalled epiblast state, maintained pluripotency |

| Somitogenesis | Regulates somite patterning | Unknown targets in presomitic mesoderm | Somitogenesis defects in mouse models |

| Myogenic differentiation | Enhances muscle commitment | MyoD, Myogenin, myomiRs | Impaired skeletal muscle differentiation |

Emerging Role in Somitogenesis

Recent research utilizing mouse gastruloids and multilayered proteomics approaches has identified a critical role for ZEB2 in mouse and human somitogenesis [11] [12]. Gastruloid differentiation studies combined with degron-based perturbations and single-cell RNA sequencing demonstrate ZEB2's essential function in somite patterning, consistent with earlier observations of somitogenesis defects in Zeb2 knockout mice [11] [5] [8].

ZEB2 in Somitogenesis: Mouse and Human Conservation

Evidence from Gastruloid Models

Recent advances in synthetic embryo models have provided unprecedented insight into ZEB2 function during somitogenesis. Studies utilizing mouse gastruloids combined with multilayered mass spectrometry-based proteomics have revealed ZEB2 as a critical regulator of somite formation in both mouse and human systems [11] [12]. These models enable precise temporal resolution of protein expression dynamics during germ layer specification and their derivatives.

Gastruloid differentiation studies employing degron-based perturbations combined with single-cell RNA sequencing have specifically identified ZEB2's essential role in somitogenesis, demonstrating conserved function across mouse and human systems [11] [12]. This approach has established gastruloids as a powerful platform for investigating ZEB2 dynamics during paraxial mesoderm patterning.

Historical Evidence and Mechanistic Insights

Earlier studies of general Zeb2-knockout mice revealed embryonic lethality shortly after E8.5 with multiple defects, including impaired somitogenesis [5] [8]. Expression analyses in amphibian and mouse embryos further identified Zeb2 transcripts in presomitic mesoderm, suggesting direct involvement in somite patterning [8].

The mechanism of ZEB2 action in somitogenesis likely involves its characteristic function as a transcriptional repressor that fine-tunes cellular responses to morphogen signaling, potentially modulating BMP, TGF-β, or Wnt pathway activity in the presomitic mesoderm, similar to its actions in other developmental contexts [9] [3] [8].

Experimental Approaches for Investigating ZEB2 Function

Stem Cell Differentiation Models

Multiple stem cell-based systems have been developed to investigate ZEB2 function during early lineage specification:

Neural Crest Differentiation Protocol [9]:

- Base model: Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs)

- Induction method: 2 days of exogenous Wnt activation

- Key markers: PAX7 (NPB), FOXD3, SOX9 (NC specifiers)

- Timeline: ZEB2 expression onset at 12h, increasing through 5 days

- Perturbation approaches: siRNA knockdown, N-terminal mutant analysis

Neural Differentiation Protocol [5] [10]:

- Base model: Mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs)

- Method: Embryoid body formation in KO DMEM + 15% FBS, then N2B27 + retinoic acid (500 nM) from day 4

- Timeline: 8-15 days to neuroprogenitor cells

- Key observations: Zeb2 upregulation essential for NPC formation

Gastruloid-Based Somitogenesis Analysis [11] [12]:

- Model system: Mouse gastruloids

- Analytical approach: Multilayered (phospho)proteomics + P300 proximity labeling

- Perturbation method: Degron-based Zeb2 depletion + scRNA-seq

- Key finding: Essential role in mouse and human somitogenesis

Signaling Pathway Modulation

ZEB2 functions as a critical modulator of multiple developmental signaling pathways. In neural crest development, ZEB2 regulates appropriate BMP signaling levels, with N-terminal truncated ZEB2 mutants causing early misexpression of BMP signaling ligands that can be rescued through BMP attenuation [9]. This positions ZEB2 as a key regulator of BMP-mediated cell fate decisions.

ZEB2 also interacts with activated SMADs of BMP and TGF-β pathways to inhibit expression of downstream targets, functioning as a nuclear fine-tuner of transcriptional responses to extracellular signals [3] [8]. This SMAD-interaction capability enables ZEB2 to integrate multiple signaling inputs during cell fate specification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for ZEB2 Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Application | Key Features/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | Zeb2-V5 mESCs [10] | ChIP-seq mapping | Endogenous tagging for DNA-binding studies |

| ZEB2 KO hiPSC (KICRi002A-4) [13] | Differentiation studies | Homozygous 790bp deletion in ZEB2 | |

| R26_Zeb2 mESCs [3] | Gain-of-function studies | cDNA expression from Rosa26 safe harbor | |

| Perturbation Tools | siRNA ZEB2 knockdown [9] | Acute depletion | ~80% protein reduction in hNC model |

| Degron-based depletion [11] | Rapid protein degradation | Gastruloid studies with scRNA-seq readout | |

| Zeb2flox/flox mice [5] | Conditional knockout | Cell-type specific deletion approaches | |

| Analytical Methods | V5-tag ChIP-seq [10] | DNA-binding mapping | 2,432 binding sites identified in NPCs |

| Multilayered proteomics [11] | Protein expression | Phosphoprotein dynamics in gastruloids | |

| P300 proximity labeling [12] | Enhancer interaction mapping | Gastruloid-specific enhancer landscapes | |

| Differentiation Systems | hESC neural crest model [9] | NC specification studies | 2-day Wnt activation, 5-day differentiation |

| Mouse gastruloids [11] [12] | Somitogenesis studies | 3D model for paraxial mesoderm patterning | |

| AZD 4407 | AZD 4407, CAS:166882-70-8, MF:C19H21NO3S2, MW:375.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Org30958 | Org30958, CAS:99957-90-1, MF:C21H30O2S2, MW:378.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

ZEB2 represents a master regulatory transcription factor with critical functions at multiple stages of early embryogenesis. From its early expression in gastrulating embryos to its essential roles in neural crest formation, pluripotency exit, and somitogenesis, ZEB2 coordinates complex developmental processes through transcriptional repression and signaling pathway modulation. The conservation of ZEB2 functions between mouse and human systems, particularly in recently identified roles in somitogenesis, underscores its fundamental importance in embryonic patterning. Continued investigation using the rapidly expanding toolkit of stem cell models, genome editing approaches, and multi-omics technologies will further elucidate ZEB2's diverse mechanisms of action and potential therapeutic applications for related developmental disorders.

The transcription factor ZEB2 (Zinc Finger E-Box Binding Homeobox 2) represents a critical regulator in mammalian embryonic development, with its functions elucidated primarily through sophisticated knockout mouse models. These models demonstrate that ZEB2 is indispensable for proper embryogenesis, particularly in somitogenesis, neural development, and hematopoietic differentiation. This guide systematically compares phenotypic outcomes across various Zeb2 knockout systems, providing researchers with consolidated experimental data and methodologies relevant to developmental biology and therapeutic discovery. The essential nature of ZEB2 is further highlighted by its association with Mowat-Wilson syndrome (MOWS) in humans, a neurodevelopmental disorder caused by ZEB2 haploinsufficiency [1].

Comparative Phenotypic Analysis of ZEB2 Knockout Models

Table 1: Developmental Defects in ZEB2 Knockout Models

| Knockout Model/System | Key Developmental Defects | Developmental Stage | Primary Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Homozygous KO [1] | Early embryonic lethality, multiple defects in somitogenesis, neural plate, and neural crest cells [5] | Lethal shortly after E8.5 [5] | Histological analysis, mRNA expression studies |

| Conditional KO (Tie2-Cre, Vav-iCre) [14] | Defective HSC/HPC differentiation and fetal liver colonization; enhanced cell adhesion; perinatal lethality with cephalic hemorrhaging [14] | Embryonic/perinatal lethality [14] | FACS analysis, histological staining, gene expression (Angpt1, β1 integrin, Cxcr4) |

| Zeb2 KO Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs) [5] | Stalled in epiblast-like state; impaired neural and mesendodermal differentiation; failed pluripotency exit [5] | In vitro differentiation (Embryoid Bodies) | RNA-sequencing, RRBS (DNA-methylation analysis), immunostaining |

| Zeb2 KO in Somitogenesis [12] | Critical role in mouse and human somitogenesis [12] | Gastrulation and early organogenesis [12] | scRNA-seq, proteomics, enhancer interactome profiling via P300 proximity labeling |

The data reveal that complete Zeb2 knockout results in early embryonic lethality (around E8.5), precluding the study of its roles in later organogenesis [5] [1]. Consequently, conditional knockout (cKO) models using Cre-loxP technology have been indispensable for elucidating ZEB2 functions in specific tissues and developmental stages, such as hematopoiesis [14]. In vitro models, particularly Zeb2 knockout embryonic stem cells (ESCs), have provided deep mechanistic insights, demonstrating the transcription factor's necessity for exiting the pluripotent state and committing to differentiated lineages [5].

Experimental Workflows in Key Knockout Studies

Workflow for Analyzing Zeb2 KO ESCs and Differentiation Potential

The following diagram outlines the core experimental workflow used to establish ZEB2's critical role in exit from pluripotency and lineage commitment.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Zeb2 KO ESC Differentiation

Detailed Methodology:

- Generation of Zeb2 KO mESC Lines: Control lines are derived from

Zeb2flox/floxmice. Knockout is achieved via nucleofection of a Cre recombinase vector into low-passage ESCs, followed by blasticidin selection [5]. - ESC Maintenance and Differentiation Initiation: ESCs are maintained feeder-free in 2i + LIF medium (containing 1 μM PD0325901, 3 μM CHIR99021, and 1000 U/mL LIF) to sustain the naive pluripotent state. Differentiation is triggered by withdrawing 2i + LIF [5].

- Embryoid Body (EB) Formation and Directed Differentiation: For neural differentiation, 3 million ESCs are plated in bacterial petri dishes in EB medium (KO DMEM, 15% FBS, NEAA, etc.). On day 4, the medium is switched to N2B27 supplemented with 500 nM retinoic acid to promote neural fate [5].

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Transcriptomics: Temporal RNA-sequencing identifies deregulated gene networks [5].

- DNA Methylation Analysis: Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) assesses genome-wide methylation changes [5].

- Functional Rescue: Knockdown of

Tet1(a gene deregulated in KO cells) is performed to test partial rescue of differentiation impairment [5].

Workflow for Conditional KO in Hematopoietic System

The methodology for defining ZEB2 function in embryonic hematopoiesis using conditional knockout models is summarized below.

Figure 2: Workflow for Hematopoietic cKO Analysis

Detailed Methodology:

- Mouse Model Generation: Conditional deletion of Zeb2 is achieved using Tie2-Cre or Vav-iCre driver lines, which induce recombination in endothelial and hematopoietic lineages [14].

- Cellular Analysis of Hematopoietic Tissues: Detailed cellular analysis is performed on the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) region, fetal liver, and bone marrow. Techniques include fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate HSCs/HPCs and functional assays to test their differentiation and colonization capacity [14].

- Molecular and Histological Examination:

Decoding ZEB2-Controlled Signaling Pathways

ZEB2 operates as a nodal point, integrating signals from multiple key developmental pathways. The following diagram synthesizes its central regulatory role.

Figure 3: ZEB2 as an Integrator of Core Developmental Pathways

ZEB2 functions primarily as a transcriptional repressor but can also activate some genes [5] [1]. Its protein structure allows it to bind activated SMADs (downstream of TGFβ/BMP receptors), thereby fine-tuning the transcriptional response to these morphogens [1]. This interaction underpins its anti-BMP activity, which is crucial for neural patterning and neural crest development [1]. Furthermore, ZEB2 is implicated in modulating cellular responses to Wnt and Notch signaling, positioning it as a central integrator of extracellular cues that determine cell fate [1].

A critical function is its regulation of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by repressing epithelial genes like E-cadherin (Cdh1) [5]. This is vital for the migration of neural crest cells and hematopoietic progenitors [14]. During differentiation, ZEB2 is required for the irreversible silencing of the core pluripotency network (e.g., Oct4, Nanog), thereby facilitating commitment [5]. Mechanistically, ZEB2 links pluripotency exit with epigenetic remodeling, as its loss leads to deregulated expression of DNA methylation regulators like TET1, resulting in failure to maintain differentiation-associated DNA methylation patterns [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for ZEB2 Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for ZEB2 Functional Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function and Application in ZEB2 Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Zeb2flox/flox Mice [5] | Enables tissue-specific knockout of Zeb2 via Cre-loxP recombination. | Generation of conditional KO models for studying tissue-specific functions (e.g., hematopoiesis [14]). |

| Cre Recombinase Lines (Tie2-Cre, Vav-iCre) [14] | Drives deletion of floxed Zeb2 alleles in specific cell lineages (endothelial, hematopoietic). | Studying Zeb2 function in embryonic HSC/HPC differentiation and mobilization [14]. |

| 2i + LIF Medium [5] | Chemical inhibitors (PD0325901, CHIR99021) + LIF cytokine maintain ESCs in naive pluripotent state. | Culture of control and Zeb2 KO mESCs prior to differentiation induction [5]. |

| R26Zeb2 ESC Line [5] | ESCs with Flag-tagged Zeb2 cDNA inserted into the Rosa26 safe-harbor locus for overexpression. | Rescue experiments; testing cell-autonomous effects of Zeb2 re-expression [5]. |

| N2B27 Medium + Retinoic Acid [5] | Defined medium for efficient neural differentiation of ESCs/EBs. | Directed neural differentiation of control and Zeb2 KO ESCs [5]. |

| P300 Proximity Labeling [12] | Maps enhancer interaction landscapes and identifies key TFs in developing systems. | Identifying ZEB2's role and interactions in mouse and human somitogenesis [12]. |

| FR 167653 | FR 167653, CAS:158876-66-5, MF:C24H20FN5O6S, MW:525.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Asparagusic acid | Asparagusic acid, CAS:2224-02-4, MF:C4H6O2S2, MW:150.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This toolkit highlights the critical reagents that enable precise manipulation and analysis of ZEB2 function. The combination of conditional mouse models and well-defined ESC culture systems provides a powerful platform for dissecting the pleiotropic roles of ZEB2 from early lineage commitment to organ-specific development.

Regulation of Germ Layer Specification and Exit from Pluripotency

The exit from pluripotency and the subsequent specification into the three primary germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) are fundamental processes in embryonic development. This transition involves a complex interplay of transcription factors, signaling pathways, and epigenetic regulators that dismantle the pluripotent state and initiate lineage-specific programs. The transcription factor ZEB2 (Zinc Finger E-Box Binding Homeobox 2) has emerged as a critical node in this regulatory network, acting as a pivotal regulator of cell fate decisions in both mouse and human models. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the mechanisms governing exit from pluripotency and germ layer specification, with a specific focus on the role of ZEB2, integrating findings from key experimental models and methodologies to serve as a resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Regulatory Circuits Governing Pluripotency Exit

The Pluripotency Network and Its Dismantling

The core pluripotency circuit, maintained by transcription factors including Oct4 (Pou5f1), Sox2, and Nanog, is intrinsically linked to the machinery that drives lineage selection [15]. These factors do not merely sustain pluripotency but also integrate external signals to guide fate decisions. During differentiation, their levels are asymmetrically modulated: Oct4 is upregulated in mesendoderm (ME) progenitors but repressed in neural ectoderm (NE) progenitors, while Sox2 shows the inverse pattern, being upregulated in NE and repressed in ME fates [15]. This reciprocal relationship helps steer cells toward distinct developmental paths.

The exit from the naïve pluripotent state is a rapid, reproducible, and irreversible process that can be modeled in vitro using mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (mESCs) [16]. Upon withdrawal of pluripotency-maintaining signals (such as 2i/LIF), cells undergo a metachronous but unidirectional transition toward a primed epiblast-like state, making this system ideal for dissecting the dynamics of enhancer activation, transcription factor binding, and transcriptional reorganization [16].

ZEB2 as a Master Regulator of Cell Fate Transition

ZEB2 is indispensable for the exit from pluripotency and the initiation of differentiation programs. In mESCs, ZEB2 protein is undetectable in the naïve state but is strongly upregulated during neural differentiation, accompanying the efficient conversion into epiblast-like cells and subsequent neuroprogenitor cells (NPCs) [10] [5].

Perturbation studies demonstrate its necessity; Zeb2 knockout (KO) mESCs fail to properly differentiate and instead stall in an early epiblast-like state, maintaining the ability to re-adapt to pluripotency conditions even after prolonged exposure to differentiation signals [5]. This stall is characterized by deregulation of the pluripotency network, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) genes, and DNA methylation machinery, including elevated levels of the demethylase TET1 [5]. Knockdown of Tet1 in Zeb2 KO cells partially rescues the differentiation impairment, indicating that ZEB2 links the pluripotency network with DNA methylation to ensure irreversible commitment [5].

Table 1: Key Regulators of Pluripotency Exit and Their Roles

| Regulator | Function in Pluripotency | Role in Lineage Specification | Consequence of Perturbation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZEB2 | Low/undetectable in naïve state [10] | Essential for exit from epiblast state; promotes neural differentiation [5] | KO causes stall in epiblast-like state; impaired neural and mesendodermal differentiation [5] |

| OCT4 | Core pluripotency factor [15] | Upregulated in mesendoderm (ME) fate [15] | Necessary for ME fate choice; repression required for NE fate [15] |

| SOX2 | Core pluripotency factor [15] | Upregulated in neural ectoderm (NE) fate [15] | Necessary for NE fate choice; repression required for ME fate [15] |

| NANOG | Core pluripotency factor [15] | Downregulated for both ME and NE lineage selection [15] | Downregulation is necessary for cells to respond to differentiation signals [15] |

Figure 1: Fate Decisions at the Exit from Pluripotency. The core pluripotency factors OCT4 and SOX2 are asymmetrically modulated by external signals to direct cells toward mesendoderm (ME) or neural ectoderm (NE) fates.

ZEB2 in Vitro Models: From Pluripotency to Neural and Somitic Fates

ZEB2 in Neural Differentiation

Studies in mESCs have detailed ZEB2's function in neural differentiation. A key methodology involves the in vitro differentiation of mESCs into neuroprogenitor cells (NPCs) via embryoid body (EB) formation [10] [5]. In one protocol, ESCs are aggregated in non-adherent dishes, treated with retinoic acid from day 4 to promote neural differentiation, and then plated on coated surfaces at day 8 to obtain NPCs [10].

To identify direct genomic targets, researchers have used CRISPR-edited mESCs carrying an epitope-tagged Zeb2 allele (Flag-V5) [10]. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) in derived NPCs mapped 2,432 high-confidence ZEB2 DNA-binding sites, with a major site located in the Zeb2 promoter itself, indicating a critical autoregulatory loop [10]. Homozygous deletion of this site demonstrated that Zeb2 autoregulation is necessary for its proper function in ESC-to-NPC differentiation [10].

ZEB2 and the Path to Somitogenesis

The in vitro modeling of paraxial mesoderm and somite differentiation from human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs) provides a system to study ZEB2-relevant processes. A key protocol leverages transcriptomic data from human embryos, which revealed that downregulation of BMP and TGFβ signaling in the presomitic mesoderm (PSM) is a major regulator unique to human somitogenesis [17].

The in vitro differentiation protocol, therefore, involves:

- Initial WNT activation using a GSK3β inhibitor (CHIR99021) to specify primitive streak and posterior PSM, marked by T (Brachyury) and TBX6 [17].

- Subsequent inhibition of BMP and TGFβ signaling following WNT activation to robustly steer pPSM cells toward anterior PSM and somite fates [17]. These hPSC-derived somite cells are multipotent and can generate skeletal myocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes under lineage-specific conditions [17].

Table 2: Key In Vitro Differentiation Models for Studying ZEB2-Related Processes

| Model System | Key Inductive Signals | Critical Markers | Utility for ZEB2 Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| mESC to NPC [10] [5] | Retinoic Acid (RA); Aggregation (EB formation) | Nestin, Sox1; Loss of Oct4/Nanog | Models ZEB2's role in neurogenesis and autoregulation; platform for ChIP-seq. |

| hPSC to Somite [17] | WNT activation (CHIR99021) → BMP/TGFβ inhibition | T (Brachyury), TBX6 (PSM); PAX3, PAX7 (somite) | Models paraxial mesoderm development; context for ZEB2's role in somitogenesis. |

ZEB2 in Mouse and Human Somitogenesis

Conserved and Divergent Somitogenesis Pathways

Somitogenesis is a rhythmic process that segments the paraxial mesoderm into somites, the precursors of vertebrae, skeletal muscle, and dermis. The "clock and wavefront" model, involving oscillating gene expression (Notch, Wnt, FGF pathways) and opposing signaling gradients, is a conserved regulator across vertebrates [18]. In mouse, high-resolution transcriptional and chromatin maps (RNA-seq and ATAC-seq) of maturing somites have revealed a conserved molecular program followed by all somites, which includes the downregulation of Wnt and Notch signaling pathways and the upregulation of cell adhesion and migration programs associated with an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [18].

However, transcriptomic profiling of human embryos revealed that BMP and TGFβ signaling are major regulators unique to human somitogenesis [17]. While these pathways are downregulated in nascent human somites, TGFβ signaling is upregulated in mouse somites, indicating a potential species-specific difference in the regulatory logic [17].

ZEB2's Role in Somitogenesis and Mowat-Wilson Syndrome

ZEB2 is expressed in the presomitic mesoderm and somites during mouse embryogenesis [8]. The crucial role of ZEB2 in this process is highlighted by the early embryonic lethality of general homozygous Zeb2-knockout mice, which display multiple defects, including in somitogenesis [8] [5]. Mowat-Wilson Syndrome (MOWS), a rare congenital disorder caused by haploinsufficiency of ZEB2, further underscores its importance in human development [10] [8]. MOWS patients display a wide array of clinical features, including intellectual disability, epilepsy, Hirschsprung disease, and various congenital heart defects, some of which may originate from disturbances in early mesodermal patterning [8].

ZEB2's function is context-dependent, mediated through its interaction with various partner proteins and signaling pathways, including TGFβ/BMP, Wnt, and Notch [8]. Its role in modulating cellular responses to these pathways positions it as a key integrator of the signals that guide somite formation and maturation.

Figure 2: Simplified Molecular Regulation of Somitogenesis. Somites form from the PSM under the control of the clock and wavefront mechanism. ZEB2 is a critical transcription factor in this process. Notably, BMP/TGFβ signaling shows a human-specific regulation pattern.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Models

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Pluripotency Exit and ZEB2 Function

| Reagent / Model | Specific Example | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gene-Edited ESC Lines | Zeb2-Flag-V5 mESCs [10] | Enables precise ChIP-seq mapping of endogenous ZEB2 binding sites in derived cell types (e.g., NPCs). |

| Conditional KO Models | Zeb2flox/flox mice [5] | Allows cell-type or temporal-specific deletion of Zeb2 to study its function in specific lineages (e.g., somites, neural crest). |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors/Activators | CHIR99021 (WNT agonist), PD0325901 (MEK inhibitor) [17] [5] | Used to direct hPSC/mESC differentiation by precisely modulating key signaling pathways (WNT, FGF). |

| Differentiation Media | N2B27 medium [5] [15] | A defined, serum-free medium used to maintain ESCs and to make them competent to respond to lineage-specific differentiation signals. |

| Lineage Reporters | Sox1-GFP mESC line [15] | Enables live tracking and isolation of neural ectoderm progenitors during fate choice experiments. |

| (Rac)-Valsartan-d9 | (Rac)-Valsartan-d9, CAS:1089736-73-1, MF:C24H29N5O3, MW:444.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Faropenem daloxate | Faropenem Daloxate|Oral Penem Antibiotic|CAS 141702-36-5 |

The journey from a pluripotent stem cell to a committed progenitor is orchestrated by a tightly regulated network. The transcription factor ZEB2 acts as a critical conduit in this process, integrating signals from core pluripotency factors like OCT4 and SOX2 with those from major developmental pathways such as TGFβ/BMP and Wnt. Its non-redundant functions, evidenced by severe developmental defects in its absence, underscore its importance as a master regulator. The continued refinement of in vitro models, including neural and somitic differentiation from PSCs, coupled with high-resolution genomic tools, provides a powerful platform to further dissect ZEB2's direct target genes, protein partners, and its potential role as a modifier in other developmental disorders. This knowledge is fundamental for advancing our understanding of embryogenesis and for developing stem cell-based regenerative therapies.

Mowat-Wilson syndrome (MOWS) is a rare congenital disorder resulting from heterozygous loss-of-function mutations or deletions in the Zinc Finger E-box-Binding Homeobox 2 (ZEB2) gene, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 50,000 to 70,000 live births [19] [8]. This multi-system neurodevelopmental disorder exemplifies the critical importance of ZEB2 in human embryogenesis and provides a clinical framework for validating findings from mouse models. The connection between basic research on ZEB2 in mouse somitogenesis and its clinical manifestations in MOWS represents a powerful paradigm for understanding gene function through the integration of animal studies and human genetics. Research has established that ZEB2 functions as a transcription factor with diverse roles in cell fate decisions, differentiation, and maturation across multiple cell lineages, with its haploinsufficiency leading to the complex phenotypic spectrum observed in MOWS patients [10] [8].

The clinical diagnosis of MOWS relies on recognition of characteristic features followed by molecular confirmation through genetic testing. Hallmark manifestations include distinct facial gestalt, moderate to severe intellectual disability, epilepsy, and various structural anomalies affecting multiple organ systems [19] [20]. The broad phenotypic variability observed among patients has prompted extensive research into genotype-phenotype correlations, with current evidence suggesting that mutation type and location within ZEB2's functional domains significantly influence clinical severity and specific symptom patterns [19] [21].

ZEB2 Gene Structure and Protein Function: Molecular Foundations

Genomic Organization and Functional Domains

The ZEB2 gene is located on chromosome 2q22.3 and consists of ten exons, with the canonical transcript encoding a multi-domain protein critical for its function as a transcriptional regulator [19]. The protein contains six key functional domains that mediate its interactions with DNA and partner proteins: the N-terminal interaction motif (NIM), N-terminal zinc finger cluster (N-ZF), SMAD-binding domain (SBD), homeodomain (HD), CtBP-interacting domain (CID), and C-terminal zinc finger cluster (C-ZF) [19]. These structured domains account for approximately 55% of the protein, while the remaining 45% consists of non-domain linker regions that facilitate the formation of transcriptional complexes through protein-protein interactions [19].

Table 1: ZEB2 Protein Functional Domains and Their Roles

| Domain | Encoded Region | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| NIM (N-terminal interaction motif) | Exon 6 | Binding to NuRD co-repressor complex |

| N-ZF (N-terminal zinc fingers) | Exons 7-8 | DNA binding to E-box sequences (CACCT) |

| SBD (SMAD-binding domain) | Exon 8 | Interaction with activated SMAD proteins |

| HD (Homeodomain) | Exon 8 | DNA binding and protein interactions |

| CID (CtBP-interacting domain) | Exon 8 | Recruitment of CtBP co-repressors |

| C-ZF (C-terminal zinc fingers) | Exon 9-10 | DNA binding to E-box sequences |

Exon 8 deserves particular attention as it represents the largest exon, encoding 54% (656 amino acids) of the total ZEB2 protein and containing four of the six functional domains (N-ZF, SBD, HD, and CID) [19]. This structural concentration explains why approximately 66% (198/298) of known pathogenic variants occur in this exon, with the c.2083 C>T variant specifically impacting the homeodomain being particularly common, found in 11% of reported MOWS patients [21].

Molecular Mechanisms of Action

ZEB2 functions primarily as a transcriptional repressor, though it can also activate gene expression in specific contexts [20]. Its repressor activity is mediated through interactions with co-repressor complexes including CtBP (C-terminal binding protein) and NuRD (nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase), which recruit histone deacetylases and other chromatin-modifying enzymes to target genes [20]. ZEB2 binds to bipartite E-box-like sequences (CACCT) in DNA via its two zinc finger clusters, enabling sequence-specific DNA recognition [10].

As a nuclear fine-tuner of transforming growth factor β (TGFβ)/bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling, ZEB2 interacts with activated SMAD proteins, integrating multiple signaling pathways during development [3] [8]. This interaction allows ZEB2 to modulate cellular responses to environmental cues, positioning it as a critical node in transcriptional networks that control cell fate decisions. Recent research has also revealed that ZEB2 regulates its own expression through autoregulation, with a major binding site identified promoter-proximal to the ZEB2 gene itself [10].

Mouse Models of ZEB2 Dysfunction: Experimental Insights

Embryonic Stem Cell Models and Pluripotency Exit

Studies using Zeb2 knockout (KO) mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) have provided fundamental insights into the earliest functions of ZEB2 in development. Research demonstrates that Zeb2 KO mESCs can exit from their naïve state but subsequently stall in an early epiblast-like state, impaired in both neural and mesendodermal differentiation [5]. This developmental arrest is associated with deregulated genes involved in pluripotency, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and DNA methylation, including TET1 [5].

Table 2: Key Experimental Models for Studying ZEB2 Function

| Model System | Experimental Utility | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Zeb2 KO mESCs | Study of early cell fate decisions | Impaired exit from epiblast state; stalled differentiation |

| Conditional KO mice | Tissue-specific function analysis | Cell-autonomous and non-autonomous roles in neurodevelopment |

| R26_Zeb2 overexpression | Gain-of-function studies | Enhanced myogenic and neural differentiation |

| Flag-V5 tagged Zeb2 ESCs | Chromatin binding mapping | Identified 2432 DNA-binding sites in neuroprogenitor cells |

The connection between Zeb2 and DNA methylation patterns represents a particularly significant finding. Zeb2 KO cells correctly acquire methyl marks early during neural differentiation but fail to maintain these marks, reverting to a more naïve methylome state [5]. This defect is associated with elevated TET1 levels in mutant cells, and significantly, knockdown of TET1 partially rescues the impaired differentiation of Zeb2 KO cells, demonstrating a functional link between ZEB2 and DNA methylation machinery [5].

Zeb2 in Somitogenesis and Mesodermal Differentiation

While the search results provide limited specific information on Zeb2 in mouse somitogenesis, they indicate its expression and function in presomitic mesoderm and emerging somites [8]. Zeb2 has been documented in transcriptional regulatory networks in the forming neural plate, brain cortex, presomitic mesoderm, and neural crest cells [8]. The early post-gastrulation embryonic lethality of general homozygous Zeb2-knockout mice further underscores its essential role in early developmental processes, including potentially somitogenesis [8].

Recent single-cell RNA sequencing studies of mouse prenatal development have provided unprecedented resolution of transcriptional dynamics during embryogenesis [22]. Although not explicitly mentioning Zeb2 in the context of somitogenesis in the available excerpt, these comprehensive datasets enable exploration of Zeb2 expression patterns and potential roles in the developing somites and their derivatives.

Mowat-Wilson Syndrome: Clinical Spectrum and Genotype-Phenotype Correlations

Core Clinical Features

Mowat-Wilson syndrome presents with a consistent yet variable phenotypic spectrum characterized by several core features. The characteristic facial gestalt includes a high forehead, frontal bossing, large eyebrows with medial flair, hypertelorism, deep-set large-appearing eyes, large and uplifted ear lobes with a central depression, a saddle nose with prominent round nasal tip, an open mouth with M-shaped upper lip, and a prominent narrow triangular pointed chin [19] [21]. These facial features become more pronounced with age, with lengthening of the face and increased prominence of the chin [21].

Neurologically, patients exhibit moderate to severe global developmental delay and intellectual disability, with a mean age of walking at four years and a wide-based gait [21]. Structural brain abnormalities are common, including agenesis or hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, hippocampal abnormalities, enlargement of cerebral ventricles, and other cortical and cerebellar malformations [20] [21]. Seizures occur in approximately 84% of patients, typically manifesting in the preschool period with a characteristic, age-related electroclinical pattern [20] [21].

Multi-System Involvement

The multi-system nature of MOWS reflects the broad expression and function of ZEB2 during embryonic development. Gastrointestinal manifestations include Hirschsprung disease (occurring in approximately 50% of patients) causing chronic constipation, obstruction, or megacolon [21] [8]. Congenital heart defects are present in about 58% of patients, with septal defects, pulmonary stenosis, and tetralogy of Fallot among the most common findings [21].

Genitourinary anomalies include hypospadias, cryptorchidism, bifid scrotum in males, and duplex kidneys or hydronephrosis in both sexes [21]. Additional features include short stature, microcephaly, eye anomalies (strabismus, refraction abnormalities), tooth abnormalities, and musculoskeletal anomalies [20] [21]. A recent study has also identified alteration of hair melanin in MOWS patients, with reduced eumelanin and elevated pheomelanin resulting in brown to red hair coloration, linked to ZEB2 regulation of SLC45A2, a melanosomal transporter gene [23].

Genotype-Phenotype Correlations

Comprehensive analysis of ZEB2 mutations in 191 individuals with MOWS has revealed important genotype-phenotype relationships [19]. The majority of pathogenic variants are nonsense (38%) or frameshift (45%) mutations, with deletions accounting for 6% and missense variants only 5% of cases [19]. The location of mutations within specific protein domains influences clinical manifestations.

Table 3: ZEB2 Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in Mowat-Wilson Syndrome

| Variant Type/Location | Frequency | Associated Clinical Features |

|---|---|---|

| Exon 8 defects | 66% of cases | Multi-organ involvement; statistically associated with gastrointestinal findings |

| Frameshift in non-domain regions | ~45% of cases | Associated with typical facial gestalt |

| Nonsense in exons 3, 4, 5 | Less common | Specifically involved in facial gestalt, brain malformations, developmental delay |

| Missense variants | 5% of cases | Milder, atypical phenotypes |

| C-terminal truncations | Rare | Generally milder phenotypes |

Exon 8 defects, which impact multiple functional domains, are statistically more associated with gastrointestinal findings compared to other exons [19]. In contrast, frameshift mutations in non-domain regions more frequently result in the characteristic facial gestalt [19]. Notably, nonsense or other variants in exons 3, 4, and 5, which encode only flanking non-domain regions, are more often specifically involved in the MWS facial gestalt, brain malformations, developmental delay, and intellectual disability when compared with other exons excluding exon 8 [19].

Diagnostic Approaches and Biomarkers

DNA Methylation Signature

A significant advance in MOWS diagnosis has been the identification of a specific DNA methylation signature associated with ZEB2 haploinsufficiency [20]. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of peripheral blood samples from 29 individuals with confirmed MOWS identified a signature involving 296 differentially methylated probes [20]. This "episignature" is highly sensitive and reproducible, providing a novel diagnostic biomarker particularly valuable for cases with variants of uncertain significance or atypical presentations.

The DNA methylation signature demonstrates prevalence of hypomethylated CpG sites, consistent with ZEB2's primary role as a transcriptional repressor [20]. Furthermore, differential methylation within the ZEB2 locus itself supports the previously proposed autoregulatory mechanism of ZEB2 expression [20]. Comparative analysis has validated the specificity of this episignature against 56 other neurodevelopmental disorders, confirming its utility as a specific diagnostic tool [20].

Genetic Testing Strategies

Molecular diagnosis of MOWS typically involves sequence analysis of the ZEB2 coding region and deletion/dulication testing to detect whole exon or gene deletions [19] [21]. Given the high proportion of protein-truncating variants, initial testing often focuses on identifying nonsense and frameshift mutations, particularly in exon 8 [19]. For cases with strong clinical suspicion but negative coding sequence analysis, investigation of noncoding regulatory elements should be considered, as evidenced by patients with clinical features fitting MOWS but without coding sequence variations [20].

Experimental Methods and Research Protocols

Key Methodologies for ZEB2 Research

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq): Mapping of Zeb2 DNA-binding sites has been achieved through epitope-tagged Zeb2 proteins in ESC-derived neuroprogenitor cells. The protocol involves crosslinking DNA-bound proteins, chromatin fragmentation, immunoprecipitation with anti-V5 antibodies (for V5-tagged Zeb2), and high-throughput sequencing [10]. This approach identified 2432 binding sites for Zeb2 in NPCs, mapping to 1952 protein-encoding genes [10].

Embryonic Stem Cell Neural Differentiation: Neural differentiation of mESCs involves forming cellular aggregates in suspension culture using DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum, followed by exposure to retinoic acid (500 nM) from day 4, and subsequent plating on poly-DL-ornithine/laminin-coated surfaces in N2 medium for neuronal maturation [10]. This protocol enables the study of Zeb2's role in the transition from pluripotency to neural commitment.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Analysis of Zeb2 function in myogenic differentiation has employed single-cell RNA sequencing of fluorescence-activated cell sorted CTR, Zeb2-null and R26_Zeb2 mCherry/MyoD-positive cells [3]. This approach reveals cell-to-cell heterogeneity and identifies distinct subpopulations in differentiating cultures, providing insights into Zeb2's cell-type specific functions.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Interactions

Diagram 1: ZEB2 in Transcriptional Repression. ZEB2 integrates TGFβ/BMP signaling through SMAD interactions and recruits co-repressor complexes (NuRD, CtBP) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) to repress target gene expression.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ZEB2 Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Zeb2-modified cell lines | Zeb2 KO mESCs; R26_Zeb2 ESCs; Zeb2-V5 ESCs | Loss-of-function and gain-of-function studies |

| Animal models | Zeb2-floxed mice; Conditional KO; Zeb2+/fl(Δex7) | Tissue-specific function analysis |

| Antibodies | Anti-ZEB2; Anti-V5; Anti-Flag | Protein detection and localization |

| Differentiation kits | Neural differentiation; Myogenic differentiation | Cell fate commitment studies |

| Epigenetic tools | RRBS; MethylationEPIC BeadChip | DNA methylation analysis |

The investigation of ZEB2 function through mouse models and its correlation with Mowat-Wilson syndrome exemplifies the power of integrative approaches in biomedical research. Studies in mouse embryonic stem cells and developing embryos have revealed ZEB2's critical roles in exit from pluripotency, neural differentiation, and likely somitogenesis, while clinical characterization of MOWS patients has illuminated the human consequences of ZEB2 haploinsufficiency. The identification of a specific DNA methylation signature provides a novel diagnostic tool and underscores ZEB2's function as a chromatin regulator. Continuing research on ZEB2 holds promise not only for better understanding of neurodevelopmental disorders but also for potential therapeutic strategies targeting the downstream consequences of ZEB2 dysfunction.

Advanced Models and Techniques for Studying ZEB2 in Somitogenesis

Mouse Gastruloids as a Model System for Studying Somitogenesis

Table 1: Comparison of Key Model Systems for Studying Somitogenesis

| Feature | Mouse Gastruloids | In Vivo Mouse Embryos | 2D Cell Culture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Scalability | High; amenable to large-scale production for omics studies [6] [24] | Low; limited by litter size and uterine development [24] | High |

| Spatial Organization | Recapitulates key aspects of axial organization and germ layer patterning in 3D [25] [24] | Full native spatial context [26] | Absent or limited |

| Temporal Control | Defined, stage-like progression; patterning and morphogenesis can be temporally separated [24] | Fixed developmental timing | Variable |

| Amenability to Perturbation | High; suitable for chemical & genetic insults, and medium manipulation [6] [24] | Low; complex in utero effects [24] | High |

| In Vivo Relevance | High fidelity to embryonic gene expression and processes like somitogenesis [25] [6] | Gold standard | Low |

| Accessibility for Imaging | High; external development allows easy observation [24] | Low; requires sophisticated imaging due to in utero development [24] | High |

| Model Complexity | Reduced; minimalistic model focusing on core patterning events [24] | Full physiological complexity [26] | Simplified |

| Utility for Metabolic Studies | High; allows controlled nutrient manipulation and large-scale metabolite sampling [24] | Challenging; influenced by maternal physiology and placenta [24] | Medium |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Somitogenesis Research

Core Protocol for Generating Murine Somitic Gastruloids

The foundational method for generating gastruloids involves the aggregation of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) under conditions that promote self-organization and axial elongation [24]. Key steps have been optimized to reduce variability and extend the culture window for studying later processes like somitogenesis [27].

Key Steps:

- Aggregation: Naïve mESCs are aggregated in low-attachment U-bottom 96-well plates in a medium lacking pluripotency-maintaining factors like LIF [24].

- Symmetry Breaking: After 48 hours, a Wnt pathway agonist (such as CHIR99021) is added to induce mesodermal fate and break the initial symmetry, establishing the posterior pole [24].

- Extended Culture for Somitogenesis: To study somitogenesis, the culture period is extended. A critical optimization involves embedding the gastruloids in a 10% Matrigel solution at 96 hours post-aggregation, which supports the structure for up to 168 hours, allowing for the observation of segmented somite-like structures [27].

Protocol for Integrative Multi-Omics Analysis

Recent advances combine gastruloids with high-throughput technologies to decipher molecular mechanisms. The following workflow was used to establish the role of Zeb2 in somitogenesis [6].

Key Steps:

- Generation of Engineered Cell Lines: Somitic gastruloids are generated from mESCs containing a Zeb2-degron tag. This tag allows for the rapid, precise degradation of the Zeb2 protein upon addition of a small molecule (e.g., dTAG-13) [6].

- Experimental Perturbation: Gastruloids are treated with either the degrader (dTAG-13) or a vehicle control (untreated) at a specified developmental time point [6].

- Downstream Analysis:

- RNA-seq: Bulk or single-cell RNA sequencing is performed on the perturbed gastruloids to transcriptomically profile the consequences of Zeb2 depletion [6].

- Proteomics: Mass spectrometry-based proteomics can be used in parallel to profile global (phospho)protein expression dynamics [6].

- Data Integration: Bioinformatics analysis compares the treated and control groups, revealing genes and pathways downstream of Zeb2 and its critical role in somitogenesis [6].

The Role of ZEB2 in Somitogenesis: Insights from Gastruloid Models

Gastruloid models have been instrumental in elucidating the specific function of the transcription factor ZEB2 during early mammalian development and its critical role in regulating somitogenesis.

- Zeb2 as a Master Regulator of Cell State Transition: Studies in mESCs show that Zeb2 is critical for the irreversible exit from the naïve pluripotent state and for entry into differentiation programs for all germ layers. In its absence, cells stall in an early epiblast-like state and fail to differentiate properly [5].

- Link to Pluripotency and DNA Methylation: Zeb2 knockout mESCs exhibit deregulated levels of DNA-methylation machinery, including elevated levels of the demethylase TET1. This prevents the cells from maintaining DNA-methylation marks required for commitment, and knocking down Tet1 can partially rescue the differentiation defect [5].

- Functional Validation in Somitogenesis: Degron-mediated depletion of Zeb2 in somitic gastruloids, combined with scRNA-seq, provided direct functional evidence that Zeb2 is required for proper mouse and human somitogenesis [6]. This experimental paradigm demonstrates the power of gastruloids for rapid genetic perturbation.

The diagrams below summarize the core gastruloid protocol and the mechanistic role of Zeb2.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Gastruloid and Somitogenesis Research

| Reagent | Function in Protocol | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Naïve mESCs | The starting cellular material capable of self-organizing into gastruloids. | E14IB10 cell line [25] |

| Wnt Agonist | Chemically induces mesodermal fate and initiates symmetry breaking. | CHIR99021 (GSK3 inhibitor) [5] [24] |

| Matrigel | Extracellular matrix providing structural support for extended culture and morphogenesis. | 10% solution for embedding [27] |

| Degron System | Enables rapid, targeted protein degradation for precise temporal perturbation of genes like Zeb2. | dTAG-13 ligand [6] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Technology to map gene expression patterns within the 3D structure of gastruloids. | Tomo-seq [25] |

| LIF Inhibitor | Withdrawal is essential to allow exit from the naïve pluripotent state. | Removal from medium [5] |

| R.A. (Retinoic Acid) | Signaling molecule used in some differentiation protocols to direct patterning. | Used in neural differentiation protocols [5] |

| FG 7142 | FG 7142, CAS:78538-74-6, MF:C13H11N3O, MW:225.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MMPSI | MMPSI, CAS:220509-74-0, MF:C14H16N2O5S, MW:324.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Mouse gastruloids represent a powerful, scalable, and highly tractable model system for dissecting the complex process of somitogenesis. They strike an effective balance between in vivo relevance and experimental practicality, enabling high-resolution omics studies and precise genetic perturbations. The successful application of this model has been pivotal in uncovering the essential role of Zeb2 in regulating the exit from pluripotency and its direct requirement for somitogenesis, showcasing its potential to accelerate discovery in developmental biology and disease modeling.

Multilayered Proteomics Approaches to Map Global Protein Dynamics

In the era of systems biology, multilayered proteomics has emerged as an indispensable approach for comprehensively characterizing protein dynamics that underlie developmental processes and disease states. Unlike genomics or transcriptomics alone, integrated proteomic analyses capture the functional effectors of cellular processes—proteins and their post-translational modifications—providing unprecedented insights into molecular mechanisms. These approaches are particularly valuable for studying complex biological phenomena such as somitogenesis, where coordinated protein expression, interaction, and modification drive the segmentation of the embryonic body plan. The transcription factor ZEB2, crucial in mouse and human development, serves as an exemplary model for demonstrating how multilayered proteomics can decode the protein networks governing fundamental biological processes. This guide compares the leading proteomic technologies and their applications in mapping global protein dynamics within the context of ZEB2 research.

Comparative Analysis of Multilayered Proteomics Technologies

Table 1: Comparison of Major Proteomics Platforms and Their Applications in Developmental Biology

| Technology | Key Strengths | Throughput | Sensitivity | Data Output | Ideal for ZEB2 Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMT-MS (Tandem Mass Tag Mass Spectrometry) | High quantification accuracy, multiplexing capability | Medium-High | ~1-10 ng | 8,000+ proteins per run | Quantifying ZEB2 expression changes during somitogenesis [28] |

| DIA/SWATH-MS (Data-Independent Acquisition) | High reproducibility, digital tissue biobanking | High | ~10-50 ng | 6,000-10,000 proteins | Longitudinal studies of ZEB2 protein dynamics [29] [30] |