Zebrafish in Genetic Research: A Versatile In Vivo Model for Human Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

This article explores the established and emerging roles of zebrafish (Danio rerio) as a powerful model organism for human genetic diseases.

Zebrafish in Genetic Research: A Versatile In Vivo Model for Human Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the established and emerging roles of zebrafish (Danio rerio) as a powerful model organism for human genetic diseases. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, we detail the foundational genetic and physiological similarities that make zebrafish a tractable system, the methodological advances in gene editing and high-throughput screening that drive its application, strategies to address inherent limitations, and the framework for validating its translational relevance. Synthesizing recent case studies and technological innovations, this review underscores how zebrafish are accelerating the path from genetic discovery to preclinical therapy development, offering a unique blend of scalability, biological complexity, and ethical compliance for modern biomedical research.

Why Zebrafish? Genetic Homology and Fundamental Advantages for Disease Modeling

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a preeminent model organism in biomedical research, occupying a unique position at the intersection of developmental biology, functional genomics, and translational medicine. Its value derives principally from a remarkable genetic conservation with humans that enables direct investigation of human disease mechanisms. The frequently cited figures—approximately 70% of human genes have at least one zebrafish ortholog, and 84% of genes known to be associated with human disease have a zebrafish counterpart—provide a quantitative foundation for this utility [1] [2]. These statistics originate from comprehensive comparative genomic studies, most notably the high-quality reference genome sequence generated by the Sanger Institute, which revealed that zebrafish possess over 26,000 protein-coding genes [1].

This genomic conservation is not merely statistical but functional, encompassing key systems such as the cardiovascular, nervous, and immune systems, which rely on similar genetic pathways in both zebrafish and humans [3] [2]. The zebrafish's rapid external development, optical transparency of embryos, and capacity for large-scale genetic screening complement this genetic similarity, creating a powerful vertebrate platform for disease modeling and therapeutic discovery [4] [5]. This article explores the depth of this genetic conservation, its implications for disease research, and the practical methodologies that leverage these advantages for advancing human health.

Quantitative Analysis of Genetic Conservation

The genetic relationship between zebrafish and humans is complex, extending beyond a simple percentage of shared genes. A detailed analysis reveals specific patterns of orthology that have practical implications for disease modeling.

Table 1: Zebrafish-Human Genetic Orthology Relationships

| Relationship Type | Number of Human Genes | Number of Zebrafish Genes | Gene Ratio (Human:Zebrafish) | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-to-One | 9,528 | 9,528 | 1:1 | Simplest case for direct functional modeling |

| One-to-Many | 3,105 | 7,078 | 1:2.28 | Result of teleost-specific genome duplication; potential subfunctionalization |

| Many-to-One | 1,247 | 489 | 2.55:1 | Gene fusion or consolidation in zebrafish lineage |

| Many-to-Many | 743 | 934 | 1:1.26 | Complex evolutionary history |

| Total Orthologous | 14,623 | 18,029 | 1:1.28 | Overall network of genetic relationships |

| Unique Genes | 5,856 | 8,177 | N/A | Species-specific biology |

Data derived from Ensembl Compara analysis [1]

The 70% genetic similarity specifically refers to the proportion of human protein-coding genes that have at least one clearly identifiable zebrafish ortholog (14,623 of approximately 20,479 human genes) [1]. The one-to-many orthology relationship, affecting approximately 3,105 human genes, is particularly significant as it often results from a teleost-specific whole-genome duplication (TSD) event that occurred approximately 340 million years ago in the zebrafish lineage [4] [1]. This duplication means that a single human gene may have two or more counterparts in zebrafish, which complicates genetic studies but also provides opportunities to study subfunctionalization—where duplicate genes have partitioned the original gene's functions [4].

Table 2: Disease Gene Conservation and Functional Assessment

| Genetic Category | Conservation Rate | Sample Size/Context | Functional Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Human Protein-Coding Genes | ~70% have at least one zebrafish ortholog | 20,479 human genes analyzed [1] | Fundamental biological processes |

| OMIM Morbid Genes | 82% have zebrafish orthologs | 3,176 human disease genes [1] | Direct disease modeling capability |

| GWAS-Associated Genes | 76% have zebrafish orthologs | 4,023 human genes [1] | Complex disease genetics |

| Disease-Relevant Genes | 84% have zebrafish counterparts | Curated disease gene databases [2] | Therapeutic discovery applications |

The 84% figure for disease gene conservation reflects the even higher functional constraint on genes implicated in human pathology [2]. Of the 3,176 genes bearing morbidity descriptions in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database, 2,601 (82%) have at least one zebrafish ortholog [1]. This elevated conservation rate underscores the zebrafish's particular utility for modeling genetic disorders.

Experimental Methodologies for Functional Genetic Studies

CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

CRISPR-Cas9 has revolutionized genetic manipulation in zebrafish, enabling precise generation of both knockout and knock-in models of human disease.

Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Knockout

- Guide RNA Design: Design and synthesize single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting exonic regions of the zebrafish gene of interest. For genes with human disease orthologs, target regions homologous to human mutation sites.

- Microinjection Setup: Prepare a solution containing sgRNA (25-50 ng/μL) and Cas9 protein (300-500 ng/μL) in nuclease-free water.

- Embryo Injection: Aliquot approximately 1-2 nL of the CRISPR-Cas9 complex into the cytoplasm or yolk of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos using a fine glass needle and micromanipulator.

- Founder Screening: Raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood and outcross to wild-type fish. Screen F1 progeny for germline transmission using PCR and sequencing of the target locus.

- Stable Line Establishment: Identify F1 fish with desired mutations and incross to establish stable homozygous lines [4] [6].

Application Example: To model autism spectrum disorder, researchers used this protocol to generate a shank3b loss-of-function mutation. The mutant zebrafish displayed autism-like behaviors, validating the role of this gene in neurodevelopment [6].

Morpholino-Mediated Gene Knockdown

Morpholino antisense oligonucleotides provide a rapid method for transient gene knockdown during early development.

Protocol: Morpholino Knockdown

- Morpholino Design: Design 25-base morpholinos to target either the translation start site (to block translation) or splice junctions (to disrupt proper splicing) of the target gene.

- Preparation and Injection: Resolve morpholinos in water to a stock concentration of 1-2 mM. Dilute to working concentration (typically 0.1-0.5 mM) and inject 1-2 nL into the yolk or cell of 1-4 cell stage embryos.

- Validation: Assess knockdown efficacy through RT-PCR (for splice-blocking morpholinos) or Western blot (for translation-blocking morpholinos).

- Phenotypic Analysis: Analyze morphological and behavioral phenotypes within the first 3-5 days post-fertilization, noting that morpholino effects are transient [4].

Critical Consideration: Morpholinos can activate p53-dependent apoptosis pathways, particularly in neural tissue. Include appropriate controls and consider validating findings with genetic mutants [4].

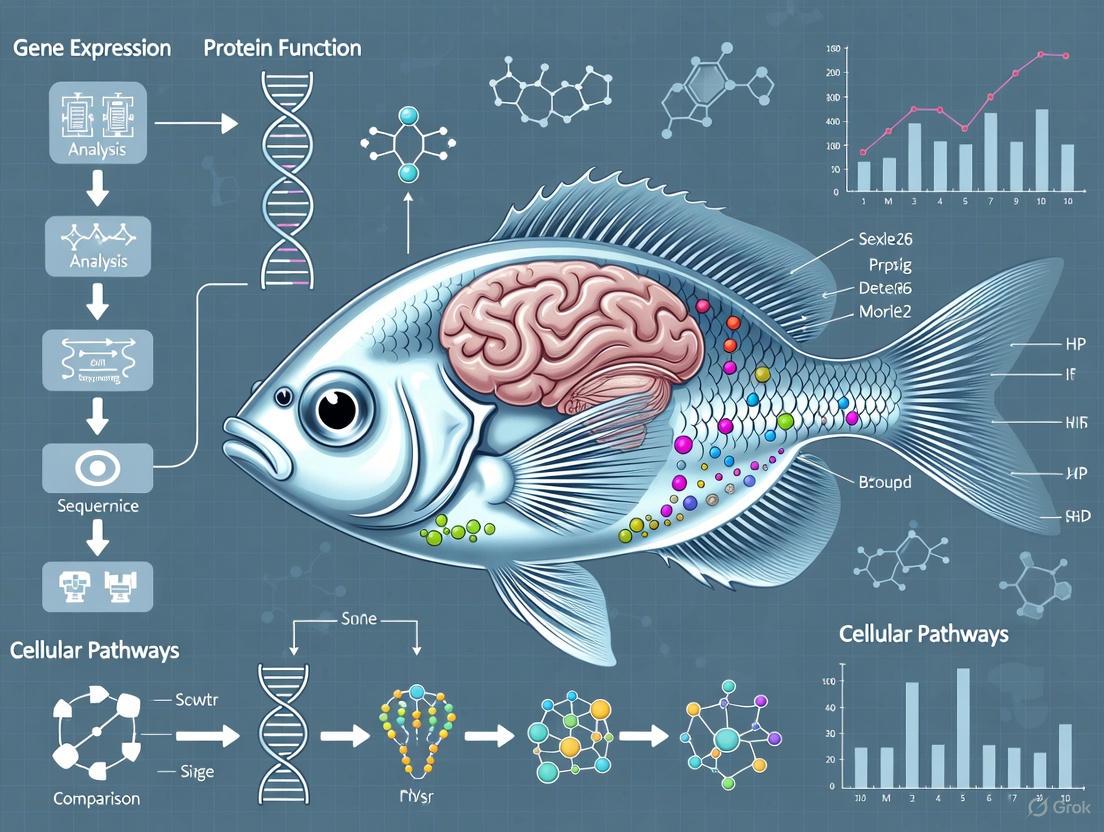

Figure 1: Genetic Perturbation Workflow. Diagram illustrating complementary approaches for transient (morpholino) and permanent (CRISPR-Cas9) genetic manipulation in zebrafish, leading to phenotypic validation.

High-Throughput Chemical Screening

The zebrafish model is exceptionally suited for high-throughput compound screening due to its small size, permeability, and genetic tractability.

Protocol: Larval Chemical Screening

- Animal Preparation: Array 3-5 days post-fertilization (dpf) larvae into 96-well plates, one larva per well.

- Compound Library Application: Add chemical compounds to each well using automated liquid handling systems. Include DMSO vehicle controls.

- Incubation and Phenotyping: Incubate plates at 28.5°C for 24-72 hours. Assess phenotypes using automated imaging systems for behavior, morphology, or fluorescence readouts.

- Data Analysis: Quantify phenotypic outcomes using image analysis software. Apply statistical methods to identify hit compounds that ameliorate disease phenotypes [3].

Disease Modeling Applications and Case Studies

The high degree of genetic conservation enables accurate modeling of diverse human diseases in zebrafish. The following examples demonstrate the translational relevance of these models.

Neurological Disorders

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): Researchers created a shank3b loss-of-function mutant zebrafish using CRISPR-Cas9 that exhibited autism-like behaviors, including social interaction deficits and repetitive behaviors. This model provides a platform for circuit-level analysis of ASD pathophysiology and drug screening [6].

Parkinson's Disease: A rotenone-induced model demonstrated dopaminergic neurodegeneration and locomotor deficits. Treatment with human metallothionein II (hMT2) mitigated these effects, highlighting the utility of zebrafish for neuroprotective compound screening [7].

Cardiovascular Diseases

Cantú Syndrome: Knock-in zebrafish lines carrying human cardiovascular-disorder-causing mutations displayed significantly enlarged ventricles with enhanced cardiac output and cerebral vasodilation, establishing a direct connection between specific mutations and disease phenotypes [6].

Congenital Heart Defects (CHDs): Zebrafish models have been instrumental in validating gene variants found in individuals with CHDs, despite anatomical differences such as the absence of pulmonary circulation in the zebrafish heart [5] [7].

Metabolic Disorders

Hypophosphatasia (HPP): The first zebrafish model of this rare metabolic disorder was created by knocking out the alpl gene using CRISPR-Cas9. The mutant zebrafish exhibited decreased bone mineralization and disturbances in vitamin B6-related metabolism, replicating hallmark features of human HPP [5].

Fatty Liver Disease: cobll1a-deficient zebrafish exhibited hepatic lipid accumulation due to disrupted retinoic acid signaling, linking this pathway to metabolic disorders and providing insights into human fatty liver disease [7].

Cancer

Melanoma: A knock-in zebrafish model with the human BRAF mutation, combined with other cancer-associated genes like SETDB1, led to rapid melanoma development. This model provides a platform for identifying key genetic contributors and testing targeted therapies [8].

Succinate Dehydrogenase-Associated Tumors: Although adult SDHB mutant zebrafish did not develop obvious tumors, they showed significantly increased succinate levels, a characteristic metabolic signature of corresponding human cancers [5].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful experimentation with zebrafish models requires specific reagents and resources tailored to their unique biology.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Zebrafish Studies

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type Strains | Tubingen (TU), AB, Tupfel long fin (TL) | Background strains for experiments; each has unique genetic and physical traits [4] | Significant genetic heterogeneity exists between strains |

| Transparent Mutants | casper, absolute, crystal |

Enable imaging of both larval and adult tissues [4] | Maintain pigmentation-free adults for long-term studies |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, ZFNs | Precise genome engineering [4] [6] | Microinjection at one-cell stage for germline transmission |

| Knockdown Reagents | Morpholinos (MOs) | Transient gene knockdown during early development [4] | Potential for p53 activation; use appropriate controls |

| Database Resources | ZFIN, ZIRC, OMIM | Genetic sequences, mutations, protocols, and mutant lines [4] | Critical for experimental design and reagent sourcing |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The 70% genetic homology and 84% disease gene overlap between zebrafish and humans provide a robust foundation for biomedical research, but several considerations are essential for optimal experimental design. The extensive genetic variability of commonly used wild-type zebrafish strains (e.g., TU, AB, TL) differs significantly from isogenic mammalian models [4]. While this heterogeneity can increase experimental noise, it more accurately models the genetic diversity of human populations, particularly for drug response studies.

The teleost-specific genome duplication presents both challenges and opportunities. While complicating the creation of null mutants (as multiple paralogs may need to be targeted), this duplication also enables studies of subfunctionalization, where duplicate genes partition ancestral functions [4] [1]. Researchers must account for potential genetic redundancy when designing experiments.

Future directions in zebrafish research include advancing personalized medicine approaches through creating models with patient-specific genetic mutations, enabling therapy testing tailored to individual needs [3] [2]. The integration of single-cell transcriptomics, computational modeling, and machine learning with zebrafish models is enhancing their translational relevance [3]. Additionally, the study of zebrafish regenerative capabilities continues to provide insights that could lead to breakthroughs in human regenerative medicine for conditions such as heart muscle and spinal cord injuries [2].

Figure 2: Zebrafish Research Value Proposition. Visual representation of how genetic conservation, combined with unique experimental features and advanced tools, enables creation of human disease models with diverse translational applications.

In conclusion, the substantial genetic conservation between zebrafish and humans, coupled with unique experimental advantages, positions this model organism as an indispensable tool in the continuum from basic biological discovery to therapeutic development. As genomic technologies continue to advance, the zebrafish model will undoubtedly play an increasingly critical role in deciphering the functional significance of human genetic variation and accelerating the development of targeted therapies for human disease.

In the evolving landscape of precision medicine, the zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a uniquely powerful vertebrate model for studying human genetic diseases, primarily due to its exceptional optical transparency during early developmental stages. This transparency provides a non-invasive window to observe dynamic biological processes in real time, from the whole organism down to the subcellular scale [3]. The zebrafish model combines high genetic homology with humans—approximately 70% of human genes have at least one zebrafish ortholog, and 84% of genes known to be linked with human diseases have zebrafish counterparts—with practical advantages for large-scale biomedical research [3] [9]. These characteristics enable researchers to bridge the critical gap between in vitro cell culture systems and more complex, costly mammalian models, accelerating insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic development [3].

Real-time live imaging leverages the natural transparency of zebrafish embryos and larvae, allowing direct observation of physiological responses as they occur. This capability is fundamental to deriving biological meaning from morphological changes, cell migration patterns, and disease progression in vivo [10]. When combined with advanced genetic editing technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9 and prime editing, zebrafish transparency transforms the model into a scalable platform for high-throughput drug screening and the functional validation of human disease variants [3] [8]. This technical guide explores how the power of transparency is being harnessed to decode complex biological processes, with a specific focus on methodologies, applications, and future directions within zebrafish-based human disease research.

Technical Foundations of Live Imaging in Zebrafish

The successful implementation of live imaging in zebrafish research relies on a foundation of specialized equipment, reagents, and methods designed to maximize data quality while ensuring specimen viability. The core principle involves balancing the need for high spatial and temporal resolution with the imperative to minimize photodamage, which can alter normal biology and compromise experimental results [11].

Imaging Modalities and Microscope Platforms

Confocal and Light-Sheet Microscopy are the two most prevalent modalities for high-resolution zebrafish imaging. Confocal microscopy is widely established and provides excellent optical sectioning, making it suitable for detailed 3D image acquisition over time [11]. However, for long-term imaging of dynamic processes, light-sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) has become the gold standard due to its high imaging speed and significantly reduced light exposure [12]. A recent advancement is the development of self-driving, multiresolution light-sheet microscopes. These platforms can automatically track regions of interest within growing organisms, enabling simultaneous observation and quantification of subcellular dynamics in the context of the entire organism over many hours [12].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

A suite of specialized reagents is required to visualize specific biological structures and processes in the transparent zebrafish. The table below summarizes key research reagent solutions essential for real-time imaging experiments.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Zebrafish Live Imaging

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Biosensors (e.g., Sensor C3) | FRET-based reporter for detecting caspase-3 activation during apoptosis; changes fluorescence from green to blue upon cleavage [13]. | Real-time tracking of motor neuron apoptosis at single-cell resolution [13]. |

| Transgenic Lines with Cell-Specific Promoters | Drive expression of fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP, RFP) in specific cell types (e.g., motor neurons) [13]. | Labeling and fate-tracking of distinct cell populations throughout development [13]. |

| Zebrafish Embedding Molds (ZEMs) | Customized molds for stable positioning of embryos/larvae in specific orientations (lateral, dorsal, ventral) [10]. | High-throughput, consistent image acquisition for quantitative morphological and toxicological analysis [10]. |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Transient knockdown of gene expression to assess gene function rapidly [3]. | Modeling genetic diseases and validating gene-disease associations in early development [3]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing | Permanent knockout or knock-in of disease-associated mutations [3] [8]. | Generating stable zebrafish models of human genetic diseases like Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy [8]. |

Experimental Workflow for Long-Term Live Imaging

A standardized workflow is critical for obtaining reproducible, high-quality imaging data. The following diagram outlines the key stages in a typical long-term live imaging experiment, from specimen preparation to data analysis.

Diagram 1: Zebrafish Live Imaging Workflow

Quantitative Advantages of the Zebrafish Model

The practical benefits of zebrafish for biomedical research are quantifiable across several key dimensions, making them a compelling alternative to traditional mammalian models. The following table provides a direct comparison based on critical parameters for disease research and drug development.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Zebrafish with Other Model Organisms

| Feature | Zebrafish | Mouse | Humans |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Similarity to Humans | ~70% of human genes have a zebrafish ortholog [3] | ~85% genetic similarity [3] | 100% |

| Optical Transparency | High (embryos/larvae; Casper adult strain) [3] | Low, typically requires invasive methods | N/A |

| High-Throughput Drug Screening | Very high; larvae fit in multi-well plates [3] | Moderate; limited by size, cost, and time [3] | Low; ethical and logistical limits |

| Embryonic Development Speed | Major organs form in 24-48 hours [3] | ~20 days | ~8 weeks |

| Offspring Number | High (200-300 eggs per clutch) [3] | Moderate (6-12 pups per litter) | Typically single offspring |

| Ethical & Cost Considerations | Lower cost, fewer ethical limitations [3] | Higher cost, stricter ethical regulations [3] | Very high ethical concerns |

The data underscores zebrafish's unique position: they offer a superior combination of genetic relevance, experimental tractability, and scalability unmatched by other vertebrate models. Their small size and aquatic nature facilitate cost-effective husbandry and enable automated imaging and behavioral tracking in multi-well plate formats, which is a cornerstone of high-throughput phenotypic and therapeutic screening [3].

Methodologies: Key Experimental Protocols

This section details specific protocols that leverage zebrafish transparency to investigate fundamental biological questions and disease mechanisms.

Protocol for Tracking Neuronal Apoptosis In Vivo

Objective: To visualize and quantify the spatiotemporal dynamics of programmed cell death in motor neurons during early development [13].

- Generate Sensor Zebrafish: Create a transgenic line (e.g.,

Tg(mnx1:sensor C3)) using a motor-neuron specific promoter (e.g.,mnx1) to drive expression of a FRET-based caspase-3 biosensor. - Specimen Mounting: Anesthetize and embed sensor zebrafish embryos (e.g., at 30-33 hours post-fertilization) in low-melting-point agarose within a Zebrafish Embedding Mold (ZEM) to ensure stable lateral orientation [10].

- Time-Lapse Imaging: Use a confocal or light-sheet microscope equipped with environmental control (temperature). Acquire 3D image stacks at high temporal resolution (e.g., every 3-5 minutes) over several hours. Excite the biosensor with a 458 nm laser and collect emission at 480 nm (CFP/blue, apoptotic signal) and 535 nm (YFP/green, live cell signal) [13].

- Image Analysis: Calculate the FRET ratio (CFP/YFP) for each motor neuron over time. A color change from green to blue indicates caspase-3 activation. Track the onset and propagation of apoptosis in individual cell bodies and axons.

- Quantification: Count the total number of green (live) and blue (apoptotic) motor neurons across multiple specimens to determine the percentage of neuronal death during a specific developmental window.

This protocol revealed that caspase-3 activation in a dying motor neuron occurs rapidly (within 5-6 minutes) and nearly simultaneously in the cell body and axon, challenging previous assumptions about the progression of neuronal apoptosis [13].

Protocol for High-Throughput Toxicological and Biodistribution Analysis

Objective: To consistently assess compound-induced morphological changes or the tissue distribution of fluorescently-labeled molecules (e.g., nanoplastics, drugs) [10].

- Experimental Exposure: Incubate zebrafish embryos/larvae in multi-well plates with the test compound or fluorescent tracer.

- Standardized Mounting: Use stage-specific ZEMs to orient a large number of specimens uniformly in lateral, dorsal, or ventral views. This standardization is crucial for comparative image analysis [10].

- Automated Image Acquisition: Utilize a high-content screening microscope with an automated stage to rapidly capture images of all mounted specimens in the desired orientation.

- Quantitative Image Analysis: Apply automated image analysis software to measure predefined endpoints, such as:

- Morphological alterations (e.g., body length, eye size, spinal curvature).

- Fluorescence intensity and distribution patterns in target organs.

- The presence of specific malformations.

This standardized pipeline ensures reproducible and quantitative data, enabling robust statistical analysis and supporting mechanistic studies of environmental pollutants or drug candidates [10].

Applications in Modeling Human Genetic Diseases

The synergy between zebrafish transparency and genetic tools has produced critical insights into a wide spectrum of human genetic disorders. The following diagram illustrates how core strengths of the model are applied to disease research.

Diagram 2: From Model Strengths to Disease Applications

Neurological and Muscular Disorders

Zebrafish models have been instrumental in studying Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), a severe disorder caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene. Zebrafish with a knocked-out dystrophin gene recapitulate key hallmarks of the human disease, including muscle fiber necrosis, inflammation, and fibrosis [8]. The transparency of larvae allows researchers to observe the progression of muscle degeneration in real time and to screen for drugs that can mitigate these effects [8]. In neuroscience, transgenic zebrafish expressing biosensors have enabled the non-invasive tracking of motor neuron apoptosis at single-cell resolution, providing novel insights into the timing and spatial characteristics of cell death in the developing spinal cord [13].

Cancer and Infectious Diseases

In oncology, zebrafish have become a premier model for studying tumor formation and metastasis. For example, a knock-in zebrafish model with the human BRAF mutation (a common driver in melanoma) successfully replicates tumor formation [8]. When combined with other cancer-associated genes, these transparent models enable researchers to visualize the earliest stages of tumorigenesis and to identify key genetic contributors. Furthermore, the similarity of the zebrafish immune system to that of humans makes it a powerful tool for studying infectious diseases and antibiotic resistance. Researchers can observe pathogen behavior in real time, providing insights into how bacteria, viruses, and fungi invade and affect host cells [8] [9].

The future of real-time imaging in zebrafish is tightly coupled with ongoing technological innovations. Current efforts are focused on pushing the limits of multiscale imaging. The development of self-driving microscopes that can automatically adjust to sample growth and movement will allow for longer, more detailed observations of processes like cancer metastasis and immune cell interactions [12]. Furthermore, the integration of live imaging data with other omics technologies, such as single-cell RNA sequencing, is creating a more holistic view of development and disease. This combination allows scientists to not only track cell movements and behaviors but also to link these dynamics to underlying molecular changes [14].

In conclusion, the power of transparency in the zebrafish model provides an unparalleled window into the dynamic cellular processes underlying human genetic diseases. By enabling real-time, high-resolution observation of development, disease progression, and drug response in a living vertebrate, zebrafish research accelerates the pace of discovery. When combined with robust genetic tools and standardized methodologies, live imaging in zebrafish solidifies its role as a versatile, scalable, and translationally relevant platform, poised to address unmet medical needs and drive innovation in personalized therapeutic strategies [3] [8].

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a cornerstone of modern biomedical research, providing a unique combination of physiological relevance and practical efficiency for modeling human genetic diseases. Its rapid lifecycle and remarkable fecundity enable experimental designs and genetic screens that would be prohibitively expensive or ethically challenging in mammalian models. This technical guide examines how these biological characteristics, when integrated with advanced genomic tools and high-throughput methodologies, accelerate the pace of discovery in functional genomics and therapeutic development.

Zebrafish occupy a critical niche in biomedical research, serving as a vertebrate model that bridges the gap between invertebrate systems and mammalian models. Their high genetic conservation with humans—approximately 70% of protein-coding genes have zebrafish orthologs, rising to 84% for disease-associated genes—makes them particularly valuable for studying human disease mechanisms [5] [3]. The external development and optical transparency of embryos further enhance their utility, allowing direct observation of developmental processes in real time [15] [16].

However, it is the combination of rapid lifecycle and high fecundity that truly enables large-scale genetic studies. These characteristics facilitate the generation of substantial sample sizes necessary for robust statistical analysis, while significantly reducing the time and cost associated with traditional vertebrate models [4]. This whitepaper explores how these attributes are leveraged to advance our understanding of human genetic diseases within the context of a broader thesis on zebrafish as preclinical models.

Quantitative Foundations: Lifecycle and Reproductive Metrics

The experimental power of zebrafish stems from quantifiable biological advantages that directly impact research scalability and efficiency. The tables below summarize key metrics that make zebrafish ideal for large-scale genetic studies.

Table 1: Zebrafish Lifecycle Characteristics Relevant to Genetic Research

| Lifecycle Stage | Timeframe | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Embryonic Development | 24-72 hours post-fertilization (hpf) | Major organs form rapidly; ideal for developmental studies [3] |

| Hatching | 2-3 days post-fertilization (dpf) | Transition to free-swimming larvae; endpoint for early screens [4] |

| Sexual Maturity | 2-4 months | Short generation time enables rapid genetic studies [4] |

| Generation Interval | 3-4 months | Facilitates tracking of hereditary diseases across generations [17] |

Table 2: Reproductive Capacity Comparison of Model Organisms

| Model Organism | Embryos/Litter | Reproduction Cycle | Annual Yield Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish | 70-300 eggs [4] [16] | Every 10 days [16] | Thousands per breeding pair |

| Mouse | 2-12 pups [4] | 21-day gestation | ~100-150 per breeding pair |

| Human | 1 (typically) | 9-month gestation | 1 per pregnancy |

These quantitative advantages translate directly to research applications. The large clutch sizes (70-300 embryos per mating) produced with a rapid 10-day reproductive cycle enable researchers to obtain substantial sample sizes from a single crossing event, enhancing statistical power while minimizing animal usage in accordance with 3R principles [16]. The short generation time of 3-4 months allows for the establishment of complex genetic lines and transgenerational studies in timeframes that are impractical in other vertebrate models [17].

Methodological Applications in Genetic Research

High-Throughput Screening Platforms

The biological characteristics of zebrafish enable unique experimental designs that combine the physiological relevance of a whole vertebrate organism with the scalability typically associated with in vitro systems. Zebrafish embryos are small enough (≤1mm diameter) to be arrayed in multi-well plate formats (e.g., 96-well plates), allowing researchers to simultaneously test numerous chemical compounds or genetic conditions [15] [16]. This compatibility with high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies enables the processing of thousands of embryos daily, generating robust datasets for statistical analysis [3].

The transparency of zebrafish embryos and larvae provides a critical advantage in these screening contexts, allowing for non-invasive imaging and phenotypic analysis without the need for sacrificial sampling. When combined with fluorescent transgenic reporters and automated microscopy systems, researchers can conduct real-time assessments of developing organs and gene expression patterns in live animals [5] [18]. This approach combines the scalability of in vitro methods with the biological complexity of an intact vertebrate organism, bridging a critical gap in preclinical research pipelines.

Genetic Manipulation and Analysis

The high fecundity of zebrafish is particularly valuable for genetic manipulation studies, where large numbers of embryos are required for microinjection and subsequent analysis. Several technologies leverage this capability:

CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing: The creation of targeted mutations using CRISPR/Cas9 requires microinjection into single-cell embryos. The hundreds of embryos produced per mating pair enable the efficient generation of multiple mutant lines in a single experiment [5]. For example, studies modeling hypophosphatasia (HPP) and intestinal inflammation have successfully used CRISPR/Cas9 to create alpl and ACE knockout zebrafish, respectively [5].

Morpholino Knockdown: Transient gene knockdown using morpholino oligonucleotides remains a valuable tool for rapid assessment of gene function, particularly during early developmental stages [4]. The external development of zebrafish enables precise microinjection of these reagents into the yolk or embryo at the 1-4 cell stage.

Transgenesis: The high embryo output facilitates the creation of stable transgenic lines through methods such as Tol2 transposon-mediated transgenesis. These lines express fluorescent reporters under tissue-specific promoters, enabling fate mapping and live imaging of biological processes [15] [4].

The following diagram illustrates how these elements integrate into a cohesive high-throughput genetic screening workflow:

Experimental Design Considerations

The genetic heterogeneity of commonly used zebrafish lines (e.g., AB, TU, TL) introduces population-level variation that more accurately models human genetic diversity compared to isogenic mouse models [4]. While this diversity increases phenotypic variability, the large sample sizes enabled by zebrafish fecundity allow researchers to account for this variation statistically, ultimately producing more translatable results that better reflect human population responses [4].

Proper experimental design must account for maternal contributions to early development. Zebrafish embryos develop using maternal RNA and proteins deposited in the egg, which can mask the phenotypic effects of homozygous mutations until the zygotic genome fully activates [4]. Researchers must consider this when interpreting early phenotype data and may need to assess both maternal and zygotic gene function for complete loss-of-function analysis.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table summarizes key reagents and resources that facilitate genetic research in zebrafish:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Zebrafish Genetic Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Targeted gene editing | Creating knockout models of human diseases (e.g., HPP, XMEA) [5] [19] |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Transient gene knockdown | Rapid assessment of gene function in early development [4] |

| Transgenic Reporter Lines | Tissue-specific expression of fluorescent proteins | Fate mapping and live imaging of biological processes [15] [18] |

| PTU (Phenyl-thio-urea) | Prevents pigment formation | Extends window for optical imaging [4] |

| Casper Mutant Line | Genetically transparent | Enables imaging of internal organs in adult fish [4] |

| ZFIN Database | Centralized genetic information | Access to sequences, mutants, and protocols [4] |

Genetic Screening Workflow and Pathway Analysis

The integration of rapid lifecycle and high fecundity enables sophisticated genetic screening approaches that systematically connect genetic perturbations to phenotypic outcomes. The following diagram illustrates a generalized pathway for identifying and validating genetic mechanisms underlying specific phenotypes:

This workflow exemplifies how zebrafish facilitate the deconstruction of complex biological processes. For instance, a study investigating axon regeneration identified that deletion of Slc1a4 suppressed Mauthner cell axon regeneration through the p53 signaling pathway, ultimately inhibiting expression of Gap43, a critical factor for axonal growth [5]. Such multifaceted studies benefit tremendously from the ability to generate large numbers of mutants and conduct comprehensive molecular analyses.

The rapid lifecycle and high fecundity of zebrafish provide a foundational advantage for large-scale genetic studies that is difficult to replicate in other vertebrate models. These characteristics enable researchers to implement robust experimental designs with appropriate statistical power, accelerate the generation and analysis of genetic variants, and translate findings more efficiently toward human therapeutic applications. When combined with advanced genomic tools and imaging technologies, these attributes position zebrafish as an indispensable component of the functional genomics toolkit, particularly for researchers investigating the mechanisms of human genetic diseases and potential therapeutic interventions.

As precision medicine continues to evolve, the scalability and physiological relevance of the zebrafish model will likely play an increasingly important role in validating genetic findings from human patients and developing personalized treatment approaches. The integration of emerging technologies such as single-cell transcriptomics, spatial genomics, and automated behavioral analysis with the inherent advantages of the zebrafish system promises to further enhance its utility in the biomedical research landscape.

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a preeminent model organism in biomedical research, offering a unique combination of ethical and economic advantages. This whitepaper details how the intrinsic biological features of zebrafish align with the 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) while simultaneously reducing the financial and logistical burdens associated with traditional mammalian models. Within the context of human genetic disease research, we demonstrate how adherence to these principles, coupled with innovative husbandry protocols, creates a robust, scalable, and cost-effective platform for disease modeling and drug discovery. Technical guidance on housing solutions, experimental design, and key research reagents is provided to empower researchers in leveraging the full potential of this model organism.

Zebrafish share a significant degree of genetic and physiological conservation with humans, making them a powerful tool for deciphering the mechanisms of human genetic diseases. Approximately 70% of human genes have at least one zebrafish ortholog, a figure that rises to 84% for genes known to be associated with human disease [3] [20]. This high level of conservation enables researchers to model a wide array of disorders, from cardiovascular and neurological conditions to cancer and metabolic syndromes [3] [20].

The utility of zebrafish extends beyond their genetic similarity. Their external fertilization, rapid extra-uterine development, and the optical transparency of embryos and larvae provide unparalleled opportunities for real-time, non-invasive observation of developmental processes and disease phenotypes [3] [21]. These inherent characteristics not only facilitate high-quality science but also naturally dovetail with the core tenets of the 3Rs, establishing zebrafish as a cornerstone of modern, ethical, and efficient biomedical research.

The 3Rs Framework in Zebrafish Research

The 3Rs principles—Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement—were first articulated by Russell and Burch and have become a foundational ethical framework for humane animal research [22]. The following sections delineate how zebrafish research aligns with and advances each of these principles.

Replacement: A Non-Protected Model

A significant aspect of Replacement in zebrafish research hinges on their regulatory status during early developmental stages. According to EU Directive 2010/63/EU, zebrafish embryos and larvae within the first 5 days post-fertilization (dpf) are not classified as protected animals, as they are not capable of independent feeding [23]. This classification permits their use in research as a form of Relative Replacement, providing a whole-organism, in vivo system that falls outside the strictest regulatory constraints for animal testing [23] [22].

During this 5-day window, zebrafish larvae possess fully developed organ systems, including a beating heart and a functional nervous system, enabling researchers to gather systemic data for toxicity screening, disease modeling, and drug discovery without the immediate use of protected vertebrates [23]. This strategic use of early-life stages makes the zebrafish a powerful bridge between purely in vitro cell cultures and complex mammalian models.

Reduction: Maximizing Data from Fewer Subjects

Zebrafish offer multiple avenues for Reducing the number of animals required in research:

- High Throughput Capabilities: A single pair of zebrafish can produce hundreds of embryos per week. This high fecundity allows researchers to study multiple experimental conditions and parameters simultaneously in a single clutch, drastically reducing the need for a large number of breeding adults and increasing the statistical power of experiments [23] [3].

- Sequential Assessment in One Organism: The optical clarity of larvae enables researchers to non-invasively assess multiple phenotypic parameters (e.g., organ function, blood flow, behavior) in the same individual over time. This sequential assessment reduces inter-individual variability and the total sample size needed to obtain data of a given precision [23].

- Pipeline Impact for Mammalian Reduction: By integrating zebrafish into early-stage drug discovery, researchers can efficiently narrow down compound selection and validate drug targets. This front-loading of research ensures that only the most promising candidates advance to later-stage testing in mammals, thereby reducing the overall number of rodents or other mammals required in the research pipeline [23].

Refinement: Minimizing Invasive Procedures

The physical and biological characteristics of zebrafish naturally lead to the Refinement of experimental techniques:

- Non-Invasive Imaging: The transparency of zebrafish embryos and larvae allows for high-resolution, real-time imaging of internal processes without the need for surgical intervention or terminal endpoints. This minimizes stress, pain, and harm to the animal, leading to more physiologically relevant data [23] [3].

- Standardized Conditions: Their small size and aquatic nature enable housing in highly controlled, standardized environments. This scalability decreases experimental variability and the incidence of artefacts, enhancing both animal welfare and the reproducibility of scientific data [23].

Economic and Market Analysis of Zebrafish Utilization

The adoption of the zebrafish model is not only an ethical imperative but also an economically sound strategy. The market for zebrafish in research is experiencing significant growth, reflecting their increasing value to the scientific community.

Table 1: Global Market Outlook for Zebrafish in Research

| Metric | Value | Source/Timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| Market Value (2024) | USD 118.8 Million | [24] |

| Projected Market Value (2033) | USD 412.8 Million | [24] |

| Projected CAGR | 14.8% | 2024-2033 [24] |

| U.S. Market Value (2024) | USD 35.1 Million | [24] |

| Alternative CAGR Projection | 12.9% | 2025-2032 [25] |

This robust market growth is driven by several key economic advantages of zebrafish over traditional mammalian models like mice:

- Lower Husbandry Costs: Zebrafish are small and can be housed at high densities in aquatic systems, which require less space and are cheaper to maintain than the housing needed for rodents [3] [24]. Their diet is also less expensive.

- High-Throughput Screening Efficiency: The small size of zebrafish larvae makes them compatible with multi-well plate formats, enabling automated, high-throughput screening (HTS) of thousands of compounds. This HTS capability, performed at a fraction of the cost and time of mammalian screens, accelerates drug discovery and reduces overall R&D expenditures [3] [24].

- Reduced Compound Quantities: The micro-volume environments used for larval testing (e.g., 96-well plates) mean that only tiny amounts of often costly experimental compounds are required [26].

Table 2: Cost and Efficiency Comparison: Zebrafish vs. Mouse Models

| Feature | Zebrafish | Mouse |

|---|---|---|

| Space & Housing Cost | Low (small aquatic tanks) | High (larger cages, specific pathogen-free facilities) |

| Diet & Maintenance | Lower cost | Higher cost |

| Reproductive Rate | High (200-300 eggs/week per pair) | Low (~5-10 pups every 3 weeks) |

| Throughput for Drug Screening | Very high (amenable to 96-well plates) | Moderate (limited by size and cost) |

| Amount of Compound Needed | Minimal (micro-liter volumes) | Significantly larger |

Protocol for Cost-Effective Larval Rearing: The FAST-MC Method

A critical component of cost-effective zebrafish research is efficient husbandry. Traditional larval rearing in static petri dishes is labor-intensive and can lead to poor water quality. The Filtered Aquatic Small Tubular Mesh-bottomed Containers (FAST-MC) method provides a low-cost, efficient alternative that improves animal welfare and data quality [26].

Background and Rationale

Conventional rearing of zebrafish larvae in petri dishes or multi-well plates requires frequent media changes due to the lack of filtration, making it taxing for long-term studies like toxicology or genetics. The FAST-MC method separates larvae into individual mesh-bottomed containers suspended in a larger, filtered aquarium. This setup provides a constant flow of filtered water, mimicking the recirculating systems used for adult fish, which leads to improved water quality, higher larval survival, and increased activity compared to standard dishes [26].

Materials and Assembly

- Aquarium: A standard glass aquarium equipped with a top power filter (intake covered with mesh to prevent clogging) and a submersible heater to maintain temperature at 28-29°C.

- PVC Float: A square frame constructed from ¾†diameter PVC piping and elbow/T-connectors, assembled without glue to be watertight.

- Mesh-Bottom Hatchery: A clear acrylic cylinder with one end sealed with 400 µm nylon mesh, affixed with aquarium silicone. A black rubber O-ring is placed around the outside.

- Assembly: The hatchery is inserted into the PVC float, with the O-ring resting on the PVC to suspend it. The entire apparatus is secured in the aquarium with airline tubing and binder clips to prevent drifting [26].

Experimental Use and Validation

In validation studies, larvae raised in FAST-MC containers for four weeks showed better survival and increased activity than those in standard petri dishes, while maintaining comparable general behaviors. This method is particularly amenable to toxicological and pharmacological studies, as the aquarium water can contain the experimental treatment, exposing all larvae in the individual containers uniformly [26].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of the FAST-MC system and its associated benefits.

Leveraging the zebrafish model to its full potential requires a suite of specialized tools and reagents. The following table details key resources for genetic manipulation, housing, and phenotypic analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Zebrafish Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Targeted genome editing for creating knock-out and knock-in disease models. | Allows for precise introduction of patient-specific mutations to study gene function [3] [21]. |

| Prime Editing | Advanced genome editing for more complex genetic modifications. | Enables a wider range of precise edits without double-strand breaks [3]. |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides (MOs) | Transient gene knockdown by blocking mRNA translation or splicing. | Useful for rapid assessment of gene function, especially in early development [3]. |

| FAST-MC Housing | Advanced larval rearing system. | Provides filtered water flow, improving water quality, survival, and reducing labor [26]. |

| Casper Strain | Genetically transparent adult zebrafish. | Enables real-time, non-invasive imaging of internal processes in adult fish [3]. |

| High-Throughput Behavioral Tracking | Automated analysis of locomotor activity and complex behaviors. | Used for modeling neuropsychiatric disorders and assessing drug effects on behavior [3]. |

The zebrafish model organism stands at the intersection of ethical responsibility and scientific-economic efficiency. Its inherent biological properties systematically address the 3Rs principles: providing a platform for Replacement of protected animals in early stages, enabling Reduction through high-throughput capabilities, and permitting Refinement via non-invasive imaging. Concurrently, the lower husbandry costs, high fecundity, and scalability of zebrafish systems translate into significant economic advantages for research institutions and pharmaceutical companies. As the field continues to evolve with advancements in gene-editing, automation, and husbandry—such as the FAST-MC method—the zebrafish is poised to remain an indispensable asset in the global effort to understand and treat human genetic diseases, firmly aligning the pursuit of scientific progress with the highest standards of animal welfare.

From Genes to Therapies: Advanced Techniques and Diverse Disease Applications

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a premier model organism for studying vertebrate gene function and modeling human genetic diseases. Several intrinsic characteristics make it particularly valuable for biomedical research. Zebrafish share a significant degree of genetic similarity with humans, with genome sequencing revealing that 71.4% of human genes have counterparts in zebrafish, and approximately 84% of genes known to be associated with human disease have a zebrafish ortholog [6]. This genetic conservation, combined with their external embryonic development, high fecundity, and optical transparency during early development, provides unique advantages for large-scale genetic studies and high-throughput drug screening that are challenging to perform in mammalian models [6] [27].

The arrival of CRISPR-based genome editing technologies has further accelerated the utility of zebrafish in functional genomics and disease modeling. CRISPR-Cas9 has revolutionized targeted mutagenesis in zebrafish, enabling efficient generation of knockout and knock-in alleles for studying gene function and disease mechanisms [28]. More recently, advanced precision genome editing tools including base editors and prime editors have been developed for zebrafish, allowing for even more precise genetic modifications without inducing double-strand DNA breaks [29] [30]. These technologies are particularly valuable for creating accurate models of human genetic diseases, which often involve specific single-nucleotide variants rather than complete gene knockouts [31]. The combination of zebrafish biology and these sophisticated editing tools provides a powerful platform for understanding disease pathogenesis and advancing therapeutic development.

Precision Editing Technologies: Mechanisms and Applications

CRISPR-Cas9 and Homology-Directed Repair

The CRISPR-Cas9 system functions by creating double-strand breaks (DSBs) at specific genomic locations guided by RNA molecules. In zebrafish, the editing process typically involves microinjecting CRISPR components into one-cell stage embryos [6]. The DSBs are then repaired by the cell's endogenous repair mechanisms, primarily non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which often results in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, or homology-directed repair (HDR), which allows for precise incorporation of designed DNA templates [28].

HDR-mediated knock-in approaches have been successfully used to model human diseases in zebrafish. For instance, researchers have generated zebrafish models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) by inserting two single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) via HDR [6]. Similarly, Cantú syndrome, caused by mutations in ABCC9, has been modeled through knock-in of human disease-causing mutations, resulting in zebrafish displaying significantly enlarged ventricles with enhanced cardiac output and distinct cerebral vasodilation [6]. However, conventional HDR efficiency in zebrafish remains relatively low, often hampered by random integration and off-target effects [32] [31].

Optimization efforts for HDR in zebrafish have investigated various parameters. Studies have examined the effects of varying Cas9 amounts, using chemically modified HDR templates, different microinjection procedures, and introducing additional synonymous guide-blocking variants in the HDR template [32]. Research indicates that optimal injected amounts of Cas9 range between 200 pg and 800 pg, with Alt-R HDR templates showing improved integration efficiency, while guide-blocking modifications generally did not enhance HDR rates [32].

Base Editing Technologies

Base editors represent a significant advancement in precision genome editing by enabling direct chemical conversion of one DNA base to another without creating DSBs. These systems utilize catalytically impaired Cas proteins fused to deaminase enzymes. Cytosine base editors (CBEs) catalyze C•G to T•A conversions, while adenine base editors (ABEs) facilitate A•T to G•C changes [29]. Since approximately 48% of human disease-causing mutations are G•C to A•T transitions and 14% are T•A to C•G transitions, these editors can address a significant proportion of disease-relevant mutations [30].

The development of base editors for zebrafish has progressed through several generations with continuous improvements. The initial application used a codon-optimized BE3 system, achieving editing efficiencies between 9.25% and 28.57% [29]. Subsequent versions like AncBE4max showed approximately threefold higher efficiency compared to BE3 [29]. More recently, PAM-independent systems such as SpRY-CBE4max and SpRY-ABE8e have been developed, bypassing the traditional NGG PAM requirement and expanding the targetable genomic space [29].

Recent research has further optimized base editing efficiency in zebrafish. A 2024 study demonstrated that incorporating the human Rad51 DNA-binding domain (Rad51DBD) into a hyperactive cytosine base editor (zhyA3A-CBE5) significantly improved editing efficiency to a maximum range of 18.86% to 62.30%, compared to 12.17% to 40.63% with the original editor [30]. This optimized editor also exhibited a broader editing window (nucleotides C3-C16) and successfully modeled human diseases including Diamond-Blackfan anemia and pseudoxanthoma elasticum in zebrafish [30].

Prime Editing

Prime editing represents a more versatile precision editing technology that can mediate all possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, without requiring DSBs or donor DNA templates. The system employs a Cas9 nickase fused to a reverse transcriptase enzyme, programmed with a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit [32] [33].

Two main prime editor architectures have been tested in zebrafish: the original PE2 system (nickase-based) and PEn (nuclease-based). Comparative studies have revealed that each system has distinct advantages depending on the type of edit required. For single-nucleotide substitutions, PE2 demonstrates higher efficiency (8.4% vs 4.4% for PEn) and precision (40.8% vs 11.4% for PEn) [33]. However, for the insertion of short DNA fragments (e.g., a 3-bp stop codon), PEn outperforms PE2 [33].

A comprehensive 2025 study comparing prime editing with conventional HDR for variant knock-in in zebrafish found that prime editing increased editing efficiency up to fourfold and expanded the F0 founder pool for four targets compared with conventional HDR editing, while also generating fewer off-target effects [32]. This superior performance positions prime editing as a highly promising methodology for creating precise genomic edits in zebrafish to model human diseases.

Comparative Analysis of Precision Editing Technologies

Table 1: Comparison of Precision Genome Editing Technologies in Zebrafish

| Technology | Editing Type | Key Components | Efficiency Range | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 HDR | Knock-in, SNP introduction | Cas9 nuclease, sgRNA, donor DNA template | Variable, typically low [31] | Can insert larger DNA fragments; established protocol | Low efficiency; requires DSBs; random integration issues |

| Cytosine Base Editors | C•G to T•A conversions | Cas9 nickase, cytidine deaminase, UGI | 18.9-62.3% (optimized systems) [30] | No DSBs; high efficiency; minimal indels | Limited to specific base changes; bystander edits possible |

| Adenine Base Editors | A•T to G•C conversions | Cas9 nickase, adenine deaminase | 9.3-28.6% (early systems) [29] | No DSBs; precise A-to-G conversion | Limited to specific base changes; potential off-target RNA editing |

| Prime Editing (PE2) | All base substitutions, small indels | Cas9 nickase, reverse transcriptase, pegRNA | Up to 8.4% (base substitution) [33] | Versatile; no DSBs; no donor DNA needed; high precision | Complex pegRNA design; lower efficiency for insertions |

| Prime Editing (PEn) | All base substitutions, small indels | Cas9 nuclease, reverse transcriptase, pegRNA | 4.4% (base substitution) [33] | Better for insertions; no donor DNA needed | Higher indel rates than PE2 |

Table 2: Optimization Strategies for Precision Genome Editing in Zebrafish

| Parameter | CRISPR-Cas9 HDR | Base Editing | Prime Editing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery Method | Microinjection of RNP complex + ssODN template [31] | Microinjection of mRNA or RNP complexes [29] [30] | Microinjection of PE mRNA + pegRNA [33] |

| Optimal Injection Site | Cell or yolk [32] | Cell [29] | Cell or yolk [32] |

| Template Design | ssODNs with homology arms; Alt-R templates show improved efficiency [32] [31] | Codon-optimized editors for zebrafish; Rad51DBD incorporation improves efficiency [30] | Refolded pegRNA prevents misfolding; optimized PBS and RTT lengths [33] |

| Detection Methods | NGS superior to ICE; germline transmission analysis essential [31] | Amplicon sequencing; HRMA for genotyping [30] | Amplicon sequencing; T7E1 assay; precision score calculation [33] |

Experimental Workflows for Precision Genome Editing in Zebrafish

Workflow for HDR-Mediated Knock-in

The workflow for HDR-mediated knock-in begins with target selection and gRNA design, prioritizing guides with high on-target efficiency and low off-target potential. Next, single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) repair templates are designed with homology arms flanking the desired edit. Research from the UAB Center for Precision Animal Modeling suggests empirically evaluating multiple oligo variations as no unified consensus for optimal orientation or size has emerged [31]. Components are prepared, typically as ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes of Cas9 protein and sgRNA, combined with ssODN templates. Microinjection into the one-cell stage embryo is performed directly into the cell or yolk, with studies showing similar efficiency for both injection sites [32]. Injected embryos are screened using next-generation sequencing (NGS) of pooled embryo DNA, which has been shown superior to Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) for determining HDR frequency [31]. Potential founders (F0) are raised to adulthood, and germline transmission is assessed by analyzing progeny rather than F0 somatic tissue, as studies reveal a "jackpot effect" where germline editing rates often exceed somatic rates [31]. Finally, stable lines are established from germline-transmitting founders, with F1 animals validated using methods such as high-resolution melting curve analysis (HRMA), allele-specific PCR, or restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis [31].

Workflow for Prime Editing

Prime editing workflow initiates with careful target site selection considering protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) orientation and local sequence context. The pegRNA is then designed, incorporating a primer binding site (PBS) sequence and reverse transcriptase (RT) template encoding the desired edit. Research suggests refolding pegRNAs to prevent misfolding between complementary sequences does not consistently enhance editing efficiency [33]. Editing components are prepared, typically as PE mRNA combined with synthetic pegRNA. Microinjection into one-cell stage embryos is followed by incubation at 32°C, as elevated temperature has been shown to improve prime editing efficiency in zebrafish [33]. Injected embryos are analyzed using amplicon sequencing to determine editing efficiency and precision scores, or T7E1 assays for initial screening. Editor selection is guided by the edit type: PE2 is preferred for single-nucleotide variants, while PEn shows advantage for insertions up to 30 bp [33]. Finally, stable lines are established from founders showing precise edits, with germline transmission rates typically higher than conventional HDR approaches [32].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Precision Genome Editing in Zebrafish

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | SpCas9, saCas9, Cas12a | DSB induction for knockout and HDR-mediated knock-in | Codon-optimize for zebrafish; use RNP complexes for reduced toxicity |

| Base Editors | zBE3, AncBE4max, zhyA3A-CBE5, ABE8e | Single-nucleotide conversions without DSBs | Incorporate Rad51DBD for improved efficiency; use SpRY variants for PAM flexibility |

| Prime Editors | PE2, PEn | Versatile editing without DSBs or donor DNA | Use PE2 for substitutions; PEn for insertions; optimize PBS and RTT lengths |

| Editing Templates | ssODNs, Alt-R HDR templates | Donor DNA for HDR-mediated precise editing | Chemical modifications (Alt-R) improve stability and integration efficiency |

| Detection Tools | NGS, HRMA, ICE, T7E1 assay | Analysis of editing efficiency and genotyping | NGS most accurate for HDR quantification; HRMA for rapid genotyping of stable lines |

| Delivery Tools | Microinjection apparatus, needles, pullers | Physical introduction of editing components into embryos | Inject into cell rather than yolk for some editors; optimize concentration and volume |

Precision genome engineering in zebrafish has evolved dramatically from initial CRISPR-Cas9 approaches to increasingly sophisticated tools including base editors and prime editors. Each technology offers distinct advantages: HDR remains valuable for larger insertions, base editors provide exceptional efficiency for specific nucleotide conversions, and prime editors offer unprecedented versatility for various precise edits. The optimization of these tools through codon optimization, protein engineering, and delivery method refinement has significantly enhanced their efficiency and specificity in zebrafish.

Future developments will likely focus on expanding the targeting scope, improving efficiency, and reducing off-target effects. The recent development of near PAM-less editors like SpRY-based systems already addresses the targeting scope limitation [29]. As these technologies continue to mature, zebrafish will play an increasingly important role in modeling human genetic diseases, validating therapeutic targets, and advancing personalized medicine approaches. The integration of these precision genome editing tools with the inherent advantages of the zebrafish model system creates a powerful platform for accelerating our understanding of gene function and disease mechanisms.

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a powerful model organism for translational biomedical research, bridging the gap between in vitro studies and mammalian systems. This technical guide examines the successful application of zebrafish models across three major disease categories: neurological, cardiovascular, and metabolic disorders. We present comprehensive data on model validation, detailed experimental methodologies, and visualization of key signaling pathways and workflows. The zebrafish model demonstrates particular strength in high-throughput screening capabilities, genetic manipulability, and physiological conservation with mammalian systems. With over 70% of human genes having at least one zebrafish ortholog and core organ systems exhibiting remarkable homology, this model system provides unprecedented opportunities for accelerating drug discovery and understanding fundamental disease mechanisms.

Zebrafish have become a cornerstone of biomedical research since their introduction as a model organism by George Streisinger in the 1970s [34]. Their value stems from a powerful combination of genetic tractability, physiological conservation, and practical advantages over traditional mammalian models. The zebrafish genome shares at least one ortholog with over 70% of all human genes, including most disease-associated genes [34] [35]. Core brain structures, neurotransmitter systems, cardiovascular organization, and metabolic pathways are evolutionarily conserved between zebrafish and humans [8] [34].

From a practical research perspective, zebrafish offer significant advantages including external embryonic development, optical transparency during early stages, rapid generation time (sexual maturity by 12 weeks), and high fecundity (hundreds of embryos per week) [34]. These characteristics enable large-scale genetic and chemical screens that would be prohibitively expensive in mammalian systems. The optical clarity of embryonic and larval stages permits real-time, in vivo imaging of pathological processes at cellular resolution [34]. These advantages have positioned zebrafish as an indispensable tool for modeling human diseases and accelerating therapeutic development.

Zebrafish Models of Neurological Disorders

Modeling Neurodegenerative Diseases

Zebrafish have proven particularly valuable for modeling neurodegenerative diseases including Parkinson's disease (PD), Alzheimer's disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Huntington's disease (HD) [34]. The zebrafish brain exhibits fundamental resemblance to human neuroanatomy and neurochemical pathways, recapitulating hallmarks of human neurodegeneration such as protein aggregation, neuronal degeneration, and glial cell activation [34].

Parkinson's Disease Modeling: Zebrafish models of PD have been created through both genetic manipulation and chemical exposure. Researchers have successfully introduced mutations in PD-associated genes including SNCA, PINK1, LRRK2, and Parkin [34]. Although zebrafish lack dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain, they possess a functional homolog of the mammalian substantia nigra in the diencephalon [34]. These models recapitulate key features of PD including dopaminergic neuron loss and motor deficits, enabling screening of neuroprotective compounds.

Alzheimer's Disease Modeling: Zebrafish have been utilized to study amyloid-beta plaque buildup, a hallmark of AD pathology [8]. Transgenic approaches expressing human mutant proteins associated with familial AD (PSEN1, PSEN2) have been developed. The ability to observe neurological processes in live zebrafish has unlocked new avenues for understanding and treating complex brain disorders [8].

Epilepsy and Seizure Disorders: Zebrafish models have been extensively used to study epileptic syndromes and channelopathies. The convulsant agent pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) induces a stereotyped, concentration-dependent sequence of behavioral changes leading to convulsions in zebrafish [35]. This model enables high-throughput antiepileptic drug screening in 96-well plates using automated video tracking systems such as Noldus Daniovision [35].

Table 1: Zebrafish Models of Neurological Disorders

| Disease Category | Genetic Targets | Key Phenotypic Readouts | Therapeutic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parkinson's Disease | SNCA, PINK1, LRRK2, Parkin | Dopaminergic neuron loss, motor deficits, α-synuclein aggregation | Neuroprotective compound screening |

| Alzheimer's Disease | PSEN1, PSEN2, APP processing | Amyloid-beta plaque formation, memory deficits | Drug screening to reduce plaque formation |

| Epilepsy | SCN1A (Dravet syndrome) | Spontaneous seizures, hyperactive locomotion, convulsive response to stimuli | Anticonvulsant screening (e.g., Clemizole) |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | SHANK3, CNTNAP2 | Social behavior deficits, repetitive behaviors | Neuropharmacological testing |

| Spinocerebellar Ataxias | Polyglutamine expansion genes | Cerebellar atrophy, motor coordination deficits | Pathogenesis studies, drug discovery |

Experimental Protocols for Neurological Research

High-Throughput Neurobehavioral Screening: Automated zebrafish platforms have revolutionized screening for neurological disorders. The following protocol enables efficient phenotypic screening:

Animal Preparation: Distribute larval zebrafish (5-7 days post-fertilization) into 96-well plates, with each larva in individual wells containing 200-300μL of system water [35].

Baseline Recording: Record spontaneous locomotion for 15 minutes under light conditions using automated video tracking systems [35].

Stimulus Response Testing: Apply visual stimuli (flashes of light) to assess convulsive responses characterized by maximum velocity and angle turn (change in direction) [35].

Locomotion Pattern Analysis: Monitor anomalies in the stereotyped dark/light larval locomotion pattern using automated tracking software [35].

Data Analysis: Quantify total distance moved, maximum velocity, and angle turn in response to stimuli. Compare experimental groups to controls using appropriate statistical tests [35].

CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing in Zebrafish: The development of "crispants" (F0 knockout models using CRISPR/Cas9) allows rapid assessment of gene function without the need for generating stable mutant lines [35]:

Guide RNA Design: Design synthetic RNA Oligo CRISPR guide RNAs targeting genes of interest.

Microinjection: Inject highly active guide RNAs and Cas9 protein into one-cell stage zebrafish embryos.

Phenotypic Screening: Identify fish with high levels of somatic mutations without genotyping through phenotypic screening systems.

Validation: Assess epilepsy features or other neurological phenotypes during first days post-fertilization [35].

This approach significantly shortens generation time compared to traditional homozygous mutant generation in the F2 generation.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for zebrafish neurological disease modeling integrating genetic manipulation, in vivo imaging, behavioral analysis, and high-throughput screening to identify therapeutic applications.

Zebrafish Models of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases

Cardiovascular Disease Modeling

Zebrafish have become an established model for studying cardiac diseases and strokes [8]. Their cardiovascular system shares fundamental similarities with humans, including a two-chambered heart that performs equivalent functions to the four-chambered mammalian heart, and conserved electrophysiological properties of cardiomyocytes. The optical transparency of embryonic stages allows direct visualization of heart development and function in real time.

Cardiac Regeneration: A distinctive advantage of zebrafish in cardiovascular research is their remarkable capacity for cardiac regeneration. Unlike adult mammals, zebrafish can fully regenerate functional myocardium following injury, making them an invaluable model for identifying pro-regenerative pathways. Researchers have developed precise cardiac injury models including ventricular resection and cryoinjury to study this process.

Vascular Disease Modeling: Zebrafish are also used to model vascular development and disease. Transgenic lines with fluorescently tagged endothelial cells enable visualization of vascular network formation and remodeling. Models for studying atherosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular permeability have been established and used in drug screening applications.

Metabolic Disease Modeling

Metabolic research has increasingly adopted zebrafish models for studying disorders such as diabetes, obesity, and related conditions. Zebrafish exhibit conserved metabolic pathways including glucose homeostasis, lipid metabolism, and endocrine regulation [8] [36].

Diabetes and Glucose Homeostasis: Zebrafish models of type 2 diabetes have been developed through both genetic and dietary manipulations. These models replicate key aspects of human disease including hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and diabetic complications such as retinopathy [8]. Metabolic studies in zebrafish utilize glucose tolerance tests and insulin sensitivity assays analogous to mammalian protocols.

Obesity and Lipid Metabolism: Zebrafish models of obesity have been created through high-fat diets, genetic manipulation, and chemical exposure. These models develop hepatosteatosis, dyslipidemia, and increased adiposity. The transparency of larval stages allows direct visualization of lipid storage and distribution in live animals using fluorescent lipid probes.

Metabolomics Approaches: Advanced metabolomic profiling in zebrafish has identified numerous metabolic biomarkers associated with cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. These include carbohydrates, amino acids, lipids, and acyl-carnitines that show conserved associations with disease states in humans [36].

Table 2: Metabolic Biomarkers Identified in Zebrafish Models with Human Correlations

| Metabolite Class | Specific Metabolites | Association with Disease | Human Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates and Glycolytic Intermediates | Glucose, Mannose, Pyruvate, Lactate | Positive association with T2DM risk | Confirmed in human cohorts [36] |

| Branched-Chain Amino Acids | Isoleucine, Leucine, Valine | Positive association with T2DM risk | Validated in meta-analyses [36] |

| Aromatic Amino Acids | Tyrosine, Phenylalanine | Positive association with T2DM risk | Consistent across populations [36] |

| Fatty Acids | MUFA, n-3 PUFA | MUFA: Increased risk\nn-3 PUFA: Decreased risk | Race-dependent associations [36] |

| Glycerolipids | TAG, MAG | Specific carbon/unsaturation patterns affect risk | Conserved lipid patterns [36] |

Experimental Protocols for Metabolic Research

Glucose Tolerance Testing in Zebrafish:

Animal Preparation: House larval or adult zebrafish in fasting conditions for 12-24 hours prior to experiment.

Glucose Administration: Immerse animals in glucose solution (concentration range 2-5%) or perform intraperitoneal injection in adults.

Blood Collection: Collect minimal blood samples from caudal vein at timed intervals (0, 30, 60, 120 minutes).

Glucose Measurement: Quantify blood glucose using adapted commercial glucometers or fluorescence-based assays.

Data Analysis: Calculate area under curve and time to baseline recovery.

Metabolomic Profiling Protocol:

Sample Collection: Collect whole larvae or dissected tissues from adult zebrafish into extraction solvent.

Metabolite Extraction: Use methanol:water or chloroform:methanol extraction systems for comprehensive metabolite coverage.

Instrumental Analysis: Employ LC-MS or GC-MS platforms for targeted or untargeted metabolomic profiling.

Data Processing: Use specialized software (XCMS, MetaboAnalyst) for peak detection, alignment, and statistical analysis.

Pathway Analysis: Identify affected metabolic pathways through enrichment analysis and metabolic network mapping.

Diagram 2: Cardiometabolic pathways in zebrafish showing key intervention points for therapeutic development. BCAA: Branched-chain amino acids; AAA: Aromatic amino acids; TAG: Triacylglycerols; FA: Fatty acids.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Zebrafish Disease Modeling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Manipulation Tools | CRISPR/Cas9, Tol2 transposon, UAS/Gal4 system | Gene knockout, knockin, transgenesis | Crispants enable rapid F0 screening [35] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | GCaMP (calcium), GEDI (cell death), lipid probes | Live imaging of neuronal activity, cell death, metabolism | Enable whole-brain imaging in vivo [34] |

| Behavioral Analysis Systems | Noldus Daniovision, ZebraBox, ViewPoint | Automated locomotor tracking, seizure quantification | High-throughput capability in 96-well format [35] |