Zebrafish Orthologous Genes: A Powerful Platform for Human Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

This article explores the pivotal role of zebrafish orthologous genes in modeling human diseases, a cornerstone of modern biomedical research.

Zebrafish Orthologous Genes: A Powerful Platform for Human Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the pivotal role of zebrafish orthologous genes in modeling human diseases, a cornerstone of modern biomedical research. With approximately 70% of human genes having at least one zebrafish ortholog and 82-84% of human disease genes having a functional counterpart, the zebrafish presents a unique and powerful vertebrate model. We detail the foundational genetic similarities, advanced methodological applications like CRISPR-Cas9 for creating precise disease models, and crucial troubleshooting strategies to overcome species-specific limitations. Furthermore, we provide a comparative analysis validating the zebrafish model against other systems, underscoring its cost-effectiveness, high-throughput capability, and growing translational relevance for accelerating drug discovery and the development of personalized therapeutic strategies.

The Genetic Blueprint: Unveiling the High Degree of Orthology Between Human and Zebrafish Genomes

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a preeminent model organism for biomedical research, a status solidified by the sequencing and detailed annotation of its genome. A foundational pillar supporting its utility is the quantifiable genetic similarity to humans. This whitepaper delineates the core genomic statistics—specifically, that approximately 70% of human genes have at least one obvious zebrafish orthologue, and this figure rises to 84% for genes associated with human diseases [1] [2] [3]. Framed within the broader thesis of using orthologous genes for disease modeling, this document provides a detailed guide to the data, the experimental methodologies used to generate it, and the essential tools for leveraging zebrafish in translational research.

Zebrafish have become a cornerstone for the study of vertebrate gene function and the modeling of human genetic diseases [1] [4]. Their utility stems from a combination of practical advantages—including external fertilization, optically transparent embryos, high fecundity, and rapid development—and profound genetic conservation with humans [2] [4] [5]. The sequencing of the zebrafish genome was a pivotal achievement, enabling a direct, systematic comparison with the human genome and providing a quantitative basis for its use in disease research [1] [3]. This high degree of conservation means that discoveries made in zebrafish concerning gene function, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic responses have a high probability of being translatable to humans, establishing the zebrafish as a powerful "bridge" organism between basic research and clinical application [4].

Quantitative Genetic Similarity: Core Data

The genetic relationship between humans and zebrafish is characterized by several key metrics derived from the reference genome sequence (Zv9 assembly) and subsequent analyses. The following tables summarize the essential quantitative data.

Table 1: Zebrafish Genome Assembly and Annotation Overview (Zv9)

| Feature | Metric |

|---|---|

| Total Assembly Length | 1.412 gigabases (Gb) |

| Protein-Coding Genes | 26,206 |

| Pseudogenes | ~218 |

| Overall Repeat Content | 52.2% |

| Predominant Repeat Type | Type II DNA Transposable Elements (39% of genome) [1] [3] |

Table 2: Orthology Relationships Between Human and Zebrafish Genes

| Relationship Type | Human Genes | Zebrafish Genes | Ratio (Human:Zebrafish) |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-to-One | 9,528 | 9,528 | 1:1 |

| One-to-Many | 3,105 | 7,078 | 1:2.28 |

| Many-to-One | 1,247 | 489 | 2.55:1 |

| Many-to-Many | 743 | 934 | 1:1.26 |

| Total with Orthologue | 14,623 | 18,029 | ~1:1.28 |

| Species-Unique | 5,856 | 8,177 | - |

| Overall Percentage | ~70% of human genes have a zebrafish orthologue [1] [3] | ~69% of zebrafish genes have a human orthologue [1] |

Table 3: Conservation of Human Disease Genes in Zebrafish

| Category | Number of Human Genes | Genes with Zebrafish Orthologue | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMIM "Morbid" Genes | 3,176 | 2,601 | 82% [1] [3] |

| GWAS-Associated Genes | 4,023 | 3,075 | 76% [1] [3] |

| Overall Human Disease Genes | - | - | ~84% [2] [6] |

Key Biological Implications

- Teleost-Specific Genome Duplication (TSD): The increased gene number in zebrafish and the prevalence of "one-to-many" orthology relationships are largely attributed to an ancestral whole-genome duplication event specific to the teleost fish lineage. The resulting duplicated genes, called ohnologues, can have partitioned functions, providing a unique system to study sub-functionalization of genes [1] [3].

- Notable Absences: Despite the high level of conservation, some human genes lack clear zebrafish orthologues, such as the leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), oncostatin M (OSM), interleukin-6 (IL6), and BRCA1. However, their receptor complexes or binding partners (e.g., lifr, osmr, il6r, BARD1) are often present, suggesting that functionally analogous pathways may exist [1] [3].

Experimental Protocols for Establishing and Utilizing Orthology

The quantitative measures of genetic similarity are derived from and validated through a series of rigorous experimental and bioinformatic protocols.

Protocol 1: Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Orthology Determination

Objective: To generate a high-quality reference genome sequence for the zebrafish and systematically identify orthologous relationships with the human genome.

Methodology:

- Sequencing Strategy: A hybrid approach was employed, combining clone-by-clone sequencing (83% of the assembly) for high accuracy with whole-genome shotgun (WGS) sequencing (17%) for coverage. The Tübingen strain was used as the reference [1] [3].

- Assembly and Anchoring: Sequence contigs were ordered and oriented using a high-resolution, high-density meiotic map (Sanger AB Tübingen map, or SATmap), creating a chromosome-level assembly (Zv9) [1] [3].

- Gene Annotation: Both automated and manual curation were used to identify and annotate protein-coding genes, transfer RNAs, ribosomal RNAs, and small nuclear RNAs [1].

- Orthology Prediction: Orthologous genes were defined using the Ensembl Compara pipeline, which performs pairwise genome comparisons and uses protein tree analyses to distinguish orthologues (genes separated by a speciation event) from paralogues (genes separated by a duplication event) [1].

Protocol 2: Functional Validation through Disease Modeling

Objective: To experimentally confirm that a human disease-associated gene with a zebrafish orthologue can recapitulate aspects of the human disease phenotype when mutated in zebrafish.

Methodology:

- Gene Selection: Identify a candidate human gene from patient genetic data (e.g., via whole-exome sequencing) that is implicated in a disease and has a documented zebrafish orthologue.

- Model Generation (Reverse Genetics):

- Knockdown: Transient gene silencing is achieved by injecting single-cell embryos with antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) that block translation or correct splicing of the target mRNA [2].

- Knockout/Knock-in: Permanent, heritable mutations are created using genome-editing technologies like CRISPR/Cas9. This allows for the introduction of frameshift mutations (knockout) or the precise recapitulation of a patient's point mutation (knock-in) [2] [4].

- Phenotypic Screening: Zebrafish (larvae or adults) with the modified gene are systematically analyzed for phenotypes that mirror the human disease. Assays may include:

- Locomotor and Behavioral Analysis: Tracking movement to model neuromuscular or neurological disorders [2].

- Microscopic Imaging: Using the transparency of embryos/larvae to visualize organ development, heart function, or neuronal architecture in real time [4] [5].

- Histological Analysis: Examining tissue sections from adult fish for degenerative changes, fibrosis, or inflammation [5].

- Therapeutic Screening: Mutant fish displaying a relevant phenotype can be used in high-throughput drug screens. Larvae are arrayed in multi-well plates and exposed to small molecule libraries, with phenotypic rescue serving the primary readout [2] [4].

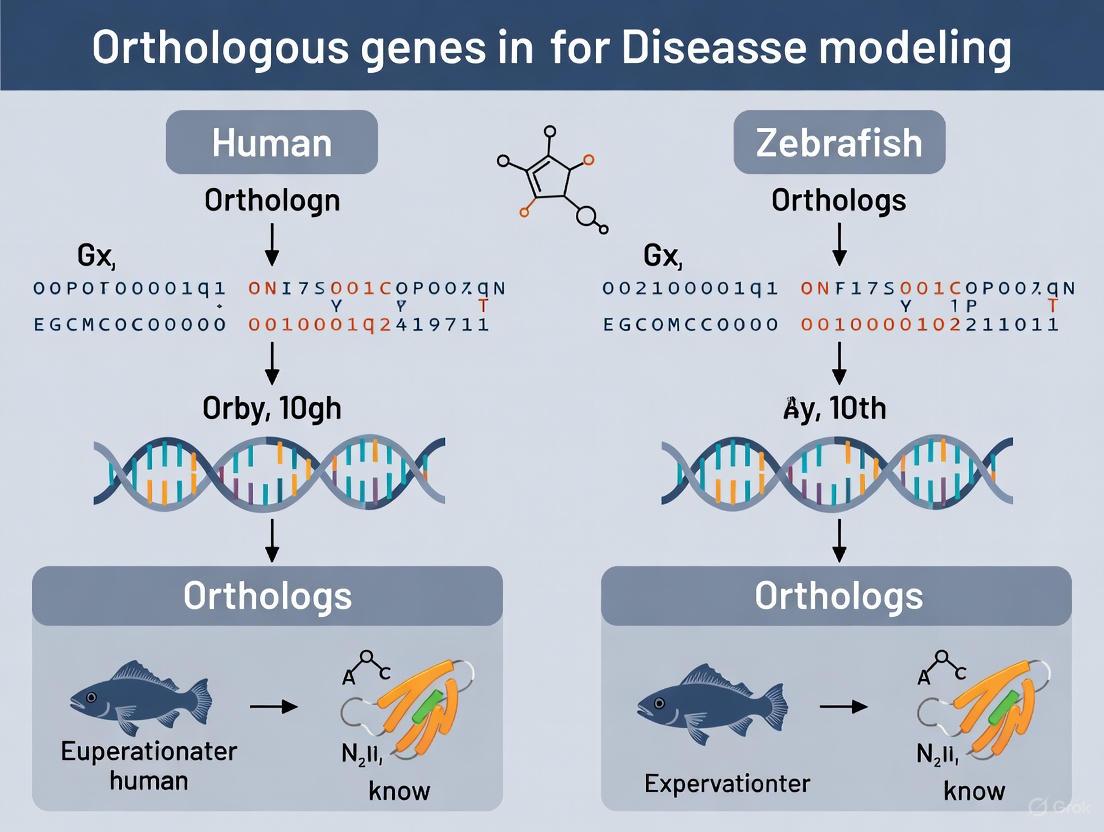

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for creating and validating a zebrafish disease model based on human genetic information.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Zebrafish Disease Modeling

| Reagent / Resource | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Enables precise, heritable genome editing (knockouts and knock-ins) to create stable disease models. The most advanced method for reverse genetics [2] [4]. |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Synthetic antisense molecules used for transient gene knockdown by blocking mRNA translation or splicing. Useful for rapid assessment of gene function in early development [2]. |

| Zebrafish TU Strain | The Tübingen reference strain, whose genome was sequenced to create the Zv9 reference assembly. Serves as a standardized genetic background [1] [3]. |

| SATmap (Meiotic Map) | A high-resolution genetic map used to anchor and validate the physical assembly of the zebrafish genome, ensuring accurate chromosome assignment [1]. |

| Ensembl Compara Database | The bioinformatics pipeline and database used to define orthology relationships between zebrafish and human genes [1]. |

Visualization of Genetic Relationships and Experimental Logic

The following diagram maps the logical relationship between a human gene, its zebrafish orthologues, and the potential outcomes for experimental modeling, which is central to the thesis of this whitepaper.

The quantitative metrics of 70% gene orthology and 84% disease gene conservation provide a powerful, data-driven foundation for the use of zebrafish in modeling human diseases. These figures are not abstract values but are derived from a high-quality genome sequence and refined through comparative genomics. When integrated with the experimental protocols and tools outlined in this whitepaper, these genetic similarities empower researchers to deconstruct disease mechanisms and accelerate drug discovery with high confidence in the translational relevance of their findings. The zebrafish model, therefore, stands as an indispensable instrument in the modern biomedical research toolkit, bridging the gap between genetic information and therapeutic application.

While the frequently cited 70% genetic similarity between zebrafish and humans provides a foundational rationale for their use in research, this figure alone is insufficient for validating functional disease pathways [6]. A more profound and informative metric reveals that 84% of human disease genes have functional orthologs in zebrafish, underscoring their exceptional utility in modeling human disease mechanisms [6] [4]. This whitepaper delves beyond simple percentage comparisons to explore the experimental frameworks and analytical tools that demonstrate the functional conservation of disease pathways between humans and zebrafish. We provide a technical guide for researchers to validate these conserved pathways, thereby enhancing the reliability of zebrafish models in drug discovery and disease mechanism research.

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) have emerged as a preeminent model organism in biomedical research, not merely due to genetic homology but because of their demonstrated capacity to recapitulate complex human disease phenotypes. The zebrafish genome contains approximately 26,000 protein-coding genes, and a significant majority of human genes have at least one zebrafish ortholog—a gene in one species that is similar due to shared ancestry [6]. This genetic conservation is particularly pronounced in genes associated with human diseases, enabling the creation of accurate disease models.

The practical advantages of zebrafish further solidify their position in translational research. Zebrafish are highly fertile, producing 200-300 embryos per clutch every 2-3 days, facilitating high-throughput studies [4]. Their embryos develop rapidly and externally, are optically transparent, and major organs form within 24 hours post-fertilization, allowing for real-time observation of developmental processes and disease progression [7] [4]. These characteristics, combined with cost-effective maintenance and fewer ethical constraints compared to mammalian models, position zebrafish as a powerful "tank-to-bedside" tool for accelerating drug discovery and personalized medicine [4].

Quantitative Landscape of Genetic Conservation

Understanding the depth of genetic similarity requires moving beyond a single percentage to examine specific conservation metrics relevant to disease research. The following tables summarize key quantitative data that underscore the functional relevance of zebrafish models.

Table 1: Key Metrics of Genetic Similarity Between Humans and Zebrafish

| Metric | Value | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Genetic Similarity | ~70% [6] | Foundational homology for comparative genomics. |

| Human Disease Genes with Zebrafish Orthologs | 84% [6] | High potential for modeling specific genetic disorders. |

| Protein-Coding Genes in Zebrafish | ~26,000 [6] | Complex genome comparable to humans. |

| Orthologs per Human Gene | ~1 or >1 [4] | Potential for gene subfunctionalization. |

Table 2: Comparative Advantages of Zebrafish Versus Rodent Models

| Basis | Zebrafish Models | Rodent Models |

|---|---|---|

| Development | External, rapid, and observable in real-time | Internal, longer gestation [4] |

| Number of Offspring | ~100-300 per week [4] | ~5-12 per month [4] |

| In-vivo Fluorescence Imaging | Highly possible due to embryo transparency [4] | Low possibility [4] |

| Genetic Manipulation | Easier, with efficient F0 screens [4] | Harder process, F0 screens not readily available [4] |

| Drug Administration | Non-invasive (water-soluble drugs), injections also possible [4] | Primarily injections [4] |

| Experimental Cycle & Cost | Short cycle, low animal care costs [4] | Long cycle, high costs [4] |

Methodologies for Establishing Functional Conservation

Establishing functional conservation requires a suite of molecular techniques to disrupt, introduce, or modify genes in zebrafish and observe resulting phenotypes. The following experimental protocols are central to this process.

Forward Genetic Screens: Unbiased Discovery

Forward genetics begins with a phenotype to identify the underlying gene.

- Protocol: Large-scale chemical mutagenesis using agents like N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) is performed on male zebrafish [7]. The F1 progeny from mutagenized males are screened for dominant phenotypes, or the F2 generation is intercrossed to reveal recessive phenotypes. Subsequent positional cloning or next-generation sequencing is used to identify the mutated gene responsible for the phenotype. This approach has been successfully used to identify mutants modeling human hematological diseases like congenital sideroblastic anemia and hemochromatosis [7].

Reverse Genetic Approaches: Targeted Validation

Reverse genetics starts with a known gene to investigate its function.

- Morpholino Knockdown: Morpholinos are antisense oligonucleotides that transiently inhibit gene translation or affect splicing [7]. They are injected into embryos at the 1- to 4-cell stage and remain active for several days, allowing for rapid assessment of gene function during early development. For instance, this method has been used to model Diamond Blackfan anemia by knocking down the ribosomal protein RSP19 [7].

- Target-Selected Mutagenesis (TILLING): This method combines standard ENU mutagenesis with high-throughput sequencing to identify point mutations in a specific target gene from a library of mutagenized fish [7]. This allows for the recovery of a series of allelic variants, including hypomorphs, which can be valuable for disease modeling.

- CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing: The CRISPR-Cas9 system enables precise, heritable gene knockouts or knock-ins [4]. Guide RNAs (gRNAs) and Cas9 mRNA are co-injected into single-cell embryos. This results in double-strand breaks in the DNA, which are repaired by error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), often leading to frameshift mutations and gene knockout. The efficiency of this system allows for the direct screening of mutants in the F0 generation. Recent advances, such as base editors (e.g., CBE4max-SpRY), allow for the introduction of precise point mutations to model specific human genetic variants with high efficiency [4].

The following workflow visualizes the typical process for creating and validating a zebrafish disease model using reverse genetics:

Transgenesis and Disease Modeling

For complex diseases like cancer, transgenic zebrafish lines can be engineered.

- Protocol: The Tol2 transposon system is widely used for germline transgenesis [8]. A DNA construct containing a tissue-specific promoter (e.g., mitfa for melanocytes) driving the expression of a human oncogene (e.g., BRAFV600E) is co-injected with Tol2 transposase mRNA into single-cell embryos [7]. To model the full spectrum of tumorigenesis, these transgenes are often combined with mutations in tumor suppressor genes (e.g., p53). This approach has successfully generated models of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and melanoma that histologically resemble human tumors and are sensitive to the same chemotherapeutic agents [7].

Analyzing Conserved Pathways and Networks

Once a model is established, pathway and network analysis is crucial for interpreting results in the context of human biology.

Pathway Enrichment Analysis

This identifies biological pathways that are over-represented in a list of genes of interest (e.g., differentially expressed genes from a zebrafish mutant).

- Workflow:

- Obtain Gene List: A ranked list of genes is generated from experimental data (e.g., RNA-seq). A common practice is to rank genes by

-log10(p-value) * sign(log2FoldChange)[9]. - Perform Enrichment Analysis:

- Over-representation Analysis (ORA): Tools like g:Profiler test whether genes from a pre-defined pathway (e.g., from GO Biological Process or Reactome) appear more frequently in your submitted list than expected by chance, using a Fisher's exact test. The foreground is typically the differentially expressed genes, and the background is all expressed genes [9].

- Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA): This method uses all genes ranked by their expression change. It determines if members of a pre-defined gene set tend to appear toward the top (or bottom) of the ranked list, indicating coordinated expression changes in that pathway [9].

- Visualize Results: Tools like Cytoscape with the EnrichmentMap app can create a network visualization of the enriched pathways, showing interconnections and helping to interpret the broader biological landscape [9].

- Obtain Gene List: A ranked list of genes is generated from experimental data (e.g., RNA-seq). A common practice is to rank genes by

Building Pathway Networks

To move beyond discrete lists of pathways, tools like PathIN can be used to visualize the functional connections between pathways related to a specific disease [10].

- Protocol: PathIN is a web-service that constructs pathway-based networks from databases like KEGG, Reactome, and WikiPathways [10]. Researchers can input a list of pathways, genes, or compounds. The tool provides several network creation methodologies:

- Direct connections between pathways of interest.

- Including first neighbours of the given pathways.

- Finding connecting pathways between the pathways of interest, which can reveal missing links in the molecular mechanism of a disease [10].

- The edge weights in these networks can represent the number of common biological entities (genes, compounds) shared between two pathways, providing a quantitative measure of their functional relatedness [10].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow for analyzing gene lists to uncover conserved pathway networks:

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Zebrafish Disease Modeling

| Tool / Resource | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System [4] | Precise genome editing for generating knock-out and knock-in mutations. | Introducing a patient-specific point mutation into the zebrafish ortholog. |

| Tol2 Transposon System [8] | Highly efficient germline transgenesis for creating stable transgenic lines. | Expressing a fluorescent reporter or human oncogene in a tissue-specific manner. |

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides [7] | Transient knockdown of gene expression by blocking translation or splicing. | Rapid assessment of gene function during early embryonic development. |

| Zebrafish Mutation Project (ZMP) [7] | Archive of mutant alleles for zebrafish genes, available from ZIRC. | Sourcing existing mutant lines instead of generating new ones. |

| ZFIN Database [11] | Central repository for zebrafish genetic, genomic, and phenotypic data. | Identifying zebrafish orthologs of human genes and finding established models. |

| PathIN [10] | Web-tool for creating and analyzing pathway-based networks. | Visualizing the functional environment and connections between pathways hit in an RNA-seq experiment. |

| g:Profiler [9] | Tool for over-representation analysis of gene lists against pathway databases. | Identifying which biological pathways are enriched in a list of differentially expressed genes. |

The power of the zebrafish model extends far beyond a simple percentage of shared DNA. Its true value lies in the demonstrable functional conservation of disease pathways, which can be systematically revealed through a combination of advanced genetic tools and sophisticated bioinformatic analyses. By employing the methodologies outlined in this guide—from targeted genome engineering and transgenesis to pathway network visualization—researchers can robustly validate zebrafish as a relevant and powerful system for deconstructing human disease mechanisms. This approach not only strengthens the foundation of basic biomedical research but also accelerates the pipeline for discovering and testing novel therapeutic strategies.

Gene duplication serves as a primary source of evolutionary innovation, providing genetic material for the emergence of novel functions. Subfunctionalization, where duplicated gene pairs (paralogs) undergo complementary degeneration of regulatory or protein modules, represents a crucial mechanism for duplicate gene retention. This technical review examines how subfunctionalized paralogs, particularly those resulting from the teleost-specific genome duplication, provide unique experimental models for elucidating gene function and regulation. Focusing on the zebrafish-human orthologous relationship, we demonstrate how subfunctionalization studies yield insights into protein structure-function relationships, genetic regulatory networks, and disease mechanisms. The conserved subfunctionalization patterns between zebrafish and mammalian systems offer powerful opportunities for modeling human genetic diseases and advancing therapeutic development.

Gene duplication represents a fundamental evolutionary mechanism for generating genetic novelty. The subsequent fate of duplicated genes typically follows several trajectories: non-functionalization (loss of one copy), neofunctionalization (acquisition of novel functions), or subfunctionalization (partitioning of ancestral functions between duplicates) [12] [13]. Subfunctionalization occurs through neutral mutations that lead to complementary degeneration of regulatory elements or protein domains, rendering both paralogs necessary to perform the complete ancestral function [14] [13].

The Duplication-Degeneration-Complementation (DDC) model provides a theoretical framework for subfunctionalization, wherein both paralogs accumulate deleterious mutations that compromise different aspects of the ancestral function, necessitating retention of both copies for complete functionality [13]. This process often manifests as tissue-specific expression patterns, developmental stage partitioning, or subcellular specialization between paralogs.

Zebrafish (Danio rerio), with their additional teleost-specific whole-genome duplication (TS-3R WGD) approximately 350 million years ago, possess abundant duplicated genes that have frequently undergone subfunctionalization [12] [15]. Approximately 70% of human protein-coding genes have at least one obvious zebrafish orthologue, making this system particularly valuable for biomedical research [3]. The zebrafish genome contains approximately 26,206 protein-coding genes, with duplicates for about 5,300 of these genes, providing rich material for studying subfunctionalization processes [12] [3].

Genomic Context: Zebrafish as a Model Organism

Evolutionary History of Genome Duplications

Vertebrates have experienced multiple rounds of whole-genome duplication throughout their evolutionary history. Two ancestral rounds (1R and 2R) occurred early in vertebrate evolution, approximately 500-600 million years ago [12]. The teleost lineage, including zebrafish, underwent an additional teleost-specific whole-genome duplication (TS-3R WGD) approximately 350 million years ago, contributing to their genetic diversification and evolutionary success [12] [15]. This event is supported by multiple lines of evidence, including the presence of seven Hox clusters in teleosts compared to four in most other vertebrates [12] [15].

Beyond the TS-3R WGD, zebrafish exhibit a remarkable propensity for small-scale duplication events. Studies demonstrate that zebrafish have the highest rate of tandem and intrachromosomal duplicates among sequenced teleost species, with duplicated genes comprising approximately 20% of their protein-coding genes [16]. These continuous duplication events have significantly expanded specific gene families, particularly those involved in immune and sensory processes [16].

Zebrafish-Human Genomic Conservation

Comparative genomic analyses reveal substantial conservation between zebrafish and human genomes. Approximately 70% of human genes have at least one obvious zebrafish orthologue, including the majority of genes implicated in human disease [3]. Furthermore, 82% of human genes with morbidity descriptions in OMIM have at least one zebrafish orthologue [3]. This high degree of conservation enables effective modeling of human genetic diseases in zebrafish.

Table 1: Zebrafish-Human Genomic Comparison

| Feature | Zebrafish | Human | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-coding genes | 26,206 | ~20,000 | Expanded gene families in zebrafish |

| Genes with orthologues | 69% have human orthologues | 71.4% have zebrafish orthologues | High functional conservation |

| Disease gene conservation | 82% of OMIM morbid genes have orthologues | - | Strong disease modeling potential |

| Genome duplication events | TS-3R WGD + frequent small-scale duplications | Only 1R and 2R WGD | More paralogs available for study |

The distribution of orthology relationships reveals that 47% of human genes maintain a one-to-one relationship with zebrafish orthologues, while a significant proportion exhibit "one-human-to-many-zebrafish" relationships, reflecting the teleost-specific genome duplication [3]. This duplication and subsequent divergence have created natural experiments for studying gene function and regulation.

Mechanisms and Models of Subfunctionalization

Theoretical Frameworks

Subfunctionalization encompasses several distinct but related models of functional partitioning between paralogs:

Expression Subfunctionalization: Paralogs evolve complementary expression patterns across tissues, developmental stages, or environmental conditions, with both copies required to cover the ancestral expression domain [14] [13]. This represents a neutral process that can lead to duplicate retention.

Protein Subfunctionalization: Complementary degeneration of protein functional domains occurs between paralogs, requiring the presence of both gene products to perform the complete ancestral function [13].

Specialization: A distinct form of subfunctionalization where both paralogs perform the same biochemical function but evolve enhanced efficiency in different contexts (tissues, developmental stages, or environmental conditions) [13]. Unlike other forms, specialization may involve positive selection.

The DDC model emphasizes that subfunctionalization typically occurs through neutral mutations that would be deleterious in a single-copy gene but become advantageous when complemented by mutations in the paralog [13]. This process effectively preserves both duplicates in the genome.

Escape from Adaptive Conflict

Adaptive conflict arises when a single-copy gene performs multiple functions, creating evolutionary constraints where improvements to one function impair another [13]. Gene duplication followed by subfunctionalization provides an evolutionary solution to adaptive conflict, allowing each paralog to specialize in different ancestral functions without compromise. This "function splitting" enables optimization of previously conflicting activities [13].

Diagram 1: Escape from adaptive conflict via subfunctionalization

Experimental Analysis of Subfunctionalized Paralogs

Identification and Validation Methods

Phylogenetic and Synteny Analysis

Orthology and paralogy relationships are established through phylogenetic reconstruction combined with synteny analysis. The presence of paralogs in double-conserved synteny (DCS) blocks provides evidence of whole-genome duplication origins [12]. In zebrafish, 3,440 gene pairs (26% of analyzed genes) exist within DCS blocks, supporting their origin from the TS-3R WGD [12].

Expression Profiling

Comprehensive expression analysis across tissues, developmental stages, and cell types identifies complementary expression patterns suggestive of subfunctionalization. Techniques include RNA sequencing, quantitative PCR, and in situ hybridization. For example, ribosomal protein paralogs Rps27 and Rps27l exhibit inversely correlated mRNA abundance across mouse cell types, with Rps27 highest in lymphocytes and Rps27l highest in mammary alveolar cells and hepatocytes [14].

Functional Complementarity Assays

Critical validation of subfunctionalization involves testing whether paralogs can functionally substitute for each other. The most definitive approach involves replacing one paralog's coding sequence with that of its counterpart at the endogenous locus. In the case of Rps27 and Rps27l, expressing Rps27 protein from the endogenous Rps27l locus (and vice versa) completely rescued loss-of-function lethality in mice, demonstrating functional equivalence despite divergent expression patterns [14].

Representative Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for studying subfunctionalization

Case Studies in Subfunctionalization

Ribosomal Protein Paralogs Rps27 and Rps27l

The ribosomal protein paralogs Rps27 (eS27) and Rps27l (eS27L) provide a compelling example of expression subfunctionalization. Evolutionary analysis indicates these paralogs likely arose during whole-genome duplication(s) in a common vertebrate ancestor [14]. Detailed investigation reveals:

- Inversely correlated expression: Rps27 and Rps27l show complementary mRNA abundance across mouse cell types, with each paralog dominating in distinct cellular contexts [14].

- Functional equivalence with expression partitioning: Endogenous tagging demonstrated that Rps27- and Rps27l-ribosomes associate preferentially with different transcripts. However, expressing Rps27 from the Rps27l locus (and vice versa) completely rescues loss-of-function lethality, indicating protein functional equivalence [14].

- Developmental stage partitioning: Murine Rps27 and Rps27l loss-of-function alleles cause lethality at different developmental stages, reflecting their distinct expression patterns rather than protein functional differences [14].

This case exemplifies how subfunctionalized expression patterns, rather than protein functional divergence, can drive duplicate gene retention.

Heat Shock Protein Hsp70 Paralogs

Gene network analyses in the Antarctic clam Laternula elliptica support subfunctionalization of duplicated inducible hsp70 paralogues [17]. Computational prediction of gene regulatory networks (GRN) from mantle-specific gene expression profiles placed hsp70A and hsp70B in unique network submodules linked by a single shared second neighbor [17].

- hsp70A primarily shares regulatory relationships with genes encoding ribosomal proteins, suggesting a role in protecting the ribosome under stress conditions.

- hsp70B interacts with genes involved in signaling pathways, cellular response to stress, and the cytoskeleton.

The contrasting submodules and associated annotations indicate that each hsp70 paralog has acquired additional separate functions beyond the traditional chaperone heat stress response, supporting subfunctionalization after gene duplication [17].

Zebrafish Visual System Genes

Zebrafish possess duplicated opsin genes with subfunctionalized expression and function:

- Red-sensitive opsin genes lws-1 and lws-2: Studies have predominantly focused on lws-1, while lws-2 has received less attention, potentially missing important aspects of their subfunctionalization [12].

- Transducin gene duplicates: Certain paralogs have distinct roles in vision versus circadian rhythms, with those involved in circadian regulation receiving less research attention than their visual counterparts [12].

- Retinoic acid metabolism genes cyp26: Among the cyp26 paralogs, cyp26a1 is more thoroughly investigated than cyp26b1 and cyp26c1, despite likely subfunctionalization [12].

These examples highlight how incomplete investigation of both paralogs in duplicated gene pairs can limit understanding of their subfunctionalized roles.

Table 2: Characteristics of Subfunctionalized Paralogs

| Paralog Pair | Organism | Subfunctionalization Type | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rps27/Rps27l | Mouse | Expression partitioning | Inverse correlation across cell types; different lethal phases |

| Hsp70A/Hsp70B | Antarctic clam | Regulatory network divergence | Distinct interaction partners; different stress response roles |

| Lws-1/Lws-2 | Zebrafish | Expression/functional | Differential retinal expression; potential spectral sensitivity differences |

| Cyp26 paralogs | Zebrafish | Spatial/temporal expression | Differential retinoic acid metabolism in development |

Technical Approaches and Research Tools

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Subfunctionalization Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Targeted gene mutagenesis | Generating loss-of-function alleles for both paralogs [12] |

| Tol2 transposon system | Transgenic line generation | Introducing reporter constructs or modified genes [12] |

| Endogenous tagging approaches | Protein localization and interaction studies | Determining subcellular localization of paralog products [14] |

| RNA sequencing | Comprehensive expression profiling | Identifying complementary expression patterns of paralogs [14] |

| Gene regulatory network analysis | Systems-level functional assignment | Placing paralogs in regulatory context [17] |

| Paralog swapping constructs | Functional complementation testing | Replacing one paralog's coding sequence with another's [14] |

Quantitative Analysis of Duplication Patterns

Comparative analysis of teleost genomes reveals distinctive duplication patterns in zebrafish compared to other model species:

Table 4: Duplication Patterns in Teleost Genomes

| Genomic Feature | Zebrafish | Medaka | Stickleback | Tetraodon |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total duplicated gene sets | 3,991 | 2,584 | 2,669 | 2,020 |

| Average set size | 4.3 genes/set | 5.4 genes/set | 5.4 genes/set | 5.4 genes/set |

| Tandem & intrachromosomal duplicates | 47% of sets | 33.9% of sets | 35.5% of sets | 38.6% of sets |

| Recent duplicates (Ks ≤1.0) | 24.4% | 1.3% | 0.97% | 0.05% |

Zebrafish exhibits exceptional characteristics including a larger number of duplicated genes, smaller duplicate set sizes, and a significant bias toward recent duplicates as measured by synonymous substitution rates (Ks) [16]. These patterns highlight the continuous and lineage-specific duplication activity in zebrafish, providing abundant material for subfunctionalization studies.

Implications for Disease Modeling and Therapeutic Development

Leveraging Natural Models of Human Variants

Naturally occurring livestock models of human functional variants provide valuable resources for studying gene function and disease mechanisms. Research demonstrates that orthologues of over 1.6 million human variants are already segregating in domesticated mammalian species, including several hundred previously linked to human traits and diseases [18]. Machine learning approaches can identify human variants more likely to have existing livestock orthologues, facilitating the discovery of natural models for functional studies [18].

The effects of functional variants are often conserved across species, acting on orthologous genes with the same direction of effect [18]. This conservation enables the use of zebrafish and other animal models to dissect the functional consequences of human disease-associated variants.

Zebrafish Models of Human Disease Genes

The high conservation between zebrafish and human genomes extends to disease-associated genes. Of 3,176 human genes bearing morbidity descriptions in OMIM, 2,601 (82%) have at least one zebrafish orthologue [3]. Similarly, 76% of human genes implicated in genome-wide association studies have detectable zebrafish orthologues [3].

Zebrafish subfunctionalized paralogs offer unique opportunities for modeling human diseases because:

- Gene dosage studies: Subfunctionalized paralogs provide insights into dosage-sensitive biological processes relevant to human diseases caused by copy number variations.

- Genetic compensation: Understanding how subfunctionalized paralogs compensate for each other informs therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating genetic compensation mechanisms.

- Tissue-specific targeting: The partitioned expression patterns of subfunctionalized paralogs can reveal tissue-specific regulatory mechanisms applicable to targeted therapies.

Subfunctionalization of duplicated genes represents a crucial evolutionary mechanism that shapes genome architecture and functional diversification. Zebrafish, with their additional teleost-specific genome duplication and high conservation with human genes, provide an ideal model system for studying subfunctionalization processes and their implications for human disease.

Future research directions should include:

- Systematic characterization of both paralogs in duplicated gene pairs, moving beyond the current focus on single paralogs.

- Integration of multi-omics data to comprehensively map expression patterns, protein interactions, and regulatory networks of subfunctionalized paralogs.

- Development of advanced genetic tools for precise manipulation and tracking of paralog function in zebrafish and other model organisms.

- Cross-species comparative analyses to identify conserved subfunctionalization patterns relevant to human biology and disease.

Leveraging the natural experiment of gene duplication and subfunctionalization provides powerful insights into gene function, regulation, and evolution, with significant implications for understanding human disease mechanisms and developing novel therapeutic approaches.

Evolutionary conservation, the phenomenon where genetic elements and developmental pathways remain unchanged across diverse species over millions of years, provides a critical foundation for biomedical research. The principle that crucial biological functions are maintained through evolution enables researchers to utilize model organisms to understand human biology and disease mechanisms. Among these models, the zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a particularly valuable system, with approximately 70% of human genes having at least one obvious zebrafish ortholog [7] [6]. This genetic similarity extends even further for disease-associated genes, with 84% of human disease genes having zebrafish counterparts [6]. Such remarkable conservation enables the creation of accurate zebrafish models for studying human genetic diseases, drug discovery, and therapeutic development, positioning this organism as a cornerstone of modern biomedical research bridging basic science and clinical applications.

Quantitative Analysis of Genetic Conservation Between Zebrafish and Humans

The utility of zebrafish for modeling human disease rests upon measurable genetic conservation across genomes, organs, and systems. The tables below provide a comprehensive quantitative overview of these conserved elements.

Table 1: Genome-Wide Conservation Metrics Between Zebrafish and Humans

| Conservation Parameter | Value | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Protein-Coding Gene Conservation | ~70% of human genes have a zebrafish ortholog [6] | Enables functional studies of majority of human genes |

| Disease Gene Conservation | 84% of human disease genes have zebrafish counterparts [6] | Facilitates modeling of genetic disorders |

| Total Protein-Coding Genes | ~26,000 in zebrafish [6] | Comparable genetic complexity to humans |

| Genome Sequencing Quality | Exceptionally high standard (comparable to human/mouse) [6] | Supports detailed genetic analysis and manipulation |

Table 2: Conservation of Key Organ Systems and Experimental Advantages

| Organ System | Level of Conservation | Key Experimental Advantages in Zebrafish |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | High structural and functional similarity [7] | External development; optical transparency for live imaging |

| Nervous System | Conserved neural patterning and brain regions [8] | Amenable to whole-brain imaging and neural circuit mapping |

| Hematopoietic System | Conserved blood lineages and disorders [7] | High fecundity enables large-scale genetic screens |

| Musculoskeletal | Conserved developmental pathways [8] | Fin regeneration models for studying tissue repair |

Molecular Mechanisms of Developmental Conservation

Conserved Gene Regulatory Networks

Deep conservation of developmental processes stems from preserved gene regulatory networks (GRNs) that control tissue patterning and organ formation. Research has revealed that although sequence conservation of cis-regulatory elements (CREs) decreases with evolutionary distance, functional conservation remains remarkably high [19]. A 2025 study demonstrated that when using synteny-based algorithms rather than sequence alignment alone, the identification of conserved regulatory elements between mouse and chicken increased dramatically—more than fivefold for enhancers (from 7.4% to 42%) [19]. This suggests that positional conservation of regulatory elements, rather than sequence similarity, may be the primary mechanism preserving developmental programs across vast evolutionary distances.

Conserved Signaling Pathways in Development

Several key signaling pathways demonstrate striking conservation between zebrafish and humans, enabling zebrafish to model complex human developmental processes and diseases:

Wnt Signaling Pathway: Essential for anterior-posterior patterning and brain development. Zebrafish headless mutants (lacking T-cell factor 3) demonstrate conserved roles in forebrain formation, mirroring Wnt functions in human neural development [8].

Notch Signaling Pathway: Critical for cell fate decisions. Activated NOTCH1 mutations in zebrafish model T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), replicating the human disease with high fidelity [7].

MAP Kinase Pathway: Central to melanoma development. Zebrafish expressing human BRAFV600E mutations under the mitfa promoter develop nevi and, in combination with p53 loss, invasive melanoma [7].

The following diagram illustrates the remarkable conservation of gene regulatory networks across evolutionary distance, showing how synteny-based mapping reveals functional conservation even with sequence divergence:

Diagram Title: Synteny-Based Mapping Reveals Conserved Regulatory Elements

Experimentation and Methodology: Utilizing Zebrafish for Disease Modeling

Experimental Protocols for Modeling Human Disease in Zebrafish

Protocol 1: Forward Genetic Screening for Disease Gene Discovery

Forward genetic approaches in zebrafish have successfully identified numerous genes essential for human development and disease:

Mutagenesis: Employ N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) to introduce random point mutations throughout the zebrafish genome [7] [8].

Phenotypic Screening: Systematically screen F2 or F3 progeny for developmental abnormalities mimicking human diseases. Historical screens identified mutants such as sauternes (congenital sideroblastic anemia) and weissherbst (hemochromatosis) [7].

Positional Cloning: Use genetic mapping techniques to identify chromosomal locations of mutated genes. This approach first demonstrated in 1998 that zebrafish alas2 mutations cause hematological disorders analogous to human congenital sideroblastic anemia [7].

Candidate Gene Analysis: Compare mapped regions with human disease loci to identify conserved disease genes.

Protocol 2: Reverse Genetic Approaches for Targeted Gene Manipulation

Reverse genetic methods allow direct investigation of genes with suspected roles in human disease:

Morpholino-Mediated Knockdown: Inject antisense morpholino oligonucleotides into 1-4 cell stage embryos to transiently inhibit translation or affect splicing of target genes. This approach successfully modeled Diamond Blackfan Anemia by targeting ribosomal protein RSP19 [7].

CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing: Utilize CRISPR/Cas9 to create stable mutant lines. The efficiency of this system has transformed zebrafish into a powerful reverse genetic system [8].

Target-Selected Mutagenesis (TILLING): Combine ENU mutagenesis with PCR-based screening to identify mutations in specific genes of interest [7].

Transgenesis: Generate stable transgenic lines using transposon-mediated systems (Sleeping Beauty, Tol2) with 50-80% germline transmission efficiency. Inducible systems (Cre-lox, GAL4/UAS) enable temporal and spatial control of gene expression [7] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Zebrafish Disease Modeling

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Morpholino Oligonucleotides | Transient gene knockdown by inhibiting translation or splicing | Modeling Diamond Blackfan Anemia via RPS19 knockdown [7] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Precise genome editing for creating stable mutant lines | Generating patient-specific mutation models for precision medicine [8] |

| Tol2 Transposon System | High-efficiency germline transgenesis | Creating tissue-specific fluorescent reporter lines [8] |

| Sleeping Beauty Transposon | Insertional mutagenesis for cancer gene discovery | Identifying novel conserved cancer genes [7] |

| PD1-PDL1-IN 1 | (2S,3R)-2-[[(1S)-3-amino-3-oxo-1-(3-piperazin-1-yl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)propyl]carbamoylamino]-3-hydroxybutanoic acid | High-purity (2S,3R)-2-[[(1S)-3-amino-3-oxo-1-(3-piperazin-1-yl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl)propyl]carbamoylamino]-3-hydroxybutanoic acid for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

| Plantanone B | Plantanone B, MF:C33H40O20, MW:756.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Analysis of Conserved Organ Systems and Their Disease Relevance

Nervous System Development and Disorders

The zebrafish nervous system shares remarkable conservation with humans, making it particularly valuable for modeling neurological and psychiatric disorders:

Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Zebrafish models of Potocki-Shaffer syndrome (via phf21a knockdown) exhibit cranial facial abnormalities and increased neuronal apoptosis, mirroring human patient phenotypes [8]. Similarly, models of Miles-Carpenter syndrome (via zc4h2 knockout) show motor hyperactivity and specific reductions in V2 GABAergic interneurons, elucidating disease mechanisms [8].

Mental Health Disorders: The identification of the samdori gene family in zebrafish, particularly sam2 expressed in habenular nuclei, has provided insights into autism spectrum disorder and anxiety-related conditions [8]. Zebrafish models of Armfield X-linked intellectual disability syndrome (via fam50a knockout) revealed connections between mRNA splicing defects and neurodevelopmental disorders [8].

Brain Regeneration: Unique to zebrafish, the discovery that the cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 (cysltr1)-leukotriene C4 pathway mediates neurogenesis after traumatic brain injury reveals mechanisms that could potentially be harnessed for human therapies [8].

Cardiovascular System Development and Disease

Zebrafish cardiovascular development and function are highly conserved with humans:

Heart Development: Conservation of cardiac patterning genes allows modeling of congenital heart diseases. The transparency of embryos enables real-time observation of heart formation and function [6].

Cardiotoxicity Screening: Zebrafish embryos serve as a high-throughput platform for assessing drug effects on heart function, with findings often predictive of human responses [6].

Hematological Disorders and Malignancies

Zebrafish have been particularly instrumental in modeling blood disorders and cancers:

Anemia Models: The sauternes mutant (ALAS2 deficiency) models congenital sideroblastic anemia, while the weissherbst mutant identified ferroportin 1 as a novel iron transporter later confirmed in human hemochromatosis [7].

Leukemia Models: Transgenic zebrafish expressing mouse c-Myc under the rag2 promoter develop T-cell leukemia that spreads to multiple organs, closely mimicking human disease progression and drug responses [7].

The following workflow illustrates how zebrafish experiments bridge basic research and clinical applications:

Diagram Title: Zebrafish Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery Workflow

Future Directions and Research Applications

The conserved biology between zebrafish and humans continues to enable innovative research approaches with significant translational potential:

Personalized Medicine: Creating zebrafish models with patient-specific mutations allows testing of individualized treatment strategies. This approach is particularly valuable for rare genetic disorders where traditional clinical trials are not feasible [6].

Regenerative Medicine: Zebrafish possess remarkable abilities to regenerate heart muscle, spinal cord, and other tissues. Studying these conserved but enhanced regenerative pathways may reveal therapeutic targets for human regenerative therapies [6].

High-Throughput Drug Discovery: The small size, external development, and transparency of zebrafish embryos facilitate large-scale drug screening. The conservation of drug metabolism pathways increases the predictive value of these screens for human applications [8] [6].

Toxicology and Environmental Health: Conservation of metabolic pathways makes zebrafish ideal for assessing toxicological responses relevant to human health, with applications in pharmaceutical safety testing and environmental risk assessment [8].

The continued integration of zebrafish research with emerging technologies like single-cell genomics, artificial intelligence, and advanced imaging promises to further leverage evolutionary conservation to understand and treat human diseases. As our knowledge of gene regulatory networks deepens, and as technologies for genetic manipulation become increasingly sophisticated, zebrafish will remain at the forefront of efforts to translate basic biological discoveries into clinical applications.

From Gene to Phenotype: Engineered Zebrafish Models for Deciphering Disease Mechanisms

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) have emerged as a pivotal model organism for precision genome editing and functional genomics, providing an essential bridge between in vitro studies and mammalian models. The genetic homology between zebrafish and humans is remarkably high; approximately 70% of human genes have at least one zebrafish ortholog, a figure that rises to 84% for genes known to be associated with human diseases [20] [4] [6]. This conservation, combined with their external fertilization, rapid embryonic development, and optical transparency, makes zebrafish an exceptionally powerful system for modeling human genetic disorders and validating pathogenic variants [20] [4].

The advent of precision genome-editing technologies—including CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, and prime editing—has revolutionized functional genomics, enabling researchers to create specific knockout and knock-in models with high efficiency. These tools allow for the direct functional testing of human disease-associated genes and variants in a vertebrate system, accelerating the path from genetic discovery to therapeutic intervention [21] [22]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to the application of these technologies within the context of zebrafish-based disease modeling.

Genome Editing Technologies: Mechanisms and Applications

Precision genome editing employs engineered nucleases and enzymes to make targeted modifications to the genome. The key platforms used in zebrafish research are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Genome Editing Technologies in Zebrafish Research

| Technology | Mechanism of Action | Primary Application in Zebrafish | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 | RNA-guided nuclease creates Double-Strand Breaks (DSBs); repaired via NHEJ (knockout) or HDR (knock-in) [23]. | High-throughput knockout screens [22], disease model generation [21] [24]. | High efficiency, easy gRNA design, scalable for high-throughput studies [23] [22]. | Off-target effects, reliance on cellular repair pathways, low efficiency of HDR [25]. |

| TALENs | Engineered protein pairs create a DSB at a specific DNA sequence [23]. | Gene knockout, particularly for loci with challenging CRISPR target sites. | High specificity, flexible targeting. | Complex protein design and cloning, lower throughput [23] [24]. |

| Base Editing | Fusion of catalytically impaired Cas nuclease (nCas9) with a deaminase enzyme directly converts one base pair to another without inducing a DSB [25]. | Introducing precise point mutations for disease modeling (e.g., oncogenic mutations) [25]. | High precision, avoids DSB-related indels, efficient single-nucleotide changes. | Limited by PAM availability, potential for bystander edits within the activity window [25]. |

| Prime Editing | Uses a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) and a fusion protein (nCas9-reverse transcriptase) to directly write new genetic information into a target site without DSBs [26] [27]. | Precision knock-in of point mutations, small insertions, and deletions; installation of suppressor tRNAs for disease-agnostic therapy [26] [27]. | Unprecedented versatility, can make all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, minimal off-target effects. | Complex pegRNA design, variable efficiency depending on the target locus [26]. |

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms of the primary genome editing tools.

Experimental Workflows for Model Generation

High-Throughput Mutagenesis Pipeline

A robust, cloning-free pipeline for generating zebrafish mutants at scale is highly effective for functional genomics. The following workflow outlines the key steps from target selection to stable line establishment, which can be completed within approximately 6 months [23].

Table 2: Timeline and Key Steps for High-Throughput Mutagenesis

| Stage | Duration | Key Activities | Output/Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Target Selection & sgRNA Synthesis | 3-4 days | Select 2 target sites per gene to ensure success (~85% of active targets generate germline mutations). Use a cloning-free, oligo-based method for sgRNA synthesis [23]. | In vitro transcribed sgRNA. |

| 2. Microinjection & Somatic Validation | 2-3 days | Co-inject 25-50 pg sgRNA and 150-300 pg Cas9 mRNA into 1-cell stage embryos. Use CRISPR Somatic Tissue Activity Test (CRISPR-STAT) with fluorescent PCR to assess editing efficiency in injected embryos [23]. | Confirmation of somatic mutagenesis efficiency. |

| 3. Founder (F0) Screening | ~3 months | Raise injected embryos to adulthood. Outcross F0 fish and screen 7-8 F1 embryos per cross using the same fluorescent PCR method to identify germline-transmitting founders [23]. | Identification of F0 fish carrying heritable mutations. |

| 4. Establishing Stable Lines | ~3 months | Raise F1 progeny from positive founders. Confirm the exact lesion in F1 fish by Sanger or next-generation sequencing. Inbreed heterozygous F1 adults to generate F2 populations for phenotyping [23]. | Stable, genotyped mutant lines for phenotypic analysis. |

Workflow Visualization

The key experimental steps for creating and validating zebrafish models are depicted in the following workflow.

Advanced Applications in Disease Modeling

From Gene Editing to Disease Models

Precision editing tools have been successfully deployed to model a wide spectrum of human diseases in zebrafish.

- Neurological Disorders: CRISPR-mediated knockout of the SHANK3 ortholog produced zebrafish displaying autism-like behaviors, elucidating the role of this gene in neural circuit formation [21].

- Cancer: Base editors like AncBE4max have been used to introduce precise oncogenic mutations in tumor suppressor genes such as tp53, creating versatile models for studying tumorigenesis [25].

- Cardiovascular Diseases: Knock-in models harboring human mutations associated with Cantú syndrome exhibited enlarged ventricles and enhanced cardiac output, demonstrating the utility of zebrafish for validating human gene variants in a whole-organism context [21].

- Rare Genetic Diseases: Prime editing has been used to install suppressor tRNAs that enable readthrough of premature termination codons (PTCs), a strategy with the potential to treat multiple rare diseases caused by nonsense mutations, such as Batten disease and Tay-Sachs disease, in a disease-agnostic manner [26] [27].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Zebrafish Genome Editing

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Protein/Nuclease | Creates the double-strand break at the target DNA site. | Can be used as mRNA or pre-complexed as a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex for microinjection [25] [23]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Directs the Cas nuclease to the specific genomic locus. | Single-guide RNA (sgRNA) can be synthesized in vitro in a cloning-free manner for high-throughput work [23]. |

| Base Editor Plasmids | Template for in vitro transcription of mRNA encoding the base editor fusion protein. | e.g., AncBE4max, a cytosine base editor optimized for zebrafish, offers higher efficiency and a broader editing window [25]. |

| Prime Editing System | For precise edits without double-strand breaks. | Includes the prime editor (PE) protein and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that specifies the target and encodes the desired edit [26] [27]. |

| Bioinformatics Tools | For target selection, gRNA design, and off-target prediction. | e.g., ACEofBASEs, an online platform for sgRNA design and off-target prediction for base editing in zebrafish [25]. UCSC genome browser tracks can identify all possible SpCas9 target sites [23]. |

Precision genome editing technologies have fundamentally transformed the utility of zebrafish in biomedical research. The high degree of genetic conservation with humans, combined with the scalability, efficiency, and precision of CRISPR-Cas9, base editing, and prime editing, positions this model organism as an indispensable platform for functional genomics and disease modeling. These tools enable the direct interrogation of human disease variants in an in vivo, vertebrate context, accelerating the validation of candidate genes and the discovery of underlying disease mechanisms. As editing technologies continue to evolve towards greater precision and versatility, zebrafish will undoubtedly play an increasingly critical role in bridging the gap between genetic discovery and the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a powerful vertebrate model organism for biomedical research, bridging the gap between invertebrate models and mammalian systems. With approximately 70-82% of human disease genes having functional orthologs in zebrafish, this model offers unparalleled advantages for studying the genetic basis of human disorders [7] [4] [8]. The Zebrafish Information Network (ZFIN) and other community resources provide curated data on genetic sequences, mutations, and experimental protocols, supporting rigorous disease modeling research [28]. This technical guide examines the application of zebrafish models across central nervous system (CNS), cardiovascular, cancer, and metabolic diseases, with emphasis on experimental methodologies and their relevance to human conditions rooted in orthologous gene relationships.

Genetic and Physiological Foundations of Zebrafish Disease Modeling

Genetic Conservation and Orthology

Zebrafish share significant genetic similarity with humans, with ~70% of human genes having at least one obvious zebrafish ortholog [8]. This conservation extends to disease-associated genes, with 82% of known human disease genes having zebrafish counterparts [28]. A genome duplication event approximately 340 million years ago resulted in many zebrafish genes having paralogs, where 47% of human orthologs have a single counterpart while the remainder have multiple orthologs that may have undergone subfunctionalization [28]. This genetic architecture presents both challenges and opportunities for modeling human diseases, particularly for studying gene dosage effects and tissue-specific functions.

Experimental Advantages for Disease Modeling

Zebrafish offer multiple advantages for disease modeling and drug discovery:

- High fecundity: Each mating pair produces 70-300 embryos per clutch, enabling high-throughput studies [7] [28]

- Rapid development: Major organs form within 24 hours post-fertilization (hpf), with embryogenesis completed by 2-3 days post-fertilization (dpf) [7] [28]

- Optical clarity: Transparent embryos and availability of pigment-deficient mutants (e.g., casper) enable non-invasive live imaging of internal processes [28]

- Genetic diversity: Outbred strains better model human genetic heterogeneity compared to isogenic mouse models [28]

- Drug administration: Water-soluble compounds can be administered directly to tank water for non-invasive screening [4]

Modeling Central Nervous System Disorders

Experimental Approaches for CNS Research

Zebrafish CNS modeling leverages several specialized methodologies. Tissue-clearing techniques enable visualization of neural networks throughout the entire adult brain, while transgenic lines with neuronal markers (e.g., HuC, an early neuronal marker 89% identical to human HuC protein) allow tracking of neurogenesis from the neural plate stage [8]. Behavioral analyses assess shoaling, schooling, and emotional responses relevant to mental disorders [8].

CNS Disease Models and Applications

Table 1: Zebrafish Models of CNS Disorders

| Disorder | Genetic Target | Zebrafish Phenotype | Orthologous Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Armfield XLID Syndrome | FAM50A knockout | Defective mRNA processing, intellectual disability models | Human FAM50A missense variants functionally validated in zebrafish [8] |

| Miles-Carpenter Syndrome | ZC4H2 knockout | Motor hyperactivity, abnormal swimming, reduced V2 GABAergic interneurons | Human ZC4H2 point mutations cause syndromic X-linked intellectual disability [8] |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | sam2 knockout | Defects in emotional responses, fear, and anxiety | Novel chemokine-like gene family involved in mental disorders [8] |

| Potocki-Shaffer Syndrome | phf21a knockdown | Head/facial/jaw abnormalities, increased neuronal apoptosis | Models human interstitial deletion of chromosome 11p11.2 [8] |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | cysltr1 expression | Enhanced proliferation and neurogenesis post-injury | Cysltr1-LTC4 pathway conserved in human inflammatory response [8] |

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disease Modeling

Cardiovascular Disease Mechanisms

Zebrafish cardiovascular models have revealed conserved disease pathways. The sauternes (sau) mutant, the first zebrafish disease model derived from positional cloning, identified mutations in the erythroid synthase δ-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS-2) gene causing congenital sideroblastic anemia [7]. The weissherbst (weh) mutant led to the discovery of ferroportin 1 as a novel iron transporter, with the human ortholog subsequently found mutated in hemochromatosis patients [7].

Cardiometabolic syndrome modeling demonstrates shared pathways between cardiovascular disease and cancer, including inflammatory pathways, oxidative stress, and metabolic reprogramming [29]. Mutations in epigenetic regulators DNMT3A and TET2 link clonal hematopoiesis to both cardiovascular pathology and cancer risk through pro-inflammatory phenotypes [29].

Metabolic Disease Applications

Zebrafish metabolic studies capitalize on the model's similar metabolic characteristics to humans and responsiveness to drugs approved for human metabolic syndromes [8]. Quantitative imaging technologies like Mueller matrix optical coherence tomography (OCT) enable non-invasive monitoring of organ development and metabolic effects [30].

Diagram 1: Cardio-Metabolic Disease Pathways. Shared mechanisms connecting metabolic syndrome components to cardiovascular disease and cancer through inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways, influenced by key orthologous genes.

Cancer Modeling in Zebrafish

Hematological Malignancies

Zebrafish cancer models recapitulate key features of human malignancies. Transgenic T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) models using rag2-driven mouse c-Myc fusions develop thymic tumors that metastasize to other organs within two months [7]. NOTCH1-activated models (mutated in >50% of human T-ALL cases) demonstrate cooperation with bcl2-mediated anti-apoptotic pathways when crossed with bcl2-overexpressing lines, producing more aggressive tumors resistant to radiation [7]. Comparative analyses of copy number aberrations (CNAs) show significant overlap between zebrafish and human T-ALL, supporting the relevance of these models [7].

Solid Tumor Models

Table 2: Zebrafish Solid Tumor Models

| Cancer Type | Genetic Manipulation | Onset & Features | Human Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | mitfa-promoter driven BRAFV600E with p53M214K | 4 months onset, invasive melanoma | 50-60% human melanomas have BRAFV600E mutations [7] |

| Melanoma | BRAFV600E alone | Nevus formation similar to human nevi | Models precursor lesions to malignant melanoma [7] |

| Various Solid Tumors | Sleeping Beauty transposon mutagenesis | Identification of conserved and novel cancer genes | Forward genetic approach for cancer gene discovery [7] |

Technical Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Genetic Manipulation Techniques

Gene Knockdown and Editing Methods

- Morpholinos (MOs): Antisense oligonucleotides injected at 1-4 cell stage that inhibit translation or affect splicing; effective for first 2-3 dpf but may increase p53 signaling, particularly in neural tissue [7] [28]

- CRISPR-Cas9: Enables efficient reverse genetic approach for generating knockout animals; CBE4max-SpRY variant allows precise point mutations with high efficiency across multiple genes simultaneously [4] [8]

- TALENs: Transcription activator-like effector nucleases that induce double-strand breaks; easier to design and assemble than ZFNs with potentially fewer off-target effects [7]

- Target-selected mutagenesis (TILLING): Combines ethylnitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis with PCR-based screening to identify mutations in specific genes [7]

Transgenesis and Line Establishment

Germ line transgenesis using Tol2-based transposon systems achieves 50-80% efficiency [7]. Inducible systems like Cre-lox with modified estrogen receptor domains allow temporal control of gene activation via tamoxifen induction [7]. The Zebrafish Mutation Project aims to create mutant alleles for all genes in the zebrafish genome, with 4,469 mutant alleles currently available through the Zebrafish International Resource Center (ZIRC) [7].

Imaging and Phenotypic Analysis

Advanced imaging technologies enable detailed characterization of disease phenotypes:

- Mueller matrix optical coherence tomography (OCT): Provides 3D images with 8.9 µm axial and 18.2 µm lateral resolution for non-invasive monitoring of organ development from 1-19 dpf [30]

- Deep learning segmentation: U-Net networks automatically segment and quantify body, eyes, spine, yolk sac, and swim bladder volumes during development [30]

- Fluorescent transgenic lines: Cell-type specific promoters drive fluorescent protein expression for live imaging of cellular dynamics in vivo [8]

Diagram 2: Genetic Manipulation Workflow. Comprehensive approaches for zebrafish genetic manipulation, from forward/reverse genetics to transgenic methodologies and their applications in disease research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Zebrafish Disease Modeling

| Reagent/Resource | Category | Function & Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morpholinos (MOs) | Gene Knockdown | Transient inhibition of translation or splicing; rapid phenotype screening 1-5 dpf | Potential p53 activation; efficacy decreases after 3 dpf [7] [28] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Gene Editing | Stable knockout mutations; multiplexed gene targeting | CBE4max-SpRY variant enables precise point mutations across multiple genes [4] [8] |

| Tol2 Transposon System | Transgenesis | Germline transgenesis with 50-80% efficiency; transgene integration | Enables tissue-specific and inducible expression systems [7] [8] |

| Cre-lox with ER(T2) | Inducible Systems | Temporal control of gene recombination; tamoxifen-inducible | Enables stage-specific genetic manipulation [7] |

| Casper Mutant Line | Imaging | Pigment-deficient adults for improved optical clarity | Enables adult internal organ imaging [28] |

| PTU (Phenyl-thio-urea) | Chemical Treatment | Prevents pigment formation until ~7 dpf | Maintains embryonic transparency for imaging [28] |

| ZINC Database | Biological Resource | Zebrafish International Resource Center; mutant and transgenic lines | Repository for ~4,469 mutant alleles [7] |

| ZFIN Database | Informational Resource | Curated genetic sequences, mutations, protocols | Primary community database for zebrafish research [28] |

Zebrafish models continue to expand our understanding of human disease mechanisms through the study of orthologous genes. The genetic heterogeneity of zebrafish lines more accurately reflects human population diversity compared to isogenic mouse models, potentially enhancing translational relevance [28]. Emerging technologies in precision genome editing, quantitative imaging, and single-cell analyses will further strengthen the zebrafish system for modeling complex disorders. As personalized medicine advances, zebrafish disease models provide a versatile platform for functional validation of human genetic variants and high-throughput therapeutic compound screening, solidifying their role in the continuum from basic research to clinical applications.

The pursuit of novel therapeutic agents increasingly relies on phenotypic screening, a biology-first approach that identifies compounds based on their observable effects on whole biological systems rather than on predefined molecular targets. Within this paradigm, the zebrafish (Danio rerio) has emerged as a powerful vertebrate model that uniquely combines the genetic tractability of in vitro systems with the physiological complexity of in vivo models. Its value is rooted in a fundamental genetic similarity to humans; approximately 70% of human genes have at least one zebrafish ortholog, and this figure rises to 84% for genes known to be associated with human disease [20] [21] [31]. This high degree of conservation means that disease pathways and drug responses are often clinically relevant when modeled in zebrafish [31].

The core advantages of the zebrafish—including its optical transparency during early development, rapid ex utero maturation, and small size—make it exceptionally suited for high-throughput and high-content phenotypic drug screening [20] [32]. These features enable researchers to conduct large-scale, in vivo drug screens that would be prohibitively expensive or ethically challenging in mammalian models, bridging a critical gap between cell-based assays and clinical trials [20] [31]. This technical guide explores how these inherent biological traits are leveraged to accelerate the drug discovery pipeline.

Orthology and Genetic Tractability: The Foundation for Disease Modeling

The utility of the zebrafish as a model for human disease is fundamentally grounded in its genetic homology with humans. The sequencing of the zebrafish genome revealed a level of conservation that allows for the direct modeling of human disease mechanisms [21]. This orthology enables researchers to create precise genetic models of human diseases.

Key Genetic and Practical Attributes

The following table summarizes the critical characteristics that make the zebrafish a genetically and practically viable model for human disease research.

Table 1: Zebrafish as a Model Organism for Human Disease Research

| Feature | Description | Implication for Disease Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Similarity | 70% of human genes have a zebrafish ortholog; rises to 84% for disease-linked genes [20] [21] [31]. | Enables modeling of a wide spectrum of human genetic diseases. |

| Disease Protein Conservation | Over 80% of human disease proteins are conserved in zebrafish [31]. | Drug targets are often conserved, ensuring pharmacologically relevant responses. |

| Vertebrate Physiology | Possesses complex organs like heart, liver, kidney, and brain [20] [31]. | Allows study of systemic drug effects and complex diseases in a whole-animal context. |

| Fecundity | A single breeding pair can produce hundreds of embryos per week [31]. | Provides the large numbers of organisms required for high-throughput statistical power. |

Advanced Genome Engineering for Disease Modeling

The functional validation of disease-associated genes is achieved through advanced gene-editing technologies. CRISPR-Cas9 has become the method of choice for generating knockout and knock-in zebrafish models with high efficiency [21].

- CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Knockout: This approach disrupts gene function to model loss-of-function disorders. A common and highly efficient protocol involves the microinjection of an in vitro complex of guide RNA and Cas9 protein into one-cell stage embryos [21]. This method has been successfully used to model a range of diseases, including Fanconi Anemia and autism spectrum disorder, by creating loss-of-function mutants for specific genes [21].

- CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Knock-In: To model human diseases caused by specific point mutations, researchers use Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) to insert human disease-associated SNPs or other genetic variants into the zebrafish genome [21]. This technique has been used to create accurate models of conditions such as Cantú syndrome and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [21].

- Crispants for Rapid Screening: The use of "crispants"—F0 generation embryos injected with CRISPR-Cas9 components—allows for the immediate assessment of gene function without the need to raise the fish to adulthood and establish stable lines [33]. This method drastically shortens the timeline for target validation and initial drug screening, enabling functional assessment in a matter of days post-fertilization [33].

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Workflows for Zebrafish Disease Modeling. This diagram outlines the primary genetic engineering pathways for creating zebrafish models of human disease, highlighting the speed and versatility of the crispant approach for rapid screening.

Technical Advantages for High-Throughput Phenotypic Screening

The biological and physical characteristics of the zebrafish directly enable its use in scalable, high-content drug discovery platforms.

Optical Transparency and Real-Time Imaging

A defining advantage of the zebrafish model is the natural optical transparency of its embryos and larvae, which allows for non-invasive, real-time imaging of internal biological processes [20]. This transparency can be extended into adulthood using genetically engineered transparent strains, such as the Casper mutant [20]. This property is crucial for high-content imaging, as it enables: